User login

TAVR safe in low-risk aortic stenosis, early data indicate

WASHINGTON – , according to results of the first U.S. study to evaluate mortality in a low-risk population.

Other complications were also low relative to those seen in previously published studies with higher-risk populations. The preliminary results are “reassuring,” Ronald Waksman, MD, associate director of the division of cardiology, Medstar Health Institute, Washington, DC, reported at CRT 2018 sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Institute at Washington Hospital Center.

In this study, a low-risk eligibility criterion is a Society of Thoracic Surgeons score of 3% or less. The mean score in the first 125 patients was 1.9%.

At 30 days, there were no myocardial infarctions, no acute kidney injuries of stage II or greater, and no transient ischemic attacks. There was one nondisabling stroke, one paravalvular leak, and one coronary obstruction that required a coronary artery bypass graft. The rates of new onset atrial fibrillation, major vascular complications, and life-threatening or major bleeding events were lower than 5%.

Surgical atrial valve replacement (SAVR) currently has a IB recommendation for the treatment of symptomatic low-risk aortic stenosis, but TAVR is not currently indicated in this population, according to 2017 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines. There is, however, substantial interest in extending TAVR to a low-risk population, according to Dr. Waksman.

“We know that there are potential benefits for TAVR versus SAVR that include reduced ICU and hospital length of stay, more rapid quality of life recovery, lower risk of bleeding, and lower risk of postprocedure AF [atrial fibrillation],” said Dr. Waksman in explaining the rationale for this and other ongoing studies testing TAVR in low-risk patients.

In this investigator-initiated study, which was conducted without industry support, 11 sites participated. Most were relatively low-volume centers with fewer than 150 TAVR procedures performed annually, according to Dr. Waksman. The choice of TAVR device was left to the discretion of the operator.

Reflecting a lower-risk population, the mean age of 74.6 years is younger than that of participants in previous TAVR trials. The mean left ventricular ejection fraction was 62.9%. Only 4.8% had a prior MI and 19.2% had a prior coronary artery bypass graft. Most procedures were performed under conscious sedation with fewer than 20% receiving general anesthesia. The mean fluoroscopy time was 16 minutes.

The degree of improvement in hemodynamics following TAVR in this population was called “excellent,” but Dr. Waksman did report a 12.5% incidence of hypo-attenuating leaflet thickening (HALT), an 11% incidence of reduced leaflet motion, and a 9.3% incidence of hypo-attenuation affecting motion. All were subclinical effects.

In a closer analysis of HALT, the rate was 14.4% in the 80.8% of patients who received antiplatelet therapy versus 4.8% in the 17.5% who received oral anticoagulation (some received neither). Dr. Waksman called the greater association of HALT with antiplatelet therapy “a potential signal” that deserves further study.

Full results from all 200 patients are expected in the fall of 2018.

Jeffrey Popma, MD, director of the interventional cardiology clinical service, Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital, Boston, and moderator of the session where the data were presented, called for a direct comparison with SAVR in low-risk patients to place the relative role of these options into context.

Neil Moat, a consultant cardiac surgeon at Royal Brompton & Harefield Hospital, London, agreed. Although he is also encouraged by the evidence of safety in low-risk patients, he labeled the rate of HALT in this study “a concern.”

Dr. Waksman reported financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Life Technologies, Med Alliance, Medtronic Vascular, and Symetis, among other companies.

WASHINGTON – , according to results of the first U.S. study to evaluate mortality in a low-risk population.

Other complications were also low relative to those seen in previously published studies with higher-risk populations. The preliminary results are “reassuring,” Ronald Waksman, MD, associate director of the division of cardiology, Medstar Health Institute, Washington, DC, reported at CRT 2018 sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Institute at Washington Hospital Center.

In this study, a low-risk eligibility criterion is a Society of Thoracic Surgeons score of 3% or less. The mean score in the first 125 patients was 1.9%.

At 30 days, there were no myocardial infarctions, no acute kidney injuries of stage II or greater, and no transient ischemic attacks. There was one nondisabling stroke, one paravalvular leak, and one coronary obstruction that required a coronary artery bypass graft. The rates of new onset atrial fibrillation, major vascular complications, and life-threatening or major bleeding events were lower than 5%.

Surgical atrial valve replacement (SAVR) currently has a IB recommendation for the treatment of symptomatic low-risk aortic stenosis, but TAVR is not currently indicated in this population, according to 2017 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines. There is, however, substantial interest in extending TAVR to a low-risk population, according to Dr. Waksman.

“We know that there are potential benefits for TAVR versus SAVR that include reduced ICU and hospital length of stay, more rapid quality of life recovery, lower risk of bleeding, and lower risk of postprocedure AF [atrial fibrillation],” said Dr. Waksman in explaining the rationale for this and other ongoing studies testing TAVR in low-risk patients.

In this investigator-initiated study, which was conducted without industry support, 11 sites participated. Most were relatively low-volume centers with fewer than 150 TAVR procedures performed annually, according to Dr. Waksman. The choice of TAVR device was left to the discretion of the operator.

Reflecting a lower-risk population, the mean age of 74.6 years is younger than that of participants in previous TAVR trials. The mean left ventricular ejection fraction was 62.9%. Only 4.8% had a prior MI and 19.2% had a prior coronary artery bypass graft. Most procedures were performed under conscious sedation with fewer than 20% receiving general anesthesia. The mean fluoroscopy time was 16 minutes.

The degree of improvement in hemodynamics following TAVR in this population was called “excellent,” but Dr. Waksman did report a 12.5% incidence of hypo-attenuating leaflet thickening (HALT), an 11% incidence of reduced leaflet motion, and a 9.3% incidence of hypo-attenuation affecting motion. All were subclinical effects.

In a closer analysis of HALT, the rate was 14.4% in the 80.8% of patients who received antiplatelet therapy versus 4.8% in the 17.5% who received oral anticoagulation (some received neither). Dr. Waksman called the greater association of HALT with antiplatelet therapy “a potential signal” that deserves further study.

Full results from all 200 patients are expected in the fall of 2018.

Jeffrey Popma, MD, director of the interventional cardiology clinical service, Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital, Boston, and moderator of the session where the data were presented, called for a direct comparison with SAVR in low-risk patients to place the relative role of these options into context.

Neil Moat, a consultant cardiac surgeon at Royal Brompton & Harefield Hospital, London, agreed. Although he is also encouraged by the evidence of safety in low-risk patients, he labeled the rate of HALT in this study “a concern.”

Dr. Waksman reported financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Life Technologies, Med Alliance, Medtronic Vascular, and Symetis, among other companies.

WASHINGTON – , according to results of the first U.S. study to evaluate mortality in a low-risk population.

Other complications were also low relative to those seen in previously published studies with higher-risk populations. The preliminary results are “reassuring,” Ronald Waksman, MD, associate director of the division of cardiology, Medstar Health Institute, Washington, DC, reported at CRT 2018 sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Institute at Washington Hospital Center.

In this study, a low-risk eligibility criterion is a Society of Thoracic Surgeons score of 3% or less. The mean score in the first 125 patients was 1.9%.

At 30 days, there were no myocardial infarctions, no acute kidney injuries of stage II or greater, and no transient ischemic attacks. There was one nondisabling stroke, one paravalvular leak, and one coronary obstruction that required a coronary artery bypass graft. The rates of new onset atrial fibrillation, major vascular complications, and life-threatening or major bleeding events were lower than 5%.

Surgical atrial valve replacement (SAVR) currently has a IB recommendation for the treatment of symptomatic low-risk aortic stenosis, but TAVR is not currently indicated in this population, according to 2017 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines. There is, however, substantial interest in extending TAVR to a low-risk population, according to Dr. Waksman.

“We know that there are potential benefits for TAVR versus SAVR that include reduced ICU and hospital length of stay, more rapid quality of life recovery, lower risk of bleeding, and lower risk of postprocedure AF [atrial fibrillation],” said Dr. Waksman in explaining the rationale for this and other ongoing studies testing TAVR in low-risk patients.

In this investigator-initiated study, which was conducted without industry support, 11 sites participated. Most were relatively low-volume centers with fewer than 150 TAVR procedures performed annually, according to Dr. Waksman. The choice of TAVR device was left to the discretion of the operator.

Reflecting a lower-risk population, the mean age of 74.6 years is younger than that of participants in previous TAVR trials. The mean left ventricular ejection fraction was 62.9%. Only 4.8% had a prior MI and 19.2% had a prior coronary artery bypass graft. Most procedures were performed under conscious sedation with fewer than 20% receiving general anesthesia. The mean fluoroscopy time was 16 minutes.

