User login

Late-window stroke thrombolysis not linked to clot migration

In patients with acute ischemic stroke, the use of thrombolysis in the late window of 4.5-9 hours after symptom onset was not associated with an increase in clot migration that would cause reduced clot accessibility to endovascular therapy, a new analysis from the EXTEND trial shows.

“There was no significant difference in the incidence of clot migration leading to clot inaccessibility in patients who received placebo or (intravenous) thrombolysis,” the authors report.

“Our results found no convincing evidence against the use of bridging thrombolysis before endovascular therapy in patients with acute ischemic stroke who present outside the 4.5-hour window,” they conclude.

“This information is important because it provides some comfort for neurointerventionists that IV thrombolysis does not unduly increase the risk of clot migration,” senior author, Bernard Yan, DMedSci, FRACP, told this news organization.

The study was published online in Stroke on Feb. 16.

The Australian researchers explain that endovascular thrombectomy is the standard of care in patients presenting with acute ischemic stroke caused by large-vessel occlusion, and current treatment guidelines recommend bridging thrombolysis for all patients receiving thrombectomy within the 4.5-hour time window.

While thrombectomy is also recommended in selected patients up to 24 hours after onset of symptoms, it remains unclear whether thrombolysis pretreatment should be administered in this setting.

One of the issues that might affect use of thrombolysis is distal clot migration. As proximal clot location is a crucial factor determining suitability for endovascular clot retrieval, distal migration may prevent successful thrombectomy, they note.

“Clot migration can happen any time and makes life more difficult for the neurointerventionist who performs the endovascular clot retrieval,” added Dr. Yan, who is a neurologist and neurointerventionist at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, Australia.

In the current paper, the researchers report a retrospective analysis of data from the EXTEND trial of late thrombolysis, defined as 4.5-9 hours after symptom onset, to investigate the association between thrombolysis and clot migration leading to clot irretrievability.

The analysis included a total of 220 patients (109 patients in the placebo group and 111 in the thrombolysis group).

Results showed that retrievable clot was seen on baseline imaging in 69% of patients in the placebo group and 61% in the thrombolysis group. Clot resolution occurred in 28% of patients in the placebo group and 50% in the thrombolysis group.

No significant difference was observed in the incidence of clot migration leading to inaccessibility between groups. Clot migration from a retrievable to nonretrievable location occurred in 19% of the placebo group and 14% of the thrombolysis group, with an odds ratio for clot migration in the thrombolysis group of 0.70 (95% confidence interval, 0.35-1.44). This outcome was consistent across subgroups.

The researchers note that, to their knowledge, this is the first randomized controlled study to assess the effect of thrombolysis on clot migration and accessibility in an extended time window.

They acknowledge that a limitation of this study is that they only assessed clot migration from a retrievable to a nonretrievable location; therefore, the true frequency of any clot migration occurring was likely to be higher, and this could explain why other reports have found higher odds ratios of clot migration.

But they point out that they chose to limit their analysis in this way specifically to guide decision-making regarding bridging thrombolysis incorporating endovascular therapy in the extended time window.

“The findings of this study are highly relevant in the current clinical environment, where there are multiple ongoing trials looking at removing thrombolysis pretreatment within the 4.5-hour time window in thrombectomy patients,” the authors write.

“We have demonstrated that thrombolysis in the 4.5- to 9-hour window is not associated with reduced clot accessibility, and this information will be useful in future trial designs incorporating this extended time window,” they add.

Commenting on the study for this news organization, Michael Hill, MD, University of Calgary (Alta.), said: “Thrombus migration does happen and is likely part of the natural history of ischemic stroke, which may be influenced by therapeutics such as thrombolysis. This paper’s top-line result is that thrombus migration occurs in both treated and untreated groups – and therefore that this is really an observation of natural history.”

Dr. Hill says that, at present, patients should be treated with thrombolysis before endovascular therapy if they are eligible, and these results do not change that recommendation.

“The results of the ongoing trials comparing direct thrombectomy with thrombolysis plus thrombectomy will help to understand the potential clinical outcome relevance of this phenomenon,” he added.

The EXTEND trial was supported by grants from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization Flagship Program. Dr. Yan reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In patients with acute ischemic stroke, the use of thrombolysis in the late window of 4.5-9 hours after symptom onset was not associated with an increase in clot migration that would cause reduced clot accessibility to endovascular therapy, a new analysis from the EXTEND trial shows.

“There was no significant difference in the incidence of clot migration leading to clot inaccessibility in patients who received placebo or (intravenous) thrombolysis,” the authors report.

“Our results found no convincing evidence against the use of bridging thrombolysis before endovascular therapy in patients with acute ischemic stroke who present outside the 4.5-hour window,” they conclude.

“This information is important because it provides some comfort for neurointerventionists that IV thrombolysis does not unduly increase the risk of clot migration,” senior author, Bernard Yan, DMedSci, FRACP, told this news organization.

The study was published online in Stroke on Feb. 16.

The Australian researchers explain that endovascular thrombectomy is the standard of care in patients presenting with acute ischemic stroke caused by large-vessel occlusion, and current treatment guidelines recommend bridging thrombolysis for all patients receiving thrombectomy within the 4.5-hour time window.

While thrombectomy is also recommended in selected patients up to 24 hours after onset of symptoms, it remains unclear whether thrombolysis pretreatment should be administered in this setting.

One of the issues that might affect use of thrombolysis is distal clot migration. As proximal clot location is a crucial factor determining suitability for endovascular clot retrieval, distal migration may prevent successful thrombectomy, they note.

“Clot migration can happen any time and makes life more difficult for the neurointerventionist who performs the endovascular clot retrieval,” added Dr. Yan, who is a neurologist and neurointerventionist at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, Australia.

In the current paper, the researchers report a retrospective analysis of data from the EXTEND trial of late thrombolysis, defined as 4.5-9 hours after symptom onset, to investigate the association between thrombolysis and clot migration leading to clot irretrievability.

The analysis included a total of 220 patients (109 patients in the placebo group and 111 in the thrombolysis group).

Results showed that retrievable clot was seen on baseline imaging in 69% of patients in the placebo group and 61% in the thrombolysis group. Clot resolution occurred in 28% of patients in the placebo group and 50% in the thrombolysis group.

No significant difference was observed in the incidence of clot migration leading to inaccessibility between groups. Clot migration from a retrievable to nonretrievable location occurred in 19% of the placebo group and 14% of the thrombolysis group, with an odds ratio for clot migration in the thrombolysis group of 0.70 (95% confidence interval, 0.35-1.44). This outcome was consistent across subgroups.

The researchers note that, to their knowledge, this is the first randomized controlled study to assess the effect of thrombolysis on clot migration and accessibility in an extended time window.

They acknowledge that a limitation of this study is that they only assessed clot migration from a retrievable to a nonretrievable location; therefore, the true frequency of any clot migration occurring was likely to be higher, and this could explain why other reports have found higher odds ratios of clot migration.

But they point out that they chose to limit their analysis in this way specifically to guide decision-making regarding bridging thrombolysis incorporating endovascular therapy in the extended time window.

“The findings of this study are highly relevant in the current clinical environment, where there are multiple ongoing trials looking at removing thrombolysis pretreatment within the 4.5-hour time window in thrombectomy patients,” the authors write.

“We have demonstrated that thrombolysis in the 4.5- to 9-hour window is not associated with reduced clot accessibility, and this information will be useful in future trial designs incorporating this extended time window,” they add.

Commenting on the study for this news organization, Michael Hill, MD, University of Calgary (Alta.), said: “Thrombus migration does happen and is likely part of the natural history of ischemic stroke, which may be influenced by therapeutics such as thrombolysis. This paper’s top-line result is that thrombus migration occurs in both treated and untreated groups – and therefore that this is really an observation of natural history.”

Dr. Hill says that, at present, patients should be treated with thrombolysis before endovascular therapy if they are eligible, and these results do not change that recommendation.

“The results of the ongoing trials comparing direct thrombectomy with thrombolysis plus thrombectomy will help to understand the potential clinical outcome relevance of this phenomenon,” he added.

The EXTEND trial was supported by grants from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization Flagship Program. Dr. Yan reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In patients with acute ischemic stroke, the use of thrombolysis in the late window of 4.5-9 hours after symptom onset was not associated with an increase in clot migration that would cause reduced clot accessibility to endovascular therapy, a new analysis from the EXTEND trial shows.

“There was no significant difference in the incidence of clot migration leading to clot inaccessibility in patients who received placebo or (intravenous) thrombolysis,” the authors report.

“Our results found no convincing evidence against the use of bridging thrombolysis before endovascular therapy in patients with acute ischemic stroke who present outside the 4.5-hour window,” they conclude.

“This information is important because it provides some comfort for neurointerventionists that IV thrombolysis does not unduly increase the risk of clot migration,” senior author, Bernard Yan, DMedSci, FRACP, told this news organization.

The study was published online in Stroke on Feb. 16.

The Australian researchers explain that endovascular thrombectomy is the standard of care in patients presenting with acute ischemic stroke caused by large-vessel occlusion, and current treatment guidelines recommend bridging thrombolysis for all patients receiving thrombectomy within the 4.5-hour time window.

