User login

Using telehealth to deliver palliative care to cancer patients

Traditional delivery of palliative care to outpatients with cancer is associated with many challenges.

Telehealth can eliminate some of these challenges but comes with issues of its own, according to results of the REACH PC trial.

Jennifer S. Temel, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, discussed the use of telemedicine in palliative care, including results from REACH PC, during an educational session at the ASCO Virtual Quality Care Symposium 2020.

Dr. Temel noted that, for cancer patients, an in-person visit with a palliative care specialist can cost time, induce fatigue, and increase financial burden from transportation and parking expenses.

For caregivers and family, an in-person visit may necessitate absence from family and/or work, require complex scheduling to coordinate with other office visits, and result in additional transportation and/or parking expenses.

For health care systems, to have a dedicated palliative care clinic requires precious space and financial expenditures for office personnel and other resources.

These issues make it attractive to consider whether telehealth could be used for palliative care services.

Scarcity of palliative care specialists

In the United States, there is roughly 1 palliative care physician for every 20,000 older adults with a life-limiting illness, according to research published in Annual Review of Public Health in 2014.

In its 2019 state-by-state report card, the Center to Advance Palliative Care noted that only 72% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds have a palliative care team.

For patients with serious illnesses and those who are socioeconomically or geographically disadvantaged, palliative care is often inaccessible.

Inefficiencies in the current system are an additional impediment. Palliative care specialists frequently see patients during a portion of the patient’s routine visit to subspecialty or primary care clinics. This limits the palliative care specialist’s ability to perform comprehensive assessments and provide patient-centered care efficiently.

Special considerations regarding telehealth for palliative care

As a specialty, palliative care involves interactions that could make the use of telehealth problematic. For example, conveyance of interest, warmth, and touch are challenging or impossible in a video format.

Palliative care specialists engage with patients regarding relatively serious topics such as prognosis and end-of-life preferences. There is uncertainty about how those discussions would be received by patients and their caregivers via video.

Furthermore, there are logistical impediments such as prescribing opioids with video or across state lines.

Despite these concerns, the ENABLE study showed that supplementing usual oncology care with weekly (transitioning to monthly) telephone-based educational palliative care produced higher quality of life and mood than did usual oncology care alone. These results were published in JAMA in 2009.

REACH PC study demonstrates feasibility of telehealth model

Dr. Temel described the ongoing REACH PC trial in which palliative care is delivered via video visits and compared with in-person palliative care for patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer.

The primary aim of REACH PC is to determine whether telehealth palliative care is equivalent to traditional palliative care in improving quality of life as a supplement to routine oncology care.

Currently, REACH PC has enrolled 581 patients at its 20 sites, spanning a geographically diverse area. Just over half of patients approached about REACH PC agreed to enroll in it. Ultimately, 1,250 enrollees are sought.

Among patients who declined to participate, 7.6% indicated “discomfort with technology” as the reason. Most refusals were due to lack of interest in research (35.1%) and/or palliative care (22.9%).

Older adults were prominent among enrollees. More than 60% were older than 60 years of age, and more than one-third were older than 70 years.

Among patients who began the trial, there were slightly more withdrawals in the telehealth participants, in comparison with in-person participants (13.6% versus 9.1%).

When palliative care clinicians were queried about video visits, 64.3% said there were no challenges. This is comparable to the 65.5% of clinicians who had no challenges with in-person visits.

When problems occurred with video visits, they were most frequently technical (19.1%). Only 1.4% of clinicians reported difficulty addressing topics that felt uncomfortable over video, and 1.5% reported difficulty establishing rapport.

The success rates of video and in-person visits were similar. About 80% of visits accomplished planned goals.

‘Webside’ manner

Strategies such as reflective listening and summarizing what patients say (to verify an accurate understanding of the patient’s perspective) are key to successful palliative care visits, regardless of the setting.

For telehealth visits, Dr. Temel described techniques she defined as “webside manner,” to compensate for the inability of the clinician to touch a patient. These techniques include leaning in toward the camera, nodding, and pausing to be certain the patient has finished speaking before the clinician speaks again.

Is telehealth the future of palliative care?

I include myself among those oncologists who have voiced concern about moving from face-to-face to remote visits for complicated consultations such as those required for palliative care. Nonetheless, from the preliminary results of the REACH PC trial, it appears that telehealth could be a valuable tool.

To minimize differences between in-person and remote delivery of palliative care, practical strategies for ensuring rapport and facilitating a trusting relationship should be defined further and disseminated.

In addition, we need to be vigilant for widening inequities of care from rapid movement to the use of technology (i.e., an equity gap). In their telehealth experience during the COVID-19 pandemic, investigators at Houston Methodist Cancer Center found that patients declining virtual visits tended to be older, lower-income, and less likely to have commercial insurance. These results were recently published in JCO Oncology Practice.

For the foregoing reasons, hybrid systems for palliative care services will probably always be needed.

Going forward, we should heed the advice of Alvin Toffler in his book Future Shock. Mr. Toffler said, “The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.”

The traditional model for delivering palliative care will almost certainly need to be reimagined and relearned.

Dr. Temel disclosed institutional research funding from Pfizer.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

Traditional delivery of palliative care to outpatients with cancer is associated with many challenges.

Telehealth can eliminate some of these challenges but comes with issues of its own, according to results of the REACH PC trial.

Jennifer S. Temel, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, discussed the use of telemedicine in palliative care, including results from REACH PC, during an educational session at the ASCO Virtual Quality Care Symposium 2020.

Dr. Temel noted that, for cancer patients, an in-person visit with a palliative care specialist can cost time, induce fatigue, and increase financial burden from transportation and parking expenses.

For caregivers and family, an in-person visit may necessitate absence from family and/or work, require complex scheduling to coordinate with other office visits, and result in additional transportation and/or parking expenses.

For health care systems, to have a dedicated palliative care clinic requires precious space and financial expenditures for office personnel and other resources.

These issues make it attractive to consider whether telehealth could be used for palliative care services.

Scarcity of palliative care specialists

In the United States, there is roughly 1 palliative care physician for every 20,000 older adults with a life-limiting illness, according to research published in Annual Review of Public Health in 2014.

In its 2019 state-by-state report card, the Center to Advance Palliative Care noted that only 72% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds have a palliative care team.

For patients with serious illnesses and those who are socioeconomically or geographically disadvantaged, palliative care is often inaccessible.

Inefficiencies in the current system are an additional impediment. Palliative care specialists frequently see patients during a portion of the patient’s routine visit to subspecialty or primary care clinics. This limits the palliative care specialist’s ability to perform comprehensive assessments and provide patient-centered care efficiently.

Special considerations regarding telehealth for palliative care

As a specialty, palliative care involves interactions that could make the use of telehealth problematic. For example, conveyance of interest, warmth, and touch are challenging or impossible in a video format.

Palliative care specialists engage with patients regarding relatively serious topics such as prognosis and end-of-life preferences. There is uncertainty about how those discussions would be received by patients and their caregivers via video.

Furthermore, there are logistical impediments such as prescribing opioids with video or across state lines.

Despite these concerns, the ENABLE study showed that supplementing usual oncology care with weekly (transitioning to monthly) telephone-based educational palliative care produced higher quality of life and mood than did usual oncology care alone. These results were published in JAMA in 2009.

REACH PC study demonstrates feasibility of telehealth model

Dr. Temel described the ongoing REACH PC trial in which palliative care is delivered via video visits and compared with in-person palliative care for patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer.

The primary aim of REACH PC is to determine whether telehealth palliative care is equivalent to traditional palliative care in improving quality of life as a supplement to routine oncology care.

Currently, REACH PC has enrolled 581 patients at its 20 sites, spanning a geographically diverse area. Just over half of patients approached about REACH PC agreed to enroll in it. Ultimately, 1,250 enrollees are sought.

Among patients who declined to participate, 7.6% indicated “discomfort with technology” as the reason. Most refusals were due to lack of interest in research (35.1%) and/or palliative care (22.9%).

Older adults were prominent among enrollees. More than 60% were older than 60 years of age, and more than one-third were older than 70 years.

Among patients who began the trial, there were slightly more withdrawals in the telehealth participants, in comparison with in-person participants (13.6% versus 9.1%).

When palliative care clinicians were queried about video visits, 64.3% said there were no challenges. This is comparable to the 65.5% of clinicians who had no challenges with in-person visits.

When problems occurred with video visits, they were most frequently technical (19.1%). Only 1.4% of clinicians reported difficulty addressing topics that felt uncomfortable over video, and 1.5% reported difficulty establishing rapport.

The success rates of video and in-person visits were similar. About 80% of visits accomplished planned goals.

‘Webside’ manner

Strategies such as reflective listening and summarizing what patients say (to verify an accurate understanding of the patient’s perspective) are key to successful palliative care visits, regardless of the setting.

For telehealth visits, Dr. Temel described techniques she defined as “webside manner,” to compensate for the inability of the clinician to touch a patient. These techniques include leaning in toward the camera, nodding, and pausing to be certain the patient has finished speaking before the clinician speaks again.

Is telehealth the future of palliative care?

I include myself among those oncologists who have voiced concern about moving from face-to-face to remote visits for complicated consultations such as those required for palliative care. Nonetheless, from the preliminary results of the REACH PC trial, it appears that telehealth could be a valuable tool.

To minimize differences between in-person and remote delivery of palliative care, practical strategies for ensuring rapport and facilitating a trusting relationship should be defined further and disseminated.

In addition, we need to be vigilant for widening inequities of care from rapid movement to the use of technology (i.e., an equity gap). In their telehealth experience during the COVID-19 pandemic, investigators at Houston Methodist Cancer Center found that patients declining virtual visits tended to be older, lower-income, and less likely to have commercial insurance. These results were recently published in JCO Oncology Practice.

For the foregoing reasons, hybrid systems for palliative care services will probably always be needed.

Going forward, we should heed the advice of Alvin Toffler in his book Future Shock. Mr. Toffler said, “The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.”

The traditional model for delivering palliative care will almost certainly need to be reimagined and relearned.

Dr. Temel disclosed institutional research funding from Pfizer.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

Traditional delivery of palliative care to outpatients with cancer is associated with many challenges.

Telehealth can eliminate some of these challenges but comes with issues of its own, according to results of the REACH PC trial.

Jennifer S. Temel, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, discussed the use of telemedicine in palliative care, including results from REACH PC, during an educational session at the ASCO Virtual Quality Care Symposium 2020.

Dr. Temel noted that, for cancer patients, an in-person visit with a palliative care specialist can cost time, induce fatigue, and increase financial burden from transportation and parking expenses.

For caregivers and family, an in-person visit may necessitate absence from family and/or work, require complex scheduling to coordinate with other office visits, and result in additional transportation and/or parking expenses.

For health care systems, to have a dedicated palliative care clinic requires precious space and financial expenditures for office personnel and other resources.

These issues make it attractive to consider whether telehealth could be used for palliative care services.

Scarcity of palliative care specialists

In the United States, there is roughly 1 palliative care physician for every 20,000 older adults with a life-limiting illness, according to research published in Annual Review of Public Health in 2014.

