User login

Drug granted fast track designation for PNH

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to Coversin™ for the treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) in patients who have polymorphisms conferring eculizumab resistance.

Coversin is a recombinant small protein (16,740 Da) derived from a native protein found in the saliva of the Ornithodoros moubata tick.

The drug is a second-generation complement inhibitor that acts on complement component C5, preventing release of C5a and formation of C5b-9, and also independently inhibits LTB4 activity.

Coversin is being developed by Akari Therapeutics.

Akari is evaluating Coversin in a pair of phase 2 trials.

In the first trial, researchers are evaluating Coversin in patients with PNH who have never received a complement-blocking therapy. Interim results from this ongoing trial are scheduled to be presented at Akari’s Research and Development Day on April 24 in New York, New York.

In the second phase 2 trial, researchers are evaluating Coversin in patients with PNH who have C5 polymorphisms that confer resistance to eculizumab.

One patient has been enrolled in this trial and has received Coversin for over a year. The treatment has resulted in significant lactate dehydrogenase reduction and complete complement blockade.

About fast track designation

The FDA created the fast track program to facilitate the development and expedite the review of drugs that show promise for treating serious or life-threatening diseases and address unmet medical needs.

Companies developing drugs that receive fast track designation benefit from more frequent communications and meetings with the FDA to review their drug’s development plan, including the design of proposed clinical trials, use of biomarkers, and the extent of data needed for approval.

Drugs with fast track designation may qualify for priority review as well, if relevant criteria are met. Priority review shortens the FDA review process from 10 months to 6 months.

Fast track designation also allows for a rolling review process, whereby completed sections of the investigational new drug application can be submitted for FDA review as they become available, instead of waiting for all sections to be completed. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to Coversin™ for the treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) in patients who have polymorphisms conferring eculizumab resistance.

Coversin is a recombinant small protein (16,740 Da) derived from a native protein found in the saliva of the Ornithodoros moubata tick.

The drug is a second-generation complement inhibitor that acts on complement component C5, preventing release of C5a and formation of C5b-9, and also independently inhibits LTB4 activity.

Coversin is being developed by Akari Therapeutics.

Akari is evaluating Coversin in a pair of phase 2 trials.

In the first trial, researchers are evaluating Coversin in patients with PNH who have never received a complement-blocking therapy. Interim results from this ongoing trial are scheduled to be presented at Akari’s Research and Development Day on April 24 in New York, New York.

In the second phase 2 trial, researchers are evaluating Coversin in patients with PNH who have C5 polymorphisms that confer resistance to eculizumab.

One patient has been enrolled in this trial and has received Coversin for over a year. The treatment has resulted in significant lactate dehydrogenase reduction and complete complement blockade.

About fast track designation

The FDA created the fast track program to facilitate the development and expedite the review of drugs that show promise for treating serious or life-threatening diseases and address unmet medical needs.

Companies developing drugs that receive fast track designation benefit from more frequent communications and meetings with the FDA to review their drug’s development plan, including the design of proposed clinical trials, use of biomarkers, and the extent of data needed for approval.

Drugs with fast track designation may qualify for priority review as well, if relevant criteria are met. Priority review shortens the FDA review process from 10 months to 6 months.

Fast track designation also allows for a rolling review process, whereby completed sections of the investigational new drug application can be submitted for FDA review as they become available, instead of waiting for all sections to be completed. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to Coversin™ for the treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) in patients who have polymorphisms conferring eculizumab resistance.

Coversin is a recombinant small protein (16,740 Da) derived from a native protein found in the saliva of the Ornithodoros moubata tick.

The drug is a second-generation complement inhibitor that acts on complement component C5, preventing release of C5a and formation of C5b-9, and also independently inhibits LTB4 activity.

Coversin is being developed by Akari Therapeutics.

Akari is evaluating Coversin in a pair of phase 2 trials.

In the first trial, researchers are evaluating Coversin in patients with PNH who have never received a complement-blocking therapy. Interim results from this ongoing trial are scheduled to be presented at Akari’s Research and Development Day on April 24 in New York, New York.

In the second phase 2 trial, researchers are evaluating Coversin in patients with PNH who have C5 polymorphisms that confer resistance to eculizumab.

One patient has been enrolled in this trial and has received Coversin for over a year. The treatment has resulted in significant lactate dehydrogenase reduction and complete complement blockade.

About fast track designation

The FDA created the fast track program to facilitate the development and expedite the review of drugs that show promise for treating serious or life-threatening diseases and address unmet medical needs.

Companies developing drugs that receive fast track designation benefit from more frequent communications and meetings with the FDA to review their drug’s development plan, including the design of proposed clinical trials, use of biomarkers, and the extent of data needed for approval.

Drugs with fast track designation may qualify for priority review as well, if relevant criteria are met. Priority review shortens the FDA review process from 10 months to 6 months.

Fast track designation also allows for a rolling review process, whereby completed sections of the investigational new drug application can be submitted for FDA review as they become available, instead of waiting for all sections to be completed. ![]()

Tetanus: Debilitating Infection

CE/CME No: CR-1704

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Recognize patients who are at risk for tetanus.

• Describe the clinical presentation of tetanus.

• Discuss proper treatment for a patient with tetanus.

• Promote widespread vaccination against tetanus.

FACULTY

Timothy W. Ferrarotti is the Director of Didactic Education and Assistant Professor in the PA Studies Program at the University of Saint Joseph, West Hartford, Connecticut.

The author has no financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid for one year from the issue date of April 2017.

Article begins on next page >>

Tetanus is a devastating disease that can be prevented by proper immunization and wound care. Although the incidence is low in the United States due to widespread routine vaccination, immunization coverage remains below target, especially in older adults. Since outcome is influenced by the clinician's ability to make a timely diagnosis and initiate appropriate care, continued appreciation of tetanus is warranted.

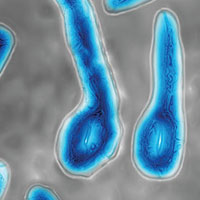

Tetanus is a neurologic disorder resulting from infection by the gram-positive, spore-forming anaerobic bacillus Clostridium tetani. The bacterium, in spore form, typically enters the body through a contaminated soft-tissue wound. Ubiquitous in the environment, C tetani spores are found throughout the world—in soil as well as in animal feces and saliva—and are resistant to temperature extremes and antiseptics. Tetanus is infectious but not contagious (not transmitted person-to-person).1 Wounds with devitalized tissue or those supporting anaerobic conditions, such as bites, puncture wounds, burns, and gangrene, are conducive to the development of tetanus. Infection can also occur following dental extractions, abortions, and illicit drug injection.1 Although vaccination programs have decreased the incidence of tetanus in the United States, C tetani infection remains an ongoing clinical concern because the spores are omnipresent, universal vaccination coverage has not been achieved, and vaccine-immunity wanes over time, placing individuals at risk.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

C tetani produces two toxins: tetanolysin and tetanospasmin (tetanus toxin). Tetanolysin may have a role in promoting the diffusion of tetanospasmin in soft tissues.2 Tetanospasmin is a highly potent toxin, with a lethal dose in humans of less than 2.5 ng/kg of body weight.3 The toxin enters the peripheral nerve at the site of injury and migrates to the central nervous system (CNS). There, it causes unopposed α-motor neuron firing by preventing the release of inhibitory neurotransmitters such as γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), resulting in muscle spasms and excess reflexive response to sensory stimuli.4 It also leads to excessive catecholamine release from the adrenal medulla.1

Tetanospasmin binds to neurons in the spinal cord and brainstem. Because toxin binding is irreversible, resolution of tetanus requires the neurons to grow new axon terminals. The effects of tetanus can persist for six to eight weeks until new terminals develop.3,5 Patients often require several weeks of ventilator support during this time.3

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Tetanus continues to be a serious cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. The majority of cases (80%) occur in Africa and Southeast Asia.6 Incidence is much lower in the United States (0.1 cases per million persons annually) because of widespread vaccination, with only 233 cases of tetanus reported between 2001 and 2008.7 However, in the absence of confirmatory tests, the diagnosis is a clinical one; furthermore, there is no laboratory reporting program for tetanus. As a result, more cases may occur in the US than are detected or reported.

