User login

In Case You Missed It: COVID

First COVID-19 human challenge study provides insights

A small droplet that contains the coronavirus can infect someone with COVID-19, according to recent results from the first COVID-19 human challenge study, which were published in Nature Medicine.

Human challenge trials deliberately infect healthy volunteers to understand how an infection occurs and develops. In the first human challenge study for COVID-19, people were infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus to better understand what has happened during the pandemic.

“Really, there’s no other type of study where you can do that, because normally, patients only come to your attention if they have developed symptoms, and so you miss all of those preceding days when the infection is brewing,” Christopher Chiu, MD, PhD, the lead study author and an infectious disease doctor and immunologist at Imperial College London, told CNN.

Starting in March 2021, Dr. Chiu and colleagues carefully selected 36 volunteers aged 18-30 years who didn’t have any risk factors for severe COVID-19, such as being overweight or having kidney, liver, heart, lung or blood problems. Participants also signed an extensive informed consent form, CNN reported.

The researchers conducted the trial in phases for safety. The first 10 participants who were infected received remdesivir, the antiviral drug, to reduce their chances of progressing to severe COVID-19. The research team also had monoclonal antibodies on hand in case any volunteers developed more severe symptoms. Ultimately, the researchers said, remdesivir was unnecessary, and they didn’t need to use the antibodies.

As part of the study, the participants had a small droplet of fluid that contained the original coronavirus strain inserted into their nose through a long tube. They stayed at London’s Royal Free Hospital for 2 weeks and were monitored by doctors 24 hours a day in rooms that had special air flow to keep the virus from spreading.

Of the 36 participants, 18 became infected, including two who never developed symptoms. The others had mild cases with symptoms such as congestion, sneezing, stuffy nose, and sore throat. Some also had headaches, muscle and joint pain, fatigue, and fever.

About 83% of participants who contracted COVID-19 lost their sense of smell to some degree, and nine people couldn’t smell at all. The symptom improved for most participants within 90 days, though one person still hadn’t fully regained their sense of smell about six months after the study ended.

The research team reported several other findings:

- Small amounts of the virus can make someone sick. About 10 mcm, or the amount in a single droplet that someone sneezes or coughs, can lead to infection.

- About 40 hours after the virus was inserted into a participant’s nose, the virus could be detected in the back of the throat.

- It took about 58 hours for the virus to appear on swabs from the nose, where the viral load eventually increased even more.

- COVID-19 has a short incubation period. It takes about 2 days after infection for someone to begin shedding the virus to others.

- People become contagious and shed high amounts of the virus before they show symptoms.

- In addition, infected people can shed high levels of the virus even if they don’t develop any symptoms.

- The study volunteers shed the virus for about 6 days on average, though some shed the virus for up to 12 days, even if they didn’t have symptoms.

- Lateral flow tests, which are used for rapid at-home tests, work well when an infected person is contagious. These tests could diagnose infection before 70%-80% of the viable virus had been generated.

The findings emphasized the importance of contagious people covering their mouth and nose when sick to protect others, Dr. Chiu told CNN.

None of the study volunteers developed lung issues as part of their infection, CNN reported. Dr. Chiu said that’s likely because they were young, healthy and received tiny amounts of the virus. All of the participants will be followed for a year to monitor for potential long-term effects.

Throughout the study, the research team also conducted cognitive tests to check the participants’ short-term memory and reaction time. The researchers are still analyzing the data, but the results “will really be informative,” Dr. Chiu told CNN.

Now the research team will conduct another human challenge trial, which will include vaccinated people who will be infected with the Delta variant. The researchers intend to study participants’ immune responses, which could provide valuable insights about new variants and vaccines.

“While there are differences in transmissibility due to the emergence of variants, such as Delta and Omicron, fundamentally, this is the same disease and the same factors will be responsible for protecting it,” Dr. Chiu said in a statement.

The research team will also study the 18 participants who didn’t get sick in the first human challenge trial. They didn’t develop antibodies, Dr. Chiu told CNN, despite receiving the same dose of the virus as those who got sick.

Before the study, all of the participants were screened for antibodies to other viruses, such as the original SARS virus. That means the volunteers weren’t cross-protected, and other factors may play into why some people don’t contract COVID-19. Future studies could help researchers provide better advice about protection if new variants emerge or a future pandemic occurs.

“There are lots of other things that help protect us,” Dr. Chiu said. “There are barriers in the nose. There are different kinds of proteins and things which are very ancient, primordial, protective systems ... and we’re really interested in trying to understand what those are.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

A small droplet that contains the coronavirus can infect someone with COVID-19, according to recent results from the first COVID-19 human challenge study, which were published in Nature Medicine.

Human challenge trials deliberately infect healthy volunteers to understand how an infection occurs and develops. In the first human challenge study for COVID-19, people were infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus to better understand what has happened during the pandemic.

“Really, there’s no other type of study where you can do that, because normally, patients only come to your attention if they have developed symptoms, and so you miss all of those preceding days when the infection is brewing,” Christopher Chiu, MD, PhD, the lead study author and an infectious disease doctor and immunologist at Imperial College London, told CNN.

Starting in March 2021, Dr. Chiu and colleagues carefully selected 36 volunteers aged 18-30 years who didn’t have any risk factors for severe COVID-19, such as being overweight or having kidney, liver, heart, lung or blood problems. Participants also signed an extensive informed consent form, CNN reported.

The researchers conducted the trial in phases for safety. The first 10 participants who were infected received remdesivir, the antiviral drug, to reduce their chances of progressing to severe COVID-19. The research team also had monoclonal antibodies on hand in case any volunteers developed more severe symptoms. Ultimately, the researchers said, remdesivir was unnecessary, and they didn’t need to use the antibodies.

As part of the study, the participants had a small droplet of fluid that contained the original coronavirus strain inserted into their nose through a long tube. They stayed at London’s Royal Free Hospital for 2 weeks and were monitored by doctors 24 hours a day in rooms that had special air flow to keep the virus from spreading.

Of the 36 participants, 18 became infected, including two who never developed symptoms. The others had mild cases with symptoms such as congestion, sneezing, stuffy nose, and sore throat. Some also had headaches, muscle and joint pain, fatigue, and fever.

About 83% of participants who contracted COVID-19 lost their sense of smell to some degree, and nine people couldn’t smell at all. The symptom improved for most participants within 90 days, though one person still hadn’t fully regained their sense of smell about six months after the study ended.

The research team reported several other findings:

- Small amounts of the virus can make someone sick. About 10 mcm, or the amount in a single droplet that someone sneezes or coughs, can lead to infection.

- About 40 hours after the virus was inserted into a participant’s nose, the virus could be detected in the back of the throat.

- It took about 58 hours for the virus to appear on swabs from the nose, where the viral load eventually increased even more.

- COVID-19 has a short incubation period. It takes about 2 days after infection for someone to begin shedding the virus to others.

- People become contagious and shed high amounts of the virus before they show symptoms.

- In addition, infected people can shed high levels of the virus even if they don’t develop any symptoms.

- The study volunteers shed the virus for about 6 days on average, though some shed the virus for up to 12 days, even if they didn’t have symptoms.

- Lateral flow tests, which are used for rapid at-home tests, work well when an infected person is contagious. These tests could diagnose infection before 70%-80% of the viable virus had been generated.

The findings emphasized the importance of contagious people covering their mouth and nose when sick to protect others, Dr. Chiu told CNN.

None of the study volunteers developed lung issues as part of their infection, CNN reported. Dr. Chiu said that’s likely because they were young, healthy and received tiny amounts of the virus. All of the participants will be followed for a year to monitor for potential long-term effects.

Throughout the study, the research team also conducted cognitive tests to check the participants’ short-term memory and reaction time. The researchers are still analyzing the data, but the results “will really be informative,” Dr. Chiu told CNN.

Now the research team will conduct another human challenge trial, which will include vaccinated people who will be infected with the Delta variant. The researchers intend to study participants’ immune responses, which could provide valuable insights about new variants and vaccines.

