User login

The times they are a-changin’ —Bob Dylan, 1964

The beginning of a new year is always associated with changes, accompanied by new challenges and opportunities. This year is no different and, in fact, begins with some significant changes. First, I am incredibly honored, and humbled, to be named your new editor-in-chief. By way of background and introduction, I am residency-trained and board-certified in emergency medicine (EM). I founded the first academic department of EM in Virginia in 1992, and continue to serve in the role of chair. From 1990 to 2010, I served as the program director of our 3-year EM residency program, which I still consider the best job in EM. Most importantly, I continue to see and care for patients in the ED primarily, in addition to supervising and teaching EM residents and fellows in the delivery of care in the clinical arena. I know first-hand the needs of practicing emergency physicians (EPs).

I feel very fortunate to have been associated with Emergency Medicine (EM) since 1988, the year the journal published my very first manuscript. I served on the editorial board from 1999 to 2006, and for the past 11 years, have served as the associate editor-in-chief. I hold a very special regard and respect for this journal, and its role in our specialty. My goal is to continue to publish high-quality content and ensure we consistently provide timely and clinically useful information to the practicing EP. We will invite the very best in our specialty to share their knowledge and clinical tips. We will of course continue some of your favorite sections, like “Emergency Ultrasound,” “Diagnosis at a Glance,” and “Case Studies in Toxicology.” We will also encourage our readers to submit interesting and informative case reports, review articles, and interesting images. While I plan to write a few editorials each year, I will invite thought leaders in EM to write on their area(s) of expertise.

Come writers and critics who prophesize with your pen.

Another major change has to do with the journal itself. This will be the last paper copy of EM (so think about keeping this one for posterity, or eBay). Starting with the February issue, all future issues will be digital and online-only. This decision was not an easy one, and has been in the making for some time. Thanks to the growth in our Web site traffic, it is clear that many of you have already become “digital-first” readers. This fact, combined with the added financial challenge of publishing a large-circulation journal within an environment of declining print advertising, convinced us that this is the right time to make the leap to the digital-only format. While some of you (including myself), will miss physically holding and reading a hard copy of EM, you may simply continue to access the journal as you have for years, on your desktop, laptop, or iPad, and never further away than your cell phone. This change has the advantage of providing opportunities to deliver valuable clinical content in new ways, through increased use of audio and video, as well as text. To ensure that you receive your copy, please e-mail our Editor, Kellie DeSantis ([email protected]) to make sure we have your correct and preferred e-mail address. While our goal is to push each issue out to you via e-mail, you will always be able to access the most recent articles by going to our Web site, www.emed-journal.com.

And don’t criticize

What you can’t understand.

Finally, 2018 promises to be a very interesting year, with the unknown implications of tax reform, the repeal of the individual mandate for health insurance, the opioid crisis, and the curious mergers within the health insurance industry (ie, CVS and Aetna). It is too soon for anyone to say how these changes will affect EM on the national stage. What will not change however, is that EPs will continue to provide outstanding care to any and every patient who presents to the ED. Emergency physicians will ensure that all patients receive the care they need (but not necessarily the care they want) and will do so without regard to gender, religion, national origin, race, age, sexual preference, or insurance status.

I wish each and every one of you a happy and healthy 2018.

The beginning of a new year is always associated with changes, accompanied by new challenges and opportunities. This year is no different and, in fact, begins with some significant changes. First, I am incredibly honored, and humbled, to be named your new editor-in-chief. By way of background and introduction, I am residency-trained and board-certified in emergency medicine (EM). I founded the first academic department of EM in Virginia in 1992, and continue to serve in the role of chair. From 1990 to 2010, I served as the program director of our 3-year EM residency program, which I still consider the best job in EM. Most importantly, I continue to see and care for patients in the ED primarily, in addition to supervising and teaching EM residents and fellows in the delivery of care in the clinical arena. I know first-hand the needs of practicing emergency physicians (EPs).

I feel very fortunate to have been associated with Emergency Medicine (EM) since 1988, the year the journal published my very first manuscript. I served on the editorial board from 1999 to 2006, and for the past 11 years, have served as the associate editor-in-chief. I hold a very special regard and respect for this journal, and its role in our specialty. My goal is to continue to publish high-quality content and ensure we consistently provide timely and clinically useful information to the practicing EP. We will invite the very best in our specialty to share their knowledge and clinical tips. We will of course continue some of your favorite sections, like “Emergency Ultrasound,” “Diagnosis at a Glance,” and “Case Studies in Toxicology.” We will also encourage our readers to submit interesting and informative case reports, review articles, and interesting images. While I plan to write a few editorials each year, I will invite thought leaders in EM to write on their area(s) of expertise.

Come writers and critics who prophesize with your pen.

Another major change has to do with the journal itself. This will be the last paper copy of EM (so think about keeping this one for posterity, or eBay). Starting with the February issue, all future issues will be digital and online-only. This decision was not an easy one, and has been in the making for some time. Thanks to the growth in our Web site traffic, it is clear that many of you have already become “digital-first” readers. This fact, combined with the added financial challenge of publishing a large-circulation journal within an environment of declining print advertising, convinced us that this is the right time to make the leap to the digital-only format. While some of you (including myself), will miss physically holding and reading a hard copy of EM, you may simply continue to access the journal as you have for years, on your desktop, laptop, or iPad, and never further away than your cell phone. This change has the advantage of providing opportunities to deliver valuable clinical content in new ways, through increased use of audio and video, as well as text. To ensure that you receive your copy, please e-mail our Editor, Kellie DeSantis ([email protected]) to make sure we have your correct and preferred e-mail address. While our goal is to push each issue out to you via e-mail, you will always be able to access the most recent articles by going to our Web site, www.emed-journal.com.

And don’t criticize

What you can’t understand.

Finally, 2018 promises to be a very interesting year, with the unknown implications of tax reform, the repeal of the individual mandate for health insurance, the opioid crisis, and the curious mergers within the health insurance industry (ie, CVS and Aetna). It is too soon for anyone to say how these changes will affect EM on the national stage. What will not change however, is that EPs will continue to provide outstanding care to any and every patient who presents to the ED. Emergency physicians will ensure that all patients receive the care they need (but not necessarily the care they want) and will do so without regard to gender, religion, national origin, race, age, sexual preference, or insurance status.

I wish each and every one of you a happy and healthy 2018.

The beginning of a new year is always associated with changes, accompanied by new challenges and opportunities. This year is no different and, in fact, begins with some significant changes. First, I am incredibly honored, and humbled, to be named your new editor-in-chief. By way of background and introduction, I am residency-trained and board-certified in emergency medicine (EM). I founded the first academic department of EM in Virginia in 1992, and continue to serve in the role of chair. From 1990 to 2010, I served as the program director of our 3-year EM residency program, which I still consider the best job in EM. Most importantly, I continue to see and care for patients in the ED primarily, in addition to supervising and teaching EM residents and fellows in the delivery of care in the clinical arena. I know first-hand the needs of practicing emergency physicians (EPs).

I feel very fortunate to have been associated with Emergency Medicine (EM) since 1988, the year the journal published my very first manuscript. I served on the editorial board from 1999 to 2006, and for the past 11 years, have served as the associate editor-in-chief. I hold a very special regard and respect for this journal, and its role in our specialty. My goal is to continue to publish high-quality content and ensure we consistently provide timely and clinically useful information to the practicing EP. We will invite the very best in our specialty to share their knowledge and clinical tips. We will of course continue some of your favorite sections, like “Emergency Ultrasound,” “Diagnosis at a Glance,” and “Case Studies in Toxicology.” We will also encourage our readers to submit interesting and informative case reports, review articles, and interesting images. While I plan to write a few editorials each year, I will invite thought leaders in EM to write on their area(s) of expertise.

Come writers and critics who prophesize with your pen.

