User login

Infective endocarditis: Refer for expert team care as soon as possible

In this issue of the Journal, Soud et al discuss the timing of referral of patients with infective endocarditis to surgery.1 When having this discussion, it is important to understand the nature of the disease and the role of surgery in its treatment.

Unless successfully treated and cured, infective endocarditis is fatal. It is associated with septic embolism (systemic with left-sided infective endocarditis and pulmonary with right-sided infective endocarditis), destruction of valve tissue, and invasion outside the aortic root or into the atrioventricular groove. Antimicrobials kill sensitive and exposed organisms but cannot reach those hiding in vegetations or biofilm, on foreign material, or in invaded extravascular tissue.

The objectives of surgery are to eliminate the source of embolism, debride and remove infected tissue and foreign material, expose and make residual organisms vulnerable to antimicrobials, and restore functional valves and cardiac integrity. Surgery to treat infective endocarditis is difficult and high-risk and requires an experienced surgeon. But final cure of the infection is still by antimicrobial treatment.

INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS NEEDS MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Every aspect of infective endocarditis—diagnosis, medical management, management of complications, and surgery—is difficult. Recent guidelines2–6 therefore favor care by a multidisciplinary team that includes an infectious disease specialist, cardiologist, and cardiac surgeon from the very beginning, with access to any other needed discipline, often including neurology, neurosurgery, nephrology, and dependence specialists. Patients with infective endocarditis should be referred early to a center with access to a full endocarditis treatment team. The need for surgery and the optimal timing of it are team decisions. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery infective endocarditis guidelines are question-based and address most aspects that surgeons must consider before, during, and after operation.2

IF SURGERY IS INDICATED, IT IS BEST DONE SOONER

Once there is an indication to operate, the operation should be expedited. Delays mean continued risk of disease progression, invasion, heart block, and embolic events. Determining the timing of surgery is difficult in patients who have suffered an embolic stroke—nonhemorrhagic or hemorrhagic—or who have suffered brain bleeding; management of these issues has recently triggered expert opinion and review articles.7,8 The recommendation for early surgery is based on the conviction that once the patient has been stabilized (or has overwhelming mechanical hemodynamic problems requiring emergency surgery) and adequate antimicrobial coverage is on board, there are no additional benefits to delaying surgery.9 When the indication to operate is large mobile vegetations associated with a high risk of stroke, surgery before another event can make all the difference.

In the operating room, the first aspect addressed is adequate debridement. There is wide agreement that repair is preferable to replacement for the mitral and tricuspid valves, but there is no agreement that an allograft (although favored by our team) is the best replacement alternative for a destroyed aortic root. The key is that surgeons and their surgical teams must have the experience and tools that work for them.

Our recommendation is to refer all patients with infective endocarditis to a center with access to a full team of experienced experts able to address all aspects of the disease and its complications.

- Soud M, Pacha HM, Alraies MC. How soon should patients with infective endocarditis be referred for valve surgery? Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(5):362–364. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a:17052

- Pettersson GB, Coselli JS, Pettersson GB, et al. 2016 The American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS) consensus guidelines: surgical treatment of infective endocarditis: executive summary. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2017; 153(6):1241–1258.e29. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2016.09.093

- Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015; 132(15):1435–1486. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000296

- Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: the Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J 2015; 36(44):3075–3128. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319

- Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease:executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014;129(23):2440–2492. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000029

- Byrne JG, Rezai K, Sanchez JA, et al. Surgical management of endocarditis: the Society of Thoracic Surgeons clinical practice guideline. Ann Thorac Surg 2011; 91(6):2012–2019. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.01.106

- Yanagawa B, Pettersson GB, Habib G, et al. Surgical management of infective endocarditis complicated by embolic stroke: practical recommendations for clinicians. Circulation 2016; 134(17):1280–1292. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024156

- Cahill TJ , Baddour LM, Habib G, et al. Challenges in infective endocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(3):325–344. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.066

- Kang DH, Kim YJ, Kim SH, et al. Early surgery versus conventional treatment for infective endocarditis. N Engl J Med 2012; 366(26):2466–2473. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1112843

In this issue of the Journal, Soud et al discuss the timing of referral of patients with infective endocarditis to surgery.1 When having this discussion, it is important to understand the nature of the disease and the role of surgery in its treatment.

Unless successfully treated and cured, infective endocarditis is fatal. It is associated with septic embolism (systemic with left-sided infective endocarditis and pulmonary with right-sided infective endocarditis), destruction of valve tissue, and invasion outside the aortic root or into the atrioventricular groove. Antimicrobials kill sensitive and exposed organisms but cannot reach those hiding in vegetations or biofilm, on foreign material, or in invaded extravascular tissue.

The objectives of surgery are to eliminate the source of embolism, debride and remove infected tissue and foreign material, expose and make residual organisms vulnerable to antimicrobials, and restore functional valves and cardiac integrity. Surgery to treat infective endocarditis is difficult and high-risk and requires an experienced surgeon. But final cure of the infection is still by antimicrobial treatment.

INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS NEEDS MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Every aspect of infective endocarditis—diagnosis, medical management, management of complications, and surgery—is difficult. Recent guidelines2–6 therefore favor care by a multidisciplinary team that includes an infectious disease specialist, cardiologist, and cardiac surgeon from the very beginning, with access to any other needed discipline, often including neurology, neurosurgery, nephrology, and dependence specialists. Patients with infective endocarditis should be referred early to a center with access to a full endocarditis treatment team. The need for surgery and the optimal timing of it are team decisions. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery infective endocarditis guidelines are question-based and address most aspects that surgeons must consider before, during, and after operation.2

IF SURGERY IS INDICATED, IT IS BEST DONE SOONER

Once there is an indication to operate, the operation should be expedited. Delays mean continued risk of disease progression, invasion, heart block, and embolic events. Determining the timing of surgery is difficult in patients who have suffered an embolic stroke—nonhemorrhagic or hemorrhagic—or who have suffered brain bleeding; management of these issues has recently triggered expert opinion and review articles.7,8 The recommendation for early surgery is based on the conviction that once the patient has been stabilized (or has overwhelming mechanical hemodynamic problems requiring emergency surgery) and adequate antimicrobial coverage is on board, there are no additional benefits to delaying surgery.9 When the indication to operate is large mobile vegetations associated with a high risk of stroke, surgery before another event can make all the difference.

In the operating room, the first aspect addressed is adequate debridement. There is wide agreement that repair is preferable to replacement for the mitral and tricuspid valves, but there is no agreement that an allograft (although favored by our team) is the best replacement alternative for a destroyed aortic root. The key is that surgeons and their surgical teams must have the experience and tools that work for them.

Our recommendation is to refer all patients with infective endocarditis to a center with access to a full team of experienced experts able to address all aspects of the disease and its complications.

In this issue of the Journal, Soud et al discuss the timing of referral of patients with infective endocarditis to surgery.1 When having this discussion, it is important to understand the nature of the disease and the role of surgery in its treatment.

Unless successfully treated and cured, infective endocarditis is fatal. It is associated with septic embolism (systemic with left-sided infective endocarditis and pulmonary with right-sided infective endocarditis), destruction of valve tissue, and invasion outside the aortic root or into the atrioventricular groove. Antimicrobials kill sensitive and exposed organisms but cannot reach those hiding in vegetations or biofilm, on foreign material, or in invaded extravascular tissue.

The objectives of surgery are to eliminate the source of embolism, debride and remove infected tissue and foreign material, expose and make residual organisms vulnerable to antimicrobials, and restore functional valves and cardiac integrity. Surgery to treat infective endocarditis is difficult and high-risk and requires an experienced surgeon. But final cure of the infection is still by antimicrobial treatment.

INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS NEEDS MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Every aspect of infective endocarditis—diagnosis, medical management, management of complications, and surgery—is difficult. Recent guidelines2–6 therefore favor care by a multidisciplinary team that includes an infectious disease specialist, cardiologist, and cardiac surgeon from the very beginning, with access to any other needed discipline, often including neurology, neurosurgery, nephrology, and dependence specialists. Patients with infective endocarditis should be referred early to a center with access to a full endocarditis treatment team. The need for surgery and the optimal timing of it are team decisions. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery infective endocarditis guidelines are question-based and address most aspects that surgeons must consider before, during, and after operation.2

IF SURGERY IS INDICATED, IT IS BEST DONE SOONER

Once there is an indication to operate, the operation should be expedited. Delays mean continued risk of disease progression, invasion, heart block, and embolic events. Determining the timing of surgery is difficult in patients who have suffered an embolic stroke—nonhemorrhagic or hemorrhagic—or who have suffered brain bleeding; management of these issues has recently triggered expert opinion and review articles.7,8 The recommendation for early surgery is based on the conviction that once the patient has been stabilized (or has overwhelming mechanical hemodynamic problems requiring emergency surgery) and adequate antimicrobial coverage is on board, there are no additional benefits to delaying surgery.9 When the indication to operate is large mobile vegetations associated with a high risk of stroke, surgery before another event can make all the difference.

In the operating room, the first aspect addressed is adequate debridement. There is wide agreement that repair is preferable to replacement for the mitral and tricuspid valves, but there is no agreement that an allograft (although favored by our team) is the best replacement alternative for a destroyed aortic root. The key is that surgeons and their surgical teams must have the experience and tools that work for them.

Our recommendation is to refer all patients with infective endocarditis to a center with access to a full team of experienced experts able to address all aspects of the disease and its complications.

- Soud M, Pacha HM, Alraies MC. How soon should patients with infective endocarditis be referred for valve surgery? Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(5):362–364. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a:17052

- Pettersson GB, Coselli JS, Pettersson GB, et al. 2016 The American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS) consensus guidelines: surgical treatment of infective endocarditis: executive summary. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2017; 153(6):1241–1258.e29. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2016.09.093

- Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015; 132(15):1435–1486. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000296

- Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: the Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J 2015; 36(44):3075–3128. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319

- Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease:executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014;129(23):2440–2492. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000029

- Byrne JG, Rezai K, Sanchez JA, et al. Surgical management of endocarditis: the Society of Thoracic Surgeons clinical practice guideline. Ann Thorac Surg 2011; 91(6):2012–2019. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.01.106

- Yanagawa B, Pettersson GB, Habib G, et al. Surgical management of infective endocarditis complicated by embolic stroke: practical recommendations for clinicians. Circulation 2016; 134(17):1280–1292. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024156

- Cahill TJ , Baddour LM, Habib G, et al. Challenges in infective endocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(3):325–344. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.066

- Kang DH, Kim YJ, Kim SH, et al. Early surgery versus conventional treatment for infective endocarditis. N Engl J Med 2012; 366(26):2466–2473. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1112843

- Soud M, Pacha HM, Alraies MC. How soon should patients with infective endocarditis be referred for valve surgery? Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(5):362–364. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a:17052

- Pettersson GB, Coselli JS, Pettersson GB, et al. 2016 The American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS) consensus guidelines: surgical treatment of infective endocarditis: executive summary. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2017; 153(6):1241–1258.e29. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2016.09.093

- Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015; 132(15):1435–1486. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000296

- Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: the Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J 2015; 36(44):3075–3128. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319

- Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease:executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014;129(23):2440–2492. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000029

- Byrne JG, Rezai K, Sanchez JA, et al. Surgical management of endocarditis: the Society of Thoracic Surgeons clinical practice guideline. Ann Thorac Surg 2011; 91(6):2012–2019. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.01.106

- Yanagawa B, Pettersson GB, Habib G, et al. Surgical management of infective endocarditis complicated by embolic stroke: practical recommendations for clinicians. Circulation 2016; 134(17):1280–1292. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024156

- Cahill TJ , Baddour LM, Habib G, et al. Challenges in infective endocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(3):325–344. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.066

- Kang DH, Kim YJ, Kim SH, et al. Early surgery versus conventional treatment for infective endocarditis. N Engl J Med 2012; 366(26):2466–2473. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1112843

An unusual complication of peritoneal dialysis

A 45-year-old man with end-stage renal disease secondary to hypertension presented with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever. He had been on peritoneal dialysis for 15 years.

Results of initial laboratory testing were as follows:

- Sodium 137 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.7 mmol/L (3.5–5.0)

- Bicarbonate 31 mmol/L (22–30)

- Creatinine 17.5 mg/dL (0.58–0.96)

- Blood urea nitrogen 57 mg/dL (7–21)

- Lactic acid 1.7 mmol/L (0.5–2.2)

- White blood cell count 14.34 × 109/L (3.70–11.0).

Blood cultures were negative. Peritoneal fluid analysis showed a white blood cell count of 1.2 × 109/L (reference range < 0.5 × 109/L) with 89% neutrophils, and an amylase level less than 3 U/L (reference range < 100). Fluid cultures were positive for coagulase-negative staphylococci and Staphylococcus epidermidis.

CAUSES AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis is a devastating complication of peritoneal dialysis, occurring in 3% of patients on peritoneal dialysis. The mortality rate is above 40%.1,2 It is characterized by an initial inflammatory phase followed by extensive intraperitoneal fibrosis and encasement of bowel. Causes include prolonged exposure to peritoneal dialysis or glucose degradation products, a history of severe peritonitis, use of acetate as a dialysate buffer, and reaction to medications such as beta-blockers.3

Clinical features result from inflammation, ileus, and peritoneal adhesions and include abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. A high peritoneal transport rate, which often heralds development of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis, leads to failure of ultrafiltration and to fluid retention.

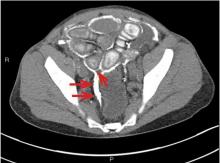

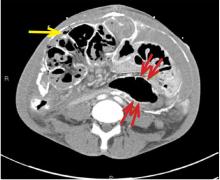

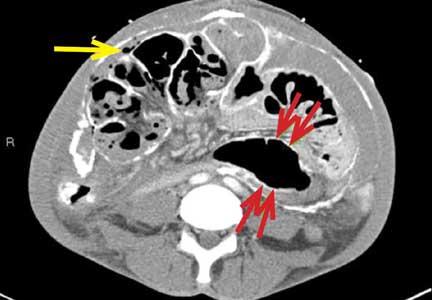

CT is recommended for diagnosis and demonstrates peritoneal calcification with bowel thickening and dilation.

TREATMENT

Treatment entails stopping peritoneal dialysis, changing to hemodialysis, bowel rest, and corticosteroids. Successful treatment has been reported with a combination of corticosteroids and azathioprine.4,5 A retrospective study showed that adding the antifibrotic agent tamoxifen was associated with a decrease in the mortality rate.6 Bowel obstruction is a common complication, and surgery may be indicated. Enterolysis is a new surgical technique that has shown improved outcomes.7

- Kawaguchi Y, Saito A, Kawanishi H, et al. Recommendations on the management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in Japan, 2005: diagnosis, predictive markers, treatment, and preventive measures. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S83–S95. pmid:16300277

- Lee HY, Kim BS, Choi HY, et al. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis as a complication of long-term continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis in Korea. Nephrology (Carlton) 2003; 8(suppl 2):S33–S39. doi:10.1046/J.1440-1797.8.S.11.X

- Kawaguchi Y, Tranaeus A. A historical review of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S7–S13. pmid:16300267

- Martins LS, Rodrigues AS, Cabrita AN, Guimaraes S. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: a case successfully treated with immunosuppression. Perit Dial Int 1999; 19(5):478–481. pmid:11379862

- Wong CF, Beshir S, Khalil A, Pai P, Ahmad R. Successful treatment of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis with azathioprine and prednisolone. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(3):285–287. pmid:15981777

- Korte MR, Fieren MW, Sampimon DE, Lingsma HF, Weimar W, Betjes MG; investigators of the Dutch Multicentre EPS Study. Tamoxifen is associated with lower mortality of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: results of the Dutch Multicentre EPS Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011; 26(2):691–697. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfq362

- Kawanishi H, Watanabe H, Moriishi M, Tsuchiya S. Successful surgical management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S39–S47. pmid:16300271

A 45-year-old man with end-stage renal disease secondary to hypertension presented with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever. He had been on peritoneal dialysis for 15 years.

Results of initial laboratory testing were as follows:

- Sodium 137 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.7 mmol/L (3.5–5.0)

- Bicarbonate 31 mmol/L (22–30)

- Creatinine 17.5 mg/dL (0.58–0.96)

- Blood urea nitrogen 57 mg/dL (7–21)

- Lactic acid 1.7 mmol/L (0.5–2.2)

- White blood cell count 14.34 × 109/L (3.70–11.0).

