User login

2020 left many GIs unhappy in life outside work

A year ago, 81% of gastroenterologists were happy outside of work. Not anymore.

In these COVID-19–pandemic times, that number is down to 54%, according to a survey of more than 12,000 physicians in 29 specialties that was conducted by Medscape.

“Whether on the front lines of treating COVID-19 patients, pivoting from in-person to virtual care, or even having to shutter their practices, physicians faced an onslaught of crises, while political tensions, social unrest, and environmental concerns probably affected their lives outside of medicine,” Keith L. Martin and Mary Lyn Koval of Medscape wrote in the Gastroenterologist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2021.

Surprisingly, perhaps, the proportion of GIs who say that they’re burned out or are both burned out and depressed now is only a little higher (40%) than in last year’s survey (36%). It’s also just under this year’s burnout rate of 42% for all physicians, which has not changed since last year.

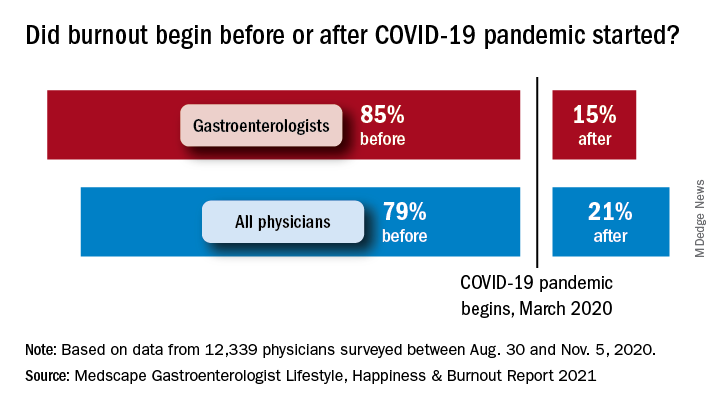

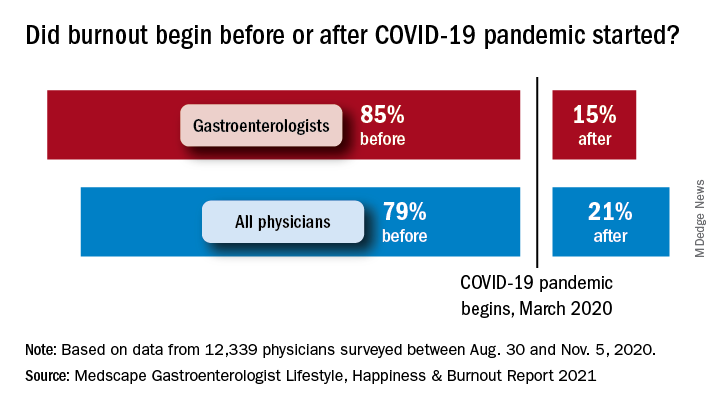

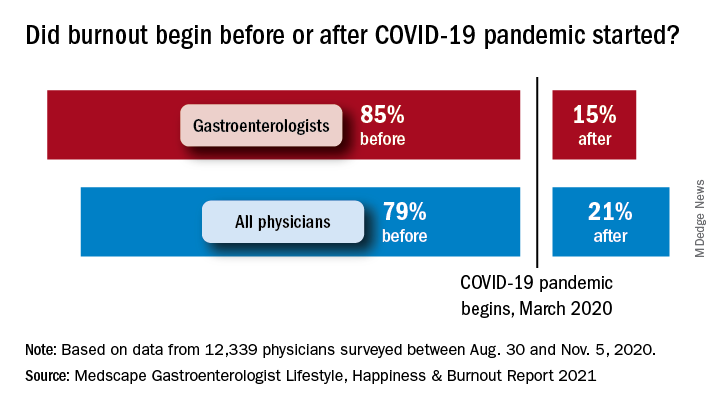

COVID-19 may have had some effect on burnout, though. Among the gastroenterologists with burnout, 15% said it began after the pandemic started, which was, again, less than physicians overall, who had a distribution of 79% before and 21% after. The GIs were slightly less likely to report that their burnout had a severe impact on their everyday lives than physicians overall – 44% versus 47% – but more likely to say that it was bad enough to consider leaving medicine – 15% versus 10%.

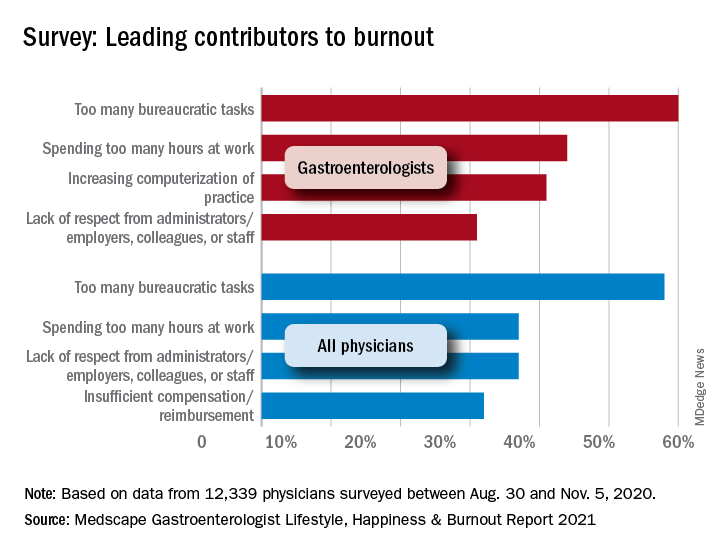

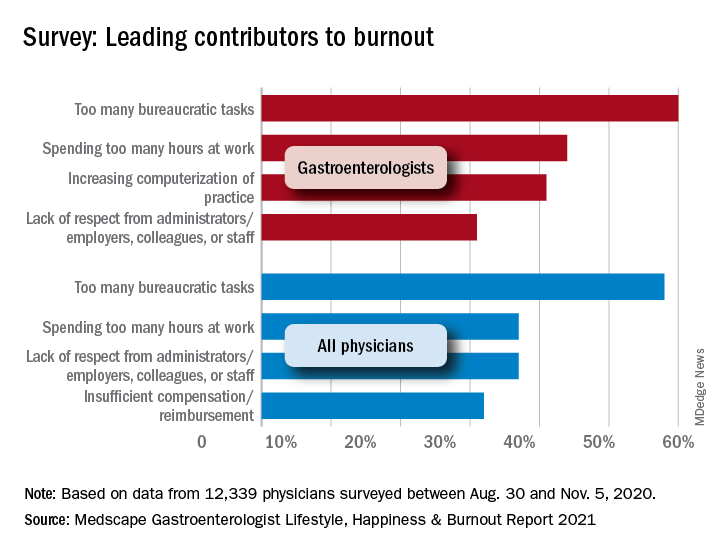

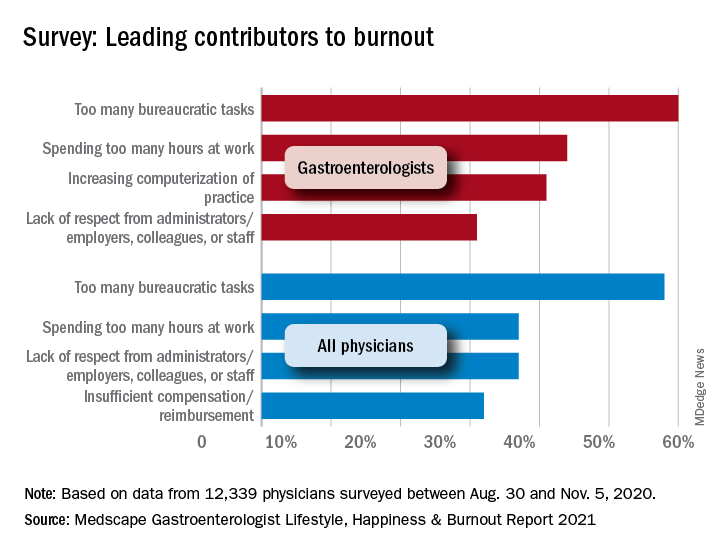

“The chief causes of burnout remain consistent from past years and are pushing physicians to the breaking point,” the Medscape report noted, citing one physician who called it “death by 1,000 cuts.” The biggest contributor to burnout over this past year was, for 60% of gastroenterologists, the excessive number of bureaucratic tasks, followed by spending too much time at work (44%) and increasing computerization (41%).

The two pandemic-related contributors included in the survey were near the bottom of the list for gastroenterologists: stress from social distancing/societal issues (15%) and stress related to treating COVID-19 patients (8%), based on data for the 12,339 physicians – of whom about 2% were GIs – polled from Aug. 30 to Nov. 5, 2020.

To deal with their burnout, many gastroenterologists are exercising – at least 51% of them, anyway. Other popular coping mechanisms include talking with family members and close friends (39%), playing or listening to music (38%), isolating themselves from others (36%), and sleeping (26%). For all physicians, the top choices were exercise (48%), talking with family members/friends (43%), and isolation (43%).

When the subject of professional help was raised, a large majority (84%) of GIs planned to forgo such care. That information was not available for physicians as a group, but 70% of internists agreed, as did 83% of nephrologists, 80% of cardiologists, 80% of oncologists, 89% of urologists, and 80% of general surgeons.

A majority of gastroenterologists (58%) said that their symptoms weren’t severe enough to warrant such help, but 38% said they were too busy, and 11% didn’t want to risk disclosure. Some physicians commented on their own situations:

- “I have no energy when I get home and I feel like I’m ignoring my family, but I need to decompress and process what I dealt with during the day” (oncologist).

- “I can’t do the things that I enjoy to relieve stress, such as traveling. My hair is falling out because I can’t destress” (ob.gyn.).

- “I’m tired and discouraged. It stresses my marriage. I have a hard time getting out of bed in the morning. I count the days until Friday” (psychiatrist).

A year ago, 81% of gastroenterologists were happy outside of work. Not anymore.

In these COVID-19–pandemic times, that number is down to 54%, according to a survey of more than 12,000 physicians in 29 specialties that was conducted by Medscape.

