User login

SNP chips deemed ‘extremely unreliable’ for identifying rare variants

In fact, SNP chips are “extremely unreliable for genotyping very rare pathogenic variants,” and a positive result for such a variant “is more likely to be wrong than right,” researchers reported in the BMJ.

The authors explained that SNP chips are “DNA microarrays that test genetic variation at many hundreds of thousands of specific locations across the genome.” Although SNP chips have proven accurate in identifying common variants, past reports have suggested that SNP chips perform poorly for genotyping rare variants.

To gain more insight, Caroline Wright, PhD, of the University of Exeter (England) and colleagues conducted a large study.

The researchers analyzed data on 49,908 people from the UK Biobank who had SNP chip and next-generation sequencing results, as well as an additional 21 people who purchased consumer genetic tests and shared their data online via the Personal Genome Project.

The researchers compared the SNP chip and sequencing results. They also selected rare pathogenic variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 for detailed analysis of clinically actionable variants in the UK Biobank, and they assessed BRCA-related cancers in participants using cancer registry data.

Largest evaluation of SNP chips

SNP chips performed well for common variants, the researchers found. Sensitivity, specificity, positive-predictive value, and negative-predictive value all exceeded 99% for 108,574 common variants.

For rare variants, SNP chips performed poorly, with a positive-predictive value of 16% for variants with a frequency below 0.001% in the UK Biobank.

“The study provides the largest evaluation of the performance of SNP chips for genotyping genetic variants at different frequencies in the population, particularly focusing on very rare variants,” Dr. Wright said. “The biggest surprise was how poorly the SNP chips we evaluated performed for rare variants.”

Dr. Wright noted that there is an inherent problem built into using SNP chip technology to genotype very rare variants.

“The SNP chip technology relies on clustering data from multiple individuals in order to determine what genotype each individual has at a specific position in their genome,” Dr. Wright explained. “Although this method works very well for common variants, the rarer the variant, the harder it is to distinguish from experimental noise.”

False positives and cancer: ‘Don’t trust the results’

The researchers found that, for rare BRCA variants (frequency below 0.01%), SNP chips had a sensitivity of 34.6%, specificity of 98.3%, negative-predictive value of 99.9%, and positive-predictive value of 4.2%.

Rates of BRCA-related cancers in patients with positive SNP chip results were similar to rates in age-matched control subjects because “the vast majority of variants were false positives,” the researchers noted.

“If these variants are incorrectly genotyped – that is, false positives detected – a woman could be offered screening or even prophylactic surgery inappropriately when she is more likely to be at population background risk [for BRCA-related cancers],” Dr. Wright said.

“For very-rare-disease–causing genetic variants, don’t trust the results from SNP chips; for example, those from direct-to-consumer genetic tests. Never use them to guide clinical action without diagnostic validation,” she added.

Heather Hampel, a genetic counselor and researcher at the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center in Columbus, agreed.

“Positive results on SNP-based tests need to be confirmed by medical-grade genetic testing using a sequencing technology,” she said. “Negative results on an SNP- based test cannot be considered to rule out mutations in BRCA1/2 or other cancer-susceptibility genes, so individuals with strong personal and family histories of cancer should be seen by a genetic counselor to consider medical-grade genetic testing using a sequencing technology.”

Practicing oncologists can trust patients’ prior germline genetic test results if the testing was performed in a cancer genetics clinic, which uses sequencing-based technologies, Ms. Hampel noted.

“If the test was performed before 2013, there are likely new genes that have been discovered for which their patient was not tested, and repeat testing may be warranted,” Ms. Hampel said. “A referral to a cancer genetic counselor would be appropriate.”

Ms. Hampel disclosed relationships with Genome Medical, GI OnDemand, Invitae Genetics, and Promega. Dr. Wright and her coauthors disclosed no conflicts of interest. The group’s research was conducted using the UK Biobank and the University of Exeter High-Performance Computing, with funding from the Wellcome Trust and the National Institute for Health Research.

In fact, SNP chips are “extremely unreliable for genotyping very rare pathogenic variants,” and a positive result for such a variant “is more likely to be wrong than right,” researchers reported in the BMJ.

The authors explained that SNP chips are “DNA microarrays that test genetic variation at many hundreds of thousands of specific locations across the genome.” Although SNP chips have proven accurate in identifying common variants, past reports have suggested that SNP chips perform poorly for genotyping rare variants.

To gain more insight, Caroline Wright, PhD, of the University of Exeter (England) and colleagues conducted a large study.

The researchers analyzed data on 49,908 people from the UK Biobank who had SNP chip and next-generation sequencing results, as well as an additional 21 people who purchased consumer genetic tests and shared their data online via the Personal Genome Project.

The researchers compared the SNP chip and sequencing results. They also selected rare pathogenic variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 for detailed analysis of clinically actionable variants in the UK Biobank, and they assessed BRCA-related cancers in participants using cancer registry data.

Largest evaluation of SNP chips

SNP chips performed well for common variants, the researchers found. Sensitivity, specificity, positive-predictive value, and negative-predictive value all exceeded 99% for 108,574 common variants.

For rare variants, SNP chips performed poorly, with a positive-predictive value of 16% for variants with a frequency below 0.001% in the UK Biobank.

“The study provides the largest evaluation of the performance of SNP chips for genotyping genetic variants at different frequencies in the population, particularly focusing on very rare variants,” Dr. Wright said. “The biggest surprise was how poorly the SNP chips we evaluated performed for rare variants.”

Dr. Wright noted that there is an inherent problem built into using SNP chip technology to genotype very rare variants.

“The SNP chip technology relies on clustering data from multiple individuals in order to determine what genotype each individual has at a specific position in their genome,” Dr. Wright explained. “Although this method works very well for common variants, the rarer the variant, the harder it is to distinguish from experimental noise.”

False positives and cancer: ‘Don’t trust the results’

The researchers found that, for rare BRCA variants (frequency below 0.01%), SNP chips had a sensitivity of 34.6%, specificity of 98.3%, negative-predictive value of 99.9%, and positive-predictive value of 4.2%.

Rates of BRCA-related cancers in patients with positive SNP chip results were similar to rates in age-matched control subjects because “the vast majority of variants were false positives,” the researchers noted.

“If these variants are incorrectly genotyped – that is, false positives detected – a woman could be offered screening or even prophylactic surgery inappropriately when she is more likely to be at population background risk [for BRCA-related cancers],” Dr. Wright said.

“For very-rare-disease–causing genetic variants, don’t trust the results from SNP chips; for example, those from direct-to-consumer genetic tests. Never use them to guide clinical action without diagnostic validation,” she added.

Heather Hampel, a genetic counselor and researcher at the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center in Columbus, agreed.

“Positive results on SNP-based tests need to be confirmed by medical-grade genetic testing using a sequencing technology,” she said. “Negative results on an SNP- based test cannot be considered to rule out mutations in BRCA1/2 or other cancer-susceptibility genes, so individuals with strong personal and family histories of cancer should be seen by a genetic counselor to consider medical-grade genetic testing using a sequencing technology.”

Practicing oncologists can trust patients’ prior germline genetic test results if the testing was performed in a cancer genetics clinic, which uses sequencing-based technologies, Ms. Hampel noted.

“If the test was performed before 2013, there are likely new genes that have been discovered for which their patient was not tested, and repeat testing may be warranted,” Ms. Hampel said. “A referral to a cancer genetic counselor would be appropriate.”

Ms. Hampel disclosed relationships with Genome Medical, GI OnDemand, Invitae Genetics, and Promega. Dr. Wright and her coauthors disclosed no conflicts of interest. The group’s research was conducted using the UK Biobank and the University of Exeter High-Performance Computing, with funding from the Wellcome Trust and the National Institute for Health Research.

In fact, SNP chips are “extremely unreliable for genotyping very rare pathogenic variants,” and a positive result for such a variant “is more likely to be wrong than right,” researchers reported in the BMJ.

The authors explained that SNP chips are “DNA microarrays that test genetic variation at many hundreds of thousands of specific locations across the genome.” Although SNP chips have proven accurate in identifying common variants, past reports have suggested that SNP chips perform poorly for genotyping rare variants.

