User login

ID Practitioner is an independent news source that provides infectious disease specialists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on the infectious disease specialist’s practice. Specialty focus topics include antimicrobial resistance, emerging infections, global ID, hepatitis, HIV, hospital-acquired infections, immunizations and vaccines, influenza, mycoses, pediatric infections, and STIs. Infectious Diseases News is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

sofosbuvir

ritonavir with dasabuvir

discount

support path

program

ritonavir

greedy

ledipasvir

assistance

viekira pak

vpak

advocacy

needy

protest

abbvie

paritaprevir

ombitasvir

direct-acting antivirals

dasabuvir

gilead

fake-ovir

support

v pak

oasis

harvoni

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-medstat-latest-articles-articles-section')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-idp')]

HHS declares coronavirus emergency, orders quarantine

The federal government declared a formal public health emergency on Jan. 31 to aid in the response to the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). The declaration, issued by Health and Human Services Secretary Alex. M. Azar II gives state, tribal, and local health departments additional flexibility to request assistance from the federal government in responding to the coronavirus.

"While this virus poses a serious public health threat, the risk to the American public remains low at this time, and we are working to keep this risk low."*

2019-nCoV—the first such action taken by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in more than 50 years.

“This decision is based on the current scientific facts,” Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said during a press briefing Jan. 31. “While we understand the action seems drastic, our goal today, tomorrow, and always continues to be the safety of the American public. We would rather be remembered for over-reacting than under-reacting.”

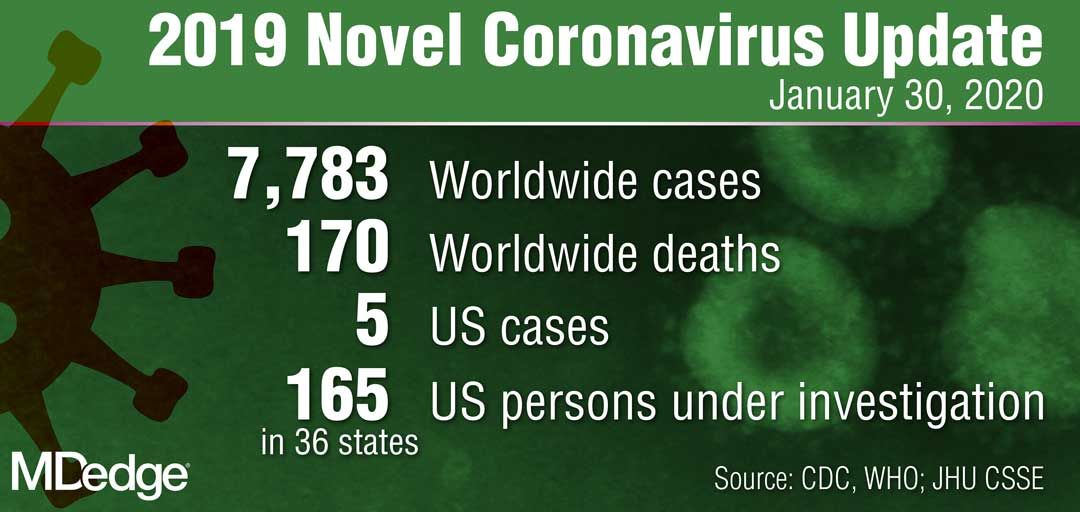

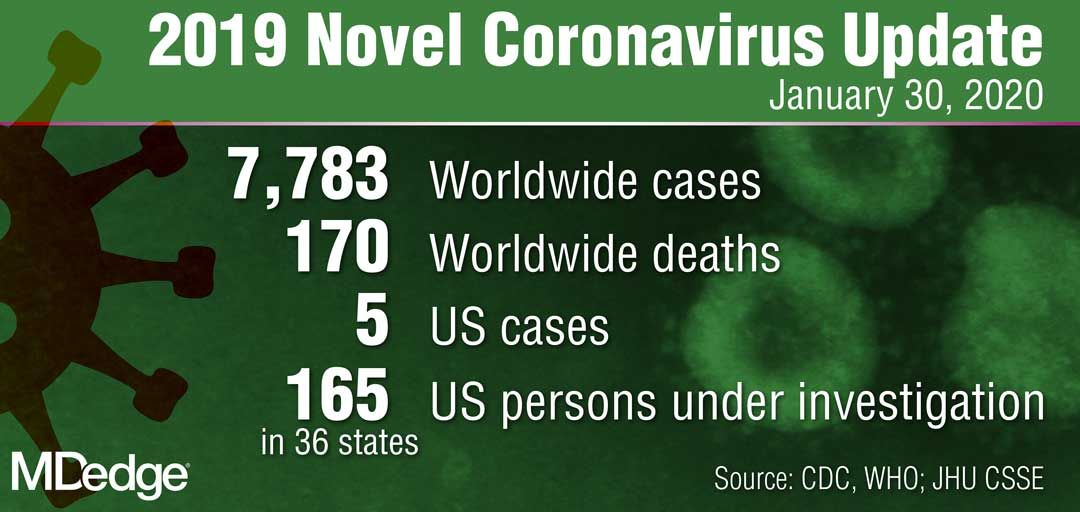

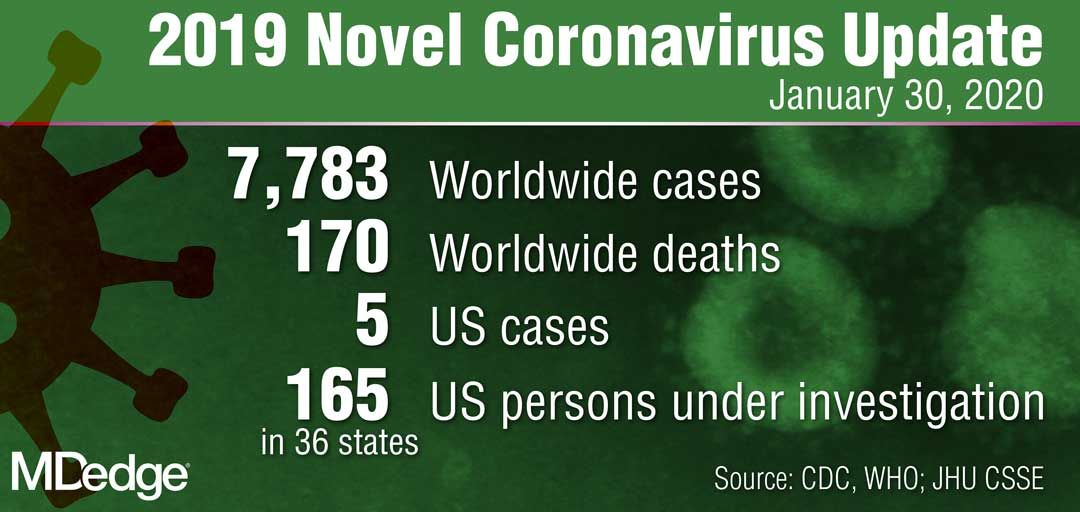

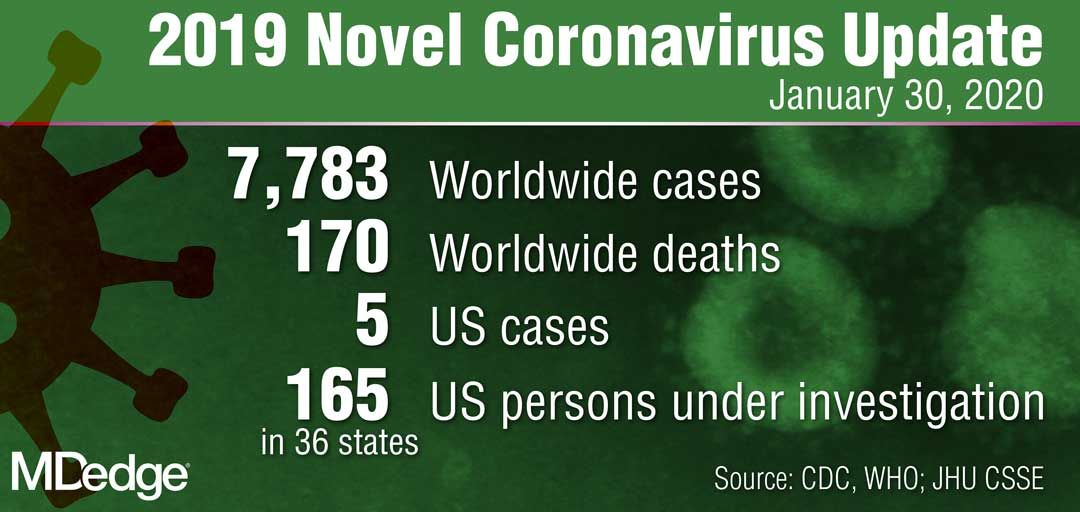

These actions come on the heels of the World Health Organization’s Jan. 30 declaration of 2019-nCoV as a public health emergency of international concern, and from a recent spike in cases reported by Chinese health officials. “Every day this week China has reported additional cases,” Dr. Messonnier said. “Today’s numbers are a 26% increase since yesterday. Over the course of the last week, there have been nearly 7,000 new cases reported. This tells us the virus is continuing to spread rapidly in China. The reported deaths have continued to rise as well. In addition, locations outside China have continued to report cases. There have been an increasing number of reports of person-to-person spread, and now, most recently, a report in the New England Journal of Medicine of asymptomatic spread.”

