User login

Pink scaly rash on torso and extremities

Tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) inhibitors are therapeutic agents used to treat a variety of inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, as well as psoriasis of the skin (PSO) and psoriatic arthritis. In a 2017 systematic review, there were 216 reported cases of new-onset TNF-alpha inhibitor–induced psoriasis, with an estimated rate of 1 per 1,000. The cases thus far have had a wide range of presentations, the most common being plaque psoriasis, scalp psoriasis, as well as palmoplantar pustular psoriasis.1

A retrospective chart review study at Mayo clinic published in 2017 evaluated children younger than 19 years seen in 2003-2015 who developed new-onset or recurrent PSO with a history of inflammatory bowel disease being treated with anti-TNF-alpha therapy. The review showed variable latency in the development of PSO in these patients, although it typically occurred during inflammatory bowel disease remission.2 It is unclear whether there is an association between a personal or family history of psoriasis and development of these lesions.

TNF-alpha, interleukin (IL)–17) and interferon-alpha (IFN-alpha) are main cytokines that contribute to the development of psoriasis. The mechanism of action for paradoxical PSO/psoriasis in patients treated with anti-TNF is not clearly understood; however, many hypotheses are based on an imbalance between TNF-alpha and interferon-alpha – more specifically, an increased production of interferon-alpha. TNF-alpha inhibits the activity of plasmacytoid dendritic cells which are key producers of IFN-alpha. Because of this blockade, there is unopposed IFN-alpha production. Interferon-alpha allows for the expression of chemokines such as CXCR3, which favor T cells homing to the skin. IFN-alpha also stimulates and activates T cells to produce TNF-alpha and IL-17, which in turn sustains inflammatory mechanisms and allows for the development of psoriatic lesions.3

There are no universal management guidelines. Most of these patients’ treatment plans mirror standard psoriasis therapies while the main question remains the decision to continue the same anti-TNF therapy, change anti-TNF agents, or entirely switch classes of biologic or other systemic therapy. This decision in management requires several considerations: treatability of TNF-alpha inhibitor-induced psoriasis, the severity of background disease (i.e., rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, other systemic condition), and whether the underlying disease is well controlled on current therapy, as well as the consideration of possible loss in efficacy if a drug is discontinued and then restarted at a later date.4

A reasonable initial approach in patients with well-controlled underlying disease and mild skin eruption is to continue anti-TNF therapy and manage skin topically with topical corticosteroids and/or phototherapy. In patients that either do not have well-controlled underlying disease or moderate skin involvement, changing to an alternative anti-TNF or other agent may be reasonable, and requires coordinated care with involved specialists. In the 2017 pediatric review mentioned previously, nearly half of the patients required a change in their initial anti-TNF-alpha agent despite conventional skin-directed therapies, and one-third of patients discontinued all anti-TNF-alpha therapy because of PSO.2

The psoriasiform papulosquamous features of this case along with the history suggests the diagnosis. Pityriasis rosea would be highly atypical on the feet and with the duration of findings. Lichen planus and atopic dermatitis morphology are inconsistent with this eruption, and coxsackie viral infection would have a shorter course.

Dr. Tracy is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Feb;76(2):334-41.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017 May;34(3):253-60.

3. RMD Open. 2016 Jul 15;2(2):e000239.

4. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2019 Apr;4(2):70-80.

Tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) inhibitors are therapeutic agents used to treat a variety of inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, as well as psoriasis of the skin (PSO) and psoriatic arthritis. In a 2017 systematic review, there were 216 reported cases of new-onset TNF-alpha inhibitor–induced psoriasis, with an estimated rate of 1 per 1,000. The cases thus far have had a wide range of presentations, the most common being plaque psoriasis, scalp psoriasis, as well as palmoplantar pustular psoriasis.1

A retrospective chart review study at Mayo clinic published in 2017 evaluated children younger than 19 years seen in 2003-2015 who developed new-onset or recurrent PSO with a history of inflammatory bowel disease being treated with anti-TNF-alpha therapy. The review showed variable latency in the development of PSO in these patients, although it typically occurred during inflammatory bowel disease remission.2 It is unclear whether there is an association between a personal or family history of psoriasis and development of these lesions.

TNF-alpha, interleukin (IL)–17) and interferon-alpha (IFN-alpha) are main cytokines that contribute to the development of psoriasis. The mechanism of action for paradoxical PSO/psoriasis in patients treated with anti-TNF is not clearly understood; however, many hypotheses are based on an imbalance between TNF-alpha and interferon-alpha – more specifically, an increased production of interferon-alpha. TNF-alpha inhibits the activity of plasmacytoid dendritic cells which are key producers of IFN-alpha. Because of this blockade, there is unopposed IFN-alpha production. Interferon-alpha allows for the expression of chemokines such as CXCR3, which favor T cells homing to the skin. IFN-alpha also stimulates and activates T cells to produce TNF-alpha and IL-17, which in turn sustains inflammatory mechanisms and allows for the development of psoriatic lesions.3

There are no universal management guidelines. Most of these patients’ treatment plans mirror standard psoriasis therapies while the main question remains the decision to continue the same anti-TNF therapy, change anti-TNF agents, or entirely switch classes of biologic or other systemic therapy. This decision in management requires several considerations: treatability of TNF-alpha inhibitor-induced psoriasis, the severity of background disease (i.e., rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, other systemic condition), and whether the underlying disease is well controlled on current therapy, as well as the consideration of possible loss in efficacy if a drug is discontinued and then restarted at a later date.4

A reasonable initial approach in patients with well-controlled underlying disease and mild skin eruption is to continue anti-TNF therapy and manage skin topically with topical corticosteroids and/or phototherapy. In patients that either do not have well-controlled underlying disease or moderate skin involvement, changing to an alternative anti-TNF or other agent may be reasonable, and requires coordinated care with involved specialists. In the 2017 pediatric review mentioned previously, nearly half of the patients required a change in their initial anti-TNF-alpha agent despite conventional skin-directed therapies, and one-third of patients discontinued all anti-TNF-alpha therapy because of PSO.2

The psoriasiform papulosquamous features of this case along with the history suggests the diagnosis. Pityriasis rosea would be highly atypical on the feet and with the duration of findings. Lichen planus and atopic dermatitis morphology are inconsistent with this eruption, and coxsackie viral infection would have a shorter course.

Dr. Tracy is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Feb;76(2):334-41.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017 May;34(3):253-60.

3. RMD Open. 2016 Jul 15;2(2):e000239.

4. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2019 Apr;4(2):70-80.

Tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) inhibitors are therapeutic agents used to treat a variety of inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, as well as psoriasis of the skin (PSO) and psoriatic arthritis. In a 2017 systematic review, there were 216 reported cases of new-onset TNF-alpha inhibitor–induced psoriasis, with an estimated rate of 1 per 1,000. The cases thus far have had a wide range of presentations, the most common being plaque psoriasis, scalp psoriasis, as well as palmoplantar pustular psoriasis.1

A retrospective chart review study at Mayo clinic published in 2017 evaluated children younger than 19 years seen in 2003-2015 who developed new-onset or recurrent PSO with a history of inflammatory bowel disease being treated with anti-TNF-alpha therapy. The review showed variable latency in the development of PSO in these patients, although it typically occurred during inflammatory bowel disease remission.2 It is unclear whether there is an association between a personal or family history of psoriasis and development of these lesions.

