User login

Endovenous thermal ablation and thrombotic complications

“CLINICAL CORRELATION OF SUCCESS AND ACUTE THROMBOTIC COMPLICATIONS OF LOWER EXTREMITY ENDOVENOUS THERMAL ABLATION.” Journal of Vascular Surgery Venous and Lymphatic Disorders, January 2018

A large single center experience with endovenous thermal ablation reveals risk factors for thrombotic complications.

Minimally invasive techniques for treating reflux disease in the saphenous system have greatly improved the quality of life and comfort of those suffering with chronic venous disease and more advanced venous insufficiency. Painful procedures of the past, sometimes including hospital stays, have largely been replaced by safe and efficacious office procedures (lasting often less than an hour) with minimal subsequent activity restrictions.

Despite these obvious advantages, these therapies do have a very low but definite risk of thrombotic complications, including endovenous heat-induced thrombosis (EHIT) superficial venous thrombosis (SVT) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT). EHIT includes development of a blood clot at the junction of one of the treated saphenous veins and the femoral or the popliteal vein.

While major DVT and pulmonary embolism are extremely rare, the diagnosis of EHIT may require a period of anticoagulation as well as follow-up visits and studies. Further, acute SVT can be painful for several weeks following the procedure. As such, further understanding the risk factors for these complications will allow therapists to better inform patients as to their specific risks for developing them.

As reported in the January 2018 edition of the Journal of Vascular Surgery: Venous and Lymphatic Disorders, researchers from Total Vascular Care and NYU Lutheran Medical Center led by Afsha Aurshina, MBBS, evaluated their large single center experience treating multiple vein types using both radiofrequency (RFA) and endovenous laser (EVLA) ablation techniques. They retrospectively studied the outcomes of 1811 procedures performed on 808 patients from 2012-2014. The aim of the study was to define better the success and thrombotic complications of these procedures with respect to technique and vein type.

Overall success (defined as absence of reflux in the targeted vein by post-operative duplex) rates included:

- RFA 98.4% (excluding perforating vein)

- EVLA 98.1%

- Great saphenous (GSV) 98.5%

- Lesser saphenous (LSV) 98.2%

- Accessory saphenous (ASV) 97.2%

- Perforator (PV) 82.4%

With regards to thrombotic complications, the authors reported EHIT rates of:

- Class 1-4 5.9%

- Class 2-4 1.16%

Acute superficial thrombosis rates included:

- Overall 4.6%

- RFA 7.7%

- EVLA 11.4% (no difference in multi-factor analysis)

- GSV 11.8%

- LSV 5.5%

- ASV 6.5%

- PV 2.4%

“Our study demonstrates that there is no significant difference in the success rate of RFA and EVLA in the treatment of venous reflux for GSV, SSV, and ASV,” notes first author Aurshina. “We found an acceptably low incidence of clinically significant thrombotic complication rates for EHIT and acute superficial thrombosis, with only a 1.16% risk of Class 2-4 EHIT, that may require short term anticoagulation. We noted risk factors for these complications, after multi-factor analysis, include higher vein diameter and type of vein, with the latter being the most important.”

Large experiences such as these are important to understand the true incidence of these complications and how practitioners might tailor their consent process with their patients.

To download the complete article (link available free from 12/14/2017 through 2/28/2018),

click: http://vsweb.org/JVSVL-EVTA

For information your patients may be interested in, click:

Regarding Varicose Veins:

https://vascular.org/patient-resources/vascular-conditions/varicose-veins

Regarding Deep Venous Thrombosis:

https://vascular.org/patient-resources/vascular-conditions/deep-vein-thrombosis

“CLINICAL CORRELATION OF SUCCESS AND ACUTE THROMBOTIC COMPLICATIONS OF LOWER EXTREMITY ENDOVENOUS THERMAL ABLATION.” Journal of Vascular Surgery Venous and Lymphatic Disorders, January 2018

A large single center experience with endovenous thermal ablation reveals risk factors for thrombotic complications.

Minimally invasive techniques for treating reflux disease in the saphenous system have greatly improved the quality of life and comfort of those suffering with chronic venous disease and more advanced venous insufficiency. Painful procedures of the past, sometimes including hospital stays, have largely been replaced by safe and efficacious office procedures (lasting often less than an hour) with minimal subsequent activity restrictions.

Despite these obvious advantages, these therapies do have a very low but definite risk of thrombotic complications, including endovenous heat-induced thrombosis (EHIT) superficial venous thrombosis (SVT) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT). EHIT includes development of a blood clot at the junction of one of the treated saphenous veins and the femoral or the popliteal vein.

While major DVT and pulmonary embolism are extremely rare, the diagnosis of EHIT may require a period of anticoagulation as well as follow-up visits and studies. Further, acute SVT can be painful for several weeks following the procedure. As such, further understanding the risk factors for these complications will allow therapists to better inform patients as to their specific risks for developing them.

As reported in the January 2018 edition of the Journal of Vascular Surgery: Venous and Lymphatic Disorders, researchers from Total Vascular Care and NYU Lutheran Medical Center led by Afsha Aurshina, MBBS, evaluated their large single center experience treating multiple vein types using both radiofrequency (RFA) and endovenous laser (EVLA) ablation techniques. They retrospectively studied the outcomes of 1811 procedures performed on 808 patients from 2012-2014. The aim of the study was to define better the success and thrombotic complications of these procedures with respect to technique and vein type.

Overall success (defined as absence of reflux in the targeted vein by post-operative duplex) rates included:

- RFA 98.4% (excluding perforating vein)

- EVLA 98.1%

- Great saphenous (GSV) 98.5%

- Lesser saphenous (LSV) 98.2%

- Accessory saphenous (ASV) 97.2%

- Perforator (PV) 82.4%

With regards to thrombotic complications, the authors reported EHIT rates of:

- Class 1-4 5.9%

- Class 2-4 1.16%

Acute superficial thrombosis rates included:

- Overall 4.6%

- RFA 7.7%

- EVLA 11.4% (no difference in multi-factor analysis)

- GSV 11.8%

- LSV 5.5%

- ASV 6.5%

- PV 2.4%

“Our study demonstrates that there is no significant difference in the success rate of RFA and EVLA in the treatment of venous reflux for GSV, SSV, and ASV,” notes first author Aurshina. “We found an acceptably low incidence of clinically significant thrombotic complication rates for EHIT and acute superficial thrombosis, with only a 1.16% risk of Class 2-4 EHIT, that may require short term anticoagulation. We noted risk factors for these complications, after multi-factor analysis, include higher vein diameter and type of vein, with the latter being the most important.”

Large experiences such as these are important to understand the true incidence of these complications and how practitioners might tailor their consent process with their patients.

To download the complete article (link available free from 12/14/2017 through 2/28/2018),

click: http://vsweb.org/JVSVL-EVTA

For information your patients may be interested in, click:

Regarding Varicose Veins:

https://vascular.org/patient-resources/vascular-conditions/varicose-veins

Regarding Deep Venous Thrombosis:

https://vascular.org/patient-resources/vascular-conditions/deep-vein-thrombosis

“CLINICAL CORRELATION OF SUCCESS AND ACUTE THROMBOTIC COMPLICATIONS OF LOWER EXTREMITY ENDOVENOUS THERMAL ABLATION.” Journal of Vascular Surgery Venous and Lymphatic Disorders, January 2018

A large single center experience with endovenous thermal ablation reveals risk factors for thrombotic complications.

Minimally invasive techniques for treating reflux disease in the saphenous system have greatly improved the quality of life and comfort of those suffering with chronic venous disease and more advanced venous insufficiency. Painful procedures of the past, sometimes including hospital stays, have largely been replaced by safe and efficacious office procedures (lasting often less than an hour) with minimal subsequent activity restrictions.

Despite these obvious advantages, these therapies do have a very low but definite risk of thrombotic complications, including endovenous heat-induced thrombosis (EHIT) superficial venous thrombosis (SVT) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT). EHIT includes development of a blood clot at the junction of one of the treated saphenous veins and the femoral or the popliteal vein.

While major DVT and pulmonary embolism are extremely rare, the diagnosis of EHIT may require a period of anticoagulation as well as follow-up visits and studies. Further, acute SVT can be painful for several weeks following the procedure. As such, further understanding the risk factors for these complications will allow therapists to better inform patients as to their specific risks for developing them.

As reported in the January 2018 edition of the Journal of Vascular Surgery: Venous and Lymphatic Disorders, researchers from Total Vascular Care and NYU Lutheran Medical Center led by Afsha Aurshina, MBBS, evaluated their large single center experience treating multiple vein types using both radiofrequency (RFA) and endovenous laser (EVLA) ablation techniques. They retrospectively studied the outcomes of 1811 procedures performed on 808 patients from 2012-2014. The aim of the study was to define better the success and thrombotic complications of these procedures with respect to technique and vein type.

