User login

Career (of your dreams) advice for young MIGS surgeons

From the 46th AAGL Global Congress on MIGS

From the 46th AAGL Global Congress on MIGS

From the 46th AAGL Global Congress on MIGS

AGA launches new registry to track patient outcomes

The AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology is excited to announce a new clinical research registry to track and evaluate patient outcomes after trans-oral endoscopic suturing procedures.

The Prospective Registry for Trans-Oral Suturing Applications (“Endoscopic Suturing Registry”) will collect real-world data related to the safety and effectiveness of procedures done with Apollo Endosurgery’s OverStitch™ Endoscopic Suturing System. Jennifer Maranki, MD, director of endoscopy, Penn State Milton S. Hershey School of Medicine, and Brian Dunkin, MD, head of endoscopic surgery and medical director, Houston Methodist Institute for Technology, Innovation and Education, will serve as principal investigators for the Endoscopic Suturing Registry. The Registry will begin collecting patient data in early 2018.

We asked Michael Kochman, MD, AGAF, past chair of the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology and director of the Center for Endoscopic Innovation, Research and Training at the University of Pennsylvania, to weigh in on the value of this new registry.

“Flexible endoscopic suturing is an important tool for the treatment of a number of GI disorders. As these procedures become more routine in GI and surgery practices across the country, the real-world data AGA will collect through the Endoscopic Suturing Registry will guide all stakeholders in making informed decisions around the continued adoption of these procedures in clinical practice.”

Learn more about AGA’s registry initiative at www.gastro.org/patient-care/registries-studies.

The AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology is excited to announce a new clinical research registry to track and evaluate patient outcomes after trans-oral endoscopic suturing procedures.

The Prospective Registry for Trans-Oral Suturing Applications (“Endoscopic Suturing Registry”) will collect real-world data related to the safety and effectiveness of procedures done with Apollo Endosurgery’s OverStitch™ Endoscopic Suturing System. Jennifer Maranki, MD, director of endoscopy, Penn State Milton S. Hershey School of Medicine, and Brian Dunkin, MD, head of endoscopic surgery and medical director, Houston Methodist Institute for Technology, Innovation and Education, will serve as principal investigators for the Endoscopic Suturing Registry. The Registry will begin collecting patient data in early 2018.

We asked Michael Kochman, MD, AGAF, past chair of the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology and director of the Center for Endoscopic Innovation, Research and Training at the University of Pennsylvania, to weigh in on the value of this new registry.

“Flexible endoscopic suturing is an important tool for the treatment of a number of GI disorders. As these procedures become more routine in GI and surgery practices across the country, the real-world data AGA will collect through the Endoscopic Suturing Registry will guide all stakeholders in making informed decisions around the continued adoption of these procedures in clinical practice.”

Learn more about AGA’s registry initiative at www.gastro.org/patient-care/registries-studies.

The AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology is excited to announce a new clinical research registry to track and evaluate patient outcomes after trans-oral endoscopic suturing procedures.

The Prospective Registry for Trans-Oral Suturing Applications (“Endoscopic Suturing Registry”) will collect real-world data related to the safety and effectiveness of procedures done with Apollo Endosurgery’s OverStitch™ Endoscopic Suturing System. Jennifer Maranki, MD, director of endoscopy, Penn State Milton S. Hershey School of Medicine, and Brian Dunkin, MD, head of endoscopic surgery and medical director, Houston Methodist Institute for Technology, Innovation and Education, will serve as principal investigators for the Endoscopic Suturing Registry. The Registry will begin collecting patient data in early 2018.

We asked Michael Kochman, MD, AGAF, past chair of the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology and director of the Center for Endoscopic Innovation, Research and Training at the University of Pennsylvania, to weigh in on the value of this new registry.

“Flexible endoscopic suturing is an important tool for the treatment of a number of GI disorders. As these procedures become more routine in GI and surgery practices across the country, the real-world data AGA will collect through the Endoscopic Suturing Registry will guide all stakeholders in making informed decisions around the continued adoption of these procedures in clinical practice.”

Learn more about AGA’s registry initiative at www.gastro.org/patient-care/registries-studies.

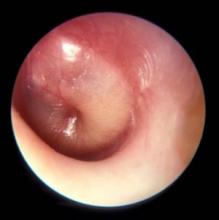

PCVs may reduce AOM severity, although they do not decrease incidence

Use of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) may have had a part in reducing the incidence of severe middle ear inflammation of acute otitis media (AOM) in Japanese children, decreasing the rate of myringotomies for AOM, said Atsushi Sasaki, of the Hiroshima (Japan) University, and associates.

To assess whether use of PCV7 and then PCV13 affected AOM incidence, the investigators looked at the incidence of visits to medical institutions (VtMI) due to all-cause AOM in children younger than 15 years in the Japan Medical Data Center Claims Database between January 2005 and December 2015. Data for children aged 10 years to younger than 15 years served as the control. The rate of myringotomies for AOM (MyfA) from January 2007 to December 2015 also was assessed.

Numerous other studies have “concluded that the preventive effect of PCV7 against AOM was very modest,” the researchers said. “In contrast, our study proposes the hypothesis that PCV7 use in 1-year-olds may contribute to the decreased incidence of severe middle ear inflammation of AOM. When evaluating the effectiveness of PCV, measures to evaluate severity may be as important as evaluating disease prevention.”

Read more in Auris Nasus Larynx (2017 Nov 1. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2017.10.006).

Use of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) may have had a part in reducing the incidence of severe middle ear inflammation of acute otitis media (AOM) in Japanese children, decreasing the rate of myringotomies for AOM, said Atsushi Sasaki, of the Hiroshima (Japan) University, and associates.

To assess whether use of PCV7 and then PCV13 affected AOM incidence, the investigators looked at the incidence of visits to medical institutions (VtMI) due to all-cause AOM in children younger than 15 years in the Japan Medical Data Center Claims Database between January 2005 and December 2015. Data for children aged 10 years to younger than 15 years served as the control. The rate of myringotomies for AOM (MyfA) from January 2007 to December 2015 also was assessed.

Numerous other studies have “concluded that the preventive effect of PCV7 against AOM was very modest,” the researchers said. “In contrast, our study proposes the hypothesis that PCV7 use in 1-year-olds may contribute to the decreased incidence of severe middle ear inflammation of AOM. When evaluating the effectiveness of PCV, measures to evaluate severity may be as important as evaluating disease prevention.”

Read more in Auris Nasus Larynx (2017 Nov 1. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2017.10.006).

Use of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) may have had a part in reducing the incidence of severe middle ear inflammation of acute otitis media (AOM) in Japanese children, decreasing the rate of myringotomies for AOM, said Atsushi Sasaki, of the Hiroshima (Japan) University, and associates.

To assess whether use of PCV7 and then PCV13 affected AOM incidence, the investigators looked at the incidence of visits to medical institutions (VtMI) due to all-cause AOM in children younger than 15 years in the Japan Medical Data Center Claims Database between January 2005 and December 2015. Data for children aged 10 years to younger than 15 years served as the control. The rate of myringotomies for AOM (MyfA) from January 2007 to December 2015 also was assessed.

