User login

Women with adult acne need more treatment options and support

Adult women with acne need to be taken more seriously and offered more treatment options, according to Hilary Baldwin, MD, clinical associate professor of dermatology at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J.

In a presentation on adult acne in women at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s Women’s & Pediatric Dermatology Seminar, Dr. Baldwin said that while acne in females typically peaks between ages 14 and 17 years, many women in the United States are experiencing adult-onset acne that can persist late into adulthood. “The adult female has been ignored in the past, when we’ve been concentrating primarily on teenagers with acne,” Dr. Baldwin explained in an interview. Women are the second most commonly population affected by acne, with an estimated prevalence in up to 50% of women in their 20s, 30% of women in their 30s, and 25% in their 40s, she added.

“It may ‘just be’ acne at 16 when it’s going to go away at 17, but it’s not ‘just acne’ in a 23-year-old who’s going to have it until menopause,” she said.

Three subtypes of acne have been described in adult women: Persistent acne, a continuation of acne from adolescence to adulthood; late onset acne, the development of acne in patients after age 25 years; and relapsing acne, the return of acne later in life in a patient who had acne as an adolescent. In adults, about 80% of acne is the persistent type.

More study is needed to determine the prevalence of the relapsing subtype, which is not well described in the literature, Dr. Baldwin noted.

Two types of acne in adult women have been described, and they may have different responses to treatment, she said. The “U zone” form is characterized by inflammatory papules and nodules – and no comedones – that primarily affect the lower third of the face, jawline, and neck, typically sparing the back and shoulders, she said. Conversely, the diffuse form is characterized by numerous comedones and inflammatory lesions, which may produce scarring.

Dr. Baldwin said that acne can have a greater impact on women than on adolescents, with a greater impact on quality of life – and emotional effects that are “similar to patients with psoriasis.”

In a survey of 128 women with acne who were asked about what they expect from their dermatologists, 56% said they felt examination with their dermatologists was too quick, and 44% said that they felt that their skin was not looked at meticulously enough. And almost half said that the discussion of different treatment options was not detailed enough, and was too short.

Most dermatologists can evaluate the severity of a patient’s acne without bringing out a magnifying glass, but for the sake of the patient’s trust, taking the time to check “more meticulously” may help the patient mentally and physically, she said. Taking this time, as well as involving patients in treatment decisions, may also improve treatment adherence, she added.

“You are more likely, if you made a decision or helped to make a decision ... to use the product,” Dr. Baldwin said about working with patients.

Dr. Baldwin disclosed serving as a speaker, adviser, and/or investigator for Allergan, Bayer, BioPharmX, Dermira, Encore, La Roche-Posay, Mayne, Novan, Johnson & Johnson, Sun, Valeant, and Galderma.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

Adult women with acne need to be taken more seriously and offered more treatment options, according to Hilary Baldwin, MD, clinical associate professor of dermatology at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J.

In a presentation on adult acne in women at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s Women’s & Pediatric Dermatology Seminar, Dr. Baldwin said that while acne in females typically peaks between ages 14 and 17 years, many women in the United States are experiencing adult-onset acne that can persist late into adulthood. “The adult female has been ignored in the past, when we’ve been concentrating primarily on teenagers with acne,” Dr. Baldwin explained in an interview. Women are the second most commonly population affected by acne, with an estimated prevalence in up to 50% of women in their 20s, 30% of women in their 30s, and 25% in their 40s, she added.

“It may ‘just be’ acne at 16 when it’s going to go away at 17, but it’s not ‘just acne’ in a 23-year-old who’s going to have it until menopause,” she said.

Three subtypes of acne have been described in adult women: Persistent acne, a continuation of acne from adolescence to adulthood; late onset acne, the development of acne in patients after age 25 years; and relapsing acne, the return of acne later in life in a patient who had acne as an adolescent. In adults, about 80% of acne is the persistent type.

More study is needed to determine the prevalence of the relapsing subtype, which is not well described in the literature, Dr. Baldwin noted.

Two types of acne in adult women have been described, and they may have different responses to treatment, she said. The “U zone” form is characterized by inflammatory papules and nodules – and no comedones – that primarily affect the lower third of the face, jawline, and neck, typically sparing the back and shoulders, she said. Conversely, the diffuse form is characterized by numerous comedones and inflammatory lesions, which may produce scarring.

Dr. Baldwin said that acne can have a greater impact on women than on adolescents, with a greater impact on quality of life – and emotional effects that are “similar to patients with psoriasis.”

In a survey of 128 women with acne who were asked about what they expect from their dermatologists, 56% said they felt examination with their dermatologists was too quick, and 44% said that they felt that their skin was not looked at meticulously enough. And almost half said that the discussion of different treatment options was not detailed enough, and was too short.

Most dermatologists can evaluate the severity of a patient’s acne without bringing out a magnifying glass, but for the sake of the patient’s trust, taking the time to check “more meticulously” may help the patient mentally and physically, she said. Taking this time, as well as involving patients in treatment decisions, may also improve treatment adherence, she added.

“You are more likely, if you made a decision or helped to make a decision ... to use the product,” Dr. Baldwin said about working with patients.

Dr. Baldwin disclosed serving as a speaker, adviser, and/or investigator for Allergan, Bayer, BioPharmX, Dermira, Encore, La Roche-Posay, Mayne, Novan, Johnson & Johnson, Sun, Valeant, and Galderma.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

Adult women with acne need to be taken more seriously and offered more treatment options, according to Hilary Baldwin, MD, clinical associate professor of dermatology at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J.

In a presentation on adult acne in women at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s Women’s & Pediatric Dermatology Seminar, Dr. Baldwin said that while acne in females typically peaks between ages 14 and 17 years, many women in the United States are experiencing adult-onset acne that can persist late into adulthood. “The adult female has been ignored in the past, when we’ve been concentrating primarily on teenagers with acne,” Dr. Baldwin explained in an interview. Women are the second most commonly population affected by acne, with an estimated prevalence in up to 50% of women in their 20s, 30% of women in their 30s, and 25% in their 40s, she added.

“It may ‘just be’ acne at 16 when it’s going to go away at 17, but it’s not ‘just acne’ in a 23-year-old who’s going to have it until menopause,” she said.

Three subtypes of acne have been described in adult women: Persistent acne, a continuation of acne from adolescence to adulthood; late onset acne, the development of acne in patients after age 25 years; and relapsing acne, the return of acne later in life in a patient who had acne as an adolescent. In adults, about 80% of acne is the persistent type.

More study is needed to determine the prevalence of the relapsing subtype, which is not well described in the literature, Dr. Baldwin noted.

Two types of acne in adult women have been described, and they may have different responses to treatment, she said. The “U zone” form is characterized by inflammatory papules and nodules – and no comedones – that primarily affect the lower third of the face, jawline, and neck, typically sparing the back and shoulders, she said. Conversely, the diffuse form is characterized by numerous comedones and inflammatory lesions, which may produce scarring.

Dr. Baldwin said that acne can have a greater impact on women than on adolescents, with a greater impact on quality of life – and emotional effects that are “similar to patients with psoriasis.”

In a survey of 128 women with acne who were asked about what they expect from their dermatologists, 56% said they felt examination with their dermatologists was too quick, and 44% said that they felt that their skin was not looked at meticulously enough. And almost half said that the discussion of different treatment options was not detailed enough, and was too short.

Most dermatologists can evaluate the severity of a patient’s acne without bringing out a magnifying glass, but for the sake of the patient’s trust, taking the time to check “more meticulously” may help the patient mentally and physically, she said. Taking this time, as well as involving patients in treatment decisions, may also improve treatment adherence, she added.

“You are more likely, if you made a decision or helped to make a decision ... to use the product,” Dr. Baldwin said about working with patients.

Dr. Baldwin disclosed serving as a speaker, adviser, and/or investigator for Allergan, Bayer, BioPharmX, Dermira, Encore, La Roche-Posay, Mayne, Novan, Johnson & Johnson, Sun, Valeant, and Galderma.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

FROM SDEF WOMEN’S & PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Preop endocervical sampling pathology can guide trachelectomy planning

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Pathologic findings from preoperative endocervical sampling were fairly consistent with the underlying pathologies identified at trachelectomy, based on a single-center, retrospective chart review presented at the AAGL Global Congress.

