User login

Therese Borden is the editor of CHEST Physician. After 20 years of research, writing, and editing in the field of international development and economics, she began working in the field of medical editing and has held a variety of editorial positions with the company. She holds a PhD in International Economics from American University, Washington, and a BA in history from the University of Washington, Seattle.

Palliative cancer surgery: Prioritize patient values

Risk-assessment tools can give surgeons a clinical framework to help inform decisions about palliative care surgery in patients with advanced malignancies, but cannot replace nuanced clinical judgment that incorporates patients’ priorities, according to results of a meta-analysis.

Ian W. Folkert, MD, and Robert E. Roses, MD, of the department of surgery at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, reviewed the available research on the indications for palliative surgery for patients with advanced disease and risk-assessment tools for patient selection. Emergent and palliative surgery in such situations require a careful consideration of many clinical factors such as overall prognosis and risk of a surgical approach, compared with nonsurgical interventions (J Surg Oncol. 2016;114:[3]311-15). But the investigators concluded that while an evidence-based approach to patient selection for palliative cancer surgery can offer some guidance on the potential for achieving clinical goals, ultimately the decision to proceed must prioritize patient values and orientation to treatment.

Tumor bleeding

Tumor-related complications often initiate the question of palliative surgical and nonsurgical interventions.

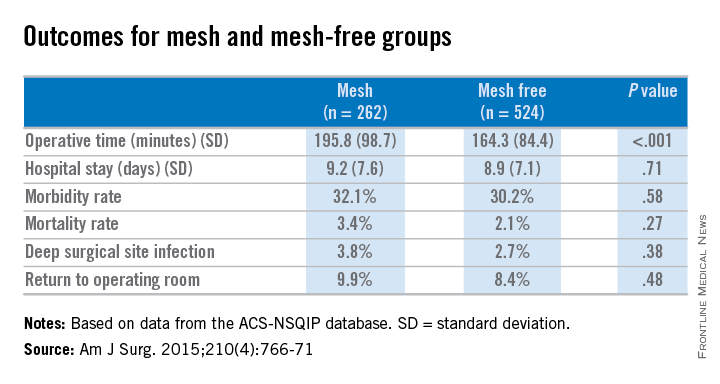

Studies of acute hemorrhage from malignancies indicate that bleeding originating from a tumor is rarely massive and usually can be managed endoscopically (Clin Endosc. 2015 Mar;48[2]:121-7; Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:144-50; Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69[8]:736-40). Transcatheter arterial embolization also is used successfully to manage tumor bleeding (J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015 Sep;26[9]:1297-304; Indian J Cancer. 2014 Feb; 51[6]56-9). The investigators stated, “Although tumor rebleeding may be frequent, repeat endoscopy is often effective and is self-recommending given the high risk of major morbidity after a palliative foregut resection ... [and] all efforts should be made to avoid emergency gastrectomy or esophagectomy.”

Obstructing tumors

Patients with acute colonic obstruction because of colon cancer typically have been treated with a proximal diverting colostomy, but palliative self-expanding metallic stent placement (SEMS) has emerged as an option. Recent studies have shown both short- and long-term clinical success of SEMS, but rates of major morbidity and mortality for emergent surgery and SEMS were similar, as were rates of overall survival (Surg Endosc. 2015;29[6];1580-5; World J Gastroenterol. 2013 Sep 7;19[33]:5565-74). SEMS-related mortality was primarily because of perforation (Endoscopy. 2008 Mar;40[3]:184-91). Stenting for esophageal and gastroesophageal (GE) function obstruction is also emerging as a nonsurgical option. The investigators noted, “There is a very limited role for palliative surgery for esophageal and GE junction tumors.” Gastric outlet obstruction, proximal duodenal obstruction, and biliary tract obstruction are treated palliatively with stents, but “gastrojejunostomy and other bypass operations may provide effective palliation in carefully selected patients.”

Tumor perforation

Few nonsurgical treatment options are available for tumor perforation. Palliative surgical intervention often is undertaken in the context of neutropenia and abdominal pain, the investigators said. These patients are at high risk for morbidity and mortality. One study reviewed found that “prolonged neutropenia and severe sepsis were associated with poor outcomes in all patients, while surgical management was associated with improved survival (Ann Surg. 2008;248[1];104-9), but nonoperative management and comfort care were deemed appropriate for those patients with advanced disease and for those in whom surgery is high risk.

Patient selection for palliative surgery

The studies examined suggest that patient selection for palliative surgical intervention requires the weighing of clinical variables of frailty, morbidity, and mortality. The investigators reviewed a variety of risk-assessment tools developed to help surgeons with that decision (J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197[1];16-21; J Palliat Med. 2014;17:37-42; Ann Surg. 2011;254[2]:333-8). Among the factors considered are the amplified risks of mortality in these patients, the high cost of emergent operations, and most importantly, the chances of extending survival. The complexity of palliative and emergent surgical indications means that risk-assessment studies are “frequently too reductive to provide meaningful guidance” to the surgeon.

Dr. Folkert and Dr. Roses concluded that risk-assessment tools underscore the poor outcomes associated with operations in this setting, and, to some extent, guide decision making, but “they do not supplant clinical judgment, nor do they account for patient values and orientation toward treatment. It remains impossible to place a uniform value on length and quality of life, and patients’ values are paramount in informing treatment decisions.”

The authors had no conflicts to disclose.

Risk-assessment tools can give surgeons a clinical framework to help inform decisions about palliative care surgery in patients with advanced malignancies, but cannot replace nuanced clinical judgment that incorporates patients’ priorities, according to results of a meta-analysis.

Ian W. Folkert, MD, and Robert E. Roses, MD, of the department of surgery at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, reviewed the available research on the indications for palliative surgery for patients with advanced disease and risk-assessment tools for patient selection. Emergent and palliative surgery in such situations require a careful consideration of many clinical factors such as overall prognosis and risk of a surgical approach, compared with nonsurgical interventions (J Surg Oncol. 2016;114:[3]311-15). But the investigators concluded that while an evidence-based approach to patient selection for palliative cancer surgery can offer some guidance on the potential for achieving clinical goals, ultimately the decision to proceed must prioritize patient values and orientation to treatment.

Tumor bleeding

Tumor-related complications often initiate the question of palliative surgical and nonsurgical interventions.

Studies of acute hemorrhage from malignancies indicate that bleeding originating from a tumor is rarely massive and usually can be managed endoscopically (Clin Endosc. 2015 Mar;48[2]:121-7; Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:144-50; Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69[8]:736-40). Transcatheter arterial embolization also is used successfully to manage tumor bleeding (J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015 Sep;26[9]:1297-304; Indian J Cancer. 2014 Feb; 51[6]56-9). The investigators stated, “Although tumor rebleeding may be frequent, repeat endoscopy is often effective and is self-recommending given the high risk of major morbidity after a palliative foregut resection ... [and] all efforts should be made to avoid emergency gastrectomy or esophagectomy.”

Obstructing tumors

Patients with acute colonic obstruction because of colon cancer typically have been treated with a proximal diverting colostomy, but palliative self-expanding metallic stent placement (SEMS) has emerged as an option. Recent studies have shown both short- and long-term clinical success of SEMS, but rates of major morbidity and mortality for emergent surgery and SEMS were similar, as were rates of overall survival (Surg Endosc. 2015;29[6];1580-5; World J Gastroenterol. 2013 Sep 7;19[33]:5565-74). SEMS-related mortality was primarily because of perforation (Endoscopy. 2008 Mar;40[3]:184-91). Stenting for esophageal and gastroesophageal (GE) function obstruction is also emerging as a nonsurgical option. The investigators noted, “There is a very limited role for palliative surgery for esophageal and GE junction tumors.” Gastric outlet obstruction, proximal duodenal obstruction, and biliary tract obstruction are treated palliatively with stents, but “gastrojejunostomy and other bypass operations may provide effective palliation in carefully selected patients.”

