User login

Rocatinlimab shows promise in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis

Key clinical point: Treatment with rocatinlimab, a novel monoclonal antibody, significantly improved disease severity at all dosing regimens in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) inadequately controlled with topical therapy, which was maintained in most patients even after treatment discontinuation.

Major finding: The least-squares mean percent reductions in the Eczema Area and Severity Index at week 16 were significantly greater with 150 mg rocatinlimab every 4 weeks vs placebo (−48.3% vs −15.0%; P = .0003), with all other active rocatinlimab dose regimens vs placebo showing improvement (all P < .05) and most patients showing sustained response during off-drug follow-up.

Study details: The data come from a multicenter phase 2b study including 274 patients with moderate-to-severe AD and inadequate response or intolerance to topical medications and who were randomly assigned to receive rocatinlimab or placebo.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Kyowa Kirin. Some authors reported ties with various sources, including Kyowa Kirin. E Esfandiari declared being an employee of Kyowa Kirin.

Source: Guttman-Yassky E et al. An anti-OX40 antibody to treat moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b study. Lancet. 2022 (Dec 9). Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02037-2

Key clinical point: Treatment with rocatinlimab, a novel monoclonal antibody, significantly improved disease severity at all dosing regimens in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) inadequately controlled with topical therapy, which was maintained in most patients even after treatment discontinuation.

Major finding: The least-squares mean percent reductions in the Eczema Area and Severity Index at week 16 were significantly greater with 150 mg rocatinlimab every 4 weeks vs placebo (−48.3% vs −15.0%; P = .0003), with all other active rocatinlimab dose regimens vs placebo showing improvement (all P < .05) and most patients showing sustained response during off-drug follow-up.

Study details: The data come from a multicenter phase 2b study including 274 patients with moderate-to-severe AD and inadequate response or intolerance to topical medications and who were randomly assigned to receive rocatinlimab or placebo.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Kyowa Kirin. Some authors reported ties with various sources, including Kyowa Kirin. E Esfandiari declared being an employee of Kyowa Kirin.

Source: Guttman-Yassky E et al. An anti-OX40 antibody to treat moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b study. Lancet. 2022 (Dec 9). Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02037-2

Key clinical point: Treatment with rocatinlimab, a novel monoclonal antibody, significantly improved disease severity at all dosing regimens in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) inadequately controlled with topical therapy, which was maintained in most patients even after treatment discontinuation.

Major finding: The least-squares mean percent reductions in the Eczema Area and Severity Index at week 16 were significantly greater with 150 mg rocatinlimab every 4 weeks vs placebo (−48.3% vs −15.0%; P = .0003), with all other active rocatinlimab dose regimens vs placebo showing improvement (all P < .05) and most patients showing sustained response during off-drug follow-up.

Study details: The data come from a multicenter phase 2b study including 274 patients with moderate-to-severe AD and inadequate response or intolerance to topical medications and who were randomly assigned to receive rocatinlimab or placebo.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Kyowa Kirin. Some authors reported ties with various sources, including Kyowa Kirin. E Esfandiari declared being an employee of Kyowa Kirin.

Source: Guttman-Yassky E et al. An anti-OX40 antibody to treat moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b study. Lancet. 2022 (Dec 9). Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02037-2

Macules and abdominal pain

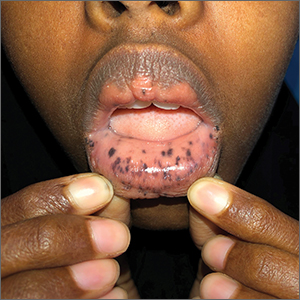

This patient was given a diagnosis of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) based on the characteristic pigmented mucocutaneous macules and numerous polyps in her stomach and small bowel. PJS is an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by mucocutaneous pigmentation, polyposis of the GI tract, and increased cancer risk. The prevalence is approximately 1 in 100,000.1 Genetic testing for the STK11 gene mutation, which is found in 70% of familial cases and 30% to 67% of sporadic cases, is not required for diagnosis.1

The bluish brown to black spots of PJS often are apparent at birth or in early infancy. They are most common on the lips, buccal mucosa, perioral region, palms, and soles.

