User login

USPSTF backs away from cotesting in cervical cancer screening

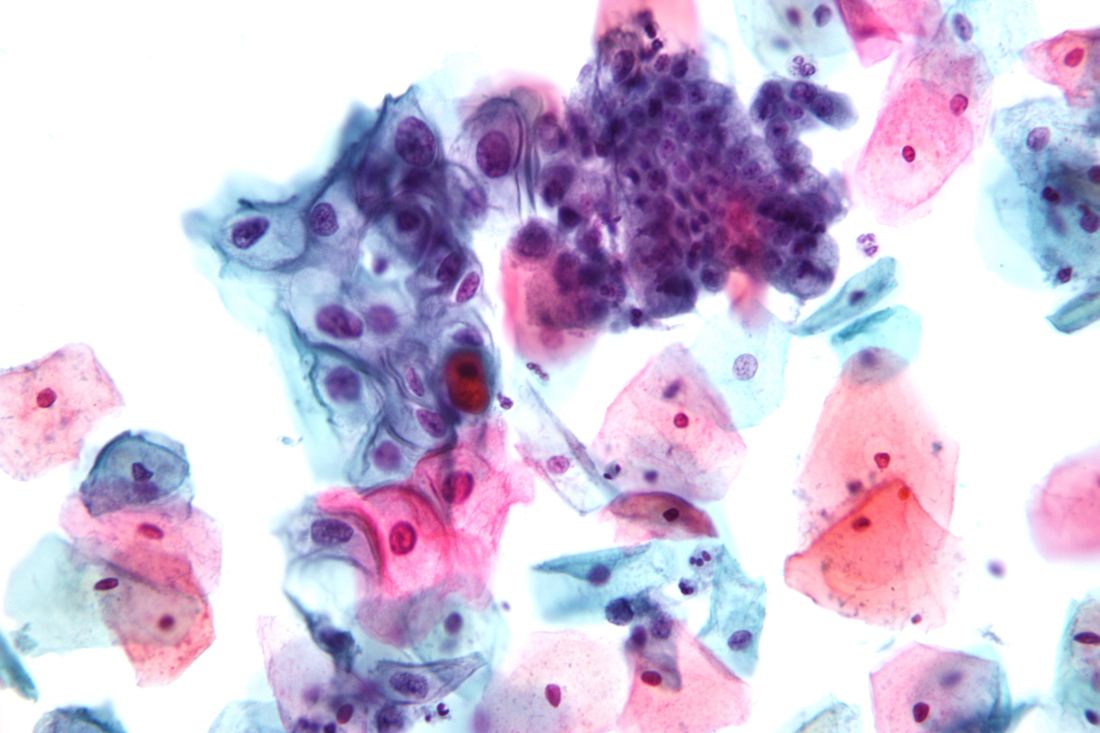

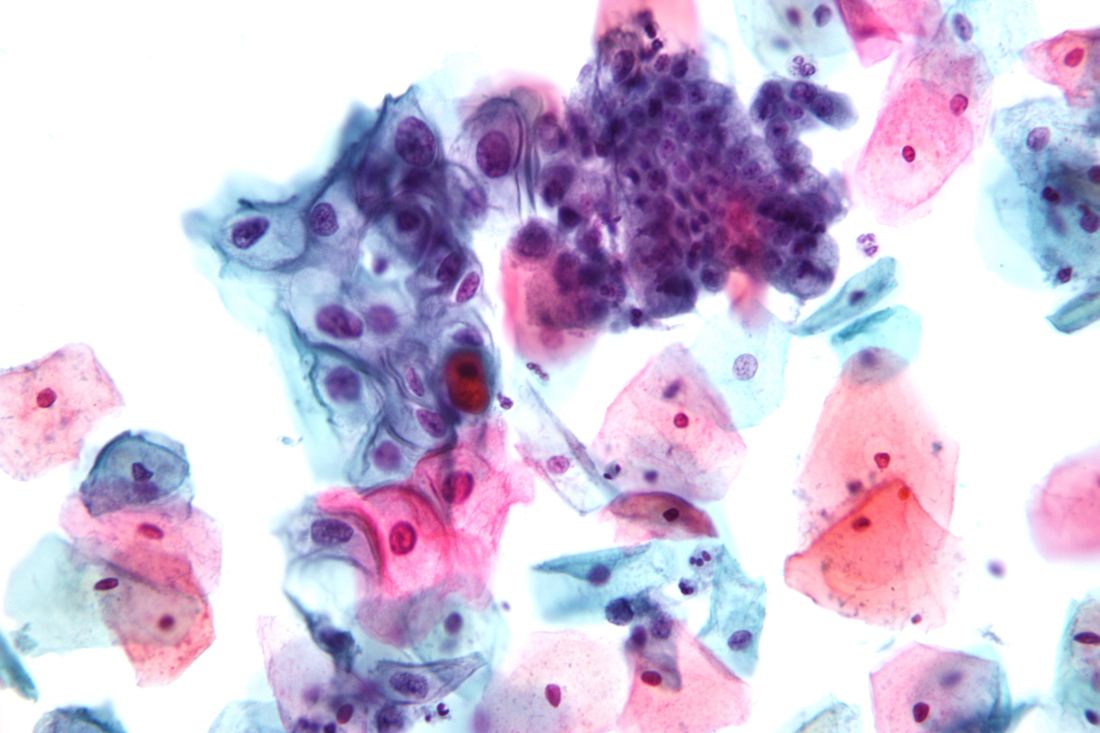

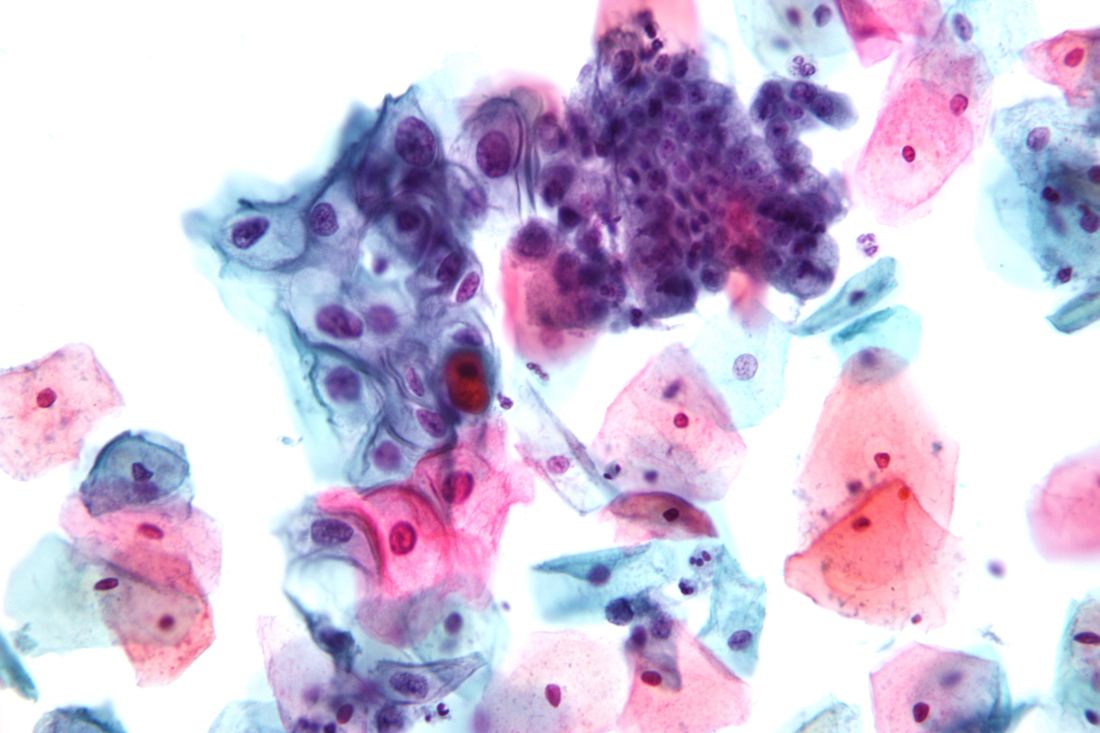

Women aged 30-65 years should be offered a choice between two cervical cancer screening methods, according to draft recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. The recommendations were released on Sept. 12.

The Task Force continues to recommend that women in their 20s be screened every 3 years via cervical cytology, but in a change from the 2012 recommendations, the researchers now advise clinicians to offer women aged 30-65 years a choice of either cytology every 3 years or the high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) test every 5 years as a method of screening for cervical cancer. Cotesting is no longer recommended.

Offering women aged 30-65 years a screening choice received an A recommendation. The draft retains the previous Task Force position and D recommendation against cervical cancer screening for certain groups, including women younger than 21 years, women aged 65 and older with a history of screening and a low risk of cervical cancer, and women who have had a hysterectomy.

The USPSTF based the draft recommendations in part on a review of four randomized, controlled trials of cotesting hrHPV and cytology that included more than 130,000 women.

“Modeling found that cotesting does not offer any benefit in terms of cancer reduction or life-years gained over hrHPV testing alone but increases the number of tests and procedures per each cancer case averted,” the Task Force members noted in the draft recommendation statement. “Therefore, the USPSTF concluded that there is convincing evidence that screening with either cytology alone or hrHPV testing alone provides substantial benefit and is preferable to cotesting” in otherwise healthy women aged 30-65 years.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists currently recommends cotesting with cytology and HPV testing every 5 years or cytology alone every 3 years in women aged 30-65 years (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128[4]:e111-30).

The USPSTF draft recommendations do not apply to women at increased risk for cervical cancer, including those with compromised immune systems or those who have cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or 3.

The draft recommendations are available online for public comment from Sept. 12 through Oct. 9, 2017, at the USPSTF website, www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

Women aged 30-65 years should be offered a choice between two cervical cancer screening methods, according to draft recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. The recommendations were released on Sept. 12.

The Task Force continues to recommend that women in their 20s be screened every 3 years via cervical cytology, but in a change from the 2012 recommendations, the researchers now advise clinicians to offer women aged 30-65 years a choice of either cytology every 3 years or the high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) test every 5 years as a method of screening for cervical cancer. Cotesting is no longer recommended.

Offering women aged 30-65 years a screening choice received an A recommendation. The draft retains the previous Task Force position and D recommendation against cervical cancer screening for certain groups, including women younger than 21 years, women aged 65 and older with a history of screening and a low risk of cervical cancer, and women who have had a hysterectomy.

The USPSTF based the draft recommendations in part on a review of four randomized, controlled trials of cotesting hrHPV and cytology that included more than 130,000 women.

“Modeling found that cotesting does not offer any benefit in terms of cancer reduction or life-years gained over hrHPV testing alone but increases the number of tests and procedures per each cancer case averted,” the Task Force members noted in the draft recommendation statement. “Therefore, the USPSTF concluded that there is convincing evidence that screening with either cytology alone or hrHPV testing alone provides substantial benefit and is preferable to cotesting” in otherwise healthy women aged 30-65 years.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists currently recommends cotesting with cytology and HPV testing every 5 years or cytology alone every 3 years in women aged 30-65 years (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128[4]:e111-30).

The USPSTF draft recommendations do not apply to women at increased risk for cervical cancer, including those with compromised immune systems or those who have cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or 3.

The draft recommendations are available online for public comment from Sept. 12 through Oct. 9, 2017, at the USPSTF website, www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

Women aged 30-65 years should be offered a choice between two cervical cancer screening methods, according to draft recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. The recommendations were released on Sept. 12.

The Task Force continues to recommend that women in their 20s be screened every 3 years via cervical cytology, but in a change from the 2012 recommendations, the researchers now advise clinicians to offer women aged 30-65 years a choice of either cytology every 3 years or the high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) test every 5 years as a method of screening for cervical cancer. Cotesting is no longer recommended.

Offering women aged 30-65 years a screening choice received an A recommendation. The draft retains the previous Task Force position and D recommendation against cervical cancer screening for certain groups, including women younger than 21 years, women aged 65 and older with a history of screening and a low risk of cervical cancer, and women who have had a hysterectomy.

The USPSTF based the draft recommendations in part on a review of four randomized, controlled trials of cotesting hrHPV and cytology that included more than 130,000 women.

“Modeling found that cotesting does not offer any benefit in terms of cancer reduction or life-years gained over hrHPV testing alone but increases the number of tests and procedures per each cancer case averted,” the Task Force members noted in the draft recommendation statement. “Therefore, the USPSTF concluded that there is convincing evidence that screening with either cytology alone or hrHPV testing alone provides substantial benefit and is preferable to cotesting” in otherwise healthy women aged 30-65 years.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists currently recommends cotesting with cytology and HPV testing every 5 years or cytology alone every 3 years in women aged 30-65 years (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128[4]:e111-30).

The USPSTF draft recommendations do not apply to women at increased risk for cervical cancer, including those with compromised immune systems or those who have cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or 3.

The draft recommendations are available online for public comment from Sept. 12 through Oct. 9, 2017, at the USPSTF website, www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

Study findings support uncapping MELD score

Uncapping the current Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score may provide a better path toward making sure that patients most in need of a liver transplant get one, results from a large, long-term analysis showed.

Established in 2002, the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scoring system “was arbitrarily capped at 40 based on the presumption that transplanting patients with MELD greater than 40 would be futile,” researchers led by Mitra K. Nadim, MD, reported in the September 2017 issue of the Journal of Hepatology (67[3]:517-25. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.04.022). “As a result, patients with MELD greater than 40 receive the same priority as patients with MELD of 40, differentiated only by their time on the wait list.”

The mean age of patients was 53 years, and most were white men. The researchers reported that 3.3% of wait-listed patients had a MELD score of 40 or greater at registration, while 7.3% had MELD scores increase to 40 or greater after wait-list registration. In all, 30,369 patients (40.6%) underwent liver transplantation during the study period. Of these, 2,615 (8.6%) had a MELD score of 40 or greater at the time of their procedure. Compared with patients who had a MELD score of 40, those who had a MELD score of greater than 40 had an increased risk of death within 30 days, and the risk increased with rising scores. Specifically, the hazard ratio was 1.4 for those with a MELD score of 40-44, an HR of 2.6 for those with a MELD score of 45-49, and an HR of 5.0 for those with a MELD score of 50 or greater. There were no survival differences between the two groups at 1 and 3 years, but there was a survival benefit associated with liver transplantation as the MELD score increased above 40, the investigators reported.

“The arbitrary capping of the MELD at 40 has resulted in an unforeseen lack of objectivity for patients with MELD [score of greater than] 40 who are unjustifiably disadvantaged in a system designed to prioritize patients most in need,” they concluded. “Uncapping the MELD score is another necessary step in the evolution of liver allocation and patient prioritization.” They added that a significant number of patients with a MELD score of 40 or greater “likely suffer from acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF), a recently recognized syndrome characterized by acute liver decompensation, other organ system failures, and high short-term mortality in patients with end-stage liver disease. A capped MELD score fails to capture acute liver decompensation adequately, and data suggest that a model incorporating sudden increases in MELD predicts wait-list mortality better.”

Dr. Nadim and her associates acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design “and that factors relating to a patient’s suitability for transplantation or to a center’s decision to accept or reject a liver allograft, both of which affect graft and patient survival, were not accounted for in the analysis. Despite these limitations, the study results have important implications for improving the current liver allocation policy.”

The study was supported in part by the Health Resources and Services Administration. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

PRIMARY SOURCE: J Hepatol. 2017;67[3]:517-25. doi: 1016/j.jhep.2017.04.022

Uncapping the current Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score may provide a better path toward making sure that patients most in need of a liver transplant get one, results from a large, long-term analysis showed.

Established in 2002, the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scoring system “was arbitrarily capped at 40 based on the presumption that transplanting patients with MELD greater than 40 would be futile,” researchers led by Mitra K. Nadim, MD, reported in the September 2017 issue of the Journal of Hepatology (67[3]:517-25. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.04.022). “As a result, patients with MELD greater than 40 receive the same priority as patients with MELD of 40, differentiated only by their time on the wait list.”

The mean age of patients was 53 years, and most were white men. The researchers reported that 3.3% of wait-listed patients had a MELD score of 40 or greater at registration, while 7.3% had MELD scores increase to 40 or greater after wait-list registration. In all, 30,369 patients (40.6%) underwent liver transplantation during the study period. Of these, 2,615 (8.6%) had a MELD score of 40 or greater at the time of their procedure. Compared with patients who had a MELD score of 40, those who had a MELD score of greater than 40 had an increased risk of death within 30 days, and the risk increased with rising scores. Specifically, the hazard ratio was 1.4 for those with a MELD score of 40-44, an HR of 2.6 for those with a MELD score of 45-49, and an HR of 5.0 for those with a MELD score of 50 or greater. There were no survival differences between the two groups at 1 and 3 years, but there was a survival benefit associated with liver transplantation as the MELD score increased above 40, the investigators reported.

“The arbitrary capping of the MELD at 40 has resulted in an unforeseen lack of objectivity for patients with MELD [score of greater than] 40 who are unjustifiably disadvantaged in a system designed to prioritize patients most in need,” they concluded. “Uncapping the MELD score is another necessary step in the evolution of liver allocation and patient prioritization.” They added that a significant number of patients with a MELD score of 40 or greater “likely suffer from acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF), a recently recognized syndrome characterized by acute liver decompensation, other organ system failures, and high short-term mortality in patients with end-stage liver disease. A capped MELD score fails to capture acute liver decompensation adequately, and data suggest that a model incorporating sudden increases in MELD predicts wait-list mortality better.”

Dr. Nadim and her associates acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design “and that factors relating to a patient’s suitability for transplantation or to a center’s decision to accept or reject a liver allograft, both of which affect graft and patient survival, were not accounted for in the analysis. Despite these limitations, the study results have important implications for improving the current liver allocation policy.”

The study was supported in part by the Health Resources and Services Administration. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

PRIMARY SOURCE: J Hepatol. 2017;67[3]:517-25. doi: 1016/j.jhep.2017.04.022

Uncapping the current Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score may provide a better path toward making sure that patients most in need of a liver transplant get one, results from a large, long-term analysis showed.

Established in 2002, the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scoring system “was arbitrarily capped at 40 based on the presumption that transplanting patients with MELD greater than 40 would be futile,” researchers led by Mitra K. Nadim, MD, reported in the September 2017 issue of the Journal of Hepatology (67[3]:517-25. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.04.022). “As a result, patients with MELD greater than 40 receive the same priority as patients with MELD of 40, differentiated only by their time on the wait list.”

The mean age of patients was 53 years, and most were white men. The researchers reported that 3.3% of wait-listed patients had a MELD score of 40 or greater at registration, while 7.3% had MELD scores increase to 40 or greater after wait-list registration. In all, 30,369 patients (40.6%) underwent liver transplantation during the study period. Of these, 2,615 (8.6%) had a MELD score of 40 or greater at the time of their procedure. Compared with patients who had a MELD score of 40, those who had a MELD score of greater than 40 had an increased risk of death within 30 days, and the risk increased with rising scores. Specifically, the hazard ratio was 1.4 for those with a MELD score of 40-44, an HR of 2.6 for those with a MELD score of 45-49, and an HR of 5.0 for those with a MELD score of 50 or greater. There were no survival differences between the two groups at 1 and 3 years, but there was a survival benefit associated with liver transplantation as the MELD score increased above 40, the investigators reported.

“The arbitrary capping of the MELD at 40 has resulted in an unforeseen lack of objectivity for patients with MELD [score of greater than] 40 who are unjustifiably disadvantaged in a system designed to prioritize patients most in need,” they concluded. “Uncapping the MELD score is another necessary step in the evolution of liver allocation and patient prioritization.” They added that a significant number of patients with a MELD score of 40 or greater “likely suffer from acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF), a recently recognized syndrome characterized by acute liver decompensation, other organ system failures, and high short-term mortality in patients with end-stage liver disease. A capped MELD score fails to capture acute liver decompensation adequately, and data suggest that a model incorporating sudden increases in MELD predicts wait-list mortality better.”

Dr. Nadim and her associates acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design “and that factors relating to a patient’s suitability for transplantation or to a center’s decision to accept or reject a liver allograft, both of which affect graft and patient survival, were not accounted for in the analysis. Despite these limitations, the study results have important implications for improving the current liver allocation policy.”

The study was supported in part by the Health Resources and Services Administration. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

PRIMARY SOURCE: J Hepatol. 2017;67[3]:517-25. doi: 1016/j.jhep.2017.04.022

FROM THE JOURNAL OF HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: .

Major finding: Compared with patients who had a MELD score of 40, the increased risk of death within 30 days was 1.4 for those with a MELD score of 40-44.

Study details: A retrospective analysis of 65,776 patients listed for a liver transplant from February 2002 to December 2012.

Disclosures: The study was supported in part by the Health Resources and Services Administration. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Mitra K. Nadim, MD, et al. Inequity in organ allocation for patients awaiting liver transplantation: Rationale for uncapping the model for end-stage liver disease. J Hepatol. 2017;67(3):517-25. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.04.022.

Lack of lupus ‘gold standard’ definition hampers estimates of its incidence, prevalence

Two new studies representing the latest efforts to determine the incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus in the United States have revealed the difficulty of ascertaining cases when definitions of the disease vary.

The two population-based registries on which the studies were based – the California Lupus Surveillance Project and the Manhattan Lupus Surveillance Program (MLSP) – confirmed that black women represent the highest risk group for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and also reaffirmed the elevated risk observed in Hispanic and Asian women, compared with white women.

The MLSP researchers applied the updated 1997 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification criteria, the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) classification criteria, or a treating rheumatologist’s diagnosis to records from hospitals, rheumatologists, and administrative databases, and looked at both the prevalence of the disease in 2007 and the incidence from the period of 2007-2009. Using the ACR’s definition of SLE, they found an age-standardized prevalence of 62.2 and an incidence rate of 4.6 per 100,000 person-years (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Sep 11. doi: 10.1002/art.40192).

The prevalence was significantly higher in women than in men (107.4 vs. 12.5 per 100,000 persons), and was highest overall in non-Hispanic black women (210.9), followed by Hispanic women (138.3), non-Hispanic Asian women (91.2), and non-Hispanic white women (64.3).

However, use of the SLICC classification criteria increased the age-standardized prevalence by 17%-19%, to a prevalence of 73.8 per 100,000 person-years and resulted in a 35% increase in incidence, to 6.2 per 100,000 person-years, compared with the ACR rates.

“The small number of cases that met the ACR but not the SLICC case definition is reassuring as it suggests that few cases met ACR criteria for SLE without the presence of autoantibodies,” wrote Peter M. Izmirly, MD, of New York (N.Y.) University, and his coauthors.

“However, given the descriptive nature of the MLSP and the absence of a gold standard test that would unambiguously identify SLE, this project cannot assess which set of classification criteria is more sensitive or specific.”

Meanwhile, the California Lupus Surveillance Project, a registry of people with lupus living in San Francisco County between 2007 and 2009, used the ACR definition to record an age-standardized annual incidence rate of 4.6 per 100,000 person-years, and an average annual prevalence of 84.8 per 100,000 persons (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Sep 11. doi: 10.1002/art.40191).

As with the MLSP, the prevalence was highest in black women (458.1), followed by Hispanic women (177.9), Asian women (149.7) and white women (109.8). The incidence was 30.5 per 100,000 person-years in black women, 8.9 in Hispanic women, 7.2 in Asian women, and 5.3 in white women.

Looking at the clinical manifestations of disease, researchers found hematologic was the most common, affecting 84% of patients, while neurologic disorder affected only 8% of the population. Immunologic manifestations were present in 80%, arthritis in 57%, renal disorders in 45%, pleuritis or pericarditis in 41%, and malar rash in 33%.

There were racial variations in manifestations, with renal manifestations being more common in black, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Hispanic patients, compared with whites. Discoid rash was most common among black patients, while it was not evident at all in Hispanic patients.

Maria Dall’Era, MD, of the Russell/Engleman Research Center at the University of California, San Francisco, and her coauthors said that given the changing demographic of the diverse San Francisco County, a reliable estimate of the burden of lupus in different racial and ethnic groups was essential for health care planning.

“Up until the recent completion of the Georgia and Michigan surveillance projects, most previous epidemiologic studies were limited by small geographic areas, homogeneous populations, varying case definitions, and incomplete case ascertainment that relied on administrative codes or patient self-reported diagnosis,” they wrote.

To overcome the previous lack of data in Asian and Hispanic populations, the authors worked with physicians serving these populations and performed extensive case-finding in hospitals and health care clinics.

“Our approach of partnering with the community and engaging culturally and linguistically concordant community members led to successful case ascertainment of these traditionally understudied populations,” they wrote. “Had we not taken these extra steps, we would have missed SLE cases in the Asian and Hispanic populations.”

Both studies noted that racial and ethnic data were determined from medical records, and may not have accurately reflected the patient’s race or ethnicity.

The Manhattan study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. The San Francisco study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Russell/Engleman Rheumatology Research Center at UCSF. No conflict of interest disclosures were available.

Together, the five national lupus registries funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provide important information about lupus in populations totaling over 6.5 million from four states and three selected Indian Health Service regions, including mixed urban and rural areas. Studies of this magnitude hold great value because case definitions and case ascertainment methodologies have been standardized, and they incorporate capture-recapture analyses to estimate the completeness of case finding.

Susan Manzi, MD, is with the department of medicine at the Allegheny Health Network, Pittsburgh, and Joan Merrill, MD, is with the department of arthritis and clinical immunology at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, Oklahoma City. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Sep 11. doi: 10.1002/art.40190). No conflicts of interest were available.

Together, the five national lupus registries funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provide important information about lupus in populations totaling over 6.5 million from four states and three selected Indian Health Service regions, including mixed urban and rural areas. Studies of this magnitude hold great value because case definitions and case ascertainment methodologies have been standardized, and they incorporate capture-recapture analyses to estimate the completeness of case finding.

Susan Manzi, MD, is with the department of medicine at the Allegheny Health Network, Pittsburgh, and Joan Merrill, MD, is with the department of arthritis and clinical immunology at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, Oklahoma City. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Sep 11. doi: 10.1002/art.40190). No conflicts of interest were available.

Together, the five national lupus registries funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provide important information about lupus in populations totaling over 6.5 million from four states and three selected Indian Health Service regions, including mixed urban and rural areas. Studies of this magnitude hold great value because case definitions and case ascertainment methodologies have been standardized, and they incorporate capture-recapture analyses to estimate the completeness of case finding.

Susan Manzi, MD, is with the department of medicine at the Allegheny Health Network, Pittsburgh, and Joan Merrill, MD, is with the department of arthritis and clinical immunology at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, Oklahoma City. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Sep 11. doi: 10.1002/art.40190). No conflicts of interest were available.

Two new studies representing the latest efforts to determine the incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus in the United States have revealed the difficulty of ascertaining cases when definitions of the disease vary.

The two population-based registries on which the studies were based – the California Lupus Surveillance Project and the Manhattan Lupus Surveillance Program (MLSP) – confirmed that black women represent the highest risk group for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and also reaffirmed the elevated risk observed in Hispanic and Asian women, compared with white women.

The MLSP researchers applied the updated 1997 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification criteria, the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) classification criteria, or a treating rheumatologist’s diagnosis to records from hospitals, rheumatologists, and administrative databases, and looked at both the prevalence of the disease in 2007 and the incidence from the period of 2007-2009. Using the ACR’s definition of SLE, they found an age-standardized prevalence of 62.2 and an incidence rate of 4.6 per 100,000 person-years (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Sep 11. doi: 10.1002/art.40192).

The prevalence was significantly higher in women than in men (107.4 vs. 12.5 per 100,000 persons), and was highest overall in non-Hispanic black women (210.9), followed by Hispanic women (138.3), non-Hispanic Asian women (91.2), and non-Hispanic white women (64.3).

However, use of the SLICC classification criteria increased the age-standardized prevalence by 17%-19%, to a prevalence of 73.8 per 100,000 person-years and resulted in a 35% increase in incidence, to 6.2 per 100,000 person-years, compared with the ACR rates.

“The small number of cases that met the ACR but not the SLICC case definition is reassuring as it suggests that few cases met ACR criteria for SLE without the presence of autoantibodies,” wrote Peter M. Izmirly, MD, of New York (N.Y.) University, and his coauthors.

“However, given the descriptive nature of the MLSP and the absence of a gold standard test that would unambiguously identify SLE, this project cannot assess which set of classification criteria is more sensitive or specific.”

Meanwhile, the California Lupus Surveillance Project, a registry of people with lupus living in San Francisco County between 2007 and 2009, used the ACR definition to record an age-standardized annual incidence rate of 4.6 per 100,000 person-years, and an average annual prevalence of 84.8 per 100,000 persons (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Sep 11. doi: 10.1002/art.40191).

As with the MLSP, the prevalence was highest in black women (458.1), followed by Hispanic women (177.9), Asian women (149.7) and white women (109.8). The incidence was 30.5 per 100,000 person-years in black women, 8.9 in Hispanic women, 7.2 in Asian women, and 5.3 in white women.

Looking at the clinical manifestations of disease, researchers found hematologic was the most common, affecting 84% of patients, while neurologic disorder affected only 8% of the population. Immunologic manifestations were present in 80%, arthritis in 57%, renal disorders in 45%, pleuritis or pericarditis in 41%, and malar rash in 33%.

There were racial variations in manifestations, with renal manifestations being more common in black, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Hispanic patients, compared with whites. Discoid rash was most common among black patients, while it was not evident at all in Hispanic patients.

Maria Dall’Era, MD, of the Russell/Engleman Research Center at the University of California, San Francisco, and her coauthors said that given the changing demographic of the diverse San Francisco County, a reliable estimate of the burden of lupus in different racial and ethnic groups was essential for health care planning.

“Up until the recent completion of the Georgia and Michigan surveillance projects, most previous epidemiologic studies were limited by small geographic areas, homogeneous populations, varying case definitions, and incomplete case ascertainment that relied on administrative codes or patient self-reported diagnosis,” they wrote.

To overcome the previous lack of data in Asian and Hispanic populations, the authors worked with physicians serving these populations and performed extensive case-finding in hospitals and health care clinics.

“Our approach of partnering with the community and engaging culturally and linguistically concordant community members led to successful case ascertainment of these traditionally understudied populations,” they wrote. “Had we not taken these extra steps, we would have missed SLE cases in the Asian and Hispanic populations.”

Both studies noted that racial and ethnic data were determined from medical records, and may not have accurately reflected the patient’s race or ethnicity.

The Manhattan study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. The San Francisco study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Russell/Engleman Rheumatology Research Center at UCSF. No conflict of interest disclosures were available.

Two new studies representing the latest efforts to determine the incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus in the United States have revealed the difficulty of ascertaining cases when definitions of the disease vary.

The two population-based registries on which the studies were based – the California Lupus Surveillance Project and the Manhattan Lupus Surveillance Program (MLSP) – confirmed that black women represent the highest risk group for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and also reaffirmed the elevated risk observed in Hispanic and Asian women, compared with white women.

The MLSP researchers applied the updated 1997 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification criteria, the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) classification criteria, or a treating rheumatologist’s diagnosis to records from hospitals, rheumatologists, and administrative databases, and looked at both the prevalence of the disease in 2007 and the incidence from the period of 2007-2009. Using the ACR’s definition of SLE, they found an age-standardized prevalence of 62.2 and an incidence rate of 4.6 per 100,000 person-years (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Sep 11. doi: 10.1002/art.40192).

The prevalence was significantly higher in women than in men (107.4 vs. 12.5 per 100,000 persons), and was highest overall in non-Hispanic black women (210.9), followed by Hispanic women (138.3), non-Hispanic Asian women (91.2), and non-Hispanic white women (64.3).

However, use of the SLICC classification criteria increased the age-standardized prevalence by 17%-19%, to a prevalence of 73.8 per 100,000 person-years and resulted in a 35% increase in incidence, to 6.2 per 100,000 person-years, compared with the ACR rates.

“The small number of cases that met the ACR but not the SLICC case definition is reassuring as it suggests that few cases met ACR criteria for SLE without the presence of autoantibodies,” wrote Peter M. Izmirly, MD, of New York (N.Y.) University, and his coauthors.

“However, given the descriptive nature of the MLSP and the absence of a gold standard test that would unambiguously identify SLE, this project cannot assess which set of classification criteria is more sensitive or specific.”

Meanwhile, the California Lupus Surveillance Project, a registry of people with lupus living in San Francisco County between 2007 and 2009, used the ACR definition to record an age-standardized annual incidence rate of 4.6 per 100,000 person-years, and an average annual prevalence of 84.8 per 100,000 persons (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Sep 11. doi: 10.1002/art.40191).

As with the MLSP, the prevalence was highest in black women (458.1), followed by Hispanic women (177.9), Asian women (149.7) and white women (109.8). The incidence was 30.5 per 100,000 person-years in black women, 8.9 in Hispanic women, 7.2 in Asian women, and 5.3 in white women.

Looking at the clinical manifestations of disease, researchers found hematologic was the most common, affecting 84% of patients, while neurologic disorder affected only 8% of the population. Immunologic manifestations were present in 80%, arthritis in 57%, renal disorders in 45%, pleuritis or pericarditis in 41%, and malar rash in 33%.

There were racial variations in manifestations, with renal manifestations being more common in black, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Hispanic patients, compared with whites. Discoid rash was most common among black patients, while it was not evident at all in Hispanic patients.

Maria Dall’Era, MD, of the Russell/Engleman Research Center at the University of California, San Francisco, and her coauthors said that given the changing demographic of the diverse San Francisco County, a reliable estimate of the burden of lupus in different racial and ethnic groups was essential for health care planning.

“Up until the recent completion of the Georgia and Michigan surveillance projects, most previous epidemiologic studies were limited by small geographic areas, homogeneous populations, varying case definitions, and incomplete case ascertainment that relied on administrative codes or patient self-reported diagnosis,” they wrote.

To overcome the previous lack of data in Asian and Hispanic populations, the authors worked with physicians serving these populations and performed extensive case-finding in hospitals and health care clinics.

“Our approach of partnering with the community and engaging culturally and linguistically concordant community members led to successful case ascertainment of these traditionally understudied populations,” they wrote. “Had we not taken these extra steps, we would have missed SLE cases in the Asian and Hispanic populations.”

Both studies noted that racial and ethnic data were determined from medical records, and may not have accurately reflected the patient’s race or ethnicity.

The Manhattan study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. The San Francisco study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Russell/Engleman Rheumatology Research Center at UCSF. No conflict of interest disclosures were available.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Black women have the highest prevalence and incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus.

Major finding: Use of the SLICC classification criteria increased the age-standardized prevalence by 17%-19% and resulted in a 35% increase in incidence, compared with the ACR criteria rates.

Data source: The Manhattan and California Lupus Surveillance Projects population-based registries.

Disclosures: The Manhattan study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. The San Francisco study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Russell/Engleman Rheumatology Research Center at UCSF. No conflict of interest disclosures were available.

COMBI-AD: Adjuvant combo halves relapses in BRAF V600-mutated melanoma

MADRID – A combination of the BRAF inhibitor dabrafenib (Tafinlar) and the MEK inhibitor trametinib (Mekinist) delivered in the adjuvant setting was associated with a halving of the risk for relapse compared with placebo among patients with advanced melanoma with BRAF V600 mutations, late-breaking results from a phase 3 trial show.

Among 438 patients with stage III BRAF V600-mutated melanoma randomly assigned after complete surgical resection to dabrafenib/trametinib in the COMBI-AD trial, the estimated rate of 3-year relapse-free survival (RFS) was 58%, compared with 39% for 432 patients assigned to double placebos. This difference translated into a hazard ratio for relapse with the dabrafenib/trametinib combination of 0.47 (P less than .001).

“The relapse-free survival benefits were observed across all 12 subgroups which have been evaluated, so there’s not a single subgroup that is an outlier,” he said in a briefing prior to his presentation of the data in a presidential symposium at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

Results of the study were published online concurrently in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In previous phase 3 trials in patients with BRAF V600 mutated metastatic or unresectable melanoma, the combination of dabrafenib and trametinib improved survival. Because treatment options for patients with resectable stage III melanomas are limited and less than optimal, the COMBI-AD investigators sought to explore whether the combination could improve outcomes when used in the adjuvant setting.

In the study reported by Dr. Hauschild, patients with completely resected, high-risk stage IIIA, IIIB, or IIIC cutaneous melanoma with the BRAF V600EK mutation who were surgically free of disease within 12 weeks of randomization were stratified by BRAF mutation status and disease stage, and then randomly assigned to receive either dabrafenib 150 mg twice daily plus trametinib 2 mg once daily, or two matched placebos.

The RFS curves separated early in the study, and at 1 year the rate of RFS was 88% among patients treated with the combinations, compared with 56% for patients who got placebo. The respective rates at 2 and 3 years of follow-up were 67% vs. 44%, and, as noted before, 58% vs. 39%.

At this first interim analysis, the 1-year OS rate with dabrafenib/trametinib was 97% compared with 94% for placebo. Respective rates at 2 and 3 years of follow-up were 91% vs. 83%, and 86% vs. 77%, but as noted, the Kaplan-Meier survival curves appear to separate, but have yet to reach the prespecified boundary for significance.

As might be expected, the incidence of any grade 3 or 4 adverse events was higher in the combination group than in the placebo group, but there were no fatal adverse events related to assigned treatment. In all, 26% of patients assigned to dabrafenib/trametinib had to discontinue treatment due to adverse events, compared with 3% of patients assigned to placebo.

Dr. Hauschild said that the results of the COMBI-AD study and the Checkmate 238 study presented on the same day “will make a change in our textbooks and our current guidelines, because we have at least two new treatment options, and I think this is a new treatment option and a good day for our melanoma patients.”

His remarks were echoed by Olivier Michielin, MD, PhD, of the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics in Lausanne. He said that “we now have, with the data, two fantastic new options. We couldn’t dream those studies to be so positive. This is really something that will open new features for our patients.”

Dr. Michielin was invited by ESMO to comment on the study.

COMBI-AD was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline. Dabrafenib and trametinib have been owned by Novartis AG since March, 2015. Dr. Hauschild disclosed trial support, honoraria, and/or consultancy fees from Novartis and others. Dr. Michielin disclosed consulting and/or honoraria from Amgen, BMS, Roche, MSD, Novartis, and GSK.

MADRID – A combination of the BRAF inhibitor dabrafenib (Tafinlar) and the MEK inhibitor trametinib (Mekinist) delivered in the adjuvant setting was associated with a halving of the risk for relapse compared with placebo among patients with advanced melanoma with BRAF V600 mutations, late-breaking results from a phase 3 trial show.

Among 438 patients with stage III BRAF V600-mutated melanoma randomly assigned after complete surgical resection to dabrafenib/trametinib in the COMBI-AD trial, the estimated rate of 3-year relapse-free survival (RFS) was 58%, compared with 39% for 432 patients assigned to double placebos. This difference translated into a hazard ratio for relapse with the dabrafenib/trametinib combination of 0.47 (P less than .001).

“The relapse-free survival benefits were observed across all 12 subgroups which have been evaluated, so there’s not a single subgroup that is an outlier,” he said in a briefing prior to his presentation of the data in a presidential symposium at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

Results of the study were published online concurrently in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In previous phase 3 trials in patients with BRAF V600 mutated metastatic or unresectable melanoma, the combination of dabrafenib and trametinib improved survival. Because treatment options for patients with resectable stage III melanomas are limited and less than optimal, the COMBI-AD investigators sought to explore whether the combination could improve outcomes when used in the adjuvant setting.

In the study reported by Dr. Hauschild, patients with completely resected, high-risk stage IIIA, IIIB, or IIIC cutaneous melanoma with the BRAF V600EK mutation who were surgically free of disease within 12 weeks of randomization were stratified by BRAF mutation status and disease stage, and then randomly assigned to receive either dabrafenib 150 mg twice daily plus trametinib 2 mg once daily, or two matched placebos.

The RFS curves separated early in the study, and at 1 year the rate of RFS was 88% among patients treated with the combinations, compared with 56% for patients who got placebo. The respective rates at 2 and 3 years of follow-up were 67% vs. 44%, and, as noted before, 58% vs. 39%.

At this first interim analysis, the 1-year OS rate with dabrafenib/trametinib was 97% compared with 94% for placebo. Respective rates at 2 and 3 years of follow-up were 91% vs. 83%, and 86% vs. 77%, but as noted, the Kaplan-Meier survival curves appear to separate, but have yet to reach the prespecified boundary for significance.

As might be expected, the incidence of any grade 3 or 4 adverse events was higher in the combination group than in the placebo group, but there were no fatal adverse events related to assigned treatment. In all, 26% of patients assigned to dabrafenib/trametinib had to discontinue treatment due to adverse events, compared with 3% of patients assigned to placebo.

Dr. Hauschild said that the results of the COMBI-AD study and the Checkmate 238 study presented on the same day “will make a change in our textbooks and our current guidelines, because we have at least two new treatment options, and I think this is a new treatment option and a good day for our melanoma patients.”

His remarks were echoed by Olivier Michielin, MD, PhD, of the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics in Lausanne. He said that “we now have, with the data, two fantastic new options. We couldn’t dream those studies to be so positive. This is really something that will open new features for our patients.”

Dr. Michielin was invited by ESMO to comment on the study.

COMBI-AD was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline. Dabrafenib and trametinib have been owned by Novartis AG since March, 2015. Dr. Hauschild disclosed trial support, honoraria, and/or consultancy fees from Novartis and others. Dr. Michielin disclosed consulting and/or honoraria from Amgen, BMS, Roche, MSD, Novartis, and GSK.

MADRID – A combination of the BRAF inhibitor dabrafenib (Tafinlar) and the MEK inhibitor trametinib (Mekinist) delivered in the adjuvant setting was associated with a halving of the risk for relapse compared with placebo among patients with advanced melanoma with BRAF V600 mutations, late-breaking results from a phase 3 trial show.

Among 438 patients with stage III BRAF V600-mutated melanoma randomly assigned after complete surgical resection to dabrafenib/trametinib in the COMBI-AD trial, the estimated rate of 3-year relapse-free survival (RFS) was 58%, compared with 39% for 432 patients assigned to double placebos. This difference translated into a hazard ratio for relapse with the dabrafenib/trametinib combination of 0.47 (P less than .001).

“The relapse-free survival benefits were observed across all 12 subgroups which have been evaluated, so there’s not a single subgroup that is an outlier,” he said in a briefing prior to his presentation of the data in a presidential symposium at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

Results of the study were published online concurrently in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In previous phase 3 trials in patients with BRAF V600 mutated metastatic or unresectable melanoma, the combination of dabrafenib and trametinib improved survival. Because treatment options for patients with resectable stage III melanomas are limited and less than optimal, the COMBI-AD investigators sought to explore whether the combination could improve outcomes when used in the adjuvant setting.

In the study reported by Dr. Hauschild, patients with completely resected, high-risk stage IIIA, IIIB, or IIIC cutaneous melanoma with the BRAF V600EK mutation who were surgically free of disease within 12 weeks of randomization were stratified by BRAF mutation status and disease stage, and then randomly assigned to receive either dabrafenib 150 mg twice daily plus trametinib 2 mg once daily, or two matched placebos.

The RFS curves separated early in the study, and at 1 year the rate of RFS was 88% among patients treated with the combinations, compared with 56% for patients who got placebo. The respective rates at 2 and 3 years of follow-up were 67% vs. 44%, and, as noted before, 58% vs. 39%.

At this first interim analysis, the 1-year OS rate with dabrafenib/trametinib was 97% compared with 94% for placebo. Respective rates at 2 and 3 years of follow-up were 91% vs. 83%, and 86% vs. 77%, but as noted, the Kaplan-Meier survival curves appear to separate, but have yet to reach the prespecified boundary for significance.

As might be expected, the incidence of any grade 3 or 4 adverse events was higher in the combination group than in the placebo group, but there were no fatal adverse events related to assigned treatment. In all, 26% of patients assigned to dabrafenib/trametinib had to discontinue treatment due to adverse events, compared with 3% of patients assigned to placebo.

Dr. Hauschild said that the results of the COMBI-AD study and the Checkmate 238 study presented on the same day “will make a change in our textbooks and our current guidelines, because we have at least two new treatment options, and I think this is a new treatment option and a good day for our melanoma patients.”

His remarks were echoed by Olivier Michielin, MD, PhD, of the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics in Lausanne. He said that “we now have, with the data, two fantastic new options. We couldn’t dream those studies to be so positive. This is really something that will open new features for our patients.”

Dr. Michielin was invited by ESMO to comment on the study.

COMBI-AD was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline. Dabrafenib and trametinib have been owned by Novartis AG since March, 2015. Dr. Hauschild disclosed trial support, honoraria, and/or consultancy fees from Novartis and others. Dr. Michielin disclosed consulting and/or honoraria from Amgen, BMS, Roche, MSD, Novartis, and GSK.

AT ESMO 2017

Key clinical point: Adjuvant therapy with a BRAF/MEK inhibitor combination significantly improved outcomes for patients with stage III completely resectable melanoma.

Major finding: The hazard ratio for relapse with the dabrafenib/trametinib combination vs. placebo was 0.47 (P less than .001).

Data source: Randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial of 870 patients with stage III, completely resectable BRAF-mutated melanoma.

Disclosures: COMBI-AD was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline. Dabrafenib and trametinib have been owned by Novartis AG since March, 2015. Dr. Hauschild disclosed trial support, honoraria, and/or consultancy fees from Novartis and others. Dr. Michielin disclosed consulting and/or honoraria from Amgen, BMS, Roche, MSD, Novartis, and GSK.

Using Multi-Condition Assessment to Optimize Management of Mental Health in Primary Care

Click Here to Read Supplement.

Topics include:

- Detecting Mental Health Conditions

- What Is the Multi-Condition M3 Checklist?

- Office Procedure for Use of Checklist

Faculty/Faculty Disclosure:

Steven Daviss, MD

Chief Medical Informatics Officer,

M3 Information,

Rockville, Maryland

Gerald Hurowitz, MD

Chief Medical Officer to M3 Information,

Rockville, Maryland

Assistant Professor of Clinical Psychiatry,

Columbia University

Larry Culpepper, MD

Professor of Family Medicine

Boston University School of Medicine

Massachusetts

Drs. Daviss, Hurowitz, and Culpepper are members in M-3 Information, LLC.

Click Here to Read Supplement.

Topics include:

- Detecting Mental Health Conditions

- What Is the Multi-Condition M3 Checklist?

- Office Procedure for Use of Checklist

Faculty/Faculty Disclosure:

Steven Daviss, MD

Chief Medical Informatics Officer,

M3 Information,

Rockville, Maryland

Gerald Hurowitz, MD

Chief Medical Officer to M3 Information,

Rockville, Maryland

Assistant Professor of Clinical Psychiatry,

Columbia University

Larry Culpepper, MD

Professor of Family Medicine

Boston University School of Medicine

Massachusetts

Drs. Daviss, Hurowitz, and Culpepper are members in M-3 Information, LLC.

Click Here to Read Supplement.

Topics include:

- Detecting Mental Health Conditions

- What Is the Multi-Condition M3 Checklist?

- Office Procedure for Use of Checklist

Faculty/Faculty Disclosure:

Steven Daviss, MD

Chief Medical Informatics Officer,

M3 Information,

Rockville, Maryland

Gerald Hurowitz, MD

Chief Medical Officer to M3 Information,

Rockville, Maryland

Assistant Professor of Clinical Psychiatry,

Columbia University

Larry Culpepper, MD

Professor of Family Medicine

Boston University School of Medicine

Massachusetts

Drs. Daviss, Hurowitz, and Culpepper are members in M-3 Information, LLC.

Clinical trial: Complex VHR using biologic or synthetic mesh

The Study Comparing the Efficacy, Safety, and Cost of a Permanent, Synthetic Prosthetic Versus a Biologic Prosthetic in the One-Stage Repair of Ventral Hernias in Clean and Contaminated Wounds is an interventional trial currently recruiting patients with ventral hernias.

The trial will compare results of ventral hernia repair in patients who have received a biologic mesh made from pig skin with those who received a synthetic mesh made in a laboratory. Both study groups will include patients with and without infection near the hernia. Synthetic mesh is hypothesized to have a higher rate of early postoperative infection, while biologic mesh is hypothesized to have a higher rate of recurrence.

Patients will be included in the trial if they have a ventral hernia; are older than 21 years; are not pregnant; and have no allergic, religious, or ethical objections to polypropylene or porcine prosthetics. Reasons for exclusion include severe malnutrition, pre-existing parenchymal liver disease, immunocompromisation, and refractory ascites.

The primary outcome measure is recurrence within 24 months of surgery, and the secondary outcome measure is wound events within 24 months of surgery. Other outcome measures include early postoperative complications within 1 month of surgery and quality of life, pain, activity level, and overall cost with 24 months of surgery.

The study will end in June 2019. About 330 people are expected to be included in the final analysis.

Find more information at the study page on Clinicaltrials.gov.

The Study Comparing the Efficacy, Safety, and Cost of a Permanent, Synthetic Prosthetic Versus a Biologic Prosthetic in the One-Stage Repair of Ventral Hernias in Clean and Contaminated Wounds is an interventional trial currently recruiting patients with ventral hernias.

The trial will compare results of ventral hernia repair in patients who have received a biologic mesh made from pig skin with those who received a synthetic mesh made in a laboratory. Both study groups will include patients with and without infection near the hernia. Synthetic mesh is hypothesized to have a higher rate of early postoperative infection, while biologic mesh is hypothesized to have a higher rate of recurrence.

Patients will be included in the trial if they have a ventral hernia; are older than 21 years; are not pregnant; and have no allergic, religious, or ethical objections to polypropylene or porcine prosthetics. Reasons for exclusion include severe malnutrition, pre-existing parenchymal liver disease, immunocompromisation, and refractory ascites.

The primary outcome measure is recurrence within 24 months of surgery, and the secondary outcome measure is wound events within 24 months of surgery. Other outcome measures include early postoperative complications within 1 month of surgery and quality of life, pain, activity level, and overall cost with 24 months of surgery.

The study will end in June 2019. About 330 people are expected to be included in the final analysis.

Find more information at the study page on Clinicaltrials.gov.

The Study Comparing the Efficacy, Safety, and Cost of a Permanent, Synthetic Prosthetic Versus a Biologic Prosthetic in the One-Stage Repair of Ventral Hernias in Clean and Contaminated Wounds is an interventional trial currently recruiting patients with ventral hernias.

The trial will compare results of ventral hernia repair in patients who have received a biologic mesh made from pig skin with those who received a synthetic mesh made in a laboratory. Both study groups will include patients with and without infection near the hernia. Synthetic mesh is hypothesized to have a higher rate of early postoperative infection, while biologic mesh is hypothesized to have a higher rate of recurrence.

Patients will be included in the trial if they have a ventral hernia; are older than 21 years; are not pregnant; and have no allergic, religious, or ethical objections to polypropylene or porcine prosthetics. Reasons for exclusion include severe malnutrition, pre-existing parenchymal liver disease, immunocompromisation, and refractory ascites.

The primary outcome measure is recurrence within 24 months of surgery, and the secondary outcome measure is wound events within 24 months of surgery. Other outcome measures include early postoperative complications within 1 month of surgery and quality of life, pain, activity level, and overall cost with 24 months of surgery.

The study will end in June 2019. About 330 people are expected to be included in the final analysis.

Find more information at the study page on Clinicaltrials.gov.

SUMMARY FROM CLINICALTRIALS.GOV

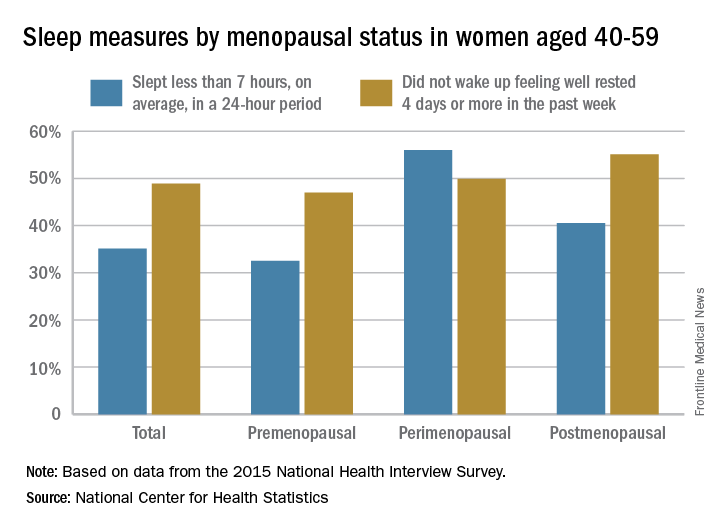

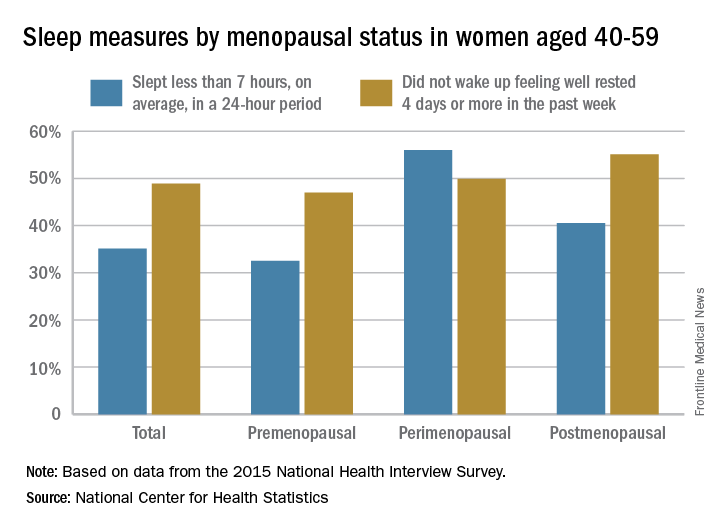

Sleep issues vary by menopausal status

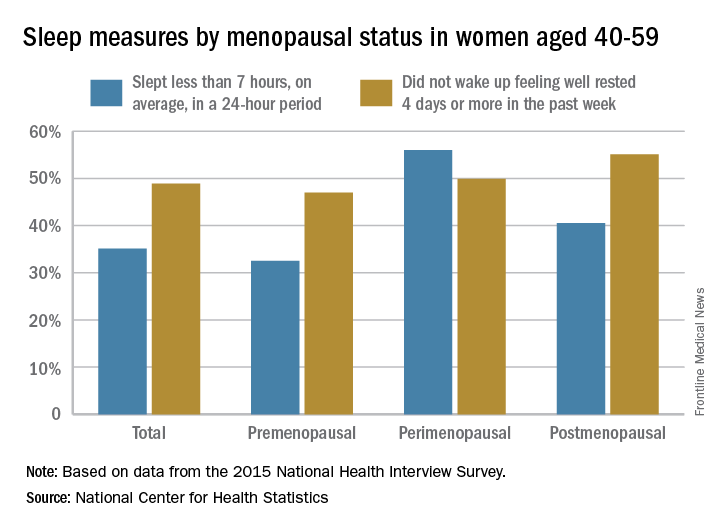

Perimenopausal women aged 40-59 years were less likely than were others in the same age group to average at least 7 hours’ sleep each night in 2015, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Among the perimenopausal women in that age group, 56% said that they slept less than 7 hours, on average, in a 24-hour period, compared with 40.5% of postmenopausal women and 32.5% of those who were premenopausal. Overall, 35.1% of women aged 40-59 did not average at least 7 hours of sleep per night, the NCHS reported in a data brief released Sept. 7.

For this analysis, about 74% of the women included were premenopausal (still had a menstrual cycle), 4% were perimenopausal (last menstrual cycle was 1 year before or less), and 22% were postmenopausal (no menstrual cycle for more than 1 year or surgical menopause after removal of their ovaries).

Perimenopausal women aged 40-59 years were less likely than were others in the same age group to average at least 7 hours’ sleep each night in 2015, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Among the perimenopausal women in that age group, 56% said that they slept less than 7 hours, on average, in a 24-hour period, compared with 40.5% of postmenopausal women and 32.5% of those who were premenopausal. Overall, 35.1% of women aged 40-59 did not average at least 7 hours of sleep per night, the NCHS reported in a data brief released Sept. 7.

For this analysis, about 74% of the women included were premenopausal (still had a menstrual cycle), 4% were perimenopausal (last menstrual cycle was 1 year before or less), and 22% were postmenopausal (no menstrual cycle for more than 1 year or surgical menopause after removal of their ovaries).

Perimenopausal women aged 40-59 years were less likely than were others in the same age group to average at least 7 hours’ sleep each night in 2015, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Among the perimenopausal women in that age group, 56% said that they slept less than 7 hours, on average, in a 24-hour period, compared with 40.5% of postmenopausal women and 32.5% of those who were premenopausal. Overall, 35.1% of women aged 40-59 did not average at least 7 hours of sleep per night, the NCHS reported in a data brief released Sept. 7.

For this analysis, about 74% of the women included were premenopausal (still had a menstrual cycle), 4% were perimenopausal (last menstrual cycle was 1 year before or less), and 22% were postmenopausal (no menstrual cycle for more than 1 year or surgical menopause after removal of their ovaries).

Your job: Provide oral health promotion, fluoride varnish

Learn the “Nuts and Bolts of Office-Based Oral Health Promotion and Fluoride Varnish” from Melinda Clark, MD, and Rocio Quiñonez, DMD.

Caries affect 50% of 5- to 9-year-olds and 78% of 17-year-olds, yet 25% of poor children don’t see a dentist by age 5. You are in an excellent position to provide “timely preventive oral health interventions” in your office, the United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends that “primary care clinicians apply fluoride varnish to the primary teeth of all infants and children starting at the age of primary tooth eruption,” and fluoride varnish was added to the Bright Futures Periodicity Schedule in 2015.

At the American Academy of Pediatrics’ annual meeting in Chicago, Dr. Clark and Dr. Quiñonez will address the importance of dealing with early childhood caries (ECC), defined as one or more decayed, missing from dental caries, or filled tooth surfaces in any primary tooth in a preschool-age child between birth and younger than 6 years of age. ECC can result in missed school, inappropriate use of over-the-counter pain medication, disturbed sleep, eating dysfunction, infection, and even death.

Dr. Clark is an associate professor of pediatrics at Albany (N.Y.) Medical College, and Dr. Quiñonez is an associate professor of pediatric dentistry and pediatrics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Dr. Clark and Dr. Quiñonez will be presenting Sunday, Sept. 17, from 4 p.m. to 5:30 p.m., and Monday, Sept. 18, from 8:30 a.m. to 10 a.m. You don’t want to miss it!

Learn the “Nuts and Bolts of Office-Based Oral Health Promotion and Fluoride Varnish” from Melinda Clark, MD, and Rocio Quiñonez, DMD.

Caries affect 50% of 5- to 9-year-olds and 78% of 17-year-olds, yet 25% of poor children don’t see a dentist by age 5. You are in an excellent position to provide “timely preventive oral health interventions” in your office, the United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends that “primary care clinicians apply fluoride varnish to the primary teeth of all infants and children starting at the age of primary tooth eruption,” and fluoride varnish was added to the Bright Futures Periodicity Schedule in 2015.

At the American Academy of Pediatrics’ annual meeting in Chicago, Dr. Clark and Dr. Quiñonez will address the importance of dealing with early childhood caries (ECC), defined as one or more decayed, missing from dental caries, or filled tooth surfaces in any primary tooth in a preschool-age child between birth and younger than 6 years of age. ECC can result in missed school, inappropriate use of over-the-counter pain medication, disturbed sleep, eating dysfunction, infection, and even death.

Dr. Clark is an associate professor of pediatrics at Albany (N.Y.) Medical College, and Dr. Quiñonez is an associate professor of pediatric dentistry and pediatrics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Dr. Clark and Dr. Quiñonez will be presenting Sunday, Sept. 17, from 4 p.m. to 5:30 p.m., and Monday, Sept. 18, from 8:30 a.m. to 10 a.m. You don’t want to miss it!

Learn the “Nuts and Bolts of Office-Based Oral Health Promotion and Fluoride Varnish” from Melinda Clark, MD, and Rocio Quiñonez, DMD.

Caries affect 50% of 5- to 9-year-olds and 78% of 17-year-olds, yet 25% of poor children don’t see a dentist by age 5. You are in an excellent position to provide “timely preventive oral health interventions” in your office, the United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends that “primary care clinicians apply fluoride varnish to the primary teeth of all infants and children starting at the age of primary tooth eruption,” and fluoride varnish was added to the Bright Futures Periodicity Schedule in 2015.

At the American Academy of Pediatrics’ annual meeting in Chicago, Dr. Clark and Dr. Quiñonez will address the importance of dealing with early childhood caries (ECC), defined as one or more decayed, missing from dental caries, or filled tooth surfaces in any primary tooth in a preschool-age child between birth and younger than 6 years of age. ECC can result in missed school, inappropriate use of over-the-counter pain medication, disturbed sleep, eating dysfunction, infection, and even death.

Dr. Clark is an associate professor of pediatrics at Albany (N.Y.) Medical College, and Dr. Quiñonez is an associate professor of pediatric dentistry and pediatrics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Dr. Clark and Dr. Quiñonez will be presenting Sunday, Sept. 17, from 4 p.m. to 5:30 p.m., and Monday, Sept. 18, from 8:30 a.m. to 10 a.m. You don’t want to miss it!

New Data Show Rise in Epilepsy

Between 2010 and 2015, the number of adults with active epilepsy rose from 2.3 million to 3 million, according to the CDC. The number of children with epilepsy rose from 450,000 to 470,000.

The increases are likely due to population growth, the CDC says, or other unknown factors, such as an increased willingness to disclose. However, most states do not have data on epilepsy prevalence. This is the first time estimates have been modeled for every state. Moreover, epilepsy has been assessed only intermittently in population surveys. Before 2010, the last national estimates were based on 1986-1990 data.

Obviously, epilepsy is not rare. It also is a serious public health issue. People with epilepsy often have other conditions, such as stroke, heart disease, depression, or developmental delay, which complicate epilepsy management, impair quality of life, and contribute to early mortality, the CDC says. Epilepsy also is the costliest and second most common of 5 chronic conditions that have adverse impact on academic and health outcomes in children and adolescents. For instance, children with seizures are more likely to live in poverty, and their parents more frequently report food insecurity.

The CDC suggests that health care providers and others can use the findings to ensure that evidence-based programs meet the complex needs of adults and children living with epilepsy and reduce the disparities resulting from it.

Between 2010 and 2015, the number of adults with active epilepsy rose from 2.3 million to 3 million, according to the CDC. The number of children with epilepsy rose from 450,000 to 470,000.

The increases are likely due to population growth, the CDC says, or other unknown factors, such as an increased willingness to disclose. However, most states do not have data on epilepsy prevalence. This is the first time estimates have been modeled for every state. Moreover, epilepsy has been assessed only intermittently in population surveys. Before 2010, the last national estimates were based on 1986-1990 data.

Obviously, epilepsy is not rare. It also is a serious public health issue. People with epilepsy often have other conditions, such as stroke, heart disease, depression, or developmental delay, which complicate epilepsy management, impair quality of life, and contribute to early mortality, the CDC says. Epilepsy also is the costliest and second most common of 5 chronic conditions that have adverse impact on academic and health outcomes in children and adolescents. For instance, children with seizures are more likely to live in poverty, and their parents more frequently report food insecurity.

The CDC suggests that health care providers and others can use the findings to ensure that evidence-based programs meet the complex needs of adults and children living with epilepsy and reduce the disparities resulting from it.

Between 2010 and 2015, the number of adults with active epilepsy rose from 2.3 million to 3 million, according to the CDC. The number of children with epilepsy rose from 450,000 to 470,000.

The increases are likely due to population growth, the CDC says, or other unknown factors, such as an increased willingness to disclose. However, most states do not have data on epilepsy prevalence. This is the first time estimates have been modeled for every state. Moreover, epilepsy has been assessed only intermittently in population surveys. Before 2010, the last national estimates were based on 1986-1990 data.

Obviously, epilepsy is not rare. It also is a serious public health issue. People with epilepsy often have other conditions, such as stroke, heart disease, depression, or developmental delay, which complicate epilepsy management, impair quality of life, and contribute to early mortality, the CDC says. Epilepsy also is the costliest and second most common of 5 chronic conditions that have adverse impact on academic and health outcomes in children and adolescents. For instance, children with seizures are more likely to live in poverty, and their parents more frequently report food insecurity.

The CDC suggests that health care providers and others can use the findings to ensure that evidence-based programs meet the complex needs of adults and children living with epilepsy and reduce the disparities resulting from it.

Biosimilar deemed equivalent to reference drug in FL

MADRID—The biosimilar GP2013 has demonstrated equivalence to its reference drug rituximab in patients with previously untreated, advanced-stage follicular lymphoma (FL), according to researchers.

Treatment with GP2013 plus cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (CVP) produced a similar overall response rate (ORR) as rituximab plus CVP in the phase 3 ASSIST-FL trial.

Survival rates were also similar between the treatment arms, as were adverse events (AEs).

Results from this study were published in The Lancet Haematology and presented at ESMO 2017 Congress (abstract 994O).

The study was funded by Hexal AG, a Sandoz company (part of the Novartis group), which is marketing GP2013 as Rixathon in Europe.

Patients and treatment

The trial included 629 patients with previously untreated, advanced-stage FL. They were randomized to receive 8 cycles of GP2013-CVP (n=314) or rituximab-CVP (n=315). Responders in either arm could receive monotherapy maintenance for up to 2 years.

The mean age was 57.5 in the GP2013 arm and 56.4 in the rituximab arm. Fifty-eight percent and 54% of patients, respectively, were female.

Fifty-seven percent of patients in the GP2013 arm and 56% in the rituximab arm had an ECOG performance status of 0. Forty percent and 39%, respectively, had a status of 1. Two percent and 4%, respectively, had a status of 2. (For the remaining 1% of patients in each arm, data on performance status were missing.)

Patients had an Ann Arbor stage of III—46% in the GP2013 arm and 43% in the GP2013 arm—or IV—54% in the GP2013 arm and 57% in the rituximab arm.

Fifty-six percent of patients in each arm were high-risk according to FLIPI. Thirty-four percent in the GP2013 arm and 33% in the rituximab arm were intermediate-risk. Ten percent and 11%, respectively, were low-risk.

Fourteen percent of patients in the GP2013 arm and 18% in the rituximab arm had bulky disease. Fifteen percent and 13%, respectively, had splenic involvement.

ORR and survival

The patients had a median follow-up of 23.8 months. The primary efficacy endpoint was equivalence in ORR, defined by a 95% confidence interval (CI) with a margin of ± 12% standard deviation.

The primary endpoint was met, as the ORR was 87% in the GP2013 arm and 88% in the rituximab arm, with a difference of –0.40% (95% CI –5.94%, 5.14%).

The complete response rate was 15% in the GP2013 arm and 13% in the rituximab arm. The partial response rates were 72% and 74%, respectively.

The median progression-free survival and overall survival have not been reached. However, the progression-free survival rate was 70% in the GP2013 arm and 76% in the rituximab arm (hazard ratio [HR]=1.31; 95% CI 1.02, 1.69).

The overall survival rate was 93% in the GP2013 arm and 91% in the rituximab arm (HR=0.77; 95% CI 0.49, 1.22).

Safety

During the combination phase, the incidence of AEs was 93% in the GP2013 arm and 91% in the rituximab arm. The incidence of serious AEs was 23% and 20%, respectively.

The most frequent AEs (in the GP2013 and rituximab arms, respectively) were neutropenia (26% and 30%), constipation (22% and 20%), and nausea (16% and 13%). The most common grade 3/4 AE was neutropenia (18% and 21%).

There were 11 deaths reported during the combination phase—4 in the GP2013 arm and 7 in the rituximab arm.

Three deaths in the GP2013 arm (sudden death, septic shock, and respiratory failure) and 2 deaths in the rituximab arm (multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and sepsis) were suspected to be related to study treatment.

During the maintenance phase, the incidence of AEs was 63% in the GP2013 arm and 57% in the rituximab arm. The incidence of serious AEs was 6% and 4%, respectively.

The most frequent AEs (in the GP2013 and rituximab arms, respectively) were infections and infestations (20% and 27%), neutropenia (10% and 6%), cough (9% and 6%), and upper respiratory tract infection (3% and 6%). The most common grade 3/4 AE was neutropenia (7% and 4%).

There were 4 deaths reported during the maintenance phase, 2 in each treatment arm. ![]()

MADRID—The biosimilar GP2013 has demonstrated equivalence to its reference drug rituximab in patients with previously untreated, advanced-stage follicular lymphoma (FL), according to researchers.

Treatment with GP2013 plus cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (CVP) produced a similar overall response rate (ORR) as rituximab plus CVP in the phase 3 ASSIST-FL trial.

Survival rates were also similar between the treatment arms, as were adverse events (AEs).

Results from this study were published in The Lancet Haematology and presented at ESMO 2017 Congress (abstract 994O).

The study was funded by Hexal AG, a Sandoz company (part of the Novartis group), which is marketing GP2013 as Rixathon in Europe.

Patients and treatment

The trial included 629 patients with previously untreated, advanced-stage FL. They were randomized to receive 8 cycles of GP2013-CVP (n=314) or rituximab-CVP (n=315). Responders in either arm could receive monotherapy maintenance for up to 2 years.

The mean age was 57.5 in the GP2013 arm and 56.4 in the rituximab arm. Fifty-eight percent and 54% of patients, respectively, were female.

Fifty-seven percent of patients in the GP2013 arm and 56% in the rituximab arm had an ECOG performance status of 0. Forty percent and 39%, respectively, had a status of 1. Two percent and 4%, respectively, had a status of 2. (For the remaining 1% of patients in each arm, data on performance status were missing.)

Patients had an Ann Arbor stage of III—46% in the GP2013 arm and 43% in the GP2013 arm—or IV—54% in the GP2013 arm and 57% in the rituximab arm.

Fifty-six percent of patients in each arm were high-risk according to FLIPI. Thirty-four percent in the GP2013 arm and 33% in the rituximab arm were intermediate-risk. Ten percent and 11%, respectively, were low-risk.

Fourteen percent of patients in the GP2013 arm and 18% in the rituximab arm had bulky disease. Fifteen percent and 13%, respectively, had splenic involvement.

ORR and survival

The patients had a median follow-up of 23.8 months. The primary efficacy endpoint was equivalence in ORR, defined by a 95% confidence interval (CI) with a margin of ± 12% standard deviation.

The primary endpoint was met, as the ORR was 87% in the GP2013 arm and 88% in the rituximab arm, with a difference of –0.40% (95% CI –5.94%, 5.14%).

The complete response rate was 15% in the GP2013 arm and 13% in the rituximab arm. The partial response rates were 72% and 74%, respectively.

The median progression-free survival and overall survival have not been reached. However, the progression-free survival rate was 70% in the GP2013 arm and 76% in the rituximab arm (hazard ratio [HR]=1.31; 95% CI 1.02, 1.69).

The overall survival rate was 93% in the GP2013 arm and 91% in the rituximab arm (HR=0.77; 95% CI 0.49, 1.22).

Safety

During the combination phase, the incidence of AEs was 93% in the GP2013 arm and 91% in the rituximab arm. The incidence of serious AEs was 23% and 20%, respectively.

The most frequent AEs (in the GP2013 and rituximab arms, respectively) were neutropenia (26% and 30%), constipation (22% and 20%), and nausea (16% and 13%). The most common grade 3/4 AE was neutropenia (18% and 21%).

There were 11 deaths reported during the combination phase—4 in the GP2013 arm and 7 in the rituximab arm.

Three deaths in the GP2013 arm (sudden death, septic shock, and respiratory failure) and 2 deaths in the rituximab arm (multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and sepsis) were suspected to be related to study treatment.

During the maintenance phase, the incidence of AEs was 63% in the GP2013 arm and 57% in the rituximab arm. The incidence of serious AEs was 6% and 4%, respectively.

The most frequent AEs (in the GP2013 and rituximab arms, respectively) were infections and infestations (20% and 27%), neutropenia (10% and 6%), cough (9% and 6%), and upper respiratory tract infection (3% and 6%). The most common grade 3/4 AE was neutropenia (7% and 4%).

There were 4 deaths reported during the maintenance phase, 2 in each treatment arm. ![]()

MADRID—The biosimilar GP2013 has demonstrated equivalence to its reference drug rituximab in patients with previously untreated, advanced-stage follicular lymphoma (FL), according to researchers.

Treatment with GP2013 plus cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (CVP) produced a similar overall response rate (ORR) as rituximab plus CVP in the phase 3 ASSIST-FL trial.

Survival rates were also similar between the treatment arms, as were adverse events (AEs).

Results from this study were published in The Lancet Haematology and presented at ESMO 2017 Congress (abstract 994O).

The study was funded by Hexal AG, a Sandoz company (part of the Novartis group), which is marketing GP2013 as Rixathon in Europe.

Patients and treatment

The trial included 629 patients with previously untreated, advanced-stage FL. They were randomized to receive 8 cycles of GP2013-CVP (n=314) or rituximab-CVP (n=315). Responders in either arm could receive monotherapy maintenance for up to 2 years.

The mean age was 57.5 in the GP2013 arm and 56.4 in the rituximab arm. Fifty-eight percent and 54% of patients, respectively, were female.

Fifty-seven percent of patients in the GP2013 arm and 56% in the rituximab arm had an ECOG performance status of 0. Forty percent and 39%, respectively, had a status of 1. Two percent and 4%, respectively, had a status of 2. (For the remaining 1% of patients in each arm, data on performance status were missing.)

Patients had an Ann Arbor stage of III—46% in the GP2013 arm and 43% in the GP2013 arm—or IV—54% in the GP2013 arm and 57% in the rituximab arm.

Fifty-six percent of patients in each arm were high-risk according to FLIPI. Thirty-four percent in the GP2013 arm and 33% in the rituximab arm were intermediate-risk. Ten percent and 11%, respectively, were low-risk.

Fourteen percent of patients in the GP2013 arm and 18% in the rituximab arm had bulky disease. Fifteen percent and 13%, respectively, had splenic involvement.

ORR and survival