User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Using lipid guidelines to manage metabolic syndrome for patients taking an antipsychotic

Your patient who has schizophrenia, Mr. W, age 48, requests that you switch him from olanzapine, 10 mg/d, to another antipsychotic because he gained 25 lb over 1 month taking the drug. He now weighs 275 lb. Mr. W reports smoking at least 2 packs of cigarettes a day and takes lisinopril, 20 mg/d, for hypertension. You decide to start risperidone, 1 mg/d. First, however, your initial work-up includes:

- high-density lipoprotein (HDL), 24 mg/dL

- total cholesterol, 220 mg/dL

- blood pressure, 154/80 mm Hgwaist circumference, 39 in

- body mass index (BMI), 29

- hemoglobin A1c, of 5.6%.

A prolactin level is pending.

How do you interpret these values?

Metabolic syndrome is defined as the cluster of central obesity, insulin resistance, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. Metabolic syndrome increases a patient's risk of diabetes 5-fold and cardiovascular disease 3-fold.1 Physical inactivity and eating high-fat foods typically precede weight gain and obesity that, in turn, develop into insulin resistance, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.1

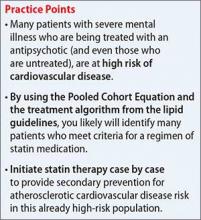

Patients with severe psychiatric illness have an increased rate of mortality from cardiovascular disease, compared with the general population.2-4 The cause of this phenomenon is multifactorial: In general, patients with severe mental illness receive insufficient preventive health care, do not eat a balanced diet, and are more likely to smoke cigarettes than other people.2-4

Also, compared with the general population, the diet of men with schizophrenia contains less vegetables and grains and women with schizophrenia consume less grains. An estimated 70% of patients with schizophrenia smoke.4 As measured by BMI, 86% of women with schizophrenia and 70% of men with schizophrenia are overweight or obese.4

Antipsychotics used to treat severe mental illness also have been implicated in metabolic syndrome, specifically second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs).5 Several theories aim to explain how antipsychotics lead to metabolic alterations.

Oxidative stress. One theory centers on the production of oxidative stress and the consequent reactive oxygen species that form after SGA treatment.6

Mitochondrial function. Another theory assesses the impact of antipsychotic treatment on mitochondrial function. Mitochondrial dysfunction causes decreased fatty acid oxidation, leading to lipid accumulation.7

The culminating affect of severe mental illness alone as well as treatment-emergent side effects of antipsychotics raises the question of how to best treat the dyslipidemia component of metabolic syndrome. This article will:

- review which antipsychotics impact lipids the most

- provide an overview of the most recent lipid guidelines

- describe how to best manage patients to prevent and treat dyslipidemia.

Impact of antipsychotics on lipids

Antipsychotic treatment can lead to metabolic syndrome; SGAs are implicated in most cases.8 A study by Liao et al9 investigated the risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia in patients with schizophrenia who received treatment with a first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) compared with patients who received a SGA. The significance-adjusted hazard ratio for the development of hyperlipidemia in patients treated with a SGA was statistically significant compared with the general population (1.41; 95% CI, 1.09-1.83). The risk of hyperlipidemia in patients treated with a FGA was not significant.

Studies have aimed to describe which SGAs carry the greatest risk of hyperlipidemia.10,11 To summarize findings, in 2004 the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and American Psychiatric Association released a consensus statement on the impact of antipsychotic medications on obesity and diabetes.12 The statement listed the following antipsychotics in order of greatest to least impact on hyperlipidemia:

- clozapine

- olanzapine

- quetiapine

- risperidone

- ziprasidone

- aripiprazole.

To evaluate newer SGAs, a systematic review and meta-analysis by De Hert et al13 aimed to assess the metabolic risks associated with asenapine, iloperidone, lurasidone, and paliperidone. In general, the studies included in the meta-analysis showed little or no clinically meaningful differences among these newer agents in terms of total cholesterol in short-term trials, except for asenapine and iloperidone.

Asenapine was found to increase the total cholesterol level in long-term trials (>12 weeks) by an average of 6.53 mg/dL. These trials also demonstrated a decrease in HDL cholesterol (−0.13 mg/dL) and a decrease in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) (−1.72 mg/dL to −0.86 mg/dL). The impact of asenapine on these lab results does not appear to be clinically significant.13,14

Iloperidone. A study evaluating the impact iloperidone on lipid values showed a statistically significant increase in total cholesterol, HDL, and LDL-C levels after 12 weeks.13,15

Overview: Latest lipid guidelines

Current literature lacks information regarding statin use for overall prevention of metabolic syndrome. However, the most recent update to the American Heart Association's guideline on treating blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults describes the role of statin therapy to address dyslipidemia, which is one component of metabolic syndrome.16,17

Some of the greatest changes seen with the latest blood cholesterol guidelines include:

- focus on atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk reduction to identify 4 statin benefit groups

- transition away from treating to a target LDL value

- use of the Pooled Cohort Equation to estimate 10-year ASCVD risk, rather than the Framingham Risk Score.

Placing patients in 1 of 4 statin benefit groups

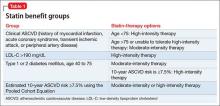

Unlike the 2002 National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) guidelines, the latest guidelines have identified 4 statin treatment benefit groups:

- patients with clinical ASCVD (including those who have had acute coronary syndrome, stroke, or myocardial infarction, or who have stable or unstable angina, transient ischemic attacks, or peripheral artery disease, or a combination of these findings)patients with LDL-C >190 mg/dL

- patients age 40 to 75 with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus

- patients with an estimated 10-year ASCVD risk of ≥7.5% that was estimated using the Pooled Cohort Equation.16,17

Table 1 represents each statin benefit group and recommended treatment options.

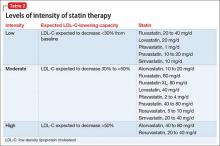

Selected statin therapy for each statin benefit group is further delineated into low-, moderate-, and high-intensity therapy. Intensity of statin therapy represents the expected LDL lowering capacity of selected statins. Low-intensity statin therapy, on average, is expected to lower LDL-C by <30%. Moderate-intensity statin therapy is expected to lower LDL-C by 30% to <50%. High-intensity statin therapy is expected to lower LDL-C by >50%.

When selecting treatment for patients, it is important to first determine the statin benefit group that the patient falls under, and then select the appropriate statin intensity. The categorization of the different statins based on LDL-C lowering capacity is described in Table 2.

Whenever a patient is started on statin therapy, order a liver function test and lipid profile at baseline. Repeat these tests 4 to 12 weeks after statin initiation, then every 3 to 12 months.

Transition away from treating to a target LDL-C goal

ATP III guidelines suggested that elevated LDL was the leading cause of coronary heart disease and recommended therapy with LDL-lowering medications.18 The panel that developed the 2013 lipid guideline concluded that there was no evidence that showed benefit in treating to a designated LDL-C goal.16,17 Arguably, treating to a target may lead to overtreatment in some patients and under-treatment in others. Treatment is now recommended based on statin intensity.

Using the Pooled Cohort Equation

In moving away from the Framingham Risk Score, the latest lipid guidelines established a new calculation to assess cardiovascular disease. The Pooled Cohort Equation estimates the 10-year ASCVD risk for patients based on selected risk factors: age, sex, race, lipids, diabetes, smoking status, and blood pressure. Although other potential cardiovascular disease risk factors have been identified, the Pooled Cohort Equation focused on those risk factors that have been correlated with cardiovascular disease since the 1960s.16,17,19 The Pooled Cohort Equation is intended to (1) more accurately identify higher-risk patients and (2) assess who would best benefit from statin therapy.

