User login

ID Practitioner is an independent news source that provides infectious disease specialists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on the infectious disease specialist’s practice. Specialty focus topics include antimicrobial resistance, emerging infections, global ID, hepatitis, HIV, hospital-acquired infections, immunizations and vaccines, influenza, mycoses, pediatric infections, and STIs. Infectious Diseases News is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

sofosbuvir

ritonavir with dasabuvir

discount

support path

program

ritonavir

greedy

ledipasvir

assistance

viekira pak

vpak

advocacy

needy

protest

abbvie

paritaprevir

ombitasvir

direct-acting antivirals

dasabuvir

gilead

fake-ovir

support

v pak

oasis

harvoni

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-medstat-latest-articles-articles-section')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-idp')]

Medical-level empathy? Yup, ChatGPT can fake that

Caution: Robotic uprisings in the rearview mirror are closer than they appear

ChatGPT. If you’ve been even in the proximity of the Internet lately, you may have heard of it. It’s quite an incredible piece of technology, an artificial intelligence that really could up-end a lot of industries. And lest doctors believe they’re safe from robotic replacement, consider this: ChatGPT took a test commonly used as a study resource by ophthalmologists and scored a 46%. Obviously, that’s not a passing grade. Job safe, right?

A month later, the researchers tried again. This time, ChatGPT got a 58%. Still not passing, and ChatGPT did especially poorly on ophthalmology specialty questions (it got 80% of general medicine questions right), but still, the jump in quality after just a month is ... concerning. It’s not like an AI will forget things. That score can only go up, and it’ll go up faster than you think.

“Sure, the robot is smart,” the doctors out there are thinking, “but how can an AI compete with human compassion, understanding, and bedside manner?”

And they’d be right. When it comes to bedside manner, there’s no competition between man and bot. ChatGPT is already winning.

In another study, researchers sampled nearly 200 questions from the subreddit r/AskDocs, which received verified physician responses. The researchers fed ChatGPT the questions – without the doctor’s answer – and a panel of health care professionals evaluated both the human doctor and ChatGPT in terms of quality and empathy.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the robot did better when it came to quality, providing a high-quality response 79% of the time, versus 22% for the human. But empathy? It was a bloodbath. ChatGPT provided an empathetic or very empathetic response 45% of the time, while humans could only do so 4.6% of the time. So much for bedside manner.

The researchers were suspiciously quick to note that ChatGPT isn’t a legitimate replacement for physicians, but could represent a tool to better provide care for patients. But let’s be honest, given ChatGPT’s quick advancement, how long before some intrepid stockholder says: “Hey, instead of paying doctors, why don’t we just use the free robot instead?” We give it a week. Or 11 minutes.

This week, on ‘As the sperm turns’

We’ve got a lot of spermy ground to cover, so let’s get right to it, starting with the small and working our way up.

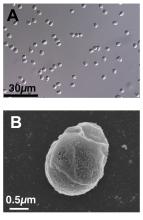

We’re all pretty familiar with the basic structure of a sperm cell, yes? Bulbous head that contains all the important genetic information and a tail-like flagellum to propel it to its ultimate destination. Not much to work with there, you’d think, but what if Mother Nature, who clearly has a robust sense of humor, had something else in mind?

We present exhibit A, Paramormyorps kingsleyae, also known as the electric elephantfish, which happens to be the only known vertebrate species with tailless sperm. Sounds crazy to us, too, but Jason Gallant, PhD, of

Michigan State University, Lansing, has a theory: “A general notion in biology is that sperm are cheap, and eggs are expensive – but these fish may be telling us that sperm are more expensive than we might think. They could be saving energy by cutting back on sperm tails.”

He and his team think that finding the gene that turns off development of the flagellum in the elephant fish could benefit humans, specifically those with a genetic disorder called primary ciliary dyskinesia, whose lack of normally functioning cilia and flagella leads to chronic respiratory infection, abnormally positioned organs, fluid on the brain, and infertility.

And that – with “that” being infertility – brings us to exhibit B, a 41-year-old Dutch man named Jonathan Meijer who clearly has too much time on his hands.

A court in the Netherlands recently ordered him, and not for the first time, to stop donating sperm to fertility clinics after it was discovered that he had fathered between 500 and 600 children around the world. He had been banned from donating to Dutch clinics in 2017, at which point he had already fathered 100 children, but managed a workaround by donating internationally and online, sometimes using another name.

The judge ordered Mr. Meijer to contact all of the clinics abroad and ask them to destroy any of his sperm they still had in stock and threatened to fine him over $100,000 for each future violation.

Okay, so here’s the thing. We have been, um, let’s call it ... warned, about the evils of tastelessness in journalism, so we’re going to do what Mr. Meijer should have done and abstain. And we can last for longer than 11 minutes.

The realm of lost luggage and lost sleep

It may be convenient to live near an airport if you’re a frequent flyer, but it really doesn’t help your sleep numbers.

The first look at how such a common sound affects sleep duration showed that people exposed to even 45 decibels of airplane noise were less likely to get the 7-9 hours of sleep needed for healthy functioning, investigators said in Environmental Health Perspectives.

How loud is 45 dB exactly? A normal conversation is about 50 dB, while a whisper is 30 dB, to give you an idea. Airplane noise at 45 dB? You might not even notice it amongst the other noises in daily life.

The researchers looked at data from about 35,000 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study who live around 90 major U.S. airports. They examined plane noise every 5 years between 1995 and 2005, focusing on estimates of nighttime and daytime levels. Short sleep was most common among the nurses who lived on the West Coast, near major cargo airports or large bodies of water, and also among those who reported no hearing loss.

The investigators noted, however, that there was no consistent association between airplane noise and quality of sleep and stopped short of making any policy recommendations. Still, sleep is a very important, yet slept-on (pun intended) factor for our overall health, so it’s good to know if anything has the potential to cause disruption.

Caution: Robotic uprisings in the rearview mirror are closer than they appear

ChatGPT. If you’ve been even in the proximity of the Internet lately, you may have heard of it. It’s quite an incredible piece of technology, an artificial intelligence that really could up-end a lot of industries. And lest doctors believe they’re safe from robotic replacement, consider this: ChatGPT took a test commonly used as a study resource by ophthalmologists and scored a 46%. Obviously, that’s not a passing grade. Job safe, right?

A month later, the researchers tried again. This time, ChatGPT got a 58%. Still not passing, and ChatGPT did especially poorly on ophthalmology specialty questions (it got 80% of general medicine questions right), but still, the jump in quality after just a month is ... concerning. It’s not like an AI will forget things. That score can only go up, and it’ll go up faster than you think.

“Sure, the robot is smart,” the doctors out there are thinking, “but how can an AI compete with human compassion, understanding, and bedside manner?”

And they’d be right. When it comes to bedside manner, there’s no competition between man and bot. ChatGPT is already winning.

In another study, researchers sampled nearly 200 questions from the subreddit r/AskDocs, which received verified physician responses. The researchers fed ChatGPT the questions – without the doctor’s answer – and a panel of health care professionals evaluated both the human doctor and ChatGPT in terms of quality and empathy.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the robot did better when it came to quality, providing a high-quality response 79% of the time, versus 22% for the human. But empathy? It was a bloodbath. ChatGPT provided an empathetic or very empathetic response 45% of the time, while humans could only do so 4.6% of the time. So much for bedside manner.

The researchers were suspiciously quick to note that ChatGPT isn’t a legitimate replacement for physicians, but could represent a tool to better provide care for patients. But let’s be honest, given ChatGPT’s quick advancement, how long before some intrepid stockholder says: “Hey, instead of paying doctors, why don’t we just use the free robot instead?” We give it a week. Or 11 minutes.

