User login

Don’t Forget the Pulses! Aortoiliac Peripheral Artery Disease Masquerading as Lumbar Radiculopathy—A Report of 3 Cases

Lumbar radiculopathy is a common problem encountered by orthopedic surgeons, and typically presents with lower back or buttock pain radiating down the leg.1 While the most common causes of lumbar radiculopathy are lumbar disc herniation and spinal stenosis, the differential diagnosis for lower extremity pain is broad and can be musculoskeletal, vascular, neurologic, or inflammatory in nature.1,2 Differentiating between orthopedic, neurologic, and vascular causes of leg pain, such as peripheral artery disease (PAD), can sometimes be challenging. This is especially true in aortoiliac PAD, which can present with hip, buttock, and thigh pain. Dorsalis pedis pulses can be palpable due to collateral circulation. A careful history and physical examination is crucial to the correct diagnosis. The history should clearly document the nature of the pain, details of walking impairment, and the alleviating effects of standing still or positional changes. A complete neurovascular examination should include observations regarding the skin, hair, and nails, examination of dorsal pedis, popliteal, and femoral pulses in comparison to the contralateral side, and documentation of dural tension signs. Misdiagnoses can send the patient down a path of unnecessary tests, unindicated procedures, and ultimately, a delay in definitive diagnosis and treatment.1

To our knowledge, this is the first report on a series of patients with thigh pain initially diagnosed as radiculopathy who underwent unproductive diagnostic tests and procedures, and ultimately were given delayed diagnoses of aortoiliac PAD. The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Case 1

An 81-year-old woman with a medical history notable for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and stroke initially presented to an outside orthopedic institution with complaints of several months of lower back and right hip, thigh, and leg pain when walking. She did not report any history of night pain, weakness, or numbness. Examination at the time was notable for painful back extension, 4/5 hip flexion strength on the right compared to 5/5 on the left, but symmetric reflexes and negative dural tension signs. X-rays showed multilevel degenerative disc disease of the lumbar spine, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a small L3/4 disc protrusion causing impingement of the L4 nerve root.

A transforaminal epidural steroid injection at the L4 level was performed with minimal resolution of symptoms. Several months later, right-sided intra-articular facet injections were performed at the L4/5 and L5/S1 levels, again with minimal relief of symptoms. At this point, the patient was sent for further physical therapy.

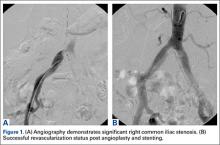

Over a year after symptom onset, the patient presented to our institution and was evaluated by a vascular surgeon. Physical examination was notable for 1+ femoral artery and dorsal pedis pulses on the right side, compared to 2+ on the left. An aortoiliac duplex ultrasound showed severe significant stenosis of the right common iliac artery (>75%).

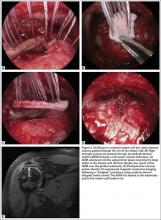

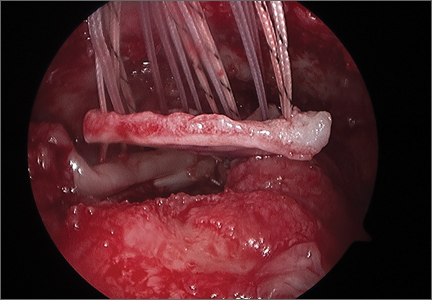

The patient underwent a right common iliac artery angioplasty and stenting (Figures 1A, 1B), which resolved her symptoms.

Case 2

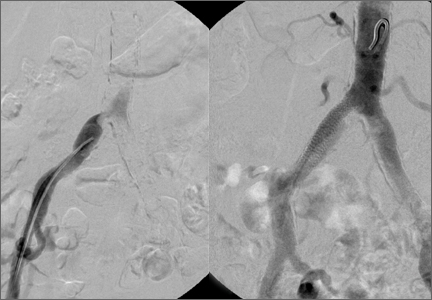

A 65-year-old man, who is a former smoker with a medical history notable for hyperlipidemia and coronary artery disease status post myocardial infarction, presented with a long history of right leg pain. He underwent a L5/S1 anterior posterior fusion at an outside institution and did well for about 5 years after the procedure (Figures 2A, 2B). The pain returned and he underwent several years of physical therapy, epidural steroid injections, and implantation of a spinal cord stimulator with no improvement. He reported right leg pain with minimal back pain, primarily in the thigh and not radiating to the feet and toes. The pain limited him from walking more than 1 block. On examination, strength was 5/5 bilaterally. Pulse examination was notable for lack of dorsalis pedis/posterior tibial pulses bilaterally. He had no bowel or bladder dysfunction.

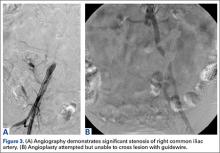

Computed tomography myelogram showed a moderate amount of stenosis at L3/4 and L4/5. He was sent for evaluation by a vascular surgeon. Arterial duplex ultrasound showed significant stenosis of the right common iliac artery.

Angioplasty was attempted but vascular surgery was unable to cross the lesion (Figures 3A, 3B), and the patient ultimately had a femoral-femoral bypass, which resolved his leg pain.

Case 3

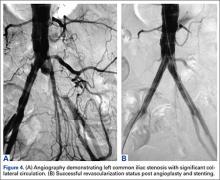

A 78-year-old woman, nonsmoker, presented with a 1-year history of left buttock and thigh pain exacerbated by ambulation. Ambulation was limited to 2 blocks. The patient was being worked up for spinal and hip etiologies of pain at an outside hospital. MRI revealed a mild posterior disc herniation at L3/4 and L4/5 and moderate narrowing of the spinal canal. She underwent 2 epidural steroid injections with no improvement. The patient’s relative, a physician, suggested that the patient receive a vascular surgery consultation, and the patient ultimately presented to our institution for evaluation by vascular surgery.

The physical examination was significant for a 1+ dorsal pedis pulse on the left compared to 2+ on the right. Moreover, the patient only demonstrated trace L femoral pulse compared to the right. Strength was 5/5 bilaterally.

The patient was taken to the operating room for angioplasty and stenting of the left common iliac artery (Figures 4A, 4B). This provided immediate symptom relief, and she has remained asymptomatic.

Discussion

Lumbar radiculopathy is a common diagnosis encountered by orthopedic surgeons. Although the diagnosis can appear to be straightforward in a patient presenting with lower back and leg pain, the etiology of lower back and leg pain can be extremely varied, and can be musculoskeletal, neurologic, vascular, rheumatologic, or oncologic in origin.1 In particular, differentiating between radiculopathy and vascular claudication can sometimes be challenging.

The 2 most common causes of lumbar radiculopathy are lumbar disc herniation and spinal stenosis.1 Lumbar disc herniation results from tear in the annulus of the intervertebral disc, resulting in herniation of disc material into the spinal canal causing compression and irritation of spinal nerve roots.1 Spinal stenosis is narrowing of the spinal canal that produces compression of neural elements before they exit the neural foramen.3 Adult degenerative spinal stenosis is most often caused by osteophytes from the facet joints or hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum, and can be broadly categorized into central spinal stenosis or lateral spinal stenosis.

PAD is defined as progressive stenosis or occlusion, or aneurysmal dilation of noncoronary arteries.2 When PAD affects the vessels of the lower extremities, the symptoms typically manifest as intermittent claudication, which is exercise-induced ischemic pain in the lower extremity that is relieved by rest.2 As the disease progresses, symptoms can progress to rest pain, ulceration, and, eventually, gangrene. The most common cause of PAD is atherosclerosis, and the risk factors include smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. The prevalence of PAD rises sharply with age, starting from <3% in ages less than 60 years to >20% in ages 75 years and older.4

A detailed and pertinent history from the patient provides important information for differentiating radiculopathy and neurogenic claudication from vascular claudication. Patients with lumbar radiculopathy typically report pain in the lower back radiating down the leg past the knee in a dermatomal distribution. The pain often begins soon if not immediately after activity, but often takes time for relief onset after rest. Positional changes in the back such as flexion can provide relief.2 Patients with neurogenic claudication from central spinal stenosis can present with bilateral thigh pain from prolonged standing and activity that is alleviated with flexion or stooping.3 Patients may admit to a positive “shopping cart sign,” with increased walking comfort stooped forward with hands on a shopping cart.

