User login

Most Americans approve of the death penalty. Do you?

As a health care provider, I have always been interested in topics that concern incarcerated citizens, whether the discussion is related to the pursuit of aggressive care or jurisprudence in general. Additionally, I have followed the issue of capital punishment for most of my career, wondering if our democracy would continue this form of punishment for violent crimes.

In the early 2000s, public opinion moved away from capital punishment. The days of executing violent criminals such as Ted Bundy (who was killed in the electric chair in 1989) seemed to be in the rearview mirror. The ability of prison systems to obtain drugs for execution had become arduous, and Americans appeared disinterested in continuing with the process. Slowly, states began opting out of executions. Currently, 27 U.S. states offer the death penalty as an option at prosecution.

Botched executions

So far in 2021, 11 prisoners have been put to death by the federal government as well as five states, using either a one-drug or three-drug intravenous protocol. Of those prisoners, one was female.

The length of time from sentencing to date of execution varied from a low of 9 years to a high of 29 years, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. Of the executions performed this year, one was considered “botched.” The victim convulsed and vomited for several minutes before his ultimate demise. In fact, in the history of using the death penalty, from 1890 to 2010, approximately 3% of total executions (276 prisoners) were botched. They involved failed electric shocks, convulsions, labored breathing, and in one particularly horrific incident, a victim who was shot in the hip and abdomen by a firing squad and took several minutes to die.

One of the more difficult tasks for conducting an execution is intravenous access, with acquisition of an intravenous site proving to be a common issue. Another concern involves intravenous efficacy, or failure of the site to remain patent until death is achieved. That is why a few states that still practice capital punishment have returned to an electric chair option for execution (the method is chosen by the prisoner).

Majority favor capital punishment

But why do most Americans believe we need the death penalty? According to a 2021 poll by the Pew Research Center, 60% of U.S. citizens favor the use of capital punishment for those convicted of murder, including 27% who strongly favor its use. About 4 in 10 oppose the punishment, but only 15% are strongly opposed. The belief of those who favor retaining execution is that use of the death penalty deters violent crime.

Surprisingly, the American South has both the highest murder rate in the country and the highest percentage of executions. This geographic area encompasses 81% of the nation’s executions. A 2012 National Research Council poll determined that studies claiming the death penalty deters violent crime are “fundamentally flawed.” States that have abolished the death penalty do not show an increase in murder rates; in fact, the opposite is true, the organization concluded.

Since 1990, states without death penalty punishment have had consistently lower murder rates than those that retain capital punishment.

Where does that leave us?

Place my attitude in the column labeled “undecided.” I would love to believe capital punishment is a deterrent to violent crime, yet statistics do not prove the hypothesis to be true. We live in one of the more violent times in history, with mass shootings becoming commonplace. Large-scale retail theft has also been on the rise, especially in recent weeks.

The idea of severe punishment for heinous crime appeals to me, yet in 2001 Timothy McVeigh was executed after eating ice cream and gazing at the moon. His treatment before execution and the length of time he served were in opposition to other inmates sentenced to death. This, despite being punished for killing 168 people (including 19 children) in the Oklahoma City bombings.

I know we cannot be complacent. Violent crime needs to be reduced, and Americans need to feel safe. The process for achieving that goal? You tell me.

Nurses in prisons

About 1% of employed nurses (i.e., close to 21,000) in the United States work in prisons. This figure does not include the many LPNs and unlicensed assistive personnel who are also working in the field and may underrepresent actual numbers.

Correctional nurses have their own scope and standards of practice. They demonstrate superb assessment skills and organization.

If you can hire a correctional nurse, or even aspire to be one, do not hesitate. Patients will thank you.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As a health care provider, I have always been interested in topics that concern incarcerated citizens, whether the discussion is related to the pursuit of aggressive care or jurisprudence in general. Additionally, I have followed the issue of capital punishment for most of my career, wondering if our democracy would continue this form of punishment for violent crimes.

In the early 2000s, public opinion moved away from capital punishment. The days of executing violent criminals such as Ted Bundy (who was killed in the electric chair in 1989) seemed to be in the rearview mirror. The ability of prison systems to obtain drugs for execution had become arduous, and Americans appeared disinterested in continuing with the process. Slowly, states began opting out of executions. Currently, 27 U.S. states offer the death penalty as an option at prosecution.

Botched executions

So far in 2021, 11 prisoners have been put to death by the federal government as well as five states, using either a one-drug or three-drug intravenous protocol. Of those prisoners, one was female.

The length of time from sentencing to date of execution varied from a low of 9 years to a high of 29 years, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. Of the executions performed this year, one was considered “botched.” The victim convulsed and vomited for several minutes before his ultimate demise. In fact, in the history of using the death penalty, from 1890 to 2010, approximately 3% of total executions (276 prisoners) were botched. They involved failed electric shocks, convulsions, labored breathing, and in one particularly horrific incident, a victim who was shot in the hip and abdomen by a firing squad and took several minutes to die.

One of the more difficult tasks for conducting an execution is intravenous access, with acquisition of an intravenous site proving to be a common issue. Another concern involves intravenous efficacy, or failure of the site to remain patent until death is achieved. That is why a few states that still practice capital punishment have returned to an electric chair option for execution (the method is chosen by the prisoner).

Majority favor capital punishment

But why do most Americans believe we need the death penalty? According to a 2021 poll by the Pew Research Center, 60% of U.S. citizens favor the use of capital punishment for those convicted of murder, including 27% who strongly favor its use. About 4 in 10 oppose the punishment, but only 15% are strongly opposed. The belief of those who favor retaining execution is that use of the death penalty deters violent crime.

Surprisingly, the American South has both the highest murder rate in the country and the highest percentage of executions. This geographic area encompasses 81% of the nation’s executions. A 2012 National Research Council poll determined that studies claiming the death penalty deters violent crime are “fundamentally flawed.” States that have abolished the death penalty do not show an increase in murder rates; in fact, the opposite is true, the organization concluded.

Since 1990, states without death penalty punishment have had consistently lower murder rates than those that retain capital punishment.

Where does that leave us?

Place my attitude in the column labeled “undecided.” I would love to believe capital punishment is a deterrent to violent crime, yet statistics do not prove the hypothesis to be true. We live in one of the more violent times in history, with mass shootings becoming commonplace. Large-scale retail theft has also been on the rise, especially in recent weeks.

