User login

AGA Clinical Practice Update: Screening for Barrett’s esophagus requires consideration for those most at risk

The evidence discussed in this article supports the current recommendation of GI societies that screening endoscopy for Barrett’s esophagus be performed only in well-defined, high-risk populations. Alternative tests for screening are not now recommended; however, some of the alternative tests show great promise, and it is expected that they will soon find a useful place in clinical practice. At the same time, there should be a complementary focus on using demographic and clinical factors as well as noninvasive tools to further define populations for screening. All tests and tools should be balanced with the cost and potential risks of the screening proposed.

Stuart Spechler, MD, of the University of Texas and his colleagues looked at a variety of techniques, both conventional and novel, as well as the cost effectiveness of these strategies in a commentary published in the May issue of Gastroenterology.

Some studies have shown that endoscopic surveillance programs have identified early-stage cancer and provided better outcomes, compared with patients presenting after they already have cancer symptoms. One meta-analysis included 51 studies with 11,028 subjects and demonstrated that patients who had surveillance-detected esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) had a 61% reduction in their mortality risk. Other studies have shown similar results, but are susceptible to certain biases. Still other studies have refuted that the surveillance programs help at all. In fact, those with Barrett’s esophagus who died of EAC underwent similar surveillance, compared with controls, in those studies, showing that surveillance did very little to improve their outcomes.

Perhaps one of the most intriguing and cost-effective strategies is to identify patients with Barrett’s esophagus and develop a tool based on demographic and historical information. Tools like this have been developed, but have shown lukewarm results, with areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) ranging from 0.61 to 0.75. One study used information concerning obesity, smoking history, and increasing age, combined with weekly symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux and found that this improved results by nearly 25%. Modified versions of this model have also shown improved detection. When Thrift et al. added additional factors like education level, body mass index, smoking status, and more serious alarm symptoms like unexplained weight loss, the model was able to improve AUROC scores to 0.85 (95% confidence interval, 0.78-0.91). Of course, the clinical utility of these models is still unclear. Nonetheless, these models have influenced certain GI societies that only believe in endoscopic screening of patients with additional risk factors.

Although predictive models may assist in identifying at-risk patients, endoscopes are still needed to diagnose. Transnasal endoscopes (TNEs), the thinner cousins of the regular endoscope, tend to be better tolerated by patients and result in less gagging. One study showed that TNEs (45.7%) improved participation, compared with standard endoscopy (40.7%), and almost 80% of TNE patients were willing to undergo the procedure again. Despite the positives, TNEs provided significantly lower biopsy acquisitions than standard endoscopes (83% vs. 100%, P = .001) because of the sheathing on the endoscope. Other studies have demonstrated the strengths of TNEs, including a study in which 38% of patients had a finding that changed management of their disease. TNEs should be considered a reliable screening tool for Barrett’s esophagus.

Other advances in imaging technology like the advent of the high-resolution complementary metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS), which is small enough to fit into a pill capsule, have led researchers to look into its effectiveness as a screening tool for Barrett’s esophagus. One meta-analysis of 618 patients found that the pooled sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis were 77% and 86%, respectively. Despite its ability to produce high-quality images, the device remains difficult to control and lacks the ability to obtain biopsy samples.

Another example of a swallowed medical device, the Cytosponge-TFF3 is an ingestible capsule that degrades in stomach acid. After 5 minutes, the capsule dissolves and releases a mesh sponge that will be withdrawn through the mouth, scraping the esophagus and gathering a sample. The Cytosponge has proven effective in the Barrett’s Esophagus Screening Trials (BEST) 1. The BEST 2 looked at 463 control and 647 patients with Barrett’s esophagus across 11 United Kingdom hospitals. The trial showed that the Cytosponge exhibited sensitivity of 79.9%, which increased to 87.2% in patients with more than 3 cm of circumferential Barrett’s metaplasia.

Breaking from the invasive nature of imaging scopes and the Cytosponge, some researchers are looking to use “liquid biopsy” or blood tests to detect abnormalities in the blood like DNA or microRNA (miRNA) to identify precursors or presence of a disease. Much remains to be done to develop a clinically meaningful test, but the use of miRNAs to detect disease is an intriguing option. miRNAs control gene expression, and their dysregulation has been associated with the development of many diseases. One study found that patients with Barrett’s esophagus had increased levels of miRNA-194, 215, and 143 but these findings were not validated in a larger study. Other studies have demonstrated similar findings, but more research must be done to validate these findings in larger cohorts.

Other novel detection therapies have been investigated, including serum adipokine and electronic nose breathing tests. The serum adipokine test looks at the metabolically active adipokines secreted in obese patients and those with metabolic syndrome to see if they could predict the presence of Barrett’s esophagus. Unfortunately, the data appear to be conflicting, but these tests can be used in conjunction with other tools to detect Barrett’s esophagus. Electronic nose breathing tests also work by detecting metabolically active compounds from human and gut bacterial metabolism. One study found that analyzing these volatile compounds could delineate between Barrett’s and non-Barrett’s patients with 82% sensitivity, 80% specificity, and 81% accuracy. Both of these technologies need large prospective studies in primary care to validate their clinical utility.

A discussion of the effectiveness of these screening tools would be incomplete without a discussion of their costs. Currently, endoscopic screening costs are high. Therefore, it is important to reserve these tools for the patients who will benefit the most – in other words, patients with clear risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus. Even the capsule endoscope is quite expensive because of the cost of materials associated with the tool.

Cost-effectivenes calculations surrounding the Cytosponge are particularly complicated. One analysis found the computed incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of endoscopy, compared with Cytosponge, to have a range of $107,583-$330,361. The potential benefit that Cytosponge offers comes at an ICER for Cytosponge screening, compared with no screening, that ranges from $26,358 to $33,307. The numbers skyrocket when you consider what society would be willing to pay (up to $50,000 per quality-adjusted life-year gained).

With all of this information in mind, it would be useful to look at Barrett’s esophagus and the tools used to diagnose it from a broader perspective.

While the adoption of a new screening strategy could succeed where others have failed, Dr. Spechler points out the potential harm.

“There also is potential for harm in identifying asymptomatic patients with Barrett’s esophagus. In addition to the high costs and small risks of standard endoscopy, the diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus can cause psychological stress, have a negative impact on quality of life, result in higher premiums for health and life insurance, and might identify innocuous lesions that lead to potentially hazardous invasive treatments. Efforts should therefore be continued to combine biomarkers for Barrett’s with risk stratification. Overall, while these vexing uncertainties must temper enthusiasm for the unqualified endorsement of any screening test for Barrett’s esophagus, the alternative of making no attempt to stem the rapidly rising incidence of a lethal malignancy also is unpalatable.”

The development of this commentary was supported solely by the American Gastroenterological Association Institute. No conflicts of interest were disclosed for this report.

SOURCE: Spechler S et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 May doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.031).

AGA Resource

AGA patient education on Barrett’s esophagus will help your patients better understand the disease and how to manage it. Learn more at gastro.org/patient-care.

The evidence discussed in this article supports the current recommendation of GI societies that screening endoscopy for Barrett’s esophagus be performed only in well-defined, high-risk populations. Alternative tests for screening are not now recommended; however, some of the alternative tests show great promise, and it is expected that they will soon find a useful place in clinical practice. At the same time, there should be a complementary focus on using demographic and clinical factors as well as noninvasive tools to further define populations for screening. All tests and tools should be balanced with the cost and potential risks of the screening proposed.

Stuart Spechler, MD, of the University of Texas and his colleagues looked at a variety of techniques, both conventional and novel, as well as the cost effectiveness of these strategies in a commentary published in the May issue of Gastroenterology.

