User login

Rise of ‘alarming’ subvariants of COVID ‘worrisome’ for winter

It’s a story perhaps more appropriate for Halloween than for the festive holiday season, given its scary implications.

Not too dire so far, until the researchers’ other findings are considered.

The BQ.1, BQ1.1, XBB, and XBB.1 subvariants are the most resistant to neutralizing antibodies, researcher Qian Wang, PhD, and colleagues wrote in a study published online in the journal Cell. This means people have no or “markedly reduced” protection against infection from these four strains, even if they’ve already had COVID-19 or are vaccinated and boosted multiple times, including with a bivalent vaccine.

On top of that, all available monoclonal antibody treatments are mostly or completely ineffective against these subvariants.

What does that mean for the immediate future? The findings are definitely “worrisome,” said Eric Topol, MD, founder and director of the Scripps Translational Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif.

But evidence from other countries, specifically Singapore and France, show that at least two of these variants turned out not to be as damaging as expected, likely because of high numbers of people vaccinated or who survived previous infections, he said.

Still, there is little to celebrate in the new findings, except that COVID-19 vaccinations and prior infections can still reduce the risk for serious outcomes such as hospitalization and death, the researchers wrote.

In fact, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data released on Dec. 16 shows that people who have received four shots of the original COVID-19 vaccines as well as the bivalent booster were 57% less likely to visit an urgent care clinic or emergency room, regardless of age.

It comes at a time when BQ.1 and BQ.1.1 account for about 70% of the circulating variants, data show. In addition, hospitalizations are up 18% over the past 2 weeks and COVID-19 deaths are up 50% nationwide, The New York Times reported.

Globally, in many places, an “immunity wall” that has been built, Dr. Topol said. That may not be the case in the United States.

“The problem in the United States, making it harder to predict, is that we have a very low rate of recent boosters, in the past 6 months, especially in seniors,” he said. For example, only 36% of Americans aged 65 years and older, the group with highest risk, have received an updated bivalent booster.

An evolving virus

The subvariants are successfully replacing BA.5, which reigned as one of the most common Omicron variants over the past year. The latest CDC data show that BA.5 now accounts for only about 10% of the circulating virus. The researchers wrote: “This rapid replacement of virus strains is raising the specter of yet another wave of infections in the coming months.”

BQ.1 and BQ.1.1 evolved directly from BA.5 – adding more and some novel mutations to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. XBB and XBB.1 are the “offspring” of a combination of two other strains, known as BJ.1 and BA.2.75.

The story sounds familiar to the researchers. “The rapid rise of these subvariants and their extensive array of spike mutations are reminiscent of the appearance of the first Omicron variant last year, thus raising concerns that they may further compromise the efficacy of current COVID-19 vaccines and monoclonal antibody therapeutics,” they wrote. “We now report findings that indicate that such concerns are, sadly, justified, especially so for the XBB and XBB.1 subvariants.”

To figure out how effective existing antibodies could be against these newer subvariants, Dr. Wang and colleagues used blood samples from five groups of people. They tested serum from people who had three doses of the original COVID-19 vaccine, four doses of the original vaccine, those who received a bivalent booster, people who experienced a breakthrough infection with the BA.2 Omicron variant, and those who had a breakthrough with a BA.4 or BA.5 variant.

Adding the new subvariants to these serum samples revealed that the existing antibodies in the blood were ineffective at wiping out or neutralizing BQ.1, BQ.1.1, XBB, and XBB.1.

The BQ.1 subvariant was six times more resistant to antibodies than BA.5, its parent strain, and XBB.1 was 63 times more resistant compared with its predecessor, BA.2.

This shift in the ability of vaccines to stop the subvariants “is particularly concerning,” the researchers wrote.

Wiping out treatments too

Dr. Wang and colleagues also tested how well a panel of 23 different monoclonal antibody drugs might work against the four subvariants. The therapies all worked well against the original Omicron variant and included some approved for use through the Food and Drug Administration emergency use authorization (EUA) program at the time of the study.

They found that 19 of these 23 monoclonal antibodies lost effectiveness “greatly or completely” against XBB and XBB.1, for example.

This is not the first time that monoclonal antibody therapies have gone from effective to ineffective. Previous variants have come out that no longer responded to treatment with bamlanivimab, etesevimab, imdevimab, casirivimab, tixagevimab, cilgavimab, and sotrovimab. Bebtelovimab now joins this list and is no longer available from Eli Lilly under EUA because of this lack of effectiveness.

The lack of an effective monoclonal antibody treatment “poses a serious problem for millions of immunocompromised individuals who do not respond robustly to COVID-19 vaccines,” the researchers wrote, adding that “the urgent need to develop active monoclonal antibodies for clinical use is obvious.”

A limitation of the study is that the work is done in blood samples. The effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination against the BQ and XBB subvariants should be evaluated in people in clinical studies, the authors noted.

Also, the current study looked at how well antibodies could neutralize the viral strains, but future research, they added, should look at how well “cellular immunity” or other aspects of the immune system might protect people.

Going forward, the challenge remains to develop vaccines and treatments that offer broad protection as the coronavirus continues to evolve.

In an alarming ending, the researchers wrote: “We have collectively chased after SARS-CoV-2 variants for over 2 years, and yet, the virus continues to evolve and evade.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s a story perhaps more appropriate for Halloween than for the festive holiday season, given its scary implications.

Not too dire so far, until the researchers’ other findings are considered.

The BQ.1, BQ1.1, XBB, and XBB.1 subvariants are the most resistant to neutralizing antibodies, researcher Qian Wang, PhD, and colleagues wrote in a study published online in the journal Cell. This means people have no or “markedly reduced” protection against infection from these four strains, even if they’ve already had COVID-19 or are vaccinated and boosted multiple times, including with a bivalent vaccine.

On top of that, all available monoclonal antibody treatments are mostly or completely ineffective against these subvariants.

What does that mean for the immediate future? The findings are definitely “worrisome,” said Eric Topol, MD, founder and director of the Scripps Translational Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif.

But evidence from other countries, specifically Singapore and France, show that at least two of these variants turned out not to be as damaging as expected, likely because of high numbers of people vaccinated or who survived previous infections, he said.

Still, there is little to celebrate in the new findings, except that COVID-19 vaccinations and prior infections can still reduce the risk for serious outcomes such as hospitalization and death, the researchers wrote.

In fact, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data released on Dec. 16 shows that people who have received four shots of the original COVID-19 vaccines as well as the bivalent booster were 57% less likely to visit an urgent care clinic or emergency room, regardless of age.

It comes at a time when BQ.1 and BQ.1.1 account for about 70% of the circulating variants, data show. In addition, hospitalizations are up 18% over the past 2 weeks and COVID-19 deaths are up 50% nationwide, The New York Times reported.

Globally, in many places, an “immunity wall” that has been built, Dr. Topol said. That may not be the case in the United States.

“The problem in the United States, making it harder to predict, is that we have a very low rate of recent boosters, in the past 6 months, especially in seniors,” he said. For example, only 36% of Americans aged 65 years and older, the group with highest risk, have received an updated bivalent booster.

An evolving virus

The subvariants are successfully replacing BA.5, which reigned as one of the most common Omicron variants over the past year. The latest CDC data show that BA.5 now accounts for only about 10% of the circulating virus. The researchers wrote: “This rapid replacement of virus strains is raising the specter of yet another wave of infections in the coming months.”

BQ.1 and BQ.1.1 evolved directly from BA.5 – adding more and some novel mutations to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. XBB and XBB.1 are the “offspring” of a combination of two other strains, known as BJ.1 and BA.2.75.

The story sounds familiar to the researchers. “The rapid rise of these subvariants and their extensive array of spike mutations are reminiscent of the appearance of the first Omicron variant last year, thus raising concerns that they may further compromise the efficacy of current COVID-19 vaccines and monoclonal antibody therapeutics,” they wrote. “We now report findings that indicate that such concerns are, sadly, justified, especially so for the XBB and XBB.1 subvariants.”

To figure out how effective existing antibodies could be against these newer subvariants, Dr. Wang and colleagues used blood samples from five groups of people. They tested serum from people who had three doses of the original COVID-19 vaccine, four doses of the original vaccine, those who received a bivalent booster, people who experienced a breakthrough infection with the BA.2 Omicron variant, and those who had a breakthrough with a BA.4 or BA.5 variant.

Adding the new subvariants to these serum samples revealed that the existing antibodies in the blood were ineffective at wiping out or neutralizing BQ.1, BQ.1.1, XBB, and XBB.1.

The BQ.1 subvariant was six times more resistant to antibodies than BA.5, its parent strain, and XBB.1 was 63 times more resistant compared with its predecessor, BA.2.

