User login

American College of Rheumatology (ACR): Annual Scientific Meeting

ACR: New Sjögren’s classification criteria on the way

SAN FRANCISCO – New classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome are ready for sign-off by the American College of Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism, Dr. Caroline Shiboski said.

“We hope this will be the last iteration of the international classification criteria that we have proposed to ACR and EULAR,” said Dr. Shiboski, professor of orofacial sciences at the University of California San Francisco School of Dentistry.

The criteria will give researchers a single set of consensus diagnostic measures for Sjögren’s syndrome, replacing both the provisional 2012 ACR criteria (Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012 Apr;64[4]:475-87) and criteria from the American-European Consensus Group, added Dr. Shiboski, who led the led the ACR steering committee that helped to create the criteria. “These criteria aim to classify clinical trial participants,” she added. “That doesn’t mean we can’t use them for diagnostic purposes, but that was not the primary purpose.”

Sjögren’s syndrome is complex, with differential diagnoses ranging from non-autoimmune sicca syndrome and IgG4-related disease to sarcoidosis, hematologic cancers, and amyloidosis, said Dr. Alan Baer, one of the clinician-experts who participated in the working group that led to the new criteria. Moreover, patients need care from rheumatologists, ophthalmologists, and oral medicine specialists to manage systemic symptoms and sequelae of sicca and xerostomia. The lack of consensus criteria has made it hard even to estimate the incidence and prevalence of the disease, researchers have noted (Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:247-55). Furthermore, some rheumatologists criticized the provisional ACR criteria for requiring a salivary gland biopsy and ophthalmologic testing, both of which are time consuming and unavailable in many practices.

The new criteria help to solve some of those problems, Dr. Shiboski and her fellow experts said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.* They add two simpler diagnostic options: the Schirmer tear test and the 5-minute salivary flow test. They also weight the various diagnostic tests, assigning 2 points each to the focus score for focal lymphocytic sialadenitis and the presence of anti–Sjögren’s syndrome antibody A; and 1 point each for a Schirmer test of 5 mm in less than 5 min, an ocular staining score of greater than 5, and salivary flow rate of less than 0.1 mL/min.

Patients need a total of 4 points for a confirmed diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome. Because diagnosis no longer requires mucosal dryness, the new criteria “are more flexible, and allow us to select patients in the earlier stages of Sjögren’s syndrome who are more likely to show improvement with treatment,” said Dr. Raphaèle Seror, a clinical rheumatologist at Hôpitaux universitaires Paris-Sud in France and a member of the EULAR Steering Committee for the criteria.

Nonetheless, the new criteria have “some recognizable limitations,” said Dr. Baer, director of the Johns Hopkins Jerome L. Greene Sjögren’s Syndrome Center in Baltimore. They are not validated for secondary or juvenile forms of Sjögren’s or for the subset of cases associated with anticentromere antibodies, he noted. They also exclude several established diagnostic tools, including CT, MRI, and sialography or scintigraphy, as well as several “emerging” tools such as parotid gland biopsy, ultrasonography, and tests for novel autoantibodies, he added.

Criteria aside, “when you go into the clinic, it’s important that you do a complete evaluation of the patient who comes to you complaining of dry eyes and a dry mouth,” Dr. Baer emphasized. “The way you ask these questions is really important. Look for daily, persistent, dry eyes and dry mouth.”

Diagnostic tests for Sjögren’s syndrome are imperfect, so clinicians should interpret them carefully. The Schirmer tear test is relatively unreliable and insensitive, and its values normally decline in older patients. Ocular surface staining results also are nonspecific and prone to inconsistent interpretation, according to Dr. Baer. The single most reliable test is a labial gland biopsy with a focus score of 1 or higher, meaning that a 4 mm2 area has at least one cluster of at least 50 lymphocytes adjacent to salivary gland acini, he said.

To draft the criteria, Dr. Shiboski and her colleagues used 1000Minds decision-making software to show 55 experts dozens of fictive clinical vignettes. For each vignette, the experts were asked to use the existing ACR criteria to determine whether or not the patient had Sjögren’s syndrome; they also could say that they were unsure. Analyzing the vignettes on which experts’ agreed approach yielded a set of draft diagnostic criteria, which were then tested among 1,200 real-life patients with Sjögren’s from the real-life Sjögren’s International Collaborative Clinical Alliance (SICCA), Paris-Sud, and Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation (OMRF) cohorts, Dr. Shiboski said. Specificity received double the weight of sensitivity, because “in clinical trials, you want specificity to be as high as possible,” she added.

The National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, the Phileona Foundation, and the Sjögren’s Syndrome Foundation helped fund the SICCA and OMRF cohort studies on which the criteria were based. Dr. Shiboski and Dr. Seror had no disclosures. Dr. Baer reported having been a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb and Glenmark Pharmaceuticals.

* Correction, 11/17/15: Dr. Shiboski's gender was previously misstated.

SAN FRANCISCO – New classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome are ready for sign-off by the American College of Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism, Dr. Caroline Shiboski said.

“We hope this will be the last iteration of the international classification criteria that we have proposed to ACR and EULAR,” said Dr. Shiboski, professor of orofacial sciences at the University of California San Francisco School of Dentistry.

The criteria will give researchers a single set of consensus diagnostic measures for Sjögren’s syndrome, replacing both the provisional 2012 ACR criteria (Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012 Apr;64[4]:475-87) and criteria from the American-European Consensus Group, added Dr. Shiboski, who led the led the ACR steering committee that helped to create the criteria. “These criteria aim to classify clinical trial participants,” she added. “That doesn’t mean we can’t use them for diagnostic purposes, but that was not the primary purpose.”

Sjögren’s syndrome is complex, with differential diagnoses ranging from non-autoimmune sicca syndrome and IgG4-related disease to sarcoidosis, hematologic cancers, and amyloidosis, said Dr. Alan Baer, one of the clinician-experts who participated in the working group that led to the new criteria. Moreover, patients need care from rheumatologists, ophthalmologists, and oral medicine specialists to manage systemic symptoms and sequelae of sicca and xerostomia. The lack of consensus criteria has made it hard even to estimate the incidence and prevalence of the disease, researchers have noted (Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:247-55). Furthermore, some rheumatologists criticized the provisional ACR criteria for requiring a salivary gland biopsy and ophthalmologic testing, both of which are time consuming and unavailable in many practices.

The new criteria help to solve some of those problems, Dr. Shiboski and her fellow experts said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.* They add two simpler diagnostic options: the Schirmer tear test and the 5-minute salivary flow test. They also weight the various diagnostic tests, assigning 2 points each to the focus score for focal lymphocytic sialadenitis and the presence of anti–Sjögren’s syndrome antibody A; and 1 point each for a Schirmer test of 5 mm in less than 5 min, an ocular staining score of greater than 5, and salivary flow rate of less than 0.1 mL/min.

Patients need a total of 4 points for a confirmed diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome. Because diagnosis no longer requires mucosal dryness, the new criteria “are more flexible, and allow us to select patients in the earlier stages of Sjögren’s syndrome who are more likely to show improvement with treatment,” said Dr. Raphaèle Seror, a clinical rheumatologist at Hôpitaux universitaires Paris-Sud in France and a member of the EULAR Steering Committee for the criteria.

