User login

Teens with PID underscreened for HIV, syphilis

CHICAGO – Adolescents with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) were unlikely to be screened for HIV or syphilis, and many didn’t receive an appropriate antibiotic regimen, according to a recent study reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Patients who were sent home rather than admitted were especially likely to miss screening, as were Hispanic patients and those with private insurance.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention strongly recommends that all women diagnosed with PID be tested for HIV, and that high-risk individuals also be tested for syphilis, wrote Amanda Jichlinski, MD, and her coauthors at Children’s National Health System, Washington.

The study, presented during a poster session, used data from the national Pediatric Health Information System database from 2010 to 2015. A total of 10,698 records with a diagnostic code for PID were included; patients were females aged 12-21 years seen in a pediatric emergency department.

In addition to the primary outcome of syphilis and HIV testing, the authors also looked at whether antibiotic administration for PID was in line with CDC recommendations – and it wasn’t. “Fewer than half of patients in the ED received antibiotic regimens adherent to CDC guidelines,” wrote Dr. Jichlinski and her coauthors.

Forty-six percent of patients received ceftriaxone and doxycycline, 21% received ceftriaxone and azithromycin, and 6% received ceftriaxone and metronidazole. Ceftriaxone monotherapy was given to 15% of patients. One in 10 patients with a PID diagnosis received no antibiotic at all; 2% of patients received some other regimen.

The researchers used multivariable analysis to examine separately which patient and hospital characteristics were associated with an increased likelihood of testing for both HIV and syphilis. With white, non-Hispanic adolescents used as the referent, Hispanic females with PID were less likely to receive screening for either HIV or syphilis (adjusted odds ratio, 0.8 for both; 95% confidence interval, 0.7-1.0 for both).

In contrast, black non-Hispanic females were screened more often; the aOR for HIV screening was 1.4 (95% CI, 1.2-1.6), and the aOR for syphilis screening was 1.8 (95% CI, 1.6-2.0) for this group of adolescents.

Patients were dichotomized into older (17-21 years of age; n = 4,737, 44%) and younger (12-16 years of age; n = 5,961, 56%) age groups; younger patients were slightly more likely to receive HIV (aOR, 1.2) and syphilis (aOR, 1.1) screening.

Just under a third of patients in the study were seen in a hospital with fewer than 300 beds, and these facilities were more likely to screen for HIV (aOR, 1.4) and syphilis (aOR, 1.1) than the larger hospitals.

By far the largest predictor of whether HIV and syphilis screening was done, though, was a hospital admission. Patients who were admitted (n = 4,043, 38%) were 7 times more likely to be screened for HIV and 4.6 times more likely to be screened for syphilis than those who were sent home from the emergency department.

Although the large, nationally representative study had many strengths, Dr. Jichlinski and her coauthors acknowledged that the data they were provided couldn’t account for medication that was prescribed, rather than administered in the emergency department. Also, the results may not be generalizable to adolescents treated in nonpediatric emergency departments or other facilities, such as urgent care centers.

“Adolescents with PID are underscreened for HIV and syphilis,” wrote Dr. Jichlinski and her coauthors. They called for pediatricians to receive more education about management of PID in adolescents. From a practical perspective, the investigators also suggested incorporating order sets for sexually transmitted infection testing and antibiotic administration into electronic medical records; in this way, a PID diagnosis code would trigger simplified testing and treatment choices.

Dr. Jichlinski reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Monika Goyal, MD, senior author on the study, reported funding support by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Goyal also holds an appointment at the George Washington University, Washington.

SOURCE: Jichlinski A et al. AAP 2017 Abstract 5, AAP Section on Emergency Medicine.

CHICAGO – Adolescents with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) were unlikely to be screened for HIV or syphilis, and many didn’t receive an appropriate antibiotic regimen, according to a recent study reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Patients who were sent home rather than admitted were especially likely to miss screening, as were Hispanic patients and those with private insurance.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention strongly recommends that all women diagnosed with PID be tested for HIV, and that high-risk individuals also be tested for syphilis, wrote Amanda Jichlinski, MD, and her coauthors at Children’s National Health System, Washington.

The study, presented during a poster session, used data from the national Pediatric Health Information System database from 2010 to 2015. A total of 10,698 records with a diagnostic code for PID were included; patients were females aged 12-21 years seen in a pediatric emergency department.

In addition to the primary outcome of syphilis and HIV testing, the authors also looked at whether antibiotic administration for PID was in line with CDC recommendations – and it wasn’t. “Fewer than half of patients in the ED received antibiotic regimens adherent to CDC guidelines,” wrote Dr. Jichlinski and her coauthors.

Forty-six percent of patients received ceftriaxone and doxycycline, 21% received ceftriaxone and azithromycin, and 6% received ceftriaxone and metronidazole. Ceftriaxone monotherapy was given to 15% of patients. One in 10 patients with a PID diagnosis received no antibiotic at all; 2% of patients received some other regimen.

The researchers used multivariable analysis to examine separately which patient and hospital characteristics were associated with an increased likelihood of testing for both HIV and syphilis. With white, non-Hispanic adolescents used as the referent, Hispanic females with PID were less likely to receive screening for either HIV or syphilis (adjusted odds ratio, 0.8 for both; 95% confidence interval, 0.7-1.0 for both).

In contrast, black non-Hispanic females were screened more often; the aOR for HIV screening was 1.4 (95% CI, 1.2-1.6), and the aOR for syphilis screening was 1.8 (95% CI, 1.6-2.0) for this group of adolescents.

Patients were dichotomized into older (17-21 years of age; n = 4,737, 44%) and younger (12-16 years of age; n = 5,961, 56%) age groups; younger patients were slightly more likely to receive HIV (aOR, 1.2) and syphilis (aOR, 1.1) screening.

Just under a third of patients in the study were seen in a hospital with fewer than 300 beds, and these facilities were more likely to screen for HIV (aOR, 1.4) and syphilis (aOR, 1.1) than the larger hospitals.

By far the largest predictor of whether HIV and syphilis screening was done, though, was a hospital admission. Patients who were admitted (n = 4,043, 38%) were 7 times more likely to be screened for HIV and 4.6 times more likely to be screened for syphilis than those who were sent home from the emergency department.

Although the large, nationally representative study had many strengths, Dr. Jichlinski and her coauthors acknowledged that the data they were provided couldn’t account for medication that was prescribed, rather than administered in the emergency department. Also, the results may not be generalizable to adolescents treated in nonpediatric emergency departments or other facilities, such as urgent care centers.

“Adolescents with PID are underscreened for HIV and syphilis,” wrote Dr. Jichlinski and her coauthors. They called for pediatricians to receive more education about management of PID in adolescents. From a practical perspective, the investigators also suggested incorporating order sets for sexually transmitted infection testing and antibiotic administration into electronic medical records; in this way, a PID diagnosis code would trigger simplified testing and treatment choices.

Dr. Jichlinski reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Monika Goyal, MD, senior author on the study, reported funding support by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Goyal also holds an appointment at the George Washington University, Washington.

SOURCE: Jichlinski A et al. AAP 2017 Abstract 5, AAP Section on Emergency Medicine.

CHICAGO – Adolescents with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) were unlikely to be screened for HIV or syphilis, and many didn’t receive an appropriate antibiotic regimen, according to a recent study reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Patients who were sent home rather than admitted were especially likely to miss screening, as were Hispanic patients and those with private insurance.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention strongly recommends that all women diagnosed with PID be tested for HIV, and that high-risk individuals also be tested for syphilis, wrote Amanda Jichlinski, MD, and her coauthors at Children’s National Health System, Washington.

The study, presented during a poster session, used data from the national Pediatric Health Information System database from 2010 to 2015. A total of 10,698 records with a diagnostic code for PID were included; patients were females aged 12-21 years seen in a pediatric emergency department.

