User login

A Peek at Our April 2018 Issue

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Empiric fluid restriction cuts transsphenoidal surgery readmissions

CHICAGO – A 70% drop in 30-day was achieved at the University of Colorado, Aurora, after endocrinologists there restricted fluid for the first 2 weeks postop, according to a report at the Endocrine Society annual meeting.

The antidiuretic hormone (ADH) rebound following pituitary adenoma resection often leads to fluid retention, and potentially dangerous hyponatremia, in about 25% of patients. It’s the leading cause of readmission for this procedure, occurring in up to 15% of patients.

To counter the problem, endocrinology fellow Kelsi Deaver, MD, and her colleagues limited patients to 1.5 L of fluid for 2 weeks after discharge, with a serum sodium check at day 7. If the sodium level was normal, patients remained on 1.5 L until the 2-week postop visit. If levels trended upward – a sign of dehydration – restrictions were eased to 2 or even 3 L, which is about the normal daily intake. If sodium levels trended downward, fluids were tightened to 1-1.2 L, or patients were brought in for further workup. The discharge packet included a 1.5-L cup so patients could track their intake.

Among 118 patients studied before the protocol was implemented in September 2015, 9 (7.6%) were readmitted for symptomatic hyponatremia within 30 days. Among 169 studied after the implementation of the fluid restriction protocol, just 4 (2.4%) were readmitted for hyponatremia (P = .044).

At present, there are no widely accepted postop fluid management guidelines for transsphenoidal surgery, but some hospitals have taken similar steps, she said.

It was the fluid restriction, not the 7-day sodium check, that drove the results. Among the four readmissions after the protocol took effect, two patients had their sodium checked, and two did not because their sodium drop was so precipitous that they were back in the hospital before the week was out. Overall, only about 70% of patients got their sodium checked as instructed.

Fluid restriction isn’t easy for patients. “The last day before discharge, we try to coach them through it,” with tips about sucking on ice chips and other strategies; “anything really to help them through it,” Dr. Deaver said.

Readmitted patients were no different from others in terms of pituitary tumor subtype, tumor size, gender, and other factors. “We couldn’t find any predictors,” she said. There were a higher percentage of macroadenomas in the preimplementation patients (91.5% versus 81.7%), but they were otherwise similar to postimplementation patients.

Those with evidence of diabetes insipidus at discharge were excluded from the study.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. The investigators did not have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Deaver KE et al. Endocrine Society 2018 annual meeting abstract SUN-572.

CHICAGO – A 70% drop in 30-day was achieved at the University of Colorado, Aurora, after endocrinologists there restricted fluid for the first 2 weeks postop, according to a report at the Endocrine Society annual meeting.

The antidiuretic hormone (ADH) rebound following pituitary adenoma resection often leads to fluid retention, and potentially dangerous hyponatremia, in about 25% of patients. It’s the leading cause of readmission for this procedure, occurring in up to 15% of patients.

To counter the problem, endocrinology fellow Kelsi Deaver, MD, and her colleagues limited patients to 1.5 L of fluid for 2 weeks after discharge, with a serum sodium check at day 7. If the sodium level was normal, patients remained on 1.5 L until the 2-week postop visit. If levels trended upward – a sign of dehydration – restrictions were eased to 2 or even 3 L, which is about the normal daily intake. If sodium levels trended downward, fluids were tightened to 1-1.2 L, or patients were brought in for further workup. The discharge packet included a 1.5-L cup so patients could track their intake.

Among 118 patients studied before the protocol was implemented in September 2015, 9 (7.6%) were readmitted for symptomatic hyponatremia within 30 days. Among 169 studied after the implementation of the fluid restriction protocol, just 4 (2.4%) were readmitted for hyponatremia (P = .044).

At present, there are no widely accepted postop fluid management guidelines for transsphenoidal surgery, but some hospitals have taken similar steps, she said.

It was the fluid restriction, not the 7-day sodium check, that drove the results. Among the four readmissions after the protocol took effect, two patients had their sodium checked, and two did not because their sodium drop was so precipitous that they were back in the hospital before the week was out. Overall, only about 70% of patients got their sodium checked as instructed.

Fluid restriction isn’t easy for patients. “The last day before discharge, we try to coach them through it,” with tips about sucking on ice chips and other strategies; “anything really to help them through it,” Dr. Deaver said.

Readmitted patients were no different from others in terms of pituitary tumor subtype, tumor size, gender, and other factors. “We couldn’t find any predictors,” she said. There were a higher percentage of macroadenomas in the preimplementation patients (91.5% versus 81.7%), but they were otherwise similar to postimplementation patients.

Those with evidence of diabetes insipidus at discharge were excluded from the study.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. The investigators did not have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Deaver KE et al. Endocrine Society 2018 annual meeting abstract SUN-572.

CHICAGO – A 70% drop in 30-day was achieved at the University of Colorado, Aurora, after endocrinologists there restricted fluid for the first 2 weeks postop, according to a report at the Endocrine Society annual meeting.

The antidiuretic hormone (ADH) rebound following pituitary adenoma resection often leads to fluid retention, and potentially dangerous hyponatremia, in about 25% of patients. It’s the leading cause of readmission for this procedure, occurring in up to 15% of patients.

To counter the problem, endocrinology fellow Kelsi Deaver, MD, and her colleagues limited patients to 1.5 L of fluid for 2 weeks after discharge, with a serum sodium check at day 7. If the sodium level was normal, patients remained on 1.5 L until the 2-week postop visit. If levels trended upward – a sign of dehydration – restrictions were eased to 2 or even 3 L, which is about the normal daily intake. If sodium levels trended downward, fluids were tightened to 1-1.2 L, or patients were brought in for further workup. The discharge packet included a 1.5-L cup so patients could track their intake.

Among 118 patients studied before the protocol was implemented in September 2015, 9 (7.6%) were readmitted for symptomatic hyponatremia within 30 days. Among 169 studied after the implementation of the fluid restriction protocol, just 4 (2.4%) were readmitted for hyponatremia (P = .044).

At present, there are no widely accepted postop fluid management guidelines for transsphenoidal surgery, but some hospitals have taken similar steps, she said.

It was the fluid restriction, not the 7-day sodium check, that drove the results. Among the four readmissions after the protocol took effect, two patients had their sodium checked, and two did not because their sodium drop was so precipitous that they were back in the hospital before the week was out. Overall, only about 70% of patients got their sodium checked as instructed.

Fluid restriction isn’t easy for patients. “The last day before discharge, we try to coach them through it,” with tips about sucking on ice chips and other strategies; “anything really to help them through it,” Dr. Deaver said.

Readmitted patients were no different from others in terms of pituitary tumor subtype, tumor size, gender, and other factors. “We couldn’t find any predictors,” she said. There were a higher percentage of macroadenomas in the preimplementation patients (91.5% versus 81.7%), but they were otherwise similar to postimplementation patients.

Those with evidence of diabetes insipidus at discharge were excluded from the study.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. The investigators did not have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Deaver KE et al. Endocrine Society 2018 annual meeting abstract SUN-572.

REPORTING FROM ENDO 2018

Key clinical point: A simple fluid restriction protocol cuts readmissions 70% following transsphenoidal surgery.

Major finding: The readmission rate among the transsphenoidal surgery patients was 7.6% before the fluid restriction protocol was implemented, compared with 2.4% (P = .044) afterward.

Study details: Review of 287 transsphenoidal surgery patients.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health supported the work. The investigators did not have any disclosures.

Source: Deaver KE et al. Abstract SUN-572

Ten-step trauma intervention offers help for foster families

WASHINGTON – Trauma-Informed Parenting Skills for Resource Parents, a new intervention program, might be an answer to addressing trauma symptoms in foster homes, according to a presentation at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

Rates of trauma exposure range from 80% to 93% in child welfare populations. In light of those statistics, foster parents are left to deal with the effects of traumatic stress symptoms without proper preparation or tools. Trauma-Informed Parenting Skills for Resource Parents targets different aspects of the way in which trauma can affect both the foster child and other members of the family.