The degree of improvement in hemodynamics following TAVR in this population was called “excellent,” but Dr. Waksman did report a 12.5% incidence of hypo-attenuating leaflet thickening (HALT), an 11% incidence of reduced leaflet motion, and a 9.3% incidence of hypo-attenuation affecting motion. All were subclinical effects.

In a closer analysis of HALT, the rate was 14.4% in the 80.8% of patients who received antiplatelet therapy versus 4.8% in the 17.5% who received oral anticoagulation (some received neither). Dr. Waksman called the greater association of HALT with antiplatelet therapy “a potential signal” that deserves further study.

Full results from all 200 patients are expected in the fall of 2018.

Jeffrey Popma, MD, director of the interventional cardiology clinical service, Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital, Boston, and moderator of the session where the data were presented, called for a direct comparison with SAVR in low-risk patients to place the relative role of these options into context.

Neil Moat, a consultant cardiac surgeon at Royal Brompton & Harefield Hospital, London, agreed. Although he is also encouraged by the evidence of safety in low-risk patients, he labeled the rate of HALT in this study “a concern.”

Dr. Waksman reported financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Life Technologies, Med Alliance, Medtronic Vascular, and Symetis, among other companies.

REPORTING FROM CRT 2018

Key clinical point: In an interim analysis, transcatheter aortic valve replacement was found safe in low-risk patients with symptomatic aortic stenosis.

Major finding: Through 30 days of follow-up, the mortality rate was 0% or lower than observed in studies conducted in higher-risk populations.

Study details: Interim analysis of 125 patients in a prospective registry study.

Disclosures: Dr. Waksman reported financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Life Technologies, Med Alliance, Medtronic Vascular, and Symetis, among other companies.

CKD triples risk of bad outcomes in HIV

BOSTON – A lot of people do well with HIV thanks to potent antiretrovirals, but there’s still at least one group that needs extra attention: HIV patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), according to Lene Ryom, MD, PhD, an HIV researcher at the University of Copenhagen.

She was the lead investigator on a review of 2,467 HIV patients with CKD – which is becoming more common in HIV as patients live longer – and 33,427 HIV patients without CKD.

The incidence of serious clinical events following CKD diagnosis was 68.9 events per 1,000 patient-years. Among the HIV patients without CKD, the incidence was 23 events per 1,000 patient-years.

“In an era when many HIV patients require much less management due to effective antiretroviral treatment, those living with CKD have a much higher burden of serious clinical events and require much closer monitoring. Modifiable risk factors ... play a central role in CKD morbidity and mortality, highlighting the need for increased awareness, effective treatment, and preventative measures. In particular, smoking seems to be quite important for all” serious adverse outcomes, “so that’s a good place to start,” Dr. Ryom said at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

Most of the 2,467 HIV patients with CKD were white men who have sex with men. At baseline, the median age was 60 years, and median CD4 cell count was above 500. One in three were smokers, 22.4% were HCV positive, and most had viral loads below 400 copies/mL. More than half of the patients were estimated to have died within 5 years of CKD diagnosis.

CKD was defined as two estimated glomerular filtration rates at or below 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 taken at least 3 months apart, or a 25% decrease in eGFR when patients entered the study at that level.

The subjects were all participants in the D:A:D project [Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs], an ongoing international cohort study based at the University of Copenhagen, and funded by pharmaceutical companies, among others.

Dr. Ryom had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Ryom L et al. CROI, Abstract 75.

BOSTON – A lot of people do well with HIV thanks to potent antiretrovirals, but there’s still at least one group that needs extra attention: HIV patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), according to Lene Ryom, MD, PhD, an HIV researcher at the University of Copenhagen.

She was the lead investigator on a review of 2,467 HIV patients with CKD – which is becoming more common in HIV as patients live longer – and 33,427 HIV patients without CKD.

The incidence of serious clinical events following CKD diagnosis was 68.9 events per 1,000 patient-years. Among the HIV patients without CKD, the incidence was 23 events per 1,000 patient-years.

“In an era when many HIV patients require much less management due to effective antiretroviral treatment, those living with CKD have a much higher burden of serious clinical events and require much closer monitoring. Modifiable risk factors ... play a central role in CKD morbidity and mortality, highlighting the need for increased awareness, effective treatment, and preventative measures. In particular, smoking seems to be quite important for all” serious adverse outcomes, “so that’s a good place to start,” Dr. Ryom said at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

Most of the 2,467 HIV patients with CKD were white men who have sex with men. At baseline, the median age was 60 years, and median CD4 cell count was above 500. One in three were smokers, 22.4% were HCV positive, and most had viral loads below 400 copies/mL. More than half of the patients were estimated to have died within 5 years of CKD diagnosis.

CKD was defined as two estimated glomerular filtration rates at or below 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 taken at least 3 months apart, or a 25% decrease in eGFR when patients entered the study at that level.

The subjects were all participants in the D:A:D project [Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs], an ongoing international cohort study based at the University of Copenhagen, and funded by pharmaceutical companies, among others.

Dr. Ryom had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Ryom L et al. CROI, Abstract 75.

BOSTON – A lot of people do well with HIV thanks to potent antiretrovirals, but there’s still at least one group that needs extra attention: HIV patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), according to Lene Ryom, MD, PhD, an HIV researcher at the University of Copenhagen.

She was the lead investigator on a review of 2,467 HIV patients with CKD – which is becoming more common in HIV as patients live longer – and 33,427 HIV patients without CKD.

The incidence of serious clinical events following CKD diagnosis was 68.9 events per 1,000 patient-years. Among the HIV patients without CKD, the incidence was 23 events per 1,000 patient-years.

“In an era when many HIV patients require much less management due to effective antiretroviral treatment, those living with CKD have a much higher burden of serious clinical events and require much closer monitoring. Modifiable risk factors ... play a central role in CKD morbidity and mortality, highlighting the need for increased awareness, effective treatment, and preventative measures. In particular, smoking seems to be quite important for all” serious adverse outcomes, “so that’s a good place to start,” Dr. Ryom said at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

Most of the 2,467 HIV patients with CKD were white men who have sex with men. At baseline, the median age was 60 years, and median CD4 cell count was above 500. One in three were smokers, 22.4% were HCV positive, and most had viral loads below 400 copies/mL. More than half of the patients were estimated to have died within 5 years of CKD diagnosis.

CKD was defined as two estimated glomerular filtration rates at or below 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 taken at least 3 months apart, or a 25% decrease in eGFR when patients entered the study at that level.

The subjects were all participants in the D:A:D project [Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs], an ongoing international cohort study based at the University of Copenhagen, and funded by pharmaceutical companies, among others.

Dr. Ryom had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Ryom L et al. CROI, Abstract 75.

REPORTING FROM CROI

Key clinical point: Smoking, diabetes, dyslipidemia, low body mass index, and poor HIV control increase the risk of poor outcomes in HIV patients who have chronic kidney disease.

Major finding: In HIV patients with CKD, the incidence of a serious clinical event is 68.9 per 1,000 patient-years; in HIV patients without CKD, it’s 23 events per 1,000 patient-years.

Study details: Review of nearly 36,000 HIV patients.

Disclosures: The lead investigator had no disclosures. Funding came from pharmaceutical companies, among others.

Source: Ryom L et al. CROI, Abstract 75.

Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: Preop measures that predict death

Four preoperative variables – age over 76 years, creatinine concentration greater than 2.0 mg/dL, pH less than 7.2, and lowest ever systolic blood pressure less than 70 mm Hg – predicted 30-day mortality following repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms (rAAAs), in a retrospective study of 303 patients treated at Harborview Medical Center at the University of Washington, Seattle.

Brandon T. Garland, MD, and his colleagues at Harborview, reviewed the data set of patients, noting 50% were aged older than 76 years and 80% were male. Many patients had typical vascular risk factors: 65% had hypertension, 39% had coronary artery disease, and 22% had chronic obstructive vascular disease. Patients who were treated for rAAA after 2007 and had preoperative computed tomography scans were assessed for endovascular aneurysm repair (rEVAR) based on infrarenal neck length and diameter and access vessel size. Noneligible patients and all patients treated prior to 2007 had open repair (rOR) surgery.

A primary screen of selected preoperative variables included age, hematocrit, systolic blood pressure values, use of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, pH, international normalized ratio, creatinine concentration, temperature, partial thromboplastin time, weight, history of coronary artery disease, and loss of consciousness at any time.