To gain more insight, Caroline Wright, PhD, of the University of Exeter (England) and colleagues conducted a large study.

The researchers analyzed data on 49,908 people from the UK Biobank who had SNP chip and next-generation sequencing results, as well as an additional 21 people who purchased consumer genetic tests and shared their data online via the Personal Genome Project.

The researchers compared the SNP chip and sequencing results. They also selected rare pathogenic variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 for detailed analysis of clinically actionable variants in the UK Biobank, and they assessed BRCA-related cancers in participants using cancer registry data.

Largest evaluation of SNP chips

SNP chips performed well for common variants, the researchers found. Sensitivity, specificity, positive-predictive value, and negative-predictive value all exceeded 99% for 108,574 common variants.

For rare variants, SNP chips performed poorly, with a positive-predictive value of 16% for variants with a frequency below 0.001% in the UK Biobank.

“The study provides the largest evaluation of the performance of SNP chips for genotyping genetic variants at different frequencies in the population, particularly focusing on very rare variants,” Dr. Wright said. “The biggest surprise was how poorly the SNP chips we evaluated performed for rare variants.”

Dr. Wright noted that there is an inherent problem built into using SNP chip technology to genotype very rare variants.

“The SNP chip technology relies on clustering data from multiple individuals in order to determine what genotype each individual has at a specific position in their genome,” Dr. Wright explained. “Although this method works very well for common variants, the rarer the variant, the harder it is to distinguish from experimental noise.”

False positives and cancer: ‘Don’t trust the results’

The researchers found that, for rare BRCA variants (frequency below 0.01%), SNP chips had a sensitivity of 34.6%, specificity of 98.3%, negative-predictive value of 99.9%, and positive-predictive value of 4.2%.

Rates of BRCA-related cancers in patients with positive SNP chip results were similar to rates in age-matched control subjects because “the vast majority of variants were false positives,” the researchers noted.

“If these variants are incorrectly genotyped – that is, false positives detected – a woman could be offered screening or even prophylactic surgery inappropriately when she is more likely to be at population background risk [for BRCA-related cancers],” Dr. Wright said.

“For very-rare-disease–causing genetic variants, don’t trust the results from SNP chips; for example, those from direct-to-consumer genetic tests. Never use them to guide clinical action without diagnostic validation,” she added.

Heather Hampel, a genetic counselor and researcher at the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center in Columbus, agreed.

“Positive results on SNP-based tests need to be confirmed by medical-grade genetic testing using a sequencing technology,” she said. “Negative results on an SNP- based test cannot be considered to rule out mutations in BRCA1/2 or other cancer-susceptibility genes, so individuals with strong personal and family histories of cancer should be seen by a genetic counselor to consider medical-grade genetic testing using a sequencing technology.”

Practicing oncologists can trust patients’ prior germline genetic test results if the testing was performed in a cancer genetics clinic, which uses sequencing-based technologies, Ms. Hampel noted.

“If the test was performed before 2013, there are likely new genes that have been discovered for which their patient was not tested, and repeat testing may be warranted,” Ms. Hampel said. “A referral to a cancer genetic counselor would be appropriate.”

Ms. Hampel disclosed relationships with Genome Medical, GI OnDemand, Invitae Genetics, and Promega. Dr. Wright and her coauthors disclosed no conflicts of interest. The group’s research was conducted using the UK Biobank and the University of Exeter High-Performance Computing, with funding from the Wellcome Trust and the National Institute for Health Research.

FROM BMJ

Survey explores impact of pandemic on dermatologist happiness, burnout

, according to Medscape’s 2021 Dermatologist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report.

In addition, 15% reported being burned out, and 3% reported being depressed, yet about half reported being too busy to seek help for burnout and/or depression.

Those are among the key findings from the Medscape report, which was published online on Feb. 19, 2021. More than 12,000 physicians from 29 specialties, including dermatology, participated in the survey, which explores how physicians are coping with burnout, maintaining their personal wellness, and viewing their workplaces and futures amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

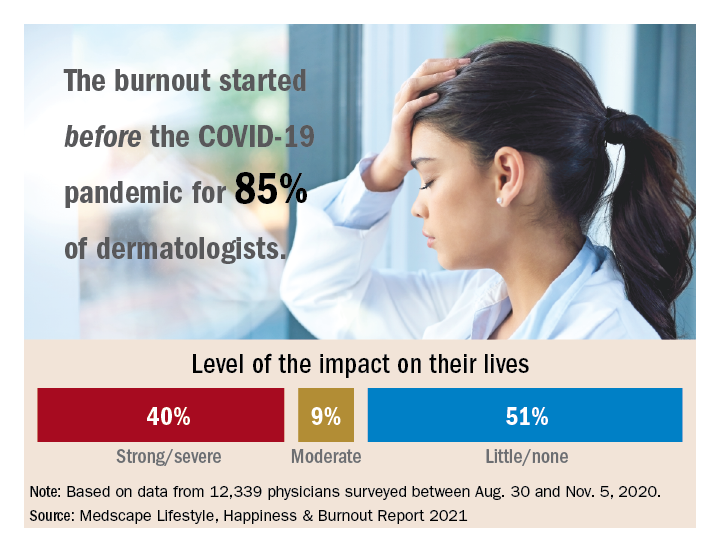

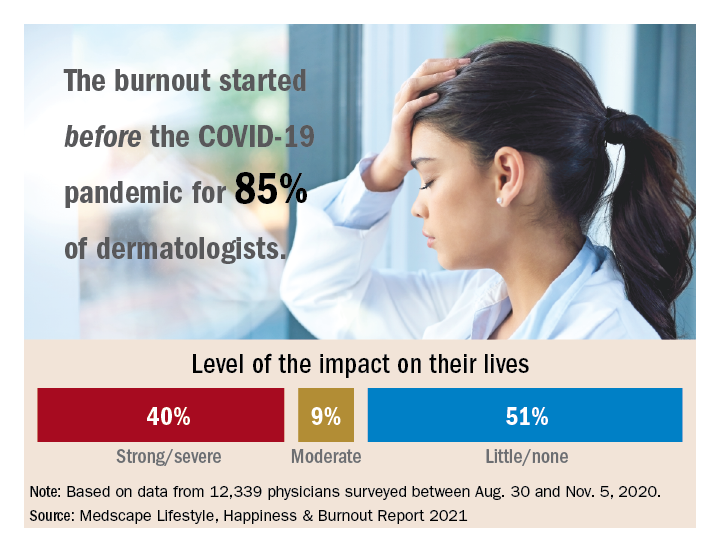

Among dermatologists who reported burnout, 85% said that it started prior to the pandemic, but 15% said it began with the pandemic. That finding resonates with Diane L. Whitaker-Worth, MD, a dermatologist with the University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington. “A lot of dermatology practices closed down for a while, which was a huge economic hit,” she said in an interview. “I work for a university, so the stress wasn’t quite as bad. We shut down for about a week, but we canceled a lot of visits. We ramped up quickly, and I would say by the summer more people were coming in. Then we got backlogged. We’re still drowning in the number of patients who want to get in sooner, who can’t get an appointment, who need to be seen. It’s unbelievable, and it’s unrelenting.”

Dermatology trainees were also upended, with many residency programs going virtual. “We had to quickly figure out how to continue educating our residents,” said Dr. Whitaker-Worth, who also directs the university’s dermatology residency program. “What’s reasonable to expect them to be doing in clinic? There were fears about becoming infected [with the] virus. Every week, I had double the amount of work in the bureaucratic realm, trying to figure out how we run our clinic and keep our residents safe but learning. That was hard and the residents were really stressed. They were afraid they were going to get pulled to the ICUs. At that time, we didn’t have adequate PPE, and patients and doctors were dying.”