The program is structured over the course of 10 weekly, 60- to 90-minute sessions for parents with foster children or those who plan to begin fostering. It is designed for caregivers of children aged 0-17 years. In addition, the intervention uses four key components: trauma awareness, caregiver relationships as the context for healing, trauma-informed parenting strategies, and creating physical and psychological safety, according to the program’s website.

“Trauma awareness is a large part of this intervention [in order to] help resource parents understand what’s happening,” Dr. Eslinger said. “There is trauma 101, orientation to what happens in the body when a child is exposed to a traumatic event, and this is followed by learning how to use the caregiver relationship.”

The 10 sessions were structured carefully, starting by addressing end goals, moving to education on the effects of early childhood trauma, transitioning to relaxation and coping skills, followed by teaching how to deal with challenging behaviors, and finishing with a final session where participants have a chance to bring it all together.

Caregivers also are instructed on using the cognitive triangle to understand their children’s feelings and build the framework to develop healthy reactions to behavior caused by traumatic stress.

“We work to help parents learn how to instill safety messages that the child needs to hear, creating a sense of safety in the home, and operating in the relationship in such a way to create psychological safety for their child,” Dr. Sprang said. “For many of [the parents], they’ve never understood that their disappointment and their hopelessness were a danger to the child – that children pick up on this.”

Neither Dr. Eslinger nor Dr. Sprang reported financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – Trauma-Informed Parenting Skills for Resource Parents, a new intervention program, might be an answer to addressing trauma symptoms in foster homes, according to a presentation at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

Rates of trauma exposure range from 80% to 93% in child welfare populations. In light of those statistics, foster parents are left to deal with the effects of traumatic stress symptoms without proper preparation or tools. Trauma-Informed Parenting Skills for Resource Parents targets different aspects of the way in which trauma can affect both the foster child and other members of the family.

The program is structured over the course of 10 weekly, 60- to 90-minute sessions for parents with foster children or those who plan to begin fostering. It is designed for caregivers of children aged 0-17 years. In addition, the intervention uses four key components: trauma awareness, caregiver relationships as the context for healing, trauma-informed parenting strategies, and creating physical and psychological safety, according to the program’s website.

“Trauma awareness is a large part of this intervention [in order to] help resource parents understand what’s happening,” Dr. Eslinger said. “There is trauma 101, orientation to what happens in the body when a child is exposed to a traumatic event, and this is followed by learning how to use the caregiver relationship.”

The 10 sessions were structured carefully, starting by addressing end goals, moving to education on the effects of early childhood trauma, transitioning to relaxation and coping skills, followed by teaching how to deal with challenging behaviors, and finishing with a final session where participants have a chance to bring it all together.

Caregivers also are instructed on using the cognitive triangle to understand their children’s feelings and build the framework to develop healthy reactions to behavior caused by traumatic stress.

“We work to help parents learn how to instill safety messages that the child needs to hear, creating a sense of safety in the home, and operating in the relationship in such a way to create psychological safety for their child,” Dr. Sprang said. “For many of [the parents], they’ve never understood that their disappointment and their hopelessness were a danger to the child – that children pick up on this.”

Neither Dr. Eslinger nor Dr. Sprang reported financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – Trauma-Informed Parenting Skills for Resource Parents, a new intervention program, might be an answer to addressing trauma symptoms in foster homes, according to a presentation at the annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

Rates of trauma exposure range from 80% to 93% in child welfare populations. In light of those statistics, foster parents are left to deal with the effects of traumatic stress symptoms without proper preparation or tools. Trauma-Informed Parenting Skills for Resource Parents targets different aspects of the way in which trauma can affect both the foster child and other members of the family.

The program is structured over the course of 10 weekly, 60- to 90-minute sessions for parents with foster children or those who plan to begin fostering. It is designed for caregivers of children aged 0-17 years. In addition, the intervention uses four key components: trauma awareness, caregiver relationships as the context for healing, trauma-informed parenting strategies, and creating physical and psychological safety, according to the program’s website.

“Trauma awareness is a large part of this intervention [in order to] help resource parents understand what’s happening,” Dr. Eslinger said. “There is trauma 101, orientation to what happens in the body when a child is exposed to a traumatic event, and this is followed by learning how to use the caregiver relationship.”

The 10 sessions were structured carefully, starting by addressing end goals, moving to education on the effects of early childhood trauma, transitioning to relaxation and coping skills, followed by teaching how to deal with challenging behaviors, and finishing with a final session where participants have a chance to bring it all together.

Caregivers also are instructed on using the cognitive triangle to understand their children’s feelings and build the framework to develop healthy reactions to behavior caused by traumatic stress.

“We work to help parents learn how to instill safety messages that the child needs to hear, creating a sense of safety in the home, and operating in the relationship in such a way to create psychological safety for their child,” Dr. Sprang said. “For many of [the parents], they’ve never understood that their disappointment and their hopelessness were a danger to the child – that children pick up on this.”

Neither Dr. Eslinger nor Dr. Sprang reported financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM THE ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION CONFERENCE 2018

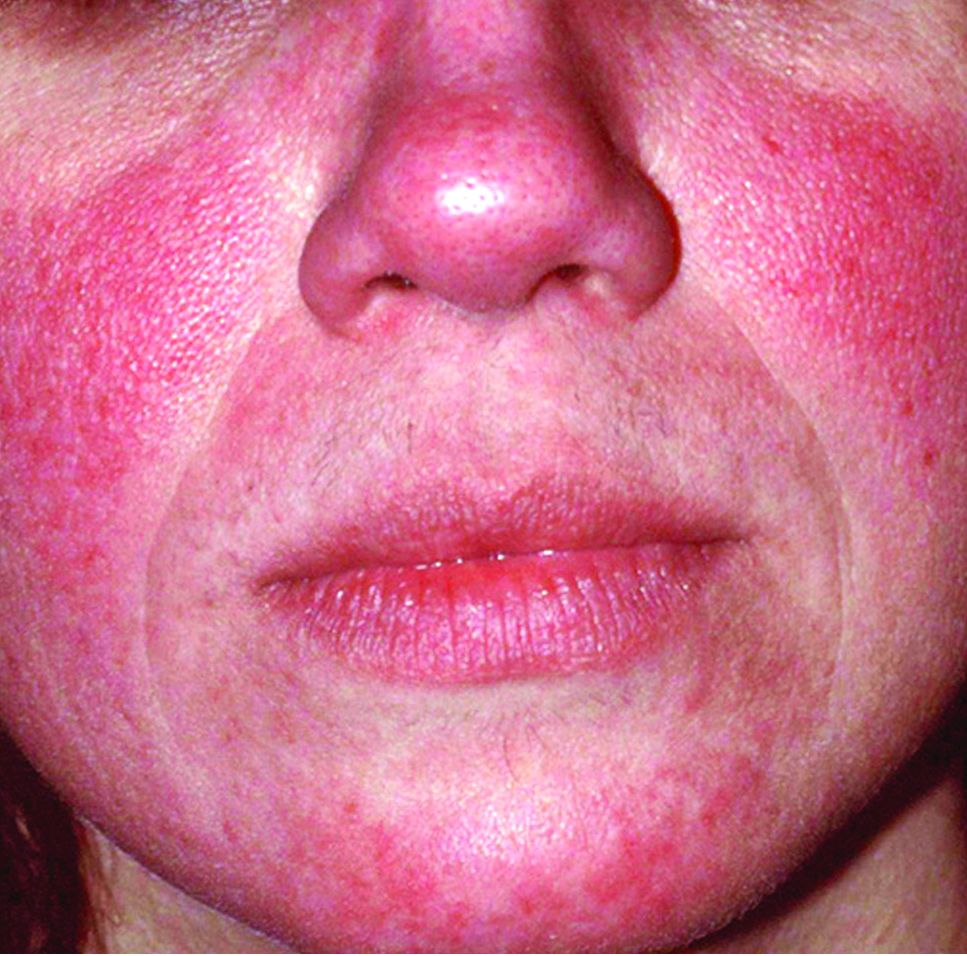

Rosacea tied to physical and psychological comorbidities

according to a review of 29 studies.