The four statistically significant associations were age over 76 years (odds ratio, 2.11; P less than 0.11), creatinine concentration over 2.0 mg/dL (OR, 3.66; P less than .001), pH less than 7.2 (OR 2.58; P less than .009) and lowest ever systolic blood pressure less than 70 mm Hg (OR, 2.70; P less than .002) Each of the four predictive preoperative rAAA variables was assigned a value of 1 point. Individualized scores are simply calculated by totaling the number of preoperative risk predictors.

Of the original 303 patients, 154 were alive at 30 days following rAAA repair, and there was a significant benefit from using rEVAR. Overall, patients with 1-, 2-, 3-, and 4-point mortality scores had 30-day mortality risks of 22%, 69%, 80%, and 100%, respectively. rEVAR mortalities dropped to 7% for a 1-point score and to 70% for a 3-point score. There were no 30-day survivors with 4-point risk scores regardless of whether they had rEVAR or rOR procedures.

The predictive risk scores for rAAA mortality outcomes provide helpful guides for patient care recommendations, and can be used to supplement the rOR-validated Glasgow Aneurysm Score, Hardman index, and Vascular Study Group of New England risk-predicting algorithms to “aid in clinical decision-making in the endovascular era,” the researchers wrote. The scores also add “prognostic information to the decision to transfer patients to tertiary care centers and aid in preoperative discussions with patients and their families.”

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Garland BT et al. J Vasc Surg. 2018 May 9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.12.075.

Four preoperative variables – age over 76 years, creatinine concentration greater than 2.0 mg/dL, pH less than 7.2, and lowest ever systolic blood pressure less than 70 mm Hg – predicted 30-day mortality following repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms (rAAAs), in a retrospective study of 303 patients treated at Harborview Medical Center at the University of Washington, Seattle.

Brandon T. Garland, MD, and his colleagues at Harborview, reviewed the data set of patients, noting 50% were aged older than 76 years and 80% were male. Many patients had typical vascular risk factors: 65% had hypertension, 39% had coronary artery disease, and 22% had chronic obstructive vascular disease. Patients who were treated for rAAA after 2007 and had preoperative computed tomography scans were assessed for endovascular aneurysm repair (rEVAR) based on infrarenal neck length and diameter and access vessel size. Noneligible patients and all patients treated prior to 2007 had open repair (rOR) surgery.

A primary screen of selected preoperative variables included age, hematocrit, systolic blood pressure values, use of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, pH, international normalized ratio, creatinine concentration, temperature, partial thromboplastin time, weight, history of coronary artery disease, and loss of consciousness at any time.

The four statistically significant associations were age over 76 years (odds ratio, 2.11; P less than 0.11), creatinine concentration over 2.0 mg/dL (OR, 3.66; P less than .001), pH less than 7.2 (OR 2.58; P less than .009) and lowest ever systolic blood pressure less than 70 mm Hg (OR, 2.70; P less than .002) Each of the four predictive preoperative rAAA variables was assigned a value of 1 point. Individualized scores are simply calculated by totaling the number of preoperative risk predictors.

Of the original 303 patients, 154 were alive at 30 days following rAAA repair, and there was a significant benefit from using rEVAR. Overall, patients with 1-, 2-, 3-, and 4-point mortality scores had 30-day mortality risks of 22%, 69%, 80%, and 100%, respectively. rEVAR mortalities dropped to 7% for a 1-point score and to 70% for a 3-point score. There were no 30-day survivors with 4-point risk scores regardless of whether they had rEVAR or rOR procedures.

The predictive risk scores for rAAA mortality outcomes provide helpful guides for patient care recommendations, and can be used to supplement the rOR-validated Glasgow Aneurysm Score, Hardman index, and Vascular Study Group of New England risk-predicting algorithms to “aid in clinical decision-making in the endovascular era,” the researchers wrote. The scores also add “prognostic information to the decision to transfer patients to tertiary care centers and aid in preoperative discussions with patients and their families.”

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Garland BT et al. J Vasc Surg. 2018 May 9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.12.075.

Four preoperative variables – age over 76 years, creatinine concentration greater than 2.0 mg/dL, pH less than 7.2, and lowest ever systolic blood pressure less than 70 mm Hg – predicted 30-day mortality following repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms (rAAAs), in a retrospective study of 303 patients treated at Harborview Medical Center at the University of Washington, Seattle.

Brandon T. Garland, MD, and his colleagues at Harborview, reviewed the data set of patients, noting 50% were aged older than 76 years and 80% were male. Many patients had typical vascular risk factors: 65% had hypertension, 39% had coronary artery disease, and 22% had chronic obstructive vascular disease. Patients who were treated for rAAA after 2007 and had preoperative computed tomography scans were assessed for endovascular aneurysm repair (rEVAR) based on infrarenal neck length and diameter and access vessel size. Noneligible patients and all patients treated prior to 2007 had open repair (rOR) surgery.

A primary screen of selected preoperative variables included age, hematocrit, systolic blood pressure values, use of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, pH, international normalized ratio, creatinine concentration, temperature, partial thromboplastin time, weight, history of coronary artery disease, and loss of consciousness at any time.

The four statistically significant associations were age over 76 years (odds ratio, 2.11; P less than 0.11), creatinine concentration over 2.0 mg/dL (OR, 3.66; P less than .001), pH less than 7.2 (OR 2.58; P less than .009) and lowest ever systolic blood pressure less than 70 mm Hg (OR, 2.70; P less than .002) Each of the four predictive preoperative rAAA variables was assigned a value of 1 point. Individualized scores are simply calculated by totaling the number of preoperative risk predictors.

Of the original 303 patients, 154 were alive at 30 days following rAAA repair, and there was a significant benefit from using rEVAR. Overall, patients with 1-, 2-, 3-, and 4-point mortality scores had 30-day mortality risks of 22%, 69%, 80%, and 100%, respectively. rEVAR mortalities dropped to 7% for a 1-point score and to 70% for a 3-point score. There were no 30-day survivors with 4-point risk scores regardless of whether they had rEVAR or rOR procedures.

The predictive risk scores for rAAA mortality outcomes provide helpful guides for patient care recommendations, and can be used to supplement the rOR-validated Glasgow Aneurysm Score, Hardman index, and Vascular Study Group of New England risk-predicting algorithms to “aid in clinical decision-making in the endovascular era,” the researchers wrote. The scores also add “prognostic information to the decision to transfer patients to tertiary care centers and aid in preoperative discussions with patients and their families.”

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Garland BT et al. J Vasc Surg. 2018 May 9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.12.075.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF VASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: Age, creatinine concentration, pH, and systolic blood pressure measures can be used to determine a 30-day mortality risk score for patients undergoing repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms (rAAAs).

Major finding: The Harborview Medical Center risk scores range from 0 to 4 points with 1-, 2-, and 3-point scores corresponding respectively to 22%, 69%, and 80% risks of 30-day mortality following rAAA repair.

Study details: A single-location retrospective study of 303 patients presenting with ruptured rAAAs.

Disclosures: The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

Source: Garland BT et al. J Vasc Surg. 2018 May 9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.12.075.

CBC values linked to CVD risk in psoriasis

ORLANDO – conducted by researchers at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.*

It’s generally accepted that psoriasis increases the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), but it’s not clear who’s most at risk. “We really wanted to find something that is cheap and easy to risk stratify these patients” said lead investigator Rosalynn Conic, MD, of Case Western’s department of dermatology.

What they found was “very impressive, for sure,” Dr. Conic said at the International Investigative Dermatology meeting.

The incidence of MI was highest among the 1,920 patients (5%) with elevated RDW and MPV (odds ratio, 3.4; 95% confidence interval, 2.7-4.2; P less than .001), followed by the 7,060 (18%) patients with high RDW and normal MPV (OR, 2.4; 95% CI, 2.1-2.8; P less than .001), as compared with normal/low MPV and RDW patients.

Elevated RDW or elevated RDW plus MPV increased the odds of atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, heart failure, and peripheral vascular disease anywhere from 2 to 8.3 times (P less than .001). Among psoriatic arthritis patients, elevated RDW almost doubled the risk of MI (OR, 1.8; P less than .001). Results were adjusted for age, gender, and hypertension.

In a subanalysis of treatment effects, 4 of 23 psoriasis patients at Case Western had elevated RDWs at baseline. Values normalized in the three patients who achieved a 75% reduction in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score after about a year of systemic treatment.