“Preoperative endocervical sampling can be performed safely and adequately with results consistent with final trachelectomy pathology,” said Sarah Krantz, MD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. Importantly, performing preoperative sampling may identify a missed diagnosis of cancer and allows for subsequent appropriate preoperative planning, she added.

Dr. Krantz and her colleagues included 47 women who had a supracervical hysterectomy and subsequently underwent trachelectomy at Vanderbilt from April 1999 to April 2015. Indications for surgery included vaginal bleeding (24), abnormal pap smears (7), pain (16), prolapse (13), and cancer (2). If patients had a prior diagnosis of gynecologic malignancy, they were excluded from the study.

Endocervical sampling was performed in 18 of the 47 women by a gynecologist. Samples were collected by way of various methods, including Pap smear, endocervical brushings and curettage, and endometrial pipelle. The pathologic findings in endocervical samples coincided with the final surgical pathology in 9 of 10 patients with benign findings, 1 of 6 patients with dysplasia, and 2 of 2 patients with cancer.

Among the 29 women who did not undergo preoperative endocervical sampling, one was diagnosed with cervical cancer at final surgical pathology.

In the 24 women with vaginal bleeding, cervicitis was identified in 1 of 10 patients who underwent preoperative endocervical sampling and was found on final pathology in 12 of 24 patients.Given the high incidence of cervicitis in women who report vaginal bleeding, consideration should be given for medical management prior to surgical excision, Dr. Krantz said.

Dr. Krantz reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Pathologic findings from preoperative endocervical sampling were fairly consistent with the underlying pathologies identified at trachelectomy, based on a single-center, retrospective chart review presented at the AAGL Global Congress.

“Preoperative endocervical sampling can be performed safely and adequately with results consistent with final trachelectomy pathology,” said Sarah Krantz, MD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. Importantly, performing preoperative sampling may identify a missed diagnosis of cancer and allows for subsequent appropriate preoperative planning, she added.

Dr. Krantz and her colleagues included 47 women who had a supracervical hysterectomy and subsequently underwent trachelectomy at Vanderbilt from April 1999 to April 2015. Indications for surgery included vaginal bleeding (24), abnormal pap smears (7), pain (16), prolapse (13), and cancer (2). If patients had a prior diagnosis of gynecologic malignancy, they were excluded from the study.

Endocervical sampling was performed in 18 of the 47 women by a gynecologist. Samples were collected by way of various methods, including Pap smear, endocervical brushings and curettage, and endometrial pipelle. The pathologic findings in endocervical samples coincided with the final surgical pathology in 9 of 10 patients with benign findings, 1 of 6 patients with dysplasia, and 2 of 2 patients with cancer.

Among the 29 women who did not undergo preoperative endocervical sampling, one was diagnosed with cervical cancer at final surgical pathology.

In the 24 women with vaginal bleeding, cervicitis was identified in 1 of 10 patients who underwent preoperative endocervical sampling and was found on final pathology in 12 of 24 patients.Given the high incidence of cervicitis in women who report vaginal bleeding, consideration should be given for medical management prior to surgical excision, Dr. Krantz said.

Dr. Krantz reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Pathologic findings from preoperative endocervical sampling were fairly consistent with the underlying pathologies identified at trachelectomy, based on a single-center, retrospective chart review presented at the AAGL Global Congress.

“Preoperative endocervical sampling can be performed safely and adequately with results consistent with final trachelectomy pathology,” said Sarah Krantz, MD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. Importantly, performing preoperative sampling may identify a missed diagnosis of cancer and allows for subsequent appropriate preoperative planning, she added.

Dr. Krantz and her colleagues included 47 women who had a supracervical hysterectomy and subsequently underwent trachelectomy at Vanderbilt from April 1999 to April 2015. Indications for surgery included vaginal bleeding (24), abnormal pap smears (7), pain (16), prolapse (13), and cancer (2). If patients had a prior diagnosis of gynecologic malignancy, they were excluded from the study.

Endocervical sampling was performed in 18 of the 47 women by a gynecologist. Samples were collected by way of various methods, including Pap smear, endocervical brushings and curettage, and endometrial pipelle. The pathologic findings in endocervical samples coincided with the final surgical pathology in 9 of 10 patients with benign findings, 1 of 6 patients with dysplasia, and 2 of 2 patients with cancer.

Among the 29 women who did not undergo preoperative endocervical sampling, one was diagnosed with cervical cancer at final surgical pathology.

In the 24 women with vaginal bleeding, cervicitis was identified in 1 of 10 patients who underwent preoperative endocervical sampling and was found on final pathology in 12 of 24 patients.Given the high incidence of cervicitis in women who report vaginal bleeding, consideration should be given for medical management prior to surgical excision, Dr. Krantz said.

Dr. Krantz reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT AAGL 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Among 18 women who had preoperative endocervical sampling, the pathology results matched those of the final surgical pathology in 9 of 10 patients with benign disorders, 1 of 6 patients with dysplasia, and 2 of 2 patients with cancer.

Data source: A retrospective chart review of 47 women who underwent trachelectomy at a single academic medical center from April 1999-April 2015.

Disclosures: Dr. Krantz reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Shoulder Pain—Is It From the Shoulder, Neck, or Both?

Neck and shoulder pain are common presenting symptoms in the general adult population with a 41.7% and 50.9% lifetime incidence in males and females, respectively.1 Generally, a single diagnosis is sought to explain a patient’s signs and symptoms, but occasionally 2 or more different causes are responsible. Only by conducting a thorough history and physical examination with proper follow-up will all contributing diseases be discovered. The following case illustrates 2 distinct etiologies responsible for the patient’s pain, one with an extremely unusual presentation.

Case Presentation

A 23-year-old male presented with a 3-month history of pain, spasm, and tightness of his right upper extremity along his posterior neck, shoulder, and triceps area. The patient reported no history of trauma, but he revealed increasing the amount of weight lifting, and his symptoms were especially worse when bench pressing or performing overhead exercises. No paresthesias were reported.

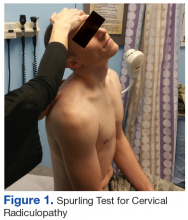

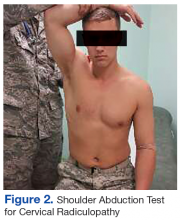

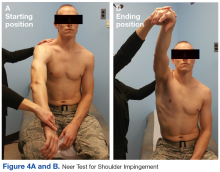

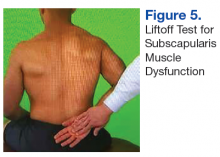

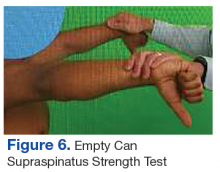

The initial examination revealed a well-developed muscular male with no visible atrophy or tenderness to palpation. He had full range of motion (ROM) of his neck, a normal motor and sensory examination of the C5-T1 nerve roots, and a negative Spurling maneuver. The patient had full ROM of both shoulders but had pain with right shoulder abduction starting at about 120° to 140°. He had pain with resisted supraspinatus muscle testing as well as pain with the liftoff test. The results of the patient’s Hawkins and Neer tests were negative (Table, Figures 1 to 6).2-4 A point-of-care shoulder ultrasound examination revealed no abnormalities.

The working diagnosis was external shoulder impingement with a differential diagnosis of internal impingement and/or cervical radiculopathy. A diagnostic/therapeutic injection of 40 mg of triamcinolone and 4 mL of 1% xylocaine without epinephrine was administered into the right subacromial bursa. The patient experienced immediate and complete relief of pain with repeat shoulder abduction, supraspinatus muscle testing, and the liftoff test. Although this procedure temporarily relieved the pain with movement, a sensation of tightness, pain, and spasm in the posterior shoulder and right posterior arm was still present. The patient was asked to perform therapeutic rotator cuff and scapular strengthening exercises, annotated on a patient information handout, for 15 minutes a day, every other day and to follow-up in 4 weeks.

At follow-up the external impingement symptoms (pain with shoulder abduction, resisted supraspinatus testing and the liftoff test) were fully resolved, but the patient reported persistent pain, spasm, and sensation of tightness in his right posterior shoulder and arm with intermittent extension into forearm and hand. A review of the history reminded the patient of a wrestling episode that caused neck pain months earlier. The patient reported that his current symptoms began after the wrestling episode.