The recognition of rosacea as an inflammatory condition similar to psoriasis suggests that, as with psoriasis, rosacea may be associated with a range of systemic diseases, but data on such an association are limited, wrote Roger Haber, MD, from the department of dermatology at Saint George Hospital University Medical Center, Beirut, Lebanon.

“To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first review analyzing available data regarding the diseases associated with rosacea,” they said.

Overall, the most common comorbidities associated with rosacea were depression (reported in 117,848 patients), hypertension (18,176 patients), cardiovascular disease (9,739 patients), anxiety disorder (9,079 patients), dyslipidemia (7,004 patients), diabetes mellitus (6,306 patients), and migraine (6,136 patients). All associations were statistically significant.

Psychological problems significantly associated with rosacea include depression and anxiety, which may be related to similar inflammatory pathways among these conditions, the researchers noted.

Cardiovascular disease risk factors significantly associated with rosacea included coronary artery disease, cardiovascular disease, peripheral artery disease, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome. The association with coronary artery disease remained significant after adjusting for multiple variables, as has been shown with psoriasis, which supports consideration of rosacea as an independent risk factor for CAD, the researchers said.

In terms of gastrointestinal comorbidities, the studies reviewed found an association between rosacea and several GI disorders, including celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis, and Helicobacter pylori infection, they wrote. Although the current data do not imply causality, clinicians should screen rosacea patients for GI disorders, they noted.

The link between rosacea and migraine may stem from the similar vascular abnormalities and triggers common to both conditions, such as stress and alcohol, the researchers added.

The review does not establish causality between rosacea and any of the comorbidities examined in part because of the inclusion of observational studies, the researchers noted. “It is also possible that the observed association with rosacea is explained by shared environmental or lifestyle factors rather than by a common genetic disposition or pathophysiologic pathways,” they said. Controlled and prospective studies are needed to better identify associations, but general physicians and dermatologists who recognize the potential risk of comorbidities in rosacea patients may be better able to manage and treat them, they added.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. There was no funding source for the study.

SOURCE: Haber R et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 April;78(4):786-92.

according to a review of 29 studies.

The recognition of rosacea as an inflammatory condition similar to psoriasis suggests that, as with psoriasis, rosacea may be associated with a range of systemic diseases, but data on such an association are limited, wrote Roger Haber, MD, from the department of dermatology at Saint George Hospital University Medical Center, Beirut, Lebanon.

“To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first review analyzing available data regarding the diseases associated with rosacea,” they said.

Overall, the most common comorbidities associated with rosacea were depression (reported in 117,848 patients), hypertension (18,176 patients), cardiovascular disease (9,739 patients), anxiety disorder (9,079 patients), dyslipidemia (7,004 patients), diabetes mellitus (6,306 patients), and migraine (6,136 patients). All associations were statistically significant.

Psychological problems significantly associated with rosacea include depression and anxiety, which may be related to similar inflammatory pathways among these conditions, the researchers noted.

Cardiovascular disease risk factors significantly associated with rosacea included coronary artery disease, cardiovascular disease, peripheral artery disease, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome. The association with coronary artery disease remained significant after adjusting for multiple variables, as has been shown with psoriasis, which supports consideration of rosacea as an independent risk factor for CAD, the researchers said.

In terms of gastrointestinal comorbidities, the studies reviewed found an association between rosacea and several GI disorders, including celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis, and Helicobacter pylori infection, they wrote. Although the current data do not imply causality, clinicians should screen rosacea patients for GI disorders, they noted.

The link between rosacea and migraine may stem from the similar vascular abnormalities and triggers common to both conditions, such as stress and alcohol, the researchers added.

The review does not establish causality between rosacea and any of the comorbidities examined in part because of the inclusion of observational studies, the researchers noted. “It is also possible that the observed association with rosacea is explained by shared environmental or lifestyle factors rather than by a common genetic disposition or pathophysiologic pathways,” they said. Controlled and prospective studies are needed to better identify associations, but general physicians and dermatologists who recognize the potential risk of comorbidities in rosacea patients may be better able to manage and treat them, they added.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. There was no funding source for the study.

SOURCE: Haber R et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 April;78(4):786-92.

according to a review of 29 studies.

The recognition of rosacea as an inflammatory condition similar to psoriasis suggests that, as with psoriasis, rosacea may be associated with a range of systemic diseases, but data on such an association are limited, wrote Roger Haber, MD, from the department of dermatology at Saint George Hospital University Medical Center, Beirut, Lebanon.

“To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first review analyzing available data regarding the diseases associated with rosacea,” they said.

Overall, the most common comorbidities associated with rosacea were depression (reported in 117,848 patients), hypertension (18,176 patients), cardiovascular disease (9,739 patients), anxiety disorder (9,079 patients), dyslipidemia (7,004 patients), diabetes mellitus (6,306 patients), and migraine (6,136 patients). All associations were statistically significant.

Psychological problems significantly associated with rosacea include depression and anxiety, which may be related to similar inflammatory pathways among these conditions, the researchers noted.

Cardiovascular disease risk factors significantly associated with rosacea included coronary artery disease, cardiovascular disease, peripheral artery disease, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome. The association with coronary artery disease remained significant after adjusting for multiple variables, as has been shown with psoriasis, which supports consideration of rosacea as an independent risk factor for CAD, the researchers said.

In terms of gastrointestinal comorbidities, the studies reviewed found an association between rosacea and several GI disorders, including celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis, and Helicobacter pylori infection, they wrote. Although the current data do not imply causality, clinicians should screen rosacea patients for GI disorders, they noted.

The link between rosacea and migraine may stem from the similar vascular abnormalities and triggers common to both conditions, such as stress and alcohol, the researchers added.

The review does not establish causality between rosacea and any of the comorbidities examined in part because of the inclusion of observational studies, the researchers noted. “It is also possible that the observed association with rosacea is explained by shared environmental or lifestyle factors rather than by a common genetic disposition or pathophysiologic pathways,” they said. Controlled and prospective studies are needed to better identify associations, but general physicians and dermatologists who recognize the potential risk of comorbidities in rosacea patients may be better able to manage and treat them, they added.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. There was no funding source for the study.

SOURCE: Haber R et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 April;78(4):786-92.

FROM JAAD

Key clinical point: Rosacea is significantly associated with several comorbidities, including depression, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and anxiety.

Major finding: Approximately 75% of studies on depression and rosacea showed a positive correlation between these conditions.

Study details: A systematic review of 29 studies: 14 case-control, 8 cross-sectional, and 7 cohort.

Disclosures: The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Haber R et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 April;78(4):786-92.

ACOG welcomes over 600 attendees to white coat Capitol Hill

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ 36th annual Congressional Leadership Conference was held in Washington March 11-13 with the theme “Facts are important: Women’s health is no exception.”

Approximately 630 fellows, junior fellows, and medical students attended, with 50% of those present being junior fellows. Another 50% were at the CLC for the first time. Forty-nine states were represented. There were a total of 359 meetings with members of Congress, including senators and representatives.

The first day and a half was spent learning about advocacy and current women’s health issues that should be addressed by Congress. Rep. Jaime Herrera Beutler (R-Wash.) discussed her cosponsorship of the House bill, H.R. 1318, the “Preventing Maternal Deaths Act.” The bill authorizes the CDC to provide $7 million annually for grants to states for Maternal Mortality Review Committees (MMRC) in order to create, expand, or support a committee that will collect data so the causes of maternal mortality can be determined and reviewed in each state.

One of the two “asks” for the CLC attendees was to discuss maternal mortality and ask their representatives to cosponsor H.R. 1318 and their senators to cosponsor S. 1112, the “Maternal Health Accountability Act.”

With more women dying from pregnancy complications in the United States than any other developed country, maternal mortality needs to be assessed. Currently 33 states have MMRC while 11 states and the District of Columbia are in the process of establishing the committee.

