User login

Do prophylactic antipyretics reduce vaccination-associated symptoms in children?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review of 13 RCTs (5077 patients) compared the effects of a prophylactic antipyretic (acetaminophen or ibuprofen, doses and schedules not described) with placebo in healthy children 6 years or younger undergoing routine childhood immunizations.1 Trials examined various schedules and combinations of vaccines. Researchers defined febrile reactions as a temperature of 38°C or higher and categorized pain as: none, mild (reaction to touch over vaccine site), moderate (protesting to limb movement), or severe (resisting limb movement).

Acetaminophen works better than ibuprofen for both fever and pain

Acetaminophen prophylaxis resulted in fewer febrile reactions in the first 24 to 48 hours after vaccine administration than placebo following both primary (odds ratio [OR] = 0.35; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26-0.48) and booster vaccinations (OR = 0.60; 95% CI, 0.39-0.93). Acetaminophen also reduced pain of all grades (primary vaccination: OR = 0.57; 95% CI, 0.47-0.7; booster vaccination: OR = 0.64; 95% CI, 0.48-0.84).

In contrast, ibuprofen prophylaxis had no effect on early febrile reactions for either primary or booster vaccinations. It reduced pain of all grades after primary vaccination (OR = 0.66; 95% CI, 0.49-0.88) but not after boosters (OR = 1.03; 95% CI, 0.59-1.81).

Reduced antibody response doesn’t affect seroprotective levels

Acetaminophen also generally reduced the antibody response compared with placebo (assessed using the geometric mean concentration [GMC], a statistical technique for comparing values that change logarithmically).1 GMC results are difficult to interpret clinically, however, and they differed by vaccine, antigen, and primary or booster vaccination status.

Nevertheless, patients mounted seroprotective antibody levels with or without acetaminophen prophylaxis, and the nasopharyngeal carriage rates of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae didn’t change. Researchers didn’t publish the antibody responses to ibuprofen, nor did they track actual infection rates.

How do antipyretics work with newer combination vaccines?

A subsequent trial evaluated the immune response in 908 children receiving newer combination vaccines (DTaP/HBV/IPV/Hib and PCV13) who were randomized to 5 groups: acetaminophen 15 mg/kg at vaccination and 6 to 8 hours later; acetaminophen 15 mg/kg starting 6 to 8 hours after vaccination with a second dose 6 to 8 hours later; ibuprofen 10 mg/kg/dose at vaccination with a second dose 6 to 8 hours later; ibuprofen 10 mg/kg starting 6 to 8 hours after vaccination with a second dose 6 to 8 hours later; and placebo.2

Patients received age-appropriate vaccination and their assigned antipyretic (or placebo) at 2, 3, 4 and 12 months of age. Researchers measured the immune response at 5 and 13 months of age.

Continue to: Overall, 5% to 10% of the prophylaxis group...

Overall, 5% to 10% of the prophylaxis group had fever on Day 1 or 2 after vaccination, compared with 10% to 20% of the placebo group (no P value given). Antipyretic use produced lower antibody GMC responses for antipertussis and antitetanus vaccines at 5 months but not at 13 months. Patients achieved the prespecified effective antibody levels at both 5 and 13 months, regardless of intervention.

Antipyretics don’t affect immune response with inactivated flu vaccine

A 2017 RCT investigated the effect of either prophylactic acetaminophen (15 mg/kg every 4 to 6 hours for 24 hours) or ibuprofen (10 mg/kg every 4 to 6 hours for 24 hours) on immune response in children receiving inactivated influenza vaccine.3 Researchers randomized 142 children into 3 treatment groups (acetaminophen, 59 children; ibuprofen, 24 children; placebo, 59 children). They defined seroconversion as a hemagglutinin inhibition assay titer of 1:40 postvaccination (if baseline titer was less than 1:10) or a 4-fold rise (if the baseline titer was ≥ 1:10).

All interventions resulted in similar seroconversion rates for all A or B influenza strains investigated. Vaccine protection-level responses ranged from 9% for B/Phuket to 100% for A/Switzerland. The trial didn’t report febrile reactions or infection rates.

RECOMMENDATIONS

In 2017, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) issued guidelines generally discouraging the use of antipyretics at the time of vaccination, but allowing their use later for local discomfort or fever that might arise after vaccination. The guidelines also noted that antipyretics at the time of vaccination didn’t reduce the risk of febrile seizures.4

Editor’s takeaway

Although ACIP doesn’t encourage giving antipyretics with vaccines, moderate-quality evidence suggests that prophylactic acetaminophen reduces fever and pain after immunizations by a reasonable amount without an apparent clinical downside.

1. Das RR, Panigrahi I, Naik SS. The effect of prophylactic antipyretic administration on post-vaccination adverse reactions and antibody response in children: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106629.

2. Wysocki J, Center, KJ, Brzostek J, et al. A randomized study of fever prophylaxis and the immunogenicity of routine pediatric vaccinations. Vaccine. 2017;35:1926-1935.

3. Walter EB, Hornok CP, Grohskopf L, et al. The effect of antipyretics on immune response and fever following receipt of inactivated influenza vaccine in young children. Vaccine. 2017;35:6664–6671.

4. Kroger AT, Duchin J, Vázquez M. General Best Practice Guidelines for Immunization. Best Practices Guidance of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review of 13 RCTs (5077 patients) compared the effects of a prophylactic antipyretic (acetaminophen or ibuprofen, doses and schedules not described) with placebo in healthy children 6 years or younger undergoing routine childhood immunizations.1 Trials examined various schedules and combinations of vaccines. Researchers defined febrile reactions as a temperature of 38°C or higher and categorized pain as: none, mild (reaction to touch over vaccine site), moderate (protesting to limb movement), or severe (resisting limb movement).

Acetaminophen works better than ibuprofen for both fever and pain

Acetaminophen prophylaxis resulted in fewer febrile reactions in the first 24 to 48 hours after vaccine administration than placebo following both primary (odds ratio [OR] = 0.35; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26-0.48) and booster vaccinations (OR = 0.60; 95% CI, 0.39-0.93). Acetaminophen also reduced pain of all grades (primary vaccination: OR = 0.57; 95% CI, 0.47-0.7; booster vaccination: OR = 0.64; 95% CI, 0.48-0.84).

In contrast, ibuprofen prophylaxis had no effect on early febrile reactions for either primary or booster vaccinations. It reduced pain of all grades after primary vaccination (OR = 0.66; 95% CI, 0.49-0.88) but not after boosters (OR = 1.03; 95% CI, 0.59-1.81).

Reduced antibody response doesn’t affect seroprotective levels

Acetaminophen also generally reduced the antibody response compared with placebo (assessed using the geometric mean concentration [GMC], a statistical technique for comparing values that change logarithmically).1 GMC results are difficult to interpret clinically, however, and they differed by vaccine, antigen, and primary or booster vaccination status.

Nevertheless, patients mounted seroprotective antibody levels with or without acetaminophen prophylaxis, and the nasopharyngeal carriage rates of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae didn’t change. Researchers didn’t publish the antibody responses to ibuprofen, nor did they track actual infection rates.

How do antipyretics work with newer combination vaccines?

A subsequent trial evaluated the immune response in 908 children receiving newer combination vaccines (DTaP/HBV/IPV/Hib and PCV13) who were randomized to 5 groups: acetaminophen 15 mg/kg at vaccination and 6 to 8 hours later; acetaminophen 15 mg/kg starting 6 to 8 hours after vaccination with a second dose 6 to 8 hours later; ibuprofen 10 mg/kg/dose at vaccination with a second dose 6 to 8 hours later; ibuprofen 10 mg/kg starting 6 to 8 hours after vaccination with a second dose 6 to 8 hours later; and placebo.2

Patients received age-appropriate vaccination and their assigned antipyretic (or placebo) at 2, 3, 4 and 12 months of age. Researchers measured the immune response at 5 and 13 months of age.

Continue to: Overall, 5% to 10% of the prophylaxis group...

Overall, 5% to 10% of the prophylaxis group had fever on Day 1 or 2 after vaccination, compared with 10% to 20% of the placebo group (no P value given). Antipyretic use produced lower antibody GMC responses for antipertussis and antitetanus vaccines at 5 months but not at 13 months. Patients achieved the prespecified effective antibody levels at both 5 and 13 months, regardless of intervention.

Antipyretics don’t affect immune response with inactivated flu vaccine

A 2017 RCT investigated the effect of either prophylactic acetaminophen (15 mg/kg every 4 to 6 hours for 24 hours) or ibuprofen (10 mg/kg every 4 to 6 hours for 24 hours) on immune response in children receiving inactivated influenza vaccine.3 Researchers randomized 142 children into 3 treatment groups (acetaminophen, 59 children; ibuprofen, 24 children; placebo, 59 children). They defined seroconversion as a hemagglutinin inhibition assay titer of 1:40 postvaccination (if baseline titer was less than 1:10) or a 4-fold rise (if the baseline titer was ≥ 1:10).

