User login

ID Practitioner is an independent news source that provides infectious disease specialists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on the infectious disease specialist’s practice. Specialty focus topics include antimicrobial resistance, emerging infections, global ID, hepatitis, HIV, hospital-acquired infections, immunizations and vaccines, influenza, mycoses, pediatric infections, and STIs. Infectious Diseases News is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

sofosbuvir

ritonavir with dasabuvir

discount

support path

program

ritonavir

greedy

ledipasvir

assistance

viekira pak

vpak

advocacy

needy

protest

abbvie

paritaprevir

ombitasvir

direct-acting antivirals

dasabuvir

gilead

fake-ovir

support

v pak

oasis

harvoni

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-medstat-latest-articles-articles-section')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-idp')]

Dr. Fauci: ‘About 40%-45% of infections are asymptomatic’

Anthony Fauci, MD, highlighting the latest COVID-19 developments on Friday, said, “It is now clear that about 40%-45% of infections are asymptomatic.”

Asymptomatic carriers can account for a large proportion — up to 50% — of virus transmissions, Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told a virtual crowd of critical care clinicians gathered by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

Such transmissions have made response strategies, such as contact tracing, extremely difficult, he said.

Lew Kaplan, MD, president of SCCM, told Medscape Medical News after the presentation: “That really supports the universal wearing of masks and the capstone message from that – you should protect one another.

“That kind of social responsibility that sits within the public health domain to me is as important as the vaccine candidates and the science behind the receptors. It underpins the necessary relationship and the interdependence of the medical community with the public,” Kaplan added.

Fauci’s plenary led the SCCM’s conference, “COVID-19: What’s Next/Preparing for the Second Wave,” running today and Saturday.

Why U.S. response lags behind Spain and Italy

“This virus has literally exploded upon the planet in a pandemic manner which is unparalleled to anything we’ve seen in the last 102 years since the pandemic of 1918,” Fauci said.

“Unfortunately, the United States has been hit harder than any other country in the world, with 6 million reported cases.”

He explained that in the European Union countries the disease spiked early on and returned to a low baseline. “Unfortunately for them,” Fauci said, “as they’re trying to open up their economy, it’s coming back up.”

The United States, he explained, plateaued at about 20,000 cases a day, then a surge of cases in Florida, California, Texas, and Arizona brought the cases to 70,000 a day. Now cases have returned to 35,000-40,000 a day.

The difference in the trajectory of the response, he said, is that, compared with Spain and Italy for example, the United States has not shut down mobility in parks, outdoor spaces, and grocery stores nearly as much as some European countries did.

He pointed to numerous clusters of cases, spread from social or work gatherings, including the well-known Skagit County Washington state choir practice in March, in which a symptomatic choir member infected 87% of the 61 people rehearsing.

Vaccine by end of the year

As for a vaccine timeline, Fauci told SCCM members, “We project that by the end of this year, namely November/December, we will know if we have a safe and effective vaccine and we are cautiously optimistic that we will be successful, based on promising data in the animal model as well as good immunological data that we see from the phase 1 and phase 2 trials.”

However, also on Friday, Fauci told MSNBC’s Andrea Mitchell that a sense of normalcy is not likely before the middle of next year.

“By the time you mobilize the distribution of the vaccinations, and you get the majority, or more, of the population vaccinated and protected, that’s likely not going to happen [until] the mid- or end of 2021,” he said.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) case tracker, as of Thursday, COVID-19 had resulted in more than 190,000 deaths overall and more than 256,000 new cases in the United States in the past 7 days.

Fauci has warned that the next few months will be critical in the virus’ trajectory, with the double onslaught of COVID-19 and the flu season.

On Thursday, Fauci said, “We need to hunker down and get through this fall and winter because it’s not going to be easy.”

Fauci remains a top trusted source in COVID-19 information, poll numbers show.

A Kaiser Family Foundation poll released Thursday found that 68% of US adults had a fair amount or a great deal of trust that Fauci would provide reliable information on COVID-19, just slightly more that the 67% who said they trust the CDC information. About half (53%) say they trust Deborah Birx, MD, the coordinator for the White House Coronavirus Task Force, as a reliable source of information.

The poll also found that 54% of Americans said they would not get a COVID-19 vaccine if one was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration before the November election and was made available and free to all who wanted it.

Kaplan and Fauci report no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Anthony Fauci, MD, highlighting the latest COVID-19 developments on Friday, said, “It is now clear that about 40%-45% of infections are asymptomatic.”

Asymptomatic carriers can account for a large proportion — up to 50% — of virus transmissions, Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told a virtual crowd of critical care clinicians gathered by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

Such transmissions have made response strategies, such as contact tracing, extremely difficult, he said.

Lew Kaplan, MD, president of SCCM, told Medscape Medical News after the presentation: “That really supports the universal wearing of masks and the capstone message from that – you should protect one another.

“That kind of social responsibility that sits within the public health domain to me is as important as the vaccine candidates and the science behind the receptors. It underpins the necessary relationship and the interdependence of the medical community with the public,” Kaplan added.

Fauci’s plenary led the SCCM’s conference, “COVID-19: What’s Next/Preparing for the Second Wave,” running today and Saturday.

Why U.S. response lags behind Spain and Italy

“This virus has literally exploded upon the planet in a pandemic manner which is unparalleled to anything we’ve seen in the last 102 years since the pandemic of 1918,” Fauci said.

“Unfortunately, the United States has been hit harder than any other country in the world, with 6 million reported cases.”

He explained that in the European Union countries the disease spiked early on and returned to a low baseline. “Unfortunately for them,” Fauci said, “as they’re trying to open up their economy, it’s coming back up.”

The United States, he explained, plateaued at about 20,000 cases a day, then a surge of cases in Florida, California, Texas, and Arizona brought the cases to 70,000 a day. Now cases have returned to 35,000-40,000 a day.

The difference in the trajectory of the response, he said, is that, compared with Spain and Italy for example, the United States has not shut down mobility in parks, outdoor spaces, and grocery stores nearly as much as some European countries did.

He pointed to numerous clusters of cases, spread from social or work gatherings, including the well-known Skagit County Washington state choir practice in March, in which a symptomatic choir member infected 87% of the 61 people rehearsing.

Vaccine by end of the year

As for a vaccine timeline, Fauci told SCCM members, “We project that by the end of this year, namely November/December, we will know if we have a safe and effective vaccine and we are cautiously optimistic that we will be successful, based on promising data in the animal model as well as good immunological data that we see from the phase 1 and phase 2 trials.”

However, also on Friday, Fauci told MSNBC’s Andrea Mitchell that a sense of normalcy is not likely before the middle of next year.

“By the time you mobilize the distribution of the vaccinations, and you get the majority, or more, of the population vaccinated and protected, that’s likely not going to happen [until] the mid- or end of 2021,” he said.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) case tracker, as of Thursday, COVID-19 had resulted in more than 190,000 deaths overall and more than 256,000 new cases in the United States in the past 7 days.

Fauci has warned that the next few months will be critical in the virus’ trajectory, with the double onslaught of COVID-19 and the flu season.

On Thursday, Fauci said, “We need to hunker down and get through this fall and winter because it’s not going to be easy.”

Fauci remains a top trusted source in COVID-19 information, poll numbers show.

A Kaiser Family Foundation poll released Thursday found that 68% of US adults had a fair amount or a great deal of trust that Fauci would provide reliable information on COVID-19, just slightly more that the 67% who said they trust the CDC information. About half (53%) say they trust Deborah Birx, MD, the coordinator for the White House Coronavirus Task Force, as a reliable source of information.

The poll also found that 54% of Americans said they would not get a COVID-19 vaccine if one was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration before the November election and was made available and free to all who wanted it.

Kaplan and Fauci report no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Anthony Fauci, MD, highlighting the latest COVID-19 developments on Friday, said, “It is now clear that about 40%-45% of infections are asymptomatic.”

Asymptomatic carriers can account for a large proportion — up to 50% — of virus transmissions, Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told a virtual crowd of critical care clinicians gathered by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

Such transmissions have made response strategies, such as contact tracing, extremely difficult, he said.

