User login

AADE: New standards for diabetes self-management programs

New standards for diabetes self-management education and support outline 10 key evidence-based standards for services that meet the Medicare diabetes self-management training regulations, although they do not guarantee coverage. The standards, produced by the American Association of Diabetes Educators in association with the American Diabetes Association, are an update to a similar document produced in 2014. The 2017 revision of the standards is the first to combine support and education to reflect the value of ongoing counsel for improved diabetes self-care, according to an accompanying statement (Diab Care. 2017 Jul 28. doi: 10.2337/dci17-0025).

The new document is full of good recommendations, but they do not cover some important areas. “I don’t disagree with any of them,” said Richard Hellman, MD, clinical professor of medicine at the University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Medicine (UMKC) and associate program director of the UMKC Endocrine Fellowship. But he pointed out that the standards did not include any mention of integrating patient care with other teams. “I think that’s unfortunate. Certainly in our small diabetes practice, we have certified diabetes educators, and all of our patients see them at some point. I hope in subsequent documents they’ll talk about that more,” said Dr. Hellman.

The standards focus on a sort of nuts-and-bolts approach and may be directed toward health care providers who operate in areas with relatively few resources to turn to for help. “It seems it’s answering what to do if you don’t have backup and support, and perhaps that is what it’s for, but the standards should be good in any setting, whether totally integrated or separate. I do think in the future they need to address that large group of people in an integrated setting, and also talk about people with behavioral health expertise. Both are very important,” said Dr. Hellman.

One recommendation he praised in particular was the call for oversight from a quality coordinator. The document calls for the quality coordinator to ensure that the standards are properly implemented, including evidence-based practice, service design, evaluation, and quality improvement. That’s a key consideration because many patients may have disabilities that interfere with comprehension, such as hearing loss or cognitive dysfunction. Such impediments may prevent patients from learning key skills, such as properly checking blood glucose. “That can have a profound effect on diabetes control,” said Dr. Hellman.

He pointed out that quality control can play a wider role in medicine. “Checking your own work isn’t something people always like to do, but it’s really essential. If you think you’re giving high quality care, why don’t you just check your work to see that it’s getting the results that you thought it would?” said Dr. Hellman.

The paper disclosed no sources of funding or conflict of interest information. Dr. Hellman reported having no financial disclosures.

From AADE: 10 standards

Diabetes self-management education and support service providers should:

• Adopt a mission statement and goals.

• Adopt ongoing input from stakeholders and experts to improve quality and participation.

• Analyze the needs of the communities they serve to ensure the best design, delivery method, and use of resources to meet their needs.

• Employ a quality coordinator to oversee services. This individual should be responsible for evidence-based practice, service design, evaluation, and continuous quality improvement.

• Include at least one registered nurse, registered dietitian nutritionist, or pharmacist with training and experience related to DSMES, or a health care professional with a certificate as a diabetes educator (CDE) or Board Certification in Advanced Diabetes Management (BC-ADM).

• Employ a curriculum that follows current evidence and practice guidelines, including a means for evaluating outcomes. The specific elements of the curriculum required will depend on the individual participant’s needs.

• Identify the needs of individual participants and be led by the participant, supported by diabetes self-management education and support team members. They should cooperatively develop an individualized diabetes self-management education and support plan.

• Provide options and resources for ongoing support that participants can choose.

• Monitor participants’ progress toward self-management goals and other outcomes.

• Have their quality control coordinators measure the impact and effectiveness of the diabetes self-management education and support services and determine potential improvements by systematically evaluating process and outcome data.

New standards for diabetes self-management education and support outline 10 key evidence-based standards for services that meet the Medicare diabetes self-management training regulations, although they do not guarantee coverage. The standards, produced by the American Association of Diabetes Educators in association with the American Diabetes Association, are an update to a similar document produced in 2014. The 2017 revision of the standards is the first to combine support and education to reflect the value of ongoing counsel for improved diabetes self-care, according to an accompanying statement (Diab Care. 2017 Jul 28. doi: 10.2337/dci17-0025).

The new document is full of good recommendations, but they do not cover some important areas. “I don’t disagree with any of them,” said Richard Hellman, MD, clinical professor of medicine at the University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Medicine (UMKC) and associate program director of the UMKC Endocrine Fellowship. But he pointed out that the standards did not include any mention of integrating patient care with other teams. “I think that’s unfortunate. Certainly in our small diabetes practice, we have certified diabetes educators, and all of our patients see them at some point. I hope in subsequent documents they’ll talk about that more,” said Dr. Hellman.

The standards focus on a sort of nuts-and-bolts approach and may be directed toward health care providers who operate in areas with relatively few resources to turn to for help. “It seems it’s answering what to do if you don’t have backup and support, and perhaps that is what it’s for, but the standards should be good in any setting, whether totally integrated or separate. I do think in the future they need to address that large group of people in an integrated setting, and also talk about people with behavioral health expertise. Both are very important,” said Dr. Hellman.

One recommendation he praised in particular was the call for oversight from a quality coordinator. The document calls for the quality coordinator to ensure that the standards are properly implemented, including evidence-based practice, service design, evaluation, and quality improvement. That’s a key consideration because many patients may have disabilities that interfere with comprehension, such as hearing loss or cognitive dysfunction. Such impediments may prevent patients from learning key skills, such as properly checking blood glucose. “That can have a profound effect on diabetes control,” said Dr. Hellman.

He pointed out that quality control can play a wider role in medicine. “Checking your own work isn’t something people always like to do, but it’s really essential. If you think you’re giving high quality care, why don’t you just check your work to see that it’s getting the results that you thought it would?” said Dr. Hellman.

The paper disclosed no sources of funding or conflict of interest information. Dr. Hellman reported having no financial disclosures.

From AADE: 10 standards

Diabetes self-management education and support service providers should:

• Adopt a mission statement and goals.

• Adopt ongoing input from stakeholders and experts to improve quality and participation.

• Analyze the needs of the communities they serve to ensure the best design, delivery method, and use of resources to meet their needs.

• Employ a quality coordinator to oversee services. This individual should be responsible for evidence-based practice, service design, evaluation, and continuous quality improvement.

• Include at least one registered nurse, registered dietitian nutritionist, or pharmacist with training and experience related to DSMES, or a health care professional with a certificate as a diabetes educator (CDE) or Board Certification in Advanced Diabetes Management (BC-ADM).

• Employ a curriculum that follows current evidence and practice guidelines, including a means for evaluating outcomes. The specific elements of the curriculum required will depend on the individual participant’s needs.

• Identify the needs of individual participants and be led by the participant, supported by diabetes self-management education and support team members. They should cooperatively develop an individualized diabetes self-management education and support plan.

• Provide options and resources for ongoing support that participants can choose.

• Monitor participants’ progress toward self-management goals and other outcomes.

• Have their quality control coordinators measure the impact and effectiveness of the diabetes self-management education and support services and determine potential improvements by systematically evaluating process and outcome data.

New standards for diabetes self-management education and support outline 10 key evidence-based standards for services that meet the Medicare diabetes self-management training regulations, although they do not guarantee coverage. The standards, produced by the American Association of Diabetes Educators in association with the American Diabetes Association, are an update to a similar document produced in 2014. The 2017 revision of the standards is the first to combine support and education to reflect the value of ongoing counsel for improved diabetes self-care, according to an accompanying statement (Diab Care. 2017 Jul 28. doi: 10.2337/dci17-0025).

The new document is full of good recommendations, but they do not cover some important areas. “I don’t disagree with any of them,” said Richard Hellman, MD, clinical professor of medicine at the University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Medicine (UMKC) and associate program director of the UMKC Endocrine Fellowship. But he pointed out that the standards did not include any mention of integrating patient care with other teams. “I think that’s unfortunate. Certainly in our small diabetes practice, we have certified diabetes educators, and all of our patients see them at some point. I hope in subsequent documents they’ll talk about that more,” said Dr. Hellman.

The standards focus on a sort of nuts-and-bolts approach and may be directed toward health care providers who operate in areas with relatively few resources to turn to for help. “It seems it’s answering what to do if you don’t have backup and support, and perhaps that is what it’s for, but the standards should be good in any setting, whether totally integrated or separate. I do think in the future they need to address that large group of people in an integrated setting, and also talk about people with behavioral health expertise. Both are very important,” said Dr. Hellman.

One recommendation he praised in particular was the call for oversight from a quality coordinator. The document calls for the quality coordinator to ensure that the standards are properly implemented, including evidence-based practice, service design, evaluation, and quality improvement. That’s a key consideration because many patients may have disabilities that interfere with comprehension, such as hearing loss or cognitive dysfunction. Such impediments may prevent patients from learning key skills, such as properly checking blood glucose. “That can have a profound effect on diabetes control,” said Dr. Hellman.

He pointed out that quality control can play a wider role in medicine. “Checking your own work isn’t something people always like to do, but it’s really essential. If you think you’re giving high quality care, why don’t you just check your work to see that it’s getting the results that you thought it would?” said Dr. Hellman.

The paper disclosed no sources of funding or conflict of interest information. Dr. Hellman reported having no financial disclosures.

From AADE: 10 standards

Diabetes self-management education and support service providers should:

• Adopt a mission statement and goals.

• Adopt ongoing input from stakeholders and experts to improve quality and participation.

• Analyze the needs of the communities they serve to ensure the best design, delivery method, and use of resources to meet their needs.

• Employ a quality coordinator to oversee services. This individual should be responsible for evidence-based practice, service design, evaluation, and continuous quality improvement.

• Include at least one registered nurse, registered dietitian nutritionist, or pharmacist with training and experience related to DSMES, or a health care professional with a certificate as a diabetes educator (CDE) or Board Certification in Advanced Diabetes Management (BC-ADM).

• Employ a curriculum that follows current evidence and practice guidelines, including a means for evaluating outcomes. The specific elements of the curriculum required will depend on the individual participant’s needs.

• Identify the needs of individual participants and be led by the participant, supported by diabetes self-management education and support team members. They should cooperatively develop an individualized diabetes self-management education and support plan.

• Provide options and resources for ongoing support that participants can choose.

• Monitor participants’ progress toward self-management goals and other outcomes.

• Have their quality control coordinators measure the impact and effectiveness of the diabetes self-management education and support services and determine potential improvements by systematically evaluating process and outcome data.

FROM DIABETES CARE

Inflammatory bowel disease rate higher among urban residents

Children born in urban areas are more likely to develop inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) when they grow up than are children born in rural areas, a Canadian study showed.

With rising rates of IBD in developing nations and urbanized areas, the investigators interpreted these findings as a positive step toward further understanding, and eventually eliminating, the risk of developing IBD.

The retrospective, population-based study gathered a total of 45,567 IBD patients: 6,662 living in rural residences and 38,905 living in urban residences in Nova Scotia, Ontario, Alberta, and Manitoba, Canada.

Patients in rural areas were on average older than urban patients (average age, 43 years vs. 40 years). Rural patients were also, on average, diagnosed later than were urban patients, with an average age at diagnosis of 42 years, compared with 38 years for urban residents.

The IBD incidence rate among urban patients was 33.16/100,000 (95% CI, 27.24-39.08), compared with 30.72/100,000 (95% CI, 23.81-37.64) among rural residents (Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Jul 25. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.208).

