User login

ID Practitioner is an independent news source that provides infectious disease specialists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on the infectious disease specialist’s practice. Specialty focus topics include antimicrobial resistance, emerging infections, global ID, hepatitis, HIV, hospital-acquired infections, immunizations and vaccines, influenza, mycoses, pediatric infections, and STIs. Infectious Diseases News is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

sofosbuvir

ritonavir with dasabuvir

discount

support path

program

ritonavir

greedy

ledipasvir

assistance

viekira pak

vpak

advocacy

needy

protest

abbvie

paritaprevir

ombitasvir

direct-acting antivirals

dasabuvir

gilead

fake-ovir

support

v pak

oasis

harvoni

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-medstat-latest-articles-articles-section')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-idp')]

Hyperbaric oxygen may improve heart function in long COVID

.

Patients with reduced left ventricular global longitudinal strain (GLS) at baseline who received HBOT had a significant increase in GLS, compared with those who received sham treatment.

GLS is a measure of systolic function that is thought to be a predictor of heart failure–related outcomes.

The study also showed that global work efficiency (GWE) and the global work index (GWI) increased in HBOT-treated patients, though not significantly.

“HBOT is an effective treatment for diabetic foot ulcers, decompression sickness in divers, and other conditions, such as cognitive impairment after stroke,” Marina Leitman, MD, of the Sackler School of Medicine, Tel Aviv, said in an interview. Her team also studied HBOT in asymptomatic older patients and found that the treatment seemed to improve left ventricular end systolic function.

“We should open our minds to thinking about this treatment for another indication,” she said. “That is the basis of precision medicine. We have this treatment and know it can be effective for cardiac pathology.

“Now we can say that post-COVID syndrome patients probably should be evaluated with echocardiography and GLS, which is the main parameter that showed improvement in our study,” she added. “If GLS is below normal values, these patients can benefit from HBOT, although additional research is needed to determine the optimal number of sessions.”

Dr. Leitman presented the study at the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging 2023, a scientific congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Biomarker changes

The study enrolled 60 hospitalized and nonhospitalized post-COVID syndrome patients with ongoing symptoms for at least 3 months after having mild to moderate symptomatic COVID-19.

Participants were randomized to receive HBOT or a sham procedure five times per week for 8 weeks, for a total of 40 sessions. They underwent echocardiography at baseline and 1-3 weeks after the final session to assess GLS.

The HBOT group received 100% oxygen through a mask at a pressure of two atmospheres for 90 minutes, with 5-minute air breaks every 20 minutes.

The sham group received 21% oxygen by mask at one atmosphere for 90 minutes.

At baseline, 29 participants (48%) had reduced GLS, despite having a normal ejection fraction, Dr. Leitman said. Of those, 16 (53%) were in the HBOT group and 13 (43%) were in the sham group.

The average GLS at baseline across all participants was –17.8%; a normal value is about –20%.

In the HBOT group, GLS increased significantly from –17.8% at baseline to –20.2% after HBOT. In the sham group, GLS was –17.8% at baseline and –19.1% at the end of the study, with no statistically significant difference between the two measurements.

In addition, GWE increased overall after HBOT from 96.3 to 97.1.

Dr. Leitman’s poster showed GLS and myocardial work indices before and after HBOT in a 45-year-old patient. Prior to treatment, GLS was –19%; GWE was 96%; and GWI was 1,833 mm Hg.

After HBOT treatment, GLS was –22%; GWE, 98%; and GWI, 1,911 mm Hg.

Clinical relevance unclear

Scott Gorenstein, MD, associate professor in the department of surgery and medical director of wound care and hyperbaric medicine at NYU Langone–Long Island, New York, commented on the study for this news organization.

“The approach certainly warrants studying, but the benefit is difficult to assess,” he said. “We still don’t understand the mechanism of long COVID, so it’s difficult to go from there to say that HBOT will be an effective therapy.”

That said, he added, “This is probably the best study I’ve seen in that it’s a randomized controlled trial, rather than a case series.”

Nevertheless, he noted, “We have no idea from this study whether the change in GLS is clinically relevant. As a clinician, I can’t now say that HBOT is going to improve heart failure secondary to long COVID. We don’t know whether the participants were New York heart failure class 3 or 4, for example, and all of a sudden went from really sick to really good.”

“There are many interventions that may change markers of cardiac function or inflammation,” he said. “But if they don’t make a difference in quantity or quality of life, is the treatment really valuable?”

Dr. Gorenstein said he would have no problem treating a patient with mild to moderate COVID-related heart failure with HBOT, since his own team’s study conducted near the outset of the pandemic showed it was safe. “But HBOT is an expensive treatment in the U.S. and there still are some risks and side effects, albeit very, very low.”

The study received no funding. Dr. Leitman and Dr. Gorenstein have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

.

Patients with reduced left ventricular global longitudinal strain (GLS) at baseline who received HBOT had a significant increase in GLS, compared with those who received sham treatment.

GLS is a measure of systolic function that is thought to be a predictor of heart failure–related outcomes.

The study also showed that global work efficiency (GWE) and the global work index (GWI) increased in HBOT-treated patients, though not significantly.

“HBOT is an effective treatment for diabetic foot ulcers, decompression sickness in divers, and other conditions, such as cognitive impairment after stroke,” Marina Leitman, MD, of the Sackler School of Medicine, Tel Aviv, said in an interview. Her team also studied HBOT in asymptomatic older patients and found that the treatment seemed to improve left ventricular end systolic function.

“We should open our minds to thinking about this treatment for another indication,” she said. “That is the basis of precision medicine. We have this treatment and know it can be effective for cardiac pathology.

“Now we can say that post-COVID syndrome patients probably should be evaluated with echocardiography and GLS, which is the main parameter that showed improvement in our study,” she added. “If GLS is below normal values, these patients can benefit from HBOT, although additional research is needed to determine the optimal number of sessions.”

Dr. Leitman presented the study at the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging 2023, a scientific congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Biomarker changes

The study enrolled 60 hospitalized and nonhospitalized post-COVID syndrome patients with ongoing symptoms for at least 3 months after having mild to moderate symptomatic COVID-19.

Participants were randomized to receive HBOT or a sham procedure five times per week for 8 weeks, for a total of 40 sessions. They underwent echocardiography at baseline and 1-3 weeks after the final session to assess GLS.

The HBOT group received 100% oxygen through a mask at a pressure of two atmospheres for 90 minutes, with 5-minute air breaks every 20 minutes.

The sham group received 21% oxygen by mask at one atmosphere for 90 minutes.

At baseline, 29 participants (48%) had reduced GLS, despite having a normal ejection fraction, Dr. Leitman said. Of those, 16 (53%) were in the HBOT group and 13 (43%) were in the sham group.

The average GLS at baseline across all participants was –17.8%; a normal value is about –20%.

In the HBOT group, GLS increased significantly from –17.8% at baseline to –20.2% after HBOT. In the sham group, GLS was –17.8% at baseline and –19.1% at the end of the study, with no statistically significant difference between the two measurements.

In addition, GWE increased overall after HBOT from 96.3 to 97.1.

Dr. Leitman’s poster showed GLS and myocardial work indices before and after HBOT in a 45-year-old patient. Prior to treatment, GLS was –19%; GWE was 96%; and GWI was 1,833 mm Hg.

After HBOT treatment, GLS was –22%; GWE, 98%; and GWI, 1,911 mm Hg.