The polyps may cause bleeding, anemia, and abdominal pain due to intussusception, obstruction, or infarction.2 Polyps usually are benign, but patients are at increased risk of GI and non-GI malignancies such as breast, pancreas, lung, and reproductive tract cancers.1

PJS can be differentiated from other causes of hyperpigmentation by clinical presentation and/or genetic testing. The diagnosis of PJS is made using the following criteria: (1) two or more histologically confirmed PJS polyps, (2) any number of PJS polyps and a family history of PJS, (3) characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation and a family history of PJS, or (4) any number of PJS polyps and characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation.2

It’s recommended that polyps be removed when technically feasible.3 Pigmented macules do not require treatment. Macules on the lips may disappear with time, while those on the buccal mucosa persist. The lip lesions can be lightened with chemical peels or laser.

This patient underwent laparotomy, which revealed a grossly dilated and gangrenous small bowel segment. Intussusception was not present and was thought to have spontaneously reduced. Resection and anastomosis of the affected small bowel was performed. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and her diarrhea and abdominal pain resolved. A colonoscopy was normal, and the health care team explained that she would require follow-up and surveillance of her condition due to the high risk of future cancers.

This case was adapted from: Warsame MO, McMichael JR. Chronic abdominal pain and diarrhea. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:365,366,368.

Photos courtesy of Mohamed Omar Warsame, MBBS, and Josette R. McMichael, MD

1. Kopacova M, Tacheci I, Rejchrt S, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: diagnostic and therapeutic approach. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5397-5408.

2. Beggs AD, Latchford AR, Vasen HF, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut. 2010;59:975-986.

3. van Lier MG, Mathus-Vliegen EM, Wagner A, et al. High cumulative risk of intussusception in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: time to update surveillance guidelines? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:940-945.

This patient was given a diagnosis of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) based on the characteristic pigmented mucocutaneous macules and numerous polyps in her stomach and small bowel. PJS is an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by mucocutaneous pigmentation, polyposis of the GI tract, and increased cancer risk. The prevalence is approximately 1 in 100,000.1 Genetic testing for the STK11 gene mutation, which is found in 70% of familial cases and 30% to 67% of sporadic cases, is not required for diagnosis.1

The bluish brown to black spots of PJS often are apparent at birth or in early infancy. They are most common on the lips, buccal mucosa, perioral region, palms, and soles.

The polyps may cause bleeding, anemia, and abdominal pain due to intussusception, obstruction, or infarction.2 Polyps usually are benign, but patients are at increased risk of GI and non-GI malignancies such as breast, pancreas, lung, and reproductive tract cancers.1

PJS can be differentiated from other causes of hyperpigmentation by clinical presentation and/or genetic testing. The diagnosis of PJS is made using the following criteria: (1) two or more histologically confirmed PJS polyps, (2) any number of PJS polyps and a family history of PJS, (3) characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation and a family history of PJS, or (4) any number of PJS polyps and characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation.2

It’s recommended that polyps be removed when technically feasible.3 Pigmented macules do not require treatment. Macules on the lips may disappear with time, while those on the buccal mucosa persist. The lip lesions can be lightened with chemical peels or laser.

This patient underwent laparotomy, which revealed a grossly dilated and gangrenous small bowel segment. Intussusception was not present and was thought to have spontaneously reduced. Resection and anastomosis of the affected small bowel was performed. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and her diarrhea and abdominal pain resolved. A colonoscopy was normal, and the health care team explained that she would require follow-up and surveillance of her condition due to the high risk of future cancers.

This case was adapted from: Warsame MO, McMichael JR. Chronic abdominal pain and diarrhea. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:365,366,368.

Photos courtesy of Mohamed Omar Warsame, MBBS, and Josette R. McMichael, MD

This patient was given a diagnosis of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) based on the characteristic pigmented mucocutaneous macules and numerous polyps in her stomach and small bowel. PJS is an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by mucocutaneous pigmentation, polyposis of the GI tract, and increased cancer risk. The prevalence is approximately 1 in 100,000.1 Genetic testing for the STK11 gene mutation, which is found in 70% of familial cases and 30% to 67% of sporadic cases, is not required for diagnosis.1

The bluish brown to black spots of PJS often are apparent at birth or in early infancy. They are most common on the lips, buccal mucosa, perioral region, palms, and soles.

