User login

Older men benefit from vascular screening

BARCELONA – Population screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms, peripheral arterial disease, and hypertension targeted to men aged 65-74 years saved lives in a highly cost-effective way in a Danish randomized study of more than 50,000 men.

During a median follow-up of 4.4 years, total mortality was 7% lower among men invited for this triple-screening panel, compared with uninvited controls – a statistically significant difference achieved without causing any identified serious adverse effects. The cost ran 2,148 euro (about $2,600) per quality adjusted year, making it very “cost attractive,” Jes S. Lindholt, DMSci, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Dr. Lindholt also said that ongoing studies are assessing the clinical- and cost- effectiveness of screening for AAA and PAD in women in a targeted age range. But for the time being, “we believe the greatest benefit is in men.”

The Viborg Vascular (VIVA) screening trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00662480) randomized all 50,156 men aged 65-74 years living in the central region of Denmark to either receive an invitation to triple disease screening or to receive no invitation and form the control group. Three-quarters of those invited for screening came to screening clinics at 14 regional centers. The examinations identified an AAA in 3%, PAD in 11%, and hypertension in 10%. About a third of people identified with AAA or PAD started treatment with aspirin, a statin, or both, and a small number of those with an AAA underwent surgical repair during the following 5 years. About a third of those newly diagnosed with hypertension began treatment with antihypertensive drugs.

The results showed that for every 169 men invited for screening the program saved one life during follow-up, compared with men in the control arm. “To our knowledge, no prior population-based screening program has shown an impact on overall mortality,” Dr. Lindholt said. Concurrently with his report, the results appeared online (Lancet. 2017 Aug 28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32250-X).

VIVA received no commercial funding. Dr. Lindholt had no disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Triple screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms, peripheral arterial disease, and hypertension is a good idea, and the new results from the VIVA trial serve as a call for broader screening initiatives.

Although the patients identified with one or more of the conditions screened received a relatively low rate of interventions, the program nonetheless produced a net benefit. The cost effectiveness of screening was very acceptable, and could potentially further improve if people identified with disease receive treatment sooner. The data showed a modest impact on quality of life, but the findings provided assurance that the screening program produced no excess adverse effects and no decrement in quality of life.

The study was also large and had a median follow-up of more than 4 years. The results also showed the risk for overdiagnosis was no worse than is seen with breast cancer screening.

Andrew M. Kates, MD , is a cardiologist and professor of medicine at Washington University in St. Louis. He had no disclosures. He made these comments as designated discussant for the VIVA trial.

Triple screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms, peripheral arterial disease, and hypertension is a good idea, and the new results from the VIVA trial serve as a call for broader screening initiatives.

Although the patients identified with one or more of the conditions screened received a relatively low rate of interventions, the program nonetheless produced a net benefit. The cost effectiveness of screening was very acceptable, and could potentially further improve if people identified with disease receive treatment sooner. The data showed a modest impact on quality of life, but the findings provided assurance that the screening program produced no excess adverse effects and no decrement in quality of life.

The study was also large and had a median follow-up of more than 4 years. The results also showed the risk for overdiagnosis was no worse than is seen with breast cancer screening.

Andrew M. Kates, MD , is a cardiologist and professor of medicine at Washington University in St. Louis. He had no disclosures. He made these comments as designated discussant for the VIVA trial.

Triple screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms, peripheral arterial disease, and hypertension is a good idea, and the new results from the VIVA trial serve as a call for broader screening initiatives.

Although the patients identified with one or more of the conditions screened received a relatively low rate of interventions, the program nonetheless produced a net benefit. The cost effectiveness of screening was very acceptable, and could potentially further improve if people identified with disease receive treatment sooner. The data showed a modest impact on quality of life, but the findings provided assurance that the screening program produced no excess adverse effects and no decrement in quality of life.

The study was also large and had a median follow-up of more than 4 years. The results also showed the risk for overdiagnosis was no worse than is seen with breast cancer screening.

Andrew M. Kates, MD , is a cardiologist and professor of medicine at Washington University in St. Louis. He had no disclosures. He made these comments as designated discussant for the VIVA trial.

BARCELONA – Population screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms, peripheral arterial disease, and hypertension targeted to men aged 65-74 years saved lives in a highly cost-effective way in a Danish randomized study of more than 50,000 men.

During a median follow-up of 4.4 years, total mortality was 7% lower among men invited for this triple-screening panel, compared with uninvited controls – a statistically significant difference achieved without causing any identified serious adverse effects. The cost ran 2,148 euro (about $2,600) per quality adjusted year, making it very “cost attractive,” Jes S. Lindholt, DMSci, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Dr. Lindholt also said that ongoing studies are assessing the clinical- and cost- effectiveness of screening for AAA and PAD in women in a targeted age range. But for the time being, “we believe the greatest benefit is in men.”

The Viborg Vascular (VIVA) screening trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00662480) randomized all 50,156 men aged 65-74 years living in the central region of Denmark to either receive an invitation to triple disease screening or to receive no invitation and form the control group. Three-quarters of those invited for screening came to screening clinics at 14 regional centers. The examinations identified an AAA in 3%, PAD in 11%, and hypertension in 10%. About a third of people identified with AAA or PAD started treatment with aspirin, a statin, or both, and a small number of those with an AAA underwent surgical repair during the following 5 years. About a third of those newly diagnosed with hypertension began treatment with antihypertensive drugs.

The results showed that for every 169 men invited for screening the program saved one life during follow-up, compared with men in the control arm. “To our knowledge, no prior population-based screening program has shown an impact on overall mortality,” Dr. Lindholt said. Concurrently with his report, the results appeared online (Lancet. 2017 Aug 28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32250-X).

VIVA received no commercial funding. Dr. Lindholt had no disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BARCELONA – Population screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms, peripheral arterial disease, and hypertension targeted to men aged 65-74 years saved lives in a highly cost-effective way in a Danish randomized study of more than 50,000 men.

During a median follow-up of 4.4 years, total mortality was 7% lower among men invited for this triple-screening panel, compared with uninvited controls – a statistically significant difference achieved without causing any identified serious adverse effects. The cost ran 2,148 euro (about $2,600) per quality adjusted year, making it very “cost attractive,” Jes S. Lindholt, DMSci, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Dr. Lindholt also said that ongoing studies are assessing the clinical- and cost- effectiveness of screening for AAA and PAD in women in a targeted age range. But for the time being, “we believe the greatest benefit is in men.”

The Viborg Vascular (VIVA) screening trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00662480) randomized all 50,156 men aged 65-74 years living in the central region of Denmark to either receive an invitation to triple disease screening or to receive no invitation and form the control group. Three-quarters of those invited for screening came to screening clinics at 14 regional centers. The examinations identified an AAA in 3%, PAD in 11%, and hypertension in 10%. About a third of people identified with AAA or PAD started treatment with aspirin, a statin, or both, and a small number of those with an AAA underwent surgical repair during the following 5 years. About a third of those newly diagnosed with hypertension began treatment with antihypertensive drugs.

The results showed that for every 169 men invited for screening the program saved one life during follow-up, compared with men in the control arm. “To our knowledge, no prior population-based screening program has shown an impact on overall mortality,” Dr. Lindholt said. Concurrently with his report, the results appeared online (Lancet. 2017 Aug 28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32250-X).

VIVA received no commercial funding. Dr. Lindholt had no disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Overall mortality during median follow-up of 4 years was 7% lower among men invited to screening, compared with unscreened controls.

Data source: VIVA, a randomized, multicenter trial of 50,156 Danish men.

Disclosures: VIVA received no commercial funding. Dr. Lindholt had no disclosures.

Psychological analysis skills can lead to safer pain care

Primary care physicians may do well to learn how to screen patients for psychological disorders to lower the risk of improper drug prescriptions when treating pain symptoms, according to Robert McCarron, DO.

The screening process looks for anxiety, mood, psychotic, and substance use disorders (AMPS) that can be used by primary care physicians to determine the best way to treat a patient’s pain symptoms, explained Dr. McCarron, professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of California, Irvine, and president-elect of the California Psychiatric Association.