“We aim to validate [the study results] with a Veterans Administration data set,” Dr. Conic said. If it pans out, “one use would be to send [patients with elevated values] to a cardiologist earlier” so other CVD risk factors can be monitored and treated. The findings also add to the case for good control, she noted.

Systemic inflammation is the common denominator between the blood value elevations and CVD. The same inflammatory cytokines that cause skin problems in psoriasis also stimulate bone marrow to release immature red blood cells, which are larger than mature cells, leading to an increased RDW. Similarly, elevated MPV indicates a higher number of larger, younger platelets in the blood.

“It’s probably something along those lines, but I think we need to go back to basic science and really figure it out,” Dr. Conic said.

Patients were 18-65 years old. The study excluded patients with diabetes, Crohn’s disease, RA, and generalized atherosclerosis.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. Dr. Conic reported no relevant financial disclosures.

*This article was updated on May 30, 2018.

SOURCE: Conic R et al. IID 2018, Abstract 550.

ORLANDO – conducted by researchers at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.*

It’s generally accepted that psoriasis increases the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), but it’s not clear who’s most at risk. “We really wanted to find something that is cheap and easy to risk stratify these patients” said lead investigator Rosalynn Conic, MD, of Case Western’s department of dermatology.

What they found was “very impressive, for sure,” Dr. Conic said at the International Investigative Dermatology meeting.

The incidence of MI was highest among the 1,920 patients (5%) with elevated RDW and MPV (odds ratio, 3.4; 95% confidence interval, 2.7-4.2; P less than .001), followed by the 7,060 (18%) patients with high RDW and normal MPV (OR, 2.4; 95% CI, 2.1-2.8; P less than .001), as compared with normal/low MPV and RDW patients.

Elevated RDW or elevated RDW plus MPV increased the odds of atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, heart failure, and peripheral vascular disease anywhere from 2 to 8.3 times (P less than .001). Among psoriatic arthritis patients, elevated RDW almost doubled the risk of MI (OR, 1.8; P less than .001). Results were adjusted for age, gender, and hypertension.

In a subanalysis of treatment effects, 4 of 23 psoriasis patients at Case Western had elevated RDWs at baseline. Values normalized in the three patients who achieved a 75% reduction in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score after about a year of systemic treatment.

“We aim to validate [the study results] with a Veterans Administration data set,” Dr. Conic said. If it pans out, “one use would be to send [patients with elevated values] to a cardiologist earlier” so other CVD risk factors can be monitored and treated. The findings also add to the case for good control, she noted.

Systemic inflammation is the common denominator between the blood value elevations and CVD. The same inflammatory cytokines that cause skin problems in psoriasis also stimulate bone marrow to release immature red blood cells, which are larger than mature cells, leading to an increased RDW. Similarly, elevated MPV indicates a higher number of larger, younger platelets in the blood.

“It’s probably something along those lines, but I think we need to go back to basic science and really figure it out,” Dr. Conic said.

Patients were 18-65 years old. The study excluded patients with diabetes, Crohn’s disease, RA, and generalized atherosclerosis.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. Dr. Conic reported no relevant financial disclosures.

*This article was updated on May 30, 2018.

SOURCE: Conic R et al. IID 2018, Abstract 550.

ORLANDO – conducted by researchers at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.*

It’s generally accepted that psoriasis increases the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), but it’s not clear who’s most at risk. “We really wanted to find something that is cheap and easy to risk stratify these patients” said lead investigator Rosalynn Conic, MD, of Case Western’s department of dermatology.

What they found was “very impressive, for sure,” Dr. Conic said at the International Investigative Dermatology meeting.

The incidence of MI was highest among the 1,920 patients (5%) with elevated RDW and MPV (odds ratio, 3.4; 95% confidence interval, 2.7-4.2; P less than .001), followed by the 7,060 (18%) patients with high RDW and normal MPV (OR, 2.4; 95% CI, 2.1-2.8; P less than .001), as compared with normal/low MPV and RDW patients.

Elevated RDW or elevated RDW plus MPV increased the odds of atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, heart failure, and peripheral vascular disease anywhere from 2 to 8.3 times (P less than .001). Among psoriatic arthritis patients, elevated RDW almost doubled the risk of MI (OR, 1.8; P less than .001). Results were adjusted for age, gender, and hypertension.

In a subanalysis of treatment effects, 4 of 23 psoriasis patients at Case Western had elevated RDWs at baseline. Values normalized in the three patients who achieved a 75% reduction in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score after about a year of systemic treatment.

“We aim to validate [the study results] with a Veterans Administration data set,” Dr. Conic said. If it pans out, “one use would be to send [patients with elevated values] to a cardiologist earlier” so other CVD risk factors can be monitored and treated. The findings also add to the case for good control, she noted.

Systemic inflammation is the common denominator between the blood value elevations and CVD. The same inflammatory cytokines that cause skin problems in psoriasis also stimulate bone marrow to release immature red blood cells, which are larger than mature cells, leading to an increased RDW. Similarly, elevated MPV indicates a higher number of larger, younger platelets in the blood.

“It’s probably something along those lines, but I think we need to go back to basic science and really figure it out,” Dr. Conic said.

Patients were 18-65 years old. The study excluded patients with diabetes, Crohn’s disease, RA, and generalized atherosclerosis.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. Dr. Conic reported no relevant financial disclosures.

*This article was updated on May 30, 2018.

SOURCE: Conic R et al. IID 2018, Abstract 550.

REPORTING FROM IID 2018

Key clinical point: Elevated red blood cell distribution width and mean platelet volume might identify psoriasis patients at risk for cardiovascular disease.

Major finding: The incidence of MI was highest among the 1,920 patients with elevated red cell distribution width and mean platelet volume (odds ratio, 3.4; 95% confidence interval, 2.7-4.2; P less than .001).

Study details: A database review of 39,510 patients with psoriasis.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health funded the work. The lead investigator had no disclosures to report.

Source: Conic R et al. IID 2018, Abstract 550.

Suicidal ideation, maladaptive beliefs appear linked in some psychotic disorders

Maladaptive beliefs and face emotion processing appear associated with suicidal ideation and behavior in psychosis, results of a retrospective, cross-sectional study suggest.

“The present findings suggest that maladaptive beliefs are associated with a tendency to misperceive neutral stimuli as threatening, and are associated with suicidal ideation and behavior,” wrote Jennifer Villa of San Diego State University and her associates.

In the study, published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research, 101 outpatients aged 18 and older with psychotic disorders were assessed via the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire–15 (INQ-15) and the Penn Emotion Recognition Task (ER-40). The participants also were assessed via several other measures, including the Modified Scale for Suicidal Ideation (MSSI), reported Ms. Villa. The INQ-15, a self-report measure, assesses interpersonal beliefs that underlie the desire for suicide. The MSSI, an 18-item instrument, measures the presence of ideation in the previous 48 hours.

Ms. Villa and her associates found that , compared with those without any past history of attempts or current ideation. In addition, MSSI total scores were correlated with INQ total scores (P = .002). When comparing disorders, patients with bipolar disorder with MSSI current ideation had higher INQ total scores than did patients without ideation (P = .010) vs. no MSSI current ideation.

They cited several limitations. One is that the findings might not be generalizable, because causal relationships between maladaptive beliefs, emotion recognition, or the risk of suicidal ideation or behavior cannot be inferred. Also, because most of the patients in the sample were middle-aged adults, the findings might not apply to patients who are experiencing first-episode psychosis. Nevertheless, they said, “the results are of clinical interest demonstrating the growing importance of social cognition to the cumulative evaluation of suicide risk in psychosis and identification of potential targets for suicide prevention.”

Ms. Villa reported no conflicts of interest. Two of the authors reported relationships with several pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Villa J et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2018 Ma;100:107-12.

Maladaptive beliefs and face emotion processing appear associated with suicidal ideation and behavior in psychosis, results of a retrospective, cross-sectional study suggest.

“The present findings suggest that maladaptive beliefs are associated with a tendency to misperceive neutral stimuli as threatening, and are associated with suicidal ideation and behavior,” wrote Jennifer Villa of San Diego State University and her associates.

In the study, published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research, 101 outpatients aged 18 and older with psychotic disorders were assessed via the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire–15 (INQ-15) and the Penn Emotion Recognition Task (ER-40). The participants also were assessed via several other measures, including the Modified Scale for Suicidal Ideation (MSSI), reported Ms. Villa. The INQ-15, a self-report measure, assesses interpersonal beliefs that underlie the desire for suicide. The MSSI, an 18-item instrument, measures the presence of ideation in the previous 48 hours.