Overall success (defined as absence of reflux in the targeted vein by post-operative duplex) rates included:

- RFA 98.4% (excluding perforating vein)

- EVLA 98.1%

- Great saphenous (GSV) 98.5%

- Lesser saphenous (LSV) 98.2%

- Accessory saphenous (ASV) 97.2%

- Perforator (PV) 82.4%

With regards to thrombotic complications, the authors reported EHIT rates of:

- Class 1-4 5.9%

- Class 2-4 1.16%

Acute superficial thrombosis rates included:

- Overall 4.6%

- RFA 7.7%

- EVLA 11.4% (no difference in multi-factor analysis)

- GSV 11.8%

- LSV 5.5%

- ASV 6.5%

- PV 2.4%

“Our study demonstrates that there is no significant difference in the success rate of RFA and EVLA in the treatment of venous reflux for GSV, SSV, and ASV,” notes first author Aurshina. “We found an acceptably low incidence of clinically significant thrombotic complication rates for EHIT and acute superficial thrombosis, with only a 1.16% risk of Class 2-4 EHIT, that may require short term anticoagulation. We noted risk factors for these complications, after multi-factor analysis, include higher vein diameter and type of vein, with the latter being the most important.”

Large experiences such as these are important to understand the true incidence of these complications and how practitioners might tailor their consent process with their patients.

To download the complete article (link available free from 12/14/2017 through 2/28/2018),

click: http://vsweb.org/JVSVL-EVTA

For information your patients may be interested in, click:

Regarding Varicose Veins:

https://vascular.org/patient-resources/vascular-conditions/varicose-veins

Regarding Deep Venous Thrombosis:

https://vascular.org/patient-resources/vascular-conditions/deep-vein-thrombosis

Register for VRIC; Abstracts due Jan. 10

Registration is now open for the Vascular Research Initiatives Conference, to be held Thursday, May 9, in San Francisco. Abstracts for VRIC are due Wednesday, Jan. 10. Learn more about VRIC, and submit your abstracts here.

Registration is now open for the Vascular Research Initiatives Conference, to be held Thursday, May 9, in San Francisco. Abstracts for VRIC are due Wednesday, Jan. 10. Learn more about VRIC, and submit your abstracts here.

Registration is now open for the Vascular Research Initiatives Conference, to be held Thursday, May 9, in San Francisco. Abstracts for VRIC are due Wednesday, Jan. 10. Learn more about VRIC, and submit your abstracts here.

JVS Access Expires Jan. 15 for Those Who Haven’t Paid Dues

Have you put off paying your 2018 SVS membership dues? Don’t wait too much longer! Access to the Journal of Vascular Surgery suite of publications expires on Jan. 15 for those who have not yet paid their 2018 dues. Renew today.

Have you put off paying your 2018 SVS membership dues? Don’t wait too much longer! Access to the Journal of Vascular Surgery suite of publications expires on Jan. 15 for those who have not yet paid their 2018 dues. Renew today.

Have you put off paying your 2018 SVS membership dues? Don’t wait too much longer! Access to the Journal of Vascular Surgery suite of publications expires on Jan. 15 for those who have not yet paid their 2018 dues. Renew today.

VAM Abstract Deadline Approaches

Abstracts are due Wednesday, Jan. 17, for the 2018 Vascular Annual Meeting, set for June 20-23 in Boston. Guidelines, submission policies and general information on VAM are available online. VAM plenaries are June 21-23 and exhibits are June 21-22. Registration and housing will open in early March.

Abstracts are due Wednesday, Jan. 17, for the 2018 Vascular Annual Meeting, set for June 20-23 in Boston. Guidelines, submission policies and general information on VAM are available online. VAM plenaries are June 21-23 and exhibits are June 21-22. Registration and housing will open in early March.

Abstracts are due Wednesday, Jan. 17, for the 2018 Vascular Annual Meeting, set for June 20-23 in Boston. Guidelines, submission policies and general information on VAM are available online. VAM plenaries are June 21-23 and exhibits are June 21-22. Registration and housing will open in early March.

Regenerative Medicine in Cosmetic Dermatology

Regenerative medicine encompasses innovative therapies that allow the body to repair or regenerate aging cells, tissues, and organs. The skin is a particularly attractive organ for the application of novel regenerative therapies due to its easy accessibility. Among these therapies, stem cells and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) have garnered interest based on their therapeutic potential in scar reduction, antiaging effects, and treatment of alopecia.

Stem cells possess the cardinal features of self-renewal and plasticity. Self-renewal refers to symmetric cell division generating daughter cells identical to the parent cell.1 Plasticity is the ability to generate cell types other than the germ line or tissue lineage from which stem cells derive.2 Stem cells can be categorized according to their differentiation potential. Totipotent stem cells may develop into any primary germ cell layer (ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm) of the embryo, as well as extraembryonic tissue such as the trophoblast, which gives rise to the placenta. Pluripotent stem cells such as embryonic stem cells have the capacity to differentiate into any derivative of the 3 germ cell layers but have lost their ability to differentiate into the trophoblast.3 Adults lack totipotent or pluripotent cells; they have multipotent or unipotent cells. Multipotent stem cells are able to differentiate into multiple cell types from similar lineages; mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), for example, can differentiate into adipogenic, osteogenic, chondrogenic, and myogenic cells.4 Unipotent stem cells have the lowest differentiation potential and can only self-regenerate. Herein, we review stem cell sources and their therapeutic potential in aesthetic dermatology.

Multipotent Stem Cells

Multipotent stem cells derived from the bone marrow, umbilical cord, adipose tissue, dermis, or hair follicle bulge have various clinical applications in dermatology. Stem cells from these sources are primarily utilized in an autologous manner in which they are processed outside the body and reintroduced into the donor. Autologous multipotent hematopoietic bone marrow cells were first successfully used for the treatment of chronic wounds and show promise for the treatment of atrophic scars.5,6 However, due to the invasive nature of extracting bone marrow stem cells and their declining number with age, other sources of multipotent stem cells have fallen into favor.

Umbilical cord blood is a source of multipotent hematopoietic stem cells for which surgical intervention is not necessary because they are retrieved after umbilical cord clamping.7 Advantages of sourcing stem cells from umbilical cord blood includes high regenerative power compared to a newborn’s skin and low immunogenicity given that the newborn is immunologically immature.8

Another popular source for autologous stem cells is adipose tissue due to its ease of accessibility and relative abundance. Given that adipose tissue–derived stem cells (ASCs) are capable of differentiating into adipocytes that help maintain volume over time, they are being used for midface contouring, lip augmentation, facial rejuvenation, facial scarring, lipodystrophy, penile girth enhancement, and vaginal augmentation. Adipose tissue–derived stem cells also are capable of differentiating into other types of tissue, including cartilage and bone. Thus, they have been successfully harnessed in the treatment of patients affected by systemic sclerosis and Parry-Romberg syndrome as well in the functional and aesthetic reconstruction of various military combat–related deformities.9,10

Adipose tissue–derived stem cells are commonly harvested from lipoaspirate of the abdomen and are combined with supportive mechanical scaffolds such as hydrogels. Lipoaspirate itself can serve as a scaffold for ASCs. Accordingly, ASCs also are being utilized as a scaffold for autologous fat transfer procedures in an effort to increase the viability of transplanted donor tissue, a process known as cell-assisted lipotransfer (CAL). In CAL, a fraction of the aspirated fat is processed for isolation of ASCs, which are then recombined with the remainder of the aspirated fat prior to grafting.11 However, there is conflicting evidence as to whether CAL leads to improved graft success relative to conventional autologous fat transfer.12,13

The skin also serves as an easily accessible and abundant autologous source of stem cells. A subtype of dermal fibroblasts has been proven to have multipotent potential.14,15 These dermal fibroblasts are harvested from one area of the skin using punch biopsy and are processed and reinjected into another desired area of the skin.16 Autologous human fibroblasts have proven to be effective for the treatment of wrinkles, rhytides, and acne scars.17 In June 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration approved azficel-T, an autologous cellular product created by harvesting fibroblasts from a patient’s own postauricular skin, culture-expanding them in vitro for 3 months, and reinjecting the cells into the desired area of dermis in a series of treatments. This product was the first personalized cell therapy approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for aesthetic uses, specifically for the improvement of nasolabial fold wrinkles.18

In adults, hair follicles contain an area known as the bulge, which is a site rich in epithelial and melanocytic stem cells. Bulge stem cells have the ability to reproduce the interfollicular epidermis, hair follicle structures, and sebaceous glands, and they have been used to construct entirely new hair follicles in an artificial in vivo system.19 Sugiyama-Nakagiri et al20 demonstrated that an entire hair follicle epithelium and interfollicular epidermis can be regenerated using cultured bulge stem cells. The cultured bulge stem cells were mixed with dermal papilla cells from neonatal rat vibrissae and engrafted into a silicone chamber implanted on the backs of severe combined immune deficient (SCID) mice. The grafts exhibited tufts of hair as well as a complete interfollicular epidermis at 4 weeks after transplantation.20 Thus, these bulge stem cells have the potential to treat male androgenic alopecia and female pattern hair loss. Bulge stem cells also have been shown to accelerate wound healing.21 Additionally, autologous melanocytic stem cells located at the hair follicle bulge are effective for treating vitiligo and are being investigated for the treatment of hair graying.22

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells

Given the ethical concerns that surround the procurement and use of embryonic stem cells, efforts have been made to retrieve pluripotent stem cells from adults. A major breakthrough occurred in 2006 when researchers altered the genes of specialized adult mouse cells to cause dedifferentiation and the return to an embryoniclike stem cell state.23 Mouse somatic cells were reprogrammed through the activation of a combination of transcription factors. The resulting cells were termed induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and have since been recreated in human cell lines. The discovery of iPSCs precipitated a translational science revolution. Physician-scientists sought ways to apply the reprogrammed cells to the pathophysiology of obscure diseases, examination of drug targets, and regeneration of human tissue.24 Tissue regeneration via induced naïve somatic cells has shown promise as a future method to treat neurologic, cardiovascular, and ophthalmologic diseases.25

As the technology of cultivating and identifying optimal sources of iPSCs continues to advance, stem cell–based treatments have evolved as leading prospects in the field of biogerontology.26-29 Although much of the research in antiaging medicine has utilized iPSCs to reprogram cell senescence, the altering of iPSCs at a cellular level also allows for the stimulation of collagen synthesis. This potential for collagen generation may have direct applicability in dermatologic practice, particularly for aesthetic treatments.