While thrombectomy is also recommended in selected patients up to 24 hours after onset of symptoms, it remains unclear whether thrombolysis pretreatment should be administered in this setting.

One of the issues that might affect use of thrombolysis is distal clot migration. As proximal clot location is a crucial factor determining suitability for endovascular clot retrieval, distal migration may prevent successful thrombectomy, they note.

“Clot migration can happen any time and makes life more difficult for the neurointerventionist who performs the endovascular clot retrieval,” added Dr. Yan, who is a neurologist and neurointerventionist at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, Australia.

In the current paper, the researchers report a retrospective analysis of data from the EXTEND trial of late thrombolysis, defined as 4.5-9 hours after symptom onset, to investigate the association between thrombolysis and clot migration leading to clot irretrievability.

The analysis included a total of 220 patients (109 patients in the placebo group and 111 in the thrombolysis group).

Results showed that retrievable clot was seen on baseline imaging in 69% of patients in the placebo group and 61% in the thrombolysis group. Clot resolution occurred in 28% of patients in the placebo group and 50% in the thrombolysis group.

No significant difference was observed in the incidence of clot migration leading to inaccessibility between groups. Clot migration from a retrievable to nonretrievable location occurred in 19% of the placebo group and 14% of the thrombolysis group, with an odds ratio for clot migration in the thrombolysis group of 0.70 (95% confidence interval, 0.35-1.44). This outcome was consistent across subgroups.

The researchers note that, to their knowledge, this is the first randomized controlled study to assess the effect of thrombolysis on clot migration and accessibility in an extended time window.

They acknowledge that a limitation of this study is that they only assessed clot migration from a retrievable to a nonretrievable location; therefore, the true frequency of any clot migration occurring was likely to be higher, and this could explain why other reports have found higher odds ratios of clot migration.

But they point out that they chose to limit their analysis in this way specifically to guide decision-making regarding bridging thrombolysis incorporating endovascular therapy in the extended time window.

“The findings of this study are highly relevant in the current clinical environment, where there are multiple ongoing trials looking at removing thrombolysis pretreatment within the 4.5-hour time window in thrombectomy patients,” the authors write.

“We have demonstrated that thrombolysis in the 4.5- to 9-hour window is not associated with reduced clot accessibility, and this information will be useful in future trial designs incorporating this extended time window,” they add.

Commenting on the study for this news organization, Michael Hill, MD, University of Calgary (Alta.), said: “Thrombus migration does happen and is likely part of the natural history of ischemic stroke, which may be influenced by therapeutics such as thrombolysis. This paper’s top-line result is that thrombus migration occurs in both treated and untreated groups – and therefore that this is really an observation of natural history.”

Dr. Hill says that, at present, patients should be treated with thrombolysis before endovascular therapy if they are eligible, and these results do not change that recommendation.

“The results of the ongoing trials comparing direct thrombectomy with thrombolysis plus thrombectomy will help to understand the potential clinical outcome relevance of this phenomenon,” he added.

The EXTEND trial was supported by grants from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization Flagship Program. Dr. Yan reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Big data ‘clinch’ link between high glycemic index diets and CVD

People who mostly ate foods with a low glycemic index had a lower likelihood of premature death and major cardiovascular disease (CVD) events, compared with those whose diet included more “poor-quality” food with a high glycemic index.

The results from the global PURE study of nearly 120,000 people provide evidence that helps cement glycemic index as a key measure of dietary health.

This new analysis from PURE (Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiological Study) – a massive prospective epidemiologic study – shows people with a diet in the highest quintile of glycemic index had a significant 25% higher rate of combined total deaths and major CVD events during a median follow-up of nearly 10 years, compared with those with a diet in the lowest glycemic index quintile, in the report published online on Feb. 24, 2021, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

David J.A. Jenkins, MD, PhD, DSc, lead author, said people do not necessarily need to closely track the glycemic index of what they eat to follow the guidance that lower is better.

The link between lower glycemic load and fewer CVD events was even stronger among people with an established history of CVD at study entry. In this subset, which included 9% of the total cohort, people in the highest quintile for glycemic index consumption had a 51% higher rate of the composite primary endpoint, compared with those in the lowest quintile, in an analysis that adjusted for several potential confounders.

A simple but accurate and effective public health message is to follow existing dietary recommendations to eat better-quality food – more unprocessed fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains – Dr. Jenkins advised. Those who prefer a more detailed approach could use the comprehensive glycemic index tables compiled by researchers at the University of Sydney.

‘All carbohydrates are not the same’

“What we’re saying is that all carbohydrates are not the same. Some seem to increase the risk for CVD, and others seem protective. This is not new, but worth restating in an era of low-carb and no-carb diets,” said Dr. Jenkins.

Low-glycemic-index foods are generally unprocessed foods in their native state, including fruits, vegetables, legumes, and unrefined whole grains. High-glycemic-index foods contain processed and refined carbohydrates that deliver jolts of glucose soon after eating, as the sugar in these carbohydrates quickly moves from the gut to the bloodstream.

An association between a diet with a lower glycemic index and better outcomes had appeared in prior reports from other studies, but not as unambiguously as in the new data from PURE, likely because of fewer study participants in previous studies.

Another feature of PURE that adds to the generalizability of the findings is the diversity of adults included in the study, from 20 countries on five continents.

“This clinches it,” Dr. Jenkins declared in an interview.

New PURE data tip the evidence balance

The NEJM article includes a new meta-analysis that adds the PURE findings to data from two large prior reports that were each less conclusive. The new calculation with the PURE numbers helps establish a clearer association between a diet with a higher glycemic index and the endpoint of CVD death, showing an overall 26% increase in the outcome.

The PURE data are especially informative because the investigators collected additional information on a range of potential confounders they incorporated into their analyses.

“We were able to include a lot of documentation on many potential confounders. That’s a strength of our data,” noted Dr. Jenkins, a professor of nutritional science and medicine at the University of Toronto.

“The present data, along with prior publications from PURE and several other studies, emphasize that consumption of poor quality carbohydrates is likely to be more adverse than the consumption of most fats in the diet,” said senior author Salim Yusuf, MD, DPhil, professor of medicine and executive director of the Population Health Research Institute at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

“This calls for a fundamental shift in our thinking of what types of diet are likely to be harmful and what types neutral or beneficial,” Dr. Yusuf said in a statement from his institution.

Higher BMI associated with greater glycemic index effect

Another important analysis in the new report calculated the impact of a higher glycemic index diet among people with a body mass index (BMI) of less than 25 kg/m2 as well as higher BMIs.

Among people in the lower BMI subgroup, greater intake of high-glycemic-index foods showed slightly more incident primary outcome events. In contrast, people with a BMI of 25 or greater showed a steady increment in primary outcome events as the glycemic index of their diet increased.

People with higher BMIs in the quartile that ate the greatest amount of high-glycemic =-index foods had a significant 38% higher rate of primary outcome events, compared with people with similar BMIs in the lowest quartile for high-glycemic-index intake.

However, the study showed no impact on the primary association of high glycemic index and increased adverse outcomes by exercise habits, smoking, use of blood pressure medications, or use of statins.

The new report complements a separate analysis from PURE published just a few weeks earlier in the BMJ that established a significant association between increased consumption of whole grains and fewer CVD events, compared with people who had more refined grains in their diet, as reported by this news organization.

This prior report on whole versus refined grains, which Dr. Jenkins coauthored, looked at carbohydrate quality using a two-pronged approach, while glycemic index is a continuous variable that provides more nuance and takes into account carbohydrates from sources other than grains, Dr. Jenkins said.

PURE enrolled roughly 225,000 people aged 35-70 years at entry. The glycemic index analysis focused on 119,575 people who had data available for the primary outcome. During a median follow-up of 9.5 years, these people had 14,075 primary outcome events, including 8,780 deaths.

Analyses that looked at the individual outcomes that comprised the composite endpoint showed significant associations between a high-glycemic-index diet and total mortality, CVD death, non-CVD death, and stroke, but showed no significant link with myocardial infarction or heart failure. These findings are consistent with prior results of other studies that showed a stronger link between stroke and a high glycemic index diet, compared with other nonfatal CVD events.

Dr. Jenkins suggested that the significant excess of non-CVD deaths linked with a high-glycemic-index diet may stem from the impact of this type of diet on cancer-associated mortality.

PURE received partial funding through unrestricted grants from several drug companies. Dr. Jenkins has reported receiving gifts from several food-related trade associations and food companies, as well as research grants from two legume-oriented trade associations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People who mostly ate foods with a low glycemic index had a lower likelihood of premature death and major cardiovascular disease (CVD) events, compared with those whose diet included more “poor-quality” food with a high glycemic index.

The results from the global PURE study of nearly 120,000 people provide evidence that helps cement glycemic index as a key measure of dietary health.

This new analysis from PURE (Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiological Study) – a massive prospective epidemiologic study – shows people with a diet in the highest quintile of glycemic index had a significant 25% higher rate of combined total deaths and major CVD events during a median follow-up of nearly 10 years, compared with those with a diet in the lowest glycemic index quintile, in the report published online on Feb. 24, 2021, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

David J.A. Jenkins, MD, PhD, DSc, lead author, said people do not necessarily need to closely track the glycemic index of what they eat to follow the guidance that lower is better.