Numerous other studies have “concluded that the preventive effect of PCV7 against AOM was very modest,” the researchers said. “In contrast, our study proposes the hypothesis that PCV7 use in 1-year-olds may contribute to the decreased incidence of severe middle ear inflammation of AOM. When evaluating the effectiveness of PCV, measures to evaluate severity may be as important as evaluating disease prevention.”

Read more in Auris Nasus Larynx (2017 Nov 1. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2017.10.006).

FROM AURIS NASUS LARYNX

Health care panhandlers: A symptom of our system’s baked-in pressures?

A few nights a week after work I have to stop by the store for this or that.

In the last 1-2 months there’s always been a couple at the parking lot exit, both in wheelchairs, with a big sign asking for money to help one of them beat cancer. They even have the amount listed.

But, by the same token, they could be quite legitimate. The American health care system is full of cracks that seriously ill people can slip through. One recent survey found that about 30% of Americans had trouble paying their medical bills.

It’s easy to look at people like this and think, “I’ll never let that happen to me.” We assume they must be smokers, or irresponsible spenders, or some other reason that makes us feel we won’t stumble into the same pitfalls. That’s reassuring, and sometimes true, but not always. And probably more often than we want to realize.

The world is full of people and families devastated by bad luck. Through no fault of their own, they develop a terrible medical condition or suffer grievous injuries, and suddenly, decent, hard-working, previously healthy people are facing foreclosure and financial ruin. It could, quite literally, be any of us.

Case in point: My family has good insurance and has averaged $10,000 in out-of-pocket medical expenses per year for the last several years. That’s for routine stuff: meeting deductibles, copays on medications, tests, and doctor visits, a few ER trips, etc. The only real “surprise” in there was when my wife broke her leg and needed surgery.

If the panhandlers really did have legitimate medical issues, I might be willing to help out. I give to charity. My grandmother and parents stressed that value to me, and I try to teach it to my kids. But, sadly, we live in a world full of con artists who try to make money by taking advantage of caring peoples’ feelings. Look at all the scams that immediately cropped up following the recent hurricane and wildfire disasters. Without knowing the truth, I’d rather give to an organization like the Salvation Army or Red Cross, hoping they have more experience than I do in sorting out who’s really in need.

As a doctor, I also try to justify it by thinking about how much care I do for “free.” This includes uninsured hospital patients we all see on call, knowing we’ll end up writing their bill off as a loss, and bounced checks for copays and deductible portions that we know we’ll never see.

But, no matter how I try to rationalize it, it still bothers me when I see them sitting there as I leave the store. I don’t know if they’re legitimate. But if they are, they aren’t alone, and there’s something seriously wrong with our health care system.

[polldaddy:9876776]

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

A few nights a week after work I have to stop by the store for this or that.

In the last 1-2 months there’s always been a couple at the parking lot exit, both in wheelchairs, with a big sign asking for money to help one of them beat cancer. They even have the amount listed.

But, by the same token, they could be quite legitimate. The American health care system is full of cracks that seriously ill people can slip through. One recent survey found that about 30% of Americans had trouble paying their medical bills.

It’s easy to look at people like this and think, “I’ll never let that happen to me.” We assume they must be smokers, or irresponsible spenders, or some other reason that makes us feel we won’t stumble into the same pitfalls. That’s reassuring, and sometimes true, but not always. And probably more often than we want to realize.

The world is full of people and families devastated by bad luck. Through no fault of their own, they develop a terrible medical condition or suffer grievous injuries, and suddenly, decent, hard-working, previously healthy people are facing foreclosure and financial ruin. It could, quite literally, be any of us.

Case in point: My family has good insurance and has averaged $10,000 in out-of-pocket medical expenses per year for the last several years. That’s for routine stuff: meeting deductibles, copays on medications, tests, and doctor visits, a few ER trips, etc. The only real “surprise” in there was when my wife broke her leg and needed surgery.

If the panhandlers really did have legitimate medical issues, I might be willing to help out. I give to charity. My grandmother and parents stressed that value to me, and I try to teach it to my kids. But, sadly, we live in a world full of con artists who try to make money by taking advantage of caring peoples’ feelings. Look at all the scams that immediately cropped up following the recent hurricane and wildfire disasters. Without knowing the truth, I’d rather give to an organization like the Salvation Army or Red Cross, hoping they have more experience than I do in sorting out who’s really in need.

As a doctor, I also try to justify it by thinking about how much care I do for “free.” This includes uninsured hospital patients we all see on call, knowing we’ll end up writing their bill off as a loss, and bounced checks for copays and deductible portions that we know we’ll never see.

But, no matter how I try to rationalize it, it still bothers me when I see them sitting there as I leave the store. I don’t know if they’re legitimate. But if they are, they aren’t alone, and there’s something seriously wrong with our health care system.

[polldaddy:9876776]

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

A few nights a week after work I have to stop by the store for this or that.

In the last 1-2 months there’s always been a couple at the parking lot exit, both in wheelchairs, with a big sign asking for money to help one of them beat cancer. They even have the amount listed.

But, by the same token, they could be quite legitimate. The American health care system is full of cracks that seriously ill people can slip through. One recent survey found that about 30% of Americans had trouble paying their medical bills.

It’s easy to look at people like this and think, “I’ll never let that happen to me.” We assume they must be smokers, or irresponsible spenders, or some other reason that makes us feel we won’t stumble into the same pitfalls. That’s reassuring, and sometimes true, but not always. And probably more often than we want to realize.

The world is full of people and families devastated by bad luck. Through no fault of their own, they develop a terrible medical condition or suffer grievous injuries, and suddenly, decent, hard-working, previously healthy people are facing foreclosure and financial ruin. It could, quite literally, be any of us.

Case in point: My family has good insurance and has averaged $10,000 in out-of-pocket medical expenses per year for the last several years. That’s for routine stuff: meeting deductibles, copays on medications, tests, and doctor visits, a few ER trips, etc. The only real “surprise” in there was when my wife broke her leg and needed surgery.

If the panhandlers really did have legitimate medical issues, I might be willing to help out. I give to charity. My grandmother and parents stressed that value to me, and I try to teach it to my kids. But, sadly, we live in a world full of con artists who try to make money by taking advantage of caring peoples’ feelings. Look at all the scams that immediately cropped up following the recent hurricane and wildfire disasters. Without knowing the truth, I’d rather give to an organization like the Salvation Army or Red Cross, hoping they have more experience than I do in sorting out who’s really in need.

As a doctor, I also try to justify it by thinking about how much care I do for “free.” This includes uninsured hospital patients we all see on call, knowing we’ll end up writing their bill off as a loss, and bounced checks for copays and deductible portions that we know we’ll never see.

But, no matter how I try to rationalize it, it still bothers me when I see them sitting there as I leave the store. I don’t know if they’re legitimate. But if they are, they aren’t alone, and there’s something seriously wrong with our health care system.

[polldaddy:9876776]

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Closing the colonoscopy loophole

What is the colonoscopy loophole?

