User login

A new protocol for RhD-negative pregnant women?

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 30-year-old G1P0 woman presents to your office for routine obstetric care at 18 weeks’ gestation. Her pregnancy has been uncomplicated, but her prenatal lab evaluation is notable for blood type A-negative. She wants to know if she really needs the anti-D immune globulin injection.

Rhesus (Rh)D-negative women carrying an RhD-positive fetus are at risk of developing anti-D antibodies, placing the fetus at risk for HDFN (hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn). If undiagnosed and/or untreated, HDFN carries significant risk of perinatal morbidity and mortality.2

With routine postnatal anti-D immunoglobulin prophylaxis of RhD-negative women who delivered an RhD-positive child (which began around 1970), the risk of maternal alloimmunization was reduced from 16% to 1.12%-1.3%.3-5 The risk was further reduced to approximately 0.28% with the addition of consistent prophylaxis at 28 weeks’ gestation.4 As a result, the current standard of care is to administer anti-D immunoglobulin at 28 weeks’ gestation, within 72 hours of delivery of an RhD-positive fetus, and after events with risk of fetal-to-maternal transfusion (eg, spontaneous, threatened, or induced abortion; invasive prenatal diagnostic procedures such as amniocentesis; blunt abdominal trauma; external cephalic version; second or third trimester antepartum bleeding).6

The problem of unnecessary Tx. However, under this current practice, many RhD-negative women are receiving anti-D immunoglobulin unnecessarily. This is because the fetus’s RhD status is not routinely known during the prenatal period.

Enter cell-free DNA testing. Cell-free DNA testing analyzes fragments of fetal DNA found in maternal blood. The use of cell-free DNA testing at 10 to 13 weeks’ gestation to screen for fetal chromosomal abnormalities is reliable (91%-99% sensitivity for trisomies 21, 18, and 137) and becoming increasingly more common.

A notable meta-analysis. A 2017 meta-analysis of 30 studies of cell-free DNA testing of RhD status in the first and second trimester calculated a sensitivity of 99.3% (95% confidence interval [CI], 98.2-99.7) and a specificity of 98.4% (95% CI, 96.4-99.3).7

This study evaluated the accuracy of using cell-free DNA testing at 27 weeks’ gestation to determine fetal RhD status compared with serologic typing of cord blood at delivery.

STUDY SUMMARY

Cell-free DNA test gets high marks in Netherlands trial

This large observational cohort trial from the Netherlands examined the accuracy of identifying RhD-positive fetuses using cell-free DNA isolates in maternal plasma. Over the 15-month study period, fetal RhD testing was conducted during Week 27 of gestation, and results were compared with those obtained using neonatal cord blood at birth. If the fetal RhD test was positive, providers administered 200 mcg anti-D immunoglobulin during the 30th week of gestation and within 48 hours of birth. If fetal RhD was negative, providers were told immunoglobulin was unnecessary.

More than 32,000 RhD-negative women were screened. The cell-free DNA test showed fetal RhD-positive results 62% of the time and RhD-negative results in the remainder. Cord blood samples were available for 25,789 pregnancies (80%).

Sensitivity, specificity. The sensitivity for identifying fetal RhD was 99% and the specificity was 98%. Both negative and positive predictive values were 99%. Overall, there were 225 false-positive results and 9 false-negative results. In the 9 false negatives, 6 were due to a lack of fetal DNA in the sample and 3 were due to technical error (defined as an operator ignoring a failure of the robot pipetting the plasma or other technical failures).

The false-negative rate (0.03%) was lower than the predetermined estimated false-negative rate of cord blood serology (0.25%). In 22 of the supposed false positives, follow-up serology or molecular testing found an RhD gene was actually present, meaning the results of the neonatal cord blood serology in these cases were falsely negative. If you recalculate with these data in mind, the false-negative rate for fetal DNA testing was actually less than half that of typical serologic determination.

WHAT’S NEW

An accurate test with the potential to reduce unnecessary Tx

Fetal RhD testing at 27 weeks’ gestation appears to be highly accurate and could reduce the unnecessary use of anti-D immunoglobulin when the fetal RhD is negative.

CAVEATS

Different results with different ethnicities?

Dutch participants are not necessarily reflective of the US population. Known variation in the rate of fetal RhD positivity among RhD-negative pregnant women by race and ethnicity could mean that the number of women able to forego anti-D-immunoglobulin prophylaxis would be different in the United States from that in other countries.

Also, in this study, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for 2 RhD sequences was run in triplicate, and a computer-based algorithm was used to automatically score samples to provide results. For safe implementation, the cell-free fetal RhD DNA testing process would need to follow similar methods.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Test cost and availability are big unknowns

Cost and availability of the test may be barriers, but there is currently too little information on either subject in the United States to make a determination. A 2013 study indicated that the use of cell-free DNA testing to determine fetal RhD status was then approximately $682.10

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. de Haas M, Thurik FF, van der Ploeg CP, et al. Sensitivity of fetal RHD screening for safe guidance of targeted anti-D immunoglobulin prophylaxis: prospective cohort study of a nationwide programme in the Netherlands. BMJ. 2016;355:i5789.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 75: Management of alloimmunization during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:457-464.

3. Urbaniak S, Greiss MA. RhD haemolytic disease of the fetus and the newborn. Blood Rev. 2000;14:44-61.

4. Mayne S, Parker JH, Harden TA, et al. Rate of RhD sensitisation before and after implementation of a community based antenatal prophylaxis programme. BMJ. 1997;315:1588-1588.

5. MacKenzie IZ, Bowell P, Gregory H, et al. Routine antenatal Rhesus D immunoglobulin prophylaxis: the results of a prospective 10 year study. Br J Obstet Gynecol: 1999;106:492-497.

6. Zolotor AJ, Carlough MC. Update on prenatal care. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:199-208.

7. Mackie FL, Hemming K, Allen S, et al. The accuracy of cell-free fetal DNA-based non-invasive prenatal testing in singleton pregnancies: a systematic review and bivariate meta-analysis. BJOG. 2017;124:32-46.

8. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 181: Prevention of Rh D Alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e57-e70.

9. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. High-throughput non-invasive prenatal testing for fetal RHD genotype 1: Recommendations. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/dg25/chapter/1-Recommendations. Accessed August 9, 2017.

10. Hawk AF, Chang EY, Shields SM, et al. Costs and clinical outcomes of noninvasive fetal RhD typing for targeted prophylaxis. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:579-585.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 30-year-old G1P0 woman presents to your office for routine obstetric care at 18 weeks’ gestation. Her pregnancy has been uncomplicated, but her prenatal lab evaluation is notable for blood type A-negative. She wants to know if she really needs the anti-D immune globulin injection.

Rhesus (Rh)D-negative women carrying an RhD-positive fetus are at risk of developing anti-D antibodies, placing the fetus at risk for HDFN (hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn). If undiagnosed and/or untreated, HDFN carries significant risk of perinatal morbidity and mortality.2

With routine postnatal anti-D immunoglobulin prophylaxis of RhD-negative women who delivered an RhD-positive child (which began around 1970), the risk of maternal alloimmunization was reduced from 16% to 1.12%-1.3%.3-5 The risk was further reduced to approximately 0.28% with the addition of consistent prophylaxis at 28 weeks’ gestation.4 As a result, the current standard of care is to administer anti-D immunoglobulin at 28 weeks’ gestation, within 72 hours of delivery of an RhD-positive fetus, and after events with risk of fetal-to-maternal transfusion (eg, spontaneous, threatened, or induced abortion; invasive prenatal diagnostic procedures such as amniocentesis; blunt abdominal trauma; external cephalic version; second or third trimester antepartum bleeding).6

The problem of unnecessary Tx. However, under this current practice, many RhD-negative women are receiving anti-D immunoglobulin unnecessarily. This is because the fetus’s RhD status is not routinely known during the prenatal period.

Enter cell-free DNA testing. Cell-free DNA testing analyzes fragments of fetal DNA found in maternal blood. The use of cell-free DNA testing at 10 to 13 weeks’ gestation to screen for fetal chromosomal abnormalities is reliable (91%-99% sensitivity for trisomies 21, 18, and 137) and becoming increasingly more common.

A notable meta-analysis. A 2017 meta-analysis of 30 studies of cell-free DNA testing of RhD status in the first and second trimester calculated a sensitivity of 99.3% (95% confidence interval [CI], 98.2-99.7) and a specificity of 98.4% (95% CI, 96.4-99.3).7

This study evaluated the accuracy of using cell-free DNA testing at 27 weeks’ gestation to determine fetal RhD status compared with serologic typing of cord blood at delivery.

STUDY SUMMARY

Cell-free DNA test gets high marks in Netherlands trial

This large observational cohort trial from the Netherlands examined the accuracy of identifying RhD-positive fetuses using cell-free DNA isolates in maternal plasma. Over the 15-month study period, fetal RhD testing was conducted during Week 27 of gestation, and results were compared with those obtained using neonatal cord blood at birth. If the fetal RhD test was positive, providers administered 200 mcg anti-D immunoglobulin during the 30th week of gestation and within 48 hours of birth. If fetal RhD was negative, providers were told immunoglobulin was unnecessary.

More than 32,000 RhD-negative women were screened. The cell-free DNA test showed fetal RhD-positive results 62% of the time and RhD-negative results in the remainder. Cord blood samples were available for 25,789 pregnancies (80%).

Sensitivity, specificity. The sensitivity for identifying fetal RhD was 99% and the specificity was 98%. Both negative and positive predictive values were 99%. Overall, there were 225 false-positive results and 9 false-negative results. In the 9 false negatives, 6 were due to a lack of fetal DNA in the sample and 3 were due to technical error (defined as an operator ignoring a failure of the robot pipetting the plasma or other technical failures).

The false-negative rate (0.03%) was lower than the predetermined estimated false-negative rate of cord blood serology (0.25%). In 22 of the supposed false positives, follow-up serology or molecular testing found an RhD gene was actually present, meaning the results of the neonatal cord blood serology in these cases were falsely negative. If you recalculate with these data in mind, the false-negative rate for fetal DNA testing was actually less than half that of typical serologic determination.

WHAT’S NEW

An accurate test with the potential to reduce unnecessary Tx

Fetal RhD testing at 27 weeks’ gestation appears to be highly accurate and could reduce the unnecessary use of anti-D immunoglobulin when the fetal RhD is negative.

CAVEATS

Different results with different ethnicities?

Dutch participants are not necessarily reflective of the US population. Known variation in the rate of fetal RhD positivity among RhD-negative pregnant women by race and ethnicity could mean that the number of women able to forego anti-D-immunoglobulin prophylaxis would be different in the United States from that in other countries.

Also, in this study, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for 2 RhD sequences was run in triplicate, and a computer-based algorithm was used to automatically score samples to provide results. For safe implementation, the cell-free fetal RhD DNA testing process would need to follow similar methods.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Test cost and availability are big unknowns

Cost and availability of the test may be barriers, but there is currently too little information on either subject in the United States to make a determination. A 2013 study indicated that the use of cell-free DNA testing to determine fetal RhD status was then approximately $682.10

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 30-year-old G1P0 woman presents to your office for routine obstetric care at 18 weeks’ gestation. Her pregnancy has been uncomplicated, but her prenatal lab evaluation is notable for blood type A-negative. She wants to know if she really needs the anti-D immune globulin injection.

Rhesus (Rh)D-negative women carrying an RhD-positive fetus are at risk of developing anti-D antibodies, placing the fetus at risk for HDFN (hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn). If undiagnosed and/or untreated, HDFN carries significant risk of perinatal morbidity and mortality.2

With routine postnatal anti-D immunoglobulin prophylaxis of RhD-negative women who delivered an RhD-positive child (which began around 1970), the risk of maternal alloimmunization was reduced from 16% to 1.12%-1.3%.3-5 The risk was further reduced to approximately 0.28% with the addition of consistent prophylaxis at 28 weeks’ gestation.4 As a result, the current standard of care is to administer anti-D immunoglobulin at 28 weeks’ gestation, within 72 hours of delivery of an RhD-positive fetus, and after events with risk of fetal-to-maternal transfusion (eg, spontaneous, threatened, or induced abortion; invasive prenatal diagnostic procedures such as amniocentesis; blunt abdominal trauma; external cephalic version; second or third trimester antepartum bleeding).6

The problem of unnecessary Tx. However, under this current practice, many RhD-negative women are receiving anti-D immunoglobulin unnecessarily. This is because the fetus’s RhD status is not routinely known during the prenatal period.

Enter cell-free DNA testing. Cell-free DNA testing analyzes fragments of fetal DNA found in maternal blood. The use of cell-free DNA testing at 10 to 13 weeks’ gestation to screen for fetal chromosomal abnormalities is reliable (91%-99% sensitivity for trisomies 21, 18, and 137) and becoming increasingly more common.

A notable meta-analysis. A 2017 meta-analysis of 30 studies of cell-free DNA testing of RhD status in the first and second trimester calculated a sensitivity of 99.3% (95% confidence interval [CI], 98.2-99.7) and a specificity of 98.4% (95% CI, 96.4-99.3).7

This study evaluated the accuracy of using cell-free DNA testing at 27 weeks’ gestation to determine fetal RhD status compared with serologic typing of cord blood at delivery.

STUDY SUMMARY

Cell-free DNA test gets high marks in Netherlands trial

This large observational cohort trial from the Netherlands examined the accuracy of identifying RhD-positive fetuses using cell-free DNA isolates in maternal plasma. Over the 15-month study period, fetal RhD testing was conducted during Week 27 of gestation, and results were compared with those obtained using neonatal cord blood at birth. If the fetal RhD test was positive, providers administered 200 mcg anti-D immunoglobulin during the 30th week of gestation and within 48 hours of birth. If fetal RhD was negative, providers were told immunoglobulin was unnecessary.

More than 32,000 RhD-negative women were screened. The cell-free DNA test showed fetal RhD-positive results 62% of the time and RhD-negative results in the remainder. Cord blood samples were available for 25,789 pregnancies (80%).

Sensitivity, specificity. The sensitivity for identifying fetal RhD was 99% and the specificity was 98%. Both negative and positive predictive values were 99%. Overall, there were 225 false-positive results and 9 false-negative results. In the 9 false negatives, 6 were due to a lack of fetal DNA in the sample and 3 were due to technical error (defined as an operator ignoring a failure of the robot pipetting the plasma or other technical failures).

The false-negative rate (0.03%) was lower than the predetermined estimated false-negative rate of cord blood serology (0.25%). In 22 of the supposed false positives, follow-up serology or molecular testing found an RhD gene was actually present, meaning the results of the neonatal cord blood serology in these cases were falsely negative. If you recalculate with these data in mind, the false-negative rate for fetal DNA testing was actually less than half that of typical serologic determination.

WHAT’S NEW

An accurate test with the potential to reduce unnecessary Tx

Fetal RhD testing at 27 weeks’ gestation appears to be highly accurate and could reduce the unnecessary use of anti-D immunoglobulin when the fetal RhD is negative.

CAVEATS

Different results with different ethnicities?

Dutch participants are not necessarily reflective of the US population. Known variation in the rate of fetal RhD positivity among RhD-negative pregnant women by race and ethnicity could mean that the number of women able to forego anti-D-immunoglobulin prophylaxis would be different in the United States from that in other countries.

Also, in this study, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for 2 RhD sequences was run in triplicate, and a computer-based algorithm was used to automatically score samples to provide results. For safe implementation, the cell-free fetal RhD DNA testing process would need to follow similar methods.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Test cost and availability are big unknowns

Cost and availability of the test may be barriers, but there is currently too little information on either subject in the United States to make a determination. A 2013 study indicated that the use of cell-free DNA testing to determine fetal RhD status was then approximately $682.10

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. de Haas M, Thurik FF, van der Ploeg CP, et al. Sensitivity of fetal RHD screening for safe guidance of targeted anti-D immunoglobulin prophylaxis: prospective cohort study of a nationwide programme in the Netherlands. BMJ. 2016;355:i5789.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 75: Management of alloimmunization during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:457-464.

