User login

Complexity of hemodynamic assessment in patients with cirrhosis and septic shock

Critical Care Network

Nonrespiratory Critical Care Section

In patients with decompensated cirrhosis, there are multiple intrahepatic and extrahepatic factors contributing to hemodynamic alterations at baseline, including endothelial cell dysfunction, hepatic stellate cell activation promoting increase in vasoconstrictors, decrease in vasodilators, and angiogenesis leading to worsening of portal hypertension. Increased resistance to hepatic blood flow leads to increased production of nitric oxide and other vasodilators leading to splanchnic vasodilation, decreased effective blood volume, activation of the renin angiotensin system, sodium, and water retention. In addition to portal hypertension and splanchnic vasodilation, there is a decrease in systemic vascular resistance and hyperdynamic circulation with increased cardiac output. As cirrhosis progresses to the decompensated stage, patients may develop cirrhotic cardiomyopathy, characterized by impaired cardiac response to stress, manifesting as systolic and diastolic dysfunction, and electrophysiological abnormalities such as QT prolongation leading to hypotension and dysregulated response to fluid resuscitation.

Elevated lactate levels in acutely ill patients are an independent risk factor for mortality in patients with cirrhosis. However, lactate levels >2mmol/L need not necessarily define sepsis in these patients, as these patients have decreased lactate clearance. Understanding the intricate interplay between the cardiac pump, vascular tone, and afterload is essential in managing shock in these individuals. Aggressive volume resuscitation may not be well tolerated, emphasizing the need for frequent hemodynamic assessments and prompt initiation of vasopressors when indicated.

Critical Care Network

Nonrespiratory Critical Care Section

In patients with decompensated cirrhosis, there are multiple intrahepatic and extrahepatic factors contributing to hemodynamic alterations at baseline, including endothelial cell dysfunction, hepatic stellate cell activation promoting increase in vasoconstrictors, decrease in vasodilators, and angiogenesis leading to worsening of portal hypertension. Increased resistance to hepatic blood flow leads to increased production of nitric oxide and other vasodilators leading to splanchnic vasodilation, decreased effective blood volume, activation of the renin angiotensin system, sodium, and water retention. In addition to portal hypertension and splanchnic vasodilation, there is a decrease in systemic vascular resistance and hyperdynamic circulation with increased cardiac output. As cirrhosis progresses to the decompensated stage, patients may develop cirrhotic cardiomyopathy, characterized by impaired cardiac response to stress, manifesting as systolic and diastolic dysfunction, and electrophysiological abnormalities such as QT prolongation leading to hypotension and dysregulated response to fluid resuscitation.

Elevated lactate levels in acutely ill patients are an independent risk factor for mortality in patients with cirrhosis. However, lactate levels >2mmol/L need not necessarily define sepsis in these patients, as these patients have decreased lactate clearance. Understanding the intricate interplay between the cardiac pump, vascular tone, and afterload is essential in managing shock in these individuals. Aggressive volume resuscitation may not be well tolerated, emphasizing the need for frequent hemodynamic assessments and prompt initiation of vasopressors when indicated.

Critical Care Network

Nonrespiratory Critical Care Section

In patients with decompensated cirrhosis, there are multiple intrahepatic and extrahepatic factors contributing to hemodynamic alterations at baseline, including endothelial cell dysfunction, hepatic stellate cell activation promoting increase in vasoconstrictors, decrease in vasodilators, and angiogenesis leading to worsening of portal hypertension. Increased resistance to hepatic blood flow leads to increased production of nitric oxide and other vasodilators leading to splanchnic vasodilation, decreased effective blood volume, activation of the renin angiotensin system, sodium, and water retention. In addition to portal hypertension and splanchnic vasodilation, there is a decrease in systemic vascular resistance and hyperdynamic circulation with increased cardiac output. As cirrhosis progresses to the decompensated stage, patients may develop cirrhotic cardiomyopathy, characterized by impaired cardiac response to stress, manifesting as systolic and diastolic dysfunction, and electrophysiological abnormalities such as QT prolongation leading to hypotension and dysregulated response to fluid resuscitation.

Elevated lactate levels in acutely ill patients are an independent risk factor for mortality in patients with cirrhosis. However, lactate levels >2mmol/L need not necessarily define sepsis in these patients, as these patients have decreased lactate clearance. Understanding the intricate interplay between the cardiac pump, vascular tone, and afterload is essential in managing shock in these individuals. Aggressive volume resuscitation may not be well tolerated, emphasizing the need for frequent hemodynamic assessments and prompt initiation of vasopressors when indicated.

CLAD prevention in lung transplant recipients: Tacrolimus vs cyclosporin

Diffuse Lung Disease and Lung Transplant Network

Lung Transplant Section

, accounting for around 40% of deaths.1 LTRs are typically maintained on a three-drug immunosuppressive regimen—a calcineurin inhibitor, antimetabolite agent, and corticosteroid—in order to prevent rejection. Strong randomized controlled trial-generated evidence guiding the choice of immunosuppressive therapy for LTRs is generally lacking.

A recent large, multicentered, randomized controlled trial in Scandinavia compared outcomes between once daily extended-release tacrolimus and twice daily cyclosporin.2 The target trough for cyclosporin was 250 to 300 ng/mL (0 to 3 months), 200 to 250 ng/mL (3 to 6 months), 150 to 200 ng/mL (6 to 12 months), and 100 to 150 ng/mL beyond 12 months. The trough target for tacrolimus was 10 to 14 ng/mL (0 to 3 months), 8 to 12 ng/mL (3 to 6 months), 8 to 10 ng/mL (6 to 12 months), and 6 to 8 ng/mL beyond 12 months.

The study demonstrated that immunosuppressive regimens containing tacrolimus significantly reduced incidence of CLAD diagnosis at 36 months. The cumulative incidence of CLAD was 39% in the cyclosporin group vs 13% in the tacrolimus group (P < .0001), and the number needed to treat was 3.9 patients to prevent one case of CLAD with tacrolimus. While mortality was not significantly different between the two treatment groups in the intention to treat models, tacrolimus had a mortality benefit in the per protocol analysis.

While there is no consensus guideline recommending a first-line immunosuppression regimen following lung transplantation, the lung transplant steering committee believes that additional trials comparing existing agents are of critical importance to reduce CLAD incidence and improve long-term outcomes in LTRs.

References

1. Verleden GM, et al. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2019;38(5):493-503.

2. Dellgren G, et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2024;12(1):34-44.

Diffuse Lung Disease and Lung Transplant Network

Lung Transplant Section

, accounting for around 40% of deaths.1 LTRs are typically maintained on a three-drug immunosuppressive regimen—a calcineurin inhibitor, antimetabolite agent, and corticosteroid—in order to prevent rejection. Strong randomized controlled trial-generated evidence guiding the choice of immunosuppressive therapy for LTRs is generally lacking.

A recent large, multicentered, randomized controlled trial in Scandinavia compared outcomes between once daily extended-release tacrolimus and twice daily cyclosporin.2 The target trough for cyclosporin was 250 to 300 ng/mL (0 to 3 months), 200 to 250 ng/mL (3 to 6 months), 150 to 200 ng/mL (6 to 12 months), and 100 to 150 ng/mL beyond 12 months. The trough target for tacrolimus was 10 to 14 ng/mL (0 to 3 months), 8 to 12 ng/mL (3 to 6 months), 8 to 10 ng/mL (6 to 12 months), and 6 to 8 ng/mL beyond 12 months.

The study demonstrated that immunosuppressive regimens containing tacrolimus significantly reduced incidence of CLAD diagnosis at 36 months. The cumulative incidence of CLAD was 39% in the cyclosporin group vs 13% in the tacrolimus group (P < .0001), and the number needed to treat was 3.9 patients to prevent one case of CLAD with tacrolimus. While mortality was not significantly different between the two treatment groups in the intention to treat models, tacrolimus had a mortality benefit in the per protocol analysis.

While there is no consensus guideline recommending a first-line immunosuppression regimen following lung transplantation, the lung transplant steering committee believes that additional trials comparing existing agents are of critical importance to reduce CLAD incidence and improve long-term outcomes in LTRs.

References

1. Verleden GM, et al. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2019;38(5):493-503.

2. Dellgren G, et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2024;12(1):34-44.

Diffuse Lung Disease and Lung Transplant Network

Lung Transplant Section

, accounting for around 40% of deaths.1 LTRs are typically maintained on a three-drug immunosuppressive regimen—a calcineurin inhibitor, antimetabolite agent, and corticosteroid—in order to prevent rejection. Strong randomized controlled trial-generated evidence guiding the choice of immunosuppressive therapy for LTRs is generally lacking.

A recent large, multicentered, randomized controlled trial in Scandinavia compared outcomes between once daily extended-release tacrolimus and twice daily cyclosporin.2 The target trough for cyclosporin was 250 to 300 ng/mL (0 to 3 months), 200 to 250 ng/mL (3 to 6 months), 150 to 200 ng/mL (6 to 12 months), and 100 to 150 ng/mL beyond 12 months. The trough target for tacrolimus was 10 to 14 ng/mL (0 to 3 months), 8 to 12 ng/mL (3 to 6 months), 8 to 10 ng/mL (6 to 12 months), and 6 to 8 ng/mL beyond 12 months.

The study demonstrated that immunosuppressive regimens containing tacrolimus significantly reduced incidence of CLAD diagnosis at 36 months. The cumulative incidence of CLAD was 39% in the cyclosporin group vs 13% in the tacrolimus group (P < .0001), and the number needed to treat was 3.9 patients to prevent one case of CLAD with tacrolimus. While mortality was not significantly different between the two treatment groups in the intention to treat models, tacrolimus had a mortality benefit in the per protocol analysis.

While there is no consensus guideline recommending a first-line immunosuppression regimen following lung transplantation, the lung transplant steering committee believes that additional trials comparing existing agents are of critical importance to reduce CLAD incidence and improve long-term outcomes in LTRs.