Lew Kaplan, MD, president of SCCM, told Medscape Medical News after the presentation: “That really supports the universal wearing of masks and the capstone message from that – you should protect one another.

“That kind of social responsibility that sits within the public health domain to me is as important as the vaccine candidates and the science behind the receptors. It underpins the necessary relationship and the interdependence of the medical community with the public,” Kaplan added.

Fauci’s plenary led the SCCM’s conference, “COVID-19: What’s Next/Preparing for the Second Wave,” running today and Saturday.

Why U.S. response lags behind Spain and Italy

“This virus has literally exploded upon the planet in a pandemic manner which is unparalleled to anything we’ve seen in the last 102 years since the pandemic of 1918,” Fauci said.

“Unfortunately, the United States has been hit harder than any other country in the world, with 6 million reported cases.”

He explained that in the European Union countries the disease spiked early on and returned to a low baseline. “Unfortunately for them,” Fauci said, “as they’re trying to open up their economy, it’s coming back up.”

The United States, he explained, plateaued at about 20,000 cases a day, then a surge of cases in Florida, California, Texas, and Arizona brought the cases to 70,000 a day. Now cases have returned to 35,000-40,000 a day.

The difference in the trajectory of the response, he said, is that, compared with Spain and Italy for example, the United States has not shut down mobility in parks, outdoor spaces, and grocery stores nearly as much as some European countries did.

He pointed to numerous clusters of cases, spread from social or work gatherings, including the well-known Skagit County Washington state choir practice in March, in which a symptomatic choir member infected 87% of the 61 people rehearsing.

Vaccine by end of the year

As for a vaccine timeline, Fauci told SCCM members, “We project that by the end of this year, namely November/December, we will know if we have a safe and effective vaccine and we are cautiously optimistic that we will be successful, based on promising data in the animal model as well as good immunological data that we see from the phase 1 and phase 2 trials.”

However, also on Friday, Fauci told MSNBC’s Andrea Mitchell that a sense of normalcy is not likely before the middle of next year.

“By the time you mobilize the distribution of the vaccinations, and you get the majority, or more, of the population vaccinated and protected, that’s likely not going to happen [until] the mid- or end of 2021,” he said.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) case tracker, as of Thursday, COVID-19 had resulted in more than 190,000 deaths overall and more than 256,000 new cases in the United States in the past 7 days.

Fauci has warned that the next few months will be critical in the virus’ trajectory, with the double onslaught of COVID-19 and the flu season.

On Thursday, Fauci said, “We need to hunker down and get through this fall and winter because it’s not going to be easy.”

Fauci remains a top trusted source in COVID-19 information, poll numbers show.

A Kaiser Family Foundation poll released Thursday found that 68% of US adults had a fair amount or a great deal of trust that Fauci would provide reliable information on COVID-19, just slightly more that the 67% who said they trust the CDC information. About half (53%) say they trust Deborah Birx, MD, the coordinator for the White House Coronavirus Task Force, as a reliable source of information.

The poll also found that 54% of Americans said they would not get a COVID-19 vaccine if one was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration before the November election and was made available and free to all who wanted it.

Kaplan and Fauci report no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 and the psychological side effects of PPE

A few months ago, I published a short thought piece on the use of “sitters” with patients who were COVID-19 positive, or patients under investigation. In it, I recommended the use of telesitters for those who normally would warrant a human sitter, to decrease the discomfort of sitting in full personal protective equipment (PPE) (gown, mask, gloves, etc.) while monitoring a suicidal patient.

I received several queries, which I want to address here. In addition, I want to draw from my Army days in terms of the claustrophobia often experienced with PPE.

The first of the questions was about evidence-based practices. The second was about the discomfort of having sitters sit for many hours in the full gear.

I do not know of any evidence-based practices, but I hope we will develop them.

I agree that spending many hours in full PPE can be discomforting, which is why I wrote the essay.

As far as lessons learned from the Army time, I briefly learned how to wear a “gas mask” or Mission-Oriented Protective Posture (MOPP gear) while at Fort Bragg. We were run through the “gas chamber,” where sergeants released tear gas while we had the mask on. We were then asked to lift it up, and then tearing and sputtering, we could leave the small wooden building.

We wore the mask as part of our Army gear, usually on the right leg. After that, I mainly used the protective mask in its bag as a pillow when I was in the field.

Fast forward to August 1990. I arrived at Camp Casey, near the Korean demilitarized zone. Four days later, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. The gas mask moved from a pillow to something we had to wear while doing 12-mile road marches in “full ruck.” In full ruck, you have your uniform on, with TA-50, knapsack, and weapon. No, I do not remember any more what TA-50 stands for, but essentially it is the webbing that holds your bullets and bandages.

Many could not tolerate it. They developed claustrophobia – sweating, air hunger, and panic. If stationed in the Gulf for Operation Desert Storm, they were evacuated home.

I wrote a couple of short articles on treatment of gas mask phobia.1,2 I basically advised desensitization. Start by watching TV in it for 5 minutes. Graduate to ironing your uniform in the mask. Go then to shorter runs. Work up to the 12-mile road march.

In my second tour in Korea, we had exercises where we simulated being hit by nerve agents and had to operate the hospital for days at a time in partial or full PPE. It was tough but we did it, and felt more confident about surviving attacks from North Korea.

So back to the pandemic present. I have gotten more used to my constant wearing of a surgical mask. I get anxious when I see others with masks below their noses.

The pandemic is not going away anytime soon, in my opinion. Furthermore, there are other viruses that are worse, such as Ebola. It is only a matter of time.

So, let us train with our PPE. If health care workers cannot tolerate them, use desensitization- and anxiety-reducing techniques to help them.

There are no easy answers here, in the time of the COVID pandemic. However, we owe it to ourselves, our patients, and society to do the best we can.

References

1. Ritchie EC. Milit Med. 1992 Feb;157(2):104-6.

2. Ritchie EC. Milit Med. 2001 Dec;166. Suppl. 2(1)83-4.

Dr. Ritchie is chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington Hospital Center and professor of psychiatry at Georgetown University, Washington. She has no disclosures and can be reached at [email protected].

A few months ago, I published a short thought piece on the use of “sitters” with patients who were COVID-19 positive, or patients under investigation. In it, I recommended the use of telesitters for those who normally would warrant a human sitter, to decrease the discomfort of sitting in full personal protective equipment (PPE) (gown, mask, gloves, etc.) while monitoring a suicidal patient.

I received several queries, which I want to address here. In addition, I want to draw from my Army days in terms of the claustrophobia often experienced with PPE.

The first of the questions was about evidence-based practices. The second was about the discomfort of having sitters sit for many hours in the full gear.

I do not know of any evidence-based practices, but I hope we will develop them.

I agree that spending many hours in full PPE can be discomforting, which is why I wrote the essay.

As far as lessons learned from the Army time, I briefly learned how to wear a “gas mask” or Mission-Oriented Protective Posture (MOPP gear) while at Fort Bragg. We were run through the “gas chamber,” where sergeants released tear gas while we had the mask on. We were then asked to lift it up, and then tearing and sputtering, we could leave the small wooden building.

We wore the mask as part of our Army gear, usually on the right leg. After that, I mainly used the protective mask in its bag as a pillow when I was in the field.

Fast forward to August 1990. I arrived at Camp Casey, near the Korean demilitarized zone. Four days later, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. The gas mask moved from a pillow to something we had to wear while doing 12-mile road marches in “full ruck.” In full ruck, you have your uniform on, with TA-50, knapsack, and weapon. No, I do not remember any more what TA-50 stands for, but essentially it is the webbing that holds your bullets and bandages.

Many could not tolerate it. They developed claustrophobia – sweating, air hunger, and panic. If stationed in the Gulf for Operation Desert Storm, they were evacuated home.

I wrote a couple of short articles on treatment of gas mask phobia.1,2 I basically advised desensitization. Start by watching TV in it for 5 minutes. Graduate to ironing your uniform in the mask. Go then to shorter runs. Work up to the 12-mile road march.