“Whether on the front lines of treating COVID-19 patients, pivoting from in-person to virtual care, or even having to shutter their practices, physicians faced an onslaught of crises, while political tensions, social unrest, and environmental concerns probably affected their lives outside of medicine,” Keith L. Martin and Mary Lyn Koval of Medscape wrote in the Gastroenterologist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2021.

Surprisingly, perhaps, the proportion of GIs who say that they’re burned out or are both burned out and depressed now is only a little higher (40%) than in last year’s survey (36%). It’s also just under this year’s burnout rate of 42% for all physicians, which has not changed since last year.

COVID-19 may have had some effect on burnout, though. Among the gastroenterologists with burnout, 15% said it began after the pandemic started, which was, again, less than physicians overall, who had a distribution of 79% before and 21% after. The GIs were slightly less likely to report that their burnout had a severe impact on their everyday lives than physicians overall – 44% versus 47% – but more likely to say that it was bad enough to consider leaving medicine – 15% versus 10%.

“The chief causes of burnout remain consistent from past years and are pushing physicians to the breaking point,” the Medscape report noted, citing one physician who called it “death by 1,000 cuts.” The biggest contributor to burnout over this past year was, for 60% of gastroenterologists, the excessive number of bureaucratic tasks, followed by spending too much time at work (44%) and increasing computerization (41%).

The two pandemic-related contributors included in the survey were near the bottom of the list for gastroenterologists: stress from social distancing/societal issues (15%) and stress related to treating COVID-19 patients (8%), based on data for the 12,339 physicians – of whom about 2% were GIs – polled from Aug. 30 to Nov. 5, 2020.

To deal with their burnout, many gastroenterologists are exercising – at least 51% of them, anyway. Other popular coping mechanisms include talking with family members and close friends (39%), playing or listening to music (38%), isolating themselves from others (36%), and sleeping (26%). For all physicians, the top choices were exercise (48%), talking with family members/friends (43%), and isolation (43%).

When the subject of professional help was raised, a large majority (84%) of GIs planned to forgo such care. That information was not available for physicians as a group, but 70% of internists agreed, as did 83% of nephrologists, 80% of cardiologists, 80% of oncologists, 89% of urologists, and 80% of general surgeons.

A majority of gastroenterologists (58%) said that their symptoms weren’t severe enough to warrant such help, but 38% said they were too busy, and 11% didn’t want to risk disclosure. Some physicians commented on their own situations:

- “I have no energy when I get home and I feel like I’m ignoring my family, but I need to decompress and process what I dealt with during the day” (oncologist).

- “I can’t do the things that I enjoy to relieve stress, such as traveling. My hair is falling out because I can’t destress” (ob.gyn.).

- “I’m tired and discouraged. It stresses my marriage. I have a hard time getting out of bed in the morning. I count the days until Friday” (psychiatrist).

A year ago, 81% of gastroenterologists were happy outside of work. Not anymore.

In these COVID-19–pandemic times, that number is down to 54%, according to a survey of more than 12,000 physicians in 29 specialties that was conducted by Medscape.

“Whether on the front lines of treating COVID-19 patients, pivoting from in-person to virtual care, or even having to shutter their practices, physicians faced an onslaught of crises, while political tensions, social unrest, and environmental concerns probably affected their lives outside of medicine,” Keith L. Martin and Mary Lyn Koval of Medscape wrote in the Gastroenterologist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2021.

Surprisingly, perhaps, the proportion of GIs who say that they’re burned out or are both burned out and depressed now is only a little higher (40%) than in last year’s survey (36%). It’s also just under this year’s burnout rate of 42% for all physicians, which has not changed since last year.

COVID-19 may have had some effect on burnout, though. Among the gastroenterologists with burnout, 15% said it began after the pandemic started, which was, again, less than physicians overall, who had a distribution of 79% before and 21% after. The GIs were slightly less likely to report that their burnout had a severe impact on their everyday lives than physicians overall – 44% versus 47% – but more likely to say that it was bad enough to consider leaving medicine – 15% versus 10%.

“The chief causes of burnout remain consistent from past years and are pushing physicians to the breaking point,” the Medscape report noted, citing one physician who called it “death by 1,000 cuts.” The biggest contributor to burnout over this past year was, for 60% of gastroenterologists, the excessive number of bureaucratic tasks, followed by spending too much time at work (44%) and increasing computerization (41%).

The two pandemic-related contributors included in the survey were near the bottom of the list for gastroenterologists: stress from social distancing/societal issues (15%) and stress related to treating COVID-19 patients (8%), based on data for the 12,339 physicians – of whom about 2% were GIs – polled from Aug. 30 to Nov. 5, 2020.

To deal with their burnout, many gastroenterologists are exercising – at least 51% of them, anyway. Other popular coping mechanisms include talking with family members and close friends (39%), playing or listening to music (38%), isolating themselves from others (36%), and sleeping (26%). For all physicians, the top choices were exercise (48%), talking with family members/friends (43%), and isolation (43%).

When the subject of professional help was raised, a large majority (84%) of GIs planned to forgo such care. That information was not available for physicians as a group, but 70% of internists agreed, as did 83% of nephrologists, 80% of cardiologists, 80% of oncologists, 89% of urologists, and 80% of general surgeons.

A majority of gastroenterologists (58%) said that their symptoms weren’t severe enough to warrant such help, but 38% said they were too busy, and 11% didn’t want to risk disclosure. Some physicians commented on their own situations:

- “I have no energy when I get home and I feel like I’m ignoring my family, but I need to decompress and process what I dealt with during the day” (oncologist).

- “I can’t do the things that I enjoy to relieve stress, such as traveling. My hair is falling out because I can’t destress” (ob.gyn.).

- “I’m tired and discouraged. It stresses my marriage. I have a hard time getting out of bed in the morning. I count the days until Friday” (psychiatrist).

Fired for good judgment a sign of physicians’ lost respect

What happened to Hasan Gokal, MD, should stick painfully in the craws of all physicians. It should serve as a call to action, because Dr. Gokal is sitting at home today without a job and under threat of further legal action while we continue about our day.

Dr. Gokal’s “crime” is that he vaccinated 10 strangers and acquaintances with soon-to-expire doses of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine. He drove to the homes of some in the dark of night and injected others on his Sugar Land, Texas, lawn. He spent hours in a frantic search for willing recipients to beat the expiration clock. With minutes to spare, he gave the last dose to his at-risk wife, who has symptomatic pulmonary sarcoidosis, but whose age meant she did not fall into a vaccine priority tier.

According to the New York Times, Dr. Gokal’s wife was hesitant, afraid he might get into trouble. But why would she be hesitant? He wasn’t doing anything immoral. Perhaps she knew how far physicians have fallen and how bitterly they both could suffer.

In Barren County, Ky., where I live, a state of emergency was declared by our judge executive because of inclement weather. This directive allows our emergency management to “waive procedures and formalities otherwise required by the law.” It’s too bad that the same courtesy was not afforded to Dr. Gokal in Texas. It’s a shame that ice and snow didn’t drive his actions. Perhaps that would have protected him against the harsh criticism. Rather, it was his oath to patients and dedication to his fellow humans that motivated him, and for that, he was made to suffer.

Dr. Gokal was right to think that pouring the last 10 vaccine doses down the toilet would be an egregious act. But he was wrong in thinking his decision to find takers for the vaccine would be viewed as expedient. Instead, he was accused of graft and even nepotism. And there is the rub. That he was fired and charged with the theft of $137 worth of vaccines says everything about how physicians are treated in the year 2021. Dr. Gokal’s lawyer says the charge carried a maximum penalty of 1 year in prison and a fine of nearly $4,000.

Thank God a sage judge threw out the case and “rebuked” the office of District Attorney Kim Ogg. That hasn’t stopped her from threatening to bring the case to a grand jury. That threat invites anyone faced with the same scenario to flush the extra vaccine doses into the septic system. It encourages us to choose the toilet handle to avoid a mug shot.

And we can’t ignore the racial slant to this story. The Times reported that Dr. Gokal asked the officials, “Are you suggesting that there were too many Indian names in this group?”

“Exactly” was the answer. Let that sink in.

None of this would have happened 20 years ago. Back then, no one would have questioned the wisdom a physician gains from all our years of training and residency. In an age when anyone who conducts an office visit is now called “doctor,” respect for the letters “MD” has been leveled. We physicians have lost our autonomy and been cowed into submission.

But whatever his profession, Hasan Gokal was fired for being a good human. Today, the sun rose on 10 individuals who now enjoy better protection against a deadly pandemic. They include a bed-bound nonagenarian. A woman in her 80s with dementia. A mother with a child who uses a ventilator. All now have antibodies against SARS-CoV2 because of the tireless actions of Dr. Gokal.

Yet Dr. Gokal’s future is uncertain. Will we help him, or will we leave him to the wolves? In an email exchange with his lawyer’s office, I learned that Dr. Gokal has received offers of employment but is unable to entertain them because the actions by the Harris County District Attorney triggered an automatic review by the Texas Medical Board. A GoFundMe page was launched, but an appreciative Dr. Gokal stated publicly that he’d rather the money go to a needy charity.

In the last paragraph of the Times article, Dr. Gokal asks, “How can I take it back?” referencing stories about “the Pakistani doctor in Houston who stole all those vaccines.”

Let’s help him take back his story. In helping him, perhaps we can take back a little control. We could start with letters of support that could be mailed to his lawyer, Paul Doyle, Esq., of Houston, or tweet, respectfully of course, to the district attorney @Kimoggforda.

We can also let the Harris County Public Health Department in Houston know what we think of their actions.

On Martin Luther King Day, Kim Ogg, the district attorney who charged Dr. Gokal, tweeted MLK’s famous quote: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

Let that motivate us to action.

Melissa Walton-Shirley, MD, is a native Kentuckian who retired from full-time invasive cardiology. She enjoys locums work in Montana and is a champion of physician rights and patient safety. In addition to opinion writing, she enjoys spending time with her husband, daughters and parents, and sidelines as a backing vocalist for local rock bands. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

What happened to Hasan Gokal, MD, should stick painfully in the craws of all physicians. It should serve as a call to action, because Dr. Gokal is sitting at home today without a job and under threat of further legal action while we continue about our day.

