User login

New HCV test approach could cut costs, streamline diagnosis

Substituting a less-expensive hepatitis C core antigen test into the standard 2-step process for diagnosing active hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection could streamline and cut the cost of HCV detection, according to the results of a study published in Annals of Internal Medicine. Dr. J. Morgan Freiman, of the Boston Medical Center, and her colleagues, performed a meta-analysis to determine the sensitivity and specificity associated with each of the 5 HCV core antigen tests. To find out which tests performed best, go to Family Practice News: http://www.familypracticenews.com/specialty-focus/infectious-diseases/single-article-page/new-hcv-test-approach-could-cut-costs-streamline-diagnosis/8d117e35547c3068dfb553f396ff7ed7.html.

Substituting a less-expensive hepatitis C core antigen test into the standard 2-step process for diagnosing active hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection could streamline and cut the cost of HCV detection, according to the results of a study published in Annals of Internal Medicine. Dr. J. Morgan Freiman, of the Boston Medical Center, and her colleagues, performed a meta-analysis to determine the sensitivity and specificity associated with each of the 5 HCV core antigen tests. To find out which tests performed best, go to Family Practice News: http://www.familypracticenews.com/specialty-focus/infectious-diseases/single-article-page/new-hcv-test-approach-could-cut-costs-streamline-diagnosis/8d117e35547c3068dfb553f396ff7ed7.html.

Substituting a less-expensive hepatitis C core antigen test into the standard 2-step process for diagnosing active hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection could streamline and cut the cost of HCV detection, according to the results of a study published in Annals of Internal Medicine. Dr. J. Morgan Freiman, of the Boston Medical Center, and her colleagues, performed a meta-analysis to determine the sensitivity and specificity associated with each of the 5 HCV core antigen tests. To find out which tests performed best, go to Family Practice News: http://www.familypracticenews.com/specialty-focus/infectious-diseases/single-article-page/new-hcv-test-approach-could-cut-costs-streamline-diagnosis/8d117e35547c3068dfb553f396ff7ed7.html.

Exercise training cuts heart failure mortality

A meta-analysis of 20 randomized controlled studies involving more than 4000 heart failure patients confirmed that an exercise training intervention run for at least 3 weeks produces a statistically significant relative reduction in all-cause mortality of 18%, according to Oriana Ciani, PhD, a health technology researcher at the University of Exeter (England). The individual patient data meta-analysis also showed a statistically significant 11% relative reduction in the incidence of all-cause hospitalization during at least 6 months of follow-up to the exercise programs. Learn more about the findings at Cardiology News, available at: http://www.ecardiologynews.com/specialty-focus/heart-failure/single-article-page/exercise-training-cuts-heart-failure-mortality/c94d2f9c4abf4eea8381de3290883eea.html.

A meta-analysis of 20 randomized controlled studies involving more than 4000 heart failure patients confirmed that an exercise training intervention run for at least 3 weeks produces a statistically significant relative reduction in all-cause mortality of 18%, according to Oriana Ciani, PhD, a health technology researcher at the University of Exeter (England). The individual patient data meta-analysis also showed a statistically significant 11% relative reduction in the incidence of all-cause hospitalization during at least 6 months of follow-up to the exercise programs. Learn more about the findings at Cardiology News, available at: http://www.ecardiologynews.com/specialty-focus/heart-failure/single-article-page/exercise-training-cuts-heart-failure-mortality/c94d2f9c4abf4eea8381de3290883eea.html.

A meta-analysis of 20 randomized controlled studies involving more than 4000 heart failure patients confirmed that an exercise training intervention run for at least 3 weeks produces a statistically significant relative reduction in all-cause mortality of 18%, according to Oriana Ciani, PhD, a health technology researcher at the University of Exeter (England). The individual patient data meta-analysis also showed a statistically significant 11% relative reduction in the incidence of all-cause hospitalization during at least 6 months of follow-up to the exercise programs. Learn more about the findings at Cardiology News, available at: http://www.ecardiologynews.com/specialty-focus/heart-failure/single-article-page/exercise-training-cuts-heart-failure-mortality/c94d2f9c4abf4eea8381de3290883eea.html.

Self-monitoring of blood glucose: Advice for providers and patients

Glucose self-monitoring not only yields valuable information on which to base diabetes treatment, it also helps motivate patients and keeps them engaged in and adherent to their care. However, choosing the most appropriate meters and supplies from the plethora available can be challenging. Working together, healthcare providers and certified diabetes educators can ensure that people with diabetes are getting the most out of self-monitoring process. To find out who should monitor blood glucose and how often, and the advances in and limitations of current devices, go to Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine: http://www.ccjm.org/past-issues/past-issue-single-view/self-monitoring-of-blood-glucose-advice-for-providers-and-patients/a077c938c36233cb5bb87ccf89270041.html.

Glucose self-monitoring not only yields valuable information on which to base diabetes treatment, it also helps motivate patients and keeps them engaged in and adherent to their care. However, choosing the most appropriate meters and supplies from the plethora available can be challenging. Working together, healthcare providers and certified diabetes educators can ensure that people with diabetes are getting the most out of self-monitoring process. To find out who should monitor blood glucose and how often, and the advances in and limitations of current devices, go to Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine: http://www.ccjm.org/past-issues/past-issue-single-view/self-monitoring-of-blood-glucose-advice-for-providers-and-patients/a077c938c36233cb5bb87ccf89270041.html.

Glucose self-monitoring not only yields valuable information on which to base diabetes treatment, it also helps motivate patients and keeps them engaged in and adherent to their care. However, choosing the most appropriate meters and supplies from the plethora available can be challenging. Working together, healthcare providers and certified diabetes educators can ensure that people with diabetes are getting the most out of self-monitoring process. To find out who should monitor blood glucose and how often, and the advances in and limitations of current devices, go to Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine: http://www.ccjm.org/past-issues/past-issue-single-view/self-monitoring-of-blood-glucose-advice-for-providers-and-patients/a077c938c36233cb5bb87ccf89270041.html.

“I Want What Kobe Had”: A Comprehensive Guide to Giving Your Patients the Biologic Solutions They Crave

The sun has finally set on Kobe Bryant’s magnificent career. After all the tributes and tearful goodbyes, he has finally played his last game and become a part of basketball history. Ever since his field trip to Germany for interleukin-1 receptor antagonist protein (IRAP) treatments to his knee, and his subsequent return to high-level play, I’ve been under siege in the office by patients who “want what Kobe had.” I’ve had to explain, time and time again, that IRAP treatment is not available in the United States and that platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is the closest alternative treatment, convince them that PRP may be even better, and then let them know that it’s considered experimental and not covered by insurance.

In the last issue, we discussed the future of orthopedics, which in my opinion will rely heavily on the biologic therapies now considered experimental. In this issue, we will look into our crystal balls and imagine what that future might look like. To do so, we should first consider what we hope to accomplish through the incorporation of biologic therapies.

The regeneration of articular cartilage, acceleration of fracture and tissue healing, and faster incorporation of tendon grafts to bone have long been considered the Holy Grail of Orthopedics. In his best seller, The Da Vinci Code, Dan Brown makes a compelling argument that the Holy Grail, the chalice thought to have held the blood of Christ, was in fact a mistranslated reference to his living descendants. Whenever I have a visitor or student in the operating room, I focus the scope on the synovial capillaries so they can see the individual red blood cells passing single-file through the vessels on their way to supply cells with the nutrients they need.

Perhaps, like in The Da Vinci Code, the solution to our greatest biologic challenges lies in the blood, already there, just waiting to be unlocked.

PRP has been utilized for everything from tendinopathy to arthropathy, with varied results in the literature. The lack of standardization of PRP preparations, which vary in inclusion of white cells and absolute platelet count, confounds these results even further. In this issue, we review its use in sports medicine and knee arthritis, taking a closer look at partial ulnar collateral ligament tears in baseball players.

In “Tips of the Trade,” we present a technique for “superior capsular reconstruction” that provides a novel solution for patients with pseudoparalysis from massive rotator cuff tears with little other options beside reverse total shoulder arthroplasty.

