User login

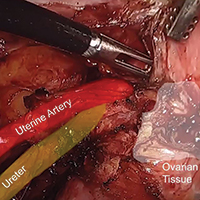

Prevention of ovarian remnant syndrome: Adnexal adhesiolysis from the pelvic sidewall

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

This video is brought to you by

A call for psychiatrists with tardive dyskinesia expertise

The CURESZ Foundation was founded in 2016 to bring hope to people suffering from schizophrenia and those who love and care for them. CURESZ was established by Bethany Yeiser and her psychiatrist, Current Psychiatry Editor-in-Chief Henry Nasrallah, MD, and was inspired by Bethany's complete recovery from schizophrenia after 4 years of delusions, hallucinations, homelessness, and disability. Bethany returned to her normal life and graduated from college with honors, thanks to clozapine, which cured her symptoms when several other medications did not work (for more of Bethany’s story, see From the Editor, Current Psychiatry. October 2014, p. 21,24-25).

We previously assembled a panel of clozapine experts to whom the CURESZ Foundation would refer patients who have never had a trial of clozapine despite ongoing delusions or hallucinations. We now have a panel of 80 clozapine experts around the country who are willing to receive referrals.

In an unexpected turn of events, after several years of receiving clozapine, Bethany developed tardive dyskinesia (TD) which, fortunately, was successfully treated. Bethany would not have been able to recover from her TD had it not been for the recent FDA approval of effective treatments. The embarrassing personal experience of oro-buccal TD movements that Bethany went through before she improved led her and me to establish a panel of experts in the recognition and treatment of TD around the country. It is estimated that hundreds of thousands of patients with schizophrenia, schizo-affective disorders, bipolar disorder and major depression, all of whom receive first or second generation antipsychotic agents, currently have TD that is not being diagnosed or treated.

We are therefore calling for psychiatric practitioners who have had experience in recognizing TD movements and have treated patients with FDA-approved treatments, to contact the CURESZ Foundation. Henry Nasrallah, MD, the Scientific Director of the CURESZ Foundation, who has had many years of federally funded research experience in TD, will serve as the Chair of this TD Panel.

This is a call for readers of Current Psychiatry who are treating TD and who practice in settings that can accommodate additional patients seeking treatment for their involuntary TD muscle movements in their face, trunk, and extremities. We hope to assemble between 50 to 100 experts to join this national TD panel.

If you would like to be a member of this national CURESZ TD Panel, please go to https://curesz.org/tardive-dyskinesia-panel/ and enter your name, email, work address, and office phone number. We will later organize the list by state and city so that patients and families around the country can contact the nearest expert to get an evaluation for assessment and treatment of their TD.

Thank you and we look forward to working with the experts who say “YESZ” to joining the TD Panel, sponsored by the CURESZ Foundation.

The CURESZ Foundation was founded in 2016 to bring hope to people suffering from schizophrenia and those who love and care for them. CURESZ was established by Bethany Yeiser and her psychiatrist, Current Psychiatry Editor-in-Chief Henry Nasrallah, MD, and was inspired by Bethany's complete recovery from schizophrenia after 4 years of delusions, hallucinations, homelessness, and disability. Bethany returned to her normal life and graduated from college with honors, thanks to clozapine, which cured her symptoms when several other medications did not work (for more of Bethany’s story, see From the Editor, Current Psychiatry. October 2014, p. 21,24-25).

We previously assembled a panel of clozapine experts to whom the CURESZ Foundation would refer patients who have never had a trial of clozapine despite ongoing delusions or hallucinations. We now have a panel of 80 clozapine experts around the country who are willing to receive referrals.

In an unexpected turn of events, after several years of receiving clozapine, Bethany developed tardive dyskinesia (TD) which, fortunately, was successfully treated. Bethany would not have been able to recover from her TD had it not been for the recent FDA approval of effective treatments. The embarrassing personal experience of oro-buccal TD movements that Bethany went through before she improved led her and me to establish a panel of experts in the recognition and treatment of TD around the country. It is estimated that hundreds of thousands of patients with schizophrenia, schizo-affective disorders, bipolar disorder and major depression, all of whom receive first or second generation antipsychotic agents, currently have TD that is not being diagnosed or treated.

We are therefore calling for psychiatric practitioners who have had experience in recognizing TD movements and have treated patients with FDA-approved treatments, to contact the CURESZ Foundation. Henry Nasrallah, MD, the Scientific Director of the CURESZ Foundation, who has had many years of federally funded research experience in TD, will serve as the Chair of this TD Panel.

This is a call for readers of Current Psychiatry who are treating TD and who practice in settings that can accommodate additional patients seeking treatment for their involuntary TD muscle movements in their face, trunk, and extremities. We hope to assemble between 50 to 100 experts to join this national TD panel.

If you would like to be a member of this national CURESZ TD Panel, please go to https://curesz.org/tardive-dyskinesia-panel/ and enter your name, email, work address, and office phone number. We will later organize the list by state and city so that patients and families around the country can contact the nearest expert to get an evaluation for assessment and treatment of their TD.

Thank you and we look forward to working with the experts who say “YESZ” to joining the TD Panel, sponsored by the CURESZ Foundation.

The CURESZ Foundation was founded in 2016 to bring hope to people suffering from schizophrenia and those who love and care for them. CURESZ was established by Bethany Yeiser and her psychiatrist, Current Psychiatry Editor-in-Chief Henry Nasrallah, MD, and was inspired by Bethany's complete recovery from schizophrenia after 4 years of delusions, hallucinations, homelessness, and disability. Bethany returned to her normal life and graduated from college with honors, thanks to clozapine, which cured her symptoms when several other medications did not work (for more of Bethany’s story, see From the Editor, Current Psychiatry. October 2014, p. 21,24-25).

We previously assembled a panel of clozapine experts to whom the CURESZ Foundation would refer patients who have never had a trial of clozapine despite ongoing delusions or hallucinations. We now have a panel of 80 clozapine experts around the country who are willing to receive referrals.

In an unexpected turn of events, after several years of receiving clozapine, Bethany developed tardive dyskinesia (TD) which, fortunately, was successfully treated. Bethany would not have been able to recover from her TD had it not been for the recent FDA approval of effective treatments. The embarrassing personal experience of oro-buccal TD movements that Bethany went through before she improved led her and me to establish a panel of experts in the recognition and treatment of TD around the country. It is estimated that hundreds of thousands of patients with schizophrenia, schizo-affective disorders, bipolar disorder and major depression, all of whom receive first or second generation antipsychotic agents, currently have TD that is not being diagnosed or treated.