Clinical relevance unclear

Scott Gorenstein, MD, associate professor in the department of surgery and medical director of wound care and hyperbaric medicine at NYU Langone–Long Island, New York, commented on the study for this news organization.

“The approach certainly warrants studying, but the benefit is difficult to assess,” he said. “We still don’t understand the mechanism of long COVID, so it’s difficult to go from there to say that HBOT will be an effective therapy.”

That said, he added, “This is probably the best study I’ve seen in that it’s a randomized controlled trial, rather than a case series.”

Nevertheless, he noted, “We have no idea from this study whether the change in GLS is clinically relevant. As a clinician, I can’t now say that HBOT is going to improve heart failure secondary to long COVID. We don’t know whether the participants were New York heart failure class 3 or 4, for example, and all of a sudden went from really sick to really good.”

“There are many interventions that may change markers of cardiac function or inflammation,” he said. “But if they don’t make a difference in quantity or quality of life, is the treatment really valuable?”

Dr. Gorenstein said he would have no problem treating a patient with mild to moderate COVID-related heart failure with HBOT, since his own team’s study conducted near the outset of the pandemic showed it was safe. “But HBOT is an expensive treatment in the U.S. and there still are some risks and side effects, albeit very, very low.”

The study received no funding. Dr. Leitman and Dr. Gorenstein have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

.

Patients with reduced left ventricular global longitudinal strain (GLS) at baseline who received HBOT had a significant increase in GLS, compared with those who received sham treatment.

GLS is a measure of systolic function that is thought to be a predictor of heart failure–related outcomes.

The study also showed that global work efficiency (GWE) and the global work index (GWI) increased in HBOT-treated patients, though not significantly.

“HBOT is an effective treatment for diabetic foot ulcers, decompression sickness in divers, and other conditions, such as cognitive impairment after stroke,” Marina Leitman, MD, of the Sackler School of Medicine, Tel Aviv, said in an interview. Her team also studied HBOT in asymptomatic older patients and found that the treatment seemed to improve left ventricular end systolic function.

“We should open our minds to thinking about this treatment for another indication,” she said. “That is the basis of precision medicine. We have this treatment and know it can be effective for cardiac pathology.

“Now we can say that post-COVID syndrome patients probably should be evaluated with echocardiography and GLS, which is the main parameter that showed improvement in our study,” she added. “If GLS is below normal values, these patients can benefit from HBOT, although additional research is needed to determine the optimal number of sessions.”

Dr. Leitman presented the study at the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging 2023, a scientific congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Biomarker changes

The study enrolled 60 hospitalized and nonhospitalized post-COVID syndrome patients with ongoing symptoms for at least 3 months after having mild to moderate symptomatic COVID-19.

Participants were randomized to receive HBOT or a sham procedure five times per week for 8 weeks, for a total of 40 sessions. They underwent echocardiography at baseline and 1-3 weeks after the final session to assess GLS.

The HBOT group received 100% oxygen through a mask at a pressure of two atmospheres for 90 minutes, with 5-minute air breaks every 20 minutes.

The sham group received 21% oxygen by mask at one atmosphere for 90 minutes.

At baseline, 29 participants (48%) had reduced GLS, despite having a normal ejection fraction, Dr. Leitman said. Of those, 16 (53%) were in the HBOT group and 13 (43%) were in the sham group.

The average GLS at baseline across all participants was –17.8%; a normal value is about –20%.

In the HBOT group, GLS increased significantly from –17.8% at baseline to –20.2% after HBOT. In the sham group, GLS was –17.8% at baseline and –19.1% at the end of the study, with no statistically significant difference between the two measurements.

In addition, GWE increased overall after HBOT from 96.3 to 97.1.

Dr. Leitman’s poster showed GLS and myocardial work indices before and after HBOT in a 45-year-old patient. Prior to treatment, GLS was –19%; GWE was 96%; and GWI was 1,833 mm Hg.

After HBOT treatment, GLS was –22%; GWE, 98%; and GWI, 1,911 mm Hg.

Clinical relevance unclear

Scott Gorenstein, MD, associate professor in the department of surgery and medical director of wound care and hyperbaric medicine at NYU Langone–Long Island, New York, commented on the study for this news organization.

“The approach certainly warrants studying, but the benefit is difficult to assess,” he said. “We still don’t understand the mechanism of long COVID, so it’s difficult to go from there to say that HBOT will be an effective therapy.”

That said, he added, “This is probably the best study I’ve seen in that it’s a randomized controlled trial, rather than a case series.”

Nevertheless, he noted, “We have no idea from this study whether the change in GLS is clinically relevant. As a clinician, I can’t now say that HBOT is going to improve heart failure secondary to long COVID. We don’t know whether the participants were New York heart failure class 3 or 4, for example, and all of a sudden went from really sick to really good.”

“There are many interventions that may change markers of cardiac function or inflammation,” he said. “But if they don’t make a difference in quantity or quality of life, is the treatment really valuable?”

Dr. Gorenstein said he would have no problem treating a patient with mild to moderate COVID-related heart failure with HBOT, since his own team’s study conducted near the outset of the pandemic showed it was safe. “But HBOT is an expensive treatment in the U.S. and there still are some risks and side effects, albeit very, very low.”

The study received no funding. Dr. Leitman and Dr. Gorenstein have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EACVI 2023

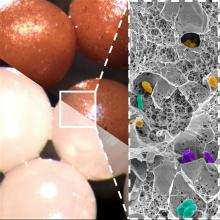

CDC: Drug-resistant ringworm reported in New York

BY ALICIA AULT

The in New York.

Tinea, or ringworm, one of the most common fungal infections, is responsible for almost 5 million outpatient visits and 690 hospitalizations annually, according to the CDC.

Over the past 10 years, severe, antifungal-resistant tinea has spread in South Asia, in part because of the rise of a new dermatophyte species known as Trichophyton indotineae, wrote the authors of a report on the two patients with the drug-resistant strain. This epidemic “has likely been driven by misuse and overuse of topical antifungals and corticosteroids,” added the authors, in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The cases were detected by a New York City dermatologist. In the first case, a 28-year-old woman developed a widespread pruritic eruption in the summer of 2021. She did not consult a dermatologist until December, when she was in the third trimester of pregnancy. She had large, annular, scaly, pruritic plaques on her neck, abdomen, pubic region, and buttocks, but had no underlying medical conditions, no known exposures to someone with a similar rash, and no recent international travel history.

After she gave birth in January, she started oral terbinafine therapy but had no improvement after 2 weeks. Clinicians administered a 4-week course of itraconazole, which resolved the infection.

The second patient, a 47-year-old woman with no medical conditions, developed a rash while in Bangladesh in the summer of 2022. Other family members had a similar rash. She was treated with topical antifungal and steroid combination creams but had no resolution. Back in the United States, she was prescribed hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment and diphenhydramine, clotrimazole cream, and terbinafine cream in three successive emergency department visits. In December 2022, dermatologists, observing widespread, discrete, scaly, annular, pruritic plaques on the thighs and buttocks, prescribed a 4-week course of oral terbinafine. When the rash did not resolve, she was given 4 weeks of griseofulvin. The rash persisted, although there was 80% improvement. Clinicians are now considering itraconazole. The woman’s son and husband are also being evaluated, as they have similar rashes.

In both cases, skin culture isolates were initially identified as Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Further analysis at the New York State Department of Health’s lab, using Sanger sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer region of the ribosomal gene, followed by phylogenetic analysis, identified the isolates as T. indotineae.