This shift in the ability of vaccines to stop the subvariants “is particularly concerning,” the researchers wrote.

Wiping out treatments too

Dr. Wang and colleagues also tested how well a panel of 23 different monoclonal antibody drugs might work against the four subvariants. The therapies all worked well against the original Omicron variant and included some approved for use through the Food and Drug Administration emergency use authorization (EUA) program at the time of the study.

They found that 19 of these 23 monoclonal antibodies lost effectiveness “greatly or completely” against XBB and XBB.1, for example.

This is not the first time that monoclonal antibody therapies have gone from effective to ineffective. Previous variants have come out that no longer responded to treatment with bamlanivimab, etesevimab, imdevimab, casirivimab, tixagevimab, cilgavimab, and sotrovimab. Bebtelovimab now joins this list and is no longer available from Eli Lilly under EUA because of this lack of effectiveness.

The lack of an effective monoclonal antibody treatment “poses a serious problem for millions of immunocompromised individuals who do not respond robustly to COVID-19 vaccines,” the researchers wrote, adding that “the urgent need to develop active monoclonal antibodies for clinical use is obvious.”

A limitation of the study is that the work is done in blood samples. The effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination against the BQ and XBB subvariants should be evaluated in people in clinical studies, the authors noted.

Also, the current study looked at how well antibodies could neutralize the viral strains, but future research, they added, should look at how well “cellular immunity” or other aspects of the immune system might protect people.

Going forward, the challenge remains to develop vaccines and treatments that offer broad protection as the coronavirus continues to evolve.

In an alarming ending, the researchers wrote: “We have collectively chased after SARS-CoV-2 variants for over 2 years, and yet, the virus continues to evolve and evade.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s a story perhaps more appropriate for Halloween than for the festive holiday season, given its scary implications.

Not too dire so far, until the researchers’ other findings are considered.

The BQ.1, BQ1.1, XBB, and XBB.1 subvariants are the most resistant to neutralizing antibodies, researcher Qian Wang, PhD, and colleagues wrote in a study published online in the journal Cell. This means people have no or “markedly reduced” protection against infection from these four strains, even if they’ve already had COVID-19 or are vaccinated and boosted multiple times, including with a bivalent vaccine.

On top of that, all available monoclonal antibody treatments are mostly or completely ineffective against these subvariants.

What does that mean for the immediate future? The findings are definitely “worrisome,” said Eric Topol, MD, founder and director of the Scripps Translational Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif.

But evidence from other countries, specifically Singapore and France, show that at least two of these variants turned out not to be as damaging as expected, likely because of high numbers of people vaccinated or who survived previous infections, he said.

Still, there is little to celebrate in the new findings, except that COVID-19 vaccinations and prior infections can still reduce the risk for serious outcomes such as hospitalization and death, the researchers wrote.

In fact, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data released on Dec. 16 shows that people who have received four shots of the original COVID-19 vaccines as well as the bivalent booster were 57% less likely to visit an urgent care clinic or emergency room, regardless of age.

It comes at a time when BQ.1 and BQ.1.1 account for about 70% of the circulating variants, data show. In addition, hospitalizations are up 18% over the past 2 weeks and COVID-19 deaths are up 50% nationwide, The New York Times reported.

Globally, in many places, an “immunity wall” that has been built, Dr. Topol said. That may not be the case in the United States.

“The problem in the United States, making it harder to predict, is that we have a very low rate of recent boosters, in the past 6 months, especially in seniors,” he said. For example, only 36% of Americans aged 65 years and older, the group with highest risk, have received an updated bivalent booster.

An evolving virus

The subvariants are successfully replacing BA.5, which reigned as one of the most common Omicron variants over the past year. The latest CDC data show that BA.5 now accounts for only about 10% of the circulating virus. The researchers wrote: “This rapid replacement of virus strains is raising the specter of yet another wave of infections in the coming months.”

BQ.1 and BQ.1.1 evolved directly from BA.5 – adding more and some novel mutations to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. XBB and XBB.1 are the “offspring” of a combination of two other strains, known as BJ.1 and BA.2.75.

The story sounds familiar to the researchers. “The rapid rise of these subvariants and their extensive array of spike mutations are reminiscent of the appearance of the first Omicron variant last year, thus raising concerns that they may further compromise the efficacy of current COVID-19 vaccines and monoclonal antibody therapeutics,” they wrote. “We now report findings that indicate that such concerns are, sadly, justified, especially so for the XBB and XBB.1 subvariants.”

To figure out how effective existing antibodies could be against these newer subvariants, Dr. Wang and colleagues used blood samples from five groups of people. They tested serum from people who had three doses of the original COVID-19 vaccine, four doses of the original vaccine, those who received a bivalent booster, people who experienced a breakthrough infection with the BA.2 Omicron variant, and those who had a breakthrough with a BA.4 or BA.5 variant.

Adding the new subvariants to these serum samples revealed that the existing antibodies in the blood were ineffective at wiping out or neutralizing BQ.1, BQ.1.1, XBB, and XBB.1.

The BQ.1 subvariant was six times more resistant to antibodies than BA.5, its parent strain, and XBB.1 was 63 times more resistant compared with its predecessor, BA.2.

This shift in the ability of vaccines to stop the subvariants “is particularly concerning,” the researchers wrote.

Wiping out treatments too

Dr. Wang and colleagues also tested how well a panel of 23 different monoclonal antibody drugs might work against the four subvariants. The therapies all worked well against the original Omicron variant and included some approved for use through the Food and Drug Administration emergency use authorization (EUA) program at the time of the study.

They found that 19 of these 23 monoclonal antibodies lost effectiveness “greatly or completely” against XBB and XBB.1, for example.

This is not the first time that monoclonal antibody therapies have gone from effective to ineffective. Previous variants have come out that no longer responded to treatment with bamlanivimab, etesevimab, imdevimab, casirivimab, tixagevimab, cilgavimab, and sotrovimab. Bebtelovimab now joins this list and is no longer available from Eli Lilly under EUA because of this lack of effectiveness.

The lack of an effective monoclonal antibody treatment “poses a serious problem for millions of immunocompromised individuals who do not respond robustly to COVID-19 vaccines,” the researchers wrote, adding that “the urgent need to develop active monoclonal antibodies for clinical use is obvious.”

A limitation of the study is that the work is done in blood samples. The effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination against the BQ and XBB subvariants should be evaluated in people in clinical studies, the authors noted.

Also, the current study looked at how well antibodies could neutralize the viral strains, but future research, they added, should look at how well “cellular immunity” or other aspects of the immune system might protect people.

Going forward, the challenge remains to develop vaccines and treatments that offer broad protection as the coronavirus continues to evolve.

In an alarming ending, the researchers wrote: “We have collectively chased after SARS-CoV-2 variants for over 2 years, and yet, the virus continues to evolve and evade.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CELL

What length antibiotic course for prostatitis?

PARIS – To date, studies of antibiotic course length for treating urinary tract infections in men have been patchy and retrospective.

Through recent randomized trials, guidelines can now be based on more solid data.

In sum, to maximize clinical and microbiologic success, a nonfebrile urinary tract infection is treated for 7 days, and a febrile urinary tract infection is treated for a minimum of 14 days.

At the 116th conference of the French urology association, Matthieu Lafaurie, MD, of the Multidisciplinary Infectious Diseases Unit U21, Saint Louis Hospital, Paris, reviewed the literature on this subject.

Guidelines for men

The European Association of Urology made its position clear in a text updated in 2022. It stated: Therefore, treatment with antimicrobial drugs that penetrate the prostate tissue is needed in men presenting with symptoms of a urinary tract infection.” In its classification of prostatitis, the National Institutes of Health distinguishes between acute prostatitis (symptoms of a urinary tract infection; stage I) and chronic prostatitis (recurrent infection with the same microorganism; stage II).

Although the French-language Society of Infectious Diseases distinguishes between febrile and nonfebrile urinary tract infections in males, the academic body does not take into account whether the patient has a fever when determining which antibiotic should be given and how long the course should be: A minimum of 14 days’ treatment is recommended when opting for fluoroquinolones, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (cotrimoxazole), or injectable beta-lactam antibiotics, and at least 21 days is recommended for other drugs or in cases in which there is an underlying urologic condition that has not been treated.

Yet the EAU recommends treating cystitis with antibiotics for at least 7 days, preferably with cotrimoxazole or fluoroquinolone, depending on the results of sensitivity testing. For acute prostatitis, the length of treatment with fluoroquinolones should be at least 14 days.