References

1. Verleden GM, et al. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2019;38(5):493-503.

2. Dellgren G, et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2024;12(1):34-44.

Eradicating uncertainty: A review of Pseudomonas aeruginosa eradication in bronchiectasis

Airways Disorders Network

Bronchiectasis Section

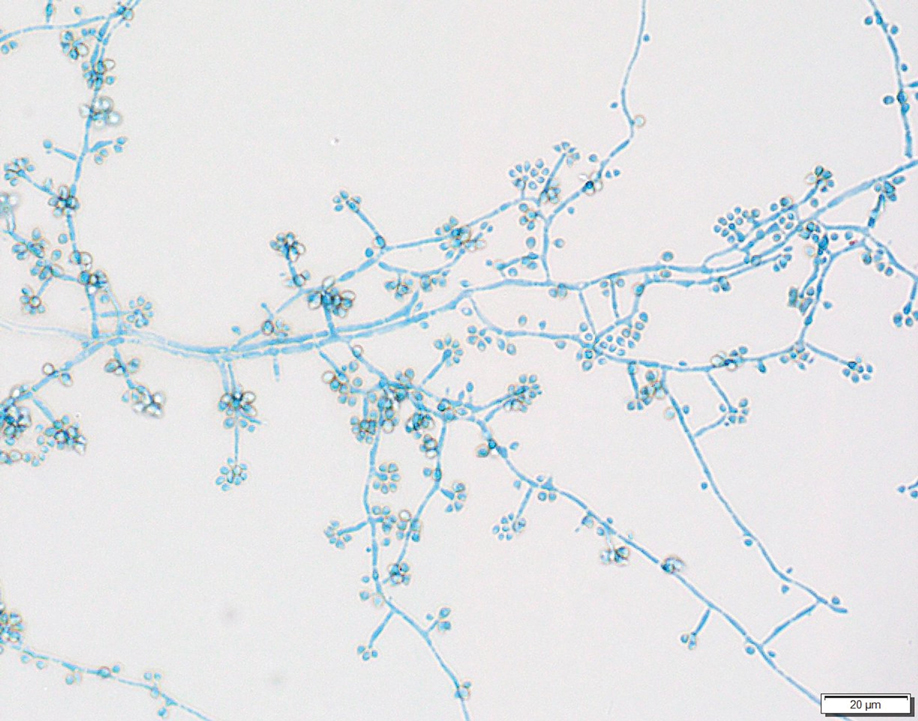

Bronchiectasis patients have dilated airways that are often colonized with bacteria, resulting in a vicious cycle of airway inflammation and progressive dilation. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a frequent airway colonizer and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in cystic fibrosis (CF) and noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (NCFB).1

Optimal NCFB eradication regimens remain unknown, though recent studies demonstrated inhaled tobramycin is safe and effective for chronic P. aeruginosa infections in NCFB.4

The 2024 meta-analysis by Conceiçã et al. revealed that P. aeruginosa eradication endures more than 12 months in only 40% of NCFB cases, but that patients who received combined therapy—both systemic and inhaled therapies—had a higher eradication rate at 48% compared with 27% in those receiving only systemic antibiotics.5 They found that successful eradication reduced exacerbation rate by 0.91 exacerbations per year without changing hospitalization rate. They were unable to comment on optimal antibiotic selection or duration.

A take-home point from Conceiçã et al. suggests trying to eradicate P. aeruginosa with combined systemic and inhaled antibiotics if possible, but other clinical questions remain around initial antibiotic selection and how to treat persistent P. aeruginosa.

References

1. Finch, et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(11):1602-1611.

2. Polverino, et al. Eur Respir J. 2017;50:1700629.

3. Mogayzel, et al. Ann ATS. 2014;11(10):1511-1761.

4. Guan, et al. CHEST. 2023;163(1):64-76.

5. Conceiçã, et al. Eur Respir Rev. 2024;33:230178.

Airways Disorders Network

Bronchiectasis Section

Bronchiectasis patients have dilated airways that are often colonized with bacteria, resulting in a vicious cycle of airway inflammation and progressive dilation. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a frequent airway colonizer and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in cystic fibrosis (CF) and noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (NCFB).1

Optimal NCFB eradication regimens remain unknown, though recent studies demonstrated inhaled tobramycin is safe and effective for chronic P. aeruginosa infections in NCFB.4

The 2024 meta-analysis by Conceiçã et al. revealed that P. aeruginosa eradication endures more than 12 months in only 40% of NCFB cases, but that patients who received combined therapy—both systemic and inhaled therapies—had a higher eradication rate at 48% compared with 27% in those receiving only systemic antibiotics.5 They found that successful eradication reduced exacerbation rate by 0.91 exacerbations per year without changing hospitalization rate. They were unable to comment on optimal antibiotic selection or duration.

A take-home point from Conceiçã et al. suggests trying to eradicate P. aeruginosa with combined systemic and inhaled antibiotics if possible, but other clinical questions remain around initial antibiotic selection and how to treat persistent P. aeruginosa.

References

1. Finch, et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(11):1602-1611.

2. Polverino, et al. Eur Respir J. 2017;50:1700629.

3. Mogayzel, et al. Ann ATS. 2014;11(10):1511-1761.

4. Guan, et al. CHEST. 2023;163(1):64-76.

5. Conceiçã, et al. Eur Respir Rev. 2024;33:230178.

Airways Disorders Network

Bronchiectasis Section

Bronchiectasis patients have dilated airways that are often colonized with bacteria, resulting in a vicious cycle of airway inflammation and progressive dilation. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a frequent airway colonizer and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in cystic fibrosis (CF) and noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (NCFB).1

Optimal NCFB eradication regimens remain unknown, though recent studies demonstrated inhaled tobramycin is safe and effective for chronic P. aeruginosa infections in NCFB.4

The 2024 meta-analysis by Conceiçã et al. revealed that P. aeruginosa eradication endures more than 12 months in only 40% of NCFB cases, but that patients who received combined therapy—both systemic and inhaled therapies—had a higher eradication rate at 48% compared with 27% in those receiving only systemic antibiotics.5 They found that successful eradication reduced exacerbation rate by 0.91 exacerbations per year without changing hospitalization rate. They were unable to comment on optimal antibiotic selection or duration.

A take-home point from Conceiçã et al. suggests trying to eradicate P. aeruginosa with combined systemic and inhaled antibiotics if possible, but other clinical questions remain around initial antibiotic selection and how to treat persistent P. aeruginosa.

References

1. Finch, et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(11):1602-1611.

2. Polverino, et al. Eur Respir J. 2017;50:1700629.

3. Mogayzel, et al. Ann ATS. 2014;11(10):1511-1761.

4. Guan, et al. CHEST. 2023;163(1):64-76.

5. Conceiçã, et al. Eur Respir Rev. 2024;33:230178.

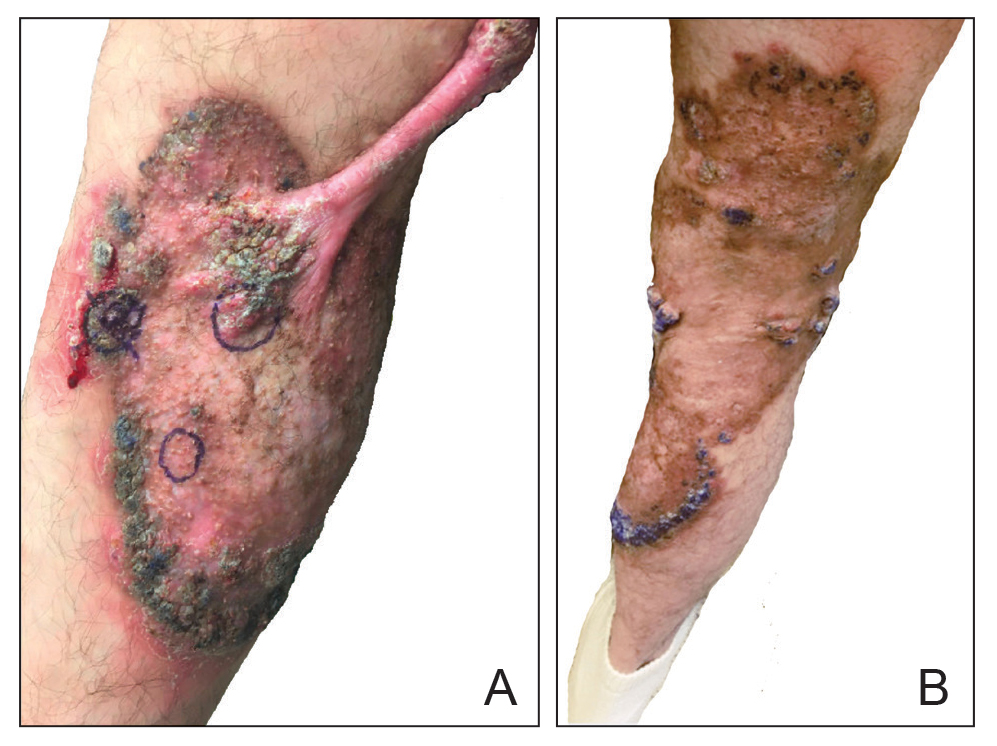

Study Highlights Some Semaglutide-Associated Skin Effects

TOPLINE:

.

METHODOLOGY:

- The Food and Drug Administration’s has not received reports of semaglutide-related safety events, and few studies have characterized skin findings associated with oral or subcutaneous semaglutide, a glucagon-like peptide 1 agonist used to treat obesity and type 2 diabetes.

- In this scoping review, researchers included 22 articles (15 clinical trials, six case reports, and one retrospective cohort study), published through January 2024, of patients receiving either semaglutide or a placebo or comparator, which included reports of semaglutide-associated adverse dermatologic events in 255 participants.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients who received 50 mg oral semaglutide weekly reported a higher incidence of altered skin sensations, such as dysesthesia (1.8% vs 0%), hyperesthesia (1.2% vs 0%), skin pain (2.4% vs 0%), paresthesia (2.7% vs 0%), and sensitive skin (2.7% vs 0%), than those receiving placebo or comparator.

- Reports of alopecia (6.9% vs 0.3%) were higher in patients who received 50 mg oral semaglutide weekly than in those on placebo, but only 0.2% of patients on 2.4 mg of subcutaneous semaglutide reported alopecia vs 0.5% of those on placebo.