We are therefore calling for psychiatric practitioners who have had experience in recognizing TD movements and have treated patients with FDA-approved treatments, to contact the CURESZ Foundation. Henry Nasrallah, MD, the Scientific Director of the CURESZ Foundation, who has had many years of federally funded research experience in TD, will serve as the Chair of this TD Panel.

This is a call for readers of Current Psychiatry who are treating TD and who practice in settings that can accommodate additional patients seeking treatment for their involuntary TD muscle movements in their face, trunk, and extremities. We hope to assemble between 50 to 100 experts to join this national TD panel.

If you would like to be a member of this national CURESZ TD Panel, please go to https://curesz.org/tardive-dyskinesia-panel/ and enter your name, email, work address, and office phone number. We will later organize the list by state and city so that patients and families around the country can contact the nearest expert to get an evaluation for assessment and treatment of their TD.

Thank you and we look forward to working with the experts who say “YESZ” to joining the TD Panel, sponsored by the CURESZ Foundation.

FDA approves Prolia for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis

at high risk of fracture, the drug’s manufacturer Amgen announced May 21.

FDA approval was based on 12-month primary analysis results from a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Patients who received a 60-mg dose of Prolia subcutaneously every 6 months had greater lumbar spine bone mineral density at 1 year than did those who received a 5-mg dose of risedronate daily in all study subpopulations. These results were maintained after researchers controlled for gender, race, geographic region, and menopausal status, as well as baseline age, lumbar spine bone mineral density T score, and glucocorticoid dose within each subpopulation.

The most common adverse events associated with Prolia during the phase 3 study were back pain, hypertension, bronchitis, and headache, which are in line with previously reported safety data.

“Patients on long-term systemic glucocorticoid medications can experience a rapid reduction in bone mineral density within a few months of beginning treatment. With this approval, patients who receive treatment with glucocorticoids now have a new option to help improve their bone mineral density,” lead study author Kenneth F. Saag, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, said in Amgen’s news release.

at high risk of fracture, the drug’s manufacturer Amgen announced May 21.

FDA approval was based on 12-month primary analysis results from a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Patients who received a 60-mg dose of Prolia subcutaneously every 6 months had greater lumbar spine bone mineral density at 1 year than did those who received a 5-mg dose of risedronate daily in all study subpopulations. These results were maintained after researchers controlled for gender, race, geographic region, and menopausal status, as well as baseline age, lumbar spine bone mineral density T score, and glucocorticoid dose within each subpopulation.

The most common adverse events associated with Prolia during the phase 3 study were back pain, hypertension, bronchitis, and headache, which are in line with previously reported safety data.

“Patients on long-term systemic glucocorticoid medications can experience a rapid reduction in bone mineral density within a few months of beginning treatment. With this approval, patients who receive treatment with glucocorticoids now have a new option to help improve their bone mineral density,” lead study author Kenneth F. Saag, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, said in Amgen’s news release.

at high risk of fracture, the drug’s manufacturer Amgen announced May 21.

FDA approval was based on 12-month primary analysis results from a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Patients who received a 60-mg dose of Prolia subcutaneously every 6 months had greater lumbar spine bone mineral density at 1 year than did those who received a 5-mg dose of risedronate daily in all study subpopulations. These results were maintained after researchers controlled for gender, race, geographic region, and menopausal status, as well as baseline age, lumbar spine bone mineral density T score, and glucocorticoid dose within each subpopulation.

The most common adverse events associated with Prolia during the phase 3 study were back pain, hypertension, bronchitis, and headache, which are in line with previously reported safety data.

“Patients on long-term systemic glucocorticoid medications can experience a rapid reduction in bone mineral density within a few months of beginning treatment. With this approval, patients who receive treatment with glucocorticoids now have a new option to help improve their bone mineral density,” lead study author Kenneth F. Saag, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, said in Amgen’s news release.

MDedge Daily News: Atopic Dermatitis severity reduced by topical microbiome treatment

Also today, a new device could detect osteoarthritis with sound and motion, seven days of antibiotics is enough for gram-negative bacteremias, and canagliflozen is linked to lower HbA1c levels in younger patients.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Also today, a new device could detect osteoarthritis with sound and motion, seven days of antibiotics is enough for gram-negative bacteremias, and canagliflozen is linked to lower HbA1c levels in younger patients.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Also today, a new device could detect osteoarthritis with sound and motion, seven days of antibiotics is enough for gram-negative bacteremias, and canagliflozen is linked to lower HbA1c levels in younger patients.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Call for AVAHO Abstracts

The Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO) is now accepting abstracts for its annual meeting, September 28-30, 2018 in Chicago, Illinois. Authors must submit abstracts electronically through the AVAHO website and adhere to the following stipulations:

- The abstract should not exceed 350 words, excluding the title;

- The title cannot exceed 20 words;

- At least 1 author must be a member of AVAHO;

- The copy should not include illustrations or bullet points; and

- All names of the contributing authors and their affiliated institutions must be provided.

All abstracts must be submitted by June 29, 2018. Accepted abstracts will be published by Federal Practitioner and mailed to AVAHO members. The abstracts also will be available at the conference for attendees. Click here for the 2016 and 2017 Abstracts.

More information on the submission process and abstract submission form can be found here.

The Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO) is now accepting abstracts for its annual meeting, September 28-30, 2018 in Chicago, Illinois. Authors must submit abstracts electronically through the AVAHO website and adhere to the following stipulations:

- The abstract should not exceed 350 words, excluding the title;

- The title cannot exceed 20 words;

- At least 1 author must be a member of AVAHO;

- The copy should not include illustrations or bullet points; and

- All names of the contributing authors and their affiliated institutions must be provided.

All abstracts must be submitted by June 29, 2018. Accepted abstracts will be published by Federal Practitioner and mailed to AVAHO members. The abstracts also will be available at the conference for attendees. Click here for the 2016 and 2017 Abstracts.

More information on the submission process and abstract submission form can be found here.

The Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO) is now accepting abstracts for its annual meeting, September 28-30, 2018 in Chicago, Illinois. Authors must submit abstracts electronically through the AVAHO website and adhere to the following stipulations:

- The abstract should not exceed 350 words, excluding the title;

- The title cannot exceed 20 words;

- At least 1 author must be a member of AVAHO;

- The copy should not include illustrations or bullet points; and

- All names of the contributing authors and their affiliated institutions must be provided.

All abstracts must be submitted by June 29, 2018. Accepted abstracts will be published by Federal Practitioner and mailed to AVAHO members. The abstracts also will be available at the conference for attendees. Click here for the 2016 and 2017 Abstracts.

More information on the submission process and abstract submission form can be found here.

How to Eliminate TB—Faster

The US goal is to get Tuberculosis (TB) rates down to > 1 case per 1 million people, but in 2017 there were 28 cases per million. After years of decline, TB rates have stagnated among people born in the US. The TB rate dropped slightly (–2.5%) from 2016 to 2017. Another even slighter decrease was seen in 2017 (–1.8%). Moreover, < 1 in 10 TB cases occurred among children aged < 15 years (a “key marker” of recent transmission, the CDC says). Half of all cases were reported in California, New York, Texas, and Florida, all 4 corners of the country.

As many as 13 million people in the US have latent TB infection but the vast majority do not know it. On average, 5% - 10% of people with latent TB infection progress to infectious TB. More than 80% of US TB cases are associated with long-standing, untreated latent TB infections.

The CDC says reaching the elimination goal will take an “intensified, dual approach” that strengthens existing systems to prevent transmission of infectious TB disease and increases efforts to detect and treat latent infection before it progresses to infectious TB.

It is essential to ensure that every active case of TB disease is effectively detected and treated, the CDC says. Treatments can be difficult to complete; however, not completing treatment can lead to drug-resistant bacteria, and even lengthier and more expensive treatment. CDC research has identified a shorter regimen for people with latent infection: 12 once-weekly doses of isoniazid and rifapentine, a simpler treatment compared with other regimens that include a 270-dose, and 9-month daily regimen of isoniazid.

Over the past 20 years, health departments and CDC TB control efforts have prevented an estimated 300,000 cases of TB disease. “Challenges remain,” says Philip LoBue, MD, director of CDC’s Division of Tuberculosis Elimination. But “[t]he good news is that the path to accelerated progress is clear.” In addition to the shorter treatment regimen, recent advances include electronic directly observed therapy (eDOT), which makes TB treatment less expensive and more convenient; and a diagnostic blood test that can provide accurate results in a single medical visit.

The US goal is to get Tuberculosis (TB) rates down to > 1 case per 1 million people, but in 2017 there were 28 cases per million. After years of decline, TB rates have stagnated among people born in the US. The TB rate dropped slightly (–2.5%) from 2016 to 2017. Another even slighter decrease was seen in 2017 (–1.8%). Moreover, < 1 in 10 TB cases occurred among children aged < 15 years (a “key marker” of recent transmission, the CDC says). Half of all cases were reported in California, New York, Texas, and Florida, all 4 corners of the country.

As many as 13 million people in the US have latent TB infection but the vast majority do not know it. On average, 5% - 10% of people with latent TB infection progress to infectious TB. More than 80% of US TB cases are associated with long-standing, untreated latent TB infections.

The CDC says reaching the elimination goal will take an “intensified, dual approach” that strengthens existing systems to prevent transmission of infectious TB disease and increases efforts to detect and treat latent infection before it progresses to infectious TB.

It is essential to ensure that every active case of TB disease is effectively detected and treated, the CDC says. Treatments can be difficult to complete; however, not completing treatment can lead to drug-resistant bacteria, and even lengthier and more expensive treatment. CDC research has identified a shorter regimen for people with latent infection: 12 once-weekly doses of isoniazid and rifapentine, a simpler treatment compared with other regimens that include a 270-dose, and 9-month daily regimen of isoniazid.

Over the past 20 years, health departments and CDC TB control efforts have prevented an estimated 300,000 cases of TB disease. “Challenges remain,” says Philip LoBue, MD, director of CDC’s Division of Tuberculosis Elimination. But “[t]he good news is that the path to accelerated progress is clear.” In addition to the shorter treatment regimen, recent advances include electronic directly observed therapy (eDOT), which makes TB treatment less expensive and more convenient; and a diagnostic blood test that can provide accurate results in a single medical visit.

The US goal is to get Tuberculosis (TB) rates down to > 1 case per 1 million people, but in 2017 there were 28 cases per million. After years of decline, TB rates have stagnated among people born in the US. The TB rate dropped slightly (–2.5%) from 2016 to 2017. Another even slighter decrease was seen in 2017 (–1.8%). Moreover, < 1 in 10 TB cases occurred among children aged < 15 years (a “key marker” of recent transmission, the CDC says). Half of all cases were reported in California, New York, Texas, and Florida, all 4 corners of the country.

As many as 13 million people in the US have latent TB infection but the vast majority do not know it. On average, 5% - 10% of people with latent TB infection progress to infectious TB. More than 80% of US TB cases are associated with long-standing, untreated latent TB infections.

The CDC says reaching the elimination goal will take an “intensified, dual approach” that strengthens existing systems to prevent transmission of infectious TB disease and increases efforts to detect and treat latent infection before it progresses to infectious TB.

It is essential to ensure that every active case of TB disease is effectively detected and treated, the CDC says. Treatments can be difficult to complete; however, not completing treatment can lead to drug-resistant bacteria, and even lengthier and more expensive treatment. CDC research has identified a shorter regimen for people with latent infection: 12 once-weekly doses of isoniazid and rifapentine, a simpler treatment compared with other regimens that include a 270-dose, and 9-month daily regimen of isoniazid.

Over the past 20 years, health departments and CDC TB control efforts have prevented an estimated 300,000 cases of TB disease. “Challenges remain,” says Philip LoBue, MD, director of CDC’s Division of Tuberculosis Elimination. But “[t]he good news is that the path to accelerated progress is clear.” In addition to the shorter treatment regimen, recent advances include electronic directly observed therapy (eDOT), which makes TB treatment less expensive and more convenient; and a diagnostic blood test that can provide accurate results in a single medical visit.

Gene therapy reduces ABR, AIR in hemophilia B

GLASGOW—New research suggests the gene therapy SPK-9001 can reduce bleeding and the need for factor IX infusions in patients with hemophilia B.

