User login

Journal of Hospital Medicine – Jan. 2018

BACKGROUND: Hospital charges and lengths of stay may be greater when adults with chronic conditions are admitted to children’s hospitals. Despite multiple efforts to improve pediatric-adult health care transitions, little guidance exists for transitioning inpatient care.

OBJECTIVE: This study sought to characterize pediatric-adult inpatient care transitions across general pediatric services at U.S. children’s hospitals.

DESIGN and SETTING: National survey of inpatient general pediatric service leaders at U.S. children’s hospitals from January 2016 to July 2016.

MEASUREMENT: Questionnaires assessed institutional characteristics, presence of inpatient transition initiatives (having a specific process and/or leader), and 22 inpatient transition activities. Scales of highly correlated activities were created using exploratory factor analysis. Logistic regression identified associations among institutional characteristics, transition activities, and presence of an inpatient transition initiative.

RESULTS: Of 195 children’s hospitals, 96 responded (49.2% response rate). Transition initiatives were present at 38% of children’s hospitals, more often where there were providers who were trained in both internal medicine and pediatrics or where there were outpatient transition processes. Specific activities were infrequent and varied widely from 2.1% (systems to track youth in transition) to 40.5% (addressing potential insurance problems). Institutions with initiatives more often consistently performed the majority of activities, including using checklists and creating patient-centered transition care plans. Of remaining activities, half involved transition planning, the essential step between readiness and transfer.

CONCLUSION: Relatively few inpatient general pediatric services at U.S. children’s hospitals have leaders or dedicated processes to shepherd transitions to adult-oriented inpatient care. Across institutions, there is wide variability in performance of activities to facilitate this transition. Feasible process and outcome measures are needed.

Also in JHM this month

Characterizing hospitalist practice and perceptions of critical care delivery

AUTHORS: Joseph R. Sweigart, MD, FACP, FHM; David Aymond, MD; Alfred Burger, MD, FACP, SFHM; Andy Kelly, MAS, MS; Nick Marzano, Med; Thomas McIlraith, MD, SFHM; Peter Morris, MD; Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, MHM; and Eric M. Siegal, MD, SFHM, FCCM

Clinical decision making: Observing the smartphone user an observational study in predicting acute surgical patients’ suitability for discharge

AUTHORS: Richard Hoffmann, MBBS; Simon Harley, MBBS; Samuel Ellison, MBBS; and Peter G. Devitt, MBBS, FRACS

BACKGROUND: Hospital charges and lengths of stay may be greater when adults with chronic conditions are admitted to children’s hospitals. Despite multiple efforts to improve pediatric-adult health care transitions, little guidance exists for transitioning inpatient care.

OBJECTIVE: This study sought to characterize pediatric-adult inpatient care transitions across general pediatric services at U.S. children’s hospitals.

DESIGN and SETTING: National survey of inpatient general pediatric service leaders at U.S. children’s hospitals from January 2016 to July 2016.

MEASUREMENT: Questionnaires assessed institutional characteristics, presence of inpatient transition initiatives (having a specific process and/or leader), and 22 inpatient transition activities. Scales of highly correlated activities were created using exploratory factor analysis. Logistic regression identified associations among institutional characteristics, transition activities, and presence of an inpatient transition initiative.

RESULTS: Of 195 children’s hospitals, 96 responded (49.2% response rate). Transition initiatives were present at 38% of children’s hospitals, more often where there were providers who were trained in both internal medicine and pediatrics or where there were outpatient transition processes. Specific activities were infrequent and varied widely from 2.1% (systems to track youth in transition) to 40.5% (addressing potential insurance problems). Institutions with initiatives more often consistently performed the majority of activities, including using checklists and creating patient-centered transition care plans. Of remaining activities, half involved transition planning, the essential step between readiness and transfer.

CONCLUSION: Relatively few inpatient general pediatric services at U.S. children’s hospitals have leaders or dedicated processes to shepherd transitions to adult-oriented inpatient care. Across institutions, there is wide variability in performance of activities to facilitate this transition. Feasible process and outcome measures are needed.

Also in JHM this month

Characterizing hospitalist practice and perceptions of critical care delivery

AUTHORS: Joseph R. Sweigart, MD, FACP, FHM; David Aymond, MD; Alfred Burger, MD, FACP, SFHM; Andy Kelly, MAS, MS; Nick Marzano, Med; Thomas McIlraith, MD, SFHM; Peter Morris, MD; Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, MHM; and Eric M. Siegal, MD, SFHM, FCCM

Clinical decision making: Observing the smartphone user an observational study in predicting acute surgical patients’ suitability for discharge

AUTHORS: Richard Hoffmann, MBBS; Simon Harley, MBBS; Samuel Ellison, MBBS; and Peter G. Devitt, MBBS, FRACS

BACKGROUND: Hospital charges and lengths of stay may be greater when adults with chronic conditions are admitted to children’s hospitals. Despite multiple efforts to improve pediatric-adult health care transitions, little guidance exists for transitioning inpatient care.

OBJECTIVE: This study sought to characterize pediatric-adult inpatient care transitions across general pediatric services at U.S. children’s hospitals.

DESIGN and SETTING: National survey of inpatient general pediatric service leaders at U.S. children’s hospitals from January 2016 to July 2016.

MEASUREMENT: Questionnaires assessed institutional characteristics, presence of inpatient transition initiatives (having a specific process and/or leader), and 22 inpatient transition activities. Scales of highly correlated activities were created using exploratory factor analysis. Logistic regression identified associations among institutional characteristics, transition activities, and presence of an inpatient transition initiative.

RESULTS: Of 195 children’s hospitals, 96 responded (49.2% response rate). Transition initiatives were present at 38% of children’s hospitals, more often where there were providers who were trained in both internal medicine and pediatrics or where there were outpatient transition processes. Specific activities were infrequent and varied widely from 2.1% (systems to track youth in transition) to 40.5% (addressing potential insurance problems). Institutions with initiatives more often consistently performed the majority of activities, including using checklists and creating patient-centered transition care plans. Of remaining activities, half involved transition planning, the essential step between readiness and transfer.

CONCLUSION: Relatively few inpatient general pediatric services at U.S. children’s hospitals have leaders or dedicated processes to shepherd transitions to adult-oriented inpatient care. Across institutions, there is wide variability in performance of activities to facilitate this transition. Feasible process and outcome measures are needed.

Also in JHM this month

Characterizing hospitalist practice and perceptions of critical care delivery

AUTHORS: Joseph R. Sweigart, MD, FACP, FHM; David Aymond, MD; Alfred Burger, MD, FACP, SFHM; Andy Kelly, MAS, MS; Nick Marzano, Med; Thomas McIlraith, MD, SFHM; Peter Morris, MD; Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, MHM; and Eric M. Siegal, MD, SFHM, FCCM

Clinical decision making: Observing the smartphone user an observational study in predicting acute surgical patients’ suitability for discharge

AUTHORS: Richard Hoffmann, MBBS; Simon Harley, MBBS; Samuel Ellison, MBBS; and Peter G. Devitt, MBBS, FRACS

Isotretinoin and shea butter

It took Jared till the end of his third month on isotretinoin to tell me he was two-timing me with another skin doctor.

“She calls herself a cosmetic dermatologist,” he said, naming a nearby practitioner I didn’t know. “She formulates special skin care products tailored to my particular skin. The one she came up with for me is based on shea butter, and it feels great.”

I am always amazed at people’s capacity to believe that there is a unique regimen just right for them, preferably one specially formulated by an expert who is privy to a secret no one else knows. Shea butter, it turns out, comes from the African shea tree (Ugandan trees are best). Africans eat the shea nuts; Westerners smear on ground-up nut contents.

Nut of shea. Tree of tea. Eye of newt. Toe of frog. The list goes on.

But I digress.

That didn’t seem very nice of her. I hadn’t murmured about her moisturizer, had I?