The quarantine of passengers will last 14 days from when the plane left Wuhan, China. Martin Cetron, MD, who directs the CDC’s Division of Global Migration and Quarantine, said that the quarantine order “offers the greatest level of protection for the American public in preventing introduction and spread. That is our primary concern. Prior epidemics suggest that when people are properly informed, they’re usually very compliant with this request to restrict their movement. This allows someone who would become symptomatic to be rapidly identified. Offering early, rapid diagnosis of their illness could alleviate a lot of anxiety and uncertainty. In addition, this is a protective effect on family members. No individual wants to be the source of introducing or exposing a family member or a loved one to their virus. Additionally, this is part of their civic responsibility to protect their communities.”

* This story was updated on 01/31/2020.

The federal government declared a formal public health emergency on Jan. 31 to aid in the response to the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). The declaration, issued by Health and Human Services Secretary Alex. M. Azar II gives state, tribal, and local health departments additional flexibility to request assistance from the federal government in responding to the coronavirus.

"While this virus poses a serious public health threat, the risk to the American public remains low at this time, and we are working to keep this risk low."*

2019-nCoV—the first such action taken by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in more than 50 years.

“This decision is based on the current scientific facts,” Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said during a press briefing Jan. 31. “While we understand the action seems drastic, our goal today, tomorrow, and always continues to be the safety of the American public. We would rather be remembered for over-reacting than under-reacting.”

These actions come on the heels of the World Health Organization’s Jan. 30 declaration of 2019-nCoV as a public health emergency of international concern, and from a recent spike in cases reported by Chinese health officials. “Every day this week China has reported additional cases,” Dr. Messonnier said. “Today’s numbers are a 26% increase since yesterday. Over the course of the last week, there have been nearly 7,000 new cases reported. This tells us the virus is continuing to spread rapidly in China. The reported deaths have continued to rise as well. In addition, locations outside China have continued to report cases. There have been an increasing number of reports of person-to-person spread, and now, most recently, a report in the New England Journal of Medicine of asymptomatic spread.”

The quarantine of passengers will last 14 days from when the plane left Wuhan, China. Martin Cetron, MD, who directs the CDC’s Division of Global Migration and Quarantine, said that the quarantine order “offers the greatest level of protection for the American public in preventing introduction and spread. That is our primary concern. Prior epidemics suggest that when people are properly informed, they’re usually very compliant with this request to restrict their movement. This allows someone who would become symptomatic to be rapidly identified. Offering early, rapid diagnosis of their illness could alleviate a lot of anxiety and uncertainty. In addition, this is a protective effect on family members. No individual wants to be the source of introducing or exposing a family member or a loved one to their virus. Additionally, this is part of their civic responsibility to protect their communities.”

* This story was updated on 01/31/2020.

The federal government declared a formal public health emergency on Jan. 31 to aid in the response to the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). The declaration, issued by Health and Human Services Secretary Alex. M. Azar II gives state, tribal, and local health departments additional flexibility to request assistance from the federal government in responding to the coronavirus.

"While this virus poses a serious public health threat, the risk to the American public remains low at this time, and we are working to keep this risk low."*

2019-nCoV—the first such action taken by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in more than 50 years.

“This decision is based on the current scientific facts,” Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said during a press briefing Jan. 31. “While we understand the action seems drastic, our goal today, tomorrow, and always continues to be the safety of the American public. We would rather be remembered for over-reacting than under-reacting.”

These actions come on the heels of the World Health Organization’s Jan. 30 declaration of 2019-nCoV as a public health emergency of international concern, and from a recent spike in cases reported by Chinese health officials. “Every day this week China has reported additional cases,” Dr. Messonnier said. “Today’s numbers are a 26% increase since yesterday. Over the course of the last week, there have been nearly 7,000 new cases reported. This tells us the virus is continuing to spread rapidly in China. The reported deaths have continued to rise as well. In addition, locations outside China have continued to report cases. There have been an increasing number of reports of person-to-person spread, and now, most recently, a report in the New England Journal of Medicine of asymptomatic spread.”

The quarantine of passengers will last 14 days from when the plane left Wuhan, China. Martin Cetron, MD, who directs the CDC’s Division of Global Migration and Quarantine, said that the quarantine order “offers the greatest level of protection for the American public in preventing introduction and spread. That is our primary concern. Prior epidemics suggest that when people are properly informed, they’re usually very compliant with this request to restrict their movement. This allows someone who would become symptomatic to be rapidly identified. Offering early, rapid diagnosis of their illness could alleviate a lot of anxiety and uncertainty. In addition, this is a protective effect on family members. No individual wants to be the source of introducing or exposing a family member or a loved one to their virus. Additionally, this is part of their civic responsibility to protect their communities.”

* This story was updated on 01/31/2020.

Is anxiety about the coronavirus out of proportion?

A number of years ago, a patient I was treating mentioned that she was not eating tomatoes. There had been stories in the news about people contracting bacterial infections from tomatoes, but I paused for a moment, then asked her: “Have there been any contaminated tomatoes here in Maryland?” There had not been and I was still happily eating salsa, but my patient thought about this differently: If disease-causing tomatoes were to come to our state, someone would be the first person to become ill. She did not want to take any risks. My patient, however, was a heavy smoker and already grappling with health issues that were caused by smoking, so I found her choice of what she should worry about and how it influenced her behavior to be perplexing. I realize it’s not the same; nicotine is an addiction, while tomatoes remain a choice for most of us, and it’s common for people to worry about very unlikely events even when we are surrounded by very real and statistically more probable threats to our well-being.

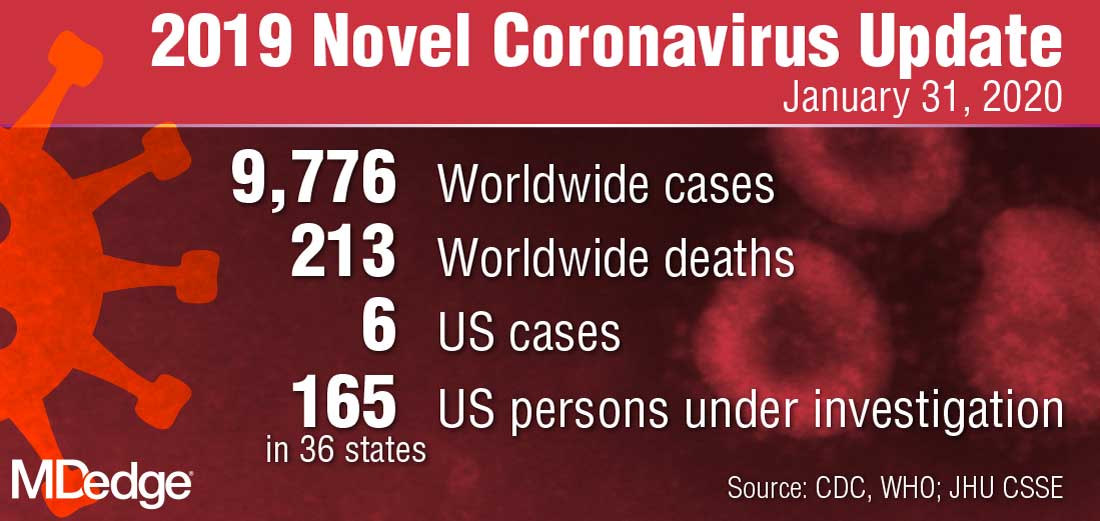

Today’s news reports are filled with stories about 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), an illness that started in Wuhan, China; as of Jan. 31, 2020, there were 9,776 confirmed cases and 213 deaths. There have been an additional 118 cases reported outside of mainland China, including 6 in the United States, and no one outside of China has died.