The link between lower glycemic load and fewer CVD events was even stronger among people with an established history of CVD at study entry. In this subset, which included 9% of the total cohort, people in the highest quintile for glycemic index consumption had a 51% higher rate of the composite primary endpoint, compared with those in the lowest quintile, in an analysis that adjusted for several potential confounders.

A simple but accurate and effective public health message is to follow existing dietary recommendations to eat better-quality food – more unprocessed fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains – Dr. Jenkins advised. Those who prefer a more detailed approach could use the comprehensive glycemic index tables compiled by researchers at the University of Sydney.

‘All carbohydrates are not the same’

“What we’re saying is that all carbohydrates are not the same. Some seem to increase the risk for CVD, and others seem protective. This is not new, but worth restating in an era of low-carb and no-carb diets,” said Dr. Jenkins.

Low-glycemic-index foods are generally unprocessed foods in their native state, including fruits, vegetables, legumes, and unrefined whole grains. High-glycemic-index foods contain processed and refined carbohydrates that deliver jolts of glucose soon after eating, as the sugar in these carbohydrates quickly moves from the gut to the bloodstream.

An association between a diet with a lower glycemic index and better outcomes had appeared in prior reports from other studies, but not as unambiguously as in the new data from PURE, likely because of fewer study participants in previous studies.

Another feature of PURE that adds to the generalizability of the findings is the diversity of adults included in the study, from 20 countries on five continents.

“This clinches it,” Dr. Jenkins declared in an interview.

New PURE data tip the evidence balance

The NEJM article includes a new meta-analysis that adds the PURE findings to data from two large prior reports that were each less conclusive. The new calculation with the PURE numbers helps establish a clearer association between a diet with a higher glycemic index and the endpoint of CVD death, showing an overall 26% increase in the outcome.

The PURE data are especially informative because the investigators collected additional information on a range of potential confounders they incorporated into their analyses.

“We were able to include a lot of documentation on many potential confounders. That’s a strength of our data,” noted Dr. Jenkins, a professor of nutritional science and medicine at the University of Toronto.

“The present data, along with prior publications from PURE and several other studies, emphasize that consumption of poor quality carbohydrates is likely to be more adverse than the consumption of most fats in the diet,” said senior author Salim Yusuf, MD, DPhil, professor of medicine and executive director of the Population Health Research Institute at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

“This calls for a fundamental shift in our thinking of what types of diet are likely to be harmful and what types neutral or beneficial,” Dr. Yusuf said in a statement from his institution.

Higher BMI associated with greater glycemic index effect

Another important analysis in the new report calculated the impact of a higher glycemic index diet among people with a body mass index (BMI) of less than 25 kg/m2 as well as higher BMIs.

Among people in the lower BMI subgroup, greater intake of high-glycemic-index foods showed slightly more incident primary outcome events. In contrast, people with a BMI of 25 or greater showed a steady increment in primary outcome events as the glycemic index of their diet increased.

People with higher BMIs in the quartile that ate the greatest amount of high-glycemic =-index foods had a significant 38% higher rate of primary outcome events, compared with people with similar BMIs in the lowest quartile for high-glycemic-index intake.

However, the study showed no impact on the primary association of high glycemic index and increased adverse outcomes by exercise habits, smoking, use of blood pressure medications, or use of statins.

The new report complements a separate analysis from PURE published just a few weeks earlier in the BMJ that established a significant association between increased consumption of whole grains and fewer CVD events, compared with people who had more refined grains in their diet, as reported by this news organization.

This prior report on whole versus refined grains, which Dr. Jenkins coauthored, looked at carbohydrate quality using a two-pronged approach, while glycemic index is a continuous variable that provides more nuance and takes into account carbohydrates from sources other than grains, Dr. Jenkins said.

PURE enrolled roughly 225,000 people aged 35-70 years at entry. The glycemic index analysis focused on 119,575 people who had data available for the primary outcome. During a median follow-up of 9.5 years, these people had 14,075 primary outcome events, including 8,780 deaths.

Analyses that looked at the individual outcomes that comprised the composite endpoint showed significant associations between a high-glycemic-index diet and total mortality, CVD death, non-CVD death, and stroke, but showed no significant link with myocardial infarction or heart failure. These findings are consistent with prior results of other studies that showed a stronger link between stroke and a high glycemic index diet, compared with other nonfatal CVD events.

Dr. Jenkins suggested that the significant excess of non-CVD deaths linked with a high-glycemic-index diet may stem from the impact of this type of diet on cancer-associated mortality.

PURE received partial funding through unrestricted grants from several drug companies. Dr. Jenkins has reported receiving gifts from several food-related trade associations and food companies, as well as research grants from two legume-oriented trade associations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People who mostly ate foods with a low glycemic index had a lower likelihood of premature death and major cardiovascular disease (CVD) events, compared with those whose diet included more “poor-quality” food with a high glycemic index.

The results from the global PURE study of nearly 120,000 people provide evidence that helps cement glycemic index as a key measure of dietary health.

This new analysis from PURE (Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiological Study) – a massive prospective epidemiologic study – shows people with a diet in the highest quintile of glycemic index had a significant 25% higher rate of combined total deaths and major CVD events during a median follow-up of nearly 10 years, compared with those with a diet in the lowest glycemic index quintile, in the report published online on Feb. 24, 2021, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

David J.A. Jenkins, MD, PhD, DSc, lead author, said people do not necessarily need to closely track the glycemic index of what they eat to follow the guidance that lower is better.

The link between lower glycemic load and fewer CVD events was even stronger among people with an established history of CVD at study entry. In this subset, which included 9% of the total cohort, people in the highest quintile for glycemic index consumption had a 51% higher rate of the composite primary endpoint, compared with those in the lowest quintile, in an analysis that adjusted for several potential confounders.

A simple but accurate and effective public health message is to follow existing dietary recommendations to eat better-quality food – more unprocessed fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains – Dr. Jenkins advised. Those who prefer a more detailed approach could use the comprehensive glycemic index tables compiled by researchers at the University of Sydney.

‘All carbohydrates are not the same’

“What we’re saying is that all carbohydrates are not the same. Some seem to increase the risk for CVD, and others seem protective. This is not new, but worth restating in an era of low-carb and no-carb diets,” said Dr. Jenkins.

Low-glycemic-index foods are generally unprocessed foods in their native state, including fruits, vegetables, legumes, and unrefined whole grains. High-glycemic-index foods contain processed and refined carbohydrates that deliver jolts of glucose soon after eating, as the sugar in these carbohydrates quickly moves from the gut to the bloodstream.

An association between a diet with a lower glycemic index and better outcomes had appeared in prior reports from other studies, but not as unambiguously as in the new data from PURE, likely because of fewer study participants in previous studies.

Another feature of PURE that adds to the generalizability of the findings is the diversity of adults included in the study, from 20 countries on five continents.

“This clinches it,” Dr. Jenkins declared in an interview.

New PURE data tip the evidence balance

The NEJM article includes a new meta-analysis that adds the PURE findings to data from two large prior reports that were each less conclusive. The new calculation with the PURE numbers helps establish a clearer association between a diet with a higher glycemic index and the endpoint of CVD death, showing an overall 26% increase in the outcome.

The PURE data are especially informative because the investigators collected additional information on a range of potential confounders they incorporated into their analyses.

“We were able to include a lot of documentation on many potential confounders. That’s a strength of our data,” noted Dr. Jenkins, a professor of nutritional science and medicine at the University of Toronto.

“The present data, along with prior publications from PURE and several other studies, emphasize that consumption of poor quality carbohydrates is likely to be more adverse than the consumption of most fats in the diet,” said senior author Salim Yusuf, MD, DPhil, professor of medicine and executive director of the Population Health Research Institute at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

“This calls for a fundamental shift in our thinking of what types of diet are likely to be harmful and what types neutral or beneficial,” Dr. Yusuf said in a statement from his institution.

Higher BMI associated with greater glycemic index effect

Another important analysis in the new report calculated the impact of a higher glycemic index diet among people with a body mass index (BMI) of less than 25 kg/m2 as well as higher BMIs.

Among people in the lower BMI subgroup, greater intake of high-glycemic-index foods showed slightly more incident primary outcome events. In contrast, people with a BMI of 25 or greater showed a steady increment in primary outcome events as the glycemic index of their diet increased.

People with higher BMIs in the quartile that ate the greatest amount of high-glycemic =-index foods had a significant 38% higher rate of primary outcome events, compared with people with similar BMIs in the lowest quartile for high-glycemic-index intake.

However, the study showed no impact on the primary association of high glycemic index and increased adverse outcomes by exercise habits, smoking, use of blood pressure medications, or use of statins.

The new report complements a separate analysis from PURE published just a few weeks earlier in the BMJ that established a significant association between increased consumption of whole grains and fewer CVD events, compared with people who had more refined grains in their diet, as reported by this news organization.

This prior report on whole versus refined grains, which Dr. Jenkins coauthored, looked at carbohydrate quality using a two-pronged approach, while glycemic index is a continuous variable that provides more nuance and takes into account carbohydrates from sources other than grains, Dr. Jenkins said.