In contrast, patients with vascular claudication often report pain in the calf, thigh, or hip, but rarely in the foot. The location of pain varies with area of stenosis; generally, patients with superficial femoral artery occlusion present with calf claudication, while patients with aortoiliac disease present with buttock and thigh pain. The pain typically occurs after a very reproducible length of walking, and is relieved by cessation of walking, often even if the patient remains standing. Back positioning should have no effect on the pain.2-5

Physical examination should begin with observation of the patient’s gait and posture, which may be hunched over in the setting of spinal stenosis. Examination of the patient’s skin may show loss of hair, shiny skin, or atrophic changes suggestive of vascular disease (Figure 5).1 Prior to proceeding to a spine examination, palpating the trochanteric bursa and testing for hip range of motion is important to rule out intra-articular hip pathology and trochanteric bursitis as common causes of pain in the area. Patients with radiculopathy may show sensory disturbances in a dermatomal distribution, muscular weakness at the corresponding spinal level, and decreased deep tendon reflexes. The straight leg raise test can elicit signs of nerve root tension. A careful examination of bilateral lower extremity pulses at the dorsal pedis, popliteal, and femoral levels can help identify any asymmetric or decreased pulses that would indicate peripheral vascular disease. With chronic aortoiliac disease, it is important to check for femoral pulses, given the dorsal pedis pulse can be present due to collateral circulation. And finally, the ankle brachial index (ABI), measured as the ratio of the systolic pressure at the ankle divided by the systolic pressure at the arm, is a good screening test for PAD.6 A normal ABI is >1.

A thorough history and physical examination can elicit important information that is helpful in evaluating orthopedic patients, especially to differentiate between spinal and vascular causes of leg pain. This can help avoid misdiagnoses, which result in unnecessary tests, procedures, and wasted time. Don’t forget the pulses!

1. Grimm BD, Blessinger BJ, Darden BV, Brigham CD, Kneisl JS, Laxer EB. Mimickers of lumbar radiculopathy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(1):7-17.

2. Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Peripheral Arterial Disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Associations for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease)--summary of recommendations. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17(9):1383-1397.

3. Spivak JM. Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(7):1053-1066.

4. Criqui MH, Fronek A, Barrett-Connor E, Klauber MR, Gabriel S, Goodman D. The prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in a defined population. Circulation. 1985;71(3):510-515.

5. Ouriel K. Peripheral arterial disease. Lancet. 2001;358(9289):1257-1264.

6. Jeon CH, Han SH, Chung NS, Hyun HS. The validity of ankle-brachial index for the differential diagnosis of peripheral arterial disease and lumbar spinal stenosis in patients with atypical claudication. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(6):1165-1170.

Lumbar radiculopathy is a common problem encountered by orthopedic surgeons, and typically presents with lower back or buttock pain radiating down the leg.1 While the most common causes of lumbar radiculopathy are lumbar disc herniation and spinal stenosis, the differential diagnosis for lower extremity pain is broad and can be musculoskeletal, vascular, neurologic, or inflammatory in nature.1,2 Differentiating between orthopedic, neurologic, and vascular causes of leg pain, such as peripheral artery disease (PAD), can sometimes be challenging. This is especially true in aortoiliac PAD, which can present with hip, buttock, and thigh pain. Dorsalis pedis pulses can be palpable due to collateral circulation. A careful history and physical examination is crucial to the correct diagnosis. The history should clearly document the nature of the pain, details of walking impairment, and the alleviating effects of standing still or positional changes. A complete neurovascular examination should include observations regarding the skin, hair, and nails, examination of dorsal pedis, popliteal, and femoral pulses in comparison to the contralateral side, and documentation of dural tension signs. Misdiagnoses can send the patient down a path of unnecessary tests, unindicated procedures, and ultimately, a delay in definitive diagnosis and treatment.1

To our knowledge, this is the first report on a series of patients with thigh pain initially diagnosed as radiculopathy who underwent unproductive diagnostic tests and procedures, and ultimately were given delayed diagnoses of aortoiliac PAD. The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Case 1

An 81-year-old woman with a medical history notable for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and stroke initially presented to an outside orthopedic institution with complaints of several months of lower back and right hip, thigh, and leg pain when walking. She did not report any history of night pain, weakness, or numbness. Examination at the time was notable for painful back extension, 4/5 hip flexion strength on the right compared to 5/5 on the left, but symmetric reflexes and negative dural tension signs. X-rays showed multilevel degenerative disc disease of the lumbar spine, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a small L3/4 disc protrusion causing impingement of the L4 nerve root.

A transforaminal epidural steroid injection at the L4 level was performed with minimal resolution of symptoms. Several months later, right-sided intra-articular facet injections were performed at the L4/5 and L5/S1 levels, again with minimal relief of symptoms. At this point, the patient was sent for further physical therapy.

Over a year after symptom onset, the patient presented to our institution and was evaluated by a vascular surgeon. Physical examination was notable for 1+ femoral artery and dorsal pedis pulses on the right side, compared to 2+ on the left. An aortoiliac duplex ultrasound showed severe significant stenosis of the right common iliac artery (>75%).

The patient underwent a right common iliac artery angioplasty and stenting (Figures 1A, 1B), which resolved her symptoms.

Case 2

A 65-year-old man, who is a former smoker with a medical history notable for hyperlipidemia and coronary artery disease status post myocardial infarction, presented with a long history of right leg pain. He underwent a L5/S1 anterior posterior fusion at an outside institution and did well for about 5 years after the procedure (Figures 2A, 2B). The pain returned and he underwent several years of physical therapy, epidural steroid injections, and implantation of a spinal cord stimulator with no improvement. He reported right leg pain with minimal back pain, primarily in the thigh and not radiating to the feet and toes. The pain limited him from walking more than 1 block. On examination, strength was 5/5 bilaterally. Pulse examination was notable for lack of dorsalis pedis/posterior tibial pulses bilaterally. He had no bowel or bladder dysfunction.

Computed tomography myelogram showed a moderate amount of stenosis at L3/4 and L4/5. He was sent for evaluation by a vascular surgeon. Arterial duplex ultrasound showed significant stenosis of the right common iliac artery.

Angioplasty was attempted but vascular surgery was unable to cross the lesion (Figures 3A, 3B), and the patient ultimately had a femoral-femoral bypass, which resolved his leg pain.

Case 3

A 78-year-old woman, nonsmoker, presented with a 1-year history of left buttock and thigh pain exacerbated by ambulation. Ambulation was limited to 2 blocks. The patient was being worked up for spinal and hip etiologies of pain at an outside hospital. MRI revealed a mild posterior disc herniation at L3/4 and L4/5 and moderate narrowing of the spinal canal. She underwent 2 epidural steroid injections with no improvement. The patient’s relative, a physician, suggested that the patient receive a vascular surgery consultation, and the patient ultimately presented to our institution for evaluation by vascular surgery.

The physical examination was significant for a 1+ dorsal pedis pulse on the left compared to 2+ on the right. Moreover, the patient only demonstrated trace L femoral pulse compared to the right. Strength was 5/5 bilaterally.

The patient was taken to the operating room for angioplasty and stenting of the left common iliac artery (Figures 4A, 4B). This provided immediate symptom relief, and she has remained asymptomatic.

Discussion

Lumbar radiculopathy is a common diagnosis encountered by orthopedic surgeons. Although the diagnosis can appear to be straightforward in a patient presenting with lower back and leg pain, the etiology of lower back and leg pain can be extremely varied, and can be musculoskeletal, neurologic, vascular, rheumatologic, or oncologic in origin.1 In particular, differentiating between radiculopathy and vascular claudication can sometimes be challenging.

The 2 most common causes of lumbar radiculopathy are lumbar disc herniation and spinal stenosis.1 Lumbar disc herniation results from tear in the annulus of the intervertebral disc, resulting in herniation of disc material into the spinal canal causing compression and irritation of spinal nerve roots.1 Spinal stenosis is narrowing of the spinal canal that produces compression of neural elements before they exit the neural foramen.3 Adult degenerative spinal stenosis is most often caused by osteophytes from the facet joints or hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum, and can be broadly categorized into central spinal stenosis or lateral spinal stenosis.