Physical examination at this time revealed pain in the right posterior arm with left lateral neck movement but no neck pain with right lateral neck movement or flexion and extension. There was again a normal motor and sensory examination in the C5-T1 nerve distribution. Of note, there was full painless abduction in the right shoulder, which had improved from the previous examination, and there was no pain with resisted supraspinatus testing or the liftoff test, both of which had been abnormal at the initial encounter.

Due to the patient’s persistent posterior shoulder pain and exacerbation of symptoms with neck movement and the now revealed antecedent event of neck trauma, a higher concern for cervical disc pathology was entertained. A cervical magnetic resonance imaging examination (MRI) was ordered. A moderately sized left paracentral herniation of the disk at C5-C6 was found. The disk herniation was compressing the left ventral hemi-cord with narrowing of the left neuronal foramina. Additionally, there was a mild posterior disc osteophyte complex that caused mild left foraminal narrowing at C6-C7.

Neurosurgical consultation was obtained. Extensive discussion of nonsurgical vs surgical options were conducted, and a trial of nonsurgical therapy was agreed on. Physical therapy with cervical traction was prescribed with 2 sessions a week for 4 weeks. The patient also continued his therapeutic rotator cuff and scapular stabilizing exercises and decreased the amount and intensity of his weight lifting.

At the next 4-week follow-up, his symptoms were greatly reduced. He was discharged from supervised physical therapy and continued his at-home neck and shoulder strengthening regimen. At the 1-year follow-up, the patient reported that the radiating pain had essentially resolved—only occasionally being present with heavy upper-extremity weight lifting or grappling activities. He continues to be symptom free of his external impingement symptoms as well.

The final diagnosis was cervical radiculopathy of C5/6 nerve root due to left paracentral disc herniation with concomitant cord compression as well as external impingement (rotator cuff dysfunction) of the right shoulder. It is unclear whether the disc herniation contributed to the external shoulder impingement due to alterations in biomechanics or whether the 2 diseases were unrelated.

Discussion

The patient’s cervical disc herniation most likely was due to his earlier grappling episode when he had acute trauma to the neck or an exacerbation of an older asymptomatic herniation. His external shoulder impingement likely was due to overuse with heavy weight lifting, which also caused enough mechanical strain to exacerbate the patient’s cervical disc herniation symptoms. What is most unusual about this case is the right-sided cervical radicular symptoms due to a left-sided cervical disc herniation.

With an annual incidence of 107.3 in men and 63.5 in women per 100,000 patients, cervical radiculopathy is caused by compression or irritation of the cervical nerve roots as they exit the spine. The most common cause of cervical radiculopathy is spondylosis followed by disc herniation, but both can be present in the same patient. Spondylosis refers to degeneration of the discs and facet joints but generally without frank disc herniation.5

External shoulder impingement and cervical radiculopathy can have nearly identical symptoms of shoulder and upper arm pain as in this illustrated case. Patients with cervical radiculopathy generally present with neck, shoulder, and arm pain or neurologic deficits. These symptoms alone are very broad and present a wide differential diagnosis. One must determine whether the pain is from the neck or shoulder region.1 The Table and Figures 1 to 6 describe the physical examination maneuvers used to differentiate the etiology.

The decision to pursue imaging should be based on injury severity and patient treatment goals. Although plain radiographic imaging may reveal spondylotic changes, such as degenerative joint changes at the vertebral facets and uncovertebral joints as well as decreased disc space, MRI is the imaging modality of choice for viewing disc herniations.6Nonoperative management of cervical radiculopathy focuses on restoration of full pain-free neck ROM, cervical muscle strengthening, and consideration for cervical traction. The use of either topical or oral medications can be considered if needed to aid in sleep and/or participation in active rehabilitation. Complimentary methods, such as acupuncture, yoga, or therapeutic massage also should be considered. Additionally, corticosteroid epidural injections can be considered, but these have increased risk compared with lumbar epidural injections.7 Surgical indications include persistent symptoms after 6 to 12 weeks of conservative therapy with no improvement of symptoms or progressively worsening motor/neurologic deficits.8

Conclusion

This case illustrates how 2 different conditions can present similarly and lead to diagnostic uncertainty. In this case, both the shoulder impingement and cervical radiculopathy manifested as shoulder and upper arm pain and could be separated only once the impingement had been treated. In addition the left-sided disc herniation causing right-sided symptoms was very unusual. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is only the second report of cervical disc herniation causing contralateral symptoms. In the only other available case report on cervical disc herniation with contralateral symptoms, the symptoms occurred in both the contralateral arm and leg.9

1. Briggs AM, Straker LM, Bear NL, Smith AJ. Neck/shoulder pain in adolescents is not related to the level or nature of self-reported physical activity or type of sedentary activity in an Australian pregnancy cohort. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10(1):87.

2. Hermans J, Luime JJ, Meuffels DE, Reijman M, Simel DL, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Does this patient with shoulder pain have rotator cuff disease? JAMA. 2013;310(8):837-847.

3. Rubinstein SM, Pool JJ, van Tulder MW, Riphagen I, Riphagen II, de Vet HC. A systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of provocative tests of the neck for diagnosing cervical radiculopathy. Eur Spine J. 2007;16(3):307-319.

4. Ghasemi M, Golabchi K, Mousavi SA, et al. The value of provocative tests in diagnosis of cervical radiculopathy. J Res Med Sci. 2013;18(suppl 1):S35-S38.

5. Woods BI, Hilibrand AS. Cervical radiculopathy: epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2015;28(5):E251-E259.

6. Green C, Butler J, Eustace S, Poynton A, O’Byrne JM. Imaging modalities for cervical spondylotic stenosis and myelopathy. Adv Orthop. 2012;2012:908324. [Epub July 20, 2011].

7. Childress MA, Beckers BA. Nonoperative management of cervical radiculopathy. Am Fam Physician. 2016;93(9):746-754.

8. Carette S, Fehlings MG. Clinical practice. Cervical radiculopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(4):392-399.

9. Yeung JT, Johnson JI, Karim AS. Cervical disc herniation presenting with neck pain and contralateral symptoms: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:166.

Neck and shoulder pain are common presenting symptoms in the general adult population with a 41.7% and 50.9% lifetime incidence in males and females, respectively.1 Generally, a single diagnosis is sought to explain a patient’s signs and symptoms, but occasionally 2 or more different causes are responsible. Only by conducting a thorough history and physical examination with proper follow-up will all contributing diseases be discovered. The following case illustrates 2 distinct etiologies responsible for the patient’s pain, one with an extremely unusual presentation.

Case Presentation

A 23-year-old male presented with a 3-month history of pain, spasm, and tightness of his right upper extremity along his posterior neck, shoulder, and triceps area. The patient reported no history of trauma, but he revealed increasing the amount of weight lifting, and his symptoms were especially worse when bench pressing or performing overhead exercises. No paresthesias were reported.

The initial examination revealed a well-developed muscular male with no visible atrophy or tenderness to palpation. He had full range of motion (ROM) of his neck, a normal motor and sensory examination of the C5-T1 nerve roots, and a negative Spurling maneuver. The patient had full ROM of both shoulders but had pain with right shoulder abduction starting at about 120° to 140°. He had pain with resisted supraspinatus muscle testing as well as pain with the liftoff test. The results of the patient’s Hawkins and Neer tests were negative (Table, Figures 1 to 6).2-4 A point-of-care shoulder ultrasound examination revealed no abnormalities.

The working diagnosis was external shoulder impingement with a differential diagnosis of internal impingement and/or cervical radiculopathy. A diagnostic/therapeutic injection of 40 mg of triamcinolone and 4 mL of 1% xylocaine without epinephrine was administered into the right subacromial bursa. The patient experienced immediate and complete relief of pain with repeat shoulder abduction, supraspinatus muscle testing, and the liftoff test. Although this procedure temporarily relieved the pain with movement, a sensation of tightness, pain, and spasm in the posterior shoulder and right posterior arm was still present. The patient was asked to perform therapeutic rotator cuff and scapular strengthening exercises, annotated on a patient information handout, for 15 minutes a day, every other day and to follow-up in 4 weeks.

At follow-up the external impingement symptoms (pain with shoulder abduction, resisted supraspinatus testing and the liftoff test) were fully resolved, but the patient reported persistent pain, spasm, and sensation of tightness in his right posterior shoulder and arm with intermittent extension into forearm and hand. A review of the history reminded the patient of a wrestling episode that caused neck pain months earlier. The patient reported that his current symptoms began after the wrestling episode.