In its 2019 state-by-state report card, the Center to Advance Palliative Care noted that only 72% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds have a palliative care team.

For patients with serious illnesses and those who are socioeconomically or geographically disadvantaged, palliative care is often inaccessible.

Inefficiencies in the current system are an additional impediment. Palliative care specialists frequently see patients during a portion of the patient’s routine visit to subspecialty or primary care clinics. This limits the palliative care specialist’s ability to perform comprehensive assessments and provide patient-centered care efficiently.

Special considerations regarding telehealth for palliative care

As a specialty, palliative care involves interactions that could make the use of telehealth problematic. For example, conveyance of interest, warmth, and touch are challenging or impossible in a video format.

Palliative care specialists engage with patients regarding relatively serious topics such as prognosis and end-of-life preferences. There is uncertainty about how those discussions would be received by patients and their caregivers via video.

Furthermore, there are logistical impediments such as prescribing opioids with video or across state lines.

Despite these concerns, the ENABLE study showed that supplementing usual oncology care with weekly (transitioning to monthly) telephone-based educational palliative care produced higher quality of life and mood than did usual oncology care alone. These results were published in JAMA in 2009.

REACH PC study demonstrates feasibility of telehealth model

Dr. Temel described the ongoing REACH PC trial in which palliative care is delivered via video visits and compared with in-person palliative care for patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer.

The primary aim of REACH PC is to determine whether telehealth palliative care is equivalent to traditional palliative care in improving quality of life as a supplement to routine oncology care.

Currently, REACH PC has enrolled 581 patients at its 20 sites, spanning a geographically diverse area. Just over half of patients approached about REACH PC agreed to enroll in it. Ultimately, 1,250 enrollees are sought.

Among patients who declined to participate, 7.6% indicated “discomfort with technology” as the reason. Most refusals were due to lack of interest in research (35.1%) and/or palliative care (22.9%).

Older adults were prominent among enrollees. More than 60% were older than 60 years of age, and more than one-third were older than 70 years.

Among patients who began the trial, there were slightly more withdrawals in the telehealth participants, in comparison with in-person participants (13.6% versus 9.1%).

When palliative care clinicians were queried about video visits, 64.3% said there were no challenges. This is comparable to the 65.5% of clinicians who had no challenges with in-person visits.

When problems occurred with video visits, they were most frequently technical (19.1%). Only 1.4% of clinicians reported difficulty addressing topics that felt uncomfortable over video, and 1.5% reported difficulty establishing rapport.

The success rates of video and in-person visits were similar. About 80% of visits accomplished planned goals.

‘Webside’ manner

Strategies such as reflective listening and summarizing what patients say (to verify an accurate understanding of the patient’s perspective) are key to successful palliative care visits, regardless of the setting.

For telehealth visits, Dr. Temel described techniques she defined as “webside manner,” to compensate for the inability of the clinician to touch a patient. These techniques include leaning in toward the camera, nodding, and pausing to be certain the patient has finished speaking before the clinician speaks again.

Is telehealth the future of palliative care?

I include myself among those oncologists who have voiced concern about moving from face-to-face to remote visits for complicated consultations such as those required for palliative care. Nonetheless, from the preliminary results of the REACH PC trial, it appears that telehealth could be a valuable tool.

To minimize differences between in-person and remote delivery of palliative care, practical strategies for ensuring rapport and facilitating a trusting relationship should be defined further and disseminated.

In addition, we need to be vigilant for widening inequities of care from rapid movement to the use of technology (i.e., an equity gap). In their telehealth experience during the COVID-19 pandemic, investigators at Houston Methodist Cancer Center found that patients declining virtual visits tended to be older, lower-income, and less likely to have commercial insurance. These results were recently published in JCO Oncology Practice.

For the foregoing reasons, hybrid systems for palliative care services will probably always be needed.

Going forward, we should heed the advice of Alvin Toffler in his book Future Shock. Mr. Toffler said, “The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.”

The traditional model for delivering palliative care will almost certainly need to be reimagined and relearned.

Dr. Temel disclosed institutional research funding from Pfizer.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

FROM ASCO QUALITY CARE SYMPOSIUM 2020

Key Studies in Ulcerative Colitis From ACG 2020 Virtual Conference

Miguel Regueiro, MD, an expert in gastroenterology at the Cleveland Clinic, reflects on the most important and clinically relevant studies on ulcerative colitis presented at the American College of Gastroenterology 2020 virtual annual scientific meeting. He starts with four studies from the OCTAVE clinical trials program. These studies examined the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib after treatment interruption and in pregnant women, presenting almost 7 years of follow-up. Long-term follow-up remains the theme as he turns to the VISIBLE open-label extension of treatment with vedolizumab SC, where the long-term safety of the drug was confirmed and clinical remission rates were maintained out to 2 years. He reports that a post-hoc analysis of the VARSITY trial appeared to show that vedolizumab achieves greater early control vs adalimumab. Dr Regueiro next discusses the late-breaking, phase 3 True North study of ozanimod for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis before finishing up with an analysis of the long-term trends for colectomy since the turn of the century.

Miguel D. Regueiro, MD, Chairman, Professor, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition; Vice-Chair, Digestive Disease Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

Miguel D. Regueiro, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Serve(d) as an advisor and/or consultant for: AbbVie; Janssen; UCB; Takeda; Pfizer; Miraca Labs; Amgen; Celgene; Seres; Allergan; Genentech; Gilead; Salix; Prometheus. Received unrestricted educational grants from: AbbVie; Janssen; UCB; Pfizer; Takeda; Salix; Shire. Received research support from AbbVie; Janssen; Takeda; Pfizer.

Miguel Regueiro, MD, an expert in gastroenterology at the Cleveland Clinic, reflects on the most important and clinically relevant studies on ulcerative colitis presented at the American College of Gastroenterology 2020 virtual annual scientific meeting. He starts with four studies from the OCTAVE clinical trials program. These studies examined the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib after treatment interruption and in pregnant women, presenting almost 7 years of follow-up. Long-term follow-up remains the theme as he turns to the VISIBLE open-label extension of treatment with vedolizumab SC, where the long-term safety of the drug was confirmed and clinical remission rates were maintained out to 2 years. He reports that a post-hoc analysis of the VARSITY trial appeared to show that vedolizumab achieves greater early control vs adalimumab. Dr Regueiro next discusses the late-breaking, phase 3 True North study of ozanimod for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis before finishing up with an analysis of the long-term trends for colectomy since the turn of the century.

Miguel D. Regueiro, MD, Chairman, Professor, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition; Vice-Chair, Digestive Disease Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

Miguel D. Regueiro, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Serve(d) as an advisor and/or consultant for: AbbVie; Janssen; UCB; Takeda; Pfizer; Miraca Labs; Amgen; Celgene; Seres; Allergan; Genentech; Gilead; Salix; Prometheus. Received unrestricted educational grants from: AbbVie; Janssen; UCB; Pfizer; Takeda; Salix; Shire. Received research support from AbbVie; Janssen; Takeda; Pfizer.

Miguel Regueiro, MD, an expert in gastroenterology at the Cleveland Clinic, reflects on the most important and clinically relevant studies on ulcerative colitis presented at the American College of Gastroenterology 2020 virtual annual scientific meeting. He starts with four studies from the OCTAVE clinical trials program. These studies examined the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib after treatment interruption and in pregnant women, presenting almost 7 years of follow-up. Long-term follow-up remains the theme as he turns to the VISIBLE open-label extension of treatment with vedolizumab SC, where the long-term safety of the drug was confirmed and clinical remission rates were maintained out to 2 years. He reports that a post-hoc analysis of the VARSITY trial appeared to show that vedolizumab achieves greater early control vs adalimumab. Dr Regueiro next discusses the late-breaking, phase 3 True North study of ozanimod for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis before finishing up with an analysis of the long-term trends for colectomy since the turn of the century.

Miguel D. Regueiro, MD, Chairman, Professor, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition; Vice-Chair, Digestive Disease Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

Miguel D. Regueiro, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Serve(d) as an advisor and/or consultant for: AbbVie; Janssen; UCB; Takeda; Pfizer; Miraca Labs; Amgen; Celgene; Seres; Allergan; Genentech; Gilead; Salix; Prometheus. Received unrestricted educational grants from: AbbVie; Janssen; UCB; Pfizer; Takeda; Salix; Shire. Received research support from AbbVie; Janssen; Takeda; Pfizer.

Siblings of patients with bipolar disorder at increased risk

The siblings of patients with bipolar disorder not only face a significantly increased lifetime risk of that affective disorder, but a whole panoply of other psychiatric disorders, according to a new Danish longitudinal national registry study.

“Our data show the healthy siblings of patients with bipolar disorder are themselves at increased risk of developing any kind of psychiatric disorder. Mainly bipolar disorder, but all other kinds as well,” Lars Vedel Kessing, MD, DMSc, said in presenting the results of the soon-to-be-published Danish study at the virtual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Moreover, the long-term Danish study also demonstrated that several major psychiatric disorders follow a previously unappreciated bimodal distribution of age of onset in the siblings of patients with bipolar disorder. For example, the incidence of new-onset bipolar disorder and unipolar depression in the siblings was markedly increased during youth and early adulthood, compared with controls drawn from the general Danish population. Then, incidence rates dropped off and plateaued at a lower level in midlife before surging after age 60 years. The same was true for somatoform disorders as well as alcohol and substance use disorders.

“Strategies to prevent onset of psychiatric illness in individuals with a first-generation family history of bipolar disorder should not be limited to adolescence and early adulthood but should be lifelong, likely with differentiated age-specific approaches. And this is not now the case.

“Generally, most researchers and clinicians are focusing more on the early part of life and not the later part of life from age 60 and up, even though this is indeed also a risk period for any kind of psychiatric illness as well as bipolar disorder,” according to Dr. Kessing, professor of psychiatry at the University of Copenhagen.

Dr. Kessing, a past recipient of the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation’s Outstanding Achievement in Mood Disorders Research Award, also described his research group’s successful innovative efforts to prevent first recurrences after a single manic episode or bipolar disorder.

Danish national sibling study

The longitudinal registry study included all 19,995 Danish patients with a primary diagnosis of bipolar disorder during 1995-2017, along with 13,923 of their siblings and 278,460 age- and gender-matched controls drawn from the general population.

The cumulative incidence of any psychiatric disorder was 66% greater in siblings than controls. Leading the way was a 374% increased risk of bipolar disorder.

Strategies to prevent a first relapse of bipolar disorder

Dr. Kessing and coinvestigators demonstrated in a meta-analysis that, with current standard therapies, the risk of recurrence among patients after a single manic or mixed episode is high in both adult and pediatric patients. In three studies of adults, the risk of recurrence was 35% during the first year after recovery from the index episode and 59% at 2 years. In three studies of children and adolescents, the risk of recurrence within 1 year after recovery was 40% in children and 52% in adolescents. This makes a compelling case for starting maintenance therapy following onset of a single manic or mixed episode, according to the investigators.