The polyps may cause bleeding, anemia, and abdominal pain due to intussusception, obstruction, or infarction.2 Polyps usually are benign, but patients are at increased risk of GI and non-GI malignancies such as breast, pancreas, lung, and reproductive tract cancers.1

PJS can be differentiated from other causes of hyperpigmentation by clinical presentation and/or genetic testing. The diagnosis of PJS is made using the following criteria: (1) two or more histologically confirmed PJS polyps, (2) any number of PJS polyps and a family history of PJS, (3) characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation and a family history of PJS, or (4) any number of PJS polyps and characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation.2

It’s recommended that polyps be removed when technically feasible.3 Pigmented macules do not require treatment. Macules on the lips may disappear with time, while those on the buccal mucosa persist. The lip lesions can be lightened with chemical peels or laser.

This patient underwent laparotomy, which revealed a grossly dilated and gangrenous small bowel segment. Intussusception was not present and was thought to have spontaneously reduced. Resection and anastomosis of the affected small bowel was performed. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and her diarrhea and abdominal pain resolved. A colonoscopy was normal, and the health care team explained that she would require follow-up and surveillance of her condition due to the high risk of future cancers.

This case was adapted from: Warsame MO, McMichael JR. Chronic abdominal pain and diarrhea. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:365,366,368.

Photos courtesy of Mohamed Omar Warsame, MBBS, and Josette R. McMichael, MD

1. Kopacova M, Tacheci I, Rejchrt S, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: diagnostic and therapeutic approach. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5397-5408.

2. Beggs AD, Latchford AR, Vasen HF, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut. 2010;59:975-986.

3. van Lier MG, Mathus-Vliegen EM, Wagner A, et al. High cumulative risk of intussusception in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: time to update surveillance guidelines? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:940-945.

1. Kopacova M, Tacheci I, Rejchrt S, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: diagnostic and therapeutic approach. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5397-5408.

2. Beggs AD, Latchford AR, Vasen HF, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut. 2010;59:975-986.

3. van Lier MG, Mathus-Vliegen EM, Wagner A, et al. High cumulative risk of intussusception in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: time to update surveillance guidelines? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:940-945.

FDA will review pediatric indication for roflumilast cream

, according to a press release from the manufacturer.

The company, Arcutis Biotherapeutics, announced the submission of a supplemental new drug application for approval of roflumilast cream (Zoryve), a topical phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) inhibitor, to treat psoriasis in children aged 2-11 years. If approved, this would be the first such product for young children with plaque psoriasis, according to the press release. In July 2022, the FDA approved roflumilast cream 0.3% for the treatment of plaque psoriasis in people 12 years of age and older, including in intertriginous areas, based on data from the phase 3 DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2 trials.

The new submission is supported by data from two 4-week Maximal Usage Systemic Exposure (MUSE) studies in children ages 2-11 years with plaque psoriasis. In these phase 2, open-label studies, one study of children aged 2-5 years and another study of children aged 6-11 years, participants were treated with roflumilast cream 0.3% once daily for 4 weeks. The MUSE studies are also intended to fulfill postmarketing requirements for roflumilast, according to the company. The MUSE results were consistent with those from DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2, according to the company press release. In DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2, significantly more patients randomized to roflumilast met criteria for Investigators Global Success (IGA) scores after 8 weeks of daily treatment compared with placebo patients, and significantly more achieved a 75% reduction in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scores compared with those on placebo.

Common adverse events associated with roflumilast include diarrhea, headache, insomnia, nausea, application site pain, upper respiratory tract infection, and urinary tract infection. None of these have been reported in more than 3% of patients, the press release noted.

, according to a press release from the manufacturer.

The company, Arcutis Biotherapeutics, announced the submission of a supplemental new drug application for approval of roflumilast cream (Zoryve), a topical phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) inhibitor, to treat psoriasis in children aged 2-11 years. If approved, this would be the first such product for young children with plaque psoriasis, according to the press release. In July 2022, the FDA approved roflumilast cream 0.3% for the treatment of plaque psoriasis in people 12 years of age and older, including in intertriginous areas, based on data from the phase 3 DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2 trials.