The Affordable Care Act covers screening colonoscopies at no cost to patients as long as no polyps are found. As Dr. Siddique explains in her article, finding a polyp changes the billing code to a therapeutic colonoscopy, a reclassification that changes the procedure from a diagnostic screening to an intervention. And this means a bill is generated. This reclassification directly affects those covered by Medicare and not commercial insurers.

AGA leaders urge Congress to correct this problem

Dr. Siddique – a member of the AGA Trainee and Early Career Committee and AGA Clinical Guidelines Committee – joined other AGA leaders for AGA Advocacy Day in late September where they spoke directly to lawmakers about patients who are blindsided by this regulation. AGA supports closing this loophole to ensure patients continue to have access to quality care and preventative screenings. We encourage all members to continue to share their patient stories, like Dr. Siddique has, to help raise awareness of this issue.

AGA can help you advocate for GI

Watch an AGA webinar at www.gastro.org/webinars/CongressionalMeeting (login required) to learn more about how to set up congressional meetings in your district, or contact Navneet Buttar, AGA government and political affairs manager, at [email protected] or 240-482-3221.

What is the colonoscopy loophole?

The Affordable Care Act covers screening colonoscopies at no cost to patients as long as no polyps are found. As Dr. Siddique explains in her article, finding a polyp changes the billing code to a therapeutic colonoscopy, a reclassification that changes the procedure from a diagnostic screening to an intervention. And this means a bill is generated. This reclassification directly affects those covered by Medicare and not commercial insurers.

AGA leaders urge Congress to correct this problem

Dr. Siddique – a member of the AGA Trainee and Early Career Committee and AGA Clinical Guidelines Committee – joined other AGA leaders for AGA Advocacy Day in late September where they spoke directly to lawmakers about patients who are blindsided by this regulation. AGA supports closing this loophole to ensure patients continue to have access to quality care and preventative screenings. We encourage all members to continue to share their patient stories, like Dr. Siddique has, to help raise awareness of this issue.

AGA can help you advocate for GI

Watch an AGA webinar at www.gastro.org/webinars/CongressionalMeeting (login required) to learn more about how to set up congressional meetings in your district, or contact Navneet Buttar, AGA government and political affairs manager, at [email protected] or 240-482-3221.

What is the colonoscopy loophole?

The Affordable Care Act covers screening colonoscopies at no cost to patients as long as no polyps are found. As Dr. Siddique explains in her article, finding a polyp changes the billing code to a therapeutic colonoscopy, a reclassification that changes the procedure from a diagnostic screening to an intervention. And this means a bill is generated. This reclassification directly affects those covered by Medicare and not commercial insurers.

AGA leaders urge Congress to correct this problem

Dr. Siddique – a member of the AGA Trainee and Early Career Committee and AGA Clinical Guidelines Committee – joined other AGA leaders for AGA Advocacy Day in late September where they spoke directly to lawmakers about patients who are blindsided by this regulation. AGA supports closing this loophole to ensure patients continue to have access to quality care and preventative screenings. We encourage all members to continue to share their patient stories, like Dr. Siddique has, to help raise awareness of this issue.

AGA can help you advocate for GI

Watch an AGA webinar at www.gastro.org/webinars/CongressionalMeeting (login required) to learn more about how to set up congressional meetings in your district, or contact Navneet Buttar, AGA government and political affairs manager, at [email protected] or 240-482-3221.

Serlopitant is itching to quell chronic pruritus

GENEVA – Serlopitant, a novel once-daily oral neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist, brought significant improvement for patients with treatment-resistant chronic pruritus as early as day 2, in a phase 2 randomized trial, Paul Kwon, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

In a separate phase 2 study presented at the congress, serlopitant showed strong efficacy in patients with prurigo nodularis.

Serlopitant is an oral small molecule with high selectivity for the neurokinin-1 receptor (NK1R). At the 5-mg dose, the drug occupies more than 90% of CNS NK1Rs. The NK1R is the primary receptor for substance P, and thus plays an important role in pruritus signaling.

Chronic pruritus is an often-debilitating condition that can have a multitude of causes. It’s associated with increased rates of anxiety, depression, and sleep deprivation. Existing treatments often fail to provide adequate relief from the severe chronic itching, or they are associated with safety or tolerability issues.

“Chronic pruritus can disrupt quality of life to a level comparable to chronic pain,” the dermatologist observed. “I think we in the medical community are hearing more and more about treatment for chronic pruritus as being a major unmet medical need.”

Dr. Kwon noted that investigators at Emory University in Atlanta have found that the quality of life disruption imposed by chronic pruritus is comparable to that of chronic pain (Arch Dermatol. 2011 Oct;147[10]:1153-6).

The phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 6-week trial comprised 257 patients with chronic pruritus at 25 U.S. centers. All were non- or inadequate responders to topical corticosteroids or oral antihistamines. This was essentially an all-comers study that was not restricted to patients with any particular specific cause of their chronic itch. They had to have severe chronic pruritus, as defined by a baseline self-rated pruritus visual analogue score of at least 7 on a 0-10 scale. Patients were randomized to once-daily oral serlopitant at 0.25 mg, 1 mg, or 5 mg, or to placebo.

The primary endpoint was change in mean visual analogue score from baseline to week 6. The serlopitant 1-mg and 5-mg groups reported mean 41.4% and 42.5% reductions, respectively, which were significantly better than the 28.3% reduction in controls.

“It seems that the drug is working in a broad set of subjects,” Dr. Kwon said. “It is not entirely shutting off itch in significant numbers, but the majority of patients appear to be deriving benefit from serlopitant.”

He highlighted the rapidity with which chronic pruritus responded to serlopitant. The first dose was taken on the evening of day 1. The next day, the 1-mg serlopitant group already showed a significantly greater improvement than did placebo-treated controls. The day after that, so did the 5-mg group. Those between-group differences grew steadily larger throughout the 6-week study period.

That rapid response is clinically highly relevant, because numerous studies have demonstrated that fast onset of therapeutic effect improves patient satisfaction, quality of life, and compliance with treatment for a variety of medical conditions, he said.

Dr. Kwon characterized the safety profile of serlopitant in the trial as “fairly robust,” with only mild or moderate treatment-emergent adverse events being seen. Diarrhea and somnolence were the only adverse events more common with serlopitant than placebo, and their incidence was in the mid single digits.

“We have not uncovered any significant safety signal in this study,” Dr. Kwon declared.

Also at the EADV Congress, Sonja Ständer, MD, presented a phase 2 study of serlopitant in patients with prurigo nodularis. The randomized, double-blind, 8-week, 127-patient trial was conducted at 15 sites in Germany, where patients were randomized to once-daily serlopitant at 5 mg or placebo. All participants had a baseline pruritus VAS of 7 or more. Thirty percent of patients had more than a 10-year history of prurigo nodularis, and 24% had the condition for 5-10 years.

The primary endpoint was the difference from baseline to weeks 4 and 8 in the average pruritus VAS over the previous 24 hours. The baseline score was 7.9. The serlopitant group averaged a 1.0-point greater reduction, compared with controls, at week 4, and a 1.7-point greater decrease at week 8.

