User login

Formerly Skin & Allergy News

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')]

The leading independent newspaper covering dermatology news and commentary.

RAP device being investigated as a way to improve appearance of cellulite

.

“The procedure is relatively painless, without anesthesia and can easily be delegated with physician oversight,” Mathew M. Avram, MD, JD, said during the virtual annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “Side effects have been minimal and transient to date. There is no down time.”

According to Dr. Avram, director of laser, cosmetics, and dermatologic surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, the RAP device emits rapid acoustic pulses (shock waves) that are transmitted through the skin to rupture or “shear” the fibrotic septa. This causes the release of septa, which results in a smoothening of skin dimples.

“Basically, what you have is a repetition rate and very short rise time that provide microscopic mechanical disruption to the targeted cellular level structures and vacuoles,” Dr. Avram explained. “There’s a high leak pressure and fast repetition rate that exploits the viscoelastic nature of the tissue. You get compressed pulses from electronic filtering and the reflector shape eliminates cavitation, heat, and pain.”

The procedure takes 20-30 minutes to perform and it generates minimal heat and pain, “which is an advantage of the treatment,” he said. “It is completely noninvasive, with no incision whatsoever. No anesthetic is required. There can be physician oversight of delivery, so it is delegable, and there is no recovery time. More study is needed, and we need to stay tuned.”

Dr. Avram disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Allergan, Merz, Sciton, and Soliton. He also reported having ownership and/or shareholder interest in Cytrellis.

.

“The procedure is relatively painless, without anesthesia and can easily be delegated with physician oversight,” Mathew M. Avram, MD, JD, said during the virtual annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “Side effects have been minimal and transient to date. There is no down time.”

According to Dr. Avram, director of laser, cosmetics, and dermatologic surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, the RAP device emits rapid acoustic pulses (shock waves) that are transmitted through the skin to rupture or “shear” the fibrotic septa. This causes the release of septa, which results in a smoothening of skin dimples.

“Basically, what you have is a repetition rate and very short rise time that provide microscopic mechanical disruption to the targeted cellular level structures and vacuoles,” Dr. Avram explained. “There’s a high leak pressure and fast repetition rate that exploits the viscoelastic nature of the tissue. You get compressed pulses from electronic filtering and the reflector shape eliminates cavitation, heat, and pain.”

The procedure takes 20-30 minutes to perform and it generates minimal heat and pain, “which is an advantage of the treatment,” he said. “It is completely noninvasive, with no incision whatsoever. No anesthetic is required. There can be physician oversight of delivery, so it is delegable, and there is no recovery time. More study is needed, and we need to stay tuned.”

Dr. Avram disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Allergan, Merz, Sciton, and Soliton. He also reported having ownership and/or shareholder interest in Cytrellis.

.

“The procedure is relatively painless, without anesthesia and can easily be delegated with physician oversight,” Mathew M. Avram, MD, JD, said during the virtual annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “Side effects have been minimal and transient to date. There is no down time.”

According to Dr. Avram, director of laser, cosmetics, and dermatologic surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, the RAP device emits rapid acoustic pulses (shock waves) that are transmitted through the skin to rupture or “shear” the fibrotic septa. This causes the release of septa, which results in a smoothening of skin dimples.

“Basically, what you have is a repetition rate and very short rise time that provide microscopic mechanical disruption to the targeted cellular level structures and vacuoles,” Dr. Avram explained. “There’s a high leak pressure and fast repetition rate that exploits the viscoelastic nature of the tissue. You get compressed pulses from electronic filtering and the reflector shape eliminates cavitation, heat, and pain.”

The procedure takes 20-30 minutes to perform and it generates minimal heat and pain, “which is an advantage of the treatment,” he said. “It is completely noninvasive, with no incision whatsoever. No anesthetic is required. There can be physician oversight of delivery, so it is delegable, and there is no recovery time. More study is needed, and we need to stay tuned.”

Dr. Avram disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Allergan, Merz, Sciton, and Soliton. He also reported having ownership and/or shareholder interest in Cytrellis.

FROM MOA 2020

Tough to tell COVID from smoke inhalation symptoms — And flu season’s coming

The patients walk into Dr. Melissa Marshall’s community clinics in Northern California with the telltale symptoms. They’re having trouble breathing. It may even hurt to inhale. They’ve got a cough, and the sore throat is definitely there.

A straight case of COVID-19? Not so fast. This is wildfire country.

Up and down the West Coast, hospitals and health facilities are reporting an influx of patients with problems most likely related to smoke inhalation. As fires rage largely uncontrolled amid dry heat and high winds, smoke and ash are billowing and settling on coastal areas like San Francisco and cities and towns hundreds of miles inland as well, turning the sky orange or gray and making even ordinary breathing difficult.

But that, Marshall said, is only part of the challenge.

“Obviously, there’s overlap in the symptoms,” said Marshall, the CEO of CommuniCare, a collection of six clinics in Yolo County, near Sacramento, that treats mostly underinsured and uninsured patients. “Any time someone comes in with even some of those symptoms, we ask ourselves, ‘Is it COVID?’ At the end of the day, clinically speaking, I still want to rule out the virus.”

The protocol is to treat the symptoms, whatever their cause, while recommending that the patient quarantine until test results for the virus come back, she said.

It is a scene playing out in numerous hospitals. Administrators and physicians, finely attuned to COVID-19’s ability to spread quickly and wreak havoc, simply won’t take a chance when they recognize symptoms that could emanate from the virus.

“We’ve seen an increase in patients presenting to the emergency department with respiratory distress,” said Dr. Nanette Mickiewicz, president and CEO of Dominican Hospital in Santa Cruz. “As this can also be a symptom of COVID-19, we’re treating these patients as we would any person under investigation for coronavirus until we can rule them out through our screening process.” During the workup, symptoms that are more specific to COVID-19, like fever, would become apparent.

For the workers at Dominican, the issue moved to the top of the list quickly. Santa Cruz and San Mateo counties have borne the brunt of the CZU Lightning Complex fires, which as of Sept. 10 had burned more than 86,000 acres, destroying 1,100 structures and threatening more than 7,600 others. Nearly a month after they began, the fires were approximately 84% contained, but thousands of people remained evacuated.

Dominican, a Dignity Health hospital, is “open, safe and providing care,” Mickiewicz said. Multiple tents erected outside the building serve as an extension of its ER waiting room. They also are used to perform what has come to be understood as an essential role: separating those with symptoms of COVID-19 from those without.

At the two Solano County hospitals operated by NorthBay Healthcare, the path of some of the wildfires prompted officials to review their evacuation procedures, said spokesperson Steve Huddleston. They ultimately avoided the need to evacuate patients, and new ones arrived with COVID-like symptoms that may actually have been from smoke inhalation.

Huddleston said NorthBay’s intake process “calls for anyone with COVID characteristics to be handled as [a] patient under investigation for COVID, which means they’re separated, screened and managed by staff in special PPE.” At the two hospitals, which have handled nearly 200 COVID cases so far, the protocol is well established.

Hospitals in California, though not under siege in most cases, are dealing with multiple issues they might typically face only sporadically. In Napa County, Adventist Health St. Helena Hospital evacuated 51 patients on a single August night as a fire approached, moving them to 10 other facilities according to their needs and bed space. After a 10-day closure, the hospital was allowed to reopen as evacuation orders were lifted, the fire having been contained some distance away.

The wildfires are also taking a personal toll on health care workers. CommuniCare’s Marshall lost her family’s home in rural Winters, along with 20 acres of olive trees and other plantings that surrounded it, in the Aug. 19 fires that swept through Solano County.