TNF-alpha, interleukin (IL)–17) and interferon-alpha (IFN-alpha) are main cytokines that contribute to the development of psoriasis. The mechanism of action for paradoxical PSO/psoriasis in patients treated with anti-TNF is not clearly understood; however, many hypotheses are based on an imbalance between TNF-alpha and interferon-alpha – more specifically, an increased production of interferon-alpha. TNF-alpha inhibits the activity of plasmacytoid dendritic cells which are key producers of IFN-alpha. Because of this blockade, there is unopposed IFN-alpha production. Interferon-alpha allows for the expression of chemokines such as CXCR3, which favor T cells homing to the skin. IFN-alpha also stimulates and activates T cells to produce TNF-alpha and IL-17, which in turn sustains inflammatory mechanisms and allows for the development of psoriatic lesions.3

There are no universal management guidelines. Most of these patients’ treatment plans mirror standard psoriasis therapies while the main question remains the decision to continue the same anti-TNF therapy, change anti-TNF agents, or entirely switch classes of biologic or other systemic therapy. This decision in management requires several considerations: treatability of TNF-alpha inhibitor-induced psoriasis, the severity of background disease (i.e., rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, other systemic condition), and whether the underlying disease is well controlled on current therapy, as well as the consideration of possible loss in efficacy if a drug is discontinued and then restarted at a later date.4

A reasonable initial approach in patients with well-controlled underlying disease and mild skin eruption is to continue anti-TNF therapy and manage skin topically with topical corticosteroids and/or phototherapy. In patients that either do not have well-controlled underlying disease or moderate skin involvement, changing to an alternative anti-TNF or other agent may be reasonable, and requires coordinated care with involved specialists. In the 2017 pediatric review mentioned previously, nearly half of the patients required a change in their initial anti-TNF-alpha agent despite conventional skin-directed therapies, and one-third of patients discontinued all anti-TNF-alpha therapy because of PSO.2

The psoriasiform papulosquamous features of this case along with the history suggests the diagnosis. Pityriasis rosea would be highly atypical on the feet and with the duration of findings. Lichen planus and atopic dermatitis morphology are inconsistent with this eruption, and coxsackie viral infection would have a shorter course.

Dr. Tracy is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Feb;76(2):334-41.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017 May;34(3):253-60.

3. RMD Open. 2016 Jul 15;2(2):e000239.

4. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2019 Apr;4(2):70-80.

A 17-year-old male with a history of Crohn's disease, well controlled on infliximab, is seen for evaluation of a pink scaly rash on the torso, upper extremities, and lower extremities. The rash began 5 months previously and has been mostly asymptomatic. The patient denies pruritus or pain at the affected areas. There is no fever or drainage from any of the sites. The patient has not undergone any treatments. He does not have a personal or family history of chronic skin conditions.

On physical exam, he is noted to have numerous pink papules and plaques with overlying scale on his trunk, as well as the dorsal aspects of bilateral hands and the plantar surfaces of bilateral feet. His skin is otherwise unremarkable.

Pneumonia with tender, dry, crusted lips

Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection commonly manifests as an upper or lower respiratory tract infection with associated fever, dyspnea, cough, and coryza. However, patients can present with extrapulmonary complications with dermatologic findings including mucocutaneous eruptions. M. pneumoniae–associated mucocutaneous disease has prominent mucositis and typically sparse cutaneous involvement. The mucositis usually involves the lips and oral mucosa, eye conjunctivae, and nasal mucosa and can involve urogenital lesions. It predominantly is observed in children and adolescents. This condition is essentially a subtype of Stevens-Johnson syndrome, with a specific infection-associated etiology, and has been called “Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis,” shortened to “MIRM.”

Severe reactive mucocutaneous eruptions include erythema multiforme (EM), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). While there has been semantic confusion over the years, there are some distinctive characteristics.

EM is characterized by typical three-ringed target papules that are predominantly acral in location and often without mucosal involvement. The lesions are “multiforme” in that they can appear polymorphous and evolve during an episode, with erythematous macules progressing to edematous papules, sometimes with a halo of pallor and concentric “target-like” appearance. Lesions of EM are fixed, meaning individual lesions last 7-10 days, unlike urticarial lesions that last hours. EM classically is associated with herpes simplex virus infections which usually precede its development.

SJS and TEN display atypical macules and papules which develop into erythematous vesicles, bullae, and potentially extensive desquamation, usually presenting with fever and systemic symptoms, with multiple mucosal sites involved. SJS usually is defined by having bullae restricted to less than 10% of body surface area (BSA), TEN as greater than 30% BSA, and “overlap SJS-TEN” as 20%-30% skin detachment.1 SJS and TEN commonly are induced by medications and on a spectrum of drug hypersensitivity–induced epidermal necrolysis.

MIRM has been highlighted as a distinct, common condition, usually mucous-membrane predominant with involvement of two or more mucosal sites, less than 10% total BSA, the presence of few vesiculobullous lesions or scattered atypical targets with or without targetoid lesions (without rash is called MIRM sine rash), and clinical and laboratory evidence of atypical pneumonia.2 Other infections can cause similar eruptions (for example, Chlamydia pneumoniae), and a recent proposal by the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance has suggested the term “Reactive Infectious Mucocutaneous Eruption” (RIME) to include MIRM and other infection-induced reactions.

Laboratory diagnosis of M. pneumoniae is via serology or polymerase chain reaction. Antibody titers begin to rise approximately 7-9 days after infection and peak at 3-4 weeks. Enzyme immunoassay is more sensitive in detecting acute infection than culture and has sensitivity comparable to the polymerase chain reaction if there has been sufficient time to develop an antibody response.

The differential diagnosis between RIME/MIRM, SJS, and TEN may be difficult to distinguish in the first few days of presentation, and consideration of infections and possible medication causes is important. DRESS syndrome (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) also is in the differential diagnosis. DRESS usually has a long latency (2-8 weeks) between drug exposure and disease onset.

Treatment of RIME/MIRM is supportive care and treatment of any underlying infection. Steroids and intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) have been used to treat reactive mucositis, as well as cyclosporine and biologic agents (such as etanercept), in an attempt to minimize the extent and duration of mucous membrane vesiculation and denudation. While these drugs may help shorten the duration of the disease course, controlled trials are lacking and there is little comparative literature on efficacy or safety of these agents.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Bhatti is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Diego. They said they have no financial disclosures. Email Dr. Eichenfield and Dr. Bhatti at [email protected].

References

1. Arch Dermatol. 1993 Jan;129(1):92-6.

2. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Feb;72(2):239-45.

Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection commonly manifests as an upper or lower respiratory tract infection with associated fever, dyspnea, cough, and coryza. However, patients can present with extrapulmonary complications with dermatologic findings including mucocutaneous eruptions. M. pneumoniae–associated mucocutaneous disease has prominent mucositis and typically sparse cutaneous involvement. The mucositis usually involves the lips and oral mucosa, eye conjunctivae, and nasal mucosa and can involve urogenital lesions. It predominantly is observed in children and adolescents. This condition is essentially a subtype of Stevens-Johnson syndrome, with a specific infection-associated etiology, and has been called “Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis,” shortened to “MIRM.”

Severe reactive mucocutaneous eruptions include erythema multiforme (EM), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). While there has been semantic confusion over the years, there are some distinctive characteristics.

EM is characterized by typical three-ringed target papules that are predominantly acral in location and often without mucosal involvement. The lesions are “multiforme” in that they can appear polymorphous and evolve during an episode, with erythematous macules progressing to edematous papules, sometimes with a halo of pallor and concentric “target-like” appearance. Lesions of EM are fixed, meaning individual lesions last 7-10 days, unlike urticarial lesions that last hours. EM classically is associated with herpes simplex virus infections which usually precede its development.

SJS and TEN display atypical macules and papules which develop into erythematous vesicles, bullae, and potentially extensive desquamation, usually presenting with fever and systemic symptoms, with multiple mucosal sites involved. SJS usually is defined by having bullae restricted to less than 10% of body surface area (BSA), TEN as greater than 30% BSA, and “overlap SJS-TEN” as 20%-30% skin detachment.1 SJS and TEN commonly are induced by medications and on a spectrum of drug hypersensitivity–induced epidermal necrolysis.

MIRM has been highlighted as a distinct, common condition, usually mucous-membrane predominant with involvement of two or more mucosal sites, less than 10% total BSA, the presence of few vesiculobullous lesions or scattered atypical targets with or without targetoid lesions (without rash is called MIRM sine rash), and clinical and laboratory evidence of atypical pneumonia.2 Other infections can cause similar eruptions (for example, Chlamydia pneumoniae), and a recent proposal by the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance has suggested the term “Reactive Infectious Mucocutaneous Eruption” (RIME) to include MIRM and other infection-induced reactions.