Multiple other measures of pruritus serving as secondary endpoints consistently showed significantly greater improvement in the serlopitant group. For example, at the week 8 assessment, 54% of serlopitant-treated patients reported no or only mild itch, compared with 29% of controls. And two-thirds of the serlopitant group reported some degree of improvement in the severity of their eruptive papulonodular lesions at week 8, versus 40% of controls, according to Dr. Ständer, professor of dermatology and neurodermatology and head of the Center for Chronic Pruritus at the University of Münster (Germany).

Of note, nasopharyngitis occurred in 17.2% of the serlopitant group and in 3.2% of controls. Diarrhea was also more common in the serlopitant group, by a margin of 10.9% versus 4.8%.

Dr. Kwon said additional phase 2 as well as phase 3 randomized trials of serlopitant are in the works for both chronic pruritus and prurigo nodularis. The drug is also under study for chronic itch due to other specific etiologies, as well as for refractory chronic cough.

Menlo Therapeutics sponsored the study. Dr. Kwon is a Menlo Therapeutics officer. Dr. Ständer, who was also principal investigator in the chronic pruritus trial, reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

GENEVA – Serlopitant, a novel once-daily oral neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist, brought significant improvement for patients with treatment-resistant chronic pruritus as early as day 2, in a phase 2 randomized trial, Paul Kwon, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

In a separate phase 2 study presented at the congress, serlopitant showed strong efficacy in patients with prurigo nodularis.

Serlopitant is an oral small molecule with high selectivity for the neurokinin-1 receptor (NK1R). At the 5-mg dose, the drug occupies more than 90% of CNS NK1Rs. The NK1R is the primary receptor for substance P, and thus plays an important role in pruritus signaling.

Chronic pruritus is an often-debilitating condition that can have a multitude of causes. It’s associated with increased rates of anxiety, depression, and sleep deprivation. Existing treatments often fail to provide adequate relief from the severe chronic itching, or they are associated with safety or tolerability issues.

“Chronic pruritus can disrupt quality of life to a level comparable to chronic pain,” the dermatologist observed. “I think we in the medical community are hearing more and more about treatment for chronic pruritus as being a major unmet medical need.”

Dr. Kwon noted that investigators at Emory University in Atlanta have found that the quality of life disruption imposed by chronic pruritus is comparable to that of chronic pain (Arch Dermatol. 2011 Oct;147[10]:1153-6).

The phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 6-week trial comprised 257 patients with chronic pruritus at 25 U.S. centers. All were non- or inadequate responders to topical corticosteroids or oral antihistamines. This was essentially an all-comers study that was not restricted to patients with any particular specific cause of their chronic itch. They had to have severe chronic pruritus, as defined by a baseline self-rated pruritus visual analogue score of at least 7 on a 0-10 scale. Patients were randomized to once-daily oral serlopitant at 0.25 mg, 1 mg, or 5 mg, or to placebo.

The primary endpoint was change in mean visual analogue score from baseline to week 6. The serlopitant 1-mg and 5-mg groups reported mean 41.4% and 42.5% reductions, respectively, which were significantly better than the 28.3% reduction in controls.

“It seems that the drug is working in a broad set of subjects,” Dr. Kwon said. “It is not entirely shutting off itch in significant numbers, but the majority of patients appear to be deriving benefit from serlopitant.”

He highlighted the rapidity with which chronic pruritus responded to serlopitant. The first dose was taken on the evening of day 1. The next day, the 1-mg serlopitant group already showed a significantly greater improvement than did placebo-treated controls. The day after that, so did the 5-mg group. Those between-group differences grew steadily larger throughout the 6-week study period.

That rapid response is clinically highly relevant, because numerous studies have demonstrated that fast onset of therapeutic effect improves patient satisfaction, quality of life, and compliance with treatment for a variety of medical conditions, he said.

Dr. Kwon characterized the safety profile of serlopitant in the trial as “fairly robust,” with only mild or moderate treatment-emergent adverse events being seen. Diarrhea and somnolence were the only adverse events more common with serlopitant than placebo, and their incidence was in the mid single digits.

“We have not uncovered any significant safety signal in this study,” Dr. Kwon declared.

Also at the EADV Congress, Sonja Ständer, MD, presented a phase 2 study of serlopitant in patients with prurigo nodularis. The randomized, double-blind, 8-week, 127-patient trial was conducted at 15 sites in Germany, where patients were randomized to once-daily serlopitant at 5 mg or placebo. All participants had a baseline pruritus VAS of 7 or more. Thirty percent of patients had more than a 10-year history of prurigo nodularis, and 24% had the condition for 5-10 years.

The primary endpoint was the difference from baseline to weeks 4 and 8 in the average pruritus VAS over the previous 24 hours. The baseline score was 7.9. The serlopitant group averaged a 1.0-point greater reduction, compared with controls, at week 4, and a 1.7-point greater decrease at week 8.

Multiple other measures of pruritus serving as secondary endpoints consistently showed significantly greater improvement in the serlopitant group. For example, at the week 8 assessment, 54% of serlopitant-treated patients reported no or only mild itch, compared with 29% of controls. And two-thirds of the serlopitant group reported some degree of improvement in the severity of their eruptive papulonodular lesions at week 8, versus 40% of controls, according to Dr. Ständer, professor of dermatology and neurodermatology and head of the Center for Chronic Pruritus at the University of Münster (Germany).

Of note, nasopharyngitis occurred in 17.2% of the serlopitant group and in 3.2% of controls. Diarrhea was also more common in the serlopitant group, by a margin of 10.9% versus 4.8%.

Dr. Kwon said additional phase 2 as well as phase 3 randomized trials of serlopitant are in the works for both chronic pruritus and prurigo nodularis. The drug is also under study for chronic itch due to other specific etiologies, as well as for refractory chronic cough.

Menlo Therapeutics sponsored the study. Dr. Kwon is a Menlo Therapeutics officer. Dr. Ständer, who was also principal investigator in the chronic pruritus trial, reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

GENEVA – Serlopitant, a novel once-daily oral neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist, brought significant improvement for patients with treatment-resistant chronic pruritus as early as day 2, in a phase 2 randomized trial, Paul Kwon, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

In a separate phase 2 study presented at the congress, serlopitant showed strong efficacy in patients with prurigo nodularis.

Serlopitant is an oral small molecule with high selectivity for the neurokinin-1 receptor (NK1R). At the 5-mg dose, the drug occupies more than 90% of CNS NK1Rs. The NK1R is the primary receptor for substance P, and thus plays an important role in pruritus signaling.

Chronic pruritus is an often-debilitating condition that can have a multitude of causes. It’s associated with increased rates of anxiety, depression, and sleep deprivation. Existing treatments often fail to provide adequate relief from the severe chronic itching, or they are associated with safety or tolerability issues.

“Chronic pruritus can disrupt quality of life to a level comparable to chronic pain,” the dermatologist observed. “I think we in the medical community are hearing more and more about treatment for chronic pruritus as being a major unmet medical need.”

