User login

VA Establishes Presumption of Service Connection for Camp Lejeune

Veterans who were exposed to contaminated water at Camp Lejeune are now eligible for VA care and benefits if they have been diagnosed with any of 8 diseases: adult leukemia, aplastic anemia and other myelodysplastic syndromes, bladder cancer, kidney cancer, liver cancer, multiple myeloma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and Parkinson disease. The presumption of service connection regulations went into effect March 14.

The newly effective rule complements the health care already provided for 15 illnesses or conditions as part of the Honoring America’s Veterans and Caring for Camp Lejeune Families Act of 2012. The Camp Lejeune Act requires the VA to provide health care to veterans who served at Camp Lejeune and to reimburse family members or pay providers for medical expenses for those who lived there for ≥ 30 days between August 1, 1953, and December 31, 1987.

The act and new rule relate to 2 on-base water wells that were contaminated with trichloroethylene, perchloroethylene, benzene, vinyl chloride, and other compounds. The wells were shut down in 1985.

The presumption of service connection applies to active-duty, reserve, and National Guard members. The presumption also includes all of Camp Lejeune, Marine Corps Air Station New River, as well as satellite camps and housing areas.

Veterans who were exposed to contaminated water at Camp Lejeune are now eligible for VA care and benefits if they have been diagnosed with any of 8 diseases: adult leukemia, aplastic anemia and other myelodysplastic syndromes, bladder cancer, kidney cancer, liver cancer, multiple myeloma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and Parkinson disease. The presumption of service connection regulations went into effect March 14.

The newly effective rule complements the health care already provided for 15 illnesses or conditions as part of the Honoring America’s Veterans and Caring for Camp Lejeune Families Act of 2012. The Camp Lejeune Act requires the VA to provide health care to veterans who served at Camp Lejeune and to reimburse family members or pay providers for medical expenses for those who lived there for ≥ 30 days between August 1, 1953, and December 31, 1987.

The act and new rule relate to 2 on-base water wells that were contaminated with trichloroethylene, perchloroethylene, benzene, vinyl chloride, and other compounds. The wells were shut down in 1985.

The presumption of service connection applies to active-duty, reserve, and National Guard members. The presumption also includes all of Camp Lejeune, Marine Corps Air Station New River, as well as satellite camps and housing areas.

Veterans who were exposed to contaminated water at Camp Lejeune are now eligible for VA care and benefits if they have been diagnosed with any of 8 diseases: adult leukemia, aplastic anemia and other myelodysplastic syndromes, bladder cancer, kidney cancer, liver cancer, multiple myeloma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and Parkinson disease. The presumption of service connection regulations went into effect March 14.

The newly effective rule complements the health care already provided for 15 illnesses or conditions as part of the Honoring America’s Veterans and Caring for Camp Lejeune Families Act of 2012. The Camp Lejeune Act requires the VA to provide health care to veterans who served at Camp Lejeune and to reimburse family members or pay providers for medical expenses for those who lived there for ≥ 30 days between August 1, 1953, and December 31, 1987.

The act and new rule relate to 2 on-base water wells that were contaminated with trichloroethylene, perchloroethylene, benzene, vinyl chloride, and other compounds. The wells were shut down in 1985.

The presumption of service connection applies to active-duty, reserve, and National Guard members. The presumption also includes all of Camp Lejeune, Marine Corps Air Station New River, as well as satellite camps and housing areas.

Half of patients retain response to CAR T-cell therapy

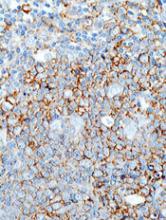

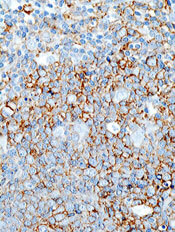

WASHINGTON, DC—Roughly half of patients who responded to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy in the ZUMA-1 trial have retained that response at a median follow-up exceeding 8 months.

The CAR T-cell therapy, axicabtagene ciloleucel (formerly KTE-C19), initially produced an objective response rate (ORR) of 82% in this trial of patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

At a median follow-up of 8.7 months, 44% of all patients (53% of responders) are still in response, and 39% are in complete response (CR).

Thirteen percent of patients had grade 3 or higher cytokine release syndrome (CRS), and 28% had neurologic events.

There were 2 deaths related to axicabtagene ciloleucel.

Frederick L. Locke, MD, of Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida, presented these updated results from ZUMA-1 at the AACR Annual Meeting 2017 (abstract CT019).

ZUMA-1 is sponsored by Kite Pharma but is also funded, in part, by the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Therapy Acceleration Program.

Patients and treatment

The trial enrolled 111 patients, 101 of whom were successfully treated with axicabtagene ciloleucel. Seven patients could not be treated due to serious adverse events, 1 due to unavailable product, and 2 due to non-measurable disease.

Seventy-seven of the patients had diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), and 24 had transformed follicular lymphoma (TFL) or primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL). Eighty-five percent of patients had stage III/IV disease.

Seventy-nine percent were refractory to chemotherapy and did not have a prior autologous stem cell transplant (auto-SCT). Twenty-one percent did undergo auto-SCT and relapsed within 12 months of the procedure.

Sixty-nine percent of patients had received 3 or more lines of prior therapy, and 54% were refractory to 2 consecutive lines of prior therapy.

For this study, the patients received a conditioning regimen of cyclophosphamide (500 mg/m2) and fludarabine (30 mg/m2) for 3 days.

Two days after the conditioning regimen was completed, patients received axicabtagene ciloleucel at a target dose of 2 × 106 CAR T cells/kg.

Efficacy

The following table shows overall response data, response data at 6 months, and ongoing responses at the primary analysis data cut-off.

| DLBCL (n=77) | TFL/PMBCL (n=24) | Combined (n=101) | ||||

| ORR (%) | CR (%) | ORR (%) | CR (%) | ORR (%) | CR (%) | |

| ORR | 82 | 49 | 83 | 71 | 82 | 54 |

| Month 6 | 36 | 31 | 54 | 50 | 41 | 36 |

| Ongoing | 36 | 31 | 67 | 63 | 44 | 39 |

The researchers said the ORR was generally consistent in key subgroups. The ORR was 83% in patients who were refractory to their second or greater line of therapy and 76% in patients who relapsed within 12 months of auto-SCT.

Overall, the median duration of response was 8.2 months. However, the median duration of response has not been reached for patients with a CR.

At a median follow-up of 8.7 months, the median overall survival has not been reached.

Safety

The most common grade 3 or higher adverse events included anemia (43%), neutropenia (39%), decreased neutrophil count (32%), febrile neutropenia (31%), decreased white blood cell count (29%), thrombocytopenia (24%), encephalopathy (21%), and decreased lymphocyte count (20%).

The incidence of grade 3 or higher CRS was 13%, and the incidence of neurologic events was 28%. These represent decreases from the interim analysis of ZUMA-1, when the rate of grade 3+ CRS was 18%, and the rate of neurological events was 34%.

“We believe the rates of CRS and neurologic events decreased over the course of the study as clinicians gained experience in the management of adverse events,” said Jeff Wiezorek, MD, senior vice-president of clinical development at Kite Pharma.

There were 3 deaths throughout the course of the trial that were not a result of disease progression.

Two deaths were deemed related to axicabtagene ciloleucel. One was a case of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. The other was cardiac arrest in the setting of CRS.

The third death was the result of a pulmonary embolism and was considered unrelated to axicabtagene ciloleucel. ![]()

WASHINGTON, DC—Roughly half of patients who responded to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy in the ZUMA-1 trial have retained that response at a median follow-up exceeding 8 months.

The CAR T-cell therapy, axicabtagene ciloleucel (formerly KTE-C19), initially produced an objective response rate (ORR) of 82% in this trial of patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

At a median follow-up of 8.7 months, 44% of all patients (53% of responders) are still in response, and 39% are in complete response (CR).

Thirteen percent of patients had grade 3 or higher cytokine release syndrome (CRS), and 28% had neurologic events.

There were 2 deaths related to axicabtagene ciloleucel.

Frederick L. Locke, MD, of Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida, presented these updated results from ZUMA-1 at the AACR Annual Meeting 2017 (abstract CT019).

ZUMA-1 is sponsored by Kite Pharma but is also funded, in part, by the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Therapy Acceleration Program.

Patients and treatment

The trial enrolled 111 patients, 101 of whom were successfully treated with axicabtagene ciloleucel. Seven patients could not be treated due to serious adverse events, 1 due to unavailable product, and 2 due to non-measurable disease.

Seventy-seven of the patients had diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), and 24 had transformed follicular lymphoma (TFL) or primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL). Eighty-five percent of patients had stage III/IV disease.

Seventy-nine percent were refractory to chemotherapy and did not have a prior autologous stem cell transplant (auto-SCT). Twenty-one percent did undergo auto-SCT and relapsed within 12 months of the procedure.

Sixty-nine percent of patients had received 3 or more lines of prior therapy, and 54% were refractory to 2 consecutive lines of prior therapy.

For this study, the patients received a conditioning regimen of cyclophosphamide (500 mg/m2) and fludarabine (30 mg/m2) for 3 days.

Two days after the conditioning regimen was completed, patients received axicabtagene ciloleucel at a target dose of 2 × 106 CAR T cells/kg.