Tumor perforation

Few nonsurgical treatment options are available for tumor perforation. Palliative surgical intervention often is undertaken in the context of neutropenia and abdominal pain, the investigators said. These patients are at high risk for morbidity and mortality. One study reviewed found that “prolonged neutropenia and severe sepsis were associated with poor outcomes in all patients, while surgical management was associated with improved survival (Ann Surg. 2008;248[1];104-9), but nonoperative management and comfort care were deemed appropriate for those patients with advanced disease and for those in whom surgery is high risk.

Patient selection for palliative surgery

The studies examined suggest that patient selection for palliative surgical intervention requires the weighing of clinical variables of frailty, morbidity, and mortality. The investigators reviewed a variety of risk-assessment tools developed to help surgeons with that decision (J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197[1];16-21; J Palliat Med. 2014;17:37-42; Ann Surg. 2011;254[2]:333-8). Among the factors considered are the amplified risks of mortality in these patients, the high cost of emergent operations, and most importantly, the chances of extending survival. The complexity of palliative and emergent surgical indications means that risk-assessment studies are “frequently too reductive to provide meaningful guidance” to the surgeon.

Dr. Folkert and Dr. Roses concluded that risk-assessment tools underscore the poor outcomes associated with operations in this setting, and, to some extent, guide decision making, but “they do not supplant clinical judgment, nor do they account for patient values and orientation toward treatment. It remains impossible to place a uniform value on length and quality of life, and patients’ values are paramount in informing treatment decisions.”

The authors had no conflicts to disclose.

Risk-assessment tools can give surgeons a clinical framework to help inform decisions about palliative care surgery in patients with advanced malignancies, but cannot replace nuanced clinical judgment that incorporates patients’ priorities, according to results of a meta-analysis.

Ian W. Folkert, MD, and Robert E. Roses, MD, of the department of surgery at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, reviewed the available research on the indications for palliative surgery for patients with advanced disease and risk-assessment tools for patient selection. Emergent and palliative surgery in such situations require a careful consideration of many clinical factors such as overall prognosis and risk of a surgical approach, compared with nonsurgical interventions (J Surg Oncol. 2016;114:[3]311-15). But the investigators concluded that while an evidence-based approach to patient selection for palliative cancer surgery can offer some guidance on the potential for achieving clinical goals, ultimately the decision to proceed must prioritize patient values and orientation to treatment.

Tumor bleeding

Tumor-related complications often initiate the question of palliative surgical and nonsurgical interventions.

Studies of acute hemorrhage from malignancies indicate that bleeding originating from a tumor is rarely massive and usually can be managed endoscopically (Clin Endosc. 2015 Mar;48[2]:121-7; Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:144-50; Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69[8]:736-40). Transcatheter arterial embolization also is used successfully to manage tumor bleeding (J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015 Sep;26[9]:1297-304; Indian J Cancer. 2014 Feb; 51[6]56-9). The investigators stated, “Although tumor rebleeding may be frequent, repeat endoscopy is often effective and is self-recommending given the high risk of major morbidity after a palliative foregut resection ... [and] all efforts should be made to avoid emergency gastrectomy or esophagectomy.”

Obstructing tumors

Patients with acute colonic obstruction because of colon cancer typically have been treated with a proximal diverting colostomy, but palliative self-expanding metallic stent placement (SEMS) has emerged as an option. Recent studies have shown both short- and long-term clinical success of SEMS, but rates of major morbidity and mortality for emergent surgery and SEMS were similar, as were rates of overall survival (Surg Endosc. 2015;29[6];1580-5; World J Gastroenterol. 2013 Sep 7;19[33]:5565-74). SEMS-related mortality was primarily because of perforation (Endoscopy. 2008 Mar;40[3]:184-91). Stenting for esophageal and gastroesophageal (GE) function obstruction is also emerging as a nonsurgical option. The investigators noted, “There is a very limited role for palliative surgery for esophageal and GE junction tumors.” Gastric outlet obstruction, proximal duodenal obstruction, and biliary tract obstruction are treated palliatively with stents, but “gastrojejunostomy and other bypass operations may provide effective palliation in carefully selected patients.”

Tumor perforation

Few nonsurgical treatment options are available for tumor perforation. Palliative surgical intervention often is undertaken in the context of neutropenia and abdominal pain, the investigators said. These patients are at high risk for morbidity and mortality. One study reviewed found that “prolonged neutropenia and severe sepsis were associated with poor outcomes in all patients, while surgical management was associated with improved survival (Ann Surg. 2008;248[1];104-9), but nonoperative management and comfort care were deemed appropriate for those patients with advanced disease and for those in whom surgery is high risk.

Patient selection for palliative surgery

The studies examined suggest that patient selection for palliative surgical intervention requires the weighing of clinical variables of frailty, morbidity, and mortality. The investigators reviewed a variety of risk-assessment tools developed to help surgeons with that decision (J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197[1];16-21; J Palliat Med. 2014;17:37-42; Ann Surg. 2011;254[2]:333-8). Among the factors considered are the amplified risks of mortality in these patients, the high cost of emergent operations, and most importantly, the chances of extending survival. The complexity of palliative and emergent surgical indications means that risk-assessment studies are “frequently too reductive to provide meaningful guidance” to the surgeon.

Dr. Folkert and Dr. Roses concluded that risk-assessment tools underscore the poor outcomes associated with operations in this setting, and, to some extent, guide decision making, but “they do not supplant clinical judgment, nor do they account for patient values and orientation toward treatment. It remains impossible to place a uniform value on length and quality of life, and patients’ values are paramount in informing treatment decisions.”

The authors had no conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF SURGICAL ONCOLOGY

Repeat SICU admissions should trigger palliative care consult

ICU readmission was most predictive of the need for palliative care among patients in the surgical intensive care unit, based on a study of six potential trigger criteria associated with in-hospital death or discharge to hospice.

To facilitate proactive case findings of patients who would benefit from a palliative care consult, a team of surgical ICU and palliative care clinicians at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, N.Y., developed and tested a system of palliative care triggers. The study was published online in the Journal of Critical Care (http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.04.010).

Based on a literature review, the researchers created a six-item list of potential triggers for palliative care: length of stay over 10 days, ICU readmission, intensivist referral, status post cardiac arrest, metastatic cancer, and a match of two or more on a set of secondary criteria.

Data were collected for the period from Sept. 4, 2013, through May 30, 2014, at the surgical ICU of a 1,170-bed tertiary medical center. Patients who received a palliative care consultation were compared with those who did not, and the trigger list was tested for accuracy in predicting patient outcomes. The primary outcomes were hospital death, hospice discharge, and a combined endpoint of these two outcomes. Patients who died in the hospital or were released to hospice care were assumed to be those most in need of a palliative care consult.

Bivariate analysis was done to calculate the unadjusted odds ratios of individual triggers to each of these outcomes. Then, the team used logistic regression analysis to calculate the adjusted odds ratios of triggers to outcomes.

Of the 512 patients admitted to the SICU in the study period, those not discharged by the end of the study were excluded, leaving 492 patients in the study.

Bivariate analysis found that all of the triggers were significantly associated with in-hospital death. With the multivariate analysis and adjusted odds ratios, SICU readmission, status post cardiac arrest, metastatic cancer, and secondary triggers were significantly associated with hospital death.

For the combined outcome of hospital death or release to hospice care, the relationships were stronger. In particular, repeat SICU readmissions and metastatic cancer triggers were strongly associated with the combined outcome (odds ratio, 19.41, CI 5.81-54.86 and OR, 16.40, CI 4.69-57.36, respectively). The secondary triggers did not show the same strength of association, although they were associated significantly with the combined outcome (OR, 4.41, CI 2.05-9.53).

The most prominent finding is the strength of repeat SICU admissions with the hospital death or release to hospice. The strong relationship between repeat SICU admission and outcomes led the researchers to conclude “that one might consider adapting this clinical criterion as a standalone criterion. This would require all patients who are readmitted to the SICU to be seen by palliative care to assess their overall goals of care and understanding of their serious illness. This approach may be particularly useful for smaller palliative care teams that do not have the resources to screen daily with a series of triggers.”

The American Federation of Aging Research and the National Institute on Aging funded the study.

