User login

Few patients follow recommendation to use OTC benzoyl peroxide

Although benzoyl peroxide is a foundation of acne treatment, many patients are not following physician recommendations for its use, and its over-the-counter (OTC) availability may actually be a hindrance to adherence.

In a letter to the editor of the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, and Annie H. Huyler, of Penn State University, Hershey, reported the results of a telephone survey of 84 acne patients, aged 12-45 years. Fewer than a third (29%) recalled having received a recommendation for an OTC medication, and just 30% could recall that benzoyl peroxide (BP) was the recommended active ingredient (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Oct;77[4]:763-4).

Curious about whether acne patients actually followed their treatment plans when it came to OTC BP, they arranged to have patients surveyed by telephone. New patients aged 12-45 years with an acne diagnosis who had been recommended BP were eligible.

The series of 10 survey questions began with more open-ended questions and moved to more close-ended questions. Of the 64% of patients who did buy an OTC product, further questioning revealed that half (32%) had actually purchased a BP-containing product. A total of 15% of patients had instead bought a face wash containing salicylic acid, and 17% of the products purchased had no active ingredient.

By contrast, the telephone survey revealed that all but one patient (93%) had filled the prescription for acne medication.

Benzoyl peroxide, which used to be available either by prescription or over the counter, has been available exclusively over the counter since 2011.

“The results from this study confirm that patient adherence to dermatologist-recommended BP is low,” they wrote. “Furthermore, of those who remembered BP by name, many were unable to find the correct product and instead had purchased an item with the wrong ingredient or no active ingredient,” they added. The findings are in line with other studies showing that patients are less likely to be adherent to recommendations to use OTC medications than they are to fill prescriptions for and take prescription medications, Ms. Huyler and Dr. Zaenglein wrote.

“Better education, in-office dispensing of BP, or fixed-dose combination prescription products are possible solutions,” they said.

The authors noted that their findings were limited by the exclusion of non-English speaking patients and by the fact that they used a nonvalidated telephone survey.

Ms. Huyler is a medical student and Dr. Zaenglein is a professor of dermatology at Penn State; they reported no conflicts of interest. The study had no external sources of funding.

Although benzoyl peroxide is a foundation of acne treatment, many patients are not following physician recommendations for its use, and its over-the-counter (OTC) availability may actually be a hindrance to adherence.

In a letter to the editor of the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, and Annie H. Huyler, of Penn State University, Hershey, reported the results of a telephone survey of 84 acne patients, aged 12-45 years. Fewer than a third (29%) recalled having received a recommendation for an OTC medication, and just 30% could recall that benzoyl peroxide (BP) was the recommended active ingredient (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Oct;77[4]:763-4).

Curious about whether acne patients actually followed their treatment plans when it came to OTC BP, they arranged to have patients surveyed by telephone. New patients aged 12-45 years with an acne diagnosis who had been recommended BP were eligible.

The series of 10 survey questions began with more open-ended questions and moved to more close-ended questions. Of the 64% of patients who did buy an OTC product, further questioning revealed that half (32%) had actually purchased a BP-containing product. A total of 15% of patients had instead bought a face wash containing salicylic acid, and 17% of the products purchased had no active ingredient.

By contrast, the telephone survey revealed that all but one patient (93%) had filled the prescription for acne medication.

Benzoyl peroxide, which used to be available either by prescription or over the counter, has been available exclusively over the counter since 2011.

“The results from this study confirm that patient adherence to dermatologist-recommended BP is low,” they wrote. “Furthermore, of those who remembered BP by name, many were unable to find the correct product and instead had purchased an item with the wrong ingredient or no active ingredient,” they added. The findings are in line with other studies showing that patients are less likely to be adherent to recommendations to use OTC medications than they are to fill prescriptions for and take prescription medications, Ms. Huyler and Dr. Zaenglein wrote.

“Better education, in-office dispensing of BP, or fixed-dose combination prescription products are possible solutions,” they said.

The authors noted that their findings were limited by the exclusion of non-English speaking patients and by the fact that they used a nonvalidated telephone survey.

Ms. Huyler is a medical student and Dr. Zaenglein is a professor of dermatology at Penn State; they reported no conflicts of interest. The study had no external sources of funding.

Although benzoyl peroxide is a foundation of acne treatment, many patients are not following physician recommendations for its use, and its over-the-counter (OTC) availability may actually be a hindrance to adherence.

In a letter to the editor of the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, and Annie H. Huyler, of Penn State University, Hershey, reported the results of a telephone survey of 84 acne patients, aged 12-45 years. Fewer than a third (29%) recalled having received a recommendation for an OTC medication, and just 30% could recall that benzoyl peroxide (BP) was the recommended active ingredient (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Oct;77[4]:763-4).

Curious about whether acne patients actually followed their treatment plans when it came to OTC BP, they arranged to have patients surveyed by telephone. New patients aged 12-45 years with an acne diagnosis who had been recommended BP were eligible.

The series of 10 survey questions began with more open-ended questions and moved to more close-ended questions. Of the 64% of patients who did buy an OTC product, further questioning revealed that half (32%) had actually purchased a BP-containing product. A total of 15% of patients had instead bought a face wash containing salicylic acid, and 17% of the products purchased had no active ingredient.

By contrast, the telephone survey revealed that all but one patient (93%) had filled the prescription for acne medication.

Benzoyl peroxide, which used to be available either by prescription or over the counter, has been available exclusively over the counter since 2011.

“The results from this study confirm that patient adherence to dermatologist-recommended BP is low,” they wrote. “Furthermore, of those who remembered BP by name, many were unable to find the correct product and instead had purchased an item with the wrong ingredient or no active ingredient,” they added. The findings are in line with other studies showing that patients are less likely to be adherent to recommendations to use OTC medications than they are to fill prescriptions for and take prescription medications, Ms. Huyler and Dr. Zaenglein wrote.

“Better education, in-office dispensing of BP, or fixed-dose combination prescription products are possible solutions,” they said.

The authors noted that their findings were limited by the exclusion of non-English speaking patients and by the fact that they used a nonvalidated telephone survey.

Ms. Huyler is a medical student and Dr. Zaenglein is a professor of dermatology at Penn State; they reported no conflicts of interest. The study had no external sources of funding.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: In a telephone interview, many acne patients said they had not obtained the recommended OTC benzoyl peroxide.

Major finding: Of the 64% of patients who had gotten an OTC acne medication, only 32% had purchased one containing benzoyl peroxide.

Study details: Single-center prospective study of 84 acne patients who received a physician recommendation for OTC benzoyl peroxide.

Disclosures: There was no funding source for the study, and the investigators had no conflicts of interest.

Combination ‘sets new standard’ for GVHD prophylaxis

A 2-drug combination sets a new standard for prevention of acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), according to an author of a new study.

The combination—sirolimus and KY1005—completely protected nonhuman primates from acute GVHD and significantly prolonged survival in the animals.

The combination controlled the expansion of effector T cells (Teffs) while augmenting the proportion of regulatory T cells (Tregs) in the primates’ bloodstreams, allowing transplanted stem cells to reconstitute the animals’ immune systems.

Researchers reported these results in Science Translational Medicine. The work was funded by Kymab, the company developing KY1005.

“KY1005, in combination with sirolimus, sets a new standard for [acute] GVHD prevention,” said study author Leslie Kean, MD, PhD, of Seattle Children’s Research Institute in Washington.

“These results in the complex and clinically relevant animal model suggest this regimen is an exceptional candidate for clinical translation.”

Dr Kean and her colleagues noted that no existing treatments for GVHD can successfully strike the delicate balance between controlling Teffs and maintaining the protective function of Tregs.

So the team decided to combine 2 treatments that partially suppress Teffs—sirolimus and KY1005, a monoclonal antibody that blocks a T-cell receptor ligand called OX40L.

The researchers tested the combination in rhesus macaques undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). The team compared the combination to each agent alone, as well as to no prophylaxis.