Dr. Kwon noted that investigators at Emory University in Atlanta have found that the quality of life disruption imposed by chronic pruritus is comparable to that of chronic pain (Arch Dermatol. 2011 Oct;147[10]:1153-6).

The phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 6-week trial comprised 257 patients with chronic pruritus at 25 U.S. centers. All were non- or inadequate responders to topical corticosteroids or oral antihistamines. This was essentially an all-comers study that was not restricted to patients with any particular specific cause of their chronic itch. They had to have severe chronic pruritus, as defined by a baseline self-rated pruritus visual analogue score of at least 7 on a 0-10 scale. Patients were randomized to once-daily oral serlopitant at 0.25 mg, 1 mg, or 5 mg, or to placebo.

The primary endpoint was change in mean visual analogue score from baseline to week 6. The serlopitant 1-mg and 5-mg groups reported mean 41.4% and 42.5% reductions, respectively, which were significantly better than the 28.3% reduction in controls.

“It seems that the drug is working in a broad set of subjects,” Dr. Kwon said. “It is not entirely shutting off itch in significant numbers, but the majority of patients appear to be deriving benefit from serlopitant.”

He highlighted the rapidity with which chronic pruritus responded to serlopitant. The first dose was taken on the evening of day 1. The next day, the 1-mg serlopitant group already showed a significantly greater improvement than did placebo-treated controls. The day after that, so did the 5-mg group. Those between-group differences grew steadily larger throughout the 6-week study period.

That rapid response is clinically highly relevant, because numerous studies have demonstrated that fast onset of therapeutic effect improves patient satisfaction, quality of life, and compliance with treatment for a variety of medical conditions, he said.

Dr. Kwon characterized the safety profile of serlopitant in the trial as “fairly robust,” with only mild or moderate treatment-emergent adverse events being seen. Diarrhea and somnolence were the only adverse events more common with serlopitant than placebo, and their incidence was in the mid single digits.

“We have not uncovered any significant safety signal in this study,” Dr. Kwon declared.

Also at the EADV Congress, Sonja Ständer, MD, presented a phase 2 study of serlopitant in patients with prurigo nodularis. The randomized, double-blind, 8-week, 127-patient trial was conducted at 15 sites in Germany, where patients were randomized to once-daily serlopitant at 5 mg or placebo. All participants had a baseline pruritus VAS of 7 or more. Thirty percent of patients had more than a 10-year history of prurigo nodularis, and 24% had the condition for 5-10 years.

The primary endpoint was the difference from baseline to weeks 4 and 8 in the average pruritus VAS over the previous 24 hours. The baseline score was 7.9. The serlopitant group averaged a 1.0-point greater reduction, compared with controls, at week 4, and a 1.7-point greater decrease at week 8.

Multiple other measures of pruritus serving as secondary endpoints consistently showed significantly greater improvement in the serlopitant group. For example, at the week 8 assessment, 54% of serlopitant-treated patients reported no or only mild itch, compared with 29% of controls. And two-thirds of the serlopitant group reported some degree of improvement in the severity of their eruptive papulonodular lesions at week 8, versus 40% of controls, according to Dr. Ständer, professor of dermatology and neurodermatology and head of the Center for Chronic Pruritus at the University of Münster (Germany).

Of note, nasopharyngitis occurred in 17.2% of the serlopitant group and in 3.2% of controls. Diarrhea was also more common in the serlopitant group, by a margin of 10.9% versus 4.8%.

Dr. Kwon said additional phase 2 as well as phase 3 randomized trials of serlopitant are in the works for both chronic pruritus and prurigo nodularis. The drug is also under study for chronic itch due to other specific etiologies, as well as for refractory chronic cough.

Menlo Therapeutics sponsored the study. Dr. Kwon is a Menlo Therapeutics officer. Dr. Ständer, who was also principal investigator in the chronic pruritus trial, reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AT THE EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Mean self-rated pruritus scores fell by 41% and 43% from baseline to week 6 in patients on serlopitant at 1 mg/day and 5 mg/day, compared with 28% in placebo-treated controls.

Data source: A randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled, 6-week, phase 2 clinical trial comprising 257 patients with treatment-resistant chronic pruritus.

Disclosures: Menlo Therapeutics sponsored the study. Dr. Kwon is a Menlo Therapeutics officer. Dr. Ständer reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

The Syphilis Epidemic: Dermatologists on the Frontline of Treatment and Diagnosis

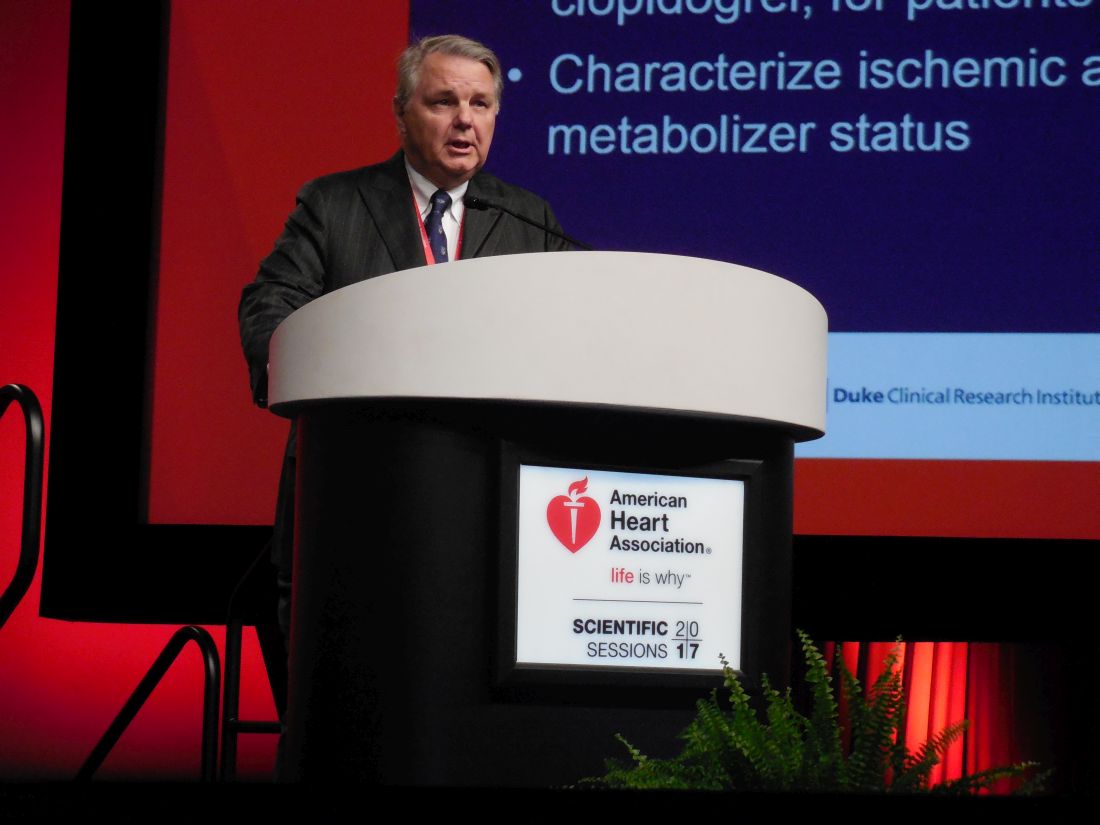

Prescribers mostly ignore clopidogrel pharmacogenomic profiling

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – The boxed warning recommending pharmacogenomic testing of patients receiving clopidogrel to identify reduced metabolizers seems to be playing to a largely deaf audience.