Dr. Gokal’s “crime” is that he vaccinated 10 strangers and acquaintances with soon-to-expire doses of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine. He drove to the homes of some in the dark of night and injected others on his Sugar Land, Texas, lawn. He spent hours in a frantic search for willing recipients to beat the expiration clock. With minutes to spare, he gave the last dose to his at-risk wife, who has symptomatic pulmonary sarcoidosis, but whose age meant she did not fall into a vaccine priority tier.

According to the New York Times, Dr. Gokal’s wife was hesitant, afraid he might get into trouble. But why would she be hesitant? He wasn’t doing anything immoral. Perhaps she knew how far physicians have fallen and how bitterly they both could suffer.

In Barren County, Ky., where I live, a state of emergency was declared by our judge executive because of inclement weather. This directive allows our emergency management to “waive procedures and formalities otherwise required by the law.” It’s too bad that the same courtesy was not afforded to Dr. Gokal in Texas. It’s a shame that ice and snow didn’t drive his actions. Perhaps that would have protected him against the harsh criticism. Rather, it was his oath to patients and dedication to his fellow humans that motivated him, and for that, he was made to suffer.

Dr. Gokal was right to think that pouring the last 10 vaccine doses down the toilet would be an egregious act. But he was wrong in thinking his decision to find takers for the vaccine would be viewed as expedient. Instead, he was accused of graft and even nepotism. And there is the rub. That he was fired and charged with the theft of $137 worth of vaccines says everything about how physicians are treated in the year 2021. Dr. Gokal’s lawyer says the charge carried a maximum penalty of 1 year in prison and a fine of nearly $4,000.

Thank God a sage judge threw out the case and “rebuked” the office of District Attorney Kim Ogg. That hasn’t stopped her from threatening to bring the case to a grand jury. That threat invites anyone faced with the same scenario to flush the extra vaccine doses into the septic system. It encourages us to choose the toilet handle to avoid a mug shot.

And we can’t ignore the racial slant to this story. The Times reported that Dr. Gokal asked the officials, “Are you suggesting that there were too many Indian names in this group?”

“Exactly” was the answer. Let that sink in.

None of this would have happened 20 years ago. Back then, no one would have questioned the wisdom a physician gains from all our years of training and residency. In an age when anyone who conducts an office visit is now called “doctor,” respect for the letters “MD” has been leveled. We physicians have lost our autonomy and been cowed into submission.

But whatever his profession, Hasan Gokal was fired for being a good human. Today, the sun rose on 10 individuals who now enjoy better protection against a deadly pandemic. They include a bed-bound nonagenarian. A woman in her 80s with dementia. A mother with a child who uses a ventilator. All now have antibodies against SARS-CoV2 because of the tireless actions of Dr. Gokal.

Yet Dr. Gokal’s future is uncertain. Will we help him, or will we leave him to the wolves? In an email exchange with his lawyer’s office, I learned that Dr. Gokal has received offers of employment but is unable to entertain them because the actions by the Harris County District Attorney triggered an automatic review by the Texas Medical Board. A GoFundMe page was launched, but an appreciative Dr. Gokal stated publicly that he’d rather the money go to a needy charity.

In the last paragraph of the Times article, Dr. Gokal asks, “How can I take it back?” referencing stories about “the Pakistani doctor in Houston who stole all those vaccines.”

Let’s help him take back his story. In helping him, perhaps we can take back a little control. We could start with letters of support that could be mailed to his lawyer, Paul Doyle, Esq., of Houston, or tweet, respectfully of course, to the district attorney @Kimoggforda.

We can also let the Harris County Public Health Department in Houston know what we think of their actions.

On Martin Luther King Day, Kim Ogg, the district attorney who charged Dr. Gokal, tweeted MLK’s famous quote: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

Let that motivate us to action.

Melissa Walton-Shirley, MD, is a native Kentuckian who retired from full-time invasive cardiology. She enjoys locums work in Montana and is a champion of physician rights and patient safety. In addition to opinion writing, she enjoys spending time with her husband, daughters and parents, and sidelines as a backing vocalist for local rock bands. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

What happened to Hasan Gokal, MD, should stick painfully in the craws of all physicians. It should serve as a call to action, because Dr. Gokal is sitting at home today without a job and under threat of further legal action while we continue about our day.

Dr. Gokal’s “crime” is that he vaccinated 10 strangers and acquaintances with soon-to-expire doses of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine. He drove to the homes of some in the dark of night and injected others on his Sugar Land, Texas, lawn. He spent hours in a frantic search for willing recipients to beat the expiration clock. With minutes to spare, he gave the last dose to his at-risk wife, who has symptomatic pulmonary sarcoidosis, but whose age meant she did not fall into a vaccine priority tier.

According to the New York Times, Dr. Gokal’s wife was hesitant, afraid he might get into trouble. But why would she be hesitant? He wasn’t doing anything immoral. Perhaps she knew how far physicians have fallen and how bitterly they both could suffer.

In Barren County, Ky., where I live, a state of emergency was declared by our judge executive because of inclement weather. This directive allows our emergency management to “waive procedures and formalities otherwise required by the law.” It’s too bad that the same courtesy was not afforded to Dr. Gokal in Texas. It’s a shame that ice and snow didn’t drive his actions. Perhaps that would have protected him against the harsh criticism. Rather, it was his oath to patients and dedication to his fellow humans that motivated him, and for that, he was made to suffer.

Dr. Gokal was right to think that pouring the last 10 vaccine doses down the toilet would be an egregious act. But he was wrong in thinking his decision to find takers for the vaccine would be viewed as expedient. Instead, he was accused of graft and even nepotism. And there is the rub. That he was fired and charged with the theft of $137 worth of vaccines says everything about how physicians are treated in the year 2021. Dr. Gokal’s lawyer says the charge carried a maximum penalty of 1 year in prison and a fine of nearly $4,000.

Thank God a sage judge threw out the case and “rebuked” the office of District Attorney Kim Ogg. That hasn’t stopped her from threatening to bring the case to a grand jury. That threat invites anyone faced with the same scenario to flush the extra vaccine doses into the septic system. It encourages us to choose the toilet handle to avoid a mug shot.

And we can’t ignore the racial slant to this story. The Times reported that Dr. Gokal asked the officials, “Are you suggesting that there were too many Indian names in this group?”

“Exactly” was the answer. Let that sink in.

None of this would have happened 20 years ago. Back then, no one would have questioned the wisdom a physician gains from all our years of training and residency. In an age when anyone who conducts an office visit is now called “doctor,” respect for the letters “MD” has been leveled. We physicians have lost our autonomy and been cowed into submission.

But whatever his profession, Hasan Gokal was fired for being a good human. Today, the sun rose on 10 individuals who now enjoy better protection against a deadly pandemic. They include a bed-bound nonagenarian. A woman in her 80s with dementia. A mother with a child who uses a ventilator. All now have antibodies against SARS-CoV2 because of the tireless actions of Dr. Gokal.

Yet Dr. Gokal’s future is uncertain. Will we help him, or will we leave him to the wolves? In an email exchange with his lawyer’s office, I learned that Dr. Gokal has received offers of employment but is unable to entertain them because the actions by the Harris County District Attorney triggered an automatic review by the Texas Medical Board. A GoFundMe page was launched, but an appreciative Dr. Gokal stated publicly that he’d rather the money go to a needy charity.

In the last paragraph of the Times article, Dr. Gokal asks, “How can I take it back?” referencing stories about “the Pakistani doctor in Houston who stole all those vaccines.”

Let’s help him take back his story. In helping him, perhaps we can take back a little control. We could start with letters of support that could be mailed to his lawyer, Paul Doyle, Esq., of Houston, or tweet, respectfully of course, to the district attorney @Kimoggforda.

We can also let the Harris County Public Health Department in Houston know what we think of their actions.

On Martin Luther King Day, Kim Ogg, the district attorney who charged Dr. Gokal, tweeted MLK’s famous quote: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

Let that motivate us to action.

Melissa Walton-Shirley, MD, is a native Kentuckian who retired from full-time invasive cardiology. She enjoys locums work in Montana and is a champion of physician rights and patient safety. In addition to opinion writing, she enjoys spending time with her husband, daughters and parents, and sidelines as a backing vocalist for local rock bands. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ACR, AAD, AAO, RDS issue joint statement on safe use of hydroxychloroquine

Hydroxychloroquine can be used safely and effectively with attention to dosing, risk factors, and screening, but communication among physicians, patients, and eye care specialists is key to optimizing outcomes and preventing complications, according to a joint statement from four medical societies.

The American College of Rheumatology, American Academy of Dermatology, Rheumatologic Dermatology Society, and the American Academy of Ophthalmology have produced a statement, published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, “to emphasize points of agreement that should be recognized by practitioners in all specialties,” lead author James T. Rosenbaum, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and colleagues wrote.

The statement was developed by a working group that included rheumatologists, ophthalmologists, and dermatologists with records of published studies on the use of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) and its toxicity. The statement updated elements of the 2016 American Academy of Ophthalmology guidelines for monitoring patients for retinal toxicity when using HCQ.

“The need for collaborative management has triggered this joint statement, which applies only to managing the risk of HCQ retinopathy and does not include consideration of cardiac, muscle, dermatologic, or other toxicities,” the authors noted.

The authors emphasized that HCQ plays a valuable role in controlling many rheumatic diseases, and should not be abandoned out of fear of retinopathy. However, proper dosing, recognition of risk factors, and screening strategies are essential.

Dosing data

Data on HCQ dosing and retinopathy are limited, but the authors cited a study of 2,361 rheumatic disease patients with an average HCQ dosing regimen of 5.0 mg/kg per day or less in which the toxicity risk was less than 2% for up to 10 years of use. Although data show some increase in risk with duration of use, “for a patient with a normal screening exam in a given year, the risk of developing retinopathy in the ensuing year is low (e.g., less than 5%), even after 20 years of use,” the authors said.

Risk factor recognition

“High daily [HCQ] dosage relative to body weight and cumulative dose are the primary risk factors for retinopathy,” the authors noted. Reduced renal function is an additional risk factor, and patients with renal insufficiency should be monitored and may need lower doses.

