User login

Central nervous system lymphoma mimicking Bell palsy

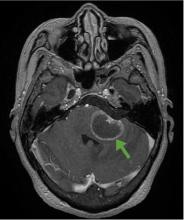

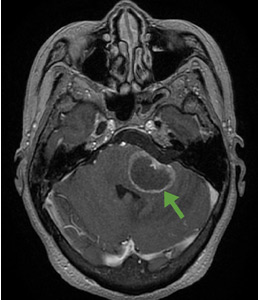

A 59-year-old woman presented with drooling out of the left side of her mouth and inability to close her left eye. She had no ear pain, hearing loss, or skin rash. The facial palsy affected all branches of the left facial nerve. This explained her inability to close her left eyelid and the generalized weakness of the left side of the face, including her forehead and angle of the mouth. No other signs of pontine dysfunction were noted.

The symptoms had begun 2 months earlier, and computed tomography (CT) of the head performed at a nearby clinic 3 days after the onset of symptoms showed no abnormalities. She was given a diagnosis of incomplete Bell palsy and was prescribed prednisolone and valacyclovir. However, her symptoms had not improved after 2 months of treatment, and so she presented to our hospital.

Physical examination revealed moderate nerve dysfunction (House-Brackmann grade III, with grade I normal and grade VI total paralysis) and generalized weakness on the left side of her face including her forehead.1 She had no loss in facial sensation or hearing and no ataxia or ocular motility disorders.

BELL PALSY

Peripheral facial nerve palsy is classified either as Bell palsy, which is idiopathic, or as secondary facial nerve palsy. Because Bell palsy accounts for 60% to 70% of all cases,2 treatment with oral steroids is indicated when no abnormal findings other than lateral peripheral facial nerve palsy are observed. Antiviral drugs may provide added benefit, although academic societies do not currently recommend combined therapy.3 However, 85% of patients with Bell palsy improve within 3 weeks without treatment, and 94% of patients with incomplete Bell palsy—defined by normal to severe dysfunction, ie, not total paralysis, based on House-Brackmann score—eventually achieve complete remission.2

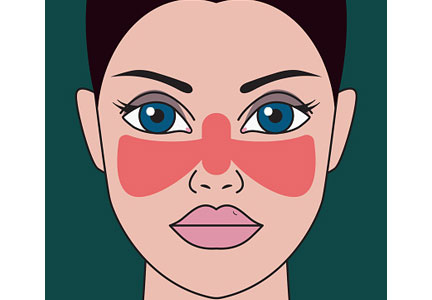

Therefore, although progression of symptoms or lack of improvement at 2 months does not rule out Bell palsy, it should prompt a detailed imaging evaluation to rule out an underlying condition such as tumor (in the pons, cerebellopontine angle, parotid gland, middle ear, or petrosal bone), infection (herpes simplex, varicella zoster, Ramsey-Hunt syndrome, or otitis media), trauma, or systemic disease (diabetes mellitus, multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, or systemic lupus erythematosus).4

According to a review of common causes of facial nerve palsy, the most common finding in 224 patients misdiagnosed with Bell palsy was tumor (38%).5 This indicates the value of magnetic resonance imaging of the head rather than CT when secondary facial nerve palsy is suspected, as CT is not sensitive to brainstem lesions.

- House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck 1985; 93(2):146–147. doi:10.1177/019459988509300202

- Peitersen E. Bell’s palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 2002; suppl 549:4–30. pmid:12482166

- De Almeida JR, Al Khabori M, Guyatt GH, et al. Combined corticosteroid and antiviral treatment for Bell palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2009; 302(9):985–993. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1243

- Alaani A, Hogg R, Saravanappa N, Irving RM. An analysis of diagnostic delay in unilateral facial paralysis. J Laryngol Otol 2005; 119(3):184–188. pmid:15845188

- May M, Klein SR. Differential diagnosis of facial nerve palsy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1991; 24(3):613–645. pmid:1762779

A 59-year-old woman presented with drooling out of the left side of her mouth and inability to close her left eye. She had no ear pain, hearing loss, or skin rash. The facial palsy affected all branches of the left facial nerve. This explained her inability to close her left eyelid and the generalized weakness of the left side of the face, including her forehead and angle of the mouth. No other signs of pontine dysfunction were noted.

The symptoms had begun 2 months earlier, and computed tomography (CT) of the head performed at a nearby clinic 3 days after the onset of symptoms showed no abnormalities. She was given a diagnosis of incomplete Bell palsy and was prescribed prednisolone and valacyclovir. However, her symptoms had not improved after 2 months of treatment, and so she presented to our hospital.

Physical examination revealed moderate nerve dysfunction (House-Brackmann grade III, with grade I normal and grade VI total paralysis) and generalized weakness on the left side of her face including her forehead.1 She had no loss in facial sensation or hearing and no ataxia or ocular motility disorders.

BELL PALSY

Peripheral facial nerve palsy is classified either as Bell palsy, which is idiopathic, or as secondary facial nerve palsy. Because Bell palsy accounts for 60% to 70% of all cases,2 treatment with oral steroids is indicated when no abnormal findings other than lateral peripheral facial nerve palsy are observed. Antiviral drugs may provide added benefit, although academic societies do not currently recommend combined therapy.3 However, 85% of patients with Bell palsy improve within 3 weeks without treatment, and 94% of patients with incomplete Bell palsy—defined by normal to severe dysfunction, ie, not total paralysis, based on House-Brackmann score—eventually achieve complete remission.2

Therefore, although progression of symptoms or lack of improvement at 2 months does not rule out Bell palsy, it should prompt a detailed imaging evaluation to rule out an underlying condition such as tumor (in the pons, cerebellopontine angle, parotid gland, middle ear, or petrosal bone), infection (herpes simplex, varicella zoster, Ramsey-Hunt syndrome, or otitis media), trauma, or systemic disease (diabetes mellitus, multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, or systemic lupus erythematosus).4

According to a review of common causes of facial nerve palsy, the most common finding in 224 patients misdiagnosed with Bell palsy was tumor (38%).5 This indicates the value of magnetic resonance imaging of the head rather than CT when secondary facial nerve palsy is suspected, as CT is not sensitive to brainstem lesions.

A 59-year-old woman presented with drooling out of the left side of her mouth and inability to close her left eye. She had no ear pain, hearing loss, or skin rash. The facial palsy affected all branches of the left facial nerve. This explained her inability to close her left eyelid and the generalized weakness of the left side of the face, including her forehead and angle of the mouth. No other signs of pontine dysfunction were noted.

The symptoms had begun 2 months earlier, and computed tomography (CT) of the head performed at a nearby clinic 3 days after the onset of symptoms showed no abnormalities. She was given a diagnosis of incomplete Bell palsy and was prescribed prednisolone and valacyclovir. However, her symptoms had not improved after 2 months of treatment, and so she presented to our hospital.

Physical examination revealed moderate nerve dysfunction (House-Brackmann grade III, with grade I normal and grade VI total paralysis) and generalized weakness on the left side of her face including her forehead.1 She had no loss in facial sensation or hearing and no ataxia or ocular motility disorders.

BELL PALSY

Peripheral facial nerve palsy is classified either as Bell palsy, which is idiopathic, or as secondary facial nerve palsy. Because Bell palsy accounts for 60% to 70% of all cases,2 treatment with oral steroids is indicated when no abnormal findings other than lateral peripheral facial nerve palsy are observed. Antiviral drugs may provide added benefit, although academic societies do not currently recommend combined therapy.3 However, 85% of patients with Bell palsy improve within 3 weeks without treatment, and 94% of patients with incomplete Bell palsy—defined by normal to severe dysfunction, ie, not total paralysis, based on House-Brackmann score—eventually achieve complete remission.2

Therefore, although progression of symptoms or lack of improvement at 2 months does not rule out Bell palsy, it should prompt a detailed imaging evaluation to rule out an underlying condition such as tumor (in the pons, cerebellopontine angle, parotid gland, middle ear, or petrosal bone), infection (herpes simplex, varicella zoster, Ramsey-Hunt syndrome, or otitis media), trauma, or systemic disease (diabetes mellitus, multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, or systemic lupus erythematosus).4

According to a review of common causes of facial nerve palsy, the most common finding in 224 patients misdiagnosed with Bell palsy was tumor (38%).5 This indicates the value of magnetic resonance imaging of the head rather than CT when secondary facial nerve palsy is suspected, as CT is not sensitive to brainstem lesions.