In developed countries, tetanus is primarily a disease of the elderly or the unvaccinated. Older persons, especially non-veterans, are less likely to have received the primary series. Because immunity decreases with age, even those who completed the primary series but have not received booster doses are at increased risk.8 Home-schooled children, who are not subject to school-entry vaccination requirements, are also at risk if unvaccinated.9

Neonatal tetanus is an ongoing problem in undeveloped countries that lack maternal vaccination programs. (Maternal immunization successfully reduces neonatal tetanus via passive immunity, and maternal tetanus via active immunity.) Unvaccinated women who undergo nonmedical abortions or unhygienic childbirth are at increased risk for tetanus.3,10

Other risk factors for tetanus include wound contamination with soil, saliva, or devitalized tissue; injection drug use; and exposure to anthropogenic or natural disasters.1 C tetani spores can contaminate heroin and may grow in abscesses of heroin users.4 Small outbreaks of tetanus among injection drug users have been reported, even among younger adults who had some immunity from childhood vaccination.7,11 In addition, patients with diabetes are at increased risk for tetanus. These patients may have chronic wounds due to slowed healing and poor vascularity, which can lead to lower oxygen tension in their wounds and create an environment conducive to anaerobic infection. These chronic wounds are often ignored as a potential nidus for tetanus; instead, focus is placed on plantar puncture wounds or lacerations.7

Though tetanus risk is greatest for those who were never fully immunized, cases have been reported in persons who were immunized in the remote past but had not received a recent booster. Such cases show that tetanus immunity is not absolute and does wane over time.12-14 Among the 233 tetanus cases reported in the US during 2001-2008, vaccination status was reported for 92. Of these, 24 patients had a complete series and 31 patients had at least one prior dose of tetanus vaccine.7 Furthermore, six cases occurred in patients known to have had the four-dose series and a booster within 10 years of diagnosis. Similarly, a 14-year-old boy who was fully vaccinated developed cephalic tetanus from a stingray wound.14 Given these data, clinicians should not assume that a patient who reports having had “a tetanus shot” is completely protected; a full series and regular boosters are required, and, in rare cases, tetanus can occur despite full vaccination.

PATIENT PRESENTATION AND TETANUS TYPES

The CDC describes tetanus as “the acute onset of hypertonia and/or painful muscle contractions (usually of the muscles of the jaw and neck) and generalized muscle spasms without other apparent medical cause.”15 Clinicians should always consider tetanus in patients with dysphagia and trismus, especially if the patient has a wound, had not received primary vaccination, or has not had a booster in several decades. Tetanus cannot be ruled out based on the lack of a wound, however, since up to 25% of patients who develop tetanus have no obvious site of inoculation.16 The incubation period ranges from 3 to 21 days, with more severe cases having shorter incubation periods (< 8 days).10 The closer the site of inoculation is to the CNS, the more serious the disease usually is—and the shorter the incubation period will be.1

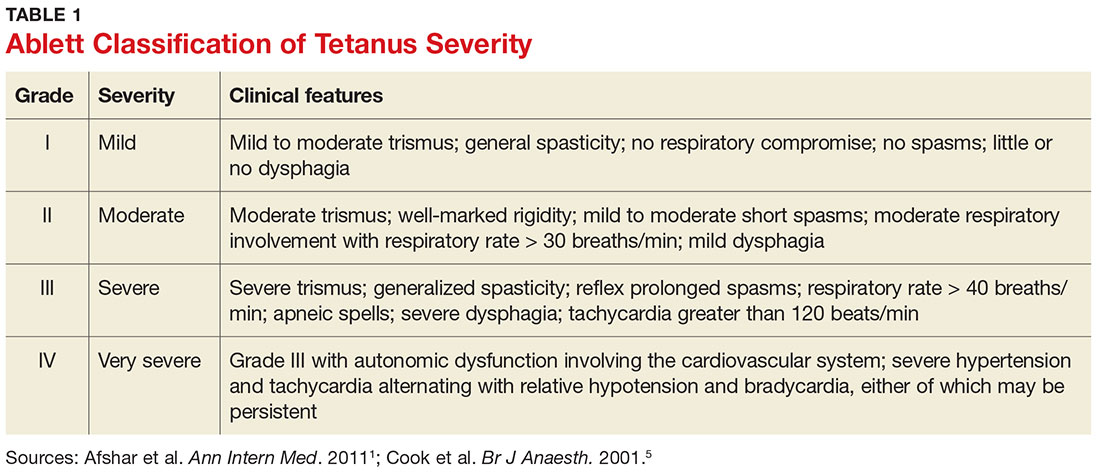

Presentation depends on the time elapsed since inoculation, the severity of illness (determined by the Ablett classification; see Table 1), and the form of tetanus involved. The patient may present early when the infection and toxin are localized to the wound and have not progressed to the CNS (localized tetanus). There may be a wound with signs of infection, including erythema, induration, edema, warmth, tenderness, and drainage. If the injury is on the head or neck, cephalic tetanus may occur, causing the patient to present with painful spasms of the extra-ocular, facial, and/or neck muscles; trismus; dysphagia; or even a Horner-like syndrome. The patient with more advanced, generalized tetanus may have decorticate posturing, abdominal wall rigidity, or opisthotonus.1,2,5,17

Four types of tetanus have been described: generalized, localized, cephalic, and neonatal.

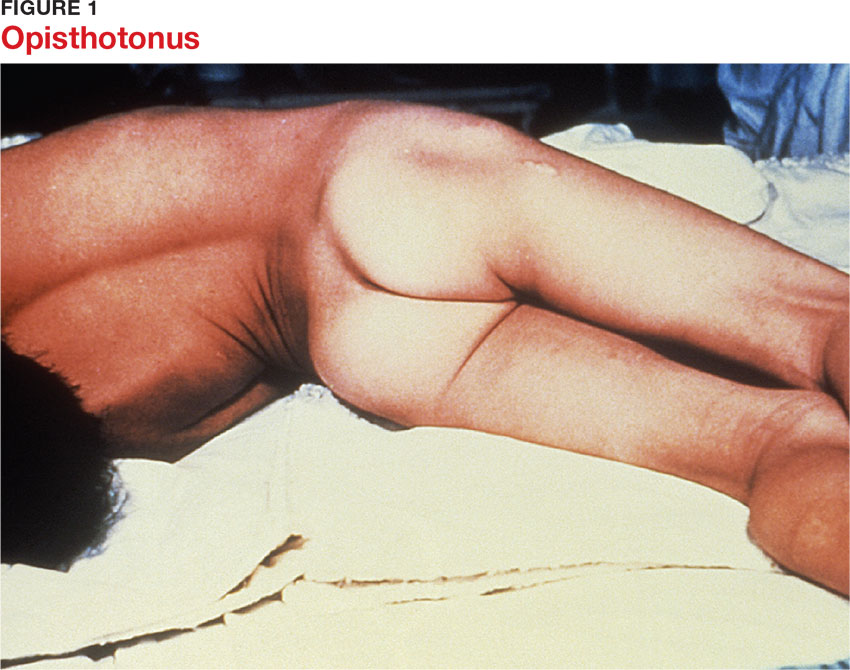

Generalized tetanus is the most common form, accounting for approximately 80% of cases.10 It may involve contractions of the masseter muscles, producing trismus; facial muscles, producing risus sardonicus (sardonic smile); neck and shoulder muscles; abdominal wall muscles, mimicking guarding; and back muscles, producing opisthotonus (arching of the back, neck, and head; see Figure 1) and decorticate posturing (flexion and adduction of the arms, clenched fists, and extension of the lower extremities).1,5,6 Patients with generalized tetanus often exhibit hyperresponsiveness to the environment. As a result, noises and sudden light changes may result in acute spasms. In addition, patients may experience painful spasms when affected muscles are palpated. Affected reflex arcs are usually hyperresponsive to stimuli.1 Intermittent spasms of the thoracic, pharyngeal, and/or laryngeal muscles may cause periods of apnea. Autonomic effects of tetanus mimic those associated with the catecholamine excess of pheochromocytoma. Patients exhibit restlessness, irritability, diaphoresis, fever, excessive salivation, gastric stasis, hypertension, tachycardia, and arrhythmia. There may be interposed hypotension and bradycardia.1,5,17

Localized tetanus involves painful spastic contraction of muscles at or near the site of inoculation. It often evolves into generalized tetanus as the toxin spreads further into the CNS.