All interventions resulted in similar seroconversion rates for all A or B influenza strains investigated. Vaccine protection-level responses ranged from 9% for B/Phuket to 100% for A/Switzerland. The trial didn’t report febrile reactions or infection rates.

RECOMMENDATIONS

In 2017, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) issued guidelines generally discouraging the use of antipyretics at the time of vaccination, but allowing their use later for local discomfort or fever that might arise after vaccination. The guidelines also noted that antipyretics at the time of vaccination didn’t reduce the risk of febrile seizures.4

Editor’s takeaway

Although ACIP doesn’t encourage giving antipyretics with vaccines, moderate-quality evidence suggests that prophylactic acetaminophen reduces fever and pain after immunizations by a reasonable amount without an apparent clinical downside.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review of 13 RCTs (5077 patients) compared the effects of a prophylactic antipyretic (acetaminophen or ibuprofen, doses and schedules not described) with placebo in healthy children 6 years or younger undergoing routine childhood immunizations.1 Trials examined various schedules and combinations of vaccines. Researchers defined febrile reactions as a temperature of 38°C or higher and categorized pain as: none, mild (reaction to touch over vaccine site), moderate (protesting to limb movement), or severe (resisting limb movement).

Acetaminophen works better than ibuprofen for both fever and pain

Acetaminophen prophylaxis resulted in fewer febrile reactions in the first 24 to 48 hours after vaccine administration than placebo following both primary (odds ratio [OR] = 0.35; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.26-0.48) and booster vaccinations (OR = 0.60; 95% CI, 0.39-0.93). Acetaminophen also reduced pain of all grades (primary vaccination: OR = 0.57; 95% CI, 0.47-0.7; booster vaccination: OR = 0.64; 95% CI, 0.48-0.84).

In contrast, ibuprofen prophylaxis had no effect on early febrile reactions for either primary or booster vaccinations. It reduced pain of all grades after primary vaccination (OR = 0.66; 95% CI, 0.49-0.88) but not after boosters (OR = 1.03; 95% CI, 0.59-1.81).

Reduced antibody response doesn’t affect seroprotective levels

Acetaminophen also generally reduced the antibody response compared with placebo (assessed using the geometric mean concentration [GMC], a statistical technique for comparing values that change logarithmically).1 GMC results are difficult to interpret clinically, however, and they differed by vaccine, antigen, and primary or booster vaccination status.

Nevertheless, patients mounted seroprotective antibody levels with or without acetaminophen prophylaxis, and the nasopharyngeal carriage rates of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae didn’t change. Researchers didn’t publish the antibody responses to ibuprofen, nor did they track actual infection rates.

How do antipyretics work with newer combination vaccines?

A subsequent trial evaluated the immune response in 908 children receiving newer combination vaccines (DTaP/HBV/IPV/Hib and PCV13) who were randomized to 5 groups: acetaminophen 15 mg/kg at vaccination and 6 to 8 hours later; acetaminophen 15 mg/kg starting 6 to 8 hours after vaccination with a second dose 6 to 8 hours later; ibuprofen 10 mg/kg/dose at vaccination with a second dose 6 to 8 hours later; ibuprofen 10 mg/kg starting 6 to 8 hours after vaccination with a second dose 6 to 8 hours later; and placebo.2

Patients received age-appropriate vaccination and their assigned antipyretic (or placebo) at 2, 3, 4 and 12 months of age. Researchers measured the immune response at 5 and 13 months of age.

Continue to: Overall, 5% to 10% of the prophylaxis group...

Overall, 5% to 10% of the prophylaxis group had fever on Day 1 or 2 after vaccination, compared with 10% to 20% of the placebo group (no P value given). Antipyretic use produced lower antibody GMC responses for antipertussis and antitetanus vaccines at 5 months but not at 13 months. Patients achieved the prespecified effective antibody levels at both 5 and 13 months, regardless of intervention.

Antipyretics don’t affect immune response with inactivated flu vaccine

A 2017 RCT investigated the effect of either prophylactic acetaminophen (15 mg/kg every 4 to 6 hours for 24 hours) or ibuprofen (10 mg/kg every 4 to 6 hours for 24 hours) on immune response in children receiving inactivated influenza vaccine.3 Researchers randomized 142 children into 3 treatment groups (acetaminophen, 59 children; ibuprofen, 24 children; placebo, 59 children). They defined seroconversion as a hemagglutinin inhibition assay titer of 1:40 postvaccination (if baseline titer was less than 1:10) or a 4-fold rise (if the baseline titer was ≥ 1:10).

All interventions resulted in similar seroconversion rates for all A or B influenza strains investigated. Vaccine protection-level responses ranged from 9% for B/Phuket to 100% for A/Switzerland. The trial didn’t report febrile reactions or infection rates.

RECOMMENDATIONS

In 2017, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) issued guidelines generally discouraging the use of antipyretics at the time of vaccination, but allowing their use later for local discomfort or fever that might arise after vaccination. The guidelines also noted that antipyretics at the time of vaccination didn’t reduce the risk of febrile seizures.4

Editor’s takeaway

Although ACIP doesn’t encourage giving antipyretics with vaccines, moderate-quality evidence suggests that prophylactic acetaminophen reduces fever and pain after immunizations by a reasonable amount without an apparent clinical downside.

1. Das RR, Panigrahi I, Naik SS. The effect of prophylactic antipyretic administration on post-vaccination adverse reactions and antibody response in children: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106629.

2. Wysocki J, Center, KJ, Brzostek J, et al. A randomized study of fever prophylaxis and the immunogenicity of routine pediatric vaccinations. Vaccine. 2017;35:1926-1935.

3. Walter EB, Hornok CP, Grohskopf L, et al. The effect of antipyretics on immune response and fever following receipt of inactivated influenza vaccine in young children. Vaccine. 2017;35:6664–6671.

4. Kroger AT, Duchin J, Vázquez M. General Best Practice Guidelines for Immunization. Best Practices Guidance of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017.

1. Das RR, Panigrahi I, Naik SS. The effect of prophylactic antipyretic administration on post-vaccination adverse reactions and antibody response in children: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106629.

2. Wysocki J, Center, KJ, Brzostek J, et al. A randomized study of fever prophylaxis and the immunogenicity of routine pediatric vaccinations. Vaccine. 2017;35:1926-1935.

3. Walter EB, Hornok CP, Grohskopf L, et al. The effect of antipyretics on immune response and fever following receipt of inactivated influenza vaccine in young children. Vaccine. 2017;35:6664–6671.

4. Kroger AT, Duchin J, Vázquez M. General Best Practice Guidelines for Immunization. Best Practices Guidance of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes for acetaminophen, not so much for ibuprofen. Prophylactic acetaminophen reduces the odds of febrile reactions in the first 48 hours after vaccination by 40% to 65% and pain of all grades by 36% to 43%. In contrast, prophylactic ibuprofen reduces pain of all grades by 34% only after primary vaccination and doesn’t alter pain after boosters. Nor does it alter early febrile reactions (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials [RCTs] with moderate-to-high risk of bias).

Prophylactic administration of acetaminophen or ibuprofen is associated with a reduction in antibody response to the primary vaccine series and to influenza vaccine, but antibody responses still achieve seroprotective levels (SOR: C, bench research).

How effective and safe is fecal microbial transplant in preventing C difficile recurrence?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

An open-label RCT enrolled 41 immunocompetent older adults who had relapsed CDI after at least one course of antibiotic therapy.1 Investigators randomized patients to 3 treatment groups:

- vancomycin therapy, bowel lavage (with 4 L nasogastric polyethylene glycol solution), and nasogastric-infused fresh donor feces;

- vancomycin with nasogastric bowel lavage without donor feces; or

- vancomycin alone.

Researchers defined cure as the absence of diarrhea or 3 negative stool samples (if patients continued to have persistent diarrhea) at 10 weeks without relapse.

Thirteen of 16 patients (81%) in the donor feces infusion group were cured with the first infusion. Two of the 3 remaining patients were cured after a second donor transplant. FMT produced higher total cure rates than those of vancomycin (94% vs 27%; P<.001; number needed to treat [NNT]=2). Bowel lavage had no effect on outcome.

FMT cures more patients than vancomycin alone

An open-label RCT of 39 patients compared healthy-donor, fresh FMT given via colonoscopy with vancomycin alone for recurrent CDIs.2 Researchers recruited immunocompetent adults who had recurrent CDIs after at least one course of vancomycin or metronidazole.

Patients in the treatment group received a short course of vancomycin, followed by bowel cleansing and fecal transplant via colonoscopy. Clinicians repeated the fecal transplant every 3 days until resolution for patients with pseudomembranous colitis. Patients in the control group were treated with vancomycin for at least 3 weeks. Researchers defined cure as the absence of diarrhea or 2 negative stool samples (if patients continued to have diarrhea) at 10 weeks without relapse.