In an ongoing, phase 1/2 trial, SPK-9001 reduced the annualized bleeding rate (ABR) by 98% and the annualized infusion rate (AIR) by 99%.

All 15 patients treated with SPK-9001 have discontinued factor IX prophylaxis.

There have been no serious adverse events (AEs), no thrombotic events, and no factor IX inhibitors observed to date.

Spencer K. Sullivan, MD, of the Mississippi Center for Advanced Medicine in Madison, Mississippi, presented these results at the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) 2018 World Congress during the “Free Papers: Gene Therapy” session on Tuesday.

The research was sponsored by Spark Therapeutics, the company developing SPK-9001 in collaboration with Pfizer.

SPK-9001 is an investigational vector that contains a bio-engineered adeno-associated virus capsid and a codon-optimized, high-activity human factor IX gene enabling endogenous production of factor IX.

Dr Sullivan reported results with SPK-9001 in 15 patients with severe or moderately severe hemophilia B.

As of the May 7, 2018, data cutoff, there were 13 patients with at least 12 weeks of follow-up after SPK-9001 infusion, which is the length of time required to achieve steady-state factor IX activity levels. All 13 patients reached stable factor IX levels of more than 12%.

The range of steady-state factor IX activity level, beginning at 12 weeks through 52 weeks of follow-up for the first 10 patients infused, was 14.3% to 76.8%.

The next 3 patients were infused with SPK-9001 manufactured using an enhanced process and reached 12 or more weeks of follow-up. For these patients, the range of steady-state factor IX activity level was 38.1% to 54.5%.

The 2 remaining patients had only 5 weeks and 11 weeks of follow-up as of the cut-off date.

Based on individual participant history for the year prior to the study, the overall ABR for all 15 patients was reduced by 98% four weeks after SPK-9001 treatment.

The ABR was 0.2 bleeds per patient after SPK-9001, compared to an ABR of 8.9 before SPK-9001.

One patient experienced a bleeding event 4 or more weeks after SPK-9001 infusion.

The overall AIR was reduced by 99% (based on data after week 4) for all 15 patients. The AIR was 0.9 infusions per patient after SPK-9001, compared to 57.2 infusions before SPK-9001.

Six patients received factor IX infusions following SPK-9001 administration—2 for reported spontaneous bleeds, 2 prior to surgery, 1 at the end of the study (discretionary, per protocol), and 1 for prophylaxis for a minor, traumatic non-bleeding event.

However, all 15 patients have discontinued regular factor IX prophylaxis.

There have been no serious AEs or factor IX inhibitors reported.

Two patients (1 who received SPK-9001 manufactured using the enhanced process) experienced related AEs of elevated transaminases, which were asymptomatic.

These patients were treated with a tapering course of oral corticosteroids, and 1 event resolved before the data cutoff.

An additional patient received a tapering course of oral corticosteroids for an increase in liver enzymes (not exceeding the upper limit of normal) temporally associated with falling levels of factor IX activity.

“We are pleased to see all 15 participants, notably including the first 4 participants who have been followed for more than 2 years, continue to show that a single administration of SPK-9001 has resulted in dramatic reductions in bleeding and factor IX infusions, with no serious adverse events,” said Katherine A. High, MD, president and head of research & development at Spark Therapeutics.

“Our commitment to gene therapy research across our hemophilia programs remains steadfast with the goal of developing a novel therapeutic approach with a positive benefit-risk profile that aims to free patients of the need for regular infusions, while eliminating spontaneous bleeding.”

GLASGOW—New research suggests the gene therapy SPK-9001 can reduce bleeding and the need for factor IX infusions in patients with hemophilia B.

In an ongoing, phase 1/2 trial, SPK-9001 reduced the annualized bleeding rate (ABR) by 98% and the annualized infusion rate (AIR) by 99%.

All 15 patients treated with SPK-9001 have discontinued factor IX prophylaxis.

There have been no serious adverse events (AEs), no thrombotic events, and no factor IX inhibitors observed to date.

Spencer K. Sullivan, MD, of the Mississippi Center for Advanced Medicine in Madison, Mississippi, presented these results at the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) 2018 World Congress during the “Free Papers: Gene Therapy” session on Tuesday.

The research was sponsored by Spark Therapeutics, the company developing SPK-9001 in collaboration with Pfizer.

SPK-9001 is an investigational vector that contains a bio-engineered adeno-associated virus capsid and a codon-optimized, high-activity human factor IX gene enabling endogenous production of factor IX.

Dr Sullivan reported results with SPK-9001 in 15 patients with severe or moderately severe hemophilia B.

As of the May 7, 2018, data cutoff, there were 13 patients with at least 12 weeks of follow-up after SPK-9001 infusion, which is the length of time required to achieve steady-state factor IX activity levels. All 13 patients reached stable factor IX levels of more than 12%.

The range of steady-state factor IX activity level, beginning at 12 weeks through 52 weeks of follow-up for the first 10 patients infused, was 14.3% to 76.8%.

The next 3 patients were infused with SPK-9001 manufactured using an enhanced process and reached 12 or more weeks of follow-up. For these patients, the range of steady-state factor IX activity level was 38.1% to 54.5%.

The 2 remaining patients had only 5 weeks and 11 weeks of follow-up as of the cut-off date.

Based on individual participant history for the year prior to the study, the overall ABR for all 15 patients was reduced by 98% four weeks after SPK-9001 treatment.

The ABR was 0.2 bleeds per patient after SPK-9001, compared to an ABR of 8.9 before SPK-9001.

One patient experienced a bleeding event 4 or more weeks after SPK-9001 infusion.

The overall AIR was reduced by 99% (based on data after week 4) for all 15 patients. The AIR was 0.9 infusions per patient after SPK-9001, compared to 57.2 infusions before SPK-9001.

Six patients received factor IX infusions following SPK-9001 administration—2 for reported spontaneous bleeds, 2 prior to surgery, 1 at the end of the study (discretionary, per protocol), and 1 for prophylaxis for a minor, traumatic non-bleeding event.

However, all 15 patients have discontinued regular factor IX prophylaxis.

There have been no serious AEs or factor IX inhibitors reported.

Two patients (1 who received SPK-9001 manufactured using the enhanced process) experienced related AEs of elevated transaminases, which were asymptomatic.