Nonetheless, the new criteria have “some recognizable limitations,” said Dr. Baer, director of the Johns Hopkins Jerome L. Greene Sjögren’s Syndrome Center in Baltimore. They are not validated for secondary or juvenile forms of Sjögren’s or for the subset of cases associated with anticentromere antibodies, he noted. They also exclude several established diagnostic tools, including CT, MRI, and sialography or scintigraphy, as well as several “emerging” tools such as parotid gland biopsy, ultrasonography, and tests for novel autoantibodies, he added.

Criteria aside, “when you go into the clinic, it’s important that you do a complete evaluation of the patient who comes to you complaining of dry eyes and a dry mouth,” Dr. Baer emphasized. “The way you ask these questions is really important. Look for daily, persistent, dry eyes and dry mouth.”

Diagnostic tests for Sjögren’s syndrome are imperfect, so clinicians should interpret them carefully. The Schirmer tear test is relatively unreliable and insensitive, and its values normally decline in older patients. Ocular surface staining results also are nonspecific and prone to inconsistent interpretation, according to Dr. Baer. The single most reliable test is a labial gland biopsy with a focus score of 1 or higher, meaning that a 4 mm2 area has at least one cluster of at least 50 lymphocytes adjacent to salivary gland acini, he said.

To draft the criteria, Dr. Shiboski and her colleagues used 1000Minds decision-making software to show 55 experts dozens of fictive clinical vignettes. For each vignette, the experts were asked to use the existing ACR criteria to determine whether or not the patient had Sjögren’s syndrome; they also could say that they were unsure. Analyzing the vignettes on which experts’ agreed approach yielded a set of draft diagnostic criteria, which were then tested among 1,200 real-life patients with Sjögren’s from the real-life Sjögren’s International Collaborative Clinical Alliance (SICCA), Paris-Sud, and Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation (OMRF) cohorts, Dr. Shiboski said. Specificity received double the weight of sensitivity, because “in clinical trials, you want specificity to be as high as possible,” she added.

The National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, the Phileona Foundation, and the Sjögren’s Syndrome Foundation helped fund the SICCA and OMRF cohort studies on which the criteria were based. Dr. Shiboski and Dr. Seror had no disclosures. Dr. Baer reported having been a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb and Glenmark Pharmaceuticals.

* Correction, 11/17/15: Dr. Shiboski's gender was previously misstated.

SAN FRANCISCO – New classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome are ready for sign-off by the American College of Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism, Dr. Caroline Shiboski said.

“We hope this will be the last iteration of the international classification criteria that we have proposed to ACR and EULAR,” said Dr. Shiboski, professor of orofacial sciences at the University of California San Francisco School of Dentistry.

The criteria will give researchers a single set of consensus diagnostic measures for Sjögren’s syndrome, replacing both the provisional 2012 ACR criteria (Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012 Apr;64[4]:475-87) and criteria from the American-European Consensus Group, added Dr. Shiboski, who led the led the ACR steering committee that helped to create the criteria. “These criteria aim to classify clinical trial participants,” she added. “That doesn’t mean we can’t use them for diagnostic purposes, but that was not the primary purpose.”

Sjögren’s syndrome is complex, with differential diagnoses ranging from non-autoimmune sicca syndrome and IgG4-related disease to sarcoidosis, hematologic cancers, and amyloidosis, said Dr. Alan Baer, one of the clinician-experts who participated in the working group that led to the new criteria. Moreover, patients need care from rheumatologists, ophthalmologists, and oral medicine specialists to manage systemic symptoms and sequelae of sicca and xerostomia. The lack of consensus criteria has made it hard even to estimate the incidence and prevalence of the disease, researchers have noted (Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:247-55). Furthermore, some rheumatologists criticized the provisional ACR criteria for requiring a salivary gland biopsy and ophthalmologic testing, both of which are time consuming and unavailable in many practices.

The new criteria help to solve some of those problems, Dr. Shiboski and her fellow experts said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.* They add two simpler diagnostic options: the Schirmer tear test and the 5-minute salivary flow test. They also weight the various diagnostic tests, assigning 2 points each to the focus score for focal lymphocytic sialadenitis and the presence of anti–Sjögren’s syndrome antibody A; and 1 point each for a Schirmer test of 5 mm in less than 5 min, an ocular staining score of greater than 5, and salivary flow rate of less than 0.1 mL/min.

Patients need a total of 4 points for a confirmed diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome. Because diagnosis no longer requires mucosal dryness, the new criteria “are more flexible, and allow us to select patients in the earlier stages of Sjögren’s syndrome who are more likely to show improvement with treatment,” said Dr. Raphaèle Seror, a clinical rheumatologist at Hôpitaux universitaires Paris-Sud in France and a member of the EULAR Steering Committee for the criteria.

Nonetheless, the new criteria have “some recognizable limitations,” said Dr. Baer, director of the Johns Hopkins Jerome L. Greene Sjögren’s Syndrome Center in Baltimore. They are not validated for secondary or juvenile forms of Sjögren’s or for the subset of cases associated with anticentromere antibodies, he noted. They also exclude several established diagnostic tools, including CT, MRI, and sialography or scintigraphy, as well as several “emerging” tools such as parotid gland biopsy, ultrasonography, and tests for novel autoantibodies, he added.

Criteria aside, “when you go into the clinic, it’s important that you do a complete evaluation of the patient who comes to you complaining of dry eyes and a dry mouth,” Dr. Baer emphasized. “The way you ask these questions is really important. Look for daily, persistent, dry eyes and dry mouth.”

Diagnostic tests for Sjögren’s syndrome are imperfect, so clinicians should interpret them carefully. The Schirmer tear test is relatively unreliable and insensitive, and its values normally decline in older patients. Ocular surface staining results also are nonspecific and prone to inconsistent interpretation, according to Dr. Baer. The single most reliable test is a labial gland biopsy with a focus score of 1 or higher, meaning that a 4 mm2 area has at least one cluster of at least 50 lymphocytes adjacent to salivary gland acini, he said.

To draft the criteria, Dr. Shiboski and her colleagues used 1000Minds decision-making software to show 55 experts dozens of fictive clinical vignettes. For each vignette, the experts were asked to use the existing ACR criteria to determine whether or not the patient had Sjögren’s syndrome; they also could say that they were unsure. Analyzing the vignettes on which experts’ agreed approach yielded a set of draft diagnostic criteria, which were then tested among 1,200 real-life patients with Sjögren’s from the real-life Sjögren’s International Collaborative Clinical Alliance (SICCA), Paris-Sud, and Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation (OMRF) cohorts, Dr. Shiboski said. Specificity received double the weight of sensitivity, because “in clinical trials, you want specificity to be as high as possible,” she added.

The National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, the Phileona Foundation, and the Sjögren’s Syndrome Foundation helped fund the SICCA and OMRF cohort studies on which the criteria were based. Dr. Shiboski and Dr. Seror had no disclosures. Dr. Baer reported having been a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb and Glenmark Pharmaceuticals.