Exposure to these environments while growing up was especially significant, with the lowest rate among children younger than 10 years in rural areas (incidence rate ratio, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.43-0.73), followed by adolescents between 10 and 17.9 years (IRR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.64-0.81), according to investigators.

The incidence rate of IBD among rural children stayed consistent from birth through age 5 years, which may be evidence that development of IBD later in life is correlated with patients’ time in rural areas, the investigators reported.

Although Dr. Benchimol and his coauthors could not point to the exact reason for these results, they said factors such as diet and early exposure to animals, which may help develop useful bacteria that could help fight IBD development, are possible explanations.

“The mechanism by which rurality protects against IBD is uncertain, and may include dietary and lifestyle factors, environmental exposures, or segregation of individuals with different genetic risk profiles,” the investigators wrote. “These effects may be stronger in children because their gut microbiome is in evolution and may be vulnerable to changes in the first 2 years of life.”

This study was limited by certain classification factors, such as what constitutes an urban or rural area, which may have affected the outcomes. A lack of information on the effects of confounding factors, particularly ethnicity, genotype, phenotype, disease severity, or family history also limited this study, the investigators said.

The Janssen Future Leaders in IBD Program funded the study. Investigators reported receiving financial support from or holding leadership positions in the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Canadian Child Health Clinician Scientist program, and the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

Children born in urban areas are more likely to develop inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) when they grow up than are children born in rural areas, a Canadian study showed.

With rising rates of IBD in developing nations and urbanized areas, the investigators interpreted these findings as a positive step toward further understanding, and eventually eliminating, the risk of developing IBD.

The retrospective, population-based study gathered a total of 45,567 IBD patients: 6,662 living in rural residences and 38,905 living in urban residences in Nova Scotia, Ontario, Alberta, and Manitoba, Canada.

Patients in rural areas were on average older than urban patients (average age, 43 years vs. 40 years). Rural patients were also, on average, diagnosed later than were urban patients, with an average age at diagnosis of 42 years, compared with 38 years for urban residents.

The IBD incidence rate among urban patients was 33.16/100,000 (95% CI, 27.24-39.08), compared with 30.72/100,000 (95% CI, 23.81-37.64) among rural residents (Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Jul 25. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.208).

Exposure to these environments while growing up was especially significant, with the lowest rate among children younger than 10 years in rural areas (incidence rate ratio, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.43-0.73), followed by adolescents between 10 and 17.9 years (IRR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.64-0.81), according to investigators.

The incidence rate of IBD among rural children stayed consistent from birth through age 5 years, which may be evidence that development of IBD later in life is correlated with patients’ time in rural areas, the investigators reported.

Although Dr. Benchimol and his coauthors could not point to the exact reason for these results, they said factors such as diet and early exposure to animals, which may help develop useful bacteria that could help fight IBD development, are possible explanations.

“The mechanism by which rurality protects against IBD is uncertain, and may include dietary and lifestyle factors, environmental exposures, or segregation of individuals with different genetic risk profiles,” the investigators wrote. “These effects may be stronger in children because their gut microbiome is in evolution and may be vulnerable to changes in the first 2 years of life.”

This study was limited by certain classification factors, such as what constitutes an urban or rural area, which may have affected the outcomes. A lack of information on the effects of confounding factors, particularly ethnicity, genotype, phenotype, disease severity, or family history also limited this study, the investigators said.

The Janssen Future Leaders in IBD Program funded the study. Investigators reported receiving financial support from or holding leadership positions in the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Canadian Child Health Clinician Scientist program, and the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

Children born in urban areas are more likely to develop inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) when they grow up than are children born in rural areas, a Canadian study showed.

With rising rates of IBD in developing nations and urbanized areas, the investigators interpreted these findings as a positive step toward further understanding, and eventually eliminating, the risk of developing IBD.

The retrospective, population-based study gathered a total of 45,567 IBD patients: 6,662 living in rural residences and 38,905 living in urban residences in Nova Scotia, Ontario, Alberta, and Manitoba, Canada.

Patients in rural areas were on average older than urban patients (average age, 43 years vs. 40 years). Rural patients were also, on average, diagnosed later than were urban patients, with an average age at diagnosis of 42 years, compared with 38 years for urban residents.

The IBD incidence rate among urban patients was 33.16/100,000 (95% CI, 27.24-39.08), compared with 30.72/100,000 (95% CI, 23.81-37.64) among rural residents (Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Jul 25. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.208).

Exposure to these environments while growing up was especially significant, with the lowest rate among children younger than 10 years in rural areas (incidence rate ratio, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.43-0.73), followed by adolescents between 10 and 17.9 years (IRR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.64-0.81), according to investigators.

The incidence rate of IBD among rural children stayed consistent from birth through age 5 years, which may be evidence that development of IBD later in life is correlated with patients’ time in rural areas, the investigators reported.

Although Dr. Benchimol and his coauthors could not point to the exact reason for these results, they said factors such as diet and early exposure to animals, which may help develop useful bacteria that could help fight IBD development, are possible explanations.

“The mechanism by which rurality protects against IBD is uncertain, and may include dietary and lifestyle factors, environmental exposures, or segregation of individuals with different genetic risk profiles,” the investigators wrote. “These effects may be stronger in children because their gut microbiome is in evolution and may be vulnerable to changes in the first 2 years of life.”

This study was limited by certain classification factors, such as what constitutes an urban or rural area, which may have affected the outcomes. A lack of information on the effects of confounding factors, particularly ethnicity, genotype, phenotype, disease severity, or family history also limited this study, the investigators said.

The Janssen Future Leaders in IBD Program funded the study. Investigators reported receiving financial support from or holding leadership positions in the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Canadian Child Health Clinician Scientist program, and the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The incidence of IBD among urban residents was 33.16/100,000 (95% CI, 27.24-39.08), compared with 30.72/100,000 (95% CI, 23.81-37.64) among rural residents.

Data source: A population-based, retrospective analysis of residents among four Canadian provinces between 1999 and 2010.

Disclosures: The Janssen Future Leaders in IBD Program sponsored the study. Investigators reported receiving financial support from or holding leadership positions in the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Canadian Child Health Clinician Scientist program, and the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation.

Ob.gyns. split on cosmetic genital surgery

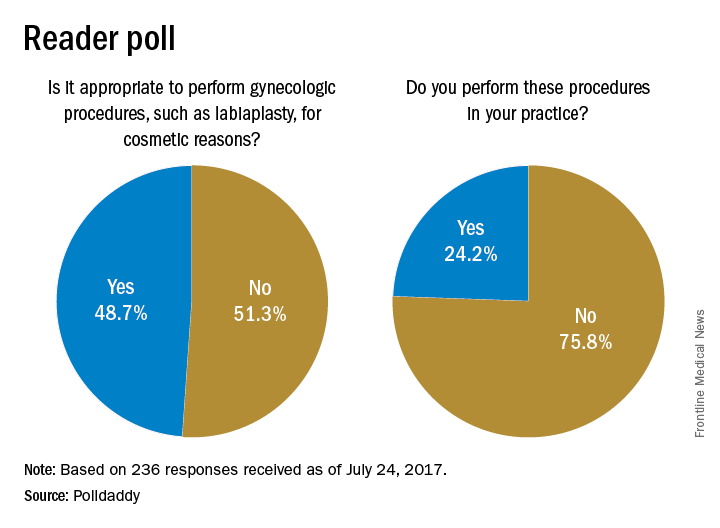

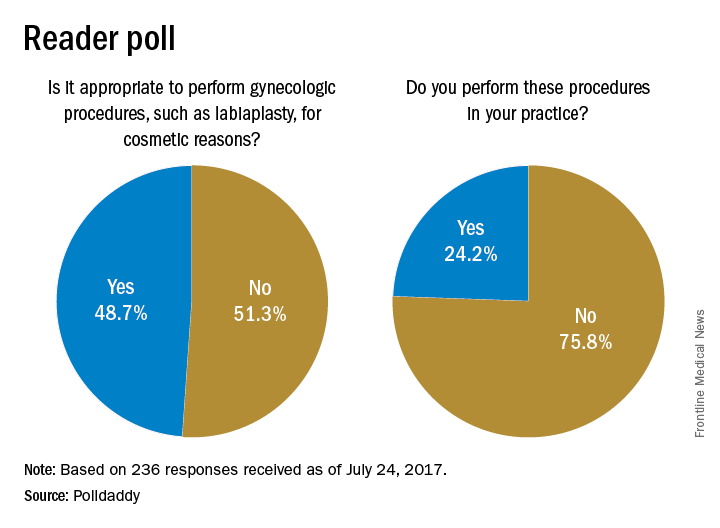

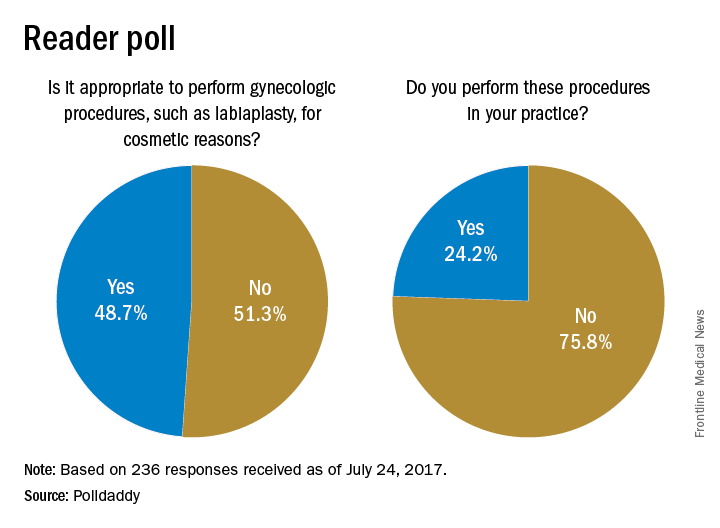

Ob.gyns. appear divided on whether it is appropriate to perform genital surgery for cosmetic reasons, according to the results of a recent online reader poll.

In a poll conducted by Ob.Gyn. News, 48.7% of respondents said it is appropriate to perform gynecologic procedures, such as labiaplasty, for cosmetic reasons, while 51.3% said it is not appropriate.

Results are based on 236 reader responses from June 29 to July 24, 2017.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

Ob.gyns. appear divided on whether it is appropriate to perform genital surgery for cosmetic reasons, according to the results of a recent online reader poll.

In a poll conducted by Ob.Gyn. News, 48.7% of respondents said it is appropriate to perform gynecologic procedures, such as labiaplasty, for cosmetic reasons, while 51.3% said it is not appropriate.

Results are based on 236 reader responses from June 29 to July 24, 2017.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

Ob.gyns. appear divided on whether it is appropriate to perform genital surgery for cosmetic reasons, according to the results of a recent online reader poll.

In a poll conducted by Ob.Gyn. News, 48.7% of respondents said it is appropriate to perform gynecologic procedures, such as labiaplasty, for cosmetic reasons, while 51.3% said it is not appropriate.