3. Urbaniak S, Greiss MA. RhD haemolytic disease of the fetus and the newborn. Blood Rev. 2000;14:44-61.

4. Mayne S, Parker JH, Harden TA, et al. Rate of RhD sensitisation before and after implementation of a community based antenatal prophylaxis programme. BMJ. 1997;315:1588-1588.

5. MacKenzie IZ, Bowell P, Gregory H, et al. Routine antenatal Rhesus D immunoglobulin prophylaxis: the results of a prospective 10 year study. Br J Obstet Gynecol: 1999;106:492-497.

6. Zolotor AJ, Carlough MC. Update on prenatal care. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:199-208.

7. Mackie FL, Hemming K, Allen S, et al. The accuracy of cell-free fetal DNA-based non-invasive prenatal testing in singleton pregnancies: a systematic review and bivariate meta-analysis. BJOG. 2017;124:32-46.

8. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 181: Prevention of Rh D Alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e57-e70.

9. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. High-throughput non-invasive prenatal testing for fetal RHD genotype 1: Recommendations. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/dg25/chapter/1-Recommendations. Accessed August 9, 2017.

10. Hawk AF, Chang EY, Shields SM, et al. Costs and clinical outcomes of noninvasive fetal RhD typing for targeted prophylaxis. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:579-585.

1. de Haas M, Thurik FF, van der Ploeg CP, et al. Sensitivity of fetal RHD screening for safe guidance of targeted anti-D immunoglobulin prophylaxis: prospective cohort study of a nationwide programme in the Netherlands. BMJ. 2016;355:i5789.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 75: Management of alloimmunization during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:457-464.

3. Urbaniak S, Greiss MA. RhD haemolytic disease of the fetus and the newborn. Blood Rev. 2000;14:44-61.

4. Mayne S, Parker JH, Harden TA, et al. Rate of RhD sensitisation before and after implementation of a community based antenatal prophylaxis programme. BMJ. 1997;315:1588-1588.

5. MacKenzie IZ, Bowell P, Gregory H, et al. Routine antenatal Rhesus D immunoglobulin prophylaxis: the results of a prospective 10 year study. Br J Obstet Gynecol: 1999;106:492-497.

6. Zolotor AJ, Carlough MC. Update on prenatal care. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:199-208.

7. Mackie FL, Hemming K, Allen S, et al. The accuracy of cell-free fetal DNA-based non-invasive prenatal testing in singleton pregnancies: a systematic review and bivariate meta-analysis. BJOG. 2017;124:32-46.

8. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 181: Prevention of Rh D Alloimmunization. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e57-e70.

9. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. High-throughput non-invasive prenatal testing for fetal RHD genotype 1: Recommendations. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/dg25/chapter/1-Recommendations. Accessed August 9, 2017.

10. Hawk AF, Chang EY, Shields SM, et al. Costs and clinical outcomes of noninvasive fetal RhD typing for targeted prophylaxis. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:579-585.

Copyright © 2018. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Employ cell-free DNA testing at 27 weeks’ gestation in your RhD-negative obstetric patients to reduce unnecessary use of anti-D immunoglobulin.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a single, prospective, cohort study.

de Haas M, Thurik FF, van der Ploeg CP, et al. Sensitivity of fetal RHD screening for safe guidance of targeted anti-D immunoglobulin prophylaxis: prospective cohort study of a nationwide programme in the Netherlands. BMJ. 2016;355:i5789.

Critical anemia • light-headedness • bilateral leg swelling • Dx?

THE CASE

A 40-year-old man was referred to the emergency department (ED) with critical anemia after routine blood work at an outside clinic showed a hemoglobin level of 3.5 g/dL. On presentation, he reported symptoms of fatigue, shortness of breath, bilateral leg swelling, dizziness (characterized as light-headedness), and frequent heartburn. He said that the symptoms began 5 weeks earlier, after he was exposed to a relative with hand, foot, and mouth disease.

Additionally, the patient reported an intentional 14-lb weight loss over the 6 months prior to presentation. He denied fever, rash, chest pain, loss of consciousness, headache, abdominal pain, hematemesis, melena, and hematochezia. His medical history was significant for peptic ulcer disease (diagnosed and treated at age 8). He did not recall the specifics, and he denied any related chronic symptoms or complications. His family history (paternal) was significant for colon cancer.

The physical exam revealed conjunctival pallor, skin pallor, jaundice, +1 bilateral lower extremity edema, tachycardia, and tachypnea. Stool Hemoccult was negative. On repeat complete blood count (performed in the ED), hemoglobin was found to be 3.1 g/dL with a mean corpuscular volume of 47 fL.