Efficacy

The following table shows overall response data, response data at 6 months, and ongoing responses at the primary analysis data cut-off.

| DLBCL (n=77) | TFL/PMBCL (n=24) | Combined (n=101) | ||||

| ORR (%) | CR (%) | ORR (%) | CR (%) | ORR (%) | CR (%) | |

| ORR | 82 | 49 | 83 | 71 | 82 | 54 |

| Month 6 | 36 | 31 | 54 | 50 | 41 | 36 |

| Ongoing | 36 | 31 | 67 | 63 | 44 | 39 |

The researchers said the ORR was generally consistent in key subgroups. The ORR was 83% in patients who were refractory to their second or greater line of therapy and 76% in patients who relapsed within 12 months of auto-SCT.

Overall, the median duration of response was 8.2 months. However, the median duration of response has not been reached for patients with a CR.

At a median follow-up of 8.7 months, the median overall survival has not been reached.

Safety

The most common grade 3 or higher adverse events included anemia (43%), neutropenia (39%), decreased neutrophil count (32%), febrile neutropenia (31%), decreased white blood cell count (29%), thrombocytopenia (24%), encephalopathy (21%), and decreased lymphocyte count (20%).

The incidence of grade 3 or higher CRS was 13%, and the incidence of neurologic events was 28%. These represent decreases from the interim analysis of ZUMA-1, when the rate of grade 3+ CRS was 18%, and the rate of neurological events was 34%.

“We believe the rates of CRS and neurologic events decreased over the course of the study as clinicians gained experience in the management of adverse events,” said Jeff Wiezorek, MD, senior vice-president of clinical development at Kite Pharma.

There were 3 deaths throughout the course of the trial that were not a result of disease progression.

Two deaths were deemed related to axicabtagene ciloleucel. One was a case of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. The other was cardiac arrest in the setting of CRS.

The third death was the result of a pulmonary embolism and was considered unrelated to axicabtagene ciloleucel. ![]()

WASHINGTON, DC—Roughly half of patients who responded to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy in the ZUMA-1 trial have retained that response at a median follow-up exceeding 8 months.

The CAR T-cell therapy, axicabtagene ciloleucel (formerly KTE-C19), initially produced an objective response rate (ORR) of 82% in this trial of patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

At a median follow-up of 8.7 months, 44% of all patients (53% of responders) are still in response, and 39% are in complete response (CR).

Thirteen percent of patients had grade 3 or higher cytokine release syndrome (CRS), and 28% had neurologic events.

There were 2 deaths related to axicabtagene ciloleucel.

Frederick L. Locke, MD, of Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida, presented these updated results from ZUMA-1 at the AACR Annual Meeting 2017 (abstract CT019).

ZUMA-1 is sponsored by Kite Pharma but is also funded, in part, by the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Therapy Acceleration Program.

Patients and treatment

The trial enrolled 111 patients, 101 of whom were successfully treated with axicabtagene ciloleucel. Seven patients could not be treated due to serious adverse events, 1 due to unavailable product, and 2 due to non-measurable disease.

Seventy-seven of the patients had diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), and 24 had transformed follicular lymphoma (TFL) or primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL). Eighty-five percent of patients had stage III/IV disease.

Seventy-nine percent were refractory to chemotherapy and did not have a prior autologous stem cell transplant (auto-SCT). Twenty-one percent did undergo auto-SCT and relapsed within 12 months of the procedure.

Sixty-nine percent of patients had received 3 or more lines of prior therapy, and 54% were refractory to 2 consecutive lines of prior therapy.

For this study, the patients received a conditioning regimen of cyclophosphamide (500 mg/m2) and fludarabine (30 mg/m2) for 3 days.

Two days after the conditioning regimen was completed, patients received axicabtagene ciloleucel at a target dose of 2 × 106 CAR T cells/kg.

Efficacy

The following table shows overall response data, response data at 6 months, and ongoing responses at the primary analysis data cut-off.

| DLBCL (n=77) | TFL/PMBCL (n=24) | Combined (n=101) | ||||

| ORR (%) | CR (%) | ORR (%) | CR (%) | ORR (%) | CR (%) | |

| ORR | 82 | 49 | 83 | 71 | 82 | 54 |

| Month 6 | 36 | 31 | 54 | 50 | 41 | 36 |

| Ongoing | 36 | 31 | 67 | 63 | 44 | 39 |

The researchers said the ORR was generally consistent in key subgroups. The ORR was 83% in patients who were refractory to their second or greater line of therapy and 76% in patients who relapsed within 12 months of auto-SCT.

Overall, the median duration of response was 8.2 months. However, the median duration of response has not been reached for patients with a CR.

At a median follow-up of 8.7 months, the median overall survival has not been reached.

Safety

The most common grade 3 or higher adverse events included anemia (43%), neutropenia (39%), decreased neutrophil count (32%), febrile neutropenia (31%), decreased white blood cell count (29%), thrombocytopenia (24%), encephalopathy (21%), and decreased lymphocyte count (20%).

The incidence of grade 3 or higher CRS was 13%, and the incidence of neurologic events was 28%. These represent decreases from the interim analysis of ZUMA-1, when the rate of grade 3+ CRS was 18%, and the rate of neurological events was 34%.

“We believe the rates of CRS and neurologic events decreased over the course of the study as clinicians gained experience in the management of adverse events,” said Jeff Wiezorek, MD, senior vice-president of clinical development at Kite Pharma.

There were 3 deaths throughout the course of the trial that were not a result of disease progression.

Two deaths were deemed related to axicabtagene ciloleucel. One was a case of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. The other was cardiac arrest in the setting of CRS.

The third death was the result of a pulmonary embolism and was considered unrelated to axicabtagene ciloleucel. ![]()

Study provides new insight into RBC resilience

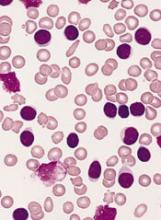

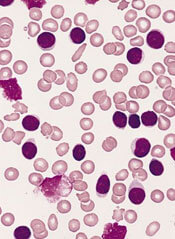

Researchers say they have developed a new system for studying the resilience of red blood cells (RBCs).

The team’s microfluidic system allowed them to look at how RBCs spring back into shape after deforming to pass through a narrow channel.

The researchers believe their findings could aid the diagnosis and treatment of blood-related diseases such as septic shock and malaria.

Hiroaki Ito, PhD, of Osaka University in Suita, Japan, and his colleagues detailed these findings in Scientific Reports.

To study RBCs, the researchers built a “catch-load-launch” microfluidic platform.

The setup included a microchannel in which a single RBC could be held in place for any desired length of time. The RBC was ultimately launched into a wider section using a robotic pump, which simulates the transition from a capillary into a larger vessel.

“The cell was precisely localized in the microchannel by the combination of pressure control and real-time visual feedback,” explained study author Makoto Kaneko, of Osaka University.

“This let us ‘catch’ an erythrocyte in front of the constriction, ‘load’ it inside for a desired time, and quickly ‘launch’ it from the constriction to monitor the shape recovery over time.”

The researchers found that, as the time the RBC was held in the constricted region was increased—from 5 seconds all the way to 5 minutes—the time it took the cell to recover its normal shape also increased.

For very short constriction times, the cells bounced back within 1/10 of a second. But it took approximately 10 seconds for cells to recover if they were held in the narrow segment longer than about 3 minutes.

The researchers also used their “catch-load-launch” system to study septic shock. This condition can occur when bacteria invade the bloodstream and release endotoxins.

Patients with septic shock may suffer from reduced circulation inside the narrow blood vessels as RBCs become too stiff. The same problem can be caused by the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum.

The researchers exposed RBCs to endotoxin from the bacteria Salmonella minnesota and found the RBCs became stiffer and less resilient.

“There is a great deal of evidence that relates certain diseases, including sepsis and malaria, to a decrease in the deformability of red blood cells,” Dr Ito said.

“Such a stiffening can lead to a disturbance in microcirculation, and our ‘catch-load-launch’ platform has the potential to be applied to the mechanical diagnosis of these diseased blood cells.” ![]()

Researchers say they have developed a new system for studying the resilience of red blood cells (RBCs).

The team’s microfluidic system allowed them to look at how RBCs spring back into shape after deforming to pass through a narrow channel.

The researchers believe their findings could aid the diagnosis and treatment of blood-related diseases such as septic shock and malaria.

Hiroaki Ito, PhD, of Osaka University in Suita, Japan, and his colleagues detailed these findings in Scientific Reports.

To study RBCs, the researchers built a “catch-load-launch” microfluidic platform.

The setup included a microchannel in which a single RBC could be held in place for any desired length of time. The RBC was ultimately launched into a wider section using a robotic pump, which simulates the transition from a capillary into a larger vessel.

“The cell was precisely localized in the microchannel by the combination of pressure control and real-time visual feedback,” explained study author Makoto Kaneko, of Osaka University.

“This let us ‘catch’ an erythrocyte in front of the constriction, ‘load’ it inside for a desired time, and quickly ‘launch’ it from the constriction to monitor the shape recovery over time.”

The researchers found that, as the time the RBC was held in the constricted region was increased—from 5 seconds all the way to 5 minutes—the time it took the cell to recover its normal shape also increased.

For very short constriction times, the cells bounced back within 1/10 of a second. But it took approximately 10 seconds for cells to recover if they were held in the narrow segment longer than about 3 minutes.

The researchers also used their “catch-load-launch” system to study septic shock. This condition can occur when bacteria invade the bloodstream and release endotoxins.

Patients with septic shock may suffer from reduced circulation inside the narrow blood vessels as RBCs become too stiff. The same problem can be caused by the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum.