The idea of severe punishment for heinous crime appeals to me, yet in 2001 Timothy McVeigh was executed after eating ice cream and gazing at the moon. His treatment before execution and the length of time he served were in opposition to other inmates sentenced to death. This, despite being punished for killing 168 people (including 19 children) in the Oklahoma City bombings.

I know we cannot be complacent. Violent crime needs to be reduced, and Americans need to feel safe. The process for achieving that goal? You tell me.

Nurses in prisons

About 1% of employed nurses (i.e., close to 21,000) in the United States work in prisons. This figure does not include the many LPNs and unlicensed assistive personnel who are also working in the field and may underrepresent actual numbers.

Correctional nurses have their own scope and standards of practice. They demonstrate superb assessment skills and organization.

If you can hire a correctional nurse, or even aspire to be one, do not hesitate. Patients will thank you.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As a health care provider, I have always been interested in topics that concern incarcerated citizens, whether the discussion is related to the pursuit of aggressive care or jurisprudence in general. Additionally, I have followed the issue of capital punishment for most of my career, wondering if our democracy would continue this form of punishment for violent crimes.

In the early 2000s, public opinion moved away from capital punishment. The days of executing violent criminals such as Ted Bundy (who was killed in the electric chair in 1989) seemed to be in the rearview mirror. The ability of prison systems to obtain drugs for execution had become arduous, and Americans appeared disinterested in continuing with the process. Slowly, states began opting out of executions. Currently, 27 U.S. states offer the death penalty as an option at prosecution.

Botched executions

So far in 2021, 11 prisoners have been put to death by the federal government as well as five states, using either a one-drug or three-drug intravenous protocol. Of those prisoners, one was female.

The length of time from sentencing to date of execution varied from a low of 9 years to a high of 29 years, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. Of the executions performed this year, one was considered “botched.” The victim convulsed and vomited for several minutes before his ultimate demise. In fact, in the history of using the death penalty, from 1890 to 2010, approximately 3% of total executions (276 prisoners) were botched. They involved failed electric shocks, convulsions, labored breathing, and in one particularly horrific incident, a victim who was shot in the hip and abdomen by a firing squad and took several minutes to die.

One of the more difficult tasks for conducting an execution is intravenous access, with acquisition of an intravenous site proving to be a common issue. Another concern involves intravenous efficacy, or failure of the site to remain patent until death is achieved. That is why a few states that still practice capital punishment have returned to an electric chair option for execution (the method is chosen by the prisoner).

Majority favor capital punishment

But why do most Americans believe we need the death penalty? According to a 2021 poll by the Pew Research Center, 60% of U.S. citizens favor the use of capital punishment for those convicted of murder, including 27% who strongly favor its use. About 4 in 10 oppose the punishment, but only 15% are strongly opposed. The belief of those who favor retaining execution is that use of the death penalty deters violent crime.

Surprisingly, the American South has both the highest murder rate in the country and the highest percentage of executions. This geographic area encompasses 81% of the nation’s executions. A 2012 National Research Council poll determined that studies claiming the death penalty deters violent crime are “fundamentally flawed.” States that have abolished the death penalty do not show an increase in murder rates; in fact, the opposite is true, the organization concluded.

Since 1990, states without death penalty punishment have had consistently lower murder rates than those that retain capital punishment.

Where does that leave us?

Place my attitude in the column labeled “undecided.” I would love to believe capital punishment is a deterrent to violent crime, yet statistics do not prove the hypothesis to be true. We live in one of the more violent times in history, with mass shootings becoming commonplace. Large-scale retail theft has also been on the rise, especially in recent weeks.

The idea of severe punishment for heinous crime appeals to me, yet in 2001 Timothy McVeigh was executed after eating ice cream and gazing at the moon. His treatment before execution and the length of time he served were in opposition to other inmates sentenced to death. This, despite being punished for killing 168 people (including 19 children) in the Oklahoma City bombings.

I know we cannot be complacent. Violent crime needs to be reduced, and Americans need to feel safe. The process for achieving that goal? You tell me.

Nurses in prisons

About 1% of employed nurses (i.e., close to 21,000) in the United States work in prisons. This figure does not include the many LPNs and unlicensed assistive personnel who are also working in the field and may underrepresent actual numbers.

Correctional nurses have their own scope and standards of practice. They demonstrate superb assessment skills and organization.

If you can hire a correctional nurse, or even aspire to be one, do not hesitate. Patients will thank you.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

NYC vaccine mandate for all businesses now in effect

As new COVID-19 cases mount in New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio began his final week in office watching a sweeping vaccine mandate for private employers take effect.

Business owners were supposed to require all workers to have at least one dose of vaccine by Monday, Dec. 27. Workers won’t be able to opt out of vaccinations, as a proposed federal mandate for private sector employees would allow. Municipal workers were already under a vaccine mandate.

Mayor De Blasio called it the strongest private sector vaccine mandate in the world – and insists it’s absolutely necessary.

“I am 110 percent convinced this was the right thing to do, remains the right thing to do, particularly with the ferocity of Omicron,” the mayor told reporters on Dec. 27. “I don’t know if there’s going to be another variant behind it, but I do know our best defense is to get everyone vaccinated and mandates have worked.”

It’s unclear if Mayor de Blasio’s successor, Mayor-Elect Eric Adams, will continue the vaccine mandate. The New York Times reported that Mr. Adams’ spokesman, Evan Thies, said in a text: “The mayor-elect will make announcements on his administration’s Covid policy this week.”

Mayor De Blasio said enforcement would be light in the first week. Not every business owner is following the law.

The New York Post said Stratis Morfogen, owner of the Brooklyn Dumpling Shop and executive managing director of Brooklyn Chop House, went on Instagram and dared the mayor and Gov. Kathy Hochul to come and arrest him.

“Not going to follow your mandate on threatening my family of employees to get the jab or lose your job!” he said.

Mr. Morfogen said he’s not against vaccines but thinks the mandate violates his employees’ constitutional rights. He said he’s taking more steps toward safety, such as frequent testing of employees.

Union Square Hospitality Group CEO Danny Meyer, who oversees restaurants such as Union Square Cafe and Blue Smoke, requires employees not only to get vaccinated, but to get the booster, too.

“Hospitality is a team sport – it’s kind of like putting on a play on Broadway or playing a basketball game,” Mr. Meyer told CNBC. “If you can’t field a full healthy team, you’re going to have to hit pause.”

Customers at Union Square Hospitality Group restaurants will soon be required to show proof of having received a booster shot.