“What did she object to?” I asked. “Did her patients have problems with it?”

“She just said the drug is very bad,” said Jared. “She doesn’t like it at all. I was a little taken aback. I wasn’t expecting her to object so strongly.”

“But you’re still OK with taking isotretinoin?” I asked.

“Oh, yes,” said Jared. “It seems to be working, and I trust you.”

That was good to hear. I wondered whether Jared’s trust was based on the rigor of my scientific background or on my kindly smile and reassuring beard.

“Thank you, Jared,” I said. “I like isotretinoin a lot. It’s not for everybody, but for the last 35 years, I’ve seen it do excellent things for the appearance and self-image of many people.”

When I teach medical students, I often emphasize, as a point of professional etiquette, the impropriety of snorting or rolling your eyes at what patients report that other colleagues said and did. First of all, patient accounts may be imprecise or colored by their wish to build you up and flatter themselves for picking you. Second, just imagine what they might say about you at the next office they visit.

Reputation aside (you can hire folks to buff yours, if you like), my little exchange with Jared points up a basic difference between the way doctors think and the way our patients do.

What’s behind doctors’ professional lives is our assumption that diseases exist outside the bodies that the diseases inhabit. We therefore can offer a “treatment of choice” (or maybe a couple of them) that is best for treating a disease, regardless of who has it. This assumption is so obvious that we rarely think about it.

Obvious to us, that is, but not to our patients, to whom every patient has (to a large if not exclusive extent) his or her own disease. If possible, every patient wants a treatment tailored to each person’s unique makeup and predicament.

Jared is far from alone in playing both ends at the same time. From me he gets universal, evidence-based truths. From his other (more jealous!) medical mistress, he gets a skin care regimen tailored lovingly just for him.

Test your unique genes, get the treatment tailored just for you. Some rigorous scientists are trying not to so much debunk this effort as to point out how its promise is massively overhyped and unlikely to be worthy of the massive research investment it attracts. Perhaps their rigorous rationality will bear fruit, but they’re up against not just vested medical/industrial/venture capital interests, but the expectations of sick people who have always known that there is – that there simply has to be – a treatment out there that’s just for them.

Mock if you must, but tell me this: If people can prosper marketing a moisturizer called Kiss My Face or rake in the bucks with a skin care line named Urban Decay, then what’s your problem with Eye of Newt? You want focus groups?

Crowdfunding, anyone?

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

It took Jared till the end of his third month on isotretinoin to tell me he was two-timing me with another skin doctor.

“She calls herself a cosmetic dermatologist,” he said, naming a nearby practitioner I didn’t know. “She formulates special skin care products tailored to my particular skin. The one she came up with for me is based on shea butter, and it feels great.”

I am always amazed at people’s capacity to believe that there is a unique regimen just right for them, preferably one specially formulated by an expert who is privy to a secret no one else knows. Shea butter, it turns out, comes from the African shea tree (Ugandan trees are best). Africans eat the shea nuts; Westerners smear on ground-up nut contents.

Nut of shea. Tree of tea. Eye of newt. Toe of frog. The list goes on.

But I digress.

That didn’t seem very nice of her. I hadn’t murmured about her moisturizer, had I?

“What did she object to?” I asked. “Did her patients have problems with it?”

“She just said the drug is very bad,” said Jared. “She doesn’t like it at all. I was a little taken aback. I wasn’t expecting her to object so strongly.”

“But you’re still OK with taking isotretinoin?” I asked.

“Oh, yes,” said Jared. “It seems to be working, and I trust you.”

That was good to hear. I wondered whether Jared’s trust was based on the rigor of my scientific background or on my kindly smile and reassuring beard.

“Thank you, Jared,” I said. “I like isotretinoin a lot. It’s not for everybody, but for the last 35 years, I’ve seen it do excellent things for the appearance and self-image of many people.”

When I teach medical students, I often emphasize, as a point of professional etiquette, the impropriety of snorting or rolling your eyes at what patients report that other colleagues said and did. First of all, patient accounts may be imprecise or colored by their wish to build you up and flatter themselves for picking you. Second, just imagine what they might say about you at the next office they visit.

Reputation aside (you can hire folks to buff yours, if you like), my little exchange with Jared points up a basic difference between the way doctors think and the way our patients do.

What’s behind doctors’ professional lives is our assumption that diseases exist outside the bodies that the diseases inhabit. We therefore can offer a “treatment of choice” (or maybe a couple of them) that is best for treating a disease, regardless of who has it. This assumption is so obvious that we rarely think about it.

Obvious to us, that is, but not to our patients, to whom every patient has (to a large if not exclusive extent) his or her own disease. If possible, every patient wants a treatment tailored to each person’s unique makeup and predicament.

Jared is far from alone in playing both ends at the same time. From me he gets universal, evidence-based truths. From his other (more jealous!) medical mistress, he gets a skin care regimen tailored lovingly just for him.

Test your unique genes, get the treatment tailored just for you. Some rigorous scientists are trying not to so much debunk this effort as to point out how its promise is massively overhyped and unlikely to be worthy of the massive research investment it attracts. Perhaps their rigorous rationality will bear fruit, but they’re up against not just vested medical/industrial/venture capital interests, but the expectations of sick people who have always known that there is – that there simply has to be – a treatment out there that’s just for them.

Mock if you must, but tell me this: If people can prosper marketing a moisturizer called Kiss My Face or rake in the bucks with a skin care line named Urban Decay, then what’s your problem with Eye of Newt? You want focus groups?

Crowdfunding, anyone?

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

It took Jared till the end of his third month on isotretinoin to tell me he was two-timing me with another skin doctor.

“She calls herself a cosmetic dermatologist,” he said, naming a nearby practitioner I didn’t know. “She formulates special skin care products tailored to my particular skin. The one she came up with for me is based on shea butter, and it feels great.”

I am always amazed at people’s capacity to believe that there is a unique regimen just right for them, preferably one specially formulated by an expert who is privy to a secret no one else knows. Shea butter, it turns out, comes from the African shea tree (Ugandan trees are best). Africans eat the shea nuts; Westerners smear on ground-up nut contents.

Nut of shea. Tree of tea. Eye of newt. Toe of frog. The list goes on.

But I digress.

That didn’t seem very nice of her. I hadn’t murmured about her moisturizer, had I?

“What did she object to?” I asked. “Did her patients have problems with it?”

“She just said the drug is very bad,” said Jared. “She doesn’t like it at all. I was a little taken aback. I wasn’t expecting her to object so strongly.”

“But you’re still OK with taking isotretinoin?” I asked.

“Oh, yes,” said Jared. “It seems to be working, and I trust you.”

That was good to hear. I wondered whether Jared’s trust was based on the rigor of my scientific background or on my kindly smile and reassuring beard.

“Thank you, Jared,” I said. “I like isotretinoin a lot. It’s not for everybody, but for the last 35 years, I’ve seen it do excellent things for the appearance and self-image of many people.”

When I teach medical students, I often emphasize, as a point of professional etiquette, the impropriety of snorting or rolling your eyes at what patients report that other colleagues said and did. First of all, patient accounts may be imprecise or colored by their wish to build you up and flatter themselves for picking you. Second, just imagine what they might say about you at the next office they visit.

Reputation aside (you can hire folks to buff yours, if you like), my little exchange with Jared points up a basic difference between the way doctors think and the way our patients do.

What’s behind doctors’ professional lives is our assumption that diseases exist outside the bodies that the diseases inhabit. We therefore can offer a “treatment of choice” (or maybe a couple of them) that is best for treating a disease, regardless of who has it. This assumption is so obvious that we rarely think about it.

Obvious to us, that is, but not to our patients, to whom every patient has (to a large if not exclusive extent) his or her own disease. If possible, every patient wants a treatment tailored to each person’s unique makeup and predicament.

