User login

Noncompete Agreements and Their Impact on the Medical Landscape

In April 2024, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) issued a nationwide rule to ban most employee noncompete agreements, including many used in health care1; however, that rule never took effect. In August 2024, a federal district court ruled that the FTC had exceeded its statutory authority and blocked the ban,2 and subsequent litigation and agency actions followed. On September 5, 2025, the FTC formally moved to accede to vacatur—in other words, it will not enforce the rule and backed away from defending it on appeal.3 As of December 2025, there is no active federal ban on physician noncompetes. The obligations of the physician employee are dictated by state law and the precise language of the contract that is signed.

In this article, we discuss the historical origins of noncompetes, employer and physician perspectives, and the downstream consequences for patient continuity, access, and health care costs.

Background

The concept of noncompete agreements is not new—this legal principle dates back several centuries, but it was not until several hundred years later, between the 1950s and 1980s, that noncompete agreements became routine in physician contracts. This trend emerged, at least in part, from the growing commoditization of medicine, the expansion of hospital infrastructure, and the rise of physicians employed by entities rather than owning a private practice. Medical practices, hospitals, and increasingly large private groups began using noncompete agreements to prevent physicians from leaving and establishing competing practices nearby. Since then, noncompetes have remained a contentious issue within both the legal system and the broader physician-employer relationship.

Employer vs Employee Perspective

From the employer’s perspective, health care systems and medical groups argue that noncompete agreements are necessary to protect legitimate business interests, citing physician training, established patient relationships, and proprietary information gained from employment with that entity as supporting reasons. Additionally, employers maintain that recouping the cost of recruitment and onboarding investments as well as sustaining continuity of care within the organization should take precedence. On occasion, health care systems will invest time and financial resources in recruiting physicians, provide administrative and clinical support, and integrate new employees into established referral pathways and patient populations. In this view, noncompetes serve as a tool to ensure stability within the health care system, discouraging abrupt departures that could fracture patient care or lead to unfair competition using institutional resources. While these arguments hold merit in certain cases, many physicians do not receive employer-funded education or training beyond what is required in residency and fellowship. As a result, the financial justifications for noncompetes often are overstated; on the contrary, the cost of a “buy-out” or the financial barrier imposed by a noncompete clause can amount to a considerable portion of a physician’s annual salary—sometimes multiple times that amount—creating an imbalance that favors the employer and limits professional mobility.

When a physician is prohibited from practicing in a specific area after leaving an employer, a complex web of adverse consequences can arise, impacting both the physician and the patients they serve. Physician mobility and career choice become restricted, effectively constraining the physicians’ livelihood and ability to provide for themselves and their dependents; in single-earner physician families, this can have devastating financial consequences. These limitations contribute to growing burnout and dissatisfaction within the medical profession, which already is facing unprecedented levels of stress and physician workforce shortages.4

Effect on Patients

When a physician is forced to relocate to a new geographic region because of a noncompete clause, their patients can experience substantial disruptions in care. Access to medical services may be affected, leading to longer wait-times and fewer available appointments, especially in areas that already have a shortage of providers. Patients may lose longstanding relationships with doctors who know their medical histories, which can interrupt treatment plans and increase the risk of complications. Those with chronic illnesses, complex conditions, or time-sensitive treatments are particularly vulnerable to adverse outcomes. Many patients must travel farther—sometimes out of their insurance network—to find replacement care, increasing both financial and logistical burdens. These abrupt transitions also can raise health care costs due to emergency department use, inefficient handoffs, and higher incidence of morbidity/mortality.5 Noncompete restrictions often prevent physicians from informing patients where they are relocating, creating confusion and fragmentation of care. As a result, trust in the health care system may decline when patients perceive that business agreements are being prioritized above their wellbeing. The impact may be even more severe in rural or underserved communities where alternative providers are scarce.

Final Thoughts

In recent years, noncompete agreements in health care have come under intensified scrutiny for their potential to stifle physician mobility, reduce competition, and inflate health care costs by limiting where and how physicians can practice. The trajectory of noncompetes in physician employment reflects broader shifts in how medicine is structured and delivered in the United States. In the latter half of the 20th century, what began as a centuries-old legal concept became a standard feature of physician employment contracts. That evolution largely was driven by the corporatization of medicine and large hospital group/private equity employment of physicians. As these agreements proliferated, public policy questions emerged: What does restricting a physician’s mobility do to patient access? To competition in provider markets? To the cost and availability of care? To the current epidemic of physician burnout?

These questions moved from the legal sidelines to center stage in the 2020s, when the FTC sought to tackle noncompetes across the entire economy—physicians included—on the theory they suppressed labor mobility, entrepreneurship, and competition. In February 2020, the American Medical Association submitted comments to the FTC on the utility of noncompete agreements in employee contracts stating that they restrict competition, can disrupt continuity of care, and may limit access to care.6 Although the FTC’s regulatory attempt in April 2024 provoked strong policy signals, it was challenged and ultimately blocked. Rather than a clear federal prohibition, the outcome is a more incremental state-based shift in rules governing physician noncompetes. For physicians today, this means more awareness and more leverage, but also more complexity. Whether a noncompete will be enforceable depends heavily on the state, the wording of the contract, the structure of the employer, and the specialty. From a negotiation standpoint, physicians need more guidance and awareness on the exact ramifications of their employee contract. For newly minted physicians, many of whom enter the workforce with considerable training debt, the priority often is securing employment to work toward financial stability, building a family, or both; however, all physicians should press for shorter durations, tighter geographic limits, narrower scopes of service, clear buy-out options, and explicit patient-continuity protections. Better yet, physicians can exercise the right of refusal to any noncompete clause at all. Becoming involved with a local medical organization or foundation can provide immense support, both in reviewing contracts as well as learning how to become advocates for physicians in this environment. As more physicians stand together to protect both practice autonomy and the right to quality care, we all become closer to rediscovering the beauty and fulfillment in the purest form of medicine.

- Federal Trade Commission. FTC announces rule banning noncompetes. April 23, 2024. Accessed December 1, 2025. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2024/04/ftc-announces-rule-banning-noncompetes

- US Chamber of Commerce. Ryan LLC v FTC. August 20, 2024. Accessed December 1, 2025. https://www.uschamber.com/cases/antitrust-and-competition-law/ryan-llc-v.-ftc

- Federal Trade Commission. Federal Trade Commission files to accede to vacatur of non-compete clause rule. September 5, 2025. Accessed December 1, 2025. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2025/09/federal-trade-commission-files-accede-vacatur-non-compete-clause-rule

- Marshall JJ, Ashwath ML, Jefferies JL, et al. Restrictive covenants and noncompete clauses for physicians. JACC Adv. 2023;2:100547.

- Sabety A. The value of relationships in healthcare. J Publich Economics. 2023;225:104927.

- American Medical Association. AMA provides comment to FTC on non-compete agreements. National Advocacy Update. February 14, 2020. Accessed November 25, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/health-care-advocacy/advocacy-update/feb-14-2020-national-advocacy-update

In April 2024, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) issued a nationwide rule to ban most employee noncompete agreements, including many used in health care1; however, that rule never took effect. In August 2024, a federal district court ruled that the FTC had exceeded its statutory authority and blocked the ban,2 and subsequent litigation and agency actions followed. On September 5, 2025, the FTC formally moved to accede to vacatur—in other words, it will not enforce the rule and backed away from defending it on appeal.3 As of December 2025, there is no active federal ban on physician noncompetes. The obligations of the physician employee are dictated by state law and the precise language of the contract that is signed.

In this article, we discuss the historical origins of noncompetes, employer and physician perspectives, and the downstream consequences for patient continuity, access, and health care costs.

Background

The concept of noncompete agreements is not new—this legal principle dates back several centuries, but it was not until several hundred years later, between the 1950s and 1980s, that noncompete agreements became routine in physician contracts. This trend emerged, at least in part, from the growing commoditization of medicine, the expansion of hospital infrastructure, and the rise of physicians employed by entities rather than owning a private practice. Medical practices, hospitals, and increasingly large private groups began using noncompete agreements to prevent physicians from leaving and establishing competing practices nearby. Since then, noncompetes have remained a contentious issue within both the legal system and the broader physician-employer relationship.

Employer vs Employee Perspective

From the employer’s perspective, health care systems and medical groups argue that noncompete agreements are necessary to protect legitimate business interests, citing physician training, established patient relationships, and proprietary information gained from employment with that entity as supporting reasons. Additionally, employers maintain that recouping the cost of recruitment and onboarding investments as well as sustaining continuity of care within the organization should take precedence. On occasion, health care systems will invest time and financial resources in recruiting physicians, provide administrative and clinical support, and integrate new employees into established referral pathways and patient populations. In this view, noncompetes serve as a tool to ensure stability within the health care system, discouraging abrupt departures that could fracture patient care or lead to unfair competition using institutional resources. While these arguments hold merit in certain cases, many physicians do not receive employer-funded education or training beyond what is required in residency and fellowship. As a result, the financial justifications for noncompetes often are overstated; on the contrary, the cost of a “buy-out” or the financial barrier imposed by a noncompete clause can amount to a considerable portion of a physician’s annual salary—sometimes multiple times that amount—creating an imbalance that favors the employer and limits professional mobility.

When a physician is prohibited from practicing in a specific area after leaving an employer, a complex web of adverse consequences can arise, impacting both the physician and the patients they serve. Physician mobility and career choice become restricted, effectively constraining the physicians’ livelihood and ability to provide for themselves and their dependents; in single-earner physician families, this can have devastating financial consequences. These limitations contribute to growing burnout and dissatisfaction within the medical profession, which already is facing unprecedented levels of stress and physician workforce shortages.4

Effect on Patients

When a physician is forced to relocate to a new geographic region because of a noncompete clause, their patients can experience substantial disruptions in care. Access to medical services may be affected, leading to longer wait-times and fewer available appointments, especially in areas that already have a shortage of providers. Patients may lose longstanding relationships with doctors who know their medical histories, which can interrupt treatment plans and increase the risk of complications. Those with chronic illnesses, complex conditions, or time-sensitive treatments are particularly vulnerable to adverse outcomes. Many patients must travel farther—sometimes out of their insurance network—to find replacement care, increasing both financial and logistical burdens. These abrupt transitions also can raise health care costs due to emergency department use, inefficient handoffs, and higher incidence of morbidity/mortality.5 Noncompete restrictions often prevent physicians from informing patients where they are relocating, creating confusion and fragmentation of care. As a result, trust in the health care system may decline when patients perceive that business agreements are being prioritized above their wellbeing. The impact may be even more severe in rural or underserved communities where alternative providers are scarce.

Final Thoughts

In recent years, noncompete agreements in health care have come under intensified scrutiny for their potential to stifle physician mobility, reduce competition, and inflate health care costs by limiting where and how physicians can practice. The trajectory of noncompetes in physician employment reflects broader shifts in how medicine is structured and delivered in the United States. In the latter half of the 20th century, what began as a centuries-old legal concept became a standard feature of physician employment contracts. That evolution largely was driven by the corporatization of medicine and large hospital group/private equity employment of physicians. As these agreements proliferated, public policy questions emerged: What does restricting a physician’s mobility do to patient access? To competition in provider markets? To the cost and availability of care? To the current epidemic of physician burnout?

These questions moved from the legal sidelines to center stage in the 2020s, when the FTC sought to tackle noncompetes across the entire economy—physicians included—on the theory they suppressed labor mobility, entrepreneurship, and competition. In February 2020, the American Medical Association submitted comments to the FTC on the utility of noncompete agreements in employee contracts stating that they restrict competition, can disrupt continuity of care, and may limit access to care.6 Although the FTC’s regulatory attempt in April 2024 provoked strong policy signals, it was challenged and ultimately blocked. Rather than a clear federal prohibition, the outcome is a more incremental state-based shift in rules governing physician noncompetes. For physicians today, this means more awareness and more leverage, but also more complexity. Whether a noncompete will be enforceable depends heavily on the state, the wording of the contract, the structure of the employer, and the specialty. From a negotiation standpoint, physicians need more guidance and awareness on the exact ramifications of their employee contract. For newly minted physicians, many of whom enter the workforce with considerable training debt, the priority often is securing employment to work toward financial stability, building a family, or both; however, all physicians should press for shorter durations, tighter geographic limits, narrower scopes of service, clear buy-out options, and explicit patient-continuity protections. Better yet, physicians can exercise the right of refusal to any noncompete clause at all. Becoming involved with a local medical organization or foundation can provide immense support, both in reviewing contracts as well as learning how to become advocates for physicians in this environment. As more physicians stand together to protect both practice autonomy and the right to quality care, we all become closer to rediscovering the beauty and fulfillment in the purest form of medicine.

In April 2024, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) issued a nationwide rule to ban most employee noncompete agreements, including many used in health care1; however, that rule never took effect. In August 2024, a federal district court ruled that the FTC had exceeded its statutory authority and blocked the ban,2 and subsequent litigation and agency actions followed. On September 5, 2025, the FTC formally moved to accede to vacatur—in other words, it will not enforce the rule and backed away from defending it on appeal.3 As of December 2025, there is no active federal ban on physician noncompetes. The obligations of the physician employee are dictated by state law and the precise language of the contract that is signed.

In this article, we discuss the historical origins of noncompetes, employer and physician perspectives, and the downstream consequences for patient continuity, access, and health care costs.

Background

The concept of noncompete agreements is not new—this legal principle dates back several centuries, but it was not until several hundred years later, between the 1950s and 1980s, that noncompete agreements became routine in physician contracts. This trend emerged, at least in part, from the growing commoditization of medicine, the expansion of hospital infrastructure, and the rise of physicians employed by entities rather than owning a private practice. Medical practices, hospitals, and increasingly large private groups began using noncompete agreements to prevent physicians from leaving and establishing competing practices nearby. Since then, noncompetes have remained a contentious issue within both the legal system and the broader physician-employer relationship.