Also starting Dec. 27, all New Yorkers 12 and up must show they’ve received two doses of vaccine to enter indoor dining, fitness, entertainment, and performance venues unless they’ve gotten the one-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

As new COVID-19 cases mount in New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio began his final week in office watching a sweeping vaccine mandate for private employers take effect.

Business owners were supposed to require all workers to have at least one dose of vaccine by Monday, Dec. 27. Workers won’t be able to opt out of vaccinations, as a proposed federal mandate for private sector employees would allow. Municipal workers were already under a vaccine mandate.

Mayor De Blasio called it the strongest private sector vaccine mandate in the world – and insists it’s absolutely necessary.

“I am 110 percent convinced this was the right thing to do, remains the right thing to do, particularly with the ferocity of Omicron,” the mayor told reporters on Dec. 27. “I don’t know if there’s going to be another variant behind it, but I do know our best defense is to get everyone vaccinated and mandates have worked.”

It’s unclear if Mayor de Blasio’s successor, Mayor-Elect Eric Adams, will continue the vaccine mandate. The New York Times reported that Mr. Adams’ spokesman, Evan Thies, said in a text: “The mayor-elect will make announcements on his administration’s Covid policy this week.”

Mayor De Blasio said enforcement would be light in the first week. Not every business owner is following the law.

The New York Post said Stratis Morfogen, owner of the Brooklyn Dumpling Shop and executive managing director of Brooklyn Chop House, went on Instagram and dared the mayor and Gov. Kathy Hochul to come and arrest him.

“Not going to follow your mandate on threatening my family of employees to get the jab or lose your job!” he said.

Mr. Morfogen said he’s not against vaccines but thinks the mandate violates his employees’ constitutional rights. He said he’s taking more steps toward safety, such as frequent testing of employees.

Union Square Hospitality Group CEO Danny Meyer, who oversees restaurants such as Union Square Cafe and Blue Smoke, requires employees not only to get vaccinated, but to get the booster, too.

“Hospitality is a team sport – it’s kind of like putting on a play on Broadway or playing a basketball game,” Mr. Meyer told CNBC. “If you can’t field a full healthy team, you’re going to have to hit pause.”

Customers at Union Square Hospitality Group restaurants will soon be required to show proof of having received a booster shot.

Also starting Dec. 27, all New Yorkers 12 and up must show they’ve received two doses of vaccine to enter indoor dining, fitness, entertainment, and performance venues unless they’ve gotten the one-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

As new COVID-19 cases mount in New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio began his final week in office watching a sweeping vaccine mandate for private employers take effect.

Business owners were supposed to require all workers to have at least one dose of vaccine by Monday, Dec. 27. Workers won’t be able to opt out of vaccinations, as a proposed federal mandate for private sector employees would allow. Municipal workers were already under a vaccine mandate.

Mayor De Blasio called it the strongest private sector vaccine mandate in the world – and insists it’s absolutely necessary.

“I am 110 percent convinced this was the right thing to do, remains the right thing to do, particularly with the ferocity of Omicron,” the mayor told reporters on Dec. 27. “I don’t know if there’s going to be another variant behind it, but I do know our best defense is to get everyone vaccinated and mandates have worked.”

It’s unclear if Mayor de Blasio’s successor, Mayor-Elect Eric Adams, will continue the vaccine mandate. The New York Times reported that Mr. Adams’ spokesman, Evan Thies, said in a text: “The mayor-elect will make announcements on his administration’s Covid policy this week.”

Mayor De Blasio said enforcement would be light in the first week. Not every business owner is following the law.

The New York Post said Stratis Morfogen, owner of the Brooklyn Dumpling Shop and executive managing director of Brooklyn Chop House, went on Instagram and dared the mayor and Gov. Kathy Hochul to come and arrest him.

“Not going to follow your mandate on threatening my family of employees to get the jab or lose your job!” he said.

Mr. Morfogen said he’s not against vaccines but thinks the mandate violates his employees’ constitutional rights. He said he’s taking more steps toward safety, such as frequent testing of employees.

Union Square Hospitality Group CEO Danny Meyer, who oversees restaurants such as Union Square Cafe and Blue Smoke, requires employees not only to get vaccinated, but to get the booster, too.

“Hospitality is a team sport – it’s kind of like putting on a play on Broadway or playing a basketball game,” Mr. Meyer told CNBC. “If you can’t field a full healthy team, you’re going to have to hit pause.”

Customers at Union Square Hospitality Group restaurants will soon be required to show proof of having received a booster shot.

Also starting Dec. 27, all New Yorkers 12 and up must show they’ve received two doses of vaccine to enter indoor dining, fitness, entertainment, and performance venues unless they’ve gotten the one-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Coronavirus can spread to heart, brain days after infection

The coronavirus that causes COVID-19 can spread to the heart and brain within days of infection and can survive for months in organs, according to a new study by the National Institutes of Health.

The virus can spread to almost every organ system in the body, which could contribute to the ongoing symptoms seen in “long COVID” patients, the study authors wrote. The study is considered one of the most comprehensive reviews of how the virus replicates in human cells and persists in the human body. It is under review for publication in the journal Nature.

“This is remarkably important work,” Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, director of the Clinical Epidemiology Center at the Veterans Affairs St. Louis Health Care System, told Bloomberg News. Dr. Al-Aly wasn’t involved with the NIH study but has researched the long-term effects of COVID-19.

“For a long time now, we have been scratching our heads and asking why long COVID seems to affect so many organ systems,” he said. “This paper sheds some light and may help explain why long COVID can occur even in people who had mild or asymptomatic acute disease.”

The NIH researchers sampled and analyzed tissues from autopsies on 44 patients who died after contracting the coronavirus during the first year of the pandemic. They found persistent virus particles in multiple parts of the body, including the heart and brain, for as long as 230 days after symptoms began. This could represent infection with defective virus particles, they said, which has also been seen in persistent infections among measles patients.

“We don’t yet know what burden of chronic illness will result in years to come,” Raina MacIntyre, PhD, a professor of global biosecurity at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, told Bloomberg News.

“Will we see young-onset cardiac failure in survivors or early-onset dementia?” she asked. “These are unanswered questions which call for a precautionary public health approach to mitigation of the spread of this virus.”

Unlike other COVID-19 autopsy research, the NIH team had a more comprehensive postmortem tissue collection process, which typically occurred within a day of the patient’s death, Bloomberg News reported. The researchers also used a variety of ways to preserve tissue to figure out viral levels. They were able to grow the virus collected from several tissues, including the heart, lungs, small intestine, and adrenal glands.

