User login

First CAR T-cell therapy approvals bolster booming immunotherapy market

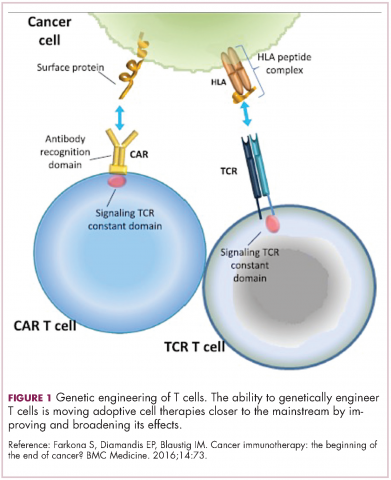

There were a number of landmark approvals by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 for cancer therapies, among them, the approval of the first two chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies for cancer: tisagenlecleucel (in August) and axicabtagene ciloluecel (in October).1 CAR T-cells are a type of adoptive cell therapy or immunotherapy, in which the patient’s own immune cells are genetically engineered to target a tumor-associated antigen, in this case CD19. In tisagenlecleucel, CD19 proteins on B cells are targeted in the treatment of B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Axicabtagene ciloluecel, the second anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy, was approved for the treatment of refractory, aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Tisagenlecleucel

Tisagenlecleucel was approved for the treatment of pediatric patients up to 25 years of age with B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) whose disease is refractory to treatment or who have relapsed after second-line therapy or beyond.2 Approval was based on the pivotal ELIANA trial, a single-arm, global phase 2 trial conducted at 25 centers worldwide during April 2015 through April 2017. Patients were eligible for enrollment if they had relapsed or refractory B-cell ALL and were at least 3 years of age at screening and no older than 21 years of age at diagnosis, had at least 5% lymphoblasts in the bone marrow at screening, had tumor expression of CD19, had adequate organ function, and a Karnofsky (adult) or Lansky (child) Performance Status of ≥50 (with the worst allowable score, 50, indicating a patient who requires considerable assistance and frequent medical care [Karnofsky] and lying around much of the day, but gets dressed; no active playing but participates in all quiet play and activities [Lansky]). Exclusion criteria included previous receipt of anti-CD19 therapy, concomitant genetic syndromes associated with bone marrow failure, previous malignancy, and/or active or latent hepatitis B or C virus (HBV/HCV) infection.

The overall remission rate (ORR) was evaluated in 75 patients who were given a single dose of tisagenlecleucel (a median weight-adjusted dose of 3.1 x 106 transduced viable T cells per kg of body weight) within 14 days of completing a lymphodepleting chemotherapy regimen. The confirmed ORR after at least 3 months of follow-up, as assessed by independent central review, was 81%, which included 60% of patients in complete remission (CR) and 21% in complete remission with incomplete hematologic recovery, all of whom were negative for minimal residual disease.

The most common adverse events (AEs) associated with tisagenlecleucel treatment were cytokine release syndrome (CRS), hypogammaglobulinemia, infection, pyrexia, decreased appetite, headache, encephalopathy, hypotension, bleeding episodes, tachycardia, nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, viral infectious disorders, hypoxia, fatigue, acute kidney injury, and delirium. AEs were of grade 3/4 severity in 84% of patients.3

To combat serious safety issues, including CRS and neurologic toxicities, the FDA approved tisagenlecleucel with a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) that, in part, requires health care providers who administer the drug to be trained in their management. It also requires the facility where treatment is administered to have immediate, onsite access to the drug tocilizumab, which was approved in conjunction with tisagenlecleucel for the treatment of patients who experience CRS.

In addition to information about the REMS, the prescribing information details warnings and precautions relating to several other common toxicities. These include hypersensitivity reactions, serious infections, prolonged cytopenias, and hypogammaglobulinemia.

Patients should be monitored for signs and symptoms of infection and treated appropriately. Viral reactivation can occur after tisagenlecleucel treatment, so patients should be screened for HBV, HCV, and human immunodeficiency virus before collection of cells.

The administration of myeloid growth factors is not recommended during the first 3 weeks after infusion or until CRS has resolved. Immunoglobulin levels should be monitored after treatment and hypogammaglobulinemia managed using infection precautions, antibiotic prophylaxis, and immunoglobulin replacement according to standard guidelines.

Patients treated with tisagenlecleucel should also be monitored for life for secondary malignancies, should not be treated with live vaccines from 2 weeks before the start of lymphodepleting chemotherapy until immune recovery after tisagenlecleucel infusion, and should be aware of the potential for neurological events to impact their ability to drive and use dangerous machinery.4

Tisagenlecleucel is marketed as Kymriah by Novartis Pharmaceuticals. The recommended dose is 1 infusion of 0.2-5 x 106 CAR-positive viable T cells per kilogram of body weight intravenously (for patients ≤50kg) and 0.1-2.5 x 108 cells/kg (for patients >50kg), administered 2-14 days after lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

Axicabtagene ciloleucel

Axicabtagene ciloleucel was approved for the treatment of adult patients with certain types of relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL), high-grade B-cell lymphoma, and DLBCL arising from follicular lymphoma.5 It is not indicated for the treatment of patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma.

Approval followed positive results from the phase 2 single-arm, multicenter ZUMA-1 trial.6 Patients were included if they were aged 18 years of age and older, had histologically confirmed aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma that was chemotherapy refractory, had received adequate previous therapy, had at least 1 measurable lesion, had completed radiation or systemic therapy at least 2 weeks before, had resolved toxicities related to previous therapy, and had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status of 0 (asymptomatic) or 1 (symptomatic), an absolute neutrophil count of ≥1000/µL, a platelet count of ≥50,000/µL, and adequate hepatic, renal and cardiac function. They were treated with a single infusion of axicabtagene ciloleucel after lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

Patients who had received previous CD19-targeted therapy, who had concomitant genetic syndromes associated with bone marrow failure, who had previous malignancy, and who had active or latent HBV/HCV infection were among those excluded from the study.

Patients were enrolled in 2 cohorts; those with DLBCL (n = 77) and those with PMBCL or transformed follicular lymphoma (n = 24). The primary endpoint was objective response rate, and after a primary analysis at a minimum of 6 months follow-up, the objective response rate was 82%, with a CR rate of 52%. Among patients who achieved CR, the median duration of response was not reached after a median follow-up of 7.9 months.

A subsequent updated analysis was performed when 108 patients had been followed for a minimum of 1 year. The objective response rate was 82%, and the CR rate was 58%, with some patients having CR in the absence of additional therapies as late as 15 months after treatment. At this updated analysis, 42% of patients continued to have a response, 40% of whom remained in CR.

The most common grade 3 or higher AEs included febrile neutropenia, fever, CRS, encephalopathy, infections, hypotension, and hypoxia. Serious AEs occurred in 52% of patients and included CRS, neurologic toxicity, prolonged cytopenias, and serious infections. Grade 3 or higher CRS or neurologic toxicities occurred in 13% and 28% of patients, respectively. Three patients died during treatment.

To mitigate the risk of CRS and neurologic toxicity, axicabtagene ciloleucel is approved with an REMS that requires appropriate certification and training before hospitals are cleared to administer the therapy.

Other warnings and precautions in the prescribing information relate to serious infections (monitor for signs and symptoms and treat appropriately), prolonged cytopenias (monitor blood counts), hypogammaglobulinemia (monitor immunoglobulin levels and manage appropriately), secondary malignancies (life-long monitoring), and the potential effects of neurologic events on a patient’s ability to drive and operate dangerous machinery (avoid for at least 8 weeks after infusion).7

Axicabtagene ciloleucel is marketed as Yescarta by Kite Pharma Inc. The recommended dose is a single intravenous infusion with a target of 2 x 106 CAR-positive viable T cells per kilogram of body weight, preceded by fludarabine and cyclophosphamide lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

1. Bosserman LD. Cancer care in 2017: the promise of more cures with the challenges of an unstable health care system. JCSO 2017;15(6):e283-e290.

2. FDA approves tisagenlecleucel for B-cell ALL and tocilizumab for cytokine release syndrome. FDA News Release. August 30, 2017. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ApprovedDrugs/

ucm574154.htm. Accessed March 31, 2018.

3. Maude S.L, Laetsch T.W, Buechner S, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with B-Cell lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:439-48.

4. Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel) suspension for intravenous use. Prescribing information. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, August, 2017. https://www.pharma.us.novartis.com/sites/www.pharma.us.novartis.

com/files/kymriah.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2018.

5. FDA approves axicabtagene ciloleucel for large B-cell lymphoma. FDA News Release. October 18, 2017. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/

InformationOnDrugs/ApprovedDrugs/ucm581296.htm. Accessed March 31, 2018.

6. Neelapu, S.S, Locke F.L, Bartlett, L.J, et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel CAR T-Cell Therapy in Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2531-44.

7. Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel) suspension for intravenous use. Prescribing information. Kite Pharma Inc. October 2017. https://www.yescarta.com/wp-content/uploads/yescarta-pi.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2018.