“They called it a ‘firenado,’ ” Marshall said. An apparent confluence of three fires raged out of control, demolishing thousands of acres. With her family safely accounted for and temporary housing arranged by a friend, she returned to work. “Our clinics interact with a very vulnerable population,” she said, “and this is a critical time for them.”

While she pondered how her family would rebuild, the CEO was faced with another immediate crisis: the clinic’s shortage of supplies. Last month, CommuniCare got down to 19 COVID test kits on hand, and ran so low on swabs “that we were literally turning to our veterinary friends for reinforcements,” the doctor said. The clinic’s COVID test results, meanwhile, were taking nearly two weeks to be returned from an overwhelmed outside lab, rendering contact tracing almost useless.

Those situations have been addressed, at least temporarily, Marshall said. But although the West Coast is in the most dangerous time of year for wildfires, generally September to December, another complication for health providers lies on the horizon: flu season.

The Southern Hemisphere, whose influenza trends during our summer months typically predict what’s to come for the U.S., has had very little of the disease this year, presumably because of restricted travel, social distancing and face masks. But it’s too early to be sure what the U.S. flu season will entail.

“You can start to see some cases of the flu in late October,” said Marshall, “and the reality is that it’s going to carry a number of characteristics that could also be symptomatic of COVID. And nothing changes: You have to rule it out, just to eliminate the risk.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente. This KHN story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation.

The patients walk into Dr. Melissa Marshall’s community clinics in Northern California with the telltale symptoms. They’re having trouble breathing. It may even hurt to inhale. They’ve got a cough, and the sore throat is definitely there.

A straight case of COVID-19? Not so fast. This is wildfire country.

Up and down the West Coast, hospitals and health facilities are reporting an influx of patients with problems most likely related to smoke inhalation. As fires rage largely uncontrolled amid dry heat and high winds, smoke and ash are billowing and settling on coastal areas like San Francisco and cities and towns hundreds of miles inland as well, turning the sky orange or gray and making even ordinary breathing difficult.

But that, Marshall said, is only part of the challenge.

“Obviously, there’s overlap in the symptoms,” said Marshall, the CEO of CommuniCare, a collection of six clinics in Yolo County, near Sacramento, that treats mostly underinsured and uninsured patients. “Any time someone comes in with even some of those symptoms, we ask ourselves, ‘Is it COVID?’ At the end of the day, clinically speaking, I still want to rule out the virus.”

The protocol is to treat the symptoms, whatever their cause, while recommending that the patient quarantine until test results for the virus come back, she said.

It is a scene playing out in numerous hospitals. Administrators and physicians, finely attuned to COVID-19’s ability to spread quickly and wreak havoc, simply won’t take a chance when they recognize symptoms that could emanate from the virus.

“We’ve seen an increase in patients presenting to the emergency department with respiratory distress,” said Dr. Nanette Mickiewicz, president and CEO of Dominican Hospital in Santa Cruz. “As this can also be a symptom of COVID-19, we’re treating these patients as we would any person under investigation for coronavirus until we can rule them out through our screening process.” During the workup, symptoms that are more specific to COVID-19, like fever, would become apparent.

For the workers at Dominican, the issue moved to the top of the list quickly. Santa Cruz and San Mateo counties have borne the brunt of the CZU Lightning Complex fires, which as of Sept. 10 had burned more than 86,000 acres, destroying 1,100 structures and threatening more than 7,600 others. Nearly a month after they began, the fires were approximately 84% contained, but thousands of people remained evacuated.

Dominican, a Dignity Health hospital, is “open, safe and providing care,” Mickiewicz said. Multiple tents erected outside the building serve as an extension of its ER waiting room. They also are used to perform what has come to be understood as an essential role: separating those with symptoms of COVID-19 from those without.

At the two Solano County hospitals operated by NorthBay Healthcare, the path of some of the wildfires prompted officials to review their evacuation procedures, said spokesperson Steve Huddleston. They ultimately avoided the need to evacuate patients, and new ones arrived with COVID-like symptoms that may actually have been from smoke inhalation.

Huddleston said NorthBay’s intake process “calls for anyone with COVID characteristics to be handled as [a] patient under investigation for COVID, which means they’re separated, screened and managed by staff in special PPE.” At the two hospitals, which have handled nearly 200 COVID cases so far, the protocol is well established.

Hospitals in California, though not under siege in most cases, are dealing with multiple issues they might typically face only sporadically. In Napa County, Adventist Health St. Helena Hospital evacuated 51 patients on a single August night as a fire approached, moving them to 10 other facilities according to their needs and bed space. After a 10-day closure, the hospital was allowed to reopen as evacuation orders were lifted, the fire having been contained some distance away.

The wildfires are also taking a personal toll on health care workers. CommuniCare’s Marshall lost her family’s home in rural Winters, along with 20 acres of olive trees and other plantings that surrounded it, in the Aug. 19 fires that swept through Solano County.

“They called it a ‘firenado,’ ” Marshall said. An apparent confluence of three fires raged out of control, demolishing thousands of acres. With her family safely accounted for and temporary housing arranged by a friend, she returned to work. “Our clinics interact with a very vulnerable population,” she said, “and this is a critical time for them.”

While she pondered how her family would rebuild, the CEO was faced with another immediate crisis: the clinic’s shortage of supplies. Last month, CommuniCare got down to 19 COVID test kits on hand, and ran so low on swabs “that we were literally turning to our veterinary friends for reinforcements,” the doctor said. The clinic’s COVID test results, meanwhile, were taking nearly two weeks to be returned from an overwhelmed outside lab, rendering contact tracing almost useless.

Those situations have been addressed, at least temporarily, Marshall said. But although the West Coast is in the most dangerous time of year for wildfires, generally September to December, another complication for health providers lies on the horizon: flu season.

The Southern Hemisphere, whose influenza trends during our summer months typically predict what’s to come for the U.S., has had very little of the disease this year, presumably because of restricted travel, social distancing and face masks. But it’s too early to be sure what the U.S. flu season will entail.

“You can start to see some cases of the flu in late October,” said Marshall, “and the reality is that it’s going to carry a number of characteristics that could also be symptomatic of COVID. And nothing changes: You have to rule it out, just to eliminate the risk.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente. This KHN story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation.

The patients walk into Dr. Melissa Marshall’s community clinics in Northern California with the telltale symptoms. They’re having trouble breathing. It may even hurt to inhale. They’ve got a cough, and the sore throat is definitely there.

A straight case of COVID-19? Not so fast. This is wildfire country.

Up and down the West Coast, hospitals and health facilities are reporting an influx of patients with problems most likely related to smoke inhalation. As fires rage largely uncontrolled amid dry heat and high winds, smoke and ash are billowing and settling on coastal areas like San Francisco and cities and towns hundreds of miles inland as well, turning the sky orange or gray and making even ordinary breathing difficult.

But that, Marshall said, is only part of the challenge.

“Obviously, there’s overlap in the symptoms,” said Marshall, the CEO of CommuniCare, a collection of six clinics in Yolo County, near Sacramento, that treats mostly underinsured and uninsured patients. “Any time someone comes in with even some of those symptoms, we ask ourselves, ‘Is it COVID?’ At the end of the day, clinically speaking, I still want to rule out the virus.”

The protocol is to treat the symptoms, whatever their cause, while recommending that the patient quarantine until test results for the virus come back, she said.

It is a scene playing out in numerous hospitals. Administrators and physicians, finely attuned to COVID-19’s ability to spread quickly and wreak havoc, simply won’t take a chance when they recognize symptoms that could emanate from the virus.

“We’ve seen an increase in patients presenting to the emergency department with respiratory distress,” said Dr. Nanette Mickiewicz, president and CEO of Dominican Hospital in Santa Cruz. “As this can also be a symptom of COVID-19, we’re treating these patients as we would any person under investigation for coronavirus until we can rule them out through our screening process.” During the workup, symptoms that are more specific to COVID-19, like fever, would become apparent.