Nonfebrile infections

Participation of men in studies of the treatment of complicated cystitis is variable; at most only 10% of patients in such trials are men. There are few data specific to men with nonfebrile urinary tract infections, and most studies are retrospective and involve small cohorts. One of these is a community-based study that involved 422 men aged 18-104 years who presented with nonfebrile urinary tract infection (acute dysuria, frequency of urination and/or urgency of urination, temperature < 38° C, no general symptoms). Antibiotic treatment was prescribed in 60% of cases. In more than 55% of cases, the length of the course of treatment was 1–7 days. Treatment was with cotrimoxazole, quinolones, and nitrofurantoin.

Another observational retrospective study showed benefit with nitrofurantoin (50 mg/8 h in 94% of cases; 69 patients) and pivmecillinam (200 mg/8 h in 65% of cases; 200 mg/12 h in 30% of patients; 57 patients) in treating lower urinary tract infections in men. The median treatment duration was 7 days. The failure rate was 1.4% and 12%, respectively, for these treatments. Compared to the so-called gold-standard treatment, trimethoprim (10 days/800 mg/12 h; 45 patients), the recurrence rate was 11% and 26% for nitrofurantoin and pivmecillinam versus 7% for trimethoprim. The most significant relapse rate with pivmecillinam was when treatment was given for fewer than 7 days.

This is the only risk factor for further antibiotic treatment and/or recurrence. There was no significant difference between the three drugs with regard to other parameters (urinary tract infection symptoms, benign prostatic hypertrophy, prostate cancer, gram-positive bacteria, etc).

Another retrospective, European study of nitrofurantoin that was published in 2015 included 485 patients (100 mg twice daily in 71% of cases). Clinical cure was defined as an absence of signs or symptoms of a urinary tract infection for 14 days after stopping nitrofurantoin, without use of other antibiotics. The cure rate was 77%. Better efficacy was achieved for patients with gram-negative (vs. gram-positive) bacteria. The treatment duration did not differ significantly (clinical success was achieved when the treatment was taken for 8.6 ± 3.6 days; clinical failure occurred when the treatment was taken for 9.3 ± 6.9 days; P = .28).

Regarding pivmecillinam, a retrospective 2010-2016 study involved 21,864 adults and included 2,524 men who had been treated empirically with pivmecillinam (400 mg three times daily) for significant bacteriuria (Escherichia coli) and a lower urinary tract infection. The researchers concluded that for men, the success rate was identical whether the treatment lasted 5 or 7 days.

An American community-based (urologists, primary care physicians, general medicine services) retrospective cohort study involving 573 men with nonfebrile lower urinary tract infections was conducted from 2011 to 2015. The patients received antibiotic treatment with fluoroquinolones (69.7%), cotrimoxazole (21.2%), nitrofurantoin (5.3%), trimethoprim, beta-lactam antibiotics, or aminoglycosides. No clinical advantage was seen in treating men with urinary tract infections for longer than 7 days.

There are some data on the use of fosfomycin. In an observational retrospective study, 25 men of 52 male adults with leukocyturia and E. coli greater than 105, ESBL, were treated with fosfomycin trometamol 3 g on days 1, 3, 5. Clinical and microbiologic success was achieved for 94% and 78.5%, respectively. No distinction was made between the sexes.

These results were confirmed in a retrospective, observational study involving 18 men (of a total of 75 adults) with no fever or hyperleukocytosis who received the same fosfomycin trometamol regimen. The rate of clinical cure or sterile urine microscopy and culture was 69% at 13 days. The risk failure factor was, as expected, infection with Klebsiella pneumoniae, which was slightly susceptible to fosfomycin, unlike E. coli.

The most recent study in this field was published in 2021. It was also the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. In all, 272 men older than 18 years were prescribed either ciprofloxacin or cotrimoxazole for 7-14 days to treat a nonfebrile urinary tract infection. To be eligible for the trial, patients were required to have disease of new onset with at least one of the following symptoms: dysuria, frequency of urination, urgency of urination, hematuria, costovertebral angle tenderness, or perineal, flank, or suprapubic pain. Urine microscopy and culture were not necessary; the approach was wholly symptomatic. Treatment was prescribed for 7 days. Patients were randomly allocated on day 8 to receive treatment for the following 7 days (molecule or placebo). The primary outcome was resolution of clinical symptoms of urinary tract infection by 14 days after completion of active antibiotic treatment. In an intention-to-treat or per-protocol analysis, the difference in efficacy between the two molecules was largely below the required 10%. The treatment duration noninferiority margin was 7 days, compared with 14 days.

“In 2022, with regard to the duration of treatment of nonfebrile urinary tract infections in men, the not completely irrefutable evidence does, however, stack up in favor of the possibility of a 7-day or even 5-day course,” pointed out Dr. Lafaurie. “Fluoroquinolones [such as] ofloxacin, levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, as well as cotrimoxazole and other antibiotics, such as pivmecillinam, nitrofurantoin, or fosfomycin trometamol, can be used, despite the fact that they pass less easily into the prostate – a not-so-obvious benefit.”

Febrile infections

In terms of febrile urinary tract infections, a single-center, prospective, open-label study from 2003 involved 72 male inpatients who were randomly to receive treatment either for 2 weeks or 4 weeks. Treatment consisted of ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily. This study provided most of the evidence to justify the recommended 14-day antibiotic course.

Another noninferiority, randomized, placebo-controlled study published in 2017 compared 7- and 14-day treatment with ciprofloxacin 500 mg to placebo twice per week. In men, 7 days of antibiotic therapy was inferior to 14 days during a short-term follow-up but was not inferior during a longer follow-up.

A decisive study, which is currently in the submission phase, could silence debate. “In our noninferiority, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, we have enrolled 240 men over the age of 18 years with a febrile infection documented by a fever of 38° C or more, clinical signs of infection, and leukocyturia at least above 10/mm3 and with symptoms lasting less than 3 months,” said Dr. Lafaurie, the trial coordinator.

The primary outcome for efficacy was microbiologic and clinical success after 6 weeks. Patients received either ofloxacin, ceftriaxone, or cefotaxime (two third-generation cephalosporins in the beta-lactam family).

“We clearly show that, for a 7-day course, the clinical success rate is 55.7%, and for a 14-day course, this goes up to 77.6%, with no difference in terms of adverse effects or selection of resistant bacteria. The predictive factors for success are a 14-day treatment and being under the age of 50 years,” said Dr. Lafaurie.

“Unlike nonfebrile urinary tract infections in men, a 7-day course is insufficient for patients with febrile urinary tract infections, and a minimum of 14 days is required to achieve clinical and microbiological success,” he concluded.

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

PARIS – To date, studies of antibiotic course length for treating urinary tract infections in men have been patchy and retrospective.

Through recent randomized trials, guidelines can now be based on more solid data.

In sum, to maximize clinical and microbiologic success, a nonfebrile urinary tract infection is treated for 7 days, and a febrile urinary tract infection is treated for a minimum of 14 days.

At the 116th conference of the French urology association, Matthieu Lafaurie, MD, of the Multidisciplinary Infectious Diseases Unit U21, Saint Louis Hospital, Paris, reviewed the literature on this subject.

Guidelines for men

The European Association of Urology made its position clear in a text updated in 2022. It stated: Therefore, treatment with antimicrobial drugs that penetrate the prostate tissue is needed in men presenting with symptoms of a urinary tract infection.” In its classification of prostatitis, the National Institutes of Health distinguishes between acute prostatitis (symptoms of a urinary tract infection; stage I) and chronic prostatitis (recurrent infection with the same microorganism; stage II).

Although the French-language Society of Infectious Diseases distinguishes between febrile and nonfebrile urinary tract infections in males, the academic body does not take into account whether the patient has a fever when determining which antibiotic should be given and how long the course should be: A minimum of 14 days’ treatment is recommended when opting for fluoroquinolones, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (cotrimoxazole), or injectable beta-lactam antibiotics, and at least 21 days is recommended for other drugs or in cases in which there is an underlying urologic condition that has not been treated.

Yet the EAU recommends treating cystitis with antibiotics for at least 7 days, preferably with cotrimoxazole or fluoroquinolone, depending on the results of sensitivity testing. For acute prostatitis, the length of treatment with fluoroquinolones should be at least 14 days.

Nonfebrile infections

Participation of men in studies of the treatment of complicated cystitis is variable; at most only 10% of patients in such trials are men. There are few data specific to men with nonfebrile urinary tract infections, and most studies are retrospective and involve small cohorts. One of these is a community-based study that involved 422 men aged 18-104 years who presented with nonfebrile urinary tract infection (acute dysuria, frequency of urination and/or urgency of urination, temperature < 38° C, no general symptoms). Antibiotic treatment was prescribed in 60% of cases. In more than 55% of cases, the length of the course of treatment was 1–7 days. Treatment was with cotrimoxazole, quinolones, and nitrofurantoin.