Some studies have shown that endoscopic surveillance programs have identified early-stage cancer and provided better outcomes, compared with patients presenting after they already have cancer symptoms. One meta-analysis included 51 studies with 11,028 subjects and demonstrated that patients who had surveillance-detected esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) had a 61% reduction in their mortality risk. Other studies have shown similar results, but are susceptible to certain biases. Still other studies have refuted that the surveillance programs help at all. In fact, those with Barrett’s esophagus who died of EAC underwent similar surveillance, compared with controls, in those studies, showing that surveillance did very little to improve their outcomes.

Perhaps one of the most intriguing and cost-effective strategies is to identify patients with Barrett’s esophagus and develop a tool based on demographic and historical information. Tools like this have been developed, but have shown lukewarm results, with areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) ranging from 0.61 to 0.75. One study used information concerning obesity, smoking history, and increasing age, combined with weekly symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux and found that this improved results by nearly 25%. Modified versions of this model have also shown improved detection. When Thrift et al. added additional factors like education level, body mass index, smoking status, and more serious alarm symptoms like unexplained weight loss, the model was able to improve AUROC scores to 0.85 (95% confidence interval, 0.78-0.91). Of course, the clinical utility of these models is still unclear. Nonetheless, these models have influenced certain GI societies that only believe in endoscopic screening of patients with additional risk factors.

Although predictive models may assist in identifying at-risk patients, endoscopes are still needed to diagnose. Transnasal endoscopes (TNEs), the thinner cousins of the regular endoscope, tend to be better tolerated by patients and result in less gagging. One study showed that TNEs (45.7%) improved participation, compared with standard endoscopy (40.7%), and almost 80% of TNE patients were willing to undergo the procedure again. Despite the positives, TNEs provided significantly lower biopsy acquisitions than standard endoscopes (83% vs. 100%, P = .001) because of the sheathing on the endoscope. Other studies have demonstrated the strengths of TNEs, including a study in which 38% of patients had a finding that changed management of their disease. TNEs should be considered a reliable screening tool for Barrett’s esophagus.

Other advances in imaging technology like the advent of the high-resolution complementary metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS), which is small enough to fit into a pill capsule, have led researchers to look into its effectiveness as a screening tool for Barrett’s esophagus. One meta-analysis of 618 patients found that the pooled sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis were 77% and 86%, respectively. Despite its ability to produce high-quality images, the device remains difficult to control and lacks the ability to obtain biopsy samples.

Another example of a swallowed medical device, the Cytosponge-TFF3 is an ingestible capsule that degrades in stomach acid. After 5 minutes, the capsule dissolves and releases a mesh sponge that will be withdrawn through the mouth, scraping the esophagus and gathering a sample. The Cytosponge has proven effective in the Barrett’s Esophagus Screening Trials (BEST) 1. The BEST 2 looked at 463 control and 647 patients with Barrett’s esophagus across 11 United Kingdom hospitals. The trial showed that the Cytosponge exhibited sensitivity of 79.9%, which increased to 87.2% in patients with more than 3 cm of circumferential Barrett’s metaplasia.

Breaking from the invasive nature of imaging scopes and the Cytosponge, some researchers are looking to use “liquid biopsy” or blood tests to detect abnormalities in the blood like DNA or microRNA (miRNA) to identify precursors or presence of a disease. Much remains to be done to develop a clinically meaningful test, but the use of miRNAs to detect disease is an intriguing option. miRNAs control gene expression, and their dysregulation has been associated with the development of many diseases. One study found that patients with Barrett’s esophagus had increased levels of miRNA-194, 215, and 143 but these findings were not validated in a larger study. Other studies have demonstrated similar findings, but more research must be done to validate these findings in larger cohorts.

Other novel detection therapies have been investigated, including serum adipokine and electronic nose breathing tests. The serum adipokine test looks at the metabolically active adipokines secreted in obese patients and those with metabolic syndrome to see if they could predict the presence of Barrett’s esophagus. Unfortunately, the data appear to be conflicting, but these tests can be used in conjunction with other tools to detect Barrett’s esophagus. Electronic nose breathing tests also work by detecting metabolically active compounds from human and gut bacterial metabolism. One study found that analyzing these volatile compounds could delineate between Barrett’s and non-Barrett’s patients with 82% sensitivity, 80% specificity, and 81% accuracy. Both of these technologies need large prospective studies in primary care to validate their clinical utility.

A discussion of the effectiveness of these screening tools would be incomplete without a discussion of their costs. Currently, endoscopic screening costs are high. Therefore, it is important to reserve these tools for the patients who will benefit the most – in other words, patients with clear risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus. Even the capsule endoscope is quite expensive because of the cost of materials associated with the tool.

Cost-effectivenes calculations surrounding the Cytosponge are particularly complicated. One analysis found the computed incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of endoscopy, compared with Cytosponge, to have a range of $107,583-$330,361. The potential benefit that Cytosponge offers comes at an ICER for Cytosponge screening, compared with no screening, that ranges from $26,358 to $33,307. The numbers skyrocket when you consider what society would be willing to pay (up to $50,000 per quality-adjusted life-year gained).

With all of this information in mind, it would be useful to look at Barrett’s esophagus and the tools used to diagnose it from a broader perspective.

While the adoption of a new screening strategy could succeed where others have failed, Dr. Spechler points out the potential harm.

“There also is potential for harm in identifying asymptomatic patients with Barrett’s esophagus. In addition to the high costs and small risks of standard endoscopy, the diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus can cause psychological stress, have a negative impact on quality of life, result in higher premiums for health and life insurance, and might identify innocuous lesions that lead to potentially hazardous invasive treatments. Efforts should therefore be continued to combine biomarkers for Barrett’s with risk stratification. Overall, while these vexing uncertainties must temper enthusiasm for the unqualified endorsement of any screening test for Barrett’s esophagus, the alternative of making no attempt to stem the rapidly rising incidence of a lethal malignancy also is unpalatable.”

The development of this commentary was supported solely by the American Gastroenterological Association Institute. No conflicts of interest were disclosed for this report.

SOURCE: Spechler S et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 May doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.031).

AGA Resource

AGA patient education on Barrett’s esophagus will help your patients better understand the disease and how to manage it. Learn more at gastro.org/patient-care.

The evidence discussed in this article supports the current recommendation of GI societies that screening endoscopy for Barrett’s esophagus be performed only in well-defined, high-risk populations. Alternative tests for screening are not now recommended; however, some of the alternative tests show great promise, and it is expected that they will soon find a useful place in clinical practice. At the same time, there should be a complementary focus on using demographic and clinical factors as well as noninvasive tools to further define populations for screening. All tests and tools should be balanced with the cost and potential risks of the screening proposed.

Stuart Spechler, MD, of the University of Texas and his colleagues looked at a variety of techniques, both conventional and novel, as well as the cost effectiveness of these strategies in a commentary published in the May issue of Gastroenterology.

Some studies have shown that endoscopic surveillance programs have identified early-stage cancer and provided better outcomes, compared with patients presenting after they already have cancer symptoms. One meta-analysis included 51 studies with 11,028 subjects and demonstrated that patients who had surveillance-detected esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) had a 61% reduction in their mortality risk. Other studies have shown similar results, but are susceptible to certain biases. Still other studies have refuted that the surveillance programs help at all. In fact, those with Barrett’s esophagus who died of EAC underwent similar surveillance, compared with controls, in those studies, showing that surveillance did very little to improve their outcomes.