Laboratory diagnosis of M. pneumoniae is via serology or polymerase chain reaction. Antibody titers begin to rise approximately 7-9 days after infection and peak at 3-4 weeks. Enzyme immunoassay is more sensitive in detecting acute infection than culture and has sensitivity comparable to the polymerase chain reaction if there has been sufficient time to develop an antibody response.

The differential diagnosis between RIME/MIRM, SJS, and TEN may be difficult to distinguish in the first few days of presentation, and consideration of infections and possible medication causes is important. DRESS syndrome (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) also is in the differential diagnosis. DRESS usually has a long latency (2-8 weeks) between drug exposure and disease onset.

Treatment of RIME/MIRM is supportive care and treatment of any underlying infection. Steroids and intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) have been used to treat reactive mucositis, as well as cyclosporine and biologic agents (such as etanercept), in an attempt to minimize the extent and duration of mucous membrane vesiculation and denudation. While these drugs may help shorten the duration of the disease course, controlled trials are lacking and there is little comparative literature on efficacy or safety of these agents.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Bhatti is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Diego. They said they have no financial disclosures. Email Dr. Eichenfield and Dr. Bhatti at [email protected].

References

1. Arch Dermatol. 1993 Jan;129(1):92-6.

2. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Feb;72(2):239-45.

Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection commonly manifests as an upper or lower respiratory tract infection with associated fever, dyspnea, cough, and coryza. However, patients can present with extrapulmonary complications with dermatologic findings including mucocutaneous eruptions. M. pneumoniae–associated mucocutaneous disease has prominent mucositis and typically sparse cutaneous involvement. The mucositis usually involves the lips and oral mucosa, eye conjunctivae, and nasal mucosa and can involve urogenital lesions. It predominantly is observed in children and adolescents. This condition is essentially a subtype of Stevens-Johnson syndrome, with a specific infection-associated etiology, and has been called “Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis,” shortened to “MIRM.”

Severe reactive mucocutaneous eruptions include erythema multiforme (EM), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). While there has been semantic confusion over the years, there are some distinctive characteristics.

EM is characterized by typical three-ringed target papules that are predominantly acral in location and often without mucosal involvement. The lesions are “multiforme” in that they can appear polymorphous and evolve during an episode, with erythematous macules progressing to edematous papules, sometimes with a halo of pallor and concentric “target-like” appearance. Lesions of EM are fixed, meaning individual lesions last 7-10 days, unlike urticarial lesions that last hours. EM classically is associated with herpes simplex virus infections which usually precede its development.

SJS and TEN display atypical macules and papules which develop into erythematous vesicles, bullae, and potentially extensive desquamation, usually presenting with fever and systemic symptoms, with multiple mucosal sites involved. SJS usually is defined by having bullae restricted to less than 10% of body surface area (BSA), TEN as greater than 30% BSA, and “overlap SJS-TEN” as 20%-30% skin detachment.1 SJS and TEN commonly are induced by medications and on a spectrum of drug hypersensitivity–induced epidermal necrolysis.

MIRM has been highlighted as a distinct, common condition, usually mucous-membrane predominant with involvement of two or more mucosal sites, less than 10% total BSA, the presence of few vesiculobullous lesions or scattered atypical targets with or without targetoid lesions (without rash is called MIRM sine rash), and clinical and laboratory evidence of atypical pneumonia.2 Other infections can cause similar eruptions (for example, Chlamydia pneumoniae), and a recent proposal by the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance has suggested the term “Reactive Infectious Mucocutaneous Eruption” (RIME) to include MIRM and other infection-induced reactions.

Laboratory diagnosis of M. pneumoniae is via serology or polymerase chain reaction. Antibody titers begin to rise approximately 7-9 days after infection and peak at 3-4 weeks. Enzyme immunoassay is more sensitive in detecting acute infection than culture and has sensitivity comparable to the polymerase chain reaction if there has been sufficient time to develop an antibody response.

The differential diagnosis between RIME/MIRM, SJS, and TEN may be difficult to distinguish in the first few days of presentation, and consideration of infections and possible medication causes is important. DRESS syndrome (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) also is in the differential diagnosis. DRESS usually has a long latency (2-8 weeks) between drug exposure and disease onset.

Treatment of RIME/MIRM is supportive care and treatment of any underlying infection. Steroids and intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) have been used to treat reactive mucositis, as well as cyclosporine and biologic agents (such as etanercept), in an attempt to minimize the extent and duration of mucous membrane vesiculation and denudation. While these drugs may help shorten the duration of the disease course, controlled trials are lacking and there is little comparative literature on efficacy or safety of these agents.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Bhatti is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Diego. They said they have no financial disclosures. Email Dr. Eichenfield and Dr. Bhatti at [email protected].

References

1. Arch Dermatol. 1993 Jan;129(1):92-6.

2. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Feb;72(2):239-45.

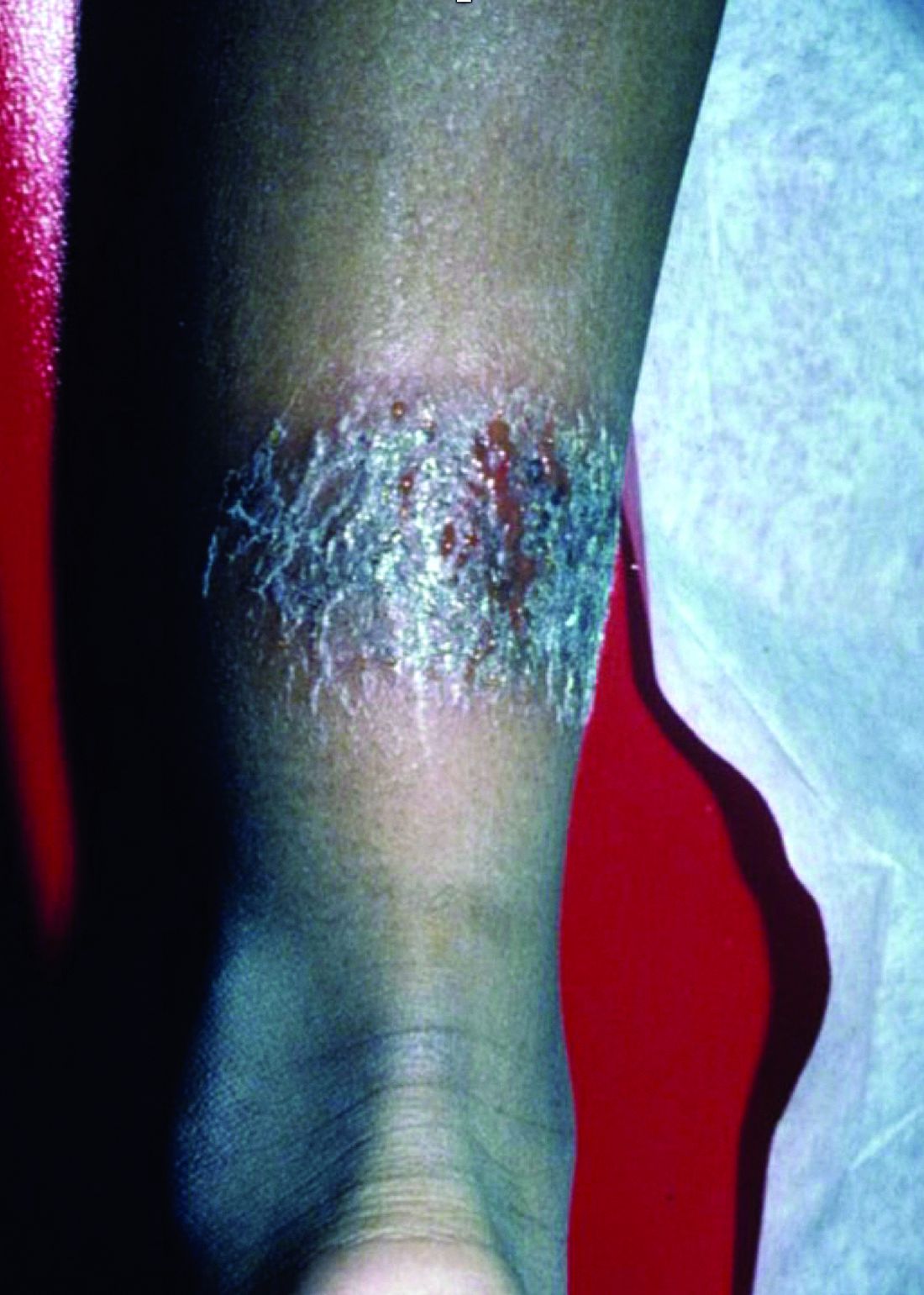

A 3-year-old is brought to the clinic for evaluation of a localized, scaling inflamed lesion on the left leg

Nummular dermatitis, or nummular eczema, is an inflammatory skin condition that is considered to be a distinctive form of idiopathic eczema, while the term also is used to describe lesional morphology associated with other conditions.