Cephalic tetanus involves facial and laryngeal muscles. It is rare, accounting for 1% to 3% of tetanus cases.6 Patients may initially have flaccid paralysis, mimicking stroke, rather than spasm, because the toxin has not completely migrated up the peripheral nerve into the CNS. As the toxin enters the CNS and induces the typical spasm (trismus), the diagnosis will be more obvious. The presence of trismus or a subacute wound on the head may be used to discriminate tetanus from stroke. Cephalic tetanus often evolves into generalized tetanus, affecting more of the body in a caudal direction.5

Neonatal tetanus develops within one week after birth. The neonate with tetanus is usually born to a mother lacking immunization. Typically, the infant sucks and feeds for the first couple of days, then develops inability/refusal to suck/feed, has difficulty opening his/her mouth, becomes weak, and develops muscle spasms.3 The affected child may develop risus sardonicus, clenched hands, dorsiflexion of the feet, and opisthotonus.3

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

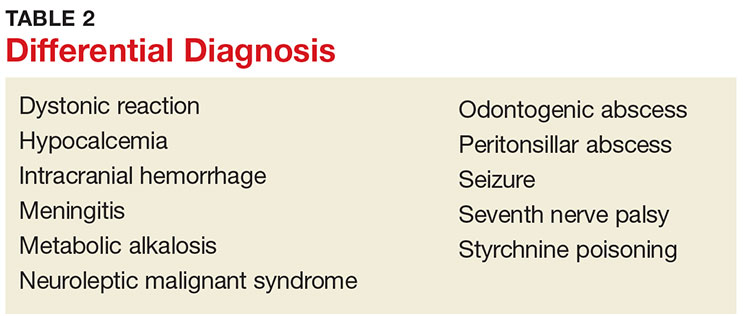

The clinician should consider other CNS conditions in the differential diagnosis (see Table 2). Although similar to generalized seizures, tetanus causes painful spasms and does not produce a loss of consciousness.1,17 Tetanus, intracranial bleed, and meningitis all can cause meningismus; meningitis, however, is more likely to manifest with other symptoms of infection, such as headache and fever. Although the autonomic dysfunction of tetanus can cause pyrexia, fever would usually coincide with other sympathetic symptoms, such as hypertension, tachycardia, and diaphoresis. Intracranial bleeding tends to have a more rapid onset than tetanus and produces headache and mental status changes. Seventh nerve palsy produces muscle flaccidity, not spasm, and is usually painless unless associated with herpetic inflammation.1,5,6,14,17

Poisoning and medication effects should also be considered. Strychnine poisoning manifests similar to tetanus but occurs without a wound.5 Blood and urine assays for strychnine can be diagnostic. Dystonic reactions resulting from neuroleptic medications—such as phenothiazines—include torticollis, oropharyngeal muscle spasms, and deviation of the eyes. Unlike tetanus, drug-induced dystonia does not cause reflex spasms and often resolves with benztropine or diphenhydramine administration.1 Neuroleptic malignant syndrome can also cause muscular rigidity and autonomic instability, but unlike tetanus, it often causes altered mental status; it should be considered in patients who recently received a causative medication.5,17

Tetanus often manifests with reflexive muscle spasms similar to those seen in electrolyte and acid-base abnormalities. Hypocalcemia may produce a reflexive spasm of the facial muscles when the facial nerve is percussed (Chvostek sign), while alkalemia may produce reflexive spasm of the hand and wrist muscles (Trousseau sign).1 Lab tests can rule out these diagnoses.1,5

A patient with an odontogenic abscess may have pain and muscle spasm/trismus, but the infection is usually easily detected on exam. The clinician should be cautious in attributing the trismus solely to the swelling, however, as C tetani has been found in odontogenic abscesses and the patient may have both.1,17 Peritonsillar abscess will often produce trismus. When abscess is the cause, careful examination of the oropharynx will usually demonstrate tonsillar exudate, hypertrophy, soft tissue erythema, and tenderness, as well as a misplaced uvula.1

DIAGNOSIS

Tetanus is a clinical diagnosis, usually made based on the findings described. Confirmatory lab tests are not readily available. The organism is infrequently recovered in cultures of specimens from suspected wounds (30% of cases).10,11 Serologic testing on specimens drawn before administration of tetanus immunoglobulin (TIG) may indicate very low or undetectable antitetanus antibody levels, but tetanus can still occur when “protective” levels of antibodies are present.11 Detection of tetanus toxin in plasma or a wound with bioassays and polymerase chain reaction might be possible, but these tests are only available in a few settings.3

THE MULTIFACETED CARE PLAN

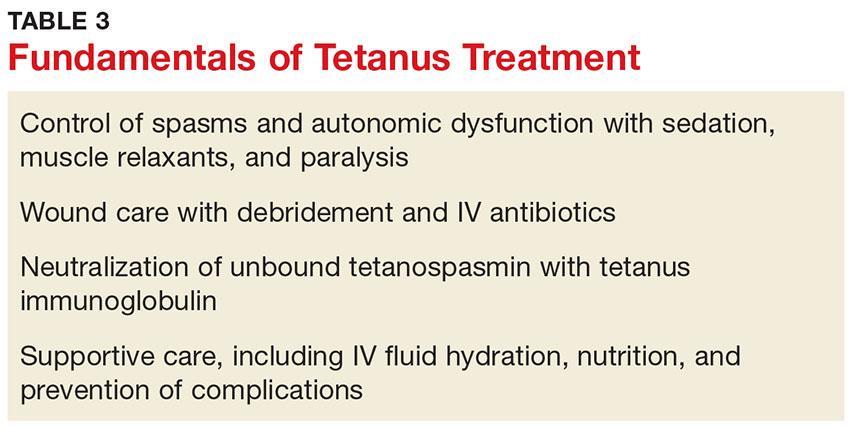

The primary care provider should refer a patient with suspected tetanus to an emergency department, preferably a tertiary care center with the necessary specialists. Patients are likely to require prolonged hospitalization. In a recent series of tetanus cases in California, the median length of hospitalization was 18 days.12 Treatment is multifaceted; interventions include immunization, wound care, administration of antibiotics and other pharmacologic agents, and supportive therapy (see Table 3).

Immunization

All patients with suspected tetanus should immediately receive both passive (with TIG) and active (tetanus toxoid–containing vaccines) immunization. Because of the extremely high potency of tetanus toxin, the very small amount of toxin that is required to cause tetanus is insufficient to prompt an immune response that would confer immunity. Therefore, treatment is the same regardless of whether the patient had prior disease.10

TIG binds to and neutralizes unbound tetanospasmin, preventing progression of the disease. As noted, TIG will not reverse the binding of the toxin to nerve structures.5 Due to a lack of prospective studies, there is disagreement regarding TIG dosage: Doses as high as 3,000-6,000 U have been recommended, but case studies indicate that the dosage recommended by the CDC (500 U) is likely effective.13 The full CDC recommendation is 500 U of human-derived TIG intramuscularly administered at locations near and away from the wound (but always away from the tetanus toxoid injection site).10,17 Outside the US, equine-based TIG may be the only option. Animal-derived TIG is less desirable because of increased allergy risk; when used, a small amount (0.1 mL) should be first administered as an intradermal test.17

Tetanus toxoid immunization produces active immunity. It is currently available in combination antigen forms (tetanus and diphtheria vaccine [Td], tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis [Tdap] vaccine). The dose of either is 0.5 mL. Patients with tetanus should receive three doses given intramuscularly: immediately, at 4 weeks, and at 6 to 12 months.10

Wound care

Wound care should include incision and drainage, removal of foreign bodies, debridement, and irrigation. These steps are taken in order to ensure an aerobic environment in the wound, ultimately decreasing C tetani survival.1

Antibiotics

The preferred antimicrobial agent for treating tetanus infection is metronidazole 500 mg intravenously (IV) every 6 hours.1,3,17 Penicillin (2 to 4 million U IV every 4 to 6 hours) is effective against C tetani, but it is a GABA-receptor antagonist and may worsen tetanus by further inhibiting the release of GABA.1,14,18 GABA-receptor antagonism may also occur with cephalosporins; however, these broader-spectrum agents may be necessary to treat mixed infections.17 Alternatives include doxycycline, macrolides, and clindamycin.1

Other pharmacologic treatment

Benzodiazepines (eg, diazepam 10 to 30 mg IV) can help control rigidity and muscle spasms and are a mainstay of tetanus treatment.18 Benzodiazepines and propofol both act on GABA receptors, producing sedation in addition to controlling muscle spasms.19 Traditionally, more severe spasms, such as opisthotonus, have required induction of complete paralysis with nondepolarizing paralytics, such as pancuronium or vecuronium. However, paralysis is not optimal therapy since it necessitates sedation, intubation, and mechanical ventilation. Because tetanus does not resolve for 6 to 8 weeks, patients who require mechanical ventilation will also require tracheostomy to prevent laryngotracheal stenosis. Paralysis and mechanical ventilation can also lead to deep venous thrombosis, decubitus ulcers, and pneumonia.5 The ideal treatment would reduce the spasms and autonomic instability without the risks associated with deep sedation and paralysis.5

Other agents used in the treatment of tetanus include magnesium sulfate, which can decrease muscle spasm and ameliorate the effects of autonomic dysfunction, and intrathecal baclofen, which can decrease muscle spasm.19,20 Patients with persistent autonomic dysfunction may require combined α- and ß-adrenergic receptor blockade.1,17-20

Supportive care

It is important to implement supportive care, including limiting auditory and tactile stimulation, as well as providing adequate hydration and nutritional support. IV fluids, parenteral feeding, and enteral feeding are required. Measures should be taken to prevent complications of prolonged immobility, paralysis, and mechanical ventilation, including deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and pressure ulcers. The quality of supportive care and the swiftness with which the diagnosis is made and appropriate treatment is initiated are key factors that determine an individual patient’s outcome.21

COMPLICATIONS AND MORTALITY

Tetanus can lead to many complications, including long bone and spine fractures from severe muscle spasms, as well as renal failure and aspiration. Most spinal fractures involve the thoracic spine, but lumbar spine fractures have been reported.22 Burst-type fractures of the vertebrae may cause cauda equina syndrome or directly injure the spinal cord if fragments are retropulsed.22 Persistent muscle spasm can also cause rhabdomyolysis and renal failure. Lab test results, including elevated levels of creatine phosphokinase and myoglobin (rhabdomyolysis) as well as blood urea nitrogen and creatinine (renal failure), can indicate presence of complications. Muscle relaxation and hydration are key to prevention.