This week, on ‘As the sperm turns’

We’ve got a lot of spermy ground to cover, so let’s get right to it, starting with the small and working our way up.

We’re all pretty familiar with the basic structure of a sperm cell, yes? Bulbous head that contains all the important genetic information and a tail-like flagellum to propel it to its ultimate destination. Not much to work with there, you’d think, but what if Mother Nature, who clearly has a robust sense of humor, had something else in mind?

We present exhibit A, Paramormyorps kingsleyae, also known as the electric elephantfish, which happens to be the only known vertebrate species with tailless sperm. Sounds crazy to us, too, but Jason Gallant, PhD, of

Michigan State University, Lansing, has a theory: “A general notion in biology is that sperm are cheap, and eggs are expensive – but these fish may be telling us that sperm are more expensive than we might think. They could be saving energy by cutting back on sperm tails.”

He and his team think that finding the gene that turns off development of the flagellum in the elephant fish could benefit humans, specifically those with a genetic disorder called primary ciliary dyskinesia, whose lack of normally functioning cilia and flagella leads to chronic respiratory infection, abnormally positioned organs, fluid on the brain, and infertility.

And that – with “that” being infertility – brings us to exhibit B, a 41-year-old Dutch man named Jonathan Meijer who clearly has too much time on his hands.

A court in the Netherlands recently ordered him, and not for the first time, to stop donating sperm to fertility clinics after it was discovered that he had fathered between 500 and 600 children around the world. He had been banned from donating to Dutch clinics in 2017, at which point he had already fathered 100 children, but managed a workaround by donating internationally and online, sometimes using another name.

The judge ordered Mr. Meijer to contact all of the clinics abroad and ask them to destroy any of his sperm they still had in stock and threatened to fine him over $100,000 for each future violation.

Okay, so here’s the thing. We have been, um, let’s call it ... warned, about the evils of tastelessness in journalism, so we’re going to do what Mr. Meijer should have done and abstain. And we can last for longer than 11 minutes.

The realm of lost luggage and lost sleep

It may be convenient to live near an airport if you’re a frequent flyer, but it really doesn’t help your sleep numbers.

The first look at how such a common sound affects sleep duration showed that people exposed to even 45 decibels of airplane noise were less likely to get the 7-9 hours of sleep needed for healthy functioning, investigators said in Environmental Health Perspectives.

How loud is 45 dB exactly? A normal conversation is about 50 dB, while a whisper is 30 dB, to give you an idea. Airplane noise at 45 dB? You might not even notice it amongst the other noises in daily life.

The researchers looked at data from about 35,000 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study who live around 90 major U.S. airports. They examined plane noise every 5 years between 1995 and 2005, focusing on estimates of nighttime and daytime levels. Short sleep was most common among the nurses who lived on the West Coast, near major cargo airports or large bodies of water, and also among those who reported no hearing loss.

The investigators noted, however, that there was no consistent association between airplane noise and quality of sleep and stopped short of making any policy recommendations. Still, sleep is a very important, yet slept-on (pun intended) factor for our overall health, so it’s good to know if anything has the potential to cause disruption.

Caution: Robotic uprisings in the rearview mirror are closer than they appear

ChatGPT. If you’ve been even in the proximity of the Internet lately, you may have heard of it. It’s quite an incredible piece of technology, an artificial intelligence that really could up-end a lot of industries. And lest doctors believe they’re safe from robotic replacement, consider this: ChatGPT took a test commonly used as a study resource by ophthalmologists and scored a 46%. Obviously, that’s not a passing grade. Job safe, right?

A month later, the researchers tried again. This time, ChatGPT got a 58%. Still not passing, and ChatGPT did especially poorly on ophthalmology specialty questions (it got 80% of general medicine questions right), but still, the jump in quality after just a month is ... concerning. It’s not like an AI will forget things. That score can only go up, and it’ll go up faster than you think.

“Sure, the robot is smart,” the doctors out there are thinking, “but how can an AI compete with human compassion, understanding, and bedside manner?”

And they’d be right. When it comes to bedside manner, there’s no competition between man and bot. ChatGPT is already winning.

In another study, researchers sampled nearly 200 questions from the subreddit r/AskDocs, which received verified physician responses. The researchers fed ChatGPT the questions – without the doctor’s answer – and a panel of health care professionals evaluated both the human doctor and ChatGPT in terms of quality and empathy.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the robot did better when it came to quality, providing a high-quality response 79% of the time, versus 22% for the human. But empathy? It was a bloodbath. ChatGPT provided an empathetic or very empathetic response 45% of the time, while humans could only do so 4.6% of the time. So much for bedside manner.

The researchers were suspiciously quick to note that ChatGPT isn’t a legitimate replacement for physicians, but could represent a tool to better provide care for patients. But let’s be honest, given ChatGPT’s quick advancement, how long before some intrepid stockholder says: “Hey, instead of paying doctors, why don’t we just use the free robot instead?” We give it a week. Or 11 minutes.

This week, on ‘As the sperm turns’

We’ve got a lot of spermy ground to cover, so let’s get right to it, starting with the small and working our way up.

We’re all pretty familiar with the basic structure of a sperm cell, yes? Bulbous head that contains all the important genetic information and a tail-like flagellum to propel it to its ultimate destination. Not much to work with there, you’d think, but what if Mother Nature, who clearly has a robust sense of humor, had something else in mind?

We present exhibit A, Paramormyorps kingsleyae, also known as the electric elephantfish, which happens to be the only known vertebrate species with tailless sperm. Sounds crazy to us, too, but Jason Gallant, PhD, of

Michigan State University, Lansing, has a theory: “A general notion in biology is that sperm are cheap, and eggs are expensive – but these fish may be telling us that sperm are more expensive than we might think. They could be saving energy by cutting back on sperm tails.”

He and his team think that finding the gene that turns off development of the flagellum in the elephant fish could benefit humans, specifically those with a genetic disorder called primary ciliary dyskinesia, whose lack of normally functioning cilia and flagella leads to chronic respiratory infection, abnormally positioned organs, fluid on the brain, and infertility.

And that – with “that” being infertility – brings us to exhibit B, a 41-year-old Dutch man named Jonathan Meijer who clearly has too much time on his hands.

A court in the Netherlands recently ordered him, and not for the first time, to stop donating sperm to fertility clinics after it was discovered that he had fathered between 500 and 600 children around the world. He had been banned from donating to Dutch clinics in 2017, at which point he had already fathered 100 children, but managed a workaround by donating internationally and online, sometimes using another name.

The judge ordered Mr. Meijer to contact all of the clinics abroad and ask them to destroy any of his sperm they still had in stock and threatened to fine him over $100,000 for each future violation.

Okay, so here’s the thing. We have been, um, let’s call it ... warned, about the evils of tastelessness in journalism, so we’re going to do what Mr. Meijer should have done and abstain. And we can last for longer than 11 minutes.

The realm of lost luggage and lost sleep

It may be convenient to live near an airport if you’re a frequent flyer, but it really doesn’t help your sleep numbers.

The first look at how such a common sound affects sleep duration showed that people exposed to even 45 decibels of airplane noise were less likely to get the 7-9 hours of sleep needed for healthy functioning, investigators said in Environmental Health Perspectives.

How loud is 45 dB exactly? A normal conversation is about 50 dB, while a whisper is 30 dB, to give you an idea. Airplane noise at 45 dB? You might not even notice it amongst the other noises in daily life.

The researchers looked at data from about 35,000 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study who live around 90 major U.S. airports. They examined plane noise every 5 years between 1995 and 2005, focusing on estimates of nighttime and daytime levels. Short sleep was most common among the nurses who lived on the West Coast, near major cargo airports or large bodies of water, and also among those who reported no hearing loss.