KY1005 was given at a dose of 10 mg/kg, starting 2 days before HSCT and continuing once weekly until planned discontinuation on day 54. Sirolimus was given daily for the entire study period as an intramuscular formulation, with doses adjusted to achieve a serum trough concentration of 5 to 15 ng/mL.

Animals treated with both sirolimus and KY1005 survived—free from GVHD—for more than 100 days after HSCT, which was significantly longer than any other group (P<0.01).

In comparison, untreated animals succumbed to GVHD within 8 days of HSCT. And the median GVHD-free survival times were 14 days for the sirolimus group and 19.5 days for the KY1005 group.

The researchers also noted that untreated animals experienced “a rapid decline” in Tregs over the study period. They had a significant decrease in the ratio of Tregs to conventional T cells (Tconv)—2.0 ± 0.4 before HSCT and 0.6 ± 0.1 at last analysis (P<0.001).

When given alone, both KY1005 and sirolimus protected animals from this drop in the Treg/Tconv ratio.

But the combination regimen significantly augmented the Treg/Tconv ratio—1.30 ± 0.30 before HSCT and 1.82 ± 0.43 at last analysis (P<0.05).

Because sirolimus is already used as GVHD prophylaxis and KY1005 is in phase 1 testing as a psoriasis treatment, the researchers believe the combination is a strong candidate for clinical testing. ![]()

A 2-drug combination sets a new standard for prevention of acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), according to an author of a new study.

The combination—sirolimus and KY1005—completely protected nonhuman primates from acute GVHD and significantly prolonged survival in the animals.

The combination controlled the expansion of effector T cells (Teffs) while augmenting the proportion of regulatory T cells (Tregs) in the primates’ bloodstreams, allowing transplanted stem cells to reconstitute the animals’ immune systems.

Researchers reported these results in Science Translational Medicine. The work was funded by Kymab, the company developing KY1005.

“KY1005, in combination with sirolimus, sets a new standard for [acute] GVHD prevention,” said study author Leslie Kean, MD, PhD, of Seattle Children’s Research Institute in Washington.

“These results in the complex and clinically relevant animal model suggest this regimen is an exceptional candidate for clinical translation.”

Dr Kean and her colleagues noted that no existing treatments for GVHD can successfully strike the delicate balance between controlling Teffs and maintaining the protective function of Tregs.

So the team decided to combine 2 treatments that partially suppress Teffs—sirolimus and KY1005, a monoclonal antibody that blocks a T-cell receptor ligand called OX40L.

The researchers tested the combination in rhesus macaques undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). The team compared the combination to each agent alone, as well as to no prophylaxis.

KY1005 was given at a dose of 10 mg/kg, starting 2 days before HSCT and continuing once weekly until planned discontinuation on day 54. Sirolimus was given daily for the entire study period as an intramuscular formulation, with doses adjusted to achieve a serum trough concentration of 5 to 15 ng/mL.

Animals treated with both sirolimus and KY1005 survived—free from GVHD—for more than 100 days after HSCT, which was significantly longer than any other group (P<0.01).

In comparison, untreated animals succumbed to GVHD within 8 days of HSCT. And the median GVHD-free survival times were 14 days for the sirolimus group and 19.5 days for the KY1005 group.

The researchers also noted that untreated animals experienced “a rapid decline” in Tregs over the study period. They had a significant decrease in the ratio of Tregs to conventional T cells (Tconv)—2.0 ± 0.4 before HSCT and 0.6 ± 0.1 at last analysis (P<0.001).

When given alone, both KY1005 and sirolimus protected animals from this drop in the Treg/Tconv ratio.

But the combination regimen significantly augmented the Treg/Tconv ratio—1.30 ± 0.30 before HSCT and 1.82 ± 0.43 at last analysis (P<0.05).

Because sirolimus is already used as GVHD prophylaxis and KY1005 is in phase 1 testing as a psoriasis treatment, the researchers believe the combination is a strong candidate for clinical testing. ![]()

A 2-drug combination sets a new standard for prevention of acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), according to an author of a new study.

The combination—sirolimus and KY1005—completely protected nonhuman primates from acute GVHD and significantly prolonged survival in the animals.

The combination controlled the expansion of effector T cells (Teffs) while augmenting the proportion of regulatory T cells (Tregs) in the primates’ bloodstreams, allowing transplanted stem cells to reconstitute the animals’ immune systems.

Researchers reported these results in Science Translational Medicine. The work was funded by Kymab, the company developing KY1005.

“KY1005, in combination with sirolimus, sets a new standard for [acute] GVHD prevention,” said study author Leslie Kean, MD, PhD, of Seattle Children’s Research Institute in Washington.

“These results in the complex and clinically relevant animal model suggest this regimen is an exceptional candidate for clinical translation.”

Dr Kean and her colleagues noted that no existing treatments for GVHD can successfully strike the delicate balance between controlling Teffs and maintaining the protective function of Tregs.

So the team decided to combine 2 treatments that partially suppress Teffs—sirolimus and KY1005, a monoclonal antibody that blocks a T-cell receptor ligand called OX40L.

The researchers tested the combination in rhesus macaques undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). The team compared the combination to each agent alone, as well as to no prophylaxis.

KY1005 was given at a dose of 10 mg/kg, starting 2 days before HSCT and continuing once weekly until planned discontinuation on day 54. Sirolimus was given daily for the entire study period as an intramuscular formulation, with doses adjusted to achieve a serum trough concentration of 5 to 15 ng/mL.

Animals treated with both sirolimus and KY1005 survived—free from GVHD—for more than 100 days after HSCT, which was significantly longer than any other group (P<0.01).

In comparison, untreated animals succumbed to GVHD within 8 days of HSCT. And the median GVHD-free survival times were 14 days for the sirolimus group and 19.5 days for the KY1005 group.

The researchers also noted that untreated animals experienced “a rapid decline” in Tregs over the study period. They had a significant decrease in the ratio of Tregs to conventional T cells (Tconv)—2.0 ± 0.4 before HSCT and 0.6 ± 0.1 at last analysis (P<0.001).

When given alone, both KY1005 and sirolimus protected animals from this drop in the Treg/Tconv ratio.

But the combination regimen significantly augmented the Treg/Tconv ratio—1.30 ± 0.30 before HSCT and 1.82 ± 0.43 at last analysis (P<0.05).

Because sirolimus is already used as GVHD prophylaxis and KY1005 is in phase 1 testing as a psoriasis treatment, the researchers believe the combination is a strong candidate for clinical testing. ![]()

SCD drug receives rare pediatric disease designation

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted rare pediatric disease designation to Altemia™ soft gelatin capsules for the treatment of children with sickle cell disease (SCD).

Altemia (formerly SC411) is being developed by Sancilio Pharmaceuticals Company, Inc. (SPCI) to treat SCD patients between the ages of 5 and 17 years.

Altemia consists of a mixture of fatty acids, primarily in the form of Ethyl Cervonate™ (a proprietary blend of docosahexaenoic acid and other omega-3 fatty acids), and surface active agents formulated using Advanced Lipid Technologies®.

According to SPCI, Advanced Lipid Technologies are proprietary formulation and manufacturing techniques used to create lipophilic drug products capable of increased bioavailability, avoidance of the first pass effect, and elimination of the food effects commonly associated with oral administration.

Altemia is designed to replenish the lipids destroyed by sickle hemoglobin. The product is intended to be taken once daily to reduce vaso-occlusive crises, anemia, organ damage, and other complications of SCD.

Altemia also has orphan drug designation from the FDA.

SPCI is currently conducting a phase 2 trial of Altemia. In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, researchers are evaluating the efficacy and safety of Altemia in pediatric patients with SCD.

The company plans to report top-line results from the study, known as the SCOT trial, early in the fourth quarter of this year.

About rare pediatric disease designation

Rare pediatric disease designation is granted to drugs that show promise to treat diseases affecting fewer than 200,000 patients in the US, primarily patients age 18 or younger.