Patients with trismus are often unable to swallow and maintain oral hygiene, leading to caries and dental abscess. The trismus itself can also cause dental or jaw fractures.2,13 Aspiration can occur when laryngeal muscles are affected, resulting in pneumonia in 50% to 70% of autopsied cases of tetanus.10 Additionally, the paralyzed patient receiving ventilatory support can develop pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism.5,13 Neonatal tetanus often results in complications such as cerebral palsy or cognitive delay.1

A number of factors influence the severity and outcome of tetanus. Untreated tetanus is typically fatal, with respiratory failure the most common cause of death in settings where mechanical ventilation is unavailable.1 Where mechanical ventilation is accessible, autonomic dysfunction accounts for most deaths.20 Ventilation aside, the case-fatality rate varies according to the medical system. The rate is often less than 20% where modern ICUs are available but can exceed 50% in undeveloped countries with limited facilities.1,5 A review of outcomes data for 197 of the 233 tetanus cases reported in the US during 2001-2008 (modern medical care was provided in all) showed an overall case-fatality rate of 13.2%.7

Age and vaccination status also affect outcomes, with higher case-fatality rates seen in older (18% in those ≥ 60, 31% in those ≥ 65) and unvaccinated (22%) patients. 7,10 In the study of tetanus cases from 2001-2008, the fatality rate was five times higher in patients ages 65 or older compared with patients younger than 65.7 This study also showed that severity of tetanus may be inversely related to the number of vaccine doses the individual has received, and that having previous vaccination was associated with improved survival, as only four of the 26 deaths occurred in patients with prior vaccination.7

Patients who survive the first two weeks of tetanus have a better chance of recovery. Those with multiple chronic comorbidities, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, or cardiovascular disease, are more likely to die because of the physiologic stress of the illness and its treatment.1,7,12 The provision of ventilator support is more complicated in those with COPD; similarly, the autonomic effects of tetanus can be more problematic for patients with chronic cardiac disease or neurologic complications of chronic diabetes.13

PATIENT EDUCATION

Widespread vaccination against tetanus, which began in the US in the mid-20th century, has greatly reduced disease incidence.7 However, vaccination coverage rates remain below target.

In 2012, only 82.5% of children ages 19 to 35 months received the recommended four doses of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTaP) vaccine, and 94.3% received at least three doses.23 Only 84.6% of teens ages 13 to 17 years received the primary four doses as well as the recommended booster dose.24 The same year, only 55% of patients ages 65 and older and 64% of adults ages 19 to 64 had received a tetanus booster within the previous 10 years.25

Vaccination rates are lower for black, Hispanic, and Asian adults in the US.25 Clinicians should proactively recommend tetanus booster immunization to all adults.

CONCLUSION

Although few clinicians in developed countries will see a case of tetanus, all should be alert for it. Elderly patients and those not fully vaccinated are at risk. Routine immunization decreases but does not eliminate the risk. Tetanus differs from other illnesses controlled by national immunization efforts in that unvaccinated persons do not benefit from herd immunity, because the disease is not contagious. The diagnosis is clinical and should always be considered in patients with trismus, dysphagia, and/or adrenergic excess. Wounds that place a patient at risk for tetanus involve devitalized tissues and anaerobic conditions. Prompt diagnosis is essential, because it allows for early neutralization of unbound tetanospasmin. Wound care including debridement, antibiotic therapy, control of muscle spasms and the effects of autonomic instability, and airway care are fundamental to the treatment of tetanus.

1. Afshar M, Raju M, Ansell D, Bleck TP. Narrative review: tetanus—a health threat after natural disasters in developing countries. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(5):329-335.

2. Demir NA, Sumer S, Ural O, et al. An alternative treatment approach in tetanus: botulinum toxin. Trop Doct. 2015;45(1): 46-48.

3. Thwaites CL, Beeching NJ, Newton CR. Maternal and neonatal tetanus. Lancet. 2015;385(9965):362-370.

4. Aronoff DM. Clostridium novyi, sordellii, and tetani: mechanisms of disease. Anaerobe. 2013;24:98-101.

5. Cook TM, Protheroe RT, Handel JM. Tetanus: a review of the literature. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87(3):477-487.

6. Doshi A, Warrell C, Dahdaleh D, Kullmann D. Just a graze? Cephalic tetanus presenting as a stroke mimic. Pract Neurol. 2014;14(1):39-41.

7. CDC. Tetanus surveillance—United States, 2001-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(12):365-369.

8. McCabe J, La Varis T, Mason D. Cephalic tetanus complicating geriatric fall. N Z Med J. 2014;127(1400):98-100.

9. Johnson MG, Bradley KK, Mendus S, et al. Vaccine-preventable disease among homeschooled children: two cases of tetanus in Oklahoma. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):e1686-e1689.

10. CDC. Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. Hamborsky J, Kroger A, Wolfe S, eds. 13th ed. Washington, DC: Public Health Foundation; 2015.

11. Tiwari TS. Chapter 16: Tetanus. In: CDC. Manual for Surveillance of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. 5th ed. Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2012.

12. Yen C, Murray E, Zipprich J, et al. Missed opportunities for tetanus postexposure prophylaxis—California, January 2008-March 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015; 64(9):243-246.

13. Aksoy M, Celik EC, Ahiskalioglu A, Karakaya MA. Tetanus is still a deadly disease: a report of six tetanus cases and reminder of our knowledge. Trop Doct. 2014;44(1):38-42.

14. Felter RA, Zinns LE. Cephalic tetanus in an immunized teenager. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31(7):511-513.

15. CDC. Tetanus (Clostridium tetani) 1996 case definition. www.cdc.gov/nndss/conditions/tetanus/case-definition/1996/. Accessed February 17, 2017.

16. Thwaites CL, Farrar JJ. Preventing and treating tetanus [commentary]. BMJ. 2003;326(7381):117-118.

17. Sexton DJ. Tetanus. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/contents/tetanus?topicKey=ID%2F5525. Accessed February 17, 2017.

18. Rodrigo C, Fernando D, Rajapakse S. Pharmacological management of tetanus: an evidence-based review. Crit Care. 2014;18(2):217.

19. Santos ML, Mota-Miranda A, Alves-Pereira A, et al. Intrathecal baclofen for the treatment of tetanus. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(3):321-328.

20. Thwaites CL, Yen LM, Loan HT, et al. Magnesium sulphate for treatment of severe tetanus: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1436-1443.

21. Govindaraj GM, Riyaz A. Current practice in the management of tetanus. Crit Care. 2014;18(3):145.

22. Wilson TJ, Orringer DA, Sullivan SE, Patil PG. An L-2 burst fracture and cauda equina syndrome due to tetanus. J Neurosurg Spine. 2012;16(1):82-85.

23. CDC. National, state and local area vaccination coverage among children aged 19-35 months—United States, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(36):733-740.

24. CDC. National and state vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(34):685-693.

25. Williams WW, Lu PJ, O’Halloran A, et al. Noninfluenza vaccination coverage among adults—United States, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(5):95-102.

CE/CME No: CR-1704

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Recognize patients who are at risk for tetanus.

• Describe the clinical presentation of tetanus.

• Discuss proper treatment for a patient with tetanus.

• Promote widespread vaccination against tetanus.

FACULTY

Timothy W. Ferrarotti is the Director of Didactic Education and Assistant Professor in the PA Studies Program at the University of Saint Joseph, West Hartford, Connecticut.

The author has no financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid for one year from the issue date of April 2017.

Article begins on next page >>

Tetanus is a devastating disease that can be prevented by proper immunization and wound care. Although the incidence is low in the United States due to widespread routine vaccination, immunization coverage remains below target, especially in older adults. Since outcome is influenced by the clinician's ability to make a timely diagnosis and initiate appropriate care, continued appreciation of tetanus is warranted.