These patients were treated with a tapering course of oral corticosteroids, and 1 event resolved before the data cutoff.

An additional patient received a tapering course of oral corticosteroids for an increase in liver enzymes (not exceeding the upper limit of normal) temporally associated with falling levels of factor IX activity.

“We are pleased to see all 15 participants, notably including the first 4 participants who have been followed for more than 2 years, continue to show that a single administration of SPK-9001 has resulted in dramatic reductions in bleeding and factor IX infusions, with no serious adverse events,” said Katherine A. High, MD, president and head of research & development at Spark Therapeutics.

“Our commitment to gene therapy research across our hemophilia programs remains steadfast with the goal of developing a novel therapeutic approach with a positive benefit-risk profile that aims to free patients of the need for regular infusions, while eliminating spontaneous bleeding.”

GLASGOW—New research suggests the gene therapy SPK-9001 can reduce bleeding and the need for factor IX infusions in patients with hemophilia B.

In an ongoing, phase 1/2 trial, SPK-9001 reduced the annualized bleeding rate (ABR) by 98% and the annualized infusion rate (AIR) by 99%.

All 15 patients treated with SPK-9001 have discontinued factor IX prophylaxis.

There have been no serious adverse events (AEs), no thrombotic events, and no factor IX inhibitors observed to date.

Spencer K. Sullivan, MD, of the Mississippi Center for Advanced Medicine in Madison, Mississippi, presented these results at the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) 2018 World Congress during the “Free Papers: Gene Therapy” session on Tuesday.

The research was sponsored by Spark Therapeutics, the company developing SPK-9001 in collaboration with Pfizer.

SPK-9001 is an investigational vector that contains a bio-engineered adeno-associated virus capsid and a codon-optimized, high-activity human factor IX gene enabling endogenous production of factor IX.

Dr Sullivan reported results with SPK-9001 in 15 patients with severe or moderately severe hemophilia B.

As of the May 7, 2018, data cutoff, there were 13 patients with at least 12 weeks of follow-up after SPK-9001 infusion, which is the length of time required to achieve steady-state factor IX activity levels. All 13 patients reached stable factor IX levels of more than 12%.

The range of steady-state factor IX activity level, beginning at 12 weeks through 52 weeks of follow-up for the first 10 patients infused, was 14.3% to 76.8%.

The next 3 patients were infused with SPK-9001 manufactured using an enhanced process and reached 12 or more weeks of follow-up. For these patients, the range of steady-state factor IX activity level was 38.1% to 54.5%.

The 2 remaining patients had only 5 weeks and 11 weeks of follow-up as of the cut-off date.

Based on individual participant history for the year prior to the study, the overall ABR for all 15 patients was reduced by 98% four weeks after SPK-9001 treatment.

The ABR was 0.2 bleeds per patient after SPK-9001, compared to an ABR of 8.9 before SPK-9001.

One patient experienced a bleeding event 4 or more weeks after SPK-9001 infusion.

The overall AIR was reduced by 99% (based on data after week 4) for all 15 patients. The AIR was 0.9 infusions per patient after SPK-9001, compared to 57.2 infusions before SPK-9001.

Six patients received factor IX infusions following SPK-9001 administration—2 for reported spontaneous bleeds, 2 prior to surgery, 1 at the end of the study (discretionary, per protocol), and 1 for prophylaxis for a minor, traumatic non-bleeding event.

However, all 15 patients have discontinued regular factor IX prophylaxis.

There have been no serious AEs or factor IX inhibitors reported.

Two patients (1 who received SPK-9001 manufactured using the enhanced process) experienced related AEs of elevated transaminases, which were asymptomatic.

These patients were treated with a tapering course of oral corticosteroids, and 1 event resolved before the data cutoff.

An additional patient received a tapering course of oral corticosteroids for an increase in liver enzymes (not exceeding the upper limit of normal) temporally associated with falling levels of factor IX activity.

“We are pleased to see all 15 participants, notably including the first 4 participants who have been followed for more than 2 years, continue to show that a single administration of SPK-9001 has resulted in dramatic reductions in bleeding and factor IX infusions, with no serious adverse events,” said Katherine A. High, MD, president and head of research & development at Spark Therapeutics.

“Our commitment to gene therapy research across our hemophilia programs remains steadfast with the goal of developing a novel therapeutic approach with a positive benefit-risk profile that aims to free patients of the need for regular infusions, while eliminating spontaneous bleeding.”

N9-GP has better PK profile than rFIXFc, team says

GLASGOW—Nonacog beta pegol (N9-GP) has a better pharmacokinetic (PK) profile than recombinant factor IX-Fc fusion protein (rFIXFc), according to researchers.

In a phase 1 trial, adults with hemophilia B who received a single dose of N9-GP achieved greater total factor IX exposure than those treated with rFIXFc, and N9-GP had a longer half-life.

Seven days after injection, factor IX activity was 6-fold greater in patients treated with N9-GP than in those treated with rFIXFc at the same dose.

“As a clinician, I know first-hand how challenging it can be to help people living with hemophilia B reach their treatment goals and be adequately protected from bleeding,” said Carmen Escuriola Ettingshausen, MD, of Haemophilia Centre Rhein Main in Frankfurt-Mörfelden, Germany.

“These data will help us better understand the different treatment options and choose the appropriate treatment for each patient.”

Dr Ettingshausen presented the data at the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) 2018 World Congress during the late-breaking abstract session on Monday.

The research was sponsored by Novo Nordisk A/S, the company marketing N9-GP (as Rebinyn or Refixia). N9-GP is an extended half-life factor IX molecule intended for replacement therapy in patients with hemophilia B.

In the Paradigm7 trial, researchers compared the PK profiles of N9-GP and rFIXFc (Alprolix).

Fifteen previously treated adult males with congenital hemophilia B (factor IX activity ≤2%) received single injections (50 IU/kg) of N9-GP and rFIXFc with at least 21 days between doses.

One patient was excluded from the analysis due to intake of a prohibited medication (an rFIXFc product that was not Alprolix). Two other patients were excluded from some analyses because they missed 2 PK time points.

The primary endpoint was dose-normalized area under the factor IX activity-time curve from 0 to infinity (AUC0-inf,norm).

The estimated AUC0-inf,norm (n=12) was significantly higher for N9-GP than rFIXFc—9656 IU*h/dL and 2199 IU*h/dL, respectively (ratio=4.39, P<0.0001).