Results are based on 236 reader responses from June 29 to July 24, 2017.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

Pruritic Eruption on the Chest

The Diagnosis: Grover Disease

Grover disease (also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis) was first described by Ralph W. Grover in 1970 as an idiopathic, acquired, monomorphous, papulovesicular eruption. Although originally characterized by solely transient acantholytic dermatosis, over time the term Grover disease has been expanded to include persistent acantholytic dermatoses. Grover disease chiefly affects white adults older than 40 years and is more prevalent in males than females. Cases generally are self-limited but correlate with age, as older adults are more likely to have prolonged eruptions.1

Grover disease typically erupts with discrete, erythematous, edematous, acneform, red-brown or flesh-colored papules, papulovesicles, or keratotic papules that primarily are seen on the trunk and anterior portion of the chest. As the rash spreads, it can erupt on the neck and thighs. The etiology of Grover disease is unknown, but many factors have been associated with the condition in a limited number of patients, including exposure to UV radiation, excessive heat or sweating, use of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and recombinant human IL-4, and infection with Malassezia furfur and Demodex folliculorum.1 Grover disease also has been associated with other conditions such as asteatotic eczema, allergic contact dermatitis, and atopic dermatitis.2

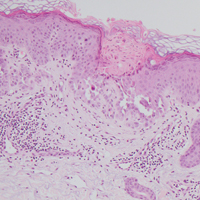

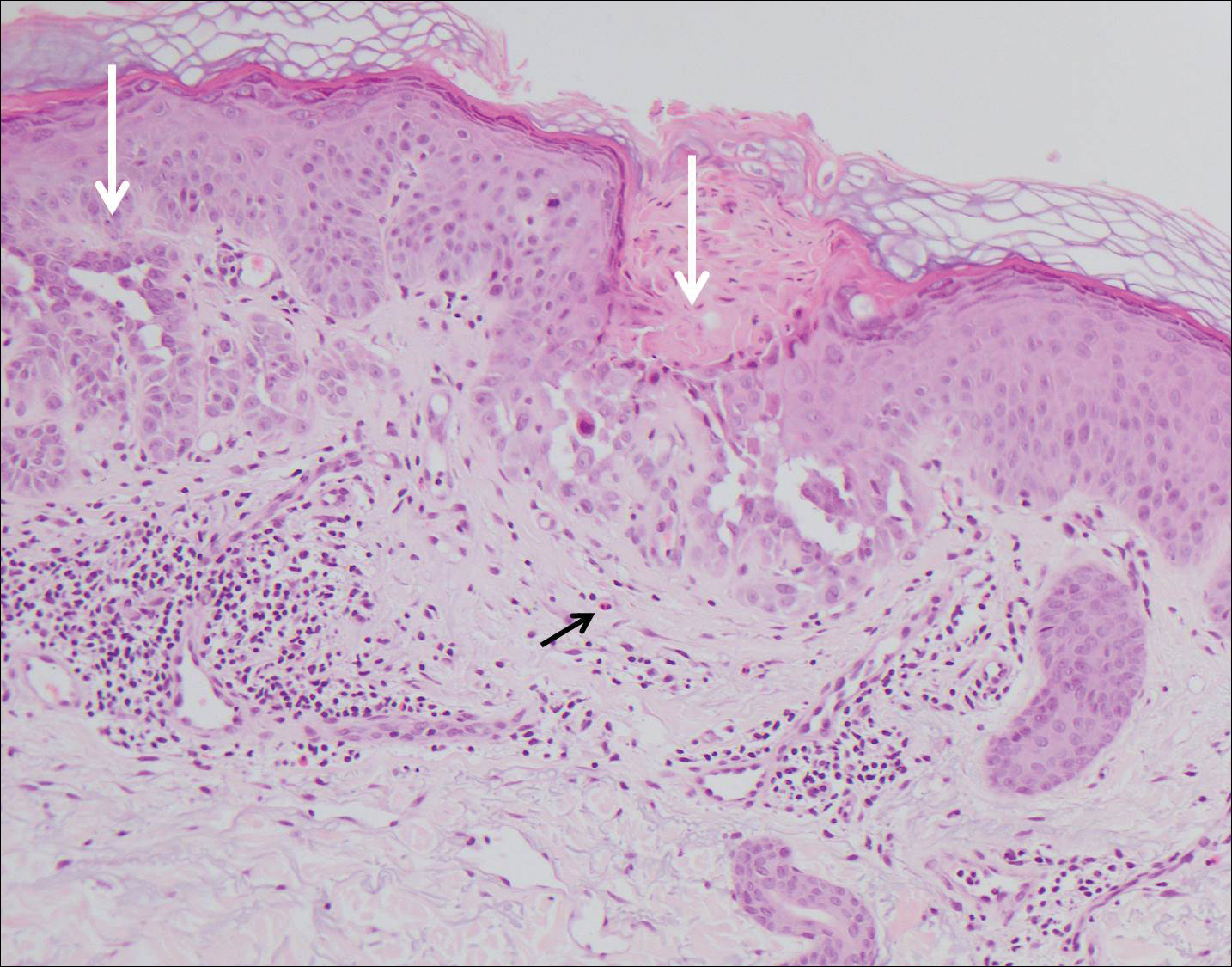

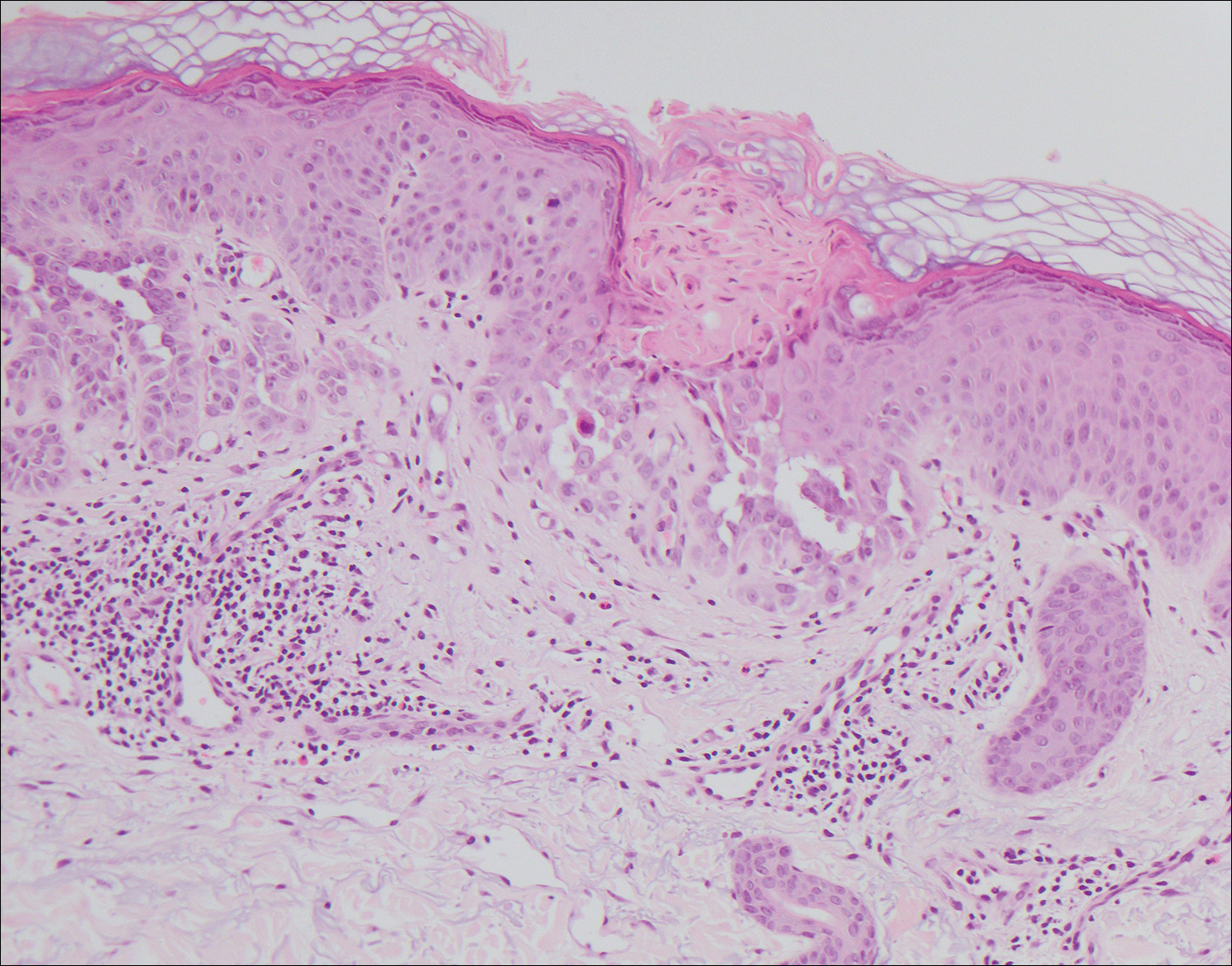

Histologically, Grover disease (Figure 1) is an acantholytic process that can exhibit dyskeratosis (corps ronds and grains). Foci often are small and multiple foci are seen on shave biopsy. There also may be spongiotic changes when associated with an eczematous element. A perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with eosinophils usually is seen.3 Basket weave keratin may be seen; however, as the lesions cause pruritus, erosions and ulcerations often are present.4

Grover disease has multiple histologic variants that may resemble Darier disease, Hailey-Hailey disease, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, and spongiotic dermatitis and can present in combination.5