For the workers at Dominican, the issue moved to the top of the list quickly. Santa Cruz and San Mateo counties have borne the brunt of the CZU Lightning Complex fires, which as of Sept. 10 had burned more than 86,000 acres, destroying 1,100 structures and threatening more than 7,600 others. Nearly a month after they began, the fires were approximately 84% contained, but thousands of people remained evacuated.

Dominican, a Dignity Health hospital, is “open, safe and providing care,” Mickiewicz said. Multiple tents erected outside the building serve as an extension of its ER waiting room. They also are used to perform what has come to be understood as an essential role: separating those with symptoms of COVID-19 from those without.

At the two Solano County hospitals operated by NorthBay Healthcare, the path of some of the wildfires prompted officials to review their evacuation procedures, said spokesperson Steve Huddleston. They ultimately avoided the need to evacuate patients, and new ones arrived with COVID-like symptoms that may actually have been from smoke inhalation.

Huddleston said NorthBay’s intake process “calls for anyone with COVID characteristics to be handled as [a] patient under investigation for COVID, which means they’re separated, screened and managed by staff in special PPE.” At the two hospitals, which have handled nearly 200 COVID cases so far, the protocol is well established.

Hospitals in California, though not under siege in most cases, are dealing with multiple issues they might typically face only sporadically. In Napa County, Adventist Health St. Helena Hospital evacuated 51 patients on a single August night as a fire approached, moving them to 10 other facilities according to their needs and bed space. After a 10-day closure, the hospital was allowed to reopen as evacuation orders were lifted, the fire having been contained some distance away.

The wildfires are also taking a personal toll on health care workers. CommuniCare’s Marshall lost her family’s home in rural Winters, along with 20 acres of olive trees and other plantings that surrounded it, in the Aug. 19 fires that swept through Solano County.

“They called it a ‘firenado,’ ” Marshall said. An apparent confluence of three fires raged out of control, demolishing thousands of acres. With her family safely accounted for and temporary housing arranged by a friend, she returned to work. “Our clinics interact with a very vulnerable population,” she said, “and this is a critical time for them.”

While she pondered how her family would rebuild, the CEO was faced with another immediate crisis: the clinic’s shortage of supplies. Last month, CommuniCare got down to 19 COVID test kits on hand, and ran so low on swabs “that we were literally turning to our veterinary friends for reinforcements,” the doctor said. The clinic’s COVID test results, meanwhile, were taking nearly two weeks to be returned from an overwhelmed outside lab, rendering contact tracing almost useless.

Those situations have been addressed, at least temporarily, Marshall said. But although the West Coast is in the most dangerous time of year for wildfires, generally September to December, another complication for health providers lies on the horizon: flu season.

The Southern Hemisphere, whose influenza trends during our summer months typically predict what’s to come for the U.S., has had very little of the disease this year, presumably because of restricted travel, social distancing and face masks. But it’s too early to be sure what the U.S. flu season will entail.

“You can start to see some cases of the flu in late October,” said Marshall, “and the reality is that it’s going to carry a number of characteristics that could also be symptomatic of COVID. And nothing changes: You have to rule it out, just to eliminate the risk.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente. This KHN story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation.

COVID-19 outcomes no worse in patients on TNF inhibitors or methotrexate

Continued use of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors or methotrexate is acceptable in most patients who acquire COVID-19, results of a recent cohort study suggest.

Among patients on tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) or methotrexate who developed COVID-19, death and hospitalization rates were similar to matched COVID-19 patients not on those medications, according to authors of the multicenter research network study.

Reassuringly, likelihood of hospitalization and mortality were not significantly different between 214 patients with COVID-19 taking TNFi or methotrexate and 31,862 matched COVID-19 patients not on those medications, according to the investigators, whose findings were published recently in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Zachary Zinn, MD, corresponding author on the study, said in an interview that the findings suggest these medicines can be safely continued in the majority of patients taking them during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“If you’re a prescribing physician who’s giving patients TNF inhibitors or methotrexate or both, I think you can comfortably tell your patients there is good data that these do not lead to worse outcomes if you get COVID-19,” said Dr. Zinn, associate professor in the department of dermatology at West Virginia University, Morgantown.

The findings from these researchers corroborate a growing body of evidence suggesting that immunosuppressive treatments can be continued in patients with dermatologic and rheumatic conditions.

In recent guidance from the National Psoriasis Foundation, released Sept. 4, an expert consensus panel cited 15 studies that they said suggested that treatments for psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis “do not meaningfully alter the risk of acquiring SARS-CoV-2 infection or having worse COVID-19 outcomes.”

That said, the data to date are mainly from small case series and registry studies based on spontaneously reported COVID-19 cases, which suggests a continued need for shared decision making. In addition, chronic systemic corticosteroids should be avoided for management of psoriatic arthritis, the guidance states, based on rheumatology and gastroenterology literature suggesting this treatment is linked to worse COVID-19 outcomes.

In the interview, Dr. Zinn noted that some previous studies of immunosuppressive treatments in patients who acquire COVID-19 have aggregated data on numerous classes of biologic medications, lessening the strength of data for each specific medication.

“By focusing specifically on TNF inhibitors and methotrexate, this study gives better guidance to prescribers of these medications,” he said.

To see whether TNFi or methotrexate increased risk of worsened COVID-19 outcomes, Dr. Zinn and coinvestigators evaluated data from TriNetX, a research network that includes approximately 53 million unique patient records, predominantly in the United States.

They identified 32,076 adult patients with COVID-19, of whom 214 had recent exposure to TNFi or methotrexate. The patients in the TNFi/methotrexate group were similar in age to those without exposure to those drugs, at 55.1 versus 53.2 years, respectively. However, patients in the drug exposure group were more frequently White, female, and had substantially more comorbidities, including diabetes and obesity, according to the investigators.

Nevertheless, the likelihood of hospitalization was not statistically different in the TNFi/methotrexate group versus the non-TNFi/methotrexate group, with a risk ratio of 0.91 (95% confidence interval, 0.68-1.22; P = .5260).

Likewise, the likelihood of death was not different between groups, with a RR of 0.87 (95% CI, 0.42-1.78; P = .6958). Looking at subgroups of patients exposed to TNFi or methotrexate only didn’t change the results, the investigators added.

Taken together, the findings argue against interruption of these treatments because of the fear of the possibly worse COVID-19 outcomes, the investigators concluded, although they emphasized the need for more research.

“Because the COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing, there is a desperate need for evidence-based data on biologic and immunomodulator exposure in the setting of COVID-19 infection,” they wrote.

Dr. Zinn and coauthors reported no conflicts of interest and no funding sources related to the study.

SOURCE: Zinn Z et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Sep 11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.009.

Continued use of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors or methotrexate is acceptable in most patients who acquire COVID-19, results of a recent cohort study suggest.

Among patients on tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) or methotrexate who developed COVID-19, death and hospitalization rates were similar to matched COVID-19 patients not on those medications, according to authors of the multicenter research network study.

Reassuringly, likelihood of hospitalization and mortality were not significantly different between 214 patients with COVID-19 taking TNFi or methotrexate and 31,862 matched COVID-19 patients not on those medications, according to the investigators, whose findings were published recently in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Zachary Zinn, MD, corresponding author on the study, said in an interview that the findings suggest these medicines can be safely continued in the majority of patients taking them during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“If you’re a prescribing physician who’s giving patients TNF inhibitors or methotrexate or both, I think you can comfortably tell your patients there is good data that these do not lead to worse outcomes if you get COVID-19,” said Dr. Zinn, associate professor in the department of dermatology at West Virginia University, Morgantown.