ICU readmission was most predictive of the need for palliative care among patients in the surgical intensive care unit, based on a study of six potential trigger criteria associated with in-hospital death or discharge to hospice.

To facilitate proactive case findings of patients who would benefit from a palliative care consult, a team of surgical ICU and palliative care clinicians at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, N.Y., developed and tested a system of palliative care triggers. The study was published online in the Journal of Critical Care (http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.04.010).

Based on a literature review, the researchers created a six-item list of potential triggers for palliative care: length of stay over 10 days, ICU readmission, intensivist referral, status post cardiac arrest, metastatic cancer, and a match of two or more on a set of secondary criteria.

Data were collected for the period from Sept. 4, 2013, through May 30, 2014, at the surgical ICU of a 1,170-bed tertiary medical center. Patients who received a palliative care consultation were compared with those who did not, and the trigger list was tested for accuracy in predicting patient outcomes. The primary outcomes were hospital death, hospice discharge, and a combined endpoint of these two outcomes. Patients who died in the hospital or were released to hospice care were assumed to be those most in need of a palliative care consult.

Bivariate analysis was done to calculate the unadjusted odds ratios of individual triggers to each of these outcomes. Then, the team used logistic regression analysis to calculate the adjusted odds ratios of triggers to outcomes.

Of the 512 patients admitted to the SICU in the study period, those not discharged by the end of the study were excluded, leaving 492 patients in the study.

Bivariate analysis found that all of the triggers were significantly associated with in-hospital death. With the multivariate analysis and adjusted odds ratios, SICU readmission, status post cardiac arrest, metastatic cancer, and secondary triggers were significantly associated with hospital death.

For the combined outcome of hospital death or release to hospice care, the relationships were stronger. In particular, repeat SICU readmissions and metastatic cancer triggers were strongly associated with the combined outcome (odds ratio, 19.41, CI 5.81-54.86 and OR, 16.40, CI 4.69-57.36, respectively). The secondary triggers did not show the same strength of association, although they were associated significantly with the combined outcome (OR, 4.41, CI 2.05-9.53).

The most prominent finding is the strength of repeat SICU admissions with the hospital death or release to hospice. The strong relationship between repeat SICU admission and outcomes led the researchers to conclude “that one might consider adapting this clinical criterion as a standalone criterion. This would require all patients who are readmitted to the SICU to be seen by palliative care to assess their overall goals of care and understanding of their serious illness. This approach may be particularly useful for smaller palliative care teams that do not have the resources to screen daily with a series of triggers.”

The American Federation of Aging Research and the National Institute on Aging funded the study.

ICU readmission was most predictive of the need for palliative care among patients in the surgical intensive care unit, based on a study of six potential trigger criteria associated with in-hospital death or discharge to hospice.

To facilitate proactive case findings of patients who would benefit from a palliative care consult, a team of surgical ICU and palliative care clinicians at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, N.Y., developed and tested a system of palliative care triggers. The study was published online in the Journal of Critical Care (http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.04.010).

Based on a literature review, the researchers created a six-item list of potential triggers for palliative care: length of stay over 10 days, ICU readmission, intensivist referral, status post cardiac arrest, metastatic cancer, and a match of two or more on a set of secondary criteria.

Data were collected for the period from Sept. 4, 2013, through May 30, 2014, at the surgical ICU of a 1,170-bed tertiary medical center. Patients who received a palliative care consultation were compared with those who did not, and the trigger list was tested for accuracy in predicting patient outcomes. The primary outcomes were hospital death, hospice discharge, and a combined endpoint of these two outcomes. Patients who died in the hospital or were released to hospice care were assumed to be those most in need of a palliative care consult.

Bivariate analysis was done to calculate the unadjusted odds ratios of individual triggers to each of these outcomes. Then, the team used logistic regression analysis to calculate the adjusted odds ratios of triggers to outcomes.

Of the 512 patients admitted to the SICU in the study period, those not discharged by the end of the study were excluded, leaving 492 patients in the study.

Bivariate analysis found that all of the triggers were significantly associated with in-hospital death. With the multivariate analysis and adjusted odds ratios, SICU readmission, status post cardiac arrest, metastatic cancer, and secondary triggers were significantly associated with hospital death.

For the combined outcome of hospital death or release to hospice care, the relationships were stronger. In particular, repeat SICU readmissions and metastatic cancer triggers were strongly associated with the combined outcome (odds ratio, 19.41, CI 5.81-54.86 and OR, 16.40, CI 4.69-57.36, respectively). The secondary triggers did not show the same strength of association, although they were associated significantly with the combined outcome (OR, 4.41, CI 2.05-9.53).

The most prominent finding is the strength of repeat SICU admissions with the hospital death or release to hospice. The strong relationship between repeat SICU admission and outcomes led the researchers to conclude “that one might consider adapting this clinical criterion as a standalone criterion. This would require all patients who are readmitted to the SICU to be seen by palliative care to assess their overall goals of care and understanding of their serious illness. This approach may be particularly useful for smaller palliative care teams that do not have the resources to screen daily with a series of triggers.”

The American Federation of Aging Research and the National Institute on Aging funded the study.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE

Key clinical point: A list of tested triggers can predict the need of surgical ICU patients for a palliative care consultation.

Major finding: Readmission to the surgical ICU was strongly associated with the study endpoint of hospital death or release to hospice (odds ratio 19.41, CI 5.81-54.86).

Data source: A case review of all 492 patients admitted to the surgical intensive care facility at a 1,170-bed, tertiary care medical center.

Disclosures: The American Federation of Aging Research and the National Institute on Aging funded the study.

Global Surgery: ‘Partnership Among Friends’

Surgery volunteerism has been on the rise for several decades. The American College of Surgeons is increasing its role in organizing and facilitating these programs via Operation Giving Back (OGB). And many ACS members are prominent participants in this endeavor.

A leader in global surgery is Michael L. Bentz, M.D., FAAP, FACS, professor of surgery, pediatrics, and neurosurgery, and chairman of the Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. Dr. Bentz has led international missions in many countries of the world over nearly 20 years and has helped a team develop a long-term program of clinical care and training in Nicaragua. We talked with him about his experiences.

Q: You have been involved in international surgical missions for many years. Can you tell us something about your early projects?

I was first exposed to international work at the University of Pittsburgh. My mentor J. William Futrell, M.D., FACS, was a veteran of over 30 international surgical trips. I went on the first trip with him to Vietnam in the 1997 and have been going ever since. For that initial trip, we worked with a nonprofit organization called Interplast. I went with a large group of 20 people from the University that included plastic surgery attendings, plastic surgery residents, pediatric attendings, pediatric residents, and nursing and anesthesia staff.

In those days, many trips were based predominantly on clinical care – adult care and pediatric care. Teams would do a certain number of operations and then go home. We did cleft lip repairs, cleft palate repairs, burn reconstruction, congenital hand deformity surgery, and tumor management.

That would result in good outcomes for those who actually had a procedure done. But in any place I have ever worked overseas – Vietnam, China, Russia, Nicaragua – the need is overwhelming. The need far outstripped what surgical missions can provide in isolated, single trips back and forth.

Q: The years have brought changes to these missions. What are the most significant changes over the years in how these missions are conducted?

The scope and direction of global health is moving toward sustainable, long-term, and longitudinal education. In those earlier trips where there was an emphasis on doing as many operations as possible, people meant well – we meant well! But the real impact comes with the longitudinal education investment.

I have never been anywhere around the world where there weren’t interested, very capable, excellent surgeons committed to taking care of their patients who only need some support and facilitation.

If you compare the cases we are able to do on a trip with our partners with the cases they are able to do independently, it’s a logarithmic curve – they are far more productive than we could ever be on any number of trips. There is a multiplier effect that allows many more patients to be taken care of.

Q: Your institution has a long-term relationship with a hospital in Nicaragua. How does this work and what is the role of your team in the program?

The University of Wisconsin Division of Plastic Surgery and the Eduplast Foundation has a team of about 10 that goes to Nicaragua twice a year. Most importantly, we support a residency program in there. We move residents through a 3-year modular program much like programs in the U.S. and then examine them. We facilitate this educational process with trips there and we bring them to our institution in the U.S.