The designation provides incentives to advance the development of drugs for rare disease, including access to the FDA’s expedited review and approval programs.

Under the FDA’s Rare Pediatric Disease Priority Review Voucher Program, if a drug with rare pediatric disease designation is approved, the drug’s developer may qualify for a voucher that can be redeemed to obtain priority review for any subsequent marketing application. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted rare pediatric disease designation to Altemia™ soft gelatin capsules for the treatment of children with sickle cell disease (SCD).

Altemia (formerly SC411) is being developed by Sancilio Pharmaceuticals Company, Inc. (SPCI) to treat SCD patients between the ages of 5 and 17 years.

Altemia consists of a mixture of fatty acids, primarily in the form of Ethyl Cervonate™ (a proprietary blend of docosahexaenoic acid and other omega-3 fatty acids), and surface active agents formulated using Advanced Lipid Technologies®.

According to SPCI, Advanced Lipid Technologies are proprietary formulation and manufacturing techniques used to create lipophilic drug products capable of increased bioavailability, avoidance of the first pass effect, and elimination of the food effects commonly associated with oral administration.

Altemia is designed to replenish the lipids destroyed by sickle hemoglobin. The product is intended to be taken once daily to reduce vaso-occlusive crises, anemia, organ damage, and other complications of SCD.

Altemia also has orphan drug designation from the FDA.

SPCI is currently conducting a phase 2 trial of Altemia. In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, researchers are evaluating the efficacy and safety of Altemia in pediatric patients with SCD.

The company plans to report top-line results from the study, known as the SCOT trial, early in the fourth quarter of this year.

About rare pediatric disease designation

Rare pediatric disease designation is granted to drugs that show promise to treat diseases affecting fewer than 200,000 patients in the US, primarily patients age 18 or younger.

The designation provides incentives to advance the development of drugs for rare disease, including access to the FDA’s expedited review and approval programs.

Under the FDA’s Rare Pediatric Disease Priority Review Voucher Program, if a drug with rare pediatric disease designation is approved, the drug’s developer may qualify for a voucher that can be redeemed to obtain priority review for any subsequent marketing application. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted rare pediatric disease designation to Altemia™ soft gelatin capsules for the treatment of children with sickle cell disease (SCD).

Altemia (formerly SC411) is being developed by Sancilio Pharmaceuticals Company, Inc. (SPCI) to treat SCD patients between the ages of 5 and 17 years.

Altemia consists of a mixture of fatty acids, primarily in the form of Ethyl Cervonate™ (a proprietary blend of docosahexaenoic acid and other omega-3 fatty acids), and surface active agents formulated using Advanced Lipid Technologies®.

According to SPCI, Advanced Lipid Technologies are proprietary formulation and manufacturing techniques used to create lipophilic drug products capable of increased bioavailability, avoidance of the first pass effect, and elimination of the food effects commonly associated with oral administration.

Altemia is designed to replenish the lipids destroyed by sickle hemoglobin. The product is intended to be taken once daily to reduce vaso-occlusive crises, anemia, organ damage, and other complications of SCD.

Altemia also has orphan drug designation from the FDA.

SPCI is currently conducting a phase 2 trial of Altemia. In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, researchers are evaluating the efficacy and safety of Altemia in pediatric patients with SCD.

The company plans to report top-line results from the study, known as the SCOT trial, early in the fourth quarter of this year.

About rare pediatric disease designation

Rare pediatric disease designation is granted to drugs that show promise to treat diseases affecting fewer than 200,000 patients in the US, primarily patients age 18 or younger.

The designation provides incentives to advance the development of drugs for rare disease, including access to the FDA’s expedited review and approval programs.

Under the FDA’s Rare Pediatric Disease Priority Review Voucher Program, if a drug with rare pediatric disease designation is approved, the drug’s developer may qualify for a voucher that can be redeemed to obtain priority review for any subsequent marketing application. ![]()

Antibiotic could help treat CML

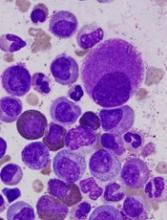

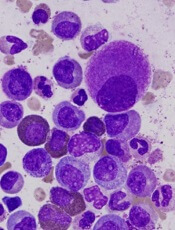

The antibiotic tigecycline may enhance the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), according to research published in Nature Medicine.

Using cells isolated from CML patients, researchers showed that treatment with tigecycline, an antibiotic used to treat bacterial infection, is effective in killing CML stem cells when used in combination with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) imatinib.

The study also suggested the combination can stave off relapse in animal models of CML.

“We were very excited to find that, when we treated CML cells with both the antibiotic tigecycline and the TKI drug imatinib, CML stem cells were selectively killed,” said study author Vignir Helgason, PhD, of the University of Glasgow in Scotland.

“We believe that our findings provide a strong basis for testing this novel therapeutic strategy in clinical trials in order to eliminate CML stem cells and provide cure for CML patients.”

The researchers said they found that, in primitive CML stem and progenitor cells, mitochondrial oxidative metabolism is crucial for the production of energy and anabolic precursors. This suggested that restraining mitochondrial functions might have a therapeutic benefit in CML.

The team knew that, in addition to inhibiting bacterial protein synthesis, tigecycline inhibits the synthesis of mitochondrion-encoded proteins, which are required for the oxidative phosphorylation machinery.

So the researchers tested tigecycline, alone or in combination with imatinib, in CML cells. Both treatments (tigecycline monotherapy and the combination) “strongly impaired” the proliferation of primary CD34+ CML cells.

However, imatinib alone had “a moderate effect.” The researchers said this is in line with the preferential effect of imatinib on differentiated CD34− cells.

Each drug alone decreased the number of short-term CML colony-forming cells (CFCs), and the combination eliminated colony formation entirely. This correlated with an increase in cell death.

Neither monotherapy nor the combination had a significant effect on non-leukemic CFCs.

The researchers then turned to a xenotransplantation model of human CML. Starting 6 weeks after transplant, mice received daily doses of vehicle, tigecycline (escalating doses of 25–100 mg per kg body weight), imatinib (100 mg per kg body weight), or both drugs. All treatment was given for 4 weeks.

The team said there were no signs of toxicity in any of the mice.

Compared to controls, tigecycline-treated mice had a marginal decrease in the total number of CML-derived CD45+ cells in the bone marrow, and imatinib-treated mice had a significant decrease in these cells. But the CML burden decreased even further with combination treatment.

The researchers noted that imatinib alone marginally decreased the number of CD45+CD34+CD38− CML cells, but combination treatment eliminated 95% of these cells.

Finally, the team tested each drug alone and in combination (as well as vehicle control) in additional cohorts of mice with CML. After receiving treatment for 4 weeks, mice were left untreated for either 2 weeks or 3 weeks.

Mice that received imatinib alone showed signs of relapse at 2 and 3 weeks, as they had similar numbers of leukemic cells as vehicle-treated mice. However, most of the mice treated with the combination had low numbers of leukemic stem cells in the bone marrow.

“Our work in this study demonstrates, for the first time, that CML stem cells are metabolically distinct from normal blood stem cells, and this, in turn, provides opportunities to selectively target them,” said study author Eyal Gottlieb, PhD, of the Cancer Research UK Beatson Institute in Glasgow.

“It’s exciting to see that using an antibiotic alongside an existing treatment could be a way to keep this type of leukemia at bay and potentially even cure it,” added Karen Vousden, PhD, Cancer Research UK’s chief scientist.

“If this approach is shown to be safe and effective in humans too, it could offer a new option for patients who, at the moment, face long-term treatment with the possibility of relapse.”

This research was funded by AstraZeneca, Cancer Research UK, The Medical Research Council, Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office, The Howat Foundation, Friends of the Paul O’Gorman Leukaemia Research Centre, Bloodwise, The Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund, Lady Tata International Award, and Leuka. ![]()

The antibiotic tigecycline may enhance the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), according to research published in Nature Medicine.