There were a number of landmark approvals by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 for cancer therapies, among them, the approval of the first two chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies for cancer: tisagenlecleucel (in August) and axicabtagene ciloluecel (in October).1 CAR T-cells are a type of adoptive cell therapy or immunotherapy, in which the patient’s own immune cells are genetically engineered to target a tumor-associated antigen, in this case CD19. In tisagenlecleucel, CD19 proteins on B cells are targeted in the treatment of B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Axicabtagene ciloluecel, the second anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy, was approved for the treatment of refractory, aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Tisagenlecleucel

Tisagenlecleucel was approved for the treatment of pediatric patients up to 25 years of age with B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) whose disease is refractory to treatment or who have relapsed after second-line therapy or beyond.2 Approval was based on the pivotal ELIANA trial, a single-arm, global phase 2 trial conducted at 25 centers worldwide during April 2015 through April 2017. Patients were eligible for enrollment if they had relapsed or refractory B-cell ALL and were at least 3 years of age at screening and no older than 21 years of age at diagnosis, had at least 5% lymphoblasts in the bone marrow at screening, had tumor expression of CD19, had adequate organ function, and a Karnofsky (adult) or Lansky (child) Performance Status of ≥50 (with the worst allowable score, 50, indicating a patient who requires considerable assistance and frequent medical care [Karnofsky] and lying around much of the day, but gets dressed; no active playing but participates in all quiet play and activities [Lansky]). Exclusion criteria included previous receipt of anti-CD19 therapy, concomitant genetic syndromes associated with bone marrow failure, previous malignancy, and/or active or latent hepatitis B or C virus (HBV/HCV) infection.

The overall remission rate (ORR) was evaluated in 75 patients who were given a single dose of tisagenlecleucel (a median weight-adjusted dose of 3.1 x 106 transduced viable T cells per kg of body weight) within 14 days of completing a lymphodepleting chemotherapy regimen. The confirmed ORR after at least 3 months of follow-up, as assessed by independent central review, was 81%, which included 60% of patients in complete remission (CR) and 21% in complete remission with incomplete hematologic recovery, all of whom were negative for minimal residual disease.

The most common adverse events (AEs) associated with tisagenlecleucel treatment were cytokine release syndrome (CRS), hypogammaglobulinemia, infection, pyrexia, decreased appetite, headache, encephalopathy, hypotension, bleeding episodes, tachycardia, nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, viral infectious disorders, hypoxia, fatigue, acute kidney injury, and delirium. AEs were of grade 3/4 severity in 84% of patients.3

To combat serious safety issues, including CRS and neurologic toxicities, the FDA approved tisagenlecleucel with a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) that, in part, requires health care providers who administer the drug to be trained in their management. It also requires the facility where treatment is administered to have immediate, onsite access to the drug tocilizumab, which was approved in conjunction with tisagenlecleucel for the treatment of patients who experience CRS.

In addition to information about the REMS, the prescribing information details warnings and precautions relating to several other common toxicities. These include hypersensitivity reactions, serious infections, prolonged cytopenias, and hypogammaglobulinemia.

Patients should be monitored for signs and symptoms of infection and treated appropriately. Viral reactivation can occur after tisagenlecleucel treatment, so patients should be screened for HBV, HCV, and human immunodeficiency virus before collection of cells.

The administration of myeloid growth factors is not recommended during the first 3 weeks after infusion or until CRS has resolved. Immunoglobulin levels should be monitored after treatment and hypogammaglobulinemia managed using infection precautions, antibiotic prophylaxis, and immunoglobulin replacement according to standard guidelines.

Patients treated with tisagenlecleucel should also be monitored for life for secondary malignancies, should not be treated with live vaccines from 2 weeks before the start of lymphodepleting chemotherapy until immune recovery after tisagenlecleucel infusion, and should be aware of the potential for neurological events to impact their ability to drive and use dangerous machinery.4

Tisagenlecleucel is marketed as Kymriah by Novartis Pharmaceuticals. The recommended dose is 1 infusion of 0.2-5 x 106 CAR-positive viable T cells per kilogram of body weight intravenously (for patients ≤50kg) and 0.1-2.5 x 108 cells/kg (for patients >50kg), administered 2-14 days after lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

Axicabtagene ciloleucel

Axicabtagene ciloleucel was approved for the treatment of adult patients with certain types of relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL), high-grade B-cell lymphoma, and DLBCL arising from follicular lymphoma.5 It is not indicated for the treatment of patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma.

Approval followed positive results from the phase 2 single-arm, multicenter ZUMA-1 trial.6 Patients were included if they were aged 18 years of age and older, had histologically confirmed aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma that was chemotherapy refractory, had received adequate previous therapy, had at least 1 measurable lesion, had completed radiation or systemic therapy at least 2 weeks before, had resolved toxicities related to previous therapy, and had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status of 0 (asymptomatic) or 1 (symptomatic), an absolute neutrophil count of ≥1000/µL, a platelet count of ≥50,000/µL, and adequate hepatic, renal and cardiac function. They were treated with a single infusion of axicabtagene ciloleucel after lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

Patients who had received previous CD19-targeted therapy, who had concomitant genetic syndromes associated with bone marrow failure, who had previous malignancy, and who had active or latent HBV/HCV infection were among those excluded from the study.

Patients were enrolled in 2 cohorts; those with DLBCL (n = 77) and those with PMBCL or transformed follicular lymphoma (n = 24). The primary endpoint was objective response rate, and after a primary analysis at a minimum of 6 months follow-up, the objective response rate was 82%, with a CR rate of 52%. Among patients who achieved CR, the median duration of response was not reached after a median follow-up of 7.9 months.

A subsequent updated analysis was performed when 108 patients had been followed for a minimum of 1 year. The objective response rate was 82%, and the CR rate was 58%, with some patients having CR in the absence of additional therapies as late as 15 months after treatment. At this updated analysis, 42% of patients continued to have a response, 40% of whom remained in CR.

The most common grade 3 or higher AEs included febrile neutropenia, fever, CRS, encephalopathy, infections, hypotension, and hypoxia. Serious AEs occurred in 52% of patients and included CRS, neurologic toxicity, prolonged cytopenias, and serious infections. Grade 3 or higher CRS or neurologic toxicities occurred in 13% and 28% of patients, respectively. Three patients died during treatment.

To mitigate the risk of CRS and neurologic toxicity, axicabtagene ciloleucel is approved with an REMS that requires appropriate certification and training before hospitals are cleared to administer the therapy.

Other warnings and precautions in the prescribing information relate to serious infections (monitor for signs and symptoms and treat appropriately), prolonged cytopenias (monitor blood counts), hypogammaglobulinemia (monitor immunoglobulin levels and manage appropriately), secondary malignancies (life-long monitoring), and the potential effects of neurologic events on a patient’s ability to drive and operate dangerous machinery (avoid for at least 8 weeks after infusion).7

Axicabtagene ciloleucel is marketed as Yescarta by Kite Pharma Inc. The recommended dose is a single intravenous infusion with a target of 2 x 106 CAR-positive viable T cells per kilogram of body weight, preceded by fludarabine and cyclophosphamide lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

There were a number of landmark approvals by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 for cancer therapies, among them, the approval of the first two chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies for cancer: tisagenlecleucel (in August) and axicabtagene ciloluecel (in October).1 CAR T-cells are a type of adoptive cell therapy or immunotherapy, in which the patient’s own immune cells are genetically engineered to target a tumor-associated antigen, in this case CD19. In tisagenlecleucel, CD19 proteins on B cells are targeted in the treatment of B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Axicabtagene ciloluecel, the second anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy, was approved for the treatment of refractory, aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Tisagenlecleucel

Tisagenlecleucel was approved for the treatment of pediatric patients up to 25 years of age with B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) whose disease is refractory to treatment or who have relapsed after second-line therapy or beyond.2 Approval was based on the pivotal ELIANA trial, a single-arm, global phase 2 trial conducted at 25 centers worldwide during April 2015 through April 2017. Patients were eligible for enrollment if they had relapsed or refractory B-cell ALL and were at least 3 years of age at screening and no older than 21 years of age at diagnosis, had at least 5% lymphoblasts in the bone marrow at screening, had tumor expression of CD19, had adequate organ function, and a Karnofsky (adult) or Lansky (child) Performance Status of ≥50 (with the worst allowable score, 50, indicating a patient who requires considerable assistance and frequent medical care [Karnofsky] and lying around much of the day, but gets dressed; no active playing but participates in all quiet play and activities [Lansky]). Exclusion criteria included previous receipt of anti-CD19 therapy, concomitant genetic syndromes associated with bone marrow failure, previous malignancy, and/or active or latent hepatitis B or C virus (HBV/HCV) infection.

The overall remission rate (ORR) was evaluated in 75 patients who were given a single dose of tisagenlecleucel (a median weight-adjusted dose of 3.1 x 106 transduced viable T cells per kg of body weight) within 14 days of completing a lymphodepleting chemotherapy regimen. The confirmed ORR after at least 3 months of follow-up, as assessed by independent central review, was 81%, which included 60% of patients in complete remission (CR) and 21% in complete remission with incomplete hematologic recovery, all of whom were negative for minimal residual disease.