The rate of maternal mortality has increased from 18.8 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 23.8 per 100,000 in 2014. African American women are three to four times more likely than non-Hispanic white women to die of pregnancy-related or associated complications in the United States. Causes of maternal death include preeclampsia, hemorrhage, overdosage, and suicide with the leading cause varying from one state to the next.

Sara Rosenbaum, professor of health law and policy at George Washington University, Washington, presented “Medicaid. Facts Matter to Women’s Health.” Rebekah Gee, MD, secretary of the Louisiana Department of Health discussed health care from a state’s perspective.

These and other presenters provided facts that were used for the second ask to the senators and representatives: Medicaid is a women’s health success story. Don’t turn the clock back on women’s health. There was not a specific bill to endorse, but the goal was to endorse continued Medicaid funding for women’s health. Medicaid covers 42.6% of U.S. births and around 75% of public family planning dollars. For every $1 spent for family planning by Medicaid there is a savings of $7.09. Medicaid expansion reduced the uninsured rate among women aged 18-64 years by nearly half from 19.3% to 10.8% in 5 years.

It has been documented that girls enrolled in Medicaid as children are more likely to attend college and experience upward mobility than their peers with the same socioeconomic status who did not have Medicaid. Medicaid helps to provide financial stability and serve as the pathway to jobs for women and girls. Nearly 80% of Medicaid beneficiaries live in working families, and 60% themselves work. Of those who don’t work, 36% do not work because of disability or illness, 30% care for home or family, 15% are in school, 9% are retired, and 6% could not find work. Work requirements add administrative complexity for states and women without long-term gains in employment.

Qualified providers should not be prevented from participating in Medicaid because they perform abortions or provide counseling or refer patients for abortion. Politicians should not select among qualified providers at the expense of women’s access to care. Very often, there are no other providers who can fill the gap, leaving low-income women without access to care.

Willie Parker, MD, addressed reproductive rights and access to care at the President’s Luncheon.

Prior to the Hill visits, attendees were given advice by fellow physicians, Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-Calif.), and Rep. Raul Ruiz, MD (D-Calif.).

As stated by ACOG President Haywood Brown, MD, “This is a critical moment in our nation’s history. People are engaging like we haven’t seen in our lifetime, and politicians are paying attention. Advocacy efforts around the country are already creating change, in policy and in elections. ... Let’s remind America of what ob.gyns. know best: Facts are important. Women’s health is no exception.”

Dr. Bohon is an ob.gyn. in private practice in Washington. She is an ACOG state legislative chair from the District of Columbia and a member of the Ob.Gyn. News Editorial Advisory Board. She reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Cuff of the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, is the current chair of the Junior Fellow Congress Advisory Council of ACOG.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ 36th annual Congressional Leadership Conference was held in Washington March 11-13 with the theme “Facts are important: Women’s health is no exception.”

Approximately 630 fellows, junior fellows, and medical students attended, with 50% of those present being junior fellows. Another 50% were at the CLC for the first time. Forty-nine states were represented. There were a total of 359 meetings with members of Congress, including senators and representatives.

The first day and a half was spent learning about advocacy and current women’s health issues that should be addressed by Congress. Rep. Jaime Herrera Beutler (R-Wash.) discussed her cosponsorship of the House bill, H.R. 1318, the “Preventing Maternal Deaths Act.” The bill authorizes the CDC to provide $7 million annually for grants to states for Maternal Mortality Review Committees (MMRC) in order to create, expand, or support a committee that will collect data so the causes of maternal mortality can be determined and reviewed in each state.

One of the two “asks” for the CLC attendees was to discuss maternal mortality and ask their representatives to cosponsor H.R. 1318 and their senators to cosponsor S. 1112, the “Maternal Health Accountability Act.”

With more women dying from pregnancy complications in the United States than any other developed country, maternal mortality needs to be assessed. Currently 33 states have MMRC while 11 states and the District of Columbia are in the process of establishing the committee.

The rate of maternal mortality has increased from 18.8 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 23.8 per 100,000 in 2014. African American women are three to four times more likely than non-Hispanic white women to die of pregnancy-related or associated complications in the United States. Causes of maternal death include preeclampsia, hemorrhage, overdosage, and suicide with the leading cause varying from one state to the next.

Sara Rosenbaum, professor of health law and policy at George Washington University, Washington, presented “Medicaid. Facts Matter to Women’s Health.” Rebekah Gee, MD, secretary of the Louisiana Department of Health discussed health care from a state’s perspective.

These and other presenters provided facts that were used for the second ask to the senators and representatives: Medicaid is a women’s health success story. Don’t turn the clock back on women’s health. There was not a specific bill to endorse, but the goal was to endorse continued Medicaid funding for women’s health. Medicaid covers 42.6% of U.S. births and around 75% of public family planning dollars. For every $1 spent for family planning by Medicaid there is a savings of $7.09. Medicaid expansion reduced the uninsured rate among women aged 18-64 years by nearly half from 19.3% to 10.8% in 5 years.

It has been documented that girls enrolled in Medicaid as children are more likely to attend college and experience upward mobility than their peers with the same socioeconomic status who did not have Medicaid. Medicaid helps to provide financial stability and serve as the pathway to jobs for women and girls. Nearly 80% of Medicaid beneficiaries live in working families, and 60% themselves work. Of those who don’t work, 36% do not work because of disability or illness, 30% care for home or family, 15% are in school, 9% are retired, and 6% could not find work. Work requirements add administrative complexity for states and women without long-term gains in employment.

Qualified providers should not be prevented from participating in Medicaid because they perform abortions or provide counseling or refer patients for abortion. Politicians should not select among qualified providers at the expense of women’s access to care. Very often, there are no other providers who can fill the gap, leaving low-income women without access to care.

Willie Parker, MD, addressed reproductive rights and access to care at the President’s Luncheon.

Prior to the Hill visits, attendees were given advice by fellow physicians, Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-Calif.), and Rep. Raul Ruiz, MD (D-Calif.).

As stated by ACOG President Haywood Brown, MD, “This is a critical moment in our nation’s history. People are engaging like we haven’t seen in our lifetime, and politicians are paying attention. Advocacy efforts around the country are already creating change, in policy and in elections. ... Let’s remind America of what ob.gyns. know best: Facts are important. Women’s health is no exception.”

Dr. Bohon is an ob.gyn. in private practice in Washington. She is an ACOG state legislative chair from the District of Columbia and a member of the Ob.Gyn. News Editorial Advisory Board. She reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Cuff of the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, is the current chair of the Junior Fellow Congress Advisory Council of ACOG.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ 36th annual Congressional Leadership Conference was held in Washington March 11-13 with the theme “Facts are important: Women’s health is no exception.”

Approximately 630 fellows, junior fellows, and medical students attended, with 50% of those present being junior fellows. Another 50% were at the CLC for the first time. Forty-nine states were represented. There were a total of 359 meetings with members of Congress, including senators and representatives.

The first day and a half was spent learning about advocacy and current women’s health issues that should be addressed by Congress. Rep. Jaime Herrera Beutler (R-Wash.) discussed her cosponsorship of the House bill, H.R. 1318, the “Preventing Maternal Deaths Act.” The bill authorizes the CDC to provide $7 million annually for grants to states for Maternal Mortality Review Committees (MMRC) in order to create, expand, or support a committee that will collect data so the causes of maternal mortality can be determined and reviewed in each state.

One of the two “asks” for the CLC attendees was to discuss maternal mortality and ask their representatives to cosponsor H.R. 1318 and their senators to cosponsor S. 1112, the “Maternal Health Accountability Act.”

With more women dying from pregnancy complications in the United States than any other developed country, maternal mortality needs to be assessed. Currently 33 states have MMRC while 11 states and the District of Columbia are in the process of establishing the committee.

The rate of maternal mortality has increased from 18.8 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 23.8 per 100,000 in 2014. African American women are three to four times more likely than non-Hispanic white women to die of pregnancy-related or associated complications in the United States. Causes of maternal death include preeclampsia, hemorrhage, overdosage, and suicide with the leading cause varying from one state to the next.