In addition, patients with a phenotype of initial parafoveal toxicity may be at increased risk for advanced disease evidenced by damage to the foveal center. “The phenotype of initial parafoveal toxicity is not universal, and in many patients (East Asians particularly) the retinal changes may appear initially along the pericentral vascular arcades,” so these patients should be screened with additional tests beyond the central macula, they emphasized.

Screening strategies

Patients should receive a baseline retinal exam within a few months of starting HCQ to rule out underlying retinal disease, according to the statement. The goal of screening is “to detect early retinopathy before a bullseye becomes visible on ophthalmoscopy, since at that severe stage the damage tends to progress even after discontinuing the medication and may eventually threaten central vision,” the authors said.

In the absence of risk factors, patients can defer screening for 5 years, but should be screened annually from 5 years and forward, they said. Examples of underlying retinal disease include “significant macular degeneration, severe diabetic retinopathy, or hereditary disorders of retinal function, but these are judgments best made by the ophthalmologist since mild and stable abnormalities that do not interfere with interpretation of critical diagnostic tests may not be a contraindication” to use of HCQ.

The consensus opinion statement has limitations, notably the shortage of data on optimum HCQ dosage and the lack of prospective studies of toxicity, including the need for studies of the impact of blood levels on toxicity and studies of pharmacogenomics to stratify risk, the authors noted.

“It is important that the drug is not stopped prematurely, but also that it is not continued in the face of definitive evidence of retinal toxicity except in some situations with unusual medical need,” they said.

“Suggestive or uncertain findings should be discussed with the patient and prescribing physician to justify further examinations, but the drug need not be stopped until evidence for retinopathy is definitive, in particular for patients with active rheumatic or cutaneous disease,” and the overall risk of retinopathy remains low if the principles described in the statement are followed, they concluded.

First author Dr. Rosenbaum disclosed financial relationships with AbbVie, UCB, Gilead, Novartis, Horizon, Roche, Eyevensys, Santen, Corvus, Affibody, Kyverna, Pfizer, Horizon, and UpToDate. Another 5 of the study’s 11 authors also disclosed relationships with multiple companies.

Hydroxychloroquine can be used safely and effectively with attention to dosing, risk factors, and screening, but communication among physicians, patients, and eye care specialists is key to optimizing outcomes and preventing complications, according to a joint statement from four medical societies.

The American College of Rheumatology, American Academy of Dermatology, Rheumatologic Dermatology Society, and the American Academy of Ophthalmology have produced a statement, published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, “to emphasize points of agreement that should be recognized by practitioners in all specialties,” lead author James T. Rosenbaum, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and colleagues wrote.

The statement was developed by a working group that included rheumatologists, ophthalmologists, and dermatologists with records of published studies on the use of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) and its toxicity. The statement updated elements of the 2016 American Academy of Ophthalmology guidelines for monitoring patients for retinal toxicity when using HCQ.

“The need for collaborative management has triggered this joint statement, which applies only to managing the risk of HCQ retinopathy and does not include consideration of cardiac, muscle, dermatologic, or other toxicities,” the authors noted.

The authors emphasized that HCQ plays a valuable role in controlling many rheumatic diseases, and should not be abandoned out of fear of retinopathy. However, proper dosing, recognition of risk factors, and screening strategies are essential.

Dosing data

Data on HCQ dosing and retinopathy are limited, but the authors cited a study of 2,361 rheumatic disease patients with an average HCQ dosing regimen of 5.0 mg/kg per day or less in which the toxicity risk was less than 2% for up to 10 years of use. Although data show some increase in risk with duration of use, “for a patient with a normal screening exam in a given year, the risk of developing retinopathy in the ensuing year is low (e.g., less than 5%), even after 20 years of use,” the authors said.

Risk factor recognition

“High daily [HCQ] dosage relative to body weight and cumulative dose are the primary risk factors for retinopathy,” the authors noted. Reduced renal function is an additional risk factor, and patients with renal insufficiency should be monitored and may need lower doses.

In addition, patients with a phenotype of initial parafoveal toxicity may be at increased risk for advanced disease evidenced by damage to the foveal center. “The phenotype of initial parafoveal toxicity is not universal, and in many patients (East Asians particularly) the retinal changes may appear initially along the pericentral vascular arcades,” so these patients should be screened with additional tests beyond the central macula, they emphasized.

Screening strategies

Patients should receive a baseline retinal exam within a few months of starting HCQ to rule out underlying retinal disease, according to the statement. The goal of screening is “to detect early retinopathy before a bullseye becomes visible on ophthalmoscopy, since at that severe stage the damage tends to progress even after discontinuing the medication and may eventually threaten central vision,” the authors said.

In the absence of risk factors, patients can defer screening for 5 years, but should be screened annually from 5 years and forward, they said. Examples of underlying retinal disease include “significant macular degeneration, severe diabetic retinopathy, or hereditary disorders of retinal function, but these are judgments best made by the ophthalmologist since mild and stable abnormalities that do not interfere with interpretation of critical diagnostic tests may not be a contraindication” to use of HCQ.

The consensus opinion statement has limitations, notably the shortage of data on optimum HCQ dosage and the lack of prospective studies of toxicity, including the need for studies of the impact of blood levels on toxicity and studies of pharmacogenomics to stratify risk, the authors noted.

“It is important that the drug is not stopped prematurely, but also that it is not continued in the face of definitive evidence of retinal toxicity except in some situations with unusual medical need,” they said.

“Suggestive or uncertain findings should be discussed with the patient and prescribing physician to justify further examinations, but the drug need not be stopped until evidence for retinopathy is definitive, in particular for patients with active rheumatic or cutaneous disease,” and the overall risk of retinopathy remains low if the principles described in the statement are followed, they concluded.

First author Dr. Rosenbaum disclosed financial relationships with AbbVie, UCB, Gilead, Novartis, Horizon, Roche, Eyevensys, Santen, Corvus, Affibody, Kyverna, Pfizer, Horizon, and UpToDate. Another 5 of the study’s 11 authors also disclosed relationships with multiple companies.

Hydroxychloroquine can be used safely and effectively with attention to dosing, risk factors, and screening, but communication among physicians, patients, and eye care specialists is key to optimizing outcomes and preventing complications, according to a joint statement from four medical societies.

The American College of Rheumatology, American Academy of Dermatology, Rheumatologic Dermatology Society, and the American Academy of Ophthalmology have produced a statement, published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, “to emphasize points of agreement that should be recognized by practitioners in all specialties,” lead author James T. Rosenbaum, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and colleagues wrote.

The statement was developed by a working group that included rheumatologists, ophthalmologists, and dermatologists with records of published studies on the use of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) and its toxicity. The statement updated elements of the 2016 American Academy of Ophthalmology guidelines for monitoring patients for retinal toxicity when using HCQ.

“The need for collaborative management has triggered this joint statement, which applies only to managing the risk of HCQ retinopathy and does not include consideration of cardiac, muscle, dermatologic, or other toxicities,” the authors noted.

The authors emphasized that HCQ plays a valuable role in controlling many rheumatic diseases, and should not be abandoned out of fear of retinopathy. However, proper dosing, recognition of risk factors, and screening strategies are essential.

Dosing data

Data on HCQ dosing and retinopathy are limited, but the authors cited a study of 2,361 rheumatic disease patients with an average HCQ dosing regimen of 5.0 mg/kg per day or less in which the toxicity risk was less than 2% for up to 10 years of use. Although data show some increase in risk with duration of use, “for a patient with a normal screening exam in a given year, the risk of developing retinopathy in the ensuing year is low (e.g., less than 5%), even after 20 years of use,” the authors said.

Risk factor recognition

“High daily [HCQ] dosage relative to body weight and cumulative dose are the primary risk factors for retinopathy,” the authors noted. Reduced renal function is an additional risk factor, and patients with renal insufficiency should be monitored and may need lower doses.

In addition, patients with a phenotype of initial parafoveal toxicity may be at increased risk for advanced disease evidenced by damage to the foveal center. “The phenotype of initial parafoveal toxicity is not universal, and in many patients (East Asians particularly) the retinal changes may appear initially along the pericentral vascular arcades,” so these patients should be screened with additional tests beyond the central macula, they emphasized.

Screening strategies

Patients should receive a baseline retinal exam within a few months of starting HCQ to rule out underlying retinal disease, according to the statement. The goal of screening is “to detect early retinopathy before a bullseye becomes visible on ophthalmoscopy, since at that severe stage the damage tends to progress even after discontinuing the medication and may eventually threaten central vision,” the authors said.

In the absence of risk factors, patients can defer screening for 5 years, but should be screened annually from 5 years and forward, they said. Examples of underlying retinal disease include “significant macular degeneration, severe diabetic retinopathy, or hereditary disorders of retinal function, but these are judgments best made by the ophthalmologist since mild and stable abnormalities that do not interfere with interpretation of critical diagnostic tests may not be a contraindication” to use of HCQ.

The consensus opinion statement has limitations, notably the shortage of data on optimum HCQ dosage and the lack of prospective studies of toxicity, including the need for studies of the impact of blood levels on toxicity and studies of pharmacogenomics to stratify risk, the authors noted.

“It is important that the drug is not stopped prematurely, but also that it is not continued in the face of definitive evidence of retinal toxicity except in some situations with unusual medical need,” they said.

“Suggestive or uncertain findings should be discussed with the patient and prescribing physician to justify further examinations, but the drug need not be stopped until evidence for retinopathy is definitive, in particular for patients with active rheumatic or cutaneous disease,” and the overall risk of retinopathy remains low if the principles described in the statement are followed, they concluded.

First author Dr. Rosenbaum disclosed financial relationships with AbbVie, UCB, Gilead, Novartis, Horizon, Roche, Eyevensys, Santen, Corvus, Affibody, Kyverna, Pfizer, Horizon, and UpToDate. Another 5 of the study’s 11 authors also disclosed relationships with multiple companies.