The most common adverse events (AEs) associated with tisagenlecleucel treatment were cytokine release syndrome (CRS), hypogammaglobulinemia, infection, pyrexia, decreased appetite, headache, encephalopathy, hypotension, bleeding episodes, tachycardia, nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, viral infectious disorders, hypoxia, fatigue, acute kidney injury, and delirium. AEs were of grade 3/4 severity in 84% of patients.3

To combat serious safety issues, including CRS and neurologic toxicities, the FDA approved tisagenlecleucel with a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) that, in part, requires health care providers who administer the drug to be trained in their management. It also requires the facility where treatment is administered to have immediate, onsite access to the drug tocilizumab, which was approved in conjunction with tisagenlecleucel for the treatment of patients who experience CRS.

In addition to information about the REMS, the prescribing information details warnings and precautions relating to several other common toxicities. These include hypersensitivity reactions, serious infections, prolonged cytopenias, and hypogammaglobulinemia.

Patients should be monitored for signs and symptoms of infection and treated appropriately. Viral reactivation can occur after tisagenlecleucel treatment, so patients should be screened for HBV, HCV, and human immunodeficiency virus before collection of cells.

The administration of myeloid growth factors is not recommended during the first 3 weeks after infusion or until CRS has resolved. Immunoglobulin levels should be monitored after treatment and hypogammaglobulinemia managed using infection precautions, antibiotic prophylaxis, and immunoglobulin replacement according to standard guidelines.

Patients treated with tisagenlecleucel should also be monitored for life for secondary malignancies, should not be treated with live vaccines from 2 weeks before the start of lymphodepleting chemotherapy until immune recovery after tisagenlecleucel infusion, and should be aware of the potential for neurological events to impact their ability to drive and use dangerous machinery.4

Tisagenlecleucel is marketed as Kymriah by Novartis Pharmaceuticals. The recommended dose is 1 infusion of 0.2-5 x 106 CAR-positive viable T cells per kilogram of body weight intravenously (for patients ≤50kg) and 0.1-2.5 x 108 cells/kg (for patients >50kg), administered 2-14 days after lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

Axicabtagene ciloleucel

Axicabtagene ciloleucel was approved for the treatment of adult patients with certain types of relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL), high-grade B-cell lymphoma, and DLBCL arising from follicular lymphoma.5 It is not indicated for the treatment of patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma.

Approval followed positive results from the phase 2 single-arm, multicenter ZUMA-1 trial.6 Patients were included if they were aged 18 years of age and older, had histologically confirmed aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma that was chemotherapy refractory, had received adequate previous therapy, had at least 1 measurable lesion, had completed radiation or systemic therapy at least 2 weeks before, had resolved toxicities related to previous therapy, and had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status of 0 (asymptomatic) or 1 (symptomatic), an absolute neutrophil count of ≥1000/µL, a platelet count of ≥50,000/µL, and adequate hepatic, renal and cardiac function. They were treated with a single infusion of axicabtagene ciloleucel after lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

Patients who had received previous CD19-targeted therapy, who had concomitant genetic syndromes associated with bone marrow failure, who had previous malignancy, and who had active or latent HBV/HCV infection were among those excluded from the study.

Patients were enrolled in 2 cohorts; those with DLBCL (n = 77) and those with PMBCL or transformed follicular lymphoma (n = 24). The primary endpoint was objective response rate, and after a primary analysis at a minimum of 6 months follow-up, the objective response rate was 82%, with a CR rate of 52%. Among patients who achieved CR, the median duration of response was not reached after a median follow-up of 7.9 months.

A subsequent updated analysis was performed when 108 patients had been followed for a minimum of 1 year. The objective response rate was 82%, and the CR rate was 58%, with some patients having CR in the absence of additional therapies as late as 15 months after treatment. At this updated analysis, 42% of patients continued to have a response, 40% of whom remained in CR.

The most common grade 3 or higher AEs included febrile neutropenia, fever, CRS, encephalopathy, infections, hypotension, and hypoxia. Serious AEs occurred in 52% of patients and included CRS, neurologic toxicity, prolonged cytopenias, and serious infections. Grade 3 or higher CRS or neurologic toxicities occurred in 13% and 28% of patients, respectively. Three patients died during treatment.

To mitigate the risk of CRS and neurologic toxicity, axicabtagene ciloleucel is approved with an REMS that requires appropriate certification and training before hospitals are cleared to administer the therapy.

Other warnings and precautions in the prescribing information relate to serious infections (monitor for signs and symptoms and treat appropriately), prolonged cytopenias (monitor blood counts), hypogammaglobulinemia (monitor immunoglobulin levels and manage appropriately), secondary malignancies (life-long monitoring), and the potential effects of neurologic events on a patient’s ability to drive and operate dangerous machinery (avoid for at least 8 weeks after infusion).7

Axicabtagene ciloleucel is marketed as Yescarta by Kite Pharma Inc. The recommended dose is a single intravenous infusion with a target of 2 x 106 CAR-positive viable T cells per kilogram of body weight, preceded by fludarabine and cyclophosphamide lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

1. Bosserman LD. Cancer care in 2017: the promise of more cures with the challenges of an unstable health care system. JCSO 2017;15(6):e283-e290.

2. FDA approves tisagenlecleucel for B-cell ALL and tocilizumab for cytokine release syndrome. FDA News Release. August 30, 2017. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ApprovedDrugs/

ucm574154.htm. Accessed March 31, 2018.

3. Maude S.L, Laetsch T.W, Buechner S, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with B-Cell lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:439-48.

4. Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel) suspension for intravenous use. Prescribing information. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, August, 2017. https://www.pharma.us.novartis.com/sites/www.pharma.us.novartis.

com/files/kymriah.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2018.

5. FDA approves axicabtagene ciloleucel for large B-cell lymphoma. FDA News Release. October 18, 2017. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/

InformationOnDrugs/ApprovedDrugs/ucm581296.htm. Accessed March 31, 2018.

6. Neelapu, S.S, Locke F.L, Bartlett, L.J, et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel CAR T-Cell Therapy in Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2531-44.

7. Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel) suspension for intravenous use. Prescribing information. Kite Pharma Inc. October 2017. https://www.yescarta.com/wp-content/uploads/yescarta-pi.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2018.

1. Bosserman LD. Cancer care in 2017: the promise of more cures with the challenges of an unstable health care system. JCSO 2017;15(6):e283-e290.

2. FDA approves tisagenlecleucel for B-cell ALL and tocilizumab for cytokine release syndrome. FDA News Release. August 30, 2017. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ApprovedDrugs/

ucm574154.htm. Accessed March 31, 2018.

3. Maude S.L, Laetsch T.W, Buechner S, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with B-Cell lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:439-48.

4. Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel) suspension for intravenous use. Prescribing information. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, August, 2017. https://www.pharma.us.novartis.com/sites/www.pharma.us.novartis.

com/files/kymriah.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2018.

5. FDA approves axicabtagene ciloleucel for large B-cell lymphoma. FDA News Release. October 18, 2017. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/

InformationOnDrugs/ApprovedDrugs/ucm581296.htm. Accessed March 31, 2018.

6. Neelapu, S.S, Locke F.L, Bartlett, L.J, et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel CAR T-Cell Therapy in Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2531-44.

7. Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel) suspension for intravenous use. Prescribing information. Kite Pharma Inc. October 2017. https://www.yescarta.com/wp-content/uploads/yescarta-pi.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2018.

An unusual case of primary cardiac prosthetic valve-associated lymphoma

Primary cardiac tumors are extremely rare neoplasms with an incidence of less than 0.4%.1-3 Primary cardiac lymphoma (PCL), the majority of which is non-Hodgkin lymphoma, accounts for around 2% of cardiac tumors and less than 0.5% of extranodal lymphomas.1,4-6 Primary lymphoma involving cardiac valves has been described in few case reports and small case series owing to its rarity.7-10 Most cases of PCL present with manifestations of congestive heart failure or cardiac arrhythmias,11 whereas primary valve-associated lymphoma (PV-AL) is usually diagnosed incidentally during valve repair or replacement. The pathophysiology remains unclear, but a few cases have been associated with Epstein Barr virus (EBV).7 Cases previously described in the literature carried an overall poor prognosis and to date there is no standardized treatment approach. We provide here an unusual case of primary prosthetic valve-associated cardiac large B-cell lymphoma, which was successfully treated with adjuvant chemotherapy after valve repair and which resulted in an excellent long-term outcome.

Case presentation and summary

The patient presented in 2012 as a 65-year-old man with a history of ascending aortic aneurysm with secondary aortic insufficiency who in 2004 had undergone composite valve replacement of the aortic valve (AV) root and ascending aorta with a St Jude Toronto root. In June 2011, he was found to have a right parietal intraparenchymal hemorrhage that was thought to be a thromboembolic hemorrhagic ischemic stroke. In March 2012, he had routine follow-up brain magnetic resonance imaging that incidentally showed a left frontal ischemic stroke with hemorrhagic conversion. In June 2012, he was found to have first degree atrioventricular block with episodic runs of supraventricular tachycardia.