In my second tour in Korea, we had exercises where we simulated being hit by nerve agents and had to operate the hospital for days at a time in partial or full PPE. It was tough but we did it, and felt more confident about surviving attacks from North Korea.

So back to the pandemic present. I have gotten more used to my constant wearing of a surgical mask. I get anxious when I see others with masks below their noses.

The pandemic is not going away anytime soon, in my opinion. Furthermore, there are other viruses that are worse, such as Ebola. It is only a matter of time.

So, let us train with our PPE. If health care workers cannot tolerate them, use desensitization- and anxiety-reducing techniques to help them.

There are no easy answers here, in the time of the COVID pandemic. However, we owe it to ourselves, our patients, and society to do the best we can.

References

1. Ritchie EC. Milit Med. 1992 Feb;157(2):104-6.

2. Ritchie EC. Milit Med. 2001 Dec;166. Suppl. 2(1)83-4.

Dr. Ritchie is chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington Hospital Center and professor of psychiatry at Georgetown University, Washington. She has no disclosures and can be reached at [email protected].

A few months ago, I published a short thought piece on the use of “sitters” with patients who were COVID-19 positive, or patients under investigation. In it, I recommended the use of telesitters for those who normally would warrant a human sitter, to decrease the discomfort of sitting in full personal protective equipment (PPE) (gown, mask, gloves, etc.) while monitoring a suicidal patient.

I received several queries, which I want to address here. In addition, I want to draw from my Army days in terms of the claustrophobia often experienced with PPE.

The first of the questions was about evidence-based practices. The second was about the discomfort of having sitters sit for many hours in the full gear.

I do not know of any evidence-based practices, but I hope we will develop them.

I agree that spending many hours in full PPE can be discomforting, which is why I wrote the essay.

As far as lessons learned from the Army time, I briefly learned how to wear a “gas mask” or Mission-Oriented Protective Posture (MOPP gear) while at Fort Bragg. We were run through the “gas chamber,” where sergeants released tear gas while we had the mask on. We were then asked to lift it up, and then tearing and sputtering, we could leave the small wooden building.

We wore the mask as part of our Army gear, usually on the right leg. After that, I mainly used the protective mask in its bag as a pillow when I was in the field.

Fast forward to August 1990. I arrived at Camp Casey, near the Korean demilitarized zone. Four days later, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. The gas mask moved from a pillow to something we had to wear while doing 12-mile road marches in “full ruck.” In full ruck, you have your uniform on, with TA-50, knapsack, and weapon. No, I do not remember any more what TA-50 stands for, but essentially it is the webbing that holds your bullets and bandages.

Many could not tolerate it. They developed claustrophobia – sweating, air hunger, and panic. If stationed in the Gulf for Operation Desert Storm, they were evacuated home.

I wrote a couple of short articles on treatment of gas mask phobia.1,2 I basically advised desensitization. Start by watching TV in it for 5 minutes. Graduate to ironing your uniform in the mask. Go then to shorter runs. Work up to the 12-mile road march.

In my second tour in Korea, we had exercises where we simulated being hit by nerve agents and had to operate the hospital for days at a time in partial or full PPE. It was tough but we did it, and felt more confident about surviving attacks from North Korea.

So back to the pandemic present. I have gotten more used to my constant wearing of a surgical mask. I get anxious when I see others with masks below their noses.

The pandemic is not going away anytime soon, in my opinion. Furthermore, there are other viruses that are worse, such as Ebola. It is only a matter of time.

So, let us train with our PPE. If health care workers cannot tolerate them, use desensitization- and anxiety-reducing techniques to help them.

There are no easy answers here, in the time of the COVID pandemic. However, we owe it to ourselves, our patients, and society to do the best we can.

References

1. Ritchie EC. Milit Med. 1992 Feb;157(2):104-6.

2. Ritchie EC. Milit Med. 2001 Dec;166. Suppl. 2(1)83-4.

Dr. Ritchie is chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington Hospital Center and professor of psychiatry at Georgetown University, Washington. She has no disclosures and can be reached at [email protected].

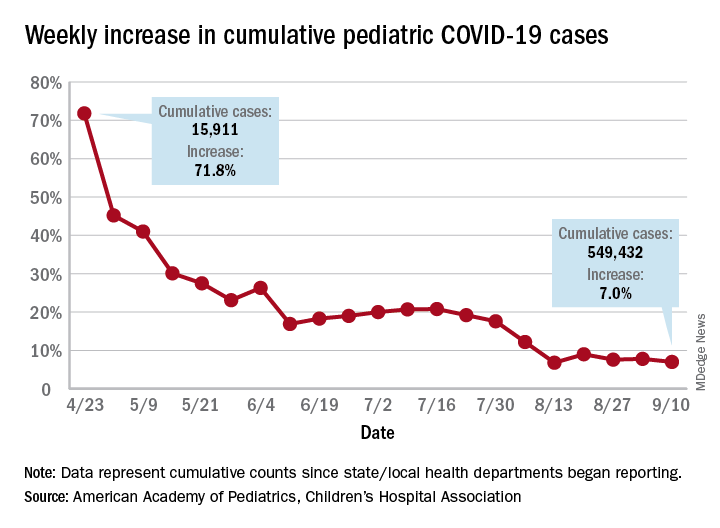

Children and COVID-19: New cases may be leveling off

Growth in new pediatric COVID-19 cases has evened out in recent weeks, but children now represent 10% of all COVID-19 cases in the United States, and that measurement has been rising throughout the pandemic, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and the CHA said in the report, based on data from 49 states (New York City is included but not New York state), the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The weekly percentage of increase in the number of new cases has not reached double digits since early August and has been no higher than 7.8% over the last 3 weeks. The number of child COVID-19 cases, however, has finally reached 10% of the total for Americans of all ages, which stands at 5.49 million in the jurisdictions included in the report, the AHA and CHA reported.

Measures, however, continue to show low levels of severe illness in children, they noted, including the following:

- Child cases as a proportion of all COVID-19 hospitalizations: 1.7%.

- Hospitalization rate for children: 1.8%.

- Child deaths as a proportion of all deaths: 0.07%.

- Percent of child cases resulting in death: 0.01%.

The number of cumulative cases per 100,000 children is now up to 728.5 nationally, with a range by state that goes from 154.0 in Vermont to 1,670.3 in Tennessee, which is one of only two states reporting cases in those aged 0-20 years as children (the other is South Carolina). The age range for children is 0-17 or 0-19 for most other states, although Florida uses a range of 0-14, the report notes.

Other than Tennessee, there are 10 states with overall rates higher than 1,000 COVID-19 cases per 100,000 children, and there are nine states with cumulative totals over 15,000 cases (California is the highest with just over 75,000), according to the report.

Growth in new pediatric COVID-19 cases has evened out in recent weeks, but children now represent 10% of all COVID-19 cases in the United States, and that measurement has been rising throughout the pandemic, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and the CHA said in the report, based on data from 49 states (New York City is included but not New York state), the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The weekly percentage of increase in the number of new cases has not reached double digits since early August and has been no higher than 7.8% over the last 3 weeks. The number of child COVID-19 cases, however, has finally reached 10% of the total for Americans of all ages, which stands at 5.49 million in the jurisdictions included in the report, the AHA and CHA reported.

Measures, however, continue to show low levels of severe illness in children, they noted, including the following:

- Child cases as a proportion of all COVID-19 hospitalizations: 1.7%.

- Hospitalization rate for children: 1.8%.

- Child deaths as a proportion of all deaths: 0.07%.

- Percent of child cases resulting in death: 0.01%.

The number of cumulative cases per 100,000 children is now up to 728.5 nationally, with a range by state that goes from 154.0 in Vermont to 1,670.3 in Tennessee, which is one of only two states reporting cases in those aged 0-20 years as children (the other is South Carolina). The age range for children is 0-17 or 0-19 for most other states, although Florida uses a range of 0-14, the report notes.