Sara Rosenbaum, professor of health law and policy at George Washington University, Washington, presented “Medicaid. Facts Matter to Women’s Health.” Rebekah Gee, MD, secretary of the Louisiana Department of Health discussed health care from a state’s perspective.

These and other presenters provided facts that were used for the second ask to the senators and representatives: Medicaid is a women’s health success story. Don’t turn the clock back on women’s health. There was not a specific bill to endorse, but the goal was to endorse continued Medicaid funding for women’s health. Medicaid covers 42.6% of U.S. births and around 75% of public family planning dollars. For every $1 spent for family planning by Medicaid there is a savings of $7.09. Medicaid expansion reduced the uninsured rate among women aged 18-64 years by nearly half from 19.3% to 10.8% in 5 years.

It has been documented that girls enrolled in Medicaid as children are more likely to attend college and experience upward mobility than their peers with the same socioeconomic status who did not have Medicaid. Medicaid helps to provide financial stability and serve as the pathway to jobs for women and girls. Nearly 80% of Medicaid beneficiaries live in working families, and 60% themselves work. Of those who don’t work, 36% do not work because of disability or illness, 30% care for home or family, 15% are in school, 9% are retired, and 6% could not find work. Work requirements add administrative complexity for states and women without long-term gains in employment.

Qualified providers should not be prevented from participating in Medicaid because they perform abortions or provide counseling or refer patients for abortion. Politicians should not select among qualified providers at the expense of women’s access to care. Very often, there are no other providers who can fill the gap, leaving low-income women without access to care.

Willie Parker, MD, addressed reproductive rights and access to care at the President’s Luncheon.

Prior to the Hill visits, attendees were given advice by fellow physicians, Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-Calif.), and Rep. Raul Ruiz, MD (D-Calif.).

As stated by ACOG President Haywood Brown, MD, “This is a critical moment in our nation’s history. People are engaging like we haven’t seen in our lifetime, and politicians are paying attention. Advocacy efforts around the country are already creating change, in policy and in elections. ... Let’s remind America of what ob.gyns. know best: Facts are important. Women’s health is no exception.”

Dr. Bohon is an ob.gyn. in private practice in Washington. She is an ACOG state legislative chair from the District of Columbia and a member of the Ob.Gyn. News Editorial Advisory Board. She reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Cuff of the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, is the current chair of the Junior Fellow Congress Advisory Council of ACOG.

Surgery after immunotherapy effective in advanced melanoma

CHICAGO – Surgical resection is an effective treatment in selected patients with advanced melanoma treated with checkpoint blockade immunotherapy, according to a study of an institutional database at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York presented at the Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium.

“In the era of improved systemic therapy, checkpoint blockade for metastatic melanoma and the ability to surgically resect all disease after treatment is associated with an estimated survival of 75%, better than what’s been previously reported,” said Danielle M. Bello, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering.

The study analyzed a cohort of 237 patients who had unresectable stage III and IV melanoma and were treated with checkpoint blockade, including CTLA-4, programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), and programmed death-ligand 1 inhibitors, and then had surgical resection during 2003-2017.

Dr. Bello noted two previous studies that had reported encouraging outcomes in advanced melanoma. The first highlighted the role for surgery in stage IV melanoma. In that phase 3 clinical trial, patients had resection of up to five sites of metastatic disease and were then randomized to one of two treatment arms: bacillus Calmette-Guérin and allogeneic whole-cell vaccine (Canvaxin) or bacillus Calmette-Guérin and placebo. While this trial found no difference in overall survival between groups, it did report a 5-year overall survival exceeding 40% in both treatment arms, which highlighted that Stage IV patients who underwent resection of all their disease had survival outcomes superior to outcomes previously reported (Ann Surg Onc. 2017 Dec;24[13]:3991-4000). The second trial, the recent Checkmate 067 trial, emphasized the role of effective systemic checkpoint blockade in advanced stage III and IV melanoma. It reported that patients treated with combined nivolumab/ipilimumab therapy had not reached median overall survival at minimum 36 months of follow-up (N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 5;377[14]:1345-56).

“We know that checkpoint inhibitor therapy has revolutionized the landscape of unresectable stage III and IV melanoma,” Dr. Bello said. However, despite encouraging trial readouts of overall survival, progression-free survival is a different story. “We know that the median progression-free survival even in our best combination therapy is 11.5 months, meaning that 50% of patients will go on to progress in a year and many will go on to surgical resection of their disease and do quite well,” she said.

Dr. Bello and her coauthors set out to describe outcomes of a “highly selective group” of patients who had surgical resection after checkpoint inhibitor therapy. “The majority of patients in our study had a cutaneous primary melanoma,” she said. Median age was 63 years, and 88% had stage IV disease. Regarding checkpoint blockade regimen, 62% received anti–CTLA-4, and 29% received combination anti–PD-1 and anti–CLTA-4 either sequentially or concomitantly prior to resection.

The median time from the start of immunotherapy to the first operation was 7 months. Forty-six percent had no further postoperative treatment after resection. In those, who did require further treatment, the majority received anti–PD-1 followed by targeted BRAF/MEK therapy, she said.

The analysis stratified patients into the following three categories based on radiological response to immunotherapy:

- Overall response to checkpoint blockade and the index lesion was either smaller since initiation of therapy or stabilized (12; 5.1%). Half of this group had a pathological complete response.

- Isolated site of progressive disease with residual stable disease elsewhere or as the only site of progressive disease (106; 44.7%).

- Multiple sites of progressive and palliative operations (119; 50.2%).

Median overall survival was 21 months in the entire study cohort with a median follow-up of 23 months, Dr. Bello said. “Those resected to no evidence of disease (NED) – 87 patients – had an estimated 5-year overall survival of 75%.” The NED group did not reach median OS.

The analysis also stratified overall survival by response to immunotherapy. “Patients with responding or stable disease had an estimated 90% 5-year overall survival,” Dr. Bellow said. “Those with one isolated progressive lesion that was resected had a 60% 5-year overall survival.” A more detailed analysis of the latter group found that those who had a resection to NED had an improved overall survival of 75% at 5 years. Resected patients who had residual remaining disease had a 30% 5-year overall survival.

“Further follow-up is needed to assess the durability and contributions of surgery, and further studies are underway to identify biomarkers associated with improved survival after immunotherapy and surgery,” Dr. Bello said.

SOURCE: Bello DM et al. SSO 2018, Abstract 5.

CHICAGO – Surgical resection is an effective treatment in selected patients with advanced melanoma treated with checkpoint blockade immunotherapy, according to a study of an institutional database at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York presented at the Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium.

“In the era of improved systemic therapy, checkpoint blockade for metastatic melanoma and the ability to surgically resect all disease after treatment is associated with an estimated survival of 75%, better than what’s been previously reported,” said Danielle M. Bello, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering.

The study analyzed a cohort of 237 patients who had unresectable stage III and IV melanoma and were treated with checkpoint blockade, including CTLA-4, programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), and programmed death-ligand 1 inhibitors, and then had surgical resection during 2003-2017.

Dr. Bello noted two previous studies that had reported encouraging outcomes in advanced melanoma. The first highlighted the role for surgery in stage IV melanoma. In that phase 3 clinical trial, patients had resection of up to five sites of metastatic disease and were then randomized to one of two treatment arms: bacillus Calmette-Guérin and allogeneic whole-cell vaccine (Canvaxin) or bacillus Calmette-Guérin and placebo. While this trial found no difference in overall survival between groups, it did report a 5-year overall survival exceeding 40% in both treatment arms, which highlighted that Stage IV patients who underwent resection of all their disease had survival outcomes superior to outcomes previously reported (Ann Surg Onc. 2017 Dec;24[13]:3991-4000). The second trial, the recent Checkmate 067 trial, emphasized the role of effective systemic checkpoint blockade in advanced stage III and IV melanoma. It reported that patients treated with combined nivolumab/ipilimumab therapy had not reached median overall survival at minimum 36 months of follow-up (N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 5;377[14]:1345-56).