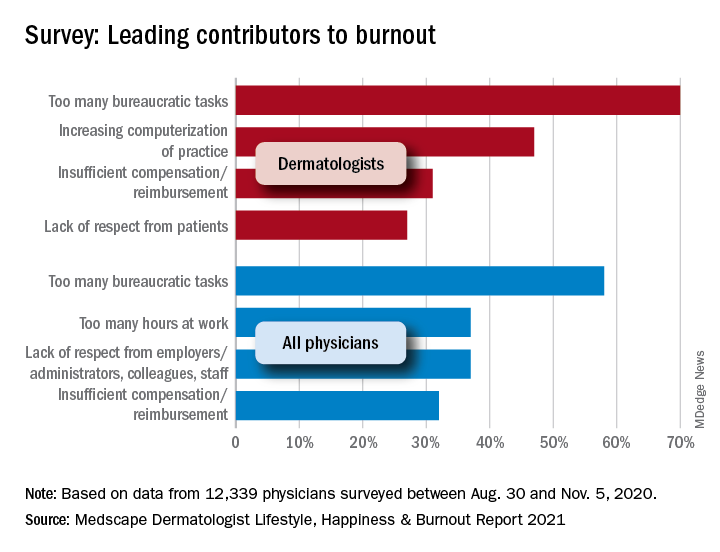

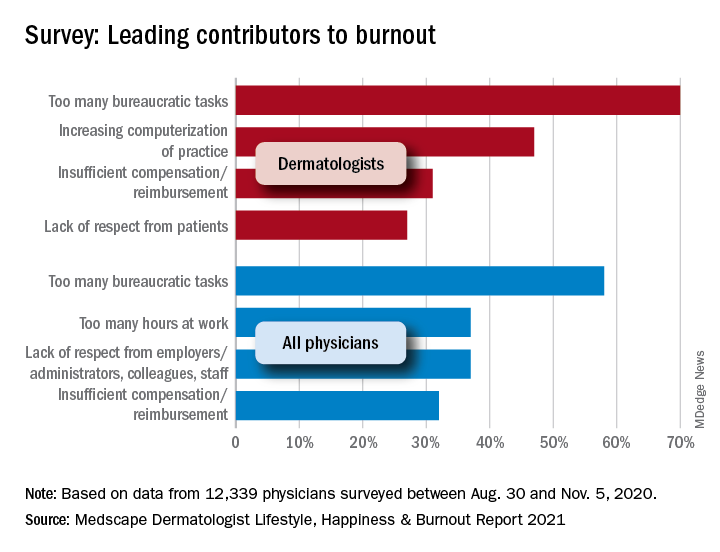

According to the dermatologists who responded to the Medscape survey and reported burnout, the seven chief contributors to burnout were too many bureaucratic tasks (70%); increasing computerization of practice (47%); insufficient compensation/reimbursement (31%); lack of respect from patients (27%); government regulations (26%); lack of respect from administrators/employers, colleagues, or staff (23%); and stress from social distancing/societal issues related to COVID-19 (15%).

“Even though dermatologists seemingly have such a nice schedule, compared to a lot of other doctors, it’s still a very stressful occupation,” said Dr. Whitaker-Worth, who coauthored a study on the topic of burnout among female dermatologists. “It is harder to practice now because there are so many people telling us how we have to do things. That will burn you out over time, when control is taken away, when tasks are handed to you randomly by different entities – insurance companies, the government, the electronic medical record.”

Among dermatologists who self-reported burnout on the survey, 51% said it had no impact on their life, 9% said the impact was moderate, while 40% indicated that it had a strong/severe impact. About half (49%) use exercise to cope with burnout, while other key coping strategies include talking with family members/close friends (40%), playing or listening to music (39%), isolating themselves from others (35%), eating junk food (35%), and drinking alcohol (30%). At the same time, only 6% indicated that they are currently seeking professional health for their burnout and/or depression, and 3% indicated that they are planning to seek professional help. When asked why they hadn’t sought help for their burnout and/or depression, 51% of respondents said they were too busy and 36% said their symptoms weren’t severe enough.

Dr. Whitaker-Worth characterized bureaucratic tasks as “a huge cause” of her burnout, but the larger contributor, she said, is managing her role as wife and mother of four children who are currently at home attending online school classes or working remotely, while she juggles her own work responsibilities. “They were stressed,” she said of her children. “The whole world was stressed. There are exceptions, but I still think that women are mostly shouldering the tasks at home. Even if they’re not doing them, they’re still feeling responsible for them. During the pandemic, every aspect of life became harder. Work was harder. Getting kids focused on school was harder. Doing basic tasks like errands was harder.”

Despite the stress and uncertainty generated by the pandemic, Dr. Whitaker-Worth considers dermatology as one of the happier specialties in medicine. “We still have a little more control of our time,” she said. “We are lucky in that we have reasonable hours, not as much in-house call, and a little more control over our day. I think work-life balance is the main thing that drives burnout – over bureaucracy, over everything.”

, according to Medscape’s 2021 Dermatologist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report.

In addition, 15% reported being burned out, and 3% reported being depressed, yet about half reported being too busy to seek help for burnout and/or depression.

Those are among the key findings from the Medscape report, which was published online on Feb. 19, 2021. More than 12,000 physicians from 29 specialties, including dermatology, participated in the survey, which explores how physicians are coping with burnout, maintaining their personal wellness, and viewing their workplaces and futures amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Among dermatologists who reported burnout, 85% said that it started prior to the pandemic, but 15% said it began with the pandemic. That finding resonates with Diane L. Whitaker-Worth, MD, a dermatologist with the University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington. “A lot of dermatology practices closed down for a while, which was a huge economic hit,” she said in an interview. “I work for a university, so the stress wasn’t quite as bad. We shut down for about a week, but we canceled a lot of visits. We ramped up quickly, and I would say by the summer more people were coming in. Then we got backlogged. We’re still drowning in the number of patients who want to get in sooner, who can’t get an appointment, who need to be seen. It’s unbelievable, and it’s unrelenting.”

Dermatology trainees were also upended, with many residency programs going virtual. “We had to quickly figure out how to continue educating our residents,” said Dr. Whitaker-Worth, who also directs the university’s dermatology residency program. “What’s reasonable to expect them to be doing in clinic? There were fears about becoming infected [with the] virus. Every week, I had double the amount of work in the bureaucratic realm, trying to figure out how we run our clinic and keep our residents safe but learning. That was hard and the residents were really stressed. They were afraid they were going to get pulled to the ICUs. At that time, we didn’t have adequate PPE, and patients and doctors were dying.”

According to the dermatologists who responded to the Medscape survey and reported burnout, the seven chief contributors to burnout were too many bureaucratic tasks (70%); increasing computerization of practice (47%); insufficient compensation/reimbursement (31%); lack of respect from patients (27%); government regulations (26%); lack of respect from administrators/employers, colleagues, or staff (23%); and stress from social distancing/societal issues related to COVID-19 (15%).

“Even though dermatologists seemingly have such a nice schedule, compared to a lot of other doctors, it’s still a very stressful occupation,” said Dr. Whitaker-Worth, who coauthored a study on the topic of burnout among female dermatologists. “It is harder to practice now because there are so many people telling us how we have to do things. That will burn you out over time, when control is taken away, when tasks are handed to you randomly by different entities – insurance companies, the government, the electronic medical record.”

Among dermatologists who self-reported burnout on the survey, 51% said it had no impact on their life, 9% said the impact was moderate, while 40% indicated that it had a strong/severe impact. About half (49%) use exercise to cope with burnout, while other key coping strategies include talking with family members/close friends (40%), playing or listening to music (39%), isolating themselves from others (35%), eating junk food (35%), and drinking alcohol (30%). At the same time, only 6% indicated that they are currently seeking professional health for their burnout and/or depression, and 3% indicated that they are planning to seek professional help. When asked why they hadn’t sought help for their burnout and/or depression, 51% of respondents said they were too busy and 36% said their symptoms weren’t severe enough.

Dr. Whitaker-Worth characterized bureaucratic tasks as “a huge cause” of her burnout, but the larger contributor, she said, is managing her role as wife and mother of four children who are currently at home attending online school classes or working remotely, while she juggles her own work responsibilities. “They were stressed,” she said of her children. “The whole world was stressed. There are exceptions, but I still think that women are mostly shouldering the tasks at home. Even if they’re not doing them, they’re still feeling responsible for them. During the pandemic, every aspect of life became harder. Work was harder. Getting kids focused on school was harder. Doing basic tasks like errands was harder.”