Employer vs Employee Perspective

From the employer’s perspective, health care systems and medical groups argue that noncompete agreements are necessary to protect legitimate business interests, citing physician training, established patient relationships, and proprietary information gained from employment with that entity as supporting reasons. Additionally, employers maintain that recouping the cost of recruitment and onboarding investments as well as sustaining continuity of care within the organization should take precedence. On occasion, health care systems will invest time and financial resources in recruiting physicians, provide administrative and clinical support, and integrate new employees into established referral pathways and patient populations. In this view, noncompetes serve as a tool to ensure stability within the health care system, discouraging abrupt departures that could fracture patient care or lead to unfair competition using institutional resources. While these arguments hold merit in certain cases, many physicians do not receive employer-funded education or training beyond what is required in residency and fellowship. As a result, the financial justifications for noncompetes often are overstated; on the contrary, the cost of a “buy-out” or the financial barrier imposed by a noncompete clause can amount to a considerable portion of a physician’s annual salary—sometimes multiple times that amount—creating an imbalance that favors the employer and limits professional mobility.

When a physician is prohibited from practicing in a specific area after leaving an employer, a complex web of adverse consequences can arise, impacting both the physician and the patients they serve. Physician mobility and career choice become restricted, effectively constraining the physicians’ livelihood and ability to provide for themselves and their dependents; in single-earner physician families, this can have devastating financial consequences. These limitations contribute to growing burnout and dissatisfaction within the medical profession, which already is facing unprecedented levels of stress and physician workforce shortages.4

Effect on Patients

When a physician is forced to relocate to a new geographic region because of a noncompete clause, their patients can experience substantial disruptions in care. Access to medical services may be affected, leading to longer wait-times and fewer available appointments, especially in areas that already have a shortage of providers. Patients may lose longstanding relationships with doctors who know their medical histories, which can interrupt treatment plans and increase the risk of complications. Those with chronic illnesses, complex conditions, or time-sensitive treatments are particularly vulnerable to adverse outcomes. Many patients must travel farther—sometimes out of their insurance network—to find replacement care, increasing both financial and logistical burdens. These abrupt transitions also can raise health care costs due to emergency department use, inefficient handoffs, and higher incidence of morbidity/mortality.5 Noncompete restrictions often prevent physicians from informing patients where they are relocating, creating confusion and fragmentation of care. As a result, trust in the health care system may decline when patients perceive that business agreements are being prioritized above their wellbeing. The impact may be even more severe in rural or underserved communities where alternative providers are scarce.

Final Thoughts

In recent years, noncompete agreements in health care have come under intensified scrutiny for their potential to stifle physician mobility, reduce competition, and inflate health care costs by limiting where and how physicians can practice. The trajectory of noncompetes in physician employment reflects broader shifts in how medicine is structured and delivered in the United States. In the latter half of the 20th century, what began as a centuries-old legal concept became a standard feature of physician employment contracts. That evolution largely was driven by the corporatization of medicine and large hospital group/private equity employment of physicians. As these agreements proliferated, public policy questions emerged: What does restricting a physician’s mobility do to patient access? To competition in provider markets? To the cost and availability of care? To the current epidemic of physician burnout?

These questions moved from the legal sidelines to center stage in the 2020s, when the FTC sought to tackle noncompetes across the entire economy—physicians included—on the theory they suppressed labor mobility, entrepreneurship, and competition. In February 2020, the American Medical Association submitted comments to the FTC on the utility of noncompete agreements in employee contracts stating that they restrict competition, can disrupt continuity of care, and may limit access to care.6 Although the FTC’s regulatory attempt in April 2024 provoked strong policy signals, it was challenged and ultimately blocked. Rather than a clear federal prohibition, the outcome is a more incremental state-based shift in rules governing physician noncompetes. For physicians today, this means more awareness and more leverage, but also more complexity. Whether a noncompete will be enforceable depends heavily on the state, the wording of the contract, the structure of the employer, and the specialty. From a negotiation standpoint, physicians need more guidance and awareness on the exact ramifications of their employee contract. For newly minted physicians, many of whom enter the workforce with considerable training debt, the priority often is securing employment to work toward financial stability, building a family, or both; however, all physicians should press for shorter durations, tighter geographic limits, narrower scopes of service, clear buy-out options, and explicit patient-continuity protections. Better yet, physicians can exercise the right of refusal to any noncompete clause at all. Becoming involved with a local medical organization or foundation can provide immense support, both in reviewing contracts as well as learning how to become advocates for physicians in this environment. As more physicians stand together to protect both practice autonomy and the right to quality care, we all become closer to rediscovering the beauty and fulfillment in the purest form of medicine.

- Federal Trade Commission. FTC announces rule banning noncompetes. April 23, 2024. Accessed December 1, 2025. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2024/04/ftc-announces-rule-banning-noncompetes

- US Chamber of Commerce. Ryan LLC v FTC. August 20, 2024. Accessed December 1, 2025. https://www.uschamber.com/cases/antitrust-and-competition-law/ryan-llc-v.-ftc

- Federal Trade Commission. Federal Trade Commission files to accede to vacatur of non-compete clause rule. September 5, 2025. Accessed December 1, 2025. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2025/09/federal-trade-commission-files-accede-vacatur-non-compete-clause-rule

- Marshall JJ, Ashwath ML, Jefferies JL, et al. Restrictive covenants and noncompete clauses for physicians. JACC Adv. 2023;2:100547.

- Sabety A. The value of relationships in healthcare. J Publich Economics. 2023;225:104927.

- American Medical Association. AMA provides comment to FTC on non-compete agreements. National Advocacy Update. February 14, 2020. Accessed November 25, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/health-care-advocacy/advocacy-update/feb-14-2020-national-advocacy-update

- Federal Trade Commission. FTC announces rule banning noncompetes. April 23, 2024. Accessed December 1, 2025. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2024/04/ftc-announces-rule-banning-noncompetes

- US Chamber of Commerce. Ryan LLC v FTC. August 20, 2024. Accessed December 1, 2025. https://www.uschamber.com/cases/antitrust-and-competition-law/ryan-llc-v.-ftc

- Federal Trade Commission. Federal Trade Commission files to accede to vacatur of non-compete clause rule. September 5, 2025. Accessed December 1, 2025. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2025/09/federal-trade-commission-files-accede-vacatur-non-compete-clause-rule

- Marshall JJ, Ashwath ML, Jefferies JL, et al. Restrictive covenants and noncompete clauses for physicians. JACC Adv. 2023;2:100547.

- Sabety A. The value of relationships in healthcare. J Publich Economics. 2023;225:104927.

- American Medical Association. AMA provides comment to FTC on non-compete agreements. National Advocacy Update. February 14, 2020. Accessed November 25, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/health-care-advocacy/advocacy-update/feb-14-2020-national-advocacy-update

PRACTICE POINTS

- There is no active federal ban on physician noncompete agreements as of late 2025.

- Physician noncompetes have expanded alongside the corporatization of medicine but raise serious concerns about physician mobility, burnout, workforce shortages, and patient access to care, particularly in underserved areas.

- Physicians should critically evaluate noncompetes prior to signing an agreement, advocating for narrower limits or refusal altogether to protect professional autonomy, continuity of care, and patient welfare.

Direct Care Dermatology: Weighing the Pros and Cons for the Early-Career Physician

Direct Care Dermatology: Weighing the Pros and Cons for the Early-Career Physician

As the health care landscape continues to shift, direct care (also known as direct pay) models have emerged as attractive alternatives to traditional insurance-based practice. For dermatology residents poised to enter the workforce, the direct care model offers potential advantages in autonomy, patient relationships, and work-life balance, but not without considerable risks and operational challenges. This article explores the key benefits and drawbacks of starting a direct care dermatology practice, providing a framework to help early-career dermatologists determine whether this path aligns with their personal and professional goals.

The transition from dermatology residency to clinical practice allows for a variety of paths, from large academic institutions to private practice to corporate entities (private equity–owned groups). In recent years, the direct care model has gained traction, particularly among physicians seeking greater autonomy and a more sustainable pace of practice.

Direct care dermatology practices operate outside the constraints of third-party payers, offering patients transparent pricing and direct access to care in exchange for fees paid out of pocket. By eliminating insurance companies as the middleman, it allows for less overhead, longer visits with patients, and increased access to care; however, though this model may seem appealing, direct care practices are not without their own set of challenges, especially amid rising concerns over physician burnout and administrative burden.

This article explores the key benefits and drawbacks of starting a direct care dermatology practice, providing a framework to help early-career dermatologists determine whether this path aligns with their personal and professional goals.

Despite its appeal, starting a direct care practice is not without substantial risks and hurdles—particularly for residents just out of training. These challenges include financial risks and startup costs, market uncertainty, lack of mentorship or support, and limitations in treating complex dermatologic conditions.

Before committing to practicing via a direct care model, dermatology residents should reflect on the following:

- Risk tolerance: Are you comfortable navigating the business and financial risk?

- Location: Does your target community have patients willing and able to pay out of pocket?

- Scope of interest: Will a direct care practice align with your clinical passions?

- Support systems: Do you have access to mentors, legal and financial advisors, and operational support?

- Long-term goals: Are you building a lifestyle practice, a scalable business, or a stepping stone to a future opportunity?

Ultimately, the decision to pursue a direct care model requires careful reflection on personal values, financial preparedness, and the unique needs of the community one intends to serve.

The direct care dermatology model offers an appealing alternative to traditional practice, especially for those prioritizing autonomy, patient connection, and work-life balance; however, it demands an entrepreneurial spirit as well as careful planning and an acceptance of financial uncertainty—factors that may pose challenges for new graduates. For dermatology residents, the decision to pursue direct care should be grounded in personal values, practical considerations, and a clear understanding of both the opportunities and limitations of this evolving practice model.

- Sinsky CA, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med.

- Dorrell DN, Feldman S, Wei-ting Huang W. The most common causes of burnout among US academic dermatologists based on a survey study. J Am Acad of Dermatol. 2019;81:269-270.

- Carlasare LE. Defining the place of direct primary care in a value-based care system. WMJ. 2018;117:106-110.

As the health care landscape continues to shift, direct care (also known as direct pay) models have emerged as attractive alternatives to traditional insurance-based practice. For dermatology residents poised to enter the workforce, the direct care model offers potential advantages in autonomy, patient relationships, and work-life balance, but not without considerable risks and operational challenges. This article explores the key benefits and drawbacks of starting a direct care dermatology practice, providing a framework to help early-career dermatologists determine whether this path aligns with their personal and professional goals.

The transition from dermatology residency to clinical practice allows for a variety of paths, from large academic institutions to private practice to corporate entities (private equity–owned groups). In recent years, the direct care model has gained traction, particularly among physicians seeking greater autonomy and a more sustainable pace of practice.

Direct care dermatology practices operate outside the constraints of third-party payers, offering patients transparent pricing and direct access to care in exchange for fees paid out of pocket. By eliminating insurance companies as the middleman, it allows for less overhead, longer visits with patients, and increased access to care; however, though this model may seem appealing, direct care practices are not without their own set of challenges, especially amid rising concerns over physician burnout and administrative burden.

This article explores the key benefits and drawbacks of starting a direct care dermatology practice, providing a framework to help early-career dermatologists determine whether this path aligns with their personal and professional goals.

Despite its appeal, starting a direct care practice is not without substantial risks and hurdles—particularly for residents just out of training. These challenges include financial risks and startup costs, market uncertainty, lack of mentorship or support, and limitations in treating complex dermatologic conditions.

Before committing to practicing via a direct care model, dermatology residents should reflect on the following:

- Risk tolerance: Are you comfortable navigating the business and financial risk?

- Location: Does your target community have patients willing and able to pay out of pocket?

- Scope of interest: Will a direct care practice align with your clinical passions?

- Support systems: Do you have access to mentors, legal and financial advisors, and operational support?

- Long-term goals: Are you building a lifestyle practice, a scalable business, or a stepping stone to a future opportunity?

Ultimately, the decision to pursue a direct care model requires careful reflection on personal values, financial preparedness, and the unique needs of the community one intends to serve.

The direct care dermatology model offers an appealing alternative to traditional practice, especially for those prioritizing autonomy, patient connection, and work-life balance; however, it demands an entrepreneurial spirit as well as careful planning and an acceptance of financial uncertainty—factors that may pose challenges for new graduates. For dermatology residents, the decision to pursue direct care should be grounded in personal values, practical considerations, and a clear understanding of both the opportunities and limitations of this evolving practice model.

As the health care landscape continues to shift, direct care (also known as direct pay) models have emerged as attractive alternatives to traditional insurance-based practice. For dermatology residents poised to enter the workforce, the direct care model offers potential advantages in autonomy, patient relationships, and work-life balance, but not without considerable risks and operational challenges. This article explores the key benefits and drawbacks of starting a direct care dermatology practice, providing a framework to help early-career dermatologists determine whether this path aligns with their personal and professional goals.

The transition from dermatology residency to clinical practice allows for a variety of paths, from large academic institutions to private practice to corporate entities (private equity–owned groups). In recent years, the direct care model has gained traction, particularly among physicians seeking greater autonomy and a more sustainable pace of practice.

Direct care dermatology practices operate outside the constraints of third-party payers, offering patients transparent pricing and direct access to care in exchange for fees paid out of pocket. By eliminating insurance companies as the middleman, it allows for less overhead, longer visits with patients, and increased access to care; however, though this model may seem appealing, direct care practices are not without their own set of challenges, especially amid rising concerns over physician burnout and administrative burden.

This article explores the key benefits and drawbacks of starting a direct care dermatology practice, providing a framework to help early-career dermatologists determine whether this path aligns with their personal and professional goals.

Despite its appeal, starting a direct care practice is not without substantial risks and hurdles—particularly for residents just out of training. These challenges include financial risks and startup costs, market uncertainty, lack of mentorship or support, and limitations in treating complex dermatologic conditions.