- House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck 1985; 93(2):146–147. doi:10.1177/019459988509300202

- Peitersen E. Bell’s palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 2002; suppl 549:4–30. pmid:12482166

- De Almeida JR, Al Khabori M, Guyatt GH, et al. Combined corticosteroid and antiviral treatment for Bell palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2009; 302(9):985–993. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1243

- Alaani A, Hogg R, Saravanappa N, Irving RM. An analysis of diagnostic delay in unilateral facial paralysis. J Laryngol Otol 2005; 119(3):184–188. pmid:15845188

- May M, Klein SR. Differential diagnosis of facial nerve palsy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1991; 24(3):613–645. pmid:1762779

- House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck 1985; 93(2):146–147. doi:10.1177/019459988509300202

- Peitersen E. Bell’s palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 2002; suppl 549:4–30. pmid:12482166

- De Almeida JR, Al Khabori M, Guyatt GH, et al. Combined corticosteroid and antiviral treatment for Bell palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2009; 302(9):985–993. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1243

- Alaani A, Hogg R, Saravanappa N, Irving RM. An analysis of diagnostic delay in unilateral facial paralysis. J Laryngol Otol 2005; 119(3):184–188. pmid:15845188

- May M, Klein SR. Differential diagnosis of facial nerve palsy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1991; 24(3):613–645. pmid:1762779

Is a detailed neurologic physical examination always necessary?

The article in this issue by Shikino et al1 on a mimic of Bell palsy gives us an opportunity to discuss the question posed by the title of this editorial. The obvious short answer is “no.”

Any experienced clinician will acknowledge that the extent of the physical examination and the extent of information obtained during the history should be determined by the problem being evaluated at the time and by the setting in which it takes place. The difficulty, of course, is that this relies on the judgment of the clinician, and this may or may not pass the test of hindsight.

Verghese et al2 have eloquently emphasized the hazards of an incomplete or inadequate physical examination. Their study was not designed to determine the prevalence of deficient physical examination, either in its extent or its accuracy. Their purpose was to promote the necessity of proper teaching and performance of examination technique.

The neurologic examination is one of the last bastions of physical assessment.3 Despite remarkable advances in imaging and physiologic techniques, the neurologic physical assessment remains critical for diagnosis and management of the neurologic patient. One of my mentors in neurology used to urge residents to examine patients and record the results of the examination as if every patient would subsequently be the subject of a clinicopathologic conference. Anyone who has reviewed a case for a conference or a case report can identify with that sentiment, wishing that some missing piece of information were available. Yet everyone also recognizes the difficulties, if not the impossibility, of achieving that ideal result.

But recording information obtained during the history or physical examination is important even in the course of a daily routine evaluation. I find myself wishing that a previous examiner had commented on whether the muscle stretch reflexes were somewhat hypoactive (eg, “1+”) or on the brisk side (“3+”) rather than “physiologic.” Was the right leg actually globally weak (“4/5”), or was there a discrepancy between proximal and distal muscles or between the physiologic flexors and the extensors?

This can make a big difference in following a patient’s neurologic progress, even over a short time span. It might tell us whether we are dealing with weakness from a peripheral neuromuscular disorder (eg, Guillain-Barré syndrome) or from a myelopathy due to impending spinal cord compression.

It should be mentioned that although Guillain-Barré syndrome is characterized as an ascending paralysis, ie, beginning distally and spreading rostrally, it is one of the few peripheral neuropathies that can present with predominant proximal weakness. It is, in fact, a radiculoneuropathy. But spinal cord (upper motor neuron) disorders preferentially weaken the physiologic flexors of the lower limbs (hamstrings and ankle dorsiflexors), leading to the characteristic extensor posture of the spastic leg. Other findings that can help differential peripheral vs spinal cord disorders include distal sensory loss and hypoactive or absent muscle stretch reflexes in a peripheral neuropathy, compared with dissociated sensory loss (eg, impaired pain and temperature sensation in one leg with reduced vibration perception and proprioception in the other) along with hyperreflexia with cord lesions.

Therefore, a careful neurologic examination may tell us whether magnetic resonance imaging of the spine or an electrodiagnostic study should be the next step.

Shikino et al describe a patient who presented with what looked like idiopathic facial palsy (Bell palsy) but turned out to be the result of a primary central nervous system (CNS) cause. Would a more detailed neurologic examination have identified this as a CNS disorder? Would more specific information about the degree and distribution of facial paresis have facilitated earlier recognition of a progressive process, making idiopathic facial palsy less likely? How much elevation of the eyebrow occurred with voluntary activation, how many millimeters of sclera were visible with gentle eyelid closure? How much space remained between the lips on attempted lip closure?

Upper facial muscle weakness is typically not seen in CNS disorders, although facial nerve or nucleus involvement at the pontine level can impair eyelid and frontalis function. Such lesions would usually be accompanied by “neighborhood” signs such as subtle ipsilateral lateral rectus or abducens palsy, involvement of the vestibular nuclei with vertigo, or facial sensory impairment from disruption of the descending trigeminal nucleus and tract. These would be “pertinent negatives” for excluding a brainstem lesion, and ipsilateral motor, sensory, or “higher cortical” functions would obviously signal a supratentorial CNS disorder.

In the case described by Shikino et al, observation and recording of the amount of facial motor function at the initial visit, 3 days after onset, could facilitate recognition of an aberrant course even a few days later and prompt further investigation at an early follow-up visit (idiopathic palsy is almost invariably maximal by 72 hours). I would assume that no additional clinical information was available to the subsequent examiner in this case, 2 months later, rather than suggesting that such information was omitted for the sake of parsimony.

Would any of this have made a difference? Probably not, but we need all the help we can get in medicine. Remember that every bit of information you obtain from your history or physical examination that you do not record disappears with you and is irretrievably lost.

- Shikino K, Suzuki S, Uehara T, Ikusaka M. Primary central nervous system lymphoma mimicking Bell palsy. Cleve Clin J Med 2018: 85(6)442–443. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17061

- Verghese A, Charlton B, Kassirer JP, Ramsey M, Ioannidis JP. Inadequacies of physical examination as a cause of medical errors and adverse events: a collection of vignettes. Am J Med 2015; 128(12):1322–1324.e3. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.06.004

- Berger JR. Neurologists: the last bedside physician-scientists. JAMA Neurol 2013; 70(8):965–966. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.2977

The article in this issue by Shikino et al1 on a mimic of Bell palsy gives us an opportunity to discuss the question posed by the title of this editorial. The obvious short answer is “no.”

Any experienced clinician will acknowledge that the extent of the physical examination and the extent of information obtained during the history should be determined by the problem being evaluated at the time and by the setting in which it takes place. The difficulty, of course, is that this relies on the judgment of the clinician, and this may or may not pass the test of hindsight.

Verghese et al2 have eloquently emphasized the hazards of an incomplete or inadequate physical examination. Their study was not designed to determine the prevalence of deficient physical examination, either in its extent or its accuracy. Their purpose was to promote the necessity of proper teaching and performance of examination technique.

The neurologic examination is one of the last bastions of physical assessment.3 Despite remarkable advances in imaging and physiologic techniques, the neurologic physical assessment remains critical for diagnosis and management of the neurologic patient. One of my mentors in neurology used to urge residents to examine patients and record the results of the examination as if every patient would subsequently be the subject of a clinicopathologic conference. Anyone who has reviewed a case for a conference or a case report can identify with that sentiment, wishing that some missing piece of information were available. Yet everyone also recognizes the difficulties, if not the impossibility, of achieving that ideal result.

But recording information obtained during the history or physical examination is important even in the course of a daily routine evaluation. I find myself wishing that a previous examiner had commented on whether the muscle stretch reflexes were somewhat hypoactive (eg, “1+”) or on the brisk side (“3+”) rather than “physiologic.” Was the right leg actually globally weak (“4/5”), or was there a discrepancy between proximal and distal muscles or between the physiologic flexors and the extensors?

This can make a big difference in following a patient’s neurologic progress, even over a short time span. It might tell us whether we are dealing with weakness from a peripheral neuromuscular disorder (eg, Guillain-Barré syndrome) or from a myelopathy due to impending spinal cord compression.

It should be mentioned that although Guillain-Barré syndrome is characterized as an ascending paralysis, ie, beginning distally and spreading rostrally, it is one of the few peripheral neuropathies that can present with predominant proximal weakness. It is, in fact, a radiculoneuropathy. But spinal cord (upper motor neuron) disorders preferentially weaken the physiologic flexors of the lower limbs (hamstrings and ankle dorsiflexors), leading to the characteristic extensor posture of the spastic leg. Other findings that can help differential peripheral vs spinal cord disorders include distal sensory loss and hypoactive or absent muscle stretch reflexes in a peripheral neuropathy, compared with dissociated sensory loss (eg, impaired pain and temperature sensation in one leg with reduced vibration perception and proprioception in the other) along with hyperreflexia with cord lesions.

Therefore, a careful neurologic examination may tell us whether magnetic resonance imaging of the spine or an electrodiagnostic study should be the next step.

Shikino et al describe a patient who presented with what looked like idiopathic facial palsy (Bell palsy) but turned out to be the result of a primary central nervous system (CNS) cause. Would a more detailed neurologic examination have identified this as a CNS disorder? Would more specific information about the degree and distribution of facial paresis have facilitated earlier recognition of a progressive process, making idiopathic facial palsy less likely? How much elevation of the eyebrow occurred with voluntary activation, how many millimeters of sclera were visible with gentle eyelid closure? How much space remained between the lips on attempted lip closure?

