User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Federal program offers free COVID, flu at-home tests, treatments

The U.S. government has expanded a program offering free COVID-19 and flu tests and treatment.

The Home Test to Treat program is virtual and offers at-home rapid tests, telehealth sessions, and at-home treatments to people nationwide. The program is a collaboration among the National Institutes of Health, the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response, and the CDC. It began as a pilot program in some locations this year.

“With its expansion, the Home Test to Treat program will now offer free testing, telehealth and treatment for both COVID-19 and for influenza (flu) A and B,” the NIH said in a press release. “It is the first public health program that includes home testing technology at such a scale for both COVID-19 and flu.”

The news release says that anyone 18 or over with a current positive test for COVID-19 or flu can get free telehealth care and medicine delivered to their home.

Adults who don’t have COVID-19 or the flu can get free tests if they are uninsured or are enrolled in Medicare, Medicaid, the Veterans Affairs health care system, or Indian Health Services. If they test positive later, they can get free telehealth care and, if prescribed, treatment.

“I think that these [telehealth] delivery mechanisms are going to be absolutely crucial to unburden the in-person offices and the lines that we have and wait times,” said Michael Mina, MD, chief science officer at eMed, the company that helped implement the new Home Test to Treat program, to ABC News.

ABC notes that COVID tests can also be ordered at covidtests.gov – four tests per household or eight for those who have yet to order any this fall.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com .

The U.S. government has expanded a program offering free COVID-19 and flu tests and treatment.

The Home Test to Treat program is virtual and offers at-home rapid tests, telehealth sessions, and at-home treatments to people nationwide. The program is a collaboration among the National Institutes of Health, the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response, and the CDC. It began as a pilot program in some locations this year.

“With its expansion, the Home Test to Treat program will now offer free testing, telehealth and treatment for both COVID-19 and for influenza (flu) A and B,” the NIH said in a press release. “It is the first public health program that includes home testing technology at such a scale for both COVID-19 and flu.”

The news release says that anyone 18 or over with a current positive test for COVID-19 or flu can get free telehealth care and medicine delivered to their home.

Adults who don’t have COVID-19 or the flu can get free tests if they are uninsured or are enrolled in Medicare, Medicaid, the Veterans Affairs health care system, or Indian Health Services. If they test positive later, they can get free telehealth care and, if prescribed, treatment.

“I think that these [telehealth] delivery mechanisms are going to be absolutely crucial to unburden the in-person offices and the lines that we have and wait times,” said Michael Mina, MD, chief science officer at eMed, the company that helped implement the new Home Test to Treat program, to ABC News.

ABC notes that COVID tests can also be ordered at covidtests.gov – four tests per household or eight for those who have yet to order any this fall.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com .

The U.S. government has expanded a program offering free COVID-19 and flu tests and treatment.

The Home Test to Treat program is virtual and offers at-home rapid tests, telehealth sessions, and at-home treatments to people nationwide. The program is a collaboration among the National Institutes of Health, the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response, and the CDC. It began as a pilot program in some locations this year.

“With its expansion, the Home Test to Treat program will now offer free testing, telehealth and treatment for both COVID-19 and for influenza (flu) A and B,” the NIH said in a press release. “It is the first public health program that includes home testing technology at such a scale for both COVID-19 and flu.”

The news release says that anyone 18 or over with a current positive test for COVID-19 or flu can get free telehealth care and medicine delivered to their home.

Adults who don’t have COVID-19 or the flu can get free tests if they are uninsured or are enrolled in Medicare, Medicaid, the Veterans Affairs health care system, or Indian Health Services. If they test positive later, they can get free telehealth care and, if prescribed, treatment.

“I think that these [telehealth] delivery mechanisms are going to be absolutely crucial to unburden the in-person offices and the lines that we have and wait times,” said Michael Mina, MD, chief science officer at eMed, the company that helped implement the new Home Test to Treat program, to ABC News.

ABC notes that COVID tests can also be ordered at covidtests.gov – four tests per household or eight for those who have yet to order any this fall.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com .

New KDIGO guideline encourages use of HCV-positive kidneys for HCV-negative recipients

The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Work Group has updated its guideline concerning the prevention, diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Of note, KDIGO now supports transplant of HCV-positive kidneys to HCV-negative recipients.

The guidance document, authored by Ahmed Arslan Yousuf Awan, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and colleagues, was written in light of new evidence that has emerged since the 2018 guideline was published.

“The focused update was triggered by new data on antiviral treatment in patients with advanced stages of CKD (G4, G5, or G5D), transplant of HCV-infected kidneys into uninfected recipients, and evolution of the viewpoint on the role of kidney biopsy in managing kidney disease caused by HCV,” the guideline panelists wrote in Annals of Internal Medicine. “This update is intended to assist clinicians in the care of patients with HCV infection and CKD, including patients receiving dialysis (CKD G5D) and patients with a kidney transplant (CKD G1T-G5T).”

Anjay Rastogi, MD, PhD, professor and clinical chief of nephrology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, said the update is both “timely and relevant,” and “will really have an impact on the organ shortage that we have for kidney transplant”

The updates are outlined below.

Expanded Access to HCV-Positive Kidneys

While the 2018 guideline recommended that HCV-positive kidneys be directed to HCV-positive recipients, the new guideline suggests that these kidneys are appropriate for all patients regardless of HCV status.

In support, the panelists cited a follow-up of THINKER-1 trial, which showed that eGFR and quality of life were not negatively affected when HCV-negative patients received an HCV-positive kidney, compared with an HCV-negative kidney. Data from 525 unmatched recipients in 16 other studies support this conclusion, the panelists noted.

Jose Debes, MD, PhD, associate professor at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, suggested that this is the most important update to the KDIGO guidelines.

“That [change] would be the main impact of these recommendations,” Dr. Debes said in an interview. “Several centers were already doing this, since some data [were] out there, but I think the fact that they’re making this into a guideline is quite important.”

Dr. Rastogi agreed that this recommendation is the most impactful update.

“That’s a big move,” Dr. Rastogi said in an interview. He predicted that the change will “definitely increase the donor pool, which is very, very important.”

For this new recommendation to have the greatest positive effect, however, Dr. Rastogi suggested that health care providers and treatment centers need to prepare an effective implementation strategy. He emphasized the importance of early communication with patients concerning the safety of HCV-positive kidneys, which depends on early initiation of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy.

In the guideline, Dr. Awan and colleagues reported three documented cases of fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis occurred in patients who did not begin DAA therapy until 30 days after transplant.

“[Patients] should start [DAA treatment] right away,” Dr. Rastogi said, “and sometimes even before the transplant.”

This will require institutional support, he noted, as centers need to ensure that patients are covered for DAA therapy and medication is readily available.

Sofosbuvir Given the Green Light

Compared with the 2018 guideline, which recommended against sofosbuvir in patients with CKD G4 and G5, including those on dialysis, because of concerns about metabolization via the kidneys, the new guideline suggests that sofosbuvir-based DAA regimens are appropriate in patients with glomerular filtration rate (GFR) less than 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2, including those receiving dialysis.

This recommendation was based on a systematic review of 106 studies including both sofosbuvir-based and non-sofosbuvir-based DAA regimens that showed high safety and efficacy for all DAA regimen types across a broad variety of patient types.

“DAAs are highly effective and well tolerated treatments for hepatitis C in patients across all stages of CKD, including those undergoing dialysis and kidney transplant recipients, with no need for dose adjustment,” Dr. Awan and colleagues wrote.

Loosened Biopsy Requirements

Unlike the 2018 guideline, which advised kidney biopsy in HCV-positive patients with clinical evidence of glomerular disease prior to initiating DAA treatment, the new guideline suggests that HCV-infected patients with a typical presentation of immune-complex proliferative glomerulonephritis do not require confirmatory kidney biopsy.

“Because almost all patients with chronic hepatitis C (with or without glomerulonephritis) should be treated with DAAs, a kidney biopsy is unlikely to change management in most patients with hepatitis C and clinical glomerulonephritis,” the panelists wrote.

If kidney disease does not stabilize or improve with achievement of sustained virologic response, or if there is evidence of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis, then a kidney biopsy should be considered before beginning immunosuppressive therapy, according to the guideline, which includes a flow chart to guide clinicians through this decision-making process.

Individualizing Immunosuppressive Therapy

Consistent with the old guideline, the new guideline recommends DAA treatment with concurrent immunosuppressive therapy for patients with cryoglobulinemic flare or rapidly progressive kidney failure. But in contrast, the new guideline calls for an individualized approach to immunosuppression in patients with nephrotic syndrome.

Dr. Awan and colleagues suggested that “nephrotic-range proteinuria (greater than 3.5 g/d) alone does not warrant use of immunosuppressive treatment because such patients can achieve remission of proteinuria after treatment with DAAs.” Still, if other associated complications — such as anasarca, thromboembolic disease, or severe hypoalbuminemia — are present, then immunosuppressive therapy may be warranted, with rituximab remaining the preferred first-line agent.

More Work Is Needed

Dr. Awan and colleagues concluded the guideline by highlighting areas of unmet need, and how filling these knowledge gaps could lead to additional guideline updates.

“Future studies of kidney donations from HCV-positive donors to HCV-negative recipients are needed to refine and clarify the timing of initiation and duration of DAA therapy and to assess long-term outcomes associated with this practice,” they wrote. “Also, randomized controlled trials are needed to determine which patients with HCV-associated kidney disease can be treated with DAA therapy alone versus in combination with immunosuppression and plasma exchange. KDIGO will assess the currency of its recommendations and the need to update them in the next 3 years.”

The guideline was funded by KDIGO. The investigators disclosed relationships with GSK, Gilead, Intercept, Novo Nordisk, and others. Dr. Rastogi and Dr. Debes had no conflicts of interest.

The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Work Group has updated its guideline concerning the prevention, diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Of note, KDIGO now supports transplant of HCV-positive kidneys to HCV-negative recipients.

The guidance document, authored by Ahmed Arslan Yousuf Awan, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and colleagues, was written in light of new evidence that has emerged since the 2018 guideline was published.

“The focused update was triggered by new data on antiviral treatment in patients with advanced stages of CKD (G4, G5, or G5D), transplant of HCV-infected kidneys into uninfected recipients, and evolution of the viewpoint on the role of kidney biopsy in managing kidney disease caused by HCV,” the guideline panelists wrote in Annals of Internal Medicine. “This update is intended to assist clinicians in the care of patients with HCV infection and CKD, including patients receiving dialysis (CKD G5D) and patients with a kidney transplant (CKD G1T-G5T).”