The term nummular derives from the Latin word for “coin,” as lesions are commonly annular plaques. Lesions of nummular dermatitis can be single or multiple. The typical distribution involves the extremities and, although less common, it can affect the trunk as well.

Nummular dermatitis may be associated with atopic dermatitis, or it can be an isolated condition.1 While the pathogenesis is uncertain, instigating factors include xerotic skin, insect bites, or scratches or scrapes.1Staphylococcus infection or colonization, contact allergies to metals such as nickel and less commonly mercury, sensitivity to formaldehyde or medicines such as neomycin, and sensitization to an environmental aeroallergen (such as Candida albicans, dust mites) are considered risk factors.2

The diagnosis of nummular dermatitis is clinical. Laboratory testing and/or biopsy generally are not necessary, although a bacterial culture can be considered in patients with exudative and/or crusted lesions to rule out impetigo as a primary process of secondary infection. In some cases, patch testing for allergic contact dermatitis may be useful.

The differential diagnosis of nummular dermatitis includes tinea corporis (ringworm), atopic dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis, impetigo, and psoriasis. Tinea corporis usually presents as annular lesions with a distinct peripheral scaling, rather than the diffuse induration of nummular dermatitis. Potassium hydroxide preparation or fungal culture can identify tinea species. Nummular dermatitis may be seen in patients with atopic dermatitis, who should have typical history, morphology, and course consistent with standard diagnostic criteria. Allergic contact dermatitis can present with regional, localized eczematous plaques in areas exposed to contact allergens. Patterns of lesions in areas of contact and worsening with repeat exposures can be clues to this diagnosis. Impetigo can present with honey-colored crusted lesions and/or superficial erosions, or purulent pyoderma. Lesions can be single or multiple and generally appear less inflammatory than nummular dermatitis. Psoriasis lesions may be annular, are more common on extensor surfaces, and usually have more prominent overlying pinkish, silvery white or micaceous scale.

Management of nummular dermatitis requires strong anti-inflammatory medications, usually mid-potency or higher topical corticosteroids, along with moisturizers and limiting exposure to skin irritants. “Wet wraps,” with application of topical corticosteroids to wet skin with occlusive wet dressings can enhance response. Transition from higher strength topical corticosteroids to lower strength agents used intermittently can help achieve remission or cure. Management practices include less frequent bathing with lukewarm water, using hypoallergenic cleansers and detergents, and applying moisturizers frequently. If plaques do recur, they tend to do so in the same location and in some patients resolution may result in hyper or hypopigmentation. Refractory disease may be managed with intralesional steroid injections, or systemic medications such as methotrexate.3

Dr. Tracy is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Neither Dr. Tracy nor Dr. Eichenfield have any relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012 Sep-Oct;29(5):580-3.

2. American Academy of Dermatology. Nummular Dermatitis Overview

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Sep;35(5):611-5.

Nummular dermatitis, or nummular eczema, is an inflammatory skin condition that is considered to be a distinctive form of idiopathic eczema, while the term also is used to describe lesional morphology associated with other conditions.

The term nummular derives from the Latin word for “coin,” as lesions are commonly annular plaques. Lesions of nummular dermatitis can be single or multiple. The typical distribution involves the extremities and, although less common, it can affect the trunk as well.

Nummular dermatitis may be associated with atopic dermatitis, or it can be an isolated condition.1 While the pathogenesis is uncertain, instigating factors include xerotic skin, insect bites, or scratches or scrapes.1Staphylococcus infection or colonization, contact allergies to metals such as nickel and less commonly mercury, sensitivity to formaldehyde or medicines such as neomycin, and sensitization to an environmental aeroallergen (such as Candida albicans, dust mites) are considered risk factors.2

The diagnosis of nummular dermatitis is clinical. Laboratory testing and/or biopsy generally are not necessary, although a bacterial culture can be considered in patients with exudative and/or crusted lesions to rule out impetigo as a primary process of secondary infection. In some cases, patch testing for allergic contact dermatitis may be useful.

The differential diagnosis of nummular dermatitis includes tinea corporis (ringworm), atopic dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis, impetigo, and psoriasis. Tinea corporis usually presents as annular lesions with a distinct peripheral scaling, rather than the diffuse induration of nummular dermatitis. Potassium hydroxide preparation or fungal culture can identify tinea species. Nummular dermatitis may be seen in patients with atopic dermatitis, who should have typical history, morphology, and course consistent with standard diagnostic criteria. Allergic contact dermatitis can present with regional, localized eczematous plaques in areas exposed to contact allergens. Patterns of lesions in areas of contact and worsening with repeat exposures can be clues to this diagnosis. Impetigo can present with honey-colored crusted lesions and/or superficial erosions, or purulent pyoderma. Lesions can be single or multiple and generally appear less inflammatory than nummular dermatitis. Psoriasis lesions may be annular, are more common on extensor surfaces, and usually have more prominent overlying pinkish, silvery white or micaceous scale.

Management of nummular dermatitis requires strong anti-inflammatory medications, usually mid-potency or higher topical corticosteroids, along with moisturizers and limiting exposure to skin irritants. “Wet wraps,” with application of topical corticosteroids to wet skin with occlusive wet dressings can enhance response. Transition from higher strength topical corticosteroids to lower strength agents used intermittently can help achieve remission or cure. Management practices include less frequent bathing with lukewarm water, using hypoallergenic cleansers and detergents, and applying moisturizers frequently. If plaques do recur, they tend to do so in the same location and in some patients resolution may result in hyper or hypopigmentation. Refractory disease may be managed with intralesional steroid injections, or systemic medications such as methotrexate.3

Dr. Tracy is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Neither Dr. Tracy nor Dr. Eichenfield have any relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012 Sep-Oct;29(5):580-3.

2. American Academy of Dermatology. Nummular Dermatitis Overview

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Sep;35(5):611-5.

Nummular dermatitis, or nummular eczema, is an inflammatory skin condition that is considered to be a distinctive form of idiopathic eczema, while the term also is used to describe lesional morphology associated with other conditions.

The term nummular derives from the Latin word for “coin,” as lesions are commonly annular plaques. Lesions of nummular dermatitis can be single or multiple. The typical distribution involves the extremities and, although less common, it can affect the trunk as well.

Nummular dermatitis may be associated with atopic dermatitis, or it can be an isolated condition.1 While the pathogenesis is uncertain, instigating factors include xerotic skin, insect bites, or scratches or scrapes.1Staphylococcus infection or colonization, contact allergies to metals such as nickel and less commonly mercury, sensitivity to formaldehyde or medicines such as neomycin, and sensitization to an environmental aeroallergen (such as Candida albicans, dust mites) are considered risk factors.2

The diagnosis of nummular dermatitis is clinical. Laboratory testing and/or biopsy generally are not necessary, although a bacterial culture can be considered in patients with exudative and/or crusted lesions to rule out impetigo as a primary process of secondary infection. In some cases, patch testing for allergic contact dermatitis may be useful.

