User login

International medical graduates facing challenges amid COVID-19

International medical graduates (IMGs) constitute more than 24% of the total percentage of active physicians, 30% of active psychiatrists, and 33% of psychiatry residents in the United States.1 IMGs serve in various medical specialties and provide medical care to socioeconomically disadvantaged patients in underserved communities.2 Evidence suggests that patient outcomes among elderly patients admitted in U.S. hospitals for those treated by IMGs were on par with outcomes of U.S. graduates. Moreover, patients who were treated by IMGs had a lower mortality rates.3

IMGs trained in the United States make considerable contributions to psychiatry and have been very successful as educators, researchers, and leaders. Over the last 3 decades, for example, three American Psychiatric Association (APA) presidents and one past president of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry were IMGs. Many of them also hold department chair positions at many academic institutions.4,5

In short, IMGs are an important part of the U.S. health care system – particularly in psychiatry.

In addition to participating in psychiatry residency programs, IMG physicians are heavily represented in subspecialties, including geriatric psychiatry (45%), addiction psychiatry (42%), child and adolescent psychiatry (36%), psychosomatic medicine (32%), and forensic psychiatry (25%).6 IMG trainees face multiple challenges that begin as they transition to psychiatry residency in the United States, including understanding the American health care system, electronic medical records and documentation, and evidence-based medicine. In addition, they need to adapt to cultural changes, and work on language barriers, communication skills, and social isolation.7,8 Training programs account for these challenges and proactively take essential steps to facilitate the transition of IMGs into the U.S. system.9,10

As training programs prepare for the new academic year starting from July 2020 and continue to provide educational experiences to current trainees, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought additional challenges for the training programs. The gravity of the novel coronavirus pandemic continues to deepen, causing immense fear and uncertainty globally. An APA poll of more than 1,000 adults conducted early in the pandemic showed that about 40% of Americans were anxious about becoming seriously ill or dying with COVID-19. Nearly half of the respondents (48%) were anxious about the possibility of getting COVID-19, and even more (62%) were anxious about the possibility of their loved ones getting infected by this virus. Also, one-third of Americans reported a serious impact on their mental health.

Furthermore, the ailing economy and increasing unemployment are raising financial concerns for individuals and families. This pandemic also has had an impact on our patients’ sleep hygiene, relationships with their loved ones, and consumption of alcohol or other drugs/substances.11 Deteriorating mental health raises concerns about increased suicide risk as a secondary consequence.12

Physicians and other frontline teams who are taking care of these patients and their families continue to provide unexcelled, compassionate care in these unprecedented times. Selfless care continues despite awareness of the high probability of getting exposed to the virus and spreading it further to family members. Physicians involved in direct patient care for COVID-19 patients are at high risk for demoralization, burnout, depression, and anxiety.13

Struggles experienced by IMGs

On the personal front, IMGs often struggle with multiple stressors, such as lack of social support, ethnic-minority prejudice, and the need to understand financial structures such as mortgages in the new countries even after extended periods of residence.14 This virus has killed many health care professionals, including physicians around the world. There was a report of suicide by an emergency medicine physician who was treating patients with COVID-19 and ended up contracting the virus. That news was devastating and overwhelming for everyone, especially health care clinicians. It also adds to the stress and worries of IMGs who are still on nonimmigrant visas.

Bigger concerns exist if there is a demise of a nonimmigrant IMG and the implications of that loss for dependent families – who might face deportation. Even for those who were recently granted permanent residency status, worries about limited support systems and financial hardships to their families can be stressors.

Also, a large number of IMGs represent the geographical area where the pandemic began. Fortunately, the World Health Organization has taken a firm stance against possible discrimination by calling for global solidarity in these times. Furthermore, the WHO has emphasized the importance of referring to the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 as “COVID-19” only – and not by the name of a particular country or city.15 Despite those official positions, people continue to express racially discriminatory opinions related to the virus, and those comments are not only disturbing to IMGs, they also are demoralizing.

Travel restrictions

In addition to the worries that IMGs might have about their own health and that of their families residing with them, the well-being of their extended families, including their aging parents back in their countries of origin, is unsettling as well. It is even more unnerving during the pandemic because the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the State Department advised avoiding all international travel at this time. Under these circumstances, IMGs are concerned about travel to their countries of origin in the event of a family emergency and the quarantine protocols in place, at both the country of origin and at residences.

Immigration issues

The U.S. administration temporarily suspended all immigration for 60 days, starting from April 2020. Recently, an executive order was signed suspending entry in the country on several visas, including the J-1 and the H1-B. Those are two categories that allow physicians to train and work in the United States.

IMGs in the United States reside and practice here under different types of immigrant and nonimmigrant visas (J-1, H1-B). This year, the Match results coincided with the timeline of those new immigration restrictions. Many IMGs are currently in the process of renewing their H1-B visas. They are worried because their visas will expire in the coming months. During the pandemic, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services suspended routine visa services and premium processing for visa renewals. This halt led to a delay in visa processing for graduating residents in June and practicing physicians seeking visa renewal. Those delays add to personal stress, and furthermore, distract these immigrant physicians from fighting this pandemic.

Another complication is that rules for J-1 visa holders have changed so that trainees must return to their countries of origin for at least 2 years after completing their training. If they decide to continue practicing medicine in the United States, they need a specific type of J-1 waiver and must gain a pathway to be a lawful permanent resident (Green Card). Many IMGs who are on waiver positions might not be able to treat patients ailing from COVID-19 to the full extent because waivers restrict them to practicing only in certain identified health systems.

IMGs who are coming from a country such India have to wait for more than 11 years after completing their accredited training to get permanent residency because of backlog for the permanent residency process.16 While waiting for a Green Card, they must continue to work on an H1-B visa, which requires periodic renewal.

Potential impact on training

Non-U.S. citizen IMGs accounted for 13% of the total of first-year positions in the 2020 Match. They will start medical training in residency programs in the United States in the coming months. The numbers for psychiatry residency matches are higher; about 16% of total first-year positions are filled by non-U.S. IMGs.17 At this time, when they should be celebrating their successful Match after many years of hard work and persistence, there is increased anxiety. They wonder whether they will be able to enter the United States to begin their training program on time. Their concerns are multifold, but the main concern is related to uncertainties around getting visas on time. With the recent executive order in place, physicians only working actively with COVID-19 patients will be able to enter the country on visas. As mental health concerns continue to rise during these times, incoming residents might not be able to start training if they are out of the country.

Furthermore, because of travel/air restrictions, there are worries about whether physicians will be able to get flights to the United States, given the lockdown in many countries around the world. Conversely, IMGs who will be graduating from residency and fellowship programs this summer and have accepted new positions also are dealing with similar uncertainty. Their new jobs will require visa processing, and the current scenario provides limited insight, so far, about whether they will be able to start their respective jobs or whether they will have to return to their home countries until their visa processing is completed.

The American Medical Association has advised the Secretary of State and acting Secretary of Homeland Security to expedite physician workforce expansion in an effort to meet the growing need for health care services during this pandemic.18 It is encouraging that, recently, the State Department declared that visa processing will continue for medical professionals and that cases would be expedited for those who meet the criteria. However, the requirement for in-person interviews remains for individuals who are seeking a U.S. visa outside the country.

As residency programs are trying their best to continue to provide educational experiences to trainees during this phase, if psychiatry residents are placed on quarantine because of either getting exposed or contracting the illness, there is a possibility that they might need to extend their training. This would bring another challenge for IMGs, requiring them to extend their visas to complete their training. Future J-1 waiver jobs could be compromised.

Investment in physician wellness critical

Psychiatrists, along with other health care workers, are front-line soldiers in the fight against COVID-19. All physicians are at high risk for demoralization, burnout, depression, anxiety, and suicide. It is of utmost importance that we invest immediately in physicians’ wellness. As noted, significant numbers of psychiatrists are IMGs who are dealing with additional challenges while responding to the pandemic. There are certain challenges for IMGs, such as the well-being of their extended families in other countries, and travel bans put in place because of the pandemic. Those issues are not easy to resolve. However, addressing visa issues and providing support to their families in the event that something happens to physicians during the pandemic would be reassuring and would help alleviate additional stress. Those kinds of actions also would allow immigrant physicians to focus on clinical work and to improve their overall well-being. Given the health risks and numerous other insecurities that go along with living amid a pandemic, IMGs should not have the additional pressure of visa uncertainty.

Public health crises such as COVID-19 are associated with increased rates of anxiety,19 depression,20 illicit substance use,21 and an increased rate of suicide.22 Patients with serious mental illness might be among the hardest hit both physically and mentally during the pandemic.23 Even in the absence of a pandemic, there is already a shortage of psychiatrists at the national level, and it is expected that this shortage will grow in the future. Rural and underserved areas are expected to experience the physician deficit more acutely.24

The pandemic is likely to resolve gradually and unpredictably – and might recur along the way over the next 1-2 years. However, the psychiatrist shortage will escalate more, as the mental health needs in the United States increase further in coming months. We need psychiatrists now more than ever, and it will be crucial that prospective residents, graduating residents, and fellows are able to come on board to join the American health care system promptly. In addition to national-level interventions, residency programs, potential employers, and communities must be aware of and do whatever they can to address the challenges faced by IMGs during these times.