Blood cultures were negative. Peritoneal fluid analysis showed a white blood cell count of 1.2 × 109/L (reference range < 0.5 × 109/L) with 89% neutrophils, and an amylase level less than 3 U/L (reference range < 100). Fluid cultures were positive for coagulase-negative staphylococci and Staphylococcus epidermidis.

CAUSES AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis is a devastating complication of peritoneal dialysis, occurring in 3% of patients on peritoneal dialysis. The mortality rate is above 40%.1,2 It is characterized by an initial inflammatory phase followed by extensive intraperitoneal fibrosis and encasement of bowel. Causes include prolonged exposure to peritoneal dialysis or glucose degradation products, a history of severe peritonitis, use of acetate as a dialysate buffer, and reaction to medications such as beta-blockers.3

Clinical features result from inflammation, ileus, and peritoneal adhesions and include abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. A high peritoneal transport rate, which often heralds development of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis, leads to failure of ultrafiltration and to fluid retention.

CT is recommended for diagnosis and demonstrates peritoneal calcification with bowel thickening and dilation.

TREATMENT

Treatment entails stopping peritoneal dialysis, changing to hemodialysis, bowel rest, and corticosteroids. Successful treatment has been reported with a combination of corticosteroids and azathioprine.4,5 A retrospective study showed that adding the antifibrotic agent tamoxifen was associated with a decrease in the mortality rate.6 Bowel obstruction is a common complication, and surgery may be indicated. Enterolysis is a new surgical technique that has shown improved outcomes.7

A 45-year-old man with end-stage renal disease secondary to hypertension presented with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever. He had been on peritoneal dialysis for 15 years.

Results of initial laboratory testing were as follows:

- Sodium 137 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.7 mmol/L (3.5–5.0)

- Bicarbonate 31 mmol/L (22–30)

- Creatinine 17.5 mg/dL (0.58–0.96)

- Blood urea nitrogen 57 mg/dL (7–21)

- Lactic acid 1.7 mmol/L (0.5–2.2)

- White blood cell count 14.34 × 109/L (3.70–11.0).

Blood cultures were negative. Peritoneal fluid analysis showed a white blood cell count of 1.2 × 109/L (reference range < 0.5 × 109/L) with 89% neutrophils, and an amylase level less than 3 U/L (reference range < 100). Fluid cultures were positive for coagulase-negative staphylococci and Staphylococcus epidermidis.

CAUSES AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis is a devastating complication of peritoneal dialysis, occurring in 3% of patients on peritoneal dialysis. The mortality rate is above 40%.1,2 It is characterized by an initial inflammatory phase followed by extensive intraperitoneal fibrosis and encasement of bowel. Causes include prolonged exposure to peritoneal dialysis or glucose degradation products, a history of severe peritonitis, use of acetate as a dialysate buffer, and reaction to medications such as beta-blockers.3

Clinical features result from inflammation, ileus, and peritoneal adhesions and include abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. A high peritoneal transport rate, which often heralds development of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis, leads to failure of ultrafiltration and to fluid retention.

CT is recommended for diagnosis and demonstrates peritoneal calcification with bowel thickening and dilation.

TREATMENT

Treatment entails stopping peritoneal dialysis, changing to hemodialysis, bowel rest, and corticosteroids. Successful treatment has been reported with a combination of corticosteroids and azathioprine.4,5 A retrospective study showed that adding the antifibrotic agent tamoxifen was associated with a decrease in the mortality rate.6 Bowel obstruction is a common complication, and surgery may be indicated. Enterolysis is a new surgical technique that has shown improved outcomes.7

- Kawaguchi Y, Saito A, Kawanishi H, et al. Recommendations on the management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in Japan, 2005: diagnosis, predictive markers, treatment, and preventive measures. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S83–S95. pmid:16300277

- Lee HY, Kim BS, Choi HY, et al. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis as a complication of long-term continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis in Korea. Nephrology (Carlton) 2003; 8(suppl 2):S33–S39. doi:10.1046/J.1440-1797.8.S.11.X

- Kawaguchi Y, Tranaeus A. A historical review of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S7–S13. pmid:16300267

- Martins LS, Rodrigues AS, Cabrita AN, Guimaraes S. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: a case successfully treated with immunosuppression. Perit Dial Int 1999; 19(5):478–481. pmid:11379862

- Wong CF, Beshir S, Khalil A, Pai P, Ahmad R. Successful treatment of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis with azathioprine and prednisolone. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(3):285–287. pmid:15981777

- Korte MR, Fieren MW, Sampimon DE, Lingsma HF, Weimar W, Betjes MG; investigators of the Dutch Multicentre EPS Study. Tamoxifen is associated with lower mortality of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: results of the Dutch Multicentre EPS Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011; 26(2):691–697. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfq362

- Kawanishi H, Watanabe H, Moriishi M, Tsuchiya S. Successful surgical management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S39–S47. pmid:16300271

- Kawaguchi Y, Saito A, Kawanishi H, et al. Recommendations on the management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in Japan, 2005: diagnosis, predictive markers, treatment, and preventive measures. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S83–S95. pmid:16300277

- Lee HY, Kim BS, Choi HY, et al. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis as a complication of long-term continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis in Korea. Nephrology (Carlton) 2003; 8(suppl 2):S33–S39. doi:10.1046/J.1440-1797.8.S.11.X

- Kawaguchi Y, Tranaeus A. A historical review of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S7–S13. pmid:16300267

- Martins LS, Rodrigues AS, Cabrita AN, Guimaraes S. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: a case successfully treated with immunosuppression. Perit Dial Int 1999; 19(5):478–481. pmid:11379862

- Wong CF, Beshir S, Khalil A, Pai P, Ahmad R. Successful treatment of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis with azathioprine and prednisolone. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(3):285–287. pmid:15981777

- Korte MR, Fieren MW, Sampimon DE, Lingsma HF, Weimar W, Betjes MG; investigators of the Dutch Multicentre EPS Study. Tamoxifen is associated with lower mortality of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: results of the Dutch Multicentre EPS Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011; 26(2):691–697. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfq362

- Kawanishi H, Watanabe H, Moriishi M, Tsuchiya S. Successful surgical management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S39–S47. pmid:16300271

What you can do for your fibromyalgia patient

Fibromyalgia may seem like a nebulous diagnosis, with its array of symptoms and pain refractory to medications. But fibromyalgia is a defined syndrome of neuronal dysregulation. It can be diagnosed from the history and physical examination and managed in a primary care setting.

CASE 1: MANY SYMPTOMS

A 43-year-old woman presents to her primary care physician with multiple complaints: pain in all joints and in her back and hips, swelling of her hands and feet, morning stiffness, chest pain and shortness of breath (not necessarily related to exertion), fatigue, generalized weakness, headaches, difficulty with memory and concentration, dry mouth and dry eyes, feeling weak and faint in the sun, cold intolerance with purple discoloration of her extremities, a self-described “butterfly” rash on the face, and hair that is thinning and falling out in clumps.

Because many of her symptoms could reflect an inflammatory process or an autoimmune disease,1 her primary care physician orders multiple tests. Her C-reactive protein level, Westergren sedimentation rate, complete blood cell count, and comprehensive metabolic panel are normal. Urinalysis shows trace leukocyte esterase. Indirect immunofluorescence assay on human laryngeal tumor (HEp-2) cells is positive for antinuclear antibody (ANA), with a titer of 1:320 (reference range ≤ 1:40) and a nuclear dense fine-speckled pattern.

In view of the positive ANA test, the patient is informed that she may have systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and will be referred to a rheumatologist. In the days before her rheumatology appointment, she becomes extremely anxious. Obsessively researching SLE online, she becomes convinced that SLE is the correct diagnosis.

Rheumatology evaluation

The rheumatologist assesses the patient’s pain and reports the following:

Location and duration: Hands, wrists, elbows, shoulders, upper and lower back, sides of hips, knees, and feet; has been ongoing for 10 years, but worse in the past 3 months.

Character: The patient describes her pain as “like an ice pick being driven through my joints,” “sometimes unbearable,” and “like being hit by a truck.” She also reports numb, tingly, burning pain in her upper neck and back.