FROM ARTHRITIS & rHEUMATOLOGY

Mindfulness can help patients manage ‘good’ change – and relief

Two themes have emerged recently in my psychotherapy practice, and in the mirror: relief and exhaustion. Some peace in the public discourse, or at least a pause in the ominous discord, has had the effect of a lightening, an unburdening. Some release from a contracted sense of tension around the specifics of violence and a broader sense of civil fracture has been palpable like a big, deep breath, exhaled. No sensible person would mistake this for being out of the metaphoric woods. A virus menaces and mutates, economic woes follow, and lots of us don’t get along. But, yes, there is some relief, some good change.

But even good change, even a downshift into relief, can pose some challenges to look for and overcome.

Consider for a moment the notion that every change represents a loss, a metaphoric “death” of the prior state of things. This is true of big, painful losses, like the death of a loved one, and small ones, like finding an empty cookie jar. It’s also true in changes we associate with benefit or relief: a refund check, a job promotion, a resolving migraine, or the breaking out of some civility.

In changes of all sorts, the world outside of one’s mind has shifted – at odds, momentarily, with our inner, now obsolete understanding of that changed world. The inside of the head does not match the outside. How we make that adjustment, so “inside = outside,” is a clinically familiar process: it’s grieving, with a sequence famously elaborated upon by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, MD,1 and others.

We all likely know the steps: shock/denial, anger, “bargaining,” depression, and acceptance. A quick review: Our initial anxious/threat reaction leads to grievous judgment, to rationalizing “woulda/coulda/shoulda’s,” then to truly landing in the disappointment of a loss or change, and the accepting of a new steady state. Inside proceeds to match outside.

So, what then of relief? How do we process “good” change? I think we still must move from “in ≠ out” to “in = out,” navigating some pitfalls along the way.

Initial threat often remains; apprehension of the “new” still can generate energy, and even a sense of threat, regardless of a kiss or a shove. Our brainstems run roughshod over this first phase.

Step two is about judgment. We can move past the threat to, “How do I feel about it?” Here’s where grievous feeling gets swapped out for something more peak-positive – joy, or relief if the change represents an ending of a state of suffering, tension, or uncertainty.

The “bargaining” step still happens, but often around a kind of testing regimen: Is this too good to be true? Is it really different? We run scenarios.

The thud of disappointment also gets a makeover. It’s a settling into the beneficial change and its associations: gratitude, a sense of energy shifting.

The bookend “OK” seems anodyne here – why would anyone not accept relief, some good change?2 But it can nevertheless represent a challenge for many. The receding tension of the last year could open into a burst of energy, but I’m finding that exhaustion is just as or more common. That’s not illness, but a weary exhaling from the longest of held breaths.

One other twist: What happens when one of those steps is an individual obstacle, trigger, or hard-to-hold state? Especially for those with deep experience in disappointment or even trauma, buying into acceptance of a new normal can feel like a fool’s game. This is an especially complex spot for individuals who won’t quite allow for joyful acceptance to break out, lest it reveals itself as a humiliating trick or a too-brief respite from the “usual.”

Mindfulness practices, such as meditation, are helpful in managing this process. Committed time and optimal conditions to witness and adapt to the various inner states that ebb and flow generate a clear therapeutic benefit. Patients improve their identification of somatic manifestations, emotional reactions, and cycling ruminations of thought. What generates distraction and loss of mindful attention becomes better recognized. Contemplative work in between sessions becomes more productive.

What else do I advise?3 Patience, and some compassion for ourselves in this unusual time. Grief, and relief, are complex but truly human processes that generate not just one state of experience, but a cascade of them. While that cascade can hurt, it’s actually normal, not illness. But it can be exhausting.

Dr. Sazima is a Northern California psychiatrist, educator, and author. He is senior behavioral faculty at the Stanford-O’Connor Family Medicine Residency Program in San José, Calif. His latest book is “Practical Mindfulness: A Physician’s No-Nonsense Guide to Meditation for Beginners,” Miami: Mango Publishing, 2021. Dr. Sazima disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. Kübler-Ross E. “On Death And Dying,” New York: Simon & Schuster, 1969.

2. Selye H. “Stress Without Distress,” New York: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 1974.

3. Sazima G. “Practical Mindfulness: A Physician’s No-Nonsense Guide to Meditation for Beginners,” Miami: Mango Publishing, 2021.

Two themes have emerged recently in my psychotherapy practice, and in the mirror: relief and exhaustion. Some peace in the public discourse, or at least a pause in the ominous discord, has had the effect of a lightening, an unburdening. Some release from a contracted sense of tension around the specifics of violence and a broader sense of civil fracture has been palpable like a big, deep breath, exhaled. No sensible person would mistake this for being out of the metaphoric woods. A virus menaces and mutates, economic woes follow, and lots of us don’t get along. But, yes, there is some relief, some good change.

But even good change, even a downshift into relief, can pose some challenges to look for and overcome.

Consider for a moment the notion that every change represents a loss, a metaphoric “death” of the prior state of things. This is true of big, painful losses, like the death of a loved one, and small ones, like finding an empty cookie jar. It’s also true in changes we associate with benefit or relief: a refund check, a job promotion, a resolving migraine, or the breaking out of some civility.

In changes of all sorts, the world outside of one’s mind has shifted – at odds, momentarily, with our inner, now obsolete understanding of that changed world. The inside of the head does not match the outside. How we make that adjustment, so “inside = outside,” is a clinically familiar process: it’s grieving, with a sequence famously elaborated upon by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, MD,1 and others.

We all likely know the steps: shock/denial, anger, “bargaining,” depression, and acceptance. A quick review: Our initial anxious/threat reaction leads to grievous judgment, to rationalizing “woulda/coulda/shoulda’s,” then to truly landing in the disappointment of a loss or change, and the accepting of a new steady state. Inside proceeds to match outside.

So, what then of relief? How do we process “good” change? I think we still must move from “in ≠ out” to “in = out,” navigating some pitfalls along the way.

Initial threat often remains; apprehension of the “new” still can generate energy, and even a sense of threat, regardless of a kiss or a shove. Our brainstems run roughshod over this first phase.

Step two is about judgment. We can move past the threat to, “How do I feel about it?” Here’s where grievous feeling gets swapped out for something more peak-positive – joy, or relief if the change represents an ending of a state of suffering, tension, or uncertainty.

The “bargaining” step still happens, but often around a kind of testing regimen: Is this too good to be true? Is it really different? We run scenarios.

The thud of disappointment also gets a makeover. It’s a settling into the beneficial change and its associations: gratitude, a sense of energy shifting.

The bookend “OK” seems anodyne here – why would anyone not accept relief, some good change?2 But it can nevertheless represent a challenge for many. The receding tension of the last year could open into a burst of energy, but I’m finding that exhaustion is just as or more common. That’s not illness, but a weary exhaling from the longest of held breaths.

One other twist: What happens when one of those steps is an individual obstacle, trigger, or hard-to-hold state? Especially for those with deep experience in disappointment or even trauma, buying into acceptance of a new normal can feel like a fool’s game. This is an especially complex spot for individuals who won’t quite allow for joyful acceptance to break out, lest it reveals itself as a humiliating trick or a too-brief respite from the “usual.”

Mindfulness practices, such as meditation, are helpful in managing this process. Committed time and optimal conditions to witness and adapt to the various inner states that ebb and flow generate a clear therapeutic benefit. Patients improve their identification of somatic manifestations, emotional reactions, and cycling ruminations of thought. What generates distraction and loss of mindful attention becomes better recognized. Contemplative work in between sessions becomes more productive.

What else do I advise?3 Patience, and some compassion for ourselves in this unusual time. Grief, and relief, are complex but truly human processes that generate not just one state of experience, but a cascade of them. While that cascade can hurt, it’s actually normal, not illness. But it can be exhausting.

Dr. Sazima is a Northern California psychiatrist, educator, and author. He is senior behavioral faculty at the Stanford-O’Connor Family Medicine Residency Program in San José, Calif. His latest book is “Practical Mindfulness: A Physician’s No-Nonsense Guide to Meditation for Beginners,” Miami: Mango Publishing, 2021. Dr. Sazima disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. Kübler-Ross E. “On Death And Dying,” New York: Simon & Schuster, 1969.

2. Selye H. “Stress Without Distress,” New York: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 1974.

3. Sazima G. “Practical Mindfulness: A Physician’s No-Nonsense Guide to Meditation for Beginners,” Miami: Mango Publishing, 2021.

Two themes have emerged recently in my psychotherapy practice, and in the mirror: relief and exhaustion. Some peace in the public discourse, or at least a pause in the ominous discord, has had the effect of a lightening, an unburdening. Some release from a contracted sense of tension around the specifics of violence and a broader sense of civil fracture has been palpable like a big, deep breath, exhaled. No sensible person would mistake this for being out of the metaphoric woods. A virus menaces and mutates, economic woes follow, and lots of us don’t get along. But, yes, there is some relief, some good change.

But even good change, even a downshift into relief, can pose some challenges to look for and overcome.

Consider for a moment the notion that every change represents a loss, a metaphoric “death” of the prior state of things. This is true of big, painful losses, like the death of a loved one, and small ones, like finding an empty cookie jar. It’s also true in changes we associate with benefit or relief: a refund check, a job promotion, a resolving migraine, or the breaking out of some civility.

In changes of all sorts, the world outside of one’s mind has shifted – at odds, momentarily, with our inner, now obsolete understanding of that changed world. The inside of the head does not match the outside. How we make that adjustment, so “inside = outside,” is a clinically familiar process: it’s grieving, with a sequence famously elaborated upon by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, MD,1 and others.

We all likely know the steps: shock/denial, anger, “bargaining,” depression, and acceptance. A quick review: Our initial anxious/threat reaction leads to grievous judgment, to rationalizing “woulda/coulda/shoulda’s,” then to truly landing in the disappointment of a loss or change, and the accepting of a new steady state. Inside proceeds to match outside.

So, what then of relief? How do we process “good” change? I think we still must move from “in ≠ out” to “in = out,” navigating some pitfalls along the way.

Initial threat often remains; apprehension of the “new” still can generate energy, and even a sense of threat, regardless of a kiss or a shove. Our brainstems run roughshod over this first phase.

Step two is about judgment. We can move past the threat to, “How do I feel about it?” Here’s where grievous feeling gets swapped out for something more peak-positive – joy, or relief if the change represents an ending of a state of suffering, tension, or uncertainty.