Nearly 60% of patients with chronic pain also have an affective disorder, with certain psychological disorders exacerbating or even causing physical pain, according to Dr. McCarron. Given that, the need for psychiatric evaluation tools and education in primary care is growing rapidly, especially because primary care physicians provide nearly 60% of all psychiatric care in the United States, he said at a meeting held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education.

“We know that 70% of psychiatrists are over the age of 50, and there also aren’t enough pain medicine doctors,” said Dr. McCarron. As of 2016, there are 4,627 mental health care professional shortage areas, with only 44.2% of those who need mental health care having their needs met, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

As primary care physicians shoulder that burden, a common complaint is not having enough time to build a relationship so patients will feel comfortable enough to talk openly about psychiatric symptoms, said Dr, McCarron.

“What I would say is make time for what is most effective,” said Dr. McCarron in an interview. “When it comes to psychiatric disorders and chronic pain management, setting aside some time during the visit to establish a relationship is critically important.”

To help primary care providers feel more comfortable in their ability to diagnose psychological disorders, Dr. McCarron and his colleagues are creating educational tools such as the AMPS assessment.

In addition, “one of the things we’ve done is create a Train New Trainers primary care psychiatry fellowship, where we train practicing primary care providers,” said Dr. McCarron. “We provide a 1-hour longitudinal training in this area, and at the end of that, they know how to diagnose effectively and treat in an evidence-based way, and they know how to train other people in their clinical site or region.”

On top of the fellowship, Dr. McCarron and his colleagues are working on a textbook covering relevant psychiatric material for primary care physicians.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

Primary care physicians may do well to learn how to screen patients for psychological disorders to lower the risk of improper drug prescriptions when treating pain symptoms, according to Robert McCarron, DO.

The screening process looks for anxiety, mood, psychotic, and substance use disorders (AMPS) that can be used by primary care physicians to determine the best way to treat a patient’s pain symptoms, explained Dr. McCarron, professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of California, Irvine, and president-elect of the California Psychiatric Association.

Nearly 60% of patients with chronic pain also have an affective disorder, with certain psychological disorders exacerbating or even causing physical pain, according to Dr. McCarron. Given that, the need for psychiatric evaluation tools and education in primary care is growing rapidly, especially because primary care physicians provide nearly 60% of all psychiatric care in the United States, he said at a meeting held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education.

“We know that 70% of psychiatrists are over the age of 50, and there also aren’t enough pain medicine doctors,” said Dr. McCarron. As of 2016, there are 4,627 mental health care professional shortage areas, with only 44.2% of those who need mental health care having their needs met, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

As primary care physicians shoulder that burden, a common complaint is not having enough time to build a relationship so patients will feel comfortable enough to talk openly about psychiatric symptoms, said Dr, McCarron.

“What I would say is make time for what is most effective,” said Dr. McCarron in an interview. “When it comes to psychiatric disorders and chronic pain management, setting aside some time during the visit to establish a relationship is critically important.”

To help primary care providers feel more comfortable in their ability to diagnose psychological disorders, Dr. McCarron and his colleagues are creating educational tools such as the AMPS assessment.

In addition, “one of the things we’ve done is create a Train New Trainers primary care psychiatry fellowship, where we train practicing primary care providers,” said Dr. McCarron. “We provide a 1-hour longitudinal training in this area, and at the end of that, they know how to diagnose effectively and treat in an evidence-based way, and they know how to train other people in their clinical site or region.”

On top of the fellowship, Dr. McCarron and his colleagues are working on a textbook covering relevant psychiatric material for primary care physicians.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

Primary care physicians may do well to learn how to screen patients for psychological disorders to lower the risk of improper drug prescriptions when treating pain symptoms, according to Robert McCarron, DO.

The screening process looks for anxiety, mood, psychotic, and substance use disorders (AMPS) that can be used by primary care physicians to determine the best way to treat a patient’s pain symptoms, explained Dr. McCarron, professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of California, Irvine, and president-elect of the California Psychiatric Association.

Nearly 60% of patients with chronic pain also have an affective disorder, with certain psychological disorders exacerbating or even causing physical pain, according to Dr. McCarron. Given that, the need for psychiatric evaluation tools and education in primary care is growing rapidly, especially because primary care physicians provide nearly 60% of all psychiatric care in the United States, he said at a meeting held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education.

“We know that 70% of psychiatrists are over the age of 50, and there also aren’t enough pain medicine doctors,” said Dr. McCarron. As of 2016, there are 4,627 mental health care professional shortage areas, with only 44.2% of those who need mental health care having their needs met, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

As primary care physicians shoulder that burden, a common complaint is not having enough time to build a relationship so patients will feel comfortable enough to talk openly about psychiatric symptoms, said Dr, McCarron.

“What I would say is make time for what is most effective,” said Dr. McCarron in an interview. “When it comes to psychiatric disorders and chronic pain management, setting aside some time during the visit to establish a relationship is critically important.”

To help primary care providers feel more comfortable in their ability to diagnose psychological disorders, Dr. McCarron and his colleagues are creating educational tools such as the AMPS assessment.

In addition, “one of the things we’ve done is create a Train New Trainers primary care psychiatry fellowship, where we train practicing primary care providers,” said Dr. McCarron. “We provide a 1-hour longitudinal training in this area, and at the end of that, they know how to diagnose effectively and treat in an evidence-based way, and they know how to train other people in their clinical site or region.”

On top of the fellowship, Dr. McCarron and his colleagues are working on a textbook covering relevant psychiatric material for primary care physicians.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

FROM PAIN CARE FOR PRIMARY CARE

Surgeons strongly influenced chances of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy

Surgeons, not clinical factors, accounted for 20% of variation in rates of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (CPM), according to the results of a large survey study.

Only 4% of patients elected CPM when their surgeons were among those who least favored it overall and most preferred breast-conserving treatment, according to Steven J. Katz, MD, MPH, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his associates. But 34% of patients chose CPM when their surgeons least favored BCT and were most willing to perform CPM, the researchers found. “Attending surgeons exert strong influence on the likelihood of receipt of CPM after diagnosis of breast cancer,” highlighting “the need to help surgeons address this growing clinical conundrum in the examination room,” they wrote (JAMA Surg. 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.3415).

Rates of CPM have risen markedly in the United States although it has not been shown to confer a survival advantage for average-risk women. To examine how surgeons themselves affected rates of CPM, the investigators sent surveys to 7,810 women treated for stage 0 to II breast cancer from 2013 to 2015 and included in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registries of Georgia and Los Angeles County. (Among the 7,810 women, 507 were ineligible.) The researchers also surveyed 488 attending surgeons of these patients.

Response rates were high – 70% among patients (5,080 of 7,303) and 77% (377 of 488) among surgeons, the investigators reported. The average age of the patients was 62 years; 28% had an elevated risk of second primary cancer, and 16% underwent CPM. Patients whose surgeons’ rates of CPM exceeded the mean by at least one standard deviation had nearly threefold greater odds of undergoing CPM themselves (odds ratio, 2.8; 95% confidence interval, 2.1-3.4) regardless of age, date of diagnosis, BRCA mutation status, or risk of second primary cancer.

“One quarter of the surgeon influence was explained by attending attitudes about initial recommendations for surgery and responses to patient requests for CPM,” the researchers wrote. Additional predictors of CPM included elevated risk of second primary breast cancer, BRCA mutation, and younger age.

“We observed a range of reasons why a surgeon would be willing to perform CPM if asked: give peace of mind, yield better cosmetic outcomes, avoid conflict with patient, reduce need for surveillance, improve long-term quality of life, reduce recurrence of invasive disease, avoid losing patient to another surgeon, or improve survival (in order of endorsement),” the researchers wrote. “Our findings reinforce the need to address better ways to communicate with patients with regard to their beliefs about the benefits of more extensive surgery and their reactions to the management plan including surgeon training and deployment of decision aids.”