Physical examination at this time revealed pain in the right posterior arm with left lateral neck movement but no neck pain with right lateral neck movement or flexion and extension. There was again a normal motor and sensory examination in the C5-T1 nerve distribution. Of note, there was full painless abduction in the right shoulder, which had improved from the previous examination, and there was no pain with resisted supraspinatus testing or the liftoff test, both of which had been abnormal at the initial encounter.

Due to the patient’s persistent posterior shoulder pain and exacerbation of symptoms with neck movement and the now revealed antecedent event of neck trauma, a higher concern for cervical disc pathology was entertained. A cervical magnetic resonance imaging examination (MRI) was ordered. A moderately sized left paracentral herniation of the disk at C5-C6 was found. The disk herniation was compressing the left ventral hemi-cord with narrowing of the left neuronal foramina. Additionally, there was a mild posterior disc osteophyte complex that caused mild left foraminal narrowing at C6-C7.

Neurosurgical consultation was obtained. Extensive discussion of nonsurgical vs surgical options were conducted, and a trial of nonsurgical therapy was agreed on. Physical therapy with cervical traction was prescribed with 2 sessions a week for 4 weeks. The patient also continued his therapeutic rotator cuff and scapular stabilizing exercises and decreased the amount and intensity of his weight lifting.

At the next 4-week follow-up, his symptoms were greatly reduced. He was discharged from supervised physical therapy and continued his at-home neck and shoulder strengthening regimen. At the 1-year follow-up, the patient reported that the radiating pain had essentially resolved—only occasionally being present with heavy upper-extremity weight lifting or grappling activities. He continues to be symptom free of his external impingement symptoms as well.

The final diagnosis was cervical radiculopathy of C5/6 nerve root due to left paracentral disc herniation with concomitant cord compression as well as external impingement (rotator cuff dysfunction) of the right shoulder. It is unclear whether the disc herniation contributed to the external shoulder impingement due to alterations in biomechanics or whether the 2 diseases were unrelated.

Discussion

The patient’s cervical disc herniation most likely was due to his earlier grappling episode when he had acute trauma to the neck or an exacerbation of an older asymptomatic herniation. His external shoulder impingement likely was due to overuse with heavy weight lifting, which also caused enough mechanical strain to exacerbate the patient’s cervical disc herniation symptoms. What is most unusual about this case is the right-sided cervical radicular symptoms due to a left-sided cervical disc herniation.

With an annual incidence of 107.3 in men and 63.5 in women per 100,000 patients, cervical radiculopathy is caused by compression or irritation of the cervical nerve roots as they exit the spine. The most common cause of cervical radiculopathy is spondylosis followed by disc herniation, but both can be present in the same patient. Spondylosis refers to degeneration of the discs and facet joints but generally without frank disc herniation.5

External shoulder impingement and cervical radiculopathy can have nearly identical symptoms of shoulder and upper arm pain as in this illustrated case. Patients with cervical radiculopathy generally present with neck, shoulder, and arm pain or neurologic deficits. These symptoms alone are very broad and present a wide differential diagnosis. One must determine whether the pain is from the neck or shoulder region.1 The Table and Figures 1 to 6 describe the physical examination maneuvers used to differentiate the etiology.

The decision to pursue imaging should be based on injury severity and patient treatment goals. Although plain radiographic imaging may reveal spondylotic changes, such as degenerative joint changes at the vertebral facets and uncovertebral joints as well as decreased disc space, MRI is the imaging modality of choice for viewing disc herniations.6Nonoperative management of cervical radiculopathy focuses on restoration of full pain-free neck ROM, cervical muscle strengthening, and consideration for cervical traction. The use of either topical or oral medications can be considered if needed to aid in sleep and/or participation in active rehabilitation. Complimentary methods, such as acupuncture, yoga, or therapeutic massage also should be considered. Additionally, corticosteroid epidural injections can be considered, but these have increased risk compared with lumbar epidural injections.7 Surgical indications include persistent symptoms after 6 to 12 weeks of conservative therapy with no improvement of symptoms or progressively worsening motor/neurologic deficits.8

Conclusion

This case illustrates how 2 different conditions can present similarly and lead to diagnostic uncertainty. In this case, both the shoulder impingement and cervical radiculopathy manifested as shoulder and upper arm pain and could be separated only once the impingement had been treated. In addition the left-sided disc herniation causing right-sided symptoms was very unusual. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is only the second report of cervical disc herniation causing contralateral symptoms. In the only other available case report on cervical disc herniation with contralateral symptoms, the symptoms occurred in both the contralateral arm and leg.9

Neck and shoulder pain are common presenting symptoms in the general adult population with a 41.7% and 50.9% lifetime incidence in males and females, respectively.1 Generally, a single diagnosis is sought to explain a patient’s signs and symptoms, but occasionally 2 or more different causes are responsible. Only by conducting a thorough history and physical examination with proper follow-up will all contributing diseases be discovered. The following case illustrates 2 distinct etiologies responsible for the patient’s pain, one with an extremely unusual presentation.

Case Presentation

A 23-year-old male presented with a 3-month history of pain, spasm, and tightness of his right upper extremity along his posterior neck, shoulder, and triceps area. The patient reported no history of trauma, but he revealed increasing the amount of weight lifting, and his symptoms were especially worse when bench pressing or performing overhead exercises. No paresthesias were reported.

The initial examination revealed a well-developed muscular male with no visible atrophy or tenderness to palpation. He had full range of motion (ROM) of his neck, a normal motor and sensory examination of the C5-T1 nerve roots, and a negative Spurling maneuver. The patient had full ROM of both shoulders but had pain with right shoulder abduction starting at about 120° to 140°. He had pain with resisted supraspinatus muscle testing as well as pain with the liftoff test. The results of the patient’s Hawkins and Neer tests were negative (Table, Figures 1 to 6).2-4 A point-of-care shoulder ultrasound examination revealed no abnormalities.

The working diagnosis was external shoulder impingement with a differential diagnosis of internal impingement and/or cervical radiculopathy. A diagnostic/therapeutic injection of 40 mg of triamcinolone and 4 mL of 1% xylocaine without epinephrine was administered into the right subacromial bursa. The patient experienced immediate and complete relief of pain with repeat shoulder abduction, supraspinatus muscle testing, and the liftoff test. Although this procedure temporarily relieved the pain with movement, a sensation of tightness, pain, and spasm in the posterior shoulder and right posterior arm was still present. The patient was asked to perform therapeutic rotator cuff and scapular strengthening exercises, annotated on a patient information handout, for 15 minutes a day, every other day and to follow-up in 4 weeks.

At follow-up the external impingement symptoms (pain with shoulder abduction, resisted supraspinatus testing and the liftoff test) were fully resolved, but the patient reported persistent pain, spasm, and sensation of tightness in his right posterior shoulder and arm with intermittent extension into forearm and hand. A review of the history reminded the patient of a wrestling episode that caused neck pain months earlier. The patient reported that his current symptoms began after the wrestling episode.

Physical examination at this time revealed pain in the right posterior arm with left lateral neck movement but no neck pain with right lateral neck movement or flexion and extension. There was again a normal motor and sensory examination in the C5-T1 nerve distribution. Of note, there was full painless abduction in the right shoulder, which had improved from the previous examination, and there was no pain with resisted supraspinatus testing or the liftoff test, both of which had been abnormal at the initial encounter.

Due to the patient’s persistent posterior shoulder pain and exacerbation of symptoms with neck movement and the now revealed antecedent event of neck trauma, a higher concern for cervical disc pathology was entertained. A cervical magnetic resonance imaging examination (MRI) was ordered. A moderately sized left paracentral herniation of the disk at C5-C6 was found. The disk herniation was compressing the left ventral hemi-cord with narrowing of the left neuronal foramina. Additionally, there was a mild posterior disc osteophyte complex that caused mild left foraminal narrowing at C6-C7.

Neurosurgical consultation was obtained. Extensive discussion of nonsurgical vs surgical options were conducted, and a trial of nonsurgical therapy was agreed on. Physical therapy with cervical traction was prescribed with 2 sessions a week for 4 weeks. The patient also continued his therapeutic rotator cuff and scapular stabilizing exercises and decreased the amount and intensity of his weight lifting.

At the next 4-week follow-up, his symptoms were greatly reduced. He was discharged from supervised physical therapy and continued his at-home neck and shoulder strengthening regimen. At the 1-year follow-up, the patient reported that the radiating pain had essentially resolved—only occasionally being present with heavy upper-extremity weight lifting or grappling activities. He continues to be symptom free of his external impingement symptoms as well.