Other than Tennessee, there are 10 states with overall rates higher than 1,000 COVID-19 cases per 100,000 children, and there are nine states with cumulative totals over 15,000 cases (California is the highest with just over 75,000), according to the report.

Growth in new pediatric COVID-19 cases has evened out in recent weeks, but children now represent 10% of all COVID-19 cases in the United States, and that measurement has been rising throughout the pandemic, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and the CHA said in the report, based on data from 49 states (New York City is included but not New York state), the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The weekly percentage of increase in the number of new cases has not reached double digits since early August and has been no higher than 7.8% over the last 3 weeks. The number of child COVID-19 cases, however, has finally reached 10% of the total for Americans of all ages, which stands at 5.49 million in the jurisdictions included in the report, the AHA and CHA reported.

Measures, however, continue to show low levels of severe illness in children, they noted, including the following:

- Child cases as a proportion of all COVID-19 hospitalizations: 1.7%.

- Hospitalization rate for children: 1.8%.

- Child deaths as a proportion of all deaths: 0.07%.

- Percent of child cases resulting in death: 0.01%.

The number of cumulative cases per 100,000 children is now up to 728.5 nationally, with a range by state that goes from 154.0 in Vermont to 1,670.3 in Tennessee, which is one of only two states reporting cases in those aged 0-20 years as children (the other is South Carolina). The age range for children is 0-17 or 0-19 for most other states, although Florida uses a range of 0-14, the report notes.

Other than Tennessee, there are 10 states with overall rates higher than 1,000 COVID-19 cases per 100,000 children, and there are nine states with cumulative totals over 15,000 cases (California is the highest with just over 75,000), according to the report.

Conspiracy theories

It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so. – Josh Billings

and intends to use COVID vaccinations as a devious way to implant microchips in us. He will then, of course, use the new 5G towers to track us all (although what Gates will do with the information that I was shopping at a Trader Joe’s yesterday is yet unknown).

It’s easy to dismiss patients with these beliefs as nuts or dumb or both. They’re neither, they’re just human. Conspiracy theories have been shared from the first time two humans met. They are, after all, simply hypotheses to explain an experience that’s difficult to understand. Making up a story to explain things feels safer than living with the unknown, and so we do. Our natural tendency to be suspicious makes conspiracy hypotheses more salient and more likely to spread. The pandemic itself is exacerbating this problem: People are alone and afraid, and dependent on social media for connection. Add a compelling story about a nefarious robber baron plotting to exploit us and you’ve got the conditions for conspiracy theories to explode like wind-driven wildfires. Astonishingly, a Pew Research poll showed 36% of Americans surveyed who have heard something about it say the Bill Gates cabal theory is “probably” or “definitely” true.

That many patients fervently believe conspiracy theories poses several problems for us. First, when a vaccine does become available, some patients will refuse to be vaccinated. The consequences to their health and the health of the community are grave. Secondly, whenever patients have cause to distrust doctors, it makes our jobs more challenging. If they don’t trust us on vaccines, it can spread to not trusting us about wearing masks or sunscreens or taking statins. Lastly, it’s near impossible to have a friendly conversation with a patient carrying forth on why Bill Gates is not in jail or how I’m part of the medical-industrial complex enabling him. Sheesh.

It isn’t their fault. The underpinning of these beliefs can be understood as a cognitive bias. In this case, an idea that is easy to imagine or recall is believed to be true more than an idea that is complex and difficult. Understanding viral replication and R0 numbers or viral vectors and protein subunit vaccines is hard. Imagining a chip being injected into your arm is easy. And, as behavioral economist Daniel Kahneman opined, we humans possess an almost unlimited ability to ignore our ignorance. We physicians can help in a way that friends and family members can’t. Here are ways you can help patients who believe in conspiracy theories:

Approach this problem like any other infirmity, with compassion. No one wants to drink too much and knock out their teeth falling off a bike. It was a mistake. Similarly, when people are steeped in self-delusion, it’s not a misdeed, it’s a lapse. Be kind and respectful.

Meet them where they are. It might be helpful to state with sincerity: So you feel that there is a government plot to use COVID to track us? Have you considered that might not be true?

Have the conversation in private. Harder even than being wrong is being publicly wrong.

Try the Socratic method. (We’re pretty good at this from teaching students and residents.) Conspiracy-believing patients have the illusion of knowledge, yet, like students, it’s often easy to show them their gaps. Do so gently by leading them to discover for themselves.

Stop when you stall. You cannot change someone’s mind by dint of force. However, you surely can damage your relationship if you keep pushing them.

Don’t worry if you fail to break through; you might yet have moved them a bit. This might make it possible for them to discover the truth later. Or, you could simply switch to explain what holds up the ground we walk upon. There’s rumor we’re supported on the backs of turtles, all the way down. Maybe Bill Gates is feeding them.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so. – Josh Billings

and intends to use COVID vaccinations as a devious way to implant microchips in us. He will then, of course, use the new 5G towers to track us all (although what Gates will do with the information that I was shopping at a Trader Joe’s yesterday is yet unknown).

It’s easy to dismiss patients with these beliefs as nuts or dumb or both. They’re neither, they’re just human. Conspiracy theories have been shared from the first time two humans met. They are, after all, simply hypotheses to explain an experience that’s difficult to understand. Making up a story to explain things feels safer than living with the unknown, and so we do. Our natural tendency to be suspicious makes conspiracy hypotheses more salient and more likely to spread. The pandemic itself is exacerbating this problem: People are alone and afraid, and dependent on social media for connection. Add a compelling story about a nefarious robber baron plotting to exploit us and you’ve got the conditions for conspiracy theories to explode like wind-driven wildfires. Astonishingly, a Pew Research poll showed 36% of Americans surveyed who have heard something about it say the Bill Gates cabal theory is “probably” or “definitely” true.

That many patients fervently believe conspiracy theories poses several problems for us. First, when a vaccine does become available, some patients will refuse to be vaccinated. The consequences to their health and the health of the community are grave. Secondly, whenever patients have cause to distrust doctors, it makes our jobs more challenging. If they don’t trust us on vaccines, it can spread to not trusting us about wearing masks or sunscreens or taking statins. Lastly, it’s near impossible to have a friendly conversation with a patient carrying forth on why Bill Gates is not in jail or how I’m part of the medical-industrial complex enabling him. Sheesh.

It isn’t their fault. The underpinning of these beliefs can be understood as a cognitive bias. In this case, an idea that is easy to imagine or recall is believed to be true more than an idea that is complex and difficult. Understanding viral replication and R0 numbers or viral vectors and protein subunit vaccines is hard. Imagining a chip being injected into your arm is easy. And, as behavioral economist Daniel Kahneman opined, we humans possess an almost unlimited ability to ignore our ignorance. We physicians can help in a way that friends and family members can’t. Here are ways you can help patients who believe in conspiracy theories:

Approach this problem like any other infirmity, with compassion. No one wants to drink too much and knock out their teeth falling off a bike. It was a mistake. Similarly, when people are steeped in self-delusion, it’s not a misdeed, it’s a lapse. Be kind and respectful.

Meet them where they are. It might be helpful to state with sincerity: So you feel that there is a government plot to use COVID to track us? Have you considered that might not be true?

Have the conversation in private. Harder even than being wrong is being publicly wrong.

Try the Socratic method. (We’re pretty good at this from teaching students and residents.) Conspiracy-believing patients have the illusion of knowledge, yet, like students, it’s often easy to show them their gaps. Do so gently by leading them to discover for themselves.

Stop when you stall. You cannot change someone’s mind by dint of force. However, you surely can damage your relationship if you keep pushing them.

Don’t worry if you fail to break through; you might yet have moved them a bit. This might make it possible for them to discover the truth later. Or, you could simply switch to explain what holds up the ground we walk upon. There’s rumor we’re supported on the backs of turtles, all the way down. Maybe Bill Gates is feeding them.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so. – Josh Billings

and intends to use COVID vaccinations as a devious way to implant microchips in us. He will then, of course, use the new 5G towers to track us all (although what Gates will do with the information that I was shopping at a Trader Joe’s yesterday is yet unknown).