There were significant differences for secondary endpoints as well.

The maximum factor IX activity dose-normalized to 50 IU/kg (n=14) was 91 IU/dL with N9-GP and 45 IU/dL with rFIXFc (ratio=2.02, P<0.001).

The incremental recovery at 30 minutes (n=14) was 1.7 (IU/dL)/(IU/kg) with N9-GP and 0.8 (IU/dL)/(IU/kg) with rFIXFc (ratio=2.20, P<0.001).

The terminal half-life (n=12) was 103.2 hours with N9-GP and 84.9 hours with rFIXFc (ratio=1.22, P<0.001).

The clearance (n=12) was 0.52 mL/h/kg with N9-GP and 2.25 mL/h/kg with rFIXFc (ratio=0.23, P<0.001).

The factor IX activity at 168 hours (n=12) was 19 IU/dL with N9-GP and 3 IU/dL with rFIXFc (ratio=5.80, P<0.001).

None of the patients developed inhibitors, and no safety concerns were identified, according to Novo Nordisk. The company did not provide additional safety information.

GLASGOW—Nonacog beta pegol (N9-GP) has a better pharmacokinetic (PK) profile than recombinant factor IX-Fc fusion protein (rFIXFc), according to researchers.

In a phase 1 trial, adults with hemophilia B who received a single dose of N9-GP achieved greater total factor IX exposure than those treated with rFIXFc, and N9-GP had a longer half-life.

Seven days after injection, factor IX activity was 6-fold greater in patients treated with N9-GP than in those treated with rFIXFc at the same dose.

“As a clinician, I know first-hand how challenging it can be to help people living with hemophilia B reach their treatment goals and be adequately protected from bleeding,” said Carmen Escuriola Ettingshausen, MD, of Haemophilia Centre Rhein Main in Frankfurt-Mörfelden, Germany.

“These data will help us better understand the different treatment options and choose the appropriate treatment for each patient.”

Dr Ettingshausen presented the data at the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) 2018 World Congress during the late-breaking abstract session on Monday.

The research was sponsored by Novo Nordisk A/S, the company marketing N9-GP (as Rebinyn or Refixia). N9-GP is an extended half-life factor IX molecule intended for replacement therapy in patients with hemophilia B.

In the Paradigm7 trial, researchers compared the PK profiles of N9-GP and rFIXFc (Alprolix).

Fifteen previously treated adult males with congenital hemophilia B (factor IX activity ≤2%) received single injections (50 IU/kg) of N9-GP and rFIXFc with at least 21 days between doses.

One patient was excluded from the analysis due to intake of a prohibited medication (an rFIXFc product that was not Alprolix). Two other patients were excluded from some analyses because they missed 2 PK time points.

The primary endpoint was dose-normalized area under the factor IX activity-time curve from 0 to infinity (AUC0-inf,norm).

The estimated AUC0-inf,norm (n=12) was significantly higher for N9-GP than rFIXFc—9656 IU*h/dL and 2199 IU*h/dL, respectively (ratio=4.39, P<0.0001).

There were significant differences for secondary endpoints as well.

The maximum factor IX activity dose-normalized to 50 IU/kg (n=14) was 91 IU/dL with N9-GP and 45 IU/dL with rFIXFc (ratio=2.02, P<0.001).

The incremental recovery at 30 minutes (n=14) was 1.7 (IU/dL)/(IU/kg) with N9-GP and 0.8 (IU/dL)/(IU/kg) with rFIXFc (ratio=2.20, P<0.001).

The terminal half-life (n=12) was 103.2 hours with N9-GP and 84.9 hours with rFIXFc (ratio=1.22, P<0.001).

The clearance (n=12) was 0.52 mL/h/kg with N9-GP and 2.25 mL/h/kg with rFIXFc (ratio=0.23, P<0.001).

The factor IX activity at 168 hours (n=12) was 19 IU/dL with N9-GP and 3 IU/dL with rFIXFc (ratio=5.80, P<0.001).

None of the patients developed inhibitors, and no safety concerns were identified, according to Novo Nordisk. The company did not provide additional safety information.

GLASGOW—Nonacog beta pegol (N9-GP) has a better pharmacokinetic (PK) profile than recombinant factor IX-Fc fusion protein (rFIXFc), according to researchers.

In a phase 1 trial, adults with hemophilia B who received a single dose of N9-GP achieved greater total factor IX exposure than those treated with rFIXFc, and N9-GP had a longer half-life.

Seven days after injection, factor IX activity was 6-fold greater in patients treated with N9-GP than in those treated with rFIXFc at the same dose.

“As a clinician, I know first-hand how challenging it can be to help people living with hemophilia B reach their treatment goals and be adequately protected from bleeding,” said Carmen Escuriola Ettingshausen, MD, of Haemophilia Centre Rhein Main in Frankfurt-Mörfelden, Germany.

“These data will help us better understand the different treatment options and choose the appropriate treatment for each patient.”

Dr Ettingshausen presented the data at the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) 2018 World Congress during the late-breaking abstract session on Monday.

The research was sponsored by Novo Nordisk A/S, the company marketing N9-GP (as Rebinyn or Refixia). N9-GP is an extended half-life factor IX molecule intended for replacement therapy in patients with hemophilia B.

In the Paradigm7 trial, researchers compared the PK profiles of N9-GP and rFIXFc (Alprolix).

Fifteen previously treated adult males with congenital hemophilia B (factor IX activity ≤2%) received single injections (50 IU/kg) of N9-GP and rFIXFc with at least 21 days between doses.

One patient was excluded from the analysis due to intake of a prohibited medication (an rFIXFc product that was not Alprolix). Two other patients were excluded from some analyses because they missed 2 PK time points.

The primary endpoint was dose-normalized area under the factor IX activity-time curve from 0 to infinity (AUC0-inf,norm).

The estimated AUC0-inf,norm (n=12) was significantly higher for N9-GP than rFIXFc—9656 IU*h/dL and 2199 IU*h/dL, respectively (ratio=4.39, P<0.0001).

There were significant differences for secondary endpoints as well.

The maximum factor IX activity dose-normalized to 50 IU/kg (n=14) was 91 IU/dL with N9-GP and 45 IU/dL with rFIXFc (ratio=2.02, P<0.001).