Another observational retrospective study showed benefit with nitrofurantoin (50 mg/8 h in 94% of cases; 69 patients) and pivmecillinam (200 mg/8 h in 65% of cases; 200 mg/12 h in 30% of patients; 57 patients) in treating lower urinary tract infections in men. The median treatment duration was 7 days. The failure rate was 1.4% and 12%, respectively, for these treatments. Compared to the so-called gold-standard treatment, trimethoprim (10 days/800 mg/12 h; 45 patients), the recurrence rate was 11% and 26% for nitrofurantoin and pivmecillinam versus 7% for trimethoprim. The most significant relapse rate with pivmecillinam was when treatment was given for fewer than 7 days.

This is the only risk factor for further antibiotic treatment and/or recurrence. There was no significant difference between the three drugs with regard to other parameters (urinary tract infection symptoms, benign prostatic hypertrophy, prostate cancer, gram-positive bacteria, etc).

Another retrospective, European study of nitrofurantoin that was published in 2015 included 485 patients (100 mg twice daily in 71% of cases). Clinical cure was defined as an absence of signs or symptoms of a urinary tract infection for 14 days after stopping nitrofurantoin, without use of other antibiotics. The cure rate was 77%. Better efficacy was achieved for patients with gram-negative (vs. gram-positive) bacteria. The treatment duration did not differ significantly (clinical success was achieved when the treatment was taken for 8.6 ± 3.6 days; clinical failure occurred when the treatment was taken for 9.3 ± 6.9 days; P = .28).

Regarding pivmecillinam, a retrospective 2010-2016 study involved 21,864 adults and included 2,524 men who had been treated empirically with pivmecillinam (400 mg three times daily) for significant bacteriuria (Escherichia coli) and a lower urinary tract infection. The researchers concluded that for men, the success rate was identical whether the treatment lasted 5 or 7 days.

An American community-based (urologists, primary care physicians, general medicine services) retrospective cohort study involving 573 men with nonfebrile lower urinary tract infections was conducted from 2011 to 2015. The patients received antibiotic treatment with fluoroquinolones (69.7%), cotrimoxazole (21.2%), nitrofurantoin (5.3%), trimethoprim, beta-lactam antibiotics, or aminoglycosides. No clinical advantage was seen in treating men with urinary tract infections for longer than 7 days.

There are some data on the use of fosfomycin. In an observational retrospective study, 25 men of 52 male adults with leukocyturia and E. coli greater than 105, ESBL, were treated with fosfomycin trometamol 3 g on days 1, 3, 5. Clinical and microbiologic success was achieved for 94% and 78.5%, respectively. No distinction was made between the sexes.

These results were confirmed in a retrospective, observational study involving 18 men (of a total of 75 adults) with no fever or hyperleukocytosis who received the same fosfomycin trometamol regimen. The rate of clinical cure or sterile urine microscopy and culture was 69% at 13 days. The risk failure factor was, as expected, infection with Klebsiella pneumoniae, which was slightly susceptible to fosfomycin, unlike E. coli.

The most recent study in this field was published in 2021. It was also the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. In all, 272 men older than 18 years were prescribed either ciprofloxacin or cotrimoxazole for 7-14 days to treat a nonfebrile urinary tract infection. To be eligible for the trial, patients were required to have disease of new onset with at least one of the following symptoms: dysuria, frequency of urination, urgency of urination, hematuria, costovertebral angle tenderness, or perineal, flank, or suprapubic pain. Urine microscopy and culture were not necessary; the approach was wholly symptomatic. Treatment was prescribed for 7 days. Patients were randomly allocated on day 8 to receive treatment for the following 7 days (molecule or placebo). The primary outcome was resolution of clinical symptoms of urinary tract infection by 14 days after completion of active antibiotic treatment. In an intention-to-treat or per-protocol analysis, the difference in efficacy between the two molecules was largely below the required 10%. The treatment duration noninferiority margin was 7 days, compared with 14 days.

“In 2022, with regard to the duration of treatment of nonfebrile urinary tract infections in men, the not completely irrefutable evidence does, however, stack up in favor of the possibility of a 7-day or even 5-day course,” pointed out Dr. Lafaurie. “Fluoroquinolones [such as] ofloxacin, levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, as well as cotrimoxazole and other antibiotics, such as pivmecillinam, nitrofurantoin, or fosfomycin trometamol, can be used, despite the fact that they pass less easily into the prostate – a not-so-obvious benefit.”

Febrile infections

In terms of febrile urinary tract infections, a single-center, prospective, open-label study from 2003 involved 72 male inpatients who were randomly to receive treatment either for 2 weeks or 4 weeks. Treatment consisted of ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily. This study provided most of the evidence to justify the recommended 14-day antibiotic course.

Another noninferiority, randomized, placebo-controlled study published in 2017 compared 7- and 14-day treatment with ciprofloxacin 500 mg to placebo twice per week. In men, 7 days of antibiotic therapy was inferior to 14 days during a short-term follow-up but was not inferior during a longer follow-up.

A decisive study, which is currently in the submission phase, could silence debate. “In our noninferiority, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, we have enrolled 240 men over the age of 18 years with a febrile infection documented by a fever of 38° C or more, clinical signs of infection, and leukocyturia at least above 10/mm3 and with symptoms lasting less than 3 months,” said Dr. Lafaurie, the trial coordinator.

The primary outcome for efficacy was microbiologic and clinical success after 6 weeks. Patients received either ofloxacin, ceftriaxone, or cefotaxime (two third-generation cephalosporins in the beta-lactam family).

“We clearly show that, for a 7-day course, the clinical success rate is 55.7%, and for a 14-day course, this goes up to 77.6%, with no difference in terms of adverse effects or selection of resistant bacteria. The predictive factors for success are a 14-day treatment and being under the age of 50 years,” said Dr. Lafaurie.

“Unlike nonfebrile urinary tract infections in men, a 7-day course is insufficient for patients with febrile urinary tract infections, and a minimum of 14 days is required to achieve clinical and microbiological success,” he concluded.

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

PARIS – To date, studies of antibiotic course length for treating urinary tract infections in men have been patchy and retrospective.

Through recent randomized trials, guidelines can now be based on more solid data.

In sum, to maximize clinical and microbiologic success, a nonfebrile urinary tract infection is treated for 7 days, and a febrile urinary tract infection is treated for a minimum of 14 days.

At the 116th conference of the French urology association, Matthieu Lafaurie, MD, of the Multidisciplinary Infectious Diseases Unit U21, Saint Louis Hospital, Paris, reviewed the literature on this subject.

Guidelines for men

The European Association of Urology made its position clear in a text updated in 2022. It stated: Therefore, treatment with antimicrobial drugs that penetrate the prostate tissue is needed in men presenting with symptoms of a urinary tract infection.” In its classification of prostatitis, the National Institutes of Health distinguishes between acute prostatitis (symptoms of a urinary tract infection; stage I) and chronic prostatitis (recurrent infection with the same microorganism; stage II).

Although the French-language Society of Infectious Diseases distinguishes between febrile and nonfebrile urinary tract infections in males, the academic body does not take into account whether the patient has a fever when determining which antibiotic should be given and how long the course should be: A minimum of 14 days’ treatment is recommended when opting for fluoroquinolones, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (cotrimoxazole), or injectable beta-lactam antibiotics, and at least 21 days is recommended for other drugs or in cases in which there is an underlying urologic condition that has not been treated.

Yet the EAU recommends treating cystitis with antibiotics for at least 7 days, preferably with cotrimoxazole or fluoroquinolone, depending on the results of sensitivity testing. For acute prostatitis, the length of treatment with fluoroquinolones should be at least 14 days.

Nonfebrile infections

Participation of men in studies of the treatment of complicated cystitis is variable; at most only 10% of patients in such trials are men. There are few data specific to men with nonfebrile urinary tract infections, and most studies are retrospective and involve small cohorts. One of these is a community-based study that involved 422 men aged 18-104 years who presented with nonfebrile urinary tract infection (acute dysuria, frequency of urination and/or urgency of urination, temperature < 38° C, no general symptoms). Antibiotic treatment was prescribed in 60% of cases. In more than 55% of cases, the length of the course of treatment was 1–7 days. Treatment was with cotrimoxazole, quinolones, and nitrofurantoin.

Another observational retrospective study showed benefit with nitrofurantoin (50 mg/8 h in 94% of cases; 69 patients) and pivmecillinam (200 mg/8 h in 65% of cases; 200 mg/12 h in 30% of patients; 57 patients) in treating lower urinary tract infections in men. The median treatment duration was 7 days. The failure rate was 1.4% and 12%, respectively, for these treatments. Compared to the so-called gold-standard treatment, trimethoprim (10 days/800 mg/12 h; 45 patients), the recurrence rate was 11% and 26% for nitrofurantoin and pivmecillinam versus 7% for trimethoprim. The most significant relapse rate with pivmecillinam was when treatment was given for fewer than 7 days.