Upper facial muscle weakness is typically not seen in CNS disorders, although facial nerve or nucleus involvement at the pontine level can impair eyelid and frontalis function. Such lesions would usually be accompanied by “neighborhood” signs such as subtle ipsilateral lateral rectus or abducens palsy, involvement of the vestibular nuclei with vertigo, or facial sensory impairment from disruption of the descending trigeminal nucleus and tract. These would be “pertinent negatives” for excluding a brainstem lesion, and ipsilateral motor, sensory, or “higher cortical” functions would obviously signal a supratentorial CNS disorder.

In the case described by Shikino et al, observation and recording of the amount of facial motor function at the initial visit, 3 days after onset, could facilitate recognition of an aberrant course even a few days later and prompt further investigation at an early follow-up visit (idiopathic palsy is almost invariably maximal by 72 hours). I would assume that no additional clinical information was available to the subsequent examiner in this case, 2 months later, rather than suggesting that such information was omitted for the sake of parsimony.

Would any of this have made a difference? Probably not, but we need all the help we can get in medicine. Remember that every bit of information you obtain from your history or physical examination that you do not record disappears with you and is irretrievably lost.

The article in this issue by Shikino et al1 on a mimic of Bell palsy gives us an opportunity to discuss the question posed by the title of this editorial. The obvious short answer is “no.”

Any experienced clinician will acknowledge that the extent of the physical examination and the extent of information obtained during the history should be determined by the problem being evaluated at the time and by the setting in which it takes place. The difficulty, of course, is that this relies on the judgment of the clinician, and this may or may not pass the test of hindsight.

Verghese et al2 have eloquently emphasized the hazards of an incomplete or inadequate physical examination. Their study was not designed to determine the prevalence of deficient physical examination, either in its extent or its accuracy. Their purpose was to promote the necessity of proper teaching and performance of examination technique.

The neurologic examination is one of the last bastions of physical assessment.3 Despite remarkable advances in imaging and physiologic techniques, the neurologic physical assessment remains critical for diagnosis and management of the neurologic patient. One of my mentors in neurology used to urge residents to examine patients and record the results of the examination as if every patient would subsequently be the subject of a clinicopathologic conference. Anyone who has reviewed a case for a conference or a case report can identify with that sentiment, wishing that some missing piece of information were available. Yet everyone also recognizes the difficulties, if not the impossibility, of achieving that ideal result.

But recording information obtained during the history or physical examination is important even in the course of a daily routine evaluation. I find myself wishing that a previous examiner had commented on whether the muscle stretch reflexes were somewhat hypoactive (eg, “1+”) or on the brisk side (“3+”) rather than “physiologic.” Was the right leg actually globally weak (“4/5”), or was there a discrepancy between proximal and distal muscles or between the physiologic flexors and the extensors?

This can make a big difference in following a patient’s neurologic progress, even over a short time span. It might tell us whether we are dealing with weakness from a peripheral neuromuscular disorder (eg, Guillain-Barré syndrome) or from a myelopathy due to impending spinal cord compression.

It should be mentioned that although Guillain-Barré syndrome is characterized as an ascending paralysis, ie, beginning distally and spreading rostrally, it is one of the few peripheral neuropathies that can present with predominant proximal weakness. It is, in fact, a radiculoneuropathy. But spinal cord (upper motor neuron) disorders preferentially weaken the physiologic flexors of the lower limbs (hamstrings and ankle dorsiflexors), leading to the characteristic extensor posture of the spastic leg. Other findings that can help differential peripheral vs spinal cord disorders include distal sensory loss and hypoactive or absent muscle stretch reflexes in a peripheral neuropathy, compared with dissociated sensory loss (eg, impaired pain and temperature sensation in one leg with reduced vibration perception and proprioception in the other) along with hyperreflexia with cord lesions.

Therefore, a careful neurologic examination may tell us whether magnetic resonance imaging of the spine or an electrodiagnostic study should be the next step.

Shikino et al describe a patient who presented with what looked like idiopathic facial palsy (Bell palsy) but turned out to be the result of a primary central nervous system (CNS) cause. Would a more detailed neurologic examination have identified this as a CNS disorder? Would more specific information about the degree and distribution of facial paresis have facilitated earlier recognition of a progressive process, making idiopathic facial palsy less likely? How much elevation of the eyebrow occurred with voluntary activation, how many millimeters of sclera were visible with gentle eyelid closure? How much space remained between the lips on attempted lip closure?

Upper facial muscle weakness is typically not seen in CNS disorders, although facial nerve or nucleus involvement at the pontine level can impair eyelid and frontalis function. Such lesions would usually be accompanied by “neighborhood” signs such as subtle ipsilateral lateral rectus or abducens palsy, involvement of the vestibular nuclei with vertigo, or facial sensory impairment from disruption of the descending trigeminal nucleus and tract. These would be “pertinent negatives” for excluding a brainstem lesion, and ipsilateral motor, sensory, or “higher cortical” functions would obviously signal a supratentorial CNS disorder.

In the case described by Shikino et al, observation and recording of the amount of facial motor function at the initial visit, 3 days after onset, could facilitate recognition of an aberrant course even a few days later and prompt further investigation at an early follow-up visit (idiopathic palsy is almost invariably maximal by 72 hours). I would assume that no additional clinical information was available to the subsequent examiner in this case, 2 months later, rather than suggesting that such information was omitted for the sake of parsimony.

Would any of this have made a difference? Probably not, but we need all the help we can get in medicine. Remember that every bit of information you obtain from your history or physical examination that you do not record disappears with you and is irretrievably lost.

- Shikino K, Suzuki S, Uehara T, Ikusaka M. Primary central nervous system lymphoma mimicking Bell palsy. Cleve Clin J Med 2018: 85(6)442–443. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17061

- Verghese A, Charlton B, Kassirer JP, Ramsey M, Ioannidis JP. Inadequacies of physical examination as a cause of medical errors and adverse events: a collection of vignettes. Am J Med 2015; 128(12):1322–1324.e3. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.06.004

- Berger JR. Neurologists: the last bedside physician-scientists. JAMA Neurol 2013; 70(8):965–966. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.2977

- Shikino K, Suzuki S, Uehara T, Ikusaka M. Primary central nervous system lymphoma mimicking Bell palsy. Cleve Clin J Med 2018: 85(6)442–443. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17061

- Verghese A, Charlton B, Kassirer JP, Ramsey M, Ioannidis JP. Inadequacies of physical examination as a cause of medical errors and adverse events: a collection of vignettes. Am J Med 2015; 128(12):1322–1324.e3. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.06.004

- Berger JR. Neurologists: the last bedside physician-scientists. JAMA Neurol 2013; 70(8):965–966. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.2977

Necrotizing fasciitis after a watercraft accident

A 57-year-old man was transferred to our hospital with leg pain and confusion. His family reported that he had injured his leg while launching a motorized personal watercraft at the North Carolina seashore 2 days before. He had a history of cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis C and alcohol abuse.

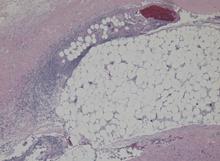

Blood and wound cultures eventually grew V vulnificus, and surgical pathology confirmed the diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis (Figure 2).

RISE IN V VULNIFICUS INFECTIONS IS ATTRIBUTED TO GLOBAL WARMING

V vulnificus infection occurs most commonly from consuming raw shellfish, especially oysters, but it also occurs after exposure of an open wound to contaminated salt water. The pathogen is a gram-negative bacterium that resides in coastal waters worldwide, but in the United States it is usually seen on the Pacific and Gulf coasts1 during the summer.2

Although only 58 cases of V vulnificus infection were reported to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 1997, the number more than doubled to 124 in 2014.1 This rise is suspected to be due in part to warmer coastal waters associated with global warming.2

Various marine pathogens can cause wound infections, but V vulnificus is most commonly implicated in deaths and hospitalizations.2 Immunocompromised patients and those with liver disease are at particularly high risk of rapid progression to septic shock.

First-line antibiotics are doxycycline plus a third-generation cephalosporin.3 Studies have shown a direct correlation between delay of antibiotics and death,4 and early surgery is critical.5

Given the rising incidence of V vulnificus infection, it is increasingly important for providers across the United States to be aware of this infection.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National enteric disease surveillance: COVIS annual summary, 2014. US Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA. 2014. www.cdc.gov/nationalsurveillance/pdfs/covis-annual-summary-2014-508c.pdf. Accessed May 8, 2018.

- Newton A, Kendall M, Vugia DJ, Henao OL, Mahon BE. Increasing rates of vibriosis in the United States, 1996–2010: review of surveillance data from 2 systems. Clinl Infect Dis 2012; 54(suppl 5):S391–S395. doi:10.1093/cid/cis243

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59(2):147-159. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu444

- Klontz KC, Lieb S, Schreiber M, Janowski HT, Baldy LM, Gunn RA. Syndromes of Vibrio vulnificus infections. Clinical and epidemiologic features in Florida cases, 1981-1987. Ann Intern Med 1988; 109:318–323. pmid:3260760

- Chao WN, Tsai CF, Chang HR, et al. Impact of timing of surgery on outcome of Vibrio vulnificus-related necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Surg 2013; 206(1):32–39. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.08.008

A 57-year-old man was transferred to our hospital with leg pain and confusion. His family reported that he had injured his leg while launching a motorized personal watercraft at the North Carolina seashore 2 days before. He had a history of cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis C and alcohol abuse.