The new submission is supported by data from two 4-week Maximal Usage Systemic Exposure (MUSE) studies in children ages 2-11 years with plaque psoriasis. In these phase 2, open-label studies, one study of children aged 2-5 years and another study of children aged 6-11 years, participants were treated with roflumilast cream 0.3% once daily for 4 weeks. The MUSE studies are also intended to fulfill postmarketing requirements for roflumilast, according to the company. The MUSE results were consistent with those from DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2, according to the company press release. In DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2, significantly more patients randomized to roflumilast met criteria for Investigators Global Success (IGA) scores after 8 weeks of daily treatment compared with placebo patients, and significantly more achieved a 75% reduction in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scores compared with those on placebo.

Common adverse events associated with roflumilast include diarrhea, headache, insomnia, nausea, application site pain, upper respiratory tract infection, and urinary tract infection. None of these have been reported in more than 3% of patients, the press release noted.

, according to a press release from the manufacturer.

The company, Arcutis Biotherapeutics, announced the submission of a supplemental new drug application for approval of roflumilast cream (Zoryve), a topical phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) inhibitor, to treat psoriasis in children aged 2-11 years. If approved, this would be the first such product for young children with plaque psoriasis, according to the press release. In July 2022, the FDA approved roflumilast cream 0.3% for the treatment of plaque psoriasis in people 12 years of age and older, including in intertriginous areas, based on data from the phase 3 DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2 trials.

The new submission is supported by data from two 4-week Maximal Usage Systemic Exposure (MUSE) studies in children ages 2-11 years with plaque psoriasis. In these phase 2, open-label studies, one study of children aged 2-5 years and another study of children aged 6-11 years, participants were treated with roflumilast cream 0.3% once daily for 4 weeks. The MUSE studies are also intended to fulfill postmarketing requirements for roflumilast, according to the company. The MUSE results were consistent with those from DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2, according to the company press release. In DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2, significantly more patients randomized to roflumilast met criteria for Investigators Global Success (IGA) scores after 8 weeks of daily treatment compared with placebo patients, and significantly more achieved a 75% reduction in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scores compared with those on placebo.

Common adverse events associated with roflumilast include diarrhea, headache, insomnia, nausea, application site pain, upper respiratory tract infection, and urinary tract infection. None of these have been reported in more than 3% of patients, the press release noted.

HR+/HER2− metastatic BC: Everolimus dose escalation+exemestane reduces grade ≥2 stomatitis

Key clinical point: A dose-escalation schema of everolimus plus exemestane was more effective than conventionally administered everolimus (10 mg) plus exemestane in reducing grade ≥2 stomatitis in patients with hormone receptor-positive (HR+)/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HER2−) metastatic breast cancer (mBC).

Major finding: Within 12 weeks, the incidence of grade ≥2 stomatitis episodes was significantly lower in the everolimus dose escalation vs the 10 mg everolimus arm (odds ratio 0.47; P = .026). Except for stomatitis, toxicity was not significantly different between both treatment arms.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 2, DESIREE trial including 160 postmenopausal women with HR+/HER2− mBC who were randomly assigned to receive exemestane with an escalating dose of everolimus (2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 mg/day at weeks 1, 2, 3, and 4-24, respectively) or 10 mg/day everolimus.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Novartis, Germany. The authors declared receiving personal fees, grants, consulting fees, honoraria, or support for attending meetings or travel from several sources, including Novartis.

Source: Schmidt M et al. A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase II study to evaluate the tolerability of an induction dose escalation of everolimus in patients with metastatic breast cancer (DESIREE). ESMO Open. 2022;7(6):100601 (Nov 7). Doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100601

Key clinical point: A dose-escalation schema of everolimus plus exemestane was more effective than conventionally administered everolimus (10 mg) plus exemestane in reducing grade ≥2 stomatitis in patients with hormone receptor-positive (HR+)/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HER2−) metastatic breast cancer (mBC).

Major finding: Within 12 weeks, the incidence of grade ≥2 stomatitis episodes was significantly lower in the everolimus dose escalation vs the 10 mg everolimus arm (odds ratio 0.47; P = .026). Except for stomatitis, toxicity was not significantly different between both treatment arms.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 2, DESIREE trial including 160 postmenopausal women with HR+/HER2− mBC who were randomly assigned to receive exemestane with an escalating dose of everolimus (2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 mg/day at weeks 1, 2, 3, and 4-24, respectively) or 10 mg/day everolimus.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Novartis, Germany. The authors declared receiving personal fees, grants, consulting fees, honoraria, or support for attending meetings or travel from several sources, including Novartis.