PURE enrolled roughly 225,000 people aged 35-70 years at entry. The glycemic index analysis focused on 119,575 people who had data available for the primary outcome. During a median follow-up of 9.5 years, these people had 14,075 primary outcome events, including 8,780 deaths.

Analyses that looked at the individual outcomes that comprised the composite endpoint showed significant associations between a high-glycemic-index diet and total mortality, CVD death, non-CVD death, and stroke, but showed no significant link with myocardial infarction or heart failure. These findings are consistent with prior results of other studies that showed a stronger link between stroke and a high glycemic index diet, compared with other nonfatal CVD events.

Dr. Jenkins suggested that the significant excess of non-CVD deaths linked with a high-glycemic-index diet may stem from the impact of this type of diet on cancer-associated mortality.

PURE received partial funding through unrestricted grants from several drug companies. Dr. Jenkins has reported receiving gifts from several food-related trade associations and food companies, as well as research grants from two legume-oriented trade associations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

No benefit seen with everolimus in early breast cancer

At a median follow-up of almost 3 years, rates of disease-free survival, distant metastasis-free survival, and overall survival were similar in the everolimus and hormone therapy-alone arms.

These findings were presented at the inaugural ESMO Virtual Plenary and published in Annals of Oncology.

The UNIRAD results contrast results from prior studies of everolimus in the advanced breast cancer setting. In the BOLERO-2 and BOLERO-4 studies, the mTOR inhibitor provided a progression-free survival benefit when added to hormone therapy.

“There clearly is rationale for targeted therapy in early ER+, HER2- breast cancer,” said Rebecca Dent, MD, of the National Cancer Center in Singapore, who chaired the ESMO Virtual Plenary in which the UNIRAD findings were presented.

“Patients with high-risk luminal breast cancer clearly have an unmet need. We probably still underestimate the risk of early and late recurrences, and chemotherapy is not necessarily the answer,” Dr. Dent said.

She observed that a lot has been learned about the mTOR pathway, including how complicated it is and its role in endocrine resistance. Since mTOR inhibition was standard care in the metastatic setting, “it really is appropriate now to test in early breast cancer,” she added.

Study details

The aim of the UNIRAD study was to compare the efficacy and safety of everolimus plus standard adjuvant hormone therapy to hormone therapy alone in women with ER+, HER2- early breast cancer who had a high risk of recurrence. High risk was defined as having more than four positive nodes, having one or more positive nodes after neoadjuvant chemotherapy or hormone therapy, or having one or more positive nodes and an EPclin score of 3.3 or higher.

The trial enrolled 1,278 patients. At baseline, their median age was 54 years (range, 48-63), 65.8% were postmenopausal, and 52.7% had four or more positive nodes.

The patients were randomized 1:1 to receive 2 years of everolimus plus hormone therapy or placebo plus hormone therapy. The type of hormone therapy was investigor’s choice.

Investigator Thomas Bachelot, MD, PhD, of Centre Leon Berard in Lyon, France, noted that the study started in 2013 and underwent several protocol amendments, first for accrual problems and then because of toxicity. This led to dropping the starting dose of everolimus from 10 mg to 5 mg.

“Acceptability was a concern; 50% of our patients stopped everolimus before study completion for toxicity or personal decision,” Dr. Bachelot acknowledged.

Grade 3 or higher adverse events were more frequent in patients taking everolimus (29.9%) than placebo (15.9%) in combination with hormone therapy. The rates of serious adverse events were a respective 11.8% and 9.3%.

Mucositis was one of the main adverse events, occurring in more than half of all patients treated with everolimus (33.8% grade 1, 25.4% grade 2, and 7.4% grade 3/4). The success of managing this side effect with a dexamethasone mouthwash was not known at the time of the UNIRAD trial design.

The study also showed no benefit of everolimus over placebo for the following efficacy outcomes:

- Disease-free survival – 88% and 89%, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.95; 95% confidence interval, 0.69-1.32; P = .78)

- Distant metastasis-free survival – 91% and 90%, respectively (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.62-1.25)

- Overall survival – both 96% (HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.62-1.92).

With the exception of patients who had received tamoxifen rather than an aromatase inhibitor, a preplanned subgroup analysis suggested there was no population of patients who benefited from the addition of everolimus.

Problems interpreting data

There are several problems in interpreting the UNIRAD data, observed study discussant Peter Schmid, MD, PhD, of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital & Barts Cancer Institute in London.

For one, “whether we like it or not,” the trial was underpowered, he said. This was because the trial had been halted early for futility at the first interim analysis when about two-thirds of the intended study cohort had been accrued.

In addition, Dr. Schmid said, this is clearly not a trial that included patients with primary endocrine resistance. In all, 43% of patients had received less than 1 year of endocrine treatment, 42% had received 2-3 years, and 15% had received more than 3 years of endocrine treatment.

Dr. Schmid said that the starting dose of everolimus had to be lowered because of toxicity or poor acceptance. “As a result, two-thirds of patients received a 5-mg dose, and we don’t know whether that had an impact on efficacy,” he said.

Furthermore, the median time on treatment was less than half of what was initially planned, and 53% of patients had to stop everolimus before the end of the study.

Dr. Schmid noted that this discontinuation rate is higher than that seen in trials of CDK4/6 inhibitors added to endocrine treatment. Dropout rates were 19% in the negative Penelope-B trial with palbociclib, 42% in the negative PALLAS trial with palbociclib, and 27% in the positive monarchE trial with abemaciclib.

With such a high discontinuation rate in the UNIRAD trial, “we’re not sure whether we can ultimately evaluate really whether this trial did work,” Dr. Schmid said.

“Could the results change over time?” he asked. “I personally think it is unlikely, as the trial clearly has already an adequate follow-up for what it was supposed to show.”

Looking at whether the trial’s hypothesis is still valid, he added: “I think that is unclear to all of us, and we need to work out whether these compounds are cytostatic in nature, or cytotoxic. And that is something we need to learn over time.”

Commending the study overall, Dr. Schmid observed: “I think it was an excellent trial design based on what we knew at that time,” and the design “was changed in a pragmatic way because of recruitment challenges.”

Something for the future would be to select patients for such trials based on the tumor biology rather than risk status, Dr. Schmid suggested. “That is something we may have to take into consideration with our increasing knowledge around primary and secondary resistance and what treatments we want to introduce to target-resistant clones,” he said.

The UNIRAD study was sponsored by UNICANCER, with funding and support from the French Ministry of Health, Cancer Research UK, Myriad Genetics (which provided Endopredict tests), and Novartis (which provided everolimus and placebo). Dr. Bachelot, Dr. Schmid, and Dr. Dent disclosed relationships with Novartis and several other pharmaceutical companies.

At a median follow-up of almost 3 years, rates of disease-free survival, distant metastasis-free survival, and overall survival were similar in the everolimus and hormone therapy-alone arms.

These findings were presented at the inaugural ESMO Virtual Plenary and published in Annals of Oncology.

The UNIRAD results contrast results from prior studies of everolimus in the advanced breast cancer setting. In the BOLERO-2 and BOLERO-4 studies, the mTOR inhibitor provided a progression-free survival benefit when added to hormone therapy.

“There clearly is rationale for targeted therapy in early ER+, HER2- breast cancer,” said Rebecca Dent, MD, of the National Cancer Center in Singapore, who chaired the ESMO Virtual Plenary in which the UNIRAD findings were presented.

“Patients with high-risk luminal breast cancer clearly have an unmet need. We probably still underestimate the risk of early and late recurrences, and chemotherapy is not necessarily the answer,” Dr. Dent said.

She observed that a lot has been learned about the mTOR pathway, including how complicated it is and its role in endocrine resistance. Since mTOR inhibition was standard care in the metastatic setting, “it really is appropriate now to test in early breast cancer,” she added.

Study details

The aim of the UNIRAD study was to compare the efficacy and safety of everolimus plus standard adjuvant hormone therapy to hormone therapy alone in women with ER+, HER2- early breast cancer who had a high risk of recurrence. High risk was defined as having more than four positive nodes, having one or more positive nodes after neoadjuvant chemotherapy or hormone therapy, or having one or more positive nodes and an EPclin score of 3.3 or higher.

The trial enrolled 1,278 patients. At baseline, their median age was 54 years (range, 48-63), 65.8% were postmenopausal, and 52.7% had four or more positive nodes.

The patients were randomized 1:1 to receive 2 years of everolimus plus hormone therapy or placebo plus hormone therapy. The type of hormone therapy was investigor’s choice.

Investigator Thomas Bachelot, MD, PhD, of Centre Leon Berard in Lyon, France, noted that the study started in 2013 and underwent several protocol amendments, first for accrual problems and then because of toxicity. This led to dropping the starting dose of everolimus from 10 mg to 5 mg.

“Acceptability was a concern; 50% of our patients stopped everolimus before study completion for toxicity or personal decision,” Dr. Bachelot acknowledged.

Grade 3 or higher adverse events were more frequent in patients taking everolimus (29.9%) than placebo (15.9%) in combination with hormone therapy. The rates of serious adverse events were a respective 11.8% and 9.3%.