Another major change has to do with the journal itself. This will be the last paper copy of EM (so think about keeping this one for posterity, or eBay). Starting with the February issue, all future issues will be digital and online-only. This decision was not an easy one, and has been in the making for some time. Thanks to the growth in our Web site traffic, it is clear that many of you have already become “digital-first” readers. This fact, combined with the added financial challenge of publishing a large-circulation journal within an environment of declining print advertising, convinced us that this is the right time to make the leap to the digital-only format. While some of you (including myself), will miss physically holding and reading a hard copy of EM, you may simply continue to access the journal as you have for years, on your desktop, laptop, or iPad, and never further away than your cell phone. This change has the advantage of providing opportunities to deliver valuable clinical content in new ways, through increased use of audio and video, as well as text. To ensure that you receive your copy, please e-mail our Editor, Kellie DeSantis ([email protected]) to make sure we have your correct and preferred e-mail address. While our goal is to push each issue out to you via e-mail, you will always be able to access the most recent articles by going to our Web site, www.emed-journal.com.

And don’t criticize

What you can’t understand.

Finally, 2018 promises to be a very interesting year, with the unknown implications of tax reform, the repeal of the individual mandate for health insurance, the opioid crisis, and the curious mergers within the health insurance industry (ie, CVS and Aetna). It is too soon for anyone to say how these changes will affect EM on the national stage. What will not change however, is that EPs will continue to provide outstanding care to any and every patient who presents to the ED. Emergency physicians will ensure that all patients receive the care they need (but not necessarily the care they want) and will do so without regard to gender, religion, national origin, race, age, sexual preference, or insurance status.

I wish each and every one of you a happy and healthy 2018.

Complications of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in the Emergency Department

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by the chronic activation of the immune system, leading to the formation of autoantibodies and multi-organ damage. The prevalence of SLE in the United States is 20 to 150 per 100,000 persons.1 Ninety percent of patients with SLE are women, and the condition is more common and often more severe among patients of black African or of Asian descent.

For patients with known SLE who present to the ED, it can be a challenge to identify whether their symptoms are due to a minor lupus flare that can be managed as an outpatient, a presentation of urgent or emergent conditions caused by SLE, or a condition unrelated to lupus. This article reviews the most common and emergent complications of SLE by organ system to assist emergency physicians (EPs) in better diagnosing and managing this complicated disease.

General Acute-Care Management

While a patient’s presentation could be secondary to a lupus-related complication, consideration must always be given to common conditions that are not related to SLE. Biomarkers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, C3 and C4 complement, and double-stranded DNA levels can be helpful in assessing lupus disease activity and differentiating a lupus-related complication from an unrelated event. Comparing these biomarkers to the patient’s baseline values can be informative; however, depending on the laboratory facilities, test results may not be available during an ED visit. Lastly, infections should be considered more strongly than usual in the differential diagnosis due to the immunocompromised status of a substantial proportion of these patients, by virtue of their disease or the cytotoxic medications used for treatment.

Musculoskeletal Complications

Common Complications

Polyarthralgias and Polymyalgias. More than 90% of SLE patients experience polyarthralgias and polymyalgias. Physical examination findings may be normal, even when joint pain is present, which is often due to mild synovitis. In some cases, Jaccoud arthropathy is seen, which presents as deformities such as swan neck deformities and ulnar deviations that are characteristically reducible on manipulation (Figures 1a and 1b). These deformities are not caused by direct joint damage, but by chronic tenosynovitis and the resulting laxity of tendons and ligaments.1 Classically, plain radiographic imaging reveals nonerosive joint changes. Muscle and joint pains may worsen with disease progression or flare.

Avascular Necrosis. Avascular necrosis affects 5% to 12% of SLE patients.2 Most commonly, this involves the femoral head, but it may also involve the femoral condyle or tibial plateau. Patients may present with acute or subacute onset of pain in the groin or buttocks when the femoral head is involved, or in the knee when the femoral condyle or tibial plateau is involved. Plain radiographs may reveal joint-space narrowing and other evidence of degenerative joint disease. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more sensitive in diagnosing avascular necrosis, and may be indicated when clinical suspicion is high despite negative plain radiographs, although this would not typically need to be performed urgently in the ED.2 While analgesics and physical therapy may provide some pain relief to patients with avascular necrosis, this condition generally requires nonemergent operative intervention.

Emergent Complications

Septic Arthritis. When a patient with SLE presents with an isolated swollen joint, septic arthritis should be suspected, and diagnosis should be confirmed by arthrocentesis. Synovial fluid samples showing a white blood cell count greater than 50 × 109/Lsuggest infection, which can be confirmed by gram stain and cultures.

For reasons that remain unclear, but may involve primary immune defects and the use of immunosuppressant medications, patients with SLE are predisposed to Salmonella joint infections. In one study, 59% of septic arthritis cases in patients with SLE were due to Salmonella species; therefore, treatment for septic arthritis in this population should include ceftriaxone in addition to vancomycin for typical organisms, such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species.3

Cutaneous Manifestations

Common Complications

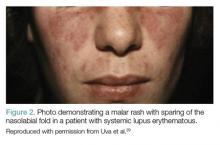

Malar Rash. Eighty percent to 90% of patients with SLE have dermatological involvement,1 the most common finding of which is the malar or butterfly facial rash, which appears as raised erythema over the bridge of the nose and cheeks while sparing the nasolabial folds (Figure 2).

Discoid Lupus. Chronic discoid lupus appears as a scarring rash often found on the face, ears, and scalp. These patients may also exhibit a photosensitive rash, which consists of an erythematous eruption if acute, or annular scaly lesions if subacute.

Oral and Nasal Ulcerations. Common mucous membrane findings include oral or nasal ulcers, which are typically painless.

Worsening of any of these skin findings may be associated with disease flare. Secondary bacterial infection of lupus rashes or ulcerations is uncommon, although cellulitis should be considered when a rash is unilateral, not in a sun-exposed area, or is otherwise different from the patient’s typical lupus rash. Sun avoidance and topical corticosteroids are the mainstays of treatment of dermatological disease in SLE.

Emergent Complications

Systemic Vasculitis. Patients with SLE are susceptible to vasculitis. Although isolated cutaneous vasculitis is not typically an emergent condition, it may portend systemic vasculitis. Any palpable purpura or other evidence of cutaneous vasculitis should prompt a careful review of systems and basic laboratory workup for systemic vasculitis, which can involve the kidneys, lungs, central or peripheral nervous system, or gastrointestinal tract.

Symptoms of systemic vasculitis may include fevers, chills, chest pain, cough, hemoptysis, abdominal pain, and changes in color or amount of urine. Laboratory workup should be tailored to symptoms, and may include basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, complete blood count, and urinalysis.4

Digital Gangrene. Patients with SLE may also develop digital gangrene related to severe Raynaud phenomenon, vasculitis, or thromboembolism. Pharmacological treatment with vasodilators such as sildenafil, endothelin receptor antagonists, or intravenous prostacyclins may be needed.5 To save the involved digit, vascular surgery services should be consulted urgently.6

Renal Complications

Common Complications

Chronic Kidney Disease. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is common among SLE patients, especially among those with a history of lupus nephritis.7 Patients with CKD may have persistently elevated serum creatinine, chronic hypertension, and/or chronic peripheral edema. Patients presenting with new development of hypertension, peripheral edema, hematuria, or polyuria should be screened for lupus nephritis with urinalysis and serum creatinine. Elevated creatinine or new or worsening proteinuria or hematuria should prompt consultation with nephrology services.

Emergent Complications

Lupus Nephritis. About 50% of SLE patients will develop lupus nephritis during the course of their lives,1 which may present as nephrotic disease with significant proteinuria, peripheral edema, and low serum albumin, or as nephritic disease, with increased serum creatinine and hematuria. Acute kidney injury in SLE patients should generally prompt admission for workup of reversible causes and evaluation for lupus nephritis, which often includes renal biopsy.8

Neuropsychiatric Complications

Common Complications

Neuropsychiatric lupus is a broad category that includes 19 manifestations of SLE in the central and peripheral nervous systems.9 Conditions range from depression or chronic headaches to seizures or psychosis.