Even when handed information on whether each clopidogrel-treated patient was a poor metabolizer of the drug, treating physicians usually did not switch them to a different antiplatelet drug, ticagrelor, that would be fully effective despite the patient’s reduced-metabolizer status. And clinicians who started patients on ticagrelor did not usually switch those with a good clopidogrel-metabolizing profile to the safer drug, clopidogrel, after learning that clopidogrel would be fully effective.

“Routine reporting of pharmacogenomics test results for acute coronary syndrome patients treated with P2Y12-inhibitor therapy had an uncertain yield and little impact on P2Y12-inhibitor switching,” E. Magnus Ohman, MBBS, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The study’s design gave each participating clinician free rein on whether to prescribe clopidogrel or ticagrelor (Brilinta) initially, and switching between the drugs was possible at any time after the initial prescription. At the trial’s start, 1,704 patients (56%) were on ticagrelor and 1,333 (44%) were on clopidogrel.

Pharmacogenomic testing showed that 34% of all patients were ultrametabolizers and 38% were extensive metabolizers. Patients in either of these categories metabolize enough clopidogrel into the active form to get full benefit from the drug and derive no additional efficacy benefit from switching to another P2Y12 inhibitor, such as ticagrelor or prasugrel (Effient) – drugs unaffected by metabolizer status. Testing also identified 25% of patients as intermediate metabolizers, who carry one loss-of-function allele for the CYP2C19 gene, and 3% were reduced metabolizers, who are homozygous for loss-of-function alleles. Standard practice is not to treat intermediate or reduced metabolizers with clopidogrel because they would not get an adequate antiplatelet effect; instead, these patients are usually treated with ticagrelor or with prasugrel when it’s an option.

After receiving the results regarding the clopidogrel-metabolizing status for each patient, attending physicians switched the drugs prescribed for only 7% of all patients: 9% of patients initially on ticagrelor and 4% of those initially on clopidogrel, reported Dr. Ohman, professor of medicine at Duke University in Durham, N.C. In addition, Dr. Ohman and his associates asked each participating physician who made a switch about his or her reasons for doing so. Of the patients who switched from clopidogrel to ticagrelor, only 23 were switched because of their pharmacogenomic results; this represents fewer than half of those who switched and only 2% of all patients who took clopidogrel. Only one patient changed from ticagrelor to clopidogrel based on pharmacogenomic results, representing 0.06% of all patients on ticagrelor.

“We believed the findings do not support the utility of mandatory testing in this context, as most did not act on the information,” Dr. Ohman said.

A major reason for the inertia, Dr. Gurbel suggested, may be the absence of any compelling data proving whether there’s any effect on clinical outcomes for switching reduced metabolizers off of clopidogrel or switching good metabolizers onto it.

“We have no large-scale, prospective data supporting pharmacogenomic-based personalization” of clopidogrel treatment leading to improved outcomes, but “we need to get over that,” he said. “It’s a challenge to get funding for this.” But “the answer is not to give ticagrelor or prasugrel to everyone because then the bleeding rate is too high.”

The findings Dr. Ohman reported came from the Study to Compare the Safety of Rivaroxaban Versus Acetylsalicylic Acid in Addition to Either Clopidogrel or Ticagrelor Therapy in Participants With Acute Coronary Syndrome (GEMINI-ACS-1), which had the primary goal of comparing the safety in acute coronary syndrome patients of a reduced dosage of rivaroxaban plus either clopidogrel or ticagrelor with the safety of aspirin plus one of these P2Y12 inhibitors. The primary endpoint was the rate of clinically significant bleeding events during a year of treatment. The study ran at 371 centers in 21 countries and showed similar bleeding rates in both treatment arms (Lancet. 2017 May 6; 389[10081]:1799-808).

The analysis also showed that patients identified as reduced metabolizers were fivefold more likely to be switched than patients identified as ultra metabolizers, and intermediate metabolizes had a 50% higher switching rate than ultra metabolizers. The rates of both ischemic and major bleeding outcomes were roughly similar across the spectrum of metabolizers, but Dr. Ohman cautioned that the trial was not designed to assess this. Dr. Gurbel urged the investigators to report on outcomes analyzed not just by metabolizer status but also by the treatment they received.

The boxed warning that clopidogrel received in 2010 regarding poor metabolizers led to “regulatory guidance” during design of the GEMINI-ACS-1 trial requiring routine pharmacogenomic testing for clopidogrel-metabolizing status, Dr. Ohman explained.

The trial was funded by Janssen and Bayer, the two companies that jointly market rivaroxaban (Xarelto). Dr. Ohman has been a consultant to Bayer and several other companies including AstraZeneca, the company that markets ticagrelor (Brilinta). He has also received research funding from Janssen, as well as Daiichi Sankyo and Gilead Sciences. Dr. Gurbel holds patents on platelet-function testing methods.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – The boxed warning recommending pharmacogenomic testing of patients receiving clopidogrel to identify reduced metabolizers seems to be playing to a largely deaf audience.

Even when handed information on whether each clopidogrel-treated patient was a poor metabolizer of the drug, treating physicians usually did not switch them to a different antiplatelet drug, ticagrelor, that would be fully effective despite the patient’s reduced-metabolizer status. And clinicians who started patients on ticagrelor did not usually switch those with a good clopidogrel-metabolizing profile to the safer drug, clopidogrel, after learning that clopidogrel would be fully effective.

“Routine reporting of pharmacogenomics test results for acute coronary syndrome patients treated with P2Y12-inhibitor therapy had an uncertain yield and little impact on P2Y12-inhibitor switching,” E. Magnus Ohman, MBBS, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The study’s design gave each participating clinician free rein on whether to prescribe clopidogrel or ticagrelor (Brilinta) initially, and switching between the drugs was possible at any time after the initial prescription. At the trial’s start, 1,704 patients (56%) were on ticagrelor and 1,333 (44%) were on clopidogrel.

Pharmacogenomic testing showed that 34% of all patients were ultrametabolizers and 38% were extensive metabolizers. Patients in either of these categories metabolize enough clopidogrel into the active form to get full benefit from the drug and derive no additional efficacy benefit from switching to another P2Y12 inhibitor, such as ticagrelor or prasugrel (Effient) – drugs unaffected by metabolizer status. Testing also identified 25% of patients as intermediate metabolizers, who carry one loss-of-function allele for the CYP2C19 gene, and 3% were reduced metabolizers, who are homozygous for loss-of-function alleles. Standard practice is not to treat intermediate or reduced metabolizers with clopidogrel because they would not get an adequate antiplatelet effect; instead, these patients are usually treated with ticagrelor or with prasugrel when it’s an option.