* Correction, 11/17/15: Dr. Shiboski's gender was previously misstated.

AT THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

ACR: Mortality gap narrows between RA patients and general population

SAN FRANCISCO – Two population-based studies provide encouraging evidence that mortality, particularly cardiovascular mortality, is declining in people with rheumatoid arthritis.

The first study – conducted in British Columbia – showed that people diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) during 2001-2006 had a lower risk of death, compared with the general population, than did those diagnosed during 1996-2000. The second study focused on cardiovascular death and also found declining death rates in people diagnosed with RA since 2000, compared with RA patients in previous decades.

Both studies suggest that improved detection and management of RA and improved vigilance in screening and managing cardiovascular disease risk factors have contributed to this decline. The studies were presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Canadian study

“The take-home message from our study is that with improved treatments and better ability to control inflammation in patients with RA, we are closing the mortality gap between RA patients and the general population. This is a reassuring message for patients and clinicians,” said lead investigator Dr. Diane Lacaille of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

It has been recognized for decades that risk of death is higher in people with RA than in the general population, mainly due to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular death, she noted.

“We have improved RA therapies to attack inflammation, and cardiovascular disease is also linked to inflammation, so we would expect improved mortality along with better treatments,” she continued.

The study compared two cohorts of RA patients with age- and gender-matched controls from the general population: early, those diagnosed with RA during 1996-2000, and late, those diagnosed during 2001-2006. All study subjects were followed from the onset of RA until death or for 5 years.

The entire RA cohort included almost 25,000 people, two thirds of them women, with a mean age of onset of 57 years.

Over the entire 10 years, there was about a 30% increased risk of death from cardiovascular disease, cancer, and infections in people with RA. The mortality was 24.43 per 1,000 person-years in RA participants versus 18.77 deaths per 1,000 person-years in controls, respectively.

When the late cohort of RA patients and controls were compared, the risk of death improved over time, whereas this was not the case in the early cohort. In the early cohort, there was a 64% increase in all-cause mortality, compared with controls. In the late cohort, there was no significant increase in risk of death in RA patients, compared with controls.

RA patients had a 66% increase in cardiovascular disease deaths when compared against controls in the early cohort, but there was no statistically significant increase in the comparison for the late cohort.

Overall, comparisons against controls showed that mortality in the late cohort improved significantly for cardiovascular disease and cancer, but not for infection. Dr. Lacaille speculated that there were too few cases of death due to infection to achieve significance.

“I should caution you that follow-up of 5 years is too short to conclude that there is no increased risk, but we can say that the gap is narrowing,” Dr. Lacaille concluded.

Focus on cardiovascular death

A second study looked for trends among 315 people diagnosed with RA during 2000-2007, 498 people diagnosed with RA in earlier years, and 813 controls without the disease. Participants were followed until death, or until they moved out of the region, or Jan. 1, 2014. These investigators found a decline since 2000 in cardiovascular deaths in people with RA, compared with RA patients in earlier years and controls.

“The implications of our study appear to be broad, that is, there is a beneficial trend in cardiovascular death rates in recent years. We don’t know for sure what factors are causative, but we can assume that improved and more aggressive screening and treatment, as well as being more vigilant about the management of cardiovascular disease in our patients might play a role. This study represents an important step forward and potentially the dawn of a new era in cardiovascular disease management in patients with RA,” said lead investigator Dr. Elena Myasoedova of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“Although the link between RA and cardiovascular disease is well established, the trends in recent years are not well characterized. We aimed to address this in our study,” she explained.

The database included adult patients older than 18 years diagnosed with incident RA during 2000-2007 and patients diagnosed with RA in the 1990s. RA diagnosis was based on 1997 ACR criteria.

They found a 57% decrease in the overall cardiovascular death rate in patients with RA onset in 2000-2007, compared with the earlier RA cohort. The improvement in deaths from myocardial infarction (coronary heart disease deaths) was particularly striking – an 80% decline in the most recent cohort versus the earlier cohort. Furthermore, the 10-year overall cardiovascular mortality and coronary heart disease mortality in those diagnosed during 2000-2007 did not differ from that of non-RA subjects, which was not observed in RA patients diagnosed in prior decades.

“We observed that cardiovascular disease deaths in patients with recent onset RA is now similar to that of the general population. This suggests that the gap in cardiovascular disease is closing, which has not been reported before,” she stated.

Both investigators emphasized the importance of screening RA patients for cardiovascular morbidity and for managing cardiovascular risk factors.

Dr. Lacaille and Dr. Myasoedova had no financial disclosures. Dr. Myasoedova’s study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

SAN FRANCISCO – Two population-based studies provide encouraging evidence that mortality, particularly cardiovascular mortality, is declining in people with rheumatoid arthritis.

The first study – conducted in British Columbia – showed that people diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) during 2001-2006 had a lower risk of death, compared with the general population, than did those diagnosed during 1996-2000. The second study focused on cardiovascular death and also found declining death rates in people diagnosed with RA since 2000, compared with RA patients in previous decades.

Both studies suggest that improved detection and management of RA and improved vigilance in screening and managing cardiovascular disease risk factors have contributed to this decline. The studies were presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Canadian study

“The take-home message from our study is that with improved treatments and better ability to control inflammation in patients with RA, we are closing the mortality gap between RA patients and the general population. This is a reassuring message for patients and clinicians,” said lead investigator Dr. Diane Lacaille of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

It has been recognized for decades that risk of death is higher in people with RA than in the general population, mainly due to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular death, she noted.

“We have improved RA therapies to attack inflammation, and cardiovascular disease is also linked to inflammation, so we would expect improved mortality along with better treatments,” she continued.

The study compared two cohorts of RA patients with age- and gender-matched controls from the general population: early, those diagnosed with RA during 1996-2000, and late, those diagnosed during 2001-2006. All study subjects were followed from the onset of RA until death or for 5 years.

The entire RA cohort included almost 25,000 people, two thirds of them women, with a mean age of onset of 57 years.

Over the entire 10 years, there was about a 30% increased risk of death from cardiovascular disease, cancer, and infections in people with RA. The mortality was 24.43 per 1,000 person-years in RA participants versus 18.77 deaths per 1,000 person-years in controls, respectively.

When the late cohort of RA patients and controls were compared, the risk of death improved over time, whereas this was not the case in the early cohort. In the early cohort, there was a 64% increase in all-cause mortality, compared with controls. In the late cohort, there was no significant increase in risk of death in RA patients, compared with controls.

RA patients had a 66% increase in cardiovascular disease deaths when compared against controls in the early cohort, but there was no statistically significant increase in the comparison for the late cohort.

Overall, comparisons against controls showed that mortality in the late cohort improved significantly for cardiovascular disease and cancer, but not for infection. Dr. Lacaille speculated that there were too few cases of death due to infection to achieve significance.

“I should caution you that follow-up of 5 years is too short to conclude that there is no increased risk, but we can say that the gap is narrowing,” Dr. Lacaille concluded.