Over the past 10 years, we have been doing a weekly live webcast of our Plastic Surgery Grand Rounds which is received on several continents. This creates a very valuable bidirectional, and even tridirectional conversation. This webcast is simple, incredibly inexpensive, and has provided hundreds of hours of education over the years in addition to the on-site work we do.

There can be a language barrier in some cases, but we broadcast in English, with occasional translation support. In addition to Nicaragua, our webcast has been received in institutions in Thailand, China, Ecuador and across the United States. We keep records of cases performed. Our plastic surgery residents can get credit for the cases they do under faculty supervision at our international sites if we meet specific criteria set by our Resident Review Committee.

It is important to note that we take care of the patients in our partner institutions in Nicaragua exactly as we would care for patients in our institution in Wisconsin. There is no “practicing” as all operations are done by surgeons appropriately credentialed and trained for the task.

Q: Do you find that there is a cultural gap that you must bridge in working with colleagues and patients in Nicaragua?

Our program has an orientation session for team participants in advance of each trip, where we talk about the mechanics of the trip – safety, medical issues. We also talk about cultural considerations of each site. It is very important that the residents embed in the culture in which we are working. They also need to know the cultural norms of how to communicate with patients, parents, and children. Some of it is simply good manners – acting like your mother taught you!

The team can reside in a local hotel, but often stays in the homes of local hosts, and this can be a beautiful opportunity to learn about local norms and communication.

Q: What is your favorite part of these missions?

I have so many favorite parts! I like caring for people who otherwise might not receive medical care. This is “giving back” and I think all of the participants would agree that we come home feeling like we received much more than we gave. These experiences remind you of why you went to medical school. It is an opportunity to provide something in return for all the investment that has been made in us for our education. In working with colleagues from other countries, I learn as much as I teach. I come back a better surgeon.

The benefits to residents from our institution are many. They learn how to operate in a resource-limited setting, and they return with a greater appreciation for the equipment and supplies we have available at our institution in Madison. The cultural competence and awareness they also learn is an invaluable life skill.

I want to stress that the friendships with our fellow surgeons are what makes this work. We achieve a degree of continuity and even watch our pediatric patients grow up over the years because of our long-term relationship with the hospital in León and our dedicated colleagues there. This is a truly a partnership among friends.

Q: Do you have some advice for a surgeon interested in participating in an international program?

For those surgeons who were not exposed to these programs during residency, finding a mentor or mentoring organization is the way to begin. A beginner should consider making the first couple of trips with someone who knows the ropes in terms of understanding cultural competency, practical issues of safety, and relevant clinical issues. Almost every surgery discipline has an organization with the capability of identifying volunteer surgery groups in their specialty. ACS’ Operation Giving Back is a particularly important resource for helping Fellows find the right international program.

If you would like to learn more about global surgery programs, contact Operation Giving Back at [email protected]. Or if you would like to share your experiences as an international surgical volunteer, please email this publication at [email protected].

Surgery volunteerism has been on the rise for several decades. The American College of Surgeons is increasing its role in organizing and facilitating these programs via Operation Giving Back (OGB). And many ACS members are prominent participants in this endeavor.

A leader in global surgery is Michael L. Bentz, M.D., FAAP, FACS, professor of surgery, pediatrics, and neurosurgery, and chairman of the Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. Dr. Bentz has led international missions in many countries of the world over nearly 20 years and has helped a team develop a long-term program of clinical care and training in Nicaragua. We talked with him about his experiences.

Q: You have been involved in international surgical missions for many years. Can you tell us something about your early projects?

I was first exposed to international work at the University of Pittsburgh. My mentor J. William Futrell, M.D., FACS, was a veteran of over 30 international surgical trips. I went on the first trip with him to Vietnam in the 1997 and have been going ever since. For that initial trip, we worked with a nonprofit organization called Interplast. I went with a large group of 20 people from the University that included plastic surgery attendings, plastic surgery residents, pediatric attendings, pediatric residents, and nursing and anesthesia staff.

In those days, many trips were based predominantly on clinical care – adult care and pediatric care. Teams would do a certain number of operations and then go home. We did cleft lip repairs, cleft palate repairs, burn reconstruction, congenital hand deformity surgery, and tumor management.

That would result in good outcomes for those who actually had a procedure done. But in any place I have ever worked overseas – Vietnam, China, Russia, Nicaragua – the need is overwhelming. The need far outstripped what surgical missions can provide in isolated, single trips back and forth.

Q: The years have brought changes to these missions. What are the most significant changes over the years in how these missions are conducted?

The scope and direction of global health is moving toward sustainable, long-term, and longitudinal education. In those earlier trips where there was an emphasis on doing as many operations as possible, people meant well – we meant well! But the real impact comes with the longitudinal education investment.

I have never been anywhere around the world where there weren’t interested, very capable, excellent surgeons committed to taking care of their patients who only need some support and facilitation.

If you compare the cases we are able to do on a trip with our partners with the cases they are able to do independently, it’s a logarithmic curve – they are far more productive than we could ever be on any number of trips. There is a multiplier effect that allows many more patients to be taken care of.

Q: Your institution has a long-term relationship with a hospital in Nicaragua. How does this work and what is the role of your team in the program?

The University of Wisconsin Division of Plastic Surgery and the Eduplast Foundation has a team of about 10 that goes to Nicaragua twice a year. Most importantly, we support a residency program in there. We move residents through a 3-year modular program much like programs in the U.S. and then examine them. We facilitate this educational process with trips there and we bring them to our institution in the U.S.

Over the past 10 years, we have been doing a weekly live webcast of our Plastic Surgery Grand Rounds which is received on several continents. This creates a very valuable bidirectional, and even tridirectional conversation. This webcast is simple, incredibly inexpensive, and has provided hundreds of hours of education over the years in addition to the on-site work we do.

There can be a language barrier in some cases, but we broadcast in English, with occasional translation support. In addition to Nicaragua, our webcast has been received in institutions in Thailand, China, Ecuador and across the United States. We keep records of cases performed. Our plastic surgery residents can get credit for the cases they do under faculty supervision at our international sites if we meet specific criteria set by our Resident Review Committee.

It is important to note that we take care of the patients in our partner institutions in Nicaragua exactly as we would care for patients in our institution in Wisconsin. There is no “practicing” as all operations are done by surgeons appropriately credentialed and trained for the task.

Q: Do you find that there is a cultural gap that you must bridge in working with colleagues and patients in Nicaragua?

Our program has an orientation session for team participants in advance of each trip, where we talk about the mechanics of the trip – safety, medical issues. We also talk about cultural considerations of each site. It is very important that the residents embed in the culture in which we are working. They also need to know the cultural norms of how to communicate with patients, parents, and children. Some of it is simply good manners – acting like your mother taught you!

The team can reside in a local hotel, but often stays in the homes of local hosts, and this can be a beautiful opportunity to learn about local norms and communication.

Q: What is your favorite part of these missions?

I have so many favorite parts! I like caring for people who otherwise might not receive medical care. This is “giving back” and I think all of the participants would agree that we come home feeling like we received much more than we gave. These experiences remind you of why you went to medical school. It is an opportunity to provide something in return for all the investment that has been made in us for our education. In working with colleagues from other countries, I learn as much as I teach. I come back a better surgeon.

The benefits to residents from our institution are many. They learn how to operate in a resource-limited setting, and they return with a greater appreciation for the equipment and supplies we have available at our institution in Madison. The cultural competence and awareness they also learn is an invaluable life skill.

I want to stress that the friendships with our fellow surgeons are what makes this work. We achieve a degree of continuity and even watch our pediatric patients grow up over the years because of our long-term relationship with the hospital in León and our dedicated colleagues there. This is a truly a partnership among friends.

Q: Do you have some advice for a surgeon interested in participating in an international program?