The researchers exposed RBCs to endotoxin from the bacteria Salmonella minnesota and found the RBCs became stiffer and less resilient.

“There is a great deal of evidence that relates certain diseases, including sepsis and malaria, to a decrease in the deformability of red blood cells,” Dr Ito said.

“Such a stiffening can lead to a disturbance in microcirculation, and our ‘catch-load-launch’ platform has the potential to be applied to the mechanical diagnosis of these diseased blood cells.” ![]()

Researchers say they have developed a new system for studying the resilience of red blood cells (RBCs).

The team’s microfluidic system allowed them to look at how RBCs spring back into shape after deforming to pass through a narrow channel.

The researchers believe their findings could aid the diagnosis and treatment of blood-related diseases such as septic shock and malaria.

Hiroaki Ito, PhD, of Osaka University in Suita, Japan, and his colleagues detailed these findings in Scientific Reports.

To study RBCs, the researchers built a “catch-load-launch” microfluidic platform.

The setup included a microchannel in which a single RBC could be held in place for any desired length of time. The RBC was ultimately launched into a wider section using a robotic pump, which simulates the transition from a capillary into a larger vessel.

“The cell was precisely localized in the microchannel by the combination of pressure control and real-time visual feedback,” explained study author Makoto Kaneko, of Osaka University.

“This let us ‘catch’ an erythrocyte in front of the constriction, ‘load’ it inside for a desired time, and quickly ‘launch’ it from the constriction to monitor the shape recovery over time.”

The researchers found that, as the time the RBC was held in the constricted region was increased—from 5 seconds all the way to 5 minutes—the time it took the cell to recover its normal shape also increased.

For very short constriction times, the cells bounced back within 1/10 of a second. But it took approximately 10 seconds for cells to recover if they were held in the narrow segment longer than about 3 minutes.

The researchers also used their “catch-load-launch” system to study septic shock. This condition can occur when bacteria invade the bloodstream and release endotoxins.

Patients with septic shock may suffer from reduced circulation inside the narrow blood vessels as RBCs become too stiff. The same problem can be caused by the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum.

The researchers exposed RBCs to endotoxin from the bacteria Salmonella minnesota and found the RBCs became stiffer and less resilient.

“There is a great deal of evidence that relates certain diseases, including sepsis and malaria, to a decrease in the deformability of red blood cells,” Dr Ito said.

“Such a stiffening can lead to a disturbance in microcirculation, and our ‘catch-load-launch’ platform has the potential to be applied to the mechanical diagnosis of these diseased blood cells.” ![]()

New BTK inhibitor may overcome resistance in CLL

WASHINGTON, DC—Preclinical research suggests a second-generation BTK inhibitor may overcome the acquired resistance observed with its predecessor in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Investigators found the non-covalent BTK inhibitor SNS-062 was unaffected by the BTK C481S mutation, which confers resistance to the first-generation BTK inhibitor ibrutinib.

“[A] subset of patients acquire resistance to ibrutinib, the current standard-of-care BTK inhibitor,” said Amy Johnson, PhD, of The Ohio State University in Columbus.

“A key resistance mechanism to covalent BTK inhibitors is a point mutation in the BTK active site, converting cysteine 481 to serine, or C481S.”

“In this study, we demonstrate that SNS-062, which binds non-covalently to BTK, is a potent inhibitor of BTK unaffected by the presence of the C481S mutation. These findings support clinical investigation of SNS-062 to address acquired resistance to covalent BTK inhibitors in patients.”

Dr Johnson and her colleagues presented these findings at the AACR Annual Meeting 2017 (abstract 1207).

SNS-062 is being developed by Sunesis Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and company investigators were involved in this research. But the study was sponsored by The Ohio State University.

For this study, Dr Johnson and her colleagues tested SNS-062 in primary CLL cells and X-linked agammaglobulinemia human cell lines.

The investigators found that SNS-062 inhibited BTK, decreased the expression of B-cell activation markers, and reduced CLL cell viability in a dose-dependent manner. And these effects were comparable to those observed with ibrutinib.

SNS-062 and ibrutinib demonstrated comparable activity against wild-type BTK. However, ibrutinib and another BTK inhibitor, acalabrutinib, were hindered by the BTK C481S mutation, while SNS-062 was not.

The investigators said SNS-062 was 6 times more potent than ibrutinib against C481S BTK and more than 640 times more potent than acalabrutinib.

The team also noted that SNS-062 exhibited high specificity, affecting a limited number of kinases outside the TEC kinase family.

Finally, the investigators found that SNS-062 diminished stromal cell protection in CLL cells, suggesting the drug can hinder protection from the tumor microenvironment. ![]()

WASHINGTON, DC—Preclinical research suggests a second-generation BTK inhibitor may overcome the acquired resistance observed with its predecessor in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Investigators found the non-covalent BTK inhibitor SNS-062 was unaffected by the BTK C481S mutation, which confers resistance to the first-generation BTK inhibitor ibrutinib.

“[A] subset of patients acquire resistance to ibrutinib, the current standard-of-care BTK inhibitor,” said Amy Johnson, PhD, of The Ohio State University in Columbus.

“A key resistance mechanism to covalent BTK inhibitors is a point mutation in the BTK active site, converting cysteine 481 to serine, or C481S.”

“In this study, we demonstrate that SNS-062, which binds non-covalently to BTK, is a potent inhibitor of BTK unaffected by the presence of the C481S mutation. These findings support clinical investigation of SNS-062 to address acquired resistance to covalent BTK inhibitors in patients.”

Dr Johnson and her colleagues presented these findings at the AACR Annual Meeting 2017 (abstract 1207).

SNS-062 is being developed by Sunesis Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and company investigators were involved in this research. But the study was sponsored by The Ohio State University.

For this study, Dr Johnson and her colleagues tested SNS-062 in primary CLL cells and X-linked agammaglobulinemia human cell lines.

The investigators found that SNS-062 inhibited BTK, decreased the expression of B-cell activation markers, and reduced CLL cell viability in a dose-dependent manner. And these effects were comparable to those observed with ibrutinib.

SNS-062 and ibrutinib demonstrated comparable activity against wild-type BTK. However, ibrutinib and another BTK inhibitor, acalabrutinib, were hindered by the BTK C481S mutation, while SNS-062 was not.

The investigators said SNS-062 was 6 times more potent than ibrutinib against C481S BTK and more than 640 times more potent than acalabrutinib.

The team also noted that SNS-062 exhibited high specificity, affecting a limited number of kinases outside the TEC kinase family.

Finally, the investigators found that SNS-062 diminished stromal cell protection in CLL cells, suggesting the drug can hinder protection from the tumor microenvironment. ![]()

WASHINGTON, DC—Preclinical research suggests a second-generation BTK inhibitor may overcome the acquired resistance observed with its predecessor in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Investigators found the non-covalent BTK inhibitor SNS-062 was unaffected by the BTK C481S mutation, which confers resistance to the first-generation BTK inhibitor ibrutinib.

“[A] subset of patients acquire resistance to ibrutinib, the current standard-of-care BTK inhibitor,” said Amy Johnson, PhD, of The Ohio State University in Columbus.

“A key resistance mechanism to covalent BTK inhibitors is a point mutation in the BTK active site, converting cysteine 481 to serine, or C481S.”

“In this study, we demonstrate that SNS-062, which binds non-covalently to BTK, is a potent inhibitor of BTK unaffected by the presence of the C481S mutation. These findings support clinical investigation of SNS-062 to address acquired resistance to covalent BTK inhibitors in patients.”

Dr Johnson and her colleagues presented these findings at the AACR Annual Meeting 2017 (abstract 1207).

SNS-062 is being developed by Sunesis Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and company investigators were involved in this research. But the study was sponsored by The Ohio State University.

For this study, Dr Johnson and her colleagues tested SNS-062 in primary CLL cells and X-linked agammaglobulinemia human cell lines.

The investigators found that SNS-062 inhibited BTK, decreased the expression of B-cell activation markers, and reduced CLL cell viability in a dose-dependent manner. And these effects were comparable to those observed with ibrutinib.

SNS-062 and ibrutinib demonstrated comparable activity against wild-type BTK. However, ibrutinib and another BTK inhibitor, acalabrutinib, were hindered by the BTK C481S mutation, while SNS-062 was not.

The investigators said SNS-062 was 6 times more potent than ibrutinib against C481S BTK and more than 640 times more potent than acalabrutinib.

The team also noted that SNS-062 exhibited high specificity, affecting a limited number of kinases outside the TEC kinase family.

Finally, the investigators found that SNS-062 diminished stromal cell protection in CLL cells, suggesting the drug can hinder protection from the tumor microenvironment. ![]()

ASCO addresses needs of SGMs with cancer

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has issued recommendations addressing the needs of sexual and gender minority (SGM) populations with cancer.

The recommendations are designed to focus attention on the challenges facing the SGM community—including discrimination and greater risk of anxiety and depression, resulting in disparate care—and concrete steps that can help minimize health disparities among SGM individuals.

The recommendations were published in a policy statement in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“Sexual and gender minorities face unique challenges related to cancer risk, discrimination, and other psychosocial issues,” said ASCO President Daniel F. Hayes, MD.

“Compounding these challenges is the fact that providers may have a lack of knowledge and sensitivity about the health risks and health needs facing their SGM patients.”

SGMs include individuals who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (also referred to as those with differences in sex development).