Focus on cardiovascular death

A second study looked for trends among 315 people diagnosed with RA during 2000-2007, 498 people diagnosed with RA in earlier years, and 813 controls without the disease. Participants were followed until death, or until they moved out of the region, or Jan. 1, 2014. These investigators found a decline since 2000 in cardiovascular deaths in people with RA, compared with RA patients in earlier years and controls.

“The implications of our study appear to be broad, that is, there is a beneficial trend in cardiovascular death rates in recent years. We don’t know for sure what factors are causative, but we can assume that improved and more aggressive screening and treatment, as well as being more vigilant about the management of cardiovascular disease in our patients might play a role. This study represents an important step forward and potentially the dawn of a new era in cardiovascular disease management in patients with RA,” said lead investigator Dr. Elena Myasoedova of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“Although the link between RA and cardiovascular disease is well established, the trends in recent years are not well characterized. We aimed to address this in our study,” she explained.

The database included adult patients older than 18 years diagnosed with incident RA during 2000-2007 and patients diagnosed with RA in the 1990s. RA diagnosis was based on 1997 ACR criteria.

They found a 57% decrease in the overall cardiovascular death rate in patients with RA onset in 2000-2007, compared with the earlier RA cohort. The improvement in deaths from myocardial infarction (coronary heart disease deaths) was particularly striking – an 80% decline in the most recent cohort versus the earlier cohort. Furthermore, the 10-year overall cardiovascular mortality and coronary heart disease mortality in those diagnosed during 2000-2007 did not differ from that of non-RA subjects, which was not observed in RA patients diagnosed in prior decades.

“We observed that cardiovascular disease deaths in patients with recent onset RA is now similar to that of the general population. This suggests that the gap in cardiovascular disease is closing, which has not been reported before,” she stated.

Both investigators emphasized the importance of screening RA patients for cardiovascular morbidity and for managing cardiovascular risk factors.

Dr. Lacaille and Dr. Myasoedova had no financial disclosures. Dr. Myasoedova’s study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

SAN FRANCISCO – Two population-based studies provide encouraging evidence that mortality, particularly cardiovascular mortality, is declining in people with rheumatoid arthritis.

The first study – conducted in British Columbia – showed that people diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) during 2001-2006 had a lower risk of death, compared with the general population, than did those diagnosed during 1996-2000. The second study focused on cardiovascular death and also found declining death rates in people diagnosed with RA since 2000, compared with RA patients in previous decades.

Both studies suggest that improved detection and management of RA and improved vigilance in screening and managing cardiovascular disease risk factors have contributed to this decline. The studies were presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Canadian study

“The take-home message from our study is that with improved treatments and better ability to control inflammation in patients with RA, we are closing the mortality gap between RA patients and the general population. This is a reassuring message for patients and clinicians,” said lead investigator Dr. Diane Lacaille of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

It has been recognized for decades that risk of death is higher in people with RA than in the general population, mainly due to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular death, she noted.

“We have improved RA therapies to attack inflammation, and cardiovascular disease is also linked to inflammation, so we would expect improved mortality along with better treatments,” she continued.

The study compared two cohorts of RA patients with age- and gender-matched controls from the general population: early, those diagnosed with RA during 1996-2000, and late, those diagnosed during 2001-2006. All study subjects were followed from the onset of RA until death or for 5 years.

The entire RA cohort included almost 25,000 people, two thirds of them women, with a mean age of onset of 57 years.

Over the entire 10 years, there was about a 30% increased risk of death from cardiovascular disease, cancer, and infections in people with RA. The mortality was 24.43 per 1,000 person-years in RA participants versus 18.77 deaths per 1,000 person-years in controls, respectively.

When the late cohort of RA patients and controls were compared, the risk of death improved over time, whereas this was not the case in the early cohort. In the early cohort, there was a 64% increase in all-cause mortality, compared with controls. In the late cohort, there was no significant increase in risk of death in RA patients, compared with controls.

RA patients had a 66% increase in cardiovascular disease deaths when compared against controls in the early cohort, but there was no statistically significant increase in the comparison for the late cohort.

Overall, comparisons against controls showed that mortality in the late cohort improved significantly for cardiovascular disease and cancer, but not for infection. Dr. Lacaille speculated that there were too few cases of death due to infection to achieve significance.

“I should caution you that follow-up of 5 years is too short to conclude that there is no increased risk, but we can say that the gap is narrowing,” Dr. Lacaille concluded.

Focus on cardiovascular death

A second study looked for trends among 315 people diagnosed with RA during 2000-2007, 498 people diagnosed with RA in earlier years, and 813 controls without the disease. Participants were followed until death, or until they moved out of the region, or Jan. 1, 2014. These investigators found a decline since 2000 in cardiovascular deaths in people with RA, compared with RA patients in earlier years and controls.

“The implications of our study appear to be broad, that is, there is a beneficial trend in cardiovascular death rates in recent years. We don’t know for sure what factors are causative, but we can assume that improved and more aggressive screening and treatment, as well as being more vigilant about the management of cardiovascular disease in our patients might play a role. This study represents an important step forward and potentially the dawn of a new era in cardiovascular disease management in patients with RA,” said lead investigator Dr. Elena Myasoedova of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“Although the link between RA and cardiovascular disease is well established, the trends in recent years are not well characterized. We aimed to address this in our study,” she explained.

The database included adult patients older than 18 years diagnosed with incident RA during 2000-2007 and patients diagnosed with RA in the 1990s. RA diagnosis was based on 1997 ACR criteria.

They found a 57% decrease in the overall cardiovascular death rate in patients with RA onset in 2000-2007, compared with the earlier RA cohort. The improvement in deaths from myocardial infarction (coronary heart disease deaths) was particularly striking – an 80% decline in the most recent cohort versus the earlier cohort. Furthermore, the 10-year overall cardiovascular mortality and coronary heart disease mortality in those diagnosed during 2000-2007 did not differ from that of non-RA subjects, which was not observed in RA patients diagnosed in prior decades.

“We observed that cardiovascular disease deaths in patients with recent onset RA is now similar to that of the general population. This suggests that the gap in cardiovascular disease is closing, which has not been reported before,” she stated.

Both investigators emphasized the importance of screening RA patients for cardiovascular morbidity and for managing cardiovascular risk factors.

Dr. Lacaille and Dr. Myasoedova had no financial disclosures. Dr. Myasoedova’s study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

AT THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Mortality, particularly for cardiovascular disease, declined in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the early to mid-2000s, compared with earlier periods.

Major finding: In patients diagnosed with RA during 2001-2006, there was no increased risk of all-cause mortality, compared with controls, and only a slightly increased risk in cardiovascular disease–related deaths. In a separate study, a 57% decline in the cardiovascular death rate and an 80% decline in deaths due to myocardial infarction were observed in 2000-2007, compared with previous decades.

Data source: Two separate population-based retrospective studies.

Disclosures: Dr. Lacaille and Dr. Myasoedova had no financial disclosures. Dr. Myasoedova’s study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

VIDEO: How to handle pregnancy and breast feeding in rheumatoid arthritis

San Francisco – Should you give rheumatoid arthritis patients tumor necrosis factor blockers during pregnancy? What can you substitute for methotrexate?