- Unspecified dermatologic reactions (4.1% vs 1.5%) were reported in more patients on subcutaneous semaglutide than those on a placebo or comparator. Several case reports described isolated cases of severe skin-related adverse effects, such as bullous pemphigoid, eosinophilic fasciitis, and leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

- On the contrary, injection site reactions (3.5% vs 6.7%) were less common in patients on subcutaneous semaglutide compared with in those on a placebo or comparator.

IN PRACTICE:

“Variations in dosage and administration routes could influence the types and severity of skin findings, underscoring the need for additional research,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Megan M. Tran, BS, from the Warren Alpert Medical School, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, led this study, which was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

This study could not adjust for confounding factors and could not establish a direct causal association between semaglutide and the adverse reactions reported.

DISCLOSURES:

This study did not report any funding sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

.

METHODOLOGY:

- The Food and Drug Administration’s has not received reports of semaglutide-related safety events, and few studies have characterized skin findings associated with oral or subcutaneous semaglutide, a glucagon-like peptide 1 agonist used to treat obesity and type 2 diabetes.

- In this scoping review, researchers included 22 articles (15 clinical trials, six case reports, and one retrospective cohort study), published through January 2024, of patients receiving either semaglutide or a placebo or comparator, which included reports of semaglutide-associated adverse dermatologic events in 255 participants.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients who received 50 mg oral semaglutide weekly reported a higher incidence of altered skin sensations, such as dysesthesia (1.8% vs 0%), hyperesthesia (1.2% vs 0%), skin pain (2.4% vs 0%), paresthesia (2.7% vs 0%), and sensitive skin (2.7% vs 0%), than those receiving placebo or comparator.

- Reports of alopecia (6.9% vs 0.3%) were higher in patients who received 50 mg oral semaglutide weekly than in those on placebo, but only 0.2% of patients on 2.4 mg of subcutaneous semaglutide reported alopecia vs 0.5% of those on placebo.

- Unspecified dermatologic reactions (4.1% vs 1.5%) were reported in more patients on subcutaneous semaglutide than those on a placebo or comparator. Several case reports described isolated cases of severe skin-related adverse effects, such as bullous pemphigoid, eosinophilic fasciitis, and leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

- On the contrary, injection site reactions (3.5% vs 6.7%) were less common in patients on subcutaneous semaglutide compared with in those on a placebo or comparator.

IN PRACTICE:

“Variations in dosage and administration routes could influence the types and severity of skin findings, underscoring the need for additional research,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Megan M. Tran, BS, from the Warren Alpert Medical School, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, led this study, which was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

This study could not adjust for confounding factors and could not establish a direct causal association between semaglutide and the adverse reactions reported.

DISCLOSURES:

This study did not report any funding sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

.

METHODOLOGY:

- The Food and Drug Administration’s has not received reports of semaglutide-related safety events, and few studies have characterized skin findings associated with oral or subcutaneous semaglutide, a glucagon-like peptide 1 agonist used to treat obesity and type 2 diabetes.

- In this scoping review, researchers included 22 articles (15 clinical trials, six case reports, and one retrospective cohort study), published through January 2024, of patients receiving either semaglutide or a placebo or comparator, which included reports of semaglutide-associated adverse dermatologic events in 255 participants.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients who received 50 mg oral semaglutide weekly reported a higher incidence of altered skin sensations, such as dysesthesia (1.8% vs 0%), hyperesthesia (1.2% vs 0%), skin pain (2.4% vs 0%), paresthesia (2.7% vs 0%), and sensitive skin (2.7% vs 0%), than those receiving placebo or comparator.

- Reports of alopecia (6.9% vs 0.3%) were higher in patients who received 50 mg oral semaglutide weekly than in those on placebo, but only 0.2% of patients on 2.4 mg of subcutaneous semaglutide reported alopecia vs 0.5% of those on placebo.

- Unspecified dermatologic reactions (4.1% vs 1.5%) were reported in more patients on subcutaneous semaglutide than those on a placebo or comparator. Several case reports described isolated cases of severe skin-related adverse effects, such as bullous pemphigoid, eosinophilic fasciitis, and leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

- On the contrary, injection site reactions (3.5% vs 6.7%) were less common in patients on subcutaneous semaglutide compared with in those on a placebo or comparator.

IN PRACTICE:

“Variations in dosage and administration routes could influence the types and severity of skin findings, underscoring the need for additional research,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Megan M. Tran, BS, from the Warren Alpert Medical School, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, led this study, which was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

This study could not adjust for confounding factors and could not establish a direct causal association between semaglutide and the adverse reactions reported.

DISCLOSURES:

This study did not report any funding sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Genetic Testing of Some Patients With Early-Onset AF Advised

Genetic testing may be considered in patients with early-onset atrial fibrillation (AF), particularly those with a positive family history and lack of conventional clinical risk factors, because specific genetic variants may underlie AF as well as “potentially more sinister cardiac conditions,” a new white paper from the Canadian Cardiovascular Society suggested.

“Given the resources and logistical challenges potentially imposed by genetic testing (that is, the majority of cardiology and arrhythmia clinics are not presently equipped to offer it), we have not recommended routine genetic testing for early-onset AF patients at this time,” lead author Jason D. Roberts, MD, associate professor of medicine at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, told this news organization.

“We do, however, recommend that early-onset AF patients undergo clinical screening for potential coexistence of a ventricular arrhythmia or cardiomyopathy syndrome through careful history, including family history, and physical examination, along with standard clinical testing, including ECG, echocardiogram, and Holter monitoring,” he said.

The white paper was published online in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology.

Routine Testing Unwarranted

The Canadian Cardiovascular Society reviewed AF research in 2022 and concluded that a guideline update was not yet warranted. One area meriting consideration but lacking sufficient evidence for a formal guideline was the clinical application of AF genetics.

Therefore, the society formed a writing group to assess the evidence linking genetic factors to AF, discuss an approach to using genetic testing for early-onset patients with AF, and consider the potential value of genetic testing in the foreseeable future.

The resulting white paper reviews familial and epidemiologic evidence for a genetic contribution to AF. As an example, the authors pointed to work from the Framingham Heart Study showing a statistically significant risk for AF among first-degree relatives of patients with AF. The overall odds ratio (OR) for AF among first-degree relatives was 1.85. But for first-degree relatives of patients with AF onset at younger than age 75 years, the OR increased to 3.23.

Other evidence included the identification of two rare genetic variants: KCNQ1 in a Chinese family and NPPA in a family with Northern European ancestry. In case-control studies, a single gene, titin (TTN), was linked to an increased burden of loss-of-function variants in patients with AF compared with controls. The variant was associated with a 2.2-fold increased risk for AF.

For example, loss-of-function SCN5A variants are implicated in Brugada syndrome and cardiac conduction system disease, whereas gain-of-function variants cause long QT syndrome type 3 and multifocal ectopic Purkinje-related premature contractions. Each of these conditions was associated with an increased prevalence of AF.

Similarly, genes implicated in various other forms of ventricular channelopathies also have been implicated in AF, as have ion channels primarily expressed in the atria and not the ventricles, such as KCNA5 and GJA5.

Nevertheless, in most cases, AF is diagnosed in the context of older age and established cardiovascular risk factors, according to the authors. The contribution of genetic factors in this population is relatively low, highlighting the limited role for genetic testing when AF develops in the presence of multiple conventional clinical risk factors.

Cardiogenetic Expertise Required

“Although significant progress has been made, additional work is needed before [beginning] routine integration of clinical genetic testing for early-onset AF patients,” Dr. Roberts said. The ideal clinical genetic testing panel for AF is still unclear, and the inclusion of genes for which there is no strong evidence of involvement in AF “creates the potential for harm.”

Specifically, “a genetic variant could be incorrectly assigned as the cause of AF, which could create confusion for the patient and family members and lead to inappropriate clinical management,” said Dr. Roberts.

“Beyond cost, routine introduction of genetic testing for AF patients will require allocation of significant resources, given that interpretation of genetic testing results can be nuanced,” he noted. “This nuance is anticipated to be heightened in AF, given that many genetic variants have low-to-intermediate penetrance and can manifest with variable clinical phenotypes.”

“Traditionally, genetic testing has been performed and interpreted, and results communicated, by dedicated cardiogenetic clinics with specialized expertise,” he added. “Existing cardiogenetic clinics, however, are unlikely to be sufficient in number to accommodate the large volume of AF patients that may be eligible for testing.”

Careful Counseling

Jim W. Cheung, MD, chair of the American College of Cardiology Electrophysiology Council, told this news organization that the white paper is consistent with the latest European Heart Rhythm Association/Heart Rhythm Society/Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society/Latin American Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement published in 2022.

Overall, the approach suggested for genetic testing “is a sound one, but one that requires implementation by clinicians with access to cardiogenetic expertise,” said Cheung, who was not involved in the study. “Any patient undergoing genetic testing needs to be carefully counseled about the potential uncertainties associated with the actual test results and their implications on clinical management.”

Variants of uncertain significance that are detected with genetic testing “can be a source of stress for clinicians and patients,” he said. “Therefore, patient education prior to and after genetic testing is essential.”

Furthermore, he said, “in many patients with early-onset AF who harbor pathogenic variants, initial imaging studies may not detect any signs of cardiomyopathy. In these patients, regular follow-up to assess for development of cardiomyopathy in the future is necessary.”

The white paper was drafted without outside funding. Dr. Roberts and Dr. Cheung reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Genetic testing may be considered in patients with early-onset atrial fibrillation (AF), particularly those with a positive family history and lack of conventional clinical risk factors, because specific genetic variants may underlie AF as well as “potentially more sinister cardiac conditions,” a new white paper from the Canadian Cardiovascular Society suggested.

“Given the resources and logistical challenges potentially imposed by genetic testing (that is, the majority of cardiology and arrhythmia clinics are not presently equipped to offer it), we have not recommended routine genetic testing for early-onset AF patients at this time,” lead author Jason D. Roberts, MD, associate professor of medicine at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, told this news organization.

“We do, however, recommend that early-onset AF patients undergo clinical screening for potential coexistence of a ventricular arrhythmia or cardiomyopathy syndrome through careful history, including family history, and physical examination, along with standard clinical testing, including ECG, echocardiogram, and Holter monitoring,” he said.

The white paper was published online in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology.

Routine Testing Unwarranted

The Canadian Cardiovascular Society reviewed AF research in 2022 and concluded that a guideline update was not yet warranted. One area meriting consideration but lacking sufficient evidence for a formal guideline was the clinical application of AF genetics.