The final diagnosis was cervical radiculopathy of C5/6 nerve root due to left paracentral disc herniation with concomitant cord compression as well as external impingement (rotator cuff dysfunction) of the right shoulder. It is unclear whether the disc herniation contributed to the external shoulder impingement due to alterations in biomechanics or whether the 2 diseases were unrelated.

Discussion

The patient’s cervical disc herniation most likely was due to his earlier grappling episode when he had acute trauma to the neck or an exacerbation of an older asymptomatic herniation. His external shoulder impingement likely was due to overuse with heavy weight lifting, which also caused enough mechanical strain to exacerbate the patient’s cervical disc herniation symptoms. What is most unusual about this case is the right-sided cervical radicular symptoms due to a left-sided cervical disc herniation.

With an annual incidence of 107.3 in men and 63.5 in women per 100,000 patients, cervical radiculopathy is caused by compression or irritation of the cervical nerve roots as they exit the spine. The most common cause of cervical radiculopathy is spondylosis followed by disc herniation, but both can be present in the same patient. Spondylosis refers to degeneration of the discs and facet joints but generally without frank disc herniation.5

External shoulder impingement and cervical radiculopathy can have nearly identical symptoms of shoulder and upper arm pain as in this illustrated case. Patients with cervical radiculopathy generally present with neck, shoulder, and arm pain or neurologic deficits. These symptoms alone are very broad and present a wide differential diagnosis. One must determine whether the pain is from the neck or shoulder region.1 The Table and Figures 1 to 6 describe the physical examination maneuvers used to differentiate the etiology.

The decision to pursue imaging should be based on injury severity and patient treatment goals. Although plain radiographic imaging may reveal spondylotic changes, such as degenerative joint changes at the vertebral facets and uncovertebral joints as well as decreased disc space, MRI is the imaging modality of choice for viewing disc herniations.6Nonoperative management of cervical radiculopathy focuses on restoration of full pain-free neck ROM, cervical muscle strengthening, and consideration for cervical traction. The use of either topical or oral medications can be considered if needed to aid in sleep and/or participation in active rehabilitation. Complimentary methods, such as acupuncture, yoga, or therapeutic massage also should be considered. Additionally, corticosteroid epidural injections can be considered, but these have increased risk compared with lumbar epidural injections.7 Surgical indications include persistent symptoms after 6 to 12 weeks of conservative therapy with no improvement of symptoms or progressively worsening motor/neurologic deficits.8

Conclusion

This case illustrates how 2 different conditions can present similarly and lead to diagnostic uncertainty. In this case, both the shoulder impingement and cervical radiculopathy manifested as shoulder and upper arm pain and could be separated only once the impingement had been treated. In addition the left-sided disc herniation causing right-sided symptoms was very unusual. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is only the second report of cervical disc herniation causing contralateral symptoms. In the only other available case report on cervical disc herniation with contralateral symptoms, the symptoms occurred in both the contralateral arm and leg.9

1. Briggs AM, Straker LM, Bear NL, Smith AJ. Neck/shoulder pain in adolescents is not related to the level or nature of self-reported physical activity or type of sedentary activity in an Australian pregnancy cohort. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10(1):87.

2. Hermans J, Luime JJ, Meuffels DE, Reijman M, Simel DL, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Does this patient with shoulder pain have rotator cuff disease? JAMA. 2013;310(8):837-847.

3. Rubinstein SM, Pool JJ, van Tulder MW, Riphagen I, Riphagen II, de Vet HC. A systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of provocative tests of the neck for diagnosing cervical radiculopathy. Eur Spine J. 2007;16(3):307-319.

4. Ghasemi M, Golabchi K, Mousavi SA, et al. The value of provocative tests in diagnosis of cervical radiculopathy. J Res Med Sci. 2013;18(suppl 1):S35-S38.

5. Woods BI, Hilibrand AS. Cervical radiculopathy: epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2015;28(5):E251-E259.

6. Green C, Butler J, Eustace S, Poynton A, O’Byrne JM. Imaging modalities for cervical spondylotic stenosis and myelopathy. Adv Orthop. 2012;2012:908324. [Epub July 20, 2011].

7. Childress MA, Beckers BA. Nonoperative management of cervical radiculopathy. Am Fam Physician. 2016;93(9):746-754.

8. Carette S, Fehlings MG. Clinical practice. Cervical radiculopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(4):392-399.

9. Yeung JT, Johnson JI, Karim AS. Cervical disc herniation presenting with neck pain and contralateral symptoms: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:166.

1. Briggs AM, Straker LM, Bear NL, Smith AJ. Neck/shoulder pain in adolescents is not related to the level or nature of self-reported physical activity or type of sedentary activity in an Australian pregnancy cohort. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10(1):87.

2. Hermans J, Luime JJ, Meuffels DE, Reijman M, Simel DL, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Does this patient with shoulder pain have rotator cuff disease? JAMA. 2013;310(8):837-847.

3. Rubinstein SM, Pool JJ, van Tulder MW, Riphagen I, Riphagen II, de Vet HC. A systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of provocative tests of the neck for diagnosing cervical radiculopathy. Eur Spine J. 2007;16(3):307-319.

4. Ghasemi M, Golabchi K, Mousavi SA, et al. The value of provocative tests in diagnosis of cervical radiculopathy. J Res Med Sci. 2013;18(suppl 1):S35-S38.

5. Woods BI, Hilibrand AS. Cervical radiculopathy: epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2015;28(5):E251-E259.

6. Green C, Butler J, Eustace S, Poynton A, O’Byrne JM. Imaging modalities for cervical spondylotic stenosis and myelopathy. Adv Orthop. 2012;2012:908324. [Epub July 20, 2011].

7. Childress MA, Beckers BA. Nonoperative management of cervical radiculopathy. Am Fam Physician. 2016;93(9):746-754.

8. Carette S, Fehlings MG. Clinical practice. Cervical radiculopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(4):392-399.

9. Yeung JT, Johnson JI, Karim AS. Cervical disc herniation presenting with neck pain and contralateral symptoms: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:166.

Product approved to treat patients with hemophilia A and inhibitors

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved use of emicizumab-kxwh (Hemlibra®), a bispecific factor IXa- and factor X-directed antibody.

Emicizumab is approved as routine prophylaxis to prevent or reduce the frequency of bleeding episodes in adults and children who have hemophilia A and factor VIII (FVIII) inhibitors.

Emicizumab can be self-administered once-weekly via subcutaneous injection.

The labeling for emicizumab contains a boxed warning noting that patients who received emicizumab in conjunction with activated prothrombin complex concentrate developed thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) and thromboembolic events (TEs).

Therefore, patients should discontinue prophylactic use of bypassing agents (BPAs) the day before starting prophylaxis with emicizumab.

The FDA granted the approval of emicizumab to Genentech, Inc. The agency granted the application for emicizumab priority review, and the product received breakthrough therapy and orphan drug designations.

Access to emicizumab

According to Genentech, emicizumab will be available shortly.

The company said it will be offering comprehensive services to help minimize barriers to access and reimbursement. Patients can call 866-436-5427 (866-HEMLIBRA) for more information.

For people who qualify, Genentech plans to offer patient assistance programs through Genentech Access Solutions. More information is available at 866-422-2377 (866-4ACCESS) or http://www.Genentech-Access.com.

Emicizumab trials

The biologics license application for emicizumab was supported by results from a pair of phase 3 studies—HAVEN 1 and HAVEN 2.

Results from HAVEN 1 were published in NEJM and presented at the 26th ISTH Congress in July. Interim results from HAVEN 2 were presented at ISTH as well.

HAVEN 1

The study enrolled 109 patients (age 12 and older) with hemophilia A and FVIII inhibitors who were previously treated with BPAs on-demand or as prophylaxis.

The patients were randomized to receive emicizumab prophylaxis or no prophylaxis. On-demand treatment of breakthrough bleeds with BPAs was allowed.

There was a significant reduction in treated bleeds of 87% with emicizumab prophylaxis compared to no prophylaxis (95% CI: 72.3; 94.3, P<0.0001). And there was an 80% reduction in all bleeds with emicizumab (95% CI: 62.5; 89.8, P<0.0001).