Blood and wound cultures eventually grew V vulnificus, and surgical pathology confirmed the diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis (Figure 2).

RISE IN V VULNIFICUS INFECTIONS IS ATTRIBUTED TO GLOBAL WARMING

V vulnificus infection occurs most commonly from consuming raw shellfish, especially oysters, but it also occurs after exposure of an open wound to contaminated salt water. The pathogen is a gram-negative bacterium that resides in coastal waters worldwide, but in the United States it is usually seen on the Pacific and Gulf coasts1 during the summer.2

Although only 58 cases of V vulnificus infection were reported to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 1997, the number more than doubled to 124 in 2014.1 This rise is suspected to be due in part to warmer coastal waters associated with global warming.2

Various marine pathogens can cause wound infections, but V vulnificus is most commonly implicated in deaths and hospitalizations.2 Immunocompromised patients and those with liver disease are at particularly high risk of rapid progression to septic shock.

First-line antibiotics are doxycycline plus a third-generation cephalosporin.3 Studies have shown a direct correlation between delay of antibiotics and death,4 and early surgery is critical.5

Given the rising incidence of V vulnificus infection, it is increasingly important for providers across the United States to be aware of this infection.

A 57-year-old man was transferred to our hospital with leg pain and confusion. His family reported that he had injured his leg while launching a motorized personal watercraft at the North Carolina seashore 2 days before. He had a history of cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis C and alcohol abuse.

Blood and wound cultures eventually grew V vulnificus, and surgical pathology confirmed the diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis (Figure 2).

RISE IN V VULNIFICUS INFECTIONS IS ATTRIBUTED TO GLOBAL WARMING

V vulnificus infection occurs most commonly from consuming raw shellfish, especially oysters, but it also occurs after exposure of an open wound to contaminated salt water. The pathogen is a gram-negative bacterium that resides in coastal waters worldwide, but in the United States it is usually seen on the Pacific and Gulf coasts1 during the summer.2

Although only 58 cases of V vulnificus infection were reported to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 1997, the number more than doubled to 124 in 2014.1 This rise is suspected to be due in part to warmer coastal waters associated with global warming.2

Various marine pathogens can cause wound infections, but V vulnificus is most commonly implicated in deaths and hospitalizations.2 Immunocompromised patients and those with liver disease are at particularly high risk of rapid progression to septic shock.

First-line antibiotics are doxycycline plus a third-generation cephalosporin.3 Studies have shown a direct correlation between delay of antibiotics and death,4 and early surgery is critical.5

Given the rising incidence of V vulnificus infection, it is increasingly important for providers across the United States to be aware of this infection.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National enteric disease surveillance: COVIS annual summary, 2014. US Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA. 2014. www.cdc.gov/nationalsurveillance/pdfs/covis-annual-summary-2014-508c.pdf. Accessed May 8, 2018.

- Newton A, Kendall M, Vugia DJ, Henao OL, Mahon BE. Increasing rates of vibriosis in the United States, 1996–2010: review of surveillance data from 2 systems. Clinl Infect Dis 2012; 54(suppl 5):S391–S395. doi:10.1093/cid/cis243

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59(2):147-159. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu444

- Klontz KC, Lieb S, Schreiber M, Janowski HT, Baldy LM, Gunn RA. Syndromes of Vibrio vulnificus infections. Clinical and epidemiologic features in Florida cases, 1981-1987. Ann Intern Med 1988; 109:318–323. pmid:3260760

- Chao WN, Tsai CF, Chang HR, et al. Impact of timing of surgery on outcome of Vibrio vulnificus-related necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Surg 2013; 206(1):32–39. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.08.008

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National enteric disease surveillance: COVIS annual summary, 2014. US Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA. 2014. www.cdc.gov/nationalsurveillance/pdfs/covis-annual-summary-2014-508c.pdf. Accessed May 8, 2018.

- Newton A, Kendall M, Vugia DJ, Henao OL, Mahon BE. Increasing rates of vibriosis in the United States, 1996–2010: review of surveillance data from 2 systems. Clinl Infect Dis 2012; 54(suppl 5):S391–S395. doi:10.1093/cid/cis243

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59(2):147-159. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu444

- Klontz KC, Lieb S, Schreiber M, Janowski HT, Baldy LM, Gunn RA. Syndromes of Vibrio vulnificus infections. Clinical and epidemiologic features in Florida cases, 1981-1987. Ann Intern Med 1988; 109:318–323. pmid:3260760

- Chao WN, Tsai CF, Chang HR, et al. Impact of timing of surgery on outcome of Vibrio vulnificus-related necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Surg 2013; 206(1):32–39. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.08.008

Reverse T3 or perverse T3? Still puzzling after 40 years

Four decades after reverse T3 (3,3´5´-triiodothyronine) was discovered, its physiologic and clinical relevance remains unclear and is still being studied. But scientific uncertainty has not stopped writers in the consumer press and on the Internet from making unsubstantiated claims about this hormone. Many patients believe their hypothyroid symptoms are due to high levels of reverse T3 and want to be tested for it, and some even bring in test results from independent laboratories.

HOW THYROID HORMONES WERE DISCOVERED

In 1970, Braverman et al9 showed that T4 is converted to T3 in athyreotic humans, and Sterling et al10 demonstrated the same in healthy humans. During that decade, techniques for measuring T4 were refined,11 and a specific radioimmunoassay for reverse T3 allowed a glimpse of its physiologic role.12 In 1975, Chopra et al13 noted reciprocal changes in the levels of T3 and reverse T3 in systemic illnesses—ie, when people are sick, their T3 levels go down and their reverse T3 levels go up.

The end of the 70s was marked by a surge of interest in T4 metabolites, including the development of a radioimmunoassay for 3,3´-diiodothyronine (3-3´ T2).18

The observed reciprocal changes in serum levels of T3 and reverse T3 suggested that T4 degradation is regulated into activating (T3) or inactivating (reverse T3) pathways, and that these changes are a presumed homeostatic process of energy conservation.19

HOW THYROID HORMONES ARE METABOLIZED

In the thyroid gland, for thyroid hormones to be synthesized, iodide must be oxidized and incorporated into the precursors 3-monoiodotyrosine (MIT) and 3,5-diiodotyrosine (DIT). This process is mediated by the enzyme thyroid peroxidase in the presence of hydrogen peroxide.20

The thyroid can make T4 and some T3

T4 is the main iodothyronine produced by the thyroid gland, at a rate of 80 to 100 µg per day.21 It is synthesized from the fusion of 2 DIT molecules.

The thyroid can also make T3 by fusing 1 DIT and 1 MIT molecule, but this process accounts for no more than 20% of the circulating T3 in humans. The rest of T3, and 95% to 98% of all reverse T3, is derived from peripheral conversion of T4 through deiodination.

T4 is converted to T3 or reverse T3

The metabolic transformation of thyroid hormones in peripheral tissues determines their biologic potency and regulates their biologic effects.

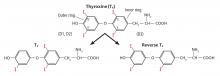

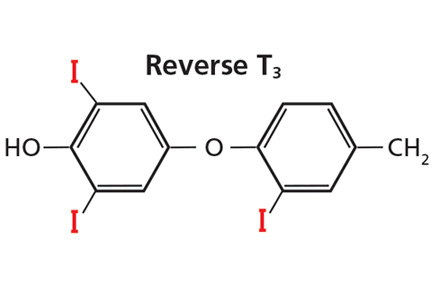

The number 4 in T4 means it has 4 iodine atoms. It can lose 1 of them, yielding either T3 or reverse T3, depending on which iodine atom it loses (Figure 3). Loss of iodine from the five-prime (5´) position on its outer ring yields T3, the most potent thyroid hormone, produced at a rate of 30 to 40 µg per day.21 On the other hand, when T4 loses an iodine atom from the five (5) position on its inner ring it yields reverse T3, produced at a rate slightly less than that of T3, 28 to 40 µg per day.21 Reverse T3 is inactive.

Both T3 and reverse T3 can shed more iodine atoms, forming in turn various isomers of T2, T1, and ultimately T0. Other pathways for thyroid hormone metabolism include glucuronidation, sulfation, oxidative deamination, and ether bond cleavage.20–22

D1 and D2 catalyze T3, D3 catalyzes reverse T3

Three types of enzymes that mediate deiodination have been identified and designated D1, D2, and D3. In humans they are expressed in variable amounts throughout the body:

- D1 mainly in the liver, kidneys, thyroid, and pituitary, but notably absent in the central nervous system

- D2 in the central nervous system, pituitary, brown adipose tissue, thyroid, placenta, skeletal muscle, and heart

- D3 in the central nervous system, skin, hemangiomas, fetal liver, placenta, and fetal tissues.23

D1 and D2 are responsible for converting T4 to T3, and D3 is responsible for converting T4 to reverse T3.