In addition to the primary outcome of syphilis and HIV testing, the authors also looked at whether antibiotic administration for PID was in line with CDC recommendations – and it wasn’t. “Fewer than half of patients in the ED received antibiotic regimens adherent to CDC guidelines,” wrote Dr. Jichlinski and her coauthors.

Forty-six percent of patients received ceftriaxone and doxycycline, 21% received ceftriaxone and azithromycin, and 6% received ceftriaxone and metronidazole. Ceftriaxone monotherapy was given to 15% of patients. One in 10 patients with a PID diagnosis received no antibiotic at all; 2% of patients received some other regimen.

The researchers used multivariable analysis to examine separately which patient and hospital characteristics were associated with an increased likelihood of testing for both HIV and syphilis. With white, non-Hispanic adolescents used as the referent, Hispanic females with PID were less likely to receive screening for either HIV or syphilis (adjusted odds ratio, 0.8 for both; 95% confidence interval, 0.7-1.0 for both).

In contrast, black non-Hispanic females were screened more often; the aOR for HIV screening was 1.4 (95% CI, 1.2-1.6), and the aOR for syphilis screening was 1.8 (95% CI, 1.6-2.0) for this group of adolescents.

Patients were dichotomized into older (17-21 years of age; n = 4,737, 44%) and younger (12-16 years of age; n = 5,961, 56%) age groups; younger patients were slightly more likely to receive HIV (aOR, 1.2) and syphilis (aOR, 1.1) screening.

Just under a third of patients in the study were seen in a hospital with fewer than 300 beds, and these facilities were more likely to screen for HIV (aOR, 1.4) and syphilis (aOR, 1.1) than the larger hospitals.

By far the largest predictor of whether HIV and syphilis screening was done, though, was a hospital admission. Patients who were admitted (n = 4,043, 38%) were 7 times more likely to be screened for HIV and 4.6 times more likely to be screened for syphilis than those who were sent home from the emergency department.

Although the large, nationally representative study had many strengths, Dr. Jichlinski and her coauthors acknowledged that the data they were provided couldn’t account for medication that was prescribed, rather than administered in the emergency department. Also, the results may not be generalizable to adolescents treated in nonpediatric emergency departments or other facilities, such as urgent care centers.

“Adolescents with PID are underscreened for HIV and syphilis,” wrote Dr. Jichlinski and her coauthors. They called for pediatricians to receive more education about management of PID in adolescents. From a practical perspective, the investigators also suggested incorporating order sets for sexually transmitted infection testing and antibiotic administration into electronic medical records; in this way, a PID diagnosis code would trigger simplified testing and treatment choices.

Dr. Jichlinski reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Monika Goyal, MD, senior author on the study, reported funding support by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Goyal also holds an appointment at the George Washington University, Washington.

SOURCE: Jichlinski A et al. AAP 2017 Abstract 5, AAP Section on Emergency Medicine.

REPORTING FROM AAP 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Hispanic females were least likely to be screened (adjusted OR, 0.8), compared with non-Hispanic white females.

Study details: Retrospective study of 10,698 adolescent patients with PID from a national database.

Disclosures: The study was funded in part by the National Institute of Child Health and Development. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Jichlinski A et al. AAP 2017 Abstract 5, AAP Section on Emergency Medicine

Simple Patient Care Instructions Translate Best: Safety Guidelines for Physician Use of Google Translate

From the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson, Tucson, AZ.

Abstract

- Objective: To determine predictors of quality and safety of machine translation (Google Translate) of patient care instructions (PCIs), and to determine if machine back translation is useful in quality assessment.

- Methods: 100 sample English PCIs were contributed by 88 clinical faculty. Each example PCI was up to 3 sentences of typical patient instruction that might be included in an after visit summary. Google Translate was used to first translate the English to Spanish, then back to English. A panel of 6 English/Spanish translators assessed the Spanish translations for safety and quality. A panel of 6 English-speaking health care workers assessed the back translation. A 5-point scale was used to assess quality. Safety was assessed as safe or unsafe.

- Results: Google Translate was usually (> 90%) capable of safe and comprehensible translation from English to Spanish. Instructions with incresed complexity, especially regarding medications, were prone to unsafe translation. Back translation was not reliable in detecting unsafe Spanish.

- Conclusion: Google Translate is a continuously evolving resource for clinicians that offers the promise of improved physician-patient communication. Simple declarative sentences are most reliably translated with high quality and safety.

Keywords: translation; machine translation; electronic health record; after-visit summary; patient safety; physician-patient communication.

Acore measure of the meaningful use of electronic health records incentive program is the generation and provision of the after visit summary (AVS), a mechanism for physicians to provide patients with a written summary of the patient encounter [1,2]. Although not a required element for meaningful use, free text patient care instructions (PCIs) provide the physician an opportunity to improve patient engagement either at the time of service or through the patient portal [3] by providing a short written summary of the key points of the office visit based upon the visit’s clinical discussion. For patients who do not speak English, a verbal translation service is required [4], but seldom are specific patient instructions provided in writing in the patient’s preferred language. A mechanism to improve communication might be through translation of the PCI into the patient’s preferred language. Spanish is the most common language, other than English, spoken at home in the United States [5,6]. For this reason, we chose to investigate if it is feasible to use machine translation (Google Translate) to safely and reliably translate a variety of PCIs from English to Spanish, and to assess the types of translation errors and ambiguities that might result in unsafe communication. We further investigate if machine back translation might allow the author of patient care instructions to evaluate the quality of the Spanish machine translation.

There is evidence to suggest that patient communication and satisfaction will improve if portions of the AVS are communicated in Spanish to primarily Spanish-speaking patients. Pavlik et al conducted a randomized controlled trial on the association of patient recall, satisfaction, and adherence to the information communicated in an AVS, in a largely Hispanic (61%) primary care clinic setting [7]. The AVS was provided in English. They noted that Spanish speakers wished to receive information in Spanish, although most had access to translation by a family member. They also noted that a lack of ability to provide an AVS in Spanish was a concern among providers. There was no difference in recall or satisfaction between English and Spanish speakers with respect to medications and allergies, suggesting that not all portions of the AVS might need to be translated.

Machine translation refers to the automated process of translating one language to another. The most recent methods of machine translation, as exemplified by Google Translate (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA), do not use rules of grammar and dictionaries to perform translations but instead use artificial neural networks to learn from “millions of examples” of translation [8]. However, unsupervised machine translation can result in serious errors [9]. Patil gives as an example of a serious error of translation from English (“Your child is fitting”) to Swahili (“Your child is dead”). In British parlance, “fitting” is a term for “having a seizure” and represents an example of a term that is context sensitive. However, others note that there is reason to be optimistic about the state of machine translation for biomedical text [10].

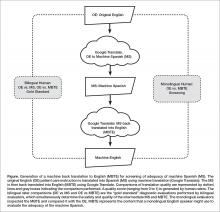

One method of assessing translation quality is through back translation, where one translator takes the author’s work into the desired target language, and then a different translator takes the target language back to the language of the author. Like the children’s game Chinese Whispers (Telephone in the United States) [11], where a “secret message” is whispered from one child to the next and spoken aloud at the end of the line of children, back translation can test to see if a message “gets through.” In this analogy, when information is machine translated from English to Spanish, and then machine translated from Spanish to English (Figure), we can compare the initial message to the final translation to see if the message “gets through.” We further investigate if machine back translation might allow a non-Spanish speaking author of PCIs to evaluate the quality of the Spanish translation.

Our intention was to determine if machine back translation [12] could be used by an English-only author to assess the quality of an intermediate Spanish translation. If poorly worded Spanish translated back into poorly worded English, the author might choose to either refine their original message until an acceptable machine back translation was achieved or to not release the Spanish translation to the patient. We were also concerned that there might be instances where the intermediate Spanish was unacceptable, but when translated back into English by machine translation, relatively acceptable English might result. If this were the case, then back translation would fail to detect a relatively poor intermediate Spanish translation.