In September 2012, transthoracic echocardiography was done for further evaluation of possible recurrent cryptogenic strokes. The results showed a hypo-echogenic mass within the proximal ascending aortic root, but this was not confirmed on transesophageal echocardiography. A chest computed-tomography (CT) scan was therefore performed, and it showed aneurysmal dilatation of the aortic root with an irregular marginal filling defect just above the AV suggestive of intraluminal thrombus. The patient was placed on full anticoagulation with warfarin and referred for cardiothoracic surgery to consider graft and valve replacement. However, 3 weeks later and before the surgery, the patient developed a third thromboembolic ischemic event (transient ischemic attack). The recurrent strokes were attributed to thromboembolic events secondary to prosthetic AV thrombosis.

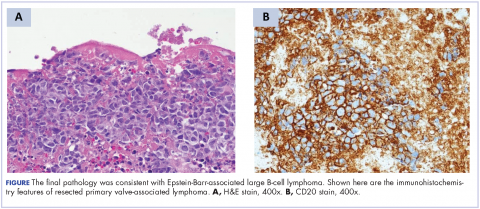

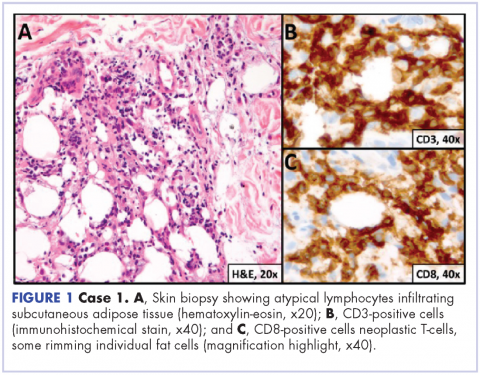

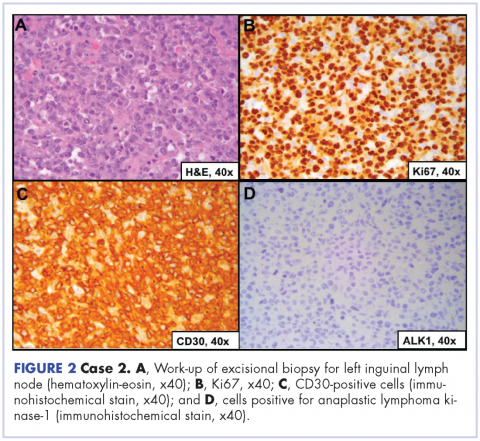

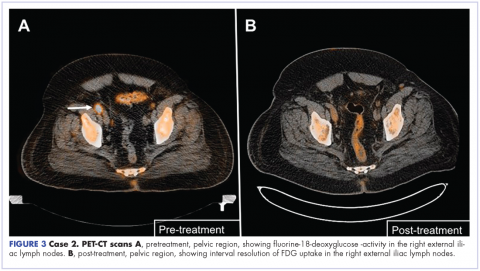

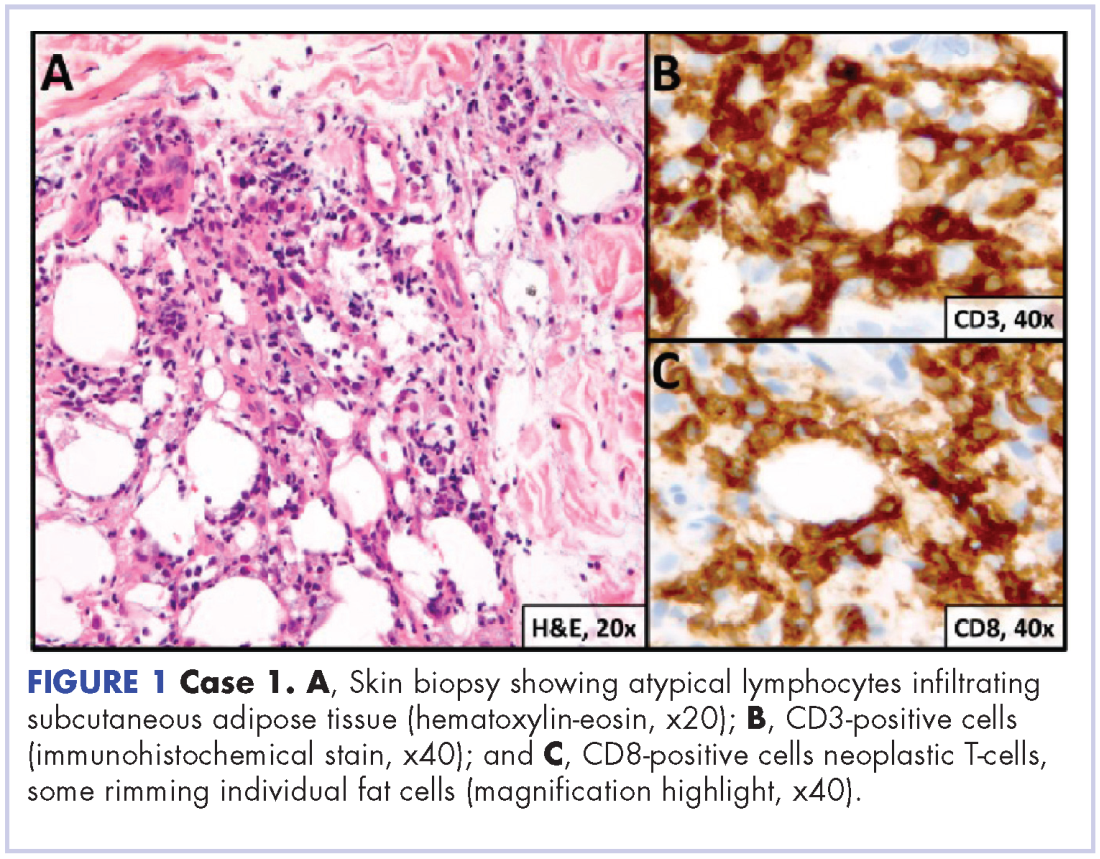

A repeat transthoracic echocardiography was significant for an abnormal AV bioprosthesis with associated thrombus extending to the ascending aorta. Surgical excision and replacement of the AV conduit explant were performed in November 2012. The final pathology was consistent with EBV-associated large B-cell lymphoma (Figure). The initial staging evaluation, including a CT and positron-emission tomography scan and bone marrow biopsy, was negative for any systemic disease. The patient received 4 cycles of R-CHOP-21 (rituximab 375 mg/m2, cyclophosphamide 750 mg/m2, doxorubicin 50 mg/m2 , vincristine 2 mg, and prednisone 100 mg) every 3 weeks in an “adjuvant” setting (because patient had no evidence of disease when given the systemic chemotherapy). The patient tolerated chemotherapy well without significant complications, and he is now over 36 months post-treatment without evidence of recurrent disease.

Discussion

Cardiac lymphoma limited only to prosthetic valves is rare, but it has been reported increasingly over the past few years. Until 2010, only six cases of PV-AL had been reported in the literature.7 Including our case, we identified four additional PubMed-indexed cases (using a PubMed search through February 2015). The patient characteristics and treatments received for all identified cases are described in the accompanying Table. The pathology from all of the cases revealed non-Hodgkin lymphoma of large B-cell subtype. PV-AL predominated among men (60%) and older patients with a median age of 62.5 years at diagnosis (range, 48-80 years). Patients had a median duration of 8 years (range, 4-24 years) from date of prosthesis placement to date of lymphoma diagnosis. The three most common presenting manifestations were valvular dysfunction, stroke, and congestive heart failure. All of the patients had surgical intervention on initial presentation. However, management after surgery was not uniform, with only 3 patients reported to have received systemic chemotherapy (Table). None of the patients received adjuvant radiation therapy. Calculated from date of diagnosis, survival duration ranged from less than a month7 to more than 36 months (as reported in our case).

The pathophysiology of PV-AL is not well understood given the rarity of the condition. Similar to other prosthetic-related neoplasms (metallic implants, breast implants),12-14 it has been hypothesized that chronic inflammation and EBV infection may play an essential role in the pathogenesis of this entity. Further, it has been suggested that Dacron, which is used in composite cardiac valve replacements, is carcinogenic and may play a role in some cases.7,15 PV-AL should be highly considered in the differential diagnosis of a suspicious prosthetic valve mass. Various imaging modalities, including echocardiography, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging have been described to have a role in the preoperative evaluation of cardiac tumors by assessing the cardiac function and defining the location and extent of the cardiac tumors.16-19

Given the rarity of this disease entity, there is no standardized approach for treatment. Surgical resection along with repair or replacement of primary involved prosthetic valve is essential for initial treatment. However, there is no consensus about the best approach for subsequent therapy. We cannot be conclusive about the optimum treatment, because of the limited number of published cases, but based on our reading of those cases, it would seem that early surgical intervention and “adjuvant” systemic therapy may have influenced prognosis. We speculate that poor outcomes in the first 6 months were most likely related to primary cardiopulmonary deterioration, whereas later poor outcomes were more likely to be attributable to recurrent lymphoma, particularly for patients who received suboptimal systemic chemotherapy treatment after surgery. All 3 patients who received chemotherapy had no evidence of recurrent disease at last follow-up. Of the 4 patients who received no chemotherapy and survived longer than 6 months (all except 1 died; Table), 2 had recurrent valve lymphoma, 1 had secondary systemic lymphoma, and 1 died of metastatic breast cancer. Those outcomes are in contrast to the 2 out of 3 patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy and who were reported to be alive at 16 and 36 months after diagnosis.