Dr. Raman Baweja is affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral health at Penn State University, Hershey. He has no conflicts of interest. Dr. Verma is affiliated with Rogers Behavioral Health in Kenosha County, Wis., and the department of psychiatry and behavioral health at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science in North Chicago. She has no conflicts of interest. Dr. Ritika Baweja is affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral health at Penn State. Dr. Ritika Baweja is the spouse of Dr. Raman Baweja. Dr. Adam is affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of Missouri, Columbia.

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. Navigating psychiatry residency in the United States. A Guide for IMG Physicians.

2. Berg S. 5 IMG physicians who speak up for patients and fellow doctors. American Medical Association. 2019 Oct 22.

3. Tsugawa Y et al. BMJ. 2017 Feb 3;256. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j273.

4. Gogineni RR et al. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2010 Oct 1;19(4):833-53.

5. Majeed MH et al. Academic Psychiatry. 2017 Dec 1;41(6):849-51.

6. Brotherton SE and Etzel SI. JAMA. 2018 Sep 11;320(10):1051-70.

7. Sockalingam S et al. Acad Psychiatry. 2012 Jul 1;36(4):277-81.

8. Singareddy R et al. Acad Psychiatry. 2008 Jul-Aug;32(4):343-4.

9. Kramer MN. Acad Psychiatry. 2005 Jul-Aug;29(3):322-4.

10. Rao NR and Kotapati VP. Pathways for success in academic medicine for an international medical graduate: Challenges and opportunities. In “Roberts Academic Medicine Handbook” 2020. Springer:163-70.

11. American Psychiatric Association. New poll: COVID-19 impacting mental well-being: Americans feeling anxious, especially for loved ones; older adults are less anxious. 2020 Mar 25.

12. Reger MA et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020 Apr 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1060.

13. Lai J et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Mar 23;3(3):e203976-e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976.

14. Kalra G et al. Acad Psychiatry. 2012 Jul;36(4):323-9.

15. WHO best practices for the naming of new human infectious diseases. World Health Organization. 2015.

16. U.S. Department of State. Bureau of Consular Affairs. Visa Bulletin for March 2020.

17. National Resident Matching Program® (NRMP®). Thousands of medical students and graduates celebrate NRMP Match results.

18. American Medical Association. AMA: U.S. should open visas to international physicians amid COVID-19. AMA press release. 2020 Mar 25.

19. McKay D et al. J Anxiety Disord. 2020 Jun;73:02233. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102233.

20. Tang W et al. J Affect Disord. 2020 May 13;274:1-7.

21. Collins F et al. NIH Director’s Blog. NIH.gov. 2020 Apr 21.

22. Reger M et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020 Apr 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1060.

23. Druss BG. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020 Apr 3. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0894.

24. American Association of Medical Colleges. “The complexities of physician supply and demand: Projections from 2018-2033.” 2020 Jun.

International medical graduates (IMGs) constitute more than 24% of the total percentage of active physicians, 30% of active psychiatrists, and 33% of psychiatry residents in the United States.1 IMGs serve in various medical specialties and provide medical care to socioeconomically disadvantaged patients in underserved communities.2 Evidence suggests that patient outcomes among elderly patients admitted in U.S. hospitals for those treated by IMGs were on par with outcomes of U.S. graduates. Moreover, patients who were treated by IMGs had a lower mortality rates.3

IMGs trained in the United States make considerable contributions to psychiatry and have been very successful as educators, researchers, and leaders. Over the last 3 decades, for example, three American Psychiatric Association (APA) presidents and one past president of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry were IMGs. Many of them also hold department chair positions at many academic institutions.4,5

In short, IMGs are an important part of the U.S. health care system – particularly in psychiatry.

In addition to participating in psychiatry residency programs, IMG physicians are heavily represented in subspecialties, including geriatric psychiatry (45%), addiction psychiatry (42%), child and adolescent psychiatry (36%), psychosomatic medicine (32%), and forensic psychiatry (25%).6 IMG trainees face multiple challenges that begin as they transition to psychiatry residency in the United States, including understanding the American health care system, electronic medical records and documentation, and evidence-based medicine. In addition, they need to adapt to cultural changes, and work on language barriers, communication skills, and social isolation.7,8 Training programs account for these challenges and proactively take essential steps to facilitate the transition of IMGs into the U.S. system.9,10

As training programs prepare for the new academic year starting from July 2020 and continue to provide educational experiences to current trainees, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought additional challenges for the training programs. The gravity of the novel coronavirus pandemic continues to deepen, causing immense fear and uncertainty globally. An APA poll of more than 1,000 adults conducted early in the pandemic showed that about 40% of Americans were anxious about becoming seriously ill or dying with COVID-19. Nearly half of the respondents (48%) were anxious about the possibility of getting COVID-19, and even more (62%) were anxious about the possibility of their loved ones getting infected by this virus. Also, one-third of Americans reported a serious impact on their mental health.

Furthermore, the ailing economy and increasing unemployment are raising financial concerns for individuals and families. This pandemic also has had an impact on our patients’ sleep hygiene, relationships with their loved ones, and consumption of alcohol or other drugs/substances.11 Deteriorating mental health raises concerns about increased suicide risk as a secondary consequence.12

Physicians and other frontline teams who are taking care of these patients and their families continue to provide unexcelled, compassionate care in these unprecedented times. Selfless care continues despite awareness of the high probability of getting exposed to the virus and spreading it further to family members. Physicians involved in direct patient care for COVID-19 patients are at high risk for demoralization, burnout, depression, and anxiety.13

Struggles experienced by IMGs

On the personal front, IMGs often struggle with multiple stressors, such as lack of social support, ethnic-minority prejudice, and the need to understand financial structures such as mortgages in the new countries even after extended periods of residence.14 This virus has killed many health care professionals, including physicians around the world. There was a report of suicide by an emergency medicine physician who was treating patients with COVID-19 and ended up contracting the virus. That news was devastating and overwhelming for everyone, especially health care clinicians. It also adds to the stress and worries of IMGs who are still on nonimmigrant visas.

Bigger concerns exist if there is a demise of a nonimmigrant IMG and the implications of that loss for dependent families – who might face deportation. Even for those who were recently granted permanent residency status, worries about limited support systems and financial hardships to their families can be stressors.

Also, a large number of IMGs represent the geographical area where the pandemic began. Fortunately, the World Health Organization has taken a firm stance against possible discrimination by calling for global solidarity in these times. Furthermore, the WHO has emphasized the importance of referring to the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 as “COVID-19” only – and not by the name of a particular country or city.15 Despite those official positions, people continue to express racially discriminatory opinions related to the virus, and those comments are not only disturbing to IMGs, they also are demoralizing.

Travel restrictions

In addition to the worries that IMGs might have about their own health and that of their families residing with them, the well-being of their extended families, including their aging parents back in their countries of origin, is unsettling as well. It is even more unnerving during the pandemic because the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the State Department advised avoiding all international travel at this time. Under these circumstances, IMGs are concerned about travel to their countries of origin in the event of a family emergency and the quarantine protocols in place, at both the country of origin and at residences.

Immigration issues

The U.S. administration temporarily suspended all immigration for 60 days, starting from April 2020. Recently, an executive order was signed suspending entry in the country on several visas, including the J-1 and the H1-B. Those are two categories that allow physicians to train and work in the United States.

IMGs in the United States reside and practice here under different types of immigrant and nonimmigrant visas (J-1, H1-B). This year, the Match results coincided with the timeline of those new immigration restrictions. Many IMGs are currently in the process of renewing their H1-B visas. They are worried because their visas will expire in the coming months. During the pandemic, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services suspended routine visa services and premium processing for visa renewals. This halt led to a delay in visa processing for graduating residents in June and practicing physicians seeking visa renewal. Those delays add to personal stress, and furthermore, distract these immigrant physicians from fighting this pandemic.

Another complication is that rules for J-1 visa holders have changed so that trainees must return to their countries of origin for at least 2 years after completing their training. If they decide to continue practicing medicine in the United States, they need a specific type of J-1 waiver and must gain a pathway to be a lawful permanent resident (Green Card). Many IMGs who are on waiver positions might not be able to treat patients ailing from COVID-19 to the full extent because waivers restrict them to practicing only in certain identified health systems.

IMGs who are coming from a country such India have to wait for more than 11 years after completing their accredited training to get permanent residency because of backlog for the permanent residency process.16 While waiting for a Green Card, they must continue to work on an H1-B visa, which requires periodic renewal.