The investigators noted, however, that there was no consistent association between airplane noise and quality of sleep and stopped short of making any policy recommendations. Still, sleep is a very important, yet slept-on (pun intended) factor for our overall health, so it’s good to know if anything has the potential to cause disruption.

FDA approves first RSV vaccine for older adults

Arexvy, manufactured by GSK, is the world’s first RSV vaccine for adults aged 60 years and older, the company said in an announcement.

Every year, RSV is responsible for 60,000–120,000 hospitalizations and 6,000–10,000 deaths among U.S. adults older than age, according to the FDA. Older adults with underlying health conditions — such as diabetes, a weakened immune system, or lung or heart disease — are at high risk for severe disease. "Today’s approval of the first RSV vaccine is an important public health achievement to prevent a disease which can be life-threatening and reflects the FDA’s continued commitment to facilitating the development of safe and effective vaccines for use in the United States," said Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, in a statement.

The FDA approval of Arexvy was based on a clinical study of approximately 25,000 patients. Half of these patients received Arexvy, while the other half received a placebo. Researchers found that the RSV vaccine reduced RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease (LRTD) by nearly 83% and reduced the risk of developing severe RSV-associated LRTD by 94%. The most commonly reported side effects were injection site pain, fatigue, muscle pain, headache, and joint stiffness/pain. Ten patients who received Arexvy and four patients who received placebo experienced atrial fibrillation within 30 days of vaccination. The company is planning to assess risk for atrial fibrillation in postmarking studies, the FDA said. The European Medicine Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use recommended approval of Arexvy on April 25, 2023, on the basis of data from the same clinical trial.

GSK said that the U.S. launch of Arexvy will occur sometime in the fall before the 2023/2024 RSV season, but the company did not provide exact dates. "Today marks a turning point in our effort to reduce the significant burden of RSV," said GSK’s chief scientific officer, Tony Wood, PhD, in a company statement. "Our focus now is to ensure eligible older adults in the U.S. can access the vaccine as quickly as possible and to progress regulatory review in other countries."

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Arexvy, manufactured by GSK, is the world’s first RSV vaccine for adults aged 60 years and older, the company said in an announcement.

Every year, RSV is responsible for 60,000–120,000 hospitalizations and 6,000–10,000 deaths among U.S. adults older than age, according to the FDA. Older adults with underlying health conditions — such as diabetes, a weakened immune system, or lung or heart disease — are at high risk for severe disease. "Today’s approval of the first RSV vaccine is an important public health achievement to prevent a disease which can be life-threatening and reflects the FDA’s continued commitment to facilitating the development of safe and effective vaccines for use in the United States," said Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, in a statement.

The FDA approval of Arexvy was based on a clinical study of approximately 25,000 patients. Half of these patients received Arexvy, while the other half received a placebo. Researchers found that the RSV vaccine reduced RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease (LRTD) by nearly 83% and reduced the risk of developing severe RSV-associated LRTD by 94%. The most commonly reported side effects were injection site pain, fatigue, muscle pain, headache, and joint stiffness/pain. Ten patients who received Arexvy and four patients who received placebo experienced atrial fibrillation within 30 days of vaccination. The company is planning to assess risk for atrial fibrillation in postmarking studies, the FDA said. The European Medicine Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use recommended approval of Arexvy on April 25, 2023, on the basis of data from the same clinical trial.

GSK said that the U.S. launch of Arexvy will occur sometime in the fall before the 2023/2024 RSV season, but the company did not provide exact dates. "Today marks a turning point in our effort to reduce the significant burden of RSV," said GSK’s chief scientific officer, Tony Wood, PhD, in a company statement. "Our focus now is to ensure eligible older adults in the U.S. can access the vaccine as quickly as possible and to progress regulatory review in other countries."

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Arexvy, manufactured by GSK, is the world’s first RSV vaccine for adults aged 60 years and older, the company said in an announcement.

Every year, RSV is responsible for 60,000–120,000 hospitalizations and 6,000–10,000 deaths among U.S. adults older than age, according to the FDA. Older adults with underlying health conditions — such as diabetes, a weakened immune system, or lung or heart disease — are at high risk for severe disease. "Today’s approval of the first RSV vaccine is an important public health achievement to prevent a disease which can be life-threatening and reflects the FDA’s continued commitment to facilitating the development of safe and effective vaccines for use in the United States," said Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, in a statement.

The FDA approval of Arexvy was based on a clinical study of approximately 25,000 patients. Half of these patients received Arexvy, while the other half received a placebo. Researchers found that the RSV vaccine reduced RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease (LRTD) by nearly 83% and reduced the risk of developing severe RSV-associated LRTD by 94%. The most commonly reported side effects were injection site pain, fatigue, muscle pain, headache, and joint stiffness/pain. Ten patients who received Arexvy and four patients who received placebo experienced atrial fibrillation within 30 days of vaccination. The company is planning to assess risk for atrial fibrillation in postmarking studies, the FDA said. The European Medicine Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use recommended approval of Arexvy on April 25, 2023, on the basis of data from the same clinical trial.

GSK said that the U.S. launch of Arexvy will occur sometime in the fall before the 2023/2024 RSV season, but the company did not provide exact dates. "Today marks a turning point in our effort to reduce the significant burden of RSV," said GSK’s chief scientific officer, Tony Wood, PhD, in a company statement. "Our focus now is to ensure eligible older adults in the U.S. can access the vaccine as quickly as possible and to progress regulatory review in other countries."

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New outbreaks of Marburg virus disease: What clinicians need to know

What do green monkeys, fruit bats, and python caves all have in common? All have been implicated in outbreaks as transmission sources of the rare but deadly Marburg virus. Marburg virus is in the same Filoviridae family of highly pathogenic RNA viruses as Ebola virus, and similarly can cause a rapidly progressive and fatal viral hemorrhagic fever.

In the first reported Marburg outbreak in 1967, laboratory workers in Marburg and Frankfurt, Germany, and in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, developed severe febrile illnesses with massive hemorrhage and multiorgan system dysfunction after contact with infected African green monkeys imported from Uganda.

The majority of MVD outbreaks have occurred in sub-Saharan Africa, and primarily in three African countries: Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Uganda. In sub-Saharan Africa, these sporadic outbreaks have had high case fatality rates (up to 80%-90%) and been linked to human exposure to the oral secretions or urinary/fecal droppings of Egyptian fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus), the animal reservoir for Marburg virus. These exposures have primarily occurred among miners or tourists frequenting bat-infested mines or caves, including Uganda’s python cave, where Centers for Disease Control and Prevention investigators have conducted ecological studies on Marburg-infected bats. Person-to-person transmission occurs from direct contact with the blood or bodily fluids of an infected person or contact with a contaminated object (for example, unsterilized needles and syringes in a large nosocomial outbreak in Angola).

On April 6, 2023, the CDC issued a Health Advisory for U.S. clinicians and public health departments regarding two separate MVD outbreaks in Equatorial Guinea and Tanzania. These first-ever MVD outbreaks in both West and East African countries appear to be epidemiologically unrelated. As of March 24, 2023, in Equatorial Guinea, a total of 15 confirmed cases, including 11 deaths, and 23 probable cases, all deceased, have been identified in multiple districts since the outbreak declaration in February 2023. In Tanzania, a total of eight cases, including five deaths, have been reported among villagers in a northwest region since the outbreak declaration in March 2023. While so far cases in the Tanzania MVD outbreak have been epidemiologically linked, in Equatorial Guinea some cases have no identified epidemiological links, raising concern for ongoing community spread.