Variation with time, activity, and weather: Worse at night, causing her to wake and toss and turn all night; better with exertion, but after activity or exercise, she is exhausted for the rest of the day and sometimes for up to a week; worse with weather changes, especially during cold or humid weather.

Associated symptoms: Occasional perceived swelling of hands and feet, especially upon wakening in the morning, and 2 to 3 hours of stiffness in the morning that sometimes lasts all day.

Physical examination. Her findings are inconsistent with her symptoms.

The patient exhibits limited range of motion. When asked to bend forward, rotate her neck, or flex and extend her neck and back, she does so only slightly. However, passive range of motion is normal in all joints.

When her joints are examined, she anticipates pain and withdraws her hands. But when she is distracted, examination reveals no evidence of swollen joints or synovitis. She has tenderness in 12 of 18 tender points. Her peripheral pulses are good, strength is normal, and reflexes are brisk.

Her facial rash looks more like rosacea than the butterfly rash of SLE. There is no indication of patchy hair loss. Heart and lung examinations are normal. She appears to have a good salivary pool without glossitis.

History reveals long-standing psychological issues

The patient reports a history of panic attacks and a prior diagnosis of anxiety. She is tested with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (www.mdcalc.com/gad-7-general-anxiety-disorder-7) and scores 17 out of 21, indicating severe anxiety.

DISCUSSION: CHARACTERIZING PAIN

Understanding categories of pain syndromes can help us understand fibromyalgia. Pain can be categorized into 3 types that sometimes overlap2:

Nociceptive or peripheral pain is related to damage of tissue by trauma or inflammation. Syndromes include osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and SLE.

Neuropathic pain is associated with damage of peripheral or central nerves. Examples are neuropathy from herpes, diabetes, or spinal stenosis.

Centralized pain has no identifiable nerve or tissue damage and is thought to result from persistent neuronal dysregulation, overactive ascending pain pathways, and a deficiency of descending inhibitory pain pathways. There is evidence of biochemical changes in muscles, possibly related to chronic ischemia and an overactive sympathetic nervous system. Dysregulation of the sympathoadrenal system and hypothalamic-pituitary axis has also been implicated. And genetic predisposition is possible. Examples of centralized pain syndromes include fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, pelvic pain syndrome, neurogenic bladder, and interstitial cystitis.

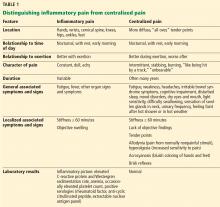

Clues to a centralized pain syndrome

For patients with suspected fibromyalgia, distinguishing peripheral pain from centralized pain can be a challenge (Table 1). For example, SLE does not cause inflammation of the spine, so neck or back pain is not typical. Although both nociceptive and centralized pain syndromes improve with exertion, only patients with centralized pain are typically exhausted and bedbound for days after activity. Patients with centralized pain tend to describe their pain in much more dramatic language than do patients with inflammatory pain. Centralized pain tends to be intermittent; inflammatory pain tends to be constant. Patients with centralized pain often have had pain for many years without a diagnosis, but this is rare for patients with an inflammatory condition.

A patient with fibromyalgia typically has a normal physical examination, although allodynia (experiencing pain from normally nonpainful stimulation), hyperalgesia (increased pain perception), and brisk reflexes may be present. Fibromyalgia may involve discoloration of the fingertips resulting from an overactive sympathetic nervous system. Laboratory results are typically normal with fibromyalgia.

Patients with either nociceptive or centralized pain report stiffness, but the cause likely differs. We typically think of stiffness as arising from swollen joints caused by inflammation, but stiffness can also be caused by abnormally tight muscles, as occurs in fibromyalgia.

FIBROMYALGIA IS A CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosing fibromyalgia does not require multiple laboratory and imaging tests. The key indicators are derived from the patient history and physical examination.

Diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia published by the American College of Rheumatology have evolved over the years. The 2011 criteria, in the form of a self-reported patient questionnaire, have 2 components3:

- The Widespread Pain Index measures the extent of pain in 19 areas.

- The Symptom Severity scale assesses 3 key symptoms associated with fibromyalgia, ie, fatigue, cognitive problems, and nonrestorative sleep (scale of 0–3 for each symptom).

There are also questions about symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome, depression, and headache.

Fibromyalgia is diagnosed if a patient reports at least 7 painful areas and has a symptom severity score of at least 5. A patient may also meet the 20113 and the 2016 criteria4 if he or she has 4 painful areas and the pain is perceived in 4 of 5 areas and the Symptom Severity Scale score is 9 or higher.4 This questionnaire is not only a rapid diagnostic tool for fibromyalgia, it also helps identify and focus on specific issues—for example, having severe pain in a few localized areas, or having headache as a predominant problem.

These criteria are useful for a variety of patients, eg, a patient with hip arthritis may score high on the questionnaire, indicating that a component of centralized pain is also present. Also, people who have undergone orthopedic surgery who score high tend to require more narcotics to meet the goals of pain improvement.

The 2016 criteria,4 the most recent, maintain that pain must be generalized, ie, present in at least 4 of 5 body areas. They also emphasize that fibromyalgia is a valid diagnosis irrespective of other conditions.

CASE 1 CONTINUED: THE PATIENT REJECTS THE DIAGNOSIS

Our patient meets the definition of fibromyalgia by each iteration of the American College of Rheumatology clinical criteria. She also has generalized anxiety disorder and a positive ANA test. She is advised to participate in a fibromyalgia educational program, start an aerobic exercise program, and consider taking an antidepressant medication with anxiolytic effects.

However, the patient rejects the diagnosis of fibromyalgia. She believes that the diagnosis of SLE has been overlooked and that her symptom severity is being discounted.

In response, the rheumatologist orders additional tests to evaluate for an autoimmune disorder: extractable nuclear antigen panel, complement C3 and C4, double-stranded DNA antibodies, and protein electrophoresis. Results are all in the normal range. The patient is still concerned that she has SLE or another autoimmune disease because of her abnormal ANA test result and remains dissatisfied with her evaluation. She states that she will complain to the clinic ombudsman.

SIGNIFICANCE OF ANA TESTING

Patients with positive test results increasingly go online to get information. The significance of ANA testing can be confusing, and it is critical to understand and be able to explain abnormal results to worried patients. Following are answers to some common questions about ANA testing:

Is ANA positivity specific for SLE or another autoimmune disease?

No. ANA is usually tested by indirect immunofluorescence assay on HEp-2 cells. The test can identify about 150 antigens targeted by antibodies, but only a small percentage are associated with an autoimmune disease, and the others do not have a known clinical association. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) ANA testing is also available but is considered less sensitive.

Abeles and Abeles5 retrospectively assessed 232 patients between 2007 and 2009 who were referred to rheumatologists for evaluation because of an elevated ANA test result. No ANA-associated rheumatic disease was found in patients who had a result of less than 1:160, and more than 90% of referrals for a positive ANA test had no evidence of ANA-associated disease. The positive predictive value was 9% for any connective tissue disease, and only 2% for SLE. The most common reason for ordering the test was widespread pain (23%). The authors concluded that ANA testing is often ordered inappropriately for patients with a low pretest probability of an ANA-associated rheumatic disease.

Screening with ANA testing generates many false-positive results and unnecessary anxiety for patients. The prevalence of SLE in the general population is about 0.1%, and other autoimmune diseases total about 5% to 7%. By indirect immunofluorescence assay, using a cutoff of 1:80 (the standard at Cleveland Clinic), about 15% of the general population test positive. By ELISA, with a cutoff of 20 ELISA units, 25% of healthy controls test positive.

It is true that ANA positivity may precede the onset of SLE.6,7 Arbuckle et al8 evaluated serum samples from the US Department of Defense Serum Repository obtained from 130 people before they received a diagnosis of SLE; in 115 (88%), at least 1 SLE-related autoantibody was present before diagnosis (up to 9.4 years earlier). However, in those who test positive for ANA, the percentage who eventually develop autoimmune disease is small.5

Is the titer of ANA significant and of diagnostic value?

The likelihood of autoimmune disease increases with increasing titer. But high titers can be seen in healthy people. Mariz et al9 examined ANA test results from 918 healthy controls and 153 patients with an autoimmune rheumatic disease. Of these, ANA was positive in 13% of healthy people and 90% of patients with an autoimmune disease. High titers were more likely in patients with an autoimmune disease, but also occurred in healthy controls.