Potential impact on training

Non-U.S. citizen IMGs accounted for 13% of the total of first-year positions in the 2020 Match. They will start medical training in residency programs in the United States in the coming months. The numbers for psychiatry residency matches are higher; about 16% of total first-year positions are filled by non-U.S. IMGs.17 At this time, when they should be celebrating their successful Match after many years of hard work and persistence, there is increased anxiety. They wonder whether they will be able to enter the United States to begin their training program on time. Their concerns are multifold, but the main concern is related to uncertainties around getting visas on time. With the recent executive order in place, physicians only working actively with COVID-19 patients will be able to enter the country on visas. As mental health concerns continue to rise during these times, incoming residents might not be able to start training if they are out of the country.

Furthermore, because of travel/air restrictions, there are worries about whether physicians will be able to get flights to the United States, given the lockdown in many countries around the world. Conversely, IMGs who will be graduating from residency and fellowship programs this summer and have accepted new positions also are dealing with similar uncertainty. Their new jobs will require visa processing, and the current scenario provides limited insight, so far, about whether they will be able to start their respective jobs or whether they will have to return to their home countries until their visa processing is completed.

The American Medical Association has advised the Secretary of State and acting Secretary of Homeland Security to expedite physician workforce expansion in an effort to meet the growing need for health care services during this pandemic.18 It is encouraging that, recently, the State Department declared that visa processing will continue for medical professionals and that cases would be expedited for those who meet the criteria. However, the requirement for in-person interviews remains for individuals who are seeking a U.S. visa outside the country.

As residency programs are trying their best to continue to provide educational experiences to trainees during this phase, if psychiatry residents are placed on quarantine because of either getting exposed or contracting the illness, there is a possibility that they might need to extend their training. This would bring another challenge for IMGs, requiring them to extend their visas to complete their training. Future J-1 waiver jobs could be compromised.

Investment in physician wellness critical

Psychiatrists, along with other health care workers, are front-line soldiers in the fight against COVID-19. All physicians are at high risk for demoralization, burnout, depression, anxiety, and suicide. It is of utmost importance that we invest immediately in physicians’ wellness. As noted, significant numbers of psychiatrists are IMGs who are dealing with additional challenges while responding to the pandemic. There are certain challenges for IMGs, such as the well-being of their extended families in other countries, and travel bans put in place because of the pandemic. Those issues are not easy to resolve. However, addressing visa issues and providing support to their families in the event that something happens to physicians during the pandemic would be reassuring and would help alleviate additional stress. Those kinds of actions also would allow immigrant physicians to focus on clinical work and to improve their overall well-being. Given the health risks and numerous other insecurities that go along with living amid a pandemic, IMGs should not have the additional pressure of visa uncertainty.

Public health crises such as COVID-19 are associated with increased rates of anxiety,19 depression,20 illicit substance use,21 and an increased rate of suicide.22 Patients with serious mental illness might be among the hardest hit both physically and mentally during the pandemic.23 Even in the absence of a pandemic, there is already a shortage of psychiatrists at the national level, and it is expected that this shortage will grow in the future. Rural and underserved areas are expected to experience the physician deficit more acutely.24

The pandemic is likely to resolve gradually and unpredictably – and might recur along the way over the next 1-2 years. However, the psychiatrist shortage will escalate more, as the mental health needs in the United States increase further in coming months. We need psychiatrists now more than ever, and it will be crucial that prospective residents, graduating residents, and fellows are able to come on board to join the American health care system promptly. In addition to national-level interventions, residency programs, potential employers, and communities must be aware of and do whatever they can to address the challenges faced by IMGs during these times.

Dr. Raman Baweja is affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral health at Penn State University, Hershey. He has no conflicts of interest. Dr. Verma is affiliated with Rogers Behavioral Health in Kenosha County, Wis., and the department of psychiatry and behavioral health at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science in North Chicago. She has no conflicts of interest. Dr. Ritika Baweja is affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral health at Penn State. Dr. Ritika Baweja is the spouse of Dr. Raman Baweja. Dr. Adam is affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of Missouri, Columbia.

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. Navigating psychiatry residency in the United States. A Guide for IMG Physicians.

2. Berg S. 5 IMG physicians who speak up for patients and fellow doctors. American Medical Association. 2019 Oct 22.

3. Tsugawa Y et al. BMJ. 2017 Feb 3;256. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j273.

4. Gogineni RR et al. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2010 Oct 1;19(4):833-53.

5. Majeed MH et al. Academic Psychiatry. 2017 Dec 1;41(6):849-51.

6. Brotherton SE and Etzel SI. JAMA. 2018 Sep 11;320(10):1051-70.

7. Sockalingam S et al. Acad Psychiatry. 2012 Jul 1;36(4):277-81.

8. Singareddy R et al. Acad Psychiatry. 2008 Jul-Aug;32(4):343-4.

9. Kramer MN. Acad Psychiatry. 2005 Jul-Aug;29(3):322-4.

10. Rao NR and Kotapati VP. Pathways for success in academic medicine for an international medical graduate: Challenges and opportunities. In “Roberts Academic Medicine Handbook” 2020. Springer:163-70.

11. American Psychiatric Association. New poll: COVID-19 impacting mental well-being: Americans feeling anxious, especially for loved ones; older adults are less anxious. 2020 Mar 25.

12. Reger MA et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020 Apr 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1060.

13. Lai J et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Mar 23;3(3):e203976-e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976.

14. Kalra G et al. Acad Psychiatry. 2012 Jul;36(4):323-9.

15. WHO best practices for the naming of new human infectious diseases. World Health Organization. 2015.

16. U.S. Department of State. Bureau of Consular Affairs. Visa Bulletin for March 2020.

17. National Resident Matching Program® (NRMP®). Thousands of medical students and graduates celebrate NRMP Match results.

18. American Medical Association. AMA: U.S. should open visas to international physicians amid COVID-19. AMA press release. 2020 Mar 25.

19. McKay D et al. J Anxiety Disord. 2020 Jun;73:02233. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102233.

20. Tang W et al. J Affect Disord. 2020 May 13;274:1-7.

21. Collins F et al. NIH Director’s Blog. NIH.gov. 2020 Apr 21.

22. Reger M et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020 Apr 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1060.

23. Druss BG. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020 Apr 3. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0894.

24. American Association of Medical Colleges. “The complexities of physician supply and demand: Projections from 2018-2033.” 2020 Jun.

International medical graduates (IMGs) constitute more than 24% of the total percentage of active physicians, 30% of active psychiatrists, and 33% of psychiatry residents in the United States.1 IMGs serve in various medical specialties and provide medical care to socioeconomically disadvantaged patients in underserved communities.2 Evidence suggests that patient outcomes among elderly patients admitted in U.S. hospitals for those treated by IMGs were on par with outcomes of U.S. graduates. Moreover, patients who were treated by IMGs had a lower mortality rates.3

IMGs trained in the United States make considerable contributions to psychiatry and have been very successful as educators, researchers, and leaders. Over the last 3 decades, for example, three American Psychiatric Association (APA) presidents and one past president of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry were IMGs. Many of them also hold department chair positions at many academic institutions.4,5

In short, IMGs are an important part of the U.S. health care system – particularly in psychiatry.

In addition to participating in psychiatry residency programs, IMG physicians are heavily represented in subspecialties, including geriatric psychiatry (45%), addiction psychiatry (42%), child and adolescent psychiatry (36%), psychosomatic medicine (32%), and forensic psychiatry (25%).6 IMG trainees face multiple challenges that begin as they transition to psychiatry residency in the United States, including understanding the American health care system, electronic medical records and documentation, and evidence-based medicine. In addition, they need to adapt to cultural changes, and work on language barriers, communication skills, and social isolation.7,8 Training programs account for these challenges and proactively take essential steps to facilitate the transition of IMGs into the U.S. system.9,10

As training programs prepare for the new academic year starting from July 2020 and continue to provide educational experiences to current trainees, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought additional challenges for the training programs. The gravity of the novel coronavirus pandemic continues to deepen, causing immense fear and uncertainty globally. An APA poll of more than 1,000 adults conducted early in the pandemic showed that about 40% of Americans were anxious about becoming seriously ill or dying with COVID-19. Nearly half of the respondents (48%) were anxious about the possibility of getting COVID-19, and even more (62%) were anxious about the possibility of their loved ones getting infected by this virus. Also, one-third of Americans reported a serious impact on their mental health.