Before committing to practicing via a direct care model, dermatology residents should reflect on the following:

- Risk tolerance: Are you comfortable navigating the business and financial risk?

- Location: Does your target community have patients willing and able to pay out of pocket?

- Scope of interest: Will a direct care practice align with your clinical passions?

- Support systems: Do you have access to mentors, legal and financial advisors, and operational support?

- Long-term goals: Are you building a lifestyle practice, a scalable business, or a stepping stone to a future opportunity?

Ultimately, the decision to pursue a direct care model requires careful reflection on personal values, financial preparedness, and the unique needs of the community one intends to serve.

The direct care dermatology model offers an appealing alternative to traditional practice, especially for those prioritizing autonomy, patient connection, and work-life balance; however, it demands an entrepreneurial spirit as well as careful planning and an acceptance of financial uncertainty—factors that may pose challenges for new graduates. For dermatology residents, the decision to pursue direct care should be grounded in personal values, practical considerations, and a clear understanding of both the opportunities and limitations of this evolving practice model.

- Sinsky CA, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med.

- Dorrell DN, Feldman S, Wei-ting Huang W. The most common causes of burnout among US academic dermatologists based on a survey study. J Am Acad of Dermatol. 2019;81:269-270.

- Carlasare LE. Defining the place of direct primary care in a value-based care system. WMJ. 2018;117:106-110.

- Sinsky CA, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med.

- Dorrell DN, Feldman S, Wei-ting Huang W. The most common causes of burnout among US academic dermatologists based on a survey study. J Am Acad of Dermatol. 2019;81:269-270.

- Carlasare LE. Defining the place of direct primary care in a value-based care system. WMJ. 2018;117:106-110.

Direct Care Dermatology: Weighing the Pros and Cons for the Early-Career Physician

Direct Care Dermatology: Weighing the Pros and Cons for the Early-Career Physician

PRACTICE POINTS

- Direct care practices may be the new horizon of health care.

- Starting a direct care practice offers autonomy but demands entrepreneurial readiness.

- New dermatologists can enjoy control over scheduling, pricing, and patient care, but success requires business acumen, financial planning, and comfort with risk.

