User login

Online Information About Hydroquinone: An Assessment of Accuracy and Readability

To the Editor:

The internet is a popular resource for patients seeking information about dermatologic treatments. Hydroquinone (HQ) cream 4% is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for skin hyperpigmentation.1 The agency enforced the CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) Act and OTC (over-the-counter) Monograph Reform on September 25, 2020, to restrict distribution of OTC HQ.2 Exogenous ochronosis is listed as a potential adverse effect in the prescribing information for HQ.1

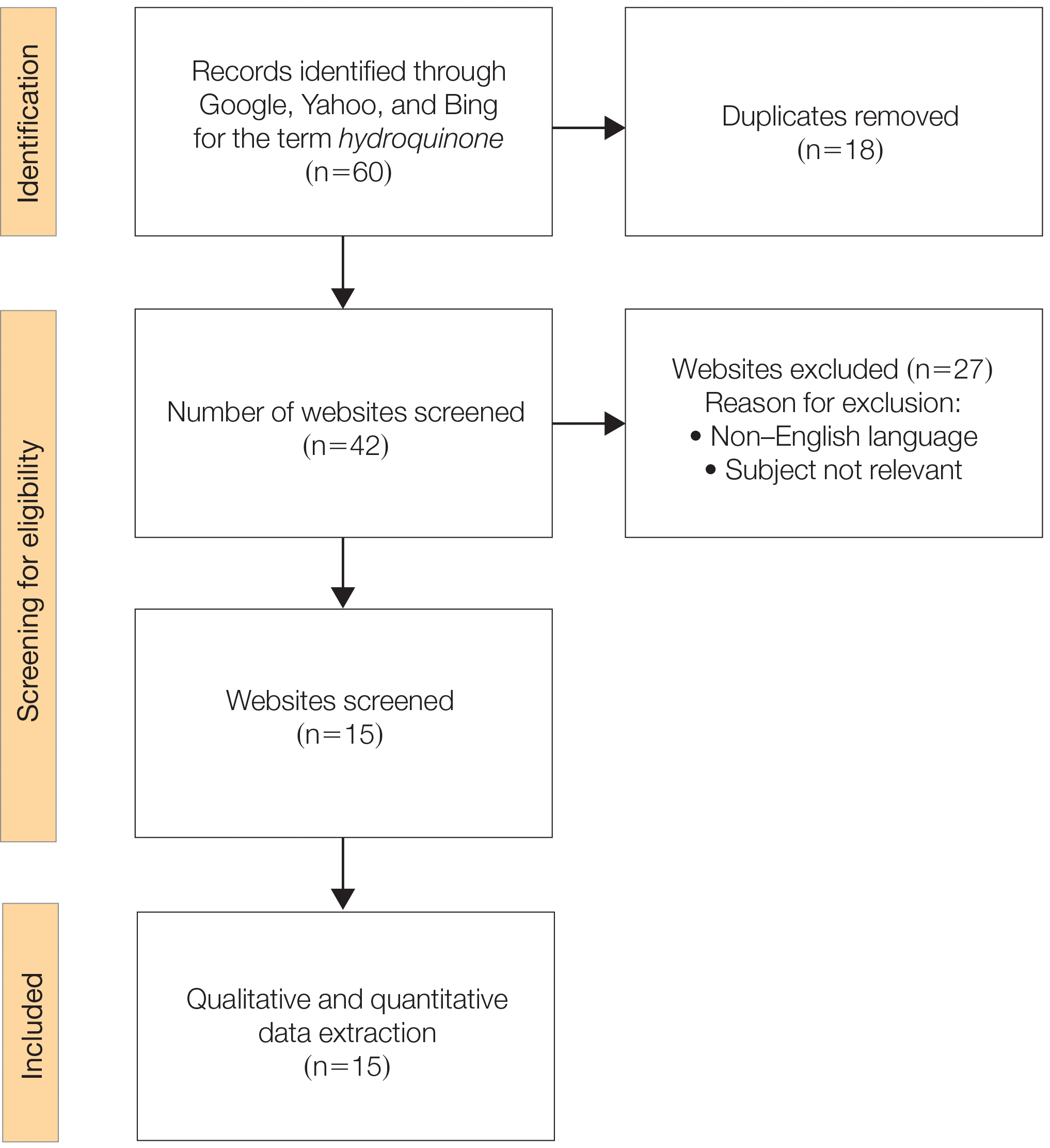

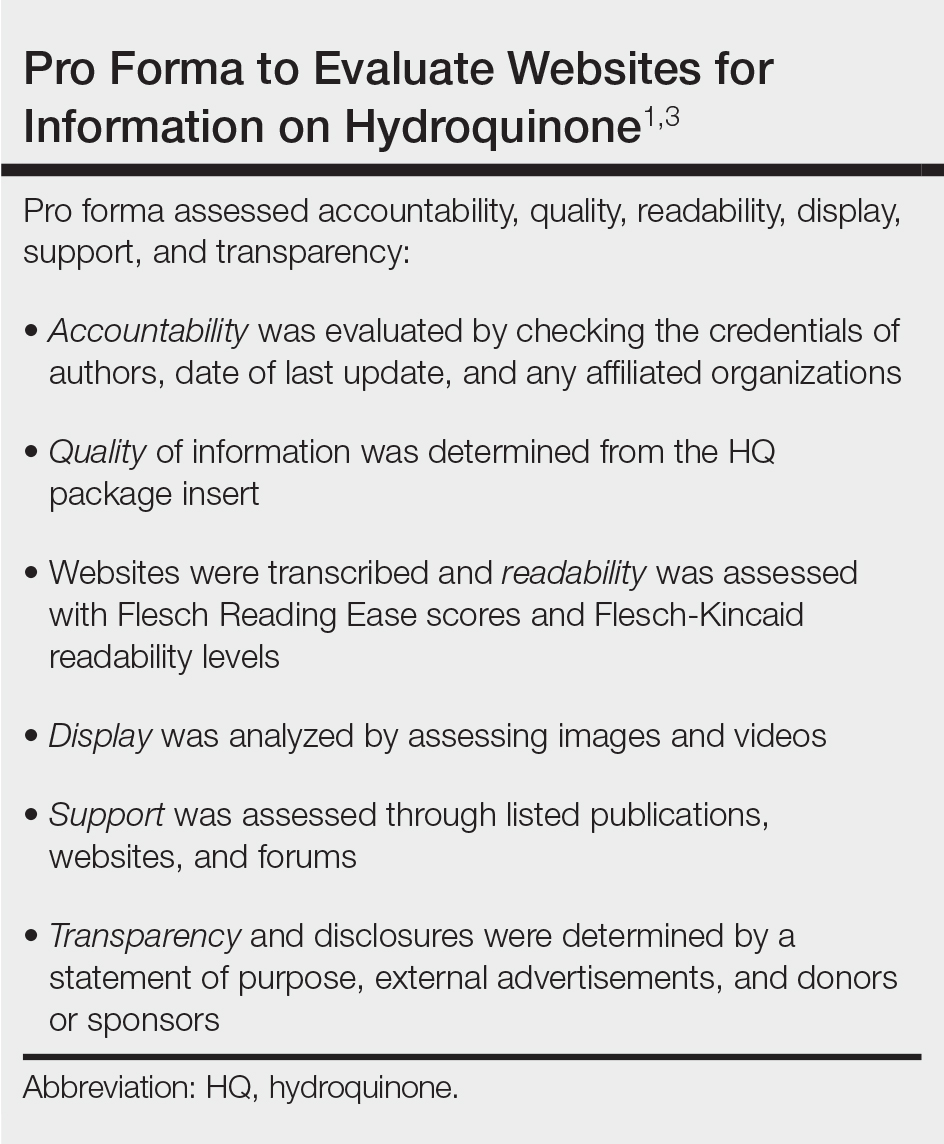

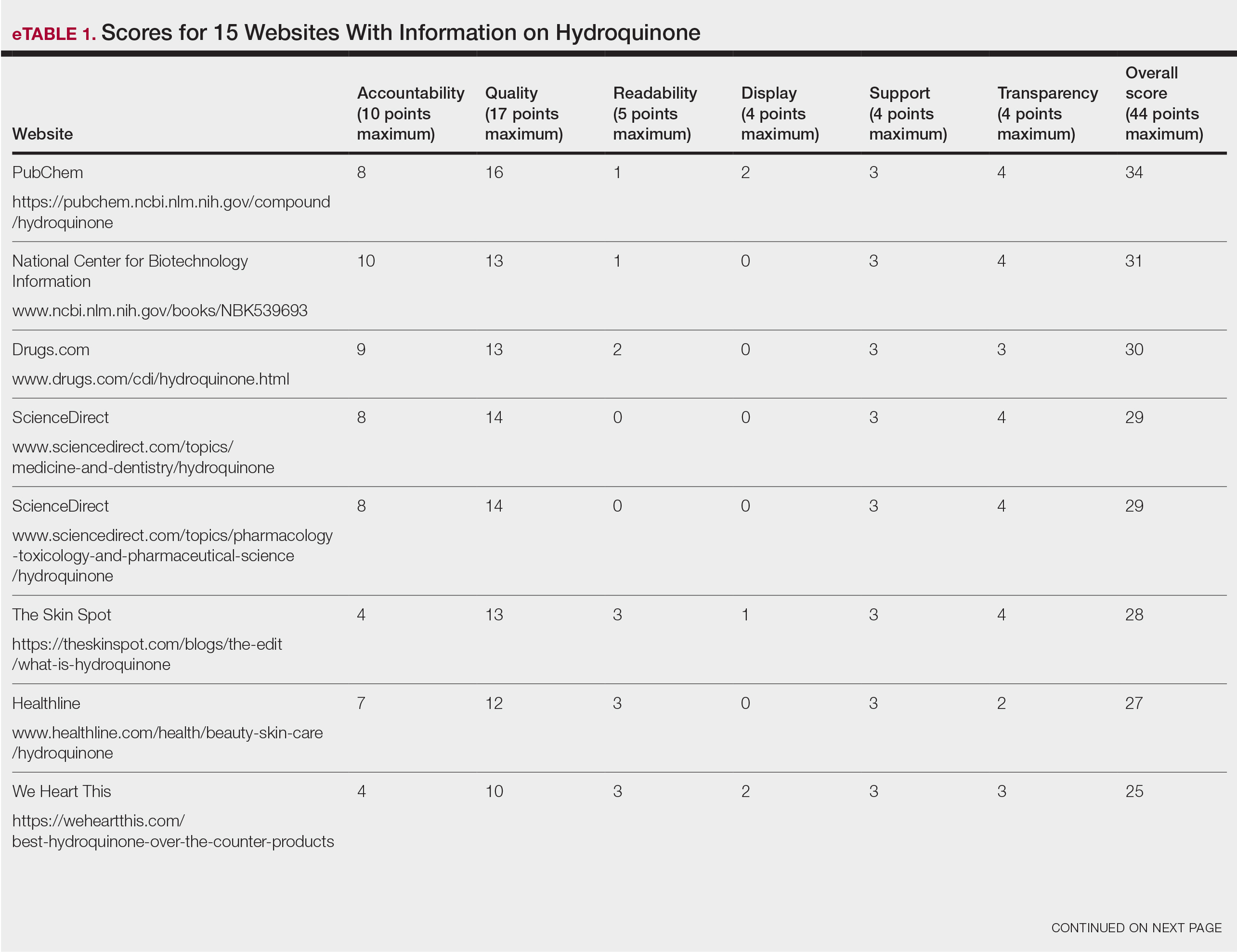

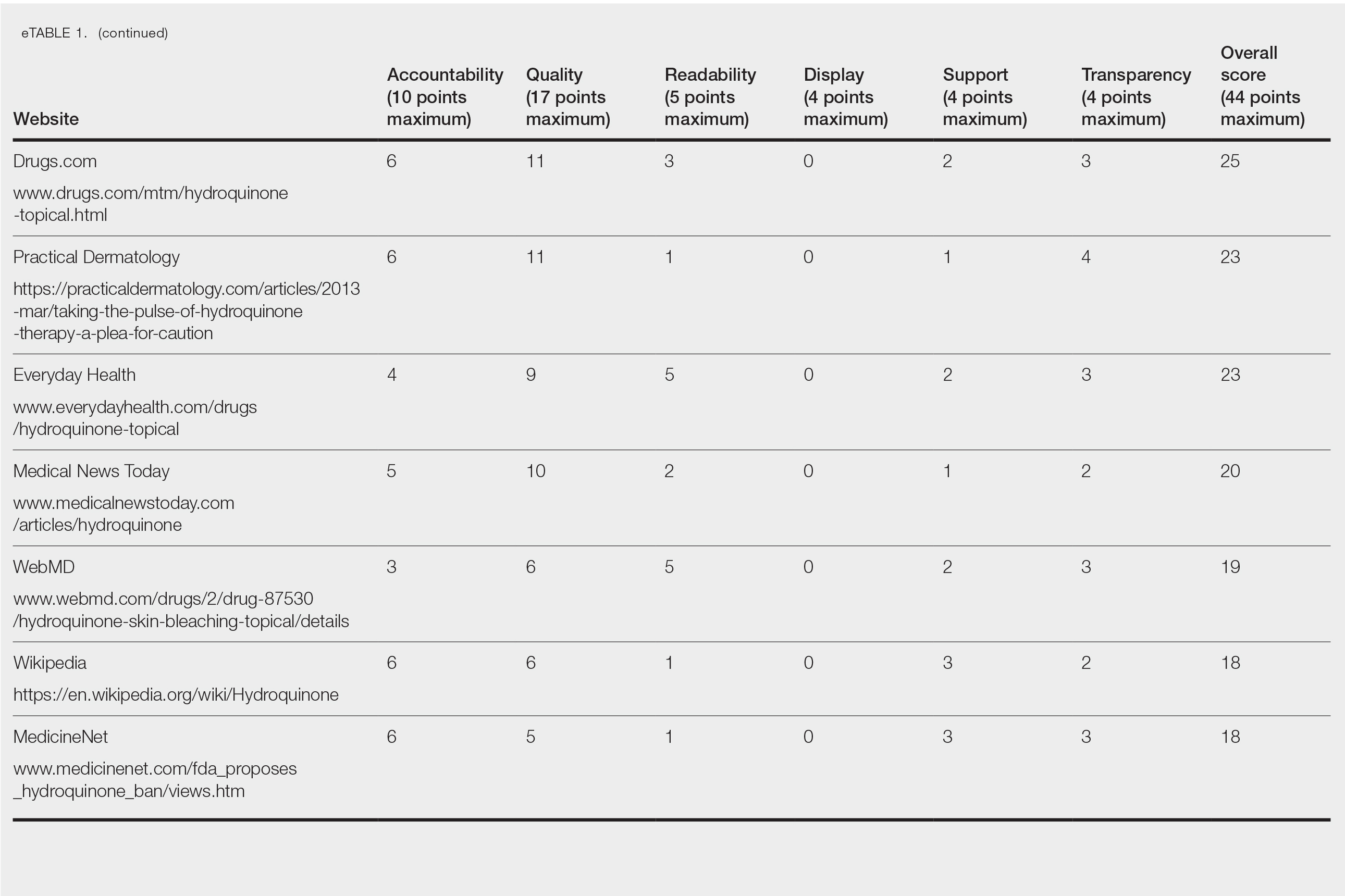

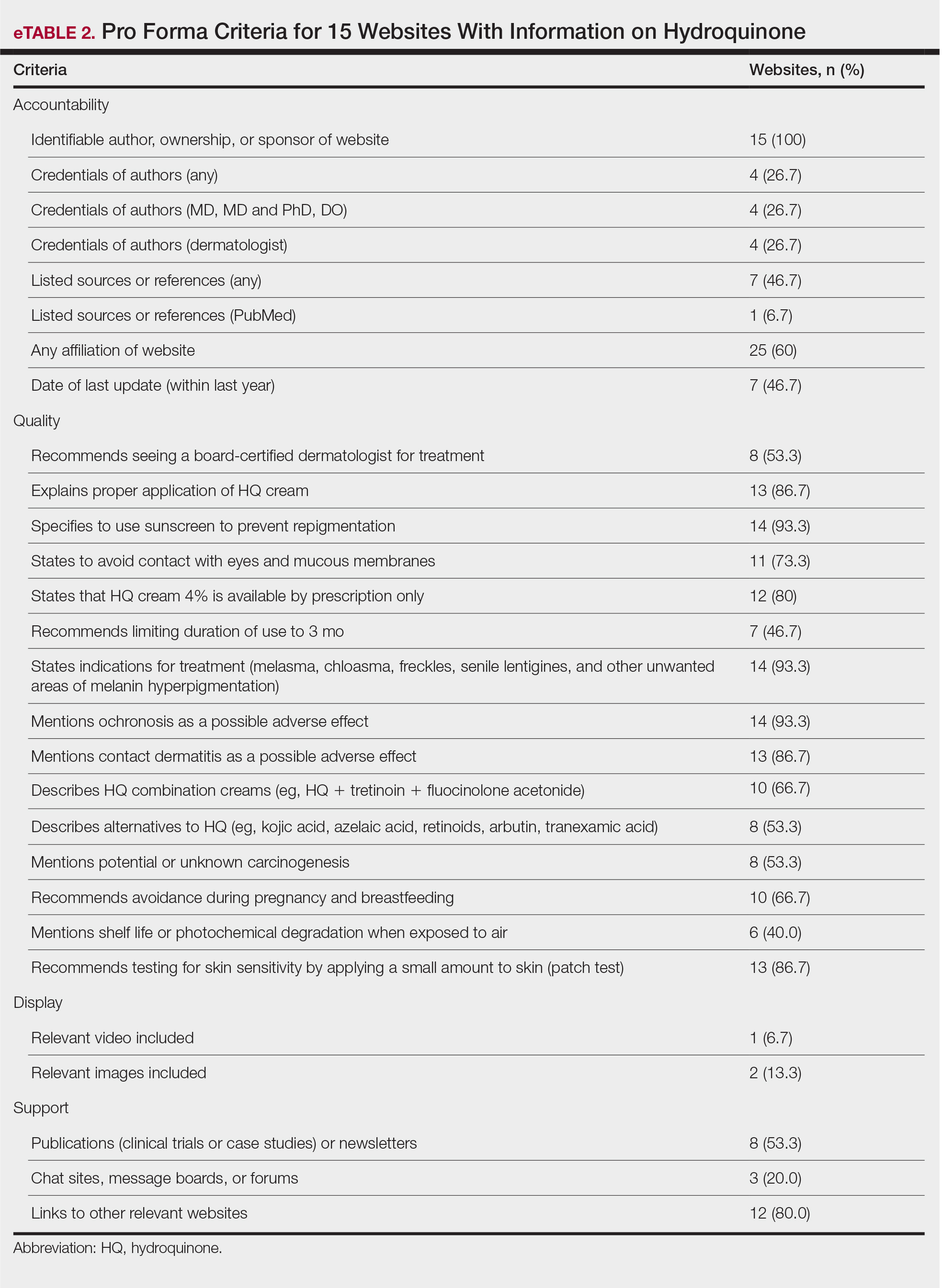

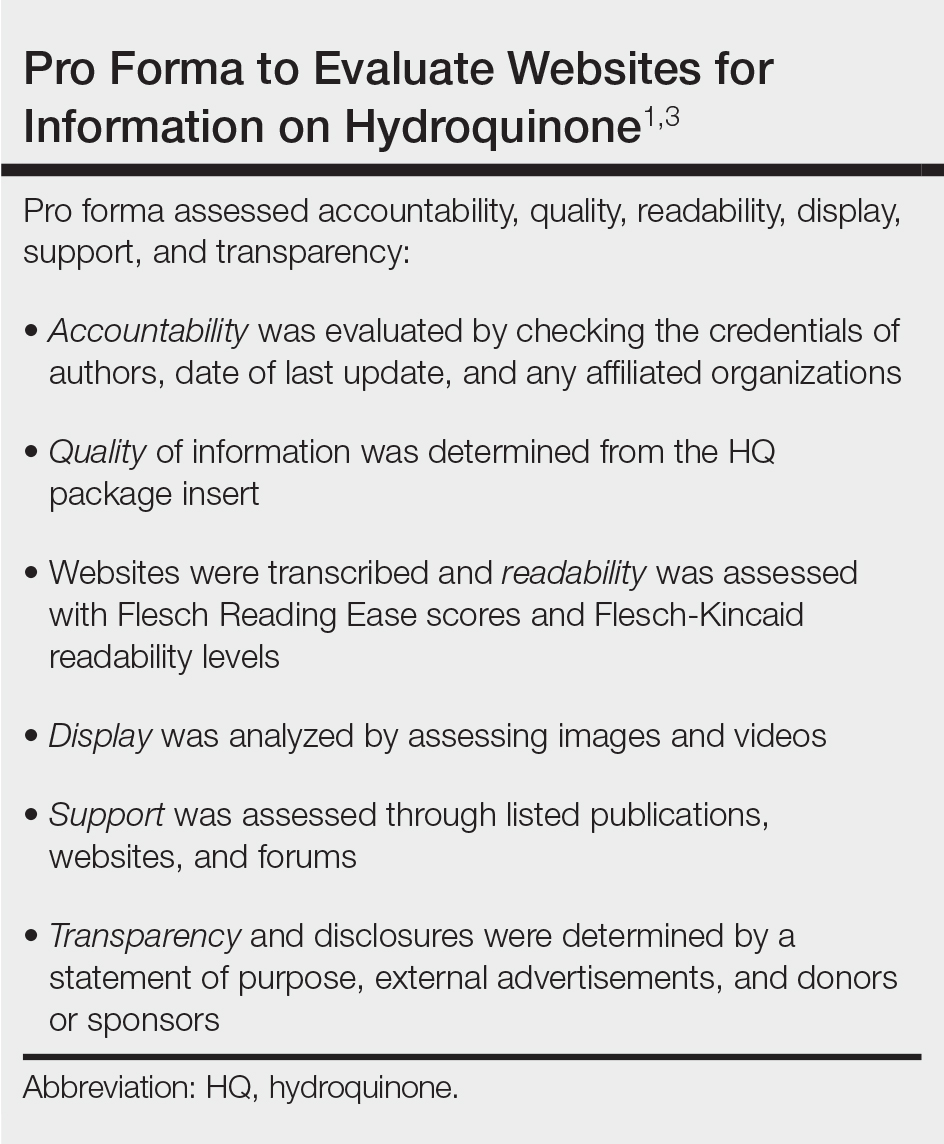

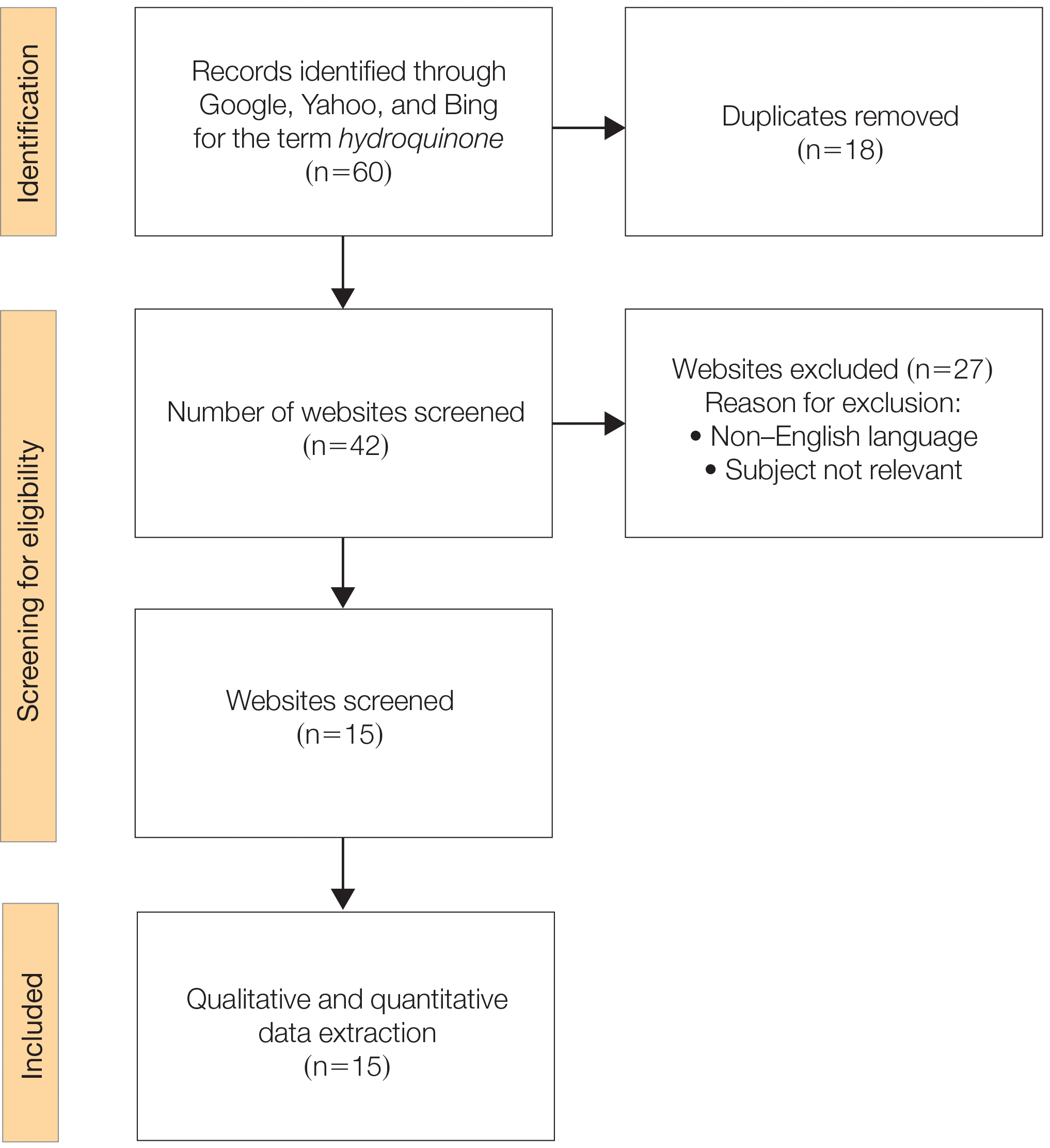