Mucositis was one of the main adverse events, occurring in more than half of all patients treated with everolimus (33.8% grade 1, 25.4% grade 2, and 7.4% grade 3/4). The success of managing this side effect with a dexamethasone mouthwash was not known at the time of the UNIRAD trial design.

The study also showed no benefit of everolimus over placebo for the following efficacy outcomes:

- Disease-free survival – 88% and 89%, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.95; 95% confidence interval, 0.69-1.32; P = .78)

- Distant metastasis-free survival – 91% and 90%, respectively (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.62-1.25)

- Overall survival – both 96% (HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.62-1.92).

With the exception of patients who had received tamoxifen rather than an aromatase inhibitor, a preplanned subgroup analysis suggested there was no population of patients who benefited from the addition of everolimus.

Problems interpreting data

There are several problems in interpreting the UNIRAD data, observed study discussant Peter Schmid, MD, PhD, of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital & Barts Cancer Institute in London.

For one, “whether we like it or not,” the trial was underpowered, he said. This was because the trial had been halted early for futility at the first interim analysis when about two-thirds of the intended study cohort had been accrued.

In addition, Dr. Schmid said, this is clearly not a trial that included patients with primary endocrine resistance. In all, 43% of patients had received less than 1 year of endocrine treatment, 42% had received 2-3 years, and 15% had received more than 3 years of endocrine treatment.

Dr. Schmid said that the starting dose of everolimus had to be lowered because of toxicity or poor acceptance. “As a result, two-thirds of patients received a 5-mg dose, and we don’t know whether that had an impact on efficacy,” he said.

Furthermore, the median time on treatment was less than half of what was initially planned, and 53% of patients had to stop everolimus before the end of the study.

Dr. Schmid noted that this discontinuation rate is higher than that seen in trials of CDK4/6 inhibitors added to endocrine treatment. Dropout rates were 19% in the negative Penelope-B trial with palbociclib, 42% in the negative PALLAS trial with palbociclib, and 27% in the positive monarchE trial with abemaciclib.

With such a high discontinuation rate in the UNIRAD trial, “we’re not sure whether we can ultimately evaluate really whether this trial did work,” Dr. Schmid said.

“Could the results change over time?” he asked. “I personally think it is unlikely, as the trial clearly has already an adequate follow-up for what it was supposed to show.”

Looking at whether the trial’s hypothesis is still valid, he added: “I think that is unclear to all of us, and we need to work out whether these compounds are cytostatic in nature, or cytotoxic. And that is something we need to learn over time.”

Commending the study overall, Dr. Schmid observed: “I think it was an excellent trial design based on what we knew at that time,” and the design “was changed in a pragmatic way because of recruitment challenges.”

Something for the future would be to select patients for such trials based on the tumor biology rather than risk status, Dr. Schmid suggested. “That is something we may have to take into consideration with our increasing knowledge around primary and secondary resistance and what treatments we want to introduce to target-resistant clones,” he said.

The UNIRAD study was sponsored by UNICANCER, with funding and support from the French Ministry of Health, Cancer Research UK, Myriad Genetics (which provided Endopredict tests), and Novartis (which provided everolimus and placebo). Dr. Bachelot, Dr. Schmid, and Dr. Dent disclosed relationships with Novartis and several other pharmaceutical companies.

At a median follow-up of almost 3 years, rates of disease-free survival, distant metastasis-free survival, and overall survival were similar in the everolimus and hormone therapy-alone arms.

These findings were presented at the inaugural ESMO Virtual Plenary and published in Annals of Oncology.

The UNIRAD results contrast results from prior studies of everolimus in the advanced breast cancer setting. In the BOLERO-2 and BOLERO-4 studies, the mTOR inhibitor provided a progression-free survival benefit when added to hormone therapy.

“There clearly is rationale for targeted therapy in early ER+, HER2- breast cancer,” said Rebecca Dent, MD, of the National Cancer Center in Singapore, who chaired the ESMO Virtual Plenary in which the UNIRAD findings were presented.

“Patients with high-risk luminal breast cancer clearly have an unmet need. We probably still underestimate the risk of early and late recurrences, and chemotherapy is not necessarily the answer,” Dr. Dent said.

She observed that a lot has been learned about the mTOR pathway, including how complicated it is and its role in endocrine resistance. Since mTOR inhibition was standard care in the metastatic setting, “it really is appropriate now to test in early breast cancer,” she added.

Study details

The aim of the UNIRAD study was to compare the efficacy and safety of everolimus plus standard adjuvant hormone therapy to hormone therapy alone in women with ER+, HER2- early breast cancer who had a high risk of recurrence. High risk was defined as having more than four positive nodes, having one or more positive nodes after neoadjuvant chemotherapy or hormone therapy, or having one or more positive nodes and an EPclin score of 3.3 or higher.

The trial enrolled 1,278 patients. At baseline, their median age was 54 years (range, 48-63), 65.8% were postmenopausal, and 52.7% had four or more positive nodes.

The patients were randomized 1:1 to receive 2 years of everolimus plus hormone therapy or placebo plus hormone therapy. The type of hormone therapy was investigor’s choice.

Investigator Thomas Bachelot, MD, PhD, of Centre Leon Berard in Lyon, France, noted that the study started in 2013 and underwent several protocol amendments, first for accrual problems and then because of toxicity. This led to dropping the starting dose of everolimus from 10 mg to 5 mg.

“Acceptability was a concern; 50% of our patients stopped everolimus before study completion for toxicity or personal decision,” Dr. Bachelot acknowledged.

Grade 3 or higher adverse events were more frequent in patients taking everolimus (29.9%) than placebo (15.9%) in combination with hormone therapy. The rates of serious adverse events were a respective 11.8% and 9.3%.

Mucositis was one of the main adverse events, occurring in more than half of all patients treated with everolimus (33.8% grade 1, 25.4% grade 2, and 7.4% grade 3/4). The success of managing this side effect with a dexamethasone mouthwash was not known at the time of the UNIRAD trial design.

The study also showed no benefit of everolimus over placebo for the following efficacy outcomes:

- Disease-free survival – 88% and 89%, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.95; 95% confidence interval, 0.69-1.32; P = .78)

- Distant metastasis-free survival – 91% and 90%, respectively (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.62-1.25)

- Overall survival – both 96% (HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.62-1.92).

With the exception of patients who had received tamoxifen rather than an aromatase inhibitor, a preplanned subgroup analysis suggested there was no population of patients who benefited from the addition of everolimus.

Problems interpreting data

There are several problems in interpreting the UNIRAD data, observed study discussant Peter Schmid, MD, PhD, of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital & Barts Cancer Institute in London.

For one, “whether we like it or not,” the trial was underpowered, he said. This was because the trial had been halted early for futility at the first interim analysis when about two-thirds of the intended study cohort had been accrued.

In addition, Dr. Schmid said, this is clearly not a trial that included patients with primary endocrine resistance. In all, 43% of patients had received less than 1 year of endocrine treatment, 42% had received 2-3 years, and 15% had received more than 3 years of endocrine treatment.

Dr. Schmid said that the starting dose of everolimus had to be lowered because of toxicity or poor acceptance. “As a result, two-thirds of patients received a 5-mg dose, and we don’t know whether that had an impact on efficacy,” he said.

Furthermore, the median time on treatment was less than half of what was initially planned, and 53% of patients had to stop everolimus before the end of the study.

Dr. Schmid noted that this discontinuation rate is higher than that seen in trials of CDK4/6 inhibitors added to endocrine treatment. Dropout rates were 19% in the negative Penelope-B trial with palbociclib, 42% in the negative PALLAS trial with palbociclib, and 27% in the positive monarchE trial with abemaciclib.

With such a high discontinuation rate in the UNIRAD trial, “we’re not sure whether we can ultimately evaluate really whether this trial did work,” Dr. Schmid said.

“Could the results change over time?” he asked. “I personally think it is unlikely, as the trial clearly has already an adequate follow-up for what it was supposed to show.”

Looking at whether the trial’s hypothesis is still valid, he added: “I think that is unclear to all of us, and we need to work out whether these compounds are cytostatic in nature, or cytotoxic. And that is something we need to learn over time.”

Commending the study overall, Dr. Schmid observed: “I think it was an excellent trial design based on what we knew at that time,” and the design “was changed in a pragmatic way because of recruitment challenges.”

Something for the future would be to select patients for such trials based on the tumor biology rather than risk status, Dr. Schmid suggested. “That is something we may have to take into consideration with our increasing knowledge around primary and secondary resistance and what treatments we want to introduce to target-resistant clones,” he said.

The UNIRAD study was sponsored by UNICANCER, with funding and support from the French Ministry of Health, Cancer Research UK, Myriad Genetics (which provided Endopredict tests), and Novartis (which provided everolimus and placebo). Dr. Bachelot, Dr. Schmid, and Dr. Dent disclosed relationships with Novartis and several other pharmaceutical companies.