Mood and Anxiety Disorders. Anxiety and depression have been observed in up to 75% of SLE patients.1 Mood and anxiety disorders are likely influenced by the psychosocial elements of this chronic disease, as well as by direct effects of SLE on the brain.1

Peripheral Neuropathy. Approximately 10% of SLE patients have a peripheral neuropathy, which generally presents as a mononeuritis (either single or multiplex), rather than the stocking-glove distribution seen in other systemic causes of neuropathy.10

Headache. Headache disorders may also develop in SLE patients, and tend to have similar patterns to primary headache disorders in the general population. In most cases, treatment for headache in SLE patients is similar to that of the general population.11 However, if a patient presents with concerning findings, such as focal neurological deficit, meningismus, or fever, or if the headache is new-onset or different from previous headaches, further investigation should be considered, including a head computed tomography (CT) scan and lumbar puncture (LP).

Emergent Complications

In general, due to the variety of neurological emergencies that may present with SLE, and the subtlety with which true emergencies may present in this population, the threshold to obtain imaging on SLE patients with any new neurological complaints should be low.

Cerebrovascular Accidents. Patients with SLE are susceptible to cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs), typically from occlusive or embolic causes. Etiologies may include primary central nervous system (CNS) vasculitis, embolic disease from antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), or embolic disease from a Libman-Sacks endocarditis.12

Successful thrombolysis has been reported in SLE patients presenting with stroke, but it remains controversial due to risk of hemorrhagic conversion if CNS vasculitis, rather than embolism, is the cause.13 Proper imaging and consultation with a neurologist familiar with the disease is critical for early treatment decisions.

Seizures. Fifteen percent to 35% of SLE patients may develop seizures. These may be focal or generalized, but generalized tonic-clonic seizures tend to be more common in SLE patients.2 Workup and management of seizures in SLE patients is the same as in the general population.

Sinus Thrombosis. Dural sinus thrombosis often presents as a new-onset headache, sometimes with focal neurological deficits. The diagnosis of dural sinus thrombosis can be challenging, as CT imaging studies may be falsely negative. There should be a low threshold for obtaining MRI/magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) in SLE patients presenting with a new-onset headache.14

CNS Vasculitis. Patients with SLE are also susceptible to CNS vasculitis, which can manifest as seizures, psychosis, cognitive decline, altered mental status, or coma. Magnetic resonance imaging/MRA studies may suggest the diagnosis, but if this is equivocal, angiography or even brain biopsy may be needed to make the diagnosis. Unless the patient’s symptoms are very mild (eg, mild cognitive decline), she or he should be admitted for diagnostic workup and consideration of aggressive immunosuppressive therapy.2

Transverse Myelitis and Spinal Artery Thrombosis. Acute loss of lower limb sensation or motor function in SLE patients may be caused by transverse myelitis or spinal artery thrombosis. Epidural abscess should also be considered, especially if the patient is immunocompromised.2

Infection. A CNS infection should be considered in any SLE patient presenting with new neurological complaints. Fever or meningismus, especially in conjunction with headache or focal neurological deficits, should prompt an LP and consideration for imaging. Immunocompromised patients are at increased risk for common organisms as well as atypical organisms, such as fungus or mycobacteria.15

Pulmonary Complications

Common Complications

Pleuritis. Many patients with SLE develop pleuritis, with or without effusion. This may be treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or corticosteroids if symptoms are more severe. Pleuritis is the most common respiratory complication of SLE, but due to the number of serious cardiopulmonary complications associated with SLE, pleuritis should be a diagnosis of exclusion.

Interstitial Lung Disease. Interstitial lung disease may be caused by SLE or may be medication-induced. This commonly presents as subacute or chronic dyspnea and/or cough. Patient workup may be done on an outpatient basis with high resolution chest CT and pulmonary function testing.

Pulmonary Hypertension. Patients with SLE may develop pulmonary hypertension, either directly due to SLE or from chronic thromboembolic disease. In general, pulmonary hypertension is managed as an outpatient, but may require emergent inpatient treatment if the condition is rapidly progressive or associated with right heart failure.

Shrinking Lung Syndrome. This condition may cause subacute or chronic dyspnea and pleuritic chest pain. Shrinking lung syndrome is caused by diaphragmatic dysfunction rather than from a primary disease of the lungs, and it is characterized by a restrictive pattern on pulmonary function testing and an elevated hemidiaphragm. Shrinking lung syndrome typically responds well to immunosuppressive therapy.16

Emergent Conditions

Pulmonary Embolism. A pulmonary embolism should be strongly considered in any patient with SLE presenting with the appropri ate clinical picture. Patients with APS are at particularly high risk for thromboembolic disease. However, even SLE patients without this APS are known to be at an increased risk of developing thromboembolism compared to the general public.17 Pulmonary embolism in SLE patients should be diagnosed and treated in the usual manner.

Pneumonia. Immunosuppressed patients are susceptible to opportunistic pulmonary infections as well as typical community pathogens. Fungal or mycobacterial infections may be suspected with a more subacute onset of symptoms.

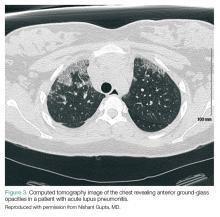

Acute Lupus Pneumonitis. This serious condition may present with severe pneumonia-like signs and symptoms, including fever, cough, dyspnea, hypoxia, and infiltrates on chest radiograph (Figure 3).

Acute lupus pneumonitis is caused by disease flare, and not by infection, although it may not be possible to distinguish it from pneumonia in the ED setting. The mortality rate of acute lupus pneumonitis is as high as 50%, and survivors often progress to chronic interstitial pneumonitis.1

Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage. A rare complication with a mortality rate of 50% to 90%, SLE patients who develop diffuse alveolar hemorrhage may present with fever, cough, dyspnea, and hypoxia.18 The condition may be suggested by infiltrates on chest radiograph, a drop in hemoglobin representing bleeding into the lungs, and/or hemoptysis. However, the absence of hemoptysis does not rule out diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, so clinical suspicion should remain high, even in the absence of this symptom.

Because emergent pulmonary conditions often present with similar symptoms, most patients with acute or new-onset symptoms will require admission for diagnostic workup (likely to include chest CT scan and/or bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage), as well as for close monitoring and initiation of treatment. If hypoxia or respiratory distress is severe, or if diffuse alveolar hemorrhage is suspected, admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) should be considered. We suggest that antibiotics be started in the ED when pneumonia is part of the differential diagnosis. As in the general population, coverage should be chosen based on the patient’s risk factors for antibiotic-resistant organisms. Initiation of corticosteroid therapy or other changes in immune therapy can be delayed until the EP consults with rheumatology and/or pulmonology services.

Cardiac Complications

Common Complications

Pericarditis. Pericarditis with or without pericardial effusion is very common in SLE patients and is usually related to lupus itself, rather than an infectious etiology. Patients may present with substernal, positional chest pain, tachycardia, and diffuse ST-segment elevation on electrocardiogram. Most effusions are small, asymptomatic, and discovered incidentally. However, among patients with symptomatic pericardial effusions, tamponade can be present in 21%.19 Corticosteroid therapy is often required to treat SLE-associated pericarditis, but colchicine is being explored as a possible steroid-sparing agent in this patient population.20,21

Valvular Abnormalities. Approximately 60% of SLE patients have valvular abnormalities detectable by echocardiography. The most common abnormalities in one study were valvular thickening or regurgitation.22 Many of these abnormalities occurred in asymptomatic patients and never progressed to clinical disease in a 5-year follow-up. However, patients with any valvular abnormality were more likely to develop complications, including stroke, peripheral embolism, infective endocarditis, need for valve replacement, congestive heart failure, or death.22

Emergent Complications

Acute Coronary Syndrome. Even in relatively young patients, acute coronary syndrome (ACS) should be considered in SLE patients presenting with chest pain, as this patient population has a 10-fold higher risk of developing coronary artery disease (CAD) than the general population, and SLE patients with CAD often lack traditional risk factors, such as advanced age, family history, or metabolic syndrome.1

A high clinical suspicion should be maintained even in patients who would traditionally be considered low-risk. The EP should have a low-threshold for ECG, cardiac biomarker testing, and stress testing for SLE patients presenting with chest pain. The treatment of ACS in SLE patients is the same as in the general population.