Therefore, the society formed a writing group to assess the evidence linking genetic factors to AF, discuss an approach to using genetic testing for early-onset patients with AF, and consider the potential value of genetic testing in the foreseeable future.

The resulting white paper reviews familial and epidemiologic evidence for a genetic contribution to AF. As an example, the authors pointed to work from the Framingham Heart Study showing a statistically significant risk for AF among first-degree relatives of patients with AF. The overall odds ratio (OR) for AF among first-degree relatives was 1.85. But for first-degree relatives of patients with AF onset at younger than age 75 years, the OR increased to 3.23.

Other evidence included the identification of two rare genetic variants: KCNQ1 in a Chinese family and NPPA in a family with Northern European ancestry. In case-control studies, a single gene, titin (TTN), was linked to an increased burden of loss-of-function variants in patients with AF compared with controls. The variant was associated with a 2.2-fold increased risk for AF.

For example, loss-of-function SCN5A variants are implicated in Brugada syndrome and cardiac conduction system disease, whereas gain-of-function variants cause long QT syndrome type 3 and multifocal ectopic Purkinje-related premature contractions. Each of these conditions was associated with an increased prevalence of AF.

Similarly, genes implicated in various other forms of ventricular channelopathies also have been implicated in AF, as have ion channels primarily expressed in the atria and not the ventricles, such as KCNA5 and GJA5.

Nevertheless, in most cases, AF is diagnosed in the context of older age and established cardiovascular risk factors, according to the authors. The contribution of genetic factors in this population is relatively low, highlighting the limited role for genetic testing when AF develops in the presence of multiple conventional clinical risk factors.

Cardiogenetic Expertise Required

“Although significant progress has been made, additional work is needed before [beginning] routine integration of clinical genetic testing for early-onset AF patients,” Dr. Roberts said. The ideal clinical genetic testing panel for AF is still unclear, and the inclusion of genes for which there is no strong evidence of involvement in AF “creates the potential for harm.”

Specifically, “a genetic variant could be incorrectly assigned as the cause of AF, which could create confusion for the patient and family members and lead to inappropriate clinical management,” said Dr. Roberts.

“Beyond cost, routine introduction of genetic testing for AF patients will require allocation of significant resources, given that interpretation of genetic testing results can be nuanced,” he noted. “This nuance is anticipated to be heightened in AF, given that many genetic variants have low-to-intermediate penetrance and can manifest with variable clinical phenotypes.”

“Traditionally, genetic testing has been performed and interpreted, and results communicated, by dedicated cardiogenetic clinics with specialized expertise,” he added. “Existing cardiogenetic clinics, however, are unlikely to be sufficient in number to accommodate the large volume of AF patients that may be eligible for testing.”

Careful Counseling

Jim W. Cheung, MD, chair of the American College of Cardiology Electrophysiology Council, told this news organization that the white paper is consistent with the latest European Heart Rhythm Association/Heart Rhythm Society/Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society/Latin American Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement published in 2022.

Overall, the approach suggested for genetic testing “is a sound one, but one that requires implementation by clinicians with access to cardiogenetic expertise,” said Cheung, who was not involved in the study. “Any patient undergoing genetic testing needs to be carefully counseled about the potential uncertainties associated with the actual test results and their implications on clinical management.”

Variants of uncertain significance that are detected with genetic testing “can be a source of stress for clinicians and patients,” he said. “Therefore, patient education prior to and after genetic testing is essential.”

Furthermore, he said, “in many patients with early-onset AF who harbor pathogenic variants, initial imaging studies may not detect any signs of cardiomyopathy. In these patients, regular follow-up to assess for development of cardiomyopathy in the future is necessary.”

The white paper was drafted without outside funding. Dr. Roberts and Dr. Cheung reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Genetic testing may be considered in patients with early-onset atrial fibrillation (AF), particularly those with a positive family history and lack of conventional clinical risk factors, because specific genetic variants may underlie AF as well as “potentially more sinister cardiac conditions,” a new white paper from the Canadian Cardiovascular Society suggested.

“Given the resources and logistical challenges potentially imposed by genetic testing (that is, the majority of cardiology and arrhythmia clinics are not presently equipped to offer it), we have not recommended routine genetic testing for early-onset AF patients at this time,” lead author Jason D. Roberts, MD, associate professor of medicine at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, told this news organization.

“We do, however, recommend that early-onset AF patients undergo clinical screening for potential coexistence of a ventricular arrhythmia or cardiomyopathy syndrome through careful history, including family history, and physical examination, along with standard clinical testing, including ECG, echocardiogram, and Holter monitoring,” he said.

The white paper was published online in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology.

Routine Testing Unwarranted

The Canadian Cardiovascular Society reviewed AF research in 2022 and concluded that a guideline update was not yet warranted. One area meriting consideration but lacking sufficient evidence for a formal guideline was the clinical application of AF genetics.

Therefore, the society formed a writing group to assess the evidence linking genetic factors to AF, discuss an approach to using genetic testing for early-onset patients with AF, and consider the potential value of genetic testing in the foreseeable future.

The resulting white paper reviews familial and epidemiologic evidence for a genetic contribution to AF. As an example, the authors pointed to work from the Framingham Heart Study showing a statistically significant risk for AF among first-degree relatives of patients with AF. The overall odds ratio (OR) for AF among first-degree relatives was 1.85. But for first-degree relatives of patients with AF onset at younger than age 75 years, the OR increased to 3.23.

Other evidence included the identification of two rare genetic variants: KCNQ1 in a Chinese family and NPPA in a family with Northern European ancestry. In case-control studies, a single gene, titin (TTN), was linked to an increased burden of loss-of-function variants in patients with AF compared with controls. The variant was associated with a 2.2-fold increased risk for AF.

For example, loss-of-function SCN5A variants are implicated in Brugada syndrome and cardiac conduction system disease, whereas gain-of-function variants cause long QT syndrome type 3 and multifocal ectopic Purkinje-related premature contractions. Each of these conditions was associated with an increased prevalence of AF.

Similarly, genes implicated in various other forms of ventricular channelopathies also have been implicated in AF, as have ion channels primarily expressed in the atria and not the ventricles, such as KCNA5 and GJA5.

Nevertheless, in most cases, AF is diagnosed in the context of older age and established cardiovascular risk factors, according to the authors. The contribution of genetic factors in this population is relatively low, highlighting the limited role for genetic testing when AF develops in the presence of multiple conventional clinical risk factors.

Cardiogenetic Expertise Required

“Although significant progress has been made, additional work is needed before [beginning] routine integration of clinical genetic testing for early-onset AF patients,” Dr. Roberts said. The ideal clinical genetic testing panel for AF is still unclear, and the inclusion of genes for which there is no strong evidence of involvement in AF “creates the potential for harm.”

Specifically, “a genetic variant could be incorrectly assigned as the cause of AF, which could create confusion for the patient and family members and lead to inappropriate clinical management,” said Dr. Roberts.

“Beyond cost, routine introduction of genetic testing for AF patients will require allocation of significant resources, given that interpretation of genetic testing results can be nuanced,” he noted. “This nuance is anticipated to be heightened in AF, given that many genetic variants have low-to-intermediate penetrance and can manifest with variable clinical phenotypes.”

“Traditionally, genetic testing has been performed and interpreted, and results communicated, by dedicated cardiogenetic clinics with specialized expertise,” he added. “Existing cardiogenetic clinics, however, are unlikely to be sufficient in number to accommodate the large volume of AF patients that may be eligible for testing.”

Careful Counseling

Jim W. Cheung, MD, chair of the American College of Cardiology Electrophysiology Council, told this news organization that the white paper is consistent with the latest European Heart Rhythm Association/Heart Rhythm Society/Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society/Latin American Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement published in 2022.

Overall, the approach suggested for genetic testing “is a sound one, but one that requires implementation by clinicians with access to cardiogenetic expertise,” said Cheung, who was not involved in the study. “Any patient undergoing genetic testing needs to be carefully counseled about the potential uncertainties associated with the actual test results and their implications on clinical management.”

Variants of uncertain significance that are detected with genetic testing “can be a source of stress for clinicians and patients,” he said. “Therefore, patient education prior to and after genetic testing is essential.”

Furthermore, he said, “in many patients with early-onset AF who harbor pathogenic variants, initial imaging studies may not detect any signs of cardiomyopathy. In these patients, regular follow-up to assess for development of cardiomyopathy in the future is necessary.”

The white paper was drafted without outside funding. Dr. Roberts and Dr. Cheung reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE CANADIAN JOURNAL OF CARDIOLOGY

Tirzepatide Offers Better Glucose Control, Regardless of Baseline Levels

TOPLINE:

Tirzepatide vs basal insulins led to greater improvements in A1c and postprandial glucose (PPG) levels in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D), regardless of different baseline PPG or fasting serum glucose (FSG) levels.

METHODOLOGY:

- Tirzepatide led to better glycemic control than insulin degludec and insulin glargine in the SURPASS-3 and SURPASS-4 trials, respectively, but the effect on FSG and PPG levels was not evaluated.

- In this post hoc analysis, the researchers assessed changes in various glycemic parameters in 3314 patients with T2D who were randomly assigned to receive tirzepatide (5, 10, or 15 mg), insulin degludec, or insulin glargine.

- Based on the median baseline glucose values, the patients were stratified into four subgroups: Low FSG/low PPG, low FSG/high PPG, high FSG/low PPG, and high FSG/high PPG.

- The outcomes of interest were changes in FSG, PPG, A1c, and body weight from baseline to week 52.

TAKEAWAY:

- Tirzepatide and basal insulins effectively lowered A1c, PPG levels, and FSG levels at 52 weeks across all patient subgroups (all P < .05).

- All three doses of tirzepatide resulted in greater reductions in both A1c and PPG levels than in basal insulins (all P < .05).

- In the high FSG/high PPG subgroup, a greater reduction in FSG levels was observed with tirzepatide 10- and 15-mg doses vs insulin glargine (both P < .05) and insulin degludec vs tirzepatide 5 mg (P < .001).

- Furthermore, at week 52, tirzepatide led to body weight reduction (P < .05), but insulin treatment led to an increase in body weight (P < .05) in all subgroups.