Despite the stress and uncertainty generated by the pandemic, Dr. Whitaker-Worth considers dermatology as one of the happier specialties in medicine. “We still have a little more control of our time,” she said. “We are lucky in that we have reasonable hours, not as much in-house call, and a little more control over our day. I think work-life balance is the main thing that drives burnout – over bureaucracy, over everything.”

, according to Medscape’s 2021 Dermatologist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report.

In addition, 15% reported being burned out, and 3% reported being depressed, yet about half reported being too busy to seek help for burnout and/or depression.

Those are among the key findings from the Medscape report, which was published online on Feb. 19, 2021. More than 12,000 physicians from 29 specialties, including dermatology, participated in the survey, which explores how physicians are coping with burnout, maintaining their personal wellness, and viewing their workplaces and futures amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Among dermatologists who reported burnout, 85% said that it started prior to the pandemic, but 15% said it began with the pandemic. That finding resonates with Diane L. Whitaker-Worth, MD, a dermatologist with the University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington. “A lot of dermatology practices closed down for a while, which was a huge economic hit,” she said in an interview. “I work for a university, so the stress wasn’t quite as bad. We shut down for about a week, but we canceled a lot of visits. We ramped up quickly, and I would say by the summer more people were coming in. Then we got backlogged. We’re still drowning in the number of patients who want to get in sooner, who can’t get an appointment, who need to be seen. It’s unbelievable, and it’s unrelenting.”

Dermatology trainees were also upended, with many residency programs going virtual. “We had to quickly figure out how to continue educating our residents,” said Dr. Whitaker-Worth, who also directs the university’s dermatology residency program. “What’s reasonable to expect them to be doing in clinic? There were fears about becoming infected [with the] virus. Every week, I had double the amount of work in the bureaucratic realm, trying to figure out how we run our clinic and keep our residents safe but learning. That was hard and the residents were really stressed. They were afraid they were going to get pulled to the ICUs. At that time, we didn’t have adequate PPE, and patients and doctors were dying.”

According to the dermatologists who responded to the Medscape survey and reported burnout, the seven chief contributors to burnout were too many bureaucratic tasks (70%); increasing computerization of practice (47%); insufficient compensation/reimbursement (31%); lack of respect from patients (27%); government regulations (26%); lack of respect from administrators/employers, colleagues, or staff (23%); and stress from social distancing/societal issues related to COVID-19 (15%).

“Even though dermatologists seemingly have such a nice schedule, compared to a lot of other doctors, it’s still a very stressful occupation,” said Dr. Whitaker-Worth, who coauthored a study on the topic of burnout among female dermatologists. “It is harder to practice now because there are so many people telling us how we have to do things. That will burn you out over time, when control is taken away, when tasks are handed to you randomly by different entities – insurance companies, the government, the electronic medical record.”

Among dermatologists who self-reported burnout on the survey, 51% said it had no impact on their life, 9% said the impact was moderate, while 40% indicated that it had a strong/severe impact. About half (49%) use exercise to cope with burnout, while other key coping strategies include talking with family members/close friends (40%), playing or listening to music (39%), isolating themselves from others (35%), eating junk food (35%), and drinking alcohol (30%). At the same time, only 6% indicated that they are currently seeking professional health for their burnout and/or depression, and 3% indicated that they are planning to seek professional help. When asked why they hadn’t sought help for their burnout and/or depression, 51% of respondents said they were too busy and 36% said their symptoms weren’t severe enough.

Dr. Whitaker-Worth characterized bureaucratic tasks as “a huge cause” of her burnout, but the larger contributor, she said, is managing her role as wife and mother of four children who are currently at home attending online school classes or working remotely, while she juggles her own work responsibilities. “They were stressed,” she said of her children. “The whole world was stressed. There are exceptions, but I still think that women are mostly shouldering the tasks at home. Even if they’re not doing them, they’re still feeling responsible for them. During the pandemic, every aspect of life became harder. Work was harder. Getting kids focused on school was harder. Doing basic tasks like errands was harder.”

Despite the stress and uncertainty generated by the pandemic, Dr. Whitaker-Worth considers dermatology as one of the happier specialties in medicine. “We still have a little more control of our time,” she said. “We are lucky in that we have reasonable hours, not as much in-house call, and a little more control over our day. I think work-life balance is the main thing that drives burnout – over bureaucracy, over everything.”

Office etiquette: Answering patient phone calls

In my office, one of the many consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic has been a dramatic increase in telephone traffic. I’m sure there are multiple reasons for this, but a major one is calls from patients who remain reluctant to visit our office in person.

Our veteran front-office staff members were adept at handling phone traffic at any level, but most of them retired because of the pandemic. The young folks who replaced them have struggled at times. You would think that millennials, who spend so much time on phones, would have little to learn in that department – until you remember that Twitter, Twitch, and TikTok do not demand polished interpersonal skills.

To address this issue, I have a memo in my office, which I have written, that establishes clear rules for proper professional telephone etiquette. If you want to adapt it for your own office, feel free to do so:

1. You only have one chance to make a first impression. The way we answer it determines, to a significant extent, how the community thinks of us, as people and as health care providers.

2. Answer all incoming calls before the third ring.

3. Answer warmly, enthusiastically, and professionally. Since the caller cannot see you, your voice is the only impression of our office a first-time caller will get.

4. Identify yourself and our office immediately. “Good morning, Doctor Eastern’s office. This is _____. How may I help you?” No one should ever have to ask what office they have reached, or to whom they are speaking.

5. Speak softly. This is to ensure confidentiality (more on that next), and because most people find loud telephone voices unpleasant.

6. Maintaining patient confidentiality is a top priority. It makes patients feel secure about being treated in our office, and it is also the law. Keep in mind that patients and others in the office may be able to overhear your phone conversations. Keep your voice down; never use the phone’s hands-free “speaker” function.

Be cautious about all information that is given over the phone. Don’t disclose any personal information unless you are absolutely certain you are talking to the correct patient. If the caller is not the patient, never discuss personal information without the patient’s permission.

7. Adopt a positive vocabulary – one that focuses on helping people. For example, rather than saying, “I don’t know,” say, “Let me find out for you,” or “I’ll find out who can help you with that.”

8. Offer to take a message if the caller has a question or issue you cannot address. Assure the patient that the appropriate staffer will call back later that day. That way, office workflow is not interrupted, and the patient still receives a prompt (and correct) answer.

9. All messages left overnight with the answering service must be returned as early as possible the very next business day. This is a top priority each morning. Few things annoy callers trying to reach their doctors more than unreturned calls. If the office will be closed for a holiday, or a response will be delayed for any other reason, make sure the service knows, and passes it on to patients.

10. Everyone in the office must answer calls when necessary. If you notice that a phone is ringing and the receptionists are swamped, please answer it; an incoming call must never go unanswered.

11. If the phone rings while you are dealing with a patient in person, the patient in front of you is your first priority. Put the caller on hold, but always ask permission before doing so, and wait for an answer. Never leave a caller on hold for more than a minute or two unless absolutely unavoidable.

12. NEVER answer, “Doctor’s office, please hold.” To a patient, that is even worse than not answering at all. No matter how often your hold message tells callers how important they are, they know they are being ignored. Such encounters never end well: Those who wait will be grumpy and rude when you get back to them; those who hang up will be even more grumpy and rude when they call back. Worst of all are those who don’t call back and seek care elsewhere – often leaving a nasty comment on social media besides.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a long-time monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

In my office, one of the many consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic has been a dramatic increase in telephone traffic. I’m sure there are multiple reasons for this, but a major one is calls from patients who remain reluctant to visit our office in person.

Our veteran front-office staff members were adept at handling phone traffic at any level, but most of them retired because of the pandemic. The young folks who replaced them have struggled at times. You would think that millennials, who spend so much time on phones, would have little to learn in that department – until you remember that Twitter, Twitch, and TikTok do not demand polished interpersonal skills.

To address this issue, I have a memo in my office, which I have written, that establishes clear rules for proper professional telephone etiquette. If you want to adapt it for your own office, feel free to do so:

1. You only have one chance to make a first impression. The way we answer it determines, to a significant extent, how the community thinks of us, as people and as health care providers.