“While there are differences in transmissibility due to the emergence of variants, such as Delta and Omicron, fundamentally, this is the same disease and the same factors will be responsible for protecting it,” Dr. Chiu said in a statement.

The research team will also study the 18 participants who didn’t get sick in the first human challenge trial. They didn’t develop antibodies, Dr. Chiu told CNN, despite receiving the same dose of the virus as those who got sick.

Before the study, all of the participants were screened for antibodies to other viruses, such as the original SARS virus. That means the volunteers weren’t cross-protected, and other factors may play into why some people don’t contract COVID-19. Future studies could help researchers provide better advice about protection if new variants emerge or a future pandemic occurs.

“There are lots of other things that help protect us,” Dr. Chiu said. “There are barriers in the nose. There are different kinds of proteins and things which are very ancient, primordial, protective systems ... and we’re really interested in trying to understand what those are.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

A small droplet that contains the coronavirus can infect someone with COVID-19, according to recent results from the first COVID-19 human challenge study, which were published in Nature Medicine.

Human challenge trials deliberately infect healthy volunteers to understand how an infection occurs and develops. In the first human challenge study for COVID-19, people were infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus to better understand what has happened during the pandemic.

“Really, there’s no other type of study where you can do that, because normally, patients only come to your attention if they have developed symptoms, and so you miss all of those preceding days when the infection is brewing,” Christopher Chiu, MD, PhD, the lead study author and an infectious disease doctor and immunologist at Imperial College London, told CNN.

Starting in March 2021, Dr. Chiu and colleagues carefully selected 36 volunteers aged 18-30 years who didn’t have any risk factors for severe COVID-19, such as being overweight or having kidney, liver, heart, lung or blood problems. Participants also signed an extensive informed consent form, CNN reported.

The researchers conducted the trial in phases for safety. The first 10 participants who were infected received remdesivir, the antiviral drug, to reduce their chances of progressing to severe COVID-19. The research team also had monoclonal antibodies on hand in case any volunteers developed more severe symptoms. Ultimately, the researchers said, remdesivir was unnecessary, and they didn’t need to use the antibodies.

As part of the study, the participants had a small droplet of fluid that contained the original coronavirus strain inserted into their nose through a long tube. They stayed at London’s Royal Free Hospital for 2 weeks and were monitored by doctors 24 hours a day in rooms that had special air flow to keep the virus from spreading.

Of the 36 participants, 18 became infected, including two who never developed symptoms. The others had mild cases with symptoms such as congestion, sneezing, stuffy nose, and sore throat. Some also had headaches, muscle and joint pain, fatigue, and fever.

About 83% of participants who contracted COVID-19 lost their sense of smell to some degree, and nine people couldn’t smell at all. The symptom improved for most participants within 90 days, though one person still hadn’t fully regained their sense of smell about six months after the study ended.

The research team reported several other findings:

- Small amounts of the virus can make someone sick. About 10 mcm, or the amount in a single droplet that someone sneezes or coughs, can lead to infection.

- About 40 hours after the virus was inserted into a participant’s nose, the virus could be detected in the back of the throat.

- It took about 58 hours for the virus to appear on swabs from the nose, where the viral load eventually increased even more.

- COVID-19 has a short incubation period. It takes about 2 days after infection for someone to begin shedding the virus to others.

- People become contagious and shed high amounts of the virus before they show symptoms.

- In addition, infected people can shed high levels of the virus even if they don’t develop any symptoms.

- The study volunteers shed the virus for about 6 days on average, though some shed the virus for up to 12 days, even if they didn’t have symptoms.

- Lateral flow tests, which are used for rapid at-home tests, work well when an infected person is contagious. These tests could diagnose infection before 70%-80% of the viable virus had been generated.

The findings emphasized the importance of contagious people covering their mouth and nose when sick to protect others, Dr. Chiu told CNN.

None of the study volunteers developed lung issues as part of their infection, CNN reported. Dr. Chiu said that’s likely because they were young, healthy and received tiny amounts of the virus. All of the participants will be followed for a year to monitor for potential long-term effects.

Throughout the study, the research team also conducted cognitive tests to check the participants’ short-term memory and reaction time. The researchers are still analyzing the data, but the results “will really be informative,” Dr. Chiu told CNN.

Now the research team will conduct another human challenge trial, which will include vaccinated people who will be infected with the Delta variant. The researchers intend to study participants’ immune responses, which could provide valuable insights about new variants and vaccines.

“While there are differences in transmissibility due to the emergence of variants, such as Delta and Omicron, fundamentally, this is the same disease and the same factors will be responsible for protecting it,” Dr. Chiu said in a statement.

The research team will also study the 18 participants who didn’t get sick in the first human challenge trial. They didn’t develop antibodies, Dr. Chiu told CNN, despite receiving the same dose of the virus as those who got sick.

Before the study, all of the participants were screened for antibodies to other viruses, such as the original SARS virus. That means the volunteers weren’t cross-protected, and other factors may play into why some people don’t contract COVID-19. Future studies could help researchers provide better advice about protection if new variants emerge or a future pandemic occurs.

“There are lots of other things that help protect us,” Dr. Chiu said. “There are barriers in the nose. There are different kinds of proteins and things which are very ancient, primordial, protective systems ... and we’re really interested in trying to understand what those are.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM NATURE MEDICINE

Ivermectin doesn’t help treat COVID-19, large study finds

according to results from a large clinical trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The findings pretty much rule out the drug as a treatment for COVID-19, the study authors wrote.

“There’s really no sign of any benefit,” David Boulware, MD, one of the coauthors and an infectious disease specialist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, told the New York Times.

The researchers shared a summary of the results in August 2021 during an online presentation hosted by the National Institutes of Health. The full data hadn’t been published until now.

“Now that people can dive into the details and the data, hopefully that will steer the majority of doctors away from ivermectin toward other therapies,” Dr. Boulware said.

In the trial, the research team compared more than 1,350 people infected with the coronavirus in Brazil who received either ivermectin or a placebo as treatment.

Between March and August 2021, 679 patients received a daily dose of ivermectin over the course of 3 days. The researchers found that ivermectin didn’t reduce the risk that people with COVID-19 would be hospitalized or go to an ED within 28 days after treatment.

In addition, the researchers looked at particular groups to understand if some patients benefited for some reason, such as taking ivermectin sooner after testing positive for COVID-19. But those who took the drug during the first 3 days after a positive coronavirus test ended up doing worse than those in the placebo group. The drug also didn’t help patients recover sooner.

The researchers found “no important effects” of treatment with ivermectin on the number of days people spent in the hospital, the number of days hospitalized people needed mechanical ventilation, or the risk of death.

Ivermectin has become a controversial focal point during the pandemic.

For decades, the drug has been widely used to treat parasitic infections. At the beginning of the pandemic, researchers checked thousands of existing drugs against the coronavirus to determine if a potential treatment already existed. Laboratory experiments on cells suggested that ivermectin might work, the New York Times reported.

But some researchers noted that the experiments worked because a high concentration of ivermectin was used, a much higher dose than would be safe for people. Despite the concerns, some doctors began prescribing ivermectin to patients. After receiving reports of people who needed medical attention, particularly after using formulations intended for livestock, the Food and Drug Administration issued a warning that the drug wasn’t approved to be used for COVID-19.

Researchers around the world have done small clinical trials to understand whether ivermectin treats COVID-19, the newspaper reported. At the end of 2020, Andrew Hill, MD, a virologist at the University of Liverpool in England, reviewed the results from 23 trials and concluded that the drug could lower the risk of death from COVID-19. He published the results in July 2021, but later reports found that many of the studies were flawed, and at least one was fraudulent.

Dr. Hill retracted his original study and began another analysis, which was published in January 2022. In this review, he and his colleagues focused on studies that were least likely to be biased. They found that ivermectin was not helpful.

Recently, Dr. Hill and associates ran another analysis using the new data from the Brazil trial, and once again they saw no benefit.

Several clinical trials are still testing ivermectin as a treatment, the New York Times reported, with results expected in upcoming months. After reviewing the data from the Brazil trial, which tested ivermectin and a variety of other drugs against COVID-19, some infectious disease experts say they’ll likely see more of the same – that ivermectin doesn’t help people with COVID-19.