The findings from these researchers corroborate a growing body of evidence suggesting that immunosuppressive treatments can be continued in patients with dermatologic and rheumatic conditions.

In recent guidance from the National Psoriasis Foundation, released Sept. 4, an expert consensus panel cited 15 studies that they said suggested that treatments for psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis “do not meaningfully alter the risk of acquiring SARS-CoV-2 infection or having worse COVID-19 outcomes.”

That said, the data to date are mainly from small case series and registry studies based on spontaneously reported COVID-19 cases, which suggests a continued need for shared decision making. In addition, chronic systemic corticosteroids should be avoided for management of psoriatic arthritis, the guidance states, based on rheumatology and gastroenterology literature suggesting this treatment is linked to worse COVID-19 outcomes.

In the interview, Dr. Zinn noted that some previous studies of immunosuppressive treatments in patients who acquire COVID-19 have aggregated data on numerous classes of biologic medications, lessening the strength of data for each specific medication.

“By focusing specifically on TNF inhibitors and methotrexate, this study gives better guidance to prescribers of these medications,” he said.

To see whether TNFi or methotrexate increased risk of worsened COVID-19 outcomes, Dr. Zinn and coinvestigators evaluated data from TriNetX, a research network that includes approximately 53 million unique patient records, predominantly in the United States.

They identified 32,076 adult patients with COVID-19, of whom 214 had recent exposure to TNFi or methotrexate. The patients in the TNFi/methotrexate group were similar in age to those without exposure to those drugs, at 55.1 versus 53.2 years, respectively. However, patients in the drug exposure group were more frequently White, female, and had substantially more comorbidities, including diabetes and obesity, according to the investigators.

Nevertheless, the likelihood of hospitalization was not statistically different in the TNFi/methotrexate group versus the non-TNFi/methotrexate group, with a risk ratio of 0.91 (95% confidence interval, 0.68-1.22; P = .5260).

Likewise, the likelihood of death was not different between groups, with a RR of 0.87 (95% CI, 0.42-1.78; P = .6958). Looking at subgroups of patients exposed to TNFi or methotrexate only didn’t change the results, the investigators added.

Taken together, the findings argue against interruption of these treatments because of the fear of the possibly worse COVID-19 outcomes, the investigators concluded, although they emphasized the need for more research.

“Because the COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing, there is a desperate need for evidence-based data on biologic and immunomodulator exposure in the setting of COVID-19 infection,” they wrote.

Dr. Zinn and coauthors reported no conflicts of interest and no funding sources related to the study.

SOURCE: Zinn Z et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Sep 11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.009.

Continued use of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors or methotrexate is acceptable in most patients who acquire COVID-19, results of a recent cohort study suggest.

Among patients on tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) or methotrexate who developed COVID-19, death and hospitalization rates were similar to matched COVID-19 patients not on those medications, according to authors of the multicenter research network study.

Reassuringly, likelihood of hospitalization and mortality were not significantly different between 214 patients with COVID-19 taking TNFi or methotrexate and 31,862 matched COVID-19 patients not on those medications, according to the investigators, whose findings were published recently in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Zachary Zinn, MD, corresponding author on the study, said in an interview that the findings suggest these medicines can be safely continued in the majority of patients taking them during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“If you’re a prescribing physician who’s giving patients TNF inhibitors or methotrexate or both, I think you can comfortably tell your patients there is good data that these do not lead to worse outcomes if you get COVID-19,” said Dr. Zinn, associate professor in the department of dermatology at West Virginia University, Morgantown.

The findings from these researchers corroborate a growing body of evidence suggesting that immunosuppressive treatments can be continued in patients with dermatologic and rheumatic conditions.

In recent guidance from the National Psoriasis Foundation, released Sept. 4, an expert consensus panel cited 15 studies that they said suggested that treatments for psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis “do not meaningfully alter the risk of acquiring SARS-CoV-2 infection or having worse COVID-19 outcomes.”

That said, the data to date are mainly from small case series and registry studies based on spontaneously reported COVID-19 cases, which suggests a continued need for shared decision making. In addition, chronic systemic corticosteroids should be avoided for management of psoriatic arthritis, the guidance states, based on rheumatology and gastroenterology literature suggesting this treatment is linked to worse COVID-19 outcomes.

In the interview, Dr. Zinn noted that some previous studies of immunosuppressive treatments in patients who acquire COVID-19 have aggregated data on numerous classes of biologic medications, lessening the strength of data for each specific medication.

“By focusing specifically on TNF inhibitors and methotrexate, this study gives better guidance to prescribers of these medications,” he said.

To see whether TNFi or methotrexate increased risk of worsened COVID-19 outcomes, Dr. Zinn and coinvestigators evaluated data from TriNetX, a research network that includes approximately 53 million unique patient records, predominantly in the United States.

They identified 32,076 adult patients with COVID-19, of whom 214 had recent exposure to TNFi or methotrexate. The patients in the TNFi/methotrexate group were similar in age to those without exposure to those drugs, at 55.1 versus 53.2 years, respectively. However, patients in the drug exposure group were more frequently White, female, and had substantially more comorbidities, including diabetes and obesity, according to the investigators.

Nevertheless, the likelihood of hospitalization was not statistically different in the TNFi/methotrexate group versus the non-TNFi/methotrexate group, with a risk ratio of 0.91 (95% confidence interval, 0.68-1.22; P = .5260).

Likewise, the likelihood of death was not different between groups, with a RR of 0.87 (95% CI, 0.42-1.78; P = .6958). Looking at subgroups of patients exposed to TNFi or methotrexate only didn’t change the results, the investigators added.

Taken together, the findings argue against interruption of these treatments because of the fear of the possibly worse COVID-19 outcomes, the investigators concluded, although they emphasized the need for more research.

“Because the COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing, there is a desperate need for evidence-based data on biologic and immunomodulator exposure in the setting of COVID-19 infection,” they wrote.

Dr. Zinn and coauthors reported no conflicts of interest and no funding sources related to the study.

SOURCE: Zinn Z et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Sep 11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.009.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Exorcising your ghosts

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected private medical practices on so many levels, not least of which is the loss of employees to illness, fear of illness, early retirement, and other reasons.

If you’re not hip to the slang, “ghosting” is the situation in which an employee disappears without any warning, notice, or explanation. It usually occurs after a candidate accepts a job offer, and you schedule their first day of work. That day dawns, but the new hire never arrives. Less commonly, an employee who has been with you for some time simply stops showing up and cannot be contacted.

Many employers think of ghosting as a relatively new phenomenon, and blame it on the irresponsibility of younger age groups – millennials, in particular. In fact, it has been an issue for many years across all age groups, and employers often share more of the responsibility than they think.

While total prevention is impossible, there are steps you can take as an employer to minimize ghosting in your practice.

- Your hiring process needs to be efficient. If you wait too long to schedule an interview with a promising candidate or to offer them the job, another job offer could lure them away. At the very least, a lengthy process or a lack of transparency may make the applicant apprehensive about accepting a job with you, particularly if other employers are pursuing them.

- Keep applicants in the loop. Follow up with every candidate; let them know where they are in your hiring process. Applicants who have no clue whether they have a shot at the job are going to start looking elsewhere. And make sure they know the job description and starting salary from the outset.

- Talk to new hires before their first day. Contact them personally to see if they have any questions or concerns, and let them know that you’re looking forward to their arrival.

- Once they start, make them feel welcome. An employee’s first few days on the job set the tone for the rest of the employment relationship. During this time, clearly communicate what the employee can expect from you and what you expect from them. Take time to discuss key issues, such as work schedules, timekeeping practices, how performance is measured, and dress codes. Introduce them to coworkers, and get them started shadowing more experienced staff members.