The National Cancer Institute provided funding. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Patients who are provided education tools regarding the decision between [breast conserving therapy] and mastectomy are more likely to opt for BCT. However, this discussion is arduous and time consuming. We offer decision-making autonomy to patients, but, in creating that autonomy, we have resigned to overtreatment, motivated by the desire to avoid creating conflict in our relationship with the patient.

How do we overcome this hurdle? Consensus statements reinforce that contralateral prophylactic mastectomy should be discouraged in average-risk patients, but it is time to move beyond consensus statements and create communication tools that guide the surgeon and patient through a stepwise informed discussion. We are participating in a multi-institutional randomized trial to develop such an aid, and we believe this will effect real change in the way surgeons counsel patients. The goal is to standardize the methods and information patients receive to ensure that their decisions are based on facts, not fear.

Julie A. Margenthaler, MD, and Amy E. Cyr, MD, are in the department of surgery, Washington University, St. Louis. They reported no conflicts of interest. These comments are from their editorial (JAMA Surg. 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.3435).

Patients who are provided education tools regarding the decision between [breast conserving therapy] and mastectomy are more likely to opt for BCT. However, this discussion is arduous and time consuming. We offer decision-making autonomy to patients, but, in creating that autonomy, we have resigned to overtreatment, motivated by the desire to avoid creating conflict in our relationship with the patient.

How do we overcome this hurdle? Consensus statements reinforce that contralateral prophylactic mastectomy should be discouraged in average-risk patients, but it is time to move beyond consensus statements and create communication tools that guide the surgeon and patient through a stepwise informed discussion. We are participating in a multi-institutional randomized trial to develop such an aid, and we believe this will effect real change in the way surgeons counsel patients. The goal is to standardize the methods and information patients receive to ensure that their decisions are based on facts, not fear.

Julie A. Margenthaler, MD, and Amy E. Cyr, MD, are in the department of surgery, Washington University, St. Louis. They reported no conflicts of interest. These comments are from their editorial (JAMA Surg. 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.3435).

Patients who are provided education tools regarding the decision between [breast conserving therapy] and mastectomy are more likely to opt for BCT. However, this discussion is arduous and time consuming. We offer decision-making autonomy to patients, but, in creating that autonomy, we have resigned to overtreatment, motivated by the desire to avoid creating conflict in our relationship with the patient.

How do we overcome this hurdle? Consensus statements reinforce that contralateral prophylactic mastectomy should be discouraged in average-risk patients, but it is time to move beyond consensus statements and create communication tools that guide the surgeon and patient through a stepwise informed discussion. We are participating in a multi-institutional randomized trial to develop such an aid, and we believe this will effect real change in the way surgeons counsel patients. The goal is to standardize the methods and information patients receive to ensure that their decisions are based on facts, not fear.

Julie A. Margenthaler, MD, and Amy E. Cyr, MD, are in the department of surgery, Washington University, St. Louis. They reported no conflicts of interest. These comments are from their editorial (JAMA Surg. 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.3435).

Surgeons, not clinical factors, accounted for 20% of variation in rates of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (CPM), according to the results of a large survey study.

Only 4% of patients elected CPM when their surgeons were among those who least favored it overall and most preferred breast-conserving treatment, according to Steven J. Katz, MD, MPH, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his associates. But 34% of patients chose CPM when their surgeons least favored BCT and were most willing to perform CPM, the researchers found. “Attending surgeons exert strong influence on the likelihood of receipt of CPM after diagnosis of breast cancer,” highlighting “the need to help surgeons address this growing clinical conundrum in the examination room,” they wrote (JAMA Surg. 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.3415).

Rates of CPM have risen markedly in the United States although it has not been shown to confer a survival advantage for average-risk women. To examine how surgeons themselves affected rates of CPM, the investigators sent surveys to 7,810 women treated for stage 0 to II breast cancer from 2013 to 2015 and included in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registries of Georgia and Los Angeles County. (Among the 7,810 women, 507 were ineligible.) The researchers also surveyed 488 attending surgeons of these patients.

Response rates were high – 70% among patients (5,080 of 7,303) and 77% (377 of 488) among surgeons, the investigators reported. The average age of the patients was 62 years; 28% had an elevated risk of second primary cancer, and 16% underwent CPM. Patients whose surgeons’ rates of CPM exceeded the mean by at least one standard deviation had nearly threefold greater odds of undergoing CPM themselves (odds ratio, 2.8; 95% confidence interval, 2.1-3.4) regardless of age, date of diagnosis, BRCA mutation status, or risk of second primary cancer.

“One quarter of the surgeon influence was explained by attending attitudes about initial recommendations for surgery and responses to patient requests for CPM,” the researchers wrote. Additional predictors of CPM included elevated risk of second primary breast cancer, BRCA mutation, and younger age.

“We observed a range of reasons why a surgeon would be willing to perform CPM if asked: give peace of mind, yield better cosmetic outcomes, avoid conflict with patient, reduce need for surveillance, improve long-term quality of life, reduce recurrence of invasive disease, avoid losing patient to another surgeon, or improve survival (in order of endorsement),” the researchers wrote. “Our findings reinforce the need to address better ways to communicate with patients with regard to their beliefs about the benefits of more extensive surgery and their reactions to the management plan including surgeon training and deployment of decision aids.”

The National Cancer Institute provided funding. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Surgeons, not clinical factors, accounted for 20% of variation in rates of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (CPM), according to the results of a large survey study.

Only 4% of patients elected CPM when their surgeons were among those who least favored it overall and most preferred breast-conserving treatment, according to Steven J. Katz, MD, MPH, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his associates. But 34% of patients chose CPM when their surgeons least favored BCT and were most willing to perform CPM, the researchers found. “Attending surgeons exert strong influence on the likelihood of receipt of CPM after diagnosis of breast cancer,” highlighting “the need to help surgeons address this growing clinical conundrum in the examination room,” they wrote (JAMA Surg. 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.3415).

Rates of CPM have risen markedly in the United States although it has not been shown to confer a survival advantage for average-risk women. To examine how surgeons themselves affected rates of CPM, the investigators sent surveys to 7,810 women treated for stage 0 to II breast cancer from 2013 to 2015 and included in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registries of Georgia and Los Angeles County. (Among the 7,810 women, 507 were ineligible.) The researchers also surveyed 488 attending surgeons of these patients.

Response rates were high – 70% among patients (5,080 of 7,303) and 77% (377 of 488) among surgeons, the investigators reported. The average age of the patients was 62 years; 28% had an elevated risk of second primary cancer, and 16% underwent CPM. Patients whose surgeons’ rates of CPM exceeded the mean by at least one standard deviation had nearly threefold greater odds of undergoing CPM themselves (odds ratio, 2.8; 95% confidence interval, 2.1-3.4) regardless of age, date of diagnosis, BRCA mutation status, or risk of second primary cancer.

“One quarter of the surgeon influence was explained by attending attitudes about initial recommendations for surgery and responses to patient requests for CPM,” the researchers wrote. Additional predictors of CPM included elevated risk of second primary breast cancer, BRCA mutation, and younger age.

“We observed a range of reasons why a surgeon would be willing to perform CPM if asked: give peace of mind, yield better cosmetic outcomes, avoid conflict with patient, reduce need for surveillance, improve long-term quality of life, reduce recurrence of invasive disease, avoid losing patient to another surgeon, or improve survival (in order of endorsement),” the researchers wrote. “Our findings reinforce the need to address better ways to communicate with patients with regard to their beliefs about the benefits of more extensive surgery and their reactions to the management plan including surgeon training and deployment of decision aids.”

The National Cancer Institute provided funding. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Key clinical point: Attending surgeons explained 20% of variation in rates of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy.

Major finding: Only 4% of patients elected CPM when their surgeons were among those who least favored it and most preferred breast-conserving treatment (BCT). However, 34% of patients chose CPM when their surgeons least favored initial BCT and were most willing to perform CPM.

Data source: Surveys of 5,080 patients with stage 0-II breast cancer and 339 attending surgeons.