Plasma concentrations of free T4 and free T3 are relatively constant; however, tissue concentrations of free T3 vary in different tissues according to the amount of hormone transported and the activity of local deiodinases.23 Most thyroid hormone actions are initiated after T3 binds to its nuclear receptor. In this setting, deiodinases play a critical role in maintaining tissue and cellular thyroid hormone levels, so that thyroid hormone signaling can change irrespective of serum hormonal concentrations.22–24 For example, in the central nervous system, production of T3 by local D2 is significantly relevant for T3 homeostasis.22,23

Deiodinases also modulate the tissue-specific concentrations of T3 in response to iodine deficiency and to changes in thyroid state.23 During iodine deficiency and hypothyroidism, tissues that express D2, especially brain tissues, increase the activity of this enzyme in order to increase local conversion of T4 to T3. In hyperthyroidism, D1 overexpression contributes to the relative excess of T3 production, while D3 up-regulation in the brain protects the central nervous system from excessive amounts of thyroid hormone.23

REVERSE T3 AND SYSTEMIC ILLNESS

D3 is the main physiologic inactivator of thyroid hormones. This enzyme plays a central role in protecting tissues from an excess of thyroid hormone.23,24 This mechanism is crucial for fetal development and explains the high expression of D3 in the human placenta and fetal tissues.

In adult tissues, the importance of D3 in the regulation of thyroid hormone homeostasis becomes apparent under certain pathophysiologic conditions, such as nonthyroidal illness and malnutrition.

Whenever a reduction in metabolism is homeostatically desirable, such as in critically ill patients or during starvation, conversion to T3 is reduced and, alternatively, conversion to reverse T3 is increased. This pathway represents a metabolic adaptation that may protect the tissues from the catabolic effects of thyroid hormone that could otherwise worsen the patient’s basic clinical condition.

Euthyroid sick syndrome or hypothyroid?

In a variety of systemic illnesses, some patients with low T3, low or normal T4, and normal thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels could in fact be “sick euthyroid” rather than hypothyroid. The first reports of the euthyroid sick syndrome or low T3 syndrome date back to about 1976, and even though assays for reverse T3 were not widely available, some authors linked the syndrome to high levels of reverse T3.15,16 The syndrome is also known as nonthyroidal illness syndrome.

Advances in techniques for measuring T3, reverse T3, and other iodothyronines filled a gap in the understanding of the alterations that occur in thyroid hormone economy during severe nonthyroidal diseases. In 1982, Wartofsky and Burman25 reviewed the alterations in thyroid function in patients with systemic illness and discussed other factors that may alter thyroid economy, such as age, stress, and diverse drugs.

More recently, the low-T3 syndrome was revisited with a generalized concept regarding the role of D3 in the syndrome.26 D3, normally undetectable in mature tissues, is reactivated in diverse cell types in response to injury and is responsible for a fall in serum T3 levels. Hypoxia induces D3 activity and mRNA in vitro and in vivo.27 Recent studies have focused on the role of cytokines in the low T3 syndrome. For instance, interleukin 6 reduces D1 and D2 activity and increases D3 activity in vitro.28

In the outpatient setting, diverse conditions may affect thyroid hormone homeostasis, compatible with mild or atypical forms of low-T3 syndrome, including caloric deprivation, heart failure, and human immunodeficiency virus infection.29

POSSIBLE CLINICAL UTILITY OF MEASURING REVERSE T3

In inpatients

Unfortunately, measuring serum reverse T3 levels has not, in general, proven clinically useful for the diagnosis of hypothyroidism in systemically ill patients. Burmeister30 demonstrated, in a retrospective study, that when illness complicates the interpretation of thyroid function tests, serum reverse T3 measurements do not reliably distinguish the hypothyroid sick patient from the euthyroid sick patient. The best way to make the diagnosis, Burmeister suggested, is by clinical assessment, combined use of free T4 and TSH measurements, and patient follow-up.

In the outpatient setting, the utility of reverse T3 measurements is controversial. In intensive care units, the differential diagnosis between hypothyroidism and nonthyroidal illness syndrome can sometimes be difficult. Reverse T3 levels can be low, normal, or high regardless of the thyroidal state of the patient.30 Moreover, endogenous changes in the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis may be further complicated by medications commonly used in intensive care units, such as dopamine and glucocorticoids. Changes in thyroid function should be evaluated in the context of the patient’s clinical condition (Table 1).20 But regardless of the T3 level, treatment with T3 or T4 should not be started without taking into consideration the patient’s general clinical context; controlled trials have not shown such therapy to be beneficial.20

In outpatients

In noncritical conditions that may be associated with mild forms of low T3 syndrome, patients generally present with low T3 concentrations concurrently with low or normal TSH. Not infrequently, however, patients present with a serum reverse T3 measurement and impute their symptoms of hypothyroidism to “abnormal” reverse T3 levels, in spite of normal TSH levels.

There is no rationale for measuring reverse T3 to initiate or to adjust levothyroxine therapy—the single test relevant for these purposes is the TSH measurement. The risks of basing treatment decisions on reverse T3 levels include the use of excessive doses of levothyroxine that may lead to a state of subclinical or even clinical hyperthyroidism.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

The existence of an inactivating pathway of thyroid hormones represents a homeostatic mechanism, and in selected circumstances measuring serum reverse T3 may be useful, such as in euthyroid sick patients. The discovery of the molecular mechanisms that lead to the reactivation of D3 in illness is an important field of research.

- Kendall EC. Landmark article, June 19, 1915. The isolation in crystalline form of the compound containing iodin, which occurs in the thyroid. Its chemical nature and physiologic activity. By E.C. Kendall. JAMA 1983; 250(15):2045–2046. doi:10.1001/jama.1983.03340150087037

- Harington CR. Chemistry of thyroxine: isolation of thyroxine from the thyroid gland. Biochem J 1926; 20(2):293–299. pmid: 16743658

- Harington CR, Barger G. Chemistry of thyroxine: constitution and synthesis of thyroxine. Biochem J 1927; 21(1):169–183. pmid:16743801

- Gross J, Pitt-Rivers R. The identification of 3,5,3’L-triiodothyronine in human plasma. Lancet 1952; 1(6705):439–441. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(52)91952-1

- Gross J, Pitt-Rivers R. 3:5:3’-triiodothyronine. 1. Isolation from thyroid gland and synthesis. Biochem J 1953; 53(4):645–650. pmid:13032123

- Pitt-Rivers R, Stanbury JB, Rapp B. Conversion of thyroxine to 3-5-3´-triiodothyronine in vivo. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1955; 15(5):616–620. doi:10.1210/jcem-15-5-616

- Maclagan NF, Bowden CH, Wilkinson JH. The metabolism of thyroid hormones. 2. Detection of thyroxine and tri-iodothyronine in human plasma. Biochem J. 1957; 67(1):5–11. pmid:13471502

- Galton VA, Pitt-Rivers R. The identification of the acetic acid analogues of thyroxine and tri-iodothyronine in mammalian tissues. Biochem J 1959; 72(2):319–321. pmid: 13662303

- Braverman LE, Ingbar SH, Sterling K. Conversion of thyroxine (T4) to triiodothyronine (T3) in athyreotic human subjects. J Clin Invest 1970; 49(5):855–864. doi:10.1172/JCI106304

- Sterling K, Brenner MA, Newman ES. Conversion of thyroxine to triiodothyronine in normal human subjects. Science 1970; 169(3950):1099–1100. doi:10.1126/science.169.3950.1099

- Chopra IJ. A radioimmunoassay for measurement of thyroxine in unextracted serum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1972; 34:938–947. doi:10.1210/jcem-34-6-938

- Chopra IJ. A radioimmunoassay for measurement of 3,3´,5´-triiodothyronine (reverse T3). J Clin Invest 1974; 54(3):583–592. doi:10.1172/JCI107795

- Chopra IJ, Chopra U, Smith SR, Reza M, Solomon DH. Reciprocal changes in serum concentrations of 3,3´,5-triiodothyronine (T3) in systemic illnesses. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1975; 41(6):1043–1049. doi:10.1210/jcem-41-6-1043

- Burman KD, Read J, Dimond RC, Strum D, et al. Measurement of 3,3’,5’-triiodothyroinine (reverse T3), 3,3’-L-diiodothyronine, T3 and T4 in human amniotic fluid and in cord and maternal serum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1976; 43(6):1351–1359. doi:10.1210/jcem-43-6-1351

- Rubenfeld S. Euthyroid sick syndrome. N Engl J Med 1978; 299(25):1414. doi:10.1056/NEJM197812212992514

- Burger A, Nicod P, Suter P, Vallotton MB, Vagenakis P, Braverman L. Reduced active thyroid hormone levels in acute illness. Lancet 1976; 1(7961):653–655. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(76)92774-4

- Burman KD, Dimond RC, Wright FD, Earll JM, Bruton J, Wartofsky L. A radioimmunoassay for 3,3´,5´-L-triiodothyronine (reverse T3): assessment of thyroid gland content and serum measurements in conditions of normal and altered thyroidal economy and following administration of thyrotropin releasing hormone (TRH) and thyrotropin (TSH). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1977; 44(4):660–672. doi:10.1210/jcem-44-4-660

- Burman KD, Strum D, Dimond RC, et al. A radioimmunoassay for 3,3´-L-diiodothyronine (3,3´T2). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1977; 45(2):339–352. doi:10.1210/jcem-45-2-339

- Burman KD. Recent developments in thyroid hormone metabolism: interpretation and significance of measurements of reverse T3, 3,3´T2, and thyroglobulin. Metabolism 1978; 27(5):615–630. doi:10.1016/0026-0495(78)90028-8.