IN PRACTICE:

“Treatment with tirzepatide was consistently associated with more reduced PPG levels compared with insulin treatment across subgroups, including in participants with lower baseline PPG levels, in turn leading to greater A1c reductions,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Francesco Giorgino, MD, PhD, of the Section of Internal Medicine, Endocrinology, Andrology, and Metabolic Diseases, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Bari, Italy, and was published online in Diabetes Care.

LIMITATIONS:

The limitations include post hoc nature of the study and the short treatment duration. The trials included only patients with diabetes and overweight or obesity, and therefore, the study findings may not be generalizable to other populations.

DISCLOSURES:

This study and the SURPASS trials were funded by Eli Lilly and Company. Four authors declared being employees and shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company. The other authors declared having several ties with various sources, including Eli Lilly and Company.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Tirzepatide vs basal insulins led to greater improvements in A1c and postprandial glucose (PPG) levels in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D), regardless of different baseline PPG or fasting serum glucose (FSG) levels.

METHODOLOGY:

- Tirzepatide led to better glycemic control than insulin degludec and insulin glargine in the SURPASS-3 and SURPASS-4 trials, respectively, but the effect on FSG and PPG levels was not evaluated.

- In this post hoc analysis, the researchers assessed changes in various glycemic parameters in 3314 patients with T2D who were randomly assigned to receive tirzepatide (5, 10, or 15 mg), insulin degludec, or insulin glargine.

- Based on the median baseline glucose values, the patients were stratified into four subgroups: Low FSG/low PPG, low FSG/high PPG, high FSG/low PPG, and high FSG/high PPG.

- The outcomes of interest were changes in FSG, PPG, A1c, and body weight from baseline to week 52.

TAKEAWAY:

- Tirzepatide and basal insulins effectively lowered A1c, PPG levels, and FSG levels at 52 weeks across all patient subgroups (all P < .05).

- All three doses of tirzepatide resulted in greater reductions in both A1c and PPG levels than in basal insulins (all P < .05).

- In the high FSG/high PPG subgroup, a greater reduction in FSG levels was observed with tirzepatide 10- and 15-mg doses vs insulin glargine (both P < .05) and insulin degludec vs tirzepatide 5 mg (P < .001).

- Furthermore, at week 52, tirzepatide led to body weight reduction (P < .05), but insulin treatment led to an increase in body weight (P < .05) in all subgroups.

IN PRACTICE:

“Treatment with tirzepatide was consistently associated with more reduced PPG levels compared with insulin treatment across subgroups, including in participants with lower baseline PPG levels, in turn leading to greater A1c reductions,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Francesco Giorgino, MD, PhD, of the Section of Internal Medicine, Endocrinology, Andrology, and Metabolic Diseases, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Bari, Italy, and was published online in Diabetes Care.

LIMITATIONS:

The limitations include post hoc nature of the study and the short treatment duration. The trials included only patients with diabetes and overweight or obesity, and therefore, the study findings may not be generalizable to other populations.

DISCLOSURES:

This study and the SURPASS trials were funded by Eli Lilly and Company. Four authors declared being employees and shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company. The other authors declared having several ties with various sources, including Eli Lilly and Company.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Tirzepatide vs basal insulins led to greater improvements in A1c and postprandial glucose (PPG) levels in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D), regardless of different baseline PPG or fasting serum glucose (FSG) levels.

METHODOLOGY:

- Tirzepatide led to better glycemic control than insulin degludec and insulin glargine in the SURPASS-3 and SURPASS-4 trials, respectively, but the effect on FSG and PPG levels was not evaluated.

- In this post hoc analysis, the researchers assessed changes in various glycemic parameters in 3314 patients with T2D who were randomly assigned to receive tirzepatide (5, 10, or 15 mg), insulin degludec, or insulin glargine.

- Based on the median baseline glucose values, the patients were stratified into four subgroups: Low FSG/low PPG, low FSG/high PPG, high FSG/low PPG, and high FSG/high PPG.

- The outcomes of interest were changes in FSG, PPG, A1c, and body weight from baseline to week 52.

TAKEAWAY:

- Tirzepatide and basal insulins effectively lowered A1c, PPG levels, and FSG levels at 52 weeks across all patient subgroups (all P < .05).

- All three doses of tirzepatide resulted in greater reductions in both A1c and PPG levels than in basal insulins (all P < .05).

- In the high FSG/high PPG subgroup, a greater reduction in FSG levels was observed with tirzepatide 10- and 15-mg doses vs insulin glargine (both P < .05) and insulin degludec vs tirzepatide 5 mg (P < .001).

- Furthermore, at week 52, tirzepatide led to body weight reduction (P < .05), but insulin treatment led to an increase in body weight (P < .05) in all subgroups.

IN PRACTICE:

“Treatment with tirzepatide was consistently associated with more reduced PPG levels compared with insulin treatment across subgroups, including in participants with lower baseline PPG levels, in turn leading to greater A1c reductions,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Francesco Giorgino, MD, PhD, of the Section of Internal Medicine, Endocrinology, Andrology, and Metabolic Diseases, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Bari, Italy, and was published online in Diabetes Care.

LIMITATIONS:

The limitations include post hoc nature of the study and the short treatment duration. The trials included only patients with diabetes and overweight or obesity, and therefore, the study findings may not be generalizable to other populations.

DISCLOSURES:

This study and the SURPASS trials were funded by Eli Lilly and Company. Four authors declared being employees and shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company. The other authors declared having several ties with various sources, including Eli Lilly and Company.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Erosive Esophagitis: 5 Things to Know

Erosive esophagitis (EE) is erosion of the esophageal epithelium due to chronic irritation. It can be caused by a number of factors but is primarily a result of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The main symptoms of EE are heartburn and regurgitation; other symptoms can include epigastric pain, odynophagia, dysphagia, nausea, chronic cough, dental erosion, laryngitis, and asthma. , including nonerosive esophagitis and Barrett esophagus (BE). EE occurs in approximately 30% of cases of GERD, and EE may evolve to BE in 1%-13% of cases.

Long-term management of EE focuses on relieving symptoms to allow the esophageal lining to heal, thereby reducing both acute symptoms and the risk for other complications. Management plans may incorporate lifestyle changes, such as dietary modifications and weight loss, alongside pharmacologic therapy. In extreme cases, surgery may be considered to repair a damaged esophagus and/or to prevent ongoing acid reflux. If left untreated, EE may progress, potentially leading to more serious conditions.

Here are five things to know about EE.

1. GERD is the main risk factor for EE, but not the only risk factor.

An estimated 1% of the population has EE. Risk factors other than GERD include:

Radiation therapy toxicity can cause acute or chronic EE. For individuals undergoing radiotherapy, radiation esophagitis is a relatively frequent complication. Acute esophagitis generally occurs in all patients taking radiation doses of 6000 cGy given in fractions of 1000 cGy per week. The risk is lower among patients on longer schedules and lower doses of radiotherapy.