The authors note that culture-based techniques used by most clinical laboratories typically misidentify T. indotineae as T. mentagrophytes or T. interdigitale. Genomic sequencing must be used to properly identify T. indotineae, they wrote.

Clinicians should consider T. indotineae in patients with widespread ringworm, especially if they do not improve with topical antifungals or oral terbinafine, said the authors. If T. indotineae is suspected, state or local public health departments can direct clinicians to testing.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

BY ALICIA AULT

The in New York.

Tinea, or ringworm, one of the most common fungal infections, is responsible for almost 5 million outpatient visits and 690 hospitalizations annually, according to the CDC.

Over the past 10 years, severe, antifungal-resistant tinea has spread in South Asia, in part because of the rise of a new dermatophyte species known as Trichophyton indotineae, wrote the authors of a report on the two patients with the drug-resistant strain. This epidemic “has likely been driven by misuse and overuse of topical antifungals and corticosteroids,” added the authors, in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The cases were detected by a New York City dermatologist. In the first case, a 28-year-old woman developed a widespread pruritic eruption in the summer of 2021. She did not consult a dermatologist until December, when she was in the third trimester of pregnancy. She had large, annular, scaly, pruritic plaques on her neck, abdomen, pubic region, and buttocks, but had no underlying medical conditions, no known exposures to someone with a similar rash, and no recent international travel history.

After she gave birth in January, she started oral terbinafine therapy but had no improvement after 2 weeks. Clinicians administered a 4-week course of itraconazole, which resolved the infection.

The second patient, a 47-year-old woman with no medical conditions, developed a rash while in Bangladesh in the summer of 2022. Other family members had a similar rash. She was treated with topical antifungal and steroid combination creams but had no resolution. Back in the United States, she was prescribed hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment and diphenhydramine, clotrimazole cream, and terbinafine cream in three successive emergency department visits. In December 2022, dermatologists, observing widespread, discrete, scaly, annular, pruritic plaques on the thighs and buttocks, prescribed a 4-week course of oral terbinafine. When the rash did not resolve, she was given 4 weeks of griseofulvin. The rash persisted, although there was 80% improvement. Clinicians are now considering itraconazole. The woman’s son and husband are also being evaluated, as they have similar rashes.

In both cases, skin culture isolates were initially identified as Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Further analysis at the New York State Department of Health’s lab, using Sanger sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer region of the ribosomal gene, followed by phylogenetic analysis, identified the isolates as T. indotineae.

The authors note that culture-based techniques used by most clinical laboratories typically misidentify T. indotineae as T. mentagrophytes or T. interdigitale. Genomic sequencing must be used to properly identify T. indotineae, they wrote.

Clinicians should consider T. indotineae in patients with widespread ringworm, especially if they do not improve with topical antifungals or oral terbinafine, said the authors. If T. indotineae is suspected, state or local public health departments can direct clinicians to testing.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

BY ALICIA AULT

The in New York.

Tinea, or ringworm, one of the most common fungal infections, is responsible for almost 5 million outpatient visits and 690 hospitalizations annually, according to the CDC.

Over the past 10 years, severe, antifungal-resistant tinea has spread in South Asia, in part because of the rise of a new dermatophyte species known as Trichophyton indotineae, wrote the authors of a report on the two patients with the drug-resistant strain. This epidemic “has likely been driven by misuse and overuse of topical antifungals and corticosteroids,” added the authors, in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The cases were detected by a New York City dermatologist. In the first case, a 28-year-old woman developed a widespread pruritic eruption in the summer of 2021. She did not consult a dermatologist until December, when she was in the third trimester of pregnancy. She had large, annular, scaly, pruritic plaques on her neck, abdomen, pubic region, and buttocks, but had no underlying medical conditions, no known exposures to someone with a similar rash, and no recent international travel history.

After she gave birth in January, she started oral terbinafine therapy but had no improvement after 2 weeks. Clinicians administered a 4-week course of itraconazole, which resolved the infection.

The second patient, a 47-year-old woman with no medical conditions, developed a rash while in Bangladesh in the summer of 2022. Other family members had a similar rash. She was treated with topical antifungal and steroid combination creams but had no resolution. Back in the United States, she was prescribed hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment and diphenhydramine, clotrimazole cream, and terbinafine cream in three successive emergency department visits. In December 2022, dermatologists, observing widespread, discrete, scaly, annular, pruritic plaques on the thighs and buttocks, prescribed a 4-week course of oral terbinafine. When the rash did not resolve, she was given 4 weeks of griseofulvin. The rash persisted, although there was 80% improvement. Clinicians are now considering itraconazole. The woman’s son and husband are also being evaluated, as they have similar rashes.

In both cases, skin culture isolates were initially identified as Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Further analysis at the New York State Department of Health’s lab, using Sanger sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer region of the ribosomal gene, followed by phylogenetic analysis, identified the isolates as T. indotineae.

The authors note that culture-based techniques used by most clinical laboratories typically misidentify T. indotineae as T. mentagrophytes or T. interdigitale. Genomic sequencing must be used to properly identify T. indotineae, they wrote.

Clinicians should consider T. indotineae in patients with widespread ringworm, especially if they do not improve with topical antifungals or oral terbinafine, said the authors. If T. indotineae is suspected, state or local public health departments can direct clinicians to testing.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Here’s how we can rebuild trust in vaccines

When people ask Paul Offit, MD, what worries him the most about the COVID-19 pandemic, he names two concerns. “One is the lack of socialization and education that came from keeping kids out of school for so long,” Dr. Offit said in a recent interview. “And I think vaccines have suffered.”

Dr. Offit is director of the Vaccine Education Center and a professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. He has watched with alarm as the American public appears to be losing faith in the lifesaving vaccines the public health community has worked hard to promote. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that the proportion of kids entering kindergarten who have received state-required vaccines dipped to 94% in the 2020-2021 school year – a full point less than the year before the pandemic – then dropped by another percentage point, to 93%, the following year.

Although a couple of percentage points may sound trivial, were only 93% of kindergarteners to receive the vaccine against measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR), approximately 250,000 vulnerable 5-year-olds could spark the next big outbreak, such as the recent measles outbreaks in Ohio and Minnesota.

Dr. Offit is one of many public health officials and clinicians who are working to reverse the concerning trends in pediatric vaccinations.

“I just don’t want to see an outbreak of something that we could have avoided because we were not protected enough,” Judith Shlay, MD, associate director of the Public Health Institute at Denver Health, said.

Official stumbles in part to blame

Disruptions in health care from the COVID-19 pandemic certainly played a role in the decline. Parents were afraid to expose their children to other sick kids, providers shifted to a telehealth model, and routine preventive care was difficult to access.

But Dr. Offit also blamed erosion of trust on mistakes made by government and public health institutions for the alarming trend. “I think that health care professionals have lost some level of trust in the Food and Drug Administration and CDC.”

He cited as an example poor messaging during a large outbreak in Massachusetts in summer 2021, when the CDC published a report that highlighted the high proportion of COVID-19 cases among vaccinated people. Health officials called those cases “breakthrough” infections, although most were mild or asymptomatic.

Dr. Offit said the CDC should have focused the message instead on the low rate (1%) of hospitalizations and the low number of deaths from the infections. Instead, they had to walk back their promise that vaccinated people didn’t need to wear masks. At other times, the Biden administration pressured public health officials by promising to make booster shots available to the American public when the FDA and CDC felt they lacked evidence to recommend the injections.

Rupali Limaye, PhD, an associate professor of international health at the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, studies vaccine behavior and decision-making. She would go a step further in characterizing the roots of worsening vaccine hesitancy.