And what in the world do you do about breast feeding?

“The management of rheumatoid arthritis in pregnancy seems to be evolving,” explained Dr. Megan Clowse, a specialist in rheumatology and pregnancy at Duke University, Durham, N.C. “The old strategy of just stopping all the medications and letting the woman flare and using some prednisone really doesn’t seem to actually be achieving the outcomes that we need to get.”

Dr. Clowse answered a host of pregnancy-related questions and more in a pearl-filled interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

San Francisco – Should you give rheumatoid arthritis patients tumor necrosis factor blockers during pregnancy? What can you substitute for methotrexate?

And what in the world do you do about breast feeding?

“The management of rheumatoid arthritis in pregnancy seems to be evolving,” explained Dr. Megan Clowse, a specialist in rheumatology and pregnancy at Duke University, Durham, N.C. “The old strategy of just stopping all the medications and letting the woman flare and using some prednisone really doesn’t seem to actually be achieving the outcomes that we need to get.”

Dr. Clowse answered a host of pregnancy-related questions and more in a pearl-filled interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

San Francisco – Should you give rheumatoid arthritis patients tumor necrosis factor blockers during pregnancy? What can you substitute for methotrexate?

And what in the world do you do about breast feeding?

“The management of rheumatoid arthritis in pregnancy seems to be evolving,” explained Dr. Megan Clowse, a specialist in rheumatology and pregnancy at Duke University, Durham, N.C. “The old strategy of just stopping all the medications and letting the woman flare and using some prednisone really doesn’t seem to actually be achieving the outcomes that we need to get.”

Dr. Clowse answered a host of pregnancy-related questions and more in a pearl-filled interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

VIDEO: ‘Spectacular’ results for anakinra in pericarditis

SAN FRANCISCO – Anakinra might be a life saver for recurrent idiopathic pericarditis when corticosteroids, colchicine, and NSAIDS aren’t working.

Anakinra (Kineret) seemed to end the cycle of recurrent attacks and get patients off corticosteroids in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial from Italy. The drug might even prove to be a steroid-sparing, first-line choice for children.

Investigator Dr. Antonio Brucato of Papa Giovanni XXIII Hospital in Bergamo, Italy, called the results “spectacular.” He explained why in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, and also explained exactly how and when to use anakinra for pericarditis.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN FRANCISCO – Anakinra might be a life saver for recurrent idiopathic pericarditis when corticosteroids, colchicine, and NSAIDS aren’t working.

Anakinra (Kineret) seemed to end the cycle of recurrent attacks and get patients off corticosteroids in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial from Italy. The drug might even prove to be a steroid-sparing, first-line choice for children.

Investigator Dr. Antonio Brucato of Papa Giovanni XXIII Hospital in Bergamo, Italy, called the results “spectacular.” He explained why in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, and also explained exactly how and when to use anakinra for pericarditis.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN FRANCISCO – Anakinra might be a life saver for recurrent idiopathic pericarditis when corticosteroids, colchicine, and NSAIDS aren’t working.

Anakinra (Kineret) seemed to end the cycle of recurrent attacks and get patients off corticosteroids in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial from Italy. The drug might even prove to be a steroid-sparing, first-line choice for children.

Investigator Dr. Antonio Brucato of Papa Giovanni XXIII Hospital in Bergamo, Italy, called the results “spectacular.” He explained why in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, and also explained exactly how and when to use anakinra for pericarditis.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

VIDEO: Trial points to using non-TNF biologic when first anti-TNF drug fails

SAN FRANCISCO – Rheumatoid arthritis patients who did not respond to the first tumor necrosis factor inhibitor they tried had a higher rate of good or moderate response when they switched to a non–TNF inhibitor biologic, rather than another anti-TNF agent, after 48 weeks in the first randomized trial to compare the two strategies.

The results of this French open-label study, called Rotation or Change, provides evidence to guide the choice of a second biologic in patients who fail first biologic treatment with an anti-TNF agent. The trial also confirms findings reported in observational registry studies, principal investigator Dr. Jacques-Eric Gottenberg said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

But in contrast to the main study results, a post hoc analysis suggested that a second TNF inhibitor may be just as effective as a non–TNF inhibitor biologic in patients who develop antidrug antibodies to the first TNF inhibitor, said Dr. Gottenberg of the department of rheumatology at Strasbourg (France) University Hospital.

He and his colleagues aimed to mimic what happens in daily practice by allowing participating rheumatologists at French academic medical centers to choose which drug each patient received after randomization. During 2009-2012, 292 patients were randomized to any of four TNF inhibitors (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, or infliximab) or any of three non–TNF inhibitor biologics (abatacept, rituximab, or tocilizumab). (Golimumab was not available in France when the trial began in 2009.)

At 12 weeks, 48% of participants who switched to another TNF inhibitor had good or moderate responses based on European League Against Rheumatism criteria, and this rose to 52% at 24 weeks and then dropped to 43% at 48 weeks. At those time points, good or moderate response occurred in an additional 16%-18% of participants who switched to a non–TNF inhibitor biologic: 64% at 12 weeks, 70% at 24 weeks, and 60% at 48 weeks.

In the post hoc analysis of 278 patients who were tested for antidrug antibodies, 20 patients with ADAs who had been randomized to a non–TNF targeted biologic had a response at 24 weeks that was similar to 12 patients with ADAs who had been randomized to a second TNF inhibitor.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN FRANCISCO – Rheumatoid arthritis patients who did not respond to the first tumor necrosis factor inhibitor they tried had a higher rate of good or moderate response when they switched to a non–TNF inhibitor biologic, rather than another anti-TNF agent, after 48 weeks in the first randomized trial to compare the two strategies.

The results of this French open-label study, called Rotation or Change, provides evidence to guide the choice of a second biologic in patients who fail first biologic treatment with an anti-TNF agent. The trial also confirms findings reported in observational registry studies, principal investigator Dr. Jacques-Eric Gottenberg said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

But in contrast to the main study results, a post hoc analysis suggested that a second TNF inhibitor may be just as effective as a non–TNF inhibitor biologic in patients who develop antidrug antibodies to the first TNF inhibitor, said Dr. Gottenberg of the department of rheumatology at Strasbourg (France) University Hospital.

He and his colleagues aimed to mimic what happens in daily practice by allowing participating rheumatologists at French academic medical centers to choose which drug each patient received after randomization. During 2009-2012, 292 patients were randomized to any of four TNF inhibitors (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, or infliximab) or any of three non–TNF inhibitor biologics (abatacept, rituximab, or tocilizumab). (Golimumab was not available in France when the trial began in 2009.)

At 12 weeks, 48% of participants who switched to another TNF inhibitor had good or moderate responses based on European League Against Rheumatism criteria, and this rose to 52% at 24 weeks and then dropped to 43% at 48 weeks. At those time points, good or moderate response occurred in an additional 16%-18% of participants who switched to a non–TNF inhibitor biologic: 64% at 12 weeks, 70% at 24 weeks, and 60% at 48 weeks.