Source: Schmidt M et al. A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase II study to evaluate the tolerability of an induction dose escalation of everolimus in patients with metastatic breast cancer (DESIREE). ESMO Open. 2022;7(6):100601 (Nov 7). Doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100601

Key clinical point: A dose-escalation schema of everolimus plus exemestane was more effective than conventionally administered everolimus (10 mg) plus exemestane in reducing grade ≥2 stomatitis in patients with hormone receptor-positive (HR+)/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HER2−) metastatic breast cancer (mBC).

Major finding: Within 12 weeks, the incidence of grade ≥2 stomatitis episodes was significantly lower in the everolimus dose escalation vs the 10 mg everolimus arm (odds ratio 0.47; P = .026). Except for stomatitis, toxicity was not significantly different between both treatment arms.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 2, DESIREE trial including 160 postmenopausal women with HR+/HER2− mBC who were randomly assigned to receive exemestane with an escalating dose of everolimus (2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 mg/day at weeks 1, 2, 3, and 4-24, respectively) or 10 mg/day everolimus.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Novartis, Germany. The authors declared receiving personal fees, grants, consulting fees, honoraria, or support for attending meetings or travel from several sources, including Novartis.

Source: Schmidt M et al. A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase II study to evaluate the tolerability of an induction dose escalation of everolimus in patients with metastatic breast cancer (DESIREE). ESMO Open. 2022;7(6):100601 (Nov 7). Doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100601

Obesity and advanced stage at diagnosis worsen recurrence rate in BC patients

Key clinical point: Obesity and advanced stage (stage III) at diagnosis of breast cancer (BC) were associated with a higher rate of recurrence and worse prognosis in patients with BC who achieved pathological complete response (pCR) after receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NCT).

Major finding: Obesity vs no obesity (P = .019) and stage III vs stage I-II BC at diagnosis (P = .0018) were significantly associated with worse invasive disease-free survival, with obesity demonstrating worse survival outcomes in stage III BC (hazard ratio 4.31; P = .006).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective real-world analysis including 241 patients with stage I-III BC who had achieved pCR after receiving NCT.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Acevedo F et al. Obesity is associated with early recurrence on breast cancer patients that achieved pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Sci Rep. 2022;12:21145 (Dec 7). Doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-25043-2

Key clinical point: Obesity and advanced stage (stage III) at diagnosis of breast cancer (BC) were associated with a higher rate of recurrence and worse prognosis in patients with BC who achieved pathological complete response (pCR) after receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NCT).

Major finding: Obesity vs no obesity (P = .019) and stage III vs stage I-II BC at diagnosis (P = .0018) were significantly associated with worse invasive disease-free survival, with obesity demonstrating worse survival outcomes in stage III BC (hazard ratio 4.31; P = .006).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective real-world analysis including 241 patients with stage I-III BC who had achieved pCR after receiving NCT.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Acevedo F et al. Obesity is associated with early recurrence on breast cancer patients that achieved pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Sci Rep. 2022;12:21145 (Dec 7). Doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-25043-2

Key clinical point: Obesity and advanced stage (stage III) at diagnosis of breast cancer (BC) were associated with a higher rate of recurrence and worse prognosis in patients with BC who achieved pathological complete response (pCR) after receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NCT).

Major finding: Obesity vs no obesity (P = .019) and stage III vs stage I-II BC at diagnosis (P = .0018) were significantly associated with worse invasive disease-free survival, with obesity demonstrating worse survival outcomes in stage III BC (hazard ratio 4.31; P = .006).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective real-world analysis including 241 patients with stage I-III BC who had achieved pCR after receiving NCT.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Acevedo F et al. Obesity is associated with early recurrence on breast cancer patients that achieved pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Sci Rep. 2022;12:21145 (Dec 7). Doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-25043-2

Prognostic impact of receptor conversion between primary breast cancer and bone metastases

Key clinical point: A substantial proportion of patients showed receptor conversion between primary breast cancer (BC) and bone metastases, which significantly impacted prognosis.