Much of the research into iPSC-derived collagen has focused on genodermatoses. Itoh et al30 examined the creation of collagen through iPSCs to identify possible treatments for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB). Recessive DEB is characterized by mutations in the COL7A1 gene, which encodes type VII collagen, a basement membrane protein and component of the anchoring fibrils essential for skin integrity.31 Itoh et al30 began with source cells obtained from a skin biopsy. The cells were dedifferentiated to iPSCs and then induced into dermal fibroblasts according to the methods established in prior studies of embryonic stem cells, namely with the use of ascorbic acid and transforming growth factor b. The newly formed fibroblasts were determined to be functional based on their ability to synthesize mature type VII collagen.30 Once the viability of the iPSC-derived fibroblasts was confirmed in vitro, the cells were further tested through combination with human keratinocytes on SCID mice. The human keratinocytes grew together with the iPSC-derived fibroblasts, producing type VII collagen in the basement membrane zone and creating an epidermis with the normal markers.30 Similarly, Robbins et al32 utilized SCID mice to successfully demonstrate that the transfection of keratinocytes from patients with junctional epidermolysis bullosa into SCID mice produced phenotypically normal skin.

Sebastiano et al33 combined the concepts of iPSCs and genome editing in another study of recessive DEB. The investigators first cultured iPSCs from biopsies of affected patients. After deriving iPSCs and correcting their mutation via adenovirus-associated viral gene editing, the COL7A1 mutation-free cells were differentiated into keratinocytes. These iPSC-derived keratinocytes were subsequently grafted onto mice, which led to the production of wild-type collagen VII and a stratified epidermis. Despite this successful outcome, the grafts of iPSC-derived epidermis did not survive longer than 1 month.33

One of the many obstacles facing the practical use of stem cells is their successful incorporation into human tissue. A possible solution was uncovered by Zhang et al34 who examined iPSC-derived MSCs. Mesenchymal stem cells communicate via paracrine mechanisms, whereby exosomes containing RNA and proteins are released to potentiate a regenerative effect.35 Zhang et al34 found that injecting exosomes from human iPSC-derived MSCs into the wound sites of rats stimulated the production of type I collagen, type III collagen, and elastin. The wound sites demonstrated accelerated closure, narrower scar widths, and increased collagen maturity.

Understanding the role that local environment plays in stem cell differentiation, Xu et al36 aimed to create an extracellular scaffold to induce fibroblast behavior from iPSCs. The authors engineered a framework similar to the normal extracellular membrane using proteoglycans, glycosaminoglycans, fibrinogen, and connective tissue growth factor. The iPSCs were then applied to the scaffolding, which led to successful fibroblast differentiation and type I collagen synthesis.36 This use of local biosignaling cues holds important ramifications for controlling the fate of stem cells that have been introduced into a new environment.

Although the application of iPSCs in clinical dermatology has yet to be achieved, progress in the field is moving at a rapid pace. Several logistical elements require further mastery before therapeutics can be delivered. These areas include the optimal environment for iPSC differentiation, methods for maximization of graft survival, and different modes of transplanting iPSC-derived cells into patients. In cosmetic practice, success will depend on intradermal injections of collagen-producing iPSC-derived cells that possess long-term proliferative potential. Current research in mice models has demonstrated viability up to 16 weeks after intradermal injection of such cells.37

Plant Stem Cells

In discussing the dermatologic applications of stem cell technology, clinicians should be aware of the plant stem cell products that have become a popular cosmeceutical trend. Companies advertise plant cells as a natural source of regenerative cells that can induce rejuvenation in human skin; however, there are no significant data to indicate that plant stem cells encourage or activate cellular growth in humans. Indeed, for stem cells to differentiate and produce viable components, the cells must first be incorporated as living components in the host tissue. Because plant stem cells do not survive in human tissue and plant cell cytokines fail to interact with the receptors on human cells, their current value in cosmeceuticals may be overstated.

Platelet-Rich Plasma

Platelet-rich plasma also is commonly associated with stem cell therapy, as PRP is known to potentiate stem cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation. However, PRP does not contain stem cells and is instead autologous plasma concentrated with platelets. In fact, platelets cannot even be classified as cells given that they lack a nucleus; platelets are considered cell fragments. The regenerative potential of PRP can be attributed to the growth factors released from platelets, which play an important role in tissue regeneration and repair. Platelet-rich plasma currently is being used in dermatology for skin rejuvenation (reduction of wrinkles and furrows) and treatment of acne scars.38 There also is evidence supporting the effectiveness of PRP for alopecia and wound therapy, as growth factors play a vital role in hair growth and wound healing.38 Apart from the use of PRP on its own, it can be used as a supplement to enhance the effects of antiaging procedures such as microneedling.39

Future Directions

Multipotent stem cells and iPSCs discussed herein provide much promise in the field of regenerative dermatology. They are increasingly accessible and circumvent the use of ethically questionable embryonic stem cells. Although there is a general consensus on the great potential of stem cells for treating aesthetic skin conditions, high-quality randomized controlled trials remain scarce within the literature. Recognizing and optimizing these opportunities remains the next step in the future delivery of evidence-based care in regenerative dermatology.

- Thomas ED, Lochte HL, Lu WC, et al. Intravenous infusion of bone marrow in patients receiving radiation and chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 1957;257:491-496.

- Ogliari KS, Marinowic D, Brum DE, et al. Stem cells in dermatology. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:286-291.

- Xu C, Inokuma MS, Denham J, et al. Feeder-free growth of undifferentiated human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:971-974.

- Zuk PA, Zhu M, Mizuno H, et al. Multilineage cells from human adipose tissue: implications for cell-based therapies. Tissue Eng. 2001;7:211-228.

- Badiavas EV, Falanga V. Treatment of chronic wounds with bone marrow-derived cells. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:510-516.

- Ibrahim ZA, Eltatawy RA, Ghaly NR, et al. Autologous bone marrow stem cells in atrophic acne scars: a pilot study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26:260-265.

- Broxmeyer HE, Douglas GW, Hangoc G, et al. Human umbilical cord blood as a potential source of transplantable hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:3828-3832.

- Gluckman E, Rocha V, Boyer-Chammard A, et al. Outcome of cord-blood transplantation from related and unrelated donors. Eurocord Transplant Group and the European Blood and Marrow Transplantation Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:373-381.

- Valerio IL, Sabino JM, Dearth CL. Plastic surgery challenges in war wounded II: regenerative medicine. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2016;5:412-419.

- Vescarelli E, D’Amici S, Onesti MG, et al. Adipose-derived stem cell: an innovative therapeutic approach in systemic sclerosis and Parry-Romberg syndrome. CellR4. 2014;2:E791-E797.

- Yoshimura K, Sato K, Aoi N, et al. Cell-assisted lipotransfer for cosmetic breast augmentation: supportive use of adipose-derived stem/stromal cells. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2008;32:48-55.

- Grabin S, Antes G, Stark GB, et al. Cell-assisted lipotransfer: a critical appraisal of the evidence. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:255.

- Zhou Y, Wang J, Li H, et al. Efficacy and safety of cell-assisted lipotransfer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137:E44-E57.

- Toma JG, Akhavan M, Fernandes KJL, et al. Isolation of multipotent adult stem cells from the dermis of mammalian skin. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:778-784.

- Toma JG, McKenzie IA, Bagli D, et al. Isolation and characterization of multipotent skin-derived precursors from human skin. Stem Cells. 2005;23:727-737.

- Homicz MR, Watson D. Review of injectable materials for soft tissue augmentation. Facial Plast Surg. 2004;20:21-29.

- Kumar S, Mahajan BB, Kaur S, et al. Autologous therapies in dermatology. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:38-45.

- Schmidt C. FDA approves first cell therapy for wrinkle-free visage. Nat Biotech. 2011;29:674-675.

- Gentile P, Scioli MG, Bielli A, et al. Stem cells from human hair follicles: first mechanical isolation for immediate autologous clinical use in androgenetic alopecia and hair loss. Stem Cell Investig. 2017;4:58.