In conclusion, cardiac PV-AL is an increasingly recognized entity that warrants greater awareness among health care providers for early diagnosis and timely surgical intervention. Most of the cases are large B-cell lymphoma. Similar to patients with limited-stage DLBCL, fit patients should be highly considered for “adjuvant” systemic chemotherapy to optimize long-term outcomes. Reporting of similar cases is highly encouraged to better define this rare iatrogenic malignancy.

1. Hudzik B, Miszalski-Jamka K, Glowacki J, et al. Malignant tumors of the heart. Cancer epidemiol. 2015;39(5):665-672.

2. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Müller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC, eds. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2004.

3. Reynen K. Frequency of primary tumors of the heart. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77(1):107.

4. Neragi-Miandoab S, Kim J, Vlahakes GJ. Malignant tumours of the heart: a review of tumour type, diagnosis and therapy. Clin Oncol. 2007;19(10):748-756.

5. Butany J, Nair V, Naseemuddin A, Nair GM, Catton C, Yau T. Cardiac tumours: diagnosis and management. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(4):219-228.

6. Burke A, Virmani R. Tumors of the heart and great vessels. In: Atlas of tumor pathology, 3rd Series, Fascicle 16. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 1996.

7. Miller DV, Firchau DJ, McClure RF, Kurtin PJ, Feldman AL. Epstein-Barr virus-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma arising on cardiac prostheses. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(3):377-384.

8. Albat B, Messner-Pellenc P, Thevenet A. Surgical treatment for primary lymphoma of the heart simulating prosthetic mitral valve thrombosis. J Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;108(1):188-189.

9. Bagwan IN, Desai S, Wotherspoon A, Sheppard MN. Unusual presentation of primary cardiac lymphoma. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2009;9(1):127-129.

10. Durrleman NM, El-Hamamsy I, Demaria RG, Carrier M, Perrault LP, Albat B. Cardiac lymphoma following mitral valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79(3):1040-1042.

11. Petrich A, Cho SI, Billett H. Primary cardiac lymphoma: an analysis of presentation, treatment, and outcome patterns. Cancer. 2011;117(3):581-589.

12. Cheuk W, Chan AC, Chan JK, Lau GT, Chan VN, Yiu HH. Metallic implant-associated lymphoma: a distinct subgroup of large B-cell lymphoma related to pyothorax-associated lymphoma? Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(6):832-836.

13. Roden AC, Macon WR, Keeney GL, Myers JL, Feldman AL, Dogan A. Seroma-associated primary anaplastic large-cell lymphoma adjacent to breast implants: an indolent T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(4):455-463.

14. de Jong D, Vasmel WL, de Boer JP, et al. Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma in women with breast implants. JAMA. 2008;300(17):2030-2035.

15. Durrleman N, El Hamamsy I, Demaria R, Carrier M, Perrault LP, Albat B. Is Dacron carcinogenic? Apropos of a case and review of the literature [In French]. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 2004 Mar;97(3):267-270.16. Peters PJ, Reinhardt S. The echocardiographic evaluation of intracardiac masses: a review. J Am Soc Echocard. 2006;19(2):230-240.

17. Gulati G, Sharma S, Kothari SS, Juneja R, Saxena A, Talwar KK. Comparison of echo and MRI in the imaging evaluation of intracardiac masses. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;27(5):459-469.

18. Krombach GA, Spuentrup E, Buecker A, et al. Heart tumors: magnetic resonance imaging and multislice spiral CT [In German]. RoFo. 2005;177(9):1205-1218.

19. Hoey ET, Mankad K, Puppala S, Gopalan D, Sivananthan MU. MRI and CT appearances of cardiac tumours in adults. Clin Radiol. 2009;64(12):1214-1230.

20. Bonnichsen CR, Dearani JA, Maleszewski JJ, Colgan JP, Williamson EE, Ammash NM. Recurrent Epstein-Barr virus-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in an ascending aorta graft. Circulation. 2013;128(13):1481-1483.

21. Berrio G, Suryadevara A, Singh NK, Wesly OH. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in an aortic valve allograft. Tex Heart Inst J. 2010;37(4):492-493.

22. Gruver AM, Huba MA, Dogan A, Hsi ED. Fibrin-associated large B-cell lymphoma: part of the spectrum of cardiac lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(10):1527-1537.

23. Farah FJ, Chiles CD. Recurrent primary cardiac lymphoma on aortic valve allograft: implications for therapy. Tex Heart Inst J. 2014;41(5):543-546.

Primary cardiac tumors are extremely rare neoplasms with an incidence of less than 0.4%.1-3 Primary cardiac lymphoma (PCL), the majority of which is non-Hodgkin lymphoma, accounts for around 2% of cardiac tumors and less than 0.5% of extranodal lymphomas.1,4-6 Primary lymphoma involving cardiac valves has been described in few case reports and small case series owing to its rarity.7-10 Most cases of PCL present with manifestations of congestive heart failure or cardiac arrhythmias,11 whereas primary valve-associated lymphoma (PV-AL) is usually diagnosed incidentally during valve repair or replacement. The pathophysiology remains unclear, but a few cases have been associated with Epstein Barr virus (EBV).7 Cases previously described in the literature carried an overall poor prognosis and to date there is no standardized treatment approach. We provide here an unusual case of primary prosthetic valve-associated cardiac large B-cell lymphoma, which was successfully treated with adjuvant chemotherapy after valve repair and which resulted in an excellent long-term outcome.

Case presentation and summary

The patient presented in 2012 as a 65-year-old man with a history of ascending aortic aneurysm with secondary aortic insufficiency who in 2004 had undergone composite valve replacement of the aortic valve (AV) root and ascending aorta with a St Jude Toronto root. In June 2011, he was found to have a right parietal intraparenchymal hemorrhage that was thought to be a thromboembolic hemorrhagic ischemic stroke. In March 2012, he had routine follow-up brain magnetic resonance imaging that incidentally showed a left frontal ischemic stroke with hemorrhagic conversion. In June 2012, he was found to have first degree atrioventricular block with episodic runs of supraventricular tachycardia.

In September 2012, transthoracic echocardiography was done for further evaluation of possible recurrent cryptogenic strokes. The results showed a hypo-echogenic mass within the proximal ascending aortic root, but this was not confirmed on transesophageal echocardiography. A chest computed-tomography (CT) scan was therefore performed, and it showed aneurysmal dilatation of the aortic root with an irregular marginal filling defect just above the AV suggestive of intraluminal thrombus. The patient was placed on full anticoagulation with warfarin and referred for cardiothoracic surgery to consider graft and valve replacement. However, 3 weeks later and before the surgery, the patient developed a third thromboembolic ischemic event (transient ischemic attack). The recurrent strokes were attributed to thromboembolic events secondary to prosthetic AV thrombosis.

A repeat transthoracic echocardiography was significant for an abnormal AV bioprosthesis with associated thrombus extending to the ascending aorta. Surgical excision and replacement of the AV conduit explant were performed in November 2012. The final pathology was consistent with EBV-associated large B-cell lymphoma (Figure). The initial staging evaluation, including a CT and positron-emission tomography scan and bone marrow biopsy, was negative for any systemic disease. The patient received 4 cycles of R-CHOP-21 (rituximab 375 mg/m2, cyclophosphamide 750 mg/m2, doxorubicin 50 mg/m2 , vincristine 2 mg, and prednisone 100 mg) every 3 weeks in an “adjuvant” setting (because patient had no evidence of disease when given the systemic chemotherapy). The patient tolerated chemotherapy well without significant complications, and he is now over 36 months post-treatment without evidence of recurrent disease.

Discussion

Cardiac lymphoma limited only to prosthetic valves is rare, but it has been reported increasingly over the past few years. Until 2010, only six cases of PV-AL had been reported in the literature.7 Including our case, we identified four additional PubMed-indexed cases (using a PubMed search through February 2015). The patient characteristics and treatments received for all identified cases are described in the accompanying Table. The pathology from all of the cases revealed non-Hodgkin lymphoma of large B-cell subtype. PV-AL predominated among men (60%) and older patients with a median age of 62.5 years at diagnosis (range, 48-80 years). Patients had a median duration of 8 years (range, 4-24 years) from date of prosthesis placement to date of lymphoma diagnosis. The three most common presenting manifestations were valvular dysfunction, stroke, and congestive heart failure. All of the patients had surgical intervention on initial presentation. However, management after surgery was not uniform, with only 3 patients reported to have received systemic chemotherapy (Table). None of the patients received adjuvant radiation therapy. Calculated from date of diagnosis, survival duration ranged from less than a month7 to more than 36 months (as reported in our case).