“Our results collectively show that, while the highest burden of SARS-CoV-2 is in the airways and lung, the virus can disseminate early during infection and infect cells throughout the entire body, including widely throughout the brain,” the study authors wrote.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The coronavirus that causes COVID-19 can spread to the heart and brain within days of infection and can survive for months in organs, according to a new study by the National Institutes of Health.

The virus can spread to almost every organ system in the body, which could contribute to the ongoing symptoms seen in “long COVID” patients, the study authors wrote. The study is considered one of the most comprehensive reviews of how the virus replicates in human cells and persists in the human body. It is under review for publication in the journal Nature.

“This is remarkably important work,” Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, director of the Clinical Epidemiology Center at the Veterans Affairs St. Louis Health Care System, told Bloomberg News. Dr. Al-Aly wasn’t involved with the NIH study but has researched the long-term effects of COVID-19.

“For a long time now, we have been scratching our heads and asking why long COVID seems to affect so many organ systems,” he said. “This paper sheds some light and may help explain why long COVID can occur even in people who had mild or asymptomatic acute disease.”

The NIH researchers sampled and analyzed tissues from autopsies on 44 patients who died after contracting the coronavirus during the first year of the pandemic. They found persistent virus particles in multiple parts of the body, including the heart and brain, for as long as 230 days after symptoms began. This could represent infection with defective virus particles, they said, which has also been seen in persistent infections among measles patients.

“We don’t yet know what burden of chronic illness will result in years to come,” Raina MacIntyre, PhD, a professor of global biosecurity at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, told Bloomberg News.

“Will we see young-onset cardiac failure in survivors or early-onset dementia?” she asked. “These are unanswered questions which call for a precautionary public health approach to mitigation of the spread of this virus.”

Unlike other COVID-19 autopsy research, the NIH team had a more comprehensive postmortem tissue collection process, which typically occurred within a day of the patient’s death, Bloomberg News reported. The researchers also used a variety of ways to preserve tissue to figure out viral levels. They were able to grow the virus collected from several tissues, including the heart, lungs, small intestine, and adrenal glands.

“Our results collectively show that, while the highest burden of SARS-CoV-2 is in the airways and lung, the virus can disseminate early during infection and infect cells throughout the entire body, including widely throughout the brain,” the study authors wrote.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The coronavirus that causes COVID-19 can spread to the heart and brain within days of infection and can survive for months in organs, according to a new study by the National Institutes of Health.

The virus can spread to almost every organ system in the body, which could contribute to the ongoing symptoms seen in “long COVID” patients, the study authors wrote. The study is considered one of the most comprehensive reviews of how the virus replicates in human cells and persists in the human body. It is under review for publication in the journal Nature.

“This is remarkably important work,” Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, director of the Clinical Epidemiology Center at the Veterans Affairs St. Louis Health Care System, told Bloomberg News. Dr. Al-Aly wasn’t involved with the NIH study but has researched the long-term effects of COVID-19.

“For a long time now, we have been scratching our heads and asking why long COVID seems to affect so many organ systems,” he said. “This paper sheds some light and may help explain why long COVID can occur even in people who had mild or asymptomatic acute disease.”

The NIH researchers sampled and analyzed tissues from autopsies on 44 patients who died after contracting the coronavirus during the first year of the pandemic. They found persistent virus particles in multiple parts of the body, including the heart and brain, for as long as 230 days after symptoms began. This could represent infection with defective virus particles, they said, which has also been seen in persistent infections among measles patients.

“We don’t yet know what burden of chronic illness will result in years to come,” Raina MacIntyre, PhD, a professor of global biosecurity at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, told Bloomberg News.

“Will we see young-onset cardiac failure in survivors or early-onset dementia?” she asked. “These are unanswered questions which call for a precautionary public health approach to mitigation of the spread of this virus.”

Unlike other COVID-19 autopsy research, the NIH team had a more comprehensive postmortem tissue collection process, which typically occurred within a day of the patient’s death, Bloomberg News reported. The researchers also used a variety of ways to preserve tissue to figure out viral levels. They were able to grow the virus collected from several tissues, including the heart, lungs, small intestine, and adrenal glands.

“Our results collectively show that, while the highest burden of SARS-CoV-2 is in the airways and lung, the virus can disseminate early during infection and infect cells throughout the entire body, including widely throughout the brain,” the study authors wrote.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Omega-3 supplementation improves sleep, mood in breast cancer patients on hormone therapy

After 4 weeks of treatment, patients who received omega-3 reported better sleep, depression, and mood outcomes than those who received placebo.

Estrogen-receptor inhibitors are used to treat breast cancer with positive hormone receptors in combination with other therapies. However, the drugs can lead to long-term side effects, including hot flashes, night sweats, and changes to mood and sleep.

These side effects are often treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and some anticonvulsant drugs. Omega-3 supplements contain various polyunsaturated fatty acids, which influence cell signaling and contribute to the production of bioactive fat mediators that counter inflammation. They are widely used in cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, depression, and other cognitive disorders. They also appear to amplify the antitumor efficacy of tamoxifen through the inhibition of proliferative and antiapoptotic pathways that that are influenced by estrogen-receptor signaling.

“This study showed that omega-3 supplementation can improve mood and sleep disorder in women suffering from breast cancer while they (are) managing with antihormone drugs. … this supplement can be proposed for the treatment of these patients,” wrote researchers led by Azadeh Moghaddas, MD, PhD, who is an associate professor of clinical pharmacy and pharmacy practice at Isfahan (Iran) University of Medical Sciences.

The study was made available as a preprint on ResearchSquare and has not yet been peer reviewed. It included 60 patients who were screened for baseline mood disorders using the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS), then randomized to 2 mg omega-3 per day for 4 weeks, or placebo.

Studies have shown that omega-3 supplementation improves menopause and mood symptoms in postmenopausal women without cancer.

Omega-3 supplementation has neuroprotective effects and improved brain function and mood in rats, and a 2019 review suggested that the evidence is strong enough to warrant clinical studies.

To determine if the supplement was also safe and effective in women with breast cancer undergoing hormone therapy, the researchers analyzed data from 32 patients in the intervention group and 28 patients in the placebo group.

At 4 weeks of follow-up, patients in the intervention group had significantly lower values on the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (mean, 22.8 vs. 30.8; P < .001), Profile of Mood State (mean, 30.8 versus 39.5; P<.001), and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (mean, 4.6 vs. 5.9; P = .04). There were no statistically significant changes in these values in the placebo group.