THE DIAGNOSIS

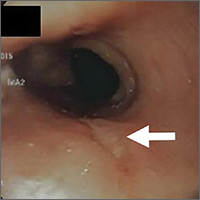

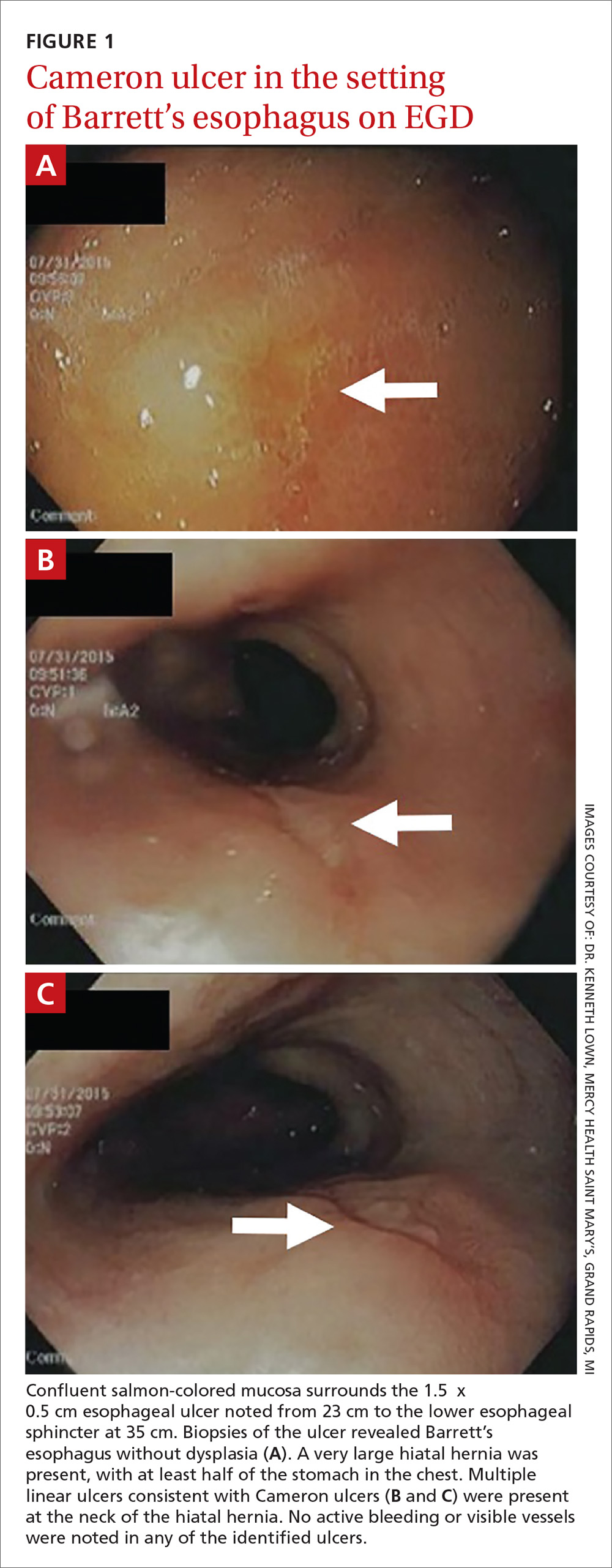

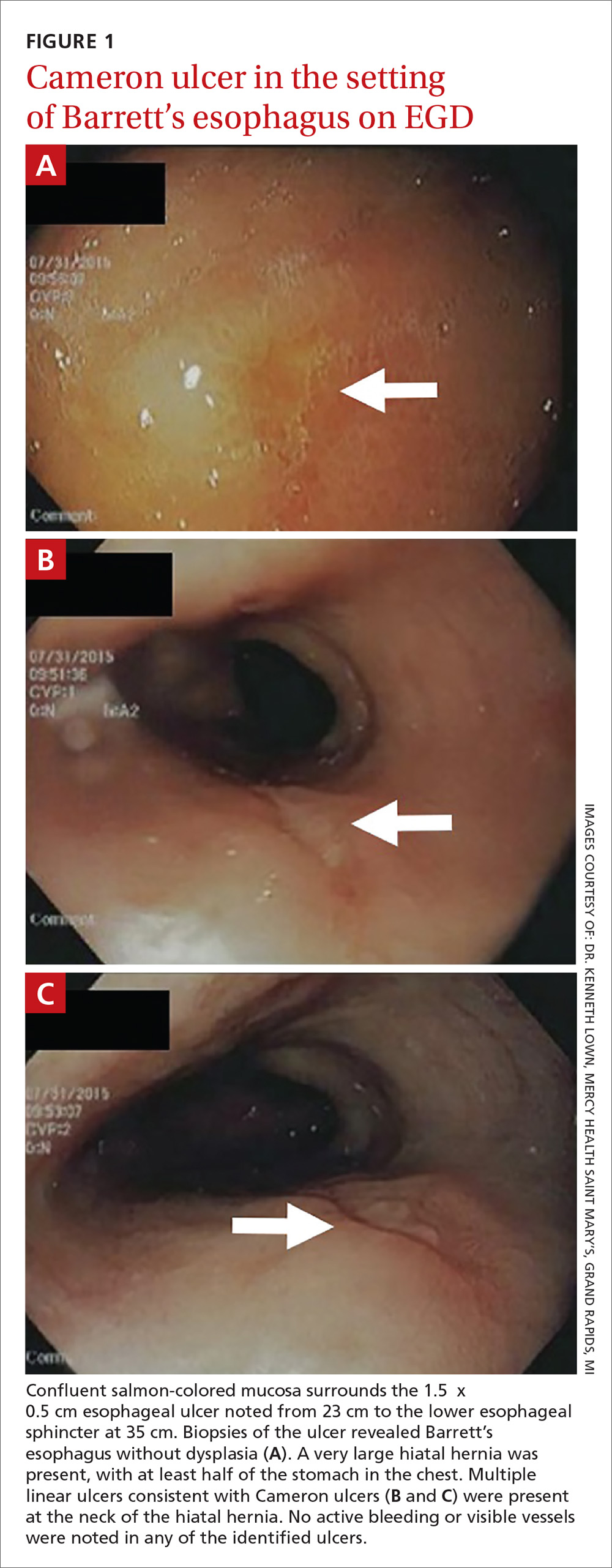

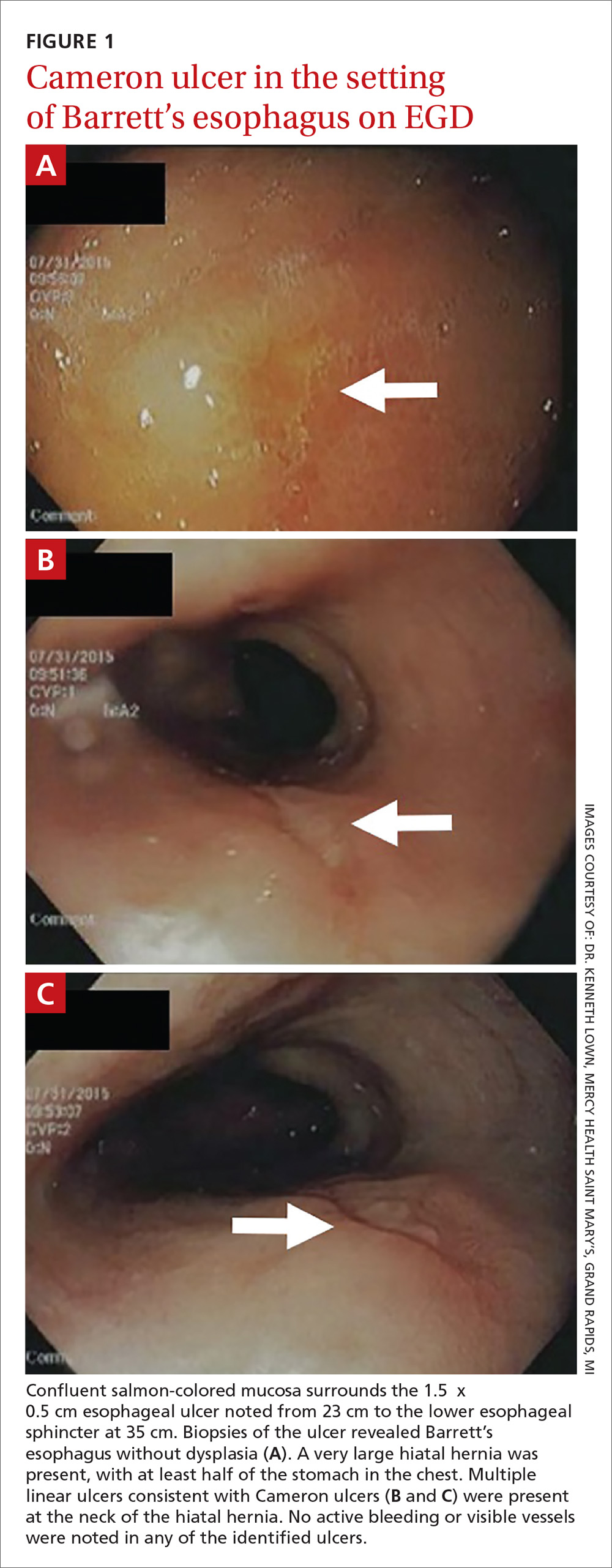

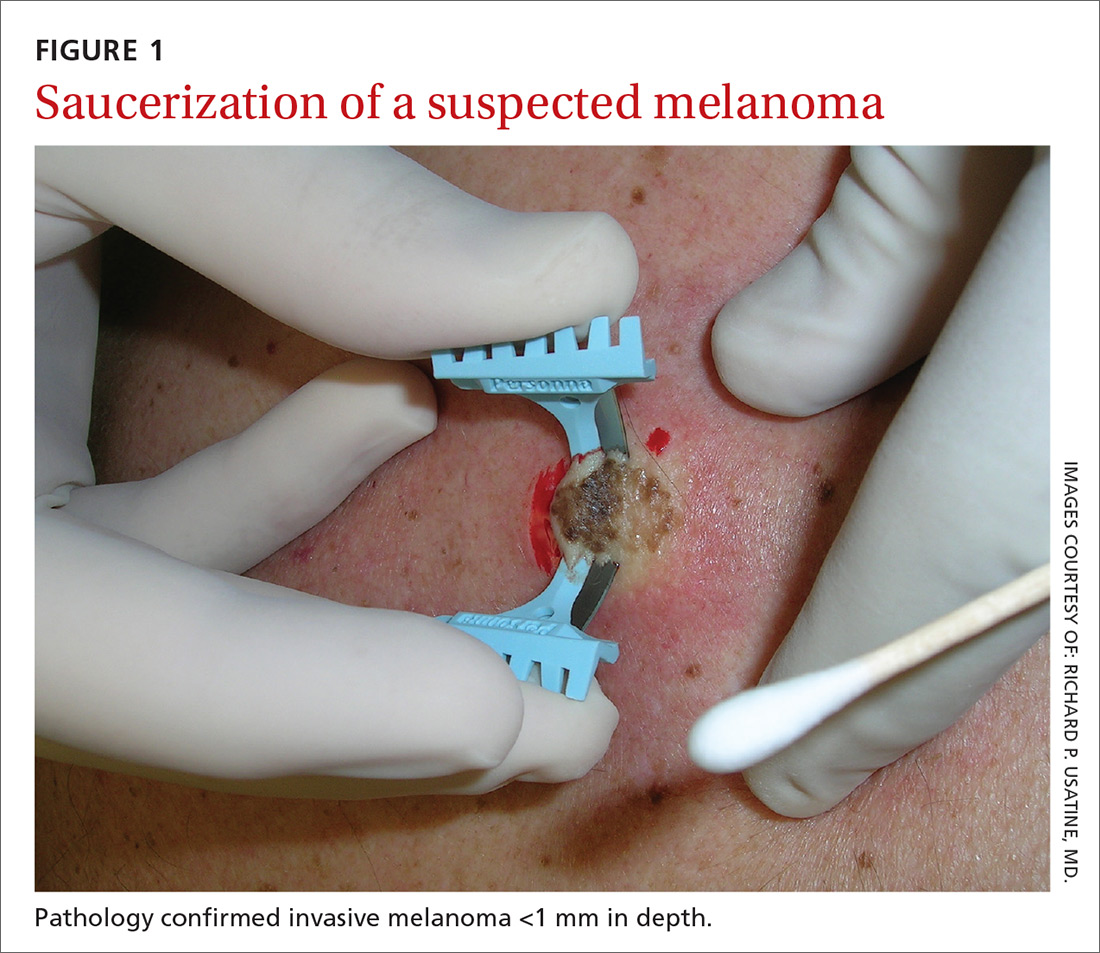

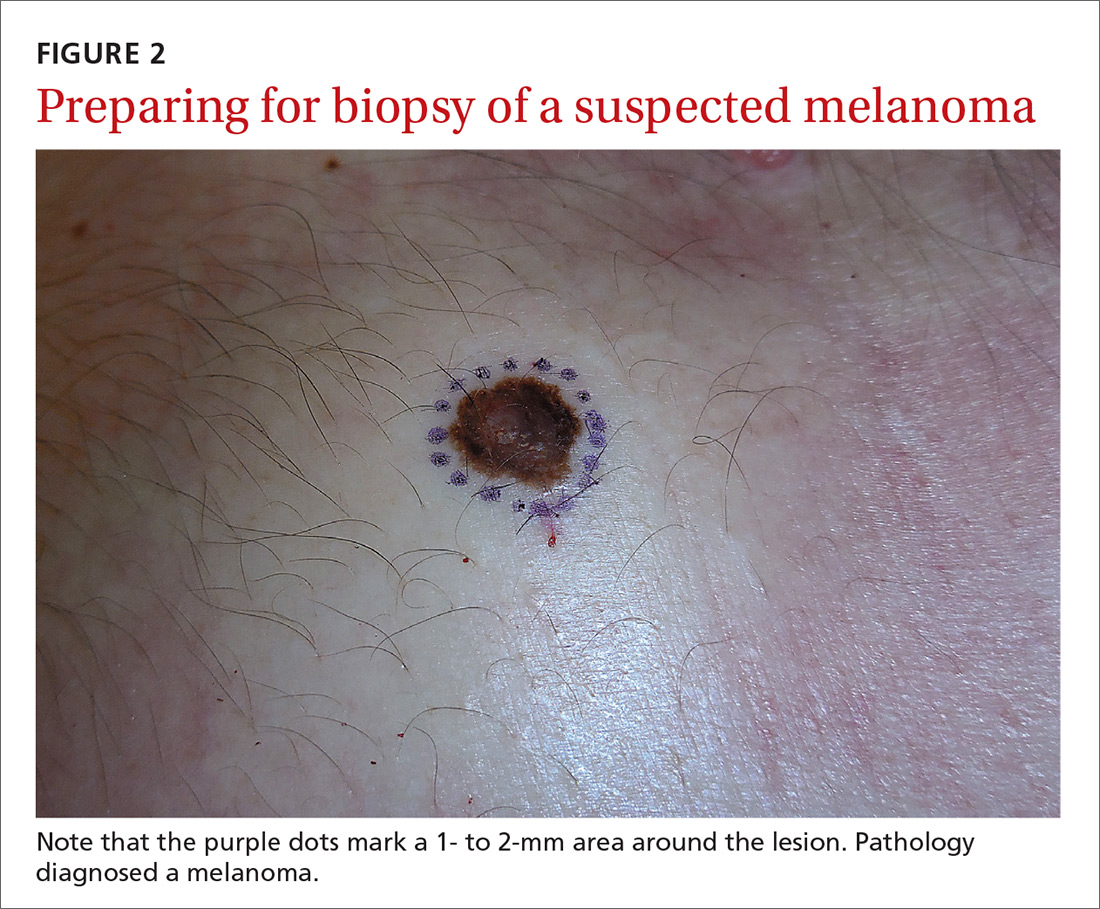

The patient was admitted to the family medicine service and received 4 units of packed red blood cells, which increased his hemoglobin to the target goal of >7 g/dL. A colonoscopy and an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) were performed (FIGURE 1A-1C), with results suggestive of diverticulosis, probable Barrett’s mucosa, esophageal ulcer, huge hiatal hernia (at least one-half of the stomach was in the chest), and Cameron ulcers. Esophageal biopsies showed cardiac mucosa with chronic inflammation. Esophageal ulcer biopsies revealed Barrett’s esophagus without dysplasia. Duodenal biopsies displayed normal mucosa.

DISCUSSION

Although rare, Cameron ulcers must be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with chronic anemia of unknown origin. The potential for these lesions to result in chronic blood loss, which could over time manifest as severe anemia or hypovolemic shock, makes proper diagnosis and prompt treatment especially important.4,5

In our patient’s case, his severe anemia was likely the result of a combination of the esophageal and Cameron ulcers evidenced on EGD, rather than any single ulcer. In our review of the literature, we found no reports of any patients with anemia and Cameron ulcers who presented with hemoglobin levels as low as our patient had.

Treat with a PPI and iron supplementation

Multiple EGDs may be needed to properly diagnose Cameron ulcers, as they can be difficult to identify. Once a patient receives the diagnosis, he or she will typically be put on a daily proton pump inhibitor (PPI) regimen, such as omeprazole 20 mg bid. However, since many patients with Cameron ulcers also have acid-related problems (as was true in this case), a multifactorial acid suppression approach may be warranted.1 This may include recommending lifestyle modifications (eg, eating small meals, avoiding foods that provoke symptoms, or losing weight) and prescribing medications in addition to a PPI, such as an H2 blocker (eg, 300 mg qid, before meals and at bedtime).

In addition, iron sulfate (325 mg/d, in this case) and blood transfusions may be required to treat the anemia. In refractory cases, endoscopic or surgical interventions, such as hemoclipping, Nissen fundoplication, or laparoscopic gastropexy, may need to be performed.2

Our patient was given a prescription for ferrous sulfate 325 mg/d and omeprazole 20 mg bid. His symptoms improved with treatment, and he was discharged on Day 5; his hemoglobin remained >7 g/dL.

THE TAKEAWAY

The association between chronic iron deficiency anemia and Cameron ulcers has been established but is commonly overlooked in patients presenting with unexplained anemia or an undiagnosed hiatal hernia. This is likely due to their rarity as a cause of anemia, in general.

Furthermore, the lesions can be missed on EGD; multiple EGDs may be needed to make the diagnosis. Once diagnosed, Cameron ulcers typically respond well to twice daily PPI treatment. Patients with refractory, recurrent, or severe lesions, or large, symptomatic hiatal hernias should be referred for surgical assessment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Megan Yee, 801 Broadward Avenue NW, Grand Rapids, MI 49504; [email protected].

1. Maganty K, Smith RL. Cameron lesions: unusual cause of gastrointestinal bleeding and anemia. Digestion. 2008;77:214-217.

2. Camus M, Jensen DM, Ohning GV, et al. Severe upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage from linear gastric ulcers in large hiatal hernias: a large prospective case series of Cameron ulcers. Endoscopy. 2013;45:397-400.

3. Kimer N, Schmidt PN, Krag, A. Cameron lesions: an often overlooked cause of iron deficiency anaemia in patients with large hiatal hernias. BMJ Case Rep. 2010;2010.

4. Kapadia S, Jagroop S, Kumar, A. Cameron ulcers: an atypical source for a massive upper gastrointestinal bleed. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4959-4961.

5. Gupta P, Suryadevara M, Das A, et al. Cameron ulcer causing severe anemia in a patient with diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Case Rep. 2015;16:733-736.

THE CASE

A 40-year-old man was referred to the emergency department (ED) with critical anemia after routine blood work at an outside clinic showed a hemoglobin level of 3.5 g/dL. On presentation, he reported symptoms of fatigue, shortness of breath, bilateral leg swelling, dizziness (characterized as light-headedness), and frequent heartburn. He said that the symptoms began 5 weeks earlier, after he was exposed to a relative with hand, foot, and mouth disease.

Additionally, the patient reported an intentional 14-lb weight loss over the 6 months prior to presentation. He denied fever, rash, chest pain, loss of consciousness, headache, abdominal pain, hematemesis, melena, and hematochezia. His medical history was significant for peptic ulcer disease (diagnosed and treated at age 8). He did not recall the specifics, and he denied any related chronic symptoms or complications. His family history (paternal) was significant for colon cancer.

The physical exam revealed conjunctival pallor, skin pallor, jaundice, +1 bilateral lower extremity edema, tachycardia, and tachypnea. Stool Hemoccult was negative. On repeat complete blood count (performed in the ED), hemoglobin was found to be 3.1 g/dL with a mean corpuscular volume of 47 fL.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient was admitted to the family medicine service and received 4 units of packed red blood cells, which increased his hemoglobin to the target goal of >7 g/dL. A colonoscopy and an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) were performed (FIGURE 1A-1C), with results suggestive of diverticulosis, probable Barrett’s mucosa, esophageal ulcer, huge hiatal hernia (at least one-half of the stomach was in the chest), and Cameron ulcers. Esophageal biopsies showed cardiac mucosa with chronic inflammation. Esophageal ulcer biopsies revealed Barrett’s esophagus without dysplasia. Duodenal biopsies displayed normal mucosa.

DISCUSSION

Although rare, Cameron ulcers must be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with chronic anemia of unknown origin. The potential for these lesions to result in chronic blood loss, which could over time manifest as severe anemia or hypovolemic shock, makes proper diagnosis and prompt treatment especially important.4,5

In our patient’s case, his severe anemia was likely the result of a combination of the esophageal and Cameron ulcers evidenced on EGD, rather than any single ulcer. In our review of the literature, we found no reports of any patients with anemia and Cameron ulcers who presented with hemoglobin levels as low as our patient had.

Treat with a PPI and iron supplementation

Multiple EGDs may be needed to properly diagnose Cameron ulcers, as they can be difficult to identify. Once a patient receives the diagnosis, he or she will typically be put on a daily proton pump inhibitor (PPI) regimen, such as omeprazole 20 mg bid. However, since many patients with Cameron ulcers also have acid-related problems (as was true in this case), a multifactorial acid suppression approach may be warranted.1 This may include recommending lifestyle modifications (eg, eating small meals, avoiding foods that provoke symptoms, or losing weight) and prescribing medications in addition to a PPI, such as an H2 blocker (eg, 300 mg qid, before meals and at bedtime).

In addition, iron sulfate (325 mg/d, in this case) and blood transfusions may be required to treat the anemia. In refractory cases, endoscopic or surgical interventions, such as hemoclipping, Nissen fundoplication, or laparoscopic gastropexy, may need to be performed.2

Our patient was given a prescription for ferrous sulfate 325 mg/d and omeprazole 20 mg bid. His symptoms improved with treatment, and he was discharged on Day 5; his hemoglobin remained >7 g/dL.

THE TAKEAWAY

The association between chronic iron deficiency anemia and Cameron ulcers has been established but is commonly overlooked in patients presenting with unexplained anemia or an undiagnosed hiatal hernia. This is likely due to their rarity as a cause of anemia, in general.

Furthermore, the lesions can be missed on EGD; multiple EGDs may be needed to make the diagnosis. Once diagnosed, Cameron ulcers typically respond well to twice daily PPI treatment. Patients with refractory, recurrent, or severe lesions, or large, symptomatic hiatal hernias should be referred for surgical assessment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Megan Yee, 801 Broadward Avenue NW, Grand Rapids, MI 49504; [email protected].

THE CASE

A 40-year-old man was referred to the emergency department (ED) with critical anemia after routine blood work at an outside clinic showed a hemoglobin level of 3.5 g/dL. On presentation, he reported symptoms of fatigue, shortness of breath, bilateral leg swelling, dizziness (characterized as light-headedness), and frequent heartburn. He said that the symptoms began 5 weeks earlier, after he was exposed to a relative with hand, foot, and mouth disease.

Additionally, the patient reported an intentional 14-lb weight loss over the 6 months prior to presentation. He denied fever, rash, chest pain, loss of consciousness, headache, abdominal pain, hematemesis, melena, and hematochezia. His medical history was significant for peptic ulcer disease (diagnosed and treated at age 8). He did not recall the specifics, and he denied any related chronic symptoms or complications. His family history (paternal) was significant for colon cancer.

The physical exam revealed conjunctival pallor, skin pallor, jaundice, +1 bilateral lower extremity edema, tachycardia, and tachypnea. Stool Hemoccult was negative. On repeat complete blood count (performed in the ED), hemoglobin was found to be 3.1 g/dL with a mean corpuscular volume of 47 fL.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient was admitted to the family medicine service and received 4 units of packed red blood cells, which increased his hemoglobin to the target goal of >7 g/dL. A colonoscopy and an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) were performed (FIGURE 1A-1C), with results suggestive of diverticulosis, probable Barrett’s mucosa, esophageal ulcer, huge hiatal hernia (at least one-half of the stomach was in the chest), and Cameron ulcers. Esophageal biopsies showed cardiac mucosa with chronic inflammation. Esophageal ulcer biopsies revealed Barrett’s esophagus without dysplasia. Duodenal biopsies displayed normal mucosa.

DISCUSSION

Although rare, Cameron ulcers must be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with chronic anemia of unknown origin. The potential for these lesions to result in chronic blood loss, which could over time manifest as severe anemia or hypovolemic shock, makes proper diagnosis and prompt treatment especially important.4,5

In our patient’s case, his severe anemia was likely the result of a combination of the esophageal and Cameron ulcers evidenced on EGD, rather than any single ulcer. In our review of the literature, we found no reports of any patients with anemia and Cameron ulcers who presented with hemoglobin levels as low as our patient had.

Treat with a PPI and iron supplementation

Multiple EGDs may be needed to properly diagnose Cameron ulcers, as they can be difficult to identify. Once a patient receives the diagnosis, he or she will typically be put on a daily proton pump inhibitor (PPI) regimen, such as omeprazole 20 mg bid. However, since many patients with Cameron ulcers also have acid-related problems (as was true in this case), a multifactorial acid suppression approach may be warranted.1 This may include recommending lifestyle modifications (eg, eating small meals, avoiding foods that provoke symptoms, or losing weight) and prescribing medications in addition to a PPI, such as an H2 blocker (eg, 300 mg qid, before meals and at bedtime).

In addition, iron sulfate (325 mg/d, in this case) and blood transfusions may be required to treat the anemia. In refractory cases, endoscopic or surgical interventions, such as hemoclipping, Nissen fundoplication, or laparoscopic gastropexy, may need to be performed.2

Our patient was given a prescription for ferrous sulfate 325 mg/d and omeprazole 20 mg bid. His symptoms improved with treatment, and he was discharged on Day 5; his hemoglobin remained >7 g/dL.