“I welcome the results of the other clinical trials and will view them with an open mind,” Paul Sax, MD, an infectious disease expert at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, who has been watching the data on the drug throughout the pandemic, told the New York Times.

“But at some point, it will become a waste of resources to continue studying an unpromising approach,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

according to results from a large clinical trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The findings pretty much rule out the drug as a treatment for COVID-19, the study authors wrote.

“There’s really no sign of any benefit,” David Boulware, MD, one of the coauthors and an infectious disease specialist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, told the New York Times.

The researchers shared a summary of the results in August 2021 during an online presentation hosted by the National Institutes of Health. The full data hadn’t been published until now.

“Now that people can dive into the details and the data, hopefully that will steer the majority of doctors away from ivermectin toward other therapies,” Dr. Boulware said.

In the trial, the research team compared more than 1,350 people infected with the coronavirus in Brazil who received either ivermectin or a placebo as treatment.

Between March and August 2021, 679 patients received a daily dose of ivermectin over the course of 3 days. The researchers found that ivermectin didn’t reduce the risk that people with COVID-19 would be hospitalized or go to an ED within 28 days after treatment.

In addition, the researchers looked at particular groups to understand if some patients benefited for some reason, such as taking ivermectin sooner after testing positive for COVID-19. But those who took the drug during the first 3 days after a positive coronavirus test ended up doing worse than those in the placebo group. The drug also didn’t help patients recover sooner.

The researchers found “no important effects” of treatment with ivermectin on the number of days people spent in the hospital, the number of days hospitalized people needed mechanical ventilation, or the risk of death.

Ivermectin has become a controversial focal point during the pandemic.

For decades, the drug has been widely used to treat parasitic infections. At the beginning of the pandemic, researchers checked thousands of existing drugs against the coronavirus to determine if a potential treatment already existed. Laboratory experiments on cells suggested that ivermectin might work, the New York Times reported.

But some researchers noted that the experiments worked because a high concentration of ivermectin was used, a much higher dose than would be safe for people. Despite the concerns, some doctors began prescribing ivermectin to patients. After receiving reports of people who needed medical attention, particularly after using formulations intended for livestock, the Food and Drug Administration issued a warning that the drug wasn’t approved to be used for COVID-19.

Researchers around the world have done small clinical trials to understand whether ivermectin treats COVID-19, the newspaper reported. At the end of 2020, Andrew Hill, MD, a virologist at the University of Liverpool in England, reviewed the results from 23 trials and concluded that the drug could lower the risk of death from COVID-19. He published the results in July 2021, but later reports found that many of the studies were flawed, and at least one was fraudulent.

Dr. Hill retracted his original study and began another analysis, which was published in January 2022. In this review, he and his colleagues focused on studies that were least likely to be biased. They found that ivermectin was not helpful.

Recently, Dr. Hill and associates ran another analysis using the new data from the Brazil trial, and once again they saw no benefit.

Several clinical trials are still testing ivermectin as a treatment, the New York Times reported, with results expected in upcoming months. After reviewing the data from the Brazil trial, which tested ivermectin and a variety of other drugs against COVID-19, some infectious disease experts say they’ll likely see more of the same – that ivermectin doesn’t help people with COVID-19.

“I welcome the results of the other clinical trials and will view them with an open mind,” Paul Sax, MD, an infectious disease expert at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, who has been watching the data on the drug throughout the pandemic, told the New York Times.

“But at some point, it will become a waste of resources to continue studying an unpromising approach,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

according to results from a large clinical trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The findings pretty much rule out the drug as a treatment for COVID-19, the study authors wrote.

“There’s really no sign of any benefit,” David Boulware, MD, one of the coauthors and an infectious disease specialist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, told the New York Times.

The researchers shared a summary of the results in August 2021 during an online presentation hosted by the National Institutes of Health. The full data hadn’t been published until now.

“Now that people can dive into the details and the data, hopefully that will steer the majority of doctors away from ivermectin toward other therapies,” Dr. Boulware said.

In the trial, the research team compared more than 1,350 people infected with the coronavirus in Brazil who received either ivermectin or a placebo as treatment.

Between March and August 2021, 679 patients received a daily dose of ivermectin over the course of 3 days. The researchers found that ivermectin didn’t reduce the risk that people with COVID-19 would be hospitalized or go to an ED within 28 days after treatment.

In addition, the researchers looked at particular groups to understand if some patients benefited for some reason, such as taking ivermectin sooner after testing positive for COVID-19. But those who took the drug during the first 3 days after a positive coronavirus test ended up doing worse than those in the placebo group. The drug also didn’t help patients recover sooner.

The researchers found “no important effects” of treatment with ivermectin on the number of days people spent in the hospital, the number of days hospitalized people needed mechanical ventilation, or the risk of death.

Ivermectin has become a controversial focal point during the pandemic.

For decades, the drug has been widely used to treat parasitic infections. At the beginning of the pandemic, researchers checked thousands of existing drugs against the coronavirus to determine if a potential treatment already existed. Laboratory experiments on cells suggested that ivermectin might work, the New York Times reported.

But some researchers noted that the experiments worked because a high concentration of ivermectin was used, a much higher dose than would be safe for people. Despite the concerns, some doctors began prescribing ivermectin to patients. After receiving reports of people who needed medical attention, particularly after using formulations intended for livestock, the Food and Drug Administration issued a warning that the drug wasn’t approved to be used for COVID-19.

Researchers around the world have done small clinical trials to understand whether ivermectin treats COVID-19, the newspaper reported. At the end of 2020, Andrew Hill, MD, a virologist at the University of Liverpool in England, reviewed the results from 23 trials and concluded that the drug could lower the risk of death from COVID-19. He published the results in July 2021, but later reports found that many of the studies were flawed, and at least one was fraudulent.

Dr. Hill retracted his original study and began another analysis, which was published in January 2022. In this review, he and his colleagues focused on studies that were least likely to be biased. They found that ivermectin was not helpful.

Recently, Dr. Hill and associates ran another analysis using the new data from the Brazil trial, and once again they saw no benefit.

Several clinical trials are still testing ivermectin as a treatment, the New York Times reported, with results expected in upcoming months. After reviewing the data from the Brazil trial, which tested ivermectin and a variety of other drugs against COVID-19, some infectious disease experts say they’ll likely see more of the same – that ivermectin doesn’t help people with COVID-19.

“I welcome the results of the other clinical trials and will view them with an open mind,” Paul Sax, MD, an infectious disease expert at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, who has been watching the data on the drug throughout the pandemic, told the New York Times.

“But at some point, it will become a waste of resources to continue studying an unpromising approach,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Psychotropic med use tied to ‘striking’ post-COVID dementia risk

, new research suggests.

Results from a large study of more than 1,700 patients who had been hospitalized with COVID showed a greater than twofold increased risk for post-COVID dementia in those taking antipsychotics and mood stabilizers/anticonvulsants – medications often used to treat schizophrenia, psychosis, bipolar disorder, and seizures.

“We know that pre-existing psychiatric illness is associated with poor COVID-19 outcomes, but our study is the first to show an association with certain psychiatric medications and dementia,” co-investigator Liron Sinvani, MD, the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, Manhasset, New York, said in an interview.

“Our study highlights the potential interaction between baseline neuropsychiatric disease, psychotropic medications, COVID-19, and dementia,” Dr. Sinvani added.

The findings were published online March 18 in Frontiers in Medicine.

‘Striking’ dementia rate

Using electronic health records, the researchers evaluated pre-COVID psychotropic medication use and post-COVID dementia onset in 1,755 adults aged 65 and older. All were hospitalized with COVID-19 at Northwell Health between March 1 and April 20, 2020.

A “striking” 13% of the participants (n = 223) developed dementia within 1-year of follow-up, the investigators report.

Among the 438 patients (25%) exposed to at least one psychotropic medication before COVID-19, 105 (24%) developed dementia in the year following COVID versus 118 of 1,317 (9%) patients with no pre-COVID exposure to psychotropic medication (odds ratio, 3.2; 95% confidence interval, 2.37-4.32).