To date, no cases in these outbreaks have been reported in the United States or outside the affected countries. Overall, the risk of MVD in nonendemic countries, like the United States, is low but there is still a risk of importation. As of May 2, 2023, CDC has issued a Level 2 travel alert (practice enhanced precautions) for Marburg in Equatorial Guinea and a Level 1 travel watch (practice usual precautions) for Marburg in Tanzania. Travelers to these countries are advised to avoid nonessential travel to areas with active outbreaks and practice preventative measures, including avoiding contact with sick people, blood and bodily fluids, dead bodies, fruit bats, and nonhuman primates. International travelers returning to the United States from these countries are advised to self-monitor for Marburg symptoms during travel and for 21 days after country departure. Travelers who develop signs or symptoms of MVD should immediately self-isolate and contact their local health department or clinician.

So, how should clinicians manage such return travelers? In the setting of these new MVD outbreaks in sub-Saharan Africa, what do U.S. clinicians need to know? Clinicians should consider MVD in the differential diagnosis of ill patients with a compatible exposure history and clinical presentation. A detailed exposure history should be obtained to determine if patients have been to an area with an active MVD outbreak during their incubation period (in the past 21 days), had concerning epidemiologic risk factors (for example, presence at funerals, health care facilities, in mines/caves) while in the affected area, and/or had contact with a suspected or confirmed MVD case.

Clinical diagnosis of MVD is challenging as the initial dry symptoms of infection are nonspecific (fever, influenza-like illness, malaise, anorexia, etc.) and can resemble other febrile infectious illnesses. Similarly, presenting alternative or concurrent infections, particularly in febrile return travelers, include malaria, Lassa fever, typhoid, and measles. From these nonspecific symptoms, patients with MVD can then progress to the more severe wet symptoms (for example, vomiting, diarrhea, and bleeding). Common clinical features of MVD have been described based on the clinical presentation and course of cases in MVD outbreaks. Notably, in the original Marburg outbreak, maculopapular rash and conjunctival injection were early patient symptoms and most patient deaths occurred during the second week of illness progression.

Supportive care, including aggressive fluid replacement, is the mainstay of therapy for MVD. Currently, there are no Food and Drug Administration–approved antiviral treatments or vaccines for Marburg virus. Despite their viral similarities, vaccines against Ebola virus have not been shown to be protective against Marburg virus. Marburg virus vaccine development is ongoing, with a few promising candidate vaccines in early phase 1 and 2 clinical trials. In 2022, in response to MVD outbreaks in Ghana and Guinea, the World Health Organization convened an international Marburg virus vaccine consortium which is working to promote global research collaboration for more rapid vaccine development.

In the absence of definitive therapies, early identification of patients with suspected MVD is critical for preventing the spread of infection to close contacts. Like Ebola virus–infected patients, only symptomatic MVD patients are infectious and all patients with suspected MVD should be isolated in a private room and cared for in accordance with infection control procedures. As MVD is a nationally notifiable disease, suspected cases should be reported to local or state health departments as per jurisdictional requirements. Clinicians should also consult with their local or state health department and CDC for guidance on testing patients with suspected MVD and consider prompt evaluation for other infectious etiologies in the patient’s differential diagnosis. Comprehensive guidance for clinicians on screening and diagnosing patients with MVD is available on the CDC website at https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/marburg/index.html.

Dr. Appiah (she/her) is a medical epidemiologist in the division of global migration and quarantine at the CDC. Dr. Appiah holds adjunct faculty appointment in the division of infectious diseases at Emory University, Atlanta. She also holds a commission in the U.S. Public Health Service and is a resident advisor, Uganda, U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative, at the CDC.

What do green monkeys, fruit bats, and python caves all have in common? All have been implicated in outbreaks as transmission sources of the rare but deadly Marburg virus. Marburg virus is in the same Filoviridae family of highly pathogenic RNA viruses as Ebola virus, and similarly can cause a rapidly progressive and fatal viral hemorrhagic fever.

In the first reported Marburg outbreak in 1967, laboratory workers in Marburg and Frankfurt, Germany, and in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, developed severe febrile illnesses with massive hemorrhage and multiorgan system dysfunction after contact with infected African green monkeys imported from Uganda.

The majority of MVD outbreaks have occurred in sub-Saharan Africa, and primarily in three African countries: Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Uganda. In sub-Saharan Africa, these sporadic outbreaks have had high case fatality rates (up to 80%-90%) and been linked to human exposure to the oral secretions or urinary/fecal droppings of Egyptian fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus), the animal reservoir for Marburg virus. These exposures have primarily occurred among miners or tourists frequenting bat-infested mines or caves, including Uganda’s python cave, where Centers for Disease Control and Prevention investigators have conducted ecological studies on Marburg-infected bats. Person-to-person transmission occurs from direct contact with the blood or bodily fluids of an infected person or contact with a contaminated object (for example, unsterilized needles and syringes in a large nosocomial outbreak in Angola).

On April 6, 2023, the CDC issued a Health Advisory for U.S. clinicians and public health departments regarding two separate MVD outbreaks in Equatorial Guinea and Tanzania. These first-ever MVD outbreaks in both West and East African countries appear to be epidemiologically unrelated. As of March 24, 2023, in Equatorial Guinea, a total of 15 confirmed cases, including 11 deaths, and 23 probable cases, all deceased, have been identified in multiple districts since the outbreak declaration in February 2023. In Tanzania, a total of eight cases, including five deaths, have been reported among villagers in a northwest region since the outbreak declaration in March 2023. While so far cases in the Tanzania MVD outbreak have been epidemiologically linked, in Equatorial Guinea some cases have no identified epidemiological links, raising concern for ongoing community spread.

To date, no cases in these outbreaks have been reported in the United States or outside the affected countries. Overall, the risk of MVD in nonendemic countries, like the United States, is low but there is still a risk of importation. As of May 2, 2023, CDC has issued a Level 2 travel alert (practice enhanced precautions) for Marburg in Equatorial Guinea and a Level 1 travel watch (practice usual precautions) for Marburg in Tanzania. Travelers to these countries are advised to avoid nonessential travel to areas with active outbreaks and practice preventative measures, including avoiding contact with sick people, blood and bodily fluids, dead bodies, fruit bats, and nonhuman primates. International travelers returning to the United States from these countries are advised to self-monitor for Marburg symptoms during travel and for 21 days after country departure. Travelers who develop signs or symptoms of MVD should immediately self-isolate and contact their local health department or clinician.

So, how should clinicians manage such return travelers? In the setting of these new MVD outbreaks in sub-Saharan Africa, what do U.S. clinicians need to know? Clinicians should consider MVD in the differential diagnosis of ill patients with a compatible exposure history and clinical presentation. A detailed exposure history should be obtained to determine if patients have been to an area with an active MVD outbreak during their incubation period (in the past 21 days), had concerning epidemiologic risk factors (for example, presence at funerals, health care facilities, in mines/caves) while in the affected area, and/or had contact with a suspected or confirmed MVD case.

Clinical diagnosis of MVD is challenging as the initial dry symptoms of infection are nonspecific (fever, influenza-like illness, malaise, anorexia, etc.) and can resemble other febrile infectious illnesses. Similarly, presenting alternative or concurrent infections, particularly in febrile return travelers, include malaria, Lassa fever, typhoid, and measles. From these nonspecific symptoms, patients with MVD can then progress to the more severe wet symptoms (for example, vomiting, diarrhea, and bleeding). Common clinical features of MVD have been described based on the clinical presentation and course of cases in MVD outbreaks. Notably, in the original Marburg outbreak, maculopapular rash and conjunctival injection were early patient symptoms and most patient deaths occurred during the second week of illness progression.

Supportive care, including aggressive fluid replacement, is the mainstay of therapy for MVD. Currently, there are no Food and Drug Administration–approved antiviral treatments or vaccines for Marburg virus. Despite their viral similarities, vaccines against Ebola virus have not been shown to be protective against Marburg virus. Marburg virus vaccine development is ongoing, with a few promising candidate vaccines in early phase 1 and 2 clinical trials. In 2022, in response to MVD outbreaks in Ghana and Guinea, the World Health Organization convened an international Marburg virus vaccine consortium which is working to promote global research collaboration for more rapid vaccine development.