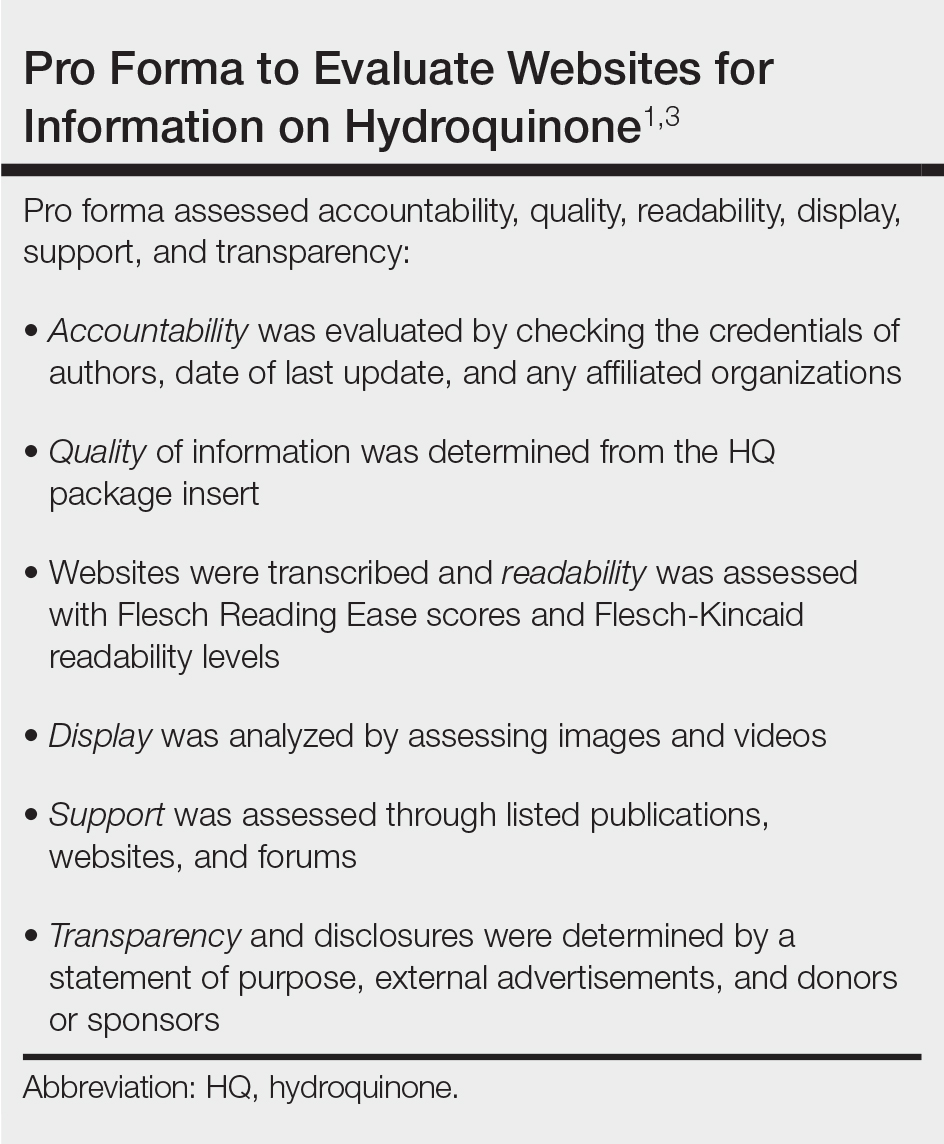

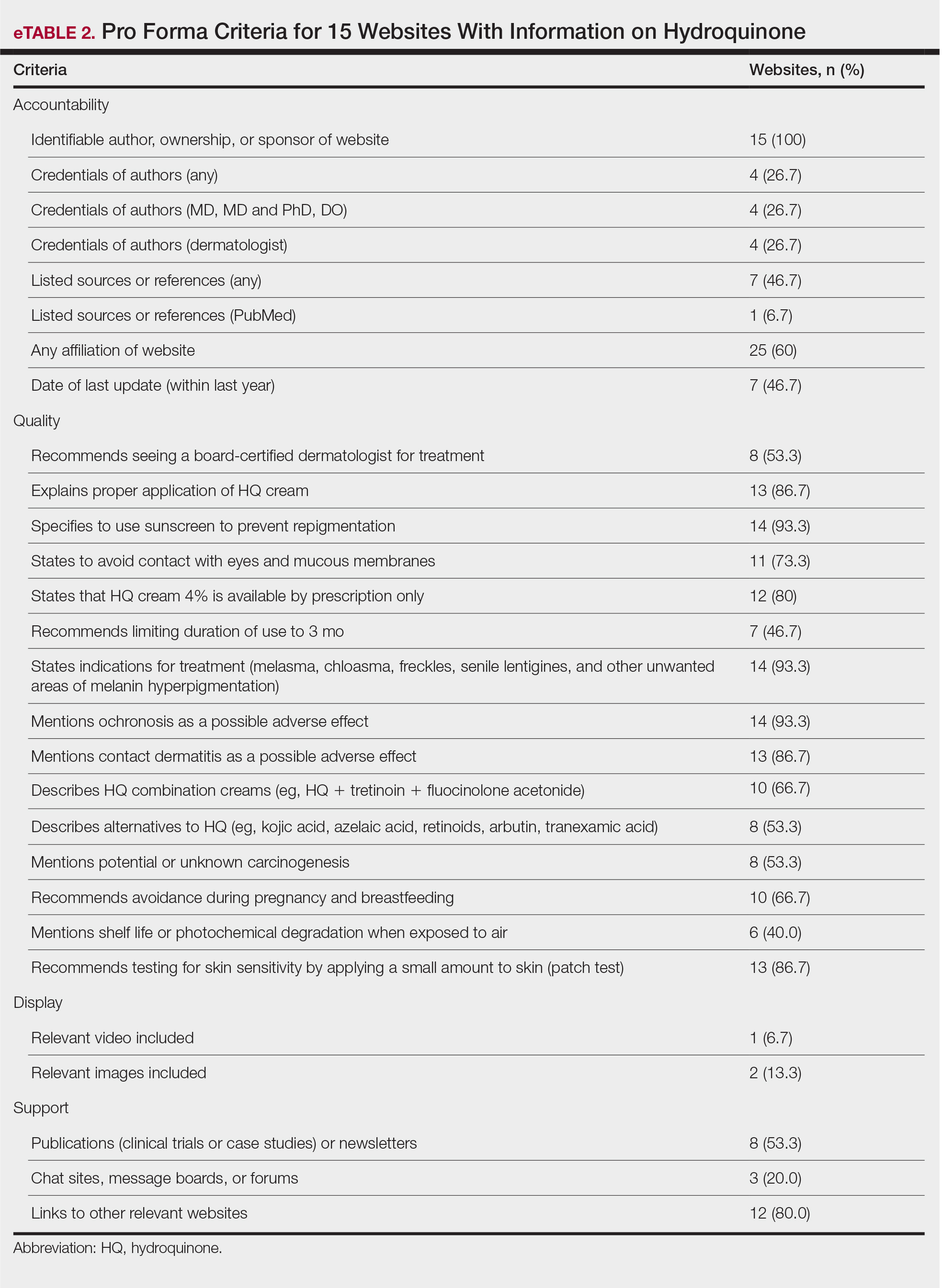

We sought to assess online resources on HQ for accuracy of information, including the recent OTC ban, as well as readability. The word hydroquinone was searched on 3 internet search engines—Google, Yahoo, and Bing—on December 12, 2020, each for the first 20 URLs (ie, websites)(total of 60 URLs). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA)(Figure) reporting guidelines were used to assess a list of relevant websites to include in the final analysis. Website data were reviewed by both authors. Eighteen duplicates and 27 irrelevant and non–English-language URLs were excluded. The remaining 15 websites were analyzed. Based on a previously published and validated tool, a pro forma was designed to evaluate information on HQ for each website based on accountability, quality, readability, display, support, and transparency (Table).1,3