More than half a decade ago, Dr. Kessing and colleagues demonstrated in a study of 4,714 Danish patients with bipolar disorder who were prescribed lithium while in a psychiatric hospital that those who started the drug for prophylaxis early – that is, following their first psychiatric contact – had a significantly higher response to lithium monotherapy than those who started it only after repeated contacts. Indeed, their risk of nonresponse to lithium prophylaxis as evidenced by repeat hospital admission after a 6-month lithium stabilization period was 13% lower than in those starting the drug later.

Early intervention aiming to stop clinical progression of bipolar disorder intuitively seems appealing, so Dr. Kessing and colleagues created a specialized outpatient mood disorders clinic combining optimized pharmacotherapy and evidence-based group psychoeducation. They then put it to the test in a clinical trial in which 158 patients discharged from an initial psychiatric hospital admission for bipolar disorder were randomized to the specialized outpatient mood disorders clinic or standard care.

The rate of psychiatric hospital readmission within the next 6 years was 40% lower in the group assigned to the specialized early intervention clinic. Their rate of adherence to medication – mostly lithium and antipsychotics – was significantly higher. So were their treatment satisfaction scores. And the clincher: The total net direct cost of treatment in the specialized mood disorders clinic averaged 3,194 euro less per patient, an 11% reduction relative to the cost of standard care, a striking economic benefit achieved mainly through avoided hospitalizations.

In a subsequent subgroup analysis of the randomized trial data, Dr. Kessing and coinvestigators demonstrated that young adults with bipolar disorder not only benefited from participation in the specialized outpatient clinic, but they appeared to have derived greater benefit than the older patients. The rehospitalization rate was 67% lower in 18- to 25-year-old patients randomized to the specialized outpatient mood disorder clinic than in standard-care controls, compared with a 32% relative risk reduction in outpatient clinic patients aged 26 years or older).

“There are now several centers around the world which also use this model involving early intervention,” Dr. Kessing said. “It is so important that, when the diagnosis is made for the first time, the patient gets sufficient evidence-based treatment comprised of mood maintenance medication as well as group-based psychoeducation, which is the psychotherapeutic intervention for which there is the strongest evidence of an effect.”

The sibling study was funded free of commercial support. Dr. Kessing reported serving as a consultant to Lundbeck.

SOURCE: Kessing LV. ECNP 2020, Session S.25.

The siblings of patients with bipolar disorder not only face a significantly increased lifetime risk of that affective disorder, but a whole panoply of other psychiatric disorders, according to a new Danish longitudinal national registry study.

“Our data show the healthy siblings of patients with bipolar disorder are themselves at increased risk of developing any kind of psychiatric disorder. Mainly bipolar disorder, but all other kinds as well,” Lars Vedel Kessing, MD, DMSc, said in presenting the results of the soon-to-be-published Danish study at the virtual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Moreover, the long-term Danish study also demonstrated that several major psychiatric disorders follow a previously unappreciated bimodal distribution of age of onset in the siblings of patients with bipolar disorder. For example, the incidence of new-onset bipolar disorder and unipolar depression in the siblings was markedly increased during youth and early adulthood, compared with controls drawn from the general Danish population. Then, incidence rates dropped off and plateaued at a lower level in midlife before surging after age 60 years. The same was true for somatoform disorders as well as alcohol and substance use disorders.

“Strategies to prevent onset of psychiatric illness in individuals with a first-generation family history of bipolar disorder should not be limited to adolescence and early adulthood but should be lifelong, likely with differentiated age-specific approaches. And this is not now the case.

“Generally, most researchers and clinicians are focusing more on the early part of life and not the later part of life from age 60 and up, even though this is indeed also a risk period for any kind of psychiatric illness as well as bipolar disorder,” according to Dr. Kessing, professor of psychiatry at the University of Copenhagen.

Dr. Kessing, a past recipient of the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation’s Outstanding Achievement in Mood Disorders Research Award, also described his research group’s successful innovative efforts to prevent first recurrences after a single manic episode or bipolar disorder.

Danish national sibling study

The longitudinal registry study included all 19,995 Danish patients with a primary diagnosis of bipolar disorder during 1995-2017, along with 13,923 of their siblings and 278,460 age- and gender-matched controls drawn from the general population.

The cumulative incidence of any psychiatric disorder was 66% greater in siblings than controls. Leading the way was a 374% increased risk of bipolar disorder.

Strategies to prevent a first relapse of bipolar disorder

Dr. Kessing and coinvestigators demonstrated in a meta-analysis that, with current standard therapies, the risk of recurrence among patients after a single manic or mixed episode is high in both adult and pediatric patients. In three studies of adults, the risk of recurrence was 35% during the first year after recovery from the index episode and 59% at 2 years. In three studies of children and adolescents, the risk of recurrence within 1 year after recovery was 40% in children and 52% in adolescents. This makes a compelling case for starting maintenance therapy following onset of a single manic or mixed episode, according to the investigators.

More than half a decade ago, Dr. Kessing and colleagues demonstrated in a study of 4,714 Danish patients with bipolar disorder who were prescribed lithium while in a psychiatric hospital that those who started the drug for prophylaxis early – that is, following their first psychiatric contact – had a significantly higher response to lithium monotherapy than those who started it only after repeated contacts. Indeed, their risk of nonresponse to lithium prophylaxis as evidenced by repeat hospital admission after a 6-month lithium stabilization period was 13% lower than in those starting the drug later.

Early intervention aiming to stop clinical progression of bipolar disorder intuitively seems appealing, so Dr. Kessing and colleagues created a specialized outpatient mood disorders clinic combining optimized pharmacotherapy and evidence-based group psychoeducation. They then put it to the test in a clinical trial in which 158 patients discharged from an initial psychiatric hospital admission for bipolar disorder were randomized to the specialized outpatient mood disorders clinic or standard care.

The rate of psychiatric hospital readmission within the next 6 years was 40% lower in the group assigned to the specialized early intervention clinic. Their rate of adherence to medication – mostly lithium and antipsychotics – was significantly higher. So were their treatment satisfaction scores. And the clincher: The total net direct cost of treatment in the specialized mood disorders clinic averaged 3,194 euro less per patient, an 11% reduction relative to the cost of standard care, a striking economic benefit achieved mainly through avoided hospitalizations.

In a subsequent subgroup analysis of the randomized trial data, Dr. Kessing and coinvestigators demonstrated that young adults with bipolar disorder not only benefited from participation in the specialized outpatient clinic, but they appeared to have derived greater benefit than the older patients. The rehospitalization rate was 67% lower in 18- to 25-year-old patients randomized to the specialized outpatient mood disorder clinic than in standard-care controls, compared with a 32% relative risk reduction in outpatient clinic patients aged 26 years or older).

“There are now several centers around the world which also use this model involving early intervention,” Dr. Kessing said. “It is so important that, when the diagnosis is made for the first time, the patient gets sufficient evidence-based treatment comprised of mood maintenance medication as well as group-based psychoeducation, which is the psychotherapeutic intervention for which there is the strongest evidence of an effect.”

The sibling study was funded free of commercial support. Dr. Kessing reported serving as a consultant to Lundbeck.

SOURCE: Kessing LV. ECNP 2020, Session S.25.

The siblings of patients with bipolar disorder not only face a significantly increased lifetime risk of that affective disorder, but a whole panoply of other psychiatric disorders, according to a new Danish longitudinal national registry study.

“Our data show the healthy siblings of patients with bipolar disorder are themselves at increased risk of developing any kind of psychiatric disorder. Mainly bipolar disorder, but all other kinds as well,” Lars Vedel Kessing, MD, DMSc, said in presenting the results of the soon-to-be-published Danish study at the virtual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Moreover, the long-term Danish study also demonstrated that several major psychiatric disorders follow a previously unappreciated bimodal distribution of age of onset in the siblings of patients with bipolar disorder. For example, the incidence of new-onset bipolar disorder and unipolar depression in the siblings was markedly increased during youth and early adulthood, compared with controls drawn from the general Danish population. Then, incidence rates dropped off and plateaued at a lower level in midlife before surging after age 60 years. The same was true for somatoform disorders as well as alcohol and substance use disorders.

“Strategies to prevent onset of psychiatric illness in individuals with a first-generation family history of bipolar disorder should not be limited to adolescence and early adulthood but should be lifelong, likely with differentiated age-specific approaches. And this is not now the case.

“Generally, most researchers and clinicians are focusing more on the early part of life and not the later part of life from age 60 and up, even though this is indeed also a risk period for any kind of psychiatric illness as well as bipolar disorder,” according to Dr. Kessing, professor of psychiatry at the University of Copenhagen.

Dr. Kessing, a past recipient of the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation’s Outstanding Achievement in Mood Disorders Research Award, also described his research group’s successful innovative efforts to prevent first recurrences after a single manic episode or bipolar disorder.

Danish national sibling study

The longitudinal registry study included all 19,995 Danish patients with a primary diagnosis of bipolar disorder during 1995-2017, along with 13,923 of their siblings and 278,460 age- and gender-matched controls drawn from the general population.

The cumulative incidence of any psychiatric disorder was 66% greater in siblings than controls. Leading the way was a 374% increased risk of bipolar disorder.

Strategies to prevent a first relapse of bipolar disorder

Dr. Kessing and coinvestigators demonstrated in a meta-analysis that, with current standard therapies, the risk of recurrence among patients after a single manic or mixed episode is high in both adult and pediatric patients. In three studies of adults, the risk of recurrence was 35% during the first year after recovery from the index episode and 59% at 2 years. In three studies of children and adolescents, the risk of recurrence within 1 year after recovery was 40% in children and 52% in adolescents. This makes a compelling case for starting maintenance therapy following onset of a single manic or mixed episode, according to the investigators.

More than half a decade ago, Dr. Kessing and colleagues demonstrated in a study of 4,714 Danish patients with bipolar disorder who were prescribed lithium while in a psychiatric hospital that those who started the drug for prophylaxis early – that is, following their first psychiatric contact – had a significantly higher response to lithium monotherapy than those who started it only after repeated contacts. Indeed, their risk of nonresponse to lithium prophylaxis as evidenced by repeat hospital admission after a 6-month lithium stabilization period was 13% lower than in those starting the drug later.

Early intervention aiming to stop clinical progression of bipolar disorder intuitively seems appealing, so Dr. Kessing and colleagues created a specialized outpatient mood disorders clinic combining optimized pharmacotherapy and evidence-based group psychoeducation. They then put it to the test in a clinical trial in which 158 patients discharged from an initial psychiatric hospital admission for bipolar disorder were randomized to the specialized outpatient mood disorders clinic or standard care.

The rate of psychiatric hospital readmission within the next 6 years was 40% lower in the group assigned to the specialized early intervention clinic. Their rate of adherence to medication – mostly lithium and antipsychotics – was significantly higher. So were their treatment satisfaction scores. And the clincher: The total net direct cost of treatment in the specialized mood disorders clinic averaged 3,194 euro less per patient, an 11% reduction relative to the cost of standard care, a striking economic benefit achieved mainly through avoided hospitalizations.