The one absolute statement I can make regarding biologics is that we currently have more questions than answers, and every hypothesis we prove simply begets more questions. More randomized controlled studies are needed in virtually every aspect of biologics, and we should all consider taking part. While the solutions our patients crave may not arrive during our careers, or even our lifetimes, the groundwork we do now will set the stage for future generations to enjoy biologically enhanced outcomes.

The sun has finally set on Kobe Bryant’s magnificent career. After all the tributes and tearful goodbyes, he has finally played his last game and become a part of basketball history. Ever since his field trip to Germany for interleukin-1 receptor antagonist protein (IRAP) treatments to his knee, and his subsequent return to high-level play, I’ve been under siege in the office by patients who “want what Kobe had.” I’ve had to explain, time and time again, that IRAP treatment is not available in the United States and that platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is the closest alternative treatment, convince them that PRP may be even better, and then let them know that it’s considered experimental and not covered by insurance.

In the last issue, we discussed the future of orthopedics, which in my opinion will rely heavily on the biologic therapies now considered experimental. In this issue, we will look into our crystal balls and imagine what that future might look like. To do so, we should first consider what we hope to accomplish through the incorporation of biologic therapies.

The regeneration of articular cartilage, acceleration of fracture and tissue healing, and faster incorporation of tendon grafts to bone have long been considered the Holy Grail of Orthopedics. In his best seller, The Da Vinci Code, Dan Brown makes a compelling argument that the Holy Grail, the chalice thought to have held the blood of Christ, was in fact a mistranslated reference to his living descendants. Whenever I have a visitor or student in the operating room, I focus the scope on the synovial capillaries so they can see the individual red blood cells passing single-file through the vessels on their way to supply cells with the nutrients they need.

Perhaps, like in The Da Vinci Code, the solution to our greatest biologic challenges lies in the blood, already there, just waiting to be unlocked.

PRP has been utilized for everything from tendinopathy to arthropathy, with varied results in the literature. The lack of standardization of PRP preparations, which vary in inclusion of white cells and absolute platelet count, confounds these results even further. In this issue, we review its use in sports medicine and knee arthritis, taking a closer look at partial ulnar collateral ligament tears in baseball players.

In “Tips of the Trade,” we present a technique for “superior capsular reconstruction” that provides a novel solution for patients with pseudoparalysis from massive rotator cuff tears with little other options beside reverse total shoulder arthroplasty.

The one absolute statement I can make regarding biologics is that we currently have more questions than answers, and every hypothesis we prove simply begets more questions. More randomized controlled studies are needed in virtually every aspect of biologics, and we should all consider taking part. While the solutions our patients crave may not arrive during our careers, or even our lifetimes, the groundwork we do now will set the stage for future generations to enjoy biologically enhanced outcomes.

The sun has finally set on Kobe Bryant’s magnificent career. After all the tributes and tearful goodbyes, he has finally played his last game and become a part of basketball history. Ever since his field trip to Germany for interleukin-1 receptor antagonist protein (IRAP) treatments to his knee, and his subsequent return to high-level play, I’ve been under siege in the office by patients who “want what Kobe had.” I’ve had to explain, time and time again, that IRAP treatment is not available in the United States and that platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is the closest alternative treatment, convince them that PRP may be even better, and then let them know that it’s considered experimental and not covered by insurance.

In the last issue, we discussed the future of orthopedics, which in my opinion will rely heavily on the biologic therapies now considered experimental. In this issue, we will look into our crystal balls and imagine what that future might look like. To do so, we should first consider what we hope to accomplish through the incorporation of biologic therapies.

The regeneration of articular cartilage, acceleration of fracture and tissue healing, and faster incorporation of tendon grafts to bone have long been considered the Holy Grail of Orthopedics. In his best seller, The Da Vinci Code, Dan Brown makes a compelling argument that the Holy Grail, the chalice thought to have held the blood of Christ, was in fact a mistranslated reference to his living descendants. Whenever I have a visitor or student in the operating room, I focus the scope on the synovial capillaries so they can see the individual red blood cells passing single-file through the vessels on their way to supply cells with the nutrients they need.

Perhaps, like in The Da Vinci Code, the solution to our greatest biologic challenges lies in the blood, already there, just waiting to be unlocked.

PRP has been utilized for everything from tendinopathy to arthropathy, with varied results in the literature. The lack of standardization of PRP preparations, which vary in inclusion of white cells and absolute platelet count, confounds these results even further. In this issue, we review its use in sports medicine and knee arthritis, taking a closer look at partial ulnar collateral ligament tears in baseball players.

In “Tips of the Trade,” we present a technique for “superior capsular reconstruction” that provides a novel solution for patients with pseudoparalysis from massive rotator cuff tears with little other options beside reverse total shoulder arthroplasty.

The one absolute statement I can make regarding biologics is that we currently have more questions than answers, and every hypothesis we prove simply begets more questions. More randomized controlled studies are needed in virtually every aspect of biologics, and we should all consider taking part. While the solutions our patients crave may not arrive during our careers, or even our lifetimes, the groundwork we do now will set the stage for future generations to enjoy biologically enhanced outcomes.

Treating and preventing acute exacerbations of COPD

In contrast to stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), acute exacerbations of COPD pose special management challenges and can significantly increase the risks of morbidity and death as well as the cost of care. This review from Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, available at http://www.ccjm.org/topics/pulmonary/single-article-page/treating-and-preventing-acute-exacerbations-of-copd/8265d5ff355c3a17c96fa34564ea7465.html, provides the latest information on the definition and diagnosis of COPD exacerbations, disease burden and costs, etiology and pathogenesis, and management and prevention strategies.

In contrast to stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), acute exacerbations of COPD pose special management challenges and can significantly increase the risks of morbidity and death as well as the cost of care. This review from Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, available at http://www.ccjm.org/topics/pulmonary/single-article-page/treating-and-preventing-acute-exacerbations-of-copd/8265d5ff355c3a17c96fa34564ea7465.html, provides the latest information on the definition and diagnosis of COPD exacerbations, disease burden and costs, etiology and pathogenesis, and management and prevention strategies.

In contrast to stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), acute exacerbations of COPD pose special management challenges and can significantly increase the risks of morbidity and death as well as the cost of care. This review from Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, available at http://www.ccjm.org/topics/pulmonary/single-article-page/treating-and-preventing-acute-exacerbations-of-copd/8265d5ff355c3a17c96fa34564ea7465.html, provides the latest information on the definition and diagnosis of COPD exacerbations, disease burden and costs, etiology and pathogenesis, and management and prevention strategies.

Sabra M. Abbott, MD, PhD

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

As preventive, H2RA poses risks for patients on clopidogrel after bleeding ulcer

SAN DIEGO – New research suggests histamine-2 receptor antagonists aren’t a viable alternative to proton pump inhibitors to prevent recurrence of bleeding peptic ulcers in clopidogrel users.

U.S. and European agencies have warned of interactions between proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and clopidogrel. But a study presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week finds significant upper GI events were much more common in patients who took famotidine (Protonix), a histamine-2 receptor antagonist (H2RA), compared with those who took pantoprazole (Pepcid), a PPI, as a preventive treatment.

“The findings will change the practice of some physicians who prescribe H2RA to prevent UGI [upper GI] events in clopidogrel users,” said study lead author Dr. Ping-I Hsu, chief of gastroenterology at Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital and professor of medicine at National Yang-Ming University, both in Taiwan.

Currently, Dr. Hsu said, “physicians often use PPIs to prevent ulcer complications in clopidogrel users because it is the only drug proven useful in the prevention of peptic ulcers and ulcer complications in clopidogrel users.”

But “both the U.S. Food & Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency have posted safety warnings and discourage the use of PPIs with clopidogrel unless absolutely necessary,” he said.

Enter the prospect of H2RA medications as an alternative. The new study, Dr. Hsu said, is the first to explore the GI protection effect and safety of H2RAs in patients on clopidogrel monotherapy.