Thirteen of 20 patients in the FMT group (65%) achieved cure after the first fecal infusion. The 7 remaining patients received multiple infusions; 5 were cured. Overall, FMT cured more patients than vancomycin alone (90% vs 26%; odds ratio=25.2; 99.9% confidence interval [CI], 1.26-502; NNT=2).

Continue to: Fresh and frozen stool are equally effective

Fresh and frozen stool are equally effective

A randomized, double-blind noninferiority trial compared the effectiveness of frozen and thawed FMT with that of fresh FMT in 219 patients ≥18 years of age with recurrent or refractory CDIs.3 Researchers prescribed suppressive antibiotics, which were discontinued within 24 to 48 hours of FMT, and then administered 50 mL of either fresh or frozen stool by enema. They repeated the FMT with the same donor stool if symptoms didn’t improve within 4 days. Any patient still unresponsive was offered repeat FMT or antibiotic therapy.

Researchers defined a 15% difference in outcome as a clinically important effect. Intention-to-treat analysis yielded no significant difference in clinical resolution between groups (75% frozen vs 70.3% fresh; P=.01 for noninferiority).

Nasogastric delivery works as well as colonoscopy

An open-label RCT (not included in the reviews described previously) evaluated the effectiveness of colonoscopically administered FMT compared with that of nasogastric administration in 20 patients with recurrent or refractory CDIs.4 Patients had experienced either a minimum of 3 episodes of mild-to-moderate CDI with a failed 6- to 8-week taper of vancomycin or 2 episodes of severe CDI resulting in hospitalization. Researchers offered patients from both groups a second FMT if symptoms didn’t improve with the initial administration.

Eight patients in the colonoscopy group and 6 in the nasogastric group were cured (all symptoms resolved) after the first FMT. One patient in the nasogastric group refused subsequent administration. All 5 remaining participants chose to have subsequent nasogastric administration (80% cure rate). Both methods of administering FMT produced comparable cure rates (80% in the initial nasogastric group vs 100% in the initial colonoscopy group; P=.53).

Continue to: A third of patients suffer adverse effects, but serious harms are rare

A third of patients suffer adverse effects, but serious harms are rare

A systematic review analyzed 50 trials (16 case series, 9 case reports, 4 RCTs, 21 unreported type; 1089 FMT-treated patients) for adverse effects of FMT.5 Most patients (831) had CDIs, 235 had inflammatory bowel disease, and 106 had both conditions. Donor screening tests for FMT included viral screenings (hepatitis A, B, and C; Epstein-Barr virus; human immunodeficiency virus; Treponema pallidum; and cytomegalovirus), stool tests for C difficile toxin, and routine bacterial culture for enteric pathogens (Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, Campylobacter), ova, and parasites.

Overall, 28.5% of patients receiving FMT experienced adverse events. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) administration resulted in more total adverse events than did lower GI delivery (43.6% vs 20.6%; P value not given), mostly abdominal discomfort. However, upper GI delivery was associated with fewer serious adverse events than was lower GI delivery (2% vs 6%; P value not given). FMT possibly or probably produced serious infections in 0.7% of patients, and there was one colonoscopy-associated death caused by aspiration (0.1% mortality).

RECOMMENDATIONS

Guidelines published by the American College of Gastroenterology in 2013 listed FMT as a treatment option for patients who have had 3 episodes of CDI and vancomycin therapy (based on moderate quality evidence).6

1. van Nood E, Vrieze A, Nieuwdorp M, et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:407-415.

2. Cammarota G, Masucci L, Ianiro G, et al. Randomised clinical trial: faecal microbiota transplantation by colonoscopy vs. vancomycin for the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:835-843.

3. Lee CH, Steiner T, Petrof EO, et al. Frozen vs fresh fecal microbiota transplantation and clinical resolution of diarrhea in patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. JAMA. 2016;315:142-149.

4. Youngster I, Sauk J, Pindar C, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant for relapsing Clostridium difficile infection using a frozen inoculum from unrelated donors: a randomized, open-label, controlled pilot study. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1515-1522.

5. Wang S, Xu M, Wang W, et al. Systematic review: adverse events of fecal microbiota transplantation. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161174.

6. Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:478-498.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

An open-label RCT enrolled 41 immunocompetent older adults who had relapsed CDI after at least one course of antibiotic therapy.1 Investigators randomized patients to 3 treatment groups:

- vancomycin therapy, bowel lavage (with 4 L nasogastric polyethylene glycol solution), and nasogastric-infused fresh donor feces;

- vancomycin with nasogastric bowel lavage without donor feces; or

- vancomycin alone.

Researchers defined cure as the absence of diarrhea or 3 negative stool samples (if patients continued to have persistent diarrhea) at 10 weeks without relapse.

Thirteen of 16 patients (81%) in the donor feces infusion group were cured with the first infusion. Two of the 3 remaining patients were cured after a second donor transplant. FMT produced higher total cure rates than those of vancomycin (94% vs 27%; P<.001; number needed to treat [NNT]=2). Bowel lavage had no effect on outcome.

FMT cures more patients than vancomycin alone

An open-label RCT of 39 patients compared healthy-donor, fresh FMT given via colonoscopy with vancomycin alone for recurrent CDIs.2 Researchers recruited immunocompetent adults who had recurrent CDIs after at least one course of vancomycin or metronidazole.

Patients in the treatment group received a short course of vancomycin, followed by bowel cleansing and fecal transplant via colonoscopy. Clinicians repeated the fecal transplant every 3 days until resolution for patients with pseudomembranous colitis. Patients in the control group were treated with vancomycin for at least 3 weeks. Researchers defined cure as the absence of diarrhea or 2 negative stool samples (if patients continued to have diarrhea) at 10 weeks without relapse.

Thirteen of 20 patients in the FMT group (65%) achieved cure after the first fecal infusion. The 7 remaining patients received multiple infusions; 5 were cured. Overall, FMT cured more patients than vancomycin alone (90% vs 26%; odds ratio=25.2; 99.9% confidence interval [CI], 1.26-502; NNT=2).

Continue to: Fresh and frozen stool are equally effective

Fresh and frozen stool are equally effective

A randomized, double-blind noninferiority trial compared the effectiveness of frozen and thawed FMT with that of fresh FMT in 219 patients ≥18 years of age with recurrent or refractory CDIs.3 Researchers prescribed suppressive antibiotics, which were discontinued within 24 to 48 hours of FMT, and then administered 50 mL of either fresh or frozen stool by enema. They repeated the FMT with the same donor stool if symptoms didn’t improve within 4 days. Any patient still unresponsive was offered repeat FMT or antibiotic therapy.

Researchers defined a 15% difference in outcome as a clinically important effect. Intention-to-treat analysis yielded no significant difference in clinical resolution between groups (75% frozen vs 70.3% fresh; P=.01 for noninferiority).

Nasogastric delivery works as well as colonoscopy

An open-label RCT (not included in the reviews described previously) evaluated the effectiveness of colonoscopically administered FMT compared with that of nasogastric administration in 20 patients with recurrent or refractory CDIs.4 Patients had experienced either a minimum of 3 episodes of mild-to-moderate CDI with a failed 6- to 8-week taper of vancomycin or 2 episodes of severe CDI resulting in hospitalization. Researchers offered patients from both groups a second FMT if symptoms didn’t improve with the initial administration.

Eight patients in the colonoscopy group and 6 in the nasogastric group were cured (all symptoms resolved) after the first FMT. One patient in the nasogastric group refused subsequent administration. All 5 remaining participants chose to have subsequent nasogastric administration (80% cure rate). Both methods of administering FMT produced comparable cure rates (80% in the initial nasogastric group vs 100% in the initial colonoscopy group; P=.53).

Continue to: A third of patients suffer adverse effects, but serious harms are rare

A third of patients suffer adverse effects, but serious harms are rare

A systematic review analyzed 50 trials (16 case series, 9 case reports, 4 RCTs, 21 unreported type; 1089 FMT-treated patients) for adverse effects of FMT.5 Most patients (831) had CDIs, 235 had inflammatory bowel disease, and 106 had both conditions. Donor screening tests for FMT included viral screenings (hepatitis A, B, and C; Epstein-Barr virus; human immunodeficiency virus; Treponema pallidum; and cytomegalovirus), stool tests for C difficile toxin, and routine bacterial culture for enteric pathogens (Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, Campylobacter), ova, and parasites.

Overall, 28.5% of patients receiving FMT experienced adverse events. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) administration resulted in more total adverse events than did lower GI delivery (43.6% vs 20.6%; P value not given), mostly abdominal discomfort. However, upper GI delivery was associated with fewer serious adverse events than was lower GI delivery (2% vs 6%; P value not given). FMT possibly or probably produced serious infections in 0.7% of patients, and there was one colonoscopy-associated death caused by aspiration (0.1% mortality).