- Sugiyama-Nakagiri Y, Akiyama M, Shimizu H. Hair follicle stem cell-targeted gene transfer and reconstitution system. Gene Ther. 2006;13:732-737.

- Heidari F, Yari A, Rasoolijazi H, et al. Bulge hair follicle stem cells accelerate cutaneous wound healing in rats. Wounds. 2016;28:132-141.

- Lee JH, Fisher DE. Melanocyte stem cells as potential therapeutics in skin disorders. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2014;14:1-11.

- Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663-676.

- Singh VK, Kalsan M, Kumar N, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells: applications in regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and drug discovery. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2015;3:2.

- Aoi T. 10th anniversary of iPS cells: The challenges that lie ahead. J Biochem. 2016;160:121-129.

- Lowry WE, Plath K. The many ways to make an iPS cell. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1246-1248.

- Kim K, Doi A, Wen B, et al. Epigenetic memory in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2010;467:285-290.

- Gafni O, Weinberger L, Mansour AA, et al. Derivation of novel human ground state naive pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2013;504:282-286.

- Pareja-Galeano H, Sanchis-Gomar F, Pérez LM, et al. IPSCs-based anti-aging therapies: Recent discoveries and future challenges. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;27:37-41.

- Itoh M, Umegaki-Arao N, Guo Z, et al. Generation of 3D skin equivalents fully reconstituted from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). PLoS One. 2013;8:e77673.

- Nyström A, Velati D, Mittapalli VR, et al. Collagen VII plays a dual role in wound healing. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3498-3509.

- Robbins PB, Lin Q, Goodnough JB, et al. In vivo restoration of laminin 5 β3 expression and function in junctional epidermolysis bullosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:5193-5198.

- Sebastiano V, Zhen HH, Haddad B, et al. Human COL7A1-corrected induced pluripotent stem cells for the treatment of recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:264ra163.

- Zhang J, Guan J, Niu X, et al. Exosomes released from human induced pluripotent stem cells-derived MSCs facilitate cutaneous wound healing by promoting collagen synthesis and angiogenesis. J Transl Med. 2015;13:49.

- Pap E, Pállinger É, Pásztói M, et al. Highlights of a new type of intercellular communication: microvesicle-based information transfer. Inflamm Res. 2009;58:1-8.

- Xu R, Taskin MB, Rubert M, et al. hiPS-MSCs differentiation towards fibroblasts on a 3D ECM mimicking scaffold. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8480.

- Wenzel D, Bayerl J, Nyström A, et al. Genetically corrected iPSCs as cell therapy for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:264ra165.

- Bednarska K, Kieszek R, Domagała P, et al. The use of platelet-rich-plasma in aesthetic and regenerative medicine. MEDtube Science. 2015;2:8-15.

- Hashim PW, Levy Z, Cohen JL, et al. Microneedling therapy with and without platelet-rich plasma. Cutis. 2017;99:239-242.

Regenerative medicine encompasses innovative therapies that allow the body to repair or regenerate aging cells, tissues, and organs. The skin is a particularly attractive organ for the application of novel regenerative therapies due to its easy accessibility. Among these therapies, stem cells and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) have garnered interest based on their therapeutic potential in scar reduction, antiaging effects, and treatment of alopecia.

Stem cells possess the cardinal features of self-renewal and plasticity. Self-renewal refers to symmetric cell division generating daughter cells identical to the parent cell.1 Plasticity is the ability to generate cell types other than the germ line or tissue lineage from which stem cells derive.2 Stem cells can be categorized according to their differentiation potential. Totipotent stem cells may develop into any primary germ cell layer (ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm) of the embryo, as well as extraembryonic tissue such as the trophoblast, which gives rise to the placenta. Pluripotent stem cells such as embryonic stem cells have the capacity to differentiate into any derivative of the 3 germ cell layers but have lost their ability to differentiate into the trophoblast.3 Adults lack totipotent or pluripotent cells; they have multipotent or unipotent cells. Multipotent stem cells are able to differentiate into multiple cell types from similar lineages; mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), for example, can differentiate into adipogenic, osteogenic, chondrogenic, and myogenic cells.4 Unipotent stem cells have the lowest differentiation potential and can only self-regenerate. Herein, we review stem cell sources and their therapeutic potential in aesthetic dermatology.

Multipotent Stem Cells

Multipotent stem cells derived from the bone marrow, umbilical cord, adipose tissue, dermis, or hair follicle bulge have various clinical applications in dermatology. Stem cells from these sources are primarily utilized in an autologous manner in which they are processed outside the body and reintroduced into the donor. Autologous multipotent hematopoietic bone marrow cells were first successfully used for the treatment of chronic wounds and show promise for the treatment of atrophic scars.5,6 However, due to the invasive nature of extracting bone marrow stem cells and their declining number with age, other sources of multipotent stem cells have fallen into favor.

Umbilical cord blood is a source of multipotent hematopoietic stem cells for which surgical intervention is not necessary because they are retrieved after umbilical cord clamping.7 Advantages of sourcing stem cells from umbilical cord blood includes high regenerative power compared to a newborn’s skin and low immunogenicity given that the newborn is immunologically immature.8

Another popular source for autologous stem cells is adipose tissue due to its ease of accessibility and relative abundance. Given that adipose tissue–derived stem cells (ASCs) are capable of differentiating into adipocytes that help maintain volume over time, they are being used for midface contouring, lip augmentation, facial rejuvenation, facial scarring, lipodystrophy, penile girth enhancement, and vaginal augmentation. Adipose tissue–derived stem cells also are capable of differentiating into other types of tissue, including cartilage and bone. Thus, they have been successfully harnessed in the treatment of patients affected by systemic sclerosis and Parry-Romberg syndrome as well in the functional and aesthetic reconstruction of various military combat–related deformities.9,10

Adipose tissue–derived stem cells are commonly harvested from lipoaspirate of the abdomen and are combined with supportive mechanical scaffolds such as hydrogels. Lipoaspirate itself can serve as a scaffold for ASCs. Accordingly, ASCs also are being utilized as a scaffold for autologous fat transfer procedures in an effort to increase the viability of transplanted donor tissue, a process known as cell-assisted lipotransfer (CAL). In CAL, a fraction of the aspirated fat is processed for isolation of ASCs, which are then recombined with the remainder of the aspirated fat prior to grafting.11 However, there is conflicting evidence as to whether CAL leads to improved graft success relative to conventional autologous fat transfer.12,13

The skin also serves as an easily accessible and abundant autologous source of stem cells. A subtype of dermal fibroblasts has been proven to have multipotent potential.14,15 These dermal fibroblasts are harvested from one area of the skin using punch biopsy and are processed and reinjected into another desired area of the skin.16 Autologous human fibroblasts have proven to be effective for the treatment of wrinkles, rhytides, and acne scars.17 In June 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration approved azficel-T, an autologous cellular product created by harvesting fibroblasts from a patient’s own postauricular skin, culture-expanding them in vitro for 3 months, and reinjecting the cells into the desired area of dermis in a series of treatments. This product was the first personalized cell therapy approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for aesthetic uses, specifically for the improvement of nasolabial fold wrinkles.18

In adults, hair follicles contain an area known as the bulge, which is a site rich in epithelial and melanocytic stem cells. Bulge stem cells have the ability to reproduce the interfollicular epidermis, hair follicle structures, and sebaceous glands, and they have been used to construct entirely new hair follicles in an artificial in vivo system.19 Sugiyama-Nakagiri et al20 demonstrated that an entire hair follicle epithelium and interfollicular epidermis can be regenerated using cultured bulge stem cells. The cultured bulge stem cells were mixed with dermal papilla cells from neonatal rat vibrissae and engrafted into a silicone chamber implanted on the backs of severe combined immune deficient (SCID) mice. The grafts exhibited tufts of hair as well as a complete interfollicular epidermis at 4 weeks after transplantation.20 Thus, these bulge stem cells have the potential to treat male androgenic alopecia and female pattern hair loss. Bulge stem cells also have been shown to accelerate wound healing.21 Additionally, autologous melanocytic stem cells located at the hair follicle bulge are effective for treating vitiligo and are being investigated for the treatment of hair graying.22

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells

Given the ethical concerns that surround the procurement and use of embryonic stem cells, efforts have been made to retrieve pluripotent stem cells from adults. A major breakthrough occurred in 2006 when researchers altered the genes of specialized adult mouse cells to cause dedifferentiation and the return to an embryoniclike stem cell state.23 Mouse somatic cells were reprogrammed through the activation of a combination of transcription factors. The resulting cells were termed induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and have since been recreated in human cell lines. The discovery of iPSCs precipitated a translational science revolution. Physician-scientists sought ways to apply the reprogrammed cells to the pathophysiology of obscure diseases, examination of drug targets, and regeneration of human tissue.24 Tissue regeneration via induced naïve somatic cells has shown promise as a future method to treat neurologic, cardiovascular, and ophthalmologic diseases.25

As the technology of cultivating and identifying optimal sources of iPSCs continues to advance, stem cell–based treatments have evolved as leading prospects in the field of biogerontology.26-29 Although much of the research in antiaging medicine has utilized iPSCs to reprogram cell senescence, the altering of iPSCs at a cellular level also allows for the stimulation of collagen synthesis. This potential for collagen generation may have direct applicability in dermatologic practice, particularly for aesthetic treatments.