Libman-Sacks Endocarditis. A sterile, fibrinous valvular vegetation, Libman-Sacks endocarditis is unique to patients with SLE. When present, patients usually develop a subacute or chronic onset of dyspnea or chest pain. However, patients may become acutely ill if they develop severe valvular regurgitation. Additionally, the valve damage from Libman-Sacks endocarditis can predispose patients to developing infective endocarditis.20

Hematological Complications

Common Complications

Patients with SLE commonly have mild-to-moderate leukopenia (especially lymphopenia), anemia, and thrombocytopenia. This may be related to the disease process or may be secondary to prescribed medications. A comparison to recent baseline laboratory studies should be sought if there is suspicion for new or worsening cytopenia.

Antiphospholipid Syndrome. Nearly 40% of SLE patients also have APS, which is defined by a clinical history of thrombosis in conjunction with one of the antiphospholipid antibodies (anticardiolipin, anti-beta-2-glycoprotein, lupus anticoagulant). Antiphospholipid syndrome causes both venous and arterial thrombosis and may be associated with recurrent miscarriage. Acute thrombotic events should be treated with heparin or enoxaparin and transitioned to warfarin. The new generation of direct oral anticoagulants have not been well studied in APS, though, multiple small case series suggest a higher thrombotic risk with these drugs than with warfarin.23Patients who have recurrent venous thromboembolism, or who have any arterial thromboembolism should be on lifelong anticoagulation therapy.2

Emergent Complications

Thrombocytopenia. Severe thrombocytopenia or hemolytic anemia can be life-threatening, and often requires inpatient admission for immunosuppressive therapy, monitoring, and supportive care.

Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome. This condition should be suspected in patients with SLE who present with multiple sites of thrombosis or new multi-organ damage. Catastrophic APS (CAPS) may occur in SLE patients who have no prior history of APS. Since the mortality rate for CAPS approaches 50%, these patients require anticoagulation, immunosuppressant therapy (high-dose corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, and/or plasma exchange), and admission to the ICU.24

Gastrointestinal Complications

Common Complications

Intestinal Pseudo-obstruction. Dysphagia related to esophageal dysmotility is present in up to 13% of SLE patients.25 Intestinal pseudo-obstruction may be seen in SLE patients, and is characterized by symptoms of intestinal obstruction caused by decreased intestinal motility, rather than from mechanical obstruction. Presenting symptoms may be acute or chronic, and include nausea, vomiting, and abdominal distension. Abdominal CT studies will show dilated bowel loops without evidence of mechanical obstruction. Manometry reveals widespread hypomotility. Intestinal pseudo-obstruction typically responds well to corticosteroids and other immunosuppressant therapies.26

Emergent Conditions

Acute Abdominal Pain. Approximately half of SLE patients who present to the ED with acute abdominal pain are found to have either mesenteric vasculitis or pancreatitis, both of which are thought to be related to SLE disease activity.27 Other causes of acute abdominal pain that are common in the general population remain common in SLE patients, including gallbladder disease, gastroenteritis, appendicitis, and peptic ulcer disease.

Mesenteric Vasculitis. Also known as lupus enteritis, mesenteric vasculitis is a unique cause of acute abdominal pain in SLE patients. The condition presents with acute, diffuse abdominal pain and may be associated with nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, or hematochezia. Abdominal CT findings suggestive of diffuse enteritis support the diagnosis. Medical management with pulse-dose corticosteroids and supportive care is generally sufficient, but if bowel necrosis or intestinal perforation is present or suspected, surgical consultation should be obtained immediately.15

Conclusion

Complications of SLE are diverse and may be difficult to diagnose. Understanding the common and emergent complications of SLE will help the EP to recognize severe illness and make appropriate treatment decisions in this complex patient population.

1. Dall’Era M, Wofsy D. Clinical Features of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. In: Firestein GS et al, eds. Kelley and Firestein’s Textbook of Rheumatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017.

2. Dvorkina O, Ginzler EM. Clinical features of systemic lupus erythematosus. In: Hochberg MC, ed. Rheumatology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

3. Huang JL, Hung JJ, Wu KC, Lee WI, Chan CK, Ou LS. Septic arthritis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: salmonella and nonsalmonella infections compared. Semin Arthritis Rheumatol. 2006;36(1):61-67. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.04.003

4. Barile-Fabris L, Hernández-Cabrera MF, Barragan-Garfias JA. Vasculitis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2014;16(9):440. doi:10.1007/s11926-014-0440-9.

5. Campion EW, Wigley FM, Flavahan NA. Raynaud’s phenomenon. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(6):556-565. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1507638.

6. Bouaziz JD, Barete S, Le Pelletier F, et al. Cutaneous lesions of the digits in systemic lupus erythematosus: 50 cases. Lupus. 2007;16(3):163-167.

7. Pokroy-Shapira E, Gelernter I, Molad Y. Evolution of chronic kidney disease in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus over a long-period follow-up: a single-center inception cohort study. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33(5):649-657. doi:10.1007/s10067-014-2527-0.

8. Almaani S, Meara A, Rovin BH. Update on lupus nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(5):825-835. doi:10.2215/CJN.05780616.

9. The American College of Rheumatology nomenclature and case definitions for neuropsychiatric lupus syndromes. Arthritis Rheumatol. 1999;42(4):599-608.

10. Oomatia A, Fang H, Petri M, et al. Peripheral neuropathies in systemic lupus erythematosus: clinical features, disease associations, and immunologic characteristics evaluated over a twenty-five year study period. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(4):1000-1009.

11. Mitsikostas DD, Sfikakis PP, Goadsby PJ. A meta-analysis for headache in systemic lupus erythematosus: the evidence and the myth. Brain. 2004;127(pt 5):1200-1209.

12. Timlin H, Petri M. Transient ischemic attack and stroke in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2013;22(12):1251-1258. doi:10.1177/0961203313497416.

13. Majdak MR, Vuletić V. Thrombolysis for acute stroke in patient with systemic lupus erythematosus: a case report. J Neurol Sci. 2016;(361):7-8. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2015.12.014.

14. Chen WL, Chang SH, Chen JH, Wu YL. Isolated headache as the sole manifestation of dural sinus thrombosis: a case report with literature review. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25(2):218-219.

15. Arntfield RT, Hicks CM. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and the Vasculitides. In: Marx JA, ed. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014.

16. Borrell H, Narváez J, Alegree JJ, et al. Shrinking lung syndrome in systemic lupus erythematosus: a case series and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(33):e4626. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000004626.

17. Aviña-Zubieta JA, Vostretsova K, De Vera MA, et al. The risk of pulmonary embolism and deep venous thrombosis in systemic lupus erythematosus: a general population-based study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;45(2):195-201. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.05.008.

18. Martínez-Martínez MU, Abud-Mendoza C. Predictors of mortality in diffuse alveolar haemorrhage associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2011;20(6):568-574. doi:10.1177/0961203310392430.

19. Rosenbaum E, Krebs E, Cohen M, Tiliakos A, Derk CT. The spectrum of clinical manifestations, outcome and treatment of pericardial tamponade in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a retrospective study and literature review. Lupus. 2009;18(7):608-612. doi:10.1177/0961203308100659.

20. Miner JJ, Kim AH. Cardiac manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2014;40(1):51-60. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2013.10.003.

21. Morel N, Bonjour M, Le Guern V, et al. Colchicine: a simple and effective treatment for pericarditis in systemic lupus erythematosus? A report of 10 cases. Lupus. 2015;24(14):1479-1485. doi:10.1177/0961203315593169.

22. Roldan CA, Shively BK, Crawford MH. An echocardiographic study of valvular heart disease associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(19):1424-1430.

23. Dufrost V, Risse J, et al. Direct oral anticoagulants use in antiphospholipid syndrome: are these drugs an effective and safe alternative to warfarin? A systematic review of the literature. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2016;18(12):74. doi:10.1007/s11926-016-0623-7.