“In the last 20 years, we’ve seen there’s less and less trust in health care providers in general,” Dr. Limaye said. “More people are turning to their social networks or social contacts for that kind of information.” In the maelstrom of the COVID-19 pandemic, digital social networks facilitated the spread of misinformation about COVID-19 faster than scientists could unravel the mysteries of the disease.

“There’s always been this underlying hesitancy for some people about vaccines,” Dr. Shlay said. But she has noticed more resistance to the COVID-19 vaccine from parents nervous about the new mRNA technology. “There was a lot of politicization of the vaccine, even though the mRNA vaccine technology has been around for a long time,” she said.

Multipronged approaches

Dr. Shlay is committed to restoring childhood vaccination uptake to prepandemic levels now that clinics are open again. To do so, she is relying on a combination of quality improvement strategies and outreach to undervaccinated populations.

Denver Health, for instance, offers vaccinations at any inpatient or outpatient visit – not just well-child visits – with the help of alerts built into their electronic health records that notify clinicians if a patient is due for a vaccine.

COVID-19 revealed marked health inequities in underserved communities as Black, Hispanic, and people from other minority communities experienced higher rates of COVID-19 cases and deaths, compared with White people. The Public Health Institute, which is part of Denver Health, has responded with vaccine outreach teams that go to schools, shelters, churches, and community-based organizations to vaccinate children. They focus their efforts on areas where immunization rates are low. Health centers in schools throughout Colorado vaccinate students, and the Public Health Institute partners with Denver-area public schools to provide vaccines to students in schools that don’t have such centers. (They also provide dental care and behavioral health services.)

But it is unlikely that restoring clinic operations and making vaccines more accessible will fill the gap. After 3 years of fear and mistrust, parents are still nervous about routine shots. To help clinicians facilitate conversations about vaccination, Denver Health trains providers in communication techniques using motivational interviewing (MI), a collaborative goal-oriented approach that encourages changes in health behaviors.

Dr. Shlay, who stressed the value of persistence, advised, “Through motivational interviewing, discussing things, talking about it, you can actually address most of the concerns.”

Giving parents a boost in the right direction

That spirit drives the work of Boost Oregon, a parent-led nonprofit organization founded in 2015 that helps parents make science-based decisions for themselves and their families. Even before the pandemic, primary care providers needed better strategies for addressing parents who had concerns about vaccines and found themselves failing in the effort while trying to see 20 patients a day.

For families that have questions about vaccines, Boost Oregon holds community meetings in which parents meet with clinicians, share their concerns with other parents, and get answers to their questions in a nonjudgmental way. The 1- to 2-hour sessions enable deeper discussions of the issues than many clinicians can manage in a 20-minute patient visit.

Boost Oregon also trains providers in communication techniques using MI. Ryan Hassan, MD, a pediatrician in private practice who serves as the medical director for the organization, has made the approach an integral part of his day. A key realization for him about the use of MI is that if providers want to build trust with parents, they need to accept that their role is not simply to educate but also to listen.

“Even if it’s the wildest conspiracy theory I’ve ever heard, that is my opportunity to show them that I’m listening and to empathize,” Dr. Hassan said.

His next step, a central tenet of MI, is to make reflective statements that summarize the parent’s concerns, demonstrate empathy, and help him get to the heart of their concerns. He then tailors his message to their issues.

Dr. Hassan tells people who are learning the technique to acknowledge that patients have the autonomy to make their own decisions. Coercing them into a decision is unhelpful and potentially counterproductive. “You can’t change anyone else’s mind,” he said. “You have to help them change their own mind.”

Dr. Limaye reinforced that message. Overwhelmed by conflicting messages on the internet, people are just trying to find answers. She trains providers not to dismiss patients’ concerns, because dismissal erodes trust.

“When you’re dealing with misinformation and conspiracy, to me, one thing to keep in mind is that it’s the long game,” Dr. Limaye said, “You’re not going to be able to sway them in one conversation.”

Can the powers of social media be harnessed for pro-vaccine messaging? Dr. Limaye has studied social media strategies to promote vaccine acceptance and has identified several elements that can be useful for swaying opinions about vaccine.

One is the messenger – as people trust their physicians less, “it’s important to find influencers that people might trust to actually spread a message,” she said. Another factor is that as society has become more polarized, interaction with the leadership of groups that hold influence has become key. To promote vaccine acceptance, for example, leaders of moms’ groups on Facebook could be equipped with evidence-based information.

“It’s important for us to reach out and engage with those that are leaders in those groups, because they kind of hold the power,” Dr. Limaye said.

Framing the message is critical. Dr. Limaye has found that personal narratives can be persuasive and that to influence vaccine behavior, it is necessary to tailor the approach to the specific audience. Danish researchers, for example, in 2017 launched a campaign to increase uptake of HPV vaccinations among teenagers. The researchers provided facts about the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine, cited posts by clinicians about the importance of immunization against the virus, and relayed personal stories, such as one about a father who chose to vaccinate his daughter and another about a blogger’s encounter with a woman with cervical cancer. The researchers found that the highest engagement rates were achieved through personal content and that such content generated the highest proportion of positive comments.

According to Dr. Limaye, to change behavior, social media messaging must address the issues of risk perception and self-efficacy. For risk perception regarding vaccines, a successful message needs to address the parents’ questions about whether their child is at risk for catching a disease, such as measles or pertussis, and if they are, whether the child will wind up in the hospital.

Self-efficacy is the belief that one can accomplish a task. An effective message would provide information on where to find free or low-cost vaccines and would identify locations that are easy to reach and that have expanded hours for working parents, Dr. Limaye said.

What’s the best approach for boosting vaccination rates in the post-pandemic era? In the 1850s, Massachusetts enacted the first vaccine mandate in the United States to prevent smallpox, and by the 1900s, similar laws had been passed in almost half of states. But recent polls suggest that support for vaccine mandates is dwindling. In a poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation last fall, 71% of adults said that healthy children should be required to be vaccinated against measles before entering school, which was down from 82% in a similar poll in 2019.

So perhaps a better approach for promoting vaccine confidence in the 21st century would involve wider use of MI by clinicians and more focus by public health agencies taking advantage of the potential power of social media. As Dr. Offit put it, “I think trust is the key thing.”

Dr. Offit, Dr. Limaye, Dr. Shlay, and Dr. Hassan report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

When people ask Paul Offit, MD, what worries him the most about the COVID-19 pandemic, he names two concerns. “One is the lack of socialization and education that came from keeping kids out of school for so long,” Dr. Offit said in a recent interview. “And I think vaccines have suffered.”

Dr. Offit is director of the Vaccine Education Center and a professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. He has watched with alarm as the American public appears to be losing faith in the lifesaving vaccines the public health community has worked hard to promote. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that the proportion of kids entering kindergarten who have received state-required vaccines dipped to 94% in the 2020-2021 school year – a full point less than the year before the pandemic – then dropped by another percentage point, to 93%, the following year.

Although a couple of percentage points may sound trivial, were only 93% of kindergarteners to receive the vaccine against measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR), approximately 250,000 vulnerable 5-year-olds could spark the next big outbreak, such as the recent measles outbreaks in Ohio and Minnesota.

Dr. Offit is one of many public health officials and clinicians who are working to reverse the concerning trends in pediatric vaccinations.

“I just don’t want to see an outbreak of something that we could have avoided because we were not protected enough,” Judith Shlay, MD, associate director of the Public Health Institute at Denver Health, said.