PAD is defined as progressive stenosis or occlusion, or aneurysmal dilation of noncoronary arteries.2 When PAD affects the vessels of the lower extremities, the symptoms typically manifest as intermittent claudication, which is exercise-induced ischemic pain in the lower extremity that is relieved by rest.2 As the disease progresses, symptoms can progress to rest pain, ulceration, and, eventually, gangrene. The most common cause of PAD is atherosclerosis, and the risk factors include smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. The prevalence of PAD rises sharply with age, starting from <3% in ages less than 60 years to >20% in ages 75 years and older.4

A detailed and pertinent history from the patient provides important information for differentiating radiculopathy and neurogenic claudication from vascular claudication. Patients with lumbar radiculopathy typically report pain in the lower back radiating down the leg past the knee in a dermatomal distribution. The pain often begins soon if not immediately after activity, but often takes time for relief onset after rest. Positional changes in the back such as flexion can provide relief.2 Patients with neurogenic claudication from central spinal stenosis can present with bilateral thigh pain from prolonged standing and activity that is alleviated with flexion or stooping.3 Patients may admit to a positive “shopping cart sign,” with increased walking comfort stooped forward with hands on a shopping cart.

In contrast, patients with vascular claudication often report pain in the calf, thigh, or hip, but rarely in the foot. The location of pain varies with area of stenosis; generally, patients with superficial femoral artery occlusion present with calf claudication, while patients with aortoiliac disease present with buttock and thigh pain. The pain typically occurs after a very reproducible length of walking, and is relieved by cessation of walking, often even if the patient remains standing. Back positioning should have no effect on the pain.2-5

Physical examination should begin with observation of the patient’s gait and posture, which may be hunched over in the setting of spinal stenosis. Examination of the patient’s skin may show loss of hair, shiny skin, or atrophic changes suggestive of vascular disease (Figure 5).1 Prior to proceeding to a spine examination, palpating the trochanteric bursa and testing for hip range of motion is important to rule out intra-articular hip pathology and trochanteric bursitis as common causes of pain in the area. Patients with radiculopathy may show sensory disturbances in a dermatomal distribution, muscular weakness at the corresponding spinal level, and decreased deep tendon reflexes. The straight leg raise test can elicit signs of nerve root tension. A careful examination of bilateral lower extremity pulses at the dorsal pedis, popliteal, and femoral levels can help identify any asymmetric or decreased pulses that would indicate peripheral vascular disease. With chronic aortoiliac disease, it is important to check for femoral pulses, given the dorsal pedis pulse can be present due to collateral circulation. And finally, the ankle brachial index (ABI), measured as the ratio of the systolic pressure at the ankle divided by the systolic pressure at the arm, is a good screening test for PAD.6 A normal ABI is >1.

A thorough history and physical examination can elicit important information that is helpful in evaluating orthopedic patients, especially to differentiate between spinal and vascular causes of leg pain. This can help avoid misdiagnoses, which result in unnecessary tests, procedures, and wasted time. Don’t forget the pulses!

Lumbar radiculopathy is a common problem encountered by orthopedic surgeons, and typically presents with lower back or buttock pain radiating down the leg.1 While the most common causes of lumbar radiculopathy are lumbar disc herniation and spinal stenosis, the differential diagnosis for lower extremity pain is broad and can be musculoskeletal, vascular, neurologic, or inflammatory in nature.1,2 Differentiating between orthopedic, neurologic, and vascular causes of leg pain, such as peripheral artery disease (PAD), can sometimes be challenging. This is especially true in aortoiliac PAD, which can present with hip, buttock, and thigh pain. Dorsalis pedis pulses can be palpable due to collateral circulation. A careful history and physical examination is crucial to the correct diagnosis. The history should clearly document the nature of the pain, details of walking impairment, and the alleviating effects of standing still or positional changes. A complete neurovascular examination should include observations regarding the skin, hair, and nails, examination of dorsal pedis, popliteal, and femoral pulses in comparison to the contralateral side, and documentation of dural tension signs. Misdiagnoses can send the patient down a path of unnecessary tests, unindicated procedures, and ultimately, a delay in definitive diagnosis and treatment.1

To our knowledge, this is the first report on a series of patients with thigh pain initially diagnosed as radiculopathy who underwent unproductive diagnostic tests and procedures, and ultimately were given delayed diagnoses of aortoiliac PAD. The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Case 1

An 81-year-old woman with a medical history notable for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and stroke initially presented to an outside orthopedic institution with complaints of several months of lower back and right hip, thigh, and leg pain when walking. She did not report any history of night pain, weakness, or numbness. Examination at the time was notable for painful back extension, 4/5 hip flexion strength on the right compared to 5/5 on the left, but symmetric reflexes and negative dural tension signs. X-rays showed multilevel degenerative disc disease of the lumbar spine, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a small L3/4 disc protrusion causing impingement of the L4 nerve root.

A transforaminal epidural steroid injection at the L4 level was performed with minimal resolution of symptoms. Several months later, right-sided intra-articular facet injections were performed at the L4/5 and L5/S1 levels, again with minimal relief of symptoms. At this point, the patient was sent for further physical therapy.

Over a year after symptom onset, the patient presented to our institution and was evaluated by a vascular surgeon. Physical examination was notable for 1+ femoral artery and dorsal pedis pulses on the right side, compared to 2+ on the left. An aortoiliac duplex ultrasound showed severe significant stenosis of the right common iliac artery (>75%).

The patient underwent a right common iliac artery angioplasty and stenting (Figures 1A, 1B), which resolved her symptoms.

Case 2

A 65-year-old man, who is a former smoker with a medical history notable for hyperlipidemia and coronary artery disease status post myocardial infarction, presented with a long history of right leg pain. He underwent a L5/S1 anterior posterior fusion at an outside institution and did well for about 5 years after the procedure (Figures 2A, 2B). The pain returned and he underwent several years of physical therapy, epidural steroid injections, and implantation of a spinal cord stimulator with no improvement. He reported right leg pain with minimal back pain, primarily in the thigh and not radiating to the feet and toes. The pain limited him from walking more than 1 block. On examination, strength was 5/5 bilaterally. Pulse examination was notable for lack of dorsalis pedis/posterior tibial pulses bilaterally. He had no bowel or bladder dysfunction.

Computed tomography myelogram showed a moderate amount of stenosis at L3/4 and L4/5. He was sent for evaluation by a vascular surgeon. Arterial duplex ultrasound showed significant stenosis of the right common iliac artery.

Angioplasty was attempted but vascular surgery was unable to cross the lesion (Figures 3A, 3B), and the patient ultimately had a femoral-femoral bypass, which resolved his leg pain.

Case 3

A 78-year-old woman, nonsmoker, presented with a 1-year history of left buttock and thigh pain exacerbated by ambulation. Ambulation was limited to 2 blocks. The patient was being worked up for spinal and hip etiologies of pain at an outside hospital. MRI revealed a mild posterior disc herniation at L3/4 and L4/5 and moderate narrowing of the spinal canal. She underwent 2 epidural steroid injections with no improvement. The patient’s relative, a physician, suggested that the patient receive a vascular surgery consultation, and the patient ultimately presented to our institution for evaluation by vascular surgery.

The physical examination was significant for a 1+ dorsal pedis pulse on the left compared to 2+ on the right. Moreover, the patient only demonstrated trace L femoral pulse compared to the right. Strength was 5/5 bilaterally.

The patient was taken to the operating room for angioplasty and stenting of the left common iliac artery (Figures 4A, 4B). This provided immediate symptom relief, and she has remained asymptomatic.

Discussion

Lumbar radiculopathy is a common diagnosis encountered by orthopedic surgeons. Although the diagnosis can appear to be straightforward in a patient presenting with lower back and leg pain, the etiology of lower back and leg pain can be extremely varied, and can be musculoskeletal, neurologic, vascular, rheumatologic, or oncologic in origin.1 In particular, differentiating between radiculopathy and vascular claudication can sometimes be challenging.