It’s easy to dismiss patients with these beliefs as nuts or dumb or both. They’re neither, they’re just human. Conspiracy theories have been shared from the first time two humans met. They are, after all, simply hypotheses to explain an experience that’s difficult to understand. Making up a story to explain things feels safer than living with the unknown, and so we do. Our natural tendency to be suspicious makes conspiracy hypotheses more salient and more likely to spread. The pandemic itself is exacerbating this problem: People are alone and afraid, and dependent on social media for connection. Add a compelling story about a nefarious robber baron plotting to exploit us and you’ve got the conditions for conspiracy theories to explode like wind-driven wildfires. Astonishingly, a Pew Research poll showed 36% of Americans surveyed who have heard something about it say the Bill Gates cabal theory is “probably” or “definitely” true.

That many patients fervently believe conspiracy theories poses several problems for us. First, when a vaccine does become available, some patients will refuse to be vaccinated. The consequences to their health and the health of the community are grave. Secondly, whenever patients have cause to distrust doctors, it makes our jobs more challenging. If they don’t trust us on vaccines, it can spread to not trusting us about wearing masks or sunscreens or taking statins. Lastly, it’s near impossible to have a friendly conversation with a patient carrying forth on why Bill Gates is not in jail or how I’m part of the medical-industrial complex enabling him. Sheesh.

It isn’t their fault. The underpinning of these beliefs can be understood as a cognitive bias. In this case, an idea that is easy to imagine or recall is believed to be true more than an idea that is complex and difficult. Understanding viral replication and R0 numbers or viral vectors and protein subunit vaccines is hard. Imagining a chip being injected into your arm is easy. And, as behavioral economist Daniel Kahneman opined, we humans possess an almost unlimited ability to ignore our ignorance. We physicians can help in a way that friends and family members can’t. Here are ways you can help patients who believe in conspiracy theories:

Approach this problem like any other infirmity, with compassion. No one wants to drink too much and knock out their teeth falling off a bike. It was a mistake. Similarly, when people are steeped in self-delusion, it’s not a misdeed, it’s a lapse. Be kind and respectful.

Meet them where they are. It might be helpful to state with sincerity: So you feel that there is a government plot to use COVID to track us? Have you considered that might not be true?

Have the conversation in private. Harder even than being wrong is being publicly wrong.

Try the Socratic method. (We’re pretty good at this from teaching students and residents.) Conspiracy-believing patients have the illusion of knowledge, yet, like students, it’s often easy to show them their gaps. Do so gently by leading them to discover for themselves.

Stop when you stall. You cannot change someone’s mind by dint of force. However, you surely can damage your relationship if you keep pushing them.

Don’t worry if you fail to break through; you might yet have moved them a bit. This might make it possible for them to discover the truth later. Or, you could simply switch to explain what holds up the ground we walk upon. There’s rumor we’re supported on the backs of turtles, all the way down. Maybe Bill Gates is feeding them.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Tough to tell COVID from smoke inhalation symptoms — And flu season’s coming

The patients walk into Dr. Melissa Marshall’s community clinics in Northern California with the telltale symptoms. They’re having trouble breathing. It may even hurt to inhale. They’ve got a cough, and the sore throat is definitely there.

A straight case of COVID-19? Not so fast. This is wildfire country.

Up and down the West Coast, hospitals and health facilities are reporting an influx of patients with problems most likely related to smoke inhalation. As fires rage largely uncontrolled amid dry heat and high winds, smoke and ash are billowing and settling on coastal areas like San Francisco and cities and towns hundreds of miles inland as well, turning the sky orange or gray and making even ordinary breathing difficult.

But that, Marshall said, is only part of the challenge.

“Obviously, there’s overlap in the symptoms,” said Marshall, the CEO of CommuniCare, a collection of six clinics in Yolo County, near Sacramento, that treats mostly underinsured and uninsured patients. “Any time someone comes in with even some of those symptoms, we ask ourselves, ‘Is it COVID?’ At the end of the day, clinically speaking, I still want to rule out the virus.”

The protocol is to treat the symptoms, whatever their cause, while recommending that the patient quarantine until test results for the virus come back, she said.

It is a scene playing out in numerous hospitals. Administrators and physicians, finely attuned to COVID-19’s ability to spread quickly and wreak havoc, simply won’t take a chance when they recognize symptoms that could emanate from the virus.

“We’ve seen an increase in patients presenting to the emergency department with respiratory distress,” said Dr. Nanette Mickiewicz, president and CEO of Dominican Hospital in Santa Cruz. “As this can also be a symptom of COVID-19, we’re treating these patients as we would any person under investigation for coronavirus until we can rule them out through our screening process.” During the workup, symptoms that are more specific to COVID-19, like fever, would become apparent.

For the workers at Dominican, the issue moved to the top of the list quickly. Santa Cruz and San Mateo counties have borne the brunt of the CZU Lightning Complex fires, which as of Sept. 10 had burned more than 86,000 acres, destroying 1,100 structures and threatening more than 7,600 others. Nearly a month after they began, the fires were approximately 84% contained, but thousands of people remained evacuated.

Dominican, a Dignity Health hospital, is “open, safe and providing care,” Mickiewicz said. Multiple tents erected outside the building serve as an extension of its ER waiting room. They also are used to perform what has come to be understood as an essential role: separating those with symptoms of COVID-19 from those without.

At the two Solano County hospitals operated by NorthBay Healthcare, the path of some of the wildfires prompted officials to review their evacuation procedures, said spokesperson Steve Huddleston. They ultimately avoided the need to evacuate patients, and new ones arrived with COVID-like symptoms that may actually have been from smoke inhalation.

Huddleston said NorthBay’s intake process “calls for anyone with COVID characteristics to be handled as [a] patient under investigation for COVID, which means they’re separated, screened and managed by staff in special PPE.” At the two hospitals, which have handled nearly 200 COVID cases so far, the protocol is well established.

Hospitals in California, though not under siege in most cases, are dealing with multiple issues they might typically face only sporadically. In Napa County, Adventist Health St. Helena Hospital evacuated 51 patients on a single August night as a fire approached, moving them to 10 other facilities according to their needs and bed space. After a 10-day closure, the hospital was allowed to reopen as evacuation orders were lifted, the fire having been contained some distance away.

The wildfires are also taking a personal toll on health care workers. CommuniCare’s Marshall lost her family’s home in rural Winters, along with 20 acres of olive trees and other plantings that surrounded it, in the Aug. 19 fires that swept through Solano County.

“They called it a ‘firenado,’ ” Marshall said. An apparent confluence of three fires raged out of control, demolishing thousands of acres. With her family safely accounted for and temporary housing arranged by a friend, she returned to work. “Our clinics interact with a very vulnerable population,” she said, “and this is a critical time for them.”

While she pondered how her family would rebuild, the CEO was faced with another immediate crisis: the clinic’s shortage of supplies. Last month, CommuniCare got down to 19 COVID test kits on hand, and ran so low on swabs “that we were literally turning to our veterinary friends for reinforcements,” the doctor said. The clinic’s COVID test results, meanwhile, were taking nearly two weeks to be returned from an overwhelmed outside lab, rendering contact tracing almost useless.

Those situations have been addressed, at least temporarily, Marshall said. But although the West Coast is in the most dangerous time of year for wildfires, generally September to December, another complication for health providers lies on the horizon: flu season.

The Southern Hemisphere, whose influenza trends during our summer months typically predict what’s to come for the U.S., has had very little of the disease this year, presumably because of restricted travel, social distancing and face masks. But it’s too early to be sure what the U.S. flu season will entail.

“You can start to see some cases of the flu in late October,” said Marshall, “and the reality is that it’s going to carry a number of characteristics that could also be symptomatic of COVID. And nothing changes: You have to rule it out, just to eliminate the risk.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente. This KHN story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation.