Recommended lab tests and subsequent treatment

With the new lipid guidelines in place to direct dyslipidemia treatment and a better understanding of how certain antipsychotics impact lipid values, the next step is monitoring parameters for patients. Before initiating antipsychotic treatment and in accordance with the 2014 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines, baseline measurements should include weight, waist circumference, pulse, blood pressure, fasting blood glucose, hemoglobin A1c, blood lipid profile, and, if risperidone or paliperidone is initiated, prolactin level.20 Additionally, patients should be assessed at baseline for any movement disorders as well as current nutritional status, diet, and level of physical activity.

Once treatment is selected on a patient-specific basis, weight should be measured weekly for the first 6 weeks, again at 12 weeks and 1 year, and then annually. Pulse and blood pressure should be obtained 12 weeks after treatment initiation and at 1 year. Fasting blood glucose, hemoglobin A1c, and blood lipid levels should be collected 12 weeks after treatment onset, then at the 1-year mark.20 These laboratory parameters should be measured annually while the patient is receiving antipsychotic treatment.

Alternately, you can follow the monitoring parameters in the more dated 2004 ADA consensus statement:

- baseline assessment to include BMI, waist circumference, blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose, fasting lipid profile, and personal and family history

- BMI measured again at 4 weeks, 8 weeks, 12 weeks, and then quarterly

- 12-week follow-up measurement of fasting plasma glucose, fasting lipids, and blood pressure

- annual measurement of fasting blood glucose, blood pressure, and waist circumference.12

In addition to the NICE guidelines and the ADA consensus statement, use of the current lipid guidelines and the Pooled Cohort Equation to assess 10-year ASCVD risk should be obtained at baseline and throughout antipsychotic treatment. If you identify an abnormality in the lipid profile, you have several options:

- Decrease the antipsychotic dosage

- Switch to an antipsychotic considered to be less risky

- Discontinue therapy

- Implement diet and exercise

- Refer the patient to a dietitian or other clinician skilled in managing overweight or obesity and hyperlipidemia.21

Furthermore, patients identified as being in 1 of the 4 statin benefit groups should be started on appropriate pharmacotherapy. Non-statin therapy as adjunct or in lieu of statin therapy is not considered to be first-line.16

CASE CONTINUED

After reviewing Mr. W's lab results, you calculate that he has a 24% ten-year ASCVD risk, using the Pooled Cohort Equation. Following the treatment algorithm for statin benefit groups, you see that Mr. W meets criteria for high-intensity statin therapy. You stop olanzapine, switch to risperidone, 1 mg/d, and initiate atorvastatin, 40 mg/d. You plan to assess Mr. W's weight weekly over the next 6 weeks and order a liver profile and lipid profile in 6 weeks.

Related Resource

- AHA/ACC 2013 Prevention Guidelines Tools CV Risk Calculator. https://professional.heart.org/professional/GuidelinesStatements/PreventionGuidelines/UCM_457698_Prevention-Guidelines.jsp.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Asenapine • Saphris

Atorvastatin • Lipitor

Clozapine • Clozaril

Fluvastatin • Lescol

Iloperidone • Fanapt

Lovastatin • Mevacor

Lurasidone • Latuda

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone • Invega

Pitavastatin • Livalo

Pravastatin • Pravachol

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Rosuvastatin • Crestor

Simvastatin • Zocor

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. The contents of this article do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Chillicothe Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Chillicothe, Ohio.

1. O’Neill S, O’Driscoll L. Metabolic syndrome: a closer look at the growing epidemic and its associated pathologies. Obes Rev. 2015;16(1):1-12.

2. McCreadie RG; Scottish Schizophrenia Lifestyle Group. Diet, smoking and cardiovascular risk in people with schizophrenia: descriptive study. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:534-539.

3. Correll CU, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Cardiometabolic risk in patients with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders: baseline results from the RAISE-ETP Study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;7(12):1350-1363.

4. Nordentoft M, Wahlbeck K, Hällgren J, et al. Excess mortality, causes of death and life expectancy in 270,770 patients with recent onset of mental disorders in Denmark, Finland and Sweden. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e55176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055176.

5. Young SL, Taylor M, Lawrie SM. “First do no harm.” A systematic review of the prevalence and management of antipsychotic adverse effects. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29(4):353-362.

6. Baig MR, Navaira E, Escamilla MA, et al. Clozapine treatment causes oxidation of proteins involved in energy metabolism in lymphoblastoid cells: a possible mechanism for antipsychotic-induced metabolic alterations. J Psychiatr Pract. 2010;16(5):325-333.

7. Schrauwen P, Schrauwen-Hinderling V, Hoeks J, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and lipotoxicity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801(3):266-271.

8. Watanabe J, Suzuki Y, Someya T. Lipid effects of psychiatric medications. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2013;15(1):292.

9. Liao HH, Chang CS, Wei WC, et al. Schizophrenia patients at higher risk of diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidemia: a population-based study. Schizophr Res. 2011;126(1-3):110-116.

10. Lidenmayer JP, Czobor P, Volavka J, et al. Changes in glucose and cholesterol levels in patients with schizophrenia treated with typical or atypical antipsychotics. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(2):290-296.

11. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Corey-Lisle P, et al. Hyperlipidemia following treatment with antipsychotic medications. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(10):1821-1825.

12. American Diabetes Association; American Psychiatric Association; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, et al. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):596-601.

13. De Hert M, Yu W, Detraux J, et al. Body weight and metabolic adverse effects of asenapine, iloperidone, lurasidone, and paliperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. CNS Drugs. 2012;26(9):733-759.

14. Kemp DE, Zhao J, Cazorla P, et al. Weight change and metabolic effects of asenapine in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiary. 2014;75(3):238-245.

15. Cutler AJ, Kalali AH, Weiden PJ, et al. Four-week, double-blind, placebo-and ziprasidone-controlled trial of iloperidone in patients with acute exacerbations of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(2 suppl 1):S20-S28.

16. Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S1-S45.

17. Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S49-S72.

18. National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106(25):3143-3421.

19. Ioannidis JP. More than a billion people taking statins? Potential implications of the new cardiovascular guidelines. JAMA. 2014;311(5):463-464.

20. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management: the NICE Guideline on Treatment and Management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178/evidence/full-guideline-490503565. Published 2014. Accessed June 8, 2016.

21. Zeier K, Connell R, Resch W, et al. Recommendations for lab monitoring of atypical antipsychotics. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(9):51-54.

Your patient who has schizophrenia, Mr. W, age 48, requests that you switch him from olanzapine, 10 mg/d, to another antipsychotic because he gained 25 lb over 1 month taking the drug. He now weighs 275 lb. Mr. W reports smoking at least 2 packs of cigarettes a day and takes lisinopril, 20 mg/d, for hypertension. You decide to start risperidone, 1 mg/d. First, however, your initial work-up includes:

- high-density lipoprotein (HDL), 24 mg/dL

- total cholesterol, 220 mg/dL

- blood pressure, 154/80 mm Hgwaist circumference, 39 in

- body mass index (BMI), 29

- hemoglobin A1c, of 5.6%.

A prolactin level is pending.

How do you interpret these values?