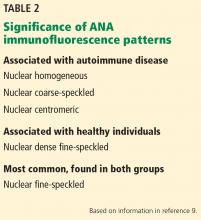

Does the immunofluorescence pattern provide diagnostic information?

It can. There are 28 identified patterns of ANA, including nuclear, cytoplasmic, and mitotic patterns. The most common, the nuclear fine-speckled pattern, is seen in healthy controls and patients with an autoimmune disease. But other patterns are either characteristic of an autoimmune disease or, conversely, of not having an autoimmune disease (Table 2).9

Our patient has a nuclear dense fine-speckled pattern, further reducing the likelihood that she has an autoimmune disease.

CASE 2: POORLY CONTROLLED,

LONG-STANDING FIBROMYALGIA

A 43-year-old woman who has had fibromyalgia for 15 years is referred to a new primary care provider. She reports severe pain all over, low back pain, fatigue, nonrefreshing sleep, chronic migraine, constipation alternating with diarrhea, heartburn, intermittent numbness and tingling in her hands and feet, and depression. At this time, she rates her pain on a visual analog scale as 9 out of 10, and her fatigue as 8 out of 10.

During the past 6 months, she has made 25 visits to specialists in 8 departments: spine, pain management, anesthesia, neurology, headache clinic, gastroenterology, sleep medicine, and physical therapy.

Her daily medications are duloxetine 120 mg, bupropion 300 mg, pregabalin 450 mg, cyclobenzaprine 30 mg, tramadol 200 mg, zolpidem 10 mg, nortriptyline 50 mg, acetaminophen 3,000 mg, and oxycodone 30 mg. She has also tried gabapentin and milnacipran without success. She reported previously taking different selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants but cannot remember why they were stopped.

How should this complex patient be managed?

BIOPSYCHOSOCIAL MANAGEMENT

Managing the pain of fibromyalgia requires a different model than used for peripheral pain from injury, in which the source of pain can be identified and treated with injections or oral therapy.

Neuronal dysregulation is not amenable to clinical measurement or treatment by medications at this time. But fortunately, many factors associated with fibromyalgia can be addressed: stressful life events, sleep disturbance, physical deconditioning, mood disorders, and maladaptive pain responses, including “catastrophizing” behavior (coping with pain in a highly dramatic and obsessive way). Modifying these factors can be much more productive than focusing on treating pain.

The goal for care providers is to change the focus from reducing pain to a biopsychosocial model of pain control aimed at increasing function.10

Mood modification

Not only are mood disorders common in patients with fibromyalgia, but the prevalence of complex psychiatric conditions is also elevated. Up to 80% of patients with fibromyalgia meet criteria for axis I (clinical psychological) disorders, and up to about 30% of patients meet criteria for axis II (personality) disorders. About 22% of patients have existing major depression, and about 58% develop it during their lifetime. In a study of 678 patients with fibromyalgia, 21% had bipolar disorder.11–15

The severity of fibromyalgia increases linearly with the severity of depression.16 Patients with fibromyalgia and a “depressive affect balance style” have worse outcomes across all Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) core symptom domains, reporting more pain, fatigue, insomnia, anxiety, depression, and function.17,18

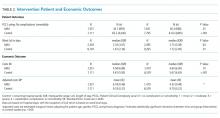

Fibromyalgia combined with mood disorders can also be costly. In one study, the mean annual employer payments (direct and indirect costs) per patient were $5,200 for patients with fibromyalgia only, $8,100 for patients with depression only, and $11,900 for patients with both.19

Obtaining a psychiatric history is important when evaluating a patient with fibromyalgia symptoms. Patients should be asked if they have a history of depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, or other conditions. The Patient Health Questionnaire – Depression 9 and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7) (both available at www.mdcalc.com) can be useful for evaluating mood disorders.

Patients with moderate depression and fibromyalgia who have not yet been treated should be prescribed duloxetine for its potential benefits for both conditions.

Patients who have already been treated with multiple drugs at high doses without benefit, such as our patient, should be referred to a psychiatrist. There is no additional benefit to referring this patient to a rheumatologist or spine clinic.

Addressing sleep problems

Sleep problems are not easy to manage but can often be helped. Epidemiologic studies indicate that poor sleep quality leads to chronic widespread pain in otherwise healthy people.20–22 In addition, experimental sleep deprivation leads to fatigue, cognitive difficulty, and a reduced pain threshold.23 In our patients with fibromyalgia, we have observed an inverse relationship between the number of hours slept and the severity of depression.

Sleep quantity and quality can be assessed by asking patients whether they have trouble sleeping, how many hours they sleep, and whether they have been diagnosed with a sleep disorder.

Because many patients with fibromyalgia are overweight or obese, they should also be evaluated for sleep apnea, narcolepsy, and restless leg syndrome.24,25

Medications shown to improve sleep include pregabalin or gabapentin (taken at bedtime), low-dose amitriptyline, trazodone, cyclobenzaprine, melatonin, and nabilone.26–29

Patients should be counseled about sleep hygiene.30 Exercise can also help sleep.

Targeting maladaptive pain responses

Patients who catastrophize tend to have higher tender point counts, a hyperalgesic response, more depression and anxiety, and more self-reported disability. They are also less likely to return to work.31 They usually respond poorly to medications and are good candidates for cognitive behavioral therapy.

A high score on a self-reported Pain Catastrophizing Scale32 can help determine whether a multidisciplinary approach is advisable, although no threshold defines an abnormal score.

Educating patients about the neurobiology underlying their pain can be therapeutic.33–37 Cognitive behavioral therapy can help patients recognize their faulty thought processes and the relationship between pain and stress, and learn better coping mechanisms.38,39 Patients who achieve the highest improvements in pain catastrophizing tend to derive the greatest benefit from cognitive behavioral therapy.40

Exercise improves symptoms

Exercise improves fibromyalgia on many fronts and is associated with a host of positive effects in the brain and peripheral muscles. Exercise improves Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire scores, increases physical function and fitness, and reduces tender point counts, depression, and catastrophizing.41–52 There is no consensus on the best type of exercise, but both strengthening and aerobic exercises appear to be important.

I tell patients that fibromyalgia is an exercise-deprivation syndrome. Many are afraid to exercise because they associate it with pain and exhaustion afterwards. Patients should be encouraged to start with something very low-impact, such as gentle exercise in a warm-water pool. It should be emphasized that exercise is a lifelong treatment.

Drug therapy

The US Food and Drug Administration has approved 3 drugs for fibromyalgia management: 2 serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (duloxetine and milnacipran) and 1 gabapentinoid (pregabalin). Our patient in Case 2 is taking 2 of them without apparent benefit and has previously had no success with the third. This is not surprising. A summary of published treatment research on these drugs found that only 50% to 60% of patients tested reported more than 30% pain reduction.53 The studies also showed a placebo response of 30% to 40%. Depending on the study, the number needed to treat to see a benefit from these drugs is 8 to 14.53

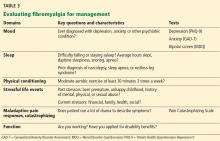

EVALUATING THE SEVERITY OF FIBROMYALGIA

Focusing on key characteristics of the patient’s history can help evaluate fibromyalgia and determine a treatment strategy (Table 3). The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire is also a useful evaluation tool.

It is important to assess the severity of fibromyalgia because patients with severe fibromyalgia are not good candidates for further referral to other specialists. They instead need chronic rehabilitation services, where they can learn to better function with a chronic pain syndrome.

In general, patients with the following features have conditions with high severity:

Symptoms: High burden and intensity

Function: Disabled, unemployed, interference with activities of daily living

Mood: Severe depression, bipolar disorder, axis II disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder

Medications: Polypharmacy, opioid drugs, multiple failed interventions

Maladaptive attitudes: High catastrophizing, refusal to accept diagnosis

Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire score: 60 or above.

The fibromyalgia of our patient in Case 2 would be categorized as severe.

MULTIFACETED MANAGEMENT

Patients with fibromyalgia are a heterogeneous group, and the syndrome does not lend itself to a single management strategy.54 Multiple guidelines have been published for managing fibromyalgia.55–57 Thieme et al58 reviewed existing guidelines and the strength of their recommendations. The guidelines unanimously strongly favor exercise, and most also strongly favor cognitive behavioral therapy. Most favor treating with amitriptyline and duloxetine; recommendations for other antidepressants vary. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opioid drugs, and benzodiazepines are not recommended.