Jared is far from alone in playing both ends at the same time. From me he gets universal, evidence-based truths. From his other (more jealous!) medical mistress, he gets a skin care regimen tailored lovingly just for him.

Test your unique genes, get the treatment tailored just for you. Some rigorous scientists are trying not to so much debunk this effort as to point out how its promise is massively overhyped and unlikely to be worthy of the massive research investment it attracts. Perhaps their rigorous rationality will bear fruit, but they’re up against not just vested medical/industrial/venture capital interests, but the expectations of sick people who have always known that there is – that there simply has to be – a treatment out there that’s just for them.

Mock if you must, but tell me this: If people can prosper marketing a moisturizer called Kiss My Face or rake in the bucks with a skin care line named Urban Decay, then what’s your problem with Eye of Newt? You want focus groups?

Crowdfunding, anyone?

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at [email protected].

Doctors to Congress: Keep Part B drug payments out of MIPS adjustment

Physician specialists are calling on Congress to isolate Medicare Part B drug reimbursements from payment adjustments under the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS).

A coalition of medical societies, large group practices, and patient advocacy groups has asked for an “intervention this year with a technical correction that ensures the [MIPS] score adjustment is not applied to Part B drug payments,” according to Jan. 18 letter sent to the leaders of the Senate Finance Committee, House Energy and Commerce Committee, and the House Ways and Means Committee. “Since the 2018 MIPS year has begun, it is imperative that Congress acts quickly to ensure that patient access to critical treatments is not negatively impacted.”

Under MIPS, physicians are scored based on their performance across three categories: quality, improvement activities, and advancing care information. A fourth category, cost, is planned but not yet included in the score. Medicare payments, which currently include Part B drug reimbursements, are subject to bonuses and penalties based on performance scores.

In their November 2017 update to the Quality Payment Program, which includes MIPS, officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said they would be moving forward with including Part B drug payments in the MIPS adjustment.

“This application of the adjustment ... is a significant departure from current policy and would disproportionately affect certain specialties,” according to the coalition’s letter.

Certain specialties, including rheumatology, oncology, and ophthalmology, have more to lose under the current policy because these specialists administer more Part B drugs than other specialists, according to health care consultancy Avalere Health.

“Certain specialists administer more Part B drugs than others and, therefore, may be exposed to significant financial risk and payment swings year-over-year under the CMS [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services] proposal,” John Feore, director at Avalere, said in a statement.

In 2018, physicians in those specialties could see drug payments increase or decrease by as much as 16%, according to Avalere research.

The policy likely will have an even greater effect on smaller practices and those in rural settings and could lead to access issues, according to the coalition letter.

“Some patients already face access challenges because the budget sequester has eroded reimbursements to physicians, and this policy would exacerbate these problems,” the letter states. “Patients would be left with fewer locations where they could receive care, resulting in less access and higher costs. A growing number of patients would then have to seek care in a hospital, which would result in higher out-of-pocket expenses and, particularly in rural communities, may require traveling longer distances to receive care.”

Physician specialists are calling on Congress to isolate Medicare Part B drug reimbursements from payment adjustments under the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS).

A coalition of medical societies, large group practices, and patient advocacy groups has asked for an “intervention this year with a technical correction that ensures the [MIPS] score adjustment is not applied to Part B drug payments,” according to Jan. 18 letter sent to the leaders of the Senate Finance Committee, House Energy and Commerce Committee, and the House Ways and Means Committee. “Since the 2018 MIPS year has begun, it is imperative that Congress acts quickly to ensure that patient access to critical treatments is not negatively impacted.”

Under MIPS, physicians are scored based on their performance across three categories: quality, improvement activities, and advancing care information. A fourth category, cost, is planned but not yet included in the score. Medicare payments, which currently include Part B drug reimbursements, are subject to bonuses and penalties based on performance scores.

In their November 2017 update to the Quality Payment Program, which includes MIPS, officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said they would be moving forward with including Part B drug payments in the MIPS adjustment.

“This application of the adjustment ... is a significant departure from current policy and would disproportionately affect certain specialties,” according to the coalition’s letter.

Certain specialties, including rheumatology, oncology, and ophthalmology, have more to lose under the current policy because these specialists administer more Part B drugs than other specialists, according to health care consultancy Avalere Health.

“Certain specialists administer more Part B drugs than others and, therefore, may be exposed to significant financial risk and payment swings year-over-year under the CMS [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services] proposal,” John Feore, director at Avalere, said in a statement.

In 2018, physicians in those specialties could see drug payments increase or decrease by as much as 16%, according to Avalere research.

The policy likely will have an even greater effect on smaller practices and those in rural settings and could lead to access issues, according to the coalition letter.

“Some patients already face access challenges because the budget sequester has eroded reimbursements to physicians, and this policy would exacerbate these problems,” the letter states. “Patients would be left with fewer locations where they could receive care, resulting in less access and higher costs. A growing number of patients would then have to seek care in a hospital, which would result in higher out-of-pocket expenses and, particularly in rural communities, may require traveling longer distances to receive care.”

Physician specialists are calling on Congress to isolate Medicare Part B drug reimbursements from payment adjustments under the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS).

A coalition of medical societies, large group practices, and patient advocacy groups has asked for an “intervention this year with a technical correction that ensures the [MIPS] score adjustment is not applied to Part B drug payments,” according to Jan. 18 letter sent to the leaders of the Senate Finance Committee, House Energy and Commerce Committee, and the House Ways and Means Committee. “Since the 2018 MIPS year has begun, it is imperative that Congress acts quickly to ensure that patient access to critical treatments is not negatively impacted.”

Under MIPS, physicians are scored based on their performance across three categories: quality, improvement activities, and advancing care information. A fourth category, cost, is planned but not yet included in the score. Medicare payments, which currently include Part B drug reimbursements, are subject to bonuses and penalties based on performance scores.

In their November 2017 update to the Quality Payment Program, which includes MIPS, officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said they would be moving forward with including Part B drug payments in the MIPS adjustment.

“This application of the adjustment ... is a significant departure from current policy and would disproportionately affect certain specialties,” according to the coalition’s letter.

Certain specialties, including rheumatology, oncology, and ophthalmology, have more to lose under the current policy because these specialists administer more Part B drugs than other specialists, according to health care consultancy Avalere Health.

“Certain specialists administer more Part B drugs than others and, therefore, may be exposed to significant financial risk and payment swings year-over-year under the CMS [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services] proposal,” John Feore, director at Avalere, said in a statement.

In 2018, physicians in those specialties could see drug payments increase or decrease by as much as 16%, according to Avalere research.

The policy likely will have an even greater effect on smaller practices and those in rural settings and could lead to access issues, according to the coalition letter.

“Some patients already face access challenges because the budget sequester has eroded reimbursements to physicians, and this policy would exacerbate these problems,” the letter states. “Patients would be left with fewer locations where they could receive care, resulting in less access and higher costs. A growing number of patients would then have to seek care in a hospital, which would result in higher out-of-pocket expenses and, particularly in rural communities, may require traveling longer distances to receive care.”

Predicting MDR Gram-negative infection mortality risk

Source control, defined as location and elimination of the source of the infection, was critical for patient survival in the case of multidrug resistant bacterial infection, according to the results of a case-control study of 62 critically ill surgical patients who were assessed between 2011 and 2014.

Researchers examined the characteristics of infected patients surviving to hospital discharge compared with those of nonsurvivors to look for predictive factors. Demographically, patients had an overall mean age of 62 years; 30.6% were women; 69.4% were white. The first culture obtained during a surgical ICU admission that grew a carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), MDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa, or MDR Acinetobacter spp. was defined as the index culture.

“In this study, 33.9% [21/62] of critically ill surgical patients with a culture positive for MDR Gram-negative bacteria died prior to hospital discharge,” according to Andrew S. Jarrell, PharmD, of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, and his colleagues.