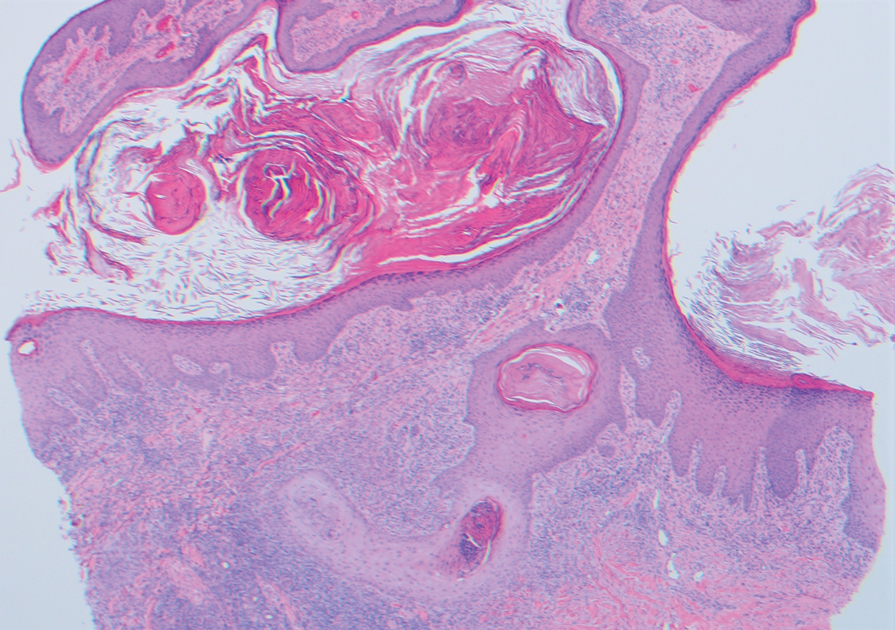

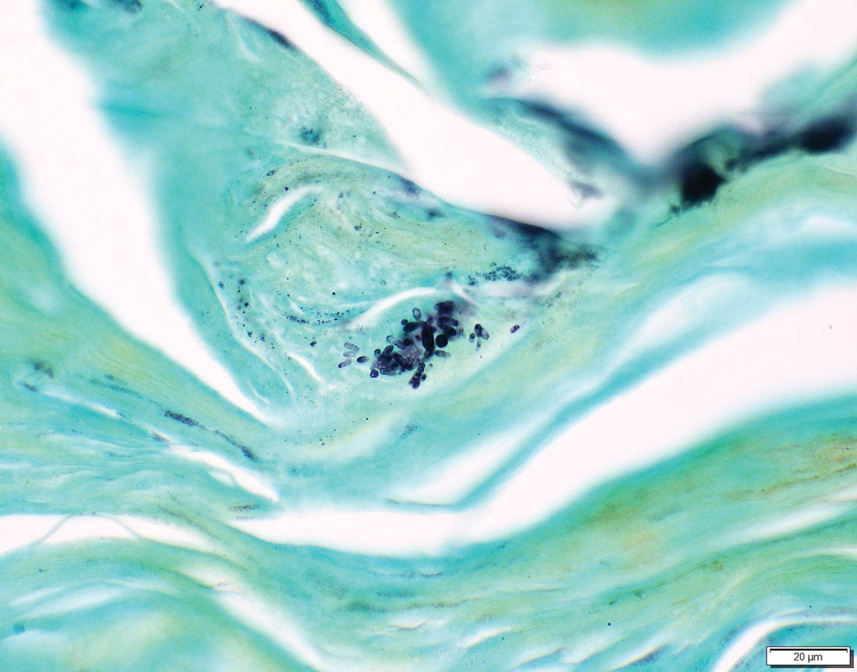

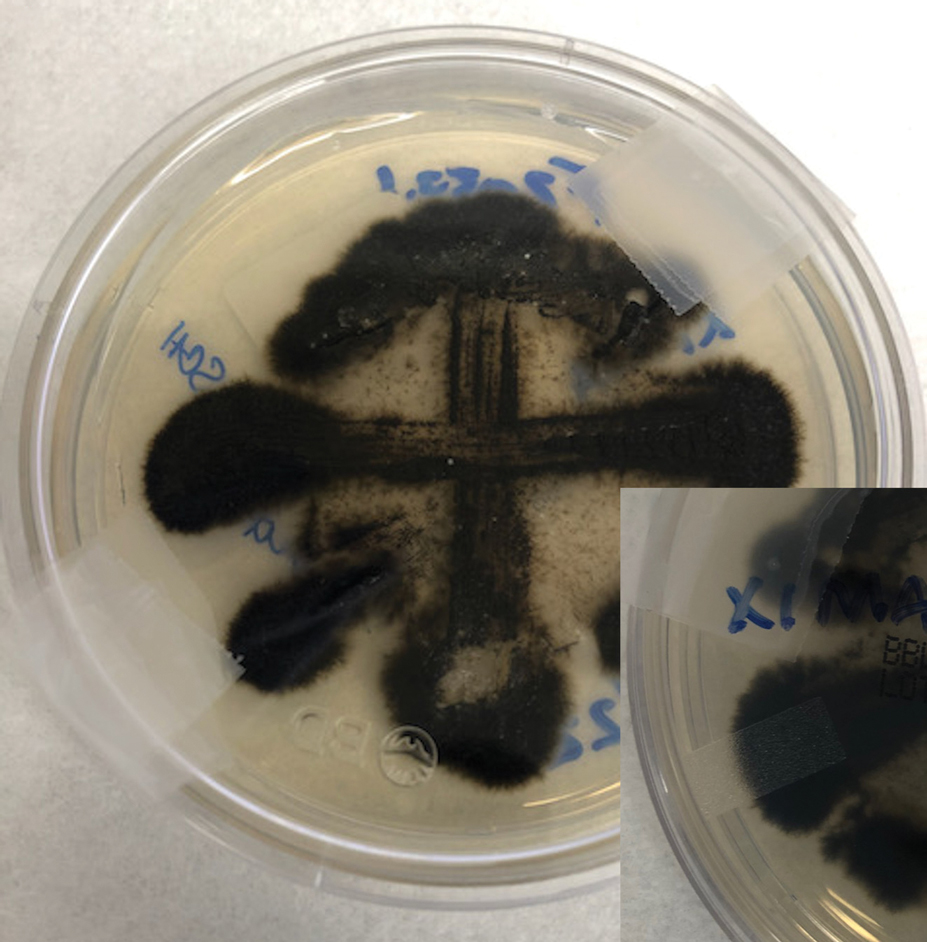

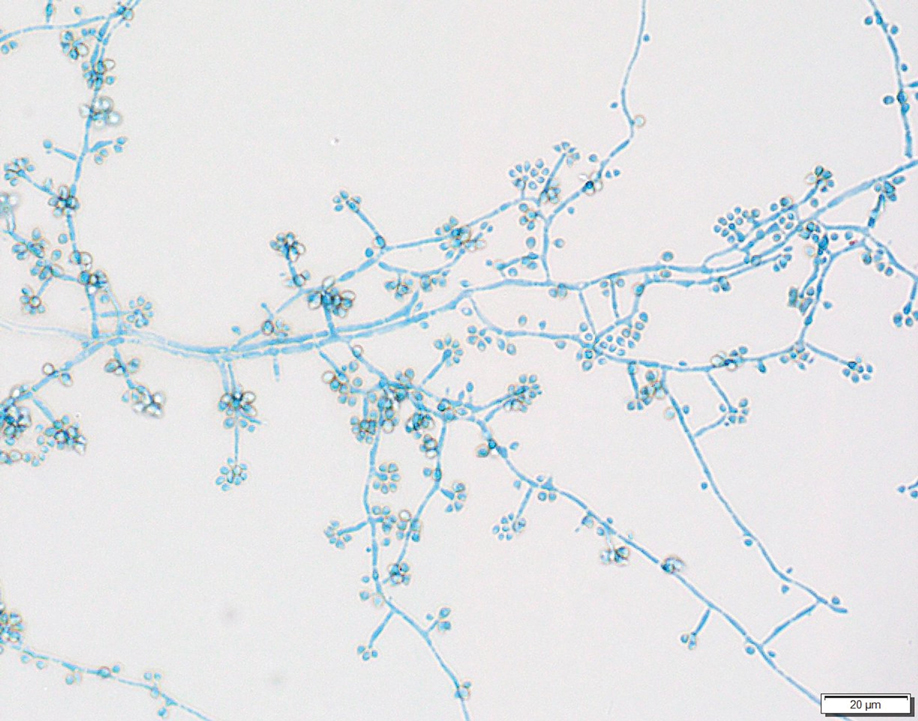

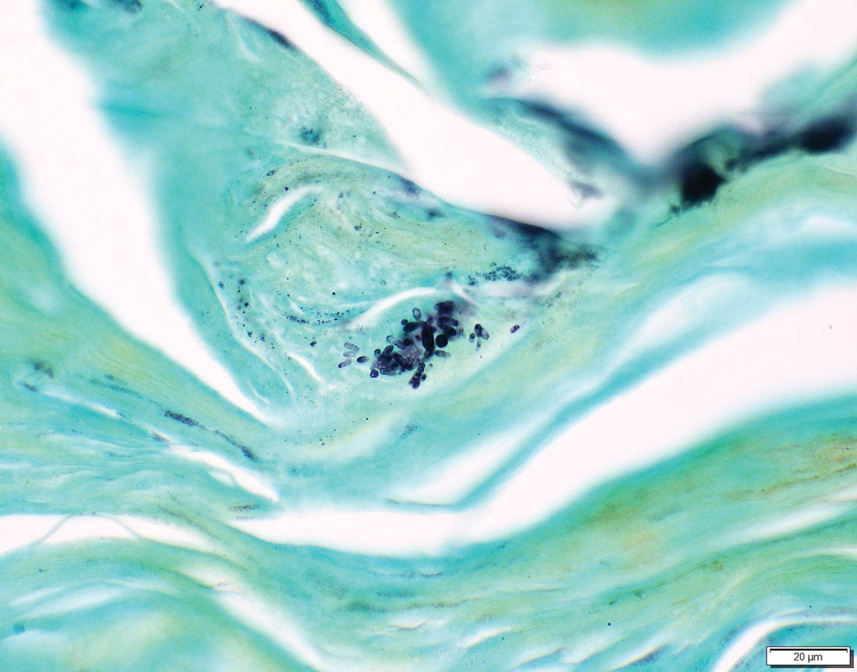

Bacterial, viral, and fungal infections can cause EE. These include herpes, CMV, HIV, Helicobacter pylori, and Candida.

Food allergies, asthma, and eczema are associated with eosinophilic esophagitis, which disproportionately affects young men and has an estimated prevalence of 55 cases per 100,000 population.

Oral medication in pill form causes esophagitis at an estimated rate of 3.9 cases per 100,000 population per year. The mean age at diagnosis is 41.5 years. Oral bisphosphonates such as alendronate are the most common agents, along with antibiotics such as tetracycline, doxycycline, and clindamycin. There have also been reports of pill-induced esophagitis with NSAIDs, aspirin, ferrous sulfate, potassium chloride, and mexiletine.

Excessive vomiting can, in rare cases, cause esophagitis.

Certain autoimmune diseases can manifest as EE.

2. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) remain the preferred treatment for EE.

Several over-the-counter and prescription medications can be used to manage the symptoms of EE. PPIs are the preferred treatment both in the acute setting and for maintenance therapy. PPIs help to alleviate symptoms and promote healing of the esophageal lining by reducing the production of stomach acid. Options include omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole, and esomeprazole. Many patients with EE require a dose that exceeds the FDA-approved dose for GERD. For instance, a 40-mg/d dosage of omeprazole is recommended in the latest guidelines, although the FDA-approved dosage is 20 mg/d.

H2-receptor antagonists, including famotidine, cimetidine, and nizatidine, may also be prescribed to reduce stomach acid production and promote healing in patients with EE due to GERD, but these agents are considered less efficacious than PPIs for either acute or maintenance therapy.

The potassium-competitive acid blocker (PCAB) vonoprazan is the latest agent to be indicated for EE and may provide more potent acid suppression for patients. A randomized comparative trial showed noninferiority compared with lansoprazole for healing and maintenance of healing of EE. In another randomized comparative study, the investigational PCAP fexuprazan was shown to be noninferior to the PPI esomeprazole in treating EE.

Mild GERD symptoms can be controlled by traditional antacids taken after each meal and at bedtime or with short-term use of prokinetic agents, which can help reduce acid reflux by improving esophageal and stomach motility and by increasing pressure to the lower esophageal sphincter. Gastric emptying is also accelerated by prokinetic agents. Long-term use is discouraged, as it may cause serious or life-threatening complications.

In patients who do not fully respond to PPI therapy, surgical therapy may be considered. Other candidates for surgery include younger patients, those who have difficulty adhering to treatment, postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, patients with cardiac conduction defects, and those for whom the cost of treatment is prohibitive. Surgery may also be warranted if there are extraesophageal manifestations of GERD, such as enamel erosion; respiratory issues (eg, coughing, wheezing, aspiration); or ear, nose, and throat manifestations (eg, hoarseness, sore throat, otitis media). For those who have progressed to BE, surgical intervention is also indicated.

The types of surgery for patients with EE have evolved to include both transthoracic and transabdominal fundoplication. Usually, a 360° transabdominal fundoplication is performed. General anesthesia is required for laparoscopic fundoplication, in which five small incisions are used to create a new valve at the level of the esophagogastric junction by wrapping the fundus of the stomach around the esophagus.