The differential diagnosis of nummular dermatitis includes tinea corporis (ringworm), atopic dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis, impetigo, and psoriasis. Tinea corporis usually presents as annular lesions with a distinct peripheral scaling, rather than the diffuse induration of nummular dermatitis. Potassium hydroxide preparation or fungal culture can identify tinea species. Nummular dermatitis may be seen in patients with atopic dermatitis, who should have typical history, morphology, and course consistent with standard diagnostic criteria. Allergic contact dermatitis can present with regional, localized eczematous plaques in areas exposed to contact allergens. Patterns of lesions in areas of contact and worsening with repeat exposures can be clues to this diagnosis. Impetigo can present with honey-colored crusted lesions and/or superficial erosions, or purulent pyoderma. Lesions can be single or multiple and generally appear less inflammatory than nummular dermatitis. Psoriasis lesions may be annular, are more common on extensor surfaces, and usually have more prominent overlying pinkish, silvery white or micaceous scale.

Management of nummular dermatitis requires strong anti-inflammatory medications, usually mid-potency or higher topical corticosteroids, along with moisturizers and limiting exposure to skin irritants. “Wet wraps,” with application of topical corticosteroids to wet skin with occlusive wet dressings can enhance response. Transition from higher strength topical corticosteroids to lower strength agents used intermittently can help achieve remission or cure. Management practices include less frequent bathing with lukewarm water, using hypoallergenic cleansers and detergents, and applying moisturizers frequently. If plaques do recur, they tend to do so in the same location and in some patients resolution may result in hyper or hypopigmentation. Refractory disease may be managed with intralesional steroid injections, or systemic medications such as methotrexate.3

Dr. Tracy is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Neither Dr. Tracy nor Dr. Eichenfield have any relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012 Sep-Oct;29(5):580-3.

2. American Academy of Dermatology. Nummular Dermatitis Overview

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Sep;35(5):611-5.

On physical exam, he is noted to have a localized eczematous plaque with erythema and edema. Also, he is noted to have diffuse, fine xerosis of the bilateral lower extremities. His skin is otherwise nonremarkable.

What is your diagnosis?

It most commonly affects young girls. The pathogenesis of LAHS is thought to involve a sporadic, autosomal dominant mutation that leads to a defect between the hair cuticle and the inner root sheath.1 This defect results in the hair being poorly anchored to the scalp, and therefore easily and painlessly plucked or lost during normal hair care.

The classic presentation of LAHS is that of hair thinning and hair that may be unruly and/or lackluster; the hair rarely, if ever, requires cutting.2 The key feature is the ability to easily and painlessly pluck hairs from the patient’s scalp. The affected area is limited to the scalp, and loss of eyebrows, eyelashes, and body hair should not be seen.

Diagnosis and consideration of the differential

The diagnosis of LAHS can in some cases be made on history and physical exam alone. Patients with LAHS typically will show hair thinning with or without dullness or unruliness. They lack evidence of scalp inflammation, such as erythema, scale, pruritus, and pain. Areas of hair thinning or aberration are typically not well demarcated, and there are typically not areas of complete hair loss. There is no scarring or atrophy of the scalp itself.

Diagnostic tests include the “hair pull test,” as well as trichogram testing. In the “hair pull test” a provider grasps a set of hair at the proximal shaft near the scalp. The traction applied should result in the painless and easy extraction of more than 10% of grasped hairs in a patient with LAHS. Removal of less than 10% of hair is a normal finding, as patients without LAHS typically have about 10% of their scalp hair in the telogen phase at any given time, which would result in removal during the hair pull test.3 In trichography, plucked hairs are examined under magnification, with or without the use of selective dyes. Cinnamaldehyde is a dye that stains citrulline, which is abundant in the inner root sheath, and can be a tool in identifying its presence and/or aberrations.4 A trichogram of the pulled hairs in a patient with LAHS may classically show ruffled appearance of the cuticle, misshapen anagen hair bulbs, and absence of the inner root sheath.5 Examination under magnification also allows providers to better identify telogen versus anagen hairs, which aids in the diagnosis. By carefully considering the patient history, physical exam, and results of additional hair tests, providers can make the diagnosis of LAHS and avoid unnecessary blood work and invasive procedures like scalp biopsies.

The differential diagnosis of hair loss frequently includes alopecia areata. However, in alopecia areata, patients typically have sharply demarcated areas of hair loss, which may involve the eyebrows, eyelids, and body hairs. In alopecia areata, providers may be able to identify the “exclamation point sign” in which the hair shaft thins proximally, leading to the appearance of more pigmented, thicker hairs floating above the scalp.

Telogen effluvium is a condition in which a medical illness or stress, such as systemic illness, surgery, severe emotional distress, childbirth, dietary changes, or another traumatic event, causes a disruption in the natural cycle of hair growth such that the percentage of hairs in the telogen phase increases from about 10% to up to 70%.6 Unlike in LAHS, in which shed hairs are in the anagen phase, the hair that is shed in telogen effluvium is in the telogen phase and will have a different appearance when magnified.

Anagen effluvium, loss of hairs in their growing phase, is typically associated with chemotherapy. The hairs become broken and fractured at the shaft leading to breakage at different points throughout the scalp. Affected areas can include the eyebrows, eyelashes, and body hair. In the absence of a history of administration of a chemotherapy agent (or other drug known to trigger hair loss), the diagnosis of anagen effluvium should not be made.

Patients with trichotillosis (also known as trichotillomania) present with areas of hair loss caused by intentional or subconscious hair pulling. It is considered a psychological condition that can be associated with obsessive compulsive disorder, although the presence of a secondary psychological diagnosis is not required. Providers may see irregular geometric shapes of hair loss, and on close inspection see broken hair shafts of different lengths. Patients most often pull hair from their scalps (over 70% of patients), but also can pull eyelashes, eyebrow hairs, and pubic hairs.7

Treatment

LAHS is self-limited and does not necessitate treatment. However, if patients or parents feel there is significant disease burden, perhaps with poor effects on quality of life or with psychosocial impairment, treatment with minoxidil 5% solution has been studied with some success reported in the literature.1,8,9

Ms. Natsis is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Ms. Natsis and Dr. Eichenfield had no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(4):501-6.

2. Int J Trichology. 2010;2(2):96-100.

3. Pediatric Dermatol. 2016:33(50):507-10.

4. Dermatol Clin. 1986;14:745-51.

5. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(10):1123-8.

6. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(9):WE01-3.

7. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(9):868-74.

8. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:e286-e287.

9. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:389-90.

It most commonly affects young girls. The pathogenesis of LAHS is thought to involve a sporadic, autosomal dominant mutation that leads to a defect between the hair cuticle and the inner root sheath.1 This defect results in the hair being poorly anchored to the scalp, and therefore easily and painlessly plucked or lost during normal hair care.

The classic presentation of LAHS is that of hair thinning and hair that may be unruly and/or lackluster; the hair rarely, if ever, requires cutting.2 The key feature is the ability to easily and painlessly pluck hairs from the patient’s scalp. The affected area is limited to the scalp, and loss of eyebrows, eyelashes, and body hair should not be seen.

Diagnosis and consideration of the differential

The diagnosis of LAHS can in some cases be made on history and physical exam alone. Patients with LAHS typically will show hair thinning with or without dullness or unruliness. They lack evidence of scalp inflammation, such as erythema, scale, pruritus, and pain. Areas of hair thinning or aberration are typically not well demarcated, and there are typically not areas of complete hair loss. There is no scarring or atrophy of the scalp itself.

