User login

The postpandemic path forward for GI research

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) recognizes the alarming impact of COVID-19 on the biomedical research community. The Institute has taken steps to address the pandemic’s immediate challenges, such as supporting COVID-19 research within its mission and implementing policies that ease grantees’ concerns about funding and lost time. The NIDDK has also sought to balance the needs brought about by the pandemic with its responsibility to continue research on the many diseases and conditions in the NIDDK’s purview.

The NIDDK continues to support most research through unsolicited R01 awards. It also continues to support organized consortia that aim to improve our understanding and treatment of digestive diseases; research centers that provide valuable sources of collaboration among researchers investigating digestive diseases and/or nutrition and obesity; and programs that encourage transitions to different career levels.

The pandemic has shown in stark relief the devastating impact of health disparities. Because many NIDDK mission diseases place disparate burdens on minority groups and people with limited resources, the NIDDK remains committed to combating health disparities, whether pandemic related or not. The Institute recruits diverse study cohorts inclusive of those most affected. It seeks to open doors for young people from underrepresented groups through training, support, and inspiration to pursue research careers, such as through partnerships with organizations like the American Gastroenterological Association. The NIDDK is also implementing strategies to promote participant engagement, not only as study volunteers, but also in study design, recruitment, and consent. And, importantly, the Institute is supporting research to identify the causes of health disparities, including research on social determinants of health.

This year, the NIDDK embarked on the development of a 5-year Strategic Plan to develop a broad vision for accelerating research on diseases and conditions across its mission. This plan is meant to be overarching and will complement the NIDDK’s disease-specific planning efforts. The first draft of the plan is currently being developed based on the input received from a Strategic Plan Working Group (which includes several AGA members), a public Request for Information, and NIDDK’s Advisory Council. The draft will be available through the NIDDK website (niddk.nih.gov) for public comment.

By taking these actions, the NIDDK aims to continue reducing the burden of digestive diseases and improving health for all people.

Dr. Rodgers is director of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases at the National Institutes of Health. He has no conflicts. Dr. Rodgers made these comments during the AGA Institute Presidential Plenary at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) recognizes the alarming impact of COVID-19 on the biomedical research community. The Institute has taken steps to address the pandemic’s immediate challenges, such as supporting COVID-19 research within its mission and implementing policies that ease grantees’ concerns about funding and lost time. The NIDDK has also sought to balance the needs brought about by the pandemic with its responsibility to continue research on the many diseases and conditions in the NIDDK’s purview.

The NIDDK continues to support most research through unsolicited R01 awards. It also continues to support organized consortia that aim to improve our understanding and treatment of digestive diseases; research centers that provide valuable sources of collaboration among researchers investigating digestive diseases and/or nutrition and obesity; and programs that encourage transitions to different career levels.

The pandemic has shown in stark relief the devastating impact of health disparities. Because many NIDDK mission diseases place disparate burdens on minority groups and people with limited resources, the NIDDK remains committed to combating health disparities, whether pandemic related or not. The Institute recruits diverse study cohorts inclusive of those most affected. It seeks to open doors for young people from underrepresented groups through training, support, and inspiration to pursue research careers, such as through partnerships with organizations like the American Gastroenterological Association. The NIDDK is also implementing strategies to promote participant engagement, not only as study volunteers, but also in study design, recruitment, and consent. And, importantly, the Institute is supporting research to identify the causes of health disparities, including research on social determinants of health.

This year, the NIDDK embarked on the development of a 5-year Strategic Plan to develop a broad vision for accelerating research on diseases and conditions across its mission. This plan is meant to be overarching and will complement the NIDDK’s disease-specific planning efforts. The first draft of the plan is currently being developed based on the input received from a Strategic Plan Working Group (which includes several AGA members), a public Request for Information, and NIDDK’s Advisory Council. The draft will be available through the NIDDK website (niddk.nih.gov) for public comment.

By taking these actions, the NIDDK aims to continue reducing the burden of digestive diseases and improving health for all people.

Dr. Rodgers is director of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases at the National Institutes of Health. He has no conflicts. Dr. Rodgers made these comments during the AGA Institute Presidential Plenary at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) recognizes the alarming impact of COVID-19 on the biomedical research community. The Institute has taken steps to address the pandemic’s immediate challenges, such as supporting COVID-19 research within its mission and implementing policies that ease grantees’ concerns about funding and lost time. The NIDDK has also sought to balance the needs brought about by the pandemic with its responsibility to continue research on the many diseases and conditions in the NIDDK’s purview.

The NIDDK continues to support most research through unsolicited R01 awards. It also continues to support organized consortia that aim to improve our understanding and treatment of digestive diseases; research centers that provide valuable sources of collaboration among researchers investigating digestive diseases and/or nutrition and obesity; and programs that encourage transitions to different career levels.

The pandemic has shown in stark relief the devastating impact of health disparities. Because many NIDDK mission diseases place disparate burdens on minority groups and people with limited resources, the NIDDK remains committed to combating health disparities, whether pandemic related or not. The Institute recruits diverse study cohorts inclusive of those most affected. It seeks to open doors for young people from underrepresented groups through training, support, and inspiration to pursue research careers, such as through partnerships with organizations like the American Gastroenterological Association. The NIDDK is also implementing strategies to promote participant engagement, not only as study volunteers, but also in study design, recruitment, and consent. And, importantly, the Institute is supporting research to identify the causes of health disparities, including research on social determinants of health.

This year, the NIDDK embarked on the development of a 5-year Strategic Plan to develop a broad vision for accelerating research on diseases and conditions across its mission. This plan is meant to be overarching and will complement the NIDDK’s disease-specific planning efforts. The first draft of the plan is currently being developed based on the input received from a Strategic Plan Working Group (which includes several AGA members), a public Request for Information, and NIDDK’s Advisory Council. The draft will be available through the NIDDK website (niddk.nih.gov) for public comment.

By taking these actions, the NIDDK aims to continue reducing the burden of digestive diseases and improving health for all people.

Dr. Rodgers is director of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases at the National Institutes of Health. He has no conflicts. Dr. Rodgers made these comments during the AGA Institute Presidential Plenary at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

The making of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine

Days after the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic, Pfizer and BioNTech announced plans to codevelop a potential mRNA-based vaccine to help prevent COVID-19. The mRNA platform was selected given its potential for high potency and capacity for rapid development. A bold decision was made to invest in R&D and manufacturing at risk.

Two candidates, BNT162b1 and BNT162b2, quickly emerged as most promising. After extensive review of preclinical and early clinical data and in consultation with regulators, we advanced BNT162b2 into a global, Phase 2/3 efficacy trial in July 2020.

Enrollment was later expanded to increase diversity, and also to include adolescents 12 and older and people with chronic, stable HIV, Hepatitis C, or Hepatitis B.

In November 2020, we announced the results of our ongoing Phase 3 study with BNT162b2 demonstrating a vaccine efficacy rate of 95% against COVID-19 beginning 28 days after dose one. This result showed our ability to leverage decades of scientific expertise to execute a rigorous Phase 3 clinical program to make a potential vaccine available as quickly and safely as possible. The emergency use authorization that followed was a big step, but our research did not stop there.

Pfizer and BioNTech continue to evaluate data from the landmark trial, which ultimately enrolled 46,331 participants. We are also conducting trials in special populations, such as pregnant women and children under 12. To date, real-world evidence has demonstrated lower COVID-19 incidence in vaccinated individuals and has not shown escape of variant viruses from BNT162b2-mediated protection. Studies are ongoing to explore the effect of a third dose on immunity and to prepare in case a variant emerges that escapes protection.

We continue to identify improvements to increase production and are on track to deliver approximately 2.5 billion doses in 2021. Next generation ready-to-use and freeze-dried formulations are in development.

This pandemic sparked an unparalleled period of innovation, investment, and partnership with lessons learned that will help us prepare for future pandemics and accelerate R&D of therapeutic candidates for other debilitating and life-threatening conditions.

The Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine has not been approved or licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration but has been authorized for emergency use to prevent COVID-19 in individuals 12+. See conditions of use: http://cvdvaccine.com

Dr. Dolsten is the Chief Scientific Officer and President of Worldwide Research, Development and Medical at Pfizer. He has no other conflicts. Dr. Dolsten made these comments during the AGA Institute Presidential Plenary at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

Days after the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic, Pfizer and BioNTech announced plans to codevelop a potential mRNA-based vaccine to help prevent COVID-19. The mRNA platform was selected given its potential for high potency and capacity for rapid development. A bold decision was made to invest in R&D and manufacturing at risk.

Two candidates, BNT162b1 and BNT162b2, quickly emerged as most promising. After extensive review of preclinical and early clinical data and in consultation with regulators, we advanced BNT162b2 into a global, Phase 2/3 efficacy trial in July 2020.

Enrollment was later expanded to increase diversity, and also to include adolescents 12 and older and people with chronic, stable HIV, Hepatitis C, or Hepatitis B.

In November 2020, we announced the results of our ongoing Phase 3 study with BNT162b2 demonstrating a vaccine efficacy rate of 95% against COVID-19 beginning 28 days after dose one. This result showed our ability to leverage decades of scientific expertise to execute a rigorous Phase 3 clinical program to make a potential vaccine available as quickly and safely as possible. The emergency use authorization that followed was a big step, but our research did not stop there.

Pfizer and BioNTech continue to evaluate data from the landmark trial, which ultimately enrolled 46,331 participants. We are also conducting trials in special populations, such as pregnant women and children under 12. To date, real-world evidence has demonstrated lower COVID-19 incidence in vaccinated individuals and has not shown escape of variant viruses from BNT162b2-mediated protection. Studies are ongoing to explore the effect of a third dose on immunity and to prepare in case a variant emerges that escapes protection.

We continue to identify improvements to increase production and are on track to deliver approximately 2.5 billion doses in 2021. Next generation ready-to-use and freeze-dried formulations are in development.

This pandemic sparked an unparalleled period of innovation, investment, and partnership with lessons learned that will help us prepare for future pandemics and accelerate R&D of therapeutic candidates for other debilitating and life-threatening conditions.

The Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine has not been approved or licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration but has been authorized for emergency use to prevent COVID-19 in individuals 12+. See conditions of use: http://cvdvaccine.com

Dr. Dolsten is the Chief Scientific Officer and President of Worldwide Research, Development and Medical at Pfizer. He has no other conflicts. Dr. Dolsten made these comments during the AGA Institute Presidential Plenary at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

Days after the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic, Pfizer and BioNTech announced plans to codevelop a potential mRNA-based vaccine to help prevent COVID-19. The mRNA platform was selected given its potential for high potency and capacity for rapid development. A bold decision was made to invest in R&D and manufacturing at risk.

Two candidates, BNT162b1 and BNT162b2, quickly emerged as most promising. After extensive review of preclinical and early clinical data and in consultation with regulators, we advanced BNT162b2 into a global, Phase 2/3 efficacy trial in July 2020.

Enrollment was later expanded to increase diversity, and also to include adolescents 12 and older and people with chronic, stable HIV, Hepatitis C, or Hepatitis B.

In November 2020, we announced the results of our ongoing Phase 3 study with BNT162b2 demonstrating a vaccine efficacy rate of 95% against COVID-19 beginning 28 days after dose one. This result showed our ability to leverage decades of scientific expertise to execute a rigorous Phase 3 clinical program to make a potential vaccine available as quickly and safely as possible. The emergency use authorization that followed was a big step, but our research did not stop there.

Pfizer and BioNTech continue to evaluate data from the landmark trial, which ultimately enrolled 46,331 participants. We are also conducting trials in special populations, such as pregnant women and children under 12. To date, real-world evidence has demonstrated lower COVID-19 incidence in vaccinated individuals and has not shown escape of variant viruses from BNT162b2-mediated protection. Studies are ongoing to explore the effect of a third dose on immunity and to prepare in case a variant emerges that escapes protection.

We continue to identify improvements to increase production and are on track to deliver approximately 2.5 billion doses in 2021. Next generation ready-to-use and freeze-dried formulations are in development.

This pandemic sparked an unparalleled period of innovation, investment, and partnership with lessons learned that will help us prepare for future pandemics and accelerate R&D of therapeutic candidates for other debilitating and life-threatening conditions.

The Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine has not been approved or licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration but has been authorized for emergency use to prevent COVID-19 in individuals 12+. See conditions of use: http://cvdvaccine.com

Dr. Dolsten is the Chief Scientific Officer and President of Worldwide Research, Development and Medical at Pfizer. He has no other conflicts. Dr. Dolsten made these comments during the AGA Institute Presidential Plenary at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

How the 2022 proposed Medicare payment rules impact GI

In July 2021, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services released the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) and Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS)/Ambulatory Surgery Center (ASC) proposed rules for calendar year (CY) 2022. While the OPPS/ASC proposed rule was largely positive for gastroenterology, the PFS proposed rule was more of a mixed bag for practices.

No more colonoscopy coinsurance “loophole”: After nearly a decade of advocacy, the Removing Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening Act was finally signed into law this year and will take effect Jan. 1, 2023. The legislation phases out Medicare beneficiary cost-sharing obligations when a polyp or lesion is found and biopsied or removed as part of a screening colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy. The American Gastroenterological Association is pleased this will finally eliminate a surprise bill for patients and remove a barrier to colorectal cancer screening.

The phase out timeline is as follows:

- 80% payment for services furnished during CY 2022 (coinsurance, 20%).

- 85% payment for services furnished during CY 2023 through CY 2026 (coinsurance, 15%).

- 90% payment for services furnished during CY 2027 through CY 2029 (coinsurance, 10%).

- 100% payment for services furnished from CY 2030 onward (coinsurance, 0%).

Providers must continue to report HCPCS modifier “PT” in the hospital outpatient and ASC during the transition period to indicate that a planned colorectal cancer screening service converted to a diagnostic service.

Proposed 2022 PFS conversion factor could fall 3.75% unless Congress acts: The proposed 2022 PFS conversion factor is $33.58. The decrease reflects the expiration of the 3.75% payment increase provided by the Consolidated Appropriations Act. This congressional intervention averted a significant cut in Medicare physician payment that would have resulted in an almost 10% cut to GI services. The GI societies are working with Congress to avert cuts to physician payments next year as practices continue to recover from the pandemic.

GI procedure payments to increase 3% for hospital outpatient and ASCs: A 2.3% increase has been proposed for the conversion factors, resulting in $84.46 for hospitals and $50.04 for ASCs meeting quality reporting requirements. However, GI endoscopy procedure payments are expected to increase on average 3% in CY 2022.

Colon capsule endoscopy and POEM get new codes and payments: CMS accepted new CPT codes for colon capsule endoscopy (CCE) and peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) beginning Jan. 1, 2022.

CMS’s proposed CCE value of 2.41 physician work relative value units (wRVUs) reflects the recommendation of the American Medical Association RVS Update Committee (RUC), which is based on data from physicians who perform the procedure. The proposed national-level physician payments are $116.52 for the professional component and $664.21 for the technical component.

However, CMS did not accept the RUC’s recommendation of 15.50 wRVUs for POEM and, instead, proposed that POEM is similar in work to hemodialysis access CPT code 36819, which has a wRVU of 13.29 and a payment of $792.82. The RUC’s valuation of 15.50 wRVUs was based on data from nearly 120 physicians who perform POEM, and we are disappointed CMS chose to reject the robust survey data. The GI societies will defend the 15.50 wRVU in our comments.

The proposed facility fee for POEM is $3,160.76 in the hospital outpatient setting and $1,848.32 in the ASC. CMS’s proposed facility fee for colon capsule endoscopy is $814.44 in the hospital outpatient setting.

CMS moves physicians to MVPs and plans to phase out MIPS: CMS proposes to revise and phase out the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and move physicians towards the MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs) system beginning in the 2023 performance year (PY). No GI MVPs were proposed for PY 2023. The GI societies are working with CMS as they develop MVPs to ensure any gastroenterology-related MVPs do not harm gastroenterologists.

CMS is statutorily required to weigh the MIPS Cost and Quality performance categories equally beginning with PY 2022. The proposed PY 2022 MIPS performance categories are:

- Quality: 30%.

- Cost: 30%.

- Promoting Interoperability: 25% (no change from 2021).

- Improvement Activities: 15% (no change from 2021).

CMS is also required by law beginning in 2022 to set the MIPS performance threshold to either the mean or median of the final scores for all MIPS eligible clinicians for a prior period. CMS proposes to use the mean final score from MIPS 2017 performance year/MIPS 2019 payment year, which would result in a performance threshold of 75 points and an additional performance threshold set at 89 points for exceptional performance.

CMS keeps all AGA-stewarded measures in MIPS 2022 program year: CMS has proposed to keep all AGA-stewarded measures in the MIPS program for the 2022 program year and accepted the substantive changes for the one-time screening for hepatitis C virus measure we received last year from the Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement. CMS proposed removal of the claims reporting option of American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy–stewarded measure for photodocumentation of cecal intubation because it is topped-out; however, the registry version is still available in MIPS.

OQR Program includes colonoscopy measure for disparities reporting: CMS has identified six priority measures included in the Hospital Outpatient Quality Reporting (OQR) Program as candidate measures for disparities reporting stratified by dual eligibility, one of which is the Facility 7-Day Risk-Standardized Hospital Visit Rate After Outpatient Colonoscopy (OP-32).

The GI societies will jointly comment on issues in the 2022 PFS and OPPS/ASC proposed rules impacting gastroenterologists. We may also organize members to take action by submitting letters during the comment period, so watch your inbox for invitations to participate. We need your help to influence change.

Shivan Mehta, MD, MBA, is with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and is an AGA adviser to the American Medical Association RVS Update Committee. David A. Leiman, MD, MSHP, is with the division of gastroenterology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., and is the chair of the AGA Quality Committee. Neither have conflicts to declare.

In July 2021, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services released the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) and Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS)/Ambulatory Surgery Center (ASC) proposed rules for calendar year (CY) 2022. While the OPPS/ASC proposed rule was largely positive for gastroenterology, the PFS proposed rule was more of a mixed bag for practices.

No more colonoscopy coinsurance “loophole”: After nearly a decade of advocacy, the Removing Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening Act was finally signed into law this year and will take effect Jan. 1, 2023. The legislation phases out Medicare beneficiary cost-sharing obligations when a polyp or lesion is found and biopsied or removed as part of a screening colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy. The American Gastroenterological Association is pleased this will finally eliminate a surprise bill for patients and remove a barrier to colorectal cancer screening.

The phase out timeline is as follows:

- 80% payment for services furnished during CY 2022 (coinsurance, 20%).

- 85% payment for services furnished during CY 2023 through CY 2026 (coinsurance, 15%).

- 90% payment for services furnished during CY 2027 through CY 2029 (coinsurance, 10%).

- 100% payment for services furnished from CY 2030 onward (coinsurance, 0%).

Providers must continue to report HCPCS modifier “PT” in the hospital outpatient and ASC during the transition period to indicate that a planned colorectal cancer screening service converted to a diagnostic service.

Proposed 2022 PFS conversion factor could fall 3.75% unless Congress acts: The proposed 2022 PFS conversion factor is $33.58. The decrease reflects the expiration of the 3.75% payment increase provided by the Consolidated Appropriations Act. This congressional intervention averted a significant cut in Medicare physician payment that would have resulted in an almost 10% cut to GI services. The GI societies are working with Congress to avert cuts to physician payments next year as practices continue to recover from the pandemic.

GI procedure payments to increase 3% for hospital outpatient and ASCs: A 2.3% increase has been proposed for the conversion factors, resulting in $84.46 for hospitals and $50.04 for ASCs meeting quality reporting requirements. However, GI endoscopy procedure payments are expected to increase on average 3% in CY 2022.

Colon capsule endoscopy and POEM get new codes and payments: CMS accepted new CPT codes for colon capsule endoscopy (CCE) and peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) beginning Jan. 1, 2022.

CMS’s proposed CCE value of 2.41 physician work relative value units (wRVUs) reflects the recommendation of the American Medical Association RVS Update Committee (RUC), which is based on data from physicians who perform the procedure. The proposed national-level physician payments are $116.52 for the professional component and $664.21 for the technical component.

However, CMS did not accept the RUC’s recommendation of 15.50 wRVUs for POEM and, instead, proposed that POEM is similar in work to hemodialysis access CPT code 36819, which has a wRVU of 13.29 and a payment of $792.82. The RUC’s valuation of 15.50 wRVUs was based on data from nearly 120 physicians who perform POEM, and we are disappointed CMS chose to reject the robust survey data. The GI societies will defend the 15.50 wRVU in our comments.

The proposed facility fee for POEM is $3,160.76 in the hospital outpatient setting and $1,848.32 in the ASC. CMS’s proposed facility fee for colon capsule endoscopy is $814.44 in the hospital outpatient setting.

CMS moves physicians to MVPs and plans to phase out MIPS: CMS proposes to revise and phase out the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and move physicians towards the MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs) system beginning in the 2023 performance year (PY). No GI MVPs were proposed for PY 2023. The GI societies are working with CMS as they develop MVPs to ensure any gastroenterology-related MVPs do not harm gastroenterologists.

CMS is statutorily required to weigh the MIPS Cost and Quality performance categories equally beginning with PY 2022. The proposed PY 2022 MIPS performance categories are:

- Quality: 30%.

- Cost: 30%.

- Promoting Interoperability: 25% (no change from 2021).

- Improvement Activities: 15% (no change from 2021).

CMS is also required by law beginning in 2022 to set the MIPS performance threshold to either the mean or median of the final scores for all MIPS eligible clinicians for a prior period. CMS proposes to use the mean final score from MIPS 2017 performance year/MIPS 2019 payment year, which would result in a performance threshold of 75 points and an additional performance threshold set at 89 points for exceptional performance.

CMS keeps all AGA-stewarded measures in MIPS 2022 program year: CMS has proposed to keep all AGA-stewarded measures in the MIPS program for the 2022 program year and accepted the substantive changes for the one-time screening for hepatitis C virus measure we received last year from the Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement. CMS proposed removal of the claims reporting option of American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy–stewarded measure for photodocumentation of cecal intubation because it is topped-out; however, the registry version is still available in MIPS.

OQR Program includes colonoscopy measure for disparities reporting: CMS has identified six priority measures included in the Hospital Outpatient Quality Reporting (OQR) Program as candidate measures for disparities reporting stratified by dual eligibility, one of which is the Facility 7-Day Risk-Standardized Hospital Visit Rate After Outpatient Colonoscopy (OP-32).

The GI societies will jointly comment on issues in the 2022 PFS and OPPS/ASC proposed rules impacting gastroenterologists. We may also organize members to take action by submitting letters during the comment period, so watch your inbox for invitations to participate. We need your help to influence change.

Shivan Mehta, MD, MBA, is with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and is an AGA adviser to the American Medical Association RVS Update Committee. David A. Leiman, MD, MSHP, is with the division of gastroenterology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., and is the chair of the AGA Quality Committee. Neither have conflicts to declare.

In July 2021, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services released the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) and Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS)/Ambulatory Surgery Center (ASC) proposed rules for calendar year (CY) 2022. While the OPPS/ASC proposed rule was largely positive for gastroenterology, the PFS proposed rule was more of a mixed bag for practices.

No more colonoscopy coinsurance “loophole”: After nearly a decade of advocacy, the Removing Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening Act was finally signed into law this year and will take effect Jan. 1, 2023. The legislation phases out Medicare beneficiary cost-sharing obligations when a polyp or lesion is found and biopsied or removed as part of a screening colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy. The American Gastroenterological Association is pleased this will finally eliminate a surprise bill for patients and remove a barrier to colorectal cancer screening.

The phase out timeline is as follows:

- 80% payment for services furnished during CY 2022 (coinsurance, 20%).

- 85% payment for services furnished during CY 2023 through CY 2026 (coinsurance, 15%).

- 90% payment for services furnished during CY 2027 through CY 2029 (coinsurance, 10%).

- 100% payment for services furnished from CY 2030 onward (coinsurance, 0%).

Providers must continue to report HCPCS modifier “PT” in the hospital outpatient and ASC during the transition period to indicate that a planned colorectal cancer screening service converted to a diagnostic service.

Proposed 2022 PFS conversion factor could fall 3.75% unless Congress acts: The proposed 2022 PFS conversion factor is $33.58. The decrease reflects the expiration of the 3.75% payment increase provided by the Consolidated Appropriations Act. This congressional intervention averted a significant cut in Medicare physician payment that would have resulted in an almost 10% cut to GI services. The GI societies are working with Congress to avert cuts to physician payments next year as practices continue to recover from the pandemic.

GI procedure payments to increase 3% for hospital outpatient and ASCs: A 2.3% increase has been proposed for the conversion factors, resulting in $84.46 for hospitals and $50.04 for ASCs meeting quality reporting requirements. However, GI endoscopy procedure payments are expected to increase on average 3% in CY 2022.

Colon capsule endoscopy and POEM get new codes and payments: CMS accepted new CPT codes for colon capsule endoscopy (CCE) and peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) beginning Jan. 1, 2022.

CMS’s proposed CCE value of 2.41 physician work relative value units (wRVUs) reflects the recommendation of the American Medical Association RVS Update Committee (RUC), which is based on data from physicians who perform the procedure. The proposed national-level physician payments are $116.52 for the professional component and $664.21 for the technical component.

However, CMS did not accept the RUC’s recommendation of 15.50 wRVUs for POEM and, instead, proposed that POEM is similar in work to hemodialysis access CPT code 36819, which has a wRVU of 13.29 and a payment of $792.82. The RUC’s valuation of 15.50 wRVUs was based on data from nearly 120 physicians who perform POEM, and we are disappointed CMS chose to reject the robust survey data. The GI societies will defend the 15.50 wRVU in our comments.

The proposed facility fee for POEM is $3,160.76 in the hospital outpatient setting and $1,848.32 in the ASC. CMS’s proposed facility fee for colon capsule endoscopy is $814.44 in the hospital outpatient setting.

CMS moves physicians to MVPs and plans to phase out MIPS: CMS proposes to revise and phase out the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and move physicians towards the MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs) system beginning in the 2023 performance year (PY). No GI MVPs were proposed for PY 2023. The GI societies are working with CMS as they develop MVPs to ensure any gastroenterology-related MVPs do not harm gastroenterologists.

CMS is statutorily required to weigh the MIPS Cost and Quality performance categories equally beginning with PY 2022. The proposed PY 2022 MIPS performance categories are:

- Quality: 30%.

- Cost: 30%.

- Promoting Interoperability: 25% (no change from 2021).

- Improvement Activities: 15% (no change from 2021).

CMS is also required by law beginning in 2022 to set the MIPS performance threshold to either the mean or median of the final scores for all MIPS eligible clinicians for a prior period. CMS proposes to use the mean final score from MIPS 2017 performance year/MIPS 2019 payment year, which would result in a performance threshold of 75 points and an additional performance threshold set at 89 points for exceptional performance.

CMS keeps all AGA-stewarded measures in MIPS 2022 program year: CMS has proposed to keep all AGA-stewarded measures in the MIPS program for the 2022 program year and accepted the substantive changes for the one-time screening for hepatitis C virus measure we received last year from the Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement. CMS proposed removal of the claims reporting option of American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy–stewarded measure for photodocumentation of cecal intubation because it is topped-out; however, the registry version is still available in MIPS.

OQR Program includes colonoscopy measure for disparities reporting: CMS has identified six priority measures included in the Hospital Outpatient Quality Reporting (OQR) Program as candidate measures for disparities reporting stratified by dual eligibility, one of which is the Facility 7-Day Risk-Standardized Hospital Visit Rate After Outpatient Colonoscopy (OP-32).

The GI societies will jointly comment on issues in the 2022 PFS and OPPS/ASC proposed rules impacting gastroenterologists. We may also organize members to take action by submitting letters during the comment period, so watch your inbox for invitations to participate. We need your help to influence change.

Shivan Mehta, MD, MBA, is with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and is an AGA adviser to the American Medical Association RVS Update Committee. David A. Leiman, MD, MSHP, is with the division of gastroenterology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., and is the chair of the AGA Quality Committee. Neither have conflicts to declare.

AGA Foundation: Gift options for your will

When life changes, so should your will. An old will can’t cover every change that may have occurred since it was first drawn. Ensure that this important document matches your current wishes by reviewing it every few years.

Use your will to give back!

Help support young investigators doing research.

- Gift us a share of what›s left in your estate after other obligations are met.

- Make a contingent bequest. That is, you give part of your estate to some individual if that person survives you; if not, then it goes to us.

- Create a charitable remainder trust to pay an income to your spouse or other loved one for life and designate the remaining principal for us.

- Create a charitable lead trust to pay income to us for a number of years, or for another person’s lifetime, with the trust assets eventually being distributed to your family.

- Donate a specific amount of cash or securities.

To make sure your will accomplishes all you intend, seek the help of an attorney who specializes in estate planning. If our organization fits into your plans, we can help you choose the method that best satisfies your wishes and our needs.

When life changes, so should your will. An old will can’t cover every change that may have occurred since it was first drawn. Ensure that this important document matches your current wishes by reviewing it every few years.

Use your will to give back!

Help support young investigators doing research.

- Gift us a share of what›s left in your estate after other obligations are met.

- Make a contingent bequest. That is, you give part of your estate to some individual if that person survives you; if not, then it goes to us.

- Create a charitable remainder trust to pay an income to your spouse or other loved one for life and designate the remaining principal for us.

- Create a charitable lead trust to pay income to us for a number of years, or for another person’s lifetime, with the trust assets eventually being distributed to your family.

- Donate a specific amount of cash or securities.

To make sure your will accomplishes all you intend, seek the help of an attorney who specializes in estate planning. If our organization fits into your plans, we can help you choose the method that best satisfies your wishes and our needs.

When life changes, so should your will. An old will can’t cover every change that may have occurred since it was first drawn. Ensure that this important document matches your current wishes by reviewing it every few years.

Use your will to give back!

Help support young investigators doing research.

- Gift us a share of what›s left in your estate after other obligations are met.

- Make a contingent bequest. That is, you give part of your estate to some individual if that person survives you; if not, then it goes to us.

- Create a charitable remainder trust to pay an income to your spouse or other loved one for life and designate the remaining principal for us.

- Create a charitable lead trust to pay income to us for a number of years, or for another person’s lifetime, with the trust assets eventually being distributed to your family.

- Donate a specific amount of cash or securities.

To make sure your will accomplishes all you intend, seek the help of an attorney who specializes in estate planning. If our organization fits into your plans, we can help you choose the method that best satisfies your wishes and our needs.

Dr. Tadataka “Tachi” Yamada dies at 76

Dr. Yamada had a storied career as a GI leader, educator, and mentor before his work as a biotech pharma research chief and a global health advocate with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

AGA President John Inadomi, MD, tweeted “We lost a mentor, sponsor, role model and true pioneer in gastroenterology – Honor his legacy.” You can share your remembrances on the AGA Community.

Over the years, Tachi made enormous contributions to AGA. He served on multiple committees, too numerous to list. He served on the AGA Governing Board multiple times and as president.

He was awarded the association’s highest honor, the Julius Friedenwald Medal, in 2003. At that time, Chung Owyang, MD, wrote a bio of Tachi and noted his critical role in shaping AGA and Digestive Disease Week® (DDW). He was the founding chair of the AGA Council working hard to reformat DDW into a major international event for our subspecialty. He was also among the group of AGA leaders who proposed the establishment of the AGA Foundation.

In 1996, Tachi assumed the presidency of AGA during a time of great turbulence in health care, where not only the practice but also the education and research missions of gastroenterology were threatened by change. Tachi took on the challenge with exemplary vision, energy, and intelligence.

Dan Podolsky, MD, a former AGA president commented at the time of Tachi’s Friedenwald Medal that “Tachi applied characteristic creativity and energy to all AGA activities. An inspirational leader, he was especially effective in promoting the AGA’s commitment to the career development of young gastroenterologists, promoting digestive diseases research, and as a tireless advocate for the field of gastroenterology.”

“Tachi has not only led our field, but he has been a global leader helping pharma rethink their role in global health, and helping the Gates Foundation save so many lives. He was soft-spoken but his worldwide contributions and vision will carry on. Heartfelt condolences to his family and friends,” said Bishr Omary, MD, PhD, past president of AGA Institute.

Dr. Yamada had a storied career as a GI leader, educator, and mentor before his work as a biotech pharma research chief and a global health advocate with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

AGA President John Inadomi, MD, tweeted “We lost a mentor, sponsor, role model and true pioneer in gastroenterology – Honor his legacy.” You can share your remembrances on the AGA Community.

Over the years, Tachi made enormous contributions to AGA. He served on multiple committees, too numerous to list. He served on the AGA Governing Board multiple times and as president.

He was awarded the association’s highest honor, the Julius Friedenwald Medal, in 2003. At that time, Chung Owyang, MD, wrote a bio of Tachi and noted his critical role in shaping AGA and Digestive Disease Week® (DDW). He was the founding chair of the AGA Council working hard to reformat DDW into a major international event for our subspecialty. He was also among the group of AGA leaders who proposed the establishment of the AGA Foundation.

In 1996, Tachi assumed the presidency of AGA during a time of great turbulence in health care, where not only the practice but also the education and research missions of gastroenterology were threatened by change. Tachi took on the challenge with exemplary vision, energy, and intelligence.

Dan Podolsky, MD, a former AGA president commented at the time of Tachi’s Friedenwald Medal that “Tachi applied characteristic creativity and energy to all AGA activities. An inspirational leader, he was especially effective in promoting the AGA’s commitment to the career development of young gastroenterologists, promoting digestive diseases research, and as a tireless advocate for the field of gastroenterology.”

“Tachi has not only led our field, but he has been a global leader helping pharma rethink their role in global health, and helping the Gates Foundation save so many lives. He was soft-spoken but his worldwide contributions and vision will carry on. Heartfelt condolences to his family and friends,” said Bishr Omary, MD, PhD, past president of AGA Institute.

Dr. Yamada had a storied career as a GI leader, educator, and mentor before his work as a biotech pharma research chief and a global health advocate with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

AGA President John Inadomi, MD, tweeted “We lost a mentor, sponsor, role model and true pioneer in gastroenterology – Honor his legacy.” You can share your remembrances on the AGA Community.

Over the years, Tachi made enormous contributions to AGA. He served on multiple committees, too numerous to list. He served on the AGA Governing Board multiple times and as president.

He was awarded the association’s highest honor, the Julius Friedenwald Medal, in 2003. At that time, Chung Owyang, MD, wrote a bio of Tachi and noted his critical role in shaping AGA and Digestive Disease Week® (DDW). He was the founding chair of the AGA Council working hard to reformat DDW into a major international event for our subspecialty. He was also among the group of AGA leaders who proposed the establishment of the AGA Foundation.

In 1996, Tachi assumed the presidency of AGA during a time of great turbulence in health care, where not only the practice but also the education and research missions of gastroenterology were threatened by change. Tachi took on the challenge with exemplary vision, energy, and intelligence.

Dan Podolsky, MD, a former AGA president commented at the time of Tachi’s Friedenwald Medal that “Tachi applied characteristic creativity and energy to all AGA activities. An inspirational leader, he was especially effective in promoting the AGA’s commitment to the career development of young gastroenterologists, promoting digestive diseases research, and as a tireless advocate for the field of gastroenterology.”

“Tachi has not only led our field, but he has been a global leader helping pharma rethink their role in global health, and helping the Gates Foundation save so many lives. He was soft-spoken but his worldwide contributions and vision will carry on. Heartfelt condolences to his family and friends,” said Bishr Omary, MD, PhD, past president of AGA Institute.

Should the starting age for CRC screening be lowered to 45?

Dear colleagues and friends,

The start age for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening in average-risk individuals has been relatively uncontroversial and unchallenged, until recent guidelines that recommended decreasing the start age from 50 to 45 years. In this edition of Perspectives, two renowned experts, Dr. Patel and Dr. Rabeneck, debate the pros and cons of this paradigm change. This will be my final Perspectives contribution as associate editor for GI & Hep News. Thank you very much for your support and feedback, and I hope you have all enjoyed and learned from the Perspectives debates as much as I have. As always, your feedback and suggestions for future topics are welcome and can be sent to [email protected].

Charles J. Kahi, MD, MS, AGAF, is professor of medicine at Indiana University, Indianapolis.

45 is the new 50

BY SWATI G. PATEL, MD, MS

The incidence and mortality rates of CRC in individuals under the age of 50 years, or early age–onset CRC, is increasing in the United States.1 We do not fully understand the cause of this trend; however, it has been observed in multiple Westernized countries, consistent with a birth cohort effect in which generation-specific risk factors are likely responsible.1 To address this rising burden of early age–onset CRC, multiple professional societies, including the United States Preventive Services Task Force,2 now recommend decreasing the starting age for CRC screening in average-risk individuals from 50 to 45 years. These recommendations are supported by the fact that CRC incidence in 45- to 49-year-olds is now the same as that of populations already eligible for screening; the yield of screening appears to be similar among those aged 45-49 years, compared to those aged 50-59 years; and modeling studies show that the benefits outweigh the risks and costs. These factors, along with the unique benefits of early detection and prevention in young patients, support that 45 is the new 50 when it comes to CRC screening.

CRC incidence rates among 45- to 49-year-olds now match populations that are already eligible for CRC screening. The rates among 45- to 49-year-olds now is similar to the incidence rates observed in 50-year-olds in 1992, before widespread CRC screening was performed. Overall incidence rates in 45- to 49-year-olds now match incidence rates observed in 45- to 49-year-old African Americans, a population in which the American College of Gastroenterology and the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force have recommended average-risk screening beginning at age 45.

Advanced colorectal neoplasia rates in 45- to 49-year-olds are similar to rates observed in 50- to 59-year-olds. One study found that advanced colorectal neoplasia rates (including advanced colorectal polyps and adenocarcinoma) in average risk–equivalent 45- to 49-year-olds are similar rates of 50- to 54-year-old average-risk individuals.3 Similarly, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 17 international studies including average-risk individuals undergoing colonoscopy found no significant difference between advanced colorectal neoplasia rates in 45- to 49-years-olds compared to 50- to 59-year-olds.4 These data suggest that expanding screening to average-risk individuals aged 45-49 years will have yield similar to that of those aged 50-59.

Modeling studies show that the benefits of screening outweigh the potential harms and costs. A recent cost-effectiveness analysis showed that starting average-risk screening at age 45 years with colonoscopy would cost $33,900 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) or $7,700 per QALY if annual FIT is selected as the screening modality.5 These costs are less than the widely accepted willingness to pay threshold of $50,000 per QALY and less than currently accepted average-risk screening, such as annual or biennial mammograms for breast cancer screening.

Expanding screening to 45- to 49-year-olds can improve early detection of CRC and prevention of CRC. Offering screening before age 50 years provides the opportunity to detect cancers at earlier stages, which can improve overall survival. Recent data have shown an increase in CRC incidence among 50- to 54-year-olds.1 Although the etiology of the rise in this age group is likely multifactorial (low screening rates or generational risk that individuals carry with them through the birth-cohort effect), diagnosis and removal of advanced colorectal polyps among 45- to 49-year-olds can have a positive impact on reversing this trend in 50- to 54-year-olds. Furthermore, initiating conversations about CRC screening at age 45 can improve uptake of screening among 50- to 54-year-olds who may have delayed screening when first offered at age 50.

There are unique benefits of early detection and prevention of CRC in young patients. Although the absolute incidence and mortality rates associated with CRC in those aged 45-49 are significantly lower than the rates observed in those over age 50, young individuals are more likely to be in the prime of their earning and fertility potential and are more likely to be caregivers to younger and older generations. They are more likely to face material, psychological, and behavioral financial hardships, such as difficulty paying bills. Absolute incidence rates and modeling studies that do not account for these intangible effects on survivorship also do not fully reflect the societal benefit of early detection and CRC prevention in those aged 45-49 years.

There are certainly many unanswered questions about the effects of expanding CRC screening to those age 45 and older. Ongoing studies are needed to determine the cause of rising incidence, whether screening test selection and intervals should be customized for those under age 50, and how best to ensure equitable access to screening services. Finally, expanding screening to younger individuals should not detract from the critical importance of ongoing efforts to improve screening in those over age 50. As these issues are addressed by the scientific community, we cannot stand by idly when there is sufficient evidence to support that 45 is the new 50.

Dr. Patel is associate professor of medicine in the divisions of gastroenterology & hepatology at the University of Colorado and Rocky Mountain Regional Veterans Affairs Medical Center, both in Aurora, Colo. She disclosed financial relationships with Olympus America, ERBE USA, and Freenome.

References

1. Siegel RL et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw322.

2. USPSTF et al. JAMA. 2021 May 18;325(19):1965-77.

3. Butterly LF et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Jan;116(1):171-9.

4. Kolb JM et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jun. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.06.006.

5. Ladabaum U et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jul;157(1):137-48.

50 is still 50

BY LINDA RABENECK, MD, MPH, FRCPC

CRC screening of women and men aged 50-75 years at average risk has contributed to the overall decrease in the incidence and mortality from the disease in the United States. In 2009, the American College of Gastroenterology recommended that CRC screening among African Americans begin at age 45 years, and a recent study from Kaiser Permanente reported favorable results from FIT screening in this group.1 In 2018 the American Cancer Society surprised the field by releasing an updated recommendation to begin CRC screening in all women and men at age 45 years (Qualified Recommendation). This spring the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force released its updated recommendation to begin screening at age 45 years (B recommendation).2 The rationale for these updated recommendations is based on new information on the epidemiology of the disease in the United States that was incorporated into updated modeling.

What was this new information? An evaluation of time trends in CRC incidence by age group showed that, although the incidence of colon and rectal cancer among those 50 years and older has been decreasing for more than 2 decades, the incidence has been increasing for those younger than 50 years. As important as these CRC incidence trends are to recognize and understand, this does not imply we should start screening everyone in the general population aged 45-49 years. We need to recognize that the absolute increase in CRC incidence in those younger than 50 years is small, that we lack empirical evidence to support such a major change in screening practice, and that we need to consider potential unintended impacts.

When the rise in incidence among younger Americans was first reported there was much discussion about what it meant. It appears that the rise in incidence is a birth cohort effect among people born in the 1960s and subsequent years. Birth cohort effects imply exposures occurring in early life or those experienced by younger generations. Sorting out what these exposures might be is an area of intense research activity currently. Regardless of the drivers of the relative increase in CRC incidence among younger persons, though, it is important to note that the absolute increase is small. What do we mean by this?

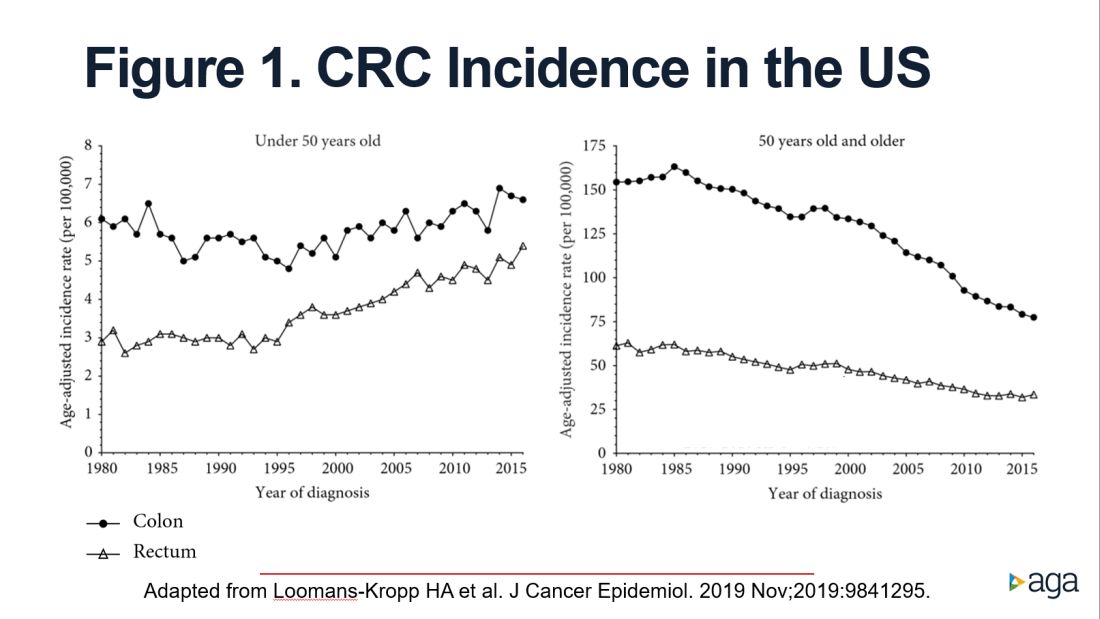

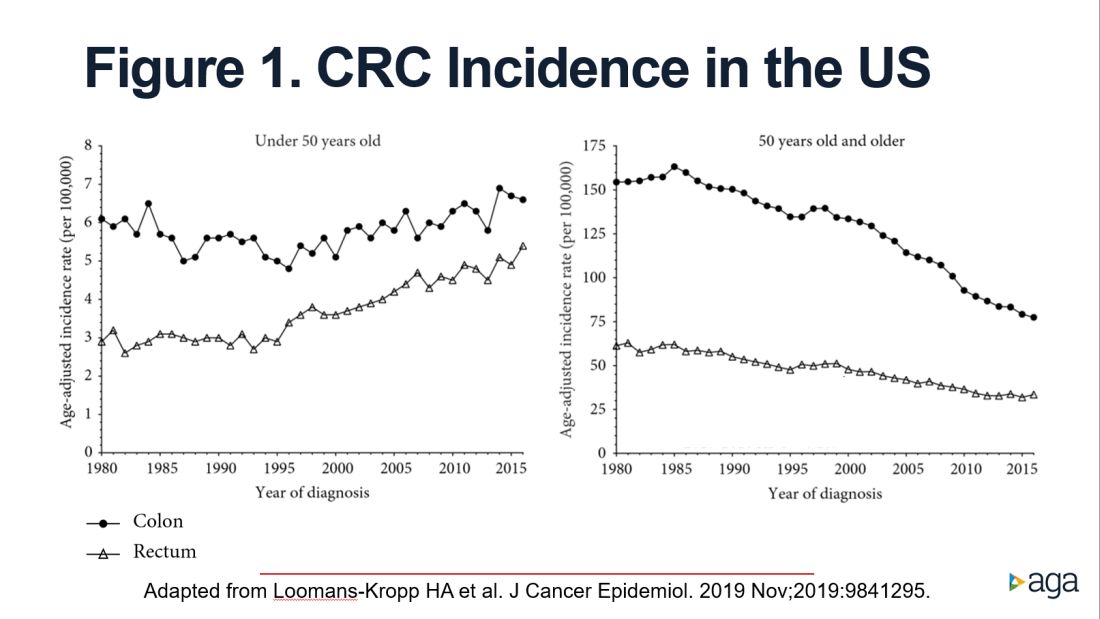

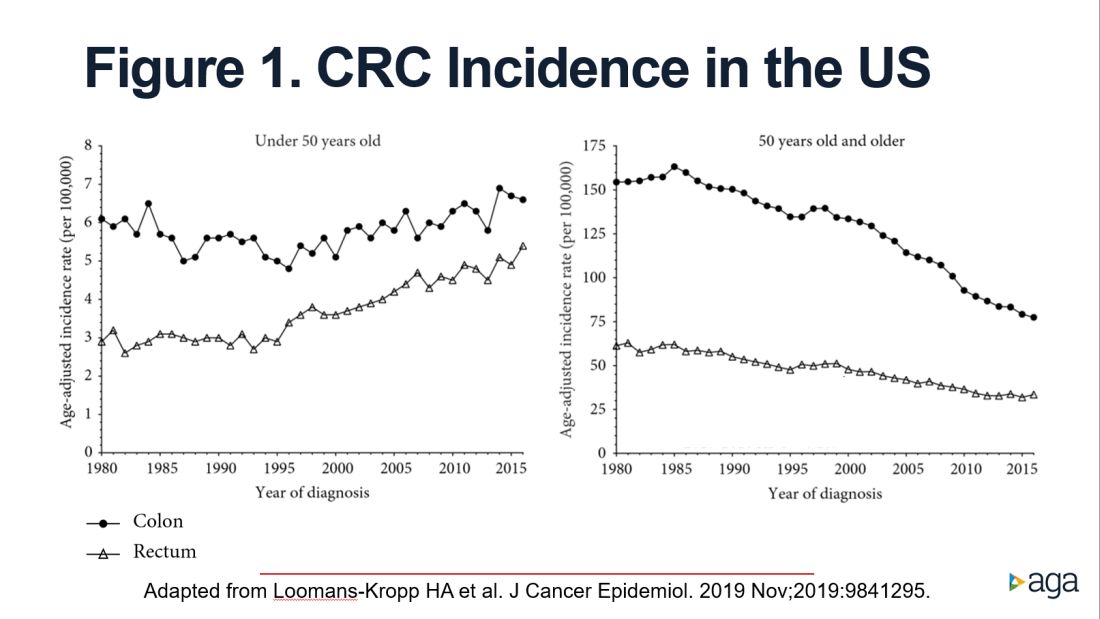

As reported by Holli Loomans-Kropp, PhD, MPH, and colleagues,3 for those under age 50 years, the age-adjusted incidence of colon cancer decreased by 0.9% annually from 1980 to 1996, and then increased by 1.3% annually from 1996 to 2016 (Figure 1).

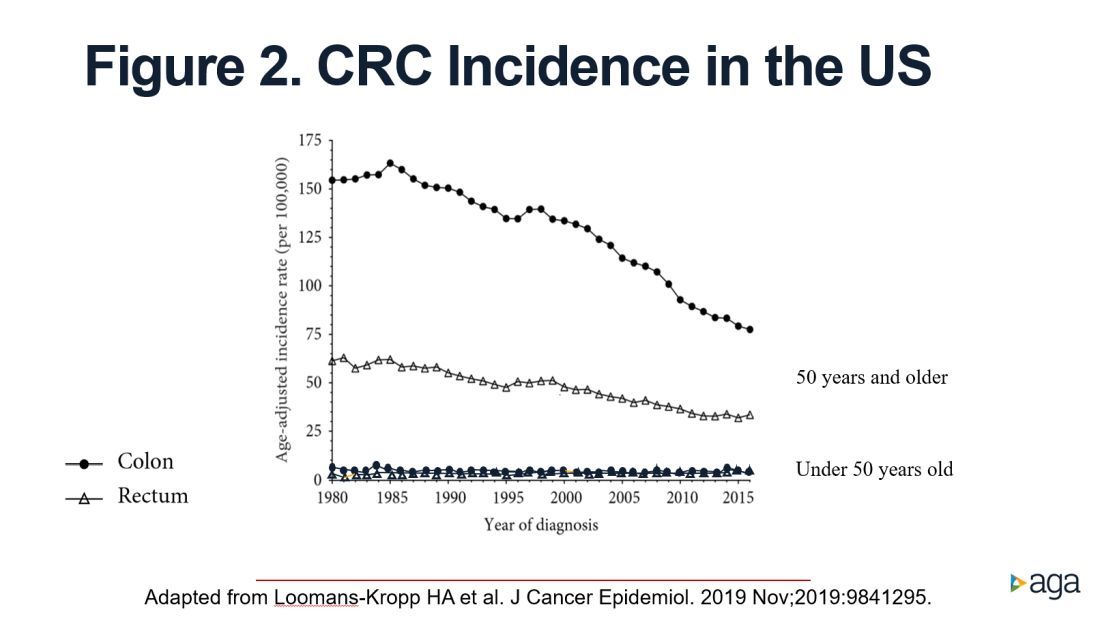

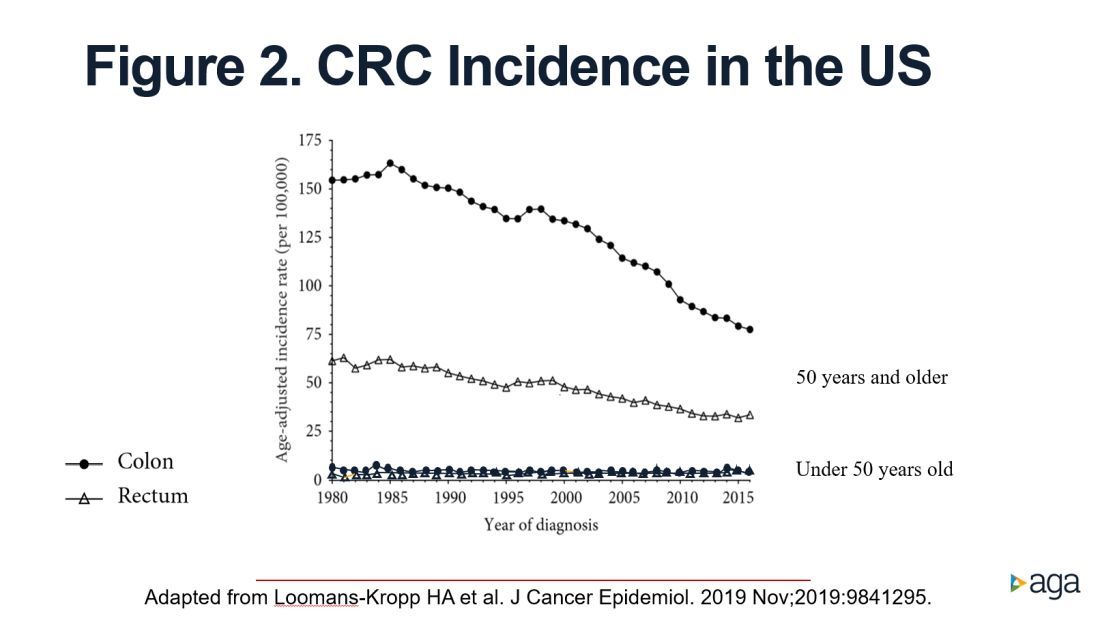

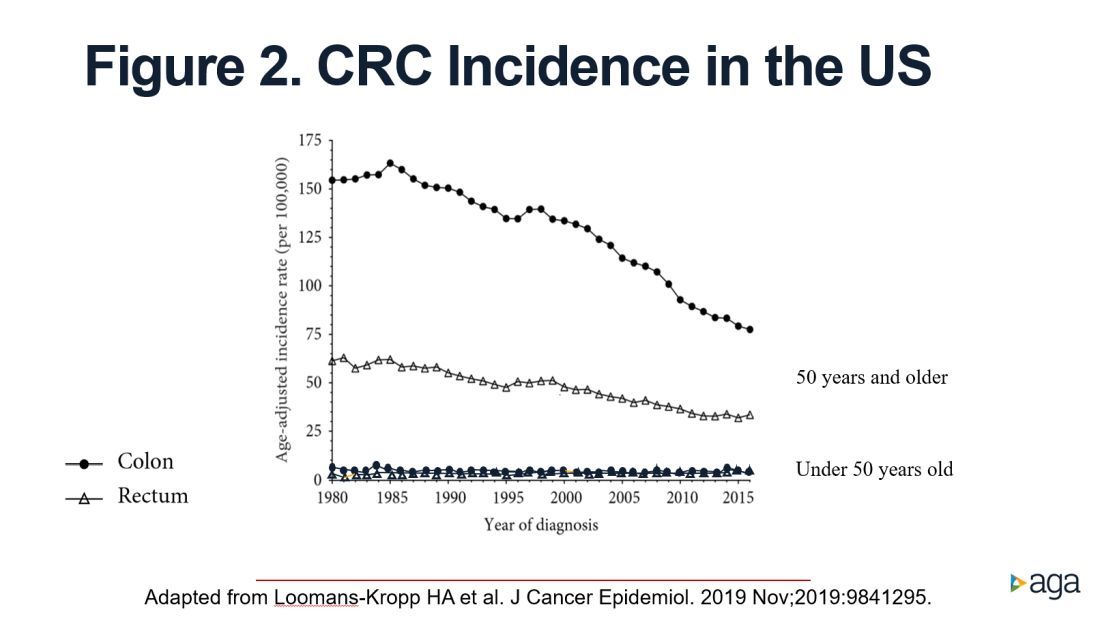

The figure shows that the age-adjusted incidence of rectal cancer among those under age 50 years increased by 2.3% annually since 1991. Figure 1 also shows declines in age-adjusted CRC incidence since 2001 for colon cancer and since 1998 for rectal cancer. However, note the differences in the scales on the Y axes between these two figures. Figure 2 shows this information plotted on the same scale (drawn by hand by author). To recap, these relative increases in incidence are real, but the absolute increases are small.