- Take a hard look at your supervision and your supervisors. Business people like to say that employees don’t quit their job, they quit their boss. If an employee quits – with or without notice – it may very well be because of a poor working relationship with you or the supervisor. To be effective, you and your supervisors need to be diligent in setting goals, managing performance, and applying workplace rules and policies. Numerous third-party companies provide training and guidance in these areas when needed.

- Recognize and reward. As I’ve written many times, positive feedback is a simple, low-cost way to improve employee retention. It demonstrates that you value an employee’s contributions and sets an excellent example for other employees. Effective recognition can come from anyone – including patients – and should be given openly. (Another old adage: “Praise publicly, criticize privately.”) It never hurts to catch an employee doing something right and acknowledge it.

- Don’t jump to conclusions. If a new hire or employee is absent without notice, don’t just assume you’ve been ghosted. There may be extenuating circumstances, such as an emergency or illness. In some states, an employee’s absence is protected under a law where the employee may not be required to provide advance notice, and taking adverse action could violate these laws. Establish procedures for attempting to contact absent employees, and make sure you’re complying with all applicable leave laws before taking any action.

If an employee does abandon their job, think before you act. Comply with all applicable laws. Act consistently with how you’ve handled similar situations in the past. Your attorney should be involved, especially if the decision involves termination. Notify the employee in writing. As with all employment decisions, keep adequate documentation in case the decision is ever challenged, or you need it to support future disciplinary decisions.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. He has no disclosures related to this column. Write to him at [email protected].

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected private medical practices on so many levels, not least of which is the loss of employees to illness, fear of illness, early retirement, and other reasons.

If you’re not hip to the slang, “ghosting” is the situation in which an employee disappears without any warning, notice, or explanation. It usually occurs after a candidate accepts a job offer, and you schedule their first day of work. That day dawns, but the new hire never arrives. Less commonly, an employee who has been with you for some time simply stops showing up and cannot be contacted.

Many employers think of ghosting as a relatively new phenomenon, and blame it on the irresponsibility of younger age groups – millennials, in particular. In fact, it has been an issue for many years across all age groups, and employers often share more of the responsibility than they think.

While total prevention is impossible, there are steps you can take as an employer to minimize ghosting in your practice.

- Your hiring process needs to be efficient. If you wait too long to schedule an interview with a promising candidate or to offer them the job, another job offer could lure them away. At the very least, a lengthy process or a lack of transparency may make the applicant apprehensive about accepting a job with you, particularly if other employers are pursuing them.

- Keep applicants in the loop. Follow up with every candidate; let them know where they are in your hiring process. Applicants who have no clue whether they have a shot at the job are going to start looking elsewhere. And make sure they know the job description and starting salary from the outset.

- Talk to new hires before their first day. Contact them personally to see if they have any questions or concerns, and let them know that you’re looking forward to their arrival.

- Once they start, make them feel welcome. An employee’s first few days on the job set the tone for the rest of the employment relationship. During this time, clearly communicate what the employee can expect from you and what you expect from them. Take time to discuss key issues, such as work schedules, timekeeping practices, how performance is measured, and dress codes. Introduce them to coworkers, and get them started shadowing more experienced staff members.

- Take a hard look at your supervision and your supervisors. Business people like to say that employees don’t quit their job, they quit their boss. If an employee quits – with or without notice – it may very well be because of a poor working relationship with you or the supervisor. To be effective, you and your supervisors need to be diligent in setting goals, managing performance, and applying workplace rules and policies. Numerous third-party companies provide training and guidance in these areas when needed.

- Recognize and reward. As I’ve written many times, positive feedback is a simple, low-cost way to improve employee retention. It demonstrates that you value an employee’s contributions and sets an excellent example for other employees. Effective recognition can come from anyone – including patients – and should be given openly. (Another old adage: “Praise publicly, criticize privately.”) It never hurts to catch an employee doing something right and acknowledge it.

- Don’t jump to conclusions. If a new hire or employee is absent without notice, don’t just assume you’ve been ghosted. There may be extenuating circumstances, such as an emergency or illness. In some states, an employee’s absence is protected under a law where the employee may not be required to provide advance notice, and taking adverse action could violate these laws. Establish procedures for attempting to contact absent employees, and make sure you’re complying with all applicable leave laws before taking any action.

If an employee does abandon their job, think before you act. Comply with all applicable laws. Act consistently with how you’ve handled similar situations in the past. Your attorney should be involved, especially if the decision involves termination. Notify the employee in writing. As with all employment decisions, keep adequate documentation in case the decision is ever challenged, or you need it to support future disciplinary decisions.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. He has no disclosures related to this column. Write to him at [email protected].

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected private medical practices on so many levels, not least of which is the loss of employees to illness, fear of illness, early retirement, and other reasons.

If you’re not hip to the slang, “ghosting” is the situation in which an employee disappears without any warning, notice, or explanation. It usually occurs after a candidate accepts a job offer, and you schedule their first day of work. That day dawns, but the new hire never arrives. Less commonly, an employee who has been with you for some time simply stops showing up and cannot be contacted.

Many employers think of ghosting as a relatively new phenomenon, and blame it on the irresponsibility of younger age groups – millennials, in particular. In fact, it has been an issue for many years across all age groups, and employers often share more of the responsibility than they think.

While total prevention is impossible, there are steps you can take as an employer to minimize ghosting in your practice.

- Your hiring process needs to be efficient. If you wait too long to schedule an interview with a promising candidate or to offer them the job, another job offer could lure them away. At the very least, a lengthy process or a lack of transparency may make the applicant apprehensive about accepting a job with you, particularly if other employers are pursuing them.

- Keep applicants in the loop. Follow up with every candidate; let them know where they are in your hiring process. Applicants who have no clue whether they have a shot at the job are going to start looking elsewhere. And make sure they know the job description and starting salary from the outset.

- Talk to new hires before their first day. Contact them personally to see if they have any questions or concerns, and let them know that you’re looking forward to their arrival.

- Once they start, make them feel welcome. An employee’s first few days on the job set the tone for the rest of the employment relationship. During this time, clearly communicate what the employee can expect from you and what you expect from them. Take time to discuss key issues, such as work schedules, timekeeping practices, how performance is measured, and dress codes. Introduce them to coworkers, and get them started shadowing more experienced staff members.

- Take a hard look at your supervision and your supervisors. Business people like to say that employees don’t quit their job, they quit their boss. If an employee quits – with or without notice – it may very well be because of a poor working relationship with you or the supervisor. To be effective, you and your supervisors need to be diligent in setting goals, managing performance, and applying workplace rules and policies. Numerous third-party companies provide training and guidance in these areas when needed.

- Recognize and reward. As I’ve written many times, positive feedback is a simple, low-cost way to improve employee retention. It demonstrates that you value an employee’s contributions and sets an excellent example for other employees. Effective recognition can come from anyone – including patients – and should be given openly. (Another old adage: “Praise publicly, criticize privately.”) It never hurts to catch an employee doing something right and acknowledge it.

- Don’t jump to conclusions. If a new hire or employee is absent without notice, don’t just assume you’ve been ghosted. There may be extenuating circumstances, such as an emergency or illness. In some states, an employee’s absence is protected under a law where the employee may not be required to provide advance notice, and taking adverse action could violate these laws. Establish procedures for attempting to contact absent employees, and make sure you’re complying with all applicable leave laws before taking any action.

If an employee does abandon their job, think before you act. Comply with all applicable laws. Act consistently with how you’ve handled similar situations in the past. Your attorney should be involved, especially if the decision involves termination. Notify the employee in writing. As with all employment decisions, keep adequate documentation in case the decision is ever challenged, or you need it to support future disciplinary decisions.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. He has no disclosures related to this column. Write to him at [email protected].