The “bargaining” step still happens, but often around a kind of testing regimen: Is this too good to be true? Is it really different? We run scenarios.

The thud of disappointment also gets a makeover. It’s a settling into the beneficial change and its associations: gratitude, a sense of energy shifting.

The bookend “OK” seems anodyne here – why would anyone not accept relief, some good change?2 But it can nevertheless represent a challenge for many. The receding tension of the last year could open into a burst of energy, but I’m finding that exhaustion is just as or more common. That’s not illness, but a weary exhaling from the longest of held breaths.

One other twist: What happens when one of those steps is an individual obstacle, trigger, or hard-to-hold state? Especially for those with deep experience in disappointment or even trauma, buying into acceptance of a new normal can feel like a fool’s game. This is an especially complex spot for individuals who won’t quite allow for joyful acceptance to break out, lest it reveals itself as a humiliating trick or a too-brief respite from the “usual.”

Mindfulness practices, such as meditation, are helpful in managing this process. Committed time and optimal conditions to witness and adapt to the various inner states that ebb and flow generate a clear therapeutic benefit. Patients improve their identification of somatic manifestations, emotional reactions, and cycling ruminations of thought. What generates distraction and loss of mindful attention becomes better recognized. Contemplative work in between sessions becomes more productive.

What else do I advise?3 Patience, and some compassion for ourselves in this unusual time. Grief, and relief, are complex but truly human processes that generate not just one state of experience, but a cascade of them. While that cascade can hurt, it’s actually normal, not illness. But it can be exhausting.

Dr. Sazima is a Northern California psychiatrist, educator, and author. He is senior behavioral faculty at the Stanford-O’Connor Family Medicine Residency Program in San José, Calif. His latest book is “Practical Mindfulness: A Physician’s No-Nonsense Guide to Meditation for Beginners,” Miami: Mango Publishing, 2021. Dr. Sazima disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. Kübler-Ross E. “On Death And Dying,” New York: Simon & Schuster, 1969.

2. Selye H. “Stress Without Distress,” New York: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 1974.

3. Sazima G. “Practical Mindfulness: A Physician’s No-Nonsense Guide to Meditation for Beginners,” Miami: Mango Publishing, 2021.

Sudden Cardiac Death in a Young Patient With Psoriasis

To the Editor:

The evolution in the understanding of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis has unfolded many new facets of this immune-mediated inflammatory disease. Once considered to be just a cutaneous disease, psoriasis is not actually confined to skin but can involve almost any other system of the body. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality are the major concerns in patients with psoriasis. We report the sudden death of a young man with severe psoriasis.