Perhaps one of the most intriguing and cost-effective strategies is to identify patients with Barrett’s esophagus and develop a tool based on demographic and historical information. Tools like this have been developed, but have shown lukewarm results, with areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) ranging from 0.61 to 0.75. One study used information concerning obesity, smoking history, and increasing age, combined with weekly symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux and found that this improved results by nearly 25%. Modified versions of this model have also shown improved detection. When Thrift et al. added additional factors like education level, body mass index, smoking status, and more serious alarm symptoms like unexplained weight loss, the model was able to improve AUROC scores to 0.85 (95% confidence interval, 0.78-0.91). Of course, the clinical utility of these models is still unclear. Nonetheless, these models have influenced certain GI societies that only believe in endoscopic screening of patients with additional risk factors.

Although predictive models may assist in identifying at-risk patients, endoscopes are still needed to diagnose. Transnasal endoscopes (TNEs), the thinner cousins of the regular endoscope, tend to be better tolerated by patients and result in less gagging. One study showed that TNEs (45.7%) improved participation, compared with standard endoscopy (40.7%), and almost 80% of TNE patients were willing to undergo the procedure again. Despite the positives, TNEs provided significantly lower biopsy acquisitions than standard endoscopes (83% vs. 100%, P = .001) because of the sheathing on the endoscope. Other studies have demonstrated the strengths of TNEs, including a study in which 38% of patients had a finding that changed management of their disease. TNEs should be considered a reliable screening tool for Barrett’s esophagus.

Other advances in imaging technology like the advent of the high-resolution complementary metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS), which is small enough to fit into a pill capsule, have led researchers to look into its effectiveness as a screening tool for Barrett’s esophagus. One meta-analysis of 618 patients found that the pooled sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis were 77% and 86%, respectively. Despite its ability to produce high-quality images, the device remains difficult to control and lacks the ability to obtain biopsy samples.

Another example of a swallowed medical device, the Cytosponge-TFF3 is an ingestible capsule that degrades in stomach acid. After 5 minutes, the capsule dissolves and releases a mesh sponge that will be withdrawn through the mouth, scraping the esophagus and gathering a sample. The Cytosponge has proven effective in the Barrett’s Esophagus Screening Trials (BEST) 1. The BEST 2 looked at 463 control and 647 patients with Barrett’s esophagus across 11 United Kingdom hospitals. The trial showed that the Cytosponge exhibited sensitivity of 79.9%, which increased to 87.2% in patients with more than 3 cm of circumferential Barrett’s metaplasia.

Breaking from the invasive nature of imaging scopes and the Cytosponge, some researchers are looking to use “liquid biopsy” or blood tests to detect abnormalities in the blood like DNA or microRNA (miRNA) to identify precursors or presence of a disease. Much remains to be done to develop a clinically meaningful test, but the use of miRNAs to detect disease is an intriguing option. miRNAs control gene expression, and their dysregulation has been associated with the development of many diseases. One study found that patients with Barrett’s esophagus had increased levels of miRNA-194, 215, and 143 but these findings were not validated in a larger study. Other studies have demonstrated similar findings, but more research must be done to validate these findings in larger cohorts.

Other novel detection therapies have been investigated, including serum adipokine and electronic nose breathing tests. The serum adipokine test looks at the metabolically active adipokines secreted in obese patients and those with metabolic syndrome to see if they could predict the presence of Barrett’s esophagus. Unfortunately, the data appear to be conflicting, but these tests can be used in conjunction with other tools to detect Barrett’s esophagus. Electronic nose breathing tests also work by detecting metabolically active compounds from human and gut bacterial metabolism. One study found that analyzing these volatile compounds could delineate between Barrett’s and non-Barrett’s patients with 82% sensitivity, 80% specificity, and 81% accuracy. Both of these technologies need large prospective studies in primary care to validate their clinical utility.

A discussion of the effectiveness of these screening tools would be incomplete without a discussion of their costs. Currently, endoscopic screening costs are high. Therefore, it is important to reserve these tools for the patients who will benefit the most – in other words, patients with clear risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus. Even the capsule endoscope is quite expensive because of the cost of materials associated with the tool.

Cost-effectivenes calculations surrounding the Cytosponge are particularly complicated. One analysis found the computed incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of endoscopy, compared with Cytosponge, to have a range of $107,583-$330,361. The potential benefit that Cytosponge offers comes at an ICER for Cytosponge screening, compared with no screening, that ranges from $26,358 to $33,307. The numbers skyrocket when you consider what society would be willing to pay (up to $50,000 per quality-adjusted life-year gained).

With all of this information in mind, it would be useful to look at Barrett’s esophagus and the tools used to diagnose it from a broader perspective.

While the adoption of a new screening strategy could succeed where others have failed, Dr. Spechler points out the potential harm.

“There also is potential for harm in identifying asymptomatic patients with Barrett’s esophagus. In addition to the high costs and small risks of standard endoscopy, the diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus can cause psychological stress, have a negative impact on quality of life, result in higher premiums for health and life insurance, and might identify innocuous lesions that lead to potentially hazardous invasive treatments. Efforts should therefore be continued to combine biomarkers for Barrett’s with risk stratification. Overall, while these vexing uncertainties must temper enthusiasm for the unqualified endorsement of any screening test for Barrett’s esophagus, the alternative of making no attempt to stem the rapidly rising incidence of a lethal malignancy also is unpalatable.”

The development of this commentary was supported solely by the American Gastroenterological Association Institute. No conflicts of interest were disclosed for this report.

SOURCE: Spechler S et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 May doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.031).

AGA Resource

AGA patient education on Barrett’s esophagus will help your patients better understand the disease and how to manage it. Learn more at gastro.org/patient-care.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

PPI use not linked to cognitive decline

Use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) is not associated with cognitive decline in two prospective, population-based studies of identical twins published in the May issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“No stated differences in [mean cognitive] scores between PPI users and nonusers were significant,” wrote Mette Wod, PhD, of the University of Southern Denmark, Odense, with her associates.

Past research has yielded mixed findings about whether using PPIs affects the risk of dementia. Preclinical data suggest that exposure to these drugs affects amyloid levels in mice, but “the evidence is equivocal, [and] the results of epidemiologic studies [of humans] have also been inconclusive, with more recent studies pointing toward a null association,” the investigators wrote. Furthermore, there are only “scant” data on whether long-term PPI use affects cognitive function, they noted.

To help clarify the issue, they analyzed prospective data from two studies of twins in Denmark: the Study of Middle-Aged Danish Twins, in which individuals underwent a five-part cognitive battery at baseline and then 10 years later, and the Longitudinal Study of Aging Danish Twins, in which participants underwent the same test at baseline and 2 years later. The cognitive test assessed verbal fluency, forward and backward digit span, and immediate and delayed recall of a 12-item list. Using data from a national prescription registry, the investigators also estimated individuals’ PPI exposure starting 2 years before study enrollment.

In the study of middle-aged twins, participants who used high-dose PPIs before study enrollment had cognitive scores that were slightly lower at baseline, compared with PPI nonusers. Mean baseline scores were 43.1 (standard deviation, 13.1) and 46.8 (SD, 10.2), respectively. However, after researchers adjusted for numerous clinical and demographic variables, the between-group difference in baseline scores narrowed to just 0.69 (95% confidence interval, –4.98 to 3.61), which was not statistically significant.

The longitudinal study of older twins yielded similar results. Individuals who used high doses of PPIs had slightly higher adjusted mean baseline cognitive score than did nonusers, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (0.95; 95% CI, –1.88 to 3.79).

Furthermore, prospective assessments of cognitive decline found no evidence of an effect. In the longitudinal aging study, high-dose PPI users had slightly less cognitive decline (based on a smaller change in test scores over time) than did nonusers, but the adjusted difference in decline between groups was not significant (1.22 points; 95% CI, –3.73 to 1.29). In the middle-aged twin study, individuals with the highest levels of PPI exposure (at least 1,600 daily doses) had slightly less cognitive decline than did nonusers, with an adjusted difference of 0.94 points (95% CI, –1.63 to 3.50) between groups, but this did not reach statistical significance.