The response to the virus has been remarkable: Wuhan, a city of more than 11 million inhabitants, is on lockdown, as are 15 other cities in China; 46 million people have been affected, the largest quarantine in human history. Travel is restricted in parts of China, airports all over the world are screening those who fly in from Wuhan, foreign governments are bringing their citizens home from Wuhan, and even Starbucks has temporarily closed half its stores in China. The economics of containing this virus are astounding.

In the meantime, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that, as of the week of Jan. 25, there have been 19 million cases of the flu in the United States. Of those stricken, 180,000 people have been hospitalized and 10,000 have died, including 68 pediatric patients. No cities are on lockdown, public transportation runs as usual, airports don’t screen passengers for flu symptoms, and Starbucks continues to serve vanilla lattes to any willing customer. Anxiety about illness is not new; we’ve seen it with SARS, Ebola, measles, and even around Chipotle’s food poisoning cases – to name just a few recent scares. We have also seen a lot of media on vaping-related deaths, and as of early January 2020, vaping-related illnesses affected 2,602 people with 59 deaths. It has been a topic of discussion among legislators, with an emphasis on either outlawing the flavoring that might appeal to younger people or simply outlawing e-cigarettes. No one, however, is talking about outlawing regular cigarettes, despite the fact that many people have switched from cigarettes to vaping products as a way to quit smoking. So, while vaping has caused 59 deaths since 2018, cigarettes are responsible for 480,000 fatalities a year in the United States and smokers live, on average, 10 years less than nonsmokers.

So what fuels anxiety about the latest health scare, and why aren’t we more anxious about the more common causes of premature mortality? Certainly, the newness and the unknown are factors in the coronavirus scare. It’s not certain how this illness was introduced into the human population, although one theory is that it started with the consumption of bats who carry the virus. It’s spreading fast, and in some people, it has been lethal. The incubation period is not known, or whether it is contagious before symptoms appear. Coronavirus is getting a lot of public health attention and the World Health Organization just announced that the virus is a public health emergency of international concern. On the televised news on Jan. 29, 2020, coronavirus was the top story in the United States, even though an impeachment trial is in progress for our country’s president.

The public health response of locking down cities may help contain the outbreak and prevent a global epidemic, although millions of people had already left Wuhan, so the heavy-handed attempt to prevent spread of the virus may well be too late. In the case of the Ebola virus – a much more lethal disease that was also thought to be introduced by bats – public health measures certainly curtailed global spread, and the epidemic of 2014-2016 was limited to 28,600 cases and 11,325 deaths, nearly all of them in West Africa.

Most of the things that cause people to die are not new and are not topics the media chooses to sensationalize. Dissemination of news has changed over the decades, with so much more of it, instant reports on social media, and competition for viewers that leads journalists to pull at our emotions. And while we may, or may not, get flu shots and avoid those who have the flu, how and where we position both our anxiety and our resources does not always make sense. Certainly some people are predisposed to worry about both common and uncommon dangers, while others seem never to worry and engage in acts that many of us would consider dangerous. If we are looking for logic, it may be hard to find – there are those who would happily go bungee jumping but wouldn’t dream of leaving the house out without hand sanitizer.

The repercussions from this massive response to the Wuhan coronavirus are significant. For the millions of people on lockdown in China, each day gets emotionally harder; some may begin to have issues procuring food, and the financial losses for the economy will be significant. It’s not really possible to know yet if this response is warranted; we do know that infectious diseases can kill millions. The AIDS pandemic has taken the lives of 36 million people since 1981, and the influenza pandemic of 1918 resulted in an estimated 20 million to 50 million deaths after infecting 500 million people. Still, one might wonder if other, more mundane causes of morbidity and mortality – the ones that no longer garner our dread or make it to the front pages – might also be worthy of more hype and resources.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

A number of years ago, a patient I was treating mentioned that she was not eating tomatoes. There had been stories in the news about people contracting bacterial infections from tomatoes, but I paused for a moment, then asked her: “Have there been any contaminated tomatoes here in Maryland?” There had not been and I was still happily eating salsa, but my patient thought about this differently: If disease-causing tomatoes were to come to our state, someone would be the first person to become ill. She did not want to take any risks. My patient, however, was a heavy smoker and already grappling with health issues that were caused by smoking, so I found her choice of what she should worry about and how it influenced her behavior to be perplexing. I realize it’s not the same; nicotine is an addiction, while tomatoes remain a choice for most of us, and it’s common for people to worry about very unlikely events even when we are surrounded by very real and statistically more probable threats to our well-being.

Today’s news reports are filled with stories about 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), an illness that started in Wuhan, China; as of Jan. 31, 2020, there were 9,776 confirmed cases and 213 deaths. There have been an additional 118 cases reported outside of mainland China, including 6 in the United States, and no one outside of China has died.

The response to the virus has been remarkable: Wuhan, a city of more than 11 million inhabitants, is on lockdown, as are 15 other cities in China; 46 million people have been affected, the largest quarantine in human history. Travel is restricted in parts of China, airports all over the world are screening those who fly in from Wuhan, foreign governments are bringing their citizens home from Wuhan, and even Starbucks has temporarily closed half its stores in China. The economics of containing this virus are astounding.

In the meantime, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that, as of the week of Jan. 25, there have been 19 million cases of the flu in the United States. Of those stricken, 180,000 people have been hospitalized and 10,000 have died, including 68 pediatric patients. No cities are on lockdown, public transportation runs as usual, airports don’t screen passengers for flu symptoms, and Starbucks continues to serve vanilla lattes to any willing customer. Anxiety about illness is not new; we’ve seen it with SARS, Ebola, measles, and even around Chipotle’s food poisoning cases – to name just a few recent scares. We have also seen a lot of media on vaping-related deaths, and as of early January 2020, vaping-related illnesses affected 2,602 people with 59 deaths. It has been a topic of discussion among legislators, with an emphasis on either outlawing the flavoring that might appeal to younger people or simply outlawing e-cigarettes. No one, however, is talking about outlawing regular cigarettes, despite the fact that many people have switched from cigarettes to vaping products as a way to quit smoking. So, while vaping has caused 59 deaths since 2018, cigarettes are responsible for 480,000 fatalities a year in the United States and smokers live, on average, 10 years less than nonsmokers.

So what fuels anxiety about the latest health scare, and why aren’t we more anxious about the more common causes of premature mortality? Certainly, the newness and the unknown are factors in the coronavirus scare. It’s not certain how this illness was introduced into the human population, although one theory is that it started with the consumption of bats who carry the virus. It’s spreading fast, and in some people, it has been lethal. The incubation period is not known, or whether it is contagious before symptoms appear. Coronavirus is getting a lot of public health attention and the World Health Organization just announced that the virus is a public health emergency of international concern. On the televised news on Jan. 29, 2020, coronavirus was the top story in the United States, even though an impeachment trial is in progress for our country’s president.

The public health response of locking down cities may help contain the outbreak and prevent a global epidemic, although millions of people had already left Wuhan, so the heavy-handed attempt to prevent spread of the virus may well be too late. In the case of the Ebola virus – a much more lethal disease that was also thought to be introduced by bats – public health measures certainly curtailed global spread, and the epidemic of 2014-2016 was limited to 28,600 cases and 11,325 deaths, nearly all of them in West Africa.

Most of the things that cause people to die are not new and are not topics the media chooses to sensationalize. Dissemination of news has changed over the decades, with so much more of it, instant reports on social media, and competition for viewers that leads journalists to pull at our emotions. And while we may, or may not, get flu shots and avoid those who have the flu, how and where we position both our anxiety and our resources does not always make sense. Certainly some people are predisposed to worry about both common and uncommon dangers, while others seem never to worry and engage in acts that many of us would consider dangerous. If we are looking for logic, it may be hard to find – there are those who would happily go bungee jumping but wouldn’t dream of leaving the house out without hand sanitizer.