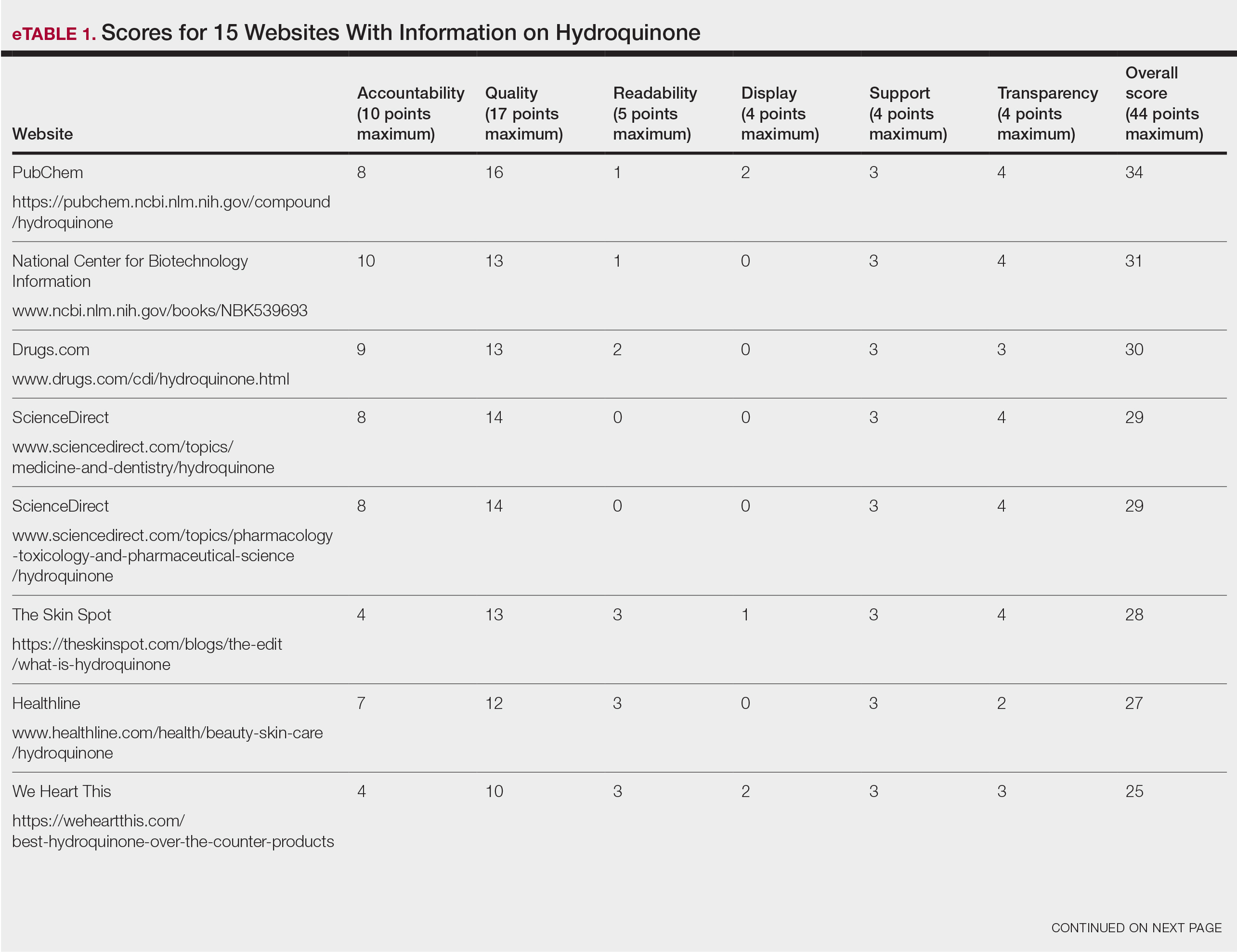

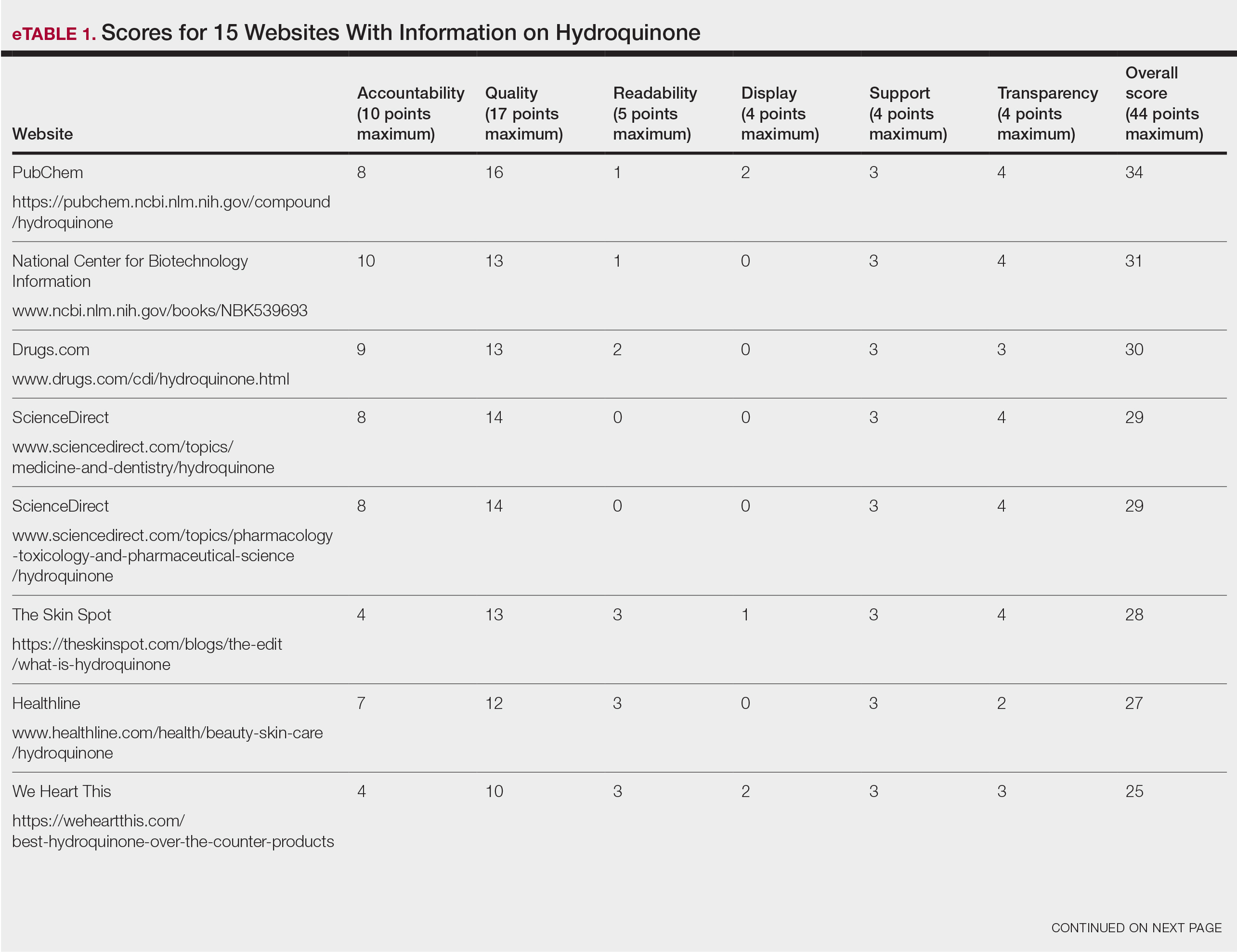

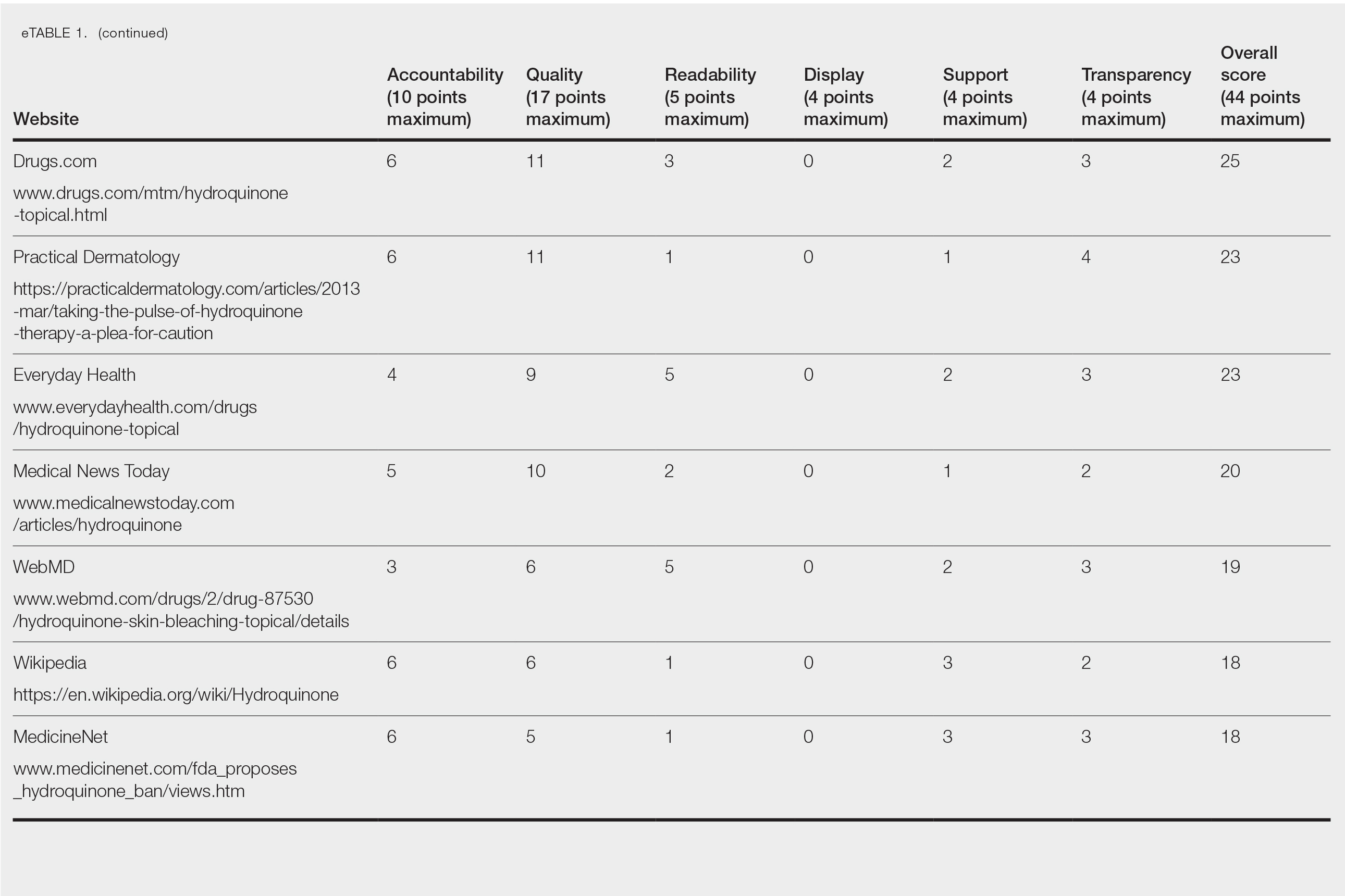

Scores for all 15 websites are listed in eTable 1. The mean overall (total) score was

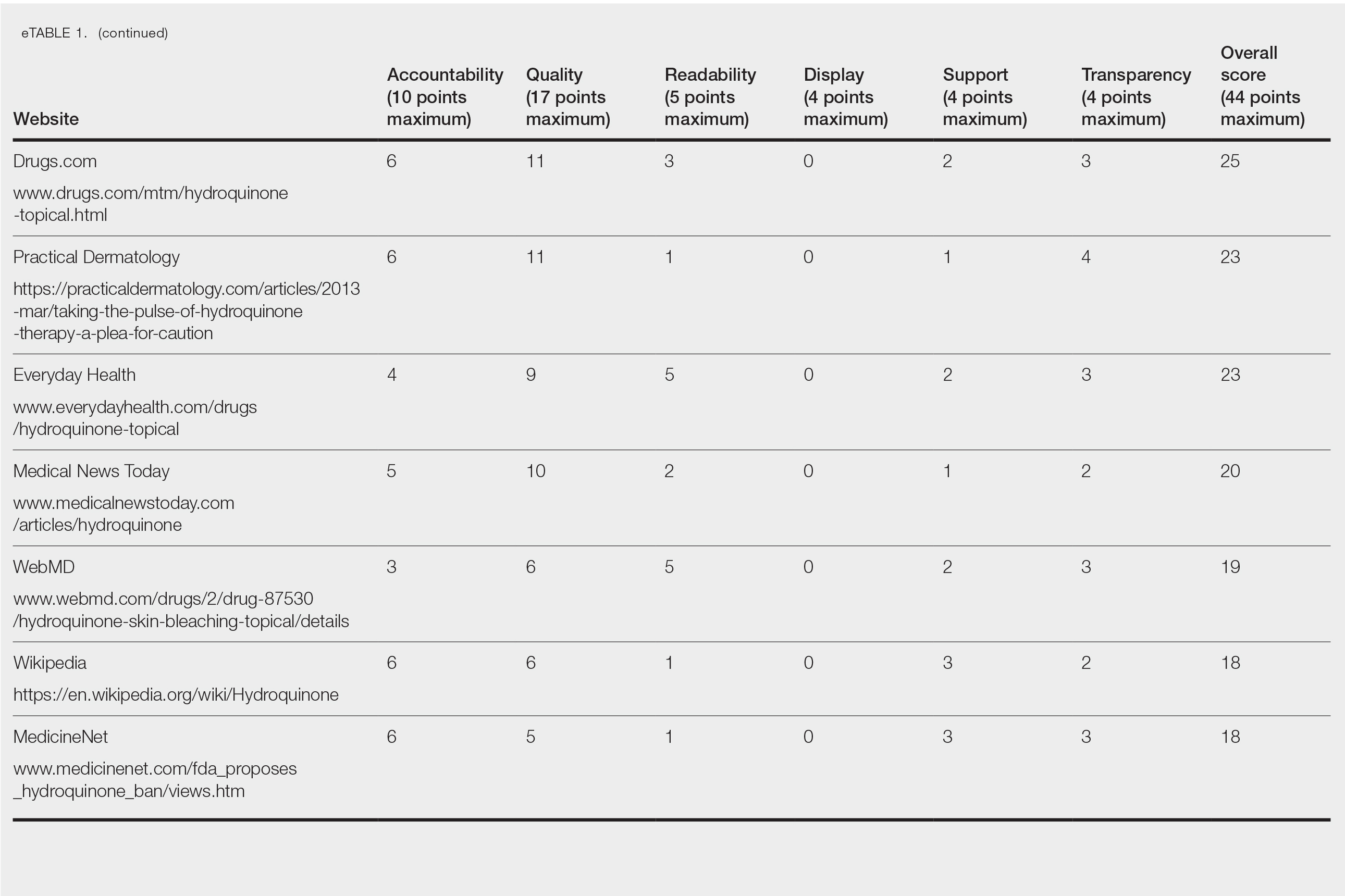

The mean display score was 0.3 (of a possible 4; range, 0–2); 66.7% of websites (10/15) had advertisements or irrelevant material. Only 6.7% and 13.3% of websites included relevant videos or images, respectively, on applying HQ (eTable 2). We identified only 3 photographs—across all 15 websites—that depicted skin, all of which were Fitzpatrick skin types II or III. Therefore, none of the websites included a diversity of images to indicate broad ethnic relatability.

The average support score was 2.5 (of a possible 4; range, 1–3); 20% (3/15) of URLs included chat sites, message boards, or forums, and approximately half (8/15 [53.3%]) included references. Only 7 URLs (46.7%) had been updated in the last 12 months. Only 4 (26.7%) were written by a board-certified dermatologist (eTable 2). Most (60%) websites contained advertising, though none were sponsored by a pharmaceutical company that manufactures HQ.

Only 46.7% (7/15) of websites recommended limiting a course of HQ treatment to 3 months; only 40% (6/15) mentioned shelf life or photochemical degradation when exposed to air. Although 93.3% (14/15) of URLs mentioned ochronosis, a clinical description of the condition was provided in only 33.3% (5/15)—none with images.

Only 2 sites (13.3%; Everyday Health and WebMD) met the accepted 7th-grade reading level for online patient education material; those sites scored lower on quality (9 of 17 and 6 of 17, respectively) than sites with higher overall scores.

None of the 15 websites studied, therefore, demonstrated optimal features on combined measures of accountability, quality, readability, display, support, and transparency regarding HQ. Notably, the American Academy of Dermatology website (www.aad.org) was not among the 15 websites studied; the AAD website mentions HQ in a section on melasma, but only minimal detail is provided.