“We know that checkpoint inhibitor therapy has revolutionized the landscape of unresectable stage III and IV melanoma,” Dr. Bello said. However, despite encouraging trial readouts of overall survival, progression-free survival is a different story. “We know that the median progression-free survival even in our best combination therapy is 11.5 months, meaning that 50% of patients will go on to progress in a year and many will go on to surgical resection of their disease and do quite well,” she said.

Dr. Bello and her coauthors set out to describe outcomes of a “highly selective group” of patients who had surgical resection after checkpoint inhibitor therapy. “The majority of patients in our study had a cutaneous primary melanoma,” she said. Median age was 63 years, and 88% had stage IV disease. Regarding checkpoint blockade regimen, 62% received anti–CTLA-4, and 29% received combination anti–PD-1 and anti–CLTA-4 either sequentially or concomitantly prior to resection.

The median time from the start of immunotherapy to the first operation was 7 months. Forty-six percent had no further postoperative treatment after resection. In those, who did require further treatment, the majority received anti–PD-1 followed by targeted BRAF/MEK therapy, she said.

The analysis stratified patients into the following three categories based on radiological response to immunotherapy:

- Overall response to checkpoint blockade and the index lesion was either smaller since initiation of therapy or stabilized (12; 5.1%). Half of this group had a pathological complete response.

- Isolated site of progressive disease with residual stable disease elsewhere or as the only site of progressive disease (106; 44.7%).

- Multiple sites of progressive and palliative operations (119; 50.2%).

Median overall survival was 21 months in the entire study cohort with a median follow-up of 23 months, Dr. Bello said. “Those resected to no evidence of disease (NED) – 87 patients – had an estimated 5-year overall survival of 75%.” The NED group did not reach median OS.

The analysis also stratified overall survival by response to immunotherapy. “Patients with responding or stable disease had an estimated 90% 5-year overall survival,” Dr. Bellow said. “Those with one isolated progressive lesion that was resected had a 60% 5-year overall survival.” A more detailed analysis of the latter group found that those who had a resection to NED had an improved overall survival of 75% at 5 years. Resected patients who had residual remaining disease had a 30% 5-year overall survival.

“Further follow-up is needed to assess the durability and contributions of surgery, and further studies are underway to identify biomarkers associated with improved survival after immunotherapy and surgery,” Dr. Bello said.

SOURCE: Bello DM et al. SSO 2018, Abstract 5.

CHICAGO – Surgical resection is an effective treatment in selected patients with advanced melanoma treated with checkpoint blockade immunotherapy, according to a study of an institutional database at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York presented at the Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium.

“In the era of improved systemic therapy, checkpoint blockade for metastatic melanoma and the ability to surgically resect all disease after treatment is associated with an estimated survival of 75%, better than what’s been previously reported,” said Danielle M. Bello, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering.

The study analyzed a cohort of 237 patients who had unresectable stage III and IV melanoma and were treated with checkpoint blockade, including CTLA-4, programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), and programmed death-ligand 1 inhibitors, and then had surgical resection during 2003-2017.

Dr. Bello noted two previous studies that had reported encouraging outcomes in advanced melanoma. The first highlighted the role for surgery in stage IV melanoma. In that phase 3 clinical trial, patients had resection of up to five sites of metastatic disease and were then randomized to one of two treatment arms: bacillus Calmette-Guérin and allogeneic whole-cell vaccine (Canvaxin) or bacillus Calmette-Guérin and placebo. While this trial found no difference in overall survival between groups, it did report a 5-year overall survival exceeding 40% in both treatment arms, which highlighted that Stage IV patients who underwent resection of all their disease had survival outcomes superior to outcomes previously reported (Ann Surg Onc. 2017 Dec;24[13]:3991-4000). The second trial, the recent Checkmate 067 trial, emphasized the role of effective systemic checkpoint blockade in advanced stage III and IV melanoma. It reported that patients treated with combined nivolumab/ipilimumab therapy had not reached median overall survival at minimum 36 months of follow-up (N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 5;377[14]:1345-56).

“We know that checkpoint inhibitor therapy has revolutionized the landscape of unresectable stage III and IV melanoma,” Dr. Bello said. However, despite encouraging trial readouts of overall survival, progression-free survival is a different story. “We know that the median progression-free survival even in our best combination therapy is 11.5 months, meaning that 50% of patients will go on to progress in a year and many will go on to surgical resection of their disease and do quite well,” she said.

Dr. Bello and her coauthors set out to describe outcomes of a “highly selective group” of patients who had surgical resection after checkpoint inhibitor therapy. “The majority of patients in our study had a cutaneous primary melanoma,” she said. Median age was 63 years, and 88% had stage IV disease. Regarding checkpoint blockade regimen, 62% received anti–CTLA-4, and 29% received combination anti–PD-1 and anti–CLTA-4 either sequentially or concomitantly prior to resection.

The median time from the start of immunotherapy to the first operation was 7 months. Forty-six percent had no further postoperative treatment after resection. In those, who did require further treatment, the majority received anti–PD-1 followed by targeted BRAF/MEK therapy, she said.

The analysis stratified patients into the following three categories based on radiological response to immunotherapy:

- Overall response to checkpoint blockade and the index lesion was either smaller since initiation of therapy or stabilized (12; 5.1%). Half of this group had a pathological complete response.

- Isolated site of progressive disease with residual stable disease elsewhere or as the only site of progressive disease (106; 44.7%).

- Multiple sites of progressive and palliative operations (119; 50.2%).

Median overall survival was 21 months in the entire study cohort with a median follow-up of 23 months, Dr. Bello said. “Those resected to no evidence of disease (NED) – 87 patients – had an estimated 5-year overall survival of 75%.” The NED group did not reach median OS.

The analysis also stratified overall survival by response to immunotherapy. “Patients with responding or stable disease had an estimated 90% 5-year overall survival,” Dr. Bellow said. “Those with one isolated progressive lesion that was resected had a 60% 5-year overall survival.” A more detailed analysis of the latter group found that those who had a resection to NED had an improved overall survival of 75% at 5 years. Resected patients who had residual remaining disease had a 30% 5-year overall survival.

“Further follow-up is needed to assess the durability and contributions of surgery, and further studies are underway to identify biomarkers associated with improved survival after immunotherapy and surgery,” Dr. Bello said.

SOURCE: Bello DM et al. SSO 2018, Abstract 5.

REPORTING FROM SSO 2018

Key clinical point: Surgery after immunotherapy can achieve good outcomes in advanced melanoma.

Major findings: Complete resection achieved an estimated 5-year overall survival of 75%.

Study details: Analysis of a cohort of 237 patients from a prospectively maintained institutional melanoma database who had surgery after immunotherapy for unresectable stage III and IV melanoma during 2003-2017.

Disclosures: Dr. Bello reported having no financial disclosures. Some coauthors reported financial relationships with various pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Bello DM et al. SSO 2018, Abstract 5.

PVT after sleeve gastrectomy treatable with anticoagulants

can be effectively treated with extended postoperative anticoagulation therapy, findings from a large-scale, retrospective study indicate.

The research was conducted using data from medical records of created by physicians from five Australian bariatric centers, reported Stephanie Bee Ming Tan, MBBS, of the Gold Coast University Hospital, Queensland, Australia, and her associates in the journal Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. Following elective laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG), a total of 18 (0.3%) of the 5,951 obese patients were diagnosed with portomesenteric vein thrombosis (PVT). The PVT-affected population was a mean age of 44 years and 61% were women. All of these patients had at least one venous thrombosis systematic predisposition factor such as morbid obesity (50%), smoking (50%), or a personal or family history of a clotting disorder (39%).

All study patients were given thromboprophylaxis of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or unfractionated heparin plus mechanical thromboprophylaxis during admission for LSG and at discharge when surgeons identified them as high risk.

PVT following LSG can be difficult to diagnose because presenting symptoms tend to be nonspecific. Within an average of 13 days following surgery, 77% of patients diagnosed with PVT reported abdominal pain, 33% reported nausea and vomiting, and also reported less common symptoms that included shoulder tip pain, problems in tolerating fluids, constipation, and diarrhea. Final diagnosis of PVT was determined with independent or a combination of CT and duplex ultrasound.