The randomized prospective study followed 120 patients with a history of peptic ulcer bleeding (but not at initial endoscopy) and atherosclerosis. All long-term users of ADP receptor antagonists, they were assigned to pantoprazole (40 mg daily) or famotidine (40 mg daily) for 48 weeks.

Patients were examined via endoscopy when they experienced events like severe epigastric discomfort.

The famotidine group had more significant upper GI events (13.3%) than the pantoprazole group (1.7%). Diarrhea was equal in both groups (1.7%). Pneumonia was comparable (0% and 1.7% for pantoprazole and famotidine, respectively), as was fracture (1.7% and 0%).

Wider differences were found in acute myocardial infarction (1.5% and 4.5%), and cerebral vascular accident (0% and 3.4%) for pantoprazole and famotidine, respectively.

According to Dr. Hsu, three earlier studies linked concurrent use of PPIs and clopidogrel to significant increases in cardiovascular events. But this study linked a higher cardiac risk to the H2RA medication.

The researchers found no differences between the drugs in sequential changes of serum magnesium levels and bone mineral densities.

Dr. Hsu made this recommendation to physicians: “Please don’t use H2RAs to prevent peptic ulcer or ulcer complications in clopidogrel users. It is ineffective to prevent UGI [upper GI] events in clopidogrel users who have a history of ulcer bleeding. PPIs can effectively prevent UGI events in clopidogrel users with a history of ulcer bleeding.”

In addition, he said, the risk of thrombotic events is lower on a PPI.

SAN DIEGO – New research suggests histamine-2 receptor antagonists aren’t a viable alternative to proton pump inhibitors to prevent recurrence of bleeding peptic ulcers in clopidogrel users.

U.S. and European agencies have warned of interactions between proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and clopidogrel. But a study presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week finds significant upper GI events were much more common in patients who took famotidine (Protonix), a histamine-2 receptor antagonist (H2RA), compared with those who took pantoprazole (Pepcid), a PPI, as a preventive treatment.

“The findings will change the practice of some physicians who prescribe H2RA to prevent UGI [upper GI] events in clopidogrel users,” said study lead author Dr. Ping-I Hsu, chief of gastroenterology at Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital and professor of medicine at National Yang-Ming University, both in Taiwan.

Currently, Dr. Hsu said, “physicians often use PPIs to prevent ulcer complications in clopidogrel users because it is the only drug proven useful in the prevention of peptic ulcers and ulcer complications in clopidogrel users.”

But “both the U.S. Food & Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency have posted safety warnings and discourage the use of PPIs with clopidogrel unless absolutely necessary,” he said.

Enter the prospect of H2RA medications as an alternative. The new study, Dr. Hsu said, is the first to explore the GI protection effect and safety of H2RAs in patients on clopidogrel monotherapy.

The randomized prospective study followed 120 patients with a history of peptic ulcer bleeding (but not at initial endoscopy) and atherosclerosis. All long-term users of ADP receptor antagonists, they were assigned to pantoprazole (40 mg daily) or famotidine (40 mg daily) for 48 weeks.

Patients were examined via endoscopy when they experienced events like severe epigastric discomfort.

The famotidine group had more significant upper GI events (13.3%) than the pantoprazole group (1.7%). Diarrhea was equal in both groups (1.7%). Pneumonia was comparable (0% and 1.7% for pantoprazole and famotidine, respectively), as was fracture (1.7% and 0%).

Wider differences were found in acute myocardial infarction (1.5% and 4.5%), and cerebral vascular accident (0% and 3.4%) for pantoprazole and famotidine, respectively.

According to Dr. Hsu, three earlier studies linked concurrent use of PPIs and clopidogrel to significant increases in cardiovascular events. But this study linked a higher cardiac risk to the H2RA medication.

The researchers found no differences between the drugs in sequential changes of serum magnesium levels and bone mineral densities.

Dr. Hsu made this recommendation to physicians: “Please don’t use H2RAs to prevent peptic ulcer or ulcer complications in clopidogrel users. It is ineffective to prevent UGI [upper GI] events in clopidogrel users who have a history of ulcer bleeding. PPIs can effectively prevent UGI events in clopidogrel users with a history of ulcer bleeding.”

In addition, he said, the risk of thrombotic events is lower on a PPI.

SAN DIEGO – New research suggests histamine-2 receptor antagonists aren’t a viable alternative to proton pump inhibitors to prevent recurrence of bleeding peptic ulcers in clopidogrel users.

U.S. and European agencies have warned of interactions between proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and clopidogrel. But a study presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week finds significant upper GI events were much more common in patients who took famotidine (Protonix), a histamine-2 receptor antagonist (H2RA), compared with those who took pantoprazole (Pepcid), a PPI, as a preventive treatment.

“The findings will change the practice of some physicians who prescribe H2RA to prevent UGI [upper GI] events in clopidogrel users,” said study lead author Dr. Ping-I Hsu, chief of gastroenterology at Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital and professor of medicine at National Yang-Ming University, both in Taiwan.

Currently, Dr. Hsu said, “physicians often use PPIs to prevent ulcer complications in clopidogrel users because it is the only drug proven useful in the prevention of peptic ulcers and ulcer complications in clopidogrel users.”

But “both the U.S. Food & Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency have posted safety warnings and discourage the use of PPIs with clopidogrel unless absolutely necessary,” he said.

Enter the prospect of H2RA medications as an alternative. The new study, Dr. Hsu said, is the first to explore the GI protection effect and safety of H2RAs in patients on clopidogrel monotherapy.

The randomized prospective study followed 120 patients with a history of peptic ulcer bleeding (but not at initial endoscopy) and atherosclerosis. All long-term users of ADP receptor antagonists, they were assigned to pantoprazole (40 mg daily) or famotidine (40 mg daily) for 48 weeks.

Patients were examined via endoscopy when they experienced events like severe epigastric discomfort.

The famotidine group had more significant upper GI events (13.3%) than the pantoprazole group (1.7%). Diarrhea was equal in both groups (1.7%). Pneumonia was comparable (0% and 1.7% for pantoprazole and famotidine, respectively), as was fracture (1.7% and 0%).

Wider differences were found in acute myocardial infarction (1.5% and 4.5%), and cerebral vascular accident (0% and 3.4%) for pantoprazole and famotidine, respectively.

According to Dr. Hsu, three earlier studies linked concurrent use of PPIs and clopidogrel to significant increases in cardiovascular events. But this study linked a higher cardiac risk to the H2RA medication.

The researchers found no differences between the drugs in sequential changes of serum magnesium levels and bone mineral densities.

Dr. Hsu made this recommendation to physicians: “Please don’t use H2RAs to prevent peptic ulcer or ulcer complications in clopidogrel users. It is ineffective to prevent UGI [upper GI] events in clopidogrel users who have a history of ulcer bleeding. PPIs can effectively prevent UGI events in clopidogrel users with a history of ulcer bleeding.”

In addition, he said, the risk of thrombotic events is lower on a PPI.

AT DDW® 2016

Key clinical point: Compared with PPIs, H2RAs pose more risks – on both GI and cardiovascular fronts – as a preventive in patients with atherosclerosis and a history of peptic ulcer bleeding.

Major finding: After 48 weeks, 1.7% of patients in the pantoprazole (PPI) group (n = 60) suffered significant upper GI events; 13.3% of patients in the famotidine (H2RA) group (n = 60) did (P = 0.017). Cardiovascular events were also more common in the H2RA group.

Data source: Randomized prospective study of 120 patients with history of peptic ulcer bleeding (but not at initial endoscopy) assigned to pantoprazole (40 mg daily) or famotidine (40 mg daily) for 48 weeks.

Disclosures: The study is hospital funded. The authors report no disclosures.

Resident transitions increase inpatients’ risk of death

SAN FRANCISCO – Hospitalized patients who have a change in the medical residents responsible for their care are more likely to die, finds a retrospective cohort study of roughly a quarter million discharges from Veterans Affairs medical centers.