FROM ESMO VIRTUAL PLENARY

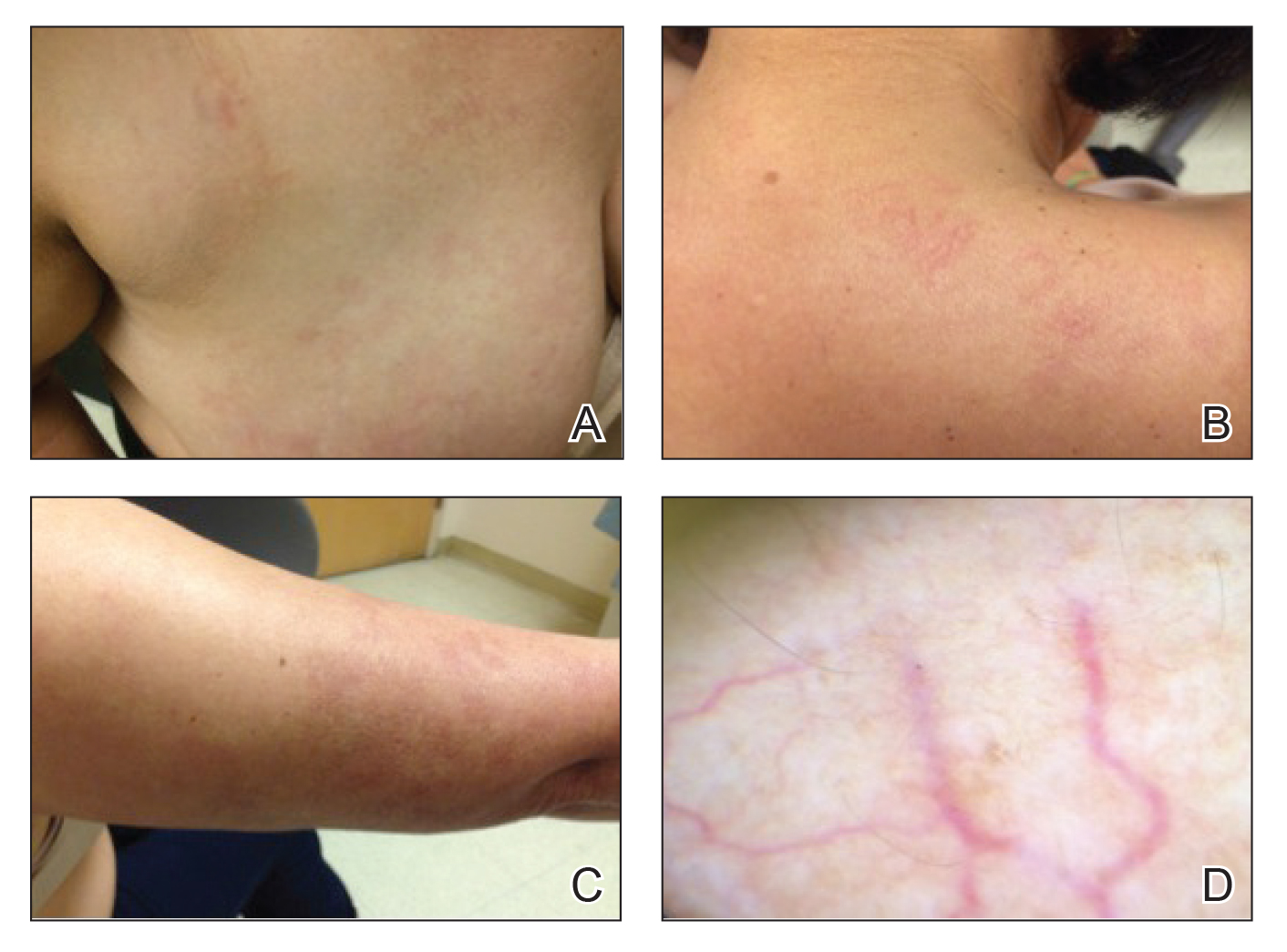

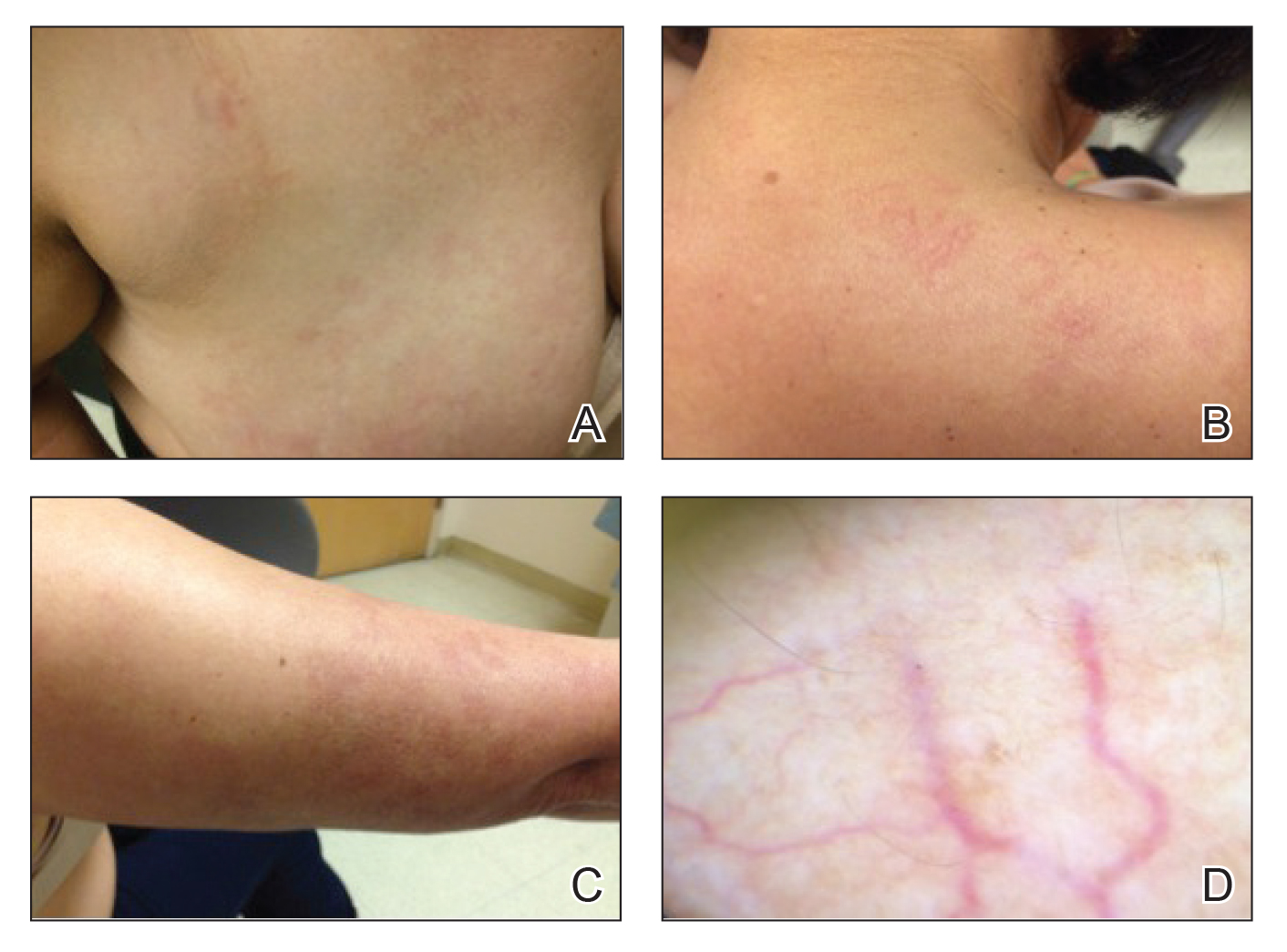

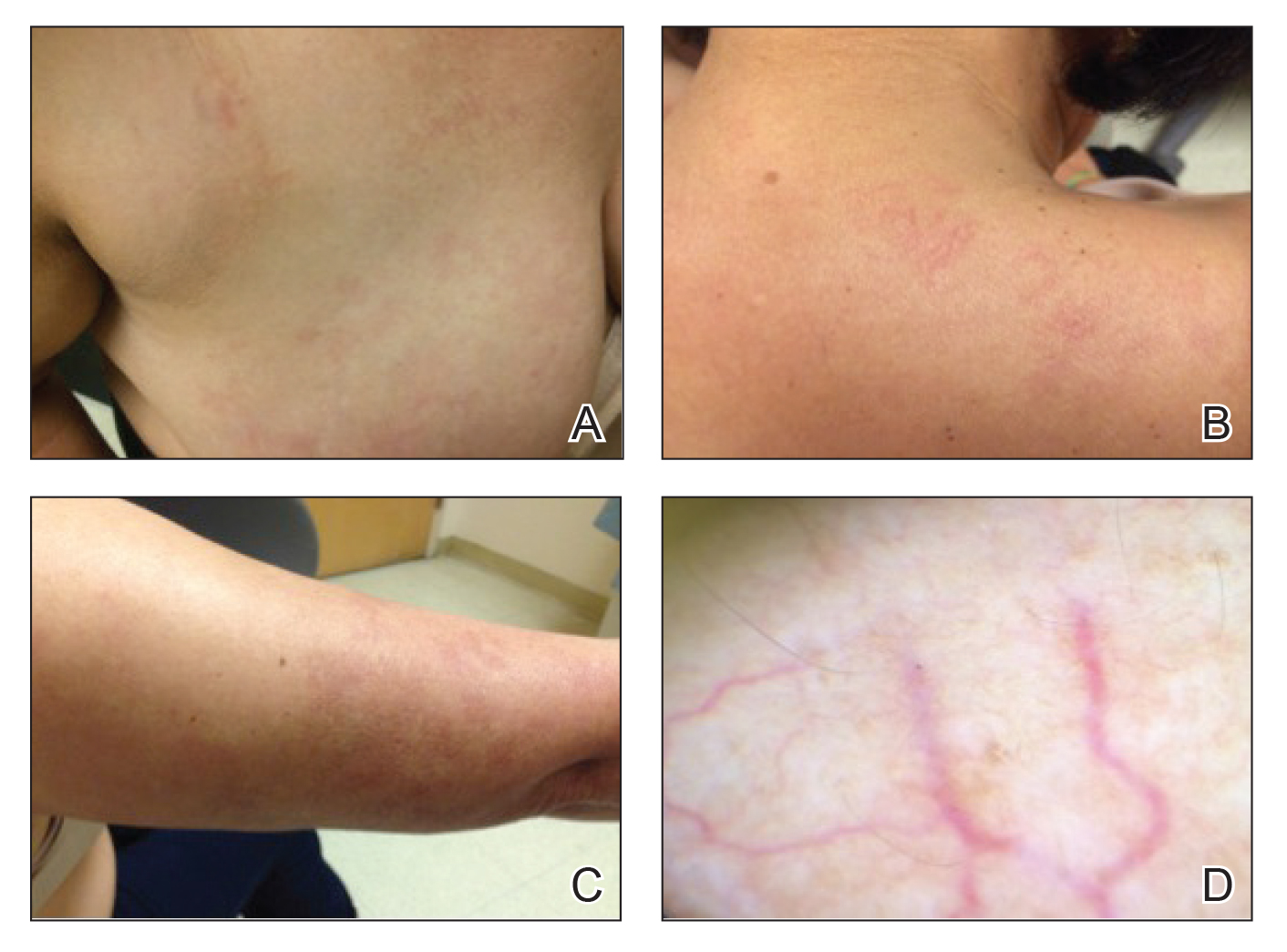

The Genital Examination in Dermatologic Practice

A casual survey of my dermatology co-residents yielded overwhelmingly unanimous results: A complete skin check goes from head to toe but does not routinely include an examination of the genital area. This observation contrasts starkly with the American Academy of Dermatology’s Basic Dermatology Curriculum, which recommends inspection of the entire skin surface including the mucous membranes (ie, eyes, mouth, anus, genital area) as part of the total-body skin examination (TBSE).1 It even draws attention to so-called hidden areas where lesions easily can be missed, such as the perianal skin. My observation seems far from anecdotal; even a recent attempt at optimizing movements in the TBSE neglected to include examination of the genitalia in the proposed method,2-4 and many practicing dermatologists seem to agree. A survey of international dermatologists at high-risk skin cancer clinics found male and female genitalia were the least frequently examined anatomy sites during the TBSE. Additionally, female genitalia were examined less frequently than male genitalia (labia majora, 28%; penis, 52%; P=.003).5 Another survey of US academic dermatologists (23 dermatologists, 1 nurse practitioner) found that only 4% always visually inspected the vulva during routine annual examinations, and 50% did not think that vulvar examination was the dermatologist’s responsibility.6 Similar findings were reported in a survey of US dermatology residents.7

Why is the genital area routinely omitted from the dermatologic TBSE? Based on the surveys of dermatologists and dermatology residents, the most common reason cited for not examining these sites was patient discomfort, but there also was a dominant belief that other specialties, such as gynecologists, urologists, or primary care providers, routinely examine these areas.5,7 Time constraints also were a concern.

Although examination of sensitive areas can be uncomfortable,8 most patients still expect these locations to be examined during the TBSE. In a survey of 500 adults presenting for TBSE at an academic dermatology clinic, 84% of respondents expected the dermatologist to examine the genital area.9 Similarly, another survey of patient preferences (N=443) for the TBSE found that only 31.3% of women and 12.5% of men preferred not to have their genital area examined.10 As providers, we may be uncomfortable examining the genital area; however, our patients mostly expect it as part of routine practice. There are a number of barriers that may prevent incorporating the genital examination into daily dermatologic practice.

Training in Genital Examinations

Adequate training may be an issue for provider comfort when examining the genital skin. In a survey of dermatology residency program directors (n=38) and residents (n=91), 61.7% reported receiving formal instruction on TBSE technique and 38.3% reported being self-taught. Examination of the genital skin was included only 40% of the time.11 Even vulvar disorder experts have admitted to receiving their training by self-teaching, with only 19% receiving vulvar training during residency and 11% during fellowship.12 Improving this training appears to be an ongoing effort.2

Passing the Buck

It may be easier to think that another provider is routinely examining genital skin based on the relative absence of this area in dermatologic training; however, that does not appear to be the case. In a 1999 survey of primary care providers, only 31% reported performing skin cancer screenings on their adult patients, citing lack of confidence in this clinical skill as the biggest hurdle.13 Similarly, changes in recommendations for the utility of the screening pelvic examination in asymptomatic, average-risk, nonpregnant adult women have decreased the performance of this examination in actual practice.14 Reviews of resident training in vulvovaginal disease also have shown that although dermatology residents receive slightly less formal training hours on vulvar skin disease, they see more than double the number of patients with vulvar disease per year when compared to obstetrics and gynecology residents.15 In practice, dermatologists generally are more confident when evaluating vulvar pigmented lesions than gynecologists.6

The Importance of the Genital Examination

Looking past these barriers seems essential to providing the best dermatologic care, as there are a multitude of neoplastic and inflammatory dermatoses that can affect the genital skin. Furthermore, early diagnosis and treatment of these conditions potentially can limit morbidity and mortality as well as improve quality of life. Genital melanomas are a good example. Although they may be rare, it is well known that genital melanomas are associated with an aggressive disease course and have worse outcomes than melanomas found elsewhere on the body.16,17 Increasing rates of genital and perianal keratinocyte carcinomas make including this as part of the TBSE even more important.18