The pathophysiology of PV-AL is not well understood given the rarity of the condition. Similar to other prosthetic-related neoplasms (metallic implants, breast implants),12-14 it has been hypothesized that chronic inflammation and EBV infection may play an essential role in the pathogenesis of this entity. Further, it has been suggested that Dacron, which is used in composite cardiac valve replacements, is carcinogenic and may play a role in some cases.7,15 PV-AL should be highly considered in the differential diagnosis of a suspicious prosthetic valve mass. Various imaging modalities, including echocardiography, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging have been described to have a role in the preoperative evaluation of cardiac tumors by assessing the cardiac function and defining the location and extent of the cardiac tumors.16-19

Given the rarity of this disease entity, there is no standardized approach for treatment. Surgical resection along with repair or replacement of primary involved prosthetic valve is essential for initial treatment. However, there is no consensus about the best approach for subsequent therapy. We cannot be conclusive about the optimum treatment, because of the limited number of published cases, but based on our reading of those cases, it would seem that early surgical intervention and “adjuvant” systemic therapy may have influenced prognosis. We speculate that poor outcomes in the first 6 months were most likely related to primary cardiopulmonary deterioration, whereas later poor outcomes were more likely to be attributable to recurrent lymphoma, particularly for patients who received suboptimal systemic chemotherapy treatment after surgery. All 3 patients who received chemotherapy had no evidence of recurrent disease at last follow-up. Of the 4 patients who received no chemotherapy and survived longer than 6 months (all except 1 died; Table), 2 had recurrent valve lymphoma, 1 had secondary systemic lymphoma, and 1 died of metastatic breast cancer. Those outcomes are in contrast to the 2 out of 3 patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy and who were reported to be alive at 16 and 36 months after diagnosis.

In conclusion, cardiac PV-AL is an increasingly recognized entity that warrants greater awareness among health care providers for early diagnosis and timely surgical intervention. Most of the cases are large B-cell lymphoma. Similar to patients with limited-stage DLBCL, fit patients should be highly considered for “adjuvant” systemic chemotherapy to optimize long-term outcomes. Reporting of similar cases is highly encouraged to better define this rare iatrogenic malignancy.

Primary cardiac tumors are extremely rare neoplasms with an incidence of less than 0.4%.1-3 Primary cardiac lymphoma (PCL), the majority of which is non-Hodgkin lymphoma, accounts for around 2% of cardiac tumors and less than 0.5% of extranodal lymphomas.1,4-6 Primary lymphoma involving cardiac valves has been described in few case reports and small case series owing to its rarity.7-10 Most cases of PCL present with manifestations of congestive heart failure or cardiac arrhythmias,11 whereas primary valve-associated lymphoma (PV-AL) is usually diagnosed incidentally during valve repair or replacement. The pathophysiology remains unclear, but a few cases have been associated with Epstein Barr virus (EBV).7 Cases previously described in the literature carried an overall poor prognosis and to date there is no standardized treatment approach. We provide here an unusual case of primary prosthetic valve-associated cardiac large B-cell lymphoma, which was successfully treated with adjuvant chemotherapy after valve repair and which resulted in an excellent long-term outcome.

Case presentation and summary

The patient presented in 2012 as a 65-year-old man with a history of ascending aortic aneurysm with secondary aortic insufficiency who in 2004 had undergone composite valve replacement of the aortic valve (AV) root and ascending aorta with a St Jude Toronto root. In June 2011, he was found to have a right parietal intraparenchymal hemorrhage that was thought to be a thromboembolic hemorrhagic ischemic stroke. In March 2012, he had routine follow-up brain magnetic resonance imaging that incidentally showed a left frontal ischemic stroke with hemorrhagic conversion. In June 2012, he was found to have first degree atrioventricular block with episodic runs of supraventricular tachycardia.

In September 2012, transthoracic echocardiography was done for further evaluation of possible recurrent cryptogenic strokes. The results showed a hypo-echogenic mass within the proximal ascending aortic root, but this was not confirmed on transesophageal echocardiography. A chest computed-tomography (CT) scan was therefore performed, and it showed aneurysmal dilatation of the aortic root with an irregular marginal filling defect just above the AV suggestive of intraluminal thrombus. The patient was placed on full anticoagulation with warfarin and referred for cardiothoracic surgery to consider graft and valve replacement. However, 3 weeks later and before the surgery, the patient developed a third thromboembolic ischemic event (transient ischemic attack). The recurrent strokes were attributed to thromboembolic events secondary to prosthetic AV thrombosis.

A repeat transthoracic echocardiography was significant for an abnormal AV bioprosthesis with associated thrombus extending to the ascending aorta. Surgical excision and replacement of the AV conduit explant were performed in November 2012. The final pathology was consistent with EBV-associated large B-cell lymphoma (Figure). The initial staging evaluation, including a CT and positron-emission tomography scan and bone marrow biopsy, was negative for any systemic disease. The patient received 4 cycles of R-CHOP-21 (rituximab 375 mg/m2, cyclophosphamide 750 mg/m2, doxorubicin 50 mg/m2 , vincristine 2 mg, and prednisone 100 mg) every 3 weeks in an “adjuvant” setting (because patient had no evidence of disease when given the systemic chemotherapy). The patient tolerated chemotherapy well without significant complications, and he is now over 36 months post-treatment without evidence of recurrent disease.

Discussion

Cardiac lymphoma limited only to prosthetic valves is rare, but it has been reported increasingly over the past few years. Until 2010, only six cases of PV-AL had been reported in the literature.7 Including our case, we identified four additional PubMed-indexed cases (using a PubMed search through February 2015). The patient characteristics and treatments received for all identified cases are described in the accompanying Table. The pathology from all of the cases revealed non-Hodgkin lymphoma of large B-cell subtype. PV-AL predominated among men (60%) and older patients with a median age of 62.5 years at diagnosis (range, 48-80 years). Patients had a median duration of 8 years (range, 4-24 years) from date of prosthesis placement to date of lymphoma diagnosis. The three most common presenting manifestations were valvular dysfunction, stroke, and congestive heart failure. All of the patients had surgical intervention on initial presentation. However, management after surgery was not uniform, with only 3 patients reported to have received systemic chemotherapy (Table). None of the patients received adjuvant radiation therapy. Calculated from date of diagnosis, survival duration ranged from less than a month7 to more than 36 months (as reported in our case).

The pathophysiology of PV-AL is not well understood given the rarity of the condition. Similar to other prosthetic-related neoplasms (metallic implants, breast implants),12-14 it has been hypothesized that chronic inflammation and EBV infection may play an essential role in the pathogenesis of this entity. Further, it has been suggested that Dacron, which is used in composite cardiac valve replacements, is carcinogenic and may play a role in some cases.7,15 PV-AL should be highly considered in the differential diagnosis of a suspicious prosthetic valve mass. Various imaging modalities, including echocardiography, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging have been described to have a role in the preoperative evaluation of cardiac tumors by assessing the cardiac function and defining the location and extent of the cardiac tumors.16-19

Given the rarity of this disease entity, there is no standardized approach for treatment. Surgical resection along with repair or replacement of primary involved prosthetic valve is essential for initial treatment. However, there is no consensus about the best approach for subsequent therapy. We cannot be conclusive about the optimum treatment, because of the limited number of published cases, but based on our reading of those cases, it would seem that early surgical intervention and “adjuvant” systemic therapy may have influenced prognosis. We speculate that poor outcomes in the first 6 months were most likely related to primary cardiopulmonary deterioration, whereas later poor outcomes were more likely to be attributable to recurrent lymphoma, particularly for patients who received suboptimal systemic chemotherapy treatment after surgery. All 3 patients who received chemotherapy had no evidence of recurrent disease at last follow-up. Of the 4 patients who received no chemotherapy and survived longer than 6 months (all except 1 died; Table), 2 had recurrent valve lymphoma, 1 had secondary systemic lymphoma, and 1 died of metastatic breast cancer. Those outcomes are in contrast to the 2 out of 3 patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy and who were reported to be alive at 16 and 36 months after diagnosis.

In conclusion, cardiac PV-AL is an increasingly recognized entity that warrants greater awareness among health care providers for early diagnosis and timely surgical intervention. Most of the cases are large B-cell lymphoma. Similar to patients with limited-stage DLBCL, fit patients should be highly considered for “adjuvant” systemic chemotherapy to optimize long-term outcomes. Reporting of similar cases is highly encouraged to better define this rare iatrogenic malignancy.

1. Hudzik B, Miszalski-Jamka K, Glowacki J, et al. Malignant tumors of the heart. Cancer epidemiol. 2015;39(5):665-672.

2. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Müller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC, eds. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2004.

3. Reynen K. Frequency of primary tumors of the heart. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77(1):107.

4. Neragi-Miandoab S, Kim J, Vlahakes GJ. Malignant tumours of the heart: a review of tumour type, diagnosis and therapy. Clin Oncol. 2007;19(10):748-756.

5. Butany J, Nair V, Naseemuddin A, Nair GM, Catton C, Yau T. Cardiac tumours: diagnosis and management. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(4):219-228.

6. Burke A, Virmani R. Tumors of the heart and great vessels. In: Atlas of tumor pathology, 3rd Series, Fascicle 16. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 1996.

7. Miller DV, Firchau DJ, McClure RF, Kurtin PJ, Feldman AL. Epstein-Barr virus-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma arising on cardiac prostheses. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(3):377-384.

8. Albat B, Messner-Pellenc P, Thevenet A. Surgical treatment for primary lymphoma of the heart simulating prosthetic mitral valve thrombosis. J Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;108(1):188-189.