“This study is the first to examine the association between long-term PPI use and cognitive decline in a population-based setting,” the researchers concluded. “Cognitive scores of more than 7,800 middle-aged and older Danish twins at baseline did not indicate an association with previous PPI use. Follow-up data on more than 4,000 of these twins did not indicate that use of this class of drugs was correlated to cognitive decline.”

Odense University Hospital provided partial funding. Dr. Wod had no disclosures. Three coinvestigators disclosed ties to AstraZeneca and Bayer AG.

SOURCE: Wod M et al. Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2018 Feb 3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.01.034.

Over the last 20 years, there have been multiple retrospective studies which have shown associations between the use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and a wide constellation of serious medical complications. However, detecting an association between a drug and a complication does not necessarily indicate that the drug was indeed responsible.

This well-done study by Wod et al, which shows no significant association between PPI use and decreased cognition and cognitive decline will, I hope, serve to allay any misplaced concerns that may exist among clinicians and patients about PPI use in this population. This paper has notable strengths, most importantly having access to results of a direct, unbiased assessment of changes in cognitive function over time and accurate assessment of PPI exposure. Short of performing a controlled, prospective trial, we are unlikely to see better evidence indicating a lack of a causal relationship between PPI use and changes in cognitive function. This provides assurance that patients with indications for PPI use can continue to use them.

Laura E. Targownik, MD, MSHS, FRCPC, is section head, section of gastroenterology, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada; Gastroenterology and Endoscopy Site Lead, Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg; associate director, University of Manitoba Inflammatory Bowel Disease Research Centre; associate professor, department of internal medicine, section of gastroenterology, University of Manitoba. She has no conflicts of interest.

Over the last 20 years, there have been multiple retrospective studies which have shown associations between the use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and a wide constellation of serious medical complications. However, detecting an association between a drug and a complication does not necessarily indicate that the drug was indeed responsible.

This well-done study by Wod et al, which shows no significant association between PPI use and decreased cognition and cognitive decline will, I hope, serve to allay any misplaced concerns that may exist among clinicians and patients about PPI use in this population. This paper has notable strengths, most importantly having access to results of a direct, unbiased assessment of changes in cognitive function over time and accurate assessment of PPI exposure. Short of performing a controlled, prospective trial, we are unlikely to see better evidence indicating a lack of a causal relationship between PPI use and changes in cognitive function. This provides assurance that patients with indications for PPI use can continue to use them.

Laura E. Targownik, MD, MSHS, FRCPC, is section head, section of gastroenterology, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada; Gastroenterology and Endoscopy Site Lead, Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg; associate director, University of Manitoba Inflammatory Bowel Disease Research Centre; associate professor, department of internal medicine, section of gastroenterology, University of Manitoba. She has no conflicts of interest.

Over the last 20 years, there have been multiple retrospective studies which have shown associations between the use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and a wide constellation of serious medical complications. However, detecting an association between a drug and a complication does not necessarily indicate that the drug was indeed responsible.

This well-done study by Wod et al, which shows no significant association between PPI use and decreased cognition and cognitive decline will, I hope, serve to allay any misplaced concerns that may exist among clinicians and patients about PPI use in this population. This paper has notable strengths, most importantly having access to results of a direct, unbiased assessment of changes in cognitive function over time and accurate assessment of PPI exposure. Short of performing a controlled, prospective trial, we are unlikely to see better evidence indicating a lack of a causal relationship between PPI use and changes in cognitive function. This provides assurance that patients with indications for PPI use can continue to use them.

Laura E. Targownik, MD, MSHS, FRCPC, is section head, section of gastroenterology, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada; Gastroenterology and Endoscopy Site Lead, Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg; associate director, University of Manitoba Inflammatory Bowel Disease Research Centre; associate professor, department of internal medicine, section of gastroenterology, University of Manitoba. She has no conflicts of interest.

Use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) is not associated with cognitive decline in two prospective, population-based studies of identical twins published in the May issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“No stated differences in [mean cognitive] scores between PPI users and nonusers were significant,” wrote Mette Wod, PhD, of the University of Southern Denmark, Odense, with her associates.

Past research has yielded mixed findings about whether using PPIs affects the risk of dementia. Preclinical data suggest that exposure to these drugs affects amyloid levels in mice, but “the evidence is equivocal, [and] the results of epidemiologic studies [of humans] have also been inconclusive, with more recent studies pointing toward a null association,” the investigators wrote. Furthermore, there are only “scant” data on whether long-term PPI use affects cognitive function, they noted.

To help clarify the issue, they analyzed prospective data from two studies of twins in Denmark: the Study of Middle-Aged Danish Twins, in which individuals underwent a five-part cognitive battery at baseline and then 10 years later, and the Longitudinal Study of Aging Danish Twins, in which participants underwent the same test at baseline and 2 years later. The cognitive test assessed verbal fluency, forward and backward digit span, and immediate and delayed recall of a 12-item list. Using data from a national prescription registry, the investigators also estimated individuals’ PPI exposure starting 2 years before study enrollment.

In the study of middle-aged twins, participants who used high-dose PPIs before study enrollment had cognitive scores that were slightly lower at baseline, compared with PPI nonusers. Mean baseline scores were 43.1 (standard deviation, 13.1) and 46.8 (SD, 10.2), respectively. However, after researchers adjusted for numerous clinical and demographic variables, the between-group difference in baseline scores narrowed to just 0.69 (95% confidence interval, –4.98 to 3.61), which was not statistically significant.

The longitudinal study of older twins yielded similar results. Individuals who used high doses of PPIs had slightly higher adjusted mean baseline cognitive score than did nonusers, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (0.95; 95% CI, –1.88 to 3.79).

Furthermore, prospective assessments of cognitive decline found no evidence of an effect. In the longitudinal aging study, high-dose PPI users had slightly less cognitive decline (based on a smaller change in test scores over time) than did nonusers, but the adjusted difference in decline between groups was not significant (1.22 points; 95% CI, –3.73 to 1.29). In the middle-aged twin study, individuals with the highest levels of PPI exposure (at least 1,600 daily doses) had slightly less cognitive decline than did nonusers, with an adjusted difference of 0.94 points (95% CI, –1.63 to 3.50) between groups, but this did not reach statistical significance.

“This study is the first to examine the association between long-term PPI use and cognitive decline in a population-based setting,” the researchers concluded. “Cognitive scores of more than 7,800 middle-aged and older Danish twins at baseline did not indicate an association with previous PPI use. Follow-up data on more than 4,000 of these twins did not indicate that use of this class of drugs was correlated to cognitive decline.”

Odense University Hospital provided partial funding. Dr. Wod had no disclosures. Three coinvestigators disclosed ties to AstraZeneca and Bayer AG.

SOURCE: Wod M et al. Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2018 Feb 3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.01.034.

Use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) is not associated with cognitive decline in two prospective, population-based studies of identical twins published in the May issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“No stated differences in [mean cognitive] scores between PPI users and nonusers were significant,” wrote Mette Wod, PhD, of the University of Southern Denmark, Odense, with her associates.

Past research has yielded mixed findings about whether using PPIs affects the risk of dementia. Preclinical data suggest that exposure to these drugs affects amyloid levels in mice, but “the evidence is equivocal, [and] the results of epidemiologic studies [of humans] have also been inconclusive, with more recent studies pointing toward a null association,” the investigators wrote. Furthermore, there are only “scant” data on whether long-term PPI use affects cognitive function, they noted.