24. Cervera R,Rodríguez-Pintó I; G Espinosa on behalf of the Task Force on Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: task force report summary. Lupus. 2014;23(12):1283-1285. doi:10.1177/0961203314540764.

25. Sultan SM, Ioannou Y, Isenberg DA. A review of gastrointestinal manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999;38(10):917-932.

26. Xu N, Zhao J, Liu J, et al. Clinical analysis of 61 systemic lupus erythematosus patients with intestinal pseudo-obstruction and/or ureterohydronephrosis: a retrospective observational study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(4):e419.

27. Vergara-Fernandez O, Zeron-Medina J, Mendez-Probst C, et al. Acute abdominal pain in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13(7):1351-1357. doi:10.1007/s11605-009-0897-4.

28. Küçükşahin O, Düzgün N, Okoh AK, Kulahçioglu E. Response to rituximab in a case of lupus associated digital ischemia. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2014;2014:763608. doi:10.1155/2014/763608.

29. Uva L, Miguel D, Pinheiro C, Freitas JP, Gomes MM, Filipe P. Cutaneous manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012:834291. doi:10.1155/2012/834291.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by the chronic activation of the immune system, leading to the formation of autoantibodies and multi-organ damage. The prevalence of SLE in the United States is 20 to 150 per 100,000 persons.1 Ninety percent of patients with SLE are women, and the condition is more common and often more severe among patients of black African or of Asian descent.

For patients with known SLE who present to the ED, it can be a challenge to identify whether their symptoms are due to a minor lupus flare that can be managed as an outpatient, a presentation of urgent or emergent conditions caused by SLE, or a condition unrelated to lupus. This article reviews the most common and emergent complications of SLE by organ system to assist emergency physicians (EPs) in better diagnosing and managing this complicated disease.

General Acute-Care Management

While a patient’s presentation could be secondary to a lupus-related complication, consideration must always be given to common conditions that are not related to SLE. Biomarkers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, C3 and C4 complement, and double-stranded DNA levels can be helpful in assessing lupus disease activity and differentiating a lupus-related complication from an unrelated event. Comparing these biomarkers to the patient’s baseline values can be informative; however, depending on the laboratory facilities, test results may not be available during an ED visit. Lastly, infections should be considered more strongly than usual in the differential diagnosis due to the immunocompromised status of a substantial proportion of these patients, by virtue of their disease or the cytotoxic medications used for treatment.

Musculoskeletal Complications

Common Complications

Polyarthralgias and Polymyalgias. More than 90% of SLE patients experience polyarthralgias and polymyalgias. Physical examination findings may be normal, even when joint pain is present, which is often due to mild synovitis. In some cases, Jaccoud arthropathy is seen, which presents as deformities such as swan neck deformities and ulnar deviations that are characteristically reducible on manipulation (Figures 1a and 1b). These deformities are not caused by direct joint damage, but by chronic tenosynovitis and the resulting laxity of tendons and ligaments.1 Classically, plain radiographic imaging reveals nonerosive joint changes. Muscle and joint pains may worsen with disease progression or flare.

Avascular Necrosis. Avascular necrosis affects 5% to 12% of SLE patients.2 Most commonly, this involves the femoral head, but it may also involve the femoral condyle or tibial plateau. Patients may present with acute or subacute onset of pain in the groin or buttocks when the femoral head is involved, or in the knee when the femoral condyle or tibial plateau is involved. Plain radiographs may reveal joint-space narrowing and other evidence of degenerative joint disease. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more sensitive in diagnosing avascular necrosis, and may be indicated when clinical suspicion is high despite negative plain radiographs, although this would not typically need to be performed urgently in the ED.2 While analgesics and physical therapy may provide some pain relief to patients with avascular necrosis, this condition generally requires nonemergent operative intervention.

Emergent Complications

Septic Arthritis. When a patient with SLE presents with an isolated swollen joint, septic arthritis should be suspected, and diagnosis should be confirmed by arthrocentesis. Synovial fluid samples showing a white blood cell count greater than 50 × 109/Lsuggest infection, which can be confirmed by gram stain and cultures.

For reasons that remain unclear, but may involve primary immune defects and the use of immunosuppressant medications, patients with SLE are predisposed to Salmonella joint infections. In one study, 59% of septic arthritis cases in patients with SLE were due to Salmonella species; therefore, treatment for septic arthritis in this population should include ceftriaxone in addition to vancomycin for typical organisms, such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species.3

Cutaneous Manifestations

Common Complications

Malar Rash. Eighty percent to 90% of patients with SLE have dermatological involvement,1 the most common finding of which is the malar or butterfly facial rash, which appears as raised erythema over the bridge of the nose and cheeks while sparing the nasolabial folds (Figure 2).

Discoid Lupus. Chronic discoid lupus appears as a scarring rash often found on the face, ears, and scalp. These patients may also exhibit a photosensitive rash, which consists of an erythematous eruption if acute, or annular scaly lesions if subacute.

Oral and Nasal Ulcerations. Common mucous membrane findings include oral or nasal ulcers, which are typically painless.

Worsening of any of these skin findings may be associated with disease flare. Secondary bacterial infection of lupus rashes or ulcerations is uncommon, although cellulitis should be considered when a rash is unilateral, not in a sun-exposed area, or is otherwise different from the patient’s typical lupus rash. Sun avoidance and topical corticosteroids are the mainstays of treatment of dermatological disease in SLE.

Emergent Complications

Systemic Vasculitis. Patients with SLE are susceptible to vasculitis. Although isolated cutaneous vasculitis is not typically an emergent condition, it may portend systemic vasculitis. Any palpable purpura or other evidence of cutaneous vasculitis should prompt a careful review of systems and basic laboratory workup for systemic vasculitis, which can involve the kidneys, lungs, central or peripheral nervous system, or gastrointestinal tract.

Symptoms of systemic vasculitis may include fevers, chills, chest pain, cough, hemoptysis, abdominal pain, and changes in color or amount of urine. Laboratory workup should be tailored to symptoms, and may include basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, complete blood count, and urinalysis.4

Digital Gangrene. Patients with SLE may also develop digital gangrene related to severe Raynaud phenomenon, vasculitis, or thromboembolism. Pharmacological treatment with vasodilators such as sildenafil, endothelin receptor antagonists, or intravenous prostacyclins may be needed.5 To save the involved digit, vascular surgery services should be consulted urgently.6

Renal Complications

Common Complications

Chronic Kidney Disease. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is common among SLE patients, especially among those with a history of lupus nephritis.7 Patients with CKD may have persistently elevated serum creatinine, chronic hypertension, and/or chronic peripheral edema. Patients presenting with new development of hypertension, peripheral edema, hematuria, or polyuria should be screened for lupus nephritis with urinalysis and serum creatinine. Elevated creatinine or new or worsening proteinuria or hematuria should prompt consultation with nephrology services.

Emergent Complications

Lupus Nephritis. About 50% of SLE patients will develop lupus nephritis during the course of their lives,1 which may present as nephrotic disease with significant proteinuria, peripheral edema, and low serum albumin, or as nephritic disease, with increased serum creatinine and hematuria. Acute kidney injury in SLE patients should generally prompt admission for workup of reversible causes and evaluation for lupus nephritis, which often includes renal biopsy.8

Neuropsychiatric Complications

Common Complications

Neuropsychiatric lupus is a broad category that includes 19 manifestations of SLE in the central and peripheral nervous systems.9 Conditions range from depression or chronic headaches to seizures or psychosis.

Mood and Anxiety Disorders. Anxiety and depression have been observed in up to 75% of SLE patients.1 Mood and anxiety disorders are likely influenced by the psychosocial elements of this chronic disease, as well as by direct effects of SLE on the brain.1

Peripheral Neuropathy. Approximately 10% of SLE patients have a peripheral neuropathy, which generally presents as a mononeuritis (either single or multiplex), rather than the stocking-glove distribution seen in other systemic causes of neuropathy.10

Headache. Headache disorders may also develop in SLE patients, and tend to have similar patterns to primary headache disorders in the general population. In most cases, treatment for headache in SLE patients is similar to that of the general population.11 However, if a patient presents with concerning findings, such as focal neurological deficit, meningismus, or fever, or if the headache is new-onset or different from previous headaches, further investigation should be considered, including a head computed tomography (CT) scan and lumbar puncture (LP).