This is the only risk factor for further antibiotic treatment and/or recurrence. There was no significant difference between the three drugs with regard to other parameters (urinary tract infection symptoms, benign prostatic hypertrophy, prostate cancer, gram-positive bacteria, etc).

Another retrospective, European study of nitrofurantoin that was published in 2015 included 485 patients (100 mg twice daily in 71% of cases). Clinical cure was defined as an absence of signs or symptoms of a urinary tract infection for 14 days after stopping nitrofurantoin, without use of other antibiotics. The cure rate was 77%. Better efficacy was achieved for patients with gram-negative (vs. gram-positive) bacteria. The treatment duration did not differ significantly (clinical success was achieved when the treatment was taken for 8.6 ± 3.6 days; clinical failure occurred when the treatment was taken for 9.3 ± 6.9 days; P = .28).

Regarding pivmecillinam, a retrospective 2010-2016 study involved 21,864 adults and included 2,524 men who had been treated empirically with pivmecillinam (400 mg three times daily) for significant bacteriuria (Escherichia coli) and a lower urinary tract infection. The researchers concluded that for men, the success rate was identical whether the treatment lasted 5 or 7 days.

An American community-based (urologists, primary care physicians, general medicine services) retrospective cohort study involving 573 men with nonfebrile lower urinary tract infections was conducted from 2011 to 2015. The patients received antibiotic treatment with fluoroquinolones (69.7%), cotrimoxazole (21.2%), nitrofurantoin (5.3%), trimethoprim, beta-lactam antibiotics, or aminoglycosides. No clinical advantage was seen in treating men with urinary tract infections for longer than 7 days.

There are some data on the use of fosfomycin. In an observational retrospective study, 25 men of 52 male adults with leukocyturia and E. coli greater than 105, ESBL, were treated with fosfomycin trometamol 3 g on days 1, 3, 5. Clinical and microbiologic success was achieved for 94% and 78.5%, respectively. No distinction was made between the sexes.

These results were confirmed in a retrospective, observational study involving 18 men (of a total of 75 adults) with no fever or hyperleukocytosis who received the same fosfomycin trometamol regimen. The rate of clinical cure or sterile urine microscopy and culture was 69% at 13 days. The risk failure factor was, as expected, infection with Klebsiella pneumoniae, which was slightly susceptible to fosfomycin, unlike E. coli.

The most recent study in this field was published in 2021. It was also the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. In all, 272 men older than 18 years were prescribed either ciprofloxacin or cotrimoxazole for 7-14 days to treat a nonfebrile urinary tract infection. To be eligible for the trial, patients were required to have disease of new onset with at least one of the following symptoms: dysuria, frequency of urination, urgency of urination, hematuria, costovertebral angle tenderness, or perineal, flank, or suprapubic pain. Urine microscopy and culture were not necessary; the approach was wholly symptomatic. Treatment was prescribed for 7 days. Patients were randomly allocated on day 8 to receive treatment for the following 7 days (molecule or placebo). The primary outcome was resolution of clinical symptoms of urinary tract infection by 14 days after completion of active antibiotic treatment. In an intention-to-treat or per-protocol analysis, the difference in efficacy between the two molecules was largely below the required 10%. The treatment duration noninferiority margin was 7 days, compared with 14 days.

“In 2022, with regard to the duration of treatment of nonfebrile urinary tract infections in men, the not completely irrefutable evidence does, however, stack up in favor of the possibility of a 7-day or even 5-day course,” pointed out Dr. Lafaurie. “Fluoroquinolones [such as] ofloxacin, levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, as well as cotrimoxazole and other antibiotics, such as pivmecillinam, nitrofurantoin, or fosfomycin trometamol, can be used, despite the fact that they pass less easily into the prostate – a not-so-obvious benefit.”

Febrile infections

In terms of febrile urinary tract infections, a single-center, prospective, open-label study from 2003 involved 72 male inpatients who were randomly to receive treatment either for 2 weeks or 4 weeks. Treatment consisted of ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily. This study provided most of the evidence to justify the recommended 14-day antibiotic course.

Another noninferiority, randomized, placebo-controlled study published in 2017 compared 7- and 14-day treatment with ciprofloxacin 500 mg to placebo twice per week. In men, 7 days of antibiotic therapy was inferior to 14 days during a short-term follow-up but was not inferior during a longer follow-up.

A decisive study, which is currently in the submission phase, could silence debate. “In our noninferiority, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, we have enrolled 240 men over the age of 18 years with a febrile infection documented by a fever of 38° C or more, clinical signs of infection, and leukocyturia at least above 10/mm3 and with symptoms lasting less than 3 months,” said Dr. Lafaurie, the trial coordinator.

The primary outcome for efficacy was microbiologic and clinical success after 6 weeks. Patients received either ofloxacin, ceftriaxone, or cefotaxime (two third-generation cephalosporins in the beta-lactam family).

“We clearly show that, for a 7-day course, the clinical success rate is 55.7%, and for a 14-day course, this goes up to 77.6%, with no difference in terms of adverse effects or selection of resistant bacteria. The predictive factors for success are a 14-day treatment and being under the age of 50 years,” said Dr. Lafaurie.

“Unlike nonfebrile urinary tract infections in men, a 7-day course is insufficient for patients with febrile urinary tract infections, and a minimum of 14 days is required to achieve clinical and microbiological success,” he concluded.