Anjay Rastogi, MD, PhD, professor and clinical chief of nephrology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, said the update is both “timely and relevant,” and “will really have an impact on the organ shortage that we have for kidney transplant”

The updates are outlined below.

Expanded Access to HCV-Positive Kidneys

While the 2018 guideline recommended that HCV-positive kidneys be directed to HCV-positive recipients, the new guideline suggests that these kidneys are appropriate for all patients regardless of HCV status.

In support, the panelists cited a follow-up of THINKER-1 trial, which showed that eGFR and quality of life were not negatively affected when HCV-negative patients received an HCV-positive kidney, compared with an HCV-negative kidney. Data from 525 unmatched recipients in 16 other studies support this conclusion, the panelists noted.

Jose Debes, MD, PhD, associate professor at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, suggested that this is the most important update to the KDIGO guidelines.

“That [change] would be the main impact of these recommendations,” Dr. Debes said in an interview. “Several centers were already doing this, since some data [were] out there, but I think the fact that they’re making this into a guideline is quite important.”

Dr. Rastogi agreed that this recommendation is the most impactful update.

“That’s a big move,” Dr. Rastogi said in an interview. He predicted that the change will “definitely increase the donor pool, which is very, very important.”

For this new recommendation to have the greatest positive effect, however, Dr. Rastogi suggested that health care providers and treatment centers need to prepare an effective implementation strategy. He emphasized the importance of early communication with patients concerning the safety of HCV-positive kidneys, which depends on early initiation of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy.

In the guideline, Dr. Awan and colleagues reported three documented cases of fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis occurred in patients who did not begin DAA therapy until 30 days after transplant.

“[Patients] should start [DAA treatment] right away,” Dr. Rastogi said, “and sometimes even before the transplant.”

This will require institutional support, he noted, as centers need to ensure that patients are covered for DAA therapy and medication is readily available.

Sofosbuvir Given the Green Light

Compared with the 2018 guideline, which recommended against sofosbuvir in patients with CKD G4 and G5, including those on dialysis, because of concerns about metabolization via the kidneys, the new guideline suggests that sofosbuvir-based DAA regimens are appropriate in patients with glomerular filtration rate (GFR) less than 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2, including those receiving dialysis.

This recommendation was based on a systematic review of 106 studies including both sofosbuvir-based and non-sofosbuvir-based DAA regimens that showed high safety and efficacy for all DAA regimen types across a broad variety of patient types.

“DAAs are highly effective and well tolerated treatments for hepatitis C in patients across all stages of CKD, including those undergoing dialysis and kidney transplant recipients, with no need for dose adjustment,” Dr. Awan and colleagues wrote.

Loosened Biopsy Requirements

Unlike the 2018 guideline, which advised kidney biopsy in HCV-positive patients with clinical evidence of glomerular disease prior to initiating DAA treatment, the new guideline suggests that HCV-infected patients with a typical presentation of immune-complex proliferative glomerulonephritis do not require confirmatory kidney biopsy.

“Because almost all patients with chronic hepatitis C (with or without glomerulonephritis) should be treated with DAAs, a kidney biopsy is unlikely to change management in most patients with hepatitis C and clinical glomerulonephritis,” the panelists wrote.

If kidney disease does not stabilize or improve with achievement of sustained virologic response, or if there is evidence of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis, then a kidney biopsy should be considered before beginning immunosuppressive therapy, according to the guideline, which includes a flow chart to guide clinicians through this decision-making process.

Individualizing Immunosuppressive Therapy

Consistent with the old guideline, the new guideline recommends DAA treatment with concurrent immunosuppressive therapy for patients with cryoglobulinemic flare or rapidly progressive kidney failure. But in contrast, the new guideline calls for an individualized approach to immunosuppression in patients with nephrotic syndrome.

Dr. Awan and colleagues suggested that “nephrotic-range proteinuria (greater than 3.5 g/d) alone does not warrant use of immunosuppressive treatment because such patients can achieve remission of proteinuria after treatment with DAAs.” Still, if other associated complications — such as anasarca, thromboembolic disease, or severe hypoalbuminemia — are present, then immunosuppressive therapy may be warranted, with rituximab remaining the preferred first-line agent.

More Work Is Needed

Dr. Awan and colleagues concluded the guideline by highlighting areas of unmet need, and how filling these knowledge gaps could lead to additional guideline updates.

“Future studies of kidney donations from HCV-positive donors to HCV-negative recipients are needed to refine and clarify the timing of initiation and duration of DAA therapy and to assess long-term outcomes associated with this practice,” they wrote. “Also, randomized controlled trials are needed to determine which patients with HCV-associated kidney disease can be treated with DAA therapy alone versus in combination with immunosuppression and plasma exchange. KDIGO will assess the currency of its recommendations and the need to update them in the next 3 years.”

The guideline was funded by KDIGO. The investigators disclosed relationships with GSK, Gilead, Intercept, Novo Nordisk, and others. Dr. Rastogi and Dr. Debes had no conflicts of interest.

The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Work Group has updated its guideline concerning the prevention, diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Of note, KDIGO now supports transplant of HCV-positive kidneys to HCV-negative recipients.

The guidance document, authored by Ahmed Arslan Yousuf Awan, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and colleagues, was written in light of new evidence that has emerged since the 2018 guideline was published.

“The focused update was triggered by new data on antiviral treatment in patients with advanced stages of CKD (G4, G5, or G5D), transplant of HCV-infected kidneys into uninfected recipients, and evolution of the viewpoint on the role of kidney biopsy in managing kidney disease caused by HCV,” the guideline panelists wrote in Annals of Internal Medicine. “This update is intended to assist clinicians in the care of patients with HCV infection and CKD, including patients receiving dialysis (CKD G5D) and patients with a kidney transplant (CKD G1T-G5T).”

Anjay Rastogi, MD, PhD, professor and clinical chief of nephrology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, said the update is both “timely and relevant,” and “will really have an impact on the organ shortage that we have for kidney transplant”

The updates are outlined below.

Expanded Access to HCV-Positive Kidneys

While the 2018 guideline recommended that HCV-positive kidneys be directed to HCV-positive recipients, the new guideline suggests that these kidneys are appropriate for all patients regardless of HCV status.

In support, the panelists cited a follow-up of THINKER-1 trial, which showed that eGFR and quality of life were not negatively affected when HCV-negative patients received an HCV-positive kidney, compared with an HCV-negative kidney. Data from 525 unmatched recipients in 16 other studies support this conclusion, the panelists noted.

Jose Debes, MD, PhD, associate professor at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, suggested that this is the most important update to the KDIGO guidelines.

“That [change] would be the main impact of these recommendations,” Dr. Debes said in an interview. “Several centers were already doing this, since some data [were] out there, but I think the fact that they’re making this into a guideline is quite important.”

Dr. Rastogi agreed that this recommendation is the most impactful update.

“That’s a big move,” Dr. Rastogi said in an interview. He predicted that the change will “definitely increase the donor pool, which is very, very important.”

For this new recommendation to have the greatest positive effect, however, Dr. Rastogi suggested that health care providers and treatment centers need to prepare an effective implementation strategy. He emphasized the importance of early communication with patients concerning the safety of HCV-positive kidneys, which depends on early initiation of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy.

In the guideline, Dr. Awan and colleagues reported three documented cases of fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis occurred in patients who did not begin DAA therapy until 30 days after transplant.

“[Patients] should start [DAA treatment] right away,” Dr. Rastogi said, “and sometimes even before the transplant.”

This will require institutional support, he noted, as centers need to ensure that patients are covered for DAA therapy and medication is readily available.

Sofosbuvir Given the Green Light

Compared with the 2018 guideline, which recommended against sofosbuvir in patients with CKD G4 and G5, including those on dialysis, because of concerns about metabolization via the kidneys, the new guideline suggests that sofosbuvir-based DAA regimens are appropriate in patients with glomerular filtration rate (GFR) less than 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2, including those receiving dialysis.

This recommendation was based on a systematic review of 106 studies including both sofosbuvir-based and non-sofosbuvir-based DAA regimens that showed high safety and efficacy for all DAA regimen types across a broad variety of patient types.

“DAAs are highly effective and well tolerated treatments for hepatitis C in patients across all stages of CKD, including those undergoing dialysis and kidney transplant recipients, with no need for dose adjustment,” Dr. Awan and colleagues wrote.

Loosened Biopsy Requirements

Unlike the 2018 guideline, which advised kidney biopsy in HCV-positive patients with clinical evidence of glomerular disease prior to initiating DAA treatment, the new guideline suggests that HCV-infected patients with a typical presentation of immune-complex proliferative glomerulonephritis do not require confirmatory kidney biopsy.

“Because almost all patients with chronic hepatitis C (with or without glomerulonephritis) should be treated with DAAs, a kidney biopsy is unlikely to change management in most patients with hepatitis C and clinical glomerulonephritis,” the panelists wrote.

If kidney disease does not stabilize or improve with achievement of sustained virologic response, or if there is evidence of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis, then a kidney biopsy should be considered before beginning immunosuppressive therapy, according to the guideline, which includes a flow chart to guide clinicians through this decision-making process.

Individualizing Immunosuppressive Therapy

Consistent with the old guideline, the new guideline recommends DAA treatment with concurrent immunosuppressive therapy for patients with cryoglobulinemic flare or rapidly progressive kidney failure. But in contrast, the new guideline calls for an individualized approach to immunosuppression in patients with nephrotic syndrome.

Dr. Awan and colleagues suggested that “nephrotic-range proteinuria (greater than 3.5 g/d) alone does not warrant use of immunosuppressive treatment because such patients can achieve remission of proteinuria after treatment with DAAs.” Still, if other associated complications — such as anasarca, thromboembolic disease, or severe hypoalbuminemia — are present, then immunosuppressive therapy may be warranted, with rituximab remaining the preferred first-line agent.

More Work Is Needed

Dr. Awan and colleagues concluded the guideline by highlighting areas of unmet need, and how filling these knowledge gaps could lead to additional guideline updates.

“Future studies of kidney donations from HCV-positive donors to HCV-negative recipients are needed to refine and clarify the timing of initiation and duration of DAA therapy and to assess long-term outcomes associated with this practice,” they wrote. “Also, randomized controlled trials are needed to determine which patients with HCV-associated kidney disease can be treated with DAA therapy alone versus in combination with immunosuppression and plasma exchange. KDIGO will assess the currency of its recommendations and the need to update them in the next 3 years.”

The guideline was funded by KDIGO. The investigators disclosed relationships with GSK, Gilead, Intercept, Novo Nordisk, and others. Dr. Rastogi and Dr. Debes had no conflicts of interest.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Why Are Prion Diseases on the Rise?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

In 1986, in Britain, cattle started dying.