A monthly change in resident care was associated with 9%-20% higher adjusted odds of death during the hospital stay and after discharge, investigators reported in a poster discussion session and press briefing at an international conference of the American Thoracic Society. Analyses suggested that such transitions accounted for 718 additional deaths in the hospital alone during the 6-year study period.

“These are very strong findings,” said Dr. Joshua L. Denson, a fellow in the divisions of pulmonary sciences and critical care medicine at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

The study results represent an important initial step in bringing the problem to light, he said. “Handoffs shift to shift have been looked at, but not this end-of-month, more permanent switching, which I think is a much more substantial transition in care.”

The factors driving the increased mortality are unclear, according to Dr. Denson; however, “when you go on to a new service [as a resident] ... you are now responsible for 20 new people all of a sudden that night.” Therefore, these transitions can be a hectic time characterized by reduced communication and inefficient discharges. In addition, the incoming residents lack familiarity with their new patients’ particulars.

“The handoffs are definitely not preventable, so this is something that has to be dealt with,” he maintained. The study’s findings hint at several possible areas for improvement.

None of the 10 residency programs surveyed provided formal education for monthly resident handoffs, focusing instead on handoffs at shift changes, and most programs lacked a standard procedure, with just one requiring that the handoff be done in person. The programs also varied greatly in their staggering of handoffs – separating transitions of interns (first-year residents) and higher-level residents by at least a few days – to minimize impact.

Despite the absence of outcomes data in this area, some hospitals are forging ahead with their own interventions intended to smooth care transitions, Dr. Denson reported. “In at least two hospitals that I’ve worked in, they are implementing what is called a warm handoff,” he explained. “Basically, a resident from the prior rotation comes the next day and rounds with the new team so he can tell them, ‘Oh, this guy looks a little worse today, you may want to watch him,’ or ‘He looks a little better.’ ”

In the study, conducted while Dr. Denson was chief resident at the NYU School of Medicine, he and his colleagues analyzed data from 10 university-affiliated Veterans Affairs hospitals and internal medicine residency programs that provided their residents’ schedules. Analyses were based on a total of 230,701 discharges of adult medical patients between July 2008 and June 2014.

Hospitalized patients were categorized as having a transition in resident care if they were admitted before the date of an end-of-month house staff transition in care and were discharged in the week after it.

In unadjusted analyses, patients who had a transition of care – whether of intern only, resident only, or both – had significantly higher odds of inpatient mortality and of 30-day mortality and 90-day postdischarge mortality, compared with counterparts who did not have the corresponding transition of care.

In adjusted analyses, patients who had an intern transition still had higher odds of in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 1.14). In addition, patients had persistently elevated odds of 30-day mortality and 90-day postdischarge mortality if they had an intern transition (odds ratios, 1.20 and 1.17, respectively), a resident transition (1.15 and 1.14), or both (1.10 and 1.09).

The findings “suggest possibly a level-of-training effect to these transitions, as it’s the most inexperienced people that have the higher rate of mortality,” noted Dr. Denson, who disclosed that he had no relevant conflicts of interest. “Interns, being the first-years, tend to carry the bulk of the work in most hospitals, which is an interesting paradigm in our organization. And that may be a good explanation for why we are seeing this.”

SAN FRANCISCO – Hospitalized patients who have a change in the medical residents responsible for their care are more likely to die, finds a retrospective cohort study of roughly a quarter million discharges from Veterans Affairs medical centers.

A monthly change in resident care was associated with 9%-20% higher adjusted odds of death during the hospital stay and after discharge, investigators reported in a poster discussion session and press briefing at an international conference of the American Thoracic Society. Analyses suggested that such transitions accounted for 718 additional deaths in the hospital alone during the 6-year study period.

“These are very strong findings,” said Dr. Joshua L. Denson, a fellow in the divisions of pulmonary sciences and critical care medicine at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

The study results represent an important initial step in bringing the problem to light, he said. “Handoffs shift to shift have been looked at, but not this end-of-month, more permanent switching, which I think is a much more substantial transition in care.”

The factors driving the increased mortality are unclear, according to Dr. Denson; however, “when you go on to a new service [as a resident] ... you are now responsible for 20 new people all of a sudden that night.” Therefore, these transitions can be a hectic time characterized by reduced communication and inefficient discharges. In addition, the incoming residents lack familiarity with their new patients’ particulars.

“The handoffs are definitely not preventable, so this is something that has to be dealt with,” he maintained. The study’s findings hint at several possible areas for improvement.

None of the 10 residency programs surveyed provided formal education for monthly resident handoffs, focusing instead on handoffs at shift changes, and most programs lacked a standard procedure, with just one requiring that the handoff be done in person. The programs also varied greatly in their staggering of handoffs – separating transitions of interns (first-year residents) and higher-level residents by at least a few days – to minimize impact.

Despite the absence of outcomes data in this area, some hospitals are forging ahead with their own interventions intended to smooth care transitions, Dr. Denson reported. “In at least two hospitals that I’ve worked in, they are implementing what is called a warm handoff,” he explained. “Basically, a resident from the prior rotation comes the next day and rounds with the new team so he can tell them, ‘Oh, this guy looks a little worse today, you may want to watch him,’ or ‘He looks a little better.’ ”

In the study, conducted while Dr. Denson was chief resident at the NYU School of Medicine, he and his colleagues analyzed data from 10 university-affiliated Veterans Affairs hospitals and internal medicine residency programs that provided their residents’ schedules. Analyses were based on a total of 230,701 discharges of adult medical patients between July 2008 and June 2014.

Hospitalized patients were categorized as having a transition in resident care if they were admitted before the date of an end-of-month house staff transition in care and were discharged in the week after it.

In unadjusted analyses, patients who had a transition of care – whether of intern only, resident only, or both – had significantly higher odds of inpatient mortality and of 30-day mortality and 90-day postdischarge mortality, compared with counterparts who did not have the corresponding transition of care.

In adjusted analyses, patients who had an intern transition still had higher odds of in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 1.14). In addition, patients had persistently elevated odds of 30-day mortality and 90-day postdischarge mortality if they had an intern transition (odds ratios, 1.20 and 1.17, respectively), a resident transition (1.15 and 1.14), or both (1.10 and 1.09).

The findings “suggest possibly a level-of-training effect to these transitions, as it’s the most inexperienced people that have the higher rate of mortality,” noted Dr. Denson, who disclosed that he had no relevant conflicts of interest. “Interns, being the first-years, tend to carry the bulk of the work in most hospitals, which is an interesting paradigm in our organization. And that may be a good explanation for why we are seeing this.”

SAN FRANCISCO – Hospitalized patients who have a change in the medical residents responsible for their care are more likely to die, finds a retrospective cohort study of roughly a quarter million discharges from Veterans Affairs medical centers.

A monthly change in resident care was associated with 9%-20% higher adjusted odds of death during the hospital stay and after discharge, investigators reported in a poster discussion session and press briefing at an international conference of the American Thoracic Society. Analyses suggested that such transitions accounted for 718 additional deaths in the hospital alone during the 6-year study period.

“These are very strong findings,” said Dr. Joshua L. Denson, a fellow in the divisions of pulmonary sciences and critical care medicine at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

The study results represent an important initial step in bringing the problem to light, he said. “Handoffs shift to shift have been looked at, but not this end-of-month, more permanent switching, which I think is a much more substantial transition in care.”

The factors driving the increased mortality are unclear, according to Dr. Denson; however, “when you go on to a new service [as a resident] ... you are now responsible for 20 new people all of a sudden that night.” Therefore, these transitions can be a hectic time characterized by reduced communication and inefficient discharges. In addition, the incoming residents lack familiarity with their new patients’ particulars.

“The handoffs are definitely not preventable, so this is something that has to be dealt with,” he maintained. The study’s findings hint at several possible areas for improvement.

None of the 10 residency programs surveyed provided formal education for monthly resident handoffs, focusing instead on handoffs at shift changes, and most programs lacked a standard procedure, with just one requiring that the handoff be done in person. The programs also varied greatly in their staggering of handoffs – separating transitions of interns (first-year residents) and higher-level residents by at least a few days – to minimize impact.