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

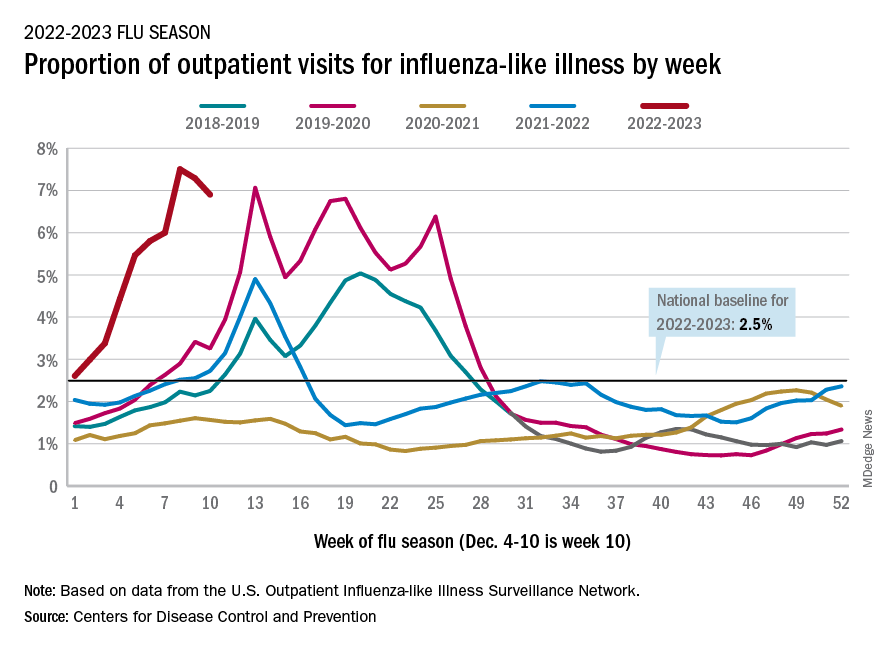

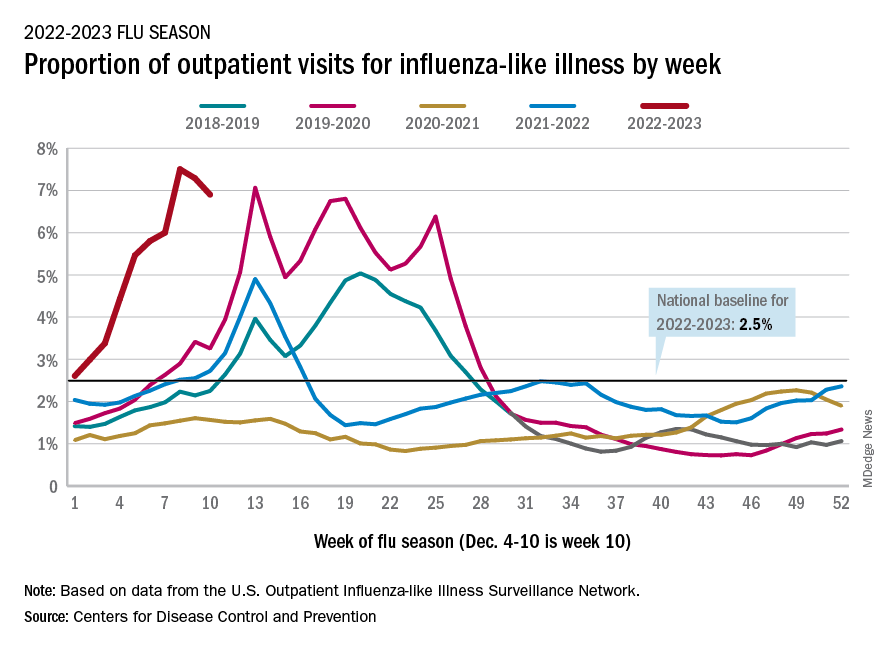

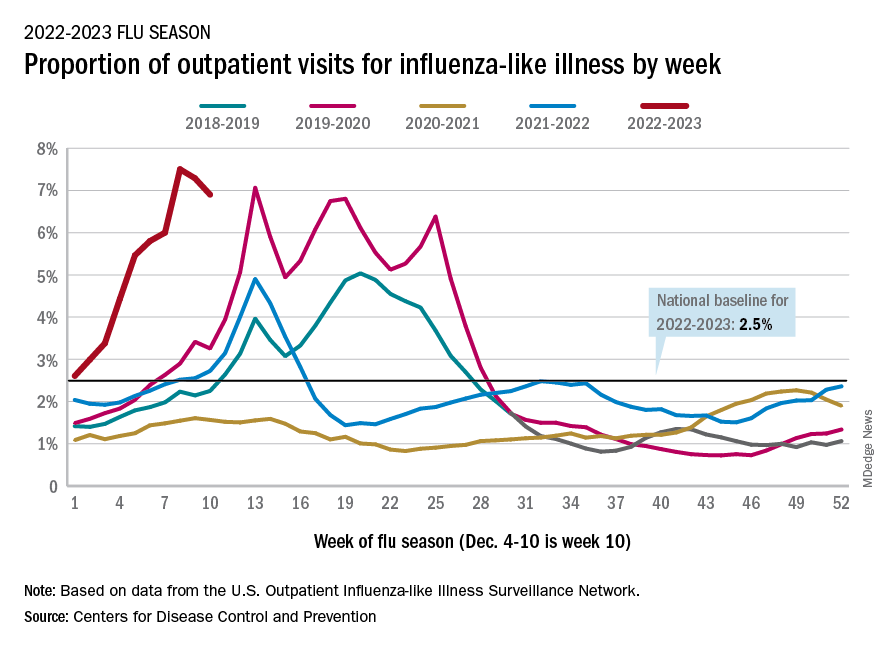

Flu hospitalizations drop amid signs of an early peak

It’s beginning to look less like an epidemic as seasonal flu activity “appears to be declining in some areas,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Declines in a few states and territories were enough to lower national activity, as measured by outpatient visits for influenza-like illness, for the second consecutive week. This reduced the weekly number of hospital admissions for the first time in the 2022-2023 season, according to the CDC influenza division’s weekly FluView report.

Flu-related hospital admissions slipped to about 23,500 during the week of Dec. 4-10, after topping 26,000 the week before, based on data reported by 5,000 hospitals from all states and territories.

which was still higher than any other December rate from all previous seasons going back to 2009-10, CDC data shows.

Visits for flu-like illness represented 6.9% of all outpatient visits reported to the CDC during the week of Dec. 4-10. The rate reached 7.5% during the last full week of November before dropping to 7.3%, the CDC said.

There were 28 states or territories with “very high” activity for the latest reporting week, compared with 32 the previous week. Eight states – Colorado, Idaho, Kentucky, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Washington – and New York City were at the very highest level on the CDC’s 1-13 scale of activity, compared with 14 areas the week before, the agency reported.

So far for the 2022-2023 season, the CDC estimated there have been at least 15 million cases of the flu, 150,000 hospitalizations, and 9,300 deaths. Among those deaths have been 30 reported in children, compared with 44 for the entire 2021-22 season and just 1 for 2020-21.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

It’s beginning to look less like an epidemic as seasonal flu activity “appears to be declining in some areas,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Declines in a few states and territories were enough to lower national activity, as measured by outpatient visits for influenza-like illness, for the second consecutive week. This reduced the weekly number of hospital admissions for the first time in the 2022-2023 season, according to the CDC influenza division’s weekly FluView report.

Flu-related hospital admissions slipped to about 23,500 during the week of Dec. 4-10, after topping 26,000 the week before, based on data reported by 5,000 hospitals from all states and territories.

which was still higher than any other December rate from all previous seasons going back to 2009-10, CDC data shows.

Visits for flu-like illness represented 6.9% of all outpatient visits reported to the CDC during the week of Dec. 4-10. The rate reached 7.5% during the last full week of November before dropping to 7.3%, the CDC said.

There were 28 states or territories with “very high” activity for the latest reporting week, compared with 32 the previous week. Eight states – Colorado, Idaho, Kentucky, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Washington – and New York City were at the very highest level on the CDC’s 1-13 scale of activity, compared with 14 areas the week before, the agency reported.

So far for the 2022-2023 season, the CDC estimated there have been at least 15 million cases of the flu, 150,000 hospitalizations, and 9,300 deaths. Among those deaths have been 30 reported in children, compared with 44 for the entire 2021-22 season and just 1 for 2020-21.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

It’s beginning to look less like an epidemic as seasonal flu activity “appears to be declining in some areas,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Declines in a few states and territories were enough to lower national activity, as measured by outpatient visits for influenza-like illness, for the second consecutive week. This reduced the weekly number of hospital admissions for the first time in the 2022-2023 season, according to the CDC influenza division’s weekly FluView report.

Flu-related hospital admissions slipped to about 23,500 during the week of Dec. 4-10, after topping 26,000 the week before, based on data reported by 5,000 hospitals from all states and territories.

which was still higher than any other December rate from all previous seasons going back to 2009-10, CDC data shows.

Visits for flu-like illness represented 6.9% of all outpatient visits reported to the CDC during the week of Dec. 4-10. The rate reached 7.5% during the last full week of November before dropping to 7.3%, the CDC said.

There were 28 states or territories with “very high” activity for the latest reporting week, compared with 32 the previous week. Eight states – Colorado, Idaho, Kentucky, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Washington – and New York City were at the very highest level on the CDC’s 1-13 scale of activity, compared with 14 areas the week before, the agency reported.

So far for the 2022-2023 season, the CDC estimated there have been at least 15 million cases of the flu, 150,000 hospitalizations, and 9,300 deaths. Among those deaths have been 30 reported in children, compared with 44 for the entire 2021-22 season and just 1 for 2020-21.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Hair supplements

in JAMA Dermatology in November 2022.

Drake and colleagues evaluated the safety and efficacy of nutritional supplements for treating hair loss. In a systematic database review from inception to Oct. 20, 2021, they evaluated and compiled the findings of all dietary and nutritional interventions for treatment of hair loss among individuals without a known baseline nutritional deficiency. Thirty articles were included, including 17 randomized clinical trials, 11 clinical trials, and 2 case series.

They found the highest-quality evidence showing the most potential benefit were for 12 of the 20 nutritional interventions in their review: Pumpkin seed oil capsules, omega-3 and -6 combined with antioxidants, tocotrienol, Pantogar, capsaicin and isoflavone, Viviscal (multiple formulations), Nourkrin, Nutrafol, apple nutraceutical, Lambdapil, total glucosides of paeony and compound glycyrrhizin tablets, and zinc. Vitamin D3, kimchi and cheonggukjang, and Forti5 had lower-quality evidence for disease course improvement. Adverse effects associated with the supplements were described as mild and rare.

In practice, for patients with nonscarring alopecia, I typically check screening labs for hair loss, in addition to the clinical exam, before starting treatment (including supplements), as addressing the underlying reason, if found, is always paramount. These labs are best performed when the patient is not taking biotin, as biotin has been shown numerous times to potentially be associated with endocrine lab abnormalities, most commonly thyroid-stimulating hormone, especially at higher doses, as well as troponin levels. Some over-the-counter hair supplements will contain much higher doses than the recommended 30 micrograms per day.

Separately, if ferritin levels are within normal range, but below 50 mcg/L, supplementation with Slow Fe or another slow-release iron supplement may also result in improved hair growth. Ferritin levels are typically rechecked 6 months after supplementation to see if levels of 50 mcg/L or above have been achieved.

Another point to consider before beginning supplementation is to educate patients about potential effects of supplementation, including increased hair growth in other areas besides the scalp. For some patients who are self-conscious about potential hirsutism, this could be an issue, whereas for others, this risk does not outweigh the benefit. Unwanted hair growth, should it occur, may also be addressed with hair removal methods including shaving, waxing, plucking, threading, depilatories, prescription eflornithine cream (Vaniqa), or laser hair removal if desired.