Disclosures: The National Cancer Institute provided funding. The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

Uninsured rate falls to record low of 8.8%

Three years after the Affordable Care Act’s coverage expansion took effect, the number of Americans without health insurance fell to 28.1 million in 2016, down from 29 million in 2015, according to a federal report released Sept. 12.

The latest numbers from the U.S. Census Bureau showed the nation’s uninsured rate dropped to 8.8%. It had been 9.1% in 2015.

Both the overall number of uninsured and the percentage are record lows.

The latest figures from the Census Bureau effectively close the book on President Barack Obama’s record on lowering the number of uninsured. He made that a linchpin of his 2008 campaign, and his administration’s effort to overhaul the nation’s health system through the ACA focused on expanding coverage.

When Mr. Obama took office in 2009, during the worst economic recession since the Great Depression, more than 50 million Americans were uninsured, or nearly 17% of the population.

The number of uninsured has fallen from 42 million in 2013 – before the ACA in 2014 allowed states to expand Medicaid, the federal-state program that provides coverage to low-income people, and provided federal subsidies to help lower- and middle-income Americans buy coverage on the insurance marketplaces. The decline also reflected the improving economy, which has put more Americans in jobs that offer health coverage.

The dramatic drop in the uninsured over the past few years played a major role in the congressional debate over the summer about whether to replace the 2010 health law. Advocates pleaded with the Republican-controlled Congress not to take steps to reverse the gains in coverage.

The Census Bureau numbers are considered the gold standard for tracking who has insurance because the survey samples are so large.

The uninsured rate has fallen in all 50 states and the District of Columbia since 2013, although the rate has been lower among the 31 states that expanded Medicaid as part of the health law. The lowest uninsured rate last year was 2.5% in Massachusetts, and the highest was 16.6% in Texas, the Census Bureau reported. States that expanded Medicaid had an average uninsured rate of 6.5%, compared with an 11.7% average among states that did not expand.

More than half of Americans – 55.7% – get health insurance through their jobs. But government coverage is becoming more common. Medicaid now covers more than 19% of the population and Medicare, nearly 17%.

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Three years after the Affordable Care Act’s coverage expansion took effect, the number of Americans without health insurance fell to 28.1 million in 2016, down from 29 million in 2015, according to a federal report released Sept. 12.

The latest numbers from the U.S. Census Bureau showed the nation’s uninsured rate dropped to 8.8%. It had been 9.1% in 2015.

Both the overall number of uninsured and the percentage are record lows.

The latest figures from the Census Bureau effectively close the book on President Barack Obama’s record on lowering the number of uninsured. He made that a linchpin of his 2008 campaign, and his administration’s effort to overhaul the nation’s health system through the ACA focused on expanding coverage.

When Mr. Obama took office in 2009, during the worst economic recession since the Great Depression, more than 50 million Americans were uninsured, or nearly 17% of the population.

The number of uninsured has fallen from 42 million in 2013 – before the ACA in 2014 allowed states to expand Medicaid, the federal-state program that provides coverage to low-income people, and provided federal subsidies to help lower- and middle-income Americans buy coverage on the insurance marketplaces. The decline also reflected the improving economy, which has put more Americans in jobs that offer health coverage.

The dramatic drop in the uninsured over the past few years played a major role in the congressional debate over the summer about whether to replace the 2010 health law. Advocates pleaded with the Republican-controlled Congress not to take steps to reverse the gains in coverage.

The Census Bureau numbers are considered the gold standard for tracking who has insurance because the survey samples are so large.

The uninsured rate has fallen in all 50 states and the District of Columbia since 2013, although the rate has been lower among the 31 states that expanded Medicaid as part of the health law. The lowest uninsured rate last year was 2.5% in Massachusetts, and the highest was 16.6% in Texas, the Census Bureau reported. States that expanded Medicaid had an average uninsured rate of 6.5%, compared with an 11.7% average among states that did not expand.

More than half of Americans – 55.7% – get health insurance through their jobs. But government coverage is becoming more common. Medicaid now covers more than 19% of the population and Medicare, nearly 17%.

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Three years after the Affordable Care Act’s coverage expansion took effect, the number of Americans without health insurance fell to 28.1 million in 2016, down from 29 million in 2015, according to a federal report released Sept. 12.

The latest numbers from the U.S. Census Bureau showed the nation’s uninsured rate dropped to 8.8%. It had been 9.1% in 2015.

Both the overall number of uninsured and the percentage are record lows.

The latest figures from the Census Bureau effectively close the book on President Barack Obama’s record on lowering the number of uninsured. He made that a linchpin of his 2008 campaign, and his administration’s effort to overhaul the nation’s health system through the ACA focused on expanding coverage.

When Mr. Obama took office in 2009, during the worst economic recession since the Great Depression, more than 50 million Americans were uninsured, or nearly 17% of the population.

The number of uninsured has fallen from 42 million in 2013 – before the ACA in 2014 allowed states to expand Medicaid, the federal-state program that provides coverage to low-income people, and provided federal subsidies to help lower- and middle-income Americans buy coverage on the insurance marketplaces. The decline also reflected the improving economy, which has put more Americans in jobs that offer health coverage.

The dramatic drop in the uninsured over the past few years played a major role in the congressional debate over the summer about whether to replace the 2010 health law. Advocates pleaded with the Republican-controlled Congress not to take steps to reverse the gains in coverage.

The Census Bureau numbers are considered the gold standard for tracking who has insurance because the survey samples are so large.

The uninsured rate has fallen in all 50 states and the District of Columbia since 2013, although the rate has been lower among the 31 states that expanded Medicaid as part of the health law. The lowest uninsured rate last year was 2.5% in Massachusetts, and the highest was 16.6% in Texas, the Census Bureau reported. States that expanded Medicaid had an average uninsured rate of 6.5%, compared with an 11.7% average among states that did not expand.

More than half of Americans – 55.7% – get health insurance through their jobs. But government coverage is becoming more common. Medicaid now covers more than 19% of the population and Medicare, nearly 17%.