The repercussions from this massive response to the Wuhan coronavirus are significant. For the millions of people on lockdown in China, each day gets emotionally harder; some may begin to have issues procuring food, and the financial losses for the economy will be significant. It’s not really possible to know yet if this response is warranted; we do know that infectious diseases can kill millions. The AIDS pandemic has taken the lives of 36 million people since 1981, and the influenza pandemic of 1918 resulted in an estimated 20 million to 50 million deaths after infecting 500 million people. Still, one might wonder if other, more mundane causes of morbidity and mortality – the ones that no longer garner our dread or make it to the front pages – might also be worthy of more hype and resources.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

A number of years ago, a patient I was treating mentioned that she was not eating tomatoes. There had been stories in the news about people contracting bacterial infections from tomatoes, but I paused for a moment, then asked her: “Have there been any contaminated tomatoes here in Maryland?” There had not been and I was still happily eating salsa, but my patient thought about this differently: If disease-causing tomatoes were to come to our state, someone would be the first person to become ill. She did not want to take any risks. My patient, however, was a heavy smoker and already grappling with health issues that were caused by smoking, so I found her choice of what she should worry about and how it influenced her behavior to be perplexing. I realize it’s not the same; nicotine is an addiction, while tomatoes remain a choice for most of us, and it’s common for people to worry about very unlikely events even when we are surrounded by very real and statistically more probable threats to our well-being.

Today’s news reports are filled with stories about 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), an illness that started in Wuhan, China; as of Jan. 31, 2020, there were 9,776 confirmed cases and 213 deaths. There have been an additional 118 cases reported outside of mainland China, including 6 in the United States, and no one outside of China has died.

The response to the virus has been remarkable: Wuhan, a city of more than 11 million inhabitants, is on lockdown, as are 15 other cities in China; 46 million people have been affected, the largest quarantine in human history. Travel is restricted in parts of China, airports all over the world are screening those who fly in from Wuhan, foreign governments are bringing their citizens home from Wuhan, and even Starbucks has temporarily closed half its stores in China. The economics of containing this virus are astounding.

In the meantime, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that, as of the week of Jan. 25, there have been 19 million cases of the flu in the United States. Of those stricken, 180,000 people have been hospitalized and 10,000 have died, including 68 pediatric patients. No cities are on lockdown, public transportation runs as usual, airports don’t screen passengers for flu symptoms, and Starbucks continues to serve vanilla lattes to any willing customer. Anxiety about illness is not new; we’ve seen it with SARS, Ebola, measles, and even around Chipotle’s food poisoning cases – to name just a few recent scares. We have also seen a lot of media on vaping-related deaths, and as of early January 2020, vaping-related illnesses affected 2,602 people with 59 deaths. It has been a topic of discussion among legislators, with an emphasis on either outlawing the flavoring that might appeal to younger people or simply outlawing e-cigarettes. No one, however, is talking about outlawing regular cigarettes, despite the fact that many people have switched from cigarettes to vaping products as a way to quit smoking. So, while vaping has caused 59 deaths since 2018, cigarettes are responsible for 480,000 fatalities a year in the United States and smokers live, on average, 10 years less than nonsmokers.

So what fuels anxiety about the latest health scare, and why aren’t we more anxious about the more common causes of premature mortality? Certainly, the newness and the unknown are factors in the coronavirus scare. It’s not certain how this illness was introduced into the human population, although one theory is that it started with the consumption of bats who carry the virus. It’s spreading fast, and in some people, it has been lethal. The incubation period is not known, or whether it is contagious before symptoms appear. Coronavirus is getting a lot of public health attention and the World Health Organization just announced that the virus is a public health emergency of international concern. On the televised news on Jan. 29, 2020, coronavirus was the top story in the United States, even though an impeachment trial is in progress for our country’s president.

The public health response of locking down cities may help contain the outbreak and prevent a global epidemic, although millions of people had already left Wuhan, so the heavy-handed attempt to prevent spread of the virus may well be too late. In the case of the Ebola virus – a much more lethal disease that was also thought to be introduced by bats – public health measures certainly curtailed global spread, and the epidemic of 2014-2016 was limited to 28,600 cases and 11,325 deaths, nearly all of them in West Africa.

Most of the things that cause people to die are not new and are not topics the media chooses to sensationalize. Dissemination of news has changed over the decades, with so much more of it, instant reports on social media, and competition for viewers that leads journalists to pull at our emotions. And while we may, or may not, get flu shots and avoid those who have the flu, how and where we position both our anxiety and our resources does not always make sense. Certainly some people are predisposed to worry about both common and uncommon dangers, while others seem never to worry and engage in acts that many of us would consider dangerous. If we are looking for logic, it may be hard to find – there are those who would happily go bungee jumping but wouldn’t dream of leaving the house out without hand sanitizer.

The repercussions from this massive response to the Wuhan coronavirus are significant. For the millions of people on lockdown in China, each day gets emotionally harder; some may begin to have issues procuring food, and the financial losses for the economy will be significant. It’s not really possible to know yet if this response is warranted; we do know that infectious diseases can kill millions. The AIDS pandemic has taken the lives of 36 million people since 1981, and the influenza pandemic of 1918 resulted in an estimated 20 million to 50 million deaths after infecting 500 million people. Still, one might wonder if other, more mundane causes of morbidity and mortality – the ones that no longer garner our dread or make it to the front pages – might also be worthy of more hype and resources.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

WHO declares public health emergency for novel coronavirus

Amid the rising spread of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV),

The declaration was made during a press briefing on Jan. 30 after a week of growing concern and pressure on WHO to designate the virus at a higher emergency level. WHO’s Emergency Committee made the nearly unanimous decision after considering the increasing number of coronavirus cases in China, the rising infections outside of China, and the questionable measures some countries are taking regarding travel, said committee chair Didier Houssin, MD, said during the press conference.

As of Jan. 30, there were 8,236 confirmed cases of the coronavirus in China and 171 deaths, with another 112 cases identified outside of China in 21 other countries.

“Declaring a Public Health Emergency of International Concern is likely to facilitate [WHO’s] leadership role for public health measures, holding countries to account concerning additional measures they may take regarding travel, trade, quarantine or screening, research efforts, global coordination and anticipation of economic impact [and] support to vulnerable states,” Dr. Houssin said during the press conference. “Declaring a PHEIC should certainly not be seen as manifestation of distrust in the Chinese authorities and people which are doing tremendous efforts on the frontlines of this outbreak, with transparency, and let us hope, with success.”

What happens next?

Once a PHEIC is declared, WHO launches a series of steps, including the release of temporary recommendations for the affected country on health measures to implement and guidance for other countries on preventing and reducing the international spread of the disease, WHO spokesman Tarik Jasarevic said in an interview.

“The purpose of declaring a PHEIC is to advise the world on what measures need to be taken to enhance global health security by preventing international transmission of an infectious hazard,” he said.

Following the Jan. 30 press conference, WHO released temporary guidance for China and for other countries regarding identifying, managing, containing, and preventing the virus. China is advised to continue updating the population about the outbreak, continue enhancing its public health measures for containment and surveillance of cases, and to continue collaboration with WHO and other partners to investigate the epidemiology and evolution of the outbreak and share data on all human cases.

Other countries should be prepared for containment, including the active surveillance, early detection, isolation, case management, and prevention of virus transmission and to share full data with WHO, according to the recommendations.

Under the International Health Regulations (IHR), countries are required to share information and data with WHO. Additionally, WHO leaders advised the global community to support low- and middle-income countries with their response to the coronavirus and to facilitate diagnostics, potential vaccines, and therapeutics in these areas.

The IHR requires that countries implementing health measures that go beyond what WHO recommends must send to WHO the public health rationale and justification within 48 hours of their implementation for WHO review, Mr. Jasarevic noted.

“WHO is obliged to share the information about measures and the justification received with other countries involved,” he said.

PHEIC travel and resource impact

Declaration of a PHEIC means WHO will now oversee any travel restrictions made by other countries in response to 2019-nCoV. The agency recommends that countries conduct a risk and cost-benefit analysis before enacting travel restrictions and other countries are required to inform WHO about any travel measures taken.

“Countries will be asked to provide public health justification for any travel or trade measures that are not scientifically based, such as refusal of entry of suspect cases or unaffected persons to affected areas,” Mr. Jasarevic said in an interview.

As far as resources, the PHEIC mechanism is not a fundraising mechanism, but some donors might consider a PHEIC declaration as a trigger for releasing additional funding to respond to the health threat, he said.

Allison T. Chamberlain, PhD, acting director for the Emory Center for Public Health Preparedness and Research at the Emory Rollins School of Public Health in Atlanta, said national governments and nongovernmental aid organizations are among the most affected by a PHEIC because they are looked at to provide assistance to the most heavily affected areas and to bolster public health preparedness within their own borders.

“In terms of resources that are deployed, a Public Health Emergency of International Concern raises levels of international support and commitment to stopping the emergency,” Dr. Chamberlain said in an interview. “By doing so, it gives countries the needed flexibility to release financial resources of their own accord to support things like response teams that might go into heavily affected areas to assist, for instance.”

WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus stressed that cooperation among countries is key during the PHEIC.

“We can only stop it together,” he said during the press conference. “This is the time for facts, not fear. This is the time for science, not rumors. This is the time for solidarity, not stigma.”

This is the sixth PHEIC declared by WHO in the last 10 years. Such declarations were made for the 2009 H1NI influenza pandemic, the 2014 polio resurgence, the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, the 2016 Zika virus, and the 2019 Kivu Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Amid the rising spread of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV),

The declaration was made during a press briefing on Jan. 30 after a week of growing concern and pressure on WHO to designate the virus at a higher emergency level. WHO’s Emergency Committee made the nearly unanimous decision after considering the increasing number of coronavirus cases in China, the rising infections outside of China, and the questionable measures some countries are taking regarding travel, said committee chair Didier Houssin, MD, said during the press conference.

As of Jan. 30, there were 8,236 confirmed cases of the coronavirus in China and 171 deaths, with another 112 cases identified outside of China in 21 other countries.

“Declaring a Public Health Emergency of International Concern is likely to facilitate [WHO’s] leadership role for public health measures, holding countries to account concerning additional measures they may take regarding travel, trade, quarantine or screening, research efforts, global coordination and anticipation of economic impact [and] support to vulnerable states,” Dr. Houssin said during the press conference. “Declaring a PHEIC should certainly not be seen as manifestation of distrust in the Chinese authorities and people which are doing tremendous efforts on the frontlines of this outbreak, with transparency, and let us hope, with success.”

What happens next?

Once a PHEIC is declared, WHO launches a series of steps, including the release of temporary recommendations for the affected country on health measures to implement and guidance for other countries on preventing and reducing the international spread of the disease, WHO spokesman Tarik Jasarevic said in an interview.

“The purpose of declaring a PHEIC is to advise the world on what measures need to be taken to enhance global health security by preventing international transmission of an infectious hazard,” he said.

Following the Jan. 30 press conference, WHO released temporary guidance for China and for other countries regarding identifying, managing, containing, and preventing the virus. China is advised to continue updating the population about the outbreak, continue enhancing its public health measures for containment and surveillance of cases, and to continue collaboration with WHO and other partners to investigate the epidemiology and evolution of the outbreak and share data on all human cases.

Other countries should be prepared for containment, including the active surveillance, early detection, isolation, case management, and prevention of virus transmission and to share full data with WHO, according to the recommendations.

Under the International Health Regulations (IHR), countries are required to share information and data with WHO. Additionally, WHO leaders advised the global community to support low- and middle-income countries with their response to the coronavirus and to facilitate diagnostics, potential vaccines, and therapeutics in these areas.

The IHR requires that countries implementing health measures that go beyond what WHO recommends must send to WHO the public health rationale and justification within 48 hours of their implementation for WHO review, Mr. Jasarevic noted.

“WHO is obliged to share the information about measures and the justification received with other countries involved,” he said.

PHEIC travel and resource impact

Declaration of a PHEIC means WHO will now oversee any travel restrictions made by other countries in response to 2019-nCoV. The agency recommends that countries conduct a risk and cost-benefit analysis before enacting travel restrictions and other countries are required to inform WHO about any travel measures taken.

“Countries will be asked to provide public health justification for any travel or trade measures that are not scientifically based, such as refusal of entry of suspect cases or unaffected persons to affected areas,” Mr. Jasarevic said in an interview.

As far as resources, the PHEIC mechanism is not a fundraising mechanism, but some donors might consider a PHEIC declaration as a trigger for releasing additional funding to respond to the health threat, he said.

Allison T. Chamberlain, PhD, acting director for the Emory Center for Public Health Preparedness and Research at the Emory Rollins School of Public Health in Atlanta, said national governments and nongovernmental aid organizations are among the most affected by a PHEIC because they are looked at to provide assistance to the most heavily affected areas and to bolster public health preparedness within their own borders.

“In terms of resources that are deployed, a Public Health Emergency of International Concern raises levels of international support and commitment to stopping the emergency,” Dr. Chamberlain said in an interview. “By doing so, it gives countries the needed flexibility to release financial resources of their own accord to support things like response teams that might go into heavily affected areas to assist, for instance.”

WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus stressed that cooperation among countries is key during the PHEIC.

“We can only stop it together,” he said during the press conference. “This is the time for facts, not fear. This is the time for science, not rumors. This is the time for solidarity, not stigma.”

This is the sixth PHEIC declared by WHO in the last 10 years. Such declarations were made for the 2009 H1NI influenza pandemic, the 2014 polio resurgence, the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, the 2016 Zika virus, and the 2019 Kivu Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Amid the rising spread of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV),

The declaration was made during a press briefing on Jan. 30 after a week of growing concern and pressure on WHO to designate the virus at a higher emergency level. WHO’s Emergency Committee made the nearly unanimous decision after considering the increasing number of coronavirus cases in China, the rising infections outside of China, and the questionable measures some countries are taking regarding travel, said committee chair Didier Houssin, MD, said during the press conference.

As of Jan. 30, there were 8,236 confirmed cases of the coronavirus in China and 171 deaths, with another 112 cases identified outside of China in 21 other countries.

“Declaring a Public Health Emergency of International Concern is likely to facilitate [WHO’s] leadership role for public health measures, holding countries to account concerning additional measures they may take regarding travel, trade, quarantine or screening, research efforts, global coordination and anticipation of economic impact [and] support to vulnerable states,” Dr. Houssin said during the press conference. “Declaring a PHEIC should certainly not be seen as manifestation of distrust in the Chinese authorities and people which are doing tremendous efforts on the frontlines of this outbreak, with transparency, and let us hope, with success.”

What happens next?

Once a PHEIC is declared, WHO launches a series of steps, including the release of temporary recommendations for the affected country on health measures to implement and guidance for other countries on preventing and reducing the international spread of the disease, WHO spokesman Tarik Jasarevic said in an interview.

“The purpose of declaring a PHEIC is to advise the world on what measures need to be taken to enhance global health security by preventing international transmission of an infectious hazard,” he said.

Following the Jan. 30 press conference, WHO released temporary guidance for China and for other countries regarding identifying, managing, containing, and preventing the virus. China is advised to continue updating the population about the outbreak, continue enhancing its public health measures for containment and surveillance of cases, and to continue collaboration with WHO and other partners to investigate the epidemiology and evolution of the outbreak and share data on all human cases.

Other countries should be prepared for containment, including the active surveillance, early detection, isolation, case management, and prevention of virus transmission and to share full data with WHO, according to the recommendations.

Under the International Health Regulations (IHR), countries are required to share information and data with WHO. Additionally, WHO leaders advised the global community to support low- and middle-income countries with their response to the coronavirus and to facilitate diagnostics, potential vaccines, and therapeutics in these areas.

The IHR requires that countries implementing health measures that go beyond what WHO recommends must send to WHO the public health rationale and justification within 48 hours of their implementation for WHO review, Mr. Jasarevic noted.

“WHO is obliged to share the information about measures and the justification received with other countries involved,” he said.

PHEIC travel and resource impact

Declaration of a PHEIC means WHO will now oversee any travel restrictions made by other countries in response to 2019-nCoV. The agency recommends that countries conduct a risk and cost-benefit analysis before enacting travel restrictions and other countries are required to inform WHO about any travel measures taken.

“Countries will be asked to provide public health justification for any travel or trade measures that are not scientifically based, such as refusal of entry of suspect cases or unaffected persons to affected areas,” Mr. Jasarevic said in an interview.

As far as resources, the PHEIC mechanism is not a fundraising mechanism, but some donors might consider a PHEIC declaration as a trigger for releasing additional funding to respond to the health threat, he said.

Allison T. Chamberlain, PhD, acting director for the Emory Center for Public Health Preparedness and Research at the Emory Rollins School of Public Health in Atlanta, said national governments and nongovernmental aid organizations are among the most affected by a PHEIC because they are looked at to provide assistance to the most heavily affected areas and to bolster public health preparedness within their own borders.

“In terms of resources that are deployed, a Public Health Emergency of International Concern raises levels of international support and commitment to stopping the emergency,” Dr. Chamberlain said in an interview. “By doing so, it gives countries the needed flexibility to release financial resources of their own accord to support things like response teams that might go into heavily affected areas to assist, for instance.”

WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus stressed that cooperation among countries is key during the PHEIC.

“We can only stop it together,” he said during the press conference. “This is the time for facts, not fear. This is the time for science, not rumors. This is the time for solidarity, not stigma.”