Adverse events occurring in at least 5% of patients treated with emicizumab were local injection site reactions, headache, fatigue, upper respiratory tract infection, and arthralgia.

Two patients experienced TEs, and 3 had TMA while receiving emicizumab prophylaxis and more than 100 u/kg/day of activated prothrombin complex concentrate, on average, for 24 hours or more before the event. Two of these patients had also received recombinant factor VIIa.

Neither TE required anticoagulation therapy, and 1 patient restarted emicizumab. The cases of TMA observed were transient, and 1 patient restarted emicizumab.

HAVEN 2

In this single-arm trial, researchers evaluated emicizumab prophylaxis in children younger than 12 years of age who had hemophilia A with FVIII inhibitors.

The interim efficacy analysis, after at least 12 weeks of treatment, included 23 children.

After a median observation time of 38.1 weeks, 87% (95% CI: 66.4; 97.2) of children who received emicizumab experienced 0 treated bleeds. The percentage with 0 treated or non-treated bleeds was lower, at 34.8% (95% CI: 16.4; 57.3).

The most common adverse events (observed in at least 10% of patients) were mild injection site reactions and nasopharyngitis. No TEs or TMAs were observed.

HAVEN 3 and 4

Emicizumab is now being studied in 2 additional phase 3 trials.

In HAVEN 3, researchers are evaluating emicizumab prophylaxis dosed once weekly or once every other week in patients age 12 and older with hemophilia A without FVIII inhibitors.

In HAVEN 4, researchers are evaluating emicizumab prophylaxis dosed every 4 weeks in patients age 12 and older with hemophilia A, with or without inhibitors. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved use of emicizumab-kxwh (Hemlibra®), a bispecific factor IXa- and factor X-directed antibody.

Emicizumab is approved as routine prophylaxis to prevent or reduce the frequency of bleeding episodes in adults and children who have hemophilia A and factor VIII (FVIII) inhibitors.

Emicizumab can be self-administered once-weekly via subcutaneous injection.

The labeling for emicizumab contains a boxed warning noting that patients who received emicizumab in conjunction with activated prothrombin complex concentrate developed thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) and thromboembolic events (TEs).

Therefore, patients should discontinue prophylactic use of bypassing agents (BPAs) the day before starting prophylaxis with emicizumab.

The FDA granted the approval of emicizumab to Genentech, Inc. The agency granted the application for emicizumab priority review, and the product received breakthrough therapy and orphan drug designations.

Access to emicizumab

According to Genentech, emicizumab will be available shortly.

The company said it will be offering comprehensive services to help minimize barriers to access and reimbursement. Patients can call 866-436-5427 (866-HEMLIBRA) for more information.

For people who qualify, Genentech plans to offer patient assistance programs through Genentech Access Solutions. More information is available at 866-422-2377 (866-4ACCESS) or http://www.Genentech-Access.com.

Emicizumab trials

The biologics license application for emicizumab was supported by results from a pair of phase 3 studies—HAVEN 1 and HAVEN 2.

Results from HAVEN 1 were published in NEJM and presented at the 26th ISTH Congress in July. Interim results from HAVEN 2 were presented at ISTH as well.

HAVEN 1

The study enrolled 109 patients (age 12 and older) with hemophilia A and FVIII inhibitors who were previously treated with BPAs on-demand or as prophylaxis.

The patients were randomized to receive emicizumab prophylaxis or no prophylaxis. On-demand treatment of breakthrough bleeds with BPAs was allowed.

There was a significant reduction in treated bleeds of 87% with emicizumab prophylaxis compared to no prophylaxis (95% CI: 72.3; 94.3, P<0.0001). And there was an 80% reduction in all bleeds with emicizumab (95% CI: 62.5; 89.8, P<0.0001).

Adverse events occurring in at least 5% of patients treated with emicizumab were local injection site reactions, headache, fatigue, upper respiratory tract infection, and arthralgia.

Two patients experienced TEs, and 3 had TMA while receiving emicizumab prophylaxis and more than 100 u/kg/day of activated prothrombin complex concentrate, on average, for 24 hours or more before the event. Two of these patients had also received recombinant factor VIIa.

Neither TE required anticoagulation therapy, and 1 patient restarted emicizumab. The cases of TMA observed were transient, and 1 patient restarted emicizumab.

HAVEN 2

In this single-arm trial, researchers evaluated emicizumab prophylaxis in children younger than 12 years of age who had hemophilia A with FVIII inhibitors.

The interim efficacy analysis, after at least 12 weeks of treatment, included 23 children.

After a median observation time of 38.1 weeks, 87% (95% CI: 66.4; 97.2) of children who received emicizumab experienced 0 treated bleeds. The percentage with 0 treated or non-treated bleeds was lower, at 34.8% (95% CI: 16.4; 57.3).

The most common adverse events (observed in at least 10% of patients) were mild injection site reactions and nasopharyngitis. No TEs or TMAs were observed.

HAVEN 3 and 4

Emicizumab is now being studied in 2 additional phase 3 trials.

In HAVEN 3, researchers are evaluating emicizumab prophylaxis dosed once weekly or once every other week in patients age 12 and older with hemophilia A without FVIII inhibitors.

In HAVEN 4, researchers are evaluating emicizumab prophylaxis dosed every 4 weeks in patients age 12 and older with hemophilia A, with or without inhibitors. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved use of emicizumab-kxwh (Hemlibra®), a bispecific factor IXa- and factor X-directed antibody.

Emicizumab is approved as routine prophylaxis to prevent or reduce the frequency of bleeding episodes in adults and children who have hemophilia A and factor VIII (FVIII) inhibitors.

Emicizumab can be self-administered once-weekly via subcutaneous injection.

The labeling for emicizumab contains a boxed warning noting that patients who received emicizumab in conjunction with activated prothrombin complex concentrate developed thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) and thromboembolic events (TEs).

Therefore, patients should discontinue prophylactic use of bypassing agents (BPAs) the day before starting prophylaxis with emicizumab.

The FDA granted the approval of emicizumab to Genentech, Inc. The agency granted the application for emicizumab priority review, and the product received breakthrough therapy and orphan drug designations.

Access to emicizumab

According to Genentech, emicizumab will be available shortly.

The company said it will be offering comprehensive services to help minimize barriers to access and reimbursement. Patients can call 866-436-5427 (866-HEMLIBRA) for more information.

For people who qualify, Genentech plans to offer patient assistance programs through Genentech Access Solutions. More information is available at 866-422-2377 (866-4ACCESS) or http://www.Genentech-Access.com.

Emicizumab trials

The biologics license application for emicizumab was supported by results from a pair of phase 3 studies—HAVEN 1 and HAVEN 2.

Results from HAVEN 1 were published in NEJM and presented at the 26th ISTH Congress in July. Interim results from HAVEN 2 were presented at ISTH as well.

HAVEN 1

The study enrolled 109 patients (age 12 and older) with hemophilia A and FVIII inhibitors who were previously treated with BPAs on-demand or as prophylaxis.

The patients were randomized to receive emicizumab prophylaxis or no prophylaxis. On-demand treatment of breakthrough bleeds with BPAs was allowed.

There was a significant reduction in treated bleeds of 87% with emicizumab prophylaxis compared to no prophylaxis (95% CI: 72.3; 94.3, P<0.0001). And there was an 80% reduction in all bleeds with emicizumab (95% CI: 62.5; 89.8, P<0.0001).

Adverse events occurring in at least 5% of patients treated with emicizumab were local injection site reactions, headache, fatigue, upper respiratory tract infection, and arthralgia.

Two patients experienced TEs, and 3 had TMA while receiving emicizumab prophylaxis and more than 100 u/kg/day of activated prothrombin complex concentrate, on average, for 24 hours or more before the event. Two of these patients had also received recombinant factor VIIa.

Neither TE required anticoagulation therapy, and 1 patient restarted emicizumab. The cases of TMA observed were transient, and 1 patient restarted emicizumab.

HAVEN 2

In this single-arm trial, researchers evaluated emicizumab prophylaxis in children younger than 12 years of age who had hemophilia A with FVIII inhibitors.

The interim efficacy analysis, after at least 12 weeks of treatment, included 23 children.

After a median observation time of 38.1 weeks, 87% (95% CI: 66.4; 97.2) of children who received emicizumab experienced 0 treated bleeds. The percentage with 0 treated or non-treated bleeds was lower, at 34.8% (95% CI: 16.4; 57.3).