In the absence of definitive therapies, early identification of patients with suspected MVD is critical for preventing the spread of infection to close contacts. Like Ebola virus–infected patients, only symptomatic MVD patients are infectious and all patients with suspected MVD should be isolated in a private room and cared for in accordance with infection control procedures. As MVD is a nationally notifiable disease, suspected cases should be reported to local or state health departments as per jurisdictional requirements. Clinicians should also consult with their local or state health department and CDC for guidance on testing patients with suspected MVD and consider prompt evaluation for other infectious etiologies in the patient’s differential diagnosis. Comprehensive guidance for clinicians on screening and diagnosing patients with MVD is available on the CDC website at https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/marburg/index.html.

Dr. Appiah (she/her) is a medical epidemiologist in the division of global migration and quarantine at the CDC. Dr. Appiah holds adjunct faculty appointment in the division of infectious diseases at Emory University, Atlanta. She also holds a commission in the U.S. Public Health Service and is a resident advisor, Uganda, U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative, at the CDC.

What do green monkeys, fruit bats, and python caves all have in common? All have been implicated in outbreaks as transmission sources of the rare but deadly Marburg virus. Marburg virus is in the same Filoviridae family of highly pathogenic RNA viruses as Ebola virus, and similarly can cause a rapidly progressive and fatal viral hemorrhagic fever.

In the first reported Marburg outbreak in 1967, laboratory workers in Marburg and Frankfurt, Germany, and in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, developed severe febrile illnesses with massive hemorrhage and multiorgan system dysfunction after contact with infected African green monkeys imported from Uganda.

The majority of MVD outbreaks have occurred in sub-Saharan Africa, and primarily in three African countries: Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Uganda. In sub-Saharan Africa, these sporadic outbreaks have had high case fatality rates (up to 80%-90%) and been linked to human exposure to the oral secretions or urinary/fecal droppings of Egyptian fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus), the animal reservoir for Marburg virus. These exposures have primarily occurred among miners or tourists frequenting bat-infested mines or caves, including Uganda’s python cave, where Centers for Disease Control and Prevention investigators have conducted ecological studies on Marburg-infected bats. Person-to-person transmission occurs from direct contact with the blood or bodily fluids of an infected person or contact with a contaminated object (for example, unsterilized needles and syringes in a large nosocomial outbreak in Angola).

On April 6, 2023, the CDC issued a Health Advisory for U.S. clinicians and public health departments regarding two separate MVD outbreaks in Equatorial Guinea and Tanzania. These first-ever MVD outbreaks in both West and East African countries appear to be epidemiologically unrelated. As of March 24, 2023, in Equatorial Guinea, a total of 15 confirmed cases, including 11 deaths, and 23 probable cases, all deceased, have been identified in multiple districts since the outbreak declaration in February 2023. In Tanzania, a total of eight cases, including five deaths, have been reported among villagers in a northwest region since the outbreak declaration in March 2023. While so far cases in the Tanzania MVD outbreak have been epidemiologically linked, in Equatorial Guinea some cases have no identified epidemiological links, raising concern for ongoing community spread.

To date, no cases in these outbreaks have been reported in the United States or outside the affected countries. Overall, the risk of MVD in nonendemic countries, like the United States, is low but there is still a risk of importation. As of May 2, 2023, CDC has issued a Level 2 travel alert (practice enhanced precautions) for Marburg in Equatorial Guinea and a Level 1 travel watch (practice usual precautions) for Marburg in Tanzania. Travelers to these countries are advised to avoid nonessential travel to areas with active outbreaks and practice preventative measures, including avoiding contact with sick people, blood and bodily fluids, dead bodies, fruit bats, and nonhuman primates. International travelers returning to the United States from these countries are advised to self-monitor for Marburg symptoms during travel and for 21 days after country departure. Travelers who develop signs or symptoms of MVD should immediately self-isolate and contact their local health department or clinician.

So, how should clinicians manage such return travelers? In the setting of these new MVD outbreaks in sub-Saharan Africa, what do U.S. clinicians need to know? Clinicians should consider MVD in the differential diagnosis of ill patients with a compatible exposure history and clinical presentation. A detailed exposure history should be obtained to determine if patients have been to an area with an active MVD outbreak during their incubation period (in the past 21 days), had concerning epidemiologic risk factors (for example, presence at funerals, health care facilities, in mines/caves) while in the affected area, and/or had contact with a suspected or confirmed MVD case.

Clinical diagnosis of MVD is challenging as the initial dry symptoms of infection are nonspecific (fever, influenza-like illness, malaise, anorexia, etc.) and can resemble other febrile infectious illnesses. Similarly, presenting alternative or concurrent infections, particularly in febrile return travelers, include malaria, Lassa fever, typhoid, and measles. From these nonspecific symptoms, patients with MVD can then progress to the more severe wet symptoms (for example, vomiting, diarrhea, and bleeding). Common clinical features of MVD have been described based on the clinical presentation and course of cases in MVD outbreaks. Notably, in the original Marburg outbreak, maculopapular rash and conjunctival injection were early patient symptoms and most patient deaths occurred during the second week of illness progression.

Supportive care, including aggressive fluid replacement, is the mainstay of therapy for MVD. Currently, there are no Food and Drug Administration–approved antiviral treatments or vaccines for Marburg virus. Despite their viral similarities, vaccines against Ebola virus have not been shown to be protective against Marburg virus. Marburg virus vaccine development is ongoing, with a few promising candidate vaccines in early phase 1 and 2 clinical trials. In 2022, in response to MVD outbreaks in Ghana and Guinea, the World Health Organization convened an international Marburg virus vaccine consortium which is working to promote global research collaboration for more rapid vaccine development.

In the absence of definitive therapies, early identification of patients with suspected MVD is critical for preventing the spread of infection to close contacts. Like Ebola virus–infected patients, only symptomatic MVD patients are infectious and all patients with suspected MVD should be isolated in a private room and cared for in accordance with infection control procedures. As MVD is a nationally notifiable disease, suspected cases should be reported to local or state health departments as per jurisdictional requirements. Clinicians should also consult with their local or state health department and CDC for guidance on testing patients with suspected MVD and consider prompt evaluation for other infectious etiologies in the patient’s differential diagnosis. Comprehensive guidance for clinicians on screening and diagnosing patients with MVD is available on the CDC website at https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/marburg/index.html.

Dr. Appiah (she/her) is a medical epidemiologist in the division of global migration and quarantine at the CDC. Dr. Appiah holds adjunct faculty appointment in the division of infectious diseases at Emory University, Atlanta. She also holds a commission in the U.S. Public Health Service and is a resident advisor, Uganda, U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative, at the CDC.

White House to end COVID vaccine mandate for federal workers

The move means vaccines will no longer be required for workers who are federal employees, federal contractors, Head Start early education employees, workers at Medicare-certified health care facilities, and those who work at U.S. borders. International air travelers will no longer be required to prove their vaccination status. The requirement will be lifted at the end of the day on May 11, which is also when the federal public health emergency declaration ends.

“While vaccination remains one of the most important tools in advancing the health and safety of employees and promoting the efficiency of workplaces, we are now in a different phase of our response when these measures are no longer necessary,” an announcement from the White House stated.

White House officials credited vaccine requirements with saving millions of lives, noting that the rules ensured “the safety of workers in critical workforces including those in the healthcare and education sectors, protecting themselves and the populations they serve, and strengthening their ability to provide services without disruptions to operations.”