Metabolic syndrome is defined as the cluster of central obesity, insulin resistance, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. Metabolic syndrome increases a patient's risk of diabetes 5-fold and cardiovascular disease 3-fold.1 Physical inactivity and eating high-fat foods typically precede weight gain and obesity that, in turn, develop into insulin resistance, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.1

Patients with severe psychiatric illness have an increased rate of mortality from cardiovascular disease, compared with the general population.2-4 The cause of this phenomenon is multifactorial: In general, patients with severe mental illness receive insufficient preventive health care, do not eat a balanced diet, and are more likely to smoke cigarettes than other people.2-4

Also, compared with the general population, the diet of men with schizophrenia contains less vegetables and grains and women with schizophrenia consume less grains. An estimated 70% of patients with schizophrenia smoke.4 As measured by BMI, 86% of women with schizophrenia and 70% of men with schizophrenia are overweight or obese.4

Antipsychotics used to treat severe mental illness also have been implicated in metabolic syndrome, specifically second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs).5 Several theories aim to explain how antipsychotics lead to metabolic alterations.

Oxidative stress. One theory centers on the production of oxidative stress and the consequent reactive oxygen species that form after SGA treatment.6

Mitochondrial function. Another theory assesses the impact of antipsychotic treatment on mitochondrial function. Mitochondrial dysfunction causes decreased fatty acid oxidation, leading to lipid accumulation.7

The culminating affect of severe mental illness alone as well as treatment-emergent side effects of antipsychotics raises the question of how to best treat the dyslipidemia component of metabolic syndrome. This article will:

- review which antipsychotics impact lipids the most

- provide an overview of the most recent lipid guidelines

- describe how to best manage patients to prevent and treat dyslipidemia.

Impact of antipsychotics on lipids

Antipsychotic treatment can lead to metabolic syndrome; SGAs are implicated in most cases.8 A study by Liao et al9 investigated the risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia in patients with schizophrenia who received treatment with a first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) compared with patients who received a SGA. The significance-adjusted hazard ratio for the development of hyperlipidemia in patients treated with a SGA was statistically significant compared with the general population (1.41; 95% CI, 1.09-1.83). The risk of hyperlipidemia in patients treated with a FGA was not significant.

Studies have aimed to describe which SGAs carry the greatest risk of hyperlipidemia.10,11 To summarize findings, in 2004 the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and American Psychiatric Association released a consensus statement on the impact of antipsychotic medications on obesity and diabetes.12 The statement listed the following antipsychotics in order of greatest to least impact on hyperlipidemia:

- clozapine

- olanzapine

- quetiapine

- risperidone

- ziprasidone

- aripiprazole.

To evaluate newer SGAs, a systematic review and meta-analysis by De Hert et al13 aimed to assess the metabolic risks associated with asenapine, iloperidone, lurasidone, and paliperidone. In general, the studies included in the meta-analysis showed little or no clinically meaningful differences among these newer agents in terms of total cholesterol in short-term trials, except for asenapine and iloperidone.

Asenapine was found to increase the total cholesterol level in long-term trials (>12 weeks) by an average of 6.53 mg/dL. These trials also demonstrated a decrease in HDL cholesterol (−0.13 mg/dL) and a decrease in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) (−1.72 mg/dL to −0.86 mg/dL). The impact of asenapine on these lab results does not appear to be clinically significant.13,14

Iloperidone. A study evaluating the impact iloperidone on lipid values showed a statistically significant increase in total cholesterol, HDL, and LDL-C levels after 12 weeks.13,15

Overview: Latest lipid guidelines

Current literature lacks information regarding statin use for overall prevention of metabolic syndrome. However, the most recent update to the American Heart Association's guideline on treating blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults describes the role of statin therapy to address dyslipidemia, which is one component of metabolic syndrome.16,17

Some of the greatest changes seen with the latest blood cholesterol guidelines include:

- focus on atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk reduction to identify 4 statin benefit groups

- transition away from treating to a target LDL value

- use of the Pooled Cohort Equation to estimate 10-year ASCVD risk, rather than the Framingham Risk Score.

Placing patients in 1 of 4 statin benefit groups

Unlike the 2002 National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) guidelines, the latest guidelines have identified 4 statin treatment benefit groups:

- patients with clinical ASCVD (including those who have had acute coronary syndrome, stroke, or myocardial infarction, or who have stable or unstable angina, transient ischemic attacks, or peripheral artery disease, or a combination of these findings)patients with LDL-C >190 mg/dL

- patients age 40 to 75 with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus

- patients with an estimated 10-year ASCVD risk of ≥7.5% that was estimated using the Pooled Cohort Equation.16,17

Table 1 represents each statin benefit group and recommended treatment options.

Selected statin therapy for each statin benefit group is further delineated into low-, moderate-, and high-intensity therapy. Intensity of statin therapy represents the expected LDL lowering capacity of selected statins. Low-intensity statin therapy, on average, is expected to lower LDL-C by <30%. Moderate-intensity statin therapy is expected to lower LDL-C by 30% to <50%. High-intensity statin therapy is expected to lower LDL-C by >50%.

When selecting treatment for patients, it is important to first determine the statin benefit group that the patient falls under, and then select the appropriate statin intensity. The categorization of the different statins based on LDL-C lowering capacity is described in Table 2.

Whenever a patient is started on statin therapy, order a liver function test and lipid profile at baseline. Repeat these tests 4 to 12 weeks after statin initiation, then every 3 to 12 months.

Transition away from treating to a target LDL-C goal

ATP III guidelines suggested that elevated LDL was the leading cause of coronary heart disease and recommended therapy with LDL-lowering medications.18 The panel that developed the 2013 lipid guideline concluded that there was no evidence that showed benefit in treating to a designated LDL-C goal.16,17 Arguably, treating to a target may lead to overtreatment in some patients and under-treatment in others. Treatment is now recommended based on statin intensity.

Using the Pooled Cohort Equation

In moving away from the Framingham Risk Score, the latest lipid guidelines established a new calculation to assess cardiovascular disease. The Pooled Cohort Equation estimates the 10-year ASCVD risk for patients based on selected risk factors: age, sex, race, lipids, diabetes, smoking status, and blood pressure. Although other potential cardiovascular disease risk factors have been identified, the Pooled Cohort Equation focused on those risk factors that have been correlated with cardiovascular disease since the 1960s.16,17,19 The Pooled Cohort Equation is intended to (1) more accurately identify higher-risk patients and (2) assess who would best benefit from statin therapy.

Recommended lab tests and subsequent treatment

With the new lipid guidelines in place to direct dyslipidemia treatment and a better understanding of how certain antipsychotics impact lipid values, the next step is monitoring parameters for patients. Before initiating antipsychotic treatment and in accordance with the 2014 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines, baseline measurements should include weight, waist circumference, pulse, blood pressure, fasting blood glucose, hemoglobin A1c, blood lipid profile, and, if risperidone or paliperidone is initiated, prolactin level.20 Additionally, patients should be assessed at baseline for any movement disorders as well as current nutritional status, diet, and level of physical activity.

Once treatment is selected on a patient-specific basis, weight should be measured weekly for the first 6 weeks, again at 12 weeks and 1 year, and then annually. Pulse and blood pressure should be obtained 12 weeks after treatment initiation and at 1 year. Fasting blood glucose, hemoglobin A1c, and blood lipid levels should be collected 12 weeks after treatment onset, then at the 1-year mark.20 These laboratory parameters should be measured annually while the patient is receiving antipsychotic treatment.