Tetanus is a neurologic disorder resulting from infection by the gram-positive, spore-forming anaerobic bacillus Clostridium tetani. The bacterium, in spore form, typically enters the body through a contaminated soft-tissue wound. Ubiquitous in the environment, C tetani spores are found throughout the world—in soil as well as in animal feces and saliva—and are resistant to temperature extremes and antiseptics. Tetanus is infectious but not contagious (not transmitted person-to-person).1 Wounds with devitalized tissue or those supporting anaerobic conditions, such as bites, puncture wounds, burns, and gangrene, are conducive to the development of tetanus. Infection can also occur following dental extractions, abortions, and illicit drug injection.1 Although vaccination programs have decreased the incidence of tetanus in the United States, C tetani infection remains an ongoing clinical concern because the spores are omnipresent, universal vaccination coverage has not been achieved, and vaccine-immunity wanes over time, placing individuals at risk.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

C tetani produces two toxins: tetanolysin and tetanospasmin (tetanus toxin). Tetanolysin may have a role in promoting the diffusion of tetanospasmin in soft tissues.2 Tetanospasmin is a highly potent toxin, with a lethal dose in humans of less than 2.5 ng/kg of body weight.3 The toxin enters the peripheral nerve at the site of injury and migrates to the central nervous system (CNS). There, it causes unopposed α-motor neuron firing by preventing the release of inhibitory neurotransmitters such as γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), resulting in muscle spasms and excess reflexive response to sensory stimuli.4 It also leads to excessive catecholamine release from the adrenal medulla.1

Tetanospasmin binds to neurons in the spinal cord and brainstem. Because toxin binding is irreversible, resolution of tetanus requires the neurons to grow new axon terminals. The effects of tetanus can persist for six to eight weeks until new terminals develop.3,5 Patients often require several weeks of ventilator support during this time.3

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Tetanus continues to be a serious cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. The majority of cases (80%) occur in Africa and Southeast Asia.6 Incidence is much lower in the United States (0.1 cases per million persons annually) because of widespread vaccination, with only 233 cases of tetanus reported between 2001 and 2008.7 However, in the absence of confirmatory tests, the diagnosis is a clinical one; furthermore, there is no laboratory reporting program for tetanus. As a result, more cases may occur in the US than are detected or reported.

In developed countries, tetanus is primarily a disease of the elderly or the unvaccinated. Older persons, especially non-veterans, are less likely to have received the primary series. Because immunity decreases with age, even those who completed the primary series but have not received booster doses are at increased risk.8 Home-schooled children, who are not subject to school-entry vaccination requirements, are also at risk if unvaccinated.9

Neonatal tetanus is an ongoing problem in undeveloped countries that lack maternal vaccination programs. (Maternal immunization successfully reduces neonatal tetanus via passive immunity, and maternal tetanus via active immunity.) Unvaccinated women who undergo nonmedical abortions or unhygienic childbirth are at increased risk for tetanus.3,10

Other risk factors for tetanus include wound contamination with soil, saliva, or devitalized tissue; injection drug use; and exposure to anthropogenic or natural disasters.1 C tetani spores can contaminate heroin and may grow in abscesses of heroin users.4 Small outbreaks of tetanus among injection drug users have been reported, even among younger adults who had some immunity from childhood vaccination.7,11 In addition, patients with diabetes are at increased risk for tetanus. These patients may have chronic wounds due to slowed healing and poor vascularity, which can lead to lower oxygen tension in their wounds and create an environment conducive to anaerobic infection. These chronic wounds are often ignored as a potential nidus for tetanus; instead, focus is placed on plantar puncture wounds or lacerations.7

Though tetanus risk is greatest for those who were never fully immunized, cases have been reported in persons who were immunized in the remote past but had not received a recent booster. Such cases show that tetanus immunity is not absolute and does wane over time.12-14 Among the 233 tetanus cases reported in the US during 2001-2008, vaccination status was reported for 92. Of these, 24 patients had a complete series and 31 patients had at least one prior dose of tetanus vaccine.7 Furthermore, six cases occurred in patients known to have had the four-dose series and a booster within 10 years of diagnosis. Similarly, a 14-year-old boy who was fully vaccinated developed cephalic tetanus from a stingray wound.14 Given these data, clinicians should not assume that a patient who reports having had “a tetanus shot” is completely protected; a full series and regular boosters are required, and, in rare cases, tetanus can occur despite full vaccination.

PATIENT PRESENTATION AND TETANUS TYPES

The CDC describes tetanus as “the acute onset of hypertonia and/or painful muscle contractions (usually of the muscles of the jaw and neck) and generalized muscle spasms without other apparent medical cause.”15 Clinicians should always consider tetanus in patients with dysphagia and trismus, especially if the patient has a wound, had not received primary vaccination, or has not had a booster in several decades. Tetanus cannot be ruled out based on the lack of a wound, however, since up to 25% of patients who develop tetanus have no obvious site of inoculation.16 The incubation period ranges from 3 to 21 days, with more severe cases having shorter incubation periods (< 8 days).10 The closer the site of inoculation is to the CNS, the more serious the disease usually is—and the shorter the incubation period will be.1

Presentation depends on the time elapsed since inoculation, the severity of illness (determined by the Ablett classification; see Table 1), and the form of tetanus involved. The patient may present early when the infection and toxin are localized to the wound and have not progressed to the CNS (localized tetanus). There may be a wound with signs of infection, including erythema, induration, edema, warmth, tenderness, and drainage. If the injury is on the head or neck, cephalic tetanus may occur, causing the patient to present with painful spasms of the extra-ocular, facial, and/or neck muscles; trismus; dysphagia; or even a Horner-like syndrome. The patient with more advanced, generalized tetanus may have decorticate posturing, abdominal wall rigidity, or opisthotonus.1,2,5,17

Four types of tetanus have been described: generalized, localized, cephalic, and neonatal.

Generalized tetanus is the most common form, accounting for approximately 80% of cases.10 It may involve contractions of the masseter muscles, producing trismus; facial muscles, producing risus sardonicus (sardonic smile); neck and shoulder muscles; abdominal wall muscles, mimicking guarding; and back muscles, producing opisthotonus (arching of the back, neck, and head; see Figure 1) and decorticate posturing (flexion and adduction of the arms, clenched fists, and extension of the lower extremities).1,5,6 Patients with generalized tetanus often exhibit hyperresponsiveness to the environment. As a result, noises and sudden light changes may result in acute spasms. In addition, patients may experience painful spasms when affected muscles are palpated. Affected reflex arcs are usually hyperresponsive to stimuli.1 Intermittent spasms of the thoracic, pharyngeal, and/or laryngeal muscles may cause periods of apnea. Autonomic effects of tetanus mimic those associated with the catecholamine excess of pheochromocytoma. Patients exhibit restlessness, irritability, diaphoresis, fever, excessive salivation, gastric stasis, hypertension, tachycardia, and arrhythmia. There may be interposed hypotension and bradycardia.1,5,17

Localized tetanus involves painful spastic contraction of muscles at or near the site of inoculation. It often evolves into generalized tetanus as the toxin spreads further into the CNS.

Cephalic tetanus involves facial and laryngeal muscles. It is rare, accounting for 1% to 3% of tetanus cases.6 Patients may initially have flaccid paralysis, mimicking stroke, rather than spasm, because the toxin has not completely migrated up the peripheral nerve into the CNS. As the toxin enters the CNS and induces the typical spasm (trismus), the diagnosis will be more obvious. The presence of trismus or a subacute wound on the head may be used to discriminate tetanus from stroke. Cephalic tetanus often evolves into generalized tetanus, affecting more of the body in a caudal direction.5

Neonatal tetanus develops within one week after birth. The neonate with tetanus is usually born to a mother lacking immunization. Typically, the infant sucks and feeds for the first couple of days, then develops inability/refusal to suck/feed, has difficulty opening his/her mouth, becomes weak, and develops muscle spasms.3 The affected child may develop risus sardonicus, clenched hands, dorsiflexion of the feet, and opisthotonus.3

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The clinician should consider other CNS conditions in the differential diagnosis (see Table 2). Although similar to generalized seizures, tetanus causes painful spasms and does not produce a loss of consciousness.1,17 Tetanus, intracranial bleed, and meningitis all can cause meningismus; meningitis, however, is more likely to manifest with other symptoms of infection, such as headache and fever. Although the autonomic dysfunction of tetanus can cause pyrexia, fever would usually coincide with other sympathetic symptoms, such as hypertension, tachycardia, and diaphoresis. Intracranial bleeding tends to have a more rapid onset than tetanus and produces headache and mental status changes. Seventh nerve palsy produces muscle flaccidity, not spasm, and is usually painless unless associated with herpetic inflammation.1,5,6,14,17

Poisoning and medication effects should also be considered. Strychnine poisoning manifests similar to tetanus but occurs without a wound.5 Blood and urine assays for strychnine can be diagnostic. Dystonic reactions resulting from neuroleptic medications—such as phenothiazines—include torticollis, oropharyngeal muscle spasms, and deviation of the eyes. Unlike tetanus, drug-induced dystonia does not cause reflex spasms and often resolves with benztropine or diphenhydramine administration.1 Neuroleptic malignant syndrome can also cause muscular rigidity and autonomic instability, but unlike tetanus, it often causes altered mental status; it should be considered in patients who recently received a causative medication.5,17