The patients walk into Dr. Melissa Marshall’s community clinics in Northern California with the telltale symptoms. They’re having trouble breathing. It may even hurt to inhale. They’ve got a cough, and the sore throat is definitely there.

A straight case of COVID-19? Not so fast. This is wildfire country.

Up and down the West Coast, hospitals and health facilities are reporting an influx of patients with problems most likely related to smoke inhalation. As fires rage largely uncontrolled amid dry heat and high winds, smoke and ash are billowing and settling on coastal areas like San Francisco and cities and towns hundreds of miles inland as well, turning the sky orange or gray and making even ordinary breathing difficult.

But that, Marshall said, is only part of the challenge.

“Obviously, there’s overlap in the symptoms,” said Marshall, the CEO of CommuniCare, a collection of six clinics in Yolo County, near Sacramento, that treats mostly underinsured and uninsured patients. “Any time someone comes in with even some of those symptoms, we ask ourselves, ‘Is it COVID?’ At the end of the day, clinically speaking, I still want to rule out the virus.”

The protocol is to treat the symptoms, whatever their cause, while recommending that the patient quarantine until test results for the virus come back, she said.

It is a scene playing out in numerous hospitals. Administrators and physicians, finely attuned to COVID-19’s ability to spread quickly and wreak havoc, simply won’t take a chance when they recognize symptoms that could emanate from the virus.

“We’ve seen an increase in patients presenting to the emergency department with respiratory distress,” said Dr. Nanette Mickiewicz, president and CEO of Dominican Hospital in Santa Cruz. “As this can also be a symptom of COVID-19, we’re treating these patients as we would any person under investigation for coronavirus until we can rule them out through our screening process.” During the workup, symptoms that are more specific to COVID-19, like fever, would become apparent.

For the workers at Dominican, the issue moved to the top of the list quickly. Santa Cruz and San Mateo counties have borne the brunt of the CZU Lightning Complex fires, which as of Sept. 10 had burned more than 86,000 acres, destroying 1,100 structures and threatening more than 7,600 others. Nearly a month after they began, the fires were approximately 84% contained, but thousands of people remained evacuated.

Dominican, a Dignity Health hospital, is “open, safe and providing care,” Mickiewicz said. Multiple tents erected outside the building serve as an extension of its ER waiting room. They also are used to perform what has come to be understood as an essential role: separating those with symptoms of COVID-19 from those without.

At the two Solano County hospitals operated by NorthBay Healthcare, the path of some of the wildfires prompted officials to review their evacuation procedures, said spokesperson Steve Huddleston. They ultimately avoided the need to evacuate patients, and new ones arrived with COVID-like symptoms that may actually have been from smoke inhalation.

Huddleston said NorthBay’s intake process “calls for anyone with COVID characteristics to be handled as [a] patient under investigation for COVID, which means they’re separated, screened and managed by staff in special PPE.” At the two hospitals, which have handled nearly 200 COVID cases so far, the protocol is well established.

Hospitals in California, though not under siege in most cases, are dealing with multiple issues they might typically face only sporadically. In Napa County, Adventist Health St. Helena Hospital evacuated 51 patients on a single August night as a fire approached, moving them to 10 other facilities according to their needs and bed space. After a 10-day closure, the hospital was allowed to reopen as evacuation orders were lifted, the fire having been contained some distance away.

The wildfires are also taking a personal toll on health care workers. CommuniCare’s Marshall lost her family’s home in rural Winters, along with 20 acres of olive trees and other plantings that surrounded it, in the Aug. 19 fires that swept through Solano County.

“They called it a ‘firenado,’ ” Marshall said. An apparent confluence of three fires raged out of control, demolishing thousands of acres. With her family safely accounted for and temporary housing arranged by a friend, she returned to work. “Our clinics interact with a very vulnerable population,” she said, “and this is a critical time for them.”

While she pondered how her family would rebuild, the CEO was faced with another immediate crisis: the clinic’s shortage of supplies. Last month, CommuniCare got down to 19 COVID test kits on hand, and ran so low on swabs “that we were literally turning to our veterinary friends for reinforcements,” the doctor said. The clinic’s COVID test results, meanwhile, were taking nearly two weeks to be returned from an overwhelmed outside lab, rendering contact tracing almost useless.

Those situations have been addressed, at least temporarily, Marshall said. But although the West Coast is in the most dangerous time of year for wildfires, generally September to December, another complication for health providers lies on the horizon: flu season.

The Southern Hemisphere, whose influenza trends during our summer months typically predict what’s to come for the U.S., has had very little of the disease this year, presumably because of restricted travel, social distancing and face masks. But it’s too early to be sure what the U.S. flu season will entail.

“You can start to see some cases of the flu in late October,” said Marshall, “and the reality is that it’s going to carry a number of characteristics that could also be symptomatic of COVID. And nothing changes: You have to rule it out, just to eliminate the risk.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente. This KHN story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation.

The patients walk into Dr. Melissa Marshall’s community clinics in Northern California with the telltale symptoms. They’re having trouble breathing. It may even hurt to inhale. They’ve got a cough, and the sore throat is definitely there.

A straight case of COVID-19? Not so fast. This is wildfire country.

Up and down the West Coast, hospitals and health facilities are reporting an influx of patients with problems most likely related to smoke inhalation. As fires rage largely uncontrolled amid dry heat and high winds, smoke and ash are billowing and settling on coastal areas like San Francisco and cities and towns hundreds of miles inland as well, turning the sky orange or gray and making even ordinary breathing difficult.

But that, Marshall said, is only part of the challenge.

“Obviously, there’s overlap in the symptoms,” said Marshall, the CEO of CommuniCare, a collection of six clinics in Yolo County, near Sacramento, that treats mostly underinsured and uninsured patients. “Any time someone comes in with even some of those symptoms, we ask ourselves, ‘Is it COVID?’ At the end of the day, clinically speaking, I still want to rule out the virus.”

The protocol is to treat the symptoms, whatever their cause, while recommending that the patient quarantine until test results for the virus come back, she said.

It is a scene playing out in numerous hospitals. Administrators and physicians, finely attuned to COVID-19’s ability to spread quickly and wreak havoc, simply won’t take a chance when they recognize symptoms that could emanate from the virus.

“We’ve seen an increase in patients presenting to the emergency department with respiratory distress,” said Dr. Nanette Mickiewicz, president and CEO of Dominican Hospital in Santa Cruz. “As this can also be a symptom of COVID-19, we’re treating these patients as we would any person under investigation for coronavirus until we can rule them out through our screening process.” During the workup, symptoms that are more specific to COVID-19, like fever, would become apparent.

For the workers at Dominican, the issue moved to the top of the list quickly. Santa Cruz and San Mateo counties have borne the brunt of the CZU Lightning Complex fires, which as of Sept. 10 had burned more than 86,000 acres, destroying 1,100 structures and threatening more than 7,600 others. Nearly a month after they began, the fires were approximately 84% contained, but thousands of people remained evacuated.

Dominican, a Dignity Health hospital, is “open, safe and providing care,” Mickiewicz said. Multiple tents erected outside the building serve as an extension of its ER waiting room. They also are used to perform what has come to be understood as an essential role: separating those with symptoms of COVID-19 from those without.

At the two Solano County hospitals operated by NorthBay Healthcare, the path of some of the wildfires prompted officials to review their evacuation procedures, said spokesperson Steve Huddleston. They ultimately avoided the need to evacuate patients, and new ones arrived with COVID-like symptoms that may actually have been from smoke inhalation.

Huddleston said NorthBay’s intake process “calls for anyone with COVID characteristics to be handled as [a] patient under investigation for COVID, which means they’re separated, screened and managed by staff in special PPE.” At the two hospitals, which have handled nearly 200 COVID cases so far, the protocol is well established.

Hospitals in California, though not under siege in most cases, are dealing with multiple issues they might typically face only sporadically. In Napa County, Adventist Health St. Helena Hospital evacuated 51 patients on a single August night as a fire approached, moving them to 10 other facilities according to their needs and bed space. After a 10-day closure, the hospital was allowed to reopen as evacuation orders were lifted, the fire having been contained some distance away.