The condition, quickly nicknamed “mad cow disease,” was clearly infectious, but the particular pathogen was difficult to identify. By 1993, 120,000 cattle in Britain were identified as being infected. As yet, no human cases had occurred and the UK government insisted that cattle were a dead-end host for the pathogen. By the mid-1990s, however, multiple human cases, attributable to ingestion of meat and organs from infected cattle, were discovered. In humans, variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) was a media sensation — a nearly uniformly fatal, untreatable condition with a rapid onset of dementia, mobility issues characterized by jerky movements, and autopsy reports finding that the brain itself had turned into a spongy mess.

The United States banned UK beef imports in 1996 and only lifted the ban in 2020.

The disease was made all the more mysterious because the pathogen involved was not a bacterium, parasite, or virus, but a protein — or a proteinaceous infectious particle, shortened to “prion.”

Prions are misfolded proteins that aggregate in cells — in this case, in nerve cells. But what makes prions different from other misfolded proteins is that the misfolded protein catalyzes the conversion of its non-misfolded counterpart into the misfolded configuration. It creates a chain reaction, leading to rapid accumulation of misfolded proteins and cell death.

And, like a time bomb, we all have prion protein inside us. In its normally folded state, the function of prion protein remains unclear — knockout mice do okay without it — but it is also highly conserved across mammalian species, so it probably does something worthwhile, perhaps protecting nerve fibers.

Far more common than humans contracting mad cow disease is the condition known as sporadic CJD, responsible for 85% of all cases of prion-induced brain disease. The cause of sporadic CJD is unknown.

But one thing is known: Cases are increasing.

I don’t want you to freak out; we are not in the midst of a CJD epidemic. But it’s been a while since I’ve seen people discussing the condition — which remains as horrible as it was in the 1990s — and a new research letter appearing in JAMA Neurology brought it back to the top of my mind.

Researchers, led by Matthew Crane at Hopkins, used the CDC’s WONDER cause-of-death database, which pulls diagnoses from death certificates. Normally, I’m not a fan of using death certificates for cause-of-death analyses, but in this case I’ll give it a pass. Assuming that the diagnosis of CJD is made, it would be really unlikely for it not to appear on a death certificate.