Tetanus often manifests with reflexive muscle spasms similar to those seen in electrolyte and acid-base abnormalities. Hypocalcemia may produce a reflexive spasm of the facial muscles when the facial nerve is percussed (Chvostek sign), while alkalemia may produce reflexive spasm of the hand and wrist muscles (Trousseau sign).1 Lab tests can rule out these diagnoses.1,5

A patient with an odontogenic abscess may have pain and muscle spasm/trismus, but the infection is usually easily detected on exam. The clinician should be cautious in attributing the trismus solely to the swelling, however, as C tetani has been found in odontogenic abscesses and the patient may have both.1,17 Peritonsillar abscess will often produce trismus. When abscess is the cause, careful examination of the oropharynx will usually demonstrate tonsillar exudate, hypertrophy, soft tissue erythema, and tenderness, as well as a misplaced uvula.1

DIAGNOSIS

Tetanus is a clinical diagnosis, usually made based on the findings described. Confirmatory lab tests are not readily available. The organism is infrequently recovered in cultures of specimens from suspected wounds (30% of cases).10,11 Serologic testing on specimens drawn before administration of tetanus immunoglobulin (TIG) may indicate very low or undetectable antitetanus antibody levels, but tetanus can still occur when “protective” levels of antibodies are present.11 Detection of tetanus toxin in plasma or a wound with bioassays and polymerase chain reaction might be possible, but these tests are only available in a few settings.3

THE MULTIFACETED CARE PLAN

The primary care provider should refer a patient with suspected tetanus to an emergency department, preferably a tertiary care center with the necessary specialists. Patients are likely to require prolonged hospitalization. In a recent series of tetanus cases in California, the median length of hospitalization was 18 days.12 Treatment is multifaceted; interventions include immunization, wound care, administration of antibiotics and other pharmacologic agents, and supportive therapy (see Table 3).

Immunization

All patients with suspected tetanus should immediately receive both passive (with TIG) and active (tetanus toxoid–containing vaccines) immunization. Because of the extremely high potency of tetanus toxin, the very small amount of toxin that is required to cause tetanus is insufficient to prompt an immune response that would confer immunity. Therefore, treatment is the same regardless of whether the patient had prior disease.10

TIG binds to and neutralizes unbound tetanospasmin, preventing progression of the disease. As noted, TIG will not reverse the binding of the toxin to nerve structures.5 Due to a lack of prospective studies, there is disagreement regarding TIG dosage: Doses as high as 3,000-6,000 U have been recommended, but case studies indicate that the dosage recommended by the CDC (500 U) is likely effective.13 The full CDC recommendation is 500 U of human-derived TIG intramuscularly administered at locations near and away from the wound (but always away from the tetanus toxoid injection site).10,17 Outside the US, equine-based TIG may be the only option. Animal-derived TIG is less desirable because of increased allergy risk; when used, a small amount (0.1 mL) should be first administered as an intradermal test.17

Tetanus toxoid immunization produces active immunity. It is currently available in combination antigen forms (tetanus and diphtheria vaccine [Td], tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis [Tdap] vaccine). The dose of either is 0.5 mL. Patients with tetanus should receive three doses given intramuscularly: immediately, at 4 weeks, and at 6 to 12 months.10

Wound care

Wound care should include incision and drainage, removal of foreign bodies, debridement, and irrigation. These steps are taken in order to ensure an aerobic environment in the wound, ultimately decreasing C tetani survival.1

Antibiotics

The preferred antimicrobial agent for treating tetanus infection is metronidazole 500 mg intravenously (IV) every 6 hours.1,3,17 Penicillin (2 to 4 million U IV every 4 to 6 hours) is effective against C tetani, but it is a GABA-receptor antagonist and may worsen tetanus by further inhibiting the release of GABA.1,14,18 GABA-receptor antagonism may also occur with cephalosporins; however, these broader-spectrum agents may be necessary to treat mixed infections.17 Alternatives include doxycycline, macrolides, and clindamycin.1

Other pharmacologic treatment

Benzodiazepines (eg, diazepam 10 to 30 mg IV) can help control rigidity and muscle spasms and are a mainstay of tetanus treatment.18 Benzodiazepines and propofol both act on GABA receptors, producing sedation in addition to controlling muscle spasms.19 Traditionally, more severe spasms, such as opisthotonus, have required induction of complete paralysis with nondepolarizing paralytics, such as pancuronium or vecuronium. However, paralysis is not optimal therapy since it necessitates sedation, intubation, and mechanical ventilation. Because tetanus does not resolve for 6 to 8 weeks, patients who require mechanical ventilation will also require tracheostomy to prevent laryngotracheal stenosis. Paralysis and mechanical ventilation can also lead to deep venous thrombosis, decubitus ulcers, and pneumonia.5 The ideal treatment would reduce the spasms and autonomic instability without the risks associated with deep sedation and paralysis.5

Other agents used in the treatment of tetanus include magnesium sulfate, which can decrease muscle spasm and ameliorate the effects of autonomic dysfunction, and intrathecal baclofen, which can decrease muscle spasm.19,20 Patients with persistent autonomic dysfunction may require combined α- and ß-adrenergic receptor blockade.1,17-20

Supportive care

It is important to implement supportive care, including limiting auditory and tactile stimulation, as well as providing adequate hydration and nutritional support. IV fluids, parenteral feeding, and enteral feeding are required. Measures should be taken to prevent complications of prolonged immobility, paralysis, and mechanical ventilation, including deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and pressure ulcers. The quality of supportive care and the swiftness with which the diagnosis is made and appropriate treatment is initiated are key factors that determine an individual patient’s outcome.21

COMPLICATIONS AND MORTALITY

Tetanus can lead to many complications, including long bone and spine fractures from severe muscle spasms, as well as renal failure and aspiration. Most spinal fractures involve the thoracic spine, but lumbar spine fractures have been reported.22 Burst-type fractures of the vertebrae may cause cauda equina syndrome or directly injure the spinal cord if fragments are retropulsed.22 Persistent muscle spasm can also cause rhabdomyolysis and renal failure. Lab test results, including elevated levels of creatine phosphokinase and myoglobin (rhabdomyolysis) as well as blood urea nitrogen and creatinine (renal failure), can indicate presence of complications. Muscle relaxation and hydration are key to prevention.

Patients with trismus are often unable to swallow and maintain oral hygiene, leading to caries and dental abscess. The trismus itself can also cause dental or jaw fractures.2,13 Aspiration can occur when laryngeal muscles are affected, resulting in pneumonia in 50% to 70% of autopsied cases of tetanus.10 Additionally, the paralyzed patient receiving ventilatory support can develop pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism.5,13 Neonatal tetanus often results in complications such as cerebral palsy or cognitive delay.1

A number of factors influence the severity and outcome of tetanus. Untreated tetanus is typically fatal, with respiratory failure the most common cause of death in settings where mechanical ventilation is unavailable.1 Where mechanical ventilation is accessible, autonomic dysfunction accounts for most deaths.20 Ventilation aside, the case-fatality rate varies according to the medical system. The rate is often less than 20% where modern ICUs are available but can exceed 50% in undeveloped countries with limited facilities.1,5 A review of outcomes data for 197 of the 233 tetanus cases reported in the US during 2001-2008 (modern medical care was provided in all) showed an overall case-fatality rate of 13.2%.7

Age and vaccination status also affect outcomes, with higher case-fatality rates seen in older (18% in those ≥ 60, 31% in those ≥ 65) and unvaccinated (22%) patients. 7,10 In the study of tetanus cases from 2001-2008, the fatality rate was five times higher in patients ages 65 or older compared with patients younger than 65.7 This study also showed that severity of tetanus may be inversely related to the number of vaccine doses the individual has received, and that having previous vaccination was associated with improved survival, as only four of the 26 deaths occurred in patients with prior vaccination.7

Patients who survive the first two weeks of tetanus have a better chance of recovery. Those with multiple chronic comorbidities, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, or cardiovascular disease, are more likely to die because of the physiologic stress of the illness and its treatment.1,7,12 The provision of ventilator support is more complicated in those with COPD; similarly, the autonomic effects of tetanus can be more problematic for patients with chronic cardiac disease or neurologic complications of chronic diabetes.13

PATIENT EDUCATION

Widespread vaccination against tetanus, which began in the US in the mid-20th century, has greatly reduced disease incidence.7 However, vaccination coverage rates remain below target.

In 2012, only 82.5% of children ages 19 to 35 months received the recommended four doses of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTaP) vaccine, and 94.3% received at least three doses.23 Only 84.6% of teens ages 13 to 17 years received the primary four doses as well as the recommended booster dose.24 The same year, only 55% of patients ages 65 and older and 64% of adults ages 19 to 64 had received a tetanus booster within the previous 10 years.25

Vaccination rates are lower for black, Hispanic, and Asian adults in the US.25 Clinicians should proactively recommend tetanus booster immunization to all adults.