The wildfires are also taking a personal toll on health care workers. CommuniCare’s Marshall lost her family’s home in rural Winters, along with 20 acres of olive trees and other plantings that surrounded it, in the Aug. 19 fires that swept through Solano County.

“They called it a ‘firenado,’ ” Marshall said. An apparent confluence of three fires raged out of control, demolishing thousands of acres. With her family safely accounted for and temporary housing arranged by a friend, she returned to work. “Our clinics interact with a very vulnerable population,” she said, “and this is a critical time for them.”

While she pondered how her family would rebuild, the CEO was faced with another immediate crisis: the clinic’s shortage of supplies. Last month, CommuniCare got down to 19 COVID test kits on hand, and ran so low on swabs “that we were literally turning to our veterinary friends for reinforcements,” the doctor said. The clinic’s COVID test results, meanwhile, were taking nearly two weeks to be returned from an overwhelmed outside lab, rendering contact tracing almost useless.

Those situations have been addressed, at least temporarily, Marshall said. But although the West Coast is in the most dangerous time of year for wildfires, generally September to December, another complication for health providers lies on the horizon: flu season.

The Southern Hemisphere, whose influenza trends during our summer months typically predict what’s to come for the U.S., has had very little of the disease this year, presumably because of restricted travel, social distancing and face masks. But it’s too early to be sure what the U.S. flu season will entail.

“You can start to see some cases of the flu in late October,” said Marshall, “and the reality is that it’s going to carry a number of characteristics that could also be symptomatic of COVID. And nothing changes: You have to rule it out, just to eliminate the risk.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente. This KHN story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation.

COVID-19 outcomes no worse in patients on TNF inhibitors or methotrexate

Continued use of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors or methotrexate is acceptable in most patients who acquire COVID-19, results of a recent cohort study suggest.

Among patients on tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) or methotrexate who developed COVID-19, death and hospitalization rates were similar to matched COVID-19 patients not on those medications, according to authors of the multicenter research network study.

Reassuringly, likelihood of hospitalization and mortality were not significantly different between 214 patients with COVID-19 taking TNFi or methotrexate and 31,862 matched COVID-19 patients not on those medications, according to the investigators, whose findings were published recently in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Zachary Zinn, MD, corresponding author on the study, said in an interview that the findings suggest these medicines can be safely continued in the majority of patients taking them during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“If you’re a prescribing physician who’s giving patients TNF inhibitors or methotrexate or both, I think you can comfortably tell your patients there is good data that these do not lead to worse outcomes if you get COVID-19,” said Dr. Zinn, associate professor in the department of dermatology at West Virginia University, Morgantown.

The findings from these researchers corroborate a growing body of evidence suggesting that immunosuppressive treatments can be continued in patients with dermatologic and rheumatic conditions.

In recent guidance from the National Psoriasis Foundation, released Sept. 4, an expert consensus panel cited 15 studies that they said suggested that treatments for psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis “do not meaningfully alter the risk of acquiring SARS-CoV-2 infection or having worse COVID-19 outcomes.”

That said, the data to date are mainly from small case series and registry studies based on spontaneously reported COVID-19 cases, which suggests a continued need for shared decision making. In addition, chronic systemic corticosteroids should be avoided for management of psoriatic arthritis, the guidance states, based on rheumatology and gastroenterology literature suggesting this treatment is linked to worse COVID-19 outcomes.

In the interview, Dr. Zinn noted that some previous studies of immunosuppressive treatments in patients who acquire COVID-19 have aggregated data on numerous classes of biologic medications, lessening the strength of data for each specific medication.

“By focusing specifically on TNF inhibitors and methotrexate, this study gives better guidance to prescribers of these medications,” he said.

To see whether TNFi or methotrexate increased risk of worsened COVID-19 outcomes, Dr. Zinn and coinvestigators evaluated data from TriNetX, a research network that includes approximately 53 million unique patient records, predominantly in the United States.

They identified 32,076 adult patients with COVID-19, of whom 214 had recent exposure to TNFi or methotrexate. The patients in the TNFi/methotrexate group were similar in age to those without exposure to those drugs, at 55.1 versus 53.2 years, respectively. However, patients in the drug exposure group were more frequently White, female, and had substantially more comorbidities, including diabetes and obesity, according to the investigators.

Nevertheless, the likelihood of hospitalization was not statistically different in the TNFi/methotrexate group versus the non-TNFi/methotrexate group, with a risk ratio of 0.91 (95% confidence interval, 0.68-1.22; P = .5260).

Likewise, the likelihood of death was not different between groups, with a RR of 0.87 (95% CI, 0.42-1.78; P = .6958). Looking at subgroups of patients exposed to TNFi or methotrexate only didn’t change the results, the investigators added.

Taken together, the findings argue against interruption of these treatments because of the fear of the possibly worse COVID-19 outcomes, the investigators concluded, although they emphasized the need for more research.

“Because the COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing, there is a desperate need for evidence-based data on biologic and immunomodulator exposure in the setting of COVID-19 infection,” they wrote.

Dr. Zinn and coauthors reported no conflicts of interest and no funding sources related to the study.

SOURCE: Zinn Z et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Sep 11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.009.

Continued use of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors or methotrexate is acceptable in most patients who acquire COVID-19, results of a recent cohort study suggest.

Among patients on tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) or methotrexate who developed COVID-19, death and hospitalization rates were similar to matched COVID-19 patients not on those medications, according to authors of the multicenter research network study.

Reassuringly, likelihood of hospitalization and mortality were not significantly different between 214 patients with COVID-19 taking TNFi or methotrexate and 31,862 matched COVID-19 patients not on those medications, according to the investigators, whose findings were published recently in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Zachary Zinn, MD, corresponding author on the study, said in an interview that the findings suggest these medicines can be safely continued in the majority of patients taking them during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“If you’re a prescribing physician who’s giving patients TNF inhibitors or methotrexate or both, I think you can comfortably tell your patients there is good data that these do not lead to worse outcomes if you get COVID-19,” said Dr. Zinn, associate professor in the department of dermatology at West Virginia University, Morgantown.

The findings from these researchers corroborate a growing body of evidence suggesting that immunosuppressive treatments can be continued in patients with dermatologic and rheumatic conditions.

In recent guidance from the National Psoriasis Foundation, released Sept. 4, an expert consensus panel cited 15 studies that they said suggested that treatments for psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis “do not meaningfully alter the risk of acquiring SARS-CoV-2 infection or having worse COVID-19 outcomes.”

That said, the data to date are mainly from small case series and registry studies based on spontaneously reported COVID-19 cases, which suggests a continued need for shared decision making. In addition, chronic systemic corticosteroids should be avoided for management of psoriatic arthritis, the guidance states, based on rheumatology and gastroenterology literature suggesting this treatment is linked to worse COVID-19 outcomes.

In the interview, Dr. Zinn noted that some previous studies of immunosuppressive treatments in patients who acquire COVID-19 have aggregated data on numerous classes of biologic medications, lessening the strength of data for each specific medication.

“By focusing specifically on TNF inhibitors and methotrexate, this study gives better guidance to prescribers of these medications,” he said.

To see whether TNFi or methotrexate increased risk of worsened COVID-19 outcomes, Dr. Zinn and coinvestigators evaluated data from TriNetX, a research network that includes approximately 53 million unique patient records, predominantly in the United States.

They identified 32,076 adult patients with COVID-19, of whom 214 had recent exposure to TNFi or methotrexate. The patients in the TNFi/methotrexate group were similar in age to those without exposure to those drugs, at 55.1 versus 53.2 years, respectively. However, patients in the drug exposure group were more frequently White, female, and had substantially more comorbidities, including diabetes and obesity, according to the investigators.

Nevertheless, the likelihood of hospitalization was not statistically different in the TNFi/methotrexate group versus the non-TNFi/methotrexate group, with a risk ratio of 0.91 (95% confidence interval, 0.68-1.22; P = .5260).