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

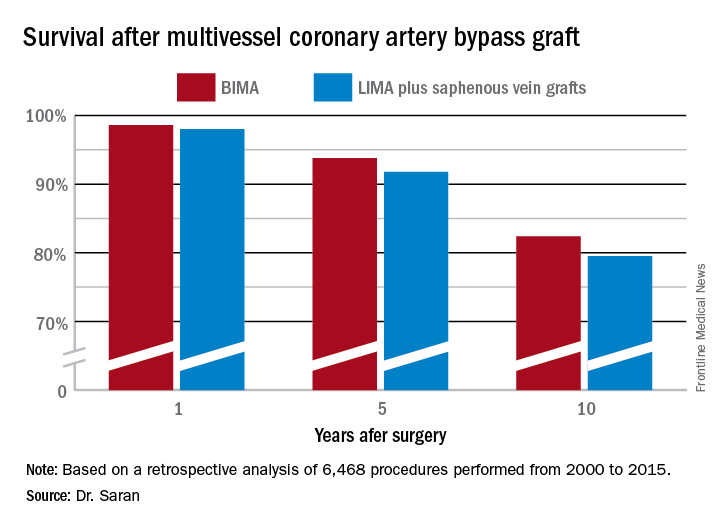

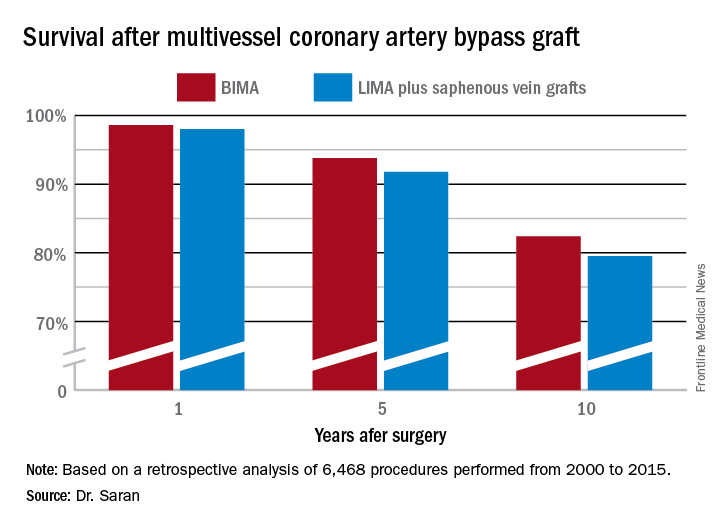

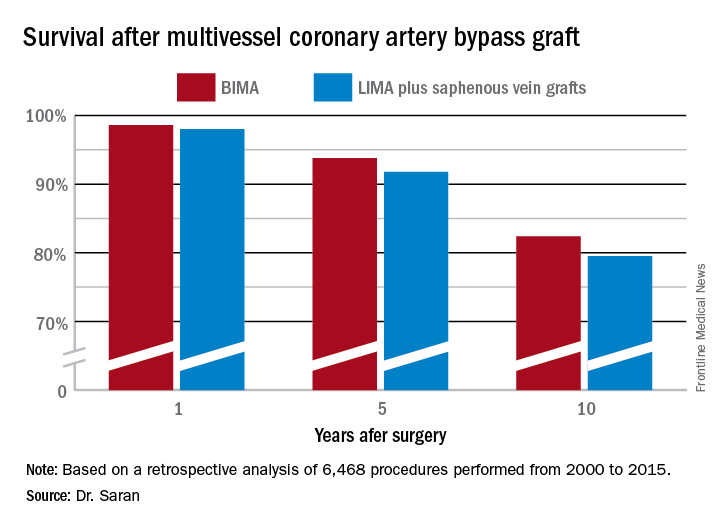

BIMA’s benefits extend to high-risk CABG patients

COLORADO SPRINGS – The survival advantage of bilateral internal over left internal mammary artery grafts persists even among multivessel CABG patients perceived to be at high surgical risk, Nishant Saran, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the Western Thoracic Surgical Association.

Many surgeons hesitate to perform bilateral internal mammary artery (BIMA) grafting in high-risk patients on the presumption that BIMA might not benefit them. It’s a concern that appears to be without merit, however, based on a retrospective analysis of the 6,468 multivessel CABG procedures performed at the Mayo Clinic during 2000-2015, said Dr. Saran of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

The BIMA patients were as a whole significantly younger, primarily men, and less likely to have diabetes or to be obese than the LIMA patients. Also, LIMA patients were fourfold more likely to have baseline heart failure, twice as likely to have a history of stroke, and had a twofold greater prevalence of chronic lung disease.

“The unmatched comparison shows the clear treatment selection bias we have: BIMA goes to the healthier patients,” Dr. Saran observed.

But is that bias justified? To find out, he and his coinvestigators performed extensive propensity score matching using several dozen baseline variables in order to identify 1,011 closely matched patient pairs. In this propensity score-matched analysis, 5- and 10-year survival rates were significantly better in the BIMA group. The gap between the two survival curves widened after about 7 years and continued to expand steadily through year 10. Incision time averaged 298 minutes in the BIMA group and 254 minutes in the propensity-matched LIMA group.

Discussant Eric J. Lehr, MD, a cardiac surgeon at Swedish Medical Center in Seattle, noted that the impressive survival benefit for BIMA in the retrospective Mayo Clinic study came at what he termed “a modest cost”: a doubled incidence of sternal site infections, from 1.4% in the LIMA group to 3% with BIMA. Importantly, though, there was no significant difference in the more serious deep sternal wound infections.

He agreed with Dr. Saran that BIMA is seriously underutilized, noting that only one cardiothoracic surgery program in the state of Washington uses BIMA more than 10% of the time in multivessel CABG.

Dr. Lehr then posed a provocative question: “Should BIMA grafting be considered a quality metric in coronary revascularization surgery, despite the small increase in sternal site infections, even though sternal wound infections have been declared a ‘never’ event and are tied to reimbursement?”

“I think BIMA should be a gold standard,” Dr. Saran replied. “The first thing that a cardiac surgeon should always think of when a patient is going to have CABG is ‘BIMA first,’ and only then look into reasons for not doing it. But I guess in current real-world practice, things are different.”

Howard K. Song, MD, commented, “I think a study like this doesn’t necessarily show that every surgeon should be using BIMA liberally, it shows that surgeons in your practice who do that have excellent outcomes.”

Dr. Song, professor of surgery and chief of the division of cardiothoracic surgery at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, added that he believes extensive use of BIMA is actually a surrogate marker for a highly skilled subspecialist who would be expected to have very good outcomes as a matter of course.

“That may be one way of looking at it; however, I do think that even very skilled surgeons still have an inherent resistance to doing BIMA,” Dr. Saran responded.

“In the current era, the surgeon is pressured to achieve improved short-term outcomes and improved OR turnover times. An extra half hour for BIMA tends to push the surgeon away,” he added.

Dr. Saran reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

COLORADO SPRINGS – The survival advantage of bilateral internal over left internal mammary artery grafts persists even among multivessel CABG patients perceived to be at high surgical risk, Nishant Saran, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the Western Thoracic Surgical Association.

Many surgeons hesitate to perform bilateral internal mammary artery (BIMA) grafting in high-risk patients on the presumption that BIMA might not benefit them. It’s a concern that appears to be without merit, however, based on a retrospective analysis of the 6,468 multivessel CABG procedures performed at the Mayo Clinic during 2000-2015, said Dr. Saran of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

The BIMA patients were as a whole significantly younger, primarily men, and less likely to have diabetes or to be obese than the LIMA patients. Also, LIMA patients were fourfold more likely to have baseline heart failure, twice as likely to have a history of stroke, and had a twofold greater prevalence of chronic lung disease.

“The unmatched comparison shows the clear treatment selection bias we have: BIMA goes to the healthier patients,” Dr. Saran observed.

But is that bias justified? To find out, he and his coinvestigators performed extensive propensity score matching using several dozen baseline variables in order to identify 1,011 closely matched patient pairs. In this propensity score-matched analysis, 5- and 10-year survival rates were significantly better in the BIMA group. The gap between the two survival curves widened after about 7 years and continued to expand steadily through year 10. Incision time averaged 298 minutes in the BIMA group and 254 minutes in the propensity-matched LIMA group.

Discussant Eric J. Lehr, MD, a cardiac surgeon at Swedish Medical Center in Seattle, noted that the impressive survival benefit for BIMA in the retrospective Mayo Clinic study came at what he termed “a modest cost”: a doubled incidence of sternal site infections, from 1.4% in the LIMA group to 3% with BIMA. Importantly, though, there was no significant difference in the more serious deep sternal wound infections.

He agreed with Dr. Saran that BIMA is seriously underutilized, noting that only one cardiothoracic surgery program in the state of Washington uses BIMA more than 10% of the time in multivessel CABG.

Dr. Lehr then posed a provocative question: “Should BIMA grafting be considered a quality metric in coronary revascularization surgery, despite the small increase in sternal site infections, even though sternal wound infections have been declared a ‘never’ event and are tied to reimbursement?”

“I think BIMA should be a gold standard,” Dr. Saran replied. “The first thing that a cardiac surgeon should always think of when a patient is going to have CABG is ‘BIMA first,’ and only then look into reasons for not doing it. But I guess in current real-world practice, things are different.”

Howard K. Song, MD, commented, “I think a study like this doesn’t necessarily show that every surgeon should be using BIMA liberally, it shows that surgeons in your practice who do that have excellent outcomes.”

Dr. Song, professor of surgery and chief of the division of cardiothoracic surgery at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, added that he believes extensive use of BIMA is actually a surrogate marker for a highly skilled subspecialist who would be expected to have very good outcomes as a matter of course.

“That may be one way of looking at it; however, I do think that even very skilled surgeons still have an inherent resistance to doing BIMA,” Dr. Saran responded.

“In the current era, the surgeon is pressured to achieve improved short-term outcomes and improved OR turnover times. An extra half hour for BIMA tends to push the surgeon away,” he added.

Dr. Saran reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

COLORADO SPRINGS – The survival advantage of bilateral internal over left internal mammary artery grafts persists even among multivessel CABG patients perceived to be at high surgical risk, Nishant Saran, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the Western Thoracic Surgical Association.

Many surgeons hesitate to perform bilateral internal mammary artery (BIMA) grafting in high-risk patients on the presumption that BIMA might not benefit them. It’s a concern that appears to be without merit, however, based on a retrospective analysis of the 6,468 multivessel CABG procedures performed at the Mayo Clinic during 2000-2015, said Dr. Saran of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

The BIMA patients were as a whole significantly younger, primarily men, and less likely to have diabetes or to be obese than the LIMA patients. Also, LIMA patients were fourfold more likely to have baseline heart failure, twice as likely to have a history of stroke, and had a twofold greater prevalence of chronic lung disease.

“The unmatched comparison shows the clear treatment selection bias we have: BIMA goes to the healthier patients,” Dr. Saran observed.

But is that bias justified? To find out, he and his coinvestigators performed extensive propensity score matching using several dozen baseline variables in order to identify 1,011 closely matched patient pairs. In this propensity score-matched analysis, 5- and 10-year survival rates were significantly better in the BIMA group. The gap between the two survival curves widened after about 7 years and continued to expand steadily through year 10. Incision time averaged 298 minutes in the BIMA group and 254 minutes in the propensity-matched LIMA group.

Discussant Eric J. Lehr, MD, a cardiac surgeon at Swedish Medical Center in Seattle, noted that the impressive survival benefit for BIMA in the retrospective Mayo Clinic study came at what he termed “a modest cost”: a doubled incidence of sternal site infections, from 1.4% in the LIMA group to 3% with BIMA. Importantly, though, there was no significant difference in the more serious deep sternal wound infections.

He agreed with Dr. Saran that BIMA is seriously underutilized, noting that only one cardiothoracic surgery program in the state of Washington uses BIMA more than 10% of the time in multivessel CABG.

Dr. Lehr then posed a provocative question: “Should BIMA grafting be considered a quality metric in coronary revascularization surgery, despite the small increase in sternal site infections, even though sternal wound infections have been declared a ‘never’ event and are tied to reimbursement?”

“I think BIMA should be a gold standard,” Dr. Saran replied. “The first thing that a cardiac surgeon should always think of when a patient is going to have CABG is ‘BIMA first,’ and only then look into reasons for not doing it. But I guess in current real-world practice, things are different.”

Howard K. Song, MD, commented, “I think a study like this doesn’t necessarily show that every surgeon should be using BIMA liberally, it shows that surgeons in your practice who do that have excellent outcomes.”

Dr. Song, professor of surgery and chief of the division of cardiothoracic surgery at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, added that he believes extensive use of BIMA is actually a surrogate marker for a highly skilled subspecialist who would be expected to have very good outcomes as a matter of course.

“That may be one way of looking at it; however, I do think that even very skilled surgeons still have an inherent resistance to doing BIMA,” Dr. Saran responded.

“In the current era, the surgeon is pressured to achieve improved short-term outcomes and improved OR turnover times. An extra half hour for BIMA tends to push the surgeon away,” he added.

Dr. Saran reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AT THE WTSA ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Ten-year survival following multivessel CABG using bilateral internal mammary artery grafting was 82.4%, significantly better than the 79.5% rate with left internal mammary artery grafting plus saphenous vein grafts.

Data source: This retrospective observational single-center included 6,468 patients who underwent multivessel CABG during 2000-2015.

Disclosures: Dr. Saran reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Postpartum NSAIDs didn’t up hypertension risk in preeclampsia

Women with severe preeclampsia who received nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs during the postpartum period had no greater risk of persistent postpartum hypertension than women who didn’t take them, a study showed.

Additionally, though the numbers of women affected were small, there was no increased risk of severe maternal morbidity. Rates of pulmonary hypertension, renal failure, eclampsia, or intensive care unit admission were similar between women who received NSAIDs during the postpartum period and women who did not.

The single-center retrospective cohort study examined the records of 399 women with severe preeclampsia, 324 of whom (81%) were still hypertensive 24 hours post delivery (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:830-5. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002247). Of this group, three-quarters (n = 243) received NSAIDs, while one-quarter (n = 81) did not.

After multivariable analysis, first author Oscar Viteri, MD, and his colleagues reported that 70% of patients who received NSAIDs had persistent postpartum hypertension, defined as a blood pressure of at least 150 mm Hg or a diastolic BP of at least 100 mm Hg obtained on two occasions at least 4 hours apart. This compared with a rate of 73% for the women who did not receive NSAIDs (adjusted odds ratio, 1.1; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.6-2.0; P = .57).

Relatively small numbers of women in each group experienced severe morbidity, limiting statistical analysis of these secondary outcome measures. Just six women who received NSAIDs and eight who did not (3% and 10%) developed pulmonary edema (OR, 4.4; 95% CI, 1.5-13.1).

Renal dysfunction occurred in 5% of the NSAIDs users vs. 8% of the nonusers (OR, 1.7; 95% CI, 0.6-4.8), and eclampsia occurred in two patients who took NSAIDs and none of the nonusers. Of those who took NSAIDs, 3% had an intensive care unit admission, compared with 8% of those who did not take these drugs (OR 2.4; 95% CI, 0.8-7.1).

Dr. Viteri and his coauthors at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, noted that a high proportion of women with severe preeclampsia received ibuprofen (40%), ketorolac (6%), or both (54%) during their postpartum hospital stay. This occurred despite a 2013 recommendation from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Task Force for Hypertension in Pregnancy urging clinicians to avoid NSAIDs in women with hypertension persisting for 24 hours post partum.

In nonpregnant women with hypertension who are taking beta-blockers or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, NSAIDs use has been associated with increased systolic and diastolic blood pressure, said Dr. Viteri and his colleagues. There are several plausible physiologic mechanisms for this effect, including increased renal sodium retention from inhibition of prostaglandin E2. This potential effect, in particular, may have implications for women in the puerperum, since 6-8 L of fluid are returned to the maternal intravascular space during the early postpartum period.

However, “evidence on the effects of NSAIDs in otherwise healthy puerperal women with preeclampsia before delivery remains conflicting,” the investigators wrote. This study helps to fill the knowledge gap, though there are some limitations, including the fact that the non-NSAIDs arm was small, leaving an unbalanced study that was underpowered to detect differences in “rare but clinically significant” severe maternal morbidity. Also, the study captured only the inpatient period; because the mean duration of hospital stay was 4.5 days, the study missed a portion of the window of fluid volume redistribution, which occurs mostly during postpartum days 3-6.

Still, the findings from this large retrospective study warrant an adequately powered clinical trial to settle the question of the safety of NSAIDs for women with preeclampsia, the investigators said.

Dr. Viteri and his colleagues reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

Women with severe preeclampsia who received nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs during the postpartum period had no greater risk of persistent postpartum hypertension than women who didn’t take them, a study showed.

Additionally, though the numbers of women affected were small, there was no increased risk of severe maternal morbidity. Rates of pulmonary hypertension, renal failure, eclampsia, or intensive care unit admission were similar between women who received NSAIDs during the postpartum period and women who did not.

The single-center retrospective cohort study examined the records of 399 women with severe preeclampsia, 324 of whom (81%) were still hypertensive 24 hours post delivery (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:830-5. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002247). Of this group, three-quarters (n = 243) received NSAIDs, while one-quarter (n = 81) did not.

After multivariable analysis, first author Oscar Viteri, MD, and his colleagues reported that 70% of patients who received NSAIDs had persistent postpartum hypertension, defined as a blood pressure of at least 150 mm Hg or a diastolic BP of at least 100 mm Hg obtained on two occasions at least 4 hours apart. This compared with a rate of 73% for the women who did not receive NSAIDs (adjusted odds ratio, 1.1; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.6-2.0; P = .57).

Relatively small numbers of women in each group experienced severe morbidity, limiting statistical analysis of these secondary outcome measures. Just six women who received NSAIDs and eight who did not (3% and 10%) developed pulmonary edema (OR, 4.4; 95% CI, 1.5-13.1).