For those surgeons who were not exposed to these programs during residency, finding a mentor or mentoring organization is the way to begin. A beginner should consider making the first couple of trips with someone who knows the ropes in terms of understanding cultural competency, practical issues of safety, and relevant clinical issues. Almost every surgery discipline has an organization with the capability of identifying volunteer surgery groups in their specialty. ACS’ Operation Giving Back is a particularly important resource for helping Fellows find the right international program.

If you would like to learn more about global surgery programs, contact Operation Giving Back at [email protected]. Or if you would like to share your experiences as an international surgical volunteer, please email this publication at [email protected].

Surgery volunteerism has been on the rise for several decades. The American College of Surgeons is increasing its role in organizing and facilitating these programs via Operation Giving Back (OGB). And many ACS members are prominent participants in this endeavor.

A leader in global surgery is Michael L. Bentz, M.D., FAAP, FACS, professor of surgery, pediatrics, and neurosurgery, and chairman of the Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. Dr. Bentz has led international missions in many countries of the world over nearly 20 years and has helped a team develop a long-term program of clinical care and training in Nicaragua. We talked with him about his experiences.

Q: You have been involved in international surgical missions for many years. Can you tell us something about your early projects?

I was first exposed to international work at the University of Pittsburgh. My mentor J. William Futrell, M.D., FACS, was a veteran of over 30 international surgical trips. I went on the first trip with him to Vietnam in the 1997 and have been going ever since. For that initial trip, we worked with a nonprofit organization called Interplast. I went with a large group of 20 people from the University that included plastic surgery attendings, plastic surgery residents, pediatric attendings, pediatric residents, and nursing and anesthesia staff.

In those days, many trips were based predominantly on clinical care – adult care and pediatric care. Teams would do a certain number of operations and then go home. We did cleft lip repairs, cleft palate repairs, burn reconstruction, congenital hand deformity surgery, and tumor management.

That would result in good outcomes for those who actually had a procedure done. But in any place I have ever worked overseas – Vietnam, China, Russia, Nicaragua – the need is overwhelming. The need far outstripped what surgical missions can provide in isolated, single trips back and forth.

Q: The years have brought changes to these missions. What are the most significant changes over the years in how these missions are conducted?

The scope and direction of global health is moving toward sustainable, long-term, and longitudinal education. In those earlier trips where there was an emphasis on doing as many operations as possible, people meant well – we meant well! But the real impact comes with the longitudinal education investment.

I have never been anywhere around the world where there weren’t interested, very capable, excellent surgeons committed to taking care of their patients who only need some support and facilitation.

If you compare the cases we are able to do on a trip with our partners with the cases they are able to do independently, it’s a logarithmic curve – they are far more productive than we could ever be on any number of trips. There is a multiplier effect that allows many more patients to be taken care of.

Q: Your institution has a long-term relationship with a hospital in Nicaragua. How does this work and what is the role of your team in the program?

The University of Wisconsin Division of Plastic Surgery and the Eduplast Foundation has a team of about 10 that goes to Nicaragua twice a year. Most importantly, we support a residency program in there. We move residents through a 3-year modular program much like programs in the U.S. and then examine them. We facilitate this educational process with trips there and we bring them to our institution in the U.S.

Over the past 10 years, we have been doing a weekly live webcast of our Plastic Surgery Grand Rounds which is received on several continents. This creates a very valuable bidirectional, and even tridirectional conversation. This webcast is simple, incredibly inexpensive, and has provided hundreds of hours of education over the years in addition to the on-site work we do.

There can be a language barrier in some cases, but we broadcast in English, with occasional translation support. In addition to Nicaragua, our webcast has been received in institutions in Thailand, China, Ecuador and across the United States. We keep records of cases performed. Our plastic surgery residents can get credit for the cases they do under faculty supervision at our international sites if we meet specific criteria set by our Resident Review Committee.

It is important to note that we take care of the patients in our partner institutions in Nicaragua exactly as we would care for patients in our institution in Wisconsin. There is no “practicing” as all operations are done by surgeons appropriately credentialed and trained for the task.

Q: Do you find that there is a cultural gap that you must bridge in working with colleagues and patients in Nicaragua?

Our program has an orientation session for team participants in advance of each trip, where we talk about the mechanics of the trip – safety, medical issues. We also talk about cultural considerations of each site. It is very important that the residents embed in the culture in which we are working. They also need to know the cultural norms of how to communicate with patients, parents, and children. Some of it is simply good manners – acting like your mother taught you!

The team can reside in a local hotel, but often stays in the homes of local hosts, and this can be a beautiful opportunity to learn about local norms and communication.

Q: What is your favorite part of these missions?

I have so many favorite parts! I like caring for people who otherwise might not receive medical care. This is “giving back” and I think all of the participants would agree that we come home feeling like we received much more than we gave. These experiences remind you of why you went to medical school. It is an opportunity to provide something in return for all the investment that has been made in us for our education. In working with colleagues from other countries, I learn as much as I teach. I come back a better surgeon.

The benefits to residents from our institution are many. They learn how to operate in a resource-limited setting, and they return with a greater appreciation for the equipment and supplies we have available at our institution in Madison. The cultural competence and awareness they also learn is an invaluable life skill.

I want to stress that the friendships with our fellow surgeons are what makes this work. We achieve a degree of continuity and even watch our pediatric patients grow up over the years because of our long-term relationship with the hospital in León and our dedicated colleagues there. This is a truly a partnership among friends.

Q: Do you have some advice for a surgeon interested in participating in an international program?

For those surgeons who were not exposed to these programs during residency, finding a mentor or mentoring organization is the way to begin. A beginner should consider making the first couple of trips with someone who knows the ropes in terms of understanding cultural competency, practical issues of safety, and relevant clinical issues. Almost every surgery discipline has an organization with the capability of identifying volunteer surgery groups in their specialty. ACS’ Operation Giving Back is a particularly important resource for helping Fellows find the right international program.

If you would like to learn more about global surgery programs, contact Operation Giving Back at [email protected]. Or if you would like to share your experiences as an international surgical volunteer, please email this publication at [email protected].

Neurosurgeon memoir illuminates the journey through cancer treatment and acceptance of mortality

Dr. Paul Kalanithi, a neurosurgeon who had just completed his residency at the Stanford (Calif.) University, died of metastatic lung cancer last year, but he left a memoir of his experiences as a physician, a patient, and a dying man that was published on Jan. 12. His book, “When Breath Becomes Air” (New York: Random House, 2016), recounts the many years of working to exhaustion and deferring of life experiences and pleasures that are necessary to complete medical training.

In a review of the book, Janet Maslin wrote, “One of the most poignant things about Dr. Kalanithi’s story is that he had postponed learning how to live while pursuing his career in neurosurgery. By the time he was ready to enjoy a life outside the operating room, what he needed to learn was how to die.”

Dr. Kalanithi reflected on the profound grief and sense of loss that comes with a diagnosis that he knew meant imminent death. The memoir also reveals his search for meaning and joy, and finally, his acceptance of mortality. He opted for palliative care and his memoir, along with the epilogue written by his wife, Dr. Lucy Kalanithi, gives insight into the value of the palliative path to patients and their families in dire medical crises.

Dr. Paul Kalanithi, a neurosurgeon who had just completed his residency at the Stanford (Calif.) University, died of metastatic lung cancer last year, but he left a memoir of his experiences as a physician, a patient, and a dying man that was published on Jan. 12. His book, “When Breath Becomes Air” (New York: Random House, 2016), recounts the many years of working to exhaustion and deferring of life experiences and pleasures that are necessary to complete medical training.

In a review of the book, Janet Maslin wrote, “One of the most poignant things about Dr. Kalanithi’s story is that he had postponed learning how to live while pursuing his career in neurosurgery. By the time he was ready to enjoy a life outside the operating room, what he needed to learn was how to die.”

Dr. Kalanithi reflected on the profound grief and sense of loss that comes with a diagnosis that he knew meant imminent death. The memoir also reveals his search for meaning and joy, and finally, his acceptance of mortality. He opted for palliative care and his memoir, along with the epilogue written by his wife, Dr. Lucy Kalanithi, gives insight into the value of the palliative path to patients and their families in dire medical crises.