Ms. Villa and her associates found that , compared with those without any past history of attempts or current ideation. In addition, MSSI total scores were correlated with INQ total scores (P = .002). When comparing disorders, patients with bipolar disorder with MSSI current ideation had higher INQ total scores than did patients without ideation (P = .010) vs. no MSSI current ideation.

They cited several limitations. One is that the findings might not be generalizable, because causal relationships between maladaptive beliefs, emotion recognition, or the risk of suicidal ideation or behavior cannot be inferred. Also, because most of the patients in the sample were middle-aged adults, the findings might not apply to patients who are experiencing first-episode psychosis. Nevertheless, they said, “the results are of clinical interest demonstrating the growing importance of social cognition to the cumulative evaluation of suicide risk in psychosis and identification of potential targets for suicide prevention.”

Ms. Villa reported no conflicts of interest. Two of the authors reported relationships with several pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Villa J et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2018 Ma;100:107-12.

Maladaptive beliefs and face emotion processing appear associated with suicidal ideation and behavior in psychosis, results of a retrospective, cross-sectional study suggest.

“The present findings suggest that maladaptive beliefs are associated with a tendency to misperceive neutral stimuli as threatening, and are associated with suicidal ideation and behavior,” wrote Jennifer Villa of San Diego State University and her associates.

In the study, published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research, 101 outpatients aged 18 and older with psychotic disorders were assessed via the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire–15 (INQ-15) and the Penn Emotion Recognition Task (ER-40). The participants also were assessed via several other measures, including the Modified Scale for Suicidal Ideation (MSSI), reported Ms. Villa. The INQ-15, a self-report measure, assesses interpersonal beliefs that underlie the desire for suicide. The MSSI, an 18-item instrument, measures the presence of ideation in the previous 48 hours.

Ms. Villa and her associates found that , compared with those without any past history of attempts or current ideation. In addition, MSSI total scores were correlated with INQ total scores (P = .002). When comparing disorders, patients with bipolar disorder with MSSI current ideation had higher INQ total scores than did patients without ideation (P = .010) vs. no MSSI current ideation.

They cited several limitations. One is that the findings might not be generalizable, because causal relationships between maladaptive beliefs, emotion recognition, or the risk of suicidal ideation or behavior cannot be inferred. Also, because most of the patients in the sample were middle-aged adults, the findings might not apply to patients who are experiencing first-episode psychosis. Nevertheless, they said, “the results are of clinical interest demonstrating the growing importance of social cognition to the cumulative evaluation of suicide risk in psychosis and identification of potential targets for suicide prevention.”

Ms. Villa reported no conflicts of interest. Two of the authors reported relationships with several pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Villa J et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2018 Ma;100:107-12.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRIC RESEARCH

SUSTAIN-7: GLP-1 receptor agonists effective in elderly

BOSTON – Efficacy and safety of two glucagonlike peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes mellitus were similar between older and younger adults, according to a post hoc analysis of the SUSTAIN 7 clinical trial data.

However, said the study’s first author, Vanita Aroda, MD, associate director for clinical diabetes research at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The SUSTAIN 7 trial compared low-dose semaglutide (0.5 mg) with low-dose dulaglutide (0.75 mg), and high-dose semaglutide (1.0 mg) with high-dose dulaglutide (1.5 mg) as add-on therapy to metformin for adults with type 2 diabetes. All medications were given as once-weekly subcutaneous injections.

Dr. Aroda and her collaborators performed a subgroup analysis of the SUSTAIN 7 data that compared 260 patients aged 65 years and older (mean, 69.3 years) with 939 patients younger than 65 years (mean, 51.9 years).

“What we found is that the efficacy results … were similar to what we saw in the general population. We did not lose the efficacy in the older adult population,” said Dr. Aroda in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Association for Clinical Endocrinology.

Weight loss was similar in older and younger patients, though there was “maybe a tiny bit more in the older adults,” said Dr. Aroda: Older participants had a 4.4-kg reduction in weight, compared with 4.9-kg reduction in the younger population, on low-dose semaglutide. For low-dose dulaglutide, losses were an average 2.6 kg in the elderly versus 2.2 kg in the younger participants.

The higher doses of each resulted in greater weight loss, up to a mean 6.7 kg in elderly participants on high-dose semaglutide, with the same marginally greater losses seen in older participants.

Both agents were efficacious in the older population, Dr. Aroda said, with slightly better efficacy than in younger patients. As a caveat, she noted that the older patients came into the study with slightly better glycemic control and slightly lower body weight.

An array of endpoints for the 40-week study included achieving hemoglobin A1c less than 7%, less than or equal to 6.5%, and less than 7% without weight gain or hypoglycemia. A higher proportion of elderly patients met these endpoints; for example, 83% of elderly patients on high-dose semaglutide reached the composite endpoint of HbA1c less than 7% with no weight gain or hypoglycemia, compared to 72.1% of younger participants.

The analysis also looked at safety data for SUSTAIN 7. “The next question is, are you seeing this efficacy in terms of glycemic change and weight loss, at any cost of hypoglycemia? And the answer to that was no,” said Dr. Aroda. There were very rare to zero hypoglycemic events in the various study arms, she said.

However, older adults taking the higher doses of both GLP-1 receptor agonists had a high incidence of nausea, vomiting, and other gastrointestinal disturbances. These adverse events were seen in 52.8% of older patients on high-dose semaglutide and 52.2% of those on high-dose dulaglutide. Rates for the younger study population at these doses were 42.5% for semaglutide and 46.6% for dulaglutide.

The clinical take-home message? Don’t be afraid to reach for a GLP-1 receptor agonist for an older patient who’s not reaching target on metformin. “You have good efficacy with both of the therapies … but you just need to watch out for tolerability at the higher doses,” said Dr. Aroda.

Dr. Aroda reported receiving research funding from AstraZeneca, Calibri, Eisai, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Theracos. She was formerly affiliated with Medstar Health Research Institute, Hyattsville, Md.

SOURCE: Aroda V et al. AACE 2018. Abstract 245.

BOSTON – Efficacy and safety of two glucagonlike peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes mellitus were similar between older and younger adults, according to a post hoc analysis of the SUSTAIN 7 clinical trial data.

However, said the study’s first author, Vanita Aroda, MD, associate director for clinical diabetes research at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The SUSTAIN 7 trial compared low-dose semaglutide (0.5 mg) with low-dose dulaglutide (0.75 mg), and high-dose semaglutide (1.0 mg) with high-dose dulaglutide (1.5 mg) as add-on therapy to metformin for adults with type 2 diabetes. All medications were given as once-weekly subcutaneous injections.

Dr. Aroda and her collaborators performed a subgroup analysis of the SUSTAIN 7 data that compared 260 patients aged 65 years and older (mean, 69.3 years) with 939 patients younger than 65 years (mean, 51.9 years).

“What we found is that the efficacy results … were similar to what we saw in the general population. We did not lose the efficacy in the older adult population,” said Dr. Aroda in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Association for Clinical Endocrinology.

Weight loss was similar in older and younger patients, though there was “maybe a tiny bit more in the older adults,” said Dr. Aroda: Older participants had a 4.4-kg reduction in weight, compared with 4.9-kg reduction in the younger population, on low-dose semaglutide. For low-dose dulaglutide, losses were an average 2.6 kg in the elderly versus 2.2 kg in the younger participants.

The higher doses of each resulted in greater weight loss, up to a mean 6.7 kg in elderly participants on high-dose semaglutide, with the same marginally greater losses seen in older participants.

Both agents were efficacious in the older population, Dr. Aroda said, with slightly better efficacy than in younger patients. As a caveat, she noted that the older patients came into the study with slightly better glycemic control and slightly lower body weight.

An array of endpoints for the 40-week study included achieving hemoglobin A1c less than 7%, less than or equal to 6.5%, and less than 7% without weight gain or hypoglycemia. A higher proportion of elderly patients met these endpoints; for example, 83% of elderly patients on high-dose semaglutide reached the composite endpoint of HbA1c less than 7% with no weight gain or hypoglycemia, compared to 72.1% of younger participants.

The analysis also looked at safety data for SUSTAIN 7. “The next question is, are you seeing this efficacy in terms of glycemic change and weight loss, at any cost of hypoglycemia? And the answer to that was no,” said Dr. Aroda. There were very rare to zero hypoglycemic events in the various study arms, she said.