With multivariate logistic regression, achievement of source control was the only variable associated with decreased in-hospital mortality (odds ratio 0.04, 95% confidence interval, 0.003-0.52); P = .01).

“Source control status was predictive of in-hospital mortality after controlling for other factors. Specifically, the odds of in-hospital mortality were 97% lower when source control was achieved as compared to when source control was not achieved,” the authors stated (J Crit Care. 2018;43:321-6).

Scenarios in which source control was not applicable (pneumonia and urinary tract infection) were also similarly distributed between survivors and nonsurvivors, they reported.

Other than source control, the only significant risk factors for mortality, as seen in univariate analysis, all occurred prior to index culture. They were: vasopressor use (46.3% of survivors, vs. 76.2% of nonsurvivors, P = .03); mechanical ventilation (63.4% vs. 100%, P = .001); and median ICU length of stay (10 days vs. 18 days, P = .001).

“Achievement of source control stands out as a critical factor for patient survival. Clinicians should take this, along with prior ICU LOS, vasopressor use, and mechanical ventilation status, into consideration when evaluating patient prognosis,” Dr. Jarrell and his colleagues concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts or source of funding.

Source: Jarrell, A.S., et al. J Crit Care. 2018;43:321-6.

Source control, defined as location and elimination of the source of the infection, was critical for patient survival in the case of multidrug resistant bacterial infection, according to the results of a case-control study of 62 critically ill surgical patients who were assessed between 2011 and 2014.

Researchers examined the characteristics of infected patients surviving to hospital discharge compared with those of nonsurvivors to look for predictive factors. Demographically, patients had an overall mean age of 62 years; 30.6% were women; 69.4% were white. The first culture obtained during a surgical ICU admission that grew a carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), MDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa, or MDR Acinetobacter spp. was defined as the index culture.

“In this study, 33.9% [21/62] of critically ill surgical patients with a culture positive for MDR Gram-negative bacteria died prior to hospital discharge,” according to Andrew S. Jarrell, PharmD, of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, and his colleagues.

With multivariate logistic regression, achievement of source control was the only variable associated with decreased in-hospital mortality (odds ratio 0.04, 95% confidence interval, 0.003-0.52); P = .01).

“Source control status was predictive of in-hospital mortality after controlling for other factors. Specifically, the odds of in-hospital mortality were 97% lower when source control was achieved as compared to when source control was not achieved,” the authors stated (J Crit Care. 2018;43:321-6).

Scenarios in which source control was not applicable (pneumonia and urinary tract infection) were also similarly distributed between survivors and nonsurvivors, they reported.

Other than source control, the only significant risk factors for mortality, as seen in univariate analysis, all occurred prior to index culture. They were: vasopressor use (46.3% of survivors, vs. 76.2% of nonsurvivors, P = .03); mechanical ventilation (63.4% vs. 100%, P = .001); and median ICU length of stay (10 days vs. 18 days, P = .001).

“Achievement of source control stands out as a critical factor for patient survival. Clinicians should take this, along with prior ICU LOS, vasopressor use, and mechanical ventilation status, into consideration when evaluating patient prognosis,” Dr. Jarrell and his colleagues concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts or source of funding.

Source: Jarrell, A.S., et al. J Crit Care. 2018;43:321-6.

Source control, defined as location and elimination of the source of the infection, was critical for patient survival in the case of multidrug resistant bacterial infection, according to the results of a case-control study of 62 critically ill surgical patients who were assessed between 2011 and 2014.

Researchers examined the characteristics of infected patients surviving to hospital discharge compared with those of nonsurvivors to look for predictive factors. Demographically, patients had an overall mean age of 62 years; 30.6% were women; 69.4% were white. The first culture obtained during a surgical ICU admission that grew a carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), MDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa, or MDR Acinetobacter spp. was defined as the index culture.

“In this study, 33.9% [21/62] of critically ill surgical patients with a culture positive for MDR Gram-negative bacteria died prior to hospital discharge,” according to Andrew S. Jarrell, PharmD, of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, and his colleagues.

With multivariate logistic regression, achievement of source control was the only variable associated with decreased in-hospital mortality (odds ratio 0.04, 95% confidence interval, 0.003-0.52); P = .01).

“Source control status was predictive of in-hospital mortality after controlling for other factors. Specifically, the odds of in-hospital mortality were 97% lower when source control was achieved as compared to when source control was not achieved,” the authors stated (J Crit Care. 2018;43:321-6).

Scenarios in which source control was not applicable (pneumonia and urinary tract infection) were also similarly distributed between survivors and nonsurvivors, they reported.

Other than source control, the only significant risk factors for mortality, as seen in univariate analysis, all occurred prior to index culture. They were: vasopressor use (46.3% of survivors, vs. 76.2% of nonsurvivors, P = .03); mechanical ventilation (63.4% vs. 100%, P = .001); and median ICU length of stay (10 days vs. 18 days, P = .001).

“Achievement of source control stands out as a critical factor for patient survival. Clinicians should take this, along with prior ICU LOS, vasopressor use, and mechanical ventilation status, into consideration when evaluating patient prognosis,” Dr. Jarrell and his colleagues concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts or source of funding.

Source: Jarrell, A.S., et al. J Crit Care. 2018;43:321-6.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CRITICAL CARE

Key clinical point: Source control was the most important predictor of MDR Gram-negative infection mortality in hospitalized patients.

Major finding: The odds of in-hospital mortality were 97% lower when source control was achieved.

Study details: Case-control study of 62 critically ill surgical patients from 2011 to 2014 who had an MDR infection.

Disclosures: The authors reported that they had no conflicts or source of funding.

Source: Jarrell, A.S., et al. J Crit Care. 2018;43:321-6.

Greater gynecological but not medical risks with hysteroscopic sterilization

Hysteroscopic sterilization is associated with a significantly greater risk of gynecological complications but not medical or surgical complications, compared with laparoscopic sterilization, according to data from a French nationwide cohort study.

In a report published Jan. 23 in JAMA, researchers conducted a study of 105,357 women – 71,303 (67.7%) of whom underwent hysteroscopic sterilization, and 34,054 (32.3%) of whom underwent laparoscopic sterilization – and who were followed for at least 1 year after the procedure.

Women who had the hysteroscopic procedure had a nearly threefold higher risk of tubal disorder or surgery, a sevenfold higher risk of sterilization failure, and a 25-fold higher risk of undergoing a second sterilization procedure at 1 year compared with those who had the laparoscopic procedure (P less than .001 for each). These risk increases persisted even at 3 years after the procedure (hazard ratios of 1.79, 4.66, and 16.63, respectively; 95% confidence interval for each).

“A second sterilization procedure following hysteroscopic sterilization is a well-identified risk already described in phase 2 and 3 studies, in which the risk varied between 4.0% and 4.5%,” wrote Kim Bouillon, MD, PhD, of the French National Agency for Medicines and Health Products Safety, and her coauthors.

“In the present study, this risk was 4.1% at the 1-year follow-up, comparable with that reported in previous studies conducted in real-life conditions in patients who received care in public or private hospitals, and much higher than after laparoscopic sterilization.”

However, hysteroscopic sterilization was associated with a significantly reduced risk of surgical complications, compared with laparoscopic sterilization (adjusted odds ratio, 0.18; 95% CI, 0.14-0.23). The overall rate of in-hospital surgical complications was 0.13% with the hysteroscopic procedure and 0.78% with the laparoscopic procedure. Medical complications occurred in 0.06% of hysteroscopic procedures and 0.11% of laparoscopic procedures.

Women who underwent hysteroscopic procedures also had a significantly lower risk of uterine disorders (adjusted HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.74-0.98), uterine bleeding, and hysterectomies at 1 year, after adjustment for known hysterectomy risk factors.

The researchers noted that in absolute terms, the differences in the risk of procedural complications were very small, compared with the differences in the risk of gynecological complications.