THE TAKEAWAY

The association between chronic iron deficiency anemia and Cameron ulcers has been established but is commonly overlooked in patients presenting with unexplained anemia or an undiagnosed hiatal hernia. This is likely due to their rarity as a cause of anemia, in general.

Furthermore, the lesions can be missed on EGD; multiple EGDs may be needed to make the diagnosis. Once diagnosed, Cameron ulcers typically respond well to twice daily PPI treatment. Patients with refractory, recurrent, or severe lesions, or large, symptomatic hiatal hernias should be referred for surgical assessment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Megan Yee, 801 Broadward Avenue NW, Grand Rapids, MI 49504; [email protected].

1. Maganty K, Smith RL. Cameron lesions: unusual cause of gastrointestinal bleeding and anemia. Digestion. 2008;77:214-217.

2. Camus M, Jensen DM, Ohning GV, et al. Severe upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage from linear gastric ulcers in large hiatal hernias: a large prospective case series of Cameron ulcers. Endoscopy. 2013;45:397-400.

3. Kimer N, Schmidt PN, Krag, A. Cameron lesions: an often overlooked cause of iron deficiency anaemia in patients with large hiatal hernias. BMJ Case Rep. 2010;2010.

4. Kapadia S, Jagroop S, Kumar, A. Cameron ulcers: an atypical source for a massive upper gastrointestinal bleed. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4959-4961.

5. Gupta P, Suryadevara M, Das A, et al. Cameron ulcer causing severe anemia in a patient with diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Case Rep. 2015;16:733-736.

1. Maganty K, Smith RL. Cameron lesions: unusual cause of gastrointestinal bleeding and anemia. Digestion. 2008;77:214-217.

2. Camus M, Jensen DM, Ohning GV, et al. Severe upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage from linear gastric ulcers in large hiatal hernias: a large prospective case series of Cameron ulcers. Endoscopy. 2013;45:397-400.

3. Kimer N, Schmidt PN, Krag, A. Cameron lesions: an often overlooked cause of iron deficiency anaemia in patients with large hiatal hernias. BMJ Case Rep. 2010;2010.

4. Kapadia S, Jagroop S, Kumar, A. Cameron ulcers: an atypical source for a massive upper gastrointestinal bleed. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4959-4961.

5. Gupta P, Suryadevara M, Das A, et al. Cameron ulcer causing severe anemia in a patient with diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Case Rep. 2015;16:733-736.

When the correct Dx is elusive

In this issue of JFP, Dr. Mendoza reminds us that “Parkinson’s disease can be a tough diagnosis to navigate.”1 Classically, Parkinson’s disease (PD) is associated with a resting tremor, but bradykinesia is actually the hallmark of the disease. PD can also present with subtle movement disorders, as well as depression and early dementia. It is, indeed, a difficult clinical diagnosis, and consultation with an expert to confirm or deny its presence can be quite helpful.

Other conundrums. PD, however, is not the only illness whose signs and symptoms can present a challenge. Chronic and intermittent shortness of breath, for example, can be very difficult to sort out. Is the shortness of breath due to congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, or a neurologic condition such as myasthenia gravis? Or is it the result of several causes?

When asthma isn’t asthma. Because it is a common illness, physicians often diagnose asthma in patients with shortness of breath or wheezing. But a recent study suggests that as many as 30% of primary care patients with a current diagnosis of asthma do not have asthma at all.2

In the study, Canadian researchers recruited 701 adults with physician-diagnosed asthma, all of whom were taking asthma medications regularly. The researchers did baseline pulmonary function testing (including methacholine challenge testing, if needed) and monitored symptoms frequently. Then they gradually withdrew asthma medications from those who did not appear to have a definitive diagnosis of asthma. They followed these patients for one year. One-third (203 of 613) of the patients with complete follow-up data were no longer taking asthma medications one year later and had no symptoms of asthma. Twelve patients had serious alternative diagnoses such as coronary artery disease and bronchiectasis.

Closer to home. In my practice, I found 2 patients with long-standing diagnoses of asthma who didn’t, in fact, have the condition at all. In both cases, my suspicion was raised by lung examination. In one case, fine bibasilar rales suggested pulmonary fibrosis, which was the correct diagnosis, and the patient is now on the lung transplant list. In the other case, a loud venous hum suggested an arteriovenous malformation. Surgery corrected the patient’s “asthma.”

I urge you to reevaluate your asthma patients to be sure they have the correct diagnosis and to keep PD in your differential for patients who present with atypical symptoms. Primary care clinicians must be expert diagnosticians, willing to question prior diagnoses.

1. Young J, Mendoza M. Parkinson’s disease: a treatment guide. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:276-286.

2. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, FitzGerald JM, et al for the Canadian Respiratory Research Network. Reevaluation of diagnosis in adults with physician-diagnosed asthma. JAMA. 2017:317:269-279.

In this issue of JFP, Dr. Mendoza reminds us that “Parkinson’s disease can be a tough diagnosis to navigate.”1 Classically, Parkinson’s disease (PD) is associated with a resting tremor, but bradykinesia is actually the hallmark of the disease. PD can also present with subtle movement disorders, as well as depression and early dementia. It is, indeed, a difficult clinical diagnosis, and consultation with an expert to confirm or deny its presence can be quite helpful.

Other conundrums. PD, however, is not the only illness whose signs and symptoms can present a challenge. Chronic and intermittent shortness of breath, for example, can be very difficult to sort out. Is the shortness of breath due to congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, or a neurologic condition such as myasthenia gravis? Or is it the result of several causes?

When asthma isn’t asthma. Because it is a common illness, physicians often diagnose asthma in patients with shortness of breath or wheezing. But a recent study suggests that as many as 30% of primary care patients with a current diagnosis of asthma do not have asthma at all.2

In the study, Canadian researchers recruited 701 adults with physician-diagnosed asthma, all of whom were taking asthma medications regularly. The researchers did baseline pulmonary function testing (including methacholine challenge testing, if needed) and monitored symptoms frequently. Then they gradually withdrew asthma medications from those who did not appear to have a definitive diagnosis of asthma. They followed these patients for one year. One-third (203 of 613) of the patients with complete follow-up data were no longer taking asthma medications one year later and had no symptoms of asthma. Twelve patients had serious alternative diagnoses such as coronary artery disease and bronchiectasis.

Closer to home. In my practice, I found 2 patients with long-standing diagnoses of asthma who didn’t, in fact, have the condition at all. In both cases, my suspicion was raised by lung examination. In one case, fine bibasilar rales suggested pulmonary fibrosis, which was the correct diagnosis, and the patient is now on the lung transplant list. In the other case, a loud venous hum suggested an arteriovenous malformation. Surgery corrected the patient’s “asthma.”

I urge you to reevaluate your asthma patients to be sure they have the correct diagnosis and to keep PD in your differential for patients who present with atypical symptoms. Primary care clinicians must be expert diagnosticians, willing to question prior diagnoses.

In this issue of JFP, Dr. Mendoza reminds us that “Parkinson’s disease can be a tough diagnosis to navigate.”1 Classically, Parkinson’s disease (PD) is associated with a resting tremor, but bradykinesia is actually the hallmark of the disease. PD can also present with subtle movement disorders, as well as depression and early dementia. It is, indeed, a difficult clinical diagnosis, and consultation with an expert to confirm or deny its presence can be quite helpful.

Other conundrums. PD, however, is not the only illness whose signs and symptoms can present a challenge. Chronic and intermittent shortness of breath, for example, can be very difficult to sort out. Is the shortness of breath due to congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, or a neurologic condition such as myasthenia gravis? Or is it the result of several causes?

When asthma isn’t asthma. Because it is a common illness, physicians often diagnose asthma in patients with shortness of breath or wheezing. But a recent study suggests that as many as 30% of primary care patients with a current diagnosis of asthma do not have asthma at all.2

In the study, Canadian researchers recruited 701 adults with physician-diagnosed asthma, all of whom were taking asthma medications regularly. The researchers did baseline pulmonary function testing (including methacholine challenge testing, if needed) and monitored symptoms frequently. Then they gradually withdrew asthma medications from those who did not appear to have a definitive diagnosis of asthma. They followed these patients for one year. One-third (203 of 613) of the patients with complete follow-up data were no longer taking asthma medications one year later and had no symptoms of asthma. Twelve patients had serious alternative diagnoses such as coronary artery disease and bronchiectasis.

Closer to home. In my practice, I found 2 patients with long-standing diagnoses of asthma who didn’t, in fact, have the condition at all. In both cases, my suspicion was raised by lung examination. In one case, fine bibasilar rales suggested pulmonary fibrosis, which was the correct diagnosis, and the patient is now on the lung transplant list. In the other case, a loud venous hum suggested an arteriovenous malformation. Surgery corrected the patient’s “asthma.”

I urge you to reevaluate your asthma patients to be sure they have the correct diagnosis and to keep PD in your differential for patients who present with atypical symptoms. Primary care clinicians must be expert diagnosticians, willing to question prior diagnoses.

1. Young J, Mendoza M. Parkinson’s disease: a treatment guide. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:276-286.

2. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, FitzGerald JM, et al for the Canadian Respiratory Research Network. Reevaluation of diagnosis in adults with physician-diagnosed asthma. JAMA. 2017:317:269-279.

1. Young J, Mendoza M. Parkinson’s disease: a treatment guide. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:276-286.

2. Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, FitzGerald JM, et al for the Canadian Respiratory Research Network. Reevaluation of diagnosis in adults with physician-diagnosed asthma. JAMA. 2017:317:269-279.

Does niacin decrease cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in CVD patients?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