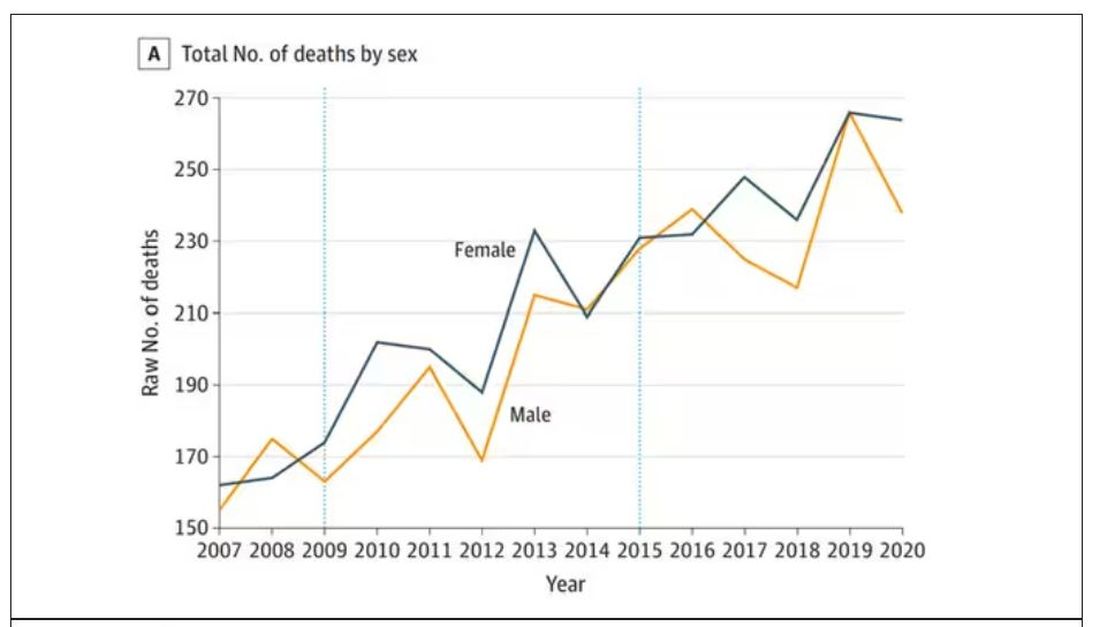

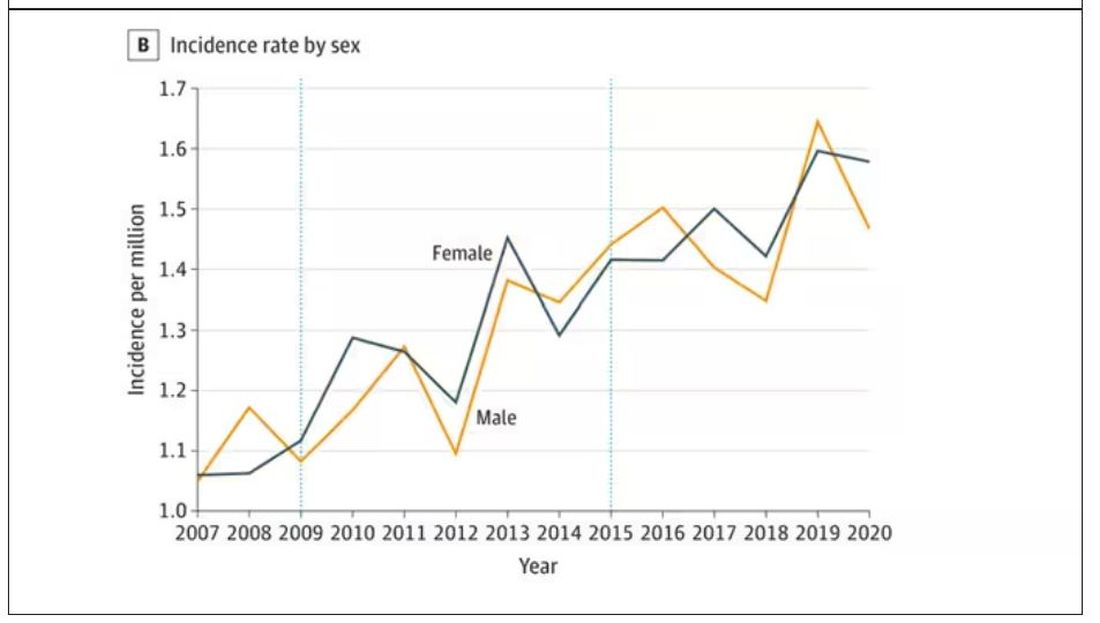

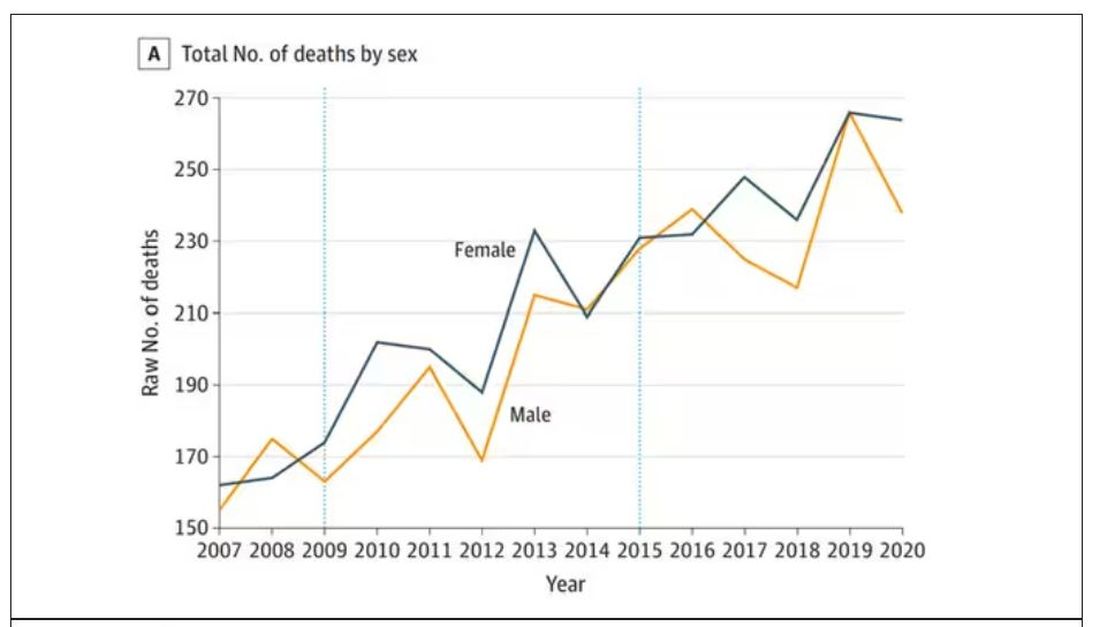

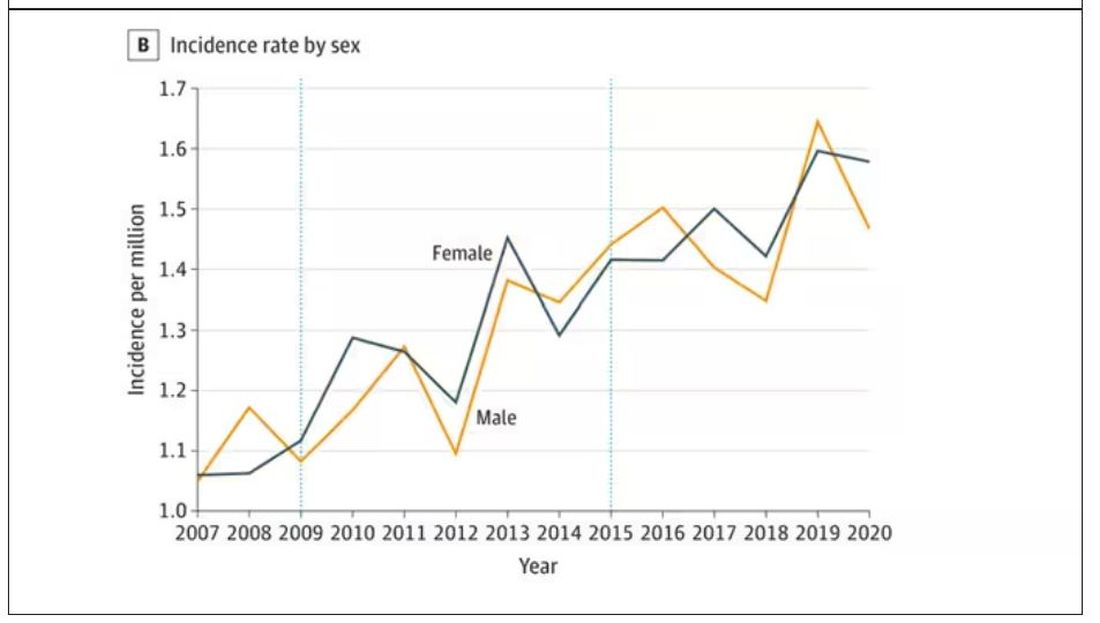

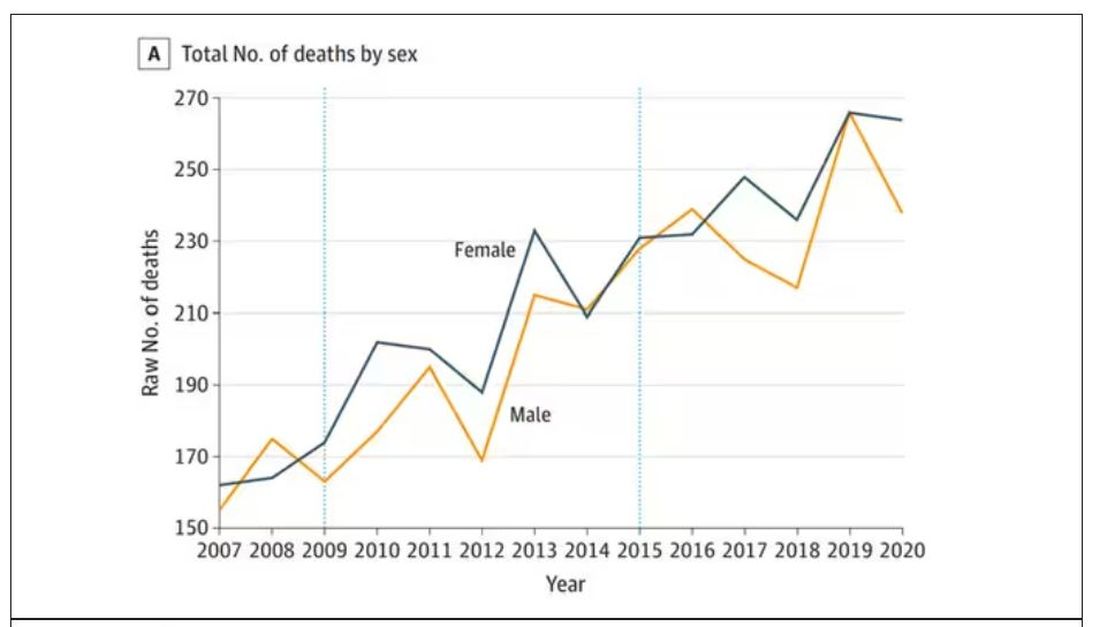

The main findings are seen here.

Note that we can’t tell whether these are sporadic CJD cases or variant CJD cases or even familial CJD cases; however, unless there has been a dramatic change in epidemiology, the vast majority of these will be sporadic.

The question is, why are there more cases?

Whenever this type of question comes up with any disease, there are basically three possibilities:

First, there may be an increase in the susceptible, or at-risk, population. In this case, we know that older people are at higher risk of developing sporadic CJD, and over time, the population has aged. To be fair, the authors adjusted for this and still saw an increase, though it was attenuated.

Second, we might be better at diagnosing the condition. A lot has happened since the mid-1990s, when the diagnosis was based more or less on symptoms. The advent of more sophisticated MRI protocols as well as a new diagnostic test called “real-time quaking-induced conversion testing” may mean we are just better at detecting people with this disease.

Third (and most concerning), a new exposure has occurred. What that exposure might be, where it might come from, is anyone’s guess. It’s hard to do broad-scale epidemiology on very rare diseases.

But given these findings, it seems that a bit more surveillance for this rare but devastating condition is well merited.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

In 1986, in Britain, cattle started dying.

The condition, quickly nicknamed “mad cow disease,” was clearly infectious, but the particular pathogen was difficult to identify. By 1993, 120,000 cattle in Britain were identified as being infected. As yet, no human cases had occurred and the UK government insisted that cattle were a dead-end host for the pathogen. By the mid-1990s, however, multiple human cases, attributable to ingestion of meat and organs from infected cattle, were discovered. In humans, variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) was a media sensation — a nearly uniformly fatal, untreatable condition with a rapid onset of dementia, mobility issues characterized by jerky movements, and autopsy reports finding that the brain itself had turned into a spongy mess.

The United States banned UK beef imports in 1996 and only lifted the ban in 2020.

The disease was made all the more mysterious because the pathogen involved was not a bacterium, parasite, or virus, but a protein — or a proteinaceous infectious particle, shortened to “prion.”

Prions are misfolded proteins that aggregate in cells — in this case, in nerve cells. But what makes prions different from other misfolded proteins is that the misfolded protein catalyzes the conversion of its non-misfolded counterpart into the misfolded configuration. It creates a chain reaction, leading to rapid accumulation of misfolded proteins and cell death.

And, like a time bomb, we all have prion protein inside us. In its normally folded state, the function of prion protein remains unclear — knockout mice do okay without it — but it is also highly conserved across mammalian species, so it probably does something worthwhile, perhaps protecting nerve fibers.

Far more common than humans contracting mad cow disease is the condition known as sporadic CJD, responsible for 85% of all cases of prion-induced brain disease. The cause of sporadic CJD is unknown.

But one thing is known: Cases are increasing.

I don’t want you to freak out; we are not in the midst of a CJD epidemic. But it’s been a while since I’ve seen people discussing the condition — which remains as horrible as it was in the 1990s — and a new research letter appearing in JAMA Neurology brought it back to the top of my mind.

Researchers, led by Matthew Crane at Hopkins, used the CDC’s WONDER cause-of-death database, which pulls diagnoses from death certificates. Normally, I’m not a fan of using death certificates for cause-of-death analyses, but in this case I’ll give it a pass. Assuming that the diagnosis of CJD is made, it would be really unlikely for it not to appear on a death certificate.

The main findings are seen here.

Note that we can’t tell whether these are sporadic CJD cases or variant CJD cases or even familial CJD cases; however, unless there has been a dramatic change in epidemiology, the vast majority of these will be sporadic.

The question is, why are there more cases?

Whenever this type of question comes up with any disease, there are basically three possibilities:

First, there may be an increase in the susceptible, or at-risk, population. In this case, we know that older people are at higher risk of developing sporadic CJD, and over time, the population has aged. To be fair, the authors adjusted for this and still saw an increase, though it was attenuated.

Second, we might be better at diagnosing the condition. A lot has happened since the mid-1990s, when the diagnosis was based more or less on symptoms. The advent of more sophisticated MRI protocols as well as a new diagnostic test called “real-time quaking-induced conversion testing” may mean we are just better at detecting people with this disease.

Third (and most concerning), a new exposure has occurred. What that exposure might be, where it might come from, is anyone’s guess. It’s hard to do broad-scale epidemiology on very rare diseases.

But given these findings, it seems that a bit more surveillance for this rare but devastating condition is well merited.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

In 1986, in Britain, cattle started dying.

The condition, quickly nicknamed “mad cow disease,” was clearly infectious, but the particular pathogen was difficult to identify. By 1993, 120,000 cattle in Britain were identified as being infected. As yet, no human cases had occurred and the UK government insisted that cattle were a dead-end host for the pathogen. By the mid-1990s, however, multiple human cases, attributable to ingestion of meat and organs from infected cattle, were discovered. In humans, variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) was a media sensation — a nearly uniformly fatal, untreatable condition with a rapid onset of dementia, mobility issues characterized by jerky movements, and autopsy reports finding that the brain itself had turned into a spongy mess.

The United States banned UK beef imports in 1996 and only lifted the ban in 2020.

The disease was made all the more mysterious because the pathogen involved was not a bacterium, parasite, or virus, but a protein — or a proteinaceous infectious particle, shortened to “prion.”

Prions are misfolded proteins that aggregate in cells — in this case, in nerve cells. But what makes prions different from other misfolded proteins is that the misfolded protein catalyzes the conversion of its non-misfolded counterpart into the misfolded configuration. It creates a chain reaction, leading to rapid accumulation of misfolded proteins and cell death.

And, like a time bomb, we all have prion protein inside us. In its normally folded state, the function of prion protein remains unclear — knockout mice do okay without it — but it is also highly conserved across mammalian species, so it probably does something worthwhile, perhaps protecting nerve fibers.

Far more common than humans contracting mad cow disease is the condition known as sporadic CJD, responsible for 85% of all cases of prion-induced brain disease. The cause of sporadic CJD is unknown.

But one thing is known: Cases are increasing.

I don’t want you to freak out; we are not in the midst of a CJD epidemic. But it’s been a while since I’ve seen people discussing the condition — which remains as horrible as it was in the 1990s — and a new research letter appearing in JAMA Neurology brought it back to the top of my mind.

Researchers, led by Matthew Crane at Hopkins, used the CDC’s WONDER cause-of-death database, which pulls diagnoses from death certificates. Normally, I’m not a fan of using death certificates for cause-of-death analyses, but in this case I’ll give it a pass. Assuming that the diagnosis of CJD is made, it would be really unlikely for it not to appear on a death certificate.

The main findings are seen here.

Note that we can’t tell whether these are sporadic CJD cases or variant CJD cases or even familial CJD cases; however, unless there has been a dramatic change in epidemiology, the vast majority of these will be sporadic.

The question is, why are there more cases?

Whenever this type of question comes up with any disease, there are basically three possibilities:

First, there may be an increase in the susceptible, or at-risk, population. In this case, we know that older people are at higher risk of developing sporadic CJD, and over time, the population has aged. To be fair, the authors adjusted for this and still saw an increase, though it was attenuated.

Second, we might be better at diagnosing the condition. A lot has happened since the mid-1990s, when the diagnosis was based more or less on symptoms. The advent of more sophisticated MRI protocols as well as a new diagnostic test called “real-time quaking-induced conversion testing” may mean we are just better at detecting people with this disease.

Third (and most concerning), a new exposure has occurred. What that exposure might be, where it might come from, is anyone’s guess. It’s hard to do broad-scale epidemiology on very rare diseases.

But given these findings, it seems that a bit more surveillance for this rare but devastating condition is well merited.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

New COVID variant JN.1 could disrupt holiday plans

No one planning holiday gatherings or travel wants to hear this, but the rise of a new COVID-19 variant, JN.1, is concerning experts, who say it may threaten those good times.