The risk of pregnancy was significantly lower in the hysteroscopic group, compared with the laparoscopic group at 1 year after the procedure, but by 3 years’ follow-up, the difference was no longer significant.

There were no significant differences seen in the risk of medical complications such as autoimmune disease and thyroid disorders, attempted suicide, or death between the two procedures. Women who underwent hysteroscopic sterilization had a slightly lower use of analgesics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines at 1 year that was more pronounced by 3 years.

There was a significantly higher risk of allergic reaction seen with hysteroscopic sterilization among women with prior allergies, but the authors suggested that a null overall effect and large number of tested interactions made the finding “hypothesis-generating” only.

The study was prompted by safety concerns about hysteroscopic sterilization, with the Food and Drug Administration in 2015 receiving a large number of reports of adverse events including bleeding, pelvic pain, fallopian tube perforation, unwanted pregnancy, hysterectomies, depression, and allergic reactions.

The FDA has since ordered the device manufacturer to undertake an open-label, nonrandomized study comparing outcomes between hysteroscopic and laparoscopic sterilization, which is expected to deliver results in 2023.

“To our knowledge, this is the first study aiming at comparing medical outcomes in addition to gynecological outcomes between hysteroscopic and laparoscopic sterilization,” the authors wrote, referring to their own work. They concluded, “these findings do not support increased medical risks associated with hysteroscopic sterilization.”

One author declared personal fees from Boston Scientific but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Bouillon K et al. JAMA. 2018 Jan 23;319:375-87.

In 2016, in response to safety concerns about the hysteroscopic sterilization implant Essure, the Food and Drug Administration placed a “black box” warning on the device to highlight potential risks, and a global patient advocacy movement called for a ban on the product. In this environment, there is therefore a need for strong scientific evidence to inform objective decision making.

This study provides reassuring evidence that adverse outcomes are not significantly higher after hysteroscopic sterilization compared with laparoscopic sterilization, at least up to 3 years after the procedure. However, given the powerful and very public grassroots effort to ban the hysteroscopic implant and the possibility of class action litigation, the future of hysteroscopic sterilization is uncertain.

Eve Espey, MD, MPH, and Lisa G. Hofler, MD, MPH, are in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. The comments are taken from an editorial (JAMA. 2018 Jan 23;319[4]:347-50). Dr. Hofler declared personal fees and nonfinancial support from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

In 2016, in response to safety concerns about the hysteroscopic sterilization implant Essure, the Food and Drug Administration placed a “black box” warning on the device to highlight potential risks, and a global patient advocacy movement called for a ban on the product. In this environment, there is therefore a need for strong scientific evidence to inform objective decision making.

This study provides reassuring evidence that adverse outcomes are not significantly higher after hysteroscopic sterilization compared with laparoscopic sterilization, at least up to 3 years after the procedure. However, given the powerful and very public grassroots effort to ban the hysteroscopic implant and the possibility of class action litigation, the future of hysteroscopic sterilization is uncertain.

Eve Espey, MD, MPH, and Lisa G. Hofler, MD, MPH, are in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. The comments are taken from an editorial (JAMA. 2018 Jan 23;319[4]:347-50). Dr. Hofler declared personal fees and nonfinancial support from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

In 2016, in response to safety concerns about the hysteroscopic sterilization implant Essure, the Food and Drug Administration placed a “black box” warning on the device to highlight potential risks, and a global patient advocacy movement called for a ban on the product. In this environment, there is therefore a need for strong scientific evidence to inform objective decision making.

This study provides reassuring evidence that adverse outcomes are not significantly higher after hysteroscopic sterilization compared with laparoscopic sterilization, at least up to 3 years after the procedure. However, given the powerful and very public grassroots effort to ban the hysteroscopic implant and the possibility of class action litigation, the future of hysteroscopic sterilization is uncertain.

Eve Espey, MD, MPH, and Lisa G. Hofler, MD, MPH, are in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. The comments are taken from an editorial (JAMA. 2018 Jan 23;319[4]:347-50). Dr. Hofler declared personal fees and nonfinancial support from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Hysteroscopic sterilization is associated with a significantly greater risk of gynecological complications but not medical or surgical complications, compared with laparoscopic sterilization, according to data from a French nationwide cohort study.

In a report published Jan. 23 in JAMA, researchers conducted a study of 105,357 women – 71,303 (67.7%) of whom underwent hysteroscopic sterilization, and 34,054 (32.3%) of whom underwent laparoscopic sterilization – and who were followed for at least 1 year after the procedure.

Women who had the hysteroscopic procedure had a nearly threefold higher risk of tubal disorder or surgery, a sevenfold higher risk of sterilization failure, and a 25-fold higher risk of undergoing a second sterilization procedure at 1 year compared with those who had the laparoscopic procedure (P less than .001 for each). These risk increases persisted even at 3 years after the procedure (hazard ratios of 1.79, 4.66, and 16.63, respectively; 95% confidence interval for each).

“A second sterilization procedure following hysteroscopic sterilization is a well-identified risk already described in phase 2 and 3 studies, in which the risk varied between 4.0% and 4.5%,” wrote Kim Bouillon, MD, PhD, of the French National Agency for Medicines and Health Products Safety, and her coauthors.

“In the present study, this risk was 4.1% at the 1-year follow-up, comparable with that reported in previous studies conducted in real-life conditions in patients who received care in public or private hospitals, and much higher than after laparoscopic sterilization.”

However, hysteroscopic sterilization was associated with a significantly reduced risk of surgical complications, compared with laparoscopic sterilization (adjusted odds ratio, 0.18; 95% CI, 0.14-0.23). The overall rate of in-hospital surgical complications was 0.13% with the hysteroscopic procedure and 0.78% with the laparoscopic procedure. Medical complications occurred in 0.06% of hysteroscopic procedures and 0.11% of laparoscopic procedures.

Women who underwent hysteroscopic procedures also had a significantly lower risk of uterine disorders (adjusted HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.74-0.98), uterine bleeding, and hysterectomies at 1 year, after adjustment for known hysterectomy risk factors.

The researchers noted that in absolute terms, the differences in the risk of procedural complications were very small, compared with the differences in the risk of gynecological complications.

The risk of pregnancy was significantly lower in the hysteroscopic group, compared with the laparoscopic group at 1 year after the procedure, but by 3 years’ follow-up, the difference was no longer significant.

There were no significant differences seen in the risk of medical complications such as autoimmune disease and thyroid disorders, attempted suicide, or death between the two procedures. Women who underwent hysteroscopic sterilization had a slightly lower use of analgesics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines at 1 year that was more pronounced by 3 years.

There was a significantly higher risk of allergic reaction seen with hysteroscopic sterilization among women with prior allergies, but the authors suggested that a null overall effect and large number of tested interactions made the finding “hypothesis-generating” only.

The study was prompted by safety concerns about hysteroscopic sterilization, with the Food and Drug Administration in 2015 receiving a large number of reports of adverse events including bleeding, pelvic pain, fallopian tube perforation, unwanted pregnancy, hysterectomies, depression, and allergic reactions.

The FDA has since ordered the device manufacturer to undertake an open-label, nonrandomized study comparing outcomes between hysteroscopic and laparoscopic sterilization, which is expected to deliver results in 2023.

“To our knowledge, this is the first study aiming at comparing medical outcomes in addition to gynecological outcomes between hysteroscopic and laparoscopic sterilization,” the authors wrote, referring to their own work. They concluded, “these findings do not support increased medical risks associated with hysteroscopic sterilization.”

One author declared personal fees from Boston Scientific but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Bouillon K et al. JAMA. 2018 Jan 23;319:375-87.

Hysteroscopic sterilization is associated with a significantly greater risk of gynecological complications but not medical or surgical complications, compared with laparoscopic sterilization, according to data from a French nationwide cohort study.