Using cells isolated from CML patients, researchers showed that treatment with tigecycline, an antibiotic used to treat bacterial infection, is effective in killing CML stem cells when used in combination with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) imatinib.

The study also suggested the combination can stave off relapse in animal models of CML.

“We were very excited to find that, when we treated CML cells with both the antibiotic tigecycline and the TKI drug imatinib, CML stem cells were selectively killed,” said study author Vignir Helgason, PhD, of the University of Glasgow in Scotland.

“We believe that our findings provide a strong basis for testing this novel therapeutic strategy in clinical trials in order to eliminate CML stem cells and provide cure for CML patients.”

The researchers said they found that, in primitive CML stem and progenitor cells, mitochondrial oxidative metabolism is crucial for the production of energy and anabolic precursors. This suggested that restraining mitochondrial functions might have a therapeutic benefit in CML.

The team knew that, in addition to inhibiting bacterial protein synthesis, tigecycline inhibits the synthesis of mitochondrion-encoded proteins, which are required for the oxidative phosphorylation machinery.

So the researchers tested tigecycline, alone or in combination with imatinib, in CML cells. Both treatments (tigecycline monotherapy and the combination) “strongly impaired” the proliferation of primary CD34+ CML cells.

However, imatinib alone had “a moderate effect.” The researchers said this is in line with the preferential effect of imatinib on differentiated CD34− cells.

Each drug alone decreased the number of short-term CML colony-forming cells (CFCs), and the combination eliminated colony formation entirely. This correlated with an increase in cell death.

Neither monotherapy nor the combination had a significant effect on non-leukemic CFCs.

The researchers then turned to a xenotransplantation model of human CML. Starting 6 weeks after transplant, mice received daily doses of vehicle, tigecycline (escalating doses of 25–100 mg per kg body weight), imatinib (100 mg per kg body weight), or both drugs. All treatment was given for 4 weeks.

The team said there were no signs of toxicity in any of the mice.

Compared to controls, tigecycline-treated mice had a marginal decrease in the total number of CML-derived CD45+ cells in the bone marrow, and imatinib-treated mice had a significant decrease in these cells. But the CML burden decreased even further with combination treatment.

The researchers noted that imatinib alone marginally decreased the number of CD45+CD34+CD38− CML cells, but combination treatment eliminated 95% of these cells.

Finally, the team tested each drug alone and in combination (as well as vehicle control) in additional cohorts of mice with CML. After receiving treatment for 4 weeks, mice were left untreated for either 2 weeks or 3 weeks.

Mice that received imatinib alone showed signs of relapse at 2 and 3 weeks, as they had similar numbers of leukemic cells as vehicle-treated mice. However, most of the mice treated with the combination had low numbers of leukemic stem cells in the bone marrow.

“Our work in this study demonstrates, for the first time, that CML stem cells are metabolically distinct from normal blood stem cells, and this, in turn, provides opportunities to selectively target them,” said study author Eyal Gottlieb, PhD, of the Cancer Research UK Beatson Institute in Glasgow.

“It’s exciting to see that using an antibiotic alongside an existing treatment could be a way to keep this type of leukemia at bay and potentially even cure it,” added Karen Vousden, PhD, Cancer Research UK’s chief scientist.

“If this approach is shown to be safe and effective in humans too, it could offer a new option for patients who, at the moment, face long-term treatment with the possibility of relapse.”

This research was funded by AstraZeneca, Cancer Research UK, The Medical Research Council, Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office, The Howat Foundation, Friends of the Paul O’Gorman Leukaemia Research Centre, Bloodwise, The Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund, Lady Tata International Award, and Leuka. ![]()

The antibiotic tigecycline may enhance the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), according to research published in Nature Medicine.

Using cells isolated from CML patients, researchers showed that treatment with tigecycline, an antibiotic used to treat bacterial infection, is effective in killing CML stem cells when used in combination with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) imatinib.

The study also suggested the combination can stave off relapse in animal models of CML.

“We were very excited to find that, when we treated CML cells with both the antibiotic tigecycline and the TKI drug imatinib, CML stem cells were selectively killed,” said study author Vignir Helgason, PhD, of the University of Glasgow in Scotland.

“We believe that our findings provide a strong basis for testing this novel therapeutic strategy in clinical trials in order to eliminate CML stem cells and provide cure for CML patients.”

The researchers said they found that, in primitive CML stem and progenitor cells, mitochondrial oxidative metabolism is crucial for the production of energy and anabolic precursors. This suggested that restraining mitochondrial functions might have a therapeutic benefit in CML.

The team knew that, in addition to inhibiting bacterial protein synthesis, tigecycline inhibits the synthesis of mitochondrion-encoded proteins, which are required for the oxidative phosphorylation machinery.

So the researchers tested tigecycline, alone or in combination with imatinib, in CML cells. Both treatments (tigecycline monotherapy and the combination) “strongly impaired” the proliferation of primary CD34+ CML cells.

However, imatinib alone had “a moderate effect.” The researchers said this is in line with the preferential effect of imatinib on differentiated CD34− cells.

Each drug alone decreased the number of short-term CML colony-forming cells (CFCs), and the combination eliminated colony formation entirely. This correlated with an increase in cell death.

Neither monotherapy nor the combination had a significant effect on non-leukemic CFCs.

The researchers then turned to a xenotransplantation model of human CML. Starting 6 weeks after transplant, mice received daily doses of vehicle, tigecycline (escalating doses of 25–100 mg per kg body weight), imatinib (100 mg per kg body weight), or both drugs. All treatment was given for 4 weeks.

The team said there were no signs of toxicity in any of the mice.

Compared to controls, tigecycline-treated mice had a marginal decrease in the total number of CML-derived CD45+ cells in the bone marrow, and imatinib-treated mice had a significant decrease in these cells. But the CML burden decreased even further with combination treatment.

The researchers noted that imatinib alone marginally decreased the number of CD45+CD34+CD38− CML cells, but combination treatment eliminated 95% of these cells.

Finally, the team tested each drug alone and in combination (as well as vehicle control) in additional cohorts of mice with CML. After receiving treatment for 4 weeks, mice were left untreated for either 2 weeks or 3 weeks.

Mice that received imatinib alone showed signs of relapse at 2 and 3 weeks, as they had similar numbers of leukemic cells as vehicle-treated mice. However, most of the mice treated with the combination had low numbers of leukemic stem cells in the bone marrow.

“Our work in this study demonstrates, for the first time, that CML stem cells are metabolically distinct from normal blood stem cells, and this, in turn, provides opportunities to selectively target them,” said study author Eyal Gottlieb, PhD, of the Cancer Research UK Beatson Institute in Glasgow.

“It’s exciting to see that using an antibiotic alongside an existing treatment could be a way to keep this type of leukemia at bay and potentially even cure it,” added Karen Vousden, PhD, Cancer Research UK’s chief scientist.

“If this approach is shown to be safe and effective in humans too, it could offer a new option for patients who, at the moment, face long-term treatment with the possibility of relapse.”

This research was funded by AstraZeneca, Cancer Research UK, The Medical Research Council, Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office, The Howat Foundation, Friends of the Paul O’Gorman Leukaemia Research Centre, Bloodwise, The Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund, Lady Tata International Award, and Leuka. ![]()

Register for ACS TQIP Conference November 11−13 in Chicago

The eighth annual Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP®) Scientific Meeting and Training will take place November 11−13 at the Hilton Chicago. Register online for the meeting at facs.org/tqipmeeting.

This meeting will bring together trauma medical directors, program managers, coordinators, and registrars from participating and prospective TQIP hospitals. The conference will have multiple presentations from TQIP participants highlighting how they are using the program to improve care in their hospitals. Breakout sessions focused on registrar and abstractor concerns, matters that relate to the trauma medical director, and trauma program manager-focused issues will enhance the learning experience and instruct participants about their role on the TQIP team. In addition, dedicated sessions for staff who are new to the TQIP program will take place and may be invaluable to medical centers joining TQIP in the near future.