Official stumbles in part to blame

Disruptions in health care from the COVID-19 pandemic certainly played a role in the decline. Parents were afraid to expose their children to other sick kids, providers shifted to a telehealth model, and routine preventive care was difficult to access.

But Dr. Offit also blamed erosion of trust on mistakes made by government and public health institutions for the alarming trend. “I think that health care professionals have lost some level of trust in the Food and Drug Administration and CDC.”

He cited as an example poor messaging during a large outbreak in Massachusetts in summer 2021, when the CDC published a report that highlighted the high proportion of COVID-19 cases among vaccinated people. Health officials called those cases “breakthrough” infections, although most were mild or asymptomatic.

Dr. Offit said the CDC should have focused the message instead on the low rate (1%) of hospitalizations and the low number of deaths from the infections. Instead, they had to walk back their promise that vaccinated people didn’t need to wear masks. At other times, the Biden administration pressured public health officials by promising to make booster shots available to the American public when the FDA and CDC felt they lacked evidence to recommend the injections.

Rupali Limaye, PhD, an associate professor of international health at the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, studies vaccine behavior and decision-making. She would go a step further in characterizing the roots of worsening vaccine hesitancy.

“In the last 20 years, we’ve seen there’s less and less trust in health care providers in general,” Dr. Limaye said. “More people are turning to their social networks or social contacts for that kind of information.” In the maelstrom of the COVID-19 pandemic, digital social networks facilitated the spread of misinformation about COVID-19 faster than scientists could unravel the mysteries of the disease.

“There’s always been this underlying hesitancy for some people about vaccines,” Dr. Shlay said. But she has noticed more resistance to the COVID-19 vaccine from parents nervous about the new mRNA technology. “There was a lot of politicization of the vaccine, even though the mRNA vaccine technology has been around for a long time,” she said.

Multipronged approaches

Dr. Shlay is committed to restoring childhood vaccination uptake to prepandemic levels now that clinics are open again. To do so, she is relying on a combination of quality improvement strategies and outreach to undervaccinated populations.

Denver Health, for instance, offers vaccinations at any inpatient or outpatient visit – not just well-child visits – with the help of alerts built into their electronic health records that notify clinicians if a patient is due for a vaccine.

COVID-19 revealed marked health inequities in underserved communities as Black, Hispanic, and people from other minority communities experienced higher rates of COVID-19 cases and deaths, compared with White people. The Public Health Institute, which is part of Denver Health, has responded with vaccine outreach teams that go to schools, shelters, churches, and community-based organizations to vaccinate children. They focus their efforts on areas where immunization rates are low. Health centers in schools throughout Colorado vaccinate students, and the Public Health Institute partners with Denver-area public schools to provide vaccines to students in schools that don’t have such centers. (They also provide dental care and behavioral health services.)

But it is unlikely that restoring clinic operations and making vaccines more accessible will fill the gap. After 3 years of fear and mistrust, parents are still nervous about routine shots. To help clinicians facilitate conversations about vaccination, Denver Health trains providers in communication techniques using motivational interviewing (MI), a collaborative goal-oriented approach that encourages changes in health behaviors.

Dr. Shlay, who stressed the value of persistence, advised, “Through motivational interviewing, discussing things, talking about it, you can actually address most of the concerns.”

Giving parents a boost in the right direction

That spirit drives the work of Boost Oregon, a parent-led nonprofit organization founded in 2015 that helps parents make science-based decisions for themselves and their families. Even before the pandemic, primary care providers needed better strategies for addressing parents who had concerns about vaccines and found themselves failing in the effort while trying to see 20 patients a day.

For families that have questions about vaccines, Boost Oregon holds community meetings in which parents meet with clinicians, share their concerns with other parents, and get answers to their questions in a nonjudgmental way. The 1- to 2-hour sessions enable deeper discussions of the issues than many clinicians can manage in a 20-minute patient visit.

Boost Oregon also trains providers in communication techniques using MI. Ryan Hassan, MD, a pediatrician in private practice who serves as the medical director for the organization, has made the approach an integral part of his day. A key realization for him about the use of MI is that if providers want to build trust with parents, they need to accept that their role is not simply to educate but also to listen.

“Even if it’s the wildest conspiracy theory I’ve ever heard, that is my opportunity to show them that I’m listening and to empathize,” Dr. Hassan said.

His next step, a central tenet of MI, is to make reflective statements that summarize the parent’s concerns, demonstrate empathy, and help him get to the heart of their concerns. He then tailors his message to their issues.

Dr. Hassan tells people who are learning the technique to acknowledge that patients have the autonomy to make their own decisions. Coercing them into a decision is unhelpful and potentially counterproductive. “You can’t change anyone else’s mind,” he said. “You have to help them change their own mind.”

Dr. Limaye reinforced that message. Overwhelmed by conflicting messages on the internet, people are just trying to find answers. She trains providers not to dismiss patients’ concerns, because dismissal erodes trust.

“When you’re dealing with misinformation and conspiracy, to me, one thing to keep in mind is that it’s the long game,” Dr. Limaye said, “You’re not going to be able to sway them in one conversation.”

Can the powers of social media be harnessed for pro-vaccine messaging? Dr. Limaye has studied social media strategies to promote vaccine acceptance and has identified several elements that can be useful for swaying opinions about vaccine.

One is the messenger – as people trust their physicians less, “it’s important to find influencers that people might trust to actually spread a message,” she said. Another factor is that as society has become more polarized, interaction with the leadership of groups that hold influence has become key. To promote vaccine acceptance, for example, leaders of moms’ groups on Facebook could be equipped with evidence-based information.

“It’s important for us to reach out and engage with those that are leaders in those groups, because they kind of hold the power,” Dr. Limaye said.

Framing the message is critical. Dr. Limaye has found that personal narratives can be persuasive and that to influence vaccine behavior, it is necessary to tailor the approach to the specific audience. Danish researchers, for example, in 2017 launched a campaign to increase uptake of HPV vaccinations among teenagers. The researchers provided facts about the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine, cited posts by clinicians about the importance of immunization against the virus, and relayed personal stories, such as one about a father who chose to vaccinate his daughter and another about a blogger’s encounter with a woman with cervical cancer. The researchers found that the highest engagement rates were achieved through personal content and that such content generated the highest proportion of positive comments.

According to Dr. Limaye, to change behavior, social media messaging must address the issues of risk perception and self-efficacy. For risk perception regarding vaccines, a successful message needs to address the parents’ questions about whether their child is at risk for catching a disease, such as measles or pertussis, and if they are, whether the child will wind up in the hospital.

Self-efficacy is the belief that one can accomplish a task. An effective message would provide information on where to find free or low-cost vaccines and would identify locations that are easy to reach and that have expanded hours for working parents, Dr. Limaye said.

What’s the best approach for boosting vaccination rates in the post-pandemic era? In the 1850s, Massachusetts enacted the first vaccine mandate in the United States to prevent smallpox, and by the 1900s, similar laws had been passed in almost half of states. But recent polls suggest that support for vaccine mandates is dwindling. In a poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation last fall, 71% of adults said that healthy children should be required to be vaccinated against measles before entering school, which was down from 82% in a similar poll in 2019.

So perhaps a better approach for promoting vaccine confidence in the 21st century would involve wider use of MI by clinicians and more focus by public health agencies taking advantage of the potential power of social media. As Dr. Offit put it, “I think trust is the key thing.”