Furthermore, the ailing economy and increasing unemployment are raising financial concerns for individuals and families. This pandemic also has had an impact on our patients’ sleep hygiene, relationships with their loved ones, and consumption of alcohol or other drugs/substances.11 Deteriorating mental health raises concerns about increased suicide risk as a secondary consequence.12

Physicians and other frontline teams who are taking care of these patients and their families continue to provide unexcelled, compassionate care in these unprecedented times. Selfless care continues despite awareness of the high probability of getting exposed to the virus and spreading it further to family members. Physicians involved in direct patient care for COVID-19 patients are at high risk for demoralization, burnout, depression, and anxiety.13

Struggles experienced by IMGs

On the personal front, IMGs often struggle with multiple stressors, such as lack of social support, ethnic-minority prejudice, and the need to understand financial structures such as mortgages in the new countries even after extended periods of residence.14 This virus has killed many health care professionals, including physicians around the world. There was a report of suicide by an emergency medicine physician who was treating patients with COVID-19 and ended up contracting the virus. That news was devastating and overwhelming for everyone, especially health care clinicians. It also adds to the stress and worries of IMGs who are still on nonimmigrant visas.

Bigger concerns exist if there is a demise of a nonimmigrant IMG and the implications of that loss for dependent families – who might face deportation. Even for those who were recently granted permanent residency status, worries about limited support systems and financial hardships to their families can be stressors.

Also, a large number of IMGs represent the geographical area where the pandemic began. Fortunately, the World Health Organization has taken a firm stance against possible discrimination by calling for global solidarity in these times. Furthermore, the WHO has emphasized the importance of referring to the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 as “COVID-19” only – and not by the name of a particular country or city.15 Despite those official positions, people continue to express racially discriminatory opinions related to the virus, and those comments are not only disturbing to IMGs, they also are demoralizing.

Travel restrictions

In addition to the worries that IMGs might have about their own health and that of their families residing with them, the well-being of their extended families, including their aging parents back in their countries of origin, is unsettling as well. It is even more unnerving during the pandemic because the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the State Department advised avoiding all international travel at this time. Under these circumstances, IMGs are concerned about travel to their countries of origin in the event of a family emergency and the quarantine protocols in place, at both the country of origin and at residences.

Immigration issues

The U.S. administration temporarily suspended all immigration for 60 days, starting from April 2020. Recently, an executive order was signed suspending entry in the country on several visas, including the J-1 and the H1-B. Those are two categories that allow physicians to train and work in the United States.

IMGs in the United States reside and practice here under different types of immigrant and nonimmigrant visas (J-1, H1-B). This year, the Match results coincided with the timeline of those new immigration restrictions. Many IMGs are currently in the process of renewing their H1-B visas. They are worried because their visas will expire in the coming months. During the pandemic, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services suspended routine visa services and premium processing for visa renewals. This halt led to a delay in visa processing for graduating residents in June and practicing physicians seeking visa renewal. Those delays add to personal stress, and furthermore, distract these immigrant physicians from fighting this pandemic.

Another complication is that rules for J-1 visa holders have changed so that trainees must return to their countries of origin for at least 2 years after completing their training. If they decide to continue practicing medicine in the United States, they need a specific type of J-1 waiver and must gain a pathway to be a lawful permanent resident (Green Card). Many IMGs who are on waiver positions might not be able to treat patients ailing from COVID-19 to the full extent because waivers restrict them to practicing only in certain identified health systems.

IMGs who are coming from a country such India have to wait for more than 11 years after completing their accredited training to get permanent residency because of backlog for the permanent residency process.16 While waiting for a Green Card, they must continue to work on an H1-B visa, which requires periodic renewal.

Potential impact on training

Non-U.S. citizen IMGs accounted for 13% of the total of first-year positions in the 2020 Match. They will start medical training in residency programs in the United States in the coming months. The numbers for psychiatry residency matches are higher; about 16% of total first-year positions are filled by non-U.S. IMGs.17 At this time, when they should be celebrating their successful Match after many years of hard work and persistence, there is increased anxiety. They wonder whether they will be able to enter the United States to begin their training program on time. Their concerns are multifold, but the main concern is related to uncertainties around getting visas on time. With the recent executive order in place, physicians only working actively with COVID-19 patients will be able to enter the country on visas. As mental health concerns continue to rise during these times, incoming residents might not be able to start training if they are out of the country.

Furthermore, because of travel/air restrictions, there are worries about whether physicians will be able to get flights to the United States, given the lockdown in many countries around the world. Conversely, IMGs who will be graduating from residency and fellowship programs this summer and have accepted new positions also are dealing with similar uncertainty. Their new jobs will require visa processing, and the current scenario provides limited insight, so far, about whether they will be able to start their respective jobs or whether they will have to return to their home countries until their visa processing is completed.

The American Medical Association has advised the Secretary of State and acting Secretary of Homeland Security to expedite physician workforce expansion in an effort to meet the growing need for health care services during this pandemic.18 It is encouraging that, recently, the State Department declared that visa processing will continue for medical professionals and that cases would be expedited for those who meet the criteria. However, the requirement for in-person interviews remains for individuals who are seeking a U.S. visa outside the country.

As residency programs are trying their best to continue to provide educational experiences to trainees during this phase, if psychiatry residents are placed on quarantine because of either getting exposed or contracting the illness, there is a possibility that they might need to extend their training. This would bring another challenge for IMGs, requiring them to extend their visas to complete their training. Future J-1 waiver jobs could be compromised.

Investment in physician wellness critical

Psychiatrists, along with other health care workers, are front-line soldiers in the fight against COVID-19. All physicians are at high risk for demoralization, burnout, depression, anxiety, and suicide. It is of utmost importance that we invest immediately in physicians’ wellness. As noted, significant numbers of psychiatrists are IMGs who are dealing with additional challenges while responding to the pandemic. There are certain challenges for IMGs, such as the well-being of their extended families in other countries, and travel bans put in place because of the pandemic. Those issues are not easy to resolve. However, addressing visa issues and providing support to their families in the event that something happens to physicians during the pandemic would be reassuring and would help alleviate additional stress. Those kinds of actions also would allow immigrant physicians to focus on clinical work and to improve their overall well-being. Given the health risks and numerous other insecurities that go along with living amid a pandemic, IMGs should not have the additional pressure of visa uncertainty.

Public health crises such as COVID-19 are associated with increased rates of anxiety,19 depression,20 illicit substance use,21 and an increased rate of suicide.22 Patients with serious mental illness might be among the hardest hit both physically and mentally during the pandemic.23 Even in the absence of a pandemic, there is already a shortage of psychiatrists at the national level, and it is expected that this shortage will grow in the future. Rural and underserved areas are expected to experience the physician deficit more acutely.24

The pandemic is likely to resolve gradually and unpredictably – and might recur along the way over the next 1-2 years. However, the psychiatrist shortage will escalate more, as the mental health needs in the United States increase further in coming months. We need psychiatrists now more than ever, and it will be crucial that prospective residents, graduating residents, and fellows are able to come on board to join the American health care system promptly. In addition to national-level interventions, residency programs, potential employers, and communities must be aware of and do whatever they can to address the challenges faced by IMGs during these times.

Dr. Raman Baweja is affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral health at Penn State University, Hershey. He has no conflicts of interest. Dr. Verma is affiliated with Rogers Behavioral Health in Kenosha County, Wis., and the department of psychiatry and behavioral health at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science in North Chicago. She has no conflicts of interest. Dr. Ritika Baweja is affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral health at Penn State. Dr. Ritika Baweja is the spouse of Dr. Raman Baweja. Dr. Adam is affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of Missouri, Columbia.

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. Navigating psychiatry residency in the United States. A Guide for IMG Physicians.

2. Berg S. 5 IMG physicians who speak up for patients and fellow doctors. American Medical Association. 2019 Oct 22.

3. Tsugawa Y et al. BMJ. 2017 Feb 3;256. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j273.

4. Gogineni RR et al. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2010 Oct 1;19(4):833-53.

5. Majeed MH et al. Academic Psychiatry. 2017 Dec 1;41(6):849-51.

6. Brotherton SE and Etzel SI. JAMA. 2018 Sep 11;320(10):1051-70.

7. Sockalingam S et al. Acad Psychiatry. 2012 Jul 1;36(4):277-81.

8. Singareddy R et al. Acad Psychiatry. 2008 Jul-Aug;32(4):343-4.

9. Kramer MN. Acad Psychiatry. 2005 Jul-Aug;29(3):322-4.

10. Rao NR and Kotapati VP. Pathways for success in academic medicine for an international medical graduate: Challenges and opportunities. In “Roberts Academic Medicine Handbook” 2020. Springer:163-70.

11. American Psychiatric Association. New poll: COVID-19 impacting mental well-being: Americans feeling anxious, especially for loved ones; older adults are less anxious. 2020 Mar 25.

12. Reger MA et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020 Apr 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1060.

13. Lai J et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Mar 23;3(3):e203976-e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976.

14. Kalra G et al. Acad Psychiatry. 2012 Jul;36(4):323-9.

15. WHO best practices for the naming of new human infectious diseases. World Health Organization. 2015.

16. U.S. Department of State. Bureau of Consular Affairs. Visa Bulletin for March 2020.

17. National Resident Matching Program® (NRMP®). Thousands of medical students and graduates celebrate NRMP Match results.