After receiving the results regarding the clopidogrel-metabolizing status for each patient, attending physicians switched the drugs prescribed for only 7% of all patients: 9% of patients initially on ticagrelor and 4% of those initially on clopidogrel, reported Dr. Ohman, professor of medicine at Duke University in Durham, N.C. In addition, Dr. Ohman and his associates asked each participating physician who made a switch about his or her reasons for doing so. Of the patients who switched from clopidogrel to ticagrelor, only 23 were switched because of their pharmacogenomic results; this represents fewer than half of those who switched and only 2% of all patients who took clopidogrel. Only one patient changed from ticagrelor to clopidogrel based on pharmacogenomic results, representing 0.06% of all patients on ticagrelor.

“We believed the findings do not support the utility of mandatory testing in this context, as most did not act on the information,” Dr. Ohman said.

A major reason for the inertia, Dr. Gurbel suggested, may be the absence of any compelling data proving whether there’s any effect on clinical outcomes for switching reduced metabolizers off of clopidogrel or switching good metabolizers onto it.

“We have no large-scale, prospective data supporting pharmacogenomic-based personalization” of clopidogrel treatment leading to improved outcomes, but “we need to get over that,” he said. “It’s a challenge to get funding for this.” But “the answer is not to give ticagrelor or prasugrel to everyone because then the bleeding rate is too high.”

The findings Dr. Ohman reported came from the Study to Compare the Safety of Rivaroxaban Versus Acetylsalicylic Acid in Addition to Either Clopidogrel or Ticagrelor Therapy in Participants With Acute Coronary Syndrome (GEMINI-ACS-1), which had the primary goal of comparing the safety in acute coronary syndrome patients of a reduced dosage of rivaroxaban plus either clopidogrel or ticagrelor with the safety of aspirin plus one of these P2Y12 inhibitors. The primary endpoint was the rate of clinically significant bleeding events during a year of treatment. The study ran at 371 centers in 21 countries and showed similar bleeding rates in both treatment arms (Lancet. 2017 May 6; 389[10081]:1799-808).

The analysis also showed that patients identified as reduced metabolizers were fivefold more likely to be switched than patients identified as ultra metabolizers, and intermediate metabolizes had a 50% higher switching rate than ultra metabolizers. The rates of both ischemic and major bleeding outcomes were roughly similar across the spectrum of metabolizers, but Dr. Ohman cautioned that the trial was not designed to assess this. Dr. Gurbel urged the investigators to report on outcomes analyzed not just by metabolizer status but also by the treatment they received.

The boxed warning that clopidogrel received in 2010 regarding poor metabolizers led to “regulatory guidance” during design of the GEMINI-ACS-1 trial requiring routine pharmacogenomic testing for clopidogrel-metabolizing status, Dr. Ohman explained.

The trial was funded by Janssen and Bayer, the two companies that jointly market rivaroxaban (Xarelto). Dr. Ohman has been a consultant to Bayer and several other companies including AstraZeneca, the company that markets ticagrelor (Brilinta). He has also received research funding from Janssen, as well as Daiichi Sankyo and Gilead Sciences. Dr. Gurbel holds patents on platelet-function testing methods.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – The boxed warning recommending pharmacogenomic testing of patients receiving clopidogrel to identify reduced metabolizers seems to be playing to a largely deaf audience.

Even when handed information on whether each clopidogrel-treated patient was a poor metabolizer of the drug, treating physicians usually did not switch them to a different antiplatelet drug, ticagrelor, that would be fully effective despite the patient’s reduced-metabolizer status. And clinicians who started patients on ticagrelor did not usually switch those with a good clopidogrel-metabolizing profile to the safer drug, clopidogrel, after learning that clopidogrel would be fully effective.

“Routine reporting of pharmacogenomics test results for acute coronary syndrome patients treated with P2Y12-inhibitor therapy had an uncertain yield and little impact on P2Y12-inhibitor switching,” E. Magnus Ohman, MBBS, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The study’s design gave each participating clinician free rein on whether to prescribe clopidogrel or ticagrelor (Brilinta) initially, and switching between the drugs was possible at any time after the initial prescription. At the trial’s start, 1,704 patients (56%) were on ticagrelor and 1,333 (44%) were on clopidogrel.

Pharmacogenomic testing showed that 34% of all patients were ultrametabolizers and 38% were extensive metabolizers. Patients in either of these categories metabolize enough clopidogrel into the active form to get full benefit from the drug and derive no additional efficacy benefit from switching to another P2Y12 inhibitor, such as ticagrelor or prasugrel (Effient) – drugs unaffected by metabolizer status. Testing also identified 25% of patients as intermediate metabolizers, who carry one loss-of-function allele for the CYP2C19 gene, and 3% were reduced metabolizers, who are homozygous for loss-of-function alleles. Standard practice is not to treat intermediate or reduced metabolizers with clopidogrel because they would not get an adequate antiplatelet effect; instead, these patients are usually treated with ticagrelor or with prasugrel when it’s an option.

After receiving the results regarding the clopidogrel-metabolizing status for each patient, attending physicians switched the drugs prescribed for only 7% of all patients: 9% of patients initially on ticagrelor and 4% of those initially on clopidogrel, reported Dr. Ohman, professor of medicine at Duke University in Durham, N.C. In addition, Dr. Ohman and his associates asked each participating physician who made a switch about his or her reasons for doing so. Of the patients who switched from clopidogrel to ticagrelor, only 23 were switched because of their pharmacogenomic results; this represents fewer than half of those who switched and only 2% of all patients who took clopidogrel. Only one patient changed from ticagrelor to clopidogrel based on pharmacogenomic results, representing 0.06% of all patients on ticagrelor.

“We believed the findings do not support the utility of mandatory testing in this context, as most did not act on the information,” Dr. Ohman said.

A major reason for the inertia, Dr. Gurbel suggested, may be the absence of any compelling data proving whether there’s any effect on clinical outcomes for switching reduced metabolizers off of clopidogrel or switching good metabolizers onto it.

“We have no large-scale, prospective data supporting pharmacogenomic-based personalization” of clopidogrel treatment leading to improved outcomes, but “we need to get over that,” he said. “It’s a challenge to get funding for this.” But “the answer is not to give ticagrelor or prasugrel to everyone because then the bleeding rate is too high.”

The findings Dr. Ohman reported came from the Study to Compare the Safety of Rivaroxaban Versus Acetylsalicylic Acid in Addition to Either Clopidogrel or Ticagrelor Therapy in Participants With Acute Coronary Syndrome (GEMINI-ACS-1), which had the primary goal of comparing the safety in acute coronary syndrome patients of a reduced dosage of rivaroxaban plus either clopidogrel or ticagrelor with the safety of aspirin plus one of these P2Y12 inhibitors. The primary endpoint was the rate of clinically significant bleeding events during a year of treatment. The study ran at 371 centers in 21 countries and showed similar bleeding rates in both treatment arms (Lancet. 2017 May 6; 389[10081]:1799-808).