Both pre-COVID psychotropic medication use (OR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.8-4.0, P < .001) and delirium (OR, 3.0; 95% CI, 1.9-4.6, P < .001) were significantly associated with post-COVID dementia at 1 year.

In a sensitivity analysis in the subset of 423 patients with at least one documented neurologic or psychiatric diagnosis at the time of COVID admission, and after adjusting for confounding factors, pre-COVID psychotropic medication use remained significantly linked to post-COVID dementia onset (OR, 3.09; 95% CI, 1.5-6.6, P = .002).

Drug classes most strongly associated with 1-year post-COVID dementia onset were antipsychotics (OR, 2.8, 95% CI, 1.7-4.4, P < .001) and mood stabilizers/anticonvulsants (OR, 2.4, 95% CI, 1.39-4.02, P = .001).

In a further exploratory analysis, the psychotropics valproic acid (multiple brands) and haloperidol (Haldol) had the largest association with post-COVID dementia.

Antidepressants as a class were not associated with post-COVID dementia, but the potential effects of two commonly prescribed antidepressants in older adults, mirtazapine (Remeron) and escitalopram (Lexapro), “warrant further investigation,” the researchers note.

Predictive risk marker?

“This research shows that psychotropic medications can be considered a predictive risk marker for post-COVID dementia. In patients taking psychotropic medications, COVID-19 could have accelerated progression of dementia after hospitalization,” lead author Yun Freudenberg-Hua, MD, the Feinstein Institutes, said in a news release.

It is unclear why psychotropic medications may raise the risk for dementia onset after COVID, the investigators note.

“It is intuitive that psychotropic medications indicate pre-existing neuropsychiatric conditions in which COVID-19 occurs. It is possible that psychotropic medications may potentiate the neurostructural changes that have been found in the brain of those who have recovered from COVID-19,” they write.

The sensitivity analysis in patients with documented neurologic and psychiatric diagnoses supports this interpretation.

COVID-19 may also accelerate the underlying brain disorders for which psychotropic medications were prescribed, leading to the greater incidence of post-COVID dementia, the researchers write.

“It is important to note that this study is in no way recommending people should stop taking antipsychotics but simply that clinicians need to factor in a patient’s medication history while considering post-COVID aftereffects,” Dr. Freudenberg-Hua said.

“Given that the number of patients with dementia is projected to triple in the next 30 years, these findings have significant public health implications,” Dr. Sinvani added.

She noted that “care partners and health care professionals” should look for early signs of dementia, such as forgetfulness and depressive symptoms, in their patients.

“Future studies must continue to evaluate these associations, which are key for potential future interventions to prevent dementia,” Dr. Sinvani said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Freudenberg-Hua co-owns stock and stock options from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Sinvani has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests.

Results from a large study of more than 1,700 patients who had been hospitalized with COVID showed a greater than twofold increased risk for post-COVID dementia in those taking antipsychotics and mood stabilizers/anticonvulsants – medications often used to treat schizophrenia, psychosis, bipolar disorder, and seizures.

“We know that pre-existing psychiatric illness is associated with poor COVID-19 outcomes, but our study is the first to show an association with certain psychiatric medications and dementia,” co-investigator Liron Sinvani, MD, the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, Manhasset, New York, said in an interview.

“Our study highlights the potential interaction between baseline neuropsychiatric disease, psychotropic medications, COVID-19, and dementia,” Dr. Sinvani added.

The findings were published online March 18 in Frontiers in Medicine.

‘Striking’ dementia rate

Using electronic health records, the researchers evaluated pre-COVID psychotropic medication use and post-COVID dementia onset in 1,755 adults aged 65 and older. All were hospitalized with COVID-19 at Northwell Health between March 1 and April 20, 2020.

A “striking” 13% of the participants (n = 223) developed dementia within 1-year of follow-up, the investigators report.

Among the 438 patients (25%) exposed to at least one psychotropic medication before COVID-19, 105 (24%) developed dementia in the year following COVID versus 118 of 1,317 (9%) patients with no pre-COVID exposure to psychotropic medication (odds ratio, 3.2; 95% confidence interval, 2.37-4.32).

Both pre-COVID psychotropic medication use (OR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.8-4.0, P < .001) and delirium (OR, 3.0; 95% CI, 1.9-4.6, P < .001) were significantly associated with post-COVID dementia at 1 year.

In a sensitivity analysis in the subset of 423 patients with at least one documented neurologic or psychiatric diagnosis at the time of COVID admission, and after adjusting for confounding factors, pre-COVID psychotropic medication use remained significantly linked to post-COVID dementia onset (OR, 3.09; 95% CI, 1.5-6.6, P = .002).

Drug classes most strongly associated with 1-year post-COVID dementia onset were antipsychotics (OR, 2.8, 95% CI, 1.7-4.4, P < .001) and mood stabilizers/anticonvulsants (OR, 2.4, 95% CI, 1.39-4.02, P = .001).

In a further exploratory analysis, the psychotropics valproic acid (multiple brands) and haloperidol (Haldol) had the largest association with post-COVID dementia.

Antidepressants as a class were not associated with post-COVID dementia, but the potential effects of two commonly prescribed antidepressants in older adults, mirtazapine (Remeron) and escitalopram (Lexapro), “warrant further investigation,” the researchers note.

Predictive risk marker?

“This research shows that psychotropic medications can be considered a predictive risk marker for post-COVID dementia. In patients taking psychotropic medications, COVID-19 could have accelerated progression of dementia after hospitalization,” lead author Yun Freudenberg-Hua, MD, the Feinstein Institutes, said in a news release.

It is unclear why psychotropic medications may raise the risk for dementia onset after COVID, the investigators note.

“It is intuitive that psychotropic medications indicate pre-existing neuropsychiatric conditions in which COVID-19 occurs. It is possible that psychotropic medications may potentiate the neurostructural changes that have been found in the brain of those who have recovered from COVID-19,” they write.

The sensitivity analysis in patients with documented neurologic and psychiatric diagnoses supports this interpretation.

COVID-19 may also accelerate the underlying brain disorders for which psychotropic medications were prescribed, leading to the greater incidence of post-COVID dementia, the researchers write.

“It is important to note that this study is in no way recommending people should stop taking antipsychotics but simply that clinicians need to factor in a patient’s medication history while considering post-COVID aftereffects,” Dr. Freudenberg-Hua said.

“Given that the number of patients with dementia is projected to triple in the next 30 years, these findings have significant public health implications,” Dr. Sinvani added.

She noted that “care partners and health care professionals” should look for early signs of dementia, such as forgetfulness and depressive symptoms, in their patients.

“Future studies must continue to evaluate these associations, which are key for potential future interventions to prevent dementia,” Dr. Sinvani said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Freudenberg-Hua co-owns stock and stock options from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Sinvani has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests.

Results from a large study of more than 1,700 patients who had been hospitalized with COVID showed a greater than twofold increased risk for post-COVID dementia in those taking antipsychotics and mood stabilizers/anticonvulsants – medications often used to treat schizophrenia, psychosis, bipolar disorder, and seizures.

“We know that pre-existing psychiatric illness is associated with poor COVID-19 outcomes, but our study is the first to show an association with certain psychiatric medications and dementia,” co-investigator Liron Sinvani, MD, the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, Manhasset, New York, said in an interview.

“Our study highlights the potential interaction between baseline neuropsychiatric disease, psychotropic medications, COVID-19, and dementia,” Dr. Sinvani added.

The findings were published online March 18 in Frontiers in Medicine.

‘Striking’ dementia rate

Using electronic health records, the researchers evaluated pre-COVID psychotropic medication use and post-COVID dementia onset in 1,755 adults aged 65 and older. All were hospitalized with COVID-19 at Northwell Health between March 1 and April 20, 2020.

A “striking” 13% of the participants (n = 223) developed dementia within 1-year of follow-up, the investigators report.

Among the 438 patients (25%) exposed to at least one psychotropic medication before COVID-19, 105 (24%) developed dementia in the year following COVID versus 118 of 1,317 (9%) patients with no pre-COVID exposure to psychotropic medication (odds ratio, 3.2; 95% confidence interval, 2.37-4.32).