18. American Medical Association. AMA: U.S. should open visas to international physicians amid COVID-19. AMA press release. 2020 Mar 25.

19. McKay D et al. J Anxiety Disord. 2020 Jun;73:02233. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102233.

20. Tang W et al. J Affect Disord. 2020 May 13;274:1-7.

21. Collins F et al. NIH Director’s Blog. NIH.gov. 2020 Apr 21.

22. Reger M et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020 Apr 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1060.

23. Druss BG. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020 Apr 3. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0894.

24. American Association of Medical Colleges. “The complexities of physician supply and demand: Projections from 2018-2033.” 2020 Jun.

Opioid use disorder in adolescents: An overview

Ms. L, age 17, seeks treatment because she has an ongoing struggle with multiple substances, including benzodiazepines, heroin, alcohol, cannabis, and prescription opioids.

She reports that she was 13 when she first used a prescription opioid that was not prescribed for her. She also reports engaging in unsafe sexual practices while using these substances, and has been diagnosed and treated for a sexually transmitted disease. She dropped out of school and is estranged from her family. She says that for a long time she has felt depressed and that she uses drugs to “self-medicate my emotions.” She endorses high anxiety and lack of motivation. Ms. L also reports having several criminal charges for theft, assault, and exchanging sex for drugs. She has undergone 3 admissions for detoxification, but promptly resumed using drugs, primarily heroin and oxycodone, immediately after discharge. Ms. L meets DSM-5 criteria for opioid use disorder (OUD).

Ms. L’s case illustrates a disturbing trend in the current opioid epidemic in the United States. Nearly 11.8 million individuals age ≥12 reported misuse of opioids in the last year.1 Adolescents who misuse prescription or illicit opioids are more likely to be involved with the legal system due to truancy, running away from home, physical altercations, prostitution, exchanging sex for drugs, robbery, and gang involvement. Adolescents who use opioids may also struggle with academic decline, drop out of school early, be unable to maintain a job, and have relationship difficulties, especially with family members.

In this article, I describe the scope of OUD among adolescents, including epidemiology, clinical manifestations, screening tools, and treatment approaches.

Scope of the problem

According to the most recent Monitoring the Future survey of more than 42,500 8th, 10th, and 12th grade students, 2.7% of 12th graders reported prescription opioid misuse (reported in the survey as “narcotics other than heroin”) in the past year.2 In addition, 0.4% of 12th graders reported heroin use over the same period.2 Although the prevalence of opioid use among adolescents has been declining over the past 5 years,2 it still represents a serious health crisis.

Part of the issue may relate to easier access to more potent opioids. For example, heroin available today can be >4 times purer than it was in the past. In 2002, t

Between 1997 and 2012, the annual incidence of youth (age 15 to 19) hospitalizations for prescription opioid poisoning increased >170%.5 Approximately 6% to 9% of youth involved in risky opioid use develop OUD 6 to 12 months after s

Continue to: In recent years...

In recent years, deaths from drug overdose have increased for all age groups; however, limited data is available regarding adolescent overdose deaths. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), from 2015 to 2016, drug overdose death rates for persons age 15 to 24 increased to 28%.9

How opioids work

Opioids activate specific transmembrane neurotransmitter receptors, including mu, kappa, and delta, in the CNS and peripheral nervous system (PNS). This leads to activation of G protein–mediated intracellular signal transduction. Mainly it is activation of endogenous mu opioid receptors that mediates the reward, withdrawal, and analgesic effects of opioids. These effects depend on the location of mu receptors. In the CNS, activation of mu opioid receptors may cause miosis, respiratory depression, euphoria, and analgesia.10

Different opioids vary in terms of their half-life; for most opioids, the half-life ranges from 2 to 4 hours.10 Heroin has a half-life of 30 minutes, but due to active metabolites its duration of action is 4 to 5 hours. Opioid metabolites can be detected in urine toxicology within approximately 1 to 2 days since last use.10

Chronic opioid use is associated with neurologic effects that change the function of areas of the brain that control pleasure/reward, stress, decision-making, and more. This leads to cravings, continued substance use, and dependence.11 After continued long-term use, patients report decreased euphoria, but typically they continue to use opioids to avoid withdrawal symptoms or worsening mood.

Criteria for opioid use disorder

In DSM-5, substance use disorders (SUDs)are no longer categorized as abuse or dependence.12 For opioids, the diagnosis is OUD. The Table12 outlines the DSM-5 criteria for OUD. Craving opioids is included for the first time in the OUD diagnosis. Having problems with the legal system is no longer considered a diagnostic criterion for OUD.

Continue to: A vulnerable population

A vulnerable population

As defined by Erik Erikson’s psychosocial stages of development, adolescents struggle between establishing their own identity vs role confusion.13 In an attempt to relate to peers or give in to peer pressure, some adolescents start by experimenting with nicotine, alcohol, and/or marijuana; however, some may move on to using other illicit drugs.14 Risk factors for the development of SUDs include early onset of substance use and a rapid progression through stages of substance use from experimentation to regular use, risky use, and dependence.15 In our case study, Ms. L’s substance use followed a similar pattern. Further, the comorbidity of SUDs and other psychiatric disorders may add a layer of complexity when caring for adolescents. Box 116-20 describes the relationship between comorbid psychiatric disorders and SUDs in adolescents.

Box 1

Disruptive behavior disorders are the most common coexisting psychiatric disorders in an adolescent with a substance use disorder (SUD), including opioid use disorder. These individuals typically present with aggression and other conduct disorder symptoms, and have early involvement with the legal system. Conversely, patients with conduct disorder are at high risk of early initiation of illicit substance use, including opioids. Early onset of substance use is a strong risk factor for developing an SUD.16

Mood disorders, particularly depression, can either precede or occur as a result of heavy and prolonged substance use.17 The estimated prevalence of major depressive disorder in individuals with an SUD is 24% to 50%. Among adolescents, an SUD is also a risk factor for suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and completed suicide.18-20

Anxiety disorders, especially social phobia, and posttraumatic stress disorder are common in individuals with SUD.

Adolescents with SUD should be carefully evaluated for comorbid psychiatric disorders and treated accordingly.

Clinical manifestations

Common clinical manifestations of opioid use vary depending on when the patient is seen. An individual with OUD may appear acutely intoxicated, be in withdrawal, or show no effects. Chronic/prolonged use can lead to tolerance, such that a user needs to ingest larger amounts of the opioid to produce the same effects.

Acute intoxication can cause sedation, slurring of speech, and pinpoint pupils. Fresh injection sites may be visible on physical examination of IV users. The effects of acute intoxication usually depend on the half-life of the specific opioid and the individual’s tolerance.10 Tolerance to heroin can occur in 10 days and withdrawal can manifest in 3 to 7 hours after last use, depending on dose and purity.3 Tolerance can lead to unintentional overdose and death.

Withdrawal. Individuals experiencing withdrawal from opioids present with flu-like physical symptoms, including generalized body ache, rhinorrhea, diarrhea, goose bumps, lacrimation, and vomiting. Individuals also may experience irritability, restlessness, insomnia, anxiety, and depression during withdrawal.

Other manifestations. Excessive and chronic/prolonged opioid use can adversely impact socio-occupational functioning and cause academic decline in adolescents and youth. Personal relationships are significantly affected. Opioid users may have legal difficulties as a result of committing crimes such as theft, prostitution, or robbery in order to obtain opioids.

Continue to: Screening for OUD

Screening for OUD

Several screening tools are available to assess adolescents for SUDs, including OUD.