Dr. Paul Kalanithi, a neurosurgeon who had just completed his residency at the Stanford (Calif.) University, died of metastatic lung cancer last year, but he left a memoir of his experiences as a physician, a patient, and a dying man that was published on Jan. 12. His book, “When Breath Becomes Air” (New York: Random House, 2016), recounts the many years of working to exhaustion and deferring of life experiences and pleasures that are necessary to complete medical training.

In a review of the book, Janet Maslin wrote, “One of the most poignant things about Dr. Kalanithi’s story is that he had postponed learning how to live while pursuing his career in neurosurgery. By the time he was ready to enjoy a life outside the operating room, what he needed to learn was how to die.”

Dr. Kalanithi reflected on the profound grief and sense of loss that comes with a diagnosis that he knew meant imminent death. The memoir also reveals his search for meaning and joy, and finally, his acceptance of mortality. He opted for palliative care and his memoir, along with the epilogue written by his wife, Dr. Lucy Kalanithi, gives insight into the value of the palliative path to patients and their families in dire medical crises.

David Bowie’s death inspires blog on palliative care

The death of David Bowie, iconic musician and artist, on Jan. 10 inspired palliative care specialist Dr. Mark Taubert to write a blog about end-of-life scenarios and the importance of advance care planning. The blog, which begins by thanking Mr. Bowie for his many artistic contributions, continues by suggesting that his planned death at home will inspire many people in similar health crises to consider palliative care. The palliative care conversation between a doctor and a patient facing death can be challenging but can lead to what Dr. Taubert called “a good death” at home with symptoms managed and loved ones nearby. Mr. Bowie’s son, Duncan Jones, tweeted a link to the blog in the days after his father’s death.

Dr. Taubert found himself speaking with a patient who was facing probable death in the near future, and both doctor and patient found inspiration in Mr. Bowie’s final music project and his death at home with his family. Dr. Taubert and his patient were able to have the conversation about palliative care at end-of-life in part because they were both impressed with what Mr. Bowie was able to achieve in his last months. “Your story became a way for us to communicate very openly about death, something many doctors and nurses struggle to introduce as a topic of conversation,” he wrote.

Dr. Taubert of the Velindre NHS Trust in Cardiff, Wales, noted that, although palliative care is a highly developed skill with many resources to help patients at the end of life, “this essential part of training is not always available for junior healthcare professionals, including doctors and nurses, and is sometimes overlooked or under-prioritized by those who plan their education. I think if you [David Bowie] were ever to return (as Lazarus did), you would be a firm advocate for good palliative care training being available everywhere.”

The death of David Bowie, iconic musician and artist, on Jan. 10 inspired palliative care specialist Dr. Mark Taubert to write a blog about end-of-life scenarios and the importance of advance care planning. The blog, which begins by thanking Mr. Bowie for his many artistic contributions, continues by suggesting that his planned death at home will inspire many people in similar health crises to consider palliative care. The palliative care conversation between a doctor and a patient facing death can be challenging but can lead to what Dr. Taubert called “a good death” at home with symptoms managed and loved ones nearby. Mr. Bowie’s son, Duncan Jones, tweeted a link to the blog in the days after his father’s death.

Dr. Taubert found himself speaking with a patient who was facing probable death in the near future, and both doctor and patient found inspiration in Mr. Bowie’s final music project and his death at home with his family. Dr. Taubert and his patient were able to have the conversation about palliative care at end-of-life in part because they were both impressed with what Mr. Bowie was able to achieve in his last months. “Your story became a way for us to communicate very openly about death, something many doctors and nurses struggle to introduce as a topic of conversation,” he wrote.

Dr. Taubert of the Velindre NHS Trust in Cardiff, Wales, noted that, although palliative care is a highly developed skill with many resources to help patients at the end of life, “this essential part of training is not always available for junior healthcare professionals, including doctors and nurses, and is sometimes overlooked or under-prioritized by those who plan their education. I think if you [David Bowie] were ever to return (as Lazarus did), you would be a firm advocate for good palliative care training being available everywhere.”

The death of David Bowie, iconic musician and artist, on Jan. 10 inspired palliative care specialist Dr. Mark Taubert to write a blog about end-of-life scenarios and the importance of advance care planning. The blog, which begins by thanking Mr. Bowie for his many artistic contributions, continues by suggesting that his planned death at home will inspire many people in similar health crises to consider palliative care. The palliative care conversation between a doctor and a patient facing death can be challenging but can lead to what Dr. Taubert called “a good death” at home with symptoms managed and loved ones nearby. Mr. Bowie’s son, Duncan Jones, tweeted a link to the blog in the days after his father’s death.

Dr. Taubert found himself speaking with a patient who was facing probable death in the near future, and both doctor and patient found inspiration in Mr. Bowie’s final music project and his death at home with his family. Dr. Taubert and his patient were able to have the conversation about palliative care at end-of-life in part because they were both impressed with what Mr. Bowie was able to achieve in his last months. “Your story became a way for us to communicate very openly about death, something many doctors and nurses struggle to introduce as a topic of conversation,” he wrote.

Dr. Taubert of the Velindre NHS Trust in Cardiff, Wales, noted that, although palliative care is a highly developed skill with many resources to help patients at the end of life, “this essential part of training is not always available for junior healthcare professionals, including doctors and nurses, and is sometimes overlooked or under-prioritized by those who plan their education. I think if you [David Bowie] were ever to return (as Lazarus did), you would be a firm advocate for good palliative care training being available everywhere.”

The Calling of Rural Surgery

Recruitment of surgeons to rural hospitals is a challenge for many communities. As the current workforce of rural surgeons reaches retirement age, this challenge will only become more acute.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) and Corrado Studios have collaborated to create “The Calling of Rural Surgery,” a 6-minute recruitment video to inspire interest and appreciation of rural surgery as a career choice. This film is a peek into the world of surgeons practicing in small towns and rural areas. It premiered at the Rural Surgeons Open Forum and Oweida Scholarship Presentation at the ACS Clinical Congress 2015 in Chicago.

The video producer, Meredith Corrado, said, “Our goals are not just to recruit surgeons to practice in the rural and underserved areas in America [but to] put our message in front of fledgling surgeons deciding on a career path, [and] those experienced surgeons looking for change.”

Ms. Corrado interviewed ACS fellows, members of the college’s Advisory Council for Rural Surgery, past ACS governors, and an ACS past vice president. Her father, Dr. Joseph Corrado, a surgeon practicing in Mexico, Mo., was a source of insight into the work life of rural surgeons

Dr. Corrado said, “The problem of succession will be critical, especially for hospitals like my own with only one or two surgeons. One thing that makes it particularly hard is that we want the best. My friends and neighbors are counting on my judgment, so I’m picky.”

He wants potential recruits to know that rural practice is “extremely rewarding. You are an integral part of a community in all aspects: economically, socially and medically. You have the ability to choose from a wide variety in how broad you want your practice to be.” In addition, he is confident that exposure to the rural surgical practice will draw the right recruits. “Once a surgeon is able to see all the surgeries we get to do and how rewarding our lives are, the right person will not be able to walk away.”

View the video at www.ruralsurgeonsfilm.com.

Recruitment of surgeons to rural hospitals is a challenge for many communities. As the current workforce of rural surgeons reaches retirement age, this challenge will only become more acute.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) and Corrado Studios have collaborated to create “The Calling of Rural Surgery,” a 6-minute recruitment video to inspire interest and appreciation of rural surgery as a career choice. This film is a peek into the world of surgeons practicing in small towns and rural areas. It premiered at the Rural Surgeons Open Forum and Oweida Scholarship Presentation at the ACS Clinical Congress 2015 in Chicago.

The video producer, Meredith Corrado, said, “Our goals are not just to recruit surgeons to practice in the rural and underserved areas in America [but to] put our message in front of fledgling surgeons deciding on a career path, [and] those experienced surgeons looking for change.”