ASCO’s policy statement notes that SGM populations bear a disproportionate cancer burden stemming from several factors, including:

- Lower rates of cancer screening, in part due to lower rates of insurance coverage, exclusion from traditional screening campaigns, and previous experience of discrimination in the healthcare system

- A hesitancy on the part of SGM patients to disclose their sexual orientation to providers due to a fear of stigmatization, which can create additional barriers to care.

ASCO’s statement calls for a coordinated effort to address health disparities among SGM populations, including:

- Increased patient access to culturally competent support services

- Expanded cancer prevention education for SGM individuals

- Robust policies prohibiting discrimination

- Adequate insurance coverage to meet the needs of SGM individuals affected by cancer

- Inclusion of SGM status as a required data element in cancer registries and clinical trials

- Increased focus on SGM populations in cancer research.

“Our objective was to raise awareness among oncology providers, patients, policy makers, and other stakeholders about the cancer care needs of SGM populations and the barriers that SGM individuals face in getting the highest-quality care,” said Jennifer J. Griggs, MD, lead author of the policy statement and a professor at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

“To address these barriers, a coordinated effort is needed to enhance education for patients and providers, to improve outreach and support, and to encourage productive policy and legislative action.” ![]()

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has issued recommendations addressing the needs of sexual and gender minority (SGM) populations with cancer.

The recommendations are designed to focus attention on the challenges facing the SGM community—including discrimination and greater risk of anxiety and depression, resulting in disparate care—and concrete steps that can help minimize health disparities among SGM individuals.

The recommendations were published in a policy statement in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“Sexual and gender minorities face unique challenges related to cancer risk, discrimination, and other psychosocial issues,” said ASCO President Daniel F. Hayes, MD.

“Compounding these challenges is the fact that providers may have a lack of knowledge and sensitivity about the health risks and health needs facing their SGM patients.”

SGMs include individuals who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (also referred to as those with differences in sex development).

ASCO’s policy statement notes that SGM populations bear a disproportionate cancer burden stemming from several factors, including:

- Lower rates of cancer screening, in part due to lower rates of insurance coverage, exclusion from traditional screening campaigns, and previous experience of discrimination in the healthcare system

- A hesitancy on the part of SGM patients to disclose their sexual orientation to providers due to a fear of stigmatization, which can create additional barriers to care.

ASCO’s statement calls for a coordinated effort to address health disparities among SGM populations, including:

- Increased patient access to culturally competent support services

- Expanded cancer prevention education for SGM individuals

- Robust policies prohibiting discrimination

- Adequate insurance coverage to meet the needs of SGM individuals affected by cancer

- Inclusion of SGM status as a required data element in cancer registries and clinical trials

- Increased focus on SGM populations in cancer research.

“Our objective was to raise awareness among oncology providers, patients, policy makers, and other stakeholders about the cancer care needs of SGM populations and the barriers that SGM individuals face in getting the highest-quality care,” said Jennifer J. Griggs, MD, lead author of the policy statement and a professor at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

“To address these barriers, a coordinated effort is needed to enhance education for patients and providers, to improve outreach and support, and to encourage productive policy and legislative action.” ![]()

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has issued recommendations addressing the needs of sexual and gender minority (SGM) populations with cancer.

The recommendations are designed to focus attention on the challenges facing the SGM community—including discrimination and greater risk of anxiety and depression, resulting in disparate care—and concrete steps that can help minimize health disparities among SGM individuals.

The recommendations were published in a policy statement in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“Sexual and gender minorities face unique challenges related to cancer risk, discrimination, and other psychosocial issues,” said ASCO President Daniel F. Hayes, MD.

“Compounding these challenges is the fact that providers may have a lack of knowledge and sensitivity about the health risks and health needs facing their SGM patients.”

SGMs include individuals who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (also referred to as those with differences in sex development).

ASCO’s policy statement notes that SGM populations bear a disproportionate cancer burden stemming from several factors, including:

- Lower rates of cancer screening, in part due to lower rates of insurance coverage, exclusion from traditional screening campaigns, and previous experience of discrimination in the healthcare system

- A hesitancy on the part of SGM patients to disclose their sexual orientation to providers due to a fear of stigmatization, which can create additional barriers to care.

ASCO’s statement calls for a coordinated effort to address health disparities among SGM populations, including:

- Increased patient access to culturally competent support services

- Expanded cancer prevention education for SGM individuals

- Robust policies prohibiting discrimination

- Adequate insurance coverage to meet the needs of SGM individuals affected by cancer

- Inclusion of SGM status as a required data element in cancer registries and clinical trials

- Increased focus on SGM populations in cancer research.

“Our objective was to raise awareness among oncology providers, patients, policy makers, and other stakeholders about the cancer care needs of SGM populations and the barriers that SGM individuals face in getting the highest-quality care,” said Jennifer J. Griggs, MD, lead author of the policy statement and a professor at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

“To address these barriers, a coordinated effort is needed to enhance education for patients and providers, to improve outreach and support, and to encourage productive policy and legislative action.” ![]()

Obese Man With Severe Pain and Swollen Hand

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Diagnosis: questions to ask

- Treatment and management

- Follow-up care

An obese 43-year-old Hispanic man presents to the emergency department (ED) with complaints of severe pain and swelling in his right hand. The patient states that he felt a bite on his hand as he was planting flowers and laying down potting soil near a tree and decorative rocks in his yard. He did not seek immediate medical treatment because the pain was minimal.

As the hours passed, though, the pain increased, and he began to notice tightness in his hand. Twelve hours after the initial bite, the pain became intolerable and his hand swelled to double its normal size, such that he could no longer bend his fingers. He then sought treatment at the ED.

The patient denies previous drug use but indicates that he smokes 1.5 packs of cigarettes daily and drinks alcohol occasionally in social settings. He has no known drug or food allergies. His history is remarkable for hypertension and hyperlipidemia, treated with simvastatin (40 mg/d) and lisinopril (10 mg/d), respectively.

The physical examination reveals an arterial blood pressure of 152/84 mm Hg; heart rate, 76 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min-1; and temperature, 99ºF. His height is 5 ft 8 in and weight, 297 lb. Cardiovascular examination reveals no irregular heart rhythm, and S1 and S2 are heard, with no murmurs or gallops. He denies chest pain and palpitations. Respiratory examination reveals clear breath sounds that are equal and unlabored. He denies shortness of breath or coughing. The patient states that he had nausea earlier that day, but it has subsided.

Dermatologic examination reveals severe erythema and 3+ edema in the patient’s right hand. A 3-cm, irregularly shaped, red, hemorrhagic blister is observed close to the thumb on the posterior side of the right hand. There are two small holes in the center and slight bruising around the lesion. The right hand is hard and warm to the touch upon palpation, and the patient rates his pain as severe (10 out of 10).

The symptoms of severe pain and swelling and the early observation of bruising and hemorrhagic blistering raise suspicion for venomous spider bite (ICD-10 code: T63.331A). Laboratory work-up, including complete blood count, electrolytes, kidney function studies, and urinalysis, is performed. The results are inconclusive, and the reported symptoms and objective assessment are used to make the diagnosis of spider bite.