In a subsequent subgroup analysis of the randomized trial data, Dr. Kessing and coinvestigators demonstrated that young adults with bipolar disorder not only benefited from participation in the specialized outpatient clinic, but they appeared to have derived greater benefit than the older patients. The rehospitalization rate was 67% lower in 18- to 25-year-old patients randomized to the specialized outpatient mood disorder clinic than in standard-care controls, compared with a 32% relative risk reduction in outpatient clinic patients aged 26 years or older).

“There are now several centers around the world which also use this model involving early intervention,” Dr. Kessing said. “It is so important that, when the diagnosis is made for the first time, the patient gets sufficient evidence-based treatment comprised of mood maintenance medication as well as group-based psychoeducation, which is the psychotherapeutic intervention for which there is the strongest evidence of an effect.”

The sibling study was funded free of commercial support. Dr. Kessing reported serving as a consultant to Lundbeck.

SOURCE: Kessing LV. ECNP 2020, Session S.25.

FROM ECNP 2020

Opt-out policy at a syringe service program increased HIV/HCV testing

Bundled opt-out HIV/hepatitis C virus (HCV) testing increased the percentage of syringe service program (SSP) clients who received HIV and HCV rapid tests at enrollment into the program. Researchers conducted a retrospective comparative analysis of patient testing patterns before and after opt-out policy implementation in a single SSP program, according to a report published online in the International Journal of Drug Policy.

Because HCV is the most common infectious disease among people who inject drugs (PWID), engaging PWID in harm reduction services, such as SSPs, is critical to reduce HCV and HIV transmission, according to Tyler S. Bartholomew of the University of Miami, and colleagues. They added that testing for HIV and HCV among PWID is important for improvement of diagnosis and linkage to care.

Their study, conducted in the 37 months between December 2016 and January 2020 assessed 512 SSP participants 15 months prior to and 547 SSP participants 22 months after implementation of bundled HIV/HCV opt-out testing.

Opt-out optimal

There was a significant increase in uptake of HIV/HCV testing by 42.4% (95% confidence interval, 26.2%-58.5%; P < 0.001) immediately after the policy changed to opt-out testing, according to the researchers. In addition, they found that the significant predictors of accepting both HIV/HCV tests were cocaine injection (adjusted odds ratio, 2.36), self-reported HIV-positive status (aOR, 0.39), and self-reported HCV-positive status (aOR, 0.27).

The authors explained that participants who injected cocaine in the previous 30 days, compared with other drugs, might have had higher odds of accepting HIV/HCV testing because of their known added risk factors. Previous studies have shown that people who use stimulants describe higher rates of condomless sex, sex work, and sex in exchange for money or drugs, compared with people who use nonstimulant drugs.

“Our paper is the first of which we are aware to suggest that implementation of routine opt-out HIV/HCV testing among PWID at SSPs could enhance HIV/HCV testing among this high incidence population,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported funding from the National Cancer Institute and the Frontlines of Communities in the United States, a program of Gilead Sciences. They provided no other disclosures.

SOURCE: Bartholomew TS et al. Int J Drug Policy. 2020; doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102875.

Bundled opt-out HIV/hepatitis C virus (HCV) testing increased the percentage of syringe service program (SSP) clients who received HIV and HCV rapid tests at enrollment into the program. Researchers conducted a retrospective comparative analysis of patient testing patterns before and after opt-out policy implementation in a single SSP program, according to a report published online in the International Journal of Drug Policy.

Because HCV is the most common infectious disease among people who inject drugs (PWID), engaging PWID in harm reduction services, such as SSPs, is critical to reduce HCV and HIV transmission, according to Tyler S. Bartholomew of the University of Miami, and colleagues. They added that testing for HIV and HCV among PWID is important for improvement of diagnosis and linkage to care.

Their study, conducted in the 37 months between December 2016 and January 2020 assessed 512 SSP participants 15 months prior to and 547 SSP participants 22 months after implementation of bundled HIV/HCV opt-out testing.

Opt-out optimal

There was a significant increase in uptake of HIV/HCV testing by 42.4% (95% confidence interval, 26.2%-58.5%; P < 0.001) immediately after the policy changed to opt-out testing, according to the researchers. In addition, they found that the significant predictors of accepting both HIV/HCV tests were cocaine injection (adjusted odds ratio, 2.36), self-reported HIV-positive status (aOR, 0.39), and self-reported HCV-positive status (aOR, 0.27).

The authors explained that participants who injected cocaine in the previous 30 days, compared with other drugs, might have had higher odds of accepting HIV/HCV testing because of their known added risk factors. Previous studies have shown that people who use stimulants describe higher rates of condomless sex, sex work, and sex in exchange for money or drugs, compared with people who use nonstimulant drugs.

“Our paper is the first of which we are aware to suggest that implementation of routine opt-out HIV/HCV testing among PWID at SSPs could enhance HIV/HCV testing among this high incidence population,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported funding from the National Cancer Institute and the Frontlines of Communities in the United States, a program of Gilead Sciences. They provided no other disclosures.

SOURCE: Bartholomew TS et al. Int J Drug Policy. 2020; doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102875.

Bundled opt-out HIV/hepatitis C virus (HCV) testing increased the percentage of syringe service program (SSP) clients who received HIV and HCV rapid tests at enrollment into the program. Researchers conducted a retrospective comparative analysis of patient testing patterns before and after opt-out policy implementation in a single SSP program, according to a report published online in the International Journal of Drug Policy.

Because HCV is the most common infectious disease among people who inject drugs (PWID), engaging PWID in harm reduction services, such as SSPs, is critical to reduce HCV and HIV transmission, according to Tyler S. Bartholomew of the University of Miami, and colleagues. They added that testing for HIV and HCV among PWID is important for improvement of diagnosis and linkage to care.

Their study, conducted in the 37 months between December 2016 and January 2020 assessed 512 SSP participants 15 months prior to and 547 SSP participants 22 months after implementation of bundled HIV/HCV opt-out testing.

Opt-out optimal

There was a significant increase in uptake of HIV/HCV testing by 42.4% (95% confidence interval, 26.2%-58.5%; P < 0.001) immediately after the policy changed to opt-out testing, according to the researchers. In addition, they found that the significant predictors of accepting both HIV/HCV tests were cocaine injection (adjusted odds ratio, 2.36), self-reported HIV-positive status (aOR, 0.39), and self-reported HCV-positive status (aOR, 0.27).

The authors explained that participants who injected cocaine in the previous 30 days, compared with other drugs, might have had higher odds of accepting HIV/HCV testing because of their known added risk factors. Previous studies have shown that people who use stimulants describe higher rates of condomless sex, sex work, and sex in exchange for money or drugs, compared with people who use nonstimulant drugs.

“Our paper is the first of which we are aware to suggest that implementation of routine opt-out HIV/HCV testing among PWID at SSPs could enhance HIV/HCV testing among this high incidence population,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported funding from the National Cancer Institute and the Frontlines of Communities in the United States, a program of Gilead Sciences. They provided no other disclosures.

SOURCE: Bartholomew TS et al. Int J Drug Policy. 2020; doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102875.

FROM INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF DRUG POLICY

Open enrollment 2021: A big start for HealthCare.gov

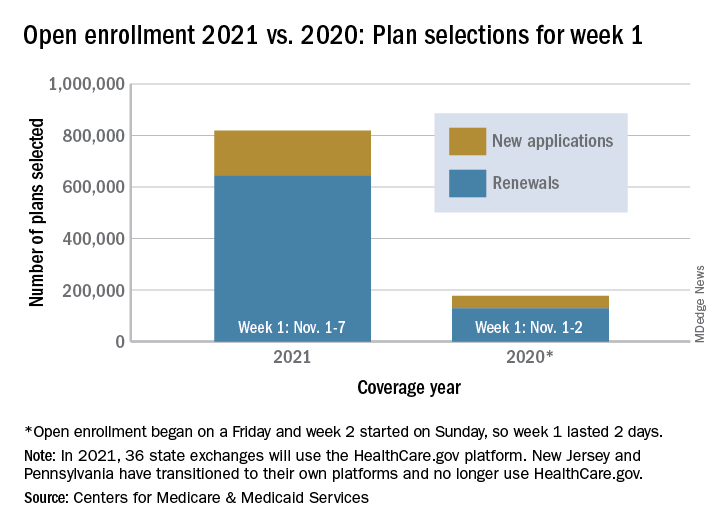

Over 818,000 plans were selected for the 2021 coverage year during the first week, Nov.1-7, of this year’s open enrollment on the federal health insurance exchange, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The bulk of those plans, nearly 79%, were renewals by consumers who had coverage through the federal exchange this year. The balance covers new plans selected by individuals who were not covered through HealthCare.gov this year, the CMS noted in a written statement.

The total enrollment for week 1 marks a considerable increase over last year’s first week of open enrollment, which saw approximately 177,000 plans selected, but Nov. 1 fell on a Friday in 2019, so that total represents only 2 days since weeks are tracked as running from Sunday to Saturday, the CMS explained.

For the 2021 benefit year, the HealthCare.gov platform covers 36 states, down from 38 for the 2020 benefit year, because New Jersey and Pennsylvania have “transitioned to their own state-based exchange platforms,” the CMS noted, adding that the two accounted for 7% of all plans selected last year.

“The final number of plan selections associated with enrollment activity during a reporting period may change due to plan modifications or cancellations,” CMS said, and its weekly snapshot “does not report the number of consumers who have paid premiums to effectuate their enrollment.”

This year’s open-enrollment period on HealthCare.gov is scheduled to conclude Dec. 15.

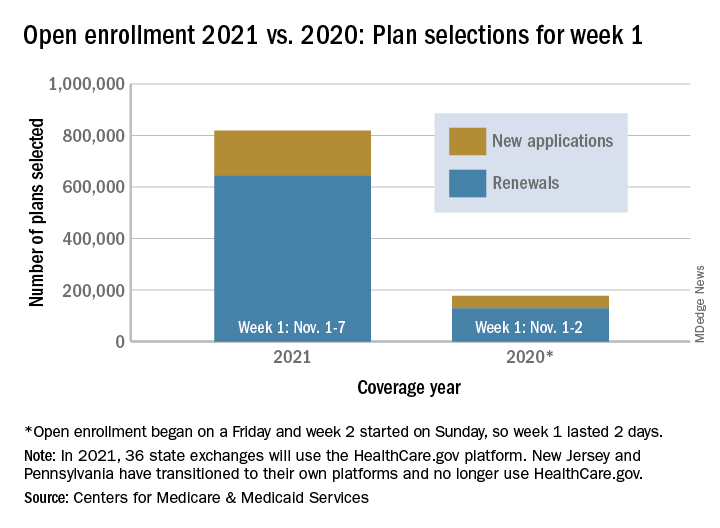

Over 818,000 plans were selected for the 2021 coverage year during the first week, Nov.1-7, of this year’s open enrollment on the federal health insurance exchange, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The bulk of those plans, nearly 79%, were renewals by consumers who had coverage through the federal exchange this year. The balance covers new plans selected by individuals who were not covered through HealthCare.gov this year, the CMS noted in a written statement.

The total enrollment for week 1 marks a considerable increase over last year’s first week of open enrollment, which saw approximately 177,000 plans selected, but Nov. 1 fell on a Friday in 2019, so that total represents only 2 days since weeks are tracked as running from Sunday to Saturday, the CMS explained.

