User login

Streptococcal pneumonia’s resistance to macrolides increasing

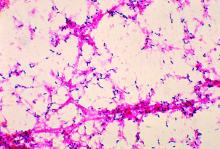

The incidence of resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae to the macrolide azithromycin – one of the most commonly prescribed antibiotics for treating pneumonia – was almost 50% in 2014, according to a report by Kara Keedy, PhD, executive director of microbiology at Cempra Pharmaceuticals, and her colleagues.

The researchers prospectively collected and investigated 4,567 nonreplicative community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP) S. pneumoniae isolates between 2008 and 2014 in the United States, according to the report presented as a poster at IDWeek 2016. The isolates were tested for susceptibility by broth microdilution methods, according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute breakpoint criteria. Macrolide resistance rates were based on azithromycin and/or clarithromycin minimal inhibitory concentrations as available, with only data on azithromycin having been collected in 2014.

The overall resistance of S. pneumoniae to azithromycin exceeded 30% in all of the nine geographical divisions of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), with the high-level resistance of this bacterial cause of CABP to azithromycin having been greater than 25% in eight of the CDC divisions.

The co-resistance of S. pneumoniae to azithromycin and penicillin was highest in the CDC’s East South Central division in 2014. The regions with the largest percentages of isolates with high-level macrolide resistance were the East South Central (43.2%), the West South Central (38.1%), and the Mid-Atlantic (35.0%). The regions with the largest percentages of overall macrolide resistance were the West South Central (62.9%), the East South Central (56.8%), and the South Atlantic (53.2%).

The analysis also determined that the 2014 overall rate of macrolide resistance in S. pneumoniae in the United States of 48.4% is higher than it was for any of the four earlier years examined. In 2008, 2009, 2010, and 2011, those macrolide resistance rates were 39.7%, 40.2%, 37.1%, and 44.3%, respectively.

The researchers concluded that S. pneumoniae is the most common bacterial cause of CABP and that antibiotic resistance to it is “a significant clinical challenge as highlighted by” the CDC having listed it as a threatening pathogen in the urgent category. Dr. Keedy and her associates noted that in the United States, macrolides, amoxicillin/clavulanate, and respiratory fluoroquinolones are the most frequent agents prescribed to treat almost all community-acquired respiratory infections.

“Macrolide resistance in S. pneumoniae is continuing to increase in the U.S.,” the researchers reported in the poster. “Both low- and high-level macrolide resistance have been reported to cause clinical failures and other negative outcomes including longer hospital stays and higher costs.”

The study also examined the abilities of several other drugs, including the fourth-generation macrolide solithromycin, to inhibit S. pneumoniae isolates. Solithromycin does not yet have approved Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute breakpoints, so only minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were presented.

According to the study, more than 50% of S. pneumoniae isolates were inhibited by 0.008 mcg/mL solithromycin. Additionally, solithromycin had one of the lowest MICs against S. pneumoniae of all of the drugs tested in the study. The higher end of the MICs against S. pneumoniae for solithromycin and moxifloxacin was 0.25, which was lower than the higher end of the MICs for any of the other drugs tested against S. pneumoniae isolates.

Solithromycin is the first fluoroketolide in Phase III clinical development. It “shows activity against all macrolide-resistant strains of S. pneumoniae isolates, irrespective of the location in the U.S.,” according to the poster.

The data included in the poster was extracted from a global study by JMI Laboratories. Cempra funded this study. Dr. Keedy and the other authors of the poster are employees of Cempra.

How many of us have heard that line? How many of us have done that ourselves? Did you do that today? Dr. Keedy and her colleagues report that in all geographic areas in the US, resistance to azithromycin for S pneumoniae now exceeds 30%. On average, 48.4% of S pneumoniae isolates display resistance in the US. Without antibiotic stewardship by all of us, azithromycin, along with other antibiotics, will become an expensive placebo.

How many of us have heard that line? How many of us have done that ourselves? Did you do that today? Dr. Keedy and her colleagues report that in all geographic areas in the US, resistance to azithromycin for S pneumoniae now exceeds 30%. On average, 48.4% of S pneumoniae isolates display resistance in the US. Without antibiotic stewardship by all of us, azithromycin, along with other antibiotics, will become an expensive placebo.

How many of us have heard that line? How many of us have done that ourselves? Did you do that today? Dr. Keedy and her colleagues report that in all geographic areas in the US, resistance to azithromycin for S pneumoniae now exceeds 30%. On average, 48.4% of S pneumoniae isolates display resistance in the US. Without antibiotic stewardship by all of us, azithromycin, along with other antibiotics, will become an expensive placebo.

The incidence of resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae to the macrolide azithromycin – one of the most commonly prescribed antibiotics for treating pneumonia – was almost 50% in 2014, according to a report by Kara Keedy, PhD, executive director of microbiology at Cempra Pharmaceuticals, and her colleagues.

The researchers prospectively collected and investigated 4,567 nonreplicative community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP) S. pneumoniae isolates between 2008 and 2014 in the United States, according to the report presented as a poster at IDWeek 2016. The isolates were tested for susceptibility by broth microdilution methods, according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute breakpoint criteria. Macrolide resistance rates were based on azithromycin and/or clarithromycin minimal inhibitory concentrations as available, with only data on azithromycin having been collected in 2014.

The overall resistance of S. pneumoniae to azithromycin exceeded 30% in all of the nine geographical divisions of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), with the high-level resistance of this bacterial cause of CABP to azithromycin having been greater than 25% in eight of the CDC divisions.

The co-resistance of S. pneumoniae to azithromycin and penicillin was highest in the CDC’s East South Central division in 2014. The regions with the largest percentages of isolates with high-level macrolide resistance were the East South Central (43.2%), the West South Central (38.1%), and the Mid-Atlantic (35.0%). The regions with the largest percentages of overall macrolide resistance were the West South Central (62.9%), the East South Central (56.8%), and the South Atlantic (53.2%).

The analysis also determined that the 2014 overall rate of macrolide resistance in S. pneumoniae in the United States of 48.4% is higher than it was for any of the four earlier years examined. In 2008, 2009, 2010, and 2011, those macrolide resistance rates were 39.7%, 40.2%, 37.1%, and 44.3%, respectively.

The researchers concluded that S. pneumoniae is the most common bacterial cause of CABP and that antibiotic resistance to it is “a significant clinical challenge as highlighted by” the CDC having listed it as a threatening pathogen in the urgent category. Dr. Keedy and her associates noted that in the United States, macrolides, amoxicillin/clavulanate, and respiratory fluoroquinolones are the most frequent agents prescribed to treat almost all community-acquired respiratory infections.

“Macrolide resistance in S. pneumoniae is continuing to increase in the U.S.,” the researchers reported in the poster. “Both low- and high-level macrolide resistance have been reported to cause clinical failures and other negative outcomes including longer hospital stays and higher costs.”

The study also examined the abilities of several other drugs, including the fourth-generation macrolide solithromycin, to inhibit S. pneumoniae isolates. Solithromycin does not yet have approved Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute breakpoints, so only minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were presented.

According to the study, more than 50% of S. pneumoniae isolates were inhibited by 0.008 mcg/mL solithromycin. Additionally, solithromycin had one of the lowest MICs against S. pneumoniae of all of the drugs tested in the study. The higher end of the MICs against S. pneumoniae for solithromycin and moxifloxacin was 0.25, which was lower than the higher end of the MICs for any of the other drugs tested against S. pneumoniae isolates.

Solithromycin is the first fluoroketolide in Phase III clinical development. It “shows activity against all macrolide-resistant strains of S. pneumoniae isolates, irrespective of the location in the U.S.,” according to the poster.

The data included in the poster was extracted from a global study by JMI Laboratories. Cempra funded this study. Dr. Keedy and the other authors of the poster are employees of Cempra.

The incidence of resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae to the macrolide azithromycin – one of the most commonly prescribed antibiotics for treating pneumonia – was almost 50% in 2014, according to a report by Kara Keedy, PhD, executive director of microbiology at Cempra Pharmaceuticals, and her colleagues.

The researchers prospectively collected and investigated 4,567 nonreplicative community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP) S. pneumoniae isolates between 2008 and 2014 in the United States, according to the report presented as a poster at IDWeek 2016. The isolates were tested for susceptibility by broth microdilution methods, according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute breakpoint criteria. Macrolide resistance rates were based on azithromycin and/or clarithromycin minimal inhibitory concentrations as available, with only data on azithromycin having been collected in 2014.

The overall resistance of S. pneumoniae to azithromycin exceeded 30% in all of the nine geographical divisions of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), with the high-level resistance of this bacterial cause of CABP to azithromycin having been greater than 25% in eight of the CDC divisions.

The co-resistance of S. pneumoniae to azithromycin and penicillin was highest in the CDC’s East South Central division in 2014. The regions with the largest percentages of isolates with high-level macrolide resistance were the East South Central (43.2%), the West South Central (38.1%), and the Mid-Atlantic (35.0%). The regions with the largest percentages of overall macrolide resistance were the West South Central (62.9%), the East South Central (56.8%), and the South Atlantic (53.2%).

The analysis also determined that the 2014 overall rate of macrolide resistance in S. pneumoniae in the United States of 48.4% is higher than it was for any of the four earlier years examined. In 2008, 2009, 2010, and 2011, those macrolide resistance rates were 39.7%, 40.2%, 37.1%, and 44.3%, respectively.

The researchers concluded that S. pneumoniae is the most common bacterial cause of CABP and that antibiotic resistance to it is “a significant clinical challenge as highlighted by” the CDC having listed it as a threatening pathogen in the urgent category. Dr. Keedy and her associates noted that in the United States, macrolides, amoxicillin/clavulanate, and respiratory fluoroquinolones are the most frequent agents prescribed to treat almost all community-acquired respiratory infections.

“Macrolide resistance in S. pneumoniae is continuing to increase in the U.S.,” the researchers reported in the poster. “Both low- and high-level macrolide resistance have been reported to cause clinical failures and other negative outcomes including longer hospital stays and higher costs.”

The study also examined the abilities of several other drugs, including the fourth-generation macrolide solithromycin, to inhibit S. pneumoniae isolates. Solithromycin does not yet have approved Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute breakpoints, so only minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were presented.

According to the study, more than 50% of S. pneumoniae isolates were inhibited by 0.008 mcg/mL solithromycin. Additionally, solithromycin had one of the lowest MICs against S. pneumoniae of all of the drugs tested in the study. The higher end of the MICs against S. pneumoniae for solithromycin and moxifloxacin was 0.25, which was lower than the higher end of the MICs for any of the other drugs tested against S. pneumoniae isolates.

Solithromycin is the first fluoroketolide in Phase III clinical development. It “shows activity against all macrolide-resistant strains of S. pneumoniae isolates, irrespective of the location in the U.S.,” according to the poster.

The data included in the poster was extracted from a global study by JMI Laboratories. Cempra funded this study. Dr. Keedy and the other authors of the poster are employees of Cempra.

FROM IDWEEK 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: S. pneumoniae isolates’ average resistance to the macrolide azithromycin was 48.4% in 2014.

Data source: A prospective collection and investigation of 4,567 non-replicative community-acquired bacterial pneumonia isolates.

Disclosures: The data included in the poster was extracted from a global study by JMI Laboratories. Cempra funded this study. Dr. Keedy and the other authors of the poster are employees of Cempra.

Top 3 things I learned at the PAGS 2016 symposium

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

LAA closure during cardiac surgery cuts late mortality

NEW ORLEANS – Surgical left atrial appendage closure at the time of open heart surgery in patients with atrial fibrillation doesn’t decrease patients’ early or late risk of stroke, but it does substantially reduce their risk of late mortality, Masahiko Ando, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Solid evidence demonstrates that percutaneous left atrial appendage (LAA) closure using the Watchman or other devices in patients with atrial fibrillation offers a potential alternative to lifelong oral anticoagulation.

In contrast, even though surgical LAA closure at the time of cardiac surgery is commonly done, the data as to its long-term impact are scanty. This was the impetus for Dr. Ando and his coinvestigators at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston to perform a comprehensive systematic review of the medical literature. They also conducted a meta-analysis that involved 7,466 patients who underwent open-heart surgery with or without surgical LAA closure in 12 studies, 3 of which were randomized controlled trials, 2 propensity-matched comparisons, and the rest cohort studies.

At 30-day follow-up, LAA closure was not associated with any significant effect on the risks of stroke, death, reexploration for bleeding, or postoperative atrial fibrillation.

At the latest follow-up in the studies, however, surgical LAA closure was associated with a highly significant 36% reduction in mortality risk compared with the no–LAA-closure control group. This remained the case even after statistical adjustment for demographics, type of cardiac surgery, and the form of preoperative atrial fibrillation.

“Given that we generally add LAA closure to those who have a higher risk of embolization, which could have negatively affected the efficacy of LAA closure, this preventive effect of LAA closure on late mortality cannot be ignored,” said Dr. Ando.

The most likely explanation for the improved survival in surgical LAA closure recipients, he continued, is that the procedure enabled them to avoid aggressive lifelong oral anticoagulation, with its attendant risks.

Dr. Ando reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

NEW ORLEANS – Surgical left atrial appendage closure at the time of open heart surgery in patients with atrial fibrillation doesn’t decrease patients’ early or late risk of stroke, but it does substantially reduce their risk of late mortality, Masahiko Ando, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Solid evidence demonstrates that percutaneous left atrial appendage (LAA) closure using the Watchman or other devices in patients with atrial fibrillation offers a potential alternative to lifelong oral anticoagulation.

In contrast, even though surgical LAA closure at the time of cardiac surgery is commonly done, the data as to its long-term impact are scanty. This was the impetus for Dr. Ando and his coinvestigators at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston to perform a comprehensive systematic review of the medical literature. They also conducted a meta-analysis that involved 7,466 patients who underwent open-heart surgery with or without surgical LAA closure in 12 studies, 3 of which were randomized controlled trials, 2 propensity-matched comparisons, and the rest cohort studies.

At 30-day follow-up, LAA closure was not associated with any significant effect on the risks of stroke, death, reexploration for bleeding, or postoperative atrial fibrillation.

At the latest follow-up in the studies, however, surgical LAA closure was associated with a highly significant 36% reduction in mortality risk compared with the no–LAA-closure control group. This remained the case even after statistical adjustment for demographics, type of cardiac surgery, and the form of preoperative atrial fibrillation.

“Given that we generally add LAA closure to those who have a higher risk of embolization, which could have negatively affected the efficacy of LAA closure, this preventive effect of LAA closure on late mortality cannot be ignored,” said Dr. Ando.

The most likely explanation for the improved survival in surgical LAA closure recipients, he continued, is that the procedure enabled them to avoid aggressive lifelong oral anticoagulation, with its attendant risks.

Dr. Ando reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

NEW ORLEANS – Surgical left atrial appendage closure at the time of open heart surgery in patients with atrial fibrillation doesn’t decrease patients’ early or late risk of stroke, but it does substantially reduce their risk of late mortality, Masahiko Ando, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Solid evidence demonstrates that percutaneous left atrial appendage (LAA) closure using the Watchman or other devices in patients with atrial fibrillation offers a potential alternative to lifelong oral anticoagulation.

In contrast, even though surgical LAA closure at the time of cardiac surgery is commonly done, the data as to its long-term impact are scanty. This was the impetus for Dr. Ando and his coinvestigators at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston to perform a comprehensive systematic review of the medical literature. They also conducted a meta-analysis that involved 7,466 patients who underwent open-heart surgery with or without surgical LAA closure in 12 studies, 3 of which were randomized controlled trials, 2 propensity-matched comparisons, and the rest cohort studies.

At 30-day follow-up, LAA closure was not associated with any significant effect on the risks of stroke, death, reexploration for bleeding, or postoperative atrial fibrillation.

At the latest follow-up in the studies, however, surgical LAA closure was associated with a highly significant 36% reduction in mortality risk compared with the no–LAA-closure control group. This remained the case even after statistical adjustment for demographics, type of cardiac surgery, and the form of preoperative atrial fibrillation.

“Given that we generally add LAA closure to those who have a higher risk of embolization, which could have negatively affected the efficacy of LAA closure, this preventive effect of LAA closure on late mortality cannot be ignored,” said Dr. Ando.

The most likely explanation for the improved survival in surgical LAA closure recipients, he continued, is that the procedure enabled them to avoid aggressive lifelong oral anticoagulation, with its attendant risks.

Dr. Ando reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Late mortality risk was reduced by 36% in patients with atrial fibrillation who underwent surgical LAA closure during open heart surgery, compared with those who did not.

Data source: This meta-analysis included 12 published studies and 7,466 patients who either did or did not undergo surgical LAA closure during open heart surgery.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Understanding SSTI admission, treatment crucial to reducing disease burden

Decreasing the burden of treating skin and soft tissue infections is critical to improving care and reducing the costs that SSTIs place on health care facilities, according to a study published in Hospital Practice.

“Despite expert panel recommendations and treatment guidelines, there is no widely accepted classification system for grading SSTIs to outcomes,” wrote the study’s lead author, Kristin E. Linder, PharmD, of Hartford (Conn.) Hospital. “This leads to a considerable variation in treatment approach on initial presentation when deciding which patients should be admitted to receive intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy or treated as outpatients.”

Dr. Linder and her coinvestigators conducted a single-center retrospective cohort study with the primary objective of determining rates of admission and re-presentation, along with average length-of-stay (LOS) and cost of care for both inpatients and outpatients with SSTIs. Patients aged 18 years and older who received a primary diagnosis of an SSTI during May and June of 2015 at Hartford Hospital were screened; 446 were deemed eligible, with 357 ultimately selected for inclusion (Hosp Pract. 2017 Jan 5. doi: 10.1080/21548331.2017.1279519).

Of the 357 patients included for analysis, 106 (29.7%) were admitted as inpatients while the remaining 251 (70.3%) were treated as outpatients. However, there were no significant differences found in re-presentation rates, either overall – 22.6% for inpatients and 28.3% for outpatients (P greater than .05) – or for SSTI-related re-presentation: 10.4% for inpatients and 15.1% for outpatients (P greater than .05). For those patients who did get admitted, mean LOS was 7.3 days.

Patients who presented with a Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score of zero were admitted at a rate of 14.1%, compared to 30.1% of those with a CCI score of one, and 60.9% of those with a CCI score of two or higher. The biggest disparity, however, was in terms of cost of care; while outpatient care cost an average of $413 per patient, inpatient care cost an average of $13,313 per patient.

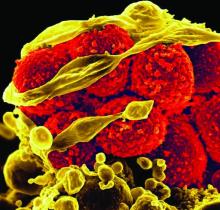

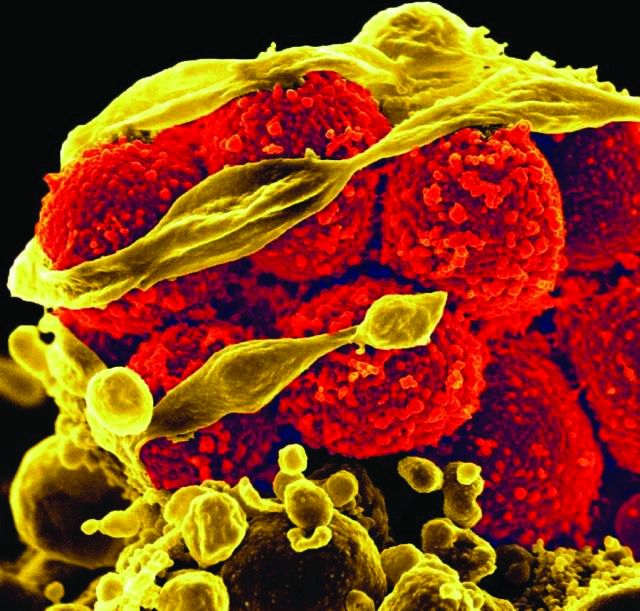

Wound and abscess cultures that were tested found methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) to be the most prevalent gram-positive organism (37.1%) found in inpatients, while for outpatients, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) was the most common (66.7%). According to the investigators, Gram-negative bacteria were not isolated in every case, so “prevalent use of combination therapy in this setting may not be warranted.

“Understanding how and where patients with SSTI are treated and their re-presentation rate is important to understand to direct resources for this high frequency disease,” the authors concluded. “This study demonstrated that approximately 70% of patients presenting to the ED with SSTI were treated as outpatients [and] while 30-day re-presentation was similar for inpatient and outpatients, readmission was more likely in those previously admitted.”

This study was not funded, according to the authors. Dr. Linder did not report any relevant financial disclosures, but her coauthors disclosed receiving speakers’ and consultants’ fees from Astellas, Theravance. Bayer, Merck and Pfizer.

Decreasing the burden of treating skin and soft tissue infections is critical to improving care and reducing the costs that SSTIs place on health care facilities, according to a study published in Hospital Practice.

“Despite expert panel recommendations and treatment guidelines, there is no widely accepted classification system for grading SSTIs to outcomes,” wrote the study’s lead author, Kristin E. Linder, PharmD, of Hartford (Conn.) Hospital. “This leads to a considerable variation in treatment approach on initial presentation when deciding which patients should be admitted to receive intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy or treated as outpatients.”

Dr. Linder and her coinvestigators conducted a single-center retrospective cohort study with the primary objective of determining rates of admission and re-presentation, along with average length-of-stay (LOS) and cost of care for both inpatients and outpatients with SSTIs. Patients aged 18 years and older who received a primary diagnosis of an SSTI during May and June of 2015 at Hartford Hospital were screened; 446 were deemed eligible, with 357 ultimately selected for inclusion (Hosp Pract. 2017 Jan 5. doi: 10.1080/21548331.2017.1279519).

Of the 357 patients included for analysis, 106 (29.7%) were admitted as inpatients while the remaining 251 (70.3%) were treated as outpatients. However, there were no significant differences found in re-presentation rates, either overall – 22.6% for inpatients and 28.3% for outpatients (P greater than .05) – or for SSTI-related re-presentation: 10.4% for inpatients and 15.1% for outpatients (P greater than .05). For those patients who did get admitted, mean LOS was 7.3 days.

Patients who presented with a Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score of zero were admitted at a rate of 14.1%, compared to 30.1% of those with a CCI score of one, and 60.9% of those with a CCI score of two or higher. The biggest disparity, however, was in terms of cost of care; while outpatient care cost an average of $413 per patient, inpatient care cost an average of $13,313 per patient.

Wound and abscess cultures that were tested found methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) to be the most prevalent gram-positive organism (37.1%) found in inpatients, while for outpatients, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) was the most common (66.7%). According to the investigators, Gram-negative bacteria were not isolated in every case, so “prevalent use of combination therapy in this setting may not be warranted.

“Understanding how and where patients with SSTI are treated and their re-presentation rate is important to understand to direct resources for this high frequency disease,” the authors concluded. “This study demonstrated that approximately 70% of patients presenting to the ED with SSTI were treated as outpatients [and] while 30-day re-presentation was similar for inpatient and outpatients, readmission was more likely in those previously admitted.”

This study was not funded, according to the authors. Dr. Linder did not report any relevant financial disclosures, but her coauthors disclosed receiving speakers’ and consultants’ fees from Astellas, Theravance. Bayer, Merck and Pfizer.

Decreasing the burden of treating skin and soft tissue infections is critical to improving care and reducing the costs that SSTIs place on health care facilities, according to a study published in Hospital Practice.

“Despite expert panel recommendations and treatment guidelines, there is no widely accepted classification system for grading SSTIs to outcomes,” wrote the study’s lead author, Kristin E. Linder, PharmD, of Hartford (Conn.) Hospital. “This leads to a considerable variation in treatment approach on initial presentation when deciding which patients should be admitted to receive intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy or treated as outpatients.”

Dr. Linder and her coinvestigators conducted a single-center retrospective cohort study with the primary objective of determining rates of admission and re-presentation, along with average length-of-stay (LOS) and cost of care for both inpatients and outpatients with SSTIs. Patients aged 18 years and older who received a primary diagnosis of an SSTI during May and June of 2015 at Hartford Hospital were screened; 446 were deemed eligible, with 357 ultimately selected for inclusion (Hosp Pract. 2017 Jan 5. doi: 10.1080/21548331.2017.1279519).

Of the 357 patients included for analysis, 106 (29.7%) were admitted as inpatients while the remaining 251 (70.3%) were treated as outpatients. However, there were no significant differences found in re-presentation rates, either overall – 22.6% for inpatients and 28.3% for outpatients (P greater than .05) – or for SSTI-related re-presentation: 10.4% for inpatients and 15.1% for outpatients (P greater than .05). For those patients who did get admitted, mean LOS was 7.3 days.

Patients who presented with a Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score of zero were admitted at a rate of 14.1%, compared to 30.1% of those with a CCI score of one, and 60.9% of those with a CCI score of two or higher. The biggest disparity, however, was in terms of cost of care; while outpatient care cost an average of $413 per patient, inpatient care cost an average of $13,313 per patient.

Wound and abscess cultures that were tested found methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) to be the most prevalent gram-positive organism (37.1%) found in inpatients, while for outpatients, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) was the most common (66.7%). According to the investigators, Gram-negative bacteria were not isolated in every case, so “prevalent use of combination therapy in this setting may not be warranted.

“Understanding how and where patients with SSTI are treated and their re-presentation rate is important to understand to direct resources for this high frequency disease,” the authors concluded. “This study demonstrated that approximately 70% of patients presenting to the ED with SSTI were treated as outpatients [and] while 30-day re-presentation was similar for inpatient and outpatients, readmission was more likely in those previously admitted.”

This study was not funded, according to the authors. Dr. Linder did not report any relevant financial disclosures, but her coauthors disclosed receiving speakers’ and consultants’ fees from Astellas, Theravance. Bayer, Merck and Pfizer.

FROM HOSPITAL PRACTICE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Re-presentation rates between inpatients and outpatients with SSTIs were not significantly different – 10.4% versus 15.1%, respectively (P greater than .05) – but cost of care was much higher for inpatients than outpatients: $13,313 versus $413, respectively.

Data source: Retrospective cohort study of 357 SSTI patients during May and June of 2015.

Disclosures: The study was not funded. Two authors reported potential financial conflicts.

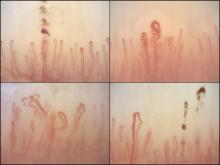

Nailfold analysis can predict cardiopulmonary complications in systemic sclerosis

Nailfold videocapillaroscopy can help to predict which patients with systemic sclerosis may develop serious cardiopulmonary complications, according to findings from a Dutch cross-sectional study.

While individual autoantibodies seen in systemic sclerosis (SSc) are known to be associated with greater or lesser risk of cardiopulmonary involvement, in this study nailfold vascularization patterns independently predicted pulmonary artery hypertension or interstitial lung disease.

All patients in the study had NVC pattern data as well as anti-extractable nuclear antigen (anti-ENA) antibodies. The mean age of the patients was 54 years; 82% were female, and median disease duration was 3 years. Just over half the cohort had interstitial lung disease, and 16% had pulmonary artery hypertension.

Among the anti-ENA autoantibody subtypes, anti-ACA was seen in 37% of patients, anti-Scl-70 in 24%, anti-RNP in 9%, and anti-RNAPIII in 5%; other subtypes were rarer. SSc-specific NVC patterns were seen in 88% of patients, with 10% of the cohort showing an early (less severe microangiopathy) pattern, 42% an active pattern, and 36% a late pattern.

One of the study’s objectives was to determine whether one or more mechanisms was responsible for both autoantibody production and the microangiopathy seen in SSc.

If a joint mechanism is implicated, “more severe NVC patterns would be determined in patients with autoantibodies (such as anti-Scl-70 and anti-RNAPIII) that are associated with more severe disease,” wrote Dr. Markusse and her colleagues. “On the other hand, if specific autoantibodies and stage of microangiopathy reflect different processes in the disease, a combination of autoantibody status and NVC could be helpful for identifying patients at highest risk for cardiopulmonary involvement.”

The investigators reported finding a similar distribution of NVC abnormalities across the major SSc autoantibody subtypes (except for anti–RNP-positive patients), suggesting that combinations of the two variables would be most predictive of cardiopulmonary involvement. More severe NVC patterns were associated with a higher risk of cardiopulmonary involvement, independent of the presence of a specific autoantibody.

Notably, the researchers wrote, “prevalence of ILD [interstitial lung disease] is generally lower among ACA-positive patients. According to our data, even among ACA-positive patients there was a trend for more ILD being associated with more severe NVC patterns (OR = 1.33).”

A similar pattern was seen for pulmonary artery hypertension. “Based on anti-RNP and anti-RNAPIII positivity, patients did not have an increased risk of a [systolic pulmonary artery pressure] greater than 35 mm Hg; however, with a severe NVC pattern, this risk was significantly increased (OR = 2.33).”

The investigators cautioned that their findings should be confirmed in larger cohorts. The study by Dr. Markusse and her colleagues was conducted without outside funding, though manufacturers donated diagnostic antibody tests. One of the 11 study coauthors disclosed receiving financial support from Actelion.

Systemic sclerosis is a profoundly heterogeneous disorder, with the overall prevalence of major organ-specific manifestations, such as pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), broadly adhering to a 15% rule. As such, the majority of patients with SSc will not develop any given organ-specific complication. The major challenge for clinicians during the early stages of the disease is predicting the future occurrence of potentially life-threatening organ-specific manifestations, such as PAH.

The complementary association of nailfold videocapillaroscopy changes and autoantibody profile in predicting cardiopulmonary involvement reported by Dr. Markusse and her colleagues is novel, but otherwise supports the findings of previous cross-sectional studies identifying associations between advanced NVC changes and SSc complications, such as digital ischemic lesions and PAH. These studies provide intriguing insight into the relationship between the evolution of microangiopathy and the emergence of organ-specific manifestations of SSc, but also represent a shift in focus from the diagnostic to the prognostic utility of NVC in SSc.

There is potential clinical utility in these observations that has yet to be unlocked fully; particularly should the predictive value and timing of NVC progression be further characterized in longitudinal studies better defining the natural history of SSc organ-specific manifestations. If evolving NVC changes (in high-risk serological subgroups) are shown to pre-date the emergence of overt organ-specific manifestations of SSc, then we might be provided with a window of opportunity for escalation of therapy with treatments targeting endothelial function (such as phosphodiesterase inhibitors and/or endothelin receptor antagonists) and/or possible immunomodulatory approaches. This could potentially usher in a new era of preventive disease-modifying therapeutic intervention in SSc.

John D. Pauling, MD, PhD, is a consultant rheumatologist at the Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases, Bath, England, and Visiting Senior Lecturer in the department of pharmacy and pharmacology at the University of Bath. His commentary is derived from an editorial accompanying the study by Dr. Markusse and her associates (Rheumatology [Oxford]. 2016 Dec 30. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew461). He disclosed having received grants and consultancy income from Actelion.

Systemic sclerosis is a profoundly heterogeneous disorder, with the overall prevalence of major organ-specific manifestations, such as pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), broadly adhering to a 15% rule. As such, the majority of patients with SSc will not develop any given organ-specific complication. The major challenge for clinicians during the early stages of the disease is predicting the future occurrence of potentially life-threatening organ-specific manifestations, such as PAH.

The complementary association of nailfold videocapillaroscopy changes and autoantibody profile in predicting cardiopulmonary involvement reported by Dr. Markusse and her colleagues is novel, but otherwise supports the findings of previous cross-sectional studies identifying associations between advanced NVC changes and SSc complications, such as digital ischemic lesions and PAH. These studies provide intriguing insight into the relationship between the evolution of microangiopathy and the emergence of organ-specific manifestations of SSc, but also represent a shift in focus from the diagnostic to the prognostic utility of NVC in SSc.

There is potential clinical utility in these observations that has yet to be unlocked fully; particularly should the predictive value and timing of NVC progression be further characterized in longitudinal studies better defining the natural history of SSc organ-specific manifestations. If evolving NVC changes (in high-risk serological subgroups) are shown to pre-date the emergence of overt organ-specific manifestations of SSc, then we might be provided with a window of opportunity for escalation of therapy with treatments targeting endothelial function (such as phosphodiesterase inhibitors and/or endothelin receptor antagonists) and/or possible immunomodulatory approaches. This could potentially usher in a new era of preventive disease-modifying therapeutic intervention in SSc.

John D. Pauling, MD, PhD, is a consultant rheumatologist at the Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases, Bath, England, and Visiting Senior Lecturer in the department of pharmacy and pharmacology at the University of Bath. His commentary is derived from an editorial accompanying the study by Dr. Markusse and her associates (Rheumatology [Oxford]. 2016 Dec 30. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew461). He disclosed having received grants and consultancy income from Actelion.

Systemic sclerosis is a profoundly heterogeneous disorder, with the overall prevalence of major organ-specific manifestations, such as pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), broadly adhering to a 15% rule. As such, the majority of patients with SSc will not develop any given organ-specific complication. The major challenge for clinicians during the early stages of the disease is predicting the future occurrence of potentially life-threatening organ-specific manifestations, such as PAH.

The complementary association of nailfold videocapillaroscopy changes and autoantibody profile in predicting cardiopulmonary involvement reported by Dr. Markusse and her colleagues is novel, but otherwise supports the findings of previous cross-sectional studies identifying associations between advanced NVC changes and SSc complications, such as digital ischemic lesions and PAH. These studies provide intriguing insight into the relationship between the evolution of microangiopathy and the emergence of organ-specific manifestations of SSc, but also represent a shift in focus from the diagnostic to the prognostic utility of NVC in SSc.

There is potential clinical utility in these observations that has yet to be unlocked fully; particularly should the predictive value and timing of NVC progression be further characterized in longitudinal studies better defining the natural history of SSc organ-specific manifestations. If evolving NVC changes (in high-risk serological subgroups) are shown to pre-date the emergence of overt organ-specific manifestations of SSc, then we might be provided with a window of opportunity for escalation of therapy with treatments targeting endothelial function (such as phosphodiesterase inhibitors and/or endothelin receptor antagonists) and/or possible immunomodulatory approaches. This could potentially usher in a new era of preventive disease-modifying therapeutic intervention in SSc.

John D. Pauling, MD, PhD, is a consultant rheumatologist at the Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases, Bath, England, and Visiting Senior Lecturer in the department of pharmacy and pharmacology at the University of Bath. His commentary is derived from an editorial accompanying the study by Dr. Markusse and her associates (Rheumatology [Oxford]. 2016 Dec 30. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew461). He disclosed having received grants and consultancy income from Actelion.

Nailfold videocapillaroscopy can help to predict which patients with systemic sclerosis may develop serious cardiopulmonary complications, according to findings from a Dutch cross-sectional study.

While individual autoantibodies seen in systemic sclerosis (SSc) are known to be associated with greater or lesser risk of cardiopulmonary involvement, in this study nailfold vascularization patterns independently predicted pulmonary artery hypertension or interstitial lung disease.

All patients in the study had NVC pattern data as well as anti-extractable nuclear antigen (anti-ENA) antibodies. The mean age of the patients was 54 years; 82% were female, and median disease duration was 3 years. Just over half the cohort had interstitial lung disease, and 16% had pulmonary artery hypertension.

Among the anti-ENA autoantibody subtypes, anti-ACA was seen in 37% of patients, anti-Scl-70 in 24%, anti-RNP in 9%, and anti-RNAPIII in 5%; other subtypes were rarer. SSc-specific NVC patterns were seen in 88% of patients, with 10% of the cohort showing an early (less severe microangiopathy) pattern, 42% an active pattern, and 36% a late pattern.

One of the study’s objectives was to determine whether one or more mechanisms was responsible for both autoantibody production and the microangiopathy seen in SSc.

If a joint mechanism is implicated, “more severe NVC patterns would be determined in patients with autoantibodies (such as anti-Scl-70 and anti-RNAPIII) that are associated with more severe disease,” wrote Dr. Markusse and her colleagues. “On the other hand, if specific autoantibodies and stage of microangiopathy reflect different processes in the disease, a combination of autoantibody status and NVC could be helpful for identifying patients at highest risk for cardiopulmonary involvement.”

The investigators reported finding a similar distribution of NVC abnormalities across the major SSc autoantibody subtypes (except for anti–RNP-positive patients), suggesting that combinations of the two variables would be most predictive of cardiopulmonary involvement. More severe NVC patterns were associated with a higher risk of cardiopulmonary involvement, independent of the presence of a specific autoantibody.

Notably, the researchers wrote, “prevalence of ILD [interstitial lung disease] is generally lower among ACA-positive patients. According to our data, even among ACA-positive patients there was a trend for more ILD being associated with more severe NVC patterns (OR = 1.33).”

A similar pattern was seen for pulmonary artery hypertension. “Based on anti-RNP and anti-RNAPIII positivity, patients did not have an increased risk of a [systolic pulmonary artery pressure] greater than 35 mm Hg; however, with a severe NVC pattern, this risk was significantly increased (OR = 2.33).”

The investigators cautioned that their findings should be confirmed in larger cohorts. The study by Dr. Markusse and her colleagues was conducted without outside funding, though manufacturers donated diagnostic antibody tests. One of the 11 study coauthors disclosed receiving financial support from Actelion.

Nailfold videocapillaroscopy can help to predict which patients with systemic sclerosis may develop serious cardiopulmonary complications, according to findings from a Dutch cross-sectional study.

While individual autoantibodies seen in systemic sclerosis (SSc) are known to be associated with greater or lesser risk of cardiopulmonary involvement, in this study nailfold vascularization patterns independently predicted pulmonary artery hypertension or interstitial lung disease.

All patients in the study had NVC pattern data as well as anti-extractable nuclear antigen (anti-ENA) antibodies. The mean age of the patients was 54 years; 82% were female, and median disease duration was 3 years. Just over half the cohort had interstitial lung disease, and 16% had pulmonary artery hypertension.

Among the anti-ENA autoantibody subtypes, anti-ACA was seen in 37% of patients, anti-Scl-70 in 24%, anti-RNP in 9%, and anti-RNAPIII in 5%; other subtypes were rarer. SSc-specific NVC patterns were seen in 88% of patients, with 10% of the cohort showing an early (less severe microangiopathy) pattern, 42% an active pattern, and 36% a late pattern.

One of the study’s objectives was to determine whether one or more mechanisms was responsible for both autoantibody production and the microangiopathy seen in SSc.

If a joint mechanism is implicated, “more severe NVC patterns would be determined in patients with autoantibodies (such as anti-Scl-70 and anti-RNAPIII) that are associated with more severe disease,” wrote Dr. Markusse and her colleagues. “On the other hand, if specific autoantibodies and stage of microangiopathy reflect different processes in the disease, a combination of autoantibody status and NVC could be helpful for identifying patients at highest risk for cardiopulmonary involvement.”

The investigators reported finding a similar distribution of NVC abnormalities across the major SSc autoantibody subtypes (except for anti–RNP-positive patients), suggesting that combinations of the two variables would be most predictive of cardiopulmonary involvement. More severe NVC patterns were associated with a higher risk of cardiopulmonary involvement, independent of the presence of a specific autoantibody.

Notably, the researchers wrote, “prevalence of ILD [interstitial lung disease] is generally lower among ACA-positive patients. According to our data, even among ACA-positive patients there was a trend for more ILD being associated with more severe NVC patterns (OR = 1.33).”

A similar pattern was seen for pulmonary artery hypertension. “Based on anti-RNP and anti-RNAPIII positivity, patients did not have an increased risk of a [systolic pulmonary artery pressure] greater than 35 mm Hg; however, with a severe NVC pattern, this risk was significantly increased (OR = 2.33).”

The investigators cautioned that their findings should be confirmed in larger cohorts. The study by Dr. Markusse and her colleagues was conducted without outside funding, though manufacturers donated diagnostic antibody tests. One of the 11 study coauthors disclosed receiving financial support from Actelion.

FROM RHEUMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Across the major autoantibody subtypes seen in an SSc cohort, NVC pattern showed a stable association with presence of interstitial lung disease (OR, 1.3-1.4) or elevated systolic pulmonary artery pressure (OR, 2.2-2.4).

Data source: A cross-section of 287 patients in a Dutch SSc cohort.

Disclosures: The study was conducted without outside funding, though manufacturers donated diagnostic antibody tests. One of the 11 study coauthors disclosed receiving financial support from Actelion.

Analyses of Fort Lauderdale shooting need a reset

Once again, there has been another senseless tragedy: a mass murder that leaves us all feeling vulnerable.

Last Friday, a gunman flew from Anchorage, Alaska, to Florida; retrieved a gun from his checked baggage; and opened fire on total strangers in the baggage claim area of the Fort Lauderdale airport, killing five people and wounding eight others. Why? The media always find a few facts that leave the public to piece together a theory that may or may not hold true.

I heard about the shooting while I was on vacation: The suspected gunman reportedly had visited ISIS websites and was killed at the scene. Later, I saw that he was not a terrorist and was not killed but had been taken into custody without a struggle.

The next reports noted that the 26-year-old man is a former soldier who had served in Iraq, and had come back traumatized and with psychological issues, according to his brother – or, according to what the media say his brother said, since the facts are sometimes selectively reported.

It was then announced that the gunman had gone to the FBI and reported that he was having concerns that U.S. intelligence agencies were infiltrating his brain and commanding him to look at ISIS websites. The FBI sent him for a psychiatric evaluation. His gun was taken by police; he spent a few days in the hospital, and had been released. Soon after, his firearm was returned, and he used it to commit a mass shooting.

So the story started as a terror attack and moved to the media’s default explanation for mass murder – mental illness. These few facts may be pieced together to tell a story of a man who was changed by war, struggled with posttraumatic symptoms that left him angry, and at some point, had a psychotic break that led him to fly across the continent and kill strangers at an airport in response to a command delusion. That’s one possible story that could be written with the very few facts we have.

My best guess is that as facts unfold, the story will change. Even if this story is right, one has to wonder why so many other young soldiers who return from military service so damaged, who also may coincidentally develop psychotic illnesses (or psychosis related to drug use) don’t routinely commit mass murder.

These stories are rare, but they capture the attention of the media in a way that common gun deaths in our inner cities do not. And they play out in a stereotyped way, regardless of how little we know: Mental health advocates use these examples to lobby for more involuntary care – “treatment before tragedy” in a population that does not recognize their own mental illnesses. Such incidents lead to calls to medicate every person with a psychotic illness, because that person may be the next killer, even though half of mass murderers don’t have mental disorders, and even though violence, in general, is more often caused by anger, substance abuse, and a history of exposure to violence. The plea for involuntary care goes out to a nation where voluntary care is often inaccessible to those who want it, where beds are scarce, where insurers – and not doctors – decide who can be hospitalized and for how long. One can only hope that if this young man was obviously dangerous, the hospital that evaluated him would not have discharged him, and that the police would not have returned his firearm. Predicting violence may seem plausible in retrospect, but it’s not always that obvious.

As more of the stereotyped response, antipsychiatry groups often assume mass murderers have been treated with psychotropic medications and use these events as one more example of how psychiatry is causing violence, suicide, and disability for unsuspecting souls who would have fared better without our interventions.

Among psychiatrists ourselves, these stories set off questions and fears. Why did a hospital release this patient? Was he given medications and follow up? What kind of follow up is even available in Alaska? Was he released because he’d taken medication that helped him, because a substance-induced psychosis cleared, or because he refused treatment and was not felt to be dangerous? Or was he released because he had no insurance, or because his insurance company refused to pay for continued treatment? Was a terrible outcome the result of negligence, or was the act of violence something that could not have been predicted? And finally, is the psychiatrist liable? The stock value for crystal balls rises, and we all wonder how we can know – and document – that our patients are safe, as it’s not unusual for distressed people to express violent fantasies. All of us have treated patients who have delusions – how many of those patients have gone on to become mass murderers? Have you ever treated a college student with depression, anxiety, and disturbing thoughts? Did he shoot 70 people in a movie theater and wire his apartment with explosives?

Finally, I’d like to share some concerns I have. First, before we talk about involuntary care to prevent such tragedies as those that happened in Fort Lauderdale last week, we need to be sure that everyone in our nation has access to high-quality, comprehensive psychiatric services, especially our veterans. In the plea for more forced psychiatric care, I believe we’ve become careless and disengaged. Patient rights’ groups have instituted barriers to involuntary treatment, while mental health advocates have touted the impossibility of convincing patients with anosognosia – an inability to see that they suffer from an illness – into accepting psychiatric treatment. Insurers chime in by managing benefits such that patients can be admitted only if they are dangerous, even if they are very sick and want to be in the hospital.

We need to use some commonsense: Patients with psychiatric disorders need to be offered voluntary care in much the same way that patients with other illnesses are approached. If someone in an ED refuses treatment for cancer or an MI, we don’t just say so be it, goodbye. Doctors cajole; they call family; they explain the risks and try quite hard to get the patient to accept help.

In psychiatry, we have stories where patients are asked if they are dangerous, and when they say no, they are sent out, without any further effort to engage them. Psychosis is often a tormenting state, and while patients may not be aware they have an illness, they can often be convinced to come into a hospital for respite, or to take medication to soothe the anxiety that accompanies paranoia or allow for restful sleep. Not everyone is beyond engagement, and the issue needs to be one of what is the best interests of any given patient – with involuntary care only as a true last resort– and not one of preventing mass murders.

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Care,” which was released last fall (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press).

Once again, there has been another senseless tragedy: a mass murder that leaves us all feeling vulnerable.

Last Friday, a gunman flew from Anchorage, Alaska, to Florida; retrieved a gun from his checked baggage; and opened fire on total strangers in the baggage claim area of the Fort Lauderdale airport, killing five people and wounding eight others. Why? The media always find a few facts that leave the public to piece together a theory that may or may not hold true.

I heard about the shooting while I was on vacation: The suspected gunman reportedly had visited ISIS websites and was killed at the scene. Later, I saw that he was not a terrorist and was not killed but had been taken into custody without a struggle.

The next reports noted that the 26-year-old man is a former soldier who had served in Iraq, and had come back traumatized and with psychological issues, according to his brother – or, according to what the media say his brother said, since the facts are sometimes selectively reported.

It was then announced that the gunman had gone to the FBI and reported that he was having concerns that U.S. intelligence agencies were infiltrating his brain and commanding him to look at ISIS websites. The FBI sent him for a psychiatric evaluation. His gun was taken by police; he spent a few days in the hospital, and had been released. Soon after, his firearm was returned, and he used it to commit a mass shooting.

So the story started as a terror attack and moved to the media’s default explanation for mass murder – mental illness. These few facts may be pieced together to tell a story of a man who was changed by war, struggled with posttraumatic symptoms that left him angry, and at some point, had a psychotic break that led him to fly across the continent and kill strangers at an airport in response to a command delusion. That’s one possible story that could be written with the very few facts we have.

My best guess is that as facts unfold, the story will change. Even if this story is right, one has to wonder why so many other young soldiers who return from military service so damaged, who also may coincidentally develop psychotic illnesses (or psychosis related to drug use) don’t routinely commit mass murder.

These stories are rare, but they capture the attention of the media in a way that common gun deaths in our inner cities do not. And they play out in a stereotyped way, regardless of how little we know: Mental health advocates use these examples to lobby for more involuntary care – “treatment before tragedy” in a population that does not recognize their own mental illnesses. Such incidents lead to calls to medicate every person with a psychotic illness, because that person may be the next killer, even though half of mass murderers don’t have mental disorders, and even though violence, in general, is more often caused by anger, substance abuse, and a history of exposure to violence. The plea for involuntary care goes out to a nation where voluntary care is often inaccessible to those who want it, where beds are scarce, where insurers – and not doctors – decide who can be hospitalized and for how long. One can only hope that if this young man was obviously dangerous, the hospital that evaluated him would not have discharged him, and that the police would not have returned his firearm. Predicting violence may seem plausible in retrospect, but it’s not always that obvious.

As more of the stereotyped response, antipsychiatry groups often assume mass murderers have been treated with psychotropic medications and use these events as one more example of how psychiatry is causing violence, suicide, and disability for unsuspecting souls who would have fared better without our interventions.

Among psychiatrists ourselves, these stories set off questions and fears. Why did a hospital release this patient? Was he given medications and follow up? What kind of follow up is even available in Alaska? Was he released because he’d taken medication that helped him, because a substance-induced psychosis cleared, or because he refused treatment and was not felt to be dangerous? Or was he released because he had no insurance, or because his insurance company refused to pay for continued treatment? Was a terrible outcome the result of negligence, or was the act of violence something that could not have been predicted? And finally, is the psychiatrist liable? The stock value for crystal balls rises, and we all wonder how we can know – and document – that our patients are safe, as it’s not unusual for distressed people to express violent fantasies. All of us have treated patients who have delusions – how many of those patients have gone on to become mass murderers? Have you ever treated a college student with depression, anxiety, and disturbing thoughts? Did he shoot 70 people in a movie theater and wire his apartment with explosives?

Finally, I’d like to share some concerns I have. First, before we talk about involuntary care to prevent such tragedies as those that happened in Fort Lauderdale last week, we need to be sure that everyone in our nation has access to high-quality, comprehensive psychiatric services, especially our veterans. In the plea for more forced psychiatric care, I believe we’ve become careless and disengaged. Patient rights’ groups have instituted barriers to involuntary treatment, while mental health advocates have touted the impossibility of convincing patients with anosognosia – an inability to see that they suffer from an illness – into accepting psychiatric treatment. Insurers chime in by managing benefits such that patients can be admitted only if they are dangerous, even if they are very sick and want to be in the hospital.

We need to use some commonsense: Patients with psychiatric disorders need to be offered voluntary care in much the same way that patients with other illnesses are approached. If someone in an ED refuses treatment for cancer or an MI, we don’t just say so be it, goodbye. Doctors cajole; they call family; they explain the risks and try quite hard to get the patient to accept help.

In psychiatry, we have stories where patients are asked if they are dangerous, and when they say no, they are sent out, without any further effort to engage them. Psychosis is often a tormenting state, and while patients may not be aware they have an illness, they can often be convinced to come into a hospital for respite, or to take medication to soothe the anxiety that accompanies paranoia or allow for restful sleep. Not everyone is beyond engagement, and the issue needs to be one of what is the best interests of any given patient – with involuntary care only as a true last resort– and not one of preventing mass murders.

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Care,” which was released last fall (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press).

Once again, there has been another senseless tragedy: a mass murder that leaves us all feeling vulnerable.

Last Friday, a gunman flew from Anchorage, Alaska, to Florida; retrieved a gun from his checked baggage; and opened fire on total strangers in the baggage claim area of the Fort Lauderdale airport, killing five people and wounding eight others. Why? The media always find a few facts that leave the public to piece together a theory that may or may not hold true.

I heard about the shooting while I was on vacation: The suspected gunman reportedly had visited ISIS websites and was killed at the scene. Later, I saw that he was not a terrorist and was not killed but had been taken into custody without a struggle.

The next reports noted that the 26-year-old man is a former soldier who had served in Iraq, and had come back traumatized and with psychological issues, according to his brother – or, according to what the media say his brother said, since the facts are sometimes selectively reported.

It was then announced that the gunman had gone to the FBI and reported that he was having concerns that U.S. intelligence agencies were infiltrating his brain and commanding him to look at ISIS websites. The FBI sent him for a psychiatric evaluation. His gun was taken by police; he spent a few days in the hospital, and had been released. Soon after, his firearm was returned, and he used it to commit a mass shooting.

So the story started as a terror attack and moved to the media’s default explanation for mass murder – mental illness. These few facts may be pieced together to tell a story of a man who was changed by war, struggled with posttraumatic symptoms that left him angry, and at some point, had a psychotic break that led him to fly across the continent and kill strangers at an airport in response to a command delusion. That’s one possible story that could be written with the very few facts we have.

My best guess is that as facts unfold, the story will change. Even if this story is right, one has to wonder why so many other young soldiers who return from military service so damaged, who also may coincidentally develop psychotic illnesses (or psychosis related to drug use) don’t routinely commit mass murder.

These stories are rare, but they capture the attention of the media in a way that common gun deaths in our inner cities do not. And they play out in a stereotyped way, regardless of how little we know: Mental health advocates use these examples to lobby for more involuntary care – “treatment before tragedy” in a population that does not recognize their own mental illnesses. Such incidents lead to calls to medicate every person with a psychotic illness, because that person may be the next killer, even though half of mass murderers don’t have mental disorders, and even though violence, in general, is more often caused by anger, substance abuse, and a history of exposure to violence. The plea for involuntary care goes out to a nation where voluntary care is often inaccessible to those who want it, where beds are scarce, where insurers – and not doctors – decide who can be hospitalized and for how long. One can only hope that if this young man was obviously dangerous, the hospital that evaluated him would not have discharged him, and that the police would not have returned his firearm. Predicting violence may seem plausible in retrospect, but it’s not always that obvious.

As more of the stereotyped response, antipsychiatry groups often assume mass murderers have been treated with psychotropic medications and use these events as one more example of how psychiatry is causing violence, suicide, and disability for unsuspecting souls who would have fared better without our interventions.

Among psychiatrists ourselves, these stories set off questions and fears. Why did a hospital release this patient? Was he given medications and follow up? What kind of follow up is even available in Alaska? Was he released because he’d taken medication that helped him, because a substance-induced psychosis cleared, or because he refused treatment and was not felt to be dangerous? Or was he released because he had no insurance, or because his insurance company refused to pay for continued treatment? Was a terrible outcome the result of negligence, or was the act of violence something that could not have been predicted? And finally, is the psychiatrist liable? The stock value for crystal balls rises, and we all wonder how we can know – and document – that our patients are safe, as it’s not unusual for distressed people to express violent fantasies. All of us have treated patients who have delusions – how many of those patients have gone on to become mass murderers? Have you ever treated a college student with depression, anxiety, and disturbing thoughts? Did he shoot 70 people in a movie theater and wire his apartment with explosives?

Finally, I’d like to share some concerns I have. First, before we talk about involuntary care to prevent such tragedies as those that happened in Fort Lauderdale last week, we need to be sure that everyone in our nation has access to high-quality, comprehensive psychiatric services, especially our veterans. In the plea for more forced psychiatric care, I believe we’ve become careless and disengaged. Patient rights’ groups have instituted barriers to involuntary treatment, while mental health advocates have touted the impossibility of convincing patients with anosognosia – an inability to see that they suffer from an illness – into accepting psychiatric treatment. Insurers chime in by managing benefits such that patients can be admitted only if they are dangerous, even if they are very sick and want to be in the hospital.

We need to use some commonsense: Patients with psychiatric disorders need to be offered voluntary care in much the same way that patients with other illnesses are approached. If someone in an ED refuses treatment for cancer or an MI, we don’t just say so be it, goodbye. Doctors cajole; they call family; they explain the risks and try quite hard to get the patient to accept help.

In psychiatry, we have stories where patients are asked if they are dangerous, and when they say no, they are sent out, without any further effort to engage them. Psychosis is often a tormenting state, and while patients may not be aware they have an illness, they can often be convinced to come into a hospital for respite, or to take medication to soothe the anxiety that accompanies paranoia or allow for restful sleep. Not everyone is beyond engagement, and the issue needs to be one of what is the best interests of any given patient – with involuntary care only as a true last resort– and not one of preventing mass murders.

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Care,” which was released last fall (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press).

Fecal transplant efficacy for Clostridium difficile infections

Clinical question: Is fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) an efficacious and safe treatment approach for patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI)?

Background: FMT restores the normal composition of gut microbiota and is recommended when antibiotics fail to clear CDI. To date, only case series and open-labeled clinical trials support the use of FMT.

Study design: Randomized, controlled, double-blinded clinical trial.

Setting: Academic medical centers.

The primary endpoint was resolution of diarrhea without anti-CDI therapy after 8 weeks of follow-up. In the donor FMT group, 90.9% achieved clinical cure, compared with 62.5% in the autologous group. Patients who developed recurrent CDI were free of further disease after subsequent donor FMT.

The study included only patients who experienced three or more recurrences but excluded immunocompromised and older patients (older than 75 years of age).

Bottom line: Donor stool administered via colonoscopy was more effective than autologous FMT in preventing further CDI episodes.

Citation: Kelly CR, Khoruts A, Staley C, et al. Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on recurrence in multiply recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(9):609-616.

Dr. Fernandez de la Vara is an instructor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and chief medical resident at the University of Miami Hospital.

Clinical question: Is fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) an efficacious and safe treatment approach for patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI)?

Background: FMT restores the normal composition of gut microbiota and is recommended when antibiotics fail to clear CDI. To date, only case series and open-labeled clinical trials support the use of FMT.

Study design: Randomized, controlled, double-blinded clinical trial.

Setting: Academic medical centers.

The primary endpoint was resolution of diarrhea without anti-CDI therapy after 8 weeks of follow-up. In the donor FMT group, 90.9% achieved clinical cure, compared with 62.5% in the autologous group. Patients who developed recurrent CDI were free of further disease after subsequent donor FMT.

The study included only patients who experienced three or more recurrences but excluded immunocompromised and older patients (older than 75 years of age).

Bottom line: Donor stool administered via colonoscopy was more effective than autologous FMT in preventing further CDI episodes.

Citation: Kelly CR, Khoruts A, Staley C, et al. Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on recurrence in multiply recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(9):609-616.

Dr. Fernandez de la Vara is an instructor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and chief medical resident at the University of Miami Hospital.

Clinical question: Is fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) an efficacious and safe treatment approach for patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI)?

Background: FMT restores the normal composition of gut microbiota and is recommended when antibiotics fail to clear CDI. To date, only case series and open-labeled clinical trials support the use of FMT.

Study design: Randomized, controlled, double-blinded clinical trial.

Setting: Academic medical centers.

The primary endpoint was resolution of diarrhea without anti-CDI therapy after 8 weeks of follow-up. In the donor FMT group, 90.9% achieved clinical cure, compared with 62.5% in the autologous group. Patients who developed recurrent CDI were free of further disease after subsequent donor FMT.

The study included only patients who experienced three or more recurrences but excluded immunocompromised and older patients (older than 75 years of age).

Bottom line: Donor stool administered via colonoscopy was more effective than autologous FMT in preventing further CDI episodes.

Citation: Kelly CR, Khoruts A, Staley C, et al. Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on recurrence in multiply recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(9):609-616.

Dr. Fernandez de la Vara is an instructor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and chief medical resident at the University of Miami Hospital.

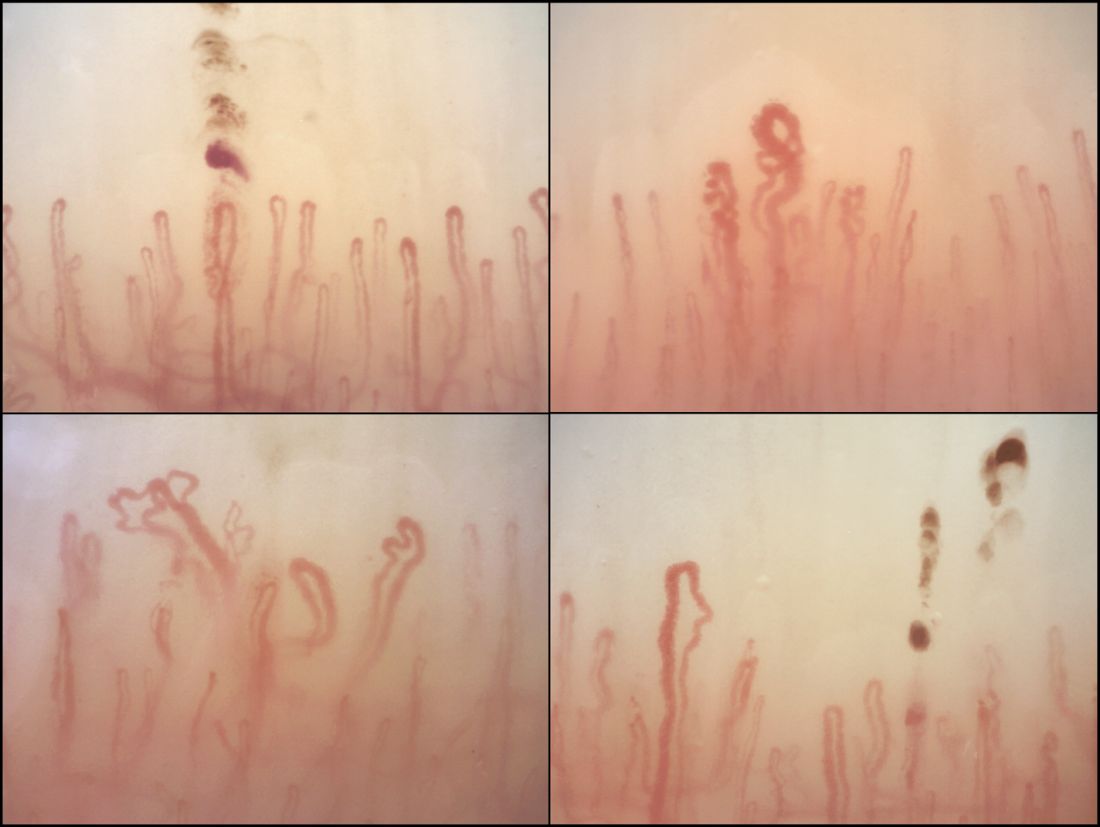

Healing of Leg Ulcers Associated With Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis (Wegener Granulomatosis) After Rituximab Therapy

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old woman with a history of arthralgia, rhinitis, sinusitis, and episodic epistaxis was admitted to the hospital with multiple nonhealing severe leg ulcerations. She noticed subcutaneous nodules on the legs 6 months prior to the development of ulcers. The lesions progressed from subcutaneous nodules to red-black skin discoloration, blister formation, and eventually ulceration. Over a period of months, the ulcers were treated with several courses of antibiotics and wound care including a single surgical debridement of one of the ulcers on the dorsum of the right foot. These interventions did not make a remarkable impact on ulcer healing.

On physical examination, the patient had scattered 4- to 5-mm palpable purpura on the knees, elbows, and feet bilaterally. She had multiple 1- to 8-cm indurated purple ulcerations with friable surfaces and raised irregular borders on the feet, toes, and lower legs bilaterally (Figure, A–C). One notably larger ulcer was found on the anterior aspect of the left thigh (Figure, A). Scattered 5- to 15-mm eschars were present on the legs bilaterally. She also had multiple large, firm, nonerythematous dermal plaques on the thighs bilaterally that measured several centimeters. There were no oral mucosal lesions and no ulcerations above the waist.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the foot showed some surrounding cellulitis but no osteomyelitis. Chest radiograph and computed tomography revealed bilateral apical nodules. Proteinase 3–antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (PR3-ANCA) testing was positive. Serum complement levels were normal. An antinuclear antibody test and rheumatoid factor were both negative. Skin biopsies were obtained from the thigh ulcer, foot ulcer, and purpuric lesions on the right knee. The results demonstrated leukocytoclastic vasculitis and neutrophilic small vessel vasculitis with necrotizing neutrophilic dermatitis and panniculitis. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) was diagnosed based on these findings.

Initial inpatient treatment included intravenous methylprednisolone (100 mg every 8 hours for 3 doses), followed by oral prednisone 60 mg daily. Two weeks later the ulcers were reevaluated and only mild improvement had occurred with the steroids. Therefore, rituximab (RTX) was initiated at 375 mg/m2 (700 mg) intravenously once weekly for 4 weeks. After 3 doses of RTX, the ulcerations were healing dramatically and the treatment was well tolerated. A rapid prednisone taper was started, and the patient received her fourth and final dose of RTX. Two months after the initial infusion, the thigh ulcer and most of the ulcerations on the feet and lower legs had almost completely resolved. Photographs were taken 5 months after initial RTX infusion (Figure, D–F). A chest radiograph 4 months after initial RTX infusion showed resolution of lung nodules. Two months after RTX induction therapy, azathioprine was added for maintenance but was stopped due to poor tolerance. Oral methotrexate 17.5 mg once weekly was added 5 months after RTX for maintenance and was well tolerated. At that time the prednisone dose was 10 mg daily and was successfully tapered to 5 mg by 9 months after RTX induction therapy.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis) is a granulomatous small- and medium-sized vessel vasculitis that traditionally affects the upper and lower respiratory tract and kidneys.1 Skin lesions also are quite common and include palpable purpura, ulcers, vesicles, papules, and subcutaneous nodules. Patients with active GPA also tend to have ANCAs directed against proteinase 3 (PR3-ANCA). Although GPA was once considered a fatal disease, treatment with cyclophosphamide combined with corticosteroids has been shown to substantially improve outcomes.1 Rituximab, a chimeric monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody, works by depleting B lymphocytes and has been used with success to treat diseases such as lymphoma and rheumatoid arthritis.2,3 The US Food and Drug Administration approved RTX for GPA and microscopic polyangiitis in 2011, with a number of trials supporting its efficacy.4