Methods

Patient Care Instructions

Original English PCIs

Example original English PCIs were solicited from the clinical faculty and resident staff of the University of Arizona College of Medicine by an email-based survey tool (Qualtrics, Inc, Provo UT). The solicitation stated the following:

We are conducting a study to assess how well Google Translate might perform in translating patient instructions from English to Spanish. Would you please take the time to type three sentences that might comprise a typical “nugget” of patient instruction using language that you would typically include in an After Visit Summary for a patient? An example might be: “Take two Tylenol 325 mg tablets every four hours while awake for the next two days. If you have a sudden increase in pain or fever, or begin vomiting, call our office. Drink plenty of fluids.”

A total of 100 PCIs were collected. The breadth of the clinical practice and writing styles of a College of Medicine faculty are represented: not all were completely clear or were well-formed sentences, but did represent examples provided by busy clinicians of typical language that they would provide in an AVS PCI.

Machine Translation into Spanish

The 100 original English (OE) PCIs were submitted to the Google Translate web interface (https://translate.google.com/) by cutting and pasting and selecting “Spanish,” resulting in machine Spanish. The translations were performed in January 2016. No specific version number is provided by Google on their web page, and the service is described to be constantly evolving (https://translate.google.com/about/intl/en_ALL/contribute.html).

Machine Back Translation into English (MBTE)

Google Translate was then used to translate the machine Spanish back into into English. MBTE represents the content that a monolingual English speaker might use to evaluate the machine Spanish.

Ratings of Translation Quality and Safety

Two panels of 6 raters evaluated machine Spanish and MBTE quality and safety. A bilingual English/Spanish speaking panel simultaneously evaluated the machine Spanish and MBTE compared to OE, with the goal of inferring where in the process an undesirable back translation error occurred. Bilingual raters were experienced bilingual clinicians or certified translators. A monolingual English speaking panel also evaluated the MBTE (compared to OE). They could only infer the quality and safety of the machine Spanish indirectly through inspection of MBTE, and their assessment was free of the potential bias of knowledge of the intermediate Spanish translation.

The raters used Likert scales to rate grammar similarity and content similarity (scale from 1 to 5: 1 = very dissimilar, 5 = identical). For each PCI, grammar and content scores for each rater were summed and then divided by 10 to yield a within-rater quality score ranging from 0 to 1. A panel-level (bilingual or monolingual) quality score was calculated by averaging the quality scores across raters.

Safety of translation was rated as 0 or Safe (“While the translation may be awkward, it is not dangerous” or 1 or Unsafe (“A dangerous translation error is present that might cause harm to the patient if instructions were followed”). If any panel member considered an item to be unsafe, the item as a whole was scored as unsafe.

Data Analysis

Descriptive Summary of PCI Contributions

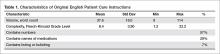

The 100 PCIs were summarized in terms of volume (word count), complexity (Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level index [13]), and content (medication names, references, formatting) (Table 1). Word count and grade level were calculated using Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corp, Redmond WA).

Safety Analysis

Concordance analysis. A safety translation concern as defined in this study (“might cause harm”) is very subjective. To reduce some of the variation in assessment of safety, we identified 4 members of the bilingual panel whose safety assessments of MBTE were most similar to the most concordant 4 monolingual raters’ assessment of MBTE safety. The goal was to select the bilingual panel of 4 that was most “typical” of the behavior of a “typical” monolingual individual with respect to assessing the safety of an individual MBTE translation. We then used this bilingual panel to identify 2 sets of “unsafe” machine Spanish and MBTE PCI translations: PCIs where ANY of the 4 bilingual raters identified a safety concern in machine Spanish or MBTE, and PCIs where MOST (at least 3) of the 4 bilingual raters agree that PCI translation was “unsafe”.

An expansion of Cohen’s kappa was used to identify the most concordant pairing of 4 bilingual panel members and 4 monolingual panel members [14]. All pairwise comparisons of monolingual and bilingual panel members were coded as follows: +1 was scored when 2 raters were concordant (both scored safe or unsafe) and –1 was scored for discordant pairs. For the 225 possible pairings of 4 panel members (15 combinations of 4 of 6 bilingual, 15 combinations of 4 of 6 monolingual raters), the 100 PCI items scores ranged from +16 (absolute agreement of the 2 panels of 4) to –16 (absolute discordance). For each pairing, we summed the scores for the 100 PCIs to determine the most concordant 4 monolingual and 4 bilingual raters (highest summed scores), which were then used for all subsequent analyses of safety and quality.

Original English characteristics of unsafe translation.

A logistic regression was performed with safety as the dependent variable (safe/unsafe defined by bilingual raters) with explanatory variables of word count, grade level, and reference to medication in OE.

Quality Assessment

Bilingual and monolingual raters assessments of translation quality. We assessed the correlation between the bilingual quality ratings of machine Spanish vs. MBTE and conducted paired t tests comparing mean bilingual machine Spanish and MBTE ratings. High correlation and absence of a significant difference in means would support the notion that MBTE could be used to reliably assess machine Spanish quality.

We also assessed the correlation between bilingual quality assessments of MS vs. monolingual raters’ assessments of MBTE, and conducted paired comparison t tests comparing bilingual machine Spanish and monolingual MBTE quality ratings. These analyses assess the ability of an English-only reader of MBTE to predict the quality of machine Spanish, as determined by a bilingual rater. High correlation and absence of a significant difference in means would support the notion that MBTE could be used by an English-only speaker to reliably assess machine Spanish quality.

Associations between original English content and translation quality. Objective measures of original English were correlated via stepwise linear regression with bilingual assessment of machine Spanish quality.

Results

PCI Contributions

Example PCIs were contributed by 88 individuals and are summarized in Table 1. The 100 original English PCIs and the machine Spanish and MBTE translations obtained via Google Translate are available from the authors upon request.

Safety

Concordance Analysis

The 6 monolingual and bilingual raters agreed on the safety of 73 MBTE PCIs. The most concordant pairings of 4 agreed on 81 items. The least and most concordant pairings had concordance values of 0.68 and 0.84, respectively. Subsequent analyses include data from only the 4 most concordant monolingual and bilingual raters.

Bilingual and Monolingual Safety Ratings

Both bilingual and monolingual raters assessed MBTE. On average, bilingual ratings of MBTE of safety were higher (0.987) than monolingual ratings (0.925) (t = –3.897, P = 0.0002).

Identification of Unsafe Translations in Machine Spanish and MBTE

The bilingual panel identified 11 translations (either machine Spanish or MBTE) as unsafe: MS translation was unsafe for 9 items, MBTE unsafe for 5 items, with some items identified as unsafe in terms of both machine Spanish and MBTE. The original English, machine Spanish, and MBTE for these PCIs are listed in Table 2. One item (#93) revealed a machine Spanish drug dosing ambiguity that was not present in the MBTE, with safety concern expressed by 3 of 4 bilingual raters.

Original English c haracteristics of Unsafe Translation

A stepwise logistic regression was performed to evaluate whether characteristics of the original English text predicted the PCI being judged as having a safe or unsafe machine Spanish translation. The explanatory variables (listed in Table 1) evaluated were word count, reading grade level, inclusion of reference to a specific medication, inclusion of numbers (as in "take 2 tablets"), and inclusion of numbered statements (as in "1. Call if your cough worsens"). The stepwise selection procedure dropped number references and numbered sentences, although post hoc analysis showed that number references and medication references occurred so commonly together that they were essentially interchangeable. The final regression model included word count, reading grade level, and medication reference. The significant factors of reading grade level and medication reference had odds ratio (95% confidence interval) of 1.12 (1.01 to 1.41) and 4.91 (1.07 to 22.7) respectively (P = 0.042 each). As reading grade level includes word count per sentence and syllable count per word as linear predictors, the inclusion of word count in the model is likely to increase the discrimination of complex words of many syllables in predicting the occurrence of unsafe machine Spanish.