However, older adults taking the higher doses of both GLP-1 receptor agonists had a high incidence of nausea, vomiting, and other gastrointestinal disturbances. These adverse events were seen in 52.8% of older patients on high-dose semaglutide and 52.2% of those on high-dose dulaglutide. Rates for the younger study population at these doses were 42.5% for semaglutide and 46.6% for dulaglutide.

The clinical take-home message? Don’t be afraid to reach for a GLP-1 receptor agonist for an older patient who’s not reaching target on metformin. “You have good efficacy with both of the therapies … but you just need to watch out for tolerability at the higher doses,” said Dr. Aroda.

Dr. Aroda reported receiving research funding from AstraZeneca, Calibri, Eisai, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Theracos. She was formerly affiliated with Medstar Health Research Institute, Hyattsville, Md.

SOURCE: Aroda V et al. AACE 2018. Abstract 245.

BOSTON – Efficacy and safety of two glucagonlike peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes mellitus were similar between older and younger adults, according to a post hoc analysis of the SUSTAIN 7 clinical trial data.

However, said the study’s first author, Vanita Aroda, MD, associate director for clinical diabetes research at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The SUSTAIN 7 trial compared low-dose semaglutide (0.5 mg) with low-dose dulaglutide (0.75 mg), and high-dose semaglutide (1.0 mg) with high-dose dulaglutide (1.5 mg) as add-on therapy to metformin for adults with type 2 diabetes. All medications were given as once-weekly subcutaneous injections.

Dr. Aroda and her collaborators performed a subgroup analysis of the SUSTAIN 7 data that compared 260 patients aged 65 years and older (mean, 69.3 years) with 939 patients younger than 65 years (mean, 51.9 years).

“What we found is that the efficacy results … were similar to what we saw in the general population. We did not lose the efficacy in the older adult population,” said Dr. Aroda in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Association for Clinical Endocrinology.

Weight loss was similar in older and younger patients, though there was “maybe a tiny bit more in the older adults,” said Dr. Aroda: Older participants had a 4.4-kg reduction in weight, compared with 4.9-kg reduction in the younger population, on low-dose semaglutide. For low-dose dulaglutide, losses were an average 2.6 kg in the elderly versus 2.2 kg in the younger participants.

The higher doses of each resulted in greater weight loss, up to a mean 6.7 kg in elderly participants on high-dose semaglutide, with the same marginally greater losses seen in older participants.

Both agents were efficacious in the older population, Dr. Aroda said, with slightly better efficacy than in younger patients. As a caveat, she noted that the older patients came into the study with slightly better glycemic control and slightly lower body weight.

An array of endpoints for the 40-week study included achieving hemoglobin A1c less than 7%, less than or equal to 6.5%, and less than 7% without weight gain or hypoglycemia. A higher proportion of elderly patients met these endpoints; for example, 83% of elderly patients on high-dose semaglutide reached the composite endpoint of HbA1c less than 7% with no weight gain or hypoglycemia, compared to 72.1% of younger participants.

The analysis also looked at safety data for SUSTAIN 7. “The next question is, are you seeing this efficacy in terms of glycemic change and weight loss, at any cost of hypoglycemia? And the answer to that was no,” said Dr. Aroda. There were very rare to zero hypoglycemic events in the various study arms, she said.

However, older adults taking the higher doses of both GLP-1 receptor agonists had a high incidence of nausea, vomiting, and other gastrointestinal disturbances. These adverse events were seen in 52.8% of older patients on high-dose semaglutide and 52.2% of those on high-dose dulaglutide. Rates for the younger study population at these doses were 42.5% for semaglutide and 46.6% for dulaglutide.

The clinical take-home message? Don’t be afraid to reach for a GLP-1 receptor agonist for an older patient who’s not reaching target on metformin. “You have good efficacy with both of the therapies … but you just need to watch out for tolerability at the higher doses,” said Dr. Aroda.

Dr. Aroda reported receiving research funding from AstraZeneca, Calibri, Eisai, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Theracos. She was formerly affiliated with Medstar Health Research Institute, Hyattsville, Md.

SOURCE: Aroda V et al. AACE 2018. Abstract 245.

REPORTING FROM AACE 2018

Melanoma in situ: It’s hard to know what you don’t know

The emergency department locum tenens staff recruiter was persuasive. “It’s a quiet little ER where you can study and sleep.” I was board certified in internal medicine and had trained in a busy urban emergency department. This was just the spot to make a little folding money and study for my mock dermatology boards, I thought.

And so, on a Saturday night in rural Texas, after grinding rust out of a pipe fitter’s eye and stitching up two brawlers from the local biker bar, I was faced with treating a comatose kid brought in after a car crash. He had not been wearing a seat belt, and his car had rolled over on his head.

I was way over my skill level, but I was lucky. I was able to stabilize him and, after several long hours, I got him on an emergency helicopter into Dallas.

But the experience changed me. I realized I did not know enough to deal with this case on my own. After making it through that night in the ED, I never put myself in that position again.

I now knew what I did not know.

The finding that jumped out to me, though, was that patients screened by a PA were significantly less likely to be diagnosed with melanoma in situ, the stage when melanoma is 100% curable. Yet, those patients screened by PAs underwent a lot more skin biopsies – 36% more skin biopsies per melanoma in situ diagnosed, compared with patients of dermatologists. Interestingly, in the health care system studied, any PA with a question about a patient can ask an attending dermatologist to see the patient. Did that factor account for the diagnostic comparability for nonmelanoma skin cancer and invasive melanoma? Did the PAs not ask for help on the missed melanomas in situ? If so, I believe this may be a situation of PAs not knowing what they didn’t know.

Now a knowledgeable friend of mine thinks this study is biased because 17% more patients with prior melanomas were seen by a dermatologist rather than by a PA. While it’s true that patients with prior melanomas are more likely to develop new melanomas, the counterargument is that the bar for a biopsy in a patient with a prior melanoma is much lower. Patients with a history of melanoma should have more skin biopsies, but the dermatologists in this study still took many fewer biopsies to diagnose melanomas in situ.

Why do these findings matter for patients and for the health care system?

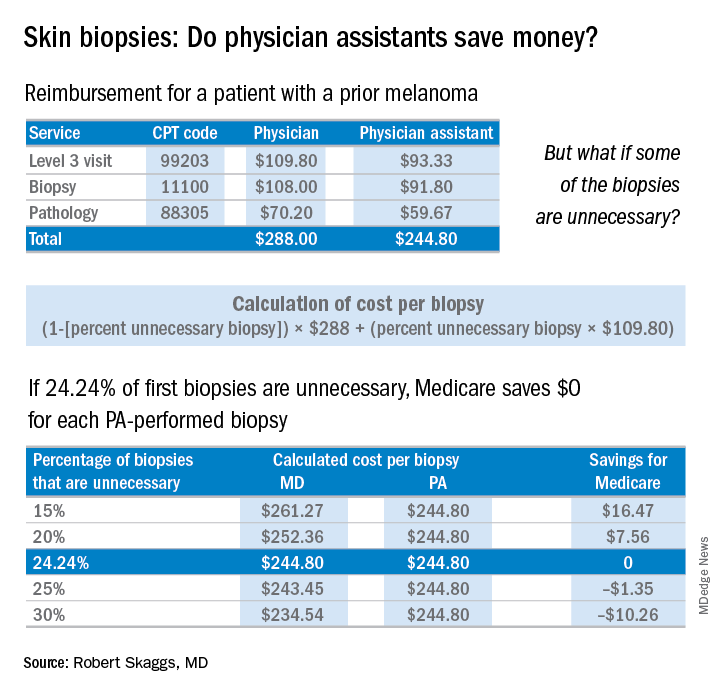

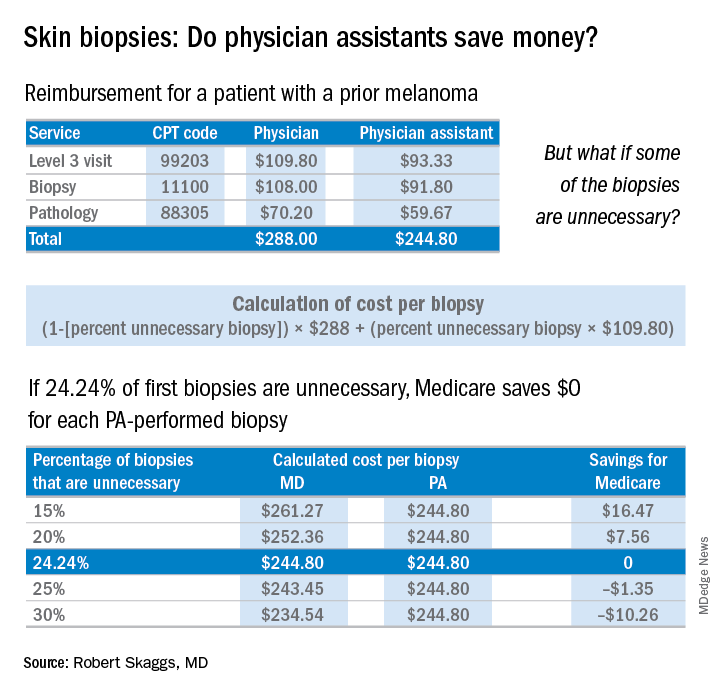

PAs billed independently for 12% of skin biopsies (including lip, ear, ear canal, vulva, penis, and eyelid) in Medicare Fee for Service in 2016. Skin biopsies paid for by Medicare have been increasing at a very rapid rate, about twice as fast as the rate reflected in the current skin cancer epidemic.