We also should not forget that inflammatory conditions can routinely involve the genitals.19-21 Although robust data are lacking, chronic vulvar concerns frequently are seen in the primary care setting. In one study in the United Kingdom, 52% of general practitioners surveyed saw more than 3 patients per month with vulvar concerns.22 Even in common dermatologic conditions such as psoriasis and lichen planus, genital involvement often is overlooked despite its relative frequency.23-27 In one study, 60% of psoriasis patients with genital involvement had not had these lesions examined by a physician.28

Theoretically, TBSEs that include genital examination would yield higher and earlier detection rates of neoplasms as well as inflammatory dermatoses.29-32 Thus, there is real value in diagnosing ailments of the genital skin, and dermatologists are well prepared to manage these conditions. Consistently incorporating a genital examination within the TBSE is the first step.

An Approach to the Genital Skin Examination

As with the TBSE, no standardized protocol for the genital skin examination exists, and there is no consensus for how best to perform this evaluation. Ideally, both male and female patients should remove all clothing, including undergarments, though one study found patients preferred to keep undergarments on during the genital examination.10,33,34

In general, adult female genital anatomy is best viewed with the patient in the supine position.6,33,35 There is no clear agreement on the use of stirrups, and the decision to use these may be left to the discretion of the patient. One randomized clinical trial found that women undergoing routine gynecologic examination without stirrups reported less physical discomfort and had a reduced sense of vulnerability than women examined in stirrups.36 During the female genital examination, the head of the bed ideally should be positioned at a 30° to 45° angle to allow the provider to maintain eye contact and face-to-face communication with the patient.33 This positioning also facilitates the use of a handheld mirror to instruct patients on techniques for medication application as well as to point out sites of disease.

For adult males, the genital examination can be performed with the patient standing facing a seated examiner.35 The patient’s gown should be raised to the level of the umbilicus to expose the entire genital region. Good lighting is essential. These recommendations apply mainly to adults, but helpful tips on how to approach evaluating prepubertal children in the dermatology clinic are available.37

The presence of a chaperone also is optional for maximizing patient comfort but also may be helpful for providing medicolegal protection for the provider. It always should be offered regardless of patient gender. A dermatology study found that when patients were examined by a same-gender physician, women and men were more comfortable without a chaperone than with a chaperone, and patients generally preferred fewer bodies in the room during sensitive examinations.9

Educating Patients About the TBSE

The most helpful recommendation for successfully incorporating and performing the genital skin examination as part of the TBSE appears to be patient education. In a randomized double-arm study, patients who received pre-education consisting of written information explaining the need for a TBSE were less likely to be concerned about a genital examination compared to patients who received no information.38 Discussing that skin diseases, including melanoma, can arise in all areas of the body including the genital skin and encouraging patients to perform genital self-examinations is critical.35 In the age of the electronic health record and virtual communication, disseminating this information has become even easier.39 It may be beneficial to explore patients’ TBSE expectations at the outset through these varied avenues to help establish a trusted physician-patient relationship.40

Final Thoughts

Dermatologists should consistently offer a genital examination to all patients who present for a routine TBSE. Patients should be provided with adequate education to assess their comfort level for the skin examination. If a patient declines this examination, the dermatologist should ensure that another physician—be it a gynecologist, primary care provider, or other specialist—is routinely examining the area.6,7

- The skin exam. American Academy of Dermatology. https://digital-catalog.aad.org/diweb/catalog/launch/package/4/did/327974/iid/327974

- Helm MF, Hallock KK, Bisbee E, et al. Optimizing the total-body skin exam: an observational cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:1115-1119.