Much of the research into iPSC-derived collagen has focused on genodermatoses. Itoh et al30 examined the creation of collagen through iPSCs to identify possible treatments for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB). Recessive DEB is characterized by mutations in the COL7A1 gene, which encodes type VII collagen, a basement membrane protein and component of the anchoring fibrils essential for skin integrity.31 Itoh et al30 began with source cells obtained from a skin biopsy. The cells were dedifferentiated to iPSCs and then induced into dermal fibroblasts according to the methods established in prior studies of embryonic stem cells, namely with the use of ascorbic acid and transforming growth factor b. The newly formed fibroblasts were determined to be functional based on their ability to synthesize mature type VII collagen.30 Once the viability of the iPSC-derived fibroblasts was confirmed in vitro, the cells were further tested through combination with human keratinocytes on SCID mice. The human keratinocytes grew together with the iPSC-derived fibroblasts, producing type VII collagen in the basement membrane zone and creating an epidermis with the normal markers.30 Similarly, Robbins et al32 utilized SCID mice to successfully demonstrate that the transfection of keratinocytes from patients with junctional epidermolysis bullosa into SCID mice produced phenotypically normal skin.

Sebastiano et al33 combined the concepts of iPSCs and genome editing in another study of recessive DEB. The investigators first cultured iPSCs from biopsies of affected patients. After deriving iPSCs and correcting their mutation via adenovirus-associated viral gene editing, the COL7A1 mutation-free cells were differentiated into keratinocytes. These iPSC-derived keratinocytes were subsequently grafted onto mice, which led to the production of wild-type collagen VII and a stratified epidermis. Despite this successful outcome, the grafts of iPSC-derived epidermis did not survive longer than 1 month.33

One of the many obstacles facing the practical use of stem cells is their successful incorporation into human tissue. A possible solution was uncovered by Zhang et al34 who examined iPSC-derived MSCs. Mesenchymal stem cells communicate via paracrine mechanisms, whereby exosomes containing RNA and proteins are released to potentiate a regenerative effect.35 Zhang et al34 found that injecting exosomes from human iPSC-derived MSCs into the wound sites of rats stimulated the production of type I collagen, type III collagen, and elastin. The wound sites demonstrated accelerated closure, narrower scar widths, and increased collagen maturity.

Understanding the role that local environment plays in stem cell differentiation, Xu et al36 aimed to create an extracellular scaffold to induce fibroblast behavior from iPSCs. The authors engineered a framework similar to the normal extracellular membrane using proteoglycans, glycosaminoglycans, fibrinogen, and connective tissue growth factor. The iPSCs were then applied to the scaffolding, which led to successful fibroblast differentiation and type I collagen synthesis.36 This use of local biosignaling cues holds important ramifications for controlling the fate of stem cells that have been introduced into a new environment.

Although the application of iPSCs in clinical dermatology has yet to be achieved, progress in the field is moving at a rapid pace. Several logistical elements require further mastery before therapeutics can be delivered. These areas include the optimal environment for iPSC differentiation, methods for maximization of graft survival, and different modes of transplanting iPSC-derived cells into patients. In cosmetic practice, success will depend on intradermal injections of collagen-producing iPSC-derived cells that possess long-term proliferative potential. Current research in mice models has demonstrated viability up to 16 weeks after intradermal injection of such cells.37

Plant Stem Cells

In discussing the dermatologic applications of stem cell technology, clinicians should be aware of the plant stem cell products that have become a popular cosmeceutical trend. Companies advertise plant cells as a natural source of regenerative cells that can induce rejuvenation in human skin; however, there are no significant data to indicate that plant stem cells encourage or activate cellular growth in humans. Indeed, for stem cells to differentiate and produce viable components, the cells must first be incorporated as living components in the host tissue. Because plant stem cells do not survive in human tissue and plant cell cytokines fail to interact with the receptors on human cells, their current value in cosmeceuticals may be overstated.

Platelet-Rich Plasma

Platelet-rich plasma also is commonly associated with stem cell therapy, as PRP is known to potentiate stem cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation. However, PRP does not contain stem cells and is instead autologous plasma concentrated with platelets. In fact, platelets cannot even be classified as cells given that they lack a nucleus; platelets are considered cell fragments. The regenerative potential of PRP can be attributed to the growth factors released from platelets, which play an important role in tissue regeneration and repair. Platelet-rich plasma currently is being used in dermatology for skin rejuvenation (reduction of wrinkles and furrows) and treatment of acne scars.38 There also is evidence supporting the effectiveness of PRP for alopecia and wound therapy, as growth factors play a vital role in hair growth and wound healing.38 Apart from the use of PRP on its own, it can be used as a supplement to enhance the effects of antiaging procedures such as microneedling.39

Future Directions

Multipotent stem cells and iPSCs discussed herein provide much promise in the field of regenerative dermatology. They are increasingly accessible and circumvent the use of ethically questionable embryonic stem cells. Although there is a general consensus on the great potential of stem cells for treating aesthetic skin conditions, high-quality randomized controlled trials remain scarce within the literature. Recognizing and optimizing these opportunities remains the next step in the future delivery of evidence-based care in regenerative dermatology.

Regenerative medicine encompasses innovative therapies that allow the body to repair or regenerate aging cells, tissues, and organs. The skin is a particularly attractive organ for the application of novel regenerative therapies due to its easy accessibility. Among these therapies, stem cells and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) have garnered interest based on their therapeutic potential in scar reduction, antiaging effects, and treatment of alopecia.

Stem cells possess the cardinal features of self-renewal and plasticity. Self-renewal refers to symmetric cell division generating daughter cells identical to the parent cell.1 Plasticity is the ability to generate cell types other than the germ line or tissue lineage from which stem cells derive.2 Stem cells can be categorized according to their differentiation potential. Totipotent stem cells may develop into any primary germ cell layer (ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm) of the embryo, as well as extraembryonic tissue such as the trophoblast, which gives rise to the placenta. Pluripotent stem cells such as embryonic stem cells have the capacity to differentiate into any derivative of the 3 germ cell layers but have lost their ability to differentiate into the trophoblast.3 Adults lack totipotent or pluripotent cells; they have multipotent or unipotent cells. Multipotent stem cells are able to differentiate into multiple cell types from similar lineages; mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), for example, can differentiate into adipogenic, osteogenic, chondrogenic, and myogenic cells.4 Unipotent stem cells have the lowest differentiation potential and can only self-regenerate. Herein, we review stem cell sources and their therapeutic potential in aesthetic dermatology.

Multipotent Stem Cells

Multipotent stem cells derived from the bone marrow, umbilical cord, adipose tissue, dermis, or hair follicle bulge have various clinical applications in dermatology. Stem cells from these sources are primarily utilized in an autologous manner in which they are processed outside the body and reintroduced into the donor. Autologous multipotent hematopoietic bone marrow cells were first successfully used for the treatment of chronic wounds and show promise for the treatment of atrophic scars.5,6 However, due to the invasive nature of extracting bone marrow stem cells and their declining number with age, other sources of multipotent stem cells have fallen into favor.

Umbilical cord blood is a source of multipotent hematopoietic stem cells for which surgical intervention is not necessary because they are retrieved after umbilical cord clamping.7 Advantages of sourcing stem cells from umbilical cord blood includes high regenerative power compared to a newborn’s skin and low immunogenicity given that the newborn is immunologically immature.8

Another popular source for autologous stem cells is adipose tissue due to its ease of accessibility and relative abundance. Given that adipose tissue–derived stem cells (ASCs) are capable of differentiating into adipocytes that help maintain volume over time, they are being used for midface contouring, lip augmentation, facial rejuvenation, facial scarring, lipodystrophy, penile girth enhancement, and vaginal augmentation. Adipose tissue–derived stem cells also are capable of differentiating into other types of tissue, including cartilage and bone. Thus, they have been successfully harnessed in the treatment of patients affected by systemic sclerosis and Parry-Romberg syndrome as well in the functional and aesthetic reconstruction of various military combat–related deformities.9,10

Adipose tissue–derived stem cells are commonly harvested from lipoaspirate of the abdomen and are combined with supportive mechanical scaffolds such as hydrogels. Lipoaspirate itself can serve as a scaffold for ASCs. Accordingly, ASCs also are being utilized as a scaffold for autologous fat transfer procedures in an effort to increase the viability of transplanted donor tissue, a process known as cell-assisted lipotransfer (CAL). In CAL, a fraction of the aspirated fat is processed for isolation of ASCs, which are then recombined with the remainder of the aspirated fat prior to grafting.11 However, there is conflicting evidence as to whether CAL leads to improved graft success relative to conventional autologous fat transfer.12,13