Limitations of this study include the small number of websites analyzed and possible selection bias because only 3 internet search engines were used to identify websites for study and analysis.

Previously, we analyzed content about HQ on the video-sharing and social media platform YouTube.4 The most viewed YouTube videos on HQ had poor-quality information (ie, only 20% mentioned ochronosis and only 28.6% recommended sunscreen [N=70]). However, average reading level of these videos was 7th grade.4,5 Therefore, YouTube HQ content, though comprehensible, generally is of poor quality.

By conducting a search for website content about HQ, we found that the most popular URLs had either accurate information with poor readability or lower-quality educational material that was more comprehensible. We conclude that there is a need to develop online patient education materials on HQ that are characterized by high-quality, up-to-date medical information; have been written by board-certified dermatologists; are comprehensible (ie, no more than approximately 1200 words and written at a 7th-grade reading level); and contain relevant clinical images and references. We encourage dermatologists to recognize the limitations of online patient education resources on HQ and educate patients on the proper use of the drug as well as its potential adverse effects

- US National Library of Medicine. Label: hydroquinone cream. DailyMed website. Updated November 24, 2020. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=dc72c0b2-4505-4dcf-8a69-889cd9f41693

- US Congress. H.R.748 - CARES Act. 116th Congress (2019-2020). Updated March 27, 2020. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748/text?fbclid=IwAR3ZxGP6AKUl6ce-dlWSU6D5MfCLD576nWNBV5YTE7R2a0IdLY4Usw4oOv4

- Kang R, Lipner S. Evaluation of onychomycosis information on the internet. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:484-487.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Assessing the impact and educational value of YouTube as a source of information on hydroquinone: a content-quality and readability analysis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020:1-3. doi:10.1080/09546634.2020.1782318

- Weiss BD. Health Literacy: A Manual for Clinicians. American Medical Association Foundation and American Medical Association; 2003. Accessed May 19, 2022. http://lib.ncfh.org/pdfs/6617.pdf

To the Editor:

The internet is a popular resource for patients seeking information about dermatologic treatments. Hydroquinone (HQ) cream 4% is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for skin hyperpigmentation.1 The agency enforced the CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) Act and OTC (over-the-counter) Monograph Reform on September 25, 2020, to restrict distribution of OTC HQ.2 Exogenous ochronosis is listed as a potential adverse effect in the prescribing information for HQ.1

We sought to assess online resources on HQ for accuracy of information, including the recent OTC ban, as well as readability. The word hydroquinone was searched on 3 internet search engines—Google, Yahoo, and Bing—on December 12, 2020, each for the first 20 URLs (ie, websites)(total of 60 URLs). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA)(Figure) reporting guidelines were used to assess a list of relevant websites to include in the final analysis. Website data were reviewed by both authors. Eighteen duplicates and 27 irrelevant and non–English-language URLs were excluded. The remaining 15 websites were analyzed. Based on a previously published and validated tool, a pro forma was designed to evaluate information on HQ for each website based on accountability, quality, readability, display, support, and transparency (Table).1,3

Scores for all 15 websites are listed in eTable 1. The mean overall (total) score was

The mean display score was 0.3 (of a possible 4; range, 0–2); 66.7% of websites (10/15) had advertisements or irrelevant material. Only 6.7% and 13.3% of websites included relevant videos or images, respectively, on applying HQ (eTable 2). We identified only 3 photographs—across all 15 websites—that depicted skin, all of which were Fitzpatrick skin types II or III. Therefore, none of the websites included a diversity of images to indicate broad ethnic relatability.

The average support score was 2.5 (of a possible 4; range, 1–3); 20% (3/15) of URLs included chat sites, message boards, or forums, and approximately half (8/15 [53.3%]) included references. Only 7 URLs (46.7%) had been updated in the last 12 months. Only 4 (26.7%) were written by a board-certified dermatologist (eTable 2). Most (60%) websites contained advertising, though none were sponsored by a pharmaceutical company that manufactures HQ.

Only 46.7% (7/15) of websites recommended limiting a course of HQ treatment to 3 months; only 40% (6/15) mentioned shelf life or photochemical degradation when exposed to air. Although 93.3% (14/15) of URLs mentioned ochronosis, a clinical description of the condition was provided in only 33.3% (5/15)—none with images.

Only 2 sites (13.3%; Everyday Health and WebMD) met the accepted 7th-grade reading level for online patient education material; those sites scored lower on quality (9 of 17 and 6 of 17, respectively) than sites with higher overall scores.

None of the 15 websites studied, therefore, demonstrated optimal features on combined measures of accountability, quality, readability, display, support, and transparency regarding HQ. Notably, the American Academy of Dermatology website (www.aad.org) was not among the 15 websites studied; the AAD website mentions HQ in a section on melasma, but only minimal detail is provided.

Limitations of this study include the small number of websites analyzed and possible selection bias because only 3 internet search engines were used to identify websites for study and analysis.

Previously, we analyzed content about HQ on the video-sharing and social media platform YouTube.4 The most viewed YouTube videos on HQ had poor-quality information (ie, only 20% mentioned ochronosis and only 28.6% recommended sunscreen [N=70]). However, average reading level of these videos was 7th grade.4,5 Therefore, YouTube HQ content, though comprehensible, generally is of poor quality.

By conducting a search for website content about HQ, we found that the most popular URLs had either accurate information with poor readability or lower-quality educational material that was more comprehensible. We conclude that there is a need to develop online patient education materials on HQ that are characterized by high-quality, up-to-date medical information; have been written by board-certified dermatologists; are comprehensible (ie, no more than approximately 1200 words and written at a 7th-grade reading level); and contain relevant clinical images and references. We encourage dermatologists to recognize the limitations of online patient education resources on HQ and educate patients on the proper use of the drug as well as its potential adverse effects

To the Editor:

The internet is a popular resource for patients seeking information about dermatologic treatments. Hydroquinone (HQ) cream 4% is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for skin hyperpigmentation.1 The agency enforced the CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) Act and OTC (over-the-counter) Monograph Reform on September 25, 2020, to restrict distribution of OTC HQ.2 Exogenous ochronosis is listed as a potential adverse effect in the prescribing information for HQ.1

We sought to assess online resources on HQ for accuracy of information, including the recent OTC ban, as well as readability. The word hydroquinone was searched on 3 internet search engines—Google, Yahoo, and Bing—on December 12, 2020, each for the first 20 URLs (ie, websites)(total of 60 URLs). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA)(Figure) reporting guidelines were used to assess a list of relevant websites to include in the final analysis. Website data were reviewed by both authors. Eighteen duplicates and 27 irrelevant and non–English-language URLs were excluded. The remaining 15 websites were analyzed. Based on a previously published and validated tool, a pro forma was designed to evaluate information on HQ for each website based on accountability, quality, readability, display, support, and transparency (Table).1,3

Scores for all 15 websites are listed in eTable 1. The mean overall (total) score was

The mean display score was 0.3 (of a possible 4; range, 0–2); 66.7% of websites (10/15) had advertisements or irrelevant material. Only 6.7% and 13.3% of websites included relevant videos or images, respectively, on applying HQ (eTable 2). We identified only 3 photographs—across all 15 websites—that depicted skin, all of which were Fitzpatrick skin types II or III. Therefore, none of the websites included a diversity of images to indicate broad ethnic relatability.

The average support score was 2.5 (of a possible 4; range, 1–3); 20% (3/15) of URLs included chat sites, message boards, or forums, and approximately half (8/15 [53.3%]) included references. Only 7 URLs (46.7%) had been updated in the last 12 months. Only 4 (26.7%) were written by a board-certified dermatologist (eTable 2). Most (60%) websites contained advertising, though none were sponsored by a pharmaceutical company that manufactures HQ.

Only 46.7% (7/15) of websites recommended limiting a course of HQ treatment to 3 months; only 40% (6/15) mentioned shelf life or photochemical degradation when exposed to air. Although 93.3% (14/15) of URLs mentioned ochronosis, a clinical description of the condition was provided in only 33.3% (5/15)—none with images.

Only 2 sites (13.3%; Everyday Health and WebMD) met the accepted 7th-grade reading level for online patient education material; those sites scored lower on quality (9 of 17 and 6 of 17, respectively) than sites with higher overall scores.

None of the 15 websites studied, therefore, demonstrated optimal features on combined measures of accountability, quality, readability, display, support, and transparency regarding HQ. Notably, the American Academy of Dermatology website (www.aad.org) was not among the 15 websites studied; the AAD website mentions HQ in a section on melasma, but only minimal detail is provided.

Limitations of this study include the small number of websites analyzed and possible selection bias because only 3 internet search engines were used to identify websites for study and analysis.

Previously, we analyzed content about HQ on the video-sharing and social media platform YouTube.4 The most viewed YouTube videos on HQ had poor-quality information (ie, only 20% mentioned ochronosis and only 28.6% recommended sunscreen [N=70]). However, average reading level of these videos was 7th grade.4,5 Therefore, YouTube HQ content, though comprehensible, generally is of poor quality.

By conducting a search for website content about HQ, we found that the most popular URLs had either accurate information with poor readability or lower-quality educational material that was more comprehensible. We conclude that there is a need to develop online patient education materials on HQ that are characterized by high-quality, up-to-date medical information; have been written by board-certified dermatologists; are comprehensible (ie, no more than approximately 1200 words and written at a 7th-grade reading level); and contain relevant clinical images and references. We encourage dermatologists to recognize the limitations of online patient education resources on HQ and educate patients on the proper use of the drug as well as its potential adverse effects

- US National Library of Medicine. Label: hydroquinone cream. DailyMed website. Updated November 24, 2020. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=dc72c0b2-4505-4dcf-8a69-889cd9f41693

- US Congress. H.R.748 - CARES Act. 116th Congress (2019-2020). Updated March 27, 2020. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748/text?fbclid=IwAR3ZxGP6AKUl6ce-dlWSU6D5MfCLD576nWNBV5YTE7R2a0IdLY4Usw4oOv4

- Kang R, Lipner S. Evaluation of onychomycosis information on the internet. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:484-487.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Assessing the impact and educational value of YouTube as a source of information on hydroquinone: a content-quality and readability analysis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020:1-3. doi:10.1080/09546634.2020.1782318

- Weiss BD. Health Literacy: A Manual for Clinicians. American Medical Association Foundation and American Medical Association; 2003. Accessed May 19, 2022. http://lib.ncfh.org/pdfs/6617.pdf

- US National Library of Medicine. Label: hydroquinone cream. DailyMed website. Updated November 24, 2020. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=dc72c0b2-4505-4dcf-8a69-889cd9f41693

- US Congress. H.R.748 - CARES Act. 116th Congress (2019-2020). Updated March 27, 2020. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748/text?fbclid=IwAR3ZxGP6AKUl6ce-dlWSU6D5MfCLD576nWNBV5YTE7R2a0IdLY4Usw4oOv4

- Kang R, Lipner S. Evaluation of onychomycosis information on the internet. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:484-487.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Assessing the impact and educational value of YouTube as a source of information on hydroquinone: a content-quality and readability analysis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020:1-3. doi:10.1080/09546634.2020.1782318

- Weiss BD. Health Literacy: A Manual for Clinicians. American Medical Association Foundation and American Medical Association; 2003. Accessed May 19, 2022. http://lib.ncfh.org/pdfs/6617.pdf

Practice Points

- Hydroquinone (HQ) 4% is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for skin hyperpigmentation including melasma.

- In September 2020, the FDA enforced the CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) Act and OTC (over-the-counter) Monograph Reform, announcing that HQ is not classified as Category II/not generally recognized as safe and effective, thus prohibiting the distribution of OTC HQ products.

- Exogenous ochronosis is a potential side effect associated with HQ.

- There is a need for dermatologists to develop online patient education materials on HQ that are characterized by high-quality and up-to-date medical information.

Are There Mobile Applications Related to Nail Disorders?

The use of mobile devices in health care settings has enhanced clinical practice through real-time communication and direct patient monitoring.1 With advancements in technology, improving the accessibility and quality of patient care using mobile devices is a hot topic. In 2018, 261.34 million people worldwide used smartphones compared to 280.54 million in 2021—a 7.3% increase.2 Revenue from sales of mobile applications (apps) is projected to reach $693 billion in 2021.3

A range of apps targeted to patients is available for acne, melanoma, and teledermatology.4-6 Nail disorders are a common concern, representing 21.1 million outpatient visits in 2007 to 2016,7 but, to date, the availability of apps related to nail disorders has not been explored. In this study, we investigated iOS (Apple’s iPhone Operating System) and Android apps to determine the types of nail health apps that are available, using psoriasis and hair loss apps as comparator groups.

Methods

A standard app analytics and market data tool (App Annie; https://www.appannie.com/en/) was utilized to search for iOS and Android nail mobile apps.4,5 The analysis was performed on a single day (March 23, 2020), given that app searches can change on a daily basis. Our search included the following keywords:

Results

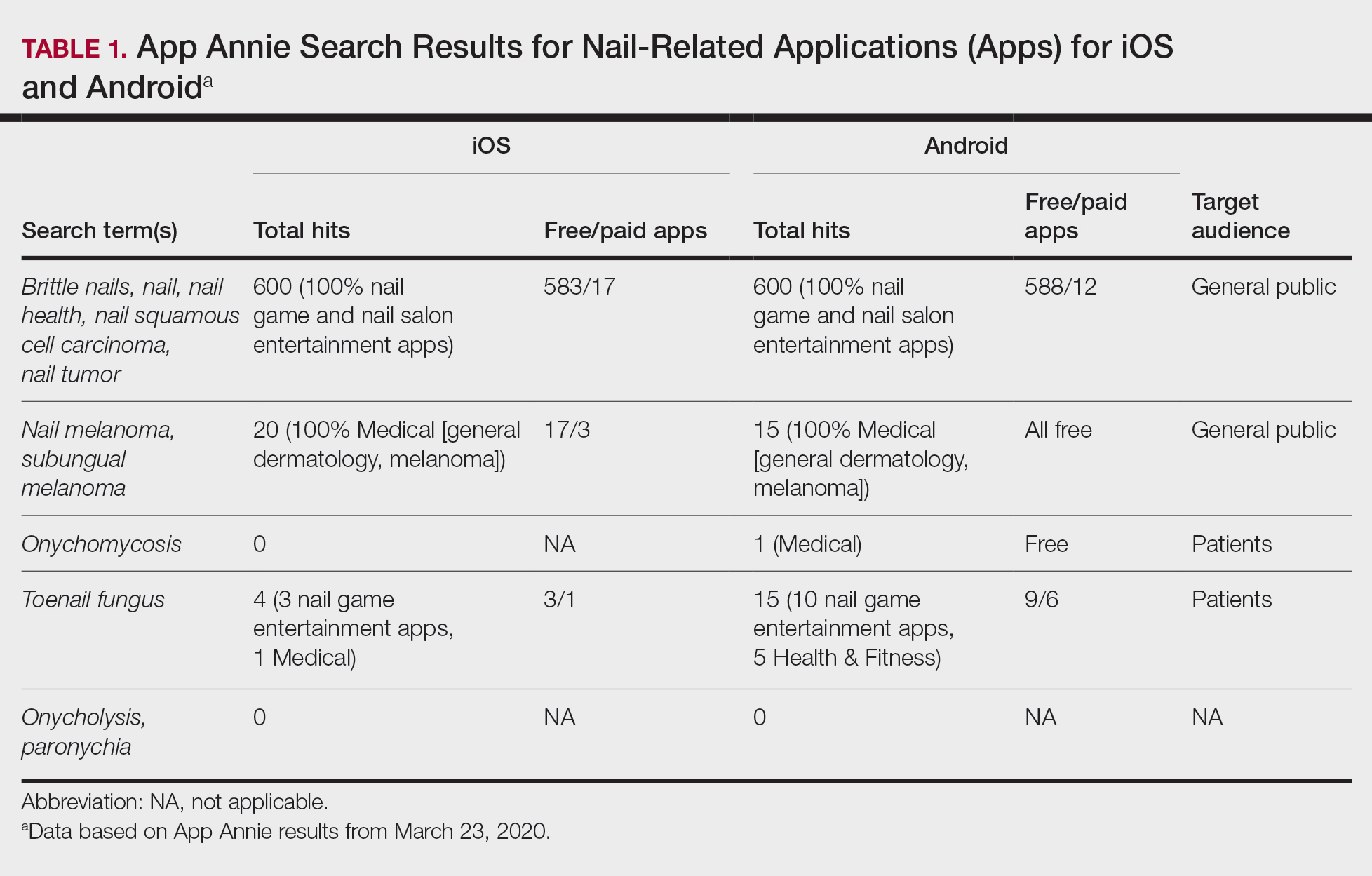

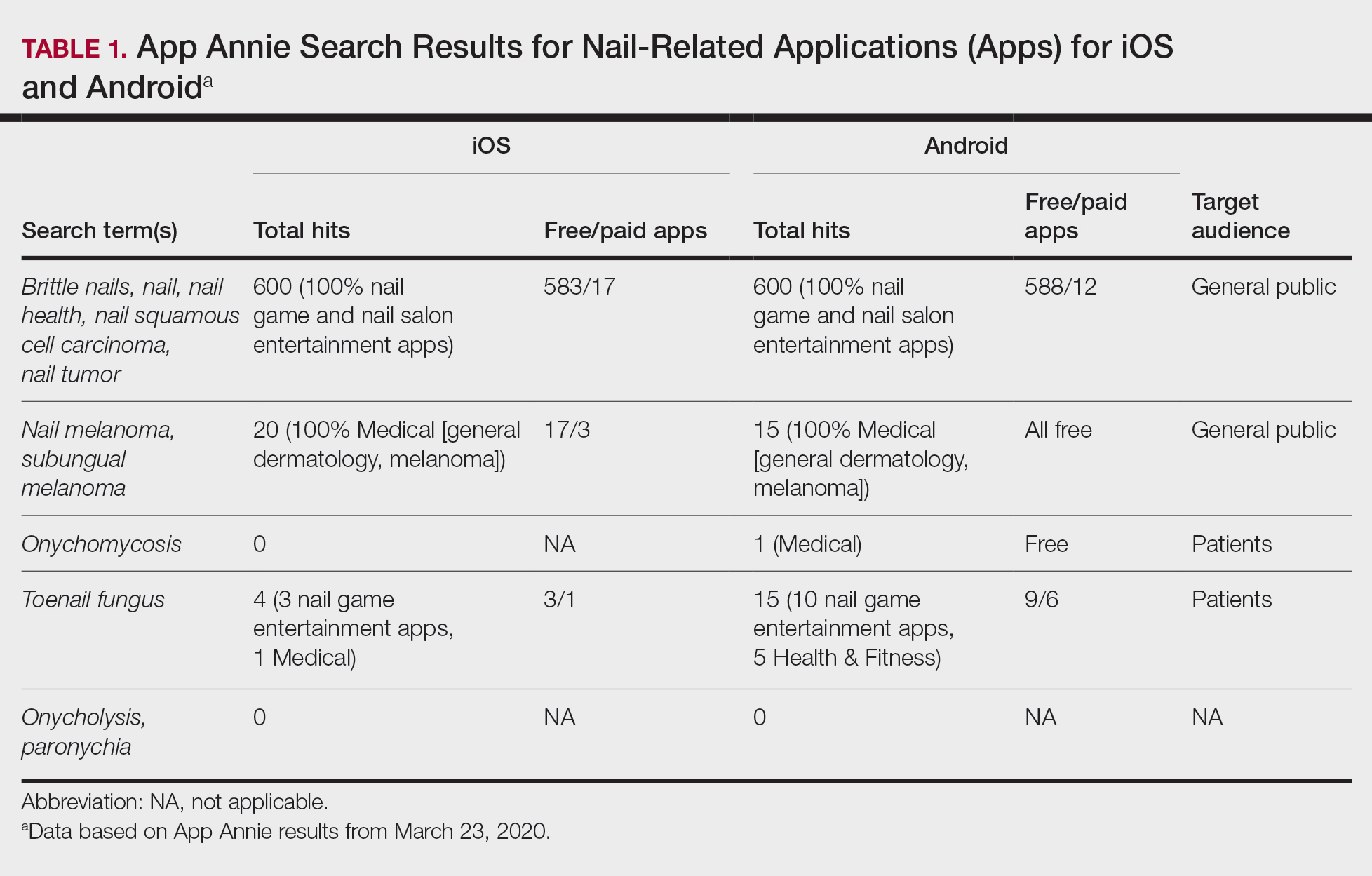

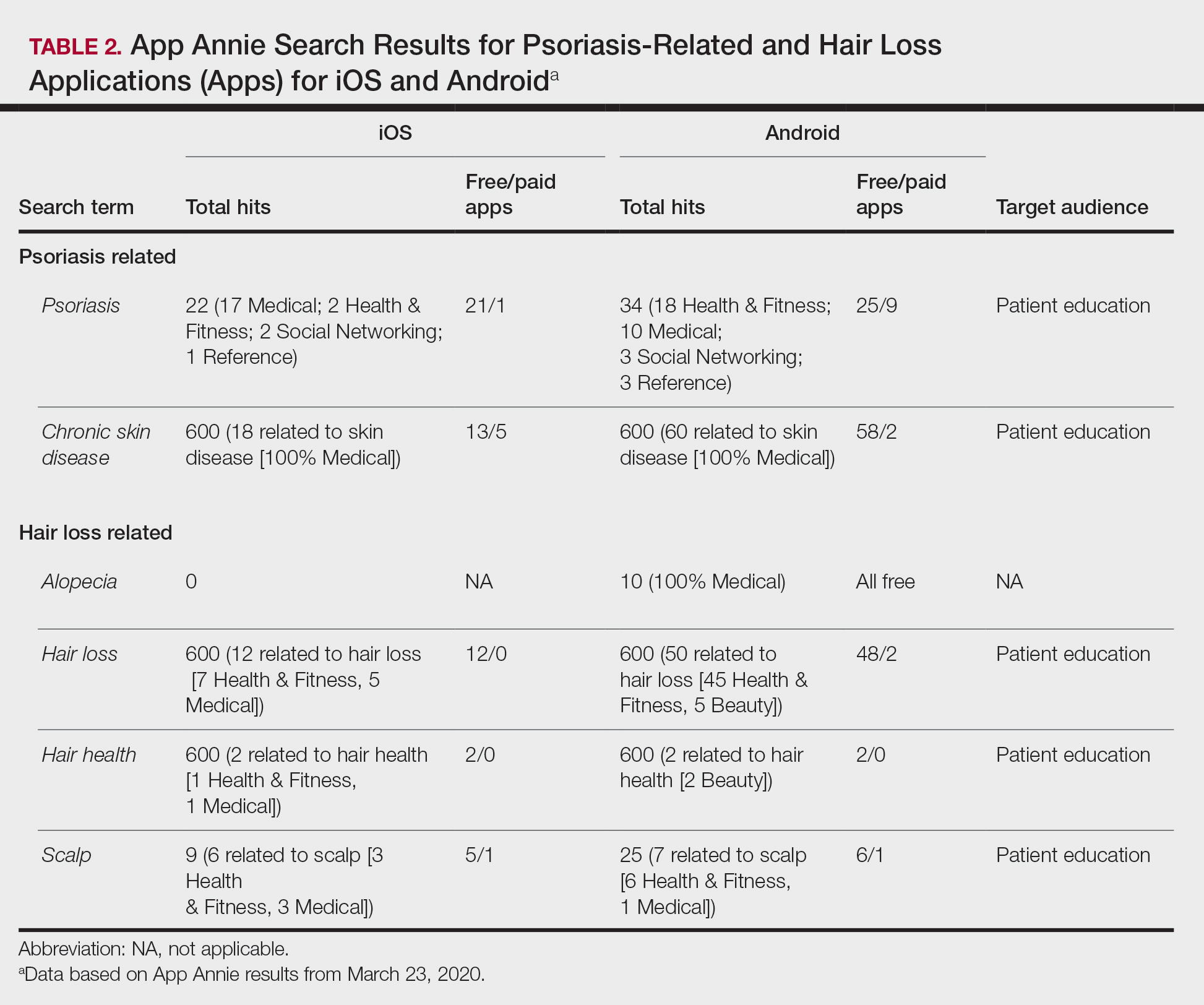

Nail-Related Apps

Using keywords for nail-related terms on iOS and Android platforms, our search returned few specific and informative apps related to nail disorders (Table 1). When the terms brittle nails, nail, nail health, nail squamous cell carcinoma, and nail tumor were searched, all available nail apps were either nail games or virtual nail salons for entertainment purposes. For the terms nail melanoma and subungual melanoma, there were no specific nail apps that appeared in the search results; rather, the App Annie search yielded only general dermatology and melanoma apps. The terms onycholysis and paronychia both yielded 0 hits for iOS and Android.

The only search terms that returned specific nail apps were onychomycosis and toenail fungus. Initially, when onychomycosis was searched, only 1 Google Play Medical category app was found: “Nail fungal infection (model onychomycosis).” Although this app recently was removed from the app store, it previously allowed the user to upload a nail photograph, with which a computing algorithm assessed whether the presentation was a fungal nail infection. Toenail fungus returned 1 iOS Medical category app and 5 Android Health & Fitness category apps with reference material for patients. Neither of the 2 medical apps for onychomycosis and toenail fungus referenced a physician involved in the app development.

Psoriasis Comparator

On the contrary, a search for

Hair Loss Comparator

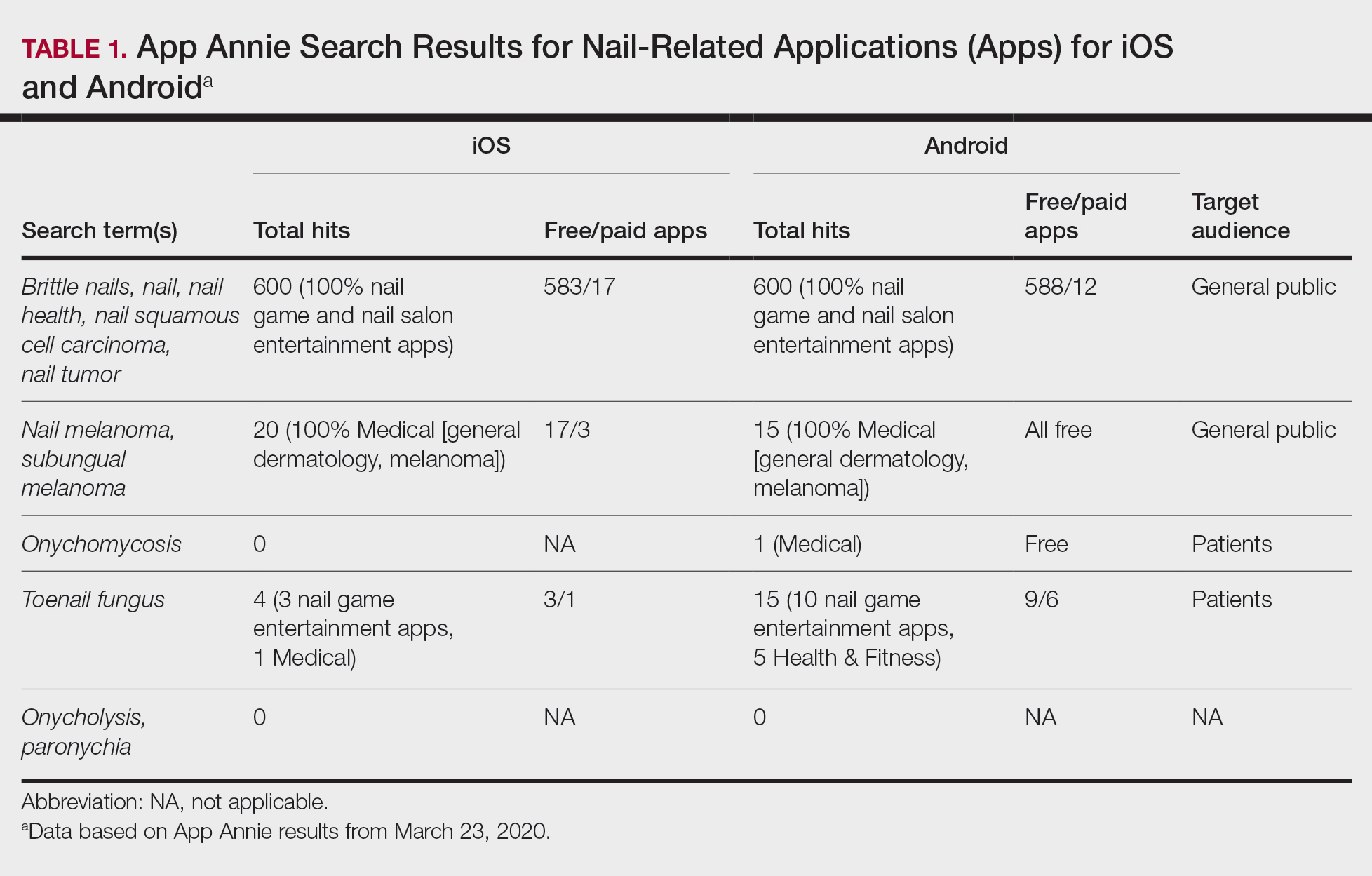

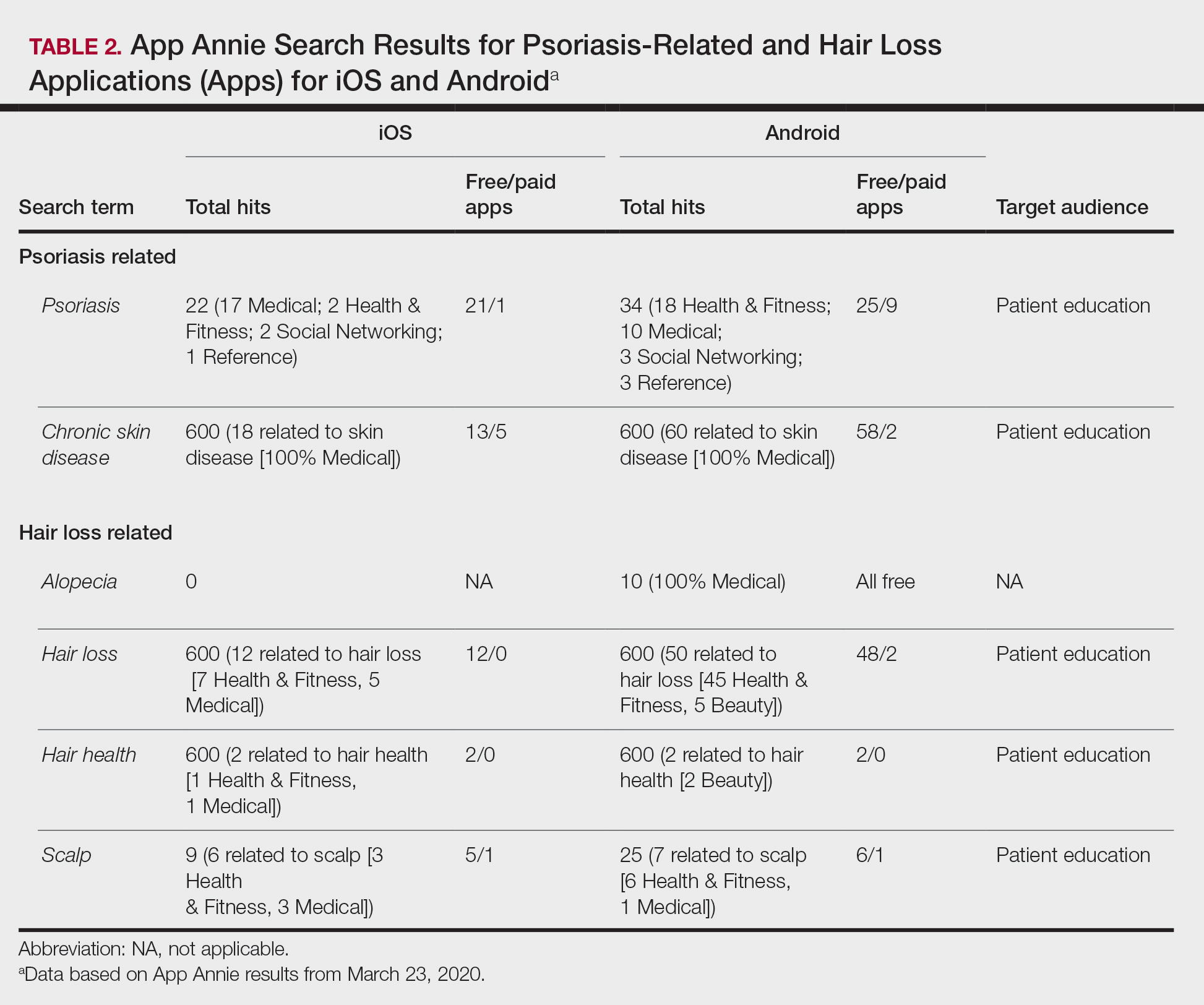

Search terms related to hair conditions—specifically, alopecia—yielded 0 apps for iOS and 10 for Android platforms (Table 2). Using the search term hair loss, 12 apps for iOS and 50 apps for Android were found within the Health & Fitness, Medical, and Beauty categories. The search terms hair health and hair loss resulted in 2 and 12 apps in both iOS and Android, respectively. In addition, the search term scalp was associated with 6 related apps in iOS and 7 in Android, both in the Health & Fitness and Medical categories.

Other Findings

Most apps for psoriasis and hair health were identified as patient focused. Although iOS and Android are different operating systems, some health apps overlapped: subungual melanoma and toenail fungus had a 20% overlap; psoriasis, 19%; chronic skin disease, 2%; alopecia, 0%; hair loss and hair health, 10%; and scalp, 18%. iOS and Android nail entertainment games had approximately a 30% overlap. Tables 1 and 2 also compare the number of free and paid apps; most available apps were free.