More than 100 million people were subject to the vaccine requirement, The Associated Press reported. All but 2% of those covered by the mandate had received at least one dose or had a pending or approved exception on file by January 2022, the Biden administration said, noting that COVID deaths have dropped 95% since January 2021 and hospitalizations are down nearly 91%.

In January, vaccine requirements were lifted for U.S. military members.

On the government-run website Safer Federal Workforce, which helped affected organizations put federal COVID rules into place, agencies were told to “take no action to implement or enforce the COVID-19 vaccination requirement” at this time.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The move means vaccines will no longer be required for workers who are federal employees, federal contractors, Head Start early education employees, workers at Medicare-certified health care facilities, and those who work at U.S. borders. International air travelers will no longer be required to prove their vaccination status. The requirement will be lifted at the end of the day on May 11, which is also when the federal public health emergency declaration ends.

“While vaccination remains one of the most important tools in advancing the health and safety of employees and promoting the efficiency of workplaces, we are now in a different phase of our response when these measures are no longer necessary,” an announcement from the White House stated.

White House officials credited vaccine requirements with saving millions of lives, noting that the rules ensured “the safety of workers in critical workforces including those in the healthcare and education sectors, protecting themselves and the populations they serve, and strengthening their ability to provide services without disruptions to operations.”

More than 100 million people were subject to the vaccine requirement, The Associated Press reported. All but 2% of those covered by the mandate had received at least one dose or had a pending or approved exception on file by January 2022, the Biden administration said, noting that COVID deaths have dropped 95% since January 2021 and hospitalizations are down nearly 91%.

In January, vaccine requirements were lifted for U.S. military members.

On the government-run website Safer Federal Workforce, which helped affected organizations put federal COVID rules into place, agencies were told to “take no action to implement or enforce the COVID-19 vaccination requirement” at this time.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The move means vaccines will no longer be required for workers who are federal employees, federal contractors, Head Start early education employees, workers at Medicare-certified health care facilities, and those who work at U.S. borders. International air travelers will no longer be required to prove their vaccination status. The requirement will be lifted at the end of the day on May 11, which is also when the federal public health emergency declaration ends.

“While vaccination remains one of the most important tools in advancing the health and safety of employees and promoting the efficiency of workplaces, we are now in a different phase of our response when these measures are no longer necessary,” an announcement from the White House stated.

White House officials credited vaccine requirements with saving millions of lives, noting that the rules ensured “the safety of workers in critical workforces including those in the healthcare and education sectors, protecting themselves and the populations they serve, and strengthening their ability to provide services without disruptions to operations.”

More than 100 million people were subject to the vaccine requirement, The Associated Press reported. All but 2% of those covered by the mandate had received at least one dose or had a pending or approved exception on file by January 2022, the Biden administration said, noting that COVID deaths have dropped 95% since January 2021 and hospitalizations are down nearly 91%.

In January, vaccine requirements were lifted for U.S. military members.

On the government-run website Safer Federal Workforce, which helped affected organizations put federal COVID rules into place, agencies were told to “take no action to implement or enforce the COVID-19 vaccination requirement” at this time.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Long-COVID rate may be higher with rheumatic diseases

MANCHESTER, England – Data from the COVAD-2 e-survey suggest that people with a rheumatic disease are twice as likely as are those without to experience long-term effects after contracting COVID-19.

The prevalence of post–COVID-19 condition (PCC), the term the World Health Organization advocates for describing the widely popularized term long COVID, was 10.8% among people with autoimmune rheumatic diseases (AIRDs) vs. 5.3% among those with no autoimmune condition (designated as “healthy controls”). The odds ratio was 2.1, with a 95% confidence interval of 1.4-3.2 and a P-value of .002.

The prevalence in people with nonrheumatic autoimmune diseases was also higher than it was in the control participants but still lower, at 7.3%, than in those with AIRDs.

“Our findings highlight the importance of close monitoring for PCC,” Arvind Nune, MBBCh, MSc, said in a virtual poster presentation at the annual meeting of the British Society for Rheumatology.

They also show the need for “appropriate referral for optimized multidisciplinary care for patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases during the recovery period following COVID-19,” added Dr. Nune, who works for Southport (England) and Ormskirk Hospital NHS Trust.

In an interview, he noted that it was patients who had a severe COVID-19 course or had other coexisting conditions that appeared to experience more long-term effects than did their less-affected counterparts.

Commenting on the study, Jeffrey A. Sparks, MD, MMSc, told this news organization: “This is one of the first studies to find that the prevalence of long COVID is higher among people with systemic rheumatic diseases than those without.”

Dr. Sparks, who is based at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, added: “Since the symptoms of long COVID and rheumatic diseases can overlap substantially, more work will need to be done to determine whether COVID may have induced flares, new symptoms, or whether the finding is due to the presence of the chronic rheumatic disease.”

The COVAD study

Using an electronic survey platform, the COVAD study has been set up to look at the long-term efficacy and safety of COVID-19 vaccinations in patients with AIRDs. It’s now a large international effort involving more than 150 collaborating clinics in 106 countries.

A huge amount of data has been collected. “We collected demographics, details of autoimmune disease, including treatment, comorbidity, COVID infection, vaccination history and outcomes, date on flares, and validated patient-reported outcomes, including pain, fatigue, physical function, and quality of life,” Dr. Nune said in his presentation.

A total of 12,358 people who were invited to participate responded to the e-survey. Of them, 2,640 were confirmed to have COVID-19. Because the analysis aimed to look at PCC, anyone who had completed the survey less than 3 months after infection was excluded. This left 1,677 eligible respondents, of whom, an overall 8.7% (n = 136) were identified as having PCC.

“The [WHO] definition for PCC was employed, which is persistent signs or symptoms beyond 3 months of COVID-19 infection lasting at least 2 months,” Dr. Nune told this news organization.

“Symptoms could be anything from fatigue to breathlessness to arthralgias,” he added. However, the focus of the present analysis was to look at how many people were experiencing the condition rather than specific symptoms.

A higher risk for PCC was seen in women than in men (OR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.1-7.7; P = .037) in the entire cohort.

In addition, those with comorbidities were found to have a greater chance of long-term sequelae from COVID-19 than were those without comorbid disease (OR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.4-5.7; P = .005).

Patients who experienced more severe acute COVID-19, such as those who needed intensive care treatment, oxygen therapy, or advanced treatment for COVID-19 with monoclonal antibodies, were significantly more likely to later have PCC than were those who did not (OR, 3.8; 95% CI, 1.1-13.6; P = .039).

Having PCC was also associated with poorer patient-reported outcomes for physical function, compared with not having PCC. “However, no association with disease flares of underlying rheumatic diseases or immunosuppressive drugs used were noted,” Dr. Nune said.

These new findings from the COVAD study should be published soon. Dr. Nune suggested that the findings might be used to help identify patients early so that they can be referred to the appropriate services in good time.

The COVAD study was independently supported. Dr. Nune reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sparks is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the R. Bruce and Joan M. Mickey Research Scholar Fund, and the Llura Gund Award for Rheumatoid Arthritis Research and Care. Dr. Sparks has received research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb and performed consultancy for AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Inova Diagnostics, Janssen, Optum, and Pfizer.

MANCHESTER, England – Data from the COVAD-2 e-survey suggest that people with a rheumatic disease are twice as likely as are those without to experience long-term effects after contracting COVID-19.

The prevalence of post–COVID-19 condition (PCC), the term the World Health Organization advocates for describing the widely popularized term long COVID, was 10.8% among people with autoimmune rheumatic diseases (AIRDs) vs. 5.3% among those with no autoimmune condition (designated as “healthy controls”). The odds ratio was 2.1, with a 95% confidence interval of 1.4-3.2 and a P-value of .002.

The prevalence in people with nonrheumatic autoimmune diseases was also higher than it was in the control participants but still lower, at 7.3%, than in those with AIRDs.