The skin also serves as an easily accessible and abundant autologous source of stem cells. A subtype of dermal fibroblasts has been proven to have multipotent potential.14,15 These dermal fibroblasts are harvested from one area of the skin using punch biopsy and are processed and reinjected into another desired area of the skin.16 Autologous human fibroblasts have proven to be effective for the treatment of wrinkles, rhytides, and acne scars.17 In June 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration approved azficel-T, an autologous cellular product created by harvesting fibroblasts from a patient’s own postauricular skin, culture-expanding them in vitro for 3 months, and reinjecting the cells into the desired area of dermis in a series of treatments. This product was the first personalized cell therapy approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for aesthetic uses, specifically for the improvement of nasolabial fold wrinkles.18

In adults, hair follicles contain an area known as the bulge, which is a site rich in epithelial and melanocytic stem cells. Bulge stem cells have the ability to reproduce the interfollicular epidermis, hair follicle structures, and sebaceous glands, and they have been used to construct entirely new hair follicles in an artificial in vivo system.19 Sugiyama-Nakagiri et al20 demonstrated that an entire hair follicle epithelium and interfollicular epidermis can be regenerated using cultured bulge stem cells. The cultured bulge stem cells were mixed with dermal papilla cells from neonatal rat vibrissae and engrafted into a silicone chamber implanted on the backs of severe combined immune deficient (SCID) mice. The grafts exhibited tufts of hair as well as a complete interfollicular epidermis at 4 weeks after transplantation.20 Thus, these bulge stem cells have the potential to treat male androgenic alopecia and female pattern hair loss. Bulge stem cells also have been shown to accelerate wound healing.21 Additionally, autologous melanocytic stem cells located at the hair follicle bulge are effective for treating vitiligo and are being investigated for the treatment of hair graying.22

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells

Given the ethical concerns that surround the procurement and use of embryonic stem cells, efforts have been made to retrieve pluripotent stem cells from adults. A major breakthrough occurred in 2006 when researchers altered the genes of specialized adult mouse cells to cause dedifferentiation and the return to an embryoniclike stem cell state.23 Mouse somatic cells were reprogrammed through the activation of a combination of transcription factors. The resulting cells were termed induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and have since been recreated in human cell lines. The discovery of iPSCs precipitated a translational science revolution. Physician-scientists sought ways to apply the reprogrammed cells to the pathophysiology of obscure diseases, examination of drug targets, and regeneration of human tissue.24 Tissue regeneration via induced naïve somatic cells has shown promise as a future method to treat neurologic, cardiovascular, and ophthalmologic diseases.25

As the technology of cultivating and identifying optimal sources of iPSCs continues to advance, stem cell–based treatments have evolved as leading prospects in the field of biogerontology.26-29 Although much of the research in antiaging medicine has utilized iPSCs to reprogram cell senescence, the altering of iPSCs at a cellular level also allows for the stimulation of collagen synthesis. This potential for collagen generation may have direct applicability in dermatologic practice, particularly for aesthetic treatments.

Much of the research into iPSC-derived collagen has focused on genodermatoses. Itoh et al30 examined the creation of collagen through iPSCs to identify possible treatments for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB). Recessive DEB is characterized by mutations in the COL7A1 gene, which encodes type VII collagen, a basement membrane protein and component of the anchoring fibrils essential for skin integrity.31 Itoh et al30 began with source cells obtained from a skin biopsy. The cells were dedifferentiated to iPSCs and then induced into dermal fibroblasts according to the methods established in prior studies of embryonic stem cells, namely with the use of ascorbic acid and transforming growth factor b. The newly formed fibroblasts were determined to be functional based on their ability to synthesize mature type VII collagen.30 Once the viability of the iPSC-derived fibroblasts was confirmed in vitro, the cells were further tested through combination with human keratinocytes on SCID mice. The human keratinocytes grew together with the iPSC-derived fibroblasts, producing type VII collagen in the basement membrane zone and creating an epidermis with the normal markers.30 Similarly, Robbins et al32 utilized SCID mice to successfully demonstrate that the transfection of keratinocytes from patients with junctional epidermolysis bullosa into SCID mice produced phenotypically normal skin.

Sebastiano et al33 combined the concepts of iPSCs and genome editing in another study of recessive DEB. The investigators first cultured iPSCs from biopsies of affected patients. After deriving iPSCs and correcting their mutation via adenovirus-associated viral gene editing, the COL7A1 mutation-free cells were differentiated into keratinocytes. These iPSC-derived keratinocytes were subsequently grafted onto mice, which led to the production of wild-type collagen VII and a stratified epidermis. Despite this successful outcome, the grafts of iPSC-derived epidermis did not survive longer than 1 month.33

One of the many obstacles facing the practical use of stem cells is their successful incorporation into human tissue. A possible solution was uncovered by Zhang et al34 who examined iPSC-derived MSCs. Mesenchymal stem cells communicate via paracrine mechanisms, whereby exosomes containing RNA and proteins are released to potentiate a regenerative effect.35 Zhang et al34 found that injecting exosomes from human iPSC-derived MSCs into the wound sites of rats stimulated the production of type I collagen, type III collagen, and elastin. The wound sites demonstrated accelerated closure, narrower scar widths, and increased collagen maturity.

Understanding the role that local environment plays in stem cell differentiation, Xu et al36 aimed to create an extracellular scaffold to induce fibroblast behavior from iPSCs. The authors engineered a framework similar to the normal extracellular membrane using proteoglycans, glycosaminoglycans, fibrinogen, and connective tissue growth factor. The iPSCs were then applied to the scaffolding, which led to successful fibroblast differentiation and type I collagen synthesis.36 This use of local biosignaling cues holds important ramifications for controlling the fate of stem cells that have been introduced into a new environment.

Although the application of iPSCs in clinical dermatology has yet to be achieved, progress in the field is moving at a rapid pace. Several logistical elements require further mastery before therapeutics can be delivered. These areas include the optimal environment for iPSC differentiation, methods for maximization of graft survival, and different modes of transplanting iPSC-derived cells into patients. In cosmetic practice, success will depend on intradermal injections of collagen-producing iPSC-derived cells that possess long-term proliferative potential. Current research in mice models has demonstrated viability up to 16 weeks after intradermal injection of such cells.37

Plant Stem Cells

In discussing the dermatologic applications of stem cell technology, clinicians should be aware of the plant stem cell products that have become a popular cosmeceutical trend. Companies advertise plant cells as a natural source of regenerative cells that can induce rejuvenation in human skin; however, there are no significant data to indicate that plant stem cells encourage or activate cellular growth in humans. Indeed, for stem cells to differentiate and produce viable components, the cells must first be incorporated as living components in the host tissue. Because plant stem cells do not survive in human tissue and plant cell cytokines fail to interact with the receptors on human cells, their current value in cosmeceuticals may be overstated.

Platelet-Rich Plasma

Platelet-rich plasma also is commonly associated with stem cell therapy, as PRP is known to potentiate stem cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation. However, PRP does not contain stem cells and is instead autologous plasma concentrated with platelets. In fact, platelets cannot even be classified as cells given that they lack a nucleus; platelets are considered cell fragments. The regenerative potential of PRP can be attributed to the growth factors released from platelets, which play an important role in tissue regeneration and repair. Platelet-rich plasma currently is being used in dermatology for skin rejuvenation (reduction of wrinkles and furrows) and treatment of acne scars.38 There also is evidence supporting the effectiveness of PRP for alopecia and wound therapy, as growth factors play a vital role in hair growth and wound healing.38 Apart from the use of PRP on its own, it can be used as a supplement to enhance the effects of antiaging procedures such as microneedling.39

Future Directions

Multipotent stem cells and iPSCs discussed herein provide much promise in the field of regenerative dermatology. They are increasingly accessible and circumvent the use of ethically questionable embryonic stem cells. Although there is a general consensus on the great potential of stem cells for treating aesthetic skin conditions, high-quality randomized controlled trials remain scarce within the literature. Recognizing and optimizing these opportunities remains the next step in the future delivery of evidence-based care in regenerative dermatology.

- Thomas ED, Lochte HL, Lu WC, et al. Intravenous infusion of bone marrow in patients receiving radiation and chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 1957;257:491-496.

- Ogliari KS, Marinowic D, Brum DE, et al. Stem cells in dermatology. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:286-291.

- Xu C, Inokuma MS, Denham J, et al. Feeder-free growth of undifferentiated human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:971-974.

- Zuk PA, Zhu M, Mizuno H, et al. Multilineage cells from human adipose tissue: implications for cell-based therapies. Tissue Eng. 2001;7:211-228.

- Badiavas EV, Falanga V. Treatment of chronic wounds with bone marrow-derived cells. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:510-516.

- Ibrahim ZA, Eltatawy RA, Ghaly NR, et al. Autologous bone marrow stem cells in atrophic acne scars: a pilot study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26:260-265.

- Broxmeyer HE, Douglas GW, Hangoc G, et al. Human umbilical cord blood as a potential source of transplantable hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:3828-3832.

- Gluckman E, Rocha V, Boyer-Chammard A, et al. Outcome of cord-blood transplantation from related and unrelated donors. Eurocord Transplant Group and the European Blood and Marrow Transplantation Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:373-381.

- Valerio IL, Sabino JM, Dearth CL. Plastic surgery challenges in war wounded II: regenerative medicine. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2016;5:412-419.