In a report published Jan. 23 in JAMA, researchers conducted a study of 105,357 women – 71,303 (67.7%) of whom underwent hysteroscopic sterilization, and 34,054 (32.3%) of whom underwent laparoscopic sterilization – and who were followed for at least 1 year after the procedure.

Women who had the hysteroscopic procedure had a nearly threefold higher risk of tubal disorder or surgery, a sevenfold higher risk of sterilization failure, and a 25-fold higher risk of undergoing a second sterilization procedure at 1 year compared with those who had the laparoscopic procedure (P less than .001 for each). These risk increases persisted even at 3 years after the procedure (hazard ratios of 1.79, 4.66, and 16.63, respectively; 95% confidence interval for each).

“A second sterilization procedure following hysteroscopic sterilization is a well-identified risk already described in phase 2 and 3 studies, in which the risk varied between 4.0% and 4.5%,” wrote Kim Bouillon, MD, PhD, of the French National Agency for Medicines and Health Products Safety, and her coauthors.

“In the present study, this risk was 4.1% at the 1-year follow-up, comparable with that reported in previous studies conducted in real-life conditions in patients who received care in public or private hospitals, and much higher than after laparoscopic sterilization.”

However, hysteroscopic sterilization was associated with a significantly reduced risk of surgical complications, compared with laparoscopic sterilization (adjusted odds ratio, 0.18; 95% CI, 0.14-0.23). The overall rate of in-hospital surgical complications was 0.13% with the hysteroscopic procedure and 0.78% with the laparoscopic procedure. Medical complications occurred in 0.06% of hysteroscopic procedures and 0.11% of laparoscopic procedures.

Women who underwent hysteroscopic procedures also had a significantly lower risk of uterine disorders (adjusted HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.74-0.98), uterine bleeding, and hysterectomies at 1 year, after adjustment for known hysterectomy risk factors.

The researchers noted that in absolute terms, the differences in the risk of procedural complications were very small, compared with the differences in the risk of gynecological complications.

The risk of pregnancy was significantly lower in the hysteroscopic group, compared with the laparoscopic group at 1 year after the procedure, but by 3 years’ follow-up, the difference was no longer significant.

There were no significant differences seen in the risk of medical complications such as autoimmune disease and thyroid disorders, attempted suicide, or death between the two procedures. Women who underwent hysteroscopic sterilization had a slightly lower use of analgesics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines at 1 year that was more pronounced by 3 years.

There was a significantly higher risk of allergic reaction seen with hysteroscopic sterilization among women with prior allergies, but the authors suggested that a null overall effect and large number of tested interactions made the finding “hypothesis-generating” only.

The study was prompted by safety concerns about hysteroscopic sterilization, with the Food and Drug Administration in 2015 receiving a large number of reports of adverse events including bleeding, pelvic pain, fallopian tube perforation, unwanted pregnancy, hysterectomies, depression, and allergic reactions.

The FDA has since ordered the device manufacturer to undertake an open-label, nonrandomized study comparing outcomes between hysteroscopic and laparoscopic sterilization, which is expected to deliver results in 2023.

“To our knowledge, this is the first study aiming at comparing medical outcomes in addition to gynecological outcomes between hysteroscopic and laparoscopic sterilization,” the authors wrote, referring to their own work. They concluded, “these findings do not support increased medical risks associated with hysteroscopic sterilization.”

One author declared personal fees from Boston Scientific but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Bouillon K et al. JAMA. 2018 Jan 23;319:375-87.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Hysteroscopic sterilization is associated with a significantly greater risk of gynecological complications – but not medical or surgical complications – compared with laparoscopic sterilization.

Major finding: The risks of repeat sterilization procedure, sterilization failure, and tubal disorder are higher with hysteroscopic sterilization than with laparoscopic sterilization, but the surgical risks are lower and there are no significant differences in other medical risks.

Data source: Nationwide cohort study of 105,357 women.

Disclosures: One author declared personal fees from Boston Scientific but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Bouillon K et al. JAMA. 2018 Jan 23;319:375-87.

Rural residents admitted for opioid overdoses increasingly are hospitalized in urban hospitals

Clinical question: Is there an association between rurality and trends and characteristics of hospitalizations for opioid overdose?

Background: Hospitalization for an opioid overdose is an opportunity for intervention, and patients may have different discharge needs depending on their rurality. Differences in patient characteristics or overall trends in opioid overdose hospitalizations by rural status have not been described.

Study design: Time trend (2007-2014) and cross-sectional analysis (2012-2014).

Setting: Nationally representative sample of U.S. hospital discharges.

Synopsis: Using weighted data from the National Inpatient Sample and the American Community Survey, the authors found that 43,935 individuals were hospitalized for opioid overdose in the United States in 2007, increasing to 71,280 in 2014. A total of 99% of urban and 37% of rural residents were admitted to urban hospitals. Hospitalization rates for prescription opioid overdoses were higher among rural residents and increased among rural and urban residents until 2011 before declining among rural residents during 2012-2014. Hospitalization rates for prescription opioid overdoses increased among all groups before they declined among large urban population residents after 2011, declined among rural residents after 2012, and continued to rise among small urban residents. Hospitalization rates for heroin overdose increased across all years in all groups and were higher among urban as compared to rural residents.

Bottom line: Opioid overdose hospitalization is associated with patient rurality and a significant proportion of rural individuals are hospitalized for opioid overdose in urban facilities. These patients may have distinct discharge needs.

Citation: Mosher H et al. Trends in hospitalization for opioid overdose among rural compared to urban residents of the United States, 2007-2014. J Hosp Med. 2017. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2793.

Dr. Simonetti is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Clinical question: Is there an association between rurality and trends and characteristics of hospitalizations for opioid overdose?

Background: Hospitalization for an opioid overdose is an opportunity for intervention, and patients may have different discharge needs depending on their rurality. Differences in patient characteristics or overall trends in opioid overdose hospitalizations by rural status have not been described.

Study design: Time trend (2007-2014) and cross-sectional analysis (2012-2014).

Setting: Nationally representative sample of U.S. hospital discharges.

Synopsis: Using weighted data from the National Inpatient Sample and the American Community Survey, the authors found that 43,935 individuals were hospitalized for opioid overdose in the United States in 2007, increasing to 71,280 in 2014. A total of 99% of urban and 37% of rural residents were admitted to urban hospitals. Hospitalization rates for prescription opioid overdoses were higher among rural residents and increased among rural and urban residents until 2011 before declining among rural residents during 2012-2014. Hospitalization rates for prescription opioid overdoses increased among all groups before they declined among large urban population residents after 2011, declined among rural residents after 2012, and continued to rise among small urban residents. Hospitalization rates for heroin overdose increased across all years in all groups and were higher among urban as compared to rural residents.

Bottom line: Opioid overdose hospitalization is associated with patient rurality and a significant proportion of rural individuals are hospitalized for opioid overdose in urban facilities. These patients may have distinct discharge needs.

Citation: Mosher H et al. Trends in hospitalization for opioid overdose among rural compared to urban residents of the United States, 2007-2014. J Hosp Med. 2017. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2793.

Dr. Simonetti is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Clinical question: Is there an association between rurality and trends and characteristics of hospitalizations for opioid overdose?

Background: Hospitalization for an opioid overdose is an opportunity for intervention, and patients may have different discharge needs depending on their rurality. Differences in patient characteristics or overall trends in opioid overdose hospitalizations by rural status have not been described.

Study design: Time trend (2007-2014) and cross-sectional analysis (2012-2014).

Setting: Nationally representative sample of U.S. hospital discharges.

Synopsis: Using weighted data from the National Inpatient Sample and the American Community Survey, the authors found that 43,935 individuals were hospitalized for opioid overdose in the United States in 2007, increasing to 71,280 in 2014. A total of 99% of urban and 37% of rural residents were admitted to urban hospitals. Hospitalization rates for prescription opioid overdoses were higher among rural residents and increased among rural and urban residents until 2011 before declining among rural residents during 2012-2014. Hospitalization rates for prescription opioid overdoses increased among all groups before they declined among large urban population residents after 2011, declined among rural residents after 2012, and continued to rise among small urban residents. Hospitalization rates for heroin overdose increased across all years in all groups and were higher among urban as compared to rural residents.