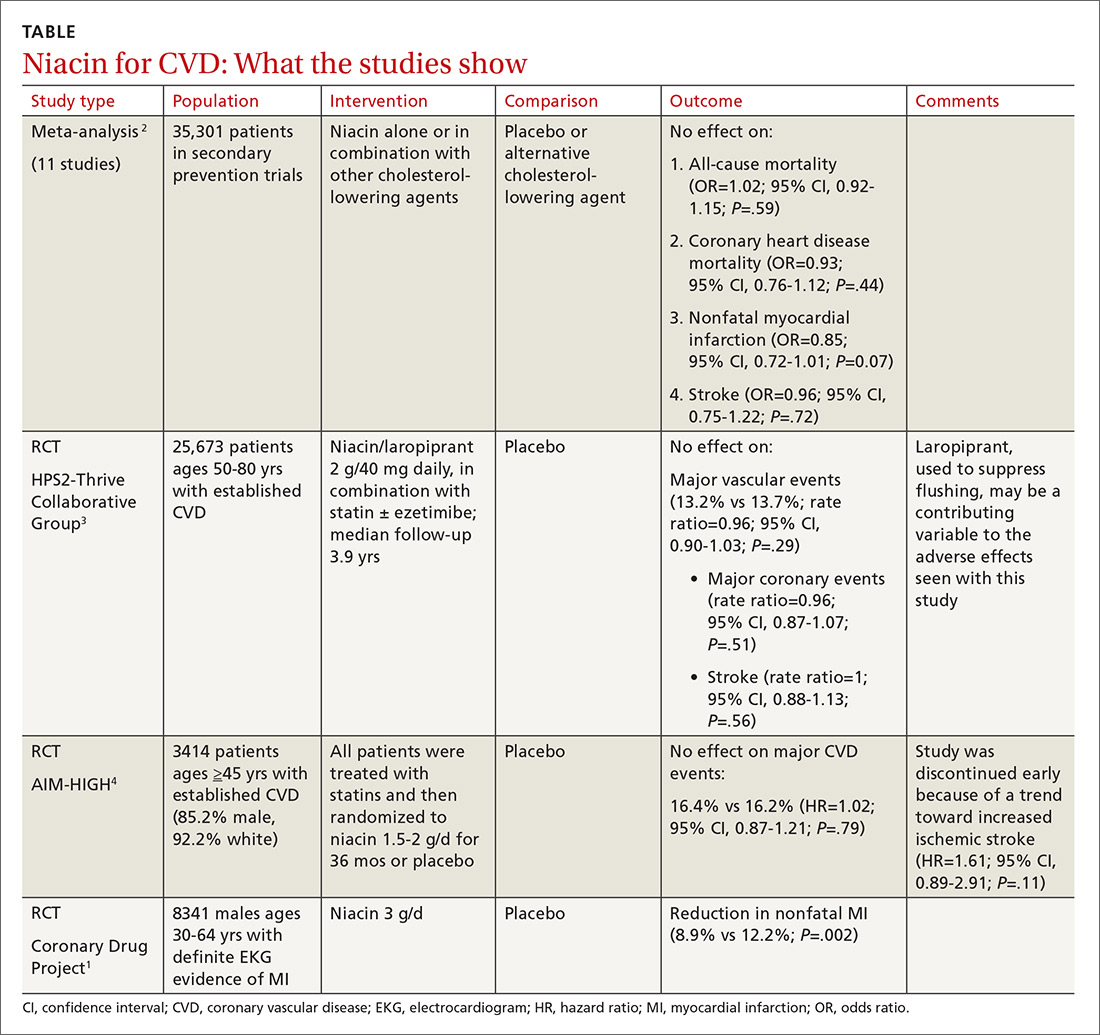

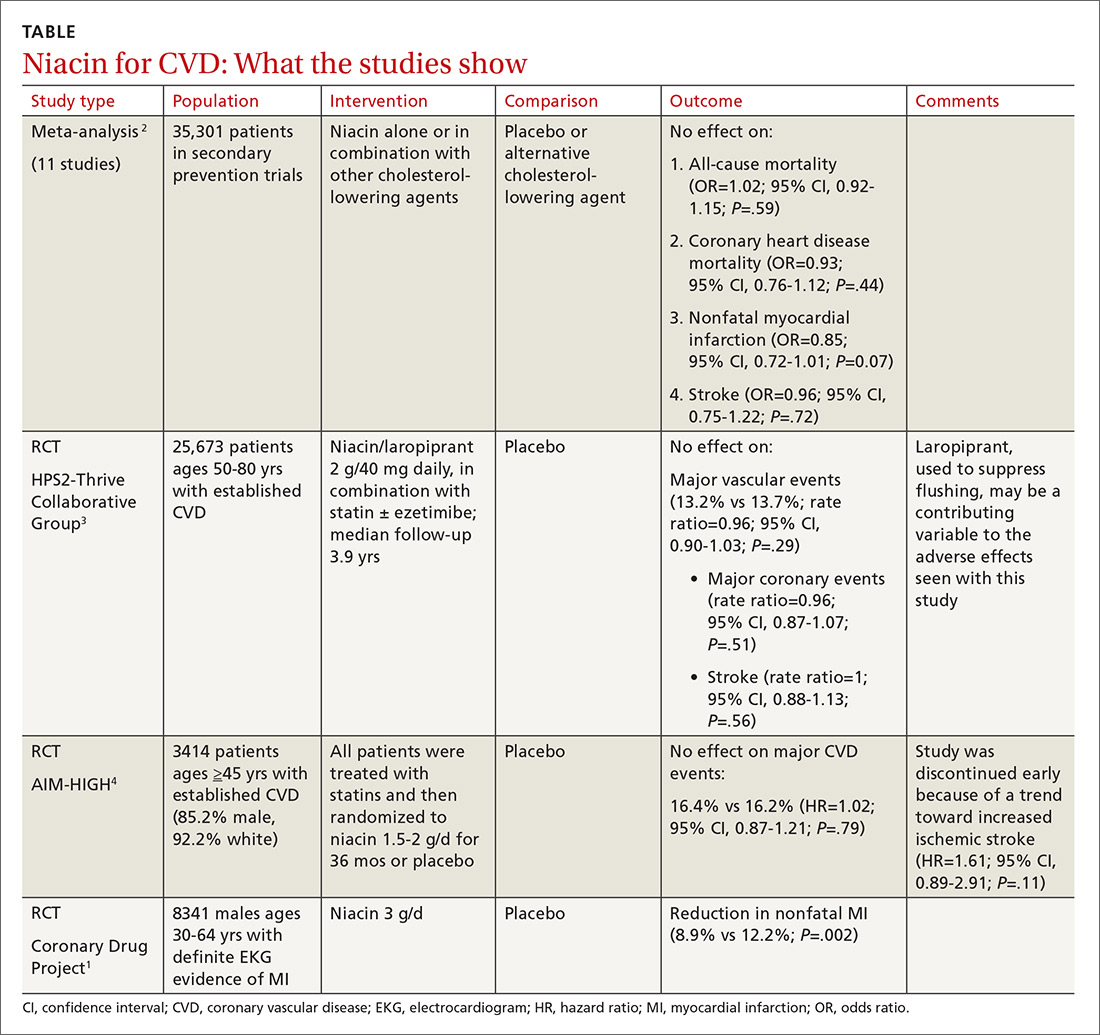

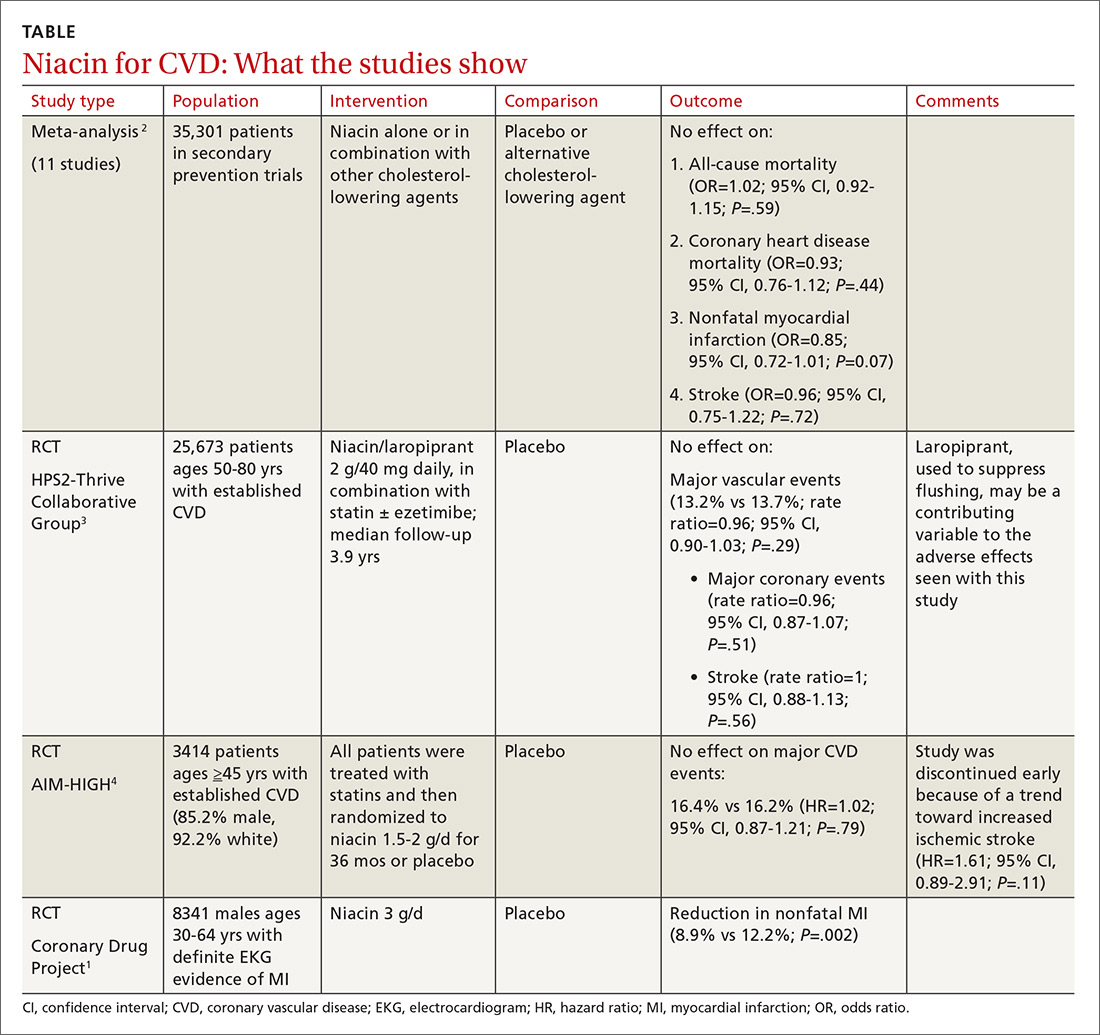

Before the statin era, the Coronary Drug Project RCT (8341 patients) showed that niacin monotherapy in patients with definite electrocardiographic evidence of previous myocardial infarction (MI) reduced nonfatal MI to 8.9% compared with 12.2% for placebo (P=.002).1 (See TABLE.1-4) It also decreased long-term mortality by 11% compared with placebo (P=.0004).5

Adverse effects such as flushing, hyperglycemia, gastrointestinal disturbance, and elevated liver enzymes interfered with adherence to niacin treatment (66.3% of patients were adherent to treatment with niacin vs 77.8% for placebo). The study was limited by the fact that flushing essentially unblinded participants and physicians.

But adding niacin to a statin has no effect

A 2014 meta-analysis driven by the power of the large HPS2-Thrive study evaluated data from 35,301 patients primarily in secondary prevention trials.2,3 It found that adding niacin to statins had no effect on all-cause mortality, coronary heart disease mortality, nonfatal MI, or stroke. The subset of 6 trials (N=4991) assessing niacin monotherapy did show a reduction in cardiovascular events (odds ratio [OR]=0.62; confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.82), whereas the 5 studies (30,310 patients) involving niacin with a statin demonstrated no effect (OR=0.94; CI, 0.83-1.06).

No benefit from niacin/statin therapy despite an improved lipid profile

A 2011 RCT included 3414 patients with coronary heart disease on simvastatin who were randomized to niacin or placebo.4 All patients received simvastatin 40 to 80 mg ± ezetimibe 10 mg/d to achieve low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels of 40 to 80 mg/dL.

At 3 years, no benefit was seen in the composite CVD primary endpoint (hazard ratio=1.02; 95% CI, 0.87-1.21; P=.79) even though the niacin group had significantly increased median high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol compared with placebo and lower triglycerides and LDL cholesterol compared with baseline.

A nonsignificant trend toward increased stroke in the niacin group compared with placebo led to early termination of the study. However, multivariate analysis showed independent associations between ischemic stroke risk and age older than 65 years, history of stroke/transient ischemic attack/carotid artery disease, and elevated baseline cholesterol.6

Niacin combined with a statin increases the risk of adverse events

The largest RCT in the 2014 meta-analysis (HPS2-Thrive) evaluated 25,673 patients with established CVD receiving cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin ± ezetimibe who were randomized to niacin or placebo for a median follow-up period of 3.9 years.3 A pre-randomization run-in phase established effective cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin ± ezetimibe.

Niacin didn’t reduce the incidence of major vascular events even though, once again, it decreased LDL and increased HDL more than placebo. Niacin increased the risk of serious adverse events 56% vs 53% (risk ratio [RR]=6; 95% CI, 3-8; number needed to harm [NNH]=35; 95% CI, 25-60), such as new onset diabetes (5.7% vs 4.3%; P<.001; NNH=71) and gastrointestinal bleeding/ulceration and other gastrointestinal disorders (4.8% vs 3.8%; P<.001; NNH=100).

A subsequent 2014 study examined the adverse events recorded in the AIM-HIGH4 study and found that niacin caused more gastrointestinal disorders (7.4% vs 5.5%; P=.02; NNH=53) and infections and infestations (8.1% vs 5.8%; P=.008; NNH=43) than placebo.7 The overall observed rate of serious hemorrhagic adverse events was low, however, showing no significant difference between the 2 groups (3.4% vs 2.9%; P=.36).

RECOMMENDATIONS

As of November 2013, the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement recommends against using niacin in combination with statins because of the increased risk of adverse events without a reduction in CVD outcomes. Niacin may be considered as monotherapy in patients who can’t tolerate statins or fibrates based on results of the Coronary Drug Project and other studies completed before the era of widespread statin use.8

Similarly, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines state that patients who are completely statin intolerant may use nonstatin cholesterol-lowering drugs, including niacin, that have been shown to reduce CVD events in RCTs if the CVD risk-reduction benefits outweigh the potential for adverse effects.9

1. Coronary Drug Project Research Group. Colofibrate and niacin in coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1975;231:360-81.

2. Keene D, Price C, Shun-Shin MJ, et al. Effect on cardiovascular risk of high density lipoprotein targeted drug treatments niacin, fibrates, and CETP inhibitors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials including 117,411 patients. BMJ. 2014;349:g4379.

3. HPS2-Thrive Collaborative Group. Effects of extended-release niacin with laropiprant in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:203-212.

4. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255-2267.

5. Canner PL, Berge KG, Wender NK, et al. Fifteen-year mortality in Coronary Drug Project patients: long-term benefit with niacin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8:1245-1255.

6. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Extended-release niacin therapy and risk of ischemic stroke in patients with cardiovascular disease: the Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome with low HDL/High Triglycerides: Impact on Global Health Outcome (AIM-HIGH) trial. Stroke. 2013;44:2688-2693.

7. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Safety profile of extended-release niacin in the AIM-HIGH trial. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:288-290.

8. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Guideline summary: Lipid management in adults. National Guideline Clearinghouse. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov. Accessed July 20, 2015.

9. Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;25 (suppl 2):S1-S45.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Before the statin era, the Coronary Drug Project RCT (8341 patients) showed that niacin monotherapy in patients with definite electrocardiographic evidence of previous myocardial infarction (MI) reduced nonfatal MI to 8.9% compared with 12.2% for placebo (P=.002).1 (See TABLE.1-4) It also decreased long-term mortality by 11% compared with placebo (P=.0004).5

Adverse effects such as flushing, hyperglycemia, gastrointestinal disturbance, and elevated liver enzymes interfered with adherence to niacin treatment (66.3% of patients were adherent to treatment with niacin vs 77.8% for placebo). The study was limited by the fact that flushing essentially unblinded participants and physicians.

But adding niacin to a statin has no effect

A 2014 meta-analysis driven by the power of the large HPS2-Thrive study evaluated data from 35,301 patients primarily in secondary prevention trials.2,3 It found that adding niacin to statins had no effect on all-cause mortality, coronary heart disease mortality, nonfatal MI, or stroke. The subset of 6 trials (N=4991) assessing niacin monotherapy did show a reduction in cardiovascular events (odds ratio [OR]=0.62; confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.82), whereas the 5 studies (30,310 patients) involving niacin with a statin demonstrated no effect (OR=0.94; CI, 0.83-1.06).

No benefit from niacin/statin therapy despite an improved lipid profile

A 2011 RCT included 3414 patients with coronary heart disease on simvastatin who were randomized to niacin or placebo.4 All patients received simvastatin 40 to 80 mg ± ezetimibe 10 mg/d to achieve low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels of 40 to 80 mg/dL.

At 3 years, no benefit was seen in the composite CVD primary endpoint (hazard ratio=1.02; 95% CI, 0.87-1.21; P=.79) even though the niacin group had significantly increased median high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol compared with placebo and lower triglycerides and LDL cholesterol compared with baseline.

A nonsignificant trend toward increased stroke in the niacin group compared with placebo led to early termination of the study. However, multivariate analysis showed independent associations between ischemic stroke risk and age older than 65 years, history of stroke/transient ischemic attack/carotid artery disease, and elevated baseline cholesterol.6

Niacin combined with a statin increases the risk of adverse events

The largest RCT in the 2014 meta-analysis (HPS2-Thrive) evaluated 25,673 patients with established CVD receiving cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin ± ezetimibe who were randomized to niacin or placebo for a median follow-up period of 3.9 years.3 A pre-randomization run-in phase established effective cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin ± ezetimibe.

Niacin didn’t reduce the incidence of major vascular events even though, once again, it decreased LDL and increased HDL more than placebo. Niacin increased the risk of serious adverse events 56% vs 53% (risk ratio [RR]=6; 95% CI, 3-8; number needed to harm [NNH]=35; 95% CI, 25-60), such as new onset diabetes (5.7% vs 4.3%; P<.001; NNH=71) and gastrointestinal bleeding/ulceration and other gastrointestinal disorders (4.8% vs 3.8%; P<.001; NNH=100).

A subsequent 2014 study examined the adverse events recorded in the AIM-HIGH4 study and found that niacin caused more gastrointestinal disorders (7.4% vs 5.5%; P=.02; NNH=53) and infections and infestations (8.1% vs 5.8%; P=.008; NNH=43) than placebo.7 The overall observed rate of serious hemorrhagic adverse events was low, however, showing no significant difference between the 2 groups (3.4% vs 2.9%; P=.36).

RECOMMENDATIONS

As of November 2013, the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement recommends against using niacin in combination with statins because of the increased risk of adverse events without a reduction in CVD outcomes. Niacin may be considered as monotherapy in patients who can’t tolerate statins or fibrates based on results of the Coronary Drug Project and other studies completed before the era of widespread statin use.8

Similarly, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines state that patients who are completely statin intolerant may use nonstatin cholesterol-lowering drugs, including niacin, that have been shown to reduce CVD events in RCTs if the CVD risk-reduction benefits outweigh the potential for adverse effects.9

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Before the statin era, the Coronary Drug Project RCT (8341 patients) showed that niacin monotherapy in patients with definite electrocardiographic evidence of previous myocardial infarction (MI) reduced nonfatal MI to 8.9% compared with 12.2% for placebo (P=.002).1 (See TABLE.1-4) It also decreased long-term mortality by 11% compared with placebo (P=.0004).5

Adverse effects such as flushing, hyperglycemia, gastrointestinal disturbance, and elevated liver enzymes interfered with adherence to niacin treatment (66.3% of patients were adherent to treatment with niacin vs 77.8% for placebo). The study was limited by the fact that flushing essentially unblinded participants and physicians.

But adding niacin to a statin has no effect

A 2014 meta-analysis driven by the power of the large HPS2-Thrive study evaluated data from 35,301 patients primarily in secondary prevention trials.2,3 It found that adding niacin to statins had no effect on all-cause mortality, coronary heart disease mortality, nonfatal MI, or stroke. The subset of 6 trials (N=4991) assessing niacin monotherapy did show a reduction in cardiovascular events (odds ratio [OR]=0.62; confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.82), whereas the 5 studies (30,310 patients) involving niacin with a statin demonstrated no effect (OR=0.94; CI, 0.83-1.06).

No benefit from niacin/statin therapy despite an improved lipid profile

A 2011 RCT included 3414 patients with coronary heart disease on simvastatin who were randomized to niacin or placebo.4 All patients received simvastatin 40 to 80 mg ± ezetimibe 10 mg/d to achieve low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels of 40 to 80 mg/dL.

At 3 years, no benefit was seen in the composite CVD primary endpoint (hazard ratio=1.02; 95% CI, 0.87-1.21; P=.79) even though the niacin group had significantly increased median high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol compared with placebo and lower triglycerides and LDL cholesterol compared with baseline.

A nonsignificant trend toward increased stroke in the niacin group compared with placebo led to early termination of the study. However, multivariate analysis showed independent associations between ischemic stroke risk and age older than 65 years, history of stroke/transient ischemic attack/carotid artery disease, and elevated baseline cholesterol.6

Niacin combined with a statin increases the risk of adverse events

The largest RCT in the 2014 meta-analysis (HPS2-Thrive) evaluated 25,673 patients with established CVD receiving cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin ± ezetimibe who were randomized to niacin or placebo for a median follow-up period of 3.9 years.3 A pre-randomization run-in phase established effective cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin ± ezetimibe.