Our armamentarium for treating hair loss includes: addressing underlying systemic causes; topical treatments including topical minoxidil; oral supplements; platelet-rich plasma injections; prescription oral medications including finasteride in men or postmenopausal women or off-label oral minoxidil; and hair transplant surgery if warranted. Having this thorough review of the most common hair supplements currently available is extremely helpful and valuable in our specialty.

Dr. Wesley and Lily Talakoub, MD, are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Write to them at [email protected]. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. She had no relevant disclosures.

in JAMA Dermatology in November 2022.

Drake and colleagues evaluated the safety and efficacy of nutritional supplements for treating hair loss. In a systematic database review from inception to Oct. 20, 2021, they evaluated and compiled the findings of all dietary and nutritional interventions for treatment of hair loss among individuals without a known baseline nutritional deficiency. Thirty articles were included, including 17 randomized clinical trials, 11 clinical trials, and 2 case series.

They found the highest-quality evidence showing the most potential benefit were for 12 of the 20 nutritional interventions in their review: Pumpkin seed oil capsules, omega-3 and -6 combined with antioxidants, tocotrienol, Pantogar, capsaicin and isoflavone, Viviscal (multiple formulations), Nourkrin, Nutrafol, apple nutraceutical, Lambdapil, total glucosides of paeony and compound glycyrrhizin tablets, and zinc. Vitamin D3, kimchi and cheonggukjang, and Forti5 had lower-quality evidence for disease course improvement. Adverse effects associated with the supplements were described as mild and rare.

In practice, for patients with nonscarring alopecia, I typically check screening labs for hair loss, in addition to the clinical exam, before starting treatment (including supplements), as addressing the underlying reason, if found, is always paramount. These labs are best performed when the patient is not taking biotin, as biotin has been shown numerous times to potentially be associated with endocrine lab abnormalities, most commonly thyroid-stimulating hormone, especially at higher doses, as well as troponin levels. Some over-the-counter hair supplements will contain much higher doses than the recommended 30 micrograms per day.

Separately, if ferritin levels are within normal range, but below 50 mcg/L, supplementation with Slow Fe or another slow-release iron supplement may also result in improved hair growth. Ferritin levels are typically rechecked 6 months after supplementation to see if levels of 50 mcg/L or above have been achieved.

Another point to consider before beginning supplementation is to educate patients about potential effects of supplementation, including increased hair growth in other areas besides the scalp. For some patients who are self-conscious about potential hirsutism, this could be an issue, whereas for others, this risk does not outweigh the benefit. Unwanted hair growth, should it occur, may also be addressed with hair removal methods including shaving, waxing, plucking, threading, depilatories, prescription eflornithine cream (Vaniqa), or laser hair removal if desired.

Our armamentarium for treating hair loss includes: addressing underlying systemic causes; topical treatments including topical minoxidil; oral supplements; platelet-rich plasma injections; prescription oral medications including finasteride in men or postmenopausal women or off-label oral minoxidil; and hair transplant surgery if warranted. Having this thorough review of the most common hair supplements currently available is extremely helpful and valuable in our specialty.

Dr. Wesley and Lily Talakoub, MD, are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Write to them at [email protected]. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. She had no relevant disclosures.

in JAMA Dermatology in November 2022.

Drake and colleagues evaluated the safety and efficacy of nutritional supplements for treating hair loss. In a systematic database review from inception to Oct. 20, 2021, they evaluated and compiled the findings of all dietary and nutritional interventions for treatment of hair loss among individuals without a known baseline nutritional deficiency. Thirty articles were included, including 17 randomized clinical trials, 11 clinical trials, and 2 case series.

They found the highest-quality evidence showing the most potential benefit were for 12 of the 20 nutritional interventions in their review: Pumpkin seed oil capsules, omega-3 and -6 combined with antioxidants, tocotrienol, Pantogar, capsaicin and isoflavone, Viviscal (multiple formulations), Nourkrin, Nutrafol, apple nutraceutical, Lambdapil, total glucosides of paeony and compound glycyrrhizin tablets, and zinc. Vitamin D3, kimchi and cheonggukjang, and Forti5 had lower-quality evidence for disease course improvement. Adverse effects associated with the supplements were described as mild and rare.

In practice, for patients with nonscarring alopecia, I typically check screening labs for hair loss, in addition to the clinical exam, before starting treatment (including supplements), as addressing the underlying reason, if found, is always paramount. These labs are best performed when the patient is not taking biotin, as biotin has been shown numerous times to potentially be associated with endocrine lab abnormalities, most commonly thyroid-stimulating hormone, especially at higher doses, as well as troponin levels. Some over-the-counter hair supplements will contain much higher doses than the recommended 30 micrograms per day.

Separately, if ferritin levels are within normal range, but below 50 mcg/L, supplementation with Slow Fe or another slow-release iron supplement may also result in improved hair growth. Ferritin levels are typically rechecked 6 months after supplementation to see if levels of 50 mcg/L or above have been achieved.

Another point to consider before beginning supplementation is to educate patients about potential effects of supplementation, including increased hair growth in other areas besides the scalp. For some patients who are self-conscious about potential hirsutism, this could be an issue, whereas for others, this risk does not outweigh the benefit. Unwanted hair growth, should it occur, may also be addressed with hair removal methods including shaving, waxing, plucking, threading, depilatories, prescription eflornithine cream (Vaniqa), or laser hair removal if desired.

Our armamentarium for treating hair loss includes: addressing underlying systemic causes; topical treatments including topical minoxidil; oral supplements; platelet-rich plasma injections; prescription oral medications including finasteride in men or postmenopausal women or off-label oral minoxidil; and hair transplant surgery if warranted. Having this thorough review of the most common hair supplements currently available is extremely helpful and valuable in our specialty.

Dr. Wesley and Lily Talakoub, MD, are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Write to them at [email protected]. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. She had no relevant disclosures.

Guidance updated for congenital hypothyroidism screening, management

Congenital hypothyroidism is one of the most common preventable causes of intellectual disabilities worldwide, but newborn screening has not been established in all countries.

Additionally, screening alone is not enough to prevent adverse outcomes in children, write authors of a technical report published online in Pediatrics (Jan. 2023;151[1]:e2022060420).

Susan R. Rose, MD, with the division of endocrinology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Ohio, led the work group that updated guidance for screening and management of congenital hypothyroidism. The group worked in conjunction with the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Endocrinology, the AAP Council on Genetics, the Pediatric Endocrine Society, and the American Thyroid Association.

In addition to screening, timely diagnosis, effective treatment, and follow-up are important.

Tests don’t always tell the full story with congenital hypothyroidism.

“Physicians need to consider hypothyroidism in the face of clinical symptoms, even if newborn screening thyroid test results are normal,” the authors write.

They add that newborn screening for congenital hypothyroidism followed by prompt levothyroxine therapy can prevent severe intellectual disability, psychomotor dysfunction, and impaired growth.

Incidence of congenital hypothyroidism ranges from approximately 1 in 2,000 to 1 in 4,000 newborn infants in countries that have newborn screening data, according to the report.

Following are highlights of the guidance:

Clinical signs

Symptoms and signs include large posterior fontanelle, lethargy, large tongue, prolonged jaundice, umbilical hernia, constipation, and/or hypothermia. With these signs, measuring serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and free thyroxine (FT4) is indicated, regardless of screening results.

Newborn screening in first days

Population screening is cost effective when performed by state or other public health laboratories working with hospitals or birthing centers in their area, the authors write.

Multidisciplinary teams are best able to conduct comprehensive care when cases are detected.

The screening includes a dried blood spot from a heel stick on an approved paper card using appropriate collection methods. The blood spots are then sent to the laboratory. The preferred age for collecting the specimen is 48-72 hours of age.

That timing may be difficult, the authors note, as 90% of infants in the United States and Europe are discharged before 48 hours, but taking the specimen before discharge is important to avoid missing the early diagnosis.

“However, collection of the NBS [newborn screening] specimen before 48 hours of age, and particularly before 24 hours of age, necessitates the use of age-specific TSH reference ranges or repeat screening, particularly to avoid false-positive results,” the authors note.

If a newborn infant is transferred to another hospital, communication about the screening is critical.

Testing strategies

Three test strategies are used for screening: a primary TSH – reflex T4 measurement; primary T4 – reflex TSH measurement; and combined T4 and TSH measurement.

“All three test strategies detect moderate to severe primary congenital hypothyroidism with similar accuracy,” the authors write.

Most newborn screening programs in the United States and worldwide use a primary TSH test strategy.

Multiple births, same-sex twins

The incidence of congenital hypothyroidism appears to be higher with multiple births (1:876 in twin births and 1:575 in higher-order multiple births in one study). Another study showed the incidence of congenital hypothyroidism in same-sex twins to be 1 in 593, compared with 1 in 3,060 in different-sex twins.