Despite the absence of outcomes data in this area, some hospitals are forging ahead with their own interventions intended to smooth care transitions, Dr. Denson reported. “In at least two hospitals that I’ve worked in, they are implementing what is called a warm handoff,” he explained. “Basically, a resident from the prior rotation comes the next day and rounds with the new team so he can tell them, ‘Oh, this guy looks a little worse today, you may want to watch him,’ or ‘He looks a little better.’ ”

In the study, conducted while Dr. Denson was chief resident at the NYU School of Medicine, he and his colleagues analyzed data from 10 university-affiliated Veterans Affairs hospitals and internal medicine residency programs that provided their residents’ schedules. Analyses were based on a total of 230,701 discharges of adult medical patients between July 2008 and June 2014.

Hospitalized patients were categorized as having a transition in resident care if they were admitted before the date of an end-of-month house staff transition in care and were discharged in the week after it.

In unadjusted analyses, patients who had a transition of care – whether of intern only, resident only, or both – had significantly higher odds of inpatient mortality and of 30-day mortality and 90-day postdischarge mortality, compared with counterparts who did not have the corresponding transition of care.

In adjusted analyses, patients who had an intern transition still had higher odds of in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 1.14). In addition, patients had persistently elevated odds of 30-day mortality and 90-day postdischarge mortality if they had an intern transition (odds ratios, 1.20 and 1.17, respectively), a resident transition (1.15 and 1.14), or both (1.10 and 1.09).

The findings “suggest possibly a level-of-training effect to these transitions, as it’s the most inexperienced people that have the higher rate of mortality,” noted Dr. Denson, who disclosed that he had no relevant conflicts of interest. “Interns, being the first-years, tend to carry the bulk of the work in most hospitals, which is an interesting paradigm in our organization. And that may be a good explanation for why we are seeing this.”

AT ATS 2016

Key clinical point: The risk of death for hospitalized patients rises when their care is handed off from one resident to another.

Major finding: Patients who had a resident transition in care during their stay had 9%-20% higher adjusted odds of death.

Data source: A multicenter retrospective cohort study of 230,701 discharges of adult medical patients from Veterans Affairs medical centers.

Disclosures: Dr. Denson disclosed that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Why be a vascular surgeon?

This edition of Vascular Specialist is being published early to coincide with the VAM. Since medical students will be attending the meeting I thought this would be a good opportunity to describe an often overlooked reason why, after all my years in practice, I still enjoy being a vascular surgeon. By doing so I hope to encourage these young people to consider a career in vascular surgery.

Some vascular surgeons, with the same goal, have volunteered to mentor these students at the VAM. I suspect most mentors would extoll vascular surgery as unique amongst surgical specialties. They will describe the variety of complex operations as well as advanced endovascular procedures that we perform. Proudly, some mentors will mention that other practitioners turn to us for help when they encounter uncontrollable hemorrhage. They will emphasize that we are the one specialty that covers the gamut of vascular interventions from open surgery and endovascular procedures to medical management. Perhaps some mentors will incorporate my mantra that vascular surgeons “Operate, Dilate, and Medicate.”

However, I suggest that the most satisfying aspect of our profession is not the procedures that we perform but rather the interaction we have with our patients. After all, most of us entered the medical profession to take care of patients, and vascular patients are very special indeed. However, sometimes we established vascular surgeons become too enthralled by technical advances to remember the more humanistic reasons for our being. Also, changes in medical practice and reimbursement have resulted in many being so overworked that we do not have time to enjoy relationships with our patients. Perhaps those who are so burdened should take heed from the stories mentors will relate to inspire these students.

Based on my personal experience I suspect the mentors will say something along the following lines: “Vascular conditions are chronic and are wont to afflict more than one part of the body. Accordingly, we are required to follow most patients for their whole lives (or ours!). Not only do we treat these patients but we also become intimately involved with their families, often treating them as well. Often our ‘treatment’ will not be procedural but rather will involve emotional support of these relatives as they deal with their recuperating or debilitated spouse, sibling, or parent. Those of us who have been in practice for many years will fondly recall patients who have become an integral part of our lives. The patient who undergoes a vascular procedure will return every 6 or 12 months to have their bypass checked or their other carotid assessed.

“We follow asymptomatic small abdominal aneurysms and claudicants. A venous ulcer often recurs and a dialysis patient may require a new intervention. Some patients come to the office so they can be made more secure that their condition has not deteriorated, and the lonely just because we are the only human they interact with on a regular basis. They bring with them their varied life stories and these vignettes become a part of our own fiction. Perhaps we will share with them our own life story. Contrast that to the general surgeon who repairs a hernia and after a few post op visits may never see the patient again.

“Vascular patients may be very young or more commonly very old and come from all walks of life. So the vascular surgeon will learn to calm the crying infant. She will provide careful optimism to allay the fears of a mother who brings in her daughter scarred by a cavernous hemangioma. He or she will reassure the young girl, mortified by embarrassing spider veins, that she will be able to wear a dress to her high school prom. Together with the obstetrician, the vascular surgeon will guide a pregnant woman with a DVT through her entire pregnancy assuring her that both she and her baby will be safe.”

The mentor will re-count how special it was to get a hug from an old lady who he operated on 25 years previously when he was a young surgeon. Or the gratification one gets when a father, after a successful limb revascularization, shows a video of himself walking down the aisle at his daughter’s wedding. Perhaps the mentor will confide her sense of dismay every time a young dialysis patient is admitted for revision of a fistula and the joy she feels when told that her patient has finally received a viable transplant. Year after year the vascular surgeon will follow a patient with early onset, widespread vascular disease whose parents died young from the ravages of familial hyperlipidemia.

He will provide encouragement to help the patient stop smoking and commiserate when a sibling dies from a heart attack. The mentor might relate how she felt when she saved the leg of a soldier injured by a land mine or how she was amazed by the 80-year-old ballroom dancer who danced a few weeks after a below knee amputation.

Mentors will also describe getting to know a patient’s daily routine so they can informatively advise a patient whether it is worth having a procedure to improve quality of life. Or the thrill we get when that patient thanks us for relieving the claudication that prevented gainful employment. We are relieved when a longstanding patient wakes up neurologically intact from an endarterectomy.

However, we are filled with remorse when we inform a family that they have lost their loved one who died from a ruptured aneurysm. Of course, our failures may be devastating but they reinforce our humility when we acknowledge that we have been defeated by a disease that resisted our every effort.

The mentor may also share that “Every Xmas you will collect cards thanking you for saving a life or, out of the blue, receive a carton of fruit from the orchard of a farmer who finally was able to walk amongst her crop. You will pass tissues to the sobbing husband whose wife always accompanied him to his yearly physical, but who recently passed from incurable cancer. You will listen to stories from veterans of past wars. You will see pictures of patients’ children and you will remark how they have grown through the years. A patient will make you look admiringly at their latest puppy or prize-winning pig. You will be given stock advice by a millionaire and you will pay for a taxi for the indigent to get home from your office. You may keep patients waiting while you hear intriguing gossip or wonder just how you can stop the little old lady rambling on about lost loves. You will be charmed by the 98-year-old who makes sure that she has her hair and makeup done prior to coming to see you, and how her face lights up when you pronounce her more beautiful than ever.

“Dear student, the technical aspects of vascular surgery are indeed demanding and exciting. We are invigorated by the knowledge that our expertise saved a life or limb, prevented a stroke or provided the nephrotic with a working fistula. Even the more simple cosmetic procedures give us pleasure. If you still need inspiration to embark on a vascular surgical career I encourage you to read the Presidential address Dr. Bruce J. Brener gave to the Society for Clinical Vascular Surgery in March 1996. His eloquent portrayal of the vascular surgical experience is unmatched (Amer J Surg, 1996; 172:97-9). However, it is our daily and often lifelong interaction with our wonderful patients that so intimately reinforces our humanity and makes this profession so uniquely satisfying.”