This is the sixth PHEIC declared by WHO in the last 10 years. Such declarations were made for the 2009 H1NI influenza pandemic, the 2014 polio resurgence, the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, the 2016 Zika virus, and the 2019 Kivu Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

2019 Novel Coronavirus: Frequently asked questions for clinicians

The 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak has unfolded so rapidly that many clinicians are scrambling to stay on top of it. Here are the answers to some frequently asked questions about how to prepare your clinic to respond to this outbreak.

Keep in mind that the outbreak is moving rapidly. Though scientific and epidemiologic knowledge has increased at unprecedented speed, there is much we don’t know, and some of what we think we know will change. Follow the links for the most up-to-date information.

What should our clinic do first?

Plan ahead with the following:

- Develop a plan for office staff to take travel histories from anyone with a respiratory illness and provide training for those who need it. Travel history at present should include asking about travel to China in the past 14 days, specifically Wuhan city or Hubei province.

- Review up-to-date infection control practices with all office staff and provide training for those who need it.

- Take an inventory of supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE), such as gowns, gloves, masks, eye protection, and N95 respirators or powered air-purifying respirators (PAPRs), and order items that are missing or low in stock.

- Fit-test users of N95 masks for maximal effectiveness.

- Plan where a potential patient would be isolated while obtaining expert advice.

- Know whom to contact at the state or local health department if you have a patient with the appropriate travel history.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has prepared a toolkit to help frontline health care professionals prepare for this virus. Providers need to stay up to date on the latest recommendations, as the situation is changing rapidly.

When should I suspect 2019-nCoV illness, and what should I do?

Take the following steps to assess the concern and respond:

- If a patient with respiratory illness has traveled to China in the past 14 days, immediately put a mask on the patient and move the individual to a private room. Use a negative-pressure room if available.

- Put on appropriate PPE (including gloves, gown, eye protection, and mask) for contact, droplet, and airborne precautions. CDC recommends an N95 respirator mask if available, although we don’t know yet if there is true airborne spread.

- Obtain an accurate travel history, including dates and cities. (Tip: Get the correct spelling, as the English spelling of cities in China can cause confusion.)

- If the patient meets the current CDC definition of “person under investigation” or PUI, or if you need guidance on how to proceed, notify infection control (if you are in a facility that has it) and call your state or local health department immediately.

- Contact public health authorities who can help decide whether the patient should be admitted to airborne isolation or monitored at home with appropriate precautions.

What is the definition of a PUI?

The current definition of a PUI is a person who has fever and symptoms of a respiratory infection (cough, shortness of breath) AND who has EITHER been in Wuhan city or Hubei province in the past 14 days OR had close contact with a person either under investigation for 2019-nCoV infection or with confirmed infection. The definition of a PUI will change over time, so check this link.

How can I test for 2019-nCoV?

As of Jan. 30, 2020, testing is by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and is available in the United States only through the CDC in Atlanta. Testing should soon be available in state health department laboratories. If public health authorities decide that your patient should be tested, they will instruct you on which samples to obtain.

The full sequence of 2019-nCoV has been shared, so some reference laboratories may develop and validate tests, ideally with assistance from CDC. If testing becomes available, make certain that it is a reputable lab that has carefully validated the test.

Should I test for other viruses?

Because the symptoms of 2019-nCoV infection overlap with those of influenza and other respiratory viruses, PCR testing for other viruses should be considered if it will change management (i.e., change the decision to provide influenza antivirals). Use appropriate PPE while collecting specimens, including eye protection. If 2019-nCoV is a consideration, you may want to send the specimen to a hospital lab for testing, where the sample will be processed under a biosafety hood, rather than doing point-of-care testing in the office.

How dangerous is 2019-nCoV?

The current estimated mortality rate is 2%-3%. That is probably an overestimate, as those with severe disease and those who die are more likely to be tested and reported early in an epidemic.

Our current knowledge is based on preliminary reports from hospitalized patients and will probably change. From the speed of spread and a single family cluster, it seems likely that there are milder cases and perhaps asymptomatic infection.

What else do I need to know about coronaviruses?

Coronaviruses are a large and diverse group of viruses, many of which are animal viruses. Before the discovery of the 2019-nCoV, six coronaviruses were known to infect humans. Four of these (HKU1, NL63, OC43, and 229E) predominantly caused mild to moderate upper respiratory illness, and they are thought to be responsible for 10%-30% of colds. They occasionally cause viral pneumonia and can be detected by some commercial multiplex panels.

Two other coronaviruses have caused outbreaks of severe respiratory illness in people: SARS, which emerged in Southern China in 2002, and MERS in the Middle East, in 2012. Unlike SARS, sporadic cases of MERS continue to occur.

The current outbreak is caused by 2019-nCoV, a previously unknown beta coronavirus. It is most closely related (~96%) to a bat virus and shares about 80% sequence homology with SARS CoV.

Andrew T. Pavia, MD, is the George and Esther Gross Presidential Professor and chief of the division of pediatric infectious disease in the department of pediatrics at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. He is also director of hospital epidemiology and associate director of antimicrobial stewardship at Primary Children’s Hospital, Salt Lake City. Dr. Pavia has disclosed that he has served as a consultant for Genentech, Merck, and Seqirus and that he has served as associate editor for The Sanford Guide.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak has unfolded so rapidly that many clinicians are scrambling to stay on top of it. Here are the answers to some frequently asked questions about how to prepare your clinic to respond to this outbreak.

Keep in mind that the outbreak is moving rapidly. Though scientific and epidemiologic knowledge has increased at unprecedented speed, there is much we don’t know, and some of what we think we know will change. Follow the links for the most up-to-date information.

What should our clinic do first?

Plan ahead with the following:

- Develop a plan for office staff to take travel histories from anyone with a respiratory illness and provide training for those who need it. Travel history at present should include asking about travel to China in the past 14 days, specifically Wuhan city or Hubei province.

- Review up-to-date infection control practices with all office staff and provide training for those who need it.

- Take an inventory of supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE), such as gowns, gloves, masks, eye protection, and N95 respirators or powered air-purifying respirators (PAPRs), and order items that are missing or low in stock.

- Fit-test users of N95 masks for maximal effectiveness.

- Plan where a potential patient would be isolated while obtaining expert advice.

- Know whom to contact at the state or local health department if you have a patient with the appropriate travel history.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has prepared a toolkit to help frontline health care professionals prepare for this virus. Providers need to stay up to date on the latest recommendations, as the situation is changing rapidly.

When should I suspect 2019-nCoV illness, and what should I do?

Take the following steps to assess the concern and respond:

- If a patient with respiratory illness has traveled to China in the past 14 days, immediately put a mask on the patient and move the individual to a private room. Use a negative-pressure room if available.

- Put on appropriate PPE (including gloves, gown, eye protection, and mask) for contact, droplet, and airborne precautions. CDC recommends an N95 respirator mask if available, although we don’t know yet if there is true airborne spread.

- Obtain an accurate travel history, including dates and cities. (Tip: Get the correct spelling, as the English spelling of cities in China can cause confusion.)

- If the patient meets the current CDC definition of “person under investigation” or PUI, or if you need guidance on how to proceed, notify infection control (if you are in a facility that has it) and call your state or local health department immediately.

- Contact public health authorities who can help decide whether the patient should be admitted to airborne isolation or monitored at home with appropriate precautions.

What is the definition of a PUI?

The current definition of a PUI is a person who has fever and symptoms of a respiratory infection (cough, shortness of breath) AND who has EITHER been in Wuhan city or Hubei province in the past 14 days OR had close contact with a person either under investigation for 2019-nCoV infection or with confirmed infection. The definition of a PUI will change over time, so check this link.

How can I test for 2019-nCoV?

As of Jan. 30, 2020, testing is by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and is available in the United States only through the CDC in Atlanta. Testing should soon be available in state health department laboratories. If public health authorities decide that your patient should be tested, they will instruct you on which samples to obtain.

The full sequence of 2019-nCoV has been shared, so some reference laboratories may develop and validate tests, ideally with assistance from CDC. If testing becomes available, make certain that it is a reputable lab that has carefully validated the test.

Should I test for other viruses?

Because the symptoms of 2019-nCoV infection overlap with those of influenza and other respiratory viruses, PCR testing for other viruses should be considered if it will change management (i.e., change the decision to provide influenza antivirals). Use appropriate PPE while collecting specimens, including eye protection. If 2019-nCoV is a consideration, you may want to send the specimen to a hospital lab for testing, where the sample will be processed under a biosafety hood, rather than doing point-of-care testing in the office.