Conference topics of note for 2017 will include TQIP Collaboratives, Pediatric TQIP, management of bleeding pelvic fractures, and the continued integration of verification, TQIP, and performance improvement and patient safety. The TQIP Best Practices project team will present on adult and pediatric imaging, followed by a discussion by a panel of experts. The keynote address will be given by Lenworth M. Jacobs, Jr., MD, MPH, FACS, Chair, Hartford Consensus Joint Committee to Enhance Survivability from Active Shooter and Intentional Mass Casualty Events.

Visit the TQIP annual meeting website at facs.org/tqipmeeting to view the conference schedule and to obtain information about lodging and transportation options.

The eighth annual Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP®) Scientific Meeting and Training will take place November 11−13 at the Hilton Chicago. Register online for the meeting at facs.org/tqipmeeting.

This meeting will bring together trauma medical directors, program managers, coordinators, and registrars from participating and prospective TQIP hospitals. The conference will have multiple presentations from TQIP participants highlighting how they are using the program to improve care in their hospitals. Breakout sessions focused on registrar and abstractor concerns, matters that relate to the trauma medical director, and trauma program manager-focused issues will enhance the learning experience and instruct participants about their role on the TQIP team. In addition, dedicated sessions for staff who are new to the TQIP program will take place and may be invaluable to medical centers joining TQIP in the near future.

Conference topics of note for 2017 will include TQIP Collaboratives, Pediatric TQIP, management of bleeding pelvic fractures, and the continued integration of verification, TQIP, and performance improvement and patient safety. The TQIP Best Practices project team will present on adult and pediatric imaging, followed by a discussion by a panel of experts. The keynote address will be given by Lenworth M. Jacobs, Jr., MD, MPH, FACS, Chair, Hartford Consensus Joint Committee to Enhance Survivability from Active Shooter and Intentional Mass Casualty Events.

Visit the TQIP annual meeting website at facs.org/tqipmeeting to view the conference schedule and to obtain information about lodging and transportation options.

The eighth annual Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP®) Scientific Meeting and Training will take place November 11−13 at the Hilton Chicago. Register online for the meeting at facs.org/tqipmeeting.

This meeting will bring together trauma medical directors, program managers, coordinators, and registrars from participating and prospective TQIP hospitals. The conference will have multiple presentations from TQIP participants highlighting how they are using the program to improve care in their hospitals. Breakout sessions focused on registrar and abstractor concerns, matters that relate to the trauma medical director, and trauma program manager-focused issues will enhance the learning experience and instruct participants about their role on the TQIP team. In addition, dedicated sessions for staff who are new to the TQIP program will take place and may be invaluable to medical centers joining TQIP in the near future.

Conference topics of note for 2017 will include TQIP Collaboratives, Pediatric TQIP, management of bleeding pelvic fractures, and the continued integration of verification, TQIP, and performance improvement and patient safety. The TQIP Best Practices project team will present on adult and pediatric imaging, followed by a discussion by a panel of experts. The keynote address will be given by Lenworth M. Jacobs, Jr., MD, MPH, FACS, Chair, Hartford Consensus Joint Committee to Enhance Survivability from Active Shooter and Intentional Mass Casualty Events.

Visit the TQIP annual meeting website at facs.org/tqipmeeting to view the conference schedule and to obtain information about lodging and transportation options.

Dr. Ronald Maier Awarded Prize of the “Société Internationale de Chirurgie”

Ronald V. Maier, MD, FACS, FRCSEd(Hon), Past-First Vice-President of the American College of Surgeons (ACS), received the prestigious Prize of the “Société Internationale de Chirurgie” at the 47th Annual World Congress of Surgery in Basel, Switzerland. The prize is awarded to “the surgeon who has published work which has made the most notable and useful contributions to surgical science.” Read more about the Prize of the “Société Internationale de Chirurgie” on the International Society of Surgery/Société Internationale de Chirurgie website.

Throughout his career, Dr. Maier has been interested in the critically ill surgical patient, focusing on the underlying pathophysiology driving the aberrant host immuno-inflammatory response, and subsequent clinical syndrome of multiple organ failure with its attendant high morbidity and mortality. He has received funding continuously from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) since 1981 and has been a member and Chair of the NIH Surgery, Anesthesiology and Trauma Study Section. His interest in trauma has also involved extensive clinical studies of the acute management of the severely injured and critically ill patient. Dr. Maier has presented his work worldwide, and has delivered more than 400 lectures on trauma, critical care, and surgical immunology. He has published more than 400 peer-reviewed articles, and contributed to or co-authored more than 60 book chapters.

Ronald V. Maier, MD, FACS, FRCSEd(Hon), Past-First Vice-President of the American College of Surgeons (ACS), received the prestigious Prize of the “Société Internationale de Chirurgie” at the 47th Annual World Congress of Surgery in Basel, Switzerland. The prize is awarded to “the surgeon who has published work which has made the most notable and useful contributions to surgical science.” Read more about the Prize of the “Société Internationale de Chirurgie” on the International Society of Surgery/Société Internationale de Chirurgie website.

Throughout his career, Dr. Maier has been interested in the critically ill surgical patient, focusing on the underlying pathophysiology driving the aberrant host immuno-inflammatory response, and subsequent clinical syndrome of multiple organ failure with its attendant high morbidity and mortality. He has received funding continuously from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) since 1981 and has been a member and Chair of the NIH Surgery, Anesthesiology and Trauma Study Section. His interest in trauma has also involved extensive clinical studies of the acute management of the severely injured and critically ill patient. Dr. Maier has presented his work worldwide, and has delivered more than 400 lectures on trauma, critical care, and surgical immunology. He has published more than 400 peer-reviewed articles, and contributed to or co-authored more than 60 book chapters.

Ronald V. Maier, MD, FACS, FRCSEd(Hon), Past-First Vice-President of the American College of Surgeons (ACS), received the prestigious Prize of the “Société Internationale de Chirurgie” at the 47th Annual World Congress of Surgery in Basel, Switzerland. The prize is awarded to “the surgeon who has published work which has made the most notable and useful contributions to surgical science.” Read more about the Prize of the “Société Internationale de Chirurgie” on the International Society of Surgery/Société Internationale de Chirurgie website.

Throughout his career, Dr. Maier has been interested in the critically ill surgical patient, focusing on the underlying pathophysiology driving the aberrant host immuno-inflammatory response, and subsequent clinical syndrome of multiple organ failure with its attendant high morbidity and mortality. He has received funding continuously from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) since 1981 and has been a member and Chair of the NIH Surgery, Anesthesiology and Trauma Study Section. His interest in trauma has also involved extensive clinical studies of the acute management of the severely injured and critically ill patient. Dr. Maier has presented his work worldwide, and has delivered more than 400 lectures on trauma, critical care, and surgical immunology. He has published more than 400 peer-reviewed articles, and contributed to or co-authored more than 60 book chapters.

From the Editors: Hanging up the scalpel

The decision to stop practicing surgery is a monumental one when you have been a surgeon for almost 40 years, have loved operating, and have defined yourself by the word “surgeon.”

The decision to cease operating should at best be a personal one that the surgeon makes, rather than one imposed by others. The “others” could be an institutional policy mandating retirement at a given age, the results of a series of psychomotor examinations, or even a kind department chair’s suggestion that you should stop operating because your complications have increased and it is in your patients’ best interests. As we approach “a certain age,” I suspect that most surgeons would prefer to decide their own fate and, especially, to avoid the last of the three above options.

Literature is emerging about the aging physician and how best the decisions should be made about ceasing practice. A recent such article published online by some dear and respected colleagues (JAMA Surg. 2017 July 19;doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.2342) proposes that institutions and professional organizations develop policies to address the aging physician that leave “flexibility to customize the approach” lest regulators and legislators impose “more draconian measures.” Their suggestions include mandatory cognitive evaluation, voluntary annual physical examinations, and confidential peer evaluations of wellness and competence as physicians reach a certain (unspecified) age.