Physician income drops, burnout spikes globally in pandemic

according to the results of a Medscape survey.

More than 7,500 physicians – nearly 5,000 in the United States, and others in Brazil, France, Germany, Mexico, Portugal, Spain, and the United Kingdom – responded to questions about their struggles to save patients and how the pandemic has changed their income and their lives at home and at work.

The pain was evident in this response from an emergency medicine physician in Spain: “It has been the worst time in my life ever, in both my personal and professional life.”

Conversely, some reported positive effects.

An internist in Brazil wrote: “I feel more proud of my career than ever before.”

One quarter of U.S. physicians considering earlier retirement

Physicians in the United States were asked what career changes, if any, they were considering in light of their experience with COVID-19. Although a little more than half (51%) said they were not planning any changes, 25% answered, “retiring earlier than previously planned,” and 12% answered, “a career change away from medicine.”

The number of physicians reporting an income drop was highest in Brazil (63% reported a drop), followed by the United States (62%), Mexico (56%), Portugal (49%), Germany (42%), France (41%), and Spain (31%). The question was not asked in the United Kingdom survey.

In the United States, the size of the drop has been substantial: 9% lost 76%-100% of their income; 14% lost 51%-75%; 28% lost 26%-50%; 33% lost 11%-25%; and 15% lost 1%-10%.

The U.S. specialists with the largest drop in income were ophthalmologists, who lost 51%, followed by allergists (46%), plastic surgeons (46%), and otolaryngologists (45%).

“I’m looking for a new profession due to economic impact,” an otolaryngologist in the United States said. “We are at risk while essentially using our private savings to keep our practice solvent.”

More than half of U.S. physicians (54%) have personally treated patients with COVID-19. Percentages were higher in France, Spain, and the United Kingdom (percentages ranged from 60%-68%).

The United States led all eight countries in treating patients with COVID-19 via telemedicine, at 26%. Germany had the lowest telemedicine percentage, at 10%.

Burnout intensifies

About two thirds of US physicians (64%) said that burnout had intensified during the crisis (70% of female physicians and 61% of male physicians said it had).

Many factors are feeding the burnout.

A critical care physician in the United States responded, “It is terrible to see people arriving at their rooms and assuming they were going to die soon; to see people saying goodbye to their families before dying or before being intubated.”

In all eight countries, a substantial percentage of physicians reported they “sometimes, often or always” treated patients with COVID-19 without the proper personal protective equipment. Spain had by far the largest percentage who answered that way (67%), followed by France (45%), Mexico (40%), the United Kingdom (34%), Brazil and Germany (28% each); and the United States and Portugal (23% each).

A U.S. rheumatologist wrote: “The fact that we were sent to take care of infectious patients without proper protection equipment made me feel we were betrayed in this fight.”

Sense of duty to volunteer to treat COVID-19 patients varied substantially among countries, from 69% who felt that way in Spain to 40% in Brazil. Half (50%) in the United States felt that way.

“Altruism must take second place where a real and present threat exists to my own personal existence,” one U.S. internist wrote.

Numbers personally infected

One fifth of physicians in Spain and the United Kingdom had personally been infected with the virus. Brazil, France, and Mexico had the next highest numbers, with 13%-15% of physicians infected; 5%-6% in the United States, Germany, and Portugal said they had been infected.

The percentage of physicians who reported that immediate family members had been infected ranged from 25% in Spain to 6% in Portugal. Among US physicians, 9% reported that family members had been diagnosed with COVID-19.

In the United States, 44% of respondents who had family living with them at home during the pandemic reported that relationships at home were more stressed because of stay-at-home guidelines and social distancing. Almost half (47%) said there had been no change, and 9% said relationships were less stressed.

Eating is coping mechanism of choice

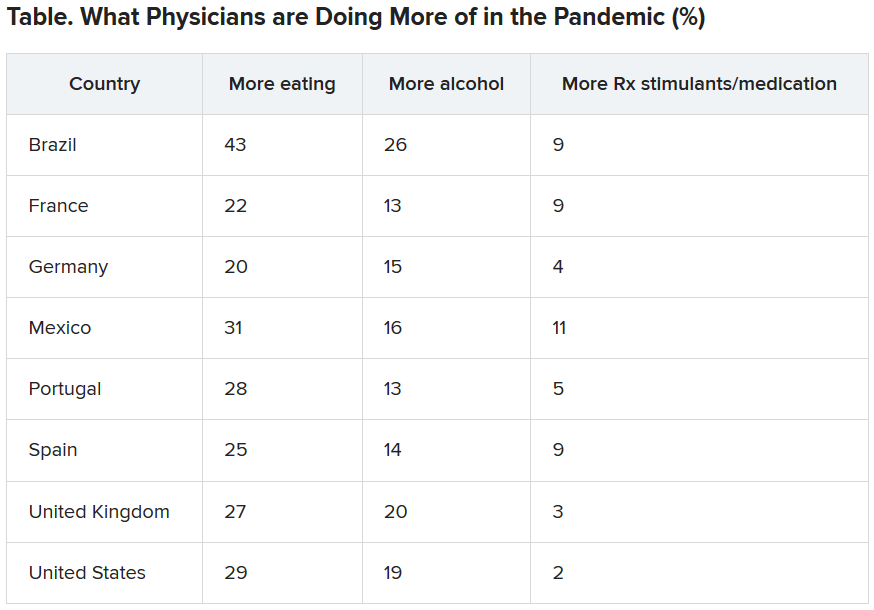

Physicians were asked what they were doing more of during the pandemic, and food seemed to be the top source of comfort in all eight countries.

Loneliness reports differ across globe

Portugal had the highest percentage (51%) of physicians reporting increased loneliness. Next were Brazil (48%), the United States (46%), the United Kingdom (42%), France (41%), Spain and Mexico (40% each), and Germany (32%).

All eight countries lacked workplace activities to help physicians with grief. More than half (55%) of U.K. physicians reported having such activities available at their workplace, whereas only 25% of physicians in Germany did; 12%-24% of respondents across the countries were unsure about the offerings.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to the results of a Medscape survey.

More than 7,500 physicians – nearly 5,000 in the United States, and others in Brazil, France, Germany, Mexico, Portugal, Spain, and the United Kingdom – responded to questions about their struggles to save patients and how the pandemic has changed their income and their lives at home and at work.

The pain was evident in this response from an emergency medicine physician in Spain: “It has been the worst time in my life ever, in both my personal and professional life.”

Conversely, some reported positive effects.

An internist in Brazil wrote: “I feel more proud of my career than ever before.”

One quarter of U.S. physicians considering earlier retirement

Physicians in the United States were asked what career changes, if any, they were considering in light of their experience with COVID-19. Although a little more than half (51%) said they were not planning any changes, 25% answered, “retiring earlier than previously planned,” and 12% answered, “a career change away from medicine.”

The number of physicians reporting an income drop was highest in Brazil (63% reported a drop), followed by the United States (62%), Mexico (56%), Portugal (49%), Germany (42%), France (41%), and Spain (31%). The question was not asked in the United Kingdom survey.

In the United States, the size of the drop has been substantial: 9% lost 76%-100% of their income; 14% lost 51%-75%; 28% lost 26%-50%; 33% lost 11%-25%; and 15% lost 1%-10%.

The U.S. specialists with the largest drop in income were ophthalmologists, who lost 51%, followed by allergists (46%), plastic surgeons (46%), and otolaryngologists (45%).

“I’m looking for a new profession due to economic impact,” an otolaryngologist in the United States said. “We are at risk while essentially using our private savings to keep our practice solvent.”