Emergent Complications

In general, due to the variety of neurological emergencies that may present with SLE, and the subtlety with which true emergencies may present in this population, the threshold to obtain imaging on SLE patients with any new neurological complaints should be low.

Cerebrovascular Accidents. Patients with SLE are susceptible to cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs), typically from occlusive or embolic causes. Etiologies may include primary central nervous system (CNS) vasculitis, embolic disease from antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), or embolic disease from a Libman-Sacks endocarditis.12

Successful thrombolysis has been reported in SLE patients presenting with stroke, but it remains controversial due to risk of hemorrhagic conversion if CNS vasculitis, rather than embolism, is the cause.13 Proper imaging and consultation with a neurologist familiar with the disease is critical for early treatment decisions.

Seizures. Fifteen percent to 35% of SLE patients may develop seizures. These may be focal or generalized, but generalized tonic-clonic seizures tend to be more common in SLE patients.2 Workup and management of seizures in SLE patients is the same as in the general population.

Sinus Thrombosis. Dural sinus thrombosis often presents as a new-onset headache, sometimes with focal neurological deficits. The diagnosis of dural sinus thrombosis can be challenging, as CT imaging studies may be falsely negative. There should be a low threshold for obtaining MRI/magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) in SLE patients presenting with a new-onset headache.14

CNS Vasculitis. Patients with SLE are also susceptible to CNS vasculitis, which can manifest as seizures, psychosis, cognitive decline, altered mental status, or coma. Magnetic resonance imaging/MRA studies may suggest the diagnosis, but if this is equivocal, angiography or even brain biopsy may be needed to make the diagnosis. Unless the patient’s symptoms are very mild (eg, mild cognitive decline), she or he should be admitted for diagnostic workup and consideration of aggressive immunosuppressive therapy.2

Transverse Myelitis and Spinal Artery Thrombosis. Acute loss of lower limb sensation or motor function in SLE patients may be caused by transverse myelitis or spinal artery thrombosis. Epidural abscess should also be considered, especially if the patient is immunocompromised.2

Infection. A CNS infection should be considered in any SLE patient presenting with new neurological complaints. Fever or meningismus, especially in conjunction with headache or focal neurological deficits, should prompt an LP and consideration for imaging. Immunocompromised patients are at increased risk for common organisms as well as atypical organisms, such as fungus or mycobacteria.15

Pulmonary Complications

Common Complications

Pleuritis. Many patients with SLE develop pleuritis, with or without effusion. This may be treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or corticosteroids if symptoms are more severe. Pleuritis is the most common respiratory complication of SLE, but due to the number of serious cardiopulmonary complications associated with SLE, pleuritis should be a diagnosis of exclusion.

Interstitial Lung Disease. Interstitial lung disease may be caused by SLE or may be medication-induced. This commonly presents as subacute or chronic dyspnea and/or cough. Patient workup may be done on an outpatient basis with high resolution chest CT and pulmonary function testing.

Pulmonary Hypertension. Patients with SLE may develop pulmonary hypertension, either directly due to SLE or from chronic thromboembolic disease. In general, pulmonary hypertension is managed as an outpatient, but may require emergent inpatient treatment if the condition is rapidly progressive or associated with right heart failure.

Shrinking Lung Syndrome. This condition may cause subacute or chronic dyspnea and pleuritic chest pain. Shrinking lung syndrome is caused by diaphragmatic dysfunction rather than from a primary disease of the lungs, and it is characterized by a restrictive pattern on pulmonary function testing and an elevated hemidiaphragm. Shrinking lung syndrome typically responds well to immunosuppressive therapy.16

Emergent Conditions

Pulmonary Embolism. A pulmonary embolism should be strongly considered in any patient with SLE presenting with the appropri ate clinical picture. Patients with APS are at particularly high risk for thromboembolic disease. However, even SLE patients without this APS are known to be at an increased risk of developing thromboembolism compared to the general public.17 Pulmonary embolism in SLE patients should be diagnosed and treated in the usual manner.

Pneumonia. Immunosuppressed patients are susceptible to opportunistic pulmonary infections as well as typical community pathogens. Fungal or mycobacterial infections may be suspected with a more subacute onset of symptoms.

Acute Lupus Pneumonitis. This serious condition may present with severe pneumonia-like signs and symptoms, including fever, cough, dyspnea, hypoxia, and infiltrates on chest radiograph (Figure 3).

Acute lupus pneumonitis is caused by disease flare, and not by infection, although it may not be possible to distinguish it from pneumonia in the ED setting. The mortality rate of acute lupus pneumonitis is as high as 50%, and survivors often progress to chronic interstitial pneumonitis.1

Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage. A rare complication with a mortality rate of 50% to 90%, SLE patients who develop diffuse alveolar hemorrhage may present with fever, cough, dyspnea, and hypoxia.18 The condition may be suggested by infiltrates on chest radiograph, a drop in hemoglobin representing bleeding into the lungs, and/or hemoptysis. However, the absence of hemoptysis does not rule out diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, so clinical suspicion should remain high, even in the absence of this symptom.

Because emergent pulmonary conditions often present with similar symptoms, most patients with acute or new-onset symptoms will require admission for diagnostic workup (likely to include chest CT scan and/or bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage), as well as for close monitoring and initiation of treatment. If hypoxia or respiratory distress is severe, or if diffuse alveolar hemorrhage is suspected, admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) should be considered. We suggest that antibiotics be started in the ED when pneumonia is part of the differential diagnosis. As in the general population, coverage should be chosen based on the patient’s risk factors for antibiotic-resistant organisms. Initiation of corticosteroid therapy or other changes in immune therapy can be delayed until the EP consults with rheumatology and/or pulmonology services.

Cardiac Complications

Common Complications

Pericarditis. Pericarditis with or without pericardial effusion is very common in SLE patients and is usually related to lupus itself, rather than an infectious etiology. Patients may present with substernal, positional chest pain, tachycardia, and diffuse ST-segment elevation on electrocardiogram. Most effusions are small, asymptomatic, and discovered incidentally. However, among patients with symptomatic pericardial effusions, tamponade can be present in 21%.19 Corticosteroid therapy is often required to treat SLE-associated pericarditis, but colchicine is being explored as a possible steroid-sparing agent in this patient population.20,21

Valvular Abnormalities. Approximately 60% of SLE patients have valvular abnormalities detectable by echocardiography. The most common abnormalities in one study were valvular thickening or regurgitation.22 Many of these abnormalities occurred in asymptomatic patients and never progressed to clinical disease in a 5-year follow-up. However, patients with any valvular abnormality were more likely to develop complications, including stroke, peripheral embolism, infective endocarditis, need for valve replacement, congestive heart failure, or death.22

Emergent Complications

Acute Coronary Syndrome. Even in relatively young patients, acute coronary syndrome (ACS) should be considered in SLE patients presenting with chest pain, as this patient population has a 10-fold higher risk of developing coronary artery disease (CAD) than the general population, and SLE patients with CAD often lack traditional risk factors, such as advanced age, family history, or metabolic syndrome.1

A high clinical suspicion should be maintained even in patients who would traditionally be considered low-risk. The EP should have a low-threshold for ECG, cardiac biomarker testing, and stress testing for SLE patients presenting with chest pain. The treatment of ACS in SLE patients is the same as in the general population.

Libman-Sacks Endocarditis. A sterile, fibrinous valvular vegetation, Libman-Sacks endocarditis is unique to patients with SLE. When present, patients usually develop a subacute or chronic onset of dyspnea or chest pain. However, patients may become acutely ill if they develop severe valvular regurgitation. Additionally, the valve damage from Libman-Sacks endocarditis can predispose patients to developing infective endocarditis.20

Hematological Complications

Common Complications

Patients with SLE commonly have mild-to-moderate leukopenia (especially lymphopenia), anemia, and thrombocytopenia. This may be related to the disease process or may be secondary to prescribed medications. A comparison to recent baseline laboratory studies should be sought if there is suspicion for new or worsening cytopenia.