This edition of Vascular Specialist is being published early to coincide with the VAM. Since medical students will be attending the meeting I thought this would be a good opportunity to describe an often overlooked reason why, after all my years in practice, I still enjoy being a vascular surgeon. By doing so I hope to encourage these young people to consider a career in vascular surgery.

Some vascular surgeons, with the same goal, have volunteered to mentor these students at the VAM. I suspect most mentors would extoll vascular surgery as unique amongst surgical specialties. They will describe the variety of complex operations as well as advanced endovascular procedures that we perform. Proudly, some mentors will mention that other practitioners turn to us for help when they encounter uncontrollable hemorrhage. They will emphasize that we are the one specialty that covers the gamut of vascular interventions from open surgery and endovascular procedures to medical management. Perhaps some mentors will incorporate my mantra that vascular surgeons “Operate, Dilate, and Medicate.”

However, I suggest that the most satisfying aspect of our profession is not the procedures that we perform but rather the interaction we have with our patients. After all, most of us entered the medical profession to take care of patients, and vascular patients are very special indeed. However, sometimes we established vascular surgeons become too enthralled by technical advances to remember the more humanistic reasons for our being. Also, changes in medical practice and reimbursement have resulted in many being so overworked that we do not have time to enjoy relationships with our patients. Perhaps those who are so burdened should take heed from the stories mentors will relate to inspire these students.

Based on my personal experience I suspect the mentors will say something along the following lines: “Vascular conditions are chronic and are wont to afflict more than one part of the body. Accordingly, we are required to follow most patients for their whole lives (or ours!). Not only do we treat these patients but we also become intimately involved with their families, often treating them as well. Often our ‘treatment’ will not be procedural but rather will involve emotional support of these relatives as they deal with their recuperating or debilitated spouse, sibling, or parent. Those of us who have been in practice for many years will fondly recall patients who have become an integral part of our lives. The patient who undergoes a vascular procedure will return every 6 or 12 months to have their bypass checked or their other carotid assessed.

“We follow asymptomatic small abdominal aneurysms and claudicants. A venous ulcer often recurs and a dialysis patient may require a new intervention. Some patients come to the office so they can be made more secure that their condition has not deteriorated, and the lonely just because we are the only human they interact with on a regular basis. They bring with them their varied life stories and these vignettes become a part of our own fiction. Perhaps we will share with them our own life story. Contrast that to the general surgeon who repairs a hernia and after a few post op visits may never see the patient again.

“Vascular patients may be very young or more commonly very old and come from all walks of life. So the vascular surgeon will learn to calm the crying infant. She will provide careful optimism to allay the fears of a mother who brings in her daughter scarred by a cavernous hemangioma. He or she will reassure the young girl, mortified by embarrassing spider veins, that she will be able to wear a dress to her high school prom. Together with the obstetrician, the vascular surgeon will guide a pregnant woman with a DVT through her entire pregnancy assuring her that both she and her baby will be safe.”

The mentor will re-count how special it was to get a hug from an old lady who he operated on 25 years previously when he was a young surgeon. Or the gratification one gets when a father, after a successful limb revascularization, shows a video of himself walking down the aisle at his daughter’s wedding. Perhaps the mentor will confide her sense of dismay every time a young dialysis patient is admitted for revision of a fistula and the joy she feels when told that her patient has finally received a viable transplant. Year after year the vascular surgeon will follow a patient with early onset, widespread vascular disease whose parents died young from the ravages of familial hyperlipidemia.

He will provide encouragement to help the patient stop smoking and commiserate when a sibling dies from a heart attack. The mentor might relate how she felt when she saved the leg of a soldier injured by a land mine or how she was amazed by the 80-year-old ballroom dancer who danced a few weeks after a below knee amputation.

Mentors will also describe getting to know a patient’s daily routine so they can informatively advise a patient whether it is worth having a procedure to improve quality of life. Or the thrill we get when that patient thanks us for relieving the claudication that prevented gainful employment. We are relieved when a longstanding patient wakes up neurologically intact from an endarterectomy.

However, we are filled with remorse when we inform a family that they have lost their loved one who died from a ruptured aneurysm. Of course, our failures may be devastating but they reinforce our humility when we acknowledge that we have been defeated by a disease that resisted our every effort.

The mentor may also share that “Every Xmas you will collect cards thanking you for saving a life or, out of the blue, receive a carton of fruit from the orchard of a farmer who finally was able to walk amongst her crop. You will pass tissues to the sobbing husband whose wife always accompanied him to his yearly physical, but who recently passed from incurable cancer. You will listen to stories from veterans of past wars. You will see pictures of patients’ children and you will remark how they have grown through the years. A patient will make you look admiringly at their latest puppy or prize-winning pig. You will be given stock advice by a millionaire and you will pay for a taxi for the indigent to get home from your office. You may keep patients waiting while you hear intriguing gossip or wonder just how you can stop the little old lady rambling on about lost loves. You will be charmed by the 98-year-old who makes sure that she has her hair and makeup done prior to coming to see you, and how her face lights up when you pronounce her more beautiful than ever.

“Dear student, the technical aspects of vascular surgery are indeed demanding and exciting. We are invigorated by the knowledge that our expertise saved a life or limb, prevented a stroke or provided the nephrotic with a working fistula. Even the more simple cosmetic procedures give us pleasure. If you still need inspiration to embark on a vascular surgical career I encourage you to read the Presidential address Dr. Bruce J. Brener gave to the Society for Clinical Vascular Surgery in March 1996. His eloquent portrayal of the vascular surgical experience is unmatched (Amer J Surg, 1996; 172:97-9). However, it is our daily and often lifelong interaction with our wonderful patients that so intimately reinforces our humanity and makes this profession so uniquely satisfying.”

This edition of Vascular Specialist is being published early to coincide with the VAM. Since medical students will be attending the meeting I thought this would be a good opportunity to describe an often overlooked reason why, after all my years in practice, I still enjoy being a vascular surgeon. By doing so I hope to encourage these young people to consider a career in vascular surgery.

Some vascular surgeons, with the same goal, have volunteered to mentor these students at the VAM. I suspect most mentors would extoll vascular surgery as unique amongst surgical specialties. They will describe the variety of complex operations as well as advanced endovascular procedures that we perform. Proudly, some mentors will mention that other practitioners turn to us for help when they encounter uncontrollable hemorrhage. They will emphasize that we are the one specialty that covers the gamut of vascular interventions from open surgery and endovascular procedures to medical management. Perhaps some mentors will incorporate my mantra that vascular surgeons “Operate, Dilate, and Medicate.”

However, I suggest that the most satisfying aspect of our profession is not the procedures that we perform but rather the interaction we have with our patients. After all, most of us entered the medical profession to take care of patients, and vascular patients are very special indeed. However, sometimes we established vascular surgeons become too enthralled by technical advances to remember the more humanistic reasons for our being. Also, changes in medical practice and reimbursement have resulted in many being so overworked that we do not have time to enjoy relationships with our patients. Perhaps those who are so burdened should take heed from the stories mentors will relate to inspire these students.

Based on my personal experience I suspect the mentors will say something along the following lines: “Vascular conditions are chronic and are wont to afflict more than one part of the body. Accordingly, we are required to follow most patients for their whole lives (or ours!). Not only do we treat these patients but we also become intimately involved with their families, often treating them as well. Often our ‘treatment’ will not be procedural but rather will involve emotional support of these relatives as they deal with their recuperating or debilitated spouse, sibling, or parent. Those of us who have been in practice for many years will fondly recall patients who have become an integral part of our lives. The patient who undergoes a vascular procedure will return every 6 or 12 months to have their bypass checked or their other carotid assessed.

“We follow asymptomatic small abdominal aneurysms and claudicants. A venous ulcer often recurs and a dialysis patient may require a new intervention. Some patients come to the office so they can be made more secure that their condition has not deteriorated, and the lonely just because we are the only human they interact with on a regular basis. They bring with them their varied life stories and these vignettes become a part of our own fiction. Perhaps we will share with them our own life story. Contrast that to the general surgeon who repairs a hernia and after a few post op visits may never see the patient again.