At 4 weeks, paired samples t-test comparisons between the intervention and the placebo groups revealed lower scores in the intervention group for mean scores in the PSQI subscales subjective sleep quality (0.8 vs. 1.4; P = .002), delay in falling asleep (1.1 vs. 1.6; P = .02), and sleep disturbances (0.8 vs. 1.1; P = .005).

There were no significant adverse reactions in either group.

The study is limited by its small sample size and the short follow-up period.

The study was funded by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. The authors declare no other conflicts of interest.

After 4 weeks of treatment, patients who received omega-3 reported better sleep, depression, and mood outcomes than those who received placebo.

Estrogen-receptor inhibitors are used to treat breast cancer with positive hormone receptors in combination with other therapies. However, the drugs can lead to long-term side effects, including hot flashes, night sweats, and changes to mood and sleep.

These side effects are often treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and some anticonvulsant drugs. Omega-3 supplements contain various polyunsaturated fatty acids, which influence cell signaling and contribute to the production of bioactive fat mediators that counter inflammation. They are widely used in cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, depression, and other cognitive disorders. They also appear to amplify the antitumor efficacy of tamoxifen through the inhibition of proliferative and antiapoptotic pathways that that are influenced by estrogen-receptor signaling.

“This study showed that omega-3 supplementation can improve mood and sleep disorder in women suffering from breast cancer while they (are) managing with antihormone drugs. … this supplement can be proposed for the treatment of these patients,” wrote researchers led by Azadeh Moghaddas, MD, PhD, who is an associate professor of clinical pharmacy and pharmacy practice at Isfahan (Iran) University of Medical Sciences.

The study was made available as a preprint on ResearchSquare and has not yet been peer reviewed. It included 60 patients who were screened for baseline mood disorders using the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS), then randomized to 2 mg omega-3 per day for 4 weeks, or placebo.

Studies have shown that omega-3 supplementation improves menopause and mood symptoms in postmenopausal women without cancer.

Omega-3 supplementation has neuroprotective effects and improved brain function and mood in rats, and a 2019 review suggested that the evidence is strong enough to warrant clinical studies.

To determine if the supplement was also safe and effective in women with breast cancer undergoing hormone therapy, the researchers analyzed data from 32 patients in the intervention group and 28 patients in the placebo group.

At 4 weeks of follow-up, patients in the intervention group had significantly lower values on the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (mean, 22.8 vs. 30.8; P < .001), Profile of Mood State (mean, 30.8 versus 39.5; P<.001), and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (mean, 4.6 vs. 5.9; P = .04). There were no statistically significant changes in these values in the placebo group.

At 4 weeks, paired samples t-test comparisons between the intervention and the placebo groups revealed lower scores in the intervention group for mean scores in the PSQI subscales subjective sleep quality (0.8 vs. 1.4; P = .002), delay in falling asleep (1.1 vs. 1.6; P = .02), and sleep disturbances (0.8 vs. 1.1; P = .005).

There were no significant adverse reactions in either group.

The study is limited by its small sample size and the short follow-up period.

The study was funded by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. The authors declare no other conflicts of interest.

After 4 weeks of treatment, patients who received omega-3 reported better sleep, depression, and mood outcomes than those who received placebo.

Estrogen-receptor inhibitors are used to treat breast cancer with positive hormone receptors in combination with other therapies. However, the drugs can lead to long-term side effects, including hot flashes, night sweats, and changes to mood and sleep.

These side effects are often treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and some anticonvulsant drugs. Omega-3 supplements contain various polyunsaturated fatty acids, which influence cell signaling and contribute to the production of bioactive fat mediators that counter inflammation. They are widely used in cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, depression, and other cognitive disorders. They also appear to amplify the antitumor efficacy of tamoxifen through the inhibition of proliferative and antiapoptotic pathways that that are influenced by estrogen-receptor signaling.

“This study showed that omega-3 supplementation can improve mood and sleep disorder in women suffering from breast cancer while they (are) managing with antihormone drugs. … this supplement can be proposed for the treatment of these patients,” wrote researchers led by Azadeh Moghaddas, MD, PhD, who is an associate professor of clinical pharmacy and pharmacy practice at Isfahan (Iran) University of Medical Sciences.

The study was made available as a preprint on ResearchSquare and has not yet been peer reviewed. It included 60 patients who were screened for baseline mood disorders using the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS), then randomized to 2 mg omega-3 per day for 4 weeks, or placebo.

Studies have shown that omega-3 supplementation improves menopause and mood symptoms in postmenopausal women without cancer.

Omega-3 supplementation has neuroprotective effects and improved brain function and mood in rats, and a 2019 review suggested that the evidence is strong enough to warrant clinical studies.

To determine if the supplement was also safe and effective in women with breast cancer undergoing hormone therapy, the researchers analyzed data from 32 patients in the intervention group and 28 patients in the placebo group.

At 4 weeks of follow-up, patients in the intervention group had significantly lower values on the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (mean, 22.8 vs. 30.8; P < .001), Profile of Mood State (mean, 30.8 versus 39.5; P<.001), and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (mean, 4.6 vs. 5.9; P = .04). There were no statistically significant changes in these values in the placebo group.

At 4 weeks, paired samples t-test comparisons between the intervention and the placebo groups revealed lower scores in the intervention group for mean scores in the PSQI subscales subjective sleep quality (0.8 vs. 1.4; P = .002), delay in falling asleep (1.1 vs. 1.6; P = .02), and sleep disturbances (0.8 vs. 1.1; P = .005).

There were no significant adverse reactions in either group.

The study is limited by its small sample size and the short follow-up period.

The study was funded by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. The authors declare no other conflicts of interest.

FROM RESEARCHSQUARE

NSCLC Diagnosis

Children and COVID: Nearly 200,000 new cases reported in 1 week

, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Available state data show that 198,551 child COVID cases were added during the week of Dec. 17-23 – up by 16.8% from the nearly 170,000 new cases reported the previous week and the highest 7-day figure since Sept. 17-23, when 207,000 cases were reported, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID report. Since Oct. 22-28, when the weekly count dropped to a seasonal low, the weekly count has nearly doubled.

The largest shares of the nearly 199,000 new cases were divided pretty equally between the Northeast and the South, while the West had just a small bump in cases and the Midwest was in the middle. The largest statewide percent increases came in the New England states, along with New Jersey, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. New York State does not report age ranges for COVID cases, the AAP/CHA report noted.