Renal dysfunction occurred in 5% of the NSAIDs users vs. 8% of the nonusers (OR, 1.7; 95% CI, 0.6-4.8), and eclampsia occurred in two patients who took NSAIDs and none of the nonusers. Of those who took NSAIDs, 3% had an intensive care unit admission, compared with 8% of those who did not take these drugs (OR 2.4; 95% CI, 0.8-7.1).

Dr. Viteri and his coauthors at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, noted that a high proportion of women with severe preeclampsia received ibuprofen (40%), ketorolac (6%), or both (54%) during their postpartum hospital stay. This occurred despite a 2013 recommendation from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Task Force for Hypertension in Pregnancy urging clinicians to avoid NSAIDs in women with hypertension persisting for 24 hours post partum.

In nonpregnant women with hypertension who are taking beta-blockers or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, NSAIDs use has been associated with increased systolic and diastolic blood pressure, said Dr. Viteri and his colleagues. There are several plausible physiologic mechanisms for this effect, including increased renal sodium retention from inhibition of prostaglandin E2. This potential effect, in particular, may have implications for women in the puerperum, since 6-8 L of fluid are returned to the maternal intravascular space during the early postpartum period.

However, “evidence on the effects of NSAIDs in otherwise healthy puerperal women with preeclampsia before delivery remains conflicting,” the investigators wrote. This study helps to fill the knowledge gap, though there are some limitations, including the fact that the non-NSAIDs arm was small, leaving an unbalanced study that was underpowered to detect differences in “rare but clinically significant” severe maternal morbidity. Also, the study captured only the inpatient period; because the mean duration of hospital stay was 4.5 days, the study missed a portion of the window of fluid volume redistribution, which occurs mostly during postpartum days 3-6.

Still, the findings from this large retrospective study warrant an adequately powered clinical trial to settle the question of the safety of NSAIDs for women with preeclampsia, the investigators said.

Dr. Viteri and his colleagues reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

Women with severe preeclampsia who received nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs during the postpartum period had no greater risk of persistent postpartum hypertension than women who didn’t take them, a study showed.

Additionally, though the numbers of women affected were small, there was no increased risk of severe maternal morbidity. Rates of pulmonary hypertension, renal failure, eclampsia, or intensive care unit admission were similar between women who received NSAIDs during the postpartum period and women who did not.

The single-center retrospective cohort study examined the records of 399 women with severe preeclampsia, 324 of whom (81%) were still hypertensive 24 hours post delivery (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:830-5. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002247). Of this group, three-quarters (n = 243) received NSAIDs, while one-quarter (n = 81) did not.

After multivariable analysis, first author Oscar Viteri, MD, and his colleagues reported that 70% of patients who received NSAIDs had persistent postpartum hypertension, defined as a blood pressure of at least 150 mm Hg or a diastolic BP of at least 100 mm Hg obtained on two occasions at least 4 hours apart. This compared with a rate of 73% for the women who did not receive NSAIDs (adjusted odds ratio, 1.1; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.6-2.0; P = .57).

Relatively small numbers of women in each group experienced severe morbidity, limiting statistical analysis of these secondary outcome measures. Just six women who received NSAIDs and eight who did not (3% and 10%) developed pulmonary edema (OR, 4.4; 95% CI, 1.5-13.1).

Renal dysfunction occurred in 5% of the NSAIDs users vs. 8% of the nonusers (OR, 1.7; 95% CI, 0.6-4.8), and eclampsia occurred in two patients who took NSAIDs and none of the nonusers. Of those who took NSAIDs, 3% had an intensive care unit admission, compared with 8% of those who did not take these drugs (OR 2.4; 95% CI, 0.8-7.1).

Dr. Viteri and his coauthors at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, noted that a high proportion of women with severe preeclampsia received ibuprofen (40%), ketorolac (6%), or both (54%) during their postpartum hospital stay. This occurred despite a 2013 recommendation from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Task Force for Hypertension in Pregnancy urging clinicians to avoid NSAIDs in women with hypertension persisting for 24 hours post partum.

In nonpregnant women with hypertension who are taking beta-blockers or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, NSAIDs use has been associated with increased systolic and diastolic blood pressure, said Dr. Viteri and his colleagues. There are several plausible physiologic mechanisms for this effect, including increased renal sodium retention from inhibition of prostaglandin E2. This potential effect, in particular, may have implications for women in the puerperum, since 6-8 L of fluid are returned to the maternal intravascular space during the early postpartum period.

However, “evidence on the effects of NSAIDs in otherwise healthy puerperal women with preeclampsia before delivery remains conflicting,” the investigators wrote. This study helps to fill the knowledge gap, though there are some limitations, including the fact that the non-NSAIDs arm was small, leaving an unbalanced study that was underpowered to detect differences in “rare but clinically significant” severe maternal morbidity. Also, the study captured only the inpatient period; because the mean duration of hospital stay was 4.5 days, the study missed a portion of the window of fluid volume redistribution, which occurs mostly during postpartum days 3-6.

Still, the findings from this large retrospective study warrant an adequately powered clinical trial to settle the question of the safety of NSAIDs for women with preeclampsia, the investigators said.

Dr. Viteri and his colleagues reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM OBSTETRICS AND GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In total, 70% of women with severe preeclampsia taking NSAIDs, and 73% of those who did not, had persistent postpartum hypertension.

Study details: A retrospective cohort study of 324 women with severe preeclampsia who remained hypertensive for more than 24 hours after delivery.

Disclosures: None of the study authors reported having relevant conflicts of interest.

PBC linked to increased risk of bone fracture

Patients with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) may have an increase in the risk of developing bone fracture, according to Jian Zhao, MD, and associates.

In four cross-sectional studies, 515 patients were examined to assess the prevalence of fracture in a PBC population. Of those patients, the estimated prevalence of fracture was 15.2%. In four additional studies, 1,002 patients and 8,805 controls were examined to assess the relative risk of fracture among PBC patients. Those results found a significantly increased risk of fracture in PBC patients with the pooled odds ratio of 1.93.

It is noted that multiple factors underlie the osteopenic bone disease in PBC. In addition to cholestasis, risk factors include female sex, low body mass index, advanced age, and history of fragility fracture. Steroid use may also contribute to bone loss in PBC, especially in autoimmune hepatitis–primary biliary cholangitis overlap syndrome.

“The prevalence of bone fracture among PBC patients is relatively high and PBC increases the risk of fracture,” the researchers concluded. “Calcium and vitamin D supplementation or even bisphosphonate therapy should be recommended for PBC patients with bone loss to decrease the risk of fracture.”

Read the study in Clinics and Research in Hepatology and Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2017.05.008).

Patients with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) may have an increase in the risk of developing bone fracture, according to Jian Zhao, MD, and associates.

In four cross-sectional studies, 515 patients were examined to assess the prevalence of fracture in a PBC population. Of those patients, the estimated prevalence of fracture was 15.2%. In four additional studies, 1,002 patients and 8,805 controls were examined to assess the relative risk of fracture among PBC patients. Those results found a significantly increased risk of fracture in PBC patients with the pooled odds ratio of 1.93.

It is noted that multiple factors underlie the osteopenic bone disease in PBC. In addition to cholestasis, risk factors include female sex, low body mass index, advanced age, and history of fragility fracture. Steroid use may also contribute to bone loss in PBC, especially in autoimmune hepatitis–primary biliary cholangitis overlap syndrome.

“The prevalence of bone fracture among PBC patients is relatively high and PBC increases the risk of fracture,” the researchers concluded. “Calcium and vitamin D supplementation or even bisphosphonate therapy should be recommended for PBC patients with bone loss to decrease the risk of fracture.”

Read the study in Clinics and Research in Hepatology and Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2017.05.008).

Patients with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) may have an increase in the risk of developing bone fracture, according to Jian Zhao, MD, and associates.