Complications from PVT can have serious consequences, including abdominal swelling from fluid accumulation, enlarged esophageal veins, terminal esophageal bleeding, and bowel infarction. As with admission thromboprophylaxis treatments, patients diagnosed with PVT received varied anticoagulation treatments with most, in equal numbers, receiving either LMWH or a heparin infusion, and the remaining 12% receiving anticoagulation with rivaroxaban and warfarin. Adjustments were made following initial treatments such that 37% and 66% of patients continued with longer-term therapy on LMWH or warfarin, respectively. Treatments generally lasted 3-6 months with only 11% continuing on warfarin because of a history of clotting disorder. The anticoagulation treatments were successful with the majority (94%) of patients with only one patient requiring surgical intervention.

Follow-up with the patients who had a PVT diagnosis of more than 6 months (with an average of 10 months) showed the overall success of the post-LSG anticoagulation and surgical therapies, without any mortalities.

The authors summarized earlier theories about confounding health conditions that may contribute to the development of PVT and the risks for PVT linked to laparoscopic surgery. In this retrospective study, they noted that PVT incidence following LSG was low at 0.3% but was still higher than with two other bariatric operative methods and suggested intraoperative and postoperative factors that could contribute to this difference. Because of the nonspecific early symptoms and the difficulty of diagnosing PVT, the investigators recommended that physicians be vigilant for this postoperative complication in LSG patients, and use “cross-sectional imagining with CT of the abdomen” for diagnosis. Furthermore, with diagnosed PVT “anticoagulation for 3 to 6 months with a target international normalized ratio of 2:3 is recommended unless the patient has additional risk factors and [is] therefore indicated for longer treatment.”

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tan SBM et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018 Mar;14:271-6.

can be effectively treated with extended postoperative anticoagulation therapy, findings from a large-scale, retrospective study indicate.

The research was conducted using data from medical records of created by physicians from five Australian bariatric centers, reported Stephanie Bee Ming Tan, MBBS, of the Gold Coast University Hospital, Queensland, Australia, and her associates in the journal Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. Following elective laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG), a total of 18 (0.3%) of the 5,951 obese patients were diagnosed with portomesenteric vein thrombosis (PVT). The PVT-affected population was a mean age of 44 years and 61% were women. All of these patients had at least one venous thrombosis systematic predisposition factor such as morbid obesity (50%), smoking (50%), or a personal or family history of a clotting disorder (39%).

All study patients were given thromboprophylaxis of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or unfractionated heparin plus mechanical thromboprophylaxis during admission for LSG and at discharge when surgeons identified them as high risk.

PVT following LSG can be difficult to diagnose because presenting symptoms tend to be nonspecific. Within an average of 13 days following surgery, 77% of patients diagnosed with PVT reported abdominal pain, 33% reported nausea and vomiting, and also reported less common symptoms that included shoulder tip pain, problems in tolerating fluids, constipation, and diarrhea. Final diagnosis of PVT was determined with independent or a combination of CT and duplex ultrasound.

Complications from PVT can have serious consequences, including abdominal swelling from fluid accumulation, enlarged esophageal veins, terminal esophageal bleeding, and bowel infarction. As with admission thromboprophylaxis treatments, patients diagnosed with PVT received varied anticoagulation treatments with most, in equal numbers, receiving either LMWH or a heparin infusion, and the remaining 12% receiving anticoagulation with rivaroxaban and warfarin. Adjustments were made following initial treatments such that 37% and 66% of patients continued with longer-term therapy on LMWH or warfarin, respectively. Treatments generally lasted 3-6 months with only 11% continuing on warfarin because of a history of clotting disorder. The anticoagulation treatments were successful with the majority (94%) of patients with only one patient requiring surgical intervention.

Follow-up with the patients who had a PVT diagnosis of more than 6 months (with an average of 10 months) showed the overall success of the post-LSG anticoagulation and surgical therapies, without any mortalities.

The authors summarized earlier theories about confounding health conditions that may contribute to the development of PVT and the risks for PVT linked to laparoscopic surgery. In this retrospective study, they noted that PVT incidence following LSG was low at 0.3% but was still higher than with two other bariatric operative methods and suggested intraoperative and postoperative factors that could contribute to this difference. Because of the nonspecific early symptoms and the difficulty of diagnosing PVT, the investigators recommended that physicians be vigilant for this postoperative complication in LSG patients, and use “cross-sectional imagining with CT of the abdomen” for diagnosis. Furthermore, with diagnosed PVT “anticoagulation for 3 to 6 months with a target international normalized ratio of 2:3 is recommended unless the patient has additional risk factors and [is] therefore indicated for longer treatment.”

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tan SBM et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018 Mar;14:271-6.

can be effectively treated with extended postoperative anticoagulation therapy, findings from a large-scale, retrospective study indicate.

The research was conducted using data from medical records of created by physicians from five Australian bariatric centers, reported Stephanie Bee Ming Tan, MBBS, of the Gold Coast University Hospital, Queensland, Australia, and her associates in the journal Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. Following elective laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG), a total of 18 (0.3%) of the 5,951 obese patients were diagnosed with portomesenteric vein thrombosis (PVT). The PVT-affected population was a mean age of 44 years and 61% were women. All of these patients had at least one venous thrombosis systematic predisposition factor such as morbid obesity (50%), smoking (50%), or a personal or family history of a clotting disorder (39%).

All study patients were given thromboprophylaxis of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or unfractionated heparin plus mechanical thromboprophylaxis during admission for LSG and at discharge when surgeons identified them as high risk.

PVT following LSG can be difficult to diagnose because presenting symptoms tend to be nonspecific. Within an average of 13 days following surgery, 77% of patients diagnosed with PVT reported abdominal pain, 33% reported nausea and vomiting, and also reported less common symptoms that included shoulder tip pain, problems in tolerating fluids, constipation, and diarrhea. Final diagnosis of PVT was determined with independent or a combination of CT and duplex ultrasound.

Complications from PVT can have serious consequences, including abdominal swelling from fluid accumulation, enlarged esophageal veins, terminal esophageal bleeding, and bowel infarction. As with admission thromboprophylaxis treatments, patients diagnosed with PVT received varied anticoagulation treatments with most, in equal numbers, receiving either LMWH or a heparin infusion, and the remaining 12% receiving anticoagulation with rivaroxaban and warfarin. Adjustments were made following initial treatments such that 37% and 66% of patients continued with longer-term therapy on LMWH or warfarin, respectively. Treatments generally lasted 3-6 months with only 11% continuing on warfarin because of a history of clotting disorder. The anticoagulation treatments were successful with the majority (94%) of patients with only one patient requiring surgical intervention.

Follow-up with the patients who had a PVT diagnosis of more than 6 months (with an average of 10 months) showed the overall success of the post-LSG anticoagulation and surgical therapies, without any mortalities.

The authors summarized earlier theories about confounding health conditions that may contribute to the development of PVT and the risks for PVT linked to laparoscopic surgery. In this retrospective study, they noted that PVT incidence following LSG was low at 0.3% but was still higher than with two other bariatric operative methods and suggested intraoperative and postoperative factors that could contribute to this difference. Because of the nonspecific early symptoms and the difficulty of diagnosing PVT, the investigators recommended that physicians be vigilant for this postoperative complication in LSG patients, and use “cross-sectional imagining with CT of the abdomen” for diagnosis. Furthermore, with diagnosed PVT “anticoagulation for 3 to 6 months with a target international normalized ratio of 2:3 is recommended unless the patient has additional risk factors and [is] therefore indicated for longer treatment.”

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tan SBM et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018 Mar;14:271-6.

FROM SURGERY FOR OBESITY AND RELATED DISEASES

Key clinical point: Anticoagulation treatments effectively managed most portomesenteric vein thrombosis cases following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy.

Major finding: PVT is rare (0.3%) but occurs more frequently with laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, compared with other bariatric surgery procedures.

Study details: A multicenter, retrospective study conducted in Australia from 2007 to 2016 with 5,951 adult obese patients who received elective laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy.