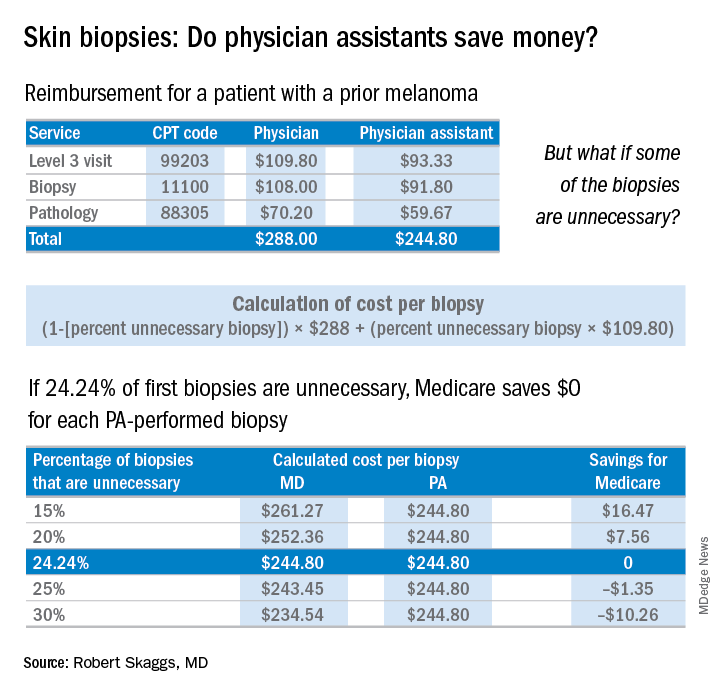

Every skin biopsy results in a pathology charge, for which Medicare pays about $70. A level 3 new patient visit pays $110. If PAs bill independently, they are paid at 85% of the fee schedule, which often is touted as a great savings. Therefore, if only 24.2% of skin biopsies by PAs were unnecessary, even at a reduced 85% reimbursement, it costs Medicare more than having these visits and biopsies provided by a dermatologist. The cost savings decrease even more with additional skin biopsies, because they pay so little ($33 for a doctor, $28 for a PA), yet the pathology charge is unchanged.

There are other costs beyond monetary ones from unnecessary skin biopsies: scarring, follow-up procedures for uncertain diagnoses such as mild dysplastic nevi, ambiguous results, and emotional angst to patients.

If the results of this large study are to be believed, many melanomas in situ are going to be missed if PAs perform unsupervised skin cancer screenings. This is not a tenable proposition, ethically or legally. Dermatologists and PAs need to work together to ensure this does not happen.

An estimated 2,520 dermatology PAs were practicing in the United States in 2016, based on membership data from the Society of Dermatology PAs (SDPA), according to a research letter published last year (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jun;76[6]:1200-2). The SDPA, as stated in an SDPA position statement published in the winter 2017 newsletter, hopes to gain access to direct billing to public and private insurers, which would include the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and for PAs to no longer report to other health care professionals.

Many dermatologists, as well as teaching programs, use PAs to perform skin cancer screenings, sometimes unsupervised, which makes diagnostic accuracy critical. The issues at hand are the safety of patients and the accuracy of diagnosis as well as the costs to the health care system. A team effort, which includes direct supervision, is needed to ensure those issues are addressed.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

The emergency department locum tenens staff recruiter was persuasive. “It’s a quiet little ER where you can study and sleep.” I was board certified in internal medicine and had trained in a busy urban emergency department. This was just the spot to make a little folding money and study for my mock dermatology boards, I thought.

And so, on a Saturday night in rural Texas, after grinding rust out of a pipe fitter’s eye and stitching up two brawlers from the local biker bar, I was faced with treating a comatose kid brought in after a car crash. He had not been wearing a seat belt, and his car had rolled over on his head.

I was way over my skill level, but I was lucky. I was able to stabilize him and, after several long hours, I got him on an emergency helicopter into Dallas.

But the experience changed me. I realized I did not know enough to deal with this case on my own. After making it through that night in the ED, I never put myself in that position again.

I now knew what I did not know.

The finding that jumped out to me, though, was that patients screened by a PA were significantly less likely to be diagnosed with melanoma in situ, the stage when melanoma is 100% curable. Yet, those patients screened by PAs underwent a lot more skin biopsies – 36% more skin biopsies per melanoma in situ diagnosed, compared with patients of dermatologists. Interestingly, in the health care system studied, any PA with a question about a patient can ask an attending dermatologist to see the patient. Did that factor account for the diagnostic comparability for nonmelanoma skin cancer and invasive melanoma? Did the PAs not ask for help on the missed melanomas in situ? If so, I believe this may be a situation of PAs not knowing what they didn’t know.

Now a knowledgeable friend of mine thinks this study is biased because 17% more patients with prior melanomas were seen by a dermatologist rather than by a PA. While it’s true that patients with prior melanomas are more likely to develop new melanomas, the counterargument is that the bar for a biopsy in a patient with a prior melanoma is much lower. Patients with a history of melanoma should have more skin biopsies, but the dermatologists in this study still took many fewer biopsies to diagnose melanomas in situ.

Why do these findings matter for patients and for the health care system?

PAs billed independently for 12% of skin biopsies (including lip, ear, ear canal, vulva, penis, and eyelid) in Medicare Fee for Service in 2016. Skin biopsies paid for by Medicare have been increasing at a very rapid rate, about twice as fast as the rate reflected in the current skin cancer epidemic.

Every skin biopsy results in a pathology charge, for which Medicare pays about $70. A level 3 new patient visit pays $110. If PAs bill independently, they are paid at 85% of the fee schedule, which often is touted as a great savings. Therefore, if only 24.2% of skin biopsies by PAs were unnecessary, even at a reduced 85% reimbursement, it costs Medicare more than having these visits and biopsies provided by a dermatologist. The cost savings decrease even more with additional skin biopsies, because they pay so little ($33 for a doctor, $28 for a PA), yet the pathology charge is unchanged.

There are other costs beyond monetary ones from unnecessary skin biopsies: scarring, follow-up procedures for uncertain diagnoses such as mild dysplastic nevi, ambiguous results, and emotional angst to patients.

If the results of this large study are to be believed, many melanomas in situ are going to be missed if PAs perform unsupervised skin cancer screenings. This is not a tenable proposition, ethically or legally. Dermatologists and PAs need to work together to ensure this does not happen.

An estimated 2,520 dermatology PAs were practicing in the United States in 2016, based on membership data from the Society of Dermatology PAs (SDPA), according to a research letter published last year (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jun;76[6]:1200-2). The SDPA, as stated in an SDPA position statement published in the winter 2017 newsletter, hopes to gain access to direct billing to public and private insurers, which would include the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and for PAs to no longer report to other health care professionals.

Many dermatologists, as well as teaching programs, use PAs to perform skin cancer screenings, sometimes unsupervised, which makes diagnostic accuracy critical. The issues at hand are the safety of patients and the accuracy of diagnosis as well as the costs to the health care system. A team effort, which includes direct supervision, is needed to ensure those issues are addressed.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

The emergency department locum tenens staff recruiter was persuasive. “It’s a quiet little ER where you can study and sleep.” I was board certified in internal medicine and had trained in a busy urban emergency department. This was just the spot to make a little folding money and study for my mock dermatology boards, I thought.

And so, on a Saturday night in rural Texas, after grinding rust out of a pipe fitter’s eye and stitching up two brawlers from the local biker bar, I was faced with treating a comatose kid brought in after a car crash. He had not been wearing a seat belt, and his car had rolled over on his head.