Diagnostic tests include the “hair pull test,” as well as trichogram testing. In the “hair pull test” a provider grasps a set of hair at the proximal shaft near the scalp. The traction applied should result in the painless and easy extraction of more than 10% of grasped hairs in a patient with LAHS. Removal of less than 10% of hair is a normal finding, as patients without LAHS typically have about 10% of their scalp hair in the telogen phase at any given time, which would result in removal during the hair pull test.3 In trichography, plucked hairs are examined under magnification, with or without the use of selective dyes. Cinnamaldehyde is a dye that stains citrulline, which is abundant in the inner root sheath, and can be a tool in identifying its presence and/or aberrations.4 A trichogram of the pulled hairs in a patient with LAHS may classically show ruffled appearance of the cuticle, misshapen anagen hair bulbs, and absence of the inner root sheath.5 Examination under magnification also allows providers to better identify telogen versus anagen hairs, which aids in the diagnosis. By carefully considering the patient history, physical exam, and results of additional hair tests, providers can make the diagnosis of LAHS and avoid unnecessary blood work and invasive procedures like scalp biopsies.

The differential diagnosis of hair loss frequently includes alopecia areata. However, in alopecia areata, patients typically have sharply demarcated areas of hair loss, which may involve the eyebrows, eyelids, and body hairs. In alopecia areata, providers may be able to identify the “exclamation point sign” in which the hair shaft thins proximally, leading to the appearance of more pigmented, thicker hairs floating above the scalp.

Telogen effluvium is a condition in which a medical illness or stress, such as systemic illness, surgery, severe emotional distress, childbirth, dietary changes, or another traumatic event, causes a disruption in the natural cycle of hair growth such that the percentage of hairs in the telogen phase increases from about 10% to up to 70%.6 Unlike in LAHS, in which shed hairs are in the anagen phase, the hair that is shed in telogen effluvium is in the telogen phase and will have a different appearance when magnified.

Anagen effluvium, loss of hairs in their growing phase, is typically associated with chemotherapy. The hairs become broken and fractured at the shaft leading to breakage at different points throughout the scalp. Affected areas can include the eyebrows, eyelashes, and body hair. In the absence of a history of administration of a chemotherapy agent (or other drug known to trigger hair loss), the diagnosis of anagen effluvium should not be made.

Patients with trichotillosis (also known as trichotillomania) present with areas of hair loss caused by intentional or subconscious hair pulling. It is considered a psychological condition that can be associated with obsessive compulsive disorder, although the presence of a secondary psychological diagnosis is not required. Providers may see irregular geometric shapes of hair loss, and on close inspection see broken hair shafts of different lengths. Patients most often pull hair from their scalps (over 70% of patients), but also can pull eyelashes, eyebrow hairs, and pubic hairs.7

Treatment

LAHS is self-limited and does not necessitate treatment. However, if patients or parents feel there is significant disease burden, perhaps with poor effects on quality of life or with psychosocial impairment, treatment with minoxidil 5% solution has been studied with some success reported in the literature.1,8,9

Ms. Natsis is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Ms. Natsis and Dr. Eichenfield had no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(4):501-6.

2. Int J Trichology. 2010;2(2):96-100.

3. Pediatric Dermatol. 2016:33(50):507-10.

4. Dermatol Clin. 1986;14:745-51.

5. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(10):1123-8.

6. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(9):WE01-3.

7. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(9):868-74.

8. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:e286-e287.

9. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:389-90.

It most commonly affects young girls. The pathogenesis of LAHS is thought to involve a sporadic, autosomal dominant mutation that leads to a defect between the hair cuticle and the inner root sheath.1 This defect results in the hair being poorly anchored to the scalp, and therefore easily and painlessly plucked or lost during normal hair care.

The classic presentation of LAHS is that of hair thinning and hair that may be unruly and/or lackluster; the hair rarely, if ever, requires cutting.2 The key feature is the ability to easily and painlessly pluck hairs from the patient’s scalp. The affected area is limited to the scalp, and loss of eyebrows, eyelashes, and body hair should not be seen.

Diagnosis and consideration of the differential

The diagnosis of LAHS can in some cases be made on history and physical exam alone. Patients with LAHS typically will show hair thinning with or without dullness or unruliness. They lack evidence of scalp inflammation, such as erythema, scale, pruritus, and pain. Areas of hair thinning or aberration are typically not well demarcated, and there are typically not areas of complete hair loss. There is no scarring or atrophy of the scalp itself.

Diagnostic tests include the “hair pull test,” as well as trichogram testing. In the “hair pull test” a provider grasps a set of hair at the proximal shaft near the scalp. The traction applied should result in the painless and easy extraction of more than 10% of grasped hairs in a patient with LAHS. Removal of less than 10% of hair is a normal finding, as patients without LAHS typically have about 10% of their scalp hair in the telogen phase at any given time, which would result in removal during the hair pull test.3 In trichography, plucked hairs are examined under magnification, with or without the use of selective dyes. Cinnamaldehyde is a dye that stains citrulline, which is abundant in the inner root sheath, and can be a tool in identifying its presence and/or aberrations.4 A trichogram of the pulled hairs in a patient with LAHS may classically show ruffled appearance of the cuticle, misshapen anagen hair bulbs, and absence of the inner root sheath.5 Examination under magnification also allows providers to better identify telogen versus anagen hairs, which aids in the diagnosis. By carefully considering the patient history, physical exam, and results of additional hair tests, providers can make the diagnosis of LAHS and avoid unnecessary blood work and invasive procedures like scalp biopsies.

The differential diagnosis of hair loss frequently includes alopecia areata. However, in alopecia areata, patients typically have sharply demarcated areas of hair loss, which may involve the eyebrows, eyelids, and body hairs. In alopecia areata, providers may be able to identify the “exclamation point sign” in which the hair shaft thins proximally, leading to the appearance of more pigmented, thicker hairs floating above the scalp.

Telogen effluvium is a condition in which a medical illness or stress, such as systemic illness, surgery, severe emotional distress, childbirth, dietary changes, or another traumatic event, causes a disruption in the natural cycle of hair growth such that the percentage of hairs in the telogen phase increases from about 10% to up to 70%.6 Unlike in LAHS, in which shed hairs are in the anagen phase, the hair that is shed in telogen effluvium is in the telogen phase and will have a different appearance when magnified.

Anagen effluvium, loss of hairs in their growing phase, is typically associated with chemotherapy. The hairs become broken and fractured at the shaft leading to breakage at different points throughout the scalp. Affected areas can include the eyebrows, eyelashes, and body hair. In the absence of a history of administration of a chemotherapy agent (or other drug known to trigger hair loss), the diagnosis of anagen effluvium should not be made.

Patients with trichotillosis (also known as trichotillomania) present with areas of hair loss caused by intentional or subconscious hair pulling. It is considered a psychological condition that can be associated with obsessive compulsive disorder, although the presence of a secondary psychological diagnosis is not required. Providers may see irregular geometric shapes of hair loss, and on close inspection see broken hair shafts of different lengths. Patients most often pull hair from their scalps (over 70% of patients), but also can pull eyelashes, eyebrow hairs, and pubic hairs.7

Treatment

LAHS is self-limited and does not necessitate treatment. However, if patients or parents feel there is significant disease burden, perhaps with poor effects on quality of life or with psychosocial impairment, treatment with minoxidil 5% solution has been studied with some success reported in the literature.1,8,9

Ms. Natsis is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Ms. Natsis and Dr. Eichenfield had no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(4):501-6.

2. Int J Trichology. 2010;2(2):96-100.

3. Pediatric Dermatol. 2016:33(50):507-10.

4. Dermatol Clin. 1986;14:745-51.

5. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(10):1123-8.

6. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(9):WE01-3.

7. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(9):868-74.

8. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:e286-e287.

9. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:389-90.

A 5-year-old female is brought to clinic for hair loss. The mother reports that when styling her daughter's hair, she has noticed areas of hair thinning, especially at the temples and at the occiput. The mother denies scale, pruritus, and erythema. The patient reports that her scalp does not hurt. She has never had a haircut because her hair hasn't grown long enough to cut. There is no history of specific bald spots. The patient has no personal history of psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, or autoimmune disease. No picking has been noted, and there is no history of compulsive behaviors or anxiety. The patient's mother has a history of Graves disease. The mother reports that the patient's older sister may have had hair thinning when she was younger as well, but no longer has thin hair.