In addition, not surprisingly, we lack results from randomized controlled trials to support the change in CRC screening recommendation. We are just beginning to see results from other types of study design that seek to address this evidence gap. For example, a recent retrospective cohort study using information recorded in Florida databases evaluated the association between CRC incidence and undergoing colonoscopy at ages 45-49 versus 50-54 years. The authors reported a reduction in CRC incidence in both age groups.4

We also need to consider the resource implications. Lowering the age to start CRC screening to 45 years would expand the target population by greater than 20 million Americans, with all that this entails in terms of additional effort and resources, including colonoscopy. Modeling studies have shown that we would achieve greater clinical benefit with lower cost from directing these colonoscopy resources to those aged 50-75 years who are under/never screened and also ensuring follow-up colonoscopy among those with a positive FIT.5 For example, a study in a U.S. safety-net system reported that among 2,238 patients with a FIT+ followed over 1 year, only 55% underwent a colonoscopy.6

Finally, we need to reflect on existing disparities. If we turn our attention and resources to focus on all those aged 45-49 years in the general population, we risk worsening these disparities.

In conclusion, we need to redouble our efforts to reduce existing disparities in CRC screening participation among those aged 50-74 years and ensure colonoscopy follow-up in those with a FIT+ rather than divert our attention and resources to all those 45- to 49-year-olds who are at lower risk.

Dr. Rabeneck is professor of medicine at the University of Toronto. She has no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Levin TR et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Nov;159(5):1695-704.e1.

2. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force et al. JAMA. 2021 May 18;325(19):1965-77.

3. Loomans-Kropp HA et al. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2019 Nov 11;2019:9841295.

4. Sehgal M et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 May;160(6):2018-28.e13.

5. Ladabaum U et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jul;157(1):137-48.

6. Issaka RB et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Feb;112(2):375-82.

Dear colleagues and friends,

The start age for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening in average-risk individuals has been relatively uncontroversial and unchallenged, until recent guidelines that recommended decreasing the start age from 50 to 45 years. In this edition of Perspectives, two renowned experts, Dr. Patel and Dr. Rabeneck, debate the pros and cons of this paradigm change. This will be my final Perspectives contribution as associate editor for GI & Hep News. Thank you very much for your support and feedback, and I hope you have all enjoyed and learned from the Perspectives debates as much as I have. As always, your feedback and suggestions for future topics are welcome and can be sent to [email protected].

Charles J. Kahi, MD, MS, AGAF, is professor of medicine at Indiana University, Indianapolis.

45 is the new 50

BY SWATI G. PATEL, MD, MS

The incidence and mortality rates of CRC in individuals under the age of 50 years, or early age–onset CRC, is increasing in the United States.1 We do not fully understand the cause of this trend; however, it has been observed in multiple Westernized countries, consistent with a birth cohort effect in which generation-specific risk factors are likely responsible.1 To address this rising burden of early age–onset CRC, multiple professional societies, including the United States Preventive Services Task Force,2 now recommend decreasing the starting age for CRC screening in average-risk individuals from 50 to 45 years. These recommendations are supported by the fact that CRC incidence in 45- to 49-year-olds is now the same as that of populations already eligible for screening; the yield of screening appears to be similar among those aged 45-49 years, compared to those aged 50-59 years; and modeling studies show that the benefits outweigh the risks and costs. These factors, along with the unique benefits of early detection and prevention in young patients, support that 45 is the new 50 when it comes to CRC screening.

CRC incidence rates among 45- to 49-year-olds now match populations that are already eligible for CRC screening. The rates among 45- to 49-year-olds now is similar to the incidence rates observed in 50-year-olds in 1992, before widespread CRC screening was performed. Overall incidence rates in 45- to 49-year-olds now match incidence rates observed in 45- to 49-year-old African Americans, a population in which the American College of Gastroenterology and the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force have recommended average-risk screening beginning at age 45.

Advanced colorectal neoplasia rates in 45- to 49-year-olds are similar to rates observed in 50- to 59-year-olds. One study found that advanced colorectal neoplasia rates (including advanced colorectal polyps and adenocarcinoma) in average risk–equivalent 45- to 49-year-olds are similar rates of 50- to 54-year-old average-risk individuals.3 Similarly, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 17 international studies including average-risk individuals undergoing colonoscopy found no significant difference between advanced colorectal neoplasia rates in 45- to 49-years-olds compared to 50- to 59-year-olds.4 These data suggest that expanding screening to average-risk individuals aged 45-49 years will have yield similar to that of those aged 50-59.

Modeling studies show that the benefits of screening outweigh the potential harms and costs. A recent cost-effectiveness analysis showed that starting average-risk screening at age 45 years with colonoscopy would cost $33,900 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) or $7,700 per QALY if annual FIT is selected as the screening modality.5 These costs are less than the widely accepted willingness to pay threshold of $50,000 per QALY and less than currently accepted average-risk screening, such as annual or biennial mammograms for breast cancer screening.

Expanding screening to 45- to 49-year-olds can improve early detection of CRC and prevention of CRC. Offering screening before age 50 years provides the opportunity to detect cancers at earlier stages, which can improve overall survival. Recent data have shown an increase in CRC incidence among 50- to 54-year-olds.1 Although the etiology of the rise in this age group is likely multifactorial (low screening rates or generational risk that individuals carry with them through the birth-cohort effect), diagnosis and removal of advanced colorectal polyps among 45- to 49-year-olds can have a positive impact on reversing this trend in 50- to 54-year-olds. Furthermore, initiating conversations about CRC screening at age 45 can improve uptake of screening among 50- to 54-year-olds who may have delayed screening when first offered at age 50.

There are unique benefits of early detection and prevention of CRC in young patients. Although the absolute incidence and mortality rates associated with CRC in those aged 45-49 are significantly lower than the rates observed in those over age 50, young individuals are more likely to be in the prime of their earning and fertility potential and are more likely to be caregivers to younger and older generations. They are more likely to face material, psychological, and behavioral financial hardships, such as difficulty paying bills. Absolute incidence rates and modeling studies that do not account for these intangible effects on survivorship also do not fully reflect the societal benefit of early detection and CRC prevention in those aged 45-49 years.

There are certainly many unanswered questions about the effects of expanding CRC screening to those age 45 and older. Ongoing studies are needed to determine the cause of rising incidence, whether screening test selection and intervals should be customized for those under age 50, and how best to ensure equitable access to screening services. Finally, expanding screening to younger individuals should not detract from the critical importance of ongoing efforts to improve screening in those over age 50. As these issues are addressed by the scientific community, we cannot stand by idly when there is sufficient evidence to support that 45 is the new 50.

Dr. Patel is associate professor of medicine in the divisions of gastroenterology & hepatology at the University of Colorado and Rocky Mountain Regional Veterans Affairs Medical Center, both in Aurora, Colo. She disclosed financial relationships with Olympus America, ERBE USA, and Freenome.

References

1. Siegel RL et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw322.

2. USPSTF et al. JAMA. 2021 May 18;325(19):1965-77.

3. Butterly LF et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Jan;116(1):171-9.

4. Kolb JM et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jun. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.06.006.

5. Ladabaum U et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jul;157(1):137-48.

50 is still 50

BY LINDA RABENECK, MD, MPH, FRCPC

CRC screening of women and men aged 50-75 years at average risk has contributed to the overall decrease in the incidence and mortality from the disease in the United States. In 2009, the American College of Gastroenterology recommended that CRC screening among African Americans begin at age 45 years, and a recent study from Kaiser Permanente reported favorable results from FIT screening in this group.1 In 2018 the American Cancer Society surprised the field by releasing an updated recommendation to begin CRC screening in all women and men at age 45 years (Qualified Recommendation). This spring the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force released its updated recommendation to begin screening at age 45 years (B recommendation).2 The rationale for these updated recommendations is based on new information on the epidemiology of the disease in the United States that was incorporated into updated modeling.