Alternately, you can follow the monitoring parameters in the more dated 2004 ADA consensus statement:

- baseline assessment to include BMI, waist circumference, blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose, fasting lipid profile, and personal and family history

- BMI measured again at 4 weeks, 8 weeks, 12 weeks, and then quarterly

- 12-week follow-up measurement of fasting plasma glucose, fasting lipids, and blood pressure

- annual measurement of fasting blood glucose, blood pressure, and waist circumference.12

In addition to the NICE guidelines and the ADA consensus statement, use of the current lipid guidelines and the Pooled Cohort Equation to assess 10-year ASCVD risk should be obtained at baseline and throughout antipsychotic treatment. If you identify an abnormality in the lipid profile, you have several options:

- Decrease the antipsychotic dosage

- Switch to an antipsychotic considered to be less risky

- Discontinue therapy

- Implement diet and exercise

- Refer the patient to a dietitian or other clinician skilled in managing overweight or obesity and hyperlipidemia.21

Furthermore, patients identified as being in 1 of the 4 statin benefit groups should be started on appropriate pharmacotherapy. Non-statin therapy as adjunct or in lieu of statin therapy is not considered to be first-line.16

CASE CONTINUED

After reviewing Mr. W's lab results, you calculate that he has a 24% ten-year ASCVD risk, using the Pooled Cohort Equation. Following the treatment algorithm for statin benefit groups, you see that Mr. W meets criteria for high-intensity statin therapy. You stop olanzapine, switch to risperidone, 1 mg/d, and initiate atorvastatin, 40 mg/d. You plan to assess Mr. W's weight weekly over the next 6 weeks and order a liver profile and lipid profile in 6 weeks.

Related Resource

- AHA/ACC 2013 Prevention Guidelines Tools CV Risk Calculator. https://professional.heart.org/professional/GuidelinesStatements/PreventionGuidelines/UCM_457698_Prevention-Guidelines.jsp.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Asenapine • Saphris

Atorvastatin • Lipitor

Clozapine • Clozaril

Fluvastatin • Lescol

Iloperidone • Fanapt

Lovastatin • Mevacor

Lurasidone • Latuda

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone • Invega

Pitavastatin • Livalo

Pravastatin • Pravachol

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Rosuvastatin • Crestor

Simvastatin • Zocor

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. The contents of this article do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Chillicothe Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Chillicothe, Ohio.

Your patient who has schizophrenia, Mr. W, age 48, requests that you switch him from olanzapine, 10 mg/d, to another antipsychotic because he gained 25 lb over 1 month taking the drug. He now weighs 275 lb. Mr. W reports smoking at least 2 packs of cigarettes a day and takes lisinopril, 20 mg/d, for hypertension. You decide to start risperidone, 1 mg/d. First, however, your initial work-up includes:

- high-density lipoprotein (HDL), 24 mg/dL

- total cholesterol, 220 mg/dL

- blood pressure, 154/80 mm Hgwaist circumference, 39 in

- body mass index (BMI), 29

- hemoglobin A1c, of 5.6%.

A prolactin level is pending.

How do you interpret these values?

Metabolic syndrome is defined as the cluster of central obesity, insulin resistance, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. Metabolic syndrome increases a patient's risk of diabetes 5-fold and cardiovascular disease 3-fold.1 Physical inactivity and eating high-fat foods typically precede weight gain and obesity that, in turn, develop into insulin resistance, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.1

Patients with severe psychiatric illness have an increased rate of mortality from cardiovascular disease, compared with the general population.2-4 The cause of this phenomenon is multifactorial: In general, patients with severe mental illness receive insufficient preventive health care, do not eat a balanced diet, and are more likely to smoke cigarettes than other people.2-4

Also, compared with the general population, the diet of men with schizophrenia contains less vegetables and grains and women with schizophrenia consume less grains. An estimated 70% of patients with schizophrenia smoke.4 As measured by BMI, 86% of women with schizophrenia and 70% of men with schizophrenia are overweight or obese.4

Antipsychotics used to treat severe mental illness also have been implicated in metabolic syndrome, specifically second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs).5 Several theories aim to explain how antipsychotics lead to metabolic alterations.

Oxidative stress. One theory centers on the production of oxidative stress and the consequent reactive oxygen species that form after SGA treatment.6

Mitochondrial function. Another theory assesses the impact of antipsychotic treatment on mitochondrial function. Mitochondrial dysfunction causes decreased fatty acid oxidation, leading to lipid accumulation.7

The culminating affect of severe mental illness alone as well as treatment-emergent side effects of antipsychotics raises the question of how to best treat the dyslipidemia component of metabolic syndrome. This article will:

- review which antipsychotics impact lipids the most

- provide an overview of the most recent lipid guidelines

- describe how to best manage patients to prevent and treat dyslipidemia.

Impact of antipsychotics on lipids

Antipsychotic treatment can lead to metabolic syndrome; SGAs are implicated in most cases.8 A study by Liao et al9 investigated the risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia in patients with schizophrenia who received treatment with a first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) compared with patients who received a SGA. The significance-adjusted hazard ratio for the development of hyperlipidemia in patients treated with a SGA was statistically significant compared with the general population (1.41; 95% CI, 1.09-1.83). The risk of hyperlipidemia in patients treated with a FGA was not significant.

Studies have aimed to describe which SGAs carry the greatest risk of hyperlipidemia.10,11 To summarize findings, in 2004 the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and American Psychiatric Association released a consensus statement on the impact of antipsychotic medications on obesity and diabetes.12 The statement listed the following antipsychotics in order of greatest to least impact on hyperlipidemia:

- clozapine

- olanzapine

- quetiapine

- risperidone

- ziprasidone

- aripiprazole.

To evaluate newer SGAs, a systematic review and meta-analysis by De Hert et al13 aimed to assess the metabolic risks associated with asenapine, iloperidone, lurasidone, and paliperidone. In general, the studies included in the meta-analysis showed little or no clinically meaningful differences among these newer agents in terms of total cholesterol in short-term trials, except for asenapine and iloperidone.

Asenapine was found to increase the total cholesterol level in long-term trials (>12 weeks) by an average of 6.53 mg/dL. These trials also demonstrated a decrease in HDL cholesterol (−0.13 mg/dL) and a decrease in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) (−1.72 mg/dL to −0.86 mg/dL). The impact of asenapine on these lab results does not appear to be clinically significant.13,14

Iloperidone. A study evaluating the impact iloperidone on lipid values showed a statistically significant increase in total cholesterol, HDL, and LDL-C levels after 12 weeks.13,15

Overview: Latest lipid guidelines

Current literature lacks information regarding statin use for overall prevention of metabolic syndrome. However, the most recent update to the American Heart Association's guideline on treating blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults describes the role of statin therapy to address dyslipidemia, which is one component of metabolic syndrome.16,17

Some of the greatest changes seen with the latest blood cholesterol guidelines include:

- focus on atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk reduction to identify 4 statin benefit groups

- transition away from treating to a target LDL value

- use of the Pooled Cohort Equation to estimate 10-year ASCVD risk, rather than the Framingham Risk Score.

Placing patients in 1 of 4 statin benefit groups

Unlike the 2002 National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) guidelines, the latest guidelines have identified 4 statin treatment benefit groups:

- patients with clinical ASCVD (including those who have had acute coronary syndrome, stroke, or myocardial infarction, or who have stable or unstable angina, transient ischemic attacks, or peripheral artery disease, or a combination of these findings)patients with LDL-C >190 mg/dL

- patients age 40 to 75 with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus

- patients with an estimated 10-year ASCVD risk of ≥7.5% that was estimated using the Pooled Cohort Equation.16,17

Table 1 represents each statin benefit group and recommended treatment options.

Selected statin therapy for each statin benefit group is further delineated into low-, moderate-, and high-intensity therapy. Intensity of statin therapy represents the expected LDL lowering capacity of selected statins. Low-intensity statin therapy, on average, is expected to lower LDL-C by <30%. Moderate-intensity statin therapy is expected to lower LDL-C by 30% to <50%. High-intensity statin therapy is expected to lower LDL-C by >50%.