The patient was previously seen by another provider who prescribed hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment, which the mother has been applying nightly without improvement.

The child is otherwise medically well and thriving, with no recent change in activity level and with growth parameters consistently around the 75th percentile for height and weight. On physical exam, the patient has blondish, fine hair with areas of poorly demarcated hair thinning at the left temple and at the occiput. The hair remaining at the occiput is normal in texture. There are no areas of complete hair loss. There is no scale, erythema, or abnormal pigmentation, and no cervical or occipital adenopathy. The patient has intact eyebrows and eyelashes.

What is your diagnosis?

Epidermal nevi are a subset of cutaneous hamartomas resulting from somatic mutations of epidermal cells, presenting as keratinocyte or epidermal appendage overgrowths. The most common type appear in a linear distribution and are termed linear epidermal nevi or linear verrucous epidermal nevi.

There are variations of epidermal nevi (EN) that can be composed of superficial epidermal keratinocytes, sebaceous glands, apocrine or eccrine glands, hair follicles, or smooth muscle. For example, many consider a nevus sebaceous to be a type of epidermal nevus as well. The incidence of EN is approximately 1 in 1,000 newborns. Postzygotic cell mutations result in a mosaic distribution that follows embryonic migration patterns, appearing in a Blaschkoid distribution.

EN present most frequently as unilateral linear or whorled hyperpigmented coalescing papules. The lesions can be present at birth or during childhood, and after appearing, grow with the patient. Typically the lesions become more raised and verrucous around puberty. The differential diagnosis of linear EN include lichen striatus, warts, and incontinentia pigmenti. Lichen striatus can be differentiated because it presents later in life and self-resolves. Verrucae are the most commonly mistaken diagnosis for EN; warts do not usually persist in the same pattern over time with proportionate growth and typically respond to locally destructive treatments such as liquid nitrogen, unlike EN. Incontinentia pigmenti presents as vesicles initially and shows a quick evolution, differentiating it from EN. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN) is a variant of linear EN that has associated chronic and intermittent erythema, scale, and pruritus. Lichen nitidus often has a pruritic presentation; however, it is flat topped and skin colored, helping differentiate it from linear EN.

There has been recent research advancing gene associations for linear EN displaying many lesions associated with mosaic mutations in oncogenes. Multiple genes have been identified with EN including RAS, FGFR3, and PIK3CA1. FGFR3 and PIK3CA mutations are associated with 50% of keratinocytic nevi. Of the RAS family, the HRAS pathway has been most closely associated with nevus sebaceous. While KRAS and NRAS genes have been associated with EN, it is to a lesser degree. However, there are multiple recent case reports demonstrating a potential association of G12D mosaicism of the KRAS gene in EN with rhabdomyosarcoma and bladder cancers2.

The diagnosis of epidermal nevus syndrome should be considered when there is a nevus with associated developmental abnormality of the central nervous system, eyes, or musculoskeletal systems. The most common systemic symptoms include delays in developmental milestones, seizure disorders, coloboma, strabismus, muscle weakness, and hemihypertrophy. To date, there are six specific epidermal nevus syndromes identified: sebaceous nevus syndrome, nevus comedonicus syndrome, Becker nevus syndrome, phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica, Proteus syndrome, congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform nevus and limb defects, and cutaneous-skeletal hypophosphatemia syndrome3. In addition to the syndromes described, there are reports of associations between keratinocytic nevi and ILVEN with hypophosphatemic rickets and precocious puberty.

Linear EN are rarely associated with malignant transformation to basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma, depending on the cell type involved. Given the low risk of malignancy, the lesions do not need to be removed routinely. For small lesions, monitoring often is the preferred management. However, lesions with functional significance, or causing strangulation or deformity, can be treated with surgical excision, curettage, or laser destruction

Dr. Kaushik is with the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego, and Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. There are no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures for Dr. Kaushik or Dr. Eichenfield. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004 Jul-Aug;21(4):432-9.

2. J Med Genet. 2010 Dec;47(12):859-62.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jan;35(1):21-9.

Epidermal nevi are a subset of cutaneous hamartomas resulting from somatic mutations of epidermal cells, presenting as keratinocyte or epidermal appendage overgrowths. The most common type appear in a linear distribution and are termed linear epidermal nevi or linear verrucous epidermal nevi.

There are variations of epidermal nevi (EN) that can be composed of superficial epidermal keratinocytes, sebaceous glands, apocrine or eccrine glands, hair follicles, or smooth muscle. For example, many consider a nevus sebaceous to be a type of epidermal nevus as well. The incidence of EN is approximately 1 in 1,000 newborns. Postzygotic cell mutations result in a mosaic distribution that follows embryonic migration patterns, appearing in a Blaschkoid distribution.

EN present most frequently as unilateral linear or whorled hyperpigmented coalescing papules. The lesions can be present at birth or during childhood, and after appearing, grow with the patient. Typically the lesions become more raised and verrucous around puberty. The differential diagnosis of linear EN include lichen striatus, warts, and incontinentia pigmenti. Lichen striatus can be differentiated because it presents later in life and self-resolves. Verrucae are the most commonly mistaken diagnosis for EN; warts do not usually persist in the same pattern over time with proportionate growth and typically respond to locally destructive treatments such as liquid nitrogen, unlike EN. Incontinentia pigmenti presents as vesicles initially and shows a quick evolution, differentiating it from EN. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN) is a variant of linear EN that has associated chronic and intermittent erythema, scale, and pruritus. Lichen nitidus often has a pruritic presentation; however, it is flat topped and skin colored, helping differentiate it from linear EN.

There has been recent research advancing gene associations for linear EN displaying many lesions associated with mosaic mutations in oncogenes. Multiple genes have been identified with EN including RAS, FGFR3, and PIK3CA1. FGFR3 and PIK3CA mutations are associated with 50% of keratinocytic nevi. Of the RAS family, the HRAS pathway has been most closely associated with nevus sebaceous. While KRAS and NRAS genes have been associated with EN, it is to a lesser degree. However, there are multiple recent case reports demonstrating a potential association of G12D mosaicism of the KRAS gene in EN with rhabdomyosarcoma and bladder cancers2.

The diagnosis of epidermal nevus syndrome should be considered when there is a nevus with associated developmental abnormality of the central nervous system, eyes, or musculoskeletal systems. The most common systemic symptoms include delays in developmental milestones, seizure disorders, coloboma, strabismus, muscle weakness, and hemihypertrophy. To date, there are six specific epidermal nevus syndromes identified: sebaceous nevus syndrome, nevus comedonicus syndrome, Becker nevus syndrome, phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica, Proteus syndrome, congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform nevus and limb defects, and cutaneous-skeletal hypophosphatemia syndrome3. In addition to the syndromes described, there are reports of associations between keratinocytic nevi and ILVEN with hypophosphatemic rickets and precocious puberty.

Linear EN are rarely associated with malignant transformation to basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma, depending on the cell type involved. Given the low risk of malignancy, the lesions do not need to be removed routinely. For small lesions, monitoring often is the preferred management. However, lesions with functional significance, or causing strangulation or deformity, can be treated with surgical excision, curettage, or laser destruction

Dr. Kaushik is with the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego, and Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. There are no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures for Dr. Kaushik or Dr. Eichenfield. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004 Jul-Aug;21(4):432-9.

2. J Med Genet. 2010 Dec;47(12):859-62.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jan;35(1):21-9.

Epidermal nevi are a subset of cutaneous hamartomas resulting from somatic mutations of epidermal cells, presenting as keratinocyte or epidermal appendage overgrowths. The most common type appear in a linear distribution and are termed linear epidermal nevi or linear verrucous epidermal nevi.

There are variations of epidermal nevi (EN) that can be composed of superficial epidermal keratinocytes, sebaceous glands, apocrine or eccrine glands, hair follicles, or smooth muscle. For example, many consider a nevus sebaceous to be a type of epidermal nevus as well. The incidence of EN is approximately 1 in 1,000 newborns. Postzygotic cell mutations result in a mosaic distribution that follows embryonic migration patterns, appearing in a Blaschkoid distribution.