Quality

Bilingual and Monolingual Raters Assessments of Quality

The bilingual evaluators found similar mean quality for machine Spanish (mean 0.855, SD 0.0859) and MBTE (0.857, SD 0.0755) (P = 0.811). However, the correlation of R2=0.355 (P = 0.000) suggests that despite similarity in mean ratings, a good forward translation from original English to machine Spanish did not assure a good back translation from machine Spanish to MBTE. No difference in mean MBTE quality was identified between bilingual (0.857, SD 0.0754) and monolingual (0.852, SD 0.126) raters (P = 0.598), with correlation R2=0.565 (P = 0.000).

Discussion

In this article, we have collected a corpus of example PCIs across a large number of authors, and investigated how well Google Translate was able to translate the example instructions first to Spanish, and then back again to English. We learned that one can not always spot a problem in the intermediate Spanish by inspection of the back-translated English. We also learned that simple sentences were least likely to be associated with troublesome translations, and that specific instructions about medication usage should probably be approached with great care.

We learned that some authors readily use simple language (eg: “Have your blood work drawn in the lab in the next two weeks,” reading level 1.2) while others gravitate to very complex language (“If you develop headache, chest pain, abdominal pain or back pain, or if you have any spontaneous bleeding please go to the emergency department, advise them that you were recently treated for rattlesnake envenomation and have them call the poison center,” reading level 20.2).

The development in confidence in machine translation can be compared to development of self-driving cars. At early stages of development, the self-driving cars had drivers with a foot near the brake and hands near the steering wheel, ready to take over at any instant. Now, after much data has been collected, there is evidence that the machine may operate more predictably and safely than some human drivers [15,16]. Should the self-driving cars always have an operator behind the wheel, supervising the function of the software, and ready to take over at any instant, or is the purpose of the self-driving car to allow non-drivers to be transported in an automobile that they either cannot operate or choose not to operate at that time?

The benefit of using professional interpreters in communicating clinically significant data is unquestioned, especially when compared to ad-hoc interpreters who lack professional understanding of context [4]. Like a good human driver (as compared to a self-driving car that is operated by a program that is still learning), a qualified human translator will outperform machine translation in complex tasks. Similarly, for relatively simple translations that are meant to be generated by human speakers to be understood by individuals with a grammar school education and vocabulary, is the state of machine translation such that less human translation is now required?

Our use of 2 teams of evaluators allowed us to use the game of Telephone analogy to provide insight into how well the machine translation proceeded, first to Spanish, then back to English. Mostly (90 times in 100), an acceptable Spanish translation resulted in an acceptable English back translation. In 2 instances (Samples 7 and 32), the first translation into Spanish was unacceptable, and a subsequent translation back to English was also unacceptable, as might be expected. In 2 instances (Samples 60 and 92), the Spanish translation was acceptable, but the translation back to English was unacceptable. The rules of Telephone worked 94 times in 100.

Still, 6 times in 100, the unexpected occurred, where a relatively poor Spanish translation returned a relatively acceptable English back translation. The rules of Telephone were not followed. The Spanish in the middle was garbled, but became acceptable when translated back to English. A fluent Spanish speaker found the intermediate Spanish to be of concern, and the back translation did not identify the concern. This argues against widespread adoption of machine back translation for quality assessment, at least until better understanding of the limitations of machine back translation are better understood. Looking at examples where back translation “worked” is useful. In the 6 instances where the intermediate Spanish was judged to be unacceptable, but the English back translation acceptable, complex sentence structures were found, along with medication instructions.

Not tested was if the raters found the original English instructions to be unclear or unsafe as a starting point. Here is where we find the potential benefit of the present study, as it provides insight into the type of content that seems to translate well in this set of data. where the machine Spanish error was not present in MBTE. Overall, ratings of translation quality by bilingual and monolingual raters was high, suggesting that there may be some utility in the machine translation with safeguards other than, or in addition to, inspection of machine back translation of machine Spanish. We found there was an astonishing range in reading difficulty across the contributed samples. While the average estimated grade level for comprehension of the original English contributions was the 8th grade, the maximum was 22, indicating extreme complexity of both words used and sentence length.

In gathering the example PCIs, we did not give any additional instructions to the authors to limit complexity, we only asked for their “typical” language, and if the examples received are indeed typical, the instructions we provide are often quite complex. Wu [17] explored the readability of medical information intended for the public and found that on average, 18 years of education would be required to read and understand the clinical trial descriptions available at ClinicalTrials.gov. It seems apparent that the first step to improving the safety of machine translation is to simplify the task of the translator, by making the language that is used for translation as unambiguous and straightforward as possible. The article by Patil and Davies on the use of Google Translate in the clinic [9] generated a considerable number of rapid responses (similar to letters to the editor) [18]. The responses emphasized the need to keep the language used simple, the sentences short, and the communication direct.

A simple and straightforward suggestion to improve all patient care instructions (not just those anticipated to be translated) would be to display the Flesch-Kincaid reading level in real time as the content is generated. The computer resources required to perform reading level analysis are nearly identical to those required for real-time spell checking: a dictionary that breaks words into syllables. Showing authors the reading level in real time would provide a tool to improve all instructions, not just those intended for translation. Limiting the dictionary to specifically exclude potentially dangerous, complex, or confusing words as well as forbidden abbreviations would further identify troublesome language to the author, and would improve communication overall. Implementing such real-time feedback to authors of patient instructions is a logical next step in adding utility to the electronic health record.

It is important that culture and contextual understanding is taken into consideration while organizations use interpretation services. In the United States, federal law requires that language interpreters employed by health care organization receiving federal funds are not only bilingual but also bicultural [16]. We did not find examples of dangerous synonyms being misapplied in translation, but we cannot rule out the possibility that such errors can occur. This is beyond the scope of typical machine translation software.

Our data suggest that use of medication names and dosing frequencies should not be repeated in the PCI where confusion can arise from imprecise language translation. Translation ambiguities that generate safety concerns in PCI might be mitigated by moving such content into structured areas of the AVS.

Conclusion

This study suggests that 9 times out of 10, the quality of machine translation using Google Translate is acceptable in terms of quality and safety. Currently, machine back translation may fail to reveal a relatively poor translation from English to Spanish. This study showed that increasing sentence complexity, as measured by the reading level index, was associated with a significant (P < 0.05) increase in unsafe machine translation. Similarly, including medication instructions in machine translations were associated with increased risk (P < 0.05) of machine translation safety error in this study.

A simple way to improve communication now would be to display the reading level to authors of patient communication content in real time, and limit the dictionary of acceptable words to forbid the use of known ambiguous terms or forbidden abbreviations. This would teach authors to use simple language, and increase the chance that translation (either human or machine) would be effective. This preliminary study suggests that keeping medication dosing instructions in a structured format is advisable, as is keeping sentences simple. As with spoken language [4], starting with clear, simple to understand English instructions provides the best machine translations into Spanish.