RECOMMENDATIONS

Guidelines published by the American College of Gastroenterology in 2013 listed FMT as a treatment option for patients who have had 3 episodes of CDI and vancomycin therapy (based on moderate quality evidence).6

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

An open-label RCT enrolled 41 immunocompetent older adults who had relapsed CDI after at least one course of antibiotic therapy.1 Investigators randomized patients to 3 treatment groups:

- vancomycin therapy, bowel lavage (with 4 L nasogastric polyethylene glycol solution), and nasogastric-infused fresh donor feces;

- vancomycin with nasogastric bowel lavage without donor feces; or

- vancomycin alone.

Researchers defined cure as the absence of diarrhea or 3 negative stool samples (if patients continued to have persistent diarrhea) at 10 weeks without relapse.

Thirteen of 16 patients (81%) in the donor feces infusion group were cured with the first infusion. Two of the 3 remaining patients were cured after a second donor transplant. FMT produced higher total cure rates than those of vancomycin (94% vs 27%; P<.001; number needed to treat [NNT]=2). Bowel lavage had no effect on outcome.

FMT cures more patients than vancomycin alone

An open-label RCT of 39 patients compared healthy-donor, fresh FMT given via colonoscopy with vancomycin alone for recurrent CDIs.2 Researchers recruited immunocompetent adults who had recurrent CDIs after at least one course of vancomycin or metronidazole.

Patients in the treatment group received a short course of vancomycin, followed by bowel cleansing and fecal transplant via colonoscopy. Clinicians repeated the fecal transplant every 3 days until resolution for patients with pseudomembranous colitis. Patients in the control group were treated with vancomycin for at least 3 weeks. Researchers defined cure as the absence of diarrhea or 2 negative stool samples (if patients continued to have diarrhea) at 10 weeks without relapse.

Thirteen of 20 patients in the FMT group (65%) achieved cure after the first fecal infusion. The 7 remaining patients received multiple infusions; 5 were cured. Overall, FMT cured more patients than vancomycin alone (90% vs 26%; odds ratio=25.2; 99.9% confidence interval [CI], 1.26-502; NNT=2).

Continue to: Fresh and frozen stool are equally effective

Fresh and frozen stool are equally effective

A randomized, double-blind noninferiority trial compared the effectiveness of frozen and thawed FMT with that of fresh FMT in 219 patients ≥18 years of age with recurrent or refractory CDIs.3 Researchers prescribed suppressive antibiotics, which were discontinued within 24 to 48 hours of FMT, and then administered 50 mL of either fresh or frozen stool by enema. They repeated the FMT with the same donor stool if symptoms didn’t improve within 4 days. Any patient still unresponsive was offered repeat FMT or antibiotic therapy.

Researchers defined a 15% difference in outcome as a clinically important effect. Intention-to-treat analysis yielded no significant difference in clinical resolution between groups (75% frozen vs 70.3% fresh; P=.01 for noninferiority).

Nasogastric delivery works as well as colonoscopy

An open-label RCT (not included in the reviews described previously) evaluated the effectiveness of colonoscopically administered FMT compared with that of nasogastric administration in 20 patients with recurrent or refractory CDIs.4 Patients had experienced either a minimum of 3 episodes of mild-to-moderate CDI with a failed 6- to 8-week taper of vancomycin or 2 episodes of severe CDI resulting in hospitalization. Researchers offered patients from both groups a second FMT if symptoms didn’t improve with the initial administration.

Eight patients in the colonoscopy group and 6 in the nasogastric group were cured (all symptoms resolved) after the first FMT. One patient in the nasogastric group refused subsequent administration. All 5 remaining participants chose to have subsequent nasogastric administration (80% cure rate). Both methods of administering FMT produced comparable cure rates (80% in the initial nasogastric group vs 100% in the initial colonoscopy group; P=.53).

Continue to: A third of patients suffer adverse effects, but serious harms are rare

A third of patients suffer adverse effects, but serious harms are rare

A systematic review analyzed 50 trials (16 case series, 9 case reports, 4 RCTs, 21 unreported type; 1089 FMT-treated patients) for adverse effects of FMT.5 Most patients (831) had CDIs, 235 had inflammatory bowel disease, and 106 had both conditions. Donor screening tests for FMT included viral screenings (hepatitis A, B, and C; Epstein-Barr virus; human immunodeficiency virus; Treponema pallidum; and cytomegalovirus), stool tests for C difficile toxin, and routine bacterial culture for enteric pathogens (Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, Campylobacter), ova, and parasites.

Overall, 28.5% of patients receiving FMT experienced adverse events. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) administration resulted in more total adverse events than did lower GI delivery (43.6% vs 20.6%; P value not given), mostly abdominal discomfort. However, upper GI delivery was associated with fewer serious adverse events than was lower GI delivery (2% vs 6%; P value not given). FMT possibly or probably produced serious infections in 0.7% of patients, and there was one colonoscopy-associated death caused by aspiration (0.1% mortality).

RECOMMENDATIONS

Guidelines published by the American College of Gastroenterology in 2013 listed FMT as a treatment option for patients who have had 3 episodes of CDI and vancomycin therapy (based on moderate quality evidence).6

1. van Nood E, Vrieze A, Nieuwdorp M, et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:407-415.

2. Cammarota G, Masucci L, Ianiro G, et al. Randomised clinical trial: faecal microbiota transplantation by colonoscopy vs. vancomycin for the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:835-843.

3. Lee CH, Steiner T, Petrof EO, et al. Frozen vs fresh fecal microbiota transplantation and clinical resolution of diarrhea in patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. JAMA. 2016;315:142-149.

4. Youngster I, Sauk J, Pindar C, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant for relapsing Clostridium difficile infection using a frozen inoculum from unrelated donors: a randomized, open-label, controlled pilot study. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1515-1522.

5. Wang S, Xu M, Wang W, et al. Systematic review: adverse events of fecal microbiota transplantation. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161174.

6. Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:478-498.

1. van Nood E, Vrieze A, Nieuwdorp M, et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:407-415.

2. Cammarota G, Masucci L, Ianiro G, et al. Randomised clinical trial: faecal microbiota transplantation by colonoscopy vs. vancomycin for the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:835-843.

3. Lee CH, Steiner T, Petrof EO, et al. Frozen vs fresh fecal microbiota transplantation and clinical resolution of diarrhea in patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. JAMA. 2016;315:142-149.

4. Youngster I, Sauk J, Pindar C, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant for relapsing Clostridium difficile infection using a frozen inoculum from unrelated donors: a randomized, open-label, controlled pilot study. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1515-1522.

5. Wang S, Xu M, Wang W, et al. Systematic review: adverse events of fecal microbiota transplantation. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161174.

6. Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:478-498.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Fecal microbial transplant (FMT) is reasonably safe and effective. In patients who have had multiple Clostridium difficile infections (CDIs), FMT results in a 65% to 80% cure rate with one treatment and 90% to 95% cure rate with repeated treatments compared with a 25% to 27% cure rate for antibiotics (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, small open-label randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Fresh and frozen donor feces, administered by either nasogastric tube or colonoscope, produce equal results (SOR B, RCTs).

FMT has an overall adverse event rate of 30%, primarily involving abdominal discomfort, but also, rarely, severe infections (0.7%) and death (0.1%) (SOR: B, systematic review not limited to RCTs).

Which interventions are effective in managing parental vaccine refusal?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review analyzed 30 predominantly US studies with more than 8000 patients published between 1990 and 2012 (4 RCTs, 7 nonrandomized clinical trials, 13 before/after intervention trials, and 6 evaluation studies) to evaluate interventions that decreased parental vaccine refusal and hesitancy.1 Interventions included: change in state law, changes in state and school policies, and family-centered education initiatives.

Four studies that evaluated the impact of state laws concerning personal exemption (in addition to religious exemption) consistently found that total nonmedical exemption rates were higher in states that allowed personal exemptions. One nationwide survey found that total nonmedical exemption rates were 2.54 times higher (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.68-3.83) in states that allowed personal exemption than in states where only religious nonmedical exemption was allowed.

Fifteen studies evaluated the impact of educational initiatives on parental attitude towards vaccination; 8 of them reported statistically significant changes. None of the studies demonstrated a change in vaccination rates, however. Citing the generally low quality of the studies, the review authors concluded that they didn’t have convincing evidence that educational interventions reduced vaccine hesitancy.

Herd immunity is an iffy motivator

A systematic review analyzed 29 studies from western nations (17 qualitative and 12 quantitative, 4650 patients) regarding willingness to immunize children for the benefit of the community.2 Of the 17 qualitative studies, only 2 (164 patients) identified benefit to others as a motivating factor in parents’ decisions to immunize their children. In the 12 quantitative studies, a wide range of parents (1% to 60%) rated the concept of benefit to others as a reason for immunization. Overall, approximately one-third of parents listed herd immunity as a motivating reason. The authors concluded that the high heterogeneity of the studies made it unclear whether herd immunity was a motivating factor in childhood immunizations.