Dr. Offit, Dr. Limaye, Dr. Shlay, and Dr. Hassan report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

When people ask Paul Offit, MD, what worries him the most about the COVID-19 pandemic, he names two concerns. “One is the lack of socialization and education that came from keeping kids out of school for so long,” Dr. Offit said in a recent interview. “And I think vaccines have suffered.”

Dr. Offit is director of the Vaccine Education Center and a professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. He has watched with alarm as the American public appears to be losing faith in the lifesaving vaccines the public health community has worked hard to promote. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that the proportion of kids entering kindergarten who have received state-required vaccines dipped to 94% in the 2020-2021 school year – a full point less than the year before the pandemic – then dropped by another percentage point, to 93%, the following year.

Although a couple of percentage points may sound trivial, were only 93% of kindergarteners to receive the vaccine against measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR), approximately 250,000 vulnerable 5-year-olds could spark the next big outbreak, such as the recent measles outbreaks in Ohio and Minnesota.

Dr. Offit is one of many public health officials and clinicians who are working to reverse the concerning trends in pediatric vaccinations.

“I just don’t want to see an outbreak of something that we could have avoided because we were not protected enough,” Judith Shlay, MD, associate director of the Public Health Institute at Denver Health, said.

Official stumbles in part to blame

Disruptions in health care from the COVID-19 pandemic certainly played a role in the decline. Parents were afraid to expose their children to other sick kids, providers shifted to a telehealth model, and routine preventive care was difficult to access.

But Dr. Offit also blamed erosion of trust on mistakes made by government and public health institutions for the alarming trend. “I think that health care professionals have lost some level of trust in the Food and Drug Administration and CDC.”

He cited as an example poor messaging during a large outbreak in Massachusetts in summer 2021, when the CDC published a report that highlighted the high proportion of COVID-19 cases among vaccinated people. Health officials called those cases “breakthrough” infections, although most were mild or asymptomatic.

Dr. Offit said the CDC should have focused the message instead on the low rate (1%) of hospitalizations and the low number of deaths from the infections. Instead, they had to walk back their promise that vaccinated people didn’t need to wear masks. At other times, the Biden administration pressured public health officials by promising to make booster shots available to the American public when the FDA and CDC felt they lacked evidence to recommend the injections.

Rupali Limaye, PhD, an associate professor of international health at the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, studies vaccine behavior and decision-making. She would go a step further in characterizing the roots of worsening vaccine hesitancy.

“In the last 20 years, we’ve seen there’s less and less trust in health care providers in general,” Dr. Limaye said. “More people are turning to their social networks or social contacts for that kind of information.” In the maelstrom of the COVID-19 pandemic, digital social networks facilitated the spread of misinformation about COVID-19 faster than scientists could unravel the mysteries of the disease.

“There’s always been this underlying hesitancy for some people about vaccines,” Dr. Shlay said. But she has noticed more resistance to the COVID-19 vaccine from parents nervous about the new mRNA technology. “There was a lot of politicization of the vaccine, even though the mRNA vaccine technology has been around for a long time,” she said.

Multipronged approaches

Dr. Shlay is committed to restoring childhood vaccination uptake to prepandemic levels now that clinics are open again. To do so, she is relying on a combination of quality improvement strategies and outreach to undervaccinated populations.

Denver Health, for instance, offers vaccinations at any inpatient or outpatient visit – not just well-child visits – with the help of alerts built into their electronic health records that notify clinicians if a patient is due for a vaccine.

COVID-19 revealed marked health inequities in underserved communities as Black, Hispanic, and people from other minority communities experienced higher rates of COVID-19 cases and deaths, compared with White people. The Public Health Institute, which is part of Denver Health, has responded with vaccine outreach teams that go to schools, shelters, churches, and community-based organizations to vaccinate children. They focus their efforts on areas where immunization rates are low. Health centers in schools throughout Colorado vaccinate students, and the Public Health Institute partners with Denver-area public schools to provide vaccines to students in schools that don’t have such centers. (They also provide dental care and behavioral health services.)

But it is unlikely that restoring clinic operations and making vaccines more accessible will fill the gap. After 3 years of fear and mistrust, parents are still nervous about routine shots. To help clinicians facilitate conversations about vaccination, Denver Health trains providers in communication techniques using motivational interviewing (MI), a collaborative goal-oriented approach that encourages changes in health behaviors.

Dr. Shlay, who stressed the value of persistence, advised, “Through motivational interviewing, discussing things, talking about it, you can actually address most of the concerns.”

Giving parents a boost in the right direction

That spirit drives the work of Boost Oregon, a parent-led nonprofit organization founded in 2015 that helps parents make science-based decisions for themselves and their families. Even before the pandemic, primary care providers needed better strategies for addressing parents who had concerns about vaccines and found themselves failing in the effort while trying to see 20 patients a day.

For families that have questions about vaccines, Boost Oregon holds community meetings in which parents meet with clinicians, share their concerns with other parents, and get answers to their questions in a nonjudgmental way. The 1- to 2-hour sessions enable deeper discussions of the issues than many clinicians can manage in a 20-minute patient visit.

Boost Oregon also trains providers in communication techniques using MI. Ryan Hassan, MD, a pediatrician in private practice who serves as the medical director for the organization, has made the approach an integral part of his day. A key realization for him about the use of MI is that if providers want to build trust with parents, they need to accept that their role is not simply to educate but also to listen.

“Even if it’s the wildest conspiracy theory I’ve ever heard, that is my opportunity to show them that I’m listening and to empathize,” Dr. Hassan said.

His next step, a central tenet of MI, is to make reflective statements that summarize the parent’s concerns, demonstrate empathy, and help him get to the heart of their concerns. He then tailors his message to their issues.

Dr. Hassan tells people who are learning the technique to acknowledge that patients have the autonomy to make their own decisions. Coercing them into a decision is unhelpful and potentially counterproductive. “You can’t change anyone else’s mind,” he said. “You have to help them change their own mind.”

Dr. Limaye reinforced that message. Overwhelmed by conflicting messages on the internet, people are just trying to find answers. She trains providers not to dismiss patients’ concerns, because dismissal erodes trust.

“When you’re dealing with misinformation and conspiracy, to me, one thing to keep in mind is that it’s the long game,” Dr. Limaye said, “You’re not going to be able to sway them in one conversation.”

Can the powers of social media be harnessed for pro-vaccine messaging? Dr. Limaye has studied social media strategies to promote vaccine acceptance and has identified several elements that can be useful for swaying opinions about vaccine.

One is the messenger – as people trust their physicians less, “it’s important to find influencers that people might trust to actually spread a message,” she said. Another factor is that as society has become more polarized, interaction with the leadership of groups that hold influence has become key. To promote vaccine acceptance, for example, leaders of moms’ groups on Facebook could be equipped with evidence-based information.

“It’s important for us to reach out and engage with those that are leaders in those groups, because they kind of hold the power,” Dr. Limaye said.

Framing the message is critical. Dr. Limaye has found that personal narratives can be persuasive and that to influence vaccine behavior, it is necessary to tailor the approach to the specific audience. Danish researchers, for example, in 2017 launched a campaign to increase uptake of HPV vaccinations among teenagers. The researchers provided facts about the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine, cited posts by clinicians about the importance of immunization against the virus, and relayed personal stories, such as one about a father who chose to vaccinate his daughter and another about a blogger’s encounter with a woman with cervical cancer. The researchers found that the highest engagement rates were achieved through personal content and that such content generated the highest proportion of positive comments.