The Clinical Machine Translation Study Group: Todd W. Altenbernd, Steven Bedrick, Mark D. Berg, Nerida Berrios, Mark A. Brown, Colleen K. Cagno, Charles B. Cairns, Elizabeth Calhoun, Raymond Carmody, Tara F. Carr, Clara Choo, Melissa L. Cox, Janiel Cragun, Rachel E.M. Cramton, Paola Davis, Archita Desai, Sarah M. Desoky, Sean Elliot, Mindi J. Fain, Albert Fiorello, Hillary Franke, Kimberly Gerhart, Victor Jose Gonzalez, Aaron John Goshinska, Lynn M. Gries, Erin M. Harvey, Karen Herbst, Elizabeth Juneman, Lauren Marie Imbornoni, Anita Koshy, Lisa Laughlin, Christina M. Laukaitis, Kwan Lee, Hong Lei, Joseph M. Miller, Prashanthinie Mohan, Wayne J. Morgan, Jarrod Mosier, Leigh A. Neumayer, Valentine Nfonsam, Vivienne Ng, Terence O'Keeffe, Merri Pendergrass, Jessie M. Pettit, John Leander Po, Claudia Marie Prospero Ponce, Sydney Rice, Marie Anoushka Ricker, Arielle E. Rubin, Robert J. Segal, Aurora A.G. Selpides, Whitney A. Smith, Jordana M. Smith, William Stevenson, Amy N. Sussman, Ole J. Thienhaus, Patrick Tsai, J. Daniel Twelker, Richard Wahl, Jillian Wang, Mingwu Wang, Samuel C. Werner, Mark D. Wheeler, Jason Wild, Sun Kun Yi, Karl Andrew Yousef, Le Yu.

Corresponding author: Joseph M. Miller, MD, MPH, Department of Ophthalmology and Vision Science, University of Arizona, 655 North Alvernon Way, Suite 108, Tucson AZ 85711, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Hummel J, Evans P. Providing clinical summaries to patients after each office visit: a technical guide. Qualis Health 2012. Accessed 14 Mar 2016 at http://hit.qualishealth.org/sites/default/files/hit.qualishealth.org/Providing-Clinical-Summaries-0712.pdf.

2. Neuberger M, Dontje K, Holzman G, et al. Examination of office visit patient preferences for the after-visit summary (AVS). Persp Health Infor Manage 2014;11:1d.

3. Kruse CS, Bolton K, Freriks G. The effect of patient portals on quality outcomes and its implications to meaningful use: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e44.

4. Schoonover, K. Using a medical interpreter with persons of limited English proficiency. J Clin Outcomes Manage 2016;23:567–75.

5. Shin HB, Bruno R. Language use and English-speaking ability: 2000. Census 2000 Brief. Accessed 9 Nov 2017 at https://census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2013/acs/acs-22.pdf.

6. Lewis MP, Simons GF, Fennig CD, editors. Ethnologue: languages of the Americas and the Pacific. 19th ed. Dallas: Sil International; 2016.

7. Pavlik V, Brown AE, Nash S, et al. Association of patient recall, satisfaction, and adherence to content of an electronic health record (EHR)-generated after visit summary: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Board Fam Med 2014;27:209–18.

8. Johnson M, Schuster M, Le QV, et al. Google’s multilingual neural machine translation system: enabling zero-shot translation. Accessed 9 Nov 2017 at https://arxiv.org/pdf/1611.04558.pdf.

9. Patil S, Davies P. Use of Google Translate in medical communication: evaluation of accuracy. BMJ 2014;349:g7392.

10. Kaliyadan F, Gopinathan Pillai S. The use of Google language tools as an interpretation aid in cross-cultural doctor-patient interaction: a pilot study. Inform Prim Care 2010;18:141–3.

11. Zhang Y, Zhou S, Zhang Z, et al. Rumor evolution in social networks. Physical Review E 2013;87.

12. Shingenobu T. Evaluation and usability of back translation for intercultural communication. In: N. Aykin, editor. Usability and internationalization. Global and local user interfaces. UI-HCII 2007, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 4560. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

13. Kincaid JP, Fishburne Jr RP, Rogers RL, et al. Derivation of new readability formulas (automated readability index, fog count and Flesch reading ease formula) for Navy enlisted personnel. Naval Technical Training Command Millington TN Research Branch. 1975. Accessed 7 May 2016 at http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a006655.pdf.

14. Kwiecien R, Kopp-Schneider A, Blettner M. Concordance analysis—part 16 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2011;108:515–21.

15. Goodall N. Ethical decision making during automated vehicle crashes. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 2014;2424:58–65.

16. Kalra N, Groves D. The enemy of good: estimating the cost of waiting for nearly perfect automated vehicles. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2017.

17. Wu DT, Hanauer DA., Mei Q, et al. Assessing the readability of ClinicalTrials.gov. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2016;23:269–75.

18. Responses to: Use of Google Translate in medical communication: evaluation of accuracy. BMJ 2014;349:g7392 Accessed 10 Dec 2017 at www.bmj.com/content/349/bmj.g7392/rapid-responses.

19. Nápoles AM, Santoyo-Olsson J, Karliner LS, et al. Inaccurate language interpretation and its clinical significance in the medical encounters of Spanish-speaking Latinos. Med Care 2015;53:940–7.

From the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson, Tucson, AZ.

Abstract

- Objective: To determine predictors of quality and safety of machine translation (Google Translate) of patient care instructions (PCIs), and to determine if machine back translation is useful in quality assessment.

- Methods: 100 sample English PCIs were contributed by 88 clinical faculty. Each example PCI was up to 3 sentences of typical patient instruction that might be included in an after visit summary. Google Translate was used to first translate the English to Spanish, then back to English. A panel of 6 English/Spanish translators assessed the Spanish translations for safety and quality. A panel of 6 English-speaking health care workers assessed the back translation. A 5-point scale was used to assess quality. Safety was assessed as safe or unsafe.

- Results: Google Translate was usually (> 90%) capable of safe and comprehensible translation from English to Spanish. Instructions with incresed complexity, especially regarding medications, were prone to unsafe translation. Back translation was not reliable in detecting unsafe Spanish.

- Conclusion: Google Translate is a continuously evolving resource for clinicians that offers the promise of improved physician-patient communication. Simple declarative sentences are most reliably translated with high quality and safety.

Keywords: translation; machine translation; electronic health record; after-visit summary; patient safety; physician-patient communication.

Acore measure of the meaningful use of electronic health records incentive program is the generation and provision of the after visit summary (AVS), a mechanism for physicians to provide patients with a written summary of the patient encounter [1,2]. Although not a required element for meaningful use, free text patient care instructions (PCIs) provide the physician an opportunity to improve patient engagement either at the time of service or through the patient portal [3] by providing a short written summary of the key points of the office visit based upon the visit’s clinical discussion. For patients who do not speak English, a verbal translation service is required [4], but seldom are specific patient instructions provided in writing in the patient’s preferred language. A mechanism to improve communication might be through translation of the PCI into the patient’s preferred language. Spanish is the most common language, other than English, spoken at home in the United States [5,6]. For this reason, we chose to investigate if it is feasible to use machine translation (Google Translate) to safely and reliably translate a variety of PCIs from English to Spanish, and to assess the types of translation errors and ambiguities that might result in unsafe communication. We further investigate if machine back translation might allow the author of patient care instructions to evaluate the quality of the Spanish machine translation.

There is evidence to suggest that patient communication and satisfaction will improve if portions of the AVS are communicated in Spanish to primarily Spanish-speaking patients. Pavlik et al conducted a randomized controlled trial on the association of patient recall, satisfaction, and adherence to the information communicated in an AVS, in a largely Hispanic (61%) primary care clinic setting [7]. The AVS was provided in English. They noted that Spanish speakers wished to receive information in Spanish, although most had access to translation by a family member. They also noted that a lack of ability to provide an AVS in Spanish was a concern among providers. There was no difference in recall or satisfaction between English and Spanish speakers with respect to medications and allergies, suggesting that not all portions of the AVS might need to be translated.

Machine translation refers to the automated process of translating one language to another. The most recent methods of machine translation, as exemplified by Google Translate (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA), do not use rules of grammar and dictionaries to perform translations but instead use artificial neural networks to learn from “millions of examples” of translation [8]. However, unsupervised machine translation can result in serious errors [9]. Patil gives as an example of a serious error of translation from English (“Your child is fitting”) to Swahili (“Your child is dead”). In British parlance, “fitting” is a term for “having a seizure” and represents an example of a term that is context sensitive. However, others note that there is reason to be optimistic about the state of machine translation for biomedical text [10].