To help clarify the issue, they analyzed prospective data from two studies of twins in Denmark: the Study of Middle-Aged Danish Twins, in which individuals underwent a five-part cognitive battery at baseline and then 10 years later, and the Longitudinal Study of Aging Danish Twins, in which participants underwent the same test at baseline and 2 years later. The cognitive test assessed verbal fluency, forward and backward digit span, and immediate and delayed recall of a 12-item list. Using data from a national prescription registry, the investigators also estimated individuals’ PPI exposure starting 2 years before study enrollment.

In the study of middle-aged twins, participants who used high-dose PPIs before study enrollment had cognitive scores that were slightly lower at baseline, compared with PPI nonusers. Mean baseline scores were 43.1 (standard deviation, 13.1) and 46.8 (SD, 10.2), respectively. However, after researchers adjusted for numerous clinical and demographic variables, the between-group difference in baseline scores narrowed to just 0.69 (95% confidence interval, –4.98 to 3.61), which was not statistically significant.

The longitudinal study of older twins yielded similar results. Individuals who used high doses of PPIs had slightly higher adjusted mean baseline cognitive score than did nonusers, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (0.95; 95% CI, –1.88 to 3.79).

Furthermore, prospective assessments of cognitive decline found no evidence of an effect. In the longitudinal aging study, high-dose PPI users had slightly less cognitive decline (based on a smaller change in test scores over time) than did nonusers, but the adjusted difference in decline between groups was not significant (1.22 points; 95% CI, –3.73 to 1.29). In the middle-aged twin study, individuals with the highest levels of PPI exposure (at least 1,600 daily doses) had slightly less cognitive decline than did nonusers, with an adjusted difference of 0.94 points (95% CI, –1.63 to 3.50) between groups, but this did not reach statistical significance.

“This study is the first to examine the association between long-term PPI use and cognitive decline in a population-based setting,” the researchers concluded. “Cognitive scores of more than 7,800 middle-aged and older Danish twins at baseline did not indicate an association with previous PPI use. Follow-up data on more than 4,000 of these twins did not indicate that use of this class of drugs was correlated to cognitive decline.”

Odense University Hospital provided partial funding. Dr. Wod had no disclosures. Three coinvestigators disclosed ties to AstraZeneca and Bayer AG.

SOURCE: Wod M et al. Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2018 Feb 3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.01.034.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Use of proton pump inhibitors was not associated with cognitive decline.

Major finding: Mean baseline cognitive scores did not significantly differ between PPI users and nonusers, nor did changes in cognitive scores over time.

Study details: Two population-based studies of twins in Denmark.

Disclosures: Odense University Hospital provided partial funding. Dr. Wod had no disclosures. Three coinvestigators disclosed ties to AstraZeneca and Bayer AG.

Source: Wod M et al. Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2018 Feb 3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.01.034.

Alpha fetoprotein boosted detection of early-stage liver cancer

For patients with cirrhosis, adding serum alpha fetoprotein testing to ultrasound significantly boosted its ability to detect early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma, according to the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis reported in the May issue of Gastroenterology.

Used alone, ultrasound detected only 45% of early-stage hepatocellular carcinomas (95% confidence interval, 30%-62%), reported Kristina Tzartzeva, MD, of the University of Texas, Dallas, with her associates. Adding alpha fetoprotein (AFP) increased this sensitivity to 63% (95% CI, 48%-75%; P = .002). Few studies evaluated alternative surveillance tools, such as CT or MRI.

Diagnosing liver cancer early is key to survival and thus is a central issue in cirrhosis management. However, the best surveillance strategy remains uncertain, hinging as it does on sensitivity, specificity, and cost. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver recommend that cirrhotic patients undergo twice-yearly ultrasound to screen for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), but they disagree about the value of adding serum biomarker AFP testing. Meanwhile, more and more clinics are using CT and MRI because of concerns about the unreliability of ultrasound. “Given few direct comparative studies, we are forced to primarily rely on indirect comparisons across studies,” the reviewers wrote.

To do so, they searched MEDLINE and Scopus and identified 32 studies of HCC surveillance that comprised 13,367 patients, nearly all with baseline cirrhosis. The studies were published from 1990 to August 2016.

Ultrasound detected HCC of any stage with a sensitivity of 84% (95% CI, 76%-92%), but its sensitivity for detecting early-stage disease was less than 50%. In studies that performed direct comparisons, ultrasound alone was significantly less sensitive than ultrasound plus AFP for detecting all stages of HCC (relative risk, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.72-0.88) and early-stage disease (0.78; 0.66-0.92). However, ultrasound alone was more specific than ultrasound plus AFP (RR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.05-1.09).

Four studies of about 900 patients evaluated cross-sectional imaging with CT or MRI. In one single-center, randomized trial, CT had a sensitivity of 63% for detecting early-stage disease, but the 95% CI for this estimate was very wide (30%-87%) and CT did not significantly outperform ultrasound (Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:303-12). In another study, MRI and ultrasound had significantly different sensitivities of 84% and 26% for detecting (usually) early-stage disease (JAMA Oncol. 2017;3[4]:456-63).

“Ultrasound currently forms the backbone of professional society recommendations for HCC surveillance; however, our meta-analysis highlights its suboptimal sensitivity for detection of hepatocellular carcinoma at an early stage. Using ultrasound in combination with AFP appears to significantly improve sensitivity for detecting early HCC with a small, albeit statistically significant, trade-off in specificity. There are currently insufficient data to support routine use of CT- or MRI-based surveillance in all patients with cirrhosis,” the reviewers concluded.

The National Cancer Institute and Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas provided funding. None of the reviewers had conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tzartzeva K et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Feb 6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.064.

For patients with cirrhosis, adding serum alpha fetoprotein testing to ultrasound significantly boosted its ability to detect early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma, according to the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis reported in the May issue of Gastroenterology.

Used alone, ultrasound detected only 45% of early-stage hepatocellular carcinomas (95% confidence interval, 30%-62%), reported Kristina Tzartzeva, MD, of the University of Texas, Dallas, with her associates. Adding alpha fetoprotein (AFP) increased this sensitivity to 63% (95% CI, 48%-75%; P = .002). Few studies evaluated alternative surveillance tools, such as CT or MRI.

Diagnosing liver cancer early is key to survival and thus is a central issue in cirrhosis management. However, the best surveillance strategy remains uncertain, hinging as it does on sensitivity, specificity, and cost. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver recommend that cirrhotic patients undergo twice-yearly ultrasound to screen for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), but they disagree about the value of adding serum biomarker AFP testing. Meanwhile, more and more clinics are using CT and MRI because of concerns about the unreliability of ultrasound. “Given few direct comparative studies, we are forced to primarily rely on indirect comparisons across studies,” the reviewers wrote.

To do so, they searched MEDLINE and Scopus and identified 32 studies of HCC surveillance that comprised 13,367 patients, nearly all with baseline cirrhosis. The studies were published from 1990 to August 2016.

Ultrasound detected HCC of any stage with a sensitivity of 84% (95% CI, 76%-92%), but its sensitivity for detecting early-stage disease was less than 50%. In studies that performed direct comparisons, ultrasound alone was significantly less sensitive than ultrasound plus AFP for detecting all stages of HCC (relative risk, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.72-0.88) and early-stage disease (0.78; 0.66-0.92). However, ultrasound alone was more specific than ultrasound plus AFP (RR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.05-1.09).

Four studies of about 900 patients evaluated cross-sectional imaging with CT or MRI. In one single-center, randomized trial, CT had a sensitivity of 63% for detecting early-stage disease, but the 95% CI for this estimate was very wide (30%-87%) and CT did not significantly outperform ultrasound (Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:303-12). In another study, MRI and ultrasound had significantly different sensitivities of 84% and 26% for detecting (usually) early-stage disease (JAMA Oncol. 2017;3[4]:456-63).