Comment

With continued growth in mobile device ownership and app development has been parallel growth in the creation and use of apps to enhance medical care.1 In a study analyzing the most popular dermatology apps, 62% (18/29) and 38% (11/29) of apps targeted patients and physicians, respectively.6 Our study showed that (1) there are few nail disorder apps available for patient education and (2) there is no evidence that a physician was consulted for content input. Because patients who can effectively communicate their health concerns before and after seeing a physician have better self-reported clinical outcomes,9 it is important to have nail disorder apps available to patients for referencing. The nail health app options differ notably from psoriasis and hair loss apps, with apps for the latter 2 topics found in Medical and Health & Fitness categories—targeting patients who seek immediate access to health care and education.

Although there are several general dermatology apps that contain reference information for patients pertaining to nail conditions,6 using any of those apps would require a patient to have prior knowledge that dermatologists specialize in nail disorders and necessitate several steps to find nail-relevant information. For example, the patient would have to search dermatology in the iOS and Android app stores, select the available app (eg, Dermatology Database), and then search within that app for nail disorders. Therefore, a patient who is concerned about a possible subungual melanoma would not be able to easily find clinical images and explanations using an app.

Study Limitations

This study was subject to several limitations. Android and iOS app stores have undisclosed computing algorithms that might have filtered apps based on specific word inquiry. Also, our queries were based on specific relevant keywords for nail conditions, psoriasis, and hair loss; use of different keywords might have yielded different results. Additionally, app options change on a daily basis, so a search today (ie, any given day) might yield slightly different results than it did on March 23, 2020.

Conclusion

Specific nail disorder apps available for patient reference are limited. App developers should consider accessibility (ie, clear language, ease of use, cost-effectiveness, usability on iOS- and Android-operated devices) and content (accurate medical information from experts) when considering new apps. A solution to this problem is for established medical organizations to create nail disorder apps specifically for patients.10 For example, the American Academy of Dermatology has iOS and Android apps that are relevant to physicians (MyDermPath+, Dialogues in Dermatology, Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria) but no comparable apps for patients; patient-appropriate nail apps are necessary.11 In addition, it would be beneficial to patients if established app companies consulted with dermatologists on pertinent nail content.

In sum, we found few available nail health apps on the iOS or Android platforms that provided accessible and timely information to patients regarding nail disorders. There is an immediate need to produce apps related to nail health for appropriate patient education.

- Wallace S, Clark M, White J. ‘It’s on my iPhone’: attitudes to the use of mobile computing devices in medical education, a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e001099.

- O’Dea S. Number of smartphone users in the United States from 2018 to 2024 (in millions). Statista website. April 21, 2020. Accessed February 19, 2021. https://www.statista.com/statistics/201182/forecast-of-smartphone-users-in-the-us/

- Clement J. Worldwide mobile app revenues in 2014 to 2023. Statista website. Published February 4, 2021. Accessed February 19, 2021.https://www.statista.com/statistics/269025/worldwide-mobile-app-revenue-forecast/

- Poushter J, Bishop C, Chwe H. Social media use continues to rise in developing countries but plateaus across developed ones. Pew Research Center Washington DC. Published June 19, 2018. Accessed February 19, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2018/06/19/social-media-use-continues-to-rise-in-developing-countries-but-plateaus-across-developed-ones/

- Flaten HK, St Claire C, Schlager E, et al. Growth of mobile applications in dermatology—2017 update. Dermatol Online J. 2018 February;24:1-4. Accessed February 19, 2021. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3hs7n9z6

- Tongdee E, Markowitz O. Mobile app rankings in dermatology. Cutis. 2018;102:252-256.

- Lipner SR, Hancock J, Fleischer AB. The ambulatory care burden of nail conditions in the United States [published online October 21, 2019]. J Dermatol Treat. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019

- Gu L, Lipner SR. Analysis of education on nail conditions at the American Academy of Dermatology annual meetings. Cutis. 2020;105:259-260.

- King A, Hoppe RB. “Best practice” for patient-centered communication: a narrative review. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;3:385-393.

- Larson RS. A path to better-quality mHealth apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6:E10414.

- Academy apps. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed February 19, 2021. https://www.aad.org/member/publications/apps

The use of mobile devices in health care settings has enhanced clinical practice through real-time communication and direct patient monitoring.1 With advancements in technology, improving the accessibility and quality of patient care using mobile devices is a hot topic. In 2018, 261.34 million people worldwide used smartphones compared to 280.54 million in 2021—a 7.3% increase.2 Revenue from sales of mobile applications (apps) is projected to reach $693 billion in 2021.3

A range of apps targeted to patients is available for acne, melanoma, and teledermatology.4-6 Nail disorders are a common concern, representing 21.1 million outpatient visits in 2007 to 2016,7 but, to date, the availability of apps related to nail disorders has not been explored. In this study, we investigated iOS (Apple’s iPhone Operating System) and Android apps to determine the types of nail health apps that are available, using psoriasis and hair loss apps as comparator groups.

Methods

A standard app analytics and market data tool (App Annie; https://www.appannie.com/en/) was utilized to search for iOS and Android nail mobile apps.4,5 The analysis was performed on a single day (March 23, 2020), given that app searches can change on a daily basis. Our search included the following keywords:

Results

Nail-Related Apps

Using keywords for nail-related terms on iOS and Android platforms, our search returned few specific and informative apps related to nail disorders (Table 1). When the terms brittle nails, nail, nail health, nail squamous cell carcinoma, and nail tumor were searched, all available nail apps were either nail games or virtual nail salons for entertainment purposes. For the terms nail melanoma and subungual melanoma, there were no specific nail apps that appeared in the search results; rather, the App Annie search yielded only general dermatology and melanoma apps. The terms onycholysis and paronychia both yielded 0 hits for iOS and Android.

The only search terms that returned specific nail apps were onychomycosis and toenail fungus. Initially, when onychomycosis was searched, only 1 Google Play Medical category app was found: “Nail fungal infection (model onychomycosis).” Although this app recently was removed from the app store, it previously allowed the user to upload a nail photograph, with which a computing algorithm assessed whether the presentation was a fungal nail infection. Toenail fungus returned 1 iOS Medical category app and 5 Android Health & Fitness category apps with reference material for patients. Neither of the 2 medical apps for onychomycosis and toenail fungus referenced a physician involved in the app development.

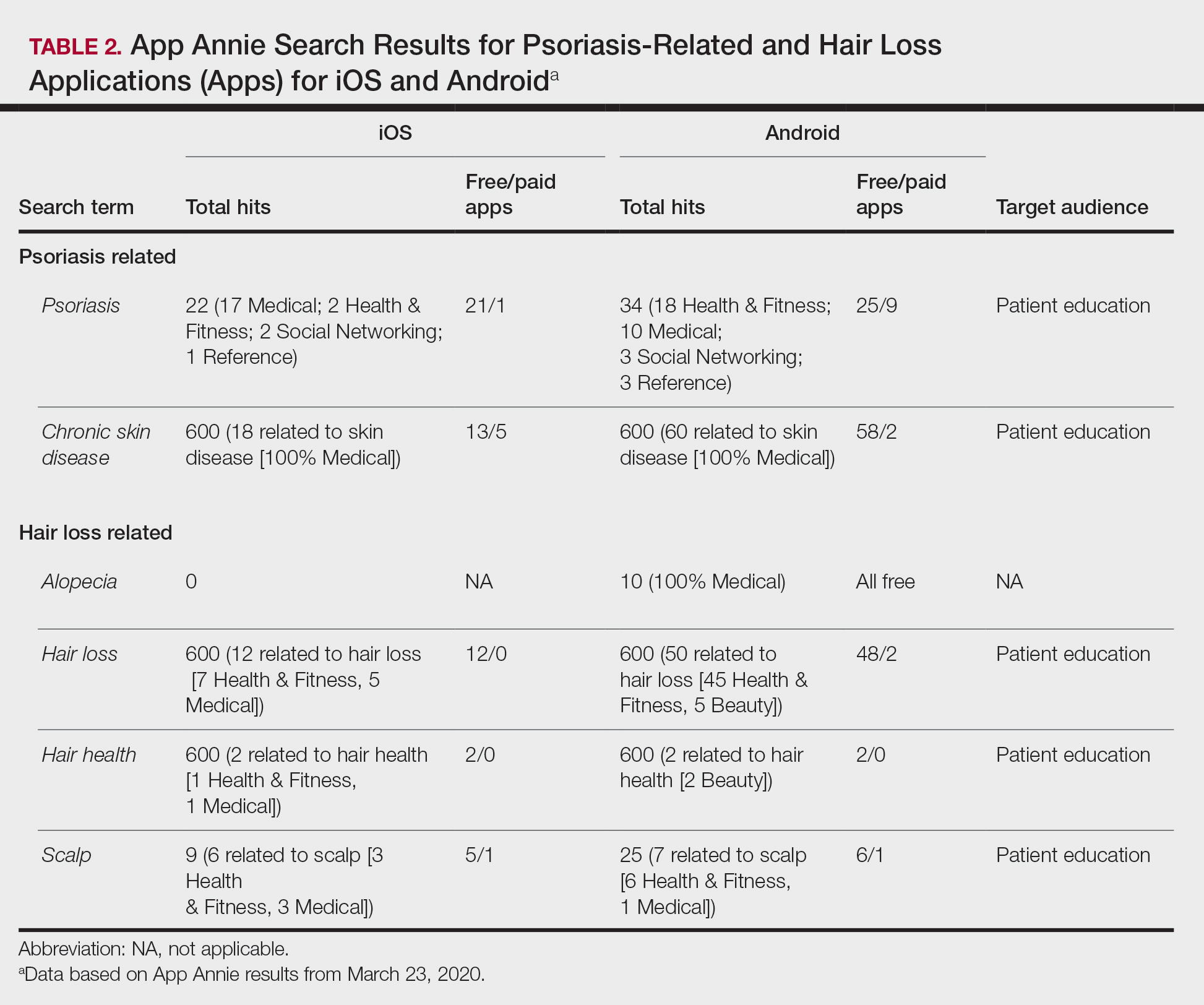

Psoriasis Comparator

On the contrary, a search for

Hair Loss Comparator

Search terms related to hair conditions—specifically, alopecia—yielded 0 apps for iOS and 10 for Android platforms (Table 2). Using the search term hair loss, 12 apps for iOS and 50 apps for Android were found within the Health & Fitness, Medical, and Beauty categories. The search terms hair health and hair loss resulted in 2 and 12 apps in both iOS and Android, respectively. In addition, the search term scalp was associated with 6 related apps in iOS and 7 in Android, both in the Health & Fitness and Medical categories.

Other Findings

Most apps for psoriasis and hair health were identified as patient focused. Although iOS and Android are different operating systems, some health apps overlapped: subungual melanoma and toenail fungus had a 20% overlap; psoriasis, 19%; chronic skin disease, 2%; alopecia, 0%; hair loss and hair health, 10%; and scalp, 18%. iOS and Android nail entertainment games had approximately a 30% overlap. Tables 1 and 2 also compare the number of free and paid apps; most available apps were free.

Comment

With continued growth in mobile device ownership and app development has been parallel growth in the creation and use of apps to enhance medical care.1 In a study analyzing the most popular dermatology apps, 62% (18/29) and 38% (11/29) of apps targeted patients and physicians, respectively.6 Our study showed that (1) there are few nail disorder apps available for patient education and (2) there is no evidence that a physician was consulted for content input. Because patients who can effectively communicate their health concerns before and after seeing a physician have better self-reported clinical outcomes,9 it is important to have nail disorder apps available to patients for referencing. The nail health app options differ notably from psoriasis and hair loss apps, with apps for the latter 2 topics found in Medical and Health & Fitness categories—targeting patients who seek immediate access to health care and education.

Although there are several general dermatology apps that contain reference information for patients pertaining to nail conditions,6 using any of those apps would require a patient to have prior knowledge that dermatologists specialize in nail disorders and necessitate several steps to find nail-relevant information. For example, the patient would have to search dermatology in the iOS and Android app stores, select the available app (eg, Dermatology Database), and then search within that app for nail disorders. Therefore, a patient who is concerned about a possible subungual melanoma would not be able to easily find clinical images and explanations using an app.

Study Limitations

This study was subject to several limitations. Android and iOS app stores have undisclosed computing algorithms that might have filtered apps based on specific word inquiry. Also, our queries were based on specific relevant keywords for nail conditions, psoriasis, and hair loss; use of different keywords might have yielded different results. Additionally, app options change on a daily basis, so a search today (ie, any given day) might yield slightly different results than it did on March 23, 2020.

Conclusion

Specific nail disorder apps available for patient reference are limited. App developers should consider accessibility (ie, clear language, ease of use, cost-effectiveness, usability on iOS- and Android-operated devices) and content (accurate medical information from experts) when considering new apps. A solution to this problem is for established medical organizations to create nail disorder apps specifically for patients.10 For example, the American Academy of Dermatology has iOS and Android apps that are relevant to physicians (MyDermPath+, Dialogues in Dermatology, Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria) but no comparable apps for patients; patient-appropriate nail apps are necessary.11 In addition, it would be beneficial to patients if established app companies consulted with dermatologists on pertinent nail content.

In sum, we found few available nail health apps on the iOS or Android platforms that provided accessible and timely information to patients regarding nail disorders. There is an immediate need to produce apps related to nail health for appropriate patient education.

The use of mobile devices in health care settings has enhanced clinical practice through real-time communication and direct patient monitoring.1 With advancements in technology, improving the accessibility and quality of patient care using mobile devices is a hot topic. In 2018, 261.34 million people worldwide used smartphones compared to 280.54 million in 2021—a 7.3% increase.2 Revenue from sales of mobile applications (apps) is projected to reach $693 billion in 2021.3

A range of apps targeted to patients is available for acne, melanoma, and teledermatology.4-6 Nail disorders are a common concern, representing 21.1 million outpatient visits in 2007 to 2016,7 but, to date, the availability of apps related to nail disorders has not been explored. In this study, we investigated iOS (Apple’s iPhone Operating System) and Android apps to determine the types of nail health apps that are available, using psoriasis and hair loss apps as comparator groups.

Methods

A standard app analytics and market data tool (App Annie; https://www.appannie.com/en/) was utilized to search for iOS and Android nail mobile apps.4,5 The analysis was performed on a single day (March 23, 2020), given that app searches can change on a daily basis. Our search included the following keywords:

Results

Nail-Related Apps

Using keywords for nail-related terms on iOS and Android platforms, our search returned few specific and informative apps related to nail disorders (Table 1). When the terms brittle nails, nail, nail health, nail squamous cell carcinoma, and nail tumor were searched, all available nail apps were either nail games or virtual nail salons for entertainment purposes. For the terms nail melanoma and subungual melanoma, there were no specific nail apps that appeared in the search results; rather, the App Annie search yielded only general dermatology and melanoma apps. The terms onycholysis and paronychia both yielded 0 hits for iOS and Android.

The only search terms that returned specific nail apps were onychomycosis and toenail fungus. Initially, when onychomycosis was searched, only 1 Google Play Medical category app was found: “Nail fungal infection (model onychomycosis).” Although this app recently was removed from the app store, it previously allowed the user to upload a nail photograph, with which a computing algorithm assessed whether the presentation was a fungal nail infection. Toenail fungus returned 1 iOS Medical category app and 5 Android Health & Fitness category apps with reference material for patients. Neither of the 2 medical apps for onychomycosis and toenail fungus referenced a physician involved in the app development.

Psoriasis Comparator

On the contrary, a search for

Hair Loss Comparator

Search terms related to hair conditions—specifically, alopecia—yielded 0 apps for iOS and 10 for Android platforms (Table 2). Using the search term hair loss, 12 apps for iOS and 50 apps for Android were found within the Health & Fitness, Medical, and Beauty categories. The search terms hair health and hair loss resulted in 2 and 12 apps in both iOS and Android, respectively. In addition, the search term scalp was associated with 6 related apps in iOS and 7 in Android, both in the Health & Fitness and Medical categories.

Other Findings

Most apps for psoriasis and hair health were identified as patient focused. Although iOS and Android are different operating systems, some health apps overlapped: subungual melanoma and toenail fungus had a 20% overlap; psoriasis, 19%; chronic skin disease, 2%; alopecia, 0%; hair loss and hair health, 10%; and scalp, 18%. iOS and Android nail entertainment games had approximately a 30% overlap. Tables 1 and 2 also compare the number of free and paid apps; most available apps were free.

Comment

With continued growth in mobile device ownership and app development has been parallel growth in the creation and use of apps to enhance medical care.1 In a study analyzing the most popular dermatology apps, 62% (18/29) and 38% (11/29) of apps targeted patients and physicians, respectively.6 Our study showed that (1) there are few nail disorder apps available for patient education and (2) there is no evidence that a physician was consulted for content input. Because patients who can effectively communicate their health concerns before and after seeing a physician have better self-reported clinical outcomes,9 it is important to have nail disorder apps available to patients for referencing. The nail health app options differ notably from psoriasis and hair loss apps, with apps for the latter 2 topics found in Medical and Health & Fitness categories—targeting patients who seek immediate access to health care and education.