Solitary Pink Plaque on the Neck

The Diagnosis: Plaque-type Syringoma

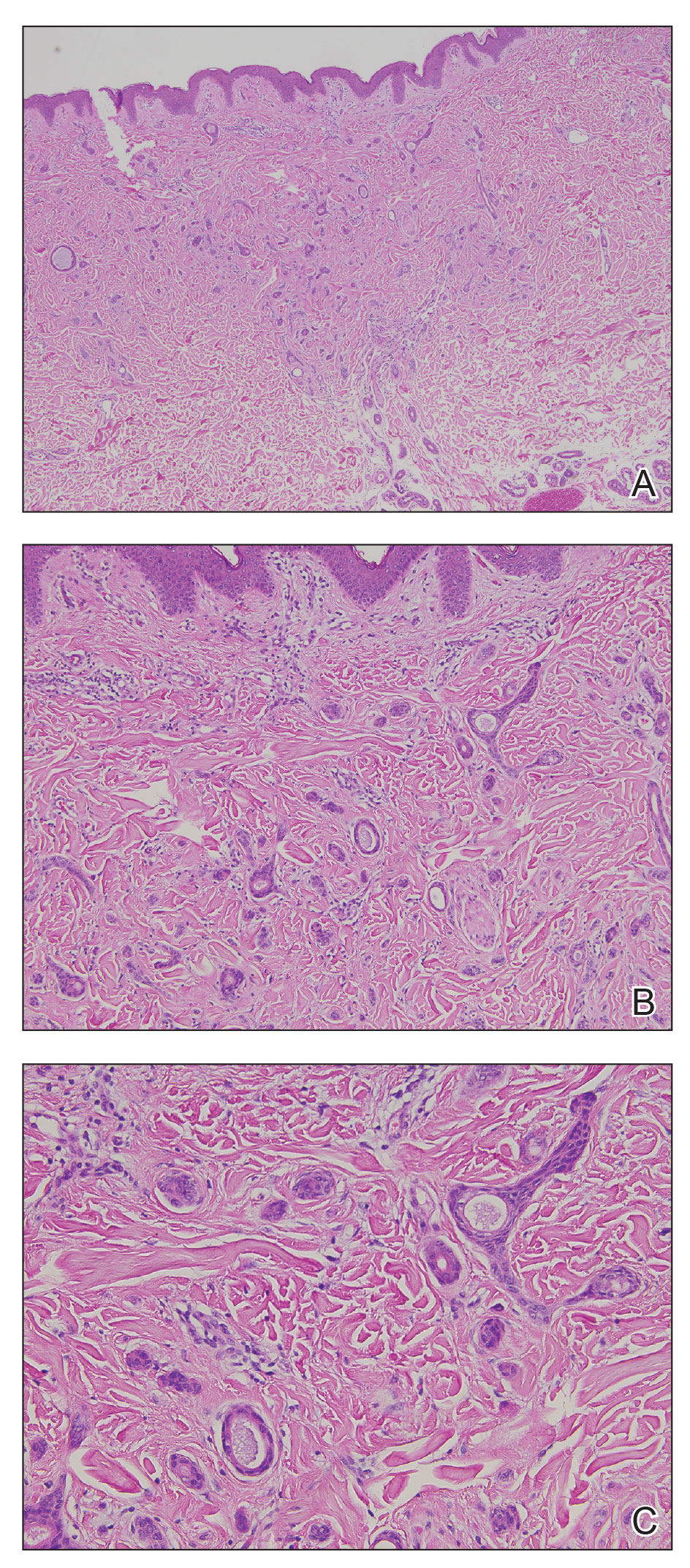

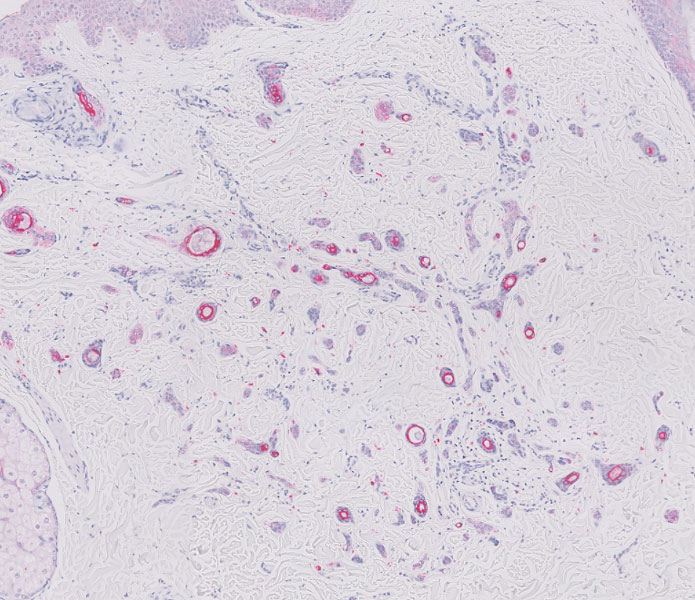

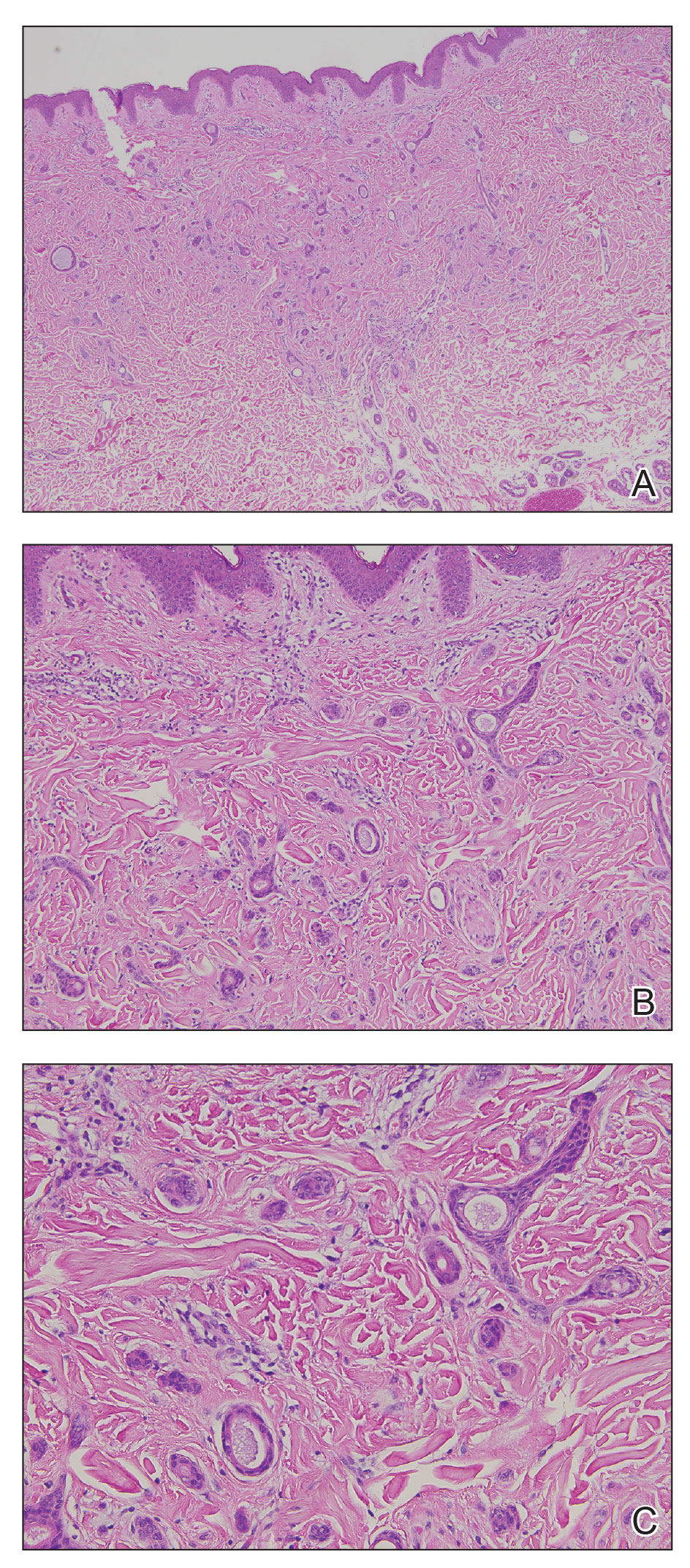

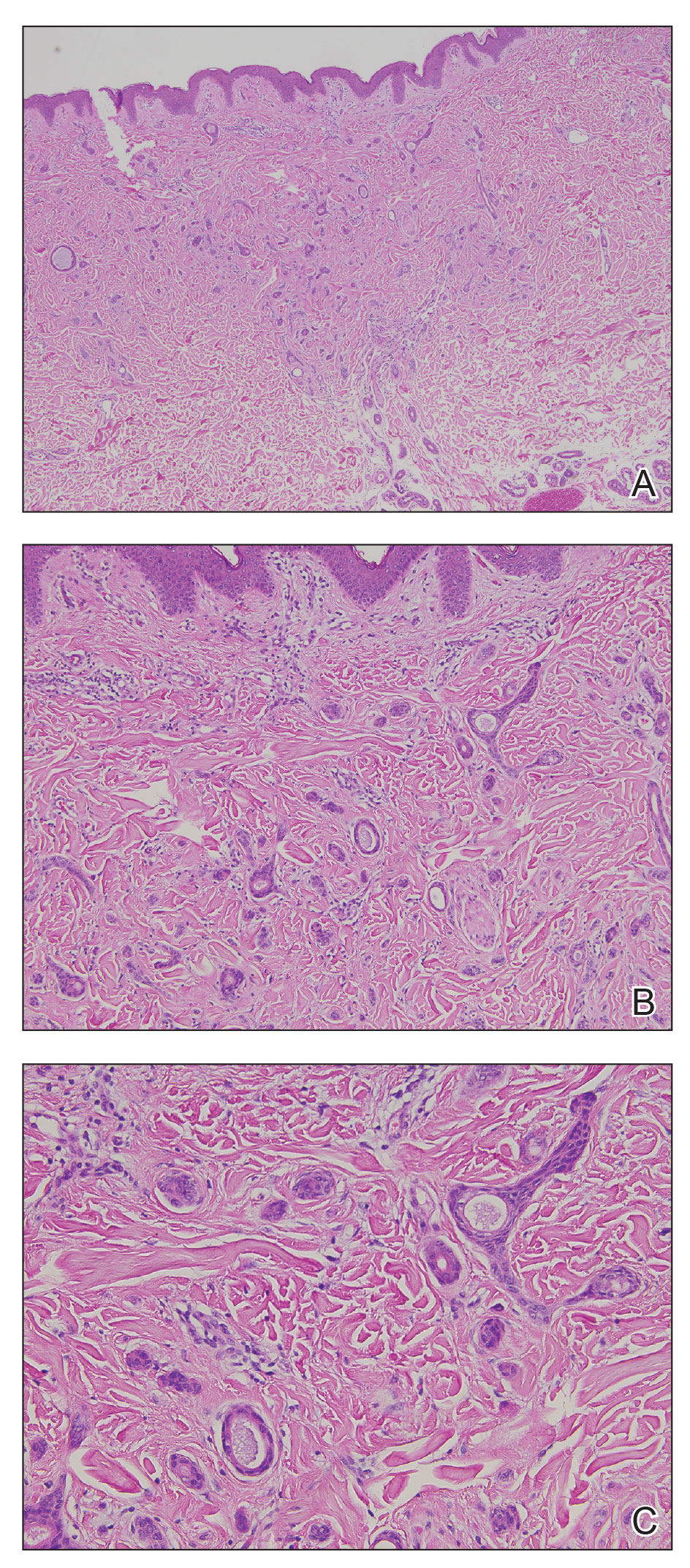

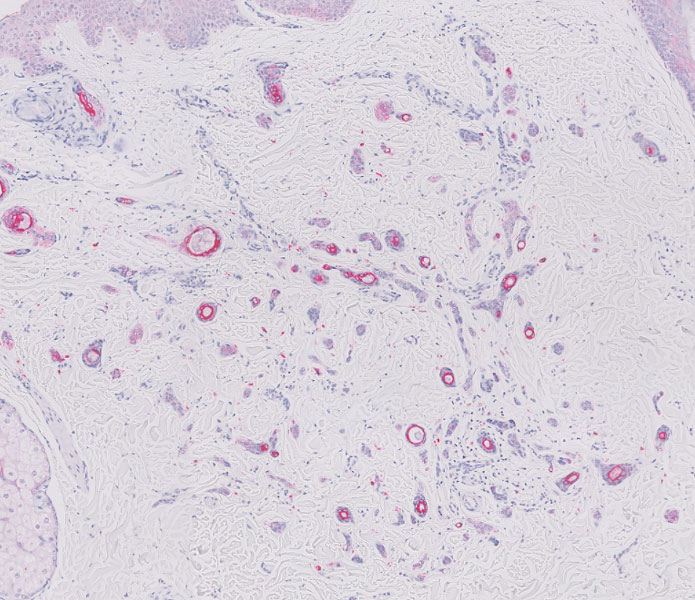

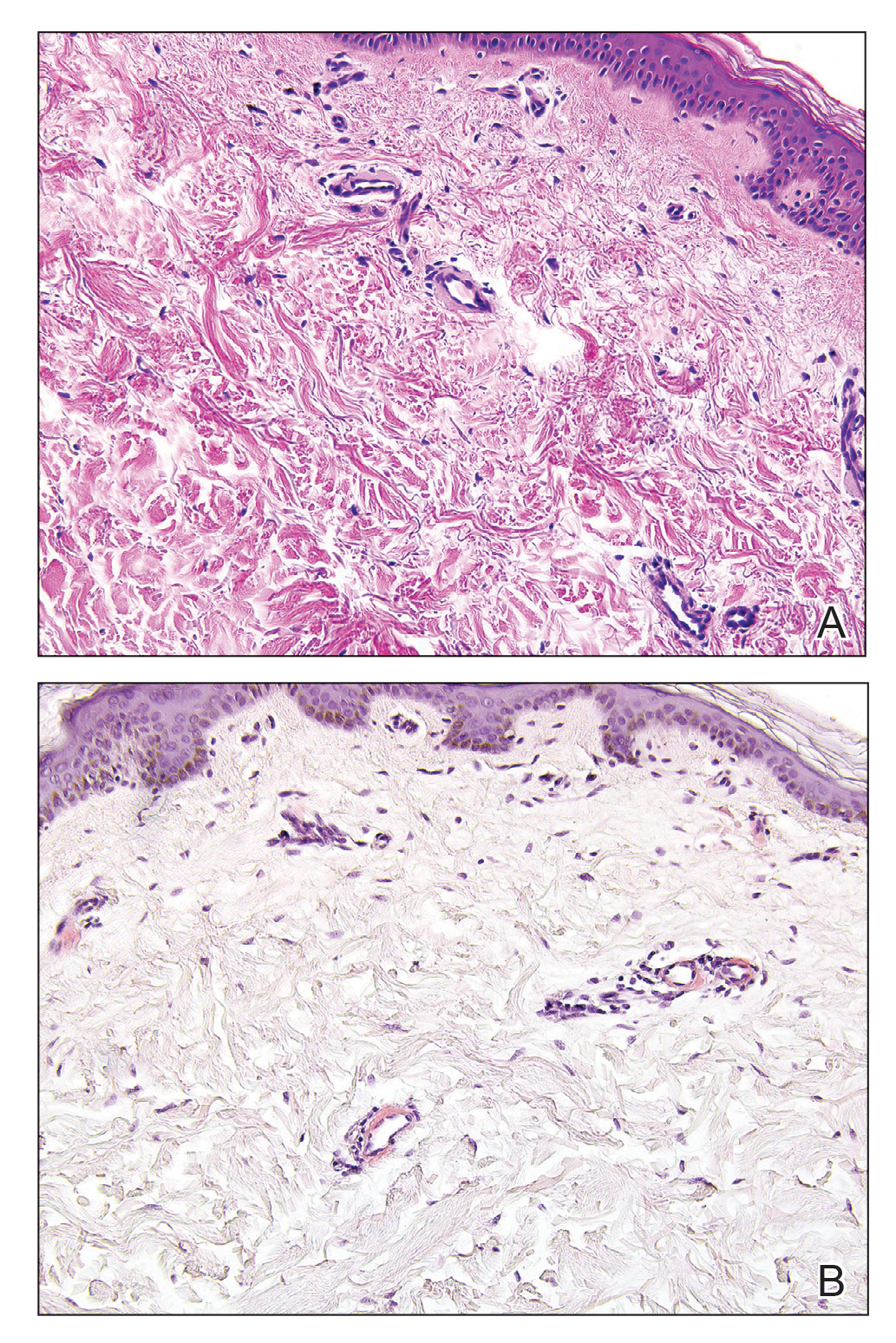

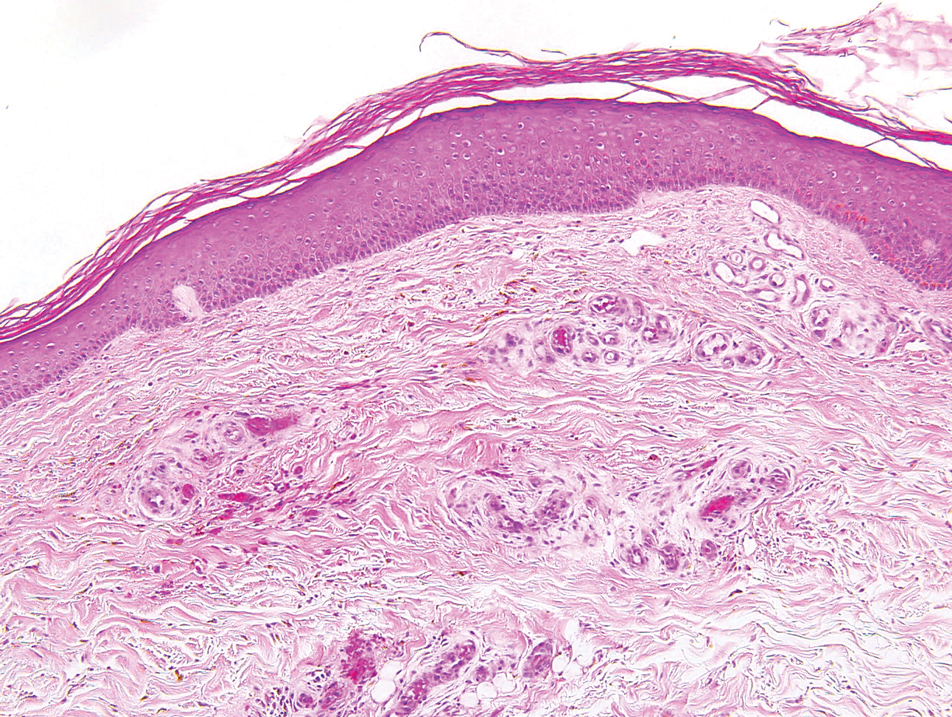

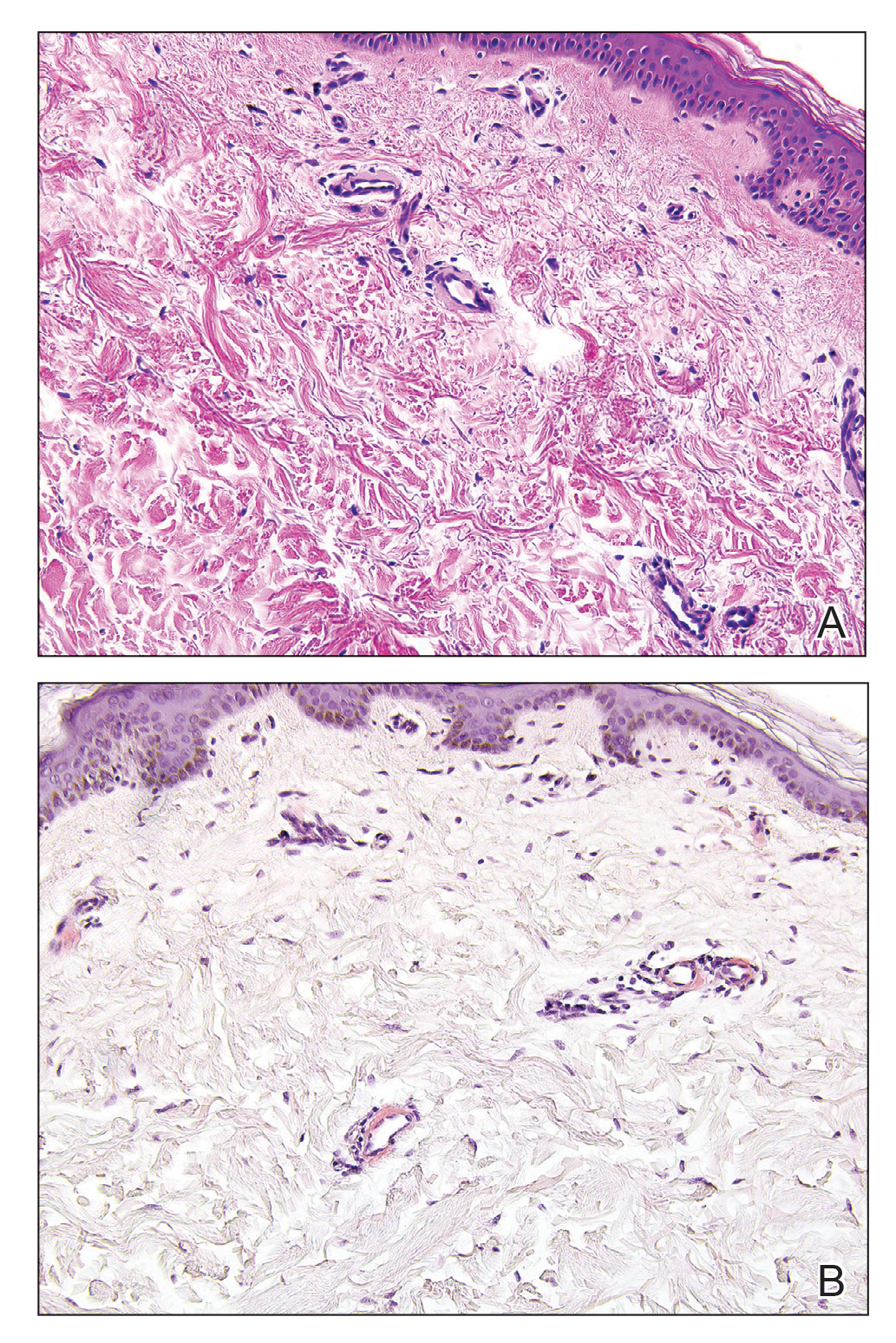

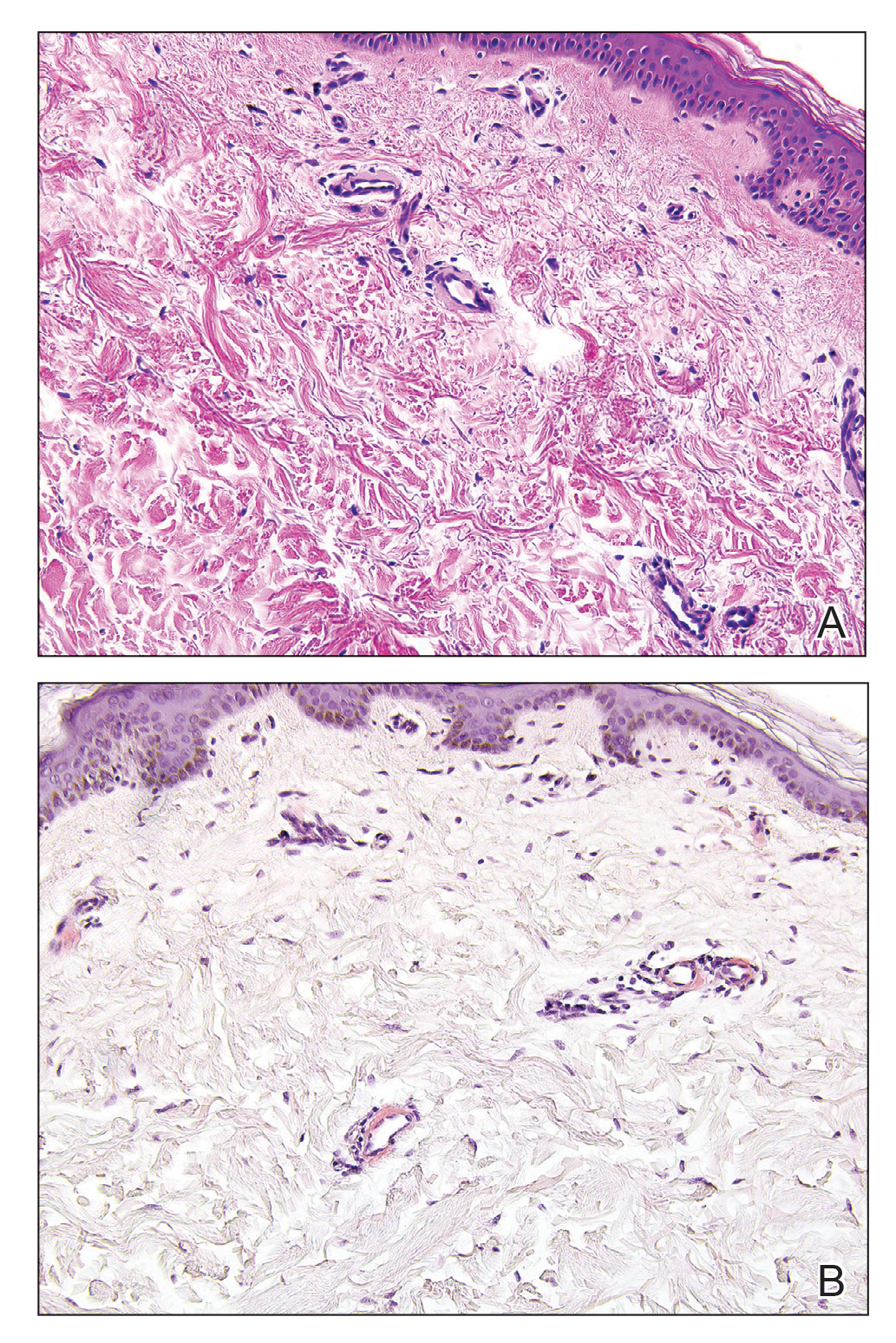

A biopsy demonstrated multiple basaloid islands of tumor cells in the reticular dermis with ductal differentiation, some with a commalike tail. The ducts were lined by 2 to 3 layers of small uniform cuboidal cells without atypia and contained inspissated secretions within the lumina of scattered ducts. There was an associated fibrotic collagenous stroma. There was no evidence of perineural invasion and no deep dermal or subcutaneous extension (Figure 1). Additional cytokeratin immunohistochemical staining highlighted the adnexal proliferation (Figure 2). A diagnosis of plaque-type syringoma (PTS) was made.