2. Answer all incoming calls before the third ring.

3. Answer warmly, enthusiastically, and professionally. Since the caller cannot see you, your voice is the only impression of our office a first-time caller will get.

4. Identify yourself and our office immediately. “Good morning, Doctor Eastern’s office. This is _____. How may I help you?” No one should ever have to ask what office they have reached, or to whom they are speaking.

5. Speak softly. This is to ensure confidentiality (more on that next), and because most people find loud telephone voices unpleasant.

6. Maintaining patient confidentiality is a top priority. It makes patients feel secure about being treated in our office, and it is also the law. Keep in mind that patients and others in the office may be able to overhear your phone conversations. Keep your voice down; never use the phone’s hands-free “speaker” function.

Be cautious about all information that is given over the phone. Don’t disclose any personal information unless you are absolutely certain you are talking to the correct patient. If the caller is not the patient, never discuss personal information without the patient’s permission.

7. Adopt a positive vocabulary – one that focuses on helping people. For example, rather than saying, “I don’t know,” say, “Let me find out for you,” or “I’ll find out who can help you with that.”

8. Offer to take a message if the caller has a question or issue you cannot address. Assure the patient that the appropriate staffer will call back later that day. That way, office workflow is not interrupted, and the patient still receives a prompt (and correct) answer.

9. All messages left overnight with the answering service must be returned as early as possible the very next business day. This is a top priority each morning. Few things annoy callers trying to reach their doctors more than unreturned calls. If the office will be closed for a holiday, or a response will be delayed for any other reason, make sure the service knows, and passes it on to patients.

10. Everyone in the office must answer calls when necessary. If you notice that a phone is ringing and the receptionists are swamped, please answer it; an incoming call must never go unanswered.

11. If the phone rings while you are dealing with a patient in person, the patient in front of you is your first priority. Put the caller on hold, but always ask permission before doing so, and wait for an answer. Never leave a caller on hold for more than a minute or two unless absolutely unavoidable.

12. NEVER answer, “Doctor’s office, please hold.” To a patient, that is even worse than not answering at all. No matter how often your hold message tells callers how important they are, they know they are being ignored. Such encounters never end well: Those who wait will be grumpy and rude when you get back to them; those who hang up will be even more grumpy and rude when they call back. Worst of all are those who don’t call back and seek care elsewhere – often leaving a nasty comment on social media besides.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a long-time monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

In my office, one of the many consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic has been a dramatic increase in telephone traffic. I’m sure there are multiple reasons for this, but a major one is calls from patients who remain reluctant to visit our office in person.

Our veteran front-office staff members were adept at handling phone traffic at any level, but most of them retired because of the pandemic. The young folks who replaced them have struggled at times. You would think that millennials, who spend so much time on phones, would have little to learn in that department – until you remember that Twitter, Twitch, and TikTok do not demand polished interpersonal skills.

To address this issue, I have a memo in my office, which I have written, that establishes clear rules for proper professional telephone etiquette. If you want to adapt it for your own office, feel free to do so:

1. You only have one chance to make a first impression. The way we answer it determines, to a significant extent, how the community thinks of us, as people and as health care providers.

2. Answer all incoming calls before the third ring.

3. Answer warmly, enthusiastically, and professionally. Since the caller cannot see you, your voice is the only impression of our office a first-time caller will get.

4. Identify yourself and our office immediately. “Good morning, Doctor Eastern’s office. This is _____. How may I help you?” No one should ever have to ask what office they have reached, or to whom they are speaking.

5. Speak softly. This is to ensure confidentiality (more on that next), and because most people find loud telephone voices unpleasant.

6. Maintaining patient confidentiality is a top priority. It makes patients feel secure about being treated in our office, and it is also the law. Keep in mind that patients and others in the office may be able to overhear your phone conversations. Keep your voice down; never use the phone’s hands-free “speaker” function.

Be cautious about all information that is given over the phone. Don’t disclose any personal information unless you are absolutely certain you are talking to the correct patient. If the caller is not the patient, never discuss personal information without the patient’s permission.

7. Adopt a positive vocabulary – one that focuses on helping people. For example, rather than saying, “I don’t know,” say, “Let me find out for you,” or “I’ll find out who can help you with that.”

8. Offer to take a message if the caller has a question or issue you cannot address. Assure the patient that the appropriate staffer will call back later that day. That way, office workflow is not interrupted, and the patient still receives a prompt (and correct) answer.

9. All messages left overnight with the answering service must be returned as early as possible the very next business day. This is a top priority each morning. Few things annoy callers trying to reach their doctors more than unreturned calls. If the office will be closed for a holiday, or a response will be delayed for any other reason, make sure the service knows, and passes it on to patients.

10. Everyone in the office must answer calls when necessary. If you notice that a phone is ringing and the receptionists are swamped, please answer it; an incoming call must never go unanswered.

11. If the phone rings while you are dealing with a patient in person, the patient in front of you is your first priority. Put the caller on hold, but always ask permission before doing so, and wait for an answer. Never leave a caller on hold for more than a minute or two unless absolutely unavoidable.

12. NEVER answer, “Doctor’s office, please hold.” To a patient, that is even worse than not answering at all. No matter how often your hold message tells callers how important they are, they know they are being ignored. Such encounters never end well: Those who wait will be grumpy and rude when you get back to them; those who hang up will be even more grumpy and rude when they call back. Worst of all are those who don’t call back and seek care elsewhere – often leaving a nasty comment on social media besides.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a long-time monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Can supplementary estrogen relieve MS symptoms in menopausal women?

, a neurologist told colleagues at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

This kind of research should explore the effects of aging, including in the brain, and “focus on what is preventable – this dramatic and abrupt loss of estrogen in women with MS,” said Rhonda Voskuhl, MD, of the Brain Research Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“This is a call to action. There’s a huge gap that needs to be filled,” she added in an interview. “Not enough attention has been paid to menopause and cognitive issues in MS and even in healthy women.”

Research has found that many women with MS experience a decline in function during menopause, she said. “They’re having a worsening of their preexisting disabilities,” she noted, due to neurodegeneration.

Dr. Voskuhl highlighted a 2016 study, for instance, that found postmenopausal women with MS on hormone replacement therapy reported better physical function and quality of life than did their counterparts after adjustment for covariates. She also pointed to a 2019 study that concluded that “natural menopause seems to be a turning point to a more progressive phase of MS.”

Estrogen appears to play a significant role. “It’s involved in synaptic plasticity,” she said. “That’s why the disabilities are worsening.”

Dr. Voskuhl supports a year-long, randomized and controlled study of estrogen supplementation in 150-200 participants. The goal, she said, is “not just to prevent loss and bad things from happening but also make improvements.”

In healthy patients, she said, outcomes should include cognitive decline in menopause, cognitive domain outcomes, and region-specific biomarkers in the frontal cortex and hippocampus instead of global cognition and global brain volume. In patients with MS, she said, the focus should be on worsening of disability with emphasis on specific disabilities such as walking and region-specific biomarkers for the motor cortex and spinal cord.

“We need to be looking at cortical gray matter, which we know is responsive to estrogen,” Dr. Voskuhl said. She led a 2018 placebo-controlled study that found women with MS who took estrogen supplements appeared to experience localized sparing of progressive gray matter, which the researchers linked to improved results in cognitive testing. The findings, the study authors wrote, suggest “a clinically relevant, disability-specific biomarker for clinical trials of candidate neuroprotective treatments in MS.”

What about men? Does hormone loss worsen their MS? Dr. Voskuhl said there seems to be a connection between lower levels of testosterone and more disability in men with MS. But their situation is different. Loss of testosterone in men is gradual and happens over decades instead of over the short period of menopause in women, she said.

Jennifer Graves, MD, a neurologist at the University of California, San Diego, agreed that it’s time for further research into estrogen supplementation in MS. As she noted, “we don’t know the exact biological mechanism that might link perimenopause with developing a more progressive type of MS.”

She added: “An overall decrease in estrogen may be at play but there are other biological changes around menopause. We must also take care in studies to try to separate out what might be due to ovarian aging versus other types of aging processes that might be happening at the same time.”