For the 2021 benefit year, the HealthCare.gov platform covers 36 states, down from 38 for the 2020 benefit year, because New Jersey and Pennsylvania have “transitioned to their own state-based exchange platforms,” the CMS noted, adding that the two accounted for 7% of all plans selected last year.

“The final number of plan selections associated with enrollment activity during a reporting period may change due to plan modifications or cancellations,” CMS said, and its weekly snapshot “does not report the number of consumers who have paid premiums to effectuate their enrollment.”

This year’s open-enrollment period on HealthCare.gov is scheduled to conclude Dec. 15.

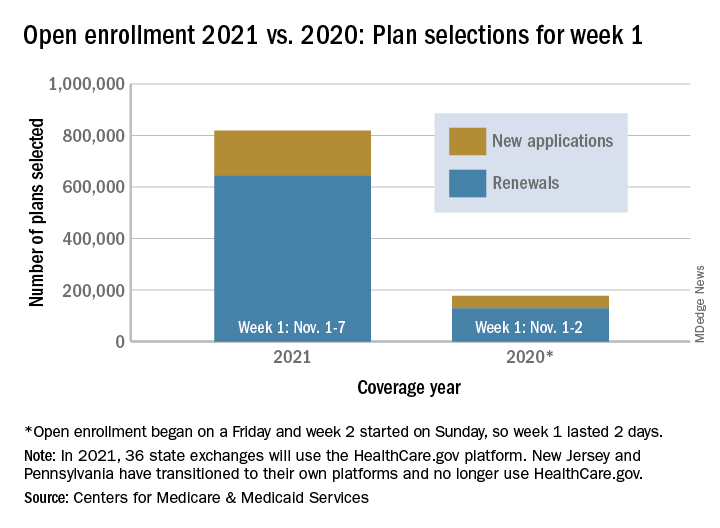

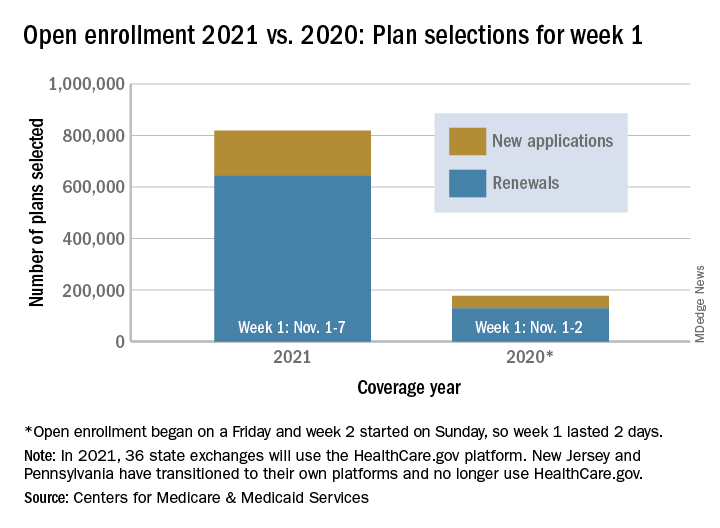

Over 818,000 plans were selected for the 2021 coverage year during the first week, Nov.1-7, of this year’s open enrollment on the federal health insurance exchange, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The bulk of those plans, nearly 79%, were renewals by consumers who had coverage through the federal exchange this year. The balance covers new plans selected by individuals who were not covered through HealthCare.gov this year, the CMS noted in a written statement.

The total enrollment for week 1 marks a considerable increase over last year’s first week of open enrollment, which saw approximately 177,000 plans selected, but Nov. 1 fell on a Friday in 2019, so that total represents only 2 days since weeks are tracked as running from Sunday to Saturday, the CMS explained.

For the 2021 benefit year, the HealthCare.gov platform covers 36 states, down from 38 for the 2020 benefit year, because New Jersey and Pennsylvania have “transitioned to their own state-based exchange platforms,” the CMS noted, adding that the two accounted for 7% of all plans selected last year.

“The final number of plan selections associated with enrollment activity during a reporting period may change due to plan modifications or cancellations,” CMS said, and its weekly snapshot “does not report the number of consumers who have paid premiums to effectuate their enrollment.”

This year’s open-enrollment period on HealthCare.gov is scheduled to conclude Dec. 15.

Nail Unit Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Updates on Diagnosis, Surgical Approach, and the Use of Mohs Micrographic Surgery

Nail unit squamous cell carcinoma (NSCC) is a malignant neoplasm that can arise from any part of the nail unit. Diagnosis often is delayed due to its clinical presentation mimicking benign conditions such as onychomycosis, warts, and paronychia. Nail unit SCC has a low rate of metastasis; however, a delayed diagnosis often can result in local destruction and bone invasion. It is imperative for dermatologists who are early in their training to recognize this entity and refer for treatment. Many approaches have been used to treat NSCC, including wide local excision, digital amputation, cryotherapy, topical modalities, and recently Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS). This article provides an overview of the clinical presentation and diagnosis of NSCC, the role of human papillomavirus (HPV) in NSCC pathogenesis, and the evidence supporting surgical management.