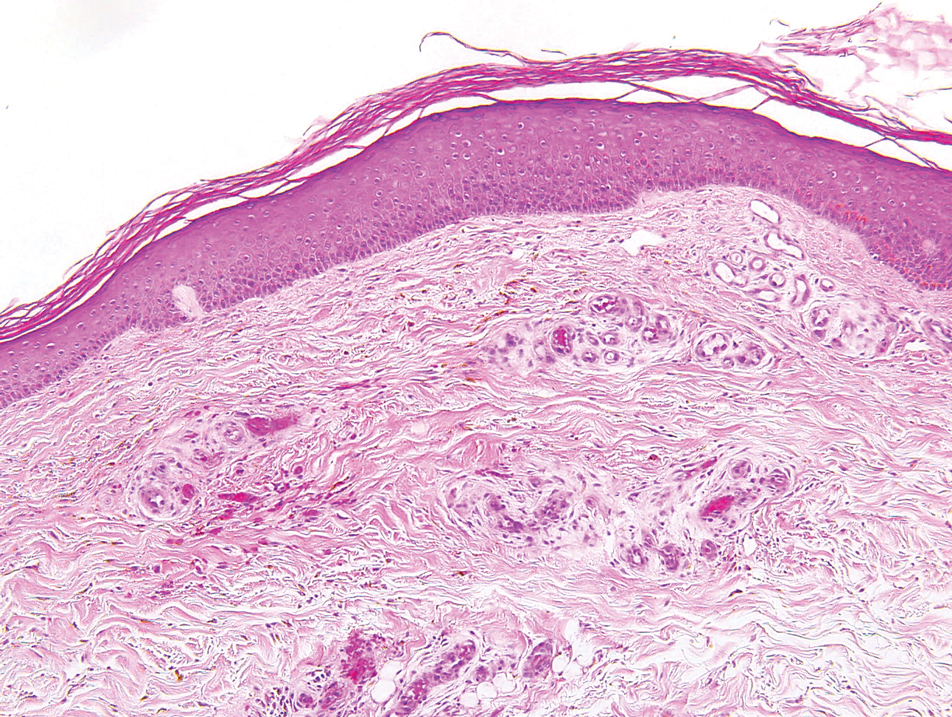

Syringomas are benign dermal sweat gland tumors that typically present as flesh-colored papules on the cheeks or periorbital area of young females. Plaque-type tumors as well as papulonodular, eruptive, disseminated, urticaria pigmentosa–like, lichen planus–like, or milialike syringomas also have been reported. Syringomas may be associated with certain medical conditions such as Down syndrome, Nicolau-Balus syndrome, and both scarring and nonscarring alopecias.1 The clear cell variant of syringoma often is associated with diabetes mellitus.2 Kikuchi et al3 first described PTS in 1979. Plaque-type syringomas rarely are reported in the literature, and sites of involvement include the head and neck region, upper lip, chest, upper extremities, vulva, penis, and scrotum.4-6

Histologically, syringomatous lesions are composed of multiple small ducts lined by 2 to 3 layers of cuboidal epithelium. The ducts may be arranged in nests or strands of basaloid cells surrounded by a dense fibrotic stroma. Occasionally, the ducts will form a comma- or teardropshaped tail; however, this also may be observed in desmoplastic trichoepithelioma (DTE).7 Perineural invasion is absent in syringomas. Syringomas exhibit a lateral growth pattern that typically is limited to the upper half of the reticular dermis and spares the underlying subcutis, muscle, and bone. The growth pattern may be discontinuous with proliferations juxtaposed by normal-appearing skin.8 Syringomas usually express progesterone receptors and are known to proliferate at puberty, suggesting that these neoplasms are under hormonal control.9 Although syringomas are benign, various treatment options that may be pursued for cosmetic purposes include radiofrequency, staged excision, laser ablation, and oral isotretinoin.8,10 If only a superficial biopsy is obtained, syringomas may display features of other adnexal neoplasms, including microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), DTE, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN).

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is a locally aggressive neoplasm first described by Goldstein et al11 in 1982 an indurated, ill-defined plaque or nodule on the face with a predilection for the upper and lower lip. Prior radiation therapy and immunosuppression are risk factors for the development of MAC.12 Histologically, the superficial portion displays small cornifying cysts interspersed with islands of basaloid cells and may mimic a syringoma. However, the deeper portions demonstrate ducts lined by a single layer of cells with a background of hyalinized and sclerotic stroma. The tumor cells may occupy the deep dermis and underlying subcutis, muscle, or bone and demonstrate an infiltrative growth pattern and perineural invasion. Treatment includes Mohs micrographic surgery.

Desmoplastic trichoepitheliomas most commonly present as solitary white to yellowish annular papules or plaques with a central dell located on sun-exposed areas of the face, cheeks, or chin. This benign neoplasm has a bimodal age distribution, primarily affecting females either in childhood or adulthood.13 Histologically, strands and nests of basaloid epithelial cells proliferate in a dense eosinophilic desmoplastic stroma. The basaloid islands are narrow and cordlike with growth parallel to the surface epidermis and do not dive deeply into the deep dermis or subcutis. Ductal differentiation with associated secretions typically is not seen in DTE.1 Calcifications and foreign body granulomatous infiltrates may be present. Merkel cells also are present in this tumor and may be highlighted by immunohistochemistry with cytokeratin 20.14 Rarely, desmoplastic trichoepitheliomas may transform into trichoblastic carcinomas. Treatment may consist of surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.

Morpheaform BCC also is included in the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnosis of infiltrative basaloid neoplasms. It is one of the more aggressive variants of BCC. The use of immunohistochemical staining may aid in differentiating between these sclerosing adnexal neoplasms.15 For example, pleckstrin homologylike domain family A member 1 (PHLDA1) is a stem cell marker that is heavily expressed in DTE as a specific follicular bulge marker but is not present in a morpheaform BCC. This highlights the follicular nature of DTEs at the molecular level. BerEP4 is a monoclonal antibody that serves as an epithelial marker for 2 glycopolypeptides: 34 and 39 kDa. This antibody may demonstrate positivity in morpheaform BCC but does not stain cells of interest in MAC.

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus clinically presents with erythematous and warty papules in a linear distribution following the Blaschko lines. The papules often are reported to be intensely pruritic and usually are localized to one extremity.16 Although adultonset forms of ILVEN have been described,17 it most commonly is diagnosed in young children. Histologically, ILVEN consists of psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with alternating areas of parakeratosis and orthokeratosis with underlying agranulosis and hypergranulosis, respectively.18 The upper dermis contains a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Treatment with laser therapy and surgical excision has led to both symptomatic and clinical improvement of ILVEN.16

Plaque-type syringomas are a rare variant of syringomas that clinically may mimic other common inflammatory and neoplastic conditions. An adequate biopsy is imperative to differentiate between adnexal neoplasms, as a small superficial biopsy of a syringoma may demonstrate features observed in other malignant or locally aggressive neoplasms. In our patient, the small ducts lined by cuboidal epithelium with no cellular atypia and no deep dermal growth or perineural invasion allowed for the diagnosis of PTS. Therapeutic options were reviewed with our patient, including oral isotretinoin, laser therapy, and staged excision. Ultimately, our patient elected not to pursue treatment, and she is being monitored clinically for any changes in appearance or symptoms.

- Suwattee P, McClelland MC, Huiras EE, et al. Plaque-type syringoma: two cases misdiagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma [published online November 12, 2007]. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:570-574.

- Furue M, Hori Y, Nakabayashi Y. Clear-cell syringoma. association with diabetes mellitus. Am J Dermatopathol. 1984;6:131-138.

- Kikuchi I, Idemori M, Okazaki M. Plaque type syringoma. J Dermatol. 1979;6:329-331.

- Kavala M, Can B, Zindanci I, et al. Vulvar pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:831-832.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA, Rapini RP. Penile syringoma: reports and review of patients with syringoma located on the penis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-42.

- Okuda H, Tei N, Shimizu K, et al. Chondroid syringoma of the scrotum. Int J Urol. 2008;15:944-945.

- Wallace JS, Bond JS, Seidel GD, et al. An important mimicker: plaquetype syringoma mistakenly diagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:810-812.

- Clark M, Duprey C, Sutton A, et al. Plaque-type syringoma masquerading as microcystic adnexal carcinoma: review of the literature and description of a novel technique that emphasizes lesion architecture to help make the diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:E98-E101.

- Wallace ML, Smoller BR. Progesterone receptor positivity supports hormonal control of syringomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:442-445.

- Mainitz M, Schmidt JB, Gebhart W. Response of multiple syringomas to isotretinoin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1986;66:51-55.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Pujol RM, LeBoit PE, Su WP. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma with extensive sebaceous differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:358-362.

- Rahman J, Tahir M, Arekemase H, et al. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma: histopathologic and immunohistochemical criteria for differentiation of a rare benign hair follicle tumor from other cutaneous adnexal tumors. Cureus. 2020;12:E9703.

- Abesamis-Cubillan E, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, LeBoit PE. Merkel cells and sclerosing epithelial neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:311-315.

- Sellheyer K, Nelson P, Kutzner H, et al. The immunohistochemical differential diagnosis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and morpheaform basal cell carcinoma using BerEP4 and stem cell markers. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:363-370.

- Gianfaldoni S, Tchernev G, Gianfaldoni R, et al. A case of “inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus” (ILVEN) treated with CO2 laser ablation. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5:454-457.

- Kawaguchi H, Takeuchi M, Ono H, et al. Adult onset of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus [published online October 27, 1999]. J Dermatol. 1999;26:599-602.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA, Prenshaw KL, et al. The psoriasiform reaction pattern. In: Patterson JW. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2021:99-120.

The Diagnosis: Plaque-type Syringoma

A biopsy demonstrated multiple basaloid islands of tumor cells in the reticular dermis with ductal differentiation, some with a commalike tail. The ducts were lined by 2 to 3 layers of small uniform cuboidal cells without atypia and contained inspissated secretions within the lumina of scattered ducts. There was an associated fibrotic collagenous stroma. There was no evidence of perineural invasion and no deep dermal or subcutaneous extension (Figure 1). Additional cytokeratin immunohistochemical staining highlighted the adnexal proliferation (Figure 2). A diagnosis of plaque-type syringoma (PTS) was made.

Syringomas are benign dermal sweat gland tumors that typically present as flesh-colored papules on the cheeks or periorbital area of young females. Plaque-type tumors as well as papulonodular, eruptive, disseminated, urticaria pigmentosa–like, lichen planus–like, or milialike syringomas also have been reported. Syringomas may be associated with certain medical conditions such as Down syndrome, Nicolau-Balus syndrome, and both scarring and nonscarring alopecias.1 The clear cell variant of syringoma often is associated with diabetes mellitus.2 Kikuchi et al3 first described PTS in 1979. Plaque-type syringomas rarely are reported in the literature, and sites of involvement include the head and neck region, upper lip, chest, upper extremities, vulva, penis, and scrotum.4-6

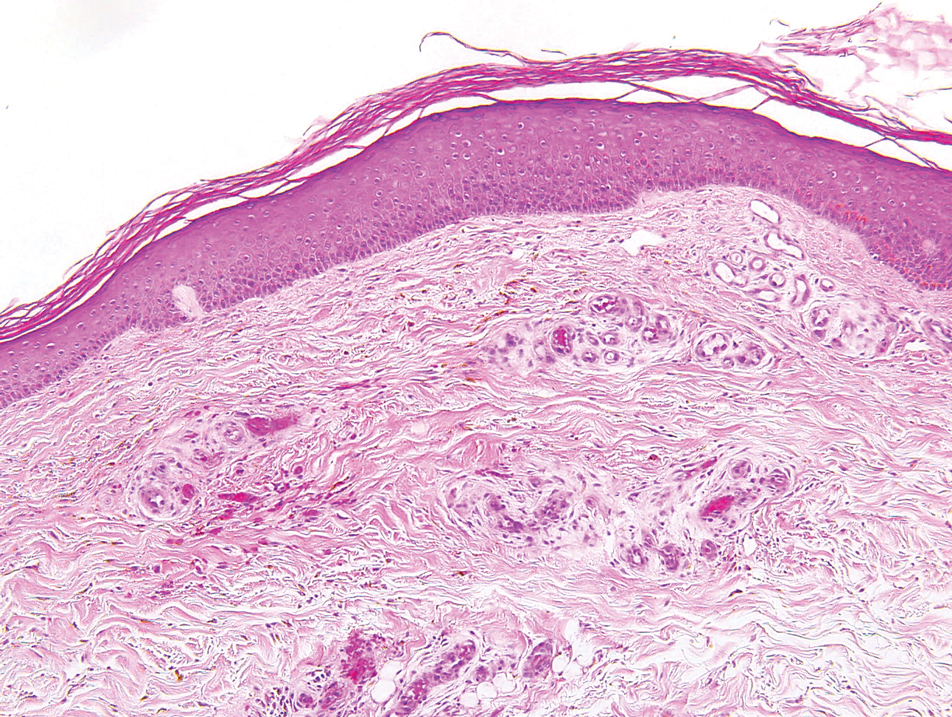

Histologically, syringomatous lesions are composed of multiple small ducts lined by 2 to 3 layers of cuboidal epithelium. The ducts may be arranged in nests or strands of basaloid cells surrounded by a dense fibrotic stroma. Occasionally, the ducts will form a comma- or teardropshaped tail; however, this also may be observed in desmoplastic trichoepithelioma (DTE).7 Perineural invasion is absent in syringomas. Syringomas exhibit a lateral growth pattern that typically is limited to the upper half of the reticular dermis and spares the underlying subcutis, muscle, and bone. The growth pattern may be discontinuous with proliferations juxtaposed by normal-appearing skin.8 Syringomas usually express progesterone receptors and are known to proliferate at puberty, suggesting that these neoplasms are under hormonal control.9 Although syringomas are benign, various treatment options that may be pursued for cosmetic purposes include radiofrequency, staged excision, laser ablation, and oral isotretinoin.8,10 If only a superficial biopsy is obtained, syringomas may display features of other adnexal neoplasms, including microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), DTE, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN).