- Salvatore D, Davies TF, Schlumberger M, Hay ID, Larsen PR. Thyroid physiology and diagnostic evaluation of patients with thyroid disorders. In: Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 13th ed. Philadelphia, PA; Elsevier; 2016:334–368.

- Engler D, Burger AG. The deiodination of the iodothyronines and of their derivatives in man. Endocr Rev 1984; 5(2):151–184. doi:10.1210/edrv-5-2-151

- Peeters RP, Visser TJ, Peeters RP. Metabolism of thyroid hormone. Thyroid Disease Manager. www.thyroidmanager.org/chapter/metabolism-of-thyroid-hormone. Accessed March 14, 2018.

- Bianco AC, Salvatore D, Gereben B, Berry MJ, Larsen PR. Biochemistry, cellular and molecular biology, and physiological roles of the iodothyronine selenodeiodinases. Endocr Rev 2002; 23(1):38–89. doi:10.1210/edrv.23.1.0455

- Dentice M, Salvatore D. Deiodinases: the balance of thyroid hormone: local impact of thyroid hormone inactivation. J Endocrinol 2011; 209(3):273–282. doi:10.1530/JOE-11-0002

- Wartofsky L, Burman KD. Alterations in thyroid function in patients with systemic illness: the “euthyroid sick syndrome.” Endocr Rev 1982; 3(2):164–217. doi:10.1210/edrv-3-2-164

- Huang SA, Bianco AC. Reawakened interest in type III iodothyronine deiodinase in critical illness and injury. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 2008; 4(3):148–155. doi:10.1038/ncpendmet0727

- Simonides WS, Mulcahey MA, Redout EM, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor induces local thyroid hormone inactivation during hypoxic-ischemic disease in rats. J Clin Invest 2008; 118(3):975–983. doi:10.1172/JCI32824

- Wajner SM, Goemann IM, Bueno AL, Larsen PR, Maia AL. IL-6 promotes nonthyroidal illness syndrome by blocking thyroxine activation while promoting thyroid hormone inactivation in human cells. J Clin Invest 2011; 121(5):1834–1845. doi:10.1172/JCI44678

- Moura Neto A, Zantut-Wittmann DE. Abnormalities of thyroid hormone metabolism during systemic illness: the low T3 syndrome in different clinical settings. Int J Endocrinol 2016; 2016:2157583. doi:10.1155/2016/2157583

- Burmeister LA. Reverse T3 does not reliably differentiate hypothyroid sick syndrome from euthyroid sick syndrome. Thyroid 1995; 5(6):435–441. doi:10.1089/thy.1995.5.435

- Huang SA, Tu HM, Harney JW, et al. Severe hypothyroidism caused by type 3 iodothyronine deiodinase in infantile hemangiomas. N Engl J Med 2000; 343(3):185–189. doi:10.1056/NEJM200007203430305

Four decades after reverse T3 (3,3´5´-triiodothyronine) was discovered, its physiologic and clinical relevance remains unclear and is still being studied. But scientific uncertainty has not stopped writers in the consumer press and on the Internet from making unsubstantiated claims about this hormone. Many patients believe their hypothyroid symptoms are due to high levels of reverse T3 and want to be tested for it, and some even bring in test results from independent laboratories.

HOW THYROID HORMONES WERE DISCOVERED

In 1970, Braverman et al9 showed that T4 is converted to T3 in athyreotic humans, and Sterling et al10 demonstrated the same in healthy humans. During that decade, techniques for measuring T4 were refined,11 and a specific radioimmunoassay for reverse T3 allowed a glimpse of its physiologic role.12 In 1975, Chopra et al13 noted reciprocal changes in the levels of T3 and reverse T3 in systemic illnesses—ie, when people are sick, their T3 levels go down and their reverse T3 levels go up.

The end of the 70s was marked by a surge of interest in T4 metabolites, including the development of a radioimmunoassay for 3,3´-diiodothyronine (3-3´ T2).18

The observed reciprocal changes in serum levels of T3 and reverse T3 suggested that T4 degradation is regulated into activating (T3) or inactivating (reverse T3) pathways, and that these changes are a presumed homeostatic process of energy conservation.19

HOW THYROID HORMONES ARE METABOLIZED

In the thyroid gland, for thyroid hormones to be synthesized, iodide must be oxidized and incorporated into the precursors 3-monoiodotyrosine (MIT) and 3,5-diiodotyrosine (DIT). This process is mediated by the enzyme thyroid peroxidase in the presence of hydrogen peroxide.20

The thyroid can make T4 and some T3

T4 is the main iodothyronine produced by the thyroid gland, at a rate of 80 to 100 µg per day.21 It is synthesized from the fusion of 2 DIT molecules.

The thyroid can also make T3 by fusing 1 DIT and 1 MIT molecule, but this process accounts for no more than 20% of the circulating T3 in humans. The rest of T3, and 95% to 98% of all reverse T3, is derived from peripheral conversion of T4 through deiodination.

T4 is converted to T3 or reverse T3

The metabolic transformation of thyroid hormones in peripheral tissues determines their biologic potency and regulates their biologic effects.

The number 4 in T4 means it has 4 iodine atoms. It can lose 1 of them, yielding either T3 or reverse T3, depending on which iodine atom it loses (Figure 3). Loss of iodine from the five-prime (5´) position on its outer ring yields T3, the most potent thyroid hormone, produced at a rate of 30 to 40 µg per day.21 On the other hand, when T4 loses an iodine atom from the five (5) position on its inner ring it yields reverse T3, produced at a rate slightly less than that of T3, 28 to 40 µg per day.21 Reverse T3 is inactive.

Both T3 and reverse T3 can shed more iodine atoms, forming in turn various isomers of T2, T1, and ultimately T0. Other pathways for thyroid hormone metabolism include glucuronidation, sulfation, oxidative deamination, and ether bond cleavage.20–22

D1 and D2 catalyze T3, D3 catalyzes reverse T3

Three types of enzymes that mediate deiodination have been identified and designated D1, D2, and D3. In humans they are expressed in variable amounts throughout the body:

- D1 mainly in the liver, kidneys, thyroid, and pituitary, but notably absent in the central nervous system

- D2 in the central nervous system, pituitary, brown adipose tissue, thyroid, placenta, skeletal muscle, and heart

- D3 in the central nervous system, skin, hemangiomas, fetal liver, placenta, and fetal tissues.23

D1 and D2 are responsible for converting T4 to T3, and D3 is responsible for converting T4 to reverse T3.

Plasma concentrations of free T4 and free T3 are relatively constant; however, tissue concentrations of free T3 vary in different tissues according to the amount of hormone transported and the activity of local deiodinases.23 Most thyroid hormone actions are initiated after T3 binds to its nuclear receptor. In this setting, deiodinases play a critical role in maintaining tissue and cellular thyroid hormone levels, so that thyroid hormone signaling can change irrespective of serum hormonal concentrations.22–24 For example, in the central nervous system, production of T3 by local D2 is significantly relevant for T3 homeostasis.22,23

Deiodinases also modulate the tissue-specific concentrations of T3 in response to iodine deficiency and to changes in thyroid state.23 During iodine deficiency and hypothyroidism, tissues that express D2, especially brain tissues, increase the activity of this enzyme in order to increase local conversion of T4 to T3. In hyperthyroidism, D1 overexpression contributes to the relative excess of T3 production, while D3 up-regulation in the brain protects the central nervous system from excessive amounts of thyroid hormone.23

REVERSE T3 AND SYSTEMIC ILLNESS

D3 is the main physiologic inactivator of thyroid hormones. This enzyme plays a central role in protecting tissues from an excess of thyroid hormone.23,24 This mechanism is crucial for fetal development and explains the high expression of D3 in the human placenta and fetal tissues.

In adult tissues, the importance of D3 in the regulation of thyroid hormone homeostasis becomes apparent under certain pathophysiologic conditions, such as nonthyroidal illness and malnutrition.

Whenever a reduction in metabolism is homeostatically desirable, such as in critically ill patients or during starvation, conversion to T3 is reduced and, alternatively, conversion to reverse T3 is increased. This pathway represents a metabolic adaptation that may protect the tissues from the catabolic effects of thyroid hormone that could otherwise worsen the patient’s basic clinical condition.