More than half of U.S. physicians (54%) have personally treated patients with COVID-19. Percentages were higher in France, Spain, and the United Kingdom (percentages ranged from 60%-68%).

The United States led all eight countries in treating patients with COVID-19 via telemedicine, at 26%. Germany had the lowest telemedicine percentage, at 10%.

Burnout intensifies

About two thirds of US physicians (64%) said that burnout had intensified during the crisis (70% of female physicians and 61% of male physicians said it had).

Many factors are feeding the burnout.

A critical care physician in the United States responded, “It is terrible to see people arriving at their rooms and assuming they were going to die soon; to see people saying goodbye to their families before dying or before being intubated.”

In all eight countries, a substantial percentage of physicians reported they “sometimes, often or always” treated patients with COVID-19 without the proper personal protective equipment. Spain had by far the largest percentage who answered that way (67%), followed by France (45%), Mexico (40%), the United Kingdom (34%), Brazil and Germany (28% each); and the United States and Portugal (23% each).

A U.S. rheumatologist wrote: “The fact that we were sent to take care of infectious patients without proper protection equipment made me feel we were betrayed in this fight.”

Sense of duty to volunteer to treat COVID-19 patients varied substantially among countries, from 69% who felt that way in Spain to 40% in Brazil. Half (50%) in the United States felt that way.

“Altruism must take second place where a real and present threat exists to my own personal existence,” one U.S. internist wrote.

Numbers personally infected

One fifth of physicians in Spain and the United Kingdom had personally been infected with the virus. Brazil, France, and Mexico had the next highest numbers, with 13%-15% of physicians infected; 5%-6% in the United States, Germany, and Portugal said they had been infected.

The percentage of physicians who reported that immediate family members had been infected ranged from 25% in Spain to 6% in Portugal. Among US physicians, 9% reported that family members had been diagnosed with COVID-19.

In the United States, 44% of respondents who had family living with them at home during the pandemic reported that relationships at home were more stressed because of stay-at-home guidelines and social distancing. Almost half (47%) said there had been no change, and 9% said relationships were less stressed.

Eating is coping mechanism of choice

Physicians were asked what they were doing more of during the pandemic, and food seemed to be the top source of comfort in all eight countries.

Loneliness reports differ across globe

Portugal had the highest percentage (51%) of physicians reporting increased loneliness. Next were Brazil (48%), the United States (46%), the United Kingdom (42%), France (41%), Spain and Mexico (40% each), and Germany (32%).

All eight countries lacked workplace activities to help physicians with grief. More than half (55%) of U.K. physicians reported having such activities available at their workplace, whereas only 25% of physicians in Germany did; 12%-24% of respondents across the countries were unsure about the offerings.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to the results of a Medscape survey.

More than 7,500 physicians – nearly 5,000 in the United States, and others in Brazil, France, Germany, Mexico, Portugal, Spain, and the United Kingdom – responded to questions about their struggles to save patients and how the pandemic has changed their income and their lives at home and at work.

The pain was evident in this response from an emergency medicine physician in Spain: “It has been the worst time in my life ever, in both my personal and professional life.”

Conversely, some reported positive effects.

An internist in Brazil wrote: “I feel more proud of my career than ever before.”

One quarter of U.S. physicians considering earlier retirement

Physicians in the United States were asked what career changes, if any, they were considering in light of their experience with COVID-19. Although a little more than half (51%) said they were not planning any changes, 25% answered, “retiring earlier than previously planned,” and 12% answered, “a career change away from medicine.”

The number of physicians reporting an income drop was highest in Brazil (63% reported a drop), followed by the United States (62%), Mexico (56%), Portugal (49%), Germany (42%), France (41%), and Spain (31%). The question was not asked in the United Kingdom survey.

In the United States, the size of the drop has been substantial: 9% lost 76%-100% of their income; 14% lost 51%-75%; 28% lost 26%-50%; 33% lost 11%-25%; and 15% lost 1%-10%.

The U.S. specialists with the largest drop in income were ophthalmologists, who lost 51%, followed by allergists (46%), plastic surgeons (46%), and otolaryngologists (45%).

“I’m looking for a new profession due to economic impact,” an otolaryngologist in the United States said. “We are at risk while essentially using our private savings to keep our practice solvent.”

More than half of U.S. physicians (54%) have personally treated patients with COVID-19. Percentages were higher in France, Spain, and the United Kingdom (percentages ranged from 60%-68%).

The United States led all eight countries in treating patients with COVID-19 via telemedicine, at 26%. Germany had the lowest telemedicine percentage, at 10%.

Burnout intensifies

About two thirds of US physicians (64%) said that burnout had intensified during the crisis (70% of female physicians and 61% of male physicians said it had).

Many factors are feeding the burnout.

A critical care physician in the United States responded, “It is terrible to see people arriving at their rooms and assuming they were going to die soon; to see people saying goodbye to their families before dying or before being intubated.”

In all eight countries, a substantial percentage of physicians reported they “sometimes, often or always” treated patients with COVID-19 without the proper personal protective equipment. Spain had by far the largest percentage who answered that way (67%), followed by France (45%), Mexico (40%), the United Kingdom (34%), Brazil and Germany (28% each); and the United States and Portugal (23% each).

A U.S. rheumatologist wrote: “The fact that we were sent to take care of infectious patients without proper protection equipment made me feel we were betrayed in this fight.”

Sense of duty to volunteer to treat COVID-19 patients varied substantially among countries, from 69% who felt that way in Spain to 40% in Brazil. Half (50%) in the United States felt that way.

“Altruism must take second place where a real and present threat exists to my own personal existence,” one U.S. internist wrote.

Numbers personally infected

One fifth of physicians in Spain and the United Kingdom had personally been infected with the virus. Brazil, France, and Mexico had the next highest numbers, with 13%-15% of physicians infected; 5%-6% in the United States, Germany, and Portugal said they had been infected.

The percentage of physicians who reported that immediate family members had been infected ranged from 25% in Spain to 6% in Portugal. Among US physicians, 9% reported that family members had been diagnosed with COVID-19.

In the United States, 44% of respondents who had family living with them at home during the pandemic reported that relationships at home were more stressed because of stay-at-home guidelines and social distancing. Almost half (47%) said there had been no change, and 9% said relationships were less stressed.

Eating is coping mechanism of choice

Physicians were asked what they were doing more of during the pandemic, and food seemed to be the top source of comfort in all eight countries.

Loneliness reports differ across globe

Portugal had the highest percentage (51%) of physicians reporting increased loneliness. Next were Brazil (48%), the United States (46%), the United Kingdom (42%), France (41%), Spain and Mexico (40% each), and Germany (32%).

All eight countries lacked workplace activities to help physicians with grief. More than half (55%) of U.K. physicians reported having such activities available at their workplace, whereas only 25% of physicians in Germany did; 12%-24% of respondents across the countries were unsure about the offerings.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Infectious COVID-19 can persist in gut for weeks

Stool tests were positive among people with no GI symptoms, and in some cases up to 6 days after nasopharyngeal swabs yielded negative results.

The small pilot study suggests a quiescent but active infection in the gut. Stool testing revealed genomic evidence of active infection in 7 of the 15 participants tested in one of two hospitals in Hong Kong.

“We found active and prolonged SARS-CoV-2 infection in the stool of patients with COVID-19, even after recovery, suggesting that coronavirus could remain in the gut of asymptomatic carriers,” senior author Siew C. Ng, MBBS, PhD, told Medscape Medical News.

“Due to the potential threat of fecal-oral transmission, it is important to maintain long-term coronavirus and health surveillance,” said Ng, Associate Director of the Centre for Gut Microbiota Research at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK).