Ms. Corrado interviewed ACS fellows, members of the college’s Advisory Council for Rural Surgery, past ACS governors, and an ACS past vice president. Her father, Dr. Joseph Corrado, a surgeon practicing in Mexico, Mo., was a source of insight into the work life of rural surgeons

Dr. Corrado said, “The problem of succession will be critical, especially for hospitals like my own with only one or two surgeons. One thing that makes it particularly hard is that we want the best. My friends and neighbors are counting on my judgment, so I’m picky.”

He wants potential recruits to know that rural practice is “extremely rewarding. You are an integral part of a community in all aspects: economically, socially and medically. You have the ability to choose from a wide variety in how broad you want your practice to be.” In addition, he is confident that exposure to the rural surgical practice will draw the right recruits. “Once a surgeon is able to see all the surgeries we get to do and how rewarding our lives are, the right person will not be able to walk away.”

View the video at www.ruralsurgeonsfilm.com.

Recruitment of surgeons to rural hospitals is a challenge for many communities. As the current workforce of rural surgeons reaches retirement age, this challenge will only become more acute.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) and Corrado Studios have collaborated to create “The Calling of Rural Surgery,” a 6-minute recruitment video to inspire interest and appreciation of rural surgery as a career choice. This film is a peek into the world of surgeons practicing in small towns and rural areas. It premiered at the Rural Surgeons Open Forum and Oweida Scholarship Presentation at the ACS Clinical Congress 2015 in Chicago.

The video producer, Meredith Corrado, said, “Our goals are not just to recruit surgeons to practice in the rural and underserved areas in America [but to] put our message in front of fledgling surgeons deciding on a career path, [and] those experienced surgeons looking for change.”

Ms. Corrado interviewed ACS fellows, members of the college’s Advisory Council for Rural Surgery, past ACS governors, and an ACS past vice president. Her father, Dr. Joseph Corrado, a surgeon practicing in Mexico, Mo., was a source of insight into the work life of rural surgeons

Dr. Corrado said, “The problem of succession will be critical, especially for hospitals like my own with only one or two surgeons. One thing that makes it particularly hard is that we want the best. My friends and neighbors are counting on my judgment, so I’m picky.”

He wants potential recruits to know that rural practice is “extremely rewarding. You are an integral part of a community in all aspects: economically, socially and medically. You have the ability to choose from a wide variety in how broad you want your practice to be.” In addition, he is confident that exposure to the rural surgical practice will draw the right recruits. “Once a surgeon is able to see all the surgeries we get to do and how rewarding our lives are, the right person will not be able to walk away.”

View the video at www.ruralsurgeonsfilm.com.

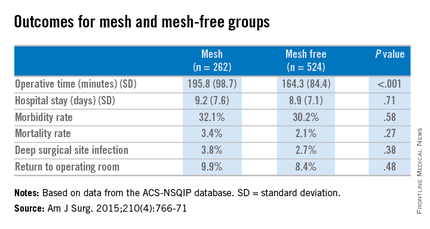

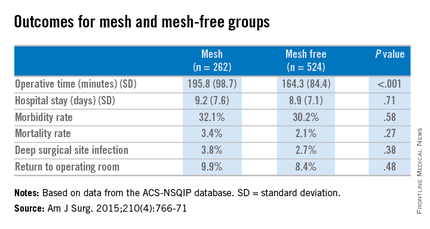

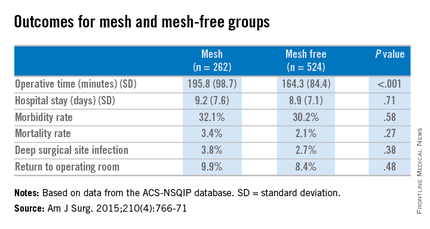

Concurrent mesh herniorrhaphy with bowel surgery doesn’t up morbidity

Concurrent colorectal surgery and mesh herniorrhaphy can be done safely, according to findings from a case-matched study based on American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data.

“Our study suggests that mesh repair for [ventral hernia] in the setting of [colorectal surgery] does not worsen 30-day postoperative outcomes,” wrote Dr. Cigdem Benlice and colleagues of the Cleveland Clinic. The study was published in the American Journal of Surgery (2015; 210[4]:766-771]

These two operations are undertaken concurrently in part to save patients from further procedures and anesthesia, but the practice is limited by safety concerns. The complications anticipated include intra-abdominal adhesions, chronic draining sinus, chronic enteric fistula, chronic wound infection, and mesh migration. Any one of these complications could entail further surgical interventions.

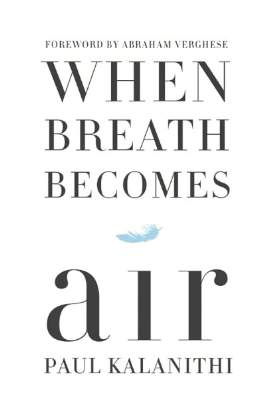

Dr. Benlice and her colleagues used the national, validated, risk-adjusted American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) database to look at short-term outcomes after concurrent ventral hernia repair (VHR) and colorectal surgery (CS), and the risk factors associated with complications. Data on 2,250 patients having CS and VHR operations simultaneously from 2005 to 2010 were reviewed. Patients having simultaneous VHR with mesh and CS (262) were matched closely with those having both procedures but without mesh (524). The case-matching criteria included diagnosis, type of bowel procedure, and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, and follow-up was limited to 30 days.

In a comparison of the mesh and nonmesh groups, morbidity rates were found to be similar (32% vs. 30%, P = .58) as were mortality rates (3.4% vs. 2.1%, P = .27). The rate of deep surgical site infections (3.8% vs. 2.7%, P = .38) were similar between the two groups, and wound disruptions (3.1% vs. 3.1%) rates were the same. The length of hospital stay was also comparable. Mean operating time, however, proved longer in patients who had hernia repair using mesh (196 minutes vs. 164 minutes, P less than .001).

A multivariate analysis showed that open colorectal procedures, III or IV ASA class, smoking, and preoperative open wound or wound infection were significant and independent risk factors (odds ratios, 2.67, 2.51, 2.06, and 2.27, respectively) for surgical site infection.

The limitations of this study reflect some of the limitations of the ACS-NSQIP database. Long-term follow-up, hernia size, type of mesh used, and type of technique used in the operation could not be assessed using the available data. In addition, further analysis of the subgroups of patients with surgical site infections would be needed to examine the impact of mesh (and types of mesh) use on clean-contaminated cases. Researchers noted that at the Cleveland Clinic, type of mesh (biologic vs. nonbiologic) used has been found to have no impact on rates of wound and mesh infection and hernia recurrence, but they were unable to do this kind of analysis with the available data for simultaneous bowel and hernia repair surgery.

The researchers concluded, “the large cohort and strict inclusion, exclusion, and case-matching criteria strengthen the clinical value of this study. When performed simultaneously with CS, VHR with mesh can be performed without increasing perioperative and short-term postoperative morbidity.”

The researchers had no relevant disclosures.

Concurrent colorectal surgery and mesh herniorrhaphy can be done safely, according to findings from a case-matched study based on American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data.

“Our study suggests that mesh repair for [ventral hernia] in the setting of [colorectal surgery] does not worsen 30-day postoperative outcomes,” wrote Dr. Cigdem Benlice and colleagues of the Cleveland Clinic. The study was published in the American Journal of Surgery (2015; 210[4]:766-771]

These two operations are undertaken concurrently in part to save patients from further procedures and anesthesia, but the practice is limited by safety concerns. The complications anticipated include intra-abdominal adhesions, chronic draining sinus, chronic enteric fistula, chronic wound infection, and mesh migration. Any one of these complications could entail further surgical interventions.

Dr. Benlice and her colleagues used the national, validated, risk-adjusted American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) database to look at short-term outcomes after concurrent ventral hernia repair (VHR) and colorectal surgery (CS), and the risk factors associated with complications. Data on 2,250 patients having CS and VHR operations simultaneously from 2005 to 2010 were reviewed. Patients having simultaneous VHR with mesh and CS (262) were matched closely with those having both procedures but without mesh (524). The case-matching criteria included diagnosis, type of bowel procedure, and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, and follow-up was limited to 30 days.