- Vescarelli E, D’Amici S, Onesti MG, et al. Adipose-derived stem cell: an innovative therapeutic approach in systemic sclerosis and Parry-Romberg syndrome. CellR4. 2014;2:E791-E797.

- Yoshimura K, Sato K, Aoi N, et al. Cell-assisted lipotransfer for cosmetic breast augmentation: supportive use of adipose-derived stem/stromal cells. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2008;32:48-55.

- Grabin S, Antes G, Stark GB, et al. Cell-assisted lipotransfer: a critical appraisal of the evidence. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:255.

- Zhou Y, Wang J, Li H, et al. Efficacy and safety of cell-assisted lipotransfer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137:E44-E57.

- Toma JG, Akhavan M, Fernandes KJL, et al. Isolation of multipotent adult stem cells from the dermis of mammalian skin. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:778-784.

- Toma JG, McKenzie IA, Bagli D, et al. Isolation and characterization of multipotent skin-derived precursors from human skin. Stem Cells. 2005;23:727-737.

- Homicz MR, Watson D. Review of injectable materials for soft tissue augmentation. Facial Plast Surg. 2004;20:21-29.

- Kumar S, Mahajan BB, Kaur S, et al. Autologous therapies in dermatology. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:38-45.

- Schmidt C. FDA approves first cell therapy for wrinkle-free visage. Nat Biotech. 2011;29:674-675.

- Gentile P, Scioli MG, Bielli A, et al. Stem cells from human hair follicles: first mechanical isolation for immediate autologous clinical use in androgenetic alopecia and hair loss. Stem Cell Investig. 2017;4:58.

- Sugiyama-Nakagiri Y, Akiyama M, Shimizu H. Hair follicle stem cell-targeted gene transfer and reconstitution system. Gene Ther. 2006;13:732-737.

- Heidari F, Yari A, Rasoolijazi H, et al. Bulge hair follicle stem cells accelerate cutaneous wound healing in rats. Wounds. 2016;28:132-141.

- Lee JH, Fisher DE. Melanocyte stem cells as potential therapeutics in skin disorders. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2014;14:1-11.

- Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663-676.

- Singh VK, Kalsan M, Kumar N, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells: applications in regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and drug discovery. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2015;3:2.

- Aoi T. 10th anniversary of iPS cells: The challenges that lie ahead. J Biochem. 2016;160:121-129.

- Lowry WE, Plath K. The many ways to make an iPS cell. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1246-1248.

- Kim K, Doi A, Wen B, et al. Epigenetic memory in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2010;467:285-290.

- Gafni O, Weinberger L, Mansour AA, et al. Derivation of novel human ground state naive pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2013;504:282-286.

- Pareja-Galeano H, Sanchis-Gomar F, Pérez LM, et al. IPSCs-based anti-aging therapies: Recent discoveries and future challenges. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;27:37-41.

- Itoh M, Umegaki-Arao N, Guo Z, et al. Generation of 3D skin equivalents fully reconstituted from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). PLoS One. 2013;8:e77673.

- Nyström A, Velati D, Mittapalli VR, et al. Collagen VII plays a dual role in wound healing. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3498-3509.

- Robbins PB, Lin Q, Goodnough JB, et al. In vivo restoration of laminin 5 β3 expression and function in junctional epidermolysis bullosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:5193-5198.

- Sebastiano V, Zhen HH, Haddad B, et al. Human COL7A1-corrected induced pluripotent stem cells for the treatment of recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:264ra163.

- Zhang J, Guan J, Niu X, et al. Exosomes released from human induced pluripotent stem cells-derived MSCs facilitate cutaneous wound healing by promoting collagen synthesis and angiogenesis. J Transl Med. 2015;13:49.

- Pap E, Pállinger É, Pásztói M, et al. Highlights of a new type of intercellular communication: microvesicle-based information transfer. Inflamm Res. 2009;58:1-8.

- Xu R, Taskin MB, Rubert M, et al. hiPS-MSCs differentiation towards fibroblasts on a 3D ECM mimicking scaffold. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8480.

- Wenzel D, Bayerl J, Nyström A, et al. Genetically corrected iPSCs as cell therapy for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:264ra165.

- Bednarska K, Kieszek R, Domagała P, et al. The use of platelet-rich-plasma in aesthetic and regenerative medicine. MEDtube Science. 2015;2:8-15.

- Hashim PW, Levy Z, Cohen JL, et al. Microneedling therapy with and without platelet-rich plasma. Cutis. 2017;99:239-242.

- Thomas ED, Lochte HL, Lu WC, et al. Intravenous infusion of bone marrow in patients receiving radiation and chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 1957;257:491-496.

- Ogliari KS, Marinowic D, Brum DE, et al. Stem cells in dermatology. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:286-291.

- Xu C, Inokuma MS, Denham J, et al. Feeder-free growth of undifferentiated human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:971-974.

- Zuk PA, Zhu M, Mizuno H, et al. Multilineage cells from human adipose tissue: implications for cell-based therapies. Tissue Eng. 2001;7:211-228.

- Badiavas EV, Falanga V. Treatment of chronic wounds with bone marrow-derived cells. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:510-516.

- Ibrahim ZA, Eltatawy RA, Ghaly NR, et al. Autologous bone marrow stem cells in atrophic acne scars: a pilot study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26:260-265.

- Broxmeyer HE, Douglas GW, Hangoc G, et al. Human umbilical cord blood as a potential source of transplantable hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:3828-3832.

- Gluckman E, Rocha V, Boyer-Chammard A, et al. Outcome of cord-blood transplantation from related and unrelated donors. Eurocord Transplant Group and the European Blood and Marrow Transplantation Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:373-381.

- Valerio IL, Sabino JM, Dearth CL. Plastic surgery challenges in war wounded II: regenerative medicine. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2016;5:412-419.

- Vescarelli E, D’Amici S, Onesti MG, et al. Adipose-derived stem cell: an innovative therapeutic approach in systemic sclerosis and Parry-Romberg syndrome. CellR4. 2014;2:E791-E797.

- Yoshimura K, Sato K, Aoi N, et al. Cell-assisted lipotransfer for cosmetic breast augmentation: supportive use of adipose-derived stem/stromal cells. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2008;32:48-55.

- Grabin S, Antes G, Stark GB, et al. Cell-assisted lipotransfer: a critical appraisal of the evidence. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:255.

- Zhou Y, Wang J, Li H, et al. Efficacy and safety of cell-assisted lipotransfer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137:E44-E57.

- Toma JG, Akhavan M, Fernandes KJL, et al. Isolation of multipotent adult stem cells from the dermis of mammalian skin. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:778-784.

- Toma JG, McKenzie IA, Bagli D, et al. Isolation and characterization of multipotent skin-derived precursors from human skin. Stem Cells. 2005;23:727-737.

- Homicz MR, Watson D. Review of injectable materials for soft tissue augmentation. Facial Plast Surg. 2004;20:21-29.

- Kumar S, Mahajan BB, Kaur S, et al. Autologous therapies in dermatology. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:38-45.

- Schmidt C. FDA approves first cell therapy for wrinkle-free visage. Nat Biotech. 2011;29:674-675.

- Gentile P, Scioli MG, Bielli A, et al. Stem cells from human hair follicles: first mechanical isolation for immediate autologous clinical use in androgenetic alopecia and hair loss. Stem Cell Investig. 2017;4:58.

- Sugiyama-Nakagiri Y, Akiyama M, Shimizu H. Hair follicle stem cell-targeted gene transfer and reconstitution system. Gene Ther. 2006;13:732-737.

- Heidari F, Yari A, Rasoolijazi H, et al. Bulge hair follicle stem cells accelerate cutaneous wound healing in rats. Wounds. 2016;28:132-141.

- Lee JH, Fisher DE. Melanocyte stem cells as potential therapeutics in skin disorders. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2014;14:1-11.

- Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663-676.

- Singh VK, Kalsan M, Kumar N, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells: applications in regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and drug discovery. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2015;3:2.

- Aoi T. 10th anniversary of iPS cells: The challenges that lie ahead. J Biochem. 2016;160:121-129.

- Lowry WE, Plath K. The many ways to make an iPS cell. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1246-1248.

- Kim K, Doi A, Wen B, et al. Epigenetic memory in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2010;467:285-290.

- Gafni O, Weinberger L, Mansour AA, et al. Derivation of novel human ground state naive pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2013;504:282-286.

- Pareja-Galeano H, Sanchis-Gomar F, Pérez LM, et al. IPSCs-based anti-aging therapies: Recent discoveries and future challenges. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;27:37-41.

- Itoh M, Umegaki-Arao N, Guo Z, et al. Generation of 3D skin equivalents fully reconstituted from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). PLoS One. 2013;8:e77673.

- Nyström A, Velati D, Mittapalli VR, et al. Collagen VII plays a dual role in wound healing. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3498-3509.

- Robbins PB, Lin Q, Goodnough JB, et al. In vivo restoration of laminin 5 β3 expression and function in junctional epidermolysis bullosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:5193-5198.

- Sebastiano V, Zhen HH, Haddad B, et al. Human COL7A1-corrected induced pluripotent stem cells for the treatment of recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:264ra163.