Multifaceted interventions, education, and tailored approaches may all work

A systematic review of international studies published between 2007 and 2013 investigated interventions to increase uptake of routinely recommended immunizations in groups with vaccine hesitancy and reduced use.3 Authors identified 189 articles (trial types and number of patients not given) that provided outcome measures.

Interventions that resulted in at least a 25% increase in vaccine uptake were primarily multifaceted, including elements of: targeting undervaccinated populations, improving access or convenience, educational initiatives, and mandates. Interventions that produced a greater than 20% increase in knowledge were generally educational interventions embedded in routine processes such as clinic visits.

The authors noted wide variation between studies in effect size, settings, and target populations. They concluded that interventions tailored to specific populations and concerns were likely to work best.

Corrective information doesn’t help with the most worried parents

A subsequent RCT tested whether correcting the myth that the flu vaccine can give people the flu would reduce belief in the misconception, increase perceptions that the flu vaccine is safe, and increase vaccination intent.4 Respondents to a national online poll of 1000 people received one of 3 interventions: correctional education (information debunking the myth), risk education (information about the risks of influenza infection), or no additional education.

Corrective information about the flu vaccine reduced the false belief that the vaccine can cause the flu by 15% to 20% and that the flu vaccine is unsafe by 5% to 10% (data from graphs; P<.05 for both effects). However, corrective information actually decreased parental intention to vaccinate among the group most concerned about the adverse effects of the vaccine (data from graph and text: +5% in the low-concern group vs −18% in the high-concern group; P<.05).

A presumptive approach works—but at a cost

A subsequent observational study videotaped 111 patient-provider vaccine discussions.5 Researchers categorized the initiation of the vaccine discussion as presumptive (eg, “We have to do some shots.”) or participatory (eg, “What do you want to do about shots?”). Using a presumptive style was more likely to result in acceptance of all recommended vaccines by the end of the visit (90% vs 17%; P<.05), but it decreased the chance of a highly rated visit experience (63% vs 95%; P<.05).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2015 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Pink Book recommends a combination of strategies, aimed at both providers and the public, for increasing and maintaining high immunization rates. The Pink Book advises providers to be ready to address vaccine safety concerns raised by parents.6

In a 2012 guideline, the CDC encouraged providers to listen attentively, be ready with scientific information and reliable resources, and use appropriate anecdotes in communicating with vaccine-hesitant parents.7 The guideline recommended against excluding families who refuse vaccination from the practice.

1. Sadaf A, Richards JL, Glanz J, et al. A systematic review of interventions for reducing parental vaccine refusal and vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine. 2013;31:4293-42304.

2. Quadri-Sheriff M, Hendrix K, Downs S, et al. The role of herd immunity in parents’ decision to vaccinate children: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2012;130:522-530.

3. Jarrett C, Wilson R, O’Leary M, et al. Strategies for addressing vaccine hesitancy: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2015;33:4180-4190.

4. Nyhan B, Reifler J. Does correcting myths about the flu vaccine work? An experimental evaluation of the effects of corrective information. Vaccine. 2015;33:459-464.

5. Opel DJ, Mangione-Smith R, Robinson JD, et al. The influence of provider communication behaviors on parental vaccine acceptance and visit experience. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:1998-2004.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Immunization Strategies for Healthcare Practices and Providers. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/strat.html. Accessed May 11, 2016.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Provider Resources for Vaccine Conversations with Parents. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/conversations/about-vacc-conversations.html. Accessed May 11, 2016.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review analyzed 30 predominantly US studies with more than 8000 patients published between 1990 and 2012 (4 RCTs, 7 nonrandomized clinical trials, 13 before/after intervention trials, and 6 evaluation studies) to evaluate interventions that decreased parental vaccine refusal and hesitancy.1 Interventions included: change in state law, changes in state and school policies, and family-centered education initiatives.

Four studies that evaluated the impact of state laws concerning personal exemption (in addition to religious exemption) consistently found that total nonmedical exemption rates were higher in states that allowed personal exemptions. One nationwide survey found that total nonmedical exemption rates were 2.54 times higher (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.68-3.83) in states that allowed personal exemption than in states where only religious nonmedical exemption was allowed.

Fifteen studies evaluated the impact of educational initiatives on parental attitude towards vaccination; 8 of them reported statistically significant changes. None of the studies demonstrated a change in vaccination rates, however. Citing the generally low quality of the studies, the review authors concluded that they didn’t have convincing evidence that educational interventions reduced vaccine hesitancy.

Herd immunity is an iffy motivator

A systematic review analyzed 29 studies from western nations (17 qualitative and 12 quantitative, 4650 patients) regarding willingness to immunize children for the benefit of the community.2 Of the 17 qualitative studies, only 2 (164 patients) identified benefit to others as a motivating factor in parents’ decisions to immunize their children. In the 12 quantitative studies, a wide range of parents (1% to 60%) rated the concept of benefit to others as a reason for immunization. Overall, approximately one-third of parents listed herd immunity as a motivating reason. The authors concluded that the high heterogeneity of the studies made it unclear whether herd immunity was a motivating factor in childhood immunizations.

Multifaceted interventions, education, and tailored approaches may all work

A systematic review of international studies published between 2007 and 2013 investigated interventions to increase uptake of routinely recommended immunizations in groups with vaccine hesitancy and reduced use.3 Authors identified 189 articles (trial types and number of patients not given) that provided outcome measures.

Interventions that resulted in at least a 25% increase in vaccine uptake were primarily multifaceted, including elements of: targeting undervaccinated populations, improving access or convenience, educational initiatives, and mandates. Interventions that produced a greater than 20% increase in knowledge were generally educational interventions embedded in routine processes such as clinic visits.

The authors noted wide variation between studies in effect size, settings, and target populations. They concluded that interventions tailored to specific populations and concerns were likely to work best.

Corrective information doesn’t help with the most worried parents

A subsequent RCT tested whether correcting the myth that the flu vaccine can give people the flu would reduce belief in the misconception, increase perceptions that the flu vaccine is safe, and increase vaccination intent.4 Respondents to a national online poll of 1000 people received one of 3 interventions: correctional education (information debunking the myth), risk education (information about the risks of influenza infection), or no additional education.

Corrective information about the flu vaccine reduced the false belief that the vaccine can cause the flu by 15% to 20% and that the flu vaccine is unsafe by 5% to 10% (data from graphs; P<.05 for both effects). However, corrective information actually decreased parental intention to vaccinate among the group most concerned about the adverse effects of the vaccine (data from graph and text: +5% in the low-concern group vs −18% in the high-concern group; P<.05).

A presumptive approach works—but at a cost

A subsequent observational study videotaped 111 patient-provider vaccine discussions.5 Researchers categorized the initiation of the vaccine discussion as presumptive (eg, “We have to do some shots.”) or participatory (eg, “What do you want to do about shots?”). Using a presumptive style was more likely to result in acceptance of all recommended vaccines by the end of the visit (90% vs 17%; P<.05), but it decreased the chance of a highly rated visit experience (63% vs 95%; P<.05).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2015 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Pink Book recommends a combination of strategies, aimed at both providers and the public, for increasing and maintaining high immunization rates. The Pink Book advises providers to be ready to address vaccine safety concerns raised by parents.6

In a 2012 guideline, the CDC encouraged providers to listen attentively, be ready with scientific information and reliable resources, and use appropriate anecdotes in communicating with vaccine-hesitant parents.7 The guideline recommended against excluding families who refuse vaccination from the practice.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review analyzed 30 predominantly US studies with more than 8000 patients published between 1990 and 2012 (4 RCTs, 7 nonrandomized clinical trials, 13 before/after intervention trials, and 6 evaluation studies) to evaluate interventions that decreased parental vaccine refusal and hesitancy.1 Interventions included: change in state law, changes in state and school policies, and family-centered education initiatives.

Four studies that evaluated the impact of state laws concerning personal exemption (in addition to religious exemption) consistently found that total nonmedical exemption rates were higher in states that allowed personal exemptions. One nationwide survey found that total nonmedical exemption rates were 2.54 times higher (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.68-3.83) in states that allowed personal exemption than in states where only religious nonmedical exemption was allowed.

Fifteen studies evaluated the impact of educational initiatives on parental attitude towards vaccination; 8 of them reported statistically significant changes. None of the studies demonstrated a change in vaccination rates, however. Citing the generally low quality of the studies, the review authors concluded that they didn’t have convincing evidence that educational interventions reduced vaccine hesitancy.

Herd immunity is an iffy motivator

A systematic review analyzed 29 studies from western nations (17 qualitative and 12 quantitative, 4650 patients) regarding willingness to immunize children for the benefit of the community.2 Of the 17 qualitative studies, only 2 (164 patients) identified benefit to others as a motivating factor in parents’ decisions to immunize their children. In the 12 quantitative studies, a wide range of parents (1% to 60%) rated the concept of benefit to others as a reason for immunization. Overall, approximately one-third of parents listed herd immunity as a motivating reason. The authors concluded that the high heterogeneity of the studies made it unclear whether herd immunity was a motivating factor in childhood immunizations.