I most certainly concur with the authors’ well-reasoned arguments. As they relate, only a handful of institutions to date have developed policies that require assessments of physician wellness and competence at a given age. Most institutions still rely on physicians’ voluntary submission to physical examinations, cognitive testing, or peer referral of a colleague if declining function is observed. Yet we all know that individuals tend to overlook signs of declining physical and cognitive function both in themselves and in colleagues. Moreover, we all know that even the most carefully designed and implemented tests have shortcomings and may fail to identify the exact nature of an individual’s malady or fail to identify a remediable issue early. And just as individuals’ physical and cognitive abilities decline at different chronological ages, problems with burnout, mental illness, and substance abuse have no reliable age threshold and may be difficult to diagnose accurately.

Whatever the age of the individual, it is critical that a decline in function of a practitioner be addressed promptly and effectively, for the benefit of the affected individual, his or her patients, and the institution. It is therefore most appropriate for every institution to develop a firm policy to deal with concerns of competency of all staff members, regardless of age.

It is also appropriate for peers to pay attention to a colleague’s stumbles and have the courage to first initiate a dialogue directly with that person, referring the issue to an individual in authority if the direct approach fails. A culture that promotes responsible self-policing protects patients and the reputations of both the affected individual and the institution.

Most of us with “seniority” will recall situations during our training when surgeons with diminished physical or cognitive capacity continued operating well beyond their prime. In those days, it was not unusual for a chief resident to be told, “Your job is to scrub with Dr. X and keep him out of trouble.” As inappropriate as that was, we complied, all the while vowing that we would never let ourselves be in the same position when we aged.

It therefore became my habit as I aged to “listen to my body” and pay attention to evidence that my skills might be declining and perhaps it was time to hang up the scalpel. As an almost lifelong runner, I marked my athletic decline by noting an increase in minutes per mile from 7 to 14 over 40 years and wondered whether my cognitive decline might be comparable, if not so obvious. I had to admit to a bit of lost hand dexterity, less sharpness of eyesight, and slowed memory for the names of people and even of surgical instruments. Although I believed that my diagnostic acumen and decisions were unaffected, I weathered a sleepless night on call less well, requiring two or more full nights of eight hours’ sleep to recover my energy completely.

Part of the reluctance to cease surgical practice that I share with many colleagues my age is the fear of becoming irrelevant and unproductive. It was therefore critical to prepare for retirement from practice by identifying activities that I considered both meaningful and also challenging: writing and editing, teaching students and residents in surgical skills labs, teaching residents “open” surgical techniques on cadavers, advising younger colleagues when they have a challenging case in my area of expertise, and filling a myriad of needs in our department that match my skill set but that my younger counterparts are too busy to attend to.

I now also have the freedom to pursue activities for which I had little time during the years of intense practice, including service on nonprofit boards and other community activities. There may even come a day when my definition of self has fully accepted the word “retired,” even though I hope that day is many years in the future.

Dr. Deveney is professor of surgery and vice chair of education in the department of surgery, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. She is the coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

The decision to stop practicing surgery is a monumental one when you have been a surgeon for almost 40 years, have loved operating, and have defined yourself by the word “surgeon.”

The decision to cease operating should at best be a personal one that the surgeon makes, rather than one imposed by others. The “others” could be an institutional policy mandating retirement at a given age, the results of a series of psychomotor examinations, or even a kind department chair’s suggestion that you should stop operating because your complications have increased and it is in your patients’ best interests. As we approach “a certain age,” I suspect that most surgeons would prefer to decide their own fate and, especially, to avoid the last of the three above options.

Literature is emerging about the aging physician and how best the decisions should be made about ceasing practice. A recent such article published online by some dear and respected colleagues (JAMA Surg. 2017 July 19;doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.2342) proposes that institutions and professional organizations develop policies to address the aging physician that leave “flexibility to customize the approach” lest regulators and legislators impose “more draconian measures.” Their suggestions include mandatory cognitive evaluation, voluntary annual physical examinations, and confidential peer evaluations of wellness and competence as physicians reach a certain (unspecified) age.

I most certainly concur with the authors’ well-reasoned arguments. As they relate, only a handful of institutions to date have developed policies that require assessments of physician wellness and competence at a given age. Most institutions still rely on physicians’ voluntary submission to physical examinations, cognitive testing, or peer referral of a colleague if declining function is observed. Yet we all know that individuals tend to overlook signs of declining physical and cognitive function both in themselves and in colleagues. Moreover, we all know that even the most carefully designed and implemented tests have shortcomings and may fail to identify the exact nature of an individual’s malady or fail to identify a remediable issue early. And just as individuals’ physical and cognitive abilities decline at different chronological ages, problems with burnout, mental illness, and substance abuse have no reliable age threshold and may be difficult to diagnose accurately.

Whatever the age of the individual, it is critical that a decline in function of a practitioner be addressed promptly and effectively, for the benefit of the affected individual, his or her patients, and the institution. It is therefore most appropriate for every institution to develop a firm policy to deal with concerns of competency of all staff members, regardless of age.

It is also appropriate for peers to pay attention to a colleague’s stumbles and have the courage to first initiate a dialogue directly with that person, referring the issue to an individual in authority if the direct approach fails. A culture that promotes responsible self-policing protects patients and the reputations of both the affected individual and the institution.

Most of us with “seniority” will recall situations during our training when surgeons with diminished physical or cognitive capacity continued operating well beyond their prime. In those days, it was not unusual for a chief resident to be told, “Your job is to scrub with Dr. X and keep him out of trouble.” As inappropriate as that was, we complied, all the while vowing that we would never let ourselves be in the same position when we aged.

It therefore became my habit as I aged to “listen to my body” and pay attention to evidence that my skills might be declining and perhaps it was time to hang up the scalpel. As an almost lifelong runner, I marked my athletic decline by noting an increase in minutes per mile from 7 to 14 over 40 years and wondered whether my cognitive decline might be comparable, if not so obvious. I had to admit to a bit of lost hand dexterity, less sharpness of eyesight, and slowed memory for the names of people and even of surgical instruments. Although I believed that my diagnostic acumen and decisions were unaffected, I weathered a sleepless night on call less well, requiring two or more full nights of eight hours’ sleep to recover my energy completely.

Part of the reluctance to cease surgical practice that I share with many colleagues my age is the fear of becoming irrelevant and unproductive. It was therefore critical to prepare for retirement from practice by identifying activities that I considered both meaningful and also challenging: writing and editing, teaching students and residents in surgical skills labs, teaching residents “open” surgical techniques on cadavers, advising younger colleagues when they have a challenging case in my area of expertise, and filling a myriad of needs in our department that match my skill set but that my younger counterparts are too busy to attend to.

I now also have the freedom to pursue activities for which I had little time during the years of intense practice, including service on nonprofit boards and other community activities. There may even come a day when my definition of self has fully accepted the word “retired,” even though I hope that day is many years in the future.

Dr. Deveney is professor of surgery and vice chair of education in the department of surgery, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. She is the coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

The decision to stop practicing surgery is a monumental one when you have been a surgeon for almost 40 years, have loved operating, and have defined yourself by the word “surgeon.”

The decision to cease operating should at best be a personal one that the surgeon makes, rather than one imposed by others. The “others” could be an institutional policy mandating retirement at a given age, the results of a series of psychomotor examinations, or even a kind department chair’s suggestion that you should stop operating because your complications have increased and it is in your patients’ best interests. As we approach “a certain age,” I suspect that most surgeons would prefer to decide their own fate and, especially, to avoid the last of the three above options.

Literature is emerging about the aging physician and how best the decisions should be made about ceasing practice. A recent such article published online by some dear and respected colleagues (JAMA Surg. 2017 July 19;doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.2342) proposes that institutions and professional organizations develop policies to address the aging physician that leave “flexibility to customize the approach” lest regulators and legislators impose “more draconian measures.” Their suggestions include mandatory cognitive evaluation, voluntary annual physical examinations, and confidential peer evaluations of wellness and competence as physicians reach a certain (unspecified) age.