The most common adverse events (observed in at least 10% of patients) were mild injection site reactions and nasopharyngitis. No TEs or TMAs were observed.

HAVEN 3 and 4

Emicizumab is now being studied in 2 additional phase 3 trials.

In HAVEN 3, researchers are evaluating emicizumab prophylaxis dosed once weekly or once every other week in patients age 12 and older with hemophilia A without FVIII inhibitors.

In HAVEN 4, researchers are evaluating emicizumab prophylaxis dosed every 4 weeks in patients age 12 and older with hemophilia A, with or without inhibitors. ![]()

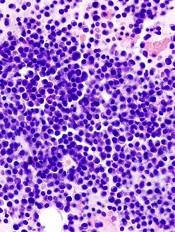

FDA expands approval of obinutuzumab

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the approved use of obinutuzumab (Gazyva®).

The drug is now approved for use in combination with chemotherapy to treat patients with previously untreated follicular lymphoma (FL) that is advanced (stage II bulky, stage III, or stage IV) .

In patients who respond to this treatment, obinutuzumab monotherapy can be given as maintenance.

The FDA granted this new approval of obinutuzumab to Genentech, Inc. The application for obinutuzumab in this indication received priority review.

The latest FDA approval means obinutuzumab is available in the US for the following indications:

- In combination with chlorambucil to treat chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in adults who have not had previous CLL treatment

- In combination with bendamustine, followed by obinutuzumab alone, to treat FL in adults who did not respond to a rituximab-containing regimen or whose FL returned after such treatment

- In combination with chemotherapy, followed by obinutuzumab alone in responders, to treat stage II bulky, stage III, or stage IV FL in adults who have not had previous FL treatment.

Phase 3 results

The latest approval of obinutuzumab is based on results from the phase 3 GALLIUM study, which were presented at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting and published in NEJM in October.

The following are updated data from the obinutuzumab prescribing information.

GALLIUM included 1385 patients with previously untreated non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and 1202 of these patients had advanced FL.

Half of the FL patients (n=601) were randomized to receive obinutuzumab plus chemotherapy (followed by obinutuzumab maintenance for up to 2 years), and half were randomized to rituximab plus chemotherapy (followed by rituximab maintenance for up to 2 years).

The different chemotherapies used were CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone), CVP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisolone), and bendamustine.

At a median observation time of 38 months, the overall response rate was 91% in the obinutuzumab arm and 88% in the rituximab arm. The complete response rates were 28% and 27%, respectively.

The median progression-free survival was not reached in either arm. The hazard ratio, for obinutuzumab compared to rituximab, was 0.72 (95% CI, 0.56-0.93, P=0.0118).

Safety was evaluated based on all 1385 patients in the study, 86% of whom had previously untreated FL and 14% of whom had marginal zone lymphoma.

Serious adverse events (AEs) occurred in 50% of patients in the obinutuzumab arm and 43% in the rituximab arm. Fatal AEs occurred in 5% and 4%, respectively. Infections and second malignancies were the leading causes of these deaths.

The most common AEs (incidence ≥ 20%) observed at least 2% more patients in the obinutuzumab arm were infusion-related reactions, neutropenia, upper respiratory tract infection, cough, constipation, and diarrhea.

The most common grade 3 to 5 AEs (incidence ≥ 5%) observed more frequently in the obinutuzumab arm were neutropenia, infusion-related reactions, febrile neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the approved use of obinutuzumab (Gazyva®).

The drug is now approved for use in combination with chemotherapy to treat patients with previously untreated follicular lymphoma (FL) that is advanced (stage II bulky, stage III, or stage IV) .

In patients who respond to this treatment, obinutuzumab monotherapy can be given as maintenance.

The FDA granted this new approval of obinutuzumab to Genentech, Inc. The application for obinutuzumab in this indication received priority review.

The latest FDA approval means obinutuzumab is available in the US for the following indications:

- In combination with chlorambucil to treat chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in adults who have not had previous CLL treatment

- In combination with bendamustine, followed by obinutuzumab alone, to treat FL in adults who did not respond to a rituximab-containing regimen or whose FL returned after such treatment

- In combination with chemotherapy, followed by obinutuzumab alone in responders, to treat stage II bulky, stage III, or stage IV FL in adults who have not had previous FL treatment.

Phase 3 results

The latest approval of obinutuzumab is based on results from the phase 3 GALLIUM study, which were presented at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting and published in NEJM in October.

The following are updated data from the obinutuzumab prescribing information.

GALLIUM included 1385 patients with previously untreated non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and 1202 of these patients had advanced FL.

Half of the FL patients (n=601) were randomized to receive obinutuzumab plus chemotherapy (followed by obinutuzumab maintenance for up to 2 years), and half were randomized to rituximab plus chemotherapy (followed by rituximab maintenance for up to 2 years).

The different chemotherapies used were CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone), CVP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisolone), and bendamustine.

At a median observation time of 38 months, the overall response rate was 91% in the obinutuzumab arm and 88% in the rituximab arm. The complete response rates were 28% and 27%, respectively.

The median progression-free survival was not reached in either arm. The hazard ratio, for obinutuzumab compared to rituximab, was 0.72 (95% CI, 0.56-0.93, P=0.0118).

Safety was evaluated based on all 1385 patients in the study, 86% of whom had previously untreated FL and 14% of whom had marginal zone lymphoma.

Serious adverse events (AEs) occurred in 50% of patients in the obinutuzumab arm and 43% in the rituximab arm. Fatal AEs occurred in 5% and 4%, respectively. Infections and second malignancies were the leading causes of these deaths.

The most common AEs (incidence ≥ 20%) observed at least 2% more patients in the obinutuzumab arm were infusion-related reactions, neutropenia, upper respiratory tract infection, cough, constipation, and diarrhea.

The most common grade 3 to 5 AEs (incidence ≥ 5%) observed more frequently in the obinutuzumab arm were neutropenia, infusion-related reactions, febrile neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the approved use of obinutuzumab (Gazyva®).

The drug is now approved for use in combination with chemotherapy to treat patients with previously untreated follicular lymphoma (FL) that is advanced (stage II bulky, stage III, or stage IV) .

In patients who respond to this treatment, obinutuzumab monotherapy can be given as maintenance.

The FDA granted this new approval of obinutuzumab to Genentech, Inc. The application for obinutuzumab in this indication received priority review.

The latest FDA approval means obinutuzumab is available in the US for the following indications:

- In combination with chlorambucil to treat chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in adults who have not had previous CLL treatment

- In combination with bendamustine, followed by obinutuzumab alone, to treat FL in adults who did not respond to a rituximab-containing regimen or whose FL returned after such treatment

- In combination with chemotherapy, followed by obinutuzumab alone in responders, to treat stage II bulky, stage III, or stage IV FL in adults who have not had previous FL treatment.

Phase 3 results

The latest approval of obinutuzumab is based on results from the phase 3 GALLIUM study, which were presented at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting and published in NEJM in October.

The following are updated data from the obinutuzumab prescribing information.

GALLIUM included 1385 patients with previously untreated non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and 1202 of these patients had advanced FL.

Half of the FL patients (n=601) were randomized to receive obinutuzumab plus chemotherapy (followed by obinutuzumab maintenance for up to 2 years), and half were randomized to rituximab plus chemotherapy (followed by rituximab maintenance for up to 2 years).

The different chemotherapies used were CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone), CVP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisolone), and bendamustine.

At a median observation time of 38 months, the overall response rate was 91% in the obinutuzumab arm and 88% in the rituximab arm. The complete response rates were 28% and 27%, respectively.

The median progression-free survival was not reached in either arm. The hazard ratio, for obinutuzumab compared to rituximab, was 0.72 (95% CI, 0.56-0.93, P=0.0118).

Safety was evaluated based on all 1385 patients in the study, 86% of whom had previously untreated FL and 14% of whom had marginal zone lymphoma.

Serious adverse events (AEs) occurred in 50% of patients in the obinutuzumab arm and 43% in the rituximab arm. Fatal AEs occurred in 5% and 4%, respectively. Infections and second malignancies were the leading causes of these deaths.

The most common AEs (incidence ≥ 20%) observed at least 2% more patients in the obinutuzumab arm were infusion-related reactions, neutropenia, upper respiratory tract infection, cough, constipation, and diarrhea.