Niacin didn’t reduce the incidence of major vascular events even though, once again, it decreased LDL and increased HDL more than placebo. Niacin increased the risk of serious adverse events 56% vs 53% (risk ratio [RR]=6; 95% CI, 3-8; number needed to harm [NNH]=35; 95% CI, 25-60), such as new onset diabetes (5.7% vs 4.3%; P<.001; NNH=71) and gastrointestinal bleeding/ulceration and other gastrointestinal disorders (4.8% vs 3.8%; P<.001; NNH=100).

A subsequent 2014 study examined the adverse events recorded in the AIM-HIGH4 study and found that niacin caused more gastrointestinal disorders (7.4% vs 5.5%; P=.02; NNH=53) and infections and infestations (8.1% vs 5.8%; P=.008; NNH=43) than placebo.7 The overall observed rate of serious hemorrhagic adverse events was low, however, showing no significant difference between the 2 groups (3.4% vs 2.9%; P=.36).

RECOMMENDATIONS

As of November 2013, the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement recommends against using niacin in combination with statins because of the increased risk of adverse events without a reduction in CVD outcomes. Niacin may be considered as monotherapy in patients who can’t tolerate statins or fibrates based on results of the Coronary Drug Project and other studies completed before the era of widespread statin use.8

Similarly, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines state that patients who are completely statin intolerant may use nonstatin cholesterol-lowering drugs, including niacin, that have been shown to reduce CVD events in RCTs if the CVD risk-reduction benefits outweigh the potential for adverse effects.9

1. Coronary Drug Project Research Group. Colofibrate and niacin in coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1975;231:360-81.

2. Keene D, Price C, Shun-Shin MJ, et al. Effect on cardiovascular risk of high density lipoprotein targeted drug treatments niacin, fibrates, and CETP inhibitors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials including 117,411 patients. BMJ. 2014;349:g4379.

3. HPS2-Thrive Collaborative Group. Effects of extended-release niacin with laropiprant in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:203-212.

4. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255-2267.

5. Canner PL, Berge KG, Wender NK, et al. Fifteen-year mortality in Coronary Drug Project patients: long-term benefit with niacin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8:1245-1255.

6. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Extended-release niacin therapy and risk of ischemic stroke in patients with cardiovascular disease: the Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome with low HDL/High Triglycerides: Impact on Global Health Outcome (AIM-HIGH) trial. Stroke. 2013;44:2688-2693.

7. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Safety profile of extended-release niacin in the AIM-HIGH trial. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:288-290.

8. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Guideline summary: Lipid management in adults. National Guideline Clearinghouse. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov. Accessed July 20, 2015.

9. Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;25 (suppl 2):S1-S45.

1. Coronary Drug Project Research Group. Colofibrate and niacin in coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1975;231:360-81.

2. Keene D, Price C, Shun-Shin MJ, et al. Effect on cardiovascular risk of high density lipoprotein targeted drug treatments niacin, fibrates, and CETP inhibitors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials including 117,411 patients. BMJ. 2014;349:g4379.

3. HPS2-Thrive Collaborative Group. Effects of extended-release niacin with laropiprant in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:203-212.

4. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255-2267.

5. Canner PL, Berge KG, Wender NK, et al. Fifteen-year mortality in Coronary Drug Project patients: long-term benefit with niacin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8:1245-1255.

6. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Extended-release niacin therapy and risk of ischemic stroke in patients with cardiovascular disease: the Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome with low HDL/High Triglycerides: Impact on Global Health Outcome (AIM-HIGH) trial. Stroke. 2013;44:2688-2693.

7. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Safety profile of extended-release niacin in the AIM-HIGH trial. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:288-290.

8. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Guideline summary: Lipid management in adults. National Guideline Clearinghouse. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov. Accessed July 20, 2015.

9. Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;25 (suppl 2):S1-S45.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

EVIDENCE BASED ANSWER:

No. Niacin doesn’t reduce cardiovascular disease (CVD) morbidity or mortality in patients with established disease (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials [RCTs] and subsequent large RCTs).

Niacin may be considered as monotherapy for patients intolerant of statins (SOR: B, one well-done RCT).

Hypothermia in adults: A strategy for detection and Tx

CASE

Patrick S, an 85-year-old man with multiple medical problems, was brought to his primary care provider after being found at home with altered mental status. His caretaker reported that Mr. S had been using extra blankets in bed and sleeping more, but he hadn’t had significant outdoor exposure. Measurement of his vital signs revealed tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, and a rectal temperature of 32°C (89.6°F).

How would you proceed with the care of this patient?

What is accidental hypothermia?

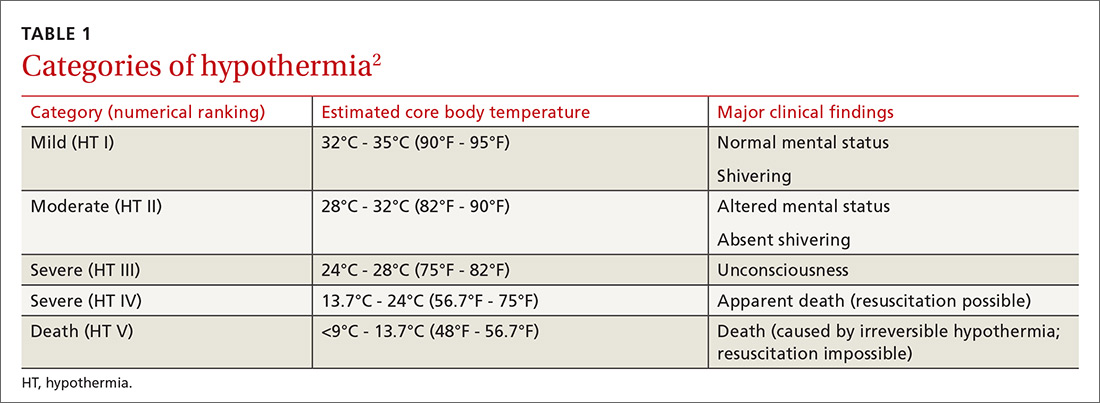

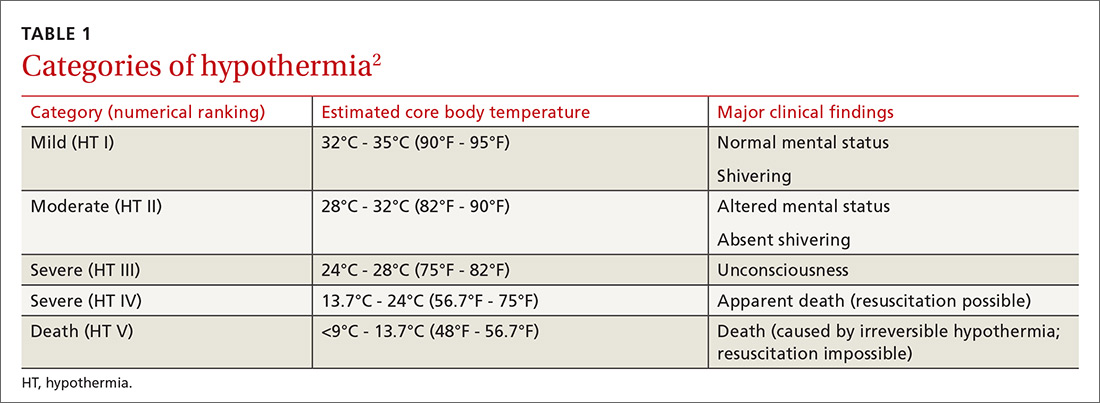

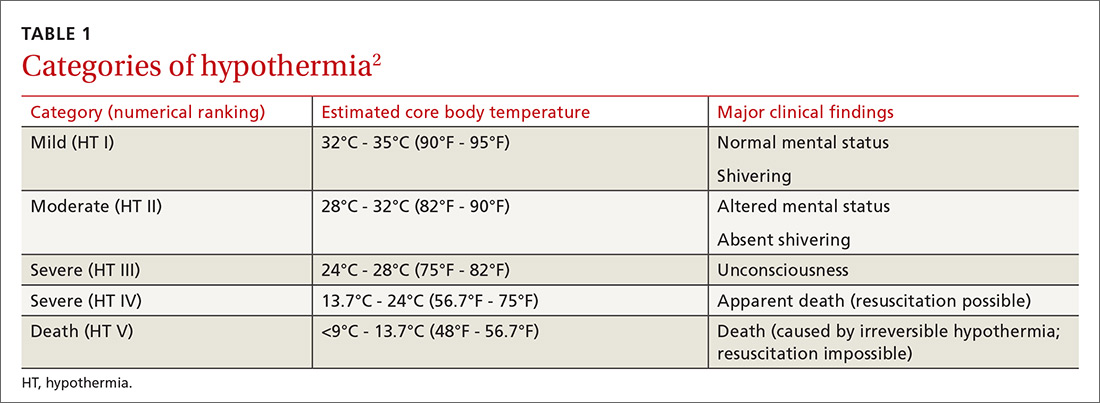

Accidental hypothermia is an unintentional drop in core body temperature to <35°C (<95°F). Mild hypothermia is defined as a core body temperature of 32°C to 35°C (90°F - 95°F); moderate hypothermia, 28°C to 32°C (82°F - 90°F); and severe hypothermia, <28°C (<82°F).1

The International Commission for Mountain Emergency Medicine divides hypothermia into 5 categories, emphasizing the clinical features of each stage as a guide to treatment (TABLE 1).2 These categories were adopted to help prehospital rescuers estimate the severity of hypothermia using physical symptoms. For example, most patients stop shivering at approximately 30°C (86°F)—the “moderate (HT II)” category of hypothermia—although this response varies widely from patient to patient. Notably, there are reports in the literature of survival in hypothermia with a temperature as low as 13.7°C (56.7°F) and with cardiac arrest for as long as 8 hours and 40 minutes, although these events are rare.3

Each year, approximately 700 deaths in the United States are the result of hypothermia.4 Between 1995 to 2004 in the United States, it is estimated that 15,574 visits were made to a health care provider or facility for hypothermia and other cold-related concerns.5 Based on reports in the international literature, the incidence of nonlethal hypothermia is much greater than the incidence of lethal hypothermia.5 Almost half of deaths from hypothermia are in people older than age 65 years; the male to female ratio is 2.5:1.1

Variables that predispose the body to temperature dysregulation include extremes of age, comorbid conditions, intoxication, chronic cold exposure, immersion accident, mental illness, impaired shivering, and lack of acclimatization.1 The most common causes of death associated with hypothermia are falls, drownings, and cardiovascular disease.4 In a 2008 study, hypothermia and other cold-related morbidity emergency department (ED) visits required more transfers of patients to a critical care unit than any other reason for visiting an ED (risk ratio, 6.73; 95% confidence interval, 1.8-25).5 Mortality among inpatients whose hypothermia is classified as moderate or severe reaches as high as 40%.3

More than just cold-weather exposure

Accidental hypothermia occurs when heat loss is superseded by the body’s ability to generate heat. It commonly happens in cold environments but can also occur at higher temperatures if the body’s thermoregulatory system malfunctions.