“Vascular patients may be very young or more commonly very old and come from all walks of life. So the vascular surgeon will learn to calm the crying infant. She will provide careful optimism to allay the fears of a mother who brings in her daughter scarred by a cavernous hemangioma. He or she will reassure the young girl, mortified by embarrassing spider veins, that she will be able to wear a dress to her high school prom. Together with the obstetrician, the vascular surgeon will guide a pregnant woman with a DVT through her entire pregnancy assuring her that both she and her baby will be safe.”

The mentor will re-count how special it was to get a hug from an old lady who he operated on 25 years previously when he was a young surgeon. Or the gratification one gets when a father, after a successful limb revascularization, shows a video of himself walking down the aisle at his daughter’s wedding. Perhaps the mentor will confide her sense of dismay every time a young dialysis patient is admitted for revision of a fistula and the joy she feels when told that her patient has finally received a viable transplant. Year after year the vascular surgeon will follow a patient with early onset, widespread vascular disease whose parents died young from the ravages of familial hyperlipidemia.

He will provide encouragement to help the patient stop smoking and commiserate when a sibling dies from a heart attack. The mentor might relate how she felt when she saved the leg of a soldier injured by a land mine or how she was amazed by the 80-year-old ballroom dancer who danced a few weeks after a below knee amputation.

Mentors will also describe getting to know a patient’s daily routine so they can informatively advise a patient whether it is worth having a procedure to improve quality of life. Or the thrill we get when that patient thanks us for relieving the claudication that prevented gainful employment. We are relieved when a longstanding patient wakes up neurologically intact from an endarterectomy.

However, we are filled with remorse when we inform a family that they have lost their loved one who died from a ruptured aneurysm. Of course, our failures may be devastating but they reinforce our humility when we acknowledge that we have been defeated by a disease that resisted our every effort.

The mentor may also share that “Every Xmas you will collect cards thanking you for saving a life or, out of the blue, receive a carton of fruit from the orchard of a farmer who finally was able to walk amongst her crop. You will pass tissues to the sobbing husband whose wife always accompanied him to his yearly physical, but who recently passed from incurable cancer. You will listen to stories from veterans of past wars. You will see pictures of patients’ children and you will remark how they have grown through the years. A patient will make you look admiringly at their latest puppy or prize-winning pig. You will be given stock advice by a millionaire and you will pay for a taxi for the indigent to get home from your office. You may keep patients waiting while you hear intriguing gossip or wonder just how you can stop the little old lady rambling on about lost loves. You will be charmed by the 98-year-old who makes sure that she has her hair and makeup done prior to coming to see you, and how her face lights up when you pronounce her more beautiful than ever.

“Dear student, the technical aspects of vascular surgery are indeed demanding and exciting. We are invigorated by the knowledge that our expertise saved a life or limb, prevented a stroke or provided the nephrotic with a working fistula. Even the more simple cosmetic procedures give us pleasure. If you still need inspiration to embark on a vascular surgical career I encourage you to read the Presidential address Dr. Bruce J. Brener gave to the Society for Clinical Vascular Surgery in March 1996. His eloquent portrayal of the vascular surgical experience is unmatched (Amer J Surg, 1996; 172:97-9). However, it is our daily and often lifelong interaction with our wonderful patients that so intimately reinforces our humanity and makes this profession so uniquely satisfying.”

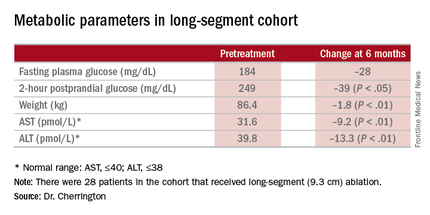

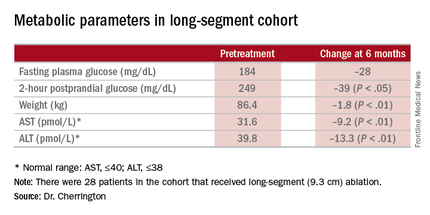

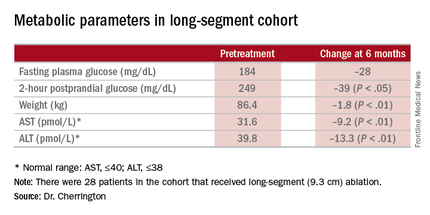

Endoscopic ablation follows gastric bypass principles

NEW ORLEANS – An investigational endoscopic procedure that aims to disrupt how the gut absorbs nutrients according to principles of gastric bypass surgery achieved reductions in hemoglobin A1c levels and improvement in other key metabolic parameters in people with type 2 diabetes participating in a single-center investigational study in Santiago, Chile.

The procedure, called duodenal mucosal resurfacing (DMR), uses a balloon catheter to thermally ablate about 10 cm of the duodenal mucosa, Alan Cherrington, Ph.D., of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“A lot of the gastric bypass surgeries have been very effective in not only creating weight loss but in improving glucose tolerance,” Dr. Cherrington said. “The problem is, of course, they are very invasive and difficult to do, so the hope here was to try and develop a technique which in fact would be simpler but perhaps achieve some of the same effects.”

The mucosa in people with type 2 diabetes has been known to be thickened, and the endocrine cells discommuted and morphed, Dr. Cherrington explained. “So the question was, is there a way to do something about that?” The procedure, he said, was “well tolerated” and achieved significant reduction of HbA1c after 3 months.

An international group of bariatric experts participated in the trial report. Dr. Cherrington said the procedure involves inserting a balloon-tipped catheter through the esophagus and stomach and into the duodenum, and then seating the balloon snugly in the mucosa at the ampulla of Vater. “You need a snug fit between the balloon and the mucosa,” Dr. Cherrington said.

Once the catheter is in place, it is filled with saline that inflates the balloon to fill the space. At that point, heated saline is run through the catheter for 10 seconds, creating a circumferential ablation of 300-500 mcm. When that step is completed, the balloon is moved down approximately 2 cm and the process repeated until the full 10 cm of the duodenal length from the ampulla of Vater to the ligament of Treitz is ablated.

A trained endoscopist performed the procedure with the patients under anesthesia, Dr. Cherrington said. The average HbA1c was 9.6% at baseline, and the 39 patients were on one or more antidiabetic agents. The average fasting plasma glucose was 187 mg/dL at baseline. Average age was 54 years, and two-thirds of patients were male.

“It was not a mechanistic study,” Dr. Cherrington said. “It was a study purely to see: Can we do this? Can it be done safely? And would there be any efficacy at all?” The patients actually received DMR of two lengths: a short-segment ablation of 3.4 cm (n = 11); and a long-segment approach of 9.3 cm (n = 28).

“Patients had no difficulty tolerating an oral diet within days of the procedure,” Dr. Cherrington said. He described the adverse events as “mild,” mostly occurring immediately after the procedure. They typically involved tenderness due to anesthesia intubation or the endoscopic procedure itself, resolving in 3 days. Three patients had stenosis “very early while the device was still in its iterative development,” Dr. Cherrington said. But since the device was modified, the episodes of stenosis were mild and “resolved easily” with dilation.

The 9.3-cm ablation achieved better outcomes than did the 3.4-cm ablation, Dr. Cherrington said. Those in the long-segment group with baseline HbA1c as high as 11% averaged 7.5% 3 months post ablation; those with HbA1c around 9% before ablation averaged “just below 7%” afterward, he said. The patients showed some “waning effect” in HbA1c after 6 months.

A cohort of patients who continued their medications achieved even better results. “They came to an HbA1c of 6.5% and drifted up minimally at 6 months,” Dr. Cherrington said. “Part of the drift upward of the others was a function that they began to come off their medications.” Other reported metabolic parameters also showed improvement.

The next step, Dr. Cherrington said, is to compile 6-month results in an ongoing trial called Revita-1 in Chile and at five centers in Europe; after that, the goal is to conduct a multicenter phase II trial, Revita-2 that will include U.S. centers. “Clearly there are many, many questions that remain to be answered, and further examination of the efficacy, of the safety, of the clinical utility, and not the least of which is what is the mechanism by which this comes about, is essential,” Dr. Cherrington said.