NSCC Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

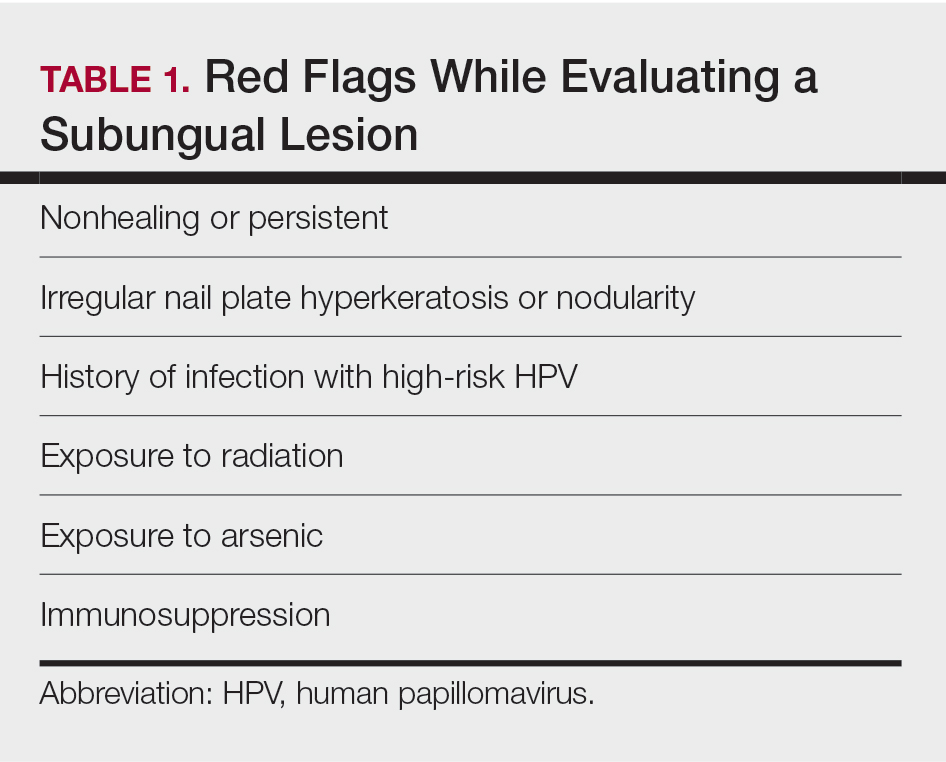

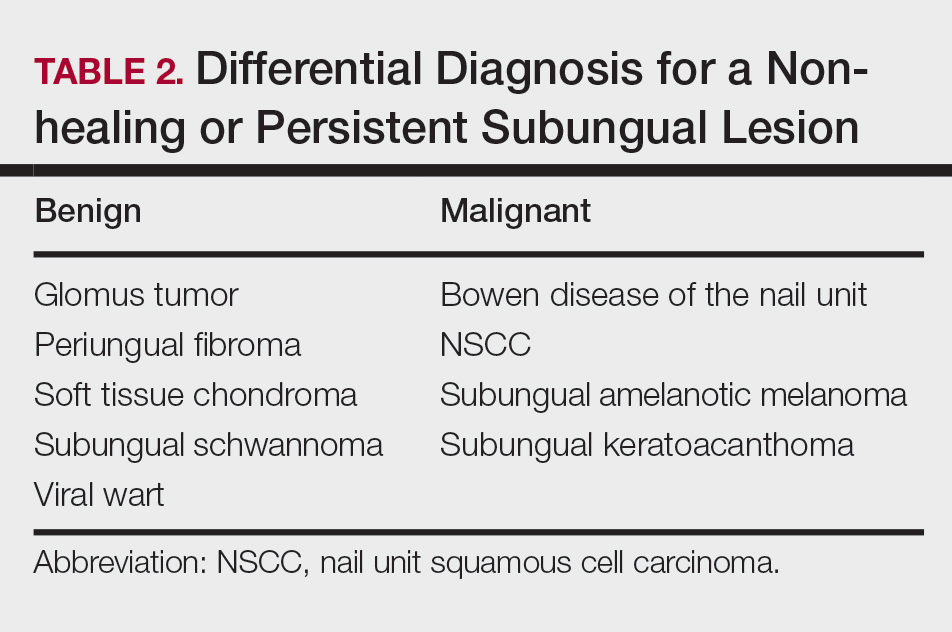

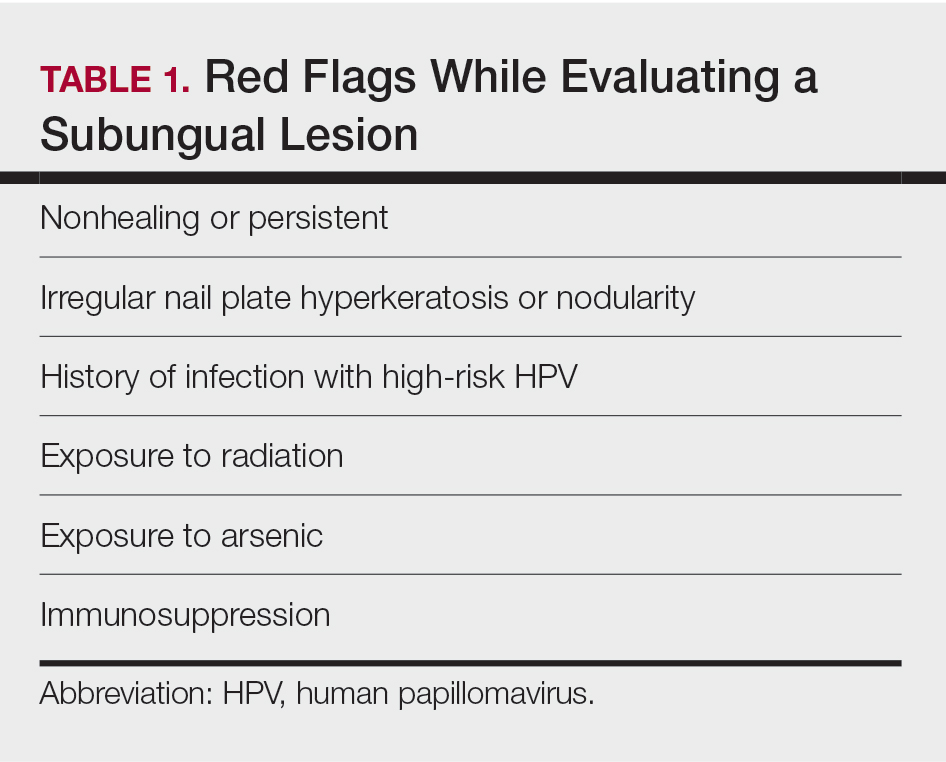

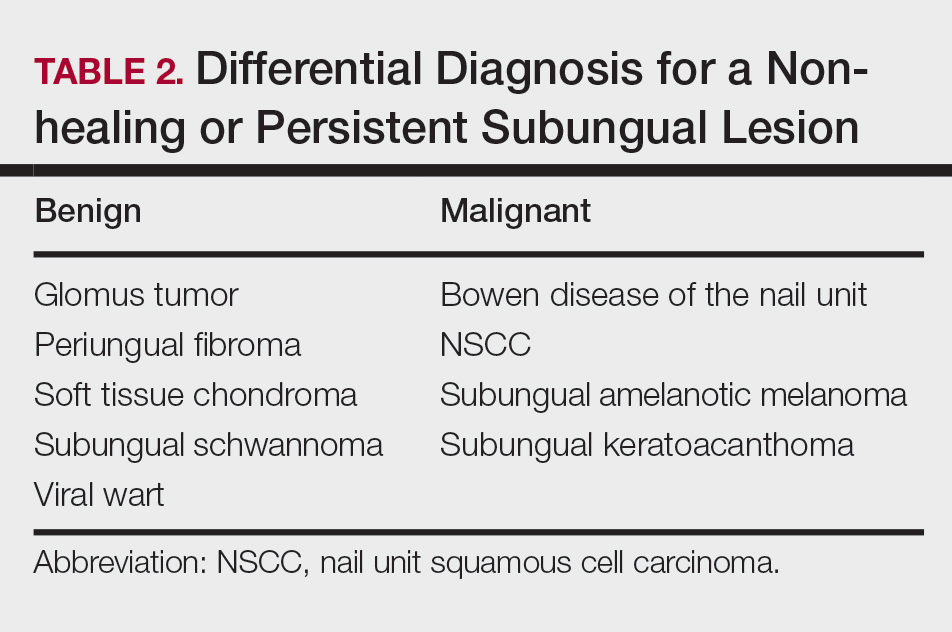

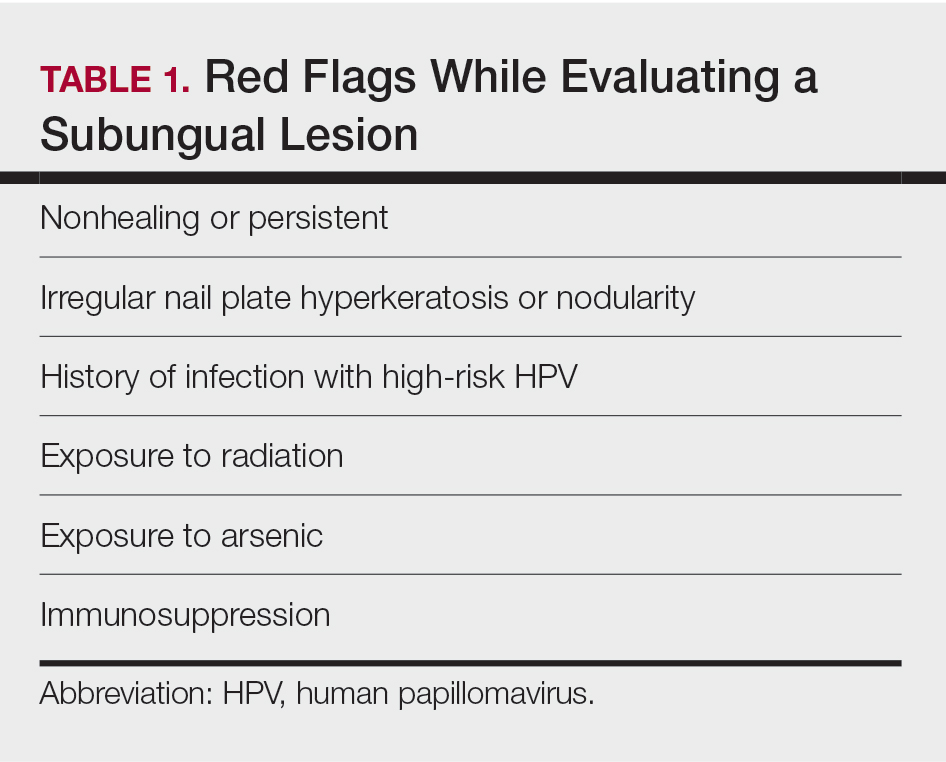

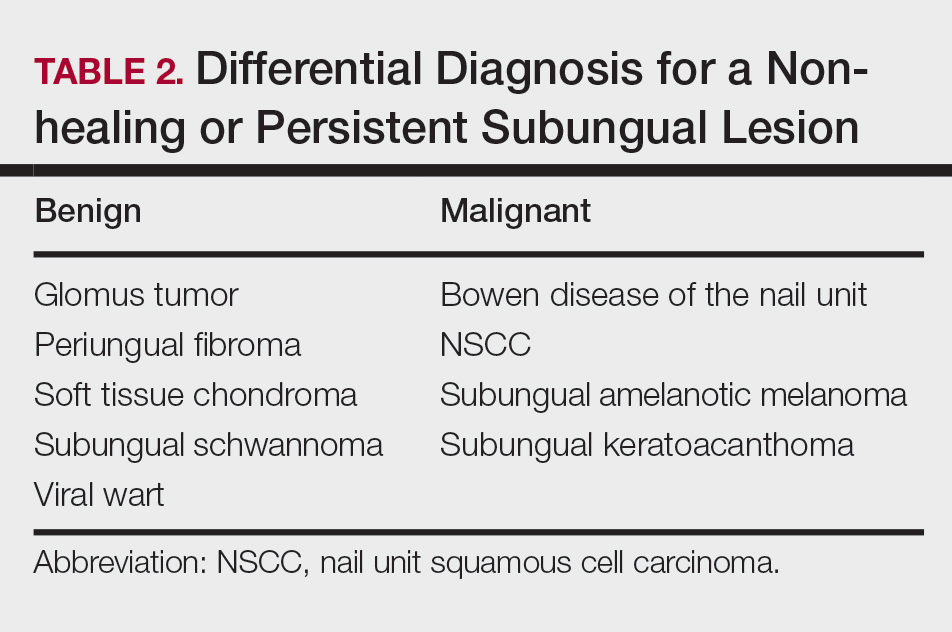

Nail unit squamous cell carcinoma is a malignant neoplasm that can arise from any part of the nail unit including the nail bed, matrix, groove, and nail fold.1 Although NSCC is the most common malignant nail neoplasm, its diagnosis often is delayed partly due to the clinical presentation of NSCC mimicking benign conditions such as onychomycosis, warts, and paronychia.2,3 Nail unit SCC most commonly is mistaken for verruca vulgaris, and thus it is important to exclude malignancy in nonresolving verrucae of the fingernails or toenails. Another reason for a delay in the diagnosis is the painless and often asymptomatic presentation of this tumor, which keeps patients from seeking care.4 While evaluating a subungual lesion, dermatologists should keep in mind red flags that would prompt a biopsy to rule out NSCC (Table 1), including chronic nonhealing lesions, nail plate nodularity, known history of infection with HPV types 16 and 18, history of radiation or arsenic exposure, and immunosuppression. Table 2 lists the differential diagnosis of a persisting or nonhealing subungual tumor.