When selecting treatment for patients, it is important to first determine the statin benefit group that the patient falls under, and then select the appropriate statin intensity. The categorization of the different statins based on LDL-C lowering capacity is described in Table 2.

Whenever a patient is started on statin therapy, order a liver function test and lipid profile at baseline. Repeat these tests 4 to 12 weeks after statin initiation, then every 3 to 12 months.

Transition away from treating to a target LDL-C goal

ATP III guidelines suggested that elevated LDL was the leading cause of coronary heart disease and recommended therapy with LDL-lowering medications.18 The panel that developed the 2013 lipid guideline concluded that there was no evidence that showed benefit in treating to a designated LDL-C goal.16,17 Arguably, treating to a target may lead to overtreatment in some patients and under-treatment in others. Treatment is now recommended based on statin intensity.

Using the Pooled Cohort Equation

In moving away from the Framingham Risk Score, the latest lipid guidelines established a new calculation to assess cardiovascular disease. The Pooled Cohort Equation estimates the 10-year ASCVD risk for patients based on selected risk factors: age, sex, race, lipids, diabetes, smoking status, and blood pressure. Although other potential cardiovascular disease risk factors have been identified, the Pooled Cohort Equation focused on those risk factors that have been correlated with cardiovascular disease since the 1960s.16,17,19 The Pooled Cohort Equation is intended to (1) more accurately identify higher-risk patients and (2) assess who would best benefit from statin therapy.

Recommended lab tests and subsequent treatment

With the new lipid guidelines in place to direct dyslipidemia treatment and a better understanding of how certain antipsychotics impact lipid values, the next step is monitoring parameters for patients. Before initiating antipsychotic treatment and in accordance with the 2014 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines, baseline measurements should include weight, waist circumference, pulse, blood pressure, fasting blood glucose, hemoglobin A1c, blood lipid profile, and, if risperidone or paliperidone is initiated, prolactin level.20 Additionally, patients should be assessed at baseline for any movement disorders as well as current nutritional status, diet, and level of physical activity.

Once treatment is selected on a patient-specific basis, weight should be measured weekly for the first 6 weeks, again at 12 weeks and 1 year, and then annually. Pulse and blood pressure should be obtained 12 weeks after treatment initiation and at 1 year. Fasting blood glucose, hemoglobin A1c, and blood lipid levels should be collected 12 weeks after treatment onset, then at the 1-year mark.20 These laboratory parameters should be measured annually while the patient is receiving antipsychotic treatment.

Alternately, you can follow the monitoring parameters in the more dated 2004 ADA consensus statement:

- baseline assessment to include BMI, waist circumference, blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose, fasting lipid profile, and personal and family history

- BMI measured again at 4 weeks, 8 weeks, 12 weeks, and then quarterly

- 12-week follow-up measurement of fasting plasma glucose, fasting lipids, and blood pressure

- annual measurement of fasting blood glucose, blood pressure, and waist circumference.12

In addition to the NICE guidelines and the ADA consensus statement, use of the current lipid guidelines and the Pooled Cohort Equation to assess 10-year ASCVD risk should be obtained at baseline and throughout antipsychotic treatment. If you identify an abnormality in the lipid profile, you have several options:

- Decrease the antipsychotic dosage

- Switch to an antipsychotic considered to be less risky

- Discontinue therapy

- Implement diet and exercise

- Refer the patient to a dietitian or other clinician skilled in managing overweight or obesity and hyperlipidemia.21

Furthermore, patients identified as being in 1 of the 4 statin benefit groups should be started on appropriate pharmacotherapy. Non-statin therapy as adjunct or in lieu of statin therapy is not considered to be first-line.16

CASE CONTINUED

After reviewing Mr. W's lab results, you calculate that he has a 24% ten-year ASCVD risk, using the Pooled Cohort Equation. Following the treatment algorithm for statin benefit groups, you see that Mr. W meets criteria for high-intensity statin therapy. You stop olanzapine, switch to risperidone, 1 mg/d, and initiate atorvastatin, 40 mg/d. You plan to assess Mr. W's weight weekly over the next 6 weeks and order a liver profile and lipid profile in 6 weeks.

Related Resource

- AHA/ACC 2013 Prevention Guidelines Tools CV Risk Calculator. https://professional.heart.org/professional/GuidelinesStatements/PreventionGuidelines/UCM_457698_Prevention-Guidelines.jsp.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Asenapine • Saphris

Atorvastatin • Lipitor

Clozapine • Clozaril

Fluvastatin • Lescol

Iloperidone • Fanapt

Lovastatin • Mevacor

Lurasidone • Latuda

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone • Invega

Pitavastatin • Livalo

Pravastatin • Pravachol

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Rosuvastatin • Crestor

Simvastatin • Zocor

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. The contents of this article do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Chillicothe Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Chillicothe, Ohio.

1. O’Neill S, O’Driscoll L. Metabolic syndrome: a closer look at the growing epidemic and its associated pathologies. Obes Rev. 2015;16(1):1-12.

2. McCreadie RG; Scottish Schizophrenia Lifestyle Group. Diet, smoking and cardiovascular risk in people with schizophrenia: descriptive study. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:534-539.

3. Correll CU, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Cardiometabolic risk in patients with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders: baseline results from the RAISE-ETP Study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;7(12):1350-1363.

4. Nordentoft M, Wahlbeck K, Hällgren J, et al. Excess mortality, causes of death and life expectancy in 270,770 patients with recent onset of mental disorders in Denmark, Finland and Sweden. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e55176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055176.

5. Young SL, Taylor M, Lawrie SM. “First do no harm.” A systematic review of the prevalence and management of antipsychotic adverse effects. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29(4):353-362.

6. Baig MR, Navaira E, Escamilla MA, et al. Clozapine treatment causes oxidation of proteins involved in energy metabolism in lymphoblastoid cells: a possible mechanism for antipsychotic-induced metabolic alterations. J Psychiatr Pract. 2010;16(5):325-333.

7. Schrauwen P, Schrauwen-Hinderling V, Hoeks J, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and lipotoxicity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801(3):266-271.

8. Watanabe J, Suzuki Y, Someya T. Lipid effects of psychiatric medications. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2013;15(1):292.

9. Liao HH, Chang CS, Wei WC, et al. Schizophrenia patients at higher risk of diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidemia: a population-based study. Schizophr Res. 2011;126(1-3):110-116.

10. Lidenmayer JP, Czobor P, Volavka J, et al. Changes in glucose and cholesterol levels in patients with schizophrenia treated with typical or atypical antipsychotics. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(2):290-296.

11. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Corey-Lisle P, et al. Hyperlipidemia following treatment with antipsychotic medications. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(10):1821-1825.

12. American Diabetes Association; American Psychiatric Association; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, et al. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):596-601.

13. De Hert M, Yu W, Detraux J, et al. Body weight and metabolic adverse effects of asenapine, iloperidone, lurasidone, and paliperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. CNS Drugs. 2012;26(9):733-759.

14. Kemp DE, Zhao J, Cazorla P, et al. Weight change and metabolic effects of asenapine in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiary. 2014;75(3):238-245.

15. Cutler AJ, Kalali AH, Weiden PJ, et al. Four-week, double-blind, placebo-and ziprasidone-controlled trial of iloperidone in patients with acute exacerbations of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(2 suppl 1):S20-S28.

16. Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S1-S45.

17. Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S49-S72.

18. National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106(25):3143-3421.

19. Ioannidis JP. More than a billion people taking statins? Potential implications of the new cardiovascular guidelines. JAMA. 2014;311(5):463-464.

20. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management: the NICE Guideline on Treatment and Management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178/evidence/full-guideline-490503565. Published 2014. Accessed June 8, 2016.

21. Zeier K, Connell R, Resch W, et al. Recommendations for lab monitoring of atypical antipsychotics. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(9):51-54.

1. O’Neill S, O’Driscoll L. Metabolic syndrome: a closer look at the growing epidemic and its associated pathologies. Obes Rev. 2015;16(1):1-12.

2. McCreadie RG; Scottish Schizophrenia Lifestyle Group. Diet, smoking and cardiovascular risk in people with schizophrenia: descriptive study. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:534-539.

3. Correll CU, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Cardiometabolic risk in patients with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders: baseline results from the RAISE-ETP Study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;7(12):1350-1363.

4. Nordentoft M, Wahlbeck K, Hällgren J, et al. Excess mortality, causes of death and life expectancy in 270,770 patients with recent onset of mental disorders in Denmark, Finland and Sweden. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e55176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055176.

5. Young SL, Taylor M, Lawrie SM. “First do no harm.” A systematic review of the prevalence and management of antipsychotic adverse effects. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29(4):353-362.

6. Baig MR, Navaira E, Escamilla MA, et al. Clozapine treatment causes oxidation of proteins involved in energy metabolism in lymphoblastoid cells: a possible mechanism for antipsychotic-induced metabolic alterations. J Psychiatr Pract. 2010;16(5):325-333.

7. Schrauwen P, Schrauwen-Hinderling V, Hoeks J, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and lipotoxicity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801(3):266-271.

8. Watanabe J, Suzuki Y, Someya T. Lipid effects of psychiatric medications. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2013;15(1):292.

9. Liao HH, Chang CS, Wei WC, et al. Schizophrenia patients at higher risk of diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidemia: a population-based study. Schizophr Res. 2011;126(1-3):110-116.

10. Lidenmayer JP, Czobor P, Volavka J, et al. Changes in glucose and cholesterol levels in patients with schizophrenia treated with typical or atypical antipsychotics. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(2):290-296.

11. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Corey-Lisle P, et al. Hyperlipidemia following treatment with antipsychotic medications. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(10):1821-1825.

12. American Diabetes Association; American Psychiatric Association; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, et al. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):596-601.

13. De Hert M, Yu W, Detraux J, et al. Body weight and metabolic adverse effects of asenapine, iloperidone, lurasidone, and paliperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. CNS Drugs. 2012;26(9):733-759.

14. Kemp DE, Zhao J, Cazorla P, et al. Weight change and metabolic effects of asenapine in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiary. 2014;75(3):238-245.

15. Cutler AJ, Kalali AH, Weiden PJ, et al. Four-week, double-blind, placebo-and ziprasidone-controlled trial of iloperidone in patients with acute exacerbations of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(2 suppl 1):S20-S28.

16. Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S1-S45.

17. Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S49-S72.

18. National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106(25):3143-3421.

19. Ioannidis JP. More than a billion people taking statins? Potential implications of the new cardiovascular guidelines. JAMA. 2014;311(5):463-464.

20. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management: the NICE Guideline on Treatment and Management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178/evidence/full-guideline-490503565. Published 2014. Accessed June 8, 2016.

21. Zeier K, Connell R, Resch W, et al. Recommendations for lab monitoring of atypical antipsychotics. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(9):51-54.

How to talk to patients and families about brain stimulation

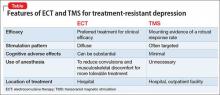

Brain stimulation often is used for treatment-resistant depression when medications and psychotherapy are not enough to elicit a meaningful response. It is both old and new again: electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been used for decades, while emerging technologies, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), are gaining acceptance.

Patients and families often arrive at the office with fears and assumptions about these types of treatments, which should be discussed openly. There are also differences between these treatment approaches that can be discussed (Table).

Electroconvulsive therapy

Although ECT has been shown to be the most efficacious treatment for treatment-resistant depression,1 the most common response from patients and families that I hear when discussing ECT use is, “Do you really still do that?” Many patients and family members associate this treatment with mass media portrayals over the past several decades, such as the motion picture One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, which paired inhumane and unnecessary use of ECT with a frontal lobotomy, thereby associating this treatment with something inherently unethical.

My approach to discussing ECT with patients and families is to convey these main points:

- Consensual. In most cases, ECT is performed with the explicit informed consent of the patient, and is not done against the patient’s will.

- Effective. ECT has a remission rate of 75% after the first 2 weeks of use in patients suffering from acute depressive illnesses.2

- Safe. ECT protocols have evolved to maximize efficacy while minimizing adverse effects. Advances in anesthesia use with paralytic agents and anti-inflammatory medications reduce convulsions and subsequent musculoskeletal discomfort.

In addition, I note that:

- Ultra-brief stimulation parameters often are used to minimize cognitive side effects.

- ECT is associated with some psychosocial limitations, including being unable to drive during acute treatment and requiring supervision for several hours after sessions.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

The field of non-invasive brain stimulation—in particular, TMS—faces a different set of complex issues to navigate. Because TMS is relatively new (approved by the FDA in 2008 for treatment-resistant depression),3 patients and families might believe that TMS may be more effective than ECT, which has not been demonstrated.4 It is important to communicate that:

- Although TMS is a FDA-approved treatment that has helped many patients with treatment-resistant depression, ECT remains the clinical treatment of choice for severe depression.

- Among antidepressant non-responders who had stopped all other antidepressant treatment, 44% of those who received deep TMS responded to treatment after 16 weeks, compared with 26% who received sham treatment.5

- Most patients usually require TMS for 4 to 6 weeks, 5 days a week, before beginning a taper phase.

- TMS has few side effects (headache being the most common); serious adverse effects (seizures, mania) have been reported but are rare.3

- Patients usually are able to continue their daily life and other outpatient treatments without the restrictions often placed on patients receiving ECT.

- If the patient responded to ECT in the past but could not tolerate adverse cognitive effects, TMS might be a better choice than other treatments.

1. Pagnin D, de Queiroz V, Pini S, et al. Efficacy of ECT in depression: a meta-analytic review. J ECT. 2004;20(1):13-20.

2. Husain MM, Rush AJ, Fink M, et al. Speed of response and remission in major depressive disorder with acute electroconvulsive therapy (ECT): a Consortium for Research in ECT (CORE) report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(4):485-491.

3. Stern AP, Cohen D. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuropsychiatry. 2013;3(1):107-115.

4. Micallef-Trigona B. Comparing the effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and electroconvulsive therapy in the treatment of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Res Treat. 2014;2014:135049. doi: 10.1155/2014/135049.

5. Levkovitz Y, Isserles M, Padberg F. Efficacy and safety of deep transcranial magnetic stimulation for major depression: a prospective, multi-center, randomized, controlled trial. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):64-73.

Brain stimulation often is used for treatment-resistant depression when medications and psychotherapy are not enough to elicit a meaningful response. It is both old and new again: electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been used for decades, while emerging technologies, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), are gaining acceptance.

Patients and families often arrive at the office with fears and assumptions about these types of treatments, which should be discussed openly. There are also differences between these treatment approaches that can be discussed (Table).

Electroconvulsive therapy

Although ECT has been shown to be the most efficacious treatment for treatment-resistant depression,1 the most common response from patients and families that I hear when discussing ECT use is, “Do you really still do that?” Many patients and family members associate this treatment with mass media portrayals over the past several decades, such as the motion picture One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, which paired inhumane and unnecessary use of ECT with a frontal lobotomy, thereby associating this treatment with something inherently unethical.