Both pre-COVID psychotropic medication use (OR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.8-4.0, P < .001) and delirium (OR, 3.0; 95% CI, 1.9-4.6, P < .001) were significantly associated with post-COVID dementia at 1 year.

In a sensitivity analysis in the subset of 423 patients with at least one documented neurologic or psychiatric diagnosis at the time of COVID admission, and after adjusting for confounding factors, pre-COVID psychotropic medication use remained significantly linked to post-COVID dementia onset (OR, 3.09; 95% CI, 1.5-6.6, P = .002).

Drug classes most strongly associated with 1-year post-COVID dementia onset were antipsychotics (OR, 2.8, 95% CI, 1.7-4.4, P < .001) and mood stabilizers/anticonvulsants (OR, 2.4, 95% CI, 1.39-4.02, P = .001).

In a further exploratory analysis, the psychotropics valproic acid (multiple brands) and haloperidol (Haldol) had the largest association with post-COVID dementia.

Antidepressants as a class were not associated with post-COVID dementia, but the potential effects of two commonly prescribed antidepressants in older adults, mirtazapine (Remeron) and escitalopram (Lexapro), “warrant further investigation,” the researchers note.

Predictive risk marker?

“This research shows that psychotropic medications can be considered a predictive risk marker for post-COVID dementia. In patients taking psychotropic medications, COVID-19 could have accelerated progression of dementia after hospitalization,” lead author Yun Freudenberg-Hua, MD, the Feinstein Institutes, said in a news release.

It is unclear why psychotropic medications may raise the risk for dementia onset after COVID, the investigators note.

“It is intuitive that psychotropic medications indicate pre-existing neuropsychiatric conditions in which COVID-19 occurs. It is possible that psychotropic medications may potentiate the neurostructural changes that have been found in the brain of those who have recovered from COVID-19,” they write.

The sensitivity analysis in patients with documented neurologic and psychiatric diagnoses supports this interpretation.

COVID-19 may also accelerate the underlying brain disorders for which psychotropic medications were prescribed, leading to the greater incidence of post-COVID dementia, the researchers write.

“It is important to note that this study is in no way recommending people should stop taking antipsychotics but simply that clinicians need to factor in a patient’s medication history while considering post-COVID aftereffects,” Dr. Freudenberg-Hua said.

“Given that the number of patients with dementia is projected to triple in the next 30 years, these findings have significant public health implications,” Dr. Sinvani added.

She noted that “care partners and health care professionals” should look for early signs of dementia, such as forgetfulness and depressive symptoms, in their patients.

“Future studies must continue to evaluate these associations, which are key for potential future interventions to prevent dementia,” Dr. Sinvani said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Freudenberg-Hua co-owns stock and stock options from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Sinvani has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM FRONTIERS IN MEDICINE

Children and COVID: The long goodbye continues

COVID-19 continues to be a diminishing issue for U.S. children, as the number of new cases declined for the ninth consecutive week, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report. The most recently infected children brought the total number of COVID-19 cases to just over 12.8 million since the pandemic began.

Other measures of COVID occurrence in children, such as hospital admissions and emergency department visits, also followed recent downward trends, although the sizes of the declines are beginning to decrease. Admissions dropped by 13.3% during the week ending March 26, but that followed declines of 25%, 20%, 26.5% and 24.4% for the 4 previous weeks, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

The slowdown in ED visits started a couple of weeks earlier, but the decline is still ongoing. As of March 25, ED visits with a confirmed COVID diagnosis represented just 0.4% of all visits for children aged 0-11 years, down from 1.1% on Feb. 25 and a peak of 14.3% on Jan. 15. For children aged 12-15, the latest figure is just 0.2%, compared with 0.5% on Feb. 25 and a peak of 14.3% on Jan. 9, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

Although he was speaking of the nation as a whole and not specifically of children, Anthony Fauci, MD, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, recently told the Washington Post that, “unless something changes dramatically,” another major surge isn’t on the horizon.

That sentiment, however, was not entirely shared by Moderna’s chief medical officer, Paul Burton, MD, PhD. In an interview with WebMD, he said that another COVID wave is inevitable and that it’s too soon to dismantle the vaccine infrastructure: “We’ve come so far. We’ve put so much into this to now take our foot off the gas. I think it would be a mistake for public health worldwide.”

Disparities during the Omicron surge

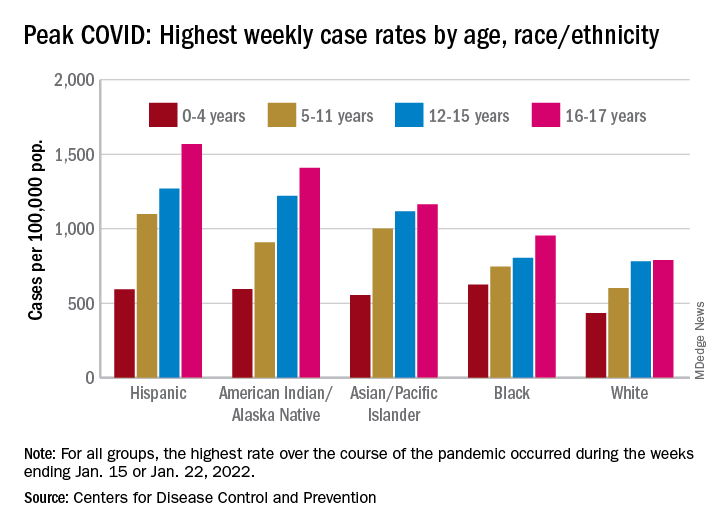

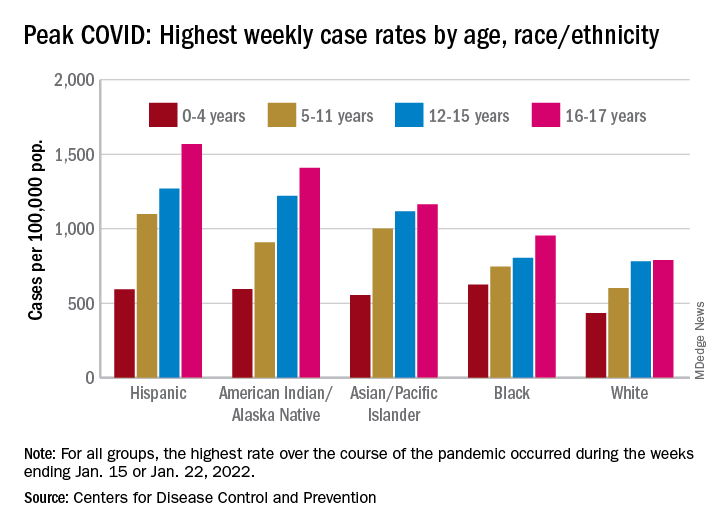

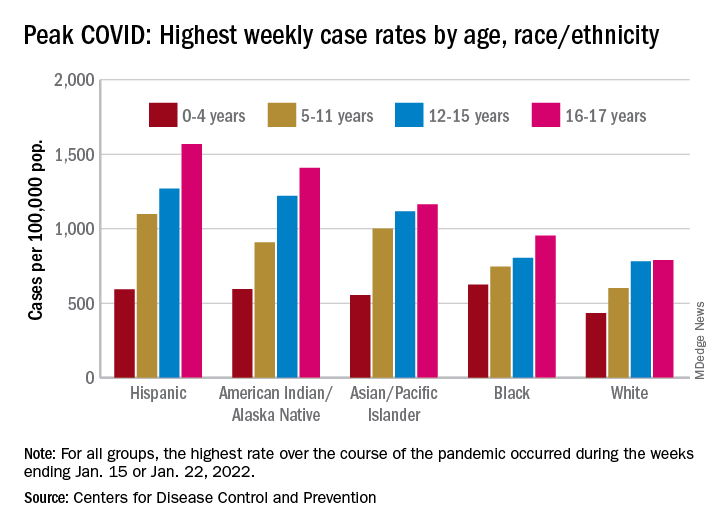

As the country puts Omicron in its rear view mirror, a quick look back at the CDC data shows some differences in how children were affected. At the surge’s peak in early to mid-January, Hispanic children were the most likely to get COVID-19, with incidence highest in the older groups. (See graph.)