The incremental recovery at 30 minutes (n=14) was 1.7 (IU/dL)/(IU/kg) with N9-GP and 0.8 (IU/dL)/(IU/kg) with rFIXFc (ratio=2.20, P<0.001).

The terminal half-life (n=12) was 103.2 hours with N9-GP and 84.9 hours with rFIXFc (ratio=1.22, P<0.001).

The clearance (n=12) was 0.52 mL/h/kg with N9-GP and 2.25 mL/h/kg with rFIXFc (ratio=0.23, P<0.001).

The factor IX activity at 168 hours (n=12) was 19 IU/dL with N9-GP and 3 IU/dL with rFIXFc (ratio=5.80, P<0.001).

None of the patients developed inhibitors, and no safety concerns were identified, according to Novo Nordisk. The company did not provide additional safety information.

Therapy can extend half-life of FVIII

GLASGOW—Preliminary data suggest an investigational therapy can extend the half-life of factor VIII (FVIII) in patients with severe hemophilia A.

Researchers are testing the therapy, BIVV001, in a phase 1/2a trial and have reported results in 4 patients.

BIVV001 extended the half-life of FVIII to 37 hours, with an average FVIII activity of 5.6% at 7 days post-infusion.

“For decades, scientists have been trying to overcome the von Willebrand factor ceiling, which imposes a limit on the half-life of FVIII, and these data demonstrate that BIVV001 has finally broken through that ceiling,” said Joachim Fruebis, PhD, senior vice president of development at Bioverativ Inc.

Dr Fruebis presented these data at the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) 2018 World Congress during the late-breaking abstract session on Monday.

The research was sponsored by Bioverativ, the company developing BIVV001.

BIVV001 (rFVIIIFc-VWF-XTEN) is a recombinant FVIII therapy that builds on Fc fusion technology by adding a region of von Willebrand factor and XTEN polypeptides to potentially extend its time in circulation.

In the phase 1/2a EXTEN-A trial, researchers are evaluating the safety and pharmacokinetics of BIVV001 in a low-dose and high-dose cohort of subjects, ages 18 to 65, who have severe hemophilia A.

In the data presented at the WFH World Congress, 4 adult males received a single dose of recombinant FVIII therapy (25 IU/kg) followed, after a washout period, by a single, low dose of BIVV001 (25 IU/kg).

Primary endpoints of this study include the occurrence of adverse events and the development of inhibitors.

No inhibitors have been detected, and BIBV001 was “generally well-tolerated,” according to Bioverativ. The company did not provide additional safety information.

BIVV001 extended the half-life of FVIII to 37 hours, which is an increase over the 13 hours seen with recombinant FVIII.

The average FVIII activity for the 4 subjects was 13.0% at 5 days and 5.6% at 7 days post-infusion.

“Importantly for the hemophilia community, the factor levels seen in this study are unparalleled in hemophilia A,” Dr Fruebis said, “and we are excited about the potential for BIVV001 to transform the treatment paradigm for patients and physicians.”

GLASGOW—Preliminary data suggest an investigational therapy can extend the half-life of factor VIII (FVIII) in patients with severe hemophilia A.

Researchers are testing the therapy, BIVV001, in a phase 1/2a trial and have reported results in 4 patients.

BIVV001 extended the half-life of FVIII to 37 hours, with an average FVIII activity of 5.6% at 7 days post-infusion.

“For decades, scientists have been trying to overcome the von Willebrand factor ceiling, which imposes a limit on the half-life of FVIII, and these data demonstrate that BIVV001 has finally broken through that ceiling,” said Joachim Fruebis, PhD, senior vice president of development at Bioverativ Inc.

Dr Fruebis presented these data at the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) 2018 World Congress during the late-breaking abstract session on Monday.

The research was sponsored by Bioverativ, the company developing BIVV001.

BIVV001 (rFVIIIFc-VWF-XTEN) is a recombinant FVIII therapy that builds on Fc fusion technology by adding a region of von Willebrand factor and XTEN polypeptides to potentially extend its time in circulation.

In the phase 1/2a EXTEN-A trial, researchers are evaluating the safety and pharmacokinetics of BIVV001 in a low-dose and high-dose cohort of subjects, ages 18 to 65, who have severe hemophilia A.

In the data presented at the WFH World Congress, 4 adult males received a single dose of recombinant FVIII therapy (25 IU/kg) followed, after a washout period, by a single, low dose of BIVV001 (25 IU/kg).

Primary endpoints of this study include the occurrence of adverse events and the development of inhibitors.

No inhibitors have been detected, and BIBV001 was “generally well-tolerated,” according to Bioverativ. The company did not provide additional safety information.

BIVV001 extended the half-life of FVIII to 37 hours, which is an increase over the 13 hours seen with recombinant FVIII.

The average FVIII activity for the 4 subjects was 13.0% at 5 days and 5.6% at 7 days post-infusion.

“Importantly for the hemophilia community, the factor levels seen in this study are unparalleled in hemophilia A,” Dr Fruebis said, “and we are excited about the potential for BIVV001 to transform the treatment paradigm for patients and physicians.”

GLASGOW—Preliminary data suggest an investigational therapy can extend the half-life of factor VIII (FVIII) in patients with severe hemophilia A.

Researchers are testing the therapy, BIVV001, in a phase 1/2a trial and have reported results in 4 patients.

BIVV001 extended the half-life of FVIII to 37 hours, with an average FVIII activity of 5.6% at 7 days post-infusion.

“For decades, scientists have been trying to overcome the von Willebrand factor ceiling, which imposes a limit on the half-life of FVIII, and these data demonstrate that BIVV001 has finally broken through that ceiling,” said Joachim Fruebis, PhD, senior vice president of development at Bioverativ Inc.

Dr Fruebis presented these data at the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) 2018 World Congress during the late-breaking abstract session on Monday.

The research was sponsored by Bioverativ, the company developing BIVV001.

BIVV001 (rFVIIIFc-VWF-XTEN) is a recombinant FVIII therapy that builds on Fc fusion technology by adding a region of von Willebrand factor and XTEN polypeptides to potentially extend its time in circulation.

In the phase 1/2a EXTEN-A trial, researchers are evaluating the safety and pharmacokinetics of BIVV001 in a low-dose and high-dose cohort of subjects, ages 18 to 65, who have severe hemophilia A.