Although there are several general dermatology apps that contain reference information for patients pertaining to nail conditions,6 using any of those apps would require a patient to have prior knowledge that dermatologists specialize in nail disorders and necessitate several steps to find nail-relevant information. For example, the patient would have to search dermatology in the iOS and Android app stores, select the available app (eg, Dermatology Database), and then search within that app for nail disorders. Therefore, a patient who is concerned about a possible subungual melanoma would not be able to easily find clinical images and explanations using an app.

Study Limitations

This study was subject to several limitations. Android and iOS app stores have undisclosed computing algorithms that might have filtered apps based on specific word inquiry. Also, our queries were based on specific relevant keywords for nail conditions, psoriasis, and hair loss; use of different keywords might have yielded different results. Additionally, app options change on a daily basis, so a search today (ie, any given day) might yield slightly different results than it did on March 23, 2020.

Conclusion

Specific nail disorder apps available for patient reference are limited. App developers should consider accessibility (ie, clear language, ease of use, cost-effectiveness, usability on iOS- and Android-operated devices) and content (accurate medical information from experts) when considering new apps. A solution to this problem is for established medical organizations to create nail disorder apps specifically for patients.10 For example, the American Academy of Dermatology has iOS and Android apps that are relevant to physicians (MyDermPath+, Dialogues in Dermatology, Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria) but no comparable apps for patients; patient-appropriate nail apps are necessary.11 In addition, it would be beneficial to patients if established app companies consulted with dermatologists on pertinent nail content.

In sum, we found few available nail health apps on the iOS or Android platforms that provided accessible and timely information to patients regarding nail disorders. There is an immediate need to produce apps related to nail health for appropriate patient education.

- Wallace S, Clark M, White J. ‘It’s on my iPhone’: attitudes to the use of mobile computing devices in medical education, a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e001099.

- O’Dea S. Number of smartphone users in the United States from 2018 to 2024 (in millions). Statista website. April 21, 2020. Accessed February 19, 2021. https://www.statista.com/statistics/201182/forecast-of-smartphone-users-in-the-us/

- Clement J. Worldwide mobile app revenues in 2014 to 2023. Statista website. Published February 4, 2021. Accessed February 19, 2021.https://www.statista.com/statistics/269025/worldwide-mobile-app-revenue-forecast/

- Poushter J, Bishop C, Chwe H. Social media use continues to rise in developing countries but plateaus across developed ones. Pew Research Center Washington DC. Published June 19, 2018. Accessed February 19, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2018/06/19/social-media-use-continues-to-rise-in-developing-countries-but-plateaus-across-developed-ones/

- Flaten HK, St Claire C, Schlager E, et al. Growth of mobile applications in dermatology—2017 update. Dermatol Online J. 2018 February;24:1-4. Accessed February 19, 2021. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3hs7n9z6

- Tongdee E, Markowitz O. Mobile app rankings in dermatology. Cutis. 2018;102:252-256.

- Lipner SR, Hancock J, Fleischer AB. The ambulatory care burden of nail conditions in the United States [published online October 21, 2019]. J Dermatol Treat. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019

- Gu L, Lipner SR. Analysis of education on nail conditions at the American Academy of Dermatology annual meetings. Cutis. 2020;105:259-260.

- King A, Hoppe RB. “Best practice” for patient-centered communication: a narrative review. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;3:385-393.

- Larson RS. A path to better-quality mHealth apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6:E10414.

- Academy apps. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed February 19, 2021. https://www.aad.org/member/publications/apps

- Wallace S, Clark M, White J. ‘It’s on my iPhone’: attitudes to the use of mobile computing devices in medical education, a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e001099.

- O’Dea S. Number of smartphone users in the United States from 2018 to 2024 (in millions). Statista website. April 21, 2020. Accessed February 19, 2021. https://www.statista.com/statistics/201182/forecast-of-smartphone-users-in-the-us/

- Clement J. Worldwide mobile app revenues in 2014 to 2023. Statista website. Published February 4, 2021. Accessed February 19, 2021.https://www.statista.com/statistics/269025/worldwide-mobile-app-revenue-forecast/

- Poushter J, Bishop C, Chwe H. Social media use continues to rise in developing countries but plateaus across developed ones. Pew Research Center Washington DC. Published June 19, 2018. Accessed February 19, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2018/06/19/social-media-use-continues-to-rise-in-developing-countries-but-plateaus-across-developed-ones/

- Flaten HK, St Claire C, Schlager E, et al. Growth of mobile applications in dermatology—2017 update. Dermatol Online J. 2018 February;24:1-4. Accessed February 19, 2021. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3hs7n9z6

- Tongdee E, Markowitz O. Mobile app rankings in dermatology. Cutis. 2018;102:252-256.

- Lipner SR, Hancock J, Fleischer AB. The ambulatory care burden of nail conditions in the United States [published online October 21, 2019]. J Dermatol Treat. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019

- Gu L, Lipner SR. Analysis of education on nail conditions at the American Academy of Dermatology annual meetings. Cutis. 2020;105:259-260.

- King A, Hoppe RB. “Best practice” for patient-centered communication: a narrative review. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;3:385-393.

- Larson RS. A path to better-quality mHealth apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6:E10414.

- Academy apps. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed February 19, 2021. https://www.aad.org/member/publications/apps

Practice Points

- Patient-targeted mobile applications (apps) might aid with clinical referencing and education.

- There are patient-directed psoriasis and hair loss apps on iOS and Android platforms, but informative apps related to nail disorders are limited.

- There is a need to develop apps related to nail health for patient education.

Use of 3D Technology to Support Dermatologists Returning to Practice Amid COVID-19

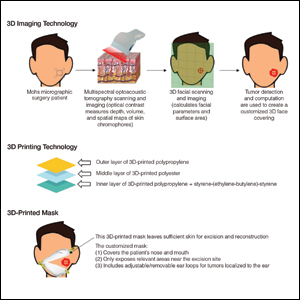

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread across all 7 continents, including 185 countries, and infected more than 21.9 million individuals worldwide as of August 18, 2020, according to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. It has strained our health care system and affected all specialties, including dermatology. Dermatologists have taken important safety measures by canceling/deferring elective and nonemergency procedures and diagnosing/treating patients via telemedicine. Many residents and attending dermatologists have volunteered to care for COVID-19 inpatients and donated

N95 masks are necessary during the COVID-19 pandemic because they effectively filter at least 95% of 0.3-μm airborne particles and provide adequate face seals.1 3-Dimensional imaging integrated with 3D printers can be used to scan precise facial parameters (eg, jawline, nose) and account for facial hair density and length to produce comfortable tailored N95 masks and face seals.1,2 3-Dimensional printing utilizes robotics and

Face shields offer an additional layer of safety for the face and mucosae and also may provide longevity for N95 masks. Using synthetic polymers such as polycarbonate and polyethylene, 3D printers can be used to construct face shields via fused deposition modeling.1 These face shields may be worn over N95 masks and then can be sanitized and reused.

Mohs surgeons and staff may be at particularly high risk for COVID-19 infection due to their close proximity to the face during surgery, use of cautery, and prolonged time spent with patients while taking layers and suturing.

As dermatologists reopen and ramp up practice volume, there will be increased PPE requirements. Using 3D technology and imaging to produce N95 masks, face shields, and face coverings, we can offer effective diagnosis and treatment while optimizing safety for dermatologists, staff, and patients.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Applications of 3D printing technology to address COVID-19-related supply shortages [published online April 21, 2020]. Am J Med. 2020;133:771-773.

- Cai M, Li H, Shen S, et al. Customized design and 3D printing of face seal for an N95 filtering facepiece respirator. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2018;3:226-234.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. A review of 3-dimensional skin bioprinting techniques: applications, approaches, and trends [published online March 17, 2020]. Dermatol Surg. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002378.

- Banerjee SS, Burbine S, Shivaprakash NK, et al. 3D-printable PP/SEBS thermoplastic elastomeric blends: preparation and properties [published online February 17, 2019]. Polymers (Basel). doi:10.3390/polym11020347.

- Chuah SY, Attia ABE, Long V. Structural and functional 3D mapping of skin tumours with non-invasive multispectral optoacoustic tomography [published online November 2, 2016]. Skin Res Technol. 2017;23:221-226.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread across all 7 continents, including 185 countries, and infected more than 21.9 million individuals worldwide as of August 18, 2020, according to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. It has strained our health care system and affected all specialties, including dermatology. Dermatologists have taken important safety measures by canceling/deferring elective and nonemergency procedures and diagnosing/treating patients via telemedicine. Many residents and attending dermatologists have volunteered to care for COVID-19 inpatients and donated

N95 masks are necessary during the COVID-19 pandemic because they effectively filter at least 95% of 0.3-μm airborne particles and provide adequate face seals.1 3-Dimensional imaging integrated with 3D printers can be used to scan precise facial parameters (eg, jawline, nose) and account for facial hair density and length to produce comfortable tailored N95 masks and face seals.1,2 3-Dimensional printing utilizes robotics and

Face shields offer an additional layer of safety for the face and mucosae and also may provide longevity for N95 masks. Using synthetic polymers such as polycarbonate and polyethylene, 3D printers can be used to construct face shields via fused deposition modeling.1 These face shields may be worn over N95 masks and then can be sanitized and reused.

Mohs surgeons and staff may be at particularly high risk for COVID-19 infection due to their close proximity to the face during surgery, use of cautery, and prolonged time spent with patients while taking layers and suturing.

As dermatologists reopen and ramp up practice volume, there will be increased PPE requirements. Using 3D technology and imaging to produce N95 masks, face shields, and face coverings, we can offer effective diagnosis and treatment while optimizing safety for dermatologists, staff, and patients.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread across all 7 continents, including 185 countries, and infected more than 21.9 million individuals worldwide as of August 18, 2020, according to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. It has strained our health care system and affected all specialties, including dermatology. Dermatologists have taken important safety measures by canceling/deferring elective and nonemergency procedures and diagnosing/treating patients via telemedicine. Many residents and attending dermatologists have volunteered to care for COVID-19 inpatients and donated

N95 masks are necessary during the COVID-19 pandemic because they effectively filter at least 95% of 0.3-μm airborne particles and provide adequate face seals.1 3-Dimensional imaging integrated with 3D printers can be used to scan precise facial parameters (eg, jawline, nose) and account for facial hair density and length to produce comfortable tailored N95 masks and face seals.1,2 3-Dimensional printing utilizes robotics and

Face shields offer an additional layer of safety for the face and mucosae and also may provide longevity for N95 masks. Using synthetic polymers such as polycarbonate and polyethylene, 3D printers can be used to construct face shields via fused deposition modeling.1 These face shields may be worn over N95 masks and then can be sanitized and reused.

Mohs surgeons and staff may be at particularly high risk for COVID-19 infection due to their close proximity to the face during surgery, use of cautery, and prolonged time spent with patients while taking layers and suturing.

As dermatologists reopen and ramp up practice volume, there will be increased PPE requirements. Using 3D technology and imaging to produce N95 masks, face shields, and face coverings, we can offer effective diagnosis and treatment while optimizing safety for dermatologists, staff, and patients.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Applications of 3D printing technology to address COVID-19-related supply shortages [published online April 21, 2020]. Am J Med. 2020;133:771-773.

- Cai M, Li H, Shen S, et al. Customized design and 3D printing of face seal for an N95 filtering facepiece respirator. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2018;3:226-234.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. A review of 3-dimensional skin bioprinting techniques: applications, approaches, and trends [published online March 17, 2020]. Dermatol Surg. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002378.

- Banerjee SS, Burbine S, Shivaprakash NK, et al. 3D-printable PP/SEBS thermoplastic elastomeric blends: preparation and properties [published online February 17, 2019]. Polymers (Basel). doi:10.3390/polym11020347.

- Chuah SY, Attia ABE, Long V. Structural and functional 3D mapping of skin tumours with non-invasive multispectral optoacoustic tomography [published online November 2, 2016]. Skin Res Technol. 2017;23:221-226.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Applications of 3D printing technology to address COVID-19-related supply shortages [published online April 21, 2020]. Am J Med. 2020;133:771-773.

- Cai M, Li H, Shen S, et al. Customized design and 3D printing of face seal for an N95 filtering facepiece respirator. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2018;3:226-234.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. A review of 3-dimensional skin bioprinting techniques: applications, approaches, and trends [published online March 17, 2020]. Dermatol Surg. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002378.

- Banerjee SS, Burbine S, Shivaprakash NK, et al. 3D-printable PP/SEBS thermoplastic elastomeric blends: preparation and properties [published online February 17, 2019]. Polymers (Basel). doi:10.3390/polym11020347.

- Chuah SY, Attia ABE, Long V. Structural and functional 3D mapping of skin tumours with non-invasive multispectral optoacoustic tomography [published online November 2, 2016]. Skin Res Technol. 2017;23:221-226.

Practice Points

- Coronavirus disease 19 has overwhelmed our health care system and affected all specialties, including dermatology.

- There are concerns about shortages of personal protective equipment to safely care for patients.

- 3-Dimensional imaging and printing technologies can be harnessed to create face coverings and face shields for the dermatology outpatient setting.

Evaluating the Impact and Educational Value of YouTube Videos on Nail Biopsy Procedures

To the Editor:

Nail biopsy is an important surgical procedure for diagnosis of nail pathology. YouTube has become a potential instrument for physicians and patients to learn about medical procedures.1,2 However, the sources, content, and quality of the information available have not been fully studied or characterized. Our objective was to analyze the efficiency of information and quality of YouTube videos on nail biopsies. We hypothesized that the quality of patient education and physician training videos would be unrepresentative on YouTube.