- Nielson CB, Grant-Kels JM. Commentary on “optimizing the total-body skin exam: an observational cohort study.” J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:E131.

- Helm MF, Hallock KK, Bisbee E, et al. Reply to: “commentary on ‘optimizing the total-body skin exam: an observational cohort study.’” J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:E133.

- Bajaj S, Wolner ZJ, Dusza SW, et al. Total body skin examination practices: a survey study amongst dermatologists at high-risk skin cancer clinics. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2019;9:132-138.

- Krathen MS, Liu CL, Loo DS. Vulvar melanoma: a missed opportunity for early intervention? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:697-698.

- Hosking AM, Chapman L, Zachary CB, et al. Anogenital examination practices among U.S. dermatology residents [published online January 9, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.061

- Grundström H, Wallin K, Berterö C. ‘You expose yourself in so many ways’: young women’s experiences of pelvic examination. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;32:59-64.

- McClatchey Connors T, Reddy P, Weiss E, et al. Patient comfort and expectations for total body skin examinations: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:615-617.

- Houston NA, Secrest AM, Harris RJ, et al. Patient preferences during skin cancer screening examination. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1052-1054.

- Milchak M, Miller J, Dellasega C, et al. Education on total body skin examination in dermatology residency. Poster presented at: Association of Professors of Dermatology Annual Meeting; September 25-26, 2015; Chicago, IL.

- Venkatesan A, Farsani T, O’Sullivan P, et al. Identifying competencies in vulvar disorder management for medical students and residents: a survey of US vulvar disorder experts. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2012;16:398-402.

- Kirsner RS, Muhkerjee S, Federman DG. Skin cancer screening in primary care: prevalence and barriers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:564-566.

- Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for gynecologic conditions with pelvic examination: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2017;317:947-953.

- Comstock JR, Endo JO, Kornik RI. Adequacy of dermatology and ob-gyn graduate medical education for inflammatory vulvovaginal skin disease: a nationwide needs assessment survey. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:182-185.

- Sanchez A, Rodríguez D, Allard CB, et al. Primary genitourinary melanoma: epidemiology and disease-specific survival in a large population-based cohort. Urol Oncol. 2016;34:E7-E14.

- Vyas R, Thompson CL, Zargar H, et al. Epidemiology of genitourinary melanoma in the United States: 1992 through 2012. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:144-150.

- Misitzis A, Beatson M, Weinstock MA. Keratinocyte carcinoma mortality in the United States as reported in death certificates, 2011-2017. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:1135-1140.

- Sullivan AK, Straughair GJ, Marwood RP, et al. A multidisciplinary vulva clinic: the role of genito-urinary medicine. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1999;13:36-40.

- Goncalves DLM, Romero RL, Ferreira PL, et al. Clinical and epidemiological profile of patients attended in a vulvar clinic of the dermatology outpatient unit of a tertiary hospital during a 4-year period. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:1311-1316.

- Bauer A, Greif C, Vollandt R, et al. Vulval diseases need an interdisciplinary approach. Dermatology. 1999;199:223-226.

- Nunns D, Mandal D. The chronically symptomatic vulva: prevalence in primary health care. Genitourin Med. 1996;72:343-344.

- Meeuwis KA, de Hullu JA, de Jager ME, et al. Genital psoriasis: a questionnaire-based survey on a concealed skin disease in the Netherlands. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1425-1430.

- Ryan C, Sadlier M, De Vol E, et al. Genital psoriasis is associated with significant impairment in quality of life and sexual functioning. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:978-983.

- Fouéré S, Adjadj L, Pawin H. How patients experience psoriasis: results from a European survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;(19 suppl 3):2-6.

- Eisen D. The evaluation of cutaneous, genital, scalp, nail, esophageal, and ocular involvement in patients with oral lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;88:431-436.

- Meeuwis KAP, Potts Bleakman A, van de Kerkhof PCM, et al. Prevalence of genital psoriasis in patients with psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29:754-760.

- Larsabal M, Ly S, Sbidian E, et al. GENIPSO: a French prospective study assessing instantaneous prevalence, clinical features and impact on quality of life of genital psoriasis among patients consulting for psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:647-656.

- Rigel DS, Friedman RJ, Kopf AW, et al. Importance of complete cutaneous examination for the detection of malignant melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(5 pt 1):857-860.

- De Rooij MJ, Rampen FH, Schouten LJ, et al. Total skin examination during screening for malignant melanoma does not increase the detection rate. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:42-45.

- Johansson M, Brodersen J, Gøtzsche PC, et al. Screening for reducing morbidity and mortality in malignant melanoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;6:CD012352.

- Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316:429-435.

- Mauskar MM, Marathe K, Venkatesan A, et al. Vulvar diseases: approach to the patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1277-1284.

- Chen C. How full is a full body skin exam? investigation into the practice of the full body skin exam as conducted by board-certified and board-eligibile dermatologists. Michigan State University. Published April 24, 2015. Accessed February 4, 2021. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.aocd.org/resource/resmgr/2015SpringMeeting/ChenSpr15.pdf

- Zikry J, Chapman LW, Korta DZ, et al. Genital melanoma: are we adequately screening our patients? Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt7zk476vn.

- Seehusen DA, Johnson DR, Earwood JS, et al. Improving women’s experience during speculum examinations at routine gynaecological visits: randomised clinical trial [published online June 27, 2006]. BMJ. 2006;333:171.

- Habeshian K, Fowler K, Gomez-Lobo V, et al. Guidelines for pediatric anogenital examination: insights from our vulvar dermatology clinic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:693-695.

- Leffell DJ, Berwick M, Bolognia J. The effect of pre-education on patient compliance with full-body examination in a public skin cancer screening. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1993;19:660-663.

- Hong J, Nguyen TV, Prose NS. Compassionate care: enhancing physician-patient communication and education in dermatology: part II: patient education. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:364.e361-310.

- Rosamilia LL. The naked truth about total body skin examination: a lesson from Goldilocks and the Three Bears. American Academy of Dermatology. Published November 13, 2019. Accessed February 4, 2021. https://www.aad.org/dw/dw-insights-and-inquiries/2019-archive/november/dwii-11-13-19-the-naked-truth-about-total-body-skin-examination-a-lesson-from-goldilocks-and-the-three-bears

A casual survey of my dermatology co-residents yielded overwhelmingly unanimous results: A complete skin check goes from head to toe but does not routinely include an examination of the genital area. This observation contrasts starkly with the American Academy of Dermatology’s Basic Dermatology Curriculum, which recommends inspection of the entire skin surface including the mucous membranes (ie, eyes, mouth, anus, genital area) as part of the total-body skin examination (TBSE).1 It even draws attention to so-called hidden areas where lesions easily can be missed, such as the perianal skin. My observation seems far from anecdotal; even a recent attempt at optimizing movements in the TBSE neglected to include examination of the genitalia in the proposed method,2-4 and many practicing dermatologists seem to agree. A survey of international dermatologists at high-risk skin cancer clinics found male and female genitalia were the least frequently examined anatomy sites during the TBSE. Additionally, female genitalia were examined less frequently than male genitalia (labia majora, 28%; penis, 52%; P=.003).5 Another survey of US academic dermatologists (23 dermatologists, 1 nurse practitioner) found that only 4% always visually inspected the vulva during routine annual examinations, and 50% did not think that vulvar examination was the dermatologist’s responsibility.6 Similar findings were reported in a survey of US dermatology residents.7

Why is the genital area routinely omitted from the dermatologic TBSE? Based on the surveys of dermatologists and dermatology residents, the most common reason cited for not examining these sites was patient discomfort, but there also was a dominant belief that other specialties, such as gynecologists, urologists, or primary care providers, routinely examine these areas.5,7 Time constraints also were a concern.

Although examination of sensitive areas can be uncomfortable,8 most patients still expect these locations to be examined during the TBSE. In a survey of 500 adults presenting for TBSE at an academic dermatology clinic, 84% of respondents expected the dermatologist to examine the genital area.9 Similarly, another survey of patient preferences (N=443) for the TBSE found that only 31.3% of women and 12.5% of men preferred not to have their genital area examined.10 As providers, we may be uncomfortable examining the genital area; however, our patients mostly expect it as part of routine practice. There are a number of barriers that may prevent incorporating the genital examination into daily dermatologic practice.

Training in Genital Examinations

Adequate training may be an issue for provider comfort when examining the genital skin. In a survey of dermatology residency program directors (n=38) and residents (n=91), 61.7% reported receiving formal instruction on TBSE technique and 38.3% reported being self-taught. Examination of the genital skin was included only 40% of the time.11 Even vulvar disorder experts have admitted to receiving their training by self-teaching, with only 19% receiving vulvar training during residency and 11% during fellowship.12 Improving this training appears to be an ongoing effort.2

Passing the Buck