At their peak week of Jan. 2-8, Hispanic children aged 16-17 years had a COVID rate of 1,568 cases per 100,000 population, versus 790 per 100,000 for White children, whose peak occurred a week later, from Jan. 9 to 15. Hispanic children aged 5-11 (1,098 per 100,000) and 12-15 (1,269 per 100,000) also had the highest recorded rates of the largest racial/ethnic groups, while Black children had the highest one-week rate, 625 per 100,000, among the 0- to 4-year-olds, according to the CDC.

COVID-19 continues to be a diminishing issue for U.S. children, as the number of new cases declined for the ninth consecutive week, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report. The most recently infected children brought the total number of COVID-19 cases to just over 12.8 million since the pandemic began.

Other measures of COVID occurrence in children, such as hospital admissions and emergency department visits, also followed recent downward trends, although the sizes of the declines are beginning to decrease. Admissions dropped by 13.3% during the week ending March 26, but that followed declines of 25%, 20%, 26.5% and 24.4% for the 4 previous weeks, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

The slowdown in ED visits started a couple of weeks earlier, but the decline is still ongoing. As of March 25, ED visits with a confirmed COVID diagnosis represented just 0.4% of all visits for children aged 0-11 years, down from 1.1% on Feb. 25 and a peak of 14.3% on Jan. 15. For children aged 12-15, the latest figure is just 0.2%, compared with 0.5% on Feb. 25 and a peak of 14.3% on Jan. 9, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

Although he was speaking of the nation as a whole and not specifically of children, Anthony Fauci, MD, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, recently told the Washington Post that, “unless something changes dramatically,” another major surge isn’t on the horizon.

That sentiment, however, was not entirely shared by Moderna’s chief medical officer, Paul Burton, MD, PhD. In an interview with WebMD, he said that another COVID wave is inevitable and that it’s too soon to dismantle the vaccine infrastructure: “We’ve come so far. We’ve put so much into this to now take our foot off the gas. I think it would be a mistake for public health worldwide.”

Disparities during the Omicron surge

As the country puts Omicron in its rear view mirror, a quick look back at the CDC data shows some differences in how children were affected. At the surge’s peak in early to mid-January, Hispanic children were the most likely to get COVID-19, with incidence highest in the older groups. (See graph.)

At their peak week of Jan. 2-8, Hispanic children aged 16-17 years had a COVID rate of 1,568 cases per 100,000 population, versus 790 per 100,000 for White children, whose peak occurred a week later, from Jan. 9 to 15. Hispanic children aged 5-11 (1,098 per 100,000) and 12-15 (1,269 per 100,000) also had the highest recorded rates of the largest racial/ethnic groups, while Black children had the highest one-week rate, 625 per 100,000, among the 0- to 4-year-olds, according to the CDC.

COVID-19 continues to be a diminishing issue for U.S. children, as the number of new cases declined for the ninth consecutive week, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report. The most recently infected children brought the total number of COVID-19 cases to just over 12.8 million since the pandemic began.

Other measures of COVID occurrence in children, such as hospital admissions and emergency department visits, also followed recent downward trends, although the sizes of the declines are beginning to decrease. Admissions dropped by 13.3% during the week ending March 26, but that followed declines of 25%, 20%, 26.5% and 24.4% for the 4 previous weeks, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

The slowdown in ED visits started a couple of weeks earlier, but the decline is still ongoing. As of March 25, ED visits with a confirmed COVID diagnosis represented just 0.4% of all visits for children aged 0-11 years, down from 1.1% on Feb. 25 and a peak of 14.3% on Jan. 15. For children aged 12-15, the latest figure is just 0.2%, compared with 0.5% on Feb. 25 and a peak of 14.3% on Jan. 9, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

Although he was speaking of the nation as a whole and not specifically of children, Anthony Fauci, MD, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, recently told the Washington Post that, “unless something changes dramatically,” another major surge isn’t on the horizon.

That sentiment, however, was not entirely shared by Moderna’s chief medical officer, Paul Burton, MD, PhD. In an interview with WebMD, he said that another COVID wave is inevitable and that it’s too soon to dismantle the vaccine infrastructure: “We’ve come so far. We’ve put so much into this to now take our foot off the gas. I think it would be a mistake for public health worldwide.”

Disparities during the Omicron surge

As the country puts Omicron in its rear view mirror, a quick look back at the CDC data shows some differences in how children were affected. At the surge’s peak in early to mid-January, Hispanic children were the most likely to get COVID-19, with incidence highest in the older groups. (See graph.)

At their peak week of Jan. 2-8, Hispanic children aged 16-17 years had a COVID rate of 1,568 cases per 100,000 population, versus 790 per 100,000 for White children, whose peak occurred a week later, from Jan. 9 to 15. Hispanic children aged 5-11 (1,098 per 100,000) and 12-15 (1,269 per 100,000) also had the highest recorded rates of the largest racial/ethnic groups, while Black children had the highest one-week rate, 625 per 100,000, among the 0- to 4-year-olds, according to the CDC.

As FDA OKs another COVID booster, some experts question need

, even though many top infectious disease experts questioned the need before the agency’s decision.

The FDA granted emergency use authorization for both Pfizer and Moderna to offer the second booster – and fourth shot overall – for adults over 50 as well as those over 18 with compromised immune systems.

The Centers for Control and Prevention must still sign off before those doses start reaching American arms. That approval could come at any time.

“The general consensus, certainly the CDC’s consensus, is that the current vaccines are still really quite effective against Omicron and this new BA.2 variant in keeping people out of the hospital, and preventing the development of severe disease,” William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville said prior to the FDA’s announcement March 29.

Of the 217.4 million Americans who are “fully vaccinated,” i.e., received two doses of either Pfizer or Moderna’s vaccines or one dose of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, only 45% have also received a booster shot, according to the CDC.

“Given that, there’s no need at the moment for the general population to get a fourth inoculation,” Dr. Schaffner says. “Our current focus ought to be on making sure that as many people as possible get that [first] booster who are eligible.”

Monica Gandhi, MD, an infectious disease specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, agreed that another booster for everyone was unnecessary. The only people who would need a fourth shot (or third, if they had the Johnson & Johnson vaccine initially) are those over age 65 or 70 years, Dr. Gandhi says.

“Older people need those antibodies up high because they’re more susceptible to severe breakthroughs,” she said, also before the latest development.

To boost or not to boost

Daniel Kuritzkes, MD, chief of infectious diseases at Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, said the timing of a booster and who should be eligible depends on what the nation is trying to achieve with its vaccination strategy.

“Is the goal to prevent any symptomatic infection with COVID-19, is the goal to prevent the spread of COVID-19, or is the goal to prevent severe disease that requires hospitalization?” asked Dr. Kuritzkes.

The current vaccine — with a booster — has prevented severe disease, he said.

An Israeli study showed, for instance, that a third Pfizer dose was 93% effective against hospitalization, 92% effective against severe illness, and 81% effective against death.

A just-published study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that a booster of the Pfizer vaccine was 95% effective against COVID-19 infection and that it did not raise any new safety issues.

A small Israeli study, also published in NEJM, of a fourth Pfizer dose given to health care workers found that it prevented symptomatic infection and illness, but that it was much less effective than previous doses — maybe 65% effective against symptomatic illness, the authors write.

Giving Americans another booster now — which has been shown to lose some effectiveness after about 4 months — means it might not offer protection this fall and winter, when there could be a seasonal surge of the virus, Dr. Kuritzkes says.

And, even if people receive boosters every few months, they are still likely to get a mild respiratory virus infection, he said.

“I’m pretty convinced that we cannot boost ourselves out of this pandemic,” said Dr. Kuritzkes. “We need to first of all ensure there’s global immunization so that all the people who have not been vaccinated at all get vaccinated. That’s far more important than boosting people a fourth time.”