“Ultrasound currently forms the backbone of professional society recommendations for HCC surveillance; however, our meta-analysis highlights its suboptimal sensitivity for detection of hepatocellular carcinoma at an early stage. Using ultrasound in combination with AFP appears to significantly improve sensitivity for detecting early HCC with a small, albeit statistically significant, trade-off in specificity. There are currently insufficient data to support routine use of CT- or MRI-based surveillance in all patients with cirrhosis,” the reviewers concluded.

The National Cancer Institute and Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas provided funding. None of the reviewers had conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tzartzeva K et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Feb 6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.064.

For patients with cirrhosis, adding serum alpha fetoprotein testing to ultrasound significantly boosted its ability to detect early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma, according to the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis reported in the May issue of Gastroenterology.

Used alone, ultrasound detected only 45% of early-stage hepatocellular carcinomas (95% confidence interval, 30%-62%), reported Kristina Tzartzeva, MD, of the University of Texas, Dallas, with her associates. Adding alpha fetoprotein (AFP) increased this sensitivity to 63% (95% CI, 48%-75%; P = .002). Few studies evaluated alternative surveillance tools, such as CT or MRI.

Diagnosing liver cancer early is key to survival and thus is a central issue in cirrhosis management. However, the best surveillance strategy remains uncertain, hinging as it does on sensitivity, specificity, and cost. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver recommend that cirrhotic patients undergo twice-yearly ultrasound to screen for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), but they disagree about the value of adding serum biomarker AFP testing. Meanwhile, more and more clinics are using CT and MRI because of concerns about the unreliability of ultrasound. “Given few direct comparative studies, we are forced to primarily rely on indirect comparisons across studies,” the reviewers wrote.

To do so, they searched MEDLINE and Scopus and identified 32 studies of HCC surveillance that comprised 13,367 patients, nearly all with baseline cirrhosis. The studies were published from 1990 to August 2016.

Ultrasound detected HCC of any stage with a sensitivity of 84% (95% CI, 76%-92%), but its sensitivity for detecting early-stage disease was less than 50%. In studies that performed direct comparisons, ultrasound alone was significantly less sensitive than ultrasound plus AFP for detecting all stages of HCC (relative risk, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.72-0.88) and early-stage disease (0.78; 0.66-0.92). However, ultrasound alone was more specific than ultrasound plus AFP (RR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.05-1.09).

Four studies of about 900 patients evaluated cross-sectional imaging with CT or MRI. In one single-center, randomized trial, CT had a sensitivity of 63% for detecting early-stage disease, but the 95% CI for this estimate was very wide (30%-87%) and CT did not significantly outperform ultrasound (Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:303-12). In another study, MRI and ultrasound had significantly different sensitivities of 84% and 26% for detecting (usually) early-stage disease (JAMA Oncol. 2017;3[4]:456-63).

“Ultrasound currently forms the backbone of professional society recommendations for HCC surveillance; however, our meta-analysis highlights its suboptimal sensitivity for detection of hepatocellular carcinoma at an early stage. Using ultrasound in combination with AFP appears to significantly improve sensitivity for detecting early HCC with a small, albeit statistically significant, trade-off in specificity. There are currently insufficient data to support routine use of CT- or MRI-based surveillance in all patients with cirrhosis,” the reviewers concluded.

The National Cancer Institute and Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas provided funding. None of the reviewers had conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tzartzeva K et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Feb 6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.064.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Ultrasound unreliably detects hepatocellular carcinoma, but adding alpha fetoprotein increases its sensitivity.

Major finding: Used alone, ultrasound detected only 47% of early-stage cases. Adding alpha fetoprotein increased this sensitivity to 63% (P = .002).

Study details: Systematic review and meta-analysis of 32 studies comprising 13,367 patients and spanning from 1990 to August 2016.

Disclosures: The National Cancer Institute and Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas provided funding. None of the researchers had conflicts of interest.

Source: Tzartzeva K et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Feb 6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.064.

DDW is a celebration of diversity

Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) is approaching rapidly. One might say, with strong justification, that the overarching theme for DDW is a celebration of diversity. We are entering the era of “omics” and current research suggests a microbiome rich in diversity is associated with health, while a less-diverse biome is associated with digestive disorders – inflammatory bowel disease for example. Multiple abstracts and presentations will be related to research into microbiome alterations in disease. In nature, diversity is a key to survival.

Farmers know the value of diversity and the devastating effects of restricted diversity. When fields are restricted to a single crop year after year, artificial fertilizers must be used to restore fertility. Organic farmers understand the need for diversity in the form of crop rotation. No forest can survive for long without rich biological diversity. Even cancer reminds us of the importance of diversity. Restricted diversity in the form of cellular monoclonality is one of the hallmarks of malignant growth.

DDW, our annual hallmark meeting, emphasizes our need for diverse thoughts and intellectual discourse as we advance the science of gastroenterology, endoscopy, hepatology, and surgery. Biology does not tolerate restrictions on diversity for long. Diversity makes DDW great.

In this month’s issue of GI & Hepatology News, we are reassured that PPIs are not linked to cognitive decline. Sessile serrated polyps, often missed at colonoscopy and CT colography might be detected with noninvasive testing as the field of blood-based cancer screening advances. Pay attention to the exciting bleeding-edge technology emerging from the AGA Tech Summit – especially technologies to treat obesity. Read about some of the continuing barriers to CRC screening in underserved populations – if we are to achieve 80% screening rates we must focus on people challenged to access our health care system.

Finally, consider the AGA Clinical Practice Update about Barrett’s esophagus. I spent a morning with Joel Richter, MD, last month and he reminded me that our current surveillance system is failing to impact annual incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Perhaps we should focus on a one-time screen for those most at risk, catching prevalent disease at an early stage.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) is approaching rapidly. One might say, with strong justification, that the overarching theme for DDW is a celebration of diversity. We are entering the era of “omics” and current research suggests a microbiome rich in diversity is associated with health, while a less-diverse biome is associated with digestive disorders – inflammatory bowel disease for example. Multiple abstracts and presentations will be related to research into microbiome alterations in disease. In nature, diversity is a key to survival.

Farmers know the value of diversity and the devastating effects of restricted diversity. When fields are restricted to a single crop year after year, artificial fertilizers must be used to restore fertility. Organic farmers understand the need for diversity in the form of crop rotation. No forest can survive for long without rich biological diversity. Even cancer reminds us of the importance of diversity. Restricted diversity in the form of cellular monoclonality is one of the hallmarks of malignant growth.

DDW, our annual hallmark meeting, emphasizes our need for diverse thoughts and intellectual discourse as we advance the science of gastroenterology, endoscopy, hepatology, and surgery. Biology does not tolerate restrictions on diversity for long. Diversity makes DDW great.

In this month’s issue of GI & Hepatology News, we are reassured that PPIs are not linked to cognitive decline. Sessile serrated polyps, often missed at colonoscopy and CT colography might be detected with noninvasive testing as the field of blood-based cancer screening advances. Pay attention to the exciting bleeding-edge technology emerging from the AGA Tech Summit – especially technologies to treat obesity. Read about some of the continuing barriers to CRC screening in underserved populations – if we are to achieve 80% screening rates we must focus on people challenged to access our health care system.