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is a locally aggressive neoplasm first described by Goldstein et al11 in 1982 an indurated, ill-defined plaque or nodule on the face with a predilection for the upper and lower lip. Prior radiation therapy and immunosuppression are risk factors for the development of MAC.12 Histologically, the superficial portion displays small cornifying cysts interspersed with islands of basaloid cells and may mimic a syringoma. However, the deeper portions demonstrate ducts lined by a single layer of cells with a background of hyalinized and sclerotic stroma. The tumor cells may occupy the deep dermis and underlying subcutis, muscle, or bone and demonstrate an infiltrative growth pattern and perineural invasion. Treatment includes Mohs micrographic surgery.

Desmoplastic trichoepitheliomas most commonly present as solitary white to yellowish annular papules or plaques with a central dell located on sun-exposed areas of the face, cheeks, or chin. This benign neoplasm has a bimodal age distribution, primarily affecting females either in childhood or adulthood.13 Histologically, strands and nests of basaloid epithelial cells proliferate in a dense eosinophilic desmoplastic stroma. The basaloid islands are narrow and cordlike with growth parallel to the surface epidermis and do not dive deeply into the deep dermis or subcutis. Ductal differentiation with associated secretions typically is not seen in DTE.1 Calcifications and foreign body granulomatous infiltrates may be present. Merkel cells also are present in this tumor and may be highlighted by immunohistochemistry with cytokeratin 20.14 Rarely, desmoplastic trichoepitheliomas may transform into trichoblastic carcinomas. Treatment may consist of surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.

Morpheaform BCC also is included in the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnosis of infiltrative basaloid neoplasms. It is one of the more aggressive variants of BCC. The use of immunohistochemical staining may aid in differentiating between these sclerosing adnexal neoplasms.15 For example, pleckstrin homologylike domain family A member 1 (PHLDA1) is a stem cell marker that is heavily expressed in DTE as a specific follicular bulge marker but is not present in a morpheaform BCC. This highlights the follicular nature of DTEs at the molecular level. BerEP4 is a monoclonal antibody that serves as an epithelial marker for 2 glycopolypeptides: 34 and 39 kDa. This antibody may demonstrate positivity in morpheaform BCC but does not stain cells of interest in MAC.

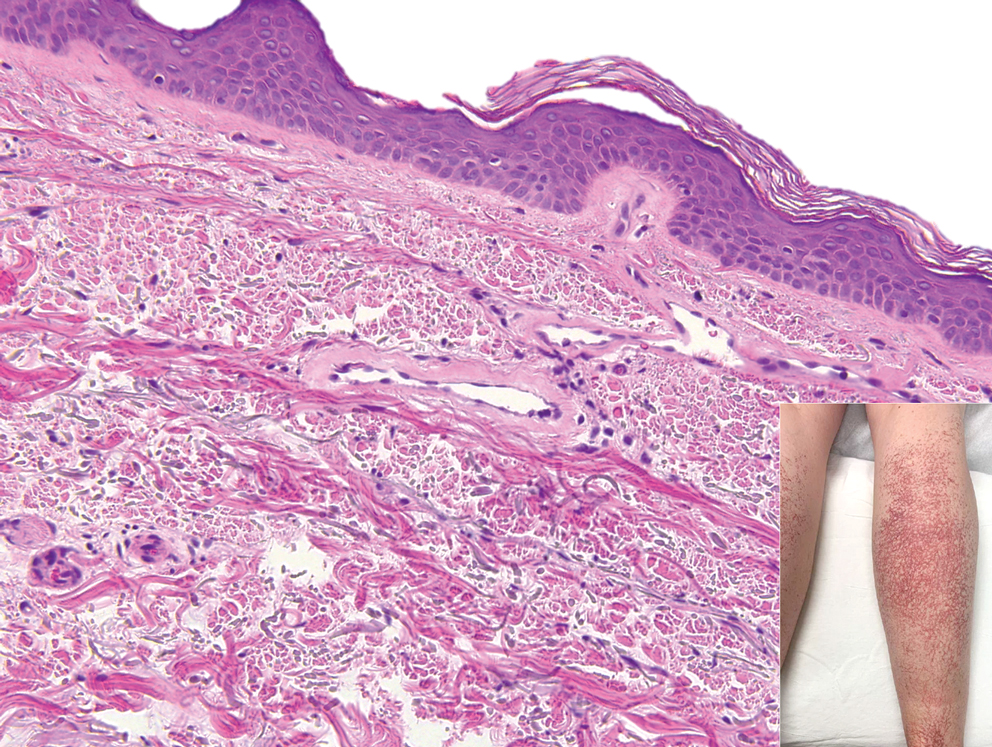

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus clinically presents with erythematous and warty papules in a linear distribution following the Blaschko lines. The papules often are reported to be intensely pruritic and usually are localized to one extremity.16 Although adultonset forms of ILVEN have been described,17 it most commonly is diagnosed in young children. Histologically, ILVEN consists of psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with alternating areas of parakeratosis and orthokeratosis with underlying agranulosis and hypergranulosis, respectively.18 The upper dermis contains a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Treatment with laser therapy and surgical excision has led to both symptomatic and clinical improvement of ILVEN.16

Plaque-type syringomas are a rare variant of syringomas that clinically may mimic other common inflammatory and neoplastic conditions. An adequate biopsy is imperative to differentiate between adnexal neoplasms, as a small superficial biopsy of a syringoma may demonstrate features observed in other malignant or locally aggressive neoplasms. In our patient, the small ducts lined by cuboidal epithelium with no cellular atypia and no deep dermal growth or perineural invasion allowed for the diagnosis of PTS. Therapeutic options were reviewed with our patient, including oral isotretinoin, laser therapy, and staged excision. Ultimately, our patient elected not to pursue treatment, and she is being monitored clinically for any changes in appearance or symptoms.

The Diagnosis: Plaque-type Syringoma

A biopsy demonstrated multiple basaloid islands of tumor cells in the reticular dermis with ductal differentiation, some with a commalike tail. The ducts were lined by 2 to 3 layers of small uniform cuboidal cells without atypia and contained inspissated secretions within the lumina of scattered ducts. There was an associated fibrotic collagenous stroma. There was no evidence of perineural invasion and no deep dermal or subcutaneous extension (Figure 1). Additional cytokeratin immunohistochemical staining highlighted the adnexal proliferation (Figure 2). A diagnosis of plaque-type syringoma (PTS) was made.

Syringomas are benign dermal sweat gland tumors that typically present as flesh-colored papules on the cheeks or periorbital area of young females. Plaque-type tumors as well as papulonodular, eruptive, disseminated, urticaria pigmentosa–like, lichen planus–like, or milialike syringomas also have been reported. Syringomas may be associated with certain medical conditions such as Down syndrome, Nicolau-Balus syndrome, and both scarring and nonscarring alopecias.1 The clear cell variant of syringoma often is associated with diabetes mellitus.2 Kikuchi et al3 first described PTS in 1979. Plaque-type syringomas rarely are reported in the literature, and sites of involvement include the head and neck region, upper lip, chest, upper extremities, vulva, penis, and scrotum.4-6

Histologically, syringomatous lesions are composed of multiple small ducts lined by 2 to 3 layers of cuboidal epithelium. The ducts may be arranged in nests or strands of basaloid cells surrounded by a dense fibrotic stroma. Occasionally, the ducts will form a comma- or teardropshaped tail; however, this also may be observed in desmoplastic trichoepithelioma (DTE).7 Perineural invasion is absent in syringomas. Syringomas exhibit a lateral growth pattern that typically is limited to the upper half of the reticular dermis and spares the underlying subcutis, muscle, and bone. The growth pattern may be discontinuous with proliferations juxtaposed by normal-appearing skin.8 Syringomas usually express progesterone receptors and are known to proliferate at puberty, suggesting that these neoplasms are under hormonal control.9 Although syringomas are benign, various treatment options that may be pursued for cosmetic purposes include radiofrequency, staged excision, laser ablation, and oral isotretinoin.8,10 If only a superficial biopsy is obtained, syringomas may display features of other adnexal neoplasms, including microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), DTE, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN).

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma is a locally aggressive neoplasm first described by Goldstein et al11 in 1982 an indurated, ill-defined plaque or nodule on the face with a predilection for the upper and lower lip. Prior radiation therapy and immunosuppression are risk factors for the development of MAC.12 Histologically, the superficial portion displays small cornifying cysts interspersed with islands of basaloid cells and may mimic a syringoma. However, the deeper portions demonstrate ducts lined by a single layer of cells with a background of hyalinized and sclerotic stroma. The tumor cells may occupy the deep dermis and underlying subcutis, muscle, or bone and demonstrate an infiltrative growth pattern and perineural invasion. Treatment includes Mohs micrographic surgery.

Desmoplastic trichoepitheliomas most commonly present as solitary white to yellowish annular papules or plaques with a central dell located on sun-exposed areas of the face, cheeks, or chin. This benign neoplasm has a bimodal age distribution, primarily affecting females either in childhood or adulthood.13 Histologically, strands and nests of basaloid epithelial cells proliferate in a dense eosinophilic desmoplastic stroma. The basaloid islands are narrow and cordlike with growth parallel to the surface epidermis and do not dive deeply into the deep dermis or subcutis. Ductal differentiation with associated secretions typically is not seen in DTE.1 Calcifications and foreign body granulomatous infiltrates may be present. Merkel cells also are present in this tumor and may be highlighted by immunohistochemistry with cytokeratin 20.14 Rarely, desmoplastic trichoepitheliomas may transform into trichoblastic carcinomas. Treatment may consist of surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.

Morpheaform BCC also is included in the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnosis of infiltrative basaloid neoplasms. It is one of the more aggressive variants of BCC. The use of immunohistochemical staining may aid in differentiating between these sclerosing adnexal neoplasms.15 For example, pleckstrin homologylike domain family A member 1 (PHLDA1) is a stem cell marker that is heavily expressed in DTE as a specific follicular bulge marker but is not present in a morpheaform BCC. This highlights the follicular nature of DTEs at the molecular level. BerEP4 is a monoclonal antibody that serves as an epithelial marker for 2 glycopolypeptides: 34 and 39 kDa. This antibody may demonstrate positivity in morpheaform BCC but does not stain cells of interest in MAC.

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus clinically presents with erythematous and warty papules in a linear distribution following the Blaschko lines. The papules often are reported to be intensely pruritic and usually are localized to one extremity.16 Although adultonset forms of ILVEN have been described,17 it most commonly is diagnosed in young children. Histologically, ILVEN consists of psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with alternating areas of parakeratosis and orthokeratosis with underlying agranulosis and hypergranulosis, respectively.18 The upper dermis contains a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Treatment with laser therapy and surgical excision has led to both symptomatic and clinical improvement of ILVEN.16

Plaque-type syringomas are a rare variant of syringomas that clinically may mimic other common inflammatory and neoplastic conditions. An adequate biopsy is imperative to differentiate between adnexal neoplasms, as a small superficial biopsy of a syringoma may demonstrate features observed in other malignant or locally aggressive neoplasms. In our patient, the small ducts lined by cuboidal epithelium with no cellular atypia and no deep dermal growth or perineural invasion allowed for the diagnosis of PTS. Therapeutic options were reviewed with our patient, including oral isotretinoin, laser therapy, and staged excision. Ultimately, our patient elected not to pursue treatment, and she is being monitored clinically for any changes in appearance or symptoms.

- Suwattee P, McClelland MC, Huiras EE, et al. Plaque-type syringoma: two cases misdiagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma [published online November 12, 2007]. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:570-574.

- Furue M, Hori Y, Nakabayashi Y. Clear-cell syringoma. association with diabetes mellitus. Am J Dermatopathol. 1984;6:131-138.

- Kikuchi I, Idemori M, Okazaki M. Plaque type syringoma. J Dermatol. 1979;6:329-331.

- Kavala M, Can B, Zindanci I, et al. Vulvar pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:831-832.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA, Rapini RP. Penile syringoma: reports and review of patients with syringoma located on the penis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-42.

- Okuda H, Tei N, Shimizu K, et al. Chondroid syringoma of the scrotum. Int J Urol. 2008;15:944-945.