Antiphospholipid Syndrome. Nearly 40% of SLE patients also have APS, which is defined by a clinical history of thrombosis in conjunction with one of the antiphospholipid antibodies (anticardiolipin, anti-beta-2-glycoprotein, lupus anticoagulant). Antiphospholipid syndrome causes both venous and arterial thrombosis and may be associated with recurrent miscarriage. Acute thrombotic events should be treated with heparin or enoxaparin and transitioned to warfarin. The new generation of direct oral anticoagulants have not been well studied in APS, though, multiple small case series suggest a higher thrombotic risk with these drugs than with warfarin.23Patients who have recurrent venous thromboembolism, or who have any arterial thromboembolism should be on lifelong anticoagulation therapy.2

Emergent Complications

Thrombocytopenia. Severe thrombocytopenia or hemolytic anemia can be life-threatening, and often requires inpatient admission for immunosuppressive therapy, monitoring, and supportive care.

Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome. This condition should be suspected in patients with SLE who present with multiple sites of thrombosis or new multi-organ damage. Catastrophic APS (CAPS) may occur in SLE patients who have no prior history of APS. Since the mortality rate for CAPS approaches 50%, these patients require anticoagulation, immunosuppressant therapy (high-dose corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, and/or plasma exchange), and admission to the ICU.24

Gastrointestinal Complications

Common Complications

Intestinal Pseudo-obstruction. Dysphagia related to esophageal dysmotility is present in up to 13% of SLE patients.25 Intestinal pseudo-obstruction may be seen in SLE patients, and is characterized by symptoms of intestinal obstruction caused by decreased intestinal motility, rather than from mechanical obstruction. Presenting symptoms may be acute or chronic, and include nausea, vomiting, and abdominal distension. Abdominal CT studies will show dilated bowel loops without evidence of mechanical obstruction. Manometry reveals widespread hypomotility. Intestinal pseudo-obstruction typically responds well to corticosteroids and other immunosuppressant therapies.26

Emergent Conditions

Acute Abdominal Pain. Approximately half of SLE patients who present to the ED with acute abdominal pain are found to have either mesenteric vasculitis or pancreatitis, both of which are thought to be related to SLE disease activity.27 Other causes of acute abdominal pain that are common in the general population remain common in SLE patients, including gallbladder disease, gastroenteritis, appendicitis, and peptic ulcer disease.

Mesenteric Vasculitis. Also known as lupus enteritis, mesenteric vasculitis is a unique cause of acute abdominal pain in SLE patients. The condition presents with acute, diffuse abdominal pain and may be associated with nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, or hematochezia. Abdominal CT findings suggestive of diffuse enteritis support the diagnosis. Medical management with pulse-dose corticosteroids and supportive care is generally sufficient, but if bowel necrosis or intestinal perforation is present or suspected, surgical consultation should be obtained immediately.15

Conclusion

Complications of SLE are diverse and may be difficult to diagnose. Understanding the common and emergent complications of SLE will help the EP to recognize severe illness and make appropriate treatment decisions in this complex patient population.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by the chronic activation of the immune system, leading to the formation of autoantibodies and multi-organ damage. The prevalence of SLE in the United States is 20 to 150 per 100,000 persons.1 Ninety percent of patients with SLE are women, and the condition is more common and often more severe among patients of black African or of Asian descent.

For patients with known SLE who present to the ED, it can be a challenge to identify whether their symptoms are due to a minor lupus flare that can be managed as an outpatient, a presentation of urgent or emergent conditions caused by SLE, or a condition unrelated to lupus. This article reviews the most common and emergent complications of SLE by organ system to assist emergency physicians (EPs) in better diagnosing and managing this complicated disease.

General Acute-Care Management

While a patient’s presentation could be secondary to a lupus-related complication, consideration must always be given to common conditions that are not related to SLE. Biomarkers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, C3 and C4 complement, and double-stranded DNA levels can be helpful in assessing lupus disease activity and differentiating a lupus-related complication from an unrelated event. Comparing these biomarkers to the patient’s baseline values can be informative; however, depending on the laboratory facilities, test results may not be available during an ED visit. Lastly, infections should be considered more strongly than usual in the differential diagnosis due to the immunocompromised status of a substantial proportion of these patients, by virtue of their disease or the cytotoxic medications used for treatment.

Musculoskeletal Complications

Common Complications

Polyarthralgias and Polymyalgias. More than 90% of SLE patients experience polyarthralgias and polymyalgias. Physical examination findings may be normal, even when joint pain is present, which is often due to mild synovitis. In some cases, Jaccoud arthropathy is seen, which presents as deformities such as swan neck deformities and ulnar deviations that are characteristically reducible on manipulation (Figures 1a and 1b). These deformities are not caused by direct joint damage, but by chronic tenosynovitis and the resulting laxity of tendons and ligaments.1 Classically, plain radiographic imaging reveals nonerosive joint changes. Muscle and joint pains may worsen with disease progression or flare.

Avascular Necrosis. Avascular necrosis affects 5% to 12% of SLE patients.2 Most commonly, this involves the femoral head, but it may also involve the femoral condyle or tibial plateau. Patients may present with acute or subacute onset of pain in the groin or buttocks when the femoral head is involved, or in the knee when the femoral condyle or tibial plateau is involved. Plain radiographs may reveal joint-space narrowing and other evidence of degenerative joint disease. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more sensitive in diagnosing avascular necrosis, and may be indicated when clinical suspicion is high despite negative plain radiographs, although this would not typically need to be performed urgently in the ED.2 While analgesics and physical therapy may provide some pain relief to patients with avascular necrosis, this condition generally requires nonemergent operative intervention.

Emergent Complications

Septic Arthritis. When a patient with SLE presents with an isolated swollen joint, septic arthritis should be suspected, and diagnosis should be confirmed by arthrocentesis. Synovial fluid samples showing a white blood cell count greater than 50 × 109/Lsuggest infection, which can be confirmed by gram stain and cultures.

For reasons that remain unclear, but may involve primary immune defects and the use of immunosuppressant medications, patients with SLE are predisposed to Salmonella joint infections. In one study, 59% of septic arthritis cases in patients with SLE were due to Salmonella species; therefore, treatment for septic arthritis in this population should include ceftriaxone in addition to vancomycin for typical organisms, such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species.3

Cutaneous Manifestations

Common Complications

Malar Rash. Eighty percent to 90% of patients with SLE have dermatological involvement,1 the most common finding of which is the malar or butterfly facial rash, which appears as raised erythema over the bridge of the nose and cheeks while sparing the nasolabial folds (Figure 2).

Discoid Lupus. Chronic discoid lupus appears as a scarring rash often found on the face, ears, and scalp. These patients may also exhibit a photosensitive rash, which consists of an erythematous eruption if acute, or annular scaly lesions if subacute.

Oral and Nasal Ulcerations. Common mucous membrane findings include oral or nasal ulcers, which are typically painless.

Worsening of any of these skin findings may be associated with disease flare. Secondary bacterial infection of lupus rashes or ulcerations is uncommon, although cellulitis should be considered when a rash is unilateral, not in a sun-exposed area, or is otherwise different from the patient’s typical lupus rash. Sun avoidance and topical corticosteroids are the mainstays of treatment of dermatological disease in SLE.

Emergent Complications

Systemic Vasculitis. Patients with SLE are susceptible to vasculitis. Although isolated cutaneous vasculitis is not typically an emergent condition, it may portend systemic vasculitis. Any palpable purpura or other evidence of cutaneous vasculitis should prompt a careful review of systems and basic laboratory workup for systemic vasculitis, which can involve the kidneys, lungs, central or peripheral nervous system, or gastrointestinal tract.