Bottom line: Opioid overdose hospitalization is associated with patient rurality and a significant proportion of rural individuals are hospitalized for opioid overdose in urban facilities. These patients may have distinct discharge needs.

Citation: Mosher H et al. Trends in hospitalization for opioid overdose among rural compared to urban residents of the United States, 2007-2014. J Hosp Med. 2017. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2793.

Dr. Simonetti is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Sotatercept promising for treatment of anemia in MDS

A novel agent holds promise as a treatment option for anemia in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes who are not helped by erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs), according to results from a phase 2 trial.

Sotatercept (ACE-011) is a first-in-class novel recombinant fusion protein, and was found to be effective and well tolerated, increasing hemoglobin concentrations and decreasing the transfusion burden in this patient population.

Nearly half (29, 47%) of 62 patients with a high transfusion burden achieved hematologic improvement–erythroid (HI-E), which for them was a reduction in red blood cell transfusion from baseline of 4 U or more for at least 56 days. Additionally, 7 of 12 patients (58%) with a low transfusion burden also achieved HI-E, defined as an increase in hemoglobin of 1.5 g/dL or more that was sustained for at least 56 days without a transfusion.

“Taken together, these findings provide proof of principle that the recombinant protein sotatercept can restore ineffective erythropoiesis in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes, with an acceptable safety profile,” Rami Komrokji, MD, of Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, and his colleagues, wrote in the Lancet Haematology.

There are few effective treatment options available for patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes who have anemia, especially after they fail primary or secondary treatment with ESAs, or for those who are not likely to benefit from ESA therapy.

In this phase 2 trial, the researchers sought to establish a safe and effective dose of sotatercept in a cohort of 74 patients. Of this group, 7 received 0.1 mg/kg sotatercept, 6 got 0.3 mg/kg, 21 received 0.5 mg/kg, 35 got 1.0 mg/kg, and 5 patients received doses up to 2.0 mg/kg. The primary efficacy endpoint of the study was the proportion of patients who achieved HI-E.

All of the patients were pretreated, having received prior therapy for myelodysplastic syndromes, including ESAs, hypomethylating agents (azacitidine or decitabine), lenalidomide, and other agents including corticosteroids and immunomodulators.

Within this cohort, 36 patients (49%; 95% confidence intervaI, 38-60) achieved HI-E while 20 patients (27%; 95% CI, 18-38) achieved independence from transfusion for at least 56 days.

Fatigue (26%) and peripheral edema (24%) were the most common adverse events reported, while grade 3-4 treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were reported in 34% of patients. Of these, 4 patients had grade 3-4 TEAEs that were probably related to the treatment. The most common grade 3-4 TEAEs were lipase increase and anemia, and each was reported in three patients. Additionally, 17 patients (23%) experienced at least one serious TEAE, including a death from a treatment-emergent subdural hematoma (which caused the patient to fall).

The study was funded by the Celgene. Dr. Komrokji reported financial relationships with Celgene and Novartis. Other study authors reported relationships with various pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Komrokji R et al. Lancet Haematol. 2018 Jan 10. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(18)30002-4.

Sotatercept appears to have promise in treating anemia in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes, and has also demonstrated an acceptable safety profile, according to Valeria Santini, MD.

“Ameliorating anemia in myelodysplastic syndromes by reversing ineffective erythropoiesis secondary to aberrant TGF [transforming growth factor]-beta stimulation is indeed an interesting new therapeutic avenue for these patients,” she wrote.

Dr. Santini also pointed out that the “most intriguing aspect of sotatercept” is its unique mechanism of action. The current study demonstrated the agent’s erythroid-stimulating and antiosteoporotic activity, which should encourage continuing research into the mutifaceted and extremely complex TGF-beta pathway.

While important results were demonstrated in this study, several questions remain, Dr. Santini noted. For example, what are the clinical characteristics of the patients who were sensitive to and responded to treatment with sotatercept? Are these patients different from those who responded to a different agent, luspatercept?

Dr. Santini is with department of hematology at the University of Florence (Italy). She reported giving lectures in supported symposia for Celgene, Janssen, and Novartis and serving on the advisory boards for Abbvie, Otsuka, and Janssen. Her remarks were adapted from an accompanying editorial (Lancet Haematol. 2018 Jan 10. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026[18]30003-6).

Sotatercept appears to have promise in treating anemia in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes, and has also demonstrated an acceptable safety profile, according to Valeria Santini, MD.

“Ameliorating anemia in myelodysplastic syndromes by reversing ineffective erythropoiesis secondary to aberrant TGF [transforming growth factor]-beta stimulation is indeed an interesting new therapeutic avenue for these patients,” she wrote.

Dr. Santini also pointed out that the “most intriguing aspect of sotatercept” is its unique mechanism of action. The current study demonstrated the agent’s erythroid-stimulating and antiosteoporotic activity, which should encourage continuing research into the mutifaceted and extremely complex TGF-beta pathway.

While important results were demonstrated in this study, several questions remain, Dr. Santini noted. For example, what are the clinical characteristics of the patients who were sensitive to and responded to treatment with sotatercept? Are these patients different from those who responded to a different agent, luspatercept?

Dr. Santini is with department of hematology at the University of Florence (Italy). She reported giving lectures in supported symposia for Celgene, Janssen, and Novartis and serving on the advisory boards for Abbvie, Otsuka, and Janssen. Her remarks were adapted from an accompanying editorial (Lancet Haematol. 2018 Jan 10. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026[18]30003-6).

Sotatercept appears to have promise in treating anemia in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes, and has also demonstrated an acceptable safety profile, according to Valeria Santini, MD.

“Ameliorating anemia in myelodysplastic syndromes by reversing ineffective erythropoiesis secondary to aberrant TGF [transforming growth factor]-beta stimulation is indeed an interesting new therapeutic avenue for these patients,” she wrote.

Dr. Santini also pointed out that the “most intriguing aspect of sotatercept” is its unique mechanism of action. The current study demonstrated the agent’s erythroid-stimulating and antiosteoporotic activity, which should encourage continuing research into the mutifaceted and extremely complex TGF-beta pathway.

While important results were demonstrated in this study, several questions remain, Dr. Santini noted. For example, what are the clinical characteristics of the patients who were sensitive to and responded to treatment with sotatercept? Are these patients different from those who responded to a different agent, luspatercept?

Dr. Santini is with department of hematology at the University of Florence (Italy). She reported giving lectures in supported symposia for Celgene, Janssen, and Novartis and serving on the advisory boards for Abbvie, Otsuka, and Janssen. Her remarks were adapted from an accompanying editorial (Lancet Haematol. 2018 Jan 10. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026[18]30003-6).

A novel agent holds promise as a treatment option for anemia in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes who are not helped by erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs), according to results from a phase 2 trial.

Sotatercept (ACE-011) is a first-in-class novel recombinant fusion protein, and was found to be effective and well tolerated, increasing hemoglobin concentrations and decreasing the transfusion burden in this patient population.

Nearly half (29, 47%) of 62 patients with a high transfusion burden achieved hematologic improvement–erythroid (HI-E), which for them was a reduction in red blood cell transfusion from baseline of 4 U or more for at least 56 days. Additionally, 7 of 12 patients (58%) with a low transfusion burden also achieved HI-E, defined as an increase in hemoglobin of 1.5 g/dL or more that was sustained for at least 56 days without a transfusion.

“Taken together, these findings provide proof of principle that the recombinant protein sotatercept can restore ineffective erythropoiesis in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes, with an acceptable safety profile,” Rami Komrokji, MD, of Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, and his colleagues, wrote in the Lancet Haematology.