The 2 most common causes of lumbar radiculopathy are lumbar disc herniation and spinal stenosis.1 Lumbar disc herniation results from tear in the annulus of the intervertebral disc, resulting in herniation of disc material into the spinal canal causing compression and irritation of spinal nerve roots.1 Spinal stenosis is narrowing of the spinal canal that produces compression of neural elements before they exit the neural foramen.3 Adult degenerative spinal stenosis is most often caused by osteophytes from the facet joints or hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum, and can be broadly categorized into central spinal stenosis or lateral spinal stenosis.

PAD is defined as progressive stenosis or occlusion, or aneurysmal dilation of noncoronary arteries.2 When PAD affects the vessels of the lower extremities, the symptoms typically manifest as intermittent claudication, which is exercise-induced ischemic pain in the lower extremity that is relieved by rest.2 As the disease progresses, symptoms can progress to rest pain, ulceration, and, eventually, gangrene. The most common cause of PAD is atherosclerosis, and the risk factors include smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. The prevalence of PAD rises sharply with age, starting from <3% in ages less than 60 years to >20% in ages 75 years and older.4

A detailed and pertinent history from the patient provides important information for differentiating radiculopathy and neurogenic claudication from vascular claudication. Patients with lumbar radiculopathy typically report pain in the lower back radiating down the leg past the knee in a dermatomal distribution. The pain often begins soon if not immediately after activity, but often takes time for relief onset after rest. Positional changes in the back such as flexion can provide relief.2 Patients with neurogenic claudication from central spinal stenosis can present with bilateral thigh pain from prolonged standing and activity that is alleviated with flexion or stooping.3 Patients may admit to a positive “shopping cart sign,” with increased walking comfort stooped forward with hands on a shopping cart.

In contrast, patients with vascular claudication often report pain in the calf, thigh, or hip, but rarely in the foot. The location of pain varies with area of stenosis; generally, patients with superficial femoral artery occlusion present with calf claudication, while patients with aortoiliac disease present with buttock and thigh pain. The pain typically occurs after a very reproducible length of walking, and is relieved by cessation of walking, often even if the patient remains standing. Back positioning should have no effect on the pain.2-5

Physical examination should begin with observation of the patient’s gait and posture, which may be hunched over in the setting of spinal stenosis. Examination of the patient’s skin may show loss of hair, shiny skin, or atrophic changes suggestive of vascular disease (Figure 5).1 Prior to proceeding to a spine examination, palpating the trochanteric bursa and testing for hip range of motion is important to rule out intra-articular hip pathology and trochanteric bursitis as common causes of pain in the area. Patients with radiculopathy may show sensory disturbances in a dermatomal distribution, muscular weakness at the corresponding spinal level, and decreased deep tendon reflexes. The straight leg raise test can elicit signs of nerve root tension. A careful examination of bilateral lower extremity pulses at the dorsal pedis, popliteal, and femoral levels can help identify any asymmetric or decreased pulses that would indicate peripheral vascular disease. With chronic aortoiliac disease, it is important to check for femoral pulses, given the dorsal pedis pulse can be present due to collateral circulation. And finally, the ankle brachial index (ABI), measured as the ratio of the systolic pressure at the ankle divided by the systolic pressure at the arm, is a good screening test for PAD.6 A normal ABI is >1.

A thorough history and physical examination can elicit important information that is helpful in evaluating orthopedic patients, especially to differentiate between spinal and vascular causes of leg pain. This can help avoid misdiagnoses, which result in unnecessary tests, procedures, and wasted time. Don’t forget the pulses!

1. Grimm BD, Blessinger BJ, Darden BV, Brigham CD, Kneisl JS, Laxer EB. Mimickers of lumbar radiculopathy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(1):7-17.

2. Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Peripheral Arterial Disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Associations for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease)--summary of recommendations. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17(9):1383-1397.

3. Spivak JM. Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(7):1053-1066.

4. Criqui MH, Fronek A, Barrett-Connor E, Klauber MR, Gabriel S, Goodman D. The prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in a defined population. Circulation. 1985;71(3):510-515.

5. Ouriel K. Peripheral arterial disease. Lancet. 2001;358(9289):1257-1264.

6. Jeon CH, Han SH, Chung NS, Hyun HS. The validity of ankle-brachial index for the differential diagnosis of peripheral arterial disease and lumbar spinal stenosis in patients with atypical claudication. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(6):1165-1170.

1. Grimm BD, Blessinger BJ, Darden BV, Brigham CD, Kneisl JS, Laxer EB. Mimickers of lumbar radiculopathy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(1):7-17.

2. Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Peripheral Arterial Disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Associations for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease)--summary of recommendations. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17(9):1383-1397.

3. Spivak JM. Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(7):1053-1066.

4. Criqui MH, Fronek A, Barrett-Connor E, Klauber MR, Gabriel S, Goodman D. The prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in a defined population. Circulation. 1985;71(3):510-515.

5. Ouriel K. Peripheral arterial disease. Lancet. 2001;358(9289):1257-1264.

6. Jeon CH, Han SH, Chung NS, Hyun HS. The validity of ankle-brachial index for the differential diagnosis of peripheral arterial disease and lumbar spinal stenosis in patients with atypical claudication. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(6):1165-1170.

Eye Findings in Dermatologic Conditions

Review the PDF of the fact sheet on eye findings in dermatologic conditions with board-relevant, easy-to-review material. This month's fact sheet will review ophthalmologic findings associated with inherited dermatologic conditions.

Practice Questions

1. Which type of EDS is most characteristically associated with blue sclerae and globe rupture?

a. arthrochalasia

b. classical

c. dermatosparaxis

d. hypermobility

e. kyphoscoliosis

2. Ankyloblepharon may be associated with mutation of which gene?

a. fibrillin 1

b. LMX1B

c. NF1

d. p53

e. p63

3. Which is a characteristic ocular tumor in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex?

a. congenital hypertrophy of retinal pigment epithelium

b. phakoma

c. pigmented iris hamartoma

d. pinguecula

e. pterygium

4. Which syndrome is not associated with blue sclerae?

a. EDS type 6

b. lipoid proteinosis

c. Marfan syndrome

d. osteogenesis imperfecta type II

e. pseudoxanthoma elasticum

5. Which term describes white spots at the periphery of the iris?

a. Brushfield spots

b. coloboma

c. Kayser-Fleischer rings

d. Lester iris

e. Lisch nodules

Answers to practice questions provided on next page

Practice Question Answers

1. Which type of EDS is most characteristically associated with blue sclerae and globe rupture?

a. arthrochalasia

b. classical

c. dermatosparaxis

d. hypermobility

e. kyphoscoliosis

2. Ankyloblepharon may be associated with mutation of which gene?

a. fibrillin 1

b. LMX1B

c. NF1

d. p53

e. p63

3. Which is a characteristic ocular tumor in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex?

a. congenital hypertrophy of retinal pigment epithelium

b. phakoma

c. pigmented iris hamartoma

d. pinguecula

e. pterygium

4. Which syndrome is not associated with blue sclerae?

a. EDS type 6

b. lipoid proteinosis

c. Marfan syndrome

d. osteogenesis imperfecta type II

e. pseudoxanthoma elasticum

5. Which term describes white spots at the periphery of the iris?

a. Brushfield spots

b. coloboma

c. Kayser-Fleischer rings

d. Lester iris

e. Lisch nodules

Review the PDF of the fact sheet on eye findings in dermatologic conditions with board-relevant, easy-to-review material. This month's fact sheet will review ophthalmologic findings associated with inherited dermatologic conditions.