In the post hoc analysis of 278 patients who were tested for antidrug antibodies, 20 patients with ADAs who had been randomized to a non–TNF targeted biologic had a response at 24 weeks that was similar to 12 patients with ADAs who had been randomized to a second TNF inhibitor.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN FRANCISCO – Rheumatoid arthritis patients who did not respond to the first tumor necrosis factor inhibitor they tried had a higher rate of good or moderate response when they switched to a non–TNF inhibitor biologic, rather than another anti-TNF agent, after 48 weeks in the first randomized trial to compare the two strategies.

The results of this French open-label study, called Rotation or Change, provides evidence to guide the choice of a second biologic in patients who fail first biologic treatment with an anti-TNF agent. The trial also confirms findings reported in observational registry studies, principal investigator Dr. Jacques-Eric Gottenberg said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

But in contrast to the main study results, a post hoc analysis suggested that a second TNF inhibitor may be just as effective as a non–TNF inhibitor biologic in patients who develop antidrug antibodies to the first TNF inhibitor, said Dr. Gottenberg of the department of rheumatology at Strasbourg (France) University Hospital.

He and his colleagues aimed to mimic what happens in daily practice by allowing participating rheumatologists at French academic medical centers to choose which drug each patient received after randomization. During 2009-2012, 292 patients were randomized to any of four TNF inhibitors (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, or infliximab) or any of three non–TNF inhibitor biologics (abatacept, rituximab, or tocilizumab). (Golimumab was not available in France when the trial began in 2009.)

At 12 weeks, 48% of participants who switched to another TNF inhibitor had good or moderate responses based on European League Against Rheumatism criteria, and this rose to 52% at 24 weeks and then dropped to 43% at 48 weeks. At those time points, good or moderate response occurred in an additional 16%-18% of participants who switched to a non–TNF inhibitor biologic: 64% at 12 weeks, 70% at 24 weeks, and 60% at 48 weeks.

In the post hoc analysis of 278 patients who were tested for antidrug antibodies, 20 patients with ADAs who had been randomized to a non–TNF targeted biologic had a response at 24 weeks that was similar to 12 patients with ADAs who had been randomized to a second TNF inhibitor.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

Psoriasis, Psoriatic Arthritis Improve With Bariatric Surgery

SAN FRANCISCO – It might be time to add psoriasis to the list of comorbidities bariatric surgery is likely to help.

New York University investigators have found a marked improvement in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis following bariatric surgery, especially with severe disease. The more weight people lose, the better they do.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, investigator Dr. Soumya Reddy, codirector of NYU’s Psoriatic Arthritis Center in Manhattan, explained how the findings can be used in the clinic and their potential impact on bariatric surgery authorization.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN FRANCISCO – It might be time to add psoriasis to the list of comorbidities bariatric surgery is likely to help.

New York University investigators have found a marked improvement in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis following bariatric surgery, especially with severe disease. The more weight people lose, the better they do.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, investigator Dr. Soumya Reddy, codirector of NYU’s Psoriatic Arthritis Center in Manhattan, explained how the findings can be used in the clinic and their potential impact on bariatric surgery authorization.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN FRANCISCO – It might be time to add psoriasis to the list of comorbidities bariatric surgery is likely to help.

New York University investigators have found a marked improvement in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis following bariatric surgery, especially with severe disease. The more weight people lose, the better they do.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, investigator Dr. Soumya Reddy, codirector of NYU’s Psoriatic Arthritis Center in Manhattan, explained how the findings can be used in the clinic and their potential impact on bariatric surgery authorization.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

VIDEO: Psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis improve with bariatric surgery

SAN FRANCISCO – It might be time to add psoriasis to the list of comorbidities bariatric surgery is likely to help.

New York University investigators have found a marked improvement in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis following bariatric surgery, especially with severe disease. The more weight people lose, the better they do.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, investigator Dr. Soumya Reddy, codirector of NYU’s Psoriatic Arthritis Center in Manhattan, explained how the findings can be used in the clinic and their potential impact on bariatric surgery authorization.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN FRANCISCO – It might be time to add psoriasis to the list of comorbidities bariatric surgery is likely to help.

New York University investigators have found a marked improvement in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis following bariatric surgery, especially with severe disease. The more weight people lose, the better they do.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, investigator Dr. Soumya Reddy, codirector of NYU’s Psoriatic Arthritis Center in Manhattan, explained how the findings can be used in the clinic and their potential impact on bariatric surgery authorization.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN FRANCISCO – It might be time to add psoriasis to the list of comorbidities bariatric surgery is likely to help.

New York University investigators have found a marked improvement in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis following bariatric surgery, especially with severe disease. The more weight people lose, the better they do.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, investigator Dr. Soumya Reddy, codirector of NYU’s Psoriatic Arthritis Center in Manhattan, explained how the findings can be used in the clinic and their potential impact on bariatric surgery authorization.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

VIDEO: Chondroitin tops celecoxib in reducing knee OA structural progression

SAN FRANCISCO – Patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis who received pharmaceutical-grade chondroitin sulfate for 2 years lost about 20% less cartilage volume than did patients treated with celecoxib, according to a randomized, double-blind trial.

Improvements were limited to the medial tibiofemoral compartment, but even such modest structural effects can significantly decrease rates of total knee replacement over time, said lead investigator Dr. Jean-Pierre Pelletier, who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The 194 participants in the study received chondroitin sulfate, 1,200 mg a day, or celecoxib, 200 mg daily. Joint effusion and pain and function improved markedly in both groups, and they had similar rates of adverse events, said Dr. Pelletier, who is a rheumatologist at Institut de recherche en rhumatologie de Montréal. He discussed the findings and plans for future research in an exclusive video interview.

Bioibérica sponsored the study and makes the chondroitin sulfate that participants received. Dr. Pelletier and his associates had no other disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN FRANCISCO – Patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis who received pharmaceutical-grade chondroitin sulfate for 2 years lost about 20% less cartilage volume than did patients treated with celecoxib, according to a randomized, double-blind trial.

Improvements were limited to the medial tibiofemoral compartment, but even such modest structural effects can significantly decrease rates of total knee replacement over time, said lead investigator Dr. Jean-Pierre Pelletier, who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The 194 participants in the study received chondroitin sulfate, 1,200 mg a day, or celecoxib, 200 mg daily. Joint effusion and pain and function improved markedly in both groups, and they had similar rates of adverse events, said Dr. Pelletier, who is a rheumatologist at Institut de recherche en rhumatologie de Montréal. He discussed the findings and plans for future research in an exclusive video interview.

Bioibérica sponsored the study and makes the chondroitin sulfate that participants received. Dr. Pelletier and his associates had no other disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN FRANCISCO – Patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis who received pharmaceutical-grade chondroitin sulfate for 2 years lost about 20% less cartilage volume than did patients treated with celecoxib, according to a randomized, double-blind trial.