Emergency department visits and hospital admissions are following a similar trend, as both have risen considerably over the last 2 months, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

COVID-related ED visits for children aged 0-11 years – measured as a proportion of all ED visits – are nearing the pandemic high of 4.1% set in late August, while visits in 12- to 15-year-olds have risen from 1.4% in early November to 5.6% on Dec. 24 and 16- to 17-year-olds have gone from 1.5% to 6% over the same period of time, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

As for hospital admissions in children aged 0-17 years, the rate was down to 0.19 per 100,000 population on Nov. 11 but had risen to 0.38 per 100,000 as of Dec. 24. The highest point reached in children during the pandemic was 0.46 per 100,000 in early September, the CDC said.

On Dec. 23, 367 children were admitted to hospitals in the United States, the highest number since Sept. 7, when 374 were hospitalized. The highest 1-day total over the course of the pandemic, 394, came just a week before that, Aug. 31, according to the Department of Health & Human Services.

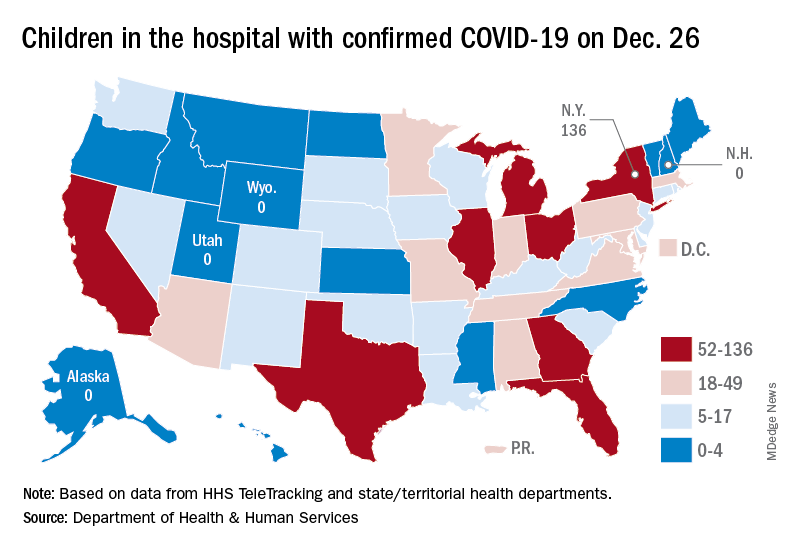

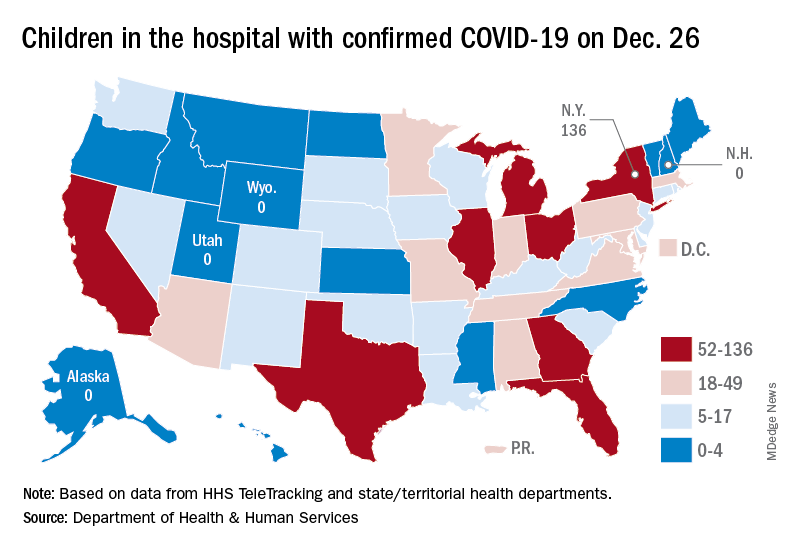

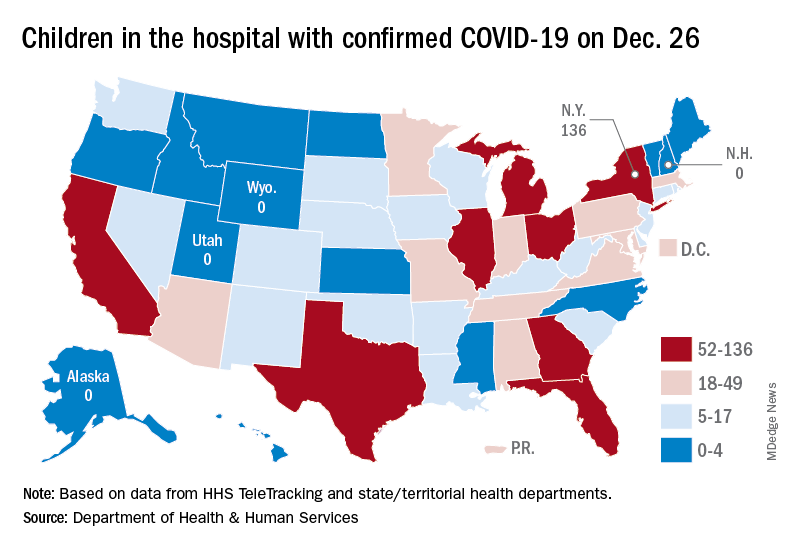

A look at the most recent HHS data shows that 1,161 children were being hospitalized in pediatric inpatient beds with confirmed COVID-19 on Dec. 26. The highest number by state was in New York (136), followed by Texas (90) and Illinois and Ohio, both with 83. There were four states – Alaska, New Hampshire, Utah, and Wyoming – with no hospitalized children, the HHS said. Puerto Rico, meanwhile, had 28 children in the hospital with COVID, more than 38 states.

, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Available state data show that 198,551 child COVID cases were added during the week of Dec. 17-23 – up by 16.8% from the nearly 170,000 new cases reported the previous week and the highest 7-day figure since Sept. 17-23, when 207,000 cases were reported, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID report. Since Oct. 22-28, when the weekly count dropped to a seasonal low, the weekly count has nearly doubled.

The largest shares of the nearly 199,000 new cases were divided pretty equally between the Northeast and the South, while the West had just a small bump in cases and the Midwest was in the middle. The largest statewide percent increases came in the New England states, along with New Jersey, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. New York State does not report age ranges for COVID cases, the AAP/CHA report noted.