CONCLUSION

Although few clinicians in developed countries will see a case of tetanus, all should be alert for it. Elderly patients and those not fully vaccinated are at risk. Routine immunization decreases but does not eliminate the risk. Tetanus differs from other illnesses controlled by national immunization efforts in that unvaccinated persons do not benefit from herd immunity, because the disease is not contagious. The diagnosis is clinical and should always be considered in patients with trismus, dysphagia, and/or adrenergic excess. Wounds that place a patient at risk for tetanus involve devitalized tissues and anaerobic conditions. Prompt diagnosis is essential, because it allows for early neutralization of unbound tetanospasmin. Wound care including debridement, antibiotic therapy, control of muscle spasms and the effects of autonomic instability, and airway care are fundamental to the treatment of tetanus.

CE/CME No: CR-1704

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Recognize patients who are at risk for tetanus.

• Describe the clinical presentation of tetanus.

• Discuss proper treatment for a patient with tetanus.

• Promote widespread vaccination against tetanus.

FACULTY

Timothy W. Ferrarotti is the Director of Didactic Education and Assistant Professor in the PA Studies Program at the University of Saint Joseph, West Hartford, Connecticut.

The author has no financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid for one year from the issue date of April 2017.

Article begins on next page >>

Tetanus is a devastating disease that can be prevented by proper immunization and wound care. Although the incidence is low in the United States due to widespread routine vaccination, immunization coverage remains below target, especially in older adults. Since outcome is influenced by the clinician's ability to make a timely diagnosis and initiate appropriate care, continued appreciation of tetanus is warranted.

Tetanus is a neurologic disorder resulting from infection by the gram-positive, spore-forming anaerobic bacillus Clostridium tetani. The bacterium, in spore form, typically enters the body through a contaminated soft-tissue wound. Ubiquitous in the environment, C tetani spores are found throughout the world—in soil as well as in animal feces and saliva—and are resistant to temperature extremes and antiseptics. Tetanus is infectious but not contagious (not transmitted person-to-person).1 Wounds with devitalized tissue or those supporting anaerobic conditions, such as bites, puncture wounds, burns, and gangrene, are conducive to the development of tetanus. Infection can also occur following dental extractions, abortions, and illicit drug injection.1 Although vaccination programs have decreased the incidence of tetanus in the United States, C tetani infection remains an ongoing clinical concern because the spores are omnipresent, universal vaccination coverage has not been achieved, and vaccine-immunity wanes over time, placing individuals at risk.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

C tetani produces two toxins: tetanolysin and tetanospasmin (tetanus toxin). Tetanolysin may have a role in promoting the diffusion of tetanospasmin in soft tissues.2 Tetanospasmin is a highly potent toxin, with a lethal dose in humans of less than 2.5 ng/kg of body weight.3 The toxin enters the peripheral nerve at the site of injury and migrates to the central nervous system (CNS). There, it causes unopposed α-motor neuron firing by preventing the release of inhibitory neurotransmitters such as γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), resulting in muscle spasms and excess reflexive response to sensory stimuli.4 It also leads to excessive catecholamine release from the adrenal medulla.1

Tetanospasmin binds to neurons in the spinal cord and brainstem. Because toxin binding is irreversible, resolution of tetanus requires the neurons to grow new axon terminals. The effects of tetanus can persist for six to eight weeks until new terminals develop.3,5 Patients often require several weeks of ventilator support during this time.3

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Tetanus continues to be a serious cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. The majority of cases (80%) occur in Africa and Southeast Asia.6 Incidence is much lower in the United States (0.1 cases per million persons annually) because of widespread vaccination, with only 233 cases of tetanus reported between 2001 and 2008.7 However, in the absence of confirmatory tests, the diagnosis is a clinical one; furthermore, there is no laboratory reporting program for tetanus. As a result, more cases may occur in the US than are detected or reported.

In developed countries, tetanus is primarily a disease of the elderly or the unvaccinated. Older persons, especially non-veterans, are less likely to have received the primary series. Because immunity decreases with age, even those who completed the primary series but have not received booster doses are at increased risk.8 Home-schooled children, who are not subject to school-entry vaccination requirements, are also at risk if unvaccinated.9

Neonatal tetanus is an ongoing problem in undeveloped countries that lack maternal vaccination programs. (Maternal immunization successfully reduces neonatal tetanus via passive immunity, and maternal tetanus via active immunity.) Unvaccinated women who undergo nonmedical abortions or unhygienic childbirth are at increased risk for tetanus.3,10

Other risk factors for tetanus include wound contamination with soil, saliva, or devitalized tissue; injection drug use; and exposure to anthropogenic or natural disasters.1 C tetani spores can contaminate heroin and may grow in abscesses of heroin users.4 Small outbreaks of tetanus among injection drug users have been reported, even among younger adults who had some immunity from childhood vaccination.7,11 In addition, patients with diabetes are at increased risk for tetanus. These patients may have chronic wounds due to slowed healing and poor vascularity, which can lead to lower oxygen tension in their wounds and create an environment conducive to anaerobic infection. These chronic wounds are often ignored as a potential nidus for tetanus; instead, focus is placed on plantar puncture wounds or lacerations.7

Though tetanus risk is greatest for those who were never fully immunized, cases have been reported in persons who were immunized in the remote past but had not received a recent booster. Such cases show that tetanus immunity is not absolute and does wane over time.12-14 Among the 233 tetanus cases reported in the US during 2001-2008, vaccination status was reported for 92. Of these, 24 patients had a complete series and 31 patients had at least one prior dose of tetanus vaccine.7 Furthermore, six cases occurred in patients known to have had the four-dose series and a booster within 10 years of diagnosis. Similarly, a 14-year-old boy who was fully vaccinated developed cephalic tetanus from a stingray wound.14 Given these data, clinicians should not assume that a patient who reports having had “a tetanus shot” is completely protected; a full series and regular boosters are required, and, in rare cases, tetanus can occur despite full vaccination.

PATIENT PRESENTATION AND TETANUS TYPES

The CDC describes tetanus as “the acute onset of hypertonia and/or painful muscle contractions (usually of the muscles of the jaw and neck) and generalized muscle spasms without other apparent medical cause.”15 Clinicians should always consider tetanus in patients with dysphagia and trismus, especially if the patient has a wound, had not received primary vaccination, or has not had a booster in several decades. Tetanus cannot be ruled out based on the lack of a wound, however, since up to 25% of patients who develop tetanus have no obvious site of inoculation.16 The incubation period ranges from 3 to 21 days, with more severe cases having shorter incubation periods (< 8 days).10 The closer the site of inoculation is to the CNS, the more serious the disease usually is—and the shorter the incubation period will be.1

Presentation depends on the time elapsed since inoculation, the severity of illness (determined by the Ablett classification; see Table 1), and the form of tetanus involved. The patient may present early when the infection and toxin are localized to the wound and have not progressed to the CNS (localized tetanus). There may be a wound with signs of infection, including erythema, induration, edema, warmth, tenderness, and drainage. If the injury is on the head or neck, cephalic tetanus may occur, causing the patient to present with painful spasms of the extra-ocular, facial, and/or neck muscles; trismus; dysphagia; or even a Horner-like syndrome. The patient with more advanced, generalized tetanus may have decorticate posturing, abdominal wall rigidity, or opisthotonus.1,2,5,17

Four types of tetanus have been described: generalized, localized, cephalic, and neonatal.

Generalized tetanus is the most common form, accounting for approximately 80% of cases.10 It may involve contractions of the masseter muscles, producing trismus; facial muscles, producing risus sardonicus (sardonic smile); neck and shoulder muscles; abdominal wall muscles, mimicking guarding; and back muscles, producing opisthotonus (arching of the back, neck, and head; see Figure 1) and decorticate posturing (flexion and adduction of the arms, clenched fists, and extension of the lower extremities).1,5,6 Patients with generalized tetanus often exhibit hyperresponsiveness to the environment. As a result, noises and sudden light changes may result in acute spasms. In addition, patients may experience painful spasms when affected muscles are palpated. Affected reflex arcs are usually hyperresponsive to stimuli.1 Intermittent spasms of the thoracic, pharyngeal, and/or laryngeal muscles may cause periods of apnea. Autonomic effects of tetanus mimic those associated with the catecholamine excess of pheochromocytoma. Patients exhibit restlessness, irritability, diaphoresis, fever, excessive salivation, gastric stasis, hypertension, tachycardia, and arrhythmia. There may be interposed hypotension and bradycardia.1,5,17

Localized tetanus involves painful spastic contraction of muscles at or near the site of inoculation. It often evolves into generalized tetanus as the toxin spreads further into the CNS.