Improvements were limited to the medial tibiofemoral compartment, but even such modest structural effects can significantly decrease rates of total knee replacement over time, said lead investigator Dr. Jean-Pierre Pelletier, who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The 194 participants in the study received chondroitin sulfate, 1,200 mg a day, or celecoxib, 200 mg daily. Joint effusion and pain and function improved markedly in both groups, and they had similar rates of adverse events, said Dr. Pelletier, who is a rheumatologist at Institut de recherche en rhumatologie de Montréal. He discussed the findings and plans for future research in an exclusive video interview.

Bioibérica sponsored the study and makes the chondroitin sulfate that participants received. Dr. Pelletier and his associates had no other disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

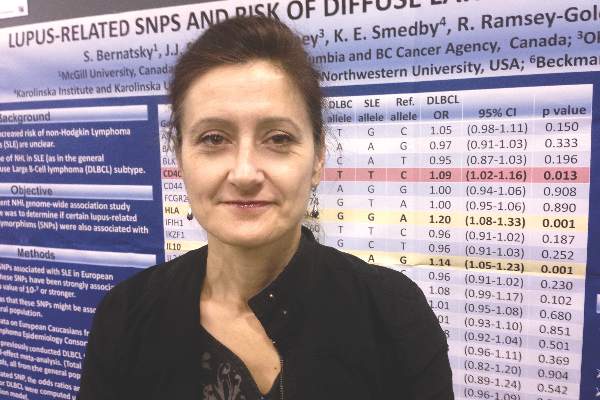

Lupus and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma share genetic risk

SAN FRANCISCO – Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in genes for interleukin 10 and human leukocyte antigen are significantly associated with both systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, according to a meta-analysis of data from three genome-wide association studies.

The findings add to existing data that exonerates immunosuppressive medications as the main causes of lymphoma in patients with SLE, said lead investigator Dr. Sasha Bernatsky of McGill University, Montreal, in an interview. “People with lupus may have a slight increase in risk for lymphoma because of genetic factors, which would be reassuring,” she said. “It may even mean that if you take your baseline risk of lupus and you control the inflammation, perhaps you can modify that small increase in risk of lymphoma and make it more like the risk in the general population.”

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, with an incidence of about one case in 3,000 person-years in the general population and about one case in 1,000 person-years in patients with SLE, Dr. Bernatsky noted. To look for shared genetic risk factors for both diseases, she and her colleagues analyzed pooled data from three genome-wide association studies conducted by the International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium. Using data from 3,857 patients with DLBCL and 7,666 controls, the investigators calculated the odds of DLBCL for each of 28 SNPs that are known genetic risk variants for SLE. “If there’s an overlap there, that might be the key,” Dr. Bernatsky said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

In fact, two SLE-related SNPs were clearly linked to an increased risk for DLBCL – rs3024505, a variant allele of the gene for interleukin 10 on chromosome 1 (odds ratio, 1.14; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.23; P = .001), and rs1270942, a variant of the gene for human leukocyte antigen on chromosome 6 (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.08-1.33; P = .0007). Both SNPs seem plausible – interleukin 10 induces the bcl-2 protein, which prevents the spontaneous death of germinal center B cells, and some evidence has linked HLA polymorphisms to DLBCL, Dr. Bernatsky said.

The study also linked two other SLE-related SNPs to increased risk for DLBCL, although the associations were not as strong. The first was rs4810485 on the CD40 gene (OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.02-1.16; P = .013), and the second was rs2205960 on the TNFSF4 gene, which encodes a cytokine from the tumor necrosis factor–superfamily (OR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.02-1.15; P = .044). “These findings kind of make sense, because tumor necrosis factor is a very important inflammatory cytokine, and CD40 is a lymphocyte marker,” Dr. Bernatsky said. “It is possible that some genetic factor that controls their expression or function might be associated with lymphoma.”

Rheumatologists have long debated why patients with lupus are at increased risk for lymphoma, and have repeatedly asked whether immunomodulatory drugs are to blame. “We can exercise some caution, but still be aware that most people who use these drugs never end up developing cancer,” Dr. Bernatsky emphasized. In past studies, the absolute risk of lymphoma in patients with SLE remained below 1%, and those patients who did develop lymphoma often had never received drugs such as azathioprine, she noted. The exception was cyclophosphamide, which caused various severe adverse effects, including blood cancers (Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Jan 8. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202099). “Although we need to use cyclophosphamide for very severe cases of autoimmune disease, it’s clearly a drug that we should use almost as a last resort,” she said.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research; the Fonds du recherche du Québec; Santé, the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre; and the Singer Family Fund for Lupus Research. Dr. Bernatsky and her coinvestigators had no disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in genes for interleukin 10 and human leukocyte antigen are significantly associated with both systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, according to a meta-analysis of data from three genome-wide association studies.

The findings add to existing data that exonerates immunosuppressive medications as the main causes of lymphoma in patients with SLE, said lead investigator Dr. Sasha Bernatsky of McGill University, Montreal, in an interview. “People with lupus may have a slight increase in risk for lymphoma because of genetic factors, which would be reassuring,” she said. “It may even mean that if you take your baseline risk of lupus and you control the inflammation, perhaps you can modify that small increase in risk of lymphoma and make it more like the risk in the general population.”

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, with an incidence of about one case in 3,000 person-years in the general population and about one case in 1,000 person-years in patients with SLE, Dr. Bernatsky noted. To look for shared genetic risk factors for both diseases, she and her colleagues analyzed pooled data from three genome-wide association studies conducted by the International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium. Using data from 3,857 patients with DLBCL and 7,666 controls, the investigators calculated the odds of DLBCL for each of 28 SNPs that are known genetic risk variants for SLE. “If there’s an overlap there, that might be the key,” Dr. Bernatsky said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

In fact, two SLE-related SNPs were clearly linked to an increased risk for DLBCL – rs3024505, a variant allele of the gene for interleukin 10 on chromosome 1 (odds ratio, 1.14; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.23; P = .001), and rs1270942, a variant of the gene for human leukocyte antigen on chromosome 6 (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.08-1.33; P = .0007). Both SNPs seem plausible – interleukin 10 induces the bcl-2 protein, which prevents the spontaneous death of germinal center B cells, and some evidence has linked HLA polymorphisms to DLBCL, Dr. Bernatsky said.

The study also linked two other SLE-related SNPs to increased risk for DLBCL, although the associations were not as strong. The first was rs4810485 on the CD40 gene (OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.02-1.16; P = .013), and the second was rs2205960 on the TNFSF4 gene, which encodes a cytokine from the tumor necrosis factor–superfamily (OR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.02-1.15; P = .044). “These findings kind of make sense, because tumor necrosis factor is a very important inflammatory cytokine, and CD40 is a lymphocyte marker,” Dr. Bernatsky said. “It is possible that some genetic factor that controls their expression or function might be associated with lymphoma.”