We offer a monthly 1-day clinic for patients and family members to provide education about fibromyalgia, discuss the importance of exercise, counsel on maladaptive responses, and demonstrate mindfulness techniques. We focus on function rather than pain. Interactive online-based interventions using cognitive behavioral techniques, such as FibroGuide: A Symptom Management Program for People Living With Fibromyalgia, developed at the University of Michigan, have proven helpful.59

RECOMMENDATIONS

For most patients, do not focus on pain reduction, as that is ineffective. Instead, target reversible factors, eg, mood, sleep, exercise status, stressors, and maladaptive attitudes toward pain. Possible treatment combinations include:

- A serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (eg, duloxetine)

- A low-dose tricyclic antidepressant at bedtime (eg, amitriptyline)

- A gabapentinoid (pregabalin or gabapentin).

If a medication within a class does not work, stop it and try another rather than add on.

Treat mild to moderate fibromyalgia with multidisciplinary interventions, with or without centrally acting medications. Treat severe fibromyalgia with more intensive psychiatric or psychologic interventions, multidisciplinary care, and medications targeted at comorbidities. Provide all patients with education and advice on exercise.

Keep laboratory tests and imaging studies to a minimum: a complete blood cell count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, thyroid-stimulating hormone, C-reactive protein, and Westergren sedimentation rate. Do not test for ANA unless the patient has objective features suggesting SLE.

- Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarcón GS, et al. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64(8):2677–2686. doi:10.1002/art.34473

- Stanos S, Brodsky M, Argoff C, et al. Rethinking chronic pain in primary care setting. Postgraduate Med 2016; 128(5):502–513. doi:10.1080/00325481.2016.1188319

- Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles M, et al. Fibromyalgia criteria and severity scales for clinical and epidemiological studies: a modification of the ACR Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol 2011; 38(6):1113–1122. doi:10.3899/jrheum.100594

- Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, et al. 2016 Revisions to the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2016; 46(3):319–329. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.08.012

- Abeles AM, Abeles M. The clinical utility of a positive antinuclear antibody test result. Am J Med 2013; 126(4):342–348. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.09.014

- Li QZ, Karp DR, Quan J, et al. Risk factors for ANA positivity in healthy persons. Arthritis Res Ther 2011; 13(2):R38. doi:10.1186/ar3271

- Slight-Webb S, Lu R, Ritterhouse LL, et al. Autoantibody-positive healthy individuals display unique immune profiles that may regulate autoimmunity. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016; 68(1):2492–2502. doi:10.1002/art.39706

- Arbuckle MR, McClain MT, Rubertone MV, et al. Development of autoantibodies before the clinical onset of systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 2003; 349(16):1526–1533. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021933

- Mariz HA, Sato EI, Barbosa SH, Rodrigues SH, Dellavance A, Andrade LE. Pattern of antinuclear antibody-HEp 2 test is a critical parameter for discriminating antinuclear antibody-positive healthy individuals and patients with autoimmune diseases. Arthritis Rheum 2011; 63(1):191–200. doi:10.1002/art.30084

- Häuser W, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA. Treat to target in fibromyalgia: opening the dialogue. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017; 69(4):462–466. doi:10.1002/acr.22970

- Forseth KO, Husby G, Gran JT, Fórre O. Prognostic factors for the development of fibromyalgia in women with self-reported musculoskeletal pain. A prospective study. J Rheumatol 1999; 26(11):2458–2567. pmid:10555910

- Thieme K, Turk DC, Flor H. Comorbid depression and anxiety in fibromyalgia syndrome: relationship to somatic and psychosocial variables. Psychosom Med 2004; 66(6):837–844. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000146329.63158.40

- Fuller-Thomson E, Mimigon-Young J, Brennenstuhl S. Individuals with fibromyalgia and depression: findings from a nationally representative Canadian survey. Rheumatol Int 2012; 32(4):853–862. doi:10.1007/s00296-010-1713-x

- Kudlow PA, Rosenblat JD, Weissman CR, et al. Prevalence of fibromyalgia and co-morbid bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2015; 188:134–142. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.030

- Corruble E, Guelfi JD. Pain complaints in depressed inpatients. Psychopathology 2000; 33(6):307–309. doi:10.1159/000029163

- Gota CE, Kaouk S, Wilke WS. The impact of depressive and bipolar symptoms on socioeconomic status, core symptoms, function and severity of fibromyalgia. Int J Rheum Dis 2017; 20(3):326–339. doi:10.1111/1756-185X.12603

- Toussaint LL, Vincent A, McAlister SJ, Oh TH, Hassett AL. A comparison of fibromyalgia symptoms in patients with healthy versus depressive, low and reactive affect balance styles. Scand J Pain 2014; 5(3):161–166. doi:10.1016/j.sjpain.2014.05.001

- Vincent A, Hoskin TL, Whipple MO, et al. OMERACT-based fibromyalgia symptom subgroups: an exploratory cluster analysis. Arthritis Res Ther 2014; 16(5):463. doi:10.1186/s13075-014-0463-7

- Robinson RL, Birnbaum HG, Morley MA, Sisitsky T, Greenberg PE, Wolfe F. Depression and fibromyalgia: treatment and cost when diagnosed separately or concurrently. J Rheumatol 2004; 31(8):1621–1629. pmid:5290744

- Choy EH. The role of sleep in pain and fibromyalgia. Nature Rev Rheumatol 2015; 11(9):513–520. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2015.56

- Mork PJ, Nilsen TI. Sleep problems and risk of fibromyalgia: longitudinal data of an adult female population in Norway. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64(1):281–284. doi:10.1002/art.33346

- McBeth J, Lacey RJ, Wilkie R. Predictors of new-onset widespread pain in older adults: results from a population-based prospective cohort study in the UK. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014; 66(3):757–767. doi:10.1002/art.38284

- Ablin JN, Clauw DJ, Lyden AK, et al. Effects of sleep restriction and exercise deprivation on somatic symptoms and mood in healthy adults. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2013; 31(6 suppl 79):S53–S59. pmid:24373363

- Russell IJ, Perkins AT, Michalek JE; Oxybate SXB-26 Fibromyalgia Syndrome Study Group. Sodium oxybate relieves pain and improves function in fibromyalgia syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 60(1):299–309. doi:10.1002/art.24142

- Spaeth M, Bennett RM, Benson BA, Wang YG, Lai C, Choy EH. Sodium oxybate therapy provides multidimensional improvement in fibromyalgia: results of an international phase 3 trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2012; 71(6):935–942. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200418

- Roth T, Bhadra-Brown P, Pitman VW, Resnick EM. Pregabalin improves fibromyalgia-related sleep disturbance. Clin J Pain 2016; 32(4):308–312. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000262

- Moldofsky H, Harris HW, Archambault WT, Kwong T, Lederman S. Effects of bedtime very low dose cyclobenzaprine on symptoms and sleep physiology in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled study. J Rheumatol 2011; 38(12):2653–2663. doi:10.3899/jrheum.110194

- Feracioli-Oda E, Qawasmi A, Bloch MH. Meta-analysis: melatonin for the treatment of primary sleep disorders. PLoS One 2013; 8(5):e63773. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0063773

- Ware MA, Fitzcharles MA, Joseph L, Shir Y. The effects of nabilone on sleep in fibromyalgia: results of a randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg 2010; 110(2):604–610. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181c76f70

- Martínez M, Miró E, Sánchez AI, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia and sleep hygiene in fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. J Behav Med 2014; 37(4):683–697. doi:10.1007/s10865-013-9520-y

- Edwards RP, Cahalan C, Mensin G, Smith M, Haythornwaite JA. Pain, catastrophizing, and depression in the rheumatic diseases. Nature Rev Rheumatol 2011; 7(4):216–224. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2011.2

- Sullivan MJL. The pain catastrophizing scale. User manual. McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, 2009. http://sullivan-painresearch.mcgill.ca/pdf/pcs/PCSManual_English.pdf. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- Louw A, Zimney K, O’Hotto C, Hilton S. The clinical application of teaching people about pain. Physiother Theory Pract 2016; 32(5):385–395. doi:10.1080/09593985.2016.1194652