In the data presented at the WFH World Congress, 4 adult males received a single dose of recombinant FVIII therapy (25 IU/kg) followed, after a washout period, by a single, low dose of BIVV001 (25 IU/kg).

Primary endpoints of this study include the occurrence of adverse events and the development of inhibitors.

No inhibitors have been detected, and BIBV001 was “generally well-tolerated,” according to Bioverativ. The company did not provide additional safety information.

BIVV001 extended the half-life of FVIII to 37 hours, which is an increase over the 13 hours seen with recombinant FVIII.

The average FVIII activity for the 4 subjects was 13.0% at 5 days and 5.6% at 7 days post-infusion.

“Importantly for the hemophilia community, the factor levels seen in this study are unparalleled in hemophilia A,” Dr Fruebis said, “and we are excited about the potential for BIVV001 to transform the treatment paradigm for patients and physicians.”

No clear benefit of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation in the community after hospital discharge

Clinical question: Does pharmacist-led medication reconciliation in the community after hospital discharge reduce health care utilization, readmission rates, ED visits, primary care visits, or primary care workload?

Background: Accurate medication reconciliation is essential to ensure safe transitions of care after hospital discharge. Studies have shown that harm from prescribed or omitted medications is higher after discharge and pharmacist-led medication reconciliation on discharge has been shown to improve clinical outcomes. The effect of medication reconciliation after discharge performed by primary care and community-based pharmacist is unclear.

Study design: A meta-analysis.

Setting: This meta-analysis included five randomized, controlled trials, six cohort studies, two pre- and postintervention studies performed in the United Kingdom and United States as well as one quality improvement project performed in Canada.

Synopsis: The studies included demonstrated that community-based pharmacists were more effective at identifying and resolving discrepancies, compared with usual care, but the clinical relevance was unclear. There was no evidence that this reduced readmission rates. Because of the the heterogeneity of the settings, methods, and data reporting in the included trials, no firm conclusion could be drawn regarding the impact on either ED visits and primary care burden, and no consistent evidence of benefit was found. The benefit in clinical outcomes seen in prior studies may be related to other interventions, including patient education, medication review, and improved communication with primary care physicians. This study aimed to specifically isolate the impact of postdischarge, pharmacist-led medication reconciliation, and further research is still needed to understand the clinical relevance of medication discrepancies and which pharmacist-led interventions are most important.

Bottom line: Community-based pharmacists can identify and resolve discrepancies while performing medication reconciliation after hospital discharge, but there is no conclusive benefit in clinical outcomes, such as readmission rates, health care utilization, and primary care visits.

Citation: McNab D et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation in the community after hospital discharge. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017 Dec 16. pii: bmjqs-2017-007087. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007087.

Dr. Rao is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Clinical question: Does pharmacist-led medication reconciliation in the community after hospital discharge reduce health care utilization, readmission rates, ED visits, primary care visits, or primary care workload?

Background: Accurate medication reconciliation is essential to ensure safe transitions of care after hospital discharge. Studies have shown that harm from prescribed or omitted medications is higher after discharge and pharmacist-led medication reconciliation on discharge has been shown to improve clinical outcomes. The effect of medication reconciliation after discharge performed by primary care and community-based pharmacist is unclear.

Study design: A meta-analysis.

Setting: This meta-analysis included five randomized, controlled trials, six cohort studies, two pre- and postintervention studies performed in the United Kingdom and United States as well as one quality improvement project performed in Canada.

Synopsis: The studies included demonstrated that community-based pharmacists were more effective at identifying and resolving discrepancies, compared with usual care, but the clinical relevance was unclear. There was no evidence that this reduced readmission rates. Because of the the heterogeneity of the settings, methods, and data reporting in the included trials, no firm conclusion could be drawn regarding the impact on either ED visits and primary care burden, and no consistent evidence of benefit was found. The benefit in clinical outcomes seen in prior studies may be related to other interventions, including patient education, medication review, and improved communication with primary care physicians. This study aimed to specifically isolate the impact of postdischarge, pharmacist-led medication reconciliation, and further research is still needed to understand the clinical relevance of medication discrepancies and which pharmacist-led interventions are most important.

Bottom line: Community-based pharmacists can identify and resolve discrepancies while performing medication reconciliation after hospital discharge, but there is no conclusive benefit in clinical outcomes, such as readmission rates, health care utilization, and primary care visits.

Citation: McNab D et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation in the community after hospital discharge. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017 Dec 16. pii: bmjqs-2017-007087. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007087.

Dr. Rao is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Clinical question: Does pharmacist-led medication reconciliation in the community after hospital discharge reduce health care utilization, readmission rates, ED visits, primary care visits, or primary care workload?

Background: Accurate medication reconciliation is essential to ensure safe transitions of care after hospital discharge. Studies have shown that harm from prescribed or omitted medications is higher after discharge and pharmacist-led medication reconciliation on discharge has been shown to improve clinical outcomes. The effect of medication reconciliation after discharge performed by primary care and community-based pharmacist is unclear.

Study design: A meta-analysis.

Setting: This meta-analysis included five randomized, controlled trials, six cohort studies, two pre- and postintervention studies performed in the United Kingdom and United States as well as one quality improvement project performed in Canada.

Synopsis: The studies included demonstrated that community-based pharmacists were more effective at identifying and resolving discrepancies, compared with usual care, but the clinical relevance was unclear. There was no evidence that this reduced readmission rates. Because of the the heterogeneity of the settings, methods, and data reporting in the included trials, no firm conclusion could be drawn regarding the impact on either ED visits and primary care burden, and no consistent evidence of benefit was found. The benefit in clinical outcomes seen in prior studies may be related to other interventions, including patient education, medication review, and improved communication with primary care physicians. This study aimed to specifically isolate the impact of postdischarge, pharmacist-led medication reconciliation, and further research is still needed to understand the clinical relevance of medication discrepancies and which pharmacist-led interventions are most important.

Bottom line: Community-based pharmacists can identify and resolve discrepancies while performing medication reconciliation after hospital discharge, but there is no conclusive benefit in clinical outcomes, such as readmission rates, health care utilization, and primary care visits.

Citation: McNab D et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation in the community after hospital discharge. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017 Dec 16. pii: bmjqs-2017-007087. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007087.

Dr. Rao is a hospitalist at Denver Health Medical Center and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.