Dr. Voskuhl disclosed that she is an inventor on university patents for use of estriol and estrogen receptor–beta ligands as treatments. Dr. Graves reports no relevant disclosures.

, a neurologist told colleagues at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

This kind of research should explore the effects of aging, including in the brain, and “focus on what is preventable – this dramatic and abrupt loss of estrogen in women with MS,” said Rhonda Voskuhl, MD, of the Brain Research Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“This is a call to action. There’s a huge gap that needs to be filled,” she added in an interview. “Not enough attention has been paid to menopause and cognitive issues in MS and even in healthy women.”

Research has found that many women with MS experience a decline in function during menopause, she said. “They’re having a worsening of their preexisting disabilities,” she noted, due to neurodegeneration.

Dr. Voskuhl highlighted a 2016 study, for instance, that found postmenopausal women with MS on hormone replacement therapy reported better physical function and quality of life than did their counterparts after adjustment for covariates. She also pointed to a 2019 study that concluded that “natural menopause seems to be a turning point to a more progressive phase of MS.”

Estrogen appears to play a significant role. “It’s involved in synaptic plasticity,” she said. “That’s why the disabilities are worsening.”

Dr. Voskuhl supports a year-long, randomized and controlled study of estrogen supplementation in 150-200 participants. The goal, she said, is “not just to prevent loss and bad things from happening but also make improvements.”

In healthy patients, she said, outcomes should include cognitive decline in menopause, cognitive domain outcomes, and region-specific biomarkers in the frontal cortex and hippocampus instead of global cognition and global brain volume. In patients with MS, she said, the focus should be on worsening of disability with emphasis on specific disabilities such as walking and region-specific biomarkers for the motor cortex and spinal cord.

“We need to be looking at cortical gray matter, which we know is responsive to estrogen,” Dr. Voskuhl said. She led a 2018 placebo-controlled study that found women with MS who took estrogen supplements appeared to experience localized sparing of progressive gray matter, which the researchers linked to improved results in cognitive testing. The findings, the study authors wrote, suggest “a clinically relevant, disability-specific biomarker for clinical trials of candidate neuroprotective treatments in MS.”

What about men? Does hormone loss worsen their MS? Dr. Voskuhl said there seems to be a connection between lower levels of testosterone and more disability in men with MS. But their situation is different. Loss of testosterone in men is gradual and happens over decades instead of over the short period of menopause in women, she said.

Jennifer Graves, MD, a neurologist at the University of California, San Diego, agreed that it’s time for further research into estrogen supplementation in MS. As she noted, “we don’t know the exact biological mechanism that might link perimenopause with developing a more progressive type of MS.”

She added: “An overall decrease in estrogen may be at play but there are other biological changes around menopause. We must also take care in studies to try to separate out what might be due to ovarian aging versus other types of aging processes that might be happening at the same time.”

Dr. Voskuhl disclosed that she is an inventor on university patents for use of estriol and estrogen receptor–beta ligands as treatments. Dr. Graves reports no relevant disclosures.

, a neurologist told colleagues at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

This kind of research should explore the effects of aging, including in the brain, and “focus on what is preventable – this dramatic and abrupt loss of estrogen in women with MS,” said Rhonda Voskuhl, MD, of the Brain Research Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“This is a call to action. There’s a huge gap that needs to be filled,” she added in an interview. “Not enough attention has been paid to menopause and cognitive issues in MS and even in healthy women.”

Research has found that many women with MS experience a decline in function during menopause, she said. “They’re having a worsening of their preexisting disabilities,” she noted, due to neurodegeneration.

Dr. Voskuhl highlighted a 2016 study, for instance, that found postmenopausal women with MS on hormone replacement therapy reported better physical function and quality of life than did their counterparts after adjustment for covariates. She also pointed to a 2019 study that concluded that “natural menopause seems to be a turning point to a more progressive phase of MS.”

Estrogen appears to play a significant role. “It’s involved in synaptic plasticity,” she said. “That’s why the disabilities are worsening.”

Dr. Voskuhl supports a year-long, randomized and controlled study of estrogen supplementation in 150-200 participants. The goal, she said, is “not just to prevent loss and bad things from happening but also make improvements.”

In healthy patients, she said, outcomes should include cognitive decline in menopause, cognitive domain outcomes, and region-specific biomarkers in the frontal cortex and hippocampus instead of global cognition and global brain volume. In patients with MS, she said, the focus should be on worsening of disability with emphasis on specific disabilities such as walking and region-specific biomarkers for the motor cortex and spinal cord.

“We need to be looking at cortical gray matter, which we know is responsive to estrogen,” Dr. Voskuhl said. She led a 2018 placebo-controlled study that found women with MS who took estrogen supplements appeared to experience localized sparing of progressive gray matter, which the researchers linked to improved results in cognitive testing. The findings, the study authors wrote, suggest “a clinically relevant, disability-specific biomarker for clinical trials of candidate neuroprotective treatments in MS.”

What about men? Does hormone loss worsen their MS? Dr. Voskuhl said there seems to be a connection between lower levels of testosterone and more disability in men with MS. But their situation is different. Loss of testosterone in men is gradual and happens over decades instead of over the short period of menopause in women, she said.

Jennifer Graves, MD, a neurologist at the University of California, San Diego, agreed that it’s time for further research into estrogen supplementation in MS. As she noted, “we don’t know the exact biological mechanism that might link perimenopause with developing a more progressive type of MS.”

She added: “An overall decrease in estrogen may be at play but there are other biological changes around menopause. We must also take care in studies to try to separate out what might be due to ovarian aging versus other types of aging processes that might be happening at the same time.”

Dr. Voskuhl disclosed that she is an inventor on university patents for use of estriol and estrogen receptor–beta ligands as treatments. Dr. Graves reports no relevant disclosures.

FROM ACTRIMS FORUM 2021

Reinstating in-person mifepristone administration requirements is harmful to patients and providers

In May 2020, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), along with other organizations and physicians (Council of University Chairs of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York State Academy of Family Physicians, SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective, Honor MacNaughton, MD), filed a civil action against the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) challenging the requirements of in-person mifepristone dispensing, which was one of the 3 restrictions placed on the medicine as part of mifepristone’s risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS). The requirements, which also include provider certification and patient signatures on specified consent forms, specifically target dosages of mifepristone for use related to abortions and miscarriages but do not apply when prescribing mifepristone for other medical conditions, even with higher doses. During the pandemic, the FDA suspended the REMS requirements for many other medications, including those more toxic than mifepristone. Additionally, the HHS activated a “telemedicine exception” that allows physicians to use telemedicine to satisfy mandatory requirements for prescribing controlled substances, including opioids, while minimizing the patient’s and provider’s risk of exposure to COVID-19 with in-person appointments. Notably, mifepristone for abortion and miscarriage management was excluded from this relaxation of the REMS requirement.

On July 13, 2020, a Federal District Court concluded that the in-person requirements were a “substantial obstacle” for women seeking abortions during the COVID-19 pandemic and granted a preliminary injunction to temporarily stop the FDA’s enforcement of the in-person requirements for mifepristone. We wrote about what that decision meant for ObGyns and urged clinicians to advocate to make the injunction permanent (OBG Manag. 2020;32(12):13-14, 23, 38. doi: 10.12788/obgm.0034.)

From there, however, the FDA worked to reverse that decision, which included applications to the District Court and to the Supreme Court for a stay of the injunction. If successful, this would suspend the injunction while the case was pending. In October, after the Supreme Court deferred review of the application (preferring a review by the lower courts), the District Court upheld the injunction of the in-person requirements citing the worsening pandemic crisis.

In-person requirement re-instated

On January 12, 2021, the United States Supreme Court granted the stay of the District Court’s injunction, which allowed the federal government to enforce the in-person requirement for mifepristone once again. The decision came down to a vote of 6 to 3. As is typical for decisions on stay orders, the court did not release a majority opinion explaining the reasoning behind this decision. In a concurring opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that the decision was not a judgment of if the requirements for in-person dispensing of mifepristone imposed an undue burden on women seeking an abortion. Instead, the Chief Justice explained that the decision came down to if a District Court could order the FDA to change their regulations based on “the court’s own evaluations of the COVID-19 pandemic,” maintaining that the court could not overrule “the politically accountable entities with the ‘background, competence, and expertise to assess public health.’”1 No other justices joined his opinion.