Major finding: The discordance rates between primary BC and bone metastases were 14.0%, 32.3%, and 9.7% for estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PgR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), respectively. The loss vs maintenance of hormone receptor expression was associated with worse first-line progression-free survival (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 3.27; P = .039) and overall survival (aHR 6.09; P = .011).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective analysis including 93 patients with BC, pathologically confirmed bone metastasis, and ER, PgR, and HER2 status available on both primary tumor and bone metastases.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and other sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Lin M et al. Incidence and prognostic significance of receptor discordance between primary breast cancer and paired bone metastases. Int J Cancer. 2022 (Nov 21). Doi: 10.1002/ijc.34365

Key clinical point: A substantial proportion of patients showed receptor conversion between primary breast cancer (BC) and bone metastases, which significantly impacted prognosis.

Major finding: The discordance rates between primary BC and bone metastases were 14.0%, 32.3%, and 9.7% for estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PgR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), respectively. The loss vs maintenance of hormone receptor expression was associated with worse first-line progression-free survival (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 3.27; P = .039) and overall survival (aHR 6.09; P = .011).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective analysis including 93 patients with BC, pathologically confirmed bone metastasis, and ER, PgR, and HER2 status available on both primary tumor and bone metastases.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and other sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Lin M et al. Incidence and prognostic significance of receptor discordance between primary breast cancer and paired bone metastases. Int J Cancer. 2022 (Nov 21). Doi: 10.1002/ijc.34365

Key clinical point: A substantial proportion of patients showed receptor conversion between primary breast cancer (BC) and bone metastases, which significantly impacted prognosis.

Major finding: The discordance rates between primary BC and bone metastases were 14.0%, 32.3%, and 9.7% for estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PgR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), respectively. The loss vs maintenance of hormone receptor expression was associated with worse first-line progression-free survival (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 3.27; P = .039) and overall survival (aHR 6.09; P = .011).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective analysis including 93 patients with BC, pathologically confirmed bone metastasis, and ER, PgR, and HER2 status available on both primary tumor and bone metastases.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and other sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Lin M et al. Incidence and prognostic significance of receptor discordance between primary breast cancer and paired bone metastases. Int J Cancer. 2022 (Nov 21). Doi: 10.1002/ijc.34365

Prognostic impact of receptor conversion between primary breast cancer and bone metastases

Key clinical point: A substantial proportion of patients showed receptor conversion between primary breast cancer (BC) and bone metastases, which significantly impacted prognosis.

Major finding: The discordance rates between primary BC and bone metastases were 14.0%, 32.3%, and 9.7% for estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PgR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), respectively. The loss vs maintenance of hormone receptor expression was associated with worse first-line progression-free survival (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 3.27; P = .039) and overall survival (aHR 6.09; P = .011).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective analysis including 93 patients with BC, pathologically confirmed bone metastasis, and ER, PgR, and HER2 status available on both primary tumor and bone metastases.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and other sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Lin M et al. Incidence and prognostic significance of receptor discordance between primary breast cancer and paired bone metastases. Int J Cancer. 2022 (Nov 21). Doi: 10.1002/ijc.34365

Key clinical point: A substantial proportion of patients showed receptor conversion between primary breast cancer (BC) and bone metastases, which significantly impacted prognosis.

Major finding: The discordance rates between primary BC and bone metastases were 14.0%, 32.3%, and 9.7% for estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PgR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), respectively. The loss vs maintenance of hormone receptor expression was associated with worse first-line progression-free survival (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 3.27; P = .039) and overall survival (aHR 6.09; P = .011).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective analysis including 93 patients with BC, pathologically confirmed bone metastasis, and ER, PgR, and HER2 status available on both primary tumor and bone metastases.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and other sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Lin M et al. Incidence and prognostic significance of receptor discordance between primary breast cancer and paired bone metastases. Int J Cancer. 2022 (Nov 21). Doi: 10.1002/ijc.34365

Key clinical point: A substantial proportion of patients showed receptor conversion between primary breast cancer (BC) and bone metastases, which significantly impacted prognosis.

Major finding: The discordance rates between primary BC and bone metastases were 14.0%, 32.3%, and 9.7% for estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PgR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), respectively. The loss vs maintenance of hormone receptor expression was associated with worse first-line progression-free survival (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 3.27; P = .039) and overall survival (aHR 6.09; P = .011).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective analysis including 93 patients with BC, pathologically confirmed bone metastasis, and ER, PgR, and HER2 status available on both primary tumor and bone metastases.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and other sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Lin M et al. Incidence and prognostic significance of receptor discordance between primary breast cancer and paired bone metastases. Int J Cancer. 2022 (Nov 21). Doi: 10.1002/ijc.34365

Selective internal radiation therapy effective and safe in patients with BC and hepatic metastasis

Key clinical point: Selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT) with 90Y demonstrated favorable survival benefits in patients with breast cancer (BC) and hepatic metastasis, particularly in those with low liver tumor burden and without extrahepatic metastasis.