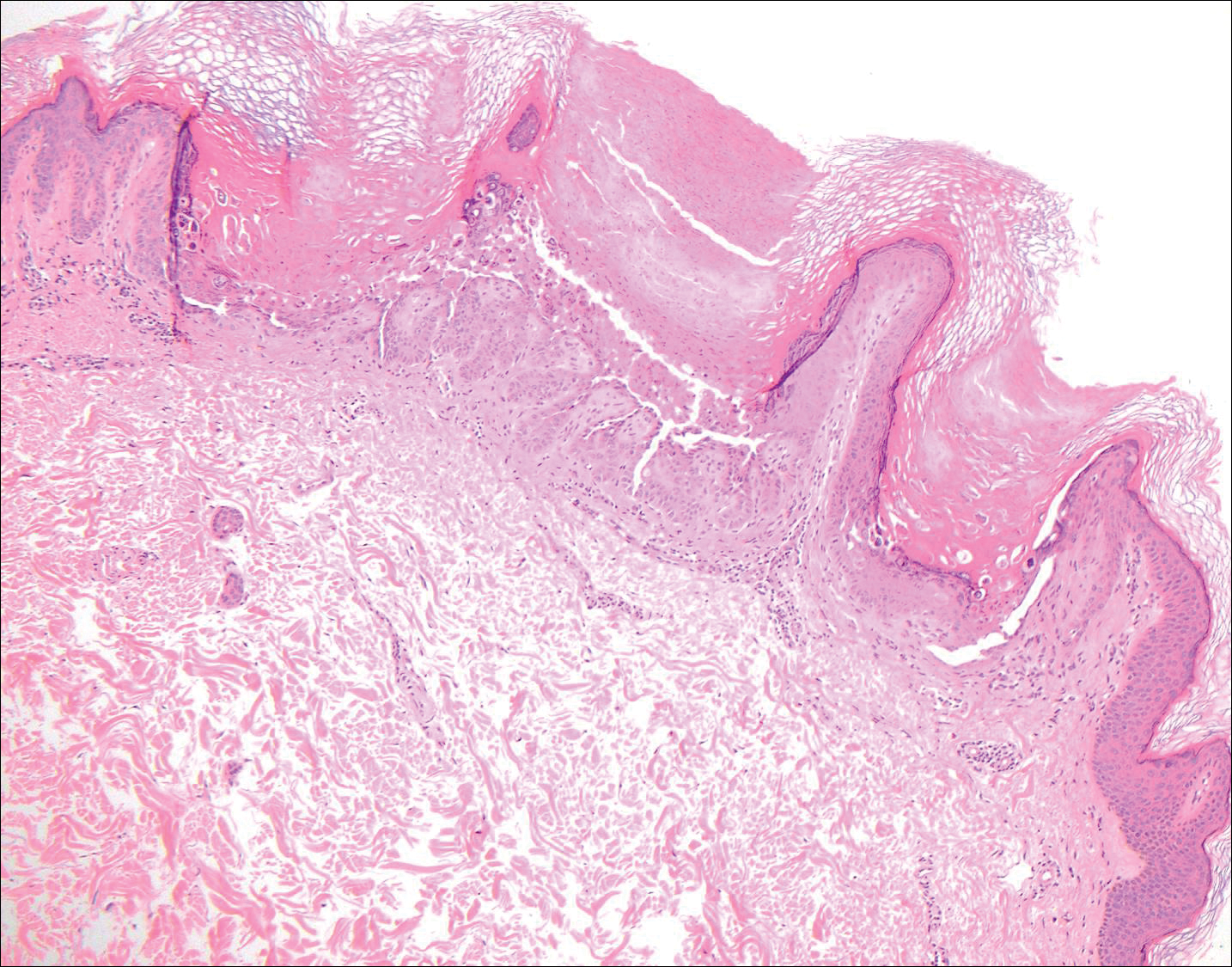

The variant of Grover disease that has a Darier-like pattern is difficult to distinguish from Darier disease, an autosomal-dominant-inherited disorder classified by small papules that emerge in seborrheic areas during childhood and adolescence. Histologically, Darier disease (Figure 2) shows broad areas of dyskeratosis and acantholysis that lead to suprabasal cleavage. Follicular extension may be present. In addition, there often is prominent vertical parakeratosis in Darier disease.6 Histologic features that favor Darier disease over the Darier-like variant of Grover disease include a broad focus of acanthotic dyskeratosis with follicular extension; the presence of a hyperkeratotic stratum corneum; and a lack of spongiosis and eosinophils, which are notably absent in Darier disease but may be present in Grover disease.4

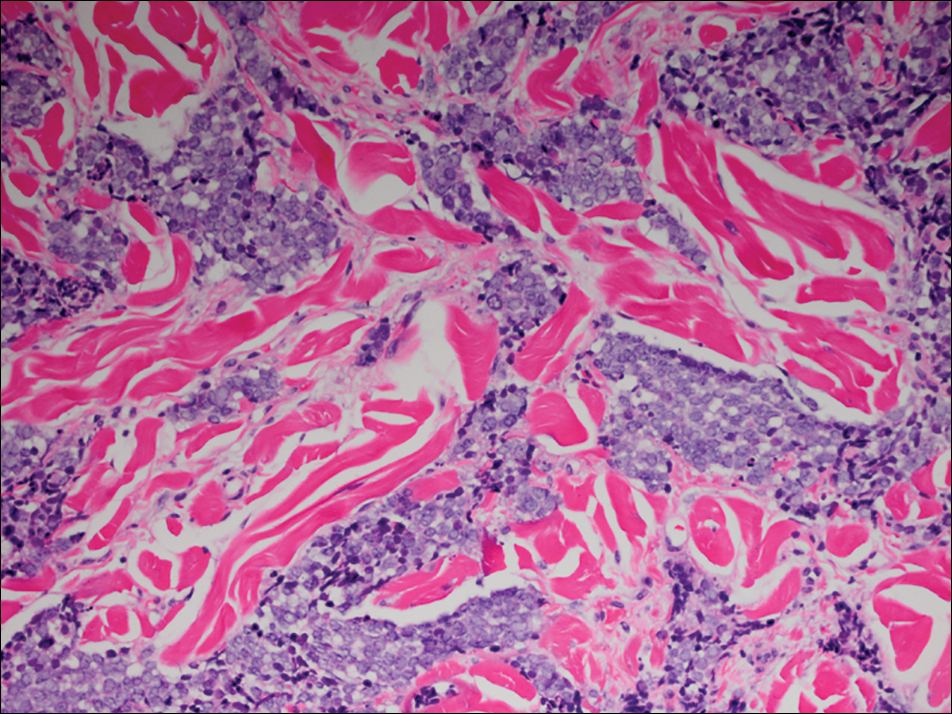

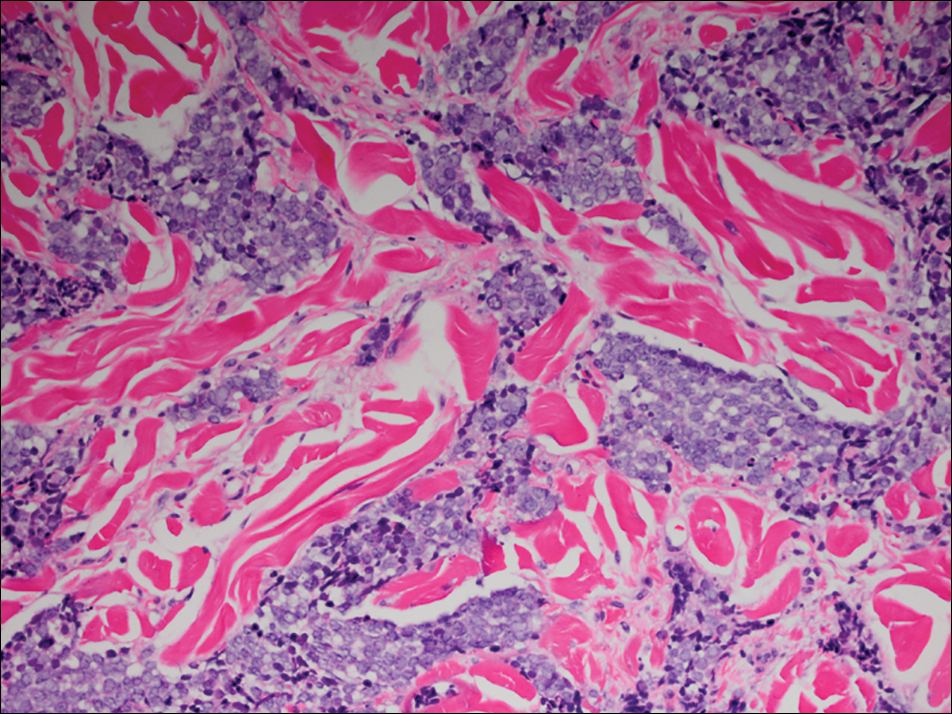

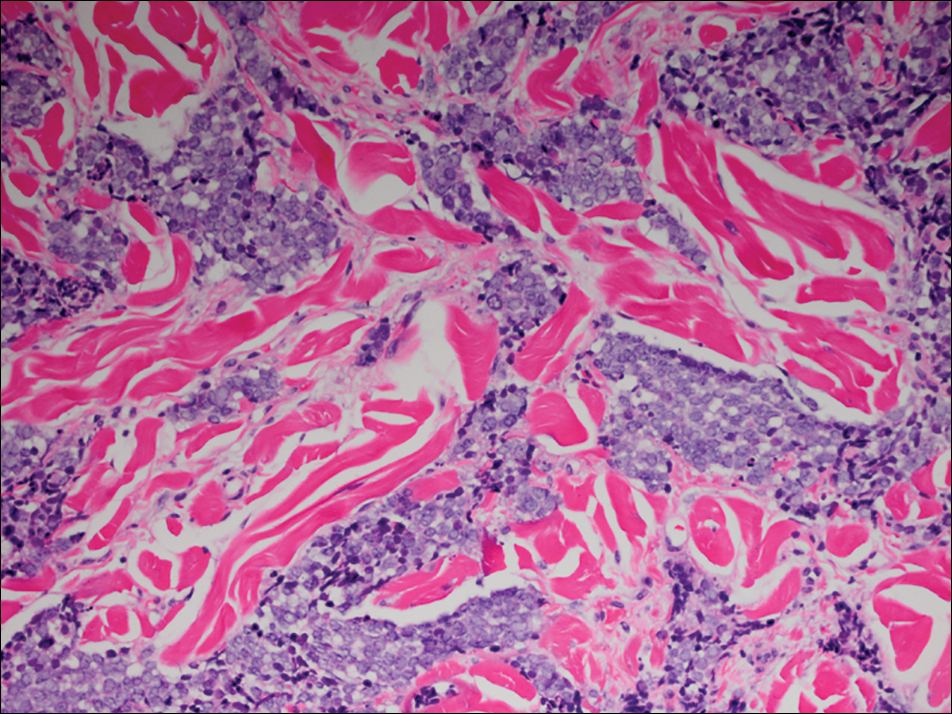

Another variant of Grover disease has a Hailey-Hailey-like pattern, which is characterized by Hailey-Hailey disease's dilapidated brick wall appearance or the diffuse suprabasal acantholysis of all epidermal layers without notable dyskeratosis.4 Hailey-Hailey disease, also known as familial benign pemphigus, is an autosomal-dominant disorder that presents with erythematous vesicular plaques in flexural areas. The plaques progress to flaccid bullae with rupture and crusting and spread peripherally.7 Pathology shows suprabasilar clefts and numerous acantholytic cells (Figure 3). Dyskeratotic keratinocytes are rare with infrequent corps ronds and rare grains. The epidermis also is less hyperplastic in Grover disease than in Hailey-Hailey disease.1

Grover disease also may present histologically with a pemphiguslike pattern, mimicking pemphigus foliaceus and pemphigus vulgaris; however, direct immunofluorescence studies are negative in Grover disease.