A worrisome pattern of a conservative supermajority

In her dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor criticized the government’s “statistically insignificant, cherry-picked data” and argued that the government did not provide any explanation from an FDA or HHS official explaining why mifepristone’s in-person requirement is more important than the in-person requirements of other drugs that have been waived during the pandemic.2 Therefore, she explained, there is “no reasoned decision” by any health official anywhere on which they can base the decision to grant the stay.

This ruling was the Supreme Court’s first major decision on reproductive health since the confirmation of Justice Amy Coney Barrett and may be an insight into future decisions of the new conservative supermajority on abortion and reproductive health issues. Particularly worrisome is what this decision could mean for stays in abortion cases that dictate whether or not the regulation is enforced during an active case. Even if cases are ruled in favor of patients and abortion providers, if the courts continue to allow enforcement of abortion restrictions during litigation, this could result in permanent closure of abortion clinics and prevent many individuals from accessing safe and legal abortion.

Looking toward the future

In the setting of almost 29 million cases of COVID-19 and more than 526,000 deaths, this stay order requires women seeking a medication abortion to make an appointment at a clinic, risking possible exposure to COVID-19, in order to access mifepristone.3,4 The Biden administration can and should remove the FDA requirement for in-person delivery of mifepristone, which would mitigate the effects of the stay order and allow women to obtain medication abortions during the pandemic.

Take action

- Contact your local ACLU (find them here) or lawyer in your area for assistance navigating the legal landscape to prescribe mifepristone after this stay order

- Minimize a patient’s wait time for mifepristone administration by blocking time in your weekly schedule for patients seeking abortion care

- Work with other providers and health care professionals in your area to submit petitions to the FDA

- FDA v American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 592 US __ (2021)(Roberts, CJ, concurring).

- FDA v American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 592 US __ (2021)(Sotomayor, J, dissenting).

- COVID data tracker. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker. Accessed March 9, 2021.

- Fulcer IR, Neill S, Bharadwa S, et al. State and federal abortion restrictions increase risk of COVID-19 exposure by mandating unnecessary clinic visits. Contraception. 2020;102:385-391.

In May 2020, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), along with other organizations and physicians (Council of University Chairs of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York State Academy of Family Physicians, SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective, Honor MacNaughton, MD), filed a civil action against the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) challenging the requirements of in-person mifepristone dispensing, which was one of the 3 restrictions placed on the medicine as part of mifepristone’s risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS). The requirements, which also include provider certification and patient signatures on specified consent forms, specifically target dosages of mifepristone for use related to abortions and miscarriages but do not apply when prescribing mifepristone for other medical conditions, even with higher doses. During the pandemic, the FDA suspended the REMS requirements for many other medications, including those more toxic than mifepristone. Additionally, the HHS activated a “telemedicine exception” that allows physicians to use telemedicine to satisfy mandatory requirements for prescribing controlled substances, including opioids, while minimizing the patient’s and provider’s risk of exposure to COVID-19 with in-person appointments. Notably, mifepristone for abortion and miscarriage management was excluded from this relaxation of the REMS requirement.

On July 13, 2020, a Federal District Court concluded that the in-person requirements were a “substantial obstacle” for women seeking abortions during the COVID-19 pandemic and granted a preliminary injunction to temporarily stop the FDA’s enforcement of the in-person requirements for mifepristone. We wrote about what that decision meant for ObGyns and urged clinicians to advocate to make the injunction permanent (OBG Manag. 2020;32(12):13-14, 23, 38. doi: 10.12788/obgm.0034.)

From there, however, the FDA worked to reverse that decision, which included applications to the District Court and to the Supreme Court for a stay of the injunction. If successful, this would suspend the injunction while the case was pending. In October, after the Supreme Court deferred review of the application (preferring a review by the lower courts), the District Court upheld the injunction of the in-person requirements citing the worsening pandemic crisis.

In-person requirement re-instated

On January 12, 2021, the United States Supreme Court granted the stay of the District Court’s injunction, which allowed the federal government to enforce the in-person requirement for mifepristone once again. The decision came down to a vote of 6 to 3. As is typical for decisions on stay orders, the court did not release a majority opinion explaining the reasoning behind this decision. In a concurring opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that the decision was not a judgment of if the requirements for in-person dispensing of mifepristone imposed an undue burden on women seeking an abortion. Instead, the Chief Justice explained that the decision came down to if a District Court could order the FDA to change their regulations based on “the court’s own evaluations of the COVID-19 pandemic,” maintaining that the court could not overrule “the politically accountable entities with the ‘background, competence, and expertise to assess public health.’”1 No other justices joined his opinion.

A worrisome pattern of a conservative supermajority

In her dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor criticized the government’s “statistically insignificant, cherry-picked data” and argued that the government did not provide any explanation from an FDA or HHS official explaining why mifepristone’s in-person requirement is more important than the in-person requirements of other drugs that have been waived during the pandemic.2 Therefore, she explained, there is “no reasoned decision” by any health official anywhere on which they can base the decision to grant the stay.

This ruling was the Supreme Court’s first major decision on reproductive health since the confirmation of Justice Amy Coney Barrett and may be an insight into future decisions of the new conservative supermajority on abortion and reproductive health issues. Particularly worrisome is what this decision could mean for stays in abortion cases that dictate whether or not the regulation is enforced during an active case. Even if cases are ruled in favor of patients and abortion providers, if the courts continue to allow enforcement of abortion restrictions during litigation, this could result in permanent closure of abortion clinics and prevent many individuals from accessing safe and legal abortion.

Looking toward the future

In the setting of almost 29 million cases of COVID-19 and more than 526,000 deaths, this stay order requires women seeking a medication abortion to make an appointment at a clinic, risking possible exposure to COVID-19, in order to access mifepristone.3,4 The Biden administration can and should remove the FDA requirement for in-person delivery of mifepristone, which would mitigate the effects of the stay order and allow women to obtain medication abortions during the pandemic.

Take action

- Contact your local ACLU (find them here) or lawyer in your area for assistance navigating the legal landscape to prescribe mifepristone after this stay order

- Minimize a patient’s wait time for mifepristone administration by blocking time in your weekly schedule for patients seeking abortion care

- Work with other providers and health care professionals in your area to submit petitions to the FDA

In May 2020, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), along with other organizations and physicians (Council of University Chairs of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York State Academy of Family Physicians, SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective, Honor MacNaughton, MD), filed a civil action against the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) challenging the requirements of in-person mifepristone dispensing, which was one of the 3 restrictions placed on the medicine as part of mifepristone’s risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS). The requirements, which also include provider certification and patient signatures on specified consent forms, specifically target dosages of mifepristone for use related to abortions and miscarriages but do not apply when prescribing mifepristone for other medical conditions, even with higher doses. During the pandemic, the FDA suspended the REMS requirements for many other medications, including those more toxic than mifepristone. Additionally, the HHS activated a “telemedicine exception” that allows physicians to use telemedicine to satisfy mandatory requirements for prescribing controlled substances, including opioids, while minimizing the patient’s and provider’s risk of exposure to COVID-19 with in-person appointments. Notably, mifepristone for abortion and miscarriage management was excluded from this relaxation of the REMS requirement.

On July 13, 2020, a Federal District Court concluded that the in-person requirements were a “substantial obstacle” for women seeking abortions during the COVID-19 pandemic and granted a preliminary injunction to temporarily stop the FDA’s enforcement of the in-person requirements for mifepristone. We wrote about what that decision meant for ObGyns and urged clinicians to advocate to make the injunction permanent (OBG Manag. 2020;32(12):13-14, 23, 38. doi: 10.12788/obgm.0034.)

From there, however, the FDA worked to reverse that decision, which included applications to the District Court and to the Supreme Court for a stay of the injunction. If successful, this would suspend the injunction while the case was pending. In October, after the Supreme Court deferred review of the application (preferring a review by the lower courts), the District Court upheld the injunction of the in-person requirements citing the worsening pandemic crisis.