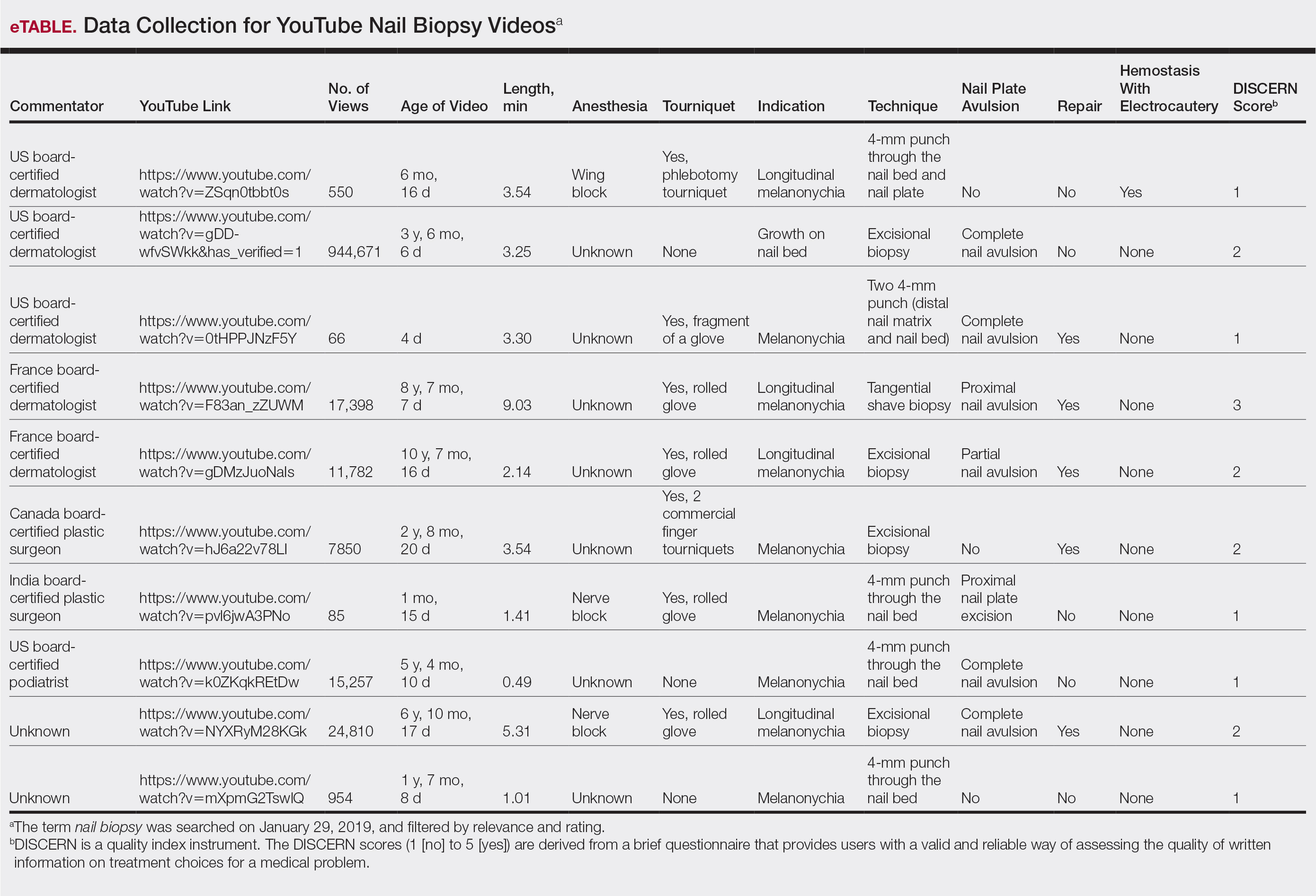

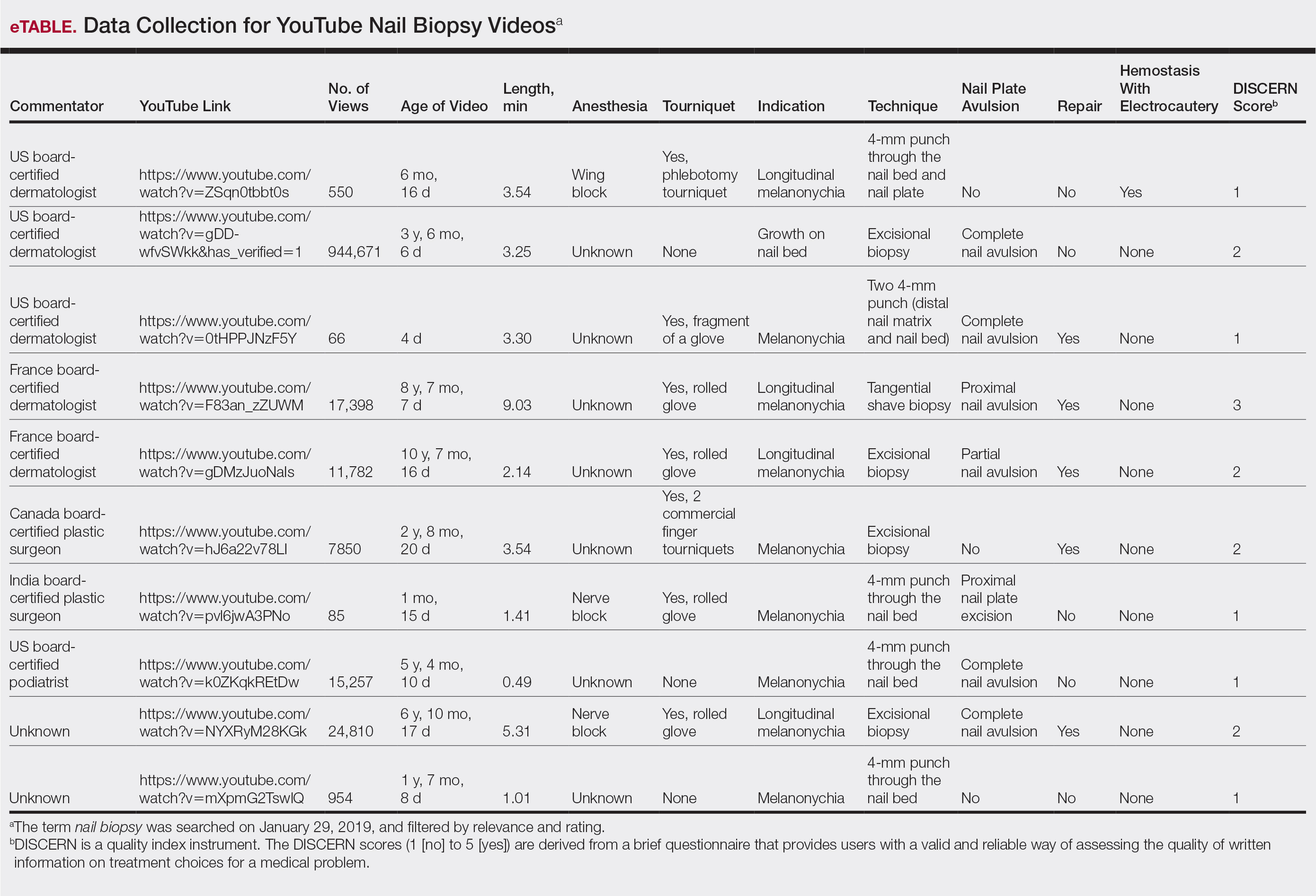

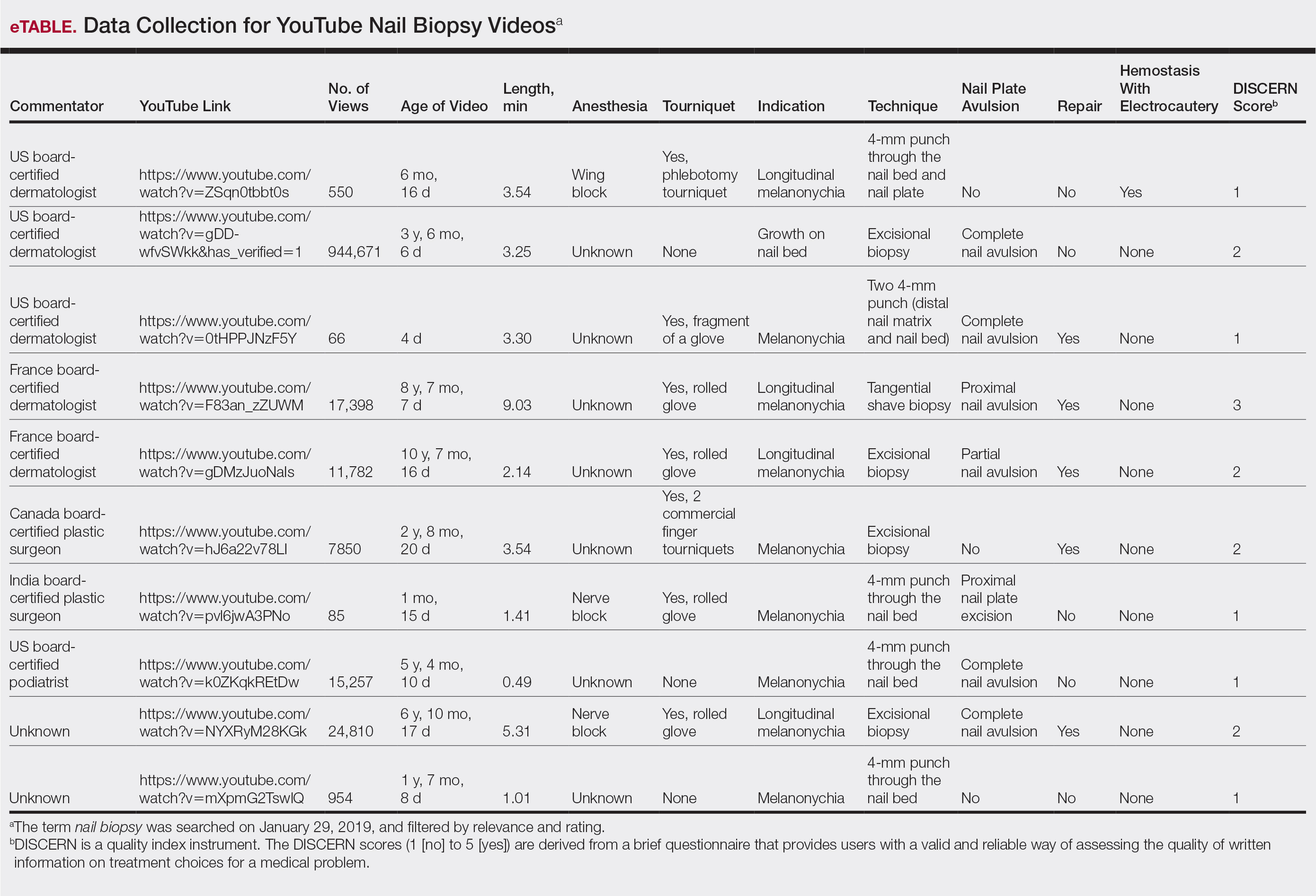

The term nail biopsy was searched on January 29, 2019, and filtered by relevance and rating using the default YouTube algorithm. Data were collected from the top 40 hits for the search term and filter coupling. All videos were viewed and sorted for nail biopsy procedures, and then those videos were categorized as being produced by a physician or other health care provider. The US medical board status of each physician videographer was determined using the American Board of Medical Specialties database.3 DISCERN criteria for assessing consumer health care information4 were used to interpret the videos by researchers (S.I. and S.R.L.) in this study.

From the queried search term collection, only 10 videos (1,023,423 combined views) were analyzed in this study (eTable). Although the other resulting videos were tagged as nail biopsy, they were excluded due to irrelevant content (eg, patient blogs, PowerPoints, nail avulsions). The mean age of the videos was 4 years (range, 4 days to 11 years), with a mean video length of 3.30 minutes (range, 49 seconds to 9.03 minutes). Four of 10 videos were performed for longitudinal melanonychia, and 5 of 10 videos were performed for melanonychia, clinically consistent with subungual hematoma. Dermatologists, plastic surgeons, and podiatrists produced the majority of the nail biopsy videos. The overall mean DISCERN rating was 1.60/5.00 (range, 1–3), meaning that the quality of content on nail biopsies was poor. This low DISCERN score signifies poor consumer health information. Video 2 (published in 2015) received a DISCERN score of 2 and received almost 1 million views, which is likely because the specific channel has a well-established subscriber pool (4.9 million subscribers). The highest DISCERN score of 3, demonstrating a tangential shave biopsy, was given to video 4 (published in 2010) and only received about 17,400 views (56 subscribers). Additionally, many videos lacked important information about the procedure. For instance, only 3 of 10 videos demonstrated the anesthetic technique and only 5 videos showed repair methods.

YouTube is an electronic learning source for general information; however, the content and quality of information on nail biopsy is not updated, reliable, or abundant. Patients undergoing nail biopsies are unlikely to find reliable and comprehensible information on YouTube; thus, there is a strong need for patient education in this area. In addition, physicians who did not learn to perform a nail biopsy during training are unlikely to learn this procedure from YouTube. Therefore, there is an unmet need for an outlet that will provide updated reliable content on nail biopsies geared toward both patients and physicians.

- Kwok TM, Singla AA, Phang K, et al. YouTube as a source of patient information for varicose vein treatment options. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2017;5:238-243.

- Ward B, Ward M, Nicheporuck A, et al. Assessment of YouTube as an informative resource on facial plastic surgery procedures. JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery. 2019;21:75-76.

- American Board of Medical Specialties. Certification Matters. https://www.certificationmatters.org. Accessed February 7, 2020.

- The DISCERN Instrument. DISCERN Online. http://www.discern.org.uk/discern_instrument.php. Published October 1999. Accessed February 7, 2020.

To the Editor:

Nail biopsy is an important surgical procedure for diagnosis of nail pathology. YouTube has become a potential instrument for physicians and patients to learn about medical procedures.1,2 However, the sources, content, and quality of the information available have not been fully studied or characterized. Our objective was to analyze the efficiency of information and quality of YouTube videos on nail biopsies. We hypothesized that the quality of patient education and physician training videos would be unrepresentative on YouTube.

The term nail biopsy was searched on January 29, 2019, and filtered by relevance and rating using the default YouTube algorithm. Data were collected from the top 40 hits for the search term and filter coupling. All videos were viewed and sorted for nail biopsy procedures, and then those videos were categorized as being produced by a physician or other health care provider. The US medical board status of each physician videographer was determined using the American Board of Medical Specialties database.3 DISCERN criteria for assessing consumer health care information4 were used to interpret the videos by researchers (S.I. and S.R.L.) in this study.

From the queried search term collection, only 10 videos (1,023,423 combined views) were analyzed in this study (eTable). Although the other resulting videos were tagged as nail biopsy, they were excluded due to irrelevant content (eg, patient blogs, PowerPoints, nail avulsions). The mean age of the videos was 4 years (range, 4 days to 11 years), with a mean video length of 3.30 minutes (range, 49 seconds to 9.03 minutes). Four of 10 videos were performed for longitudinal melanonychia, and 5 of 10 videos were performed for melanonychia, clinically consistent with subungual hematoma. Dermatologists, plastic surgeons, and podiatrists produced the majority of the nail biopsy videos. The overall mean DISCERN rating was 1.60/5.00 (range, 1–3), meaning that the quality of content on nail biopsies was poor. This low DISCERN score signifies poor consumer health information. Video 2 (published in 2015) received a DISCERN score of 2 and received almost 1 million views, which is likely because the specific channel has a well-established subscriber pool (4.9 million subscribers). The highest DISCERN score of 3, demonstrating a tangential shave biopsy, was given to video 4 (published in 2010) and only received about 17,400 views (56 subscribers). Additionally, many videos lacked important information about the procedure. For instance, only 3 of 10 videos demonstrated the anesthetic technique and only 5 videos showed repair methods.

YouTube is an electronic learning source for general information; however, the content and quality of information on nail biopsy is not updated, reliable, or abundant. Patients undergoing nail biopsies are unlikely to find reliable and comprehensible information on YouTube; thus, there is a strong need for patient education in this area. In addition, physicians who did not learn to perform a nail biopsy during training are unlikely to learn this procedure from YouTube. Therefore, there is an unmet need for an outlet that will provide updated reliable content on nail biopsies geared toward both patients and physicians.

To the Editor:

Nail biopsy is an important surgical procedure for diagnosis of nail pathology. YouTube has become a potential instrument for physicians and patients to learn about medical procedures.1,2 However, the sources, content, and quality of the information available have not been fully studied or characterized. Our objective was to analyze the efficiency of information and quality of YouTube videos on nail biopsies. We hypothesized that the quality of patient education and physician training videos would be unrepresentative on YouTube.

The term nail biopsy was searched on January 29, 2019, and filtered by relevance and rating using the default YouTube algorithm. Data were collected from the top 40 hits for the search term and filter coupling. All videos were viewed and sorted for nail biopsy procedures, and then those videos were categorized as being produced by a physician or other health care provider. The US medical board status of each physician videographer was determined using the American Board of Medical Specialties database.3 DISCERN criteria for assessing consumer health care information4 were used to interpret the videos by researchers (S.I. and S.R.L.) in this study.

From the queried search term collection, only 10 videos (1,023,423 combined views) were analyzed in this study (eTable). Although the other resulting videos were tagged as nail biopsy, they were excluded due to irrelevant content (eg, patient blogs, PowerPoints, nail avulsions). The mean age of the videos was 4 years (range, 4 days to 11 years), with a mean video length of 3.30 minutes (range, 49 seconds to 9.03 minutes). Four of 10 videos were performed for longitudinal melanonychia, and 5 of 10 videos were performed for melanonychia, clinically consistent with subungual hematoma. Dermatologists, plastic surgeons, and podiatrists produced the majority of the nail biopsy videos. The overall mean DISCERN rating was 1.60/5.00 (range, 1–3), meaning that the quality of content on nail biopsies was poor. This low DISCERN score signifies poor consumer health information. Video 2 (published in 2015) received a DISCERN score of 2 and received almost 1 million views, which is likely because the specific channel has a well-established subscriber pool (4.9 million subscribers). The highest DISCERN score of 3, demonstrating a tangential shave biopsy, was given to video 4 (published in 2010) and only received about 17,400 views (56 subscribers). Additionally, many videos lacked important information about the procedure. For instance, only 3 of 10 videos demonstrated the anesthetic technique and only 5 videos showed repair methods.

YouTube is an electronic learning source for general information; however, the content and quality of information on nail biopsy is not updated, reliable, or abundant. Patients undergoing nail biopsies are unlikely to find reliable and comprehensible information on YouTube; thus, there is a strong need for patient education in this area. In addition, physicians who did not learn to perform a nail biopsy during training are unlikely to learn this procedure from YouTube. Therefore, there is an unmet need for an outlet that will provide updated reliable content on nail biopsies geared toward both patients and physicians.

- Kwok TM, Singla AA, Phang K, et al. YouTube as a source of patient information for varicose vein treatment options. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2017;5:238-243.

- Ward B, Ward M, Nicheporuck A, et al. Assessment of YouTube as an informative resource on facial plastic surgery procedures. JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery. 2019;21:75-76.

- American Board of Medical Specialties. Certification Matters. https://www.certificationmatters.org. Accessed February 7, 2020.

- The DISCERN Instrument. DISCERN Online. http://www.discern.org.uk/discern_instrument.php. Published October 1999. Accessed February 7, 2020.

- Kwok TM, Singla AA, Phang K, et al. YouTube as a source of patient information for varicose vein treatment options. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2017;5:238-243.

- Ward B, Ward M, Nicheporuck A, et al. Assessment of YouTube as an informative resource on facial plastic surgery procedures. JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery. 2019;21:75-76.

- American Board of Medical Specialties. Certification Matters. https://www.certificationmatters.org. Accessed February 7, 2020.

- The DISCERN Instrument. DISCERN Online. http://www.discern.org.uk/discern_instrument.php. Published October 1999. Accessed February 7, 2020.

Practice Points

- A nail biopsy is sometimes necessary for histopathologic confirmation of a clinical diagnosis.

- YouTube has become a potential educational platform for physicians and patients to learn about nail biopsy procedures.

- Physicians and patients interested in learning more about nail biopsies are unlikely to find reliable and comprehensible information on YouTube; therefore, there is a need for updated reliable video content on nail biopsies geared toward both physicians and patients.