9. Bagwan IN, Desai S, Wotherspoon A, Sheppard MN. Unusual presentation of primary cardiac lymphoma. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2009;9(1):127-129.

10. Durrleman NM, El-Hamamsy I, Demaria RG, Carrier M, Perrault LP, Albat B. Cardiac lymphoma following mitral valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79(3):1040-1042.

11. Petrich A, Cho SI, Billett H. Primary cardiac lymphoma: an analysis of presentation, treatment, and outcome patterns. Cancer. 2011;117(3):581-589.

12. Cheuk W, Chan AC, Chan JK, Lau GT, Chan VN, Yiu HH. Metallic implant-associated lymphoma: a distinct subgroup of large B-cell lymphoma related to pyothorax-associated lymphoma? Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(6):832-836.

13. Roden AC, Macon WR, Keeney GL, Myers JL, Feldman AL, Dogan A. Seroma-associated primary anaplastic large-cell lymphoma adjacent to breast implants: an indolent T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(4):455-463.

14. de Jong D, Vasmel WL, de Boer JP, et al. Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma in women with breast implants. JAMA. 2008;300(17):2030-2035.

15. Durrleman N, El Hamamsy I, Demaria R, Carrier M, Perrault LP, Albat B. Is Dacron carcinogenic? Apropos of a case and review of the literature [In French]. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 2004 Mar;97(3):267-270.16. Peters PJ, Reinhardt S. The echocardiographic evaluation of intracardiac masses: a review. J Am Soc Echocard. 2006;19(2):230-240.

17. Gulati G, Sharma S, Kothari SS, Juneja R, Saxena A, Talwar KK. Comparison of echo and MRI in the imaging evaluation of intracardiac masses. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;27(5):459-469.

18. Krombach GA, Spuentrup E, Buecker A, et al. Heart tumors: magnetic resonance imaging and multislice spiral CT [In German]. RoFo. 2005;177(9):1205-1218.

19. Hoey ET, Mankad K, Puppala S, Gopalan D, Sivananthan MU. MRI and CT appearances of cardiac tumours in adults. Clin Radiol. 2009;64(12):1214-1230.

20. Bonnichsen CR, Dearani JA, Maleszewski JJ, Colgan JP, Williamson EE, Ammash NM. Recurrent Epstein-Barr virus-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in an ascending aorta graft. Circulation. 2013;128(13):1481-1483.

21. Berrio G, Suryadevara A, Singh NK, Wesly OH. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in an aortic valve allograft. Tex Heart Inst J. 2010;37(4):492-493.

22. Gruver AM, Huba MA, Dogan A, Hsi ED. Fibrin-associated large B-cell lymphoma: part of the spectrum of cardiac lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(10):1527-1537.

23. Farah FJ, Chiles CD. Recurrent primary cardiac lymphoma on aortic valve allograft: implications for therapy. Tex Heart Inst J. 2014;41(5):543-546.

1. Hudzik B, Miszalski-Jamka K, Glowacki J, et al. Malignant tumors of the heart. Cancer epidemiol. 2015;39(5):665-672.

2. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Müller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC, eds. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2004.

3. Reynen K. Frequency of primary tumors of the heart. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77(1):107.

4. Neragi-Miandoab S, Kim J, Vlahakes GJ. Malignant tumours of the heart: a review of tumour type, diagnosis and therapy. Clin Oncol. 2007;19(10):748-756.

5. Butany J, Nair V, Naseemuddin A, Nair GM, Catton C, Yau T. Cardiac tumours: diagnosis and management. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(4):219-228.

6. Burke A, Virmani R. Tumors of the heart and great vessels. In: Atlas of tumor pathology, 3rd Series, Fascicle 16. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 1996.

7. Miller DV, Firchau DJ, McClure RF, Kurtin PJ, Feldman AL. Epstein-Barr virus-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma arising on cardiac prostheses. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(3):377-384.

8. Albat B, Messner-Pellenc P, Thevenet A. Surgical treatment for primary lymphoma of the heart simulating prosthetic mitral valve thrombosis. J Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;108(1):188-189.

9. Bagwan IN, Desai S, Wotherspoon A, Sheppard MN. Unusual presentation of primary cardiac lymphoma. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2009;9(1):127-129.

10. Durrleman NM, El-Hamamsy I, Demaria RG, Carrier M, Perrault LP, Albat B. Cardiac lymphoma following mitral valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79(3):1040-1042.

11. Petrich A, Cho SI, Billett H. Primary cardiac lymphoma: an analysis of presentation, treatment, and outcome patterns. Cancer. 2011;117(3):581-589.

12. Cheuk W, Chan AC, Chan JK, Lau GT, Chan VN, Yiu HH. Metallic implant-associated lymphoma: a distinct subgroup of large B-cell lymphoma related to pyothorax-associated lymphoma? Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(6):832-836.

13. Roden AC, Macon WR, Keeney GL, Myers JL, Feldman AL, Dogan A. Seroma-associated primary anaplastic large-cell lymphoma adjacent to breast implants: an indolent T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(4):455-463.

14. de Jong D, Vasmel WL, de Boer JP, et al. Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma in women with breast implants. JAMA. 2008;300(17):2030-2035.

15. Durrleman N, El Hamamsy I, Demaria R, Carrier M, Perrault LP, Albat B. Is Dacron carcinogenic? Apropos of a case and review of the literature [In French]. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 2004 Mar;97(3):267-270.16. Peters PJ, Reinhardt S. The echocardiographic evaluation of intracardiac masses: a review. J Am Soc Echocard. 2006;19(2):230-240.

17. Gulati G, Sharma S, Kothari SS, Juneja R, Saxena A, Talwar KK. Comparison of echo and MRI in the imaging evaluation of intracardiac masses. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;27(5):459-469.

18. Krombach GA, Spuentrup E, Buecker A, et al. Heart tumors: magnetic resonance imaging and multislice spiral CT [In German]. RoFo. 2005;177(9):1205-1218.

19. Hoey ET, Mankad K, Puppala S, Gopalan D, Sivananthan MU. MRI and CT appearances of cardiac tumours in adults. Clin Radiol. 2009;64(12):1214-1230.

20. Bonnichsen CR, Dearani JA, Maleszewski JJ, Colgan JP, Williamson EE, Ammash NM. Recurrent Epstein-Barr virus-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in an ascending aorta graft. Circulation. 2013;128(13):1481-1483.

21. Berrio G, Suryadevara A, Singh NK, Wesly OH. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in an aortic valve allograft. Tex Heart Inst J. 2010;37(4):492-493.

22. Gruver AM, Huba MA, Dogan A, Hsi ED. Fibrin-associated large B-cell lymphoma: part of the spectrum of cardiac lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(10):1527-1537.

23. Farah FJ, Chiles CD. Recurrent primary cardiac lymphoma on aortic valve allograft: implications for therapy. Tex Heart Inst J. 2014;41(5):543-546.

Leadership 101: Learning to trust

Dr. Ramin Yazdanfar grows into the role of medical director

Editor’s note: SHM occasionally puts the spotlight on our most active members who are making substantial contributions to hospital medicine. Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org for more information on how you can lend your expertise to help improve the care of hospitalized patients.

This month, The Hospitalist spotlights Ramin Yazdanfar, MD, hospitalist and Harrisburg (Pa.) site medical director at UPMC Pinnacle. Dr. Ramin has been a member of SHM since 2016, has attended two annual conferences as well as Leadership Academy, and together with his team received SHM’s Award of Excellence in Teamwork.

How did you learn about SHM and why did you become a member?

I first heard about SHM during my initial job out of residency. At that time, our medical director encouraged engagement in the field of hospital medicine, and he was quite involved in local meetings and national conferences. I became a member because I felt it would be a good way to connect with other hospitalists who might have been going through similar experiences and struggles, and in the hopes of gaining something I could take back to use in my daily practice.

Which SHM conferences have you attended and why?

I have attended two national conferences thus far. The first was the 2016 SHM Annual Conference in San Diego, where our hospitalist team won the Excellence in Teamwork and Quality Improvement Award for our active bed management program under Mary Ellen Pfeiffer, MD, and William “Tex” Landis, MD, among others. I also attended the 2017 Leadership Academy in Scottsdale, Ariz. As a new site director for a new hospitalist group, I thought it would be a valuable learning experience, with the goal of improving my communication as a leader. I also will be attending the 2018 SHM Leadership Academy in Vancouver. I am excited to reconnect with peers I met last year and to advance my leadership skills further.

What were the main takeaways from Leadership: Mastering Teamwork, and how have you applied them in your practice?

My most vivid and actionable memory of Leadership: Mastering Teamwork was the initial session around the five dysfunctions of a team and how to build a cohesive leadership team. Allowing ourselves to be vulnerable and open creates the foundation of trust, on which we can build everything else, such as handling conflict and creating commitment, accountability, and results. I have tried to use these principles in our own practice, at UPMC Pinnacle Health in Harrisburg, Pa. We have an ever-growing health system with an expanding regional leadership team. We base our foundation on trust in one another, and in our vision, so the rest follows suit.

As a separate takeaway, I really enjoyed sessions with Leonard Marcus, PhD, on SWARM Intelligence and Meta-Leadership. He is a very engaging speaker whom I would recommend to anyone considering the Mastering Teamwork session.