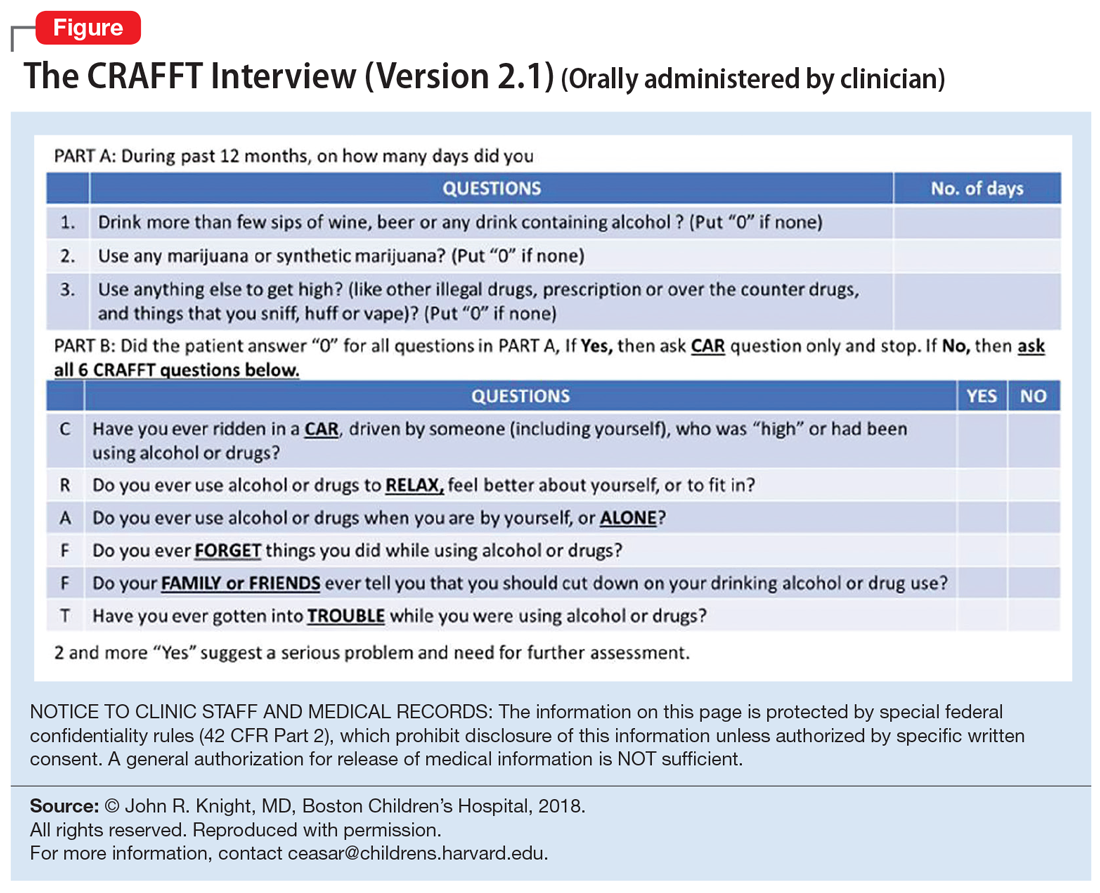

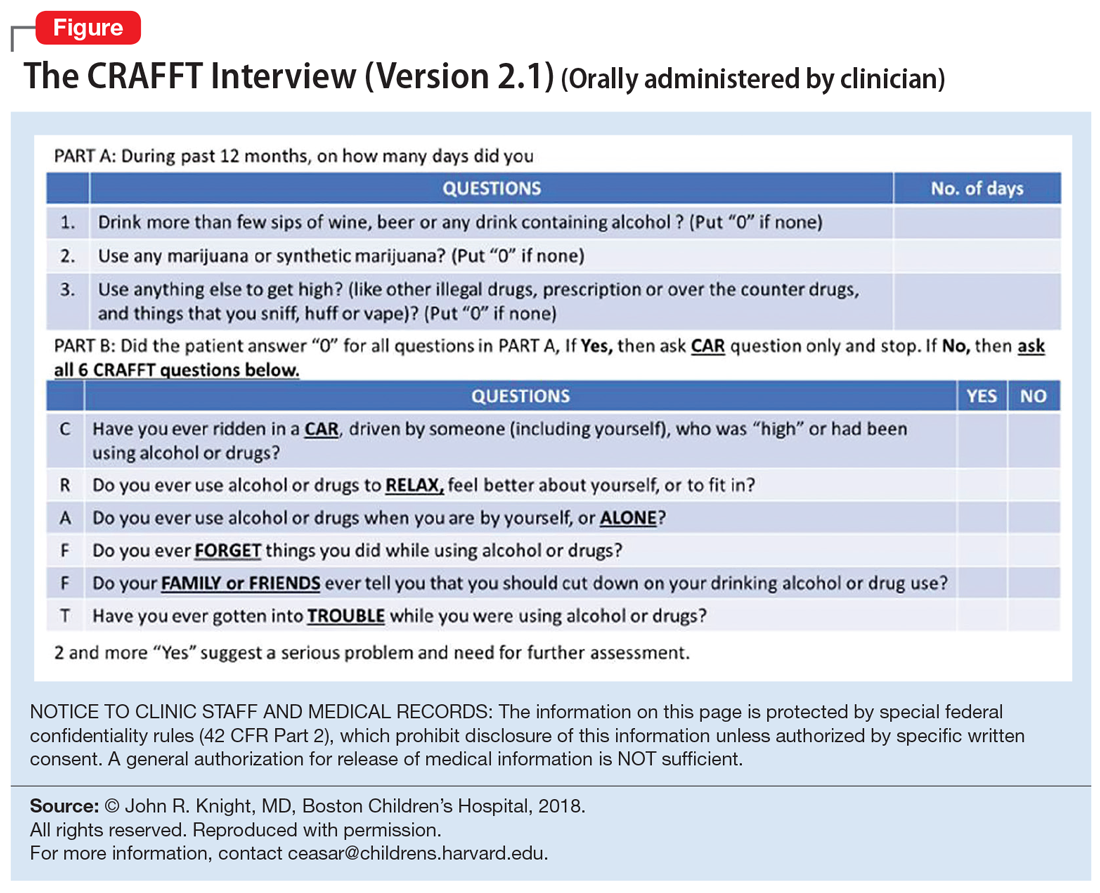

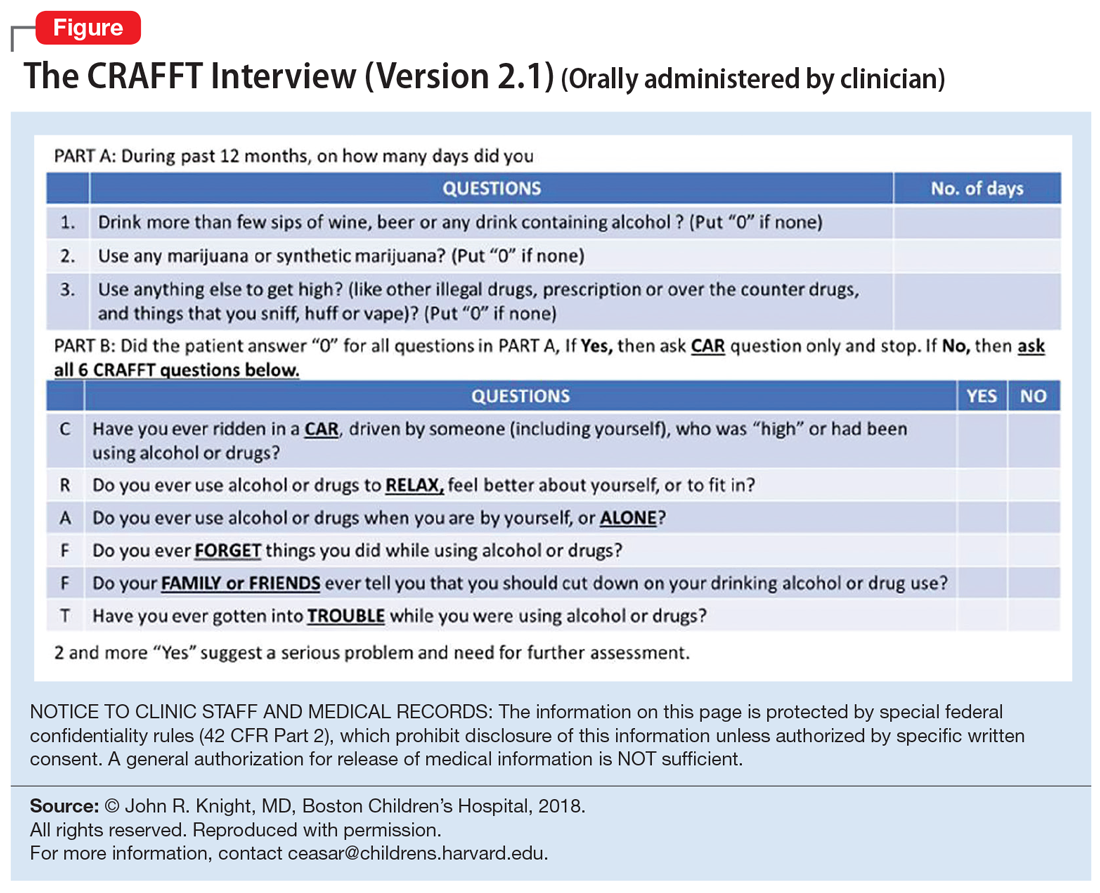

CRAFFT is a 6-item, clinician-administered screening tool that has been approved by American Academy of Pediatrics’ Committee on Substance Abuse for adolescents and young adults age <21.21-23 This commonly used tool can assess for alcohol, cannabis, and other drug use. A score ≥2 is considered positive for drug use, indicating that the individual would require further evaluation and assessment22,23 (Figure). There is also a self-administered CRAFFT questionnaire that can be completed by the patient.

NIDA-modified ASSIST. The American Psychiatric Association has adapted the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)-modified ASSIST. One version is designated for parents/guardians to administer to their children (age 6 to 17), and one is designated for adolescents (age 11 to 17) to self-administer.24,25 Each screening tool has 2 levels: Level 1 screens for substance use and other mental health symptoms, and Level 2 is more specific for substance use alone.