Likewise, the likelihood of death was not different between groups, with a RR of 0.87 (95% CI, 0.42-1.78; P = .6958). Looking at subgroups of patients exposed to TNFi or methotrexate only didn’t change the results, the investigators added.

Taken together, the findings argue against interruption of these treatments because of the fear of the possibly worse COVID-19 outcomes, the investigators concluded, although they emphasized the need for more research.

“Because the COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing, there is a desperate need for evidence-based data on biologic and immunomodulator exposure in the setting of COVID-19 infection,” they wrote.

Dr. Zinn and coauthors reported no conflicts of interest and no funding sources related to the study.

SOURCE: Zinn Z et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Sep 11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.009.

Continued use of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors or methotrexate is acceptable in most patients who acquire COVID-19, results of a recent cohort study suggest.

Among patients on tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) or methotrexate who developed COVID-19, death and hospitalization rates were similar to matched COVID-19 patients not on those medications, according to authors of the multicenter research network study.

Reassuringly, likelihood of hospitalization and mortality were not significantly different between 214 patients with COVID-19 taking TNFi or methotrexate and 31,862 matched COVID-19 patients not on those medications, according to the investigators, whose findings were published recently in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Zachary Zinn, MD, corresponding author on the study, said in an interview that the findings suggest these medicines can be safely continued in the majority of patients taking them during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“If you’re a prescribing physician who’s giving patients TNF inhibitors or methotrexate or both, I think you can comfortably tell your patients there is good data that these do not lead to worse outcomes if you get COVID-19,” said Dr. Zinn, associate professor in the department of dermatology at West Virginia University, Morgantown.

The findings from these researchers corroborate a growing body of evidence suggesting that immunosuppressive treatments can be continued in patients with dermatologic and rheumatic conditions.

In recent guidance from the National Psoriasis Foundation, released Sept. 4, an expert consensus panel cited 15 studies that they said suggested that treatments for psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis “do not meaningfully alter the risk of acquiring SARS-CoV-2 infection or having worse COVID-19 outcomes.”

That said, the data to date are mainly from small case series and registry studies based on spontaneously reported COVID-19 cases, which suggests a continued need for shared decision making. In addition, chronic systemic corticosteroids should be avoided for management of psoriatic arthritis, the guidance states, based on rheumatology and gastroenterology literature suggesting this treatment is linked to worse COVID-19 outcomes.

In the interview, Dr. Zinn noted that some previous studies of immunosuppressive treatments in patients who acquire COVID-19 have aggregated data on numerous classes of biologic medications, lessening the strength of data for each specific medication.

“By focusing specifically on TNF inhibitors and methotrexate, this study gives better guidance to prescribers of these medications,” he said.

To see whether TNFi or methotrexate increased risk of worsened COVID-19 outcomes, Dr. Zinn and coinvestigators evaluated data from TriNetX, a research network that includes approximately 53 million unique patient records, predominantly in the United States.

They identified 32,076 adult patients with COVID-19, of whom 214 had recent exposure to TNFi or methotrexate. The patients in the TNFi/methotrexate group were similar in age to those without exposure to those drugs, at 55.1 versus 53.2 years, respectively. However, patients in the drug exposure group were more frequently White, female, and had substantially more comorbidities, including diabetes and obesity, according to the investigators.

Nevertheless, the likelihood of hospitalization was not statistically different in the TNFi/methotrexate group versus the non-TNFi/methotrexate group, with a risk ratio of 0.91 (95% confidence interval, 0.68-1.22; P = .5260).

Likewise, the likelihood of death was not different between groups, with a RR of 0.87 (95% CI, 0.42-1.78; P = .6958). Looking at subgroups of patients exposed to TNFi or methotrexate only didn’t change the results, the investigators added.

Taken together, the findings argue against interruption of these treatments because of the fear of the possibly worse COVID-19 outcomes, the investigators concluded, although they emphasized the need for more research.

“Because the COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing, there is a desperate need for evidence-based data on biologic and immunomodulator exposure in the setting of COVID-19 infection,” they wrote.

Dr. Zinn and coauthors reported no conflicts of interest and no funding sources related to the study.

SOURCE: Zinn Z et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Sep 11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.009.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Physician income drops, burnout spikes globally in pandemic

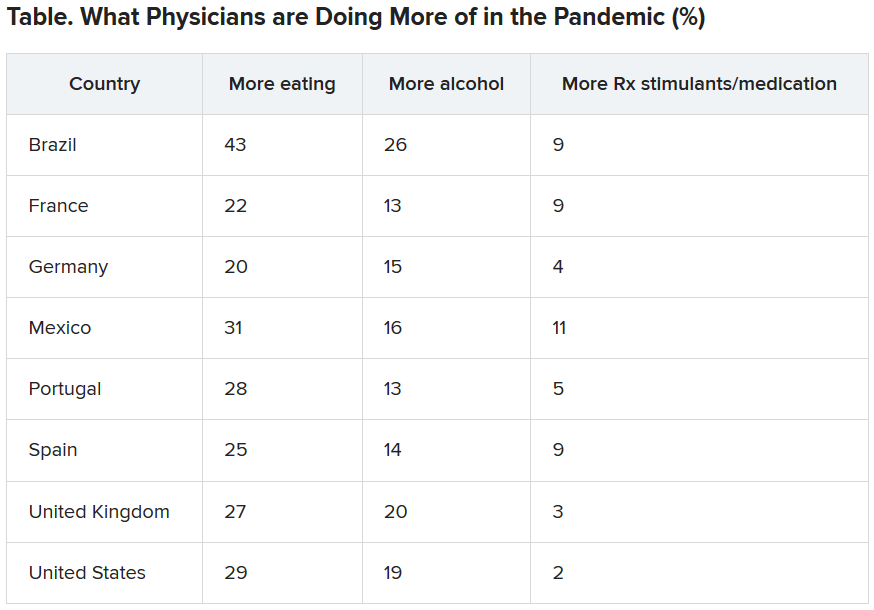

according to the results of a Medscape survey.

More than 7,500 physicians – nearly 5,000 in the United States, and others in Brazil, France, Germany, Mexico, Portugal, Spain, and the United Kingdom – responded to questions about their struggles to save patients and how the pandemic has changed their income and their lives at home and at work.

The pain was evident in this response from an emergency medicine physician in Spain: “It has been the worst time in my life ever, in both my personal and professional life.”

Conversely, some reported positive effects.

An internist in Brazil wrote: “I feel more proud of my career than ever before.”

One quarter of U.S. physicians considering earlier retirement

Physicians in the United States were asked what career changes, if any, they were considering in light of their experience with COVID-19. Although a little more than half (51%) said they were not planning any changes, 25% answered, “retiring earlier than previously planned,” and 12% answered, “a career change away from medicine.”

The number of physicians reporting an income drop was highest in Brazil (63% reported a drop), followed by the United States (62%), Mexico (56%), Portugal (49%), Germany (42%), France (41%), and Spain (31%). The question was not asked in the United Kingdom survey.

In the United States, the size of the drop has been substantial: 9% lost 76%-100% of their income; 14% lost 51%-75%; 28% lost 26%-50%; 33% lost 11%-25%; and 15% lost 1%-10%.

The U.S. specialists with the largest drop in income were ophthalmologists, who lost 51%, followed by allergists (46%), plastic surgeons (46%), and otolaryngologists (45%).

“I’m looking for a new profession due to economic impact,” an otolaryngologist in the United States said. “We are at risk while essentially using our private savings to keep our practice solvent.”

More than half of U.S. physicians (54%) have personally treated patients with COVID-19. Percentages were higher in France, Spain, and the United Kingdom (percentages ranged from 60%-68%).

The United States led all eight countries in treating patients with COVID-19 via telemedicine, at 26%. Germany had the lowest telemedicine percentage, at 10%.

Burnout intensifies

About two thirds of US physicians (64%) said that burnout had intensified during the crisis (70% of female physicians and 61% of male physicians said it had).

Many factors are feeding the burnout.