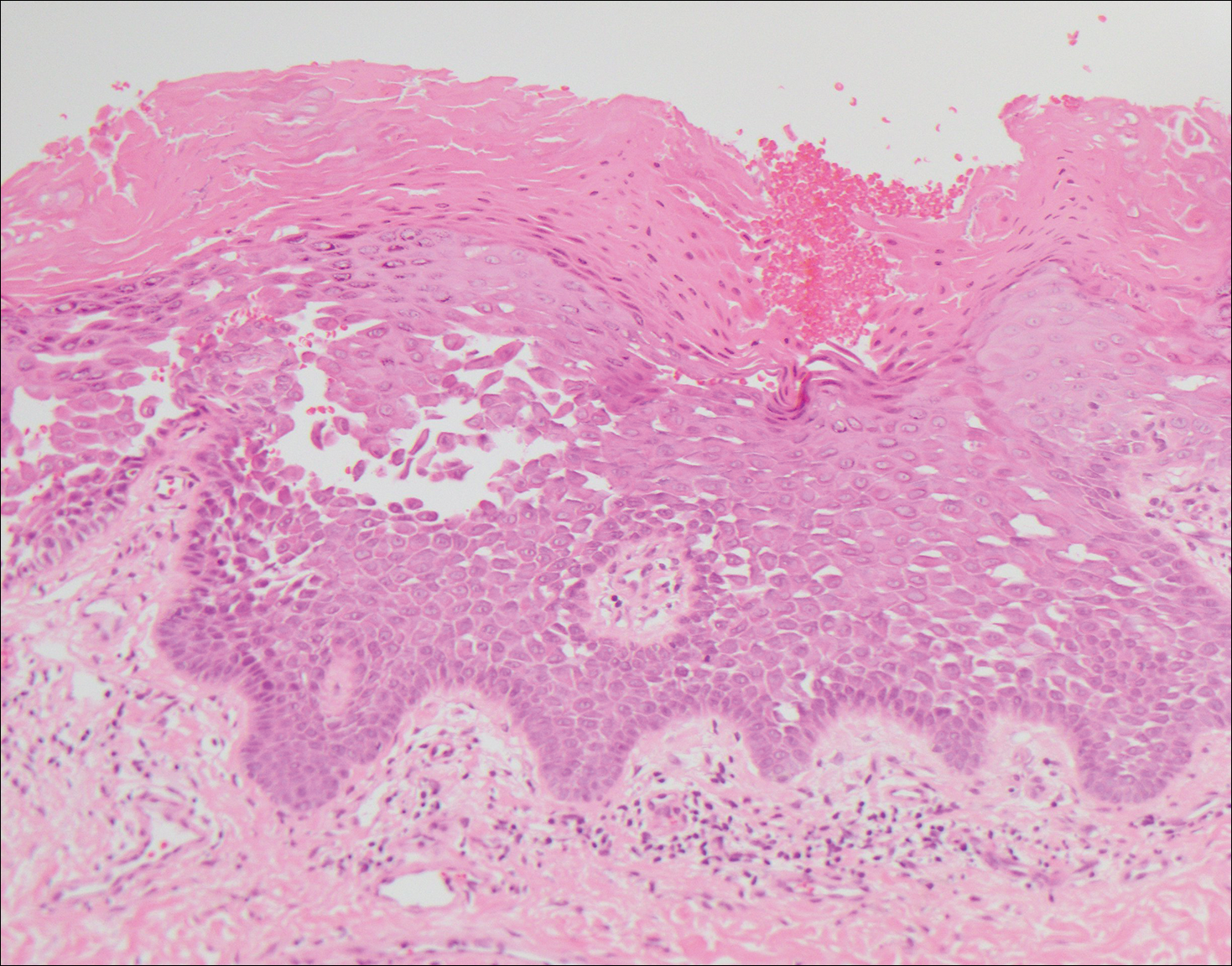

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune disorder caused by autoantibodies to desmoglein 1, which are present on the surfaces of keratinocytes, and is characterized by scaly crusts and blisters.8 Histologically, pemphigus foliaceus (Figure 4) shows a superficial epidermal blistering process. The acantholysis may be subtle and is commonly localized to the stratum granulosum, extending into the stratum corneum. Complete loss of the stratum corneum can be seen, resulting in only scattered acantholytic cells. Spongiosis also may be seen. The dermis shows a perivascular infiltrate that often contains eosinophils. Pemphigus foliaceus is confirmed by direct immunofluorescence.9

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune blistering disorder that is characterized by IgG autoantibodies to desmoglein 3, a component of desmosomes that are involved in keratinocyte-to-keratinocyte adhesion. Clinically, patients present with flaccid fragile blisters on the skin and mucous membranes that rupture easily, leading to painful erosions.10 Intraepidermal blisters are seen histologically (Figure 5) with the loss of cohesion (acantholysis) seen classically in the lower portions of the epidermis where desmoglein 3 is most prominent. When only the basal layer remains, the histology has been likened to a tombstone row.11 Extension of the blister along the adnexa is common. The underlying dermis shows a perivascular infiltrate with eosinophils. Early lesions may show only eosinophilic spongiosis. Direct immunofluorescence studies show IgG and C3 in an intercellular pattern that resembles a fish net or chicken wire.4,11

The spongioticlike pattern of Grover disease is marked by epidermal edema with separation of the keratinocytes and the revelation of their intracellular bridges,4 which manifests as vesiculation in the stratum corneum or upper layers of the epidermis.12

Grover disease is self-limited and may spontaneously resolve; however, the disease may be responsive to topical and systemic steroids. Additionally, avoidance of aggravating factors such as sunlight, heat, and sweating can improve symptoms.2

- Parsons JM. Transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover's disease): a global perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(5, pt 1):653-666; quiz 667-670.

- Quirk CJ, Heenan PJ. Grover's disease: 34 years on. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:83-86.

- Davis MD, Dinneen AM, Landa N, et al. Grover's disease: clinicopathologic review of 72 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:229-234.

- Weaver J, Bergfeld WF. Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1490-1494.

- Chalet M, Grover R, Ackerman AB. Transient acantholytic dermatosis: a reevaluation. Arch Dermatol. 1977;133:431-435.

- Takagi A, Kamijo M, Ikeda S. Darier disease. J Dermatol. 2016;43:275-279.

- Engin B, Kutlubay Z, Celik U, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease: a fold (intertriginous) dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:452-455.

- de Sena Nogueira Maehara L, Huizinga J, Jonkman MF. Rituximab therapy in pemphigus foliaceus: report of 12 cases and review of recent literature [published online March 31, 2015]. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1420-1423.

- James KA, Culton DA, Diaz LA. Diagnosis and clinical features of pemphigus foliaceus. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:405-412.

- Black M, Mignogna MD, Scully C. Number II. pemphigus vulgaris. Oral Dis. 2005;11:119-130.

- Madke B, Doshi B, Khopkar U, et al. Appearances in dermatopathology: the diagnostic and the deceptive. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2013;79:338-348.

- Motaparthi K. Pseudoherpetic transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease): case series and review of the literature [published online February 16, 2017]. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:486-489.

The Diagnosis: Grover Disease

Grover disease (also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis) was first described by Ralph W. Grover in 1970 as an idiopathic, acquired, monomorphous, papulovesicular eruption. Although originally characterized by solely transient acantholytic dermatosis, over time the term Grover disease has been expanded to include persistent acantholytic dermatoses. Grover disease chiefly affects white adults older than 40 years and is more prevalent in males than females. Cases generally are self-limited but correlate with age, as older adults are more likely to have prolonged eruptions.1

Grover disease typically erupts with discrete, erythematous, edematous, acneform, red-brown or flesh-colored papules, papulovesicles, or keratotic papules that primarily are seen on the trunk and anterior portion of the chest. As the rash spreads, it can erupt on the neck and thighs. The etiology of Grover disease is unknown, but many factors have been associated with the condition in a limited number of patients, including exposure to UV radiation, excessive heat or sweating, use of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and recombinant human IL-4, and infection with Malassezia furfur and Demodex folliculorum.1 Grover disease also has been associated with other conditions such as asteatotic eczema, allergic contact dermatitis, and atopic dermatitis.2

Histologically, Grover disease (Figure 1) is an acantholytic process that can exhibit dyskeratosis (corps ronds and grains). Foci often are small and multiple foci are seen on shave biopsy. There also may be spongiotic changes when associated with an eczematous element. A perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with eosinophils usually is seen.3 Basket weave keratin may be seen; however, as the lesions cause pruritus, erosions and ulcerations often are present.4

Grover disease has multiple histologic variants that may resemble Darier disease, Hailey-Hailey disease, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, and spongiotic dermatitis and can present in combination.5

The variant of Grover disease that has a Darier-like pattern is difficult to distinguish from Darier disease, an autosomal-dominant-inherited disorder classified by small papules that emerge in seborrheic areas during childhood and adolescence. Histologically, Darier disease (Figure 2) shows broad areas of dyskeratosis and acantholysis that lead to suprabasal cleavage. Follicular extension may be present. In addition, there often is prominent vertical parakeratosis in Darier disease.6 Histologic features that favor Darier disease over the Darier-like variant of Grover disease include a broad focus of acanthotic dyskeratosis with follicular extension; the presence of a hyperkeratotic stratum corneum; and a lack of spongiosis and eosinophils, which are notably absent in Darier disease but may be present in Grover disease.4

Another variant of Grover disease has a Hailey-Hailey-like pattern, which is characterized by Hailey-Hailey disease's dilapidated brick wall appearance or the diffuse suprabasal acantholysis of all epidermal layers without notable dyskeratosis.4 Hailey-Hailey disease, also known as familial benign pemphigus, is an autosomal-dominant disorder that presents with erythematous vesicular plaques in flexural areas. The plaques progress to flaccid bullae with rupture and crusting and spread peripherally.7 Pathology shows suprabasilar clefts and numerous acantholytic cells (Figure 3). Dyskeratotic keratinocytes are rare with infrequent corps ronds and rare grains. The epidermis also is less hyperplastic in Grover disease than in Hailey-Hailey disease.1

Grover disease also may present histologically with a pemphiguslike pattern, mimicking pemphigus foliaceus and pemphigus vulgaris; however, direct immunofluorescence studies are negative in Grover disease.

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune disorder caused by autoantibodies to desmoglein 1, which are present on the surfaces of keratinocytes, and is characterized by scaly crusts and blisters.8 Histologically, pemphigus foliaceus (Figure 4) shows a superficial epidermal blistering process. The acantholysis may be subtle and is commonly localized to the stratum granulosum, extending into the stratum corneum. Complete loss of the stratum corneum can be seen, resulting in only scattered acantholytic cells. Spongiosis also may be seen. The dermis shows a perivascular infiltrate that often contains eosinophils. Pemphigus foliaceus is confirmed by direct immunofluorescence.9

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune blistering disorder that is characterized by IgG autoantibodies to desmoglein 3, a component of desmosomes that are involved in keratinocyte-to-keratinocyte adhesion. Clinically, patients present with flaccid fragile blisters on the skin and mucous membranes that rupture easily, leading to painful erosions.10 Intraepidermal blisters are seen histologically (Figure 5) with the loss of cohesion (acantholysis) seen classically in the lower portions of the epidermis where desmoglein 3 is most prominent. When only the basal layer remains, the histology has been likened to a tombstone row.11 Extension of the blister along the adnexa is common. The underlying dermis shows a perivascular infiltrate with eosinophils. Early lesions may show only eosinophilic spongiosis. Direct immunofluorescence studies show IgG and C3 in an intercellular pattern that resembles a fish net or chicken wire.4,11

The spongioticlike pattern of Grover disease is marked by epidermal edema with separation of the keratinocytes and the revelation of their intracellular bridges,4 which manifests as vesiculation in the stratum corneum or upper layers of the epidermis.12

Grover disease is self-limited and may spontaneously resolve; however, the disease may be responsive to topical and systemic steroids. Additionally, avoidance of aggravating factors such as sunlight, heat, and sweating can improve symptoms.2

The Diagnosis: Grover Disease

Grover disease (also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis) was first described by Ralph W. Grover in 1970 as an idiopathic, acquired, monomorphous, papulovesicular eruption. Although originally characterized by solely transient acantholytic dermatosis, over time the term Grover disease has been expanded to include persistent acantholytic dermatoses. Grover disease chiefly affects white adults older than 40 years and is more prevalent in males than females. Cases generally are self-limited but correlate with age, as older adults are more likely to have prolonged eruptions.1