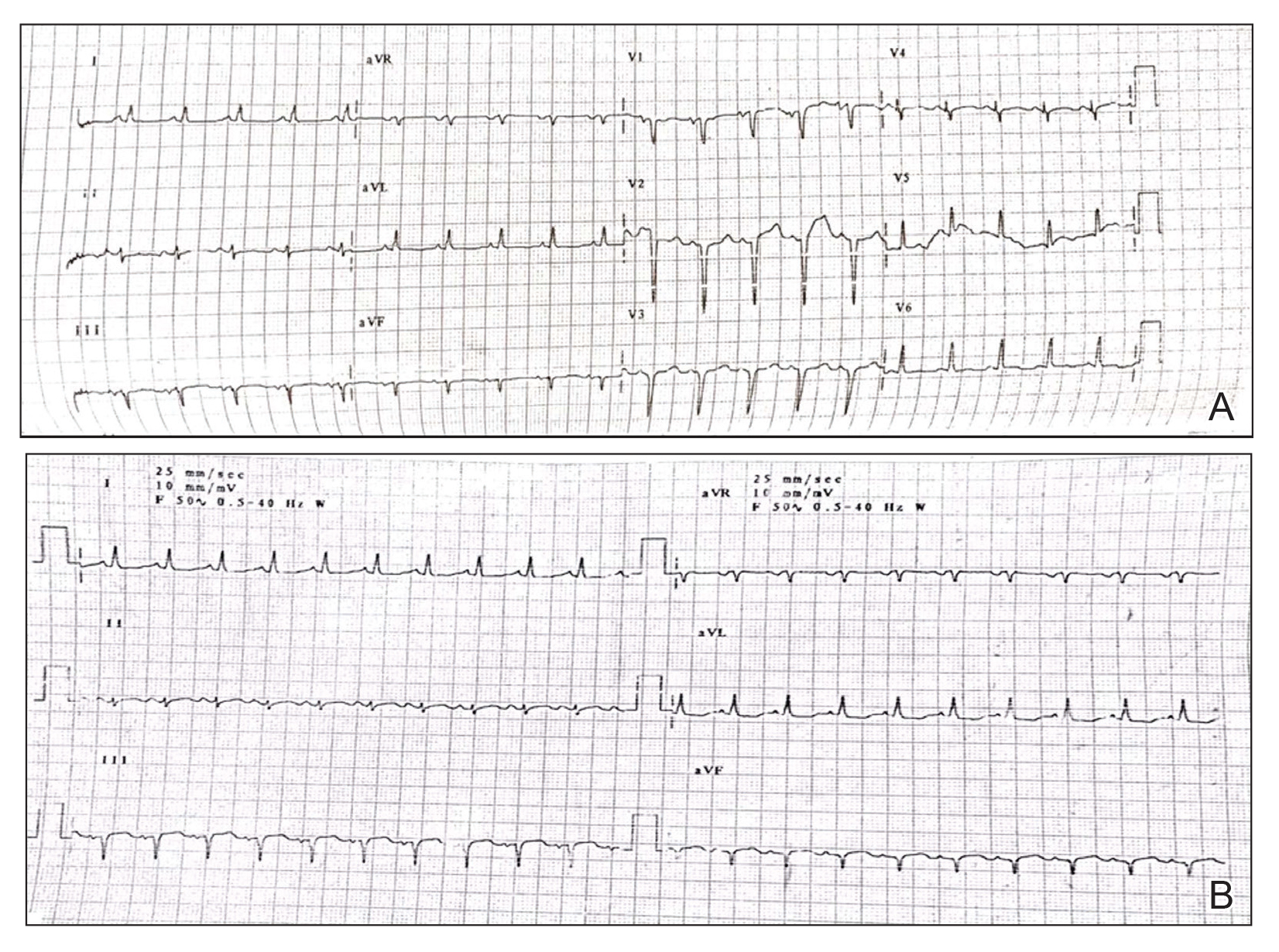

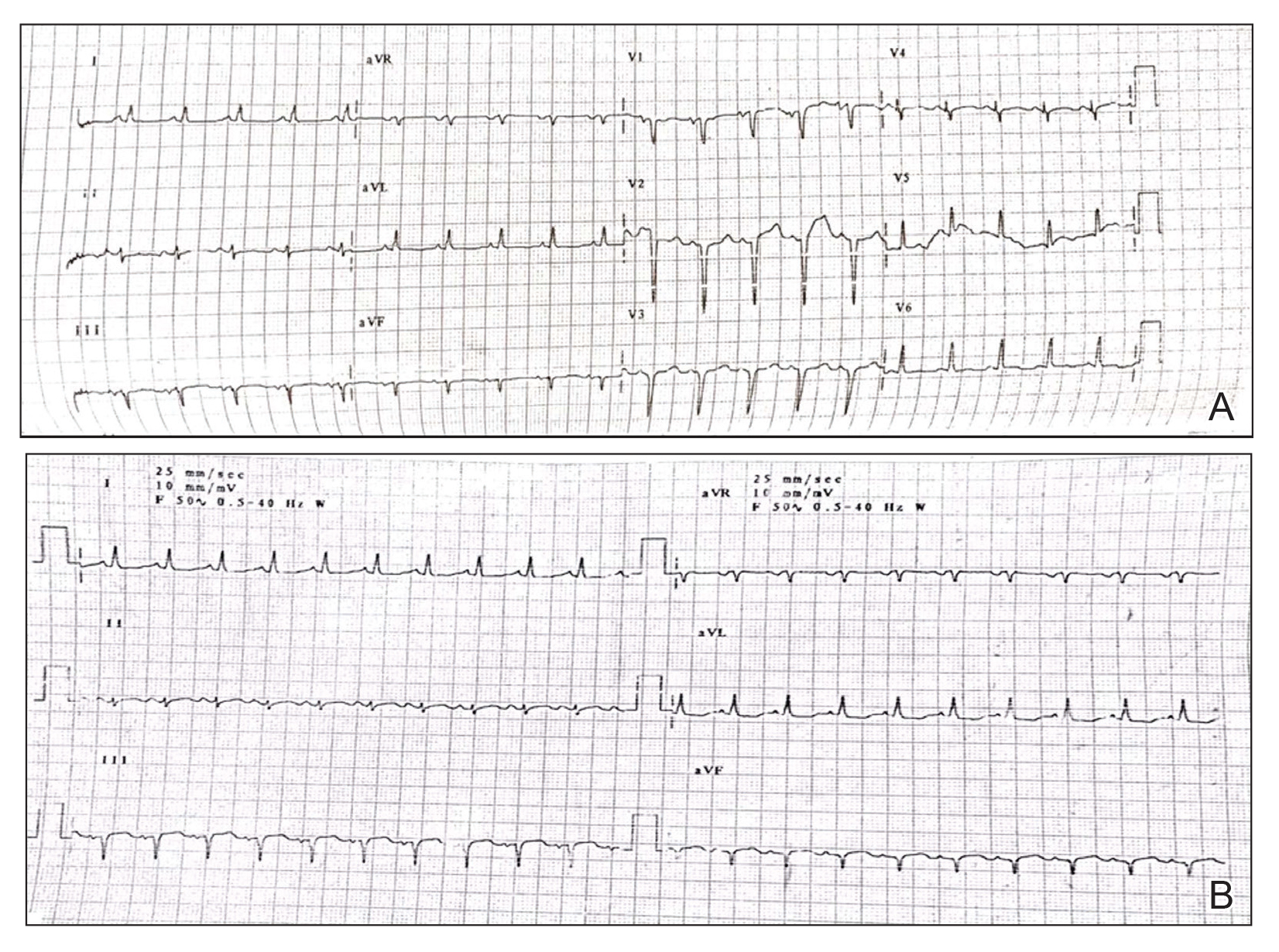

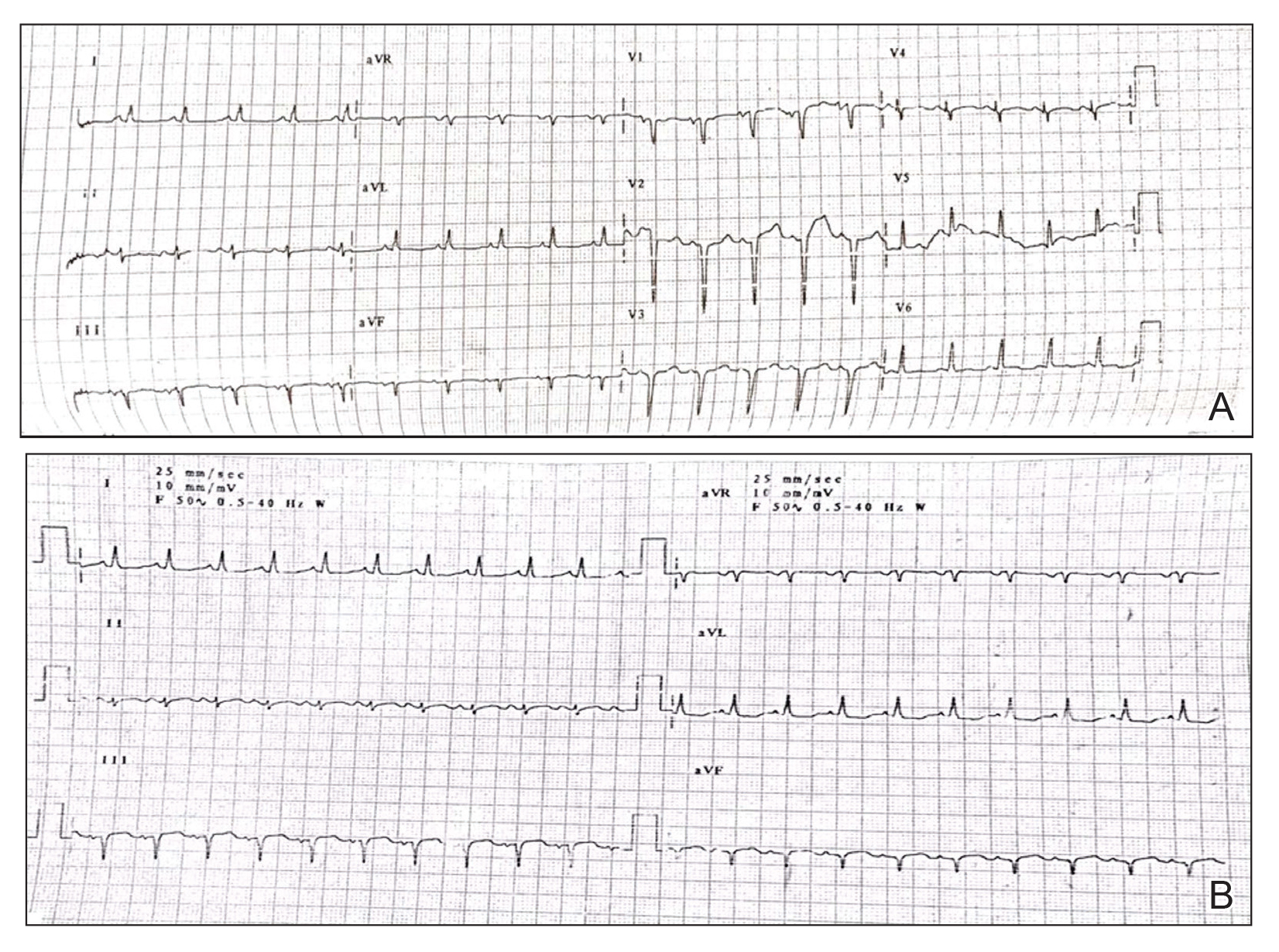

A 31-year-old man was admitted for severe psoriasis with pustular exacerbation (Figures 1A and 1B). He had moderate to severe unstable disease during the last 8 years and was managed with oral methotrexate (0.3–0.5 mg/kg/wk). He was not compliant with treatment, which led to multiple relapses. There was no personal or family history of risk factors for cardiovascular events (CVEs). At the time of present hospitalization, his vital parameters were normal. Physical examination revealed erythematous scaly plaques on more than 75% of the body surface area. Multiple pustules also were noted, often coalescing to form plaques (Figure 1C). Baseline investigations consisting of complete blood cell count, lipid profile, liver and renal functions, and chest radiography were within reference range. Baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) at admission was unremarkable (Figure 2A), except for sinus tachycardia. Low-voltage complexes in limb leads were appreciated as well as a corrected QT interval of 420 milliseconds (within reference range). Echocardiography was normal (visual ejection fraction of 60%).

The patient was unable to tolerate methotrexate due to excessive nausea; he was started on oral acitretin 25 mg once daily. There was no improvement in psoriasis over the following week, and he reported mild upper abdominal discomfort. He did not have any chest pain or dyspnea, and his pulse and blood pressure were normal. Serum electrolytes, liver function, lipid profile, and an ultrasound of the abdomen revealed no abnormalities. A repeat ECG showed no changes, and cardiac biomarkers were not elevated. Two days later, the patient collapsed while still in the hospital. A cardiac monitor and ECG showed ventricular tachycardia (VT)(Figure 2B); however, serum electrolytes, calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus levels were within reference range. Aggressive resuscitative measures including multiple attempts at cardioversion with up to 200 J (biphasic) and intravenous amiodarone infusion failed to revive the patient, and he died.

Proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor α are increased in young people with ventricular arrhythmias who have no evidence of myocardial injury (MI), suggesting an inflammatory background is involved.1 Psoriasis, a common immune-mediated inflammatory disease, has a chronic state of systemic inflammation with notably higher serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, and IL-18 compared to controls.2 This inflammation is not confined to skin but can involve blood vessels, joints, and the liver, as demonstrated by increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake.3 It also seems to exert its influence on supraventricular beat development in patients with psoriasis who do not have a history of CVEs.4 Tumor necrosis factor α is one of the major cytokines playing a role in the inflammatory process of psoriasis. Studies have shown serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α to correlate with the clinical symptoms of heart failure and to supraventricular arrhythmia in animal models.4 Various extreme CVEs can be an expression of this ongoing dynamic process. It would be interesting to know which specific factors among these inflammatory cytokines lead to rhythm irregularities.

Another theory is that young patients may experience micro-MI during the disease course. These small infarcted areas may act as aberrant pulse generators or lead to conduction disturbances. One study found increased correct QT interval dispersion, a predictor of ventricular arrhythmias, to be associated with psoriasis.5 A nationwide population-based matched cohort study by Chiu et al6 revealed that patients with psoriasis have a higher risk for arrhythmia independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Our patient also had severe unstable psoriasis for 8 years that may have led to increased accumulation of proarrhythmogenic cytokines in the heart and could have led to VT.

Acitretin as a potential cause of sudden cardiac death remains a possibility in our case; however, the exact mechanism leading to such sudden arrhythmia is lacking. Acitretin is known to increase serum triglycerides and cholesterol, specifically by shifting high-density lipoproteins to low-density lipoproteins, thereby increasing the risk for CVE. However, it takes time for such derangement to occur, eventually leading to CVE. Mittal et al7 reported a psoriasis patient who died secondary to MI after 5 days of low-dose acitretin. Lack of evidence makes acitretin a less likely cause of mortality.

We present a case of sudden cardiac death secondary to VT in a young patient with psoriasis and no other traditional cardiovascular risk factors. This case highlights the importance of being vigilant for adverse CVEs such as arrhythmia in psoriatic patients, especially in younger patients with severe unstable disease.

- Kowalewski M, Urban M, Mroczko B, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-alpha) and cardiac troponin I (cTnI) in serum of young people with ventricular arrhythmias. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2002;108:647-651.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;2005:273-279.

- Mehta NN, Yu Y, Saboury B, et al. Systemic and vascular inflammation in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis as measured by [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT): a pilot study. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1031-1039.

- Markuszeski L, Bissinger A, Janusz I, et al. Heart rate and arrhythmia in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Arch Med Res. 2007;38:64-69.

- Simsek H, Sahin M, Akyol A, et al. Increased risk of atrial and ventricular arrhythmia in long-lasting psoriasis patients. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:901215.

- Chiu HY, Chang WL, Huang WF, et al. Increased risk of arrhythmia in patients with psoriatic disease: a nationwide population-based matched cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:429-438.

- Mittal R, Malhotra S, Pandhi P, et al. Efficacy and safety of combination acitretin and pioglitazone therapy in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque-type psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:387-393.

To the Editor:

The evolution in the understanding of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis has unfolded many new facets of this immune-mediated inflammatory disease. Once considered to be just a cutaneous disease, psoriasis is not actually confined to skin but can involve almost any other system of the body. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality are the major concerns in patients with psoriasis. We report the sudden death of a young man with severe psoriasis.

A 31-year-old man was admitted for severe psoriasis with pustular exacerbation (Figures 1A and 1B). He had moderate to severe unstable disease during the last 8 years and was managed with oral methotrexate (0.3–0.5 mg/kg/wk). He was not compliant with treatment, which led to multiple relapses. There was no personal or family history of risk factors for cardiovascular events (CVEs). At the time of present hospitalization, his vital parameters were normal. Physical examination revealed erythematous scaly plaques on more than 75% of the body surface area. Multiple pustules also were noted, often coalescing to form plaques (Figure 1C). Baseline investigations consisting of complete blood cell count, lipid profile, liver and renal functions, and chest radiography were within reference range. Baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) at admission was unremarkable (Figure 2A), except for sinus tachycardia. Low-voltage complexes in limb leads were appreciated as well as a corrected QT interval of 420 milliseconds (within reference range). Echocardiography was normal (visual ejection fraction of 60%).