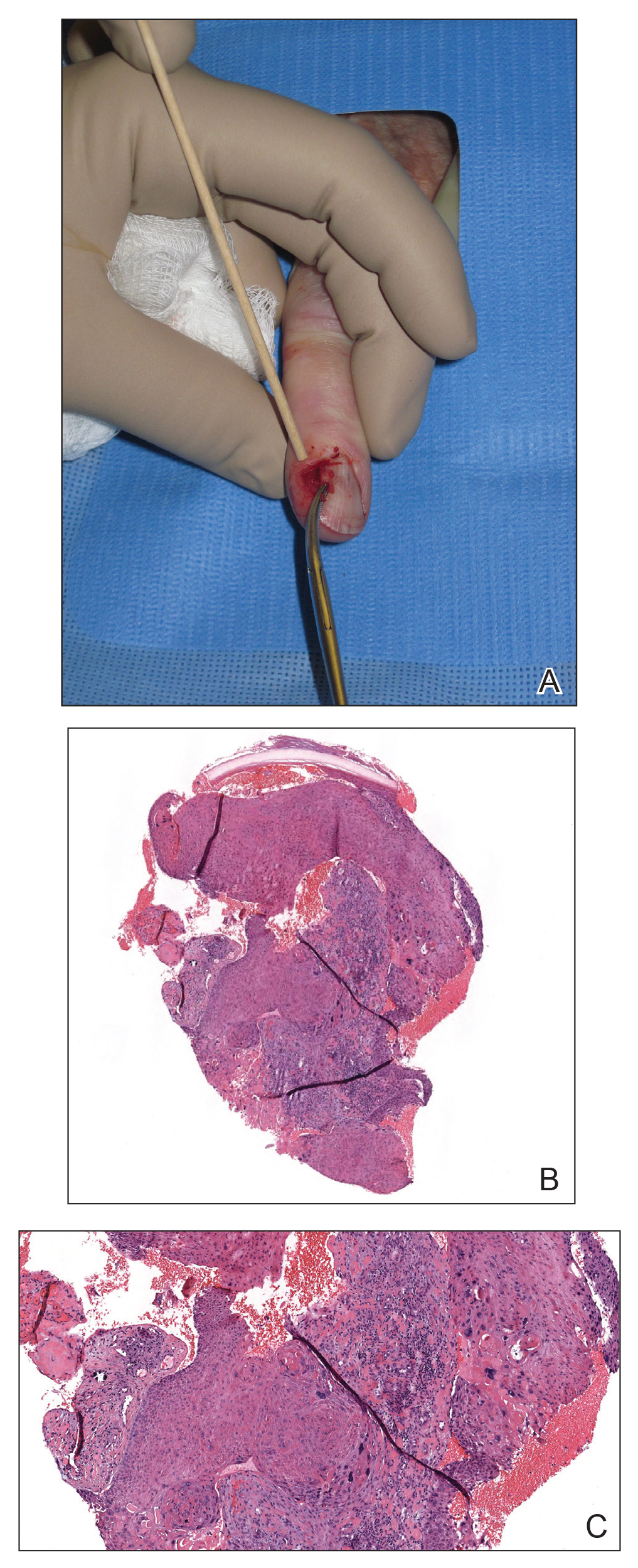

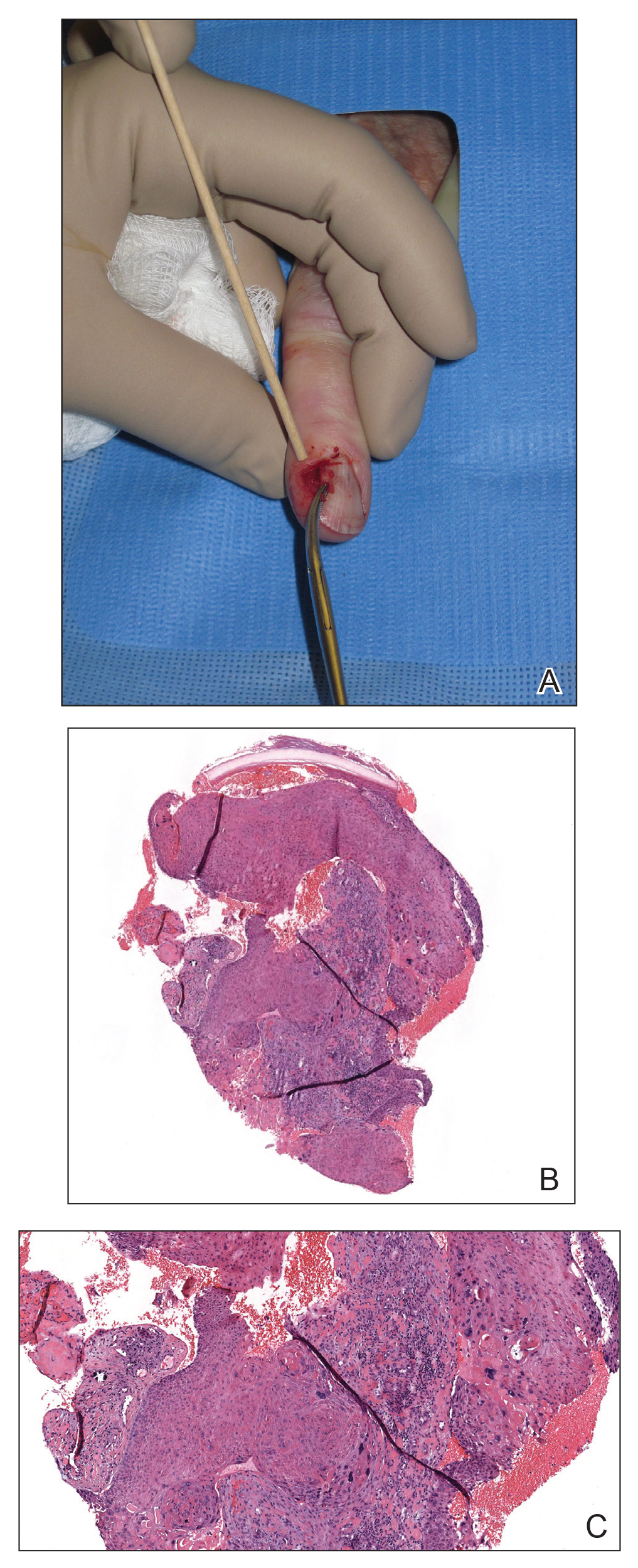

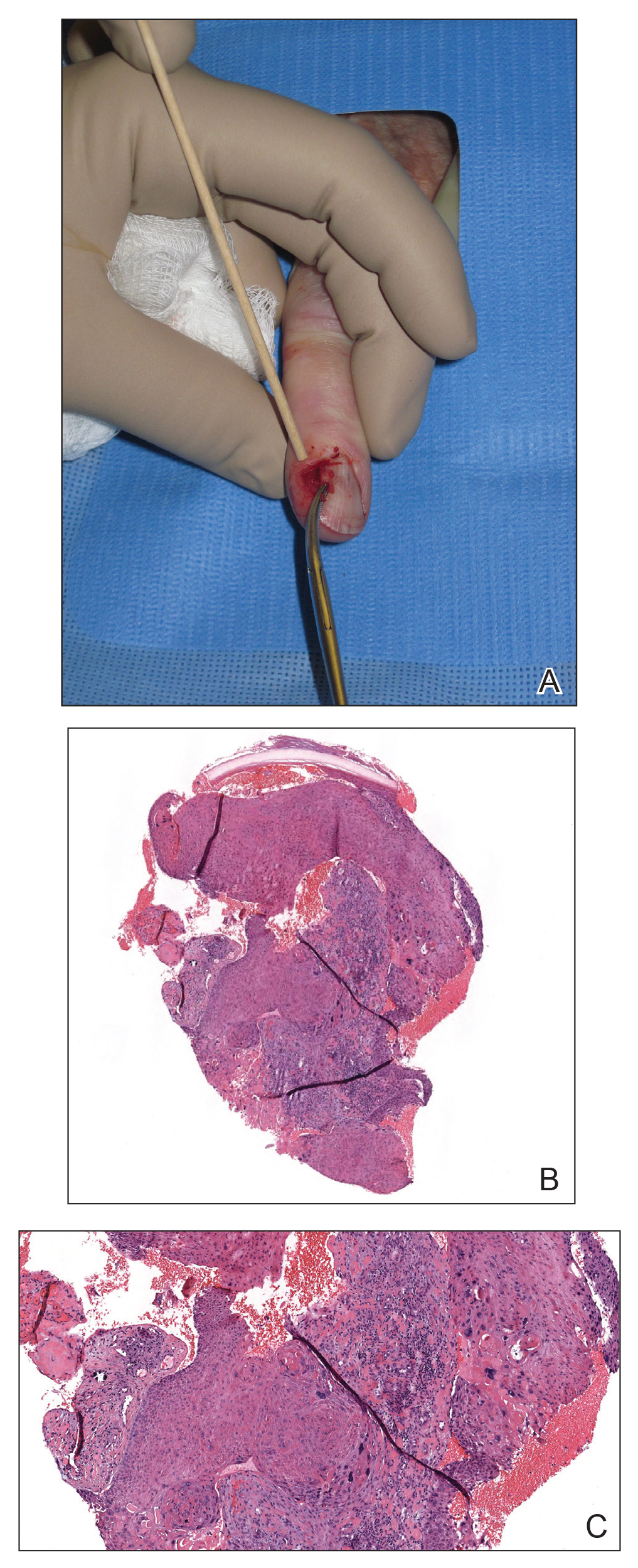

Nail unit SCC has a low rate of metastasis; however, a delayed diagnosis often can result in local destruction and bone invasion.5 Based on several reports, NSCC more commonly is found in middle-aged and older individuals, has a male predilection, and more often is seen on fingernails than toenails.1,2,6 Figure A shows an example of the clinical presentation of NSCC affecting the right thumb.

Although there often is a delay in the presentation and biopsy of NSCC, no correlation has been observed between time to biopsy and rate of disease invasion and recurrence.7 Nevertheless, Starace et al7 noted that a low threshold for biopsy of nail unit lesions is necessary. It is recommended to perform a deep shave or a nail matrix biopsy, especially if matrical involvement is suspected.8 Patients should be closely followed after a diagnosis of NSCC is made, especially if they are immunocompromised or have genetic skin cancer syndromes, as multiple NSCCs can occur in the same individual.9 For instance, one report discussed a patient with xeroderma pigmentosum who developed 3 separate NSCCs. Interestingly, in this patient, the authors suspected HPV as a cause for the field cancerization, as 2 of 3 NSCCs were noted on initial histopathology to have arisen from verrucae.10

Histologic Features

A biopsy from an NSCC tumor shows features similar to cutaneous SCC in the affected areas (ie, nail bed, nail matrix, nail groove, nail fold). Characteristic histologic findings include tongues or whorls of atypical squamous epithelium that invade deeply into the dermis.11 The cells appear as atypical keratinocytes, exhibit distinct intracellular bridges, and possess hyperchromatic and pleomorphic nuclei with dyskeratosis and keratin pearls within the dermis.12 Immunoperoxidase staining for cytokeratin AE1/AE3 can be helpful to confirm the diagnosis and assess whether the depth of invasion involves the bone.13 Figures B and C demonstrate the histopathology of NSCC biopsied from the tumor shown in Figure A.

Role of HPV in NSCC Pathogenesis

There is no clear pathogenic etiology for NSCC; however, there have been some reports of HPV as a risk factor. Shimizu et al14 reviewed 136 cases of HPV-associated NSCC and found that half of the cases were associated with high-risk HPV. They also found that 24% of the patients with NSCC had a history of other HPV-associated diseases. As such, the authors hypothesized that there is a possibility for genitodigital HPV transmission and that NSCC could be a reservoir for sexually transmitted high-risk HPV.14 Other risk factors are radiation exposure, chemical insult, and chronic trauma.15 The higher propensity for fingernails likely is reflective of the role of UV light exposure and infection with HPV in the development of these tumors.14,15

Several nonsurgical approaches have been suggested to treat NSCC, including topical agents, cryotherapy, CO2 laser, and photodynamic therapy.3,16 Unfortunately, there are no large case series to demonstrate the cure rate or effectiveness of these methods.17 In one study, the authors did not recommend use of photodynamic therapy or topical modalities such as imiquimod cream 5% or fluorouracil cream 5% as first-line treatments of NSCC due to the difficulty in ensuring complete treatment of the sulci of the lateral and proximal nail folds.18

More evidence in the literature supports surgical approaches, including wide local excision, MMS, and digital amputation. Clinicians should consider relapse rates and the impact on digital functioning when choosing a surgical approach.

For wide local excisions, the most common approach is en bloc excision of the nail unit including the lateral nail folds, the proximal nail fold, and the distal nail fold. The excision starts with a transverse incision on the base of the distal phalanx, which is then prolonged laterally and distally to the distal nail fold down to the bone. After the incision is made to the depth of the bone, the matrical horns are destroyed by electrocoagulation, and the defect is closed either by a full-thickness skin graft or secondary intent.19

Topin-Ruiz et al19 followed patients with biopsy-proven NSCC without bone invasion who underwent en bloc excision followed by full-thickness skin graft. In their consecutive series of 55 patients with 5 years of follow-up, the rate of recurrence was only 4%. There was a low rate of complications including graft infection, delayed wound healing, and severe pain in a small percentage of patients. They also reported a high patient satisfaction rate.19 Due to the low recurrence rate, this study suggested that total excision of the nail unit followed by a full-thickness skin graft is a safe and efficient treatment of NSCC without bone involvement. Similarly, in another case series, wide local excision of the entire nail apparatus had a relapse rate of only 5%, in contrast to partial excision of the nail unit with a relapse of 56%.20 These studies suggest that wide nail unit excision is an acceptable and effective approach; however, in cases in which invasion cannot be ruled out, histologic clearance would be a reasonable approach.21 As such, several case series demonstrated the merits of MMS for NSCC. de Berker et al22 reported 8 patients with NSCC treated using slow MMS and showed tumor clearance after a mean of 3 stages over a mean period of 6.9 days. In all cases, the wounds were allowed to heal by secondary intention, and the distal phalanx was preserved. During a mean follow-up period of 3.1 years, no recurrence was seen, and involved digits remained functional.22