- Zhang J, Guan J, Niu X, et al. Exosomes released from human induced pluripotent stem cells-derived MSCs facilitate cutaneous wound healing by promoting collagen synthesis and angiogenesis. J Transl Med. 2015;13:49.

- Pap E, Pállinger É, Pásztói M, et al. Highlights of a new type of intercellular communication: microvesicle-based information transfer. Inflamm Res. 2009;58:1-8.

- Xu R, Taskin MB, Rubert M, et al. hiPS-MSCs differentiation towards fibroblasts on a 3D ECM mimicking scaffold. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8480.

- Wenzel D, Bayerl J, Nyström A, et al. Genetically corrected iPSCs as cell therapy for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:264ra165.

- Bednarska K, Kieszek R, Domagała P, et al. The use of platelet-rich-plasma in aesthetic and regenerative medicine. MEDtube Science. 2015;2:8-15.

- Hashim PW, Levy Z, Cohen JL, et al. Microneedling therapy with and without platelet-rich plasma. Cutis. 2017;99:239-242.

Practice Points

- Multipotent stem cells derived from the bone marrow, umbilical cord, adipose tissue, dermis, and hair follicle bulge show promise in tissue regeneration for various dermatologic conditions and aesthetic applications.

- Induced pluripotent stem cells, progenitor cells that result from the dedifferentiation of specialized adult cells, have potential for collagen generation.

What’s Eating You? Clinical Manifestations of Dermacentor Tick Bites

Background and Distribution

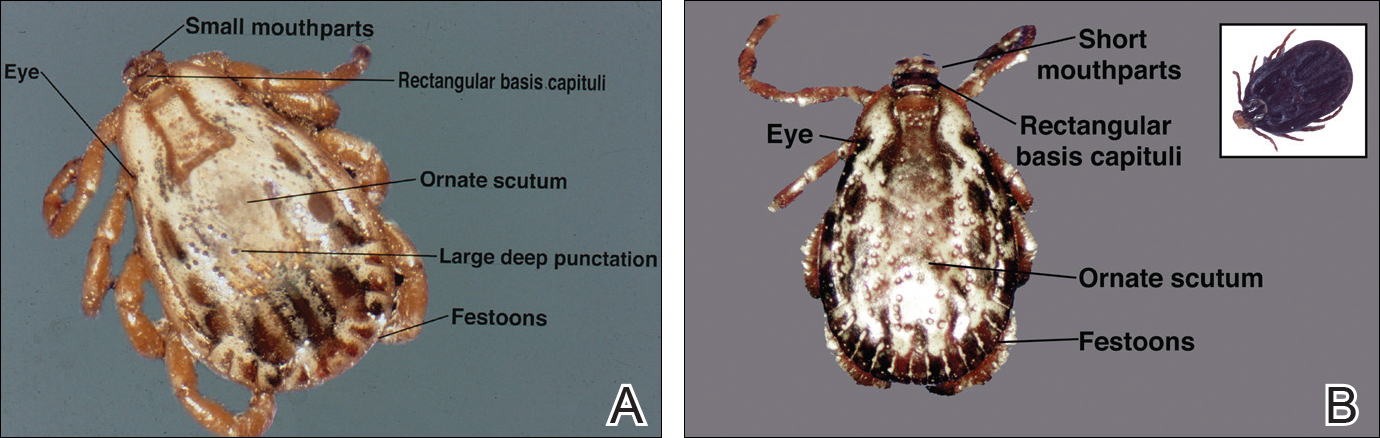

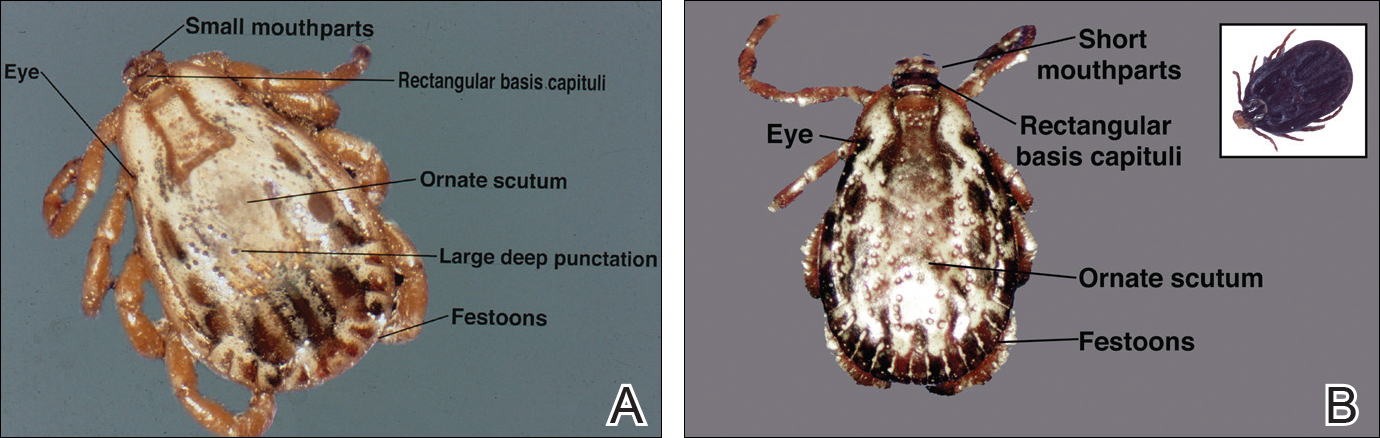

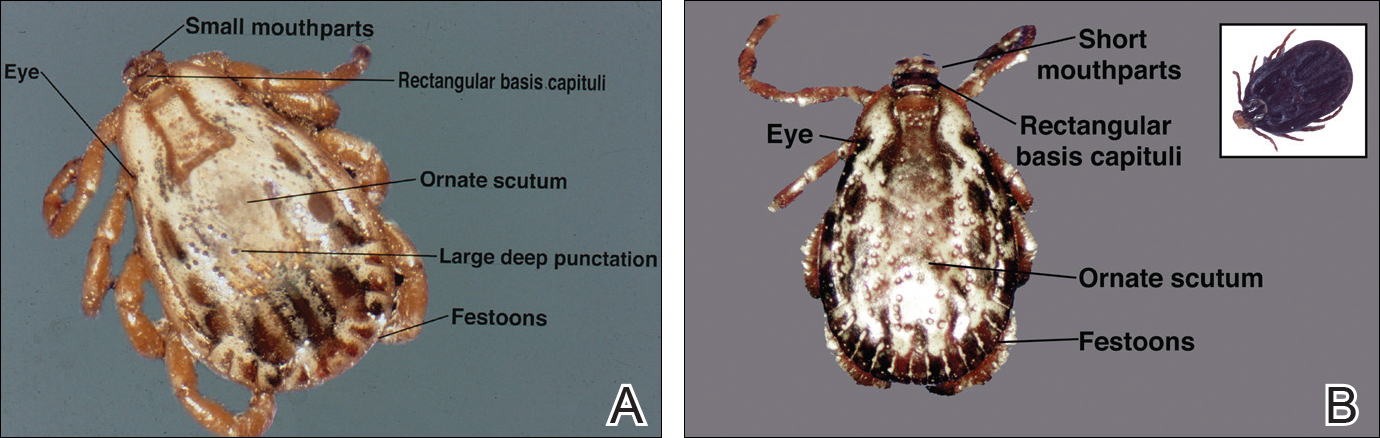

The Dermacentor ticks belong to the family Ixodidae (hard ticks). The 2 best-known ticks of the genus are Dermacentor andersoni (Rocky Mountain wood tick)(Figure, A) and Dermacentor variabilis (American dog tick)(Figure, B). The Dermacentor ticks are large ticks with small anterior mouthparts that attach to a rectangular basis capituli (Figure, A). Both ticks exhibit widely spaced eyes and posterior festoons as well as bifid coxa 1 (the attachment site for the first pair of legs) and enlarged coxa 4. As adults, these ticks display an ornate hard dorsal plate, or scutum, with numerous pits. Female ticks have a much smaller scutum, allowing for abdominal engorgement during feeding.1 Although D andersoni tends to have a brown to yellow hue, the specimens of D variabilis display a somewhat silver color pattern.

Dermacentor ticks can be found throughout most of North America, with the northern distribution limits of both species previously occurring in the province of Saskatchewan, Canada. Although the range of D andersoni has remained relatively stable within this distribution, the distribution of D variabilis recently has expanded westward and northward of these limits.2 The ranges of the 2 species overlap in certain areas, though D andersoni primarily is found in the Rocky Mountain and northwestern states as well as southwestern Canada, whereas D variabilis can be found throughout most parts of the United States, except in the Rocky Mountain states.3 Within these regions the ticks can be found in heavily wooded areas, but they most commonly inhabit fields with tall grass, crops, bushes, and shrubbery, often clustering where these types of vegetation form clearly defined edges.4 The diseases transmitted by the Dermacentor ticks include Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), Colorado tick fever, tularemia, tick paralysis, and even human monocytic erlichiosis, though Amblyomma americanum is the major vector for human monocytic erlichiosis.

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever