User login

Immunologic testing is key to diagnosing autoimmune blistering diseases

SAN FRANCISCO –

“You have to have some kind of immunological test,” according to Peter Marinkovich, MD. “Pathologists will try to give you as much information as they can on the routine histology, but don’t use that as a diagnostic.”

If not properly identified, autoimmune blistering diseases can lead to chronic overexposure to steroids and resultant side effects without addressing the underlying problem, said Dr. Marinkovich of the department of dermatology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Dr. Marinkovich gave one example of a patient who had been diagnosed with bullous pemphigoid several years before, and who was becoming Cushingoid as a result of steroids. But the diagnosis was made on the basis of histopathology and clinical appearance alone.

“Nobody had done the immunofluorescence test,” he explained at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “I did it, and it turned out she had linear IgA disease. The patient went through 2 years of toxicity just because nobody had done the immunofluorescence test.” Instead, the patient improved when placed on dapsone, which is much less toxic than prednisone.

Direct/indirect immunofluorescence is the highest-yield test for patients with blistering disease. “It’s the best way, I believe, to make the diagnosis,” Dr. Marinkovich said. If that test isn’t available, serum taken during an active phase can also be used. But serum samples can turn up false negatives, so dermatologists should consider collecting and testing serum samples several times.

Another useful tool is salt-split skin analysis, which will demarcate antigens to the roof or floor of the blister. Specifically, it helps distinguish bullous pemphigoid and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.

In the future, Dr. Marinkovich said, ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) testing will have greater importance for diagnosis and disease monitoring, not just for pemphigus but for subepidermal bullous disorders as well.

Autoimmune blistering diseases do respond to prednisone treatment, although not as well as some other conditions. However, symptom improvement can mask the true cause of the disease.

“It’s easy for physicians to give steroids, and the patients will be happy for the time being; but that doesn’t solve the problem in the long term,” Dr. Marinkovich cautioned. “These are chronic conditions, and the patient will continue to require prednisone, and they’ll get more and more side effects, which could have been avoided if someone had done a more thorough investigation.”

Topical agents such as tetracycline, niacinamide, and topical steroids are more useful in pemphigoid than for pemphigus, because pemphigoid involves local immune factors that the agents can target, while pemphigus can be driven by antibodies alone, which are not as responsive to these treatments.

When systemic therapies are necessary, prednisone is a useful tool, but aim for the lowest possible dose, he said. Reducing prednisone dose is challenging in and of itself. Dropping the dose too quickly can lead to more long-term exposure, because a steep drop can lead to a rebound in the disease, which leads to a higher dose.

“The patient is on this roller coaster ride, up and down, up and down, and that alone can ramp up disease activity,” said Dr. Marinkovich. “Lowering steroid more steadily is a better way to go. This calms the disease down by itself.”

When steroids can’t be completely tapered, which is almost always the case in pemphigus and common in pemphigoid, add steroid-sparing agents such as mycophenolate and azathioprine.

If the steroid-sparing agents don’t get patients down to 10 mg/day prednisone or below, then consider using rituximab and intravenous IgG.

In Europe, physicians are using rituximab earlier in the course of disease, a strategy that appeared effective in a study published in the Lancet (2017 May 20;389[10083]:2031-40). “The evidence suggests to me that earlier use of rituximab tends to reduce the total amount of steroids that the patients are using and has the potential to reduce the duration of the disease,” Dr. Marinkovich said. “That’s a trend that will be going on in the next couple of years here in the United States.”

Dr. Marinkovich is an investigator on a clinical trial funded by Syntimmune.

SAN FRANCISCO –

“You have to have some kind of immunological test,” according to Peter Marinkovich, MD. “Pathologists will try to give you as much information as they can on the routine histology, but don’t use that as a diagnostic.”

If not properly identified, autoimmune blistering diseases can lead to chronic overexposure to steroids and resultant side effects without addressing the underlying problem, said Dr. Marinkovich of the department of dermatology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Dr. Marinkovich gave one example of a patient who had been diagnosed with bullous pemphigoid several years before, and who was becoming Cushingoid as a result of steroids. But the diagnosis was made on the basis of histopathology and clinical appearance alone.

“Nobody had done the immunofluorescence test,” he explained at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “I did it, and it turned out she had linear IgA disease. The patient went through 2 years of toxicity just because nobody had done the immunofluorescence test.” Instead, the patient improved when placed on dapsone, which is much less toxic than prednisone.

Direct/indirect immunofluorescence is the highest-yield test for patients with blistering disease. “It’s the best way, I believe, to make the diagnosis,” Dr. Marinkovich said. If that test isn’t available, serum taken during an active phase can also be used. But serum samples can turn up false negatives, so dermatologists should consider collecting and testing serum samples several times.

Another useful tool is salt-split skin analysis, which will demarcate antigens to the roof or floor of the blister. Specifically, it helps distinguish bullous pemphigoid and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.

In the future, Dr. Marinkovich said, ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) testing will have greater importance for diagnosis and disease monitoring, not just for pemphigus but for subepidermal bullous disorders as well.

Autoimmune blistering diseases do respond to prednisone treatment, although not as well as some other conditions. However, symptom improvement can mask the true cause of the disease.

“It’s easy for physicians to give steroids, and the patients will be happy for the time being; but that doesn’t solve the problem in the long term,” Dr. Marinkovich cautioned. “These are chronic conditions, and the patient will continue to require prednisone, and they’ll get more and more side effects, which could have been avoided if someone had done a more thorough investigation.”

Topical agents such as tetracycline, niacinamide, and topical steroids are more useful in pemphigoid than for pemphigus, because pemphigoid involves local immune factors that the agents can target, while pemphigus can be driven by antibodies alone, which are not as responsive to these treatments.

When systemic therapies are necessary, prednisone is a useful tool, but aim for the lowest possible dose, he said. Reducing prednisone dose is challenging in and of itself. Dropping the dose too quickly can lead to more long-term exposure, because a steep drop can lead to a rebound in the disease, which leads to a higher dose.

“The patient is on this roller coaster ride, up and down, up and down, and that alone can ramp up disease activity,” said Dr. Marinkovich. “Lowering steroid more steadily is a better way to go. This calms the disease down by itself.”

When steroids can’t be completely tapered, which is almost always the case in pemphigus and common in pemphigoid, add steroid-sparing agents such as mycophenolate and azathioprine.

If the steroid-sparing agents don’t get patients down to 10 mg/day prednisone or below, then consider using rituximab and intravenous IgG.

In Europe, physicians are using rituximab earlier in the course of disease, a strategy that appeared effective in a study published in the Lancet (2017 May 20;389[10083]:2031-40). “The evidence suggests to me that earlier use of rituximab tends to reduce the total amount of steroids that the patients are using and has the potential to reduce the duration of the disease,” Dr. Marinkovich said. “That’s a trend that will be going on in the next couple of years here in the United States.”

Dr. Marinkovich is an investigator on a clinical trial funded by Syntimmune.

SAN FRANCISCO –

“You have to have some kind of immunological test,” according to Peter Marinkovich, MD. “Pathologists will try to give you as much information as they can on the routine histology, but don’t use that as a diagnostic.”

If not properly identified, autoimmune blistering diseases can lead to chronic overexposure to steroids and resultant side effects without addressing the underlying problem, said Dr. Marinkovich of the department of dermatology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Dr. Marinkovich gave one example of a patient who had been diagnosed with bullous pemphigoid several years before, and who was becoming Cushingoid as a result of steroids. But the diagnosis was made on the basis of histopathology and clinical appearance alone.

“Nobody had done the immunofluorescence test,” he explained at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “I did it, and it turned out she had linear IgA disease. The patient went through 2 years of toxicity just because nobody had done the immunofluorescence test.” Instead, the patient improved when placed on dapsone, which is much less toxic than prednisone.

Direct/indirect immunofluorescence is the highest-yield test for patients with blistering disease. “It’s the best way, I believe, to make the diagnosis,” Dr. Marinkovich said. If that test isn’t available, serum taken during an active phase can also be used. But serum samples can turn up false negatives, so dermatologists should consider collecting and testing serum samples several times.

Another useful tool is salt-split skin analysis, which will demarcate antigens to the roof or floor of the blister. Specifically, it helps distinguish bullous pemphigoid and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.

In the future, Dr. Marinkovich said, ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) testing will have greater importance for diagnosis and disease monitoring, not just for pemphigus but for subepidermal bullous disorders as well.

Autoimmune blistering diseases do respond to prednisone treatment, although not as well as some other conditions. However, symptom improvement can mask the true cause of the disease.

“It’s easy for physicians to give steroids, and the patients will be happy for the time being; but that doesn’t solve the problem in the long term,” Dr. Marinkovich cautioned. “These are chronic conditions, and the patient will continue to require prednisone, and they’ll get more and more side effects, which could have been avoided if someone had done a more thorough investigation.”

Topical agents such as tetracycline, niacinamide, and topical steroids are more useful in pemphigoid than for pemphigus, because pemphigoid involves local immune factors that the agents can target, while pemphigus can be driven by antibodies alone, which are not as responsive to these treatments.

When systemic therapies are necessary, prednisone is a useful tool, but aim for the lowest possible dose, he said. Reducing prednisone dose is challenging in and of itself. Dropping the dose too quickly can lead to more long-term exposure, because a steep drop can lead to a rebound in the disease, which leads to a higher dose.

“The patient is on this roller coaster ride, up and down, up and down, and that alone can ramp up disease activity,” said Dr. Marinkovich. “Lowering steroid more steadily is a better way to go. This calms the disease down by itself.”

When steroids can’t be completely tapered, which is almost always the case in pemphigus and common in pemphigoid, add steroid-sparing agents such as mycophenolate and azathioprine.

If the steroid-sparing agents don’t get patients down to 10 mg/day prednisone or below, then consider using rituximab and intravenous IgG.

In Europe, physicians are using rituximab earlier in the course of disease, a strategy that appeared effective in a study published in the Lancet (2017 May 20;389[10083]:2031-40). “The evidence suggests to me that earlier use of rituximab tends to reduce the total amount of steroids that the patients are using and has the potential to reduce the duration of the disease,” Dr. Marinkovich said. “That’s a trend that will be going on in the next couple of years here in the United States.”

Dr. Marinkovich is an investigator on a clinical trial funded by Syntimmune.

AT PDA 2017

Survival in lupus patients has plateaued

The major improvement in survival that patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) have experienced from 1950 to the mid-1990s has plateaued ever since, reported Maria Tektonidou, MD, and her colleagues. The study was published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

Dr. Tektonidou of National and Kapodistrian University of Athens and her coauthors at the U.S. National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases performed a meta-analysis on studies examining survival in adult and pediatric SLE patients from the 1950s to the mid-1990s. Ultimately, they analyzed 125 adult studies, including 82 from high-income countries and 43 from low- to middle-income countries (LMIC), and 51 pediatric studies, of which 33 were from high-income countries and 18 from LMIC.

In adult studies, researchers found that both high-income and LMIC experienced gradual increases in survival from the 1950s to mid-1990s. After this period of time, the survival estimates stabilized. “In 2008–2016, the 5-year, 10-year, and 15-year survival estimates in high-income countries were 0.95 (95% credible interval, 0.94 to 0.96), 0.89 (0.88 to 0.90) and 0.82 (0.81 to 0.83), respectively” (Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Aug 9. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211663).

Although there were no data for LMIC prior to 1970, researchers identified survival trends similar to those in high-income countries in more recent years. Over the same time period between 2008 and 2016, “the 5-year, 10-year, and 15-year survival estimates in LMIC were 0.92 (0.91 to 0.93), 0.85 (0.84 to 0.87) and 0.79 (0.78 to 0.81), respectively,” according to the report.

Unlike the steady improvement seen over a 40-year period with adult studies, pediatric SLE patients in high-income countries experienced dramatic increases in survival rates from the 1960s to the 1970s, followed by slower increases in survival rates. The researchers reported that between 2008 and 2016,“the 5-year and 10-year survival estimates from high-income countries were 0.99 (0.98 to 1.00) and 0.97 (0.96 to 0.98), respectively.”

LMIC had significantly worse survival in pediatric SLE patients than did their wealthy counterparts. “Survival persistently lagged [behind] that of high-income countries” between 1980 and 2000. Dr. Tektonidou and her associates found that “5-year and 10-year survival estimates from LMIC were 0.85 (0.83 to 0.88) and 0.79 (0.76 to 0.82), respectively.” Due to the small number of studies reporting 15-year survival rates, this time point was not included in the pediatric analysis.

The researchers also analyzed the cause of death for adult and pediatric SLE patients in both high-income countries and LMIC. High-income countries showed lower rates of SLE-associated deaths over time in adults, although infection-related deaths increased in adults in both high-income countries and LMIC. There were not enough studies and data to assess cause of death in pediatric studies in high-income countries, but pediatric patients in LMIC had an upward trend in SLE-associated deaths.

The Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases supported the study. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The major improvement in survival that patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) have experienced from 1950 to the mid-1990s has plateaued ever since, reported Maria Tektonidou, MD, and her colleagues. The study was published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

Dr. Tektonidou of National and Kapodistrian University of Athens and her coauthors at the U.S. National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases performed a meta-analysis on studies examining survival in adult and pediatric SLE patients from the 1950s to the mid-1990s. Ultimately, they analyzed 125 adult studies, including 82 from high-income countries and 43 from low- to middle-income countries (LMIC), and 51 pediatric studies, of which 33 were from high-income countries and 18 from LMIC.

In adult studies, researchers found that both high-income and LMIC experienced gradual increases in survival from the 1950s to mid-1990s. After this period of time, the survival estimates stabilized. “In 2008–2016, the 5-year, 10-year, and 15-year survival estimates in high-income countries were 0.95 (95% credible interval, 0.94 to 0.96), 0.89 (0.88 to 0.90) and 0.82 (0.81 to 0.83), respectively” (Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Aug 9. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211663).

Although there were no data for LMIC prior to 1970, researchers identified survival trends similar to those in high-income countries in more recent years. Over the same time period between 2008 and 2016, “the 5-year, 10-year, and 15-year survival estimates in LMIC were 0.92 (0.91 to 0.93), 0.85 (0.84 to 0.87) and 0.79 (0.78 to 0.81), respectively,” according to the report.

Unlike the steady improvement seen over a 40-year period with adult studies, pediatric SLE patients in high-income countries experienced dramatic increases in survival rates from the 1960s to the 1970s, followed by slower increases in survival rates. The researchers reported that between 2008 and 2016,“the 5-year and 10-year survival estimates from high-income countries were 0.99 (0.98 to 1.00) and 0.97 (0.96 to 0.98), respectively.”

LMIC had significantly worse survival in pediatric SLE patients than did their wealthy counterparts. “Survival persistently lagged [behind] that of high-income countries” between 1980 and 2000. Dr. Tektonidou and her associates found that “5-year and 10-year survival estimates from LMIC were 0.85 (0.83 to 0.88) and 0.79 (0.76 to 0.82), respectively.” Due to the small number of studies reporting 15-year survival rates, this time point was not included in the pediatric analysis.

The researchers also analyzed the cause of death for adult and pediatric SLE patients in both high-income countries and LMIC. High-income countries showed lower rates of SLE-associated deaths over time in adults, although infection-related deaths increased in adults in both high-income countries and LMIC. There were not enough studies and data to assess cause of death in pediatric studies in high-income countries, but pediatric patients in LMIC had an upward trend in SLE-associated deaths.

The Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases supported the study. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The major improvement in survival that patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) have experienced from 1950 to the mid-1990s has plateaued ever since, reported Maria Tektonidou, MD, and her colleagues. The study was published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

Dr. Tektonidou of National and Kapodistrian University of Athens and her coauthors at the U.S. National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases performed a meta-analysis on studies examining survival in adult and pediatric SLE patients from the 1950s to the mid-1990s. Ultimately, they analyzed 125 adult studies, including 82 from high-income countries and 43 from low- to middle-income countries (LMIC), and 51 pediatric studies, of which 33 were from high-income countries and 18 from LMIC.

In adult studies, researchers found that both high-income and LMIC experienced gradual increases in survival from the 1950s to mid-1990s. After this period of time, the survival estimates stabilized. “In 2008–2016, the 5-year, 10-year, and 15-year survival estimates in high-income countries were 0.95 (95% credible interval, 0.94 to 0.96), 0.89 (0.88 to 0.90) and 0.82 (0.81 to 0.83), respectively” (Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Aug 9. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211663).

Although there were no data for LMIC prior to 1970, researchers identified survival trends similar to those in high-income countries in more recent years. Over the same time period between 2008 and 2016, “the 5-year, 10-year, and 15-year survival estimates in LMIC were 0.92 (0.91 to 0.93), 0.85 (0.84 to 0.87) and 0.79 (0.78 to 0.81), respectively,” according to the report.

Unlike the steady improvement seen over a 40-year period with adult studies, pediatric SLE patients in high-income countries experienced dramatic increases in survival rates from the 1960s to the 1970s, followed by slower increases in survival rates. The researchers reported that between 2008 and 2016,“the 5-year and 10-year survival estimates from high-income countries were 0.99 (0.98 to 1.00) and 0.97 (0.96 to 0.98), respectively.”

LMIC had significantly worse survival in pediatric SLE patients than did their wealthy counterparts. “Survival persistently lagged [behind] that of high-income countries” between 1980 and 2000. Dr. Tektonidou and her associates found that “5-year and 10-year survival estimates from LMIC were 0.85 (0.83 to 0.88) and 0.79 (0.76 to 0.82), respectively.” Due to the small number of studies reporting 15-year survival rates, this time point was not included in the pediatric analysis.

The researchers also analyzed the cause of death for adult and pediatric SLE patients in both high-income countries and LMIC. High-income countries showed lower rates of SLE-associated deaths over time in adults, although infection-related deaths increased in adults in both high-income countries and LMIC. There were not enough studies and data to assess cause of death in pediatric studies in high-income countries, but pediatric patients in LMIC had an upward trend in SLE-associated deaths.

The Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases supported the study. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Five-year survival for SLE in adults and children in high-income countries is greater than 0.95.

Data source: Systematic literature review and Bayesian meta-analysis of 171 published cohort studies of survival in SLE patients from 1950 to the present.

Disclosures: The Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases supported the study. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

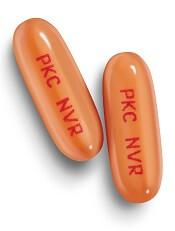

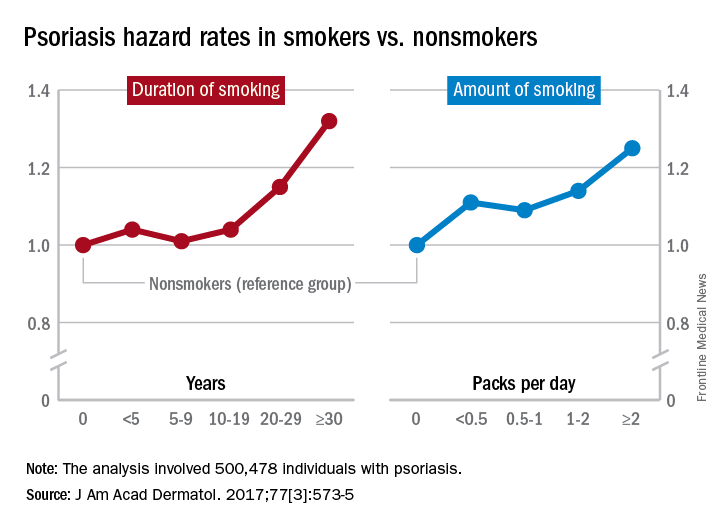

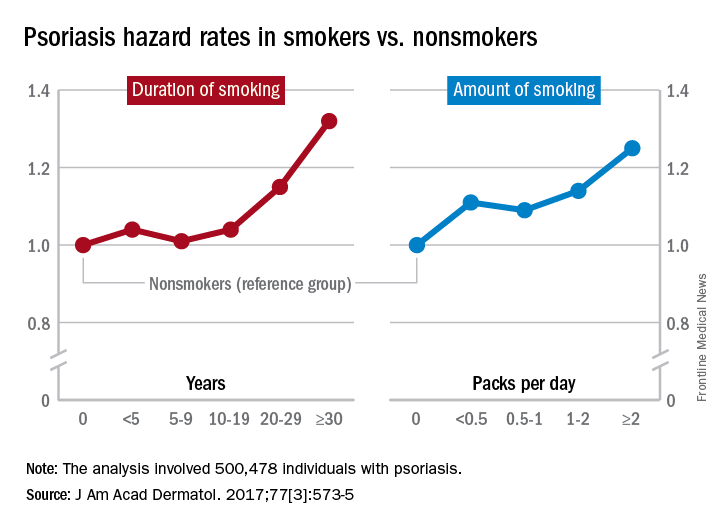

Smoking linked to increased psoriasis risk

Current and former smokers were significantly more likely to have psoriasis than were nonsmokers in an analysis of the Korean National Health Insurance database.

Multivariate analyses produced adjusted incidence rates of 1.14 for current smokers (n = 132,566) and 1.11 for former smokers (n = 47,477), compared with nonsmokers (n = 320,435), indicating “that smoking status is an independent potential risk factor for psoriasis,” reported Eun Joo Lee, PhD, of the National Health Insurance Service in Wonjusi, South Korea, and associates (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77[3]:573-5).

The study was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea that was funded by the Korean government. The investigators did not declare any conflicts of interest.

Current and former smokers were significantly more likely to have psoriasis than were nonsmokers in an analysis of the Korean National Health Insurance database.

Multivariate analyses produced adjusted incidence rates of 1.14 for current smokers (n = 132,566) and 1.11 for former smokers (n = 47,477), compared with nonsmokers (n = 320,435), indicating “that smoking status is an independent potential risk factor for psoriasis,” reported Eun Joo Lee, PhD, of the National Health Insurance Service in Wonjusi, South Korea, and associates (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77[3]:573-5).

The study was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea that was funded by the Korean government. The investigators did not declare any conflicts of interest.

Current and former smokers were significantly more likely to have psoriasis than were nonsmokers in an analysis of the Korean National Health Insurance database.

Multivariate analyses produced adjusted incidence rates of 1.14 for current smokers (n = 132,566) and 1.11 for former smokers (n = 47,477), compared with nonsmokers (n = 320,435), indicating “that smoking status is an independent potential risk factor for psoriasis,” reported Eun Joo Lee, PhD, of the National Health Insurance Service in Wonjusi, South Korea, and associates (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77[3]:573-5).

The study was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea that was funded by the Korean government. The investigators did not declare any conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Young Faculty Hot Topics: How to find mentors

As someone less than 1 year into practice, I believe mentorship is one of the most critical essentials as a trainee and a junior attending. I have been privileged to have excellent mentors throughout my training and now, in my first job. A lot of this is luck, but I also have always put mentorship at the top of my list when looking for fellowships and jobs. In fact, part of the reason I took the job I currently have is because the contract clearly stated who my clinical and academic mentors would be. This showed the department’s dedication to grooming junior staff appropriately. Below is my take on how to find mentors.

Have multiple mentors

It’s good to have multiple mentors, each of whom can provide a different kind of mentorship. For junior faculty, key areas of mentorship include:

- Building clinical volume.

- Establishing your reputation as a safe and competent clinician/surgeon.

- Designing your academic/research career.

- Planning your overall career.

- Solving any political/administrative issues.

Currently, my division chief is my clinical/general mentor, from whom I seek clinical advice, political advice should I find myself in a tough situation as a junior attending, and personal advice, as well. We meet monthly to go over various things including clinical/research projects and any clinical issues. I have an academic mentor, who is a basic scientist; we review research ideas together. He reads over and critiques my grants, and he picks apart my presentations. I also have a very senior mentor, a retired thoracic surgeon, whom I seek when I have a challenging case; it is crucial to identify a senior surgeon who has an abundance of experience so you can pick his or her brain – a true resource. This is in addition to the mentors I have from my training, with whom I am still in contact. I think it is important to have mentors outside of your current work for certain situations.

Mentors do not have to be in your discipline

It’s useful to have mentors from different fields. As I stated above, my academic mentor is a basic scientist. I am a thoracic surgeon, but I consider my general surgery residency chair, who is an accomplished surgical oncologist, and my residency program director, a general surgeon, to be two of my important mentors. I think it’s a good idea to have someone outside of your discipline as your mentor, even someone in a nonsurgical discipline, as long as she or he provides what you need, such as general career decisions and research mentorship. Having people from different disciplines adds more perspective and depth. For women, female mentors may provide input on career decisions at different life stages.

Do your homework about your would-be mentors

When deciding among different jobs, I did as much homework as possible in researching my would-be clinical mentors, who in most cases are also your senior partners. This included speaking with other junior faculty members within the division, people who had worked with the person in the past, and current mentors who may know them. In my mind, I found the most valuable resources to be people who had worked in the past with potential new mentors or senior partners. They can provide unbiased, sometimes negative, opinions that others might be less willing to provide. In fact, I probably spent more time trying to understand to the negative comments, since this provided valuable information, too.

I always asked questions specific to the mentorship. Were they around to help you in the OR when needed, or was it more of a verbal “I’ll be around”? Were they good about giving the juniors clinical volume and sharing OR time? Did you feel like you grew under his or her mentorship?

In conclusion, my advice about mentorship is to have multiple mentors, each for different purposes. For those looking for fellowships and jobs, learning all you can about your would-be mentors goes a long way toward ensuring an ideal position.

Dr. Suzuki is a general thoracic surgeon at Boston Medical Center.

As someone less than 1 year into practice, I believe mentorship is one of the most critical essentials as a trainee and a junior attending. I have been privileged to have excellent mentors throughout my training and now, in my first job. A lot of this is luck, but I also have always put mentorship at the top of my list when looking for fellowships and jobs. In fact, part of the reason I took the job I currently have is because the contract clearly stated who my clinical and academic mentors would be. This showed the department’s dedication to grooming junior staff appropriately. Below is my take on how to find mentors.

Have multiple mentors

It’s good to have multiple mentors, each of whom can provide a different kind of mentorship. For junior faculty, key areas of mentorship include:

- Building clinical volume.

- Establishing your reputation as a safe and competent clinician/surgeon.

- Designing your academic/research career.

- Planning your overall career.

- Solving any political/administrative issues.

Currently, my division chief is my clinical/general mentor, from whom I seek clinical advice, political advice should I find myself in a tough situation as a junior attending, and personal advice, as well. We meet monthly to go over various things including clinical/research projects and any clinical issues. I have an academic mentor, who is a basic scientist; we review research ideas together. He reads over and critiques my grants, and he picks apart my presentations. I also have a very senior mentor, a retired thoracic surgeon, whom I seek when I have a challenging case; it is crucial to identify a senior surgeon who has an abundance of experience so you can pick his or her brain – a true resource. This is in addition to the mentors I have from my training, with whom I am still in contact. I think it is important to have mentors outside of your current work for certain situations.

Mentors do not have to be in your discipline

It’s useful to have mentors from different fields. As I stated above, my academic mentor is a basic scientist. I am a thoracic surgeon, but I consider my general surgery residency chair, who is an accomplished surgical oncologist, and my residency program director, a general surgeon, to be two of my important mentors. I think it’s a good idea to have someone outside of your discipline as your mentor, even someone in a nonsurgical discipline, as long as she or he provides what you need, such as general career decisions and research mentorship. Having people from different disciplines adds more perspective and depth. For women, female mentors may provide input on career decisions at different life stages.

Do your homework about your would-be mentors

When deciding among different jobs, I did as much homework as possible in researching my would-be clinical mentors, who in most cases are also your senior partners. This included speaking with other junior faculty members within the division, people who had worked with the person in the past, and current mentors who may know them. In my mind, I found the most valuable resources to be people who had worked in the past with potential new mentors or senior partners. They can provide unbiased, sometimes negative, opinions that others might be less willing to provide. In fact, I probably spent more time trying to understand to the negative comments, since this provided valuable information, too.

I always asked questions specific to the mentorship. Were they around to help you in the OR when needed, or was it more of a verbal “I’ll be around”? Were they good about giving the juniors clinical volume and sharing OR time? Did you feel like you grew under his or her mentorship?

In conclusion, my advice about mentorship is to have multiple mentors, each for different purposes. For those looking for fellowships and jobs, learning all you can about your would-be mentors goes a long way toward ensuring an ideal position.

Dr. Suzuki is a general thoracic surgeon at Boston Medical Center.

As someone less than 1 year into practice, I believe mentorship is one of the most critical essentials as a trainee and a junior attending. I have been privileged to have excellent mentors throughout my training and now, in my first job. A lot of this is luck, but I also have always put mentorship at the top of my list when looking for fellowships and jobs. In fact, part of the reason I took the job I currently have is because the contract clearly stated who my clinical and academic mentors would be. This showed the department’s dedication to grooming junior staff appropriately. Below is my take on how to find mentors.

Have multiple mentors

It’s good to have multiple mentors, each of whom can provide a different kind of mentorship. For junior faculty, key areas of mentorship include:

- Building clinical volume.

- Establishing your reputation as a safe and competent clinician/surgeon.

- Designing your academic/research career.

- Planning your overall career.

- Solving any political/administrative issues.

Currently, my division chief is my clinical/general mentor, from whom I seek clinical advice, political advice should I find myself in a tough situation as a junior attending, and personal advice, as well. We meet monthly to go over various things including clinical/research projects and any clinical issues. I have an academic mentor, who is a basic scientist; we review research ideas together. He reads over and critiques my grants, and he picks apart my presentations. I also have a very senior mentor, a retired thoracic surgeon, whom I seek when I have a challenging case; it is crucial to identify a senior surgeon who has an abundance of experience so you can pick his or her brain – a true resource. This is in addition to the mentors I have from my training, with whom I am still in contact. I think it is important to have mentors outside of your current work for certain situations.

Mentors do not have to be in your discipline

It’s useful to have mentors from different fields. As I stated above, my academic mentor is a basic scientist. I am a thoracic surgeon, but I consider my general surgery residency chair, who is an accomplished surgical oncologist, and my residency program director, a general surgeon, to be two of my important mentors. I think it’s a good idea to have someone outside of your discipline as your mentor, even someone in a nonsurgical discipline, as long as she or he provides what you need, such as general career decisions and research mentorship. Having people from different disciplines adds more perspective and depth. For women, female mentors may provide input on career decisions at different life stages.

Do your homework about your would-be mentors

When deciding among different jobs, I did as much homework as possible in researching my would-be clinical mentors, who in most cases are also your senior partners. This included speaking with other junior faculty members within the division, people who had worked with the person in the past, and current mentors who may know them. In my mind, I found the most valuable resources to be people who had worked in the past with potential new mentors or senior partners. They can provide unbiased, sometimes negative, opinions that others might be less willing to provide. In fact, I probably spent more time trying to understand to the negative comments, since this provided valuable information, too.

I always asked questions specific to the mentorship. Were they around to help you in the OR when needed, or was it more of a verbal “I’ll be around”? Were they good about giving the juniors clinical volume and sharing OR time? Did you feel like you grew under his or her mentorship?

In conclusion, my advice about mentorship is to have multiple mentors, each for different purposes. For those looking for fellowships and jobs, learning all you can about your would-be mentors goes a long way toward ensuring an ideal position.

Dr. Suzuki is a general thoracic surgeon at Boston Medical Center.

Young Faculty Hot Topics: Saying “yes” or saying “no”

The vast majority of us did not end up where we are today by saying “no” to opportunities throughout medical school, surgical training and now early in our clinical practice. In fact, many of us likely said “yes” to just about everything that came our way, and this was reasonable as the number of opportunities was manageable. As you move along your career as a cardiothoracic surgeon, the opportunities increase, especially if you consistently turn in a high performance.

A discussion of what to say “yes” or “no” to would be remiss without considering your individual career goals and time management. You’ve heard it before and here it is again: Write down your 5- and 10-year career plan. If you do not know where you are heading, you cannot plot the course. Then, based on those long-term career goals, drill down to your annual goals. Begin by identifying deadlines on the academic calendar each year and then work backward to determine what needs to be done in the months prior to those deadlines. Once you have a clear idea of what needs to be done on a month-by-month basis, on the Sunday of each week, create a list of daily goals. This method turns your long-term career goals into doable-size pieces of a larger puzzle that will keep you on trajectory.

Once you have charted your course using the above methods or some variation of them, you will have a clear idea of what opportunities are aligned with your long-term career plan. For example, if your goals are to build your clinical practice and become a program director, you may prioritize attending a course to introduce a new surgical technique into your practice and becoming the clerkship director for medical students instead of serving on hospital committees. Solicit advice from mentors and colleagues regarding certain opportunities if you are unsure whether these will help you achieve your career goals. Furthermore, identify senior cardiothoracic surgeons who have achieved the goals you are aiming for and ask them how they arrived at their position.

Oftentimes, it’s not about saying “yes” or “no,” but rather seeking out opportunities. Saying “yes” to opportunities that are pertinent to your career goals is critical, but there are other factors to consider when deciding whether to accept an opportunity. A major factor is the ratio of benefit to time commitment; clearly, the greater the benefit and the lower the time commitment, the better. However, there may be some opportunities that are beneficial and require a fair amount of time. Only you can decide whether the time necessary to commit to an opportunity is worth the benefit. Another factor to consider is what academic milestones are necessary for promotion at your institution; this may also vary by academic track within an institution. Be familiar with these requirements, and factor them into your goals as they are the foundation upon which you climb the academic ladder within your department.

Lastly, consider all the potential advantages of certain opportunities. For example, every year the STS solicits self-nominations for committees: Are there any committees that pertain to your career goals that will allow you to network with other cardiothoracic surgeons who may then become a mentor, sponsor, or collaborator?

I’m going to state the obvious: Only you know how you are spending every minute of every hour of each day. Why do I mention this? If you have said “yes” to too many things and are stretched too thin, you are at risk of underperforming and may begin to feel underappreciated; nobody else may realize how many hours you are working, but they will notice if your performance is subpar. Not only that, but you may be at risk of burnout. Unlike residency training, where we sprinted every day (and sometimes all night) and the light at the end of the tunnel was within view, we are now in an endurance race and need to pace ourselves for long, successful, and fulfilling careers. Ideally, we deliver what we promise, but if that balance is tipped, err on the side of underpromising and overdelivering. That scenario is much better than overpromising and underdelivering since the latter not only leads to a performance that might be less than your best but also could decrease your future opportunities.

When offered an opportunity, do not say “yes” immediately; collect some intel regarding the time commitment, determine whether it is aligned with your career goals and, if need be, discuss it with mentors and trusted colleagues before you say “yes.” Once you decide to say “yes,” jump in and hit the ground running! The beginning of your career is an exciting time with some flexibility in terms of choosing your own career adventures. Always be realistic about your goals and time to ensure a long, rewarding career.

Dr. Brown is a general thoracic surgeon at UC Davis Medical Center, Calif.

The vast majority of us did not end up where we are today by saying “no” to opportunities throughout medical school, surgical training and now early in our clinical practice. In fact, many of us likely said “yes” to just about everything that came our way, and this was reasonable as the number of opportunities was manageable. As you move along your career as a cardiothoracic surgeon, the opportunities increase, especially if you consistently turn in a high performance.

A discussion of what to say “yes” or “no” to would be remiss without considering your individual career goals and time management. You’ve heard it before and here it is again: Write down your 5- and 10-year career plan. If you do not know where you are heading, you cannot plot the course. Then, based on those long-term career goals, drill down to your annual goals. Begin by identifying deadlines on the academic calendar each year and then work backward to determine what needs to be done in the months prior to those deadlines. Once you have a clear idea of what needs to be done on a month-by-month basis, on the Sunday of each week, create a list of daily goals. This method turns your long-term career goals into doable-size pieces of a larger puzzle that will keep you on trajectory.

Once you have charted your course using the above methods or some variation of them, you will have a clear idea of what opportunities are aligned with your long-term career plan. For example, if your goals are to build your clinical practice and become a program director, you may prioritize attending a course to introduce a new surgical technique into your practice and becoming the clerkship director for medical students instead of serving on hospital committees. Solicit advice from mentors and colleagues regarding certain opportunities if you are unsure whether these will help you achieve your career goals. Furthermore, identify senior cardiothoracic surgeons who have achieved the goals you are aiming for and ask them how they arrived at their position.

Oftentimes, it’s not about saying “yes” or “no,” but rather seeking out opportunities. Saying “yes” to opportunities that are pertinent to your career goals is critical, but there are other factors to consider when deciding whether to accept an opportunity. A major factor is the ratio of benefit to time commitment; clearly, the greater the benefit and the lower the time commitment, the better. However, there may be some opportunities that are beneficial and require a fair amount of time. Only you can decide whether the time necessary to commit to an opportunity is worth the benefit. Another factor to consider is what academic milestones are necessary for promotion at your institution; this may also vary by academic track within an institution. Be familiar with these requirements, and factor them into your goals as they are the foundation upon which you climb the academic ladder within your department.

Lastly, consider all the potential advantages of certain opportunities. For example, every year the STS solicits self-nominations for committees: Are there any committees that pertain to your career goals that will allow you to network with other cardiothoracic surgeons who may then become a mentor, sponsor, or collaborator?

I’m going to state the obvious: Only you know how you are spending every minute of every hour of each day. Why do I mention this? If you have said “yes” to too many things and are stretched too thin, you are at risk of underperforming and may begin to feel underappreciated; nobody else may realize how many hours you are working, but they will notice if your performance is subpar. Not only that, but you may be at risk of burnout. Unlike residency training, where we sprinted every day (and sometimes all night) and the light at the end of the tunnel was within view, we are now in an endurance race and need to pace ourselves for long, successful, and fulfilling careers. Ideally, we deliver what we promise, but if that balance is tipped, err on the side of underpromising and overdelivering. That scenario is much better than overpromising and underdelivering since the latter not only leads to a performance that might be less than your best but also could decrease your future opportunities.

When offered an opportunity, do not say “yes” immediately; collect some intel regarding the time commitment, determine whether it is aligned with your career goals and, if need be, discuss it with mentors and trusted colleagues before you say “yes.” Once you decide to say “yes,” jump in and hit the ground running! The beginning of your career is an exciting time with some flexibility in terms of choosing your own career adventures. Always be realistic about your goals and time to ensure a long, rewarding career.

Dr. Brown is a general thoracic surgeon at UC Davis Medical Center, Calif.

The vast majority of us did not end up where we are today by saying “no” to opportunities throughout medical school, surgical training and now early in our clinical practice. In fact, many of us likely said “yes” to just about everything that came our way, and this was reasonable as the number of opportunities was manageable. As you move along your career as a cardiothoracic surgeon, the opportunities increase, especially if you consistently turn in a high performance.

A discussion of what to say “yes” or “no” to would be remiss without considering your individual career goals and time management. You’ve heard it before and here it is again: Write down your 5- and 10-year career plan. If you do not know where you are heading, you cannot plot the course. Then, based on those long-term career goals, drill down to your annual goals. Begin by identifying deadlines on the academic calendar each year and then work backward to determine what needs to be done in the months prior to those deadlines. Once you have a clear idea of what needs to be done on a month-by-month basis, on the Sunday of each week, create a list of daily goals. This method turns your long-term career goals into doable-size pieces of a larger puzzle that will keep you on trajectory.

Once you have charted your course using the above methods or some variation of them, you will have a clear idea of what opportunities are aligned with your long-term career plan. For example, if your goals are to build your clinical practice and become a program director, you may prioritize attending a course to introduce a new surgical technique into your practice and becoming the clerkship director for medical students instead of serving on hospital committees. Solicit advice from mentors and colleagues regarding certain opportunities if you are unsure whether these will help you achieve your career goals. Furthermore, identify senior cardiothoracic surgeons who have achieved the goals you are aiming for and ask them how they arrived at their position.

Oftentimes, it’s not about saying “yes” or “no,” but rather seeking out opportunities. Saying “yes” to opportunities that are pertinent to your career goals is critical, but there are other factors to consider when deciding whether to accept an opportunity. A major factor is the ratio of benefit to time commitment; clearly, the greater the benefit and the lower the time commitment, the better. However, there may be some opportunities that are beneficial and require a fair amount of time. Only you can decide whether the time necessary to commit to an opportunity is worth the benefit. Another factor to consider is what academic milestones are necessary for promotion at your institution; this may also vary by academic track within an institution. Be familiar with these requirements, and factor them into your goals as they are the foundation upon which you climb the academic ladder within your department.

Lastly, consider all the potential advantages of certain opportunities. For example, every year the STS solicits self-nominations for committees: Are there any committees that pertain to your career goals that will allow you to network with other cardiothoracic surgeons who may then become a mentor, sponsor, or collaborator?

I’m going to state the obvious: Only you know how you are spending every minute of every hour of each day. Why do I mention this? If you have said “yes” to too many things and are stretched too thin, you are at risk of underperforming and may begin to feel underappreciated; nobody else may realize how many hours you are working, but they will notice if your performance is subpar. Not only that, but you may be at risk of burnout. Unlike residency training, where we sprinted every day (and sometimes all night) and the light at the end of the tunnel was within view, we are now in an endurance race and need to pace ourselves for long, successful, and fulfilling careers. Ideally, we deliver what we promise, but if that balance is tipped, err on the side of underpromising and overdelivering. That scenario is much better than overpromising and underdelivering since the latter not only leads to a performance that might be less than your best but also could decrease your future opportunities.

When offered an opportunity, do not say “yes” immediately; collect some intel regarding the time commitment, determine whether it is aligned with your career goals and, if need be, discuss it with mentors and trusted colleagues before you say “yes.” Once you decide to say “yes,” jump in and hit the ground running! The beginning of your career is an exciting time with some flexibility in terms of choosing your own career adventures. Always be realistic about your goals and time to ensure a long, rewarding career.

Dr. Brown is a general thoracic surgeon at UC Davis Medical Center, Calif.

Building a High Performance VA Oncology Network

As the VA Precision Oncology Program (POP) matures, it is working to ensure that all veterans have access to appropriate therapies no matter the location. At the Association of VA Hematology and Oncology (AVAHO) meeting in Denver, Colorado, Michael Kelley, director of the VA National Program for Medical Oncology outlined the latest POP updates and strongly encouraged VA oncologists to take advantage of its resources.

Kelley noted that POP also is working to increase access to clinical trials. The VA has partnered with the National Cancer Institute (NCI) on NAVIGATE to get more VA patients involved in NCI trials. The NAVIGATE program is expected to kick off soon and be up and running in 2018. Grant Huang, acting director for the Cooperative Studies Program in the Office of Research & Development has been helping to lead that initiative.

As the VA Precision Oncology Program (POP) matures, it is working to ensure that all veterans have access to appropriate therapies no matter the location. At the Association of VA Hematology and Oncology (AVAHO) meeting in Denver, Colorado, Michael Kelley, director of the VA National Program for Medical Oncology outlined the latest POP updates and strongly encouraged VA oncologists to take advantage of its resources.

Kelley noted that POP also is working to increase access to clinical trials. The VA has partnered with the National Cancer Institute (NCI) on NAVIGATE to get more VA patients involved in NCI trials. The NAVIGATE program is expected to kick off soon and be up and running in 2018. Grant Huang, acting director for the Cooperative Studies Program in the Office of Research & Development has been helping to lead that initiative.

As the VA Precision Oncology Program (POP) matures, it is working to ensure that all veterans have access to appropriate therapies no matter the location. At the Association of VA Hematology and Oncology (AVAHO) meeting in Denver, Colorado, Michael Kelley, director of the VA National Program for Medical Oncology outlined the latest POP updates and strongly encouraged VA oncologists to take advantage of its resources.

Kelley noted that POP also is working to increase access to clinical trials. The VA has partnered with the National Cancer Institute (NCI) on NAVIGATE to get more VA patients involved in NCI trials. The NAVIGATE program is expected to kick off soon and be up and running in 2018. Grant Huang, acting director for the Cooperative Studies Program in the Office of Research & Development has been helping to lead that initiative.

New Tools for Radiation Oncology Quality at VA

At the recent Association of VA Hematology and Oncology (AVAHO) meeting in Denver, Colorado, Michael Hagan, MD, PhD, director of the VA National Radiation Oncology Program, outlined a new program designed to improve quality and standardize radiation oncology practice across VA. Hagan introduced Radiation Oncology Practice Assessment (ROPA), which pulls data from treatment and compares it to quality metrics.

Hagan outlined the various steps taken to build the information technology infrastructure for ROPA. The quality metrics were developed in conjunction with American Society of Radiation Oncology disease site-specific experts and other peer reviewers.

The ROPA tool provides VA access to a new data source. “ROPA gives us the ability to drill down to an individual data point to see why a patient result does not meet quality measures,” Hagan told the AVAHO attendees. In FY 2018, ROPA will provide a scorecard to each practice for each case, comparing local results against quality measures. The VA hopes that ROPA will help identify outliers and alert service chiefs of areas, “where there is room for improvement.”

The new technology will allow radiation oncology to see trends across VHA, confront challenges, and potentially realign resources. So far, the data are promising. According to Hagan in initial analyses, VA providers had higher scores overall than did community providers. In early analyses, ROPA produced 11,030 observations across 51 quality metrics, which included 489 patients at 11 sites. Quality measures fall off with follow-up but are useful for treatment.

At the recent Association of VA Hematology and Oncology (AVAHO) meeting in Denver, Colorado, Michael Hagan, MD, PhD, director of the VA National Radiation Oncology Program, outlined a new program designed to improve quality and standardize radiation oncology practice across VA. Hagan introduced Radiation Oncology Practice Assessment (ROPA), which pulls data from treatment and compares it to quality metrics.

Hagan outlined the various steps taken to build the information technology infrastructure for ROPA. The quality metrics were developed in conjunction with American Society of Radiation Oncology disease site-specific experts and other peer reviewers.

The ROPA tool provides VA access to a new data source. “ROPA gives us the ability to drill down to an individual data point to see why a patient result does not meet quality measures,” Hagan told the AVAHO attendees. In FY 2018, ROPA will provide a scorecard to each practice for each case, comparing local results against quality measures. The VA hopes that ROPA will help identify outliers and alert service chiefs of areas, “where there is room for improvement.”

The new technology will allow radiation oncology to see trends across VHA, confront challenges, and potentially realign resources. So far, the data are promising. According to Hagan in initial analyses, VA providers had higher scores overall than did community providers. In early analyses, ROPA produced 11,030 observations across 51 quality metrics, which included 489 patients at 11 sites. Quality measures fall off with follow-up but are useful for treatment.

At the recent Association of VA Hematology and Oncology (AVAHO) meeting in Denver, Colorado, Michael Hagan, MD, PhD, director of the VA National Radiation Oncology Program, outlined a new program designed to improve quality and standardize radiation oncology practice across VA. Hagan introduced Radiation Oncology Practice Assessment (ROPA), which pulls data from treatment and compares it to quality metrics.

Hagan outlined the various steps taken to build the information technology infrastructure for ROPA. The quality metrics were developed in conjunction with American Society of Radiation Oncology disease site-specific experts and other peer reviewers.

The ROPA tool provides VA access to a new data source. “ROPA gives us the ability to drill down to an individual data point to see why a patient result does not meet quality measures,” Hagan told the AVAHO attendees. In FY 2018, ROPA will provide a scorecard to each practice for each case, comparing local results against quality measures. The VA hopes that ROPA will help identify outliers and alert service chiefs of areas, “where there is room for improvement.”

The new technology will allow radiation oncology to see trends across VHA, confront challenges, and potentially realign resources. So far, the data are promising. According to Hagan in initial analyses, VA providers had higher scores overall than did community providers. In early analyses, ROPA produced 11,030 observations across 51 quality metrics, which included 489 patients at 11 sites. Quality measures fall off with follow-up but are useful for treatment.

Tips for Trusting Evidence

Echoing some of the themes from the previous night’s keynote, a morning breakout session at the 13th annual Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO) meeting focused on helping researchers interpret statistics and determine the usefulness of clinical studies or guidelines. Three presentations comprised the session, titled, “Making Sense of the Evidence: Useful Strategies to Appraise Clinical Trials and Guidelines”

The session opened with a discussion of critical appraisal. According to Melissa V. Taylor, PhD, RN, associate chief nurse for research at VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System, critical appraisal involves the systematic examination of research to accomplish an assessment of validity, results, and relevance to inform clinical practice. This, according to Taylor, involves 2 steps: appraise an individual piece of research, then appraise all the research studies that collectively examine the same clinical issue or question.

“While critical appraisal won’t necessarily give us the right answer about that research study,” said Taylor, “it will give us some insight into whether a piece of research is good enough to use in clinical decision making.”

Beverly Priefer, PhD, RN, focused her presentation on the usefulness of clinical guidelines and whether or not they should be followed. Preifer defined clinical practice guidelines as statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options. She stressed that these are not mandates and health care providers can focus an appraisal of guidelines on the following metrics found in the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II:

- Scope and purpose;

- Stakeholder involvement;

- Rigor of development;

- Clarity of presentation;

- Applicability;

- Editorial independence; and

- Overall assessment.

The final presentation of the session, “Beyond the P Value: What is the Evidence Telling Us,” examined the usefulness of P values in research studies. Although ubiquitous in the literature, “a p value is just one tool in your tool box…there are other models that might be just as valid and not incompatible with the data,” according to Paula K. Roberson, PhD, professor and chair of the department of biostatistics at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. Roberson dove into the 6 principals of the American Statistical Association’s statement that address misconceptions and misuse of the P value. She also suggested that other measures, such as confidence intervals or odds ratios, may provide insight that P values cannot.

Echoing some of the themes from the previous night’s keynote, a morning breakout session at the 13th annual Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO) meeting focused on helping researchers interpret statistics and determine the usefulness of clinical studies or guidelines. Three presentations comprised the session, titled, “Making Sense of the Evidence: Useful Strategies to Appraise Clinical Trials and Guidelines”

The session opened with a discussion of critical appraisal. According to Melissa V. Taylor, PhD, RN, associate chief nurse for research at VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System, critical appraisal involves the systematic examination of research to accomplish an assessment of validity, results, and relevance to inform clinical practice. This, according to Taylor, involves 2 steps: appraise an individual piece of research, then appraise all the research studies that collectively examine the same clinical issue or question.

“While critical appraisal won’t necessarily give us the right answer about that research study,” said Taylor, “it will give us some insight into whether a piece of research is good enough to use in clinical decision making.”

Beverly Priefer, PhD, RN, focused her presentation on the usefulness of clinical guidelines and whether or not they should be followed. Preifer defined clinical practice guidelines as statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options. She stressed that these are not mandates and health care providers can focus an appraisal of guidelines on the following metrics found in the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II:

- Scope and purpose;

- Stakeholder involvement;

- Rigor of development;

- Clarity of presentation;

- Applicability;

- Editorial independence; and

- Overall assessment.

The final presentation of the session, “Beyond the P Value: What is the Evidence Telling Us,” examined the usefulness of P values in research studies. Although ubiquitous in the literature, “a p value is just one tool in your tool box…there are other models that might be just as valid and not incompatible with the data,” according to Paula K. Roberson, PhD, professor and chair of the department of biostatistics at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. Roberson dove into the 6 principals of the American Statistical Association’s statement that address misconceptions and misuse of the P value. She also suggested that other measures, such as confidence intervals or odds ratios, may provide insight that P values cannot.

Echoing some of the themes from the previous night’s keynote, a morning breakout session at the 13th annual Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO) meeting focused on helping researchers interpret statistics and determine the usefulness of clinical studies or guidelines. Three presentations comprised the session, titled, “Making Sense of the Evidence: Useful Strategies to Appraise Clinical Trials and Guidelines”

The session opened with a discussion of critical appraisal. According to Melissa V. Taylor, PhD, RN, associate chief nurse for research at VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System, critical appraisal involves the systematic examination of research to accomplish an assessment of validity, results, and relevance to inform clinical practice. This, according to Taylor, involves 2 steps: appraise an individual piece of research, then appraise all the research studies that collectively examine the same clinical issue or question.

“While critical appraisal won’t necessarily give us the right answer about that research study,” said Taylor, “it will give us some insight into whether a piece of research is good enough to use in clinical decision making.”

Beverly Priefer, PhD, RN, focused her presentation on the usefulness of clinical guidelines and whether or not they should be followed. Preifer defined clinical practice guidelines as statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options. She stressed that these are not mandates and health care providers can focus an appraisal of guidelines on the following metrics found in the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II:

- Scope and purpose;

- Stakeholder involvement;

- Rigor of development;

- Clarity of presentation;

- Applicability;

- Editorial independence; and

- Overall assessment.

The final presentation of the session, “Beyond the P Value: What is the Evidence Telling Us,” examined the usefulness of P values in research studies. Although ubiquitous in the literature, “a p value is just one tool in your tool box…there are other models that might be just as valid and not incompatible with the data,” according to Paula K. Roberson, PhD, professor and chair of the department of biostatistics at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. Roberson dove into the 6 principals of the American Statistical Association’s statement that address misconceptions and misuse of the P value. She also suggested that other measures, such as confidence intervals or odds ratios, may provide insight that P values cannot.

Midostaurin approved to treat AML, SM in Europe

The European Commission has approved the multi-targeted kinase inhibitor midostaurin (Rydapt®) to treat acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and 3 types of advanced systemic mastocytosis (SM).

Midostaurin is approved to treat adults with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) who are FLT3 mutation-positive. In these patients, midostaurin can be used in combination with standard daunorubicin and cytarabine induction, followed by high-dose cytarabine consolidation. Patients who achieve a complete response can then receive midostaurin as maintenance therapy.

Midostaurin is also approved as monotherapy for adults with aggressive SM (ASM), SM with associated hematological neoplasm (SM-AHN), and mast cell leukemia (MCL).

Midostaurin in AML

The approval of midostaurin in AML is based on results from the phase 3 RATIFY trial, which were published in NEJM last month.

In RATIFY, researchers compared midostaurin plus standard chemotherapy to placebo plus standard chemotherapy in 717 adults younger than age 60 who had FLT3-mutated AML.

The median overall survival was significantly longer in the midostaurin arm than the placebo arm—74.7 months and 25.6 months, respectively (hazard ratio=0.77, P=0.016).

And the median event-free survival was significantly longer in the midostaurin arm than the placebo arm—8.2 months and 3.0 months, respectively (hazard ratio=0.78, P=0.004).

The most frequent adverse events (AEs) in the midostaurin arm (occurring in at least 20% of patients) were febrile neutropenia, nausea, vomiting, mucositis, headache, musculoskeletal pain, petechiae, device-related infection, epistaxis, hyperglycemia, and upper respiratory tract infection.

The most frequent grade 3/4 AEs (occurring in at least 10% of patients) were febrile neutropenia, device-related infection, and mucositis. Nine percent of patients in the midostaurin arm stopped treatment due to AEs, as did 6% in the placebo arm.

Midostaurin in advanced SM

The approval of midostaurin in advanced SM is based on results from a pair of phase 2, single-arm studies, hereafter referred to as Study 2 and Study 3. Data from Study 2 were published in NEJM in June 2016, and data from Study 3 were presented at the 2010 ASH Annual Meeting.

Study 2 included 116 patients, 115 of whom were evaluable for response.

The overall response rate (ORR) was 17% in the entire cohort, 31% among patients with ASM, 11% among patients with SM-AHN, and 19% among patients with MCL. The complete response rates were 2%, 6%, 0%, and 5%, respectively.

Study 3 included 26 patients with advanced SM. In 3 of the patients, the subtype of SM was unconfirmed.

Among the 17 patients with SM-AHN, there were 10 responses (ORR=59%), including 1 partial response and 9 major responses. In the 6 patients with MCL, there were 2 responses (ORR=33%), which included 1 partial response and 1 major response.

In both studies combined, there were 142 adults with ASM, SM-AHN, or MCL.

The most frequent AEs (excluding laboratory abnormalities) that occurred in at least 20% of these patients were nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, edema, musculoskeletal pain, abdominal pain, fatigue, upper respiratory tract infection, constipation, pyrexia, headache, and dyspnea.

The most frequent grade 3 or higher AEs (excluding laboratory abnormalities) that occurred in at least 5% of patients were fatigue, sepsis, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, pneumonia, diarrhea, febrile neutropenia, edema, dyspnea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and renal insufficiency.

Serious AEs occurred in 68% of patients, most commonly infections and gastrointestinal disorders.

Twenty-one percent of patients discontinued treatment due to AEs, the most frequent of which were infection, nausea or vomiting, QT prolongation, and gastrointestinal hemorrhage. ![]()

The European Commission has approved the multi-targeted kinase inhibitor midostaurin (Rydapt®) to treat acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and 3 types of advanced systemic mastocytosis (SM).

Midostaurin is approved to treat adults with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) who are FLT3 mutation-positive. In these patients, midostaurin can be used in combination with standard daunorubicin and cytarabine induction, followed by high-dose cytarabine consolidation. Patients who achieve a complete response can then receive midostaurin as maintenance therapy.

Midostaurin is also approved as monotherapy for adults with aggressive SM (ASM), SM with associated hematological neoplasm (SM-AHN), and mast cell leukemia (MCL).

Midostaurin in AML

The approval of midostaurin in AML is based on results from the phase 3 RATIFY trial, which were published in NEJM last month.

In RATIFY, researchers compared midostaurin plus standard chemotherapy to placebo plus standard chemotherapy in 717 adults younger than age 60 who had FLT3-mutated AML.

The median overall survival was significantly longer in the midostaurin arm than the placebo arm—74.7 months and 25.6 months, respectively (hazard ratio=0.77, P=0.016).

And the median event-free survival was significantly longer in the midostaurin arm than the placebo arm—8.2 months and 3.0 months, respectively (hazard ratio=0.78, P=0.004).

The most frequent adverse events (AEs) in the midostaurin arm (occurring in at least 20% of patients) were febrile neutropenia, nausea, vomiting, mucositis, headache, musculoskeletal pain, petechiae, device-related infection, epistaxis, hyperglycemia, and upper respiratory tract infection.

The most frequent grade 3/4 AEs (occurring in at least 10% of patients) were febrile neutropenia, device-related infection, and mucositis. Nine percent of patients in the midostaurin arm stopped treatment due to AEs, as did 6% in the placebo arm.

Midostaurin in advanced SM

The approval of midostaurin in advanced SM is based on results from a pair of phase 2, single-arm studies, hereafter referred to as Study 2 and Study 3. Data from Study 2 were published in NEJM in June 2016, and data from Study 3 were presented at the 2010 ASH Annual Meeting.

Study 2 included 116 patients, 115 of whom were evaluable for response.

The overall response rate (ORR) was 17% in the entire cohort, 31% among patients with ASM, 11% among patients with SM-AHN, and 19% among patients with MCL. The complete response rates were 2%, 6%, 0%, and 5%, respectively.

Study 3 included 26 patients with advanced SM. In 3 of the patients, the subtype of SM was unconfirmed.

Among the 17 patients with SM-AHN, there were 10 responses (ORR=59%), including 1 partial response and 9 major responses. In the 6 patients with MCL, there were 2 responses (ORR=33%), which included 1 partial response and 1 major response.

In both studies combined, there were 142 adults with ASM, SM-AHN, or MCL.

The most frequent AEs (excluding laboratory abnormalities) that occurred in at least 20% of these patients were nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, edema, musculoskeletal pain, abdominal pain, fatigue, upper respiratory tract infection, constipation, pyrexia, headache, and dyspnea.

The most frequent grade 3 or higher AEs (excluding laboratory abnormalities) that occurred in at least 5% of patients were fatigue, sepsis, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, pneumonia, diarrhea, febrile neutropenia, edema, dyspnea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and renal insufficiency.

Serious AEs occurred in 68% of patients, most commonly infections and gastrointestinal disorders.

Twenty-one percent of patients discontinued treatment due to AEs, the most frequent of which were infection, nausea or vomiting, QT prolongation, and gastrointestinal hemorrhage. ![]()

The European Commission has approved the multi-targeted kinase inhibitor midostaurin (Rydapt®) to treat acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and 3 types of advanced systemic mastocytosis (SM).

Midostaurin is approved to treat adults with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) who are FLT3 mutation-positive. In these patients, midostaurin can be used in combination with standard daunorubicin and cytarabine induction, followed by high-dose cytarabine consolidation. Patients who achieve a complete response can then receive midostaurin as maintenance therapy.

Midostaurin is also approved as monotherapy for adults with aggressive SM (ASM), SM with associated hematological neoplasm (SM-AHN), and mast cell leukemia (MCL).

Midostaurin in AML

The approval of midostaurin in AML is based on results from the phase 3 RATIFY trial, which were published in NEJM last month.

In RATIFY, researchers compared midostaurin plus standard chemotherapy to placebo plus standard chemotherapy in 717 adults younger than age 60 who had FLT3-mutated AML.

The median overall survival was significantly longer in the midostaurin arm than the placebo arm—74.7 months and 25.6 months, respectively (hazard ratio=0.77, P=0.016).

And the median event-free survival was significantly longer in the midostaurin arm than the placebo arm—8.2 months and 3.0 months, respectively (hazard ratio=0.78, P=0.004).

The most frequent adverse events (AEs) in the midostaurin arm (occurring in at least 20% of patients) were febrile neutropenia, nausea, vomiting, mucositis, headache, musculoskeletal pain, petechiae, device-related infection, epistaxis, hyperglycemia, and upper respiratory tract infection.

The most frequent grade 3/4 AEs (occurring in at least 10% of patients) were febrile neutropenia, device-related infection, and mucositis. Nine percent of patients in the midostaurin arm stopped treatment due to AEs, as did 6% in the placebo arm.

Midostaurin in advanced SM

The approval of midostaurin in advanced SM is based on results from a pair of phase 2, single-arm studies, hereafter referred to as Study 2 and Study 3. Data from Study 2 were published in NEJM in June 2016, and data from Study 3 were presented at the 2010 ASH Annual Meeting.

Study 2 included 116 patients, 115 of whom were evaluable for response.

The overall response rate (ORR) was 17% in the entire cohort, 31% among patients with ASM, 11% among patients with SM-AHN, and 19% among patients with MCL. The complete response rates were 2%, 6%, 0%, and 5%, respectively.

Study 3 included 26 patients with advanced SM. In 3 of the patients, the subtype of SM was unconfirmed.

Among the 17 patients with SM-AHN, there were 10 responses (ORR=59%), including 1 partial response and 9 major responses. In the 6 patients with MCL, there were 2 responses (ORR=33%), which included 1 partial response and 1 major response.

In both studies combined, there were 142 adults with ASM, SM-AHN, or MCL.