The good news is recent research suggests the 2023-2024 COVID-19 vaccine appears to work against this newest variant. But so few people have gotten the latest vaccine — less than 16% of U.S. adults — that some experts suggest it’s time for the CDC to urge the public who haven’t it to do so now, so the antibodies can kick in before the festivities.

“A significant wave [of JN.1] has started here and could be blunted with a high booster rate and mitigation measures,” said Eric Topol, MD, professor and executive vice president of Scripps Research in La Jolla, CA, and editor-in-chief of Medscape, a sister site of this news organization.

COVID metrics, meanwhile, have started to climb again. Nearly 10,000 people were hospitalized for COVID in the U.S. for the week ending Nov. 25, the CDC said, a 10% increase over the previous week.

Who’s Who in the Family Tree

JN.1, an Omicron subvariant, was first detected in the U.S. in September and is termed “a notable descendent lineage” of Omicron subvariant BA.2.86 by the World Health Organization. When BA.2.86, also known as Pirola, was first identified in August, it appeared very different from other variants, the CDC said. That triggered concerns it might be more infectious than previous ones, even for people with immunity from vaccination and previous infections.

“JN.1 is Pirola’s kid,” said Rajendram Rajnarayanan, PhD, assistant dean of research and associate professor at the New York Institute of Technology at Arkansas State University, who maintains a COVID-19 variant database. The variant BA.2.86 and offspring are worrisome due to the mutations, he said.

How Widespread Is JN.1?

As of Nov. 27, the CDC says, BA.2.86 is projected to comprise 5%-15% of circulating variants in the U.S. “The expected public health risk of this variant, including its offshoot JN.1, is low,” the agency said.

Currently, JN.1 is reported more often in Europe, Dr. Rajnarayanan said, but some countries have better reporting data than others. “It has probably spread to every country tracking COVID,’’ he said, due to the mutations in the spike protein that make it easier for it to bind and infect.

Wastewater data suggest the variant’s rise is helping to fuel a wave, Dr. Topol said.

Vaccine Effectiveness Against JN.1, Other New Variants

The new XBB.1.5 monovalent vaccine, protects against XBB.1.5, another Omicron subvariant, but also JN.1 and other “emergent” viruses, a team of researchers reported Nov. 26 in a study on bioRxiv that has not yet been certified by peer review.

The updated vaccine, when given to uninfected people, boosted antibodies about 27-fold against XBB.1.5 and about 13- to 27-fold against JN.1 and other emergent viruses, the researchers reported.

While even primary doses of the COVID vaccine will likely help protect against the new JN.1 subvariant, “if you got the XBB.1.5 booster, it is going to be protecting you better against this new variant,” Dr. Rajnarayanan said.

2023-2024 Vaccine Uptake Low

In November, the CDC posted the first detailed estimates of who did. As of Nov. 18, less than 16% of U.S. adults had, with nearly 15% saying they planned to get it.

Coverage among children is lower, with just 6.3% of children up to date on the newest vaccine and 19% of parents saying they planned to get the 2023-2024 vaccine for their children.

Predictions, Mitigation

While some experts say a peak due to JN.1 is expected in the weeks ahead, Dr. Topol said it’s impossible to predict exactly how JN.1 will play out.

“It’s not going to be a repeat of November 2021,” when Omicron surfaced, Dr. Rajnarayanan predicted. Within 4 weeks of the World Health Organization declaring Omicron as a virus of concern, it spread around the world.

Mitigation measures can help, Dr. Rajnarayanan said. He suggested:

Get the new vaccine, and especially encourage vulnerable family and friends to do so.

If you are gathering inside for holiday festivities, improve circulation in the house, if possible.

Wear masks in airports and on planes and other public transportation.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

No one planning holiday gatherings or travel wants to hear this, but the rise of a new COVID-19 variant, JN.1, is concerning experts, who say it may threaten those good times.

The good news is recent research suggests the 2023-2024 COVID-19 vaccine appears to work against this newest variant. But so few people have gotten the latest vaccine — less than 16% of U.S. adults — that some experts suggest it’s time for the CDC to urge the public who haven’t it to do so now, so the antibodies can kick in before the festivities.

“A significant wave [of JN.1] has started here and could be blunted with a high booster rate and mitigation measures,” said Eric Topol, MD, professor and executive vice president of Scripps Research in La Jolla, CA, and editor-in-chief of Medscape, a sister site of this news organization.

COVID metrics, meanwhile, have started to climb again. Nearly 10,000 people were hospitalized for COVID in the U.S. for the week ending Nov. 25, the CDC said, a 10% increase over the previous week.

Who’s Who in the Family Tree

JN.1, an Omicron subvariant, was first detected in the U.S. in September and is termed “a notable descendent lineage” of Omicron subvariant BA.2.86 by the World Health Organization. When BA.2.86, also known as Pirola, was first identified in August, it appeared very different from other variants, the CDC said. That triggered concerns it might be more infectious than previous ones, even for people with immunity from vaccination and previous infections.

“JN.1 is Pirola’s kid,” said Rajendram Rajnarayanan, PhD, assistant dean of research and associate professor at the New York Institute of Technology at Arkansas State University, who maintains a COVID-19 variant database. The variant BA.2.86 and offspring are worrisome due to the mutations, he said.

How Widespread Is JN.1?

As of Nov. 27, the CDC says, BA.2.86 is projected to comprise 5%-15% of circulating variants in the U.S. “The expected public health risk of this variant, including its offshoot JN.1, is low,” the agency said.

Currently, JN.1 is reported more often in Europe, Dr. Rajnarayanan said, but some countries have better reporting data than others. “It has probably spread to every country tracking COVID,’’ he said, due to the mutations in the spike protein that make it easier for it to bind and infect.

Wastewater data suggest the variant’s rise is helping to fuel a wave, Dr. Topol said.

Vaccine Effectiveness Against JN.1, Other New Variants

The new XBB.1.5 monovalent vaccine, protects against XBB.1.5, another Omicron subvariant, but also JN.1 and other “emergent” viruses, a team of researchers reported Nov. 26 in a study on bioRxiv that has not yet been certified by peer review.

The updated vaccine, when given to uninfected people, boosted antibodies about 27-fold against XBB.1.5 and about 13- to 27-fold against JN.1 and other emergent viruses, the researchers reported.

While even primary doses of the COVID vaccine will likely help protect against the new JN.1 subvariant, “if you got the XBB.1.5 booster, it is going to be protecting you better against this new variant,” Dr. Rajnarayanan said.

2023-2024 Vaccine Uptake Low

In November, the CDC posted the first detailed estimates of who did. As of Nov. 18, less than 16% of U.S. adults had, with nearly 15% saying they planned to get it.

Coverage among children is lower, with just 6.3% of children up to date on the newest vaccine and 19% of parents saying they planned to get the 2023-2024 vaccine for their children.

Predictions, Mitigation

While some experts say a peak due to JN.1 is expected in the weeks ahead, Dr. Topol said it’s impossible to predict exactly how JN.1 will play out.

“It’s not going to be a repeat of November 2021,” when Omicron surfaced, Dr. Rajnarayanan predicted. Within 4 weeks of the World Health Organization declaring Omicron as a virus of concern, it spread around the world.

Mitigation measures can help, Dr. Rajnarayanan said. He suggested:

Get the new vaccine, and especially encourage vulnerable family and friends to do so.

If you are gathering inside for holiday festivities, improve circulation in the house, if possible.

Wear masks in airports and on planes and other public transportation.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

No one planning holiday gatherings or travel wants to hear this, but the rise of a new COVID-19 variant, JN.1, is concerning experts, who say it may threaten those good times.

The good news is recent research suggests the 2023-2024 COVID-19 vaccine appears to work against this newest variant. But so few people have gotten the latest vaccine — less than 16% of U.S. adults — that some experts suggest it’s time for the CDC to urge the public who haven’t it to do so now, so the antibodies can kick in before the festivities.

“A significant wave [of JN.1] has started here and could be blunted with a high booster rate and mitigation measures,” said Eric Topol, MD, professor and executive vice president of Scripps Research in La Jolla, CA, and editor-in-chief of Medscape, a sister site of this news organization.

COVID metrics, meanwhile, have started to climb again. Nearly 10,000 people were hospitalized for COVID in the U.S. for the week ending Nov. 25, the CDC said, a 10% increase over the previous week.

Who’s Who in the Family Tree

JN.1, an Omicron subvariant, was first detected in the U.S. in September and is termed “a notable descendent lineage” of Omicron subvariant BA.2.86 by the World Health Organization. When BA.2.86, also known as Pirola, was first identified in August, it appeared very different from other variants, the CDC said. That triggered concerns it might be more infectious than previous ones, even for people with immunity from vaccination and previous infections.

“JN.1 is Pirola’s kid,” said Rajendram Rajnarayanan, PhD, assistant dean of research and associate professor at the New York Institute of Technology at Arkansas State University, who maintains a COVID-19 variant database. The variant BA.2.86 and offspring are worrisome due to the mutations, he said.

How Widespread Is JN.1?

As of Nov. 27, the CDC says, BA.2.86 is projected to comprise 5%-15% of circulating variants in the U.S. “The expected public health risk of this variant, including its offshoot JN.1, is low,” the agency said.

Currently, JN.1 is reported more often in Europe, Dr. Rajnarayanan said, but some countries have better reporting data than others. “It has probably spread to every country tracking COVID,’’ he said, due to the mutations in the spike protein that make it easier for it to bind and infect.

Wastewater data suggest the variant’s rise is helping to fuel a wave, Dr. Topol said.

Vaccine Effectiveness Against JN.1, Other New Variants

The new XBB.1.5 monovalent vaccine, protects against XBB.1.5, another Omicron subvariant, but also JN.1 and other “emergent” viruses, a team of researchers reported Nov. 26 in a study on bioRxiv that has not yet been certified by peer review.

The updated vaccine, when given to uninfected people, boosted antibodies about 27-fold against XBB.1.5 and about 13- to 27-fold against JN.1 and other emergent viruses, the researchers reported.

While even primary doses of the COVID vaccine will likely help protect against the new JN.1 subvariant, “if you got the XBB.1.5 booster, it is going to be protecting you better against this new variant,” Dr. Rajnarayanan said.

2023-2024 Vaccine Uptake Low

In November, the CDC posted the first detailed estimates of who did. As of Nov. 18, less than 16% of U.S. adults had, with nearly 15% saying they planned to get it.

Coverage among children is lower, with just 6.3% of children up to date on the newest vaccine and 19% of parents saying they planned to get the 2023-2024 vaccine for their children.

Predictions, Mitigation

While some experts say a peak due to JN.1 is expected in the weeks ahead, Dr. Topol said it’s impossible to predict exactly how JN.1 will play out.