I most certainly concur with the authors’ well-reasoned arguments. As they relate, only a handful of institutions to date have developed policies that require assessments of physician wellness and competence at a given age. Most institutions still rely on physicians’ voluntary submission to physical examinations, cognitive testing, or peer referral of a colleague if declining function is observed. Yet we all know that individuals tend to overlook signs of declining physical and cognitive function both in themselves and in colleagues. Moreover, we all know that even the most carefully designed and implemented tests have shortcomings and may fail to identify the exact nature of an individual’s malady or fail to identify a remediable issue early. And just as individuals’ physical and cognitive abilities decline at different chronological ages, problems with burnout, mental illness, and substance abuse have no reliable age threshold and may be difficult to diagnose accurately.

Whatever the age of the individual, it is critical that a decline in function of a practitioner be addressed promptly and effectively, for the benefit of the affected individual, his or her patients, and the institution. It is therefore most appropriate for every institution to develop a firm policy to deal with concerns of competency of all staff members, regardless of age.

It is also appropriate for peers to pay attention to a colleague’s stumbles and have the courage to first initiate a dialogue directly with that person, referring the issue to an individual in authority if the direct approach fails. A culture that promotes responsible self-policing protects patients and the reputations of both the affected individual and the institution.

Most of us with “seniority” will recall situations during our training when surgeons with diminished physical or cognitive capacity continued operating well beyond their prime. In those days, it was not unusual for a chief resident to be told, “Your job is to scrub with Dr. X and keep him out of trouble.” As inappropriate as that was, we complied, all the while vowing that we would never let ourselves be in the same position when we aged.

It therefore became my habit as I aged to “listen to my body” and pay attention to evidence that my skills might be declining and perhaps it was time to hang up the scalpel. As an almost lifelong runner, I marked my athletic decline by noting an increase in minutes per mile from 7 to 14 over 40 years and wondered whether my cognitive decline might be comparable, if not so obvious. I had to admit to a bit of lost hand dexterity, less sharpness of eyesight, and slowed memory for the names of people and even of surgical instruments. Although I believed that my diagnostic acumen and decisions were unaffected, I weathered a sleepless night on call less well, requiring two or more full nights of eight hours’ sleep to recover my energy completely.

Part of the reluctance to cease surgical practice that I share with many colleagues my age is the fear of becoming irrelevant and unproductive. It was therefore critical to prepare for retirement from practice by identifying activities that I considered both meaningful and also challenging: writing and editing, teaching students and residents in surgical skills labs, teaching residents “open” surgical techniques on cadavers, advising younger colleagues when they have a challenging case in my area of expertise, and filling a myriad of needs in our department that match my skill set but that my younger counterparts are too busy to attend to.

I now also have the freedom to pursue activities for which I had little time during the years of intense practice, including service on nonprofit boards and other community activities. There may even come a day when my definition of self has fully accepted the word “retired,” even though I hope that day is many years in the future.

Dr. Deveney is professor of surgery and vice chair of education in the department of surgery, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. She is the coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

From the Washington Office: Receiving an increase in Medicare payment and avoiding a penalty

We are now well over halfway through 2017, the initial year of the new Quality Payment Program (QPP) mandated by MACRA. Accordingly, I thought it might be useful to revisit the topic of the QPP and MIPS (Merit-based Incentive Payment System) for purposes of emphasizing the key steps surgeons should take if they want to potentially see an increase in their Medicare physician payment in 2019 based on their performance in 2017. At the same time, I also want to make sure that all surgeons understand the ease with which they can avoid a payment penalty.

First, I want to assure all who have yet to take any action that there is still more than adequate time to do so. You absolutely can still compete for a positive update, or at a minimum, avoid a penalty. Further, it is so easy to avoid a penalty that no surgeon should be resigned to accepting a penalty without having a look at the minimal reporting requirements necessary to avoid it.

One of the resources available on the ACS’ QPP website is an algorhythm intended to simplify surgeons’ decision making at their initial starting point. It is reproduced below:

1. Determine if all of your MIPS data will be reported by your institution or group via a Group Reporting option (GPRO).

a. If “YES,” you are done.

b. If “NO,” move to number 2.

2. Has CMS notified you that you are exempt from participating in MIPS due to the low-volume threshold?

a. If “YES,” you are done.

b. If “NO,” move to number 3.

3. If you want to compete for positive updates in your Medicare payment rates in 2019 (based on 2017 reporting), read the ACS Quality Payment Program Manual, watch the videos, and develop your plan.

4. If your goal is simply to avoid a penalty, CMS only requires data be reported for one of the following:

a. Required Base Score measures for your EHR (now known as Advancing Care Information) OR

b. One Improvement Activity for 90 days (report by attestation) OR

c. One Quality Measure on one patient (report by registry, QCDR, EHR, or claims)

Note: One is NOT required to have a certified EHR to avoid a penalty for 2017

5. If you did not report PQRS data and did not participate in the electronic health record meaningful use program in 2016 and have no intention of participating in MIPS in 2017:

a. Your lack of participation in 2016 programs will lead to a 10% negative payment adjustment in 2018.

b. Your lack of participation in MIPS in 2017 will lead to a 4% negative payment adjustment in 2019.

Note: This option is not recommended, as in future years the annual cuts will gradually increase to 9%.

MIPS is set up as a tournament model. In other words, “Losers” pay for “Winners.” Please do not put your money in someone else’s pocket. The ACS strongly encourages all Fellows to, at the minimum, participate at the level sufficient to avoid a penalty in 2017 and, thus, not serve as the “pay for” for another provider.

If you are not exempt from MIPS and therefore, one whose performance will be assessed in 2017, you still have plenty of time to start the process of reporting enough data to compete for a positive update. On the other hand, if your goal is simply to avoid a penalty in 2019, (based on your performance in 2017), you should take the few simple steps necessary to preclude such as outlined above.

We believe the QPP website, (www.facs.org/qpp), is an excellent resource for surgeons. It was designed to facilitate participation by those surgeons who must report for MIPS. As always, ACS staff are also available to answer your questions by phone or via e-mail: [email protected].

Until next month ….

Dr. Bailey is a pediatric surgeon and Medical Director, Advocacy, for the Division of Advocacy and Health Policy in the ACS offices in Washington, DC.

We are now well over halfway through 2017, the initial year of the new Quality Payment Program (QPP) mandated by MACRA. Accordingly, I thought it might be useful to revisit the topic of the QPP and MIPS (Merit-based Incentive Payment System) for purposes of emphasizing the key steps surgeons should take if they want to potentially see an increase in their Medicare physician payment in 2019 based on their performance in 2017. At the same time, I also want to make sure that all surgeons understand the ease with which they can avoid a payment penalty.

First, I want to assure all who have yet to take any action that there is still more than adequate time to do so. You absolutely can still compete for a positive update, or at a minimum, avoid a penalty. Further, it is so easy to avoid a penalty that no surgeon should be resigned to accepting a penalty without having a look at the minimal reporting requirements necessary to avoid it.

One of the resources available on the ACS’ QPP website is an algorhythm intended to simplify surgeons’ decision making at their initial starting point. It is reproduced below:

1. Determine if all of your MIPS data will be reported by your institution or group via a Group Reporting option (GPRO).

a. If “YES,” you are done.

b. If “NO,” move to number 2.

2. Has CMS notified you that you are exempt from participating in MIPS due to the low-volume threshold?

a. If “YES,” you are done.

b. If “NO,” move to number 3.

3. If you want to compete for positive updates in your Medicare payment rates in 2019 (based on 2017 reporting), read the ACS Quality Payment Program Manual, watch the videos, and develop your plan.