Major finding: Postembolization median survival time (MST) was 9.8 months, with MST being significantly higher in patients with <25% vs >25% hepatic metastatic burden (10.5 vs 6.8 months; P < .0001) and localized vs additional hepatic metastasis (15.0 vs 5.3 months; P < .0001). None of the adverse events were life-threatening.

Study details: Findings are from a meta-analysis of 24 studies including 412 patients with metastatic BC and hepatic metastasis who had received SIRT.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Liu C et al. Selective internal radiation therapy of metastatic breast cancer to the liver: A meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2022;12:887653 (Nov 24). Doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.887653

Key clinical point: Selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT) with 90Y demonstrated favorable survival benefits in patients with breast cancer (BC) and hepatic metastasis, particularly in those with low liver tumor burden and without extrahepatic metastasis.

Major finding: Postembolization median survival time (MST) was 9.8 months, with MST being significantly higher in patients with <25% vs >25% hepatic metastatic burden (10.5 vs 6.8 months; P < .0001) and localized vs additional hepatic metastasis (15.0 vs 5.3 months; P < .0001). None of the adverse events were life-threatening.

Study details: Findings are from a meta-analysis of 24 studies including 412 patients with metastatic BC and hepatic metastasis who had received SIRT.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Liu C et al. Selective internal radiation therapy of metastatic breast cancer to the liver: A meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2022;12:887653 (Nov 24). Doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.887653

Key clinical point: Selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT) with 90Y demonstrated favorable survival benefits in patients with breast cancer (BC) and hepatic metastasis, particularly in those with low liver tumor burden and without extrahepatic metastasis.

Major finding: Postembolization median survival time (MST) was 9.8 months, with MST being significantly higher in patients with <25% vs >25% hepatic metastatic burden (10.5 vs 6.8 months; P < .0001) and localized vs additional hepatic metastasis (15.0 vs 5.3 months; P < .0001). None of the adverse events were life-threatening.

Study details: Findings are from a meta-analysis of 24 studies including 412 patients with metastatic BC and hepatic metastasis who had received SIRT.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Liu C et al. Selective internal radiation therapy of metastatic breast cancer to the liver: A meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2022;12:887653 (Nov 24). Doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.887653

Triple-positive BC: Neoadjuvant pyrotinib+letrozole+dalpiciclib shows promise in phase 2

Key clinical point: A chemotherapy-free combination of pyrotinib, letrozole, and dalpiciclib demonstrated promising antitumor activity and an acceptable safety profile in the neoadjuvant setting in patients with triple-positive breast cancer (TPBC).

Major finding: After 5 cycles of the 4-week treatment, a substantial proportion (30.4%) of patients achieved pathological complete response in both the breast and lymph nodes. The most common adverse events were neutropenia (93%), leukopenia (90%), diarrhea (86%), anemia (68%), and oral mucositis (63%).

Study details: Findings are from the phase 2, MUKDEN 01 trial including 81 patients with stage II-III TPBC who were assigned to receive neoadjuvant treatment with pyrotinib+letrozole+dalpiciclib.

Disclosures: This study did not report a source of funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Niu N et al. A multicentre single arm phase 2 trial of neoadjuvant pyrotinib and letrozole plus dalpiciclib for triple-positive breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2022;13:7043 (Nov 17). Doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34838-w

Key clinical point: A chemotherapy-free combination of pyrotinib, letrozole, and dalpiciclib demonstrated promising antitumor activity and an acceptable safety profile in the neoadjuvant setting in patients with triple-positive breast cancer (TPBC).

Major finding: After 5 cycles of the 4-week treatment, a substantial proportion (30.4%) of patients achieved pathological complete response in both the breast and lymph nodes. The most common adverse events were neutropenia (93%), leukopenia (90%), diarrhea (86%), anemia (68%), and oral mucositis (63%).

Study details: Findings are from the phase 2, MUKDEN 01 trial including 81 patients with stage II-III TPBC who were assigned to receive neoadjuvant treatment with pyrotinib+letrozole+dalpiciclib.