Practice Questions

1. Which type of EDS is most characteristically associated with blue sclerae and globe rupture?

a. arthrochalasia

b. classical

c. dermatosparaxis

d. hypermobility

e. kyphoscoliosis

2. Ankyloblepharon may be associated with mutation of which gene?

a. fibrillin 1

b. LMX1B

c. NF1

d. p53

e. p63

3. Which is a characteristic ocular tumor in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex?

a. congenital hypertrophy of retinal pigment epithelium

b. phakoma

c. pigmented iris hamartoma

d. pinguecula

e. pterygium

4. Which syndrome is not associated with blue sclerae?

a. EDS type 6

b. lipoid proteinosis

c. Marfan syndrome

d. osteogenesis imperfecta type II

e. pseudoxanthoma elasticum

5. Which term describes white spots at the periphery of the iris?

a. Brushfield spots

b. coloboma

c. Kayser-Fleischer rings

d. Lester iris

e. Lisch nodules

Answers to practice questions provided on next page

Practice Question Answers

1. Which type of EDS is most characteristically associated with blue sclerae and globe rupture?

a. arthrochalasia

b. classical

c. dermatosparaxis

d. hypermobility

e. kyphoscoliosis

2. Ankyloblepharon may be associated with mutation of which gene?

a. fibrillin 1

b. LMX1B

c. NF1

d. p53

e. p63

3. Which is a characteristic ocular tumor in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex?

a. congenital hypertrophy of retinal pigment epithelium

b. phakoma

c. pigmented iris hamartoma

d. pinguecula

e. pterygium

4. Which syndrome is not associated with blue sclerae?

a. EDS type 6

b. lipoid proteinosis

c. Marfan syndrome

d. osteogenesis imperfecta type II

e. pseudoxanthoma elasticum

5. Which term describes white spots at the periphery of the iris?

a. Brushfield spots

b. coloboma

c. Kayser-Fleischer rings

d. Lester iris

e. Lisch nodules

Review the PDF of the fact sheet on eye findings in dermatologic conditions with board-relevant, easy-to-review material. This month's fact sheet will review ophthalmologic findings associated with inherited dermatologic conditions.

Practice Questions

1. Which type of EDS is most characteristically associated with blue sclerae and globe rupture?

a. arthrochalasia

b. classical

c. dermatosparaxis

d. hypermobility

e. kyphoscoliosis

2. Ankyloblepharon may be associated with mutation of which gene?

a. fibrillin 1

b. LMX1B

c. NF1

d. p53

e. p63

3. Which is a characteristic ocular tumor in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex?

a. congenital hypertrophy of retinal pigment epithelium

b. phakoma

c. pigmented iris hamartoma

d. pinguecula

e. pterygium

4. Which syndrome is not associated with blue sclerae?

a. EDS type 6

b. lipoid proteinosis

c. Marfan syndrome

d. osteogenesis imperfecta type II

e. pseudoxanthoma elasticum

5. Which term describes white spots at the periphery of the iris?

a. Brushfield spots

b. coloboma

c. Kayser-Fleischer rings

d. Lester iris

e. Lisch nodules

Answers to practice questions provided on next page

Practice Question Answers

1. Which type of EDS is most characteristically associated with blue sclerae and globe rupture?

a. arthrochalasia

b. classical

c. dermatosparaxis

d. hypermobility

e. kyphoscoliosis

2. Ankyloblepharon may be associated with mutation of which gene?

a. fibrillin 1

b. LMX1B

c. NF1

d. p53

e. p63

3. Which is a characteristic ocular tumor in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex?

a. congenital hypertrophy of retinal pigment epithelium

b. phakoma

c. pigmented iris hamartoma

d. pinguecula

e. pterygium

4. Which syndrome is not associated with blue sclerae?

a. EDS type 6

b. lipoid proteinosis

c. Marfan syndrome

d. osteogenesis imperfecta type II

e. pseudoxanthoma elasticum

5. Which term describes white spots at the periphery of the iris?

a. Brushfield spots

b. coloboma

c. Kayser-Fleischer rings

d. Lester iris

e. Lisch nodules

Efficacy of Unloader Bracing in Reducing Symptoms of Knee Osteoarthritis

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a progressive, degenerative joint disease characterized by pain and dysfunction. OA is a leading cause of disability in middle-aged and older adults,1 affecting an estimated 27 million Americans.2 With the continued aging of the baby boomer population and rising obesity rates, the incidence of OA is estimated to increase by 40% by 2025.3 The clinical and economic burdens of OA on our society—medical costs and workdays lost—are significant and will continue to be a problem for years to come.4

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is an option for severe end-stage OA. Most patients with mild to moderate OA follow nonsurgical strategies in an attempt to avoid invasive procedures. As there is no established cure, initial treatment of knee OA is geared toward alleviating pain and improving function. A multimodal approach is typically used and recommended.5,6 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, and narcotic analgesics are commonly prescribed. NSAIDs can be effective7 but have well-known cardiovascular, renal, and gastrointestinal risks. If possible, narcotic analgesics should be avoided because of the risk of addiction and the problems associated with dependence. Intra-articular injections of corticosteroids or hyaluronic acid (viscosupplementation) are often recommended to reduce pain associated with arthritis. Braces designed to “off-load” the more diseased medial or lateral compartment of the knee have also been used in an effort to provide symptomatic relief. These low-risk, noninvasive unloader braces have increasingly been advanced as a conservative treatment modality for knee OA,6,8-10despite modest evidence and lack of appropriately powered randomized controlled trials.11 As more research on the efficacy of these braces is needed, we conducted a study to determine whether an unloader brace is an acceptable and valid treatment modality for knee OA.

Patients and Methods

This was a prospective, randomized, controlled trial of patients with symptomatic, predominantly unicompartmental OA involving the medial compartment of the knee. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Baptist Hospital in Pensacola, Florida. Patients were excluded if they had a rheumatologic disorder other than OA; a history of knee surgery other than a routine arthroscopic procedure; any soft-tissue, neurologic, or vascular compromise preventing long-term brace use; or obesity preventing effective or comfortable brace use. It is generally felt that unloader bracing may not be effective for patients with severe contractures or significant knee deformity; therefore, those lacking more than 10° of extension or 20° of flexion, or those who had a varus deformity of more than 8° of varus, were not offered enrollment.

Ideal sizes for the proposed study groups were determined through power analysis using standard deviations from prior similar investigations. The target was 30 patients per group.

Patients gave informed consent to the work. A computer-generated randomization schedule was used to randomize patients either to receive a medial unloader brace (Fusion OA; Breg, Inc) or not to receive a brace. Patients in these brace and control groups were allowed to continue their standard conservative OA treatment modalities, including NSAID use, home exercises, and joint supplement use. Patients were restricted from receiving any injection therapy or narcotic pain medication in an effort to isolate the effects of bracing on relief of pain and other symptoms.

All patients were examined by an orthopedic surgeon or fellowship-trained primary care sports medicine specialist. Age, sex, height, and weight data were recorded. Body mass index was calculated. Anteroposterior, lateral, flexion weight-bearing, and long-leg standing radiographs were obtained. Two orthopedic surgeons blindly graded OA12 and calculated knee varus angles.13 Values were averaged, and intraobserver reliability and interobserver reliability were calculated.

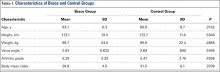

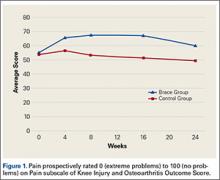

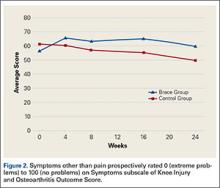

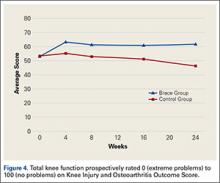

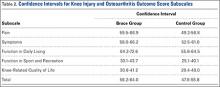

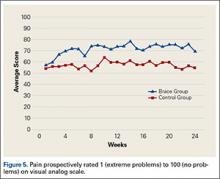

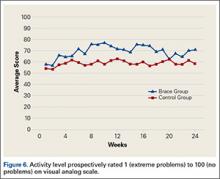

Prospective subjective outcomes were evaluated with the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), administered on study entry and at 4, 8, 16, and 24 weeks during the study. The KOOS has 5 subscales: Pain, Symptoms, Function in Daily Living, Function in Sport and Recreation, and Knee-Related Quality of Life. Each subscale is scored separately. Items are rated 0 (extreme problems) to 100 (no problems). Patients were also asked to complete a weekly diary, which included visual analog scale (VAS) ratings of pain, NSAID use, sleep, and activity level. VAS items were rated 1 (extreme problems) to 100 (no problems). For brace-group patients, hours of brace use per day were recorded. Patients were required to use the brace for a minimum of 4 hours per day.

KOOS and VAS data were analyzed with repeated-measures analysis of variance. Significance level was set at P < .05.

Results

Of the 50 patients randomized, 31 (16 brace, 15 control) completed the study. Of the 19 dropouts, 10 were in the brace group (4 dropped out because of brace discomfort) and 9 in the control group (5 dropped out because of significant pain and the desire for more aggressive treatment with injections). The target patient numbers based on the power analysis were not achieved because of patient enrollment difficulties resulting from the strict criteria established in the study design.

The brace group consisted of 8 men and 8 women. Braces were worn an average of 6.7 hours per day. The control group consisted of 8 men and 7 women. The groups were not significantly different in age, height, weight, body mass index, measured varus knee angle, or arthritis grade (Table 1).

Radiographs were assessed by 2 orthopedic surgeons. Varus angle measurements showed high interobserver reliability (.904, P = .03) and high intraobserver reliability (.969, P = .05); arthritis grades showed low interobserver reliability (.469, P = .59) and high intraobserver reliability (.810, P = .001).

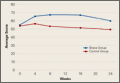

KOOS results showed that, compared with control patients, brace patients had significantly less pain (P < .001), fewer arthritis symptoms (P = .007), better ability to engage in activities of daily living (ADLs) (P = .008), and better total knee function (P = .004) (Figures 1-4). The groups did not differ in ability to engage in sport and recreation (P = .402) or in knee-related quality of life (P = .718), but each parameter showed a trend to be better in the brace group. There was no effect of time in any KOOS subscale. Confidence intervals for these data are listed in Table 2.

VAS results showed that, compared with control patients, brace patients had significantly less pain throughout the day (P = .021) and better activity levels (P = .035) (Figures 5, 6). The groups did not differ in ability to sleep (P = .117) or NSAID use (P = .138), but each parameter showed a trend to be better in the brace group. There was no effect of time in either VAS.

Discussion

We conducted this study to determine the efficacy of a medial unloader brace in reducing the pain and symptoms associated with varus knee OA.

Although TKA is an option for patients with significant end-stage knee OA, mild OA and moderate OA typically are managed with nonoperative modalities. These modalities can be effective and may delay or eliminate the need for surgery, which poses a small but definite risk. Delaying surgery, especially in younger, active patients, has the potential to reduce the number of wear-related revision surgeries.14

Braces designed to off-load the more diseased medial or lateral compartment of the knee have been used in an effort to provide relief from symptomatic OA. There is a lack of appropriately powered, randomized controlled studies on the efficacy of these braces. With the evidence being inconclusive, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons is unable to recommend for or against use of a brace in medial unicompartmental OA.11 More research on the efficacy of these braces is needed. In the present study, we asked 2 questions: Does use of an unloader brace lessen the pain associated with knee OA? Is the unloader brace an acceptable and valid treatment modality for knee OA?

The 2 clinical outcome tools used in this study showed significant improvement in pain in brace patients compared with control patients. KOOS results showed reduced pain and arthritis symptoms. VAS results showed less pain experienced throughout the day. Pain reduction is probably the most important benefit of any nonoperative modality for knee OA. Pain typically is the driving force and the major indication for TKA. Other investigators have found pain reduced with use of unloader braces, but few long-term prospective randomized trials have been conducted. Ramsey and colleagues15 compared a neutral stabilizing brace with a medial unloading brace and found that both helped reduce pain and functional disability. This led to discussion about the 2 major potential mechanisms for symptom relief. One theory holds that bracing unloads the diseased portion of the joint and thereby helps improve symptoms.16-18 According to the other theory, bracing stabilizes the knee, reducing muscle cocontractions and joint compression.15,19,20 Draganich and colleagues21 found that both off-the-shelf and adjustable unloader braces reduced pain. In a short-term (8-week) study, Barnes and colleagues22 found substantial improvement in knee pain with use of an unloader brace. In one of the larger, better designed, prospective studies, Brouwer and colleagues23 found borderline but significant improvements in pain. Larsen and colleagues,24 in another short-term study, found no improvement in pain but did report improved activity levels with use of a medial unloader brace.

In addition to demonstrating pain reduction, our results showed that, compared with control patients, brace patients had fewer arthritis symptoms, better ability to engage in ADLs, and increased activity levels. Other studies have identified additional benefits of bracing for knee arthritis. Larsen and colleagues24 found that valgus bracing for medial compartment knee OA improved walking and sit-to-stand activities. Although pain relief results were modest, Brouwer and colleagues23 found significantly better knee function and longer walking distances for patients who used a medial unloader brace. Hewett and colleagues25 found that pain, ADLs, and walking distance were all improved after 9 weeks of brace wear.

Our study had a few limitations. Although injections and narcotic pain medications were not allowed, NSAIDs, home exercises, and other modalities were permitted. We did not think it was reasonable to eliminate every nonoperative modality during the 6-month study period. Therefore, it is possible that some of the study population’s improvements are attributable to these other modalities, which were not rigidly controlled.

Patient enrollment was difficult because of the strict inclusion and exclusion criteria used. The result was a smaller than anticipated patient population. Although there were many excellent study candidates, most declined enrollment when they learned they could be randomized to the control group. These patients were not willing to forgo injections or bracing for 6 months. We thought it was important to maintain our study design because it allowed us to evaluate the true effect of brace use while eliminating confounding variables. Nearly equal numbers of brace and control patients dropped out of the study. The majority of control group dropouts wanted more treatment options, indicating that NSAIDs and exercises alone were not controlling patients’ symptoms. This finding supports recommendations for a multimodal approach to treatment. As expected, some patients dropped out because their brace was uncomfortable—an important finding that should be considered when counseling patients about treatment options for OA.

Not all patients are candidates for braces. Braces can be irritating and uncomfortable for obese patients and patients with skin or vascular issues. Some patients find braces inconvenient. As discussed, a multimodal OA treatment approach is encouraged, but not every mode fits every patient. Physician and patient should thoroughly discuss the benefits and potential problems of brace use before prescribing. Our study results showed trends toward better improvements for brace patients (compared with control patients) in quality of life, ability to engage in sport and recreation, ability to sleep, and need for NSAIDs. Had we enrolled more patients, we might have found statistical significance for these trends. Despite the challenges with patient enrollment and study population size, the data make clear that unloader braces can benefit appropriate patients.

Our findings support use of a medial unloader brace as an acceptable and valid treatment modality for mild and moderate knee OA. The medial unloader brace should be considered a reasonable alternative, as part of a multimodal approach, to more invasive options, such as TKA.

1. Michaud C, McKenna M, Begg S, et al. The burden of disease and injury in the United States 1996. Popul Health Metr. 2006;4:11.

2. Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al; National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):26-35.

3. Woolf AD, Pfleger B. Burden of major musculoskeletal conditions. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81(9):646-656.

4. London NJ, Miller LE, Block JE. Clinical and economic consequences of the treatment gap in knee osteoarthritis management. Med Hypotheses. 2011;76(6):887-892.

5. Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al; American College of Rheumatology. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64(4):465-474.

6. McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(3):363-388.

7. Gallelli L, Galasso O, Falcone D, et al. The effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on clinical outcomes, synovial fluid cytokine concentration and signal transduction pathways in knee osteoarthritis. A randomized open label trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21(9):1400-1408.

8. Pollo FE, Jackson RW. Knee bracing for unicompartmental osteoarthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(1):5-11.

9. Ramsey DK, Russell ME. Unloader braces for medial compartment knee osteoarthritis: implications on mediating progression. Sports Health. 2009;1(5):416-426.

10. Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16(2):137-162.

11. Richmond J, Hunter D, Irrgang J, et al; American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons clinical practice guideline on the treatment of osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(4):990-993.

12. Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16(4):494-502.

13. Dugdale TW, Noyes FR, Styer D. Preoperative planning for high tibial osteotomy. The effect of lateral tibiofemoral separation and tibiofemoral length. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(274):248-264.

14. Weinstein AM, Rome BN, Reichmann WM, et al. Estimating the burden of total knee replacement in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(5):385-392.

15. Ramsey DK, Briem K, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. A mechanical theory for the effectiveness of bracing for medial compartment osteoarthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(11):2398-2407.

16. Haim A, Wolf A, Rubin G, Genis Y, Khoury M, Rozen N. Effect of center of pressure modulation on knee adduction moment in medial compartment knee osteoarthritis. J Orthop Res. 2011;29(11):1668-1674.

17. Pollo FE, Otis JC, Backus SI, Warren RF, Wickiewicz TL. Reduction of medial compartment loads with valgus bracing of the osteoarthritic knee. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(3):414-421.

18. Shelburne KB, Torry MR, Steadman JR, Pandy MG. Effects of foot orthoses and valgus bracing on the knee adduction moment and medial joint load during gait. Clin Biomech. 2008;23(6):814-821.

19. Lewek MD, Ramsey DK, Snyder-Mackler L, Rudolph KS. Knee stabilization in patients with medial compartment knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(9):2845-2853.

20. Lewek MD, Rudolph KS, Snyder-Mackler L. Control of frontal plane knee laxity during gait in patients with medial compartment knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12(9):745-751.

21. Draganich L, Reider B, Rimington T, Piotrowski G, Mallik K, Nasson S. The effectiveness of self-adjustable custom and off-the-shelf bracing in the treatment of varus gonarthrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(12):2645-2652.

22. Barnes CL, Cawley PW, Hederman B. Effect of CounterForce brace on symptomatic relief in a group of patients with symptomatic unicompartmental osteoarthritis: a prospective 2-year investigation. Am J Orthop. 2002;31(7):396-401.

23. Brouwer RW, van Raaij TM, Verhaar JA, Coene LN, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Brace treatment for osteoarthritis of the knee: a prospective randomized multi-centre trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14(8):777-783.

24. Larsen BL, Jacofsky MC, Brown JA, Jacofsky DJ. Valgus bracing affords short-term treatment solution across walking and sit-to-stand activities. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(5):792-797.

25. Hewett TE, Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD, Heckmann TP. Decrease in knee joint pain and increase in function in patients with medial compartment arthrosis: a prospective analysis of valgus bracing. Orthopedics. 1998;21(2):131-138.

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a progressive, degenerative joint disease characterized by pain and dysfunction. OA is a leading cause of disability in middle-aged and older adults,1 affecting an estimated 27 million Americans.2 With the continued aging of the baby boomer population and rising obesity rates, the incidence of OA is estimated to increase by 40% by 2025.3 The clinical and economic burdens of OA on our society—medical costs and workdays lost—are significant and will continue to be a problem for years to come.4

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is an option for severe end-stage OA. Most patients with mild to moderate OA follow nonsurgical strategies in an attempt to avoid invasive procedures. As there is no established cure, initial treatment of knee OA is geared toward alleviating pain and improving function. A multimodal approach is typically used and recommended.5,6 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, and narcotic analgesics are commonly prescribed. NSAIDs can be effective7 but have well-known cardiovascular, renal, and gastrointestinal risks. If possible, narcotic analgesics should be avoided because of the risk of addiction and the problems associated with dependence. Intra-articular injections of corticosteroids or hyaluronic acid (viscosupplementation) are often recommended to reduce pain associated with arthritis. Braces designed to “off-load” the more diseased medial or lateral compartment of the knee have also been used in an effort to provide symptomatic relief. These low-risk, noninvasive unloader braces have increasingly been advanced as a conservative treatment modality for knee OA,6,8-10despite modest evidence and lack of appropriately powered randomized controlled trials.11 As more research on the efficacy of these braces is needed, we conducted a study to determine whether an unloader brace is an acceptable and valid treatment modality for knee OA.

Patients and Methods

This was a prospective, randomized, controlled trial of patients with symptomatic, predominantly unicompartmental OA involving the medial compartment of the knee. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Baptist Hospital in Pensacola, Florida. Patients were excluded if they had a rheumatologic disorder other than OA; a history of knee surgery other than a routine arthroscopic procedure; any soft-tissue, neurologic, or vascular compromise preventing long-term brace use; or obesity preventing effective or comfortable brace use. It is generally felt that unloader bracing may not be effective for patients with severe contractures or significant knee deformity; therefore, those lacking more than 10° of extension or 20° of flexion, or those who had a varus deformity of more than 8° of varus, were not offered enrollment.

Ideal sizes for the proposed study groups were determined through power analysis using standard deviations from prior similar investigations. The target was 30 patients per group.

Patients gave informed consent to the work. A computer-generated randomization schedule was used to randomize patients either to receive a medial unloader brace (Fusion OA; Breg, Inc) or not to receive a brace. Patients in these brace and control groups were allowed to continue their standard conservative OA treatment modalities, including NSAID use, home exercises, and joint supplement use. Patients were restricted from receiving any injection therapy or narcotic pain medication in an effort to isolate the effects of bracing on relief of pain and other symptoms.

All patients were examined by an orthopedic surgeon or fellowship-trained primary care sports medicine specialist. Age, sex, height, and weight data were recorded. Body mass index was calculated. Anteroposterior, lateral, flexion weight-bearing, and long-leg standing radiographs were obtained. Two orthopedic surgeons blindly graded OA12 and calculated knee varus angles.13 Values were averaged, and intraobserver reliability and interobserver reliability were calculated.

Prospective subjective outcomes were evaluated with the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), administered on study entry and at 4, 8, 16, and 24 weeks during the study. The KOOS has 5 subscales: Pain, Symptoms, Function in Daily Living, Function in Sport and Recreation, and Knee-Related Quality of Life. Each subscale is scored separately. Items are rated 0 (extreme problems) to 100 (no problems). Patients were also asked to complete a weekly diary, which included visual analog scale (VAS) ratings of pain, NSAID use, sleep, and activity level. VAS items were rated 1 (extreme problems) to 100 (no problems). For brace-group patients, hours of brace use per day were recorded. Patients were required to use the brace for a minimum of 4 hours per day.

KOOS and VAS data were analyzed with repeated-measures analysis of variance. Significance level was set at P < .05.

Results

Of the 50 patients randomized, 31 (16 brace, 15 control) completed the study. Of the 19 dropouts, 10 were in the brace group (4 dropped out because of brace discomfort) and 9 in the control group (5 dropped out because of significant pain and the desire for more aggressive treatment with injections). The target patient numbers based on the power analysis were not achieved because of patient enrollment difficulties resulting from the strict criteria established in the study design.

The brace group consisted of 8 men and 8 women. Braces were worn an average of 6.7 hours per day. The control group consisted of 8 men and 7 women. The groups were not significantly different in age, height, weight, body mass index, measured varus knee angle, or arthritis grade (Table 1).

Radiographs were assessed by 2 orthopedic surgeons. Varus angle measurements showed high interobserver reliability (.904, P = .03) and high intraobserver reliability (.969, P = .05); arthritis grades showed low interobserver reliability (.469, P = .59) and high intraobserver reliability (.810, P = .001).

KOOS results showed that, compared with control patients, brace patients had significantly less pain (P < .001), fewer arthritis symptoms (P = .007), better ability to engage in activities of daily living (ADLs) (P = .008), and better total knee function (P = .004) (Figures 1-4). The groups did not differ in ability to engage in sport and recreation (P = .402) or in knee-related quality of life (P = .718), but each parameter showed a trend to be better in the brace group. There was no effect of time in any KOOS subscale. Confidence intervals for these data are listed in Table 2.

VAS results showed that, compared with control patients, brace patients had significantly less pain throughout the day (P = .021) and better activity levels (P = .035) (Figures 5, 6). The groups did not differ in ability to sleep (P = .117) or NSAID use (P = .138), but each parameter showed a trend to be better in the brace group. There was no effect of time in either VAS.

Discussion

We conducted this study to determine the efficacy of a medial unloader brace in reducing the pain and symptoms associated with varus knee OA.

Although TKA is an option for patients with significant end-stage knee OA, mild OA and moderate OA typically are managed with nonoperative modalities. These modalities can be effective and may delay or eliminate the need for surgery, which poses a small but definite risk. Delaying surgery, especially in younger, active patients, has the potential to reduce the number of wear-related revision surgeries.14

Braces designed to off-load the more diseased medial or lateral compartment of the knee have been used in an effort to provide relief from symptomatic OA. There is a lack of appropriately powered, randomized controlled studies on the efficacy of these braces. With the evidence being inconclusive, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons is unable to recommend for or against use of a brace in medial unicompartmental OA.11 More research on the efficacy of these braces is needed. In the present study, we asked 2 questions: Does use of an unloader brace lessen the pain associated with knee OA? Is the unloader brace an acceptable and valid treatment modality for knee OA?

The 2 clinical outcome tools used in this study showed significant improvement in pain in brace patients compared with control patients. KOOS results showed reduced pain and arthritis symptoms. VAS results showed less pain experienced throughout the day. Pain reduction is probably the most important benefit of any nonoperative modality for knee OA. Pain typically is the driving force and the major indication for TKA. Other investigators have found pain reduced with use of unloader braces, but few long-term prospective randomized trials have been conducted. Ramsey and colleagues15 compared a neutral stabilizing brace with a medial unloading brace and found that both helped reduce pain and functional disability. This led to discussion about the 2 major potential mechanisms for symptom relief. One theory holds that bracing unloads the diseased portion of the joint and thereby helps improve symptoms.16-18 According to the other theory, bracing stabilizes the knee, reducing muscle cocontractions and joint compression.15,19,20 Draganich and colleagues21 found that both off-the-shelf and adjustable unloader braces reduced pain. In a short-term (8-week) study, Barnes and colleagues22 found substantial improvement in knee pain with use of an unloader brace. In one of the larger, better designed, prospective studies, Brouwer and colleagues23 found borderline but significant improvements in pain. Larsen and colleagues,24 in another short-term study, found no improvement in pain but did report improved activity levels with use of a medial unloader brace.

In addition to demonstrating pain reduction, our results showed that, compared with control patients, brace patients had fewer arthritis symptoms, better ability to engage in ADLs, and increased activity levels. Other studies have identified additional benefits of bracing for knee arthritis. Larsen and colleagues24 found that valgus bracing for medial compartment knee OA improved walking and sit-to-stand activities. Although pain relief results were modest, Brouwer and colleagues23 found significantly better knee function and longer walking distances for patients who used a medial unloader brace. Hewett and colleagues25 found that pain, ADLs, and walking distance were all improved after 9 weeks of brace wear.

Our study had a few limitations. Although injections and narcotic pain medications were not allowed, NSAIDs, home exercises, and other modalities were permitted. We did not think it was reasonable to eliminate every nonoperative modality during the 6-month study period. Therefore, it is possible that some of the study population’s improvements are attributable to these other modalities, which were not rigidly controlled.

Patient enrollment was difficult because of the strict inclusion and exclusion criteria used. The result was a smaller than anticipated patient population. Although there were many excellent study candidates, most declined enrollment when they learned they could be randomized to the control group. These patients were not willing to forgo injections or bracing for 6 months. We thought it was important to maintain our study design because it allowed us to evaluate the true effect of brace use while eliminating confounding variables. Nearly equal numbers of brace and control patients dropped out of the study. The majority of control group dropouts wanted more treatment options, indicating that NSAIDs and exercises alone were not controlling patients’ symptoms. This finding supports recommendations for a multimodal approach to treatment. As expected, some patients dropped out because their brace was uncomfortable—an important finding that should be considered when counseling patients about treatment options for OA.

Not all patients are candidates for braces. Braces can be irritating and uncomfortable for obese patients and patients with skin or vascular issues. Some patients find braces inconvenient. As discussed, a multimodal OA treatment approach is encouraged, but not every mode fits every patient. Physician and patient should thoroughly discuss the benefits and potential problems of brace use before prescribing. Our study results showed trends toward better improvements for brace patients (compared with control patients) in quality of life, ability to engage in sport and recreation, ability to sleep, and need for NSAIDs. Had we enrolled more patients, we might have found statistical significance for these trends. Despite the challenges with patient enrollment and study population size, the data make clear that unloader braces can benefit appropriate patients.

Our findings support use of a medial unloader brace as an acceptable and valid treatment modality for mild and moderate knee OA. The medial unloader brace should be considered a reasonable alternative, as part of a multimodal approach, to more invasive options, such as TKA.

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a progressive, degenerative joint disease characterized by pain and dysfunction. OA is a leading cause of disability in middle-aged and older adults,1 affecting an estimated 27 million Americans.2 With the continued aging of the baby boomer population and rising obesity rates, the incidence of OA is estimated to increase by 40% by 2025.3 The clinical and economic burdens of OA on our society—medical costs and workdays lost—are significant and will continue to be a problem for years to come.4

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is an option for severe end-stage OA. Most patients with mild to moderate OA follow nonsurgical strategies in an attempt to avoid invasive procedures. As there is no established cure, initial treatment of knee OA is geared toward alleviating pain and improving function. A multimodal approach is typically used and recommended.5,6 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, and narcotic analgesics are commonly prescribed. NSAIDs can be effective7 but have well-known cardiovascular, renal, and gastrointestinal risks. If possible, narcotic analgesics should be avoided because of the risk of addiction and the problems associated with dependence. Intra-articular injections of corticosteroids or hyaluronic acid (viscosupplementation) are often recommended to reduce pain associated with arthritis. Braces designed to “off-load” the more diseased medial or lateral compartment of the knee have also been used in an effort to provide symptomatic relief. These low-risk, noninvasive unloader braces have increasingly been advanced as a conservative treatment modality for knee OA,6,8-10despite modest evidence and lack of appropriately powered randomized controlled trials.11 As more research on the efficacy of these braces is needed, we conducted a study to determine whether an unloader brace is an acceptable and valid treatment modality for knee OA.

Patients and Methods

This was a prospective, randomized, controlled trial of patients with symptomatic, predominantly unicompartmental OA involving the medial compartment of the knee. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Baptist Hospital in Pensacola, Florida. Patients were excluded if they had a rheumatologic disorder other than OA; a history of knee surgery other than a routine arthroscopic procedure; any soft-tissue, neurologic, or vascular compromise preventing long-term brace use; or obesity preventing effective or comfortable brace use. It is generally felt that unloader bracing may not be effective for patients with severe contractures or significant knee deformity; therefore, those lacking more than 10° of extension or 20° of flexion, or those who had a varus deformity of more than 8° of varus, were not offered enrollment.

Ideal sizes for the proposed study groups were determined through power analysis using standard deviations from prior similar investigations. The target was 30 patients per group.

Patients gave informed consent to the work. A computer-generated randomization schedule was used to randomize patients either to receive a medial unloader brace (Fusion OA; Breg, Inc) or not to receive a brace. Patients in these brace and control groups were allowed to continue their standard conservative OA treatment modalities, including NSAID use, home exercises, and joint supplement use. Patients were restricted from receiving any injection therapy or narcotic pain medication in an effort to isolate the effects of bracing on relief of pain and other symptoms.

All patients were examined by an orthopedic surgeon or fellowship-trained primary care sports medicine specialist. Age, sex, height, and weight data were recorded. Body mass index was calculated. Anteroposterior, lateral, flexion weight-bearing, and long-leg standing radiographs were obtained. Two orthopedic surgeons blindly graded OA12 and calculated knee varus angles.13 Values were averaged, and intraobserver reliability and interobserver reliability were calculated.

Prospective subjective outcomes were evaluated with the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), administered on study entry and at 4, 8, 16, and 24 weeks during the study. The KOOS has 5 subscales: Pain, Symptoms, Function in Daily Living, Function in Sport and Recreation, and Knee-Related Quality of Life. Each subscale is scored separately. Items are rated 0 (extreme problems) to 100 (no problems). Patients were also asked to complete a weekly diary, which included visual analog scale (VAS) ratings of pain, NSAID use, sleep, and activity level. VAS items were rated 1 (extreme problems) to 100 (no problems). For brace-group patients, hours of brace use per day were recorded. Patients were required to use the brace for a minimum of 4 hours per day.

KOOS and VAS data were analyzed with repeated-measures analysis of variance. Significance level was set at P < .05.

Results

Of the 50 patients randomized, 31 (16 brace, 15 control) completed the study. Of the 19 dropouts, 10 were in the brace group (4 dropped out because of brace discomfort) and 9 in the control group (5 dropped out because of significant pain and the desire for more aggressive treatment with injections). The target patient numbers based on the power analysis were not achieved because of patient enrollment difficulties resulting from the strict criteria established in the study design.