The patient was unable to tolerate methotrexate due to excessive nausea; he was started on oral acitretin 25 mg once daily. There was no improvement in psoriasis over the following week, and he reported mild upper abdominal discomfort. He did not have any chest pain or dyspnea, and his pulse and blood pressure were normal. Serum electrolytes, liver function, lipid profile, and an ultrasound of the abdomen revealed no abnormalities. A repeat ECG showed no changes, and cardiac biomarkers were not elevated. Two days later, the patient collapsed while still in the hospital. A cardiac monitor and ECG showed ventricular tachycardia (VT)(Figure 2B); however, serum electrolytes, calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus levels were within reference range. Aggressive resuscitative measures including multiple attempts at cardioversion with up to 200 J (biphasic) and intravenous amiodarone infusion failed to revive the patient, and he died.

Proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor α are increased in young people with ventricular arrhythmias who have no evidence of myocardial injury (MI), suggesting an inflammatory background is involved.1 Psoriasis, a common immune-mediated inflammatory disease, has a chronic state of systemic inflammation with notably higher serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, and IL-18 compared to controls.2 This inflammation is not confined to skin but can involve blood vessels, joints, and the liver, as demonstrated by increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake.3 It also seems to exert its influence on supraventricular beat development in patients with psoriasis who do not have a history of CVEs.4 Tumor necrosis factor α is one of the major cytokines playing a role in the inflammatory process of psoriasis. Studies have shown serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α to correlate with the clinical symptoms of heart failure and to supraventricular arrhythmia in animal models.4 Various extreme CVEs can be an expression of this ongoing dynamic process. It would be interesting to know which specific factors among these inflammatory cytokines lead to rhythm irregularities.

Another theory is that young patients may experience micro-MI during the disease course. These small infarcted areas may act as aberrant pulse generators or lead to conduction disturbances. One study found increased correct QT interval dispersion, a predictor of ventricular arrhythmias, to be associated with psoriasis.5 A nationwide population-based matched cohort study by Chiu et al6 revealed that patients with psoriasis have a higher risk for arrhythmia independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Our patient also had severe unstable psoriasis for 8 years that may have led to increased accumulation of proarrhythmogenic cytokines in the heart and could have led to VT.

Acitretin as a potential cause of sudden cardiac death remains a possibility in our case; however, the exact mechanism leading to such sudden arrhythmia is lacking. Acitretin is known to increase serum triglycerides and cholesterol, specifically by shifting high-density lipoproteins to low-density lipoproteins, thereby increasing the risk for CVE. However, it takes time for such derangement to occur, eventually leading to CVE. Mittal et al7 reported a psoriasis patient who died secondary to MI after 5 days of low-dose acitretin. Lack of evidence makes acitretin a less likely cause of mortality.

We present a case of sudden cardiac death secondary to VT in a young patient with psoriasis and no other traditional cardiovascular risk factors. This case highlights the importance of being vigilant for adverse CVEs such as arrhythmia in psoriatic patients, especially in younger patients with severe unstable disease.

To the Editor:

The evolution in the understanding of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis has unfolded many new facets of this immune-mediated inflammatory disease. Once considered to be just a cutaneous disease, psoriasis is not actually confined to skin but can involve almost any other system of the body. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality are the major concerns in patients with psoriasis. We report the sudden death of a young man with severe psoriasis.

A 31-year-old man was admitted for severe psoriasis with pustular exacerbation (Figures 1A and 1B). He had moderate to severe unstable disease during the last 8 years and was managed with oral methotrexate (0.3–0.5 mg/kg/wk). He was not compliant with treatment, which led to multiple relapses. There was no personal or family history of risk factors for cardiovascular events (CVEs). At the time of present hospitalization, his vital parameters were normal. Physical examination revealed erythematous scaly plaques on more than 75% of the body surface area. Multiple pustules also were noted, often coalescing to form plaques (Figure 1C). Baseline investigations consisting of complete blood cell count, lipid profile, liver and renal functions, and chest radiography were within reference range. Baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) at admission was unremarkable (Figure 2A), except for sinus tachycardia. Low-voltage complexes in limb leads were appreciated as well as a corrected QT interval of 420 milliseconds (within reference range). Echocardiography was normal (visual ejection fraction of 60%).

The patient was unable to tolerate methotrexate due to excessive nausea; he was started on oral acitretin 25 mg once daily. There was no improvement in psoriasis over the following week, and he reported mild upper abdominal discomfort. He did not have any chest pain or dyspnea, and his pulse and blood pressure were normal. Serum electrolytes, liver function, lipid profile, and an ultrasound of the abdomen revealed no abnormalities. A repeat ECG showed no changes, and cardiac biomarkers were not elevated. Two days later, the patient collapsed while still in the hospital. A cardiac monitor and ECG showed ventricular tachycardia (VT)(Figure 2B); however, serum electrolytes, calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus levels were within reference range. Aggressive resuscitative measures including multiple attempts at cardioversion with up to 200 J (biphasic) and intravenous amiodarone infusion failed to revive the patient, and he died.

Proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor α are increased in young people with ventricular arrhythmias who have no evidence of myocardial injury (MI), suggesting an inflammatory background is involved.1 Psoriasis, a common immune-mediated inflammatory disease, has a chronic state of systemic inflammation with notably higher serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, and IL-18 compared to controls.2 This inflammation is not confined to skin but can involve blood vessels, joints, and the liver, as demonstrated by increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake.3 It also seems to exert its influence on supraventricular beat development in patients with psoriasis who do not have a history of CVEs.4 Tumor necrosis factor α is one of the major cytokines playing a role in the inflammatory process of psoriasis. Studies have shown serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α to correlate with the clinical symptoms of heart failure and to supraventricular arrhythmia in animal models.4 Various extreme CVEs can be an expression of this ongoing dynamic process. It would be interesting to know which specific factors among these inflammatory cytokines lead to rhythm irregularities.

Another theory is that young patients may experience micro-MI during the disease course. These small infarcted areas may act as aberrant pulse generators or lead to conduction disturbances. One study found increased correct QT interval dispersion, a predictor of ventricular arrhythmias, to be associated with psoriasis.5 A nationwide population-based matched cohort study by Chiu et al6 revealed that patients with psoriasis have a higher risk for arrhythmia independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Our patient also had severe unstable psoriasis for 8 years that may have led to increased accumulation of proarrhythmogenic cytokines in the heart and could have led to VT.

Acitretin as a potential cause of sudden cardiac death remains a possibility in our case; however, the exact mechanism leading to such sudden arrhythmia is lacking. Acitretin is known to increase serum triglycerides and cholesterol, specifically by shifting high-density lipoproteins to low-density lipoproteins, thereby increasing the risk for CVE. However, it takes time for such derangement to occur, eventually leading to CVE. Mittal et al7 reported a psoriasis patient who died secondary to MI after 5 days of low-dose acitretin. Lack of evidence makes acitretin a less likely cause of mortality.

We present a case of sudden cardiac death secondary to VT in a young patient with psoriasis and no other traditional cardiovascular risk factors. This case highlights the importance of being vigilant for adverse CVEs such as arrhythmia in psoriatic patients, especially in younger patients with severe unstable disease.

- Kowalewski M, Urban M, Mroczko B, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-alpha) and cardiac troponin I (cTnI) in serum of young people with ventricular arrhythmias. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2002;108:647-651.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;2005:273-279.

- Mehta NN, Yu Y, Saboury B, et al. Systemic and vascular inflammation in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis as measured by [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT): a pilot study. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1031-1039.

- Markuszeski L, Bissinger A, Janusz I, et al. Heart rate and arrhythmia in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Arch Med Res. 2007;38:64-69.

- Simsek H, Sahin M, Akyol A, et al. Increased risk of atrial and ventricular arrhythmia in long-lasting psoriasis patients. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:901215.

- Chiu HY, Chang WL, Huang WF, et al. Increased risk of arrhythmia in patients with psoriatic disease: a nationwide population-based matched cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:429-438.

- Mittal R, Malhotra S, Pandhi P, et al. Efficacy and safety of combination acitretin and pioglitazone therapy in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque-type psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:387-393.

- Kowalewski M, Urban M, Mroczko B, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-alpha) and cardiac troponin I (cTnI) in serum of young people with ventricular arrhythmias. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2002;108:647-651.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;2005:273-279.

- Mehta NN, Yu Y, Saboury B, et al. Systemic and vascular inflammation in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis as measured by [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT): a pilot study. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1031-1039.

- Markuszeski L, Bissinger A, Janusz I, et al. Heart rate and arrhythmia in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Arch Med Res. 2007;38:64-69.

- Simsek H, Sahin M, Akyol A, et al. Increased risk of atrial and ventricular arrhythmia in long-lasting psoriasis patients. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:901215.

- Chiu HY, Chang WL, Huang WF, et al. Increased risk of arrhythmia in patients with psoriatic disease: a nationwide population-based matched cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:429-438.

- Mittal R, Malhotra S, Pandhi P, et al. Efficacy and safety of combination acitretin and pioglitazone therapy in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque-type psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:387-393.

Practice Points

- Low-grade chronic inflammation in patients with psoriasis can lead to vascular inflammation, which can further lead to the development of major adverse cardiovascular events (CVEs) and arrhythmia.

- The need for a multidisciplinary approach and close monitoring of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with psoriasis to prevent a CVE is vital.

- Baseline electrocardiogram and biomarkers for cardiovascular disease also should be performed in young patients with severe or unstable psoriasis.

ACOG advises on care for transgender patients

Transgender patients have unique needs regarding obstetric and gynecologic care as well as preventive care, and ob.gyns. can help by providing support, education, and understanding, according to new guidance from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists opposes discrimination on the basis of gender identity, urges public and private health insurance plans to cover necessary services for individuals with gender dysphoria, and advocates for inclusive, thoughtful, and affirming care for transgender individuals,” according to the committee opinion, published in the March issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology. The opinion was developed jointly by ACOG’s Committee on Gynecologic Practice and Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, led by Beth Cronin, MD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and Colleen K, Stockdale, MD, of the University of Iowa, Iowa City.