Disclosures: This study did not report a source of funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Niu N et al. A multicentre single arm phase 2 trial of neoadjuvant pyrotinib and letrozole plus dalpiciclib for triple-positive breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2022;13:7043 (Nov 17). Doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34838-w

Key clinical point: A chemotherapy-free combination of pyrotinib, letrozole, and dalpiciclib demonstrated promising antitumor activity and an acceptable safety profile in the neoadjuvant setting in patients with triple-positive breast cancer (TPBC).

Major finding: After 5 cycles of the 4-week treatment, a substantial proportion (30.4%) of patients achieved pathological complete response in both the breast and lymph nodes. The most common adverse events were neutropenia (93%), leukopenia (90%), diarrhea (86%), anemia (68%), and oral mucositis (63%).

Study details: Findings are from the phase 2, MUKDEN 01 trial including 81 patients with stage II-III TPBC who were assigned to receive neoadjuvant treatment with pyrotinib+letrozole+dalpiciclib.

Disclosures: This study did not report a source of funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Niu N et al. A multicentre single arm phase 2 trial of neoadjuvant pyrotinib and letrozole plus dalpiciclib for triple-positive breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2022;13:7043 (Nov 17). Doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34838-w

Acupuncture relieves AI-related joint pain for up to a year in BC patients

Key clinical point: In patients with early-stage breast cancer (BC), a 12-week true acupuncture (TA) treatment was more effective than sham acupuncture (SA) or no acupuncture (waiting list control; WC) treatment in reducing aromatase inhibitor (AI)-related joint pain through 52 weeks.

Major finding: At week 52, the TA group reported a significantly higher improvement in the mean Brief Pain Inventory Worst Pain (BPI-WP) item score than the SA group (difference 1.08 points; P = .01) or the WC group (difference 0.99 points; P = .03).

Study details: Findings are from a multicenter trial including 226 postmenopausal women with stage I-III BC receiving a third-generation AI who had a BPI-WP item score of ≥3 and were randomly assigned to receive TA, SA, or WC.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health and other sources. Some authors declared being employees of or receiving payments and personal fees from several sources.

Source: Hershman DL et al. Comparison of acupuncture vs sham acupuncture or waiting list control in the treatment of aromatase inhibitor-related joint pain: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2241720 (Nov 11). Doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.41720

Key clinical point: In patients with early-stage breast cancer (BC), a 12-week true acupuncture (TA) treatment was more effective than sham acupuncture (SA) or no acupuncture (waiting list control; WC) treatment in reducing aromatase inhibitor (AI)-related joint pain through 52 weeks.

Major finding: At week 52, the TA group reported a significantly higher improvement in the mean Brief Pain Inventory Worst Pain (BPI-WP) item score than the SA group (difference 1.08 points; P = .01) or the WC group (difference 0.99 points; P = .03).

Study details: Findings are from a multicenter trial including 226 postmenopausal women with stage I-III BC receiving a third-generation AI who had a BPI-WP item score of ≥3 and were randomly assigned to receive TA, SA, or WC.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health and other sources. Some authors declared being employees of or receiving payments and personal fees from several sources.

Source: Hershman DL et al. Comparison of acupuncture vs sham acupuncture or waiting list control in the treatment of aromatase inhibitor-related joint pain: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2241720 (Nov 11). Doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.41720

Key clinical point: In patients with early-stage breast cancer (BC), a 12-week true acupuncture (TA) treatment was more effective than sham acupuncture (SA) or no acupuncture (waiting list control; WC) treatment in reducing aromatase inhibitor (AI)-related joint pain through 52 weeks.

Major finding: At week 52, the TA group reported a significantly higher improvement in the mean Brief Pain Inventory Worst Pain (BPI-WP) item score than the SA group (difference 1.08 points; P = .01) or the WC group (difference 0.99 points; P = .03).

Study details: Findings are from a multicenter trial including 226 postmenopausal women with stage I-III BC receiving a third-generation AI who had a BPI-WP item score of ≥3 and were randomly assigned to receive TA, SA, or WC.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health and other sources. Some authors declared being employees of or receiving payments and personal fees from several sources.

Source: Hershman DL et al. Comparison of acupuncture vs sham acupuncture or waiting list control in the treatment of aromatase inhibitor-related joint pain: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2241720 (Nov 11). Doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.41720