“It’s not going to be a repeat of November 2021,” when Omicron surfaced, Dr. Rajnarayanan predicted. Within 4 weeks of the World Health Organization declaring Omicron as a virus of concern, it spread around the world.

Mitigation measures can help, Dr. Rajnarayanan said. He suggested:

Get the new vaccine, and especially encourage vulnerable family and friends to do so.

If you are gathering inside for holiday festivities, improve circulation in the house, if possible.

Wear masks in airports and on planes and other public transportation.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

Global measles deaths increased by 43% in 2022

The number of total reported cases rose by 18% over the same period, accounting for approximately 9 million cases and 136,000 deaths globally, mostly among children. This information comes from a new report by the World Health Organization (WHO), published in partnership with the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

More Measles Outbreaks

The report also notes an increase in the number of countries experiencing significant measles outbreaks. There were 37 such countries in 2022, compared with 22 the previous year. The most affected continents were Africa and Asia.

“The rise in measles outbreaks and deaths is impressive but, unfortunately, not surprising, given the decline in vaccination rates in recent years,” said John Vertefeuille, PhD, director of the CDC’s Global Immunization Division.

Vertefeuille emphasized that measles cases anywhere in the world pose a risk to “countries and communities where people are undervaccinated.” In recent years, several regions have fallen short of their immunization targets.

Vaccination Trends

In 2022, there was a slight increase in measles vaccination after a decline exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on global healthcare systems. However, 33 million children did not receive at least one dose of the vaccine last year: 22 million missed the first dose, and 11 million missed the second.

For communities to be considered protected against outbreaks, immunization coverage with the full vaccine cycle should be at least 95%. The global coverage rate for the first dose was 83%, and for the second, it was 74%.

Nevertheless, immunization recovery has not reached the poorest countries, where the immunization rate stands at 66%. Brazil is among the top 10 countries where more children missed the first dose in 2022. These nations account for over half of the 22 million unadministered vaccines. According to the report, half a million children did not receive the vaccine in Brazil.

Measles in Brazil

Brazil’s results highlight setbacks in vaccination efforts. In 2016, the country was certified to have eliminated measles, but after experiencing outbreaks in 2018, the certification was lost in 2019. In 2018, Brazil confirmed 9325 cases. The situation worsened in 2019 with 20,901 diagnoses. Since then, numbers have been decreasing: 8100 in 2020, 676 in 2021, and 44 in 2022.

Last year, four Brazilian states reported confirmed virus cases: Rio de Janeiro, Pará, São Paulo, and Amapá. Ministry of Health data indicated no confirmed measles cases in Brazil as of June 15, 2023.

Vaccination in Brazil

Vaccination coverage in Brazil, which once reached 95%, has sharply declined in recent years. The rate of patients receiving the full immunization scheme was 59% in 2021.

Globally, although the COVID-19 pandemic affected measles vaccination, measures like social isolation and mask use potentially contributed to reducing measles cases. The incidence of the disease decreased in 2020 and 2021 but is now rising again.

“From 2021 to 2022, reported measles cases increased by 67% worldwide, and the number of countries experiencing large or disruptive outbreaks increased by 68%,” the report stated.

Because of these data, the WHO and the CDC urge increased efforts for vaccination, along with improvements in epidemiological surveillance systems, especially in developing nations. “Children everywhere have the right to be protected by the lifesaving measles vaccine, no matter where they live,” said Kate O’Brien, MD, director of immunization, vaccines, and biologicals at the WHO.

“Measles is called the virus of inequality for a good reason. It is the disease that will find and attack those who are not protected.”

This article was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition.

The number of total reported cases rose by 18% over the same period, accounting for approximately 9 million cases and 136,000 deaths globally, mostly among children. This information comes from a new report by the World Health Organization (WHO), published in partnership with the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

More Measles Outbreaks

The report also notes an increase in the number of countries experiencing significant measles outbreaks. There were 37 such countries in 2022, compared with 22 the previous year. The most affected continents were Africa and Asia.

“The rise in measles outbreaks and deaths is impressive but, unfortunately, not surprising, given the decline in vaccination rates in recent years,” said John Vertefeuille, PhD, director of the CDC’s Global Immunization Division.

Vertefeuille emphasized that measles cases anywhere in the world pose a risk to “countries and communities where people are undervaccinated.” In recent years, several regions have fallen short of their immunization targets.

Vaccination Trends

In 2022, there was a slight increase in measles vaccination after a decline exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on global healthcare systems. However, 33 million children did not receive at least one dose of the vaccine last year: 22 million missed the first dose, and 11 million missed the second.

For communities to be considered protected against outbreaks, immunization coverage with the full vaccine cycle should be at least 95%. The global coverage rate for the first dose was 83%, and for the second, it was 74%.

Nevertheless, immunization recovery has not reached the poorest countries, where the immunization rate stands at 66%. Brazil is among the top 10 countries where more children missed the first dose in 2022. These nations account for over half of the 22 million unadministered vaccines. According to the report, half a million children did not receive the vaccine in Brazil.

Measles in Brazil

Brazil’s results highlight setbacks in vaccination efforts. In 2016, the country was certified to have eliminated measles, but after experiencing outbreaks in 2018, the certification was lost in 2019. In 2018, Brazil confirmed 9325 cases. The situation worsened in 2019 with 20,901 diagnoses. Since then, numbers have been decreasing: 8100 in 2020, 676 in 2021, and 44 in 2022.

Last year, four Brazilian states reported confirmed virus cases: Rio de Janeiro, Pará, São Paulo, and Amapá. Ministry of Health data indicated no confirmed measles cases in Brazil as of June 15, 2023.

Vaccination in Brazil

Vaccination coverage in Brazil, which once reached 95%, has sharply declined in recent years. The rate of patients receiving the full immunization scheme was 59% in 2021.

Globally, although the COVID-19 pandemic affected measles vaccination, measures like social isolation and mask use potentially contributed to reducing measles cases. The incidence of the disease decreased in 2020 and 2021 but is now rising again.

“From 2021 to 2022, reported measles cases increased by 67% worldwide, and the number of countries experiencing large or disruptive outbreaks increased by 68%,” the report stated.

Because of these data, the WHO and the CDC urge increased efforts for vaccination, along with improvements in epidemiological surveillance systems, especially in developing nations. “Children everywhere have the right to be protected by the lifesaving measles vaccine, no matter where they live,” said Kate O’Brien, MD, director of immunization, vaccines, and biologicals at the WHO.

“Measles is called the virus of inequality for a good reason. It is the disease that will find and attack those who are not protected.”

This article was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition.

The number of total reported cases rose by 18% over the same period, accounting for approximately 9 million cases and 136,000 deaths globally, mostly among children. This information comes from a new report by the World Health Organization (WHO), published in partnership with the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

More Measles Outbreaks

The report also notes an increase in the number of countries experiencing significant measles outbreaks. There were 37 such countries in 2022, compared with 22 the previous year. The most affected continents were Africa and Asia.

“The rise in measles outbreaks and deaths is impressive but, unfortunately, not surprising, given the decline in vaccination rates in recent years,” said John Vertefeuille, PhD, director of the CDC’s Global Immunization Division.

Vertefeuille emphasized that measles cases anywhere in the world pose a risk to “countries and communities where people are undervaccinated.” In recent years, several regions have fallen short of their immunization targets.

Vaccination Trends

In 2022, there was a slight increase in measles vaccination after a decline exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on global healthcare systems. However, 33 million children did not receive at least one dose of the vaccine last year: 22 million missed the first dose, and 11 million missed the second.

For communities to be considered protected against outbreaks, immunization coverage with the full vaccine cycle should be at least 95%. The global coverage rate for the first dose was 83%, and for the second, it was 74%.

Nevertheless, immunization recovery has not reached the poorest countries, where the immunization rate stands at 66%. Brazil is among the top 10 countries where more children missed the first dose in 2022. These nations account for over half of the 22 million unadministered vaccines. According to the report, half a million children did not receive the vaccine in Brazil.

Measles in Brazil

Brazil’s results highlight setbacks in vaccination efforts. In 2016, the country was certified to have eliminated measles, but after experiencing outbreaks in 2018, the certification was lost in 2019. In 2018, Brazil confirmed 9325 cases. The situation worsened in 2019 with 20,901 diagnoses. Since then, numbers have been decreasing: 8100 in 2020, 676 in 2021, and 44 in 2022.

Last year, four Brazilian states reported confirmed virus cases: Rio de Janeiro, Pará, São Paulo, and Amapá. Ministry of Health data indicated no confirmed measles cases in Brazil as of June 15, 2023.

Vaccination in Brazil

Vaccination coverage in Brazil, which once reached 95%, has sharply declined in recent years. The rate of patients receiving the full immunization scheme was 59% in 2021.

Globally, although the COVID-19 pandemic affected measles vaccination, measures like social isolation and mask use potentially contributed to reducing measles cases. The incidence of the disease decreased in 2020 and 2021 but is now rising again.

“From 2021 to 2022, reported measles cases increased by 67% worldwide, and the number of countries experiencing large or disruptive outbreaks increased by 68%,” the report stated.

Because of these data, the WHO and the CDC urge increased efforts for vaccination, along with improvements in epidemiological surveillance systems, especially in developing nations. “Children everywhere have the right to be protected by the lifesaving measles vaccine, no matter where they live,” said Kate O’Brien, MD, director of immunization, vaccines, and biologicals at the WHO.

“Measles is called the virus of inequality for a good reason. It is the disease that will find and attack those who are not protected.”

This article was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition.

Are you sure your patient is alive?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Much of my research focuses on what is known as clinical decision support — prompts and messages to providers to help them make good decisions for their patients. I know that these things can be annoying, which is exactly why I study them — to figure out which ones actually help.

When I got started on this about 10 years ago, we were learning a lot about how best to message providers about their patients. My team had developed a simple alert for acute kidney injury (AKI). We knew that providers often missed the diagnosis, so maybe letting them know would improve patient outcomes.

As we tested the alert, we got feedback, and I have kept an email from an ICU doctor from those early days. It read:

Dear Dr. Wilson: Thank you for the automated alert informing me that my patient had AKI. Regrettably, the alert fired about an hour after the patient had died. I feel that the information is less than actionable at this time.

Our early system had neglected to add a conditional flag ensuring that the patient was still alive at the time it sent the alert message. A small oversight, but one that had very large implications. Future studies would show that “false positive” alerts like this seriously degrade physician confidence in the system. And why wouldn’t they?

Not knowing the vital status of a patient can have major consequences.