One method of assessing translation quality is through back translation, where one translator takes the author’s work into the desired target language, and then a different translator takes the target language back to the language of the author. Like the children’s game Chinese Whispers (Telephone in the United States) [11], where a “secret message” is whispered from one child to the next and spoken aloud at the end of the line of children, back translation can test to see if a message “gets through.” In this analogy, when information is machine translated from English to Spanish, and then machine translated from Spanish to English (Figure), we can compare the initial message to the final translation to see if the message “gets through.” We further investigate if machine back translation might allow a non-Spanish speaking author of PCIs to evaluate the quality of the Spanish translation.

Our intention was to determine if machine back translation [12] could be used by an English-only author to assess the quality of an intermediate Spanish translation. If poorly worded Spanish translated back into poorly worded English, the author might choose to either refine their original message until an acceptable machine back translation was achieved or to not release the Spanish translation to the patient. We were also concerned that there might be instances where the intermediate Spanish was unacceptable, but when translated back into English by machine translation, relatively acceptable English might result. If this were the case, then back translation would fail to detect a relatively poor intermediate Spanish translation.

Methods

Patient Care Instructions

Original English PCIs

Example original English PCIs were solicited from the clinical faculty and resident staff of the University of Arizona College of Medicine by an email-based survey tool (Qualtrics, Inc, Provo UT). The solicitation stated the following:

We are conducting a study to assess how well Google Translate might perform in translating patient instructions from English to Spanish. Would you please take the time to type three sentences that might comprise a typical “nugget” of patient instruction using language that you would typically include in an After Visit Summary for a patient? An example might be: “Take two Tylenol 325 mg tablets every four hours while awake for the next two days. If you have a sudden increase in pain or fever, or begin vomiting, call our office. Drink plenty of fluids.”

A total of 100 PCIs were collected. The breadth of the clinical practice and writing styles of a College of Medicine faculty are represented: not all were completely clear or were well-formed sentences, but did represent examples provided by busy clinicians of typical language that they would provide in an AVS PCI.

Machine Translation into Spanish

The 100 original English (OE) PCIs were submitted to the Google Translate web interface (https://translate.google.com/) by cutting and pasting and selecting “Spanish,” resulting in machine Spanish. The translations were performed in January 2016. No specific version number is provided by Google on their web page, and the service is described to be constantly evolving (https://translate.google.com/about/intl/en_ALL/contribute.html).

Machine Back Translation into English (MBTE)

Google Translate was then used to translate the machine Spanish back into into English. MBTE represents the content that a monolingual English speaker might use to evaluate the machine Spanish.

Ratings of Translation Quality and Safety

Two panels of 6 raters evaluated machine Spanish and MBTE quality and safety. A bilingual English/Spanish speaking panel simultaneously evaluated the machine Spanish and MBTE compared to OE, with the goal of inferring where in the process an undesirable back translation error occurred. Bilingual raters were experienced bilingual clinicians or certified translators. A monolingual English speaking panel also evaluated the MBTE (compared to OE). They could only infer the quality and safety of the machine Spanish indirectly through inspection of MBTE, and their assessment was free of the potential bias of knowledge of the intermediate Spanish translation.

The raters used Likert scales to rate grammar similarity and content similarity (scale from 1 to 5: 1 = very dissimilar, 5 = identical). For each PCI, grammar and content scores for each rater were summed and then divided by 10 to yield a within-rater quality score ranging from 0 to 1. A panel-level (bilingual or monolingual) quality score was calculated by averaging the quality scores across raters.

Safety of translation was rated as 0 or Safe (“While the translation may be awkward, it is not dangerous” or 1 or Unsafe (“A dangerous translation error is present that might cause harm to the patient if instructions were followed”). If any panel member considered an item to be unsafe, the item as a whole was scored as unsafe.

Data Analysis

Descriptive Summary of PCI Contributions

The 100 PCIs were summarized in terms of volume (word count), complexity (Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level index [13]), and content (medication names, references, formatting) (Table 1). Word count and grade level were calculated using Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corp, Redmond WA).

Safety Analysis

Concordance analysis. A safety translation concern as defined in this study (“might cause harm”) is very subjective. To reduce some of the variation in assessment of safety, we identified 4 members of the bilingual panel whose safety assessments of MBTE were most similar to the most concordant 4 monolingual raters’ assessment of MBTE safety. The goal was to select the bilingual panel of 4 that was most “typical” of the behavior of a “typical” monolingual individual with respect to assessing the safety of an individual MBTE translation. We then used this bilingual panel to identify 2 sets of “unsafe” machine Spanish and MBTE PCI translations: PCIs where ANY of the 4 bilingual raters identified a safety concern in machine Spanish or MBTE, and PCIs where MOST (at least 3) of the 4 bilingual raters agree that PCI translation was “unsafe”.

An expansion of Cohen’s kappa was used to identify the most concordant pairing of 4 bilingual panel members and 4 monolingual panel members [14]. All pairwise comparisons of monolingual and bilingual panel members were coded as follows: +1 was scored when 2 raters were concordant (both scored safe or unsafe) and –1 was scored for discordant pairs. For the 225 possible pairings of 4 panel members (15 combinations of 4 of 6 bilingual, 15 combinations of 4 of 6 monolingual raters), the 100 PCI items scores ranged from +16 (absolute agreement of the 2 panels of 4) to –16 (absolute discordance). For each pairing, we summed the scores for the 100 PCIs to determine the most concordant 4 monolingual and 4 bilingual raters (highest summed scores), which were then used for all subsequent analyses of safety and quality.

Original English characteristics of unsafe translation.

A logistic regression was performed with safety as the dependent variable (safe/unsafe defined by bilingual raters) with explanatory variables of word count, grade level, and reference to medication in OE.

Quality Assessment

Bilingual and monolingual raters assessments of translation quality. We assessed the correlation between the bilingual quality ratings of machine Spanish vs. MBTE and conducted paired t tests comparing mean bilingual machine Spanish and MBTE ratings. High correlation and absence of a significant difference in means would support the notion that MBTE could be used to reliably assess machine Spanish quality.

We also assessed the correlation between bilingual quality assessments of MS vs. monolingual raters’ assessments of MBTE, and conducted paired comparison t tests comparing bilingual machine Spanish and monolingual MBTE quality ratings. These analyses assess the ability of an English-only reader of MBTE to predict the quality of machine Spanish, as determined by a bilingual rater. High correlation and absence of a significant difference in means would support the notion that MBTE could be used by an English-only speaker to reliably assess machine Spanish quality.

Associations between original English content and translation quality. Objective measures of original English were correlated via stepwise linear regression with bilingual assessment of machine Spanish quality.

Results

PCI Contributions

Example PCIs were contributed by 88 individuals and are summarized in Table 1. The 100 original English PCIs and the machine Spanish and MBTE translations obtained via Google Translate are available from the authors upon request.

Safety

Concordance Analysis

The 6 monolingual and bilingual raters agreed on the safety of 73 MBTE PCIs. The most concordant pairings of 4 agreed on 81 items. The least and most concordant pairings had concordance values of 0.68 and 0.84, respectively. Subsequent analyses include data from only the 4 most concordant monolingual and bilingual raters.

Bilingual and Monolingual Safety Ratings

Both bilingual and monolingual raters assessed MBTE. On average, bilingual ratings of MBTE of safety were higher (0.987) than monolingual ratings (0.925) (t = –3.897, P = 0.0002).

Identification of Unsafe Translations in Machine Spanish and MBTE

The bilingual panel identified 11 translations (either machine Spanish or MBTE) as unsafe: MS translation was unsafe for 9 items, MBTE unsafe for 5 items, with some items identified as unsafe in terms of both machine Spanish and MBTE. The original English, machine Spanish, and MBTE for these PCIs are listed in Table 2. One item (#93) revealed a machine Spanish drug dosing ambiguity that was not present in the MBTE, with safety concern expressed by 3 of 4 bilingual raters.

Original English c haracteristics of Unsafe Translation

A stepwise logistic regression was performed to evaluate whether characteristics of the original English text predicted the PCI being judged as having a safe or unsafe machine Spanish translation. The explanatory variables (listed in Table 1) evaluated were word count, reading grade level, inclusion of reference to a specific medication, inclusion of numbers (as in "take 2 tablets"), and inclusion of numbered statements (as in "1. Call if your cough worsens"). The stepwise selection procedure dropped number references and numbered sentences, although post hoc analysis showed that number references and medication references occurred so commonly together that they were essentially interchangeable. The final regression model included word count, reading grade level, and medication reference. The significant factors of reading grade level and medication reference had odds ratio (95% confidence interval) of 1.12 (1.01 to 1.41) and 4.91 (1.07 to 22.7) respectively (P = 0.042 each). As reading grade level includes word count per sentence and syllable count per word as linear predictors, the inclusion of word count in the model is likely to increase the discrimination of complex words of many syllables in predicting the occurrence of unsafe machine Spanish.

Quality

Bilingual and Monolingual Raters Assessments of Quality

The bilingual evaluators found similar mean quality for machine Spanish (mean 0.855, SD 0.0859) and MBTE (0.857, SD 0.0755) (P = 0.811). However, the correlation of R2=0.355 (P = 0.000) suggests that despite similarity in mean ratings, a good forward translation from original English to machine Spanish did not assure a good back translation from machine Spanish to MBTE. No difference in mean MBTE quality was identified between bilingual (0.857, SD 0.0754) and monolingual (0.852, SD 0.126) raters (P = 0.598), with correlation R2=0.565 (P = 0.000).

Discussion

In this article, we have collected a corpus of example PCIs across a large number of authors, and investigated how well Google Translate was able to translate the example instructions first to Spanish, and then back again to English. We learned that one can not always spot a problem in the intermediate Spanish by inspection of the back-translated English. We also learned that simple sentences were least likely to be associated with troublesome translations, and that specific instructions about medication usage should probably be approached with great care.

We learned that some authors readily use simple language (eg: “Have your blood work drawn in the lab in the next two weeks,” reading level 1.2) while others gravitate to very complex language (“If you develop headache, chest pain, abdominal pain or back pain, or if you have any spontaneous bleeding please go to the emergency department, advise them that you were recently treated for rattlesnake envenomation and have them call the poison center,” reading level 20.2).

The development in confidence in machine translation can be compared to development of self-driving cars. At early stages of development, the self-driving cars had drivers with a foot near the brake and hands near the steering wheel, ready to take over at any instant. Now, after much data has been collected, there is evidence that the machine may operate more predictably and safely than some human drivers [15,16]. Should the self-driving cars always have an operator behind the wheel, supervising the function of the software, and ready to take over at any instant, or is the purpose of the self-driving car to allow non-drivers to be transported in an automobile that they either cannot operate or choose not to operate at that time?

The benefit of using professional interpreters in communicating clinically significant data is unquestioned, especially when compared to ad-hoc interpreters who lack professional understanding of context [4]. Like a good human driver (as compared to a self-driving car that is operated by a program that is still learning), a qualified human translator will outperform machine translation in complex tasks. Similarly, for relatively simple translations that are meant to be generated by human speakers to be understood by individuals with a grammar school education and vocabulary, is the state of machine translation such that less human translation is now required?

Our use of 2 teams of evaluators allowed us to use the game of Telephone analogy to provide insight into how well the machine translation proceeded, first to Spanish, then back to English. Mostly (90 times in 100), an acceptable Spanish translation resulted in an acceptable English back translation. In 2 instances (Samples 7 and 32), the first translation into Spanish was unacceptable, and a subsequent translation back to English was also unacceptable, as might be expected. In 2 instances (Samples 60 and 92), the Spanish translation was acceptable, but the translation back to English was unacceptable. The rules of Telephone worked 94 times in 100.

Still, 6 times in 100, the unexpected occurred, where a relatively poor Spanish translation returned a relatively acceptable English back translation. The rules of Telephone were not followed. The Spanish in the middle was garbled, but became acceptable when translated back to English. A fluent Spanish speaker found the intermediate Spanish to be of concern, and the back translation did not identify the concern. This argues against widespread adoption of machine back translation for quality assessment, at least until better understanding of the limitations of machine back translation are better understood. Looking at examples where back translation “worked” is useful. In the 6 instances where the intermediate Spanish was judged to be unacceptable, but the English back translation acceptable, complex sentence structures were found, along with medication instructions.

Not tested was if the raters found the original English instructions to be unclear or unsafe as a starting point. Here is where we find the potential benefit of the present study, as it provides insight into the type of content that seems to translate well in this set of data. where the machine Spanish error was not present in MBTE. Overall, ratings of translation quality by bilingual and monolingual raters was high, suggesting that there may be some utility in the machine translation with safeguards other than, or in addition to, inspection of machine back translation of machine Spanish. We found there was an astonishing range in reading difficulty across the contributed samples. While the average estimated grade level for comprehension of the original English contributions was the 8th grade, the maximum was 22, indicating extreme complexity of both words used and sentence length.

In gathering the example PCIs, we did not give any additional instructions to the authors to limit complexity, we only asked for their “typical” language, and if the examples received are indeed typical, the instructions we provide are often quite complex. Wu [17] explored the readability of medical information intended for the public and found that on average, 18 years of education would be required to read and understand the clinical trial descriptions available at ClinicalTrials.gov. It seems apparent that the first step to improving the safety of machine translation is to simplify the task of the translator, by making the language that is used for translation as unambiguous and straightforward as possible. The article by Patil and Davies on the use of Google Translate in the clinic [9] generated a considerable number of rapid responses (similar to letters to the editor) [18]. The responses emphasized the need to keep the language used simple, the sentences short, and the communication direct.

A simple and straightforward suggestion to improve all patient care instructions (not just those anticipated to be translated) would be to display the Flesch-Kincaid reading level in real time as the content is generated. The computer resources required to perform reading level analysis are nearly identical to those required for real-time spell checking: a dictionary that breaks words into syllables. Showing authors the reading level in real time would provide a tool to improve all instructions, not just those intended for translation. Limiting the dictionary to specifically exclude potentially dangerous, complex, or confusing words as well as forbidden abbreviations would further identify troublesome language to the author, and would improve communication overall. Implementing such real-time feedback to authors of patient instructions is a logical next step in adding utility to the electronic health record.

It is important that culture and contextual understanding is taken into consideration while organizations use interpretation services. In the United States, federal law requires that language interpreters employed by health care organization receiving federal funds are not only bilingual but also bicultural [16]. We did not find examples of dangerous synonyms being misapplied in translation, but we cannot rule out the possibility that such errors can occur. This is beyond the scope of typical machine translation software.

Our data suggest that use of medication names and dosing frequencies should not be repeated in the PCI where confusion can arise from imprecise language translation. Translation ambiguities that generate safety concerns in PCI might be mitigated by moving such content into structured areas of the AVS.

Conclusion

This study suggests that 9 times out of 10, the quality of machine translation using Google Translate is acceptable in terms of quality and safety. Currently, machine back translation may fail to reveal a relatively poor translation from English to Spanish. This study showed that increasing sentence complexity, as measured by the reading level index, was associated with a significant (P < 0.05) increase in unsafe machine translation. Similarly, including medication instructions in machine translations were associated with increased risk (P < 0.05) of machine translation safety error in this study.

A simple way to improve communication now would be to display the reading level to authors of patient communication content in real time, and limit the dictionary of acceptable words to forbid the use of known ambiguous terms or forbidden abbreviations. This would teach authors to use simple language, and increase the chance that translation (either human or machine) would be effective. This preliminary study suggests that keeping medication dosing instructions in a structured format is advisable, as is keeping sentences simple. As with spoken language [4], starting with clear, simple to understand English instructions provides the best machine translations into Spanish.

The Clinical Machine Translation Study Group: Todd W. Altenbernd, Steven Bedrick, Mark D. Berg, Nerida Berrios, Mark A. Brown, Colleen K. Cagno, Charles B. Cairns, Elizabeth Calhoun, Raymond Carmody, Tara F. Carr, Clara Choo, Melissa L. Cox, Janiel Cragun, Rachel E.M. Cramton, Paola Davis, Archita Desai, Sarah M. Desoky, Sean Elliot, Mindi J. Fain, Albert Fiorello, Hillary Franke, Kimberly Gerhart, Victor Jose Gonzalez, Aaron John Goshinska, Lynn M. Gries, Erin M. Harvey, Karen Herbst, Elizabeth Juneman, Lauren Marie Imbornoni, Anita Koshy, Lisa Laughlin, Christina M. Laukaitis, Kwan Lee, Hong Lei, Joseph M. Miller, Prashanthinie Mohan, Wayne J. Morgan, Jarrod Mosier, Leigh A. Neumayer, Valentine Nfonsam, Vivienne Ng, Terence O'Keeffe, Merri Pendergrass, Jessie M. Pettit, John Leander Po, Claudia Marie Prospero Ponce, Sydney Rice, Marie Anoushka Ricker, Arielle E. Rubin, Robert J. Segal, Aurora A.G. Selpides, Whitney A. Smith, Jordana M. Smith, William Stevenson, Amy N. Sussman, Ole J. Thienhaus, Patrick Tsai, J. Daniel Twelker, Richard Wahl, Jillian Wang, Mingwu Wang, Samuel C. Werner, Mark D. Wheeler, Jason Wild, Sun Kun Yi, Karl Andrew Yousef, Le Yu.

Corresponding author: Joseph M. Miller, MD, MPH, Department of Ophthalmology and Vision Science, University of Arizona, 655 North Alvernon Way, Suite 108, Tucson AZ 85711, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson, Tucson, AZ.

Abstract

- Objective: To determine predictors of quality and safety of machine translation (Google Translate) of patient care instructions (PCIs), and to determine if machine back translation is useful in quality assessment.

- Methods: 100 sample English PCIs were contributed by 88 clinical faculty. Each example PCI was up to 3 sentences of typical patient instruction that might be included in an after visit summary. Google Translate was used to first translate the English to Spanish, then back to English. A panel of 6 English/Spanish translators assessed the Spanish translations for safety and quality. A panel of 6 English-speaking health care workers assessed the back translation. A 5-point scale was used to assess quality. Safety was assessed as safe or unsafe.

- Results: Google Translate was usually (> 90%) capable of safe and comprehensible translation from English to Spanish. Instructions with incresed complexity, especially regarding medications, were prone to unsafe translation. Back translation was not reliable in detecting unsafe Spanish.

- Conclusion: Google Translate is a continuously evolving resource for clinicians that offers the promise of improved physician-patient communication. Simple declarative sentences are most reliably translated with high quality and safety.

Keywords: translation; machine translation; electronic health record; after-visit summary; patient safety; physician-patient communication.

Acore measure of the meaningful use of electronic health records incentive program is the generation and provision of the after visit summary (AVS), a mechanism for physicians to provide patients with a written summary of the patient encounter [1,2]. Although not a required element for meaningful use, free text patient care instructions (PCIs) provide the physician an opportunity to improve patient engagement either at the time of service or through the patient portal [3] by providing a short written summary of the key points of the office visit based upon the visit’s clinical discussion. For patients who do not speak English, a verbal translation service is required [4], but seldom are specific patient instructions provided in writing in the patient’s preferred language. A mechanism to improve communication might be through translation of the PCI into the patient’s preferred language. Spanish is the most common language, other than English, spoken at home in the United States [5,6]. For this reason, we chose to investigate if it is feasible to use machine translation (Google Translate) to safely and reliably translate a variety of PCIs from English to Spanish, and to assess the types of translation errors and ambiguities that might result in unsafe communication. We further investigate if machine back translation might allow the author of patient care instructions to evaluate the quality of the Spanish machine translation.

There is evidence to suggest that patient communication and satisfaction will improve if portions of the AVS are communicated in Spanish to primarily Spanish-speaking patients. Pavlik et al conducted a randomized controlled trial on the association of patient recall, satisfaction, and adherence to the information communicated in an AVS, in a largely Hispanic (61%) primary care clinic setting [7]. The AVS was provided in English. They noted that Spanish speakers wished to receive information in Spanish, although most had access to translation by a family member. They also noted that a lack of ability to provide an AVS in Spanish was a concern among providers. There was no difference in recall or satisfaction between English and Spanish speakers with respect to medications and allergies, suggesting that not all portions of the AVS might need to be translated.

Machine translation refers to the automated process of translating one language to another. The most recent methods of machine translation, as exemplified by Google Translate (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA), do not use rules of grammar and dictionaries to perform translations but instead use artificial neural networks to learn from “millions of examples” of translation [8]. However, unsupervised machine translation can result in serious errors [9]. Patil gives as an example of a serious error of translation from English (“Your child is fitting”) to Swahili (“Your child is dead”). In British parlance, “fitting” is a term for “having a seizure” and represents an example of a term that is context sensitive. However, others note that there is reason to be optimistic about the state of machine translation for biomedical text [10].

One method of assessing translation quality is through back translation, where one translator takes the author’s work into the desired target language, and then a different translator takes the target language back to the language of the author. Like the children’s game Chinese Whispers (Telephone in the United States) [11], where a “secret message” is whispered from one child to the next and spoken aloud at the end of the line of children, back translation can test to see if a message “gets through.” In this analogy, when information is machine translated from English to Spanish, and then machine translated from Spanish to English (Figure), we can compare the initial message to the final translation to see if the message “gets through.” We further investigate if machine back translation might allow a non-Spanish speaking author of PCIs to evaluate the quality of the Spanish translation.

Our intention was to determine if machine back translation [12] could be used by an English-only author to assess the quality of an intermediate Spanish translation. If poorly worded Spanish translated back into poorly worded English, the author might choose to either refine their original message until an acceptable machine back translation was achieved or to not release the Spanish translation to the patient. We were also concerned that there might be instances where the intermediate Spanish was unacceptable, but when translated back into English by machine translation, relatively acceptable English might result. If this were the case, then back translation would fail to detect a relatively poor intermediate Spanish translation.

Methods

Patient Care Instructions

Original English PCIs

Example original English PCIs were solicited from the clinical faculty and resident staff of the University of Arizona College of Medicine by an email-based survey tool (Qualtrics, Inc, Provo UT). The solicitation stated the following:

We are conducting a study to assess how well Google Translate might perform in translating patient instructions from English to Spanish. Would you please take the time to type three sentences that might comprise a typical “nugget” of patient instruction using language that you would typically include in an After Visit Summary for a patient? An example might be: “Take two Tylenol 325 mg tablets every four hours while awake for the next two days. If you have a sudden increase in pain or fever, or begin vomiting, call our office. Drink plenty of fluids.”

A total of 100 PCIs were collected. The breadth of the clinical practice and writing styles of a College of Medicine faculty are represented: not all were completely clear or were well-formed sentences, but did represent examples provided by busy clinicians of typical language that they would provide in an AVS PCI.

Machine Translation into Spanish

The 100 original English (OE) PCIs were submitted to the Google Translate web interface (https://translate.google.com/) by cutting and pasting and selecting “Spanish,” resulting in machine Spanish. The translations were performed in January 2016. No specific version number is provided by Google on their web page, and the service is described to be constantly evolving (https://translate.google.com/about/intl/en_ALL/contribute.html).

Machine Back Translation into English (MBTE)