Emergency department visits and hospital admissions are following a similar trend, as both have risen considerably over the last 2 months, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

COVID-related ED visits for children aged 0-11 years – measured as a proportion of all ED visits – are nearing the pandemic high of 4.1% set in late August, while visits in 12- to 15-year-olds have risen from 1.4% in early November to 5.6% on Dec. 24 and 16- to 17-year-olds have gone from 1.5% to 6% over the same period of time, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

As for hospital admissions in children aged 0-17 years, the rate was down to 0.19 per 100,000 population on Nov. 11 but had risen to 0.38 per 100,000 as of Dec. 24. The highest point reached in children during the pandemic was 0.46 per 100,000 in early September, the CDC said.

On Dec. 23, 367 children were admitted to hospitals in the United States, the highest number since Sept. 7, when 374 were hospitalized. The highest 1-day total over the course of the pandemic, 394, came just a week before that, Aug. 31, according to the Department of Health & Human Services.

A look at the most recent HHS data shows that 1,161 children were being hospitalized in pediatric inpatient beds with confirmed COVID-19 on Dec. 26. The highest number by state was in New York (136), followed by Texas (90) and Illinois and Ohio, both with 83. There were four states – Alaska, New Hampshire, Utah, and Wyoming – with no hospitalized children, the HHS said. Puerto Rico, meanwhile, had 28 children in the hospital with COVID, more than 38 states.

, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Available state data show that 198,551 child COVID cases were added during the week of Dec. 17-23 – up by 16.8% from the nearly 170,000 new cases reported the previous week and the highest 7-day figure since Sept. 17-23, when 207,000 cases were reported, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID report. Since Oct. 22-28, when the weekly count dropped to a seasonal low, the weekly count has nearly doubled.

The largest shares of the nearly 199,000 new cases were divided pretty equally between the Northeast and the South, while the West had just a small bump in cases and the Midwest was in the middle. The largest statewide percent increases came in the New England states, along with New Jersey, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. New York State does not report age ranges for COVID cases, the AAP/CHA report noted.

Emergency department visits and hospital admissions are following a similar trend, as both have risen considerably over the last 2 months, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

COVID-related ED visits for children aged 0-11 years – measured as a proportion of all ED visits – are nearing the pandemic high of 4.1% set in late August, while visits in 12- to 15-year-olds have risen from 1.4% in early November to 5.6% on Dec. 24 and 16- to 17-year-olds have gone from 1.5% to 6% over the same period of time, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

As for hospital admissions in children aged 0-17 years, the rate was down to 0.19 per 100,000 population on Nov. 11 but had risen to 0.38 per 100,000 as of Dec. 24. The highest point reached in children during the pandemic was 0.46 per 100,000 in early September, the CDC said.

On Dec. 23, 367 children were admitted to hospitals in the United States, the highest number since Sept. 7, when 374 were hospitalized. The highest 1-day total over the course of the pandemic, 394, came just a week before that, Aug. 31, according to the Department of Health & Human Services.

A look at the most recent HHS data shows that 1,161 children were being hospitalized in pediatric inpatient beds with confirmed COVID-19 on Dec. 26. The highest number by state was in New York (136), followed by Texas (90) and Illinois and Ohio, both with 83. There were four states – Alaska, New Hampshire, Utah, and Wyoming – with no hospitalized children, the HHS said. Puerto Rico, meanwhile, had 28 children in the hospital with COVID, more than 38 states.

Most cancer patients with breakthrough COVID-19 infection experience severe outcomes

Of 54 fully vaccinated patients with cancer and COVID-19, 35 (65%) were hospitalized, 10 (19%) were admitted to the intensive care unit or required mechanical ventilation, and 7 (13%) died within 30 days.

Although the study did not assess the rate of breakthrough infection among fully vaccinated patients with cancer, the findings do underscore the need for continued vigilance in protecting this vulnerable patient population by vaccinating close contacts, administering boosters, social distancing, and mask-wearing.

“Overall, vaccination remains an invaluable strategy in protecting vulnerable populations, including patients with cancer, against COVID-19. However, patients with cancer who develop breakthrough infection despite full vaccination remain at risk of severe outcomes,” Andrew L. Schmidt, MB, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and associates wrote.

The analysis, which appeared online in Annals of Oncology Dec. 24 as a pre-proof but has not yet been peer reviewed, analyzed registry data from 1,787 adults with current or prior invasive cancer and laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 between Nov. 1, 2020, and May 31, 2021, before COVID vaccination was widespread. Of those, 1,656 (93%) were unvaccinated, 77 (4%) were partially vaccinated, and 54 (3%) were considered fully vaccinated at the time of COVID-19 infection.

Of the fully vaccinated patients with breakthrough infection, 52 (96%) experienced a severe outcome: two-thirds had to be hospitalized, nearly 1 in 5 went to the ICU or needed mechanical ventilation, and 13% died within 30 days.

“Comparable rates were observed in the unvaccinated group,” the investigators write, adding that there was no statistical difference in 30-day mortality between the fully vaccinated patients and the unvaccinated cohort (adjusted odds ratio, 1.08).

Factors associated with increased 30-day mortality among unvaccinated patients included lymphopenia (aOR, 1.68), comorbidities (aORs, 1.66-2.10), worse performance status (aORs, 2.26-4.34), and baseline cancer status (active/progressing vs. not active/ progressing, aOR, 6.07).

No significant differences were observed in ICU, mechanical ventilation, or hospitalization rates between the vaccinated and unvaccinated cohort after adjustment for confounders (aORs,1.13 and 1.25, respectively).

Notably, patients with an underlying hematologic malignancy were overrepresented among those with breakthrough COVID-19 (35% vs. 20%). Compared with those with solid cancers, patients with hematologic malignancies also had significantly higher rates of ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and hospitalization.

This finding is “consistent with evidence that these patients may have a blunted serologic response to vaccination secondary to disease or therapy,” the authors note.

Although the investigators did not evaluate the risk of breakthrough infection post vaccination, recent research indicates that receiving a COVID-19 booster increases antibody levels among patients with cancer under active treatment and thus may provide additional protection against the virus.

Given the risk of breakthrough infection and severe outcomes in patients with cancer, the authors propose that “a mitigation approach that includes vaccination of close contacts, boosters, social distancing, and mask-wearing in public should be continued for the foreseeable future.” However, “additional research is needed to further categorize the patients that remain at risk of symptomatic COVID-19 following vaccination and test strategies that may reduce this risk.”

The findings are from a pre-proof that has not yet been peer reviewed or published. First author Dr. Schmidt reported nonfinancial support from Astellas, nonfinancial support from Pfizer, outside the submitted work. Other coauthors reported a range of disclosures as well. The full list can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Of 54 fully vaccinated patients with cancer and COVID-19, 35 (65%) were hospitalized, 10 (19%) were admitted to the intensive care unit or required mechanical ventilation, and 7 (13%) died within 30 days.