Euthyroid sick syndrome or hypothyroid?

In a variety of systemic illnesses, some patients with low T3, low or normal T4, and normal thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels could in fact be “sick euthyroid” rather than hypothyroid. The first reports of the euthyroid sick syndrome or low T3 syndrome date back to about 1976, and even though assays for reverse T3 were not widely available, some authors linked the syndrome to high levels of reverse T3.15,16 The syndrome is also known as nonthyroidal illness syndrome.

Advances in techniques for measuring T3, reverse T3, and other iodothyronines filled a gap in the understanding of the alterations that occur in thyroid hormone economy during severe nonthyroidal diseases. In 1982, Wartofsky and Burman25 reviewed the alterations in thyroid function in patients with systemic illness and discussed other factors that may alter thyroid economy, such as age, stress, and diverse drugs.

More recently, the low-T3 syndrome was revisited with a generalized concept regarding the role of D3 in the syndrome.26 D3, normally undetectable in mature tissues, is reactivated in diverse cell types in response to injury and is responsible for a fall in serum T3 levels. Hypoxia induces D3 activity and mRNA in vitro and in vivo.27 Recent studies have focused on the role of cytokines in the low T3 syndrome. For instance, interleukin 6 reduces D1 and D2 activity and increases D3 activity in vitro.28

In the outpatient setting, diverse conditions may affect thyroid hormone homeostasis, compatible with mild or atypical forms of low-T3 syndrome, including caloric deprivation, heart failure, and human immunodeficiency virus infection.29

POSSIBLE CLINICAL UTILITY OF MEASURING REVERSE T3

In inpatients

Unfortunately, measuring serum reverse T3 levels has not, in general, proven clinically useful for the diagnosis of hypothyroidism in systemically ill patients. Burmeister30 demonstrated, in a retrospective study, that when illness complicates the interpretation of thyroid function tests, serum reverse T3 measurements do not reliably distinguish the hypothyroid sick patient from the euthyroid sick patient. The best way to make the diagnosis, Burmeister suggested, is by clinical assessment, combined use of free T4 and TSH measurements, and patient follow-up.

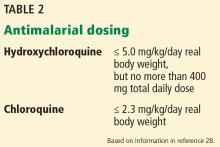

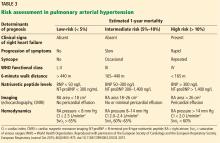

In the outpatient setting, the utility of reverse T3 measurements is controversial. In intensive care units, the differential diagnosis between hypothyroidism and nonthyroidal illness syndrome can sometimes be difficult. Reverse T3 levels can be low, normal, or high regardless of the thyroidal state of the patient.30 Moreover, endogenous changes in the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis may be further complicated by medications commonly used in intensive care units, such as dopamine and glucocorticoids. Changes in thyroid function should be evaluated in the context of the patient’s clinical condition (Table 1).20 But regardless of the T3 level, treatment with T3 or T4 should not be started without taking into consideration the patient’s general clinical context; controlled trials have not shown such therapy to be beneficial.20

In outpatients

In noncritical conditions that may be associated with mild forms of low T3 syndrome, patients generally present with low T3 concentrations concurrently with low or normal TSH. Not infrequently, however, patients present with a serum reverse T3 measurement and impute their symptoms of hypothyroidism to “abnormal” reverse T3 levels, in spite of normal TSH levels.

There is no rationale for measuring reverse T3 to initiate or to adjust levothyroxine therapy—the single test relevant for these purposes is the TSH measurement. The risks of basing treatment decisions on reverse T3 levels include the use of excessive doses of levothyroxine that may lead to a state of subclinical or even clinical hyperthyroidism.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

The existence of an inactivating pathway of thyroid hormones represents a homeostatic mechanism, and in selected circumstances measuring serum reverse T3 may be useful, such as in euthyroid sick patients. The discovery of the molecular mechanisms that lead to the reactivation of D3 in illness is an important field of research.

Four decades after reverse T3 (3,3´5´-triiodothyronine) was discovered, its physiologic and clinical relevance remains unclear and is still being studied. But scientific uncertainty has not stopped writers in the consumer press and on the Internet from making unsubstantiated claims about this hormone. Many patients believe their hypothyroid symptoms are due to high levels of reverse T3 and want to be tested for it, and some even bring in test results from independent laboratories.

HOW THYROID HORMONES WERE DISCOVERED

In 1970, Braverman et al9 showed that T4 is converted to T3 in athyreotic humans, and Sterling et al10 demonstrated the same in healthy humans. During that decade, techniques for measuring T4 were refined,11 and a specific radioimmunoassay for reverse T3 allowed a glimpse of its physiologic role.12 In 1975, Chopra et al13 noted reciprocal changes in the levels of T3 and reverse T3 in systemic illnesses—ie, when people are sick, their T3 levels go down and their reverse T3 levels go up.

The end of the 70s was marked by a surge of interest in T4 metabolites, including the development of a radioimmunoassay for 3,3´-diiodothyronine (3-3´ T2).18

The observed reciprocal changes in serum levels of T3 and reverse T3 suggested that T4 degradation is regulated into activating (T3) or inactivating (reverse T3) pathways, and that these changes are a presumed homeostatic process of energy conservation.19

HOW THYROID HORMONES ARE METABOLIZED

In the thyroid gland, for thyroid hormones to be synthesized, iodide must be oxidized and incorporated into the precursors 3-monoiodotyrosine (MIT) and 3,5-diiodotyrosine (DIT). This process is mediated by the enzyme thyroid peroxidase in the presence of hydrogen peroxide.20

The thyroid can make T4 and some T3

T4 is the main iodothyronine produced by the thyroid gland, at a rate of 80 to 100 µg per day.21 It is synthesized from the fusion of 2 DIT molecules.

The thyroid can also make T3 by fusing 1 DIT and 1 MIT molecule, but this process accounts for no more than 20% of the circulating T3 in humans. The rest of T3, and 95% to 98% of all reverse T3, is derived from peripheral conversion of T4 through deiodination.

T4 is converted to T3 or reverse T3

The metabolic transformation of thyroid hormones in peripheral tissues determines their biologic potency and regulates their biologic effects.

The number 4 in T4 means it has 4 iodine atoms. It can lose 1 of them, yielding either T3 or reverse T3, depending on which iodine atom it loses (Figure 3). Loss of iodine from the five-prime (5´) position on its outer ring yields T3, the most potent thyroid hormone, produced at a rate of 30 to 40 µg per day.21 On the other hand, when T4 loses an iodine atom from the five (5) position on its inner ring it yields reverse T3, produced at a rate slightly less than that of T3, 28 to 40 µg per day.21 Reverse T3 is inactive.

Both T3 and reverse T3 can shed more iodine atoms, forming in turn various isomers of T2, T1, and ultimately T0. Other pathways for thyroid hormone metabolism include glucuronidation, sulfation, oxidative deamination, and ether bond cleavage.20–22

D1 and D2 catalyze T3, D3 catalyzes reverse T3

Three types of enzymes that mediate deiodination have been identified and designated D1, D2, and D3. In humans they are expressed in variable amounts throughout the body:

- D1 mainly in the liver, kidneys, thyroid, and pituitary, but notably absent in the central nervous system

- D2 in the central nervous system, pituitary, brown adipose tissue, thyroid, placenta, skeletal muscle, and heart

- D3 in the central nervous system, skin, hemangiomas, fetal liver, placenta, and fetal tissues.23

D1 and D2 are responsible for converting T4 to T3, and D3 is responsible for converting T4 to reverse T3.

Plasma concentrations of free T4 and free T3 are relatively constant; however, tissue concentrations of free T3 vary in different tissues according to the amount of hormone transported and the activity of local deiodinases.23 Most thyroid hormone actions are initiated after T3 binds to its nuclear receptor. In this setting, deiodinases play a critical role in maintaining tissue and cellular thyroid hormone levels, so that thyroid hormone signaling can change irrespective of serum hormonal concentrations.22–24 For example, in the central nervous system, production of T3 by local D2 is significantly relevant for T3 homeostasis.22,23

Deiodinases also modulate the tissue-specific concentrations of T3 in response to iodine deficiency and to changes in thyroid state.23 During iodine deficiency and hypothyroidism, tissues that express D2, especially brain tissues, increase the activity of this enzyme in order to increase local conversion of T4 to T3. In hyperthyroidism, D1 overexpression contributes to the relative excess of T3 production, while D3 up-regulation in the brain protects the central nervous system from excessive amounts of thyroid hormone.23

REVERSE T3 AND SYSTEMIC ILLNESS

D3 is the main physiologic inactivator of thyroid hormones. This enzyme plays a central role in protecting tissues from an excess of thyroid hormone.23,24 This mechanism is crucial for fetal development and explains the high expression of D3 in the human placenta and fetal tissues.