“Our findings highlight the importance of close monitoring for PCC,” Arvind Nune, MBBCh, MSc, said in a virtual poster presentation at the annual meeting of the British Society for Rheumatology.

They also show the need for “appropriate referral for optimized multidisciplinary care for patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases during the recovery period following COVID-19,” added Dr. Nune, who works for Southport (England) and Ormskirk Hospital NHS Trust.

In an interview, he noted that it was patients who had a severe COVID-19 course or had other coexisting conditions that appeared to experience more long-term effects than did their less-affected counterparts.

Commenting on the study, Jeffrey A. Sparks, MD, MMSc, told this news organization: “This is one of the first studies to find that the prevalence of long COVID is higher among people with systemic rheumatic diseases than those without.”

Dr. Sparks, who is based at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, added: “Since the symptoms of long COVID and rheumatic diseases can overlap substantially, more work will need to be done to determine whether COVID may have induced flares, new symptoms, or whether the finding is due to the presence of the chronic rheumatic disease.”

The COVAD study

Using an electronic survey platform, the COVAD study has been set up to look at the long-term efficacy and safety of COVID-19 vaccinations in patients with AIRDs. It’s now a large international effort involving more than 150 collaborating clinics in 106 countries.

A huge amount of data has been collected. “We collected demographics, details of autoimmune disease, including treatment, comorbidity, COVID infection, vaccination history and outcomes, date on flares, and validated patient-reported outcomes, including pain, fatigue, physical function, and quality of life,” Dr. Nune said in his presentation.

A total of 12,358 people who were invited to participate responded to the e-survey. Of them, 2,640 were confirmed to have COVID-19. Because the analysis aimed to look at PCC, anyone who had completed the survey less than 3 months after infection was excluded. This left 1,677 eligible respondents, of whom, an overall 8.7% (n = 136) were identified as having PCC.

“The [WHO] definition for PCC was employed, which is persistent signs or symptoms beyond 3 months of COVID-19 infection lasting at least 2 months,” Dr. Nune told this news organization.

“Symptoms could be anything from fatigue to breathlessness to arthralgias,” he added. However, the focus of the present analysis was to look at how many people were experiencing the condition rather than specific symptoms.

A higher risk for PCC was seen in women than in men (OR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.1-7.7; P = .037) in the entire cohort.

In addition, those with comorbidities were found to have a greater chance of long-term sequelae from COVID-19 than were those without comorbid disease (OR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.4-5.7; P = .005).

Patients who experienced more severe acute COVID-19, such as those who needed intensive care treatment, oxygen therapy, or advanced treatment for COVID-19 with monoclonal antibodies, were significantly more likely to later have PCC than were those who did not (OR, 3.8; 95% CI, 1.1-13.6; P = .039).

Having PCC was also associated with poorer patient-reported outcomes for physical function, compared with not having PCC. “However, no association with disease flares of underlying rheumatic diseases or immunosuppressive drugs used were noted,” Dr. Nune said.

These new findings from the COVAD study should be published soon. Dr. Nune suggested that the findings might be used to help identify patients early so that they can be referred to the appropriate services in good time.

The COVAD study was independently supported. Dr. Nune reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sparks is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the R. Bruce and Joan M. Mickey Research Scholar Fund, and the Llura Gund Award for Rheumatoid Arthritis Research and Care. Dr. Sparks has received research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb and performed consultancy for AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Inova Diagnostics, Janssen, Optum, and Pfizer.

MANCHESTER, England – Data from the COVAD-2 e-survey suggest that people with a rheumatic disease are twice as likely as are those without to experience long-term effects after contracting COVID-19.

The prevalence of post–COVID-19 condition (PCC), the term the World Health Organization advocates for describing the widely popularized term long COVID, was 10.8% among people with autoimmune rheumatic diseases (AIRDs) vs. 5.3% among those with no autoimmune condition (designated as “healthy controls”). The odds ratio was 2.1, with a 95% confidence interval of 1.4-3.2 and a P-value of .002.

The prevalence in people with nonrheumatic autoimmune diseases was also higher than it was in the control participants but still lower, at 7.3%, than in those with AIRDs.

“Our findings highlight the importance of close monitoring for PCC,” Arvind Nune, MBBCh, MSc, said in a virtual poster presentation at the annual meeting of the British Society for Rheumatology.

They also show the need for “appropriate referral for optimized multidisciplinary care for patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases during the recovery period following COVID-19,” added Dr. Nune, who works for Southport (England) and Ormskirk Hospital NHS Trust.

In an interview, he noted that it was patients who had a severe COVID-19 course or had other coexisting conditions that appeared to experience more long-term effects than did their less-affected counterparts.

Commenting on the study, Jeffrey A. Sparks, MD, MMSc, told this news organization: “This is one of the first studies to find that the prevalence of long COVID is higher among people with systemic rheumatic diseases than those without.”

Dr. Sparks, who is based at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, added: “Since the symptoms of long COVID and rheumatic diseases can overlap substantially, more work will need to be done to determine whether COVID may have induced flares, new symptoms, or whether the finding is due to the presence of the chronic rheumatic disease.”

The COVAD study

Using an electronic survey platform, the COVAD study has been set up to look at the long-term efficacy and safety of COVID-19 vaccinations in patients with AIRDs. It’s now a large international effort involving more than 150 collaborating clinics in 106 countries.

A huge amount of data has been collected. “We collected demographics, details of autoimmune disease, including treatment, comorbidity, COVID infection, vaccination history and outcomes, date on flares, and validated patient-reported outcomes, including pain, fatigue, physical function, and quality of life,” Dr. Nune said in his presentation.

A total of 12,358 people who were invited to participate responded to the e-survey. Of them, 2,640 were confirmed to have COVID-19. Because the analysis aimed to look at PCC, anyone who had completed the survey less than 3 months after infection was excluded. This left 1,677 eligible respondents, of whom, an overall 8.7% (n = 136) were identified as having PCC.

“The [WHO] definition for PCC was employed, which is persistent signs or symptoms beyond 3 months of COVID-19 infection lasting at least 2 months,” Dr. Nune told this news organization.

“Symptoms could be anything from fatigue to breathlessness to arthralgias,” he added. However, the focus of the present analysis was to look at how many people were experiencing the condition rather than specific symptoms.

A higher risk for PCC was seen in women than in men (OR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.1-7.7; P = .037) in the entire cohort.

In addition, those with comorbidities were found to have a greater chance of long-term sequelae from COVID-19 than were those without comorbid disease (OR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.4-5.7; P = .005).

Patients who experienced more severe acute COVID-19, such as those who needed intensive care treatment, oxygen therapy, or advanced treatment for COVID-19 with monoclonal antibodies, were significantly more likely to later have PCC than were those who did not (OR, 3.8; 95% CI, 1.1-13.6; P = .039).

Having PCC was also associated with poorer patient-reported outcomes for physical function, compared with not having PCC. “However, no association with disease flares of underlying rheumatic diseases or immunosuppressive drugs used were noted,” Dr. Nune said.

These new findings from the COVAD study should be published soon. Dr. Nune suggested that the findings might be used to help identify patients early so that they can be referred to the appropriate services in good time.

The COVAD study was independently supported. Dr. Nune reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sparks is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the R. Bruce and Joan M. Mickey Research Scholar Fund, and the Llura Gund Award for Rheumatoid Arthritis Research and Care. Dr. Sparks has received research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb and performed consultancy for AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Inova Diagnostics, Janssen, Optum, and Pfizer.