- Wallace JS, Bond JS, Seidel GD, et al. An important mimicker: plaquetype syringoma mistakenly diagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:810-812.

- Clark M, Duprey C, Sutton A, et al. Plaque-type syringoma masquerading as microcystic adnexal carcinoma: review of the literature and description of a novel technique that emphasizes lesion architecture to help make the diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:E98-E101.

- Wallace ML, Smoller BR. Progesterone receptor positivity supports hormonal control of syringomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:442-445.

- Mainitz M, Schmidt JB, Gebhart W. Response of multiple syringomas to isotretinoin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1986;66:51-55.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Pujol RM, LeBoit PE, Su WP. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma with extensive sebaceous differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:358-362.

- Rahman J, Tahir M, Arekemase H, et al. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma: histopathologic and immunohistochemical criteria for differentiation of a rare benign hair follicle tumor from other cutaneous adnexal tumors. Cureus. 2020;12:E9703.

- Abesamis-Cubillan E, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, LeBoit PE. Merkel cells and sclerosing epithelial neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:311-315.

- Sellheyer K, Nelson P, Kutzner H, et al. The immunohistochemical differential diagnosis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and morpheaform basal cell carcinoma using BerEP4 and stem cell markers. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:363-370.

- Gianfaldoni S, Tchernev G, Gianfaldoni R, et al. A case of “inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus” (ILVEN) treated with CO2 laser ablation. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5:454-457.

- Kawaguchi H, Takeuchi M, Ono H, et al. Adult onset of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus [published online October 27, 1999]. J Dermatol. 1999;26:599-602.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA, Prenshaw KL, et al. The psoriasiform reaction pattern. In: Patterson JW. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2021:99-120.

- Suwattee P, McClelland MC, Huiras EE, et al. Plaque-type syringoma: two cases misdiagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma [published online November 12, 2007]. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:570-574.

- Furue M, Hori Y, Nakabayashi Y. Clear-cell syringoma. association with diabetes mellitus. Am J Dermatopathol. 1984;6:131-138.

- Kikuchi I, Idemori M, Okazaki M. Plaque type syringoma. J Dermatol. 1979;6:329-331.

- Kavala M, Can B, Zindanci I, et al. Vulvar pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:831-832.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA, Rapini RP. Penile syringoma: reports and review of patients with syringoma located on the penis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-42.

- Okuda H, Tei N, Shimizu K, et al. Chondroid syringoma of the scrotum. Int J Urol. 2008;15:944-945.

- Wallace JS, Bond JS, Seidel GD, et al. An important mimicker: plaquetype syringoma mistakenly diagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:810-812.

- Clark M, Duprey C, Sutton A, et al. Plaque-type syringoma masquerading as microcystic adnexal carcinoma: review of the literature and description of a novel technique that emphasizes lesion architecture to help make the diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:E98-E101.

- Wallace ML, Smoller BR. Progesterone receptor positivity supports hormonal control of syringomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:442-445.

- Mainitz M, Schmidt JB, Gebhart W. Response of multiple syringomas to isotretinoin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1986;66:51-55.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Pujol RM, LeBoit PE, Su WP. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma with extensive sebaceous differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:358-362.

- Rahman J, Tahir M, Arekemase H, et al. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma: histopathologic and immunohistochemical criteria for differentiation of a rare benign hair follicle tumor from other cutaneous adnexal tumors. Cureus. 2020;12:E9703.

- Abesamis-Cubillan E, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, LeBoit PE. Merkel cells and sclerosing epithelial neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:311-315.

- Sellheyer K, Nelson P, Kutzner H, et al. The immunohistochemical differential diagnosis of microcystic adnexal carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma and morpheaform basal cell carcinoma using BerEP4 and stem cell markers. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:363-370.

- Gianfaldoni S, Tchernev G, Gianfaldoni R, et al. A case of “inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus” (ILVEN) treated with CO2 laser ablation. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5:454-457.

- Kawaguchi H, Takeuchi M, Ono H, et al. Adult onset of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus [published online October 27, 1999]. J Dermatol. 1999;26:599-602.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA, Prenshaw KL, et al. The psoriasiform reaction pattern. In: Patterson JW. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2021:99-120.

A 17-year-old adolescent girl presented with a solitary, 8-cm, pink plaque on the anterior aspect of the neck of 5 years’ duration. No similar skin findings were present elsewhere on the body. The rash was not painful or pruritic, and she denied prior trauma to the site. The patient previously had tried a salicylic acid bodywash as well as mupirocin cream 2% and mometasone ointment with no improvement. Her medical history was unremarkable, and she had no known allergies. There was no family history of a similar rash. Physical examination revealed no palpable subcutaneous lumps or masses and no lymphadenopathy of the head or neck. An incisional biopsy was performed.

Progressive Telangiectatic Rash

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an idiopathic microangiopathy of the small vessels in the superficial dermis. A condition first identified by Salama and Rosenthal1 in 2000, CCV likely is underreported, as its clinical mimickers are not routinely biopsied.2 It presents as asymptomatic telangiectatic macules, initially on the lower extremities and often spreading to the trunk. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy often is seen in middle-aged adults, and most patients have comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or cardiovascular disease. The exact etiology of this disease is unknown.3,4

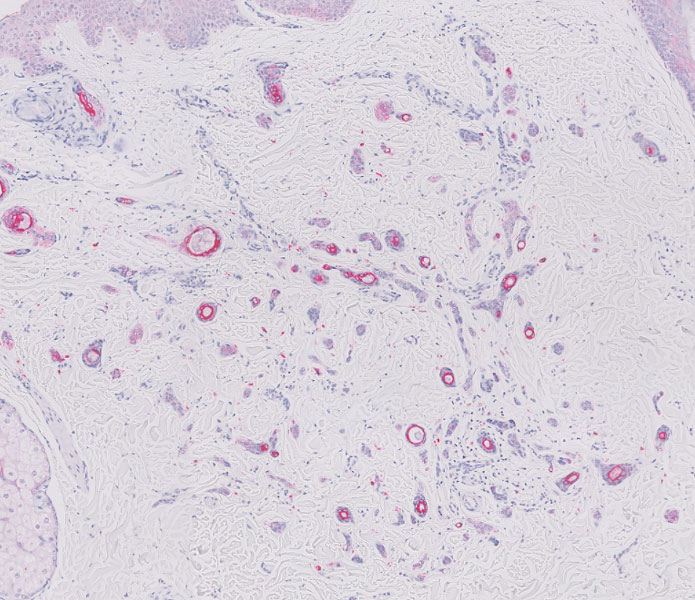

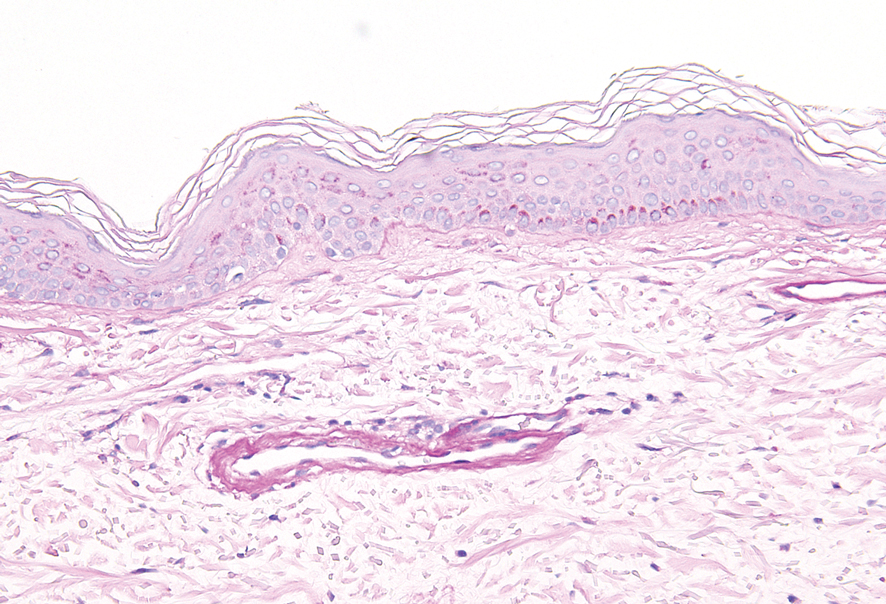

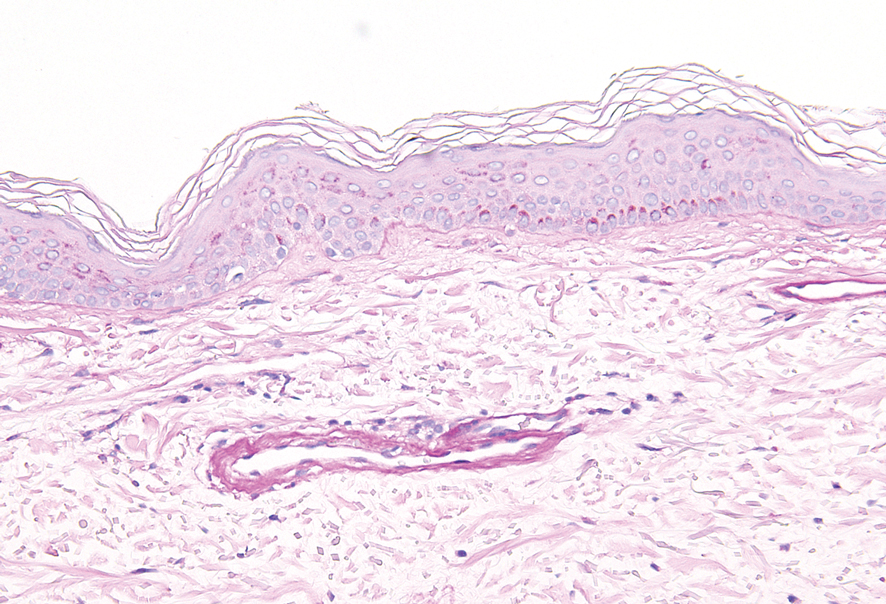

Histopathologically, CCV is characterized by dilated superficial vessels with thickened eosinophilic walls. The eosinophilic material is composed of hyalinized type IV collagen, which is periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant (Figure 1).3,4 Stains for amyloid are negative.

Generalized essential telangiectasia (GET) is a condition that presents with symmetric, blanchable, erythematous telangiectases.5 These lesions can occur alone or can accompany systemic diseases. Similar to CCV, the telangiectases tend to begin on the legs before gradually spreading to the trunk; however, this process more often is seen in females and occurs at an earlier age. Unlike CCV, GET can occur on mucosal surfaces, with cases of conjunctival and oral involvement reported.6 Generalized essential telangiectasia usually is a diagnosis of exclusion.7,8 It is thought that many CCV lesions have been misclassified clinically as GET, which highlights the importance of biopsy. Microscopically, GET is distinct from CCV in that the superficial dermis lacks thick-walled vessels.5,7 Although usually not associated with systemic diseases or progressive morbidity, treatment options are limited.8