In-person requirement re-instated

On January 12, 2021, the United States Supreme Court granted the stay of the District Court’s injunction, which allowed the federal government to enforce the in-person requirement for mifepristone once again. The decision came down to a vote of 6 to 3. As is typical for decisions on stay orders, the court did not release a majority opinion explaining the reasoning behind this decision. In a concurring opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that the decision was not a judgment of if the requirements for in-person dispensing of mifepristone imposed an undue burden on women seeking an abortion. Instead, the Chief Justice explained that the decision came down to if a District Court could order the FDA to change their regulations based on “the court’s own evaluations of the COVID-19 pandemic,” maintaining that the court could not overrule “the politically accountable entities with the ‘background, competence, and expertise to assess public health.’”1 No other justices joined his opinion.

A worrisome pattern of a conservative supermajority

In her dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor criticized the government’s “statistically insignificant, cherry-picked data” and argued that the government did not provide any explanation from an FDA or HHS official explaining why mifepristone’s in-person requirement is more important than the in-person requirements of other drugs that have been waived during the pandemic.2 Therefore, she explained, there is “no reasoned decision” by any health official anywhere on which they can base the decision to grant the stay.

This ruling was the Supreme Court’s first major decision on reproductive health since the confirmation of Justice Amy Coney Barrett and may be an insight into future decisions of the new conservative supermajority on abortion and reproductive health issues. Particularly worrisome is what this decision could mean for stays in abortion cases that dictate whether or not the regulation is enforced during an active case. Even if cases are ruled in favor of patients and abortion providers, if the courts continue to allow enforcement of abortion restrictions during litigation, this could result in permanent closure of abortion clinics and prevent many individuals from accessing safe and legal abortion.

Looking toward the future

In the setting of almost 29 million cases of COVID-19 and more than 526,000 deaths, this stay order requires women seeking a medication abortion to make an appointment at a clinic, risking possible exposure to COVID-19, in order to access mifepristone.3,4 The Biden administration can and should remove the FDA requirement for in-person delivery of mifepristone, which would mitigate the effects of the stay order and allow women to obtain medication abortions during the pandemic.

Take action

- Contact your local ACLU (find them here) or lawyer in your area for assistance navigating the legal landscape to prescribe mifepristone after this stay order

- Minimize a patient’s wait time for mifepristone administration by blocking time in your weekly schedule for patients seeking abortion care

- Work with other providers and health care professionals in your area to submit petitions to the FDA

- FDA v American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 592 US __ (2021)(Roberts, CJ, concurring).

- FDA v American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 592 US __ (2021)(Sotomayor, J, dissenting).

- COVID data tracker. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker. Accessed March 9, 2021.

- Fulcer IR, Neill S, Bharadwa S, et al. State and federal abortion restrictions increase risk of COVID-19 exposure by mandating unnecessary clinic visits. Contraception. 2020;102:385-391.

- FDA v American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 592 US __ (2021)(Roberts, CJ, concurring).

- FDA v American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 592 US __ (2021)(Sotomayor, J, dissenting).

- COVID data tracker. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker. Accessed March 9, 2021.

- Fulcer IR, Neill S, Bharadwa S, et al. State and federal abortion restrictions increase risk of COVID-19 exposure by mandating unnecessary clinic visits. Contraception. 2020;102:385-391.

Type 2 diabetes linked to increased risk for Parkinson’s

New analyses of both observational and genetic data have provided “convincing evidence” that type 2 diabetes is associated with an increased risk for Parkinson’s disease.

“The fact that we see the same effects in both types of analysis separately makes it more likely that these results are real – that type 2 diabetes really is a driver of Parkinson’s disease risk,” Alastair Noyce, PhD, senior author of the new studies, said in an interview.

The two analyses are reported in one paper published online March 8 in the journal Movement Disorders.

Dr. Noyce, clinical senior lecturer in the preventive neurology unit at the Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine, Queen Mary University of London, explained that his group is interested in risk factors for Parkinson’s disease, particularly those relevant at the population level and which might be modifiable.

“Several studies have looked at diabetes as a risk factor for Parkinson’s but very few have focused on type 2 diabetes, and, as this is such a growing health issue, we wanted to look at that in more detail,” he said.

The researchers performed two different analyses: a meta-analysis of observational studies investigating an association between type 2 diabetes and Parkinson’s; and a separate Mendelian randomization analysis of genetic data on the two conditions.

They found similar results in both studies, with the observational data suggesting type 2 diabetes was associated with a 21% increased risk for Parkinson’s disease and the genetic data suggesting an 8% increased risk. There were also hints that type 2 diabetes might also be associated with faster progression of Parkinson’s symptoms.

“I don’t think type 2 diabetes is a major cause of Parkinson’s, but it probably makes some contribution and may increase the risk of a more aggressive form of the condition,” Dr. Noyce said.

“I would say the increased risk of Parkinson’s disease attributable to type 2 diabetes may be similar to that of head injury or pesticide exposure, but it is important, as type 2 diabetes is very prevalent and is increasing,” he added. “As we see the growth in type 2 diabetes, this could lead to a later increase in Parkinson’s, which is already one of the fastest-growing diseases worldwide.”

For the meta-analysis of observational data, the researchers included nine studies that investigated preceding type 2 diabetes specifically and its effect on the risk for Parkinson’s disease and progression.

The pooled effect estimates showed that type 2 diabetes was associated with an increased risk for Parkinson’s disease (odds ratio, 1.21; 95% confidence interval, 1.07-1.36), and there was some evidence that type 2 diabetes was associated with faster progression of motor symptoms (standardized mean difference [SMD], 0.55) and cognitive decline (SMD, −0.92).

The observational meta-analysis included seven cohort studies and two case-control studies, and these different types of studies showed different results in regard to the association between diabetes and Parkinson’s. While the cohort studies showed a detrimental effect of diabetes on Parkinson’s risk (OR, 1.29), the case-control studies suggested protective effect (OR, 0.51).

Addressing this, Dr. Noyce noted that the case-control studies may be less reliable as they suffered more from survivor bias. “Diabetes may cause deaths in mid-life before people go on to develop Parkinson’s, and this would cause a protective effect to be seen, but we believe this to be a spurious result. Cohort studies are generally more reliable and are less susceptible to survivor bias,” he said.

For the genetic analysis, the researchers combined results from two large publicly available genome-wide association studies – one for type 2 diabetes and one for Parkinson’s disease to assess whether individuals with a genetic tendency to type 2 diabetes had a higher risk of developing Parkinson’s.

Results showed an increased risk for Parkinson’s in those individuals with genetic variants associated with type 2 diabetes, with an odds ratio of 1.08 (P = .010). There was also some evidence of an effect on motor progression (OR, 1.10; P = .032) but not on cognitive progression.

On the possible mechanism behind this observation, Dr. Noyce noted type 2 diabetes and Parkinson’s have some similarities in biology, including abnormal protein aggregation.

In the study, the authors also suggest that circulating insulin may have a neuroprotective role, whereas systemic and local insulin resistance can influence pathways known to be important in Parkinson’s pathogenesis, including those that relate to mitochondrial dysfunction, neuroinflammation, synaptic plasticity, and mitochondrial dysfunction.

Dr. Noyce further pointed out that several drugs used for the treatment of type 2 diabetes have been repurposed as possible treatments for Parkinson’s disease and are now being tested for this new indication. “Our results support that approach and raise the idea that some of these drugs may even prevent Parkinson’s in people at risk,” he said.

Most people who have type 2 diabetes won’t get Parkinson’s disease, he added. Other outcomes such as heart disease, kidney disease, and microvascular complications are far more likely, and the main aim of preventing and treating type 2 diabetes is to prevent these far more common outcomes. “But our data suggests that this could also have a possible benefit in reducing future Parkinson’s risk,” he said.

Not on the horizon at present is the possibility of screening patients with type 2 diabetes for signs of early Parkinson’s, Dr. Noyce said.

“There isn’t a test for identifying presymptomatic neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s yet, but perhaps in the future there will be, and type 2 diabetes may be one risk factor to take into account when considering such screening,” he added.