Laparoscopic insertion of a small band known as the LINX Reflux Management System is FDA approved to augment the lower esophageal sphincter. The system creates a natural barrier to reflux by placing a band consisting of titanium beads with magnetic cores around the esophagus just above the stomach. The magnetic bond is temporarily disrupted by swallowing, allowing food and liquid to pass.

Endoscopic therapies are another treatment option for certain patients who are not considered candidates for surgery or long-term therapy. Among the types of endoscopic procedures are radiofrequency therapy, suturing/plication, and mucosal ablation/resection techniques at the gastroesophageal junction. Full-thickness endoscopic suturing is an area of interest because this technique offers significant durability of the recreated lower esophageal sphincter.

3. PPI therapy for GERD should be stopped before endoscopy is performed to confirm a diagnosis of EE.

A clinical diagnosis of GERD can be made if the presenting symptoms are heartburn and regurgitation, without chest pain or alarm symptoms such as dysphagia, weight loss, or gastrointestinal bleeding. In this setting, once-daily PPIs are generally prescribed for 8 weeks to see if symptoms resolve. If symptoms have not resolved, a twice-daily PPI regimen may be prescribed. In patients who do not respond to PPIs, or for whom GERD returns after stopping therapy, an upper endoscopy with biopsy is recommended after 2-4 weeks off therapy to rule out other causes. Endoscopy should be the first step in diagnosis for individuals experiencing chest pain without heartburn; those in whom heart disease has been ruled out; individuals experiencing dysphagia, weight loss, or gastrointestinal bleeding; or those who have multiple risk factors for BE.

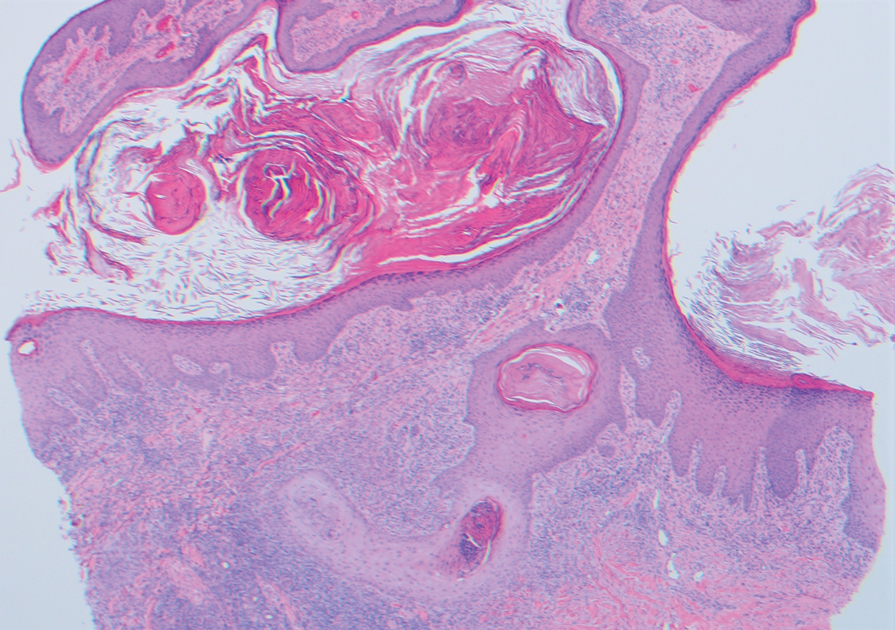

4. The most serious complication of EE is BE, which can lead to esophageal cancer.

Several complications can arise from EE. The most serious of these is BE, which can lead to esophageal adenocarcinoma. BE is characterized by the conversion of normal distal squamous esophageal epithelium to columnar epithelium. It has the potential to become malignant if it exhibits intestinal-type metaplasia. In the industrialized world, adenocarcinoma currently represents more than half of all esophageal cancers. The most common symptom of esophageal cancer is dysphagia. Other signs and symptoms include weight loss, hoarseness, chronic or intractable cough, bleeding, epigastric or retrosternal pain, frequent pneumonia, and, if metastatic, bone pain.

5. Lifestyle modifications can help control the symptoms of EE.

Guidelines recommend a number of lifestyle modification strategies to help control the symptoms of EE. Smoking cessation and weight loss are two evidence-based strategies for relieving symptoms of GERD and, ultimately, lowering the risk for esophageal cancer. One large prospective Norwegian cohort study (N = 29,610) found that stopping smoking improved GERD symptoms, but only in those with normal body mass index. In a smaller Japanese study (N = 191) specifically surveying people attempting smoking cessation, individuals who successfully stopped smoking had a 44% improvement in GERD symptoms at 1 year, vs an 18% improvement in those who continued to smoke, with no statistical difference between the success and failure groups based on patient body mass index (P = .60).

Other recommended strategies for nonpharmacologic management of EE symptoms include elevation of the head when lying down in bed and avoidance of lying down after eating, cessation of alcohol consumption, avoidance of food close to bedtime, and avoidance of trigger foods that can incite or worsen symptoms of acid reflux. Such trigger foods vary among individuals, but they often include fatty foods, coffee, chocolate, carbonated beverages, spicy foods, citrus fruits, and tomatoes.

Dr. Puerta has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Erosive esophagitis (EE) is erosion of the esophageal epithelium due to chronic irritation. It can be caused by a number of factors but is primarily a result of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The main symptoms of EE are heartburn and regurgitation; other symptoms can include epigastric pain, odynophagia, dysphagia, nausea, chronic cough, dental erosion, laryngitis, and asthma. , including nonerosive esophagitis and Barrett esophagus (BE). EE occurs in approximately 30% of cases of GERD, and EE may evolve to BE in 1%-13% of cases.

Long-term management of EE focuses on relieving symptoms to allow the esophageal lining to heal, thereby reducing both acute symptoms and the risk for other complications. Management plans may incorporate lifestyle changes, such as dietary modifications and weight loss, alongside pharmacologic therapy. In extreme cases, surgery may be considered to repair a damaged esophagus and/or to prevent ongoing acid reflux. If left untreated, EE may progress, potentially leading to more serious conditions.

Here are five things to know about EE.

1. GERD is the main risk factor for EE, but not the only risk factor.

An estimated 1% of the population has EE. Risk factors other than GERD include:

Radiation therapy toxicity can cause acute or chronic EE. For individuals undergoing radiotherapy, radiation esophagitis is a relatively frequent complication. Acute esophagitis generally occurs in all patients taking radiation doses of 6000 cGy given in fractions of 1000 cGy per week. The risk is lower among patients on longer schedules and lower doses of radiotherapy.

Bacterial, viral, and fungal infections can cause EE. These include herpes, CMV, HIV, Helicobacter pylori, and Candida.

Food allergies, asthma, and eczema are associated with eosinophilic esophagitis, which disproportionately affects young men and has an estimated prevalence of 55 cases per 100,000 population.

Oral medication in pill form causes esophagitis at an estimated rate of 3.9 cases per 100,000 population per year. The mean age at diagnosis is 41.5 years. Oral bisphosphonates such as alendronate are the most common agents, along with antibiotics such as tetracycline, doxycycline, and clindamycin. There have also been reports of pill-induced esophagitis with NSAIDs, aspirin, ferrous sulfate, potassium chloride, and mexiletine.

Excessive vomiting can, in rare cases, cause esophagitis.

Certain autoimmune diseases can manifest as EE.

2. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) remain the preferred treatment for EE.

Several over-the-counter and prescription medications can be used to manage the symptoms of EE. PPIs are the preferred treatment both in the acute setting and for maintenance therapy. PPIs help to alleviate symptoms and promote healing of the esophageal lining by reducing the production of stomach acid. Options include omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole, and esomeprazole. Many patients with EE require a dose that exceeds the FDA-approved dose for GERD. For instance, a 40-mg/d dosage of omeprazole is recommended in the latest guidelines, although the FDA-approved dosage is 20 mg/d.

H2-receptor antagonists, including famotidine, cimetidine, and nizatidine, may also be prescribed to reduce stomach acid production and promote healing in patients with EE due to GERD, but these agents are considered less efficacious than PPIs for either acute or maintenance therapy.

The potassium-competitive acid blocker (PCAB) vonoprazan is the latest agent to be indicated for EE and may provide more potent acid suppression for patients. A randomized comparative trial showed noninferiority compared with lansoprazole for healing and maintenance of healing of EE. In another randomized comparative study, the investigational PCAP fexuprazan was shown to be noninferior to the PPI esomeprazole in treating EE.

Mild GERD symptoms can be controlled by traditional antacids taken after each meal and at bedtime or with short-term use of prokinetic agents, which can help reduce acid reflux by improving esophageal and stomach motility and by increasing pressure to the lower esophageal sphincter. Gastric emptying is also accelerated by prokinetic agents. Long-term use is discouraged, as it may cause serious or life-threatening complications.

In patients who do not fully respond to PPI therapy, surgical therapy may be considered. Other candidates for surgery include younger patients, those who have difficulty adhering to treatment, postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, patients with cardiac conduction defects, and those for whom the cost of treatment is prohibitive. Surgery may also be warranted if there are extraesophageal manifestations of GERD, such as enamel erosion; respiratory issues (eg, coughing, wheezing, aspiration); or ear, nose, and throat manifestations (eg, hoarseness, sore throat, otitis media). For those who have progressed to BE, surgical intervention is also indicated.

The types of surgery for patients with EE have evolved to include both transthoracic and transabdominal fundoplication. Usually, a 360° transabdominal fundoplication is performed. General anesthesia is required for laparoscopic fundoplication, in which five small incisions are used to create a new valve at the level of the esophagogastric junction by wrapping the fundus of the stomach around the esophagus.

Laparoscopic insertion of a small band known as the LINX Reflux Management System is FDA approved to augment the lower esophageal sphincter. The system creates a natural barrier to reflux by placing a band consisting of titanium beads with magnetic cores around the esophagus just above the stomach. The magnetic bond is temporarily disrupted by swallowing, allowing food and liquid to pass.