Drug Use Screening Inventory (DUSI) is a self-report questionnaire that has 149 items that assess the use of numerous drugs. It is designed to quantify the severity of consequences associated with drug and alcohol use.26,27

Problem-Oriented Screening Instrument for Teenagers (PO

Continue to: Personal Experience Screening Questionnaire (PESQ)...

Personal Experience Screening Questionnaire (PESQ) is a brief, 40-item, cost-effective, self-report questionnaire that can help identify adolescents (age 12 to 18) who should be referred for further evaluation.30

Addressing treatment expectations

For an adolescent with OUD, treatment should begin in the least restrictive environment that is perceived as safe for the patient. An adolescent’s readiness and motivation to achieve and maintain abstinence are crucial. Treatment planning should include the adolescent as well as his/her family to ensure they are able to verbalize their expectations. Start with a definitive treatment plan that addresses an individual’s needs. The plan should provide structure and an understanding of treatment expectations. The treatment team should clarify the realistic plan and goals based on empirical and clinical evidence. Treatment goals should include interventions to strengthen interpersonal relationships and assist with rehabilitation, such as establishing academic and/or vocational goals. Addressing readiness and working on a patient’s motivation is extremely important for most of these interventions.

In order for any intervention to be successful, clinicians need to establish and foster rapport with the adolescent. By law, substance use or behaviors related to substance use are not allowed to be shared outside the patient-clinician relationship, unless the adolescent gives consent or there are concerns that such behaviors might put the patient or others at risk. It is important to prime the adolescent and help them understand that any information pertaining to their safety or the safety of others may need to be shared outside the patient-clinician relationship.

Choosing an intervention

Less than 50% of a nationally representative sample of 345 addiction treatment programs serving adolescents and adults offer medications for treating OUD.31 Even in programs that offer pharmacotherapy, medications are significantly underutilized. Fewer than 30% of patients in addiction treatment programs receive medication, compared with 74% of patients receiving treatment for other mental health disorders.31 A

Psychotherapy may be used to treat OUD in adolescents. Several family therapies have been studied and are considered as critical psychotherapeutic interventions for treating SUDs, including structural family treatment and functional family therapy approaches.34 An integrated behavioral and family therapy model is also recommended for adolescent patients with SUDs. Cognitive distortions and use of self-deprecatory statements are common among adolescents.35 Therefore, using approaches of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), or CBT plus motivational enhancement therapy, also might be effective for this population.36 The adolescent community reinforcement approach (A-CRA) is a behavioral treatment designed to help adolescents and their families learn how to lead a healthy and happy life without the use of drugs or alcohol by increasing access to social, familial, and educational/vocational reinforcers. Support groups and peer and family support should be encouraged as adjuncts to other interventions. In some areas, sober housing options for adolescents are also available.

Continue to: Harm-reduction strategies

Harm-reduction strategies. Although the primary goal of treatment for adolescents with OUD is to achieve and maintain abstinence from opioid use, implicit and explicit goals can be set. Short-term implicit goals may include harm-reduction strategies that emphasize decreasing the duration, frequency, and amount of substance use and limiting the chances of adverse effects, while the long-term explicit goal should be abstinence from opioid use.

Naloxone nasal spray is used as a harm-reduction strategy. It is an FDA-approved formulation that can reverse the effects of unintentional opioid overdoses and potentially prevent death from respiratory depression.37 Other harm-reduction strategies include needle exchange programs, which provide sterile needles to individuals who inject drugs in an effort to prevent or reduce the transmission of human immunodeficiency virus and other bloodborne viruses that can be spread via shared injection equipment. Fentanyl testing strips allow opioid users to test for the presence fentanyl and fentanyl analogs in the unregulated “street” opioid supply.

Pharmacologic interventions. Because there is limited empirical evidence on the efficacy of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for adolescents with OUD, clinicians need to rely on evidence from research and experience with adults. Unfortunately, MAT is offered to adolescents considerably less often than it is to adults. Feder et al38 reported that only 2.4% of adolescents received MAT for heroin use and only 0.4% of adolescents received MAT for prescription opioid use, compared with 26.3% and 12% of adults, respectively.

Detoxification. Medications available for detoxification from opioids include opiates (such as methadone or buprenorphine) and clonidine (a central sympathomimetic). If the patient has used heroin for a short period (<1 year) and has no history of detoxification, consider a detoxification strategy with a longer-term taper (90 to 180 days) to allow for stabilization.

Maintenance treatment. Consider maintenance treatment for adolescents with a history of long-term opioid use and at least 2 prior short-term detoxification attempts or nonpharmacotherapy-based treatment within 12 months. Be sure to receive consent from a legal guardian and the patient. Maintenance treatment is usually recommended to continue for 1 to 6 years. Maintenance programs with longer durations have shown higher rates of abstinence, improved engagement, and retention in treatment.39

Continue to: According to guidelines from...

According to guidelines from the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM), adolescents age >16 should be offered MAT; the first-line treatment is buprenorphine.40 To avoid risks of abuse and diversion, a combination of buprenorphine/naloxone may be administered.

Maintenance with buprenorphine

In order to prescribe and dispense buprenorphine, clinicians need to obtain a waiver from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Before initiating buprenorphine, consider the type of opioid the individual used (short- or long-acting), the severity of the OUD, and the last reported use. The 3 phases of buprenorphine treatment are41:

- Induction phase. Buprenorphine can be initiated at 2 to 4 mg/d. Some patients may require up to 8 mg/d on the first day, which can be administered in divided doses.42 Evaluate and monitor patients carefully during the first few hours after the first dose. Patients should be in early withdrawal; otherwise, the buprenorphine might precipitate withdrawal. The induction phase can be completed in 2 to 4 days by titrating the dose so that the signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal are minimal, and the patient is able to continue treatment. It may be helpful to have the patient’s legal guardian nearby in case the patient does not tolerate the medication or experiences withdrawal. The initial target dose for buprenorphine is approximately 12 to 16 mg/d.

- Stabilization phase. Patients no longer experience withdrawal symptoms and no longer have cravings. This phase can last 6 to 8 weeks. During this phase, patients should be seen weekly and doses should be adjusted if necessary. As a partial mu agonist, buprenorphine does not activate mu receptors fully and reaches a ceiling effect. Hence, doses >24 mg/d have limited added agonist properties.

- Maintenance phase. Because discontinuation of buprenorphine is associated with high relapse rates, patients may need to be maintained long-term on their stabilization dose, and for some patients, the length of time could be indefinite.39 During this phase, patients continue to undergo follow-up, but do so less frequently.

Methadone maintenance is generally not recommended for individuals age <18.

Preventing opioid diversion

Prescription medications that are kept in the home are a substantial source of opioids for adolescents. In 2014, 56% of 12th graders who did not need medications for medical purposes were able to acquire them from their friends or relatives; 36% of 12th graders used their own prescriptions.21 Limiting adolescents’ access to prescription opioids is the first line of prevention. Box 2 describes interventions and strategies to limit adolescents’ access to opioids.

Box 2

Many adolescents obtain opioids for recreational use from medications that were legitimately prescribed to family or friends. Both clinicians and parents/ guardians can take steps to reduce or prevent this type of diversion

Health care facilities. Regulating the number of pills dispensed to patients is crucial. It is highly recommended to prescribe only the minimal number of opioids necessary. In most cases, 3 to 7 days’ worth of opioids at a time might be sufficient, especially after surgical procedures.

Home. Families can limit adolescents’ access to prescription opioids in the home by keeping all medications in a lock box.

Proper disposal. Various entities offer locations for patients to drop off their unused opioids and other medications for safe disposal. These include police or fire departments and retail pharmacies. The US Drug Enforcement Administration sponsors a National Prescription Drug Take Back Day; see https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drug_disposal/takeback/index.html. The FDA also offers information on where and how to dispose of unused medicines at https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/where-and-how-dispose-unused-medicines.

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. L is initially prescribed, clonidine, 0.1 mg every 6 hours, to address opioid withdrawal. Clonidine is then tapered and maintained at 0.1 mg twice a day for irritability and impulse control. She is also prescribed sertraline, 100 mg/d, for depression and anxiety, and trazodone, 75 mg as needed at night, to assist with sleep.

Continue to: Following inpatient hospitalization...

Following inpatient hospitalization, during 12 weeks of partial hospital treatment, Ms. L participates in individual psychotherapy sessions 5 days/week; family therapy sessions once a week; and experiential therapy along with group sessions with other peers. She undergoes medication evaluations and adjustments on a weekly basis. Ms. L is now working at a store and is pursuing a high school equivalency certificate. She manages to avoid high-risk behaviors, although she reports having occasional cravings. Ms. L is actively involved in Narcotics Anonymous and has a sponsor. She has reconciled with her mother and moved back home, so she can stay away from her former acquaintances who are still using.