According to Dr. Limaye, to change behavior, social media messaging must address the issues of risk perception and self-efficacy. For risk perception regarding vaccines, a successful message needs to address the parents’ questions about whether their child is at risk for catching a disease, such as measles or pertussis, and if they are, whether the child will wind up in the hospital.

Self-efficacy is the belief that one can accomplish a task. An effective message would provide information on where to find free or low-cost vaccines and would identify locations that are easy to reach and that have expanded hours for working parents, Dr. Limaye said.

What’s the best approach for boosting vaccination rates in the post-pandemic era? In the 1850s, Massachusetts enacted the first vaccine mandate in the United States to prevent smallpox, and by the 1900s, similar laws had been passed in almost half of states. But recent polls suggest that support for vaccine mandates is dwindling. In a poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation last fall, 71% of adults said that healthy children should be required to be vaccinated against measles before entering school, which was down from 82% in a similar poll in 2019.

So perhaps a better approach for promoting vaccine confidence in the 21st century would involve wider use of MI by clinicians and more focus by public health agencies taking advantage of the potential power of social media. As Dr. Offit put it, “I think trust is the key thing.”

Dr. Offit, Dr. Limaye, Dr. Shlay, and Dr. Hassan report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medical students gain momentum in effort to ban legacy admissions

, which they say offer preferential treatment to applicants based on their association with donors or alumni.

While an estimated 25% of public colleges and universities still use legacy admissions, a growing list of top medical schools have moved away from the practice over the last decade, including Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and Tufts University, Medford, Mass.

Legacy admissions contradict schools’ more inclusive policies, Senila Yasmin, MPH, a second-year medical student at Tufts University, said in an interview. While Tufts maintains legacy admissions for its undergraduate applicants, the medical school stopped the practice in 2021, said Ms. Yasmin, a member of a student group that lobbied against the school’s legacy preferences.

Describing herself as a low-income, first-generation Muslim-Pakistani American, Ms. Yasmin wants to use her experience at Tufts to improve accessibility for students like herself.

As a member of the American Medical Association (AMA) Medical Student Section, she coauthored a resolution stating that legacy admissions go against the AMA’s strategic plan to advance racial justice and health equity. The Student Section passed the resolution in November, and in June, the AMA House of Delegates will vote on whether to adopt the policy.

Along with a Supreme Court decision that could strike down race-conscious college admissions, an AMA policy could convince medical schools to rethink legacy admissions and how to maintain diverse student bodies. In June, the court is expected to issue a decision in the Students for Fair Admissions lawsuit against Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., and the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, which alleges that considering race in holistic admissions constitutes racial discrimination and violates the Equal Protection Clause.

Opponents of legacy admissions, like Ms. Yasmin, say it penalizes students from racial minorities and lower socioeconomic backgrounds, hampering a fair and equitable admissions process that attracts diverse medical school admissions.

Diversity of medical applicants

Diversity in medical schools continued to increase last year with more Black, Hispanic, and female students applying and enrolling, according to a recent report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). However, universities often include nonacademic criteria in their admission assessments to improve educational access for underrepresented minorities.

Medical schools carefully consider each applicant’s background “to yield a diverse class of students,” Geoffrey Young, PhD, AAMC’s senior director of transforming the health care workforce, told this news organization.

Some schools, such as Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, and the University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson, perform a thorough review of candidates while offering admissions practices designed specifically for legacy applicants. The schools assert that legacy designation doesn’t factor into the student’s likelihood of acceptance.

The arrangement may show that schools want to commit to equity and fairness but have trouble moving away from entrenched traditions, two professors from Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pa., who sit on separate medical admissions subcommittees, wrote last year in Bioethics Today.

Legislation may hasten legacies’ end

In December, Ms. Yasmin and a group of Massachusetts Medical Society student-members presented another resolution to the state medical society, which adopted it.

The society’s new policy opposes the use of legacy status in medical school admissions and supports mechanisms to eliminate its inclusion from the application process, Theodore Calianos II, MD, FACS, president of the Massachusetts Medical Society, said in an interview.

“Legacy preferences limit racial and socioeconomic diversity on campuses, so we asked, ‘What can we do so that everyone has equal access to medical education?’ It is exciting to see the students and young physicians – the future of medicine – become involved in policymaking.”

Proposed laws may also hasten the end of legacy admissions. Last year, the U.S. Senate began considering a bill prohibiting colleges receiving federal financial aid from giving preferential treatment to students based on their relations to donors or alumni. However, the bill allows the Department of Education to make exceptions for institutions serving historically underrepresented groups.

The New York State Senate and the New York State Assembly also are reviewing bills that ban legacy and early admissions policies at public and private universities. Connecticut announced similar legislation last year. Massachusetts legislators are considering two bills: one that would ban the practice at the state’s public universities and another that would require all schools using legacy status to pay a “public service fee” equal to a percentage of its endowment. Colleges with endowment assets exceeding $2 billion must pay at least $2 million, according to the bill’s text.

At schools like Harvard, whose endowment surpasses $50 billion, the option to pay the penalty will make the law moot, Michael Walls, DO, MPH, president of the American Medical Student Association (AMSA), said in an interview. “Smaller schools wouldn’t be able to afford the fine and are less likely to be doing [legacy admissions] anyway,” he said. “The schools that want to continue doing it could just pay the fine.”

Dr. Walls said AMSA supports race-conscious admissions processes and anything that increases fairness for medical school applicants. “Whatever [fair] means is up for interpretation, but it would be great to eliminate legacy admissions,” he said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, which they say offer preferential treatment to applicants based on their association with donors or alumni.

While an estimated 25% of public colleges and universities still use legacy admissions, a growing list of top medical schools have moved away from the practice over the last decade, including Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and Tufts University, Medford, Mass.

Legacy admissions contradict schools’ more inclusive policies, Senila Yasmin, MPH, a second-year medical student at Tufts University, said in an interview. While Tufts maintains legacy admissions for its undergraduate applicants, the medical school stopped the practice in 2021, said Ms. Yasmin, a member of a student group that lobbied against the school’s legacy preferences.

Describing herself as a low-income, first-generation Muslim-Pakistani American, Ms. Yasmin wants to use her experience at Tufts to improve accessibility for students like herself.

As a member of the American Medical Association (AMA) Medical Student Section, she coauthored a resolution stating that legacy admissions go against the AMA’s strategic plan to advance racial justice and health equity. The Student Section passed the resolution in November, and in June, the AMA House of Delegates will vote on whether to adopt the policy.

Along with a Supreme Court decision that could strike down race-conscious college admissions, an AMA policy could convince medical schools to rethink legacy admissions and how to maintain diverse student bodies. In June, the court is expected to issue a decision in the Students for Fair Admissions lawsuit against Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., and the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, which alleges that considering race in holistic admissions constitutes racial discrimination and violates the Equal Protection Clause.

Opponents of legacy admissions, like Ms. Yasmin, say it penalizes students from racial minorities and lower socioeconomic backgrounds, hampering a fair and equitable admissions process that attracts diverse medical school admissions.

Diversity of medical applicants

Diversity in medical schools continued to increase last year with more Black, Hispanic, and female students applying and enrolling, according to a recent report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). However, universities often include nonacademic criteria in their admission assessments to improve educational access for underrepresented minorities.

Medical schools carefully consider each applicant’s background “to yield a diverse class of students,” Geoffrey Young, PhD, AAMC’s senior director of transforming the health care workforce, told this news organization.

Some schools, such as Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, and the University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson, perform a thorough review of candidates while offering admissions practices designed specifically for legacy applicants. The schools assert that legacy designation doesn’t factor into the student’s likelihood of acceptance.