Grover disease typically erupts with discrete, erythematous, edematous, acneform, red-brown or flesh-colored papules, papulovesicles, or keratotic papules that primarily are seen on the trunk and anterior portion of the chest. As the rash spreads, it can erupt on the neck and thighs. The etiology of Grover disease is unknown, but many factors have been associated with the condition in a limited number of patients, including exposure to UV radiation, excessive heat or sweating, use of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and recombinant human IL-4, and infection with Malassezia furfur and Demodex folliculorum.1 Grover disease also has been associated with other conditions such as asteatotic eczema, allergic contact dermatitis, and atopic dermatitis.2

Histologically, Grover disease (Figure 1) is an acantholytic process that can exhibit dyskeratosis (corps ronds and grains). Foci often are small and multiple foci are seen on shave biopsy. There also may be spongiotic changes when associated with an eczematous element. A perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with eosinophils usually is seen.3 Basket weave keratin may be seen; however, as the lesions cause pruritus, erosions and ulcerations often are present.4

Grover disease has multiple histologic variants that may resemble Darier disease, Hailey-Hailey disease, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, and spongiotic dermatitis and can present in combination.5

The variant of Grover disease that has a Darier-like pattern is difficult to distinguish from Darier disease, an autosomal-dominant-inherited disorder classified by small papules that emerge in seborrheic areas during childhood and adolescence. Histologically, Darier disease (Figure 2) shows broad areas of dyskeratosis and acantholysis that lead to suprabasal cleavage. Follicular extension may be present. In addition, there often is prominent vertical parakeratosis in Darier disease.6 Histologic features that favor Darier disease over the Darier-like variant of Grover disease include a broad focus of acanthotic dyskeratosis with follicular extension; the presence of a hyperkeratotic stratum corneum; and a lack of spongiosis and eosinophils, which are notably absent in Darier disease but may be present in Grover disease.4

Another variant of Grover disease has a Hailey-Hailey-like pattern, which is characterized by Hailey-Hailey disease's dilapidated brick wall appearance or the diffuse suprabasal acantholysis of all epidermal layers without notable dyskeratosis.4 Hailey-Hailey disease, also known as familial benign pemphigus, is an autosomal-dominant disorder that presents with erythematous vesicular plaques in flexural areas. The plaques progress to flaccid bullae with rupture and crusting and spread peripherally.7 Pathology shows suprabasilar clefts and numerous acantholytic cells (Figure 3). Dyskeratotic keratinocytes are rare with infrequent corps ronds and rare grains. The epidermis also is less hyperplastic in Grover disease than in Hailey-Hailey disease.1

Grover disease also may present histologically with a pemphiguslike pattern, mimicking pemphigus foliaceus and pemphigus vulgaris; however, direct immunofluorescence studies are negative in Grover disease.

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune disorder caused by autoantibodies to desmoglein 1, which are present on the surfaces of keratinocytes, and is characterized by scaly crusts and blisters.8 Histologically, pemphigus foliaceus (Figure 4) shows a superficial epidermal blistering process. The acantholysis may be subtle and is commonly localized to the stratum granulosum, extending into the stratum corneum. Complete loss of the stratum corneum can be seen, resulting in only scattered acantholytic cells. Spongiosis also may be seen. The dermis shows a perivascular infiltrate that often contains eosinophils. Pemphigus foliaceus is confirmed by direct immunofluorescence.9

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune blistering disorder that is characterized by IgG autoantibodies to desmoglein 3, a component of desmosomes that are involved in keratinocyte-to-keratinocyte adhesion. Clinically, patients present with flaccid fragile blisters on the skin and mucous membranes that rupture easily, leading to painful erosions.10 Intraepidermal blisters are seen histologically (Figure 5) with the loss of cohesion (acantholysis) seen classically in the lower portions of the epidermis where desmoglein 3 is most prominent. When only the basal layer remains, the histology has been likened to a tombstone row.11 Extension of the blister along the adnexa is common. The underlying dermis shows a perivascular infiltrate with eosinophils. Early lesions may show only eosinophilic spongiosis. Direct immunofluorescence studies show IgG and C3 in an intercellular pattern that resembles a fish net or chicken wire.4,11

The spongioticlike pattern of Grover disease is marked by epidermal edema with separation of the keratinocytes and the revelation of their intracellular bridges,4 which manifests as vesiculation in the stratum corneum or upper layers of the epidermis.12

Grover disease is self-limited and may spontaneously resolve; however, the disease may be responsive to topical and systemic steroids. Additionally, avoidance of aggravating factors such as sunlight, heat, and sweating can improve symptoms.2

- Parsons JM. Transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover's disease): a global perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(5, pt 1):653-666; quiz 667-670.

- Quirk CJ, Heenan PJ. Grover's disease: 34 years on. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:83-86.

- Davis MD, Dinneen AM, Landa N, et al. Grover's disease: clinicopathologic review of 72 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:229-234.

- Weaver J, Bergfeld WF. Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1490-1494.

- Chalet M, Grover R, Ackerman AB. Transient acantholytic dermatosis: a reevaluation. Arch Dermatol. 1977;133:431-435.

- Takagi A, Kamijo M, Ikeda S. Darier disease. J Dermatol. 2016;43:275-279.

- Engin B, Kutlubay Z, Celik U, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease: a fold (intertriginous) dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:452-455.

- de Sena Nogueira Maehara L, Huizinga J, Jonkman MF. Rituximab therapy in pemphigus foliaceus: report of 12 cases and review of recent literature [published online March 31, 2015]. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1420-1423.

- James KA, Culton DA, Diaz LA. Diagnosis and clinical features of pemphigus foliaceus. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:405-412.

- Black M, Mignogna MD, Scully C. Number II. pemphigus vulgaris. Oral Dis. 2005;11:119-130.

- Madke B, Doshi B, Khopkar U, et al. Appearances in dermatopathology: the diagnostic and the deceptive. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2013;79:338-348.

- Motaparthi K. Pseudoherpetic transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease): case series and review of the literature [published online February 16, 2017]. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:486-489.

- Parsons JM. Transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover's disease): a global perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(5, pt 1):653-666; quiz 667-670.

- Quirk CJ, Heenan PJ. Grover's disease: 34 years on. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:83-86.

- Davis MD, Dinneen AM, Landa N, et al. Grover's disease: clinicopathologic review of 72 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:229-234.

- Weaver J, Bergfeld WF. Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1490-1494.

- Chalet M, Grover R, Ackerman AB. Transient acantholytic dermatosis: a reevaluation. Arch Dermatol. 1977;133:431-435.

- Takagi A, Kamijo M, Ikeda S. Darier disease. J Dermatol. 2016;43:275-279.

- Engin B, Kutlubay Z, Celik U, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease: a fold (intertriginous) dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:452-455.

- de Sena Nogueira Maehara L, Huizinga J, Jonkman MF. Rituximab therapy in pemphigus foliaceus: report of 12 cases and review of recent literature [published online March 31, 2015]. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1420-1423.

- James KA, Culton DA, Diaz LA. Diagnosis and clinical features of pemphigus foliaceus. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:405-412.

- Black M, Mignogna MD, Scully C. Number II. pemphigus vulgaris. Oral Dis. 2005;11:119-130.

- Madke B, Doshi B, Khopkar U, et al. Appearances in dermatopathology: the diagnostic and the deceptive. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2013;79:338-348.

- Motaparthi K. Pseudoherpetic transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease): case series and review of the literature [published online February 16, 2017]. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:486-489.

A 55-year-old man presented with small, erythematous, nonfollicular, pruritic papules on the mid chest.

Tips for navigating pityriasis lichenoides in children

CHICAGO – Pityriasis lichenoides chronica (PLC) is a benign, chronic disorder that can last from 1 to 5 years, yet no formal treatment standards exist.

“Topical corticosteroids will not alter the course of the disease, but they provide symptomatic relief when there is pruritus,” Sibel Ersoy-Evans, MD, said at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology. “Oral antibiotics, especially erythromycin, and phototherapy are the most common modalities used in children. Systemic immunosuppressants are rarely needed.”

Dr. Ersoy-Evans, a dermatologist at Hacettepe University in Ankara, Turkey, described pityriasis lichenoides (PL) as a spectrum with two polar ends: PLC and pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA). Its incidence and prevalence are unknown, but age distribution peaks at 2, 5, and 10 years of age. The average age of onset is 6.5 years, it’s slightly more common in boys, and there is no racial or ethnic predilection.

PLEVA presents with symmetrical, reddish-brown papules that later evolve into vesicular, purpuric, necrotic papules. The scalp, face, mucosa, palms, and soles are spared. Resolution occurs with varioliform scarring and dyspigmentation in 2-18 months. On the other hand, chronic PL is characterized by asymptomatic scaly papules and plaques. The lesions start de novo or evolve from PLEVA lesions and they resolve with hypo-hyperpigmentation in about 8-20 months. In what is believed to be the largest study of its kind, Dr. Ersoy-Evans and her associates respectively reviewed 124 patients with PL. They observed that 57% of patients had PLEVA, primarily those who were white, and 37% had PLC (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56[2]:205-10). The median age of onset was 6 years in PLC patients, versus 5 years in those with PLEVA. Age peaks were observed at 2-3 years and 5-7 years.

They also observed that 30% of cases had a history of recent infection prior to the eruption. “Most patients had generalized distribution, and there wasn’t a significant difference in duration according to the distribution of the lesions,” she said. “Postinflammatory pigmentary changes were observed in 90% of the cases, most commonly hypopigmentation. Pruritus was the most common symptom observed, and the disease was relapsing/recurring in 77% of patients. The duration was longer in PL patients.”

A separate study of 25 children and 32 adults with PL found that hypopigmentation was more common in children (72% vs. 19%, respectively), fewer children experienced remission (20% vs. 78%), and phototherapy was more effective than oral antibiotics in children (Br J Dermatol. 2007;157[5]:941-5).

PL runs a chronic, remitting course in 25%-77% of patients, but there are infrequent reports about progression into cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. “We have not observed any lymphoma development in our cohort with a 10-year follow-up, but long-term follow-up is necessary, especially if clonality is present,” Dr. Ersoy-Evans said. The diagnosis of PL is mostly clinical, but histologic examination may be necessary in some cases. “CD8-positive cells predominate in PLEVA, whereas CD4-positive cells predominate in PLC,” she said.

In the review of 124 patients that she and her associates published in 2007, erythromycin estolate or ethylsuccinate was administered to 80% of children, and 67% of these children showed at least a partial response, with a median response time of 2 months.

In a separate study of 24 children with PL, the response rate was highest (83%) after 3.8 months of erythromycin therapy (Ped Dermatol. 2012; 29[6]:719-24). Dr. Ersoy-Evans stated that oral erythromycin should be continued at least 2 months for a response.

A separate study evaluated the use of phototherapy in 18 children with PLC for a mean of 3.7 months (Ped Dermatol 2008;25[6]:599-605). Among 12 patients who received broadband ultraviolet B radiation for a mean of 3.7 months, the response rate was 83%, which was achieved after a mean of 18 sessions. All five patients who received narrow-band UVB cleared, and the mean number of sessions for a response was 22. One patient who received psoralen and ultraviolet A therapy had no response. A larger review of the published literature found that the delivery of narrow-band UVB has the lowest recurrence rate in PL patients treated with phototherapy (Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:583-91). “Given the efficacy and favorable side effects, I think that phototherapy can be a promising option for PL in children,” Dr. Ersoy-Evans said.