How dangerous is 2019-nCoV?

The current estimated mortality rate is 2%-3%. That is probably an overestimate, as those with severe disease and those who die are more likely to be tested and reported early in an epidemic.

Our current knowledge is based on preliminary reports from hospitalized patients and will probably change. From the speed of spread and a single family cluster, it seems likely that there are milder cases and perhaps asymptomatic infection.

What else do I need to know about coronaviruses?

Coronaviruses are a large and diverse group of viruses, many of which are animal viruses. Before the discovery of the 2019-nCoV, six coronaviruses were known to infect humans. Four of these (HKU1, NL63, OC43, and 229E) predominantly caused mild to moderate upper respiratory illness, and they are thought to be responsible for 10%-30% of colds. They occasionally cause viral pneumonia and can be detected by some commercial multiplex panels.

Two other coronaviruses have caused outbreaks of severe respiratory illness in people: SARS, which emerged in Southern China in 2002, and MERS in the Middle East, in 2012. Unlike SARS, sporadic cases of MERS continue to occur.

The current outbreak is caused by 2019-nCoV, a previously unknown beta coronavirus. It is most closely related (~96%) to a bat virus and shares about 80% sequence homology with SARS CoV.

Andrew T. Pavia, MD, is the George and Esther Gross Presidential Professor and chief of the division of pediatric infectious disease in the department of pediatrics at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. He is also director of hospital epidemiology and associate director of antimicrobial stewardship at Primary Children’s Hospital, Salt Lake City. Dr. Pavia has disclosed that he has served as a consultant for Genentech, Merck, and Seqirus and that he has served as associate editor for The Sanford Guide.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak has unfolded so rapidly that many clinicians are scrambling to stay on top of it. Here are the answers to some frequently asked questions about how to prepare your clinic to respond to this outbreak.

Keep in mind that the outbreak is moving rapidly. Though scientific and epidemiologic knowledge has increased at unprecedented speed, there is much we don’t know, and some of what we think we know will change. Follow the links for the most up-to-date information.

What should our clinic do first?

Plan ahead with the following:

- Develop a plan for office staff to take travel histories from anyone with a respiratory illness and provide training for those who need it. Travel history at present should include asking about travel to China in the past 14 days, specifically Wuhan city or Hubei province.

- Review up-to-date infection control practices with all office staff and provide training for those who need it.

- Take an inventory of supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE), such as gowns, gloves, masks, eye protection, and N95 respirators or powered air-purifying respirators (PAPRs), and order items that are missing or low in stock.

- Fit-test users of N95 masks for maximal effectiveness.

- Plan where a potential patient would be isolated while obtaining expert advice.

- Know whom to contact at the state or local health department if you have a patient with the appropriate travel history.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has prepared a toolkit to help frontline health care professionals prepare for this virus. Providers need to stay up to date on the latest recommendations, as the situation is changing rapidly.

When should I suspect 2019-nCoV illness, and what should I do?

Take the following steps to assess the concern and respond:

- If a patient with respiratory illness has traveled to China in the past 14 days, immediately put a mask on the patient and move the individual to a private room. Use a negative-pressure room if available.

- Put on appropriate PPE (including gloves, gown, eye protection, and mask) for contact, droplet, and airborne precautions. CDC recommends an N95 respirator mask if available, although we don’t know yet if there is true airborne spread.

- Obtain an accurate travel history, including dates and cities. (Tip: Get the correct spelling, as the English spelling of cities in China can cause confusion.)

- If the patient meets the current CDC definition of “person under investigation” or PUI, or if you need guidance on how to proceed, notify infection control (if you are in a facility that has it) and call your state or local health department immediately.

- Contact public health authorities who can help decide whether the patient should be admitted to airborne isolation or monitored at home with appropriate precautions.

What is the definition of a PUI?

The current definition of a PUI is a person who has fever and symptoms of a respiratory infection (cough, shortness of breath) AND who has EITHER been in Wuhan city or Hubei province in the past 14 days OR had close contact with a person either under investigation for 2019-nCoV infection or with confirmed infection. The definition of a PUI will change over time, so check this link.

How can I test for 2019-nCoV?

As of Jan. 30, 2020, testing is by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and is available in the United States only through the CDC in Atlanta. Testing should soon be available in state health department laboratories. If public health authorities decide that your patient should be tested, they will instruct you on which samples to obtain.

The full sequence of 2019-nCoV has been shared, so some reference laboratories may develop and validate tests, ideally with assistance from CDC. If testing becomes available, make certain that it is a reputable lab that has carefully validated the test.

Should I test for other viruses?

Because the symptoms of 2019-nCoV infection overlap with those of influenza and other respiratory viruses, PCR testing for other viruses should be considered if it will change management (i.e., change the decision to provide influenza antivirals). Use appropriate PPE while collecting specimens, including eye protection. If 2019-nCoV is a consideration, you may want to send the specimen to a hospital lab for testing, where the sample will be processed under a biosafety hood, rather than doing point-of-care testing in the office.

How dangerous is 2019-nCoV?

The current estimated mortality rate is 2%-3%. That is probably an overestimate, as those with severe disease and those who die are more likely to be tested and reported early in an epidemic.

Our current knowledge is based on preliminary reports from hospitalized patients and will probably change. From the speed of spread and a single family cluster, it seems likely that there are milder cases and perhaps asymptomatic infection.

What else do I need to know about coronaviruses?

Coronaviruses are a large and diverse group of viruses, many of which are animal viruses. Before the discovery of the 2019-nCoV, six coronaviruses were known to infect humans. Four of these (HKU1, NL63, OC43, and 229E) predominantly caused mild to moderate upper respiratory illness, and they are thought to be responsible for 10%-30% of colds. They occasionally cause viral pneumonia and can be detected by some commercial multiplex panels.

Two other coronaviruses have caused outbreaks of severe respiratory illness in people: SARS, which emerged in Southern China in 2002, and MERS in the Middle East, in 2012. Unlike SARS, sporadic cases of MERS continue to occur.

The current outbreak is caused by 2019-nCoV, a previously unknown beta coronavirus. It is most closely related (~96%) to a bat virus and shares about 80% sequence homology with SARS CoV.

Andrew T. Pavia, MD, is the George and Esther Gross Presidential Professor and chief of the division of pediatric infectious disease in the department of pediatrics at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. He is also director of hospital epidemiology and associate director of antimicrobial stewardship at Primary Children’s Hospital, Salt Lake City. Dr. Pavia has disclosed that he has served as a consultant for Genentech, Merck, and Seqirus and that he has served as associate editor for The Sanford Guide.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CDC: First person-to-person spread of novel coronavirus in U.S.

A Chicago woman in her 60s who tested positive for the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) after returning from Wuhan, China, earlier this month has infected her husband, becoming the first known instance of person-to-person transmission of the 2019-nCoV in the United States.

“Limited person-to-person spread of this new virus outside of China has already been seen in nine close contacts, where travelers were infected and transmitted the virus to someone else,” Robert R. Redfield, MD, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said during a press briefing on Jan. 30, 2020. “However, the full picture of how easy and how sustainable this virus can spread is unclear. Today’s news underscores the important risk-dependent exposure. The vast majority of Americans have not had recent travel to China, where sustained human-to-human transmission is occurring. Individuals who are close personal contacts of cases, though, could have a risk.”

The affected man, also in his 60s, is the spouse of the first confirmed travel-associated case of 2019-nCoV to be reported in the state of Illinois, according to Ngozi O. Ezike, MD, director of the Illinois Department of Public Health. The man had no history of recent travel to China. “This person-to-person spread was between two very close contacts: a wife and husband,” said Dr. Ezike, who added that 21 individuals in the state are under investigation for 2019-nCoV. “The virus is not spreading widely across the community. At this time, we are not recommending that people in the general public take additional precautions such as canceling activities or avoiding going out. While there is concern with this second case, public health officials are actively monitoring close contacts, including health care workers, and we believe that people in Illinois are at low risk.”

Jennifer Layden, MD, state epidemiologist at the Illinois Department of Public Health, said that the infected Chicago woman returned from Wuhan, China on Jan. 13, 2020. She is hospitalized in stable condition “and continues to do well,” Dr. Layden said. “Public health officials have been actively and closely monitoring individuals who had contacts with her, including her husband, who had close contact for symptoms. He recently began reporting symptoms and was immediately admitted to the hospital and placed in an isolation room, where he is in stable condition. We are actively monitoring individuals such as health care workers, household contacts, and others who were in contact with either of the confirmed cases in the goal to contain and reduce the risk of additional transmission.”