DISCUSSION

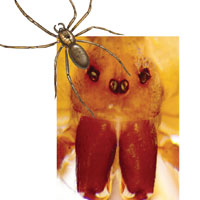

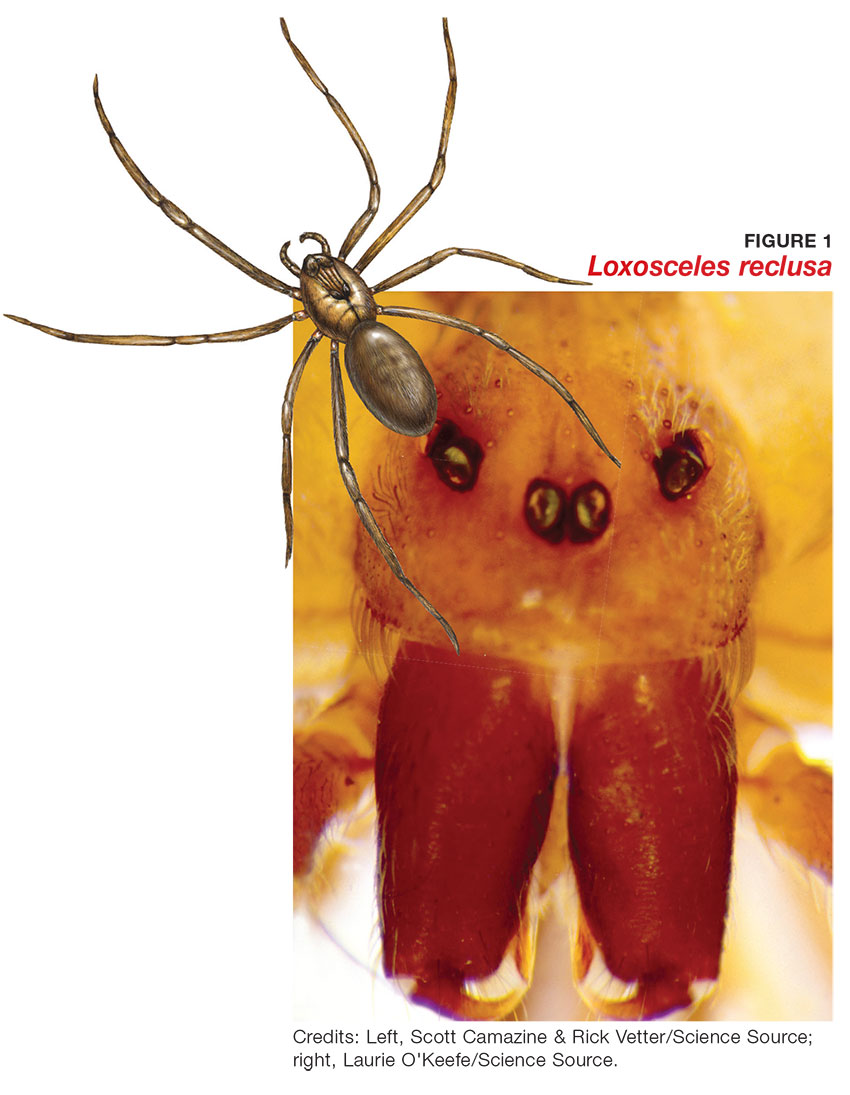

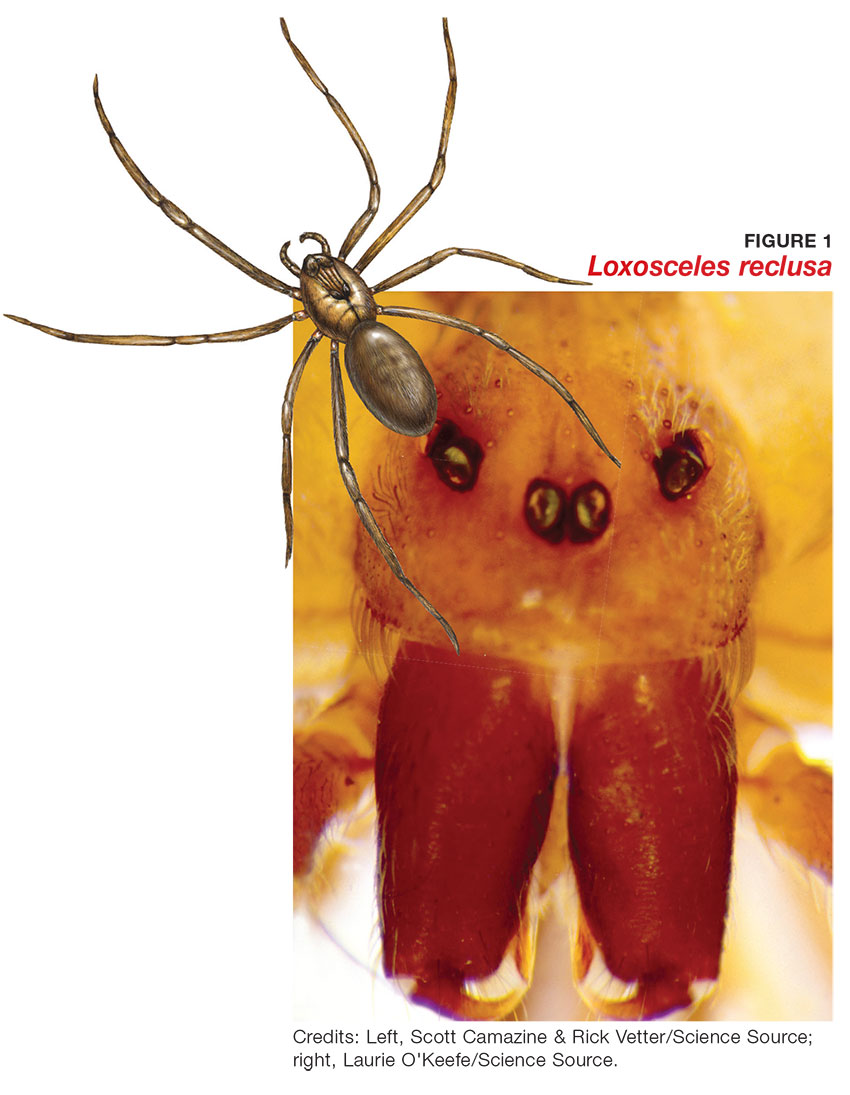

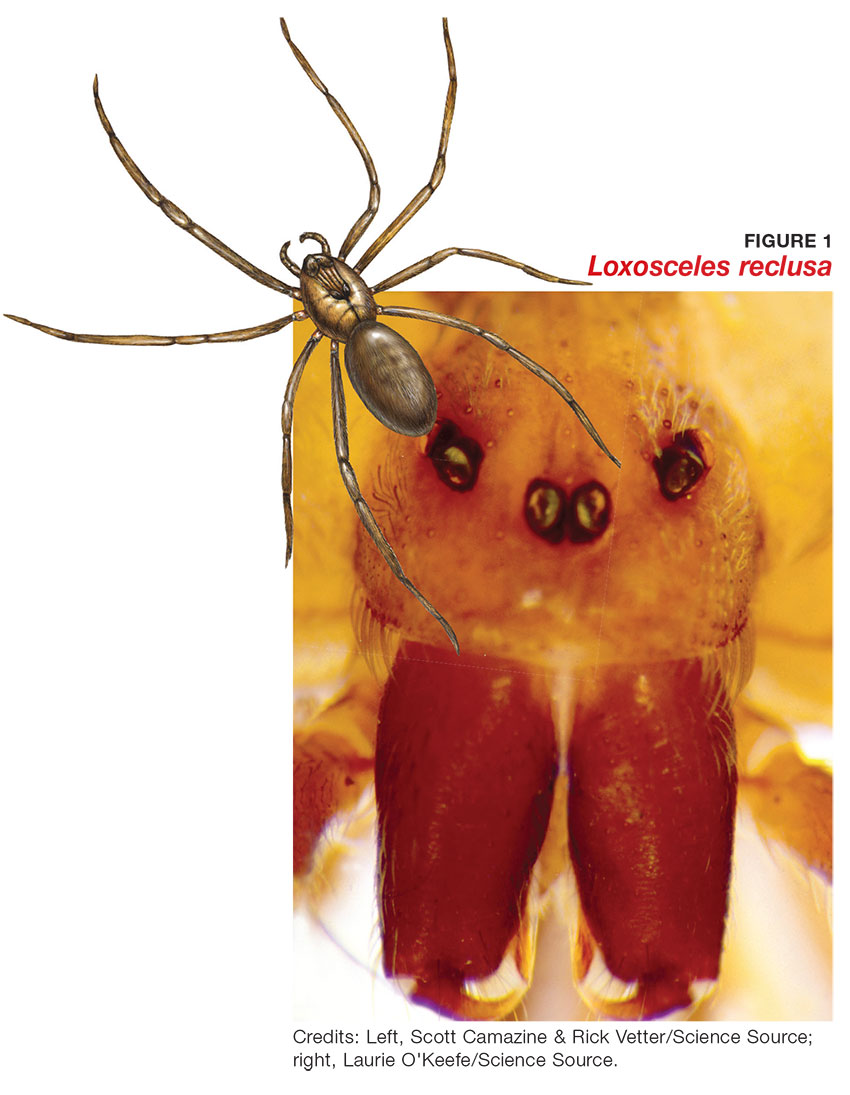

The brown recluse spider (Loxosceles reclusa) is notorious for its bite, which can result in dermonecrosis within 24 to 48 hours. It inhabits the lower Midwest, south central, and southeastern regions of the United States and is not endemic in the West, Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, or Coastal South. Brown recluse spiders are nonaggressive and prefer warm, dark, dry habitats, dwelling under rocks, logs, woodpiles, and debris, as well as in attics, sheds, basements, boxes, travel bags, and motor vehicles.1,2 They can survive for months without food and can withstand temperatures ranging from 46.4°F to 109.4°F.3 They build irregular, cottony webs that serve as housing but are not used to capture prey.3 (Note that webs found strung along walls, ceilings, outdoor vegetation, and in other exposed areas are nearly always associated with other types of spiders.) The brown recluse is nocturnal, seeking insect prey, either alive or dead.

Brown recluse spiders range in size from 6 mm to 20 mm; they have a violin-shaped pattern on the cephalothorax and long legs that allow them to move quickly (see Figure 1). A distinguishing feature is their six eyes, arranged in three pairs (most spiders have eight eyes).

Venom production is influenced by the size and sex of the spider as well as ambient temperature.4 The venom contains at least eight enzyme and protein components, including the most active enzyme, sphingomyelinase D.3 This enzyme causes dermonecrosis, platelet aggregation, and complement-mediated hemolysis in vitro, and it may also be responsible for the ulcerating and systemic effects observed in humans.5 Sphingomyelinase D has been shown to induce grossly visible tissue necrosis in rabbit tissue within 24 hours after envenomation.3

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The brown recluse spider bite may be imperceptible at the time of envenomation, requiring no medical attention. Depending on a person’s sensitivity level and the amount of venom injected, however, a mild stinging sensation at the site may be felt, which is usually accompanied by redness and inflammation that may disappear within seconds or last for a couple of hours.6

Within two to eight hours, severe pain may occur, progressing to a burning sensation.5 The bite site will become pale, due to venom-induced vasoconstriction, with increasing erythema and swelling in the surrounding tissue.5 This extreme pain could be due to absorption of the venom by the muscle tissues; if untreated, further tissue damage can occur. Within 12 to 24 hours, there is painful edema with induration and an irregular area of ecchymosis and ischemia.7 Occasionally, the site will develop red, white, and blue hemorrhagic blisters, with the blue ischemic portion centrally located and the red erythematous areas on the periphery.8 In almost half of all cases, the lesion is associated with nonspecific systemic symptoms, such as generalized pruritus and rash, headache, nausea, vomiting, and low-grade fever in the first 24 to 48 hours.7

Three days after envenomation, the wound will expand and deepen, with skin breakdown noted not sooner than 72 hours after the bite (see Figure 2).7,8 After five to seven days, the cutaneous lesion forms a dry necrotic eschar with a well-demarcated border. Within two to three weeks after the bite, the necrotic tissue should detach, and the wound should develop granulated tissue that indicates healing.8 Complete healing can take weeks or months, depending on the extent and depth of the wound, with scarring possible in severe cases.7

Severe systemic illness (ie, systemic loxoscelism)—rare in the US—is a potential complication of the brown recluse spider bite.4 It manifests with fever, malaise, vomiting, headache, and rash; in rare instances, it results in death.7

Diagnosis

Brown recluse bite is diagnosed based on history and clinical presentation and, when possible, identification of the spider. However, patients often do not realize they have been bitten before they develop symptoms, making it impossible to confirm the etiology of the lesion. It is often helpful to ask the following questions during the assessment

- Did you feel the bite take place?

- Did you see or capture the spider? If so, can you describe it?

- Where were you when the spider bit you?

- Did you recently clean any clutter or debris?

Furthermore, patients who recall seeing a spider after being bitten typically do not bring the arachnid to their health care facility. Another complicating factor is the numerous possible causes of necrotic skin lesions that can be mistaken for spider bites.5 The differential diagnosis can include allergic dermatitis, cellulitis, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection, skin abscesses, other arthropod bites, necrotizing fasciitis, or bee sting.

TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT

One of the most important factors in successful treatment is timeliness of medical attention after the initial bite; because the most damaging tissue effects occur within the first three to six hours after envenomation, intervention during this time is imperative.8 Initial treatment of cutaneous brown recluse spider bite is often conservative, given the variation in clinical presentation, inability to predict the future extent of lesions, and lack of evidence-based treatment options.9 The goals of therapy are to ensure that skin integrity is maintained, infection is avoided, and circulation is preserved.10

Nonpharmacologic treatments for brown recluse spider bite consist of cleaning the wound, treating the bite area with “RICE” (rest-ice-compression-elevation) therapy during the first 72 hours to reduce tissue damage, and ensuring adequate hydration.1,10-13 The affected area should be cleaned thoroughly; infected wounds require topical antiseptics and sterile dressings. Applying a cold compress to the bite area at 20-minute intervals during the first 72 hours after envenomation has been shown to reduce tissue damage.10 Heat should not be applied to the area, as it may increase tissue damage.

Pharmacologic treatment. Patients who experience systemic symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, pain, fever, and pruritus should be provided antipyretics, hydration, and analgesics for symptomatic relief, as needed.9 Antihistamines and benzodiazepines have been found to be useful in relieving symptoms of anxiety and pruritus. To help manage mild pain, OTC NSAIDs are recommended.10

If the date of the last tetanus shot is unknown, a prophylactic tetanus booster (tetanus/diphtheria [Td] or TDaP) should be administered.10 The prophylactic use of cephalosporins to treat infection is indicated in patients with tissue breakdown.1

Among the more controversial treatment choices are use of corticosteroids and dapsone, prescribed frequently in the past. Use of oral corticosteroids for cutaneous forms of spider bite is not supported by current evidence.5,10,14 Research does, however, support their role in the treatment of bite-induced systemic illness, particularly for preventing kidney failure and hemolysis in children.1,15

Dapsone, prescribed for the necrotic lesions, may be useful in limiting the inflammatory response at the site of envenomation.1,3 However, human studies have shown conflicting results with dapsone administration, with some demonstrating no improvement in patient outcomes.8 The risks of dapsone’s many adverse effects, including dose-related hemolysis, sore throat, pallor, agranulocytosis, aplastic anemia, and cholestatic jaundice, may outweigh its benefits.1,12 Furthermore, dapsone treatment is restricted in patients with G6PD (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) deficiency because of their increased risk for hemolytic anemia.1 Accordingly, dapsone is recommended only for moderate-to-severe or rapidly progressing cases in adults.1

FOLLOW-UP CARE

A patient's follow-up care should be assessed individually, based on the nature of his/her reaction to the bite. In all instances, however, ask the patient to report worsening of symptoms and changes in the skin around the bite area; if systemic symptoms develop, patients should proceed to the ED. If, after six to eight weeks, the necrotic lesion is large and has stabilized in size, consider referring to a wound care clinic for surgical excision of the eschar.9

To avoid future spider bites, advise patients to clear all clutter, move beds away from the wall, remove bed skirts or ruffles, avoid using underbed storage containers, avoid leaving clothing on the floor in piles, and check shoes before dressing.5

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

Initial supportive treatment for this patient included cleaning the bite area with antiseptic soap and water. A cold compress was applied to the bite area at 20-minute intervals, and the right hand was elevated. Hydrocodone bitartrate/acetaminophen (5/325 mg qid) was administered to alleviate pain. The patient was also given a tetanus booster because the date of his last immunization was unknown.

After two hours of monitoring, the patient was no longer able to move his hand, swelling around the affected area increased, and the bite site began to appear necrotic. Cephalexin (500 mg bid) was ordered along with dapsone (100 mg/d). The patient was referred for consultation with wound care and infectious disease specialists because of possible tissue necrosis.

CONCLUSION

Brown recluse spider bites are uncommon, and most are unremarkable and self-healing. Patients who present following a brown recluse bite typically can be managed successfully with supportive care (RICE) and careful observation. In rare cases, however, bites may result in significant tissue necrosis or even death.

The diagnosis is typically based on thorough physical examination, with attention to the lesion characteristics and appropriate questions about the spider and the development of the lesion over time. Diagnosis through identification of the spider seldom occurs, since patients typically do not capture the spider and bring it with them for identification. The geographic region where the bite occurs is an important factor as well, since brown recluse envenomation is higher on the differential diagnosis of necrotic skin lesions in areas where these spiders are endemic (the lower Midwest, south central, and southeastern regions of the US).

1. Andersen RJ, Campoli J, Johar SK, et al. Suspected brown recluse envenomation: a case report and review of different treatment modalities. J Emerg Med. 2011;41(2):e31-e37.

2. Vetter RS. Seasonality of brown recluse spiders, Loxosceles reclusa, submitted by the general public: implications for physicians regarding loxoscelism diagnoses. Toxicon. 2011;58(8):623-625.

3. Forks TP. Brown recluse spider bites. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2000;13(6):415-423.

4. Peterson ME. Brown spider envenomation. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract. 2006;21(4):191-193.

5. Vetter RS, Isbister GK. Medical aspects of spider bites. Ann Rev Entomol. 2008;53:409-429.

6. Szalay J. Brown recluse spiders: facts, bites & symptoms (2014). www.livescience.com/39996-brown-recluse-spiders.html. Accessed March 1, 2017.

7. Isbister GK, Fan HW. Spider bite. Lancet. 2011;378:2039-2047.

8. Hogan CJ, Barbaro KC, Winkel K. Loxoscelism: old obstacles, new directions. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;44:608-624.

9. Bernstein B, Ehrlich F. Brown recluse spider bites. J Emerg Med. 1986;4:457-462.

10. Rhoads J. Epidemiology of the brown recluse spider bite. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2007;19(2):79-85.

11. Carlson DS. Spider bite. Nursing. 2013;43(2):72.

12. Frundle TC. Management of spider bites. Air Med J. 2004; 23(4):24-26.

13. Sams HH, King LE Jr. Brown recluse spider bites. Dermatol Nurs. 1999;11(6):427-433.

14. Nunnelee JD. Brown recluse spider bites: a case report. J Perianesth Nurs. 2006;21(1):12-15.

15. Wendell RP. Brown recluse spiders: a review to help guide physicians in nonendemic areas. South Med J. 2003; 96(5):486-490.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Diagnosis: questions to ask

- Treatment and management

- Follow-up care

An obese 43-year-old Hispanic man presents to the emergency department (ED) with complaints of severe pain and swelling in his right hand. The patient states that he felt a bite on his hand as he was planting flowers and laying down potting soil near a tree and decorative rocks in his yard. He did not seek immediate medical treatment because the pain was minimal.

As the hours passed, though, the pain increased, and he began to notice tightness in his hand. Twelve hours after the initial bite, the pain became intolerable and his hand swelled to double its normal size, such that he could no longer bend his fingers. He then sought treatment at the ED.

The patient denies previous drug use but indicates that he smokes 1.5 packs of cigarettes daily and drinks alcohol occasionally in social settings. He has no known drug or food allergies. His history is remarkable for hypertension and hyperlipidemia, treated with simvastatin (40 mg/d) and lisinopril (10 mg/d), respectively.

The physical examination reveals an arterial blood pressure of 152/84 mm Hg; heart rate, 76 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min-1; and temperature, 99ºF. His height is 5 ft 8 in and weight, 297 lb. Cardiovascular examination reveals no irregular heart rhythm, and S1 and S2 are heard, with no murmurs or gallops. He denies chest pain and palpitations. Respiratory examination reveals clear breath sounds that are equal and unlabored. He denies shortness of breath or coughing. The patient states that he had nausea earlier that day, but it has subsided.