In adult tissues, the importance of D3 in the regulation of thyroid hormone homeostasis becomes apparent under certain pathophysiologic conditions, such as nonthyroidal illness and malnutrition.

Whenever a reduction in metabolism is homeostatically desirable, such as in critically ill patients or during starvation, conversion to T3 is reduced and, alternatively, conversion to reverse T3 is increased. This pathway represents a metabolic adaptation that may protect the tissues from the catabolic effects of thyroid hormone that could otherwise worsen the patient’s basic clinical condition.

Euthyroid sick syndrome or hypothyroid?

In a variety of systemic illnesses, some patients with low T3, low or normal T4, and normal thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels could in fact be “sick euthyroid” rather than hypothyroid. The first reports of the euthyroid sick syndrome or low T3 syndrome date back to about 1976, and even though assays for reverse T3 were not widely available, some authors linked the syndrome to high levels of reverse T3.15,16 The syndrome is also known as nonthyroidal illness syndrome.

Advances in techniques for measuring T3, reverse T3, and other iodothyronines filled a gap in the understanding of the alterations that occur in thyroid hormone economy during severe nonthyroidal diseases. In 1982, Wartofsky and Burman25 reviewed the alterations in thyroid function in patients with systemic illness and discussed other factors that may alter thyroid economy, such as age, stress, and diverse drugs.

More recently, the low-T3 syndrome was revisited with a generalized concept regarding the role of D3 in the syndrome.26 D3, normally undetectable in mature tissues, is reactivated in diverse cell types in response to injury and is responsible for a fall in serum T3 levels. Hypoxia induces D3 activity and mRNA in vitro and in vivo.27 Recent studies have focused on the role of cytokines in the low T3 syndrome. For instance, interleukin 6 reduces D1 and D2 activity and increases D3 activity in vitro.28

In the outpatient setting, diverse conditions may affect thyroid hormone homeostasis, compatible with mild or atypical forms of low-T3 syndrome, including caloric deprivation, heart failure, and human immunodeficiency virus infection.29

POSSIBLE CLINICAL UTILITY OF MEASURING REVERSE T3

In inpatients

Unfortunately, measuring serum reverse T3 levels has not, in general, proven clinically useful for the diagnosis of hypothyroidism in systemically ill patients. Burmeister30 demonstrated, in a retrospective study, that when illness complicates the interpretation of thyroid function tests, serum reverse T3 measurements do not reliably distinguish the hypothyroid sick patient from the euthyroid sick patient. The best way to make the diagnosis, Burmeister suggested, is by clinical assessment, combined use of free T4 and TSH measurements, and patient follow-up.

In the outpatient setting, the utility of reverse T3 measurements is controversial. In intensive care units, the differential diagnosis between hypothyroidism and nonthyroidal illness syndrome can sometimes be difficult. Reverse T3 levels can be low, normal, or high regardless of the thyroidal state of the patient.30 Moreover, endogenous changes in the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis may be further complicated by medications commonly used in intensive care units, such as dopamine and glucocorticoids. Changes in thyroid function should be evaluated in the context of the patient’s clinical condition (Table 1).20 But regardless of the T3 level, treatment with T3 or T4 should not be started without taking into consideration the patient’s general clinical context; controlled trials have not shown such therapy to be beneficial.20

In outpatients

In noncritical conditions that may be associated with mild forms of low T3 syndrome, patients generally present with low T3 concentrations concurrently with low or normal TSH. Not infrequently, however, patients present with a serum reverse T3 measurement and impute their symptoms of hypothyroidism to “abnormal” reverse T3 levels, in spite of normal TSH levels.

There is no rationale for measuring reverse T3 to initiate or to adjust levothyroxine therapy—the single test relevant for these purposes is the TSH measurement. The risks of basing treatment decisions on reverse T3 levels include the use of excessive doses of levothyroxine that may lead to a state of subclinical or even clinical hyperthyroidism.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

The existence of an inactivating pathway of thyroid hormones represents a homeostatic mechanism, and in selected circumstances measuring serum reverse T3 may be useful, such as in euthyroid sick patients. The discovery of the molecular mechanisms that lead to the reactivation of D3 in illness is an important field of research.

- Kendall EC. Landmark article, June 19, 1915. The isolation in crystalline form of the compound containing iodin, which occurs in the thyroid. Its chemical nature and physiologic activity. By E.C. Kendall. JAMA 1983; 250(15):2045–2046. doi:10.1001/jama.1983.03340150087037

- Harington CR. Chemistry of thyroxine: isolation of thyroxine from the thyroid gland. Biochem J 1926; 20(2):293–299. pmid: 16743658

- Harington CR, Barger G. Chemistry of thyroxine: constitution and synthesis of thyroxine. Biochem J 1927; 21(1):169–183. pmid:16743801

- Gross J, Pitt-Rivers R. The identification of 3,5,3’L-triiodothyronine in human plasma. Lancet 1952; 1(6705):439–441. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(52)91952-1

- Gross J, Pitt-Rivers R. 3:5:3’-triiodothyronine. 1. Isolation from thyroid gland and synthesis. Biochem J 1953; 53(4):645–650. pmid:13032123

- Pitt-Rivers R, Stanbury JB, Rapp B. Conversion of thyroxine to 3-5-3´-triiodothyronine in vivo. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1955; 15(5):616–620. doi:10.1210/jcem-15-5-616

- Maclagan NF, Bowden CH, Wilkinson JH. The metabolism of thyroid hormones. 2. Detection of thyroxine and tri-iodothyronine in human plasma. Biochem J. 1957; 67(1):5–11. pmid:13471502

- Galton VA, Pitt-Rivers R. The identification of the acetic acid analogues of thyroxine and tri-iodothyronine in mammalian tissues. Biochem J 1959; 72(2):319–321. pmid: 13662303

- Braverman LE, Ingbar SH, Sterling K. Conversion of thyroxine (T4) to triiodothyronine (T3) in athyreotic human subjects. J Clin Invest 1970; 49(5):855–864. doi:10.1172/JCI106304

- Sterling K, Brenner MA, Newman ES. Conversion of thyroxine to triiodothyronine in normal human subjects. Science 1970; 169(3950):1099–1100. doi:10.1126/science.169.3950.1099

- Chopra IJ. A radioimmunoassay for measurement of thyroxine in unextracted serum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1972; 34:938–947. doi:10.1210/jcem-34-6-938

- Chopra IJ. A radioimmunoassay for measurement of 3,3´,5´-triiodothyronine (reverse T3). J Clin Invest 1974; 54(3):583–592. doi:10.1172/JCI107795

- Chopra IJ, Chopra U, Smith SR, Reza M, Solomon DH. Reciprocal changes in serum concentrations of 3,3´,5-triiodothyronine (T3) in systemic illnesses. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1975; 41(6):1043–1049. doi:10.1210/jcem-41-6-1043

- Burman KD, Read J, Dimond RC, Strum D, et al. Measurement of 3,3’,5’-triiodothyroinine (reverse T3), 3,3’-L-diiodothyronine, T3 and T4 in human amniotic fluid and in cord and maternal serum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1976; 43(6):1351–1359. doi:10.1210/jcem-43-6-1351

- Rubenfeld S. Euthyroid sick syndrome. N Engl J Med 1978; 299(25):1414. doi:10.1056/NEJM197812212992514

- Burger A, Nicod P, Suter P, Vallotton MB, Vagenakis P, Braverman L. Reduced active thyroid hormone levels in acute illness. Lancet 1976; 1(7961):653–655. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(76)92774-4

- Burman KD, Dimond RC, Wright FD, Earll JM, Bruton J, Wartofsky L. A radioimmunoassay for 3,3´,5´-L-triiodothyronine (reverse T3): assessment of thyroid gland content and serum measurements in conditions of normal and altered thyroidal economy and following administration of thyrotropin releasing hormone (TRH) and thyrotropin (TSH). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1977; 44(4):660–672. doi:10.1210/jcem-44-4-660

- Burman KD, Strum D, Dimond RC, et al. A radioimmunoassay for 3,3´-L-diiodothyronine (3,3´T2). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1977; 45(2):339–352. doi:10.1210/jcem-45-2-339

- Burman KD. Recent developments in thyroid hormone metabolism: interpretation and significance of measurements of reverse T3, 3,3´T2, and thyroglobulin. Metabolism 1978; 27(5):615–630. doi:10.1016/0026-0495(78)90028-8.

- Salvatore D, Davies TF, Schlumberger M, Hay ID, Larsen PR. Thyroid physiology and diagnostic evaluation of patients with thyroid disorders. In: Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 13th ed. Philadelphia, PA; Elsevier; 2016:334–368.

- Engler D, Burger AG. The deiodination of the iodothyronines and of their derivatives in man. Endocr Rev 1984; 5(2):151–184. doi:10.1210/edrv-5-2-151

- Peeters RP, Visser TJ, Peeters RP. Metabolism of thyroid hormone. Thyroid Disease Manager. www.thyroidmanager.org/chapter/metabolism-of-thyroid-hormone. Accessed March 14, 2018.