Nancy Messonnier, MD, director, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, expects that more cases of 2019-nCoV will transpire in the United States.

“More cases means the potential for more person-to-person spread,” Dr. Messonnier said. “We’re trying to strike a balance in our response right now. We want to be aggressive, but we want our actions to be evidence-based and appropriate for the current circumstance. For example, CDC does not currently recommend use of face masks for the general public. The virus is not spreading in the general community.”

A Chicago woman in her 60s who tested positive for the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) after returning from Wuhan, China, earlier this month has infected her husband, becoming the first known instance of person-to-person transmission of the 2019-nCoV in the United States.

“Limited person-to-person spread of this new virus outside of China has already been seen in nine close contacts, where travelers were infected and transmitted the virus to someone else,” Robert R. Redfield, MD, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said during a press briefing on Jan. 30, 2020. “However, the full picture of how easy and how sustainable this virus can spread is unclear. Today’s news underscores the important risk-dependent exposure. The vast majority of Americans have not had recent travel to China, where sustained human-to-human transmission is occurring. Individuals who are close personal contacts of cases, though, could have a risk.”

The affected man, also in his 60s, is the spouse of the first confirmed travel-associated case of 2019-nCoV to be reported in the state of Illinois, according to Ngozi O. Ezike, MD, director of the Illinois Department of Public Health. The man had no history of recent travel to China. “This person-to-person spread was between two very close contacts: a wife and husband,” said Dr. Ezike, who added that 21 individuals in the state are under investigation for 2019-nCoV. “The virus is not spreading widely across the community. At this time, we are not recommending that people in the general public take additional precautions such as canceling activities or avoiding going out. While there is concern with this second case, public health officials are actively monitoring close contacts, including health care workers, and we believe that people in Illinois are at low risk.”

Jennifer Layden, MD, state epidemiologist at the Illinois Department of Public Health, said that the infected Chicago woman returned from Wuhan, China on Jan. 13, 2020. She is hospitalized in stable condition “and continues to do well,” Dr. Layden said. “Public health officials have been actively and closely monitoring individuals who had contacts with her, including her husband, who had close contact for symptoms. He recently began reporting symptoms and was immediately admitted to the hospital and placed in an isolation room, where he is in stable condition. We are actively monitoring individuals such as health care workers, household contacts, and others who were in contact with either of the confirmed cases in the goal to contain and reduce the risk of additional transmission.”

Nancy Messonnier, MD, director, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, expects that more cases of 2019-nCoV will transpire in the United States.

“More cases means the potential for more person-to-person spread,” Dr. Messonnier said. “We’re trying to strike a balance in our response right now. We want to be aggressive, but we want our actions to be evidence-based and appropriate for the current circumstance. For example, CDC does not currently recommend use of face masks for the general public. The virus is not spreading in the general community.”

A Chicago woman in her 60s who tested positive for the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) after returning from Wuhan, China, earlier this month has infected her husband, becoming the first known instance of person-to-person transmission of the 2019-nCoV in the United States.

“Limited person-to-person spread of this new virus outside of China has already been seen in nine close contacts, where travelers were infected and transmitted the virus to someone else,” Robert R. Redfield, MD, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said during a press briefing on Jan. 30, 2020. “However, the full picture of how easy and how sustainable this virus can spread is unclear. Today’s news underscores the important risk-dependent exposure. The vast majority of Americans have not had recent travel to China, where sustained human-to-human transmission is occurring. Individuals who are close personal contacts of cases, though, could have a risk.”

The affected man, also in his 60s, is the spouse of the first confirmed travel-associated case of 2019-nCoV to be reported in the state of Illinois, according to Ngozi O. Ezike, MD, director of the Illinois Department of Public Health. The man had no history of recent travel to China. “This person-to-person spread was between two very close contacts: a wife and husband,” said Dr. Ezike, who added that 21 individuals in the state are under investigation for 2019-nCoV. “The virus is not spreading widely across the community. At this time, we are not recommending that people in the general public take additional precautions such as canceling activities or avoiding going out. While there is concern with this second case, public health officials are actively monitoring close contacts, including health care workers, and we believe that people in Illinois are at low risk.”

Jennifer Layden, MD, state epidemiologist at the Illinois Department of Public Health, said that the infected Chicago woman returned from Wuhan, China on Jan. 13, 2020. She is hospitalized in stable condition “and continues to do well,” Dr. Layden said. “Public health officials have been actively and closely monitoring individuals who had contacts with her, including her husband, who had close contact for symptoms. He recently began reporting symptoms and was immediately admitted to the hospital and placed in an isolation room, where he is in stable condition. We are actively monitoring individuals such as health care workers, household contacts, and others who were in contact with either of the confirmed cases in the goal to contain and reduce the risk of additional transmission.”

Nancy Messonnier, MD, director, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, expects that more cases of 2019-nCoV will transpire in the United States.

“More cases means the potential for more person-to-person spread,” Dr. Messonnier said. “We’re trying to strike a balance in our response right now. We want to be aggressive, but we want our actions to be evidence-based and appropriate for the current circumstance. For example, CDC does not currently recommend use of face masks for the general public. The virus is not spreading in the general community.”

Occult HCV infection is correlated to unfavorable genotypes in hemophilia patients

The presence of occult hepatitis C virus infection is determined by finding HCV RNA in the liver and peripheral blood mononuclear cells, with no HCV RNA in the serum. Researchers have shown that the presence of occult HCV infection (OCI) was correlated with unfavorable polymorphisms near interferon lambda-3/4 (IFNL3/4), which has been associated with spontaneous HCV clearance.

This study was conducted to assess the frequency of OCI in 450 hemophilia patients in Iran with negative HCV markers, and to evaluate the association of three IFNL3 single nucleotide polymorphisms (rs8099917, rs12979860, and rs12980275) and the IFNL4 ss469415590 SNP with OCI positivity.

The estimated OCI rate was 10.2%. Among the 46 OCI patients, 56.5%, 23.9%, and 19.6% were infected with HCV-1b, HCV-1a, and HCV-3a, respectively. The researchers found that, compared with patients without OCI, unfavorable IFNL3 rs12979860, IFNL3 rs8099917, IFNL3 rs12980275, and IFNL4 ss469415590 genotypes were more frequently found in OCI patients. Multivariate analysis showed that ALT, cholesterol, triglyceride, as well as the aforementioned unfavorable interferon SNP geneotypes were associated with OCI positivity.

“10.2% of anti-HCV seronegative Iranian patients with hemophilia had OCI in our study; therefore, risk of this infection should be taken into consideration. We also showed that patients with unfavorable IFNL3 SNPs and IFNL4 ss469415590 genotypes were exposed to a higher risk of OCI, compared to hemophilia patients with other genotypes,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Nafari AH et al. Infect Genet Evol. 2019 Dec 13. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2019.104144.

The presence of occult hepatitis C virus infection is determined by finding HCV RNA in the liver and peripheral blood mononuclear cells, with no HCV RNA in the serum. Researchers have shown that the presence of occult HCV infection (OCI) was correlated with unfavorable polymorphisms near interferon lambda-3/4 (IFNL3/4), which has been associated with spontaneous HCV clearance.

This study was conducted to assess the frequency of OCI in 450 hemophilia patients in Iran with negative HCV markers, and to evaluate the association of three IFNL3 single nucleotide polymorphisms (rs8099917, rs12979860, and rs12980275) and the IFNL4 ss469415590 SNP with OCI positivity.

The estimated OCI rate was 10.2%. Among the 46 OCI patients, 56.5%, 23.9%, and 19.6% were infected with HCV-1b, HCV-1a, and HCV-3a, respectively. The researchers found that, compared with patients without OCI, unfavorable IFNL3 rs12979860, IFNL3 rs8099917, IFNL3 rs12980275, and IFNL4 ss469415590 genotypes were more frequently found in OCI patients. Multivariate analysis showed that ALT, cholesterol, triglyceride, as well as the aforementioned unfavorable interferon SNP geneotypes were associated with OCI positivity.

“10.2% of anti-HCV seronegative Iranian patients with hemophilia had OCI in our study; therefore, risk of this infection should be taken into consideration. We also showed that patients with unfavorable IFNL3 SNPs and IFNL4 ss469415590 genotypes were exposed to a higher risk of OCI, compared to hemophilia patients with other genotypes,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Nafari AH et al. Infect Genet Evol. 2019 Dec 13. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2019.104144.