Dr. John M. Miles of the University of Kansas Hospital in Kansas City gave a preview of some of those questions: “I would love to know whether metformin pharmacokinetics are altered by this procedure.” Dr. Miles asked for an explanation of the initial weight loss in study patients. “I would love to see self-reported calorie counts with these people,” he said.

Dr. Cherrington said the ensuing trials would aim to answer the first question, but that no information on calorie counts was available. The patients experienced an immediate weight loss after DMR but then some rebound effect after that, he said.

Dr. Cherrington disclosed relationships with Biocon, Fractyl, Merck, Metavention, NuSirt Biopharma, Sensulin, Zafgen, Eli Lilly, Silver Lake, Islet Sciences, Novo Nordisk, Profil Institute for Clinical Research, Thermalin Diabetes, Thetis Pharmaceuticals, vTv Therapeutics, ViaCyte, and Viking.

NEW ORLEANS – An investigational endoscopic procedure that aims to disrupt how the gut absorbs nutrients according to principles of gastric bypass surgery achieved reductions in hemoglobin A1c levels and improvement in other key metabolic parameters in people with type 2 diabetes participating in a single-center investigational study in Santiago, Chile.

The procedure, called duodenal mucosal resurfacing (DMR), uses a balloon catheter to thermally ablate about 10 cm of the duodenal mucosa, Alan Cherrington, Ph.D., of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“A lot of the gastric bypass surgeries have been very effective in not only creating weight loss but in improving glucose tolerance,” Dr. Cherrington said. “The problem is, of course, they are very invasive and difficult to do, so the hope here was to try and develop a technique which in fact would be simpler but perhaps achieve some of the same effects.”

The mucosa in people with type 2 diabetes has been known to be thickened, and the endocrine cells discommuted and morphed, Dr. Cherrington explained. “So the question was, is there a way to do something about that?” The procedure, he said, was “well tolerated” and achieved significant reduction of HbA1c after 3 months.

An international group of bariatric experts participated in the trial report. Dr. Cherrington said the procedure involves inserting a balloon-tipped catheter through the esophagus and stomach and into the duodenum, and then seating the balloon snugly in the mucosa at the ampulla of Vater. “You need a snug fit between the balloon and the mucosa,” Dr. Cherrington said.

Once the catheter is in place, it is filled with saline that inflates the balloon to fill the space. At that point, heated saline is run through the catheter for 10 seconds, creating a circumferential ablation of 300-500 mcm. When that step is completed, the balloon is moved down approximately 2 cm and the process repeated until the full 10 cm of the duodenal length from the ampulla of Vater to the ligament of Treitz is ablated.

A trained endoscopist performed the procedure with the patients under anesthesia, Dr. Cherrington said. The average HbA1c was 9.6% at baseline, and the 39 patients were on one or more antidiabetic agents. The average fasting plasma glucose was 187 mg/dL at baseline. Average age was 54 years, and two-thirds of patients were male.

“It was not a mechanistic study,” Dr. Cherrington said. “It was a study purely to see: Can we do this? Can it be done safely? And would there be any efficacy at all?” The patients actually received DMR of two lengths: a short-segment ablation of 3.4 cm (n = 11); and a long-segment approach of 9.3 cm (n = 28).

“Patients had no difficulty tolerating an oral diet within days of the procedure,” Dr. Cherrington said. He described the adverse events as “mild,” mostly occurring immediately after the procedure. They typically involved tenderness due to anesthesia intubation or the endoscopic procedure itself, resolving in 3 days. Three patients had stenosis “very early while the device was still in its iterative development,” Dr. Cherrington said. But since the device was modified, the episodes of stenosis were mild and “resolved easily” with dilation.

The 9.3-cm ablation achieved better outcomes than did the 3.4-cm ablation, Dr. Cherrington said. Those in the long-segment group with baseline HbA1c as high as 11% averaged 7.5% 3 months post ablation; those with HbA1c around 9% before ablation averaged “just below 7%” afterward, he said. The patients showed some “waning effect” in HbA1c after 6 months.

A cohort of patients who continued their medications achieved even better results. “They came to an HbA1c of 6.5% and drifted up minimally at 6 months,” Dr. Cherrington said. “Part of the drift upward of the others was a function that they began to come off their medications.” Other reported metabolic parameters also showed improvement.

The next step, Dr. Cherrington said, is to compile 6-month results in an ongoing trial called Revita-1 in Chile and at five centers in Europe; after that, the goal is to conduct a multicenter phase II trial, Revita-2 that will include U.S. centers. “Clearly there are many, many questions that remain to be answered, and further examination of the efficacy, of the safety, of the clinical utility, and not the least of which is what is the mechanism by which this comes about, is essential,” Dr. Cherrington said.

Dr. John M. Miles of the University of Kansas Hospital in Kansas City gave a preview of some of those questions: “I would love to know whether metformin pharmacokinetics are altered by this procedure.” Dr. Miles asked for an explanation of the initial weight loss in study patients. “I would love to see self-reported calorie counts with these people,” he said.

Dr. Cherrington said the ensuing trials would aim to answer the first question, but that no information on calorie counts was available. The patients experienced an immediate weight loss after DMR but then some rebound effect after that, he said.

Dr. Cherrington disclosed relationships with Biocon, Fractyl, Merck, Metavention, NuSirt Biopharma, Sensulin, Zafgen, Eli Lilly, Silver Lake, Islet Sciences, Novo Nordisk, Profil Institute for Clinical Research, Thermalin Diabetes, Thetis Pharmaceuticals, vTv Therapeutics, ViaCyte, and Viking.

NEW ORLEANS – An investigational endoscopic procedure that aims to disrupt how the gut absorbs nutrients according to principles of gastric bypass surgery achieved reductions in hemoglobin A1c levels and improvement in other key metabolic parameters in people with type 2 diabetes participating in a single-center investigational study in Santiago, Chile.

The procedure, called duodenal mucosal resurfacing (DMR), uses a balloon catheter to thermally ablate about 10 cm of the duodenal mucosa, Alan Cherrington, Ph.D., of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“A lot of the gastric bypass surgeries have been very effective in not only creating weight loss but in improving glucose tolerance,” Dr. Cherrington said. “The problem is, of course, they are very invasive and difficult to do, so the hope here was to try and develop a technique which in fact would be simpler but perhaps achieve some of the same effects.”

The mucosa in people with type 2 diabetes has been known to be thickened, and the endocrine cells discommuted and morphed, Dr. Cherrington explained. “So the question was, is there a way to do something about that?” The procedure, he said, was “well tolerated” and achieved significant reduction of HbA1c after 3 months.

An international group of bariatric experts participated in the trial report. Dr. Cherrington said the procedure involves inserting a balloon-tipped catheter through the esophagus and stomach and into the duodenum, and then seating the balloon snugly in the mucosa at the ampulla of Vater. “You need a snug fit between the balloon and the mucosa,” Dr. Cherrington said.

Once the catheter is in place, it is filled with saline that inflates the balloon to fill the space. At that point, heated saline is run through the catheter for 10 seconds, creating a circumferential ablation of 300-500 mcm. When that step is completed, the balloon is moved down approximately 2 cm and the process repeated until the full 10 cm of the duodenal length from the ampulla of Vater to the ligament of Treitz is ablated.

A trained endoscopist performed the procedure with the patients under anesthesia, Dr. Cherrington said. The average HbA1c was 9.6% at baseline, and the 39 patients were on one or more antidiabetic agents. The average fasting plasma glucose was 187 mg/dL at baseline. Average age was 54 years, and two-thirds of patients were male.

“It was not a mechanistic study,” Dr. Cherrington said. “It was a study purely to see: Can we do this? Can it be done safely? And would there be any efficacy at all?” The patients actually received DMR of two lengths: a short-segment ablation of 3.4 cm (n = 11); and a long-segment approach of 9.3 cm (n = 28).