I was way over my skill level, but I was lucky. I was able to stabilize him and, after several long hours, I got him on an emergency helicopter into Dallas.

But the experience changed me. I realized I did not know enough to deal with this case on my own. After making it through that night in the ED, I never put myself in that position again.

I now knew what I did not know.

The finding that jumped out to me, though, was that patients screened by a PA were significantly less likely to be diagnosed with melanoma in situ, the stage when melanoma is 100% curable. Yet, those patients screened by PAs underwent a lot more skin biopsies – 36% more skin biopsies per melanoma in situ diagnosed, compared with patients of dermatologists. Interestingly, in the health care system studied, any PA with a question about a patient can ask an attending dermatologist to see the patient. Did that factor account for the diagnostic comparability for nonmelanoma skin cancer and invasive melanoma? Did the PAs not ask for help on the missed melanomas in situ? If so, I believe this may be a situation of PAs not knowing what they didn’t know.

Now a knowledgeable friend of mine thinks this study is biased because 17% more patients with prior melanomas were seen by a dermatologist rather than by a PA. While it’s true that patients with prior melanomas are more likely to develop new melanomas, the counterargument is that the bar for a biopsy in a patient with a prior melanoma is much lower. Patients with a history of melanoma should have more skin biopsies, but the dermatologists in this study still took many fewer biopsies to diagnose melanomas in situ.

Why do these findings matter for patients and for the health care system?

PAs billed independently for 12% of skin biopsies (including lip, ear, ear canal, vulva, penis, and eyelid) in Medicare Fee for Service in 2016. Skin biopsies paid for by Medicare have been increasing at a very rapid rate, about twice as fast as the rate reflected in the current skin cancer epidemic.

Every skin biopsy results in a pathology charge, for which Medicare pays about $70. A level 3 new patient visit pays $110. If PAs bill independently, they are paid at 85% of the fee schedule, which often is touted as a great savings. Therefore, if only 24.2% of skin biopsies by PAs were unnecessary, even at a reduced 85% reimbursement, it costs Medicare more than having these visits and biopsies provided by a dermatologist. The cost savings decrease even more with additional skin biopsies, because they pay so little ($33 for a doctor, $28 for a PA), yet the pathology charge is unchanged.

There are other costs beyond monetary ones from unnecessary skin biopsies: scarring, follow-up procedures for uncertain diagnoses such as mild dysplastic nevi, ambiguous results, and emotional angst to patients.

If the results of this large study are to be believed, many melanomas in situ are going to be missed if PAs perform unsupervised skin cancer screenings. This is not a tenable proposition, ethically or legally. Dermatologists and PAs need to work together to ensure this does not happen.

An estimated 2,520 dermatology PAs were practicing in the United States in 2016, based on membership data from the Society of Dermatology PAs (SDPA), according to a research letter published last year (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jun;76[6]:1200-2). The SDPA, as stated in an SDPA position statement published in the winter 2017 newsletter, hopes to gain access to direct billing to public and private insurers, which would include the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and for PAs to no longer report to other health care professionals.

Many dermatologists, as well as teaching programs, use PAs to perform skin cancer screenings, sometimes unsupervised, which makes diagnostic accuracy critical. The issues at hand are the safety of patients and the accuracy of diagnosis as well as the costs to the health care system. A team effort, which includes direct supervision, is needed to ensure those issues are addressed.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

Psychotherapy helps patients with chronic digestive disorders

Patients with chronic digestive disorders can better cope with their symptoms and the effects on their daily lives when they receive support from mental health professionals specializing in psychogastroenterology, according to a new AGA Clinical Practice Update, published in the April issue of Gastroenterology (gastrojournal.org). , which will help reduce patient symptom burden and health care resource utilization. These therapies are optimally delivered by mental health professionals specializing in psychogastroenterology, a field dedicated to applying effective psychological techniques to GI problems.

According to best practice advice, to help promote the use of brain-gut psychotherapies in routine GI care, gastroenterologists should:

1. Routinely assess health-related quality of life, symptom-specific anxieties, early life adversity and functional impairment related to a patient’s digestive symptoms.

2. Master patient-friendly language on the following topics: the brain–gut pathway and how this pathway can become dysregulated by any number of factors; the psychosocial risk, perpetuating and maintaining factors of GI diseases; and why the gastroenterologist is referring a patient to a mental health provider.

3. Know the structure and core features of the most effective brain–gut psychotherapies.

4. Establish a direct referral and ongoing communication pathway with one to two qualified mental health providers and assure patients that he or she will remain part of their care team.

5. Familiarize themselves with one or two neuromodulators that can be used to augment behavioral therapies when necessary.

Patients with chronic digestive disorders can better cope with their symptoms and the effects on their daily lives when they receive support from mental health professionals specializing in psychogastroenterology, according to a new AGA Clinical Practice Update, published in the April issue of Gastroenterology (gastrojournal.org). , which will help reduce patient symptom burden and health care resource utilization. These therapies are optimally delivered by mental health professionals specializing in psychogastroenterology, a field dedicated to applying effective psychological techniques to GI problems.

According to best practice advice, to help promote the use of brain-gut psychotherapies in routine GI care, gastroenterologists should:

1. Routinely assess health-related quality of life, symptom-specific anxieties, early life adversity and functional impairment related to a patient’s digestive symptoms.

2. Master patient-friendly language on the following topics: the brain–gut pathway and how this pathway can become dysregulated by any number of factors; the psychosocial risk, perpetuating and maintaining factors of GI diseases; and why the gastroenterologist is referring a patient to a mental health provider.

3. Know the structure and core features of the most effective brain–gut psychotherapies.

4. Establish a direct referral and ongoing communication pathway with one to two qualified mental health providers and assure patients that he or she will remain part of their care team.

5. Familiarize themselves with one or two neuromodulators that can be used to augment behavioral therapies when necessary.

Patients with chronic digestive disorders can better cope with their symptoms and the effects on their daily lives when they receive support from mental health professionals specializing in psychogastroenterology, according to a new AGA Clinical Practice Update, published in the April issue of Gastroenterology (gastrojournal.org). , which will help reduce patient symptom burden and health care resource utilization. These therapies are optimally delivered by mental health professionals specializing in psychogastroenterology, a field dedicated to applying effective psychological techniques to GI problems.

According to best practice advice, to help promote the use of brain-gut psychotherapies in routine GI care, gastroenterologists should:

1. Routinely assess health-related quality of life, symptom-specific anxieties, early life adversity and functional impairment related to a patient’s digestive symptoms.

2. Master patient-friendly language on the following topics: the brain–gut pathway and how this pathway can become dysregulated by any number of factors; the psychosocial risk, perpetuating and maintaining factors of GI diseases; and why the gastroenterologist is referring a patient to a mental health provider.

3. Know the structure and core features of the most effective brain–gut psychotherapies.

4. Establish a direct referral and ongoing communication pathway with one to two qualified mental health providers and assure patients that he or she will remain part of their care team.

5. Familiarize themselves with one or two neuromodulators that can be used to augment behavioral therapies when necessary.

AGA Fellows application period now open

The application period for the 2019 AGA Fellowship is now open. Members whose professional achievements demonstrate personal commitment to the field of gastroenterology and meet the AGA Fellows program criteria are encouraged to apply.

Learn more about joining this community of excellence or to how to apply online at www.gastro.org/fellowship.

AGA Fellows receive:

• The privilege of using the designation “AGAF” in professional activities.

• An official certificate and pin denoting your status.

• A listing on AGA’s website alongside esteemed peers.

• And more.

Apply and gain international recognition for your achievements when you become an AGA Fellow.

The application period for the 2019 AGA Fellowship is now open. Members whose professional achievements demonstrate personal commitment to the field of gastroenterology and meet the AGA Fellows program criteria are encouraged to apply.

Learn more about joining this community of excellence or to how to apply online at www.gastro.org/fellowship.

AGA Fellows receive:

• The privilege of using the designation “AGAF” in professional activities.

• An official certificate and pin denoting your status.

• A listing on AGA’s website alongside esteemed peers.

• And more.

Apply and gain international recognition for your achievements when you become an AGA Fellow.

The application period for the 2019 AGA Fellowship is now open. Members whose professional achievements demonstrate personal commitment to the field of gastroenterology and meet the AGA Fellows program criteria are encouraged to apply.

Learn more about joining this community of excellence or to how to apply online at www.gastro.org/fellowship.

AGA Fellows receive:

• The privilege of using the designation “AGAF” in professional activities.