Booster confusion

The April 6 FDA meeting of the agency’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee comes as the two major COVID vaccine makers — Pfizer and Moderna — have applied for emergency use authorization for an additional booster.

Pfizer had asked for authorization for a fourth shot in patients over age 65 years, while Moderna wanted a booster to be available to all Americans over 18. The FDA instead granted authorization to both companies for those over 50 and anyone 18 or older who is immunocompromised.

What this means for the committee’s April 6 meeting is not clear. The original agenda says the committee will consider the evidence on safety and effectiveness of the additional vaccine doses and discuss how to set up a process — similar to that used for the influenza vaccine — to be able to determine the makeup of COVID vaccines as new variants emerge. That could lay the groundwork for an annual COVID shot, if needed.

The FDA advisers will not make recommendations nor vote on whether — and which — Americans should get a COVID booster. That is the job of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

The last time a booster was considered, CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, overrode the committee and recommended that all Americans — not just older individuals — get an additional COVID shot, which became the first booster.

That past action worries Dr. Gandhi, who calls it confusing, and says it may have contributed to the fact that less than half of Americans have since chosen to get a booster.

Dr. Schaffner says he expects the FDA to authorize emergency use for fourth doses of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, but he doesn’t think the CDC committee will recommend routine use. As was seen before, however, the CDC director does not have to follow the committee’s advice.

The members of ACIP “might be more conservative or narrower in scope in terms of recommending who needs to be boosted and when boosting is appropriate,” Dr. Kuritzkes says.

Dr. Gandhi says she’s concerned the FDA’s deliberations could be swayed by Moderna and Pfizer’s influence and that “pharmaceutical companies are going to have more of a say than they should in the scientific process.”

There are similar worries for Dr. Schaffner. He says he’s “a bit grumpy” that the vaccine makers have been using press releases to argue for boosters.

“Press releases are no way to make vaccine recommendations,” Dr. Schaffner said, adding that he “would advise [vaccine makers] to sit down and be quiet and let the FDA and CDC advisory committee do their thing.”

Moderna Chief Medical Officer Paul Burton, MD, however, told WebMD last week that the signs point to why a fourth shot may be needed.

“We see waning of effectiveness, antibody levels come down, and certainly effectiveness against Omicron comes down in 3 to 6 months,” Burton said. “The natural history, from what we’re seeing around the world, is that BA.2 is definitely here, it’s highly transmissible, and I think we are going to get an additional wave of BA.2 here in the United States.”

Another wave is coming, he said, and “I think there will be waning of effectiveness. We need to be prepared for that, so that’s why we need the fourth dose.”

Supply issues?

Meanwhile, the United Kingdom has begun offering boosters to anyone over 75, and Sweden’s health authority has recommended a fourth shot to people over age 80.

That puts pressure on the United States — at least on its politicians and policymakers — to, in a sense, keep up, said the infectious disease specialists.

Indeed, the White House has been keeping fourth shots in the news, warning that it is running out of money to ensure that all Americans would have access to one, if recommended.

On March 23, outgoing White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator Jeff Zients said the federal government had enough vaccine for the immunocompromised to get a fourth dose “and, if authorized in the coming weeks, enough supply for fourth doses for our most vulnerable, including seniors.”

But he warned that without congressional approval of a COVID-19 funding package, “We can’t procure the necessary vaccine supply to support fourth shots for all Americans.”

Mr. Zients also noted that other countries, including Japan, Vietnam, and the Philippines had already secured future booster doses and added, “We should be securing additional supply right now.”

Dr. Schaffner says that while it would be nice to “have a booster on the shelf,” the United States needs to put more effort into creating a globally-coordinated process for ensuring that vaccines match circulating strains and that they are manufactured on a timely basis.

He says he and others “have been reminding the public that the COVID pandemic may indeed be diminishing and moving into the endemic, but that doesn’t mean COVID is over or finished or disappeared.”

Dr. Schaffner says that it may be that “perhaps we’d need a periodic reminder to our immune system to remain protected. In other words, we might have to get boosted perhaps annually like we do with influenza.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, even though many top infectious disease experts questioned the need before the agency’s decision.

The FDA granted emergency use authorization for both Pfizer and Moderna to offer the second booster – and fourth shot overall – for adults over 50 as well as those over 18 with compromised immune systems.

The Centers for Control and Prevention must still sign off before those doses start reaching American arms. That approval could come at any time.

“The general consensus, certainly the CDC’s consensus, is that the current vaccines are still really quite effective against Omicron and this new BA.2 variant in keeping people out of the hospital, and preventing the development of severe disease,” William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville said prior to the FDA’s announcement March 29.

Of the 217.4 million Americans who are “fully vaccinated,” i.e., received two doses of either Pfizer or Moderna’s vaccines or one dose of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, only 45% have also received a booster shot, according to the CDC.

“Given that, there’s no need at the moment for the general population to get a fourth inoculation,” Dr. Schaffner says. “Our current focus ought to be on making sure that as many people as possible get that [first] booster who are eligible.”

Monica Gandhi, MD, an infectious disease specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, agreed that another booster for everyone was unnecessary. The only people who would need a fourth shot (or third, if they had the Johnson & Johnson vaccine initially) are those over age 65 or 70 years, Dr. Gandhi says.

“Older people need those antibodies up high because they’re more susceptible to severe breakthroughs,” she said, also before the latest development.

To boost or not to boost

Daniel Kuritzkes, MD, chief of infectious diseases at Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, said the timing of a booster and who should be eligible depends on what the nation is trying to achieve with its vaccination strategy.

“Is the goal to prevent any symptomatic infection with COVID-19, is the goal to prevent the spread of COVID-19, or is the goal to prevent severe disease that requires hospitalization?” asked Dr. Kuritzkes.

The current vaccine — with a booster — has prevented severe disease, he said.

An Israeli study showed, for instance, that a third Pfizer dose was 93% effective against hospitalization, 92% effective against severe illness, and 81% effective against death.

A just-published study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that a booster of the Pfizer vaccine was 95% effective against COVID-19 infection and that it did not raise any new safety issues.

A small Israeli study, also published in NEJM, of a fourth Pfizer dose given to health care workers found that it prevented symptomatic infection and illness, but that it was much less effective than previous doses — maybe 65% effective against symptomatic illness, the authors write.

Giving Americans another booster now — which has been shown to lose some effectiveness after about 4 months — means it might not offer protection this fall and winter, when there could be a seasonal surge of the virus, Dr. Kuritzkes says.

And, even if people receive boosters every few months, they are still likely to get a mild respiratory virus infection, he said.

“I’m pretty convinced that we cannot boost ourselves out of this pandemic,” said Dr. Kuritzkes. “We need to first of all ensure there’s global immunization so that all the people who have not been vaccinated at all get vaccinated. That’s far more important than boosting people a fourth time.”

Booster confusion

The April 6 FDA meeting of the agency’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee comes as the two major COVID vaccine makers — Pfizer and Moderna — have applied for emergency use authorization for an additional booster.

Pfizer had asked for authorization for a fourth shot in patients over age 65 years, while Moderna wanted a booster to be available to all Americans over 18. The FDA instead granted authorization to both companies for those over 50 and anyone 18 or older who is immunocompromised.

What this means for the committee’s April 6 meeting is not clear. The original agenda says the committee will consider the evidence on safety and effectiveness of the additional vaccine doses and discuss how to set up a process — similar to that used for the influenza vaccine — to be able to determine the makeup of COVID vaccines as new variants emerge. That could lay the groundwork for an annual COVID shot, if needed.

The FDA advisers will not make recommendations nor vote on whether — and which — Americans should get a COVID booster. That is the job of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

The last time a booster was considered, CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, overrode the committee and recommended that all Americans — not just older individuals — get an additional COVID shot, which became the first booster.

That past action worries Dr. Gandhi, who calls it confusing, and says it may have contributed to the fact that less than half of Americans have since chosen to get a booster.

Dr. Schaffner says he expects the FDA to authorize emergency use for fourth doses of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, but he doesn’t think the CDC committee will recommend routine use. As was seen before, however, the CDC director does not have to follow the committee’s advice.