Other studies tested the efficacy of MMS for NSCC. Young et al23 reported the outcomes of 14 NSCC cases treated with MMS. In their case series, they found that the mean number of MMS surgical stages required to achieve histologic clearance was 2, while the mean number of tissue sections was 4.23 All cases were allowed to heal by secondary intent with excellent outcomes, except for 1 patient who received primary closure of a small defect. They reported a 78% cure rate with an average time to recurrence of 47 months.23 In a series of 42 cases of NSCC treated with MMS, Gou et al17 noted a cure rate close to 93%. In their study, recurrences were observed in only 3 patients (7.1%). These recurrent cases were then successfully treated with another round of MMS.17 This study’s cure rate was comparable to the cure rate of MMS for SCC in other cutaneous areas. Goldminz and Bennett24 demonstrated a cure rate of 92% in their case series of 25 patients. Two patients developed recurrent disease and were treated again with MMS resulting in no subsequent recurrence. In this study, the authors allowed all defects to heal by secondary intention and found that there were excellent cosmetic and functional outcomes.24 Dika et al25 evaluated the long-term effectiveness of MMS in the treatment of NSCC, in particular its ability to reduce the number of digital amputations. Fifteen patients diagnosed with NSCC were treated with MMS as the first-line surgical approach and were followed for 2 to 5 years. They found that in utilizing MMS, they were able to avoid amputations in 13 of 15 cases with no recurrence in any of these tumors. Two cases, however, still required amputation of the distal phalanx.25

Although these studies suggest that MMS achieves a high cure rate ranging from 78% to 93%, it is not yet clear in the literature whether MMS is superior to wide local excision. More studies and clinical trials comparing these 2 surgical approaches should be performed to identify which surgical approach would be the gold standard for NSCC and which select cases would benefit from MMS as first-line treatment.

Final Thoughts

Nail unit SCC is one of the most common nail unit malignancies and can mimic several benign entities. Dermatologists who are early in their training should consider biopsy of subungual lesions with certain red flags (Table 1). It is important to diagnose NSCC for early intervention. Referral for wide local excision or MMS would be ideal. There are data in the literature supporting both surgical approaches as being effective; however, there are no trials comparing both approaches. Distal amputation should be considered as a last resort when wide local excision is not reasonable or when MMS fails to achieve clear margins, thereby reducing unnecessary amputations and patient morbidity.17

- Dika E, Starace M, Patrizi A, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the nail unit: a clinical histopathologic study and a proposal for classification. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:365-370.

- Lee TM, Jo G, Kim M, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the nail unit: a retrospective review of 19 cases in Asia and comparative review of Western literature. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:428-432.

- Tambe SA, Patil PD, Saple DG, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the nail bed: the great mimicker. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2017;10:59-60.

- Perrin C. Tumors of the nail unit. a review. part II: acquired localized longitudinal pachyonychia and masked nail tumors. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:693-712.

- Li PF, Zhu N, Lu H. Squamous cell carcinoma of the nail bed: a case report. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:3590-3594.

- Kaul S, Singal A, Grover C, et al. Clinical and histological spectrum of nail psoriasis: a cross-sectional study. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:824-830.

- Starace M, Alessandrini A, Dika E, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the nail unit. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2018;8:238-244.

- Kelly KJ, Kalani AD, Storrs S, et al. Subungual squamous cell carcinoma of the toe: working toward a standardized therapeutic approach. J Surg Educ. 2008;65:297-301.

- Ormerod E, De Berker D. Nail unit squamous cell carcinoma in people with immunosuppression. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:701-712.

- Ventéjou S, Bagny K, Waldmeyer J, et al. Skin cancers in patients of skin phototype V or VI with xeroderma pigmentosum type C (XP-C): a retrospective study. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2019;146:192-203.

- Mikhail GR. Subungual epidermoid carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:291-298.

- Lecerf P, Richert B, Theunis A, et al. A retrospective study of squamous cell carcinoma of the nail unit diagnosed in a Belgian general hospital over a 15-year period. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:253-261.

- Kurokawa I, Senba Y, Kakeda M, et al. Cytokeratin expression in subungual squamous cell carcinoma. J Int Med Res. 2006;34:441-443.

- Shimizu A, Kuriyama Y, Hasegawa M, et al. Nail squamous cell carcinoma: a hidden high-risk human papillomavirus reservoir for sexually transmitted infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:1358-1370.

- Tang N, Maloney ME, Clark AH, et al. A retrospective study of nail squamous cell carcinoma at 2 institutions. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42(suppl 1):S8-S17.

- An Q, Zheng S, Zhang L, et al. Subungual squamous cell carcinoma treated by topical photodynamic therapy. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020;133:881-882.

- Gou D, Nijhawan RI, Srivastava D. Mohs micrographic surgery as the standard of care for nail unit squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:725-732.

- Dika E, Fanti PA, Patrizi A, et al. Mohs surgery for squamous cell carcinoma of the nail unit: 10 years of experience. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:1015-1019.

- Topin-Ruiz S, Surinach C, Dalle S, et al. Surgical treatment of subungual squamous cell carcinoma by wide excision of the nail unit and skin graft reconstruction: an evaluation of treatment efficiency and outcomes. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:442-448.

- Dalle S, Depape L, Phan A, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the nail apparatus: clinicopathological study of 35 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:871-874.

- Zaiac MN, Weiss E. Mohs micrographic surgery of the nail unit and squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:246-251.

- de Berker DA, Dahl MG, Malcolm AJ, et al. Micrographic surgery for subungual squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Plast Surg. 1996;49:414-419.

- Young LC, Tuxen AJ, Goodman G. Mohs’ micrographic surgery as treatment for squamous dysplasia of the nail unit. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:123-127.

- Goldminz D, Bennett RG. Mohs micrographic surgery of the nail unit. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:721-726.

- Dika E, Piraccini BM, Balestri R, et al. Mohs surgery for squamous cell carcinoma of the nail: report of 15 cases. our experience and a long-term follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1310-1314.

Nail unit squamous cell carcinoma (NSCC) is a malignant neoplasm that can arise from any part of the nail unit. Diagnosis often is delayed due to its clinical presentation mimicking benign conditions such as onychomycosis, warts, and paronychia. Nail unit SCC has a low rate of metastasis; however, a delayed diagnosis often can result in local destruction and bone invasion. It is imperative for dermatologists who are early in their training to recognize this entity and refer for treatment. Many approaches have been used to treat NSCC, including wide local excision, digital amputation, cryotherapy, topical modalities, and recently Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS). This article provides an overview of the clinical presentation and diagnosis of NSCC, the role of human papillomavirus (HPV) in NSCC pathogenesis, and the evidence supporting surgical management.

NSCC Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Nail unit squamous cell carcinoma is a malignant neoplasm that can arise from any part of the nail unit including the nail bed, matrix, groove, and nail fold.1 Although NSCC is the most common malignant nail neoplasm, its diagnosis often is delayed partly due to the clinical presentation of NSCC mimicking benign conditions such as onychomycosis, warts, and paronychia.2,3 Nail unit SCC most commonly is mistaken for verruca vulgaris, and thus it is important to exclude malignancy in nonresolving verrucae of the fingernails or toenails. Another reason for a delay in the diagnosis is the painless and often asymptomatic presentation of this tumor, which keeps patients from seeking care.4 While evaluating a subungual lesion, dermatologists should keep in mind red flags that would prompt a biopsy to rule out NSCC (Table 1), including chronic nonhealing lesions, nail plate nodularity, known history of infection with HPV types 16 and 18, history of radiation or arsenic exposure, and immunosuppression. Table 2 lists the differential diagnosis of a persisting or nonhealing subungual tumor.

Nail unit SCC has a low rate of metastasis; however, a delayed diagnosis often can result in local destruction and bone invasion.5 Based on several reports, NSCC more commonly is found in middle-aged and older individuals, has a male predilection, and more often is seen on fingernails than toenails.1,2,6 Figure A shows an example of the clinical presentation of NSCC affecting the right thumb.

Although there often is a delay in the presentation and biopsy of NSCC, no correlation has been observed between time to biopsy and rate of disease invasion and recurrence.7 Nevertheless, Starace et al7 noted that a low threshold for biopsy of nail unit lesions is necessary. It is recommended to perform a deep shave or a nail matrix biopsy, especially if matrical involvement is suspected.8 Patients should be closely followed after a diagnosis of NSCC is made, especially if they are immunocompromised or have genetic skin cancer syndromes, as multiple NSCCs can occur in the same individual.9 For instance, one report discussed a patient with xeroderma pigmentosum who developed 3 separate NSCCs. Interestingly, in this patient, the authors suspected HPV as a cause for the field cancerization, as 2 of 3 NSCCs were noted on initial histopathology to have arisen from verrucae.10

Histologic Features

A biopsy from an NSCC tumor shows features similar to cutaneous SCC in the affected areas (ie, nail bed, nail matrix, nail groove, nail fold). Characteristic histologic findings include tongues or whorls of atypical squamous epithelium that invade deeply into the dermis.11 The cells appear as atypical keratinocytes, exhibit distinct intracellular bridges, and possess hyperchromatic and pleomorphic nuclei with dyskeratosis and keratin pearls within the dermis.12 Immunoperoxidase staining for cytokeratin AE1/AE3 can be helpful to confirm the diagnosis and assess whether the depth of invasion involves the bone.13 Figures B and C demonstrate the histopathology of NSCC biopsied from the tumor shown in Figure A.

Role of HPV in NSCC Pathogenesis

There is no clear pathogenic etiology for NSCC; however, there have been some reports of HPV as a risk factor. Shimizu et al14 reviewed 136 cases of HPV-associated NSCC and found that half of the cases were associated with high-risk HPV. They also found that 24% of the patients with NSCC had a history of other HPV-associated diseases. As such, the authors hypothesized that there is a possibility for genitodigital HPV transmission and that NSCC could be a reservoir for sexually transmitted high-risk HPV.14 Other risk factors are radiation exposure, chemical insult, and chronic trauma.15 The higher propensity for fingernails likely is reflective of the role of UV light exposure and infection with HPV in the development of these tumors.14,15

Several nonsurgical approaches have been suggested to treat NSCC, including topical agents, cryotherapy, CO2 laser, and photodynamic therapy.3,16 Unfortunately, there are no large case series to demonstrate the cure rate or effectiveness of these methods.17 In one study, the authors did not recommend use of photodynamic therapy or topical modalities such as imiquimod cream 5% or fluorouracil cream 5% as first-line treatments of NSCC due to the difficulty in ensuring complete treatment of the sulci of the lateral and proximal nail folds.18

More evidence in the literature supports surgical approaches, including wide local excision, MMS, and digital amputation. Clinicians should consider relapse rates and the impact on digital functioning when choosing a surgical approach.

For wide local excisions, the most common approach is en bloc excision of the nail unit including the lateral nail folds, the proximal nail fold, and the distal nail fold. The excision starts with a transverse incision on the base of the distal phalanx, which is then prolonged laterally and distally to the distal nail fold down to the bone. After the incision is made to the depth of the bone, the matrical horns are destroyed by electrocoagulation, and the defect is closed either by a full-thickness skin graft or secondary intent.19