- Burckhardt CS, Mannerkorpi K, Hedenberg L, Bjelle A. A randomized, controlled clinical trial of education and physical training for women with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol 1994; 21(4):714–720. pmid:8035399

- King SJ, Wessel J, Bhambhani Y, Sholter D, Maksymowych W. The effects of exercise and education, individually or combined, in women with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol 2002; 29(12):2620–2627. pmid:12465163

- Rooks DS, Gautam S, Romeling M, et al. Group exercise, education, and combination self-management in women with fibromyalgia: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167(20):2192–2200. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.20.2192

- White KP, Nielson WR, Harth M, Ostbye T, Speechley M. Does the label ”fibromyalgia” alter health care status, function, and health service utilization? A prospective, within-group comparison in a community cohort of adults with chronic widespread pain. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 47(3):260–265. doi:10.1002/art.10400

- Bernardy K, Klose P, Busch AJ, Choy EH, Häuser W. Cognitive behavioural therapies for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 9:CD009796. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009796.pub2

- Lazridou A, Kim J, Cahalan CM, et al. Effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy on brain connectivity supporting catastrophizing in fibromyalgia. Clin J Pain 2017; 33(3):215–221. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000422

- Campbell CM, McCauley L, Bounds SC, et al. Changes in pain catastrophizing predict later changes in fibromyalgia clinical and experimental pain report: cross-lagged panel analyses of dispositional and situational catastrophizing. Arthritis Res Ther 2012; 14(5):R231. doi:10.1186/ar4073

- Vierck CJ. A mechanism-based approach to prevention of and therapy for fibromyalgia. Pain Res Treat 2012; 2012:951354. doi:10.1155/2012/951354

- Gerdle B, Ernberg M, Mannerkorpi K, et al. Increased interstitial concentrations of glutamate and pyruvate in vastus lateralis of women with fibromyalgia syndrome are normalized after exercise intervention—a case-control study. PLoS One 2016; 11(10):e0162010. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0162010

- Jones J, Rutledge DN, Jones KD, Matallana L, Rooks DS. Self-assessed physical function levels of women with fibromyalgia: a national survey. Womens Health Issues 2008; 18(5):406–412. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2008.04.005

- Kelley GA, Kelley KS, Jones DL. Efficacy and effectiveness of exercise on tender points in adults with fibromyalgia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis 2011; 2011:125485. doi:10.1155/2011/125485

- Valim V, Natour J, Ziao Y, et al. Effects of physical exercise on serum levels of serotonin and its metabolite in fibromyalgia: a randomized pilot study. Rev Bras Reumatol 2013; 53(6):538–541. doi:10.1016/j.rbr.2013.02.001

- Bidonde J, Busch AJ, Webber SC, et al. Aquatic exercise training for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 10:CD011336. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011336

- Busch AJ, Webber SC, Richards RS, et al. Resistance exercise training for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 12:CD010884. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010884

- Soriano-Maldonado A, Ruiz JR, Aparicio VA, et al. Association of physical fitness with pain in women with fibromyalgia: the al-Ándalus Project. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015; 67(11):1561–1570. doi:10.1002/acr.22610

- Häuser W, Klose P, Langhorst J, et al. Efficacy of different types of aerobic exercise in fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Res Ther 2010; 12(3):R79. doi:10.1186/ar3002

- Häuser W, Perrot S, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA. Unraveling fibromyalgia—steps towards individualized management. J Pain 2018; 19(2):125–134. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2017.08.009

- Flodin P, Martinsen S, Mannerkorpi K, et al. Normalization of aberrant resting state functional connectivity in fibromyalgia patients following a three month physical exercise therapy. Neuroimage Clin 2015; 9:134–139. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2015.08.004

- Dinoff A, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, et al. The effect of exercise training on resting concentrations of peripheral brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF): a meta-analysis. PLOS One 2016. 11(9):e0163037. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0163037

- Okifuji A, Gao J, Bokat C, Hare BD. Management of fibromyalgia syndrome in 2016. Pain Manag 2016; 6(4):383–400. doi:10.2217/pmt-2016-0006

- Masi AT, Vincent A. A historical and clinical perspective endorsing person-centered management of fibromyalgia syndrome. Curr Rheumatol Rev 2015; 11(2):86–95. pmid:26088217

- Fitzcharles MA, Ste-Marie PA, Goldenberg DL, et al; National Fibromyalgia Guideline Advisory Panel. 2012 Canadian guidelines for the diagnosis and management of fibromyalgia syndrome: executive summary. Pain Res Manag 2013: 18(3):119–126. pmid:23748251

- Ablin J, Fitzcharles MA, Buskila D, Shir Y, Sommer C, Häuser W. Treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome: recommendations of recent evidence-based interdisciplinary guidelines with special emphasis on complementary and alternative therapies. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013; 2013:485272. doi:10.1155/2013/485272

- MacFarlane GJ, Kronisch C, Dean LE, et al. EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76(2)318–328. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209724

- Thieme K, Mathys M, Turk DC. Evidence-based guidelines on the treatment of fibromyalgia patients: are they consistent and if not, why not? Have effective psychological treatments been overlooked? J Pain 2017; 18(7):747–756. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2016.12.006

- Williams DA, Kuper D, Segar M, Mohan N, Sheth M, Clauw DJ. Internet-enhanced management of fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Pain 2010; 151(3):694–702. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.08.034

Fibromyalgia may seem like a nebulous diagnosis, with its array of symptoms and pain refractory to medications. But fibromyalgia is a defined syndrome of neuronal dysregulation. It can be diagnosed from the history and physical examination and managed in a primary care setting.

CASE 1: MANY SYMPTOMS

A 43-year-old woman presents to her primary care physician with multiple complaints: pain in all joints and in her back and hips, swelling of her hands and feet, morning stiffness, chest pain and shortness of breath (not necessarily related to exertion), fatigue, generalized weakness, headaches, difficulty with memory and concentration, dry mouth and dry eyes, feeling weak and faint in the sun, cold intolerance with purple discoloration of her extremities, a self-described “butterfly” rash on the face, and hair that is thinning and falling out in clumps.

Because many of her symptoms could reflect an inflammatory process or an autoimmune disease,1 her primary care physician orders multiple tests. Her C-reactive protein level, Westergren sedimentation rate, complete blood cell count, and comprehensive metabolic panel are normal. Urinalysis shows trace leukocyte esterase. Indirect immunofluorescence assay on human laryngeal tumor (HEp-2) cells is positive for antinuclear antibody (ANA), with a titer of 1:320 (reference range ≤ 1:40) and a nuclear dense fine-speckled pattern.

In view of the positive ANA test, the patient is informed that she may have systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and will be referred to a rheumatologist. In the days before her rheumatology appointment, she becomes extremely anxious. Obsessively researching SLE online, she becomes convinced that SLE is the correct diagnosis.

Rheumatology evaluation

The rheumatologist assesses the patient’s pain and reports the following:

Location and duration: Hands, wrists, elbows, shoulders, upper and lower back, sides of hips, knees, and feet; has been ongoing for 10 years, but worse in the past 3 months.

Character: The patient describes her pain as “like an ice pick being driven through my joints,” “sometimes unbearable,” and “like being hit by a truck.” She also reports numb, tingly, burning pain in her upper neck and back.

Variation with time, activity, and weather: Worse at night, causing her to wake and toss and turn all night; better with exertion, but after activity or exercise, she is exhausted for the rest of the day and sometimes for up to a week; worse with weather changes, especially during cold or humid weather.

Associated symptoms: Occasional perceived swelling of hands and feet, especially upon wakening in the morning, and 2 to 3 hours of stiffness in the morning that sometimes lasts all day.

Physical examination. Her findings are inconsistent with her symptoms.

The patient exhibits limited range of motion. When asked to bend forward, rotate her neck, or flex and extend her neck and back, she does so only slightly. However, passive range of motion is normal in all joints.

When her joints are examined, she anticipates pain and withdraws her hands. But when she is distracted, examination reveals no evidence of swollen joints or synovitis. She has tenderness in 12 of 18 tender points. Her peripheral pulses are good, strength is normal, and reflexes are brisk.