There are few effective treatment options available for patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes who have anemia, especially after they fail primary or secondary treatment with ESAs, or for those who are not likely to benefit from ESA therapy.

In this phase 2 trial, the researchers sought to establish a safe and effective dose of sotatercept in a cohort of 74 patients. Of this group, 7 received 0.1 mg/kg sotatercept, 6 got 0.3 mg/kg, 21 received 0.5 mg/kg, 35 got 1.0 mg/kg, and 5 patients received doses up to 2.0 mg/kg. The primary efficacy endpoint of the study was the proportion of patients who achieved HI-E.

All of the patients were pretreated, having received prior therapy for myelodysplastic syndromes, including ESAs, hypomethylating agents (azacitidine or decitabine), lenalidomide, and other agents including corticosteroids and immunomodulators.

Within this cohort, 36 patients (49%; 95% confidence intervaI, 38-60) achieved HI-E while 20 patients (27%; 95% CI, 18-38) achieved independence from transfusion for at least 56 days.

Fatigue (26%) and peripheral edema (24%) were the most common adverse events reported, while grade 3-4 treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were reported in 34% of patients. Of these, 4 patients had grade 3-4 TEAEs that were probably related to the treatment. The most common grade 3-4 TEAEs were lipase increase and anemia, and each was reported in three patients. Additionally, 17 patients (23%) experienced at least one serious TEAE, including a death from a treatment-emergent subdural hematoma (which caused the patient to fall).

The study was funded by the Celgene. Dr. Komrokji reported financial relationships with Celgene and Novartis. Other study authors reported relationships with various pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Komrokji R et al. Lancet Haematol. 2018 Jan 10. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(18)30002-4.

A novel agent holds promise as a treatment option for anemia in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes who are not helped by erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs), according to results from a phase 2 trial.

Sotatercept (ACE-011) is a first-in-class novel recombinant fusion protein, and was found to be effective and well tolerated, increasing hemoglobin concentrations and decreasing the transfusion burden in this patient population.

Nearly half (29, 47%) of 62 patients with a high transfusion burden achieved hematologic improvement–erythroid (HI-E), which for them was a reduction in red blood cell transfusion from baseline of 4 U or more for at least 56 days. Additionally, 7 of 12 patients (58%) with a low transfusion burden also achieved HI-E, defined as an increase in hemoglobin of 1.5 g/dL or more that was sustained for at least 56 days without a transfusion.

“Taken together, these findings provide proof of principle that the recombinant protein sotatercept can restore ineffective erythropoiesis in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes, with an acceptable safety profile,” Rami Komrokji, MD, of Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, and his colleagues, wrote in the Lancet Haematology.

There are few effective treatment options available for patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes who have anemia, especially after they fail primary or secondary treatment with ESAs, or for those who are not likely to benefit from ESA therapy.

In this phase 2 trial, the researchers sought to establish a safe and effective dose of sotatercept in a cohort of 74 patients. Of this group, 7 received 0.1 mg/kg sotatercept, 6 got 0.3 mg/kg, 21 received 0.5 mg/kg, 35 got 1.0 mg/kg, and 5 patients received doses up to 2.0 mg/kg. The primary efficacy endpoint of the study was the proportion of patients who achieved HI-E.

All of the patients were pretreated, having received prior therapy for myelodysplastic syndromes, including ESAs, hypomethylating agents (azacitidine or decitabine), lenalidomide, and other agents including corticosteroids and immunomodulators.

Within this cohort, 36 patients (49%; 95% confidence intervaI, 38-60) achieved HI-E while 20 patients (27%; 95% CI, 18-38) achieved independence from transfusion for at least 56 days.

Fatigue (26%) and peripheral edema (24%) were the most common adverse events reported, while grade 3-4 treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were reported in 34% of patients. Of these, 4 patients had grade 3-4 TEAEs that were probably related to the treatment. The most common grade 3-4 TEAEs were lipase increase and anemia, and each was reported in three patients. Additionally, 17 patients (23%) experienced at least one serious TEAE, including a death from a treatment-emergent subdural hematoma (which caused the patient to fall).

The study was funded by the Celgene. Dr. Komrokji reported financial relationships with Celgene and Novartis. Other study authors reported relationships with various pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Komrokji R et al. Lancet Haematol. 2018 Jan 10. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(18)30002-4.

FROM LANCET HAEMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In all, 36 patients (49%) achieved hematologic improvement–erythroid and 20 patients (27%) achieved independence from transfusion for at least 56 days.

Data source: A phase 2 trial that included 74 patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes who did not respond to erythropoiesis-stimulating agents.

Disclosures: Celgene funded the study. Dr. Komrokji reported financial relationships with Celgene and Novartis. Other study authors reported relationships with various pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Komrokji R et al. Lancet Haematol. 2018 Jan 10. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(18)30002-4.

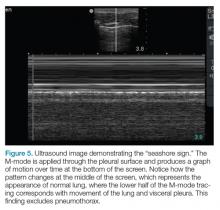

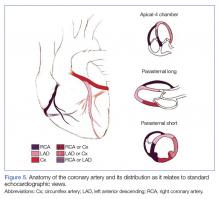

Emergency Ultrasound: Focused Ultrasound for Respiratory Distress: The BLUE Protocol

Acute dyspnea, with or without hypoxia, is a common patient presentation in the ED, and can be the result of a myriad of mainly cardiac, pulmonary, and metabolic conditions—many of which are life-threatening. Therefore, it is crucial to determine or narrow the diagnosis promptly and initiate appropriate treatment. Focused ultrasound of the lungs can provide important information that can change a patient’s clinical course within minutes of initial evaluation.

Background

Prior to the 1990s, the lung was considered unsuitable for evaluation by ultrasound given the scatter of the ultrasound beam that is produced by the presence of aerated tissue. Lung pathology, however, produces distinct artifacts and signs on ultrasound that correspond with specific disease patterns.

The Bedside Lung Ultrasound in Emergencies (BLUE) protocol1 was developed by Daniel Lichtenstein, a French intensivist, and published in 2008. The goal of the examination is to improve the speed and precision of identifying common causes of acute dyspnea. The sensitivity of ultrasound for cardiogenic pulmonary edema, asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and pneumothorax were reported as exceeding 88%.2 Strictly speaking, the BLUE protocol includes an evaluation of the deep veins as well to exclude thrombus; however, this article will focus on ultrasound imaging of the lung.

Relevant Findings

A-line Artifact

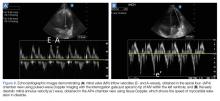

The A-line seen on lung ultrasound (Figure 1) originates from the pleura and can be seen in a normal lung.

B-line Artifact

B-lines, also referred to as “lung rockets,” are a comet-tail artifact arising from the pleura (Figure 2).

Lung Profiles

A patient can have one of three predominant lung profiles: A-profile, B-profile, or AB-profile.

A-profile. A-lines appear bilaterally with lung sliding in the anterior surface of lungs, suggestive of COPD, or pulmonary embolism. Exacerbation of congestive heart failure can be ruled out.

B-profile. The appearance of prominent B-lines bilaterally, suggestive of heart failure, essentially rules out COPD, pulmonary embolism, and pneumothorax.

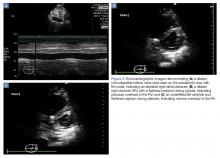

AB-profile. The appearance of predominant B-lines on one lung and predominant A-lines on the other lung, is consistent with an AB profile. This is usually associated with unilateral pneumonia, especially if seen with other findings such as subpleural consolidation (Figure 3) and air bronchograms (Figure 4).

Lung Point

The lung point sign is the only specific finding in the BLUE protocol, and signifies the limits of a pneumothorax by showing the interface between normal lung sliding and the edge of the pneumothorax. Without a specific search for the lung point, it may not be seen in the anterior assessment of lung sliding, although lung sliding will still be abolished.

Imaging Technique