EN present most frequently as unilateral linear or whorled hyperpigmented coalescing papules. The lesions can be present at birth or during childhood, and after appearing, grow with the patient. Typically the lesions become more raised and verrucous around puberty. The differential diagnosis of linear EN include lichen striatus, warts, and incontinentia pigmenti. Lichen striatus can be differentiated because it presents later in life and self-resolves. Verrucae are the most commonly mistaken diagnosis for EN; warts do not usually persist in the same pattern over time with proportionate growth and typically respond to locally destructive treatments such as liquid nitrogen, unlike EN. Incontinentia pigmenti presents as vesicles initially and shows a quick evolution, differentiating it from EN. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN) is a variant of linear EN that has associated chronic and intermittent erythema, scale, and pruritus. Lichen nitidus often has a pruritic presentation; however, it is flat topped and skin colored, helping differentiate it from linear EN.

There has been recent research advancing gene associations for linear EN displaying many lesions associated with mosaic mutations in oncogenes. Multiple genes have been identified with EN including RAS, FGFR3, and PIK3CA1. FGFR3 and PIK3CA mutations are associated with 50% of keratinocytic nevi. Of the RAS family, the HRAS pathway has been most closely associated with nevus sebaceous. While KRAS and NRAS genes have been associated with EN, it is to a lesser degree. However, there are multiple recent case reports demonstrating a potential association of G12D mosaicism of the KRAS gene in EN with rhabdomyosarcoma and bladder cancers2.

The diagnosis of epidermal nevus syndrome should be considered when there is a nevus with associated developmental abnormality of the central nervous system, eyes, or musculoskeletal systems. The most common systemic symptoms include delays in developmental milestones, seizure disorders, coloboma, strabismus, muscle weakness, and hemihypertrophy. To date, there are six specific epidermal nevus syndromes identified: sebaceous nevus syndrome, nevus comedonicus syndrome, Becker nevus syndrome, phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica, Proteus syndrome, congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform nevus and limb defects, and cutaneous-skeletal hypophosphatemia syndrome3. In addition to the syndromes described, there are reports of associations between keratinocytic nevi and ILVEN with hypophosphatemic rickets and precocious puberty.

Linear EN are rarely associated with malignant transformation to basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma, depending on the cell type involved. Given the low risk of malignancy, the lesions do not need to be removed routinely. For small lesions, monitoring often is the preferred management. However, lesions with functional significance, or causing strangulation or deformity, can be treated with surgical excision, curettage, or laser destruction

Dr. Kaushik is with the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego, and Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. There are no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures for Dr. Kaushik or Dr. Eichenfield. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004 Jul-Aug;21(4):432-9.

2. J Med Genet. 2010 Dec;47(12):859-62.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jan;35(1):21-9.

A 6-year-old, otherwise-healthy male is brought into clinic for evaluation of papules on his neck. The rash has been present since 1 year of age and has been growing in size proportionately. He claims there is occasional itching but no pain or redness. He does not seem to be disturbed by his rash. He has two siblings, aged 2 and 4 years, without lesions.

On physical exam, he is noted to have a linear plaque of hyperpigmented verrucous papules on his neck.

What is your diagnosis?

Lichen nitidus, which literally means “shiny moss,” is a relatively rare, chronic skin eruption that is characterized clinically by asymptomatic, flat-topped, sharply-demarcated, skin-colored papules, which are sometimes described as being “pinpoint.”

Lichen nitidus mainly affects children and young adults. The most common sites of involvement are the trunk, flexor aspects of upper extremities, dorsal aspects of hands, and genitalia, but lesions can occur anywhere on the skin. The lesions also can develop in sites of trauma (Koebner phenomenon), and this can be a significant clinical clue to aid in the diagnosis of lichen nitidus in favor of other conditions which may present as many small papules.1 Nail changes can occur but are rare, presenting as dystrophy, pitting, riding, or loss of nail(s).2

Lichen nitidus can be a challenging diagnosis to make, especially if a practitioner is not used to seeing it. Many dermatologic conditions present with many fine papules, including the other answer choices in the given quiz question (molluscum contagiosum, keratosis pilaris, verruca vulgaris, papular eczema). What allows for a clearer diagnosis of lichen nitidus is the history provided by the patient as well as the exam. Lichen nitidus lesions typically arise without a known trigger and often persist for months while remaining asymptomatic.

Molluscum contagiosum tends to include papules that are larger and more substantial than lichen nitidus papules and may be accompanied by background hyperpigmentation or erythema, known as the “beginning of the end” sign. Keratosis pilaris is commonly thought of as a skin type more so than a skin condition, and is more commonly seen in fair-skinned individuals along the lateral arms and cheeks. It is commonly paired with a background of erythema and skin than tends to be more xerotic. Verruca are typically larger lesions, sometimes with a rough surface, and are not typically shiny. Verruca are more likely to present as a single lesion or a few lesions at a given location, as opposed to lichen nitidus which has many individual papules at a single location. Papular eczema typically is intensely pruritic and is associated with xerosis and atopy.

The cause of lichen nitidus is unknown, and there are no reported genetic factors that contribute to its presentation.3 It is thought to be a subtype of lichen planus, although this is still debated. There is more work that needs to be done to find answers to these questions and to assess what triggers these fine papules to present and in whom.

The dermatoscopic features of lichen nitidus were reported in a series of eight cases and include absent dermatoglyphics, radial ridges, ill-defined hypopigmentation, diffuse erythema, linear vessels within the lesion, and peripheral scaling.4 These features are distinctive in combination and can in some cases be used to clinically diagnose lichen nitidus without the need for a skin biopsy, which is an invasive procedure that should be avoided when possible, especially given the benign nature of lichen nitidus.

If a biopsy is performed, the histologic features that commonly are seen include well-circumscribed granuloma-like lymphohistiocytic infiltrates in the papillary dermis adjacent to ridges, mimicking a “ball-and-claw” formation.1,5

Lichen nitidus generally is self-limiting, with minimal cosmetic disruption; therefore, treatment usually is not necessary. The lesions typically resolve within 1 year of presentation – and often sooner. Topical steroids can be used for symptomatic relief of pruritus, but generally do not hasten resolution of the papules themselves. Additionally, there have been reports in the literature of the successful resolution of lesions using topical calcineurin inhibitors and UVB therapy.

In a case report of an 8-year-old child with histologically confirmed lichen nitidus that had been present for 2 years, pimecrolimus 1% cream was used twice daily for 2 months with improvement and flattening of the papules.6 This report is compelling because the lesions persisted for twice the expected time of resolution without improvement and then showed relatively quick response to pimecrolimus. In a case of a 32-year-old male with lichen nitidus on his penis, tacrolimus 0.1% was used for 4 weeks with resolution of the papules.7 Although given that lichen nitidus can self-resolve in this same time period, it is unclear in this case whether the tacrolimus was the independent cause of the resolution.

With regard to UVB therapy, there have been reports of lichen nitidus resolution after 17-30 irradiation sessions in patients with lesions present for 3-6 months, although again, it is possible that the resolution observed was simply the natural course of the lichen nitidus for these patients rather than a therapeutic benefit of UVB therapy.8,9

Given that lichen nitidus is benign and typically asymptomatic or with mild pruritus, it is reasonable to monitor the lesions without treating them. If the lesions persist beyond 1 year, it also is reasonable to trial therapies, such as topical calcineurin inhibitors and UVB therapy, although using these treatments earlier in the disease course has only limited supporting data and any improvement seen within 1 year of onset may be attributed to the natural disease course as opposed to an effect of the intervention. Considerations of the cost of therapy, as well as the degree to which the patient is bothered by the lesions and how long the lesions have persisted, should be undertaken when considering whether an intervention should be made.

Ms. Natsis is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. There are no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures for Ms. Natsis or Dr. Eichenfield. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Cutis. 1999 Aug 1;64(2):135-6.

2. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004 Oct;51(4):606-24.