What advice do you have for early-career hospitalists looking to advance their career in hospital medicine?

My advice to early-career hospitalists is to be open to opportunity. There is so much change and development in the field of hospital medicine. While the foundation of our job is in the patient care realm, many of us find a niche that interests us. My advice is pursue it and be open to what follows, without forgetting that we do this for our patients and community.

Ms. Steele is a marketing communications specialist at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Dr. Ramin Yazdanfar grows into the role of medical director

Dr. Ramin Yazdanfar grows into the role of medical director

Editor’s note: SHM occasionally puts the spotlight on our most active members who are making substantial contributions to hospital medicine. Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org for more information on how you can lend your expertise to help improve the care of hospitalized patients.

This month, The Hospitalist spotlights Ramin Yazdanfar, MD, hospitalist and Harrisburg (Pa.) site medical director at UPMC Pinnacle. Dr. Ramin has been a member of SHM since 2016, has attended two annual conferences as well as Leadership Academy, and together with his team received SHM’s Award of Excellence in Teamwork.

How did you learn about SHM and why did you become a member?

I first heard about SHM during my initial job out of residency. At that time, our medical director encouraged engagement in the field of hospital medicine, and he was quite involved in local meetings and national conferences. I became a member because I felt it would be a good way to connect with other hospitalists who might have been going through similar experiences and struggles, and in the hopes of gaining something I could take back to use in my daily practice.

Which SHM conferences have you attended and why?

I have attended two national conferences thus far. The first was the 2016 SHM Annual Conference in San Diego, where our hospitalist team won the Excellence in Teamwork and Quality Improvement Award for our active bed management program under Mary Ellen Pfeiffer, MD, and William “Tex” Landis, MD, among others. I also attended the 2017 Leadership Academy in Scottsdale, Ariz. As a new site director for a new hospitalist group, I thought it would be a valuable learning experience, with the goal of improving my communication as a leader. I also will be attending the 2018 SHM Leadership Academy in Vancouver. I am excited to reconnect with peers I met last year and to advance my leadership skills further.

What were the main takeaways from Leadership: Mastering Teamwork, and how have you applied them in your practice?

My most vivid and actionable memory of Leadership: Mastering Teamwork was the initial session around the five dysfunctions of a team and how to build a cohesive leadership team. Allowing ourselves to be vulnerable and open creates the foundation of trust, on which we can build everything else, such as handling conflict and creating commitment, accountability, and results. I have tried to use these principles in our own practice, at UPMC Pinnacle Health in Harrisburg, Pa. We have an ever-growing health system with an expanding regional leadership team. We base our foundation on trust in one another, and in our vision, so the rest follows suit.

As a separate takeaway, I really enjoyed sessions with Leonard Marcus, PhD, on SWARM Intelligence and Meta-Leadership. He is a very engaging speaker whom I would recommend to anyone considering the Mastering Teamwork session.

What advice do you have for early-career hospitalists looking to advance their career in hospital medicine?

My advice to early-career hospitalists is to be open to opportunity. There is so much change and development in the field of hospital medicine. While the foundation of our job is in the patient care realm, many of us find a niche that interests us. My advice is pursue it and be open to what follows, without forgetting that we do this for our patients and community.

Ms. Steele is a marketing communications specialist at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s note: SHM occasionally puts the spotlight on our most active members who are making substantial contributions to hospital medicine. Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org for more information on how you can lend your expertise to help improve the care of hospitalized patients.

This month, The Hospitalist spotlights Ramin Yazdanfar, MD, hospitalist and Harrisburg (Pa.) site medical director at UPMC Pinnacle. Dr. Ramin has been a member of SHM since 2016, has attended two annual conferences as well as Leadership Academy, and together with his team received SHM’s Award of Excellence in Teamwork.

How did you learn about SHM and why did you become a member?

I first heard about SHM during my initial job out of residency. At that time, our medical director encouraged engagement in the field of hospital medicine, and he was quite involved in local meetings and national conferences. I became a member because I felt it would be a good way to connect with other hospitalists who might have been going through similar experiences and struggles, and in the hopes of gaining something I could take back to use in my daily practice.

Which SHM conferences have you attended and why?

I have attended two national conferences thus far. The first was the 2016 SHM Annual Conference in San Diego, where our hospitalist team won the Excellence in Teamwork and Quality Improvement Award for our active bed management program under Mary Ellen Pfeiffer, MD, and William “Tex” Landis, MD, among others. I also attended the 2017 Leadership Academy in Scottsdale, Ariz. As a new site director for a new hospitalist group, I thought it would be a valuable learning experience, with the goal of improving my communication as a leader. I also will be attending the 2018 SHM Leadership Academy in Vancouver. I am excited to reconnect with peers I met last year and to advance my leadership skills further.

What were the main takeaways from Leadership: Mastering Teamwork, and how have you applied them in your practice?

My most vivid and actionable memory of Leadership: Mastering Teamwork was the initial session around the five dysfunctions of a team and how to build a cohesive leadership team. Allowing ourselves to be vulnerable and open creates the foundation of trust, on which we can build everything else, such as handling conflict and creating commitment, accountability, and results. I have tried to use these principles in our own practice, at UPMC Pinnacle Health in Harrisburg, Pa. We have an ever-growing health system with an expanding regional leadership team. We base our foundation on trust in one another, and in our vision, so the rest follows suit.

As a separate takeaway, I really enjoyed sessions with Leonard Marcus, PhD, on SWARM Intelligence and Meta-Leadership. He is a very engaging speaker whom I would recommend to anyone considering the Mastering Teamwork session.

What advice do you have for early-career hospitalists looking to advance their career in hospital medicine?

My advice to early-career hospitalists is to be open to opportunity. There is so much change and development in the field of hospital medicine. While the foundation of our job is in the patient care realm, many of us find a niche that interests us. My advice is pursue it and be open to what follows, without forgetting that we do this for our patients and community.

Ms. Steele is a marketing communications specialist at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Aggressive drainage regimen may promote spontaneous pleurodesis

Compared with patients who underwent that was guided by symptoms, patients who underwent once-daily drainage had similar breathless scores but an increased rate of spontaneous pleurodesis and better quality of life scores, according to recent research published in the Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

“In patients in whom pleurodesis is an important goal (e.g., those undertaking strategies involving an indwelling pleural catheter plus pleurodesing agents), aggressive drainage should be done for at least 60 days,” Sanjeevan Muruganandan, FRACP, MBBS, from Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital in Perth, Australia, and his colleagues wrote in their study. “Future studies will need to establish if more aggressive (e.g., twice daily) regimens for the initial phase could further enhance success rates.”

Dr. Muruganandan and his colleagues evaluated 87 patients with symptomatic malignant pleural effusions between July 2015 and January 2017 from 11 centers in Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong, and Malaysia in the randomized controlled AMPLE-2 trial, in which patients received either once daily (43 patients) or symptom-guided (44 patients) drainage for 60 days with a 6-month follow-up. Patients were excluded if they had a pleural infection, were pregnant, had a previous pneumonectomy or ipsilateral lobectomy, had “significant loculations likely to preclude effective fluid drainage,” or had an estimated survival of less than 3 months. Patients were identified and grouped based on whether they had mesothelioma- or nonmesothelioma-type cancer, with cancer type being minimalized during randomization.

At 60 days, patients in the aggressive daily drainage group had a mean daily breathless score of 13.1 mm (geometric means; 95% confidence interval, 9.8-17.4), compared with a mean of 17.3 mm (95% CI, 13.0-22.0) in the symptom-guided drainage group. In the aggressive drainage group, 16 of 43 patients (37.2%) achieved spontaneous pleurodesis at 60 days, compared with 11 of 44 patients (11.4%) in the symptom-guided drainage group (P = .0049). At 6 months, 19 of 43 (44.2%) patients in the aggressive drainage group had spontaneous pleurodesis, compared with 7 of 44 patients (15.9%; P = .004) in the symptom-guided drainage group (hazard ratio, 3.287; 95% CI, 1.396-7.740; P = .0065).

In each group, the investigators noted adverse events: 11 of 43 (25.6%) patients in the aggressive drainage group and 12 of 44 patients (27.3%) in the symptom-guided drainage group reported a severe adverse event. There were no significant differences in mortality, pain scores, and hospital stay between the groups. Regarding quality of life, the investigators found patients in the aggressive drainage group reported better scores using the EuroQoL-5 Dimensions-5 Levels assessment (estimated means, 0.713; 95% CI, 0.647-0.779) than did patients in the symptom-guided group (0.601; 95% CI, 0.536-0.667), with an estimated difference in means of 0.112 (95% CI, 0.0198-0.204; P = .0174).

The investigators suggested that aggressive drainage may have some unmeasured benefits. “Daily removal of the fluid might have provided benefits in symptoms not captured with our breathlessness and pain measurements. The higher pleurodesis rate, with resultant freedom from fluid (and symptom) recurrence and of the catheter, might have contributed to the better reported quality of life. Additionally, it has been suggested that indwelling pleural catheter drainage gives patients an important sense of control when they are feeling helpless with their advancing cancer.”