Symptoms of systemic vasculitis may include fevers, chills, chest pain, cough, hemoptysis, abdominal pain, and changes in color or amount of urine. Laboratory workup should be tailored to symptoms, and may include basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, complete blood count, and urinalysis.4

Digital Gangrene. Patients with SLE may also develop digital gangrene related to severe Raynaud phenomenon, vasculitis, or thromboembolism. Pharmacological treatment with vasodilators such as sildenafil, endothelin receptor antagonists, or intravenous prostacyclins may be needed.5 To save the involved digit, vascular surgery services should be consulted urgently.6

Renal Complications

Common Complications

Chronic Kidney Disease. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is common among SLE patients, especially among those with a history of lupus nephritis.7 Patients with CKD may have persistently elevated serum creatinine, chronic hypertension, and/or chronic peripheral edema. Patients presenting with new development of hypertension, peripheral edema, hematuria, or polyuria should be screened for lupus nephritis with urinalysis and serum creatinine. Elevated creatinine or new or worsening proteinuria or hematuria should prompt consultation with nephrology services.

Emergent Complications

Lupus Nephritis. About 50% of SLE patients will develop lupus nephritis during the course of their lives,1 which may present as nephrotic disease with significant proteinuria, peripheral edema, and low serum albumin, or as nephritic disease, with increased serum creatinine and hematuria. Acute kidney injury in SLE patients should generally prompt admission for workup of reversible causes and evaluation for lupus nephritis, which often includes renal biopsy.8

Neuropsychiatric Complications

Common Complications

Neuropsychiatric lupus is a broad category that includes 19 manifestations of SLE in the central and peripheral nervous systems.9 Conditions range from depression or chronic headaches to seizures or psychosis.

Mood and Anxiety Disorders. Anxiety and depression have been observed in up to 75% of SLE patients.1 Mood and anxiety disorders are likely influenced by the psychosocial elements of this chronic disease, as well as by direct effects of SLE on the brain.1

Peripheral Neuropathy. Approximately 10% of SLE patients have a peripheral neuropathy, which generally presents as a mononeuritis (either single or multiplex), rather than the stocking-glove distribution seen in other systemic causes of neuropathy.10

Headache. Headache disorders may also develop in SLE patients, and tend to have similar patterns to primary headache disorders in the general population. In most cases, treatment for headache in SLE patients is similar to that of the general population.11 However, if a patient presents with concerning findings, such as focal neurological deficit, meningismus, or fever, or if the headache is new-onset or different from previous headaches, further investigation should be considered, including a head computed tomography (CT) scan and lumbar puncture (LP).

Emergent Complications

In general, due to the variety of neurological emergencies that may present with SLE, and the subtlety with which true emergencies may present in this population, the threshold to obtain imaging on SLE patients with any new neurological complaints should be low.

Cerebrovascular Accidents. Patients with SLE are susceptible to cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs), typically from occlusive or embolic causes. Etiologies may include primary central nervous system (CNS) vasculitis, embolic disease from antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), or embolic disease from a Libman-Sacks endocarditis.12

Successful thrombolysis has been reported in SLE patients presenting with stroke, but it remains controversial due to risk of hemorrhagic conversion if CNS vasculitis, rather than embolism, is the cause.13 Proper imaging and consultation with a neurologist familiar with the disease is critical for early treatment decisions.

Seizures. Fifteen percent to 35% of SLE patients may develop seizures. These may be focal or generalized, but generalized tonic-clonic seizures tend to be more common in SLE patients.2 Workup and management of seizures in SLE patients is the same as in the general population.

Sinus Thrombosis. Dural sinus thrombosis often presents as a new-onset headache, sometimes with focal neurological deficits. The diagnosis of dural sinus thrombosis can be challenging, as CT imaging studies may be falsely negative. There should be a low threshold for obtaining MRI/magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) in SLE patients presenting with a new-onset headache.14

CNS Vasculitis. Patients with SLE are also susceptible to CNS vasculitis, which can manifest as seizures, psychosis, cognitive decline, altered mental status, or coma. Magnetic resonance imaging/MRA studies may suggest the diagnosis, but if this is equivocal, angiography or even brain biopsy may be needed to make the diagnosis. Unless the patient’s symptoms are very mild (eg, mild cognitive decline), she or he should be admitted for diagnostic workup and consideration of aggressive immunosuppressive therapy.2

Transverse Myelitis and Spinal Artery Thrombosis. Acute loss of lower limb sensation or motor function in SLE patients may be caused by transverse myelitis or spinal artery thrombosis. Epidural abscess should also be considered, especially if the patient is immunocompromised.2

Infection. A CNS infection should be considered in any SLE patient presenting with new neurological complaints. Fever or meningismus, especially in conjunction with headache or focal neurological deficits, should prompt an LP and consideration for imaging. Immunocompromised patients are at increased risk for common organisms as well as atypical organisms, such as fungus or mycobacteria.15

Pulmonary Complications

Common Complications

Pleuritis. Many patients with SLE develop pleuritis, with or without effusion. This may be treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or corticosteroids if symptoms are more severe. Pleuritis is the most common respiratory complication of SLE, but due to the number of serious cardiopulmonary complications associated with SLE, pleuritis should be a diagnosis of exclusion.

Interstitial Lung Disease. Interstitial lung disease may be caused by SLE or may be medication-induced. This commonly presents as subacute or chronic dyspnea and/or cough. Patient workup may be done on an outpatient basis with high resolution chest CT and pulmonary function testing.

Pulmonary Hypertension. Patients with SLE may develop pulmonary hypertension, either directly due to SLE or from chronic thromboembolic disease. In general, pulmonary hypertension is managed as an outpatient, but may require emergent inpatient treatment if the condition is rapidly progressive or associated with right heart failure.

Shrinking Lung Syndrome. This condition may cause subacute or chronic dyspnea and pleuritic chest pain. Shrinking lung syndrome is caused by diaphragmatic dysfunction rather than from a primary disease of the lungs, and it is characterized by a restrictive pattern on pulmonary function testing and an elevated hemidiaphragm. Shrinking lung syndrome typically responds well to immunosuppressive therapy.16

Emergent Conditions

Pulmonary Embolism. A pulmonary embolism should be strongly considered in any patient with SLE presenting with the appropri ate clinical picture. Patients with APS are at particularly high risk for thromboembolic disease. However, even SLE patients without this APS are known to be at an increased risk of developing thromboembolism compared to the general public.17 Pulmonary embolism in SLE patients should be diagnosed and treated in the usual manner.

Pneumonia. Immunosuppressed patients are susceptible to opportunistic pulmonary infections as well as typical community pathogens. Fungal or mycobacterial infections may be suspected with a more subacute onset of symptoms.

Acute Lupus Pneumonitis. This serious condition may present with severe pneumonia-like signs and symptoms, including fever, cough, dyspnea, hypoxia, and infiltrates on chest radiograph (Figure 3).

Acute lupus pneumonitis is caused by disease flare, and not by infection, although it may not be possible to distinguish it from pneumonia in the ED setting. The mortality rate of acute lupus pneumonitis is as high as 50%, and survivors often progress to chronic interstitial pneumonitis.1

Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage. A rare complication with a mortality rate of 50% to 90%, SLE patients who develop diffuse alveolar hemorrhage may present with fever, cough, dyspnea, and hypoxia.18 The condition may be suggested by infiltrates on chest radiograph, a drop in hemoglobin representing bleeding into the lungs, and/or hemoptysis. However, the absence of hemoptysis does not rule out diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, so clinical suspicion should remain high, even in the absence of this symptom.

Because emergent pulmonary conditions often present with similar symptoms, most patients with acute or new-onset symptoms will require admission for diagnostic workup (likely to include chest CT scan and/or bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage), as well as for close monitoring and initiation of treatment. If hypoxia or respiratory distress is severe, or if diffuse alveolar hemorrhage is suspected, admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) should be considered. We suggest that antibiotics be started in the ED when pneumonia is part of the differential diagnosis. As in the general population, coverage should be chosen based on the patient’s risk factors for antibiotic-resistant organisms. Initiation of corticosteroid therapy or other changes in immune therapy can be delayed until the EP consults with rheumatology and/or pulmonology services.

Cardiac Complications

Common Complications