Finally, consider the AGA Clinical Practice Update about Barrett’s esophagus. I spent a morning with Joel Richter, MD, last month and he reminded me that our current surveillance system is failing to impact annual incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Perhaps we should focus on a one-time screen for those most at risk, catching prevalent disease at an early stage.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) is approaching rapidly. One might say, with strong justification, that the overarching theme for DDW is a celebration of diversity. We are entering the era of “omics” and current research suggests a microbiome rich in diversity is associated with health, while a less-diverse biome is associated with digestive disorders – inflammatory bowel disease for example. Multiple abstracts and presentations will be related to research into microbiome alterations in disease. In nature, diversity is a key to survival.

Farmers know the value of diversity and the devastating effects of restricted diversity. When fields are restricted to a single crop year after year, artificial fertilizers must be used to restore fertility. Organic farmers understand the need for diversity in the form of crop rotation. No forest can survive for long without rich biological diversity. Even cancer reminds us of the importance of diversity. Restricted diversity in the form of cellular monoclonality is one of the hallmarks of malignant growth.

DDW, our annual hallmark meeting, emphasizes our need for diverse thoughts and intellectual discourse as we advance the science of gastroenterology, endoscopy, hepatology, and surgery. Biology does not tolerate restrictions on diversity for long. Diversity makes DDW great.

In this month’s issue of GI & Hepatology News, we are reassured that PPIs are not linked to cognitive decline. Sessile serrated polyps, often missed at colonoscopy and CT colography might be detected with noninvasive testing as the field of blood-based cancer screening advances. Pay attention to the exciting bleeding-edge technology emerging from the AGA Tech Summit – especially technologies to treat obesity. Read about some of the continuing barriers to CRC screening in underserved populations – if we are to achieve 80% screening rates we must focus on people challenged to access our health care system.

Finally, consider the AGA Clinical Practice Update about Barrett’s esophagus. I spent a morning with Joel Richter, MD, last month and he reminded me that our current surveillance system is failing to impact annual incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Perhaps we should focus on a one-time screen for those most at risk, catching prevalent disease at an early stage.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

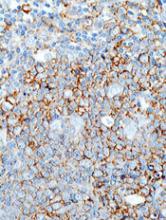

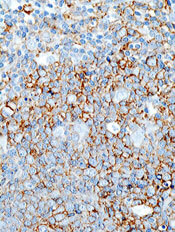

Predicting response to CAR T-cell therapy in CLL

Researchers may have discovered why some patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) don’t respond to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.

The team found that CLL patients with elevated levels of “early memory” T cells prior to receiving CAR T-cell therapy had a partial or complete response to treatment, while patients with lower levels of these T cells did not respond.

The early memory T cells were marked by the expression of CD8 and CD27, as well as the absence of CD45RO.

The researchers validated the association between the early memory T cells and response in a small group of patients, predicting with 100% accuracy which patients would achieve a complete response.

Joseph A. Fraietta, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and his colleagues reported these findings in Nature Medicine. This research was supported, in part, by Novartis.

For this study, the researchers retrospectively analyzed 41 patients with advanced, heavily pretreated, high-risk CLL who received at least 1 dose of CD19-directed CAR T cells.

Consistent with the team’s previously reported findings, they were not able to identify patient or disease-specific factors that predict who responds best to the therapy.

Therefore, the researchers compared the gene expression profiles and phenotypes of T cells in patients who had a complete response, partial response, or no response to therapy.

The CAR T cells that persisted and expanded in complete responders were enriched in genes that regulate early memory and effector T cells and possess the IL-6/STAT3 signature.

Non-responders, on the other hand, expressed genes involved in late T-cell differentiation, glycolysis, exhaustion, and apoptosis. These characteristics make for a weaker set of T cells to persist, expand, and fight the CLL.

“Pre-existing T-cell qualities have previously been associated with poor clinical response to cancer therapy, as well differentiation in the T cells,” Dr Fraietta said. “What is special about what we have done here is finding that critical cell subset and signature.”

Elevated levels of the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway in these early T cells correlated with clinical responses to CAR T-cell therapy.

To validate these findings, the researchers screened for the early memory T cells in a group of 8 CLL patients, before and after CAR T-cell therapy. The team identified the complete responders with 100% specificity and sensitivity.

“With a very robust biomarker like this, we can take a blood sample, measure the frequency of this T-cell population, and decide with a degree of confidence whether we can apply this therapy and know the patient would have a response,” Dr Fraietta said.

“The ability to select patients most likely to respond would have tremendous clinical impact, as this therapy would be applied only to patients most likely to benefit, allowing patients unlikely to respond to pursue other options.”

These findings also suggest the possibility of improving CAR T-cell therapy by selecting for cell manufacturing the subpopulation of T cells responsible for driving responses. However, this approach would come with challenges.

“What we’ve seen in these non-responders is that the frequency of these T cells is low, so it would be very hard to infuse them as starting populations,” said study author J. Joseph Melenhorst, PhD, also of the University of Pennsylvania.

“But one way to potentially boost their efficacy is by adding checkpoint inhibitors with the therapy to block the negative regulation prior to CAR T-cell therapy, which a past, separate study has shown can help elicit responses in these patients.”

The researchers also noted that it’s unclear why some patients’ T cells are suboptimal prior to treatment. However, the team believes this could have to do with prior therapies.

Future studies with a larger group of CLL patients should be conducted to help answer these questions and validate the findings from this study, the researchers said.

Researchers may have discovered why some patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) don’t respond to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.

The team found that CLL patients with elevated levels of “early memory” T cells prior to receiving CAR T-cell therapy had a partial or complete response to treatment, while patients with lower levels of these T cells did not respond.

The early memory T cells were marked by the expression of CD8 and CD27, as well as the absence of CD45RO.

The researchers validated the association between the early memory T cells and response in a small group of patients, predicting with 100% accuracy which patients would achieve a complete response.

Joseph A. Fraietta, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and his colleagues reported these findings in Nature Medicine. This research was supported, in part, by Novartis.

For this study, the researchers retrospectively analyzed 41 patients with advanced, heavily pretreated, high-risk CLL who received at least 1 dose of CD19-directed CAR T cells.

Consistent with the team’s previously reported findings, they were not able to identify patient or disease-specific factors that predict who responds best to the therapy.

Therefore, the researchers compared the gene expression profiles and phenotypes of T cells in patients who had a complete response, partial response, or no response to therapy.

The CAR T cells that persisted and expanded in complete responders were enriched in genes that regulate early memory and effector T cells and possess the IL-6/STAT3 signature.

Non-responders, on the other hand, expressed genes involved in late T-cell differentiation, glycolysis, exhaustion, and apoptosis. These characteristics make for a weaker set of T cells to persist, expand, and fight the CLL.

“Pre-existing T-cell qualities have previously been associated with poor clinical response to cancer therapy, as well differentiation in the T cells,” Dr Fraietta said. “What is special about what we have done here is finding that critical cell subset and signature.”

Elevated levels of the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway in these early T cells correlated with clinical responses to CAR T-cell therapy.

To validate these findings, the researchers screened for the early memory T cells in a group of 8 CLL patients, before and after CAR T-cell therapy. The team identified the complete responders with 100% specificity and sensitivity.

“With a very robust biomarker like this, we can take a blood sample, measure the frequency of this T-cell population, and decide with a degree of confidence whether we can apply this therapy and know the patient would have a response,” Dr Fraietta said.

“The ability to select patients most likely to respond would have tremendous clinical impact, as this therapy would be applied only to patients most likely to benefit, allowing patients unlikely to respond to pursue other options.”

These findings also suggest the possibility of improving CAR T-cell therapy by selecting for cell manufacturing the subpopulation of T cells responsible for driving responses. However, this approach would come with challenges.

“What we’ve seen in these non-responders is that the frequency of these T cells is low, so it would be very hard to infuse them as starting populations,” said study author J. Joseph Melenhorst, PhD, also of the University of Pennsylvania.