Dermatologic examination reveals severe erythema and 3+ edema in the patient’s right hand. A 3-cm, irregularly shaped, red, hemorrhagic blister is observed close to the thumb on the posterior side of the right hand. There are two small holes in the center and slight bruising around the lesion. The right hand is hard and warm to the touch upon palpation, and the patient rates his pain as severe (10 out of 10).

The symptoms of severe pain and swelling and the early observation of bruising and hemorrhagic blistering raise suspicion for venomous spider bite (ICD-10 code: T63.331A). Laboratory work-up, including complete blood count, electrolytes, kidney function studies, and urinalysis, is performed. The results are inconclusive, and the reported symptoms and objective assessment are used to make the diagnosis of spider bite.

DISCUSSION

The brown recluse spider (Loxosceles reclusa) is notorious for its bite, which can result in dermonecrosis within 24 to 48 hours. It inhabits the lower Midwest, south central, and southeastern regions of the United States and is not endemic in the West, Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, or Coastal South. Brown recluse spiders are nonaggressive and prefer warm, dark, dry habitats, dwelling under rocks, logs, woodpiles, and debris, as well as in attics, sheds, basements, boxes, travel bags, and motor vehicles.1,2 They can survive for months without food and can withstand temperatures ranging from 46.4°F to 109.4°F.3 They build irregular, cottony webs that serve as housing but are not used to capture prey.3 (Note that webs found strung along walls, ceilings, outdoor vegetation, and in other exposed areas are nearly always associated with other types of spiders.) The brown recluse is nocturnal, seeking insect prey, either alive or dead.

Brown recluse spiders range in size from 6 mm to 20 mm; they have a violin-shaped pattern on the cephalothorax and long legs that allow them to move quickly (see Figure 1). A distinguishing feature is their six eyes, arranged in three pairs (most spiders have eight eyes).

Venom production is influenced by the size and sex of the spider as well as ambient temperature.4 The venom contains at least eight enzyme and protein components, including the most active enzyme, sphingomyelinase D.3 This enzyme causes dermonecrosis, platelet aggregation, and complement-mediated hemolysis in vitro, and it may also be responsible for the ulcerating and systemic effects observed in humans.5 Sphingomyelinase D has been shown to induce grossly visible tissue necrosis in rabbit tissue within 24 hours after envenomation.3

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The brown recluse spider bite may be imperceptible at the time of envenomation, requiring no medical attention. Depending on a person’s sensitivity level and the amount of venom injected, however, a mild stinging sensation at the site may be felt, which is usually accompanied by redness and inflammation that may disappear within seconds or last for a couple of hours.6

Within two to eight hours, severe pain may occur, progressing to a burning sensation.5 The bite site will become pale, due to venom-induced vasoconstriction, with increasing erythema and swelling in the surrounding tissue.5 This extreme pain could be due to absorption of the venom by the muscle tissues; if untreated, further tissue damage can occur. Within 12 to 24 hours, there is painful edema with induration and an irregular area of ecchymosis and ischemia.7 Occasionally, the site will develop red, white, and blue hemorrhagic blisters, with the blue ischemic portion centrally located and the red erythematous areas on the periphery.8 In almost half of all cases, the lesion is associated with nonspecific systemic symptoms, such as generalized pruritus and rash, headache, nausea, vomiting, and low-grade fever in the first 24 to 48 hours.7

Three days after envenomation, the wound will expand and deepen, with skin breakdown noted not sooner than 72 hours after the bite (see Figure 2).7,8 After five to seven days, the cutaneous lesion forms a dry necrotic eschar with a well-demarcated border. Within two to three weeks after the bite, the necrotic tissue should detach, and the wound should develop granulated tissue that indicates healing.8 Complete healing can take weeks or months, depending on the extent and depth of the wound, with scarring possible in severe cases.7

Severe systemic illness (ie, systemic loxoscelism)—rare in the US—is a potential complication of the brown recluse spider bite.4 It manifests with fever, malaise, vomiting, headache, and rash; in rare instances, it results in death.7

Diagnosis

Brown recluse bite is diagnosed based on history and clinical presentation and, when possible, identification of the spider. However, patients often do not realize they have been bitten before they develop symptoms, making it impossible to confirm the etiology of the lesion. It is often helpful to ask the following questions during the assessment

- Did you feel the bite take place?

- Did you see or capture the spider? If so, can you describe it?

- Where were you when the spider bit you?

- Did you recently clean any clutter or debris?

Furthermore, patients who recall seeing a spider after being bitten typically do not bring the arachnid to their health care facility. Another complicating factor is the numerous possible causes of necrotic skin lesions that can be mistaken for spider bites.5 The differential diagnosis can include allergic dermatitis, cellulitis, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection, skin abscesses, other arthropod bites, necrotizing fasciitis, or bee sting.

TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT

One of the most important factors in successful treatment is timeliness of medical attention after the initial bite; because the most damaging tissue effects occur within the first three to six hours after envenomation, intervention during this time is imperative.8 Initial treatment of cutaneous brown recluse spider bite is often conservative, given the variation in clinical presentation, inability to predict the future extent of lesions, and lack of evidence-based treatment options.9 The goals of therapy are to ensure that skin integrity is maintained, infection is avoided, and circulation is preserved.10

Nonpharmacologic treatments for brown recluse spider bite consist of cleaning the wound, treating the bite area with “RICE” (rest-ice-compression-elevation) therapy during the first 72 hours to reduce tissue damage, and ensuring adequate hydration.1,10-13 The affected area should be cleaned thoroughly; infected wounds require topical antiseptics and sterile dressings. Applying a cold compress to the bite area at 20-minute intervals during the first 72 hours after envenomation has been shown to reduce tissue damage.10 Heat should not be applied to the area, as it may increase tissue damage.

Pharmacologic treatment. Patients who experience systemic symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, pain, fever, and pruritus should be provided antipyretics, hydration, and analgesics for symptomatic relief, as needed.9 Antihistamines and benzodiazepines have been found to be useful in relieving symptoms of anxiety and pruritus. To help manage mild pain, OTC NSAIDs are recommended.10

If the date of the last tetanus shot is unknown, a prophylactic tetanus booster (tetanus/diphtheria [Td] or TDaP) should be administered.10 The prophylactic use of cephalosporins to treat infection is indicated in patients with tissue breakdown.1

Among the more controversial treatment choices are use of corticosteroids and dapsone, prescribed frequently in the past. Use of oral corticosteroids for cutaneous forms of spider bite is not supported by current evidence.5,10,14 Research does, however, support their role in the treatment of bite-induced systemic illness, particularly for preventing kidney failure and hemolysis in children.1,15

Dapsone, prescribed for the necrotic lesions, may be useful in limiting the inflammatory response at the site of envenomation.1,3 However, human studies have shown conflicting results with dapsone administration, with some demonstrating no improvement in patient outcomes.8 The risks of dapsone’s many adverse effects, including dose-related hemolysis, sore throat, pallor, agranulocytosis, aplastic anemia, and cholestatic jaundice, may outweigh its benefits.1,12 Furthermore, dapsone treatment is restricted in patients with G6PD (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) deficiency because of their increased risk for hemolytic anemia.1 Accordingly, dapsone is recommended only for moderate-to-severe or rapidly progressing cases in adults.1

FOLLOW-UP CARE

A patient's follow-up care should be assessed individually, based on the nature of his/her reaction to the bite. In all instances, however, ask the patient to report worsening of symptoms and changes in the skin around the bite area; if systemic symptoms develop, patients should proceed to the ED. If, after six to eight weeks, the necrotic lesion is large and has stabilized in size, consider referring to a wound care clinic for surgical excision of the eschar.9

To avoid future spider bites, advise patients to clear all clutter, move beds away from the wall, remove bed skirts or ruffles, avoid using underbed storage containers, avoid leaving clothing on the floor in piles, and check shoes before dressing.5

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

Initial supportive treatment for this patient included cleaning the bite area with antiseptic soap and water. A cold compress was applied to the bite area at 20-minute intervals, and the right hand was elevated. Hydrocodone bitartrate/acetaminophen (5/325 mg qid) was administered to alleviate pain. The patient was also given a tetanus booster because the date of his last immunization was unknown.

After two hours of monitoring, the patient was no longer able to move his hand, swelling around the affected area increased, and the bite site began to appear necrotic. Cephalexin (500 mg bid) was ordered along with dapsone (100 mg/d). The patient was referred for consultation with wound care and infectious disease specialists because of possible tissue necrosis.

CONCLUSION

Brown recluse spider bites are uncommon, and most are unremarkable and self-healing. Patients who present following a brown recluse bite typically can be managed successfully with supportive care (RICE) and careful observation. In rare cases, however, bites may result in significant tissue necrosis or even death.

The diagnosis is typically based on thorough physical examination, with attention to the lesion characteristics and appropriate questions about the spider and the development of the lesion over time. Diagnosis through identification of the spider seldom occurs, since patients typically do not capture the spider and bring it with them for identification. The geographic region where the bite occurs is an important factor as well, since brown recluse envenomation is higher on the differential diagnosis of necrotic skin lesions in areas where these spiders are endemic (the lower Midwest, south central, and southeastern regions of the US).

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Diagnosis: questions to ask

- Treatment and management

- Follow-up care

An obese 43-year-old Hispanic man presents to the emergency department (ED) with complaints of severe pain and swelling in his right hand. The patient states that he felt a bite on his hand as he was planting flowers and laying down potting soil near a tree and decorative rocks in his yard. He did not seek immediate medical treatment because the pain was minimal.