Multifaceted interventions, education, and tailored approaches may all work

A systematic review of international studies published between 2007 and 2013 investigated interventions to increase uptake of routinely recommended immunizations in groups with vaccine hesitancy and reduced use.3 Authors identified 189 articles (trial types and number of patients not given) that provided outcome measures.

Interventions that resulted in at least a 25% increase in vaccine uptake were primarily multifaceted, including elements of: targeting undervaccinated populations, improving access or convenience, educational initiatives, and mandates. Interventions that produced a greater than 20% increase in knowledge were generally educational interventions embedded in routine processes such as clinic visits.

The authors noted wide variation between studies in effect size, settings, and target populations. They concluded that interventions tailored to specific populations and concerns were likely to work best.

Corrective information doesn’t help with the most worried parents

A subsequent RCT tested whether correcting the myth that the flu vaccine can give people the flu would reduce belief in the misconception, increase perceptions that the flu vaccine is safe, and increase vaccination intent.4 Respondents to a national online poll of 1000 people received one of 3 interventions: correctional education (information debunking the myth), risk education (information about the risks of influenza infection), or no additional education.

Corrective information about the flu vaccine reduced the false belief that the vaccine can cause the flu by 15% to 20% and that the flu vaccine is unsafe by 5% to 10% (data from graphs; P<.05 for both effects). However, corrective information actually decreased parental intention to vaccinate among the group most concerned about the adverse effects of the vaccine (data from graph and text: +5% in the low-concern group vs −18% in the high-concern group; P<.05).

A presumptive approach works—but at a cost

A subsequent observational study videotaped 111 patient-provider vaccine discussions.5 Researchers categorized the initiation of the vaccine discussion as presumptive (eg, “We have to do some shots.”) or participatory (eg, “What do you want to do about shots?”). Using a presumptive style was more likely to result in acceptance of all recommended vaccines by the end of the visit (90% vs 17%; P<.05), but it decreased the chance of a highly rated visit experience (63% vs 95%; P<.05).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2015 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Pink Book recommends a combination of strategies, aimed at both providers and the public, for increasing and maintaining high immunization rates. The Pink Book advises providers to be ready to address vaccine safety concerns raised by parents.6

In a 2012 guideline, the CDC encouraged providers to listen attentively, be ready with scientific information and reliable resources, and use appropriate anecdotes in communicating with vaccine-hesitant parents.7 The guideline recommended against excluding families who refuse vaccination from the practice.

1. Sadaf A, Richards JL, Glanz J, et al. A systematic review of interventions for reducing parental vaccine refusal and vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine. 2013;31:4293-42304.

2. Quadri-Sheriff M, Hendrix K, Downs S, et al. The role of herd immunity in parents’ decision to vaccinate children: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2012;130:522-530.

3. Jarrett C, Wilson R, O’Leary M, et al. Strategies for addressing vaccine hesitancy: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2015;33:4180-4190.

4. Nyhan B, Reifler J. Does correcting myths about the flu vaccine work? An experimental evaluation of the effects of corrective information. Vaccine. 2015;33:459-464.

5. Opel DJ, Mangione-Smith R, Robinson JD, et al. The influence of provider communication behaviors on parental vaccine acceptance and visit experience. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:1998-2004.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Immunization Strategies for Healthcare Practices and Providers. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/strat.html. Accessed May 11, 2016.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Provider Resources for Vaccine Conversations with Parents. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/conversations/about-vacc-conversations.html. Accessed May 11, 2016.

1. Sadaf A, Richards JL, Glanz J, et al. A systematic review of interventions for reducing parental vaccine refusal and vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine. 2013;31:4293-42304.

2. Quadri-Sheriff M, Hendrix K, Downs S, et al. The role of herd immunity in parents’ decision to vaccinate children: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2012;130:522-530.

3. Jarrett C, Wilson R, O’Leary M, et al. Strategies for addressing vaccine hesitancy: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2015;33:4180-4190.

4. Nyhan B, Reifler J. Does correcting myths about the flu vaccine work? An experimental evaluation of the effects of corrective information. Vaccine. 2015;33:459-464.

5. Opel DJ, Mangione-Smith R, Robinson JD, et al. The influence of provider communication behaviors on parental vaccine acceptance and visit experience. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:1998-2004.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Immunization Strategies for Healthcare Practices and Providers. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/strat.html. Accessed May 11, 2016.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Provider Resources for Vaccine Conversations with Parents. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/conversations/about-vacc-conversations.html. Accessed May 11, 2016.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

It’s unclear whether educational initiatives alone alter vaccine refusal. Although about a third of parents cite herd immunity as motivation for vaccination, its efficacy in addressing vaccine hesitancy isn’t clear (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, systematic reviews not limited to randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Multifaceted interventions (encompassing improved access to vaccines, immunization mandates, and patient education) may produce a ≥25% increase in vaccine uptake in groups with vaccine hesitancy and low utilization (SOR: B, extrapolated from a meta-analysis across diverse cultures).

Correcting false information about influenza vaccination improves perceptions about the vaccine, but may decrease intention to vaccinate in parents who already have strong concerns about safety (SOR: C, low-quality RCT).

Discussions about vaccines that are more paternalistic (presumptive rather than participatory) are associated with higher vaccination rates, but lower visit satisfaction (SOR: C, observational study).

Providers should thoroughly address patient concerns about safety and encourage vaccine use (SOR: C, expert opinion).

Do pedometers increase activity and improve health outcomes?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review and meta-analysis identified 26 studies evaluating activity and health outcomes with the use of pedometers.1 The studies included 8 RCTs and 18 observational studies with 2767 patients (mean body mass index [BMI]: 30 kg/m2; mean age: 49 years; 85% women). The studies ranged from 3 to 104 weeks. From the RCT data, patients using pedometers had an increase of 2491 steps per day (about one mile) more than control group patients (8 trials, n=305; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1098-3885 steps/day; P<.001).

Across all of the observational studies, pedometer users had a 26.9% increase from their baseline physical activity (P=.001). When data from all of the studies were combined, the researchers found a decrease from baseline BMI (18 studies, n=562; mean difference [MD]=0.38 kg/m2; 95% CI, 0.05-0.72; P=.03) and a decrease in systolic BP (12 studies, n=468; MD=3.8 mm Hg; 95% CI, 1.7-5.9 mm Hg; P<.001). No statistically significant change was noted in cholesterol or fasting glucose levels. Weaknesses of this review include the heterogeneity of the interventions, relatively small study sizes, and short study durations.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 RCTs (N=1258) evaluated pedometer effects in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes.2 (One RCT was included in the above meta-analysis.) Studies ran from 6 to 48 weeks, and mean enrollment BMI (where reported) was 30 kg/m2 or more in at least one treatment arm. Compared to controls, patients using pedometers had greater reductions in weight (weighted mean difference [WMD]= -0.65 kg; 95% CI, -1.12 to -0.17 kg) and BMI (WMD= -0.15 kg/m2; 95% CI, -0.29 to -0.02 kg/m2). The effect persisted in the subset of studies in which the intervention and control groups both received dietary counseling (WMD weight= -0.86 kg; 95% CI, -1.45 to -0.27 kg; WMD BMI= -0.30 kg/m2; 95% CI, -0.50 to -0.10 kg/m2). Study quality was low to moderate, and 5 studies used per-protocol analysis instead of intention-to-treat analysis.

Pedometer use benefits patients with musculoskeletal diseases, too

A systematic review and meta-analysis examined the use of pedometers in patients with musculoskeletal diseases.3 It included 7 RCTs lasting 4 weeks to one year with 484 adults, 40 to 82 years of age, with musculoskeletal disorders (eg, back pain, knee pain, hip pain). (One RCT was also included in the diabetes meta-analysis.) Pedometer use resulted in a mean increase in physical activity of 1950 steps per day above baseline (range=818-2829 steps/day; P<.05). The authors noted that 4 of the 7 studies also demonstrated significant improvement in pain scores and physical function. BMI data were not tracked in this review.

Pedometers increase walking in older patients

A RCT compared the effects of pedometer-based activity prescriptions with standard time-based activity prescriptions in 330 patients ≥65 years of age with baseline low activity levels.4 All patients received an initial physician visit followed by 3 telephone counseling sessions encouraging increased activity. The pedometer group was counseled on increasing steps (without specific targets), while the standard activity prescription group received time-related activity goals.

At one year, “leisure walking” had increased more for the pedometer group than for the standard group (mean 50 minutes/week vs 28 minutes/week; P=.03), although both groups equally increased their amount of “total activity.”

1. Bravata DM, Smith-Spangler C, Sundaram V, et al. Using pedometers to increase physical activity and improve health: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;298:2296-2304.