Rheumatologists have long debated why patients with lupus are at increased risk for lymphoma, and have repeatedly asked whether immunomodulatory drugs are to blame. “We can exercise some caution, but still be aware that most people who use these drugs never end up developing cancer,” Dr. Bernatsky emphasized. In past studies, the absolute risk of lymphoma in patients with SLE remained below 1%, and those patients who did develop lymphoma often had never received drugs such as azathioprine, she noted. The exception was cyclophosphamide, which caused various severe adverse effects, including blood cancers (Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Jan 8. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202099). “Although we need to use cyclophosphamide for very severe cases of autoimmune disease, it’s clearly a drug that we should use almost as a last resort,” she said.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research; the Fonds du recherche du Québec; Santé, the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre; and the Singer Family Fund for Lupus Research. Dr. Bernatsky and her coinvestigators had no disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in genes for interleukin 10 and human leukocyte antigen are significantly associated with both systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, according to a meta-analysis of data from three genome-wide association studies.

The findings add to existing data that exonerates immunosuppressive medications as the main causes of lymphoma in patients with SLE, said lead investigator Dr. Sasha Bernatsky of McGill University, Montreal, in an interview. “People with lupus may have a slight increase in risk for lymphoma because of genetic factors, which would be reassuring,” she said. “It may even mean that if you take your baseline risk of lupus and you control the inflammation, perhaps you can modify that small increase in risk of lymphoma and make it more like the risk in the general population.”

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, with an incidence of about one case in 3,000 person-years in the general population and about one case in 1,000 person-years in patients with SLE, Dr. Bernatsky noted. To look for shared genetic risk factors for both diseases, she and her colleagues analyzed pooled data from three genome-wide association studies conducted by the International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium. Using data from 3,857 patients with DLBCL and 7,666 controls, the investigators calculated the odds of DLBCL for each of 28 SNPs that are known genetic risk variants for SLE. “If there’s an overlap there, that might be the key,” Dr. Bernatsky said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

In fact, two SLE-related SNPs were clearly linked to an increased risk for DLBCL – rs3024505, a variant allele of the gene for interleukin 10 on chromosome 1 (odds ratio, 1.14; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.23; P = .001), and rs1270942, a variant of the gene for human leukocyte antigen on chromosome 6 (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.08-1.33; P = .0007). Both SNPs seem plausible – interleukin 10 induces the bcl-2 protein, which prevents the spontaneous death of germinal center B cells, and some evidence has linked HLA polymorphisms to DLBCL, Dr. Bernatsky said.

The study also linked two other SLE-related SNPs to increased risk for DLBCL, although the associations were not as strong. The first was rs4810485 on the CD40 gene (OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.02-1.16; P = .013), and the second was rs2205960 on the TNFSF4 gene, which encodes a cytokine from the tumor necrosis factor–superfamily (OR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.02-1.15; P = .044). “These findings kind of make sense, because tumor necrosis factor is a very important inflammatory cytokine, and CD40 is a lymphocyte marker,” Dr. Bernatsky said. “It is possible that some genetic factor that controls their expression or function might be associated with lymphoma.”

Rheumatologists have long debated why patients with lupus are at increased risk for lymphoma, and have repeatedly asked whether immunomodulatory drugs are to blame. “We can exercise some caution, but still be aware that most people who use these drugs never end up developing cancer,” Dr. Bernatsky emphasized. In past studies, the absolute risk of lymphoma in patients with SLE remained below 1%, and those patients who did develop lymphoma often had never received drugs such as azathioprine, she noted. The exception was cyclophosphamide, which caused various severe adverse effects, including blood cancers (Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Jan 8. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202099). “Although we need to use cyclophosphamide for very severe cases of autoimmune disease, it’s clearly a drug that we should use almost as a last resort,” she said.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research; the Fonds du recherche du Québec; Santé, the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre; and the Singer Family Fund for Lupus Research. Dr. Bernatsky and her coinvestigators had no disclosures.

AT THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Two genetic risk variants for systemic lupus erythematosus also were clearly linked to risk of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Major finding: The single-nucleotide polymorphisms were rs3024505 on chromosome 1 (OR, 1.14; P = .001), and rs1270942 on chromosome 6 (OR, 1.2; P = .0007).

Data source: A fixed-effect meta-analysis of 28 SLE-related SNPs from 3,857 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and 7,666 controls.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research; the Fonds du recherche du Québec; Santé, the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre; and the Singer Family Fund for Lupus Research. Dr. Bernatsky and her coinvestigators had no disclosures.

VIDEO: Obesity decreased chances of sustained RA remission

SAN FRANCISCO – Obese patients with rheumatoid arthritis are significantly less likely to achieve sustained disease remission than are their peers who are normal weight or overweight, based on data reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

In an analysis of more than 1,000 patients with RA from the multicenter, prospective CATCH (Canadian Early Arthritis Cohort) study, about 28% of obese (body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater) patients achieved sustained remission, defined as a 28-joint Disease Activity Score of 2.6 or less at two consecutive clinical visits.

In contrast, 38% of overweight (BMI 25-29.9) and 48% of normal-weight (BMI 18.5-24.9) patients reached that goal, said Dr. Vivian P. Bykerk, director of the Inflammatory Arthritis Center of Excellence at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, and a clinical researcher at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. In an exclusive video interview, Dr. Bykerk discusses the findings and their implications.

Dr. Bykerk is the founder and principal investigator for the CATCH study, which is sponsored by Amgen, Pfizer, Hoffmann-La Roche, UCB Canada, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AbbVie, and Janssen Biotech.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN FRANCISCO – Obese patients with rheumatoid arthritis are significantly less likely to achieve sustained disease remission than are their peers who are normal weight or overweight, based on data reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

In an analysis of more than 1,000 patients with RA from the multicenter, prospective CATCH (Canadian Early Arthritis Cohort) study, about 28% of obese (body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater) patients achieved sustained remission, defined as a 28-joint Disease Activity Score of 2.6 or less at two consecutive clinical visits.

In contrast, 38% of overweight (BMI 25-29.9) and 48% of normal-weight (BMI 18.5-24.9) patients reached that goal, said Dr. Vivian P. Bykerk, director of the Inflammatory Arthritis Center of Excellence at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, and a clinical researcher at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. In an exclusive video interview, Dr. Bykerk discusses the findings and their implications.

Dr. Bykerk is the founder and principal investigator for the CATCH study, which is sponsored by Amgen, Pfizer, Hoffmann-La Roche, UCB Canada, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AbbVie, and Janssen Biotech.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN FRANCISCO – Obese patients with rheumatoid arthritis are significantly less likely to achieve sustained disease remission than are their peers who are normal weight or overweight, based on data reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

In an analysis of more than 1,000 patients with RA from the multicenter, prospective CATCH (Canadian Early Arthritis Cohort) study, about 28% of obese (body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater) patients achieved sustained remission, defined as a 28-joint Disease Activity Score of 2.6 or less at two consecutive clinical visits.

In contrast, 38% of overweight (BMI 25-29.9) and 48% of normal-weight (BMI 18.5-24.9) patients reached that goal, said Dr. Vivian P. Bykerk, director of the Inflammatory Arthritis Center of Excellence at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, and a clinical researcher at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. In an exclusive video interview, Dr. Bykerk discusses the findings and their implications.

Dr. Bykerk is the founder and principal investigator for the CATCH study, which is sponsored by Amgen, Pfizer, Hoffmann-La Roche, UCB Canada, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AbbVie, and Janssen Biotech.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING