User login

Colchicine before PCI for acute MI fails to improve major outcomes

In a placebo-controlled randomized trial, a preprocedural dose of colchicine administered immediately before percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for an acute ST-segment elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI) did not reduce the no-reflow phenomenon or improve outcomes.

No-reflow, in which insufficient myocardial perfusion is present even though the coronary artery appears patent, was the primary outcome, and the proportion of patients experiencing this event was exactly the same (14.4%) in the colchicine and placebo groups, reported Yaser Jenab, MD, at CRT 2021 sponsored by MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute.

The hypothesis that colchicine would offer benefit in this setting was largely based on the Colchicine Cardiovascular Outcomes Trial (COLCOT). In that study, colchicine was associated with a 23% reduction in risk for major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) relative to placebo when administered within 30 days after a myocardial infarction (hazard ratio, 0.77; P = .02).

The benefit in that trial was attributed to an anti-inflammatory effect, according to Dr. Jenab, associate professor of cardiology at Tehran (Iran) Heart Center. In particular as it relates to vascular disease, he cited experimental studies associating colchicine with a reduction in neutrophil activation and adherence to vascular endothelium.

The rationale for a preprocedural approach to colchicine was supplied by a subsequent time-to-treatment COLCOT analysis. In this study, MACE risk reduction for colchicine climbed to 48% (HR 0.52) for those treated within 3 days of the MI but largely disappeared (HR 0.96) if treatment was started at least 8 days post MI.

PodCAST-PCI trial

In the preprocedural study, called the PodCAST-PCI trial, 321 acute STEMI patients were randomized. Patients received a 1-mg dose of oral colchicine or placebo at the time PCI was scheduled. Another dose of colchicine (0.5 mg) or placebo was administered 1 hour after the procedure.

Of secondary outcomes, which included MACE at 1 month and 1 year, ST-segment resolution at 1 month, and change in inflammatory markers at 1 month, none were significant. Few even trended for significance.

For MACE, which included cardiac death, stroke, nonfatal MI, new hospitalization due to heart failure, or target vessel revascularization, the rates were lower in the colchicine group at 1 month (4.3% vs. 7.5%) and 1 year (9.3% vs. 11.2%), but neither approached significance.

For ST-segment resolution, the proportions were generally comparable among the colchicine and placebo groups, respectively, for the proportion below 50% (18.6% vs. 23.1%), between 50% and 70% (16.8% vs. 15.6%), and above 70% (64.6% vs. 61.3%).

The average troponin levels were nonsignificantly lower at 6 hours (1,847 vs. 2,883 ng/mL) in the colchicine group but higher at 48 hours (1,197 vs. 1,147 ng/mL). The average C-reactive protein (CRP) levels at 48 hours were nonsignificantly lower on colchicine (176.5 vs. 244.5 mg/L).

There were no significant differences in postprocedural perfusion, as measured with TIMI blood flow, or in the rate of stent thrombosis, which occurred in roughly 3% of each group of patients.

The small sample size was one limitation of this study, Dr. Jenab acknowledged. For this and other reasons, he cautioned that these data are not definitive and do not preclude a benefit on clinical outcomes in a study with a larger size, a different design, or different dosing.

Timing might be the issue

However, even if colchicine has a potential benefit in this setting, timing might be a major obstacle, according to Binata Shah, MD, associate director of research for the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory at New York University.

“We have learned from our rheumatology colleagues that peak plasma levels of colchicine are not achieved for at least 1 hour after the full loading dose,” Dr. Shah said. “With us moving so quickly in a primary PCI setting, it is hard to imagine that colchicine would have had time to really kick in and exert its anti-inflammatory effect.”

Indeed, the problem might be worse than reaching the peak plasma level.

“Even though peak plasma levels occur as early as 1 hour after a full loading dose, we see that it takes about 24 hours to really see the effects translate downstream into more systemic inflammatory markers such as CRP and interleukin-6,” she added. If lowering these signals of inflammation is predictive of benefit, than this might be the biggest obstacle to benefit from colchicine in an urgent treatment setting.

Dr. Jenab and Dr. Shah reported no potential conflicts of interest.

In a placebo-controlled randomized trial, a preprocedural dose of colchicine administered immediately before percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for an acute ST-segment elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI) did not reduce the no-reflow phenomenon or improve outcomes.

No-reflow, in which insufficient myocardial perfusion is present even though the coronary artery appears patent, was the primary outcome, and the proportion of patients experiencing this event was exactly the same (14.4%) in the colchicine and placebo groups, reported Yaser Jenab, MD, at CRT 2021 sponsored by MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute.

The hypothesis that colchicine would offer benefit in this setting was largely based on the Colchicine Cardiovascular Outcomes Trial (COLCOT). In that study, colchicine was associated with a 23% reduction in risk for major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) relative to placebo when administered within 30 days after a myocardial infarction (hazard ratio, 0.77; P = .02).

The benefit in that trial was attributed to an anti-inflammatory effect, according to Dr. Jenab, associate professor of cardiology at Tehran (Iran) Heart Center. In particular as it relates to vascular disease, he cited experimental studies associating colchicine with a reduction in neutrophil activation and adherence to vascular endothelium.

The rationale for a preprocedural approach to colchicine was supplied by a subsequent time-to-treatment COLCOT analysis. In this study, MACE risk reduction for colchicine climbed to 48% (HR 0.52) for those treated within 3 days of the MI but largely disappeared (HR 0.96) if treatment was started at least 8 days post MI.

PodCAST-PCI trial

In the preprocedural study, called the PodCAST-PCI trial, 321 acute STEMI patients were randomized. Patients received a 1-mg dose of oral colchicine or placebo at the time PCI was scheduled. Another dose of colchicine (0.5 mg) or placebo was administered 1 hour after the procedure.

Of secondary outcomes, which included MACE at 1 month and 1 year, ST-segment resolution at 1 month, and change in inflammatory markers at 1 month, none were significant. Few even trended for significance.

For MACE, which included cardiac death, stroke, nonfatal MI, new hospitalization due to heart failure, or target vessel revascularization, the rates were lower in the colchicine group at 1 month (4.3% vs. 7.5%) and 1 year (9.3% vs. 11.2%), but neither approached significance.

For ST-segment resolution, the proportions were generally comparable among the colchicine and placebo groups, respectively, for the proportion below 50% (18.6% vs. 23.1%), between 50% and 70% (16.8% vs. 15.6%), and above 70% (64.6% vs. 61.3%).

The average troponin levels were nonsignificantly lower at 6 hours (1,847 vs. 2,883 ng/mL) in the colchicine group but higher at 48 hours (1,197 vs. 1,147 ng/mL). The average C-reactive protein (CRP) levels at 48 hours were nonsignificantly lower on colchicine (176.5 vs. 244.5 mg/L).

There were no significant differences in postprocedural perfusion, as measured with TIMI blood flow, or in the rate of stent thrombosis, which occurred in roughly 3% of each group of patients.

The small sample size was one limitation of this study, Dr. Jenab acknowledged. For this and other reasons, he cautioned that these data are not definitive and do not preclude a benefit on clinical outcomes in a study with a larger size, a different design, or different dosing.

Timing might be the issue

However, even if colchicine has a potential benefit in this setting, timing might be a major obstacle, according to Binata Shah, MD, associate director of research for the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory at New York University.

“We have learned from our rheumatology colleagues that peak plasma levels of colchicine are not achieved for at least 1 hour after the full loading dose,” Dr. Shah said. “With us moving so quickly in a primary PCI setting, it is hard to imagine that colchicine would have had time to really kick in and exert its anti-inflammatory effect.”

Indeed, the problem might be worse than reaching the peak plasma level.

“Even though peak plasma levels occur as early as 1 hour after a full loading dose, we see that it takes about 24 hours to really see the effects translate downstream into more systemic inflammatory markers such as CRP and interleukin-6,” she added. If lowering these signals of inflammation is predictive of benefit, than this might be the biggest obstacle to benefit from colchicine in an urgent treatment setting.

Dr. Jenab and Dr. Shah reported no potential conflicts of interest.

In a placebo-controlled randomized trial, a preprocedural dose of colchicine administered immediately before percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for an acute ST-segment elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI) did not reduce the no-reflow phenomenon or improve outcomes.

No-reflow, in which insufficient myocardial perfusion is present even though the coronary artery appears patent, was the primary outcome, and the proportion of patients experiencing this event was exactly the same (14.4%) in the colchicine and placebo groups, reported Yaser Jenab, MD, at CRT 2021 sponsored by MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute.

The hypothesis that colchicine would offer benefit in this setting was largely based on the Colchicine Cardiovascular Outcomes Trial (COLCOT). In that study, colchicine was associated with a 23% reduction in risk for major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) relative to placebo when administered within 30 days after a myocardial infarction (hazard ratio, 0.77; P = .02).

The benefit in that trial was attributed to an anti-inflammatory effect, according to Dr. Jenab, associate professor of cardiology at Tehran (Iran) Heart Center. In particular as it relates to vascular disease, he cited experimental studies associating colchicine with a reduction in neutrophil activation and adherence to vascular endothelium.

The rationale for a preprocedural approach to colchicine was supplied by a subsequent time-to-treatment COLCOT analysis. In this study, MACE risk reduction for colchicine climbed to 48% (HR 0.52) for those treated within 3 days of the MI but largely disappeared (HR 0.96) if treatment was started at least 8 days post MI.

PodCAST-PCI trial

In the preprocedural study, called the PodCAST-PCI trial, 321 acute STEMI patients were randomized. Patients received a 1-mg dose of oral colchicine or placebo at the time PCI was scheduled. Another dose of colchicine (0.5 mg) or placebo was administered 1 hour after the procedure.

Of secondary outcomes, which included MACE at 1 month and 1 year, ST-segment resolution at 1 month, and change in inflammatory markers at 1 month, none were significant. Few even trended for significance.

For MACE, which included cardiac death, stroke, nonfatal MI, new hospitalization due to heart failure, or target vessel revascularization, the rates were lower in the colchicine group at 1 month (4.3% vs. 7.5%) and 1 year (9.3% vs. 11.2%), but neither approached significance.

For ST-segment resolution, the proportions were generally comparable among the colchicine and placebo groups, respectively, for the proportion below 50% (18.6% vs. 23.1%), between 50% and 70% (16.8% vs. 15.6%), and above 70% (64.6% vs. 61.3%).

The average troponin levels were nonsignificantly lower at 6 hours (1,847 vs. 2,883 ng/mL) in the colchicine group but higher at 48 hours (1,197 vs. 1,147 ng/mL). The average C-reactive protein (CRP) levels at 48 hours were nonsignificantly lower on colchicine (176.5 vs. 244.5 mg/L).

There were no significant differences in postprocedural perfusion, as measured with TIMI blood flow, or in the rate of stent thrombosis, which occurred in roughly 3% of each group of patients.

The small sample size was one limitation of this study, Dr. Jenab acknowledged. For this and other reasons, he cautioned that these data are not definitive and do not preclude a benefit on clinical outcomes in a study with a larger size, a different design, or different dosing.

Timing might be the issue

However, even if colchicine has a potential benefit in this setting, timing might be a major obstacle, according to Binata Shah, MD, associate director of research for the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory at New York University.

“We have learned from our rheumatology colleagues that peak plasma levels of colchicine are not achieved for at least 1 hour after the full loading dose,” Dr. Shah said. “With us moving so quickly in a primary PCI setting, it is hard to imagine that colchicine would have had time to really kick in and exert its anti-inflammatory effect.”

Indeed, the problem might be worse than reaching the peak plasma level.

“Even though peak plasma levels occur as early as 1 hour after a full loading dose, we see that it takes about 24 hours to really see the effects translate downstream into more systemic inflammatory markers such as CRP and interleukin-6,” she added. If lowering these signals of inflammation is predictive of benefit, than this might be the biggest obstacle to benefit from colchicine in an urgent treatment setting.

Dr. Jenab and Dr. Shah reported no potential conflicts of interest.

FROM CRT 2021

We’re all vaccinated: Can we go back to the office (unmasked) now?

Congratulations, you’ve been vaccinated!

It’s been a year like no other, and outpatient psychiatrists turned to Zoom and other telemental health platforms to provide treatment for our patients. Offices sit empty as the dust lands and the plants wilt. Perhaps a few patients are seen in person, masked and carefully distanced, after health screening and temperature checks, with surfaces sanitized between visits, all in accordance with health department regulations. But now the vaccine offers both safety and the promise of a return to a new normal, one that is certain to look different from the normal that was left behind.

I have been vaccinated and many of my patients have also been vaccinated. I began to wonder if it was safe to start seeing patients in person; could I see fully vaccinated patients, unmasked and without temperature checks and sanitizing? I started asking this question in February, and the response I got then was that it was too soon to tell; we did not have any data on whether vaccinated people could transmit the novel coronavirus. Two vaccinated people might be at risk of transmitting the virus and then infecting others, and the question of whether the vaccines would protect against illness caused by variants remained. Preliminary data out of Israel indicated that the vaccine did reduce transmission, but no one was saying that it was fine to see patients without masks, and video-conferencing remained the safest option.

On Monday, March 8, 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released long-awaited interim public health guidelines for fully vaccinated people. The guidelines allowed for two vaccinated people to be in a room together unmasked, and for a fully-vaccinated person to be in a room unmasked with an unvaccinated person who did not have risk factors for becoming severely ill with COVID. Was this the green light that psychiatrists were waiting for? Was there new data about transmission, or was this part of the CDC’s effort to make vaccines more desirable?

Michael Chang, MD, is a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. We spoke 2 days after the CDC interim guidelines were released. Dr. Chang was optimistic.

“, including data about variants and about transmission. At some point, however, the risk is low enough, and we should probably start thinking about going back to in-person visits,” Dr. Chang said. He said he personally would feel safe meeting unmasked with a vaccinated patient, but noted that his institution still requires doctors to wear masks. “Most vaccinations reduce transmission of illness,” Dr. Chang said, “but SARS-CoV-2 continues to surprise us in many ways.”

Katelyn Jetelina, PhD, MPH, an epidemiologist at the University of Texas School of Public Health in Dallas, distributes a newsletter, “Your Local Epidemiologist,” where she discusses data pertaining to the pandemic. In her newsletter dated March 14, 2021, Dr. Jetelina wrote, “There are now 7 sub-studies/press releases that confirm a 50-95% reduced transmission after vaccination. This is a big range, which is typical for such drastically different scientific studies. Variability is likely due to different sample sizes, locations, vaccines, genetics, cultures, etc. It will be a while until we know the ‘true’ percentage for each vaccine.”

Leslie Walker, MD, is a fully vaccinated psychiatrist in private practice in Shaker Heights, Ohio. She has recently started seeing fully vaccinated patients in person.

“So far it’s only 1 or 2 patients a day. I’m leaving it up to the patient. If they prefer masks, we stay masked. I may reverse course, depending on what information comes out.” She went on to note, “There are benefits to being able to see someone’s full facial expressions and whether they match someone’s words and body language, so the benefit of “unmasking” extends beyond comfort and convenience and must be balanced against the theoretical risk of COVID exposure in the room.”

While the CDC has now said it is safe to meet, the state health departments also have guidelines for medical practices, and everyone is still worried about vulnerable people in their households and potential spread to the community at large.

In Maryland, where I work, Aliya Jones, MD, MBA, is the head of the Behavioral Health Administration (BHA) for the Maryland Department of Health. “It remains risky to not wear masks, however, the risk is low when both individuals are vaccinated,” Dr. Jones wrote. “BHA is not recommending that providers see clients without both parties wearing a mask. All of our general practice recommendations for infection control are unchanged. People should be screened before entering clinical practices and persons who are symptomatic, whether vaccinated or not, should not be seen face-to-face, except in cases of an emergency, in which case additional precautions should be taken.”

So is it safe for a fully-vaccinated psychiatrist to have a session with a fully-vaccinated patient sitting 8 feet apart without masks? I’m left with the idea that it is for those two people, but when it comes to unvaccinated people in their households, we want more certainty than we currently have. The messaging remains unclear. The CDC’s interim guidelines offer hope for a future, but the science is still catching up, and to feel safe enough, we may want to wait a little longer for more definitive data – or herd immunity – before we reveal our smiles.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

Congratulations, you’ve been vaccinated!

It’s been a year like no other, and outpatient psychiatrists turned to Zoom and other telemental health platforms to provide treatment for our patients. Offices sit empty as the dust lands and the plants wilt. Perhaps a few patients are seen in person, masked and carefully distanced, after health screening and temperature checks, with surfaces sanitized between visits, all in accordance with health department regulations. But now the vaccine offers both safety and the promise of a return to a new normal, one that is certain to look different from the normal that was left behind.

I have been vaccinated and many of my patients have also been vaccinated. I began to wonder if it was safe to start seeing patients in person; could I see fully vaccinated patients, unmasked and without temperature checks and sanitizing? I started asking this question in February, and the response I got then was that it was too soon to tell; we did not have any data on whether vaccinated people could transmit the novel coronavirus. Two vaccinated people might be at risk of transmitting the virus and then infecting others, and the question of whether the vaccines would protect against illness caused by variants remained. Preliminary data out of Israel indicated that the vaccine did reduce transmission, but no one was saying that it was fine to see patients without masks, and video-conferencing remained the safest option.

On Monday, March 8, 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released long-awaited interim public health guidelines for fully vaccinated people. The guidelines allowed for two vaccinated people to be in a room together unmasked, and for a fully-vaccinated person to be in a room unmasked with an unvaccinated person who did not have risk factors for becoming severely ill with COVID. Was this the green light that psychiatrists were waiting for? Was there new data about transmission, or was this part of the CDC’s effort to make vaccines more desirable?

Michael Chang, MD, is a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. We spoke 2 days after the CDC interim guidelines were released. Dr. Chang was optimistic.

“, including data about variants and about transmission. At some point, however, the risk is low enough, and we should probably start thinking about going back to in-person visits,” Dr. Chang said. He said he personally would feel safe meeting unmasked with a vaccinated patient, but noted that his institution still requires doctors to wear masks. “Most vaccinations reduce transmission of illness,” Dr. Chang said, “but SARS-CoV-2 continues to surprise us in many ways.”

Katelyn Jetelina, PhD, MPH, an epidemiologist at the University of Texas School of Public Health in Dallas, distributes a newsletter, “Your Local Epidemiologist,” where she discusses data pertaining to the pandemic. In her newsletter dated March 14, 2021, Dr. Jetelina wrote, “There are now 7 sub-studies/press releases that confirm a 50-95% reduced transmission after vaccination. This is a big range, which is typical for such drastically different scientific studies. Variability is likely due to different sample sizes, locations, vaccines, genetics, cultures, etc. It will be a while until we know the ‘true’ percentage for each vaccine.”

Leslie Walker, MD, is a fully vaccinated psychiatrist in private practice in Shaker Heights, Ohio. She has recently started seeing fully vaccinated patients in person.

“So far it’s only 1 or 2 patients a day. I’m leaving it up to the patient. If they prefer masks, we stay masked. I may reverse course, depending on what information comes out.” She went on to note, “There are benefits to being able to see someone’s full facial expressions and whether they match someone’s words and body language, so the benefit of “unmasking” extends beyond comfort and convenience and must be balanced against the theoretical risk of COVID exposure in the room.”

While the CDC has now said it is safe to meet, the state health departments also have guidelines for medical practices, and everyone is still worried about vulnerable people in their households and potential spread to the community at large.

In Maryland, where I work, Aliya Jones, MD, MBA, is the head of the Behavioral Health Administration (BHA) for the Maryland Department of Health. “It remains risky to not wear masks, however, the risk is low when both individuals are vaccinated,” Dr. Jones wrote. “BHA is not recommending that providers see clients without both parties wearing a mask. All of our general practice recommendations for infection control are unchanged. People should be screened before entering clinical practices and persons who are symptomatic, whether vaccinated or not, should not be seen face-to-face, except in cases of an emergency, in which case additional precautions should be taken.”

So is it safe for a fully-vaccinated psychiatrist to have a session with a fully-vaccinated patient sitting 8 feet apart without masks? I’m left with the idea that it is for those two people, but when it comes to unvaccinated people in their households, we want more certainty than we currently have. The messaging remains unclear. The CDC’s interim guidelines offer hope for a future, but the science is still catching up, and to feel safe enough, we may want to wait a little longer for more definitive data – or herd immunity – before we reveal our smiles.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

Congratulations, you’ve been vaccinated!

It’s been a year like no other, and outpatient psychiatrists turned to Zoom and other telemental health platforms to provide treatment for our patients. Offices sit empty as the dust lands and the plants wilt. Perhaps a few patients are seen in person, masked and carefully distanced, after health screening and temperature checks, with surfaces sanitized between visits, all in accordance with health department regulations. But now the vaccine offers both safety and the promise of a return to a new normal, one that is certain to look different from the normal that was left behind.

I have been vaccinated and many of my patients have also been vaccinated. I began to wonder if it was safe to start seeing patients in person; could I see fully vaccinated patients, unmasked and without temperature checks and sanitizing? I started asking this question in February, and the response I got then was that it was too soon to tell; we did not have any data on whether vaccinated people could transmit the novel coronavirus. Two vaccinated people might be at risk of transmitting the virus and then infecting others, and the question of whether the vaccines would protect against illness caused by variants remained. Preliminary data out of Israel indicated that the vaccine did reduce transmission, but no one was saying that it was fine to see patients without masks, and video-conferencing remained the safest option.

On Monday, March 8, 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released long-awaited interim public health guidelines for fully vaccinated people. The guidelines allowed for two vaccinated people to be in a room together unmasked, and for a fully-vaccinated person to be in a room unmasked with an unvaccinated person who did not have risk factors for becoming severely ill with COVID. Was this the green light that psychiatrists were waiting for? Was there new data about transmission, or was this part of the CDC’s effort to make vaccines more desirable?

Michael Chang, MD, is a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. We spoke 2 days after the CDC interim guidelines were released. Dr. Chang was optimistic.

“, including data about variants and about transmission. At some point, however, the risk is low enough, and we should probably start thinking about going back to in-person visits,” Dr. Chang said. He said he personally would feel safe meeting unmasked with a vaccinated patient, but noted that his institution still requires doctors to wear masks. “Most vaccinations reduce transmission of illness,” Dr. Chang said, “but SARS-CoV-2 continues to surprise us in many ways.”

Katelyn Jetelina, PhD, MPH, an epidemiologist at the University of Texas School of Public Health in Dallas, distributes a newsletter, “Your Local Epidemiologist,” where she discusses data pertaining to the pandemic. In her newsletter dated March 14, 2021, Dr. Jetelina wrote, “There are now 7 sub-studies/press releases that confirm a 50-95% reduced transmission after vaccination. This is a big range, which is typical for such drastically different scientific studies. Variability is likely due to different sample sizes, locations, vaccines, genetics, cultures, etc. It will be a while until we know the ‘true’ percentage for each vaccine.”

Leslie Walker, MD, is a fully vaccinated psychiatrist in private practice in Shaker Heights, Ohio. She has recently started seeing fully vaccinated patients in person.

“So far it’s only 1 or 2 patients a day. I’m leaving it up to the patient. If they prefer masks, we stay masked. I may reverse course, depending on what information comes out.” She went on to note, “There are benefits to being able to see someone’s full facial expressions and whether they match someone’s words and body language, so the benefit of “unmasking” extends beyond comfort and convenience and must be balanced against the theoretical risk of COVID exposure in the room.”

While the CDC has now said it is safe to meet, the state health departments also have guidelines for medical practices, and everyone is still worried about vulnerable people in their households and potential spread to the community at large.

In Maryland, where I work, Aliya Jones, MD, MBA, is the head of the Behavioral Health Administration (BHA) for the Maryland Department of Health. “It remains risky to not wear masks, however, the risk is low when both individuals are vaccinated,” Dr. Jones wrote. “BHA is not recommending that providers see clients without both parties wearing a mask. All of our general practice recommendations for infection control are unchanged. People should be screened before entering clinical practices and persons who are symptomatic, whether vaccinated or not, should not be seen face-to-face, except in cases of an emergency, in which case additional precautions should be taken.”

So is it safe for a fully-vaccinated psychiatrist to have a session with a fully-vaccinated patient sitting 8 feet apart without masks? I’m left with the idea that it is for those two people, but when it comes to unvaccinated people in their households, we want more certainty than we currently have. The messaging remains unclear. The CDC’s interim guidelines offer hope for a future, but the science is still catching up, and to feel safe enough, we may want to wait a little longer for more definitive data – or herd immunity – before we reveal our smiles.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

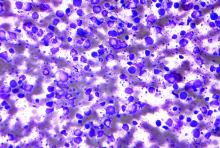

High-dose chemo no better than standard dose for B-cell lymphoma

After 10 years of follow-up, event-free survival and overall survival were similar between conventional chemotherapy treated patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma and those receiving high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT), according to a report published online in the Lancet Hematology.

The open-label, randomized, phase 3 trial (NCT00129090) was conducted across 61 centers in Germany on patients aged 18-60 years who had newly diagnosed, high-risk, aggressive B-cell lymphoma, according to Fabian Frontzek, MD, of the University Hospital Münster (Germany) and colleagues.

Between March 2003 and April 2009, patients were randomly assigned to eight cycles of conventional chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, etoposide, and prednisolone) plus rituximab (R-CHOEP-14) or four cycles of high-dose chemotherapy plus rituximab followed by autologous HSCT (R-MegaCHOEP). The intention-to-treat population comprised 130 patients in the R-CHOEP-14 group and 132 patients in the R-MegaCHOEP group. The median follow-up was 9.3 years.

Similar outcomes

The 10-year event-free survival was 51% in the R-MegaCHOEP group and 57% in the R-CHOEP-14 group, a nonsignificant difference (P = .23). Similarly, the 10-year progression-free survival was 59% in the

R-MegaCHOEP group and 60% (P = .64). The 10-year overall survival was 66% in the R-MegaCHOEP group and 72% in the R-CHOEP-14 group (P = .26). Among the 190 patients who had complete remission or unconfirmed complete remission, relapse occurred in 30 (16%); 17 (17%) of 100 patients in the R-CHOEP-14 group and 13 (14%) of 90 patients in the R-MegaCHOEP group.

In terms of secondary malignancies, 22 were reported in the intention-to-treat population; comprising 12 (9%) of 127 patients in the R-CHOEP-14 group and 10 (8%) of 126 patients in the R-MegaCHOEP group.

Patients who relapsed with aggressive histology and with CNS involvement in particular had worse outcomes and “represent a group with an unmet medical need, for which new molecular and cellular therapies should be studied,” the authors stated.

“This study shows that, in the rituximab era, high-dose therapy and autologous HSCT in first-line treatment does not improve long-term survival of younger high-risk patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma. The R-CHOEP-14 regimen led to favorable outcomes, supporting its continued use in such patients,” the researchers concluded.

In an accompanying commentary, Gita Thanarajasingam, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues added that the issue of long-term outcomes is critical to evaluating these new regimens.

They applauded the inclusion of secondary malignancies in the long-term follow-up, but regretted the lack of the, admittedly resource-intensive, information on long-term nonneoplastic adverse events. They added that “the burden of late adverse events such as cardiotoxicity, cumulative neuropathy, delayed infections, or lasting cognitive effects, among others that might drive substantial morbidity, does matter to lymphoma survivors.”

They also commented on the importance of considering effects on fertility in these patients, noting that R-MegaCHOEP patients would be unable to conceive naturally, but that the effect of R-CHOEP-14 was less clear.

“We encourage ongoing emphasis on this type of longitudinal follow-up of secondary malignancies and other nonneoplastic late toxicities in phase 3 studies as well as in the real world in hematological malignancies, so that after prioritizing cure in the front-line setting, we do not neglect the life we have helped survivors achieve for years and decades to come,” they concluded.

The study was sponsored by the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Study Group. The authors reported grants, personal fees, and non-financial support from multiple pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies. Dr. Thanarajasingam and her colleagues reported that they had no competing interests.

After 10 years of follow-up, event-free survival and overall survival were similar between conventional chemotherapy treated patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma and those receiving high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT), according to a report published online in the Lancet Hematology.

The open-label, randomized, phase 3 trial (NCT00129090) was conducted across 61 centers in Germany on patients aged 18-60 years who had newly diagnosed, high-risk, aggressive B-cell lymphoma, according to Fabian Frontzek, MD, of the University Hospital Münster (Germany) and colleagues.

Between March 2003 and April 2009, patients were randomly assigned to eight cycles of conventional chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, etoposide, and prednisolone) plus rituximab (R-CHOEP-14) or four cycles of high-dose chemotherapy plus rituximab followed by autologous HSCT (R-MegaCHOEP). The intention-to-treat population comprised 130 patients in the R-CHOEP-14 group and 132 patients in the R-MegaCHOEP group. The median follow-up was 9.3 years.

Similar outcomes

The 10-year event-free survival was 51% in the R-MegaCHOEP group and 57% in the R-CHOEP-14 group, a nonsignificant difference (P = .23). Similarly, the 10-year progression-free survival was 59% in the

R-MegaCHOEP group and 60% (P = .64). The 10-year overall survival was 66% in the R-MegaCHOEP group and 72% in the R-CHOEP-14 group (P = .26). Among the 190 patients who had complete remission or unconfirmed complete remission, relapse occurred in 30 (16%); 17 (17%) of 100 patients in the R-CHOEP-14 group and 13 (14%) of 90 patients in the R-MegaCHOEP group.

In terms of secondary malignancies, 22 were reported in the intention-to-treat population; comprising 12 (9%) of 127 patients in the R-CHOEP-14 group and 10 (8%) of 126 patients in the R-MegaCHOEP group.

Patients who relapsed with aggressive histology and with CNS involvement in particular had worse outcomes and “represent a group with an unmet medical need, for which new molecular and cellular therapies should be studied,” the authors stated.

“This study shows that, in the rituximab era, high-dose therapy and autologous HSCT in first-line treatment does not improve long-term survival of younger high-risk patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma. The R-CHOEP-14 regimen led to favorable outcomes, supporting its continued use in such patients,” the researchers concluded.

In an accompanying commentary, Gita Thanarajasingam, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues added that the issue of long-term outcomes is critical to evaluating these new regimens.

They applauded the inclusion of secondary malignancies in the long-term follow-up, but regretted the lack of the, admittedly resource-intensive, information on long-term nonneoplastic adverse events. They added that “the burden of late adverse events such as cardiotoxicity, cumulative neuropathy, delayed infections, or lasting cognitive effects, among others that might drive substantial morbidity, does matter to lymphoma survivors.”

They also commented on the importance of considering effects on fertility in these patients, noting that R-MegaCHOEP patients would be unable to conceive naturally, but that the effect of R-CHOEP-14 was less clear.

“We encourage ongoing emphasis on this type of longitudinal follow-up of secondary malignancies and other nonneoplastic late toxicities in phase 3 studies as well as in the real world in hematological malignancies, so that after prioritizing cure in the front-line setting, we do not neglect the life we have helped survivors achieve for years and decades to come,” they concluded.

The study was sponsored by the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Study Group. The authors reported grants, personal fees, and non-financial support from multiple pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies. Dr. Thanarajasingam and her colleagues reported that they had no competing interests.

After 10 years of follow-up, event-free survival and overall survival were similar between conventional chemotherapy treated patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma and those receiving high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT), according to a report published online in the Lancet Hematology.

The open-label, randomized, phase 3 trial (NCT00129090) was conducted across 61 centers in Germany on patients aged 18-60 years who had newly diagnosed, high-risk, aggressive B-cell lymphoma, according to Fabian Frontzek, MD, of the University Hospital Münster (Germany) and colleagues.

Between March 2003 and April 2009, patients were randomly assigned to eight cycles of conventional chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, etoposide, and prednisolone) plus rituximab (R-CHOEP-14) or four cycles of high-dose chemotherapy plus rituximab followed by autologous HSCT (R-MegaCHOEP). The intention-to-treat population comprised 130 patients in the R-CHOEP-14 group and 132 patients in the R-MegaCHOEP group. The median follow-up was 9.3 years.

Similar outcomes

The 10-year event-free survival was 51% in the R-MegaCHOEP group and 57% in the R-CHOEP-14 group, a nonsignificant difference (P = .23). Similarly, the 10-year progression-free survival was 59% in the

R-MegaCHOEP group and 60% (P = .64). The 10-year overall survival was 66% in the R-MegaCHOEP group and 72% in the R-CHOEP-14 group (P = .26). Among the 190 patients who had complete remission or unconfirmed complete remission, relapse occurred in 30 (16%); 17 (17%) of 100 patients in the R-CHOEP-14 group and 13 (14%) of 90 patients in the R-MegaCHOEP group.

In terms of secondary malignancies, 22 were reported in the intention-to-treat population; comprising 12 (9%) of 127 patients in the R-CHOEP-14 group and 10 (8%) of 126 patients in the R-MegaCHOEP group.

Patients who relapsed with aggressive histology and with CNS involvement in particular had worse outcomes and “represent a group with an unmet medical need, for which new molecular and cellular therapies should be studied,” the authors stated.

“This study shows that, in the rituximab era, high-dose therapy and autologous HSCT in first-line treatment does not improve long-term survival of younger high-risk patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma. The R-CHOEP-14 regimen led to favorable outcomes, supporting its continued use in such patients,” the researchers concluded.

In an accompanying commentary, Gita Thanarajasingam, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues added that the issue of long-term outcomes is critical to evaluating these new regimens.

They applauded the inclusion of secondary malignancies in the long-term follow-up, but regretted the lack of the, admittedly resource-intensive, information on long-term nonneoplastic adverse events. They added that “the burden of late adverse events such as cardiotoxicity, cumulative neuropathy, delayed infections, or lasting cognitive effects, among others that might drive substantial morbidity, does matter to lymphoma survivors.”

They also commented on the importance of considering effects on fertility in these patients, noting that R-MegaCHOEP patients would be unable to conceive naturally, but that the effect of R-CHOEP-14 was less clear.

“We encourage ongoing emphasis on this type of longitudinal follow-up of secondary malignancies and other nonneoplastic late toxicities in phase 3 studies as well as in the real world in hematological malignancies, so that after prioritizing cure in the front-line setting, we do not neglect the life we have helped survivors achieve for years and decades to come,” they concluded.

The study was sponsored by the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Study Group. The authors reported grants, personal fees, and non-financial support from multiple pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies. Dr. Thanarajasingam and her colleagues reported that they had no competing interests.

FROM THE LANCET HEMATOLOGY

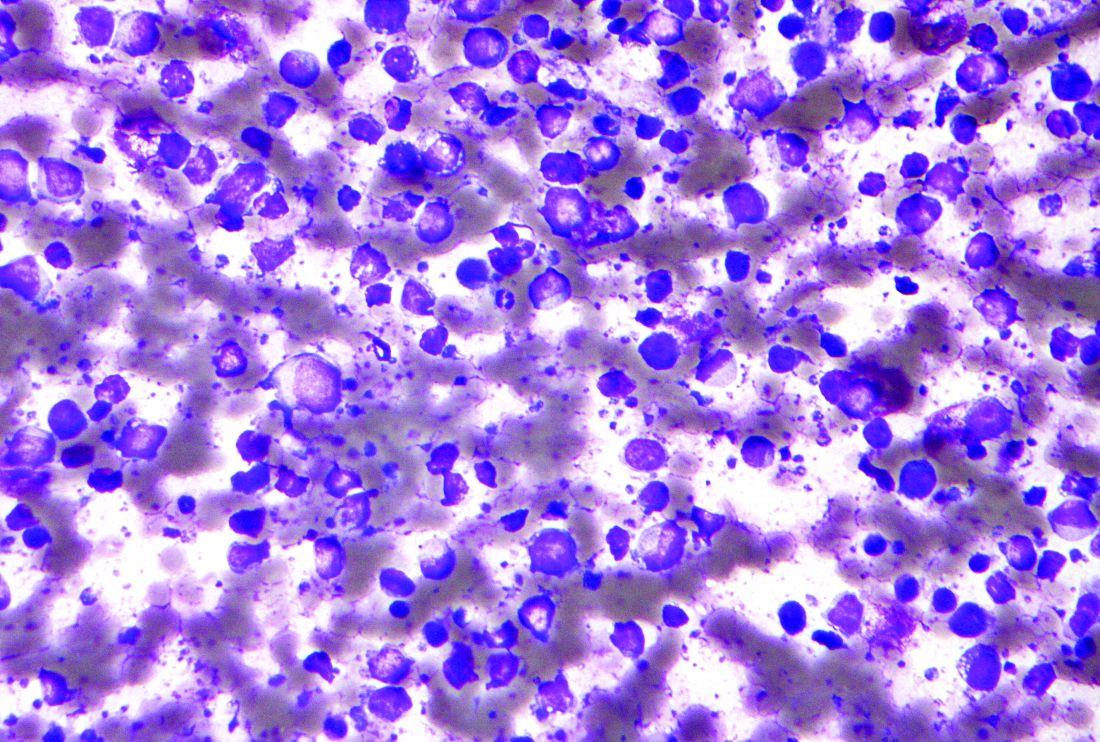

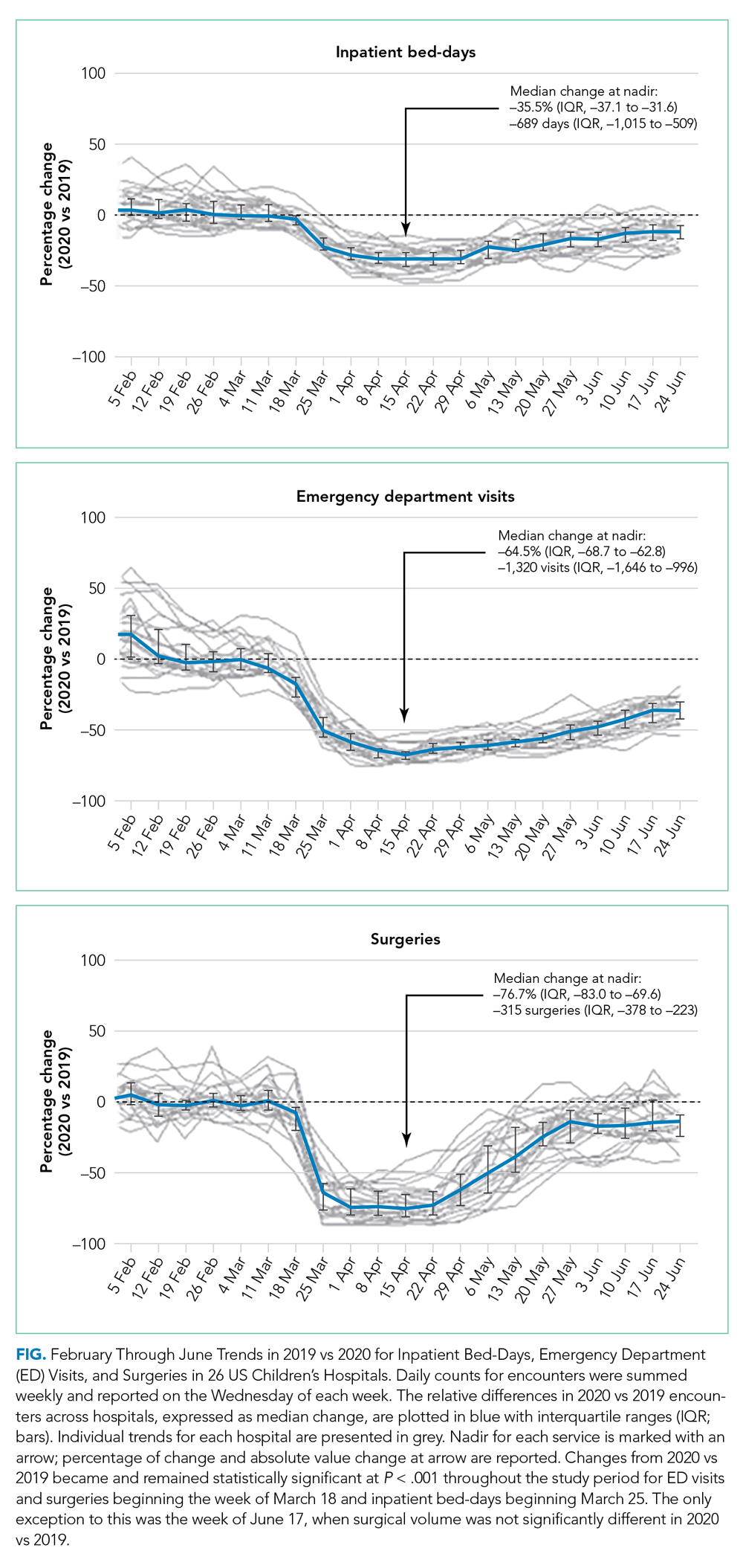

Healthcare Encounter and Financial Impact of COVID-19 on Children’s Hospitals

To benefit patients and the public health of their communities, children’s hospitals across the United States prepared for and responded to COVID-19 by conserving personal protective equipment, suspending noncritical in-person healthcare encounters (including outpatient visits and elective surgeries), and implementing socially distanced essential care.1,2 These measures were promptly instituted during a time of both substantial uncertainty about the pandemic’s behavior in children—including its severity and duration—and extreme variation in local and state governments’ responses to the pandemic.

Congruent with other healthcare institutions, children’s hospitals calibrated their clinical operations to the evolving nature of the pandemic, prioritizing the safety of patients and staff while striving to maintain financial viability in the setting of increased costs and decreased revenue. In some cases, children’s hospitals aided adult hospitals and health systems by admitting young and middle-aged adult patients and by centralizing all pediatric patients requiring intensive care within a region. These efforts occurred while many children’s hospitals remained the sole source of specialized pediatric care, including care for rare complex health problems.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, there is a critical need to assess how the initial phase of the pandemic affected healthcare encounters and related finances in children’s hospitals. Understanding these trends will position children’s hospitals to project and prepare for subsequent COVID-19 surges, as well as future related public health crises that necessitate widespread social distancing. Therefore, we compared year-over-year trends in healthcare encounters and hospital charges across US children’s hospitals before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on the beginning of COVID-19 in the United States, which was defined as February through June 2020.

METHODS

This is a retrospective analysis of 26 children’s hospitals (22 freestanding, 4 nonfreestanding) from all US regions (12 South, 7 Midwest, 5 West, 2 Northeast) contributing encounter and financial data to the PROSPECT database (Children’s Hospital Association, Lenexa, Kansas) from February 1 to June 30 in both 2019 (before COVID-19) and 2020 (during COVID-19). In response to COVID-19, hospitals participating in PROSPECT increased the efficiency of data centralization and reporting in 2020 during the period February 1 to June 30 to expedite analysis and dissemination of findings.

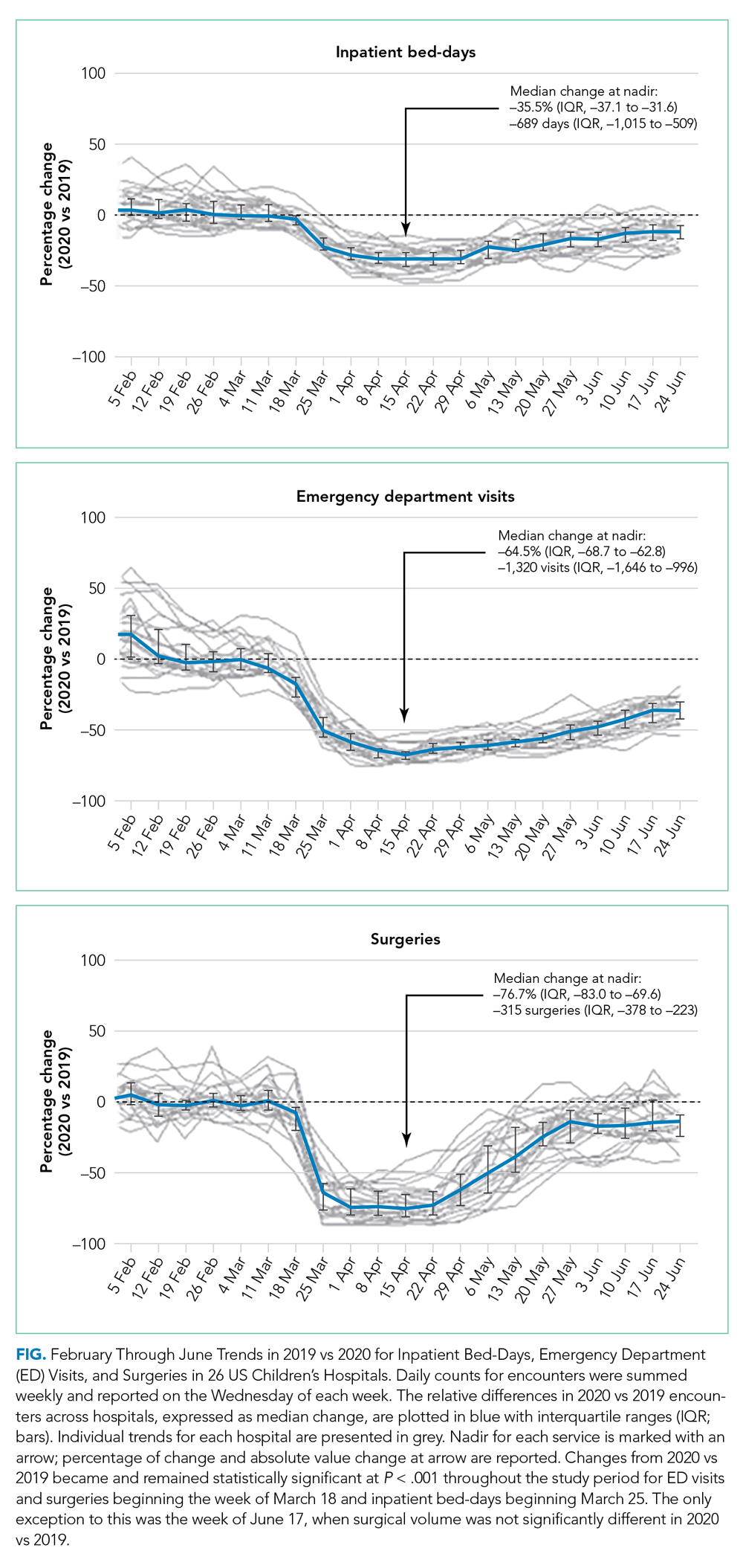

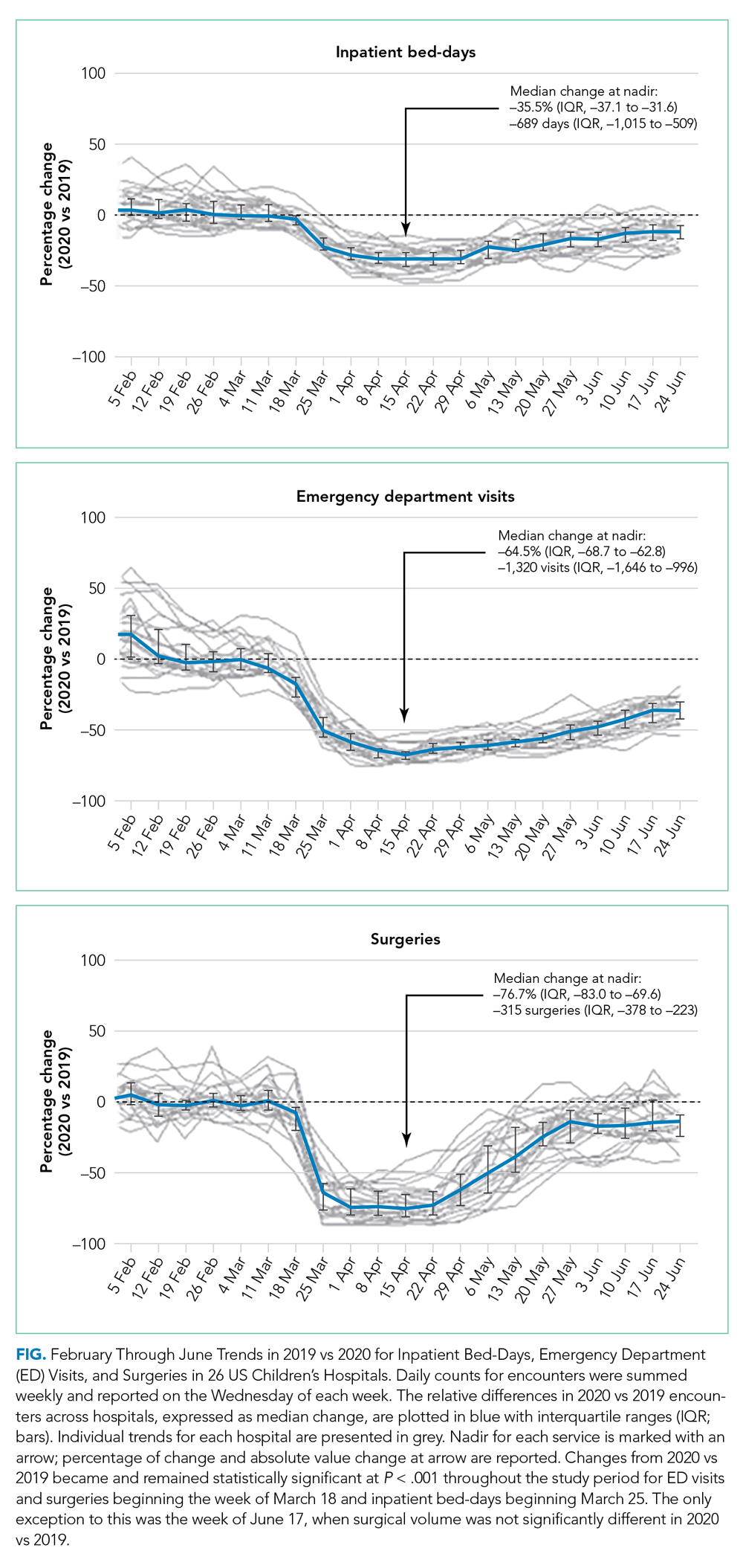

The main outcome measures were the percentage of change in weekly encounters (inpatient bed-days, emergency department [ED] visits, and surgeries) and inflation-adjusted charges (categorized as inpatient care and outpatient care, such as ambulatory surgery, clinics, and ED visits) before vs during COVID-19.

RESULTS

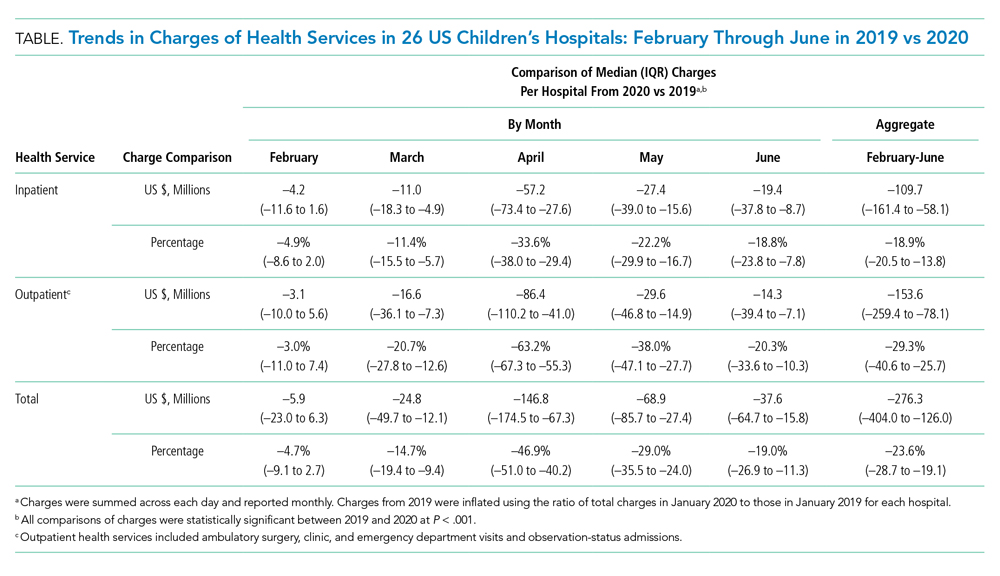

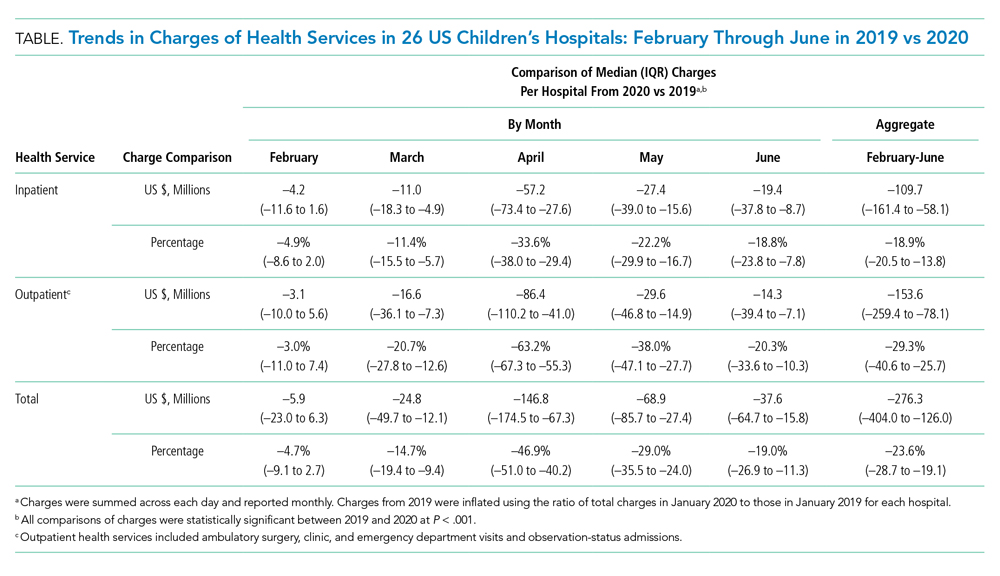

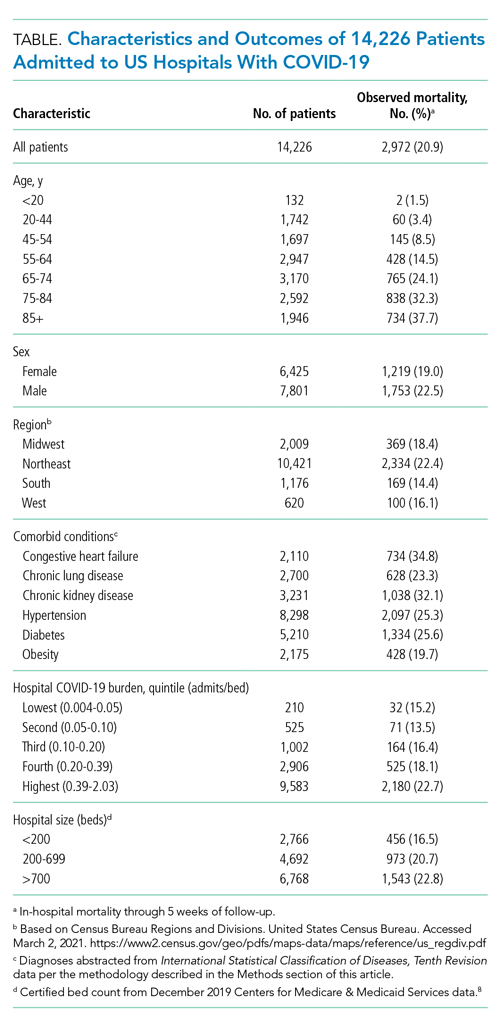

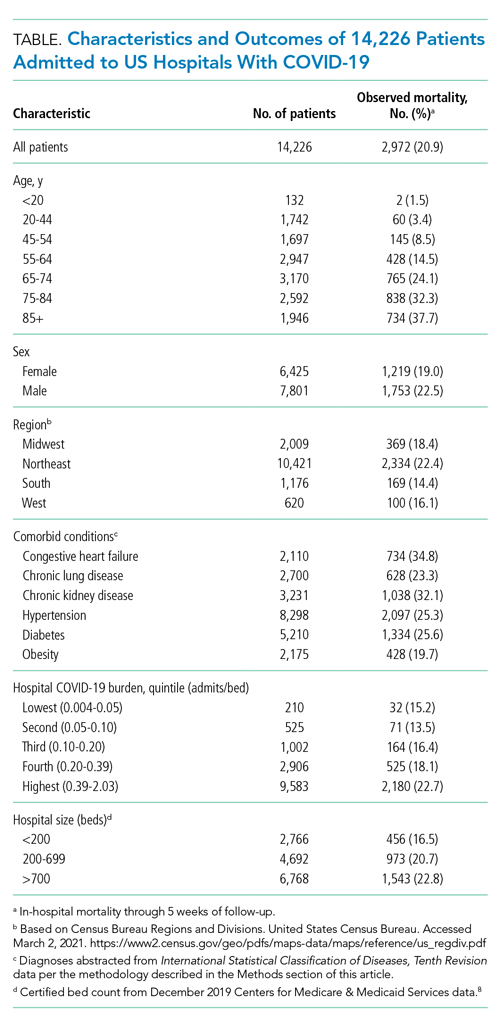

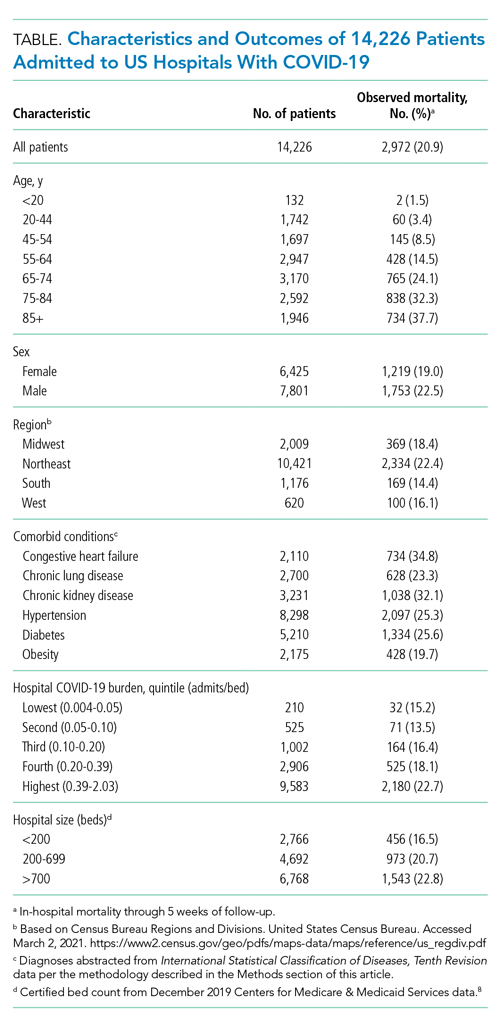

Charges that accrued from February 1 to June 30 were lower in 2020 by a median 23.6% (IQR, –28.7% to –19.1%) per children’s hospital than they were in 2019, corresponding to a median decrease of $276.3 million (IQR, $404.0-$126.0 million) in charges per hospital (Table). Forty percent of this decrease was attributable to decreased charges resulting from fewer inpatient healthcare encounters.

DISCUSSION

These findings beg the question of how well children’s hospitals are positioned to weather a recurrent surge in COVID-19. Because the severity of illness of COVID-19 has been lower to date in the pediatric vs adult populations, an increase in COVID-19-related visits to EDs and admissions to offset the decreased resource use of other pediatric healthcare problems is not anticipated. Existing hospital financial reserves as well as federal aid from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act that helped mitigate the initial encounter and financial losses during the beginning of COVID-19 may not be readily available over time.4,5 Certainly, the findings from the current study support continued lobbying for additional state and federal funds allocated through future relief packages to children’s hospitals.

Additional approaches to financial solvency in children’s hospitals during the sustained COVID-19 pandemic include addressing surgical backlogs and sharing best practices for safe and sustained reopening of clinical operations and financial practices across institutions. Although the PROSPECT database does not contain information on the types of surgeries present within this backlog, our experiences suggest that both same-day and inpatient elective surgeries have been affected, especially lengthy procedures (eg, spinal fusion for neuromuscular scoliosis). Spread and scale of feasible and efficient solutions to reengineer and expand patient capacities and throughput for operating rooms, postanesthesia recovery areas, and intensive care and floor units are needed. Enhanced analytics that accurately predict postoperative length of hospital stay, coupled with early recovery after surgery clinical protocols, could help optimize hospital bed management. Effective ways to convert hospital rooms from single to double occupancy, to manage family visitation, and to proactively test asymptomatic patients, family, and hospital staff will mitigate continued COVID-19 penetration through children’s hospitals.

One important limitation of the current study is the measurement of hospitals’ charges. The charge data were not positioned to comprehensively measure each hospital’s financial state during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the decrease in hospital charges reported by the children’s hospitals in the current study is comparable with the financial losses reported for many adult hospitals during the pandemic.6,7

CONCLUSION

Children’s hospitals’ ability to serve the nation’s pediatric patients depends on the success of the hospitals’ plans to manage current and future COVID-19 surges and to reopen and recover from the surges that have passed. Additional investigation is needed to identify best operational and financial practices among children’s hospitals that have enabled them to endure the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. COVID-19: ways to prepare your children’s hospital now. Children’s Hospital Association. March 12, 2020. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.childrenshospitals.org/Newsroom/Childrens-Hospitals-Today/Articles/2020/03/COVID-19-11-Ways-to-Prepare-Your-Hospital-Now

2. Chopra V, Toner E, Waldhorn R, Washer L. How should U.S. hospitals prepare for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)? Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):621-622. https://doi.org/10.7326/m20-0907

3. Oseran AS, Nash D, Kim C, et al. Changes in hospital admissions for urgent conditions during COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(8):327-328. https://doi.org/10.37765/ajmc.2020.43837

4. Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act or the CARES Act. 15 USC Chapter 116 (2020). Pub L No. 116-36, 134 Stat 281. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748

5. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act Provider Relief Fund: general information. US Department of Health & Human Services. June 25, 2020. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.hhs.gov/coronavirus/cares-act-provider-relief-fund/general-information/index.html

6. Hospitals and health systems face unprecedented financial pressures due to COVID-19. American Hospital Association. May 2020. Accessed July 13, 2020. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2020/05/aha-covid19-financial-impact-0520-FINAL.pdf

7. Birkmeyer J, Barnato A, Birkmeyer N, Bessler R, Skinner J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital admissions in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(11):2010-2017. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00980

To benefit patients and the public health of their communities, children’s hospitals across the United States prepared for and responded to COVID-19 by conserving personal protective equipment, suspending noncritical in-person healthcare encounters (including outpatient visits and elective surgeries), and implementing socially distanced essential care.1,2 These measures were promptly instituted during a time of both substantial uncertainty about the pandemic’s behavior in children—including its severity and duration—and extreme variation in local and state governments’ responses to the pandemic.

Congruent with other healthcare institutions, children’s hospitals calibrated their clinical operations to the evolving nature of the pandemic, prioritizing the safety of patients and staff while striving to maintain financial viability in the setting of increased costs and decreased revenue. In some cases, children’s hospitals aided adult hospitals and health systems by admitting young and middle-aged adult patients and by centralizing all pediatric patients requiring intensive care within a region. These efforts occurred while many children’s hospitals remained the sole source of specialized pediatric care, including care for rare complex health problems.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, there is a critical need to assess how the initial phase of the pandemic affected healthcare encounters and related finances in children’s hospitals. Understanding these trends will position children’s hospitals to project and prepare for subsequent COVID-19 surges, as well as future related public health crises that necessitate widespread social distancing. Therefore, we compared year-over-year trends in healthcare encounters and hospital charges across US children’s hospitals before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on the beginning of COVID-19 in the United States, which was defined as February through June 2020.

METHODS

This is a retrospective analysis of 26 children’s hospitals (22 freestanding, 4 nonfreestanding) from all US regions (12 South, 7 Midwest, 5 West, 2 Northeast) contributing encounter and financial data to the PROSPECT database (Children’s Hospital Association, Lenexa, Kansas) from February 1 to June 30 in both 2019 (before COVID-19) and 2020 (during COVID-19). In response to COVID-19, hospitals participating in PROSPECT increased the efficiency of data centralization and reporting in 2020 during the period February 1 to June 30 to expedite analysis and dissemination of findings.

The main outcome measures were the percentage of change in weekly encounters (inpatient bed-days, emergency department [ED] visits, and surgeries) and inflation-adjusted charges (categorized as inpatient care and outpatient care, such as ambulatory surgery, clinics, and ED visits) before vs during COVID-19.

RESULTS

Charges that accrued from February 1 to June 30 were lower in 2020 by a median 23.6% (IQR, –28.7% to –19.1%) per children’s hospital than they were in 2019, corresponding to a median decrease of $276.3 million (IQR, $404.0-$126.0 million) in charges per hospital (Table). Forty percent of this decrease was attributable to decreased charges resulting from fewer inpatient healthcare encounters.

DISCUSSION

These findings beg the question of how well children’s hospitals are positioned to weather a recurrent surge in COVID-19. Because the severity of illness of COVID-19 has been lower to date in the pediatric vs adult populations, an increase in COVID-19-related visits to EDs and admissions to offset the decreased resource use of other pediatric healthcare problems is not anticipated. Existing hospital financial reserves as well as federal aid from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act that helped mitigate the initial encounter and financial losses during the beginning of COVID-19 may not be readily available over time.4,5 Certainly, the findings from the current study support continued lobbying for additional state and federal funds allocated through future relief packages to children’s hospitals.

Additional approaches to financial solvency in children’s hospitals during the sustained COVID-19 pandemic include addressing surgical backlogs and sharing best practices for safe and sustained reopening of clinical operations and financial practices across institutions. Although the PROSPECT database does not contain information on the types of surgeries present within this backlog, our experiences suggest that both same-day and inpatient elective surgeries have been affected, especially lengthy procedures (eg, spinal fusion for neuromuscular scoliosis). Spread and scale of feasible and efficient solutions to reengineer and expand patient capacities and throughput for operating rooms, postanesthesia recovery areas, and intensive care and floor units are needed. Enhanced analytics that accurately predict postoperative length of hospital stay, coupled with early recovery after surgery clinical protocols, could help optimize hospital bed management. Effective ways to convert hospital rooms from single to double occupancy, to manage family visitation, and to proactively test asymptomatic patients, family, and hospital staff will mitigate continued COVID-19 penetration through children’s hospitals.

One important limitation of the current study is the measurement of hospitals’ charges. The charge data were not positioned to comprehensively measure each hospital’s financial state during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the decrease in hospital charges reported by the children’s hospitals in the current study is comparable with the financial losses reported for many adult hospitals during the pandemic.6,7

CONCLUSION

Children’s hospitals’ ability to serve the nation’s pediatric patients depends on the success of the hospitals’ plans to manage current and future COVID-19 surges and to reopen and recover from the surges that have passed. Additional investigation is needed to identify best operational and financial practices among children’s hospitals that have enabled them to endure the COVID-19 pandemic.

To benefit patients and the public health of their communities, children’s hospitals across the United States prepared for and responded to COVID-19 by conserving personal protective equipment, suspending noncritical in-person healthcare encounters (including outpatient visits and elective surgeries), and implementing socially distanced essential care.1,2 These measures were promptly instituted during a time of both substantial uncertainty about the pandemic’s behavior in children—including its severity and duration—and extreme variation in local and state governments’ responses to the pandemic.

Congruent with other healthcare institutions, children’s hospitals calibrated their clinical operations to the evolving nature of the pandemic, prioritizing the safety of patients and staff while striving to maintain financial viability in the setting of increased costs and decreased revenue. In some cases, children’s hospitals aided adult hospitals and health systems by admitting young and middle-aged adult patients and by centralizing all pediatric patients requiring intensive care within a region. These efforts occurred while many children’s hospitals remained the sole source of specialized pediatric care, including care for rare complex health problems.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, there is a critical need to assess how the initial phase of the pandemic affected healthcare encounters and related finances in children’s hospitals. Understanding these trends will position children’s hospitals to project and prepare for subsequent COVID-19 surges, as well as future related public health crises that necessitate widespread social distancing. Therefore, we compared year-over-year trends in healthcare encounters and hospital charges across US children’s hospitals before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on the beginning of COVID-19 in the United States, which was defined as February through June 2020.

METHODS

This is a retrospective analysis of 26 children’s hospitals (22 freestanding, 4 nonfreestanding) from all US regions (12 South, 7 Midwest, 5 West, 2 Northeast) contributing encounter and financial data to the PROSPECT database (Children’s Hospital Association, Lenexa, Kansas) from February 1 to June 30 in both 2019 (before COVID-19) and 2020 (during COVID-19). In response to COVID-19, hospitals participating in PROSPECT increased the efficiency of data centralization and reporting in 2020 during the period February 1 to June 30 to expedite analysis and dissemination of findings.

The main outcome measures were the percentage of change in weekly encounters (inpatient bed-days, emergency department [ED] visits, and surgeries) and inflation-adjusted charges (categorized as inpatient care and outpatient care, such as ambulatory surgery, clinics, and ED visits) before vs during COVID-19.

RESULTS

Charges that accrued from February 1 to June 30 were lower in 2020 by a median 23.6% (IQR, –28.7% to –19.1%) per children’s hospital than they were in 2019, corresponding to a median decrease of $276.3 million (IQR, $404.0-$126.0 million) in charges per hospital (Table). Forty percent of this decrease was attributable to decreased charges resulting from fewer inpatient healthcare encounters.

DISCUSSION

These findings beg the question of how well children’s hospitals are positioned to weather a recurrent surge in COVID-19. Because the severity of illness of COVID-19 has been lower to date in the pediatric vs adult populations, an increase in COVID-19-related visits to EDs and admissions to offset the decreased resource use of other pediatric healthcare problems is not anticipated. Existing hospital financial reserves as well as federal aid from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act that helped mitigate the initial encounter and financial losses during the beginning of COVID-19 may not be readily available over time.4,5 Certainly, the findings from the current study support continued lobbying for additional state and federal funds allocated through future relief packages to children’s hospitals.

Additional approaches to financial solvency in children’s hospitals during the sustained COVID-19 pandemic include addressing surgical backlogs and sharing best practices for safe and sustained reopening of clinical operations and financial practices across institutions. Although the PROSPECT database does not contain information on the types of surgeries present within this backlog, our experiences suggest that both same-day and inpatient elective surgeries have been affected, especially lengthy procedures (eg, spinal fusion for neuromuscular scoliosis). Spread and scale of feasible and efficient solutions to reengineer and expand patient capacities and throughput for operating rooms, postanesthesia recovery areas, and intensive care and floor units are needed. Enhanced analytics that accurately predict postoperative length of hospital stay, coupled with early recovery after surgery clinical protocols, could help optimize hospital bed management. Effective ways to convert hospital rooms from single to double occupancy, to manage family visitation, and to proactively test asymptomatic patients, family, and hospital staff will mitigate continued COVID-19 penetration through children’s hospitals.

One important limitation of the current study is the measurement of hospitals’ charges. The charge data were not positioned to comprehensively measure each hospital’s financial state during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the decrease in hospital charges reported by the children’s hospitals in the current study is comparable with the financial losses reported for many adult hospitals during the pandemic.6,7

CONCLUSION

Children’s hospitals’ ability to serve the nation’s pediatric patients depends on the success of the hospitals’ plans to manage current and future COVID-19 surges and to reopen and recover from the surges that have passed. Additional investigation is needed to identify best operational and financial practices among children’s hospitals that have enabled them to endure the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. COVID-19: ways to prepare your children’s hospital now. Children’s Hospital Association. March 12, 2020. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.childrenshospitals.org/Newsroom/Childrens-Hospitals-Today/Articles/2020/03/COVID-19-11-Ways-to-Prepare-Your-Hospital-Now

2. Chopra V, Toner E, Waldhorn R, Washer L. How should U.S. hospitals prepare for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)? Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):621-622. https://doi.org/10.7326/m20-0907

3. Oseran AS, Nash D, Kim C, et al. Changes in hospital admissions for urgent conditions during COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(8):327-328. https://doi.org/10.37765/ajmc.2020.43837

4. Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act or the CARES Act. 15 USC Chapter 116 (2020). Pub L No. 116-36, 134 Stat 281. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748

5. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act Provider Relief Fund: general information. US Department of Health & Human Services. June 25, 2020. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.hhs.gov/coronavirus/cares-act-provider-relief-fund/general-information/index.html

6. Hospitals and health systems face unprecedented financial pressures due to COVID-19. American Hospital Association. May 2020. Accessed July 13, 2020. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2020/05/aha-covid19-financial-impact-0520-FINAL.pdf

7. Birkmeyer J, Barnato A, Birkmeyer N, Bessler R, Skinner J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital admissions in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(11):2010-2017. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00980

1. COVID-19: ways to prepare your children’s hospital now. Children’s Hospital Association. March 12, 2020. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.childrenshospitals.org/Newsroom/Childrens-Hospitals-Today/Articles/2020/03/COVID-19-11-Ways-to-Prepare-Your-Hospital-Now

2. Chopra V, Toner E, Waldhorn R, Washer L. How should U.S. hospitals prepare for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)? Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):621-622. https://doi.org/10.7326/m20-0907

3. Oseran AS, Nash D, Kim C, et al. Changes in hospital admissions for urgent conditions during COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(8):327-328. https://doi.org/10.37765/ajmc.2020.43837

4. Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act or the CARES Act. 15 USC Chapter 116 (2020). Pub L No. 116-36, 134 Stat 281. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748

5. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act Provider Relief Fund: general information. US Department of Health & Human Services. June 25, 2020. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.hhs.gov/coronavirus/cares-act-provider-relief-fund/general-information/index.html

6. Hospitals and health systems face unprecedented financial pressures due to COVID-19. American Hospital Association. May 2020. Accessed July 13, 2020. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2020/05/aha-covid19-financial-impact-0520-FINAL.pdf

7. Birkmeyer J, Barnato A, Birkmeyer N, Bessler R, Skinner J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital admissions in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(11):2010-2017. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00980

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Variation in COVID-19 Mortality Across 117 US Hospitals in High- and Low-Burden Settings

It is clear that certain patient-level factors, such as age, sex, and comorbidities, predict outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection.1,2 Less is known about whether hospital-level factors, including surges of patients with COVID-19, are associated with patient outcomes.