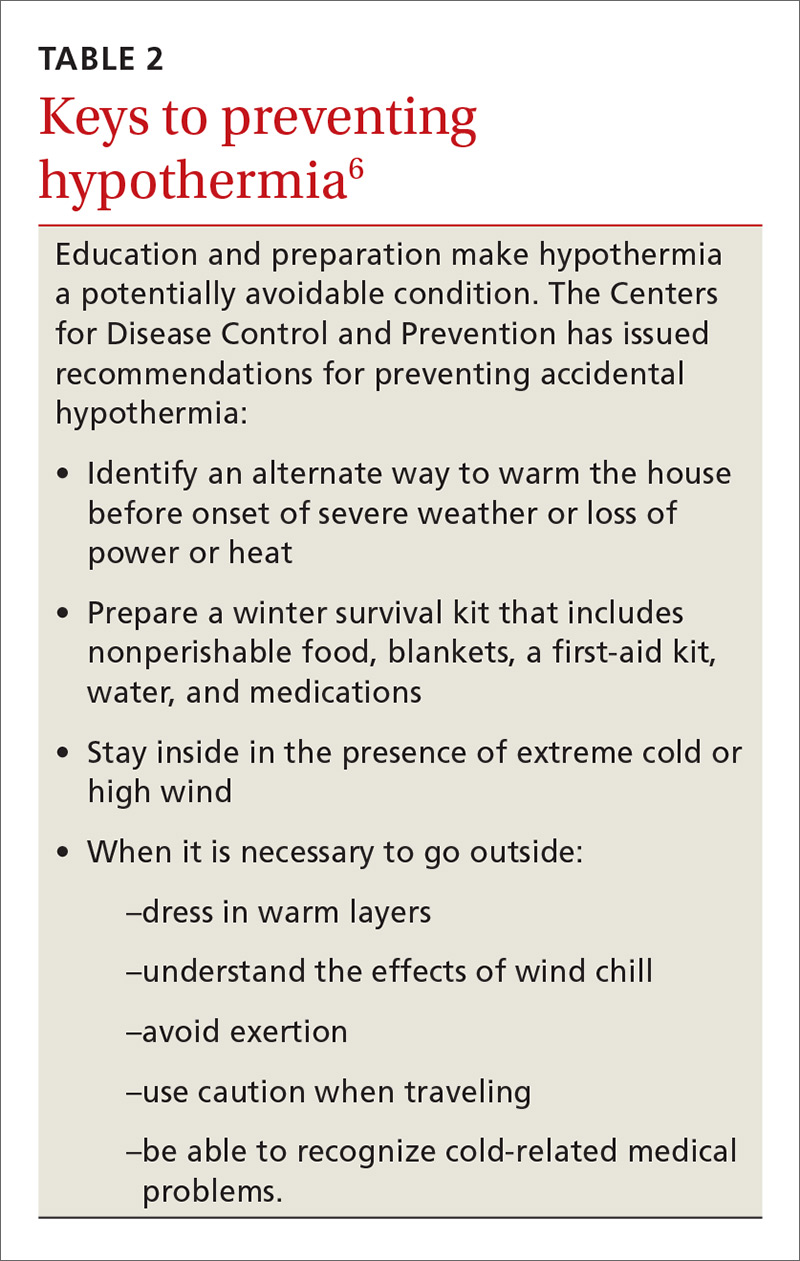

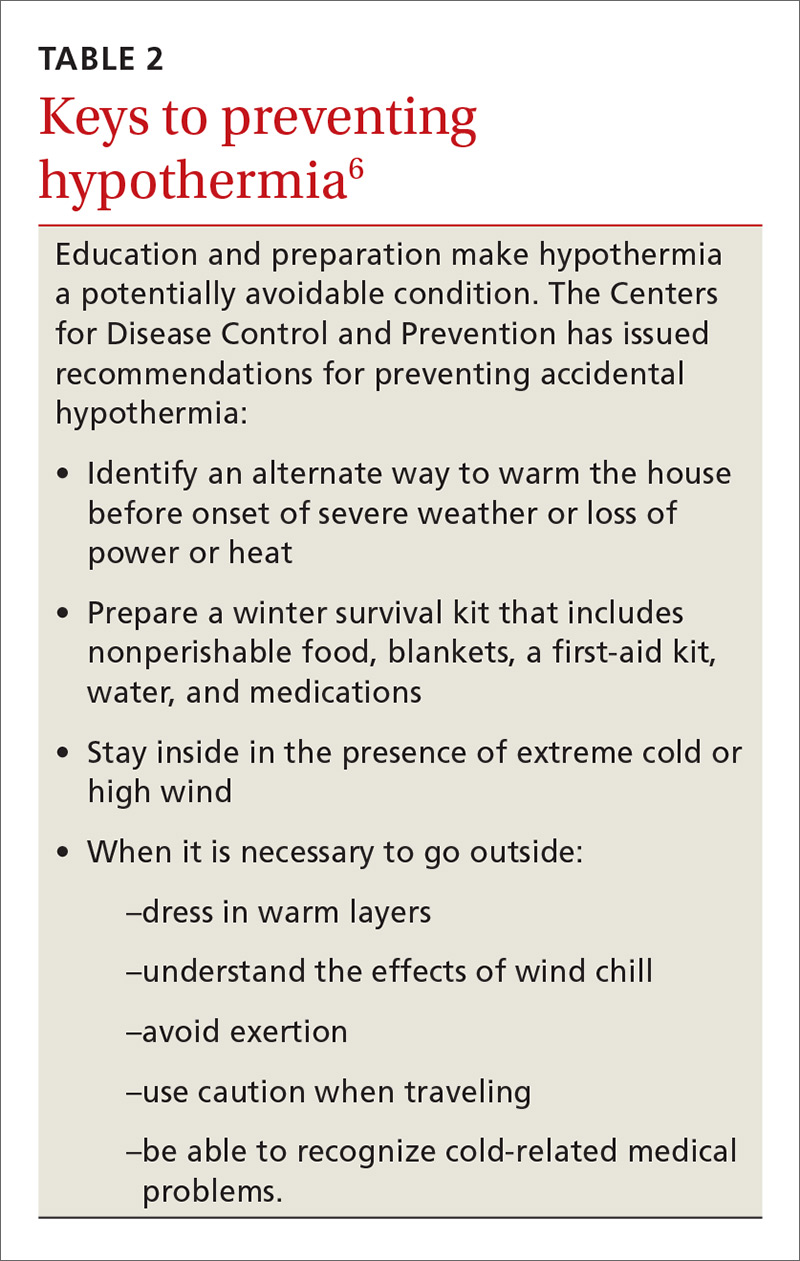

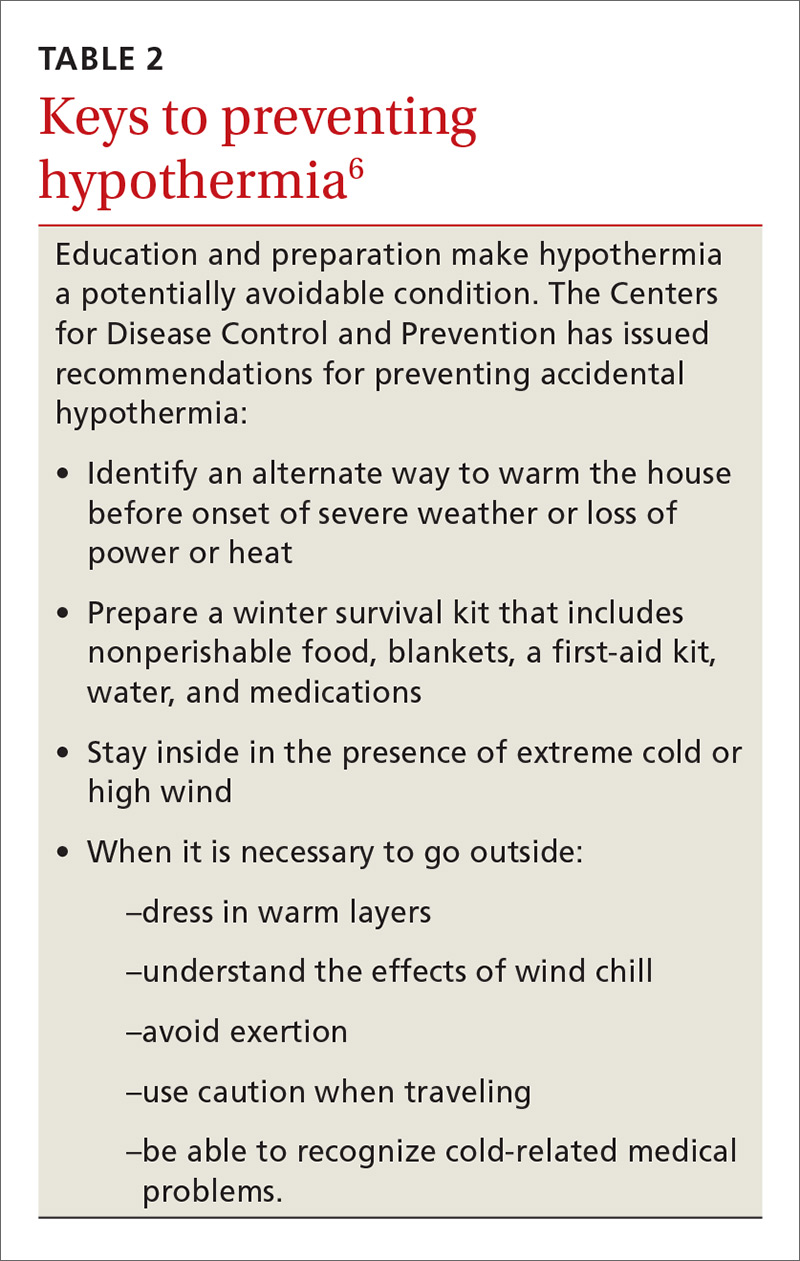

Environmental or iatrogenic factors (ie, primary hypothermia), such as wind, water immersion, wetness, aggressive fluid resuscitation, and heat stroke treatment can make people more susceptible to hypothermia. Medical conditions (ie, secondary hypothermia), such as burns, exfoliative dermatitis, severe psoriasis, hypoadrenalism, hypopituitarism, hypothyroidism, acute spinal cord transection, head trauma, stroke, tumor, pneumonia, Wernicke’s disease (encephalopathy), and sepsis can also predispose to hypothermia.1 Drugs, such as ethanol, phenothiazines, and sedative–hypnotics may decrease the hypothermia threshold.1 (For information on preventing hypothermia, see TABLE 2.6)

Pathophysiology: The role of the hypothalamus

Humans maintain body temperature by balancing heat production and heat loss to the environment. Heat is lost through the skin and lungs by 5 different mechanisms: radiation, conduction, convection, evaporation, and respiration. Convective heat loss to cold air and conductive heat loss to water are the most common mechanisms of accidental hypothermia.7

To maintain temperature homeostasis at 37°C (98.6°F) (±0.5°C [±0.9°F]), the hypothalamus receives input from central and peripheral thermal receptors and stimulates heat production through shivering, increasing the basal metabolic rate 2-fold to 5-fold.1 The hypothalamus also increases thyroid, catecholamine, and adrenal activity to increase the body’s production of heat and raise core temperature.

Heat conservation occurs by activation of sympathetically mediated vasoconstriction, reducing conduction to the skin, where cooling is greatest. After time, temperature regulation in the body becomes overwhelmed and catecholamine levels return to a pre-hypothermic state.

At 35°C (95°F), neurologic function begins to decline; at 32°C (89.6°F), metabolism, ventilation, and cardiac output decrease until shivering ceases. Changes in peripheral blood flow can create a false warming sensation, causing a person to remove clothing, a phenomenon referred to as paradoxical undressing. As hypothermia progresses, the neurologic, respiratory, and cardiac systems continue to slow until there is eventual cardiorespiratory failure.

Assessment and diagnosis

History and physical examination. A high index of suspicion for the diagnosis of hypothermia is essential, especially when caring for the elderly or patients presenting with unexplained illness. Often, symptoms of a primary condition may overshadow those reflecting hypothermia. In a multicenter survey that reviewed 428 cases of accidental hypothermia in the United States, 44% of patients had an underlying illness; 18%, coexisting infection; 19%, trauma; and 6%, overdose.3

There are no strict diagnostic criteria for hypothermia other than a core body temperature <35°C (<95°F). Standard thermometers often do not read below 34.4°C (93.2°F), so it is recommended that a rectal thermometer capable of reading low body temperatures be used for accurate measurement.

Hypothermic patients can exhibit a variety of symptoms, depending on the degree of decrease in core body temperature1:

- A mildly hypothermic patient might present with any combination of tachypnea, tachycardia, ataxia, impaired judgment, shivering, and vasoconstriction.

- Moderate hypothermia typically manifests as a decreased heart rate, decreased blood pressure, decreased level of consciousness, decreased respiratory effort, dilated pupils, extinction of shivering, and hyporeflexia. Cardiac abnormalities, such as atrial fibrillation and junctional bradycardia, may be seen in moderate hypothermia.

- Severe hypothermia presents with apnea, coma, nonreactive pupils, oliguria, areflexia, hypotension, bradycardia, and continued cardiac abnormalities, such as ventricular arrhythmias and asystole.

Laboratory evaluation. No specific laboratory tests are needed to diagnose hypothermia. General lab tests, however, may help determine whether hypothermia is the result, or the cause, of the clinical scenario. Recommended laboratory tests for making that determination include a complete blood count (CBC), chemistry panel, arterial blood gases, fingerstick glucose, and coagulation panel.

Results of lab tests may be abnormal because of the body’s decreased core body temperature. White blood cells and platelets in the CBC, for example, may be decreased due to splenic sequestration; these findings reverse with rewarming. With every 1°C (1.8°F) drop in core body temperature, hematocrit increases 2%.3 Sodium, chloride, and magnesium concentrations do not display consistent abnormalities with any core body temperature >25°C (77°F),3,8 but potassium levels may fluctuate because of acid-base changes that occur during rewarming.1 Creatinine and creatine kinase levels may be increased secondary to rhabdomyolysis or acute tubular necrosis.1

Arterial blood gases typically show metabolic acidosis or respiratory alkalosis, or both.8 Prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time are typically elevated in vivo, secondary to temperature-dependent enzymes in the coagulation cascade, but are reported normal in a blood specimen that is heated to 37°C (98.6°F) prior to analysis.1,8

Both hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia can be associated with hypothermia. The lactate level can be elevated, due to hypoperfusion. Hepatic impairment may be seen secondary to decreased cardiac output. An increase in the lipase level may also occur.3

When a hypothermic patient fails to respond to rewarming, or there is no clear source of cold exposure, consider testing for other causes of the problem, including hypothyroidism and adrenal insufficiency (see “Differential diagnosis”). Hypothermia may also decrease thyroid function in people with preexisting disease.

Other laboratory studies that can be considered include fibrinogen, blood-alcohol level, urine toxicology screen, and blood and fluid cultures.3

Imaging. Imaging studies are not performed routinely in the setting of hypothermia; however:

- Chest radiography can be considered to assess for aspiration pneumonia, vascular congestion, and pulmonary edema.

- Computed tomography (CT) of the head is helpful in the setting of trauma or if mental status does not clear with rewarming.3

- Bedside ultrasonography can assess for cardiac activity, volume status, pulmonary edema, free fluid, and trauma. (See "Point-of-care ultrasound: Coming soon to primary care?" J Fam Pract. 2018;67:70-80.)

Electrocardiography. An electrocardiogram is essential to evaluate for arrhythmias. Findings associated with hypothermia are prolongation of PR, QRS, and QT intervals; ST-segment elevation, T-wave inversion; and Osborn waves (J waves), which represent a positive deflection at the termination of the QRS complex with associated J-point elevation.8 Osborn waves generally present when the core body temperature is <32°C (89.6°F) and become larger as the core body temperature drops further.3

