User login

Systematic approach to pain helps avoid opioid issues for dermatologists

, according to an expert who outlined his strategies at the American Academy of Dermatology Virtual Meeting Experience.

The exceptions relate primarily to patients with issues complicating pain control, such as those with psychosocial problems exacerbating the pain response, drug-seeking behavior, or both, according to Robert G. Micheletti, MD, chief of hospital dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

To stay out of trouble, Dr. Micheletti advocated a systematic approach to the control of pain that includes documentation, clear expectations, and a sparing use of opioids only at the lowest acceptable dose for periods measured in days.

Using a case of pyoderma gangrenosum to make several points, he recognized that some patients do have a level of pain that warrants a short course of opioids, but this is not his first step. Rather, the initial focus, after administering standard therapies for this disease, is wound care, which often attenuates symptoms. He adds non-pharmacologic treatments, such as ice, heat, and rest when appropriate. The initial pharmacologic approach is alternating doses of an NSAID and acetaminophen.

“If necessary, a short course of opioids is reasonable for patients with acute pain,” he acknowledged. But he wants to avoid providing more opioids than needed to address the initial period of acute pain. In the case of pyoderma gangrenosum, he suggested a typical prescription might be 12 pills of 5 mg oxycodone taken every six hours. A followup appointment within a week provides the opportunity to reassess.

“Set clear expectations,” Dr. Micheletti said. This includes explaining that the goal is manageable pain, not complete pain relief, which is often unobtainable. For painful conditions such as pyoderma gangrenosum, hidradenitis suppurativa, or vasculitis, a short course will generally be sufficient to get past the most significant discomfort.

There are several reasons that Dr. Micheletti encourages dermatologists to take responsibility for pain related to skin diseases. One is the potential for inefficiencies and delays common to referrals, but another is the value of the dermatologist’s expertise in judging pain as a symptom of the disorder. With effective treatment, pain should self-resolve.

“If the patient is not getting better medically, then change therapies,” Dr. Micheletti said. When referred to a non-dermatologist, the pain expert might not recognize what persistent pain is revealing about the underlying condition.

Repeatedly, Dr. Micheletti made the point that dermatologists should manage pain related to skin disorders because of their ability to assess complaints in the context of the disease.

“We are the experts. We should understand when what we are seeing should or should not be painful,” he said. He added that dermatologists are also in the best position to judge “when analgesia is no longer needed.”

With this same logic, dermatologists are in a good position to distinguish nociceptive from neuropathic pain. Some conditions are likely to have both, and this should influence choice of pain relief. Citing a patient with calciphylaxis as an example, Dr. Micheletti suggested that drugs with efficacy against neuropathic pain, such as gabapentin, should be one of the options to consider before moving to opioids. In those with sufficient pain to warrant an opioid, however, Dr. Micheletti would consider tramadol, which acts on both types of pain.

Treating pain is not always straightforward, Dr. Micheletti acknowledged. For example, depression and mood disorders are known to exacerbate pain and are reasonable targets of pain control. The stress related to disruptive psychosocial problems can be another factor in risk of pain.

“Be prepared to acknowledge and address these types of issues,” Dr. Micheletti said. Although these are the types of patients some dermatologists might prefer to refer to a pain specialist, he said that the contribution of factors outside of skin disease should not be allowed to obscure a dermatologic source of pain.

“Just because a patient has psychosocial issues does not mean that there is no pain,” he said.

A systematic approach to the assessment and treatment of pain will help sort out these issues, but Dr. Micheletti also said, “Know your comfort zone.” When patients require opioids, there are several appropriate steps important or mandatory to provide adequate protection for the patient and the physician. In addition to documentation, it is reasonable to verify that the patient is not obtaining opioids from other prescribers, a step that is mandatory in some states.

When opioids are needed, Dr. Micheletti suggested a standard approach that includes short courses without refills. He recommended avoiding long-acting opioids and drugs not commonly used by non-pain specialists, such as codeine, hydrocodone, or fentanyl.

“This is not a prescribe and walk away situation,” he said.

Although the same general approach is employed by Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, he is a little less reluctant to refer patients to pain specialists.

“For complex situations, you need complex solutions. In the case of significant pain and even itch, I will collaborate with the GW Pain Center,” he said. For severe pain, the solutions might include nerve blocks or even intravenous ketamine for in-patients.

He also made the point that dermatologists, even if they are uncomfortable prescribing opioids, “should be equipped to use relevant medications such as topical anesthetics, gabapentinoids, and SSRIs” to control pain related to skin conditions.

Dr. Micheletti reports no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Friedman has consulting relationships with several pharmaceutical companies, including Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, and Valeant.

, according to an expert who outlined his strategies at the American Academy of Dermatology Virtual Meeting Experience.

The exceptions relate primarily to patients with issues complicating pain control, such as those with psychosocial problems exacerbating the pain response, drug-seeking behavior, or both, according to Robert G. Micheletti, MD, chief of hospital dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

To stay out of trouble, Dr. Micheletti advocated a systematic approach to the control of pain that includes documentation, clear expectations, and a sparing use of opioids only at the lowest acceptable dose for periods measured in days.

Using a case of pyoderma gangrenosum to make several points, he recognized that some patients do have a level of pain that warrants a short course of opioids, but this is not his first step. Rather, the initial focus, after administering standard therapies for this disease, is wound care, which often attenuates symptoms. He adds non-pharmacologic treatments, such as ice, heat, and rest when appropriate. The initial pharmacologic approach is alternating doses of an NSAID and acetaminophen.

“If necessary, a short course of opioids is reasonable for patients with acute pain,” he acknowledged. But he wants to avoid providing more opioids than needed to address the initial period of acute pain. In the case of pyoderma gangrenosum, he suggested a typical prescription might be 12 pills of 5 mg oxycodone taken every six hours. A followup appointment within a week provides the opportunity to reassess.

“Set clear expectations,” Dr. Micheletti said. This includes explaining that the goal is manageable pain, not complete pain relief, which is often unobtainable. For painful conditions such as pyoderma gangrenosum, hidradenitis suppurativa, or vasculitis, a short course will generally be sufficient to get past the most significant discomfort.

There are several reasons that Dr. Micheletti encourages dermatologists to take responsibility for pain related to skin diseases. One is the potential for inefficiencies and delays common to referrals, but another is the value of the dermatologist’s expertise in judging pain as a symptom of the disorder. With effective treatment, pain should self-resolve.

“If the patient is not getting better medically, then change therapies,” Dr. Micheletti said. When referred to a non-dermatologist, the pain expert might not recognize what persistent pain is revealing about the underlying condition.

Repeatedly, Dr. Micheletti made the point that dermatologists should manage pain related to skin disorders because of their ability to assess complaints in the context of the disease.

“We are the experts. We should understand when what we are seeing should or should not be painful,” he said. He added that dermatologists are also in the best position to judge “when analgesia is no longer needed.”

With this same logic, dermatologists are in a good position to distinguish nociceptive from neuropathic pain. Some conditions are likely to have both, and this should influence choice of pain relief. Citing a patient with calciphylaxis as an example, Dr. Micheletti suggested that drugs with efficacy against neuropathic pain, such as gabapentin, should be one of the options to consider before moving to opioids. In those with sufficient pain to warrant an opioid, however, Dr. Micheletti would consider tramadol, which acts on both types of pain.

Treating pain is not always straightforward, Dr. Micheletti acknowledged. For example, depression and mood disorders are known to exacerbate pain and are reasonable targets of pain control. The stress related to disruptive psychosocial problems can be another factor in risk of pain.

“Be prepared to acknowledge and address these types of issues,” Dr. Micheletti said. Although these are the types of patients some dermatologists might prefer to refer to a pain specialist, he said that the contribution of factors outside of skin disease should not be allowed to obscure a dermatologic source of pain.

“Just because a patient has psychosocial issues does not mean that there is no pain,” he said.

A systematic approach to the assessment and treatment of pain will help sort out these issues, but Dr. Micheletti also said, “Know your comfort zone.” When patients require opioids, there are several appropriate steps important or mandatory to provide adequate protection for the patient and the physician. In addition to documentation, it is reasonable to verify that the patient is not obtaining opioids from other prescribers, a step that is mandatory in some states.

When opioids are needed, Dr. Micheletti suggested a standard approach that includes short courses without refills. He recommended avoiding long-acting opioids and drugs not commonly used by non-pain specialists, such as codeine, hydrocodone, or fentanyl.

“This is not a prescribe and walk away situation,” he said.

Although the same general approach is employed by Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, he is a little less reluctant to refer patients to pain specialists.

“For complex situations, you need complex solutions. In the case of significant pain and even itch, I will collaborate with the GW Pain Center,” he said. For severe pain, the solutions might include nerve blocks or even intravenous ketamine for in-patients.

He also made the point that dermatologists, even if they are uncomfortable prescribing opioids, “should be equipped to use relevant medications such as topical anesthetics, gabapentinoids, and SSRIs” to control pain related to skin conditions.

Dr. Micheletti reports no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Friedman has consulting relationships with several pharmaceutical companies, including Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, and Valeant.

, according to an expert who outlined his strategies at the American Academy of Dermatology Virtual Meeting Experience.

The exceptions relate primarily to patients with issues complicating pain control, such as those with psychosocial problems exacerbating the pain response, drug-seeking behavior, or both, according to Robert G. Micheletti, MD, chief of hospital dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

To stay out of trouble, Dr. Micheletti advocated a systematic approach to the control of pain that includes documentation, clear expectations, and a sparing use of opioids only at the lowest acceptable dose for periods measured in days.

Using a case of pyoderma gangrenosum to make several points, he recognized that some patients do have a level of pain that warrants a short course of opioids, but this is not his first step. Rather, the initial focus, after administering standard therapies for this disease, is wound care, which often attenuates symptoms. He adds non-pharmacologic treatments, such as ice, heat, and rest when appropriate. The initial pharmacologic approach is alternating doses of an NSAID and acetaminophen.

“If necessary, a short course of opioids is reasonable for patients with acute pain,” he acknowledged. But he wants to avoid providing more opioids than needed to address the initial period of acute pain. In the case of pyoderma gangrenosum, he suggested a typical prescription might be 12 pills of 5 mg oxycodone taken every six hours. A followup appointment within a week provides the opportunity to reassess.

“Set clear expectations,” Dr. Micheletti said. This includes explaining that the goal is manageable pain, not complete pain relief, which is often unobtainable. For painful conditions such as pyoderma gangrenosum, hidradenitis suppurativa, or vasculitis, a short course will generally be sufficient to get past the most significant discomfort.

There are several reasons that Dr. Micheletti encourages dermatologists to take responsibility for pain related to skin diseases. One is the potential for inefficiencies and delays common to referrals, but another is the value of the dermatologist’s expertise in judging pain as a symptom of the disorder. With effective treatment, pain should self-resolve.

“If the patient is not getting better medically, then change therapies,” Dr. Micheletti said. When referred to a non-dermatologist, the pain expert might not recognize what persistent pain is revealing about the underlying condition.

Repeatedly, Dr. Micheletti made the point that dermatologists should manage pain related to skin disorders because of their ability to assess complaints in the context of the disease.

“We are the experts. We should understand when what we are seeing should or should not be painful,” he said. He added that dermatologists are also in the best position to judge “when analgesia is no longer needed.”

With this same logic, dermatologists are in a good position to distinguish nociceptive from neuropathic pain. Some conditions are likely to have both, and this should influence choice of pain relief. Citing a patient with calciphylaxis as an example, Dr. Micheletti suggested that drugs with efficacy against neuropathic pain, such as gabapentin, should be one of the options to consider before moving to opioids. In those with sufficient pain to warrant an opioid, however, Dr. Micheletti would consider tramadol, which acts on both types of pain.

Treating pain is not always straightforward, Dr. Micheletti acknowledged. For example, depression and mood disorders are known to exacerbate pain and are reasonable targets of pain control. The stress related to disruptive psychosocial problems can be another factor in risk of pain.

“Be prepared to acknowledge and address these types of issues,” Dr. Micheletti said. Although these are the types of patients some dermatologists might prefer to refer to a pain specialist, he said that the contribution of factors outside of skin disease should not be allowed to obscure a dermatologic source of pain.

“Just because a patient has psychosocial issues does not mean that there is no pain,” he said.

A systematic approach to the assessment and treatment of pain will help sort out these issues, but Dr. Micheletti also said, “Know your comfort zone.” When patients require opioids, there are several appropriate steps important or mandatory to provide adequate protection for the patient and the physician. In addition to documentation, it is reasonable to verify that the patient is not obtaining opioids from other prescribers, a step that is mandatory in some states.

When opioids are needed, Dr. Micheletti suggested a standard approach that includes short courses without refills. He recommended avoiding long-acting opioids and drugs not commonly used by non-pain specialists, such as codeine, hydrocodone, or fentanyl.

“This is not a prescribe and walk away situation,” he said.

Although the same general approach is employed by Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, he is a little less reluctant to refer patients to pain specialists.

“For complex situations, you need complex solutions. In the case of significant pain and even itch, I will collaborate with the GW Pain Center,” he said. For severe pain, the solutions might include nerve blocks or even intravenous ketamine for in-patients.

He also made the point that dermatologists, even if they are uncomfortable prescribing opioids, “should be equipped to use relevant medications such as topical anesthetics, gabapentinoids, and SSRIs” to control pain related to skin conditions.

Dr. Micheletti reports no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Friedman has consulting relationships with several pharmaceutical companies, including Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, and Valeant.

FROM AAD VMX 2021

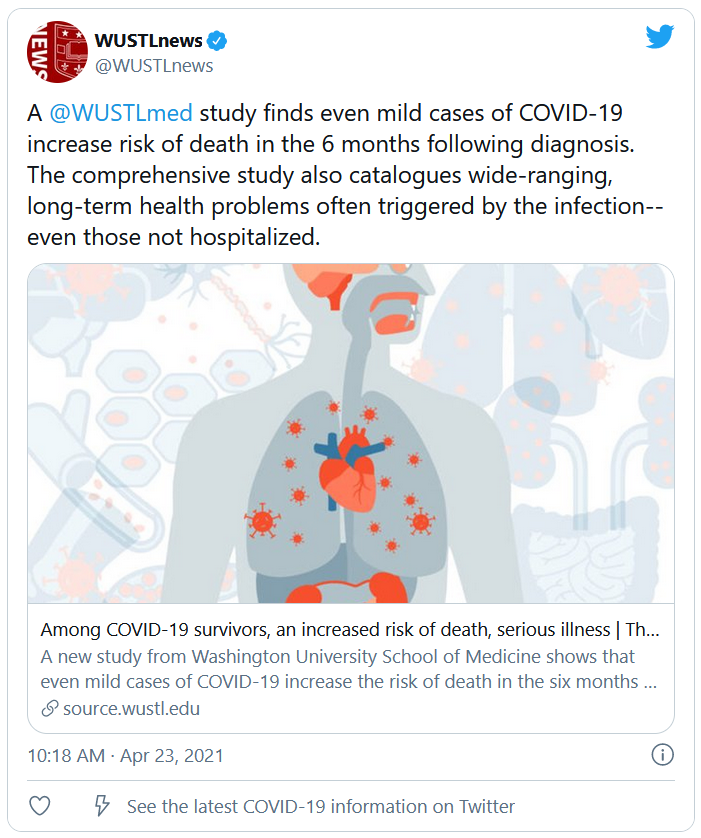

Feds lift pause of J&J COVID vaccine, add new warning

Use of the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine should resume in the United States for all adults, the Food and Drug Administration and Centers for Disease Contol and Prevention said April 23, although health care providers should warn patients of the risk of developing the rare and serious blood clots that caused the agencies to pause the vaccine’s distribution earlier this month.

“What we are seeing is the overall rate of events was 1.9 cases per million people. In women 18 to 29 years there was an approximate 7 cases per million. The risk is even lower in women over the age of 50 at .9 cases per million,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said in a news briefing the same day.

In the end, the potential benefits of the vaccine far outweighed its risks.

“In terms of benefits, we found that for every 1 million doses of this vaccine, the J&J vaccine could prevent over 650 hospitalizations and 12 deaths among women ages 18-49,” Dr. Walensky said. The potential benefits to women over 50 were even greater: It could prevent 4,700 hospitalizations and 650 deaths.

“In the end, this vaccine was shown to be safe and effective for the vast majority of people,” Dr. Walensky said.

The recommendation to continue the vaccine’s rollout came barely 2 hours after a CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted to recommend the pause be lifted. The vote was 10-4 with one abstention.

The decision also includes instructions for the warning directed at women under 50 who have an increased risk of a rare but serious blood clot disorder called thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS).

As of April 21, 15 cases of TTS, all in women and 13 of them in women under 50, have been confirmed among 7.98 million doses of the J&J vaccine administered in the United States. Three women have died.

The FDA and CDC recommended the pause on April 13 after reports that 6 women developed a blood clotting disorder 6 to 13 days after they received the J&J vaccine.

William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease expert at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, and a non-voting ACIP member, said in an interview the panel made the right recommendation.

He applauded both the decision to restart the vaccine and the updated warning information that “will explain [TTS] more fully to people, particularly women, who are coming to be vaccinated.”

As to women in the risk group needing to have a choice of vaccines, Dr. Schaffner said that will be addressed differently across the country.

“Every provider will not have alternative vaccines in their location so there will be many different ways to do this. You may have to get this information and select which site you’re going to depending on which vaccine is available if this matter is important to you,” he noted.

ACIP made the decision after a 6-hour emergency meeting to hear evidence on the Johnson & Johnson vaccine's protective benefits against COVID-19 vs. risk of TTS.

In the CDC-FDA press briefing, Dr. Walensky pointed out that over the past few days, as regulators have reviewed the rare events, newly identified patients had been treated appropriately, without the use of heparin, which is not advised for treating TTS.

As a result, regulators felt as if their messages had gotten out to doctors who now knew how to take special precautions when treating patients with the disorder.

She said the Johnson & Johnson shot remained an important option because it was convenient to give and easier to store than the other vaccines currently authorized in the United States.

Peter Marks, MD, the director of FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said the agency had already added information describing the risk of the rare clotting disorder to its fact sheets for patients and doctors.

Janet Woodcock, MD, acting commissioner of the FDA, said vaccination centers could resume giving the “one and done” shots as early as April 24.

This article was updated April 24, 2021, and first appeared on WebMD.com.

Use of the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine should resume in the United States for all adults, the Food and Drug Administration and Centers for Disease Contol and Prevention said April 23, although health care providers should warn patients of the risk of developing the rare and serious blood clots that caused the agencies to pause the vaccine’s distribution earlier this month.

“What we are seeing is the overall rate of events was 1.9 cases per million people. In women 18 to 29 years there was an approximate 7 cases per million. The risk is even lower in women over the age of 50 at .9 cases per million,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said in a news briefing the same day.

In the end, the potential benefits of the vaccine far outweighed its risks.

“In terms of benefits, we found that for every 1 million doses of this vaccine, the J&J vaccine could prevent over 650 hospitalizations and 12 deaths among women ages 18-49,” Dr. Walensky said. The potential benefits to women over 50 were even greater: It could prevent 4,700 hospitalizations and 650 deaths.

“In the end, this vaccine was shown to be safe and effective for the vast majority of people,” Dr. Walensky said.

The recommendation to continue the vaccine’s rollout came barely 2 hours after a CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted to recommend the pause be lifted. The vote was 10-4 with one abstention.

The decision also includes instructions for the warning directed at women under 50 who have an increased risk of a rare but serious blood clot disorder called thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS).

As of April 21, 15 cases of TTS, all in women and 13 of them in women under 50, have been confirmed among 7.98 million doses of the J&J vaccine administered in the United States. Three women have died.

The FDA and CDC recommended the pause on April 13 after reports that 6 women developed a blood clotting disorder 6 to 13 days after they received the J&J vaccine.

William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease expert at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, and a non-voting ACIP member, said in an interview the panel made the right recommendation.

He applauded both the decision to restart the vaccine and the updated warning information that “will explain [TTS] more fully to people, particularly women, who are coming to be vaccinated.”

As to women in the risk group needing to have a choice of vaccines, Dr. Schaffner said that will be addressed differently across the country.

“Every provider will not have alternative vaccines in their location so there will be many different ways to do this. You may have to get this information and select which site you’re going to depending on which vaccine is available if this matter is important to you,” he noted.

ACIP made the decision after a 6-hour emergency meeting to hear evidence on the Johnson & Johnson vaccine's protective benefits against COVID-19 vs. risk of TTS.

In the CDC-FDA press briefing, Dr. Walensky pointed out that over the past few days, as regulators have reviewed the rare events, newly identified patients had been treated appropriately, without the use of heparin, which is not advised for treating TTS.

As a result, regulators felt as if their messages had gotten out to doctors who now knew how to take special precautions when treating patients with the disorder.

She said the Johnson & Johnson shot remained an important option because it was convenient to give and easier to store than the other vaccines currently authorized in the United States.

Peter Marks, MD, the director of FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said the agency had already added information describing the risk of the rare clotting disorder to its fact sheets for patients and doctors.

Janet Woodcock, MD, acting commissioner of the FDA, said vaccination centers could resume giving the “one and done” shots as early as April 24.

This article was updated April 24, 2021, and first appeared on WebMD.com.

Use of the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine should resume in the United States for all adults, the Food and Drug Administration and Centers for Disease Contol and Prevention said April 23, although health care providers should warn patients of the risk of developing the rare and serious blood clots that caused the agencies to pause the vaccine’s distribution earlier this month.

“What we are seeing is the overall rate of events was 1.9 cases per million people. In women 18 to 29 years there was an approximate 7 cases per million. The risk is even lower in women over the age of 50 at .9 cases per million,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said in a news briefing the same day.

In the end, the potential benefits of the vaccine far outweighed its risks.

“In terms of benefits, we found that for every 1 million doses of this vaccine, the J&J vaccine could prevent over 650 hospitalizations and 12 deaths among women ages 18-49,” Dr. Walensky said. The potential benefits to women over 50 were even greater: It could prevent 4,700 hospitalizations and 650 deaths.

“In the end, this vaccine was shown to be safe and effective for the vast majority of people,” Dr. Walensky said.

The recommendation to continue the vaccine’s rollout came barely 2 hours after a CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted to recommend the pause be lifted. The vote was 10-4 with one abstention.

The decision also includes instructions for the warning directed at women under 50 who have an increased risk of a rare but serious blood clot disorder called thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS).

As of April 21, 15 cases of TTS, all in women and 13 of them in women under 50, have been confirmed among 7.98 million doses of the J&J vaccine administered in the United States. Three women have died.

The FDA and CDC recommended the pause on April 13 after reports that 6 women developed a blood clotting disorder 6 to 13 days after they received the J&J vaccine.

William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease expert at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, and a non-voting ACIP member, said in an interview the panel made the right recommendation.

He applauded both the decision to restart the vaccine and the updated warning information that “will explain [TTS] more fully to people, particularly women, who are coming to be vaccinated.”

As to women in the risk group needing to have a choice of vaccines, Dr. Schaffner said that will be addressed differently across the country.

“Every provider will not have alternative vaccines in their location so there will be many different ways to do this. You may have to get this information and select which site you’re going to depending on which vaccine is available if this matter is important to you,” he noted.

ACIP made the decision after a 6-hour emergency meeting to hear evidence on the Johnson & Johnson vaccine's protective benefits against COVID-19 vs. risk of TTS.

In the CDC-FDA press briefing, Dr. Walensky pointed out that over the past few days, as regulators have reviewed the rare events, newly identified patients had been treated appropriately, without the use of heparin, which is not advised for treating TTS.

As a result, regulators felt as if their messages had gotten out to doctors who now knew how to take special precautions when treating patients with the disorder.

She said the Johnson & Johnson shot remained an important option because it was convenient to give and easier to store than the other vaccines currently authorized in the United States.

Peter Marks, MD, the director of FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said the agency had already added information describing the risk of the rare clotting disorder to its fact sheets for patients and doctors.

Janet Woodcock, MD, acting commissioner of the FDA, said vaccination centers could resume giving the “one and done” shots as early as April 24.

This article was updated April 24, 2021, and first appeared on WebMD.com.

Dyssynergic defecation

Introduction

About 40% of the population experiences lower GI symptoms suggestive of gastrointestinal motility disorders.1,2 The global prevalence of chronic constipation is 18%, and the condition includes multiple overlapping subtypes.3 Evacuation disorders affect over half (59%) of patients and include dyssynergic defecation (DD).4 The inability to coordinate the abdominal, rectal, pelvic floor, and anal/puborectalis muscles to evacuate stools causes DD.5 The etiology of DD remains unclear and is often misdiagnosed. Clinically, the symptoms of DD overlap with other lower GI disorders, often leading to unnecessary and invasive procedures.2 We describe the clinical characteristics, diagnostic tools, treatment options, and evidence-based approach for the management of DD.

Clinical presentation

Over two-thirds of patients with DD acquire this disorder during adulthood, and one-third have symptoms from childhood.6 Though there is not usually an inciting event, 29% of patients report that symptoms began after events such as pregnancy or back injury,6 and opioid users have higher prevalence and severity of DD.7

Over 80% of patients report excessive straining, feelings of incomplete evacuation, and hard stools, and 50% report sensation of anal blockage or use of digital maneuvers.2 Other symptoms include infrequent bowel movements, abdominal pain, anal pain, and stool leakage.2 Evaluation of DD includes obtaining a detailed history utilizing the Bristol Stool Form Scale;8 however, patients’ recall of stool habit is often inaccurate, which results in suboptimal care.9,10 Prospective stool diaries can help to provide more objective assessment of patients’ symptoms, eliminate recall bias, and provide more reliable information. Several useful questionnaires are available for clinical and research purposes to characterize lower-GI symptoms, including the Constipation Scoring System,11 Patient Assessment of Constipation Symptoms (PAC-SYM),12 and Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life (PAC-QOL).2,13 The Constipation Stool digital app enhances accuracy of data capture and offers a reliable and user-friendly method for recording bowel symptoms for patients, clinicians, and clinical investigators.14

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of DD requires careful physical and digital rectal examination together with anorectal manometry and a balloon expulsion test. Defecography and colonic transit studies provide additional assessment.

Physical examination

Abdominal examination should include palpation for stool in the colon and identification of abdominal mass or fecal impaction.2A high-quality digital rectal examination can help to identify patients who could benefit from physiological testing to confirm and treat DD.15 Rectal examination is performed by placing examiner’s lubricated gloved right index finger in a patient’s rectum, with the examiner’s left hand on patient’s abdomen, and asking the patient to push and bear down as if defecating.15 The contraction of the abdominal muscles is felt using the left hand, while the anal sphincter relaxation and degree of perineal descent are felt using the right-hand index finger.15 A diagnosis of dyssynergia is suspected if the digital rectal examination reveals two or more of the following abnormalities: inability to contract abdominal muscles (lack of push effort), inability to relax or paradoxical contraction of the anal sphincter and/or puborectalis, or absence of perineal descent.15 Digital rectal examination has good sensitivity (75%), specificity (87%), and positive predictive value (97%) for DD.16

High resolution anorectal manometry

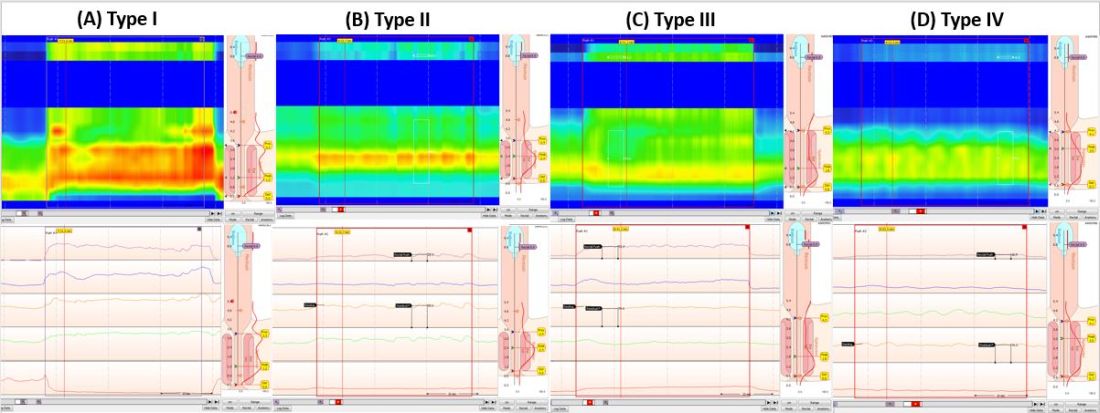

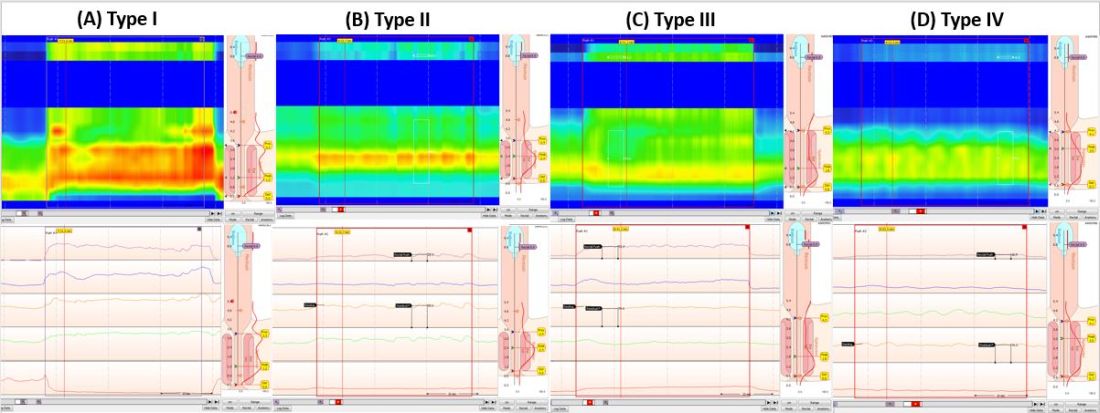

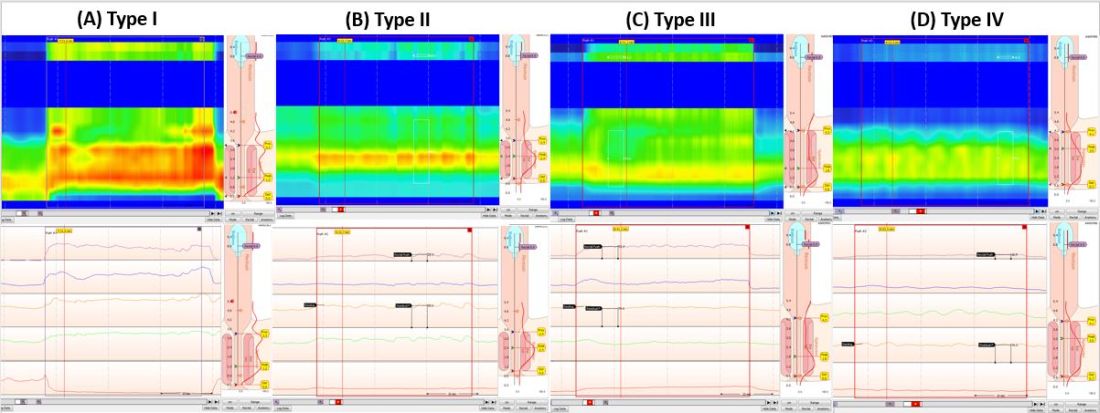

Anorectal manometry (ARM) is the preferred method for the evaluation of defecatory disorders.17,18 ARM is best performed using the high-resolution anorectal manometry (HRAM) systems19 that consist of a flexible probe – 0.5-cm diameter with multiple circumferential sensors along the anal canal – and another two sensors inside a rectal balloon.18 It provides a topographic and waveform display of manometric pressure data (Figure). The 3D high-definition ARM probe is a rigid 1-cm probe that provides 3D topographic profiles.18 ARM is typically performed in both the left lateral position and in a more physiological seated position.20,21 There is considerable variation amongst different institutions on how to perform HRAM, and a recent International Anorectal Physiology Working Group (IAPWG) has provided consensus recommendations for performing this test.22 The procedure for performing HRAM is reviewed elsewhere, but the key elements are summarized below.18

Push maneuver: On HRAM, after the assessment of resting and squeeze anal sphincter pressures, the patient is asked to push or bear down as if to defecate while lying in left lateral decubitus position. The best of two attempts that closely mimics a normal bearing down maneuver is used for categorizing patient’s defecatory pattern.18 In patients with DD, at least four distinct dyssynergia phenotypes have been recognized (Figure),23 though recent studies suggest eight patterns.24 Defecation index (maximum rectal pressure/minimum residual anal pressure when bearing down) greater than 1.2 is considered normal.18

Simulated defecation on commode: The subject is asked to attempt defecation while seated on a commode with intrarectal balloon filled with 60 cc of air, and both the defecation pattern(s) and defecation index are calculated. A lack of coordinated push effort is highly suggestive of DD.21

Rectoanal Inhibitory Reflex (RAIR): RAIR describes the reflex relaxation of the internal anal sphincter after rectal distension. RAIR is dependent on intact autonomic ganglia and myenteric plexus25and is mediated by the release of nitric oxide and vasoactive intestinal peptide.26 The absence of RAIR suggests Hirschsprung disease.22.27.28

Rectal sensory testing: Intermittent balloon distension of the rectum with incremental volumes of air induces a range of rectal sensations that include first sensation, desire to defecate, urgency to defecate, and maximum tolerable volume. Rectal hyposensitivity is diagnosed when two or more sensory thresholds are higher than those seen in normal subjects29.30 and likely results from disruption of afferent gut-brain pathways, cortical perception/rectal wall dysfunction, or both.29 Rectal hyposensitivity affects 40% of patients with constipation30and is associated with DD but not delayed colonic transit.31 Rectal hyposensitivity may also be seen in patients with diabetes or fecal incontinence.18 About two-thirds of patients with rectal hyposensitivity have rectal hypercompliance, and some have megarectum.32 Some patients with DD have coexisting irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and may have rectal hypersensitivity.18,33 Rectal compliance is measured alongside rectal sensitivity analysis by plotting a graph between the change in intraballoon volume (mL) and change in intrarectal pressures (mm Hg) during incremental balloon distensions.18.34 Rectal hypercompliance may be seen in megarectum and dyssynergic defecation.34,35 Rectal hypocompliance may be seen in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, postpelvic radiation, chronic ischemia, and advanced age.18

Balloon expulsion test: This test is performed by placing a plastic probe with a balloon in the rectum and filling it with 50 cc of warm water. Patients are given 5 minutes to expel the balloon while sitting on a commode. Balloon expulsion time of more than 1 minute suggests a diagnosis of DD,21 although 2 minutes provides a higher level of agreement with manometric findings.36 Balloon type and body position can influence the results.37 Inability to expel the balloon with normal manometric findings is considered an inconclusive finding per the recent London Classification (i.e., it may be associated with generation of anorectal symptoms, but the clinical relevance of this finding is unclear as it may also be seen in healthy subjects).22

Defecography

Defecography is a dynamic fluoroscopic study performed in the sitting position after injecting 150 mL of barium paste into the patient’s rectum. Defecography provides useful information about structural changes (e.g., rectoceles, enteroceles, rectal prolapse, and intussusception), DD, and descending perineum syndrome.38 Methodological differences, radiation exposure, and poor interobserver agreement have limited its wider use; therefore, anorectal manometry and the balloon expulsion test are recommended for the initial evaluation of DD.39 Magnetic resonance defecography may be more useful.17,38

Colonic transit studies

Colonic transit study can be assessed using radiopaque markers, wireless motility capsule, or scintigraphy. Wireless motility capsule and scintigraphy have the advantage of determining gastric, small bowel, and whole gut transit times as well. About two-thirds of patients with DD have slow transit constipation (STC),6 which improves after treatment of DD.40 Hence, in patients with chronic constipation, evaluation and management of DD is recommended first. If symptoms persist, then consider colonic transit assessment.41 Given the overlapping nature of the conditions, documentation of STC at the outset could facilitate treatment of both.

Diagnostic criteria for DD

Patients should fulfill the following criteria for diagnosis of DD:42,43

- Fulfill symptom(s) diagnostic criteria for functional constipation and/or constipation-predominant IBS.

- Demonstrate dyssynergic pattern (Types I-IV; Figure) during attempted defecation on manometry recordings.

- Meet one or more of the following criteria:

- Inability to expel an artificial stool (50 mL water-filled balloon) within 1 minute.

- Inability to evacuate or retention of 50% or more of barium during defecography. (Some institutions use a prolonged colonic transit time: greater than 5 markers or 20% or higher marker retention on a plain abdominal x-Ray at 120 hours after ingestion of one radio-opaque marker capsule containing 24 radio-opaque markers.)

Treatment of DD

The treatment modalities for DD depend on several factors: patient’s age, comorbidities, underlying pathophysiology, and patient expectations. Treatment options include standard management of constipation, but biofeedback therapy is the mainstay.

Standard management

Medications that cause or worsen constipation should be avoided. The patient should consume adequate fluid and exercise regularly. Patients should receive instructions for timed toilet training (twice daily, 30 minutes after meals). Patients should push at about 50%-70% of their ability for no longer than 5 minutes and avoid postponing defecation or use of digital maneuvers to facilitate defecation.42 The patients should take 25 g of soluble fiber (e.g., psyllium) daily. Of note, the benefits of fiber can take days to weeks44 and may be limited in patients with STC and DD.45 Medications including laxatives and intestinal secretagogues (lubiprostone, linaclotide, plecanatide), and enterokinetic agents (prucalopride) can be used as adjunct therapy for management of DD.42 Their use is titrated during and after biofeedback therapy and may decrease after successful treatment.46

Biofeedback therapy

Biofeedback therapy involves operant conditioning techniques using either a solid state anorectal manometry system, electromyography, simulated balloon, or home biofeedback training devices.42,47 The goals of biofeedback therapy are to correct the abdominal pelvic muscle discoordination during defecation and improve rectal sensation to stool if impaired. Biofeedback therapy involves patient education and active training (typically six sessions, 1-2 weeks apart, with each about 30-60 minutes long), followed by a reinforcement stage (three sessions at 3, 6, and 12 months), though there are variations in training protocols.42

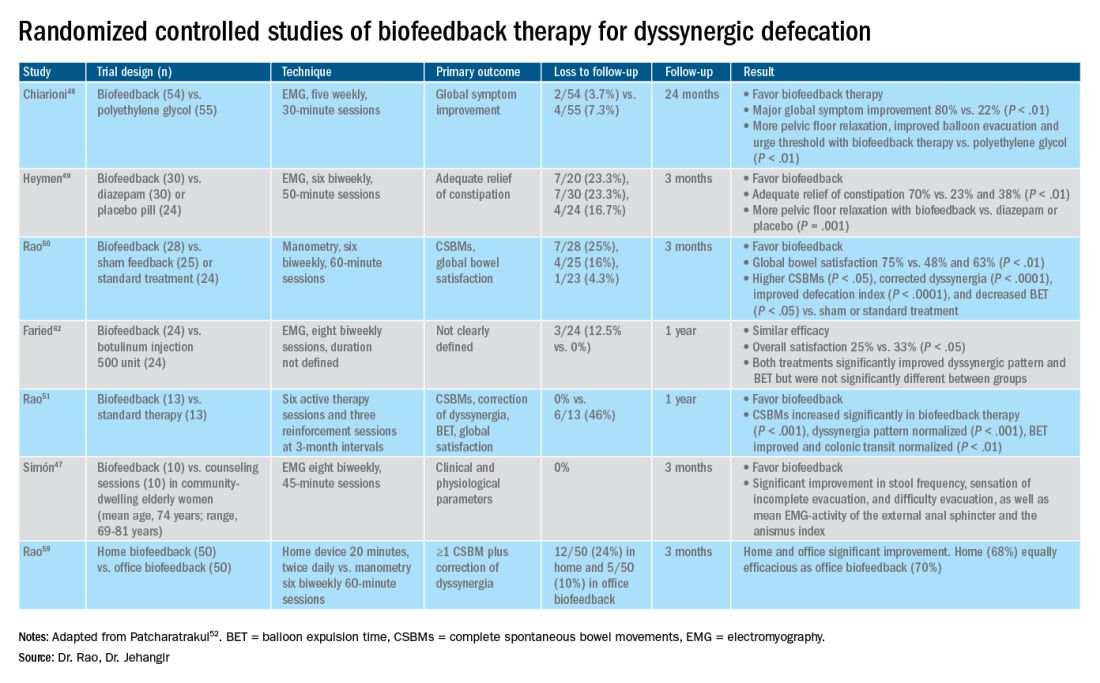

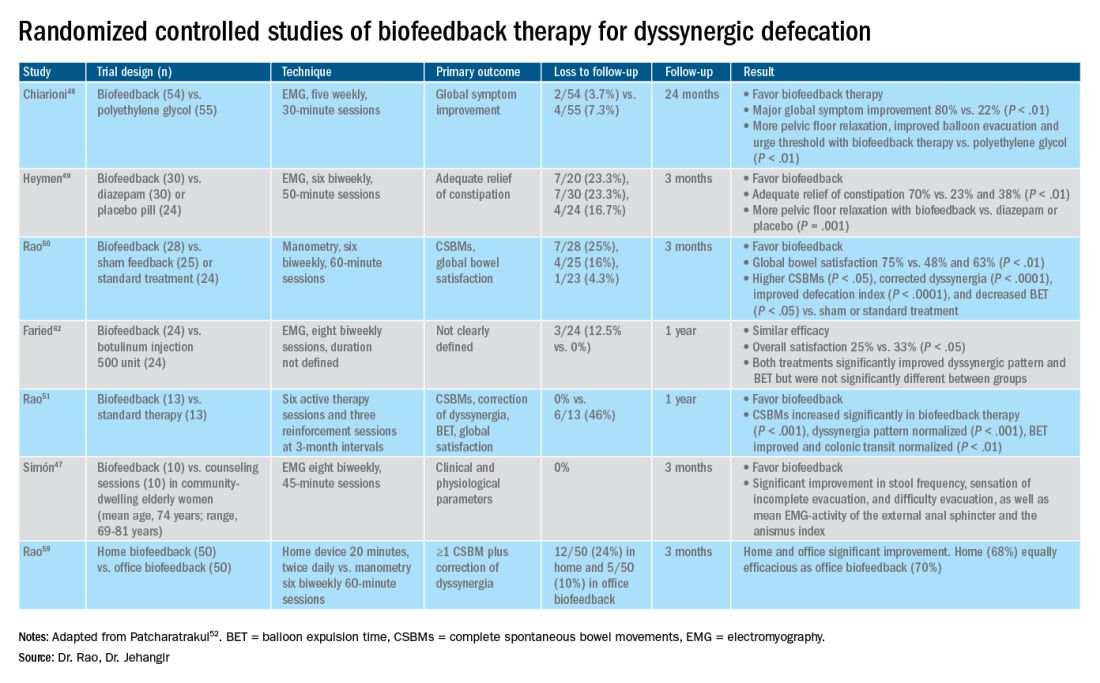

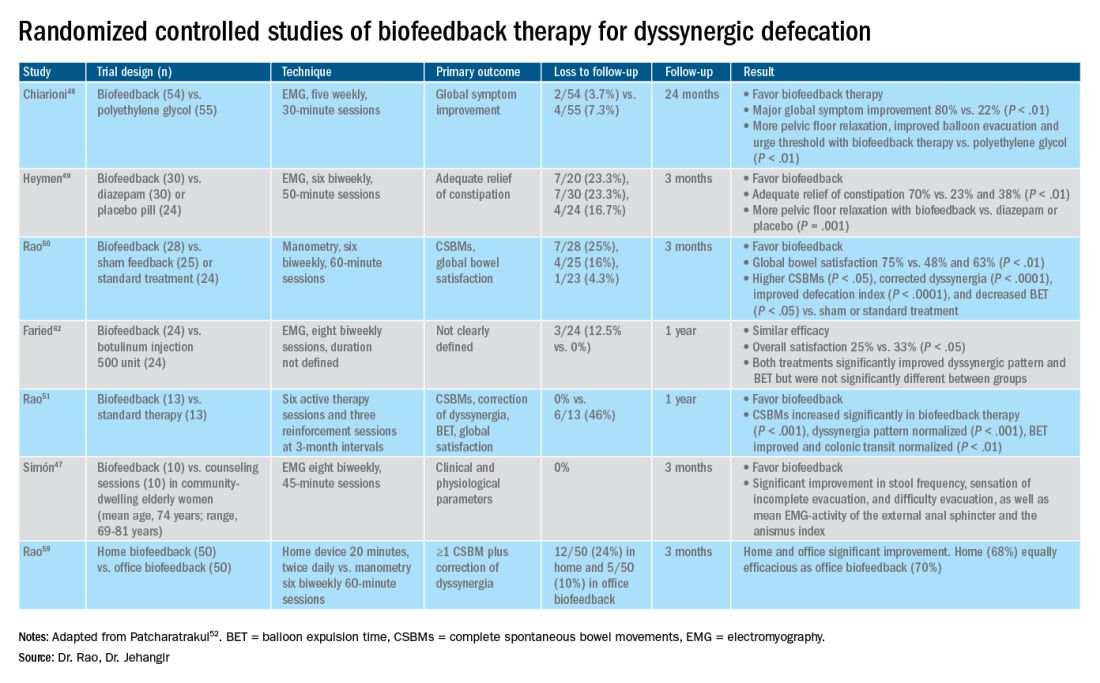

The success of biofeedback therapy depends on the patient’s motivation and the therapist’s skills.42 Compared with standard therapy (diet, exercise, pharmacotherapy), biofeedback therapy provides sustained improvement of bowel symptoms and anorectal function. Up to 70%-80% of DD patients show significant improvement of symptoms in randomized controlled trials (Table).48-52 Biofeedback therapy may also improve dyspeptic symptoms.53 Patients with harder stool consistency, greater willingness to participate, lower baseline bowel satisfaction, lower baseline anal sphincter relaxation, and prolonged balloon expulsion time, as well as patients who used digital maneuvers for defection, more commonly respond to biofeedback therapy.54,55 Longstanding laxative use has been associated with decreased response to biofeedback therapy.56 In patients with rectal hyposensitivity, barostat-assisted sensory training is more effective than a hand-held syringe technique.30 In patients with constipation predominant IBS and rectal hyposensitivity, sensory adaption training is more efficacious and better tolerated than escitalopram.30 Biofeedback therapy was afforded a grade A recommendation for treatment of DD by the American and European Societies of Neurogastroenterology and Motility.57

The access to office-based biofeedback therapy may be limited because of costs and low availability. The time required to attend multiple sessions may be burdensome for some patients, especially if they are taking time off from work. A recent study showed that patients with higher level of education may be less likely to adhere to biofeedback therapy.58 Recently, home biofeedback was shown to be noninferior to office biofeedback and was more cost-effective, which provides an alternative option for treating more patients.59

Endoscopic/surgical options

Other less effective treatment options for DD include botulinum toxin injection and myectomy.60-62 Botulinum toxin injection appears to have mixed effects with less than 50% of patients reporting symptomatic improvement, and it may cause fecal incontinence.60,63

Conclusion

DD is a common yet poorly recognized cause of constipation. Its clinical presentation overlaps with other lower-GI disorders. Its diagnosis requires detailed history, digital rectal examination, prospective stool diaries, anorectal manometry, and balloon expulsion tests. Biofeedback therapy offers excellent and sustained symptomatic improvement; however, access to office-based biofeedback is limited, and there is an urgent need for home-based biofeedback therapy programs.59

Dr. Rao is J. Harold Harrison Distinguished University Chair, professor of medicine, director of neurogastroenterology/motility, and director of digestive health at the Digestive Health Clinical Research Center Augusta (Georgia) University. He is supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01DK121003-02 and U01DK115572. Dr. Jehangir is a gastroenterology and Hepatology Fellow at the Digestive Health Clinical Research Center at Augusta University. They reported having no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Peery AF, et al. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(5):1179-1187.e3 .

2. Curtin B, et al. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020 30;26(4):423-36.

3. Suares NC & Ford AC. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Sep;106(9):1582-91.

4. Mertz H, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(3):609-15.

5. Rao SS, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(7):1042-50.

6. Rao SSC, et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(8):680-5.

7. Nojkov B, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(11):1772-7.

8. Heaton KW, et al. Gut. 1992;33(6):818-24.

9. Prichard DO & Bharucha AE. 2018 Oct 15;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1640.

10. Ashraf W, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91(1):26-32.

11. Agachan F, et al.. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39(6):681-5.

12. Frank L, et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34(9):870-7.

13. Marquis P, et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40(5):540-51.

14. Yan Y, et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):S-400.

15. Rao SSC. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(5):635-8.

16. Tantiphlachiva K, et al. Digital rectal examination is a useful tool for identifying patients with dyssynergia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(11):955-60.

17. Carrington EV, et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(5):309-23.

18. Tetangco EP, et al. Performing and analyzing high-resolution anorectal manometry. NeuroGastroLatam Rev. 2018;2:120-32.

19. Lee YY, et al. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15(12):360.

20. Sharma M, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(10):e13910.

21. Rao SSC, et al.. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(12):2790-6.

22. Carrington EV, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(1):e13679.

23. Rao SSC. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37(3):569-86, viii.

24. Rao SSC, et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(4):S158-9.

25. Guinet A, et al. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26(4):507-13.

26. Rattan S, et al. Gastroenterology. 1992;103(1):43-50.

27. Remes-Troche JM & Rao SSC. 2008;2(3):323-35.

28. Zaafouri H, et al..Int J Surgery. 2015. 2(1):9-17.

29. Remes-Troche JM, et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53(7):1047-54.

30. Rao SSC, et al. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(5):S-363.

31. Yu T, et al. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(19):e3667.

32. Gladman MA, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21(5):508-16, e4-5.

33. Lee KJ, et al. Digestion. 2006;73(2-3):133-41 .

34. Rao SSC, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2002;14(5):553-9.

35. Coss-Adame E, et al.. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(6):1143-1150.e1.

36. Chiarioni G, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(12):2049-54.

37. Gu G, et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(6):S-545–S-546.

38. Savoye-Collet C, et al.. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37(3):553-67, viii.

39. Videlock EJ, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25(6):509-20.

40. Rao SSC, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16(5):589-96.

41. Wald A, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(8):1141-57 ; (Quiz) 1058.

42. Rao SSC & Patcharatrakul T. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22(3):423-35.

43. Rao SS, et al. Functional Anorectal Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016. S0016-5085(16)00175-X.

44. Bharucha AE, et al.. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(1):218-38.

45. Voderholzer WA, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(1):95-8.

46. Lee HJ, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(6):787-95.

47. Simón MA & Bueno AM. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(10):e90-4.

48. Chiarioni G,et al.. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(3):657-64.

49. Heymen S, et al.. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(4):428-41.

50. Rao SSC, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(3):331-8.

51. Rao SSC, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(4):890-6.

52. Patcharatrakul T, et al. Biofeedback therapy. In Clinical and basic neurogastroenterology and motility. India: Stacy Masucci; 2020:517-32.

53. Huaman J-W, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(11):2463-2470.e1.

54. Patcharatrakul T, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(5):715-21.

55. Chaudhry A, et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):S-382–S-383.

56. Shim LSE, et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(11):1245-51.

57. Rao SSC, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(5):594-609.

58. Jangsirikul S, et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):S-383.

59. Rao SSC, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(6):938-44.

60. Ron Y, et al.. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44(12):1821-6.

61. Podzemny V, et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(4):1053-60.

62. Faried M, et al. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14(8):1235-43.

63. Hallan RI, et al. Lancet. 1988;2(8613):714-7.

Introduction

About 40% of the population experiences lower GI symptoms suggestive of gastrointestinal motility disorders.1,2 The global prevalence of chronic constipation is 18%, and the condition includes multiple overlapping subtypes.3 Evacuation disorders affect over half (59%) of patients and include dyssynergic defecation (DD).4 The inability to coordinate the abdominal, rectal, pelvic floor, and anal/puborectalis muscles to evacuate stools causes DD.5 The etiology of DD remains unclear and is often misdiagnosed. Clinically, the symptoms of DD overlap with other lower GI disorders, often leading to unnecessary and invasive procedures.2 We describe the clinical characteristics, diagnostic tools, treatment options, and evidence-based approach for the management of DD.

Clinical presentation

Over two-thirds of patients with DD acquire this disorder during adulthood, and one-third have symptoms from childhood.6 Though there is not usually an inciting event, 29% of patients report that symptoms began after events such as pregnancy or back injury,6 and opioid users have higher prevalence and severity of DD.7

Over 80% of patients report excessive straining, feelings of incomplete evacuation, and hard stools, and 50% report sensation of anal blockage or use of digital maneuvers.2 Other symptoms include infrequent bowel movements, abdominal pain, anal pain, and stool leakage.2 Evaluation of DD includes obtaining a detailed history utilizing the Bristol Stool Form Scale;8 however, patients’ recall of stool habit is often inaccurate, which results in suboptimal care.9,10 Prospective stool diaries can help to provide more objective assessment of patients’ symptoms, eliminate recall bias, and provide more reliable information. Several useful questionnaires are available for clinical and research purposes to characterize lower-GI symptoms, including the Constipation Scoring System,11 Patient Assessment of Constipation Symptoms (PAC-SYM),12 and Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life (PAC-QOL).2,13 The Constipation Stool digital app enhances accuracy of data capture and offers a reliable and user-friendly method for recording bowel symptoms for patients, clinicians, and clinical investigators.14

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of DD requires careful physical and digital rectal examination together with anorectal manometry and a balloon expulsion test. Defecography and colonic transit studies provide additional assessment.

Physical examination

Abdominal examination should include palpation for stool in the colon and identification of abdominal mass or fecal impaction.2A high-quality digital rectal examination can help to identify patients who could benefit from physiological testing to confirm and treat DD.15 Rectal examination is performed by placing examiner’s lubricated gloved right index finger in a patient’s rectum, with the examiner’s left hand on patient’s abdomen, and asking the patient to push and bear down as if defecating.15 The contraction of the abdominal muscles is felt using the left hand, while the anal sphincter relaxation and degree of perineal descent are felt using the right-hand index finger.15 A diagnosis of dyssynergia is suspected if the digital rectal examination reveals two or more of the following abnormalities: inability to contract abdominal muscles (lack of push effort), inability to relax or paradoxical contraction of the anal sphincter and/or puborectalis, or absence of perineal descent.15 Digital rectal examination has good sensitivity (75%), specificity (87%), and positive predictive value (97%) for DD.16

High resolution anorectal manometry

Anorectal manometry (ARM) is the preferred method for the evaluation of defecatory disorders.17,18 ARM is best performed using the high-resolution anorectal manometry (HRAM) systems19 that consist of a flexible probe – 0.5-cm diameter with multiple circumferential sensors along the anal canal – and another two sensors inside a rectal balloon.18 It provides a topographic and waveform display of manometric pressure data (Figure). The 3D high-definition ARM probe is a rigid 1-cm probe that provides 3D topographic profiles.18 ARM is typically performed in both the left lateral position and in a more physiological seated position.20,21 There is considerable variation amongst different institutions on how to perform HRAM, and a recent International Anorectal Physiology Working Group (IAPWG) has provided consensus recommendations for performing this test.22 The procedure for performing HRAM is reviewed elsewhere, but the key elements are summarized below.18

Push maneuver: On HRAM, after the assessment of resting and squeeze anal sphincter pressures, the patient is asked to push or bear down as if to defecate while lying in left lateral decubitus position. The best of two attempts that closely mimics a normal bearing down maneuver is used for categorizing patient’s defecatory pattern.18 In patients with DD, at least four distinct dyssynergia phenotypes have been recognized (Figure),23 though recent studies suggest eight patterns.24 Defecation index (maximum rectal pressure/minimum residual anal pressure when bearing down) greater than 1.2 is considered normal.18

Simulated defecation on commode: The subject is asked to attempt defecation while seated on a commode with intrarectal balloon filled with 60 cc of air, and both the defecation pattern(s) and defecation index are calculated. A lack of coordinated push effort is highly suggestive of DD.21

Rectoanal Inhibitory Reflex (RAIR): RAIR describes the reflex relaxation of the internal anal sphincter after rectal distension. RAIR is dependent on intact autonomic ganglia and myenteric plexus25and is mediated by the release of nitric oxide and vasoactive intestinal peptide.26 The absence of RAIR suggests Hirschsprung disease.22.27.28

Rectal sensory testing: Intermittent balloon distension of the rectum with incremental volumes of air induces a range of rectal sensations that include first sensation, desire to defecate, urgency to defecate, and maximum tolerable volume. Rectal hyposensitivity is diagnosed when two or more sensory thresholds are higher than those seen in normal subjects29.30 and likely results from disruption of afferent gut-brain pathways, cortical perception/rectal wall dysfunction, or both.29 Rectal hyposensitivity affects 40% of patients with constipation30and is associated with DD but not delayed colonic transit.31 Rectal hyposensitivity may also be seen in patients with diabetes or fecal incontinence.18 About two-thirds of patients with rectal hyposensitivity have rectal hypercompliance, and some have megarectum.32 Some patients with DD have coexisting irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and may have rectal hypersensitivity.18,33 Rectal compliance is measured alongside rectal sensitivity analysis by plotting a graph between the change in intraballoon volume (mL) and change in intrarectal pressures (mm Hg) during incremental balloon distensions.18.34 Rectal hypercompliance may be seen in megarectum and dyssynergic defecation.34,35 Rectal hypocompliance may be seen in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, postpelvic radiation, chronic ischemia, and advanced age.18

Balloon expulsion test: This test is performed by placing a plastic probe with a balloon in the rectum and filling it with 50 cc of warm water. Patients are given 5 minutes to expel the balloon while sitting on a commode. Balloon expulsion time of more than 1 minute suggests a diagnosis of DD,21 although 2 minutes provides a higher level of agreement with manometric findings.36 Balloon type and body position can influence the results.37 Inability to expel the balloon with normal manometric findings is considered an inconclusive finding per the recent London Classification (i.e., it may be associated with generation of anorectal symptoms, but the clinical relevance of this finding is unclear as it may also be seen in healthy subjects).22

Defecography

Defecography is a dynamic fluoroscopic study performed in the sitting position after injecting 150 mL of barium paste into the patient’s rectum. Defecography provides useful information about structural changes (e.g., rectoceles, enteroceles, rectal prolapse, and intussusception), DD, and descending perineum syndrome.38 Methodological differences, radiation exposure, and poor interobserver agreement have limited its wider use; therefore, anorectal manometry and the balloon expulsion test are recommended for the initial evaluation of DD.39 Magnetic resonance defecography may be more useful.17,38

Colonic transit studies

Colonic transit study can be assessed using radiopaque markers, wireless motility capsule, or scintigraphy. Wireless motility capsule and scintigraphy have the advantage of determining gastric, small bowel, and whole gut transit times as well. About two-thirds of patients with DD have slow transit constipation (STC),6 which improves after treatment of DD.40 Hence, in patients with chronic constipation, evaluation and management of DD is recommended first. If symptoms persist, then consider colonic transit assessment.41 Given the overlapping nature of the conditions, documentation of STC at the outset could facilitate treatment of both.

Diagnostic criteria for DD

Patients should fulfill the following criteria for diagnosis of DD:42,43

- Fulfill symptom(s) diagnostic criteria for functional constipation and/or constipation-predominant IBS.

- Demonstrate dyssynergic pattern (Types I-IV; Figure) during attempted defecation on manometry recordings.

- Meet one or more of the following criteria:

- Inability to expel an artificial stool (50 mL water-filled balloon) within 1 minute.

- Inability to evacuate or retention of 50% or more of barium during defecography. (Some institutions use a prolonged colonic transit time: greater than 5 markers or 20% or higher marker retention on a plain abdominal x-Ray at 120 hours after ingestion of one radio-opaque marker capsule containing 24 radio-opaque markers.)

Treatment of DD

The treatment modalities for DD depend on several factors: patient’s age, comorbidities, underlying pathophysiology, and patient expectations. Treatment options include standard management of constipation, but biofeedback therapy is the mainstay.

Standard management

Medications that cause or worsen constipation should be avoided. The patient should consume adequate fluid and exercise regularly. Patients should receive instructions for timed toilet training (twice daily, 30 minutes after meals). Patients should push at about 50%-70% of their ability for no longer than 5 minutes and avoid postponing defecation or use of digital maneuvers to facilitate defecation.42 The patients should take 25 g of soluble fiber (e.g., psyllium) daily. Of note, the benefits of fiber can take days to weeks44 and may be limited in patients with STC and DD.45 Medications including laxatives and intestinal secretagogues (lubiprostone, linaclotide, plecanatide), and enterokinetic agents (prucalopride) can be used as adjunct therapy for management of DD.42 Their use is titrated during and after biofeedback therapy and may decrease after successful treatment.46

Biofeedback therapy

Biofeedback therapy involves operant conditioning techniques using either a solid state anorectal manometry system, electromyography, simulated balloon, or home biofeedback training devices.42,47 The goals of biofeedback therapy are to correct the abdominal pelvic muscle discoordination during defecation and improve rectal sensation to stool if impaired. Biofeedback therapy involves patient education and active training (typically six sessions, 1-2 weeks apart, with each about 30-60 minutes long), followed by a reinforcement stage (three sessions at 3, 6, and 12 months), though there are variations in training protocols.42

The success of biofeedback therapy depends on the patient’s motivation and the therapist’s skills.42 Compared with standard therapy (diet, exercise, pharmacotherapy), biofeedback therapy provides sustained improvement of bowel symptoms and anorectal function. Up to 70%-80% of DD patients show significant improvement of symptoms in randomized controlled trials (Table).48-52 Biofeedback therapy may also improve dyspeptic symptoms.53 Patients with harder stool consistency, greater willingness to participate, lower baseline bowel satisfaction, lower baseline anal sphincter relaxation, and prolonged balloon expulsion time, as well as patients who used digital maneuvers for defection, more commonly respond to biofeedback therapy.54,55 Longstanding laxative use has been associated with decreased response to biofeedback therapy.56 In patients with rectal hyposensitivity, barostat-assisted sensory training is more effective than a hand-held syringe technique.30 In patients with constipation predominant IBS and rectal hyposensitivity, sensory adaption training is more efficacious and better tolerated than escitalopram.30 Biofeedback therapy was afforded a grade A recommendation for treatment of DD by the American and European Societies of Neurogastroenterology and Motility.57

The access to office-based biofeedback therapy may be limited because of costs and low availability. The time required to attend multiple sessions may be burdensome for some patients, especially if they are taking time off from work. A recent study showed that patients with higher level of education may be less likely to adhere to biofeedback therapy.58 Recently, home biofeedback was shown to be noninferior to office biofeedback and was more cost-effective, which provides an alternative option for treating more patients.59

Endoscopic/surgical options

Other less effective treatment options for DD include botulinum toxin injection and myectomy.60-62 Botulinum toxin injection appears to have mixed effects with less than 50% of patients reporting symptomatic improvement, and it may cause fecal incontinence.60,63

Conclusion

DD is a common yet poorly recognized cause of constipation. Its clinical presentation overlaps with other lower-GI disorders. Its diagnosis requires detailed history, digital rectal examination, prospective stool diaries, anorectal manometry, and balloon expulsion tests. Biofeedback therapy offers excellent and sustained symptomatic improvement; however, access to office-based biofeedback is limited, and there is an urgent need for home-based biofeedback therapy programs.59

Dr. Rao is J. Harold Harrison Distinguished University Chair, professor of medicine, director of neurogastroenterology/motility, and director of digestive health at the Digestive Health Clinical Research Center Augusta (Georgia) University. He is supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01DK121003-02 and U01DK115572. Dr. Jehangir is a gastroenterology and Hepatology Fellow at the Digestive Health Clinical Research Center at Augusta University. They reported having no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Peery AF, et al. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(5):1179-1187.e3 .

2. Curtin B, et al. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020 30;26(4):423-36.

3. Suares NC & Ford AC. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Sep;106(9):1582-91.

4. Mertz H, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(3):609-15.

5. Rao SS, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(7):1042-50.

6. Rao SSC, et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(8):680-5.

7. Nojkov B, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(11):1772-7.

8. Heaton KW, et al. Gut. 1992;33(6):818-24.

9. Prichard DO & Bharucha AE. 2018 Oct 15;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1640.

10. Ashraf W, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91(1):26-32.

11. Agachan F, et al.. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39(6):681-5.

12. Frank L, et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34(9):870-7.

13. Marquis P, et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40(5):540-51.

14. Yan Y, et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):S-400.

15. Rao SSC. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(5):635-8.

16. Tantiphlachiva K, et al. Digital rectal examination is a useful tool for identifying patients with dyssynergia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(11):955-60.

17. Carrington EV, et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(5):309-23.

18. Tetangco EP, et al. Performing and analyzing high-resolution anorectal manometry. NeuroGastroLatam Rev. 2018;2:120-32.

19. Lee YY, et al. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15(12):360.

20. Sharma M, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(10):e13910.

21. Rao SSC, et al.. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(12):2790-6.

22. Carrington EV, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(1):e13679.

23. Rao SSC. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37(3):569-86, viii.

24. Rao SSC, et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(4):S158-9.

25. Guinet A, et al. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26(4):507-13.

26. Rattan S, et al. Gastroenterology. 1992;103(1):43-50.

27. Remes-Troche JM & Rao SSC. 2008;2(3):323-35.

28. Zaafouri H, et al..Int J Surgery. 2015. 2(1):9-17.

29. Remes-Troche JM, et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53(7):1047-54.

30. Rao SSC, et al. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(5):S-363.

31. Yu T, et al. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(19):e3667.

32. Gladman MA, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21(5):508-16, e4-5.

33. Lee KJ, et al. Digestion. 2006;73(2-3):133-41 .

34. Rao SSC, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2002;14(5):553-9.

35. Coss-Adame E, et al.. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(6):1143-1150.e1.

36. Chiarioni G, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(12):2049-54.

37. Gu G, et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(6):S-545–S-546.

38. Savoye-Collet C, et al.. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37(3):553-67, viii.

39. Videlock EJ, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25(6):509-20.

40. Rao SSC, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16(5):589-96.

41. Wald A, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(8):1141-57 ; (Quiz) 1058.

42. Rao SSC & Patcharatrakul T. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22(3):423-35.

43. Rao SS, et al. Functional Anorectal Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016. S0016-5085(16)00175-X.

44. Bharucha AE, et al.. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(1):218-38.

45. Voderholzer WA, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92(1):95-8.

46. Lee HJ, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(6):787-95.

47. Simón MA & Bueno AM. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(10):e90-4.

48. Chiarioni G,et al.. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(3):657-64.

49. Heymen S, et al.. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(4):428-41.

50. Rao SSC, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(3):331-8.

51. Rao SSC, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(4):890-6.

52. Patcharatrakul T, et al. Biofeedback therapy. In Clinical and basic neurogastroenterology and motility. India: Stacy Masucci; 2020:517-32.

53. Huaman J-W, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(11):2463-2470.e1.

54. Patcharatrakul T, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(5):715-21.

55. Chaudhry A, et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):S-382–S-383.

56. Shim LSE, et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(11):1245-51.

57. Rao SSC, et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(5):594-609.

58. Jangsirikul S, et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):S-383.

59. Rao SSC, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(6):938-44.

60. Ron Y, et al.. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44(12):1821-6.

61. Podzemny V, et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(4):1053-60.

62. Faried M, et al. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14(8):1235-43.

63. Hallan RI, et al. Lancet. 1988;2(8613):714-7.

Introduction

About 40% of the population experiences lower GI symptoms suggestive of gastrointestinal motility disorders.1,2 The global prevalence of chronic constipation is 18%, and the condition includes multiple overlapping subtypes.3 Evacuation disorders affect over half (59%) of patients and include dyssynergic defecation (DD).4 The inability to coordinate the abdominal, rectal, pelvic floor, and anal/puborectalis muscles to evacuate stools causes DD.5 The etiology of DD remains unclear and is often misdiagnosed. Clinically, the symptoms of DD overlap with other lower GI disorders, often leading to unnecessary and invasive procedures.2 We describe the clinical characteristics, diagnostic tools, treatment options, and evidence-based approach for the management of DD.

Clinical presentation

Over two-thirds of patients with DD acquire this disorder during adulthood, and one-third have symptoms from childhood.6 Though there is not usually an inciting event, 29% of patients report that symptoms began after events such as pregnancy or back injury,6 and opioid users have higher prevalence and severity of DD.7

Over 80% of patients report excessive straining, feelings of incomplete evacuation, and hard stools, and 50% report sensation of anal blockage or use of digital maneuvers.2 Other symptoms include infrequent bowel movements, abdominal pain, anal pain, and stool leakage.2 Evaluation of DD includes obtaining a detailed history utilizing the Bristol Stool Form Scale;8 however, patients’ recall of stool habit is often inaccurate, which results in suboptimal care.9,10 Prospective stool diaries can help to provide more objective assessment of patients’ symptoms, eliminate recall bias, and provide more reliable information. Several useful questionnaires are available for clinical and research purposes to characterize lower-GI symptoms, including the Constipation Scoring System,11 Patient Assessment of Constipation Symptoms (PAC-SYM),12 and Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life (PAC-QOL).2,13 The Constipation Stool digital app enhances accuracy of data capture and offers a reliable and user-friendly method for recording bowel symptoms for patients, clinicians, and clinical investigators.14

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of DD requires careful physical and digital rectal examination together with anorectal manometry and a balloon expulsion test. Defecography and colonic transit studies provide additional assessment.

Physical examination

Abdominal examination should include palpation for stool in the colon and identification of abdominal mass or fecal impaction.2A high-quality digital rectal examination can help to identify patients who could benefit from physiological testing to confirm and treat DD.15 Rectal examination is performed by placing examiner’s lubricated gloved right index finger in a patient’s rectum, with the examiner’s left hand on patient’s abdomen, and asking the patient to push and bear down as if defecating.15 The contraction of the abdominal muscles is felt using the left hand, while the anal sphincter relaxation and degree of perineal descent are felt using the right-hand index finger.15 A diagnosis of dyssynergia is suspected if the digital rectal examination reveals two or more of the following abnormalities: inability to contract abdominal muscles (lack of push effort), inability to relax or paradoxical contraction of the anal sphincter and/or puborectalis, or absence of perineal descent.15 Digital rectal examination has good sensitivity (75%), specificity (87%), and positive predictive value (97%) for DD.16

High resolution anorectal manometry

Anorectal manometry (ARM) is the preferred method for the evaluation of defecatory disorders.17,18 ARM is best performed using the high-resolution anorectal manometry (HRAM) systems19 that consist of a flexible probe – 0.5-cm diameter with multiple circumferential sensors along the anal canal – and another two sensors inside a rectal balloon.18 It provides a topographic and waveform display of manometric pressure data (Figure). The 3D high-definition ARM probe is a rigid 1-cm probe that provides 3D topographic profiles.18 ARM is typically performed in both the left lateral position and in a more physiological seated position.20,21 There is considerable variation amongst different institutions on how to perform HRAM, and a recent International Anorectal Physiology Working Group (IAPWG) has provided consensus recommendations for performing this test.22 The procedure for performing HRAM is reviewed elsewhere, but the key elements are summarized below.18

Push maneuver: On HRAM, after the assessment of resting and squeeze anal sphincter pressures, the patient is asked to push or bear down as if to defecate while lying in left lateral decubitus position. The best of two attempts that closely mimics a normal bearing down maneuver is used for categorizing patient’s defecatory pattern.18 In patients with DD, at least four distinct dyssynergia phenotypes have been recognized (Figure),23 though recent studies suggest eight patterns.24 Defecation index (maximum rectal pressure/minimum residual anal pressure when bearing down) greater than 1.2 is considered normal.18

Simulated defecation on commode: The subject is asked to attempt defecation while seated on a commode with intrarectal balloon filled with 60 cc of air, and both the defecation pattern(s) and defecation index are calculated. A lack of coordinated push effort is highly suggestive of DD.21

Rectoanal Inhibitory Reflex (RAIR): RAIR describes the reflex relaxation of the internal anal sphincter after rectal distension. RAIR is dependent on intact autonomic ganglia and myenteric plexus25and is mediated by the release of nitric oxide and vasoactive intestinal peptide.26 The absence of RAIR suggests Hirschsprung disease.22.27.28

Rectal sensory testing: Intermittent balloon distension of the rectum with incremental volumes of air induces a range of rectal sensations that include first sensation, desire to defecate, urgency to defecate, and maximum tolerable volume. Rectal hyposensitivity is diagnosed when two or more sensory thresholds are higher than those seen in normal subjects29.30 and likely results from disruption of afferent gut-brain pathways, cortical perception/rectal wall dysfunction, or both.29 Rectal hyposensitivity affects 40% of patients with constipation30and is associated with DD but not delayed colonic transit.31 Rectal hyposensitivity may also be seen in patients with diabetes or fecal incontinence.18 About two-thirds of patients with rectal hyposensitivity have rectal hypercompliance, and some have megarectum.32 Some patients with DD have coexisting irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and may have rectal hypersensitivity.18,33 Rectal compliance is measured alongside rectal sensitivity analysis by plotting a graph between the change in intraballoon volume (mL) and change in intrarectal pressures (mm Hg) during incremental balloon distensions.18.34 Rectal hypercompliance may be seen in megarectum and dyssynergic defecation.34,35 Rectal hypocompliance may be seen in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, postpelvic radiation, chronic ischemia, and advanced age.18

Balloon expulsion test: This test is performed by placing a plastic probe with a balloon in the rectum and filling it with 50 cc of warm water. Patients are given 5 minutes to expel the balloon while sitting on a commode. Balloon expulsion time of more than 1 minute suggests a diagnosis of DD,21 although 2 minutes provides a higher level of agreement with manometric findings.36 Balloon type and body position can influence the results.37 Inability to expel the balloon with normal manometric findings is considered an inconclusive finding per the recent London Classification (i.e., it may be associated with generation of anorectal symptoms, but the clinical relevance of this finding is unclear as it may also be seen in healthy subjects).22

Defecography

Defecography is a dynamic fluoroscopic study performed in the sitting position after injecting 150 mL of barium paste into the patient’s rectum. Defecography provides useful information about structural changes (e.g., rectoceles, enteroceles, rectal prolapse, and intussusception), DD, and descending perineum syndrome.38 Methodological differences, radiation exposure, and poor interobserver agreement have limited its wider use; therefore, anorectal manometry and the balloon expulsion test are recommended for the initial evaluation of DD.39 Magnetic resonance defecography may be more useful.17,38

Colonic transit studies

Colonic transit study can be assessed using radiopaque markers, wireless motility capsule, or scintigraphy. Wireless motility capsule and scintigraphy have the advantage of determining gastric, small bowel, and whole gut transit times as well. About two-thirds of patients with DD have slow transit constipation (STC),6 which improves after treatment of DD.40 Hence, in patients with chronic constipation, evaluation and management of DD is recommended first. If symptoms persist, then consider colonic transit assessment.41 Given the overlapping nature of the conditions, documentation of STC at the outset could facilitate treatment of both.

Diagnostic criteria for DD

Patients should fulfill the following criteria for diagnosis of DD:42,43

- Fulfill symptom(s) diagnostic criteria for functional constipation and/or constipation-predominant IBS.

- Demonstrate dyssynergic pattern (Types I-IV; Figure) during attempted defecation on manometry recordings.

- Meet one or more of the following criteria:

- Inability to expel an artificial stool (50 mL water-filled balloon) within 1 minute.