The analysis also showed that patients identified as reduced metabolizers were fivefold more likely to be switched than patients identified as ultra metabolizers, and intermediate metabolizes had a 50% higher switching rate than ultra metabolizers. The rates of both ischemic and major bleeding outcomes were roughly similar across the spectrum of metabolizers, but Dr. Ohman cautioned that the trial was not designed to assess this. Dr. Gurbel urged the investigators to report on outcomes analyzed not just by metabolizer status but also by the treatment they received.

The boxed warning that clopidogrel received in 2010 regarding poor metabolizers led to “regulatory guidance” during design of the GEMINI-ACS-1 trial requiring routine pharmacogenomic testing for clopidogrel-metabolizing status, Dr. Ohman explained.

The trial was funded by Janssen and Bayer, the two companies that jointly market rivaroxaban (Xarelto). Dr. Ohman has been a consultant to Bayer and several other companies including AstraZeneca, the company that markets ticagrelor (Brilinta). He has also received research funding from Janssen, as well as Daiichi Sankyo and Gilead Sciences. Dr. Gurbel holds patents on platelet-function testing methods.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Physicians switched P2Y12 inhibitors for only 2% of patients on clopidogrel and only 0.06% on ticagrelor on the basis of their pharmacogenomic results.

Data source: GEMINI-ACS-1, a multicenter, prospective trial with 3,037 patients.

Disclosures: The GEMINI-ACS-1 trial was funded by Janssen and Bayer, the two companies that jointly market rivaroxaban (Xarelto). Dr. Ohman has been a consultant to Bayer and several other companies, including AstraZeneca, the company that markets ticagrelor (Brilinta). He has also received research funding from Janssen, as well as Daiichi Sankyo and Gilead Sciences. Dr. Gurbel holds patents on platelet-function testing methods.

The Pathological Underpinning of Drug-Resistant Epilepsy

Among patients with drug resistant focal epilepsy who underwent surgery, an examination of resected brain specimens revealed hippocampal sclerosis to be the most common histopathological diagnosis in adults. The same analysis, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, found children were most likely to have focal cortical dysplasia.

- The study included analysis of brain specimens from 9523 patients who underwent epilepsy surgery in 36 centers in 12 European countries over 25 years.

- About 3 of 4 patients began having seizures before age 18 years.

- 72.5% of patient had surgery as adults.

- On average, adult patients had endured epilepsy for about 20 years before having surgery while children waited 5.3 years for surgical resection.

- Hippocampal sclerosis was found in 36.4% of patients, including 88.7% of adults.

- Tumors were detected in 23.6%, most of which were ganglioglioma.

- Malformations of cortical development affected 19.8% of patients.

Blumcke I, Spreafico R, Haaker G, et al. Histopathological findings in brain tissue obtained during epilepsy surgery. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(17):1648-1656.

Among patients with drug resistant focal epilepsy who underwent surgery, an examination of resected brain specimens revealed hippocampal sclerosis to be the most common histopathological diagnosis in adults. The same analysis, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, found children were most likely to have focal cortical dysplasia.

- The study included analysis of brain specimens from 9523 patients who underwent epilepsy surgery in 36 centers in 12 European countries over 25 years.

- About 3 of 4 patients began having seizures before age 18 years.

- 72.5% of patient had surgery as adults.

- On average, adult patients had endured epilepsy for about 20 years before having surgery while children waited 5.3 years for surgical resection.

- Hippocampal sclerosis was found in 36.4% of patients, including 88.7% of adults.

- Tumors were detected in 23.6%, most of which were ganglioglioma.

- Malformations of cortical development affected 19.8% of patients.

Blumcke I, Spreafico R, Haaker G, et al. Histopathological findings in brain tissue obtained during epilepsy surgery. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(17):1648-1656.

Among patients with drug resistant focal epilepsy who underwent surgery, an examination of resected brain specimens revealed hippocampal sclerosis to be the most common histopathological diagnosis in adults. The same analysis, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, found children were most likely to have focal cortical dysplasia.

- The study included analysis of brain specimens from 9523 patients who underwent epilepsy surgery in 36 centers in 12 European countries over 25 years.

- About 3 of 4 patients began having seizures before age 18 years.

- 72.5% of patient had surgery as adults.

- On average, adult patients had endured epilepsy for about 20 years before having surgery while children waited 5.3 years for surgical resection.

- Hippocampal sclerosis was found in 36.4% of patients, including 88.7% of adults.

- Tumors were detected in 23.6%, most of which were ganglioglioma.

- Malformations of cortical development affected 19.8% of patients.

Blumcke I, Spreafico R, Haaker G, et al. Histopathological findings in brain tissue obtained during epilepsy surgery. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(17):1648-1656.

Extending Insular Glioma Resection Cuts Seizure Recurrence

In patients who have had surgical resection of an insular glioma, the wider the extent of the resection, the longer they remain free from seizures, according to a study from the department of neurological surgery at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

- The analysis included 109 patients who had surgery for insular tumors from 1997 to 2015 at UCSF.

- At final follow-up, 42 patients (39%) remained seizure free.

- Increasing the extent of the resection predicted freedom from seizures.

- The analysis also revealed that performing a second resection provided even greater seizure control; 8/22 patients with recurrent seizures no longer had them after the second surgery.

- Patients who experienced a second seizure after resection were more likely to have had tumor progression.

Wang DD, Deng H, Hervey-Jumper SL, Molinaro AA, Chang EF, Berger MS. Seizure outcome after surgical resection of insular glioma. [Published online ahead of print Nov 8, 2017] Neurosurgery. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyx486.

In patients who have had surgical resection of an insular glioma, the wider the extent of the resection, the longer they remain free from seizures, according to a study from the department of neurological surgery at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

- The analysis included 109 patients who had surgery for insular tumors from 1997 to 2015 at UCSF.

- At final follow-up, 42 patients (39%) remained seizure free.

- Increasing the extent of the resection predicted freedom from seizures.

- The analysis also revealed that performing a second resection provided even greater seizure control; 8/22 patients with recurrent seizures no longer had them after the second surgery.

- Patients who experienced a second seizure after resection were more likely to have had tumor progression.

Wang DD, Deng H, Hervey-Jumper SL, Molinaro AA, Chang EF, Berger MS. Seizure outcome after surgical resection of insular glioma. [Published online ahead of print Nov 8, 2017] Neurosurgery. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyx486.

In patients who have had surgical resection of an insular glioma, the wider the extent of the resection, the longer they remain free from seizures, according to a study from the department of neurological surgery at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

- The analysis included 109 patients who had surgery for insular tumors from 1997 to 2015 at UCSF.

- At final follow-up, 42 patients (39%) remained seizure free.

- Increasing the extent of the resection predicted freedom from seizures.

- The analysis also revealed that performing a second resection provided even greater seizure control; 8/22 patients with recurrent seizures no longer had them after the second surgery.

- Patients who experienced a second seizure after resection were more likely to have had tumor progression.

Wang DD, Deng H, Hervey-Jumper SL, Molinaro AA, Chang EF, Berger MS. Seizure outcome after surgical resection of insular glioma. [Published online ahead of print Nov 8, 2017] Neurosurgery. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyx486.