As the hours passed, though, the pain increased, and he began to notice tightness in his hand. Twelve hours after the initial bite, the pain became intolerable and his hand swelled to double its normal size, such that he could no longer bend his fingers. He then sought treatment at the ED.

The patient denies previous drug use but indicates that he smokes 1.5 packs of cigarettes daily and drinks alcohol occasionally in social settings. He has no known drug or food allergies. His history is remarkable for hypertension and hyperlipidemia, treated with simvastatin (40 mg/d) and lisinopril (10 mg/d), respectively.

The physical examination reveals an arterial blood pressure of 152/84 mm Hg; heart rate, 76 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min-1; and temperature, 99ºF. His height is 5 ft 8 in and weight, 297 lb. Cardiovascular examination reveals no irregular heart rhythm, and S1 and S2 are heard, with no murmurs or gallops. He denies chest pain and palpitations. Respiratory examination reveals clear breath sounds that are equal and unlabored. He denies shortness of breath or coughing. The patient states that he had nausea earlier that day, but it has subsided.

Dermatologic examination reveals severe erythema and 3+ edema in the patient’s right hand. A 3-cm, irregularly shaped, red, hemorrhagic blister is observed close to the thumb on the posterior side of the right hand. There are two small holes in the center and slight bruising around the lesion. The right hand is hard and warm to the touch upon palpation, and the patient rates his pain as severe (10 out of 10).

The symptoms of severe pain and swelling and the early observation of bruising and hemorrhagic blistering raise suspicion for venomous spider bite (ICD-10 code: T63.331A). Laboratory work-up, including complete blood count, electrolytes, kidney function studies, and urinalysis, is performed. The results are inconclusive, and the reported symptoms and objective assessment are used to make the diagnosis of spider bite.

DISCUSSION

The brown recluse spider (Loxosceles reclusa) is notorious for its bite, which can result in dermonecrosis within 24 to 48 hours. It inhabits the lower Midwest, south central, and southeastern regions of the United States and is not endemic in the West, Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, or Coastal South. Brown recluse spiders are nonaggressive and prefer warm, dark, dry habitats, dwelling under rocks, logs, woodpiles, and debris, as well as in attics, sheds, basements, boxes, travel bags, and motor vehicles.1,2 They can survive for months without food and can withstand temperatures ranging from 46.4°F to 109.4°F.3 They build irregular, cottony webs that serve as housing but are not used to capture prey.3 (Note that webs found strung along walls, ceilings, outdoor vegetation, and in other exposed areas are nearly always associated with other types of spiders.) The brown recluse is nocturnal, seeking insect prey, either alive or dead.

Brown recluse spiders range in size from 6 mm to 20 mm; they have a violin-shaped pattern on the cephalothorax and long legs that allow them to move quickly (see Figure 1). A distinguishing feature is their six eyes, arranged in three pairs (most spiders have eight eyes).

Venom production is influenced by the size and sex of the spider as well as ambient temperature.4 The venom contains at least eight enzyme and protein components, including the most active enzyme, sphingomyelinase D.3 This enzyme causes dermonecrosis, platelet aggregation, and complement-mediated hemolysis in vitro, and it may also be responsible for the ulcerating and systemic effects observed in humans.5 Sphingomyelinase D has been shown to induce grossly visible tissue necrosis in rabbit tissue within 24 hours after envenomation.3

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The brown recluse spider bite may be imperceptible at the time of envenomation, requiring no medical attention. Depending on a person’s sensitivity level and the amount of venom injected, however, a mild stinging sensation at the site may be felt, which is usually accompanied by redness and inflammation that may disappear within seconds or last for a couple of hours.6

Within two to eight hours, severe pain may occur, progressing to a burning sensation.5 The bite site will become pale, due to venom-induced vasoconstriction, with increasing erythema and swelling in the surrounding tissue.5 This extreme pain could be due to absorption of the venom by the muscle tissues; if untreated, further tissue damage can occur. Within 12 to 24 hours, there is painful edema with induration and an irregular area of ecchymosis and ischemia.7 Occasionally, the site will develop red, white, and blue hemorrhagic blisters, with the blue ischemic portion centrally located and the red erythematous areas on the periphery.8 In almost half of all cases, the lesion is associated with nonspecific systemic symptoms, such as generalized pruritus and rash, headache, nausea, vomiting, and low-grade fever in the first 24 to 48 hours.7

Three days after envenomation, the wound will expand and deepen, with skin breakdown noted not sooner than 72 hours after the bite (see Figure 2).7,8 After five to seven days, the cutaneous lesion forms a dry necrotic eschar with a well-demarcated border. Within two to three weeks after the bite, the necrotic tissue should detach, and the wound should develop granulated tissue that indicates healing.8 Complete healing can take weeks or months, depending on the extent and depth of the wound, with scarring possible in severe cases.7

Severe systemic illness (ie, systemic loxoscelism)—rare in the US—is a potential complication of the brown recluse spider bite.4 It manifests with fever, malaise, vomiting, headache, and rash; in rare instances, it results in death.7

Diagnosis

Brown recluse bite is diagnosed based on history and clinical presentation and, when possible, identification of the spider. However, patients often do not realize they have been bitten before they develop symptoms, making it impossible to confirm the etiology of the lesion. It is often helpful to ask the following questions during the assessment

- Did you feel the bite take place?

- Did you see or capture the spider? If so, can you describe it?

- Where were you when the spider bit you?

- Did you recently clean any clutter or debris?

Furthermore, patients who recall seeing a spider after being bitten typically do not bring the arachnid to their health care facility. Another complicating factor is the numerous possible causes of necrotic skin lesions that can be mistaken for spider bites.5 The differential diagnosis can include allergic dermatitis, cellulitis, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection, skin abscesses, other arthropod bites, necrotizing fasciitis, or bee sting.

TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT

One of the most important factors in successful treatment is timeliness of medical attention after the initial bite; because the most damaging tissue effects occur within the first three to six hours after envenomation, intervention during this time is imperative.8 Initial treatment of cutaneous brown recluse spider bite is often conservative, given the variation in clinical presentation, inability to predict the future extent of lesions, and lack of evidence-based treatment options.9 The goals of therapy are to ensure that skin integrity is maintained, infection is avoided, and circulation is preserved.10

Nonpharmacologic treatments for brown recluse spider bite consist of cleaning the wound, treating the bite area with “RICE” (rest-ice-compression-elevation) therapy during the first 72 hours to reduce tissue damage, and ensuring adequate hydration.1,10-13 The affected area should be cleaned thoroughly; infected wounds require topical antiseptics and sterile dressings. Applying a cold compress to the bite area at 20-minute intervals during the first 72 hours after envenomation has been shown to reduce tissue damage.10 Heat should not be applied to the area, as it may increase tissue damage.

Pharmacologic treatment. Patients who experience systemic symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, pain, fever, and pruritus should be provided antipyretics, hydration, and analgesics for symptomatic relief, as needed.9 Antihistamines and benzodiazepines have been found to be useful in relieving symptoms of anxiety and pruritus. To help manage mild pain, OTC NSAIDs are recommended.10

If the date of the last tetanus shot is unknown, a prophylactic tetanus booster (tetanus/diphtheria [Td] or TDaP) should be administered.10 The prophylactic use of cephalosporins to treat infection is indicated in patients with tissue breakdown.1

Among the more controversial treatment choices are use of corticosteroids and dapsone, prescribed frequently in the past. Use of oral corticosteroids for cutaneous forms of spider bite is not supported by current evidence.5,10,14 Research does, however, support their role in the treatment of bite-induced systemic illness, particularly for preventing kidney failure and hemolysis in children.1,15

Dapsone, prescribed for the necrotic lesions, may be useful in limiting the inflammatory response at the site of envenomation.1,3 However, human studies have shown conflicting results with dapsone administration, with some demonstrating no improvement in patient outcomes.8 The risks of dapsone’s many adverse effects, including dose-related hemolysis, sore throat, pallor, agranulocytosis, aplastic anemia, and cholestatic jaundice, may outweigh its benefits.1,12 Furthermore, dapsone treatment is restricted in patients with G6PD (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) deficiency because of their increased risk for hemolytic anemia.1 Accordingly, dapsone is recommended only for moderate-to-severe or rapidly progressing cases in adults.1

FOLLOW-UP CARE

A patient's follow-up care should be assessed individually, based on the nature of his/her reaction to the bite. In all instances, however, ask the patient to report worsening of symptoms and changes in the skin around the bite area; if systemic symptoms develop, patients should proceed to the ED. If, after six to eight weeks, the necrotic lesion is large and has stabilized in size, consider referring to a wound care clinic for surgical excision of the eschar.9

To avoid future spider bites, advise patients to clear all clutter, move beds away from the wall, remove bed skirts or ruffles, avoid using underbed storage containers, avoid leaving clothing on the floor in piles, and check shoes before dressing.5

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

Initial supportive treatment for this patient included cleaning the bite area with antiseptic soap and water. A cold compress was applied to the bite area at 20-minute intervals, and the right hand was elevated. Hydrocodone bitartrate/acetaminophen (5/325 mg qid) was administered to alleviate pain. The patient was also given a tetanus booster because the date of his last immunization was unknown.

After two hours of monitoring, the patient was no longer able to move his hand, swelling around the affected area increased, and the bite site began to appear necrotic. Cephalexin (500 mg bid) was ordered along with dapsone (100 mg/d). The patient was referred for consultation with wound care and infectious disease specialists because of possible tissue necrosis.

CONCLUSION