The arrangement may show that schools want to commit to equity and fairness but have trouble moving away from entrenched traditions, two professors from Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pa., who sit on separate medical admissions subcommittees, wrote last year in Bioethics Today.

Legislation may hasten legacies’ end

In December, Ms. Yasmin and a group of Massachusetts Medical Society student-members presented another resolution to the state medical society, which adopted it.

The society’s new policy opposes the use of legacy status in medical school admissions and supports mechanisms to eliminate its inclusion from the application process, Theodore Calianos II, MD, FACS, president of the Massachusetts Medical Society, said in an interview.

“Legacy preferences limit racial and socioeconomic diversity on campuses, so we asked, ‘What can we do so that everyone has equal access to medical education?’ It is exciting to see the students and young physicians – the future of medicine – become involved in policymaking.”

Proposed laws may also hasten the end of legacy admissions. Last year, the U.S. Senate began considering a bill prohibiting colleges receiving federal financial aid from giving preferential treatment to students based on their relations to donors or alumni. However, the bill allows the Department of Education to make exceptions for institutions serving historically underrepresented groups.

The New York State Senate and the New York State Assembly also are reviewing bills that ban legacy and early admissions policies at public and private universities. Connecticut announced similar legislation last year. Massachusetts legislators are considering two bills: one that would ban the practice at the state’s public universities and another that would require all schools using legacy status to pay a “public service fee” equal to a percentage of its endowment. Colleges with endowment assets exceeding $2 billion must pay at least $2 million, according to the bill’s text.

At schools like Harvard, whose endowment surpasses $50 billion, the option to pay the penalty will make the law moot, Michael Walls, DO, MPH, president of the American Medical Student Association (AMSA), said in an interview. “Smaller schools wouldn’t be able to afford the fine and are less likely to be doing [legacy admissions] anyway,” he said. “The schools that want to continue doing it could just pay the fine.”

Dr. Walls said AMSA supports race-conscious admissions processes and anything that increases fairness for medical school applicants. “Whatever [fair] means is up for interpretation, but it would be great to eliminate legacy admissions,” he said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, which they say offer preferential treatment to applicants based on their association with donors or alumni.

While an estimated 25% of public colleges and universities still use legacy admissions, a growing list of top medical schools have moved away from the practice over the last decade, including Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and Tufts University, Medford, Mass.

Legacy admissions contradict schools’ more inclusive policies, Senila Yasmin, MPH, a second-year medical student at Tufts University, said in an interview. While Tufts maintains legacy admissions for its undergraduate applicants, the medical school stopped the practice in 2021, said Ms. Yasmin, a member of a student group that lobbied against the school’s legacy preferences.

Describing herself as a low-income, first-generation Muslim-Pakistani American, Ms. Yasmin wants to use her experience at Tufts to improve accessibility for students like herself.

As a member of the American Medical Association (AMA) Medical Student Section, she coauthored a resolution stating that legacy admissions go against the AMA’s strategic plan to advance racial justice and health equity. The Student Section passed the resolution in November, and in June, the AMA House of Delegates will vote on whether to adopt the policy.

Along with a Supreme Court decision that could strike down race-conscious college admissions, an AMA policy could convince medical schools to rethink legacy admissions and how to maintain diverse student bodies. In June, the court is expected to issue a decision in the Students for Fair Admissions lawsuit against Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., and the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, which alleges that considering race in holistic admissions constitutes racial discrimination and violates the Equal Protection Clause.

Opponents of legacy admissions, like Ms. Yasmin, say it penalizes students from racial minorities and lower socioeconomic backgrounds, hampering a fair and equitable admissions process that attracts diverse medical school admissions.

Diversity of medical applicants

Diversity in medical schools continued to increase last year with more Black, Hispanic, and female students applying and enrolling, according to a recent report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). However, universities often include nonacademic criteria in their admission assessments to improve educational access for underrepresented minorities.

Medical schools carefully consider each applicant’s background “to yield a diverse class of students,” Geoffrey Young, PhD, AAMC’s senior director of transforming the health care workforce, told this news organization.

Some schools, such as Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, and the University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson, perform a thorough review of candidates while offering admissions practices designed specifically for legacy applicants. The schools assert that legacy designation doesn’t factor into the student’s likelihood of acceptance.

The arrangement may show that schools want to commit to equity and fairness but have trouble moving away from entrenched traditions, two professors from Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pa., who sit on separate medical admissions subcommittees, wrote last year in Bioethics Today.

Legislation may hasten legacies’ end

In December, Ms. Yasmin and a group of Massachusetts Medical Society student-members presented another resolution to the state medical society, which adopted it.

The society’s new policy opposes the use of legacy status in medical school admissions and supports mechanisms to eliminate its inclusion from the application process, Theodore Calianos II, MD, FACS, president of the Massachusetts Medical Society, said in an interview.

“Legacy preferences limit racial and socioeconomic diversity on campuses, so we asked, ‘What can we do so that everyone has equal access to medical education?’ It is exciting to see the students and young physicians – the future of medicine – become involved in policymaking.”

Proposed laws may also hasten the end of legacy admissions. Last year, the U.S. Senate began considering a bill prohibiting colleges receiving federal financial aid from giving preferential treatment to students based on their relations to donors or alumni. However, the bill allows the Department of Education to make exceptions for institutions serving historically underrepresented groups.

The New York State Senate and the New York State Assembly also are reviewing bills that ban legacy and early admissions policies at public and private universities. Connecticut announced similar legislation last year. Massachusetts legislators are considering two bills: one that would ban the practice at the state’s public universities and another that would require all schools using legacy status to pay a “public service fee” equal to a percentage of its endowment. Colleges with endowment assets exceeding $2 billion must pay at least $2 million, according to the bill’s text.

At schools like Harvard, whose endowment surpasses $50 billion, the option to pay the penalty will make the law moot, Michael Walls, DO, MPH, president of the American Medical Student Association (AMSA), said in an interview. “Smaller schools wouldn’t be able to afford the fine and are less likely to be doing [legacy admissions] anyway,” he said. “The schools that want to continue doing it could just pay the fine.”

Dr. Walls said AMSA supports race-conscious admissions processes and anything that increases fairness for medical school applicants. “Whatever [fair] means is up for interpretation, but it would be great to eliminate legacy admissions,” he said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Five ways docs may qualify for discounts on medical malpractice premiums

Getting a better deal might simply mean taking advantage of incentives and discounts your insurer may already offer. These include claims-free, new-to-practice, and working part-time discounts.

However, if you decide to shop around, keep in mind that discounts are just one factor that can affect your premium price – insurers look at your specialty, location, and claims history.

One of the most common ways physicians can earn discounts is by participating in risk management programs. With this type of program, physicians evaluate elements of their practice and documentation practices and identify areas that might leave them at risk for a lawsuit. While they save money, physician risk management programs also are designed to reduce malpractice claims, which ultimately minimizes the potential for bigger financial losses, insurance experts say.

“It’s a win-win situation when liability insurers and physicians work together to minimize risk, and it’s a win for patients,” said Gary Price, MD, president of The Physicians Foundation.

Doctors in private practice or employed by small hospitals that are not self-insured can qualify for these discounts, said David Zetter, president of Zetter HealthCare Management Consultants.

“I do a lot of work with medical malpractice companies trying to find clients policies. All the carriers are transparent about what physicians have to do to lower their premiums. Physicians can receive the discounts if they follow through and meet the insurer’s requirements,” said Mr. Zetter.