Disclosures: The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Tan SBM et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. Mar 2018;14:271-6.

Delaying lumbar punctures for a head CT may result in increased mortality in acute bacterial meningitis

Background: ABM is a diagnosis with high morbidity and mortality. Early antimicrobial and corticosteroid therapy is beneficial. Current practice tends to defer LP prior to imaging when there is potential risk of herniation. Sweden’s guidelines for getting a CT scan prior to LP differ substantially from the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA), which recommends obtaining CT in patients with immunocompromised state, history of CNS disease, or impaired mental status.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: 815 adult patients (older than 16 years old) in Sweden with confirmed acute bacterial meningitis.

Synopsis: The authors looked at adherence to guidelines for when to obtain a CT prior to LP, as well as compared mortality and neurologic outcomes when an LP was performed promptly versus when delayed for prior neuroimaging. CT neuroimaging was required in much smaller populations under Swedish guidelines (7%), compared with IDSA (65%), with improved mortality and outcomes in patients managed with the Swedish guidelines. Mortality was lower in patients who had a prompt LP than for those who got CT prior to the LP (4% vs. 10%). This mortality benefit was seen even in patients with immunocompromised state or altered mental status, confirming that earlier administration of appropriate therapy is associated with lower mortality. A major limitation is that the study included patients with confirmed meningitis rather than more clinically relevant cases of suspected bacterial meningitis.

Bottom line: Patients with suspected bacterial meningitis should have appropriate antimicrobial and corticosteroid therapy started as soon as possible, regardless of the decision to obtain CT scan prior to performing lumbar puncture.

Citation: Glimaker M et al. Lumbar puncture performed promptly or after neuroimaging in acute bacterial meningitis in adults: a prospective national cohort study evaluating different guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 Sep 9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix806 (epub ahead of print).

Dr. Maleque is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine, Emory University, Atlanta.

Background: ABM is a diagnosis with high morbidity and mortality. Early antimicrobial and corticosteroid therapy is beneficial. Current practice tends to defer LP prior to imaging when there is potential risk of herniation. Sweden’s guidelines for getting a CT scan prior to LP differ substantially from the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA), which recommends obtaining CT in patients with immunocompromised state, history of CNS disease, or impaired mental status.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: 815 adult patients (older than 16 years old) in Sweden with confirmed acute bacterial meningitis.

Synopsis: The authors looked at adherence to guidelines for when to obtain a CT prior to LP, as well as compared mortality and neurologic outcomes when an LP was performed promptly versus when delayed for prior neuroimaging. CT neuroimaging was required in much smaller populations under Swedish guidelines (7%), compared with IDSA (65%), with improved mortality and outcomes in patients managed with the Swedish guidelines. Mortality was lower in patients who had a prompt LP than for those who got CT prior to the LP (4% vs. 10%). This mortality benefit was seen even in patients with immunocompromised state or altered mental status, confirming that earlier administration of appropriate therapy is associated with lower mortality. A major limitation is that the study included patients with confirmed meningitis rather than more clinically relevant cases of suspected bacterial meningitis.

Bottom line: Patients with suspected bacterial meningitis should have appropriate antimicrobial and corticosteroid therapy started as soon as possible, regardless of the decision to obtain CT scan prior to performing lumbar puncture.

Citation: Glimaker M et al. Lumbar puncture performed promptly or after neuroimaging in acute bacterial meningitis in adults: a prospective national cohort study evaluating different guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 Sep 9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix806 (epub ahead of print).

Dr. Maleque is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine, Emory University, Atlanta.

Background: ABM is a diagnosis with high morbidity and mortality. Early antimicrobial and corticosteroid therapy is beneficial. Current practice tends to defer LP prior to imaging when there is potential risk of herniation. Sweden’s guidelines for getting a CT scan prior to LP differ substantially from the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA), which recommends obtaining CT in patients with immunocompromised state, history of CNS disease, or impaired mental status.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: 815 adult patients (older than 16 years old) in Sweden with confirmed acute bacterial meningitis.

Synopsis: The authors looked at adherence to guidelines for when to obtain a CT prior to LP, as well as compared mortality and neurologic outcomes when an LP was performed promptly versus when delayed for prior neuroimaging. CT neuroimaging was required in much smaller populations under Swedish guidelines (7%), compared with IDSA (65%), with improved mortality and outcomes in patients managed with the Swedish guidelines. Mortality was lower in patients who had a prompt LP than for those who got CT prior to the LP (4% vs. 10%). This mortality benefit was seen even in patients with immunocompromised state or altered mental status, confirming that earlier administration of appropriate therapy is associated with lower mortality. A major limitation is that the study included patients with confirmed meningitis rather than more clinically relevant cases of suspected bacterial meningitis.

Bottom line: Patients with suspected bacterial meningitis should have appropriate antimicrobial and corticosteroid therapy started as soon as possible, regardless of the decision to obtain CT scan prior to performing lumbar puncture.

Citation: Glimaker M et al. Lumbar puncture performed promptly or after neuroimaging in acute bacterial meningitis in adults: a prospective national cohort study evaluating different guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 Sep 9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix806 (epub ahead of print).

Dr. Maleque is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine, Emory University, Atlanta.

Tanning is the new tobacco

I was driving to work the other day, perched up in my pickup truck (somehow you knew that) and noticed a fancy race car in front of me with a vanity tag. It read HRTATTK 4. Well, I thought after four heart attacks maybe I would splurge on a special car too (more likely a newer truck). Then I noticed smoke coming out of the driver’s window, and I could see this guy in his side view mirror, presumably Mr. “Heart Attack 4,” puffing away on a cigarette. Wow.

Then I got to work and saw my secretary, who works with her oxygen on, out back puffing a cigarette. Wow.

It turns out that cigarette smoke contains substances that act as a monoamine oxidase (MAO) A inhibitor, prolonging the dopamine high in the brain (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996 Nov 26;93[24]:14065-9). Makes sense and may explain the above smoking behavior. I truly believe cigarettes are as or more addictive than any other dopamine enhancing drug.

More than 50 years ago, a national campaign against smoking was launched after the 1964 Surgeon General’s report concluded that smoking was a major health hazard. (Looking back, one of the few losses of not having to pull journal articles from the stacks in the library, is that medical students and residents can’t shake their heads in wonder at the cigarette ads in old medical journals.) The impact of the national antismoking campaign has been dramatic, but smoking remains the leading preventable cause of death in the United States and globally, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

in 2006, from 1992 (Arch Dermatol. 2010;146[3]:283-7), dermatologists had good footing on which to start a major prevention campaign. The American Cancer Society got on board, and in 2014, acting surgeon general Boris Lushniak, MD, issued a call to action to prevent skin cancer along with Howard Koh, MD, the assistant secretary of health, in “The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Skin Cancer” in 2014, and the campaign was on.

Well, I am delighted to pass on a report from Leonard Lichtenfeld, MD, deputy chief medical officer for the American Cancer Society, who recently described in his March 2018 blog what may the first signs of the effectiveness of efforts to promote protection from ultraviolet ray exposure (JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154[3]:361-2). He writes: “In young white women ages 15 to 24, the incidence of melanoma has declined an average of 5.5% per year from January 2005 through December 2014. Not 5.5% over those ten years but 5.5 % PER YEAR. That’s remarkable, to say the least.”

As for the reasons behind these trends, he says, “no one can say for certain,” but he refers to national data indicating that indoor tanning has decreased in the past few years, especially among adolescents and young adults.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

I was driving to work the other day, perched up in my pickup truck (somehow you knew that) and noticed a fancy race car in front of me with a vanity tag. It read HRTATTK 4. Well, I thought after four heart attacks maybe I would splurge on a special car too (more likely a newer truck). Then I noticed smoke coming out of the driver’s window, and I could see this guy in his side view mirror, presumably Mr. “Heart Attack 4,” puffing away on a cigarette. Wow.

Then I got to work and saw my secretary, who works with her oxygen on, out back puffing a cigarette. Wow.