2. Cai X, Qiu SH, Yin H, et al. Pedometer intervention and weight loss in overweight and obese adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2016;33:1035-1044.

3. Mansi S, Milosavljevic S, Baxter GD, et al. A systematic review of studies using pedometers as an intervention for musculoskeletal diseases. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2014;15:231.

4. Kolt GS, Schofield GM, Kerse N, et al. Healthy Steps trial: pedometer-based advice and physical activity for low-active older adults. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:206-212.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review and meta-analysis identified 26 studies evaluating activity and health outcomes with the use of pedometers.1 The studies included 8 RCTs and 18 observational studies with 2767 patients (mean body mass index [BMI]: 30 kg/m2; mean age: 49 years; 85% women). The studies ranged from 3 to 104 weeks. From the RCT data, patients using pedometers had an increase of 2491 steps per day (about one mile) more than control group patients (8 trials, n=305; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1098-3885 steps/day; P<.001).

Across all of the observational studies, pedometer users had a 26.9% increase from their baseline physical activity (P=.001). When data from all of the studies were combined, the researchers found a decrease from baseline BMI (18 studies, n=562; mean difference [MD]=0.38 kg/m2; 95% CI, 0.05-0.72; P=.03) and a decrease in systolic BP (12 studies, n=468; MD=3.8 mm Hg; 95% CI, 1.7-5.9 mm Hg; P<.001). No statistically significant change was noted in cholesterol or fasting glucose levels. Weaknesses of this review include the heterogeneity of the interventions, relatively small study sizes, and short study durations.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 RCTs (N=1258) evaluated pedometer effects in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes.2 (One RCT was included in the above meta-analysis.) Studies ran from 6 to 48 weeks, and mean enrollment BMI (where reported) was 30 kg/m2 or more in at least one treatment arm. Compared to controls, patients using pedometers had greater reductions in weight (weighted mean difference [WMD]= -0.65 kg; 95% CI, -1.12 to -0.17 kg) and BMI (WMD= -0.15 kg/m2; 95% CI, -0.29 to -0.02 kg/m2). The effect persisted in the subset of studies in which the intervention and control groups both received dietary counseling (WMD weight= -0.86 kg; 95% CI, -1.45 to -0.27 kg; WMD BMI= -0.30 kg/m2; 95% CI, -0.50 to -0.10 kg/m2). Study quality was low to moderate, and 5 studies used per-protocol analysis instead of intention-to-treat analysis.

Pedometer use benefits patients with musculoskeletal diseases, too

A systematic review and meta-analysis examined the use of pedometers in patients with musculoskeletal diseases.3 It included 7 RCTs lasting 4 weeks to one year with 484 adults, 40 to 82 years of age, with musculoskeletal disorders (eg, back pain, knee pain, hip pain). (One RCT was also included in the diabetes meta-analysis.) Pedometer use resulted in a mean increase in physical activity of 1950 steps per day above baseline (range=818-2829 steps/day; P<.05). The authors noted that 4 of the 7 studies also demonstrated significant improvement in pain scores and physical function. BMI data were not tracked in this review.

Pedometers increase walking in older patients

A RCT compared the effects of pedometer-based activity prescriptions with standard time-based activity prescriptions in 330 patients ≥65 years of age with baseline low activity levels.4 All patients received an initial physician visit followed by 3 telephone counseling sessions encouraging increased activity. The pedometer group was counseled on increasing steps (without specific targets), while the standard activity prescription group received time-related activity goals.

At one year, “leisure walking” had increased more for the pedometer group than for the standard group (mean 50 minutes/week vs 28 minutes/week; P=.03), although both groups equally increased their amount of “total activity.”

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review and meta-analysis identified 26 studies evaluating activity and health outcomes with the use of pedometers.1 The studies included 8 RCTs and 18 observational studies with 2767 patients (mean body mass index [BMI]: 30 kg/m2; mean age: 49 years; 85% women). The studies ranged from 3 to 104 weeks. From the RCT data, patients using pedometers had an increase of 2491 steps per day (about one mile) more than control group patients (8 trials, n=305; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1098-3885 steps/day; P<.001).

Across all of the observational studies, pedometer users had a 26.9% increase from their baseline physical activity (P=.001). When data from all of the studies were combined, the researchers found a decrease from baseline BMI (18 studies, n=562; mean difference [MD]=0.38 kg/m2; 95% CI, 0.05-0.72; P=.03) and a decrease in systolic BP (12 studies, n=468; MD=3.8 mm Hg; 95% CI, 1.7-5.9 mm Hg; P<.001). No statistically significant change was noted in cholesterol or fasting glucose levels. Weaknesses of this review include the heterogeneity of the interventions, relatively small study sizes, and short study durations.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 RCTs (N=1258) evaluated pedometer effects in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes.2 (One RCT was included in the above meta-analysis.) Studies ran from 6 to 48 weeks, and mean enrollment BMI (where reported) was 30 kg/m2 or more in at least one treatment arm. Compared to controls, patients using pedometers had greater reductions in weight (weighted mean difference [WMD]= -0.65 kg; 95% CI, -1.12 to -0.17 kg) and BMI (WMD= -0.15 kg/m2; 95% CI, -0.29 to -0.02 kg/m2). The effect persisted in the subset of studies in which the intervention and control groups both received dietary counseling (WMD weight= -0.86 kg; 95% CI, -1.45 to -0.27 kg; WMD BMI= -0.30 kg/m2; 95% CI, -0.50 to -0.10 kg/m2). Study quality was low to moderate, and 5 studies used per-protocol analysis instead of intention-to-treat analysis.

Pedometer use benefits patients with musculoskeletal diseases, too

A systematic review and meta-analysis examined the use of pedometers in patients with musculoskeletal diseases.3 It included 7 RCTs lasting 4 weeks to one year with 484 adults, 40 to 82 years of age, with musculoskeletal disorders (eg, back pain, knee pain, hip pain). (One RCT was also included in the diabetes meta-analysis.) Pedometer use resulted in a mean increase in physical activity of 1950 steps per day above baseline (range=818-2829 steps/day; P<.05). The authors noted that 4 of the 7 studies also demonstrated significant improvement in pain scores and physical function. BMI data were not tracked in this review.

Pedometers increase walking in older patients

A RCT compared the effects of pedometer-based activity prescriptions with standard time-based activity prescriptions in 330 patients ≥65 years of age with baseline low activity levels.4 All patients received an initial physician visit followed by 3 telephone counseling sessions encouraging increased activity. The pedometer group was counseled on increasing steps (without specific targets), while the standard activity prescription group received time-related activity goals.

At one year, “leisure walking” had increased more for the pedometer group than for the standard group (mean 50 minutes/week vs 28 minutes/week; P=.03), although both groups equally increased their amount of “total activity.”

1. Bravata DM, Smith-Spangler C, Sundaram V, et al. Using pedometers to increase physical activity and improve health: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;298:2296-2304.

2. Cai X, Qiu SH, Yin H, et al. Pedometer intervention and weight loss in overweight and obese adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2016;33:1035-1044.

3. Mansi S, Milosavljevic S, Baxter GD, et al. A systematic review of studies using pedometers as an intervention for musculoskeletal diseases. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2014;15:231.

4. Kolt GS, Schofield GM, Kerse N, et al. Healthy Steps trial: pedometer-based advice and physical activity for low-active older adults. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:206-212.

1. Bravata DM, Smith-Spangler C, Sundaram V, et al. Using pedometers to increase physical activity and improve health: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;298:2296-2304.

2. Cai X, Qiu SH, Yin H, et al. Pedometer intervention and weight loss in overweight and obese adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2016;33:1035-1044.

3. Mansi S, Milosavljevic S, Baxter GD, et al. A systematic review of studies using pedometers as an intervention for musculoskeletal diseases. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2014;15:231.

4. Kolt GS, Schofield GM, Kerse N, et al. Healthy Steps trial: pedometer-based advice and physical activity for low-active older adults. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:206-212.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes. In overweight and obese patients, exercise interventions using a pedometer increase steps by about a mile per day over the same interventions without access to pedometer information (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]) and are associated with a modest 4 mm Hg reduction in systolic blood pressure (BP) over baseline (SOR: B, meta-analysis of RCTs and cohort studies). In overweight patients with diabetes, pedometer use with nutritional counseling is associated with 0.86 kg greater weight loss than nutritional counseling alone (SOR: B, meta-analysis of lower quality RCTs).

Pedometers increase activity in patients with various musculoskeletal conditions and may help reduce pain (SOR: B, meta-analysis of RCTs with heterogeneous outcomes). In low-activity elderly patients, pedometers do not appear to increase total activity when added to an exercise program, but they do appear to increase walking (SOR: B, RCT).

There is no evidence concerning the impact of pedometers on cardiovascular outcomes.

Is arthroscopic subacromial decompression effective for shoulder impingement?