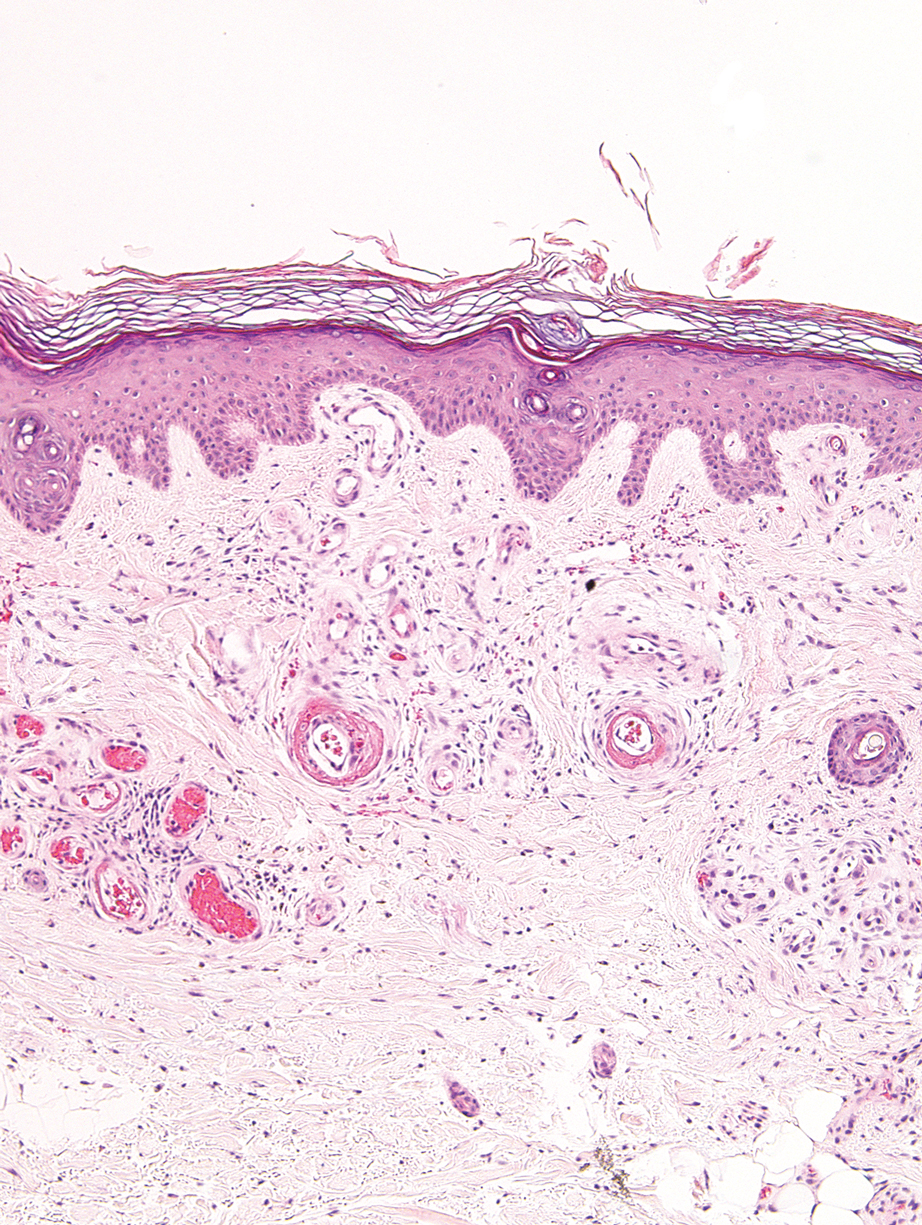

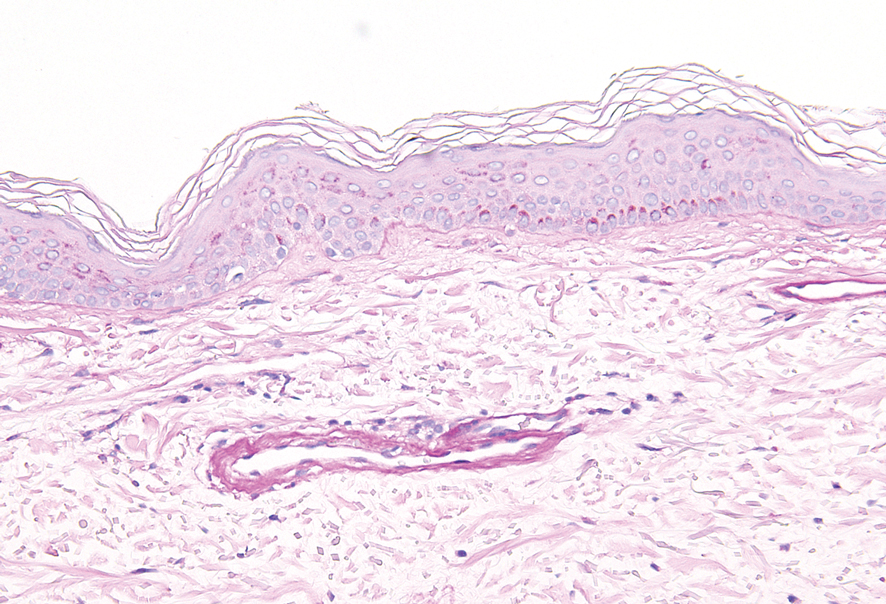

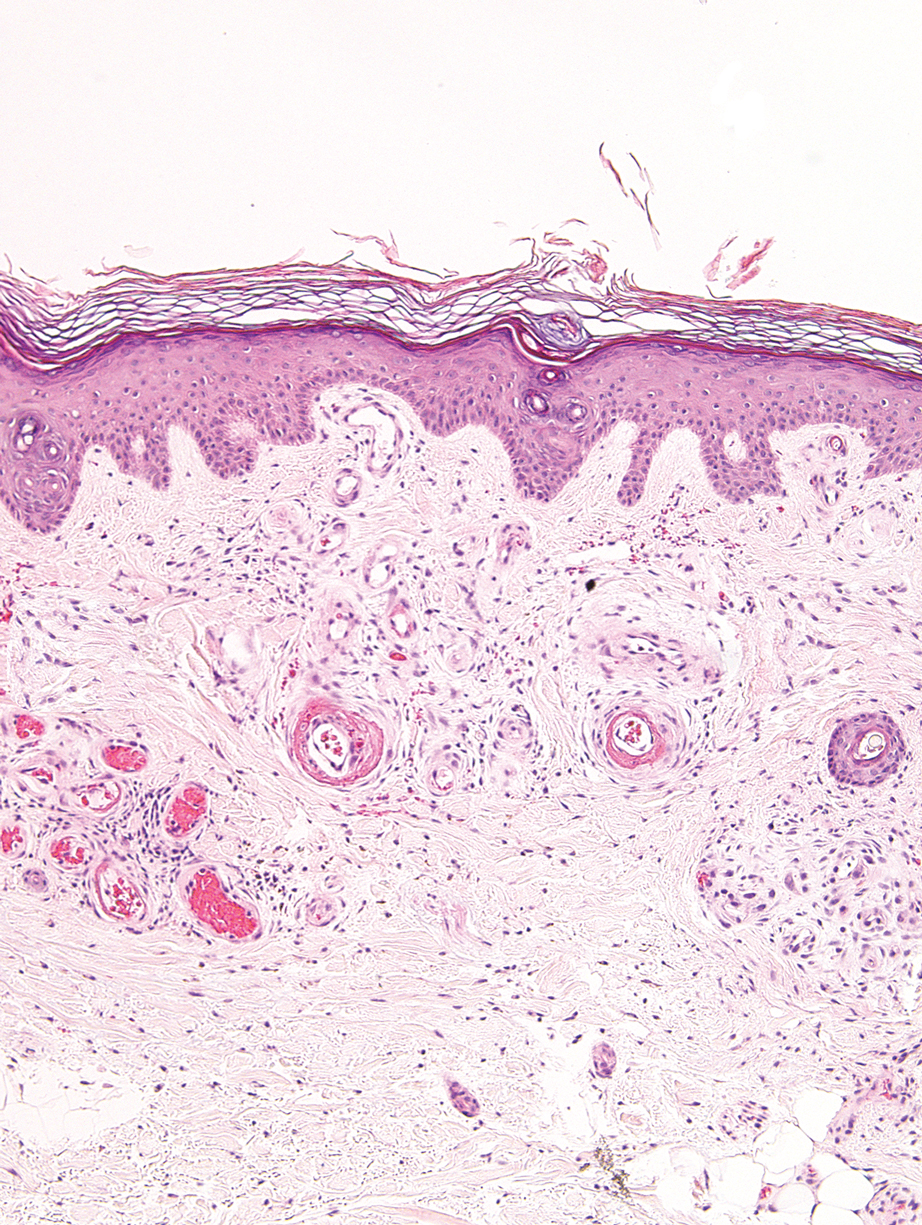

Livedoid vasculopathy, also known as atrophie blanche, is caused by fibrin thrombi occlusion of dermal vessels. Clinically, patients have recurrent telangiectatic papules and painful ulcers on the lower extremities that gradually heal, leaving behind white stellate scars. It is caused by an underlying prothrombotic state with a superimposed inflammatory response.9 Livedoid vasculopathy primarily affects middle-aged women, and many patients have comorbidities such as scleroderma or systemic lupus erythematosus. Histologically, the epidermis often is ulcerated, and thrombi are visualized within small vessels. Eosinophilic fibrinoid material is deposited in vessel walls, including but not confined to vessels at the base of the epidermal ulcer (Figure 2). The fibrinoid material is periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant and can be highlighted with immunofluorescence, which may help to distinguish this entity from CCV.1,9 As the disease progresses, vessels are diffusely hyalinized, and there is epidermal atrophy and dermal sclerosis. Treatment options include antiplatelet and fibrinolytic drugs with a multidisciplinary approach to resolve pain and scarring.9

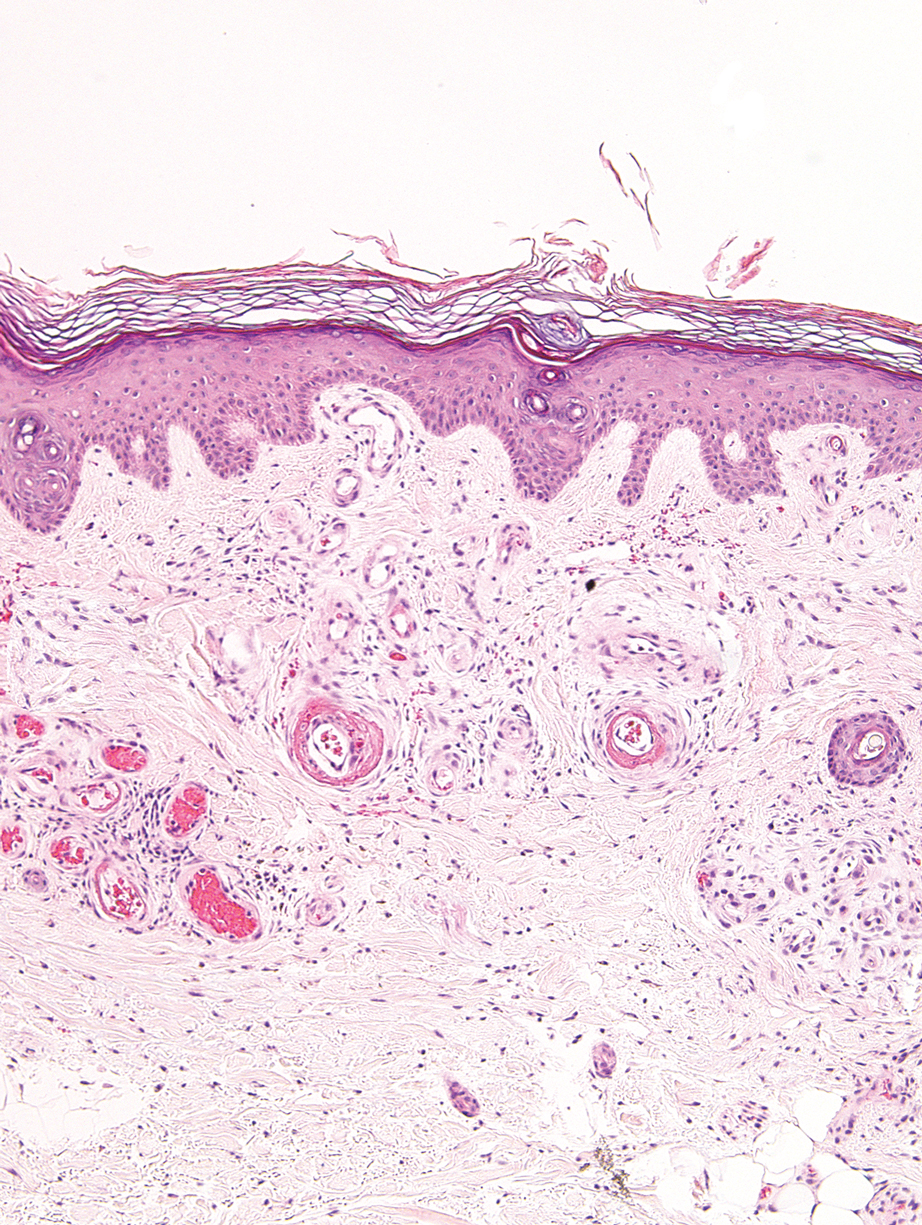

Primary systemic amyloidosis is a rare condition, and cutaneous manifestations are seen in approximately one-third of affected individuals. Amyloid deposition results in waxy papules that predominantly affect the face and periorbital areas but also may occur on the neck, flexural areas, and genitalia.5 Because the amyloid deposits also can be found within vessel walls, hemorrhagic lesions may occur. Microscopically, amorphous eosinophilic material can be found within the vessel walls, similar to CCV (Figure 3A); however, when stained with Congo red, cutaneous amyloidosis shows waxy red-orange material involving the vessel walls and exhibits apple green birefringence under polarization (Figure 3B).10 Amyloid also will be negative for type IV collagen, fibronectin, and laminin, whereas CCV will be positive.5

- Salama S, Rosenthal D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with generalized telangiectasia: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:40-48.

- Bondier L, Tardieu M, Leveque P, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: report of two cases presenting as disseminated telangiectasias and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:682-688.

- Sartori DS, Almeida HL Jr, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52.

- Patterson JW, ed. Vascular tumors. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016:1069-1115.

- Knöpfel N, Martín-Santiago A, Saus C, et al. Extensive acquired telangiectasias: comparison of generalized essential telangiectasia and cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:E21-E26.

- Karimkhani C, Boyers LN, Olivere J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. Cutis. 2019;103:E7-E8.

- McGrae JD, Winkelmann RK. Generalized essential telangiectasia: report of a clinical and histochemical study of 13 patients with acquired cutaneous lesions. JAMA. 1963;185:909-913.

- Vasudeva B, Neema S, Verma R. Livedoid vasculopathy: a review of pathogenesis and principles of management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:478.

- Ko CJ, Barr RJ. Color--pink. In: Ko CJ, Barr RJ, eds. Dermatopathology: Diagnosis by First Impression. 3rd ed. Wiley; 2016:303-322.

- Clark ML, McGuinness AE, Vidal CI. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a unique case with positive direct immunofluorescence findings. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:77-79.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an idiopathic microangiopathy of the small vessels in the superficial dermis. A condition first identified by Salama and Rosenthal1 in 2000, CCV likely is underreported, as its clinical mimickers are not routinely biopsied.2 It presents as asymptomatic telangiectatic macules, initially on the lower extremities and often spreading to the trunk. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy often is seen in middle-aged adults, and most patients have comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or cardiovascular disease. The exact etiology of this disease is unknown.3,4

Histopathologically, CCV is characterized by dilated superficial vessels with thickened eosinophilic walls. The eosinophilic material is composed of hyalinized type IV collagen, which is periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant (Figure 1).3,4 Stains for amyloid are negative.

Generalized essential telangiectasia (GET) is a condition that presents with symmetric, blanchable, erythematous telangiectases.5 These lesions can occur alone or can accompany systemic diseases. Similar to CCV, the telangiectases tend to begin on the legs before gradually spreading to the trunk; however, this process more often is seen in females and occurs at an earlier age. Unlike CCV, GET can occur on mucosal surfaces, with cases of conjunctival and oral involvement reported.6 Generalized essential telangiectasia usually is a diagnosis of exclusion.7,8 It is thought that many CCV lesions have been misclassified clinically as GET, which highlights the importance of biopsy. Microscopically, GET is distinct from CCV in that the superficial dermis lacks thick-walled vessels.5,7 Although usually not associated with systemic diseases or progressive morbidity, treatment options are limited.8