My approach to discussing ECT with patients and families is to convey these main points:

- Consensual. In most cases, ECT is performed with the explicit informed consent of the patient, and is not done against the patient’s will.

- Effective. ECT has a remission rate of 75% after the first 2 weeks of use in patients suffering from acute depressive illnesses.2

- Safe. ECT protocols have evolved to maximize efficacy while minimizing adverse effects. Advances in anesthesia use with paralytic agents and anti-inflammatory medications reduce convulsions and subsequent musculoskeletal discomfort.

In addition, I note that:

- Ultra-brief stimulation parameters often are used to minimize cognitive side effects.

- ECT is associated with some psychosocial limitations, including being unable to drive during acute treatment and requiring supervision for several hours after sessions.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

The field of non-invasive brain stimulation—in particular, TMS—faces a different set of complex issues to navigate. Because TMS is relatively new (approved by the FDA in 2008 for treatment-resistant depression),3 patients and families might believe that TMS may be more effective than ECT, which has not been demonstrated.4 It is important to communicate that:

- Although TMS is a FDA-approved treatment that has helped many patients with treatment-resistant depression, ECT remains the clinical treatment of choice for severe depression.

- Among antidepressant non-responders who had stopped all other antidepressant treatment, 44% of those who received deep TMS responded to treatment after 16 weeks, compared with 26% who received sham treatment.5

- Most patients usually require TMS for 4 to 6 weeks, 5 days a week, before beginning a taper phase.

- TMS has few side effects (headache being the most common); serious adverse effects (seizures, mania) have been reported but are rare.3

- Patients usually are able to continue their daily life and other outpatient treatments without the restrictions often placed on patients receiving ECT.

- If the patient responded to ECT in the past but could not tolerate adverse cognitive effects, TMS might be a better choice than other treatments.

Brain stimulation often is used for treatment-resistant depression when medications and psychotherapy are not enough to elicit a meaningful response. It is both old and new again: electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been used for decades, while emerging technologies, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), are gaining acceptance.

Patients and families often arrive at the office with fears and assumptions about these types of treatments, which should be discussed openly. There are also differences between these treatment approaches that can be discussed (Table).

Electroconvulsive therapy

Although ECT has been shown to be the most efficacious treatment for treatment-resistant depression,1 the most common response from patients and families that I hear when discussing ECT use is, “Do you really still do that?” Many patients and family members associate this treatment with mass media portrayals over the past several decades, such as the motion picture One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, which paired inhumane and unnecessary use of ECT with a frontal lobotomy, thereby associating this treatment with something inherently unethical.

My approach to discussing ECT with patients and families is to convey these main points:

- Consensual. In most cases, ECT is performed with the explicit informed consent of the patient, and is not done against the patient’s will.

- Effective. ECT has a remission rate of 75% after the first 2 weeks of use in patients suffering from acute depressive illnesses.2

- Safe. ECT protocols have evolved to maximize efficacy while minimizing adverse effects. Advances in anesthesia use with paralytic agents and anti-inflammatory medications reduce convulsions and subsequent musculoskeletal discomfort.

In addition, I note that:

- Ultra-brief stimulation parameters often are used to minimize cognitive side effects.

- ECT is associated with some psychosocial limitations, including being unable to drive during acute treatment and requiring supervision for several hours after sessions.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

The field of non-invasive brain stimulation—in particular, TMS—faces a different set of complex issues to navigate. Because TMS is relatively new (approved by the FDA in 2008 for treatment-resistant depression),3 patients and families might believe that TMS may be more effective than ECT, which has not been demonstrated.4 It is important to communicate that:

- Although TMS is a FDA-approved treatment that has helped many patients with treatment-resistant depression, ECT remains the clinical treatment of choice for severe depression.

- Among antidepressant non-responders who had stopped all other antidepressant treatment, 44% of those who received deep TMS responded to treatment after 16 weeks, compared with 26% who received sham treatment.5

- Most patients usually require TMS for 4 to 6 weeks, 5 days a week, before beginning a taper phase.

- TMS has few side effects (headache being the most common); serious adverse effects (seizures, mania) have been reported but are rare.3

- Patients usually are able to continue their daily life and other outpatient treatments without the restrictions often placed on patients receiving ECT.

- If the patient responded to ECT in the past but could not tolerate adverse cognitive effects, TMS might be a better choice than other treatments.

1. Pagnin D, de Queiroz V, Pini S, et al. Efficacy of ECT in depression: a meta-analytic review. J ECT. 2004;20(1):13-20.

2. Husain MM, Rush AJ, Fink M, et al. Speed of response and remission in major depressive disorder with acute electroconvulsive therapy (ECT): a Consortium for Research in ECT (CORE) report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(4):485-491.

3. Stern AP, Cohen D. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuropsychiatry. 2013;3(1):107-115.

4. Micallef-Trigona B. Comparing the effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and electroconvulsive therapy in the treatment of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Res Treat. 2014;2014:135049. doi: 10.1155/2014/135049.

5. Levkovitz Y, Isserles M, Padberg F. Efficacy and safety of deep transcranial magnetic stimulation for major depression: a prospective, multi-center, randomized, controlled trial. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):64-73.

1. Pagnin D, de Queiroz V, Pini S, et al. Efficacy of ECT in depression: a meta-analytic review. J ECT. 2004;20(1):13-20.

2. Husain MM, Rush AJ, Fink M, et al. Speed of response and remission in major depressive disorder with acute electroconvulsive therapy (ECT): a Consortium for Research in ECT (CORE) report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(4):485-491.

3. Stern AP, Cohen D. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuropsychiatry. 2013;3(1):107-115.

4. Micallef-Trigona B. Comparing the effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and electroconvulsive therapy in the treatment of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Res Treat. 2014;2014:135049. doi: 10.1155/2014/135049.

5. Levkovitz Y, Isserles M, Padberg F. Efficacy and safety of deep transcranial magnetic stimulation for major depression: a prospective, multi-center, randomized, controlled trial. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):64-73.

Rediscovering clozapine: After a turbulent history, current guidance on initiating and monitoring

Although clozapine is the medication with the clearest benefits in treatment-resistant schizophrenia, many eligible patients never receive it. In the United States, 20% to 30% of patients with schizophrenia can be classified as treatment resistant, but clozapine accounts for <5% of antipsychotics prescribed.1,2 Clinicians worldwide tend to under-prescribe clozapine3—a reluctance one author coined as “clozaphobia.”4

Admittedly, clozapine has had a turbulent history—both lauded as a near-miracle drug and condemned as a deadly agent. The FDA has overhauled its prescribing and monitoring guidelines, however, offering psychiatrists a perfect opportunity to reacquaint themselves with this potentially life-changing intervention.

We begin this article with clozapine’s story, then spotlight new terrain the FDA created in 2015 when the agency introduced the Clozapine Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS). Our goal in the 3 articles of this series is to deepen your appreciation for this tricyclic antipsychotic and provide practical clinical guidance for using it safely and effectively.