In a comparison of the mesh and nonmesh groups, morbidity rates were found to be similar (32% vs. 30%, P = .58) as were mortality rates (3.4% vs. 2.1%, P = .27). The rate of deep surgical site infections (3.8% vs. 2.7%, P = .38) were similar between the two groups, and wound disruptions (3.1% vs. 3.1%) rates were the same. The length of hospital stay was also comparable. Mean operating time, however, proved longer in patients who had hernia repair using mesh (196 minutes vs. 164 minutes, P less than .001).

A multivariate analysis showed that open colorectal procedures, III or IV ASA class, smoking, and preoperative open wound or wound infection were significant and independent risk factors (odds ratios, 2.67, 2.51, 2.06, and 2.27, respectively) for surgical site infection.

The limitations of this study reflect some of the limitations of the ACS-NSQIP database. Long-term follow-up, hernia size, type of mesh used, and type of technique used in the operation could not be assessed using the available data. In addition, further analysis of the subgroups of patients with surgical site infections would be needed to examine the impact of mesh (and types of mesh) use on clean-contaminated cases. Researchers noted that at the Cleveland Clinic, type of mesh (biologic vs. nonbiologic) used has been found to have no impact on rates of wound and mesh infection and hernia recurrence, but they were unable to do this kind of analysis with the available data for simultaneous bowel and hernia repair surgery.

The researchers concluded, “the large cohort and strict inclusion, exclusion, and case-matching criteria strengthen the clinical value of this study. When performed simultaneously with CS, VHR with mesh can be performed without increasing perioperative and short-term postoperative morbidity.”

The researchers had no relevant disclosures.

Concurrent colorectal surgery and mesh herniorrhaphy can be done safely, according to findings from a case-matched study based on American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data.

“Our study suggests that mesh repair for [ventral hernia] in the setting of [colorectal surgery] does not worsen 30-day postoperative outcomes,” wrote Dr. Cigdem Benlice and colleagues of the Cleveland Clinic. The study was published in the American Journal of Surgery (2015; 210[4]:766-771]

These two operations are undertaken concurrently in part to save patients from further procedures and anesthesia, but the practice is limited by safety concerns. The complications anticipated include intra-abdominal adhesions, chronic draining sinus, chronic enteric fistula, chronic wound infection, and mesh migration. Any one of these complications could entail further surgical interventions.

Dr. Benlice and her colleagues used the national, validated, risk-adjusted American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) database to look at short-term outcomes after concurrent ventral hernia repair (VHR) and colorectal surgery (CS), and the risk factors associated with complications. Data on 2,250 patients having CS and VHR operations simultaneously from 2005 to 2010 were reviewed. Patients having simultaneous VHR with mesh and CS (262) were matched closely with those having both procedures but without mesh (524). The case-matching criteria included diagnosis, type of bowel procedure, and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, and follow-up was limited to 30 days.

In a comparison of the mesh and nonmesh groups, morbidity rates were found to be similar (32% vs. 30%, P = .58) as were mortality rates (3.4% vs. 2.1%, P = .27). The rate of deep surgical site infections (3.8% vs. 2.7%, P = .38) were similar between the two groups, and wound disruptions (3.1% vs. 3.1%) rates were the same. The length of hospital stay was also comparable. Mean operating time, however, proved longer in patients who had hernia repair using mesh (196 minutes vs. 164 minutes, P less than .001).

A multivariate analysis showed that open colorectal procedures, III or IV ASA class, smoking, and preoperative open wound or wound infection were significant and independent risk factors (odds ratios, 2.67, 2.51, 2.06, and 2.27, respectively) for surgical site infection.

The limitations of this study reflect some of the limitations of the ACS-NSQIP database. Long-term follow-up, hernia size, type of mesh used, and type of technique used in the operation could not be assessed using the available data. In addition, further analysis of the subgroups of patients with surgical site infections would be needed to examine the impact of mesh (and types of mesh) use on clean-contaminated cases. Researchers noted that at the Cleveland Clinic, type of mesh (biologic vs. nonbiologic) used has been found to have no impact on rates of wound and mesh infection and hernia recurrence, but they were unable to do this kind of analysis with the available data for simultaneous bowel and hernia repair surgery.

The researchers concluded, “the large cohort and strict inclusion, exclusion, and case-matching criteria strengthen the clinical value of this study. When performed simultaneously with CS, VHR with mesh can be performed without increasing perioperative and short-term postoperative morbidity.”

The researchers had no relevant disclosures.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SURGERY

Key clinical point: Simultaneous bowel and hernia surgery with mesh are comparable to a nonmesh operation in terms of postoperative morbidity.

Major finding: In a comparison of the mesh and nonmesh groups, morbidity rates were found to be similar (32% vs. 30%, P = .27) as was the rate of deep surgical site infections (3.8% vs. 2.7%, P = .38).

Data source: ACS-NSQIP data on case-matched patients having concurrent bowel and hernia surgery, with mesh (262) and without mesh (524).

Disclosures: The researchers had no relevant disclosures.

Surgical follow-up after ED cholelithiasis episode cuts long-term costs, complications

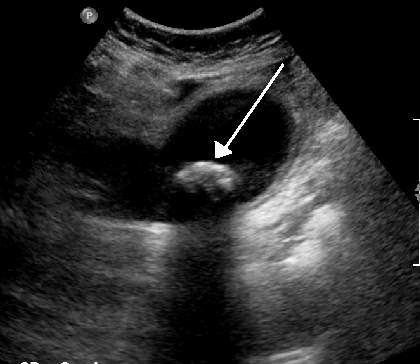

Patients who don’t receive surgical follow-up after an emergency department visit for cholelithiasis are at increased risk for further ED visits, extraneous imaging, and complications from the disease and from emergent cholecystectomy, according to the findings of a retrospective study.

“Our study identifies lack of surgical follow-up [as] a major contributor to the failure to perform cholecystecomy and highlights the importance of prompt surgical evaluation,” stated Taylor P. Williams of the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB), Galveston, and co-investigators.

Between August 2009 and May 2014, 71 patients were discharged from the ED at UTMB with a diagnosis of symptomatic gallstones. The study charted the care of these patients for a follow-up period of 2 years, and the findings were published the August issue of the Journal of Surgical Research (2015;197:318-23).

The mean age of patients was 41 years; 86% were women, and 49% were white. A majority of the patients (56.3%) had no health insurance, while 11.3% had Medicare, 11.3% were on Medicaid, and 21.1% had private insurance.

Of the 71 patients, 18 (25.4%) had outpatient surgical follow-up after an ED visit for a cholelithiasis episode, and they saw the surgeon an average of 7.7 days after the initial ED visit. In the 9 patients who then had an elective cholecystectomy, 8 of these operations occurred within a month of the initital ED visit.

A total of 53 (74.6%) had no immediate surgical follow-up after their ED visit.

The 62 patients who did not have a cholecystectomy had a different trajectory of care than did those who had surgery soon after their ED visit. Of the non-cholecystectomy group, 14.5% of this group eventually had outpatient surgical follow-up within a mean time of 137 days and 37.1% had repeat visits to the ED for gallstone symptoms (17.7% had two or more additional ED visits). Over half of those visits resulted in additional CT or ultrasound imaging. A total of 8 (12.9%) of the total group ended up with an emergent cholecystectomy.

The investigators looked at factors associated with surgical follow-up and eventual or emergent cholecystectomy. Laboratory values, demographics, and radiographic findings were similar between those who underwent cholecystectomy and those who did not. Patients with insurance were more likely to achieve surgical follow-up and more likely to have an elective cholecystectomy. Nausea and vomiting on presentation at the initial ED visit were associated with a greater likelihood of having a cholecystectomy.

The study showed that the 71 patients who presented at the ED with symptoms of cholelithiasis had a similar number of elective and emergent cholecystectomies. But those who did not pursue follow-up and delayed in having surgery incurred additional risks and costs.

A limitation of the study, according to the investigators, is that it involves a small sample from a single center in a community with a high proportion of patients who lack health insurance. In addition, UTMB protocol for acute gallbladder disease leads to a higher rate of admissions than is typical in the United States.