Health systems send messages to their patients all the time: reminders of appointments, reminders for preventive care, reminders for vaccinations, and so on.

But what if the patient being reminded has died? It’s a waste of resources, of course, but more than that, it can be painful for their families and reflects poorly on the health care system. Of all the people who should know whether someone is alive or dead, shouldn’t their doctor be at the top of the list?

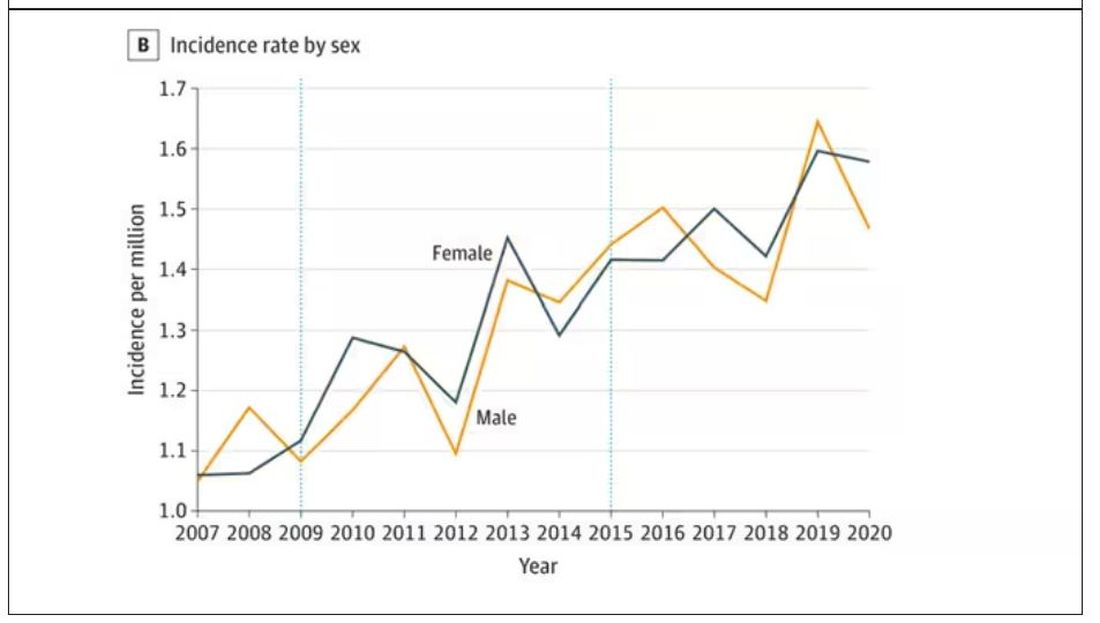

A new study in JAMA Internal Medicine quantifies this very phenomenon.

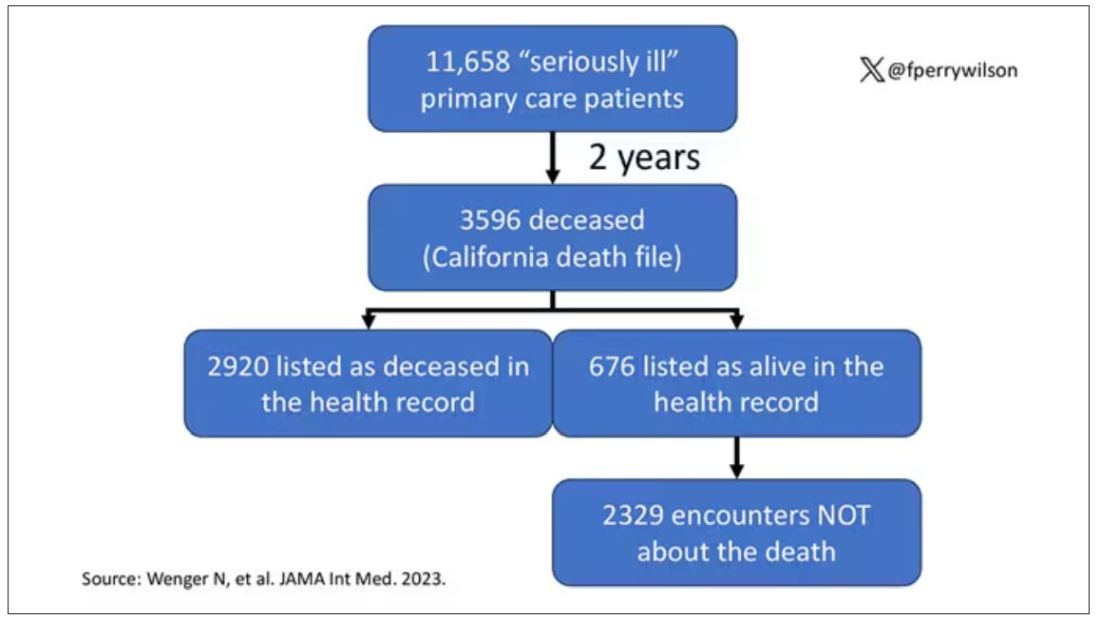

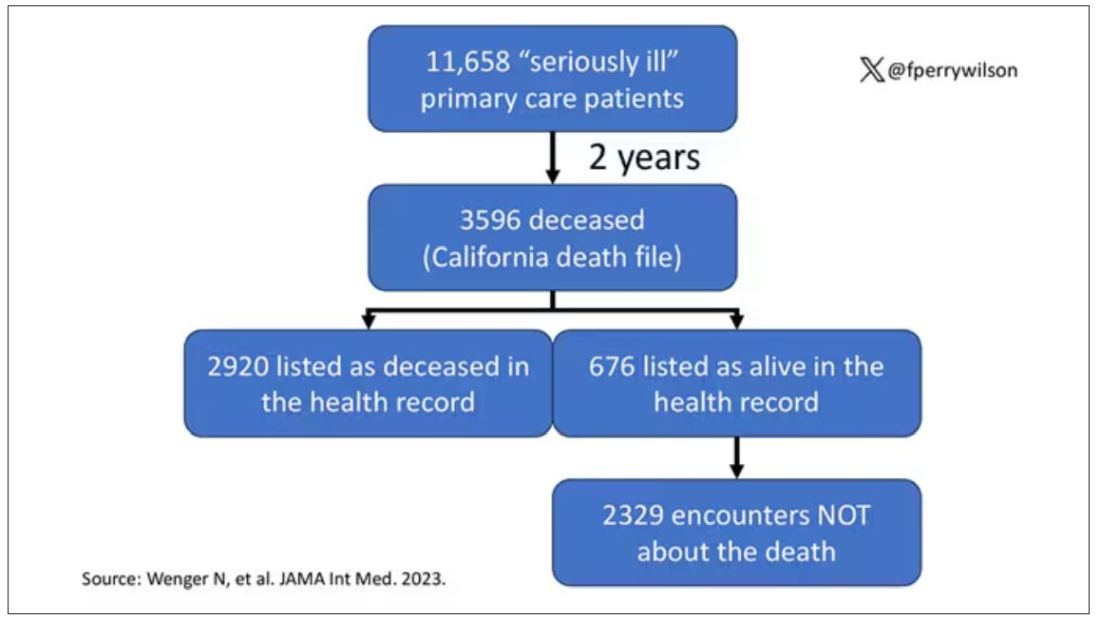

Researchers examined 11,658 primary care patients in their health system who met the criteria of being “seriously ill” and followed them for 2 years. During that period of time, 25% were recorded as deceased in the electronic health record. But 30.8% had died. That left 676 patients who had died, but were not known to have died, left in the system.