She reported having no financial disclosures

CHICAGO – Pityriasis lichenoides chronica (PLC) is a benign, chronic disorder that can last from 1 to 5 years, yet no formal treatment standards exist.

“Topical corticosteroids will not alter the course of the disease, but they provide symptomatic relief when there is pruritus,” Sibel Ersoy-Evans, MD, said at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology. “Oral antibiotics, especially erythromycin, and phototherapy are the most common modalities used in children. Systemic immunosuppressants are rarely needed.”

Dr. Ersoy-Evans, a dermatologist at Hacettepe University in Ankara, Turkey, described pityriasis lichenoides (PL) as a spectrum with two polar ends: PLC and pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA). Its incidence and prevalence are unknown, but age distribution peaks at 2, 5, and 10 years of age. The average age of onset is 6.5 years, it’s slightly more common in boys, and there is no racial or ethnic predilection.

PLEVA presents with symmetrical, reddish-brown papules that later evolve into vesicular, purpuric, necrotic papules. The scalp, face, mucosa, palms, and soles are spared. Resolution occurs with varioliform scarring and dyspigmentation in 2-18 months. On the other hand, chronic PL is characterized by asymptomatic scaly papules and plaques. The lesions start de novo or evolve from PLEVA lesions and they resolve with hypo-hyperpigmentation in about 8-20 months. In what is believed to be the largest study of its kind, Dr. Ersoy-Evans and her associates respectively reviewed 124 patients with PL. They observed that 57% of patients had PLEVA, primarily those who were white, and 37% had PLC (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56[2]:205-10). The median age of onset was 6 years in PLC patients, versus 5 years in those with PLEVA. Age peaks were observed at 2-3 years and 5-7 years.

They also observed that 30% of cases had a history of recent infection prior to the eruption. “Most patients had generalized distribution, and there wasn’t a significant difference in duration according to the distribution of the lesions,” she said. “Postinflammatory pigmentary changes were observed in 90% of the cases, most commonly hypopigmentation. Pruritus was the most common symptom observed, and the disease was relapsing/recurring in 77% of patients. The duration was longer in PL patients.”

A separate study of 25 children and 32 adults with PL found that hypopigmentation was more common in children (72% vs. 19%, respectively), fewer children experienced remission (20% vs. 78%), and phototherapy was more effective than oral antibiotics in children (Br J Dermatol. 2007;157[5]:941-5).

PL runs a chronic, remitting course in 25%-77% of patients, but there are infrequent reports about progression into cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. “We have not observed any lymphoma development in our cohort with a 10-year follow-up, but long-term follow-up is necessary, especially if clonality is present,” Dr. Ersoy-Evans said. The diagnosis of PL is mostly clinical, but histologic examination may be necessary in some cases. “CD8-positive cells predominate in PLEVA, whereas CD4-positive cells predominate in PLC,” she said.

In the review of 124 patients that she and her associates published in 2007, erythromycin estolate or ethylsuccinate was administered to 80% of children, and 67% of these children showed at least a partial response, with a median response time of 2 months.

In a separate study of 24 children with PL, the response rate was highest (83%) after 3.8 months of erythromycin therapy (Ped Dermatol. 2012; 29[6]:719-24). Dr. Ersoy-Evans stated that oral erythromycin should be continued at least 2 months for a response.

A separate study evaluated the use of phototherapy in 18 children with PLC for a mean of 3.7 months (Ped Dermatol 2008;25[6]:599-605). Among 12 patients who received broadband ultraviolet B radiation for a mean of 3.7 months, the response rate was 83%, which was achieved after a mean of 18 sessions. All five patients who received narrow-band UVB cleared, and the mean number of sessions for a response was 22. One patient who received psoralen and ultraviolet A therapy had no response. A larger review of the published literature found that the delivery of narrow-band UVB has the lowest recurrence rate in PL patients treated with phototherapy (Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:583-91). “Given the efficacy and favorable side effects, I think that phototherapy can be a promising option for PL in children,” Dr. Ersoy-Evans said.

She reported having no financial disclosures

CHICAGO – Pityriasis lichenoides chronica (PLC) is a benign, chronic disorder that can last from 1 to 5 years, yet no formal treatment standards exist.

“Topical corticosteroids will not alter the course of the disease, but they provide symptomatic relief when there is pruritus,” Sibel Ersoy-Evans, MD, said at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology. “Oral antibiotics, especially erythromycin, and phototherapy are the most common modalities used in children. Systemic immunosuppressants are rarely needed.”

Dr. Ersoy-Evans, a dermatologist at Hacettepe University in Ankara, Turkey, described pityriasis lichenoides (PL) as a spectrum with two polar ends: PLC and pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA). Its incidence and prevalence are unknown, but age distribution peaks at 2, 5, and 10 years of age. The average age of onset is 6.5 years, it’s slightly more common in boys, and there is no racial or ethnic predilection.

PLEVA presents with symmetrical, reddish-brown papules that later evolve into vesicular, purpuric, necrotic papules. The scalp, face, mucosa, palms, and soles are spared. Resolution occurs with varioliform scarring and dyspigmentation in 2-18 months. On the other hand, chronic PL is characterized by asymptomatic scaly papules and plaques. The lesions start de novo or evolve from PLEVA lesions and they resolve with hypo-hyperpigmentation in about 8-20 months. In what is believed to be the largest study of its kind, Dr. Ersoy-Evans and her associates respectively reviewed 124 patients with PL. They observed that 57% of patients had PLEVA, primarily those who were white, and 37% had PLC (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56[2]:205-10). The median age of onset was 6 years in PLC patients, versus 5 years in those with PLEVA. Age peaks were observed at 2-3 years and 5-7 years.

They also observed that 30% of cases had a history of recent infection prior to the eruption. “Most patients had generalized distribution, and there wasn’t a significant difference in duration according to the distribution of the lesions,” she said. “Postinflammatory pigmentary changes were observed in 90% of the cases, most commonly hypopigmentation. Pruritus was the most common symptom observed, and the disease was relapsing/recurring in 77% of patients. The duration was longer in PL patients.”

A separate study of 25 children and 32 adults with PL found that hypopigmentation was more common in children (72% vs. 19%, respectively), fewer children experienced remission (20% vs. 78%), and phototherapy was more effective than oral antibiotics in children (Br J Dermatol. 2007;157[5]:941-5).

PL runs a chronic, remitting course in 25%-77% of patients, but there are infrequent reports about progression into cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. “We have not observed any lymphoma development in our cohort with a 10-year follow-up, but long-term follow-up is necessary, especially if clonality is present,” Dr. Ersoy-Evans said. The diagnosis of PL is mostly clinical, but histologic examination may be necessary in some cases. “CD8-positive cells predominate in PLEVA, whereas CD4-positive cells predominate in PLC,” she said.

In the review of 124 patients that she and her associates published in 2007, erythromycin estolate or ethylsuccinate was administered to 80% of children, and 67% of these children showed at least a partial response, with a median response time of 2 months.

In a separate study of 24 children with PL, the response rate was highest (83%) after 3.8 months of erythromycin therapy (Ped Dermatol. 2012; 29[6]:719-24). Dr. Ersoy-Evans stated that oral erythromycin should be continued at least 2 months for a response.

A separate study evaluated the use of phototherapy in 18 children with PLC for a mean of 3.7 months (Ped Dermatol 2008;25[6]:599-605). Among 12 patients who received broadband ultraviolet B radiation for a mean of 3.7 months, the response rate was 83%, which was achieved after a mean of 18 sessions. All five patients who received narrow-band UVB cleared, and the mean number of sessions for a response was 22. One patient who received psoralen and ultraviolet A therapy had no response. A larger review of the published literature found that the delivery of narrow-band UVB has the lowest recurrence rate in PL patients treated with phototherapy (Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:583-91). “Given the efficacy and favorable side effects, I think that phototherapy can be a promising option for PL in children,” Dr. Ersoy-Evans said.

She reported having no financial disclosures

AT WCPD 2017

Hyaluronic Acid Gel Filler for Nipple Enhancement Following Breast Reconstruction

The most frequently used surgical techniques in nipple-areola complex (NAC) reconstruction involve the use of local tissue flaps and yield the fewest complications, though these techniques can be associated with up to a 75% loss in nipple projection over time.1 In a best-case scenario for both the surgeon and the patient, the NAC is preserved during mastectomy; however, even when the tissues are spared, an eventual loss of nipple projection is expected due to atrophy and contraction of the healing skin.2 Loss of nipple projection is the most common attribute that patients dislike regarding their NAC reconstruction results.Additional efforts made to restore the natural look and feel of the NAC provides undeniable benefit to the patient in the form of improved body image and psychosocial well-being.3

Augmentation with a grafted material can include cartilage or fat (autologous grafts), calcium hydroxylapatite or polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA)(alloplastic grafts), and acellular dermal matrix or biologic collagen (allografts). Among these options, successive treatment with autologous fat has been shown to provide satisfactory projections over time with minimal complications.4 However, an additional consideration associated with graft augmentation is the need for an additional surgical site (autologous grafts) or the possibility that graft material may not be compatible with subsequent breast examination techniques. For example, calcium hydroxylapatite is a radiopaque material that may interfere with the interpretation of radiography and mammography.5

The use of injectable hyaluronic acid (HA) dermal fillers to enhance nipple projection represents a noninvasive procedure with immediate and adjustable results. A variety of dermal fillers that do not interfere with subsequent breast imaging needs have already been successfully used for nipple reconstruction including HA 60% plus acrylic hydrogel 40%, PMMA microspheres in a bovine collagen 3.5% gel, and poly-L-lactic acid.5-7

The results achieved with HA 60% plus acrylic hydrogel 40% were as much as a 2.5-mm mean increase in nipple projection after 12 months for 70 nipples reconstructed using a small wedge from the labia minora.5 In these treatments, an initial injection of 0.1 to 0.3 mL of filler into each nipple along with a 0.2-mL injection at the base of each nipple was made. Further optional treatments at 2 and 4 months after the initial injection were made using up to 0.3 mL additional volume depending on filler reabsorption.5 Results achieved with PMMA microspheres in a bovine collagen 3.5% gel included a 1.6-mm mean increase in nipple projection at 9 months versus baseline for 33 nipples in 23 patients, which involved up to 2 injections at baseline and again at 3 months.6 Treatment with poly-L-lactic acid provided a 2.3-mm mean increase in nipple projection for 12 patients after 1 year of treatment, which involved 0.5-mL injections every 4 weeks over a series of 4 treatments.7

This report describes the technique and cosmetic outcome using an injectable HA gel to postoperatively restore the 3-dimensional contour of the nipple following surgical breast reconstruction. This chemically cross-linked, stabilized HA gel suspended in phosphate-buffered saline at a pH of 7 and a concentration of 20 mg/mL with lidocaine 0.3% is indicated for mid to deep dermal implantation for the correction of moderate to severe facial wrinkles and folds, such as the nasolabial folds.8

Case Report

A 49-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer with a focal, high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ underwent a complete bilateral mastectomy. The sentinel lymph nodes were negative at the time of mastectomy. One year later, the patient elected to have breast and nipple-areola (flap) reconstruction. Following the reconstructive surgery, her nipples had become visibly atrophic and flat, and she was interested in cosmetic enhancement.