Although the study did not assess the rate of breakthrough infection among fully vaccinated patients with cancer, the findings do underscore the need for continued vigilance in protecting this vulnerable patient population by vaccinating close contacts, administering boosters, social distancing, and mask-wearing.

“Overall, vaccination remains an invaluable strategy in protecting vulnerable populations, including patients with cancer, against COVID-19. However, patients with cancer who develop breakthrough infection despite full vaccination remain at risk of severe outcomes,” Andrew L. Schmidt, MB, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and associates wrote.

The analysis, which appeared online in Annals of Oncology Dec. 24 as a pre-proof but has not yet been peer reviewed, analyzed registry data from 1,787 adults with current or prior invasive cancer and laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 between Nov. 1, 2020, and May 31, 2021, before COVID vaccination was widespread. Of those, 1,656 (93%) were unvaccinated, 77 (4%) were partially vaccinated, and 54 (3%) were considered fully vaccinated at the time of COVID-19 infection.

Of the fully vaccinated patients with breakthrough infection, 52 (96%) experienced a severe outcome: two-thirds had to be hospitalized, nearly 1 in 5 went to the ICU or needed mechanical ventilation, and 13% died within 30 days.

“Comparable rates were observed in the unvaccinated group,” the investigators write, adding that there was no statistical difference in 30-day mortality between the fully vaccinated patients and the unvaccinated cohort (adjusted odds ratio, 1.08).

Factors associated with increased 30-day mortality among unvaccinated patients included lymphopenia (aOR, 1.68), comorbidities (aORs, 1.66-2.10), worse performance status (aORs, 2.26-4.34), and baseline cancer status (active/progressing vs. not active/ progressing, aOR, 6.07).

No significant differences were observed in ICU, mechanical ventilation, or hospitalization rates between the vaccinated and unvaccinated cohort after adjustment for confounders (aORs,1.13 and 1.25, respectively).

Notably, patients with an underlying hematologic malignancy were overrepresented among those with breakthrough COVID-19 (35% vs. 20%). Compared with those with solid cancers, patients with hematologic malignancies also had significantly higher rates of ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and hospitalization.

This finding is “consistent with evidence that these patients may have a blunted serologic response to vaccination secondary to disease or therapy,” the authors note.

Although the investigators did not evaluate the risk of breakthrough infection post vaccination, recent research indicates that receiving a COVID-19 booster increases antibody levels among patients with cancer under active treatment and thus may provide additional protection against the virus.

Given the risk of breakthrough infection and severe outcomes in patients with cancer, the authors propose that “a mitigation approach that includes vaccination of close contacts, boosters, social distancing, and mask-wearing in public should be continued for the foreseeable future.” However, “additional research is needed to further categorize the patients that remain at risk of symptomatic COVID-19 following vaccination and test strategies that may reduce this risk.”

The findings are from a pre-proof that has not yet been peer reviewed or published. First author Dr. Schmidt reported nonfinancial support from Astellas, nonfinancial support from Pfizer, outside the submitted work. Other coauthors reported a range of disclosures as well. The full list can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Of 54 fully vaccinated patients with cancer and COVID-19, 35 (65%) were hospitalized, 10 (19%) were admitted to the intensive care unit or required mechanical ventilation, and 7 (13%) died within 30 days.

Although the study did not assess the rate of breakthrough infection among fully vaccinated patients with cancer, the findings do underscore the need for continued vigilance in protecting this vulnerable patient population by vaccinating close contacts, administering boosters, social distancing, and mask-wearing.

“Overall, vaccination remains an invaluable strategy in protecting vulnerable populations, including patients with cancer, against COVID-19. However, patients with cancer who develop breakthrough infection despite full vaccination remain at risk of severe outcomes,” Andrew L. Schmidt, MB, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and associates wrote.

The analysis, which appeared online in Annals of Oncology Dec. 24 as a pre-proof but has not yet been peer reviewed, analyzed registry data from 1,787 adults with current or prior invasive cancer and laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 between Nov. 1, 2020, and May 31, 2021, before COVID vaccination was widespread. Of those, 1,656 (93%) were unvaccinated, 77 (4%) were partially vaccinated, and 54 (3%) were considered fully vaccinated at the time of COVID-19 infection.

Of the fully vaccinated patients with breakthrough infection, 52 (96%) experienced a severe outcome: two-thirds had to be hospitalized, nearly 1 in 5 went to the ICU or needed mechanical ventilation, and 13% died within 30 days.

“Comparable rates were observed in the unvaccinated group,” the investigators write, adding that there was no statistical difference in 30-day mortality between the fully vaccinated patients and the unvaccinated cohort (adjusted odds ratio, 1.08).

Factors associated with increased 30-day mortality among unvaccinated patients included lymphopenia (aOR, 1.68), comorbidities (aORs, 1.66-2.10), worse performance status (aORs, 2.26-4.34), and baseline cancer status (active/progressing vs. not active/ progressing, aOR, 6.07).

No significant differences were observed in ICU, mechanical ventilation, or hospitalization rates between the vaccinated and unvaccinated cohort after adjustment for confounders (aORs,1.13 and 1.25, respectively).

Notably, patients with an underlying hematologic malignancy were overrepresented among those with breakthrough COVID-19 (35% vs. 20%). Compared with those with solid cancers, patients with hematologic malignancies also had significantly higher rates of ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and hospitalization.

This finding is “consistent with evidence that these patients may have a blunted serologic response to vaccination secondary to disease or therapy,” the authors note.

Although the investigators did not evaluate the risk of breakthrough infection post vaccination, recent research indicates that receiving a COVID-19 booster increases antibody levels among patients with cancer under active treatment and thus may provide additional protection against the virus.

Given the risk of breakthrough infection and severe outcomes in patients with cancer, the authors propose that “a mitigation approach that includes vaccination of close contacts, boosters, social distancing, and mask-wearing in public should be continued for the foreseeable future.” However, “additional research is needed to further categorize the patients that remain at risk of symptomatic COVID-19 following vaccination and test strategies that may reduce this risk.”

The findings are from a pre-proof that has not yet been peer reviewed or published. First author Dr. Schmidt reported nonfinancial support from Astellas, nonfinancial support from Pfizer, outside the submitted work. Other coauthors reported a range of disclosures as well. The full list can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ANNALS OF ONCOLOGY