Cephalic tetanus involves facial and laryngeal muscles. It is rare, accounting for 1% to 3% of tetanus cases.6 Patients may initially have flaccid paralysis, mimicking stroke, rather than spasm, because the toxin has not completely migrated up the peripheral nerve into the CNS. As the toxin enters the CNS and induces the typical spasm (trismus), the diagnosis will be more obvious. The presence of trismus or a subacute wound on the head may be used to discriminate tetanus from stroke. Cephalic tetanus often evolves into generalized tetanus, affecting more of the body in a caudal direction.5

Neonatal tetanus develops within one week after birth. The neonate with tetanus is usually born to a mother lacking immunization. Typically, the infant sucks and feeds for the first couple of days, then develops inability/refusal to suck/feed, has difficulty opening his/her mouth, becomes weak, and develops muscle spasms.3 The affected child may develop risus sardonicus, clenched hands, dorsiflexion of the feet, and opisthotonus.3

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The clinician should consider other CNS conditions in the differential diagnosis (see Table 2). Although similar to generalized seizures, tetanus causes painful spasms and does not produce a loss of consciousness.1,17 Tetanus, intracranial bleed, and meningitis all can cause meningismus; meningitis, however, is more likely to manifest with other symptoms of infection, such as headache and fever. Although the autonomic dysfunction of tetanus can cause pyrexia, fever would usually coincide with other sympathetic symptoms, such as hypertension, tachycardia, and diaphoresis. Intracranial bleeding tends to have a more rapid onset than tetanus and produces headache and mental status changes. Seventh nerve palsy produces muscle flaccidity, not spasm, and is usually painless unless associated with herpetic inflammation.1,5,6,14,17

Poisoning and medication effects should also be considered. Strychnine poisoning manifests similar to tetanus but occurs without a wound.5 Blood and urine assays for strychnine can be diagnostic. Dystonic reactions resulting from neuroleptic medications—such as phenothiazines—include torticollis, oropharyngeal muscle spasms, and deviation of the eyes. Unlike tetanus, drug-induced dystonia does not cause reflex spasms and often resolves with benztropine or diphenhydramine administration.1 Neuroleptic malignant syndrome can also cause muscular rigidity and autonomic instability, but unlike tetanus, it often causes altered mental status; it should be considered in patients who recently received a causative medication.5,17

Tetanus often manifests with reflexive muscle spasms similar to those seen in electrolyte and acid-base abnormalities. Hypocalcemia may produce a reflexive spasm of the facial muscles when the facial nerve is percussed (Chvostek sign), while alkalemia may produce reflexive spasm of the hand and wrist muscles (Trousseau sign).1 Lab tests can rule out these diagnoses.1,5

A patient with an odontogenic abscess may have pain and muscle spasm/trismus, but the infection is usually easily detected on exam. The clinician should be cautious in attributing the trismus solely to the swelling, however, as C tetani has been found in odontogenic abscesses and the patient may have both.1,17 Peritonsillar abscess will often produce trismus. When abscess is the cause, careful examination of the oropharynx will usually demonstrate tonsillar exudate, hypertrophy, soft tissue erythema, and tenderness, as well as a misplaced uvula.1

DIAGNOSIS

Tetanus is a clinical diagnosis, usually made based on the findings described. Confirmatory lab tests are not readily available. The organism is infrequently recovered in cultures of specimens from suspected wounds (30% of cases).10,11 Serologic testing on specimens drawn before administration of tetanus immunoglobulin (TIG) may indicate very low or undetectable antitetanus antibody levels, but tetanus can still occur when “protective” levels of antibodies are present.11 Detection of tetanus toxin in plasma or a wound with bioassays and polymerase chain reaction might be possible, but these tests are only available in a few settings.3

THE MULTIFACETED CARE PLAN

The primary care provider should refer a patient with suspected tetanus to an emergency department, preferably a tertiary care center with the necessary specialists. Patients are likely to require prolonged hospitalization. In a recent series of tetanus cases in California, the median length of hospitalization was 18 days.12 Treatment is multifaceted; interventions include immunization, wound care, administration of antibiotics and other pharmacologic agents, and supportive therapy (see Table 3).

Immunization

All patients with suspected tetanus should immediately receive both passive (with TIG) and active (tetanus toxoid–containing vaccines) immunization. Because of the extremely high potency of tetanus toxin, the very small amount of toxin that is required to cause tetanus is insufficient to prompt an immune response that would confer immunity. Therefore, treatment is the same regardless of whether the patient had prior disease.10

TIG binds to and neutralizes unbound tetanospasmin, preventing progression of the disease. As noted, TIG will not reverse the binding of the toxin to nerve structures.5 Due to a lack of prospective studies, there is disagreement regarding TIG dosage: Doses as high as 3,000-6,000 U have been recommended, but case studies indicate that the dosage recommended by the CDC (500 U) is likely effective.13 The full CDC recommendation is 500 U of human-derived TIG intramuscularly administered at locations near and away from the wound (but always away from the tetanus toxoid injection site).10,17 Outside the US, equine-based TIG may be the only option. Animal-derived TIG is less desirable because of increased allergy risk; when used, a small amount (0.1 mL) should be first administered as an intradermal test.17

Tetanus toxoid immunization produces active immunity. It is currently available in combination antigen forms (tetanus and diphtheria vaccine [Td], tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis [Tdap] vaccine). The dose of either is 0.5 mL. Patients with tetanus should receive three doses given intramuscularly: immediately, at 4 weeks, and at 6 to 12 months.10

Wound care

Wound care should include incision and drainage, removal of foreign bodies, debridement, and irrigation. These steps are taken in order to ensure an aerobic environment in the wound, ultimately decreasing C tetani survival.1

Antibiotics

The preferred antimicrobial agent for treating tetanus infection is metronidazole 500 mg intravenously (IV) every 6 hours.1,3,17 Penicillin (2 to 4 million U IV every 4 to 6 hours) is effective against C tetani, but it is a GABA-receptor antagonist and may worsen tetanus by further inhibiting the release of GABA.1,14,18 GABA-receptor antagonism may also occur with cephalosporins; however, these broader-spectrum agents may be necessary to treat mixed infections.17 Alternatives include doxycycline, macrolides, and clindamycin.1

Other pharmacologic treatment

Benzodiazepines (eg, diazepam 10 to 30 mg IV) can help control rigidity and muscle spasms and are a mainstay of tetanus treatment.18 Benzodiazepines and propofol both act on GABA receptors, producing sedation in addition to controlling muscle spasms.19 Traditionally, more severe spasms, such as opisthotonus, have required induction of complete paralysis with nondepolarizing paralytics, such as pancuronium or vecuronium. However, paralysis is not optimal therapy since it necessitates sedation, intubation, and mechanical ventilation. Because tetanus does not resolve for 6 to 8 weeks, patients who require mechanical ventilation will also require tracheostomy to prevent laryngotracheal stenosis. Paralysis and mechanical ventilation can also lead to deep venous thrombosis, decubitus ulcers, and pneumonia.5 The ideal treatment would reduce the spasms and autonomic instability without the risks associated with deep sedation and paralysis.5

Other agents used in the treatment of tetanus include magnesium sulfate, which can decrease muscle spasm and ameliorate the effects of autonomic dysfunction, and intrathecal baclofen, which can decrease muscle spasm.19,20 Patients with persistent autonomic dysfunction may require combined α- and ß-adrenergic receptor blockade.1,17-20

Supportive care

It is important to implement supportive care, including limiting auditory and tactile stimulation, as well as providing adequate hydration and nutritional support. IV fluids, parenteral feeding, and enteral feeding are required. Measures should be taken to prevent complications of prolonged immobility, paralysis, and mechanical ventilation, including deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and pressure ulcers. The quality of supportive care and the swiftness with which the diagnosis is made and appropriate treatment is initiated are key factors that determine an individual patient’s outcome.21

COMPLICATIONS AND MORTALITY

Tetanus can lead to many complications, including long bone and spine fractures from severe muscle spasms, as well as renal failure and aspiration. Most spinal fractures involve the thoracic spine, but lumbar spine fractures have been reported.22 Burst-type fractures of the vertebrae may cause cauda equina syndrome or directly injure the spinal cord if fragments are retropulsed.22 Persistent muscle spasm can also cause rhabdomyolysis and renal failure. Lab test results, including elevated levels of creatine phosphokinase and myoglobin (rhabdomyolysis) as well as blood urea nitrogen and creatinine (renal failure), can indicate presence of complications. Muscle relaxation and hydration are key to prevention.

Patients with trismus are often unable to swallow and maintain oral hygiene, leading to caries and dental abscess. The trismus itself can also cause dental or jaw fractures.2,13 Aspiration can occur when laryngeal muscles are affected, resulting in pneumonia in 50% to 70% of autopsied cases of tetanus.10 Additionally, the paralyzed patient receiving ventilatory support can develop pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism.5,13 Neonatal tetanus often results in complications such as cerebral palsy or cognitive delay.1