Bottom Line

Adolescents with opioid use disorder can benefit from an individualized treatment plan that includes psychosocial interventions, pharmacotherapy, or a combination of the two. Treatment planning should include the adolescent and his/her family to ensure they are able to verbalize their expectations. Treatment should focus on interventions that strengthen interpersonal relationships and assist with rehabilitation. Ongoing follow-up care is necessary for maintaining abstinence.

Related Resource

- Patkar AA, Weisler RH. Opioid abuse and overdose: Keep your patients safe. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(8):8-12,14-16.

Drug Brand Names

Buprenorphine • Subutex, Sublocade

Buprenorphine/naloxone • Suboxone

Clonidine • Clorpres

Methadone • Methadose

Naloxone • Narcan

Oxycodone • OxyContin

Sertraline • Zoloft

Tramadol • Ultram

Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

1. Davis JP, Prindle JJ, Eddie D, et al. Addressing the opioid epidemic with behavioral interventions for adolescents and young adults: a quasi-experimental design. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2019;87(10):941-951.

2. National Institute on Drug Abuse; National Institutes of Health; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Monitoring the Future Survey: High School and Youth Trends. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/monitoring-future-survey-high-school-youth-trends. Updated December 2019. Accessed January 13, 2020.

3. Hopfer CJ, Khuri E, Crowley TJ. Treating adolescent heroin use. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(5):609-611.

4. US Department of Justice, Drug Enforcement Agency, Diversion Control Division. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/. Accessed January 21, 2020.

5. Gaither JR, Leventhal JM, Ryan SA, et al. National trends in hospitalizations for opioid poisonings among children and adolescents, 1997-2012. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(12):1195-1201.

6. Parker MA, Anthony JC. Epidemiological evidence on extra-medical use of prescription pain relievers: transitions from newly incident use to dependence among 12-21 year olds in United States using meta-analysis, 2002-13. Peer J. 2015;3:e1340. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1340. eCollection 2015.

7. Subramaniam GA, Fishman MJ, Woody G. Treatment of opioid-dependent adolescents and young adults with buprenorphine. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11(5):360-363.

8. Borodovsky JT, Levy S, Fishman M. Buprenorphine treatment for adolescents and young adults with opioid use disorders: a narrative review. J Addict Med. 2018;12(3):170-183.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National Center for Health Statistics. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2016. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db294.htm. Published December 2017. Accessed January 15, 2020.

10. Strain E. Opioid use disorder: epidemiology, pharmacology, clinical manifestation, course, screening, assessment, diagnosis. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/opioid-use-disorder-epidemiology-pharmacology-clinical-manifestations-course-screening-assessment-and-diagnosis. Updated August 15, 2019. Accessed January 21, 2020.

11. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Substance Use and Prevention. Policy statement: medication-assisted treatment of adolescents with opioid use disorder. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20161893. doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1893.

12. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:514.

13. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Chapter 6: Theories of personality and psychopathology. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, eds. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007:209.

14. Kandel DB. Stages and pathways of drug involvement: examining the gateway hypothesis. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2002.

15. Robins LN, McEvoy L. Conduct problems as predictors of substance abuse. In: Robins LN, Rutter M, eds. Straight and devious pathways from childhood to adulthood. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1990;182-204.

16. Hopfer C, Salomonsen-Sautel S, Mikulich-Gilbertson S, et al. Conduct disorder and initiation of substance use: a prospective longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(5):511-518.e4.

17. Armstrong TD, Costello EJ. Community studies on adolescent substance use, abuse, or dependence and psychiatric comorbidity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70(6):1224-1239.

18. Crumley FE. Substance abuse and adolescent suicidal behavior. JAMA. 1990;263(22):3051-3056.

19. Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts: prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1996;3(1):25-46.

20. Kendler KS, Bulik CM, Silberg J, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorder in women: an epidemiological and cotwin control analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(10):953-959.

21. Yule AM, Wilens TE, Rausch PK. The opioid epidemic: what a child psychiatrist is to do? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(7);541-543.

22. CRAFFT. https://crafft.org. Accessed January 21, 2020.

23. Knight JR, Sherritt L, Harris SK, et al. Validity of brief alcohol screening tests among adolescents: a comparison of the AUDIT, POSIT, CAGE, and CRAFFT. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(1):67-73.

24. American Psychiatric Association. Online assessment measures. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm/educational-resources/assessment-measures. Accessed January 15, 2020.

25. National Institute of Drug Abuse. American Psychiatric Association adapted NIDA modified ASSIST tools. https://www.drugabuse.gov/nidamed-medical-health-professionals/tool-resources-your-practice/screening-assessment-drug-testing-resources/american-psychiatric-association-adapted-nida. Updated November 15, 2015. Accessed January 21, 2020.

26. Canada’s Mental Health & Addiction Network. Drug Use Screening Inventory (DUSI). https://www.porticonetwork.ca/web/knowledgex-archive/amh-specialists/screening-for-cd-in-youth/screening-both-mh-sud/dusi. Published 2009. Accessed January 21, 2020.

27. Tarter RE. Evaluation and treatment of adolescent substance abuse: a decision tree method. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1990;16(1-2):1-46.

28. Klitzner M, Gruenwald PJ, Taff GA, et al. The adolescent assessment referral system-final report. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Rockville, MD: 1993. NIDA Contract No. 271-89-8252.

29. Slesnick N, Tonigan JS. Assessment of alcohol and other drug use by runaway youths: a test-retest study of the Form 90. Alcohol Treat Q. 2004;22(2):21-34.

30. Winters KC, Kaminer Y. Screening and assessing adolescent substance use disorders in clinical populations. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(7):740-744.

31. Knudsen HK, Abraham AJ, Roman PM. Adoption and implementation of medications in addiction treatment programs. J Addict Med. 2011;5(1):21-27.

32. Deas D, Thomas SE. An overview of controlled study of adolescent substance abuse treatment. Am J Addiction. 2001;10(2):178-189.

33. William RJ, Chang, SY. A comprehensive and comparative review of adolescent substance abuse treatment outcome. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2000;7(2):138-166.

34. Bukstein OG, Work Group on Quality Issues. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with substance use disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(6):609-621.

35. Van Hasselt VB, Null JA, Kempton T, et al. Social skills and depression in adolescent substance abusers. Addict Behav. 1993;18(1):9-18.

36. Dennis M, Godley SH, Diamond G, et al. The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) study: main findings from two randomized trials. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;27(3):197-213.

37. US Food and Drug Administration. Information about naloxone. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/information-about-naloxone. Updated December 19, 2019. Accessed January 21, 2020.

38. Feder KA, Krawcyzk N, Saloner, B. Medication-assisted treatment for adolescents in specialty treatment for opioid use disorder. J Adolesc Health. 2018;60(6):747-750.

39. Woody GE, Poole SA, Subramaniam G, et al. Extended vs short-term buprenorphine-naloxone for treatment of opioid-addicted youth: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;300(17):2003-2011.

40. US Department of Health and Human Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Ser-vices Administration. Medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction in opioid treatment programs: a treatment improvement protocol TIP 43. https://www.asam.org/docs/advocacy/samhsa_tip43_matforopioidaddiction.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Published 2005. Accessed January 15, 2020.

41. US Department of Health and Human Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Medication-assisted treatment (MAT). https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment. Updated September 9, 2019. Accessed January 21, 2020.

42. Johnson RE, Strain EC, Amass L. Buprenorphine: how to use it right. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;70(suppl 2):S59-S77.

Ms. L, age 17, seeks treatment because she has an ongoing struggle with multiple substances, including benzodiazepines, heroin, alcohol, cannabis, and prescription opioids.

She reports that she was 13 when she first used a prescription opioid that was not prescribed for her. She also reports engaging in unsafe sexual practices while using these substances, and has been diagnosed and treated for a sexually transmitted disease. She dropped out of school and is estranged from her family. She says that for a long time she has felt depressed and that she uses drugs to “self-medicate my emotions.” She endorses high anxiety and lack of motivation. Ms. L also reports having several criminal charges for theft, assault, and exchanging sex for drugs. She has undergone 3 admissions for detoxification, but promptly resumed using drugs, primarily heroin and oxycodone, immediately after discharge. Ms. L meets DSM-5 criteria for opioid use disorder (OUD).

Ms. L’s case illustrates a disturbing trend in the current opioid epidemic in the United States. Nearly 11.8 million individuals age ≥12 reported misuse of opioids in the last year.1 Adolescents who misuse prescription or illicit opioids are more likely to be involved with the legal system due to truancy, running away from home, physical altercations, prostitution, exchanging sex for drugs, robbery, and gang involvement. Adolescents who use opioids may also struggle with academic decline, drop out of school early, be unable to maintain a job, and have relationship difficulties, especially with family members.