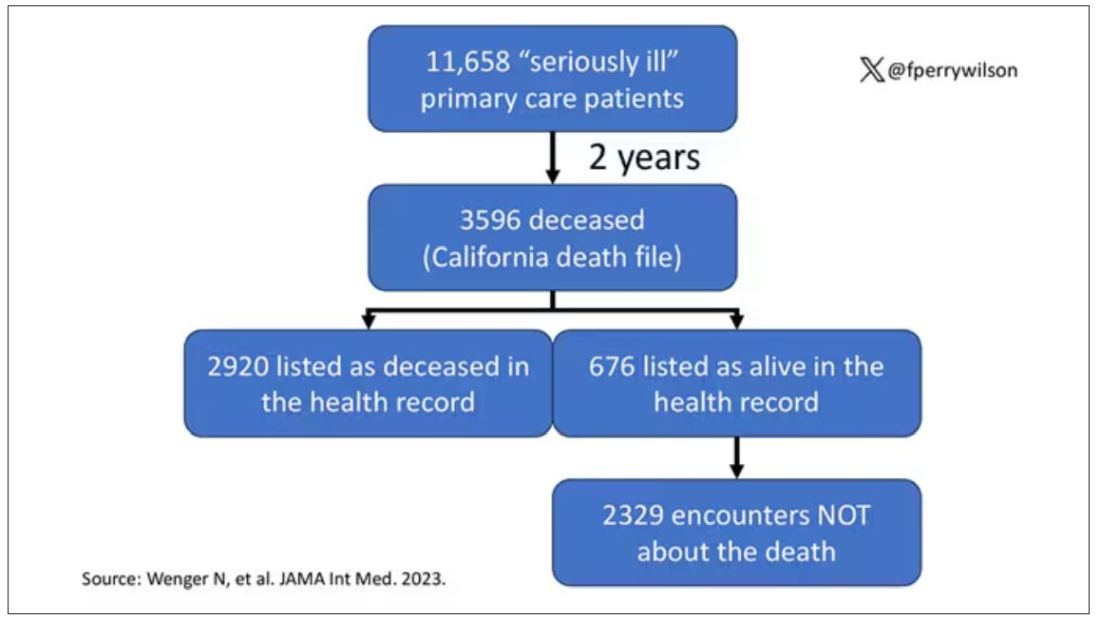

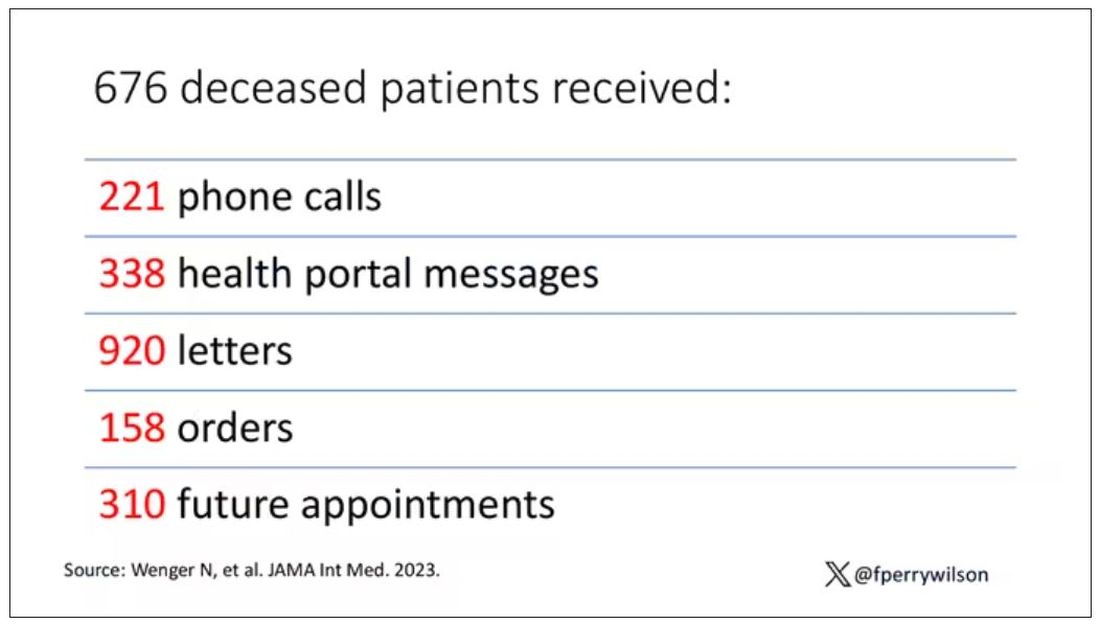

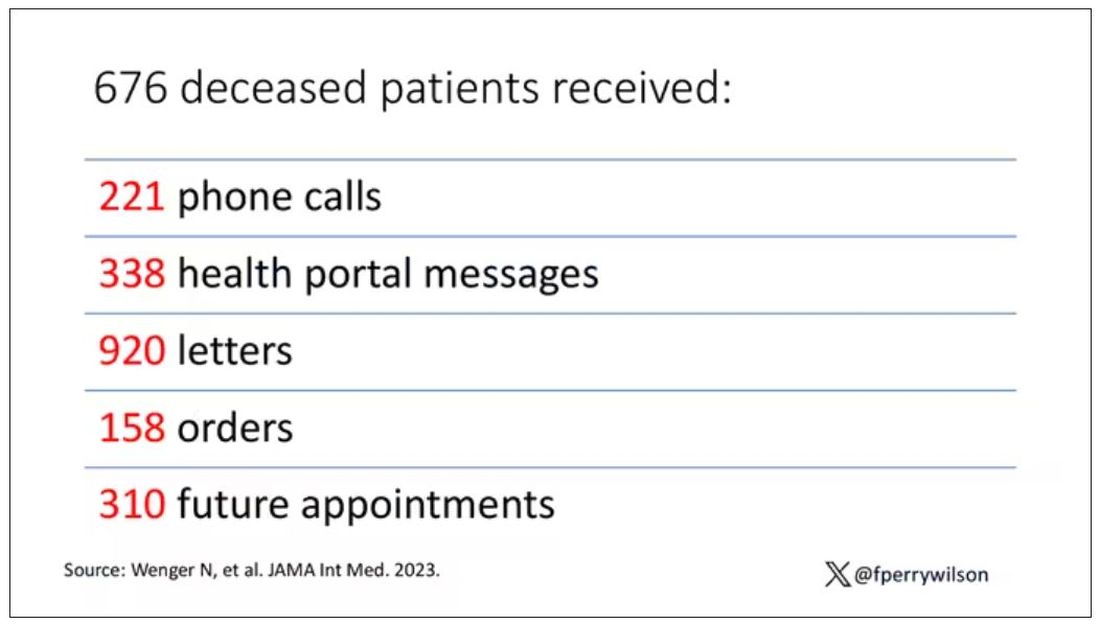

And those 676 were not left to rest in peace. They received 221 telephone and 338 health portal messages not related to death, and 920 letters reminding them about unmet primary care metrics like flu shots and cancer screening. Orders were entered into the health record for things like vaccines and routine screenings for 158 patients, and 310 future appointments — destined to be no-shows — were still on the books. One can only imagine the frustration of families checking their mail and finding yet another letter reminding their deceased loved one to get a mammogram.

How did the researchers figure out who had died? It turns out it’s not that hard. California keeps a record of all deaths in the state; they simply had to search it. Like all state death records, they tend to lag a bit so it’s not clinically terribly useful, but it works. California and most other states also have a very accurate and up-to-date death file which can only be used by law enforcement to investigate criminal activity and fraud; health care is left in the lurch.

Nationwide, there is the real-time fact of death service, supported by the National Association for Public Health Statistics and Information Systems. This allows employers to verify, in real time, whether the person applying for a job is alive. Healthcare systems are not allowed to use it.

Let’s also remember that very few people die in this country without some health care agency knowing about it and recording it. But sharing of medical information is so poor in the United States that your patient could die in a hospital one city away from you and you might not find out until you’re calling them to see why they missed a scheduled follow-up appointment.

These events — the embarrassing lack of knowledge about the very vital status of our patients — highlight a huge problem with health care in our country. The fragmented health care system is terrible at data sharing, in part because of poor protocols, in part because of unfounded concerns about patient privacy, and in part because of a tendency to hoard data that might be valuable in the future. It has to stop. We need to know how our patients are doing even when they are not sitting in front of us. When it comes to life and death, the knowledge is out there; we just can’t access it. Seems like a pretty easy fix.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com .

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Much of my research focuses on what is known as clinical decision support — prompts and messages to providers to help them make good decisions for their patients. I know that these things can be annoying, which is exactly why I study them — to figure out which ones actually help.

When I got started on this about 10 years ago, we were learning a lot about how best to message providers about their patients. My team had developed a simple alert for acute kidney injury (AKI). We knew that providers often missed the diagnosis, so maybe letting them know would improve patient outcomes.

As we tested the alert, we got feedback, and I have kept an email from an ICU doctor from those early days. It read:

Dear Dr. Wilson: Thank you for the automated alert informing me that my patient had AKI. Regrettably, the alert fired about an hour after the patient had died. I feel that the information is less than actionable at this time.

Our early system had neglected to add a conditional flag ensuring that the patient was still alive at the time it sent the alert message. A small oversight, but one that had very large implications. Future studies would show that “false positive” alerts like this seriously degrade physician confidence in the system. And why wouldn’t they?

Not knowing the vital status of a patient can have major consequences.

Health systems send messages to their patients all the time: reminders of appointments, reminders for preventive care, reminders for vaccinations, and so on.

But what if the patient being reminded has died? It’s a waste of resources, of course, but more than that, it can be painful for their families and reflects poorly on the health care system. Of all the people who should know whether someone is alive or dead, shouldn’t their doctor be at the top of the list?

A new study in JAMA Internal Medicine quantifies this very phenomenon.

Researchers examined 11,658 primary care patients in their health system who met the criteria of being “seriously ill” and followed them for 2 years. During that period of time, 25% were recorded as deceased in the electronic health record. But 30.8% had died. That left 676 patients who had died, but were not known to have died, left in the system.

And those 676 were not left to rest in peace. They received 221 telephone and 338 health portal messages not related to death, and 920 letters reminding them about unmet primary care metrics like flu shots and cancer screening. Orders were entered into the health record for things like vaccines and routine screenings for 158 patients, and 310 future appointments — destined to be no-shows — were still on the books. One can only imagine the frustration of families checking their mail and finding yet another letter reminding their deceased loved one to get a mammogram.

How did the researchers figure out who had died? It turns out it’s not that hard. California keeps a record of all deaths in the state; they simply had to search it. Like all state death records, they tend to lag a bit so it’s not clinically terribly useful, but it works. California and most other states also have a very accurate and up-to-date death file which can only be used by law enforcement to investigate criminal activity and fraud; health care is left in the lurch.

Nationwide, there is the real-time fact of death service, supported by the National Association for Public Health Statistics and Information Systems. This allows employers to verify, in real time, whether the person applying for a job is alive. Healthcare systems are not allowed to use it.

Let’s also remember that very few people die in this country without some health care agency knowing about it and recording it. But sharing of medical information is so poor in the United States that your patient could die in a hospital one city away from you and you might not find out until you’re calling them to see why they missed a scheduled follow-up appointment.

These events — the embarrassing lack of knowledge about the very vital status of our patients — highlight a huge problem with health care in our country. The fragmented health care system is terrible at data sharing, in part because of poor protocols, in part because of unfounded concerns about patient privacy, and in part because of a tendency to hoard data that might be valuable in the future. It has to stop. We need to know how our patients are doing even when they are not sitting in front of us. When it comes to life and death, the knowledge is out there; we just can’t access it. Seems like a pretty easy fix.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com .

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Much of my research focuses on what is known as clinical decision support — prompts and messages to providers to help them make good decisions for their patients. I know that these things can be annoying, which is exactly why I study them — to figure out which ones actually help.

When I got started on this about 10 years ago, we were learning a lot about how best to message providers about their patients. My team had developed a simple alert for acute kidney injury (AKI). We knew that providers often missed the diagnosis, so maybe letting them know would improve patient outcomes.

As we tested the alert, we got feedback, and I have kept an email from an ICU doctor from those early days. It read:

Dear Dr. Wilson: Thank you for the automated alert informing me that my patient had AKI. Regrettably, the alert fired about an hour after the patient had died. I feel that the information is less than actionable at this time.

Our early system had neglected to add a conditional flag ensuring that the patient was still alive at the time it sent the alert message. A small oversight, but one that had very large implications. Future studies would show that “false positive” alerts like this seriously degrade physician confidence in the system. And why wouldn’t they?

Not knowing the vital status of a patient can have major consequences.

Health systems send messages to their patients all the time: reminders of appointments, reminders for preventive care, reminders for vaccinations, and so on.

But what if the patient being reminded has died? It’s a waste of resources, of course, but more than that, it can be painful for their families and reflects poorly on the health care system. Of all the people who should know whether someone is alive or dead, shouldn’t their doctor be at the top of the list?

A new study in JAMA Internal Medicine quantifies this very phenomenon.

Researchers examined 11,658 primary care patients in their health system who met the criteria of being “seriously ill” and followed them for 2 years. During that period of time, 25% were recorded as deceased in the electronic health record. But 30.8% had died. That left 676 patients who had died, but were not known to have died, left in the system.

And those 676 were not left to rest in peace. They received 221 telephone and 338 health portal messages not related to death, and 920 letters reminding them about unmet primary care metrics like flu shots and cancer screening. Orders were entered into the health record for things like vaccines and routine screenings for 158 patients, and 310 future appointments — destined to be no-shows — were still on the books. One can only imagine the frustration of families checking their mail and finding yet another letter reminding their deceased loved one to get a mammogram.