What was this new information? An evaluation of time trends in CRC incidence by age group showed that, although the incidence of colon and rectal cancer among those 50 years and older has been decreasing for more than 2 decades, the incidence has been increasing for those younger than 50 years. As important as these CRC incidence trends are to recognize and understand, this does not imply we should start screening everyone in the general population aged 45-49 years. We need to recognize that the absolute increase in CRC incidence in those younger than 50 years is small, that we lack empirical evidence to support such a major change in screening practice, and that we need to consider potential unintended impacts.

When the rise in incidence among younger Americans was first reported there was much discussion about what it meant. It appears that the rise in incidence is a birth cohort effect among people born in the 1960s and subsequent years. Birth cohort effects imply exposures occurring in early life or those experienced by younger generations. Sorting out what these exposures might be is an area of intense research activity currently. Regardless of the drivers of the relative increase in CRC incidence among younger persons, though, it is important to note that the absolute increase is small. What do we mean by this?

As reported by Holli Loomans-Kropp, PhD, MPH, and colleagues,3 for those under age 50 years, the age-adjusted incidence of colon cancer decreased by 0.9% annually from 1980 to 1996, and then increased by 1.3% annually from 1996 to 2016 (Figure 1).

The figure shows that the age-adjusted incidence of rectal cancer among those under age 50 years increased by 2.3% annually since 1991. Figure 1 also shows declines in age-adjusted CRC incidence since 2001 for colon cancer and since 1998 for rectal cancer. However, note the differences in the scales on the Y axes between these two figures. Figure 2 shows this information plotted on the same scale (drawn by hand by author). To recap, these relative increases in incidence are real, but the absolute increases are small.

In addition, not surprisingly, we lack results from randomized controlled trials to support the change in CRC screening recommendation. We are just beginning to see results from other types of study design that seek to address this evidence gap. For example, a recent retrospective cohort study using information recorded in Florida databases evaluated the association between CRC incidence and undergoing colonoscopy at ages 45-49 versus 50-54 years. The authors reported a reduction in CRC incidence in both age groups.4

We also need to consider the resource implications. Lowering the age to start CRC screening to 45 years would expand the target population by greater than 20 million Americans, with all that this entails in terms of additional effort and resources, including colonoscopy. Modeling studies have shown that we would achieve greater clinical benefit with lower cost from directing these colonoscopy resources to those aged 50-75 years who are under/never screened and also ensuring follow-up colonoscopy among those with a positive FIT.5 For example, a study in a U.S. safety-net system reported that among 2,238 patients with a FIT+ followed over 1 year, only 55% underwent a colonoscopy.6

Finally, we need to reflect on existing disparities. If we turn our attention and resources to focus on all those aged 45-49 years in the general population, we risk worsening these disparities.

In conclusion, we need to redouble our efforts to reduce existing disparities in CRC screening participation among those aged 50-74 years and ensure colonoscopy follow-up in those with a FIT+ rather than divert our attention and resources to all those 45- to 49-year-olds who are at lower risk.

Dr. Rabeneck is professor of medicine at the University of Toronto. She has no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Levin TR et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Nov;159(5):1695-704.e1.

2. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force et al. JAMA. 2021 May 18;325(19):1965-77.

3. Loomans-Kropp HA et al. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2019 Nov 11;2019:9841295.

4. Sehgal M et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 May;160(6):2018-28.e13.

5. Ladabaum U et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jul;157(1):137-48.

6. Issaka RB et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Feb;112(2):375-82.

Dear colleagues and friends,

The start age for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening in average-risk individuals has been relatively uncontroversial and unchallenged, until recent guidelines that recommended decreasing the start age from 50 to 45 years. In this edition of Perspectives, two renowned experts, Dr. Patel and Dr. Rabeneck, debate the pros and cons of this paradigm change. This will be my final Perspectives contribution as associate editor for GI & Hep News. Thank you very much for your support and feedback, and I hope you have all enjoyed and learned from the Perspectives debates as much as I have. As always, your feedback and suggestions for future topics are welcome and can be sent to [email protected].

Charles J. Kahi, MD, MS, AGAF, is professor of medicine at Indiana University, Indianapolis.

45 is the new 50

BY SWATI G. PATEL, MD, MS

The incidence and mortality rates of CRC in individuals under the age of 50 years, or early age–onset CRC, is increasing in the United States.1 We do not fully understand the cause of this trend; however, it has been observed in multiple Westernized countries, consistent with a birth cohort effect in which generation-specific risk factors are likely responsible.1 To address this rising burden of early age–onset CRC, multiple professional societies, including the United States Preventive Services Task Force,2 now recommend decreasing the starting age for CRC screening in average-risk individuals from 50 to 45 years. These recommendations are supported by the fact that CRC incidence in 45- to 49-year-olds is now the same as that of populations already eligible for screening; the yield of screening appears to be similar among those aged 45-49 years, compared to those aged 50-59 years; and modeling studies show that the benefits outweigh the risks and costs. These factors, along with the unique benefits of early detection and prevention in young patients, support that 45 is the new 50 when it comes to CRC screening.

CRC incidence rates among 45- to 49-year-olds now match populations that are already eligible for CRC screening. The rates among 45- to 49-year-olds now is similar to the incidence rates observed in 50-year-olds in 1992, before widespread CRC screening was performed. Overall incidence rates in 45- to 49-year-olds now match incidence rates observed in 45- to 49-year-old African Americans, a population in which the American College of Gastroenterology and the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force have recommended average-risk screening beginning at age 45.

Advanced colorectal neoplasia rates in 45- to 49-year-olds are similar to rates observed in 50- to 59-year-olds. One study found that advanced colorectal neoplasia rates (including advanced colorectal polyps and adenocarcinoma) in average risk–equivalent 45- to 49-year-olds are similar rates of 50- to 54-year-old average-risk individuals.3 Similarly, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 17 international studies including average-risk individuals undergoing colonoscopy found no significant difference between advanced colorectal neoplasia rates in 45- to 49-years-olds compared to 50- to 59-year-olds.4 These data suggest that expanding screening to average-risk individuals aged 45-49 years will have yield similar to that of those aged 50-59.

Modeling studies show that the benefits of screening outweigh the potential harms and costs. A recent cost-effectiveness analysis showed that starting average-risk screening at age 45 years with colonoscopy would cost $33,900 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) or $7,700 per QALY if annual FIT is selected as the screening modality.5 These costs are less than the widely accepted willingness to pay threshold of $50,000 per QALY and less than currently accepted average-risk screening, such as annual or biennial mammograms for breast cancer screening.

Expanding screening to 45- to 49-year-olds can improve early detection of CRC and prevention of CRC. Offering screening before age 50 years provides the opportunity to detect cancers at earlier stages, which can improve overall survival. Recent data have shown an increase in CRC incidence among 50- to 54-year-olds.1 Although the etiology of the rise in this age group is likely multifactorial (low screening rates or generational risk that individuals carry with them through the birth-cohort effect), diagnosis and removal of advanced colorectal polyps among 45- to 49-year-olds can have a positive impact on reversing this trend in 50- to 54-year-olds. Furthermore, initiating conversations about CRC screening at age 45 can improve uptake of screening among 50- to 54-year-olds who may have delayed screening when first offered at age 50.

There are unique benefits of early detection and prevention of CRC in young patients. Although the absolute incidence and mortality rates associated with CRC in those aged 45-49 are significantly lower than the rates observed in those over age 50, young individuals are more likely to be in the prime of their earning and fertility potential and are more likely to be caregivers to younger and older generations. They are more likely to face material, psychological, and behavioral financial hardships, such as difficulty paying bills. Absolute incidence rates and modeling studies that do not account for these intangible effects on survivorship also do not fully reflect the societal benefit of early detection and CRC prevention in those aged 45-49 years.

There are certainly many unanswered questions about the effects of expanding CRC screening to those age 45 and older. Ongoing studies are needed to determine the cause of rising incidence, whether screening test selection and intervals should be customized for those under age 50, and how best to ensure equitable access to screening services. Finally, expanding screening to younger individuals should not detract from the critical importance of ongoing efforts to improve screening in those over age 50. As these issues are addressed by the scientific community, we cannot stand by idly when there is sufficient evidence to support that 45 is the new 50.

Dr. Patel is associate professor of medicine in the divisions of gastroenterology & hepatology at the University of Colorado and Rocky Mountain Regional Veterans Affairs Medical Center, both in Aurora, Colo. She disclosed financial relationships with Olympus America, ERBE USA, and Freenome.

References

1. Siegel RL et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw322.

2. USPSTF et al. JAMA. 2021 May 18;325(19):1965-77.

3. Butterly LF et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Jan;116(1):171-9.

4. Kolb JM et al. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jun. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.06.006.

5. Ladabaum U et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jul;157(1):137-48.

50 is still 50

BY LINDA RABENECK, MD, MPH, FRCPC

CRC screening of women and men aged 50-75 years at average risk has contributed to the overall decrease in the incidence and mortality from the disease in the United States. In 2009, the American College of Gastroenterology recommended that CRC screening among African Americans begin at age 45 years, and a recent study from Kaiser Permanente reported favorable results from FIT screening in this group.1 In 2018 the American Cancer Society surprised the field by releasing an updated recommendation to begin CRC screening in all women and men at age 45 years (Qualified Recommendation). This spring the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force released its updated recommendation to begin screening at age 45 years (B recommendation).2 The rationale for these updated recommendations is based on new information on the epidemiology of the disease in the United States that was incorporated into updated modeling.