“But one way to potentially boost their efficacy is by adding checkpoint inhibitors with the therapy to block the negative regulation prior to CAR T-cell therapy, which a past, separate study has shown can help elicit responses in these patients.”

The researchers also noted that it’s unclear why some patients’ T cells are suboptimal prior to treatment. However, the team believes this could have to do with prior therapies.

Future studies with a larger group of CLL patients should be conducted to help answer these questions and validate the findings from this study, the researchers said.

Researchers may have discovered why some patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) don’t respond to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.

The team found that CLL patients with elevated levels of “early memory” T cells prior to receiving CAR T-cell therapy had a partial or complete response to treatment, while patients with lower levels of these T cells did not respond.

The early memory T cells were marked by the expression of CD8 and CD27, as well as the absence of CD45RO.

The researchers validated the association between the early memory T cells and response in a small group of patients, predicting with 100% accuracy which patients would achieve a complete response.

Joseph A. Fraietta, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and his colleagues reported these findings in Nature Medicine. This research was supported, in part, by Novartis.

For this study, the researchers retrospectively analyzed 41 patients with advanced, heavily pretreated, high-risk CLL who received at least 1 dose of CD19-directed CAR T cells.

Consistent with the team’s previously reported findings, they were not able to identify patient or disease-specific factors that predict who responds best to the therapy.

Therefore, the researchers compared the gene expression profiles and phenotypes of T cells in patients who had a complete response, partial response, or no response to therapy.

The CAR T cells that persisted and expanded in complete responders were enriched in genes that regulate early memory and effector T cells and possess the IL-6/STAT3 signature.

Non-responders, on the other hand, expressed genes involved in late T-cell differentiation, glycolysis, exhaustion, and apoptosis. These characteristics make for a weaker set of T cells to persist, expand, and fight the CLL.

“Pre-existing T-cell qualities have previously been associated with poor clinical response to cancer therapy, as well differentiation in the T cells,” Dr Fraietta said. “What is special about what we have done here is finding that critical cell subset and signature.”

Elevated levels of the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway in these early T cells correlated with clinical responses to CAR T-cell therapy.

To validate these findings, the researchers screened for the early memory T cells in a group of 8 CLL patients, before and after CAR T-cell therapy. The team identified the complete responders with 100% specificity and sensitivity.

“With a very robust biomarker like this, we can take a blood sample, measure the frequency of this T-cell population, and decide with a degree of confidence whether we can apply this therapy and know the patient would have a response,” Dr Fraietta said.

“The ability to select patients most likely to respond would have tremendous clinical impact, as this therapy would be applied only to patients most likely to benefit, allowing patients unlikely to respond to pursue other options.”

These findings also suggest the possibility of improving CAR T-cell therapy by selecting for cell manufacturing the subpopulation of T cells responsible for driving responses. However, this approach would come with challenges.

“What we’ve seen in these non-responders is that the frequency of these T cells is low, so it would be very hard to infuse them as starting populations,” said study author J. Joseph Melenhorst, PhD, also of the University of Pennsylvania.

“But one way to potentially boost their efficacy is by adding checkpoint inhibitors with the therapy to block the negative regulation prior to CAR T-cell therapy, which a past, separate study has shown can help elicit responses in these patients.”

The researchers also noted that it’s unclear why some patients’ T cells are suboptimal prior to treatment. However, the team believes this could have to do with prior therapies.

Future studies with a larger group of CLL patients should be conducted to help answer these questions and validate the findings from this study, the researchers said.

One in seven Americans had fecal incontinence

One in seven respondents to a national survey reported a history of fecal incontinence, including one-third within the preceding week, investigators reported.

“Fecal incontinence [FI] is age-related and more prevalent among individuals with inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, irritable bowel syndrome, or diabetes than people without these disorders. Proactive screening for FI among these groups is warranted,” Stacy B. Menees, MD, and her associates wrote in the May issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.062).

Accurately determining the prevalence of FI is difficult because patients are reluctant to disclose symptoms and physicians often do not ask. In one study of HMO enrollees, about a third of patients had a history of FI but fewer than 3% had a medical diagnosis. In other studies, the prevalence of FI has ranged from 2% to 21%. Population aging fuels the need to narrow these estimates because FI becomes more common with age, the investigators noted.

Accordingly, in October 2015, they used a mobile app called MyGIHealth to survey nearly 72,000 individuals about fecal incontinence and other GI symptoms. The survey took about 15 minutes to complete, in return for which respondents could receive cash, shop online, or donate to charity. The investigators assessed FI severity by analyzing responses to the National Institutes of Health FI Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System questionnaire.

Of the 10,033 respondents reporting a history of fecal incontinence (14.4%), 33.3% had experienced at least one episode in the past week. About a third of individuals with FI said it interfered with their daily activities. “Increasing age and concomitant diarrhea and constipation were associated with increased odds [of] FI,” the researchers wrote. Compared with individuals aged 18-24 years, the odds of having ever experienced FI rose by 29% among those aged 25-45 years, by 72% among those aged 45-64 years, and by 118% among persons aged 65 years and older.

Self-reported FI also was significantly more common among individuals with Crohn’s disease (41%), ulcerative colitis (37%), celiac disease (34%), irritable bowel syndrome (13%), or diabetes (13%) than it was among persons without these conditions. Corresponding odds ratios ranged from about 1.5 (diabetes) to 2.8 (celiac disease).

For individuals reporting FI within the past week, greater severity (based on their responses to the NIH FI Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System questionnaire) significantly correlated with being non-Hispanic black (P = .03) or Latino (P = .02) and with having Crohn’s disease (P less than .001), celiac disease (P less than .001), diabetes (P = .04), human immunodeficiency syndrome (P = .001), or chronic idiopathic constipation (P less than .001). “Our study is the first to find differences among racial/ethnic groups regarding FI severity,” the researchers noted. They did not speculate on reasons for the finding, but stressed the importance of screening for FI and screening patients with FI for serious GI diseases.

Ironwood Pharmaceuticals funded the National GI Survey, but the investigators received no funding for this study. Three coinvestigators reported ties to Ironwood Pharmaceuticals and My Total Health.

SOURCE: Menees SB et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 Feb 3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.062.

Fecal incontinence (FI) is a common problem associated with significant social anxiety and decreased quality of life for patients who experience it. Unfortunately, patients are not always forthcoming regarding their symptoms, and physicians often fail to inquire directly about incontinence symptoms.

Previous studies have shown the prevalence of FI to vary widely across different populations. Using novel technology through a mobile app, researchers at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, have been able to perform the largest population-based study of community-dwelling Americans. They confirmed that FI is indeed a common problem experienced across the spectrum of age, sex, race, and socioeconomic status and interferes with the daily activities of more than one-third of those who experience it.

This study supports previous findings of an age-related increase in FI, with the highest prevalence in patients over age 65 years. Interestingly, males were more likely than female to have experienced FI within the past week, but not more likely to have ever experienced FI. While FI is often thought of as a primarily female problem (related to past obstetrical injury), it is important to remember that it likely affects both sexes equally.

Other significant risk factors include diabetes and gastrointestinal disorders. This study also confirms prior population-based findings that patients with chronic constipation are more likely to suffer FI. Finally, this study also identified risk factors associated with FI symptom severity including diabetes, HIV/AIDS, Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, and chronic constipation. This is also the first study to show differences between racial/ethnic groups, suggesting higher FI symptom scores in Latinos and African-Americans.

The strengths of this study include its size and the anonymity provided by an internet-based survey regarding a potentially embarrassing topic; however, it also may have led to the potential exclusion of older individuals or those without regular internet access.