In a multicenter cohort study of 2,215 patients with COVID-19 in 65 intensive care units (ICU) across the United States, mortality rates varied widely (6.6%-80.8%), with improved survival for patients admitted to a hospital with more (>100) rather than fewer (<50) ICU beds.3 A different study found that at the state level, COVID-19 mortality increased with increasing COVID-19 admissions.4 Together, these studies suggest that surges in COVID-19 patient volume may be associated with excess mortality. However, the first study was restricted to the ICU population, limiting generalizability, and did not consider admission volume, only ICU bed count. Meanwhile, the second study considered both hospital capacity and patient volume, but it describes a relatively small sample, did not adjust for patient-level predictors of mortality, and does not report outcomes at the hospital level.

Here, we used a large dataset to compare in-hospital mortality rates for patients with COVID-19 across US hospitals, hypothesizing that mortality would be higher in hospitals with the highest burden of COVID-19 admissions. By adjusting for patient-level predictors of mortality and normalizing admission volume for hospital size, we are able to describe residual variability in mortality that may be attributable to differences in COVID-19 patient volume.

METHODS

We included patients with an International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD)-10 diagnosis of COVID-19 (U07.1) who were admitted to a US hospital that contracts with CarePort Health.5 CarePort is a platform for discharge planning and care coordination that contracts with hospitals in all US regions and auto-extracts data using interface feeds.

We restricted the population to patients admitted between April 1 and April 30, 2020, after a new ICD-10 code for confirmed COVID-19 infection became available, and to hospitals that provided real-time ICD-10 data and pertinent demographic information and could be linked to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) data by National Provider Identifier. We assumed that the 145 patients (1.0%) who remained hospitalized at 5 weeks all survived. For the 5.9% of patients with multiple admissions during the study period, we included only the first admission with a diagnosis code for COVID-19.

We adjusted for patient age, sex, and the 31 comorbidities in the Elixhauser index, defined by ICD-10 codes. This set of comorbidities includes those previously associated with COVID-19 survival.1,2,6 Unfortunately, inconsistent reporting of vital signs and laboratory data precluded adjusting for acute illness severity. For those patients whose residence zip code was known, we report the racial breakdown (White vs non-White) and adjusted gross income (AGI), based on linked information from the 2018 American Community Survey.7

We defined COVID-19 burden as the quotient of COVID-19 admissions in April 2020 and each hospital’s certified bed count, as reported to the CMS.8 This allowed us to normalize COVID-19 patient volume for variation in hospital size, acknowledging that admitting 10 patients with COVID-19 to a 1,000-bed hospital is different from admitting 10 patients with COVID-19 to a 20-bed hospital. Certified bed count seemed the ideal denominator because it excludes beds not readily deployable to care for patients with COVID-19 (eg, radiology suites, labor and delivery rooms).

We computed hospital-specific adjusted mortality proportions and 95% confidence intervals based on hierarchical multivariable logistic regression, adjusting for age, sex, and comorbidities, and a random effect for each hospital.9,10 Hypothesizing that there may be a threshold of burden beyond which mortality begins to rise, we compared the in-hospital mortality rate at hospitals in the highest quintile of COVID-19 burden to all other hospitals.

We conducted eight post-hoc sensitivity analyses: (1) restricting the study population to patients aged 75 years and older; (2) restricting study hospitals to those with at least 100 beds and 20 COVID-19 admissions; (3) assuming that all patients who remained hospitalized at 5 weeks had died; (4) using each patient’s last admission during the month of April rather than the first; sequentially incorporating (5) zip code–level information on race (limited to White, non-White) and (6) AGI (treated as a continuous variable) into our model; (7) computing two burdens for each hospital (one for each half of April) and using whichever was higher; and (8) treating COVID-19 burden as a continuous predictor. Analyses were performed using SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) using the GLIMMIX procedure. This study was deemed exempt by the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

The study population included 14,226 patients with COVID-19 (median age, 66 years [range, 0-110 years]; 45.2% women) at 117 US hospitals. Based on patients’ zip code of residence, we estimate that 47.0% of patients were White and 29.1% Black, and that the mean household AGI was $61,956. Most hospitals were nonprofit (56%) or private (39%), with approximately one quarter coming from each US census region (range, 25 hospitals [21%] in Midwest to 33 hospitals [28%] in Northeast). Nine hospitals (8%) had more than 700 beds, 40 (34%) had 300 to 700 beds, and 68 (58%) had fewer than 300 beds. Thirty-six hospitals (30.8%) admitted fewer than 20 patients with COVID-19, while six hospitals (5.1%) admitted more than 500 such patients. COVID burden ranged from 0.004 to 2.03 admissions per bed.

As of June 5, 2020, 78.1% of patients had been discharged alive, 20.9% had died, and 1.0% remained hospitalized. At the hospital level, the observed mortality ranged from 0% to 44.4%, was 17.1% among hospitals in COVID-19 burden quintiles one through four, and was 22.7% in the highest burden quintile (Table).

Results were similar across multiple sensitivity analyses (see Appendix Table), although the relationship between COVID-19 burden and in-hospital mortality was attenuated and not significant when the sample was restricted to hospitals with at least 100 beds and 20 COVID-19 admissions, or in analyses adjusted for race and AGI.

DISCUSSION

In this study of 14,226 patients with COVID-19 across 117 US hospitals, those patients admitted to the most burdened hospitals had a higher odds of death. This relationship, which persisted after adjusting for age, sex, and comorbid conditions, suggests that a threshold exists at which patient surges may cause excess mortality.

Notably, in sensitivity analyses adjusting for race and AGI, COVID-19 burden was no longer associated with in-hospital mortality and the point estimate was attenuated. This raises the possibility that our primary results are confounded by these factors. However, prior studies of hospitalized patients have not found race to be predictive of mortality, after adjusting for other factors.11,12

We also note that the relationship between COVID-19 burden and mortality was not significant (P = .07) when the sample was restricted to larger hospitals with more than 20 COVID-19 admissions; again, the point estimate was attenuated. This suggests that larger hospitals may be more resilient in the face of patient surges. Whether this is due to increased availability of staff who can be redeployed to patient care (as with researchers at academic centers), increased experience managing severe respiratory failure, or other factors is uncertain.

Interestingly, in-hospital mortality varied widely across study hospitals, even among the most-burdened hospitals. The reasons for this residual variability—after adjusting for age, sex, and comorbidities and stratifying by COVID-19 burden—are uncertain. To the extent that this variability reflects differences in patient management, hospital staffing, or use of investigational or advanced therapies, it will be critical to identify and disseminate any replicable best practices from high-burden hospitals with low mortality rates.

Whereas other reports have often described single-center or regional experiences,13-15 leaving open the possibility that their results were highly influenced by the local nature of the pandemic in their respective settings, our report from a large sample of hospitals across the United States in high- and low-burden settings provides a more generalizable description of mortality rates for hospitalized patients. Additional study strengths include our adjustment for comorbidities known to be associated with COVID-19 survival, the reporting of definitive outcomes for 99% of patients, and the inclusion of multiple sensitivity analyses to assess the stability of findings.

Our principal limitation is the inability to adjust for severity of acute illness due to inconsistent reporting of laboratory and vital signs data from study hospitals and missing information on interhospital transfers. While our adjusted analyses clearly suggest an association between COVID-19 burden and patient outcomes, our results may still be confounded by differences in illness severity at study hospitals. Thus, our findings should be considered hypothesis-generating and will require confirmation in future studies that include adjustment for acute illness severity.

Other limitations of our study include overrepresentation of large urban hospitals in the Northeast, although this represents the geography of the US pandemic during the study period. Our adjustment for race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status was limited in that we only had zip code-of-residence level information, did not know the zip code of residence for one quarter of study patients, and had to bifurcate the population into White/non-White categories. Finally, our definition of burden does not account for hospital resources, including staffing, ICU capacity, and the availability of advanced or investigational therapies.

CONCLUSION

In this study of 14,226 patients with COVID-19 admitted to 1 of 117 US hospitals, we found that the odds of in-hospital mortality were higher in hospitals that had the highest burden of COVID-19 admissions. This relationship, which persisted after adjustment for age, sex, and comorbid conditions, suggests that patient surges may be an independent risk factor for in-hospital death among patients with COVID-19.

ACKNOWLEGMENTS

The authors thank Bocheng Jing, MS, Senior Statistician at the UCSF Pepper Center, for providing code to identify Elixhauser conditions from ICD-10 data; and Scott Kerber, BS, and Scott Magnoni, MS, both of CarePort Health, for assistance with data extraction. They were not compensated for this work beyond their regular salaries.

1. Evidence used to update the list of underlying medical conditions that increase a person’s risk of severe illness from COVID-19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 2, 2020. Accessed December 29, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/evidence-table.html

2. Cummings MJ, Baldwin MR, Abrams D, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1763-1770. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2

3. Gupta S, Hayek SS, Wang W, et al. Factors associated with death in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(11):1-12. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.4568

4. Karaca-Mandic P, Sen S, Georgiou A, Zhu Y, Basu A. Association of COVID-19-related hospital use and overall covid-19 mortality in the USA. J Gen Intern Med. 2020:1-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06084-7