AT BSR 2023

Researchers seek to understand post-COVID autoimmune disease risk

Since the COVID-19 pandemic started more than 3 years ago, the longer-lasting effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection have continued to reveal themselves. Approximately 28% of Americans report having ever experienced post-COVID conditions, such as brain fog, postexertional malaise, and joint pain, and 11% say they are still experiencing these long-term effects. Now, new research is showing that people who have had COVID are more likely to newly develop an autoimmune disease. Exactly why this is happening is less clear, experts say.

Two preprint studies and one study published in a peer-reviewed journal provide strong evidence that patients who have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 are at elevated risk of developing an autoimmune disease. The studies retrospectively reviewed medical records from three countries and compared the incidence of new-onset autoimmune disease among patients who had polymerase chain reaction–confirmed COVID-19 and those who had never been diagnosed with the virus.

A study analyzing the health records of 3.8 million U.S. patients – more than 888,460 with confirmed COVID-19 – found that the COVID-19 group was two to three times as likely to develop various autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and systemic sclerosis. A U.K. preprint study that included more than 458,000 people with confirmed COVID found that those who had previously been infected with SARS-CoV-2 were 22% more likely to develop an autoimmune disease compared with the control group. In this cohort, the diseases most strongly associated with COVID-19 were type 1 diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, and psoriasis. A preprint study from German researchers found that COVID-19 patients were almost 43% more likely to develop an autoimmune disease, compared with those who had never been infected. COVID-19 was most strongly linked to vasculitis.

These large studies are telling us, “Yes, this link is there, so we have to accept it,” Sonia Sharma, PhD, of the Center for Autoimmunity and Inflammation at the La Jolla (Calif.) Institute for Immunology, told this news organization. But this is not the first time that autoimmune diseases have been linked to previous infections.

Researchers have known for decades that Epstein-Barr virus infection is linked to several autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis. More recent research suggests the virus may activate certain genes associated with these immune disorders. Hepatitis C virus can induce cryoglobulinemia, and infection with cytomegalovirus has been implicated in several autoimmune diseases. Bacterial infections have also been linked to autoimmunity, such as group A streptococcus and rheumatic fever, as well as salmonella and reactive arthritis, to name only a few.

“In a way, this isn’t necessarily a new concept to physicians, particularly rheumatologists,” said Jeffrey A. Sparks, MD, a rheumatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. “There’s a fine line between appropriately clearing an infection and the body overreacting and setting off a cascade where the immune system is chronically overactive that can manifest as an autoimmune disease,” he told this news organization.

A dysregulated response to infection

It takes the immune system a week or two to develop antigen-specific antibodies to a new pathogen. But for patients with serious infections – in this instance, COVID-19 – that’s time they don’t have. Therefore, the immune system has an alternative pathway, called extrafollicular activation, that creates fast-acting antibodies, explained Matthew Woodruff, PhD, an instructor of immunology and rheumatology at Emory University, Atlanta.

The trade-off is that these antibodies are not as specific and can target the body’s own tissues. This dysregulation of antibody selection is generally short lived and fades when more targeted antibodies are produced and take over, but in some cases, this process can lead to high levels of self-targeting antibodies that can harm the body’s organs and tissues. Research also suggests that for patients who experience long COVID, the same autoantibodies that drive the initial immune response are detectable in the body months after infection, though it is not known whether these lingering immune cells cause these longer-lasting symptoms.

“If you have a virus that causes hyperinflammation plus organ damage, that is a recipe for disaster,” Dr. Sharma said. “It’s a recipe for autoantibodies and autoreactive T cells that down the road can attack the body’s own tissues, especially in people whose immune system is trained in such a way to cause self-reactivity,” she added.

This hyperinflammation can result in rare but serious complications, such as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adults, which can occur 2-6 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection. But even in these patients with severe illness, organ-specific complications tend to resolve in 6 months with “no significant sequelae 1 year after diagnosis,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And while long COVID can last for a year or longer, data suggest that symptoms do eventually resolve for most people. What is not clear is why acute autoimmunity triggered by COVID-19 can become a chronic condition in certain patients.

Predisposition to autoimmunity

P. J. Utz, MD, PhD, professor of immunology and rheumatology at Stanford (Calif.) University, said that people who develop autoimmune disease after SARS-CoV-2 infection may have already been predisposed toward autoimmunity. Especially for autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes and lupus, autoantibodies can appear and circulate in the body for more than a decade in some people before they present with any clinical symptoms. “Their immune system is primed such that if they get infected with something – or they have some other environmental trigger that maybe we don’t know about yet – that is enough to then push them over the edge so that they get full-blown autoimmunity,” he said. What is not known is whether these patients’ conditions would have advanced to true clinical disease had they not been infected, he said.

He also noted that the presence of autoantibodies does not necessarily mean someone has autoimmune disease; healthy people can also have autoantibodies, and everyone develops them with age. “My advice would be, ‘Don’t lose sleep over this,’ “ he said.

Dr. Sparks agreed that while these retrospective studies did show an elevated risk of autoimmune disease after COVID-19, that risk appears to be relatively small. “As a practicing rheumatologist, we aren’t seeing a stampede of patients with new-onset rheumatic diseases,” he said. “It’s not like we’re overwhelmed with autoimmune patients, even though almost everyone’s had COVID. So, if there is a risk, it’s very modest.”

Dr. Sparks is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the R. Bruce and Joan M. Mickey Research Scholar Fund, and the Llura Gund Award for Rheumatoid Arthritis Research and Care. Dr. Utz receives research funding from Pfizer. Dr. Sharma and Dr. Woodruff have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic started more than 3 years ago, the longer-lasting effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection have continued to reveal themselves. Approximately 28% of Americans report having ever experienced post-COVID conditions, such as brain fog, postexertional malaise, and joint pain, and 11% say they are still experiencing these long-term effects. Now, new research is showing that people who have had COVID are more likely to newly develop an autoimmune disease. Exactly why this is happening is less clear, experts say.

Two preprint studies and one study published in a peer-reviewed journal provide strong evidence that patients who have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 are at elevated risk of developing an autoimmune disease. The studies retrospectively reviewed medical records from three countries and compared the incidence of new-onset autoimmune disease among patients who had polymerase chain reaction–confirmed COVID-19 and those who had never been diagnosed with the virus.

A study analyzing the health records of 3.8 million U.S. patients – more than 888,460 with confirmed COVID-19 – found that the COVID-19 group was two to three times as likely to develop various autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and systemic sclerosis. A U.K. preprint study that included more than 458,000 people with confirmed COVID found that those who had previously been infected with SARS-CoV-2 were 22% more likely to develop an autoimmune disease compared with the control group. In this cohort, the diseases most strongly associated with COVID-19 were type 1 diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, and psoriasis. A preprint study from German researchers found that COVID-19 patients were almost 43% more likely to develop an autoimmune disease, compared with those who had never been infected. COVID-19 was most strongly linked to vasculitis.

These large studies are telling us, “Yes, this link is there, so we have to accept it,” Sonia Sharma, PhD, of the Center for Autoimmunity and Inflammation at the La Jolla (Calif.) Institute for Immunology, told this news organization. But this is not the first time that autoimmune diseases have been linked to previous infections.

Researchers have known for decades that Epstein-Barr virus infection is linked to several autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis. More recent research suggests the virus may activate certain genes associated with these immune disorders. Hepatitis C virus can induce cryoglobulinemia, and infection with cytomegalovirus has been implicated in several autoimmune diseases. Bacterial infections have also been linked to autoimmunity, such as group A streptococcus and rheumatic fever, as well as salmonella and reactive arthritis, to name only a few.

“In a way, this isn’t necessarily a new concept to physicians, particularly rheumatologists,” said Jeffrey A. Sparks, MD, a rheumatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. “There’s a fine line between appropriately clearing an infection and the body overreacting and setting off a cascade where the immune system is chronically overactive that can manifest as an autoimmune disease,” he told this news organization.

A dysregulated response to infection