The members of ACIP “might be more conservative or narrower in scope in terms of recommending who needs to be boosted and when boosting is appropriate,” Dr. Kuritzkes says.

Dr. Gandhi says she’s concerned the FDA’s deliberations could be swayed by Moderna and Pfizer’s influence and that “pharmaceutical companies are going to have more of a say than they should in the scientific process.”

There are similar worries for Dr. Schaffner. He says he’s “a bit grumpy” that the vaccine makers have been using press releases to argue for boosters.

“Press releases are no way to make vaccine recommendations,” Dr. Schaffner said, adding that he “would advise [vaccine makers] to sit down and be quiet and let the FDA and CDC advisory committee do their thing.”

Moderna Chief Medical Officer Paul Burton, MD, however, told WebMD last week that the signs point to why a fourth shot may be needed.

“We see waning of effectiveness, antibody levels come down, and certainly effectiveness against Omicron comes down in 3 to 6 months,” Burton said. “The natural history, from what we’re seeing around the world, is that BA.2 is definitely here, it’s highly transmissible, and I think we are going to get an additional wave of BA.2 here in the United States.”

Another wave is coming, he said, and “I think there will be waning of effectiveness. We need to be prepared for that, so that’s why we need the fourth dose.”

Supply issues?

Meanwhile, the United Kingdom has begun offering boosters to anyone over 75, and Sweden’s health authority has recommended a fourth shot to people over age 80.

That puts pressure on the United States — at least on its politicians and policymakers — to, in a sense, keep up, said the infectious disease specialists.

Indeed, the White House has been keeping fourth shots in the news, warning that it is running out of money to ensure that all Americans would have access to one, if recommended.

On March 23, outgoing White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator Jeff Zients said the federal government had enough vaccine for the immunocompromised to get a fourth dose “and, if authorized in the coming weeks, enough supply for fourth doses for our most vulnerable, including seniors.”

But he warned that without congressional approval of a COVID-19 funding package, “We can’t procure the necessary vaccine supply to support fourth shots for all Americans.”

Mr. Zients also noted that other countries, including Japan, Vietnam, and the Philippines had already secured future booster doses and added, “We should be securing additional supply right now.”

Dr. Schaffner says that while it would be nice to “have a booster on the shelf,” the United States needs to put more effort into creating a globally-coordinated process for ensuring that vaccines match circulating strains and that they are manufactured on a timely basis.

He says he and others “have been reminding the public that the COVID pandemic may indeed be diminishing and moving into the endemic, but that doesn’t mean COVID is over or finished or disappeared.”

Dr. Schaffner says that it may be that “perhaps we’d need a periodic reminder to our immune system to remain protected. In other words, we might have to get boosted perhaps annually like we do with influenza.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, even though many top infectious disease experts questioned the need before the agency’s decision.

The FDA granted emergency use authorization for both Pfizer and Moderna to offer the second booster – and fourth shot overall – for adults over 50 as well as those over 18 with compromised immune systems.

The Centers for Control and Prevention must still sign off before those doses start reaching American arms. That approval could come at any time.

“The general consensus, certainly the CDC’s consensus, is that the current vaccines are still really quite effective against Omicron and this new BA.2 variant in keeping people out of the hospital, and preventing the development of severe disease,” William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville said prior to the FDA’s announcement March 29.

Of the 217.4 million Americans who are “fully vaccinated,” i.e., received two doses of either Pfizer or Moderna’s vaccines or one dose of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, only 45% have also received a booster shot, according to the CDC.

“Given that, there’s no need at the moment for the general population to get a fourth inoculation,” Dr. Schaffner says. “Our current focus ought to be on making sure that as many people as possible get that [first] booster who are eligible.”

Monica Gandhi, MD, an infectious disease specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, agreed that another booster for everyone was unnecessary. The only people who would need a fourth shot (or third, if they had the Johnson & Johnson vaccine initially) are those over age 65 or 70 years, Dr. Gandhi says.

“Older people need those antibodies up high because they’re more susceptible to severe breakthroughs,” she said, also before the latest development.

To boost or not to boost

Daniel Kuritzkes, MD, chief of infectious diseases at Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, said the timing of a booster and who should be eligible depends on what the nation is trying to achieve with its vaccination strategy.

“Is the goal to prevent any symptomatic infection with COVID-19, is the goal to prevent the spread of COVID-19, or is the goal to prevent severe disease that requires hospitalization?” asked Dr. Kuritzkes.

The current vaccine — with a booster — has prevented severe disease, he said.

An Israeli study showed, for instance, that a third Pfizer dose was 93% effective against hospitalization, 92% effective against severe illness, and 81% effective against death.

A just-published study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that a booster of the Pfizer vaccine was 95% effective against COVID-19 infection and that it did not raise any new safety issues.

A small Israeli study, also published in NEJM, of a fourth Pfizer dose given to health care workers found that it prevented symptomatic infection and illness, but that it was much less effective than previous doses — maybe 65% effective against symptomatic illness, the authors write.

Giving Americans another booster now — which has been shown to lose some effectiveness after about 4 months — means it might not offer protection this fall and winter, when there could be a seasonal surge of the virus, Dr. Kuritzkes says.

And, even if people receive boosters every few months, they are still likely to get a mild respiratory virus infection, he said.

“I’m pretty convinced that we cannot boost ourselves out of this pandemic,” said Dr. Kuritzkes. “We need to first of all ensure there’s global immunization so that all the people who have not been vaccinated at all get vaccinated. That’s far more important than boosting people a fourth time.”

Booster confusion

The April 6 FDA meeting of the agency’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee comes as the two major COVID vaccine makers — Pfizer and Moderna — have applied for emergency use authorization for an additional booster.

Pfizer had asked for authorization for a fourth shot in patients over age 65 years, while Moderna wanted a booster to be available to all Americans over 18. The FDA instead granted authorization to both companies for those over 50 and anyone 18 or older who is immunocompromised.

What this means for the committee’s April 6 meeting is not clear. The original agenda says the committee will consider the evidence on safety and effectiveness of the additional vaccine doses and discuss how to set up a process — similar to that used for the influenza vaccine — to be able to determine the makeup of COVID vaccines as new variants emerge. That could lay the groundwork for an annual COVID shot, if needed.

The FDA advisers will not make recommendations nor vote on whether — and which — Americans should get a COVID booster. That is the job of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

The last time a booster was considered, CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, overrode the committee and recommended that all Americans — not just older individuals — get an additional COVID shot, which became the first booster.

That past action worries Dr. Gandhi, who calls it confusing, and says it may have contributed to the fact that less than half of Americans have since chosen to get a booster.

Dr. Schaffner says he expects the FDA to authorize emergency use for fourth doses of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, but he doesn’t think the CDC committee will recommend routine use. As was seen before, however, the CDC director does not have to follow the committee’s advice.

The members of ACIP “might be more conservative or narrower in scope in terms of recommending who needs to be boosted and when boosting is appropriate,” Dr. Kuritzkes says.

Dr. Gandhi says she’s concerned the FDA’s deliberations could be swayed by Moderna and Pfizer’s influence and that “pharmaceutical companies are going to have more of a say than they should in the scientific process.”

There are similar worries for Dr. Schaffner. He says he’s “a bit grumpy” that the vaccine makers have been using press releases to argue for boosters.

“Press releases are no way to make vaccine recommendations,” Dr. Schaffner said, adding that he “would advise [vaccine makers] to sit down and be quiet and let the FDA and CDC advisory committee do their thing.”

Moderna Chief Medical Officer Paul Burton, MD, however, told WebMD last week that the signs point to why a fourth shot may be needed.

“We see waning of effectiveness, antibody levels come down, and certainly effectiveness against Omicron comes down in 3 to 6 months,” Burton said. “The natural history, from what we’re seeing around the world, is that BA.2 is definitely here, it’s highly transmissible, and I think we are going to get an additional wave of BA.2 here in the United States.”

Another wave is coming, he said, and “I think there will be waning of effectiveness. We need to be prepared for that, so that’s why we need the fourth dose.”

Supply issues?