“Discharged patients and their caretakers should remain vigilant and observe strict personal and toileting hygiene,” she added.

The prospective, observational study was published online July 20 in Gut.

Ramping up COVID-19 testing

As a follow-up to these and other findings – including the testing of more than 2,000 stool samples in children and the needy arriving at Hong Kong airports starting March 29 – the same investigators are establishing a CUHK Coronavirus Testing Center.

As of Aug. 31, the detection rate in tested children was 0.28%. The Center plans to offer as many as 2,000 COVID-19 tests daily going forward to help identify asymptomatic carriers, the investigators announced in a Sept. 7 news release.

In contrast to nasopharyngeal sampling, stool specimens are “more convenient, safe and non-invasive to collect in the pediatric population,” professor Paul Chan, chairman of the Department of Microbiology, CU Medicine, said in the release. “This makes the stool test a better option for COVID-19 screening in babies, young children and those whose respiratory samples are difficult to collect.”

Even though previous researchers identified SARS-CoV-2 in the stool, the activity and infectivity of the virus in the gastrointestinal tract during and after COVID-19 respiratory positivity remained largely unknown.

Active infection detected in stool

This prospective study involved 15 people hospitalized with COVID-19 in March and April. Participants were a median 55 years old (range, 22-71 years) and all presented with respiratory symptoms. Only one patient had concurrent GI symptoms at admission. Median length of stay was 21 days.

Investigators collected fecal samples serially until discharge. They extracted viral DNA to test for transcriptional genetic evidence of active infection, which they detected in 7 of 15 patients. The patient with GI symptoms was not in this positive group.

The findings suggest a “quiescent but active GI infection,” the researchers note.

Three of the seven patients continued to test positive for active infection in their stool up to 6 days after respiratory clearance of SARS-CoV-2.

Microbiome matters

The investigators also extracted, amplified, and sequenced DNA from the stool samples. Their “metagenomic” profile revealed the type and amounts of bacterial strains in each patient’s gut microbiome.

Interestingly, bacterial strains differed between people with high SARS-CoV-2 infectivity versus participants with low to no evidence of active infection.

“Stool with high viral activity had higher abundance of pathogenic bacteria,” Ng said. In contrast, people with low or no infectivity had more beneficial bacterial strains, including bacteria that play critical roles in boosting host immunity.

Each patient’s microbiome composition changed during the course of the study. Whether the microbiome alters the course of COVID-19 or COVID-19 alters the composition of the microbiome requires further study, the authors note.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration and officials in other countries have contacted the Hong Kong investigators for more details on their stool testing strategy, professor Francis K.L. Chan, dean of the faculty of medicine and director of the Centre for Gut Microbiota Research at CUHK, stated in the news release.

Further research into revealing the infectivity and pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 in the GI tract is warranted. The value of modulating the human gut microbiome in this patient population could be worthwhile to investigate as well, the researchers said.

Novel finding

“Some of it is not-so-new news and some is new,” David A. Johnson, MD, told Medscape Medical News when asked to comment on the study.

For example, previous researchers have detected SARS-CoV-2 virus in the stool. However, this study takes it a step further and shows that the virus present in stool can remain infectious on the basis of metagenomic signatures.

Furthermore, the virus can remain infectious in the gut even after a patient tests negative for COVID-19 through nasopharyngeal sampling – in this report up to 6 days later, said Johnson, professor of medicine, chief of gastroenterology, Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, Va.

The study carries important implications for people who currently test negative following active COVID-19 infection, he added. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria clear a person as negative after two nasopharyngeal swabs at least 24 hours apart.

People in this category could believe they are no longer infectious and might return to a setting where they could infect others, Johnson said.

One potential means for spreading SARS-CoV-2 from the gut is from a toilet plume, as Johnson previously highlighted in a video report for Medscape Medical News.

The study authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Johnson serves as an adviser to WebMD/Medscape.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Stool tests were positive among people with no GI symptoms, and in some cases up to 6 days after nasopharyngeal swabs yielded negative results.

The small pilot study suggests a quiescent but active infection in the gut. Stool testing revealed genomic evidence of active infection in 7 of the 15 participants tested in one of two hospitals in Hong Kong.

“We found active and prolonged SARS-CoV-2 infection in the stool of patients with COVID-19, even after recovery, suggesting that coronavirus could remain in the gut of asymptomatic carriers,” senior author Siew C. Ng, MBBS, PhD, told Medscape Medical News.

“Due to the potential threat of fecal-oral transmission, it is important to maintain long-term coronavirus and health surveillance,” said Ng, Associate Director of the Centre for Gut Microbiota Research at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK).

“Discharged patients and their caretakers should remain vigilant and observe strict personal and toileting hygiene,” she added.

The prospective, observational study was published online July 20 in Gut.

Ramping up COVID-19 testing

As a follow-up to these and other findings – including the testing of more than 2,000 stool samples in children and the needy arriving at Hong Kong airports starting March 29 – the same investigators are establishing a CUHK Coronavirus Testing Center.

As of Aug. 31, the detection rate in tested children was 0.28%. The Center plans to offer as many as 2,000 COVID-19 tests daily going forward to help identify asymptomatic carriers, the investigators announced in a Sept. 7 news release.

In contrast to nasopharyngeal sampling, stool specimens are “more convenient, safe and non-invasive to collect in the pediatric population,” professor Paul Chan, chairman of the Department of Microbiology, CU Medicine, said in the release. “This makes the stool test a better option for COVID-19 screening in babies, young children and those whose respiratory samples are difficult to collect.”

Even though previous researchers identified SARS-CoV-2 in the stool, the activity and infectivity of the virus in the gastrointestinal tract during and after COVID-19 respiratory positivity remained largely unknown.

Active infection detected in stool

This prospective study involved 15 people hospitalized with COVID-19 in March and April. Participants were a median 55 years old (range, 22-71 years) and all presented with respiratory symptoms. Only one patient had concurrent GI symptoms at admission. Median length of stay was 21 days.

Investigators collected fecal samples serially until discharge. They extracted viral DNA to test for transcriptional genetic evidence of active infection, which they detected in 7 of 15 patients. The patient with GI symptoms was not in this positive group.

The findings suggest a “quiescent but active GI infection,” the researchers note.

Three of the seven patients continued to test positive for active infection in their stool up to 6 days after respiratory clearance of SARS-CoV-2.

Microbiome matters

The investigators also extracted, amplified, and sequenced DNA from the stool samples. Their “metagenomic” profile revealed the type and amounts of bacterial strains in each patient’s gut microbiome.

Interestingly, bacterial strains differed between people with high SARS-CoV-2 infectivity versus participants with low to no evidence of active infection.

“Stool with high viral activity had higher abundance of pathogenic bacteria,” Ng said. In contrast, people with low or no infectivity had more beneficial bacterial strains, including bacteria that play critical roles in boosting host immunity.

Each patient’s microbiome composition changed during the course of the study. Whether the microbiome alters the course of COVID-19 or COVID-19 alters the composition of the microbiome requires further study, the authors note.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration and officials in other countries have contacted the Hong Kong investigators for more details on their stool testing strategy, professor Francis K.L. Chan, dean of the faculty of medicine and director of the Centre for Gut Microbiota Research at CUHK, stated in the news release.

Further research into revealing the infectivity and pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 in the GI tract is warranted. The value of modulating the human gut microbiome in this patient population could be worthwhile to investigate as well, the researchers said.

Novel finding

“Some of it is not-so-new news and some is new,” David A. Johnson, MD, told Medscape Medical News when asked to comment on the study.

For example, previous researchers have detected SARS-CoV-2 virus in the stool. However, this study takes it a step further and shows that the virus present in stool can remain infectious on the basis of metagenomic signatures.