In four cross-sectional studies, 515 patients were examined to assess the prevalence of fracture in a PBC population. Of those patients, the estimated prevalence of fracture was 15.2%. In four additional studies, 1,002 patients and 8,805 controls were examined to assess the relative risk of fracture among PBC patients. Those results found a significantly increased risk of fracture in PBC patients with the pooled odds ratio of 1.93.

It is noted that multiple factors underlie the osteopenic bone disease in PBC. In addition to cholestasis, risk factors include female sex, low body mass index, advanced age, and history of fragility fracture. Steroid use may also contribute to bone loss in PBC, especially in autoimmune hepatitis–primary biliary cholangitis overlap syndrome.

“The prevalence of bone fracture among PBC patients is relatively high and PBC increases the risk of fracture,” the researchers concluded. “Calcium and vitamin D supplementation or even bisphosphonate therapy should be recommended for PBC patients with bone loss to decrease the risk of fracture.”

Read the study in Clinics and Research in Hepatology and Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2017.05.008).

FROM CLINICS AND RESEARCH IN HEPATOLOGY AND GASTROENTEROLOGY

Most type 2 diabetes patients skipping metformin as first-line therapy

Few patients who are initiated on second-line treatment for type 2 diabetes mellitus show evidence of recommended use of first-line treatment with metformin, according to research published online Sept. 13 in Diabetes Care.

A retrospective cross-sectional study examined Aetna member claims data from 52,544 individuals with type 2 diabetes. It showed that of the 22,956 individuals given second-line treatment, only 8.2% had claims evidence of recommended use of metformin in the previous 60 days.

Furthermore, 28% had no claims evidence at all of having taken metformin, and only a small number of these patients had evidence of contraindications to metformin, such as heart failure (2.9%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (3.1%), liver diseases (4.3%), or renal diseases (4.1%).

“Although gastrointestinal adverse effects related to metformin therapy might lead to guideline nonadherence and early second-line medication initiation, we did not find evidence for gastrointestinal upset in the claims data,” wrote Yi-Ju Tseng, PhD, of the Computational Health Informatics Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, and her coauthors.

Even at the top range of sensitivity, researchers argued that less than half of the patients on second-line treatment could have had prior recommended use of metformin as the first-line treatment, while at the lower end of sensitivity, that figure was less than 10% (Diabetes Care. 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.2337/dc17-0213).

Around one-third of patients received some metformin before beginning a second-line treatment, but the duration of metformin treatment was less than the 2 months recommended by current guidelines. Of these patients, just over half were prescribed both metformin and the second-line medication on the same day.

“What may be taken as evidence of treatment failure by clinicians may instead represent failure of adherence to established treatment guidelines, which in turn may lead to the use of insulin or additional second-line medications,” the authors wrote. “Point-of-care decision support and population health–level approaches should focus on improving adherence to first-line therapy.”

The study also found that patients who were given a second-line treatment without evidence of recommended first-line use of metformin were significantly more likely to be given insulin or an additional second-line antihyperglycemic medication. They were also more likely to be male.

However, the authors acknowledged that retrospective claims-based analyses were limited by the exclusion of uninsured patients, and a lack of detailed clinical or behavioral information, or information on out-of-pocket medications.

The study was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and one author was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan and Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Linkou, Taiwan. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Few patients who are initiated on second-line treatment for type 2 diabetes mellitus show evidence of recommended use of first-line treatment with metformin, according to research published online Sept. 13 in Diabetes Care.

A retrospective cross-sectional study examined Aetna member claims data from 52,544 individuals with type 2 diabetes. It showed that of the 22,956 individuals given second-line treatment, only 8.2% had claims evidence of recommended use of metformin in the previous 60 days.

Furthermore, 28% had no claims evidence at all of having taken metformin, and only a small number of these patients had evidence of contraindications to metformin, such as heart failure (2.9%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (3.1%), liver diseases (4.3%), or renal diseases (4.1%).

“Although gastrointestinal adverse effects related to metformin therapy might lead to guideline nonadherence and early second-line medication initiation, we did not find evidence for gastrointestinal upset in the claims data,” wrote Yi-Ju Tseng, PhD, of the Computational Health Informatics Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, and her coauthors.

Even at the top range of sensitivity, researchers argued that less than half of the patients on second-line treatment could have had prior recommended use of metformin as the first-line treatment, while at the lower end of sensitivity, that figure was less than 10% (Diabetes Care. 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.2337/dc17-0213).

Around one-third of patients received some metformin before beginning a second-line treatment, but the duration of metformin treatment was less than the 2 months recommended by current guidelines. Of these patients, just over half were prescribed both metformin and the second-line medication on the same day.

“What may be taken as evidence of treatment failure by clinicians may instead represent failure of adherence to established treatment guidelines, which in turn may lead to the use of insulin or additional second-line medications,” the authors wrote. “Point-of-care decision support and population health–level approaches should focus on improving adherence to first-line therapy.”

The study also found that patients who were given a second-line treatment without evidence of recommended first-line use of metformin were significantly more likely to be given insulin or an additional second-line antihyperglycemic medication. They were also more likely to be male.

However, the authors acknowledged that retrospective claims-based analyses were limited by the exclusion of uninsured patients, and a lack of detailed clinical or behavioral information, or information on out-of-pocket medications.

The study was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and one author was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan and Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Linkou, Taiwan. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Few patients who are initiated on second-line treatment for type 2 diabetes mellitus show evidence of recommended use of first-line treatment with metformin, according to research published online Sept. 13 in Diabetes Care.

A retrospective cross-sectional study examined Aetna member claims data from 52,544 individuals with type 2 diabetes. It showed that of the 22,956 individuals given second-line treatment, only 8.2% had claims evidence of recommended use of metformin in the previous 60 days.

Furthermore, 28% had no claims evidence at all of having taken metformin, and only a small number of these patients had evidence of contraindications to metformin, such as heart failure (2.9%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (3.1%), liver diseases (4.3%), or renal diseases (4.1%).

“Although gastrointestinal adverse effects related to metformin therapy might lead to guideline nonadherence and early second-line medication initiation, we did not find evidence for gastrointestinal upset in the claims data,” wrote Yi-Ju Tseng, PhD, of the Computational Health Informatics Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, and her coauthors.

Even at the top range of sensitivity, researchers argued that less than half of the patients on second-line treatment could have had prior recommended use of metformin as the first-line treatment, while at the lower end of sensitivity, that figure was less than 10% (Diabetes Care. 2017 Sep 13. doi: 10.2337/dc17-0213).

Around one-third of patients received some metformin before beginning a second-line treatment, but the duration of metformin treatment was less than the 2 months recommended by current guidelines. Of these patients, just over half were prescribed both metformin and the second-line medication on the same day.

“What may be taken as evidence of treatment failure by clinicians may instead represent failure of adherence to established treatment guidelines, which in turn may lead to the use of insulin or additional second-line medications,” the authors wrote. “Point-of-care decision support and population health–level approaches should focus on improving adherence to first-line therapy.”

The study also found that patients who were given a second-line treatment without evidence of recommended first-line use of metformin were significantly more likely to be given insulin or an additional second-line antihyperglycemic medication. They were also more likely to be male.

However, the authors acknowledged that retrospective claims-based analyses were limited by the exclusion of uninsured patients, and a lack of detailed clinical or behavioral information, or information on out-of-pocket medications.

The study was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and one author was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan and Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Linkou, Taiwan. No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM DIABETES CARE

Key clinical point: Most patients with type 2 diabetes are not taking the recommended first-line metformin treatment or are skipping straight to second-line therapies altogether.

Major finding: Fewer than 1 in 10 patients with type 2 diabetes have evidence of recommended use of metformin as a first-line treatment for type 2 diabetes.

Data source: A retrospective cross-sectional study of member claims data from 52,544 individuals with type 2 diabetes.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and one author was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan and Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Capillary leakage predicts hysterectomy in postpartum group A strep

PARK CITY, UTAH – Systemic capillary leakage – which involves acute respiratory distress, ascites, pleural effusion, and abdominal distention – significantly increases the risk of hysterectomy in women with postpartum group A Streptococcus infection, according to findings from a single-site study.