Her facial rash looks more like rosacea than the butterfly rash of SLE. There is no indication of patchy hair loss. Heart and lung examinations are normal. She appears to have a good salivary pool without glossitis.

History reveals long-standing psychological issues

The patient reports a history of panic attacks and a prior diagnosis of anxiety. She is tested with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (www.mdcalc.com/gad-7-general-anxiety-disorder-7) and scores 17 out of 21, indicating severe anxiety.

DISCUSSION: CHARACTERIZING PAIN

Understanding categories of pain syndromes can help us understand fibromyalgia. Pain can be categorized into 3 types that sometimes overlap2:

Nociceptive or peripheral pain is related to damage of tissue by trauma or inflammation. Syndromes include osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and SLE.

Neuropathic pain is associated with damage of peripheral or central nerves. Examples are neuropathy from herpes, diabetes, or spinal stenosis.

Centralized pain has no identifiable nerve or tissue damage and is thought to result from persistent neuronal dysregulation, overactive ascending pain pathways, and a deficiency of descending inhibitory pain pathways. There is evidence of biochemical changes in muscles, possibly related to chronic ischemia and an overactive sympathetic nervous system. Dysregulation of the sympathoadrenal system and hypothalamic-pituitary axis has also been implicated. And genetic predisposition is possible. Examples of centralized pain syndromes include fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, pelvic pain syndrome, neurogenic bladder, and interstitial cystitis.

Clues to a centralized pain syndrome

For patients with suspected fibromyalgia, distinguishing peripheral pain from centralized pain can be a challenge (Table 1). For example, SLE does not cause inflammation of the spine, so neck or back pain is not typical. Although both nociceptive and centralized pain syndromes improve with exertion, only patients with centralized pain are typically exhausted and bedbound for days after activity. Patients with centralized pain tend to describe their pain in much more dramatic language than do patients with inflammatory pain. Centralized pain tends to be intermittent; inflammatory pain tends to be constant. Patients with centralized pain often have had pain for many years without a diagnosis, but this is rare for patients with an inflammatory condition.

A patient with fibromyalgia typically has a normal physical examination, although allodynia (experiencing pain from normally nonpainful stimulation), hyperalgesia (increased pain perception), and brisk reflexes may be present. Fibromyalgia may involve discoloration of the fingertips resulting from an overactive sympathetic nervous system. Laboratory results are typically normal with fibromyalgia.

Patients with either nociceptive or centralized pain report stiffness, but the cause likely differs. We typically think of stiffness as arising from swollen joints caused by inflammation, but stiffness can also be caused by abnormally tight muscles, as occurs in fibromyalgia.

FIBROMYALGIA IS A CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosing fibromyalgia does not require multiple laboratory and imaging tests. The key indicators are derived from the patient history and physical examination.

Diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia published by the American College of Rheumatology have evolved over the years. The 2011 criteria, in the form of a self-reported patient questionnaire, have 2 components3:

- The Widespread Pain Index measures the extent of pain in 19 areas.

- The Symptom Severity scale assesses 3 key symptoms associated with fibromyalgia, ie, fatigue, cognitive problems, and nonrestorative sleep (scale of 0–3 for each symptom).

There are also questions about symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome, depression, and headache.

Fibromyalgia is diagnosed if a patient reports at least 7 painful areas and has a symptom severity score of at least 5. A patient may also meet the 20113 and the 2016 criteria4 if he or she has 4 painful areas and the pain is perceived in 4 of 5 areas and the Symptom Severity Scale score is 9 or higher.4 This questionnaire is not only a rapid diagnostic tool for fibromyalgia, it also helps identify and focus on specific issues—for example, having severe pain in a few localized areas, or having headache as a predominant problem.

These criteria are useful for a variety of patients, eg, a patient with hip arthritis may score high on the questionnaire, indicating that a component of centralized pain is also present. Also, people who have undergone orthopedic surgery who score high tend to require more narcotics to meet the goals of pain improvement.

The 2016 criteria,4 the most recent, maintain that pain must be generalized, ie, present in at least 4 of 5 body areas. They also emphasize that fibromyalgia is a valid diagnosis irrespective of other conditions.

CASE 1 CONTINUED: THE PATIENT REJECTS THE DIAGNOSIS

Our patient meets the definition of fibromyalgia by each iteration of the American College of Rheumatology clinical criteria. She also has generalized anxiety disorder and a positive ANA test. She is advised to participate in a fibromyalgia educational program, start an aerobic exercise program, and consider taking an antidepressant medication with anxiolytic effects.

However, the patient rejects the diagnosis of fibromyalgia. She believes that the diagnosis of SLE has been overlooked and that her symptom severity is being discounted.

In response, the rheumatologist orders additional tests to evaluate for an autoimmune disorder: extractable nuclear antigen panel, complement C3 and C4, double-stranded DNA antibodies, and protein electrophoresis. Results are all in the normal range. The patient is still concerned that she has SLE or another autoimmune disease because of her abnormal ANA test result and remains dissatisfied with her evaluation. She states that she will complain to the clinic ombudsman.

SIGNIFICANCE OF ANA TESTING

Patients with positive test results increasingly go online to get information. The significance of ANA testing can be confusing, and it is critical to understand and be able to explain abnormal results to worried patients. Following are answers to some common questions about ANA testing:

Is ANA positivity specific for SLE or another autoimmune disease?

No. ANA is usually tested by indirect immunofluorescence assay on HEp-2 cells. The test can identify about 150 antigens targeted by antibodies, but only a small percentage are associated with an autoimmune disease, and the others do not have a known clinical association. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) ANA testing is also available but is considered less sensitive.

Abeles and Abeles5 retrospectively assessed 232 patients between 2007 and 2009 who were referred to rheumatologists for evaluation because of an elevated ANA test result. No ANA-associated rheumatic disease was found in patients who had a result of less than 1:160, and more than 90% of referrals for a positive ANA test had no evidence of ANA-associated disease. The positive predictive value was 9% for any connective tissue disease, and only 2% for SLE. The most common reason for ordering the test was widespread pain (23%). The authors concluded that ANA testing is often ordered inappropriately for patients with a low pretest probability of an ANA-associated rheumatic disease.

Screening with ANA testing generates many false-positive results and unnecessary anxiety for patients. The prevalence of SLE in the general population is about 0.1%, and other autoimmune diseases total about 5% to 7%. By indirect immunofluorescence assay, using a cutoff of 1:80 (the standard at Cleveland Clinic), about 15% of the general population test positive. By ELISA, with a cutoff of 20 ELISA units, 25% of healthy controls test positive.

It is true that ANA positivity may precede the onset of SLE.6,7 Arbuckle et al8 evaluated serum samples from the US Department of Defense Serum Repository obtained from 130 people before they received a diagnosis of SLE; in 115 (88%), at least 1 SLE-related autoantibody was present before diagnosis (up to 9.4 years earlier). However, in those who test positive for ANA, the percentage who eventually develop autoimmune disease is small.5

Is the titer of ANA significant and of diagnostic value?

The likelihood of autoimmune disease increases with increasing titer. But high titers can be seen in healthy people. Mariz et al9 examined ANA test results from 918 healthy controls and 153 patients with an autoimmune rheumatic disease. Of these, ANA was positive in 13% of healthy people and 90% of patients with an autoimmune disease. High titers were more likely in patients with an autoimmune disease, but also occurred in healthy controls.

Does the immunofluorescence pattern provide diagnostic information?

It can. There are 28 identified patterns of ANA, including nuclear, cytoplasmic, and mitotic patterns. The most common, the nuclear fine-speckled pattern, is seen in healthy controls and patients with an autoimmune disease. But other patterns are either characteristic of an autoimmune disease or, conversely, of not having an autoimmune disease (Table 2).9

Our patient has a nuclear dense fine-speckled pattern, further reducing the likelihood that she has an autoimmune disease.

CASE 2: POORLY CONTROLLED,

LONG-STANDING FIBROMYALGIA

A 43-year-old woman who has had fibromyalgia for 15 years is referred to a new primary care provider. She reports severe pain all over, low back pain, fatigue, nonrefreshing sleep, chronic migraine, constipation alternating with diarrhea, heartburn, intermittent numbness and tingling in her hands and feet, and depression. At this time, she rates her pain on a visual analog scale as 9 out of 10, and her fatigue as 8 out of 10.