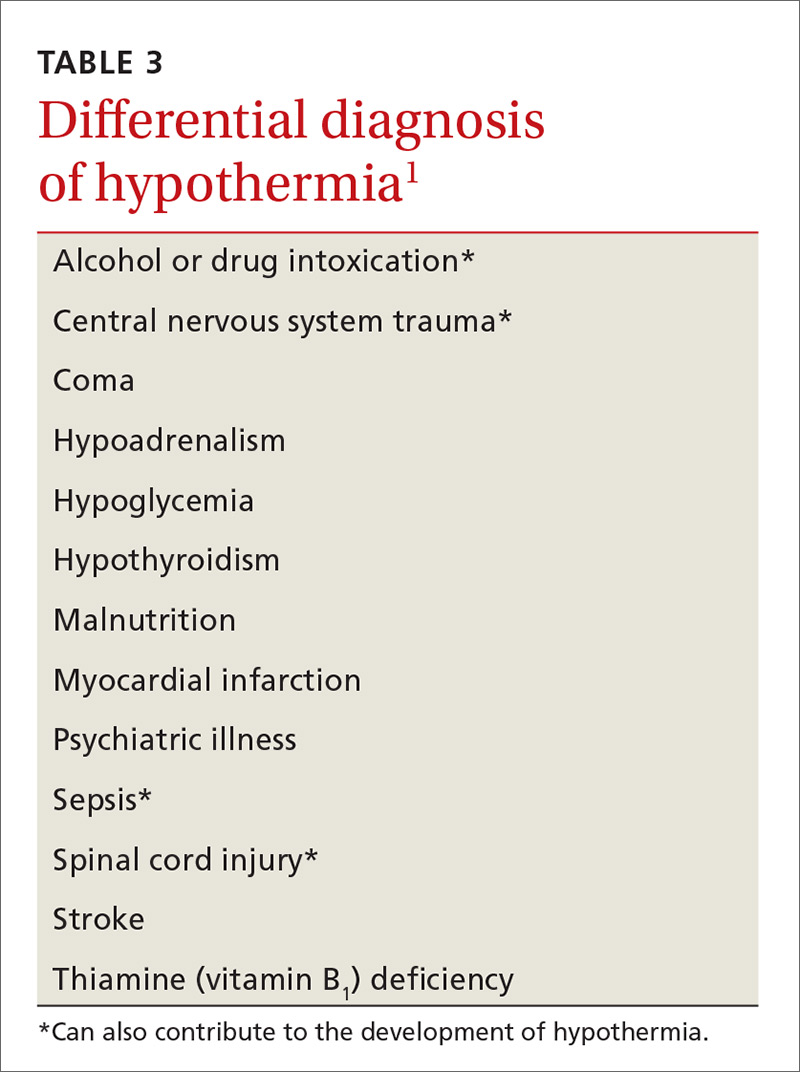

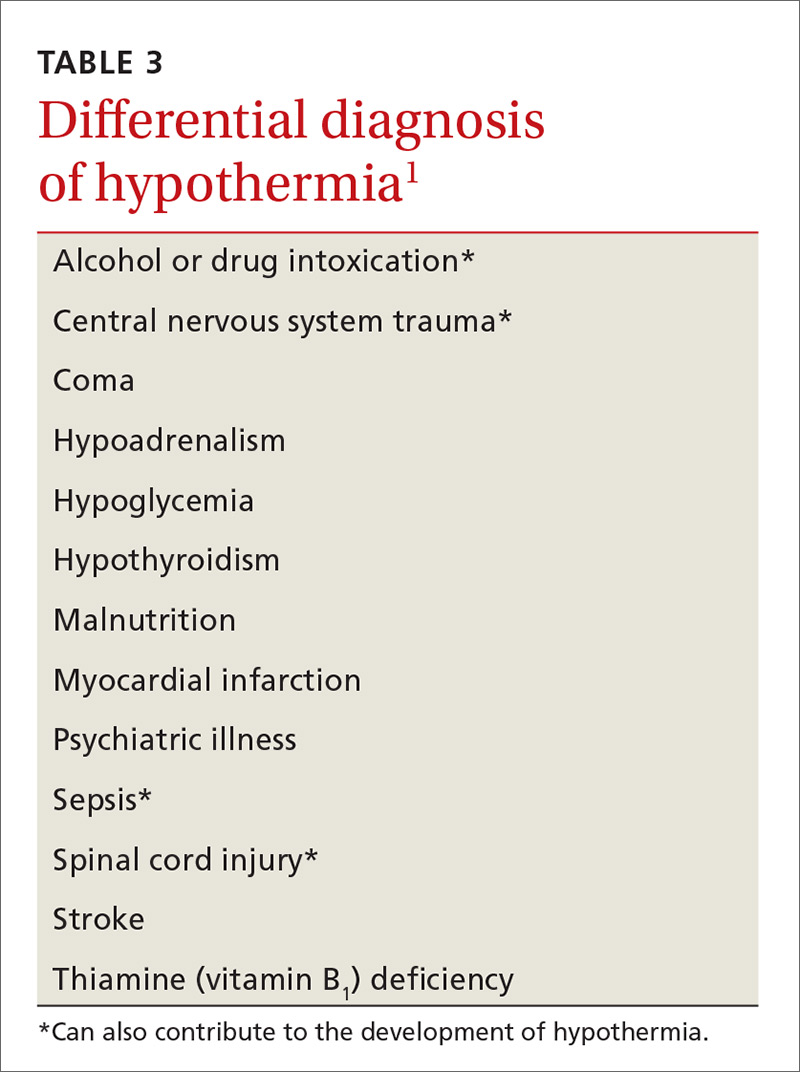

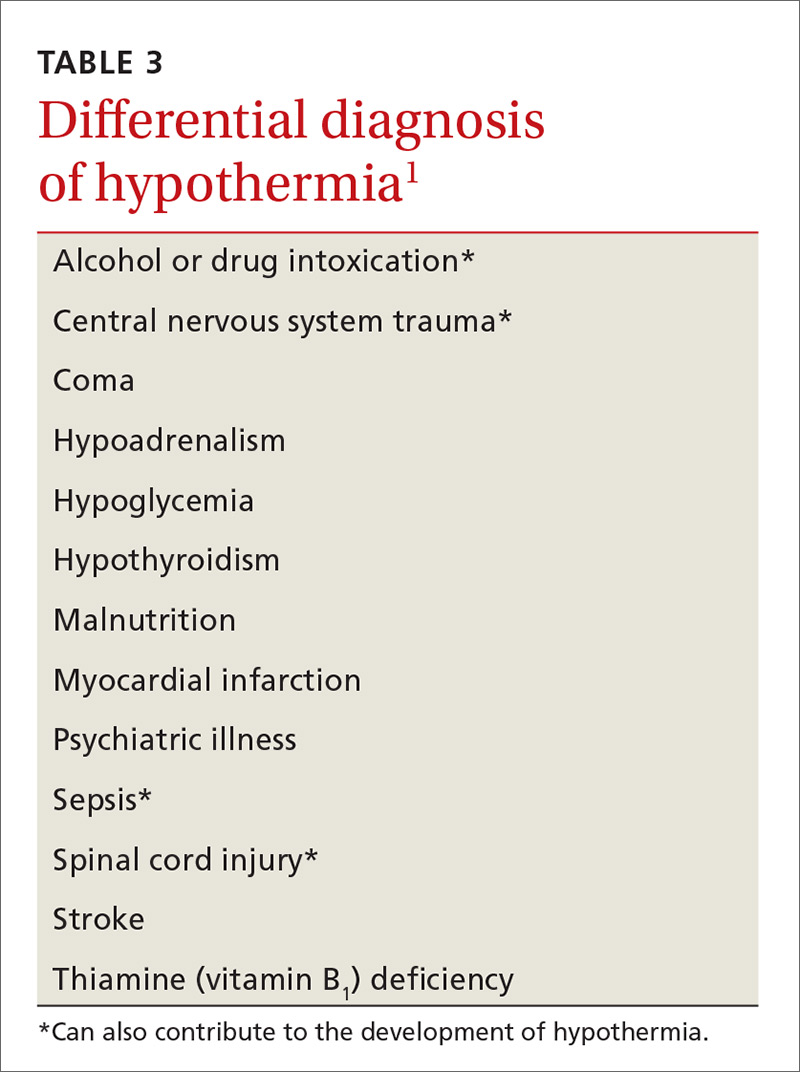

Differential diagnosis. Hypothermia is most commonly caused by environmental exposure, but the differential diagnosis is broad: many medical conditions, as well as drug and alcohol intoxication, can contribute to hypothermia (TABLE 31).

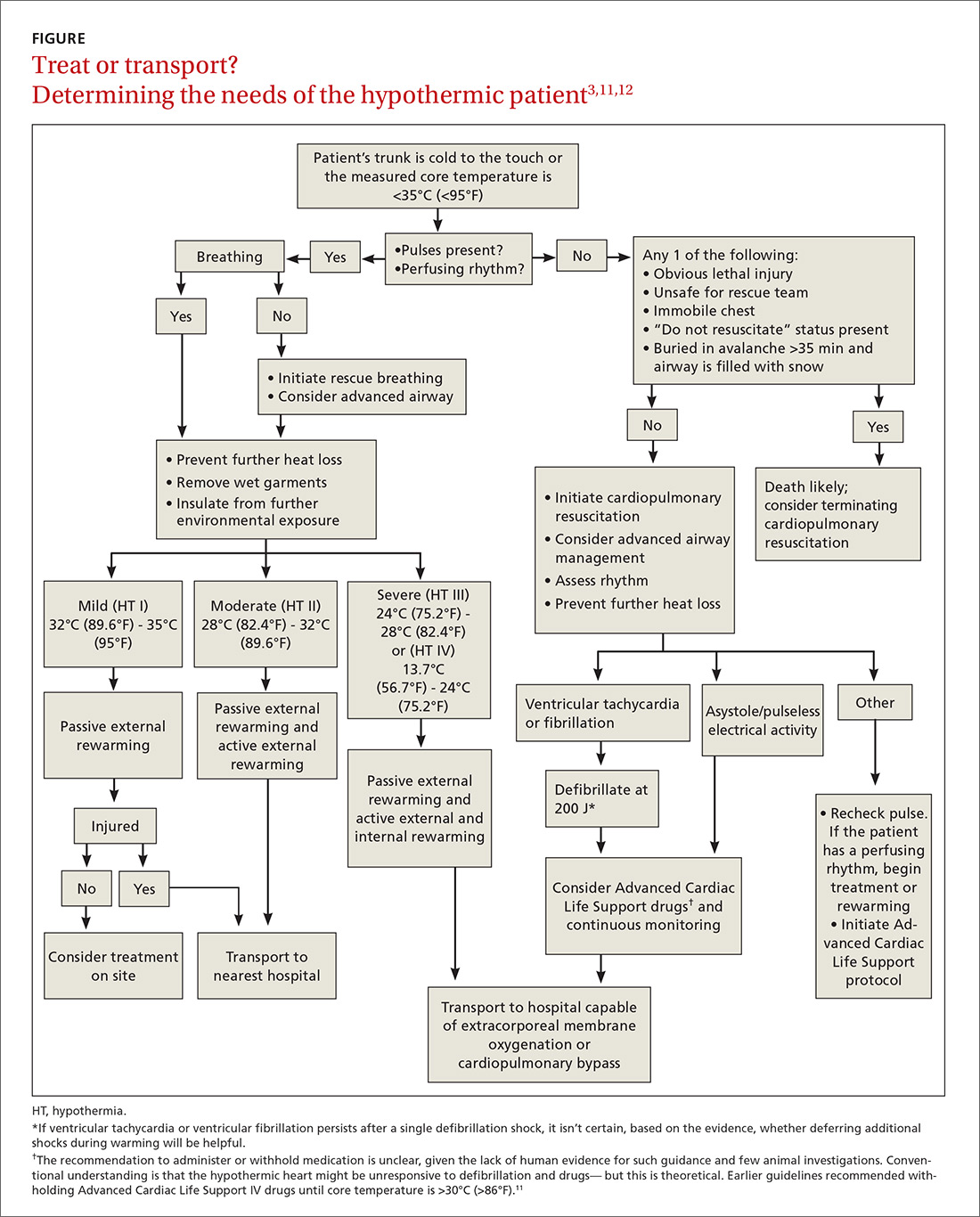

Treatment: Usually unnecessary, sometimes crucial

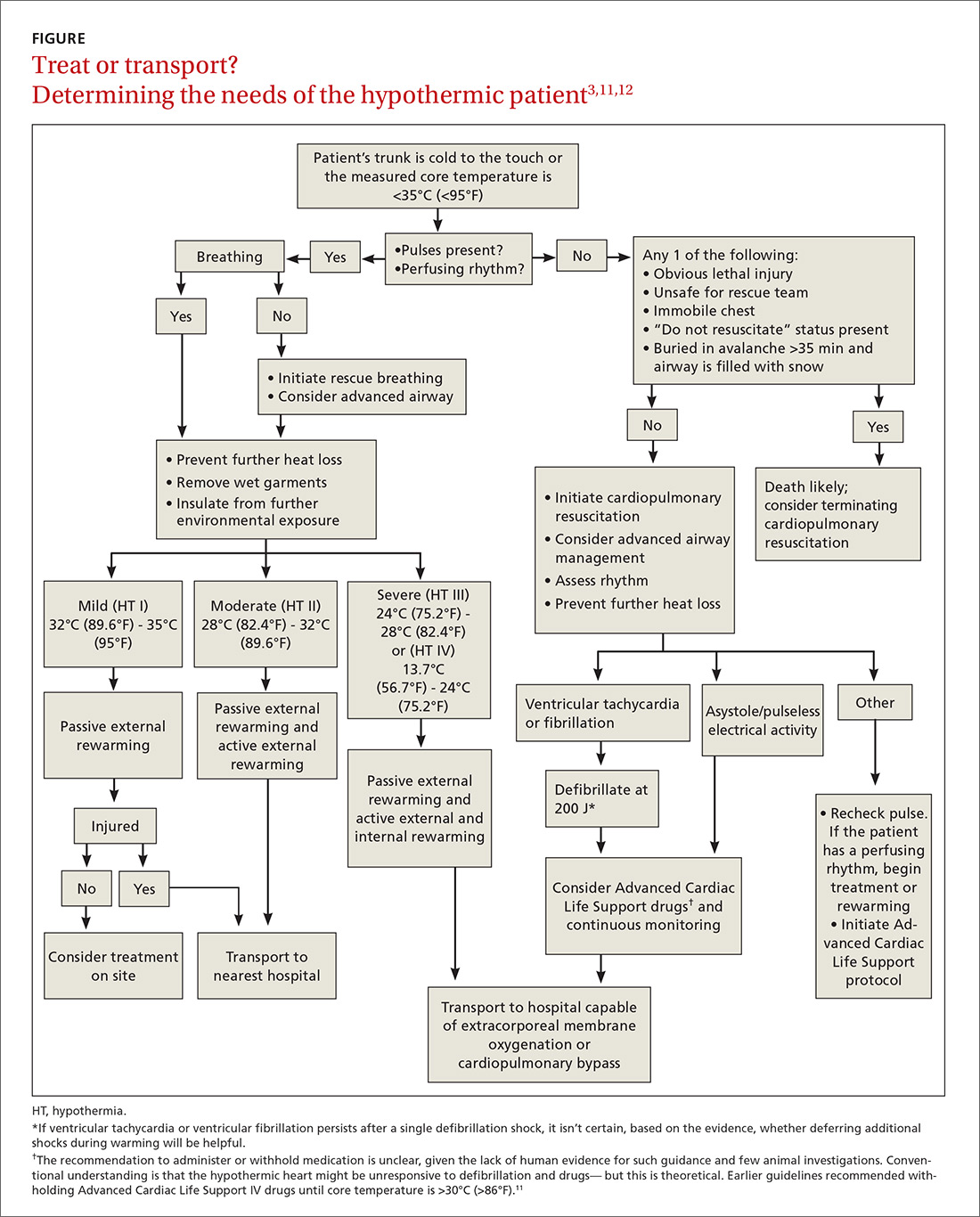

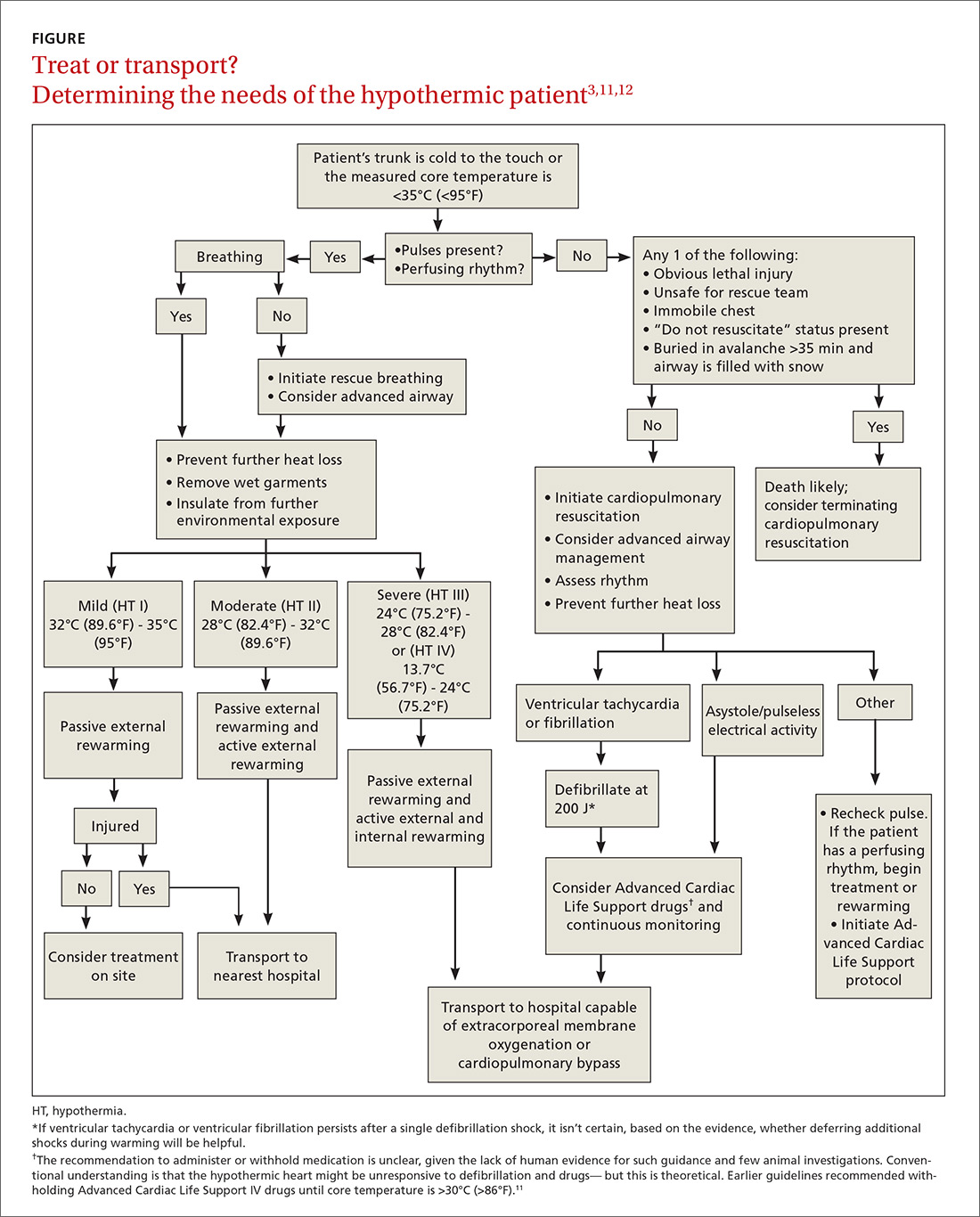

Most patients with mild hypothermia recover completely with little intervention. These patients should be evaluated for cognitive irregularities and observed in the ED before discharge.9 Moderate and severe hypothermia patients should be assessed using pre-hospital protocols and given cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) for cardiac arrest. Pre-hospital providers should rely more on symptoms in guiding their treatment response because core body temperature measurements can be difficult to obtain, and the response to a drop in core body temperature varies from patient to patient.10

Early considerations: Airway, breathing, circulation (ABC)