Endoscopic therapies are another treatment option for certain patients who are not considered candidates for surgery or long-term therapy. Among the types of endoscopic procedures are radiofrequency therapy, suturing/plication, and mucosal ablation/resection techniques at the gastroesophageal junction. Full-thickness endoscopic suturing is an area of interest because this technique offers significant durability of the recreated lower esophageal sphincter.

3. PPI therapy for GERD should be stopped before endoscopy is performed to confirm a diagnosis of EE.

A clinical diagnosis of GERD can be made if the presenting symptoms are heartburn and regurgitation, without chest pain or alarm symptoms such as dysphagia, weight loss, or gastrointestinal bleeding. In this setting, once-daily PPIs are generally prescribed for 8 weeks to see if symptoms resolve. If symptoms have not resolved, a twice-daily PPI regimen may be prescribed. In patients who do not respond to PPIs, or for whom GERD returns after stopping therapy, an upper endoscopy with biopsy is recommended after 2-4 weeks off therapy to rule out other causes. Endoscopy should be the first step in diagnosis for individuals experiencing chest pain without heartburn; those in whom heart disease has been ruled out; individuals experiencing dysphagia, weight loss, or gastrointestinal bleeding; or those who have multiple risk factors for BE.

4. The most serious complication of EE is BE, which can lead to esophageal cancer.

Several complications can arise from EE. The most serious of these is BE, which can lead to esophageal adenocarcinoma. BE is characterized by the conversion of normal distal squamous esophageal epithelium to columnar epithelium. It has the potential to become malignant if it exhibits intestinal-type metaplasia. In the industrialized world, adenocarcinoma currently represents more than half of all esophageal cancers. The most common symptom of esophageal cancer is dysphagia. Other signs and symptoms include weight loss, hoarseness, chronic or intractable cough, bleeding, epigastric or retrosternal pain, frequent pneumonia, and, if metastatic, bone pain.

5. Lifestyle modifications can help control the symptoms of EE.

Guidelines recommend a number of lifestyle modification strategies to help control the symptoms of EE. Smoking cessation and weight loss are two evidence-based strategies for relieving symptoms of GERD and, ultimately, lowering the risk for esophageal cancer. One large prospective Norwegian cohort study (N = 29,610) found that stopping smoking improved GERD symptoms, but only in those with normal body mass index. In a smaller Japanese study (N = 191) specifically surveying people attempting smoking cessation, individuals who successfully stopped smoking had a 44% improvement in GERD symptoms at 1 year, vs an 18% improvement in those who continued to smoke, with no statistical difference between the success and failure groups based on patient body mass index (P = .60).

Other recommended strategies for nonpharmacologic management of EE symptoms include elevation of the head when lying down in bed and avoidance of lying down after eating, cessation of alcohol consumption, avoidance of food close to bedtime, and avoidance of trigger foods that can incite or worsen symptoms of acid reflux. Such trigger foods vary among individuals, but they often include fatty foods, coffee, chocolate, carbonated beverages, spicy foods, citrus fruits, and tomatoes.

Dr. Puerta has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Erosive esophagitis (EE) is erosion of the esophageal epithelium due to chronic irritation. It can be caused by a number of factors but is primarily a result of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The main symptoms of EE are heartburn and regurgitation; other symptoms can include epigastric pain, odynophagia, dysphagia, nausea, chronic cough, dental erosion, laryngitis, and asthma. , including nonerosive esophagitis and Barrett esophagus (BE). EE occurs in approximately 30% of cases of GERD, and EE may evolve to BE in 1%-13% of cases.

Long-term management of EE focuses on relieving symptoms to allow the esophageal lining to heal, thereby reducing both acute symptoms and the risk for other complications. Management plans may incorporate lifestyle changes, such as dietary modifications and weight loss, alongside pharmacologic therapy. In extreme cases, surgery may be considered to repair a damaged esophagus and/or to prevent ongoing acid reflux. If left untreated, EE may progress, potentially leading to more serious conditions.

Here are five things to know about EE.

1. GERD is the main risk factor for EE, but not the only risk factor.

An estimated 1% of the population has EE. Risk factors other than GERD include:

Radiation therapy toxicity can cause acute or chronic EE. For individuals undergoing radiotherapy, radiation esophagitis is a relatively frequent complication. Acute esophagitis generally occurs in all patients taking radiation doses of 6000 cGy given in fractions of 1000 cGy per week. The risk is lower among patients on longer schedules and lower doses of radiotherapy.

Bacterial, viral, and fungal infections can cause EE. These include herpes, CMV, HIV, Helicobacter pylori, and Candida.

Food allergies, asthma, and eczema are associated with eosinophilic esophagitis, which disproportionately affects young men and has an estimated prevalence of 55 cases per 100,000 population.

Oral medication in pill form causes esophagitis at an estimated rate of 3.9 cases per 100,000 population per year. The mean age at diagnosis is 41.5 years. Oral bisphosphonates such as alendronate are the most common agents, along with antibiotics such as tetracycline, doxycycline, and clindamycin. There have also been reports of pill-induced esophagitis with NSAIDs, aspirin, ferrous sulfate, potassium chloride, and mexiletine.

Excessive vomiting can, in rare cases, cause esophagitis.

Certain autoimmune diseases can manifest as EE.

2. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) remain the preferred treatment for EE.

Several over-the-counter and prescription medications can be used to manage the symptoms of EE. PPIs are the preferred treatment both in the acute setting and for maintenance therapy. PPIs help to alleviate symptoms and promote healing of the esophageal lining by reducing the production of stomach acid. Options include omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole, and esomeprazole. Many patients with EE require a dose that exceeds the FDA-approved dose for GERD. For instance, a 40-mg/d dosage of omeprazole is recommended in the latest guidelines, although the FDA-approved dosage is 20 mg/d.

H2-receptor antagonists, including famotidine, cimetidine, and nizatidine, may also be prescribed to reduce stomach acid production and promote healing in patients with EE due to GERD, but these agents are considered less efficacious than PPIs for either acute or maintenance therapy.

The potassium-competitive acid blocker (PCAB) vonoprazan is the latest agent to be indicated for EE and may provide more potent acid suppression for patients. A randomized comparative trial showed noninferiority compared with lansoprazole for healing and maintenance of healing of EE. In another randomized comparative study, the investigational PCAP fexuprazan was shown to be noninferior to the PPI esomeprazole in treating EE.

Mild GERD symptoms can be controlled by traditional antacids taken after each meal and at bedtime or with short-term use of prokinetic agents, which can help reduce acid reflux by improving esophageal and stomach motility and by increasing pressure to the lower esophageal sphincter. Gastric emptying is also accelerated by prokinetic agents. Long-term use is discouraged, as it may cause serious or life-threatening complications.

In patients who do not fully respond to PPI therapy, surgical therapy may be considered. Other candidates for surgery include younger patients, those who have difficulty adhering to treatment, postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, patients with cardiac conduction defects, and those for whom the cost of treatment is prohibitive. Surgery may also be warranted if there are extraesophageal manifestations of GERD, such as enamel erosion; respiratory issues (eg, coughing, wheezing, aspiration); or ear, nose, and throat manifestations (eg, hoarseness, sore throat, otitis media). For those who have progressed to BE, surgical intervention is also indicated.

The types of surgery for patients with EE have evolved to include both transthoracic and transabdominal fundoplication. Usually, a 360° transabdominal fundoplication is performed. General anesthesia is required for laparoscopic fundoplication, in which five small incisions are used to create a new valve at the level of the esophagogastric junction by wrapping the fundus of the stomach around the esophagus.

Laparoscopic insertion of a small band known as the LINX Reflux Management System is FDA approved to augment the lower esophageal sphincter. The system creates a natural barrier to reflux by placing a band consisting of titanium beads with magnetic cores around the esophagus just above the stomach. The magnetic bond is temporarily disrupted by swallowing, allowing food and liquid to pass.

Endoscopic therapies are another treatment option for certain patients who are not considered candidates for surgery or long-term therapy. Among the types of endoscopic procedures are radiofrequency therapy, suturing/plication, and mucosal ablation/resection techniques at the gastroesophageal junction. Full-thickness endoscopic suturing is an area of interest because this technique offers significant durability of the recreated lower esophageal sphincter.

3. PPI therapy for GERD should be stopped before endoscopy is performed to confirm a diagnosis of EE.

A clinical diagnosis of GERD can be made if the presenting symptoms are heartburn and regurgitation, without chest pain or alarm symptoms such as dysphagia, weight loss, or gastrointestinal bleeding. In this setting, once-daily PPIs are generally prescribed for 8 weeks to see if symptoms resolve. If symptoms have not resolved, a twice-daily PPI regimen may be prescribed. In patients who do not respond to PPIs, or for whom GERD returns after stopping therapy, an upper endoscopy with biopsy is recommended after 2-4 weeks off therapy to rule out other causes. Endoscopy should be the first step in diagnosis for individuals experiencing chest pain without heartburn; those in whom heart disease has been ruled out; individuals experiencing dysphagia, weight loss, or gastrointestinal bleeding; or those who have multiple risk factors for BE.

4. The most serious complication of EE is BE, which can lead to esophageal cancer.

Several complications can arise from EE. The most serious of these is BE, which can lead to esophageal adenocarcinoma. BE is characterized by the conversion of normal distal squamous esophageal epithelium to columnar epithelium. It has the potential to become malignant if it exhibits intestinal-type metaplasia. In the industrialized world, adenocarcinoma currently represents more than half of all esophageal cancers. The most common symptom of esophageal cancer is dysphagia. Other signs and symptoms include weight loss, hoarseness, chronic or intractable cough, bleeding, epigastric or retrosternal pain, frequent pneumonia, and, if metastatic, bone pain.

5. Lifestyle modifications can help control the symptoms of EE.

Guidelines recommend a number of lifestyle modification strategies to help control the symptoms of EE. Smoking cessation and weight loss are two evidence-based strategies for relieving symptoms of GERD and, ultimately, lowering the risk for esophageal cancer. One large prospective Norwegian cohort study (N = 29,610) found that stopping smoking improved GERD symptoms, but only in those with normal body mass index. In a smaller Japanese study (N = 191) specifically surveying people attempting smoking cessation, individuals who successfully stopped smoking had a 44% improvement in GERD symptoms at 1 year, vs an 18% improvement in those who continued to smoke, with no statistical difference between the success and failure groups based on patient body mass index (P = .60).