After informed consent had been obtained from the patient, a baseline measurement of each nipple was made while the patient was standing. Each nipple was then injected with up to 0.1 to 0.2 mL of HA gel filler using a 30-gauge needle inserted 2-mm deep (bilaterally) into each nipple. The patient tolerated the procedure well with no pain, bleeding, or bruising. Although HA gel filler contains lidocaine 0.3% and tricaine can further be used to ensure patient comfort, the nipple reconstruction surgery left the patient with little sensation in the treatment area. Rubbing alcohol was used to prepare the skin prior to the procedure, and fractionated coconut oil spray with a nonadherent dressing was used postprocedure.

Following the injection, an immediate increase of 1.6 and 1.5 mm in nipple projection in the right and left breasts, respectively, was achieved with HA gel. The nipple projection of the right breast was 1.7 mm before injection (Figure, A) and 3.3 mm immediately postinjection (Figure, C). The nipple projection of the left breast was 1.8 mm before injection (Figure, B) and 3.3 mm immediately postinjection (Figure, D).

Comment

With a single treatment consisting of 0.2 mL or less of filler volume, the HA gel used in this procedure provided an immediate mean increase in nipple projection of 1.5 mm. Although our assessment involved a single patient evaluated at baseline and immediately post-injection of HA filler only, it is reasonable to assume that subsequent reinjections would provide results comparable to other fillers. Although other fillers that are semipermanent (acrylic hydrogel) and nonbiodegradable (PMMA) make them more durable, these properties also make the augmentation less reversible in the case of overfilling. As with all dermal fillers, rare side effects associated with injection of HA gel filler could potentially include injection-site inflammation, extrusion of filler at the needle insertion site, minimal pain or discomfort during or after injections, bruising, swelling, or delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction. Ideally, HA gel is a soft transparent filler that is reversible with hyaluronidase, an advantage not shared by other filler materials.9

Conclusion

Nipple augmentation with HA gel is a simple noninvasive

- Sisti A, Grimaldi L, Tassinari J, et al. Nipple-areola complex reconstruction techniques: a literature review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:441-465.

- Murthy V, Chamberlain RS. Defining a place for nipple sparing mastectomy in modern breast care: an evidence based review. Breast J. 2013;19:571-581.

- Jabor MA, Shayani P, Collins DR Jr, et al. Nipple-areola reconstruction: satisfaction and clinical determinants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:457-463.

- Kaoutzanis C, Xin M, Ballard TN, et al. Autologous fat grafting after breast reconstruction in postmastectomy patients: complications, biopsy rates, and locoregional cancer recurrence rates. Ann Plast Surg. 2016;76:270-275.

- Panettiere P, Marchetti L, Accorsi D. Filler injection enhances the projection of the reconstructed nipple: an original easy technique. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2005;29:287-294.

- McCarthy CM, Van Laeken N, Lennox P, et al. The efficacy of Artecoll injections for the augmentation of nipple projection in breast reconstruction. Eplasty. 2010;10:E7.

- Dessy LA, Troccola A, Ranno RL, et al. The use of Poly-lactic acid to improve projection of reconstructed nipple. Breast. 2011;20:220-224.

- Restylane L [package insert]. Fort Worth, TX: Galderma Laboratories, LP; 2016.

- Funt D, Pavicic T. Dermal fillers in aesthetics: an overview of adverse events and treatment approaches. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:295-316.

The most frequently used surgical techniques in nipple-areola complex (NAC) reconstruction involve the use of local tissue flaps and yield the fewest complications, though these techniques can be associated with up to a 75% loss in nipple projection over time.1 In a best-case scenario for both the surgeon and the patient, the NAC is preserved during mastectomy; however, even when the tissues are spared, an eventual loss of nipple projection is expected due to atrophy and contraction of the healing skin.2 Loss of nipple projection is the most common attribute that patients dislike regarding their NAC reconstruction results.Additional efforts made to restore the natural look and feel of the NAC provides undeniable benefit to the patient in the form of improved body image and psychosocial well-being.3

Augmentation with a grafted material can include cartilage or fat (autologous grafts), calcium hydroxylapatite or polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA)(alloplastic grafts), and acellular dermal matrix or biologic collagen (allografts). Among these options, successive treatment with autologous fat has been shown to provide satisfactory projections over time with minimal complications.4 However, an additional consideration associated with graft augmentation is the need for an additional surgical site (autologous grafts) or the possibility that graft material may not be compatible with subsequent breast examination techniques. For example, calcium hydroxylapatite is a radiopaque material that may interfere with the interpretation of radiography and mammography.5

The use of injectable hyaluronic acid (HA) dermal fillers to enhance nipple projection represents a noninvasive procedure with immediate and adjustable results. A variety of dermal fillers that do not interfere with subsequent breast imaging needs have already been successfully used for nipple reconstruction including HA 60% plus acrylic hydrogel 40%, PMMA microspheres in a bovine collagen 3.5% gel, and poly-L-lactic acid.5-7

The results achieved with HA 60% plus acrylic hydrogel 40% were as much as a 2.5-mm mean increase in nipple projection after 12 months for 70 nipples reconstructed using a small wedge from the labia minora.5 In these treatments, an initial injection of 0.1 to 0.3 mL of filler into each nipple along with a 0.2-mL injection at the base of each nipple was made. Further optional treatments at 2 and 4 months after the initial injection were made using up to 0.3 mL additional volume depending on filler reabsorption.5 Results achieved with PMMA microspheres in a bovine collagen 3.5% gel included a 1.6-mm mean increase in nipple projection at 9 months versus baseline for 33 nipples in 23 patients, which involved up to 2 injections at baseline and again at 3 months.6 Treatment with poly-L-lactic acid provided a 2.3-mm mean increase in nipple projection for 12 patients after 1 year of treatment, which involved 0.5-mL injections every 4 weeks over a series of 4 treatments.7

This report describes the technique and cosmetic outcome using an injectable HA gel to postoperatively restore the 3-dimensional contour of the nipple following surgical breast reconstruction. This chemically cross-linked, stabilized HA gel suspended in phosphate-buffered saline at a pH of 7 and a concentration of 20 mg/mL with lidocaine 0.3% is indicated for mid to deep dermal implantation for the correction of moderate to severe facial wrinkles and folds, such as the nasolabial folds.8

Case Report

A 49-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer with a focal, high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ underwent a complete bilateral mastectomy. The sentinel lymph nodes were negative at the time of mastectomy. One year later, the patient elected to have breast and nipple-areola (flap) reconstruction. Following the reconstructive surgery, her nipples had become visibly atrophic and flat, and she was interested in cosmetic enhancement.

After informed consent had been obtained from the patient, a baseline measurement of each nipple was made while the patient was standing. Each nipple was then injected with up to 0.1 to 0.2 mL of HA gel filler using a 30-gauge needle inserted 2-mm deep (bilaterally) into each nipple. The patient tolerated the procedure well with no pain, bleeding, or bruising. Although HA gel filler contains lidocaine 0.3% and tricaine can further be used to ensure patient comfort, the nipple reconstruction surgery left the patient with little sensation in the treatment area. Rubbing alcohol was used to prepare the skin prior to the procedure, and fractionated coconut oil spray with a nonadherent dressing was used postprocedure.

Following the injection, an immediate increase of 1.6 and 1.5 mm in nipple projection in the right and left breasts, respectively, was achieved with HA gel. The nipple projection of the right breast was 1.7 mm before injection (Figure, A) and 3.3 mm immediately postinjection (Figure, C). The nipple projection of the left breast was 1.8 mm before injection (Figure, B) and 3.3 mm immediately postinjection (Figure, D).

Comment

With a single treatment consisting of 0.2 mL or less of filler volume, the HA gel used in this procedure provided an immediate mean increase in nipple projection of 1.5 mm. Although our assessment involved a single patient evaluated at baseline and immediately post-injection of HA filler only, it is reasonable to assume that subsequent reinjections would provide results comparable to other fillers. Although other fillers that are semipermanent (acrylic hydrogel) and nonbiodegradable (PMMA) make them more durable, these properties also make the augmentation less reversible in the case of overfilling. As with all dermal fillers, rare side effects associated with injection of HA gel filler could potentially include injection-site inflammation, extrusion of filler at the needle insertion site, minimal pain or discomfort during or after injections, bruising, swelling, or delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction. Ideally, HA gel is a soft transparent filler that is reversible with hyaluronidase, an advantage not shared by other filler materials.9

Conclusion

Nipple augmentation with HA gel is a simple noninvasive

The most frequently used surgical techniques in nipple-areola complex (NAC) reconstruction involve the use of local tissue flaps and yield the fewest complications, though these techniques can be associated with up to a 75% loss in nipple projection over time.1 In a best-case scenario for both the surgeon and the patient, the NAC is preserved during mastectomy; however, even when the tissues are spared, an eventual loss of nipple projection is expected due to atrophy and contraction of the healing skin.2 Loss of nipple projection is the most common attribute that patients dislike regarding their NAC reconstruction results.Additional efforts made to restore the natural look and feel of the NAC provides undeniable benefit to the patient in the form of improved body image and psychosocial well-being.3

Augmentation with a grafted material can include cartilage or fat (autologous grafts), calcium hydroxylapatite or polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA)(alloplastic grafts), and acellular dermal matrix or biologic collagen (allografts). Among these options, successive treatment with autologous fat has been shown to provide satisfactory projections over time with minimal complications.4 However, an additional consideration associated with graft augmentation is the need for an additional surgical site (autologous grafts) or the possibility that graft material may not be compatible with subsequent breast examination techniques. For example, calcium hydroxylapatite is a radiopaque material that may interfere with the interpretation of radiography and mammography.5

The use of injectable hyaluronic acid (HA) dermal fillers to enhance nipple projection represents a noninvasive procedure with immediate and adjustable results. A variety of dermal fillers that do not interfere with subsequent breast imaging needs have already been successfully used for nipple reconstruction including HA 60% plus acrylic hydrogel 40%, PMMA microspheres in a bovine collagen 3.5% gel, and poly-L-lactic acid.5-7

The results achieved with HA 60% plus acrylic hydrogel 40% were as much as a 2.5-mm mean increase in nipple projection after 12 months for 70 nipples reconstructed using a small wedge from the labia minora.5 In these treatments, an initial injection of 0.1 to 0.3 mL of filler into each nipple along with a 0.2-mL injection at the base of each nipple was made. Further optional treatments at 2 and 4 months after the initial injection were made using up to 0.3 mL additional volume depending on filler reabsorption.5 Results achieved with PMMA microspheres in a bovine collagen 3.5% gel included a 1.6-mm mean increase in nipple projection at 9 months versus baseline for 33 nipples in 23 patients, which involved up to 2 injections at baseline and again at 3 months.6 Treatment with poly-L-lactic acid provided a 2.3-mm mean increase in nipple projection for 12 patients after 1 year of treatment, which involved 0.5-mL injections every 4 weeks over a series of 4 treatments.7