It’s impossible to say for certain in the absence of randomized controlled trials. However, in patients whose impingement symptoms don’t improve after 3 to 6 months, arthroscopic subacromial decompression (ASD) is associated with modest (about 10%) long-term improvement in pain and function compared with open acromioplasty or baseline (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, cohort studies).

Patients older than 57 years may do better with surgery than physical therapy (SOR: B, single cohort study).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

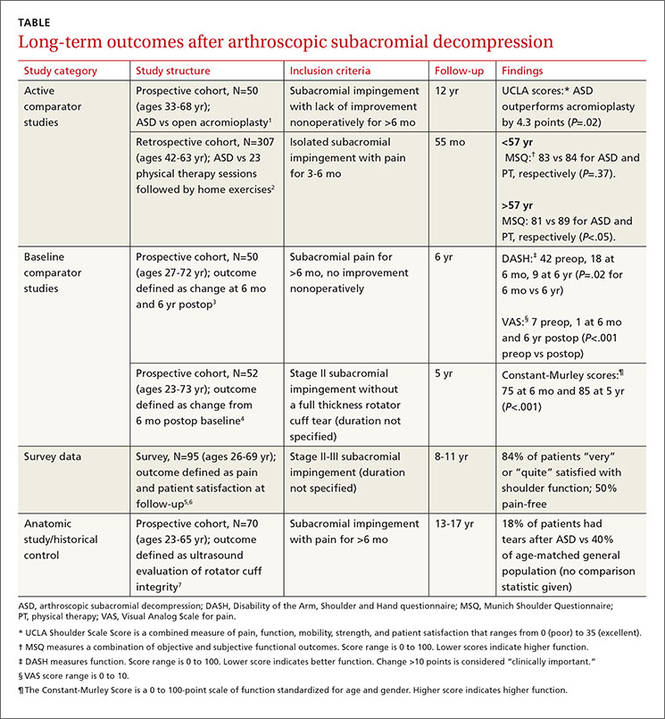

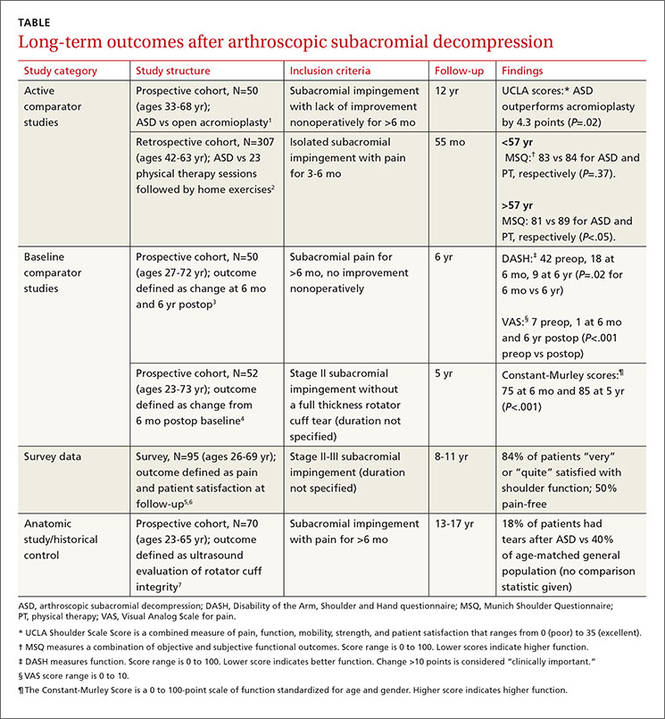

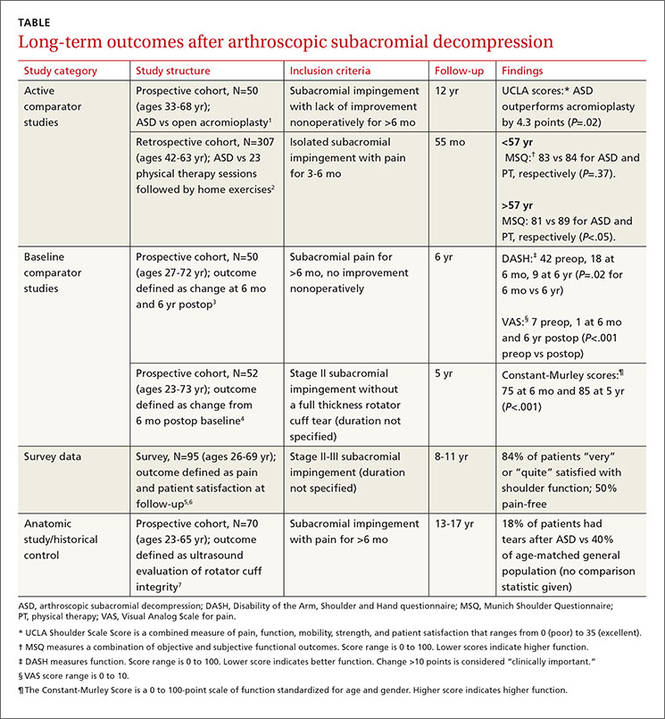

Six cohort studies found that patients who underwent ASD for subacromial impingement had improved pain and function scores at 4.5 to 12 years after surgery (TABLE1-7). Weaknesses of the overall data set include use of heterogeneous outcome measures across studies, lack of sham surgical controls, and lack of blinding.

ASD improves pain and function slightly more than other treatments

One prospective and one retrospective cohort trial compared ASD with another intervention. In the prospective trial, ASD was associated with a 10% better combined pain and function score than open acromioplasty at 12 years.1 In the retrospective trial, ASD was also associated with a 10% better combined pain and function score than prolonged physical therapy in patients older than 57 years (the median age of study participants) but not patients younger than 57 years.2

Two other studies found improvements in pain and function

Two other prospective cohort studies didn’t use a comparison group but followed changes in standardized shoulder pain and function scores for 5 to 6 years after ASD. In one study, pain decreased 6 points on a 10-point visual analog scale by 6 months postop (P<.001).3 In both studies, a 9% to 10% improvement in function was seen between 6 months and 5 to 6 years after surgery.3,4

A third cohort study that asked patients about overall pain and satisfaction 8 to 11 years after ASD found that most were “very” or “quite” satisfied and half were pain-free.5,6

Rotator cuff tears found less likely with ASD

An anatomic study obtained ultrasounds of patients 13 to 17 years after ASD and compared the findings to rotator cuff ultrasounds of the general population.7 Patients who had ASD were 22% less likely to demonstrate rotator cuff tears at the end of the study (no statistics were reported to measure significance).

RECOMMENDATIONS

Guidelines from the Washington State Department of Labor and Industry state that patients who should undergo isolated subacromial decompression (with or without acromioplasty) need to have documented subacromial impingement syndrome with magnetic resonance imaging evidence of rotator cuff tendonopathy or tear, have undergone 12 weeks of conservative therapy (including at least active assisted range of motion and home-based exercises), and have had a subacromial injection with a local anesthetic that has provided documented relief of pain.8

No current guidelines are available from national or international orthopedic or sports medicine organizations.

1. Odenbring S, Wagner P, Atroshi I. Long-term outcomes of arthroscopic acromioplasty of chronic shoulder impingement syndrome: a prospective cohort study with a minimum of 12 years’ follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:1092–1098.

2. Biberthaler P, Beirer M, Kirchhoff S, et al. Significant benefit for older patients after arthroscopic subacromial decompression: a long-term follow-up study. Int Orthop. 2013;37:457–462.

3. Lunsjo K, Bengtsson M, Nordqvist A, et al. Patients with shoulder impingement remain satisfied 6 years after arthroscopic subacromial decompression. Acta Orthop. 2011;82:711–713.

4. Dom K, Van Glabbeek F, Van Riet RP, et al. Arthroscopic subacromial decompression for advanced (stage II) impingement syndrome: a study of 52 patients with 5 year follow-up. Acta Orthop Belg. 2003;69:13–17.

5. Klintberg IH, Karlsson J, Svantesson U. Health-related quality of life, patient satisfaction, and physical activity 8–11 years after arthroscopic subacromial decompression. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:598–608.

6. Klintberg IH, Svantesson U, Karlsson J. Long-term patient satisfaction and functional outcome 8-11 years after subacromial decompression. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18:394–403.

7. Bjornsson H, Norlin R, Knutsson A, et al. Fewer rotator cuff tears fifteen years after arthroscopic subacromial decompression. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:111–115.

8. Washington State Department of Labor and Industries. Shoulder Conditions Diagnosis and Treatment Guideline. Available at: http://www.lni.wa.gov/ClaimsIns/Files/OMD/MedTreat/FINALguidelineShoulderConditionsOct242013.pdf. Accessed October 20, 2015.

It’s impossible to say for certain in the absence of randomized controlled trials. However, in patients whose impingement symptoms don’t improve after 3 to 6 months, arthroscopic subacromial decompression (ASD) is associated with modest (about 10%) long-term improvement in pain and function compared with open acromioplasty or baseline (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, cohort studies).