“Most twin pairs (> 95%) are discordant for congenital hypothyroidism,” the authors write. “However, in monozygotic twins who share placental circulation, blood from a euthyroid fetal twin with normal thyroid hormone levels may cross to a fetal twin with congenital hypothyroidism, temporarily correcting the hypothyroidism and preventing its detection by newborn screening at 24-72 hours of life. Thus, all monozygotic twins, or same-sex twins for whom zygosity is unknown, should undergo repeat newborn screening around 2 weeks of age.”

Down syndrome

Congenital hypothyroidism incidence in infants with trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) is high and ranges from 1% to 12% in various reports. The infants tend to have lower T4 concentrations and higher TSH concentrations than do infants without trisomy. Down syndrome is associated with other comorbidities, including congenital heart disease, “that may further increase the risk of abnormal newborn screening results because of acute illness or excess iodine exposure,” the authors write.

Even infants with Down syndrome who don’t have congenital hypothyroidism are still at significant risk of developing primary hypothyroidism in their first year (approximately 7% in one prospective study).

“Therefore, in these infants, a second newborn screening should be performed at 2-4 weeks of life and serum TSH should be measured at 6 and 12 months of life,” the authors say.

Communication with primary care provider

Direct communication between the newborn screening program and the primary care physician is important for appropriate follow-up. Consulting a pediatric endocrinologist can speed diagnosis and management.

Serum confirmation after abnormal screening

The next step if any child’s screening results suggest congenital hypothyroidism is to perform a physical exam (for goiter, lingual thyroid gland, and/or physical signs of hypothyroidism) and to measure the concentrations of TSH and FT4 (or total T4) in the blood.

For confirmation of abnormal screening results, the authors say, measurement of FT4 is preferred over measuring total T4.

Interpreting serum confirmation

Some interpretations are clear cut: “Elevated TSH with low FT4 on the confirmatory serum testing indicates overt primary hypothyroidism,” the authors write.

But there are various other outcomes with more controversy.

Elevated TSH and normal FT4, for instance, is known as hyperthyrotropinemia or subclinical hypothyroidism and represents a mild primary thyroid abnormality.

In this scenario, there is controversy regarding the need for L-T4 therapy because there are few and conflicting studies regarding how mild congenital hypothyroidism affects cognitive development.

“[E]xpert opinion suggests that persistent TSH elevation > 10 mIU/L is an indication to initiate L-T4 treatment,” the authors write.

Normal TSH and low T4 is seen in patients with central hypothyroidism, prematurity, low birth weight, acute illness, or thyroxine-binding globulin deficiency.

“The concept that central hypothyroidism is usually mild appears unfounded: A study from the Netherlands found that mean pretreatment serum FT4 levels in central congenital hypothyroidism were similar to those of patients with moderately severe primary congenital hypothyroidism. Therefore, L-T4 treatment of central congenital hypothyroidism is indicated.”

Imaging

Routine thyroid imaging is controversial for patients with congenital hypothyroidism. In most cases, it won’t alter clinical management before age 3 years.

Thyroid ultrasonography can find thyroid tissue without radiation exposure and can be performed at any time after a congenital hypothyroidism diagnosis.

“Ultrasonography has lower sensitivity than scintigraphy for detecting ectopic thyroid tissue, the most common cause of congenital hypothyroidism, although its sensitivity is improved by the use of color Doppler,” the authors write.

Infants with normal thyroid imaging at birth may have transient hypothyroidism. In these patients, reevaluation of thyroid hormone therapy after 3 years of age to assess for persistent hypothyroidism may be beneficial.

Treatment

Congenital hypothyroidism is treated with enteral L-T4 at a starting dose of 10-15 mcg/kg per day, given once a day.

L-T4 tablets are the treatment of choice and generic tablets are fine for most children, the authors write, adding that a brand name formulation may be more consistent and better for children with severe congenital hypothyroidism.

An oral solution of L-T4 has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in children.

“[H]owever, limited experience with its use showed that dosing may not be equivalent to dosing with tablet formulations,” the guidance states.

The goal of initial L-T4 therapy is to normalize serum FT4 and TSH levels as quickly as possible. The outlook is poorer for infants whose hypothyroidism is detected later in life, who receive inadequate doses of L-T4, or who have more severe forms.

Age-specific TSH reference ranges vary by laboratory, but recent studies indicate the top limit of normal TSH in infants in the first 3 months of life is 4.1-4.8 mIU/L.

“[T]herefore, TSH values above 5 mIU/L generally are abnormal if observed after 3 months of age. Whether overtreatment (defined by elevated serum FT4) is harmful remains unclear and evidence is conflicting,” the authors write.

Monitoring

In the near-term follow-up, close laboratory monitoring is necessary during L-T4 treatment to maintain blood TSH and FT4 in the target ranges. Studies support measuring those levels every 1-2 months in the first 6 months of life for children with congenital hypothyroidism, every 2-3 months in the second 6 months, and then every 3-4 months between 1 and 3 years of age.

In long-term follow-up, attention to behavioral and cognitive development is important, because children with congenital hypothyroidism may be at higher risk for neurocognitive and socioemotional dysfunction compared with their peers, even with adequate treatment of congenital hypothyroidism. Hearing deficits are reported in about 10% of children with congenital hypothyroidism.

Developmental outcomes

When L-T4 therapy is maintained and TSH and FT4 are within target range, growth and adult height are generally normal in children with congenital hypothyroidism.

In contrast, the neurodevelopmental prognosis is less certain when treatment starts late.

“[I]nfants with severe congenital hypothyroidism and intrauterine hypothyroidism (as indicated by retarded skeletal maturation at birth) may have low-to-normal intelligence,” the report states. “Similarly, although more than 80% of infants given L-T4 replacement therapy before 3 months of age have an intelligence [quotient] greater than 85, 77% of these infants show signs of cognitive impairment in arithmetic ability, speech, or fine motor coordination later in life.”

If a child is properly treated for congenital hypothyroidism but growth or development is abnormal, testing for other illness, hearing deficit, or other hormone deficiency is needed, the report states.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Congenital hypothyroidism is one of the most common preventable causes of intellectual disabilities worldwide, but newborn screening has not been established in all countries.

Additionally, screening alone is not enough to prevent adverse outcomes in children, write authors of a technical report published online in Pediatrics (Jan. 2023;151[1]:e2022060420).

Susan R. Rose, MD, with the division of endocrinology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Ohio, led the work group that updated guidance for screening and management of congenital hypothyroidism. The group worked in conjunction with the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Endocrinology, the AAP Council on Genetics, the Pediatric Endocrine Society, and the American Thyroid Association.

In addition to screening, timely diagnosis, effective treatment, and follow-up are important.

Tests don’t always tell the full story with congenital hypothyroidism.

“Physicians need to consider hypothyroidism in the face of clinical symptoms, even if newborn screening thyroid test results are normal,” the authors write.

They add that newborn screening for congenital hypothyroidism followed by prompt levothyroxine therapy can prevent severe intellectual disability, psychomotor dysfunction, and impaired growth.

Incidence of congenital hypothyroidism ranges from approximately 1 in 2,000 to 1 in 4,000 newborn infants in countries that have newborn screening data, according to the report.

Following are highlights of the guidance:

Clinical signs

Symptoms and signs include large posterior fontanelle, lethargy, large tongue, prolonged jaundice, umbilical hernia, constipation, and/or hypothermia. With these signs, measuring serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and free thyroxine (FT4) is indicated, regardless of screening results.

Newborn screening in first days

Population screening is cost effective when performed by state or other public health laboratories working with hospitals or birthing centers in their area, the authors write.

Multidisciplinary teams are best able to conduct comprehensive care when cases are detected.

The screening includes a dried blood spot from a heel stick on an approved paper card using appropriate collection methods. The blood spots are then sent to the laboratory. The preferred age for collecting the specimen is 48-72 hours of age.

That timing may be difficult, the authors note, as 90% of infants in the United States and Europe are discharged before 48 hours, but taking the specimen before discharge is important to avoid missing the early diagnosis.

“However, collection of the NBS [newborn screening] specimen before 48 hours of age, and particularly before 24 hours of age, necessitates the use of age-specific TSH reference ranges or repeat screening, particularly to avoid false-positive results,” the authors note.

If a newborn infant is transferred to another hospital, communication about the screening is critical.

Testing strategies

Three test strategies are used for screening: a primary TSH – reflex T4 measurement; primary T4 – reflex TSH measurement; and combined T4 and TSH measurement.

“All three test strategies detect moderate to severe primary congenital hypothyroidism with similar accuracy,” the authors write.

Most newborn screening programs in the United States and worldwide use a primary TSH test strategy.

Multiple births, same-sex twins