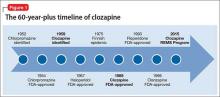

Setbacks, but the drug has an enduring presenceThe 1950s was an exciting era of exploration for new psychotropic medications. While searching for tricyclic antidepressants, Wander Laboratories discovered neuroleptic tricyclics, with clozapine identified in 1959 (Figure 1). Haloperidol’s development and release in the 1960s reinforced the prevailing dogma of the time that effective neuroleptics correlated with extrapyramidal symptoms, thus limiting interest in the newly discovered, but pharmacologically unique, clozapine. Throughout the 1960s, most research on clozapine was published in German, with less of an international presence.5

Agranulocytosis deaths. Clozapine earned its scarlet letter in 1975, when 8 patients in Finland died of agranulocytosis.6 Sandoz, its manufacturer, withdrew clozapine from the market and halted all clinical trials. The Finnish epidemic triggered detailed investigations into blood dyscrasias and early identification of agranulocytosis associated with clozapine and other antipsychotics.7

Clozapine endured only because of its unique efficacy. When psychiatrists witnessed relapses in patients who had to discontinue clozapine, some countries allowed its use with strict monitoring.5 The FDA kept clozapine minimally available in the United States by allowing so-called “compassionate need programs” to continue.7

New data, FDA approval. Two studies in 1987 and 1988 that compared clozapine with chlorpromazine for treatment-refractory schizophrenia demonstrated clozapine’s superior effect on both negative and positive symptoms.8,9 The FDA approved clozapine for refractory schizophrenia in 1989, and clozapine became clinically available in 1990.

Initially, the high annual cost of clozapine’s required “bundle” ($8,900 per patient for medication and monitoring) led to political outcry. As patients and their family struggled to afford the newly released medication, multiple states filed antitrust lawsuits. A federal court found both the manufacturer and individual states at fault and required expanded access to clozapine and its necessary monitoring. National clozapine registries were formed, and bundling was eliminated.7

The clozapine REMS programSix clozapine registries operated independently, each managed by a different manufacturer,10 until the FDA introduced REMS in September 2015. The REMS program created a centralized registry to monitor all U.S. patients treated with clozapine and made important changes to prescribing and monitoring guidelines.11,12 It also incorporated the National Non-Rechallenge Master File (NNRMF).

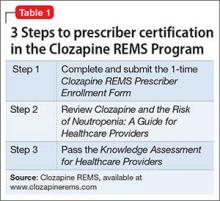

Initially, the REMS program was scheduled for rollout October 12, 2015, the closing date of the 6 registries. Since November 2015, pharmacies have been required to register with the program to dispense clozapine. A similar registration deadline for clozapine prescribers was extended indefinitely, however, because of technical problems. Once the deadline is finalized, all clozapine prescribers must complete 3 steps to be certified in the REMS program (Table 1).11

New requirements. Certified clozapine prescribers will have new responsibilities: enrolling patients and submitting lab results. They can designate someone else to perform these tasks on their behalf, but designees must enroll in the REMS program and the prescriber must confirm the designee. Pharmacists can no longer enroll patients for clozapine therapy unless they are confirmed as a prescriber designee. For outpatients, the absolute neutrophil count (ANC) must be reported before the pharmacy can dispense clozapine. For inpatients, the ANC must be reported within 7 days of the patient’s most recent blood draw.

Once the system is fully operational, Social Security numbers will no longer be used as patient identification for dispensing clozapine. Instead, outpatient pharmacies will obtain a predispense authorization, or PDA, from the REMS program. A person initiated on clozapine as an inpatient must be re-enrolled after discharge by their outpatient prescriber.

The REMS program includes information about clozapine patients who were maintained through the 6 registries, and these patients have been allowed to continue clozapine treatment. Data pertaining to patients last prescribed clozapine before October 1, 2012, did not transfer into the new system unless their name was on the NNRMF.

CASE

Is Mr. A a candidate for clozapine?Age 28, with schizophrenia, Mr. A is highly disorganized and psychotic when brought to the emergency room by police for inappropriate behavior. His family arrives and reports that similar events have occurred several times over the past few years. Mr. A’s outpatient psychiatrist has prescribed 3 different antipsychotic medications at adequate dosages, including 1 long-acting injectable, but Mr. A has remained consistently symptomatic.

Although disorganized and psychotic, Mr. A does not meet criteria for long-term involuntary hospitalization. His family wants to take him home, and the treatment team discusses clozapine as an antipsychotic option. Mr. A and his family agree to a trial of clozapine during voluntary hospitalization, but they would like him home within a week to attend his sister’s birthday party.

The treatment team decides to initiate clozapine and monitor his response in a controlled setting for a few days before transitioning him to outpatient care.

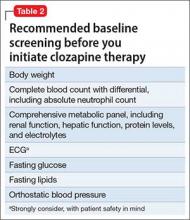

Initiating clozapine therapyThe case of Mr. A exemplifies a situation in which initiating clozapine is a reasonable clinical consideration. As the first step, we recommend checking baseline lab values and vital signs (Table 2), keeping in mind that the REMS program requires a baseline ANC within 7 days of initiating clozapine. When working with a highly disorganized or agitated patient, balance benefits of testing against the risk of harm to staff and patient.

REMS guidelines recommend a baseline ANC ≥1,500/µL for a new patient starting clozapine, except when benign ethnic neutropenia (BEN) has been confirmed. (Initiation guidelines for BEN are discussed later in this article.)

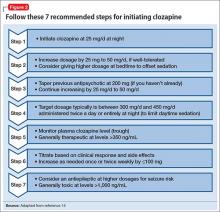

Dosing alternatives. We recommend following the manufacturer’s dosing guidelines when initiating clozapine (Figure 2).13,14 Three oral forms are available: tablet, disintegrating tablet, and suspension. All can be titrated using the schedule suggested with tablets. The disintegrating tablets or suspension might be beneficial for a patient with either:

- a history of “cheeking” or otherwise disposing of tablets

- a medical condition that affects swallowing or absorption.

The disintegrating tablet is available in 12.5-mg, 25-mg, 100-mg, 150-mg, and 200-mg doses. It dissolves without requiring additional liquids. Each mL of the suspension contains 50 mg of clozapine.

Rapid titration? One group, working in Romania, examined the safety and efficacy of rapid titration of clozapine in 111 inpatients with schizophrenia.15 In the absence of additional studies, we do not recommend routine rapid titration of clozapine.

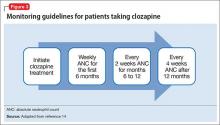

Monitoring: Greater flexibilityUnder the REMS program, laboratory monitoring of clozapine treatment must continue indefinitely. If not, pharmacies cannot dispense clozapine. Fortunately, the ANC is the only lab value tracked by the registry, and the frequency of required blood draws decreases over time (Figure 3).

Other guideline changes provide clinicians with greater flexibility to make patient-specific treatment decisions; for example, the allowable ANC to continue clozapine therapy has decreased. Usually, clozapine therapy should be interrupted for an ANC <1,000/µL if the prescriber suspects clozapine-induced neutropenia. Even when the ANC drops below 1,000/µL, however, prescribers can now continue clozapine treatment if they consider the benefits to outweigh risks for a given patient.

Separate guidelines now exist for patients with BEN, most commonly observed in persons of certain ethnic groups. BEN typically is diagnosed based on repeated ANC values <1,500/µL over several months. Patients with BEN do not have an increased risk of oral or systemic infections, as occur with other congenital neutropenias.16 In patients with BEN, clozapine therapy:

- can be initiated only after at least 2 baseline ANC measurements ≥1,000/µL

- should be interrupted for an ANC <500/µL if the prescriber suspects clozapine-induced neutropenia.

Substantial drops in ANC no longer require action (repeat lab draws) unless the drop causes neutropenia. Prescribers will receive an automated notification any time a patient experiences neutropenia that is considered mild (ANC 1,000 to 1,499/µL), moderate (ANC 500 to 999/µL), or severe (ANC <500/µL).

The NNRMF list is no longer definitive. All patients are now eligible for rechallenge, assuming they meet the new clozapine initiation criteria.