4. If your goal is simply to avoid a penalty, CMS only requires data be reported for one of the following:

a. Required Base Score measures for your EHR (now known as Advancing Care Information) OR

b. One Improvement Activity for 90 days (report by attestation) OR

c. One Quality Measure on one patient (report by registry, QCDR, EHR, or claims)

Note: One is NOT required to have a certified EHR to avoid a penalty for 2017

5. If you did not report PQRS data and did not participate in the electronic health record meaningful use program in 2016 and have no intention of participating in MIPS in 2017:

a. Your lack of participation in 2016 programs will lead to a 10% negative payment adjustment in 2018.

b. Your lack of participation in MIPS in 2017 will lead to a 4% negative payment adjustment in 2019.

Note: This option is not recommended, as in future years the annual cuts will gradually increase to 9%.

MIPS is set up as a tournament model. In other words, “Losers” pay for “Winners.” Please do not put your money in someone else’s pocket. The ACS strongly encourages all Fellows to, at the minimum, participate at the level sufficient to avoid a penalty in 2017 and, thus, not serve as the “pay for” for another provider.

If you are not exempt from MIPS and therefore, one whose performance will be assessed in 2017, you still have plenty of time to start the process of reporting enough data to compete for a positive update. On the other hand, if your goal is simply to avoid a penalty in 2019, (based on your performance in 2017), you should take the few simple steps necessary to preclude such as outlined above.

We believe the QPP website, (www.facs.org/qpp), is an excellent resource for surgeons. It was designed to facilitate participation by those surgeons who must report for MIPS. As always, ACS staff are also available to answer your questions by phone or via e-mail: [email protected].

Until next month ….

Dr. Bailey is a pediatric surgeon and Medical Director, Advocacy, for the Division of Advocacy and Health Policy in the ACS offices in Washington, DC.

We are now well over halfway through 2017, the initial year of the new Quality Payment Program (QPP) mandated by MACRA. Accordingly, I thought it might be useful to revisit the topic of the QPP and MIPS (Merit-based Incentive Payment System) for purposes of emphasizing the key steps surgeons should take if they want to potentially see an increase in their Medicare physician payment in 2019 based on their performance in 2017. At the same time, I also want to make sure that all surgeons understand the ease with which they can avoid a payment penalty.

First, I want to assure all who have yet to take any action that there is still more than adequate time to do so. You absolutely can still compete for a positive update, or at a minimum, avoid a penalty. Further, it is so easy to avoid a penalty that no surgeon should be resigned to accepting a penalty without having a look at the minimal reporting requirements necessary to avoid it.

One of the resources available on the ACS’ QPP website is an algorhythm intended to simplify surgeons’ decision making at their initial starting point. It is reproduced below:

1. Determine if all of your MIPS data will be reported by your institution or group via a Group Reporting option (GPRO).

a. If “YES,” you are done.

b. If “NO,” move to number 2.

2. Has CMS notified you that you are exempt from participating in MIPS due to the low-volume threshold?

a. If “YES,” you are done.

b. If “NO,” move to number 3.

3. If you want to compete for positive updates in your Medicare payment rates in 2019 (based on 2017 reporting), read the ACS Quality Payment Program Manual, watch the videos, and develop your plan.

4. If your goal is simply to avoid a penalty, CMS only requires data be reported for one of the following:

a. Required Base Score measures for your EHR (now known as Advancing Care Information) OR

b. One Improvement Activity for 90 days (report by attestation) OR

c. One Quality Measure on one patient (report by registry, QCDR, EHR, or claims)

Note: One is NOT required to have a certified EHR to avoid a penalty for 2017

5. If you did not report PQRS data and did not participate in the electronic health record meaningful use program in 2016 and have no intention of participating in MIPS in 2017:

a. Your lack of participation in 2016 programs will lead to a 10% negative payment adjustment in 2018.

b. Your lack of participation in MIPS in 2017 will lead to a 4% negative payment adjustment in 2019.

Note: This option is not recommended, as in future years the annual cuts will gradually increase to 9%.

MIPS is set up as a tournament model. In other words, “Losers” pay for “Winners.” Please do not put your money in someone else’s pocket. The ACS strongly encourages all Fellows to, at the minimum, participate at the level sufficient to avoid a penalty in 2017 and, thus, not serve as the “pay for” for another provider.

If you are not exempt from MIPS and therefore, one whose performance will be assessed in 2017, you still have plenty of time to start the process of reporting enough data to compete for a positive update. On the other hand, if your goal is simply to avoid a penalty in 2019, (based on your performance in 2017), you should take the few simple steps necessary to preclude such as outlined above.

We believe the QPP website, (www.facs.org/qpp), is an excellent resource for surgeons. It was designed to facilitate participation by those surgeons who must report for MIPS. As always, ACS staff are also available to answer your questions by phone or via e-mail: [email protected].

Until next month ….

Dr. Bailey is a pediatric surgeon and Medical Director, Advocacy, for the Division of Advocacy and Health Policy in the ACS offices in Washington, DC.

Richard J. Finley, MD, FACS, FRCSC, to receive Distinguished Service Award

The Board of Regents of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) has chosen Richard J. Finley, MD, FACS, FRCSC, a general thoracic surgeon, Vancouver General and Surrey Memorial Hospitals, BC, and emeritus professor, department of surgery, University of British Columbia (UBC), Vancouver, to receive the 2017 Distinguished Service Award (DSA). The Regents will present the award—the College’s highest honor—Sunday, October 22, during the Convocation preceding Clinical Congress 2017 at the San Diego Convention Center, CA.

The Board of Regents is presenting the DSA to Dr. Finley in appreciation for his longstanding and devoted service as an ACS Fellow, the Chair (1993−1995) and Vice-Chair (1992−1993) of the Board of Governors (B/G), a member of the Board of Regents (2000−2009), and as ACS First Vice-President (2010). The award citation recognizes his “long-term commitment to improving graduate education for future generations” and his pioneering contributions in the area of health information technology, including his service as Chair of the ACS Web Portal Editorial Board (2005−2012) and Chair of the ACS Education Task Force on Practice-Based Learning and Improvement (2002−2009).

Commitment to education

Dr. Finley has devoted much of his career to surgical education. The many residents and fellows he has trained describe Dr. Finley as an outstanding teacher and mentor, enthusiastic and innovative, and an asset to residency education. Dr. Finley has participated in the training of 14 general thoracic surgeons who now practice in academic hospitals across Canada. He is the recipient of several teaching and scholarship awards, including the UBC department of surgery Master Teaching Award (1991) and Best Teacher, Interns and Residents, University of Western Ontario, London.

Prior to assuming the position of emeritus professor at UBC, he was professor of surgery (1989−2016); head, department of surgery (1989−2001); and head, division of thoracic surgery (1994−2014) at UBC. In addition, Dr. Finley was surgeon-in-chief at Vancouver Hospital (1997–2001); head (1989–2001), department of surgery, and medical director (1992), clinical practice unit, Vancouver Hospital & Health Sciences Center, BC; and consultant staff at British Columbia Cancer Agency, Vancouver (1989–2015). Previously, Dr. Finley was chief of surgery (1985–1988) and attending surgeon, Victoria Hospital, London, ON, and a consulting surgeon, University Hospital & Ontario Cancer Foundation (1979–1988).

After graduating with honors from the University of Western Ontario Medical School, he did an internship at Vancouver General Hospital, followed by residency in surgery and cardiothoracic surgery at the University of Western Ontario. He then completed a medical research fellowship at Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, and another year of postgraduate training at the University of Toronto, department of surgery, division of thoracic surgery. Dr. Finley then returned to the University of Western Ontario, working his way up from assistant professor (1979–1983) to associate professor (1983–1989), department of surgery.

He has chaired multiple committees at the institutions where he has practiced and taught, including the faculty executive committee and surgical advisory committee at UBC and the surgical advisory committee, minimally invasive surgery, operating room council, and operating room executive team at Vancouver Hospital & Health Sciences Centre.