The most common grade 3 to 5 AEs (incidence ≥ 5%) observed more frequently in the obinutuzumab arm were neutropenia, infusion-related reactions, febrile neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia. ![]()

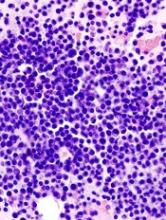

CAR T-cell therapy on fast track with FDA, EMA

A chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, bb2121, has received breakthrough therapy designation from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and was granted access to the European Medicines Agency’s (EMA’s) PRIority MEdicines (PRIME) program.

The CAR T-cell therapy is designed to target B-cell maturation antigen in previously treated patients with multiple myeloma.

bb2121 is being developed by bluebird bio, Inc., and Celgene Corporation.

The EMA’s and FDA’s decisions on bb2121 were based on preliminary data from an ongoing phase 1 study, CRB-401 (NCT02658929).

Results from this study were presented at the 2017 ASCO Annual Meeting (abstract 3010).

The study enrolled patients with relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma. As of the May 4, 2017 data cut-off, 21 patients had been enrolled.

Patients had a median of 7 prior lines of therapy (range, 3-14). Their previous treatments included lenalidomide and bortezomib (100%), pomalidomide and carfilzomib (91%), daratumumab (71%), and autologous stem cell transplant (100% at least once).

Twenty-nine percent of patients were refractory to bortezomib, lenalidomide, carfilzomib, pomalidomide, and daratumumab.

Patients received a conditioning regimen of cyclophosphamide and fludarabine, followed by an infusion of bb2121 at 1 of 4 doses: 50 x 106, 150 x 106, 450 x 106 and 800 x 106 CAR+ T cells.

All 21 patients were evaluable for safety.

The most common treatment-emergent grade 3-4 adverse events were cytopenias commonly associated with the lymphodepletion regimen, as well as grade 3 events of hyponatremia (n=4), upper respiratory infection (n=2), syncope (n=2), and cytokine release syndrome (CRS, n=2).

In all, 71% of patients (15/21) had CRS, mostly grade 1 and 2. For the 2 patients with grade 3 CRS, it resolved within 24 hours. To manage CRS, 4 patients received tocilizumab, and 1 (with grade 2) received steroids as well.

Eighteen patients were evaluable for efficacy, and the overall response rate was 89% (16/18).

There were 4 complete responses—2 in the 150 x 106 cohort, 1 in the 450 x 106 cohort, and 1 in the 800 x 106 cohort. The complete responder in the 450 x 106 cohort ultimately died of cardiopulmonary arrest that was deemed unrelated to treatment.

Five patients had a partial response—2 in the 450 x 106 cohort and 1 in each of the other cohorts. Seven patients had a very good partial response—5 in the 450 x 106 cohort and 1 each in the 150 x 106 cohort and 800 x 106 cohort.

Updated data from this study are scheduled to be presented at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 740).

About breakthrough designation

The FDA’s breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new treatments for serious or life-threatening conditions.

The designation entitles the company developing a therapy to more intensive FDA guidance on an efficient and accelerated development program, as well as eligibility for other actions to expedite FDA review, such as rolling submission and priority review.

To earn breakthrough designation, a treatment must show encouraging early clinical results demonstrating substantial improvement over available therapies with regard to a clinically significant endpoint, or it must fulfill an unmet need.

About PRIME

The EMA launched its PRIME program to enhance support for the development of medicines that target an unmet medical need.

The program involves enhanced interaction and early dialogue with developers of promising medicines to optimize development plans and speed up evaluation so these medicines can reach patients earlier.

PRIME focuses on medicines that may offer a major therapeutic advantage over existing treatments or benefit patients without treatment options. To be accepted for PRIME, a medicine must have demonstrated the potential to benefit patients with unmet medical needs based on early clinical data. ![]()

A chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, bb2121, has received breakthrough therapy designation from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and was granted access to the European Medicines Agency’s (EMA’s) PRIority MEdicines (PRIME) program.

The CAR T-cell therapy is designed to target B-cell maturation antigen in previously treated patients with multiple myeloma.

bb2121 is being developed by bluebird bio, Inc., and Celgene Corporation.

The EMA’s and FDA’s decisions on bb2121 were based on preliminary data from an ongoing phase 1 study, CRB-401 (NCT02658929).

Results from this study were presented at the 2017 ASCO Annual Meeting (abstract 3010).

The study enrolled patients with relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma. As of the May 4, 2017 data cut-off, 21 patients had been enrolled.

Patients had a median of 7 prior lines of therapy (range, 3-14). Their previous treatments included lenalidomide and bortezomib (100%), pomalidomide and carfilzomib (91%), daratumumab (71%), and autologous stem cell transplant (100% at least once).

Twenty-nine percent of patients were refractory to bortezomib, lenalidomide, carfilzomib, pomalidomide, and daratumumab.

Patients received a conditioning regimen of cyclophosphamide and fludarabine, followed by an infusion of bb2121 at 1 of 4 doses: 50 x 106, 150 x 106, 450 x 106 and 800 x 106 CAR+ T cells.

All 21 patients were evaluable for safety.

The most common treatment-emergent grade 3-4 adverse events were cytopenias commonly associated with the lymphodepletion regimen, as well as grade 3 events of hyponatremia (n=4), upper respiratory infection (n=2), syncope (n=2), and cytokine release syndrome (CRS, n=2).

In all, 71% of patients (15/21) had CRS, mostly grade 1 and 2. For the 2 patients with grade 3 CRS, it resolved within 24 hours. To manage CRS, 4 patients received tocilizumab, and 1 (with grade 2) received steroids as well.

Eighteen patients were evaluable for efficacy, and the overall response rate was 89% (16/18).

There were 4 complete responses—2 in the 150 x 106 cohort, 1 in the 450 x 106 cohort, and 1 in the 800 x 106 cohort. The complete responder in the 450 x 106 cohort ultimately died of cardiopulmonary arrest that was deemed unrelated to treatment.

Five patients had a partial response—2 in the 450 x 106 cohort and 1 in each of the other cohorts. Seven patients had a very good partial response—5 in the 450 x 106 cohort and 1 each in the 150 x 106 cohort and 800 x 106 cohort.

Updated data from this study are scheduled to be presented at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 740).

About breakthrough designation

The FDA’s breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new treatments for serious or life-threatening conditions.

The designation entitles the company developing a therapy to more intensive FDA guidance on an efficient and accelerated development program, as well as eligibility for other actions to expedite FDA review, such as rolling submission and priority review.

To earn breakthrough designation, a treatment must show encouraging early clinical results demonstrating substantial improvement over available therapies with regard to a clinically significant endpoint, or it must fulfill an unmet need.

About PRIME

The EMA launched its PRIME program to enhance support for the development of medicines that target an unmet medical need.

The program involves enhanced interaction and early dialogue with developers of promising medicines to optimize development plans and speed up evaluation so these medicines can reach patients earlier.

PRIME focuses on medicines that may offer a major therapeutic advantage over existing treatments or benefit patients without treatment options. To be accepted for PRIME, a medicine must have demonstrated the potential to benefit patients with unmet medical needs based on early clinical data. ![]()

A chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, bb2121, has received breakthrough therapy designation from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and was granted access to the European Medicines Agency’s (EMA’s) PRIority MEdicines (PRIME) program.

The CAR T-cell therapy is designed to target B-cell maturation antigen in previously treated patients with multiple myeloma.

bb2121 is being developed by bluebird bio, Inc., and Celgene Corporation.

The EMA’s and FDA’s decisions on bb2121 were based on preliminary data from an ongoing phase 1 study, CRB-401 (NCT02658929).

Results from this study were presented at the 2017 ASCO Annual Meeting (abstract 3010).

The study enrolled patients with relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma. As of the May 4, 2017 data cut-off, 21 patients had been enrolled.

Patients had a median of 7 prior lines of therapy (range, 3-14). Their previous treatments included lenalidomide and bortezomib (100%), pomalidomide and carfilzomib (91%), daratumumab (71%), and autologous stem cell transplant (100% at least once).

Twenty-nine percent of patients were refractory to bortezomib, lenalidomide, carfilzomib, pomalidomide, and daratumumab.

Patients received a conditioning regimen of cyclophosphamide and fludarabine, followed by an infusion of bb2121 at 1 of 4 doses: 50 x 106, 150 x 106, 450 x 106 and 800 x 106 CAR+ T cells.

All 21 patients were evaluable for safety.